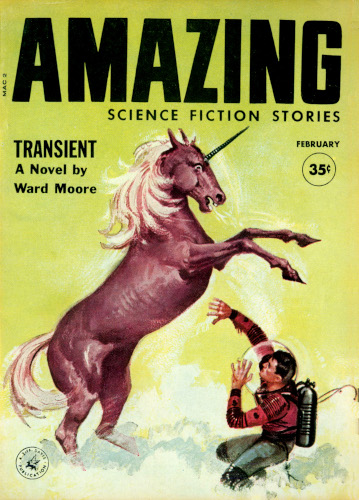

By WARD MOORE

ILLUSTRATED by FINLAY

COMPLETE BOOK-LENGTH NOVEL

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Amazing Stories February 1960.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

CHAPTER 1

The Governor, a widower in his earliest fifties, turned off the ignition, noting with satisfaction the absence of street signs limiting parking time. Governor Lampley, serving out the unexpired term of his predecessor and not entirely hopeless of nomination and election in his own right, pictured the stupid or fanatical cop who under any circumstances would write a ticket for the car with the license GOV-001. He and Marvin had made a big joke out of those zeros, Marvin showing his hostility under the kidding, the Governor hiding his dislike for his secretary under his self-deprecation.

Before getting out he dusted the knees of his trousers and looked up and down the shabby street. The Odd Fellows Hall was built of concrete blocks; Almon Lampley was reasonably sure it hadn't been there thirty years before. The other buildings seemed to be as he remembered them, if anything so fragile as the reconstruction in his mind could be called a memory. He'd forgotten the name of the place, its very location. Only the highway marker, the one so close it rooted the town briefly from obscurity to pinpoint it fleetingly: so many miles from the capital behind him, so many miles to the destination before him, hit the chord. Why, it was here. This was the place. How very long, long ago. Goodness (he curbed the natural profanity of even his thoughts lest he offend some straitlaced voter), goodness—years and years. A generation. Before he met Mattie, before he switched from selling agricultural implements to vote-getting.

And the sign just outside, Pop. 1,983. Pathetic lack of 17 more pop. With 2,000 they could have boasted: We're on our way, on our third thousand, the biggest little town between here and there. Watch us grow. If you lived here, you'd be home now. Get in on the ground floor and expand with us, Tomorrow's metropolis. Under two thousand was stagnation, decay, surrender. 1,983: possibly a thousand registered voters; more likely eight hundred—two precincts. How many Republicans, how many Democrats? Maybe three screwballs: one voting Prohibition, one writing in his own name, one casting a ballot for Pogo. A sad town, a dead town. Surely it hadn't been so thirty years ago?

But there had been the railroad then, and young Almon Lampley swinging down from the daycoach before the wheels stopped turning, bursting with enthusiasm, eager, cocky, invincible. The railroad gone, its tracks melted into scrap, its ties piled up and burned, its place taken by trucking lines, buses, cars. You had to have progress. So what if the town got lost in the process, fell behind? There were other towns, equally deserving, equally promising, equally anxious to get ahead. The state was full of them: chicory capital of the world, hub of mink breeding, where the juiciest pickles are made, home-owners' heaven, the friendliest city, Santa Claus' summer residence, host to the annual girly festival, gateway to the alkali flats. Thousands of them. And he was governor of the whole state. It would be non-feasance if not mis-feasance in him to regret this one bypassed settlement.

Evidently progress, before it withered, had brought the Odd Fellows Hall. No more. The false fronted stores were as he remembered—as he thought he ought to have remembered—and the dwelling set back from the street, forgotten or held in irascible obstinacy, petunias and geraniums growing too lush in the overgrowned front yard. The Hay, Grain & Feed where he had called—where he must have called—the garage, the Chevrolet agency, the hotel.

The Governor gave a final brush to his trousers, pocketed the keys, and picked up his overnight case from the seat beside him. The hotel was unquestionably the most prominent building on either side of the street yet he had unconsciously left noticing it to the last. It was a square three stories high, probably older than anything else in town, of no identifiable style, with a sign saying glumly ROOMS, MEALS, in paint so ancient its surface had peeled away, leaving only fossil pigment to take the weather and continue the message. The brown clapboards had grayed, they were parted—driven asunder—by a vertical column of match-fencing, mincingly precise in its senility, pierced by multipaned windows with random blue, brown, green and yellow glass. The verandah, empty of chairs but suggestive of a place for drummers to sit with their heels on the collapsing railing, sagged in a twisted list. The two balconies above it had been mended with scrap lumber, unpainted, and the repairs themselves mended again.

Governor Lampley could easily have driven another thirty, forty, fifty miles—it was only mid-afternoon and he was not tired—to find modern accommodations. He could have driven all the way to his destination. He chose to stop here. As a sentimental gesture? As an uncomfortable (fleas, lumpy beds, creaky floors) amusement? As a whim? Call it a whim. The Governor was on an unofficial, very limited, vacation.

He admitted feeling slightly foolish as he took the three steps to the verandah and walked over the uneasy boards to the plate-glass doors and into the darkened, dusty lobby. In this position one didn't give way to sudden impulse. Any yielding to sentiment was calculated, studied, designed, to be milked for good publicity. He could see the bored, competent photographers, the casual—well-planned—chat with the reporters. Marvin would have arranged it all; the Governor would have only to move gracefully through his part.

Responsibly he ought to phone Marvin, let him know he was staying here, give his attention to whatever business Marvin would say couldn't wait till tomorrow. In imagination he could hear the querulous, nagging tones beneath the surface respectfulness, the barely suppressed astonishment (what do you suppose he's up to now? a woman? a meeting with one of the doughboys? a drunk?), the assurance Marvin would call if anything came up. He ought to phone Marvin immediately.

The thought of Marvin made him turn and glance back through the doorway, to reassure himself he was not part of a scheduled program after all. But there was no car on the street save his own, no busy technicians, no curious onlookers, no one. Only the afternoon sunlight, the swirling motes, the faint smell of oil and dust.

As soon as he accustomed his eyes to the dimness he saw there was no one in the lobby. An artificial palm, its raffia swathings loose as a two year old's diaper, stood in a wooden tub. Eight chairs were placed in neatly opposing rows, four covered in once-black leather, cracked and split, the wrinkles worn brown, four wooden, humbly straight. There was an air of peacefulness independent of the dark, the quiet, the emptiness, an assertion that there was no need to hurry here, that there was never a need to hurry here.

He lifted his arm to look at his watch. The sweep-second hand was not revolving. He put the watch to his ear; there was no tick. He wound it, shook it; it didn't start. He slipped it off his wrist into his pocket, and loosened his necktie.

He stood in front of the brown counter whose top was shiny with the patina of leaning elbows. There was a bell with inverted triple chins and outpopping pimple, an open register turned indifferently toward him, a bank of empty pigeonholes. He picked up the chewed pen with the splayed nib, bronze-shiny where the ink had dried on it. He had to tip the black scumcrusty inkwell far over to moisten it. It scratch-scratched across the top line on the page, engraving his name but only staining the depressions here and there, mostly on the downstrokes. Oddly, instead of the capital, he wrote down the city he had once lived in, the city where he got his first job.

After registering he hesitated over the bell. Instead of ringing it he picked up his bag and walked to the shadowed stairway. Up ahead he saw a low-watt bulb staring bleakly on the wall. The area around the globe was a grimy green, outside the magic circle the pervading dark brown was undisturbed. The carpet under his feet was threadbare and gritty; through his shoe-soles he felt the lumps of resistant knots in the wood, and the nailheads raised by the wearing-down around them. He gazed ahead.

There was a landing halfway up, opening on a narrow hall. Light came through fogged windows set close together along one wall. The other was papered with circus posters, the brightly lithographed elephants and hippopotami faded almost to indiscernibility, the creases burst open like scored chestnuts. The Governor hesitated, went on up.

At the second floor he turned left, noting how spacious this hall was in contrast to the one below, how comparatively bright and clean. Most of the doors were slightly ajar, not inviting perhaps, merely indicating they were receptive to a tenant.

