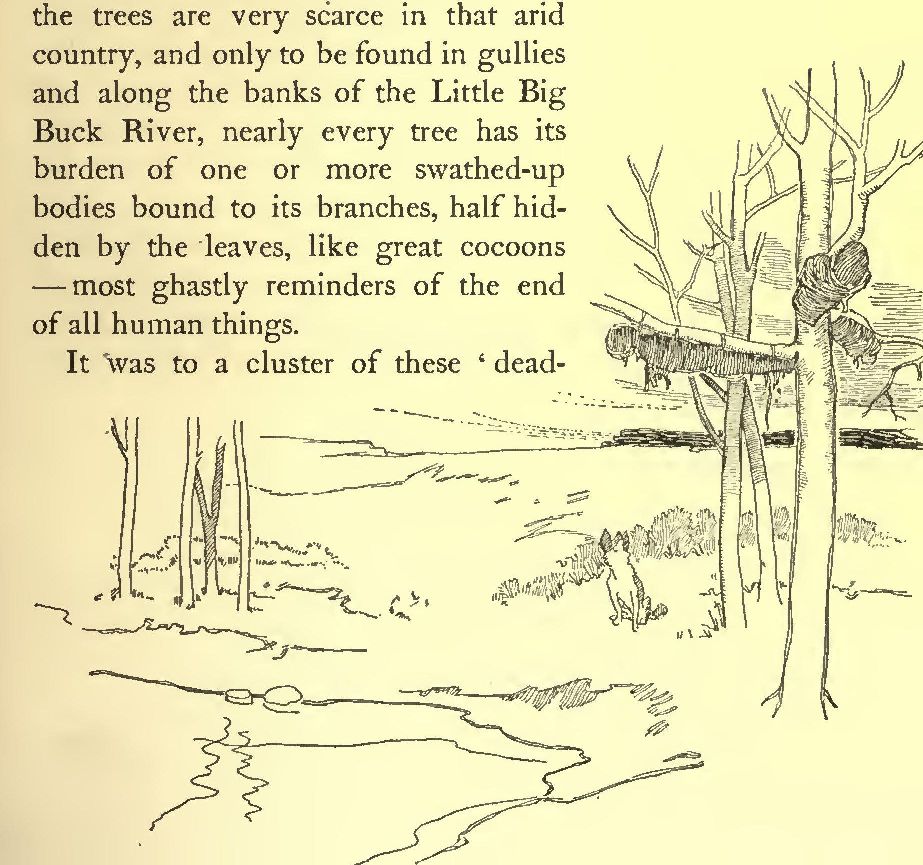

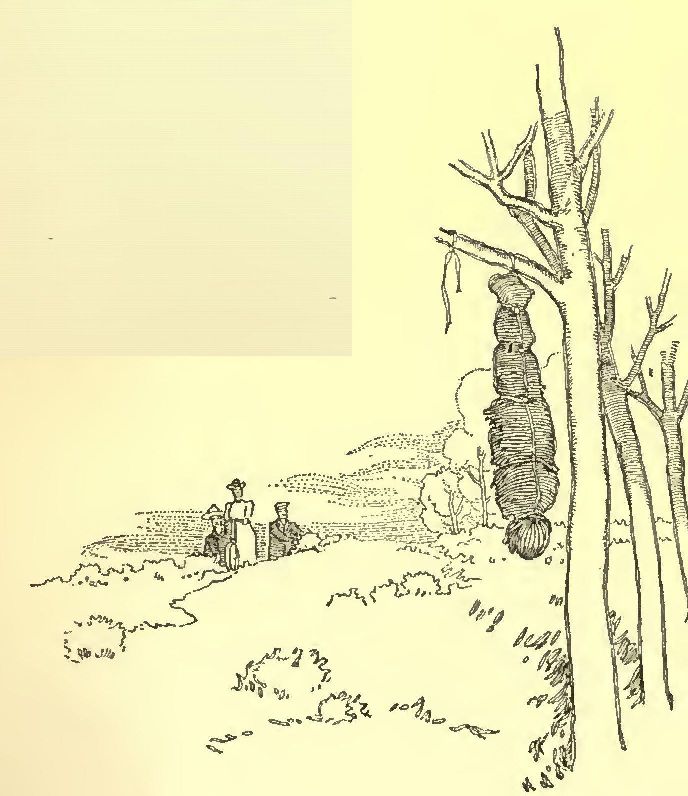

Project Gutenberg's A Woman Tenderfoot, by Grace Gallatin Seton-Thompson This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: A Woman Tenderfoot Author: Grace Gallatin Seton-Thompson Release Date: December, 2005 [EBook #9412] This file was first posted on September 30, 2003 Last Updated: March 6, 2014 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A WOMAN TENDERFOOT *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Mary Meehan, and Project Gutenberg Distributed Proofreaders from images generously made available by the Canadian Institute for Historical Microreproductions Illustrated HTML file produced by David Widger

In this Book the full-page Drawings were made by Ernest Seton-Thompson, G. Wright and E.M. Ashe, and the Marginals by S.N. Abbott. The cover, title-page and general make-up were designed by the Author. Thanks are due to Miller Christy for proof revision, and to A.A. Anderson for valuable suggestions on camp outfitting. (No illustrations are included in this file.)

THIS BOOK IS A TRIBUTE TO THE WEST.

I have used many Western phrases as necessary to the Western setting.

I can only add that the events related really happened in the Rocky Mountains of the United States and Canada; and this is why, being a woman, I wanted to tell about them, in the hope that some going-to-Europe-in-the-summer-woman may be tempted to go West instead.

G.G.S.-T.

New York City, September 1st, 1900.

A LIST OF FULL-PAGE DRAWINGS (in the original printed book)

