Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

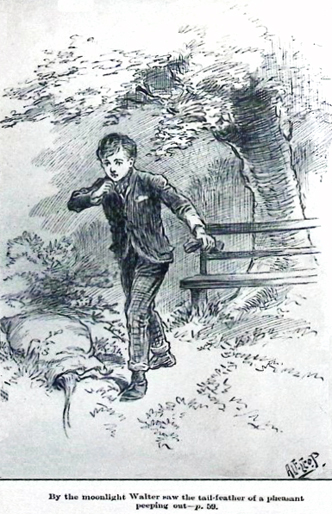

By the moonlight Walter saw the tail-feather of a

pheasant peeping out.

And what came of it

BY

C. O'BRIEN

Author of "Little Gipsy Marion," "Dominick's Trials,"

& c., & c.

London

GALL AND INGLIS, 25 PATERNOSTER SQUARE;

AND EDINBURGH.

PRINTED

AND BOUND BY

GALL AND INGLIS

LUTTON PLACE

EDINBURGH

CONTENTS.

——————

CHAPTER VI. THE SECRET OF SUCCESS

————————

THE EIGHT BELLS AND THEIR VOICES

THE TWO PATHS.

ONE evening in autumn, two lads stood talking together at the corner of a road in the small seaside village of Springcliffe.

"What are you thinking of doing about it then, Frank?" said the boy who seemed the younger of the two.

"Just nothing at all."

"Have you made up your mind, then?"

"Quite."

"And you will not join them?"

"Not I."

"Why not, Frank?"

"Why not?—Why, because when one is sixteen, I think one has a right to all the spare time one can get; and it's little enough at the best, working from morning to night as we do."

The speaker uttered these words in a decided tone, as much as to say, "There, that will settle the matter." But it did not appear to have the desired effect, for the boy who had first spoken said,—

"I don't think any one wants to take away our spare time, Frank."

"I don't know what you call it then, Walter, I'm sure. There we leave off work at six, and then, instead of having the evening to ourselves, we are asked to make ourselves tidy, and go to the evening school at seven! I should like to know where our spare time goes to!"

"It's only three times a week, Frank."

"And that's three times too many! No; I'm for liberty."

A young man, two or three years older than Frank, passed by at that moment, and whispered something in his ear.

"All right," said Frank, "I'll—"

"Hush!—" And the newcomer looked distrustfully at Walter as he walked away whistling.

"Why don't you speak to Tom Haines, Walter?" said Frank. "You used to be friends at one time."

"Mother doesn't think Tom a good companion for me," replied Walter, "and she says—"

"Are you always going to mind what your mother says?" cried Frank, in a mocking tone.

"I hope so, Frank. I think she is the best friend I have in the world."

"And of course she insists on your going to this evening school."

"Not at all," replied Walter; "she leaves me quite free to decide for myself, after she has given me her opinion on the subject. Mother says I am a rational being, and able to judge between right and wrong."

"And, pray, what is her opinion?"

"Very much the same, only in different words, as what our rector told us in church last Sunday, at the end of his sermon, when he spoke about the evening school; but you were not there, Frank, were you?"

"No," replied Frank. "Well, and what did he say?"

"He spoke of the great value of learning, and said that any knowledge we could gain now would be like so much capital to trade with when we got older. He said, too, that an ignorant man was like one who lived in a dark and gloomy house into which the bright sun never shone; and he called getting knowledge like opening a window in the dark house. He told us also that a young man who can read well, write a good hand, keep accounts, and who knows something about the country in which he lives, is sure to rise in the world—always providing that he is steady and industrious. There was a great deal more, which I cannot remember; but it seemed to me that it all meant pretty nearly the same thing; and I had made up my mind before ever I left the church."

Frank gave a derisive laugh.

"I wonder what writing and accounts have to do with planing smoothly, or driving a nail well home."

Frank and Walter were both learning the trade of a carpenter, and worked together at the same bench.

"I have heard say," said Walter, "that our master was himself only a poor boy not many years ago; but that he was a good scholar, and so gradually rose to be first foreman, and afterwards master. Very likely we can either of us plane a deal, or drive in a nail as well as he can; but I'm sure we could not have told how much glass would be required for Squire Forbes's new greenhouse, nor have been able to reckon exactly how much it would all cost, as master did when the Squire came into the yard yesterday morning.

"And did you see, Frank, the pretty drawing he made of a greenhouse, so that Squire Forbes could see that he understood what he wanted? They are going to teach drawing, amongst other things, at the evening school, and I mean to learn, if I possibly can manage it."

"I see it is of no use talking to you, Walter, but you'll not convince me; so I shall go my own way."

"And I shall go mine," said Walter, with a smile, "and we shall see whose way turns out the best in the end. I hadn't much schooling when I was a little boy, for I had to leave off going to school when poor father died; so I know I am very backward in a great many things; but now I hope I shall be able to make up for lost time."

"I believe you know far more than I do," replied Frank honestly; "for although I was at school long after you left, I don't think I did much good there. I was always a sad dunce, Walter; and, between ourselves, the chief reason why I told father I should like to be a carpenter was because I thought there wasn't much learning wanted to hammer in nails and plane wood. And as to being master, I'll leave that for you, and shall content myself with being one of your workmen, should you ever arrive at the high position to which you aspire."

The lads separated—Frank to keep his appointment, whatever it might be, with Tom Haines, and Walter to go to the Rectory, to enter down his name as one who would wish to attend the evening school, then about to be formed, for the first time, in Springcliffe.

And here let us say a few words about the benefit of evening classes. It is a fact that there are very, very many men and women, even at the present day, who scarcely know how to read and write. There are, indeed, few who do not, as children, go to school for some portion of time; but it is also a fact that, as a rule, the working-classes withdraw their children from school as soon as their labour can be turned to any account, so that, with very few exceptions, all education may be said to have ceased before the age of twelve, and, more commonly at nine or ten years of age. When to this is added the irregular attendance, even during the few years they are nominally at school, the result is that the working-classes remain almost without education, very few having so far mastered the difficulties of reading and writing as to keep up the habit in after-life, and thus they soon lose the little knowledge they acquired.

It was to meet this evil that evening schools were first established. It is not enough to have made a beginning in reading, writing, or counting, unless such a degree of facility is gained as to render the exercise a pleasure, the little that was learned is very soon forgotten. Evening schools, then, are meant to make up to the young working man or woman for the short period of their early school life, by giving them opportunities of learning thoroughly what in most cases was only learned imperfectly.

Reading and writing are, in themselves not so much knowledge, as the means whereby we gain knowledge; and those who can read and write well will be always able to acquire information. The attendance at evening schools being for the most part entirely voluntary, resulting from a wish to improve themselves on the part of those who attend, the progress made is generally very much more rapid on that account; and a lad will frequently be found to have learned more during a few months' regular attendance at an evening school than he did in two or three years of his earlier school life.

A lad who is worth anything is generally able, at sixteen or seventeen to defray the expenses of the evening school out of his own pocket; and this works well in two ways: it relieves the parents from the outlay, and serves to maintain a spirit of self-respect in the young scholar, who is thus wisely laying out his hardly earned sixpences in buying a stock of useful knowledge. Walter and Frank were both apprentices, and any little money they earned was for working overtime. It was a pleasure to Walter to feel that his mother would not have to put her hand in her pocket to pay for his attendance at the evening school, and he knew that he could not spend his pocket-money in a better way.

When Walter arrived at the Rectory, he found a number of the village lads about his own age already assembled there. Several gentlemen were seated at the table, and amongst them Walter recognised Squire Forbes.

The Squire recognised Walter.

"Are you not one of Mr. King's apprentices?" he asked, as Walter came up to the table to give in his name.

"Yes, sir."

"I thought I remembered your face; you seemed to take a great interest in the sketch for my new greenhouse; do you draw at all?"

"No, sir; but I should so like to learn."