From the outside there was nothing to choose between them yet he felt the choice was important. Further, it seemed to him that opening a door would commit him; he must choose without inspection. Thoughtfully he passed several. The one he finally entered opened on a large room with two tall windows. Thin, brittle curtains drooped palely from the rods. Two dressers, the high one bellying forward, the low one supporting a tilted metal-dull mirror, were thick with cheap varnish that wept long blob-ended tears. The double bed was made, the coverlet turned down, the lumpy pillows smooth and gray. On a whatnot in one corner a glass bell enclosed two wax figures, a bride and groom in wedding finery. The wax bride was wringing her waxen hands.

The Governor put his bag on the foot of the bed, took off his jacket, rolled up his sleeves, went to the sink. The faucets were black-spotted, green-flecked, with remnants of nickelplating and long dark scratches. The basin was orange-brown and gray-white. He turned on the HOT. There was a quick hiss and a slurp of thick, liquid rust. He tried the COLD. The slurp was the same but there was no hiss. He looked around the room again, saw the washstand. The knobbly-spouted pitcher stood in the center of the knobbly-rimmed bowl. The water appeared good despite the dust floating on top. He poured some in the basin and rinsed his face and hands.

As a small child he had been sure water was life. Once he sprinkled some on a dead bird, stiff and ruffled. He found a towel, hard and grainy, dried his hands, shrinking slightly from the contact. He took his comb from his jacket and ran it through his still thick hair, only lightly graying. It was a minor pride that his campaign pictures were always the latest, never one taken when he was much younger.

He became aware he was being watched and turned inquiringly toward the door. The man standing there wore heavy work-shoes, blue denim pants, a denim jacket buttoned to his neck. His face was dark, his straight black hair long. His eyes slanted ever so little above his high cheekbones. He smiled at Lampley. "Everything OK?"

"Everything OK," said Lampley. "Except the plumbing."

The man nodded thoughtfully.

"Oh, the plumbing. It went out." He gestured vaguely with his hands, indicating leaks, stoppages, broken pipes, hopeless fittings, worn-out heaters. "So we put in washstands."

"I see. Maybe it would have been better to have it fixed."

The other shook a doubtful head. "This was change. Advance. Improvement. Maybe next we'll put a well in every room, with a rope and bucket reaching straight down. Plop! And then rrrrr, up she comes full and slopping over. Or artesians with the water bubbling up like a billiard ball on the end of a cue. That would be hard to beat, ay? Or perhaps wooden pipes from the rain gutters."

"I see," said Lampley. The plans didn't seem unreasonable. "You're the clerk?" he asked politely.

"Clerk is good as any. Everyone has lots to do."

"That's right. Well, thanks."

"Don't mention it."

Lampley rolled down his sleeves, refastened his cufflinks, put his jacket back on. "Can I get something to eat here?"

"Why not? Come on."

The Governor followed him into the hall, closing the door. He thought briefly of asking about telephoning since there was no phone in his room. Still it wasn't really necessary; Marvin could take care of everything. The clerk led him, not to the stairs he had come up, but in the opposite direction. Some of the partially open doors were painted in vivid colors and marked with symbols strange to Lampley.

The backstairs were narrower, steeper, darker; the Governor had a constant fear of overestimating the width of the treads and placing a searching foot upon insubstantial air. They came to the halfway landing but instead of the windowed hall with the circus posters, they entered a low room, low as a ship's cabin compressed between decks. Exposed beams held up the ceiling. A long plank table ran between two benches, a high ladderback chair at the head and foot. One of the benches was built into the battened wall.

On it a man with an infantile face and bulging forehead under coarse black hair crouched over the table guarding his food with tiny kangaroo arms. A stained and spotted napkin was tied around his neck like a bib. He slobbered and gurgled over a bowl of thick porridge, smearing it around his mouth, spilling on the napkin as he scooped the mess from the bowl.

At the head of the table an old man, white-haired, hook-nosed, chewed silently. On the outside bench was a middle-aged woman with sagging, placid features, and a girl in her teens. All looked Indian or Mexican except the idiot, none paid attention to their arrival.

The clerk sat down at the foot of the table. Lampley saw there was no place for him except on the bench next to the defective. He edged his way in, staying far as possible from him. The room was suddenly oppressive; he had the notion they must be near a furnace, a boiler, a dynamo. He took out his carefully folded handkerchief and wiped his forehead. The old man glanced at him sympathetically.

The young girl reached under the table and came up with a bright green crepe paper party favor. She extended it diffidently toward the Governor. Smiling, he took hold of the stiff cardboard strip inside the ruffle with his thumb and forefinger. She giggled, holding the other end; they pulled. The cracker popped, a red tissue paper phrygian cap fell out. She clapped her hands and motioned him to put it on. Slightly embarrassed, he complied.

She searched through the torn favor for the motto, unfolded it. She shook her head and handed it to him. He read, AN UNOPENED BOOK HAS NO PRINTING. She put a bowl of beans, cut-up chicken, and rice before him. "Thank you," he said.

"For nothing," she responded, shyly polite. Her young breasts pushed out against her white shirt. Her dark eyes looked into his before her long lashes fell. Her mouth was wide and supple. Lampley realized she was beautiful. He thought with pain of walking with her through knee-high grass and lying beside her under spreading trees.

He spooned up some of the food; it was overcooked and tasteless. It didn't matter. Between spoonfuls he looked furtively at the woman—he dared not let his eyes return to the girl—and thought he saw a resemblance to.... To whom? The face was pleasant, ordinary, memorable neither for charm nor repulsiveness. It was a matter of professional pride, an occupational necessity for him to remember faces; he could not recall this one. It nagged at the back of his mind.

The old man rose, wiping his mouth with the back of his hand, bowing clumsily toward the Governor. He pulled a wrinkled pack of cigarettes from his shirt pocket and extended it. "Thanks," acknowledged Lampley, "I don't use them." The old man shook his head, tipped the pack to his mouth, replaced it, lit the cigarette with a match struck on the seat of his trousers. His fingers were thick and twisted; they still appeared capable of delicate manipulation.

The clerk pushed back his chair. "We might put self-service in here," he remarked to no one in particular. "Individual stoves, maybe mechanized farms or hydroponic tanks." He belched, holding his hand diffidently before his mouth.

Lampley emptied his bowl. The girl looked questioningly at him. "No more," he said. "Thank you."

She smiled at him, followed the clerk and the old man from the room; he was alone with the woman and the idiot. He wanted to get up and go too; something held him. "A long time," said the woman gently.

He knew what she meant; he refused to accept understanding. "I'm sorry."

"Since you were here. You forgot?"

There was coldness in his stomach. "No ... not exactly. I'm sorry."

She shrugged. Her arms and shoulders were rounded and graceful but their grace did not obscure the fact that she was old as he, or nearly. Why was it so reprehensible to long for freshness and beauty in women but the stamp of taste to want these qualities in anything else? "I'm sorry," he said for the third time, aware of the phrase's futility.

She smiled, showing a gold tooth. The others were white but uneven. "For nothing," she echoed the girl. "What is there to be sorry for?"

His eyes went from the creature on the bench to her and back again.

"Yours," she said calmly.

He had known, but knowing and knowing were different things. "Impossible!"

She showed the gold tooth again. "Why impossible? You make love, you have babies."

"But—like that?"

"Does everything have to be perfect for you?"

He regarded her with greater horror than he had his—his son. A beast, an animal, giving birth to beasts and animals. "Not perfect. But not ... this."

She laughed and moved around the table to the unfortunate. She untied the napkin and tenderly wiped his vacant face and the undeveloped hands. She kissed him passionately on the forehead. "You think it is possible to love only perfection? You couldn't love one like this, or an old woman, or a corpse?"

Lampley ran from the room, past a curtained entrance, and stumbled through a hall lit with yellow, grease-filmed light. The hall smelled of food, acrid, sickening. There was a swinging door at the end, padded, outlined with brass nails. Many were missing, their absence commemorated by the dark outline of where they had been. He pushed through it.

The kitchen was oddly constructed. Its ceiling seemed to be two stories high; just under it were niches for sooty plaster figures, all horribly distorted, figures with one arm twice the length of the other, phalluses long as legs, monstrous heads, steatopygian buttocks, goiters resting on sagittarian knees. Through a rose window yellow-pink beams streamed to the flagged floor. Scrubbed and sanded butchers' blocks splattered with gobs of fat, drying entrails, scabs of hard blood stood against the wall. Gleaming knives and cleavers were racked in the sides of the blocks. Tomb-like ranges were hooded in a row; opposite them empty spits turned before cold, blackened fireplaces.