Costume for cross saddle riding

Tears starting from your smoke-inflamed eyes

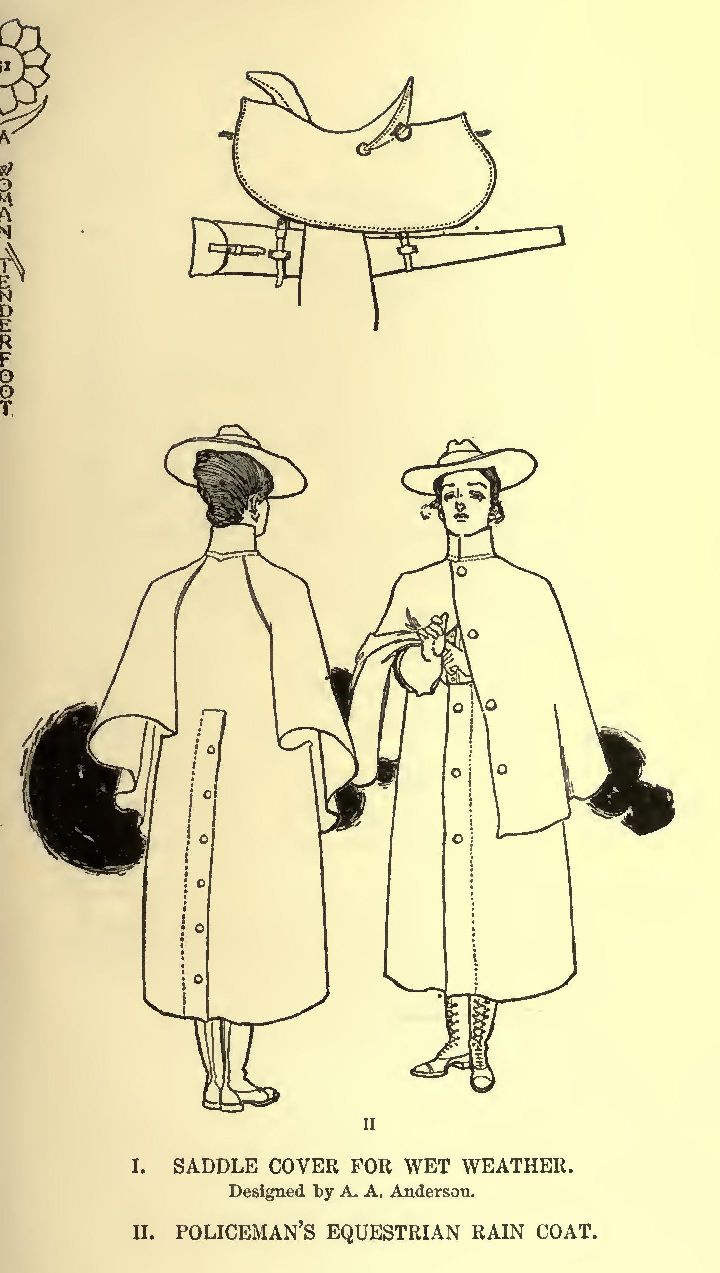

Saddle cover for wet weather Policeman's equestrian rain coat

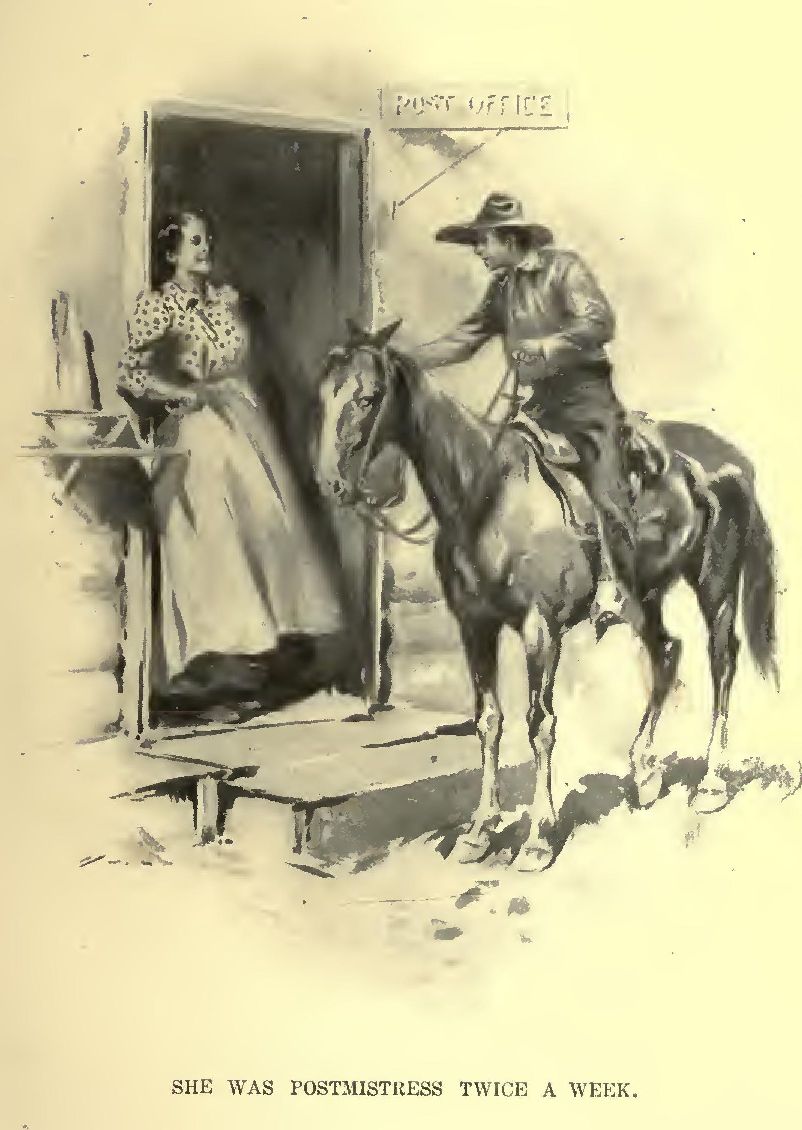

She was postmistress twice a week

The trail was lost in a gully

Whetted one to a razor edge and threw it into a tree where it stuck quivering

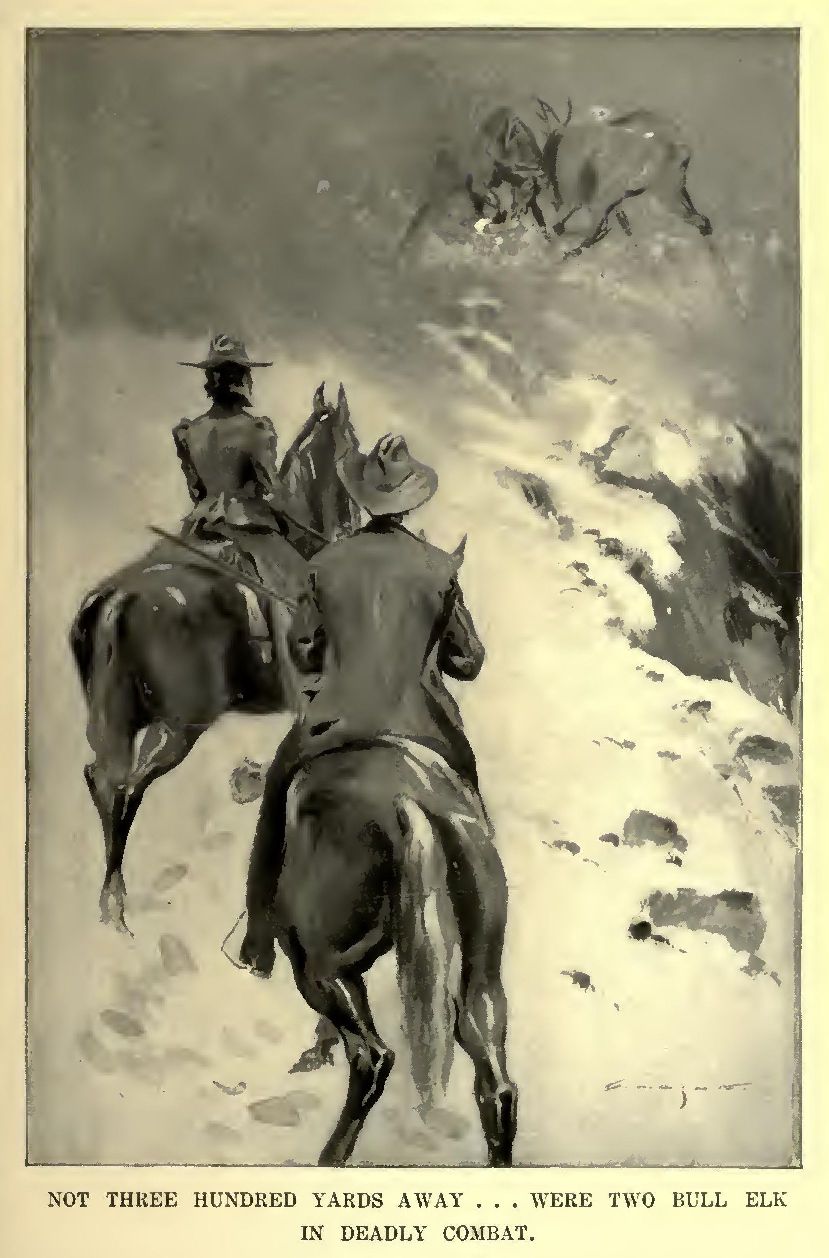

Not three hundred yards away ... were two bull elk in deadly combat

Down the path came two of the prettiest Blacktails

A misstep would have sent us flying over the cliff

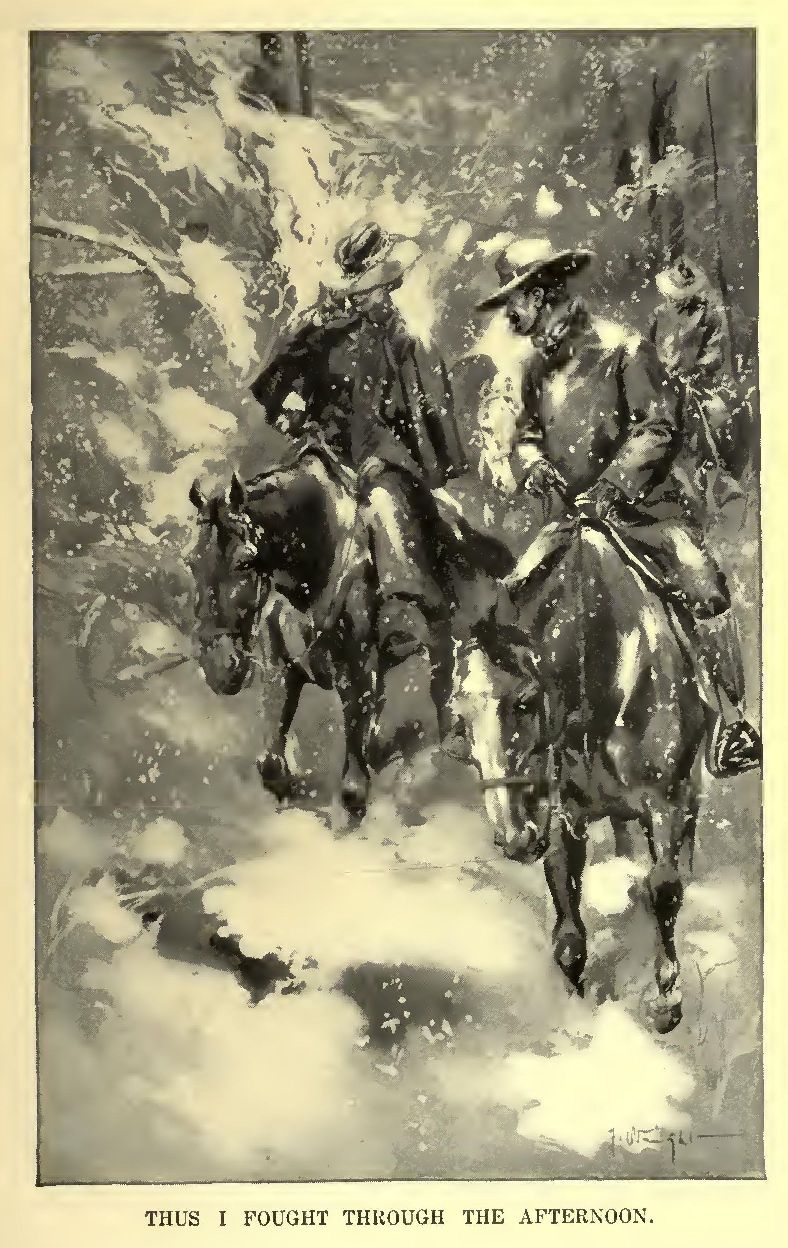

Thus I fought through the afternoon

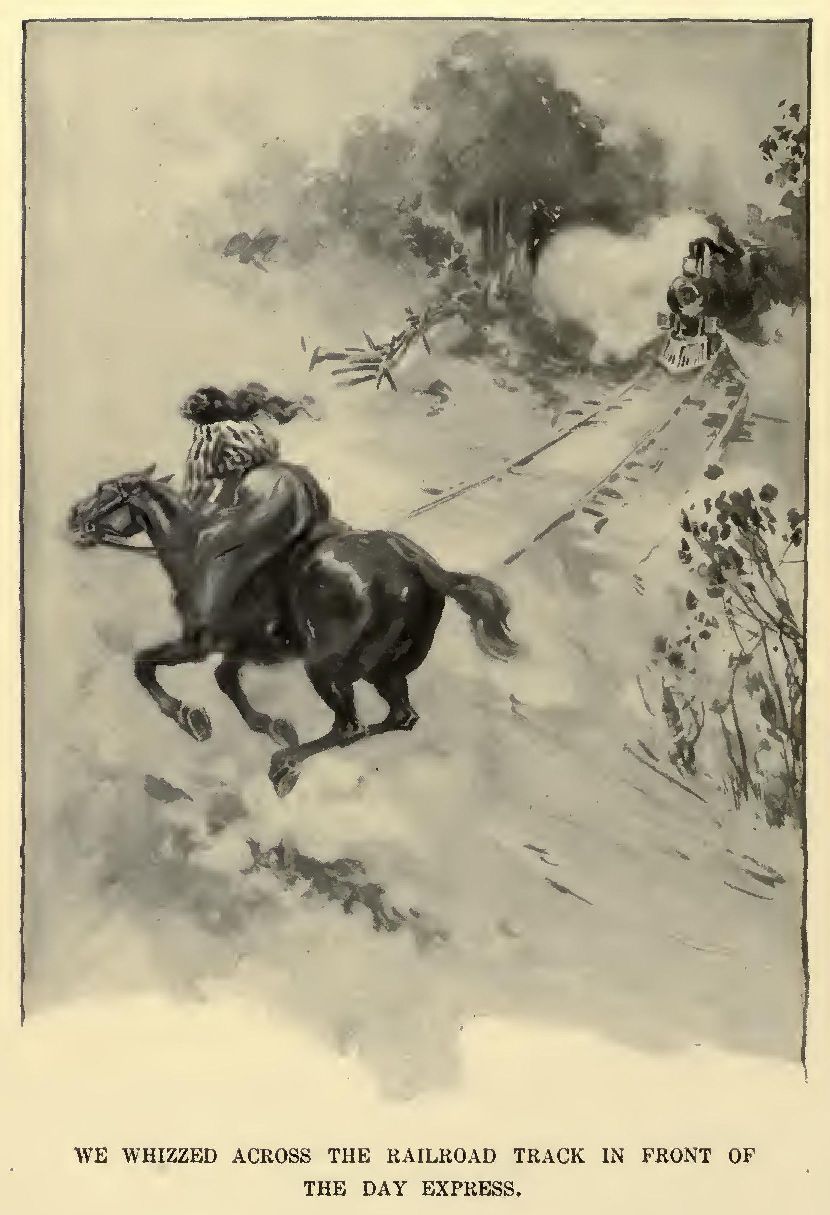

We whizzed across the railroad track in front of the Day Express

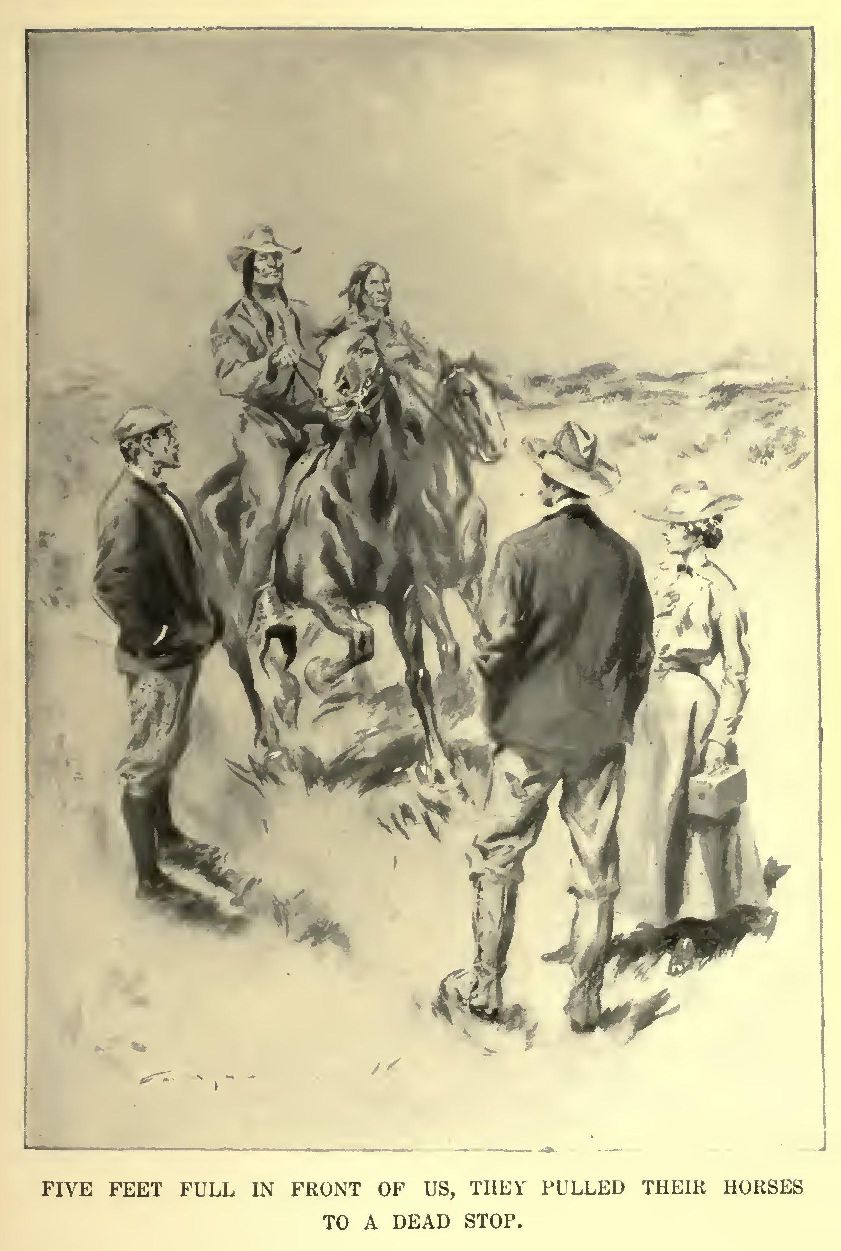

Five feet full in front of us, they pulled their horses to a dead stop

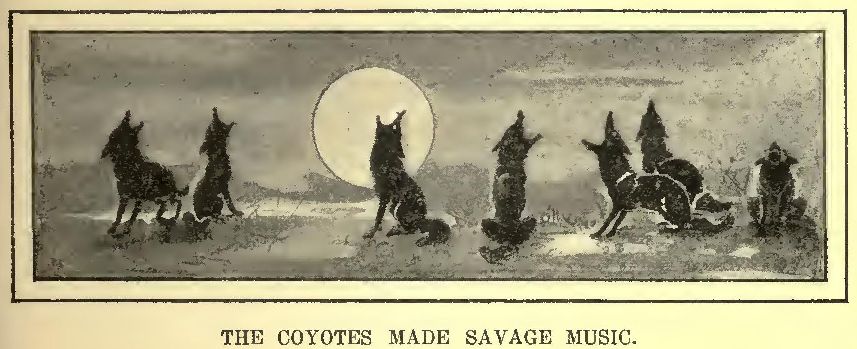

The coyotes made savage music

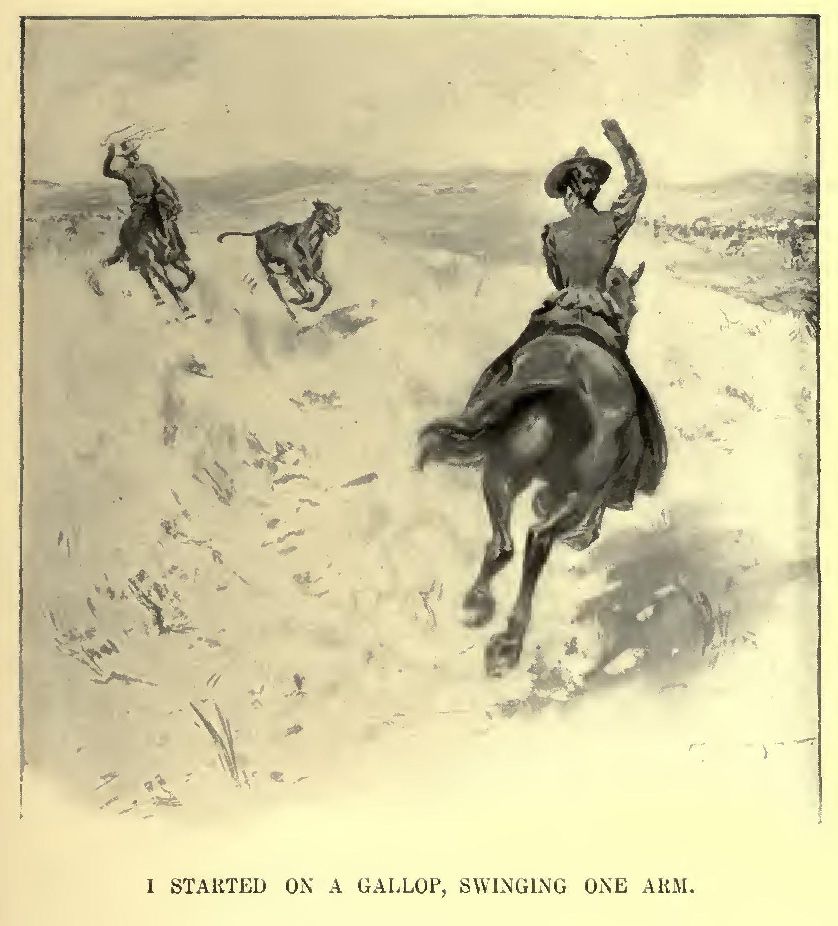

The horrid thing was ready for me I started on a gallop, swinging one arm

The warm beating heart of a mountain sheep

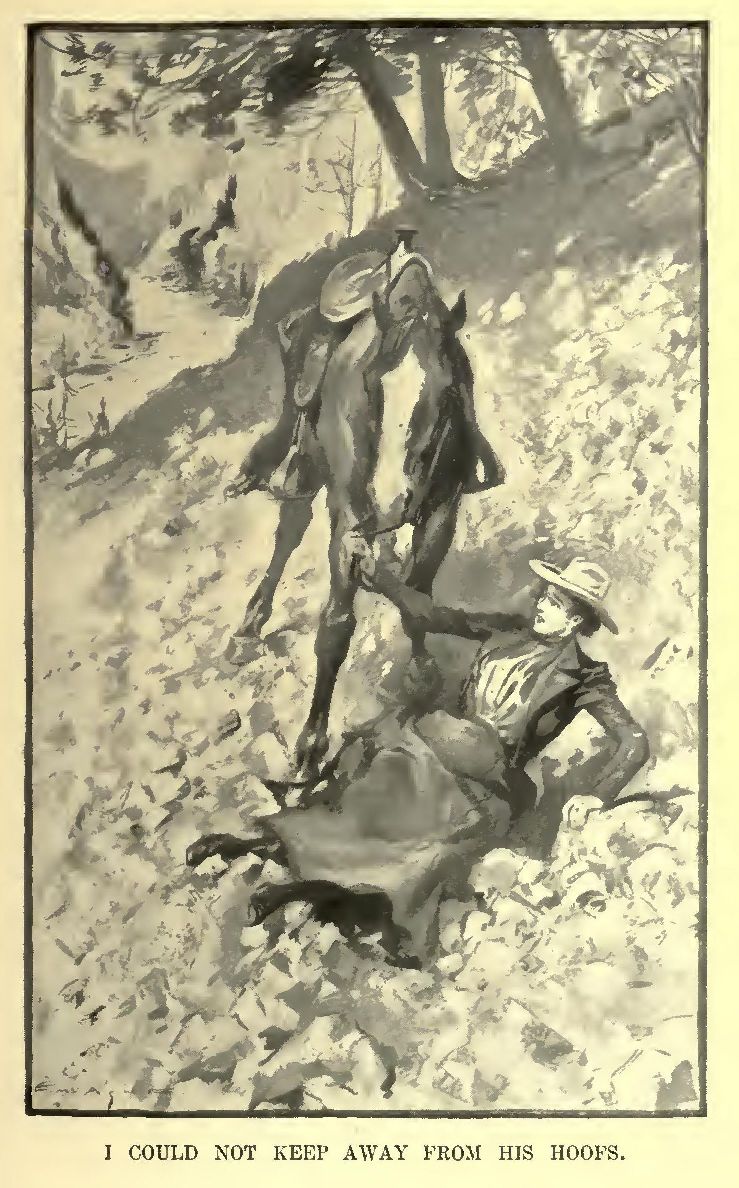

I could not keep away from his hoofs

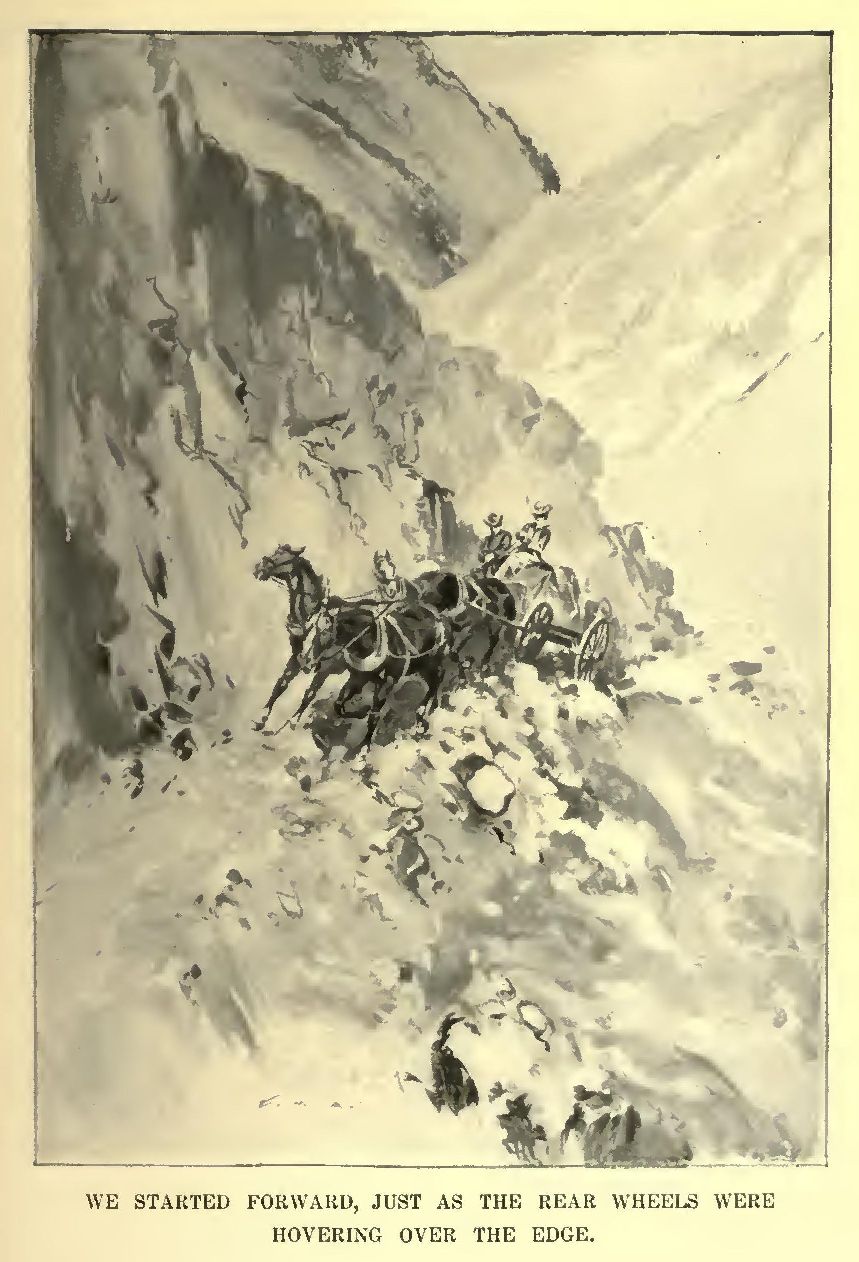

We started forward, just as the rear wheels were hovering over the edge

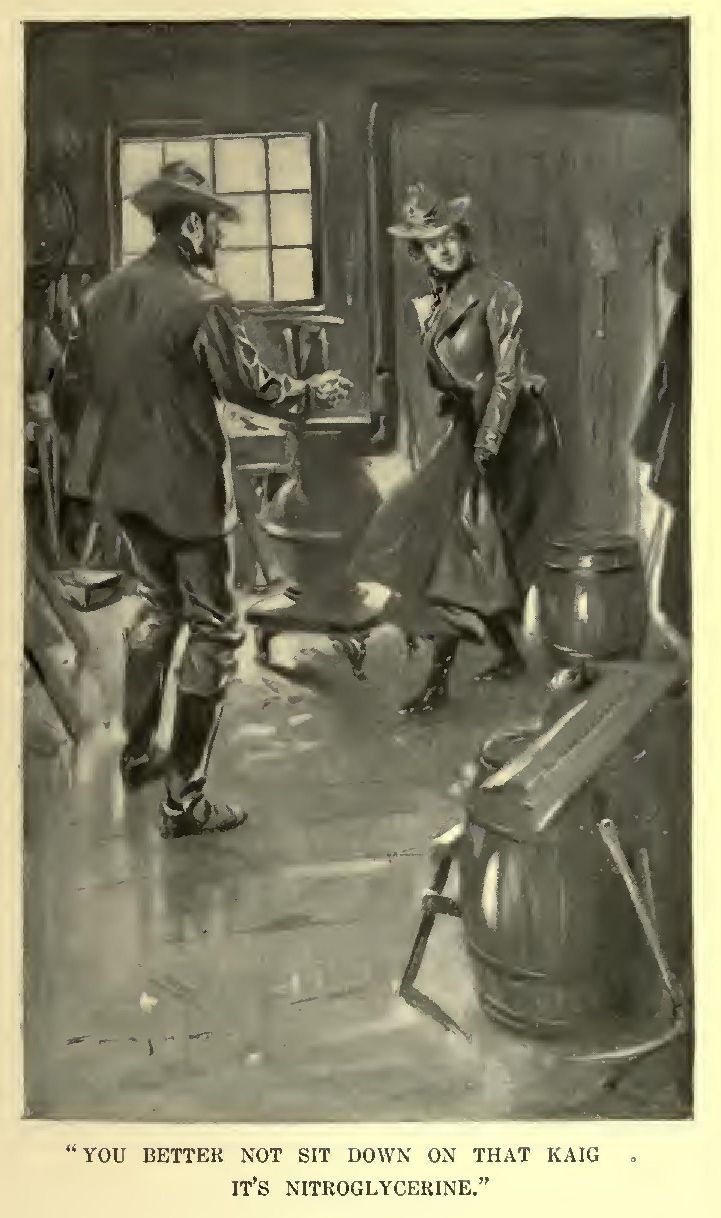

"You better not sit down on that kaig ... It's nitroglycerine"

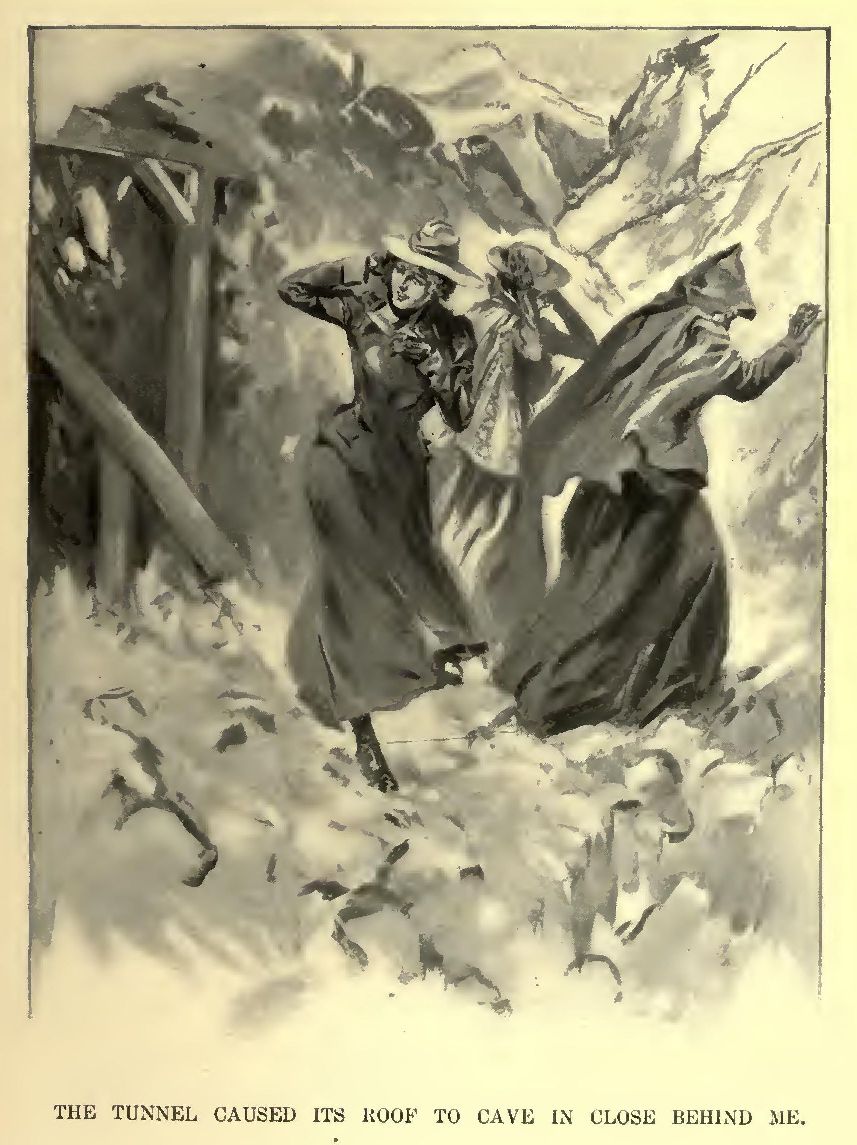

The tunnel caused its roof to cave in close behind me

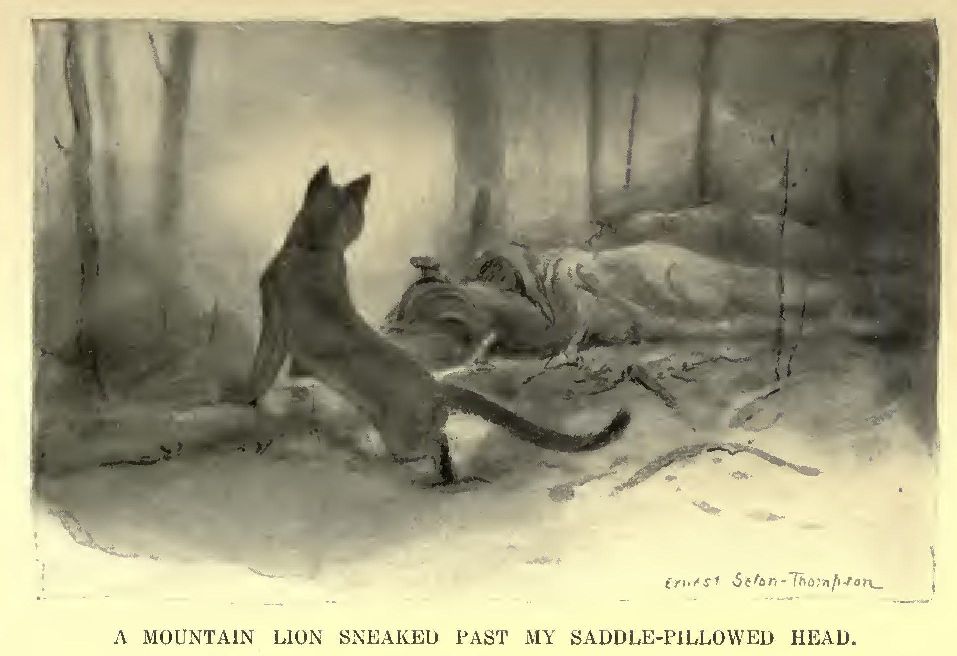

A mountain lion sneaked past my saddle-pillowed head

CONTENTS

II. OUTFIT AND ADVICE FOR THE WOMAN-WHO-GOES-HUNTING-WITH-HER-HUSBAND.

III. THE FIRST PLUNGE OF THE WOMAN TENDERFOOT.

IV. WHICH TREATS OF THE IMPS AND MY ELK.

XI. WHAT I KNOW ABOUT WAHB OF THE BIGHORN BASIN.

XV. THE SWEET PEA LADY SOMEONE ELSE'S MOUNTAIN SHEEP.

XVI. IN WHICH THE TENDERFOOT LEARNS A NEW TRICK.

Theoretically, I have always agreed with the Quaker wife who reformed her husband—"Whither thou goest, I go also, Dicky dear." What thou doest, I do also, Dicky dear. So when, the year after our marriage, Nimrod announced that the mountain madness was again working in his blood, and that he must go West and take up the trail for his holiday, I tucked my summer-watering-place-and-Europe-flying-trip mind away (not without regret, I confess) and cautiously tried to acquire a new vocabulary and some new ideas.

Of course, plenty of women have handled guns and have gone to the Rocky Mountains on hunting trips—but they were not among my friends. However, my imagination was good, and the outfit I got together for my first trip appalled that good man, my husband, while the number of things I had to learn appalled me.

