| N. C. CREEDE. | D. H. MOFFAT. | CAPT. L. E. CAMPBELL. |

| S. T. SMITH. | WALTER S. CHEESMAN. |

STORY OF THE LIFE OF

NICHOLAS C. CREEDE.

BY

CY WARMAN.

DENVER

The Great Divide Publishing Company

1894.

Copyrighted 1894, by Cy Warman,

Denver, Colorado.

The purpose of these pages is to tell the simple story of the life of an unpretentious man, and to show what the Prospector has endured and accomplished for the West.

The Author.

The convulsion was over. An ocean had been displaced. Out of its depths had risen a hemisphere; not a land finished for the foot of man, but a seething, waving mass of matter, surging with the mighty forces and energies of deep-down, eternal fires. The winds touched the angry billows and leveled out the plains. One last, mighty throe, and up rose the mountains of stone and silver and gold that stand to tell of that awful hour when a continent was born. The rain and gentle dew kissed the newborn world, and it was arrayed in a mantle of green. Forests grew, and the Father of Waters, with all his tributaries, began his journey in search of the Lost Sea.

[10]That miniature race, the Cliff Dwellers, ruled the land, and in the process of evolution, the Red Man, followed by our hero, the Prospector, who brushed away the mysteries and disclosed the wonders, the grandeur, the riches of the infant world. Before him the greatest of the earth may well bow their heads in recognition of his achievements. His monument has not been reared by the hands of those who build to commemorate heroic deeds, but in thriving villages and splendid cities you may read the history of his privation and hardship and valor. He it was who first laid down his rifle to lift from secretive sands the shining flakes of gold that planted in the hearts of men the desire to clasp and possess the West.

It was the Prospector who, with a courage sublime, attacked the granite forehead of the world, and proclaimed[11] that, locked in the bosom of the Rocky Mountains, were silver and gold, for which men strive and die. He strode into the dark cañon where the sword of the Almighty had cleft the mountain chain, and climbed the rugged steeps where man had never trod before, and there, above and beyond the line that marked the farthest reach of the Bluebell and the Pine, he slept with the whisperings of God. His praises are unsung, but his deeds are recorded on every page that tells of the progress and glory of the West. He has for his home the grand mountains and verdant vales, whose wondrous beauty is beyond compare.

From the day the earth feels the first touch of spring, when the first flower blooms in the valley, all through the sunny summer time, when the hills hide behind a veil of heliotrope and a world[12] of wild flowers; all through the hazy, dreamy autumn, this land of the Prospector is marvelously beautiful.

When the flowers fade, and all the land begins to lose its lustre; when the tall grass goes to seed and the winds blow brisker and colder from the west, there comes a change to the Alpine fields, bringing with it all the bright and beautiful colors of the butterfly, all the rays of the rainbow, all the burning brilliancy and golden glory of a Salt Lake sunset. Now, like a thief at night, the first frost steals from the high hills, touching and tinting the trees, biting and blighting the flowers and foliage. The helpless columbine and the blushing rose bend to the passionless kisses of the cold frost, and in the ashes of other roses their graves are made.

When the God of Day comes back,[13] he sees upon the silent, saddened face of Nature the ruin wrought by the touch of Time. The leaves, by his light kept alive so long, are blushing and burning, and all the fields are aflame, fired by the fever of death. Even the winged camp robber screams and flies from the blasted fields where bloom has changed to blight, and the willows weep by the icy rills. All these wondrous changes are seen by the Prospector as he sits on a lofty mountain, where the autumn winds sigh softly in the golden aspen, shaking the dead leaves down among the withered grasses, gathering the perfume of the pines, the faint odor of the dying columbine and wafting them away to the lowlands and out o’er the waste of a sun-parched plain.

[14]

[15]

THE PROSPECTOR.

BIRTHPLACE—SCHOOL DAYS—BOY LIFE ON THE FRONTIER—FAVORITE SPORTS.

FIFTY years and one ago, near Fort Wayne, Indiana, Nicholas C. Creede, the story of whose eventful life I shall attempt to tell you, first saw the light of day. When but four years old his parents removed to the Territory of Iowa, a country but thinly settled and still in the grasp of hostile tribes whose crimes, and the crimes of their enemies, have reddened every river from the Hudson to the Yosemite.

In those broad prairies, abounding[16] with buffalo and wild game of every kind, began a career which, followed for a half century, written down in a modest way, will read like a romance.

When but a mere lad, young Creede became proficient in the use of the rifle and made for himself a lasting reputation as a successful hunter. He was known in the remote settlements as the crack shot of the Territory, and being of a daring, fearless nature, spent much of his time in the trackless forest and on the treeless plain.

As the years went by, a ceaseless tide of immigration flowed in upon the beautiful Territory until the locality where the Creedes had their home was thickly dotted with cabins and tents, and fields of golden grain supplanted the verdure of the virgin sod. As the population increased, game became scarce, and then, as the recognized[17] leader, young Creede, at the head of a band of boyish associates, penetrated the wilds far to the northward in pursuit of their favorite sport. On some of these hunting expeditions they pushed as far north as the British line, camping where game was abundant, until they had secured as much as their horses could carry back to the settlements.

This life in the western wilds awoke in the soul of the young hunter a love for adventure, and his whole career since that time has been characterized by a strong preference for the danger and excitement of frontier life.

The facilities for acquiring an education during young Creede’s boyhood were extremely limited. A small school-house was erected about three miles from his home, and there the boys and girls of the settlement flocked[18] to study the simplest branches under a male teacher, who, the boys said, was “too handy with the gad.” The boy scout might have acquired more learning than he did, but he had heart trouble. A little prairie flower bloomed in life’s way, and the young knight of the plain paused to taste its perfume. He had no fear of man or beast, but when he looked into the liquid, love-lit eyes of this prairie princess he was always embarrassed. He had walked and tried to talk with her, but the words would stick in his throat and choke him. At last he learned to write and thought to woo her in an easier way. One day she entered the school-room, fresh and ruddy as the rosy morn; her cherried lips made redder by the biting breeze; and when the eyes of the lass and the lover met, all the pent-up passion and fettered affection flashed aflame from her heart to his, and he wrote upon her slate:

N. C. CREEDE.

[19]The cold, calculating teacher saw the fire that flashed from her heart to her cheek, and he stepped to her desk. She saw him coming and she spat upon the slate and smote the sentiment at one swift sweep. Then the teacher stormed. He said the very fact that she rubbed it out was equal to a confession of guilt, and he “reckoned he’d haf to flog her.” A school-mate of Creede’s told this story to me, and he said all the big boys held their breath when the teacher went for his whip, and young Creede sat pale and impatient. “He’ll never dare to strike that pretty creature,” they[20] thought; “she is so sweet, so gentle, and so good.”

The trembling maiden was not so sure about that as she stepped to the whipping corner, shaking like an aspen. “Swish” went the switch, the pretty shoulders shrugged, and the young gallant saw two tears in his sweetheart’s eyes, and in a flash he stood between her and the teacher and said: “Strike me, you Ingin, and I’ll strike you.” “So’ll I, so’ll I,” said a dozen voices, and the teacher laid down his hand.

HIS FATHER’S DEATH—DRIFTING WESTWARD—ADVENTURES ON THE MISSOURI.

DEATH came to the Creede family when young Creede was but eight years old. A few years later the youth found a step-father in the family, and they were never very good friends. The boy’s home-life was not what he thought it should be, and he bade his mother good-by and started forth to face the world. In that thinly settled country, the young man found it very difficult to secure work of any kind, and more than once he was forced to fancy himself the “merry monarch of the hay-mow,” or a shepherd guarding his father’s flocks, as he lay down to sleep in the cornfield and covered with[22] the stars. The men, for the most part, he said, were gruff and harsh, but the women everywhere were his friends, and many a season of fasting was shortened by reason of a gentle woman’s sympathy and kindness of heart. The brave boy battled with life’s storms alone; and when but eighteen years old he set his face to the West.

Omaha was the one bright star in the western horizon toward which the eyes of restless humanity were turned, and on the breast of the tide of immigration our young man reached the uncouth capital of Nebraska. Perhaps he had not read these unkind remarks by the poet Saxe:

Omaha was then the great outfitting point for the country to the westward,

[24]In the language of Field, “money flowed like liquor,” and a man who was willing to work could find plenty to do; but the rush and bustle of the busy, frontier town was not in keeping with the taste of our hero, and he began to pine for the broad fields and the open prairie. At first it was all new and strangely interesting to him; and often, after his day’s work was done, he would wander about the town, looking on at the gaming tables and viewing the festivities in the concert halls; and when weary of the sights and scenes, he would go forth into the stilly night and walk the broad, smooth streets till the moon went down. At last he resolved to leave its busy throng, and joining a party of wood-choppers, he went away up the river where the willows grew tall and slim. He was busy on the banks of the sullen stream; he felt the breath of Spring and the sunshine, and while the wild[25] birds sang in the willows, he wielded the ax and was happy.