"You will be able to do so now; for drawing will form one of the subjects taught at the evening school, and a knowledge of drawing will be of great use to you in your trade. Where is your fellow-apprentice?—The lad I saw working with you yesterday; is he here to-night?"

"No, sir; he is not going to join."

"More's the pity; what is his name?"

"Hardy, sir; Frank Hardy."

"Do you mean one of the Hardy's who live down by the mill?"

"Yes, sir. His father works for Mr. Giles, the miller."

"Just the very lad, of all others, who ought to join," said the Rector. "In the first place, he is very ignorant, and secondly, the occupation of an evening would help to keep him out of mischief, and take him away from bad companions. I have seen him very often with Tom Haines lately; and I am sure no good can possibly come to him from such an acquaintance. Does Frank know of your coming here this evening, Walter?"

"Yes, sir, and I tried to get him to come too; and I told him as well as I could, sir, all about what you said to us in church on Sunday, but it was of no good; so we've each chosen our own path, and are going to see which turns out the best."

"I am glad to see that very few seem to have followed Frank's example," said the Rector, looking at the long list of names which lay on the table before him. "There are thirty-three lads already entered, and I call that a very good beginning."

The Rector then made a few remarks to the boys before they left, bidding them remember that they had all that evening enlisted to fight against ignorance—not with guns and swords, but with books and pens and ink. He bade them beat up for recruits wherever they could, and never to rest until they got their companions to join the evening school. Then he besought them, one and all, to ask for God's blessing on their studies, and reminded them of that text—"Whatsoever ye do, do it heartily, as to the Lord, and not unto men."

"It is a great mistake," he continued, "to imagine that any one's duties are ever so common-place or so trifling that they have no religious value. The Bible is clear enough on that point. It exempts nothing from the compass of God's service. It is God's will that men should follow different pursuits, according to the position of life in which He has placed them. It may be that we are called to very humble duties—duties very far down in the social scale. Are we, then, to think such duties insignificant? Far from it. Low as they are, they are still held from God, for it is He who hath appointed them, and they constitute a stewardship for which we shall hereafter have to give an account. Our wisdom and happiness, then, will consist in endeavouring, through God's grace, to do, as far as in us lies, the work which He has set us to do. May God's blessing rest upon you all in your honest efforts after self-improvement; and may He, by His Holy Spirit, pour into your hearts that heavenly wisdom without which all the learning of the world is but 'foolishness.'"

"Good-night, lads," said Squire Forbes, as the boys made their bows and were preparing to leave the room. "I shall hope to meet you all on Monday night at the school-room, when I intend taking a class myself. And you, Walter, try again what you can do with your companion, Frank Hardy."

"It's of no use, sir; he won't come."

"You don't know that; try again," said the Squire.

RIGHT AND WRONG.

MRS. WHITE, Walter's mother, kept a small shop in Springcliffe. Her stock-in-trade consisted in all the numerous articles comprehended under the general term "haberdashery," in addition to which she also sold stationery and toys. She was much respected in the neighbourhood.

In years gone by, when Walter was a little boy, her circumstances had been very different. Then her husband lived, and rented a small farm not far from Springcliffe, and everything seemed to prosper with them. But after that there came a year when the crops failed, and a long and severe winter succeeded. Mr. White, never a very strong man, caught a violent cold, from the effects of which he did not recover. He died in the early spring time, and the sale of the farming implements and stock barely sufficed to pay his debts, and the widow found herself left almost penniless, with her little son, then about nine years old.

She bore up under her trials with Christian fortitude; feeling that God's way with us is the "right way," how rough soever it may seem to be. In all her trouble she had one great comfort, and that was her boy Walter. For his sake she nerved herself to recommence—and this time alone—the battle of life; and, with the assistance of a few kind friends, who had respected her husband, she raised a sum sufficient to stock her little shop. By industry and frugality she managed to earn a decent livelihood for herself and child, and to save money enough to apprentice Walter to Mr. King, the carpenter.

"All's settled, mother," cried Walter, as he entered the homely but comfortable room, half-kitchen, half-parlour, in which Mrs. White was sitting.

The widow always closed her shop at seven o'clock, and she was now seated at work by a bright fire, with a little round table before her. At the other side of the fire Walter's chair was ready for him, and his slippers were warming in the fender.

"All's right, mother, and we are to begin school on Monday evening. Ain't I glad, that's all!"

"And so am I, Walter, I can assure you. It will be a nice occupation for you during the long winter evenings, when there are so many hours after work in which you have literally nothing to do, and—"

"And what, mother?" said Walter, with a half-smile, for he guessed what she meant, although she had not finished her sentence.

"Well, you are a dear good boy, Walter; but you know I was always a little afraid of that Frank Hardy."

"You needn't fear, mother, dear; he tried to laugh me out of joining the evening school, but he did not succeed."

"Thank God he did not, Walter; there are more people turned away from doing what they know to be right by being laughed at than in any other way. I am glad to think you were firm."

"Yes, mother, and I tried to turn him, but didn't succeed either; and Squire Forbes says I must try again."

"You will have opportunities for doing so when you are working together at the bench; but I would rather you did not go to the mill cottage. I cannot tell you all my reasons just now, but you may rest assured that they are good ones."

"Yours always are, mother; but what about little Gracie?"

"The poor child would miss you sadly, Walter, so you can still go and see her once or twice a week, as you may be able to find time. It is the evenings I am afraid of, when Frank takes home Tom Haines, and other bad companions."

"I shall have enough to do of an evening to prepare my lessons, mother; and as for Tom Haines, I fancy he likes me just as little as I like him."

"I should be sorry to see you ever do him or any one else an unkind turn, Walter; but he is no good companion for you. Squire Forbes's gamekeeper was in Springcliffe this afternoon, and called for a little parcel I had ready for the young ladies. He told me there had been another affray with the poachers out at Oaklands; and he says there is a desperate gang of them about, and that he knows, for a certainty, that some young men from Springcliffe have joined them."

"Oh! Mother," cried Walter, "then, perhaps—" He checked himself; whatever suspicions he might have formed, it was not right to utter them, when he had no foundation for them except in his own mind.

He refrained, then, from telling his mother that the idea had struck him that Tom Haines was one of the party, and that he was trying to get Frank to join them.

"I may be wrong after all, mother; so I had better say nothing about it."

"Have you and Frank had any talk about Tom Haines?"

"Only a few words this evening, when he asked me why I never seemed to care to speak to Tom now, and I told him plainly the reason. The other morning, though, whilst we were at work, Frank began defending the poachers, at least making excuses for them; and I scarcely knew how to reason against him, although I felt that all he said was wrong. What ought I to have said, mother?"

"Simply the truth, Walter, namely, that poaching is only a milder name for stealing. Of this, too, you may be very sure that the poacher of game will soon become the stealer of other things. Your poor father used often to say he never knew an exception to the rule."

Much more the mother and son spoke of as they sat over the cheerful fire. Happy mother, in having a son willing to trust to her judgment, and to be guided by her advice! And happy, thrice happy son, in having so good a friend and adviser!

Then Walter read a chapter in the Bible to his mother, a practice he never missed. After which they had their frugal supper, and retired to rest, at peace with the whole world, and happy in each other's love.

Sound and peaceful were Walter's slumbers, and he arose early in the morning, so as to light the fire for his mother before he went to work. Frank was late at the yard that morning, and Walter fancied that he looked tired and sleepy when he arrived. The foreman reproved him for being behind time, and Frank answered impertinently; upon which the foreman threatened to complain of him to Mr. King when he came to the yard. He came earlier than usual that day, and almost the first thing he did was to commend Walter for having joined the night school.

"I shall have much pleasure in giving you a set of

drawing instruments," said his master.