In fact, the first four months spent 'Out West' were taken up in learning how to ride, how to dress for it, how to shoot, and how to philosophise, each of which lessons is a story in itself. But briefly, in order to come to this story, I must have a side talk with the Woman-who-goes-hunting-with-her-husband. Those not interested please omit the next chapter.

Is it really so that most women say no to camp life because they are afraid of being uncomfortable and looking unbeautiful? There is no reason why a woman should make a freak of herself even if she is going to rough it; as a matter of fact I do not rough it, I go for enjoyment and leave out all possible discomforts. There is no reason why a woman should be more uncomfortable out in the mountains, with the wild west wind for companion and the big blue sky for a roof, than sitting in a 10 by 12 whitewashed bedroom of the summer hotel variety, with the tin roof to keep out what air might be passing. A possible mosquito or gnat in the mountains is no more irritating than the objectionable personality that is sure to be forced upon you every hour at the summer hotel. The usual walk, the usual drive, the usual hop, the usual novel, the usual scandal,—in a word, the continual consciousness of self as related to dress, to manners, to position, which the gregarious living of a hotel enforces—are all right enough once in a while; but do you not get enough of such life in the winter to last for all the year?

Is one never to forget that it is not proper to wear gold beads with crape? Understand, I am not to be set down as having any charity for the ignoramus who would wear that combination, but I wish to record the fact that there are times, under the spell of the West, when I simply do not care whether there are such things as gold beads and crape; when the whole business of city life, the music, arts, drama, the pleasant friends, equally with the platitudes of things and people you care not about—civilization, in a word—when all these fade away from my thoughts as far as geographically they are, and in their place comes the joy of being at least a healthy, if not an intelligent, animal. It is a pleasure to eat when the time comes around, a good old-fashioned pleasure, and you need no dainty serving to tempt you. It is another pleasure to use your muscles, to buffet with the elements, to endure long hours of riding, to run where walking would do, to jump an obstacle instead of going around it, to return, physically at least, to your pinafore days when you played with your brother Willie. Red blood means a rose-colored world. Did you feel like that last summer at Newport or Narragansett?

So enough; come with me and learn how to be vulgarly robust.

