An amazing man-hunt in Arctic snows—and how Sergeant Hardy and Keith Morely played the game, each according to his own strict code.

“Halt!”

The curt command cut through the frost-bound silence. The Northern mail driver froze in his tracks.

He shot a glance at his companion, Sergeant Hardy, and saw the officer had whipped his .45 Colt from its holster.

“Quick on the draw, aren’t you? But I’ve got you both covered. Put that gun back in your holster before I count three, or this load of shot will blow your head off.”

The voice came from above. Intently the two men on the narrow defile below scanned the overhanging show-covered rocks, but no form was visible.

“One—” The relentless voice had begun to count.

“Two—”

Grimly Sergeant Hardy slipped his gun in its holster. “The winner of the opening hand does not always win the game,” he thought, dispassionately.

“I want the mail bag,” the unseen speaker went on. “Put the bag on that rock shelf on the right, and be quick.”

Intently the officer listened to that voice. So carefully did he memorize every inflection in it, he would recognize it immediately, anywhere.

“Keep cool, King. He has the advantage now.” Sergeant Hardy’s voice was low, reassuring, but his eyes, hard, vigilant swept the rocks above him carefully.

“Must I put the mail—”

“Yes, or he’ll blow both of our heads off. He has you covered now.”

“Hurry up there.” Impatiently the voice rang out. The man, in his eagerness, leaned over the jutting rock on which he lay. In that instant Hardy obtained a good look at the face of the man.

It was a young face. Not more than thirty or so, clean-shaven. The features were fine, regular, with well molded chin. The man drew back swiftly as his eyes met the officer’s.

Reluctantly the driver deposited the bag of mail on the designated shelf.

“Now, keep going. And, remember, the trail is straight ahead. I can see you both for a mile. Try to double back and I’ll be waiting for you.”

“Nevertheless I’ll see you—again.” Hardy’s voice was still cool, dispassionate. It was as though he said, “this is fine traveling weather.”

“Mush on, King,” Hardy urged in a low voice.

The trail lay clear. Not a dark spot broke its gleaming covering.

Repeatedly Hardy looked back. The fur-clad figure of the man stood motionless. He had descended from his rocky perch, and now stood on the trail watching the swiftly moving dogs, sled and men.

Eagerly he bent over the mail.

Hardy, in a swift backward glance, saw that stooping figure. Instantly he fell out of the dog train.

“Keep going. Notify district headquarters. I’m going back for my man.” The words came with shot-like swiftness.

Keith Morely straightened from the mail bags, gazed ahead. Surely there was but one man with the team! Yet the trail still led straight, unbroken by any dark object, save the one man, the dogs and sled.

Unbelieving, he rubbed his eyes. A man could not vanish in thin air?

The mail driver plied the whip, the dogs raced. He would rather have stayed with the sergeant, fought the thing through, shoulder to shoulder. But the officer had spoken, and he was the law!

Half drowned in the drift into which he had plunged, Hardy lay motionless for a time.

Finally he cautiously raised his snow-covered hooded head. He saw the man standing motionless, then watched him turn, scale the slabs of rock until he reached the top, and disappear.

Lithe as a cat, Hardy scaled the overhanging rocks. Crouching like an Indian, his soft ankle-depth moccasins over his boots as noiseless as the footfall of a cougar, he sped after Keith Morely.

“Thank the powers for a fine day,” Hardy thought. The sun shone dazzlingly. The prisms of a million ice-drops on shrub and tree flashed like jewels, bewilderingly beautiful.

Warily, Hardy followed the moccasin imprints left on the crusted snow.

“He is heading directly away from the trail, and he knows exactly where he’s going. No hesitation in his stride. Ha, he has stopped here to put on his webs.”

The snow was crushed into a circular basin where the man had sat to don his snow shoes.

At a little distance ahead came the shrill scolding voices of a pair of chickadees. Hardy nodded in satisfaction. He knew some passing creature had startled the birds. It was their custom to give warning thus from their lofty perches.

The trail led from the rocky plateau through a narrow ravine to the open ground beyond. Keeping a sharp lookout, Hardy paused in this ravine to don his webs, then took up the trail.

“The man is a bird; he doesn’t web, he flies!” the officer muttered. “I’m pretty fast myself, but he is faster.”

For hours he followed. The sun was casting crimson shadows; the sparse woods grew denser; the short day became the short twilight.

Hardy was strangely tired, but he was not growing cold, though the air was sharpening. It became too dark to distinguish the faint imprint of the webs. Hardy paused, debating whether to build a fire, then walked on, seeking suitable site for night camp.

There appeared to be a clearing ahead. A dark snow-capped smudge sprang before his eyes. “A cabin,” he ejaculated. “I’ll spend the night there.”

For hours a strange lassitude, a sensation of heat; an increasing throbbing headache had been creeping on him.

“What’s the matter with me?” he thought irritably. “Somehow I’m glad to be under a roof to-night.”

There was no yellow winking eye of light in the one window of the squat cabin. The officer approached warily, keeping in the deepest shadows. Apparently the cabin was deserted.

With his finger on the trigger of his gun, he raised the latch on the heavy log-built door, kicked it in swiftly.

His eyes strained through the gloom of the cabin. One swift searching look revealed the tenantless interior.

Hardy stepped into the cold room and slammed the door behind him. He dropped into a chair, breathing heavily. A sudden sensation of suffocation seized him. He pushed the fur hood back from his head, loosened the belt of the parka covering his uniform.

