The Project Gutenberg eBook, From Whose Bourne, by Robert Barr This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: From Whose Bourne Author: Robert Barr Release Date: November 17, 2004 [eBook #9312] Last Updated: August 3, 2018 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FROM WHOSE BOURNE*** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, David Widger and PG Distributed Proofreaders from images generously made available by the Canadian Institute for Historical Microreproductions

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

"Do You Think I Shall Be Missed?"

He Again Sat in the Rocking-chair.

He Saw Standing Beside Him a Stranger.

"I Feel Very Grateful to You."

"My dear," said William Brenton to his wife, "do you think I shall be missed if I go upstairs for a while? I am not feeling at all well."

"Oh, I'm so sorry, Will," replied Alice, looking concerned; "I will tell them you are indisposed."

"No, don't do that," was the answer; "they are having a very good time, and I suppose the dancing will begin shortly; so I don't think they will miss me. If I feel better I will be down in an hour or two; if not, I shall go to bed. Now, dear, don't worry; but have a good time with the rest of them."

William Brenton went quietly upstairs to his room, and sat down in the darkness in a rocking chair. Remaining there a few minutes, and not feeling any better, he slowly undressed and went to bed. Faint echoes reached him of laughter and song; finally, music began, and he felt, rather than heard, the pulsation of dancing feet. Once, when the music had ceased for a time, Alice tiptoed into the room, and said in a quiet voice—

"How are you feeling, Will? any better?"

"A little," he answered drowsily. "Don't worry about me; I shall drop off to sleep presently, and shall be all right in the morning. Good night."

He still heard in a dreamy sort of way the music, the dancing, the laughter; and gradually there came oblivion, which finally merged into a dream, the most strange and vivid vision he had ever experienced. It seemed to him that he sat again in the rocking chair near the bed. Although he knew the room was dark, he had no difficulty in seeing everything perfectly. He heard, now quite plainly, the music and dancing downstairs, but what gave a ghastly significance to his dream was the sight of his own person on the bed. The eyes were half open, and the face was drawn and rigid. The colour of the face was the white, greyish tint of death.

"This is a nightmare," said Brenton to himself; "I must try and wake myself." But he seemed powerless to do this, and he sat there looking at his own body while the night wore on. Once he rose and went to the side of the bed. He seemed to have reached it merely by wishing himself there, and he passed his hand over the face, but no feeling of touch was communicated to him. He hoped his wife would come and rouse him from this fearful semblance of a dream, and, wishing this, he found himself standing at her side, amidst the throng downstairs, who were now merrily saying good-bye. Brenton tried to speak to his wife, but although he was conscious of speaking, she did not seem to hear him, or know he was there.

The party had been one given on Christmas Eve, and as it was now two o'clock in the morning, the departing guests were wishing Mrs. Brenton a merry Christmas. Finally, the door closed on the last of the revellers, and Mrs. Brenton stood for a moment giving instructions to the sleepy servants; then, with a tired sigh, she turned and went upstairs, Brenton walking by her side until they came to the darkened room, which she entered on tiptoe.

"Now," said Brenton to himself, "she will arouse me from this appalling dream." It was not that there was anything dreadful in the dream itself, but the clearness with which he saw everything, and the fact that his mind was perfectly wide awake, gave him an uneasiness which he found impossible to shake off.

In the dim light from the hall his wife prepared to retire. The horrible thought struck Brenton that she imagined he was sleeping soundly, and was anxious not to awaken him—for of course she could have no realization of the nightmare he was in—so once again he tried to communicate with her. He spoke her name over and over again, but she proceeded quietly with her preparations for the night. At last she crept in at the other side of the bed, and in a few moments was asleep. Once more Brenton struggled to awake, but with no effect. He heard the clock strike three, and then four, and then five, but there was no apparent change in his dream. He feared that he might be in a trance, from which, perhaps, he would not awake until it was too late. Grey daylight began to brighten the window, and he noticed that snow was quietly falling outside, the flakes noiselessly beating against the window pane. Every one slept late that morning, but at last he heard the preparations for breakfast going on downstairs—the light clatter of china on the table, the rattle of the grate; and, as he thought of these things, he found himself in the dining-room, and saw the trim little maid, who still yawned every now and then, laying the plates in their places. He went upstairs again, and stood watching the sleeping face of his wife. Once she raised her hand above her head, and he thought she was going to awake; ultimately her eyes opened, and she gazed for a time at the ceiling, seemingly trying to recollect the events of the day before.

"Will," she said dreamily, "are you still asleep?"

There was no answer from the rigid figure at the front of the bed. After a few moments she placed her hand quietly over the sleeper's face. As she did so, her startled eyes showed that she had received a shock. Instantly she sat upright in bed, and looked for one brief second on the face of the sleeper beside her; then, with a shriek that pierced the stillness of the room, she sprang to the floor.

"Will! Will!" she cried, "speak to me! What is the matter with you? Oh, my God! my God!" she cried, staggering back from the bed. Then, with shriek after shriek, she ran blindly through the hall to the stairway, and there fell fainting on the floor.

William Brenton knelt beside the fallen lady, and tried to soothe and comfort her, but it was evident that she was insensible.

"It is useless," said a voice by his side.

Brenton looked up suddenly, and saw standing beside him a stranger. Wondering for a moment how he got there, and thinking that after all it was a dream, he said—

"What is useless? She is not dead."

"No," answered the stranger, "but you are."

"I am what?" cried Brenton.

"You are what the material world calls dead, although in reality you have just begun to live."

"And who are you?" asked Brenton. "And how did you get in here?"

The other smiled.

"How did you get in here?" he said, repeating Brenton's words.

"I? Why, this is my own house."

"Was, you mean."

"I mean that it is. I am in my own house. This lady is my wife."

"Was," said the other.

"I do not understand you," cried Brenton, very much annoyed. "But, in any case, your presence and your remarks are out of place here."

"My dear sir," said the other, "I merely wish to aid you and to explain to you anything that you may desire to know about your new condition. You are now free from the incumbrance of your body. You have already had some experience of the additional powers which that riddance has given you. You have also, I am afraid, had an inkling of the fact that the spiritual condition has its limitations. If you desire to communicate with those whom you have left, I would strongly advise you to postpone the attempt, and to leave this place, where you will experience only pain and anxiety. Come with me, and learn something of your changed circumstances."

"I am in a dream," said Brenton, "and you are part of it. I went to sleep last night, and am still dreaming. This is a nightmare and it will soon be over."

"You are saying that," said the other, "merely to convince yourself. It is now becoming apparent to you that this is not a dream. If dreams exist, it was a dream which you left, but you have now become awake. If you really think it is a dream, then do as I tell you—come with me and leave it, because you must admit that this part of the dream is at least very unpleasant."

"It is not very pleasant," assented Brenton. As he spoke the bewildered servants came rushing up the stairs, picked up their fallen mistress, and laid her on a sofa. They rubbed her hands and dashed water in her face. She opened her eyes, and then closed them again with a shudder.

"Sarah," she cried, "have I been dreaming, or is your master dead?"

The two girls turned pale at this, and the elder of them went boldly into the room which her mistress had just left. She was evidently a young woman who had herself under good control, but she came out sobbing, with her apron to her eyes.

"Come, come," said the man who stood beside Brenton, "haven't you had enough of this? Come with me; you can return to this house if you wish;" and together they passed out of the room into the crisp air of Christmas morning. But, although Brenton knew it must be cold, he had no feeling of either cold or warmth.

"There are a number of us," said the stranger to Brenton, "who take turns at watching the sick-bed when a man is about to die, and when his spirit leaves his body, we are there to explain, or comfort, or console. Your death was so sudden that we had no warning of it. You did not feel ill before last night, did you?"

"No," replied Brenton. "I felt perfectly well, until after dinner last night."

"Did you leave your affairs in reasonably good order?"

"Yes," said Brenton, trying to recollect. "I think they will find everything perfectly straight."

"Tell me a little of your history, if you do not mind," inquired the other; "it will help me in trying to initiate you into our new order of things here."

"Well," replied Brenton, and he wondered at himself for falling so easily into the other's assumption that he was a dead man, "I was what they call on the earth in reasonably good circumstances. My estate should be worth $100,000. I had $75,000 insurance on my life, and if all that is paid, it should net my widow not far from a couple of hundred thousand."

"How long have you been married?" said the other.

"Only about six months. I was married last July, and we went for a trip abroad. We were married quietly, and left almost immediately afterwards, so we thought, on our return, it would not be a bad plan to give a Christmas Eve dinner, and invite some of our friends. That," he said, hesitating a moment, "was last night. Shortly after dinner, I began to feel rather ill, and went upstairs to rest for a while; and if what you say is true, the first thing I knew I found myself dead."

