Books by

WILLIAM J. LONG

WOOD-FOLK COMEDIES

HOW ANIMALS TALK

HARPER & BROTHERS, NEW YORK

Established 1817

[See p. 105

“Deer appear on the opposite shore, stepping daintily; the wild ducks glide out of their hiding place.”

WOOD-FOLK COMEDIES

The Play of Wild-Animal Life

on a Natural Stage

BY

William J. Long

Author of

“How Animals Talk” “Brier-Patch Philosophy”

“School of the Woods” “Northern Trails” etc.

Illustrated

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

Wood-folk Comedies

Copyright, 1920, by Harper & Brothers

Printed in the United States of America

Published October, 1920

I-U

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | Prelude: Morning on Moosehead | 3 |

| II. | The Birds’ Table | 15 |

| III. | Fox Comedy | 32 |

| IV. | Players in Sable | 44 |

| V. | Wolves and Wolf Tales | 57 |

| VI. | Ears for Hearing | 78 |

| VII. | Health and a Day | 90 |

| VIII. | Night Life of the Wilderness | 113 |

| IX. | Stories from the Trail | 138 |

| X. | Two Ends of a Bear Story | 176 |

| XI. | When Beaver Meets Otter | 184 |

| XII. | A Night Bewitched | 214 |

| XIII. | The Trail of the Loup-Garou | 233 |

| XIV. | From a Beaver Lodge | 256 |

| XV. | Comedians All | 283 |

| “Deer Appear on the Opposite Shore, Stepping Daintily; the Wild Ducks Glide Out of Their Hiding Place” | Frontispiece | |

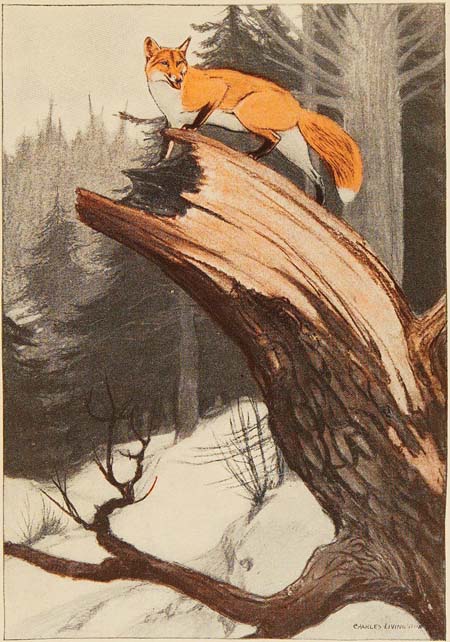

| “He Scrambled Up It With Almost the Ease of a Squirrel and Disappeared into the Top” | Facing p. | 42 |

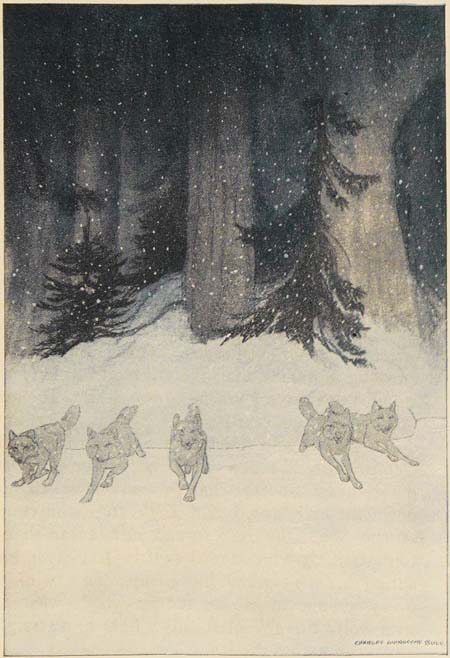

| “The Rest Spread into a Fan-shaped Formation as They Came Straight On” | “ | 74 |

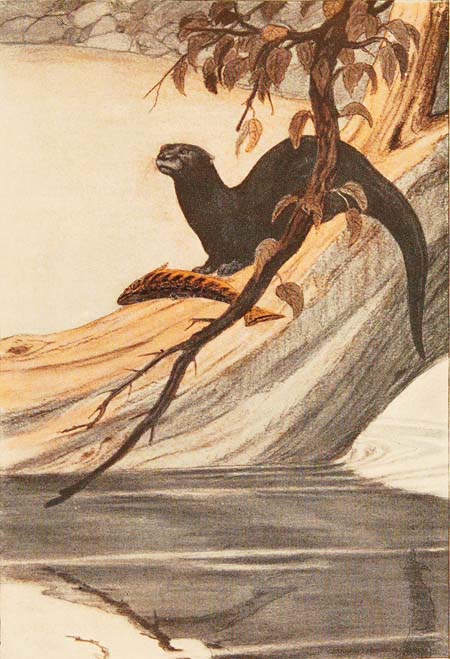

| “He Is a Very Expert Fisherman, and Finds Plenty to Eat Without Interfering With Any Other” | “ | 188 |

| “Their Very Attitude Made Me Feel Queer, for They Were in Touch With a Matter of Which I Had No Warning” | “ | 226 |

| “With a Sudden Access of Courage He Pounced on His Find, Whirled It Up in the Air, Scampered Hither and Yon Like a Playing Kitten” | “ | 242 |

| “The Silhouette of That Quiet Beaver Stood Out Like a Watchman Against the Evening Twilight” | “ | 266 |

| “Then He Peeks Cautiously Around the Tree, and Very Likely Finds a Black Nose Coming to Meet Him” | “ | 296 |

WOOD-FOLK COMEDIES

[2]

SUNRISE in the big woods, morning and springtime and fishing weather! For the new day Killooleet the white-throated sparrow has a song of welcome; fishing has its gleeman in Koskomenos the kingfisher, sounding his merry rattle along every shore where minnows are shoaling; and for the springtime even these dumb trees grow eloquent. Yesterday they were gray and dun, as if life had lost its sense of beauty; to-day a mist of tender green appears on every birch tree, a blush of rose color spreads over the hardwood ridges. Woods that all winter have been silent, as if deserted, are now alive with the rustling of eager feet, the flutter of wings, the call of birds returning with joy to familiar nesting places.

Above these quiet voices of rejoicing sounds another note, loud, rhythmic, jubilant, which says[4] that Comedy, light of foot and heart, has once more renewed her lease of the wilderness. High on a towering hemlock a logcock has his sounding board, dry and resonant, where he makes all the hills echo to his lusty drumming. The morning light flames on his scarlet crest as he turns his head alertly, this way for the answer of a mate, that way for the challenge of a rival. Nearer, on the roof of my fishing camp, a downy woodpecker is thumping the metal cover of the stovepipe, a wonderful drum, on which he can easily make more noise than the big logcock.

Every day before sunrise that same little fellow appears on my roof, so punctually that one wonders if he keeps a clock, and bids me “Top o’ the Morning” by sending a fearful din clattering down the stovepipe. It is a love-call to his mate, no doubt; but the Seven Sleepers in my place must be roused by it as by dynamite. This morning he exploded me out of sleep at four-twenty, as usual; and so persistent was his rackety-packety that I lost patience, and threw a stick of wood at him. Away he went, crying “Yip! Yip!” at the meddlesome Philistine who had no heart for love, no ear for music. He was heading briskly for the horizon when, remembering his shy mate, he darted aside to the shell of a white pine, where he drummed out another message, only to meet violent opposition[5] from another Philistine. He had sounded one call, listened for the effect, and was in the midst of another ecstatic vibration when there came a scurry of leaves, a shaking of boughs, and Meeko the red squirrel appeared, threatening death and destruction to all drummers.

Evidently Meeko was planning a nest of his own in that vicinity, and had no mind to tolerate such a noisy fellow as a near neighbor. As he came headlong upon the scene, hurling abuse ahead of him, the woodpecker vanished like a wink, leaving the enemy to threaten the empty air; which he did in a fashion to make one shudder at what might happen if a red squirrel were half as big as his temper. Once I saw a bull-moose accidentally shake a branch on which Meeko happened to be sitting while he ate a mushroom, turning it around in his paws as he nibbled the edges; and the peppery little beast followed the sober great beast two or three hundred yards, running just above the antlered head, calling down the wrath of squirrel-heaven on all the tribe of moose. Now, in greater rage because the object of it was so small, he whisked all over the pine, declaring it, kilch-kilch! to be his property, and warning all woodpeckers, zit-zit! to keep forever away from it. Hardly had he ended his demonstration of squirrel rights and gone away, swearing,[6] to his interrupted affairs when another hammering, louder and more jubilant, began on the pine shell.

