Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

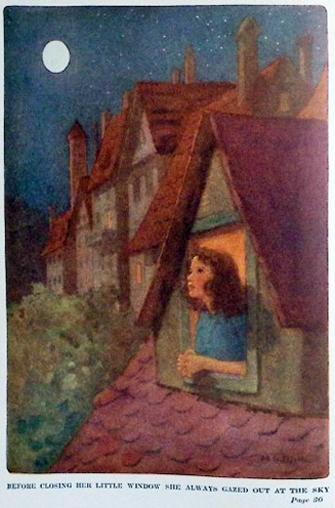

BEFORE CLOSING HER LITTLE WINDOW,

SHE ALWAYS GAZED OUT AT THE SKY.

BY

JOHANNA SPYRI

AUTHOR OF "HEIDI," "MÄZLI," ETC.

TRANSLATED BY

ELISABETH P. STORK

ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOR BY

MARIA L. KIRK

PHILADELPHIA & LONDON

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1924, BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

PRINTED BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

AT THE WASHINGTON SQUARE PRESS

PHILADELPHIA, U. S. A.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

III. THE OTHER SIDE OF THE HEDGE

V. BEFORE AND AFTER THE DELUGE

VIII. STILL MORE RIDDLES AND THEIR SOLUTIONS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Before closing her little window, she always gazed out at the sky. Frontispiece

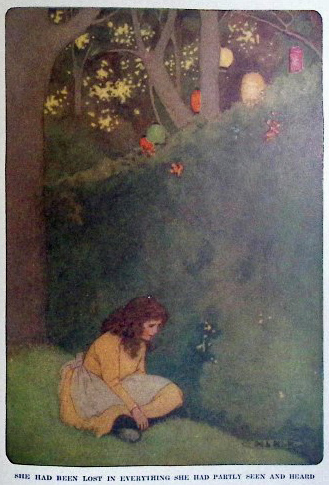

She had been lost in everything she had partly seen and heard.

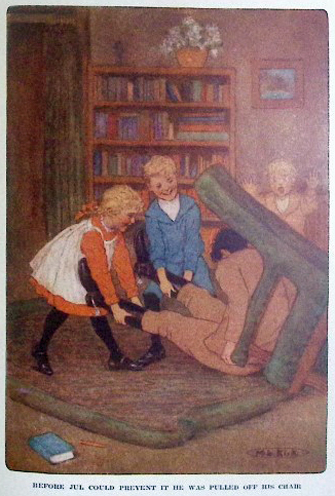

Before Jul could prevent it, he was pulled off his chair.

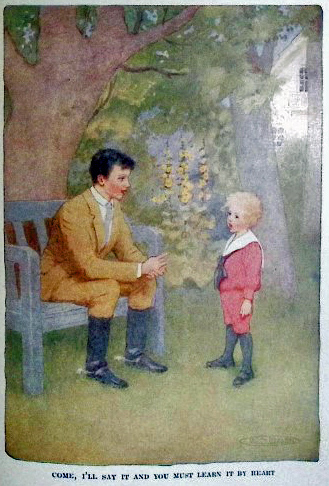

"Come, I'll say it and you must learn it by heart."

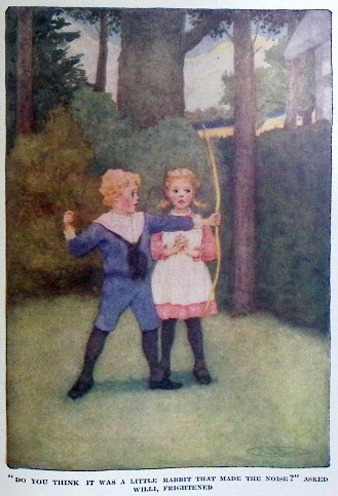

"Do you think it was a little rabbit that made the noise?" asked Willi, frightened.

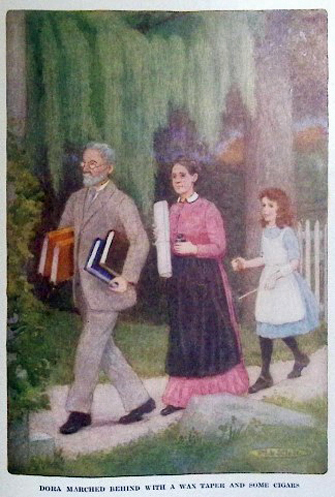

Dora marched behind with a wax taper and some cigars.

"I suppose it is patrimony, my son," said Mr. Titus, patting Rolf's shoulder.

Dora and Paula returned to the garden arm in arm singing gaily.

DORA

UNDER THE LINDEN TREES

IN A beautiful park in Karlsruhe, a gentleman was seen walking under the shady linden trees every sunny afternoon. The passers-by could not help being touched when they saw him leaning upon a little girl, his daily companion. He was apparently very ill, for they walked slowly and he carried in his right hand a cane, while he often took his left from the child's shoulder, inquiring affectionately, "Tell me, child, if I press on you too heavily."

But the little girl always drew back his hand and reassured him gladly, "I can hardly feel it, papa. Just lean on me as heavily as you want."

After walking up and down for a while the pair always settled beneath the lovely trees.

The sick man, a certain Major Falk, lived with his daughter Dora and an elderly housekeeper who attended to his wants. They had only recently come to Karlsruhe. Dora had never known her mother, who had died soon after the child's birth, and she therefore clung to her father with double affection, and he, with great tenderness, did his best to make up to Dora for her early loss.

A year before he had been obliged to leave his child and fight in a war against the enemy. When he returned he was very ill and miserable, having received a dangerous wound in the chest, which physicians pronounced as hopeless. Major Falk, who had no relatives or connections in Hamburg, had lived a very retired life there, and the only relative he had in the world was an elderly step-sister who was married to a scholar in Karlsruhe by the name of Titus Ehrenreich. When Major Falk realized the hopelessness of his condition, he decided to move to Karlsruhe, where his step-sister could come to his and his eleven-year-old daughter's assistance, if his illness became acute. The resolution was soon carried out and he found pleasant lodgings near his sister.

He enjoyed these beautiful spring days with his lovely daughter as daily companion on his walks, and when the two sat hand in hand on the bench, the father told about his past experiences and Dora never grew tired of listening. She was quite sure nobody in the world was as wonderful and splendid and interesting as her father. Most of all, she loved to hear about her mother, who had been so merry, bringing sunshine wherever she went. Everyone had loved her and no one who had loved her could forget her. When the father was lost in such recollections, he often forgot completely where he was till it grew late and the damp evening air made him shiver and reminded him that it was time to go home. The pair walked slowly till they came to a narrow street with high houses on both sides.

Here the father usually stopped, saying: "We must go to see Uncle Titus and Aunt Ninette." And climbing up the stairs, he daily reminded his little daughter: "Be very quiet, Dora! You know Uncle Titus writes very learned books and must not be disturbed, and Aunt Ninette is not used to noise, either."

Dora climbed upstairs on tiptoe, and the bell was rung most discreetly.

Usually Aunt Ninette opened the door herself and said, "Come in, dear brother, but please be very quiet. Your brother-in-law is much lost in his work as usual."

With scarcely a sound, the three went along the corridor to the living room which was next to Uncle Titus's study. Here, too, one had to be very quiet, which Major Falk never forgot, though Aunt Ninette herself often broke out into sad complaints about many things that troubled her.

June had come and the two could stay out quite long under the linden trees. But they found themselves obliged to return sooner than was their wish, because otherwise Aunt Ninette worried dreadfully. On one such warm summer evening, when the sky gleamed all golden, and rosy and fluffy clouds were sailing along the sky, Major Falk stayed seated on the bench until quite late. Holding his child's hand in his, he quietly watched the radiant sunset with Dora, who gazed up with wonder at her father.

Quite overwhelmed by her impression, she cried out, "Oh, father, you should just see yourself; you look all golden the way the angels in heaven must look."

Smilingly, her father answered, "I think I shall not live much longer, and I feel as if your mother were looking down upon us from that sky." But before long her father had grown pale again and all the glow in the sky had faded. When he rose, Dora had to follow, quite depressed that the beautiful glow had paled so soon. But her father spoke these words of comfort, "It will glow again some day and much more splendidly than today, when your mother, you and I will be all together again. It won't ever fade then."

When the pair came up the stairs to greet Dora's uncle and aunt, the latter stood upstairs at the open door showing visible signs of agitation, and as her visitors entered her living room, she gave free vent to her excitement.