The old man was seated on a stool before a slanting table, methodically chopping onions in a wooden bowl. He turned his head. "She gave you a hard time, hay?"

Blackmail, extortion, exposure, disgrace. "I don't know."

The old man wrinkled his forehead. The peculiar light made the creases unnaturally deep, like well-healed scars. "Who does know?" He laid down his cleaver. "Come."

Will-less, the Governor followed. The old man had a limp, formerly unnoticed. They went past the ranges to a massive steel door with a red lamp beside it. The old man lifted the tight latch. Lampley noted a safety device preventing the door from fully closing except from the outside.

They were in a large refrigerator. Sides of beef, barred red and pale, hung from hooks. Whole sheep and pigs, encased in stiff, unarmoring fat, thrust dead forefeet toward the unattainable sawdust-covered floor. Barrels of pickling brine, boxes of fish and seafood (the lobsters waving feelers uncertainly) were arranged neatly. It was cold; the Governor shivered. Plucked fowl dangled in rows. Beyond them wild ducks and geese, still sadly feathered, were suspended in bunches, three ducks, two geese to a bunch. The Governor touched a mallard's breast as he passed; the down was strangely warm in this chilling place.

They crossed an empty space. The whole carcass of an animal hung from gray hooks curving through the tendons of its legs. It had been skinned and gutted but the head was intact and untouched. The shaggy hair drooped forward, the horns pointed at nothing. The glazed eyes absorbed the light, the tongue, clenched between dead teeth, protruded.

"Buffalo," cried the Governor. "Surely it's against the law to kill them?"

The old man ran his dark, heavily veined hand gloatingly over the bison's hump and down the shoulder. "Tasty. Very tasty."

"You can't do things like this," insisted the Governor.

"Ah," sighed the old man. "Boom boom."

Lampley came closer. There were no signs of the buffalo having been shot. Its throat was cut and dark blood had congealed around the jagged wound. The old man picked out several clots of dried blood and put them in his mouth, sucking appreciatively. He rubbed his cheek against the head of the animal. "Soft," he said. "See yourself."

The Governor drew back.

The old man stared contemptuously at him. "No wonder."

"How do I get out of here?" asked Lampley.

The old man gestured indifferently. "Try that way." He waved his arm.

Lampley turned. Either the refrigerator had gotten colder or he was newly vulnerable to the chill. He shivered; hoarfrost crunched under his feet, the wall glistened with ice crystals. He realized he was not retracing his steps when he passed braces of partridges—or had he merely not noticed them before?—grouse, pheasants. He looked back; the old man was still nuzzling the bison head.

He came to a mound of snow and was puzzled, less at its presence than at its use and origin. Who would manufacture snow, and for what purpose? And if not manufactured it must have been brought a long way at great expense for it did not snow in this part of the state more than once in a dozen years.

But it was not a simple mound after all but an igloo, crudely constructed, as though by a child. Impulsively he got down on his knees and crawled through the entrance-tunnel until his head was inside. It was warm under the dome, warm and soothing and safe. He backed out quickly, frightened at the thought of becoming too content there, of not being able to leave its comfort.

The cold of the refrigerator was accentuated by the contrast; his breath came in steamy puffs. He hurried to a door opening from the inside. He leaned against the wall of a dark corridor and breathed deeply. The picture of the old man fondling the buffalo head was still before him. He felt his way slowly along the wall, and then he was in the lobby again. There was something wrong here: the room where they had eaten had been a half level higher.

There was no point in wondering over the layout of the hotel. He would retrieve his bag, get in the car and go on to his destination. He stumbled through the gloom, missing the stairs, and saw he was in front of an antique elevator, the doors open, the ancient basketwork cage an inch or two below the floor.

"Get in," invited the clerk, "I'll take you."

Lampley entered, panting a little, smoothing his tie with his palm. "Thank you."

The clerk pulled the grill shut; there was no door on the elevator itself. "Ninety-three million miles to the sun," he said. "We'd fry before we got there."

The Governor considered the idea. "Explode from lack of pressure, asphyxiate from lack of air first."

The clerk looked at him curiously. "We could shut our eyes and hold our breath, you know."

Lampley did not answer.

"All right." The clerk grasped the control lever. The cage fell with sickening velocity.

CHAPTER 2

Lampley knew something had broken but his fear was not absolute. He bent his knees (go limp: drunks and babies were less liable to injury than the stiffly erect); the drop would not be fatal, he might not even break a leg. How far to the basement? Twenty feet at most. If he just relaxed—or jumped to the top of the cage and clung to the fretwork?—he would not be hurt. He must not be hurt; the implications of the headlines would destroy him.

The elevator dived in darkness, far further than any conceivable excavation beneath the hotel. It fell through night, blacker and more terrifying than any moonless, starless reality. It plunged into total, unrelieved absence of light, a devastation to the senses, a mockery to the eyes.

Then, subtly, there was a difference. The blackness was still black but now it could be seen and valued. It was blackness, not blindness. Then increasingly there was a faint diminution of the darkness itself, and the shaft changed from sable to the deepest gray.

After they had fallen still further Lampley saw the shaft was lined with porcelain tiles, yellowed with neglect. Could it be they were no longer falling at all, just descending normally? To where?

They flashed past doors, cavernous rectangles in the shiny wall. Shiny? Yes, the tiles were brighter, cleaner, whiter. The cage slowed, came to a bouncing halt. The repressed fear surged through Lampley, making his feet and ankles weak and helpless. The clerk slid the door open smartly, with a sharp click.

"What's here?" asked the Governor, conscious of the inadequacy of the question.

"Odds," replied the clerk. "Odds. No ends to speak of but plenty of odds."

He half led, half pushed Lampley out of the elevator. They were in a great chamber, so far stretching that though it was adequately lit the defining walls were lost, far, far off. So close to each other that they almost touched, grand pianos with their lids thrown back and strings exposed, stood, rank after rank. From the ceiling long stalactites dripped on the pianos: plink plink, plink plink, plink plunk! A thousand pianotuners might have been at work simultaneously.

"Nobody here," said the clerk. "All right." He turned swiftly back into the elevator, slamming the door.

"Wait!" cried Lampley in panic. "Wait for me." He heard the softly whirring mechanism as the elevator started, leaving him alone.

Lampley pounded the door with his fists. He shouted for the clerk to come back, not to desert him. He kicked the door. He screamed. Plink plink, plink plink, plink plunk.

He could die down here. He could die down here and no one would ever know it. He dared not go away from the elevator shaft—he might never find it again. He dared not stay—the clerk might not return until he was dead and the flesh rotted from his skeleton.

Plink plink. No, long before he died he would be raving mad. Plink plink. "Give us a tune at least," he pleaded. His voice produced no echo. No echo at all. Plink plunk.

Calm, almost ease, succeeded panic. He walked between the rows of pianos. They could not stretch to infinity, he reasoned, there must be an end to them somewhere. But reason also argued the pianos couldn't be here at all, there couldn't be seven or seventeen or seventy sub-basements beneath the hotel. Once an impossibility happened there was no limit to the impossibilities to follow.

He had been six when Miss Brewster came to give him piano lessons. And is this our little Paderooski she asked so brightly. Do-do. C natural. Treble clef, bass clef. Above the staff, below the staff. She smacked his hands when Mother wasn't looking. He kicked Miss Brewster's shins. After a while the lessons stopped.

A unicorn pranced out from between the pianos. His coat was white and sleek, his mane and tail shone like coal, his eyes were blue as sapphires. The long spiralling horn was pale gold, glistening bright. The Governor tried to approach him, to stroke the soft nose, to clutch the heavy mane. The unicorn stamped a nervous hoof and circled away, always barely out of reach. Lampley followed him down the long aisle between the pianos.

The unicorn looked back, his nostrils wide. Lampley put out his hand, almost touched him. The animal snorted, broke into a trot, a gallop. Its hooves pounded the hard floor: tata-rumpp, tata-rumpp, t-rump t-rump. The Governor ran too, shouting, calling. His lungs were sawed by jagged breaths, his heart burst through his ribs and left only a helpless, pounding pain behind. He wanted to stop, to give up, to faint; he kept on pursuing.