Here was defiance as well as trespass, and Meeko came rushing back to deal with it properly. Sputtering like a lighted fuse he darted up the pine and took a flying leap after the drummer, determined this time to make an end of him or chase him clean out of the woods. Into a thicket of spruce he went, shrilling his battle yell. Out of the thicket flashed the woodpecker, unseen, and doubled back to the starting point. There a curious thing happened, one which strengthened my impression that all birds have more or less ventriloquial power to make their calling sound near or far at will. The woodpecker lit on precisely the same spot he had used before, and hammered it with the same rapidity and rhythm; but now his drum sounded faintly, distantly, as if on the other side of the ridge. Growing bolder he changed his note, put more hallelujah into it, and was in the midst of a glorious rub-a-dub when Meeko came tearing back through the spruce thicket and hunted him away.

So the little comedy ran on, charge and retreat, till a second Meeko appeared and held the fort, while the first ran after the drummer. Now, as I watch the play, there is triumphant squirrel talk on the pine shell, and the woodpecker is again drumming lustily on the stovepipe cover.

[7]Farther back in the woods sounds the roll of another drum, a muffled brum, brum, brum, which you must hear many times before you learn to locate it accurately. Of all forest sounds it is the vaguest, the most mysterious, the hardest to associate with distance or direction. Now it comes to you from above, like a dim echo of distant thunder, and suddenly you understand the bird’s Indian name, Seksagadagee, little thunder-maker; again it drifts in vaguely from all directions, filling the air like the surge of a waterfall at night. Listen attentively, and the drum seems to be near at hand, quite distinctly in front of you; but take a few careless steps in that direction and it is gone, like a flame that is blown out, and when you hear it once more it sounds faintly from the valley behind you.

Somewhere out yonder, not nearly so remote as you think, a cock partridge or ruffed grouse is finding a mate by the odd method of drumming her up; for he never goes in quest of her, but rumbles his drum day after day, sometimes also on moonlit nights, till she appears in answer to his summons. Though I have often seen little Thunder-maker when he was filling hill and valley with his love-call, never yet have I learned how he sounds his drum; so I must have another look at him. Taking every precaution against noise, moving only when the muffled thunder rolls[8] through the woods, I creep nearer and nearer till I locate a great mossy log and— Ah! there he is, a beautiful creature, standing tense as if listening. There is a flash of wings up and down, so swift that I cannot follow the motion or tell whether the hollow brum sounds when the stiffened wings are above the bird’s back or in front of his pouting chest. He does not beat the log; I have an impression that the booming sound is made by columns of air caught under the wings and driven together when the grouse strikes forward. If you cup your hands and drive them almost against your ears, repeating the action till you hear the air boom, you will have a faint but excellent imitation of the partridge’s drum call. The explanation remains theoretical, however, for even with the bird under my eyes I cannot say for a certainty how the sound is made. I see flash after flash of the wings, and with each comes an answering brum; then the wing-beats follow faster and faster till individual sounds merge in a continuous roll; which suddenly grows faint, as if moving away, and seems to vanish in the far distance.

Thunder-maker now stands at attention, his ear cocked to something I cannot hear. In a few moments, as if well satisfied, he droops his wing-tips, spreads wide his tail, erects his crest and his bronzed ruff, and begins to strut, showing all his[9] fine feathers. There is a stir beyond him; from behind a yellow birch a hen-grouse appears and glides on, pretending to be merely passing this way; while the drummer pretends not to see her or to be interested in anything save his own performance. So it seems to me, watching the play through the branches of a low fir. Thunder-maker drums again, as if his mate were yet to come; while the audience moves coyly away, picking at a seed here or there, till she enters the shadowy underbrush. There she hides and remains motionless, where she can see without being seen.

As I creep away, trying not to disturb the little comedy, I am startled by a rush behind me, and have glimpse of two deer bounding through the leafless woods. They take needlessly high jumps for such easy going, it seems; one has an impression that they are kicking up their heels in delight at being out of their winter yard, free to wander at will and find abundance of fresh food, tender and delicious, wherever they seek. A loon blows his wild bugle from the lake below. Multitudes of little warblers, the first ripple of a mighty wave, are sweeping northward with exultation, singing as they go. Frogs are piping, kingfishers clattering, thrushes chiming their silver bells,—everywhere the full tide of life, the impulse of play, the spirit of happy adventure.

[10]One such morning, when every blessed bird or beast appears like a bit of happiness astray, should be enough to open one’s eyes to the meaning of nature; but yesterday was just like this in the woods, and in the back of my head is a memory of other mornings in that far, misty time when all days came as holidays, when one leaped out of bed with the wordless thought that life was too precious to waste any of its sunny hours in sleeping. Suddenly it occurs to me, looking out from my “Commoosie” at the sunrise on Moosehead, while the woods around are vocal and jubilant, that this inspiring morning is simply natural and as it should be; that this new day, with its tingle of life and joy, is typical of the whole existence of the wood folk. For them every day is a new day, joyous and expectant, without regret for yesterday or anxiety for the morrow.

“Ah, but wait!” you say. “Wait till winter returns with its hunger and snow and bitter cold. Then we shall see nothing of this springtime comedy, but a stern and terrible struggle for existence.”

That owlish hoot expresses the prevalent theory of wild life, I know; but forget all such borrowed notions here in the budding woods, and open your eyes to behold life as it is. “Ask now the beasts and they shall teach thee, or the fowls of the air and they shall tell thee” that animal life is from[11] beginning to end a gladsome comedy. The “tragedy” is a romantic invention of our story-writers; the “struggle for existence” is a bookish theory passed from lip to lip without a moment’s thought or observation to justify it. I would call it mythical were it not that myths commonly have some hint of truth or gleam of beauty in them; but this struggle notion is the crude, unlovely superstition of one who used neither his eyes nor his imagination. To quote Darwin as an authority is to deceive yourself; for he borrowed the notion of natural struggle from the economist Malthus, who invented it not as a theory of nature (of which he knew nothing), but to explain from his easy-chair the vice and misery of massed humanity. Moreover, Darwin used the “struggle for existence” as a crude figure of speech; but later writers accept it as a literal gospel, or rather bodespel, without once putting it to the test of out-door observation.[1]

[12]A moment’s reflection here may suggest two things: first, that from lowly protozoans, which always unite in colonies, to the mighty elephant that finds comfort and safety in a herd of his fellows, coöperation of kind with kind is the universal law of nature; second, that the evolutionary processes, to which the violent name of struggle is thoughtlessly applied, are all so leisurely that centuries must pass before the change is noticeable, and so effortless that subject creatures are not even aware they are being changed. Meanwhile individual birds and beasts go their alert ways, finding pleasure in the exercise of every natural faculty. Singing or feeding, playing or resting, courting their mates or roving freely with their little ones, all wild creatures have every appearance of gladness, but give you never a sign that they are under a terrible law of strife or competition. And why? Because there is absolutely no such thing as a struggle for existence in nature. There is no evidence of struggle, no reason for struggle, no impression of the spirit of struggle, when you look on the natural world with frank unprejudiced eyes.

As for the coming winter, let not theory be as a veil over your sight to obscure the facts or to blur your impressions. One who camps in these big woods when they are white with snow finds[13] them quite as cheery as the woods of spring or summer. Most of the birds that now fill the solitude with rejoicing will then be far away, pursuing the happy adventure under other skies; but the friendliest of them all, the tiny chickadee, will bide contentedly in his cold domain, and greet the sunrise with a note in which you detect no lack of cheerfulness. A few of the animals will then be snug in their dens, with the bear and chipmunk; others will show the same spirit of play—a little subdued, but still brave and confident—which moves them now as they go seeking their mates to the sound of running brooks and the fragrance of swelling buds. Keeonekh the otter will spend a large part of his time happily sliding downhill. Pequam the fisher will save his short legs much travel by putting his nose into every fox track till he finds one which tells him that Eleemos has been digging at a frozen carcass, and has the smell of it on his feet; then he will cunningly back-trail that fellow, knowing that food is somewhere ahead of him. Tookhees the wood mouse will be building his assembly rooms deep under the snow, and Meeko the red squirrel (mischief-maker the Indians call him) will still be making tragi-comedy of every passing event, berating the jays that spy upon him when he hides food, chasing the woodpeckers that hammer[14] on his hollow tree, and scolding every big beast that pays no attention to him.