"You've been a good steady lad to me," said his master, "and I am glad to find you seeking to improve yourself. I think you have a taste for drawing, and, as a knowledge of that art will be of the greatest possible use to you in your trade, it is a great advantage to be able to acquire it. I shall have much pleasure in giving you a set of drawing instruments, as a proof of my satisfaction with your conduct, and I hope you will derive both pleasure and profit from their use."

Walter's gratitude shone forth in his eyes. His master's generosity had relieved him from the only difficulty he had foreseen in the way of his attending the drawing-class at the night school. He had been told that drawing instruments would be required, and he knew that his mother could not afford to buy them for him; now this only obstacle was removed, and he would be able to study the art for which he felt he had a taste.

Walter's love for his mother was unselfish, and he had never mentioned the subject of drawing instruments to her, knowing that she would at once have deprived herself of some necessary sooner than that he should not have them. And he had generously determined to give up the drawing-class, rather than cause his mother any expense which he felt she could not afford.

How many there are who love their parents with a selfish love! And how comparatively few there are who imitate Walter's unselfish example. As Walter resumed his work after thanking his master, he caught, Frank's eyes fixed upon him with a look of jealous dislike. Working together at the same bench, as the two lads had now done for some years, there was a degree of intimacy between them which, from the difference in their respective characters, might not otherwise have arisen.

Walter had never harboured an unkind thought against Frank; and now, when he saw the evil look on the face of his companion, he thought within himself—"What can I have done to have offended Frank?"

Walter had yet to learn that the first decided step which we take in a right direction never fails to bring upon us the ill-will and jealousy of those companions who have not taken the same step in advance. Idle people do not like to see others more industrious than themselves; and it was the fact of Walter's joining the evening school which had first excited the ill-feeling of Frank Hardy.

His master's open commendation of Walter's conduct that morning, and the present to him of the drawing instruments, had put the finishing stroke to Frank's ill-humour, and from that hour, he became Walter's enemy.

What is true in mere worldly matters is still more the case in religion. Our Saviour says—"Whosoever shall confess Me before men, him will the Son of Man also confess before the angels of God; but he that denieth Me before men shall be denied before the angels of God."

What is meant by confessing Christ? Is it not to let all men see that we believe in Christ, serve Christ, love Christ, and care more for His praise than for all the praise of men?

This is the duty of every Christian. It is not for martyrs only, but for members of Christ's Church in every rank of life,—the rich man among the rich, the labourer among labourers, the young among the young. May we all have grace to fear God! It is the best and only antidote against the fear of man.

THE LAW OF LOVE.

SPRINGCLIFFE is a long straggling village, stretching inland for nearly a mile in length, and consisting of but one principal street, in many parts of which the houses are but very thinly scattered. The lower village, or that portion of it which is near the sea, presents all the well-known peculiarities of a fishing village; whilst in the upper portion, everything wears an agricultural aspect. Springcliffe church is in the upper village; it is a plain stone structure, with a Norman tower, and a sweet peal of bells.

A stream runs through some rich pasture meadows on its way to the sea; and in its course works a large flour-mill, belonging to the proprietor of one of the large farms in the neighbourhood, who thus combines the trade of farmer and miller. In the mill cottage, close to the stream, lived Frank Hardy's parents and their numerous family. On the other side of the stream, steep wooded hills rise almost perpendicularly from the water's edge; and from the summit of the hills the eye wanders far away over a richly-wooded country, a great proportion of which is the property of Squire Forbes, Oak Glen.

John Hardy and his wife had a large family of children, of whom Frank was the eldest. They had lived for many years in the mill cottage; for, although Hardy was by no means a steady man, and did not bear the best of characters in the place, his master kept him on out of kindly feeling towards his wife, who had lived many years as servant at the farm before she married John Hardy. Then she had been an active, bright-looking girl, full of life and spirits; now, she was a poor, sickly, slatternly woman, finding it hard work to get food for herself and her nine children.

Had John Hardy been steady and industrious, he might, long since, have been foreman at the mill; but, more than once, he had seen younger but steadier men promoted to the post, whilst he remained in the same position he had held for years.

There was a roadside public-house, called "The Plough," not far from the mill; and there John Hardy spent a good part of his weekly earning. Whether, in former days, Mrs. Hardy had done her best to make her husband's home comfortable, whether she had at all times remembered that "a soft answer turneth away wrath," is very doubtful; but at the time of which we are writing, John Hardy rarely spent an evening at home, and his wife and children were frequently without food.

It was Mr. Giles, the farmer and miller, who had apprenticed Frank to Mr. King, and who paid for the schooling of the elder children; always upon condition, however, that they should be sent regularly to the Sunday-school and to church. Hardy and his wife were seldom seen in God's house; and it is not to be wondered at if very little of that charity which "suffereth long, and is kind," was to be found in such a godless home.

"Whatever brawls disturb the streets," says good Dr. Watts, "there should be peace at home;" but there was little peace at the mill cottage. Both parents were very passionate, and it was scarcely to be expected that their children would be otherwise. Never taught to control their tempers, the young Hardys were notorious in the village as quarrelsome, disobedient, noisy children. There was one exception, and that was little Grace Hardy, or "blind Gracie," as she was generally called. When only two or three years old, she had been thrown down by her father, who had stumbled against her as he entered his cottage in a fit of intoxication. The child fell against the sharp edge of the fender, and received such severe injury in the eyes that, after much suffering, she became totally blind.

At the time when the accident happened, Mrs. White lived in a small cottage near the Hardys. It was shortly after her husband's death, and she had not yet been set up in her little shop. Always kind-hearted, and clever at nursing, she had assisted Mrs. Hardy in her care of poor Gracie, and the child became much attached both to her and to Walter, who would sit for the hour together, endeavouring to amuse the blind child.

Gracie's affliction had proved a blessing to her. Our greatest trials are often blessings in disguise. In Gracie's case, God had sent His Holy Spirit to soften the little girl's naturally self-willed and passionate nature; and the once peevish, ill-tempered child became gentle and patient under its blessed influence. The greatest pleasure little Grace knew was going to the Sunday-school, where her gentle ways and her loving disposition made her a great favourite with her teacher. She had a sweet voice, and would sit in the summer time, for hours together, by the banks of the stream, at the end of the garden, singing over the hymns she had learned at school, and repeating over to herself what texts of Scripture she could remember. The memory of blind persons is generally more retentive than that of other people; God in His great mercy seeming to make up to them in this way for the loss of sight.

No one could look at Little Gracie and fail to see that her blindness was to her a great mercy. Living in a little world of her own, shut out from seeing the unkind looks, the angry gestures, which so embittered the lives of all the other members of her family, she was the only happy inmate of the mill cottage. Her one real sorrow was the dislike which her father ever seemed to feel towards her since the time of the accident. Whether or not it was that Gracie's sightless eyes seemed a constant reproach to him for his conduct, and that her presence continually reminded him that the fearful lesson had been thrown away upon him, it is certain that he scarcely ever addressed a kindly word to her, and would coldly repel any little affectionate advances on her part. John Hardy little knew the depth of love in his child's heart which he thus wantonly rejected, and dreamed not that the day would come when he would have given worlds to have possessed it; but it was too late.

"If father would only love me!" Gracie would say to her mother.

And then, Mrs. Hardy, who was gentle towards her blind child, though harsh and cold to everybody else, would whisper words of comfort, always ending with, "Some day he will, Gracie."

At one time the child had tried by numberless little endearing ways to win her father's love. She would creep gently up to him as he sat by the fire in the winter having his supper, and once, but only once, she had ventured to put her hand in his. But the little hand had been thrust from him with angry words, and the child had crept sorrowfully to her bed. After that she never went near her father, if she could help it; and the sound of his coming footsteps, or of his voice, was the signal for her to retreat. In summer she would hide herself in the garden; in winter, in the little room where she and her sister slept.

One of Walter White's first efforts at carpentering on his own account had been to erect a little rustic seat for Gracie, under an old elm tree which grew near the bunks of the stream at the bottom of her father's garden.

