Project Gutenberg's Punchinello, Vol. 1, No. 11, June 11, 1870, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punchinello, Vol. 1, No. 11, June 11, 1870 Author: Various Posting Date: January 18, 2013 [EBook #9545] Release Date: December, 2005 First Posted: October 7, 2003 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCHINELLO, JUNE 11, 1870 *** Produced by Cornell University, Joshua Hutchinson, Sandra Brown and PG Distributed Proofreaders

TRAINS LEAVE DEPOTS

Foot of Chambers Street

and

Foot of Twenty-Third Street,

AS FOLLOWS:

Through Express Trains leave Chambers Street at 8 A.M., 10 A.M., 5:30 P.M., and 7:00 P.M., (daily); leave 23d Street at 7:45 A.M., 9:45 A.M., and 5:15 and 6:45 P.M. (daily.) New and improved Drawing-Room Coaches will accompany the 10:00 A.M. train through to Buffalo, connecting at Hornellsville with magnificent Sleeping Coaches running through to Cleveland and Galion. Sleeping Coaches will accompany the 8:00 A.M. train from Susquehanna to Buffalo, the 5:30 P.M. train from New York to Buffalo, and the 7:00 P.M. train from New York to Rochester, Buffalo and Cincinnati. An Emigrant train leaves daily at 7:30 P.M.

FOR PORT JERVIS AND WAY, *11:30 A.M., and 4:30 P.M., (Twenty-third Street, *11:15 A.M. and 4:15 P.M.)

FOR MIDDLETOWN AND WAY, at 3:30 P.M.,(Twenty-third Street, 3:15 P.M.); and, Sundays only, 8:30 A.M. (Twenty-third Street, 8:15 P.M.)

FOR GREYCOURT AND WAY, at *8:30 A.M., (Twenty-third Street, 8:15 A.M.)

FOR NEWBURGH AND WAY, at 8:00 A.M., 3:30 and 4:30 P.M. (Twenty-third Street 7:45 A.M., 3:15 and 4:15 P.M.)

FOR SUFFERN AND WAY, 5:00 P.M. and 6:00 P.M. (Twenty-third Street, 4:45 and 5:45 P.M.) Theatre Train, *ll:30 P.M. (Twenty-third Street, *11 P.M.)

FOR PATERSON AND WAY, from Twenty-third Street Depot, at 6:45, 10:15 and 11:45 A.M.; *1:45 3:45, 5:15 and 6:45 P.M. From Chambers Street Depot at 6:45, 10:l5 A.M.; 12 M.; *1:45, 4:00, 5:15 and 6:45 P.M.

FOR HACKENSACK AND HILLSDALE, from Twenty-third Street Depot, at 8:45 and 11:45 A.M.; $7:15 3:45, $5:15, 5:45, and $6:45 P.M. From Chambers Street Depot, at 9:00 A.M.; 12:00 M.; $2:l5, 4:00 $5:l5, 6:00, and $6:45 P.M.

FOR PIERMONT, MONSEY AND WAY, from Twenty-third Street Depot, at 8:45 A.M.; 12:45, {3:l5 4:15, 4:46 and {6:15 P.M., and, Saturdays only, {12 midnight. From Chambers Street Depot, at 9:00 A.M.; 1:00, {3:30, 4:15, 5:00 and {6:30 P.M. Saturdays, only, {12:00 midnight.

Tickets for passage and for apartments in Drawing-Room and Sleeping Coaches can be obtained, and orders for the Checking and Transfer of Baggage may be left at the

COMPANY'S OFFICES:

241, 529, and 957 BroadFway. 205 Chambers Street. Cor. 125th Street & Third Ave., Harlem. 338 Fulton Street, Brooklyn. Depots, foot of Chambers Street and foot of Twenty-third Street, New York. 3 Exchange Place. Long Dock Depot, Jersey City, And of the Agents at the principal Hotels

WM. R. BARR, General Passenger Agent.

L. D. RUCKER, General Superintendent.

Daily. $For Hackensack only, {For Piermont only.

May 2D, 1870.

Clinton Hall, Astor Place,

NEW YORK.

This is now the largest Circulating Library in America, the number of volumes on its shelves being 114,000. About 1000 volumes are added each month; and very large purchases are made of all new and popular works. Books are delivered at members' residences for five cents each delivery.

TERMS OF MEMBERSHIP:

TO CLERKS, $1 INITIATION, $3 ANNUAL DUES. TO OTHERS, $5 A YEAR.

Subscriptions Taken for Six Months.

BRANCH OFFICES

at

No. 76 Cedar St., New York,

and at

Yonkers, Norwalk, Stamford, and Elizabeth.

AMERICAN

BUTTONHOLE, OVERSEAMING,

AND

SEWING-MACHINE CO.,

572 and 574 Broadway, New-York.

This great combination machine is the last and greatest improvement on all the former machines, making, in addition to all work done on best Lock-Stitch machines, beautiful

BUTTON AND EYELET HOLES,

in all fabrics.

Machine, with finely finished

OILED WALNUT TABLE AND COVER

complete, $75. Same machine, without the buttonhole parts,$50. This last is beyond all question the simplest, easiest to manage and to keep in order, of any machine in the market. Machines warranted, and full instruction given to purchasers.

J. NICKINSON

begs to announce to the friends of

"PUNCHINELLO"

residing in the country, that, for their convenience, he has Made arrangements by which, on receipt of the price of

ANY STANDARD BOOK PUBLISHED.

the same will be forwarded, postage paid.

Parties desiring Catalogues of any of our Publishing Houses can have the same forwarded by inclosing two stamps.

OFFICE OF

PUNCHINELLO PUBLISHING CO.

83 Nassau Street,

[P.O. Box 2783.]

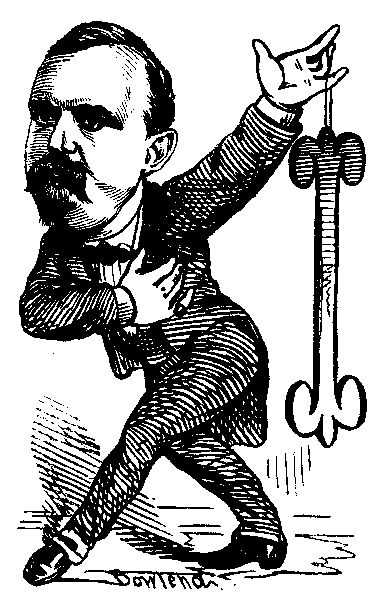

[The American Press's Young Gentlemen, when taking their shady literary walks among the Columns of Interesting Matter, have been known to remark—with a glibness and grace, by Jove, greatly in excess of their salaries—that the reason why we don't produce great works of imagination in this country, as they do in other countries, is because we haven't the genius, you know. They think—do they?—that the bran-new localities, post-office addresses, and official titles, characteristic of the United States of America, are rife with all the grand old traditional suggestions so useful in helping along the romantic interest of fiction. They think—do they?—that if an American writer could write a Novel in the exact style of COLLINS, or TROLLOPE, or DICKENS: only laying its scenes and having its characters in this country; the work would be as romantically effective as one by COLLINS, or TROLLOPE, or DICKENS; and that the possibly necessary incidental mention of such native places as Schermerhorn Street, Dobb's Ferry, or Chicago, wouldn't disturb the nicest dramatic illusion of the imaginative tale. Very well, then! All right! Just look here!—O A.P's Young Gentlemen, just look here—]

CHAPTER I.

DAWNATION.

A modern American Ritualistic Spire! How can the modern American Ritualistic Spire be here! The well-known tapering brown Spire, like a closed umbrella on end? How can that be here? There is no rusty rim of a shocking bad hat between the eye and that Spire in the real prospect. What is the rusty rim that now intervenes, and confuses the vision of at least one eye? It must be an intoxicated hat that wants to see, too. It is so, for ritualistic choirs strike up, acolytes swing censers dispensing the heavy odor of punch, and the ritualistic rector and his gaudily robed assistants in alb, chasuble, maniple and tunicle, intone a Nux Vomica in gorgeous procession. Then come twenty young clergymen in stoles and birettas, running after twenty marriageable young ladies of the congregation who have sent them worked slippers. Then follow ten thousand black monkies swarming all over everybody and up and down everything, chattering like fiends. Still the Ritualistic Spire keeps turning up in impossible places, and still the intervening rusty rim of a hat inexplicably clouds one eye. There dawns a sensation as of writhing grim figures of snakes in one's boots, and the intervening rusty rim of the hat that was not in the original prospect takes a snake-like—But stay! Is this the rim of my own hat tumbled all awry? I' mushbe! A few reflective moments, not unrelieved by hiccups, mush be d'voted to co'shider-ERATION of th' posh'bil'ty.