“Haven’t been feeling really fit for the past three days,” he muttered. Pulling himself together with an effort, he came to his feet, investigated the one room and built-on woodshed adjoining. He struck a match to the candle fixed in a bottle, for the room was growing dark.

“Well stocked cabin,” he said as he gazed around.

Again he fell heavily in a chair, gazing before him with anxious eyes. After a time he kindled a fire on the big stone hearth.

Slowly the weather changed as the night wore on. The north wind came with a bellow and roar.

Half dozing, Hardy listened to the mingled voices of the wind and fire as he sat before a blazing log. His eyes were glittering with the fever that ran in his veins.

“Glad I came across this cabin,” he muttered, with thick tongue and dry, swollen lips. “Must be bilious. Be all right to-morrow. I must!”

The storm increased in fury. The blizzard howled and tore over the squat cabin. The snow piled up against its wall logs as though seeking the warmth within.

During the night came the crunch, crunch of webs. A white wraith-like figure came through the gloom, eager expectant eyes peered from frozen eyelashes at the light wavering from the cabin’s fire-lit frost glazed window.

Stiff hands fumbled at the latch, finally released it. The wind swept the door in with a crash.

Hardy raised heavy-lidded eyes and started to rise, but the effort was too much for him. He sank back like a sack of meal.

Keith Morely kicked the door shut.

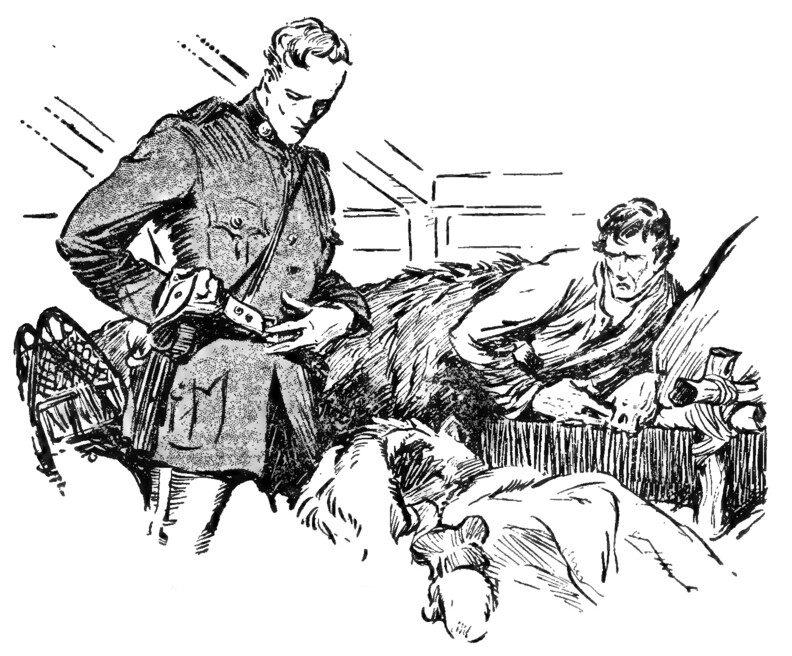

Hardy’s nerveless hand reached for the gun in his holster, but it was strangely fumbling and uncertain. The two men stared at each other.

“So we both chanced across the same cabin. Put up your hands!” Hardy’s voice was thick. The gun wavered in his hand. It seemed intolerably heavy.

Morely stared curiously at that unsteady hand, at the swollen, flushed face of the officer. Despite a tremendous effort it was impossible for Hardy to hold that gun. It clattered to the floor.

Keith Morely’s increasing amazement turned slowly to conviction. He sprang swiftly to Hardy as the man’s head fell back. The room was filled with his gasping, shallow breathing.

Keith Morely lifted the officer in his powerful arms, carried him to the bunk.

“You’re a sick man,” he exclaimed. “Tell me quick, while you are still able to talk, have you been exposed to any disease?”

The words penetrated Hardy’s fast numbing consciousness.

“A few weeks ago, I laid over a night in an Indian’s cabin.”

“How long since you were vaccinated?” The question came quick and sharp.

Hardy heard the words, though they seemed to come from a great distance. He struggled to answer, but unconsciousness sealed his tongue.

Swiftly Keith Morely stripped the man, gazed with grave eyes at the all-revealing eruption on the broad chest and armpits.

“Smallpox!” he ejaculated. “There’s a lot of it in the north this winter.”

Turning to the officer’s pack, he opened it up and took out the medicine kit. It was a well stocked case, revealing the thoroughness of the equipment the northern patrol men carry.

“One thing is certain. The officer cannot make me prisoner now, and I can’t leave him here to die from neglect. When the owner of this cabin returns, I’ll go on. But not before,” Morely said grimly.

With peculiar expertness, he bathed the fevered body of Hardy at regular intervals. He administered medicine taken from the case, he applied an ointment to the rapidly increasing eruptions.

“What a freak of fate,” he muttered. “The hunter is laid low, and the hunted cares for him.” The man’s lips lifted in a mirthless smile, but his eyes were somber, haunted.

Slowly the days dragged their length. The snow beat back the sun, the country sank under an impenetrable shroud of white.

The owner of the cabin did not return. “Snowed under, some place,” Morely thought as grimly he battled for the life of the officer. No great physician could have shown more interest in the work of a difficult case than did Keith Morely. For hours he sat by the sick man’s side, listening to the disjointed delirium.