There, in the summer time, the blind child would pass hours together, listening to the song of the birds, the hum of the insects, the rustling of the leaves stirred by the passing breeze, and the pleasant rushing sound of the mill-stream. At such times the child's thoughts would wander far away into the distant future—to that blessed day when, as her Bible told her, "the eyes of the blind shall be opened, and the ears of the deaf unstopped. Then shall the lame man leap as an hart, and the tongue of the dumb sing: for in the wilderness shall waters break out, and streams in the desert. And the ransomed of the Lord shall return, and come to Zion with songs, and everlasting joy upon their heads: they shall obtain joy and gladness, and sorrow and sighing shall flee away." (Isa. xxxv. 5-6, 10).

Gracie knew every word of the chapter whence these verses are taken; she had learned it at the Sunday-school, and was never tired of repeating it to herself.

"It sends away all my troubles," she would say to Walter, who was the only one to whom she ever talked on the subject; none of her own family would have understood her.

Even her mother, kind though she was to the blind child, could not enter into her feelings on religious subjects. Gracie's "precious Bible" was not yet "precious" to her mother. It is only through God's grace that the Bible can ever be to any one what it was to little blind Gracie,—

"Mine to comfort in distress,

If the Holy Spirit bless,"

as says the poet. What need, then, for us to pray that God would, of His tender mercy, make His Word to be indeed a lamp unto our feet, shining through the darkest earthly day, and guiding our steps towards that heavenly country where there will be no more need of sun or candle, "for the Lord God giveth them light?"

Gracie's brothers and sisters had each Bibles of their own, given them by Farmer Giles; but they never opened them, except at school; and whenever Gracie asked either of them to read a little to her in the evening, they would burst into an unfeeling laugh, and say they were not going to read unless they were obliged.

So the blind girl had to content herself with such passages as she could remember, and would look forward to the visit which Walter generally managed to pay her every Sunday afternoon, when he always read chapter to her, in spite of the ridicule with which Frank and the other Hardy boys never failed to assail him. Walter heeded them not. He knew that he was doing a kind action, and that there was nothing "unmanly," as they called it, in reading God's Holy Word to a blind child.

"What are they all laughing at so?" asked Gracie, when Walter joined her at the seat under the elm tree. They always sat there when the weather was fine. "Were they laughing at you?" continued the child, as Walter returned no answer to her question.

"I think they were, Gracie, but I don't mind."

"But please, Walter, I mind, and I don't like that you should be laughed at for my sake."

Walter laughed at Gracie's serious tone. "Being laughed at breaks no bones, as mother says, Gracie, and, somehow, it always makes me feel stronger; that is, when my conscience tells me I am only doing what is right. That's the true test, Gracie; doing wrong is the only thing one need really feel ashamed of."

"You are very brave, Walter," said the child, and tears rolled down her cheeks as she spoke. "I am not so; Frank laughed at me the other day for singing a hymn, and I could not bear his laughing, and so I left off singing. Was it very wicked, Walter?"

"Little girls are not as strong as—" men, Walter was going to say, but he checked himself. "I mean, you can't expect to be as strong as I am, Gracie; but still you ought to try and not be ashamed of doing what is right. Our Saviour says we are not to be ashamed of confessing Him before men; and when you let your brother's laughter make you stop singing your hymn, it would seem to him as if you were really ashamed of showing that you loved your Saviour."

"I didn't mean that; indeed I didn't, Walter," cried Grace, in distress.

"I don't think you did, Gracie; but there is a verse in the Bible which says we are to keep 'from all appearance of evil'. (1 Thess. v. 22). I was reading the chapter to mother last night, and she explained it to me as meaning that it is not enough for us to feel in our hearts that we do not mean wrong,—we must so act that there can be no mistake about our motives. We must boldly do what we know to be right, regardless of consequences. You may have made Frank think that, after all, you do not really care about God and Jesus Christ, or you would never allow yourself to be laughed out of your singing your hymn. Perhaps, too, he did it for the very purpose of trying you."

"I will pray to God to make me braver next time, Walter." And then she added, with a sigh, "How I wish my mother would talk to me as yours does to you!"

"My mother is one of my great blessings, Gracie; I often think of those lines:

"'Not more than others I deserve,

Yet God has given me more.'

"But where is Frank, Gracie? He was not in the kitchen when I passed through. There was only Joe and Ned there. I made sure he would have been at home this afternoon, and I wanted to speak a word to him."

"I heard him and Tom Haines unfastening the boat about half an hour since," said Gracie, "and I think they went across into the wood, for I heard the rustle under their feet."

"Is Tom Haines often here?"

"Almost every night; sometimes quite late. I hear them coming across in the boat after I have been in bed a long, long time. He says it is such a near way for him to come, now that he works near Oak Glen."

Walter was on the point of saying that Tom could not be coming home from work so late at night; but he refrained himself, and merely said,—

"I don't think Tom a good companion for Frank, Gracie. I wish he would not go with him."

"I don't like him, because he has such a loud, rough voice," said the blind child; "and once when I was sitting in the boat, he said in a loud whisper to Frank, he wondered what business I had there, and that I should do something. I could not catch what he said, but Frank answered I was safe enough, for I was blind. What do you think they meant, Walter?"

Walter guessed what they meant full well, but he did not wish to alarm Gracie; so he told her to keep as much out of their way as possible.

"Frank said I was never to sit in the boat again," said Gracie, "and I don't much care about it; so now I always sit here, and then mother says they cannot see me when they come down to the boat, because the laurel hedge hides me from them."

"THE PLOUGH."

"I WISH you were coming with me to-night, Frank," said Walter, as he and his companion were at work together the following morning.

"Is that what you wanted to speak to me about yesterday?" said Frank.

"Yes it was; I thought I would just try once more whether I could not turn you."

"Then you might just as well have saved yourself the trouble, Walter. What can it possibly signify to you whether I go to the evening school or not?"

"Simply this, that it would be nice and sociable-like, Frank; we've been working together now for these two years and more, and it would be pleasant for us both to go together to the night school."

"Speak for yourself, Walter, when you talk of it being 'pleasant.'"

"What I mean is, that it would only seem natural for us to do so; our interests are the same, or ought to be. What is good for me must surely be good for you; what will help me on in my trade would do the same for you; and I do think it's a pity to throw away a chance like the present one."

"One would think you were going to set up for a parson, to hear you talk, Walter. But you might as well spare yourself all this trouble; you'll not change me. You go your path, and leave me to follow mine."

"Well, don't be angry, Frank; I meant no harm; and if your mind is made up, why, I'll say no more about it."

"I don't set myself up for being better than other people," said Frank, "but I want my time to myself. It's little enough we have when our work is over."

"See that you make a good use of it, then," said Mr. King, who had entered the yard unobserved by the lads, and had overheard Frank's last remark. "Time is a precious gift, lad, and one for the use or misuse of which God will call us all one day to give an account. Don't think I wish to stop young people from enjoying themselves at proper times; I know full well that all work and no play would be good for no one. We all want some sort of relaxation from our daily labours; but what young people call enjoyment is not always innocent; and a lad of your age, with much spare time on his hands, is exposed to much temptation.

"I have no right to dictate to you how you should employ your time when you leave the yard; I have then no further claim upon you. But as your friend and well-wisher, as one who has lived very much longer in the world than you have, I should not be doing my duty by you did I not warn you against the many devices which Satan makes use of to lead young lads into sin, and almost the first of all is the tempting them to idle away their time. I was sorry to find you had not joined the evening school. You little know what advantages you are throwing away by neglecting to do so; but I trust you may yet think better of it. In these days, education is better than money to a young man; for with a head well-stocked with useful knowledge, he is sure, so long as he conducts himself well, to go ahead in life. I should never have been what I am now had it not been for the opportunities of improving myself which offered when I was about your age, and which, I am thankful to say, I availed myself of."