To sum up this prelude of the sunrise: whether you enter the solitude in the expectant spring or the restful winter, “nothing is here to wail or knock the breast.” The wood folk are invincibly cheerful, and need no pity for their alleged tragic fate. If I dared voice their unconscious philosophy, I might say that the lines are fallen unto them in pleasant places, and that, if ever they grow discontented with the place, they quickly change it for a better or for hope of a better. The world is wide and all theirs, and through it they go like perpetual Canterbury pilgrims.

THE impression of comedy among natural birds and beasts first came to me in childhood, a time when eyes are frankly open to behold the natural world as God made it. Long before it became the excellent fashion to feed our winter birds, I used to prepare a table under the grapevines and spread it with crumbs, raisins, cracked nuts, everything a child could think of that feathered folk might like. Scores of wild birds came daily to my table in bitter weather. Squirrels frisked over it, and were sometimes hungry enough to eat before they began to hide things away, as squirrels commonly do when they find unexpected abundance. Several times a family of Bob Whites, graceful and light footed, came swiftly over the wall, gurgling exquisite low calls as they sensed[16] the feast; and once a beautiful cock partridge appeared from nowhere, gliding, turning, balancing like a dancing master, and hopped upon the table and ate all the raisins as his first morsel.

Unless a door were noisily opened or a sneaky cat crept into the scene, none of these dainty creatures gave me any impression of fearfulness, and such a notion as pity for their tragic existence could hardly enter one’s head; certainly not so long as one kept his eyes open. Though always finely alert, they seemed a contented folk, gay even in midwinter, and they quickly accepted the child who watched with eager eyes from the window or sat motionless out-of-doors within a few feet of their dining table. When their hunger was satisfied many would stay a little time, basking in the sunshine on the grapevines or the pear tree, as if they liked to be near the house. Some of them sang, and their note was low and sweet, very different from their springtime jubilation. A few uttered what seemed to be a food call, since it brought more of the same feather hurrying in; now and then it appeared that birds which are perforce solitary in winter (because of the necessity of seeking food over wide areas) were glad to be once more with their own kind. Among these were certain small groups, noticeable because they chattered together after the feast, and I wondered[17] if they were not a mother bird and her reunited nestlings. I think they were, for I have since learned that family ties hold longer among the birds than we have been led to imagine.

One of the first things I noticed in the conduct of my little guests was that they were never quarrelsome so long as they were downright hungry. Indeed, unlike our imported house sparrow, very few of them showed a pugnacious disposition at any time; but now and then appeared a thrifty or grasping fellow who, after satisfying his hunger, would get a notion into his head that the food was all his if he could claim or corner it; and he was apt to be a trouble-maker. This early observation is one which I have since confirmed many times, both at home and in the snows of the North: the hunger which is supposed to make wild creatures ferocious invariably softens and tames them.

Another matter which soon became evident was that birds of the same species were not all alike. Their forms, their colors, even their faces distinguished them one from another. I began to recognize many of them at sight, and presently to note individual whims or humors which reminded me pleasantly of my neighbors; so much so that I called certain birds by names which might be found in the town records, but not in books of natural history. Some came with grace to the[18] table, eating daintily or moving aside for a newcomer, as if timid of giving offense. Others swooped in and fed rudely, unmindful of others, as if eating had no savor of society or the Sacrament, but were a trivial matter to be finished quickly, with no regard for that natural courtesy and dignity which we now call manners.

Among these graceful or graceless birds there was constant individual variety. Alert juncos, forever on tiptoe, would be followed by some sleepy or indifferent junco; woodpeckers that seemed wholly intent on the marrow of a hollow bone would be replaced by a Paul-Pry woodpecker, who was always watching the other guests from behind a limb; and sooner or later in the day I would bid welcome to “Saryjane,” a fussy and suspicious bird that reminded me of a woman who had only to look at a boy to make him shamefully conscious that his face needed washing or his clothes mending.

No sooner did “Saryjane” light on the table than peace took to flight. Before she picked up a crumb she would lay down the law how crumbs must be picked up, and by her bossy or meddlesome ways she drove many of the birds into the grapevines; whither they went gladly, it seemed, to be rid of her. They soon learned to anticipate[19] her ways; at her approach some dainty tree sparrow or cheerful titmouse would flit away with an air of “Here she comes!” in his hasty exit. She was a nuthatch, one of a half-dozen that came at odd times, peaceably enough, to explore a lump of suet suspended over the birds’ table; and whenever I see her like now, or hear her critical yank-yank, I always think of “Saryjane” rather than of Sitta carolinensis.

When I translate the latter jargon, using a monkey-wrench on the grammar, I get, “A she-thing that squats, inhabitating a place named after an imaginary counterpart of a he-one miscalled Carolus”; which illuminates the ornithologists somewhat, but leaves the nuthatch in obscurity. The other name has power, at least, to evoke a smile and a happy memory. The real or human “Saryjane” used to stipulate, when she hired a boy to pick her cherries, that he must whistle while he worked or lose his pay.

One morning—I remember only that the snow lay deep, and that all birds were uncommonly eager at their breakfast—a stranger appeared at the birds’ table, a sober fellow whom I had never before seen. Without paying the slightest attention to other guests he plumped into the feast, ate enough for two birds of his size, and then sat for a long time beside a pile of crumbs, as if[20] waiting for another appetite. Thereafter he came regularly, and always acted in the same greedy way. He would light fair in the middle of the food, and gobble the first thing in sight, as if fearful that the supply might fail or that other birds might devour everything before he was satisfied. After eating he would sit at the edge of the table, his feathers puffed, a disconsolate droop to his tail, looking in a sad way at the abundance of things he could not eat, being too full. With the joy of Adam when he gave names to creatures that were brought before him, I promptly called this bird “Jake” after a boy about my size, one of a numerous and shiftless brood, whom I had brought most unexpectedly to our human table on Thanksgiving Day.

The table happened to be loaded, in the country fashion of that time, with every tasty or substantial thing that the farm provided, and Jake stuffed himself in a way to threaten famine. Turkey with cranberry sauce, sparerib with apple sauce, game potpie, mashed potatoes with cream, Hubbard squash with butter,—whatever was offered him vanished in fearful haste, and his eyes were fixed hungrily on something else. He said never a word; as I watched him, fascinated, he seemed to swell as he ate. Then came a great tray of plum pudding, with mince and pumpkin[21] pies flanked by raisins and fruit; and the waif sat appalled, his greasy cheeks puffed out, tears rolling down over them into his plate. “I can’t eat no puddin’; I—can’t—eat—no—pie!” he wailed; while we forgot all courtesy to our guest and howled at the comedy. Poor little chap! he had more hunger and less discretion than any wild thing I ever fed.

That was long ago, when I knew most of the birds without naming them, and when no one within my ken could have given me book names for the half of them had I cared to ask. It was the bird himself, not his ticket or his species, that always interested me.

Among the visitors was one gorgeous blue-and-white fellow, a jay, as I guessed at once, who puzzled me all winter. He always came most politely, and would light on the pear tree to whistle a pleasant too-loo-loo! a greeting it seemed, before he approached the table. I took to him at once, with his gay attire and gallant crest, and immediately he proved himself the most courteous guest at the feast. He invariably lit at some empty place; he would move aside for the smallest bird, with deference in his manner; when he took a morsel it was always with an air of “By your leave, sir,” which showed his breeding.

The puzzle was that other birds disdained this[22] handsome Chesterfield, refusing to have anything to do with him. Now and then, when he was most polite, some tiny sparrow would fly at his head or chivvy him angrily from the table; but for the most part they kept him at a distance until they had eaten, when they would move scornfully aside, leaving him to eat by himself. At first I thought they had bad tempers; but a child’s instinct is quick to measure any social situation, and when the jay had returned a few times I began to suspect that the fault was with him. Yes, surely there was something wrong, some pretense or imposture, in this fine fellow whom nobody trusted; but what?

The answer came in the spring, and was my own discovery. I am still more proud of it than of the time, years later, when I first touched a wild deer in the woods with my hand. Near my home was a woodsy dell with a brook singing through it, which I named “Bird Hollow” from the number of feathered folk that gathered or nested there. What attracted them I know not; perhaps the brook, with its shallows for bathing; or the perfect solitude of the place, for though cultivated fields lay about it, and from its edge a distant house could be seen, I never once met a human being there. It was just such a place as a child loves, because it is all his own, and because it is[23] sure to furnish something new or old every day of the year,—birds’ nests, wood for whistles, early woodcock, frogs for pickerel bait, pools for sailing a fleet of cucumber boats, a mink’s track, a rabbit’s form, an owl’s cavernous tree, a thousand interesting matters.

