The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | Building Materials and Methods | 7 |

| II. | Buildings and Streets | 33 |

| III. | Walls, Gates and Bridge | 57 |

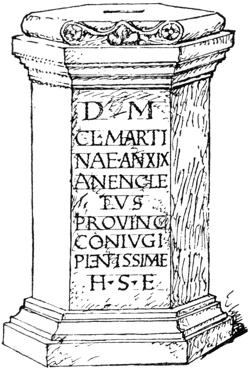

| IV. | Cemeteries and Tombs | 84 |

| V. | Some Larger Monuments | 101 |

| VI. | Sculpture | 120 |

| VII. | The Mosaics | 142 |

| VIII. | Wall Paintings and Marble Linings | 162 |

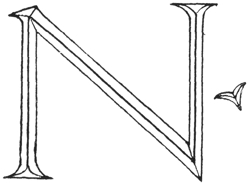

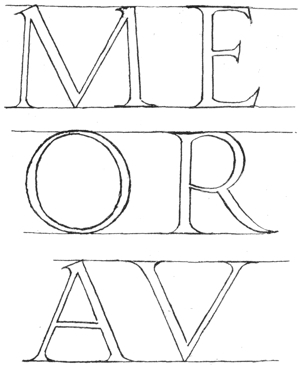

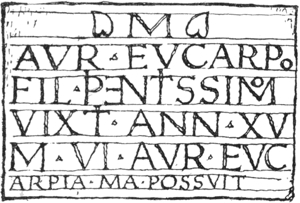

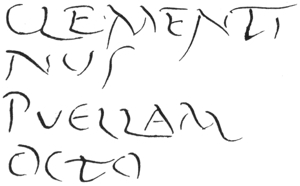

| IX. | Lettering and Inscriptions | 176 |

| X. | The Crafts | 193 |

| XI. | Early Christian London | 214 |

| XII. | The Origin of London | 228 |

| Index | 247 |

6These chapters were first printed in “The Builder” during the year 1921. For that reason, and because the earlier records of Roman discoveries in London given in this Journal seemed to have been less worked over than other sources, a large number of references are given to its pages. The account of Roman London in the “Victoria County History,” C. Roach Smith’s “Illustrations of Roman London,” and Mr. T. Ward’s “Roman Era in Britain,” and “Roman British Buildings,” may be specially mentioned among the works consulted. The first named is cited as V.C.H. Mr. A. H. Lyell’s “Bibliographical List of Romano-British Remains” (1912) is indispensable to the student.

IT is curious that Roman buildings and crafts in Britain have hardly been studied as part of the story of our national art. The subject has been neglected by architects and left aside for antiquaries. Yet when this story is fully written, it will appear how important it is as history, and how suggestive in the fields of practice. This provincial Roman art was, in fact, very different from the “classical style” of ordinary architectural treatises. M. Louis Gillet in the latest history of French art considers this phenomenon. “It is very difficult to measure exactly the part of the Gauls in the works of the Roman epoch which cover the land, such, for instance, as the Maison Carrée and the Mausoleum at St. Remy. There is in these chefs d’œuvre something not of Rome. The elements are used with liberty and delicacy more like the work of the Renaissance than of Vitruvius. In three centuries Gaul had become educated: these Gallo-Roman works, like certain verses of Ausonius, show little of Rome, they are already French.” We should hesitate to say just this in Britain, although the Brito-Roman arts were intimately allied 8to those of Gaul. In fuller truth and wider fact, they were closely related to the provincial Roman art as practised in Spain, North Africa, Syria, and Asia Minor. Alexandria was probably the chief centre from which the new experimenting spirit radiated. We may agree, however, that in the centuries of the Roman occupation, Britain like Gaul became educated and absorbed the foreign culture with some national difference. In attempting to give some account of Roman building and minor arts in London, I wish to bring out and deepen our sense of the antiquity and dignity of the City, so as to suggest an historical background against which we may see our modern ways and works in proper perspective and proportion.

Tools, etc.—Roman building methods were remarkably like our own of a century ago. The large number of tools which have been found and brought together in our museums are one proof of this. We have adzes and axes, hammers, chisels and gouges, saws, drills and files; also foot-rules, plumb-bobs and a plane. The plane found at Silchester was an instrument of precision; the plumb-bob of bronze, from Wroxeter, in the British Museum, is quite a beautiful thing, and exactly like one figured by Daremberg and Saglio under the word Perpendicularum. At the Guildhall are masons’ chisels and trowels; the latter with long leaf-shaped blades. At the British Museum is the model of a frame saw. Only last year (1922) many tools were found at Colchester. (For the history of tools in antiquity, see Prof. Flinders Petrie’s volume.)

A foot-rule found at Warrington gave a length of 11·54 in. The normal Roman foot is said to be 911·6496 in. (also 0·2957 m.). This agrees closely with the Greek foot and the Chaldean. (What is the history of the English foot?) The length of the Roman foot, a little over 11½ of our inches, is worth remembering, for measurements would have been set out by this standard. For example, we may examine the ordinary building “tile” used in Londinium. In the Lombard Street excavations of 1785 many Roman bricks were found which are said to have measured about 18 in. by 12 in. I have found this measurement many times repeated, and also three more precise estimates. Dr. Woodward said that bricks from London Wall were 17-4/10 in. by 11-6/10 in., and he observed that this would be 1½ by 1 Roman foot. Mr. Loftus Brock gave the size of one found in London Wall as 17 in. by 11⅝ in. Dr. P. Norman gave the size of another tile as about 17½ in. by nearly 12 in. At the Guildhall are several flue and roof tiles about 17½ in. long, and a large tile 23¼ in. long. We shall see when we come to examine buildings that the dimensions in many cases are likely to have been round numbers of Roman feet.

Masonry.—Walling had three main origins in mud, timber and stone. Walling stones were at first, and for long, packed together without mortar. Mud and stone were then combined; later, lime mortar took the place of mud, being a sort of mud which will set harder. In concrete, again, the mortar became the principal element. Stone walling was at first formed of irregular lumps. When hewn blocks came to be used a practice arose of linking them with wood or metal cramps. There are also three main types of wall construction—aggregation of mud, framing of timber, and association 10of blocks of stone. A later development of mud walling was to break up the material, by analogy with hewn stone, into regular lumps separately dried before they were used; thus crude bricks, the commonest building material in antiquity, were formed. Roofing tiles were developed from pottery, and such tiles came to be used for covering the tops of crude brick walls. Then, later, whole walls were formed of baked material, and thus the tile or brick wall was obtained. An alternative method of using mud was to daub it over timber or wattle (basket work) of sticks; and this seems to have been a common procedure in Celtic Britain.

Interesting varieties of concrete walling were developed by Roman builders. One of these was the use of little stones for the faces of a wall, tailing back into the concrete mass and forming a hard skin or mail on the surfaces, very like modern paving. Triangular tiles with their points toothed into the concrete mass were also used. Then tile courses were set in stone and concrete walls at every few feet of height.

I have been speaking of general principles and history, not limiting myself to Britain and Londinium, but the evolution of the wall is an interesting introduction to our proper subject.

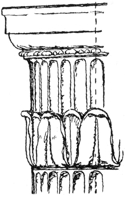

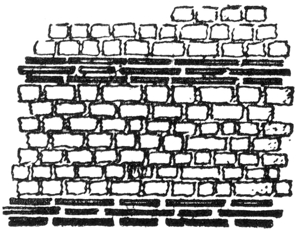

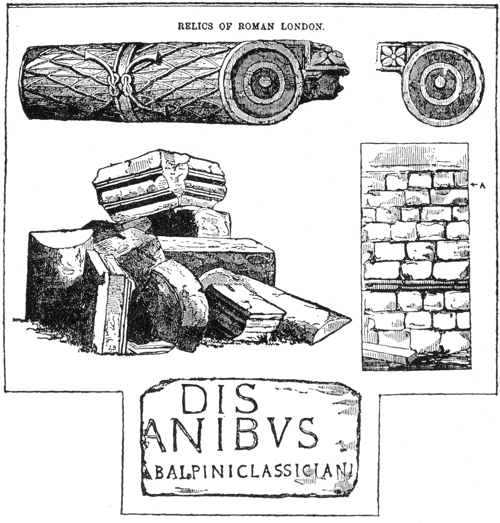

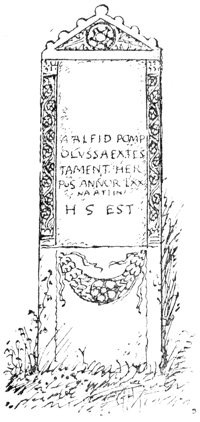

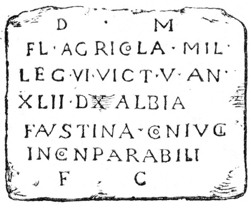

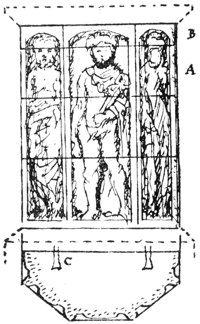

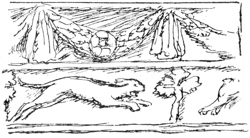

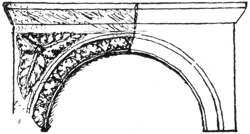

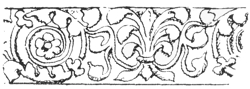

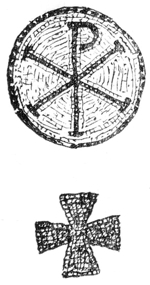

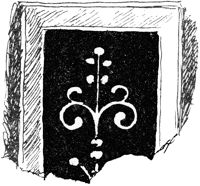

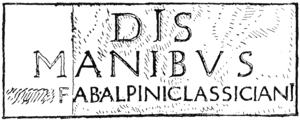

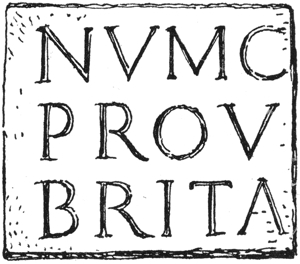

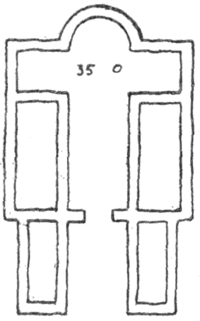

Fig. 1.