Nodding excessively to himself with unspeakable gravity, the gentleman whose diluted mind has thus played the Dickens with him, slowly arises to an upright position by a series of complicated manoeuvres with both hands and feet; and, having carefully balanced himself on one leg, and shaking his aggressive old hat still farther down over his left eye, proceeds to take a cloudy view of his surroundings. He is in a room going on one side to a bar, and on the other side to a pair of glass doors and a window, through the broken panes of which various musty cloth substitutes for glass ejaculate toward the outer Mulberry Street. Tilted back in chairs against the wall, in various attitudes of dislocation of the spine and compound fracture of the neck, are an Alderman of the ward, an Assistant-Assessor, and the lady who keeps the hotel. The first two are shapeless with a slumber defying every law of comfortable anatomy; the last is dreamily attempting to light a stumpy pipe with the wrong end of a match, and shedding tears, in the dim morning ghastliness, at her repeated failures.

"Thry another," says this woman, rather thickly, to the gentleman balanced on one leg, who is gazing at her and winking very much. "Have another, wid some bitters."

He straightens himself extremely, to an imminent peril of falling over backward, sways slightly to and fro, and becomes as severe in expression of countenance as his one uncovered eye will allow.

The woman falls back in her chair again asleep, and he, walking with one shoulder depressed, and a species of sidewise, running gait, approaches and poises himself over her.

"What vision can she have?" the man muses, with his hat now fully upon the bridge of his nose. He smiles unexpectedly; as suddenly frowns with great intensity; and involuntarily walks backward against the sleeping Alderman. Him he abstractedly sits down upon, and then listens intently for any casual remark he may make. But one word comes— "Wairzernat'chal'zationc'tif'kits."

"Unintelligent!" mutters the man, weariedly; and, rising dejectedly from the Alderman, lurches, with a crash, upon the Assistant-Assessor. Him he shakes fiercely for being so bony to fall on, and then hearkens for a suitable apology.

"Warzwaz-yourwifesincome-lash'—lash'-year?"

A thoughtful pause, partaking of a doze.

"Unintelligent!"

Complicatedly arising from the Assessor, with his hat now almost hanging by an ear, the gentleman, after various futile but ingenious efforts to face towards the door by turning his head alone that way, finally succeeds by walking in a circle until the door is before him. Then, with his whole countenance charged with almost scowling intensity of purpose, though finding it difficult to keep his eyes very far open, he balances himself with the utmost care, throws his shoulders back, steps out daringly, and goes off at an acute slant toward the Alderman again. Recovering himself by a tremendous effort of will and a few wild backward movements, he steps out jauntily once more, and can not stop himself until he has gone twice around a chair on his extreme left and reached almost exactly the point from which he started the first time. He pauses, panting, but with the scowl of determination still more intense, and concentrated chiefly in his right eye. Very cautiously extending his dexter hand, that he may not destroy the nicety of his perpendicular balance, he points with a finger at the knob of the door, and suffers his stronger eye to fasten firmly upon the same object. A moment's balancing, to make sure, and then, in three irresistible, rushing strides, he goes through the glass doors with a burst, without stopping to turn the latch, strikes an ash-box on the edge of the sidewalk, rebounds to a lamp-post, and then, with the irresistible rush still on him, describes a hasty wavy line, marked by irregular heel-strokes, up the street.

That same afternoon, the modern American Ritualistic Spire rises in duplicate illusion before the multiplying vision of a traveller recently off the ferry-boat, who, as though not satisfied with the length of his journey, makes frequent and unexpected trials of its width. The bells are ringing for vesper service; and, having fairly made the right door at last, after repeatedly shooting past and falling short of it, he reaches his place in the choir and performs voluntaries and involuntaries upon the organ, in a manner not distinguishable from almost any fashionable church-music of the period.

CHAPTER II.

A DEAN, AND A CHAP OR TWO ALSO.

Whosoever has noticed a party of those sedate and Germanesquely philosophical animals, the pigs, scrambling precipitately under a gate from out a cabbage-patch toward nightfall, may, perhaps, have observed, that, immediately upon emerging from the sacred vegetable preserve, a couple of the more elderly and designing of them assumed a sudden air of abstracted musing, and reduced their progress to a most dignified and leisurely walk, as though to convince the human beholder that their recent proximity to the cabbages had been but the trivial accident of a meditative stroll.

Similarly, service in the church being over, and divers persons of piggish solemnity of aspect dispersing, two of the latter detach themselves from the rest and try an easy lounge around toward a side door of the building, as though willing to be taken by the outer world for a couple of unimpeachable low-church gentlemen who merely happened to be in that neighborhood at that hour for an airing.

The day and year are waning, and the setting sun casts a ruddy but not warming light upon two figures under the arch of the side door; while one of these figures locks the door, the other, who seems to have a music book under his arm, comes out, with a strange, screwy motion, as though through an opening much too narrow for him, and, having poised a moment to nervously pull some imaginary object from his right boot and hurl it madly from him, goes unexpectedly off with the precipitancy and equilibriously concentric manner of a gentleman in his first private essay on a tight-rope.

"Was that Mr. BUMSTEAD, SMYTHE?"

"It wasn't anybody else, your Reverence."

"Say 'his identity with the person mentioned scarcely comes within the legitimate domain of doubt,' SMYTHE—to Father Dean, the younger of the piggish persons softly interposes,

"Is Mr. BUMSTEAD unwell, SMYTHE?"

"He's got 'em bad to-night."

"Say 'incipient cerebral effusion marks him especially for its prey at this vesper hour.' SMYTHE—to Father DEAN," again softly interposes Mr. SIMPSON, the Gospeler.

"Mr. SIMPSON," pursues Father DEAN, whose name has been modified, by various theological stages, from its original form of Paudean, to Pere DEAN—Father DEAN, "I regret to hear that Mr. BUMSTEAD is so delicate in health; you may stop at his boarding-house on your way home, and ask him how he is, with my compliments." Pax vobiscum.

Shining so with a sense of his own benignity that the retiring sun gives up all rivalry at once and instantly sets in despair, Father DEAN departs to his dinner, and Mr. SIMPSON, the Gospeler, betakes himself cheerily to the second-floor-back where Mr. BUMSTEAD lives. Mr. BUMSTEAD is a shady-looking man of about six and twenty, with black hair and whiskers of the window-brush school, and a face reminding you of the BOURBONS. As, although lighting his lamp, he has, abstractedly, almost covered it with his hat, his room is but imperfectly illuminated, and you can just detect the accordeon on the window-sill, and, above the mantel, an unfinished sketch of a school-girl. (There is no artistic merit in this picture; in which, indeed, a simple triangle on end represents the waist, another and slightly larger triangle the skirts, and straight-lines with rake-like terminations the arms and hands.)

"Called to ask how you are, and offer Father DEAN'S compliments," says the Gospeler.

"I'm allright, shir!" says Mr. BUMSTEAD, rising from the rug where he has been temporarily reposing, and dropping his umbrella. He speaks almost with ferocity.

"You are awaiting your nephew, EDWIN DROOD?"

"Yeshir." As he answers, Mr. BUMSTEAD leans languidly far across the table, and seems vaguely amazed at the aspect of the lamp with his hat upon it.

Mr. SIMPSON retires softly, stops to greet some one at the foot of the stairs, and, in another moment, a young man fourteen years old enters the room with his carpet-bag.

"My dear boys! My dear EDWINS!"

Thus speaking, Mr. BUMSTEAD sidles eagerly at the new comer, with open arms, and, in falling upon his neck, does so too heavily, and bears him with a crash to the ground.

"Oh, see here! this is played out, you know," ejaculates the nephew, almost suffocated with travelling-shawl and BUMSTEAD.

Mr. BUMSTEAD rises from him slowly and with dignity.

