JERUSALEM—ANCIENT TEMPLE COURT WALL.

JERUSALEM—ANCIENT TEMPLE COURT WALL.

THE EAST:

BEING

A NARRATIVE OF PERSONAL IMPRESSIONS

OF

A Tour in Egypt, Palestine, and Syria.

BY

WILLIAM YOUNG MARTIN.

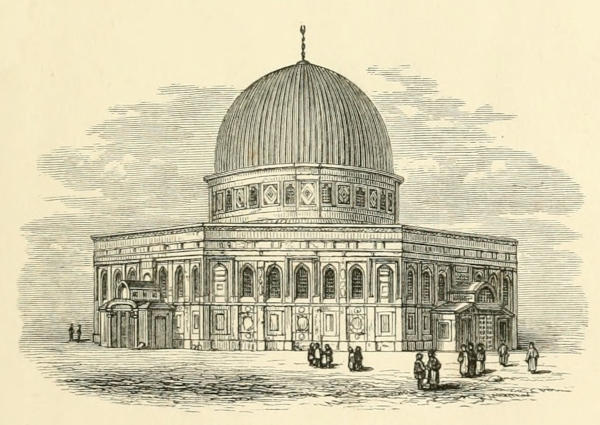

MOUNT MORIAH—DOME OF THE ROCK.

LONDON:

TINSLEY BROTHERS, 8, CATHERINE STREET, STRAND.

1876.

THE EAST:

BEING

A NARRATIVE OF PERSONAL IMPRESSIONS

OF

A TOUR IN EGYPT, PALESTINE, AND SYRIA,

WITH NUMEROUS REFERENCES TO

THE MANNERS AND PRESENT CONDITION OF THE

TURKS AND TO CURRENT EVENTS.

BY

WILLIAM YOUNG MARTIN.

“The domestic life of Turkey is still best illustrated by ‘Bluebeard and his Wives;’ the great curved scimitar, somewhat stained, is nowadays hung overhead, suspended by a thread. Sister Ann is silent for she sees nobody coming, and the whilom gallant Knight St. George is amissing.”

LONDON:

TINSLEY BROTHERS, 8, CATHERINE STREET, STRAND.

1876.

[All rights of Translation and Reproduction are reserved.]

LONDON:

SAVILL, EDWARDS AND CO., PRINTERS, CHANDOS STREET,

COVENT GARDEN.

At present any new book on the East will naturally be looked upon as got up in view of the existing excitement on the subject of the “Turkish Atrocities.” Hence a few lines of preface may be necessary.

This book was originally written more than a year ago, and was in the publishers’ hands before the Bulgarian massacres were made public; but I have since had time to add a Chapter and several Notes still farther illustrating Turkish character, as well as Mahomedan domestic, religious, and political life. I think that in the present crisis every little fact and observation, even of an ordinary Eastern tourist, may add to a knowledge of what has I fear been too long—not intentionally,[vi] but inadvertently—concealed from the general reader.

Prominence is given to the inevitable results of Moslem domestic life—the slavery and imprisonment of women. Industry, art, and patriotism have disappeared, as also national probity, and even the fertility of the land! Turkey has no Shakspeare, no Burns, no Béranger, because the sentiment of tenderness, in which all poetry has its root, is extinct. Need we be very much surprised if such a people should become fiendlike?

In view of the important events now transpiring in Eastern Europe, I have not hesitated to express an opinion of the Turkish Government and the condition of that unhappy country, but have been careful to avoid a political tone. To act otherwise would, I feel, be entirely out of place; and besides, I think that either both political parties are to blame for the present condition of Turkey, or that neither party really is so.

Except the securing by Government open navigation and the freedom of commerce, the only duty that seems imposed upon Great Britain now, is to fulfil her treaty obligation of twenty years ago—namely, the seeing that complete protection and religious liberty be secured, not only to the Greek Church, but to all sects alike—Christian and Jew. This may prove no easy task, however, and requires unanimity. There is very great danger that, in befriending Turkey, Great Britain may unintentionally strengthen her in evil, and this it now appears was pointed out by the late Prince Consort. It is remarkable that of all our statesmen he was the one who some twenty years ago foresaw and pointed out this danger; and every new revelation we obtain of his life shows more and more the enlightened character of that great Prince, who seems to have lived in advance of his age.

W. Y. M.

October 16th, 1876.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | Egypt and the Outward Journey | 1 |

| II. | Palestine, Judea, Jerusalem, &c. | 49 |

| III. | Palestine, Bethlehem, Dead Sea, Jordan, &c. | 91 |

| IV. | Palestine, Samaria, Tent Life, &c. | 133 |

| V. | Syria, Damascus, Balbec, Beyrout, Homeward Journey, &c. | 172 |

| VI. | Postscript.—Recent Events | 238 |

| Notes—New Route to India—Domestic Life in Turkey | 265 |

The subject of my little book is “The East”—one on which more books have been written, and more lectures given, than any other perhaps which could be named.

Nothing therefore could be easier than to write a lecture in the usual style out of such an immense mass of material—to build, as it were, a beautiful house, with stones already shaped and polished. For that very reason, however, I do not propose to lecture at all, in the ordinary acceptation of that term, but to[2] give, in a number of personal recollections, the impressions produced on my own mind by what I saw and felt in the course of a recent tour. They have no pretension to any merit except that of genuineness; not a note was written during my tour; and as it was entered upon somewhat hastily, no book on the subject was consulted, nor did I carry any with me, for nothing was farther from my intention than writing on this subject. Perhaps these circumstances were not altogether disadvantageous; for if my impressions be sometimes at fault, they ought to be original and fresh, because often obtained from a new stand-point.

I need not describe the journey South, which is already familiar to all who travel. Leaving Forfarshire in the beginning of January, with snow falling and ice on the ground, we passed through France in weather such as the French are inclined to call “English.” It was raining when we entered the Cenis Tunnel, and when we emerged in Italy at the other end it was[3] snowing; and during the journey southwards, and especially during our short stay in Turin and Milan, the weather was very nearly as cold as in Scotland—although certainly much more bright. These two are fine models of Western cities, and altogether, Northern Italy showed ample signs of life and progress with great agricultural wealth, but there was a plethora of paper money and a sad scarcity of coin everywhere evident.

It is unnecessary to detain the reader with any attempted description of the art treasures of Bologna and Florence and Rome, where also the weather, although pleasant, was by no means warm. Rome is not disappointing: it is really grand. Its churches, with St. Peter’s at their head, are extremely rich, and beautified with all manner of precious stones, and gold, and silver, and mosaics, and pictures in abundance; but still its ancient ruins are by far the grandest of all.

St. Peter’s, like every building I think which[4] is highly finished, is at first disappointing as to size, and rendered still further so, perhaps, by the wide-spreading base of the Vatican and other buildings forming its approach. Its vastness is however apparent when seen at a distance, towering high above all the buildings of the city. Inside St. Peter’s there is again the same unconsciousness of its vast height. Every part is so perfect in proportion and finish that, as has been often remarked, it is only realized by comparison with the height of the human figures moving about on its paved floor. Perhaps there is also an architectural reason which in a large degree accounts for this difference between apparent and actual height. Thus in St. Paul’s, London—of a style somewhat similar—I have felt it impossible to realize its well-known great dimensions of altitude. The horizontal lines of its walls inside are so numerous and so strictly carried along the entire fabric, that no single pier, column, or upright line is left bold or unbroken on which the eye can rest.

Of course I could not appreciate Michael Angelo nor the merits of the “Grand Pictures,” but a few of them did impress me as really great. I may instance as such Guido’s “Aurora,” a beautiful fresco painted upon the ceiling of a gallery, and especially Leonardo’s fresco of the “Last Supper,” painted upon the wall of an old convent, at Milan, and which I was surprised to find in a most deplorable state of decay. But notwithstanding, nothing in Art has impressed me so much with its greatness as this work, except indeed the equally defaced Sphinx of the Egyptian Pyramids. Of the Paintings, I came to appreciate in some measure “The Transfiguration,” “The St. Agnes,” one of the “Madonnas,” and the “Ecce Homo”—Guido’s I think. Of Sculpture the Greek Statuary was, I thought, very beautiful. In works of Art the wealth of Italy is enormous.

