HIS LITTLE FORM HURLED ITSELF THROUGH THE AIR (See Page 37)

by

ELMER SHERWOOD

Illustrated by Alice Carsey

Whitman Publishing Co.

RACINE, WISCONSIN

COPYRIGHT, 1916

By

WHITMAN PUBLISHING COMPANY

Printed in U. S. A.

To the Boy Scout

Who Strives to

Live Up to His

Pledge

| I. | LUCKY MEETS JOHN DEAN | 13 |

| II. | MISS WHITE’S STORY | 20 |

| III. | THE FIRE | 31 |

| IV. | JOHN DEAN FINDS A “FRIEND” | 41 |

| V. | NEWS FOR THE DOUBLE X | 47 |

| VI. | DEAN MEETS COLONEL SANDS | 56 |

| VII. | TED AT HOME AT THE DOUBLE X | 63 |

| VIII. | RED MACK AND TED INVESTIGATE | 69 |

| IX. | THE MARSHES PAY A DEBT | 77 |

| X. | A LOSING GAME | 83 |

| XI. | TED AT WAYLAND | 92 |

| XII. | THE TRAIN-WRECKERS | 102 |

| XIII. | TED IS CHOSEN FOR A MISSION | 111 |

| XIV. | BOUND FOR CHICAGO | 118 |

| XV. | PLANS ARE MADE TO MEET TED | 126 |

| XVI. | TED ARRIVES IN CHICAGO | 135 |

| XVII. | TED MEETS STRONG | 141 |

| XVIII. | SETTING A TRAP | 149 |

| XIX. | STRONG SEEMS CHECKMATED | 159 |

| XX. | THE DICTAPHONE AT WORK | 170 |

| XXI. | WINCKEL CALLS A HALT | 182 |

| XXII. | AT OTTAWA | 189 |

| XXIII. | TED RECEIVES A REWARD | 196 |

| XXIV. | TED GOES BACK | 203 |

| XXV. | THE MARSHES REUNITED | 210 |

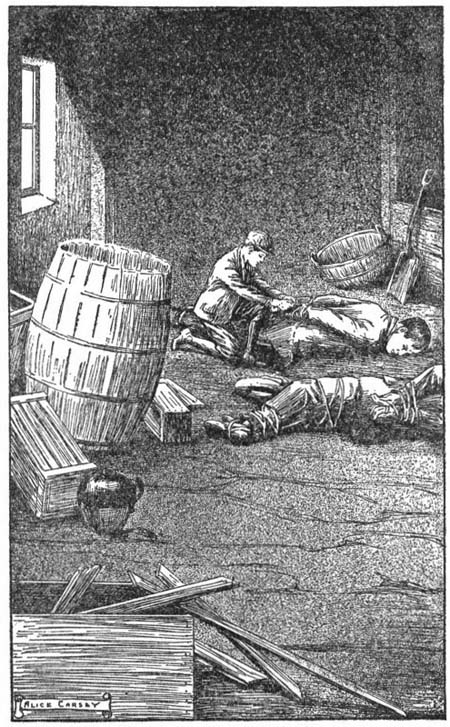

| HIS LITTLE FORM HURLED ITSELF THROUGH THE AIR | FRONTISPIECE |

| DOWN TO THE LAKE FOR A SWIM | 27 |

| RED CAME SHEEPISHLY FORWARD | 61 |

| TWENTY MEN WERE OFF TO BRAND CATTLE | 70 |

| THE MEN FROM THE OUTSIDE CREPT CLOSER | 90 |

| THE TWO BOYS WENT ON A FISHING TRIP | 97 |

| HE WAVED THE RED SWEATER | 109 |

| TED FREES THE PRISONERS | 179 |

Lucky, the Boy Scout

“WATCH my papers, will you please, Mister?” Scarcely waiting for a reply, the bright eyed little newsboy left his stand and darted across the street, where he confronted a ragamuffin, nearly a head taller than himself.

“You have to play fair,” he began hotly, “or you can’t sell papers in this block.” Then calling to a youngster who looked little more than a baby, and who was standing several yards away where the bigger boy had chased him, he said:

“Come back here, Billy! You have as much right to this corner as Spot. And don’t you forget that, you Spot,” he flung back over his shoulder as he recrossed the street.

The big stranger who had been left in[14] charge of the papers, watched the proceedings with considerable amusement.