"Alive," corrected the other.

"Well, alive, though at present I feel I belong more to the world I have left than I do to the world I appear to be in. I must confess, although you are a very plausible gentleman to talk to, that I expect at any moment to wake and find this to have been one of the most horrible nightmares that I ever had the ill luck to encounter."

The other smiled.

"There is very little danger of your waking up, as you call it. Now, I will tell you the great trouble we have with people when they first come to the spirit-land, and that is to induce them to forget entirely the world they have relinquished. Men whose families are in poor circumstances, or men whose affairs are in a disordered state, find it very difficult to keep from trying to set things right again. They have the feeling that they can console or comfort those whom they have left behind them, and it is often a long time before they are convinced that their efforts are entirely futile, as well as very distressing for themselves."

"Is there, then," asked Brenton, "no communication between this world and the one that I have given up?"

The other paused for a moment before he replied.

"I should hardly like to say," he answered, "that there is no communication between one world and the other; but the communication that exists is so slight and unsatisfactory, that if you are sensible you will see things with the eyes of those who have very much more experience in this world than you have. Of course, you can go back there as much as you like; there will be no interference and no hindrance. But when you see things going wrong, when you see a mistake about to be made, it is an appalling thing to stand there helpless, unable to influence those you love, or to point out a palpable error, and convince them that your clearer sight sees it as such. Of course, I understand that it must be very difficult for a man who is newly married, to entirely abandon the one who has loved him, and whom he loves. But I assure you that if you follow the life of one who is as young and handsome as your wife, you will find some one else supplying the consolations you are unable to bestow. Such a mission may lead you to a church where she is married to her second husband. I regret to say that even the most imperturbable spirits are ruffled when such an incident occurs. The wise men are those who appreciate and understand that they are in an entirely new world, with new powers and new limitations, and who govern themselves accordingly from the first, as they will certainly do later on."

"My dear sir," said Brenton, somewhat offended, "if what you say is true, and I am really a dead man——"

"Alive," corrected the other.

"Well, alive, then. I may tell you that my wife's heart is broken. She will never marry again."

"Of course, that is a subject of which you know a great deal more than I do. I all the more strongly advise you never to see her again. It is impossible for you to offer any consolation, and the sight of her grief and misery will only result in unhappiness for yourself. Therefore, take my advice. I have given it very often, and I assure you those who did not take it expressed their regret afterwards. Hold entirely aloof from anything relating to your former life."

Brenton was silent for some moments; finally he said—

"I presume your advice is well meant; but if things are as you state, then I may as well say, first as last, that I do not intend to accept it."

"Very well," said the other; "it is an experience that many prefer to go through for themselves."

"Do you have names in this spirit-land?" asked Brenton, seemingly desirous of changing the subject.

"Yes," was the answer; "we are known by names that we have used in the preparatory school below. My name is Ferris."

"And if I wish to find you here, how do I set about it?"

"The wish is sufficient," answered Ferris. "Merely wish to be with me, and you are with me."

"Good gracious!" cried Brenton, "is locomotion so easy as that?"

"Locomotion is very easy. I do not think anything could be easier than it is, and I do not think there could be any improvement in that matter."

"Are there matters here, then, that you think could be improved?"

"As to that I shall not say. Perhaps you will be able to give your own opinion before you have lived here much longer."

"Taking it all in all," said Brenton, "do you think the spirit-land is to be preferred to the one we have left?"

"I like it better," said Ferris, "although I presume there are some who do not. There are many advantages; and then, again, there are many—well, I would not say disadvantages, but still some people consider them such. We are free from the pangs of hunger or cold, and have therefore no need of money, and there is no necessity for the rush and the worry of the world below."

"And how about heaven and hell?" said Brenton. "Are those localities all a myth? Is there nothing of punishment and nothing of reward in this spirit-land?"

There was no answer to this, and when Brenton looked around he found that his companion had departed.

William Brenton pondered long on the situation. He would have known better how to act if he could have been perfectly certain that he was not still the victim of a dream. However, of one thing there was no doubt—namely, that it was particularly harrowing to see what he had seen in his own house. If it were true that he was dead, he said to himself, was not the plan outlined for him by Ferris very much the wiser course to adopt? He stood now in one of the streets of the city so familiar to him. People passed and repassed him—men and women whom he had known in life—but nobody appeared to see him. He resolved, if possible, to solve the problem uppermost in his mind, and learn whether or not he could communicate with an inhabitant of the world he had left. He paused for a moment to consider the best method of doing this. Then he remembered one of his most confidential friends and advisers, and at once wished himself at his office. He found the office closed, but went in to wait for his friend. Occupying the time in thinking over his strange situation, he waited long, and only when the bells began to ring did he remember it was Christmas forenoon, and that his friend would not be at the office that day. The next moment he wished himself at his friend's house, but he was as unsuccessful as at the office; the friend was not at home. The household, however, was in great commotion, and, listening to what was said, he found that the subject of conversation was his own death, and he learned that his friend had gone to the Brenton residence as soon as he heard the startling news of Christmas morning.

Once more Brenton paused, and did not know what to do. He went again into the street. Everything seemed to lead him toward his own home. Although he had told Ferris that he did not intend to take his advice, yet as a sensible man he saw that the admonition was well worth considering, and if he could once become convinced that there was no communication possible between himself and those he had left; if he could give them no comfort and no cheer; if he could see the things which they did not see, and yet be unable to give them warning, he realized that he would merely be adding to his own misery, without alleviating the troubles of others.

He wished he knew where to find Ferris, so that he might have another talk with him. The man impressed him as being exceedingly sensible. No sooner, however, had he wished for the company of Mr. Ferris than he found himself beside that gentleman.

"By George!" he said in astonishment, "you are just the man I wanted to see."

"Exactly," said Ferris; "that is the reason you do see me."

"I have been thinking over what you said," continued the other, "and it strikes me that after all your advice is sensible."

"Thank you," replied Ferris, with something like a smile on his face.

"But there is one thing I want to be perfectly certain about. I want to know whether it is not possible for me to communicate with my friends. Nothing will settle that doubt in my mind except actual experience."

"And have you not had experience enough?" asked Ferris.

"Well," replied the other, hesitating, "I have had some experience, but it seems to me that, if I encounter an old friend, I could somehow make myself felt by him."

"In that case," answered Ferris, "if nothing will convince you but an actual experiment, why don't you go to some of your old friends and try what you can do with them?"

"I have just been to the office and to the residence of one of my old friends. I found at his residence that he had gone to my"—Brenton paused for a moment—"former home. Everything seems to lead me there, and yet, if I take your advice, I must avoid that place of all others."

"I would at present, if I were you," said Ferris. "Still, why not try it with any of the passers-by?"

Brenton looked around him. People were passing and repassing where the two stood talking with each other. "Merry Christmas" was the word on all lips. Finally Brenton said, with a look of uncertainty on his face—

"My dear fellow, I can't talk to any of these people. I don't know them."

Ferris laughed at this, and replied—

"I don't think you will shock them very much; just try it."

"Ah, here's a friend of mine. You wait a moment, and I will accost him." Approaching him, Brenton held out his hand and spoke, but the traveller paid no attention. He passed by as one who had seen or heard nothing.

"I assure you," said Ferris, as he noticed the look of disappointment on the other's face, "you will meet with a similar experience, however much you try. You know the old saying about one not being able to have his cake and eat it too. You can't have the privileges of this world and those of the world you left as well. I think, taking it all in all, you should rest content, although it always hurts those who have left the other world not to be able to communicate with their friends, and at least assure them of their present welfare."

"It does seem to me," replied Brenton, "that would be a great consolation, both for those who are here and those who are left."

"Well, I don't know about that," answered the other. "After all, what does life in the other world amount to? It is merely a preparation for this. It is of so short a space, as compared with the life we live here, that it is hardly worth while to interfere with it one way or another. By the time you are as long here as I have been, you will realize the truth of this."

"Perhaps I shall," said Brenton, with a sigh; "but, meanwhile, what am I to do with myself? I feel like the man who has been all his life in active business, and who suddenly resolves to enjoy himself doing nothing. That sort of thing seems to kill a great number of men, especially if they put off taking a rest until too late, as most of us do."

"Well," said Ferris, "there is no necessity of your being idle here, I assure you. But before you lay out any work for yourself, let me ask you if there is not some interesting part of the world that you would like to visit?"

"Certainly; I have seen very little of the world. That is one of my regrets at leaving it."