"How can you frighten me so, dear brother!" she wailed. "Oh, I imagined such terrible things! What can have kept you so long? How can you be so forgetful, and not remember that you must not be out after sunset. Just think what dreadful things might happen if you caught cold."

"Calm yourself, dear Ninette," said the Major as soon as he had a chance to speak. "The air is so mild and warm today that it could do me no harm and the evening was simply glorious. Please let me enjoy the few lovely evenings that are still left to me on earth. They neither hasten nor hinder what is sure to happen very soon."

These words spoken so quietly brought forth new outbursts of despair.

"How can you speak that way? How can you frighten me so? Why do you say such awful things?" cried the excited woman. "It cannot happen and it must not happen! What is to be done then with—yes, tell me—you know whom I mean." Here the aunt threw an expressive glance at Dora. "No, Charles, a terrible misfortune like that must not break in upon us—no, it would be too much. I would not even know what to do. What is to happen then, for we shall never get along."

"But, my dear Ninette," the brother retorted, "don't forget these words:"

"'Though sad afflictions prove us

And none his fate can tell,

Yet God keeps watch above us

And doeth all things well.'"

"Oh, yes, I know, and I know it is true," agreed the sister. "But where one sees no help anywhere, one feels like dying from fright, while you talk of such dreadful things as if they were quite natural."

"We'll have to say good-night now, and please try not to complain any more, dear Ninette," said the Major, stretching out his hand. "We must remember the lines:"

"'Yet God keeps watch above us

And doeth all things well.'"

"Yes, yes, I know it is true, I know it is true," assented the aunt once more, "but don't catch cold on the street, and do go downstairs without making any noise. Do you hear, Dora? Also, shut the downstairs door quietly, and when you go across the street, try not to be in the draft too long."

During these last injunctions, the father had already gone downstairs with Dora and home across the narrow street.

The following day, when they sat on the bench again under the lindens, Dora asked, "Papa, didn't Aunt Ninette know that:"

"'Yet God keeps watch above us

And doeth all things well.'"

"Of course she knows it," replied the father, "but at times when she gets anxious, she forgets it a little. She regains her balance when she thinks of it."

After musing a while Dora asked again, "But, papa, what shall one do to keep from being frightened and dying from fear as Aunt Ninette says?"

"Dear child," the father answered, "I will tell you what to do. Whatever happens, we must always think that it comes from God. If it is a joy, we must be grateful, and if it is a sorrow, we must not be too sad, because we know God our Father sends everything for our good. In that way we need never suffer from fear. Even if a misfortune comes and we see no help at hand, God is sure to find some succor for us. He alone can let good come out of evil, even one that seems to crush us. Can you understand me, Dora, and will you think of that if you should ever be unhappy? You see hard days come to everybody and to you, too, dear child."

"Yes, yes, I understand and I'll think of it, papa," Dora assured him. "I'll try not to be frightened."

"There is another thing which we must not forget," continued the father. "We must not only think of God when something special happens to us. We must ask Him at every action if He is satisfied with us. When a misfortune comes, we are near to Him already if we do that and we experience a certainty at once of receiving help. If we forget Him, on the contrary, and a sorrow comes, we do not find the way to Him so easily and we are apt to remain in darkness."

"I'll try never to lose the way, papa," said Dora eagerly, "and ask God every day: 'Am I doing right?'"

Tenderly stroking his child's head, the father remained silent, but in his eyes lay such a light that she felt herself surrounded by a loving care.

The sun sank behind the trees and father and child happily walked home.

LONG, LONG DAYS

A few days after this lovely evening, Dora sat at her father's bedside, her head prostrate beside his. She was sobbing bitterly, for he lay quite still with a smile on his white face. Dora could not fully comprehend what had happened yet, and all she knew was that he had joined her mother in heaven.

That morning when her father had not come as usual to her bedside to wake her, she had gone to his room instead. She found him lying motionless on his bed, and, thinking him asleep, she had kept very quiet.

When the housekeeper, who came in with breakfast, had cast a glance in his direction, Dora heard her exclaim, "Oh God, he is dead! I must quickly fetch your aunt." With this she had run away.

This word had fallen on Dora like a thunderbolt, and she had laid her head on the pillow beside her father, where she stayed a long while, sobbing bitterly. Then Dora heard the door open and her aunt came in. Lifting her head, she used all her strength to control her sorrow, for she knew that a wild outburst of grief was coming. She was dreadfully afraid of this and most anxious not to contribute to it further. She wept quietly, pressing her head into her arms in order not to let her sobs escape. The aunt loudly moaned and cried, wailing that this dreadful misfortune should just have happened and saying she saw no help for any of them.

What should be seen to first, she wondered. In the open drawer of the table beside her brother's bed several papers lay about, which the aunt folded up in order to lock away. Among them was a letter addressed to her. Opening it she read:

"DEAREST SISTER NINETTE:"

"I feel that I shall leave you soon, but I don't want to speak

of it, in order not to cause you dark hours before I have to. I have

a last request to make to you. Please take care of my child as long

as she needs you. As I am unable to leave her any fortune to speak of,

I beg you to use the small sum she owns to let her learn some useful

work by which Dora, with God's help, will be able to support herself

when she is old enough. Be not too much overcome with sorrow and

believe as I do that God does His share for all His children whom we

recommend to His care, and for whom we ourselves cannot do very much.

Accept my warm thanks for all your kindness to me and Dora. May God

repay you!"

The letter must have soothed the aunt a little, for instead of wailing loudly she turned to Dora, who, with her head pressed into her arms, was still quietly weeping.

"Come with me, Dora," said the aunt; "from now on you shall live with us. If we didn't know that your father is happy now, we should have to despair."

Dora obediently got up and followed, but she felt as if everything was over and she could not live any longer. When she entered the quiet dwelling, the aunt for the first time did not have to remind her to be quiet, feeling sure this was unnecessary. As the child came to her new home, it seemed as if no joyful sounds could ever again escape her.

The aunt had a store-room in the garret which she wanted to fit up for Dora. This change could not take place without some wailing, but it was at last accomplished and a bed placed in it for her niece. The maid went at once to fetch the child's belongings, and the little wardrobe in the corner was also set in order.

Dora silently obeyed her aunt's directions and, as bidden, came down afterwards to the quiet supper. Uncle Titus said nothing, being occupied with his own thoughts. Later on, Dora went up to her little chamber where she cried into her pillow till she fell asleep.

On the following day, Dora begged to be allowed to go over to her father, and the aunt accompanied her with expressions of renewed sorrow. Dora quietly said goodbye to her beloved father, sobbing softly all the while. Only later on, in her own little room, did she break out into violent sobs, for she knew that soon he would be carried away and she would never see him any more on earth.

From then on, Dora's days were planned quite differently. For the short time she had been in Karlsruhe, her father had not sent her to any school, only reviewing with her the studies she had taken in Hamburg. Apparently, he had been anxious to leave such decisions to his sister when the time came. Aunt Ninette had an acquaintance who was the head of a girls' private school and Dora was to go there in the mornings. For the afternoon a seamstress was engaged to teach Dora to make shirts, cut them out and sew them. Aunt Ninette considered this a very useful occupation, and by it, Dora was to make her livelihood. All clothing began with the shirt, so the knowledge of dressmaking also began with that. If Dora later on might get as far as dressmaking, even her aunt would be immensely pleased.

Dora sat every morning on the school-bench, studying hard, and in the afternoons on a little stool beside the seamstress. Sewing a big heavy shirt made her feel very hot and tired. In the mornings, she was quite happy with the other children, for Dora was eager to learn and the time went by pleasantly without too many sad thoughts about her father.

But the afternoons were different. Sitting in a little room opposite her teacher, she had a hard time handling the shirts and she would get very weary. The long hot summer afternoons had come and with her best exertions, she could hardly move the needle. The flannel felt so damp and heavy and the needle grew dull from heat. If Dora would look up to the large clock, whose regular ticking went on, time seemed to have stood still and it never seemed to be more than half past three. How long and hot these afternoons were! Once in a while, the sounds of a distant piano reached her—probably some lucky child was playing her exercises and learning lovely melodies and pieces.

This seemed, in these hard times, the greatest possible bliss to Dora. She actually hungered and thirsted for these sounds, which were the only thing to cheer her, as few carriages passed in the narrow street below and the voices of the passers-by did not reach them. The scales and exercises she heard were a real diversion, and if Dora heard even a little piece of music she was quite overjoyed and lost not a note. What a lucky child! she thought to herself, to be able to sit at the piano and learn such pretty pieces.