Mr. King then took out of his pocket a neat mahogany case, and gave it to Walter.

"Here are the drawing instruments I promised you."

"Here are the drawing instruments I promised you," he said, "and I daresay I shall look in this evening and see how you all get on."

Squire Forbes called at the yard during the day to give some further directions about his greenhouse.

"I have tried again, sir," said Walter to him, "and it's of no use; Frank won't join."

"It's his loss, then," said the Squire, "and you have done your duty."

When Walter left the yard that evening, he hurried home to his tea; and then, having "tidied himself," as he called it, he went towards the school-house in which the classes were to be held.

It was nearly dark when he passed through the village, but he saw Frank lounging against a gate at the corner of the little lane which led to the Mill Cottage. Tom Haines was with him, and Walter heard them laughing as he passed.

He seemed not to notice the laugh, however, and called out "Good evening," in his usual tone.

The only answer was another laugh.

Walter passed on without taking any further notice of them. A saying of his mother's—"Let those laugh that win" recurred to his mind, and he felt that he had more real cause for merriment than they had.

There were nearly thirty boys assembled in the school-room that evening, varying in ages from twelve to eighteen. The clergyman of the parish, the national schoolmaster, and several gentlemen resident in the neighbourhood, all took classes. Lessons were given in reading, writing, arithmetic, and drawing. The teachers were kind and painstaking, the scholars well-behaved and attentive, and Walter was surprised when he found it was time to leave off; the two hours had passed away so pleasantly.

Squire Forbes, who had taken the arithmetic class, told the boys before they left, that he hoped to be able once a week to give them a few interesting particulars about modern geography, English history, and the sun, moon, and stars.

"I shall not call it a lecture, boys, first, because most of you will fancy I am going to deliver a long, dry discourse, to which you will not care to listen; and, secondly, because, as it will not last more than a quarter of an hour, it will not deserve the name. I shall call it, then, a pleasant talk; and I hope to make it so entertaining that you may not feel I have given it a wrong name. You can ask me any questions you like when I have finished, and I will answer them to the best of my power.

"I have read a great many more books in my life than you are likely to do, and I think that if I take a number of great and interesting facts out of some of those books, and tell them to you in simple language, such as even the youngest amongst you will be able to understand, it may give you a little stock of useful general knowledge, which will be of service to you in life, and which it would take more time than you have at command to acquire from books. I congratulate you, boys, upon your good behaviour this evening, and I hope we shall live to spend many more such pleasant and profitable hours together."

Walter walked home with William Day, a neighbour's son. It was a cloudy night, and the moon, which was nearly at its full, was partially obscured. All was quiet as they passed the turning to the Mill Cottage, but they had not proceeded far before they met Frank Hardy and Tom Haines. The latter had evidently been drinking, for he was staggering along the road, and would have fallen had not Frank supported him.

Walter shuddered as he passed them by. He thanked God in his heart, and with all humility, that he had hitherto been kept from such acquaintances as Tom Haines, and that he had a mother who had brought him up to see all the horror and evil of intemperance. What might not Frank Hardy become with such an example as Tom Haines always before him! Then he remembered Frank's uncomfortable home, the constant scenes of ill-humour and selfishness which were going on there, and he thought of that text which says, "To whom much is given, of him shall much be required."

"How much more have I than Frank!" he thought, and the thought made him humble.

"How silent you are, Walter!" said Willy Day.

"I was thinking very sad thoughts, Willy."

"Why, you seemed so happy at the school, Walter."

"Yes, I know; but it was meeting Tom Haines and Frank that set me thinking. Suppose we should ever come to be like Tom, Willy!"

"We need not, unless we like, Walter."

"But we can never tell how soon we may fall into temptation; I think mother is right, after all."

"What about?" asked Willy.

"She says it would be better for the world if there were no such places as 'The Plough.'"

"Oh, Walter!"

"It's quite true, Willy; and she says also that beer and spirits are really necessary to no one, and that at least a fourth part of the earnings of every working man who drinks beer are spent in the public-house."

Willy Day know that his father went every evening for an hour or so to "The Plough," but he never remembered seeing him the worse for drink, and he told Walter so.

"I was not speaking of regular drunkards, Willy, when I spoke about a fourth part of a man's wages. Drunkards often spend half, and sometimes more than that, of what they earn in the public-house. That is why Frank Hardy's family are so badly off; the greater part of all the money earned by Frank's father goes to 'The Plough.' But even those people who never 'get the worse for drink,' as you call it, how much money they spend upon it, and what a number of home-comforts—better food, better clothes, and something put by against a rainy day—that money would have procured!"

Walter had arrived at the door of his mother's house as he uttered the last words, and he and Willy stood still for a moment.

"Did your mother tell you all this, Walter?"

"And much more, Willy, I can tell you."

"She must be as good as a book, Walter."

"She always tells me, too, that it is so easy for young people to learn a bad habit, and so difficult to un-learn it; and therefore I have promised her never to go into such places as 'The Plough,' for fear of being tempted to do what it might afterwards be so hard to leave off."

Willy Day wished his friend good-night, and the boys separated.

Willy was a thoughtful boy, and as he walked homewards, he pondered upon all that Walter had said. He remembered many instances in his own home life when an extra three or four shillings a week would have been a great help, and when the want of it was the cause of much inconvenience.

He particularly recollected the time when his sister Lucy was kept away from school for many weeks through having no shoes fit to go in. His mother had told him she could not afford to buy her any. Now, if what Walter's mother said was true, the money which his father spent in one fortnight only at "The Plough," would have bought Lucy a capital pair of shoes.

When he reached home, he found his mother sitting by the fire, nursing the youngest child, a baby of a year old, who was crying as if in great pain.

"Is baby no better, mother?"

"No, Willy; the doctor came again this evening, and he says its chest is very delicate, and that it must wear flannel. I am sure I don't know where the money is to come from."

"How much would the flannel cost, mother?"

"Three or four shillings at least, Willy."

"Just one week at 'The Plough,'" thought Willy.

———————

"Who were you talking to at the gate, Walter?" said his mother, as he entered the house; "I heard your voice for several minutes before you came in."

"It was Willy Day, mother; I was trying to make him understand all that you told me about the harm done by public-houses, and I think I made him see things in a different light to what he had ever done before."

Mrs. White smiled at her son's enthusiasm. "That's right, Walter; there is no one but what has opportunities, at some time or another, of influencing a companion, either by his advice or example. Take advantage of every such occasion; and remember that, as in the old fable, the efforts of a tiny mouse were of service in setting free a great lion, so even young people have it in their power to help forward great and important results."

Mrs. White then asked her son all about the evening school, and Walter gave her an animated description of all that passed there.

"Squire Forbes told us, mother, that every fresh piece of knowledge we acquire is like opening a new window in our minds."

"True, Walter; but we must guard against pride of self-conceit in our knowledge. It is quite right to resolve, in the strength of God, never to spend an unprofitable hour; it is quite right to try and improve our talents to the very utmost, and to employ them to the best advantage; but the motive throughout all should be, not an over-anxiety to appear more clever than other people, or to obtain the praise of men for our superior knowledge; but rather how we shall best be fulfilling God's will in that path of life in which He has placed us."

"Mother, I think you know everything; I am afraid I did feel a little conceited when talking to Willy Day, at least I know I thought how much more I knew than he did. It is hard to think right thoughts, mother."

"God only can enable us to do so, my son. Jeremiah says, in speaking of man's thoughts, 'The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked.' And David earnestly prays to God that the 'meditations,' that is, the thoughts of his heart, may be acceptable in God's sight."

"There's one thing I don't quite understand, mother; if God places us in a 'path of life,' how can we be said to choose our path?"

Mrs. White took down her Bible, and turning to the second chapter of the Epistle to the Ephesians, she bade Walter read the 10th verse: "'For we are His workmanship, created in Christ Jesus unto good works, which God hath before ordained that we should walk in them.'"