“He’s been through a lot. The men on the northern patrol have a tough time,” the listening man thought.

Occasionally, as the days passed, Morely went out with his rifle, returning with fresh meat.

The fever abated, the crisis passed. “Pulled him through,” Morely thought, a light of professional satisfaction in his eyes.

He closed the blue service book, belonging to Hardy. The book he had been studying and memorizing. While Hardy slept, his first deep natural sleep since his illness, Morely stripped off his own clothing.

“Fortunate thing we are the same height and build,” he thought as he donned Hardy’s uniform, which he had fumigated.

Completely garbed in Sergeant Hardy’s uniform, he was remarkably like the officer, in figure. Only the face was different, and that would be partly concealed by the fur parka hood.

“In this uniform I can get to Montreal, without pursuit. There, I can secure other clothing, draw funds from the bank, and get to the border. From now, until I reach Montreal, I’m Sergeant Porter Hardy!” The man’s shoulders straightened, his head went up.

“I am absolutely safe. It will be weeks before the officer can get out, renew pursuit. By that time, I’ll be in the States.”

He turned, walked to the bunk, stood staring down at the quietly sleeping man. “Glad I didn’t leave him to die like a dog,” he murmured. “Haven’t that on my conscience.”

Hardy turned, opened his eyes with the light of returned reason in them. He stared at the uniformed figure beside him. A perplexed gaze was in his eyes, then slowly he looked around the cabin.

“Ha, I remember. Was taken sick!” He attempted to sit up, but fell back weakly. “I’ve had a siege,” he thought. “Glad to see another man of the service here. How long have I been ill? And what’s the matter with me?”

Morely stared down at him. Finally:

“You’ve had the smallpox. But you are right-o now. On the mend.”

Hardy drew a startled breath. That voice! No two voices in the world were identical.

Why was this officer before him speaking with the voice of the mail robber whom he was pursuing? He closed his eyes. Weakness, no doubt, had caused hallucination.

“You have been ill three weeks. You’ve been a very sick man, but you are on the highway now,” that tormenting voice went on. “I’ll stay with you until you are able to get out of bed, and help yourself, then—I’ll go on.”

Hallucination be damned! Hardy’s eyes jerked open. Long and steadily he stared at the uniform. His own, of course—there was that mended rent on the tunic sleeve, and that smudge of oil on the left trouser leg!

His eyes swung to the man’s face.

“I recognize you. And what are you doing here? Why didn’t you get away?” The voice was weak but steady.

“And leave you to die! I’m not that sort of a rotter,” Morely said scornfully.

“Then I owe—my recovery—to you?”

“You owe your life to me, to put it plainly. No one has been near the cabin, for I tacked a red rag over the door. A few Indians have passed. I hailed them from a distance. Smallpox is raging from the James Bay waters to the lake country of the Athabasca, they said.”

“My God!”

“Yes. And for the service I have rendered you, I am appropriating your uniform,” Morely went on coolly. “When you are well, you can wear my clothes.”

The men looked at each other silently.

He turned, strode to the hearth over which an iron kettle was suspended. Presently he returned.

“A cup of good strong caribou broth.” He tendered the cup, lifted and held Hardy while the officer ate.

“All you need now, is to recover your strength. Within a few days you’ll be able to hobble around, enough to keep up your fire. The wood house is filled. I have repaired my forage on it. There is a quantity of meat, and I’ll leave a big mess cooked, so you won’t have to cook for several days. By that time you’ll be strong enough—”

“You are singularly thoughtful—under the circumstances,” Hardy commented.

“Thoughtfulness be damned. I’m only doing the sporting thing—”

“Criminals usually do not consider that,” Hardy interrupted dryly.

Morely raised a startled head. Hardy who was watching him closely, saw the swift dilation of his eyes, noted the sharply drawn breath.

“Now you have talked enough. And by the bye your voice is remarkably strong. You will make a quick mend. No doubt you owe that to the constitution you men of the service have. Now go to sleep again. I want you to get strength quickly, for I’m anxious to be off.”

A few days later he left. The cabin seemed strangely lonely, strangely desolate to Hardy, as he lay on the bunk listening to the retreating crunch, crunch of webs, as Morely headed from the cabin onto the trail.

The following morning, before Morely had emerged from his sleeping bag, he heard the tinkle of bells.

An Indian coming from the opposite direction which he traveled, appeared on the trail. His dogs were lean and traveled slowly.

“How is the pest?” Morely asked in the Cree tongue.

The Indian paused. His figure drooped, his shoulders sagged.

“It spreads as does the bush fire. It has struck the Crees, on Woelaston Lake. It is wiping out the Chippewayans between Albany and the Churchill.”

The Indian spoke with impassive bronze face, but his eyes were deep with melancholy. Morely waited, a great fear in his heart.

“The Crees are wailing their death dirges as they seek the bones of their dead from beneath the charred cabins, for the white men are burning all cabins wherein the pest has been. Our dogs are howling mournfully for masters whose voices are still.

“I passed many trap-houses. They were unbaited; in some, the traps were sprung, yet the trappers came not to gather their catch. The snowshoe trails were many suns old.”

“Where do you come from? Have you passed Nichikun Lake post?”

“I came through there—”

“Are there many sick?” Morely interrupted quickly.

“Many are sick. The factor, his squaw and his clerk have answered the call of the Great Spirit.”

Morely’s face was white. “Who cares for the sick?”