In the long, dreary afternoons, Dora was visited by melancholy thoughts and she remembered the time when she had strolled with her father under the linden trees. This time would never come again, she would never see and hear him any more. Then the consolation her father himself had given her came into her mind. Some day, of course, she would be with both her parents in the golden glow, but that was probably a long way off, unless something unusual happened and she were taken ill and should die from sewing shirts. But her final consolation was always the words her father had taught her:

"'Yet God keeps watch above us

And doeth all things well.'"

She tried to believe this firmly and, feeling happier in her heart, made her needle travel more easily and more lightly, as if driven by a joyful confidence. Just the same, the days were long and dreary, and when Dora came home in the evening to Aunt Ninette and Uncle Titus, everything about her was so still. At supper, Uncle Titus read and ate behind a big newspaper and the aunt talked very little in order not to disturb her husband. Dora said nothing, either, for she had become adapted to their quiet ways. In the few hours she spent at home between her lessons, Dora never had to be told to be quiet; all her movements had become subdued and she had no real heart in anything.

By nature, Dora was really very lively and her interests had been keen. Her father had often exclaimed with satisfaction: "The child is her mother's image!—The same merriment and inexhaustible joy in life." All that was now entirely gone and the child very seldom gave her aunt occasion to complain. Dora avoided this because she feared such outbreaks. Every time, after such a demonstration, she repressed for a long time every natural utterance and her joy of life would be completely gone. One evening, Dora returned from her work full of enthusiasm, for the young pianist across the street had played the well-known song Dora loved and could even sing:

"Rejoice, rejoice in life

While yet the lamp is glowing

And pluck the fragrant rose

In Maytime zephyrs blowing!"

"Oh, Aunt Ninette!" she cried upon entering the room, "It must be the greatest pleasure in the world to play the piano. Do you think I could ever learn it?"

"For heaven's sake, child, how do you get such ideas?" wailed Aunt Ninette. "How can you frighten me so? How could such a thing be possible? Only think what noise a piano would make in the house. How could we do it? And where, besides, should we get the time and money? How do you get such unfortunate ideas, Dora? The troubles we have are enough without adding new ones."

Dora promised to make no more suggestions. She never breathed another word about the subject, though her soul pined for music.

Late in the evening, when Dora had finished her work for school, while the aunt either knitted, mended or sometimes dropped asleep, Dora climbed up to her garret room. Before closing her little window, she always gazed out at the sky, especially when the stars gleamed brightly. Five stars stood close together right above her head, and by and by, Dora got to know them well. They seemed like old friends come especially to beckon to her and comfort her. Dora even felt in some mysterious way as if they were sent to her little window by her father and mother to bring her greetings and keep her company. They were a real consolation, for her little chamber was only dimly lighted by a tiny candle. After saying her evening prayer while looking at the starry heavens, she regained a feeling of confidence that God was looking down at her and that she was not quite forsaken. Her father had told her that she had nothing to fear, if she prayed to God for protection, for then His loving care would enfold her.

In this fashion, a dreary hot summer went by, followed by the autumn and then a long, long winter. Those days were dark and chilly and made Dora long for warmth and sunshine, for she could not even open her little window and gaze at her bright stars. It was bitter chill in her little garret room so near the roof, and often she could not fall asleep, she was so cold. But spring and summer came at last again and still things went their accustomed rounds in the quiet household. Dora was working harder than ever at her large shirts because she could now sew quite well, and was expected really to help the seamstress.

When the hot days had come, something unusual happened. Uncle Titus had a fainting spell and the doctor had to be fetched. Of course, Aunt Ninette was dreadfully upset.

"I suppose you have not gone away from Karlsruhe for thirty years, and you only leave your desk to eat and sleep?" asked the physician after a searching glance at Uncle Titus and a short examination.

The question had to be answered in the affirmative. It was the truth.

"Good!" continued the doctor. "You must go away at once and the sooner the better. Try to go tomorrow. I advise Swiss mountain air, but not too high up. You need no medicine at all except the journey, and I advise you to stay away at least six weeks. Have you any preferences? No? We can both think it over and tomorrow I'll come again. I want to find you ready to leave, remember."

The doctor was out of the door before Aunt Ninette could stop him. Eager to ask a thousand questions, she followed. This sudden resolution had paralyzed her and she could not at first find her tongue. She had to consult the doctor about so many important points, though, and he soon found that his abruptness availed him nothing. He was held up outside the door three times as long as he had been in the house. Returning after some time the aunt found her husband at his desk, absorbed as usual, in his studies.

"My dear Titus!" she cried out amazed, "Is it possible you have not heard what is to happen? Do you know we have to start at once and leave everything and without even knowing where to go? To stay away six weeks and not to know where, with whom and in what neighborhood! It frightens me to death, and here you sit and write as if nothing particular had happened!"

"My dear, I am making use of my time just for the very reason that we have to leave," replied Mr. Titus, eagerly writing.

"My dear Titus, I can't help admiring how quickly you can adapt yourself to unexpected situations. This matter, though, must be discussed, otherwise it might have serious consequences," insisted Aunt Ninette. "Just think, we might go to a dreadful place!"

"It doesn't matter where we go so long as it is quiet, and the country is always quiet," replied Mr. Titus, still working.

"That is the very point I am worried about," continued his wife. "How can we guard ourselves, for instance, against an overcrowded house. Just think if we should come into a noisy neighborhood with a school or mill or even a waterfall, which are so plentiful in Switzerland. How can we know that some frightful factory is not near us, or a place where they have conventions to which people from all cantons come together. Oh, what a tumult this would make and it must be prevented at all costs. I have an idea, though, dearest Titus. I'll write to Hamburg, where an old uncle of my sister-in-law lives. At one time his family lived in Switzerland and I can make inquiries there."

"That seems decidedly far-fetched to me," replied Uncle Titus, "and as far as I know, the family had some disagreeable experiences in Switzerland. They probably have severed all connections with it."

"Just let me look after it. I'll see to everything, dear Titus," concluded Aunt Ninette.

After writing a letter to Hamburg, she went to Dora's sewing-teacher, a very decent woman, and asked her to take care of Dora while they were away in Switzerland. After some suggestions from both women, it was decided that Dora should spend her free time at the seamstress's house, and at night, the woman would come home with the child in order to have someone in the house. When Dora was told about these plans that evening, she said nothing and went up to her lonely garret. Here she sat down on the bed, and sad memories crowded upon her mind of the times when she and her father had been so happy. They had spent every evening together and when he had been tired and had gone to bed early, she had come to his bedside. She was conscious how forsaken she would be when her uncle and aunt had left, more lonely even than she was now. Nobody would be here to love her and nobody she could love, either.

Gradually, poor Dora grew so sad that she drooped her head and began to cry bitterly, and the more she wept the more forlorn she felt. If her uncle and aunt should die, not a soul would be left on earth belonging to her and her whole life would be spent in sewing horrid heavy shirts. She knew that this was the only way by which she could earn her livelihood and the prospect was very dreary. She would not have minded if only she had someone to be fond of, for working alone all day, year in and year out, seemed very dreadful.

She sat there a long time crying, till the striking of the nearby church clock startled her. When at last she raised her head it was completely dark. Her little candle was burnt out and no more street lamps threw their light up from the street. But through the little window her five stars gaily gleamed, making Dora feel as if her father were looking down affectionately upon her, reminding her confidently as on that memorable evening:

"'Yet God keeps watch above us

And doeth all things well.'"

The sparkling starlight sank deep into her heart and made it bright again, for what her father had said to her must be the truth. She must have confidence and needn't be frightened at what was coming. Dora could now lie down quietly, and until her eyes closed of themselves, she looked at her bright stars which had grown to be such faithful comforters.

The evening of the following day, the doctor appeared again as promised with many suggestions to Mr. Ehrenreich about where to go. But Aunt Ninette lost no time in stepping up and declaring that she was already on the search for a suitable place. Many conditions had to be fulfilled if the unusual event was to have no fearful consequences for her husband, every detail had to be looked into, and when everything was settled, she would ask for his approval.

"Don't wait too long, go as soon as possible; don't wait," urged the doctor in an apparent hurry to leave, but nearly falling over Dora who had entered noiselessly just a moment before.