"St. Paul here plainly tells us that we were created by God unto 'good works.' When, through the disobedience of our first parents, sin entered into the world, man's whole nature became changed and corrupted, and he who had been made in God's holy image, became the servant and slave of sin. But God's purpose still remained unchanged; He had created us unto 'good works,' not unto 'evil,' and 'for His great love wherewith He loved us, even when we were dead in sins,' He now brings us nigh unto Him through Christ's blood, who is our 'peace' with God.

"In God's strength, then, and through His Holy Spirit strengthening us, we may still do those good works which He hath before ordained that we should walk in; and it is when we are thus, for Jesus Christ's sake, led by the Spirit, that we regain our lost place as God's children, and walk in the path of holiness which He has appointed us. How many of us resist God's Holy Spirit, and choose the path of sin! And how thankful we ought to be when we are enabled to walk in the path of God's commandments, which can only be through His grace helping us. 'For by grace are ye saved through faith, and that not of yourselves; it is the gift of God: not of works, lest any man should boast.'"

"I think I understand it all now," said Walter; and then, he added, "Oh, mother, Gracie says she wishes her mother would talk to her as you do to me."

UNJUST SUSPICIONS.

WALTER was at work in good time the following morning, but the foreman and Frank were both at the yard before him, and the foreman spoke angrily to Walter as he entered the workshop. "If this is what is to come of your going to the evening school, Walter, why I, for one, should say the sooner you give it up the better."

As he spoke, he held up before Walter's astonished gaze a large chisel and a fine saw, both of them covered with rust.

Walter and Frank took it by turns, for a week together, to put away all the tools carefully before leaving the yard at night. It was then Walter's week, and he felt sure that he had in no way neglected his duty, and that he had left everything in proper order before going home the previous evening.

The sight of the tools, rusted as they were by exposure to the damp night air, puzzled him extremely.

He held up a large chisel and a fine saw,

both covered with rust.

"I'm quite sure," he said, "that I did not leave those tools out last night."

"Nay, nay, that is only making bad, worse. I found them myself lying on the ground in the open shed yonder. You are generally such a careful lad, that I was the more surprised when I learned that it was your week. All I say is, be more particular for the future, or Mr. King will find that your lessons will cost him dear."

"But, indeed," cried Walter, with a bewildered look, "indeed I put them all away. I recollect perfectly doing so; and it is not so long ago that I could be mistaken."

"I'll not hear another word," replied the foreman, angrily. "Facts speak for themselves, and it is perfectly useless trying to make me disbelieve my own eyes. Who do you think would come here and take the tools out after you had put them away?"

"Who indeed?" thought Walter.

And at that moment he raised his eyes, and met those of Frank Hardy fixed upon him with a malicious expression, as if rejoicing in his trouble.

A strange thought flashed across Walter's mind: "What if Frank had done it out of spite?" He looked him full in the face, almost inquiringly, and Frank's eyes fell beneath the earnest gaze of his companion.

"Some one must have done it out of ill-feeling to me," said Walter quietly.

"A very likely story!" said the foreman. "Did you never hear that a bad excuse is worse than none? My advice to you is to hold your tongue about the matter, and to be more careful for the future."

Walter saw that he was not believed; and when Mr. King came to the yard, in the course of the day, he felt sure that the foreman had told him about the tools being left out, as his master's manner to him was not so cordial as usual.

"You be sure and see that all is straight before you leave this evening," said Mr. King to Walter. "Your evening studies must not interfere with your duty to me, remember."

Walter coloured deeply, knowing to what his master alluded.

"I never yet failed in my duty, sir, and I hope I never shall."

"The least said about that the better, Walter," said his master. "I am quite ready, however, to make allowance for a first offence; only don't let it happen again."

Mr. King left the yard as he uttered these words, and Walter turned towards Frank with tears in his eyes.

"Do you know anything about the tools, Frank?"

"I! What should I know about them? It wasn't my business to put them away."

"No, I know it wasn't; only I thought that perhaps you might have wanted to use them after I had put them away; and, if you did so, I would not say a word about it, Frank, if you would only just tell me; for I feel so certain I put them all away, and it makes me feel so unhappy to be suspected."

"I know nothing about them," said Frank, doggedly.

"What is the matter with you, Walter?" said his mother that evening, as her son sat poring over the fire, and scarcely speaking a word.

"Nothing, mother, nothing; at least, nothing very particular," he added.

"Nay, Walter, it cannot be a mere trifle which has made you so different from what you generally are. Tell me what it is, my son; maybe I can help you."

"I never did yet keep anything from you, dear mother," said Walter; "only, in this instance, I thought I might be mistaken, and I did not like to say anything to you until I was quite certain."

Walter then told his mother all that had taken place at the yard that morning, and ended by assuring her that he had left nothing undone when he left work the previous evening.

"It is hard, mother, is it not, that both Mr. King and the foreman suspect me?"

"And yet it is only one of the little daily crosses which, as servants of Christ, we are called upon to bear," said Mrs. White. "If our blessed Saviour, 'who did no sin,' suffered unjustly, we should think it no strange thing that we should; and knowing how patiently and meekly He bore insult and wrong, we should pray for His Spirit to enable us to do so also."

Walter sighed; he felt that all his mother said was true.

"But yet 'Commit thy way unto the Lord; trust in Him, and He shall bring it to pass. And He shall bring forth thy righteousness as the light, and thy judgment as the noon-day' (Psalm xxxvii. 5-6). All will come right, Walter, in God's own time; rest assured of that. Meanwhile do your duty strictly to your master; bear no ill-will towards any one; seek for no revenge, even if you come to be certain of the justice of your suspicions; remember that Jesus Christ prayed for His enemies, and that, in every action of His most sinless life, He left us an example that we should follow in His steps."

"Mother, it always does me good to talk to you; and, indeed, I bear no ill-will towards Frank."

"Would you go out of your way to do him a kindness, Walter?"

"I hope so, mother," replied Walter.

Several days passed by after the above conversation, and nothing took place of any consequence in the yard. Mr. King and the foreman appeared to have forgotten all about the tools, and behaved in their usual cordial manner towards Walter, who regained all his former cheerfulness, and had almost forgotten that anything unpleasant had ever taken place.

They were very busy at the yard. Mr. King had a great deal of work to do in the lower village, where several houses were being built on the sea-shore, and they were working hard to get them completed before the winter set in. Both Frank and Walter worked overtime every evening, for which they were paid; but Walter never missed going to the night school, although by so doing, he lost the extra pay he would have received. His lessons were a pleasure to him, and he felt sure they would hereafter be a profit as well. He was making great progress in drawing, and also in mensuration and the higher branches of arithmetic—all of which would tend to advance him in the trade he was learning.

By degrees, all the boys and young lads of the neighbourhood had joined the classes, with the exception of Frank and his brothers and Tom Haines. Frank would often ridicule Walter for giving up all his evenings to his lessons, and more than once, he mysteriously hinted that he knew an easier way of making money than by fagging away at books every spare moment, as Walter was doing.

Walter recalled to mind the fact that twice, within the past few weeks, Frank had wanted to borrow money of him, although he was earning more money than Walter, on account of working overtime. This did not look as if Frank was very rich, and Walter told him so, adding—"I'm quite contented with my path, Frank, and I wish I could have persuaded you to follow it also."

"Thank you for your good wishes," said Frank, laughing, as he took up his cap and left the yard.

Walter heard him the next moment talking to Tom Haines, who had been waiting for him outside. There was something about Tom which made Walter shrink from any companionship with him. Once it had not been so; he remembered, when his mother had first cautioned him against being intimate with Tom Haines, that he had thought it a little hard, having been flattered, as a great many foolish boys are apt to be, by the attention of one who was several years older than himself. He had obeyed his mother, however, as he always tried to do; and now, in this case, as in every other, he had come to feel how right she was in the advice she had given him.