"Bless me," said the other, "you haven't left it."

"Why, I thought you said I was a dead man?"

"On the contrary," replied his companion, "I have several times insisted that you have just begun to live. Now where shall we spend the day?"

"How would London do?"

"I don't think it would do; London is apt to be a little gloomy at this time of the year. But what do you say to Naples, or Japan, or, if you don't wish to go out of the United States, Yellowstone Park?"

"Can we reach any of those places before the day is over?" asked Brenton, dubiously.

"Well, I will soon show you how we manage all that. Just wish to accompany me, and I will take you the rest of the way."

"How would Venice do?" said Brenton. "I didn't see half as much of that city as I wanted to."

"Very well," replied his companion, "Venice it is;" and the American city in which they stood faded away from them, and before Brenton could make up his mind exactly what was happening, he found himself walking with his comrade in St. Mark's Square.

"Well, for rapid transit," said Brenton, "this beats anything I've ever had any idea of; but it increases the feeling that I am in a dream."

"You'll soon get used to it," answered Ferris; "and, when you do, the cumbersome methods of travel in the world itself will show themselves in their right light. Hello!" he cried, "here's a man whom I should like you to meet. By the way, I either don't know your name or I have forgotten it."

"William Brenton," answered the other.

"Mr. Speed, I want to introduce you to Mr. Brenton."

"Ah," said Speed, cordially, "a new-comer. One of your victims, Ferris?"

"Say one of his pupils, rather," answered Brenton.

"Well, it is pretty much the same thing," said Speed. "How long have you been with us, and how do you like the country?"

"You see, Mr. Brenton," interrupted Ferris, "John Speed was a newspaper man, and he must ask strangers how they like the country. He has inquired so often while interviewing foreigners for his paper that now he cannot abandon his old phrase. Mr. Brenton has been with us but a short time," continued Ferris, "and so you know, Speed, you can hardly expect him to answer your inevitable question."

"What part of the country are you from?" asked Speed.

"Cincinnati," answered Brenton, feeling almost as if he were an American tourist doing the continent of Europe.

"Cincinnati, eh? Well, I congratulate you. I do not know any place in America that I would sooner die in, as they call it, than Cincinnati. You see, I am a Chicago man myself."

Brenton did not like the jocular familiarity of the newspaper man, and found himself rather astonished to learn that in the spirit-world there were likes and dislikes, just as on earth.

"Chicago is a very enterprising city," he said, in a non-committal way.

"Chicago, my dear sir," said Speed, earnestly, "is the city. You will see that Chicago is going to be the great city of the world before you are a hundred years older. By the way, Ferris," said the Chicago man, suddenly recollecting something, "I have got Sommers over here with me."

"Ah!" said Ferris; "doing him any good?"

"Well, precious little, as far as I can see."

"Perhaps it would interest Mr. Brenton to meet him," said Ferris. "I think, Brenton, you asked me a while ago if there was any hell here, or any punishment. Mr. Speed can show you a man in hell."

"Really?" asked Brenton.

"Yes," said Speed; "I think if ever a man was in misery, he is. The trouble with Sommers was this. He—well, he died of delirium tremens, and so, of course, you know what the matter was. Sommers had drunk Chicago whisky for thirty-five years straight along, and never added to it the additional horror of Chicago water. You see what his condition became, both physical and mental. Many people tried to reform Sommers, because he was really a brilliant man; but it was no use. Thirst had become a disease with him, and from the mental part of that disease, although his physical yearning is now gone of course, he suffers. Sommers would give his whole future for one glass of good old Kentucky whisky. He sees it on the counters, he sees men drink it, and he stands beside them in agony. That's why I brought him over here. I thought that he wouldn't see the colour of whisky as it sparkles in the glass; but now he is in the Caf� Quadra watching men drink. You may see him sitting there with all the agony of unsatisfied desire gleaming from his face."

"And what do you do with a man like that?" asked Brenton.

"Do? Well, to tell the truth, there is nothing to do. I took him away from Chicago, hoping to ease his trouble a little; but it has had no effect."

"It will come out all right by-and-by," said Ferris, who noticed the pained look on Brenton's face. "It is the period of probation that he has to pass through. It will wear off. He merely goes through the agonies he would have suffered on earth if he had suddenly been deprived of his favourite intoxicant."

"Well," said Speed, "you won't come with me, then? All right, good-bye. I hope to see you again, Mr. Brenton," and with that they separated.

Brenton spent two or three days in Venice, but all the time the old home hunger was upon him. He yearned for news of Cincinnati. He wanted to be back, and several times the wish brought him there, but he instantly returned. At last he said to Ferris—

"I am tired. I must go home. I have got to see how things are going."

"I wouldn't if I were you," replied Ferris.

"No, I know you wouldn't. Your temperament is indifferent. I would rather be miserable with knowledge than happy in ignorance. Good-bye."

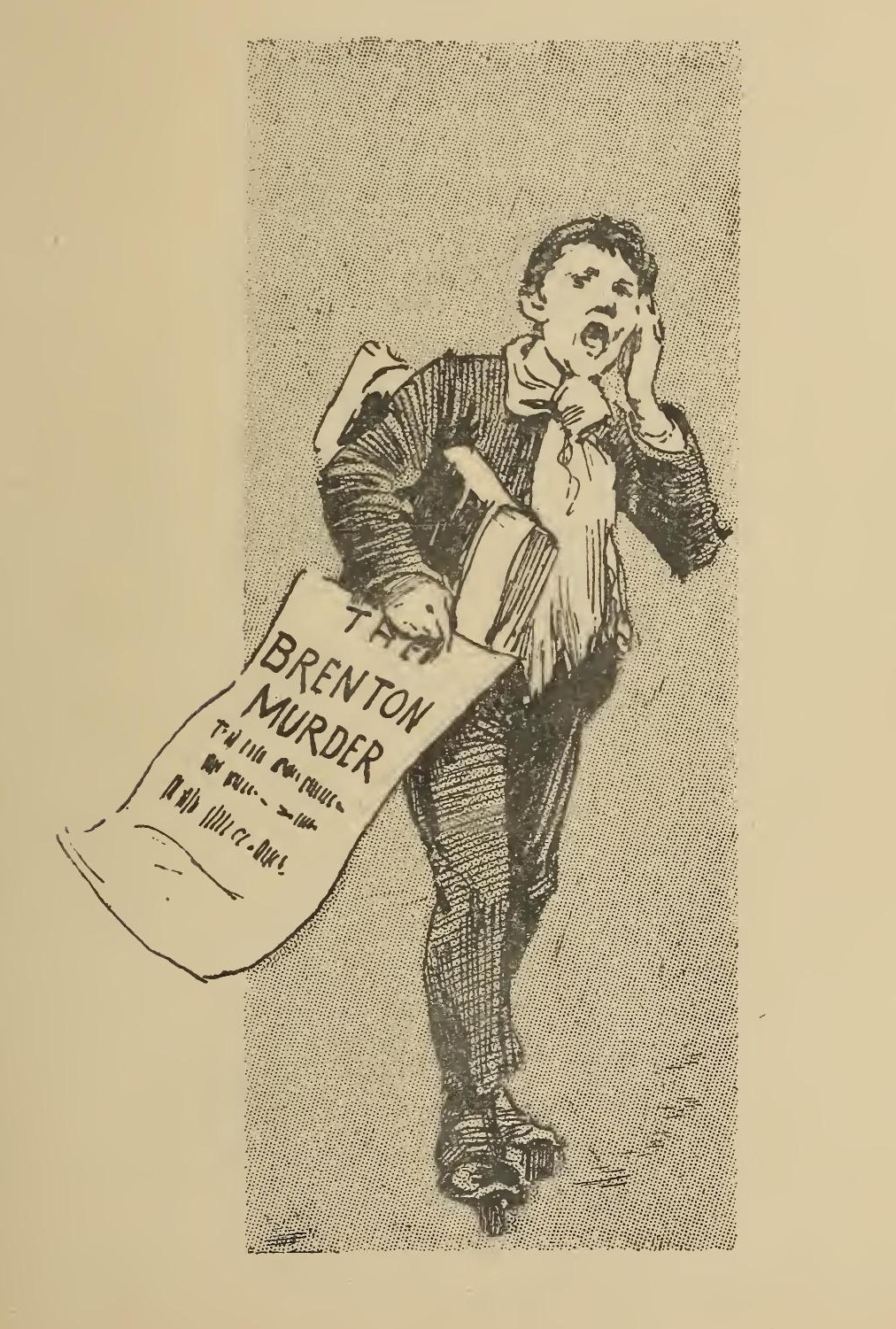

It was evening when he found himself in Cincinnati. The weather was bright and clear, and apparently cold. Men's feet crisped on the frozen pavement, and the streets had that welcome, familiar look which they always have to the returned traveller when he reaches the city he calls his home. The newsboys were rushing through the streets yelling their papers at the top of their voices. He heard them, but paid little attention.