"Oh, I hope I didn't hurt you?" he asked, stroking the frightened child's shoulder. "The trip will do that pale girl good. Be sure to give her lots and lots of milk there. There is nothing like milk for such a frail little girl."

"We have decided to leave Dora at home, doctor," remarked Aunt Ninette.

"That is your affair, of course, Mrs. Ehrenreich! Only look out or her health will give you more worry than your husband's. May I leave now?"

The next moment he was gone.

"Oh, doctor, doctor! What do you mean? How did you mean that?" Aunt Ninette cried loudly, following him down the stairs.

"I mean," called the doctor back, "that the little thing is dreadfully anaemic and she can't live long, if she doesn't get new blood."

"Oh, my heavens! Must every misfortune break in upon us?" exclaimed Aunt Ninette, desperately wringing her hands. Then she returned to her husband. "Please, dear Titus, put your pen away for just a second. You didn't hear the dreadful thing the doctor prophesied, if Dora doesn't get more color in her cheeks."

"Take her along, she makes no noise," decided Uncle Titus, writing all the while.

"But, dear Titus, how can you make such decisions in half a second. Yes, I know she doesn't make any noise, and that is the most important thing. But so many matters have to be weighed and decided—and—and—" but Aunt Ninette became conscious that further words were fruitless. Her husband was once more absorbed in his work. In her room, she carefully thought everything over, and after weighing every point at least three times, she came to the conclusion to follow the doctor's advice and take Dora with her.

A few days later, the old uncle's brief answer arrived from Hamburg. He knew of no connections his brother had kept up with people in Switzerland, for it was at least thirty years since he had lived there. The name of the small village where he had stayed was Tannenberg, and he was certain it was a quiet, out of the way place, as he remembered his brother complaining of the lack of company there. That was all.

Aunt Ninette resolved to turn to the pastorate of Tannenberg at once in order to inquire for a suitable place to live. The sparse information from the letter pleased her and her husband well enough: quiet and solitude were just the things they looked for. The answer was not slow in coming and proved very satisfactory. The pastor wrote that Tannenberg was a small village consisting of scattered cottages and houses and suitable rooms could be had at the home of a school teacher's widow. She could rent two good rooms and a tiny chamber, and for further questions, the pastor enclosed the widow's address.

This proved an urgent need to Aunt Ninette's anxious mind and she wrote to the widow at once, asking for a detailed description of the neighborhood. Beginning with expressions of joy at the knowledge that Tannenberg was a scattered village, she yet questioned the widow if by any chance her house was in the neighborhood possibly of a blacksmith's or locksmith's shop, or stonemason's, or a butcher's, also if any school, mill, or still worse, a waterfall were near—all objects especially to be avoided by the patient.

The widow wrote a most pleasant letter, answering all these questions in the most satisfactory way. No workshops were near, the school and mill were far away and there were no waterfalls in the whole neighborhood. The widow informed her correspondent further that she lived in a most pleasant location with no near dwellings except Mr. Birkenfeld's large house, which was surrounded by a splendid garden, fine fields and meadows. His was the most distinguished family in the whole county; Mr. Birkenfeld was in every council, and he and his wife were the benefactors of the whole neighborhood. She herself owed this family much, as her little house was Mr. Birkenfeld's property, which he had offered to her after her husband's death. He was a landlord such as few others were.

Everything sounded most propitious, and a day was set for the departure. Dora was joyfully surprised when she heard that she was to go along, and she happily packed the heavy linen for the six large shirts she was to sew there. The prospect of working in such new surroundings delighted her so much that even the thought of sewing those long seams was quite pleasant. After several wearisome days, all the chests and trunks stood ready in the hall and the maid was sent to get a carriage. Dora, all prepared, stood on the top of the staircase. Her heart beat in anticipation of the journey and all the new things she would see during the next six weeks. It seemed like immeasurable bliss to her after the long, long hours in the seamstress's tiny room.

Finally Aunt Ninette and Uncle Titus came out of their rooms, laden with numerous boxes and umbrellas. Their walk down stairs and into the waiting carriage proved rather difficult, but at last each object had found a place. A little exhausted uncle and aunt leaned back in the seat and expectantly drove off to their destination in the country.

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE HEDGE

LOOKING far out over the wooded valleys and the glimmering lake stood a green height covered by meadows, in which during the spring, summer and fall, red, blue and yellow flowers gleamed in the sunshine. On top of the height was Mr. Birkenfeld's large house, and beside it, a barn and a stable where four lively horses stamped the ground and glossy cows stood at their cribs quietly chewing the fragrant grass, with which Battist, the factotum of long years' standing, supplied them from time to time.

When Hans, the young stable boy, and the other men employed on the place were busy, Battist always made the round of the stable to see if everything had been attended to. He knew all the work connected with animals, and had entered Mr. Birkenfeld's father's service as a young lad. He was the head man on the place now and kept a vigilant eye on all the work done by the other men. In the hay-lofts lay high heaps of freshly gathered hay in splendid rows, and in the store rooms in the barn all the partitions were stacked up to the ceiling with oats, corn and groats. All these were raised on Mr. Birkenfeld's property, which stretched down the incline into the valley on all sides.

On the other side of the house stood a roomy laundry, and not far from there, but divided off by a high, thick hedge from the large house and garden, was a cottage also belonging to the property. Several years ago, Mr. Birkenfeld had turned this over to Mrs. Kurd after her husband's death.

The warm sunshine spread a glow over the height, and the red and white daisies gazed up merrily from the meadow at the sky above. On a free space before the house lay a shaggy dog, who blinked from time to time in order to see if anything was going on. But everything remained still, and he shut his eyes again to slumber on in the warm sunlight. Once in a while a young gray cat would appear in the doorway, looking at the sleeper with an enterprising air. But as he did not stir, she again retired with a disdainful glance. A great peace reigned in the front part of the house, while towards the garden in the back much chattering seemed to be going on and a great running to and fro. These sounds penetrated through the hallway to the front of the house.

Approaching wheels could now be heard, and a carriage drove up in front of the widow's cottage. For a moment, the dog opened his eyes and raised his ears, but not finding it worth while to growl, slept on. The arrival of the guests went off most quietly indeed. Mrs. Kurd, the schoolmaster's widow, after politely receiving her new arrivals, led them into the house and at once took them up to their new quarters. Soon after, Aunt Ninette stood in the large room unpacking the big trunk, while Dora busied herself in her little chamber unpacking her small one. Uncle Titus sat in his room at a square table, carefully sorting out his writing things.

From time to time, Dora ran to the window, for it was lovelier here than in any place she had ever been. Green meadows spread out in front with red and yellow flowers, below were woods and further off a blue lake, above which the snow-white mountains gleamed. Just now, a golden sunset glow was spread over the near hills, and Dora could hardly keep away from the window. She did not know the world could be so beautiful. Then her aunt called over to her, as some of her things had been packed in the large trunk and she had to take them to her room.

"Oh, Aunt Ninette, isn't it wonderful here?" exclaimed Dora upon entering. She spoke much louder than she had ever done since she had come to her uncle's house to live. The excitement of the arrival had awakened her true, happy nature again.

"Sh-sh! How can you be so noisy?" the aunt immediately subdued her. "Don't you know that your uncle is already working in the next room?"

Dora received her things, and going by the window, asked in a low voice, "May I take a peep out of this window, aunt?"

"You can look out a minute, but nobody is there," replied the aunt. "We look out over a beautiful quiet garden, and from the window at the other side we can see a big yard before the house. Nothing is to be seen there except a sleeping dog, and I hope it will stay that way. You can look out from over there, too."

As soon as Dora opened the window, a wonderful fragrance of jessamine and mignonette rose to her from the flower beds in the garden. The garden was so large that the hedge surrounding green lawns, blooming flower beds and luxurious arbors seemed endless. How beautiful it must be over there! Nobody was visible but there were traces of recent human activity from a curious triumphal arch made out of two bean poles tightly bound together at the top by fir twigs. A large pasteboard sign hanging down from the structure swayed to and fro in the wind, bearing a long inscription written in huge letters.

Suddenly, a noise from the yard before the house made Dora rush to the other window. Looking out, she saw a roomy coach standing in the middle of the yard with two impatiently stamping brown horses, and from the house rushed one—two—three—four—yes, still more—five—six boys and girls. "Oh, I want to go on top," they all cried out at once, louder and ever louder. In the middle of the group, the dog jumped up first on one child, then on another, barking with delight. Aunt Ninette had not heard such noise for years and years.