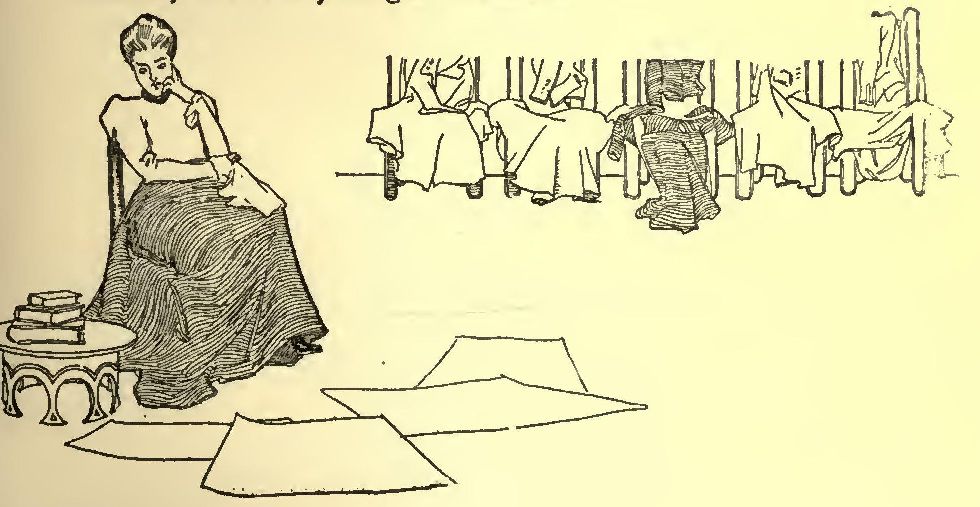

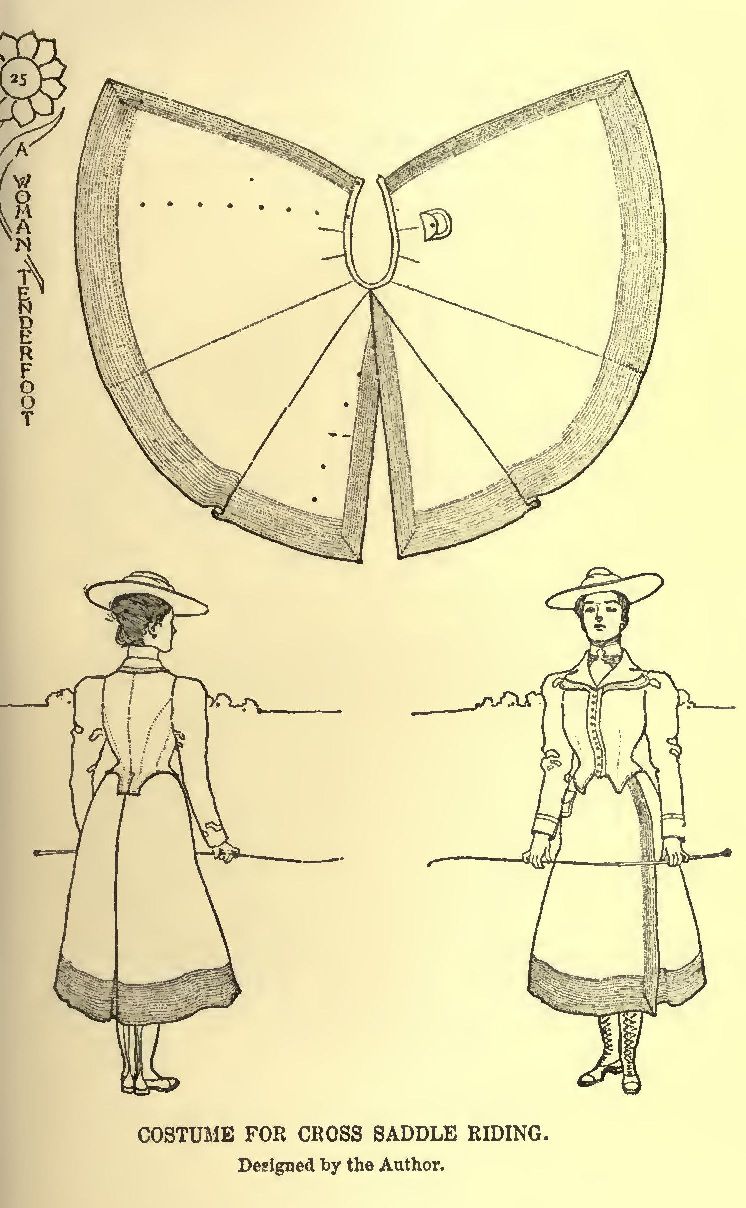

Of course one must have clothes and personal comforts, so, while we are still in the city humor, let us order a habit suitable for riding astride. Whipcord, or a closely woven homespun, in some shade of grayish brown that harmonizes with the landscape, is best. Corduroy is pretty, if you like it, but rather clumsy. Denham will do, but it wrinkles and becomes untidy. Indeed it has been my experience that it is economy to buy the best quality of cloth you can afford, for then the garment always keeps its shape, even after hard wear, and can be cleaned and made ready for another year, and another, and another. You will need it, never fear. Once you have opened your ears, "the Red Gods" will not cease to "call for you."

In Western life you are on and off your horse at the change of a thought. Your horse is not an animate exercise-maker that John brings around for a couple of hours each morning; he is your companion, and shares the vicissitudes of your life. You even consult him on occasion, especially on matters relating to the road. Therefore your costume must look equally well on and off the horse. In meeting this requirement, my woes were many. I struggled valiantly with everything in the market, and finally, from five varieties of divided skirts and bloomers, the following practical and becoming habit was evolved.

I speak thus modestly, as there is now a trail of patterns of this habit from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast. Wherever it goes, it makes converts, especially among the wives of army officers at the various Western posts where we have been—for the majority of women in the West, and I nearly said all the sensible ones, now ride astride.

When off the horse, there is nothing about this habit to distinguish it from any trim golf suit, with the stitching up the left front which is now so popular. When on the horse, it looks, as some one phrased it, as though one were riding side saddle on both sides. This is accomplished by having the fronts of the skirt double, free nearly to the waist, and, when off the horse, fastened by patent hooks. The back seam is also open, faced for several inches, stitched and closed by patent fasteners. Snug bloomers of the same material are worn underneath. The simplicity of this habit is its chief charm; there is no superfluous material to sit upon—oh, the torture of wrinkled cloth in the divided skirt!—and it does not fly up even in a strong wind, if one knows how to ride. The skirt is four inches from the ground—it should not bell much on the sides—and about three and a half yards at the bottom, which is finished with a five-inch stitched hem.

Any style of jacket is of course suitable. One that looks well on the horse is tight fitting, with postilion back, short on hips, sharp pointed in front, with single-breasted vest of reddish leather (the habit material of brown whipcord), fastened by brass buttons, leather collar and revers, and a narrow leather band on the close-fitting sleeves. A touch of leather on the skirt in the form of a patch pocket is harmonious, but any extensive leather trimming on the skirt makes it unnecessarily heavy.

A suit of this kind should be as irreproachable in fit and finish as a tailor can make it. This is true economy, for when you return in the autumn it is ready for use as a rainy-day costume.

Once you have your habit, the next purchase should be stout, heavy soled boots, 13 or 14 inches high, which will protect the leg in walking and from the stirrup leather while riding. One needs two felt hats (never straw), one of good quality for sun or rain, with large firm brim. This is important, for if the brim be not firm the elements will soon reduce it to raglike limpness and it will flap up and down in your face as you ride. This can be borne with composure for five or ten minutes, but not for days and weeks at a time. The other felt hat may be as small and as cheap as you like. Only see that it combines the graces of comfort and becomingness. It is for evenings, and sunless rainless days. A small brown felt, with a narrow leather band, gilt buckle, and a twist of orange veiling around the crown, is pretty for the whipcord costume.

One can do a wonderful amount of smartening up with tulle, hat pins, belts, and fancy neck ribbons, all of which comparatively take up no room and add no weight, always the first consideration. Be sure you supply yourself with a reserve of hat pins. Two devices by which they may be made to stay in the hat are here shown. The spiral can be given to any hat pin. The chain and small brooch should be used if the hat pin is of much value.

At this point, if any man, a reviewer perhaps, has delved thus far into the mysteries of feminine outfit, he will probably remark, "Why take a hat pin of much value?" to which I reply; "Why not? Can you suggest any more harmless or useful vent for woman's desire to ornament herself? And unless you want her to be that horror of horrors, a strong-minded woman, do you think you can strip her for three months of all her gewgaws and still have her filled with the proper desire to be pleasing in your eyes? No; better let her have the hat pins—and you know they really are useful—and then she will dress up to those hat pins, if it is only with a fresh neck ribbon and a daisy at her belt."

I had a man's saddle, with a narrow tree and high pommel and cantle, such as is used out West, and as I had not ridden a horse since the hazy days of my infancy, I got on the huge creature's back with everything to learn. Fear enveloped me as in a cloud during my first ride, and the possibilities of the little cow pony they put me on seemed more awe-inspiring than those of a locomotive. But I have been reading Professor William James and acquired from him the idea (I hope I do not malign him) that the accomplishment of a thing depends largely upon one's mental attitude, and this was mine all nicely taken—in New York:—

"This thing has been done before, and done well. Good; then I can do it, and enjoy it too."

I particularly insisted upon the latter clause—in the East. This formula is applicable in any situation. I never should have gotten through my Western experiences without it, and I advise you, my dear Woman-who-goes-hunting-with-her-husband, to take a large stock of it made up and ready for use. There is one other rule for your conduct, if you want to be a success: think what you like, but unless it is pleasant, don't say it.

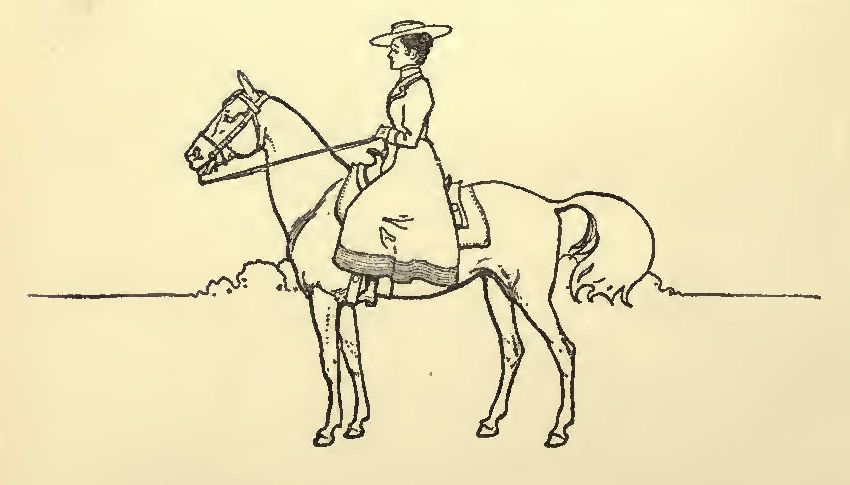

Is it better to ride astride? I will not carry the battle ground into the East, although even here I have my opinion; but in the West, in the mountains, there can be no question that it is the only way. Here is an example to illustrate: Two New York women, mother and daughter, took a trip of some three hundred miles over the pathless Wind River Mountains. The mother rode astride, but the daughter preferred to exhibit her Durland Academy accomplishment, and rode sidesaddle, according to the fashion set by an artful queen to hide her deformity. The advantages of health, youth and strength were all with the daughter; yet in every case on that long march it was the daughter who gave out first and compelled the pack train to halt while she and her horse rested. And the daughter was obliged to change from one horse to another, while the same horse was able to carry the mother, a slightly heavier woman, through the trip. And the back of the horse which the daughter had ridden chiefly was in such a condition from saddle galls that the animal, two months before a magnificent creature, had to be shot.

I hear you say, "But that was an extreme case." Perhaps it was, but it supports the verdict of the old mountaineers who refuse to let any horse they prize be saddled with "those gol-darned woman fripperies."

There is also another side. A woman at best is physically handicapped when roughing it with husband or brother. Then why increase that handicap by wearing trailing skirts that catch on every log and bramble, and which demand the services of at least one hand to hold up (fortunately this battle is already won), and by choosing to ride side-saddle, thus making it twice as difficult to mount and dismount by yourself, which in fact compels you to seek the assistance of a log, or stone, or a friendly hand for a lift? Western riding is not Central Park riding, nor is it Rotten Row riding. The cowboy's, or military, seat is much simpler and easier for both man and beast than the Park seat—though, of course, less stylish. That is the glory of it; you can go galloping over the prairie and uplands with never a thought that the trot is more proper, and your course, untrammelled by fenced-in roads, is straight to the setting sun or to yonder butte. And if you want a spice of danger, it is there, sometimes more than you want, in the presence of badger and gopher holes, to step into which while at high speed may mean a broken leg for your horse, perhaps a broken neck for yourself. But to return to the independence of riding astride:

One day I was following a game trail along a very steep bank which ended a hundred feet below in a granite precipice. It had been raining and snowing in a fitful fashion, and the clay ground was slippery, making a most treacherous footing. One of the pack animals just ahead of my horse slipped, fell to his knees, the heavy pack overbalanced him, and away he rolled over and over down the slope, to be stopped from the precipice only by the happy accident of a scrub tree in the way. Frightened by this sight, my animal plunged, and he, too, lost his footing. Had I been riding side-saddle, nothing could have saved me, for the downhill was on the near side; but instead I swung out of the saddle on the off side and landed in a heap on the uphill, still clutching the bridle. That act saved my horse's life, probably, as well as my own. For the sudden weight I put on the upper side as I swung off enabled him to recover his balance just in time. I do not pretend to say that I can dismount from the off side as easily as from the near, because I am not accustomed to it. But I have frequently done it in emergencies, while a side-saddle leaves one helpless in this case as in many others.

Besides being unable to mount and dismount without assistance it is very difficult to get side-saddle broken horses, and it usually means a horse so broken in health and spirits that he does not care what is being strapped on his back and dangling on one side of him only. And to be on such an animal means that you are on the worst mount of the outfit, and I am sure that it requires little imagination on any one's part to know therein lies misery. Oh! the weariness of being the weakest of the party and the worst mounted—to be always at the tail end of the line, never to be able to keep up with the saddle horses when they start off for a canter, to expend your stock of vitality, which you should husband for larger matters, in urging your beast by voice and quirt to further exertion! Never place yourself in such a position. The former you cannot help, but you can lessen it by making use of such aids to greater independence as wearing short skirts and riding astride, and having at least as good a horse as there is in the outfit. Then you will get the pleasure from your outing that you have the right to expect—that is, if you adhere to one other bit of advice, or rather two.

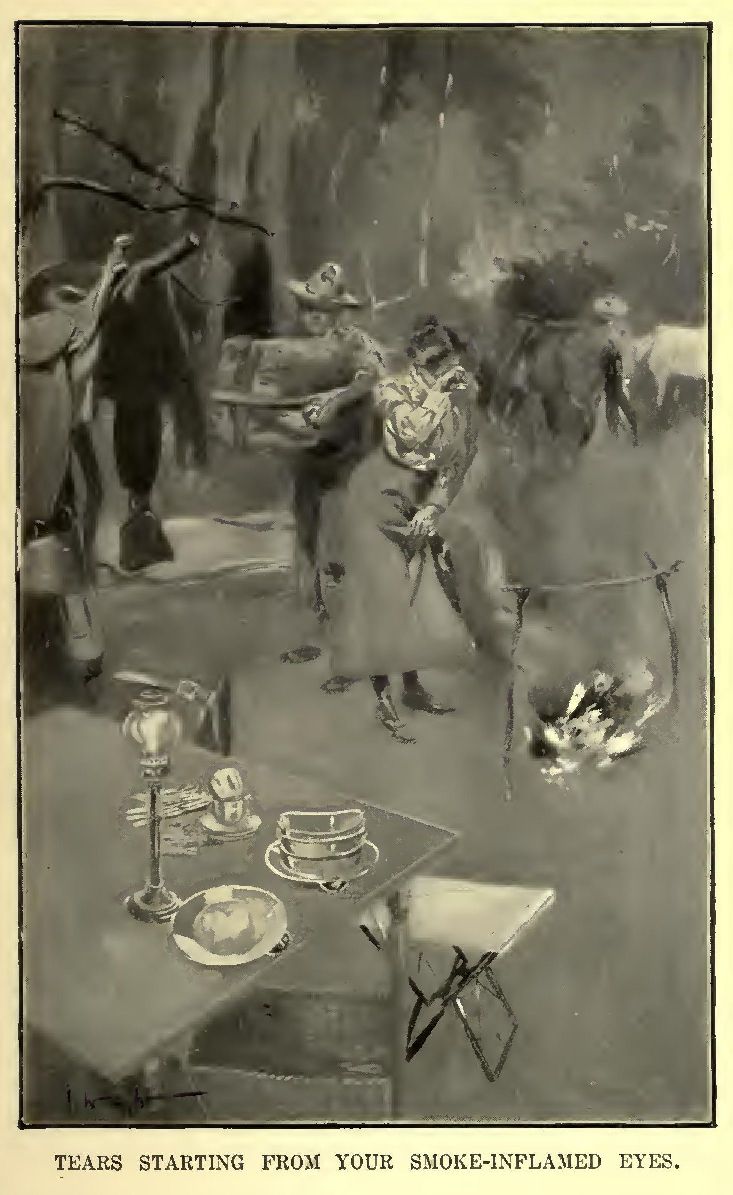

The first is: See that for your camping trip is provided a man cook.

I wish that I could put a charm over the next few words so that only the woman reader could understand, but as I cannot I must repeat boldly: Dear woman who goes hunting with her husband, be sure that you have it understood that you do no cooking, or dishwashing. I think that the reason women so often dislike camping out is because the only really disagreeable part of it is left to them as a matter of course. Cooking out of doors at best is trying, and certainly you cannot be care free, camp-life's greatest charm, when you have on your mind the boiling of prunes and beans, or when tears are starting from your smoke-inflamed eyes as you broil the elk steak for dinner. No, indeed! See that your guide or your horse wrangler knows how to cook, and expects to do it. He is used to it, and, anyway, is paid for it. He is earning his living, you are taking a vacation.

Now for the second advice, which is a codicil to the above: In return for not having to potter with the food and tinware, never complain about it. Eat everything that is set before you, shut your eyes to possible dirt, or, if you cannot, leave the particular horror in question untouched, but without comment. Perhaps in desperation you may assume the role of cook yourself. Oh, foolish woman, if you do, you only exchange your woes for worse ones.

If you provide yourself with the following articles and insist upon having them reserved for you, and then let the cook furnish everything else, you will be all right:—

An aluminum plate made double for hot water. This is a very little trouble to fill, and insures a comfortable meal; otherwise, your meat and vegetables will be cold before you can eat them, and the gravy will have a thin coating of ice on it. It is always cold night and morning in the mountains. And if you do not need the plate heated you do not have to fill it; that's all. I am sure my hot-water plate often saved me from indigestion and made my meals things to enjoy instead of to endure.

