The Project Gutenberg EBook of Lord Kilgobbin, by Charles Lever This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Lord Kilgobbin Author: Charles Lever Release Date: August 14, 2004 [EBook #8941] Last Updated: September 3, 2016 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LORD KILGOBBIN *** Produced by Distributed Proofreaders. Illustrated HTML version by David Widger

TO THE MEMORY OF ONE

WHOSE COMPANIONSHIP MADE THE

HAPPINESS OF A LONG LIFE,

AND WHOSE LOSS HAS LEFT ME HELPLESS,

I

DEDICATE THIS WORK,

WRITTEN IN BREAKING HEALTH AND BROKEN SPIRITS.

THE TASK, THAT ONCE WAS MY JOY AND MY PRIDE,

I HAVE LIVED TO FIND

ASSOCIATED WITH MY SORROW:

IT IS NOT, THEN, WITHOUT A CAUSE I SAY,

I HOPE THIS EFFORT MAY BE MY LAST.

CHARLES LEVER.

TRIESTE, January 20, 1872.

‘Lord Kilgobbin’ appeared originally as a serial, (illustrated by Luke Fildes) in ‘The Cornhill Magazine,’ commencing in the issue for October 1870, and ending in the issue for March 1872. It was first published in book form in three volumes in 1872, with the following title-page:

LORD KILGOBBIN | A TALE OF IRELAND IN OUR OWN TIME | BY | CHARLES LEVER, LL.D. | AUTHOR OF | ‘THE BRAMLEIGHS OF BISHOP’S FOLLY,’ ‘THAT BOY OF NORCOTT’S,’ | ETC., ETC. | IN THREE VOLUMES | [VOL. I.] | LONDON | SMITH, ELDER, AND CO., 15 WATERLOO PLACE | 1872. | [THE RIGHT OF TRANSLATION IS RESERVED.]

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

She Suffered Her Hand to Remain

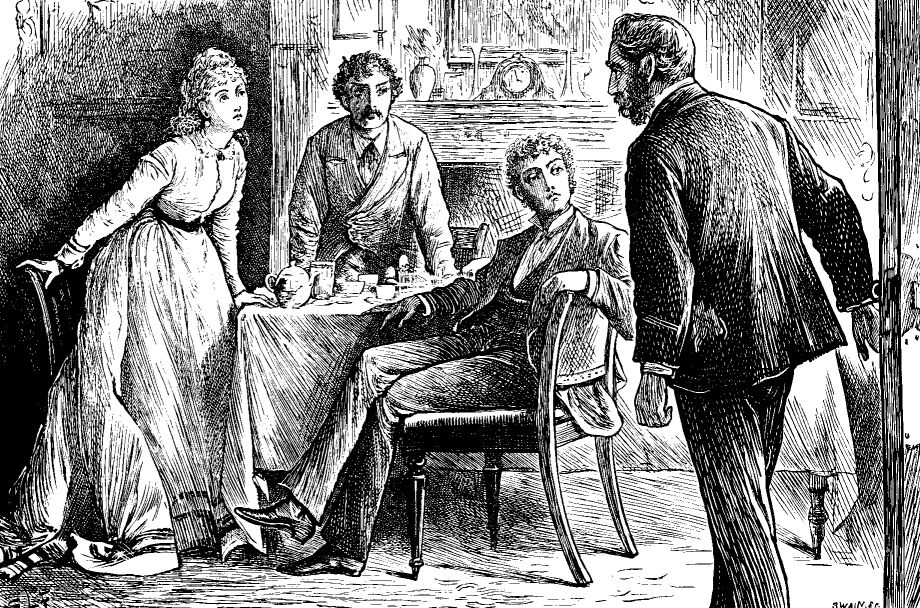

‘What Lark Have You Been On, Master Joe?’

‘One More Sitting I Must Have, Sir, for the Hair’

‘How That Song Makes Me Wish We Were Back Again Where I Heard It First’

He Entered and Nina Arose As he Came Forward.

‘You Are Right, I See It All,’ and Now he Seized Her Hand And Kissed It

Kate, Still Dressed, Had Thrown Herself on the Bed, and Was Sound Asleep

‘Is Not That As Fine As Your Boasted Campagna?’

‘You Wear a Ring of Great Beauty—may I Look at It?’

‘True, There is No Tender Light There,’ Muttered He, Gazing At Her Eyes

He Knelt Down on One Knee Before Her

Nina Came Forward at That Moment

Nina Kostalergi Was Busily Engaged in Pinning up the Skirt Of Her Dress

The Balcony Creaked and Trembled, And at Last Gave Way

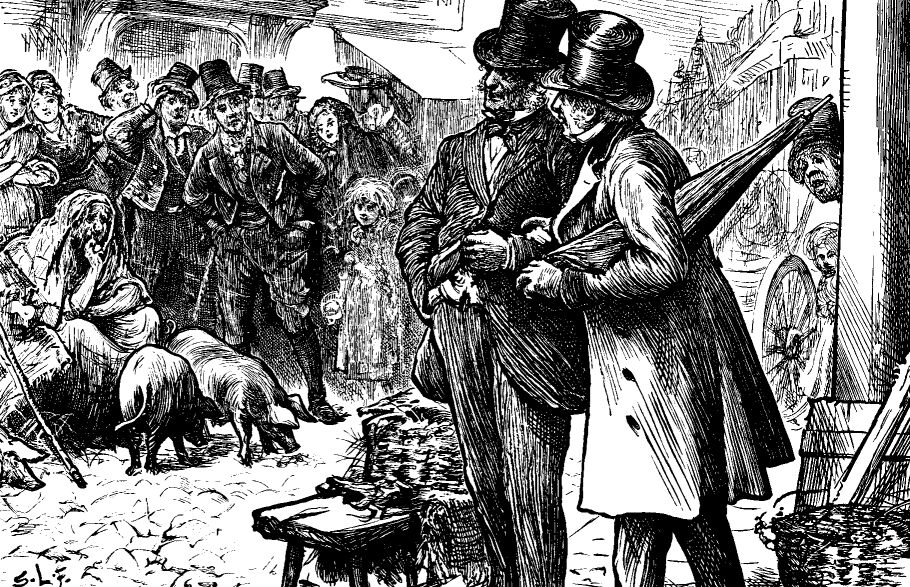

‘Just Look at the Crowd That is Watching Us Already’

‘I Should Like to Have Back My Letters’

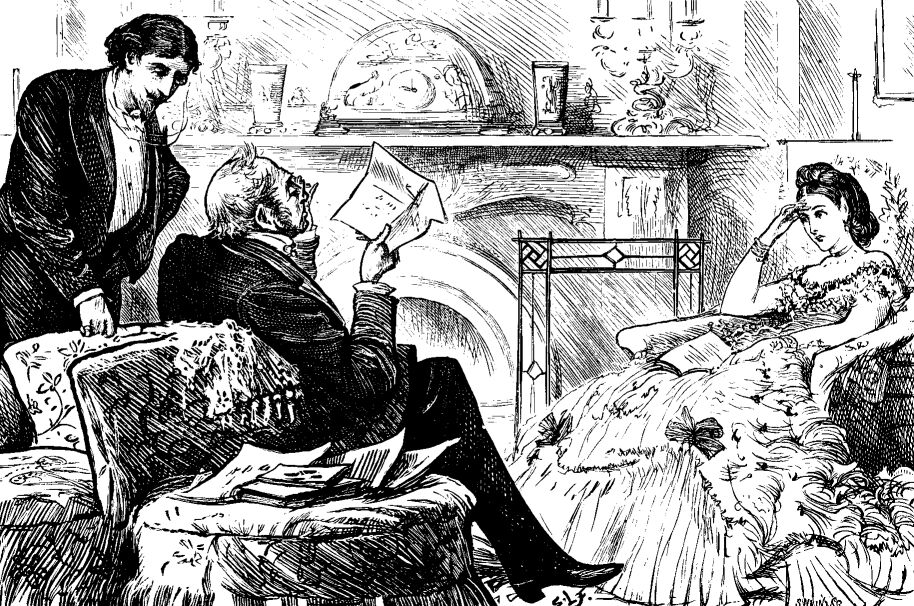

Walpole Looked Keenly at the Other’s Face As he Read The Paper

Some one has said that almost all that Ireland possesses of picturesque beauty is to be found on, or in the immediate neighbourhood of, the seaboard; and if we except some brief patches of river scenery on the Nore and the Blackwater, and a part of Lough Erne, the assertion is not devoid of truth. The dreary expanse called the Bog of Allen, which occupies a tableland in the centre of the island, stretches away for miles—flat, sad-coloured, and monotonous, fissured in every direction by channels of dark-tinted water, in which the very fish take the same sad colour. This tract is almost without trace of habitation, save where, at distant intervals, utter destitution has raised a mud-hovel, undistinguishable from the hillocks of turf around it.