"Excuse me, dear EDWIN, I thought there were two of you."

EDWIN DROOD regains his feet with alacrity and casts aside his shawl.

"Whatever you thought, uncle, I am still a single man, although your way of coming down on a chap was enough to make me beside myself. Any grub, JACK?"

With a check upon his enthusiasm and a sudden gloom of expression amounting almost to a squint, Mr. BUMSTEAD motions with his whole right side toward an adjacent room in which a table is spread, and leads the way thither in a half-circle.

"Ah, this is prime!" cries the young fellow, rubbing his hands; the while he realizes that Mr. BUMSTEAD'S squint is an attempt to include both himself and the picture over the mantel in the next room in one incredibly complicated look.

Not much is said during dinner, as the strength of the boarding-house butter requires all the nephew's energies for single combat with it, and the uncle is so absorbed in a dreamy effort to make a salad with his hash and all the contents of the castor, that he can attend to nothing else. At length the cloth is drawn, EDWIN produces some peanuts from his pocket and passes some to Mr. BUMSTEAD, and the latter, with a wet towel pinned about his head, drinks a great deal of water.

"This is Sissy's birthday, you know, JACK," says the nephew, with a squint through the door and around the corner of the adjoining apartment toward the crude picture over the mantel, "and, if our respective respected parents hadn't bound us by will to marry, I'd be mad after her."

Crack. On EDWIN DROOD'S part.

Hic. On Mr. BUMSTEAD'S part.

"Nobody's dictated a marriage for you, JACK. You can choose for yourself. Life for you is still fraught with freedom's intoxicating—"

Mr. BUMSTEAD has suddenly become very pale, and perspires heavily on the forehead.

"Good Heavens, JACK! I haven't hurt your feelings?"

Mr. BUMSTEAD makes a feeble pass at him with the water-decanter, and smiles in a very ghastly manner.

"Lem me be a mis'able warning to you, EDWIN," says Mr. BUMSTEAD, shedding tears.

The scared face of the younger recalls him to himself, and he adds: "Don't mind me, my dear boys. It's cloves; you may notice them on my breath. I take them for nerv'shness." Here he rises in a series of trembles to his feet, and balances, still very pale, on one leg.

"You want cheering up," says EDWIN DROOD, kindly.

"Yesh—cheering up. Let's go and walk in the graveyard," says Mr. BUMSTEAD.

"By all means. You won't mind my slipping out for half a minute to the Alms House to leave a few gum-drops for Sissy? Rather spoony, JACK."

Mr. BUMSTEAD almost loses his balance in an imprudent attempt to wink archly, and says, "Norring-half-sh'-shweet-'n-life." He is very thick with EDWIN DROOD, for he loves him.

"Well, let's skedaddle, then."

Mr. BUMSTEAD very carefully poises himself on both feet, puts on his hat over the wet towel, gives a sudden horrified glance downward toward one of his boots, and leaps frantically over an object.

"Why, that was only my cane," says EDWIN.

Mr. BUMSTEAD breathes hard, and leans heavily on his nephew as they go out together.

(To be Continued.)

PUNCHINELLO has heard, of course, of the good time coming. It has not come yet. It won't come till the stars sing together in the morning, after going home, like festive young men, early. It won't come till Chicago has got its growth in population, morals and ministers. It won't come till the women are all angels, and men are all honest and wise; not until politicians and retailers learn to tell the truth. You may think the Millennium a long way off. Perhaps so. But mighty revolutions are sometimes wrought in a mighty fast time. Many a fast man has been known to turn over a new leaf in a single night, and forever afterwards be slow. Such a thing is dreadful to contemplate, but it has been. Many a vain woman has seen the folly of her ways at a glance, and at once gone back on them. This is not dreadful to contemplate, since to go back on folly is to go onward in wisdom. The female sex is not often guilty of this eccentricity, but instances have been known. It is that which fills the proud bosom of man with hope and consolation, and makes him feel really that woman is coming; which is all the more evident since she began her "movement." The good time coming is nowhere definitely named in the almanacs. The goings and comings of the heavenly bodies, from the humble star to the huge planet, are calculated with the facility of the cut of the newest fashion; and the revolutions of dynasties can be fixed upon with tolerable certainty; but the period of the good time coming is lost in the mists of doubt and the vapors of uncertainty. It is very sure in expectancy, like the making of matrimonial matches. Everybody is looking for it, but nobody sees it. The sharpest of eyes only discern the bluest and gloomiest objects. But PUNCHINELLO may reasonably expect to see, feel and know, this good time. The coming will yet be to it the time come. Perhaps it will be when it visits two hundred thousand readers weekly, when mothers sigh, children cry, and fathers well-nigh die for it. At all events, somewhen or other—it may be the former period, but possibly the latter—the good time will come. And great will be the coming thereof, with no discount to the biggest or richest man out.

What a luxury is Hope! It springs eternal in the human breast. Rather an awkward place for a spring, but as poets know more than other people, no doubt it is all right. Hope is an institution. What is the White House, or the Capitol at Washington, to Hope? What is the Central Park, or Boston Common, or the Big Organ, to Hope? Not much—not anything, like the man's religion, to speak of. Hope bears up many a man, though it pays no bills to the grocer, milliner, tailor, or market man. It is the vertebra which steadies him plumb up to a positive perpendicular. A hopeless man or woman—how fearful! They very soon become round-shouldered, limp and weak, and drink little but unsizable sighs, and feed on all manner of dark and unhealthy things. It is TODD'S deliberate opinion that if a cent can't be laid up, Hope should. Hope with empty pockets is rich compared to wealth with "nary a" hope. Hope is a good thing to have about the house. It always comes handy, and is acceptable even to company. So believes, and he acts on the faith, does

TIMOTHY TODD.

~Capitol Punishment.~

Abolition of the franking privilege.