The unicorn paused, wary. He stamped a hoof, tossed his mane, pointed his horn. Lampley, gasping, was hardly able to totter forward. He took a step, two, leaned against the nearest piano. Plink, plink, plink, plink, plink plunk. The unicorn suddenly ran his horn into one of the instruments, withdrawing it to leave a splintered hole in the wood. A man came out of the shadows with a sledgehammer over his shoulder. He was a dwarf, naked to the waist, with writhing biceps, wearing a grease-matted brimless cap over thick curly hair. The growth on his chest curled also, an obscene felt. He swung the hammer down on the piano, smashing in the top, caving in one of the legs.

"What are you doing?" demanded Lampley before he realized he didn't care what the man was doing. "How do you get out of here?" he amended.

The dwarf went on methodically wrecking the piano. The unicorn disappeared, the sound of its hooves growing fainter and fainter. Lampley approached the dwarf, ready to clutch his shoulder, to extort a way out. He was afraid. Afraid of the blunt, lethal hammer, afraid of the strength and rage which had reduced the piano to junk. Afraid of the answer to his question. Afraid there might be no answer.

The dwarf slung the maul back on his shoulder and walked away. The Governor wept. There was no strength in his arms or legs. He fell down and crawled weakly forward, sobbing and retching, the sour taste of vomit in his mouth. Plink plink, plink plink, plink plunk. Destruction of the offending piano made not the slightest difference in the cacophony.

The weight of all the floors above him, the overwhelmingly massive structure of steel and stone reaching to the surface, bowed him down in lonely, strangling terror. What mind, what mathematical faculty could estimate the thousands, the hundreds of thousands, the millions of crushing tons overhead, malign, implacable, waiting? He closed his eyes, moved his arms and legs convulsively. It was more than he could bear.

He was at the elevator again. If he could pry the door open perhaps he could climb the cables or brace himself between the rails on which the counter-weights slid and inch his way upward. Or fall to destruction. He knew he could never get the door open. He was condemned to stay amid the pianos. He sobbed hopelessly.

Without belief he heard the sound of the machinery and the tip-tip-tip of the halting car. It was the young girl who opened the door and helped him in. She took a handkerchief, soft as fog, delicate as a petal, smelling of herself, and wiped his tears. She held his head between her breasts and he breathed in the scent of her untouched body. She pressed his wrists with her fingers. She put her hands under his arms and guided him against the wall of the cage.

"Thank you," he cried. "Oh thank you, thank you." He felt he was about to weep again, tears of shame and weakness. He held her tightly to reassure himself of the reality of the rescue, greedy for her gentle soothing. "Why did he do it? Tell me, why did he leave me down here?"

"Oh," she said, as though disappointed. "You want answers."

He shrank from her disapproval. "No, no. Please. I'm satisfied to be out of there."

She shut the door. The elevator shot upward, past the glistening white tiles, past the yellow ones, past the area of light. It rose—more slowly it seemed—through the darkness. The creak of machinery increased, as though illumination were a lubricant and the deprived dark full of grit.

His heart was full of reverence and gratitude for her rescue, for her purity. He was bowed down by the simple fact of being alone with her in the cage. They passed the open grillwork of the first floor and ascended at snails' pace—no doubt now—to the second. She stopped the car, and taking his hand, led him out. He was thankful beyond counting when she took him to the bedroom, shutting the door behind them, and helped him out of his jacket. She wet a towel in the pitcher and bathed his face.

"You are very lovely," he said humbly. "As lovely as you are kind."

She took the paper cap from his head and smoothed his hair. If he had been humble, now he was humiliated beyond endurance. All that suffering, all that torture and anguish—with an absurd gaud perched atop him. It was beyond bearing. Fear and gratitude had not deprived him of all final dignity; the picture of the tissue paper cap jaunty upon him was too ridiculous for contemplation.

She smiled at him, magically healing his pride. Her mouth was a flower cut in soft pink stone. Her mouth was a velvet hope. Her mouth was red satin. She bent and touched him with it. He held his breath, felt himself tremble and die.

He kissed her, delicately, very delicately at first, savoring the soft, soft lips. He was dedicated to keeping her undefiled. He put his arms around her, touched his tongue-tip to her eyelids, her ears. He found her mouth again, pressed it tenderly. Then fiercely, lustfully, devouringly. She did not draw back. He lifted her shirt, intoxicating himself upon her small, perfect breasts.

"You will not hurt me?" she pleaded. "No man has been with me before."

He swore to himself he would not hurt her; it was not in him to be anything but loving. He would be wise, kind, compassionate; he would sacrifice his burning lust to her timidity. He would deflower her without rage.

He seized her, and seeing panic struggling against the consent in her eyes, ravished her brutally, violated her without thought of anything but his own triumph. Crying and reproaching himself, he begged her forgiveness. When she gave it, so readily, so understandingly, he repeated the act as heedlessly.

Remorse-stricken, he pressed his face against her knees, smoothed her long hair, kissed her temples, touched her body pleadingly. She smiled up at him, wound her arms around his so that their hands came together, palm to palm.

His penitence dissolved slowly in her grace. He remembered the creature downstairs—his son. "Are you her daughter?" he asked harshly.

She seemed to know whom he meant. "She is my sister."

"And the clerk?"

"The clerk?" She shook her head in incomprehension. She shut her eyes, breathing evenly.

Without disengaging himself from her he raised his head to look around. This was not his room. The furniture was similar, but the washstand was where the highboy had been, the highboy in the bureau's place. And the figures under the glass bell, the two dressed in black and white, were not the wedding couple but two duelists, crossing swords. Their faces were alike: father and son, older and younger brother, the same man at different periods. The older had got under the younger's guard and was pressing his advantage.

He should have phoned Mattie ... no, Mattie was dead, the doctor shaking his enlightened head. The prognosis is always unfavorable unless we get it early ... vulnerable womb.... He should have phoned Marvin. It had been irresponsible of him to take this trip all by himself, impulsively, secretively, as though he were hiding something—he who could afford to have nothing to hide. And it had been doubly foolish to take this unusual, little-traveled route, to stop on whim at this obscure place.

He put his head down next to the girl's, feeling the comfort of her flesh against his body. He was not sleepy, no longer tired. She had refreshed and renewed him. He raised his head to look at her loveliness again.

The long hair was lusterless, streaked with gray. The smooth, fresh cheeks had relaxed into fatty lumps, coarse and raddled. The slack mouth turned downward, the flesh of her throat was loose and crepey. He pulled back in horror and saw that the tight, round breasts were long and flaccid, the flat belly soft and puffy, the slender arms and legs heavy and mottled.

Her eyes opened and looked dully into his. "What did you expect?" she asked.

He stood trembling by the side of the bed. "Only a little while ago...."

Her lips parted to show yellow teeth with gaps between. "There is no time here," she said and went back to sleep.

He did not look at her again, equally fearful of confirming or denying. Instead he picked up her clothes and scrutinized them as though they would reveal the truth. They were only the remembered white shirt and dark skirt, the small, narrow sandals, the flimsy scrap of underwear. By sight and scent they belonged to the girl who had brought him here, not to the woman on the bed.

He dressed with his back to her. The paper cap was on the floor where she had dropped it; he did not pick it up. He tip-toed out, avoiding noise, though the woman save no sign of waking. He searched for his own room but none of the doors he opened showed the identifying arrangement of furniture or the wax figures of the wedding couple. He could not have confused the floor: he had climbed one flight from the lobby and the girl had taken the elevator only the same distance. If the elevator and the stairs were on different sides of the hotel...? That would account for the muddle.

The hall turned a corner. Instead of more doors it was blocked to its full width by a stairway. He took it in preference to retracing his steps; logically there would be a matching one back to the second floor further along.

Now the carpet under his feet was thick and soft instead of thin and sleazy. Strong bright light shone down from the floor above, showing walls panelled in pale wood, clean and elegant. It was a fleeting puzzle that this stairway should contrast so strongly—should have been preserved so carefully—with the rest of the hotel.

The sound of many voices, the clatter and movement of people came to him distantly. He reached the top. The third floor was decorated in pinks and grays: pink walls and ceiling, gray carpets, doors and woodwork. Couches and sofas occupied the wall-space not cut by doors. On the nearest one was sprawled an oversize ragdoll onto which pendulous blue breasts had been carelessly sewn.