The wood was easily worked and commanded a good price at Omaha, and the young chopper soon found that he was quite prosperous; was his own master, and he whistled and chopped while the she-deer fondled her fawn and the pheasant fluttered near him, friendly and unafraid. Once a week the wood was loaded on a “mackinaw” and floated down to the city, where barges were always waiting, and where sharp competition often sent prices way above the expectation of the settlers.

One day, while making one of these innocent and profitable trips down the river, young Creede nearly lost his life. For some reason, they were trying to make a landing above the city, and Creede was in the bow of[26] the boat, pulling a long sweep oar fixed there on a wooden pin. While exercising all his strength to turn the boat shoreward in the stiff current, the pin broke, he was thrown headlong into the water and the boat drifted above him. As often as he rose to the surface, his head would strike the bottom of the boat and he would be forced down again. It seemed to him, he said, that the boat was a mile long and moving with snail-like speed. He was finally rescued more dead than alive, so full of muddy water that they had to roll him over a water-keg a long time before he could be bailed out and brought back to life.

When he reached Omaha and received his share of the cash from the sale of the wood, he abandoned that[27] line of labor, and with the restlessness of spirit and love for adventure which has characterized his whole life, again started westward.

INDIAN FIGHTING—THE UNION PACIFIC—BUFFALO HUNTING.

CREEDE’S arrival at the Pawnee Indian Reservations on the Loop fork of the Platte River marked an era in his eventful life. He began at this place a period of seven years’ Indian fighting and scouting, which made him known in the valley of the Platte, and gave him a fame which would have been world-wide had he, like later border celebrities, sought for notoriety in print and courted the favor of writers of yellow covered literature.

Being naturally of a retiring, uncommunicative nature, he shrank from public attention; and no writer of fiction, or even a newspaper correspondent[30] could wrest from him a single point on which to hang a sensational story. While genial and sociable among his associates on the trail, his lips were locked when a correspondent was in camp.

At that time the Union Pacific railway was in course of construction, and hostile Indians continually harassed the workers and did all in their power to retard the progress of the work. United States Cavalry troops were put into the field to protect the working corps, and workmen themselves were provided with arms for their own defense. The Pawnee Indians were lying quietly on their reservation, at peace with the whites, never going forth except on periodical buffalo hunts, or on the war-path against their hereditary enemies, the Sioux.

Under these circumstances was begun[31] the building of a line across the plains. It was here that the now famous “Buffalo Bill” made his reputation as a buffalo killer, which has enabled him to travel around the world, giving exhibitions of life on the western wilds of America.

Mr. Frank North, then a resident of the Pawnee country, and thoroughly familiar with their language and customs, conceived the idea that the Pawnees would prove valuable allies to the regular troops in battling with the hostile Sioux, and with but little difficulty[32] secured governmental authority to enlist two or three companies and officer them with whites of his own choosing. One of the very first men he hit upon was Creede, whom he made a first lieutenant of one of the companies, a relative of the organizer being placed in command with a captain’s rank. This man was a corpulent, easy-going fellow, who sought the place for the pay. There was nothing in his nature that seemed to say to him that he should go forth and do battle with the fearless hair-lifters of the plain. Even at his worst, two men could hold him when the fight was on. He was a very sensible man, who preferred the quiet of the camp and the government barber to the prairie wilds and the irate red man.

With Creede it was different. He was young and ambitious, and having[33] been brought up by the firm hand of a step-father, peace troubled his mind. Nothing pleased him more than to have the captain herd the horses while he went out with his hand-painted Pawnees to chase the frescoed Sioux. He set to work assiduously to learn the language of the Pawnees and soon mastered it. By his recklessness in battle and remarkable bravery in every time of danger, he gained the admiration and confidence of the savage men, who followed fearlessly where their leader led. They looked upon Creede as their commander, regarding the Captain as a sort of camp fixture, not made for field work, and many of their achievements under their favorite leader awoke amazement in their own breasts and made them a terror to their Indian foes. If there are those who think these pages are printed to please[34] rather than from a desire to tell the truth and do justice to a name long neglected, I need but state that it stands to-day as a prominent page of the history of Indian warfare in the West, that during their several years of service, the Pawnee scouts were never defeated in battle. The intrepid, dashing spirit of their white leaders inspired their savage natures with a confidence in their own powers which seemed to render them invincible.

E. DICKINSON.

Major North was himself a brave, energetic officer, fearless in battle and skilled in Indian craft, and not a few of his appointments proved to be valuable ones from a fighting standpoint. Because he was always with them, sharing their danger and leading fearlessly when the fight was fierce, the red scouts came to regard Lieutenant Creede as the great “war chief”; and[35] never did they falter a moment when they were needed most by the Government. Every perilous expedition was intrusted to Creede and his invincibles. A favoritism was shown which permitted certain officers to remain in camp away from danger. They never knew how proud the Lieutenant was to lead his gallant scouts. It was a comparatively easy road to fame with so brave a band of warriors, and the attendant danger only served to appease the leader’s appetite for adventures.

The notable incidents which marked Lieutenant Creede’s career during his seven years’ service as a scout would fill many volumes such as this. But a few can be touched upon; just enough to exhibit his fearless nature and his often reckless daring in the face of danger.

LIEUTENANT MURIE—“GOOD INDIANS”—“DON’T LET HER KNOW.”

“READ to me, Jim,” said the sweet girl-wife of Lieutenant Murie.

“I can’t read long, my love,” said the gallant scout. “I have just learned that there is trouble out West and I must away to the front. That beardless telegrapher, Dick, has been here with an order from Major North and they will run us out special at 11:30 to-night.”

[37]The Lieutenant picked up a collection of poems and read where he opened the book:

“Oh, Jim,” she broke in, “why don’t they try to civilize these poor, hunted Indians? Are they all so very bad? Are there no good ones among them?”

“Yes,” said the soldier, with a half smile. “They are all good except those that escape in battle.”

“But tell me, love, how long will this Indian war last?”

“As long as the Sioux hold out,” said the soldier.

At eleven o’clock the young Lieutenant said good-by to his girl-wife and went away.

This was in the ’60’s. The scouts[38] were stationed near Julesburg, which was then the terminus of the Union Pacific track. The special engine and car that brought Lieutenant Murie from Omaha, arrived at noon, the next day after its departure from the banks of the muddy Missouri.

Murie had been married less than six months. For many moons the love-letters that came to camp from his sweetheart’s hand had been the sunshine of his life, and now they were married and all the days of doubt and danger were passed.

An hour after the arrival of the special, a scout came into camp to say that a large band of hostile Sioux had come down from the foot-hills and were at that moment standing, as if waiting—even inviting an attack, and not a thousand yards away. If we except the officers, the scouts were[39] nearly all Pawnee Indians, who, at the sight or scent of a Sioux, were as restless as caged tigers. They had made a treaty with this hostile tribe once, and were cruelly murdered by the Sioux. This crime was never forgotten, and when the Government asked the Pawnees to join the scouts they did so.

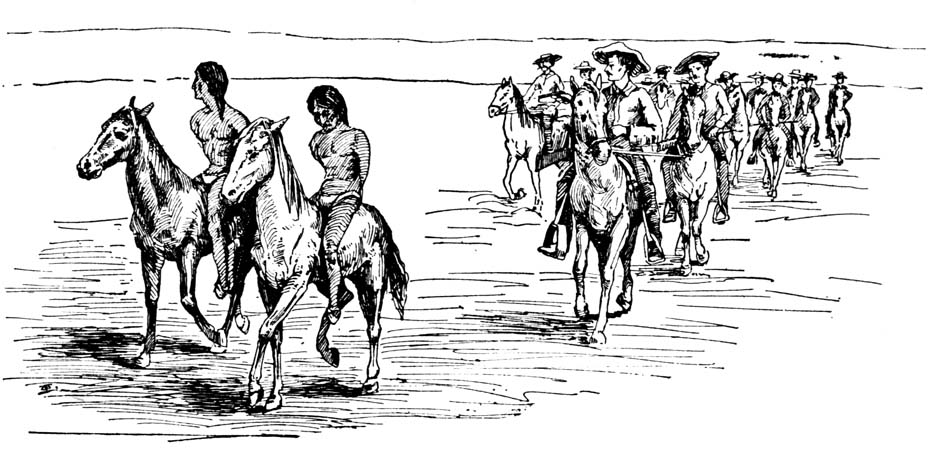

The scouts did not keep the warriors waiting long. In less than an hour, Lieutenant Murie was riding in the direction of the Sioux, with Lieutenant Creede second in command, followed by two hundred Pawnee scouts, who were spoiling for trouble. The Sioux, as usual, outnumbered the Government forces, but, as usual, the dash of the daring scouts was too much for the hostiles and they were forced from the field.

Early in the exercises, Murie and Creede were surrounded by a party of[40] Sioux and completely cut off from the rest of the command. From these embarrassing environments they escaped almost miraculously. All through the fight, which lasted twenty minutes or more, Creede noticed that Murie acted very strangely. He would yell and rave like a mad man—dashing here and there, in the face of the greatest danger. At times he would battle single-handed, with a half dozen of the fiercest of the foe, and his very frenzy seemed to fill them with fear.