“The priest whose hair is white as the new snow and whose step is slow with the weight of many suns.” He glanced at the motionless white man. “I have spoken.” His voice fell low, grave. The long line of dogs moved slowly down the trail.

“This is the worst epidemic the North has known,” Morely thought.

It was the year in which the north fought grimly the great cataclysm. The scourge took a thousand lives before it finally surrendered to the heroic efforts of a handful of white men and women.

“And Father du Bois, that gentle, kindly old saint, is fighting alone at the post. Living through the stench, the horror of it! And he is old, frail. I am young, strong, have knowledge and skill.” The man stared across the great waste.

“If I go back it means prison for me, for sooner or later I will be caught. When Hardy recovers, he will take up the trail. And yet, my God, to run like a coward! To leave suffering, dying humanity, when I can prevent many deaths, when I can help check the spread of this epidemic.

“McAndrews, his wife and the clerk gone! And Father du Bois, patiently, laboriously, is waging his lonely fight. He needs me, the North needs me. What a service I could render!”

He stared in the direction where lay Nichikun Post. Silently his battle went on. Finally he turned, got his pack together, without pausing to make his breakfast. The message of the throbbing Arctic sky had reached his soul. With grim lips and unwavering eyes he turned his face toward Nichikun Post.

“I am making poor time, afoot. If only I could raise a sled and dogs!” Morely muttered.

With the dawn came the snow. After a quick breakfast he moved on. The wind increased, drove the snow like millions of ice points through the gray atmosphere.

Toward noon Morely saw a cabin sitting like a squat black insect on a field of white. His pulses quickened as he saw the pillar of black smoke vomiting from its chimney and a team of five dogs and sled standing before the place. Head down against the wind that buffeted him at every step, he made his way. The dogs set up a chorus of howls at his approach. A door was flung open.

“Bad day,” a laconic voice remarked as he slipped off his webs and entered. The warmth of the room smote him gratefully. Morely passed his arms through the straps, set the pack outside the cabin. His lips were stiff with cold. For a moment it was impossible for him to speak, or to see in the bright firelight.

“Was just leaving, but I’ll wait awhile and hear the news. How’s the pest?”

As the man spoke another figure entered the little cabin, from the wood house.

“Eh bien, Jacques he ’ave more company?” a warm friendly voice shouted.

“I’m not staying long. In a hurry. I want those dogs of yours. Sent out on detail, must make haste,” Morely said quietly.

He removed his parka, shaking the snow from it, and stood revealed in the uniform he wore.

“Well met. What district are you from and your name? I’m Corporal English, out of Moose Factory.”

Morely wheeled. So blinded had he been by snow and wind, he had not seen the man’s uniform when he entered.

“Jacques, he ’ave an honor. Two men of ze Mounted under hees roof,” the French trapper murmured. His round black eyes gazed admiringly at the splendid proportions of the two men. Both of them standing six foot, deep chests, stalwart shoulders, slim waisted.

Regretfully he rubbed his hand over his rotund stomach.

“I’m Hardy, Lake St. John,” Morely said coolly, returning the other’s steady gaze.

He turned to Jacques. “I’ll have to commandeer your team.”

“You are Porter Hardy?” Corporal English asked.

“Yes.” There was no hesitation in Morely’s answer. He dared not hesitate!

“Wha’ can I do? M’sieu Eng-leesh ’ave bought my team and sled before you come.” Jacques spread his hand despairingly.

“And I’ll keep them. Put up your hands while you explain to me why you’re wearing a uniform of the service and passing yourself off as Sergeant Hardy! I know Hardy. Give an account of yourself. Who are you?”

The words came like a shot.

Morely gazed from a pair of inexorable eyes to the blue barrel of English’s gun.

With the motion of a cougar, so swift it was, Morely ducked, sprang at English. An upward thrust and the gun clattered to the floor.

Jacques, wide-eyed, moved to a corner, watching the two men as they grappled. He had not understood those few swift words of English’s.

The men, their arms gripped around each other, rolled over and over, each seeking an opening. Finally English tore an arm loose. His great hand went around Morely’s throat, shutting out the air.

But not for long. As they had rolled on the floor Morely had inch by inch controlled their movements, so that he lay near the fallen revolver.

Desperately stretching an arm and long fingers, he touched the butt of the gun. His chest was rising in shallow gasps, as he attempted to breathe. There was a roar in his eardrums, a fleck of blood dropped from his nostrils.

With one long finger he drew the butt of the gun nearer. His fingers closed around it.

Jacques in his corner watched with fascinated eyes. He saw that English’s face was turned away from that outflung arm, and so was unconscious of Morely’s action.

Suddenly English felt the barrel against his side. He turned his head, read the desperation in Morely’s eyes.

His grip relaxed. Morely drew in a breath of air that eased his tortured lungs.

Slowly English came to his feet. With a catlike bound Morely faced him, finger curled on trigger.

Without removing his eyes from the officer’s face, Morely addressed the fascinated Jacques.

“I must take your dogs, but do not fear. They will either be returned to you, or I will send payment. Write your name on a slip of paper. Then step outside. Put my pack in the sled. Have you any cooked meat on hand?”

“Oui, m’sieu” Jacques responded with glowing eyes. He had warmed instantly to this man.

“Put all you have in the sled. Also what fish you can spare, for the dogs.”

He addressed English, as Jacques sprang to do his bidding.

“If you darken that doorway until I am out of gunshot, I’ll shoot. And there’s no better shot in the north than myself.”