"For heaven's sake, what is going on?" she cried out, perplexed. "Where on earth have we gotten to?"

"O come, aunt, look, look, they are all getting into the coach," Dora cried with visible delight, for she had never in her life seen anything so jolly.

One boy leaped up over the wheel into the seat beside the driver, then stooping far down, stretched out his arm towards the barking, jumping dog.

"Come, Schnurri, come Schnurri!" cried the boy, trying in vain to catch hold of the shaggy dog's paw or ears.

At last, Hans, the coachman, almost flung the pet up to the boy. Meanwhile, the oldest boy lifted up a dangling little girl and, swinging her up, set her in the coach.

"Me, too, Jul, me, too! Lift me still higher, lift me still higher!" cried out two little boys, one as round as a ball, the other a little taller. They jumped up, begging their elder brother, crowing with anticipation at what was coming.

Then came twice more the swinging motion and their delight was accompanied by considerable noise. The big boy, followed by the eldest girl, who had waited until the little ones were seated, stepped in and the door was shut with a terrific bang by Jul's powerful arm. When the horses started, quite a different noise began.

"If Schnurri can go, Philomele can go too! Trine, Trine!" cried the little girl loudly. "Give me Philomele."

The energetic young kitchen-maid, at once comprehending the situation, appeared at the door. Giving a hearty laugh, she took hold of the gray cat that sat squatting on the stone steps, and looking up mistrustfully at Schnurri on top, and threw her right into the middle of the carriage. With a sharp crack of the whip the company departed.

Full of fright, Aunt Ninette had hastened to her husband's room to see what impression this incident had made upon him. He sat unmoved at his table with his window tightly shut.

"My dear Titus, who could have guessed such a thing? What shall we do?" moaned the aunt.

"The house over there seems rather blessed with children. Well, we can't help it, and must keep our windows shut," he replied, unmoved.

"But my dear Titus, do you forget that you came here chiefly for the fresh mountain air? If you don't go out, you have to let the strengthening air into your room. What shall we do? If it begins that way, what shall we do if they keep it up?" wailed the aunt.

"Then we must move," replied the husband, while at work.

This thought calmed his wife a little, and she returned to her room.

Meanwhile, Dora had busily set her things in order. A burning wish had risen in her heart, and she knew this could not be granted unless everything was neatly put in its right place. The crowd of merry children, their fun and laughter had so thrilled Dora that she longed to witness their return. She wondered what would happen when they all got out again. Would they, perhaps, come to the garden where the triumphal arch was raised? She wanted to see them from below, as the garden was only separated from Mrs. Kurd's little plot of ground by a hedge. There must be a little hole somewhere in this hedge through which she could look and watch the children.

Dora was so filled with this thought, that it never occurred to her that her aunt might not let her go out so late. But her desire was greater than the fear of being denied. She went at once to her aunt's door, where she met Mrs. Kurd, who was just announcing supper. Dora quickly begged to be allowed to go down to the garden, but the aunt immediately answered that they were going to supper now, after which it would be nearly night.

Mrs. Kurd assured her aunt that anybody could stay out here as long as they wished, as nobody ever came by, and that it was quite safe for Dora to go about alone. Finally, Aunt Ninette gave Dora permission to run in the garden a little after supper. Dora, hardly able to eat from joy and anticipation, kept listening for the carriage to return with the children. But no sound was heard.

"You can go now, but don't leave the little garden," said the aunt at last. Dora gave this promise gladly, and running out eagerly, began to look for some opening in the hedge. It was a hawthorne hedge and so high and thick that Dora could look neither through it nor over the top. Only at the bottom, far down, one could peep through a hole here and there. It meant stooping low, but that was no obstacle for Dora. Her heart simply longed to see and hear the children again. Never in her life had she known such a large family with such happy looking boys and girls. She had never seen such a crowd of children driving out alone in a coach. What fun this must be!

Dora, squatting close to the ground, gazed expectantly through the opening, but not a sound could be heard. Twilight lay over the garden, and the flowers sent out such a delicious fragrance that Dora could not get enough of it. How glorious it must be to be able to walk to and fro between those flower beds, and how delightful to sit under that tree laden with apples, under which stood a half hidden table! It looked white with various indistinct objects upon it. Dora was completely lost in contemplation of the charming sight before her, when suddenly the merry voices could be heard, gaily chattering, and Dora was sure the children had returned. For awhile, everything was still, as they had gone into the house. Now it grew noisy again, and they all came out into the garden.

Mr. Birkenfeld had just returned from a long journey and his children had driven down to meet him at the steamboat-landing on the lake. The mother had made the last preparations for his reception during that time and arranged the festive banquet under the apple tree in the garden. As the father had been away several weeks, his return was a joyous occasion, to be duly celebrated.

As soon as the carriage arrived, the mother came out to greet him. Then one child after another jumped out, followed by Philomele and Schnurri, who accompanied the performance with joyous barks. All climbed up the steps and went into the large living room. Here the greetings grew so stormy that their father was left quite helpless in the midst of the many hands and voices that were crowding in upon him.

"Take turns, children! Wait! One after another, or I can't really greet you," he called into the hubbub. "First comes the youngest, and then up according to age. Come here, little Hun! What have you to say to me?"

Herewith, the father drew his youngest forward, a little boy about five years old, originally called Huldreich. As a baby, when asked his name, the little one had always called himself Hun and the name had stuck to him, remaining a great favorite with his brothers and sisters and all the other inmates of the house. Even father and mother called him Hun now. Jul,* the eldest son, had even made the statement that the small Hun's flat little nose most curiously reminded one of his Asiatic brothers. But the mother would never admit this.

This small boy had so much to tell his father, that the latter had to turn from him long before he was done with his news.

"You can tell us more later on, small Hun. I must greet Willi and Lili now. Always merry? And have you been very obedient while I was away?"

* Pronounced Yule in the original.

"Mostly," answered Willi, with slight hesitation, while Lili, remembering their various deviations from the paths of righteousness, decided to change the subject of conversation, and gaily embraced her father instead. Willi and Lili, the twins, were exactly eight years old and were so inseparable that nobody even spoke of them separately. They always played together, and often undertook things which they had a clear glimmering that they should not do.

"And you, Rolf, how are you?" said the father, next, to a boy about twelve years old with a broad forehead and sturdy frame. "Are you working hard at your Latin and have you made up some nice riddles?"

"Yes, both, papa. But the others won't ever try to guess them. Their minds are so lazy, and mamma never has time."

"That is too bad, and you, Paula?" continued the father, drawing to him his eldest daughter, who was nearly thirteen. "Are you still longing for a girl friend, and do you still have to walk about the garden alone?"

"I haven't found anybody yet! But I am glad you are back again, papa," said the girl, embracing her father.

"I suppose you are spending your holidays in a useful fashion, Jul?" asked the father, shaking hands with his eldest.

"I try to combine my pleasure with something useful," replied Jul, returning his father's handshake. "The hazel nuts are ripe now, and I am watching over their harvest. I also ride young Castor every day, so he won't get lazy."

Julius, who was seventeen years old, and studied at a high school of the nearest town, was home for his holidays just now. As he was very tall for his age, everybody called him "big Jul."

"I must ask you to continue your greetings in the garden, papa. All kinds of surprises await you there," began Jul again, coming up to his father, who was pleasantly greeting Miss Hanenwinkel, the children's governess and teacher.

But Jul had to pay dearly for this last remark. Immediately Willi and Lili flew at him from behind, enjoining him to silence by pinching and squeezing him violently. Fighting them off as best he could, he turned to Lili: "Let me go, little gad-fly. Just wait, I'll lead up to it better." And turning towards his father he said loudly, "I mean in the garden where mother has prepared all kinds of surprises you won't despise. We must celebrate by having something to eat, papa."

"I agree with you; how splendid! Perhaps we shall even find a table spread under my apple tree. I should call that a real surprise!" cried the father, delighted. "Come now!"

Giving the mother his arm, he went out, followed by the whole swarm. Lili and Willi were thrilled that their papa thought this was the only surprise in store for him.

Upon stepping outside, the parents stood immediately under a triumphal arch; at both sides hung small red lanterns which lit up the large hanging board on which was a long inscription.

"Oh, oh," said the father, amazed, "a beautiful triumphal arch and a verse for my welcome. I must read it." And he read aloud:

"We all are here to welcome you beside the garden gate;

And since you've come, we're happy now, we've had so long to wait.