[41]When the fight was over, Lieutenant Murie called Creede to him and said he had been shot in the leg. Hastily dismounting, the anxious scout pulled off the officer’s boot, but could see no wound nor sign of blood. Others came up and told the Lieutenant that his leg was as good as new; but he insisted that he was wounded and silently and sullenly pulled his boot on, mounted, and the little band of invincibles started for camp. The Pawnees began to sing their wild, weird songs of victory as they went along; but they had proceeded only a short distance when Murie began to complain again, and again his boot was removed to show him that he was not hurt. Some of the party chaffed him for getting rattled over a little brush like that, and[42] again in silence he pulled on his boot and they continued on to camp.

Dismounting, Murie limped to the surgeon’s tent, and some of his companions followed him, thinking to have a good laugh when the doctor should say it was all the result of imagination, and that there was no wound at all.

When the surgeon had examined the limb, he looked up at the face of the soldier, which was a picture of pain, and the bystanders could not account for the look of tender sympathy and pity in the doctor’s eyes.

Can it be, thought Creede, that he is really hurt and that I have failed to find the wound? “Forgive me, Jim,” he said, holding out his hand to the sufferer, but the surgeon waved him away.

“Why, you—you couldn’t help it, Nick,” said Murie. “You couldn’t[43] kill all of them; but we made it warm for them till I was shot. You won’t let her know, will you?” he said, turning his eyes toward the medical man. “It would break her heart. Poor dear, how she cried and clung to me last night and begged me to stay with her and let the country die for itself awhile. Most wish I had now. Is it very bad, Doctor? Is the bone broken?”

“Oh no,” said the surgeon. “It’s only painful; you’ll be better soon.”

“Good! Don’t let her know, will you?”

They laid him on a cot and he closed his eyes, whispering as he did so: “Don’t let her know.”

“Where is the hurt, Doctor?” Creede whispered.

“Here,” said the surgeon, touching[44] his own forehead with his finger. “He is crazy—hopelessly insane.”

All night they watched by his bed, and every few moments he would raise up suddenly, look anxiously around the tent, and say in a stage whisper: “Don’t let her know.”

A few days later they took him away. He was not to lead his brave scouts again. His reason failed to return. I never knew what became of his wife, but I have been told that she is still watching for the window of his brain to open up, when his absent soul will look out and see her waiting with the old-time love for him.

One of his old comrades called to see him at the asylum, a few years ago, and was recognized by the demented man. To him his wound was as painful as ever, and as he limped to his old friend, his face wore a look of[45] intense agony, while he repeated, just as his comrades had heard him repeat an hundred times, this from Swinburne:

“Good-by, Jim,” said the visitor, with tears in his voice.

“Good-by,” said Jim. Then glancing about, he came closer and whispered: “Don’t let her know.”

It is a quarter of a century since Murie lost his reason and was locked up in a mad-house, and these years have wrought wondrous changes. The little projected line across the plain has become one of the great railway systems of the earth. “Dick,” the beardless operator who gave Murie his orders at Omaha, is now General Manager[46] Dickinson. The delicate and spare youth, who wore a Winchester and red light at the rear end of the special, is now General Superintendent Deuel, and Creede, poor fellow, he would give half of his millions to be able to brush the mysteries from Murie’s mind.

TURNING PROSPECTOR—TRADING HORSES.

HAD N. C. Creede remained a poor prospector all his days, these pages would never have been printed. That is a cold, hard statement; but it is true. Shortly after the fickle Goddess of Fortune sat up a flirtation with the patient prospector, the writer met with a gentleman who had served on the plains with the man of whom you are reading, and he told some interesting stories. We became very well acquainted and my interest in the hunter, scout, prospector and miner increased with every new tale told by his companion on the plains. Those who know this silent man of the mountains are well aware of his inborn modesty and[48] of the reticence he manifests when questioned about his own personal experiences. Hence, the writer as well as the reader must rely largely upon the stories told by his old comrade, the first of which was this:

A large body of Sioux Indians were camped near North Platte, Nebraska, having come there to meet some peace commissioners sent out from Washington. We were camped about eight miles below them, quietly resting during the cessation of hostilities, yet constantly on the alert to guard against a foray from our foes above. The Sioux and the Pawnees were bitter enemies, constantly at war with each other, and as we knew they were aware of the existence of our camp, we feared some of them might run down and endeavor to capture our stock. Our best scouts were sent out every evening in the direction[49] of North Platte to note any evidences of a night raid that might appear, and our Indians were instructed to have their arms in perfect order and in easy reach when they rolled up in their blankets for sleep.

Creede’s horse had become lame and was next to useless for field work. We did not have an extra animal in camp, and for three or four days he tried hard to trade the crippled horse to an Indian scout for a good one. He offered extravagant odds for a trade, but the Indians knew too well the near proximity of a natural enemy and would take no risks on being without a mount should trouble come.

We were sitting in the tent one evening, taking a good-night smoke, when some one began to chaff Creede about his “three-legged horse.” Nick took it all good-naturedly, smiling in his own[50] quiet way at our remarks, and soon he sat with his eyes bent on the ground, as if in deep reflection. Suddenly he arose, buckled on his pistols, picked up his rifle and started from the tent without a word.

“Where are you going, Nick?” some one asked.

“Going to see that the pickets are out all right,” he replied, as the tent flap closed behind him.

This seemed natural enough, and we soon turned into our blankets and thought no more of the matter. When we rolled out at daybreak next morning, it was noticed that Creede’s blankets had not been used and that he was not in the tent. One of the boys remarked that he had lain down out in the grass to sleep and would put in an appearance at breakfast time, and we all accepted this as the true explanation of[51] his absence. Half an hour later, when we were about to eat breakfast, one of the pickets came in and reported something coming from up the river. Our field-glasses soon demonstrated the fact that it was a man riding one horse and leading four others. As he came closer, we recognized Creede, and he soon rode in, dismounted and began to uncinch his saddle, with the quiet remark:

[52]“Guess I ought to get one good mount out of this bunch.”

“Where did you get them?” Major North asked.

“Up the river a little ways.”

“How did you get up there? Walk?”

“Not much I didn’t. I rode my lame horse.”

“What did you do with your own horse?”

“Traded him for these even up.”

He had gone alone in the night, stolen into the herd of the Sioux near North Platte, unsaddled his lame horse and placed the saddle on an Indian’s, and, leading four others, got away unobserved and reached camp safely. It was a bold and desperate undertaking, but one entirely in keeping with his adventurous spirit.

INDIANS OFF THE RESERVATION—ALONE IN CAMP—PROMPT ACTION.

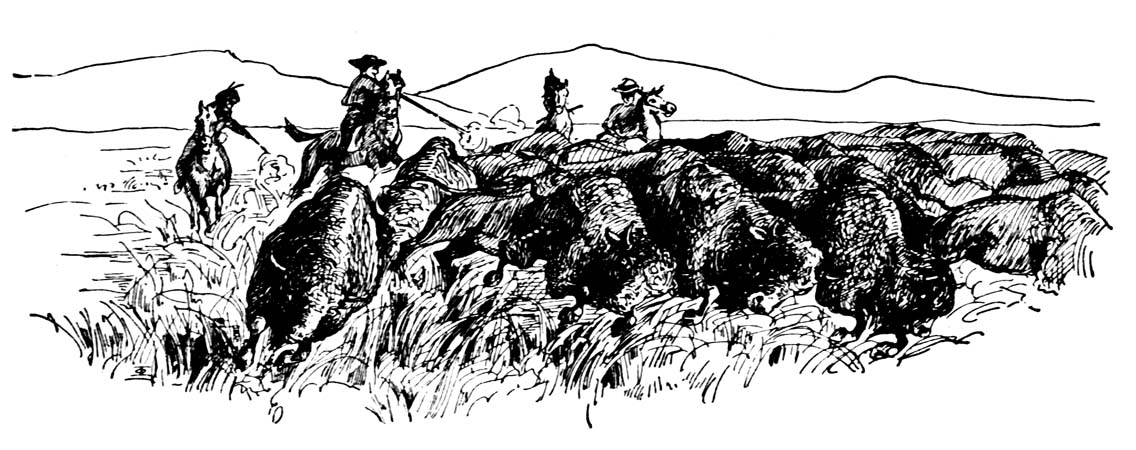

DURING the summer of ’68, a large party of Pawnee Indians, men and squaws, left the reservation on the Loop fork for a buffalo hunt in the country lying between the Platte and Republican Rivers. These semi-annual hunts were events of great interest to the tribe, for by them they not only secured supplies of meat, but also large numbers of robes, which were tanned by the squaws and disposed of to traders for flour and groceries, and for any other goods which might strike the Indian fancy.

At this time the Pawnee scouts were lying in camp on Wood River, about a[54] mile from the Union Pacific Railroad station of that name. The hostile Indians had for some weeks made no aggressive demonstration, and our duties were scarcely sufficient to edge up the dull monotony of camp life. Once a week about half of the company would be sent on a scout to the west along the railway, two days’ march, four days of the week being consumed by these expeditions.