In Londinium wrought stonework must have been very sparingly used because of the difficulty and cost of transit. There were columns, pilasters, plinths, cornices, etc., but it may be doubted whether there were any buildings other than small monuments wholly of such masonry. Even in the first century the “details” of masonry were far from being “correctly classical,” and ornaments were very redundant and inventive. Provincial 11Roman building was something very different from the grammars propounded by architects. As we may study it in the fine museums of Trèves, Lyons, and London, it seems more like proto-Romanesque than a late form of “classic.” The Corinthian capitals of Cirencester are very fine works indeed; the acanthus is treated freshly, the points of the leaves being sharp and arranged as in Byzantine work; a sculptured pediment and ornamental frieze at Bath are also free and fine. On the other hand, moulded work is usually coarse and poor. An interesting architectural fragment found in London was the upper drum of a column which had several bands of leafage around the shaft and was a remote descendant of the acanthus column at Delphi (Fig. 1). Parts of small columns and their bases have been found, the latter with crude mouldings. I mention them because small circular work was usually turned in a lathe like Saxon baluster-shafts. A small capital from Silchester in the Reading Museum is of the bowl form so characteristic of Romanesque art.

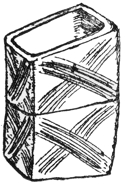

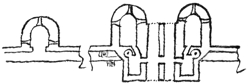

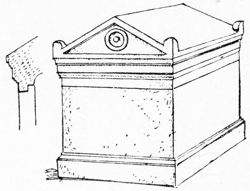

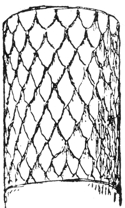

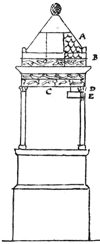

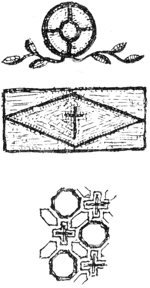

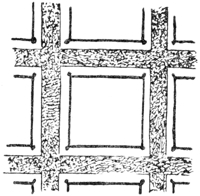

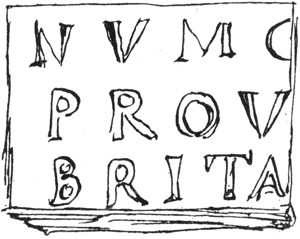

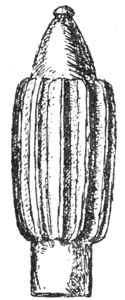

Fig. 2.

A few fragments of mouldings and other stones are in our museums (Fig. 2), and a considerable number of semicircular stones have been found which must have been copings. Large wrought 12stones were usually cramped together; lewis holes show how they were hoisted; smaller wall-facings were, I think, cut with an axe instead of a chisel. We find mention of one stone arch (a small niche?) in a Minute of the Society of Antiquaries: “Mar. 8, 1732: Mr. Sam Gale acquainted the Society, yt in digging up some old foundations near ye new Fabric erected Anno 1732 for ye Bank of England Mr. Sampson ye architect discovered a large old wall, eight foot under ye surface of ye ground, consisting of chalk stone and rubble, next to Threadneedle Street, in which was an arch of stone and a Busto of a man placed in it standing upon ye plinth, which he carefully covered up again: there was no inscription but he believed it to be Roman.”

Mortar and Concrete.—Roman builders early learnt how to make good mortar and concrete, being careful to use clean coarse gravel and finely divided lime. They also found that an addition of crushed tiles and pottery was an improvement, and for their good work used so much of this that the mortar became quite red. “Roman mortar was generally composed of lime, pounded tiles, sand and gravel, more or less coarse, and even small pebbles. At Richborough the mortar used in the interior of the walls is composed of lime and sand and pebbles or sea-beach, but the facing stones throughout are cemented with a much finer mortar in which powdered tile is introduced” (T. Wright).

One of the advantages of coarsely-crushed tiles is that it absorbs and holds water so that the mortar made with it dries very slowly and thus hardens perfectly. In Archæologia (lx.) an analysis is given of “mortar made with crushed tiles as grit in place 13of, or in conjunction with, sand.” In Rochester Museum a dishful of the crushed tile is shown which was taken from a heap found ready for use at the Roman villa at Darenth. I may say here that I have found mortar prepared in this way wonderfully tenacious, and suitable for special purposes like stopping holes in ancient walls. A strong cement made of finely powdered tiles, lime and oil was used by Byzantine and mediæval builders and probably by the Romans also. Villars de Honnecourt (thirteenth century) gives a recipe: “Take lime and pounded pagan tile in equal quantities until its colour predominates; moisten this with oil and with it you can make a tank hold water.” The use of crushed pottery in cement goes back to Minoan days in Crete.

In London a long, thick wall of concrete formed between timbering was recently found between Knightrider and Friday Streets; it showed prints of half-round upright posts and horizontal planking; it bent in its course and may have been the boundary of a stream. On the site of the old Post Office a Roman rubbish pit was found, about 50 ft. by 35 ft. in size. “In late Roman times the whole pit had been covered with concrete about a foot thick and a building had been erected on the spot” (Archæol. lxvi.). At Newgate the Roman structure was erected on a “raft” of rubble in clay finished with a layer of concrete. Rubble in clay formed the foundation of the City Wall.

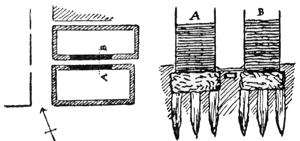

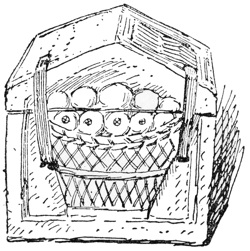

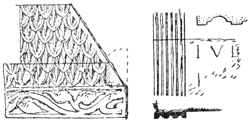

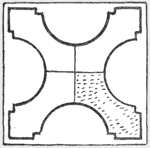

Fig. 3.

Many walls, described as of chalk, rubble or rag-masonry, have been found in London—one instance at the Bank has been quoted above. Chalk and flints were the most accessible material after local gravel, clay and wood. Mr. F. W. Troup 14tells me that “in the foundations for the Blackfriars House, New Bridge Street, we exposed a remarkable foundation (possibly not Roman). It consisted of rammed chalk, fine white material about 4 ft. wide and high, laid on great planks of elm 6 in. thick, which appeared to be sawn. These were laid side by side in the direction of the length of the wall, which ran along the west bank of the Fleet River.” I mention this, although it was probably a mediæval wall, as an example of a record; we ought to have every excavation registered. The walls of a room found in Leadenhall Street in 1830 were of rubble forming a hard concretion, with a single row of bond tiles through the thickness of the wall at about every 2 ft. in height. A sketch of this wall at the Society of Antiquaries shows it plastered outside and in. This was one of the common types of walling. Better stone walls were formed with face casings of roughly-squared little stones—what the French call petit appareil—as described above. An immense amount of piling was used in wet ground under streets and wharves, as well as walls. Foundations have been discovered of three rows of piles close together with a wall coming directly on their heads (Fig. 3). A wall found on the site of the Mansion House seems to have had only one row of piles; it was plastered outside.

Tile Walling.—The brick commonly used in Rome was a crude or unbaked block; the burnt walling tile was, as said above, developed from 15pottery, and it always remained pottery-like in texture and thin in substance. As Mr. T. May has said of bricks: “They were made of heavy clay, well tempered and long exposed; the modern practice is to use the lightest possible clay right off without tempering.” Walling tiles were used in Londinium not only as bonding courses, but for the entire substance of walls. It is usual to write “Roman tiles or bricks” interchangeably, but in origin and character the thing was a tile, and, indeed, roofing tiles with flanged edges were used as a walling material occasionally. Tiles were of various sizes and shapes, but an oblong, 1½ ft. by 1 ft. and about 1½ in. thick, was most usual. In the Guildhall Museum are several triangular tiles which must, I think, have been used for facing walls with concrete cores. Solid tile walling was used in Londinium so extensively that it was evidently a common material for better buildings. The Lombard Street excavations of 1785 exposed “a wall which consisted of the smaller-sized Roman bricks, in which were two perpendicular flues, one semicircular and the other rectangular; the height of the wall was 10 ft. and the depth to the top from the surface was also 10 ft.” Here we have evidence of a brick wall rising the full height of one story at least (Archæol. viii.). Roach Smith noticed a wall in Scott’s Yard “8 ft. thick, entirely composed of oblong tiles in mortar.” Mr. Lambert has recently described some walls of brick 3¼ ft. thick found at Miles Lane. A building in Lower Thames Street had walls of red and yellow tiles in alternate layers. This fact I learn from a sketch by Fairholt at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and such use of bricks of two colours was a common practice. In 16Hodge’s sketches of the tile walls of a great building discovered at Leadenhall Market it is noted that some of the courses were red and buff. Price recorded of walls, 2½ ft. thick, found in the Bucklersbury excavations, that “the tiles were the usual kind of red and yellow brick.”

More recently a bath chamber has been found in Cannon Street built of tiles which on the illustration are indicated in alternate courses of red and yellow. In the description in Archæologia, it is remarked: “It would appear that the yellow was preferred, the red being employed where they were not visible.” Years ago Charles Knight observed that the tiles used in the City Wall at America Square varied from “bright red to palish yellow.” This has been confirmed by more recent accounts in Archæologia. Finally, Roach Smith, describing the discovery of a part of the South or River Wall of the City (Archæological Journal, vol. i.), says that the tiles used as bonding bands were straight and curved-edged (that is, flanged roof tiles), red and yellow in colour. At the Guildhall there are a roof tile and a flue tile of yellow colour. Building with tiles may for long have been customary, but the use of red and yellow tiles in the way described would probably have been a fashion during a limited time only, and in that case it follows that the buildings erected with red and yellow tiles are likely to be nearly contemporary; the date would, I suppose, be the fourth century. Specially made tiles were used for columns. At the Guildhall are several round tiles 8 in. diameter, suitable for the piers of a hypocaust. Also some semicircular tiles 12 in. in diameter. In Rochester Museum are some quadrants making up a circle about 1½ ft. in 17diameter. Tiles, eight of which made up a circle, have lately been found at Colchester, and in the Guildhall Museum is a course of a round column made up of twelve tiles around a small central circle. A large number of columns were evidently of such bricks plastered.

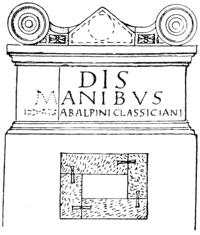

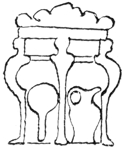

Fig. 4.

Arches and Vaults.—The arches in the City Wall, where it passed across the Walbrook, described by Roach Smith, were of no great span (3¼ ft.). They were constructed of ordinary tiles and were of a roughly-pointed shape. Arches of this form were not infrequently used in Roman works; they were not the result of inaccurate building. About a dozen years ago a well-built pointed arch of alternate tile and tufa, found at Naples, was described in Archæologia. The tiles, although thin, were sometimes made slightly wedge-shaped, and the city gates at Silchester seem to have had arches of such bricks.

The only London vault which I can find mentioned is one found exactly two hundred years since at St. Martin-in-the-Fields. A Minute of the Society of Antiquaries reads: “May 2, 1722: Mr. Stukely related that the Roman building in St. Martin’s Church was an arch built of Roman brick and at the bottom laid with a most strong cement of an unusual composition, of which he has got a lump. There was a square duct in each wall its whole length, of 9 in. breadth; there were several of these side by side: this building is below the springs on the gravel.” This building that was an arch, with its many flues, and cement floor—doubtless opus signinum—was obviously a Roman bath chamber, but probably it was quite small.