Fringing this broad waste, little patches of cultivation are to be seen: small potato-gardens, as they are called, or a few roods of oats, green even in the late autumn; but, strangely enough, with nothing to show where the humble tiller of the soil is living, nor, often, any visible road to these isolated spots of culture. Gradually, however—but very gradually—the prospect brightens. Fields with inclosures, and a cabin or two, are to be met with; a solitary tree, generally an ash, will be seen; some rude instrument of husbandry, or an ass-cart, will show that we are emerging from the region of complete destitution and approaching a land of at least struggling civilisation. At last, and by a transition that is not always easy to mark, the scene glides into those rich pasture-lands and well-tilled farms that form the wealth of the midland counties. Gentlemen’s seats and waving plantations succeed, and we are in a country of comfort and abundance.

On this border-land between fertility and destitution, and on a tract which had probably once been part of the Bog itself, there stood—there stands still—a short, square tower, battlemented at top, and surmounted with a pointed roof, which seems to grow out of a cluster of farm-buildings, so surrounded is its base by roofs of thatch and slates. Incongruous, vulgar, and ugly in every way, the old keep appears to look down on them—time-worn and battered as it is—as might a reduced gentleman regard the unworthy associates with which an altered fortune had linked him. This is all that remains of Kilgobbin Castle.

In the guidebooks we read that it was once a place of strength and importance, and that Hugh de Lacy—the same bold knight ‘who had won all Ireland for the English from the Shannon to the sea’—had taken this castle from a native chieftain called Neal O’Caharney, whose family he had slain, all save one; and then it adds: ‘Sir Hugh came one day, with three Englishmen, that he might show them the castle, when there came to him a youth of the men of Meath—a certain Gilla Naher O’Mahey, foster-brother of O’Caharney himself—with his battle-axe concealed beneath his cloak, and while De Lacy was reading the petition he gave him, he dealt him such a blow that his head flew off many yards away, both head and body being afterwards buried in the ditch of the castle.’

The annals of Kilronan further relate that the O’Caharneys became adherents of the English—dropping their Irish designation, and calling themselves Kearney; and in this way were restored to a part of the lands and the castle of Kilgobbin—‘by favour of which act of grace,’ says the chronicle, ‘they were bound to raise a becoming monument over the brave knight, Hugh de Lacy, whom their kinsman had so treacherously slain; but they did no more of this than one large stone of granite, and no inscription thereon: thus showing that at all times, and with all men, the O’Caharneys were false knaves and untrue to their word.’

In later times, again, the Kearneys returned to the old faith of their fathers and followed the fortunes of King James; one of them, Michael O’Kearney, having acted as aide-de-camp at the ‘Boyne,’ and conducted the king to Kilgobbin, where he passed the night after the defeat, and, as the tradition records, held a court the next morning, at which he thanked the owner of the castle for his hospitality, and created him on the spot a viscount by the style and title of Lord Kilgobbin.

It is needless to say that the newly-created noble saw good reason to keep his elevation to himself. They were somewhat critical times just then for the adherents of the lost cause, and the followers of King William were keen at scenting out any disloyalty that might be turned to good account by a confiscation. The Kearneys, however, were prudent. They entertained a Dutch officer, Van Straaten, on King William’s staff, and gave such valuable information besides as to the condition of the country, that no suspicions of disloyalty attached to them.

To these succeeded more peaceful times, during which the Kearneys were more engaged in endeavouring to reconstruct the fallen condition of their fortunes than in political intrigue. Indeed, a very small portion of the original estate now remained to them, and of what once had produced above four thousand a year, there was left a property barely worth eight hundred.

The present owner, with whose fortunes we are more Immediately concerned, was a widower. Mathew Kearney’s family consisted of a son and a daughter: the former about two-and-twenty, the latter four years younger, though to all appearance there did not seem a year between them.

Mathew Kearney himself was a man of about fifty-four or fifty-six; hale, handsome, and powerful; his snow-white hair and bright complexion, with his full grey eyes and regular teeth giving him an air of genial cordiality at first sight which was fully confirmed by further acquaintance. So long as the world went well with him, Mathew seemed to enjoy life thoroughly, and even its rubs he bore with an easy jocularity that showed what a stout heart he could oppose to Fortune. A long minority had provided him with a considerable sum on his coming of age, but he spent it freely, and when it was exhausted, continued to live on at the same rate as before, till at last, as creditors grew pressing, and mortgages threatened foreclosure, he saw himself reduced to something less than one-fifth of his former outlay; and though he seemed to address himself to the task with a bold spirit and a resolute mind, the old habits were too deeply rooted to be eradicated, and the pleasant companionship of his equals, his life at the club in Dublin, his joyous conviviality, no longer possible, he suffered himself to descend to an inferior rank, and sought his associates amongst humbler men, whose flattering reception of him soon reconciled him to his fallen condition. His companions were now the small farmers of the neighbourhood and the shopkeepers in the adjoining town of Moate, to whose habits and modes of thought and expression he gradually conformed, till it became positively irksome to himself to keep the company of his equals. Whether, however, it was that age had breached the stronghold of his good spirits, or that conscience rebuked him for having derogated from his station, certain it is that all his buoyancy failed him when away from society, and that in the quietness of his home he was depressed and dispirited to a degree; and to that genial temper, which once he could count on against every reverse that befell him, there now succeeded an irritable, peevish spirit, that led him to attribute every annoyance he met with to some fault or shortcoming of others.

By his neighbours in the town and by his tenantry he was always addressed as ‘My lord,’ and treated with all the deference that pertained to such difference of station. By the gentry, however, when at rare occasions he met them, he was known as Mr. Kearney; and in the village post-office, the letters with the name Mathew Kearney, Esq., were perpetual reminders of what rank was accorded him by that wider section of the world that lived beyond the shadow of Kilgobbin Castle.

Perhaps the impossible task of serving two masters is never more palpably displayed than when the attempt attaches to a divided identity—when a man tries to be himself in two distinct parts in life, without the slightest misgiving of hypocrisy while doing so. Mathew Kearney not only did not assume any pretension to nobility amongst his equals, but he would have felt that any reference to his title from one of them would have been an impertinence, and an impertinence to be resented; while, at the same time, had a shopkeeper of Moate, or one of the tenants, addressed him as other than ‘My lord,’ he would not have deigned him a notice.

Strangely enough, this divided allegiance did not merely prevail with the outer world, it actually penetrated within his walls. By his son, Richard Kearney, he was always called ‘My lord’; while Kate as persistently addressed and spoke of him as papa. Nor was this difference without signification as to their separate natures and tempers.

Had Mathew Kearney contrived to divide the two parts of his nature, and bequeathed all his pride, his vanity, and his pretensions to his son, while he gave his light-heartedness, his buoyancy, and kindliness to his daughter, the partition could not have been more perfect. Richard Kearney was full of an insolent pride of birth. Contrasting the position of his father with that held by his grandfather, he resented the downfall as the act of a dominant faction, eager to outrage the old race and the old religion of Ireland. Kate took a very different view of their condition. She clung, indeed, to the notion of their good blood; but as a thing that might assuage many of the pangs of adverse fortune, not increase or embitter them; and ‘if we are ever to emerge,’ thought she, ‘from this poor state, we shall meet our class without any of the shame of a mushroom origin. It will be a restoration, and not a new elevation.’ She was a fine, handsome, fearless girl, whom many said ought to have been a boy; but this was rather intended as a covert slight on the narrower nature and peevish temperament of her brother—another way, indeed, of saying that they should have exchanged conditions.

The listless indolence of her father’s life, and the almost complete absence from home of her brother, who was pursuing his studies at the Dublin University, had given over to her charge not only the household, but no small share of the management of the estate—all, in fact, that an old land-steward, a certain Peter Gill, would permit her to exercise; for Peter was a very absolute and despotic Grand-Vizier, and if it had not been that he could neither read nor write, it would have been utterly impossible to have wrested from him a particle of power over the property. This happy defect in his education—happy so far as Kate’s rule was concerned—gave her the one claim she could prefer to any superiority over him, and his obstinacy could never be effectually overcome, except by confronting him with a written document or a column of figures. Before these, indeed, he would stand crestfallen and abashed. Some strange terror seemed to possess him as to the peril of opposing himself to such inscrutable testimony—a fear, be it said, he never felt in contesting an oral witness.

Peter had one resource, however, and I am not sure that a similar stronghold has not secured the power of greater men and in higher functions. Peter’s sway was of so varied and complicated a kind; the duties he discharged were so various, manifold, and conflicting; the measures he took with the people, whose destinies were committed to him, were so thoroughly devised, by reference to the peculiar condition of each man—what he could do, or bear, or submit to—and not by any sense of justice; that a sort of government grew up over the property full of hitches, contingencies, and compensations, of which none but the inventor of the machinery could possibly pretend to the direction. The estate being, to use his own words, ‘so like the old coach-harness, so full of knots, splices, and entanglements, there was not another man in Ireland could make it work, and if another were to try it, it would all come to pieces in his hands.’