Slowly, he backed to the door, picked up his parka, backed across the threshold.

The door slammed to behind him.

He sprang in the sled, lay flat. As his “mush” cry arose, a bullet from English’s rifle, the barrel protruding from under the window roared through the storm.

The dogs sprang forward, instinctively headed for the trail, a stone’s throw from the cabin.

Morely smiled grimly. “Good thing I laid flat, or he’d have had me.”

Again bullets spat toward the fleeing man. The snow and sleet were so heavy, the wind so high that visibility was poor at even a few yards.

When that trail was reached the cabin was blotted from sight.

Morely sprang from the sled, drew the fur parka over his head, headed the dogs toward Nichikun.

He reentered the long light sled, the hiss of a moose-hide whip cut through the sleet. The dogs, well fed, in good condition, sprang forward with a will. Speed was wanted. Speed they would give.

Daily Hardy’s strength was increasing.

Longer each day he sat in the big chair before the crackling fire; then a few steps farther until he could reach the door.

Constantly his thoughts revolved around the man who had stayed with him, brought him through this siege.

The weeks dragged by until a month had passed since Morely’s departure.

The weather settled fine, clear, with brilliant sunshine. The white world glittered and sparkled like a sea of flashing jewels.

“I’m strong enough now. If I had dogs I should have left a week ago.”

Hardy stood in the open door of the cabin gazing across the country. Far down the trail came several dark specks. Gradually the specks took on shape and substance, became a moving team of dogs, with sled, and a man at the gee-pole.

Opposite the cabin the team turned, made their way to the little building.

“Don’t come too near. Smallpox!” he shouted.

Steadily the half-breed came on. When near the cabin he paused.

“Me, I heard you, mais eet not matter. I am jus’ over ze pest.” The trapper lifted a scarred and pitted face to Hardy.

“Dese ees my cabin. I was away in a line-cabin when ze sickness took me. Many weeks ’ave I been gone, but now I, Le Massan, am well, and ’ave come home.

“Eh bien, eet ees good to be home.” He loosed the dogs from their harness, stepped into the cabin, shut the door behind him.

Rapidly Hardy explained his presence in the man’s cabin; told of the fugitive he pursued.

“Many strange things ’appen in de time of de pest. Zis man, he save your life,” Le Massan said thoughtfully, “an’ now you go to catch heem an’ imprison heem? Zat ees strange.” He shrugged.

“Personal obligation has nothing to do with my duty.”

“Oui? Me, I am glad I am onlee a trapper, for ze squaw who find me w’en I am sick and nurse me back to life, I will marry. So does Le Massan gif hees thanks. M’sieu l’officier ’ave no value on hees life w’en he gif no thanks?”

Le Massan’s voice and manner were disapproving. He gazed reproachfully at Hardy.

“It is not as simple as you think,” he said wearily. “Now, my friend, I want your dogs and sled, also an outfit. I will pay you in cash. I have currency in my money belt.”

“An’ zis man, he did not take your monee?”

“No, he is not that type of—thief.” Within an hour Hardy left. Le Massan watched with disapproving eyes as Hardy swung onto the trail.

“Which way has he gone? North or south? I would be inclined to think south, perhaps to the nearest railway station. Yet that assumption seems so simple—too simple. Therefore, I turn north.”

The day was magnificent. Clear, sparkling, the sun of dazzling brilliance.

It was that transition period between the darkness of winter and the coming of spring, when the world takes on an unearthly aspect. The brilliant sun gave a glaring light. Tree and bush glittered with indescribable beauty.

Hardy had been on the trail several days when he began to notice his blurred vision. “Eyes are weak. Smallpox often leaves a weakened condition of sight,” he reassured himself.

Yet the following morning when he awakened he found his lids glued together with a thick sticky substance. By feel only he built his fire, melted a small pail of snow. For an hour he bathed his swollen lids, separating them at last. But his sight was poor, and an intolerable pain pierced his eyeballs.

All day he kept going, closing his eyes as much as possible against a world that glistened like polished steel. Dimmer grew his vision. By mid-afternoon darkness closed in.

“Snowblind!” For a moment panic seized him, but his iron will quickly controlled it.

“Other men have had the same experience and came through,” he told himself grimly.

He sat in the sled, while the dogs trotted up the wind-swept ice, his ears straining for the sound of other sled runners, or the crunch of webs.

“Must be about sundown,” Hardy muttered. “Better call a halt.”

Suddenly there was a startled yelp from the lead dog, followed by a hoarse chorus of howls.

Desperately Hardy strained his blind eyes. A sharp report, an ominous volley of cracks, the sound of a swift current flowing under the ice told the story. Amid a terrified din from the struggling dogs, Hardy sprang from the sled. The cracks were spreading, widening into a sunburst. Hardy felt the water under his boots.

Swiftly he sprang back. “Oh, God, for a second of sight!” he breathed. Slowly, cautiously he backed. The ice became firm under his boots. He paused, listening to the frenzied struggles and wild howling of the team, until one by one their voices were stilled.

He heard the suction as the sled was drawn into the water.

It is not an uncommon thing in northern waters, that strange, warm undercurrent on which a thin layer of ice forms. Ice deceptive in appearance, but when surmounted by a weight it gives suddenly and treacherously.

Hardy continued to walk backward, realizing if he turned he would be at a loss to know in which direction he walked.

“Looks bad,” he muttered. “Blankets and supplies gone down with the sled. I’ll have to keep moving to keep up the circulation.”