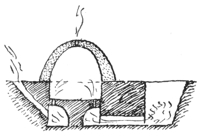

Fig. 5.

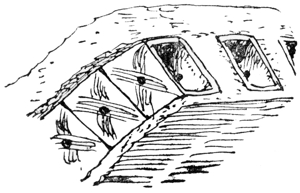

Evidence of the existence of fairly large vaults 18has been found at the Baths of Silchester, Wroxeter and Bath. These were all constructed in a most interesting and suggestive way of voussoirs made as hollow boxes in the tile material. Similar box voussoirs have been discovered at Chedworth and elsewhere.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 8.

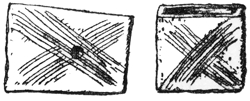

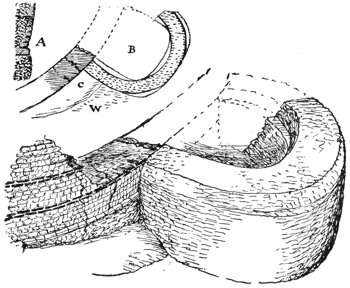

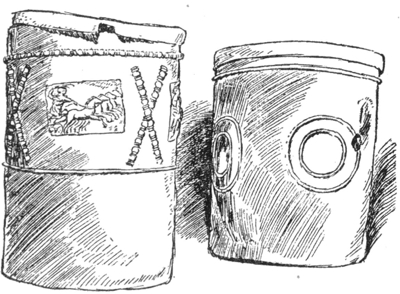

I have found two such box voussoirs in the Rochester Museum, each about 9 in. by 6 in. on the face and 5 in. on the soffit (Fig. 4). The surfaces are roughly scored across with parallel lines forming an Χ. These two tiles together show an obvious curvature; they came from a villa at Darenth. In the Guildhall Museum I have also found a box voussoir which is almost identical with those at Rochester. It is thus described: “74, Flue (?) tile, red brick, the front decorated with incised cross lines; in the centre both front and back is a circular perforation: 9½ in. long, 6¾ in. high, 6½ in. wide.” The longest dimension is not in the direction of the tube, and the height is greater at one end than the other, so that the wedge form is quite apparent. The small holes in both the larger sides were doubtless to give better hold to the mortar in which they were set (Fig. 5). Roach Smith recorded what must have been broken parts of similar voussoirs as found in Thames Street in 1848 (Journ. Brit. Archæol. Assoc., vol. iv.), but here they seem to have been used as waste material 19in building the little piers of hypocausts. Roman builders also constructed vaults of pipes and pots set in mortar concrete as were our box voussoirs, but I know of no British examples. Vaults of wide span seem to have covered large chambers in the Basilica at Verulam (see Victoria County History). The method of using the box voussoirs has been well explained from the Silchester examples by the late Mr. Fox in Archæologia (cf. Fig. 6). A fragment at Westminster Abbey is either part of a voussoir or of a short flue tile (Fig.7).

Some notes made at Bath further explain the interesting methods of building vaults with box voussoirs. There are several such voussoirs in the ruins of the Great Bath, 12 in. to 13 in. deep by 6 in. and 6½ in.; 6¾ in. and 7½ in.; 8¼ in. and 10 in.; 208 in. and 11 in. at the top and bottom. Fig. 9 is a sketch of the third; it is scored on the face. The notches cut in the sides take the place of the holes in the London examples, and doubtless were for the mortar to get a better key; Fig. 10 is from a vault of this construction which was further strengthened by a series of curved tiles set in the outer concrete mass, which was 6 in. thick; Fig. 11 shows the ridge of such a vault—this may be an imagination of my own. One of the fragments showed six or eight flat tiles set longitudinally crossing the lines of the box-tiles (Fig. 12). The ridge termination (Fig. 16) is also from Bath.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 10.

Some large voussoir box-tiles from Gaul are shown in the British Museum, No. 394, in the section of Greek and Roman life.

Fig. 11.

Fig. 12.

Well-constructed arched sewers have been found in the City (see Victoria County History).

Many socketed water-pipes are in our museums. Such pipes were occasionally used in Rome as down-pipes, and we might do worse than revert to the custom and get rid of the iron rust nuisance. In the British Museum there are some larger socketed pipes with small holes cut in them along a line. These must, I think, have been for draining surface water, for which purpose flue tiles were also used. Larger sewers were of brick or stone.

Carpentry.—In mediæval days the carpenter was the chief house builder, and much timber would have been used in Roman London. In 1901-2 remains of piling was found in the bed of the Walbrook at London Wall. These piles had served as supports for dwellings. “The large quantities of loose nails indicated that the superimposed dwellings were of timber” (Builder, December 13, 1902). Timber piling has also been found at St. Martin’s le Grand and other sites. There was clearly much soft wet ground in the City. The better-class dwelling in Bucklersbury, to which belonged the fine mosaic floor now at the Guildhall, seems to have been largely of timber. In December last (1921) Mr. Lambert described at the Society of Antiquaries a remarkable piece of wharfing on the river bank at Miles Lane. This was a solid wall of squared balks of timber about 2 ft. square, laid one over the other and having ties into the ground behind. The construction showed an interesting set of tenons, halvings and housings. A bored wood pipe was also found. In Thames Street a house found in 1848 had a well-made drain made with 2 in. planks forming bottom and 22sides, which is said to have been covered in with tiles.

Wattle and Daub.—It was ever a problem in London how to build without stone. Wood, gravel and mud were plentiful, and these were the common walling materials during the Middle Ages. As lately as the eighteenth century some of the suburban churches were described by Hatton as being of “boulder work,” that is, a concrete of coarse gravel; and the walls of the Temple Church, before the falsifying restorations, were of some sort of concreted rubble skinned over with plaster on the face. Hearne reports that Wren said that there were few masons in London when he was young. Mud walls are mentioned in mediæval records, and “daubers” were, I suppose, primarily those who did the filling in of post and pan work. The smaller houses of Londinium were largely of wattle and daub, and doubtless others were of crude brick. For the use of wattle and daub we have plentiful direct evidence. In the account of the excavations in and about Lombard Street in 1785 (Archæol. viii.) curious fragments were found which are thus described: “About this spot and in many other places large pieces of porous brick were met with of a very loose texture, seeming as if mixed with straw before they were burnt. They are commonly channelled on the surface; their size is quite uncertain, being mere fragments, their thickness about 1½ in. or 2 in.” Again, chalk-stone foundations and “channelled brick” are mentioned together. The “brick” fragments were of daubing, and the channels were the marks of laths, as has been shown by other finds. Similar remnants have recently been discovered on the Post 23Office site and in King William Street. “Débris of a wood and daub house which had been destroyed by fire.... In several cases the plaster was still adhering to the daub” (Archæol. lxvi.). Other fragments are preserved in the Silchester collection at Reading. The London fragments were found under conditions which showed that they had belonged to first-century dwellings. This method of building had been practised by the Celts, and we may imagine that the “populace” of Londinium was housed in small huts of wattle and clay roofed with reed thatch. In the country, old garden walls are occasionally found, I believe, built of mud daubing on both sides of wattle work, and sheep shelters of wattle-hurdles and dry fern are, I suppose, direct descendants of the old British manner of building.

Mr. Bushe-Fox has remarked that one of the earliest houses at Silchester and the earliest houses at Wroxeter were of wattle and daub construction. See also Mr. Lambert’s paper in Archæologia, December 1921.

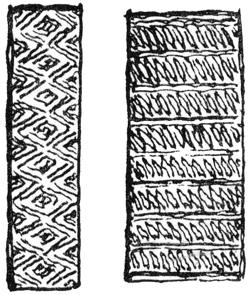

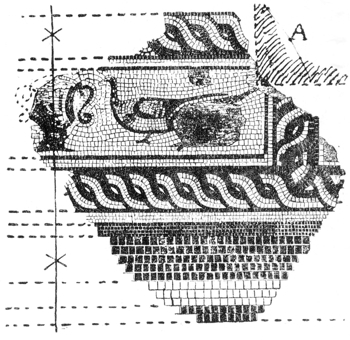

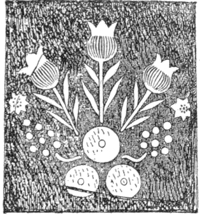

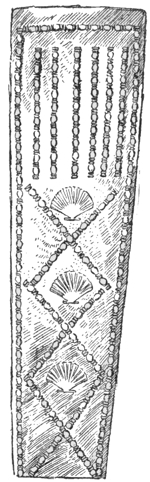

Hypocausts and Flue Tiles and Wall Linings.—Several examples have been found in London of the Roman system of heating buildings by hypocausts. These were low under-floor spaces a foot or two high connected with an external stoke-hole in one direction and having a flue or flues in the other. When the hypocaust, as was frequently the case, occupied the whole space below a chamber the floor was supported on a large number of roughly-built little piers with a row or two of flat tiles above spanning the intervals, and over them a layer of concrete and a mosaic or other floor. The flues were usually box-tiles, and in the case of the hot 24chambers of a bath one side of a wall or even more might be lined with them. A hypocaust with its stoke-hole and flue or flues was really a kiln of low power, in which people were warmed on a similar principle to the baking of pottery. The box-tiles were much the shape of a modern brick, and about twice as big; they were hollow and usually had scorings or impressed patterns on the surface to make mortar or plaster adhere (Figs. 6 and 7). Frequently they had a hole or two holes in their narrow sides, so that the mortar might better hold them in place. In the British Museum there is a long and large pipe with ornamental scratchings on the surface which may possibly be a chimney.

The system of central heating by the hypocaust seems to have been an admirable contrivance. Lysons illustrated an example at Littlecote where flue tiles ran up in the angles of a room like Tobin tubes, being cased round only by the plaster. The two best known London hypocausts were found in Lower Thames Street and in Bucklersbury. The former extended under the floors of two adjoining apartments. The Bucklersbury example had channels under the floor spreading to several wall flues, each being of two box-tiles placed side by side. (See Price’s account and V.C.H.) Occasionally flue tiles had two smaller channels; there is a broken example of such a tile in the British Museum. Flue tiles were sometimes of a rounded form ∩, and in this case the wall itself must have served to enclose the flue. In the excavations in Lombard Street in 1785 (Archæol. viii.) a brick wall is described which had two flues, one being “semicircular.” A long and well-made ∩-shaped flue in the British Museum, with an impressed lozenge 25pattern on the surface, is described as a ridge-tile. There is also a fragment of still larger diameter at the Guildhall. Similar flues found at Woodchester were used as horizontal heating channels under the floor.