Kate was shrewd enough to see this; and in the same way that she had admiringly watched Peter as he knotted a trace here and supplemented a strap there, strengthening a weak point, and providing for casualties even the least likely, she saw him dealing with the tenantry on the property; and in the same spirit that he made allowance for sickness here and misfortune there, he would be as prompt to screw up a lagging tenant to the last penny, and secure the landlord in the share of any season of prosperity.

Had the Government Commissioner, sent to report on the state of land-tenure in Ireland, confined himself to a visit to the estate of Lord Kilgobbin—for so we like to call him—it is just possible that the Cabinet would have found the task of legislation even more difficult than they have already admitted it to be.

First of all, not a tenant on the estate had any certain knowledge of how much land he held. There had been no survey of the property for years. ‘It will be made up to you,’ was Gill’s phrase about everything. ‘What matters if you have an acre more or an acre less?’ Neither had any one a lease, nor, indeed, a writing of any kind. Gill settled that on the 25th March and 25th September a certain sum was to be forthcoming, and that was all. When ‘the lord’ wanted them, they were always to give him a hand, which often meant with their carts and horses, especially in harvest-time. Not that they were a hard-worked or hard-working population: they took life very easy, seeing that by no possible exertion could they materially better themselves; and even when they hunted a neighbour’s cow out of their wheat, they would execute the eviction with a lazy indolence and sluggishness that took away from the act all semblance of ungenerousness.

They were very poor, their hovels were wretched, their clothes ragged, and their food scanty; but, with all that, they were not discontented, and very far from unhappy. There was no prosperity at hand to contrast with their poverty. The world was, on the whole, pretty much as they always remembered it. They would have liked to be ‘better off’ if they knew how, but they did not know if there were a ‘better off,’ much less how to come at it; and if there were, Peter Gill certainly did not tell them of it.

If a stray visitor to fair or market brought back the news that there was an agitation abroad for a new settlement of the land, that popular orators were proclaiming the poor man’s rights and denouncing the cruelties of the landlord, if they heard that men were talking of repealing the laws which secured property to the owner, and only admitted him to a sort of partnership with the tiller of the soil, old Gill speedily assured them that these were changes only to be adopted in Ulster, where the tenants were rack-rented and treated like slaves. ‘Which of you here,’ would he say, ‘can come forward and say he was ever evicted?’ Now as the term was one of which none had the very vaguest conception—it might, for aught they knew, have been an operation in surgery—the appeal was an overwhelming success. ‘Sorra doubt of it, but ould Peter’s right, and there’s worse places to live in, and worse landlords to live under, than the lord.’ Not but it taxed Gill’s skill and cleverness to maintain this quarantine against the outer world; and he often felt like Prince Metternich in a like strait—that it would only be a question of time, and, in the long run, the newspaper fellows must win.

From what has been said, therefore, it may be imagined that Kilgobbin was not a model estate, nor Peter Gill exactly the sort of witness from which a select committee would have extracted any valuable suggestions for the construction of a land-code.

Anything short of Kate Kearney’s fine temper and genial disposition would have broken down by daily dealing with this cross-grained, wrong-headed, and obstinate old fellow, whose ideas of management all centred in craft and subtlety—outwitting this man, forestalling that—doing everything by halves, so that no boon came unassociated with some contingency or other by which he secured to himself unlimited power and uncontrolled tyranny.

As Gill was in perfect possession of her father’s confidence, to oppose him in anything was a task of no mean difficulty; and the mere thought that the old fellow should feel offended and throw up his charge—a threat he had more than once half hinted—was a terror Kilgobbin could not have faced. Nor was this her only care. There was Dick continually dunning her for remittances, and importuning her for means to supply his extravagances. ‘I suspected how it would be,’ wrote he once, ‘with a lady paymaster. And when my father told me I was to look to you for my allowance, I accepted the information as a heavy percentage taken off my beggarly income. What could you—what could any young girl—know of the requirements of a man going out into the best society of a capital? To derive any benefit from associating with these people, I must at least seem to live like them. I am received as the son of a man of condition and property, and you want to bound my habits by those of my chum, Joe Atlee, whose father is starving somewhere on the pay of a Presbyterian minister. Even Joe himself laughs at the notion of gauging my expenses by his.

‘If this is to go on—I mean if you intend to persist in this plan—be frank enough to say so at once, and I will either take pupils, or seek a clerkship, or go off to Australia; and I care precious little which of the three.

‘I know what a proud thing it is for whoever manages the revenue to come forward and show a surplus. Chancellors of the Exchequer make great reputations in that fashion; but there are certain economies that lie close to revolutions; now don’t risk this, nor don’t be above taking a hint from one some years older than you, though he neither rules his father’s house nor metes out his pocket-money.’

Such, and such like, were the epistles she received from time to time, and though frequency blunted something of their sting, and their injustice gave her a support against their sarcasm, she read and thought over them in a spirit of bitter mortification. Of course she showed none of these letters to her father. He, indeed, only asked if Dick were well, or if he were soon going up for that scholarship or fellowship—he did not know which, nor was he to blame—‘which, after all, it was hard on a Kearney to stoop to accept, only that times were changed with us! and we weren’t what we used to be’—a reflection so overwhelming that he generally felt unable to dwell on it.

Mathew Kearney had once a sister whom he dearly loved, and whose sad fate lay very heavily on his heart, for he was not without self-accusings on the score of it. Matilda Kearney had been a belle of the Irish Court and a toast at the club when Mathew was a young fellow in town; and he had been very proud of her beauty, and tasted a full share of those attentions which often fall to the lot of brothers of handsome girls.

Then Matty was an heiress, that is, she had twelve thousand pounds in her own right; and Ireland was not such a California as to make a very pretty girl with twelve thousand pounds an everyday chance. She had numerous offers of marriage, and with the usual luck in such cases, there were commonplace unattractive men with good means, and there were clever and agreeable fellows without a sixpence, all alike ineligible. Matty had that infusion of romance in her nature that few, if any, Irish girls are free from, and which made her desire that the man of her choice should be something out of the common. She would have liked a soldier who had won distinction in the field. The idea of military fame was very dear to her Irish heart, and she fancied with what pride she would hang upon the arm of one whose gay trappings and gold embroidery emblematised the career he followed. If not a soldier, she would have liked a great orator, some leader in debate that men would rush down to hear, and whose glowing words would be gathered up and repeated as though inspirations; after that a poet, and perhaps—not a painter—a sculptor, she thought, might do.

With such aspirations as these, it is not surprising that she rejected the offers of those comfortable fellows in Meath, or Louth, whose military glories were militia drills, and whose eloquence was confined to the bench of magistrates.

At three-and-twenty she was in the full blaze of her beauty; at three-and-thirty she was still unmarried, her looks on the wane, but her romance stronger than ever, not untinged perhaps with a little bitterness towards that sex which had not afforded one man of merit enough to woo and win her. Partly out of pique with a land so barren of all that could minister to imagination, partly in anger with her brother who had been urging her to a match she disliked, she went abroad to travel, wandered about for a year or two, and at last found herself one winter at Naples.

There was at that time, as secretary to the Greek legation, a young fellow whom repute called the handsomest man in Europe; he was a certain Spiridion Kostalergi, whose title was Prince of Delos, though whether there was such a principality, or that he was its representative, society was not fully agreed upon. At all events, Miss Kearney met him at a Court ball, when he wore his national costume, looking, it must be owned, so splendidly handsome that all thought of his princely rank was forgotten in presence of a face and figure that recalled the highest triumphs of ancient art. It was Antinous come to life in an embroidered cap and a gold-worked jacket, and it was Antinous with a voice like Mario, and who waltzed to perfection. This splendid creature, a modern Alcibiades in gifts of mind and graces, soon heard, amongst his other triumphs, how a rich and handsome Irish girl had fallen in love with him at first sight. He had himself been struck by her good looks and her stylish air, and learning that there could be no doubt about her fortune, he lost no time in making his advances. Before the end of the first week of their acquaintance he proposed. She referred him to her brother before she could consent; and though, when Kostalergi inquired amongst her English friends, none had ever heard of a Lord Kilgobbin, the fact of his being Irish explained their ignorance, not to say that Kearney’s reply, being a positive refusal of consent, so fully satisfied the Greek that it was ‘a good thing,’ he pressed his suit with a most passionate ardour: threatened to kill himself if she persisted in rejecting him, and so worked upon her heart by his devotion, or on her pride by the thought of his position, that she yielded, and within three weeks from the day they first met, she became the Princess of Delos.