We all are glad, as glad can be, our wishes have come true;

You've got back safe, and we have made this arch to welcome you."

"Beautiful, beautiful! I suppose Rolf is the originator of this?"

But Willi and Lili rushed forward crying, "Yes, yes, Rolf made it, but we invented it. He made the poem, and Jul set up the poles, and we got the fir twigs."

"I call this a wonderful reception, children," cried the delighted father. "What lovely little red, blue and yellow lights you have put everywhere; the place looks like a magic garden! And now I must go to my apple tree."

The garden really looked like an enchanted place. Long ago the small colored lanterns had been made, and Jul had fastened them that morning on all the trees and high bushes of the garden. While the greetings were taking place in the house, old Battist and Trine had quickly lit them. The branches of the apple tree also were decorated with lights, making it look like a Christmas tree, with the apples gleaming out between the lanterns. They threw their light down on the table with its white cloth on which the mother had set the large roast, tempting the guests with the special wine for the occasion and the high pile of apple tarts.

"This is the nicest festival hall I can imagine!" exclaimed the father happily, as he stood under the sparkling tree. "How wonderful our dinner will taste here! Oh, here is a second inscription."

Another white board hung down on two strings from the high branches behind the trees. On it was written:

"Happy all at my first are reckoned,

Christmas is in the state of my second,

And for my whole the feast is spread

With candy, nuts and gingerbread."

"Oh, I see, a riddle; Rolf must have made this for me!" said the father, kindly patting the boy's shoulder. "I'll set to work guessing as soon as we have settled down. Whoever guesses the riddle first may touch glasses with me before the others. Oh, how pleasant it is to be together again."

The family sat down under the tree, and the conversation soon began to flow. From big Jul down to little Hun there seemed to be no end of all the experiences everybody had to tell.

A sudden silence fell when the father pulled out from under his chair a large package, which he promptly began to unpack. The children watched his motions with suspense, knowing that a present for everybody would now come to light. First, came shining spurs for Jul, then a large blue book for Paula. Next emerged a rather curious object, turning out to be a large bow with a quiver and two feathered arrows, a present for Rolf. As the father took out the fine arrows with sharp iron points, he said with great emphasis:

"This weapon belongs to Rolf only, who knows how to use it. As it is no toy, Willi and Lili must never think of playing with it. Otherwise they might hurt somebody with it. It is dangerous, remember."

A gorgeous Noah's ark containing many kinds of animals in pairs and a Noah's family was presented to the twins. The men all held big staffs and the women carried large umbrellas, much needed while going on board the ark. For little Hun, who came last, a wonderful nutcracker came to light, whose face seemed doomed to uninterrupted sorrow for all the tragedies of this world. His mouth stood wide open when not in action, but when screwed together, he cracked nuts in the neatest fashion with his large, white teeth. The presents had to be shown properly and commented upon, and the admiration and joy knew no bounds.

Finally the mother resolutely got up to tell the children to go to bed. Their usual bedtime was long since past. As the father got up, he asked with a loud voice, "Yes, but who had guessed the riddle?"

No one had done so, as all except Rolf had completely forgotten it.

SHE HAD BEEN LOST IN EVERYTHING

SHE HAD PARTLY SEEN AND HEARD

"But I guessed it," said the father, no other answer being heard. "I suppose it is homecoming. Isn't it, Rolf? Let me touch your glass now and also let me thank you for the riddle."

While Rolf joyfully stepped up to his father, several frightened voices cried out, "Fire, fire!"

The next moment, everyone leaped from their seats, Battist and Trine came running out with bottles and buckets from the kitchen, and Hans came from the stable with another bucket. All rushed about shrieking wildly, "The bush is on fire, the hedge is on fire." The confusion and noise was truly amazing.

"Dora, Dora!" a wailing voice called down to the little garden of the neighboring cottage, and the next moment Dora hastened into the house from her place of observation. She had been so lost in everything she had partly seen and heard that she had not realized that she had been squatting on the ground for two full hours.

Upstairs, the aunt in grief and fright had pulled her belongings from the wardrobes and drawers and had piled them high as for immediate flight.

"Aunt Ninette," said Dora timidly, conscious of having remained away too long. "Don't be frightened any more. Look, it is dark again in the garden over there and all the lights are out."

Upon gazing over, the aunt saw that everything was dark and the last lights had been put out. Now a very dim lantern approached the apple tree. Probably somebody was setting things in order there.

"Oh, it is too terrible! Who could have guessed it!" moaned the aunt. "Go to bed now, Dora. We'll see tomorrow whether we shall move or leave the place entirely."

Dora quickly retired to her room but she could not go to sleep for a long, long while.

She saw before her the garden and the gleaming apple tree, heard the merry children's voices and also, their father's pleasant, happy words. She could not help thinking of her own dear father who had always been willing to listen to her, and she realized how fortunate her little neighbors were. She had felt so drawn to the children and their kind parents, that the thought of moving away from the house quite upset her. She could not go to sleep for a long, long while, for her mind was filled with the recent impressions. Finally her own beloved father seemed to be gazing down at her and saying the comforting words as he used to do:

"'Yet God keeps watch above us

And doeth all things well.'"

These words were still in her mind as she went to sleep, while the lights, the gleaming tree and merry children across the way followed her into her dreams.

After the fire was put out, Willi and Lili were found to be the culprits. Thinking that Rolf's riddle would look more beautiful if made transparent from behind like the inscription used every Christmas behind their tree, "Glory to God on High," they had fetched two lights. Then standing on a high step which had been used for fastening the inscription, they held the lights very near the riddle. When no joyful surprise was shown on any of the faces, they put the lights still nearer, till at last the paper was set on fire, catching the nearby branches. They owned up to their unfortunate undertaking at once and, in honor of the festive occasion, were sent to bed with only mild reproof. Of course they were forbidden to make further experiments with fire.

Soon after, deep quiet reigned in the house, and peacefully the moon shone down over the sleeping garden and the splendid tall trees.

ALL SIX

"We shall have to move away from here, Mrs. Kurd," were Aunt Ninette's first words the following morning when she came down to breakfast. "We seem to have come into a dreadful neighborhood. We had better move today."

Speechless with surprise, Mrs. Kurd stood still in the middle of the room. She looked at Mrs. Ehrenreich as if she could not comprehend the meaning of her words.

"I mean it seriously, Mrs. Kurd, we must move today," repeated Aunt Ninette.

"But you could not possibly find more delightful neighbors in all Tannenberg, Mrs. Ehrenreich, than we have here," began Mrs. Kurd as soon as she had recovered from her amazement.

"But, Mrs. Kurd, is it possible you did not hear the terrific noise last evening? It was worse than any of the things we especially meant to avoid."

"It was only the children, Mrs. Ehrenreich. They happened to be especially lively because they had a family party last evening."

"If such feasts are celebrated first by a wild explosion of joy, and end with a fire and an unspeakable confusion, I call such a neighborhood not only noisy but dangerous. We had better move at once, Mrs. Kurd, at once."

"I don't believe the fire was intended to take place at the party," Mrs. Kurd reassured the aunt. "It was probably a little accident and was at once put out. Everything is most orderly in that household, and I really cannot believe that the lady and gentleman can possibly want to move on account of such neighbors as we have. You would be sure to repent such a decision, for no better rooms can be had in all Tannenberg."

Aunt Ninette calmed down a trifle, and began breakfast with Dora and Uncle Titus.

Breakfast was over by that time in the big house, and the father was attending to business while the mother was looking after her household duties. Rolf, who had a daily Latin lesson with a pastor of the neighboring parish, had long ago left the house. Paula was having a music lesson with Miss Hanenwinkel, while Willi and Lili were supposed to review their work for the coming lessons. Little Hun sat at his table in the corner, examining his sorrowful looking nutcracker-man.

Now Big Jul, who had just returned from his morning ride, entered the room, his whip in his hand and the new spurs on his feet.

"Who'll take off my riding boots?" he shouted, flinging himself into a chair and admiring his shiny spurs. Immediately Willi and Lili flew towards him, glad of a chance to leave their work.

With not the slightest hesitation, Willi and Lili took hold, and before Jul could prevent it, he was pulled off his chair, Willi and Lili having hold of him and not the boots. At the last instant, he had been able to seize the chair, which, however, tumbled forward with him.

Jul cried loudly, "Stop, stop!" which brought little Hun to his big brother's rescue.