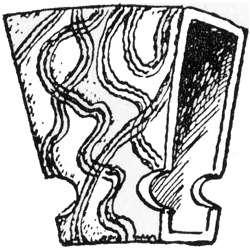

Here also one of the walls was found to be lined with flanged tiles, set thus, │__││__│, with the flanges against the walls. This may have been a provision against a damp wall. I have seen a similar wall in Rome—I believe subterranean—also another very similar where large flat tiles, having four projections at the back like short legs to a low stool, were used as linings. Each of the four studs was pierced for a nail. Fragments of tiles found at Newgate in 1877 were about 1½ ft. square and 1¼ in. thick, “with rough clay stubs for attachment”; they were scored over the surface with wavy lines, and were probably used internally. (In V.C.H. it is said that these may have been mediæval, but the examples just given show that they were Roman.) In the British Museum and at the Guildhall are some flat tiles, scored on one side to receive plastering, and with four notches in the sides to allow of nails being driven between two adjoining tiles. These, too, must have been for wall linings.

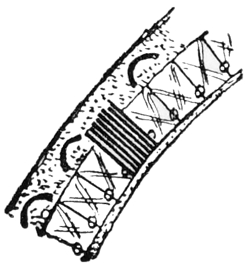

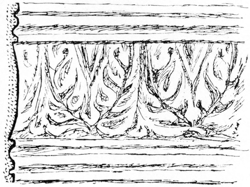

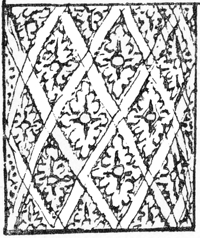

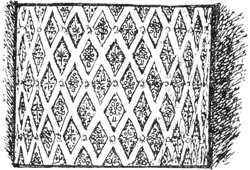

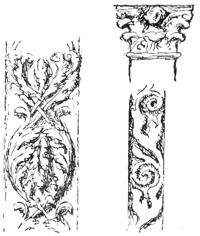

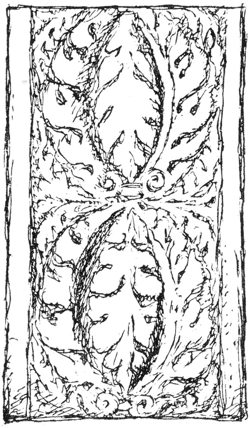

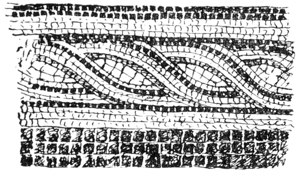

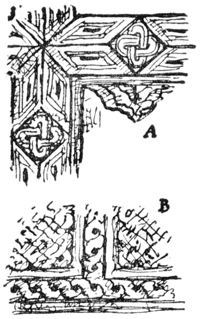

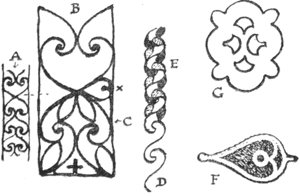

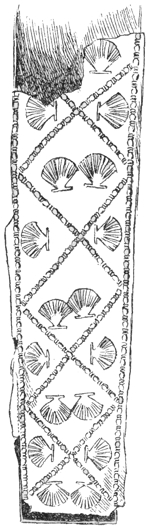

The impressed patterns on the surfaces of some of these flue tiles are quite neat and pretty, and they are interesting in the history of design as being “all-over patterns.” In some cases at least, they seem to have been produced by a roller having a unit of the design cut on it in the style of a butter print. A tile found in Kent, illustrated by Haverfield (Romanization, p. 33), has the inscription: “Cabriabanus made this wall-tile” (parietalam)—“The 26man who made the tiles apparently incised the legend on a wooden cylinder and rolled it over the tiles, producing a recurrent inscription.” The patterns superseded the scorings and seem to have been for the same purpose—to afford a better hold for the plaster than a plain face. Fig. 13 is of tiles found in Thames Street. Fig. 14 is a fragment illustrated in Roach Smith’s Catalogue.

Fig. 13.

Fig. 14.

Inscriptions roughly scratched on tiles led the late Dr. Haverfield to the conclusion that ordinary workers in Britain wrote Latin. At the Guildhall a tile has a humorous note about a workman who went off “on his own” too often. In the British Museum a tile has Primus, and one from Silchester has Satis.

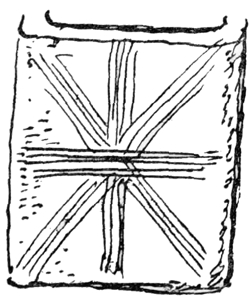

Floors.—The floors which have been found were most generally of concrete, tiles and mosaic. In Rochester Museum are some lumps of material from concrete floors. There were also floors of “rough stones” and of “chalk stones.” A better kind of concrete floor was that known as opus signinum, made of lime and broken pottery polished on the surface; this made an admirable floor. 27Another excellent and much used surface was obtained by coarse tesseræ of tile from 1 in. to 2 in. square; sometimes pieces of yellow, black and white were intermixed. In Rochester Museum is a tile fragment subdivided by indented lines imitating this coarse kind of mosaic, also a square of light buff tile. At the Guildhall is a tile a Roman foot square, having incised squares. Tiles were of various forms and sizes. In the Reading Museum are round and polygonal tiles, and a very pretty floor formed of such tiles with coarse tesseræ intermixed. Some small paving tiles have been found (not in London) with patterns impressed on the surface (Fowler’s engravings). In the British Museum is a tile 7 in. square, and a large tile about 18 by 14 in. is scored on the surface neatly, like the crosses of a Union Jack (cf. Fig. 7); it seems to be abraded on the surface, and may be a paving tile—if so, it must have made an excellent floor. Roach Smith mentions large tiles about 2 ft. square and 3 in. thick, and some of these are in the British Museum. Such tiles, as large as paving slabs, were useful in covering hypocausts, spanning the intervals between the little piers on which the corners rested.

In the British Museum and at the Guildhall are portions of paving of small tiles set on edge in a herring-bone pattern. The former is described as having been found at Bush Lane, the latter near Dowgate Hill on the Walbrook. “Near by was piling and the cill of a bridge which crossed the brook from E. to W.” This seems to be the same pavement as that described in The Builder, 1884, as being on the west bank facing the brook; there was a second landing-stage in Trinity Square Gardens, on “the edge of a haven,” with a pavement 28over oak piling. (The haven at the tidal inlet to Walbrook was doubtless the original port of London.) I have seen similar herring-bone pavement of tiles on edge in Rome. I doubt there having been a bridge here.

Plastering.—External walls would mostly have been plastered. C. Knight mentioned the discovery near the Bank of traces of a Roman building, and of what was “apparently the basis of a Roman pillar (circular?) built of large flat bricks incrusted with a very hard cement, in which the mouldings were formed exactly as is done in the present day.”

Rome itself must have been a city of plastered walls; the Pantheon, the great Basilica of Constantine in the Forum, and the splendid Baths were all, as may be seen to-day, plastered. The tile walls of the Basilica at Trèves were covered with red plastering. The Baths at Silchester were plastered externally. Of the great villa at Woodchester we are told the walls were “plastered on the outside and painted a dull red colour” (T. Wright). At Caerwent the Basilica was plastered a reddish-brown colour. The best description I have found of such plastering is that in Archæologia of a round temple or tomb building found at Holmwood Hill, which was covered outside with “a mixture of lime and gravel and coarse fragments of broken tile. On this was laid a coat of stucco composed of lime and tile more minutely broken, the latter being rendered very smooth was covered with a dark pigment ... a sort of ochre.” It is clear that external plastering was generally finished with a red surface.

Of internal plastering we have many fragments covered with painted decoration in the museums; 29it was generally very thick and smoothly finished on the surface; against the floor there was usually a projecting quarter-round fillet about 3 in. high, of hard cement. Such a skirting was found around the Bucklersbury mosaic pavement (Price). Sometimes a similar fillet ran up the angles of a room, as at a bath at Hartlip Villa, illustrated by T. Wright. I have seen a similar treatment in Rome, also a hollow curve.

Roofs, Windows, etc.—Roofs were generally covered with tiles, stone-slates, and doubtless thatch. Examples of the two former are in our museums. The flat tiles had turned-up edges; these were removed near the top for the next tile to lap over. The flanges were covered by half-round tiles, larger below than above, so that one lapped over the other. The flat tiles were frequently if not always of a key-stone shape, so that the bottom of the upper one set into the wider top of the lower one. (See one figured in Allen’s London.) Some have a single nail-hole near the top; but others, I suppose, can only have been nailed against the slanting sides. (See V. le Duc’s article “Tuille” for the Romanesque system.) In better work ante-fix tiles covered the terminations of the round tiles at the eaves. “Part of an ante-fix of red terra-cotta in the form of a lion’s mask” was found in the Strand (V.C.H.). There are several in Reading Museum and one in the British Museum from Chester. The slates were thick and of a pointed shape below, forming diagonal lines when laid. Both the stones and tiles were very heavy, and must have required strong roof timbering.

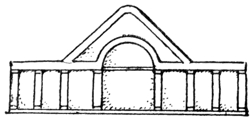

Fig. 15.

Fig. 16.

Ridges were of tile or stone. A fragment in 30the Reading Museum from Silchester has a knob rising from the saddle-back of a ridge-tile strangely mediæval in appearance (Fig. 8). Probably one came at each end of the ridge only (cf. V. le Duc’s “Faîtière”). Ridges were frequently terminated by stone gable knobs, which have been found in many places (see Ward’s Roman Buildings), and occasionally in such a position as to show that a gable end fronted a street. A ridge termination in Exeter Museum is shown upside down as if it were a corbel (Fig. 15 is a memory sketch, and compare Fig. 16 from Bath). These terminations are late derivations from acroteria and prototypes of gable crosses; they are links in a continuous chain from Greek to Gothic.

Fig. 17.

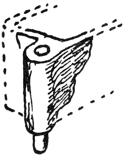

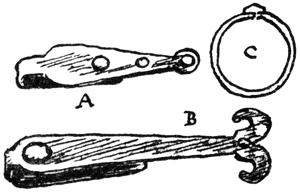

Little joiner’s work has survived to our day. Doors would not have been very different from our own, as is shown by many examples of framed panel work from foreign sites in museums. A 31bronze pivot in the Museum at Westminster Abbey must have been a hinge of a door (Fig. 17). Iron strap-hinges in the museums are very similar to our own. There are two in the British Museum (Fig. 18). The plane found at Silchester is evidence for joiner’s work. In Leicester Museum is a fragment of a lion’s head and leg from a piece of furniture—probably a table. Turning in a lathe was practised, as some wooden dishes at the Guildhall show. There are many excellent locks and keys and hinges and handles in our museums.

Fig. 18.