"All about the murder! Latest edition! All about the poison case!"

He felt that he must have a glimpse at a paper, and, entering the office of an hotel where a man was reading one, he glanced over his shoulder at the page before him, and was horror-stricken to see the words in startling headlines—

THE BRENTON MURDER.

The Autopsy shows that Morphine was the Poison used.

Enough found to have killed a Dozen Men.

Mrs. Brenton arrested for Committing the Horrible

Deed.

For a moment Brenton was so bewildered and amazed at the awful headlines which he read, that he could hardly realize what had taken place. The fact that he had been poisoned, although it gave him a strange sensation, did not claim his attention as much as might have been thought. Curiously enough he was more shocked at finding himself, as it were, the talk of the town, the central figure of a great newspaper sensation. But the thing that horrified him was the fact that his wife had been arrested for his murder. His first impulse was to go to her at once, but he next thought it better to read what the paper said about the matter, so as to become possessed of all the facts. The headlines, he said to himself, often exaggerated things, and there was a possibility that the body of the article would not bear out the naming announcement above it. But as he read on and on, the situation seemed to become more and more appalling. He saw that his friends had been suspicious of his sudden death, and had insisted on a post-mortem examination. That examination had been conducted by three of the most eminent physicians of Cincinnati, and the three doctors had practically agreed that the deceased, in the language of the verdict, had come to his death through morphia poisoning, and the coroner's jury had brought in a verdict that "the said William Brenton had been poisoned by some person unknown." Then the article went on to state how suspicion had gradually fastened itself upon his wife, and at last her arrest had been ordered. The arrest had taken place that day.

After reading this, Brenton was in an agony of mind. He pictured his dainty and beautiful wife in a stone cell in the city prison. He foresaw the horrors of the public trial, and the deep grief and pain which the newspaper comments on the case would cause to a woman educated and refined. Of course, Brenton had not the slightest doubt in his own mind about the result of the trial. His wife would be triumphantly acquitted; but, all the same, the terrible suspense which she must suffer in the meanwhile would not be compensated for by the final verdict of the jury.

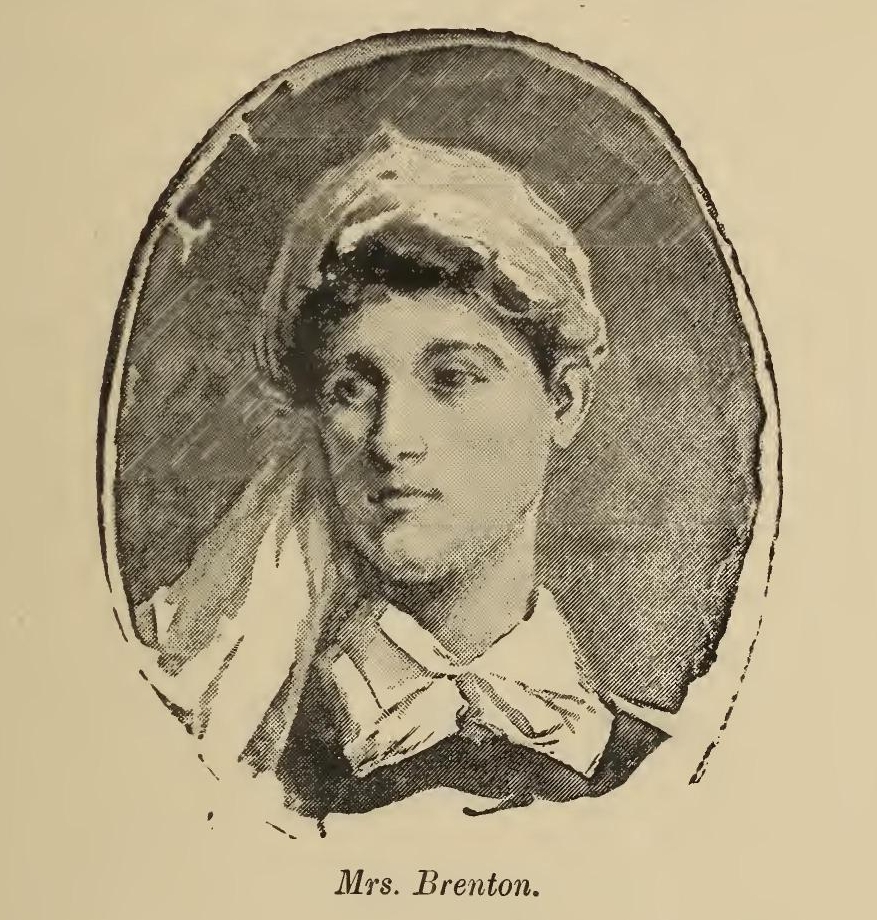

Brenton at once went to the jail, and wandered through that gloomy building, searching for his wife. At last he found her, but it was in a very comfortable room in the sheriffs residence. The terror and the trials of the last few days had aged her perceptibly, and it cut Brenton to the heart to think that he stood there before her, and could not by any means say a soothing word that she would understand. That she had wept many bitter tears since the terrible Christmas morning was evident; there were dark circles under her beautiful eyes that told of sleepless nights. She sat in a comfortable armchair, facing the window; and looked steadily out at the dreary winter scene with eyes that apparently saw nothing. Her hands lay idly on her lap, and now and then she caught her breath in a way that was half a sob and half a gasp.

Presently the sheriff himself entered the room.

"Mrs. Brenton," he said, "there is a gentleman here who wishes to see you. Mr. Roland, he tells me his name is, an old friend of yours. Do you care to see any one?"

The lady turned her head slowly round, and looked at the sheriff for a moment, seemingly not understanding what he said. Finally she answered, dreamily—

"Roland? Oh, Stephen! Yes, I shall be very glad to see him. Ask him to come in, please."

The next moment Stephen Roland entered, and somehow the fact that he had come to console Mrs. Brenton did not at all please the invisible man who stood between them.

"My dear Mrs. Brenton," began Roland, "I hope you are feeling better to-day? Keep up your courage, and be brave. It is only for a very short time. I have retained the noted criminal lawyers, Benham and Brown, for the defence. You could not possibly have better men."

At the word "criminal" Mrs. Brenton shuddered.

"Alice," continued Roland, sitting down near her, and drawing his chair closer to her, "tell me that you will not lose your courage. I want you to be brave, for the sake of your friends."

He took her listless hand in his own, and she did not withdraw it.

Brenton felt passing over him the pangs of impotent rage, as he saw this act on the part of Roland.

Roland had been an unsuccessful suitor for the hand which he now held in his own, and Brenton thought it the worst possible taste, to say the least, that he should take advantage now of her terrible situation to ingratiate himself into her favour.

The nearest approach to a quarrel that Brenton and his wife had had during their short six months of wedded life was on the subject of the man who now held her hand in his own. It made Brenton impatient to think that a woman with all her boasted insight into character, her instincts as to what was right and what was wrong, had such little real intuition that she did not see into the character of the man whom they were discussing; but a woman never thinks it a crime for a man to have been in love with her, whatever opinion of that man her husband may hold.

"It is awful! awful! awful!" murmured the poor lady, as the tears again rose to her eyes.

"Of course it is," said Roland; "it is particularly awful that they should accuse you, of all persons in the world, of this so-called crime. For my part I do not believe that he was poisoned at all, but we will soon straighten things out. Benham and Brown will give up everything and devote their whole attention to this case until it is finished. Everything will be done that money or friends can do, and all that we ask is that you keep up your courage, and do not be downcast with the seeming awfulness of the situation."

Mrs. Brenton wept silently, but made no reply. It was evident, however, that she was consoled by the words and the presence of her visitor. Strange as it may appear, this fact enraged Brenton, although he had gone there for the very purpose of cheering and comforting his wife. All the bitterness he had felt before against his former rival was revived, and his rage was the more agonizing because it was inarticulate. Then there flashed over him Ferris's sinister advice to leave things alone in the world that he had left. He felt that he could stand this no longer, and the next instant he found himself again in the wintry streets of Cincinnati.