The hall was a large quadrangle with a square well in the center, guarded by a heavy wrought iron railing. The Governor rested his arms on the rail and gazed down at a concourse thronged with people. Women in sequined evening gowns, men in gaudy uniforms, gathered in knots, moved briskly, or sat idly on chairs and benches. A few of the women wore vivid strips of silk around their thighs or as skirts, the exposed parts of their bodies tattooed in blues and reds. A bearded man with shaggy hair had the skin of an animal caught over one shoulder. He saw a girl in hoopskirts, another in ruff and farthingale, but most wore the "formals" of his young manhood.

He had no feeling that this was a masquerade, a costume party: all wore their clothes with the assurance of habit, without self-consciousness or interest in the garb of others. Even at this distance he recognized a man in the green uniform of the United States Dragoons, obsolete since the 1840's, another in the white greatcoat of royal France. A Californio, silver pesoed trousers and all, talked earnestly with his companion in the dropped-waist sack of the Coolidge era while a hobble-skirted eavesdropper hovered close.

The throng was so tightly pressed together that Lampley did not at first make out the rococo fountain in the center. A sudden movement, a concerted parting, revealed its marble nymphs and cherubs spouting water in scatological attitudes. A sailor, wearing the characteristic British dickey, climbed to embrace one of the statues. He fell into the basin and was pulled out by an Attic shepherdess.

The Governor longed to join them, to dissolve his desires and disappointments in their gaiety and laughter. He knew there was no hope of happiness with them, as he knew there was no way for him to get down to them, but the knowledge did not quench his yearning.

He turned away and began circling the quadrangle. The doors on his right were all shut, no sound came from behind them. They were not consecutively numbered, nor in any conceivable order, not even in the same numerical system. 3103 was followed by 44, the next was XIX, then 900, 211, CCCV. One was marked with egg-shaped figures which he took to be possibly Mayan. It was slightly ajar. He pushed it open.

It was a schoolroom. Disciplined desks marched side-by-side toward the teacher's raised podium hemmed in by blackboards gray with hastily erased chalk. Only the four seats in front were occupied. He tip-toed forward and slid into the second row. The teacher was a caricature Chinese mandarin with queue, emerald-buttoned skullcap, gold fingernail guards, tortoiseshell spectacles, brocaded robe.

"You have brought your homework?" he inquired, peering severely over the top of his spectacles.

"No sir," answered Lampley, getting up again.

"For what purpose does the honorable delegate arise?" mocked the teacher.

Lampley felt himself blushing. "I—I thought it was customary."

"All is custom as Herodotus said," remarked the teacher. "Herodotus was a barbarian," he explained genially to the class. "Sit down."

In front of Lampley sat a child with long blonde pigtails, one with a pink, the other with a white bow. She read aloud, "See little Almon. Little Almon lives with his mother and his uncle. Almon has the cat. Almon wants to play with the cat. The cat—"

"Quite enough," said the teacher. "Meditate."

The pupil next to the girl was the idiot. On the other side of the aisle were a boy of twelve and a girl a little older. When the girl turned her head Lampley saw her face was heavily bandaged. The Governor lifted the top of his desk and took out a book. It had no covers, the pages were torn and thumbed.

In the fifth year of the present reign, (he read) there appeared at court a magician from the East who claimed alcheminical learning to such a degree he was able to divine secret thoughts. A demonstration being required of him, he demanded that divers ladies-in-waiting who....

The Governor turned the page. The next leaf was written in runes. He riffled swiftly through the book. None of the rest of it was in the Latin alphabet. He turned back to the page he had read. The letters were all jumbled together, KJDRBWLSAYPZUQMXRQOTVBFLAIH, so that they made no sense. He held up his hand. The teacher pulled down his spectacles nearly to the end of his nose.

"No one is excused here," he announced. "Your attention, please."

Lampley let his hand fall. The children rustled and squirmed.

"I have here a button," said the teacher. "It is not a true button but a sort of courtesy button. It is in fact a mere plug, connected by the demon of electricity to an ingenious apparatus located in the antipodes of the Flowery, Middle or Celestial Kingdom. By pressing this button I can cause the instant and painless demise of an anonymous foreign devil. I repeat, the operation will cause the big-nosed one no distress at all; he will know nothing. By pushing the button I destroy him; also I bring untold happiness to all the sons of Han, whose ricebowls will then be full, whose fields, wives and concubines will be fertile, whose lords and tax-gatherers will become unbelievably merciful. My problem: shall I press the button?"

He leaned back triumphantly in his chair and took from a desk drawer a bowl and chopsticks. Steam ascended from the bowl as the teacher deftly picked out long strings of noodles and sucked them into his mouth. Lampley could smell the sharp odor of the soup in the bowl. The class was silent while the teacher ate.

He put down the bowl and laid the chopsticks across it. "It is an ethical problem, you understand. Luckily, since I am unfitted for manual tasks—" he held up his fingernails for them to see "—I am absolved from considering it. I shall never have to press the button or not press the button."

Lampley raised his hand again.

"I told you no one is excused here," said the teacher.

"I was young," protested Lampley.

The teacher turned away disgustedly. He wrote on the blackboard in angular, unconnected letters, "Death knows no youth."

The pupils in the front row all turned around to stare at the Governor. The face of his son was set in a horrid grimace, teeth showing, eyes watering gummy white in the corners.

"She was ambitious for me. It seemed best at the time," muttered Lampley.

They all laughed together, snarling like dogs. Lampley hurled the book at them. The pages fluttered as it fell with a thud on the floor. The teacher wrote on the board in his singular script, Ambition, Doubt, Subservience, Conformity, Treachery, Heat, Bravery, Murder, Hope, Trifles, Treasure, Pity, Shame, Confession, Humility, Procreation, Final. "No alternatives!" he shouted.

CHAPTER 3

The Governor stumbled into the aisle and ran. Before the door a coffin rested on trestles. Tall candles burned at the head and foot. He did not have to look in to know it was Mattie or that beside her was the child she had never borne. He fell to his knees and crawled under the coffin. The trestles lowered; he had to squirm forward flat on his stomach to get clear of the casket. He got up and through the door, slamming it behind him.

The lights were bright as before but the people below had all disappeared. The fountain was dry; dust and lichen mottled the marble figures. Beneath the railing hung tattered battle-flags, dulled, tarnished, with great rips and tears. The floor, which he saw had been paved with great tile slabs, was broken and humped. Pale, sickly weeds thrust through the cracks. A sickening stench rose to make him gasp and turn away.

He had been seeking a stairway back to the second floor. He followed the quadrangle, came upon an unexpected hall between two rooms. At the end of the hall a square chamber was flooded with brilliance from a skylight. A legless man, many-chinned, frog-eyed, sat in a wheelchair. Across his monstrous chest a row of medals glittered. "Come in, come in," he roared jovially. "Any friend of nobody's a friend of mine."

"Can you tell me—" began the Governor.

"My boy," burst in the legless man, "if you want telling, I'm your pigeon; if I can't tell you no one can. I've shot cassowaries and peccarries, hunted dolphin and penguin, searched the seven seas for albatross and Charlie Ross. Oh the yarns I could spin about sin and tin and gin, about rounding the Horn in an August morn or lying becalmed in the horse latitudes with a cargo of bridles and harnesses. I've whaled off South Georgia, been jailed by Nova Zembla, failed on Easter Island, entailed in the West Indies. I'm a rip-roarer, a snip-snorter, a razzle-dazzle hearty-ho."

"You were a seaman?" asked the Governor politely.

"A seaman, v-d man, hard-a-lee man, a demon," sang the sailor. "Blast and damn me, I've fathered six hundred bastards in all colors—white don't count, naturally—from Chile to Chihili, from Timbuctoo to Kalamazoo. Have a drink."

The Governor looked around. On a long bar were ranged dozens of bottles, most of them empty. He picked up the nearest full one. It was cold, green, opened, and full of beer. He put it to his lips, tilted it, realized his throat had been dry, parched. "Thanks," he muttered, taking it away reluctantly.

"Ah," said the cripple, "you should know the thanks I've had." He indicated his medals carelessly. "Decorated, cited, saluted, handshook, kissed on both cheeks. I've been thanked in Java and Ungava, in the Hebrides and the Celebes, in Tripoli and Trincomalee, in Lombok and Vladivostock. Have another drink."

"Thanks," repeated Lampley.