Wearily he walked during that long night. By morning his muscles stiffened to the consistency of raw cowhide. Weakened from his illness, his vitality lessened swiftly.

Toward morning he stumbled over a low-growing snow-capped bush. Unconsciously he had half circled across the river and reached its wooded shore.

Eagerly with panting breath he felt among the brush, got a pile together, carried them to the shore ice. There were matches in the waterproof case in the parka pocket. Quickly he kindled a fire, a fitful, smoldering little flame, but its warmth was inexpressively grateful to the chilled man.

Many round balls of eyes from culvert and hilltop watched that fire curiously, fearfully.

Hardy did not know it, but death was near, lurking in fangs and claw. If he allowed that blaze to extinguish, the gray terrors of the wild would be on him.

The old priest raised a shaking hand, touched Morely’s face half fearfully. “Ees eet really you, my son? So often ’ave I dreamed that you came like this, only to awaken. Are you real or ees this but another dream?”

His tired, sunken eyes gazed anxiously at the man.

Morely threw an arm around the bowed shoulders, held the thin body to him for a moment. “It is I, father. And the first thing I do is to put you to bed. You are worn out. You need rest. I shall take charge here—”

“Le bon Dieu! How often ’ave I prayed for your return, my son! God ees good.”

Morely arrived at the peak of the epidemic and threw himself body and mind into the battle. Day and night he worked with but brief intervals for rest.

“If only I had fresh vaccine!” he groaned. Vigorously he segregated the well from the sick; battled to keep wailing mothers from dying children, fought to keep fathers from stricken sons.

“My son, you mus’ rest. So hard you work,” the old priest said anxiously.

“Does a soldier rest in the midst of battle, father? When the enemy is in retreat, when it is beaten, then I will rest,” Morely said gravely.

For a time the bell in the chapel tolled daily. Gradually at fewer intervals, until a week had passed without a death.

“We’ve licked it, father!” An exultant light shone in Morely’s eyes, but his face was drawn, white from fatigue.

A week passed without a new case. The convalescent were growing stronger.

“There is little to do now at the Post, father. I have time to visit some cabins in the woods. There may be sick in them.”

In one cabin he found a dead body. The cabin was burned.

Toward evening he saw the blaze from a camp fire.

“Some traveler. Better investigate,” he thought.

His webs were almost soundless as he approached, yet Hardy’s keen ears heard the faint crunch.

“Help,” he called.

Hoarse though the voice was, Morely recognized it. He froze in his tracks, motionless, scarcely breathing, cold with astonishment.

Screened behind a great tree, Morely watched Hardy take hesitating steps forward, saw him crash into a tree. Amazement held the watching man.

It was growing dark, but there was still light enough to see the trees and brush.

“Blind! Left the cabin too soon. And what a bloodhound he is! He’s trailed me almost to the Post!”

Rapidly Morely thought, planned. He webbed to the officer.

“Ha, here you are,” the blind man cried. “Thought you had gone on. I need help. Snowblind.”

Morely gazed at the swollen lids, glued together over the sightless eyes. He grasped Hardy’s arm. In a hoarse, guttural voice he spoke a few words of Cree.

“You’re an Indian? Then take me to your cabin. The blindness of the sun-on-the-snow has fallen on me.”

“I take you to my lodge,” he grunted in Cree. Hardy heaved a sigh of relief.

Morely, who was known and admired as a great medicine man among the Crees of Northern Quebec, knew he could depend on Migisi.

When the Indian heard the men approaching he threw open his door. Morely shook his head and pointed warningly at Hardy.

He led the officer into the warm candle-lit room.

The fragrant odor of broiling deer steak lay in the air.

“Ha, this feels and smells good,” Hardy exclaimed.

Beckoning to Migisi, Morely left the cabin, the Indian following.

Lowering his voice cautiously, he told the Indian:

“I have brought this man to you. He is snowblind. I found him on the shore trail. But I do not want him to hear my voice. He thinks an Indian found him, for I spoke to him in Cree. Let him think no one is in the cabin save himself and you. Migisi understands?”

The Indian nodded.

“Watch me, how I care for his eyes. When I leave with the rising sun, you continue the treatment until the light again pierces his eyes.

“If he cannot see by the third sun, come to me. Care for him, Migisi. A two-pound tin of tobacco shall reward you.”

Migisi’s moccasined footfalls were noiseless as he prepared the supper.

“Migisi care for your eyes now,” the Indian grunted. For an hour he watched Morely apply the snow applications on pieces of flour-sacking which he had made sterile by long boiling.

With the dawn Morely left, made his way to the Post.

“He will not leave the cabin until his eyes are thoroughly freed of the inflammation. He realizes it would be too dangerous to his sight, and no matter how impatient he may be, he knows a blind man is out of the Service.” Morely thought.

“I have a week. But I must be gone before then. I’ll take no chances, for he will make for the Post first thing. God!” The bitter exclamation came like a shot. “How different this has turned out from what I planned! And all my own fault. If I had kept hidden, if Hardy had not seen my face when I stopped the mail, all would have been well.

“I would never have been suspected, could have got back to the Post as I planned. Everything gone wrong, because of that one mishap. Also, I did not know a man of the Mounted would be traveling with the carrier.”

There was a continual sound of ax and saw in the air. The men of the Post were busily felling logs, erecting new cabins, making new tables, chairs and bunks. The Post was emerging from her weeks of horror.