When a Greek, holding any public employ, marries money, his Government is usually prudent enough to promote him. It is a recognition of the merit that others have discovered, and a wise administration marches with the inventions of the age it lives in. Kostalergi’s chief was consequently recalled, suffered to fall back upon his previous obscurity—he had been a commission-agent for a house in the Greek trade—and the Prince of Delos gazetted as Minister Plenipotentiary of Greece, with the first class of St. Salvador, in recognition of his services to the state; no one being indiscreet enough to add that the aforesaid services were comprised in marrying an Irishwoman with a dowry of—to quote the Athenian Hemera—‘three hundred and fifty thousand drachmas.’

For a while—it was a very brief while—the romantic mind of the Irish girl was raised to a sort of transport of enjoyment. Here was everything—more than everything—her most glowing imagination had ever conceived. Love, ambition, station all gratified, though, to be sure, she had quarrelled with her brother, who had returned her last letters unopened. Mathew, she thought, was too good-hearted to bear a long grudge: he would see her happiness, he would hear what a devoted and good husband her dear Spiridion had proved himself, and he would forgive her at last.

Though, as was well known, the Greek envoy received but a very moderate salary from his Government, and even that not paid with a strict punctuality, the legation was maintained with a splendour that rivalled, if it did not surpass, those of France, England, or Russia. The Prince of Delos led the fashion in equipage, as did the Princess in toilet; their dinners, their balls, their fêtes attracted the curiosity of even the highest to witness them; and to such a degree of notoriety had the Greek hospitality attained, that Naples at last admitted that without the Palazzo Kostalergi there would be nothing to attract strangers to the capital.

Play, so invariably excluded from the habits of an embassy, was carried on at this legation to such an excess that the clubs were completely deserted, and all the young men of gambling tastes flocked here each night, sure to find lansquenet or faro, and for stakes which no public table could possibly supply. It was not alone that this life of a gambler estranged Kostalergi from his wife, but that the scandal of his infidelities had reached her also, just at the time when some vague glimmering suspicions of his utter worthlessness were breaking on her mind. The birth of a little girl did not seem in the slightest degree to renew the ties between them; on the contrary, the embarrassment of a baby, and the cost it must entail, were the only considerations he would entertain, and it was a constant question of his—uttered, too, with a tone of sarcasm that cut her to the heart: ‘Would not her brother—the Lord Irlandais—like to have that baby? Would she not write and ask him?’ Unpleasant stories had long been rife about the play at the Greek legation, when a young Russian secretary, of high family and influence, lost an immense sum under circumstances which determined him to refuse payment. Kostalergi, who had been the chief winner, refused everything like inquiry or examination; in fact, he made investigation impossible, for the cards, which the Russian had declared to be marked, the Greek gathered up slowly from the table and threw into the fire, pressing his foot upon them in the flames, and then calmly returning to where the other stood, he struck him across the face with his open hand, saying, as he did it: ‘Here is another debt to repudiate, and before the same witnesses also!’

The outrage did not admit of delay. The arrangements were made in an instant, and within half an hour—merely time enough to send for a surgeon—they met at the end of the garden of the legation. The Russian fired first, and though a consummate pistol-shot, agitation at the insult so unnerved him that he missed: his ball cut the knot of Kostalergi’s cravat. The Greek took a calm and deliberate aim, and sent his bullet through the other’s forehead. He fell without a word, stone dead.

Though the duel had been a fair one, and the procès-verbal drawn up and agreed on both sides showed that all had been done loyally, the friends of the young Russian had influence to make the Greek Government not only recall the envoy, but abolish the mission itself.

For some years the Kostalergis lived in retirement at Palermo, not knowing nor known to any one. Their means were now so reduced that they had barely sufficient for daily life, and though the Greek prince—as he was called—constantly appeared on the public promenade well dressed, and in all the pride of his handsome figure, it was currently said that his wife was literally dying of want.

It was only after long and agonising suffering that she ventured to write to her brother, and appeal to him for advice and assistance. But at last she did so, and a correspondence grew up which, in a measure, restored the affection between them. When Kostalergi discovered the source from which his wretched wife now drew her consolation and her courage, he forbade her to write more, and himself addressed a letter to Kearney so insulting and offensive—charging him even with causing the discord of his home, and showing the letter to his wife before sending it—that the poor woman, long failing in health and broken down, sank soon after, and died so destitute, that the very funeral was paid for by a subscription amongst her countrymen. Kostalergi had left her some days before her death, carrying the girl along with him, nor was his whereabouts learned for a considerable time.

When next he emerged into the world it was at Rome, where he gave lessons in music and modern languages, in many in which he was a proficient. His splendid appearance, his captivating address, his thorough familiarity with the modes of society, gave him the entrée to many houses where his talents amply requited the hospitality he received. He possessed, amongst his other gifts, an immense amount of plausibility, and people found it, besides, very difficult to believe ill of that well-bred, somewhat retiring man, who, in circumstances of the very narrowest fortunes, not only looked and dressed like a gentleman, but actually brought up a daughter with a degree of care and an amount of regard to her education that made him appear a model parent.

Nina Kostalergi was then about seventeen, though she looked at least three years older. She was a tall, slight, pale girl, with perfectly regular features—so classic in the mould, and so devoid of any expression, that she recalled the face one sees on a cameo. Her hair was of wondrous beauty—that rich gold colour which has reflets through it, as the light falls full or faint, and of an abundance that taxed her ingenuity to dress it. They gave her the sobriquet of the Titian Girl at Rome whenever she appeared abroad.

In the only letter Kearney had received from his brother-in-law after his sister’s death was an insolent demand for a sum of money, which he alleged that Kearney was unjustly withholding, and which he now threatened to enforce by law. ‘I am well aware,’ wrote he, ‘what measure of honour or honesty I am to expect from a man whose very name and designation are a deceit. But probably prudence will suggest how much better it would be on this occasion to simulate rectitude than risk the shame of an open exposure.’

To this gross insult Kearney never deigned any reply; and now more than two years passed without any tidings of his disreputable relative, when there came one morning a letter with the Roman postmark, and addressed, ‘À Monsieur le Vicomte de Kilgobbin, à son Château de Kilgobbin, en Irlande.’ To the honour of the officials in the Irish post-office, it was forwarded to Kilgobbin with the words, ‘Try Mathew Kearney, Esq.,’ in the corner.

A glance at the writing showed it was not in Kostalergi’s hand, and, after a moment or two of hesitation, Kearney opened it. He turned at once for the writer’s name, and read the words, ‘Nina Kostalergi’—his sister’s child! ‘Poor Matty,’ was all he could say for some minutes. He remembered the letter in which she told him of her little girl’s birth, and implored his forgiveness for herself and his love for her baby.’ I want both, my dear brother,’ wrote she; ‘for though the bonds we make for ourselves by our passions—’ And the rest of the sentence was erased—she evidently thinking she had delineated all that could give a clue to a despondent reflection.

The present letter was written in English, but in that quaint, peculiar hand Italians often write. It began by asking forgiveness for daring to write to him, and recalling the details of the relationship between them, as though he could not have remembered it. ‘I am, then, in my right,’ wrote she, ‘when I address you as my dear, dear uncle, of whom I have heard so much, and whose name was in my prayers ere I knew why I knelt to pray.’

Then followed a piteous appeal—it was actually a cry for protection. Her father, she said, had determined to devote her to the stage, and already had taken steps to sell her—she said she used the word advisedly—for so many years to the impresario of the ‘Fenice’ at Venice, her voice and musical skill being such as to give hope of her becoming a prima donna. She had, she said, frequently sung at private parties at Rome, but only knew within the last few days that she had been, not a guest, but a paid performer. Overwhelmed with the shame and indignity of this false position, she implored her mother’s brother to compassionate her. ‘If I could not become a governess, I could be your servant, dearest uncle,’ she wrote. ‘I only ask a roof to shelter me, and a refuge. May I go to you? I would beg my way on foot if I only knew that at the last your heart and your door would be open to me, and as I fell at your feet, knew that I was saved.’

Until a few days ago, she said, she had by her some little trinkets her mother had left her, and on which she counted as a means of escape, but her father had discovered them and taken them from her.

‘If you answer this—and oh! let me not doubt you will—write to me to the care of the Signori Cayani and Battistella, bankers, Rome. Do not delay, but remember that I am friendless, and but for this chance hopeless.—Your niece,

‘NINA KOSTALERGI.’

While Kearney gave this letter to his daughter to read, he walked up and down the room with his head bent and his hands deep in his pockets.

‘I think I know the answer you’ll send to this, papa,’ said the girl, looking up at him with a glow of pride and affection in her face. ‘I do not need that you should say it.’

‘It will take fifty—no, not fifty, but five-and-thirty pounds to bring her over here, and how is she to come all alone?’

Kate made no reply; she knew the danger sometimes of interrupting his own solution of a difficulty.

‘She’s a big girl, I suppose, by this—fourteen or fifteen?’

‘Over nineteen, papa.’

‘So she is, I was forgetting. That scoundrel, her father, might come after her; he’d have the right if he wished to enforce it, and what a scandal he’d bring upon us all!’