Naples, where we stayed for a week, appeared a much larger city than I had supposed—much the largest in Italy—and for the first[6] time I was struck by the changed aspect of everything around—mosquito netting for our beds, a temperature which felt warm even in January, and already everything beginning to assume an Eastern aspect.

All are familiar with the surroundings of Naples—Vesuvius, Pompeii, Herculaneum, the celebrated Bay of Naples, Capri, Sorrento—altogether a landscape which has excited the rivalry of poets to describe. Of these, the ruins of Pompeii are peculiarly interesting, and the jealous care with which they are protected from pilfering relic-seekers, by the Italian soldiers in charge, is a model of watchfulness as remarkable as it is rare.

The Neapolitans seem a pleasure-loving and still somewhat a lawless people, especially those living in the district south-west of Vesuvius. We witnessed a visitation ceremonial by the Archbishop, in the large Cathedral—imposing for its show if not interesting from its teachings. Its once famous,[7] or rather infamous, dungeons are no longer in use for political offences. The Neapolitans owe much to William Gladstone, as well as to Garibaldi.

Our point of embarkation for the East proper was Brindisi, a small ancient-looking town near the heel of the “Boot,” with a good pier and a new hotel, and amply supplied with churches—old, dusty, and gloomy. Here being joined by the Overland India passengers and mails, we sailed for Egypt on the 1st February, on board the P. & O. steamer, embarking during a wonderful evening sky phenomenon, prognosticating a storm.

The voyage to Alexandria is nearly 1000 miles. Our first morning at sea showed the rocky coast of Greece on the left, and soon afterwards the Island of Crete in the distance—all barren, and white, and lifeless, as the rocks in the Mediterranean seem to be. This is occasioned partly by the nature of the rock—which is (like almost all the mountains[8] we saw in the East) of limestone formation, more or less pure—and by the fact that there are no tides in the Mediterranean, and consequently no marine vegetation except under the surface. The voyage, which lasts three or four days, was, except on the second one, moderately pleasant. The Mediterranean is by no means as smooth as a lake. Storms somewhat violent arise suddenly, but rarely last over a day or two.

Our first glimpse of Africa was far from pleasing—nothing but dreary barren sand, or rather mud-looking mounds, formed its frontier, with very few traces of habitation except numerous windmills on the hilltops—which are of no great elevation. Vegetation there appeared to be none. By-and-by, however, we entered upon the magnificent Bay of Alexandria, for shipping one of the largest and finest in the world.

Here all is life, bustle, and excitement. A hundred vessels—many of them steamers of[9] large size—crowded the bay—where they lay at anchor for the purpose of unloading and loading cargo. This is carried by lighters betwixt them and the quays, along side of which only small craft lie—I suppose in consequence of the silting of the mud from the many mouths of the Nile rendering the water there insufficiently deep. In the bay, and surrounding us on all sides, were steamers of the five Maritime Powers who compete for the navigation of the Mediterranean—viz., the P. & O. (British), the Austrian Lloyd’s (perhaps the most numerous, and all bearing names of the heathen gods, from Jupiter down to Mercury), the French, the Russian, and the Egyptian. I have put them down in the order of their merit, I think, although not of their numbers. I understand, however, that the French steamer service (Messageries Maritimes) has very recently been greatly improved in every respect, and that now the P. & O. require to look to their laurels in the East[10] generally. The confusion of landing is, as almost everywhere else, apt to end in a scramble, and sometimes in a fight for possession of the luggage by the porters of the hotels, or by the Arabs on their own account for the sake of “Bakshish”—a word we heard for the first time, but which we were not allowed to forget.

Viewed from the deck of the steamer the appearance of Alexandria is fine. The grand modern breakwater on the left forms its northern boundary; the quays themselves are immediately in front, and the shore or beach of the city on the right side—forming nearly a semicircle of great extent. The ancient Pharos no longer exists. The buildings, which appear more prominently in view, being regular and of a whitish coloured stone or cement, have a somewhat French appearance. Alexandria is indeed the Liverpool of the Mediterranean, and here are to be met with ships and flags of all countries, and men of all[11] costumes. As everywhere else under Turkish rule, the custom-house business is conducted by the officers with a good deal of state and formality. A boat from the shore with the Egyptian flag, rowed by half a dozen or more Arabs, and containing half as many Turks—sitting in the stern seats, richly dressed, and wearing the inevitable red fez cap—boarded us. No communication whatever was allowed to be held with any of the surrounding boats until they had examined the ship’s papers, and declared us to have a clean bill of health. I was struck by the dignified appearance of these Turks, who somewhat resembled Englishmen, both in personal appearance and that dignified reserve of which, with rare exceptions, the Arabs are devoid.

Rain had fallen heavily for two days previous to our landing, but now the sun shone out brightly. We put up at Abbat’s Oriental Hotel, one of, if not the largest in the city, and found at the table-d’hôte an assembly of[12] travellers of all nations, of whom perhaps the best-looking, and certainly the best-dressed, were the Greeks. The inhabitants consist of Turks, Arabs in great variety, Copts, Jews and Greeks, and other Europeans. The Copts claim to be the only Egyptians. One of them, whom I found well read in Ancient History and English Literature, told me so with evident pride—the Arabs, he added, were there only by conquest. The Copts are, however, a small portion of the inhabitants—resembling, I think, the gentle-looking Hindoos—somewhat “sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought”—and physically inferior to the Arabs. Their religion is a kind of mongrel Christianity.

Some of the business parts of Alexandria present a European appearance, but the other parts are crowded, narrow, and decidedly Eastern. The most remarkable feature in the city is, I think, the number and excellence of the donkeys—and the Egyptian donkey is[13] really an interesting and wonderful quadruped. Their speed is excellent, and they are extremely sure-footed; occasionally, however, some very amusing scenes occur in the streets, in which the English sailors, turned equestrians, form prominent actors.

Pompey’s Pillar stands on the sand outside the walls. It is a finely executed obelisk of red granite, nearly one hundred feet high, on a pedestal. It seemed about nine feet in diameter, and is covered with hieroglyphics. Cleopatra’s Needle lies flat upon the sand near to the sea margin. It is similar to Pompey’s Pillar, but seemed rather smaller, and is a painful picture of fallen greatness utterly neglected.

There are some European open carriages, but few or no carts or waggons, almost the whole traffic, both equestrian and of goods, being carried on the donkeys’ backs, of which the number in the city must be very large indeed. Passing along one of the streets, I observed a train of donkeys[14] carrying corn in bags to the harbour for shipment. Except a very narrow strip at one edge, the street, being entirely formed of mud, was, in consequence of the recent rains, a perfect puddle. A large bag filled with corn having fallen from the back of a donkey not so big as itself, it so bespattered the poor animal with mud right over one eye that it presented a most ludicrous appearance to the passers-by—standing stock-still beside the bag, and quite beyond the reach of the boy who always attends them. The next following donkey and boy passed on, perfectly regardless of the difficulty, and there the poor donkey stood, nearly up to his nose in the slime, with a scorching sun overhead, which quickly dried the mud that bespattered its head to a white colour just like a great plaster. I never witnessed, even in a pantomime, a more comic picture. The scene was entirely Egyptian, where no one seems to consider it necessary to help another in a difficulty; and how long the poor donkey stood there I cannot tell. It[15] besides exhibited the extraordinary patience of the Egyptians—donkeys and people. I may here mention, once for all, that these Eastern donkeys are worthy of a better name. They are as much superior to the obstinate and stupid donkeys of this country in breeding as the celebrated Arab horse is to an English dray one; and though smaller in size—at least those of Egypt—they carry a much greater burden without complaining. I am surprised that these animals are not introduced into this country. If acclimatized, they would be extremely useful in carrying equestrians and traffic generally on hilly roads, or equally well where there are no roads at all. They are generally of a light mouse colour, and the boys who have charge of them pride themselves in keeping their hair cut short and in curious figured patterns, somewhat in imitation of damask.

Here almost every article is to be had, in the shops near the harbour, which an Englishman can desire, not excepting “Bass’s Beer”[16] and “Scotch Whisky,” which I observed nowhere else in the East except at Port Said.