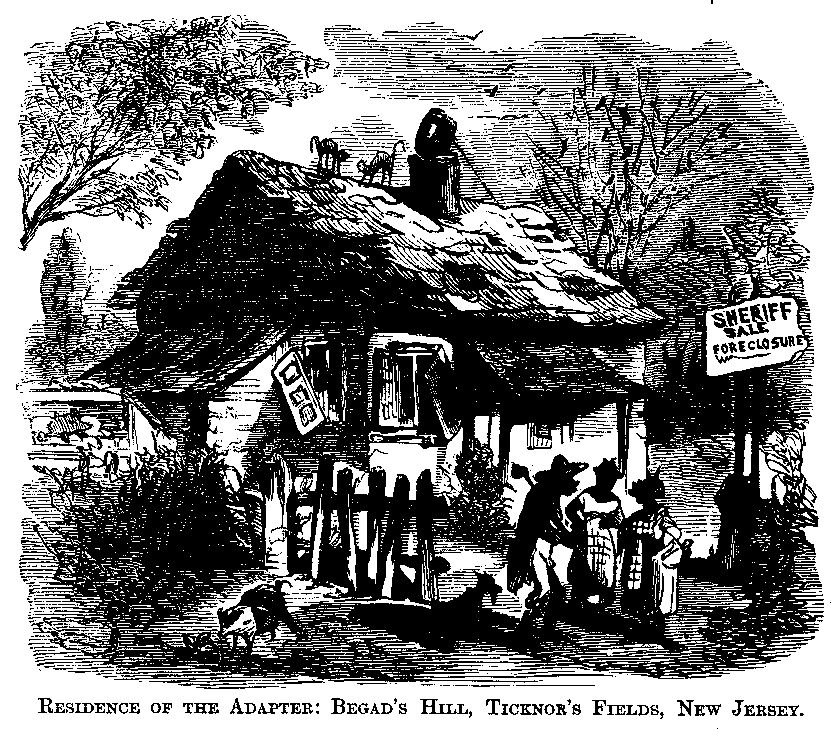

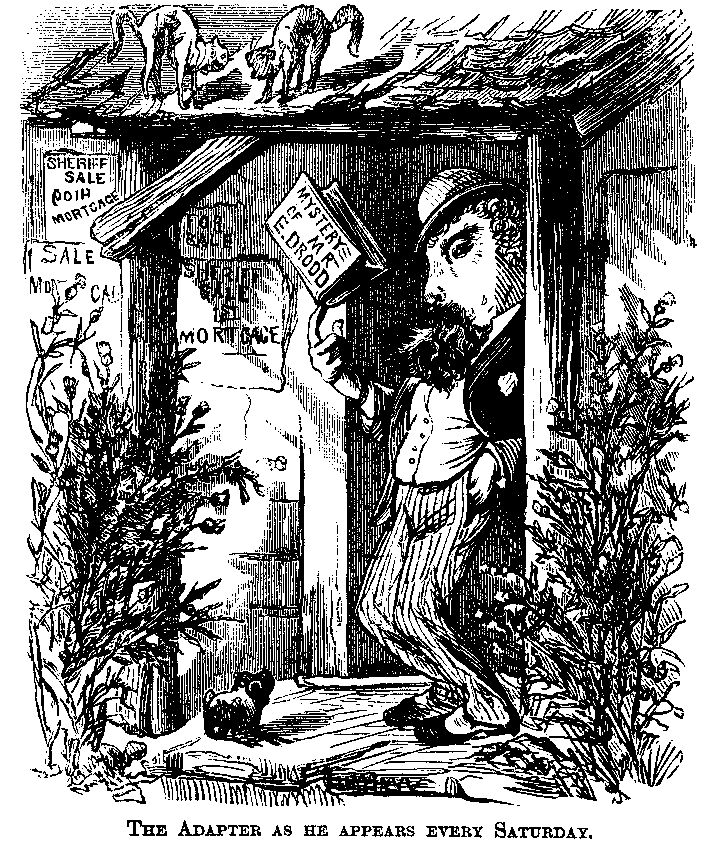

It is now nearly a twelfth of a century since the veracious Historian of the imperishable Mackerel Brigade first manoeuvred that incomparably strategical military organization in public, and caused it to illustrate the fine art of waging heroic war upon a life-insurance principle. Equally renowned in arms for its feats and legs, and for being always on hand when any peculiarly daring retrograde movement was on foot, this limber martial body continually fell back upon victory throughout the war, and has been coming forward with hand-organs ever since. Its complete History, by the same gentleman who is now adapting the literary struggles of MR. E. DROOD to American minds and matters, was subsequently issued from the press of CARLETON, in more or less volumes, and at once attracted profound attention from the author's creditors. One great American journal said of it: "We find the paper upon which this production is printed of a most amusing quality." Another observed: "The binding of this tedious military work is the most humorous we ever saw." A third added: "In typographical details, the volumes now under consideration are facetious beyond compare."

The present residence of the successful Historian is Begad's Hill, New Jersey, and, if not existing in SHAKSPEARE'S time, it certainly looks old enough to have been built at about that period. Its architecture is of the no-capital Corinthian order; there are mortgages both front and back, and hot and cold water at the nearest hotel. From the central front window, which belongs to the author's library, in which he keeps his Patent Office Reports, there is a fine view of the top of the porch; while from the rear casements you get a glimpse of blind-shutters which won't open. It is reported of this fine old place, that the present proprietor wished to own it even when a child; never dreaming the mortgaged halls would yet be his without a hope of re-selling.

Although fully thirty years of age, the owner of Begad's Hill Place still writes with a pen; and, perhaps, with a finer thoughtfulness as to not suffusing his fingers with ink than in his more youthful moments of composition. He is sound and kind in both single and double harness; would undoubtedly be good to the Pole if he could get there; and, although living many miles from the city, walks into his breakfast every morning in the year. Let us, however,

|

"No longer seek his virtues to disclose, Nor draw his frailties from their dread abode." |

but advise PUNCHINELLO'S readers to peruse the "Mystery of Mr. E. DROOD," for further glimpses of Mr. ORPHEUS C. KERR.

It is a very lamentable fact that the married people of Niagara have not attained even the dignity and comfort of insanity. A paragraph informs us that "The Niagara hotels have already forty-seven men trying to look as if married for years, and who only succeed in resembling imbeciles." To a Niagara tourist this must be an Eye-aggravating spectacle. But, fortunately, none of this class of the Double-Blest will shoot anybody. They don't look as if they had been married long! They are imbecile, not insane!

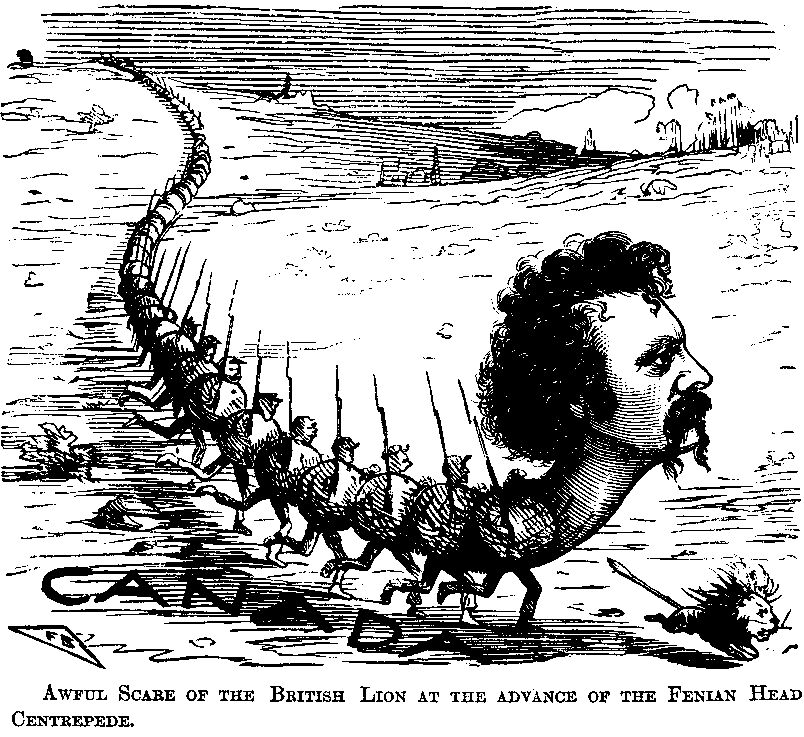

The Southern Cell proposes that the Fenians shall make a new Ireland of Winnipeg. Except on the principle of Hibernating, PUNCHINELLO cannot discover why his Irish fellow-citizens are ambitious to winter in the Red River country. Wouldn't Greenland do as well, and wear better?

Though but one of the Fenian leaders was killed in the late Frontier Fizzle, yet many of them are reported as being badly wounded—as to their feelings. General O'NEIL'S feelings are dreadfully hurt by the ignominy of a constable and a cell, which was a bad Cell for a Celt. The feelings of General GLEASON (and they must be multitudinous, since he is nearly seven feet high,) were so badly wounded by circumstances over which he didn't seem to have any control, that he retired from the field "in disgust." Mental afflictions, in fact, are so numerous among the Fenians since their Fizzle, as to suggest the advisability of their Head-Centre founding a Hospital for Wounded Feelings with the surplus of the funds wrung by him from simple, hard-working BRIDGET.

Persons who are drowned while bathing in the surf are said to experience but little pain. In fact, their Sufferings are short.

The first movement of the Fenians on reaching Canadian soil was to "throw out their skirmishers into a hop field," where the Hops gathered by them were of the precipitate and retrogressive kind sometimes traced to Spanish origin.

~THE HOLY GRAIL AND OTHER POEMS.~(This is one of the other Poems.) BY A HALF-RED DENIZEN OF THE WEST.

SIR PELLEAS, lord of many a barren isle, "Mother!" he cried, "I love!" Said she, "Ah, who?" Turned then his mother from the hearth-stone hot; Then said her son, "If I may make so bold, He said no more, and on the next bright day PELLEAS glistened with a wild delight; Then from his spear—at least he thought he did— He shoo-ed the fly from the flower-pots, And broken sheds, all sad and strange. He only said, "This thing is dreary. So PELLEAS made his moan. And every day, But ceaseless shoo-ing made the lady mad, A bush of wild marsh-marigold, He clasped his neck with crooked hands; |

(To be Continued.)

No. IV.

D. Oh, Pa, if we only had a Moon! What is life without one?

F. Well, my child, we've w'iggled along, so far. It is true, our Telluric friends may be said to have the advantage of us; but then, there's no lunacy here! Everything is on the square on this planet!