The name of the lawyers, Benham and Brown, kept repeating itself in his mind, and he resolved to go to their office and hear, if he could, what preparations were being made for the defence of a woman whom he knew to be innocent. He found, when he got to the office of these noted lawyers, that the two principals were locked in their private room; and going there, he found them discussing the case with the coolness and impersonal feeling that noted lawyers have even when speaking of issues that involve life or death.

"Yes," Benham was saying, "I think that, unless anything new turns up, that is the best line of defence we can adopt."

"What do you think might turn up?" asked Brown.

"Well, you can never tell in these cases. They may find something else—they may find the poison, for instance, or the package that contained it. Perhaps a druggist will remember having sold it to this woman, and then, of course, we shall have to change our plans. I need not say that it is strictly necessary in this case to give out no opinions whatever to newspaper men. The papers will be full of rumours, and it is just as well if we can keep our line of defence hidden until the time for action comes."

"Still," said Brown, who was the younger partner, "it is as well to keep in with the newspaper fellows; they'll be here as soon as they find we have taken charge of the defence."

"Well, I have no doubt you can deal with them in such a way as to give them something to write up, and yet not disclose anything we do not wish known."

"I think you can trust me to do that," said Brown, with a self-satisfied air.

"I shall leave that part of the matter entirely in your hands," replied Benham. "It is better not to duplicate or mix matters, and if any newspaper man comes to see me I will refer him to you. I will say I know nothing of the case whatever."

"Very well," answered Brown. "Now, between ourselves, what do you think of the case?"

"Oh, it will make a great sensation. I think it will probably be one of the most talked-of cases that we have ever been connected with."

"Yes, but what do you think of her guilt or innocence?"

"As to that," said Benham, calmly, "I haven't the slightest doubt. She murdered him."

As he said this, Brenton, forgetting himself for a moment, sprang forward as if to strangle the lawyer. The statement Benham had made seemed the most appalling piece of treachery. That men should take a woman's money for defending her, and actually engage in a case when they believed their client guilty, appeared to Brenton simply infamous.

"I agree with you," said Brown. "Of course she was the only one to benefit by his death. The simple fool willed everything to her, and she knew it; and his doing so is the more astounding when you remember he was quite well aware that she had a former lover whom she would gladly have married if he had been as rich as Brenton. The supreme idiocy of some men as far as their wives are concerned is something awful."

"Yes," answered Benham, "it is. But I tell you, Brown, she is no ordinary woman. The very conception of that murder had a stroke of originality about it that I very much admire. I do not remember anything like it in the annals of crime. It is the true way in which a murder should be committed. The very publicity of the occasion was a safeguard. Think of poisoning a man at a dinner that he has given himself, in the midst of a score of friends. I tell you that there was a dash of bravery about it that commands my admiration."

"Do you imagine Roland had anything to do with it?"

"Well, I had my doubts about that at first, but I think he is innocent, although from what I know of the man he will not hesitate to share the proceeds of the crime. You mark my words, they will be married within a year from now if she is acquitted. I believe Roland knows her to be guilty."

"I thought as much," said Brown, "by his actions here, and by some remarks he let drop. Anyhow, our credit in the affair will be all the greater if we succeed in getting her off. Yes," he continued, rising and pushing back his chair, "Madam Brenton is a murderess."

Brenton found himself once more in the streets of Cincinnati, in a state of mind that can hardly be described. Rage and grief struggled for the mastery, and added to the tumult of these passions was the uncertainty as to what he should do, or what he could do. He could hardly ask the advice of Ferris again, for his whole trouble arose from his neglect of the counsel that gentleman had already given him. In his new sphere he did not know where to turn. He found himself wondering whether in the spirit-land there was any firm of lawyers who could advise him, and he remembered then how singularly ignorant he was regarding the conditions of existence in the world to which he now belonged. However, he felt that he must consult with somebody, and Ferris was the only one to whom he could turn. A moment later he was face to face with him.

"Mr. Ferris," he said, "I am in the most grievous trouble, and I come to you in the hope that, if you cannot help me, you can at least advise me what to do."

"If your trouble has come," answered Ferris, with a shade of irony in his voice, "through following the advice that I have already given you, I shall endeavour, as well as I am able, to help you out of it."

"You know very well," cried Brenton, hotly, "that my whole trouble has occurred through neglecting your advice, or, at least, through deliberately not following it. I could not follow it."

"Very well, then," said Ferris, "I am not surprised that you are in a difficulty. You must remember that such a crisis is an old story with us here."

"But, my dear sir," said Brenton, "look at the appalling condition of things, the knowledge of which has just come to me. It seems I was poisoned, but of course that doesn't matter. I feel no resentment against the wretch who did it. But the terrible thing is that my wife has been arrested for the crime, and I have just learned that her own lawyers actually believe her guilty."

"That fact," said Ferris, calmly, "will not interfere with their eloquent pleading when the case comes to trial."

Brenton glared at the man who was taking things so coolly, and who proved himself so unsympathetic; but an instant after he realized the futility of quarrelling with the only person who could give him advice, so he continued, with what patience he could command—

"The situation is this: My wife has been arrested for the crime of murdering me. She is now in the custody of the sheriff. Her trouble and anxiety of mind are fearful to contemplate."

"My dear sir," said Ferris, "there is no reason why you or anybody else should contemplate it."

"How can you talk in that cold-blooded way?" cried Brenton, indignantly. "Could you see your wife, or any one you held dear, incarcerated for a dreadful crime, and yet remain calm and collected, as you now appear to be when you hear of another's misfortune?"

"My dear fellow," said Ferris, "of course it is not to be expected that one who has had so little experience with this existence should have any sense of proportion. You appear to be speaking quite seriously. You do not seem at all to comprehend the utter triviality of all this."

"Good gracious!" cried Brenton, "do you call it a trivial thing that a woman is in danger of her life for a crime which she never committed?"

"If she is innocent," said the other, in no way moved by the indignation of his comrade, "surely that state of things will be brought out in the courts, and no great harm will be done, even looking at things from the standpoint of the world you have left. But I want you to get into the habit of looking at things from the standpoint of this world, and not of the other. Suppose that what you would call the worst should happen—suppose she is hanged—what then?"

Brenton stood simply speechless with indignation at this brutal remark.

"If you will just look at things correctly," continued Ferris, imperturbably, "you will see that there is probably a moment of anguish, perhaps not even that moment, and then your wife is here with you in the land of spirits. I am sure that is a consummation devoutly to be wished. Even a man in your state of mind must see the reasonableness of this. Now, looking at the question in what you would call its most serious aspect, see how little it amounts to. It isn't worth a moment's thought, whichever way it goes."

"You think nothing, then, of the disgrace of such a death—of the bitter injustice of it?"

"When you were in the world did you ever see a child cry over a broken toy? Did the sight pain you to any extent? Did you not know that a new toy could be purchased that would quite obliterate all thoughts of the other? Did the simple griefs of childhood carry any deep and lasting consternation to the mind of a grown-up man? Of course it did not. You are sensible enough to know that. Well, we here in this world look on the pain and struggles and trials of people in the world you have left, just as an aged man looks on the tribulations of children over a broken doll. That is all it really amounts to. That is what I mean when I say that you have not yet got your sense of proportion. Any grief and misery there is in the world you have left is of such an ephemeral, transient nature, that when we think for a moment of the free, untrammelled, and painless life there is beyond, those petty troubles sink into insignificance. My dear fellow, be sensible, take my advice. I have really a strong interest in you, and I advise you, entirely for your own welfare, to forget all about it. Very soon you will have something much more important to do than lingering around the world you have left. If your wife comes amongst us I am sure you will be glad to welcome her, and to teach her the things that you will have already found out of your new life. If she does not appear, then you will know that, even from the old-world standpoint, things have gone what you would call 'all right.' Let these trivial matters go, and attend to the vastly more important concerns that will soon engage your attention here."

Ferris talked earnestly, and it was evident, even to Brenton, that he meant what he said. It was hard to find a pretext for a quarrel with a man at once so calm and so perfectly sure of himself.

"We will not talk any more about it," said Brenton. "I presume people here agree to differ, just as they did in the world we have both left."

"Certainly, certainly," answered Ferris. "Of course, you have just heard my opinion; but you will find myriads of others who do not share it with me. You will meet a great many who are interested in the subject of communication with the world they have left. You will, of course, excuse me when I say that I consider such endeavours not worth talking about."

"Do you know any one who is interested in that sort of thing? and can you give me an introduction to him?"

"Oh! for that matter," said Ferris, "you have had an introduction to one of the most enthusiastic investigators of the subject. I refer to Mr. John Speed, late of Chicago."

"Ah!" said Brenton, rather dubiously. "I must confess that I was not very favourably impressed with Mr. Speed. Probably I did him an injustice."