The government of Egypt is thoroughly despotic, and the Arabs, who form the great bulk of the population, appear to hold a very humble position—little above that of slavery. All departments of the government seem to be carried on by command, and in many of them foreigners exercise control. There are no newspapers, and no public opinion—with the Moslem Arabs “whatever is, is right,” and nothing seems to occasion resistance, complaint, or even surprise. Their misfortunes are by the will of Allah—it is vain to resist fate.

There is a very good story told in the hotels, which, whether true or not, illustrates this submissive nature well. The railway is much used by the Arabs and common people. One afternoon a train, when on the eve of starting from the Alexandria Station for Cairo, was, to make way for a special train required[17] for some official purpose, temporarily shunted out of the station into a waggon shed to clear the line. There, out of sight, it was quickly forgotten, in the bustle of the other station business of the day. The poor Arabs, by no means unaccustomed to treatment of this kind, waited patiently till night fell without complaining, and, submitting to their fate, after duly performing their sunset devotions, composed themselves to sleep as they best could for the night—very likely without any supper. Next morning they were discovered by the railway officials, who meantime had received a telegram from Cairo asking what had become of that afternoon’s train! Can we imagine such an absurdity occurring at an English railway station? I suppose here the station-master would have been made acquainted with the oversight within as many minutes as the poor Arabs waited hours, and that by a clamour which he would never have forgotten. There, such a thing might have happened and no one[18] but the poor passengers have known or inquired, except perchance some stray traveller in the hotel.

Alexandria has a good English Church, a neat Presbyterian one, and several Protestant schools. There is an excellent hospital for sick sailors and others, under the protection of Prussia, and conducted by the German Protestant Sisters. One of these ladies (Sister Gertrude) visited England and Scotland a few years ago and made several friends. Having an introduction forwarded to me from home, I visited the house—a very good well-aired building, about a mile out of the city. Sister Gertrude had left for the well-known Fatherland Head Institution, but I received a welcome from the matron at the head of the establishment, who assured me that her Sister had spoken with pleasure of the reception she had received. It was a warm day, and I enjoyed the coolness of the hospital and its extreme cleanliness after my dusty ride. Such a retreat[19] must be a real oasis in the desert to many a sick and solitary stranger. I may here mention that all the Prussian Consulates in the East appear to foster schools as well as hospitals.

The French influence is evidently suffering an eclipse since the Franco-German war—perhaps because heretofore too much asserted. The young everywhere were, I was told, now preferring to learn English instead of the French language, which hitherto had been taught in almost all classes of schools along with the native language of the place. Indeed, I saw many indications that our national popularity in the East generally was steadily rising—probably because England has always shown the greatest deference and consideration to the Turkish governments, or perhaps I should rather say Turkish misrule.

In returning to our hotel I was addressed (somewhat aside) by a middle-aged, sailor-looking Arab. He spoke a few broken English[20] and French words, which I did not well comprehend, nor he mine; but I understood he wished me to engage as a servant for my travels a young man about eighteen, with a fine open face, very black, but not negro, who stood a few paces off. He was dressed in a blue cotton sailor’s jacket, but otherwise like an Arab, and I think he was said to be from Nubia. On mentioning this circumstance to a gentleman at the hotel, he said the man was a slave dealer from the south, who was trying to sell me some of his stolen property! This certainly had not occurred to me at the time, but it is possible, because such things are, I was told, still occasionally done—privately of course.

By rail to Cairo, along the Nile Valley, is 130 miles—a most interesting journey. The engines and plant are English or French make, the fuel being artificial coal. The villages, “highways,” and irrigation works are specially novel. In the distance the former seem like[21] large-sized square huts clustered in groups. They are built of sun-dried bricks, which are quite as black as and not unlike Scotch peat. This locality is thickly populated, and we saw in the distance several considerable towns and numerous villages.

In this delta the Nile is broken into numerous branches. Standing north and south is a beautiful long line of palms so remarkably uniform as to give the idea of a vast line of columns of singular architectural merit. Seen from a distance the illusion was in my eyes perfect, and I have no doubt the famous Moorish Arch was originally suggested by some such row of palm trees, not only in its form, but even in its details.

Egypt gets drier and more healthy as we travel inland. There no rain falls; the soil is sandy, and the temperature so high that vegetable or animal matters not devoured by the dogs get so quickly dried up that putrefaction or fermentation is rarely seen. Otherwise[22] the country would not enjoy the high hygienic repute it does. The Nile water tastes pleasantly, but after a time many travellers find it necessary to drink it sparingly.

We stayed about a fortnight in the Grand New Hotel, a very fine stone building, of great size, and conducted quite in the Parisian style—cooking somewhat inferior, as also the viands—and here, at the large table-d’hôte, a citizen of the world is quite at home. The only other great hotel is Shepherd’s—equally well known. In such a ménagerie of travellers, one occasionally meets with most desirable company, but caution and selection are needful, and in this matter our party was fortunate. The dinner table was too large for general conversation, but it was carried on partially in groups; and I noticed that while the adventures of the day—the Nile, the Pyramids, the bazaars, the opera, and the circus—were all freely discussed, and the dishes of the table occasionally (but with bated breath), politics, social questions, and religion were carefully avoided. Just[23] recently the postal system in Egypt has been made excellent, but then complaints were many and loud.

“I thought I heard you say, sir, that the mails were in this morning.”

“Yes, so they are, for I came from Brindisi along with them.”

“Then we must go and ask for letters at the Consul’s.”

“No,” a third would say, “you need not: the Consul, or his Vice, or perhaps his Cavasse, or somebody, has got a headache, so the mail bags cannot be opened till he gets better—I intend inquiring again to-morrow.”

“Any news going? What about Sir Roger?”

“Oh, the case is in court, you know. But I heard in Alexandria last night that the Governor has resigned, and that the Ministry will be out-voted.”

“Oh! indeed! Ah, well!—a bad job—a telegram—but of course it won’t be true, you know;” and so on.

Several gentlemen seemed to live there for months spending the time in a state of luxurious ease, subsisting, as it were, in a “Castle of Indolence,” and breathing with lazy enjoyment the balmy Egyptian air. They were to be seen often sauntering under the piazzas, or witnessing the trick of some conjuror in the outer courtyard, or lounging on cushions in the large vestibule of the hotel, or listening to the brass band in the Viceroy’s music garden opposite.

“I say, Jones, just close that curtain another inch, will you? don’t you see the sun is taking the shine out of me?”

“No, thank you, old boy; I am not lazy, you know, but I was born ‘tired.’”

“Ah! just so, and I suppose you have now got a bone in your arm too;” and so on, with similar bits of small wit.

The very air of Egypt here suggests repose, and some travellers—after “doing the Pyramids” and climbing the citadel, where the finest[25] view of Cairo is to be had—often thus saunter away day after day. Some lounge in the bazaars, probably on a donkey or in an open carriage, bargaining for half an hour over some purchase of a few francs’ value, and when completed all the cheapening is pretty sure to be lost in getting small change for a sovereign. Gold seems with these Easterns the one supremely precious thing in the world; and when you despair of obtaining any article at your offer, the presentation of your purse of gold coins will sometimes carry the day. To change and exchange other coins for gold seems a passion with all bankers, bazaar keepers, dragomans, hotel people, and barbers, as well as the money changers, who sit at almost every street corner with their case of coins of all nations freely displayed.