“What’s the trouble, sonny?” he asked, and beneath the stern lines of his face lurked a smile that invited confidence.

The boy recognized him as a rancher, for many of his type came to this great packing center, bringing their herds from the big ranches of the West. You could easily tell them by their breezy manners and friendly ways.

“Oh, that Spot chases every little feller off the block, so there won’t be any com—com—”

“Competition?” the ranchman suggested.

“That’s it—competition. Spot’s nothing but a bully. He won’t pick on anyone his size.”

“And you take it upon yourself to ‘beard the lion in his den’ and act as champion?”

“I don’t know anything about that,” replied the boy, flushing, “but how are all these little fellows going to get a start in business unless somebody takes their part?”

The cattleman eyed the boy keenly. He was quite different from the other little “newsies” shouting hoarsely the startling[15] news of their papers’ headlines. He appeared underfed, as did many of the children of the slums crowding the streets; his clothes were patched and repatched, but they were clean. His face, too, was clean, and his hair, somewhat ragged and uncut, showed the industrious use of comb and brush. He was a lad of about twelve.

John Dean—for that was the stranger’s name—looked down the narrow, dirty, ill-smelling street, with its crowds of surging humanity, down the dingy rows of tenement houses with their crying children and their scolding mothers standing in the doorways. He saw the heavy trucks pounding over the brick pavements, and the rattling wagons, and he thought of the calm that rested over his own boundless country. What a difference there was between the fetid air that rose from this cavernous street and the invigorating breeze that swept across his prairie lands out West! What a difference there was between his stalwart, robust cowboys and the wan-faced, hollow-chested men he saw about him!

The boy before him, according to all the rules of the game should have been another victim of the environment in which he lived.[16] Dean found himself liking the lad, his actions, and especially his championship of the weak. Was there much of such material in this crowded, unwholesome place, he wondered, as he continued on his way.

The business that had called Mr. Dean to Chicago was completed and yet he was compelled to wait four days more because he had promised to meet a certain man, who would not arrive in Chicago until then. Time would hang heavily on his hands, he thought. His thoughts traveled back to the newsboy.

There came to him a sudden impulse; he decided to follow it and so he retraced his steps to where the boy was stationed.

“Back again, mister?” The boy smiled in greeting as if to an old friend. But it could be no more than a second’s greeting, for customers kept him busy.

“What’s your name, sonny?” the man asked, when the opportunity offered.

“Ted—Ted Marsh,” answered the boy.

“Will you soon be through?” Dean inquired. “I’ll tell you why I ask. I should like you to take me about the city. I know something about it, but there are lots of[17] places I want to see which you can show me. I will pay you for your time, of course.”

The boy thought for a minute. He turned and looked squarely at the man. Dean liked that—he met his eye.

“You will have to wait until I finish my papers,” the boy said. “Then I will have to run home and let my mother know. Otherwise she would worry. But I’ll tell you what, sir”—a new idea had come to him—“I can take you down to the Settlement; you can see that while I finish up.”

“That’s all right, lad. I’ll watch awhile and see you doing business.”

This promised to be quite interesting, John Dean decided, with a sudden zest. He looked forward to the evening before him. He watched the boy, his quickness and his method, and he noted that Ted was the least bit quicker than the other boys and that he seemed to enjoy the competition and the struggle of selling papers. Dean decided it was a hard game. The boy’s stock of papers was rapidly diminishing.

“I can take you over now, Mr.——”

[18]“Dean,” answered the owner of that name, smiling.

“Then I can return and finish up, get home and be back, all in about an hour. Will that be all right?”

“It will—fine,” was the reply.

The two walked down to the Settlement. On the way Ted explained how fine a place it was, just what it did, the clubs in it, and the gymnasium classes. He told the man, quite proudly, that he was a Scout.

“My! I wish you could meet Miss Wells,” the boy added.

The man started. He turned eagerly at the name. He was about to ask a question—stopped—changed his mind and allowed the boy to continue telling of the many fine points of the place to which he was being taken. The boy did so with tremendous pride.

“I suppose you go to the Settlement often?” he remarked.

“Sure,” was the reply. “It’s better than idling about on the corners. More fun, too,” he added.

The man’s interest grew. He asked many[19] questions, all of which the boy answered as best he could.