‘But would he care to do it? Is he not more likely to be glad to be disembarrassed of her charge?’

‘Not if he was going to sell her—not if he could convert her into money.’

‘He has never been in England; he may not know how far the law would give him any power over her.’

‘Don’t trust that, Kate; a blackguard always can find out how much is in his favour everywhere. If he doesn’t know it now, he’d know it the day after he landed.’ He paused an instant, and then said: ‘There will be the devil to pay with old Peter Gill, for he’ll want all the cash I can scrape together for Loughrea fair. He counts on having eighty sheep down there at the long crofts, and a cow or two besides. That’s money’s worth, girl!’

Another silence followed, after which he said, ‘And I think worse of the Greek scoundrel than all the cost.’

‘Somehow, I have no fear that he’ll come here?’

‘You’ll have to talk over Peter, Kitty’—he always said Kitty when he meant to coax her. ‘He’ll mind you, and at all events, you don’t care about his grumbling. Tell him it’s a sudden call on me for railroad shares, or’—and here he winked knowingly—‘say, it’s going to Rome the money is, and for the Pope!’

‘That’s an excellent thought, papa,’ said she, laughing; ‘I’ll certainly tell him the money is going to Rome, and you’ll write soon—you see with what anxiety she expects your answer.’

‘I’ll write to-night when the house is quiet, and there’s no racket nor disturbance about me.’ Now though Kearney said this with a perfect conviction of its truth and reasonableness, it would have been very difficult for any one to say in what that racket he spoke of consisted, or wherein the quietude of even midnight was greater than that which prevailed there at noonday. Never, perhaps, were lives more completely still or monotonous than theirs. People who derive no interests from the outer world, who know nothing of what goes on in life, gradually subside into a condition in which reflection takes the place of conversation, and lose all zest and all necessity for that small talk which serves, like the changes of a game, to while away time, and by the aid of which, if we do no more, we often delude the cares and worries of existence.

A kind good-morning when they met, and a few words during the day—some mention of this or that event of the farm or the labourers, and rare enough too—some little incident that happened amongst the tenants, made all the materials of their intercourse, and filled up lives which either would very freely have owned were far from unhappy.

Dick, indeed, when he came home and was weather-bound for a day, did lament his sad destiny, and mutter half-intelligible nonsense of what he would not rather do than descend to such a melancholy existence; but in all his complainings he never made Kate discontented with her lot, or desire anything beyond it.

‘It’s all very well,’ he would say, ‘till you know something better.’

‘But I want no better.’

‘Do you mean you’d like to go through life in this fashion?’

‘I can’t pretend to say what I may feel as I grow older; but if I could be sure to be as I am now, I could ask nothing better.’

‘I must say, it’s a very inglorious life?’ said he, with a sneer.

‘So it is, but how many, may I ask, are there who lead glorious lives? Is there any glory in dining out, in dancing, visiting, and picnicking? Where is the great glory of the billiard-table, or the croquet-lawn? No, no, my dear Dick, the only glory that falls to the share of such humble folks as we are, is to have something to do, and to do it.’

Such were the sort of passages which would now and then occur between them, little contests, be it said, in which she usually came off the conqueror.

If she were to have a wish gratified, it would have been a few more books—something besides those odd volumes of Scott’s novels, Zeluco by Doctor Moore, and Florence McCarthy, which comprised her whole library, and which she read over and over unceasingly. She was now in her usual place—a deep window-seat—intently occupied with Amy Robsart’s sorrows, when her father came to read what he had written in answer to Nina. If it was very brief it was very affectionate. It told her in a few words that she had no need to recall the ties of their relationship; that his heart never ceased to remind him of them; that his home was a very dull one, but that her cousin Kate would try and make it a happy one to her; entreated her to confer with the banker, to whom he remitted forty pounds, in what way she could make the journey, since he was too broken in health himself to go and fetch her. ‘It is a bold step I am counselling you to take. It is no light thing to quit a father’s home, and I have my misgivings how far I am a wise adviser in recommending it. There is, however, a present peril, and I must try, if I can, to save you from it. Perhaps, in my old-world notions, I attach to the thought of the stage ideas that you would only smile at; but none of our race, so far as I know, fell to that condition—nor must you while I have a roof to shelter you. If you would write and say about what time I might expect you, I will try to meet you on your landing in England at Dover. Kate sends you her warmest love, and longs to see you.’

This was the whole of it. But a brief line to the bankers said that any expense they judged needful to her safe convoy across Europe would be gratefully repaid by him.

‘Is it all right, dear? Have I forgotten anything?’ asked he, as Kate read it over.

‘It’s everything, papa—everything. And I do long to see her.’

‘I hope she’s like Matty—if she’s only like her poor mother, it will make my heart young again to look at her.’

In that old square of Trinity College, Dublin, one side of which fronts the Park, and in chambers on the ground-floor, an oak door bore the names of ‘Kearney and Atlee.’ Kearney was the son of Lord Kilgobbin; Atlee, his chum, the son of a Presbyterian minister in the north of Ireland, had been four years in the university, but was still in his freshman period, not from any deficiency of scholarlike ability to push on, but that, as the poet of the Seasons lay in bed, because he ‘had no motive for rising,’ Joe Atlee felt that there need be no urgency about taking a degree which, when he had got, he should be sorely puzzled to know what to do with. He was a clever, ready-witted, but capricious fellow, fond of pleasure, and self-indulgent to a degree that ill suited his very smallest of fortunes, for his father was a poor man, with a large family, and had already embarrassed himself heavily by the cost of sending his eldest son to the university. Joe’s changes of purpose—for he had in succession abandoned law for medicine, medicine for theology, and theology for civil engineering, and, finally, gave them all up—had so outraged his father that he declared he would not continue any allowance to him beyond the present year; to which Joe replied by the same post, sending back the twenty pounds inclosed him, and saying: ‘The only amendment I would make to your motion is—as to the date—let it begin from to-day. I suppose I shall have to swim without corks some time. I may as well try now as later on.’

The first experience of his ‘swimming without corks’ was to lie in bed two days and smoke; the next was to rise at daybreak and set out on a long walk into the country, from which he returned late at night, wearied and exhausted, having eaten but once during the day.

Kearney, dressed for an evening party, resplendent with jewellery, essenced and curled, was about to issue forth when Atlee, dusty and wayworn, entered and threw himself into a chair.

‘What lark have you been on, Master Joe?’ he said. ‘I have not seen you for three days, if not four!’

‘No; I’ve begun to train,’ said he gravely. ‘I want to see how long a fellow could hold on to life on three pipes of Cavendish per diem. I take it that the absorbents won’t be more cruel than a man’s creditors, and will not issue a distraint where there are no assets, so that probably by the time I shall have brought myself down to, let us say, seven stone weight, I shall have reached the goal.’

This speech he delivered slowly and calmly, as though enunciating a very grave proposition.

‘What new nonsense is this? Don’t you think health worth something?’

‘Next to life, unquestionably; but one condition of health is to be alive, and I don’t see how to manage that. Look here, Dick, I have just had a quarrel with my father; he is an excellent man and an impressive preacher, but he fails in the imaginative qualities. Nature has been a niggard to him in inventiveness. He is the minister of a little parish called Aghadoe, in the North, where they give him two hundred and ten pounds per annum. There are eight in family, and he actually does not see his way to allow me one hundred and fifty out of it. That’s the way they neglect arithmetic in our modern schools!’

‘Has he reduced your allowance?’

‘He has done more, he has extinguished it.’

‘Have you provoked him to this?’

‘I have provoked him to it.’

‘But is it not possible to accommodate matters? It should not be very difficult, surely, to show him that once you are launched in life—’

‘And when will that be, Dick?’ broke in the other. ‘I have been on the stocks these four years, and that launching process you talk of looks just as remote as ever. No, no; let us be fair; he has all the right on his side, all the wrong is on mine. Indeed, so far as conscience goes, I have always felt it so, but one’s conscience, like one’s boots, gets so pliant from wear, that it ceases to give pain. Still, on my honour, I never hip-hurraed to a toast that I did not feel: there goes broken boots to one of the boys, or, worse again, the cost of a cotton dress for one of the sisters. Whenever I took a sherry-cobbler I thought of suicide after it. Self-indulgence and self-reproach got linked in my nature so inseparably, it was hopeless to summon one without the other, till at last I grew to believe it was very heroic in me to deny myself nothing, seeing how sorry I should be for it afterwards. But come, old fellow, don’t lose your evening; we’ll have time enough to talk over these things—where are you going?’

‘To the Clancys’.’

‘To be sure; what a fellow I am to forget it was Letty’s birthday, and I was to have brought her a bouquet! Dick, be a good fellow and tell her some lie or other—that I was sick in bed, or away to see an aunt or a grandmother, and that I had a splendid bouquet for her, but wouldn’t let it reach her through other hands than my own, but to-morrow—to-morrow she shall have it.’