Of course we visited all the “Lions.” Of these the chief are the Pyramids, which are at first disappointing, as all great things appear to be, especially when first seen from a distance.[26] But the nearer they are approached and the longer looked at they seem to swell in size, and with each new visit their vastness more and more impresses the mind. There are seventy Pyramids in all, but most of them are of sun-burnt brick of inferior size and considerably decayed. Seven are situated at Ghizeh, some seven miles south-west of Cairo on the west of the Nile. The finest is that of Cheops, of sandstone or limestone, and is evidently more destroyed by the builders of Cairo than by time, notwithstanding its immense age. Its height is 480 feet with a square base line of 764 feet; its sides front to the four cardinal points, and the opening is on its north face, as indeed is the case with all the Pyramids.[1]

The ascent of the great Pyramid is very exciting and amusing, and by no means difficult. I think it was our ladies who were first[27] on the top. The view from its summit is very fine, especially southward, up the course of that hitherto mysterious Nile as far as the eye can reach—and that a very small part certainly of its fifteen hundred miles of sparkling water. The Nile river is unique; instead of increasing in volume like other rivers as it flows downward, it gradually decreases, because it receives no additional streams, while—besides its annual inundation—it constantly enriches with its water all its thirsty banks, and the hot atmosphere refreshes itself all along that vast length with its evaporation. On the east the Nile valley is bounded by the white range of hills bordering the Red Sea, and on the west is a similar range bordering upon the great African desert of Sahara. In the foreground of the vast panorama is Cairo, and northward the Delta. How refreshing the green verdure was to the eye beside the rich warm tints of all else within its range! The Sphinx, which stands below on the south[28] distant about 300 feet, is a colossal and very wonderful piece of art, apparently rising out of the sand, and standing sixty feet high. It should if possible be seen at sundown when the stars begin to peep out. The face, with an absorbed mystic expression, gazes afar off up the Nile, and notwithstanding that it is barbarously defaced by violence, and effaced by forty centuries of time, the expression of this prince of statues is altogether most memorable—a singular personification of oracular Wisdom, Majesty, and Repose.[2]

The numerous mosques of Cairo are interesting, but in general have an air of dilapidation and decay I did not expect in this great centre. They have a peculiar picturesque appearance, from their exterior walls being red and white in horizontal stripes, about ten inches wide. Inside there is shade, with quietude and repose well befitting the[29] tombs of royalty—richly gilded—which some of them contain. Our guide Josef, reverentially approaching a small pedestal, gently moved aside a little faded silk curtain which covered its sacred surface, and, kneeling down, devoutly kissed it. This was a piece of rock on which the great prophet had stood, and he showed me the black mark of his foot, which of course remains in proof of the fact.

When we got outside I only remarked that Mahomet must have had a very large and very hot foot! Josef, when I accused him of having neglected both his noon and sunset prayers on the previous day, explained that the priest told him that when on duty in our service he might postpone his devotions till next occasion, if he then performed them in duplicate or triplicate, which he seriously assured me he had since done! Although a man approaching to forty, and married, he had, along with the peculiar cunning of his tribe, the apparent simplicity and openness of a schoolboy.

The Egyptians are an abstemious people: a pennyworth of rice, and a “joint” of sugar-cane costing a halfpenny, with perhaps an orange, and Nile water to drink, may suffice for the day. There is a very superior orange, somewhat costly, always supplied at the hotel table, called “Loose Jacket.” It is similar to, but not quite so small as, the “Mandarin” of Eastern Asia. The bazaar people appear to subsist by slowly sipping coffee, almost black, out of toy-sized cups, and smoking with placid enjoyment the never-absent Nargile pipe.

Driving through Cairo in an open carriage and pair is a favourite enjoyment with English and American travellers. The speed is high for a city, and before the carriage there runs a tall Arab in his white calico dress—somewhat scant—flourishing his long arms and a still longer white rod, and crying aloud to all natives to make way for the man the Pasha delights to honour; or if not that, something not very dissimilar I suppose. This is more[31] ludicrous than pleasant, but costs nothing extra; and in vain you assure your driver that you are in no hurry, and prefer dispensing with so noisy an “avant coureur.” Even in the bazaars—which are narrow streets, and always very crowded—every one stands aside, and a way opens up for your carriage in a marvellously sudden and systematic way. The same honour does not seem given to riders on horseback, no matter how well mounted. If you drive out beyond the city, your Arab footman falls off at the city walls; and when you return—it may be many hours after—there again he will reappear and probably resume his race and cry as energetically as before.

Having, by virtue of an order from the Consul (given only for certain hours one day a week), procured admission into the private gardens of the Khedive, we obtained a view of the Palace of the Harem. It is a plain building, of moderate size, with closely latticed windows, and having a fairy-like erection at some distance behind, into which we entered[32] through a lofty open arch. In the centre of its quadrangle is a small lake with a gondola, and at the four corners are luxuriously furnished rooms or divans, evidently for the use of his Highness and ladies of his harem. All was built and paved with pure white marble, and in the bright sunlight presented a scene more like a dream than an everyday reality. Surrounding the whole was a large garden of beautiful flowers and plants, gently flowing fountains for irrigation, singing birds in hundreds, and everything to delight the eye and the ear.

I thought here of Sardanapalus, Mark Antony, and Cleopatra, as well as of Haroun-al-Raschid. Had I not at last realized the wonders of the “Arabian Nights’ Entertainments!” But yet the scene was unsatisfactory. Everything was artificial and confined, and I doubt if the poor ladies within were as happy amidst this luxurious ease as their sisters in our own land. After all, the only true type of[33] civilization is the Christian, and its best evidence the perfect freedom of the gentler sex. As to the beauty of Eastern females, I believe it is almost all fable. These Cairo beauties have recently obtained some freedom; they drive through the city in carriages with glass fronts or curtains—under guard, no doubt—but we got frequent glimpses of portions of their faces. They seemed insipid—without character or individuality—and distinguishable mainly by height and age. They sometimes showed an interest in looking after the English ladies in our party, and I imagined would willingly have exchanged places. These Eastern ladies seem to paint their eyebrows and tint their eyelids with a very faint black shade, evidently with a view of giving the white eyes more brilliancy by contrast. But we see at home more brilliant eyes without paint, and certainly more homely, honest, and comely faces. A Moslem holiday, somewhat akin to Christmas, is celebrated annually in[34] February. The Khedive or Viceroy drove through the streets in a grand open carriage; his harem ladies accompanied in another, but were protected from observation by curtains. There was more than the usual expenditure of gunpowder on the occasion.

We also gained admission to the Khedive’s Zoological Gardens. The animals were rare, but not numerous. The ostriches, of which there were about a dozen, were to us the most interesting. The size of these birds surprised me, and I can now believe some of the wonderful stories of their extraordinary swiftness, and even the possibility of their carrying a rider, if a skilful jockey of sufficient lightness could be found. They had a very nude appearance, with skin of a much fairer colour than that of the bipeds of Egypt. Perhaps they had lately lost their feathers, which are now of great mercantile value.

The city itself is very large, and its bazaars extremely novel and interesting to a European.[35] They are always crowded, and seem to serve as a daily social as well as business Exchange, frequented by both males and matrons. There are several interesting manufactures in silk and mixed textile fabrics at moderate prices, but I think less so than those at Damascus, which are somewhat similar but more Eastern. A number of buildings, with a few fine shops in the Paris style, indicate the prevalence of French fashions. The Cairo Museum contains many very curious objects of fabulous antiquity, including a statue of Adam in wood!

The Mosque of the dancing dervishes we visited, and, arriving early, were received in a large upper room, and entertained with a cup of coffee. There were in the chapel more than a hundred visitors—mostly strangers. The worship consisted in the usual devotions, with singing, bowings, and dancing. Fourteen dervishes or priests I suppose in the centre of the church commenced to spin round upon their toes and heels, and generally with outspread[36] arms, at the same time revolving round the fence or ring on the floor. This they did to music, consisting of pipes, drums, and I think some stringed instruments. It was monotonous and simple. The speed at first seemed steadily to increase till the dancers became pale or livid, and after about twenty minutes they dropped off, evidently only when nature was perfectly exhausted. They were of various ages—from twelve to sixty.

The whole ceremonial concluded with prayers, and then genuflexions to the high priest or sheik, who presided standing upon a bit of carpet on the margin of the ring, near the prayer-niche in the wall, with his face towards Mecca. The affair did not excite laughter, as I had expected. It was in some sense dignified throughout, but left a painful impression upon the mind. The female worshippers were kept apart in a gallery, as usual in the Mahomedan churches, and protected from observation by a latticed screen. The motion of the dancers was twofold, as if in imitation of that of the planets, one round[37] their own axis, and one around the ring centre. Whether intentional or not, their several velocities of revolution were different, as also seemed to be the diameters of the orbits of their several dances. They threw their heads back, and were evidently blind as in a trance, although their eyelids were open, and yet while apparently imminent I noticed no collision. I presume their worship has no intentional reference to the sun, but may it not possibly be the remains of some very ancient religious ceremonial—probably descended from that of the original worship in the “Temples of the Sun”—evidently the oldest of idolatries?