Two cups and saucers of white enamel ware. They always look clean and do not break.

One silver-plated knife and fork and two teaspoons.

One folding camp chair.

N.B.—Provide your husband or brother or sister precisely the same; no more, no less.

Japanese napkins, enough to provide two a day for the party.

Two white enamel vegetable dishes.

One folding camp table.

One candle lamp, with enough candles. Then leave all the rest of the cooking outfit to your cook and trust in Providence. (If you do not approve of Providence, a full aluminum cooking outfit can be bought so that one pot or pan nests in the other, the whole very complete, compact and light.)

Come what may, you have your own particular clean hot plate, cup and saucer, knife, fork, spoon and napkin, with a table to eat from and a chair to sit on and a lamp to see by, if you are eating after dark—which often happens—and nothing else matters, but food.

If you want to be canny you will have somewhere in your own pack a modest supply of condensed soups and vegetables, a box or two of meat crackers, and three or four bottles of bouillon, to be brought out on occasions of famine. Anyway it is a comfort to know that you have provided against the wolf. So much for your part of the eating; now for the sleeping. If you do not sleep warm and comfortable at night, the joys of camping are as dust in the mouth. The most glorious morning that Nature ever produced is a weariness to the flesh of the owl-eyed. So whatever else you leave behind, be sure your sleeping arrangements are comfortable. The following is the result of three years' experience:—

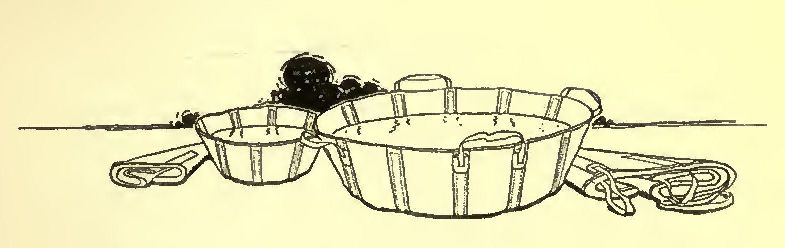

A piece of waterproof brown canvas, 7 by 10 feet, bound with tape and supplied with two heavy leather straps nine feet long, with strong buckles at one end and fastened to the canvas by means of canvas loops, and one leather strap six feet long that crosses the other two at right angles.

One rubber air bed, 36 by 76 inches (don't take a narrower size or you will be uncomfortable), fitted with large size double valve at each end. This bed is six inches thick when blown full of air. Be sure that sides are inserted, thus making two seams to join together the top and bottom six inches apart. If the top and bottom are fastened directly together, your bed slopes down at the sides, which is always disagreeable.

A sleeping bag, with the canvas cover made the full 36 inches wide. This cover should hold two blanket bags of different weight, and if you are wise you will have made an eider-down bag to fit inside all of these for very cold weather. The eider bag costs about $16.00 or $18.00, but is worth it if you are going to camp out in the mountains after August. Do without one or two summer hats, but get it, for it is the keynote of camp comfort.

Then you want a lamb's wool night wrapper, a neutral grey or brown in color, a set of heavy night flannels, some heavy woollen stockings and a woollen tam o' shanter large enough to pull down over the ears. A hot-water bag, also, takes up no room and is heavenly on a freezing night when the wind is howling through the trees and snow threatens. N.B.—See that your husband or brother has a similar outfit, or he will borrow yours.

The sleeping bags should be separated and dried either by sun or fire every other day.

Always keep all your sleeping things together in your bed roll, and your husband's things together in his bed bundle. It will save you many a sigh and weary hunt in the dark and cold. The tent and such things, you can afford to leave to your guide or to luck. If one wishes to provide a tent, brown canvas is far preferable to white. It does not make a glare of light, nor does it stand out aggressively in the landscape. You have your little nightly kingdom waiting for you and can sleep cosily if nothing else is provided. Whenever possible, get your bed blown up and your sleeping bags in order on top and your sleeping things together where you can put your hands on them during the daylight, or if that is impossible, make it the first thing you do when you make camp, while the cook is getting supper. Then, as you eat supper and sit near the camp fire to keep warm, you have the sweet consciousness that over there, in the blackness is a snug little nest all ready to receive your tired self. And if some morning you want to see what you have escaped, just unscrew the air valve to your bed before you rise, and when you come down on the hard, bumpy ground, in less time than it takes to tell, you will agree with me that there is nothing so rare as resting on air. Nimrod used to play this trick on me occasionally when it was time to get up—it is more efficacious than any alarm clock—but somehow he never seemed to enjoy it when I did it to him.

For riding, it is better to carry your own saddle and bridle and to buy a saddle horse upon leaving the railroad. You can look to the guides for all the rest, such as pack saddles, pack animals, etc.

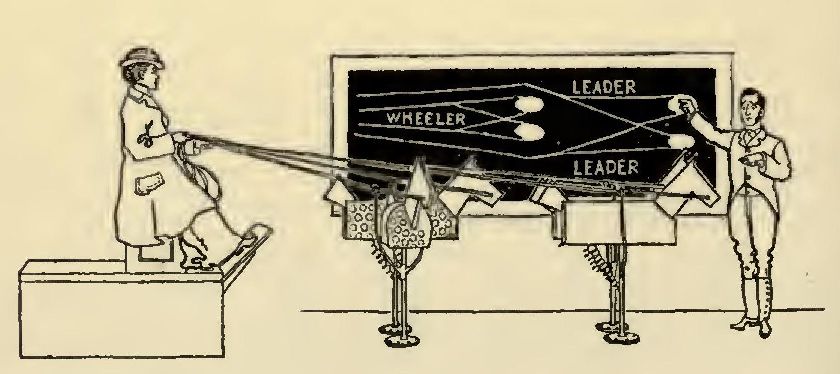

My saddle is a strong but light-weight California model; that is, with pommel and cantle on a Whitman tree. It is fitted with gun-carrying case of the same leather and saddle-bag on the skirt of each side, and has a leather roll at the back strapped on to carry an extra jacket and a slicker. (A rain-coat is most important. I use a small size of the New York mounted policemen's mackintosh, made by Goodyear. It opens front and back and has a protecting cape for the hands.) The saddle has also small pommel bags in which are matches, compass, leather thongs, knife and a whistle (this last in case I get lost), and there are rings and strings in which other bundles such as lunch can be attached while on the march. A horsehair army saddle blanket saves the animal's back. Nimrod's saddle is exactly like mine, only with longer and larger stirrups.

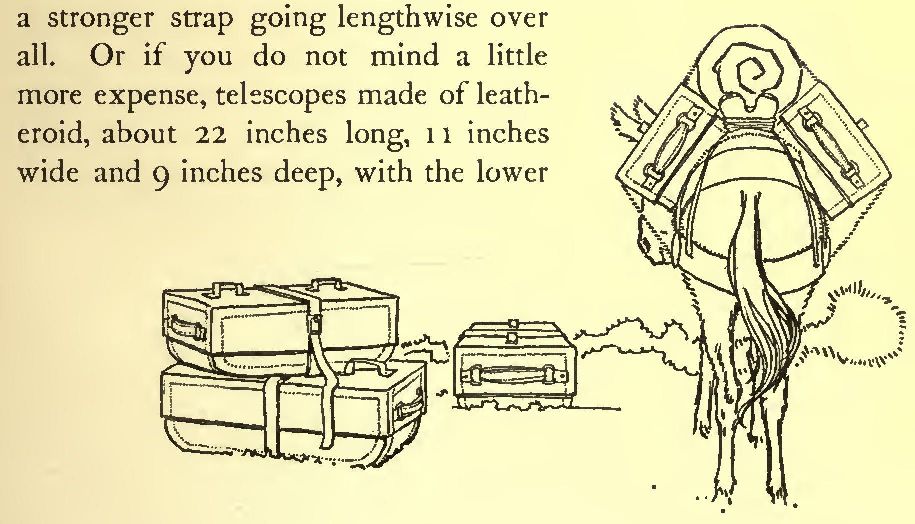

You have now your personal things for eating, sleeping and riding. It remains but to clothe yourself and you are ready to start. Provide yourself with two or three champagne baskets covered with brown waterproof canvas, with stout handles at each end and two leather straps going round the basket to buckle the lid down, and a stronger strap going lengthwise over all. Or if you do not mind a little more expense, telescopes made of leatheroid, about 22 inches long, 11 inches wide and 9 inches deep, with the lower corners rounded so they will not stick into the horse, and fitted with straps and handles, make the ideal travelling case; for they can be shipped from place to place on the railroad and can be packed, one on each side of a horse. They are much to be preferred to the usual Klondike bag for convenience in packing and unpacking one's things and in protecting them.

It is hardly necessary to say that clothes have to be kept down to the limit of comfort. Into the telescopes or baskets should go warm flannels, extra pair of heavy boots, several flannel shirt waists, extra riding habit and bloomers, fancy neck ribbons and a belt or two—for why look worse than your best at any time?—a long warm cloak and a chamois jacket for cold weather, snow overshoes, warm gloves and mittens too, and some woollen stockings. Be sure you take flannels. This is the advice of one who never wears them at any other time. A veil or two is very useful, as the wind is often high and biting, and I was much annoyed with wisps of hair around my eyes, and also with my hair coming down while on horseback, until I hit upon the device of tying a brown liberty silk veil over the hair and partially over the ears before putting on a sombrero. This veil was not at all unbecoming, being the same color as my hair, and it served the double purpose of keeping unruly locks in order and keeping my ears warm. A hair net is also useful.

Then you must not forget a rubber bath tub, a rubber wash basin, sponge, towels, soap, and toilet articles generally, including camphor ice for chapped lips and pennyroyal vaseline salve for insect bites. A brown linen case is invaluable to hold all these toilet necessaries, so that you can find them quickly. A sewing kit should be supplied, a flask of whiskey, and a small "first-aid" outfit; a bottle of Perry Davis pain killer or Pond's extract; but no more bottles than must be, as they are almost sure to be broken.

In your husband's box, ammunition takes the place of toilet articles. I shall pass over the guns with the bare mention that I use a 30.30 Winchester, smokeless. For railroad purposes all this outfit for two goes into two trunks and a box—one trunk for all the bedding and night things: the other for all the clothing, guns, ammunition, eating things, and incidentals. The box holds the saddles, bridles, and horse things.

In a pack train, the bed-rolls, weighing about fifty pounds each, go on either side of one horse, and the telescopes on each side of another horse—in both cases not a full load, and leaving room on the top of the pack for a tent and other camp things. The saddles, of course, go on the saddle horses. The cost of such an outfit, in New York, is about two hundred dollars each; but it lasts for years and brings you in large returns in health and consequent happiness.

I am willing to wager my horsehair rope (specially designed for keeping off snakes) that a summer in the Rockies would enable you to cheat time of at least two years, and you would come home and join me in the ranks of converts from the usual summer sort of thing. Will you try it? If you do, how you will pity your unfortunate friends who have never known what it is to sleep on the south side of a sage brush, and honestly say in the morning, "It is wonderful how well I am feeling."

But to begin:—

It was about midnight in the end of August when Nimrod and I tumbled off the train at Market Lake, Idaho. Next morning, after a comfortable night's rest at the "hotel," our rubber beds, sleeping bags, saddles, guns, clothing, and ourselves were packed into a covered wagon, drawn by four horses, and we started for Jackson's Hole in charge of a driver who knew the road perfectly. At least, that was what he said, so of course he must have known it. But his memory failed him sadly the first day out, which reduced him to the necessity of inquiring of the neighbours. As these were unsociably placed from thirty to fifty miles apart, there were many times when the little blind god of chance ruled our course.

We put up for the night at Rexburgh, after forty long miles of alkali dust. The Mormon religion has sent a thin arm up into that country, and the keeper of the log building he called a hotel was of that faith. The history of our brief stay there belongs properly to the old torture days of the Inquisition, for the Mormon's possessions of living creatures were many, and his wives and children were the least of them.

Another day of dust and long hard miles over gradually rising hills, with the huge mass of the Tetons looming ever nearer, and the next day we climbed the Teton Pass.

There is nothing extraordinary about climbing the Teton Pass—to tell about. We just went up, and then we went down. It took six horses half a day to draw us up the last mile—some twenty thousand seconds of conviction on my part (unexpressed, of course; see side talk) that the next second would find us dashed to everlasting splinters. And it took ten minutes to get us down!

Of the two, I preferred going up. If you have ever climbed a greased pole during Fourth of July festivities in your grandmother's village, you will understand.

When we got to the bottom there was something different. Our driver informed us that in two hours we should be eating dinner at the ranch house in Jackson's Hole, where we expected to stop for a while to recuperate from the past year's hard grind and the past two weeks of travel. This was good news, as it was then five o'clock and our midday meal had been light—despite the abundance of coffee, soggy potatoes, salt pork, wafer slices of meat swimming in grease, and evaporated apricots wherein some nice red ants were banqueting.

"We'll just cross the Snake River, and then it'll be plain sailing," he said. Perhaps it was so. I was inexperienced in the West. This was what followed:—Closing the door on the memory of my recent perilous passage, I prepared to be calm inwardly, as I like to think I was outwardly. The Snake River is so named because for every mile it goes ahead it retreats half way alongside to see how well it has been done. I mention this as a pleasing instance of a name that really describes the thing named. But this is after knowledge.

About half past five, we came to a rolling tumbling yellow stream where the road stopped abruptly with a horrid drop into water that covered the hubs of the wheels. The current was strong, and the horses had to struggle hard to gain the opposite bank. I began to thank my patron saint that the Snake River was crossed.

Crossed? Oh, no! A narrow strip of pebbly road, and the high willows suddenly parted to disclose another stream like the last, but a little deeper, a little wider, a little worse. We crossed it. I made no comments.

At the third stream the horses rebelled. There are many things four horses can do on the edge of a wicked looking river to make it uncomfortable, but at last they had to go in, plunging madly, and dragging the wagon into the stream nearly broadside, which made at least one in the party consider the frailty of human contrivances when matched against a raging flood.

Soon there was another stream. I shall not describe it. When we eventually got through it, the driver stopped his horses to rest, wiped his brow, went around the wagon and pulled a few ropes tighter, cut a willow stick and mended his broken whip, gave a hitch to his trousers, and remarked as he started the horses:

"Now, when we get through the Snake River on here a piece, we'll be all right."

"I thought we had been crossing it for the past hour," I was feminine enough to gasp.

"Oh, yes, them's forks of it; but the main stream's on ahead, and it's mighty treacherous, too," was the calm reply.

When we reached the Snake River, there was no doubt that the others were mere forks. Fortunately, Joe Miller and his two sons live on the opposite bank, and make a living by helping people escape destruction from the mighty waters. Two men waved us back from the place where our driver was lashing his horses into the rushing current, and guided us down stream some distance. One of them said:

"This yere ford changes every week, but I reckon you might try here."

We did.

Had my hair been of the dramatic kind that realises situations, it would have turned white in the next ten minutes. The water was over the horses' backs immediately, the wagon box was afloat, and we were being borne rapidly down stream in the boiling seething flood, when the wheels struck a shingly bar which gave the horses a chance to half swim, half plunge. The two men, who were on horseback, each seized one of the leaders, and kept his head pointed for a cut in the bank, the only place where we could get out.

Everything in the wagon was afloat. A leather case with a forty dollar fishing rod stowed snugly inside slipped quietly off down stream. I rescued my camera from the same fate just in time. Overshoes, wraps, field glasses, guns, were suddenly endowed with motion. Another moment and we should surely have sunk, when the horses, by a supreme effort, managed to scramble on to the bank, but were too exhausted to draw more than half of the wagon after them, so that it was practically on end in the water, our outfit submerged, of course, and ourselves reclining as gracefully as possible on the backs of the seats.

Had anything given away then, there might have been a tragedy. The two men immediately fastened a rope to the tongue of the wagon, and each winding an end around the pommel of his saddle, set his cow pony pulling. Our horses made another effort, and up we came out of the water, wet, storm tossed, but calm. Oh, yes—calm! After that, earth had no terrors for me; the worst road that we could bump over was but an incident. I was not surprised that it grew dark very soon, and that we blundered on and on for hours in the night until the near wheeler just lay down in the dirt, a dark spot in the dark road, and our driver, after coming back from a tour of inspection on foot, looked worried. I mildly asked if we would soon cross Snake River, but his reply was an admission that he was lost. There was nothing visible but the twinkling stars and a dim outline of the grim Tetons. The prospect was excellent for passing the rest of the night where we were, famished, freezing, and so tired I could hardly speak.