The use of window glass was very general. It was cast in small panes, as is shown by the large proportion of existing fragments which have edges and corners. Practically a whole pane, about 12 in. by 12 in., is in the Rochester Museum. Near Warrington, on a Roman site, was found a stone slab with a shallow recess 12 in. by 8 in., which Mr. May regarded as a mould for glass (Ward). The average size of panes would have been about one Roman foot long. Glassware seems to have been made in London, Silchester and elsewhere, doubtless from imported “metal.” Some windows, 32possibly unglazed, were protected by iron gratings. An iron star X in the Guildhall Museum came from such a window guard as is shown by a complete example I sketched many years ago in the Strasbourg Museum (see Arch. Rev., May 1913) (Fig. 19). It had been suggested that such X-pieces were “holdfasts,” to keep the glass panes in position (Ward); but this is not the case; moreover, the pane at Rochester shows that it was “cemented” into place.

Fig. 19.

Lead must have been largely used; there are a dozen large “pigs” in the British Museum. Melted lead was found at Verulam in a position which suggested that it had been used on an important building. In the Guildhall Museum are some sections of lead water-pipes found in London, and at Westminster Abbey is a piece 4 in. in diameter, which must, I think, be Roman (Fig. 18, C).

A study of Roman building methods may suggest to us many points for our consideration and emulation. I would especially mention their excellent mortar made of crushed tile, opus signinum, and coarse tesseræ floors, cement skirtings, red external plastering, the tile-shaped brick, tile wall linings and down-pipes, hip and gable knobs, vaults of box-tiles and pipes, the hypocaust system of heating, turning of stonework, painted decorations, marble linings, cast leadwork. Some day I hope our sterile histories of “architectural styles” will make way for accounts of practical building methods.

BASILICA.—In 1880 the extensive foundations of an important building with massive walls were found on the site of Leadenhall Market, and a survey of the ruins made by Henry Hodge was published in Archæologia (vol. lxvi.). This great building was exceptional, not only in its scale but in its manner of workmanship. I know no other case where the walls of a building had wrought and coursed facings like the City Wall (Fig. 20).

Fig. 20.

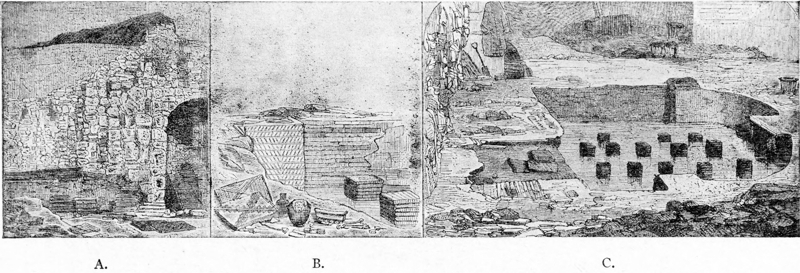

In 1881 Mr. E. P. L. Brock exhibited at a meeting of the British Archæological Association “plans of excavations recently carried out in Leadenhall Market, showing the foundations of an apse 33 ft. wide and indications of four different conflagrations. He also exhibited fragments of fresco painting with ornamental patterns.... The 34building appears to have had the form of a Basilica in some respects, with eastern apse, western nave, and two chambers like transepts on the south side” (Archæol. lxvi.). From the wording of this it appears that Brock meant that the building had a general resemblance to an early Christian church. Mr. Lambert in publishing Hodge’s drawings in Archæologia seems to have understood Brock to mean that it was the Civil Basilica of Londinium. This, indeed, I have no doubt it was, but at the time Brock wrote such buildings in Britain were hardly known.

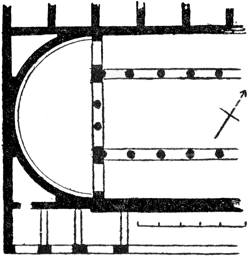

Fig. 21.

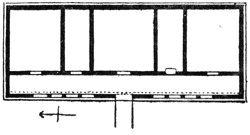

The Civil Basilica or Public Hall was generally the “complement of the Forum; it was, in fact, a covered Forum used for commerce, exchange, and administration, or simply as a promenade” (Daremberg and Saglio). At Silchester the Forum and Basilica filled an “island” site, about 315 ft. by 280 ft., at the centre of the city. The Forum was a quadrangle included within a single row of buildings on three sides, having a colonnaded walk on the inside, while the Basilica occupied the fourth side facing the central avenue of the town. It was 233 ft. long by 58 ft. wide, and was divided into a “nave” and “aisles,” the former being terminated at each end by a large apse. In the interior were two ranges of Corinthian columns about 3 ft. in diameter, some capitals from which 35are now in Reading Museum. Cirencester Basilica was still larger, being about 77 ft. wide, divided into nave and aisles by fine Corinthian columns; at one end a great Hemicycle embraced both nave and aisles. It must have been a noble building (Fig. 21 is a restored plan of one end). At Wroxeter the Basilica was 67 ft. wide, divided into nave and aisles by ranges of Corinthian columns.

The columns in the interior of the Basilica at Caerwent were also of Corinthian fashion: the shafts were 3 ft. in diameter and decorated with a leaf pattern. Under the floor were wide sleeper walls, one of which ran across the front of the Tribune. The exterior was covered with reddish-brown plastering, and the interior had painted decorations of large scale.

The Basilica at Verulam had a very long hall, 26 ft. wide and about 360 ft. in length. From it three great chambers opened at right angles. The central chamber was 40 ft. wide. The others were 34½ ft. wide, having apses at the farther ends included within square outer walls. There was evidence that these side chambers had been vaulted. Some painted wall plaster was found, and it was clear that the whole of the interior walls and vaults had been painted, mostly in floral designs, in dark olive green and other colours. Fragments of drapery indicated that there had been figures also. In front of the Basilica was a great quadrangle court, with a block of masonry on the central axis, which can hardly have been other than a pedestal for a statue (see V.C.H.).

The Basilica at Trèves is built wholly of tile-bricks, and was once covered with red plaster, of which some fragments remain in the window 36jambs. It is about 240 ft. long, the flank wall having six bays recessed between pilasters each containing an upper and a lower window. A large apse exists at one end, about 40 ft. wide. It has been restored to serve as a church, and is a noble building, big and bare. The British Basilicas, so far as they are now known, were of the following dimensions in width. The English measures may probably be equated with Roman feet as suggested: Silchester, 58 (60); Caerwent, 62 (65); Wroxeter, 67 (70); Cirencester, 78 (80); Chester, 76 (?).

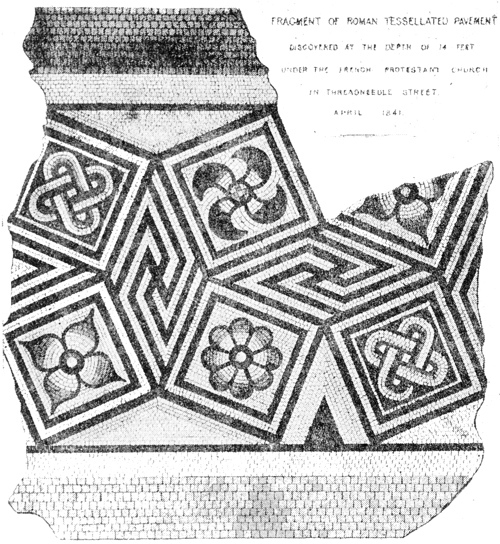

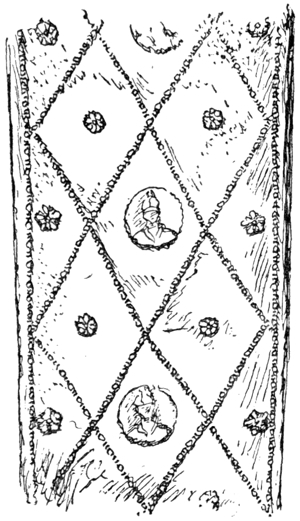

The foundations discovered on the site of Leadenhall Market represented some very large and exceptional structures. The following account is condensed from Mr. Lambert’s description in Archæologia: “The plans show at the eastern end a quarter-circle of 27 ft. 7 in. radius, which seems to represent the eastern apse mentioned by Brock; and in continuation of its southern line, a wall about 150 ft. long, having the extraordinary breadth of 12 ft. 7 in., runs to the line of and apparently underneath Gracechurch Street.... From the south side at the east end, spring at right angles three walls, which doubtless enclosed the ‘two chambers like transepts’ mentioned by Brock.... It is probable that work of different periods is included in this plan.... The northern half of the great wall appears to be brick, the rest stone or rubble, as though one wall had been built along the face of another.... It is clear from the drawings that the bulk of the eastern portions of the remains is homogeneous in structure. The extra thickness of the great wall and the fragments of solid brick walls at either end of the site represent perhaps later additions.... These remains 37form the most extensive fragment of a Roman building recorded within the Walls of London.” From the thick mortar joints of the brick walls, Mr. Lambert concludes that they were probably built in the third or fourth century. The more or less alternating use of red and buff bricks, as I have already suggested, is also evidence that this part of the work should be assigned to the fourth century. Concrete, tessellated and herring-bone floors were found, also flue tiles (Price, Athen., 1881).

Some of the bricks used were of larger size than the ordinary, being 20 in. by 12½ in., and the drawings show that they were carefully laid with alternate headers and stretchers (Fig. 17). They were 1¾ in. thick, and four courses made 10-12 in.; the joints were thus about 1¼ in. thick. At the Guildhall is a fragment of brickwork from Leadenhall Market, with bricks and joints both 1½ in. thick. The stone walling was of concreted rubble, with facings on each side in small, roughly wrought but carefully-coursed stones; the layers of bonding tiles passed through the thickness of these walls (Fig. 20). A large drain ran parallel to the outer south wall about 4 ft. wide, including its brick sides.

The general plan shows a total length from the apse at the east to the broken wall at the west against Gracechurch Street of about 210 ft. About 44 ft. to the north of the Great Wall a parallel wall is shown on the plan, but no details are given, and it may not have been Roman.

The interior curve of the upper wall of the apse had a radius of about 22 ft., and the width of a central “nave” agreeing with this can hardly have been less than 50 ft.; the total internal width, supposing there were “aisles” in line with the 38“chambers” at the end, would have been about 110 ft. There were thick transverse walls across the front of the apse, and again about 20 ft. to the west. I give (Fig. 22) a plan adapted from Archæologia; the walls shown black were not necessarily all above the floor level, although they are thinner than the lowest foundations. (Note that in the plan in Archæologia the scale is given in divisions of 12 ft., and not of 10 ft. as usual.)

Fig. 22.

My plan is restored as a possible reading of the evidence; the most certain parts are those in black (A); the foundations (B) may be of a different age; at the left (C) is the brick pier or wall against Gracechurch Street.

A structure perhaps 110 ft. wide with a central avenue of 50 ft. would have been exceptional; on the other hand, a Basilica 220 ft. to 250 ft. long including the apse would have been rather short. One of the walls found to the west of Gracechurch 39Street was bent in its line as if it might have been against a stream. The nature of the site might have dictated a rather short and very wide building. It should be noticed that the line of Gracechurch Street is nearly or exactly at right angles to the great building. Hodge’s drawings show that the walls of Leadenhall Market were built directly on the Roman foundations, and hence square with them.