The hundred mosques and multitudes of minarets of this large city—the famous bucket well on the citadel—the Nileometer—the Nile bridge—the Khedive’s wonderful stud of horses—the snake charmers[3]—and all the other well-known sights—I need not describe.

By rail we visited the site of the ancient[38] royal city of Memphis, about nine miles south of Cairo. We took good donkeys with us, and were ferried across the Nile in a passage boat. The well-known wood of palm trees and the great colossal image of Rameses are the only objects of interest now remaining of this the former residence of the Egyptian kings. This ancient statue—perhaps the finest in Egypt—is a beautifully finished piece of sculpture, sixty feet high, in bluish black granite, and lies prostrate in the mud, but in perfect preservation, as fresh looking as if finished the previous day!

Returning by the western bank of the Nile, we—with several other travellers from our hotel—had a most amusing donkey race upon the sands northwards viâ the Pyramids of Ghizeh to Cairo. This valley seems one vast graveyard: numerous finely built tombs have been, and are still from time to time being uncovered; and near the locality is the famous temple containing “the tombs of the sacred[39] bulls.” It is a large underground cavern cut out of the soft rock, and contains empty sarcophagi—I think about ten in number, each large enough to contain a live prize ox—cut out of an immense block of black granite, beautifully polished and covered with hieroglyphics. Even in this nineteenth century, with all our appliances, these would be considered works of high art and engineering skill. As to labour, the expenditure must have been immense.

Heliopolis stands north of Cairo, and about eighteen miles distant from Memphis. The drive from Cairo is along a fine wide road, lined on both sides with large healthy trees, carefully irrigated, whose branches meet overhead, and form the longest and finest natural arch I have ever seen. It reminded me of a similar one at Drummond Castle in Scotland, but this seemed much wider and loftier.

Heliopolis is said to be the site of the most ancient city of Egypt. It is otherwise called On and sometimes Noph; but nothing remains[40] of it except a fine obelisk of granite covered with hieroglyphics, and about sixty-five feet high: perhaps there is no column still standing erect of greater antiquity. There was here a great Temple of the Sun, and the patriarch Joseph’s wife is mentioned as a daughter of a priest or prince of On. In New Testament times it is said to have been the retreat of Joseph and Mary with the infant Jesus. A very aged tree—I think a sycamore, of large size—and a well of excellent water, are still shown in connexion with that event. The country around seemed rich and fertile.

I do not propose giving any general description of Egypt and the Nile, although the subject is an extremely rich and interesting one. But before leaving it, I must remark that one is very much struck by the evidence everywhere around of progress and improvement, mercantile, agricultural, mechanical, and social, although probably not all judiciously carried on. The Khedive is Egypt, and Egypt is the Khedive—the claim of Turkey to[41] the sovereignty being now very little more than a name. The present Viceroy is an impulsive man of extraordinary energy, and evidently aims at making Cairo an Eastern Paris, which he will very soon do if money do not fail him. But Egypt has less need of French opera-dancers and experimental engineers than of sugar-crushing machinery and irrigation works, neither of which, however, it must be allowed, has he neglected. But it appeared to me that by an ample and judicious extension of the latter the rich crops of the Nile valley might be doubled, and especially of sugar-cane, flax, and cotton.

The irrigation works are extremely important and admit of indefinite extension. When the Nile falls below the “high level” the country assumes the appearance of being cut up by a series of narrow irregular canals of different levels. The irrigation is carried on by numerous water mills or pumps which are worked by oxen, donkeys, and camels. Their construction is remarkably primitive and defective.[42] Their snail, treadmill-like pace is a picture of waste, and the work done seemed not to exceed one-third of the power expended. This is inexcusable, because mechanical power of advanced construction is in general use by the Egyptian Government in almost all other departments. Much of the irrigation, however, is done by water-drawers whose energetic and efficient action it is pleasant to see, being just the reverse of that of the quadrupeds. With a light bucket having two cords attached, two young Arabs by alternate plunges and upward jerks raised water nearly ten feet, from a lower channel level to the higher, and seemed to continue with singular steadiness at the rate of some twenty bucketfuls a minute, even with a scorching sun overhead.

Ladies of the middle and upper classes are never seen unless veiled—all except the eyes and part of the nose—in a most unbecoming fashion. They are enveloped in a loose robe of pure black or white, covering the head and partially fastened at the neck; under this they[43] seem to wear some kind of jacket or dress of rich-looking silk, green or other bright colour, and this, with loose leather slippers, constitutes their outward dress. Most frequently they ride on donkeys, and consequently on the dusty roads their feet appear in disadvantageous contrast with their spotless dress otherwise. They seem notable housewives at bargain-making in the bazaars, otherwise I never noticed them speak to a male, and no male speaks to them in public. Generally speaking I saw no “beautiful old women” anywhere after crossing the English Channel eastward—such as are frequently met with at home. The Bedouin women are rarely veiled, the girls are employed in degrading menial work, such as serving as mason’s labourers; and I was very much shocked to see a number of them carrying wet mortar on their backs up to a building in a piece of cloth, with the water running down their dress, which consisted apparently of only a frock of blue cotton cloth.

The handsomeness of the Bedouin women[44] has often been noticed—brought our very much by their habit of carrying water jars upon their heads, and also frequently upon their shoulders. The married women frequently so carry their babies from a very early age. Sitting astride the mother’s shoulder, and holding on by resting one arm upon her head, they quickly learn to sit with safety and extreme freedom. This habit gives excellent training to the eye, the muscles, and the lungs, and in the open air of Egypt the little ones seem to thrive immensely. Besides, the mother does not appear much hampered in her movements, and carries on her daily avocations with singular facility.

We would gladly have visited Upper Egypt and its ruins. Besides steamboats there are excellent commodious vessels from Cairo which go south as far as the first cataracts, but as the voyage often takes about six weeks, we found that this might detain us too late, and interfere with our other plans. The voyage is tiresome to some travellers, but to sportsmen very enjoyable,[45] and I believe those who study ease and care for a good table may make it more pleasant than the new hotel.

Here we were beset with overtures from dragomans for our Palestine and Syria travels, and after an amusing amount of talk, pro and con., we agreed upon terms with a Syrian, named Braham, who spoke English, French, Turkish, Syrian, and Arabic, and, I think, Italian, all as printed upon his card—and then his testimonials, which he insisted upon our reading, showed him to be a man of matchless ability, probity, and good fortune. With him, travellers were safe from all evils, and then his equipments were in a style of unequalled completeness and perfection. Were not his referees Sir Moses Montefiore, bankers from America and England, and had he not conducted even a marquis and his spiritual director, Monsignor Capel? The terms and conditions of a treaty of travel were accordingly drawn up, and again read over to both parties, and signed and sealed with all the formalities of a national[46] league, by and in presence of H.B.M. Consul at Cairo. Everything new—new tents and new beds, horses and donkeys, with harness, provisions, hotel bills, and bakshish were provided—everything necessary, in short, for a consideration—somewhat heavy—and payable in gold. We agreed upon a fixed sum per week for our party of four for a specified time, commencing on our arrival at Jaffa, and ending on our embarkation homewards, but leaving us to determine at pleasure our own routes and mode of travel anywhere in Palestine and Syria. In short, we were to have the fullest power—to have our own choice in everything. Braham was only to hear and obey!

It really was so throughout the journey. We found him all he professed; but when we differed in opinion, Braham always showed us—and convinced us against our will—that our plan was either impracticable or highly dangerous, and, in point of fact, we found that his way was always the best. Although the[47] terms of the treaty were strictly carried out by both the contracting parties, the choice so left with us was in practice very much a dead letter. On the whole, however, I can safely recommend our Syrian as an A 1 dragoman in every respect. Dressed in his turban, his professional Damascus striped shawl, with the orthodox tassels, and Cairo divining-rod in hand, he looked quite the character. The business of dragoman is a special one, requiring education and habits of a superior order. Braham stood high in his profession, and, although careful not to show it, was, I think, a man of substance.