D. I don't care; I want a Moon, square or no square! There's no excuse for being sentimental here. Who is ever imaginative, right after supper? And yet Twilight is all the time we have.

F. But still, HELENE, I think our young folks are not really deficient in sentiment. What they would be, with six or seven moons, like those of SATURN or URANUS, is frightful to think of! Heavens! what poetry would spring up, like asparagus, in the genial spring-time! We should see Raptures, I warrant you! And oh, the frensies, the homicidal energies, the child-roastings! Yes, Moonshine would make it livelier here, no doubt. A fine time, truly, for Ogres, with their discriminating scent!—And what a moony sky! How odd, if one had a parlor with six windows.

D. Seven would be odder.

F. Well, seven, and a moon looking into each one of 'em! An artist would perhaps object to the cross-lights, but he needn't paint by them.

D. What kind of "lights" were you speaking of?

F. Satellites.

D. Oh, pshaw! don't tantalize me!

F. Well, cross-lights.

D. Now, pray, what may a cross-light be? An unamiable and inhospitable light, like that which gleams from the eyes of an astronomer when he is interrupted in the midst of a calculation?

F. No, nor yet the sarcastic sparkle in the eyes of a witty but selfish and unfilial young lady! Cross-lights are lights whose rays, coming from opposite quarters, cross each other.

D. (Then yours and mine are cross-lights, I guess!) If two American twenty-five cent pieces were to be placed at a distance from each other, and you stood between them——

F. My child, I could never come between friends who would gladly see each other after so long an absence!

D. I was only trying to realize your idea of "light from opposite quarters."

F. The most of 'em must be far too rusty to reflect light.

D. Oh, I dare say their reflections are heavy enough.

F. And so will mine be, soon, if you go on in that style.

D. Well, pa, I do drivel—that's a fact! Let us turn to something of more importance.

F. Suppose we now attend the Celestial Bull Fight always going on over there in the sky. On one side you perceive that gamey matador, ORION (not the "Gold Beater,") with his club and his lion's skin, a la Hercules. You observe how "unreservedly and unconditionally" he pitches into the Bull, and how superb is the attitude and ardor of his opponent. It is a splendid set-to, full of alarming possibilities. Every moment you expect to see those enormous horns engaged with the bowels of ORION, or, in default of this, to behold that truculent Club come down, Whack! on that curly pate!

D. And yet, they don't!

F. True enough,—they don't. It reminds me of one JOHN BULL, and his familiar vis-a-vis, O'RYAN the Fenian. As the celestial parties have maintained their portentous attitudes for ages, and nothing has come of it, so we may look placidly for a similar suspension in the earthly copy.

D. But their very attitudes are startling! Wasn't ORION something of a boaster?

F. Oh, yes; he was in the habit of declaring that there wasn't an animal on earth that he couldn't whip. He got come up with, however. By the way, ORION was the original Homoeopathist. His proposed father-in-law, DON OEROPION, having unfortunately put out his eyes, in a little operation for misplaced affection, he hit on the now famous principle, which, if fit for HAHNE-MAN, was fit for ORION. He went to gazing at the sun. What would have destroyed his vision if he had had any, now restored it when he didn't have any, and his sight became so keen that he was able to see through OEROPION—though, I believe, he reinforced his powers of ocular penetration with a pod-auger.

D. (Drivelling again! More Bitters, I guess!) Father, why were the Pleiades placed in the Head of TAURUS?

F. Well, my child, there are various explanations. On the Earth, they pretend to say it was meant to signify that the English women are the finest in the universe—the most sensible, the most charming, the most virtuous. No wonder, if this is so, we find their sign up there! What said MAGNUS APOLLO to young IULUS,—"Proceed, youngster, you'll get there eventually!" And MAG. was right.

D. Pa, why do they say, "the Seven Pleiades," when there are only six?

F. Well, dear, [kissing her,] perhaps there's a vacancy for you! I expect the Universe will be called in, one of these nights, to admire a new winking, blinking, and saucy little violet star—the neatest thing going! But not, I hope, just yet.

D. Boo—hoo—hoo—hoo!

F. Well, hang the Pleiades! Boo—hoo—hoo—too!

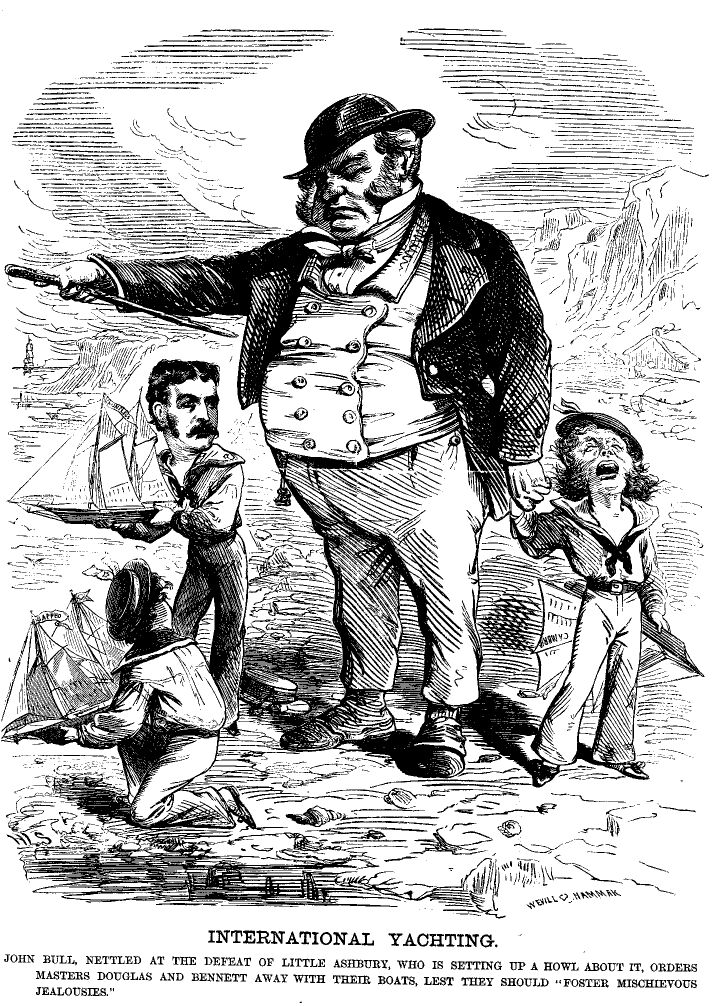

We like enthusiasm. We are ourselves quite given to the admiration of great people, as they, in their turn, we have reason to believe, are given to admiration of their dear PUNCHINELLO. But when an English adorer says that he considers "MR. CHARLES SUMNER fit for a throne," we are tempted to inquire what throne there is fit for him? The fact is, thrones have come to be rather more disreputable than three-legged stools. "Every inch a king" may mean six feet of mad-man, or five feet of mad-woman. We sincerely hope that there is no intention in England of making MR. SUMNER the King of Spain—we mean of abducting him for the purpose; for of course, he would never voluntarily assume the purple.

Fenian General O'NEILL bore down upon Canada with a martial charge, but he was sent back in a Marshal's charge.

In a speech which sounds like a six-shooter, that deadly woman, Mrs. F.H.M. BROWN, of San Francisco, gives notice that "when she goes to cast her ballot, if any man insults her, she will shoot him!" Who will now dare to question woman's ability to exercise both the franchise and the franchised? PUNCHINELLO sadly foresees that Shooters for the hands of women will take the place of Suitors. Nevertheless, he guarantees that the Constitutional right of women to bear arms shall not be infringed, and that they shall enjoy the inestimable privilege to shoot and be shot at. Every woman shall be at perfect liberty to cast her bullet for the man of her choice!

Miss BRITTAIN delivers a lecture on the High-caste women of India. She should supplement it with one on the High-strung women of Indiana, and thus illustrate the extremes of marriage and divorce.

Voice. "Has anything been gained by General O'NEIL?"

Echo. O Nihil!

The London Illustrated News calls the new Province of the Dominion, Manetoda, instead of Manitobah. Perhaps the mistake originated from the rumor of the Many Tods by which certain members of the Canadian Cabinet are said to be habitually inspired.