The Basilica would have had ranges of Corinthian columns and perhaps a transverse row on the foundation in front of the apse, as at the Basilica Ulpia in Rome and at Pompeii: compare also the transverse walls at the Basilicas of Cirencester and Caerwent. The roof would probably have had trusses of low pitch exposed to the interior, like those of the early Christian churches.

In 1908 a Roman wall, 3½ ft. wide, parallel to Gracechurch Street, was found at No. 85. In 1912 a fine Roman wall, 4½ ft. wide, running north and south, was found just south of Corbet’s Court; turning at right angles it passed under Gracechurch Street. It was of ragstone with double courses of tiles; the base was 27 ft. below the present level; a piece of thinner wall ran close and parallel with the roadway (Archæologia, lxiii.). Kelsey noted that in 1834 massive walls were found in Gracechurch Street from Corbet’s Court to the head of the street (Archæologia, lx.).

The discovery was announced in January 1922 of a wall 2¾ ft. thick of ragstone and bond tiles “in the centre of Gracechurch Street a little south of the Cornhill crossing (to the west or left of Fig. 22). A length of about 10 ft. has been disclosed following the central line of Gracechurch Street. The 40presence of this Roman building in the middle of the highway proves that the mediæval street did not follow the line of the Roman street. Close at hand is Leadenhall. When the present market was reconstructed, excavations disclosed remains of an important Roman building. It is probable that the remains now unearthed are associated with the same group of buildings.” Another wall, 4½ ft. thick, was found at right angles to the thinner wall; the finds were at a depth of about 13 ft. This building, which must have been part of the Basilica or adjacent to it and square with it, was thus as far west as the middle of the street, and doubtless farther, for the thinner wall in association with a thicker one would not have been an external wall. Other walls have recently been found under St. Peter’s, Cornhill, corresponding with those under Leadenhall Market. “All these finds seem to be part of a great building more than 400 ft. long, which crowned the eastern hill of London” (Antiquaries’ Journal, vol. ii. p. 260; see also p. 225, below).

The smaller inset plan on Fig. 22 is a very visionary reading of the possibilities. A street in line with Fish Street Hill and the Bridge, which I will call Axis Street, may not have pointed to the centre of this great building, but rather by its west end as suggested (X). If this is too far west for the Axis Street, then we must suppose that it was directed towards some point in the south front of the Forum. (It is desirable that all the walls found in this locality should be accurately laid down on a plan.) A parallel street to the east, which I will call North Gate Street (Y), would not be in continuation with Axis Street. The question whether Bishopsgate 41and Gracechurch Street represent a Roman street from the Bridge to the Gate has been much argued over (see Archæologia, 1906), and it seems to have been shown that the line was interrupted in some way. The southern part, however, must, I think, represent the Roman street from the Bridge, although it may later have been bent aside to tend more directly to Bishopsgate. The facts and the fault in the line may be reconciled in some such way as suggested. (Hodge’s drawings are in the old Gardner collection, and it would be interesting to know what other Roman records are included.)

Beyond the statement quoted from Brock no identification of the building is offered in Archæologia, and Mr. Bushe-Fox thought that if the walls were contemporary they could not belong to a Basilica. “If there were a nave with two aisles and an apse there would be no reason for the cross wall, nor for the excessive thickness of the side wall. The building had perhaps been a bath; the wall which ended abruptly at the west end was probably a flue for heating the apse, and the large drain would be accounted for” (Proceedings, 1914-5). That the building was indeed the civil Basilica of Londinium is proved to my mind by: A comparison of the plan with those of other British Basilicas—notice the way that the apse is within straight external walls, and compare Fig. 21; by the great scale of the work; by its central position in the City; by the scale and character of the construction; by the fact that the only possible alternative seems to be the supposition that it was the great Bath of the City, and for this neither the planning nor the situation seems suitable; by the exceptional wall decorations described below; by the fact that a 42tile bearing the official stamp PR-BRILON was found on the site (Price). It is a remarkable fact that Leadenhall was the market, and that the Crossing at Cornhill was the carfax of London during the Middle Ages.

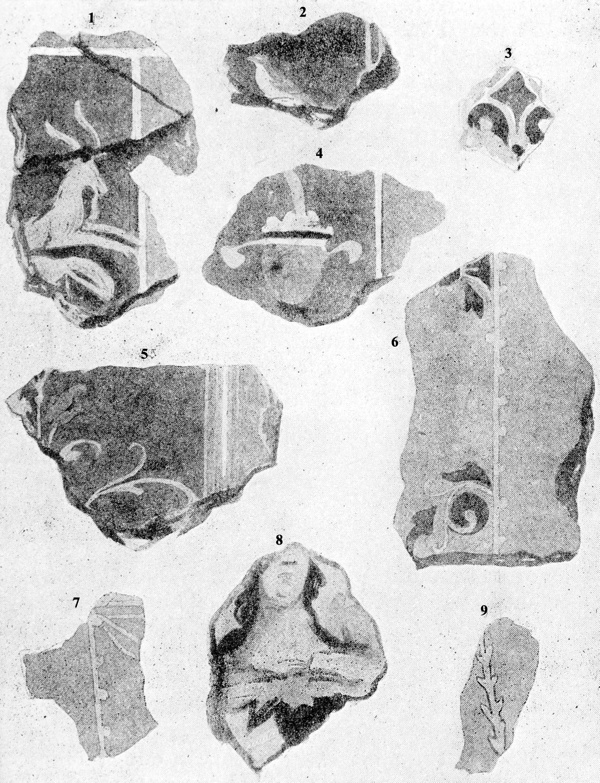

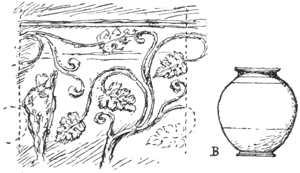

We have seen above that Brock said that fragments of painting were found on the site. In the British Museum are four pieces of wall painting, given by Mr. Hilton Price—1 and 2 in 1882, and 3 and 4 in 1883; the first pair are said to be from Leadenhall, the second pair from Leadenhall Market. One and 3 are fragments of large-scale scrolls of ornamental foliage of a grey-green colour; 2 is a piece of large-scale drapery, and 4 is part of a life-sized foot. These four remarkable fragments evidently form one group and came from the Basilica. The large scale of the ornament and figure work differentiates these pieces of painted plaster from all others found in London. At Silchester and Cirencester fragments of marble wall linings have been found on the sites of the Basilicas, and some of the marble fragments in the British Museum may have come from our Basilica, which must have been a handsome, indeed splendid, civic centre. In the Forum would have been statues of Emperors, and in the Basilica some impersonation of Londinium itself (cf. the fragment of such a figure found at Silchester, now at Reading).

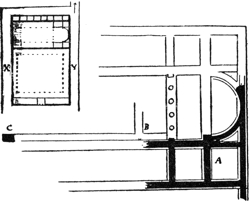

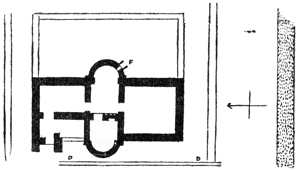

Fig. 23.

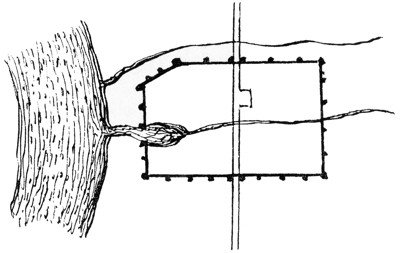

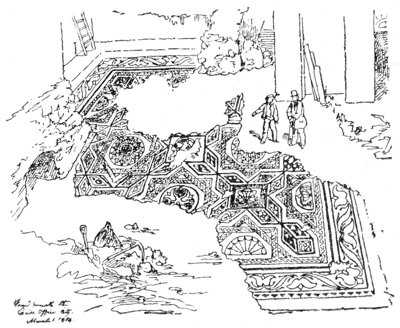

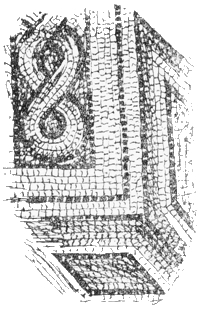

Houses.—In 1869 a mosaic pavement was discovered in Bucklersbury which is now at the Guildhall (Builder, May 15 and 29). It was fully described in a volume by Price. The floor was that of a small round-ended chamber, and belonged to a building on the western bank of the Walbrook, 43Around the apsidal end of the room which had the mosaic was a wall of stone and chalk, built upon piling; this wall contained the flues of the heating-system, and it terminated in piers at the ends of the semicircle. From the fact that no more walling was found and the evidence of an attached lobby which had a wooden sill around it, we may suppose that the rest of the house was of timber work (Fig. 23). The curved apse would be a strong form in which to build a mass of wall to contain the vertical wall flues; and it is an interesting example of building contrivance. We have already seen that timber and clay construction was frequent in Londinium. Near this building a well was found (built of square blocks of chalk, The Builder says). This building with the mosaic floor must have been a superior house on the bank of the Walbrook. To the west, as we shall see, seems to have been a street possibly of shops; we can thus imagine a little group of buildings and streets, 44and a bridge over the Walbrook at the end of Bucklersbury.

Fig. 24.

The well mentioned above is one of a great number which have been discovered; for instance, in excavating for Copthall Avenue “a pit or well, boarded, and filled with earthenware vessels,” etc., was found (Builder, October 5, 1889). Such wells with boarding like a long barrel have been excavated at Silchester. Again to the south of Aldgate High Street two wells were found (Builder, May 3, 1884).

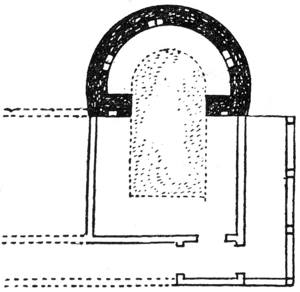

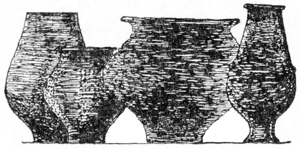

The most complete Roman building which has been recovered and planned is one excavated in Lower Thames Street in 1848 and again in 1859 (Builder, February 5, 1848, and June 11, 1859). A restored plan was given in the Journal of the British Archæological Association, vol. xxiv. (see Fig. 21). The two apsed chambers had hypocausts beneath their floors, supported on little piers built of tiles 8½ in. square, and broken materials. Fig. 25 is reproduced from the illustration of the eastern chamber given in The Builder. Several sketches and some notes, by Fairholt, of this building are in the Victoria and Albert Museum. About 4 or 5 ft. of the walls remained in places, all of tiles with mortar joints nearly as thick as themselves.

Fig. 25.—(A, old masonry; B, brickwork with a flue tile; C, foundations of chamber.)