Miss White, one of the workers, came to the door.

“Hello, Ted,” she greeted him pleasantly. She also smiled a welcome to the man.

“This is Mr. Dean, a friend of mine,” said Ted. “Is Miss Wells in, Miss White?”

“No, she will not be in until late in the evening. Can I do anything?”

The boy explained and added that he wanted Mr. Dean to know the place. Miss White promised to show it to him, while Ted hurried back to finish the sale of his papers before going home.

To Miss White, who was very friendly and likable, Dean explained his impulse and his impressions, his desire to know more of the boy. Miss White was fully acquainted with the facts, she knew Ted quite well and also knew his family.

The man listened closely while she told the boy’s history.

THE story, as Miss White told it, was not unusual in that part of the city, but to John Dean there was every element of newness in it.

He listened without interruption as the story unfolded itself.

Mrs. Marsh, Ted’s mother, had had a hard time of it. Bill Marsh had married her eighteen years ago. Bill was a good mechanic, but after about six years of happiness things began to go wrong. He lost his position and at that time work was not easy to get. Day after day he had searched for something to do. Discouraged, he had taken to drink. Then there was a day when Bill did not return. In all these years Mrs. Marsh had never heard of him. She felt he was dead, yet even that she did not know.

It was a hard struggle afterward. Sewing[21] and washing, early and late, and many a day she went hungry, so that the two children could eat. The mother often spoke of how Ted, when eight years old, had gone out one afternoon and had not returned until seven o’clock. Without a word he had put fifteen cents on the table and then had turned to eat. He showed by the way he ate how hungry he was. After the meal was over, he explained how he had made up his mind to support the family, and so he had bought some papers; the fifteen cents was profit. His capital, also some extra pennies, was intact, so that he could buy more papers.

“I’m going to support this family,” Ted had said, “I’m the man and it’s up to me.”

That was the beginning of Ted as a newsboy. He was very proud of his newsboy badge, and gradually, as he grew older, his help was quite a big share of the family expense, it counted against the family burden.

When Ted was almost eleven, he had joined the Settlement. Miss Wells, who grew to know the boy, his fine qualities, his independence and manliness had had a wonderful influence upon him. But there was also in Ted that mischievous streak, that[22] spirit of fun, and even of trouble-making that every healthy, normal boy has.

It was through one of these mischievous pranks that Miss Wells had first met Ted. One day the boys had shut themselves in a room, six or seven of them, and bolted the door. When Mr. Jones, who was the Settlement Boys’ Worker, had asked them to come out, none of them wanted to show the white feather, and so they had not answered him, but had continued to stay in there. Mr. Jones locked the door with a key and left them, expecting that very soon they would call out, send an S. O. S., and beg to be let out. But there was no call, and after a half hour or so he had gone back to the door. It was very quiet within, unusually so. He managed to open the door after quite a lot of work. The room was empty.

There was only one other way out, through the window. It was a sheer drop of twenty or more feet, so to escape from there seemed out of the question. The last boy dropping out of the window could not, of course, stop to close it, and the fact remained that the window was closed.

Could they have come out through the door? He was sure they had not done so,[23] as he had been very near the room all of the time. Then, too, it was hardly likely that any of the boys would have had a key to fit the rather unusual lock.

Cautious was Mr. Jones. These observations had to be made without creating any suspicion in any of the other watching, grinning boys all about. He did not wish them to know that things were not as they should be and that he was at sea as to how they had made their escape. Pretty soon the boys who had been in that room, one after another, came into the building. They were all so innocent looking, butter would not have melted in the mouths of any of them. They never did tell him, but they did tell Miss Wells and the rest of the workers, how Ted would not let them open the door and had refused to let them call Mr. Jones when the door had been locked a half hour. How he had called for help to some older boys who had been passing in the street below. They were not members of the Settlement and were ready for any mischief. They had obtained a ladder that Ted told them was lying on the ground near a close-by fence. He had been the last to leave on that ladder, which almost touched the window-sill,[24] and he had carefully closed the window after him. He warned them not to tell Mr. Jones, but it was too good a joke not to tell others.