One morning I was at the Hollow alone, watching some nests at a time when mother birds chanced to be away for a hurried mouthful. Presently came my blue jay, and he seemed a different creature from the Chesterfield I had known. No more polite or gallant ways now; he fairly sneaked along, hiding, listening, like a boy sent to plunder a neighbor’s garden. Without knowing why, I felt suddenly ashamed of him.

Just over a catbird’s nest the jay stopped and called, but very softly. That was a “feeler,” I think, for at the call he pressed against the stem of a tree, as if to hide, and he stood alert, ready to flit at a moment’s notice. Then he dropped swiftly to the nest, drove his bill into it, and tip-tilted his head with a speared egg. A dribble of yellow ran down the corner of his mouth as he ate. He finished off two more eggs, and went straight as a bee to another nest, which I had not discovered. Evidently he knew where they all were. He speared an egg here, and was eating it when there came a rush of wings, the challenge of an excited[24] robin, and away went the jay screaming, “Thief! Thief!” at the top of his voice. A score of little birds came with angry cries to the robin’s challenge, and together they chased the nest-robber out of hearing.

And then I understood why the other guests had no patience with the jay’s comedy when he played the part of a fine fellow at the winter table. They knew him better than I did.

It was an experience, not a theory, of life that I sought in those early days, when nature spoke a language that I seemed to understand; and a host of experiences soon confirmed me in the belief that birds and beasts accept life, unconsciously perhaps, as a kind of game and play it to the end in a spirit of comedy. Later came the literature and alleged science of wild life, one filling the pleasant woods with tragedy, the other with a pitiless struggle for existence; but no sooner do I go out-of-doors to front life as it is than all such borrowed notions appear in their true light, the tragic stories as mere inventions, the scientific theories as bookish delusions.

The cheery lesson of the winter birds, for example, is one which I have since proved in many places, especially in the North, where I always spread a table for the birds before I dine at my[25] own. The typical table is a broad and bountiful affair, set just outside the window on the sunny side of camp; but sometimes, when I am following the wolf trails, it is only a bit of bark on the snow beside my midday fire.

When the halt comes, and the glow of snowshoeing is replaced by the chill of a zero wind, a fire is quickly kindled and a dipper of tea set to brew. Next comes the birds’ table with its sprinkling of crumbs, and hardly is one returned to the fire before Ch’geegee appears, calling blithely as he comes to share the feast. His summons invariably brings more chickadees, each with gray, warm coat and jaunty black cap; their eager voices attract other hungry ones, a woodpecker, a pair of Canada jays (they always go in pairs, as if expecting another ark), and a shy, elusive visitor who is no less welcome because you cannot name him in his winter garb. Suddenly from aloft comes a new call, very wild and sweet; there is a whirl of wings in the top of a spruce, where Little Far-to-go, as the Indians name him, calls halt to his troop of crossbills at sight of the fire and the gathering birds. A brief moment of rest, a babel of soft voices, another flurry of wings, and the crossbills are gone, speeding away into the far distance. Next to arrive are the nuthatches, a squirrel or two, and then—well, then you never[26] know who may answer your invitation. Before your feast ends you may learn two things: that these snow-filled woods shelter an abundant life, and that the life is invincibly cheerful.

So it happens that, though I have often been alone in the winter wilderness, I have never eaten a lonely meal there; always I have had guests, friendly, well-mannered little guests, and the pleasure they bring to the solitary man is beyond words. Very companionable it is, as one says grace over his bread and meat, to hear “Amen” from a score of pleasant voices making Thanksgiving of the homely fare. Warm as the radiance of the fire, soothing as the fragrance of a restful pipe, is the inner glow of satisfaction when one sees his guests linger awhile, gossiping over the unexpected, questioning the flame or the smoke, and anon turning up an inquisitive eye at the silent host from whose table they have just eaten. When I hear speaker or writer urging his audience to feed our winter birds because of their earthly or economic value, I find myself wondering why he does not emphasize the heavenly fun of the thing.

As I recall these many tables, spread in the snow at a season when, as we imagine, the pitiless struggle for existence is at its height, they all speak to strengthen the early impression of gladness, of good cheer, of a general spirit of play or[27] comedy among wild creatures. I have counted over sixty chickadees, woodpeckers, grouse, jays, squirrels and other wayfarers around the table beside my camp; but though some of these have their enmities in the nesting season, when jays and squirrels are overfond of eggs, it was still a lively and a happy company, because all the wood folk have an excellent way of ending an unpleasantness by forgetting it. They live wholly in the present, being too full of vitality to dwell in the past, and too carefree to burden life by carrying a grudge.

Some of these remembered guests came boldly to my table, some with the exquisite shyness born of the silent places; but all were natural at first, and therefore peaceable. Unlike our mannerless house sparrows, they fed very daintily for the most part, and would chatter pleasantly before going away, to return when they were again hungry; but now and then some graceless bird or squirrel would insist on having the biggest morsel, or might even try to drive others away while he made sure of it; and it was these exceptional individuals who caused whatever brief, unnatural bickerings I have chanced to witness.

I remember especially one nuthatch that visited my winter camp in Ontario; he was different from all others of his kind, even from my early acquaintance,[28] “Saryjane,” in that he seemed possessed of the notion that whatever I put out-doors in the way of food was his private property. He was always first at the table, arriving before the sun; and sometimes, when an angry chatter would break through my dawn dreams, I would go to the window to find him driving other early comers away from the relicts of yesterday’s abundance. “Food Baron” we dubbed him when some of his notions struck us as familiar and quite human.

As the sun rose, and more hungry birds appeared for the breakfast I always spread for them, the Baron would change his methods. Finding the hungry ones too many or too lively to be managed, he would proceed hurriedly to remove as much food as possible to a cache which he had somewhere back in the woods. In this individual whim of hiding food, as well as in his peculiar challenge, he was different from any other nuthatch I ever met. Returning from one of these hurried flights, he would perch a moment on a branch over the table, eye the feeding guests angrily, pick out one who was busy at a big morsel, and launch himself straight at the offender’s head. Deep in his throat sounded a terrifying chur-churr as he made his swoop.

The odd thing is that he always got the morsel he wanted. Though he often charged a jay or a[29] squirrel much bigger than himself, I never saw one that had the nerve to stand against his headlong rush. Being peaceable and a little timid, as all wild things naturally are, they dropped whatever they were eating and dodged aside; whereupon the nuthatch swept over the table like a fury, whirring his wings and crying, “Churr! Away with you! Vamoose!” which sent most of the little birds with startled peeps into the trees. Then, with the board cleared, he would drag off his morsel, hide it, and come back as quickly as he could to repeat his extraordinary performance.

How the other birds regarded him would be hard to tell. At times they seemed to get a bit of fun or excitement out of the game by slipping in to steal a mouthful while the Baron was chasing some luckless fellow who had claimed too big a crumb. At other times they would wait patiently in the trees, basking in the sunshine, till the trouble-maker was gone away to hide things, when they would come down and feed alertly. In this way they would soon get all they wanted for the time, and flit away to their own affairs. Another odd thing is that the Baron, after storing things without opposition for a few minutes, would tire of it and disappear, leaving plenty still on the table.

Occasionally in the woods one meets a bird that by some freak of heredity seems to have been[30] born without his proper instincts: a young wild goose sees his companions depart from the North, but feels no impulse to follow them, and remains to die in the winter snow; or a cow-bunting has no instinct to build a nest of her own, and makes a farce of life by leaving an egg here or there in some other bird’s household. Among the beasts it is the same story: a rare beaver has no instinct to build a house with his fellows, but lives by himself in a den in the bank; or some timid creature that has fled from you unnumbered times on a sudden upsets all your generalizations by showing the boldness of lunacy.