"You certainly did," said Ferris. "You will find Speed a man well worth knowing, even if he does waste himself on such futile projects as a scheme for communicating with a community so evanescent as that of Chicago. You will like Speed better the more you know him. He really is very philanthropic, and has Sommers on his hands just now. From what he said after you left Venice, I imagine he does not entertain the same feeling toward you as you do toward him. I would see Speed if I were you."

"I will think about it," said Brenton, as they separated.

To know that a man thinks well of a person is no detriment to further acquaintance with that man, even if the first impressions have not been favourable; and after Ferris told Brenton that Speed had thought well of him, Brenton found less difficulty in seeking the Chicago enthusiast.

"I have been in a good deal of trouble," Brenton said to Speed, "and have been talking to Ferris about it. I regret to say that he gave me very little encouragement, and did not seem at all to appreciate my feelings in the matter."

"Oh, you mustn't mind Ferris," said Speed. "He is a first-rate fellow, but he is as cold and unsympathetic as—well, suppose we say as an oyster. His great hobby is non-intercourse with the world we have left. Now, in that I don't agree with him, and there are thousands who don't agree with him. I admit that there are cases where a man is more unhappy if he frequents the old world than he would be if he left it alone. But then there are other cases where just the reverse is true. Take my own experience, for example; I take a peculiar pleasure in rambling around Chicago. I admit that it is a grievance to me, as an old newspaper man, to see the number of scoops I could have on my esteemed contemporaries, but—"

"Scoop? What is that?" asked Brenton, mystified.

"Why, a scoop is a beat, you know."

"Yes, but I don't know. What is a beat?"

"A beat or a scoop, my dear fellow, is the getting of a piece of news that your contemporary does not obtain. You never were in the newspaper business? Well, sir, you missed it. Greatest business in the world. You know everything that is going on long before anybody else does, and the way you can reward your friends and jump with both feet on your enemies is one of the delights of existence down there."

"Well, what I wanted to ask you was this," said Brenton. "You have made a speciality of finding out whether there could be any communication between one of us, for instance, and one who is an inhabitant of the other world. Is such communication possible?"

"I have certainly devoted some time to it, but I can't say that my success has been flattering. My efforts have been mostly in the line of news. I have come on some startling information which my facilities here gave me access to, and I confess I have tried my best to put some of the boys on to it. But there is a link loose somewhere. Now, what is your trouble? Do you want to get a message to anybody?"

"My trouble is this," said Brenton, briefly, "I am here because a few days ago I was poisoned."

"George Washington!" cried the other, "you don't say so! Have the newspapers got on to the fact?"

"I regret to say that they have."

"What an item that would have been if one paper had got hold of it and the others hadn't! I suppose they all got on to it at the same time?"

"About that," said Brenton, "I don't know, and I must confess that I do not care very much. But here is the trouble—my wife has been arrested for my murder, and she is as innocent as I am."

"Sure of that?"

"Sure of it?" cried the other indignantly. "Of course I am sure of it."

"Then who is the guilty person?"

"Ah, that," said Brenton, "I do not yet know."

"Then how can you be sure she is not guilty?"

"If you talk like that," exclaimed Brenton, "I have nothing more to say."

"Now, don't get offended, I beg of you. I am merely looking at this from a newspaper standpoint, you know. You must remember it is not you who will decide the matter, but a jury of your very stupid fellow-countrymen. Now, you can never tell what a jury will do, except that it will do something idiotic. Therefore, it seems to me that the very first step to be taken is to find out who the guilty party is. Don't you see the force of that?"

"Yes, I do."

"Very well, then. Now, what were the circumstances of this crime? who was to profit by your death?"

Brenton winced at this.

"I see how it is," said the other, "and I understand why you don't answer. Now—you'll excuse me if I am frank—your wife was the one who benefited most by your death, was she not?"

"No," cried the other indignantly, "she was not the one. That is what the lawyers said. Why in the world should she want to poison me, when she had all my wealth at her command as it was?"

"Yes, that's a strong point," said Speed. "You were a reasonably good husband, I suppose? Rather generous with the cash?"

"Generous?" cried the other. "My wife always had everything she wanted."

"Ah, well, there was no—you'll excuse me, I am sure—no former lover in the case, was there?"

Again Brenton winced, and he thought of Roland sitting beside his wife with her hand in his.

"I see," said Speed; "you needn't answer. Now what were the circumstances, again?"

"They were these: At a dinner which I gave, where some twenty or twenty-five of my friends were assembled, poison, it appears, was put into my cup of coffee. That is all I know of it."

"Who poured out that cup of coffee?"

"My wife did."

"Ah! Now, I don't for a moment say she is guilty, remember; but you must admit that, to a stupid jury, the case might look rather bad against her."

"Well, granted that it does, there is all the more need that I should come to her assistance if possible."

"Certainly, certainly!" said Speed. "Now, I'll tell you what we have to do. We must get, if possible, one of the very brightest Chicago reporters on the track of this thing, and we have to get him on the track of it early. Come with me to Chicago. We will try an experiment, and I am sure you will lend your mind entirely to the effort. We must act in conjunction in this affair, and you are just the man I've been wanting, some one who is earnest and who has something at stake in the matter. We may fail entirely, but I think it's worth the trying. Will you come?"

"Certainly," said Brenton; "and I cannot tell you how much I appreciate your interest and sympathy."

Arriving at a brown stone building on the corner of two of the principal streets in Chicago, Brenton and Speed ascended quickly to one of the top floors. It was nearly midnight, and two upper stories of the huge dark building were brilliantly lighted, as was shown on the outside by the long rows of glittering windows. They entered a room where a man was seated at a table, with coat and vest thrown off, and his hat set well back on his head. Cold as it was outside, it was warm in this man's room, and the room was blue with smoke. A black corn-cob pipe was in his teeth, and the man was writing away as if for dear life, on sheets of coarse white copy paper, stopping now and then to fill up his pipe or to relight it after it had gone out.

"There," said Speed, waving his hand towards the writer with a certain air of proprietory pride, "there sits one of the very cleverest men on the Chicago press. That fellow, sir, is gifted with a nose for news which has no equal in America. He will ferret out a case that he once starts on with an unerringness that would charm you. Yes, sir, I got him his present situation on this paper, and I can tell you it was a good one."

"He must have been a warm friend of yours?" said Brenton, indifferently, as if he did not take much interest in the eulogy.

"Quite the contrary," said Speed. "He was a warm enemy, made it mighty warm for me sometimes. He was on an opposition paper, but I tell you, although I was no chicken in newspaper business, that man would scoop the daylight out of me any time he tried. So, to get rid of opposition, I got the managing editor to appoint him to a place on our paper; and I tell you, he has never regretted it. Yes, sir, there sits George Stratton, a man who knows his business. Now," he said, "let us concentrate our attention on him. First let us see whether, by putting our whole minds to it, we can make any impression on his mind whatever. You see how busily he is engaged. He is thoroughly absorbed in his work. That is George all over. Whatever his assignment is, George throws himself right into it, and thinks of nothing else until it is finished. Now then."

In that dingy, well-lighted room George Stratton sat busily pencilling out the lines that were to appear in next morning's paper. He was evidently very much engrossed in his task, as Speed had said. If he had looked about him, which he did not, he would have said that he was entirely alone. All at once his attention seemed to waver, and he passed his hand over his brow, while perplexity came into his face. Then he noticed that his pipe was out, and, knocking the ashes from it by rapping the bowl on the side of the table, he filled it with an absent-mindedness unusual with him. Again he turned to his writing, and again he passed his hand over his brow. Suddenly, without any apparent cause, he looked first to the right and then to the left of him. Once more he tried to write, but, noticing his pipe was out, he struck another match and nervously puffed away, until clouds of blue smoke rose around him. There was a look of annoyance and perplexity in his face as he bent resolutely to his writing. The door opened, and a man appeared on the threshold.

"Anything more about the convention, George?" he said.

"Yes; I am just finishing this. Sort of pen pictures, you know."

"Perhaps you can let me have what you have done. I'll fix it up."

"All right," said Stratton, bunching up the manuscript in front of him, and handing it to the city editor.

That functionary looked at the number of pages, and then at the writer.

"Much more of this, George?" he said. "We'll be a little short of room in the morning, you know."

"Well," said the other, sitting back in his chair, "it is pretty good stuff that. Folks always like the pen pictures of men engaged in the skirmish better than the reports of what most of them say."

"Yes," said the city editor, "that's so."

"Still," said Stratton, "we could cut it off at the last page. Just let me see the last two pages, will you?"