It was after this that Miss Wells had spoken to Ted and had realized how much fineness there was in the boy, in spite of his mischievous, fun-loving disposition. There were other times Ted had been caught in mischief, but there never had been any suspicion of meanness in any of the escapades. He was honest, you felt that, and he looked at you fearlessly, truthfully. He learned to love Miss Wells; she could do things with him, when others could not. She could make him see what was right and what was wrong, what was fair and what was not fair. She made him see ahead, too; to have ambitions and a desire to be something worth while. He had a good head and he often used it, too.

A great opportunity came to Ted and to the other boys. A scout master came to the Settlement and Ted, now over 12, became a Scout. He did many extra little things so that he could earn the necessary money for the suit and the other expenses, such as initiation and dues. The sale of the Posts[25] helped him and he eagerly watched the announcements of the many awards of the Saturday Evening Post. While not often successful in prize-winning, the help he received from his sales was invaluable. He soon passed his tenderfoot test and earnestly and successfully tried to understand woodcraft and all the other things a Scout should know. He was loyal to his oath. It had to be a very good deed each day for him to be satisfied. Being a good Scout was a great ambition, so he found.

Much trouble he had had with the boys of the neighborhood. Once he had seen three or four of them laughing at and poking a tiny mongrel to whose tail they had tied a tin can almost as big as the pup itself. There was a good deed to do, and so he sprang at the laughing, jeering urchins, who gave way for but a moment and then proceeded to pound him. It was a hard fight and they were succeeding fairly well when two of the Settlement boys came along and the other youngsters scampered.

The poor pup, after Ted had untied the string, licked his shoes, whining eagerly, and so, with a sudden impulse, the boy had picked up the pup and brought him home.[26] Mrs. Marsh had not been specially pleased, but she let Ted have his way. The dog stayed.

Between school and the Settlement Ted was receiving an education equal to that of any one. Only the summer before Miss Wells had spoken to Mrs. Marsh and then both of them had insisted that Ted was to go to the Settlement Camp for two weeks.

“I can’t go,” answered Ted. There was regret in his voice. To go seemed the most wonderful thing in the world. “Who’s going to tend to my papers and my Posts? I’m not going to lose my customers; can’t afford to build up a new business.” The voice sounded final.

“You can get some of the other boys to do it for the two weeks,” Miss Wells replied. “I’m sure Tom and Arthur would do it for you and then, when they go, you can help them.”

That plan suited Tom and Arthur just as much as it did Ted. So he went to camp for two weeks. I do not have to tell any of the boys who read this of the fun he had. Tramping, going to the village, swimming, rowing.

[27]

DOWN TO THE LAKE FOR A SWIM

[28]The bugle awakened them at six-thirty. Down to the lake for a swim and setting-up exercises. Or, if you happened to be on the Cook, Waiters’ or Mess Tent Committee, you had to arise at five-thirty to prepare breakfast. At seven you were so hungry you could eat shoeleather. At seven-fifteen, you went to it.

Then your work, whatever committee you were on, Grounds, Tent, Water, such as it was, had to be done. At ten-thirty, inspection, then a tramp or another swim, perhaps rowing or reading, if you were lazy. Dinner, for which you were quite ready, or, perhaps, this was the day for a long “hike” and you were off somewhere, with lunch.

There usually was a baseball game in the afternoon. Some of the boys, Ted too, caddied for a neighboring golf club several afternoons of the week. The money thus earned paid for Ted’s stay at camp.

At night there was a campfire and songs. Ted had a wonderful time, but the two weeks were up very, very soon. Without a useless regret, he went back to his papers and his daily job.

Mrs. Marsh’s lot became a little easier.[29] Thanks to her daughter Helen’s wages and Ted’s earnings, things had been bettered.

Miss White went on to explain about Helen. She was sixteen years old, for more than a year she had been one of the many salesgirls in one of the big department stores of Chicago. She was a bright girl, always willing, and so attentive that the miserable wage with which she had started had been doubled in the one year. It was still pitifully small notwithstanding.

“Mrs. Marsh has often said, ‘I am rich in my children, if in nothing else’,” she quoted.

“She certainly is,” John Dean answered heartily.

There were more things Miss White told John Dean. As he listened he made up his mind to do what he could, for here was a youngster who had the makings of a fine man. Dean felt that this was a great opportunity for him.

When Ted came in soon after he found his two friends going through the Settlement and Miss White explaining to an interested and earnest listener the things the Settlement was doing, just how it was making good future citizens.