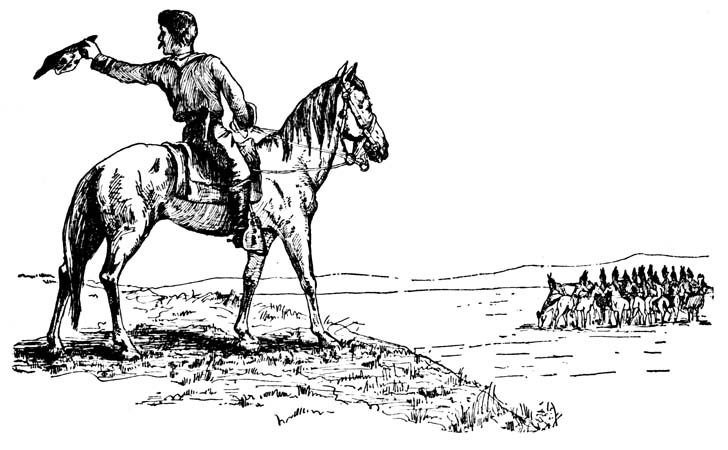

Half of the company had gone on this weekly scout, leaving but one white officer in camp, Lieutenant Creede. He had, if I recollect aright, but eighteen men fit for duty, a number of others being disabled by wounds received in recent battles. The second day after the hunting party left, the section men from the west came into Wood River Station on their hand-car, and excitedly reported that a band of about fifty Sioux had[55] crossed the track near them, headed south. Joe Adams was the agent at Wood River, and he at once sent a messenger to the Pawnee camp to tell Lieutenant Creede of the presence of the hostiles. Creede hastily mounted his handful of warriors, and in less than twenty minutes was dashing forward on the trail of the Sioux. The time consumed by the section men in running into the station, a distance of about four miles, and the consequent delay caused by sending the news to Creede, and the catching up and saddling of the ponies had given the Sioux a good start, and when the scouts had reached the Platte the hostiles had crossed over and were concealed from view in the sand-hills beyond.

Crossing the wide stream with all possible haste, the game little ponies, struggling with the treacherous quicksand for[56] which that historic river is noted, the scouts struck the trail on the opposite bank and pushed rapidly forward. Although they knew that the Sioux outnumbered them three to one, the Pawnees were eager for the fray—an eagerness shared in by their intrepid commander. Chanting their war-songs, their keen eyes scanning the country ahead from the summit of each sand-hill, they pushed onward with the remorseless persistence of blood-hounds up the trail of fleeing fugitives.

About three miles from the river, on reaching the top of a sand-hill, the enemy was discovered a mile ahead, moving carelessly along, oblivious of the fact that they were being pursued. Concealed by the crest of the hill, the Pawnees halted to view the situation, and Lieutenant Creede covered the hostiles with his field-glass. An imprecation[57] came from his lips as he studied the scene in front, and crying out a sentence in the Pawnee tongue, his warriors crowded about him. His experienced eye had shown him that they were Yankton Indians, then at peace with the whites. He took in the situation in a moment. They had learned of the departure of the Pawnee village on a buffalo hunt, and were after them to stampede and capture their horses, kill all of their hated enemy they could and escape back to their reservation.

All this he told to his warriors, and the field-glass in the hands of various members of the party corroborated the fact that, as United States scouts, they had no right to molest the Yankton bands. The impetuous warriors chafed like caged lions, and demanded in vigorous terms that the chase should be resumed. One cool-headed old man, a[58] chief of some importance in the tribe, addressed Lieutenant Creede substantially as follows:

“Father; you are a white man, an officer under the great war chief at Washington, and you would rouse his anger by battling with Indians not at war with him and his soldiers. We are Pawnee Indians, and the men yonder are our hated foes. They go to attack our people, to kill our fathers, sons, brothers, the squaws and children, and steal their horses. It is our duty to protect our people. It is not your duty to help us. Go back, father, to our camp, and we, not as soldiers, but as Indians, will push on to the defense of our people. Listen to the words of wisdom and go back.”

The situation was a trying one. The Lieutenant well knew that if he led his scouts against the Yanktons he would[59] have to face serious trouble at Washington and meet with severe censure from General Augur, then commanding the Department of the Platte. He realized that his official position would be endangered, and that he might even subject himself to arrest and trial in the United States Courts for his action. For some moments he stood with his eyes bent upon the ground in deep reflection, the Indians eying him keenly and almost breathlessly awaiting his reply. It was a tableau, thrilling, well worthy the brush of a painter. The hideously painted faces of the Indians scowling with rage; their blazing, eager eyes reflecting the spirit of impatience which swayed their savage souls; the hardy, faithful ponies cropping at the scant grass which had pierced the sand; the Lieutenant standing as immovable as a rock, his face betraying no trace of[60] excitement, calmly, silently gazing at the ground, carefully weighing the responsibilities resting upon him,—all went to make up a picture so intensely thrilling that the mind can scarcely grasp its wild features.

When the Lieutenant spoke, he did so quietly and calmly. There was a light in his eyes which boded no good to the pursued, but his voice betrayed not the least excitement. He said:

“For several years I have been with you—have been one of you. We have often met the enemy in unequal numbers, but we have never been defeated. In all the battles in which I have led you, you never deserted me. Should I desert you now? I know that I will be censured, perhaps punished, but those Yanktons shall never harm your people. I will lead you against them as I would against a hostile band, and on me will[61] rest all the responsibility. We go now as Pawnee Indians, not as United States scouts, and go to fight for our people. Mount!”

Grunts of satisfaction greeted his words. They would have been followed by wild yells of savage delight had there been no fear of such a demonstration disclosing their presence to the Yanktons. Horses were quickly mounted, and the band again took the trail with an impatience which could scarcely be curbed.

The Yanktons were soon again sighted, and the scouts adopted the Indian tactics of stealing upon their foes. Skirting the bases of sand-hills, keeping from sight in low grounds and following the bed of gulches, they pressed on, until the enemy was discovered less than three-fourths of a[62] mile ahead, and yet unconscious of the presence of a foe.

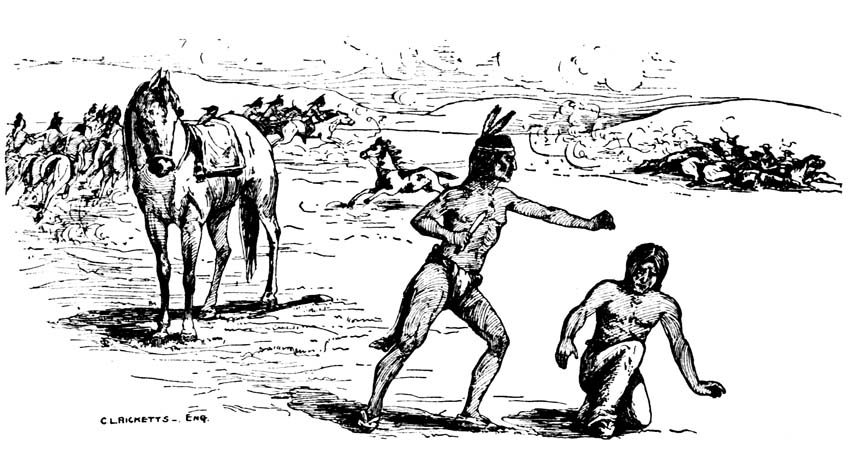

Halting in a low spot in the hills, the Pawnees hastily unsaddled their ponies and stripped for the fight. Indians invariably go into a battle on bareback horses, as saddles impede the speed of the animals in quick movements. When again mounted, the Lieutenant gave the command to advance. On reaching the crest of a sand-hill, the Pawnees discovered their enemy just gaining the summit of the next, about five hundred yards distant. The Yanktons discovered their pursuers at the same moment, and great commotion was observed in their ranks. They hastily formed themselves for battle, and then one of them who could speak English, cried out:

“Who are you, and what do you want?”

[63]“We are Pawnee Indians, and we want to know where you are going,” Creede shouted in reply.

“You are Pawnee scouts, and are soldiers of the United States. We are Yankton Sioux at peace with the Government, and you cannot molest us.”

“You are moving against the Pawnee village, now on a buffalo hunt,” Creede replied. “You want to kill our people and steal their horses. We are Pawnee Indians, and are here to fight for our people. If you take the trail back across the Platte, we will not disturb you, but if you attempt to move forward, we will fight you. Decide quick!”

The leaders of the Yankton band gathered about the interpreter in council, while Creede interpreted what had been said to his warriors. It was with difficulty he could restrain them[64] from dashing forward to the attack. In a few moments the Yankton interpreter shouted:

“If you attack us, the Government will punish you and reward us for our loss. We do not fear you as Pawnees, but we are at peace and do not want to fight you because you are soldiers of the great father at Washington. We are many and you are few, and we could soon kill you all, or drive you back to your camp. Go away and let us alone.”

“You are the enemy of our people, and you go to kill them,” the Lieutenant replied. “We will fight for them, not as soldiers, but as Pawnees. You must make a move now, instantly. We will wait but a minute. If you take the back trail, it will be good. If you move forward, we will make you halt and go back.”