‘You know well enough you don’t mean anything of the sort.’

‘On my honour, I’ll keep my promise. I’ve an old silver watch yonder—I think it knows the way to the pawn-office by itself. There, now be off, for if I begin to think of all the fun you’re going to, I shall just dress and join you.’

‘No, I’d not do that,’ said Dick gravely, ‘nor shall I stay long myself. Don’t go to bed, Joe, till I come back. Good-bye.’

‘Say all good and sweet things to Letty for me. Tell her—’ Kearney did not wait for his message, but hurried down the steps and drove off.

Joe sat down at the fire, filled his pipe, looked steadily at it, and then laid it on the mantel-piece. ‘No, no, Master Joe. You must be thrifty now. You have smoked twice since—I can afford to say—since dinner-time, for you haven’t dined. It is strange, now that the sense of hunger has passed off, what a sense of excitement I feel. Two hours back I could have been a cannibal. I believe I could have eaten the vice-provost—though I should have liked him strongly devilled—and now I feel stimulated. Hence it is, perhaps, that so little wine is enough to affect the heads of starving people—almost maddening them. Perhaps Dick suspected something of this, for he did not care that I should go along with him. Who knows but he may have thought the sight of a supper might have overcome me. If he knew but all. I’m much more disposed to make love to Letty Clancy than to go in for galantine and champagne. By the way, I wonder if the physiologists are aware of that? It is, perhaps, what constitutes the ethereal condition of love. I’ll write an essay on that, or, better still, I’ll write a review of an imaginary French essay. Frenchmen are permitted to say so much more than we are, and I’ll be rebukeful on the score of his excesses. The bitter way in which a Frenchman always visits his various incapacities—whether it be to know something, or to do something, or to be something—on the species he belongs to; the way in which he suggests that, had he been consulted on the matter, humanity had been a much more perfect organisation, and able to sustain a great deal more of wickedness without disturbance, is great fun. I’ll certainly invent a Frenchman, and make him an author, and then demolish him. What if I make him die of hunger, having tasted nothing for eight days but the proof-sheets of his great work—the work I am then reviewing? For four days—but stay—if I starve him to death, I cannot tear his work to pieces. No; he shall be alive, living in splendour and honour, a frequenter of the Tuileries, a favoured guest at Compiègne.’

Without perceiving it, he had now taken his pipe, lighted it, and was smoking away. ‘By the way, how those same Imperialists have played the game!—the two or three middle-aged men that Kinglake says, “put their heads together to plan for a livelihood.” I wish they had taken me into the partnership. It’s the sort of thing I’d have liked well; ay, and I could have done it, too! I wonder,’ said he aloud—‘I wonder if I were an emperor should I marry Letty Clancy? I suspect not. Letty would have been flippant as an empress, and her cousins would have made atrocious princes of the imperial family, though, for the matter of that—Hullo! Here have I been smoking without knowing it! Can any one tell us whether the sins we do inadvertently count as sins, or do we square them off by our inadvertent good actions? I trust I shall not be called on to catalogue mine. There, my courage is out!’ As he said this he emptied the ashes of his pipe, and gazed sorrowfully at the empty bowl.

‘Now, if I were the son of some good house, with a high-sounding name, and well-to-do relations, I’d soon bring them to terms if they dared to cast me off. I’d turn milk or muffin man, and serve the street they lived in. I’d sweep the crossing in front of their windows, or I’d commit a small theft, and call on my high connections for a character—but being who and what I am, I might do any or all o these, and shock nobody.

‘Next to take stock of my effects. Let me see what my assets will bring when reduced to cash, for this time it shall be a sale.’ And he turned to a table where paper and pens were lying, and proceeded to write. ‘Personal, sworn under, let us say, ten thousand pounds. Literature first. To divers worn copies of Virgil, Tacitus, Juvenal, and Ovid, Cæsar’s Commentaries, and Catullus; to ditto ditto of Homer, Lucian, Aristophanes, Balzac, Anacreon, Bacon’s Essays, and Moore’s Melodies; to Dwight’s Theology—uncut copy, Heine’s Poems—very much thumbed, Saint Simon—very ragged, two volumes of Les Causes Célèbres, Tone’s Memoirs, and Beranger’s Songs; to Cuvier’s Comparative Anatomy, Shroeder on Shakespeare, Newman’s Apology, Archbold’s Criminal Law and Songs of the Nation; to Colenso, East’s Cases for the Crown, Carte’s Ormonde, and Pickwick. But why go on? Let us call it the small but well-selected library of a distressed gentleman, whose cultivated mind is reflected in the marginal notes with which these volumes abound. Will any gentleman say, “£10 for the lot”? Why the very criticisms are worth—I mean to a man of literary tastes—five times the amount. No offer at £10? Who is it that says “five”? I trust my ears have deceived me. You repeat the insulting proposal? Well, sir, on your own head be it! Mr. Atlee’s library—or the Atlee collection is better—was yesterday disposed of to a well-known collector of rare books, and, if we are rightly informed, for a mere fraction of its value. Never mind, sir, I bear you no ill-will! I was irritable, and to show you my honest animus in the matter, I beg to present you in addition with this, a handsomely-bound and gilt copy of a sermon by the Reverend Isaac Atlee, on the opening of the new meeting-house in Coleraine—a discourse that cost my father some sleepless nights, though I have heard the effect on the congregation was dissimilar.

‘The pictures are few. Cardinal Cullen, I believe, is Kearney’s; at all events, he is the worse for being made a target for pistol firing, and the archiepiscopal nose has been sorely damaged. Two views of Killarney in the weather of the period—that means July, and raining in torrents—and consequently the scene, for aught discoverable, might be the Gaboon. Portrait of Joe Atlee, ætatis four years, with a villainous squint, and something that looks like a plug in the left jaw. A Skye terrier, painted, it is supposed, by himself; not to recite unframed prints of various celebrities of the ballet, in accustomed attitudes, with the Reverend Paul Bloxham blessing some children—though from the gesture and the expression of the juveniles it might seem cuffing them—on the inauguration of the Sunday school at Kilmurry Macmacmahon.

‘Lot three, interesting to anatomical lecturers and others, especially those engaged in palæontology. The articulated skeleton of an Irish giant, representing a man who must have stood in his no-stockings eight feet four inches. This, I may add, will be warranted as authentic, in so far that I made him myself out of at least eighteen or twenty big specimens, with a few slight “divergencies” I may call them, such as putting in eight more dorsal vertebrae than the regulation, and that the right femur is two inches longer than the left. The inferior maxillary, too, was stolen from a “Pithacus Satyrus” in the Cork Museum by an old friend, since transported for Fenianism. These blemishes apart, he is an admirable giant, and fully as ornamental and useful as the species generally.

‘As to my wardrobe, it is less costly than curious; an alpaca paletot of a neutral tint, which I have much affected of late, having indisposed me to other wear. For dinner and evening duty I usually wear Kearney’s, though too tight across the chest, and short in the sleeves. These, with a silver watch which no pawnbroker—and I have tried eight—will ever advance more on than seven-and-six. I once got the figure up to nine shillings by supplementing an umbrella, which was Dick’s, and which still remains, “unclaimed and unredeemed.”

‘Two o’clock, by all that is supperless! evidently Kearney is enjoying himself. Ah, youth, youth! I wish I could remember some of the spiteful things that are said of you—not but on the whole, I take it, you have the right end of the stick. Is it possible there is nothing to eat in this inhospitable mansion?’ He arose and opened a sort of cupboard in the wall, scrutinising it closely with the candle. ‘“Give me but the superfluities of life,” says Gavarni, “and I’ll not trouble you for its necessaries.” What would he say, however, to a fellow famishing with hunger in presence of nothing but pickled mushrooms and Worcester sauce! Oh, here is a crust! “Bread is the staff of life.” On my oath, I believe so; for this eats devilish like a walking-stick.

‘Hullo! back already?’ cried he, as Kearney flung wide the door and entered. ‘I suppose you hurried away back to join me at supper.’

‘Thanks; but I have supped already, and at a more tempting banquet than this I see before you.’

‘Was it pleasant? was it jolly? Were the girls looking lovely? Was the champagne-cup well iced? Was everybody charming? Tell me all about it. Let me have second-hand pleasure, since I can’t afford the new article.’

‘It was pretty much like every other small ball here, where the garrison get all the prettiest girls for partners, and take the mammas down to supper after.’

‘Cunning dogs, who secure flirtation above stairs and food below! And what is stirring in the world? What are the gaieties in prospect? Are any of my old flames about to get married?’

‘I didn’t know you had any.’

‘Have I not! I believe half the parish of St. Peter’s might proceed against me for breach of promise; and if the law allowed me as many wives as Brigham Young, I’d be still disappointing a large and interesting section of society in the suburbs.’

‘They have made a seizure on the office of the Pike, carried off the press and the whole issue, and are in eager pursuit after Madden, the editor.’