Hard, indeed, is the life of the poor trapper of the Plains. Driven by stress of hunger, he is often obliged to eat rattle-snake; but, as he cannot eat the head of the reptile, though the tail is good at a pinch, he fails, you perceive, to make both ends ~Meat.~

The Hon. JOHN BRIGHT is said to while away the time, in his retirement, by knitting garters. It seems very strange that such a usurpation of Woman's Rights should be carried into effect by one of the stoutest advocates of them.

One of the narrators of the late Fenian fizzle on the Canadian border describes General O'NEIL as having invaded the Dominion, "mounted on a small Red horse."

An exchange, after praising our recent Cartoon representing the "Barnacles on American Commerce," moves to refer us to the House Committee on Commerce and Manufactures. PUNCHINELLO never did love the ways of the Washington Circumlocution Office, but if there is one thing which he dislikes more than anything else, 'tis the idea of being pigeonholed by the Committee on Commerce. The uses to which valuable information is put by that august body of traffickers in public credulity, are not for us. That we might penetrate their benighted minds with many rays of knowledge is not to be doubted, but that we should be snubbed in proportion to the value of our opinions is also equally clear. There are some pretty dark places in this world: the Black Hole of Calcutta; the oubliette of Chillon Castle, the Torture Chambers of Nuremberg, and the grottoes of the Mammoth Cave, for instance; but there is no such utter exclusion of light, such profound oblivion, such blackness of darkness, as awaits anything which may be committed to the dungeon of a Congressional Committee. Most decidedly, therefore, we would rather not be referred.

Learned men in Massachusetts are just now confronted with an alarming possibility. They have been racking their brains to solve the problem whether population is increasing there faster than the means of subsistence, and with the expectation of discovering that it is, they have reached a precisely opposite result. The awful announcement is put forth, that the supply of babies is diminishing, and the question "What shall we do to remedy it?" is asked. So persistently is this interrogatory urged, that young unmarried men perambulating the streets of Boston, or sauntering leisurely about the Common, are liable at any moment to be accosted by advanced single ladies with wild, haggard looks, who stop them face to face, seize them by the shoulders, and gazing at them with keen, imploring glances, as if they would read their souls through their eyes, seem to cry "And what have you got to say about it, O wifeless youth? and why do you let the precious moments fly when we are willing and ready to be sacrificed? and what are we all coming to, and where are you all going to, and where will Boston be if this thing goes on?" But these thoughtless and jeering bachelors will not stop to hear the wail of their challengers; they feel no pity for their despair; they have no stomach for their agony; but go their ways, leaving the wretched females rooted, transfixed, the picture of perfect hopelessness, and greeting them, ere they disappear from sight, with shouts of scoffing laughter, which the winds catch up and carry away out of earshot.

~Something that most People would like a Little Longer.~

Strawberry Short Cake.

|

SENATE.In spite of the obstinate silence of SUMNER, the Senate has been lively. Its first proceeding was to pass a bill—an interminable and long-drawn bill—ostensibly to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment. But the title is a little joke. As no single person can read this bill and live, and as no person other than a member of the bar of Philadelphia could understand it, if he survived the reading of it, PUNCHINELLO deemed it his duty to have the bill read by relays of strong men. What, is the result? Six of his most valued contributors sleep in the valley. But what are their lives to the welfare of the universe, for which he exists. The bill provides, 1. That any person of a darker color than chrome yellow shall hereafter be entitled to vote to any extent at any election, without reference to age, sex, or previous condition, anything anywhere to the contrary notwithstanding. 2. That any person who says that any such person ought not to vote shall be punishable by fine to the extent of his possessions, and shall be anathema. 3. That any person who shall, with intent to prevent the voting of any such person, strike such person upon the nose, eye, mouth, or other feature, within one mile of any place of voting, within one week of any day of voting, shall be punishable by fine to the extent of twice his possessions, and shall be disentitled to vote forever after. Moreover he shall be anathema. |

4. That any person who shall advise any other person to question the right of any person of the hue hereinbefore specified to vote, or to do any other act whatsoever, shall be punishable by fine to the extent of three times his possessions, and shall be anathema.

5. That all the fines collected under this act shall be expended upon the endowment of "The Society for Securing the Pursuit of Happiness to American Citizens of African Descent." And if any person shall call in question the justice of such a disposition of such fines, he shall be punishable by fine to the extent of four times his possessions, and shall be anathema.

Mr. WILSON objected to anathema. He said nobody in the Senate but SUMNER knew what it meant. Besides, it was borrowed from the syllabus of a degraded superstition. He moved to substitute the simple and intelligible expression, "Hebedam."

The Senate settled their little dispute about who was entitled to a medal for coming first to the defence of the Capital. They decided to give medals to everybody. Mr. CAMERON was satisfied. If the Senate only medalled enough, that was all he asked. There were about five thousand wavering voters in his district, whom he thought he could fix, if he could give them a medal apiece.

Mr. CONKLING said he would like to medal some men. But he did not like such meddlesome men as CAMERON.

Mr. DRAKE moved to deprive anybody in Missouri who differed from him in politics of practicing any profession. He said that many of the citizens of that State were incarnate demons—so much so that when they had an important law case they would rather intrust it to somebody else than himself. Was this right? He asked the Senate to protect him as a native industry.

Mr. INGERSOLL floated his powerful mind in air-line railroads. He wanted "that air" line from Washington to New York. This 'ere line didn't suit him. He appealed to the House to protect its members from the untold horrors of passing through Philadelphia. He had no doubt that much of the imbecility which he remarked in his colleagues, and possibly some of the imbecility they had remarked in him, were due to this dreadful ordeal. He admitted that good juleps were to be had at he Mint. But juleps had beguiled even SAMSON, and cut his hair off. His colleague, LOGAN, might not be as strong as SAMSON, but he would be as entirely useless and unimpressive an object with his hair off.

Then there was a debate upon the proposition to abolish the mission to Rome.

Mr. BROOKS said most of his constituents were Roman Catholics. Therefore there should be a mission to Rome.

Mr. DAWES said that BROOKS used to be a Know-Nothing. Therefore there should not be a mission to Rome.

Mr. COX said that they used to burn witches in Massachusetts. Therefore there should be a mission to Rome.

Mr. HOAR said they didn't. Therefore there should not be a mission to Rome.

Mr. VOORHEES said they burnt a Roman Catholic Asylum in Boston. Therefore there should be a mission to Rome.

Mr. DAWES said they burnt a Negro Asylum in New York. Therefore there should not be a mission to Rome.

Mr. VOORHEES said DAWES was another. Therefore there should be a mission to Rome.

Mr. BINGHAM said POWELL was a much better painter than TITIAN, and VINNIE REAM a much better sculptor than MICHAEL ANGELO. Therefore there should not be a mission to Rome.

Republican Chorus. You are.

Democratic Chorus. We ain't.

Republican Chorus. You did.

Democratic Chorus. We didn't.

Solo by the Speaker. Order.

Democratic Chorus. There should be (da capo with gavel accompaniment.)

Republican Chorus. There should not be (ditto, ditto.) After weighing these arguments, the House adjourned without doing anything about it.

"The Coroner's Jury investigating the Missouri Pacific Railroad slaughter have found that it was all caused by the disobedience and negligence of WILLIAM ODOR, conductor of the extra freight train!"—Daily Paper.

This "conductor" is as dangerous as some (of the "lightning" species) which we have seen dangling disjointed from the roofs and walls of dwelling-houses in the country. At the first shock, good-bye to you! if you are anywhere around. Or, rather, he may be compared to the miasma from ditches and stagnant ponds, inhaled at all times by our rustic fellow citizens, with the trustfulness (if not relish) of the most extreme simplicity. And yet, it kills them, all the same. No one out West would have cared a pin about WILLIAM'S "disobedience" and "negligence," if these trifling eccentricities hadn't occasioned the killing or maiming of several car-loads of passengers. It is hard to shock these Western folks' sense of honor and fidelity; but kill a few of them, and the rest begin to feel it. We suppose that just now this BILL can't pass there. But, our word for it, he'll soon be in circulation again. Perhaps he may yet have the pleasure of Conducting some of us to that Station from which, etc., etc. Before we take our contemplated trip to the West, therefore, we fervently desire to have this ODOR neutralised, even though one should do it with strychnine.