Holding the chair from the back, the small boy pushed with all his strength against the twins. But he was pulled forward, too, and found himself sliding along the floor as on an ice-slide. Willi and Lili anxious to complete their task, kept up their efforts in utter disregard of Jul's insistent commands to stop, and the words:

"O, Willi and Lili,

You twins, would you kill me?"

BEFORE JUL COULD PREVENT IT,

HE WAS PULLED OFF HIS CHAIR.

Little Hun shrieked loudly for assistance, till at last, the mother came upon the scene. Willi and Lili let go suddenly, Jul swung himself back to the chair, and little Hun, after swaying about for a few seconds, regained his balance.

"But, Jul, how can you make the little ones so wild? Can't you be doing something more profitable?" the mother admonished her eldest son.

"Yes, yes, I'll soon be at a more profitable occupation, dear mamma. But I feel as if I helped you with their education," he began in a conciliating tone. "If I keep Willi and Lili busy with innocent exercise like taking my boots off, I keep them out of mischief and any dreadful exploits of their own."

"You had better go to your profitable occupation, Jul. What nonsense you talk!" declared the mother. "And Lili, you go to the piano downstairs at once and practice, till Miss Hanenwinkel has finished with Paula. Till then Willi must study. I should call it a better thing, Jul, if you saw to the little ones in a sensible way, till I come back."

Jul, quite willing, promised to do his best. Lili hastened to the piano, but being in a rather excited mood, she found her fingers stumbling over each other while doing scales. The little pieces therefore tempted her more and she gaily and loudly began to play:

"Rejoice, rejoice in life

While yet the lamp is glowing

And pluck the fragrant rose

In Maytime zephyrs blowing!"

Uncle Titus and his wife had just finished breakfast when the riding-boot scene took place in the big house. Uncle Titus went straight to his room and barred the windows, while his wife called to the landlady, begging her to listen to the noise, herself. But the whole affair made a different impression on Mrs. Kurd than she had hoped.

"Oh, they have such times over there," said Mrs. Kurd, amused. When Mrs. Ehrenreich tried to explain to her that such a noise was not suitable for delicate people in need of rest, Mrs. Kurd suggested Mr. Ehrenreich's taking a little walk for recreation to the beautiful and peaceful woods in the neighborhood. The noise over there would not last very long. The young gentleman just happened to be home for the holidays and would not stay long. Lili's joyful piece, thrummed vigorously and sounding far from muffled, reached their ears now.

"What is that? Is that the young gentleman who is going away soon?" inquired Aunt Ninette excitedly. "What is coming next, I wonder? Some new noise and something more dreadful every moment. Is it possible, Mrs. Kurd, you have never heard it?"

"I never really noticed it very much. I think the little one plays so nicely, one can't help liking it," Mrs. Kurd declared.

"And where has Dora gone? She seems to be becoming corrupted already, and I can't manage her any more," wailed the aunt again. "Dora, Dora, where are you? This is dreadful, for she must start on her work today."

Dora was at the hedge again, happily listening to the song Lili was drumming on the piano. She appeared as soon as her aunt called to her, and a place was immediately chosen near the window, where she was to sew for the rest of the day.

"We can't possibly stay here," were the aunt's last words before leaving the room, and they nearly brought tears to Dora's eyes. The greatest wish of her heart was to stay just here where so many interesting things were going on, and of which she could get a glimpse now and then. Through her opening, she could hear a great deal and could watch how the children amused themselves in their pretty garden. Dora puzzled hard to find a way which would prevent their moving. However, she could find none.

Meanwhile eleven o'clock had come, and Rolf came rushing home. Seeing his mother through the open kitchen door, he ran to her.

"Mamma, mamma!" he cried before he was inside. "Can you guess? My first makes—"

"Dear Rolf," the mother interrupted, "I beg you earnestly to look for somebody else; I have no time just now. Go to Paula. She is in the living room." Rolf obeyed.

"Paula!" he cried from below. "Guess: My first makes—"

"Not now, please, Rolf!" retorted Paula. "I am looking for my notebook. I need it for making a French translation. Here comes Miss Hanenwinkel, try her. She can guess well."

Rolf threw himself upon the newcomer, Miss Hanenwinkel. "My first makes—"

"No time, Rolf, no time," interrupted the governess. "Go to Mr. Jul. He is in the corner over there, having his nuts cracked for him. Go to him. See you again."

Miss Hanenwinkel, who had once been in Italy, had in that country acquired the habit usual there of taking leave of people, and used it now on all occasions. If, for instance, the knife-sharpener arrived, she would say, "You here again. Better stay where you belong! See you again." With that she quickly closed the door. If the governess were sent to meet peddlers, or travelling salesmen coming to the house on business, she would say, "You know quite well we need nothing. Better not come again. See you again," and the door was quickly shut. This was Miss Hanenwinkel's peculiarity.

Jul was sitting in a corner, and in front of him, sat little Hun, busy giving his sorrowful looking nutcracker nuts to crack, which he conscientiously divided with Jul.

Rolf stepped up to the pair. "You both have time to guess. Listen!"

"'My first is just an animal forlorn.

My second that to which we should be heir,

And with my whole some lucky few are born

While others win it if they fight despair.'"

"Yes, you are right. It is courage," explained the quick older brother.

"Oh, but you guessed that quickly!" said Rolf, surprised.

"It is my turn now, Rolf. Listen, for it needs a lot of thinking. I have made it up just this minute," and Jul declaimed:

"'My first is sharp as any needle's end,

My second is the place where money grows,

My whole is used a pungent taste to lend,

And one you'd know, if only with your nose.'"

"That is hard," said Rolf, who needed time for thinking. "Just wait, Jul, I'll find it." Herewith, Rolf sat down on a chair in order to think in comfort.

Big Jul and small Hun meanwhile kept on cracking and eating nuts, Jul varying the game by sometimes trying to hit some goal in the room with a shell.

"I know it!" cried Rolf, overjoyed. "It is pick-pocket."

"Oh, ho, Rolf, how can you be so absurd! How can a pick-pocket smell?" cried Jul, disgusted. "It is something very different. It's spearmint."

"Yes, I see!" said Rolf, a little disappointed. "Wait, Jul, what is this?"

"'My first within the alphabet is found,

My second is a bread that's often sweet;

My third is something loved by active feet.

My whole means something more than just to go around.'"

"Cake-walk," said Jul with not the slightest hesitation.

"Oh ho, entirely wrong," laughed Rolf, "that doesn't work out. It has three syllables."

"Oh, I forgot," said Jul.

"You see you are wrong," triumphed Rolf. "It is abundance. Wait, I know still another."

"The first—"

"No, I beg to be spared now, for it is too much of an exertion, and besides I must see to Castor." Jul had jumped up and was running to the stable.

"Oh, what a shame, what a shame!" sighed Rolf. "Nobody will listen to me any more and I made up four more nice riddles. You can't guess, Hun, you are too foolish."

"Yes, I can!" declared the little boy, offended.

"All right, try then; but listen well and leave these things for a while. You can crack nuts later on," urged Rolf and began:

"'My first is closest bonds that can two unite,

My second like the shining sun is bright;

My whole's a flower that thrives best in wet ground

And like my second in its color found.'"

"A nutcracker," said little Hun at once. Jul being the little one's admired model, he thought that to have something to say at once was the chief point of the game.

"I'll never bother with you again, Hun; there is nothing to be done with you," cried Rolf, anxious to run away. But that did not work so simply, little Hun, who had caught the riddle fever, insisted upon trying out his first attempt.

"Wait, Rolf, wait!" he cried, holding on to Rolf's jacket. "It is my turn now and you must guess. My first can be eaten, but you can't drink it—"

"I suppose it's going to be nutcracker!" cried Rolf, running away from such a stupid riddle as fast as his legs could carry him.

But the small boy ran after him, crying all the time, "You didn't guess it! You didn't guess it! Guess it, Rolf, guess!"

All at once, Willi and Lili came racing towards him from the other side, crying loudly, "Rolf, Rolf, a riddle, guess it! Look at it, you must guess it!" and Lili held a piece of paper directly under Rolf's nose, while Hun kept on crying, "Guess, Rolf, guess!" The inventor of riddles was now in an extremity himself.

"Give me a chance, and I'll guess it," he cried, waving his arms to fight them off.

"As you can't guess mine, I'll go to Jul," said Hun disdainfully, turning his back.