I remember one occasion when darkness and rain overtook me on the trail, and sent me to sleep in a deserted lumber camp; which is the most sleepless place on earth, I think, being full of creaks, groans, rustling porcupines, wild-eyed cats, spooks, mice, evil smells, and other distractions. Except in a downpour, any tree or bush offers more cheerful shelter. About the middle of the night I was awakened, or rather galvanized, by the impression that some creature was trying to get at me. In the black darkness of the place the very presence of the thing seemed to fill the whole shanty. I foolishly jumped up, charged with a yell, and ran bang into a huge, hairy object. There was a grunt, and a hasty, flaring match[31] showed the grotesque head of a cow-moose sticking into the open window. Having been scared stiff, I belted her away roughly; but hardly had I straightened my poor nerves in sleep when she came again, head, neck, shoulders, all she could crowd into the low doorway. I shooed her off, hastening her flight with clubs, ax heads, old moccasins, everything throwable that I could lay hands on; yet she lingered about the yard for an hour or two, and once more came snuffling with her camel’s nose at the window. How do I account for her? I don’t. You can say that she mistook me for her lost calf, and I shall not contradict you.

So this nuthatch, at odds with all his kind, may possibly have been born without the common instinct of sociability and decency. The other birds were sometimes seen watching him curiously, as they watch any other strange thing. Now and then one of them would resent some personal indignity by giving the greedy one tit for tat; but for the most part they seemed well content to keep aloof from the nuisance. They had enough to eat, with a little sauce of excitement, and I think they accepted the nuthatch as a harmless kind of lunatic.

THOUGH my early impressions of wild life were mostly heart-warming, one thing always troubled me, and that was the clamor of a pack of hounds running a fox to death. There were fox hunters in the neighborhood; I had shivered at stories of men who had been chased by wolves, and whenever I heard the winter woods ringing to dog voices I pictured the poor fox as running desperately for his life, with terror lifting his heels or tugging at his heart. I could see no comedy in that picture, probably because, never having witnessed a fox chase, I was viewing it with my imagination rather than with my eyes.

There came a day when the hounds were out in full cry, and I was in the snowy woods alone. For some time I had heard dogs in the distance, and when a louder clamor came on the breath[33] of the wind I hid beside a hemlock fronting a stream, all eyes and ears for whatever might befall. Presently came the fox, the hunted beast, and my first glimpse of him was reassuring. He was moving easily, confidently, his beautiful fur fluffed out as if each individual hair were alive, his great brush floating like a plume behind him. There was no sign of terror, no evidence of haste in his graceful action. Though he could run like a red streak, as I well knew, having watched fox cubs playing outside their den, he was now trotting leisurely on his way, stopping often to listen or to sniff the air, while far behind him the heavy-footed hounds were wailing their hearts out over a tangled trail.

So Eleemos came to the water and ran lightly beside it, heading downstream, taking in the possibilities of the situation with cunning glances of his bright eyes. The water was low; above it showed the heads of many rocks, from which the sun had melted all the snow, leaving dry spots that would hold no scent. Suddenly a beautiful jump landed Eleemos on a flat rock well out from shore; without losing momentum he turned and went flying upstream, leaping from rock to rock, till he was twenty yards above where he had first approached the water, and a broad stretch called halt to his rush. Again without losing speed, he whirled in[34] to my side, leaped ashore, flashed up through the woods, and scrambled to the top of a ledge, where he could overlook his trail. When I saw him stretch himself comfortably in the sunshine, as if for a nap, and when, as the hounds came pounding into sight, he lifted his head to cock his ears and wrinkle his eyebrows at the lunatic beasts that were yelling up and down a peaceful world, trying to find out where or how he had crossed the stream—well, then and there I put imagination aside, and concluded that perhaps the fox was getting more fun out of the chase than any of the dogs. He had this advantage, moreover, that whenever he wearied of the play he had only to slip into the nearest ledge or den to make a safe end of it.

Another day when I was roaming the woods I heard in the distance the melodious voice of Old Roby, best of all possible foxhounds. It was a springlike morning, with melting snow; and Roby, thinking it an excellent time for smelling things, had pulled the collar over his head and gone off for a solitary hunt, as he often did. When his voice rose triumphant over a ridge and headed in my direction, I hurried to the edge of a wild meadow and stood against a big chestnut tree, waiting for the fox and growing more expectant that I should have a glimpse of him.

A short distance in front of me a cart-path came[35] winding down through the leafless woods. Where this path entered the meadow was a dry ditch; over the ditch was a bridge of slabwood, and some loaded wagon had recently broken through it, crushing the slabs on one side down into the earth. On that side, therefore, the ditch was closed; but on the other side it appeared as a dark tunnel, hardly a foot high and three or four times as long,—an excellent refuge for any beastie that cared to shelter therein, since it was too low for a hound to enter bodily, and if he thrust his head in too far, the beastie would have a fine chance to teach him manners by nipping his nose.

I had waited but a few minutes when down the cart-path came the fox, running fast but not easily. One could see that at a glance. The soft snow made hard going; as he plunged into it, moisture got into his great brush, making it heavy, so that it no longer floated like a gallant plume. A gray fox would have taken to earth within a few minutes of the start, and now even this fleet red fox had run as far as he cared to go under such circumstances. At sight of the open meadow he put on speed, flying gloriously down the hill. One jump landed him fair in the middle of the bridge; a marvelous side spring carried him into the ditch, and with a final wave of his brush he disappeared into the tunnel.

[36]A little later Old Roby hove into sight, singing ough! ough! oooooooh! in jubilation of the melancholy joy he followed. Clean over the bridge he went, head up, picking the rich scent from the air rather than from the ground, and took three or four jumps into the meadow before he discovered that the fox was no longer ahead of him. Then he came out of his trance, circled over the bridge, poked his nose into the tunnel. There before his bulging eyes was the fox, and in his nostrils was a reek to drive any foxhound crazy. “Ow-wow! here’s the villain at last! And, woooo! what won’t I do to him!” yelled Roby, pulling out his head and lifting it over the edge of the bridge for a mighty howl of exultation. Again he thrust his nose into the tunnel and began to dig furiously; but the sight of the fox, so near, so reeky, so surely caught at last, set the old dog’s heart leaping and his tongue a-clamoring. Every other minute he would stop digging, back out of the tunnel for room, for air, and lifting his head over the bridge send up to heaven another jubilation.

Now Roby was bow-legged, as many foxhounds are that run too young; also he was apt to spread his feet as he howled, so that there was plenty of room to pass under him, and when his head was lifted up for joy he could see nothing but the sky. He had been alternately digging and celebrating[37] for some time, working his way farther under the bridge, when as he raised his head for another bowl of relief a flash of yellow passed between his bowlegs, out under his belly and up over the hill. The thing was done so boldly that it made one gasp, so quickly that a living streak seemed to be drawn through the woods; but the entranced old dog saw nothing of it. When he thrust his head confidently into the tunnel once more, there was no fox and no pungent odor of fox where landscape and smellscape had just been filled with foxiness.

Roby looked a second time and sniffed with a loud sniffing to be sure he was not dreaming. He looked all over the bridge, and sat down upon it. He examined the ditch on the other or closed side, and took a final squint into the tunnel; while every line and hair of him from furrowed face to ratty tail proclaimed that he considered himself the foolishest of all fool dogs that ever thought they could catch a fox. Then he shook his ears violently, as if ridding himself of hallucinations, and began to cast about methodically in circles. A fresh reek of fox poured into his nostrils, filling him with the old ecstasy; he threw up his head for a glad hoot, and went pounding up the hill after his nose, singing ough! ough! oooooh! as an epitome of all fox hunting.

[38]Whenever I heard the hounds after that, I pictured comedy afoot and followed it eagerly, still roaming alone in hope of meeting the fox, and making myself a nuisance to many a proper fox hunter who, waiting expectantly for a shot, heard the chase draw away and fell to cursing the luck or the mischief that had turned the fox from his runway. So it befell, one winter, that I saw Old Roby and a pack of hounds completely fooled by a fox that lay quietly watching them while they hunted and howled for his lost trail.

The place was a deep gully in some big woods. Its sides were covered with a mat of vines and bushes; at the bottom ran a stream, too broad to jump and too swift to freeze even in severe weather. Several times an old fox had been “lost” here, his trail leading straight to the gully, and vanishing as completely as if the river had swallowed him up. He was frequently started in some rugged hills to the westward, and would commonly play back and forth from one ridge to another till he wearied of the game, or till he met a hunter and felt the sting of shot on a runway, when he would break away eastward at top speed. For a mile or more his course could be traced by the hounds giving tongue on a hot scent until they reached the gully, where their steady trail-cry changed to howls of vexation. And that was the end of the[39] chase for that day, unless the weary dogs had ambition enough to hunt up another fox.