‘What for? What is it all about?’

‘A new ballad he has published; but which, for the matter of that, they were singing at every corner as I came along.’

‘Was it good? Did you buy a copy?’

‘Buy a copy? I should think not.’

‘Couldn’t your patriotism stand the test of a penny?’

‘It might if I wanted the production, which I certainly did not; besides, there is a run upon this, and they were selling it at sixpence.’

‘Hurrah! There’s hope for Ireland after all! Shall I sing it for you, old fellow? Not that you deserve it. English corruption has damped the little Irish ardour that old rebellion once kindled in your heart; and if you could get rid of your brogue, you’re ready to be loyal. You shall hear it, however, all the same.’ And taking up a very damaged-looking guitar, he struck a few bold chords, and began:—

‘Is there anything more we can fight or can hate for? The “drop” and the famine have made our ranks thin. In the name of endurance, then, what do we wait for? Will nobody give us the word to begin? ‘Some brothers have left us in sadness and sorrow, In despair of the cause they had sworn to win; They owned they were sick of that cry of “to-morrow”; Not a man would believe that we meant to begin. ‘We’ve been ready for months—is there one can deny it? Is there any one here thinks rebellion a sin? We counted the cost—and we did not decry it, And we asked for no more than the word to begin? ‘At Vinegar Hill, when our fathers were fighters, With numbers against them, they cared not a pin; They needed no orders from newspaper writers, To tell them the day it was time to begin. ‘To sit here in sadness and silence to bear it, Is harder to face than the battle’s loud din; ‘Tis the shame that will kill me—I vow it, I swear it? Now or never’s the time, if we mean to begin.’

There was a wild rapture in the way he struck the last chords, that, if it did not evince ecstasy, seemed to counterfeit enthusiasm.

‘Very poor doggerel, with all your bravura,’ said Kearney sneeringly.

‘What would you have? I only got three-and-six for it.’

‘You! Is that thing yours?’

‘Yes, sir; that thing is mine. And the Castle people think somewhat more gravely about it than you do.’

‘At which you are pleased, doubtless?’

‘Not pleased, but proud, Master Dick, let me tell you. It’s a very stimulating reflection to the man who dines on an onion, that he can spoil the digestion of another fellow who has been eating turtle.’

‘But you may have to go to prison for this.’

‘Not if you don’t peach on me, for you are the only one who knows the authorship. You see, Dick, these things are done cautiously. They are dropped into a letter-box with an initial letter, and a clerk hands the payment to some of those itinerant hags that sing the melody, and who can be trusted with the secret as implicitly as the briber at a borough election.’

‘I wish you had a better livelihood, Joe.’

‘So do I, or that my present one paid better. The fact is, Dick, patriotism never was worth much as a career till one got to the top of the profession. But if you mean to sleep at all, old fellow, “it’s time to begin,”’ and he chanted out the last words in a clear and ringing tone, as he banged the door behind him.

It was while the two young men were seated at breakfast that the post arrived, bringing a number of country newspapers, for which, in one shape or other, Joe Atlee wrote something. Indeed, he was an ‘own correspondent,’ dating from London, or Paris, or occasionally from Rome, with an easy freshness and a local colour that vouched for authenticity. These journals were of a very political tint, from emerald green to the deepest orange; and, indeed, between two of them—the Tipperary Pike and the Boyne Water, hailing from Carrickfergus—there was a controversy of such violence and intemperance of language, that it was a curiosity to see the two papers on the same table: the fact being capable of explanation, that they were both written by Joe Atlee—a secret, however, that he had not confided even to his friend Kearney.

‘Will that fellow that signs himself Terry O’Toole in the Pike stand this?’ cried Kearney, reading aloud from the Boyne Water:—

‘“We know the man who corresponds with you under the signature of Terry O’Toole, and it is but one of the aliases under which he has lived since he came out of the Richmond Bridewell, filcher, forger, and false witness. There is yet one thing he has never tried, which is to behave with a little courage. If he should, however, be able to persuade himself, by the aid of his accustomed stimulants, to accept the responsibility of what he has written, we bind ourselves to pay his expenses to any part of France or Belgium, where he will meet us, and we shall also bind ourselves to give him what his life little entitles him to, a Christian burial afterwards.

‘“No SURRENDER.”’

‘I am just reading the answer,’ said Joe. ‘It is very brief: here it is:—

“‘If ‘No Surrender’—who has been a newsvender in your establishment since you yourself rose from that employ to the editor’s chair—will call at this office any morning after distributing his eight copies of your daily issue, we promise to give him such a kicking as he has never experienced during his literary career. TERRY O’TOOLE.’”

‘And these are the amenities of journalism,’ cried Kearney.

‘For the matter of that, you might exclaim at the quack doctor of a fair, and ask, Is this the dignity of medicine?’ said Joe. ‘There’s a head and a tail to every walk in life: even the law has a Chief-Justice at one end and a Jack Ketch at the other.’

‘Well, I sincerely wish that those blackguards would first kick and then shoot each other.’

‘They’ll do nothing of the kind! It’s just as likely that they wrote the whole correspondence at the same table and with the same jug of punch between them.’

‘If so, I don’t envy you your career or your comrades.’

‘It’s a lottery with big prizes in the wheel all the same! I could tell you the names of great swells, Master Dick, who have made very proud places for themselves in England by what you call “journalism.” In France it is the one road to eminence. Cannot you imagine, besides, what capital fun it is to be able to talk to scores of people you were never introduced to? to tell them an infinity of things on public matters, or now and then about themselves; and in so many moods as you have tempers, to warn them, scold, compassionate, correct, console, or abuse them? to tell them not to be over-confident or bumptious, or purse-proud—’

‘And who are you, may I ask, who presume to do all this?’

‘That’s as it may be. We are occasionally Guizot, Thiers, Prévot Paradol, Lytton, Disraeli, or Joe Atlee.’

‘Modest, at all events.’

‘And why not say what I feel—not what I have done, but what is in me to do? Can’t you understand this: it would never occur to me that I could vault over a five-bar gate if I had been born a cripple? but the conscious possession of a little pliant muscularity might well tempt me to try it.’

‘And get a cropper for your pains.’

‘Be it so. Better the cropper than pass one’s life looking over the top rail and envying the fellow that had cleared it; but what’s this? here’s a letter here: it got in amongst the newspapers. I say, Dick, do you stand this sort of thing?’ said he, as he read the address.

‘Stand what sort of thing?’ asked the other, half angrily.

‘Why, to be addressed in this fashion? The Honourable Richard Kearney, Trinity College, Dublin.’

‘It is from my sister,’ said Kearney, as he took the letter impatiently from his hand; ‘and I can only tell you, if she had addressed me otherwise, I’d not have opened her letter.’

‘But come now, old fellow, don’t lose temper about it. You have a right to this designation, or you have not—’

‘I’ll spare all your eloquence by simply saying, that I do not look on you as a Committee of Privilege, and I’m not going to plead before you. Besides,’ added he, ‘it’s only a few minutes ago you asked me to credit you for something you have not shown yourself to be, but that you intended and felt that the world should see you were, one of these days.’

‘So, then, you really mean to bring your claim before the Lords?’

Kearney, if he heard, did not heed this question, but went on to read his letter. ‘Here’s a surprise!’ cried he. ‘I was telling you, the other day, about a certain cousin of mine we were expecting from Italy.’

‘The daughter of that swindler, the mock prince?’

‘The man’s character I’ll not stand up for, but his rank and title are alike indisputable,’ said Kearney haughtily.

‘With all my heart. We have soared into a high atmosphere all this day, and I hope my respiration will get used to it in time. Read away!’

It was not till after a considerable interval that Kearney had recovered composure enough to read, and when he did so it was with a brow furrowed with irritation:—

‘KILGOBBIN.

‘My dear Dick,—We had just sat down to tea last night, and papa was fidgeting about the length of time his letter to Italy had remained unacknowledged, when a sharp ring at the house-door startled us. We had been hearing a good deal of searches for arms lately in the neighbourhood, and we looked very blankly at each other for a moment. We neither of us said so, but I feel sure our thoughts were on the same track, and that we believed Captain Rock, or the head-centre, or whatever be his latest title, had honoured us with a call. Old Mathew seemed of the same mind too, for he appeared at the door with that venerable blunderbuss we have so often played with, and which, if it had any evil thoughts in its head, I must have been tried for a murder years ago, for I know it was loaded since I was a child, but that the lock has for the same space of time not been on speaking terms with the barrel. While, then, thus confirmed in our suspicions of mischief by Mat’s warlike aspect, we both rose from the table, the door opened, and a young girl rushed in, and fell—actually threw herself into papa’s arms. It was Nina herself, who had come all the way from Rome alone, that is, without any one she knew, and made her way to us here, without any other guidance than her own good wits.