After a residence in Cairo of about a fortnight, we proceeded to Palestine, viâ Port Said, which is the new shipping port of the Suez Canal upon the Mediterranean, and presents a somewhat lively scene. During our stay there we sailed up the Canal a short distance, for the purpose of inspection; however undoubted the utility of this great Canal, it is[48] entirely devoid of beauty, the banks being high mounds of mud and sand, without a single spot of vegetation, and from the deck of our boat they entirely concealed the country on both sides. Sporting in the Canal, we saw a good many fish somewhat resembling our porpoises in their gambols, and which the sailors called “Black Jacks”—I understood they had come up from the Red Sea.

In now leaving Egypt I did so with considerable hope of her future. Recent events have proved the sad waste of money, but unlike Turkey there is something to show in the shape of improvements and public works of utility which more or less tend to enrich the country. Nothing seems wanting except honest administration of the revenue and a personal supervision by the Khedive of his expenditure. The Government if despotic is supreme, and there is not only safety for all, but even a considerable degree of religious liberty.

From Port Said we sailed for Jaffa, the ancient Joppa of Scripture; and the landing here was the most novel and exciting scene I had yet witnessed in that way. So difficult is the landing sometimes that passengers are always conditionally booked for Jaffa, and to be landed, at the option of the captain, at Beyrout. In our case it was resolved to land, but after some hesitation. The eastern border of the Mediterranean although low is generally rocky, and is extremely subject to sudden and violent storms of waves and breakers on the coast, and no place so much so as Jaffa. There is no harbour, and passengers and goods[50] are landed on the beach; in front is a barrier of three low rocks, the passage between which is only wide enough to admit a boat; the surf often runs very high, and the least deviation would inevitably result in boat-wreck. The pilotage of the boat few but a practised Arab would undertake, and the excitement and bustle on the beach on such occasions are something extraordinary. When we landed, nearly a thousand Arabs, all of the lower class, and not overburdened with garments, congregated ready to fish us out in the event of such an accident.

The moment our boat touched the beach, a crowd of these fellows—who seem all legs and arms—rushed forward, up to the chest in the water, and seized me, one by each limb, bearing me aloft to the shore without leave asked, and carrying on all the while a violent quarrel amongst themselves as to whom I belonged—each of them claiming me as his salvage. The ladies certainly were treated with some measure of respect; but all the other passengers[51] and every article of our luggage passed through the same ordeal, and notwithstanding the violence of the surf we were all landed wonderfully dry—but still in custody of at least four clamorous proprietors, each vociferously demanding payment for our rescue. How we escaped with our luggage safe is wonderful: I presume it could not have been managed but for our dragoman and his lieutenant. The clamour was somewhat more than amusing; but on this as on numerous similar occasions I remarked that, however threatening these Arab quarrels are, I never saw one seriously wound or strike another, even where I was prepared by violence of language and fierceness of gesticulation, to see a murder perpetrated. When no weapon is at hand, they arm themselves with large stones, which are certainly plentiful everywhere.

The hotel, occupied I think by a Frenchman, is situated about a mile beyond the town, beside an orange grove and a few new buildings[52] entirely in the European style. The town itself has a fine appearance from a distance. It is walled and very old, of small size, but extremely crowded, and built upon a rock rising almost out of the sea; the streets—narrow, filthy, and crooked—are besides, generally speaking, very steep. The buildings look as if they had been meant each for a fort, with nothing pleasant-looking about them except the roofs, on which the families appeared chiefly to live. The people at the bazaars seemed a very bustling mixed class, and of a lower morale than any we had met—blacklegs, gamblers, showmen, loafers, and waifs of many lands.

Here, as elsewhere, we found travellers of all nationalities—the Americans perhaps the most numerous. Ladies formed no small fraction of the number, and were in general—at least the Americans—the most thoroughly in earnest, and best equipped. With many of them every possible nook and corner must be explored,[53] and while others were content to see the tombs of patriarchs and saints, Pharaohs and sacred bulls, some preferred to climb into and at least temporarily occupy the empty sarcophagus or cell—often under circumstances of difficulty. As for Eastern relics, I think America—if not England also—must now contain waggon-loads of them.

We sometimes met the same faces again and again in our wanderings. Among others here was an English lady from Cornwall whom we had met in the drawing-room at Cairo. There she had told me she was obliged to travel a second tour to take care of her nephew—a strong, handsome-looking youth, apparently fit for the Life Guards—whose health, she assured me, was suffering from overwork. He certainly became his illness remarkably well, as half the invalids in Egypt do.

“I was,” said she, “first told, ‘Go to Cairo and die!’ and I went; then I am told, ‘Go to Jerusalem and die!’ and so I am en route now.”

About a month later, as we rode up the beautiful valley of the Lebanons to Balbec, we passed her party riding down—she was an excellent rider and well mounted.

“Go to Damascus and die!” she cried.

She has been to Damascus, but I trust has not died even yet; and hope she may live long enough to “Go to Livingstonia and die!”

Of course we visited the house and stood upon the roof said to be that from which Peter saw the wonderful vision of the net let down from Heaven. I did not believe the story, because the house could not be more than a few hundred years old at the most; but it is by no means improbable that it is built upon the site—the description answers so well. In the neighbourhood of Jaffa, and not far from the hotel, is a colony founded several years ago by a party of Latter Day Saints from America. Although this proved a painful failure, and the parties subsequently returned[55] to their own country, they spent both money and labour in the building of a few good houses, and introduced important agricultural improvements, traces of which are yet visible.

I cannot leave Jaffa without making mention of the “Jaffa oranges,” which are famous all the East over for their extraordinary size and excellence. I should say that, on an average, each is nearly as large as four ordinary oranges, and it was a very pleasant sight to see this splendid yellow fruit hanging overhead in passing along the groves, which are all irrigated artificially. Here the crop of fruits generally seemed rich, and prepared us to expect many such gardens in our after journey in the land of milk and honey. How great the disappointment was we shall see.

After a night’s rest, we found ourselves on horseback, en route for Jerusalem. The Jaffa horses are Arabians, of small size, spirited, but very sure-footed; and mine was one of the surest-footed of the lot—a little vicious, but I[56] afterwards found its skin was sadly broken under the saddle, and so am now not surprised that he was frequently somewhat restless. In fairness to our dragoman, however, it should be mentioned that a German prince had started two days before us, who, with his large suite, had taken all the best horses in the place. The Jaffa horse “boys” are, I think, a somewhat mongrel class of Arabs—cruel and cunning, and seemed to delight in mischief of every description.

Almost every one breaks the journey at Ramleh, which lies only an easy journey south-eastwards, and is said to have been the property of Joseph of Arimathea. Here there is a tower somewhat similar to the old Norman square towers at home, and it did not appear to be much more ancient. From its summit we obtained an extensive view of the country. On the west, and northward along the coast, lay the once fertile plains of Sharon, which we had just crossed; on the southward, the country[57] of the Philistines—Gaza, Askelon, Gath—the scene of Samson’s exploits and sufferings, and of David’s victory over Goliath; and, later on, along the plain south-west was the Ethiopian eunuch’s carriage stopped to take up Philip the Evangelist. On the east was the “hill country of Judea,” which we had already partly ascended.

Instead of erecting our tents, we put up in one of the convents, of which there are two always ready to receive strangers—the Russian and the French—both of which have very much the appearance of fortresses, and may have been founded during the Crusades. We were not asked to join in any religious service in the convent, which seemed to be almost deserted at the time.

Next morning, after an early breakfast, we were again in the saddle, and from this point upwards to Jerusalem the ascent was very considerable almost all the way, and rendered even more steep by a very deep wady or ravine in our route. Hitherto the road had been[58] partly made, but now we lost for a time all trace of it, other than the usual Palestine bridle-track over hill and gully, and along paths which it is difficult to describe, and which are in some places barely discernible.

Being our first day’s long journey, we gladly stopped at noon for lunch, which, as on most other occasions, consisted of wheaten loaves, cold fowl, fruit, and wine; the donkeys carrying the tents in the meantime moved on, as they travel somewhat more slowly. The ascent had become extremely wearisome both for horse and rider before we came in sight of the great city, and, as in the case of the Crusaders of old, many an eager outlook was made for Mount Sion before it actually came in sight. But we had tarried so much on the way that the sun was rapidly sinking in the west as we approached the walls of Jerusalem. The gates were just being shut, and our first sight of it was therefore very imperfect.