At first it was assumed that the game had run into a ledge, as red foxes do when they are fagged or wounded; but when hunters followed their baffled dogs time and again, they always found them running wildly up and down both banks of the stream, looking for a trail which they never found. Then some said that the fox had a secret den, which he approached by running over a tangle of vines where the hounds could not follow; but one old hunter, who had chased foxes for half a century, settled the matter briefly. “My dogs,” he said, “can follow anything that runs above ground. They can’t follow this fox. Therefore he takes to water, like a buck, and swims so far downstream that we never find where he comes out.” Though nobody had ever seen a fox take to water, a man who has followed foxes half a century is ready to believe almost anything within reason.

On stormy nights the hunters would forgather at the village store, and whenever the talk turned to the old fox of the gully I was all ears. I knew the place well, and wondered why some Nimrod, instead of merely shooting foxes or theorizing about them, did not take the simplest means of solving the mystery; but it would have been foolhardy in that veteran company to venture a new[40] opinion on the ancient sport of fox hunting. I remember once, when they were swapping yarns, of breaking rashly into the conversation to tell of a fox I had seen at a lucky moment when he did not see me. He was nosing along the edge of a wood, and I threw a chunk of wood after him as he moved away. It missed him by a foot, and he pounced upon it like a flash as it went bouncing among the dead leaves.

Now that was perhaps the most natural thing for any hungry fox to do, to catch a thing which ran away, instead of asking where it came from; but the veterans received the tale in grim silence. One told me that I had surely seen a “sidehill garger”; another wished he could have seen it, too; the rest pestered me unmercifully about the beast all winter. One of them is now in his dotage; but he never meets me without asking, “Son, did that ’ere fox really run arter that chunk of wood you hove at him?” And when I answer, “Yes, he did, and caught it,” he says, “Well, well, well!” in a way to indicate that he has been straining at that gnat for forty years. Heaven only knows how many fox-hunting camels he has swallowed in the interim.

One Saturday morning (a glorious day it was, with all signs pointing to a good fox run) I went early to the gully, crossed it, and hid where I had[41] a view up or down the stream. Several times during the day I heard hounds in the offing, but the chase did not head in my direction. When the winter sunset came, and an owl began to hoot in the darkening woods, it was time for a hungry boy to go home.

The next time I had better luck. From some hills far away the hoot of hounds came clear and sweet through the still air; then the flat report of a gun, a brief silence, a renewed clamor, and my ears began to tingle as the hunt drew my way, louder and louder. Suddenly there was a flash of ruddy color, warm and brilliant on the snow; the fox appeared on the farther side of the gully, slipped over the edge at a slow trot, and disappeared among the vines.

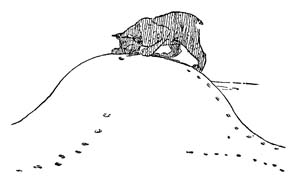

I was watching the stream keenly when the same flash of color caught my eye, again on the other side, but some fifty yards above where the fox had vanished. He bounded lightly up the steep bank, sprang to the level above, listened a moment to the dogs, ran along the edge a short distance, dropped down into the vines, came up quickly, and scuttled back again in another place. There were fleeting glimpses of orange fur as he dodged here or there, now near the stream, now among the thickest vines; then he tiptoed up and stood alert in the open, at the precise spot, apparently,[42] where he had first entered the gully. After cocking his ears once more at the increasing clamor of hounds, he headed back toward them into the woods; and I had the impression that he was carefully stepping in his own footprints, back-tracking, as many hunted creatures do. So he went, cat-footedly at first, then in swift jumps, till he came to a huge tree that had been twisted off by a gale, leaving a slanting stub some fifteen feet high. Here Eleemos took a flying leap at the stub, scrambled up it with almost the ease of a squirrel, and disappeared into the top.

“He scrambled up it with almost the ease of a squirrel and disappeared into the top.”

The hounds were by this time close at hand. A wild burst of music preceded them as they rushed into sight, heads up, giving tongue at every jump, and followed the hot trail headlong over the gully’s edge into the vines. Evidently the fox had run about most liberally there; in a moment the bounds were tangled in a pretty crisscross, lost all sense of direction, and broke out in lamentation. Most of them went threshing about the gully till the delicate fox trail was covered by a maze of dog tracks; but one old fellow, who had been through the same mill before, lay down in an open spot and rolled about on his back, his feet in the air, as if to say, “Well, here’s the end of this chase.” Another veteran with furrowed face and a deep, sad voice (it was Roby again), managed to[43] nose out half the puzzle, for he came creeping up over the edge of the gully at the point where the fox had first leaped out; but there he ran up and down, up and down, finding plenty of fresh scent everywhere without being able to follow it to any end except the empty vines. Another hound, a youngster with a notion in his head that anything which runs must go ahead, plunged into the stream, swam it, and went casting about the woods on the farther side.

Meanwhile there was a stir, the ghost of a motion, in the leaning stub. Over the top of it came two furry ears, then a pointed nose and a bright yellow eye. The fox was there, watching every play of the game with intense interest; and in his cocked ears, his inquisitive nose, his wrinkling eyebrows, were the same lively expressions that you see in the face of a fox when he is hunting mice, and thinks he hears one rustling about in the frozen grass.

IN severe weather, when snow lay deep on the silent fields, a few crows would enter the yard in view of my birds’ table, sitting aloof in trees where they could view the feast, but making no attempt to join it. I did not then know that crows are nest-robbers, like the jay, or that the smallest bird at the table was ready to bristle his feathers if one of the black bandits approached too near.

For several days, while the crows grew pinched, I waited expectantly for hunger to tame them, only to learn that a crow never ventures into a flock of smaller birds, being absurdly afraid of their quickness of wing and temper. Then, because any hungry thing always appealed to me, I spread a variety of food, scraps of meat and the[45] entrails of fish or fowl, on a special table at a distance; but the crows would not go near it, probably thinking it some new device to insnare them. They have waged a long battle with the farmer, and the battle has bred in them a suspicion that not even hunger can heal. As a last resort, I scattered food carelessly on the snow, and within the hour the hungry fellows were eating it. Their first meal was a revelation to me; no gobbling or quarreling, but a stately and courteous affair of very fine manners. Nor have I ever seen a crow do anything to belie that first impression.

Among the scraps was some field corn, dry and hard from the crib; but the canny birds knew too much to swallow the grain whole, ravenous though they were. Green or soft corn they will eat with gusto, but ripened field corn calls for proper treatment. Each crow would take a single kernel (never more than that at one time) to a flat rock on the nearest wall, and there, holding the kernel between the toes of a foot, would strike it a powerful blow with his pointed beak. I used to tremble for his toes, remembering my own experience with hammer or hatchet; but every crow proved himself a good shot. Occasionally a descending beak might glance from the outer edge of a kernel, sending it spinning out from under the crow’s foot; whereupon he hopped nimbly after it and[46] brought it back to the block. After a trial or two he would hit it squarely in the “eye”; it would fly into bits, and he would gather up every morsel before going back for a fresh supply.

Once when a hungry crow splintered a kernel in this way, I saw a piece fly to the feet of another crow, who bent his head to eat it as the owner came running up. The two bandits bumped together; but instead of fighting over the titbit, as I expected, they drew back quickly with a sense of “Oh, excuse me!” in their nodding heads and half-spread wings. Then they went through a little comedy of manners, “After you, my dear Alphonse” or “You first, my dear Gaston,” till they settled the order of precedence in some way of their own, when the owner ate his morsel and went back to the wall to find the rest of the fragments.

Watching these crows, with their sable dress and stately manners, it was hard to imagine them off their dignity; but I soon learned that they are rare comedians, that they spend more time in play or mere fooling than any other wild creature of my acquaintance, excepting only the otters. I have repeatedly watched them play games, somewhat similar in outward appearance to games that boys used to play in country school yards, and once I witnessed what seemed to be a good crow joke.[47] Indeed, so sociable are they, so dependent on one another for amusement, that a solitary crow is a great rarity at any season. Twice have I seen a white crow (an albino), but never a crow living by himself.

The joke, or what looked like a joke, occurred when I was a small boy. I was eating my lunch in a shady spot at the edge of a berry pasture when a young crow appeared silently in a pine tree, only a few yards away. A deformed tree it was, with a splintered top. In the distance a flock of crows were calling idly, and the youngster seemed to cock his ears to listen. Presently he set up a distressed wailing, which the flock answered on the instant. When a flurry of wings leaped into sight above the trees, the youngster dodged into the splintered pine, and remained there while a score of his fellows swept back and forth over him, and then went to search a grove of pines beyond. When they flew back across the berry pasture, and only an occasional haw came from the distance, the young crow came out and set up another wail; and again the flock went clamoring all over the place without finding where he was hidden.