[65]The only reply was a command from the Yankton leader to his followers, in obedience to which they started forward in their original direction. Creede shouted a command to his men, and with wild yells they dashed down the slope and up the side of the hill on which their enemy had last been seen. On a level flat beyond the hill, the Yanktons were found hastily forming for battle, and with tiger-like impetuosity, the scouts dashed forward, firing as they advanced.

The wild dash of the Pawnees seemed to bewilder the Yanktons, and they were thrown into confusion. They quickly rallied, however, and for fully an half-hour they fought desperately. The mad impetuosity of the Pawnee again threw them into confusion, and scattering like frightened sheep, they fled from the field. The Pawnees[66] pursued them, and a running fight was maintained over several miles of country. The Yanktons were at last so scattered that they could make no show of resistance, and with all possible speed sought the river crossing and fled toward their agency. It was afterwards learned that they sustained a loss of eight killed and quite a large number wounded. The Pawnees lost but one man killed, but many were wounded on the field. Several horses were killed. Creede’s army blouse was riddled with bullets and arrows.

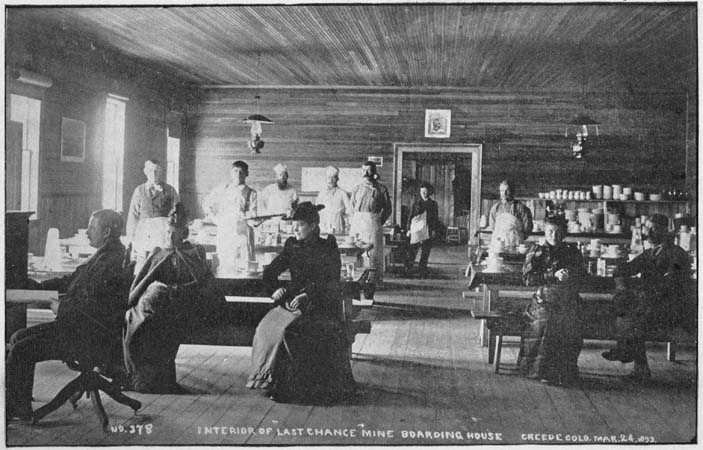

AMETHYST MINE.

Returning from the field, “Bob White,” a Pawnee, reached Wood River in advance of the scouts, and by making motions as of a man falling from a horse, and, repeating the word, “Lieutenant,” created the impression that Creede had been killed, and the agent[67] telegraphed the news to Omaha, where it was published in the daily papers. When the scouts reached the station, however, the gallant Lieutenant was at their head. When he dismounted, it was observed that he limped painfully, and in explanation said, that in one of the charges his horse had fallen upon him, severely bruising and spraining one of his legs. This was what “Bob” had tried to tell, but the agent interpreted his signs to mean that the intrepid leader had been killed in battle.

When the Yanktons reached their agency, they reported that while quietly moving across the country, the Pawnee scouts, being in the service of the United States, had attacked them in overwhelming numbers and driven them back to their reservation. The matter was laid before the authorities at Washington, referred to General Augur, and by him[68] to Major North, who was already in possession of Creede’s explanation of the affair. Considerable red-tape correspondence followed, and as the Yanktons were off their reservation without permission, and in direct violation of orders, the matter was allowed to drop. Creede was doubly a hero in the eyes of his scouts after this episode, and when the Pawnee village returned, and it was learned how the Lieutenant had battled in their behalf, they bestowed upon him the most marked expressions of gratitude and adoration.

TRAIL OF INDIAN PONY TRACKS—DESPERATE ENCOUNTER—HARD TO MAKE THE SCOUTS BELIEVE HIS STORY.

ONE of the most daring acts in the history of this daring man was committed in Western Nebraska in 1866. From boyhood days, he had been noted as a hunter, and during the years which he spent in the scouting service, his splendid marksmanship and extraordinary achievements in the pursuit of game earned for him the reputation of being the best hunter west of the Missouri River. His success in that line was phenomenal and elicited expressions of surprise from all who had a knowledge of his work, and from those who were told of it.

[70]Killing buffalo was not regarded by Creede, or by any of the hunters, as the best evidence of skill in marksmanship or in hunting. Any one who could ride a horse and fire a rifle or revolver could kill those clumsy, shaggy animals much easier than they could pursue and kill the ordinary steers on the western ranges to-day. In fact, the range steer is a far more dangerous animal when enraged than was the buffalo, for it possesses greater activity, and is more fleet of foot. The men who have gained notoriety on account of the number of buffalo they have killed are looked upon with quiet contempt by the true hunters of the plains and mountains, who justly claim that hunting excellence can only be shown in the still hunt, where tact and skill are required to approach within shooting distance of the elk, deer or antelope, and[71] proficient marksmanship is necessary to kill it. When buffalo were plenty on the western plains, it was not at all unusual for women to ride after and kill them, and incur little, if any, risk of personal danger. Miss Emma Woodruff, a school teacher on Wood River in the sixties, and who afterwards married a telegraph operator at Wood River Station, became quite noted as a buffalo hunter, and regarded it but as an ordinary achievement to mount her pony and kill one of the shaggy monsters. The long-haired showmen who infest the country and tell thrilling stories of their desperate adventures and narrow escapes while hunting the buffalo, draw largely upon their imagination for bait to throw out to the gullible. No one in a dozen of them ever reached the west bank of the Missouri River. Every frontier man will agree that the[72] so-called scouts, cowboys and Indian fighters who pose in dime museums, dime novels or behind theatrical foot-lights, are in nearly every instance the most shameless frauds, whose long hair and unlimited “gall” make them heroes in unexperienced eyes. Since the death of Kit Carson, but one long-haired man has earned a reputation as a scout, and while he was once, for a brief season, allured into the dramatic business, and now gives platform entertainments when his duties will permit him to do so, he is not a showman, but is yet in Government employ. He is a trusted secret agent of the Department of Justice, and is engaged in a calling almost as dangerous as was his scouting service—that of running down the desperate men who are engaged in selling liquor to Indians. Long hair is the exception and not the rule among scouts, and a[73] cowboy who permits his locks to cluster over his shoulders is laughed at by his fellow knights of the saddle and classed as a crank.

You shall read this story as it fell from Creede’s own lips when I pressed him to tell it to me. It was this incident which first gained from him the full confidence and unstinted admiration of the Indian scouts:

“Game, through some cause, was very scarce near our camp, and one day I saddled my favorite horse and rode southward, determined to get meat of some kind before returning. I went about fifteen miles from camp, and after hunting some four or five hours without success, made up my mind the game had all left the country. I started to return by a circuitous route, desiring to cover as large a scope of country as possible, and get some meat if it was[74] at all to be found. After traveling perhaps an hour through the sand-hills, I came upon a fresh trail of pony tracks, and I knew the tracks were made by Indian ponies, and hostile Indians, too, for none of our scouts were away from camp. I determined to follow the trail and ascertain if the ponies all bore riders, and, if possible, to get close enough unobserved to see from the appearance of the Indians who they were, and if it was a hunting or war party. They were headed in the direction in which I desired to go, and after tightening up my saddle cinches and looking to see if my pistols were in order, I took the trail. I judged from the trail that there were about twenty-five or thirty Indians in the party, and I soon learned that my estimate was a nearly correct one.

“When I reached the top of the first[75] little hill ahead of me, I came in full view of the party not more than a quarter of a mile distant. They saw me at the same time, as I knew from the confusion in their ranks. I tell you, in a case of that kind, one wants to do some quick thinking, and if ever a man jogged his brain for a scheme to get out of an ugly scrape, I did right then and there. If I tried to run, I knew they would scatter and get me, and in less time than it takes me to tell it, I had made my plan and started to put[76] it into execution. I saw that my only chance, though a desperate one, would be to make them believe I was ahead of a party in their pursuit, and taking off my hat, I made frantic motions to the rear, as if hurrying up a body of troops, and then, putting spurs to my horse, dashed right toward them, and when close enough, began firing at them with my rifle. The scheme worked beautifully, for without firing a shot, they seemed to become terror-stricken and fled on through the hills. The course lay through low sand-hills which often concealed them from view, but I pressed on, firing at every chance. I chased them for fully three miles; two of them died and I captured three ponies which fell behind, and then left the trail and made for camp. I found it hard to make the scouts believe my story, and some of them quite[77] plainly hinted that I had found the ponies in the hills and had seen no Indians. I saw at once that they doubted me, and determined to convince them of the truth of what I had told them. The next morning I took a dozen or more of them and went back to the scene of the chase, and we were not long in finding all the coyotes had left of the two bodies.

“That affair firmly established my reputation with the scouts, and ever after they fully relied on my judgment as a war chief. Through all our future operations, they trusted me implicitly, and would follow me any place I chose to lead them.”

WHEN NEW FLOWERS BLOOM ON THE GRAVES OF OTHER ROSES—PLUNKETY PLUNK OF UNSHOD FEET—HE HAD RECKONED WELL.

IN the early springtime, at that time of the year when all the world grows glad; when the green grass springs from the cold, brown earth; when new flowers bloom on the graves of other roses; when every animal, man, bird and beast, each to his own kind turns with a look of love and tender sympathy, we find the restless Red Men of the Plains on the war-path.