The correspondent of a Boston paper writes as follows, after having visited the Reichstag:

"You may be sure that that man is BISMARCK; if from time to time he irons out his face wearily with his hands, as he studies a long document, or if by chance some unlucky member, attracting his disdain, calls his mind to the fact that he is in Parliament, then he starts to his feet like a war-horse, and talks with great grace and ease, always rapidly, always briefly."

Why is it that BISMARCK irons out his face? Is it because he has just washed it—or is it to conceal his identity, as the features of the Man in the Mask were ironed out?

And why does the great Minister start to his feet like a war-horse? PUNCHINELLO, not having been an Alderman or Member of Congress, recently, is not very familiar with the getting up of war horses; but the ordinary equine animal does not assume the upright posture with great readiness or grace. If PUNCHINELLO were to become a member of the Reichstag, an event now highly probable, he would like to have every adversary in debate "start to his feet like a war-horse."

~THE ROMAUNT OF THE OYSTER.~ In the moonlight at Cattawampus Then I said, "Would were mine the power, "Where the oysters are roystering together "O, there would my spirit conduct thee. 'Twas enough: for I saw her eye stir, Did she take me, alas! for a friar, Then we reached the hotel together |

Leaving Rome, I have called next on NAPOLEON, at Paris. He sent word, through OLLIVIER, that be wanted to see me. He looks old. Some medical man has put forth the idea that he has BRIGHT'S disease. An English attache just asked me whether that has any reference to JOHN BRIGHT. As the latter is a Quaker, the first symptom of this disease must have been shown long ago, when the Emperor said, "The Empire is Peace." I satisfied my friend, however, that the case was not one of that Kidney.

Well, the Emperor asked me, "What do they say of me in America?"

"Sire, we think you are very wise, to accept the inevitable, and make a virtue of it."

"Wise, of course. Disinterested, too!"

"Pardonnez moi. Not ever wise, of course. Mexico was a folly, you know."

"I know; though if you were not PUNCHINELLO, you should not say it. Will my son reign in France?"

"Sire, I am not an oracle. But they have a proverb in my country, that it never rains but it pours."

"Je n'entends pas. The plebiscite was rather a neat thing!"

"Worthy of its author. The old story; heads I win, tails you lose. But, will your Majesty say what you think of the Pope?"

"That old Popinjay! He has been my folly, greater than Mexico. He would have gone to Gaeta, or to perdition, long ago, but for Madame!"

"And the Council?"

"Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha!"

"What do you think of BISMARCK?"

"Monsieur, I detain you too long. You have, I am sure, an engagement. Bon jour!"

Apropos of the Emperor, it is said that, on the suggestion of England's proposal to take charge of Greece, and clean out the brigands, if the King and ministers there would resign,—Col. FISK telegraphed on to NAPOLEON, offering to take charge of the government of France, as a recreation, among his various engagements. He does not even require the Emperor to withdraw; be can run the machine about as well with him as without him.

As to the Plebisculum, they say that EUGENIE asked for masses to be said in all the churches for its success. NAPOLEON preferred to make his appeal to the masses outside of the churches.

ITALY.

Bishop VERELLI last week declared, in a sermon, that railroads, telegraphs, and the press, were all inventions of the devil. A correspondent of the Tribune at once sent him word that this was a mistake. HORACE GREELEY had already proved that railroads and telegraphs were inventions of British Free Trade; and that the press had been invented by his grandfather, for the promulgation of protection.

Since the telegram came through Florence, of a serious riot at Filadelfia, in Italy, a tourist from Penn's city of brotherly love understood it to be that Col. TOM FLORENCE was seriously hurt in a riot at Philadelphia! I telegraphed for him, to my old friend the Colonel, and learned, with satisfaction, that not a hair of TOM'S head had been shortened.

ENGLAND.

In Parliament, an interesting debate occurred the other night. Mr. DAWSON moved a resolution condemning the raising of large revenue in India from opium. Mr. WINGFIELD opposed the resolution, arguing that opium was less hurtful than alcohol. Mr. TITMOUSE, a young member, added that arsenic is less hurtful than strychnine; also, that this is less injurious than prussic acid. Mr. GLADSTONE did not see what that had to do with the case. Neither did I.

Mr. DENNISON hoped that mere sentiment would not be suffered to interfere with the prosperity of India. Mr. TITMOUSE then suggested the sending of the volunteer Rifles to take immediate possession of China; that would not be sentimental, but practical. Mr. HENLEY believed that to be a more costly affair than he was prepared for; but, whenever the interest of England required it, he was ready. What are the lives of a hundred million Chinese to the financial prosperity of England? Mr. GLADSTONE considered that opium was merely a drug, after all. It was not worth while to consume the time of the House about it. And so the resolution was lost.

PRIME.

If one United States Marshal can capture a Fenian General surrounded by his army, in five minutes, how long would it take him to capture the army?

|

THE PLAYS AND SHOWS.Kant is admitted to be one of the greatest of the German philosophers. (That fact has nothing whatever to do with the Plays and Shows, but the artist insisting upon making K the initial letter of this column, the writer was obliged to begin with Kant—Kelley being hopelessly associated in the public mind with pig-iron, and all other metaphorical quays from which he might have launched his weekly bark being unreasonably spelled with a Q.) German philosophy, however, resembles Italian Opera in one particular: it consists more of sound than of sense. Both have a like effect upon the undersigned, in that they lead him into the paths of innocence and peace; in short, they put him to sleep. A few nights since he went to hear Miss KELLOGG in Poliuto. He listened with attention through the first act, drowsily through the second, and from the shades of dreamland in the third. Between the acts he lounged in the lobbies and heard the critics speak with sneering derision of the complimentary notices of the American Nightingale which they were about to write, while they expressed, with sardonic smiles, a longing for the day when they would be "allowed"—such was their singular expression—to "speak the truth about Miss KELLOGG as a prima donna." And while he sat with closed eyes during the third act, wondering whether he should believe the critics in the flesh, or their criticisms in the columns of their respective journals, he saw rehearsed before him a new operatic perversion of MACBETH, as unlike the original as even VERDI'S MACBETTO, and quite as inexplicable to the unsophisticated mind. And this is what he saw: |

Scene, the Dark Cave in fourteenth street. In the middle a Cauldron boiling. Thunder—and probably small beer—behind the scenes. Enter three Witches.

1st Witch. Thrice the Thomas cat hath yowled.

2d Witch. Thrice; and once the hedge-hog howled.

3d Witch. All of which is wholly irrelevant to our present purpose, which is to summon what my friend Sir BULWER LYTTON would call the Scin-Laeca, or, apparition of each living critic from the nasty deep of the cauldron, and to interview him in order to hear what he really thinks of Miss KELLOGG.

|

lst Witch |

Enter MACSTRAKOSCH. "How now, you secret black and midnight hags, what is't you do?"

All "A deed that under present circumstances it would be superfluous to name."

MacStrakosch. "I conjure you by that which you profess, (how'er you come to know it,) answer me to what I ask you."

lst Witch. "Speak."

2d Witch. "Proceed."

3d Witch. "Out with it, old boy."

MacStrakosch. "What do these fellows really think, whom we compel to write so sweetly of our own Connecticut prima donna?"

All

"Come high or low, come jack or even game,

We'll answer all your questions just the same."

Thunder. An apparition of a critic rises.

MacStrakosch.

"Tell me, thou unknown power, what thinkest thou Of our own native nightingale?"

|

Apparition. "Her voice is clear and bright, but far too thin MacStrakosch. "Dismissed thou shalt be if thy editor Thunder. Second apparition of a critic rises. Apparition. "Her voice is good in quality, but then MacStrakosch. "Yea; and I will unless thy master's ear Thunder. Third apparition of a critic rises. Apparition. "Her lower notes are bad, her upper notes MacStrakosch. "Sacrilegious wretch! I have thy name Thunder. Fourth apparition of a critic rises. Apparition. "Her acting, like her voice, is cold and hard; MacStralosch. "Thon diest ere to-morrow's sun shall set, Thunder. Fifth apparition of a critic rises. Apparition. "She in the same in everything she sings; MacStrakosch. "This is past bearing. Are there any more |

Thunder. Eight apparitions of critics rise and pass over the stage, reciting the following chorus:

Apparitions.

|

"She has a pretty little voice, and uses it |

The apparitions vanish. An alarm of drums is heard, and MATADOR awakes to find that he is still enduring Poliuto, and that a sporadic drum in the orchestra, which has broken loose from the weak restraints of the conductor's discipline, is making Verdi unnecessarily hideous.