The play ended in an uproar, as such affairs commonly end among the crows; but whether the uproar spelled anger or hilarity would be hard to tell. The youngster had called and hidden several[48] times; each time the flock returned in great excitement, circled over the neighborhood, and straggled back to the place whence they had come. Then one crow must have hidden and watched, I think, for he came with a rush behind the youngster, and caught him in the midst of his wailing. A sharp signal brought the flock straight to the spot, and with riotous haw-hawing they chased the joker out of sight and hearing.

It was this little comedy which taught me how easily crows can be called, and I began to have no end of fun with them. In the spring when they were mating, or in autumn when immense flocks gathered in preparation for sending the greater part of their number to the seacoast for winter, I had only to hide and imitate the distressed call I had heard, and presto! a flock of excited crows would be clamoring over my head. Yet I noticed this peculiarity: at times every crow within hearing would come to my first summons; while at other times they would bide in their trees or hold steadily on their way, answering my call, but paying no further attention to it. I mark that crows still act in the same puzzling way, now coming instantly, again holding aloof; but what causes one or the other action, aside from mere curiosity, I have never learned. In the northern wilderness, where crows are comparatively scarce,[49] it is almost impossible to call them at any season. They live there in small family groups, each holding its own bit of territory; and apparently they know each voice so perfectly that they recognize my imposture on the instant.

Whenever the “civilized” crows found me, after hearing my invitation, they rarely seemed to associate me with the crow talk they had just heard; for they would go searching elsewhere, and would readily come to my call in another part of the wood. If I were well concealed, and they found nothing to account for the disturbance, most of the flock would go about their affairs; but some were almost sure to wait near at hand for hours, apparently standing guard over the place where I had been calling.

Once at midday I called a large flock to a thicket of scrub pine, and resolved to see the end of the adventure. Though they circled over me again and again, they learned nothing; for I kept well hidden, and a crow will not enter thick scrub where he cannot use his wings freely. Late in the afternoon it set in to rain, and I thought that the crows were all gone away, since they paid no more attention to my calling; but the first thing I saw when my head came out of the scrub was a solitary crow on guard. He was on the tip of a hickory tree, hunched up in the rain, and he gave one derisive[50] haw as I appeared. From behind came an answering haw, and I had a glimpse of another crow that had evidently been keeping watch over the other side of the thicket.

Next I discovered that my dignified crows are always ready for fun at the expense of other birds or beasts, and especially do they make holiday of an owl whenever they have the luck to find one asleep for the day. To wake him up, berate him, and follow him with peace-shattering clamor from one retreat to another, seems to furnish them unfailing entertainment. I have watched them many times when they were pestering an owl or a hawk or a running fox, and once I saw them square themselves for all the indignity they had suffered at the beaks of little birds by paying it back with interest to a bald eagle. These last were certainly making a picnic of their rare occasion; never again have I seen crows so crazily happy, or a free eagle so helpless and so furious.

It was on the shore of a river, near the sea, in midwinter. The eagle may have come down to earth after a dead fish, unmindful of crows that were ranging about; but I think it more likely that they had cornered him in an unguarded moment, as they are themselves often cornered by sparrows or robins. Have you seen a crowd of small birds chivvy a crow that they catch in[51] the open, whirling about his slow flight till they drive him to cover and sit around him, scolding him violently for all the nests he has robbed; while he cowers in the middle of the angry circle, very uncomfortable where he is, but afraid to move lest he bring another tempest around his ears? That is how the lordly eagle now stood on the open shore, twisting his head uneasily, his eyes flashing impotent fury. Around him in a jubilant circle were half-a-hundred crows, some watchfully silent, some jeering; and behind him on a rock perched one glossy old bandit, his head cocked for trouble, his eye shining. “Oh, if I could only grip some of you!” said the eagle. “If I could only get these” (working his great claws) “into your black hides! If I could once get aloft, where I could use my—”

He crouched suddenly and sprang, his broad wings threshing heavily. “Haw! haw! To him, my bullies!” yelled the old crow on the rock, hurling himself into the air, shooting over the eagle and ripping a white feather from the royal neck. In a flash the whole rabble was over and around the laboring lord of the air, pecking at his head, interfering with his flight, making a din to crack his ears. He stood it for a turbulent moment, then dropped, and the jeering circle closed around him instantly. He was a thousand[52] times more powerful, more dangerous than any crow; but they were smaller and quicker than he, and they knew it, and he knew it. That was the comedy of what might have been imagined a tragical situation.

Twice, while I watched, the eagle tried to escape, and twice the crows chivvied him down to earth, the only place where he is impotent. Then he gave up all thought of the blue sky and freedom, standing majestically on his dignity, his eyes half closed, as if the sight of such puny babblers wearied him. But under the narrowed lids was a fierce gleam that kept his tormentors at a safe distance. Then a man with a gun blundered upon the stage, and spoiled the play.

One day, as I watched a crowd of crows yelling themselves hoarse over an owl, an idea fell upon me with the freshness, the delight of inspiration. In the barn was a dilapidated stuffed owl, once known in the house as Bunsby, which had been gathering dust for many seasons. Somehow, for some occult reason, people never throw a stuffed bird on the rubbish heap, where it belongs; when they can stand its ugliness no longer, they store it away in barn or attic till they can give it as a precious thing to some beaming naturalist. Bunsby was in this unappreciated stage when I rescued him. With some filched hairpins I poked him[53] together, so as to make him more presentable; gave him a glass eye, the only one I could find, and sewed up the other in a grotesque wink. Then I perched him in the woods, where the crows, coming blithely to my call, proceeded to give him a hazing.

Thereafter, when I heard crows playing, I sometimes used Bunsby to raise a terrible pother among them. By twos or threes they would come streaming in from all directions till the trees were full of them, all vociferating at once, hurling advice at one another or insults at the solemn caricature. Once a more venturesome crow struck a blow with his wing as he shot past (an accident, I think), which knocked Bunsby from his upright balance and dignity. He was an absurd figure at any time, and now with one wing flapping and one foot in the air he was clean ridiculous; but the crows evidently thought they had him groggy at last, and let loose a tumult of whooping.

Another day, when some clamoring crows would pay no attention to my call, I stole through the woods in their direction till I reached the edge of an upland pasture, where a score of the birds were deeply intent on some affair of their own. On the ground, holding the center of the stage, was a small crow that either could not or would not fly, and was acting very queerly. At times he would[54] stand drooping, while a circle of crows waited for his next move in profound silence. After keeping them expectant awhile, he would stretch his neck and say, ker-aw! kerrrr-aw! an odd call, like the cry of a rooster when he spies a hawk, such as I had never before heard from a crow. Instantly from the waiting circle a crow would step briskly up to the invalid, if such he was, and feel him all over, rubbing a beak down from shoulder to tail and going around to repeat on the other side. This rubbing, or whatever it was, would last several seconds, while not a sound was heard; then the investigator would fly to a cedar bush and begin a violent harangue, bobbing his head and striking the branches as he talked. The other crows would apparently listen, then break out in what seemed noisy approval or opposition, and fly wildly about the field. After circling for a time, their tongues clamorous, they would gather around the odd one on the ground, hush their jabber, and the silent play or investigation would begin all over again.

Whether this were another comedy or something deeper I cannot say. Crows do not act in this noisy, aimless way when they find a wounded member of the flock. I have watched them when they gathered to a wing-broken or dying crow, and while some perched silent in the trees a few[55] others were beside the stricken one, seemingly trying to find out what he wanted. An element of play is suggested by the fact that, when I showed myself, the small crow on the ground flew away with the others. Moreover, I have repeatedly seen crows go through a somewhat similar performance, with alternate silence and yelling, when they were listening to a performer, as I judge, who was clucking or barking or making some other sound that crows ordinarily cannot make. As you may learn by keeping tame crows, a few of these sable comedians have ability to imitate other birds or beasts. I have heard from them, early and late, a variety of calls from a deep whistle to a gruff bark, and have noticed that, when one of the mimics chances to display his gift in the woods, he has what appears to be a circle of applauding crows close about him.

On the other hand, I once saw a pack of wolves on the ice of a northern lake acting in a way which strongly reminded me of the crows in the upland pasture; and these wolves were certainly not playing or fooling. One of the pack had just been hit by a bullet, which came at long range from a hidden rifle, against a wind that blew all sound of the report away, and the wounded brute did not know what was suddenly the matter with him. When he was silent, the other wolves would watch[56] or follow him in silence. When he raised his head to whine, as he several times did, instantly a wolf or two would come close to nose him all over, and then all the wolves would run about with muzzles lifted to the sky in wild howling.