There was something in Tom Haines' manner to Frank which struck Walter particularly. It seemed to the boy as if Tom felt that he had Frank in his power in some way or other, and could make any use of him he liked. The following day, Frank paid Walter the two small sums he had borrowed from him, and rattled some money, which sounded like silver, in his waistcoat pocket, to show that he had more remaining.

"Are you sure you can spare it, Frank?" said Walter, as he held the money in his hand.

"Don't you hear I have plenty more?" replied his companion, rattling his pocket again as he spoke.

"Yes; but is it your own, your very own, Frank?" And then, feeling ashamed of the suspicions which arose in his mind, he added—"I beg your pardon, Frank, only I thought that perhaps you had been borrowing money in order to pay me, on account of what I said yesterday; and I am in no hurry, and would rather wait than—"

Here Walter stopped again, and seemed at a loss what to say.

"Don't be afraid, Walter; I earned it all, I tell you. Didn't I tell you yesterday that I had found an easy way of earning money and a pleasant way enough as well?"

Frank spoke in such a cheerful tone that, Walter thought he must have been mistaken in thinking that there was anything wrong in the matter. So he took the money, and thought how nice it really must be to be able to earn money so easily. His mother wanted a warm cloak against the cold weather set in; what if he could get enough to buy her one? He almost felt as though he should like to ask Frank something about the way in which he earned his money.

The lads were preparing to leave work, and, as Walter was hesitating whether to ask Frank about his "easy way," Tom Haines put his head in at the door of the yards and beckoned to Frank. There was a bad expression on Tom's face.

"Make haste," he muttered; "I've been waiting ever so long."

Walter glanced at Frank. The lively, boastful manner was all gone, and he looked pale and nervous.

"I'll come in a minute; I did not know it was so late." And then, turning to Walter, he asked him to help in putting away the tools.

Walter at once complied with Frank's request, although it was the class-evening, and he wanted to be home early.

He was ready to do Frank a kindness, even at inconvenience to himself.

"You are a good-natured fellow," said Frank.

"Don't talk so," said Walter. "We should always be ready to help one another."

Then, looking round to see that Tom was not within hearing, he said, in a low voice, "Oh, Frank, I wish you would not be so much with Tom Haines; I am sure it is not for your good, and—"

"It's too late now, Walter; I must go on with it."

There was a sad, reckless tone in Frank's voice, and Walter fancied he saw tears in his eyes.

"It is never too late to do better whilst God spares our lives. Frank, can I help you?" whispered Walter. "Or can mother? She would in a minute, I know, and I will ask her this very evening."

"No, no; it's too late, Walter." And Frank darted out of the yard into the darkness.

"It is not an 'easy way' after all," thought Walter. "Thank God, I have never been tempted to try it, whatever it may be."

THE SECRET OF SUCCESS.

THAT evening, on his way from the school, Walter called at the Mill Cottage to inquire after Gracie, who had been very ill for some weeks past, having caught a violent cold, which had settled on her chest.

The night was fine, and the moon at the full. A slight frostiness in the air had strewn the roads with autumn leaves, telling the fast approaching winter season.

When Walter entered the kitchen, there was no one there but Mrs. Hardy and her daughters. Neither John Hardy nor Frank was visible. Walter thought that Mrs. Hardy seemed put out at his coming, and answered his inquiries about Gracie in a hastier manlier than usual.

"The child will do well enough after a bit. She wants better food, though, than I can afford her; the doctor said she was to have nourishing things. It's easy for such-like to talk."

"Has she been up yet?" asked Walter.

"I got her up to-day for a little while; but she said she was so tired that she was glad to get to bed again."

"Is that Walter, mother?" cried a voice from an adjoining room.

Mrs. Hardy looked annoyed—she evidently wished to get rid of Walter as quickly as possible.

"Yes, child, yes; but you ought to be asleep now," said her mother, not in a very kind or gentle tone.

"Let him just come to the door; I want so to speak to him, mother."

Walter moved across the kitchen towards the door where Gracie's voice proceeded.

"I am glad you are better, Gracie dear."

"I do hope I shall soon be well," cried the child; "it seems so long since I had a talk with you. And oh, Walter, my little seat at the bottom of the garden has got broken—and will you mend it for me? I know you will, for you are so kind. When I was so very ill, it made me so sad to think I should perhaps never see you again, Walter."

Here a violent fit of coughing interrupted Gracie's speech. And Mrs. Hardy made a sign to Walter not to talk much more to her.

"I must go now, Gracie dear," said Walter, when the child's coughing had ceased, "but I will come again very soon, and then I hope you will be able to be up; and I will see what your seat wants this very evening, so that it shall be ready for you by the time you want it. The moon shines so brightly that I can see as well as by daylight. Good-night, dear."

"Never mind the seat to-night," said Mrs. Hardy in a low voice, so that Grace could not hear. "There will be plenty of opportunity to see to it before Gracie will want it."

"It will not take me a minute, Mrs. Hardy," replied Walter, "and then I can bring whatever is wanted with me when I come again."

Walter wished Mrs. Hardy good evening, and left the cottage. He had not gone many steps along the little path leading to the water-side when he heard a rustling among the bushes, and saw, or fancied he saw, one of Gracie's sisters hastening in the same direction in which he was going, but by another path.

Presently a low whistle was heard.

A minute afterwards, he had reached the little seat which he had put up for Gracie. One of the legs had been wrenched off, evidently on purpose. Walter had taken the size of it, and was about to return towards the cottage, when, on looking towards the stream, upon which the moon shone full, he saw several figures on the opposite bank. They were either getting in or out of the boat; and again he heard the same low whistle.

He had no desire to pry into other people's business, and, least of all, did he care to have anything to do with the Hardys and their mysterious doings. He turned hastily away to retrace his steps, and in so doing nearly stumbled over a sack which lay partly concealed by a bush at one side of the seat. The sack was full, and by the bright moonlight Walter saw the tail-feather of a pheasant peeping out at the mouth of the sack.

He felt quite glad when he was once more out on the high-road. Once or twice he fancied he had heard voices calling after him; but he never stopped for a moment until he had got clear of Mill Cottage and the lane leading to it. Then he stood still for a moment to take breath.

"How right mother was to caution me against that Tom Haines!" thought Walter. "And how I wish that Frank would be warned in time before he gets into some terrible trouble, which he will do sooner or later."

Walter said nothing to his mother that evening about his having seen the sack, but he told her about poor Gracie's illness; and Mrs. White promised to make some broth and some light pudding for the sick child. When Walter, after reading his Bible as usual by the light of the fire, knelt down to say his prayers that evening, he prayed for Frank Hardy that he might have grace given him to turn aside from the evil way upon which he had entered.

It is to be feared that few of us act as if we felt the full value and the great privileges of prayer—of intercessory prayer. We all can pray when we want anything for ourselves, or for those who, by the ties of relationship, are most near and dear to us; but how few of us pray for our acquaintances, let alone our enemies. And yet what is our blessed Saviour's express command?—"Pray for them that despitefully use you and persecute you."

No one can pray for his enemies and not feel kindly towards them. The very act of praying for another is unselfish in itself; and it is impossible to feel anger and bitterness towards one for whom we are asking God's grace and favour. So that the praying for our enemies brings down a blessing for ourselves by subduing in us the uncharitable feelings which we might have previously entertained towards the subject of our prayers.

When Walter met Frank the following morning, he looked confused and uneasy; and, taking advantage of a few moments when the foreman was absent from the shed, and the two lads were quite alone, he said,—

"What were you doing at our place last evening, Walter? And what made you walk away so fast? Did you not hear me calling to you?"

"I heard some one calling, but I did not recognise your voice, Frank. I had only gone down to the banks of the stream to see what was the matter with Gracie's seat, and she had asked me to mend it for her."