The morning of the third day since his finding of Hardy, Migisi came to the Post, sought out Morely.

“The white man’s eyes have been pierced by the light. This morning he could see me.”

Morely turned to his supply shelves, took a tin of tobacco, gave it to the expectant Indian. When the Indian had gone, Morely walked swiftly to the old priest’s cabin.

“I must leave to-night. It is hard to go, but you can handle the convalescent, and any day the new factor will be here. Our moccasin telegraph has carried word of the deaths of McAndrews, his wife and his clerk to the major posts. They no doubt have long since notified the company.

“Father, I am leaving to-night. I—” Morely paused. It was hard to lie looking in those kindly, loving eyes.

There was a crunch of webs on the snow outside. Some one stopped to remove his webs, then knocked at the cabin door. The old priest hurried to the door, threw it open.

The man in the doorway looked over the white head, directly into the eyes of Morely.

“We meet again,” said he. The voice fell curt, hard.

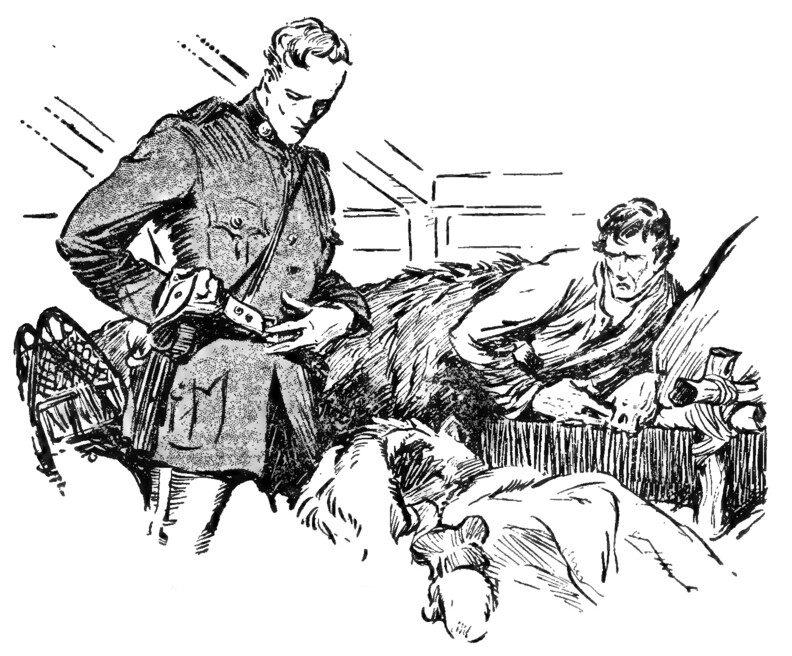

Morely looked from the barrel of the drawn gun into the eyes of Sergeant Hardy!

“I arrest you for the robbery of the mail. Up with your hands!” Sergeant Hardy’s curt voice broke the silence.

“Arrest—mail—wha’ you mean?” the old priest faltered.

He turned to Hardy. “Who are you?” he half whispered.

“I am Sergeant Hardy of the Mounted. I was with Jim King, the mail driver, when this man stopped us.” Hardy’s voice softened as he gazed into the stricken eyes of the old priest.

“Of a certainty there ees some mistake. This ees Dr. Keith Morely—”

“No mistake, father. Look at him. Ask him, if that is necessary.”

“My son, you a mail robber? In God’s name, why?”

“I should like to know that myself,” Hardy commented dryly.

“Tell us.” Again that half whispering voice of Father du Bois.

“There was something in the mail I had to have.” Morley’s voice fell low. “I cut across the country to intercept it. I intended getting what I wanted and return here.

“All would have gone as I had planned, save that Sergeant Hardy happened to be traveling for a distance with the driver. He saw my face. I knew then that I would have to leave the country. I intended doing so, but fate willed otherwise.”

“Mais, you were gone so long.” Father du Bois paused in bewilderment.

“A blizzard came up. The sergeant and I both sought shelter in the same cabin. He was sick—with the pest. I stayed with him until he was convalescent.”

“He saved my life, father.” For the first time during Morely’s narrative Hardy spoke.

Morely studied the officer’s reddened eyelids.

“You recovered your sight quickly,” he said, “but you must be careful of your eyes.”

Hardy stared at him incredulously. How did this man know of his recent blindness?

“How do you know I have been blind?” Hardy asked quickly.

“I did not intend to mention it. It slipped out unawares, but it was I who found you by your camp fire and led you to the Indian’s cabin. I spoke to you in Cree so you would not recognize my voice.”

“Another obligation, Morely. Seems I am pretty deep in your debt.” The men gazed at each other silently.

“Will you continue your narrative?” There was a strange quality in Hardy’s voice. “Why did you return here, when you had planned differently?”

“I met an Indian on the trail. He told me of the factor’s and his wife’s deaths. I realized I was needed. I knew Father du Bois was fighting it alone. I had to return.”

Grimly Hardy nodded. The three sat silent. After a time Morely said: “You got the sack of mail, sergeant? It was in good condition, I trust?”

Hardy stared at Morely blankly.

“What do you mean?” he barked.

“Why, surely you returned for the sack? It was not far from the cabin in which we stayed.” It was Morely’s turn to speak sharply. Incredulously he stared at Hardy’s blank face. “Surely you read my note?”

“What note?”

“The note I placed in the parka pocket. The one you are wearing.”