THERE must be something in a wolf which appeals powerfully to the imagination; otherwise there would be no proper wolf stories. You shall understand that “something” if ever you are alone in the winter woods at night, and suddenly from the trail behind you comes a wolf outcry, savage and exultant. There is really no more danger in such a cry than in the clamor of dogs that bay the moon; but, whether it be due to the shadow-filled woods or the remembrance of old nursery tales or the terrible voice of the beast, no sooner does that fierce howling shake your ears than your imagination stirs wildly, your heels also, unless you put a brake on them.

Therefore it befalls, whenever I venture to say, that wolves do not chase men, that some fellow[58] appears with a story to contradict me. Indeed, I contradict myself after a fashion, for I was once rushed by a pack of timber wolves; but that was pure comedy in the end, while the man with a wolf tale always makes a near-tragedy of it. Like this, from a friend who once escaped by the skin of his teeth from a wolf pack:

“It happened out in Minnesota one winter, when I was a boy. The season was fearfully bitter, and the cold had brought down from the north a pest of wolves, big, savage brutes that killed the settlers’ stock whenever they had a chance. We often heard them at night, and it was hard to say whether we were more scared when we heard them howling through the woods or when we didn’t hear them, but knew they were about. Nobody ventured far from the house after dark that winter, I can tell you; not unless he had to.”

Here, though I am following my friend intently, I must jot down a mental note that all good wolf stories are born of just such an atmosphere. They are like trout eggs, which hatch only in chilly water. But let the tale go on:

“Well, father and I were delayed by a broken sled one afternoon, and it was getting dusky when we started on our way home. And a mighty lonely way it was, with nothing but woods, snow, frozen ponds, and one deserted shack on the ten-mile[59] road. This winter road ran five or six miles through solid forest; then to save rough going it cut across a lake and through a smaller patch of woods, coming out by the clearing where our farm was. I remember vividly the night, so still, so moonlit, so killing-cold. I can hear the sled runners squealing in the snow, and see the horses’ breath in spurts of white rime.

“We came through the first woods all right, hurrying as much as we dared with a light load, and were slipping easily over the ice of the lake when—Woooo! a wolf howled like a lost soul in the woods behind us. I pricked up my ears at that; so did the horses; but before we could catch breath there came an uproar that bristled the hair under our caps. It sounded as if a hundred wolves were yelling all at once; they were right on our trail, and they were coming.

“Father gave just one look behind; then he lashed the horses. They were nervous, and they jumped in the traces, jerking the sled along at a gallop. Only speed and marvelous good luck kept us from upsetting; for there was no pole to steady the sled, only tugs and loose chains, and it slithered over the bare spots like a mad thing. Flying lumps of ice from the horses’ hoofs blinded or half stunned us; all the while we could hear a devilish uproar coming nearer and nearer.

[60]“That rush over the ice was hair-raising enough, but worse was waiting for us on the rough trail. We were dreading it; at least I was, for I knew the horses could never keep up the pace, when we hit the shore of the lake, and hit it foul. The sled jumped in the air and came bang-up against a stump, splintering a runner. I was pitched off on my head; but father flew out like a cat and landed at the horses’ bridles. He had his hands full, too. Before I was on my feet I heard him shouting, ‘Where are you, son? Unhitch! unhitch!’ Almost as quick as I can tell it we had freed the horses, leaped for their backs, and started up the road on the dead run. I was ahead, father pounding along behind, and behind him the howling.

“So we tore out of the woods into the clearing, smashed through the bars, and reached the barn all blowing. There I slid off to swing the door open; but I didn’t have sense enough left to get out of the way of it. My horse was crazy with fright; hardly had I started the door when he bolted against it and knocked me flat. At his heels came father on the jump, and whisked through the doorway, thinking me safe inside. That is the moment which comes back to me most keenly, the moment when he disappeared, and my heart went down with a horrible sinking. The thought of being left out there alone fairly paralyzed[61] me for a moment; then I yelled like a loon, and father came out faster than he went in. He picked me up like a sack, ran into the barn, and slammed the door to. ‘Safe, boy, safe!’ was all he said; but his voice had a queer crack when he said it.

“Then we realized, all of a sudden, that the wolves had quit their howling. Inside the barn we could hear the horses wheezing; outside, the world and everything in it was dead-still. Somehow that awful stillness scared us worse than the noise; we could feel the brutes coming at us from all sides. After watching through a window and listening at cracks for a while, we made a break for the house, and got there before the wolves could catch us.”

I have given only the outline and atmosphere of this wolf story, and it is really too bad to spoil it so; for as my friend tells it, with vivid or picturesque detail, it is very thrilling and all true so far as it goes. After showing my appreciation by letting the tale soak into me, I venture to ask, “Did you see any wolves that night?”

“No,” he says, frankly, “I didn’t, and I didn’t want to. The howling was plenty for me.”

And there you have it, a right good wolf story with everything properly in it except the wolves. There were no wolf tracks about the sled when[62] father and son went back with guns in hand next morning; but there were numerous fresh signs in the distant woods, and these with the howling were enough to convince any reasonable imagination that only the speed of two good horses saved two good men from death or mutilation.

Another friend of mine, a mining engineer in Alaska, is also quite sure that wolves may be dangerous, and in support of this opinion he quotes a personal experience. He went astray in a snowstorm one fall afternoon, and it was growing dark when he sighted a familiar ridge, beyond which was his camp. He was hurrying along silently, as a man goes after nightfall, and had reached a natural opening with evergreens standing thickly all about, when a terrific howling of wolves broke out on a hillside behind him.

The sudden clamor scared him stiff. He listened a moment, his heart thumping as he remembered all the wolf stories he had ever heard; then he started to run, but stopped to listen again. The howling changed to an eager whimper; it came rapidly on, and thinking himself as good as a dead man he jumped for a spruce, and climbed it almost to the top. Hardly was he hidden when a pack of wolves, dark and terrible looking, swept into the open and ran all over it with their noses out, sniffing, sniffing. Suspicion was in every[63] movement, and to the watcher in the tree the suspicion seemed to point mostly in his direction.

Presently a wolf yelped, and began scratching at a pile of litter on the edge of a thicket. The pack joined him at his digging, dragged out a carcass of some kind from where they had covered it, ate what they wanted, and slipped away into the woods. But once, at some vague alarm, they all stopped eating while two of the largest wolves came slowly across the opening, heads up and muzzles working, like pointers with the scent of game in their nose. And then my friend thought surely that his last night on earth had come, that the ferocious brutes would discover him and hold him on his perch till he fell from cold or exhaustion. Which shows that he, too, gets his notions of a wolf from the story books.

By northern camp fires I have listened to many other wolf tales; but these two seem to me the most typical, having one element of undoubted truth, and another of unbridled imagination. That wolves howl at night with a clamor that is startling to an unhoused man; that when pinched by hunger they grow bold, like other beasts; that they have a little of the dog’s curiosity, and much of the dog’s tendency to run after anything that runs away,—all that is natural and wolflike; but that they will ever chase a man, knowing that he is a[64] man, seems very doubtful to one who had always found the wolf to be as wary as any eagle, and even more difficult of approach. In a word, one’s experience of the natural wolf is sure to run counter to all the wolf stories.

For example, if you surprise a pack of wolves (rarely do they let themselves be seen, night or day), they vanish slyly or haltingly or in a headlong rush, according to the fashion of your approach; but if ever they surprise you in a quiet moment, you have a rare chance to see a fascinating bit of animal nature. The older wolves, after one keen look, pass on as if you did not exist, and pretend to be indifferent so long as you are in sight; after which they run like a scared bear for a mile or two, as you may learn by following their tracks. Meanwhile some young wolf is almost sure to take the part that a fox plays in similar circumstances. He studies you intently, puzzled by your quietness, till he thinks he is mistaken or has the wrong angle on you; then he disappears, and you are wondering where he has gone when his nose is pushed cautiously from behind a bush. Learning nothing there he draws back, and now you must not move or even turn your head while he goes to have a look at you from the rear. When you see him again he will be on the other flank; for he will not leave this interesting new thing till[65] he has nosed it out from all sides. And to frighten him at such a time, or to let him frighten you, is to miss all that is worth seeing.