One day at sunset, Lieutenant Creede rode out from Ogallala, where the scouts were stationed, guarding the railway builders. It was customary for some[79] one to take a look about at the close of day, to see if any stray Sioux were prowling around. About six miles from camp, he came to a clump of trees covering a half dozen acres of ground. Through this grove the scout rode, thinking perhaps an elk or deer might be seen; but nothing worth shooting was sighted, till suddenly he found himself at the farther edge of the wood and on the banks of the Platte. Looking across the stream, he saw a small band of hostile Sioux riding in the direction of the river, and not more than a mile away. His field-glasses showed him that there were seven of the Sioux, and without the aid of that instrument, he could see that they had a majority of six over his party. They were riding slowly in the direction of the camp. Creede concluded that they intended to cross over, kill the guards,[80] and capture the Government horses. His first thought was to ride back to camp, keeping the clump of trees between him and the Indians, and arrange a reception for the Sioux.

The river was half a mile wide and three feet deep. Horses can’t travel very rapidly in three feet of water.

In a short time they had reached the water’s edge and the scout could hardly resist the temptation to await their approach, dash out, take a shot at them, and then return to camp. That was dangerous, he thought; for, if he got one, there would still be a half a dozen bullets to dodge. A better plan would be to leave his horse in the grove, crawl out to the bank, lie concealed in the grass until the enemy was within sixty yards of him, then stand up and work his Winchester. The first shot would surprise them. They would[81] all look at their falling friend; the second would show them where he was, and the third shot would leave but four Indians. By the time they swung their rifles up another would have passed to the Happy Land, and one man on shore, with his rifle working, was as good as three frightened Indians in the middle of the river.

Thus reasoned the scout, and he crept to the shore of the stream. He had no time to lose, as the Indian ponies had finished drinking and were already on the move.

As the sound of the sinking feet of the horses grew louder, the hunter was obliged to own a feeling of regret. If he could have gotten back to his horse without them seeing him, he thought it would be as well to return to camp and receive the visitors there. Just once he lifted his head above the[82] grass, and then he saw how useless it would be to attempt to fly, for the Indians were but a little more than a hundred yards away. Realizing that he was in for it, he made up his mind to remain in the grass until the Sioux were so near that it would be impossible to miss them. Nearer and nearer sounded the plunkety-plunk of the unshod feet of the little horses in the shallow stream, till at last they seemed to be in short-rifle range, and the trained hunter sprang to his feet. He had reckoned well, for the Indians were not over sixty yards away, riding tandem. Creede’s rifle echoed in the little grove; the lead leaped out and the head Indian pitched forward into the river. The riderless horse stopped short. The rifle cracked again, and the second Red Man rolled slowly from the saddle; so slowly that he[83] barely got out of the way in time to permit the next brave, who was almost directly behind him, to get killed when it was his turn. The remaining four Indians, instead of returning the fire, sat still and stone-like, so terrified were they that they never raised a hand. Two more seconds; two more shots from the trusty rifle of the scout and two more Indians went down, head first, into the stream. Panic-stricken, the other two dropped into the river and began to swim down stream with all their might. They kept an eye on the scout and at the flash of his gun they ducked their heads and the ball bounded away over the still water. Soon they were beyond the reach of the rifle. Returning to their own side of the river, they crept away in the twilight, and the ever sad and thoughtful scout stood still by the silent[84] stream, watching the little red pools of blood on the broad bosom of the slowly running river.

Three of the abandoned bronchos turned back. Four crossed over to Creede and were taken to camp.

The two sad and lonely Sioux had gone but a short distance from the river, when one of them fell fainting and soon bled to death. He had been wounded by a bullet which had passed through one of his companions who was killed in the stream. The remaining Indian was afterwards captured in battle and he told this story to his captors, just as it was told to the writer by the man who risked his life so fearlessly in the service of Uncle Sam.

SIT-TA-RE-KIT SCALPED ALIVE—AN INDIAN NEVER CARES TO LIVE AFTER HE HAS LOST HIS SCALP.

DURING the month of May, 1865, the scouts were given permission to go with the Pawnees on their annual buffalo hunt. The Pawnees were greatly pleased, for where there are buffaloes there are Indians; and the Sioux were ever on the lookout for an opportunity to drop in on the Pawnees when they were least expected. Late one afternoon a party, eight in number, of the scouts became separated from the main force during the excitement incident to a chase after buffaloes; and, before they had the slightest hint of danger, were completely surrounded by a band of at[86] least two hundred Sioux. The hunters were in a small basin in the sand-hills while the low bluffs fairly bristled with feathers. The Sioux would dash forward, shoot, and then retreat. Lieutenant Creede, two other white men and five Pawnees composed the party of scouts. This little band formed a circle of their horses, but at the first charge of the savage Sioux, the poor animals sank to the sand and died. The scouts now crouched by the dead horses, and half a dozen Sioux fell during the next charge. One savage who appeared to be more fearless than the rest, dashed forward, evidently intending to ride over the little band of scouts. Alas for him! there were besides the Lieutenant, three sure shots in that little circle, and before this daring brave had gotten within fifty yards of the horse-works, a bullet pierced his brain. Instead of[87] dropping to the ground and dying as most men do, this Indian began to leap and bound about, exactly like a chicken with its head cut off, never stopping until he rolled down within fifteen feet of the scouts.

There was a boy in Creede’s party, Sit-ta-re-kit by name, a very intelligent Pawnee, eighteen years old, who had gone with the Lieutenant to Washington to see the President of the United States. There seemed to be no shadow of hope for the scouts; and this young man started to run. Inasmuch as he started in the direction of the camp, which was but a mile away, it is but fair to suggest that he may have taken this fatal step with the hope of notifying the Pawnees of the state of affairs. This was the opinion of Lieutenant Creede; while others thought he was driven wild by the desperate surroundings.[88] He had gone less than a hundred yards when a Sioux rode up beside him and felled him to the ground with a war club. The young scout started to rise, was on his knees, when the Sioux, having dismounted, reached for the scout’s hair with his left hand. All this was seen by the boy’s companions.

“Oh, it was awful!” said Creede, relating this story to the writer. “We had been together so much. He was[89] so brave, so honest and so good. Of course, he was only an Indian; but I had learned to love him, and when I saw the steel blade glistening in the setting sun—saw the savage at one swift stroke sever the scalp from that brave boy’s head, I was sick at heart.” After he had been scalped, the boy got up and walked on, right by the savage Sioux. He was safe enough now. Nothing on earth would tempt an Indian to touch a man who had been scalped, not even to kill him.

A Pawnee squaw was working in the field one day when a Sioux came down and scalped her. She knew if she returned to her people she would be killed. It was not fashionable to keep short-haired women about; and, in her desperate condition, she wandered back to the agency. The agent was sorry for her and he took her in and cured[90] her head and sent her back to her people. But they killed her; she had been scalped.

But let us return to the little band in the basin surrounded by the Sioux. It is indeed a small band now. Four of them are dead, one scalped and gone; but as often as their Winchesters bark, a Sioux drops. There was nothing left for them now but to fight on to the end.

Death in this way was better than being burned alive. There was no hope—not a shadow; for, how were they to know that one of their companions had seen the Sioux surround them and that the whole force of Pawnee scouts were riding to the relief of this handful of men, who were amusing themselves at rifle practice while they waited for death.

With a wild yell, they dashed down[91] upon the murderous Sioux, and, without firing a shot, they fled from the field, leaving thirteen unlucky Indians upon the battle ground.

The brave boy never returned. He took his own life, perhaps; for an Indian never cares to live after he has lost his scalp, knowing that his companions look upon him as they look upon the dead.

LOYAL IN FRIENDSHIP, TRUE TO A TRUST—A CRUEL CAPTAIN.

N. C. CREEDE, the Prince of Prospectors and new-made millionaire, is one of the gentlest men I have ever met, notwithstanding most of his life has been spent in scenes not conducive to gentleness. His friendship is loyal and lasting; and he is as true to a trust as the sunflower is to the sun. Although a daring scout and fearless Indian fighter, he is as tender and sympathetic as the hero of the “Light of Asia.”

Creede and I were traveling by the same train one day, when he asked me if I knew a certain soldier-man—a Captain Somebody; and I said, “No.”

[93]“I raised my rifle to kill him one day and an Indian saved his life,” said he, musingly.

I looked at the sad face of my companion in great surprise. I could hardly believe him capable of taking a human life, and I asked him to tell me the story.

“It was in ’65, I believe,” he began. “We had just captured a village on a tributary of the Yellowstone, and were returning to our quarters on Pole Creek. Just before going into camp, we came upon five stray Sioux, who had been hunting and were returning to their camp on foot. Two of the Sioux were killed and three captured. On the following morning, General Augur, who was in command, gave orders to my Captain to take thirty picked scouts and go on an exploring trip, and to take the three captives[94] with us, giving special orders to see that none of the prisoners escaped.