Hardy dug deep in the pocket. Pressed into a corner was a small folded piece of paper. He had not noticed it before. He drew it out, glanced at it blankly.

Aloud he read:

“I got what I wanted. You will find the mail sack in that wedge of rocks, where I stopped you and the driver, I piled stones over the crevice to protect it.”

The room was silent. After a time: “What did you take from the sack?” Hardy asked.

“A letter. I had no interest in the mail, otherwise. I intended placing it where it eventually would be recovered. Of course my gun threat was only a bluff. I would not have shot—”

“Whose letter was it you ran such risks to secure?” Hardy asked swiftly.

“The factor’s, McAndrews. I had to have it.”

“Explain, Morely.”

“I will explain at headquarters,” he said slowly.

Father du Bois laid a trembling hand on Hardy’s arm.

“Sergeant, I beg of you, do not take this man. You can free heem if you would. You are not onlee an exponent of ze law. You are ze law itself. You who are clad with ze authority of courts, can make your own court here, try, an’ release this man.”

Hardy was silent, his troubled gaze on the priest’s pleading eyes.

“There ees so much sickness. Ze people need ze doctor. Of a certainty he ees needed. Do not take heem away.”

“Father, this is not a case wherein I could act as judge.” Hardy’s voice was low. “I realize all you say. And I also realize my own obligation to my prisoner. Yet, father, you, who would not betray a confession, cannot ask me to violate the code of the Mounted? I cannot possibly consider my personal wishes.”

Keith Morely came to his feet.

“I am ready, sergeant. And by the way, your uniform is at my cabin. No doubt you want to wear it? It has been fumigated and aired. We shall stop at the store and get a pair of very dark goggles for your eyes. You must be careful.”

Hardy glowed with admiration. Dammit but he liked this man. No cringing, no begging for quarter. Voice cool and steady.

Morely turned. Silently the hands of the priest gripped his.

“When you are shut away between dark walls, have courage, my son. Always my prayers are with you an’ I shall be waiting for your return.” The gentle voice faltered.

The two men walked to the door. With misty eyes the priest listened to the retreating crunch of their webs.

“It seems you overstep in pleading this man’s case, sergeant.”

Inspector McKenzie looked narrowly at Hardy’s earnest face.

“I have but given you a detailed report, sir. Only adding that the prisoner saved my life. I believe, twice. I have also reported what I have heard concerning him. I made inquiries at every Post on the way here. I questioned people who know him. He is honored by all.

“He has given three years of his life to the North without reward. His services are invaluable, for you know, sir, we cannot get half the physicians we need up here. He stamped out the pest at Nichikun. In other Posts, it is still raging. And Jim King, the driver, is dead, too.”

The inspector sat silent. “Bring in your prisoner,” he said finally.

Hardy saluted, left the inspector’s court. Morely raised haggard eyes, questioning.

“He is ready for you. And Dr. Morely, I want to tell you, I’m sorry. Dammit, I’m sorry. I wish I could have—”

“I understand, sergeant.” The voice was low, strained.

Inspector McKenzie looked sharply at the man before him.

“What have you got to say?” he snapped.

“I had to have that letter.”

“Why?” the inspector barked.

“Haven’t you read it? I gave it to the sergeant.”

“I want your story first. Then I’ll read it.”

“McAndrews and I had quarreled bitterly. He accused me of too friendly relations with a half-breed girl at the Post. The accusation was false. The girl was only grateful for my pulling her through a siege of pneumonia. Some one aroused McAndrews’s suspicions and he was stubborn. Wouldn’t listen to me, or believe me.

“His daughter Alice and I are engaged. She is spending the winter in Quebec, and we were to be married on her return.

“He wrote her, telling her the sort of man he thought I was, and told her to break our engagement immediately.

“She is a type of girl who believes absolutely in her father. Thinks he can do no wrong, that he’s never mistaken. She is loyal and devoted to him. He insisted on my reading his letter, doubtless to convince me that Alice was lost to me, irrevocably. And she would have been. She would never have listened to me.” Morely paused a moment.

“I knew the letter went out on that mail. I determined to get it. And I did.”

Involuntarily McKenzie nodded. Did a memory of his own hot-blooded youth return to him? Youth that will dare much for the loved one?

“I intended returning immediately to the Post. My short absence would not have been noticed, for I often go in the woods where sickness has been reported. Within a week or so, I intended going to Quebec, and urge Alice to marry me there. I think she would have—for we love each other. Then we would have returned to the Post. For my work is here, in the North, that I love.”

Morely fell silent.

“Seems to me it was an act of—er—Providence that Alice McAndrews never received that letter. Her father and mother dead, the poor girl needs the man she loves,” Hardy ventured. He kept a wary eye on the inspector as he spoke.

McKenzie stared at his sergeant fixedly, then picked up McAndrews’s letter. He read it thoughtfully, his heavy brows drawn together, his face grave.

Morely’s hopes died. There was no softness, no sympathy in that rock-like face.

To be locked in prison, while the pest still raged! When he was so badly needed! And Alice, alone in her bereavement—he groaned aloud.

Hardy’s face was moody as he watched McKenzie.

“The law recognizes extenuating circumstances.” McKenzie was speaking. “I feel that I am justified in dismissing this case. You are free, Dr. Morely.”

He rose, held out his hand. Inspector McKenzie’s eyes twinkled as he looked at his sergeant.

This story appeared in the October 20, 1928 issue of Argosy All-Story Weekly magazine.