Frank appeared relieved by Walter's open and straightforward answer. Still there seemed something more upon his mind, although he hardly knew how to put the question. At length he said, "I wish you were one of us, Walter; it seems unnatural to have secrets from you; and if you would only come with me some evening, I could put you in the way of earning a nice little sum of money with very little trouble."

"I can never come with you, Frank," said Walter, earnestly. "I have seen quite enough, and—"

"What did you see?" interrupted Frank, with a scared look. "What did you see, I should like to know?" And then he added, in a quieter tone—"You won't tell any one, will you, Walter? You won't?"

"Don't be afraid, Frank; I have nothing to tell. When I say I have seen enough, I mean that Tom Haines' look last evening was quite enough for me. I would not be in his power for all the world."

"I am not in his power," exclaimed Frank, angrily.

"Nay, Frank, I saw you quail beneath his eye when he told you to make haste, and all your merriment seemed gone. Oh, Frank, it cannot be a good friend who can have such power over you."

The return of the foreman put a stop to the conversation, and there was no further opportunity for renewing it during the day, as Walter accompanied his master down to the lower village, and was at work there the whole of the afternoon.

Although so short a time had elapsed since the opening of the evening school, Walter had already made great progress both in mensuration and drawing; and he was now generally preferred before Frank to go with Mr. King when he wanted any assistance. That afternoon they were busy putting up the mouldings round the doors and windows of one of the houses on the shore, which they were hurrying to finish, as the gentleman who had purchased it wished to come and live in it as soon as possible. They were busily at work, when a message came for Mr. King, who was obliged to absent himself for a time.

"Can I trust you, Walter, do you think, to finish putting up this moulding by yourself? I promised that it should be done this evening, and I am obliged to go to the upper village for an hour at least."

"I can do it, sir, I know," said Walter, his eyes sparkling with pleasure at the thought of being trusted; "you shall see that you can trust me."

"Very well," said Mr. King, smiling. "You are a sharp lad, and a steady one too, and will rise in the world, if I am not very much mistaken."

Walter worked on steadily. He was really fond of his business, especially those parts of it which required peculiar nicety. Quite absorbed in what he was about, and whistling merrily as he worked, he was unconscious of the entrance of a good-natured-looking elderly gentleman, who stood for some minutes watching Walter as he was finishing a corner of a moulding which he had fitted with great exactness.

"Well done, youngster," said a cheerful voice; and Walter started as he looked up and saw the old gentleman watching him. "You are rather young to be trusted with such work as that; but you seem to know what you are about."

"Master was obliged to go away for a short time, sir, and he said I might try how I could get on in his absence."

"I am sorry Mr. King is not here, for I wanted to speak to him about putting some slight ornament in wood-work round that gable. I am leaving Springcliffe this evening, and shall be away a week. I know he could give me an idea of what I want on paper in a moment. I cannot draw a stroke myself, more's the pity; for I have often felt the loss of it, knowing quite well what I want, but being utterly unable to make others understand it."

While the gentleman was speaking, Walter had taken up a smoothly-planed piece of deal, which was lying upon the ground, and was drawing something upon it. Strange to say, he had been lately copying some designs for ornamental gables at the evening school, and he remembered enough of some of the patterns to give a very fair idea in his sketch.

"Is this anything like what you mean, sir?" he said, showing what he had just been drawing.

"It is something very like it," exclaimed the gentleman, with a look of surprise. "Where did you learn to draw like this?"

"At the evening school, sir. I go there three times a week, and practise at home besides."

"Your sketch does you great credit, my lad, and with a very little alteration would be just what I want. Can you round off that corner a little, and give that part rather more of a curve?"

Walter did as the gentleman suggested and his sketch was pronounced perfect.

"Is this anything like what you want, sir?"

"Is this your first attempt at drawing a design?"

"Yes, sir; except what I have done at school."

"It does you great credit, and I shall tell your master so." He wrote a few lines on a card as he spoke, and putting it in an envelope which he had in his pocket, he gave it to Walter to give to Mr. King. "Here is half-a-crown for your first design, youngster," said the gentleman, "and it will not be the last you'll get, if you go on as you are now doing."

The gentleman left the house, and Walter worked doubly hard to make up for the time he had lost. He was most anxious to get as much done as possible before his master returned. When at last Mr. King did come back, he was much pleased with all that Walter had done, and praised him for his industry.

"But what is all this, Walter, eh?" said his master, as he opened the envelope which had been left for him by the old gentleman. "Mr. Danvers talks about a design of yours, with which he was much pleased. Where is it?"

"It is nothing particular, sir," said Walter, colouring, as he showed Mr. King the sketch he had drawn. "I took the idea from some designs we have been copying lately at the class, and it seemed to be just what Mr. Danvers wanted."

"I am very glad you are able to apply what you learn, Walter," said his master. "Those classes will make a man of you, if you go on at this rate."

Walter's face beamed with pleasure as his master spoke these words. He showed Mr. King the half-crown which Mr. Danvers had given him.

"You deserved it, Walter, and I will add another to it," continued Mr. King, taking his purse out of his pocket. "Now, put that five shillings into the Post-Office Savings' Bank this very evening, Walter, as the first fruits of the benefit you have reaped from having listened to good advice, and from having sacrificed a little of your leisure time to the laudable desire of improving yourself. I only wish Frank Hardy deserved the same encouragement.

"By the bye, Walter—I don't want you to tell any tales—but do you know how Frank employs himself in the evening? I rarely see him about the village, and he is always in a hurry to leave the yard."

"I don't know much about Frank, sir," replied Walter—"at least, I mean what he does after he leaves the yard; but I think he is a great deal with Tom Haines."

"Just so," said Mr. King; "I fear so also; and a worse companion it is impossible for a young lad to have; but why Tom Haines troubles himself about Frank is a mystery to me."

THE POACHERS.

SHALL we explain to our readers what it was that made Tom Haines "trouble himself," as Mr. King called it, about Frank Hardy? The reason was simply this. Tom was mixed up with the gang of poachers of whom Walter's mother had spoken as infesting the preserves on Squire Forbes' estate.

Now, it so happened that the Mill Cottage was a place where the stolen game could be very conveniently deposited, as nothing was easier than to bring the spoil through the woods down to the other side of the stream which ran at the end of the Hardys garden, and then to convey it across in the boat, which was always lying there. This done, the stolen game was concealed among some thick bushes in the garden until it was transferred to the care of a carrier, whose tilted cart passed the end of the little lane before daybreak every other day on its way to a distant market town.

The carrier was in league with the poachers, so there was no difficulty about him; the only thing was, how to secure the services of the Hardys.

"Leave that to me," Tom Haines had said; and he soon managed the matter.

He began by flattering Frank, who was weak enough to be flattered by the notice taken of him by one so much older than himself, and then, when once he had got Frank to commit himself, and to take part in one of their midnight excursions, and even to accept a sum of money as his share in the spoil, he turned round upon him, and dared him to refuse to do anything he bid him.

"You are in my power now, Frank," said Tom.

And Frank knew it only too well, and became the tool of Haines and his associates. At all times the bondage was very bitter; and some seasons there were, too, when better thoughts would come over Frank, and he would have given anything to have been free, to have been like Walter, whose sunny face and blithe whistle would, at such moments, add to Frank's miserable feelings.

"I never whistle like that now," he would say to himself; "once I used to, but now—"

Yes, but that "once" was before Frank had sold himself to work wickedness, since which time there had been no real happiness for him.

"There is no peace, saith my God, to the wicked."

Did John Hardy and his wife know what was going on? John's evenings were regularly spent at "The Plough," whence he generally returned home more or less the worse for drink. His son's absence from home at night was, therefore, rarely remarked by him; and if occasionally a suspicion had arisen in his mind, a bribe from Haines had made him conveniently blind to anything that took place afterwards. Frank's mother also must have known that something wrong was going on; but an occasional present of a rabbit at a time when food chanced to be particularly dear kept her silent, and thus caused her to aid and abet in her son's road to ruin.