“When everything was in readiness, the three Sioux were brought out and placed on unsaddled ponies, with their hands tied behind them. Not a word could they utter that we could understand; but O, the mute pleading and silent prayers of those poor captives! It was a dreary April morning; the clouds hung low and the very heavens seemed ready to weep for the poor, helpless Indians.

“I don’t know why they did, but every few moments, as we rode slowly and silently across the dank plain, they would turn their sad eyes to me, so full of voiceless pleading that I found it was impossible to hold my peace longer. Riding up to the side of the Captain, I asked him what he intended to do with the captives. ‘Wait and[95] you will see,’ was his answer. ‘What,’ said I, ‘you don’t mean to kill them? That would be cold-blooded murder.’ ‘I’ll see that they don’t get away,’ said the cruel Captain. I thought if he would only give them a show, and suggested that we let them go two hundred yards, untie their hands and tell them to fly; but to this proposition he made no reply. Then we went on silently, the poor captives riding with bowed heads, dreaming day-dreams, no doubt, of leafy arboles and running streams; of the herds of buffalo that were bounding away o’er the distant plain.

“The scouts were all Pawnees, and their hatred for the Sioux dated from the breaking of a treaty by the latter, some time previous. After the treaty had been completed, the two tribes started on a buffalo hunt. When they[96] arrived at the Republican River, and the Pawnees had partly crossed, and the rest were in the stream, the Sioux opened fire upon them and slew them without mercy. The Pawnee were divided into three bands by this treacherous slaughter and never got together afterward. The bitterest hatred existed between the two tribes, and the Government was using one to suppress the other.

“The three captives would never have surrendered to the Pawnees had they not seen the white men, to whom they looked for mercy. How unworthy they were of this confidence, we shall soon see.

“The Pawnees were by no means merciful. I have heard them tell often, how they skinned a man alive at Rawhide, a little stream in Nebraska, with all the gruesome and blood-curdling[97] gestures. The white man, the victim of the skinners, had made a threat that he would kill the first Indian he saw. It happened to be a squaw; but the man kept his word. His rifle cracked and the squaw dropped dead. The train had gone but a few miles when the Indians overtook the wagons and forced them to return to the scene of the shooting, where they formed a circle, led the victim to the center, and actually skinned him alive, while his companions were compelled to look on.”

I agreed that all this was interesting; but insisted upon hearing the story of the cruel Captain and the captives.

“Oh, yes,” said the prospector. “Well, I had dropped back a few feet, two of the naked Indians were riding in front of the Captain, when he lifted his pistol; it cracked and I saw a little[98] red spot in the bare back of one of the bound captives. His fettered arms raised slightly; his head went back, and he dropped from the horse, dead. The pistol cracked again: Another little red spot showed up between the shoulders of the other Indian. I felt the hot blood rush to my face, and impulsively raised my rifle—mechanically, as the natural helper of the oppressed—when a Pawnee, who was riding at my[99] side, reached out, grasped my gun, and said, ‘No shoot ’im.’

“The third captive, who was riding behind with the Indian scouts, attempted to escape, seeing how his companions were being murdered, but was killed by the guard.

“The Captain dismounted and scalped the two victims with a dull pocket-knife, and afterward told how they rolled up their eyes and looked at him like a dying calf.

“I could tell you more; but when I think of that murder, it makes me sick at heart, and I can see that awful scene enacted again.”

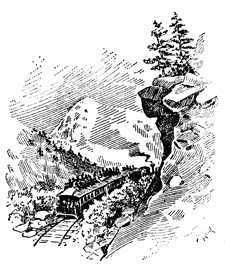

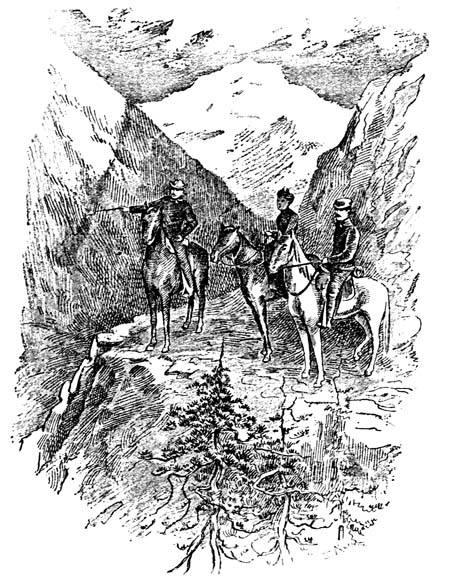

A GLIMPSE OF THE ROCKIES—THE PATH OF THE PROSPECTOR, LIKE THAT OF THE POET, LIES IN A STONY WAY.

MR. CREEDE’S success is due largely to his lasting love for the mountains, which was love at first sight. It was in 1862 that the scouts were ordered to Dakota; and it was then he saw for the first time the grand old Rockies. They were nearing the Big Horn Range, and the sight of snow in August was something the Indians of the plains could not understand. In fact, they insisted that it was not snow, but white earth, and offered to stake their savings on the proposition. Some of them were foolish enough to bet their ponies that there was no snow on the ground in summer time. Late that[101] evening they camped at the foot of the range, and on the following morning, four men were sent up to investigate and decide the bets. The result was a change of horses, in which the Indians got the worst of the bargain. For nearly a week they lingered in the shadows of the cooling mountains and were loth to leave them.

[102]When, some years later, the scouts were mustered out of service, Creede returned to his old home in Iowa. But he soon tired of the dull, prosy life they led there; and, remembering the scent of wild flowers and the balmy breeze that blew down the cool cañons of the Big Horn Mountains, he determined to return to the region of the Rockies. Already he had seen his share of service, it would seem. For more than a dozen years he had slept where night had found him, with no place he could call his home; and yet there are still a dozen years of doubt and danger through which he must pass. For him the trail that leads to fortune and fame, is a long one; and many camps must be made between his pallet on the plains and his mansion by the sea. The path of the prospector, like that of the poet, lies in a[103] stony way, and nothing is truer than the declaration that:

IN COLORADO—THE PROSPECTOR LABORED AND LOOKED AWAY TO THE MOUNTAINS.

THE life of a prospector is one fraught with hardships and privations and, in locations infested by Indians, often one of peril. But in his search for the precious metals, the hardy prospector gives but little thought to personal danger. With his bedding, tools and provisions, packed upon the backs of trusty little burros, he turns from the haunts of men and plunges into the trackless wilds of the mountains. Guided by the star of hope, he pursues his ceaseless explorations in the face of hardships which would appall any heart not buoyed up by a keen expectation of “striking it rich”[105] in the near future, and springing at one bound from poverty to wealth.

Of the great army of prospectors constantly seeking to unearth the vast treasure hidden in the rocky breast of the mountain ranges of the West, few attain a realization of the hopes which lead them onward, and secure the wealth for which they so persistently toil. The instances are very rare in which the prospector has reaped an adequate reward for his discoveries. In the great majority of cases where really valuable leads have been located, the discoverers, not possessing the capital necessary to develop them, have accepted the first offer for their purchase, and have sold for a mere song properties which have brought millions to those who secured them. The most notable instance in the annals of mining in the West, where fortune has[106] rewarded the prospector for his labors, is that in which figures Mr. N. C. Creede. His is a life tinged with romance from boyhood to the present time. This story may serve as an incentive to less fortunate prospectors to push onward with renewed hopes; for in the great mountain ranges of the West, untold riches yet lie hidden from the eye of man.

The register at the Drover’s Hotel, Pueblo, if it had a register, held the name of N. C. Creede, some time in the fall of 1870. He marveled much at the Mexicans. For years he had lived among the Indians and was well acquainted with many tribes; but this dark, sad-faced man, was a new sort of Red Skin.

Pueblo in ’70, was not the city we see there to-day. It was a dreary cluster of adobe houses, built about a big[107] cotton-wood tree on the banks of a poor little river that went creeping away toward the plain, pausing in every pool to rest, having run all the way from Tennessee Pass over a rocky road through the Royal Gorge.

Less than thirty summers had brought their bloom to him, but he felt old. Life was long and the seven years of hard service on the plains had made him a sad and silent man. So much of sorrow, so much of suffering had he seen that he seldom smiled and was much alone. Away from his old companions, a stranger in a strange land, he looked away to the snow-capped crest of the Sangre de Christo and said: “There will I go and find my fortune.” Then he remembered he was poor. But he was young, strong and willing to work, and he soon found employment with Mr. Robert Grant,[108] who was very kind to this lone man in many ways. For six months he labored and looked away to the mountains, whose stony vaults held a fortune and fame for him. In the spring of 1871, the amateur prospector went away to the hills and spent the summer hunting, fishing and looking for quartz. After this, life away from the grand old mountains was not the life for him. Here was his habitation. This should be his home.

FRUITLESS SEARCHES—MET A STREAK OF HARD LUCK—BUT LATER HE STOOD ON THE SUN-KISSED SUMMIT.