Entering by the Jaffa gate, which fronts[59] the south-west, we found ourselves suddenly involved in darkness so great that our party lost sight of each other before we reached the hotel. This was the Hotel Damas, or Damascus Hotel, the only other good one being the Mediterranean Hotel, which was occupied entirely by the Grand Duke Mecklenburg and suite. A very large portion of travellers, however, obtain lodgings in the several convents and hospices of the various religious houses.

How shall I describe Jerusalem? With its form all are familiar, but no description which I can give would, I think, convey a correct idea of the place; at least all the descriptions I previously read had completely failed to do so to me. No doubt these descriptions are literally true more or less, but there was an awful sense of desolation which seemed to hang over the whole scene that no words can describe; and I can only express my own feelings, which were those of absolute pain.

The Jerusalem of to-day is in no sense, except[60] its site, the Jerusalem of the Bible—Salem the Peaceful—Mount Moriah—Mount Sion—Calvary—names which awaken by their very sound ideas of grandeur and victory! Jerusalem the Golden—compassed about by the everlasting hills—beautiful for situation, the joy of the whole earth—the city of the Great King!

Instead of these, there was only the idea of desolation and defeat. “Is this the city that men call the perfection of beauty?”—a confused mass of shapeless, dirty, half ruinous houses, built without plan, and almost resembling the wreck of a conquered citadel. Yet every spot has a history: here the house of Pilate—there the Temple site—yonder the tomb of David; and deep in the chasms on the east and south the brook Kedron and Gethsemane, with the tombs of Absalom and those of the Prophets, the valleys of Jehoshaphat and Hinnom, of Gihon and the Field of Blood—all really one vast overcrowded graveyard.

Much vain effort has no doubt been made[61] to re-gild the departed glory, but the illusion did not satisfy my mind, and I found it impossible to realize the enthusiastic feelings of sanctity generally attached to these or to the so-called “Holy Places.” I felt that many of them were obviously false, and almost all of them improbable; indeed, it is perhaps well that such is the case. Jerusalem the beautiful now sits in the dust, and how indeed should we expect it to be otherwise when we read its foretold fatal doom, or consider that even since the beginning of the Christian era the city has been destroyed four times after long sieges—that of Titus being a complete destruction? Josephus gives upwards of 450 acres as the area within the walls then—now it is only 213. The very streets we walked through are evidently formed of the rubbish of fallen houses, the original streets being probably in many cases ten to fifty feet beneath the present surface. For here it is emphatically true that “as the tree falls so it must lie,” and so of the fallen houses—nothing[62] is removed, and the new one is erected literally upon the ruins of the old. And yet no question arises as to the identity of the chosen city. The mountains still stand round about Jerusalem, but her glory is gone, and there remains merely the skeleton of her former beauty and comeliness.

There are very few Jews in Palestine, but in Jerusalem, which contains only 20,000 inhabitants, about 5000 are Jews, the balance consisting one-half of Arabs and Turks; the other of Armenians, Greeks, and Roman Catholics—Latin Christians, as the latter are called; besides Maronites, Copts, Druses, and others of less importance. Each of these has a church of its own, and all vie with each other in rivalry for a precedence by no means Christian. The Jews are poor and uninfluential; they have seven small synagogues—very mean-looking buildings—once there were several hundreds. However, under some unseen influence the Jews are by immigration at present rapidly increasing.[63] By far the largest and finest erection in the city is the Mosque of Omar, and second is the El Aska, both erected upon the Haram or Court of the ancient Temple, and partly upon the original walls. These are beautiful buildings, and are rendered more so by their site, than which a finer cannot be imagined. Worthy, indeed, I think it must have been even of that magnificent Temple which Solomon built upon it.

The Mosque of Omar is an octagonal building, about 180 feet in diameter. Its marginal roof, nearly flat, but having a drum and large dome over its centre, resting upon its inner row of marble columns. The walls are covered externally and internally with marble, and higher up with Persian tiles of porcelain, the blue and white giving a very fine effect. There is round the frieze (written in large characters of gold upon blue) texts from the Koran, and the small windows in the roof are of beautifully variegated coloured glass of peculiarly subdued tints, but without figures, which Mahomedans[64] and Jews alike reject in their places of worship as savouring of idolatry—they shed a pleasant light very grateful to the eye when all outside is bathed in bright sunshine. The outer circle of inside columns are of marble or granite, somewhat mixed, I thought, in colour and design. This building is of doubtful age. Some suppose it may have been originally erected for a Christian church. It is evidently of Byzantine design, although its architecture is somewhat of mixed character, and by no means of solid workmanship. The linings of marble and porcelain tiles are a kind of mosaic ornamentation more rich and beautiful than substantial and enduring. Suspended from the dome by a long chain is a large crystal candelabrum over the centre of the rock, the gift of a former sultan, and there are, as usual, numerous silver lamps so suspended. There is an elegant marble pulpit, with columns and arches of Arabic design, and altogether the interior is richly but not showily[65] ornamented. The marble mosaic floor is partly covered with straw matting. Near the prayer niche in the wall I noticed several very ancient-looking copies of the Koran, which Braham told us infidels were not welcome to handle. This building may be called beautiful, but I think the word “grand” is not applicable, and I doubt if it is so to any Byzantine or Moorish architecture. Compared even with the second temple or its successor, that of Herod, whose site it partially occupies, I presume it would appear flimsy. With the grandeur and material glory of that of Solomon, of course, it need not be named.

Standing here on the site of Solomon’s Temple, how crowded is the mind with sacred associations! For it is probable that either on this spot or on Mount Sion adjoining was Salem the Peaceful, the seat of Melchisedek’s priesthood. And there seems no reason to doubt that this is the summit of that same Mount Moriah where God provided Abraham and Isaac with a lamb for a burnt-offering—typical[66] of that Lamb “prepared from the foundation of the world,” and to be offered up near the same spot nearly nineteen centuries afterwards.

The building next in importance is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, a large, circular, domed building, erected upon what is supposed with far less certainty to be Mount Calvary. The present is quite a modern erection, as are also many of its contents, and of very poor architectural merit, but the original erection was very old, probably of the third century. It has been destroyed again and again by violence and fire. Within its walls are the sites of the “Holy Cross,” a small hole or socket cut into the rock, with those of the two thieves. Also the Tomb of Christ, enclosed in the Rotunda, a small unseemly tabernacle under the dome. This is the great object of veneration, where yearly is performed at Easter that holy-fire miracle so long scandalous to Christendom, and near it is a pillar[67] marking the centre of the world! Indeed, the objects of interest are so very numerous that, excepting perhaps to a devotee, they become very confusing. The whole place is overlaid with artificial trappings and ornaments, and monster-size wax candles, silver lamps, jewels, polished marbles, and woodwork, wholly incongruous with the ideas of a cross or a sepulchre. All is under lock and key, and a Turkish soldier opens and shuts the gate at his good pleasure, in a way very tantalizing and insulting to all the sects. This is only tolerated because of their mutual jealousy—frequently breaking out in quarrels and fights—in all which this Moslem must be the arbiter. His manner of showing his authority scarcely conceals his contempt for Christianity, and with such examples of it as are practised before him—such masquerades, and fights, and holy fires, and other incredible wonders and superstition—need we be surprised?

The Tomb of David is situate on Mount[68] Sion, enclosed in a large plain stone building, which is in possession of the Government, and is guarded with much care. It is regarded with great veneration by all parties, and especially so by the Mahomedans. No admission can be in ordinary circumstances obtained into its interior, but it is said there are inside upon its floor two very curiously constructed and ornamented tombs.

There is a small English Church on Mount Sion, which we attended on Sunday, and enjoyed an excellent sermon from Bishop Gobat. Here, as elsewhere in the East, Sabbath is scarcely different from other days. The Mahomedans observe Friday, the Jews Saturday, and the Christians the first day of the week; but all of these days seem only partially observed at the best.

Outside the walls, of course, and on the south of the city, is the small cluster of “Houses of the Lepers.” There seems always some inhabiting them. No one appears to[69] visit them except at some distance. The sight is in no sense a pleasant one.