"Pleasure," responded the cripple. "Never drink alone, sleep alone, die alone. You haven't been here before?"

Lampley was puzzled how to answer. "Yes and no," he said at last.

The other nodded approvingly, tossed a ball into the air and caught it. "Caution. Many a poor sailor's been drowned dead because the captain or the mate yessed when he should have noed. Yes-and-no's a snug berth in a landlocked harbor."

"I only meant...."

The man had another ball in the air now. "The meaning of meaning. Semantics—that's a pun. Think you'll get the nomination?"

"It's touch and go," confessed the Governor. "I'm hoping."

The sailor was juggling three balls. He didn't look at them, just kept catching and tossing in rhythm. "Touch and go. Skill and chance," he said.

"That's right," agreed Lampley, drinking again.

"Comfortable?"

"Yes, thanks."

"Always said they should have put steam heat in here."

"But it's quite warm."

"Just wait till it snows. Drifts high as the roof, drifts high as the trees, drifts high as mountains. Buried in snow, white on top, green under the light here. A wonder we don't smother."

"Oh no," said the Governor, recalling the igloo in the refrigerator. "It's porous or something. The air comes through."

The juggler had seven balls and three oranges in the air. He added two empty bottles. "Nothing comes through. The outside never knows the inside, the inside's locked away from the outside."

"But it's always possible to break through," argued the Governor.

The juggler's arms were knotted muscles of skill. He had many bottles in the air besides the oranges and balls. "No man knows his fellow."

"Knowing and communicating are two different things."

"Yes and no," said the juggler judiciously. "You know a woman; do you...?"

"Yes," insisted the Governor defiantly.

Still more bottles were tossed and caught. "You think so," said the juggler. "What happens when you fail?"

All the bottles were in play now. Deftly the juggler wriggled to the floor and added his wheelchair. "We fail yet nothing falls: the supremacy of perpetual motion. Try the fourth floor."

"There isn't any fourth floor," said Lampley.

"That's right. Try it."

Still juggling the balls, oranges, bottles and chair, the legless man threw himself into the air and joined the circle of whirling objects. The Governor left, went through the passageway again to the quadrangle and looked over the railing. The fountain was gone. Goats nibbled at young trees growing through the obscured tiles. A man rode a pony listlessly and disappeared out of sight. A yellow wildcat prowled around, pausing to hiss menacingly at the goats. Lampley walked past closed doors, found himself in front of the elevator. He hadn't seen it—then it was there.

"Down," announced the clerk.

"I don't want ..." began Lampley doubtfully.

"Going down," repeated the clerk firmly. "There's no up from here."

"How do all these people live?" asked the Governor. "The soldiers, the women, the schoolmaster, the juggler?"

The clerk shrugged. "No differently than anyone else. Osmosis. Symbiosis. Ventriloquism. Saprophytism. Necrophilism. The usual ways."

"Imagination? Illusion? Hallucination? Mirage?"

"We are what we are," said the clerk. "Can you say as much? Going down."

"I want to know," persisted Lampley.

"Don't we all? What's the use?"

The Governor temporized. "Will you let me off at my floor?"

"Do you know which it is?"

The Governor could not answer. He moved away from the elevator. There was a hole in the carpet going deep into the floor. In the hole was a heap of pennies, new-minted, bright coppery orange. He picked up a handful and sifted them through his fingers. None of them seemed to be dated, all had an eagle on one side and a scale on the other. A lump of untreated metal, hedgehog sharp, pricked his flesh. He dropped the pennies and put his hand to his mouth to suck the wound.

"Going down," the clerk called warningly.

Lampley said, "I only want—"

The clerk slapped his knee, doubling with laughter. He did a little dance, his hands holding his abdomen. "Only!" he screamed between gusts of mirth. "Only! That's all. He only wants."

With what dignity he had left the Governor entered the elevator. The clerk, abruptly sober-faced, straightened up and shut the door. The openwork of the cage was now interwoven with rattan in which trailing fronds of greenery were stuck. Birds of somber hue—gray, black, slate, dark blue—climbed with silent intensity over the basketry, hung beak down from the roof, pecked quietly at the green. "Down."

Lampley held his breath, sucked in his stomach. But there was no sudden drop. The elevator glided with dignity past the second floor, the dim lobby without acceleration, into the dark depths. He strained his eyes for the first sign of light, of the tiled walls. Only the subtle sensations of descent told him they were not stopped, rigid, just below the first floor.

The clerk said, "The teacher has a list of all those who cheated."

"It must be long."

"It's not as long as the guilty think, nor as short as the innocent believe."

"A youthful indiscretion," said the Governor lightly.

"The piano-smasher knows all about false references."

"Everyone does it," said the Governor. "You have to, to get a job."

"The juggler has suffered from the effects of kicked-back commissions."

"The custom is old. Who was I to change it?"

"The people in the concourse voted to send a man to the legislature who promised to do certain things."

"Campaign oratory," said the Governor.

"The girl—"

"Stop," ordered the Governor. "Are you taking it on yourself to punish sins?"

"Ah," said the clerk. "You think absolution should be automatic, instant and painless?"

Lampley thought, if I had a heavy wrench or a knife or a gun I could kill him and no one would know. His fingers tingled, his knees ached. He tried to speak casually, to stop any further words the clerk might utter. As he sought for some innocuous topic he saw the walls lighten, recognized the yellowed tiles.

The clerk bent over the control lever as though in prayer, the birds were all still and unmoving. Passing the shining white tiles Lampley strained to catch the faint sound of the pianos. He could not be sure he heard it, still less that he hadn't. The walls of the shaft gradually became a pale green, deepening into skyblue so natural they seemed to expand outward.

Smoothly the elevator tilted at an angle just steep enough to force him to put one foot on the side of the cage in order to stay upright. The clerk, clinging to the lever, had no trouble. They slid down the incline at moderate speed. The tiled walls fell away; they were traveling on a sort of funicular diagonally through the floors of a vast department store. Counters of chinaware were set parallel and perpendicular, the cups and dishes cunningly tilted to catch the light: experimental, modern, conventional, traditional, all the familiar patterns including sets and sets of blue willowware. Some of the pieces were so curiously shaped it was impossible to guess their use: platters with humps in their centers, cups pierced with holes, plates shaped like partly open bivalves, cones, spheres and pyramids with handles but no apparent openings.

They passed a millinery department where women were trying on feathered helmets, fur busbies, brass-and-leather shakos, woolen balaclavas, wide-brimmed straws, tight-fitting caps of interwoven fresh flowers. Lampley saw they were all using long hatpins, jamming them recklessly through the headgear under consideration. The discarded hats were not put back in stock but thrown into large wastebaskets.

The spaces between floors were open, revealing the heavy steel girders with which they were braced. Through the openings in the girders lean dogs chased scurrying rats, snakes twined themselves, bats hung upside-down, land-crabs scuttled, stopping only to turn their eye-stalks balefully toward the elevator.

Governor Lampley continued to drop further and further into an abyss of gnawing terror.

On another floor lined with mirrors that shot their dazzle into his eyes like a volley of arrows, more women pulled and tugged girdles over obstinate hips with concentrated effort, bending reverently over unfolded brassieres to match the arbitrary cups against overflowing breasts, holding up corsets which coldly mocked. Breech-clouted boys waved huge fans, stirring the piles of garments on the tables.

The elevator continued downward. Shoppers strolled by book counters with untempted glances, heading for the infants' wear to examine tiny shirts, diapers, kimonos, blankets, fingering the embroidery, pursing lips, smiling, shaking their heads. They stood abstractedly before bright prints, sat stiffly on padded chairs, thumped mattresses, fiddled with gifts and notions.

On a lower floor overhead lights glared down on roulette tables, card games where the players squinted suspiciously over their hands, blankets on which dice-throwers were shooting craps. The walls were covered with posters: LAMPLEY FOR SUPERVISOR; A VOTE FOR LAMPLEY IS A VOTE FOR YOU! The Governor was puzzled; he had never run for that office.

The walls closed in again, the elevator tilted further, so that the Governor was sitting on the side of the cage. It picked up speed now, whizzing along, rounding banked curves, allowing momentary glimpses of open spaces like railroad stations. "How far are you going?" Lampley asked.

"Not far," said the clerk, coming out of his lethargy. "We're almost there."

"Where?"

"There. Where else?"