And as he passed once more and finally through the lobby, he heard a critic remark, "She is the same in everything she sings;" and another reply, "Yes, she has a pretty little voice, and uses it nicely, but she is by no means a great singer." Struck by the similarity of these remarks to those made by the apparitions in his vision, he began to doubt whether his dream did not, after all, contain a large alloy of truth, and the more he thought on the subject the more he was led to believe that for once he had really heard the critics of the New York press indulging in an unrestrained expression of honest opinion.

MATADOR

"Talk to me at this time of day about Borne being the Mother of Arts!" cries Mr. BUNCOMBE BINGHAM, M.C. PUNCHINELLO fervently hopes that at no time of the day will anybody ever talk to BINGHAM about Borne being the Mother of Arts. The reason therefor is obvious. "Why, sir," says BINGHAM, "there is more of that genius which makes even the marble itself wear the divine beauty of life, more of that power to-day in living America, than was ever dreamed of in Rome, living or dead!" We think we hear BINGHAM exclaim, with the gladiator-like championship of Art for which he is renowned—"Bring on your MICHAEL ANGELOS; produce your CHIAROSCUROS, your MASANIELLOS, your SAVONAROLAS and the rest of 'em—but show me a match for VINNIE REAM!"

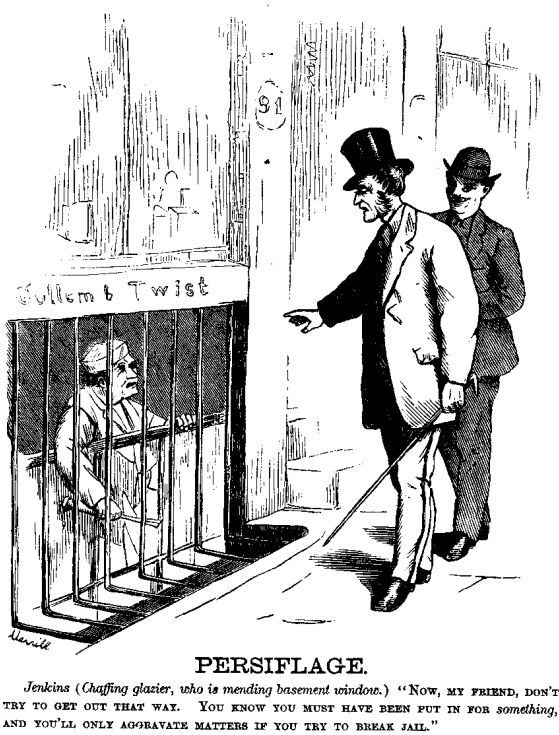

Jenkins (Chaffing glazier, who is mending basement window.) "NOW, MY FRIEND, TRY TO GET OUT THAT WAY. YOU KNOW YOU MUST HAVE BEEN PUT IN FOR something, AND YOU'LL ONLY AGGRAVATE MATTERS IF YOU TRY TO BREAK JAIL."]

Did the gentleman who threw a brick at a dog on a very hot day (when no doubt that inoffensive animal was in a stew) imagine that he had hit upon the whole of the common Chinese materia medica? PUNCHINELLO is gravely told that a Celestial doctor is about to come to New York, whose favorite prescriptions, in accordance with Chinese practice, "will be baked clay-dust, similar to brick-dust and dog-soup." In one of these remedies the medical acumen of PUNCHINELLO recognizes a homoeopathic principle. Man having been made out of the dust of the earth, nothing is so well adapted to cure him as baked clay. Every man's house is now not only his castle, but his apothecary shop. A brick may be considered a panacea, and may be carried in the hat. Taken internally, it will go to the building up of the system. Applied to the head it is good for fractures. Dog-soup has an evident advantage over the usual prescriptions of Bark.

We learn that "a naval architect named DUNKIN claims to have constructed a new style of vessel, impervious to rams, shell, or shot." Now, then, where is our friend, Captain ERICSSON? The Captain has a torpedo which he is anxious to explode, near a strong vessel belonging to somebody else. He says it will blow up anything. DUNIN says nothing can blow up his vessel. A contest between these very positive inventors would be a positive luxury—to those who had nothing to risk. We bet on the torpedo.

It was a mere joke, that stuff about the "new muscle in the human body," said to have been found by an English anatomist. It simply meant that, the Oyster Months being past, the "human body" begins to be nourished with soft-shell clams.

The undersigned offers for sale to the highest bidder, up to Doomsday next, several choice lots of tombstones. Bidders will state price and terms of payment, and accepted purchasers will remove the monuments from their present localities, at their own risk. The lots are:

1st. A gravestone of white marble. It is about 65 feet square at the base, and is the frustrum of a pyramid, truncated at about 140 feet. It is filled with a square hole, upon the sides of which are inscriptions let into various colored marbles, and in the languages of the peoples who inhabited a great country ages ago. The stone was designed to be put over the remains of PRO PATRIA, a personage once celebrated for loyalty and wisdom, but whose teachings are now well nigh forgotten, and whose name even is fast being obliterated from the memories of radical improvers of governments and republican institutions. This lot may be seen south of the mouth of Goose Creek, in a district called Columbia.

2d. A gravestone consisting of a square house of Illinois marble, with a piece of a smoke-stack protruding from the roof. About one-third of the estimated cost had been expended, when the persons who were to furnish the means suddenly concluded that the Little Giant could sleep just as well in a filthy unmarked hole in the ground, as under a pile of marble. Besides, being dead, he couldn't get any more offices for his constituents, so they found out they didn't care a cuss for him. Further information about this stone can be obtained by applying to any citizen of Chicago.

3d. A monument which we haven't seen, and so can't describe. It is supposed to be at Springfield, Illinois, and was intended for a person once called a railsplitter—a man much homelier than the typical hedge fence, but as good as homely. He was thought to be a second PRO PATRIA, MOSES, or some such person, and was sworn by, by millions of people who would now almost deny ever having heard of him. At the time he went out everybody wanted to put up a gravestone immediately—almost before he needed one. Now, everybody isn't altogether enough to provide one. For further particulars about the Springfield stone, inquire of any red-hot radical.

There are some other lots, but we will not offer them until we see how the present ones go off.

GHOUL, Undertaker.

The Irrepressible Black having been repressed, here comes the Irrepressible Red! HIAWATHA is cutting up a great variety of capers as well as of unfortunate settlers. Should you ask us why this bloodshed, Why this scalping and this burning, Why this conduct most disgraceful, Why these crimes of the Piegans, Why this sending forth of soldiers, Why the perils of the railway, known as and called the way Pacific, (which it won't be if these actions are allowed to go unpunished,) We should tell you—whiskey! to say nothing of the indomitable propensity which rises in the Piegan bosom for scalps. The noble Son of the Forest is an amateur in scalps; as some of us are all for old books and others for old coins. But however much we may respect the enthusiasm of the wild Rover of the Plains, in making these collections of cranial curiosities, we feel that the red virtuoso is really going too far—at least we should feel so, we have no doubt, if he were taking off our own private scalp, which is a very handsome one, and which we hope to be buried in. No; the Piegan passion for scalps must be suppressed. But how? Some say by more whiskey. Some say by less. Some say by none at all. We are for the more instead of the less. There is whiskey and whiskey. Now our idea would be to send an unlimited supply of the more deadly variety of that exhilarating fluid, (highly camphened,) to the convivial Piegans. After an extensive debauch upon this potent tipple, very few Piegans would be likely to take the field, either this summer or any other. They would be Dead Reds, every rascal of them.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punchinello, Vol. 1, No. 11, June 11,

1870, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCHINELLO, JUNE 11, 1870 ***

***** This file should be named 9545-h.htm or 9545-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/9/5/4/9545/

Produced by Cornell University, Joshua Hutchinson, Sandra

Brown and PG Distributed Proofreaders

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation information page at www.gutenberg.org

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at 809

North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email