These were handed to him, and, running his eye through them, he drew his knife across one of the pages, and put at the bottom the cabalistic mark which indicated the end of the copy.

"There! I think I will let it go at that. Old Rickenbeck don't amount to much, anyhow. We'll let him go."

"All right," said the city editor. "I think we won't want anything more to-night."

Stratton put his hands behind his head, with his fingers interlaced, and leaned back in his chair, placing his heels upon the table before him. A thought-reader, looking at his face, could almost have followed the theme that occupied his mind. Suddenly bringing his feet down with a crash to the floor, he rose and went into the city editor's room.

"See here," he said. "Have you looked into that Cincinnati case at all?"

"What Cincinnati case?" asked the local editor, looking up.

"Why, that woman who is up for poisoning her husband."

"Oh yes; we had something of it in the despatches this morning. It's rather out of the local line, you know."

"Yes, I know it is. But it isn't out of the paper's line. I tell you that case is going to make a sensation. She's pretty as a picture. Been married only six months, and it seems to be a dead sure thing that she poisoned her husband. That trial's going to make racy reading, especially if they bring in a verdict of guilty."

The city editor looked interested.

"Want to go down there, George?"

"Well, do you know, I think it'll pay."

"Let me see, this is the last day of the convention, isn't it? And Clark comes back from his vacation to-morrow. Well, if you think it's worth it, take a trip down there, and look the ground over, and give us a special article that we can use on the first day of the trial."

"I'll do it," said George.

Speed looked at Brenton.

"What would old Ferris say now, eh?"

Next morning George Stratton was on the railway train speeding towards Cincinnati. As he handed to the conductor his mileage book, he did not say to him, lightly transposing the old couplet—

"Here, railroad man, take thrice thy fee, For spirits twain do ride with me."

George Stratton was a practical man, and knew nothing of spirits, except those which were in a small flask in his natty little valise.

When he reached Cincinnati, he made straight for the residence of the sheriff. He felt that his first duty was to become friends with such an important official. Besides this, he wished to have an interview with the prisoner. He had arranged in his mind, on the way there, just how he would write a preliminary article that would whet the appetite of the readers of the Chicago Argus for any further developments that might occur during and after the trial. He would write the whole thing in the form of a story.

First, there would be a sketch of the life of Mrs. Brenton and her husband. This would be number one, and above it would be the Roman numeral I. Under the heading II. would be a history of the crime. Under III. what had occurred afterwards—the incidents that had led suspicion towards the unfortunate woman, and that sort of thing. Under the numeral IV. would be his interview with the prisoner, if he were fortunate enough to get one. Under V. he would give the general opinion of Cincinnati on the crime, and on the guilt or innocence of Mrs. Brenton. This article he already saw in his mind's eye occupying nearly half a page of the Argus. All would be in leaded type, and written in a style and manner that would attract attention, for he felt that he was first on the ground, and would not have the usual rush in preparing his copy which had been the bane of his life. It would give the Argus practically the lead in this case, which he was convinced would become one of national importance.

The sheriff received him courteously, and, looking at the card he presented, saw the name Chicago Argus in the corner. Then he stood visibly on his guard—an attitude assumed by all wise officials when they find themselves brought face to face with a newspaper man; for they know, however carefully an article may be prepared, it will likely contain some unfortunate overlooked phrase which may have a damaging effect in a future political campaign.

"I wanted to see you," began Stratton, coming straight to the point, "in reference to the Brenton murder."

"I may say at once," replied the sheriff, "that if you wish an interview with the prisoner, it is utterly impossible, because her lawyers, Benham and Brown, have positively forbidden her to see a newspaper man."

"That shows," said Stratton, "they are wise men who understand their business. Nevertheless, I wish to have an interview with Mrs. Brenton. But what I wanted to say to you is this: I believe the case will be very much talked about, and that before many weeks are over. Of course you know the standing the Argus has in newspaper circles. What it says will have an influence, even over the Cincinnati press. I think you will admit that. Now a great many newspaper men consider an official their natural enemy. I do not; at least, I do not until I am forced to. Any reference that I may make to you I am more than willing to submit to you before it goes to Chicago. I will give you my word, if you want it, that nothing will be said referring to your official position, or to yourself personally, that you do not see before it appears in print. Of course you will be up for re-election. I never met a sheriff who wasn't."

The sheriff smiled at this, and did not deny it.

"Very well. Now, I may tell you my belief is that this case is going to have a powerful influence on your re-election. Here is a young and pretty woman who is to be tried for a terrible crime. Whether she is guilty or innocent, public sympathy is going to be with her. If I were in your place, I would prefer to be known as her friend rather than as her enemy."

"My dear sir," said the sheriff, "my official position puts me in the attitude of neither friend nor enemy of the unfortunate woman. I have simply a certain duty to do, and that duty I intend to perform."

"Oh, that's all right!" exclaimed the newspaper man, jauntily. "I, for one, am not going to ask you to take a step outside your duties; but an official may do his duty, and yet, at the same time, do a friendly act for a newspaper man, or even for a prisoner. In the language of the old chestnut, 'If you don't help me, don't help the bear.' That's all I ask."

"You maybe sure, Mr. Stratton, that anything I can do to help you I shall be glad to do; and now let me give you a hint. If you want to see Mrs. Brenton, the best thing is to get permission from her lawyers. If I were you I would not see Benham—he's rather a hard nut, Benham is, although you needn't tell him I said so. You get on the right side of Brown. Brown has some political aspirations himself, and he does not want to offend a man on so powerful a paper as the Argus, even if it is not a Cincinnati paper. Now, if you make him the same offer you have made to me, I think it will be all right. If he sees your copy before it goes into print, and if you keep your word with him that nothing will appear that he does not see, I think you will succeed in getting an interview with Mrs. Brenton. If you bring me a note from Brown, I shall be very glad to allow you to see her."

Stratton thanked the sheriff for his hint. He took down in his note-book the address of the lawyers, and the name especially of Mr. Brown. The two men shook hands, and Stratton felt that they understood each other.

When Mr. Stratton was ushered into the private office of Brown, and handed that gentleman his card, he noticed the lawyer perceptibly freeze over.

"Ahem," said the legal gentleman; "you will excuse me if I say that my time is rather precious. Did you wish to see me professionally?"

"Yes," replied Stratton, "that is, from a newspaper standpoint of the profession."

"Ah," said the other, "in reference to what?"

"To the Brenton case."

"Well, my dear sir, I have had, very reluctantly, to refuse information that I would have been happy to give, if I could, to our own newspaper men; and so I may say to you at once that I scarcely think it will be possible for me to be of any service to an outside paper like the Argus"

"Local newspaper men," said Stratton, "represent local fame. That you already possess. I represent national fame, which, if you will excuse my saying so, you do not yet possess. The fact that I am in Cincinnati to-day, instead of in Chicago, shows what we Chicago people think of the Cincinnati case. I believe, and the Argus believes, that this case is going to be one of national importance. Now, let me ask you one question. Will you state frankly what your objection is to having a newspaper man, for instance, interview Mrs. Brenton, or get any information relating to this case from her or others whom you have the power of controlling?"

"I shall answer that question," said Brown, "as frankly as you put it. You are a man of the world, and know, of course, that we are all selfish, and in business matters look entirely after our own interests. My interest in this case is to defend my client. Your interest in this case is to make a sensational article. You want to get facts if possible, but, in any event, you want to write up a readable column or two for your paper. Now, if I allowed you to see Mrs. Brenton, she might say something to you, and you might publish it, that would not only endanger her chances, but would seriously embarrass us, as her lawyers, in our defence of the case."

"You have stated the objection very plainly and forcibly," said Stratton, with a look of admiration, as if the powerful arguments of the lawyer had had a great effect on him. "Now, if I understand your argument, it simply amounts to this, that you would have no objection to my interviewing Mrs. Brenton if you have the privilege of editing the copy. In other words, if nothing were printed but what you approve of, you would not have the slightest hesitancy about allowing me that interview."

"No, I don't know that I would," admitted the lawyer.

"Very well, then. Here is my proposition to you: I am here to look after the interests of our paper in this particular case. The Argus is probably going to be the first paper outside of Cincinnati that will devote a large amount of space to the Brenton trial, in addition to what is received from the Associated Press dispatches. Now you can give me a great many facilities in this matter if you care to do so, and in return I am perfectly willing to submit to you every line of copy that concerns you or your client before it is sent, and I give you my word of honour that nothing shall appear but what you have seen and approved of. If you want to cut out something that I think is vitally important, then I shall tell you frankly that I intend to print it, but will modify it as much as I possibly can to suit your views."