They rounded another curve and shot down a grade. A bird near the Governor ruffled its feathers sleepily. "I just want to get back."

"Who doesn't?" demanded the clerk harshly.

The walls of the shaft—it was a tunnel now—were transparent. There was water pressing against them, a powerful stream, judging by the exertions of the fish swimming against it. They ran a long way through the river—Lampley was sure it was a river from occasional sight of a far-off, muddy bank—and then the glass walls showed only earth, with the roots of trees reaching down and piling up, baffled, against them.

The walls became opaque, then vanished. They were running down the side of a mountain covered with patches of snow. In places the snow was piled in great drifts, carved by winds into tortured peaks; elsewhere it lay in thin ruffled streaks and ovals. Out of these shallow patches dark bushes sprang bearing red and yellow fruit. The bare spaces between the snow were of moist, eroded earth where small brown plants grew spikil.

The Governor could not see the sky nor the roof of the cavern—if they were in some sort of cavern—only the ridges and spurs of the mountain slope. There were scars on the rugged ground as from landslides, great bites where the drop was sheer and jagged rocks stood out like drifting teeth, but none of the slips could have been recent for the mounds at their feet were firm-looking and grassy. They rounded still another curve and the elevator slowed to a stop.

The clerk, who had clung protectively to the controls, straightened up and looked inquiringly over his shoulder. Lampley stared back at him. "All out," said the clerk, waving his hands. The birds fluttered, cawed and shrieked, flying through the open door with an angry whir of wings. They wheeled in uncertain circles and then made off in small, separate flights. "All out," he repeated.

"I don't want to get out," said Lampley. "There's nothing for me here."

"Are you sure?" asked the clerk.

"I...." Lampley paused, uncertain.

"You see?" demanded the clerk triumphantly.

Resigned, the Governor made his way out. The clerk smiled at him, not unfriendly, and Lampley almost begged him not to leave, not to abandon him but to take him back. If the right words came to his tongue, if the earnest feeling projected them into sound, he was sure he would not be deserted. Then the elevator started slowly backing, gathering speed as it went, running silently, shrinking in size until it was merely a small speck on the side of the slope. Only the terminal bumpers and the greasy track on which it had run remained.

CHAPTER 4

Lampley looked about him. Mountains shut off every horizon; the near ones sharp, serrated, detailed, those far-off hazy, soft and rounded. It was impossible to make out the character of the more remote, but those on either side gradually melted into foothills with twisting streams appearing from between shoulders and disappearing again behind ridges. The light overhead, nebulous, indefinite, emanated from no discernible body. It had the quality of sunlight filtered through thin clouds, soothing to the eye as the balmy air was pleasant to the skin. He felt refreshed.

Beneath his feet a fan-shaped plateau canted downward until it merged with a mighty plain far off, a plain enclosing a vast lake. A broad river meandered across the plateau and continued, as near as he could tell, on the plain below. Dense blue-green grass grew lushly, heavily powdered with yellow, white, and purple violets, dandelions, daisies, buttercups and tiny pale blue flowers. The Governor took off his shoes and socks, stuffing the socks into the shoes and knotting the laces together. He slung them over his shoulder. The grass felt electric, rejuvenating his feet as he trod on it.

A black fox crossed his path and paused to stare over his sharp nose before continuing on. A squirrel balanced its body erect for a swift, curious scrutiny before it was off with a flick of its tail. Other small animals bounded past him, none seemed afraid. He thought he saw deer in the distance, and a bear, but he was not sure.

He came to a bank of the river and followed it down. He could see now it was joined by a number of tributaries before it emptied into the blue, unruffled lake. Other rivers foamed down the more rugged mountains on each side of the plain, all made their way to the lake which seemed to have an island in it, a long way from shore.

When he reached a confluence with one of the branches he hesitated and followed the smaller stream back until he came to a place where it was crossed by high, flat-topped steppingstones nosed into the splashing and spuming water. He tested the rocks gingerly, but they were firm, and though wet, not slippery. Each time his progress was stopped by such a meeting he found a similar set of stones not far away.

Nearing the lake he saw its color was a warm blue, with violet tones. There was no hint of paleness in it; it was majestic, assured, unique. He quickened his pace. The island assumed more definite shape. It was large and irregular, with capes and promontories thrusting out into the lake. Heavily wooded, willows came down to the shore, behind them oaks and maples spread red and yellow leaves. Still further back the blue tips of firs pointed above.

He came to the shore, a rocky beach, where the water lay perfectly still over and between round, mossy stones. He waded in; the water was delightfully cool without a suggestion of coldness. He reached down and laved his face with it. When he straightened up he saw a rowboat a little further out, unanchored, its bow resting on the rocks, its stern hardly moving. The boat was the color of the lake save for a silvery trim and silvery oars were neatly shipped in bright metal rowlocks.

The Governor made his way carefully to the boat, freeing it from the rocks. He climbed in, laid his shoes in the stern, began rowing toward the island. After a few strokes he paused and looked upward. The haze was evidently permanent, which might somehow account for the unvarying, equable climate. He shipped the oars and allowed the boat to drift. A fish jumped in the water and splashed a widening circle. A bird, white and gold with carmine beak, flew overhead. Everything was serene.

There was no wind but there seemed to be a weak current, for the boat drifted very slowly, equidistant between the shore and the island. The features he had noticed before became more differentiated; he noted a number of landspits, small coves, moonshaped beaches. The woods did not everywhere come right down to the water; in places they retreated to make room for soft green meadows. He picked up the oars and rowed a long distance before coming even with a particularly inviting cove.

He debated whether or not there might be a still more desirable one farther along. The temptation to refuse decision was great. It was with a distinct effort that he turned the bow and ran the boat ashore.

The sands were fine and soft and golden, darkening a short way from the lake into a pale brown border between the beach and the greensward. He stepped out of the boat and hauled it clear of the water. Impulsively he took off his clothes and put them with his shoes. He rolled on the grass like a boy or a horse. The grass was soft as down, yet springy and lithe beneath his body. He lay prone, snuffing in the smell of the bruised stems. He stretched out his hands to reach into a patch of clover with the idle thought that one of them might be four-leaved. He saw with horror he was reaching with the reddish, vestigial, unteachable hands on foreshortened arms of his son.

He felt sweat on his forehead as he shivered in terror. He jumped up and ran for the boat, slipping and sliding on the crushed grass. He lay trembling, eyes shut. Fearfully he drew his hands toward him and opened his eyes. These were his own hands, familiar, middle-aged and freckled, normally colored, still fairly smooth despite the raised veins, still cunning to hold and twist and manipulate. His own hands, attached to his own arms. Shaken, he sighed in shuddering relief.

He walked slowly over the grass toward the interior of the island. Under the nearest trees—larch, beech, hickory—wild strawberries grew thickly. He picked quantities of the elusive fruit, crushing it with his tongue against the roof of his mouth, enjoying its sweetness, allowing the juice to trickle slowly, deliciously down his throat. He had not tasted wild strawberries since the day he and Mattie decided to get married (No children till we can give them the things they should have).

The trees were well spaced, letting the light enter freely between them. There was no young growth, no saplings; all the trees were full grown and healthy, with no sign of deadfalls or rotted logs. Only, far apart, raspberry canes bearing their garnet, black, white or green thimbles.

The trees didn't thin, they stopped abruptly. Ahead was a natural clearing; in the center of the clearing a jungle growth of stalks and vines rose in a high and inextricably tangled mound. Lampley advanced, irresistibly attracted. He tried to part the interwoven stems but they refused to give. On the ground were flat stones, some with sharp edges. He picked up a fair-sized one and went back to the woods. With some trouble he used it to saw off an oak branch.

He shaped the club to the right heft and bound the stone to it with vines. He was dubious of its strength and his doubts proved justified when, after hacking through some of the growth, the head came loose. With new patience he reaffixed it and continued to cut away. His arms began to ache; short, blinding flashes darted behind his eyes. He persisted; there was no reason, no goal—he was simply impelled to clear his way into whatever lay hidden by the tangle.

After refitting his crude ax again and again, he tore away the loosened vines to reveal a white stone column, tapered slightly at base and capital, its smooth sides spotted with the marks of the sucking disks and clinging tendrils he had torn free. Beyond the column he was faced by an enclosed, roofed rectangle. In this dim area no vines grew except the sickly, inhibited, baffled ends whose invading thrust had faltered in complete discouragement. Doubling back, they had interwoven in their attempt to return to the light, but they had not been able to make a curtain impervious enough to prevent him seeing the backs of the other pillars and the high roof they supported.