But Nimrod now took command. His first duty, of course, being a man, was to express his opinion of the driver in terms plain and comprehensive; then he loaded his rifle and fired a shot. If there were any mountaineers around, they would understand the signal and answer.

We waited. All was silent as before. Two more horses dropped to the ground. Then he sent another loud report into the darkness. In a few moments we thought we heard a distant shout, then the report of a gun not far away.

Nimrod mounted the only standing horse and went in the direction of the sound. Then followed an interminable silence. I hallooed, but got no answer. The wildest fears for Nimrod's safety tormented me. He had fallen into a gully, the horse had thrown him, he was lost.

Then I heard a noise and listened eagerly. The driver said it was a coyote howling up on the mountain. At last voices did come to me from out of the blackness, and Nimrod returned with a man and a fresh horse. The man was no other than the owner of the house for which we were searching, and in ten minutes I was drying myself by his fireplace, while his hastily aroused wife was preparing a midnight supper for us.

To this day, I am sure that driver's worst nightmare is when he lives over again the time when he took a tenderfoot and his wife into Jackson's Hole, and, but for the tenderfoot, would have made them stay out overnight, wet, famished, frozen, within a stone's throw of the very house for which they were looking.

"If you want to see elk, you just follow up the road till you strike a trail on the left, up over that hog's back, and that will bring you in a mile or so on to a grassy flat, and in two or three miles more you come to a lake back in the mountains."

Mrs. Cummings, the speaker, was no ordinary woman of Western make. She had been imported from the East by her husband three years before. She had been 'forelady in a corset factory,' when matrimony had enticed her away, and the thought that walked beside her as she baked, and washed, and fed the calves, was that some day she would go 'back East.' And this in spite of the fact that for those parts she was very comfortable.

Her log house was the largest in the country, barring Captain Jones's, her nearest neighbour, ten miles up at Jackson's Lake, and his was a hotel. Hers could boast of six rooms and two clothes' closets. The ceilings were white muslin to shut off the rafters, the sitting room had wall-paper and a rag carpet, and in one corner was the post-office.

The United States Government Post-office of Deer, Wyoming, took up two compartments of Mrs. Cummings' writing desk, and she was called upon to be postmistress fifteen minutes twice a week, when the small boy, mounted on a tough little pony, happened around with the leather bag which carried the mail to and from Jackson, thirty miles below.

"I'd like some elk meat mighty well for dinner," Mrs. Cummings continued, as she leaned against the kitchen door and watched us mount our newly acquired horses, "but you won't find game around here without a guide—Easterners never do."

Nimrod and I started off in joyous mood. The secret of it, the fascination of the wild life, was revealed to me. At last I understood why the birds sing. The glorious exhilaration of the mountains, the feeling that life is a rosy dream, and that all the worry and the fever and the fret of man's making is a mere illusion that has faded away into the past, and is not worth while; that the real life is to be free, to fly over the grassy mountain meadow with never a limitation of fence or house, with the eternal peaks towering around you, terrible in their grandeur and vastness, yet inviting.

We struck the trail all right, we thought, but it soon disappeared and we had to govern our course by imagination, an uncertain guide at best. We got into dreadful tangles of timber; the country was all strange, and the trees spread over the mountain for miles, so that it was like trying to find the way under a blanket; but we kept on riding our horses over fallen logs and squeezing them between trees, all the time keeping a sharp watch over them, for they were fresh and scary.

Finally, after three hours' hard climbing, we emerged from the forest on to a great bare shoulder of the mountain, from which the whole country around, vast and beautiful, could be seen. We took bearings and tried to locate that lake, and we finally decided that a wooded basin three miles away looked likely to contain it.

In order to get to it, we had to cross a wooded ravine, very steep and torn out by a recent cloudburst. We rode the horses down places that I shudder in remembering, and I had great trouble in keeping away from the front feet of my horse as I led him, especially when there were little gullies that had to be jumped.

It was exciting enough, and hard work, too, every nerve on a tingle and one's heart thumping with the unwonted exercise at that altitude; but oh, the glorious air, the joy of life and motion that was quite unknown to my reception and theatre-going self in the dim far away East!

We searched for that lake all day, and at nightfall went home confident that we could find it on the morrow.

Mrs. Cummings' smile clearly expressed 'I told you so,' and she remarked as she served supper: "When my husband comes home next week, he will take you where you can find game."

The next morning we again took some lunch in the saddle bag and started for that elusive spot we had christened Cummings' Lake. About three o'clock we found it—a beautiful patch of water in the heart of the forest, nestling like a jewel, back in the mountains.

We picketed the horses at a safe distance, so that they could not be seen or heard from the lake. At one end the shore sloped gradually into the water, and here Nimrod discovered many tracks of elk, a few deer, and one set of black bear. He said the lake was evidently a favourite drinking place, that a band of elk had been coming daily to water, and that, according to their habits, they ought to come again before dusk.

So we concealed ourselves on a little bluff to the right and waited. The sun had begun to cast long lines on the earth, and the little circle of water was already in shadow when Nimrod held up his finger as a warning for silence. We listened. We were so still that the whole world seemed to be holding its breath.

I heard a faint noise as of a snapping branch, then some light thuds along the ground, and to the left of us out of the dark forest, a dainty creature flitted along the trail and playfully splashed into the water. Six others of her sisters followed her, with two little ones, and they were all splashing about in the water like so many sportive mermaids when their lordly master appeared—a fine bull elk who seemed to me, as he sedately approached the edge of the lake, to be nothing but horns.

I shall never forget the picture of this family at home—the quiet lake encircled by forest and towered over by mountains; the gentle graceful creatures full of life playing about in the water, now drinking, now splashing it in cooling showers upon one another; the solicitude of a mother that her young one should come to no harm; and then the head of them all proceeding with dignity to bathe with his harem.

Had I to do again what followed, I hope I should act differently. Nimrod was watching them with a rapt expression, quite forgetful of the rifle in his hands, when I, who had never seen anything killed, touched his arm and whispered: "Shoot, shoot now, if you are going to."

The report of the rifle rang out like a cannon. The does fled away as if by magic. The stag tried also to get to shore, but the ball had inflicted a wound which partially paralysed his hindquarters. At the sight of the blood and the big fellow's struggles to get away, the horror of the thing swept over me. "Oh, kill him, kill him!" I wailed. "Don't let him suffer!"

But here the hunter in Nimrod answered: "If I kill him now, I shall never be able to get him. Wait until he gets out of the water."

The next few seconds, with that struggling thing in the water, seemed an eternity of agony to me. Then another loud bang caused the proud head with its weight of antlers to sink to the wet bank never to rise again.

Later, as I dried my tears, I asked Nimrod:

"Where is the place to aim if you want to kill an animal instantly, so that he will not suffer, and never know what hit him?"

"The best place is the shoulder." He showed me the spot on his elk.

"But wouldn't he suffer at all?"

"Well, of course, if you hit him in the brain, he will never know; but that is a very fine shot. Your target is only an inch or two, here between the eye and the ear, and the head moves more than the body. But," he said, "you would not kill an elk after the way you have wept over this one?"

"If—if I were sure he would not suffer, I might kill just one," I said, conscious of my inconsistencies. My woman's soul revolted, and yet I was out West for all the experiences that the life could give me, and I knew, if the chance came just right, that one elk would be sacrificed to that end.

The next day, much to Mrs. Cummings' surprise, we had elk steak, the most delicious of meat when properly cooked. The next few days slipped by. We were always in the open air, riding about in those glorious mountains, and it was the end of the week when a turn of the wheel brought my day.

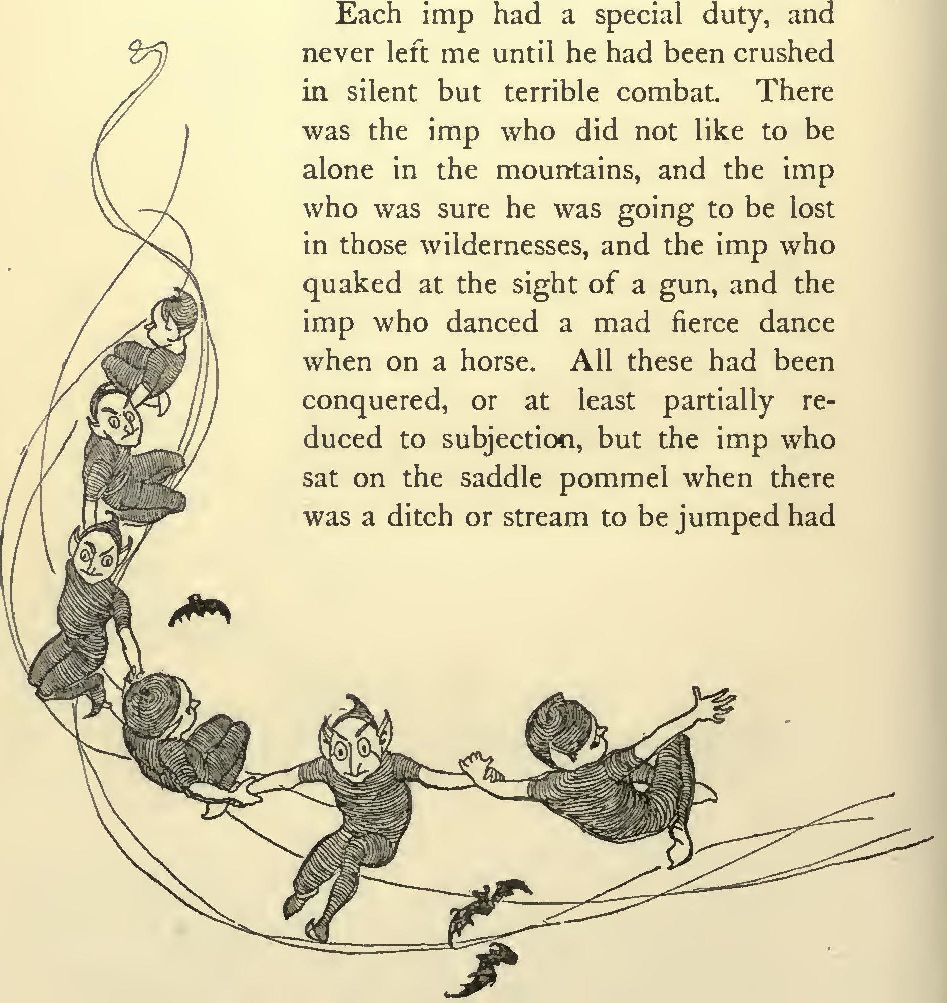

First, it becomes necessary to confide in you. Fear is a very wicked companion who, since nursery days, had troubled me very little; but when I arrived out West, he was waiting for me, and, so that I need never be without him, he divided himself into a band of little imps.

Each imp had a special duty, and never left me until he had been crushed in silent but terrible combat. There was the imp who did not like to be alone in the mountains, and the imp who was sure he was going to be lost in those wildernesses, and the imp who quaked at the sight of a gun, and the imp who danced a mad fierce dance when on a horse. All these had been conquered, or at least partially reduced to subjection, but the imp who sat on the saddle pommel when there was a ditch or stream to be jumped had hitherto obliged me to dismount and get over the space on foot.

This morning, when we came to a nasty boggy place, with several small water cuts running through it, I obeyed the imp with reluctance. Well, we got over it—Blondey, the imp, and I—with nothing worse than wet feet and shattered nerves.

I attempted to mount, and had one foot in the stirrup and one hand on the pommel, when Blondey started. Like the girl in the song, I could not get up, I could not get down, and although I had hold of the reins, I had no free hand to pull them in tighter, and you may be sure the imp did not help me. Blondey, realising there was something wrong, broke into a wild gallop across country, but I clung on, expecting every moment the saddle would turn, until I got my foot clear from the stirrup. Then I let go just as Blondey was gathering himself together for another ditch.

I was stunned, but escaped any serious hurt. Nimrod was a great deal more undone than I. He had not dared to go fast for fear of making Blondey go faster, and he now came rushing up, with the fear of death upon his face and the most terrible swears on his lips.

Although a good deal shaken, I began to laugh, the combination was so incongruous. Nimrod rarely swears, and was now quite unconscious what his tongue was doing. Upon being assured that all was well, he started after Blondey and soon brought him back to me; but while he was gone the imp and I had a mortal combat.

I did up my hair, rearranged my habit, and, rejecting Nimrod's offer of his quieter horse, remounted Blondey. We all jumped the next ditch, but the shock was too much for the imp in his weakened condition; he tumbled off the pommel, and I have never seen him since.

Our course lay along the hills on the east bank of Snake River that day. We discovered another beautiful sapphire lake in a setting of green hills. Several ducks were gliding over its surface. We watched them, in concealment of course, and we saw a fish hawk capture his dinner. Then we quietly continued along the ridge of a high bluff until we came to an outstretched point, where beneath us lay the Snake Valley with its fickle-minded river winding through.

The sun was just dropping behind the great Tetons, massed in front of us across the valley. We sat on our horses motionless, looking at the peaceful and majestic scene, when out from the shadows on the sandy flats far below us came a dark shadow, and then leisurely another and another. They were elk, two bulls and a doe, grazing placidly in a little meadow surrounded by trees.

We kept as still as statues.

Nimrod said. "There is your chance."

"Yes," I echoed, "here is my chance."

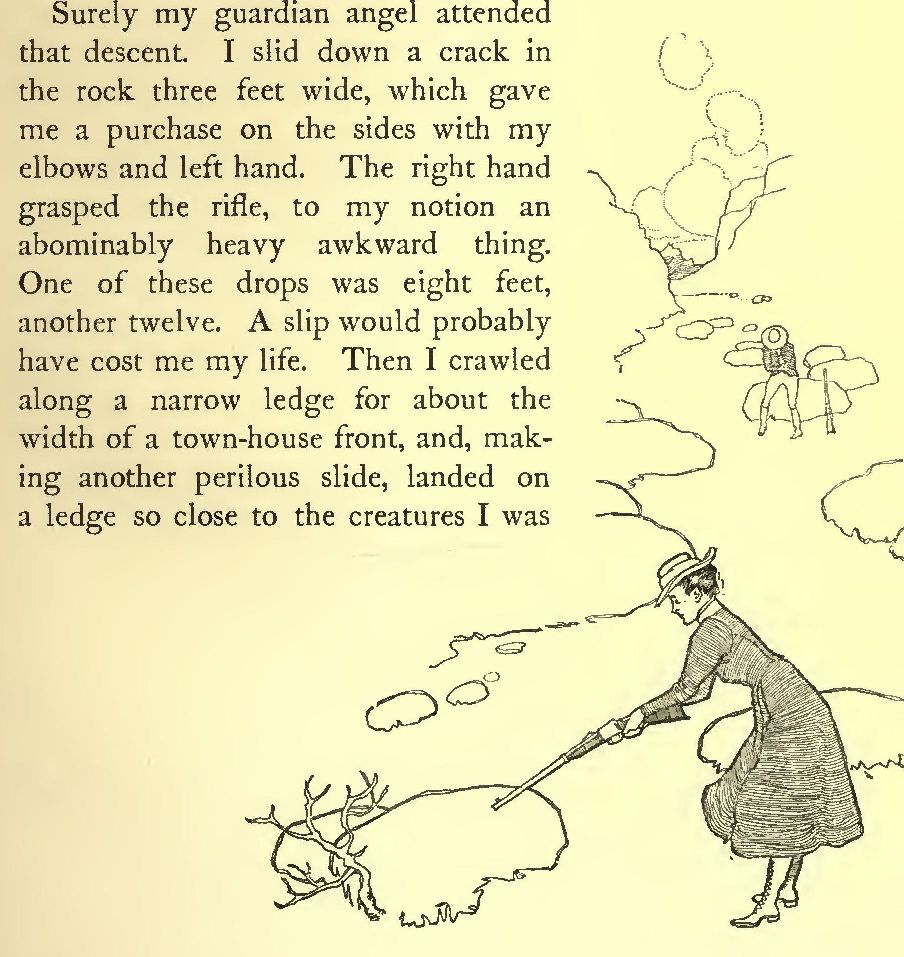

We waited until they passed into the trees again. Then we dismounted. Nimrod handed me the rifle, saying:

"There are seven shots in it. I will stay behind with the horses."