Foundations discovered in Lower Thames Street in 1859.

46“The walls were of red and yellow brick in alternate layers composed of 18 in. tiles.” Outside the walls was “a drain of wooden planks, 18 in. deep by 10 wide, running towards the river” (see plan). The walls were erected on piles. The sketches show some of the box-flue tiles which had impressed patterns (see Fig. 25). Some additional information is given on a lithograph by A. J. Stothard (1848). The walls were 3 ft. thick. Above the floor of the south room, which was of coarse red and yellow tesseræ, was a second, about a foot higher in level; this was “a layer of red concrete 2½ in. thick, hard, and the upper surface almost glazed” (compare a floor found in Eastcheap, “concrete stuccoed over and painted red.”—V.C.H.). This building was doubtless a house; at the time it was found it was called a bath, but it seems too small to have been even a secondary public bath. As Thos. Wright says: “Many writers have concluded hastily that every house with a hypocaust was a public bath” (cf. the plan of a house at Lymne, The Roman, etc., p. 160). The stoke-hole of the hypocaust was at F, and there were flues up the middle wall and the western apse. The large room was 23 ft. square; some tiles of 2 ft. square were found here, also window glass and an iron key. The plan lay square with the south City Wall (Fig. 24), and the building can hardly be earlier than this wall. It may thus be accepted as a late fourth-century house, and we may further infer that box-tiles with impressed patterns were a characteristic of this century. On two sides of the house were lanes about 10 ft. wide. As in so many cases modern walls seem to have been laid out on the same alignment as the Roman building.

47The house just described had two apses, and the Bucklersbury house also had an apse. This was in agreement with general custom. As Thos. Wright remarked: “One peculiarity which is observed almost invariably in Roman houses in Britain is that one room has a semicircular alcove, and in some instances more than one room possesses this adjunct.” In the plan given in Archæologia of the Roman walls and floors found in and about Lombard Street in 1785 two apses seem to be indicated; thus we have evidence for five in the scanty records; altogether there must have been scores in the city.

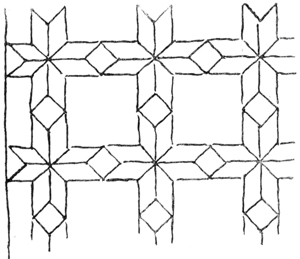

Within the walls of the City were many large houses of the villa type as well as minor dwellings and streets of shops. Roach Smith speaks of such great houses about Crosby Square; he also describes a mosaic floor under Paternoster Row which extended 40 ft.; a second important floor on the site of India House, Leadenhall Street, was at least 22 ft. square, and may have been considerably more; a third large floor which was found under the Excise Office, Broad Street, was about 28 ft. square (probably 30 Roman ft.). All these must have been the floors of the chief central rooms of large houses of the villa type. Tite saw this of the Broad Street floor as his speaking of the “triclinium, other rooms, and the garden” shows. This Broad Street pavement was lying square with more modern walls surrounding it, and it may not be doubted that buildings continuously occupied the site.

The supposition that there were important houses of the villa type within the walls of the City has been fully confirmed by the excavations at Silchester, and I may here quote Dr. Haverfield’s 48general conclusions as to Roman towns in Britain. “Roman British towns were of fair size, Roman London, perhaps even Roman Cirencester were larger than Roman Cologne or Bordeaux. They possessed, too, the buildings proper to a Roman town—town hall, market-place, public baths, chess-board street-plan, all of Roman fashion; they had also shops and temples and here and there a hotel.... The dwelling-houses in them were not town houses fitted to stand side by side to form regular streets; they were country houses, dotted about like cottages in a village. But in one way or another and to a real amount, Britain shared in that expansion of town life which formed a special achievement of the Roman Empire.” The evidence as to the isolation of the houses is here a little overstated, but in the main the passage gives a true impression. Fragments of wall decorations and mosaics found in Southwark suggest that there were big houses on that side of the river, and doubtless others occupied sites along the Strand and Holborn.

Fig. 26.

I give here a little sketch plan (Fig. 26) of a house found about a century since at Worplesdon, Surrey, from a survey at the Society of Antiquaries. This house is interesting as its unaltered plan gives an example of a simple “Corridor House.” It was 62 ft. long by 22½ ft. wide within the foundations, and faced west. The slight foundations of flint, not much more than a foot wide, show that the walls 49must have been of timbering or wattle work. The rooms and passage had floors of plain coarse tesseræ, except that the outer side of the passage had a simple twist border in mosaic. Possibly there had been some pattern in the central room as the floor was there missing, and a note reads: “Near this place was found the lozenge-shaped tessellated pavement.”

Baths, Temples, etc.—Remnants of important buildings have been found in Cannon Street from time to time, and London Stone is probably a fragment of one of them. Wren was of the opinion “by reason of its large foundations that it was some more considerable monument in the Forum; for in the adjoining ground to the south were discovered some tessellated pavements, and other extensive remains of Roman workmanship and buildings.” Under Cannon Street a building with one apartment 40 ft. by 50 ft., and many other chambers, is mentioned in V.C.H. At Dowgate Hill the foundations of large edifices are listed in V.C.H., and of Bush Lane it is remarked: “That there must have been extensive buildings here seems clear.” At Trinity Lane, Great Queen Street, “great portions of immense walls with bonding tiles” have been found (V.C.H.). There was a house on the south side of St. Paul’s known as Camera or Domus Dianæ which may have taken its name from some Roman monument. In a St. Paul’s deed of 1220 it appears as a messuage or inn, domum que fuit Diane.

In December 1921 Mr. Lambert described the foundations of a building by Miles Lane. The plan of this suggested a house of the corridor type facing east. The site seems to have been levelled 50up by timber walling or wharfing against the river and running back into the sloping ground.

One of the most important public buildings in the City would have been the Public Baths, as those of Silchester and Wroxeter show. At Trèves the great Baths cover acres of ground by the river. Bagford says that after the fire of London some Roman water-pipes were found in Creed Lane “which had been carried round a Bath that was built in a round form with niches at equal intervals for seats.” This suggests a part of important Baths, and Creed Lane does not seem an unlikely situation for the Public Baths. (In V.C.H. the site is said to have been in Ludgate Square.)

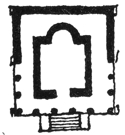

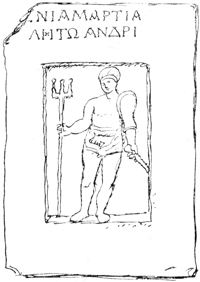

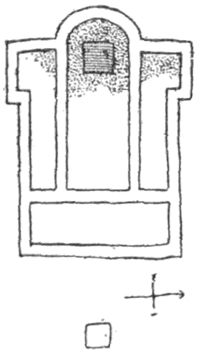

Fig. 27.

The only certain evidence we have for Temples are some inscriptions and sculptures. For the most part they would, like those found at Silchester and elsewhere, have been small square and polygonal structures set on a rather high podium approached by steps. Fig. 27 is a restored plan of the little Temple found at Caerwent. Doubtless here and in most cases, the roof of the cella ran on to cover the podium. At the foot of the steps an external altar would have stood. The column illustrated before (Fig. 1) seems suitable for a temple. Roach Smith, speaking of the group of Mother Goddesses found in Crutched Friars (see Builder, October 30, 1847), says: “It is the only instance with the exception of the discovery made in Nicholas Lane in which the site of a temple can with reason be identified” (Ill. Rom. Lon., p. 33). The find in Nicholas Lane was part of an important and early 51inscription which may have been on the chief temple in Londinium. Some sculptures found on the bank of the Walbrook suggest that a cell of Mithras occupied the site. In the fourth century a Christian church would, as at Silchester, have occupied an important site in the City.

A large Theatre or Amphitheatre, or both, would have been necessary in such a town. Roach Smith, who had a wonderful instinct of insight, thought that such a building probably occupied a site against the bank of the Fleet, called “Breakneck Steps.” Lately it has been suggested that the drawing-in of the line of the City Walls at the north-west angle was done to avoid an amphitheatre; more probably, I think, it was to avoid wet ground. There is evidence that gladiator contests and chariot races were popular. For gladiators, compare two small bone figures at the British Museum, evidently from one shop, with the fragment of a little statuette at the Guildhall. The bronze trident-head, also at the Guildhall, really does seem to be a gladiator’s weapon as suggested in the catalogue. For chariot races, see the fragments of glass bowls, which may have been made in London, in the British Museum. I have found an additional little point of evidence on chariot races. Amongst Fairholt’s sketches at the Victoria and Albert Museum, is one of an enigmatical little fragment of a Castor vase, found in Bishopsgate Street, which seems to represent four heads of dogs running neck and neck. Now there is a whole vase in the British Museum (found in Colchester) which was practically a replica of the other, and this shows that the four running animals of the fragment were chariot horses, and the whole 52represented a race. Above the horses of the fragment is scratched ITALVS, which, I suggest, must have been the name of some favourite “winner” in Londinium.

Streets.—In his account of the Bucklersbury pavement, Price describes also some walls which were found “about 30 yds. westerly from the pavement” (the position is shown on his plan). “Two Roman walls running nearly in line with Bucklersbury directly towards the Walbrook.” In the space between them had been laid a drain to fall towards the brook with a tile pavement above, and mortar fillets against the walls. The walls were 2¾ ft. thick, and built on three rows of piles, and the space between was 2¼ ft. The tiles are of the usual kind of red and yellow brick. Above these walls were others of chalk and stone 3 ft. apart, of later date. This is one of a great number of instances where we find that mediæval buildings were founded directly on Roman walls. The space Price suggested was “an open passage-way, or it may be of an alley between two buildings.” Comparison makes it certain that the walls were those of neighbouring houses in a street; similar conditions have been found at Caerwent, Silchester, etc. At the former “the shops along the main street were probably roofed with gables; this is substantiated by the finding of a finial in front of a house. The narrow space between the houses would serve to carry away the water which would drop from the eaves” (Archæol., 1906). The walls are shown in Fig. 28.

The Bucklersbury paved passage, only just wide enough for a man to get at it, with the underlying drain, is obviously a similar space. The tradition of 53dividing houses in streets from one another in this way lasted into the Middle Ages (see V. le Duc’s Dict., “Maison”) and, of course, occasionally to modern times. By this means party walls and difficult roof gutters are avoided. From the two parallel walls we are justified in inferring a row of houses—possibly shops—and a street running to the west of them; moreover, the example suggests to some extent what continuous streets of houses must have been like. In Southwark a passage-way between houses was found 3 ft. 8 in. wide. A wall with tile paving against the outside, found under the Mansion House, suggests a similar passage.

Fig. 28.