He shouldered his way in and peered through the dusk to make out a table flanked by two wide couches. Both table and couches were of the same stone as the columns—marble, Lampley guessed—the couches piled with soft furs. He took a tentative step forward.

Something glinted dully on the table, it was a bronze ax. He picked it up, balanced it, tried the edge with his thumb. It was reasonably sharp and the handle was firmly fitted into the head.

With mounting enthusiasm he attacked the vines from the rear, chopping and slicing, confident in this fine tool. Triumphantly he cleared the space between two pillars, dragged the cut growth clear, returned to his task. He freed another pillar, opened another space, dragged more vines away.

Now the interior was lucid enough to show the floor as one large mosaic of gleaming stones. The picture they composed was of a central fire, the flames red, blue and yellow, surrounded by smaller, less brilliant fires. On the outer edge animals turned their heads toward the warmth: horses, oxen, elephants, lynx, hippopotami, wolves, lions, zebras, elk.

He resumed his work, finished clearing one of the long sides and pulling down the severed branches from the roof before stopping again. Backing away to the trees he saw the building was so simple in design, so artfully proportioned, that it might have grown in this spot. The low pitched roof was copper, untarnished, like the new-minted pennies he had picked up in the hotel.

There was almost full visibility inside the little temple now; on impulse he hacked holes in the ivy on the other three sides for crude windows. The fresh light illuminated the ceiling, intricately painted in abstract designs with colors as bright as those of the mosaic. The table and couches were the only furniture, but on the floor, neatly laid out against columns, was a variety of fishing equipment.

He picked up a rod and held it out. It was limber, fitted with silk line and a dry fly. A searching vine-tip had tried to loop around the reel; he disentangled it. Carrying the rod, he left the temple and sauntered into the woods. There were no paths, no need of any beneath the widely spaced trees, yet he seemed to be following a definite avenue, broad and almost straight. Despite his nakedness and recent exertions he felt no chill in the shade; there was no tiredness in his muscles nor discomfort from the ground under his feet.

He passed natural clearings where saplings had not encroached upon the low-growing plants he recognized as edible, though clearly uncultivated. There were peas and beans of strange species, large and succulent, spattered with rainbow tints, purple melons, green cucumbers, golden-yellow leeks and onions as well as unfamiliar shrubs with broad green leaves and many kinds of flowers.

In a much larger clearing there was a pool of the same deep blue as the lake, roughly oval and perhaps twice the size of the little temple. At one end rushes grew tall, at the other, lotus offered their heavy flowers haughtily upward. The rest of the pool was covered with waterlilies and lily pads on which there was constant movement.

He thought they must be teeming with water beetles or very small frogs; when he squatted at the water's edge he discovered the figures to be tiny men and women leaping and frolicking on the moss, rolling smooth pebbles tall as themselves, swimming out to the pads, climbing the lilies and diving from them, sporting in the water, showing no signs of alarm at his presence.

He lay down flat for a closer look. Some wore loincloths or loose robes, most did not. Their graceful movements accented their strength and endurance; they performed feats easily, which, if done in proportion by any full-sized man would have exhausted him quickly, yet these went from one game to another without flagging. They moved so swiftly it was hard to estimate their number; he thought there might be fifty of them here. He had no way of knowing if this was all of them or whether those in sight constituted a part of their number, with the rest engaged, perhaps, in less active pursuits.

As he became accustomed enough to tell them apart he saw there were no children among them. Lampley could understand why they should segregate their young, for some of their amusements were startling even to a worldly adult; however the simpler variations suggested that they did perpetuate themselves in the customary way. Except when forced by circumstance to take a position on obscene literature, sex-offences or unconventional behavior, Lampley was morally relaxed; he viewed their recreation with the detached interest of an anthropologist, the appreciation of an aesthete, the envy of a man past his youth. He remained silent and watched for quite some time.

He noticed one female wandering apart from the rest, neither joining the others nor being sought by them. He thought there was dejection or despondency in the set of her shoulders, in the aimless way she placed one slender leg before the other or clasped her hands behind her neck. All of the tiny people were exquisite, but she, because of her repose and aloofness, seemed even more beautiful than the others. Without quite intending to, he reached out his free hand and lifted her close to his face.

She gave no sign of surprise or fear, but stared back into his eyes whose irises were the size of her head. He marveled at the fineness of her features, the flowing lines of her body, the gracefulness of her arms and legs, the regal carriage of her head. Her loveliness was poignant and perfect. He could not take his eyes from her.

It was impossible for him to put her down again, to part from her, to walk away as though he had not touched and held her. Guiltily, furtively, he carried her back to the temple, holding her against his chest, fearful that the beating of his heart must be a frightening thunder in her ears. He told himself he would not keep her long; before she was missed he would take her back.

He placed her on the table and sat on the couch admiring her. The diminutive face was haughty and sullen but in no way distressed. Her dark hair was piled on top of her head, falling with seeming artlessness to her shoulders, her breasts were high and taut—round, defiant shields—her thighs long and sleek. Even allowing for the difficulty of discerning blemish in so small a being, the glowing color, pale yet warm, the smooth hands and feet, the clustered body hair, all spoke of such flawlessness that he had to control his fingers lest they close in upon her to squeeze out the essence of beauty.

He whispered, "Do you hear me? Can you understand me?"

She moved her head slightly aside. Whether from outrage, annoyance or indifference he could not tell. He did not think it was incomprehension. When he repeated his questions she made no response at all.

She seemed to weary; he thought he detected an effort to keep her head erect, her eyelids from drooping. He placed her gently on the couch, ran a fingertip lightly over her side. She trembled and stiffened. When he took his hand away she curled in a graceful pose and closed her eyes. He covered her with one of the furs from the other couch; she did not move.

He picked up the fishing rod from where he dropped it outside when he had brought her in. The vines appeared to have grown; he must chop them closer, root them out if possible, clear the remaining sides entirely. There was no reason to allow the temple to be covered again.

He strode purposefully back to the lake. By chance he did not arrive at the cove where the boat was but further along the shore where a narrow pier, no more than a series of poles stuck into the lake bottom with planks laid on the cross-pieces, jutted out a few yards over the water.

He walked to the end and gazed into the clear depths. Marine flowers—vegetable, mineral or animal—wavered in a multitude of bright hues. Swimming, basking, or feeding among them were myriads of translucent fish, large and small, silver, blue, red, orange, green, nacreous gray. Below them flatfish moved slowly, rippling their bodies in lazy humps. Above them torpedo-shaped swimmers sped madly with barely perceptible flicks of tail and fins. Just under the surface, breaking into the air every now and then, thickly clustered schools of shiny fingerlings raced and darted in confusion.

Lampley was not a practiced angler, he was dubious of his ability to cast the dry fly and he saw he had brought along the wrong equipment. He let out a length of line awkwardly and watched the fly float on the surface, then very slowly sink downward. The excitement which had fevered him since he came upon the figures at the pool subsided. He was content.

The crimson fish shot from nowhere at the now invisible fly and the rod jumped almost from his hands as the reel unwound. The fish ran out toward the channel, the line lifting clear, like a knife cutting up through jelly. It circled and leapt, a dazzling blot of whirling color against the lake's placid blue.

He gained back considerable line before the fish ran again. He reeled in, the fish dived; each time it took less line. At last Lampley brought it gasping and thrashing on its side to the end of the pier. Lying flat, he was able to reach down and hook two fingers under the distending gills to lift it into the air.

He carried the fish back to the temple. The vines were winding around the base of the columns again; loose tendrils crept toward each other, ready to intertwine upon meeting. He came in nervously, eyes averted, as though by deliberately not searching for her he would assure her still being there. She was on the couch where he had left her, one tiny arm—was his memory playing him tricks? It did not seem so small as it had—thrown over her eyes.

He had no knife to scale the fish, no fire to cook it. He was not hungry himself but his captive might be. He put his rod away, took the bronze ax and the fish outside. With the edge of the ax he managed clumsily to cut the flesh from the backbone in a crude filet, then he scraped the filet free of the skin. Tentatively he tasted a piece; it was delicious.