I took the gun without a word and crept down the mountain side, keeping under cover as much as possible. The sunset quiet surrounded me; the deadly quiet of but one idea—to creep upon that elk and kill him—possessed me. That gradual painful drawing nearer to my prey seemed a lifetime. I was conscious of nothing to the right, or to the left of me; only of what I was going to do. There were pine woods and scrub brush and more woods. Then, suddenly, I saw him standing by the river about to drink. I crawled nearer until I was within one hundred and fifty yards of him, when at the snapping of a twig he raised his head with its crown of branching horn. He saw nothing, so turned again to drink.

Now was the time. I crawled a few feet nearer and raised the deadly weapon. The stag turned partly away from me. In another moment he would be gone. I sighted along the metal barrel and a terrible bang went booming through the dim secluded spot. The elk raised his proud, antlered head and looked in my direction. Another shot tore through the air. Without another move the animal dropped where he stood. He lay as still as the stones beside him, and all was quiet again in the twilight.

I sat on the ground where I was and made no attempt to go near him. So that was all. One instant a magnificent breathing thing, the next—nothing.

Death had been so sudden. I had no regret, I had no triumph—just a sort of wonder at what I had done—a surprise that the breath of life could be taken away so easily.

Meanwhile, Nimrod had become alarmed at the long silence, and, tying the horses, had followed me down the mountain. He was nearly down when he heard the shots, and now came rushing up.

"I have done it," I said in a dull tone, pointing at the dark, quiet object on the bank.

"You surely have."

Nimrod paced the distance—it was one hundred and thirty-five yards—as we went up to the elk. How beautiful his coat was, glossy and shaded in browns, and those great horns—eleven points—that did not seem so big now to my eyes.

Nimrod examined the carcass.

"You are an apt pupil," he said. "You put a bullet through his heart and another through his brain."

"Yes," I said; "he never knew what killed him." But I felt no glory in the achievement.

Have you ever been lost in the mountains?—not the peaceful, cultivated child hills of the Catskills, but in real mountains, where the first outpost of civilisation, a lonely ranch house, is two weeks' travel away, and where that stream on your left is bound for the Pacific Ocean, and that stream on your right over there will, after four thousand miles, find its way into the Atlantic Ocean, and where the air you breathe is twelve thousand feet above those seas? I have.

The situation is naturally one you would not fish out of the grab bag of fate if you could avoid it. When you suddenly find it on your hands, however, there is only one thing to do—keep your nerve, grasp it firmly, and look at it closely. If you have a horse and a gun and a cartridge, it is not so bad. I had these and I had better than all these, I had Nimrod—but only half of Nimrod. The working half was chained up by my fears, for such is the power of a woman. I will explain. In crossing over the Continental Divide of the Rocky Mountains, we were guests in the pack train of a man who was equally at home in a New York drawing-room or on a Wyoming bear hunt, and he had made mountain travelling a fine art. Besides ourselves, there were the horse wrangler, the cook (of whom you shall hear later), and sixteen horses, and we started from Jackson's Lake for the Big Horn Basin, several hundred miles over the pathless uninhabited mountains.

No one who has not tried it knows how difficult it is for two or three men to keep so many pack animals in line, with no pathway to guide; and once they are started going nicely, it is nothing short of a calamity to stop them, especially when it is necessary to cover a certain number of miles before nightfall in order that they may have feed.

We were on the Pacific side of the Wind River Divide, and must get to the top that night. The horses were travelling nicely up the difficult ascent, so when Nimrod got his feet wet crossing a stream about noon, he and I thought we would just stop and have a little lunch, dry the shoes, and catch up with the pack train in half an hour.

From the minute the last horse vanished out of sight behind a rock, desolation settled upon me. That slender line of living beings somewhere on ahead was the only link between us and civilisation—civilisation which I understood, which was human and touchable—and the awful vastness of those endless peaks, wherein lurked a hundred dangers, and which seemed made but to annihilate me.

Of course, the fire would not burn, and the shoes would not dry. Blondey wandered off and had to be brought back, and it seemed an age before we were again in the saddle, following the trail the animals had made.

But Nimrod was blithe and unconcerned, so I made no sign of the craven soul within me. For an hour or two we followed the trail, urging our horses as much as possible, but the ascent was difficult, and we could not gain on the speed of the pack train. Then the trail was lost in a gully where the animals had gone in every direction to get through. My nerves were now on the rack of suspense.

Where were they? Surely, we must have passed them! We were on the wrong trail, perhaps going away from them at every step!

The screws of fear grew tighter every moment during the following hours. Nimrod soon found what he considered to be the trail, and we proceeded.

At last we got to the top. No sign of them. I could have screamed aloud; a great wave of soul destroying fear encompassed me—wild black fear. I could not reason it out. We were lost!

Nimrod scoffed at me. The track was still plain, he said; but I could not read the hieroglyphics at my feet, and there was no room in my mind for confidence or hope. Fear filled it all.

There we were with the mighty forces of the insensate world around, so pitiless, so silently cruel, it seemed to my city-bred soul. It was the spot where Nature spread her wonders before us, one tiny spring dividing its waters east and west for the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, for this was the highest point.

We attempted to cross that hateful divide, that at another time might have looked so beautiful, when suddenly Nimrod's horse plunged withers deep in a bog, and in his struggles to get out threw Nimrod head first from the saddle into the mud, where he lay quite still.

I faced the horror of death at that moment. Of course, this was what I had been expecting, but had not been able to put into words. Nimrod killed! My other fears dwindled away before this one, or, rather, it seemed to wrap them in itself, as in a cloak. For an instant I could not move—there alone with a dead or wounded man on that awful mountain top.

But here was an emergency where I could do something besides blindly follow another's lead. I caught the frightened animal as it dashed out of the treacherous place (to be horseless is almost a worse fate than to be wounded), and Nimrod, who was little hurt, quickly recovered and managed to scramble to dry ground, and again into the saddle.

Forcing our tired horses onward, we again found a trail, supposedly the right one, but there was that haunting fear that it was not. For the only signs were the bending of the grass and the occasional rubbing of the trees where the animals had passed. And these might have been done by a band of elk.

It was growing dusk and still no pack train in sight. No criminal on trial for his life could have felt more wretchedly apprehensive than I. At last we came to a stream. Nimrod, who had dismounted to examine more closely, said:

"The trail turns off here, but it is very dim in the grass."

"Where?" I asked, anxiously.

He pointed to the ground. I could make out nothing. "Oh, let us hurry! They must have gone on."

"I think it would be safer to follow these tracks for a time at least, to see where they come out. There are some tracks across the stream there, but they are older and dimmer and might have been made by elk."

"Oh, do go on! Surely the tracks across the stream must be the ones." To go on, on, and hurry, was my one thought, my one cry.

Nimrod yielded. Thus I and my wild fear betrayed the hunter's instinct. We went on for many weary minutes. We lost all tracks. Then Nimrod fired a shot into the air. He would not do it before, because he said we were not lost, and that there was no need for worry—worry, when for hours blind fear had held me in torture!

There was no answer to the shot.

In five minutes he fired again. Then we heard a report, very faint. I would not believe that I had heard it at all. I raised my gun and fired. This time a shot rattled through the branches overhead, unpleasantly near. It was clearly from behind us. We turned, and after another interchange of shots, the cook appeared.

I was too exhausted to be glad, but a feeling of relief glided over me. He led us to the stream where Nimrod had wanted to turn off, and from there we were quickly in camp, very much to our host's relief. I dropped at the foot of a tree, and said nothing for an hour—my companions were men, so I did not have to talk if I could not—then I arose as usual and was ready for supper.

Of course, Nimrod was blamed for not being a better mountaineer. 'He ought to have seen that broken turf by the trail,' or those 'blades of fresh pulled grass in the pine fork.' How could they know that a woman and her fears had hampered him at every step, especially as you see there was no need?

Always regulate your fears according to the situation, and then you will not go into the valley of the shadow of death, when you are only lost in the mountains.

I had but a bare speaking acquaintance with the grim silent mountaineer who was cook to our party. Two days after he had appeared like an angel of heaven on our gloomy path I had an opportunity of knowing him better. I quote from my journal:

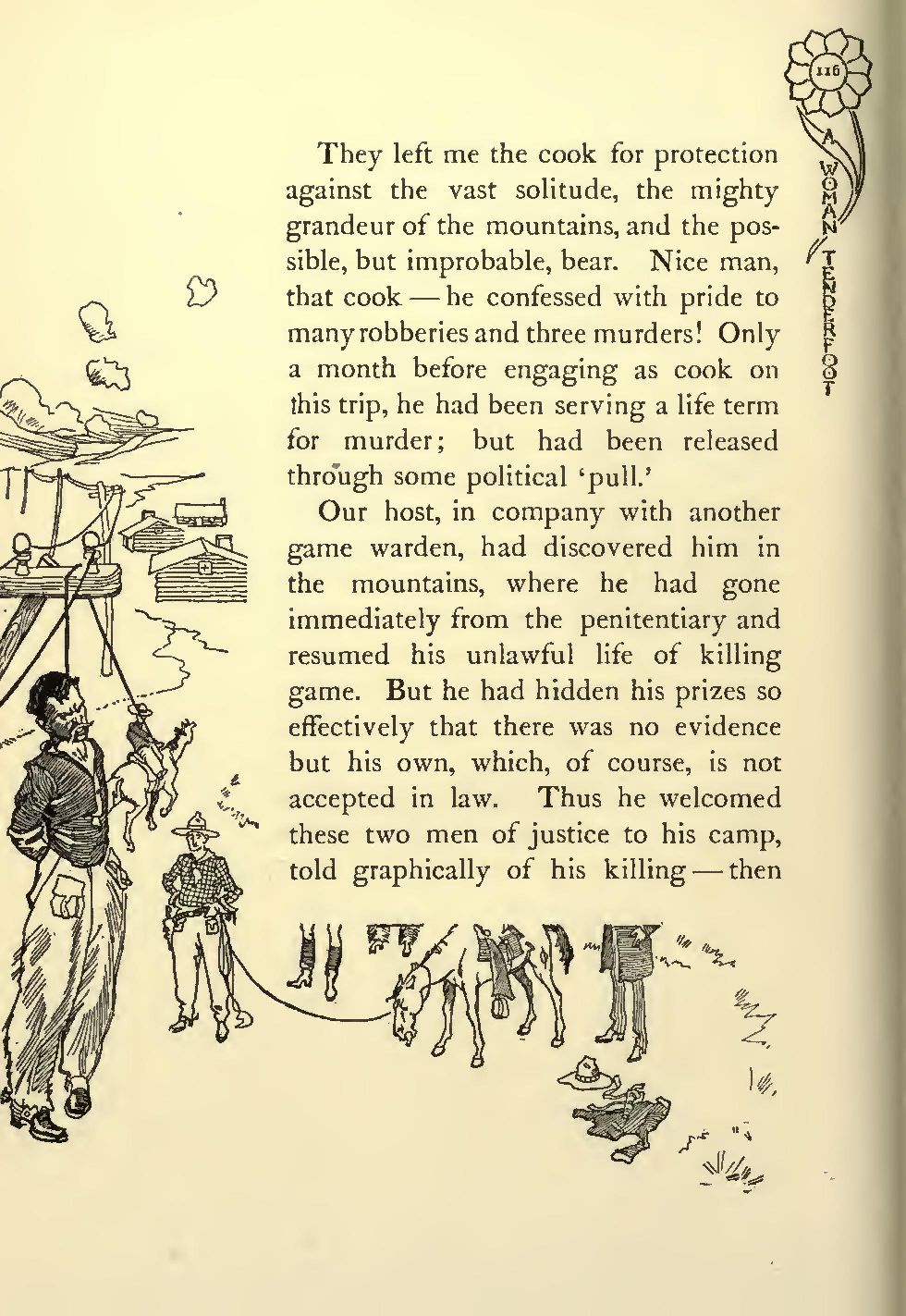

Camp Jim, Shoshone Range, September 23: They left me alone in camp today. No, the cook was there. They left me the cook for protection against the vast solitude, the mighty grandeur of the mountains, and the possible, but improbable, bear. Nice man, that cook—he confessed with pride to many robberies and three murders! Only a month before engaging as cook on this trip, he had been serving a life term for murder; but had been released through some political 'pull.'

Our host, in company with another game warden, had discovered him in the mountains, where he had gone immediately from the penitentiary and resumed his unlawful life of killing game. But he had hidden his prizes so effectively that there was no evidence but his own, which, of course, is not accepted in law. Thus he welcomed these two men of justice to his camp, told graphically of his killing—then offered them a smoke, smiling the while at their discomfiture.

Both his face and hands were scarred from many bar room encounters, and he unblushingly dated most of his remarks by the period when he 'was rusticatin' in the Pen.' He had brought his own bed and saddle and pack horses on the trip so that he could 'cut loose' from the party in case 'things got too hot' for him.

Such was the cook.

Immediately after breakfast Nimrod and our host equipped themselves for the day's hunt, and went off in opposite directions, like Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer on the occasion of their memorable first smoke.

Our camp was beside a rushing brook in a little glade that was tucked at the foot of towering mountains where no man track had been for years, if ever. Around us sighed the mighty pines of the limitless forest. Hundreds of miles away, beyond the barrier of nature, were human hives weary of the noise and strife of their own making. Here, alone in the solitudes, were two human atoms wandering on the trail of the hunted, and—the cook and I. I sat on my rubber bed in the tent and thought—there was nothing else to do—and was cold, cold from the outside in, and from the inside out. There wasn't a thing alive, not even myself—no one but the cook.

Outside, I could hear him washing the breakfast tinware, and whistling some kind of a jiggling tune that ran up and down me like a shiver. This went on for an eternity.

Suddenly it stopped, and I heard the faintest crunch on the thin layer of snow and the rattling of more snow as it slid off my tent from a blow that had been struck on the outside.

I jumped to the door of the tent. It was the cook.

"Purty cold in there, ain't it? You'd a good sight better come to the fire. Ain't you got a slicker?"

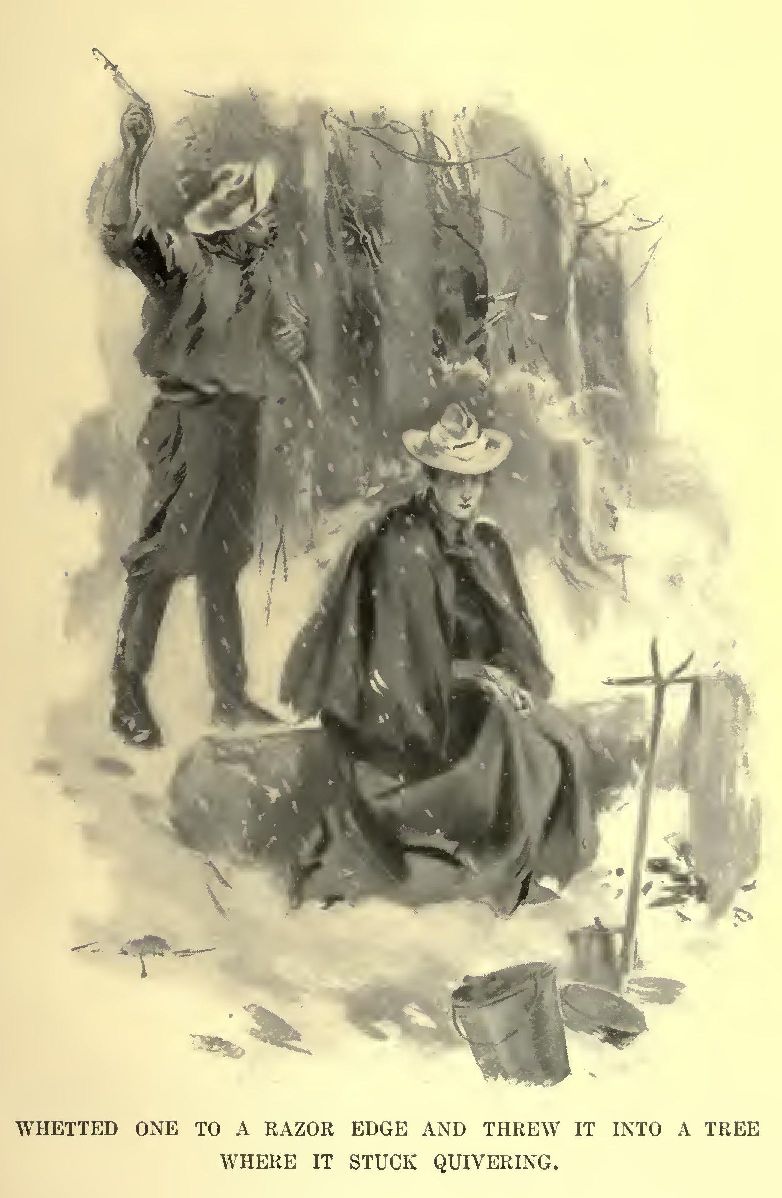

I put on a mackintosh and overshoes and went to the fire. The weather was now indulging in a big flake snow that slid stealthily to the ground and disappeared into water on whatever obstacle it found there. It found me. The cook was cleaning knives—the cooking knives, the eating knives, and a full set of hunting knives, long and short, slim and broad, all sharp and efficacious.