Rolf seized the small slip of paper, yellow from age, which Lili was showing him. He looked perplexed at the following puzzling words written apparently by a child's hand:

"My hand.

Lay firmly

Wanted to be

But otherwise

One stays

And each

And now will

This leaf

When the time comes

That the pieces

fit

We'll rejoice

And we'll go

Never."

"Perhaps this is a Rebus," said Rolf thoughtfully. "I'll guess it, if you leave me alone a minute. But I must think hard."

There was not time for that just then, for the dinner bell rang loudly and the family began to gather around the large dining' room table.

"What did you do this morning, little Hun?" asked the father, as soon as everybody had settled down to eating.

"I made a riddle, papa, but Rolf won't guess my riddles, and I can't ever find Jul. The others are no good, either."

"Yes, papa," eagerly interposed Rolf now, "I made four or five lovely riddles, but no one has time to guess except those who have no brains. When Jul has guessed one, he is exhausted. That is so disappointing, because I usually have at least six new ones for him every day."

"Yes, papa," Willi and Lili joined in simultaneously, "and we found a very difficult puzzle. It is even too hard for Rolf to guess. We think it is a Rebus."

"If you give me time, I'll guess it," declared Rolf.

"The whole house seems to be teeming with riddles," said the father, "and the riddle fever has taken possession of us all. We ought to employ a person for the sole purpose of guessing riddles."

"Yes, if only I could find such a person," sighed Rolf. To make riddles for some one who would really listen and solve them intelligently seemed to him the most desirable thing on earth.

After lunch the whole family, including Miss Hanenwinkel, went outside to sit in a circle under the apple tree, the women and girls with some sewing or knitting. Even little Hun held a rather doubtful looking piece of material in his hand into which he planted large stitches with some crimson thread. It was to be a present for Jul in the shape of a cover for his horse. Jul, according to his mother's wish, had brought out a book from which he was supposed to read aloud. Rolf sat under the mountain-ash some distance away, studying Latin. Willi, who was expected to learn some verses by heart, sat beside him. The small boy gazed in turn at the birds on the branches overhead, at the workmen in the field below, and at the tempting red apples. Willi preferred visible objects to invisible ones and found it difficult to get anything into his head. It was a great exertion even to try, and he generally accomplished it, only with Lili's help. His study-hour in the afternoon, therefore, consisted mostly in contemplating the landscape round about.

Jul, that day, seemed to prefer similar observations to reading aloud. He had not even opened his book yet, and after letting his glances roam far and wide, they always came back to his sister Paula.

"Paula," he said now, "you have a face today as if you were a living collection of worries and annoyances."

"Why don't you read aloud, Jul, instead of making comparisons nobody can understand?" retorted Paula.

"Why don't you begin, Jul?" said the mother. "But, Paula, I can't help wondering, either, why you have been in such a wretched humor lately. What makes you so reserved and out of sorts?"

"I should like to know why I should be confiding, when there is no one to confide in. I have not a single girl friend in Tannenberg, and nobody at all to talk to."

The mother advised Paula to spend more time either with her small sister or Miss Hanenwinkel, who was only twenty years old and a very nice companion for her. But Paula declared that the first was by far too young and the other much too old, for twenty seemed a great age to Paula. For a real friendship, people must be the same age, must feel and think the same. They must at once be attractive to each other and hate the thought of ever being separated. Unless one had such a friend to share one's joys and experiences, nothing could give one pleasure and life was very dull.

"Paula evidently belongs to the romantic age," said Jul seriously. "I am sure she expects every little girl who sells strawberries to produce a flag and turn into a Joan of Arc, and every field laborer to be some banished king looking for his lost kingdom among the furrows."

"Don't be so sarcastic, Jul," his mother reproved. "The sort of friendship Paula is looking for is a beautiful thing. I experienced it myself, and the memories connected with mine are the sweetest of my whole life."

"Tell us about your best friend, mamma," begged Paula, who several times already had heard her mother speak of this friendship which had become a sort of ideal for her. Lili wanted to hear about it, too. She knew nothing except that she recalled the name of her mother's friend.

"Didn't you call me after your friend's name, mamma?" asked the little girl, and her mother assured her this was so.

"You all know the large factory at the foot of the mountain and the lovely house beside it with the big shady garden," began the mother. "That's where Lili lived, and I remember so vividly seeing her for the first time."

"I was about six years old, and was playing in the rectory garden with my simple little dolls. They were sitting around on fiat stones, for I did not have elaborate rooms for them furnished with chairs and sofas like you. Your grandfather, as you know, was rector in Tannenberg and we lived extremely simply. Several children from the neighborhood, my playmates, stood around me watching without a single word. This was their way, and as they hardly ever showed any interest in anything I did, and usually just stared at everything I brought out, they annoyed me very much. It didn't matter what I brought out to play with, they never joined in my games."

"That evening, as I knelt on the ground setting my dolls around a circle, a lady came into the garden and asked for my father. Before I could answer, a child who had come with the lady ran up to me and, squatting on the ground, began to examine all my dolls. Behind each flat stone, I had stuck up another so the dolls could lean against it. This pleased her so much, that she at once began to play with the dolls and made them act. She was so lively that she kept me spellbound, and I watched her gaily bobbing curls and wondered at her pretty language, forgetting everything for the moment except what she was doing with my dolls. Finally, the lady had to ask for my father again."

"From that day on, Lili and I were inseparable friends, and an ideal existence began for me at Lili's house. I shall never forget the blissful days I spent with her in her beautiful home, where her lovely mother and excellent father showed me as much affection as if I were their own child. Lili's parents had come from the North. Her father, through some agents, had bought the factory and expected to settle here for life. Lili, was their only child, and as we were so congenial, we wished to be together all the time. Whenever we were separated, we longed for each other again, and it seemed quite impossible for us to live apart.

"Lili's parents were extremely kind, and often begged my parents as an especial favor to let me stay with Lili for long visits, which seemed like regular long feasts to me. I had never seen such wonderful toys as Lili had, and some I shall never forget as long as I live. Some were little figures which we played with for whole days. Each had a large family with many members, of which everyone had a special name and character. We lived through many experiences with them, which filled us with joy and sorrow. I always returned home to the rectory laden with gifts, and soon after, I was invited again."

"Later, we had our lessons together, sometimes from the school teacher, Mr. Kurd, and sometimes from my father. We began to read together and shared our heroes and heroines, whose experiences thrilled us so much that we lived them all through ourselves. Lili had great fire and temperament, and it was a constant joy to be with her. Her merry eyes sparkled and her curls were always flying. We lived in this happy companionship, perfectly unconscious that our blissful life could ever change."

"But just before we were twelve years old, my father said one day that Mr. Blank was going to leave the factory and return home. These words were such a blow, that I could hardly comprehend them at first. They made such an impression on me, that I remember the exact spot where my father told me. All I could understand was that Mr. Blank had been misinformed about the business in the beginning and was obliged to give it up after a severe loss. My father was much grieved, and said that a great wrong had been done to Lili's father by his dishonest agents. He had lost his whole fortune as a result."

"I was quite crushed by the thought of losing Lili, and by her changed circumstances besides. It made me so unhappy that I remember being melancholy for a long, long time after. The following day, Lili came to say goodbye, and we both cried bitterly, quite sure of not being able to endure the grief of our separation. We swore eternal friendship to each other, and decided to do everything in our power to meet as often as possible. Finally, we sat down to compose a poem together, something we had frequently done before. We cut the verses through in the middle—we had written it for that purpose—and each took a half. We promised to keep this half as a firm bond, and if we met again, to join it together as a sign of our friendship."

"Lili left, and we wrote to each other with great diligence and warm affection for many years. These letters proved the only consolation to me in my lonely, monotonous life in the country. When we were young girls of about sixteen or seventeen, Lili wrote to me that her father had decided to emigrate to America. She promised to write to me as soon as they got settled there, but from then on, I never heard another word. Whether the letters were lost, or Lili did not write because her family did not settle definitely anywhere, I cannot say. Possibly she thought our lives had drifted too far apart to keep up our intercourse. Perhaps Lili is dead. She may have died soon after her last letter—all this is possible. I mourned long years for my unforgettable and dearest friend to whom I owed so much. All my inquiries and my attempts to trace her were in vain. I never found out anything about her."

The mother was silent and a sad expression had spread over her features, while the children also were quite depressed by the melancholy end of the story.

One after the other said, sighing, "Oh, what a shame, what a shame!"