It has been mentioned above how in several cases, as is clear even from our imperfect records, that later walls were founded directly on Roman walls. Modern buildings were thus in direct and unbroken succession to Roman ones and maintained the same alignment. In the Archer collection at the British Museum is a drawing of “a Roman pavement and foundations, supposed to be remains of Tower Royal” in Cannon Street; this again was square with modern work. Roman remains have been found under several churches. Massive walls of chalk were found under St. Benet’s, Gracechurch. Roach Smith, speaking of a floor found at the corner 54of Clement’s Lane, says: “This adds another to the numerous instances of churches in London standing on foundations of Roman buildings.” In 1724 Roman foundations were found under St. Mary, Woolnoth, and “three foundations of churches in the same place” (Minutes Soc. Ant., June 17). Even Westminster Abbey and St. Martin’s in the Fields were built on Roman sites, and so probably was St. Andrew’s, Holborn.

This continuity of the buildings from the Roman Age is not only an interesting fact, but it is a strong argument for the general continuity of the street lines as well. The plan of the extensive finds in and about Lombard Street in 1785 shows the building to have conformed very much to lines parallel with, and at right angles to St. Swithin, Sherborne, Abchurch, Nicholas, Birchin and Clement’s Lanes, and I cannot doubt that these lanes are in some degree the successors of Roman streets. In “Lombard Street and Birchin Lane the discoveries are said to have indicated a row of houses” (V.C.H.). If all the evidence as to the “orientation” of buildings and walls was laid down on a plan, merely marking the direction of the minor ones with a cross, we might build up further results in regard to the direction of the streets. At the same time it would be vain to expect any large and simple scheme of lay-out of the chess-board type, the Walbrook and other streams, and probably the persistence of some earlier lines (Watling Street to St. Albans?) would have interfered with that. The Walbrook seems to have been crossed by two chief bridges, which must have been governing facts in the lay-out. One was at Bucklersbury, the other, Horseshoe Bridge farther south, is recorded from the thirteenth 55century. Cannon Street, I cannot doubt, represents one east to west street. Thames Street must have been formed when the south City Wall was built. I have spoken of the north-south lines above. Saint Benet “Gerschereche” is mentioned in a charter of 1053 (Athen., February 3, 1906).

Wren found a “causeway” made up of stones and tiles by Bow Church (under the present tower). It is suggested in V.C.H. that this was an embankment, but causeway was one of the regular names for a Roman road. At Rochester one 5 ft. or 6 ft. thick of hard stuff has been found crossing some soft ground.

The best way now to see again the old Roman City of London is to go to the foot of the hill below St. Magnus the Martyr and then, turning away from the riverside quays of the seaport, to walk up the street which still retains something of the look of a High Street in an old market town. Behind it we may still discern the ghost of the Roman Axis Street. Right and left are narrow streets with red plastered houses separated by little “drangways.” Here at a corner is a small temple with a dedication to the deified emperor. There is the great City Bath. Farther on is the civic centre, the market-place and hall; one, a square piazza containing imperial statues in gilt bronze, and the other a big building having internal ranks of tall Corinthian columns, a wide apse, and an open timber roof—sombre but noble. Round about are many isolated and widespreading mansions, one doubtless being the palace of the Governor of the province. Beyond are the walls and gates which will be next described, and in the background rise the northern heaths 56and wooded hills now called Hampstead and Highgate.

“Gem of all Joy and Jasper of Jocundity, Strong be thy walls that about thee stand; London, thou art the flower of cities all.”

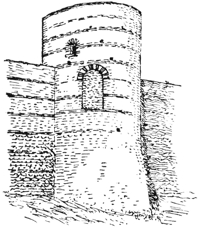

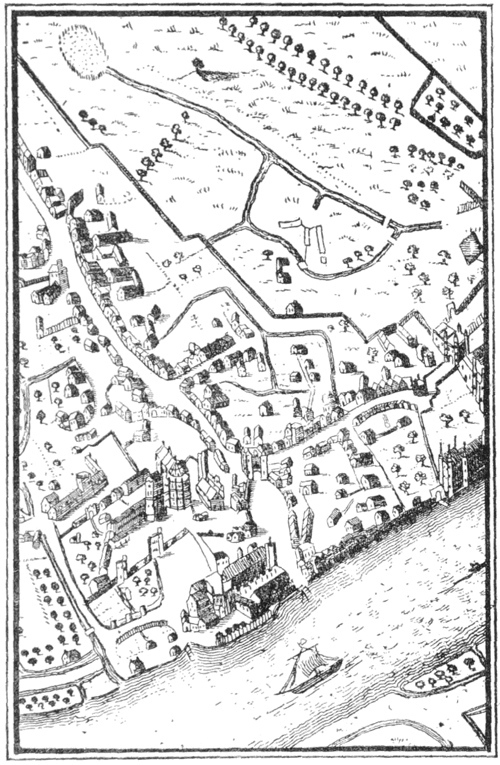

THE walls, gates and bastions of the City may be traced by the record of early maps such as that of Braun and Hogenberg. The bastions of the east side are particularly shown on a plan of Holy Trinity Priory made in the sixteenth century; the west side from Ludgate to Cripplegate plainly appears in Hollar’s plan after the fire, 1667. There were two bastions between Ludgate and Newgate, then an angle bastion to the north; three more on the straight length to Aldersgate, then one beyond that gate at the angle where the wall turned north again; two bastions occurred between this angle and the bastion at the corner where the wall again turned east, which now exists in Cripplegate Churchyard.

Several of the gates stood until 1760. In an old MS. book of notes I find under the heading “Remarkable Transactions in ye Mayoralty of Sir J. Chitty.”—“In July, ye gates of Aldgate, Cripplegate and Ludgate were sold by public auction in ye council chamber, Guildhall, and were accordingly taken down without obstructing 58either ye foot or cartway, and their sites laid into ye streets. Aldgate for £157, 10s.; Cripplegate, £93; and Ludgate for £148.” Many old drawings of parts of the wall are preserved in the Crace, the Archer and other collections. The exact line of the wall and positions of the bastions has been verified by modern excavations and discoveries. For full description and a plan, see the Victoria County History and Archæologia, lxii. (1912). A good description of what was visible in 1855 is given in The Builder for that year.

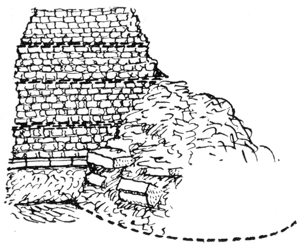

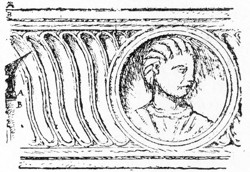

Fig. 29. See p. 61.

Fig. 30.

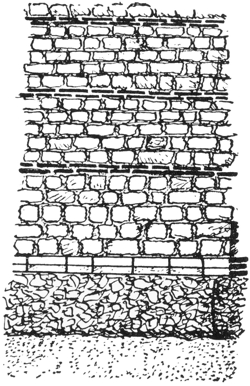

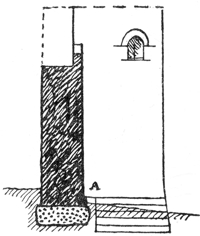

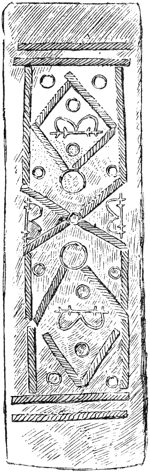

In September 1903 an important section of the Roman wall was found in excavating the site of Newgate Prison; in some parts it was about a dozen feet high. I saw it in October and noted—“The wall is about 8½ ft. wide. On the outside and inside one or two courses of facing stones were first raised and the core of rubble was then filled in to that height; first there was a thick couch of mortar, then a layer of rubble stones, then 59another liberal supply of mortar running down between the stones as grout; there were two or three such levellings-up in the heights between the tile bonding courses.” The wall had a rough rubble foundation, then a course of plinth stones on the outside, with three tile courses corresponding to it on the inside of the wall, then followed five courses of the fairly square facing stones on both sides of the wall, then two rows of tile, five courses more stone and two rows of tile, then five more stone courses; above this level the wall had been destroyed. The stones and tiles were set in mortar, and the latter, except for the three courses at the bottom on the inside, which served as a plinth, were carried right through the thickness of the wall; the “tiles” were Roman bricks about 18 in. by 12 in. and 1½ in. thick, laid in what we call Flemish bond. The stone facing courses were a little higher at the bottom than upwards, but all were comparatively small and square; there was a clear distinction between the wrought facings and the rubble filling, which was practically concrete. The “facings” were hard skins adhering 60to the filling and required by the method of building as described above (Fig. 30).

The mode of construction of the wall is likely to be misunderstood when we speak as we almost necessarily do of facings and filling and of bond tiles. The “facing” stones were small, roughly wrought, and set in much mortar; they formed outer skins to the concreted mass into which they tailed back. The whole was homogeneous. The method was analogous to the facing of concrete with triangular bricks notching back into the core.

The tile courses in the City Wall were doubtless bonds, but they also divided the wall into strata locking up the moisture of the mortar from too rapid absorption and evaporation. I have little doubt that the wall was carried up a stratum at a time over long lengths; it would thus have been available as a defence from an early stage, and scaffolding would not have been required. The building of this wall and casting the ditch about it required a great constructive effort. A strip of ground some 100 feet wide must have been cleared as a preliminary. Then the immense quantity of stone required would have been brought by ships and barges. It is often said that old material was not re-used in the wall, but I can hardly think that two miles of chamfered plinth had to be provided out of new stone at the very beginning of the work. And material from destroyed monuments was doubtless broken up for the small facing stones. The lime-burning, brick-making, stone-cutting, as well as the actual building, called for much labour. It would be interesting to have the quantities taken out and an estimate prepared.

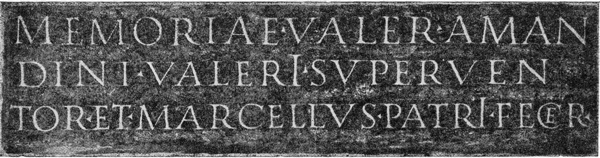

The south wall along the river front is well 61described in V.C.H. Roach Smith, in an article in vol. i. of the Archæological Journal, recorded the fact that it had “alternate layers of red and yellow plain and curve-edged (i.e. flanged) tiles”; the rest being of ragstone and flint. It was founded on piles. In The Builder (January 19, 1912) it is recorded that in digging for a foundation at No. 125 Lower Thames Street, between Fish Street Hill and Pudding Lane, there was found the base of the Roman wall resting upon long and thick timber balks laid crosswise, with piles beneath them; there were three courses of rough rag and sandstone capped with two courses of yellow bonding tiles, all in reddish mortar; what remained was about 3 ft. high and 10 ft. wide, and was at 24 ft. below the existing pavement. Full evidence of the course of the City Wall along the river front has been found (Archæol. xliii.). It may be noticed that in mediæval regulations foreign sailors might not go beyond Thames Street; that is, pass where the wall had been, into the City proper. This south wall, like the bastions, contained remnants of Roman monuments.