"I see," said the lawyer. "In other words, as you have just remarked, I am to give you special facilities in this matter, and then, when you find out some fact which I wish kept secret, and which you have obtained because of the facilities I have given to you, you will quite frankly tell me that it must go in, and then, of course, I shall be helpless except to debar you from any further facilities, as you call them. No, sir, I do not care to make any such bargain."

"Well, suppose I strike out that clause of agreement, and say to you that I will send nothing but what you approve of, would you then write me a note to the sheriff and allow me to see the prisoner?"

"I am sorry to say"—the lawyer hesitated for a moment, and glanced at the card, then added—"Mr. Stratton, that I do not see my way clear to granting your request."

"I think," said Stratton, rising, "that you are doing yourself an injustice. You are refusing—I may as well tell you first as last—what is a great privilege. Now, you have had some experience in your business, and I have had some experience in mine, and I beg to inform you that men who are much more prominent in the history of their country than any one I can at present think of in Cincinnati, have tried to balk me in the pursuit of my business, and have failed."

"In that matter, of course," said Brown, "I must take my chances. I don't see the use of prolonging this interview. As you have been so frank as to—I won't say threaten, perhaps warn is the better word—as you have been so good as to warn me, I may, before we part, just give you a word of caution. Of course we, in Cincinnati, are perfectly willing to admit that Chicago people are the smartest on earth, but I may say that if you print a word in your paper which is untrue and which is damaging to our side of the case, or if you use any methods that are unlawful in obtaining the information you so much desire, you will certainly get your paper into trouble, and you will run some little personal risk yourself."

"Well, as you remarked a moment ago, Mr. Brown, I shall have to take the chances of that. I am here to get the news, and if I don't succeed it will be the first time in my life."

"Very well, sir," said the lawyer. "I wish you good evening."

"Just one thing more," said the newspaper man, "before I leave you."

"My dear sir," said the lawyer, impatiently, "I am very busy. I've already given you a liberal share of my time. I must request that this interview end at once."

"I thought," said Mr. Stratton, calmly, "that perhaps you might be interested in the first article that I am going to write. I shall devote one column in the Argus of the day after to-morrow to your defence of the case, and whether your theory of defence is a tenable one or not."

Mr. Brown pushed back his chair and looked earnestly at the young man. That individual was imperturbably pulling on his gloves, and at the moment was buttoning one of them.

"Our defence!" cried the lawyer. "What do you know of our defence?"

"My dear sir," said Stratton, "I know all about it."

"Sir, that is impossible. Nobody knows what our defence is to be except Mr. Benham and myself."

"And Mr. Stratton, of the Chicago Argus," replied the young man, as he buttoned his coat.

"May I ask, then, what the defence is?"

"Certainly," answered the Chicago man. "Your defence is that Mr. Brenton was insane, and that he committed suicide."

Even Mr. Brown's habitual self-control, acquired by long years of training in keeping his feelings out of sight, for the moment deserted him. He drew his breath sharply, and cast a piercing glance at the young man before him, who was critically watching the lawyer's countenance, although he appeared to be entirely absorbed in buttoning his overcoat. Then Mr. Brown gave a short, dry laugh.

"I have met a bluff before," he said carelessly; "but I should like to know what makes you think that such is our defence?"

"Think!" cried the young man. "I don't think at all; I know it."

"How do you know it?"

"Well, for one thing, I know it by your own actions a moment ago. What first gave me an inkling of your defence was that book which is on your table. It is Forbes Winslow on the mind and the brain; a very interesting book, Mr. Brown, very interesting indeed. It treats of suicide, and the causes and conditions of the brain that will lead up to it. It is a very good book, indeed, to study in such a case. Good evening, Mr. Brown. I am sorry that we cannot co-operate in this matter."

Stratton turned and walked toward the door, while the lawyer gazed after him with a look of helpless astonishment on his face. As Stratton placed his hand on the door knob, the lawyer seemed to wake up as from a dream.

"Stop!" he cried; "I will give you a letter that will admit you to Mrs. Brenton."

"There!" said Speed to Brenton, triumphantly, "what do you think of that? Didn't I say George Stratton was the brightest newspaper man in Chicago? I tell you, his getting that letter from old Brown was one of the cleverest bits of diplomacy I ever saw. There you had quickness of perception, and nerve. All the time he was talking to old Brown he was just taking that man's measure. See how coolly he acted while he was drawing on his gloves and buttoning his coat as if ready to leave. Flung that at Brown all of a sudden as quiet as if he was saying nothing at all unusual, and all the time watching Brown out of the tail of his eye. Well, sir, I must admit, that although I have known George Stratton for years, I thought he was dished by that Cincinnati lawyer. I thought that George was just gracefully covering up his defeat, and there he upset old Brown's apple-cart in the twinkling of an eye. Now, you see the effect of all this. Brown has practically admitted to him what the line of defence is. Stratton won't publish it, of course; he has promised not to, but you see he can hold that over Brown's head, and get everything he wants unless they change their defence."

"Yes," remarked Brenton, slowly, "he seems to be a very sharp newspaper man indeed; but I don't like the idea of his going to interview my wife."

"Why, what is there wrong about that?"

"Well, there is this wrong about it—that she in her depression may say something that will tell against her."

"Even if she does, what of it? Isn't the lawyer going to see the letter before it is sent to the paper?"

"I am not so sure about that. Do you think Stratton will show the article to Brown if he gets what you call a scoop or a beat?"

"Why, of course he will," answered Speed, indignantly; "hasn't he given him his word that he will?"

"Yes, I know he has," said Brenton, dubiously; "but he is a newspaper man."

"Certainly he is," answered Speed, with strong emphasis; "that is the reason he will keep his word."

"I hope so, I hope so; but I must admit that the more I know you newspaper men, the more I see the great temptation you are under to preserve if possible the sensational features of an article."

"I'll bet you a drink—no, we can't do that," corrected Speed; "but you shall see that, if Brown acts square with Stratton, he will keep his word to the very letter with Brown. There is no use in our talking about the matter here. Let us follow Stratton, and see what comes of the interview."

"I think I prefer to go alone," said Brenton, coldly.

"Oh, as you like, as you like," answered the other, shortly. "I thought you wanted my help in this affair; but if you don't, I am sure I shan't intrude."

"That's all right," said Brenton; "come along. By the way, Speed, what do you think of that line of defence?"

"Well, I don't know enough of the circumstances of the case to know what to think of it. It seems to me rather a good line."

"It can't be a good line when it is not true. It is certain to break down."

"That's so," said Speed; "but I'll bet you four dollars and a half that they'll prove you a raving maniac before they are through with you. They'll show very likely that you tried to poison yourself two or three times; bring on a dozen of your friends to prove that they knew all your life you were insane."

"Do you think they will?" asked Brenton, uneasily.

"Think it? Why, I am sure of it. You'll go down to posterity as one of the most complete lunatics that ever, lived in Cincinnati. Oh, there won't be anything left of you when they get through with you."

Meanwhile, Stratton was making his way to the residence of the sheriff.

"Ah," said that official, when they met, "you got your letter, did you? Well, I thought you would."

"If you had heard the conversation between my estimable friend Mr. Brown and myself, up to the very last moment, you wouldn't have thought it."

"Well, Brown is generally very courteous towards newspaper men, and that's one reason you see his name in the papers a great deal."

"If I were a Cincinnati newspaper man, I can assure you that his name wouldn't appear very much in the columns of my paper."

"I am sorry to hear you say that. I thought Brown was very popular with the newspaper men. You got the letter, though, did you?"

"Yes; I got it. Here it is. Read it."

The sheriff scanned the brief note over, and put it in his pocket.

"Just take a chair for a moment, will you, and I will see if Mrs. Brenton is ready to receive you."

Stratton seated himself, and, pulling a paper from his pocket, was busily reading when the sheriff again entered.

"I am sorry to say," he began, "after you have had all this trouble, that Mrs. Brenton positively refuses to see you. You know I cannot compel a prisoner to meet any one. You understand that, of course."

"Perfectly," said Stratton, thinking for a moment. "See here, sheriff, I have simply got to have a talk with that woman. Now, can't you tell her I knew her husband, or something of that sort? I'll make it all right when I see her."

"The scoundrel!" said Brenton to Speed, as Stratton made this remark.

"My dear sir," said Speed, "don't you see he is just the man we want? This is not the time to be particular."

"Yes, but think of the treachery and meanness of telling a poor unfortunate woman that he was acquainted with her husband, who is only a few days dead."