THE winter of 1871-2 was spent at Del Norte, and in the following spring Creede, with a party of prospectors, went to Elizabethtown, New Mexico. This town was a new one, but was attracting considerable attention as a placer field. Like a great many other mining camps, the place was overdone, and unless a man had money to live on, the outlook was not very cheerful. Finding no work to do the young prospector staked a placer claim and commenced operations single-handed and alone, and the end of the third day, cleaned up and found himself in possession[110] of nine dollars’ worth of gold dust. This gave him new courage. He worked all the summer; but when winter came on, he discovered that after paying his living expenses which are always lofty in a new camp, he had only made fair wages; the most he had made in a single day was nine dollars.

The winter following found the prospector in Pueblo again, working for another stake, this time in the employ of Mr. George Gilbert. Early in the spring of 1873, he took the trail. Upon this occasion, he found his way to Rosita in Custer County where the famous Bassick Mine was afterward discovered, and within a few miles of Silver Cliff, which was destined to attract the attention of so many prospectors, bringing into the mining world so much shadow and so little shine.

[111]From Rosita he went to the San Juan district and prospected for several months, returned to the east side of the range, and finally made a second trip to the San Juan, but found nothing worth the assessment work.

About this time the Gunnison country began to attract attention and with other fortune-seekers Creede went there. This trip, like all his prospecting tours west of the “Great Divide” panned poorly. Never did he make a discovery of importance on the western slope, and now he made a trip to Leadville. Here he met with a well-defined streak of hard luck. After hunting in vain for a fortune, he was taken with pneumonia, lingered for a long time between life and death, but finally recovered. If Creede had died then, he would have received, probably, four lines in the Herald, which would have[112] been to the effect that a prospector had died of pneumonia in his cabin at the head of California Gulch, and had been dead some time when discovered, as the corpse was cold and the fire out. He was of no great importance at that time, but since then he has marched from Monarch to the banks of the Rio Grande, leaving a silver trail behind him, until at last, standing on the sun-kissed summit of Bachelor mountain, he can look back along the trail and see the camp-fires that he lighted with tired hands, trembling in the cold, burning brightly where the waste places have been made glad by the building of hundreds of happy homes.

Creede has labored long and faithfully for what he has, never shrinking from the task the gods seem to have set before him. Almost from his infancy he has been compelled to do[113] battle with the world alone, and the writer is proud of the privilege of telling the story of his life, giving credit where credit is due, and putting the stamp of perfidity upon the band of stool-pigeons who have camped on his trail for the purpose of claiming credit for what he did.

THE MONARCH CAMP—JEALOUS MINERS WANTED THE NAME CHANGED.

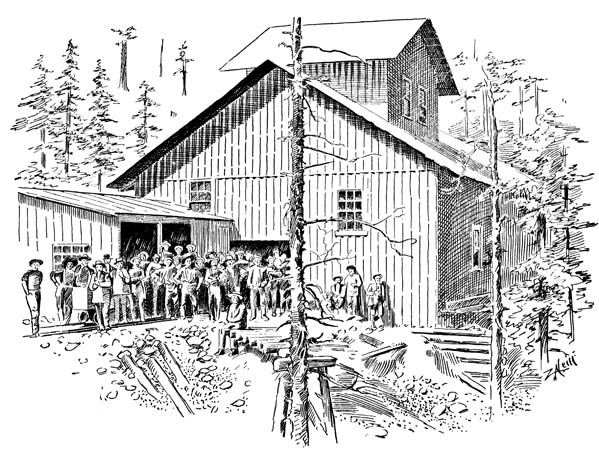

FOREST fires started by the Indians, carelessly or out of pure deviltry, had swept the hills to the east of the divide in Chaffee County, and sufficient time had elapsed to allow a pompadour of pine to grow in the crest of the continent, so thick that it was almost impenetrable. In July, 1878, having chopped a trail through this forest, Creede came to the head of the little stream where the prosperous town of Monarch now stands. For thirteen days the prospector was there alone, not a soul nearer than Poncha Springs, fifteen or twenty miles away.

[115]Elk, deer and bear were there in abundance, and the prospector had little difficulty in supplying himself with fresh meat. In fact, the bear were most too convenient,—they insisted upon coming in and dining with the silver-seeker.

Creede located a claim, called it the Monarch, and gave the same name to the camp. Among the first claims located was one called the “Little Charm.” It proved to be a good property—but not till it had passed into other hands. The formation in the Monarch district was limestone, and in limestone the prospector never knows what he has. To-day he may be in pay ore and to-morrow pick it all out. Creede had picked out some promising prospects in the same formation. He had discovered the Madonna, but had more than he could handle. He[116] took Smith and Gray up there and told them where to dig; they dug and located the Madonna claim. They kept it and worked the assessments for five years and then sold it to Eylers of Pueblo for sixty thousand dollars.

AMETHYST TRAMWAY.

[117]The ore is very low grade, but was of great value to these men, who were smelters, for the lead it carried.

By the time the snow began to fall there were a number of prospectors in the new camp, and having tired of the place, which was one of the hardest, roughest regions in the state, Creede sold what claims he had for one thousand seven hundred dollars, but returned every summer for five years, cleaning up in all about three thousand dollars.

In Monarch, as in his last success, there were a number of jealous miners who wanted the name of the camp changed.

They were, or most of them, at least, light-weight politicians, who didn’t care a cent what the town was called so long as they had the honor of naming it, but the name was never changed.

BONANZA CAMP—THE PONCHA BANK—CREEDE DETERMINES TO SEE OTHER SECTIONS.

LEAVING Monarch, the prospector journeyed through Poncha Pass, over into the San Luis Valley, and began to climb the hills behind the Sangre de Christo range. On a little stream called Silver Creek he made a number of locations, among them the Bonanza, and he called the new camp by that name, just as he named Monarch after what he considered his best claim. The country here was more accessible and consequently a more desirable field for prospecting. South of Bonanza, Creede located the “Twin Mines,” which proved to be good property. The ore in the[119] twin claims carried two ounces of gold to the ton.

A year later when the pioneer prospector decided to pull out and seek new fields, he was able to realize fifteen thousand dollars in good, hard-earned money. One claim was sold for two thousand dollars, the money to be deposited in Raynolds’ bank at Salida; but the purchasers for some reason insisted that the money be deposited in a Poncha bank, very little known at that time, but whose president shortly afterward killed his man and became well, but not favorably, known. Creede’s two thousand dollars went to the banker’s lawyers. The bank closed, and now you may see the ex-president in a little mountain town pleading at the bar—not the bar of justice.

The camp has never astonished the mining world, but it has furnished[120] employment for a number of people, and that is good and shows that the West and the whole world is richer and better because of the discoveries of Creede.

Creede now determined to see a little, and learn something of mining in other sections of the West. Leaving Colorado, he traveled through Utah, Nevada, Arizona and California, prospecting and studying the formation of the country in the different mining camps. The knowledge gained on this trip proved valuable to the prospector in after years. This was his school. The wide West was his school-house, and Nature was his teacher.

A BEAR STORY—THE BEAST INFURIATED—A NEW DANGER CONFRONTS HIM.

AN old prospecting partner of Mr. Creede’s told the following story to the writer, after the discovery of the Amethyst, which lifted the discoverer into prominence, gave him fame and a bank account—and gave every adventuress who heard of his fortune, a new field:

A man by the name of Chester, Creede and I were prospecting in San Miguel County, Colorado, in the 80’s. We had our camp in a narrow cañon by a little mountain stream. It was summer time; the berries were ripe, and bear were as thick as sheep in New Mexico. About sunset one evening[122] I called Creede out to show him a cow which I had discovered on a steep hillside near our cabin.

The moment the Captain saw the animal he said in a stage whisper: “Bear!” I thought he was endeavoring to frighten me; but he soon convinced me that he was in earnest.

Without taking his eyes from the animal, he spoke again in the same stage whisper, instructing me to hasten and bring Chester with a couple of rifles. When I returned with the shooting irons I gave the one I carried to Creede, who instructed me to climb upon a sharp rock that stood up like a church spire in the bottom of the cañon. From my high place I was to signal the sharp-shooters, keeping them posted as to the movements of the bear.

“You come with me,” said Creede to the man who stood at his side. It[123] occurred to me now for the first time that there was some danger attached to this sport. I couldn’t help wondering what would become of me in case the bear got the best of my two partners.

If the bear captured them and got possession of the only two guns in the camp, my position on that rock would become embarrassing, if not actually dangerous. I turned to look at Chester, who did not seem to start when Creede did. Poor fellow, he was as pale as a ghost. “See here,” he said, addressing the man who was looking back, smiling and beckoning him on as he led the way down toward the noisy little creek which they must cross to get in rifle range of the bear, “I’m a man of a family, an’ don’t see why I should run headlong into a fight with a grizzly bear. I suppose if I was a single man, I would do as you do; but[124] when I think of my poor wife and dear little children, it makes me homesick.” Creede kept smiling and beckoning with his forefinger. I laughed at Chester for being so scared. He finally followed, after asking me to look after his family in case he failed to return. Just as a man would who was on his way to the Tower.

Having reached the summit of the rock, I was surprised to see the big bear coming down the hill, headed for the spot where the hunters stood counseling as to how they should proceed. I tried to shout a warning to them, but the creek made such a fuss falling over the rocks that they were unable to hear me.