It is calculated that there are about 10,000 pilgrims visiting Jerusalem per annum; of these, of course, our party was reckoned, but the real pilgrims, I think, are the Jews, who come from all parts of the world. They are chiefly elderly people, of both sexes, venerable-looking, and evidently very much in earnest. Weekly, on Fridays, a number of them may always be seen at the “Wailing Place,” which is situated in a quiet alley, bounded on the one side by a portion of the walls of the ancient Temple Court—a few courses of the large stones of which are generally admitted to be of the original building. Here they stand with their faces to the wall in the attitude of prayer, apparently unconscious of the presence of straggling on-lookers like ourselves. A few of those we saw were evidently educated Jews, furnished with manuscript copies of the Law and the Prophets. They read earnestly,[70] in a low tone of voice, each for himself, alternately kissing the stones, smiting their breast, and weeping. Some of them were seated on the ground, a few feet distant, apparently exhausted by fatigue. It was impossible to laugh in such a presence, and indeed even the Arabs seemed in pity to pay them an outward respect.

The Mahomedan pilgrims, although they allow Christ was a true prophet, did not appear to visit the sepulchre at all; their devotions were performed in the Mosque of St. Omar, the sacredness of which is held second only to that of Mecca. This is because of the famous vision related by Mahomet, in which he declares that in one night he was carried by the angel Gabriel from Mecca to Jerusalem, to the summit of a rock on Mount Moriah, and from thence he ascended on a winged pegasus to heaven, returning back to Mecca the same day laden with new inspirations! The mark of his presence he of course left behind on the rock in[71] the shape of a large hole, and hence the Moslems call St. Omar the “Dome of the Rock.” This rock is supposed by some to have formed the great altar of burnt-offering of Solomon’s Temple, and over it is now built this temple of the False Prophet!

The rock is of great size, covering a space of about fifty feet diameter, but is irregular in shape, and may be about six feet high, and, in accordance with Moslem ideas, is strictly watched and enclosed. It is also partly veiled, and rests, they say, upon nothing. To my eyes, it palpably rested on its own edges, inasmuch as there is a hollow excavation cut out under it, communicating, as some suppose, with the underground drains by which the blood and water of the sacrifices may have been washed away.

Although the followers of Mahomet look with contempt upon the credulous superstition of other religions, there is nothing too absurd for the devout Moslem to believe in connexion with his own, however contrary to the evidence[72] of his senses; many curious instances of this I might relate, did space permit. But some Christians are not much more enlightened. There is a very crooked street called the “Via Dolorosa,” because that by which the Saviour walked from Pilate’s Judgment Hall to Calvary. Here the monks show a built-up arch in a wall where once stood the now famous “Holy Stair” by which Jesus descended from the hall. This stair we were shown at Rome, whence it was transported, some say by miracle, and is now erected in St. Giovanni, one of the churches there. When in Rome we witnessed several female devotees climbing painfully up its steps upon their bare knees, while some who proposed walking up upon their feet were prohibited. Farther north in Via Dolorosa is shown the “Ecce Homo” Arch, also the house of Dives, with the stone on which Lazarus sat; and there is shown an indentation in the stone wall made by Jesus in leaning there to rest, wearied with His heavy cross; and so[73] on, with many other interesting spots equally authentic!

Amongst travellers generally the subject of religion is very seldom introduced, although the Bible narrative is evidently in most men’s thoughts as these scenes pass before the eye. Here in Jerusalem we were privately informed, on very good authority, that a well-known wealthy Scotch marquis, probably to confirm his recent conversion, or perversion, was, through some very potent influence, permitted to remain within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre all night, which he either passed in religious devotions or slept in the so-called Saviour’s grave! He was attended only by his religious director and his dragoman, and I am not aware that such liberty has ever been accorded by the Turkish Government in any other instance. The story I believe to be quite true, and probably somewhat reveals the secret working of his mind at the time.

The Hall of Pilate, subsequently called the[74] Castle of Antonia, was situated adjoining the Haram or Temple Court on the north, an eminence commanding that portion of the city, and on its site now stands the Turkish barracks. The Pasha until of recent years was subsidiary to the Governor of Syria. There is a telegraphic wire connecting Jerusalem with Damascus, Nabulous, and other centres, very necessary for military purposes.

The inhabitants of Jerusalem consist largely of Arabs, who appear to be rather more domesticated than we had hitherto seen them. They are, as well as the Turks (of whom the chief men are the governing class), all strict Mahomedans. The Arabs are, like the Jews, descendants of Abraham, and are probably—next to them—the most remarkable people on the globe. They are, as it were, the Anglo-Saxons of the East, occupying only the fertile and tropical, as the latter do the more temperate and arctic portions of the world, and both possessing in a high degree the faculty of displacing other races. Physically they are a[75] fine race, living generally in the open air, and having a high degree of elasticity and muscle. I think no other nation could long compete with them in running a race. They seem governed by numerous sheiks, and are formed into clans, very much like the Scotch Highlanders of old. They frequently look and act like boys set free for the holidays—noisy, restless, and quarrelsome as boys are. Mentally they do not appear to rank high; and yet this people have overrun all others with whom they came in contact, and occupy the places of the most renowned ancient races. The Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes, and Egyptians have disappeared, with many others, and Arabs fill their place. They have supplied kings for vacant thrones in abundance; and although at present largely governed by Turks (whom even now they maintain by their swords upon the Byzantine throne of the Cæsars) they are to be found swarming with semi-independence from Syria and the Great Valley of the Euphrates on the north to the islands in the Indian Ocean.[76] Dr. Livingstone found them in Central Africa, the real although not the nominal masters. To describe them in the mass, I know no way of doing so better than saying that they are simple and purely practical in character, and extremely migratory in habits. Under no king, nor government, nor army, nor fortification, nor priesthood, except his own sheik (unless by force), each is a king, a priest, a government to himself; and so he declares no wars, but lets other potentates fight to clear the way for his own occupation and profit, or that of his sheik.

Between them and the Jews there is, I think, a remarkable resemblance as well as contrast. Both are descended from Abraham, and both inherited the temporal blessings promised to his seed, but with Isaac only was the spiritual covenant established. “As for Ishmael, I will multiply him exceedingly; twelve princes shall he beget, and I will make him a great nation. But my covenant will I establish with Isaac.” The Jews were confined[77] within the narrow compass of an extremely rich and fertile land, whose “defence was the munition of rocks.” The Arabs, while “living in presence of their brethren,” and indeed nearly surrounding the Holy Land, were at the same time scattered far and wide, and the Desert and Wilderness everywhere around has been their home—their hand against every man and every man’s hand against them. By them the Eastern slave trade is even yet carried on in defiance of all laws; and yet Arabia, their native home, has never been really violated by foreign step, but preserved intact for forty centuries—I think a fact unparalleled in the history of the world! And still it remains a sealed country; we know really far less of Arabia than of Japan. Like the Jews, they seem almost impervious to religious teaching; and while all other races are in some degree being Christianized, we never hear of any real breach made amongst the Arabs.

We saw no manufactures in Jerusalem except a little pottery work, some hand-spinning[78] of wool and cotton for home use, and the making of numerous articles for pilgrims, such as beads, crosses, little olive-wood boxes, and the like, which I found were of very poor material and workmanship. There is quite a market for the sale of such articles on the paved outer court of the Church of the Sepulchre, where are two rows of sellers, chiefly monks, daily watching for buyers, and almost every visitor becomes one. There are also many articles of lace and fine sewed work to be obtained at one of the Latin religious houses, called “The Sisters of Sion.”

One day we endeavoured to walk round the city on the top of the walls, which are about twelve feet wide, and, commencing on the north, we obtained a very good view of the interior of the city, but the walls were so filthy that we were obliged to give up our walk. The houses have generally flat roofs, or otherwise dome-shaped. The gates are large, and arched over—the spacious porches[79] just inside would still do for holding Courts of Justice as of old. The finest one—the Golden Gate, on the east—is built up because of some Moslem superstition that the Christians are at some future day to take the Holy City, entering by the Golden Gate! The walls have, of course, been rebuilt again and again. There are several remains of the original to be seen, especially the deep foundation of the south-east corner, and the remains of an ancient arch at the south-west angle of the Haram wall. These indicate a noble and very different style of building from the present.