He handled them lovingly, rubbed off some blood rust here and there, and occasionally whetted one to a still more razor edge and threw it into a near by tree, where it stuck, quivering.

There was no conversation, but I did not feel forgotten.

I turned my back on the cook and gazed into the fire, a miserable smouldering affair, and speculated on why I had never before noticed how much spare time there was in a minute. It may have been five of these spacious minutes, it may have been fifteen, that had passed away when the cook approached me. I could feel him coming. He came very close to me—and to the fire.

He put on some beans.

Then he went away, and there were many more minutes, many more.

Then something touched my arm. At last it had come (what we expect, if it be disagreeable, usually does come). I never moved a muscle. This time the pressure on my arm was unmistakable. I turned quickly and saw—the cook—with a gun!

The cook, gun, knives, fire, snow, and stars danced a mad jig before me for an instant. Then the cook suddenly resumed his proper position, and I saw that his disengaged hand was held in an attitude of warning for silence. He pointed off into the woods and appeared to be listening. Soon I thought I heard a snapping of a branch away off up the mountain.

"Bear," the cook whispered. "Follow me."

I followed. It was hard work to get over logs and stones without noise, in a long mackintosh, and, besides, I wished that I had brought a gun. I should have felt more comfortable about both man and beast. I struggled on for a while, when the thought suddenly struck home that if I went farther I should not be able to find my way back to camp. Everything is relative, and those empty tents and smouldering fire seemed a haven of security compared to the situation of being unarmed, and lost in the wilderness—with the cook.

I watched my chance and sneaked back to camp to get a gun. I was willing to believe the cook's bear story, but I wanted a gun. When I got to camp there were many good reasons for not going back.

After a time I heard two shots close at hand, and soon the cook appeared. He said he could not find the bear's track, and lost me, so thought he had better look me up and be on hand in case I had returned to camp, and the bear should come.

I thanked the cook for his solicitude.

To while away the time, I put up a target and commenced practising with a 30-30 rifle at fifty yards range.

I shot very badly.

The cook obligingly interested himself in my performance and kept tally on my aim, pointing out to me when it was high, when it was low, to the right or to the left.

Then he took his six shooter and put a half dozen bullets in the bull's-eye offhand.

I lost my interest in shooting.

The cook gave me some lunch, and while I was eating he stood before the fire looking at it through the fingers of his. Outstretched hand, with a queer squint in his cold gray eyes, as though sighting along a rifle barrel, while a cigarette hung limply from his mouth.

Then in response to a winning smile (after all, a woman's best weapon) he opened the floodgates of his thoughts and poured into my ears a succession of bloodcurdling adventures over which the big, big 'I' had dominated. "Yes," he said musingly of his second murder, as he removed his squint from the fire to me, and a ghost of a smile played around his lips; "yes, it took six shots to keep him quiet, and you could have covered all the holes with a cap box—and his pard nearly got me."

"That was the year I lost my pard, Dick Elsen. We was at camp near Fort Fetterman. We called a man 'Red'—his name was Jim Capse. Drink was at the bottom of it. Red he sees my pard passing a saloon, and he says, 'Hello, where did you come from? Come and have a drink!' Pard says, 'No, I don't want nothing!' 'Oh, come along and have a drink!' Dick says, 'No, thanks, pard, I'm not drinking to-night.' 'Well, I guess you'll have a drink with me'; and Red pulls out his six shooter. Dick wasn't quick enough about throwing up his hands, and he gets killed. Then Irish Mike says to Red, 'You better hit the breeze,' but we ketched him—a telegraph pole was handy—I says, 'Have you got anything to say?' 'You write to my mother and tell her that, a horse fell on me. Don't tell her that I got hung,' Red says; and we swung him."

By the time he had thus proudly stretched out his three dead men before my imagination, in a setting of innumerable shooting scraps and horse stealings, the hunters returned—my day with the multi-murderous cook was over—and nothing had happened.

It is only fair to quote Nimrod's reply to one who criticised him for leaving me thus:

"Humph! Do you think I don't know those wild mountaineers? They are perfectly chivalrous, and I could feel a great deal safer in leaving my wife in care of that desperado than with one of your Eastern dudes."

Many a time as a child I used to lie on my back in the grass and stare far into the wide blue sky above. It seemed so soft, so caressing, so far away, and yet so near. Then, perhaps, a tiny woolly cloud would drift across its face, meet another of its kind, then another and another, until the massed up curtain hid the playful blue, and amid grayness and chill, where all had been so bright, I would hurry under shelter to avoid the storm. That, outside of fairy books, an earthbound being could actually be in a cloud, was beyond my imagination. Indeed, it seems strange now, and were it not for the absence of a cherished quirt, I should be ready to think that my cloud experience had been a dream.

The day before, we had been in a great hurry to cross the Wind River Divide before a heavy snowfall made travel difficult, if not impossible. We had no wish to be snowbound for the winter in those wilds, with only two weeks' supply of food, and it was for this same reason we had not stopped to hunt that grizzly who had left a fourteen inch track over on Wiggins' Creek—the same being Wahb of the Big Horn Basin, about whom I shall have something to say later.

We were now camped in a little valley whose creek bubbled pleasantly under the ice. Having cleared away three feet of snow for our tents, we decided to rest a day or two and hunt, as we were within two days' easy travel of the first ranch house.

It was cold and snowy when Nimrod and I started out next morning to look for mountain sheep. I followed Nimrod's horse for several miles as in a trance, the white flakes falling silently around me, and wondered how it would be possible for any human being to find his way back to camp; but I had been taught my lesson, and kept silent.

I even tried to make mental notes of various rocks and trees we passed, but it was hopeless. They all looked alike to me. In a city, no matter how big or how strange, I can find home unerringly, and Nimrod is helpless as a babe. In the mountains it is different. When I finally raised my eyes from the horse's tail in front, it was because the tail and the horse belonging to it had stopped suddenly.

We were in the middle of a brook. It is highly unpleasant to be stopped in the middle of an icy brook when your horse's feet break through the ice at each step, and you cannot be sure how deep the water is, nor how firm the bottom he is going to strike, especially as ice-covered brooks are Blondey's pet abhorrence, and the uncertainty of my progress, was emphasised by Blondey's attempts to cross on one or two feet instead of four.

However, I looked dutifully in the direction Nimrod indicated and saw a long line of elk heads peering over the ridge in front and showing darkly against the snow. They were not startled.

Those inquisitive heads, with ears alert, looked at us for some time, and then leisurely moved out of sight. We scrambled out of the stream and commenced ascending the mountain after them. The damp snow packed on Blondey's hoofs, so that he was walking on snowballs. When these got about five inches high, they would drop off and begin again. It is needless to say that these varying snowballs did not help Blondey's sure-footedness, especially as the snow was just thick enough to conceal the treacherous slaty rocks beneath. For the first time I understood the phrase, to be 'all balled up.'

Between being ready to clear myself from the saddle and jump off on the up side, in case Blondey should fall, and keeping in sight of the tail of the other horse, I had given no attention to the landscape.

Suddenly I lost Nimrod, and everything was swallowed up in a dark misty vapour that cut me off from every object. Even Blondey's nose and the ground at my feet were blurred. Regardless of possibly near-by elk, I raised a frightened, yell. My voice swirled around me and dropped. I tried again, but the sound would not carry.

The icy vapour swept through me—a very lonely forlorn little being indeed. I just clung to the saddle, trusting to Blondey's instinct to follow the other animal, and tried to enjoy the fact that I was getting a new sensation. Even when one could see, every step was treacherous, but in that black fog I might as well have been blind and deaf. Then Blondey dislodged some loose rock, and went sliding down the mountain with it. There was not a thing I could do, so I shut my eyes for an instant. We brought up against a boulder, fortunately, with no special damage—except to my nerves. Not being a man, I don't pretend to having enjoyed that experience—and there, not six feet away, was a ghostly figure that I knew must be Nimrod.

He did not greet me as a long lost, for such I surely felt, but merely remarked in a whisper:

"We are in a cloud cap. It is settling down. The elk are over there. Keep close to me." And he started along the ridge. I felt it was so thoughtful of him to give me this admonition. I would much rather have been returned safely to camp without further injury and before I froze to the saddle; but I grimly kept Blondey's nose overlapping his mate's back and said nothing—not even when I discovered that my cherished riding whip had left me. It probably was not fifty feet away, on that toboggan slide, but it seemed quite hopeless to find anything in the freezing misty grayness that surrounded us.

We continued our perilous passage. Then I was rewarded by a sight seldom accorded to humans. It was worth all the fatigue, cold, and bruises, for that appallingly illogical cloud cap took a new vagary. It split and lifted a little, and there, not three hundred yards away, in the twilight of that cold wet cloud, on that mountain in the sky, were two bull elk in deadly combat. Their far branching horns were locked together, and they swayed now this way, now that, as they wrestled for the supremacy of the herd of does, which doubtless was not far away. We could not see clearly: all was as in a dream. There was not a sound, only the blurred outlines through the blank mist of two mighty creatures struggling for victory. One brief glimpse of this mountain drama; then they sank out of sight, and the numbing grayness and darkness once more closed around us.

On the way back to camp, Blondey shied at a heap of decaying bones that were still attached to a magnificent pair of antlers. They were at the foot of a cliff, over which the animal had probably fallen. The gruesome sight was suggestive of the end of one of those shadowy creatures, fighting back there high up on the mountain in the mist and the darkness.

We saw no mountain sheep, but oh, the joy of our camp fire that night! For we got back in due time all right—Nimrod and the gods know how. To feel the cheery dancing warmth from the pine needles driving away cold and misery was pure bliss. One thing is certain about roughing it for a woman:—there is no compromise. She either sits in the lap of happiness or of misery. The two are side by side, and toss her about a dozen times a day—but happiness never lets her go for long.

Life at Yeddar's ranch on Green River, where Nimrod and I left the pack train, is different from life in New York; likewise the people are different. And as every Woman-who-goes-hunting-with-her-husband is sure to go through a Yeddar experience, I offer a few observations by way of enlightenment before telling how I killed my antelope. (If you wish to be proper, always use the possessive for animals you have killed. It is a Western abbreviation in great favour.)

A two-story log house, a one-room log office, a log barn, and, across the creek, the log shack we occupied, fifty miles from the railroad, and no end of miles from anything else, but wilderness—that was Yeddar's.

Old Yeddar—Uncle John, the guides and trappers and teamsters called him—had solved the problem of ideal existence. He ran this rough road house without any personal expenditure of labour or money. He sold whisky in his office to the passing teamsters and guides, and relied upon the same to do the chores around the place, for which he gave them grub, the money for which came from the occasional summer tourist, such as we.

Mrs. Spiker 'did' for him in the summer for her board and that of her little girl, and in the winter he and a pard or two rustled for themselves, on bacon, coffee, and that delectable compound of bread and water known as camp sinkers. He got some money for letting the horses from two Eastern outfits run over the surrounding country and eat up the Wyoming government hay. Thus he loafs on through the years, outside or inside his office, without a care beyond the getting of his whisky and his tobacco. Of course he has a history. He claims to be from a 'high up' Southern family, but has been a plainsman since 1851. He has lived among the Indians, has several red-skinned children somewhere on this planet, and seems to have known all the wild tribe of stage drivers, miners, and frontiersmen with rapid-firing histories.

Once a week, if the weather were fine, Uncle John would tie a towel and a clean shirt to his saddle, throw one leg across the back of Jim, his cow pony, blind in one eye and weighted with years unknown, and the two would jog a mile or so back in the mountains, to a hot sulphur spring, where Yeddar would perform his weekly toilet. He was not known to take off his clothes at any other time, and if the weather were disagreeable the pilgrimage was omitted.

The cheapest thing at Yeddar's, except time, was advice. You could not tie up a dog without the entire establishment of loafers bossing the job. A little active co-operation was not so easy to get, however. One day I watched a freighter get stuck in the mud down the road 'a piece.' One by one, the whole number of freighters, mountaineers and guides then at Yeddar's lounged to the place, until there were nine able-bodied men ranged in a row watching the freighter dig out his wagon. No one offered to help him, but all contented themselves with criticising his methods freely and inquiring after his politics.

During the third week of our stay, Uncle John raised the price of our board—and such board!—giving as an excuse that when we came he did not know that we were going to like it so well, or stay so long! Please place this joke where it belongs.

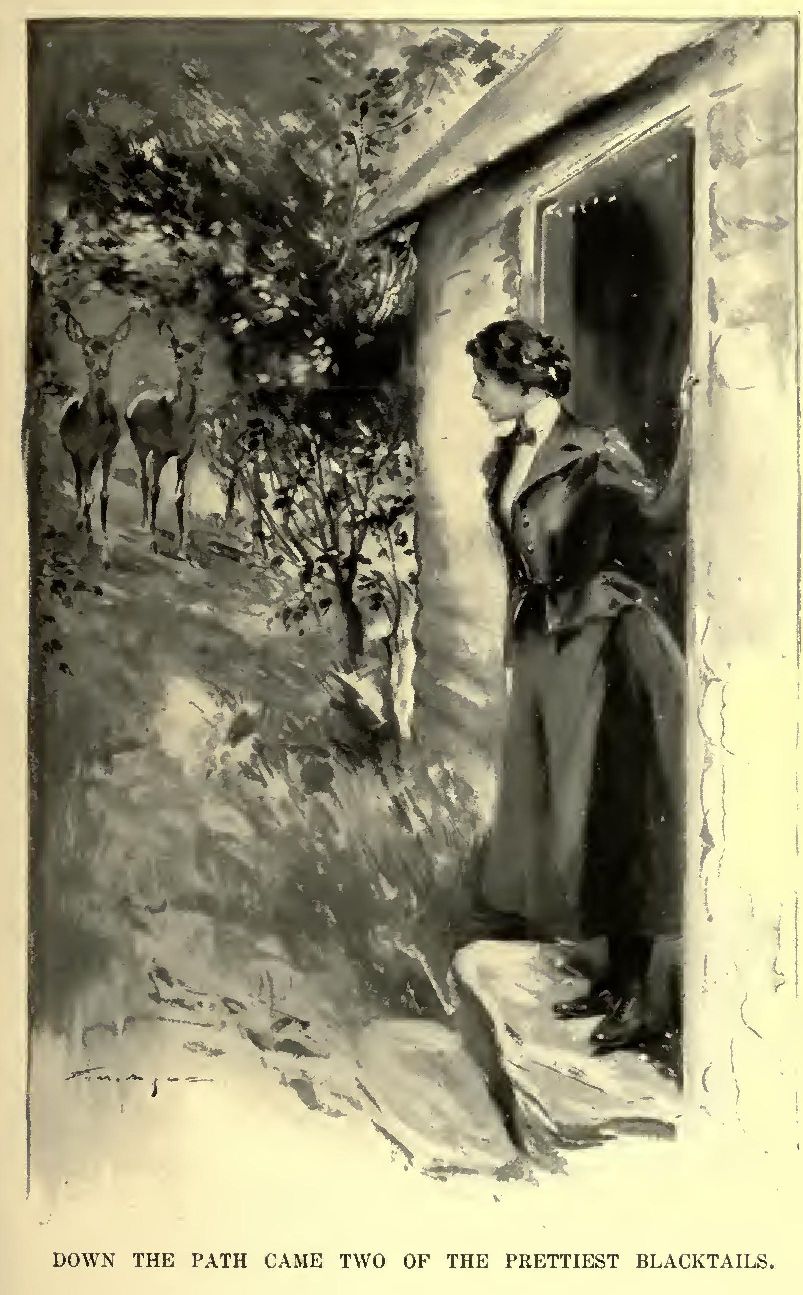

The charm that held us to this rough place was the abundance of game. The very night we got there, I was standing quietly by the cabin door at dusk, when down the path came two of the prettiest does that the whole of the Blacktail tribe could muster. Shoulder to shoulder, with their big ears alert, they picked their way along, and under cover of the deepening twilight advanced to examine the dwelling of the white man.