‘I cannot tell you how delighted we are with her. She is the loveliest girl I ever saw, so gentle, so nicely mannered, so soft-voiced, and so winning—I feel myself like a peasant beside her. The least thing she says—her laugh, her slightest gesture, the way she moves about the room, with a sort of swinging grace, which I thought affected at first, but now I see is quite natural—is only another of her many fascinations.

‘I fancied for a while that her features were almost too beautifully regular for expression, and that even when she smiled and showed her lovely teeth, her eyes got no increase of brightness; but, as I talked more with her, and learned to know her better, I saw that those eyes have meanings of softness and depths in them of wonderful power, and, stranger than all, an archness that shows she has plenty of humour.

‘Her English is charming, but slightly foreign; and when she is at a loss for a word, there is just that much of difficulty in finding it which gives a heightened expression to her beautifully calm face, and makes it lovely. You may see how she has fascinated me, for I could go on raving about her for hours.

‘She is very anxious to see you, and asks me over and over again, Shall you like her? I was almost candid enough to say “too well.” I mean that you could not help falling in love with her, my dear Dick, and she is so much above us in style, in habit, and doubtless in ambition, that such would be only madness. When she saw your photo she smiled, and said, “Is he not superb?—I mean proud?” I owned you were, and then she added, “I hope he will like me.” I am not perhaps discreet if I tell you she does not like the portrait of your chum, Atlee. She says “he is very good-looking, very clever, very witty, but isn’t he false?” and this she says over and over again. I told her I believed not; that I had never seen him myself, but that I knew that you liked him greatly, and felt to him as a brother. She only shook her head, and said, “Badate bene a quel che dico. I mean,” said she, “I’m right, but he’s very nice for all that!” If I tell you this, Dick, it is just because I cannot get it out of my head, and I will keep saying over and over to myself—“If Joe Atlee be what she suspects, why does she call him very nice for all that?” I said you intended to ask him down here next vacation, and she gave the drollest little laugh in the world—and does she not look lovely when she shows those small pearly teeth? Heaven help you, poor Dick, when you see her! but, if I were you, I should leave Master Joe behind me, for she smiles as she looks at his likeness in a way that would certainly make me jealous, if I were only Joe’s friend, and not himself.

‘We sat up in Nina’s room till nigh morning, and to-day I have scarcely seen her, for she wants to be let sleep, after that long and tiresome journey, and I take the opportunity to write you this very rambling epistle; for you may feel sure I shall be less of a correspondent now than when I was without companionship, and I counsel you to be very grateful if you hear from me soon again.

‘Papa wants to take Duggan’s farm from him, and Lanty Moore’s meadows, and throw them into the lawn; but I hope he won’t persist in the plan; not alone because it is a mere extravagance, but that the county is very unsettled just now about land-tenure, and the people are hoping all sorts of things from Parliament, and any interference with them at this time would be ill taken. Father Cody was here yesterday, and told me confidentially to prevent papa—not so easy a thing as he thinks, particularly if he should come to suspect that any intimidation was intended—and Miss O’Shea unfortunately said something the other day that papa cannot get out of his head, and keeps on repeating. “So, then, it’s our turn now,” the fellows say; “the landlords have had five hundred years of it; it’s time we should come in.” And this he says over and over with a little laugh, and I wish to my heart Miss Betty had kept it to herself. By the way, her nephew is to come on leave, and pass two months with her; and she says she hopes you will be here at the same time, to keep him company; but I have a notion that another playfellow may prove a dangerous rival to the Hungarian hussar; perhaps, however, you would hand over Joe Atlee to him.

‘Be sure you bring us some new books, and some music, when you come, or send them, if you don’t come soon. I am terrified lest Nina should think the place dreary, and I don’t know how she is to live here if she does not take to the vulgar drudgeries that fill my own life. When she abruptly asked me, “What do you do here?” I was sorely puzzled to know what to answer, and then she added quickly: “For my own part, it’s no great matter, for I can always dream. I’m a great dreamer!” Is it not lucky for her, Dick? She’ll have ample time for it here.

‘I suppose I never wrote so long a letter as this in my life; indeed I never had a subject that had such a fascination for myself. Do you know, Dick, that though I promised to let her sleep on till nigh dinner-time, I find myself every now and then creeping up gently to her door, and only bethink me of my pledge when my hand is on the lock; and sometimes I even doubt if she is here at all, and I am half crazy at fearing it may be all a dream.

‘One word for yourself, and I have done. Why have you not told us of the examination? It was to have been on the 10th, and we are now at the 18th. Have you got—whatever it was? the prize, or the medal, or—the reward, in short, we were so anxiously hoping for? It would be such cheery tidings for poor papa, who is very low and depressed of late, and I see him always reading with such attention any notice of the college he can find in the newspaper. My dear, dear brother, how you would work hard if you only knew what a prize success in life might give you. Little as I have seen of her, I could guess that she will never bestow a thought on an undistinguished man. Come down for one day, and tell me if ever, in all your ambition, you had such a goal before you as this?

‘The hoggets I sent in to Tullamore fair were not sold; but I believe Miss Betty’s steward will take them; and, if so, I will send you ten pounds next week. I never knew the market so dull, and the English dealers now are only eager about horses, and I’m sure I couldn’t part with any if I had them. With all my love, I am your ever affectionate sister,

‘KATE KEARNEY.’

‘I have just stepped into Nina’s room and stolen the photo I send you. I suppose the dress must have been for some fancy ball; but she is a hundred million times more beautiful. I don’t know if I shall have the courage to confess my theft to her.’

‘Is that your sister, Dick?’ said Joe Atlee, as young Kearney withdrew the carte from the letter, and placed it face downwards on the breakfast-table.

‘No,’ replied he bluntly, and continued to read on; while the other, in the spirit of that freedom that prevailed between them, stretched out his hand and took up the portrait.

‘Who is this?’ cried he, after some seconds. ‘She’s an actress. That’s something like what the girl wears in Don Cæsar de Bazan. To be sure, she is Maritana. She’s stunningly beautiful. Do you mean to tell me, Dick, that there’s a girl like that on your provincial boards?’

‘I never said so, any more than I gave you leave to examine the contents of my letters,’ said the other haughtily.

‘Egad, I’d have smashed the seal any day to have caught a glimpse of such a face as that. I’ll wager her eyes are blue grey. Will you have a bet on it?’

‘When you have done with your raptures, I’ll thank you to hand the likeness to me.’

‘But who is she? what is she? where is she? Is she the Greek?’

‘When a fellow can help himself so coolly to his information as you do, I scarcely think he deserves much aid from others; but, I may tell you, she is not Maritana, nor a provincial actress, nor any actress at all, but a young lady of good blood and birth, and my own first cousin.’

‘On my oath, it’s the best thing I ever knew of you.’

Kearney laughed out at this moment at something in the letter, and did not hear the other’s remark.

‘It seems, Master Joe, that the young lady did not reciprocate the rapturous delight you feel, at sight of your picture. My sister says—I’ll read you her very words—“she does not like the portrait of your friend Atlee; he may be clever and amusing, she says, but he is undeniably false.” Mind that—undeniably false.’

‘That’s all the fault of the artist. The stupid dog would place me in so strong a light that I kept blinking.’

‘No, no. She reads you like a book,’ said the other.

‘I wish to Heaven she would, if she would hold me like one.’

‘And the nice way she qualifies your cleverness, by calling you amusing.’

‘She could certainly spare that reproach to her cousin Dick,’ said he, laughing; ‘but no more of this sparring. When do you mean to take me down to the country with you? The term will be up on Tuesday.’

‘That will demand a little consideration now. In the fall of the year, perhaps. When the sun is less powerful the light will be more favourable to your features.’

‘My poor Dick, I cram you with good advice every day; but one counsel I never cease repeating, “Never try to be witty.” A dull fellow only cuts his finger with a joke; he never catches it by the handle. Hand me over that letter of your sister’s; I like the way she writes. All that about the pigs and the poultry is as good as the Farmer’s Chronicle.’

The other made no other reply than by coolly folding up the letter and placing it in his pocket; and then, after a pause, he said—

‘I shall tell Miss Kearney the favourable impression her epistolary powers have produced on my very clever and accomplished chum, Mr. Atlee.’

‘Do so; and say, if she’d take me for a correspondent instead of you, she’d be “exchanging with a difference.” On my oath,’ said he seriously, ‘I believe a most finished education might be effected in letter-writing. I’d engage to take a clever girl through a whole course of Latin and Greek, and a fair share of mathematics and logic, in a series of letters, and her replies would be the fairest test of her acquirement.’

‘Shall I propose this to my sister?’

‘Do so, or to your cousin. I suspect Maritana would be an apter pupil.’

‘The bell has stopped. We shall be late in the hall,’ said Kearney, throwing on his gown hurriedly and hastening away; while Atlee, taking some proof-sheets from the chimney-piece, proceeded to correct them, a slight flicker of a smile still lingering over his dark but handsome face.