[30]As Mr. Dean turned to leave, he asked Miss White for pen and ink and left a check for a large amount with her.

“Just a little to help in the work,” he remarked. And because he was a modest and a very bashful man, he blushed. Ted and he hurried out.

“TED,” Dean turned to the boy, “I should like to go through that part of the city in which you live. I want to see the streets around there and what is on them.”

Ted wondered why anyone should want to see that part if they did not have to do it. But he did not question; after all, it was for his friend to say what to do and where to go.

So they walked that way. After fifteen minutes or so, Ted turned to Dean and said:

“This is my street.”

They walked a few more blocks and Ted added, “I live a little way further up.” The man continued observing and made no comment. He was thinking—thinking hard. He turned to the boy and was about to speak.

“Ted, how long—”

[32]Even as he spoke came the distant, insistent clang of bells, the blare and blast of many whistles, shrieking their warnings. It seemed but a second later when a belching fire-engine, followed by a stream of trucks, dashed perilously through the crowded street, while in their wake came a mob of hurrying people pouring from the dark doorways of the tenements. From a side street came a police patrol.

The boy climbed to the top of a stand and from that vantage point he saw a cloud of smoke issuing from a tenement building a couple of blocks away. As he looked a tongue of fire shot from one of its windows and licked its way up the side of the building.

“That’s down near where I live,” John Dean heard the boy say, as he leaped down from the box and started on a run. The rancher hastened after him, threading his way through the crowd. Back of them came another newsboy.

“Your house is burning up, Ted,” he shouted, but Ted had already seen the disaster that had come upon his home. It was a poor one indeed, but a home, nevertheless,[33] that sheltered his mother. Ted wondered where she was. He knew that Helen at least was not there.

The cattleman had never seen a city fire. Before they arrived at the burning building, the police had driven back the fighting crowds and had drawn ropes across the street, past which no one dared go. Helmeted firemen rushed through doorways, drawing long lines of hose, while now and then, through the smoke and fire pouring from the windows, heroic men could be seen clinging to the face of the dingy building, pushing upward from ledge to ledge with their line of ladders.

Some of the men entered through the broken windows, only to appear again suffocated and choking from the smoke and flames, then returning to risk life and limb for those who might still be in the house, cut off from escape.

John Dean saw little of this, however. Back and forth he tramped through the crowds, never losing sight of his little newsboy friend. Ted’s face was white and tense.

“Has anybody seen Mrs. Marsh? Anybody[34] seen mother?” he inquired on every hand, and the man took up the question, “Has anyone seen Mrs. Marsh?” But no one had.

They pressed their way to the rope, searching the faces of the long line of spectators.

“Move back there!” commanded the officer, and pushed the crowd from the straining rope. Ted scarcely heard the warning. He was standing gazing at a certain curling line of flame eating its way up the casement of a fourth floor window, and as the heated pane cracked and fell shattered to the pavement below, a sob broke from his lips. An instant later he darted beneath the rope, past the officer and toward the burning building.

“Stop that boy!” shouted the officer. “The little fool! Heaven help him get out of there,” for Ted had slipped past the clutching hands of the firemen and had entered the burning building.

People who had seen the boy rush in, shuddered with apprehension. A second officer stood threatening big John Dean, forcing him back into the crowd.

[35]“You go after that kid and I’ll arrest you,” he said, flourishing his club. “His mother isn’t in there, anyhow. The firemen will take care of the boy.”

The restless, surging crowd, after a time, became hushed and silent. Only the hissing engines and the captain’s orders could be heard above the crackling flames, except as shattering glass and falling brick told how surely the fire was gaining headway.

As moment followed moment and Ted failed to appear, the officer took the anxious cattleman by the arm.

“Stay where you are,” he admonished. “You couldn’t get the boy if you went in. I have a youngster of my own,” he added. Then excitedly they pointed to an upper window. “They’ve got him,” he cried, and all through the crowd went a ripple of expectancy.

But the form that was slung across the fireman’s shoulder, as he climbed through the window onto the ladder, was not that of the little newsboy. It was the limp body of a brother fireman rescued from the smoke, the last of the firemen who had followed[36] Ted into the seething tenement. A waiting ambulance hurried the unconscious man to a hospital.

Presently a warning cry from the chief caused the firemen to retreat hastily, withdrawing their lines of hose, as their attention was called to a long, widening crack zigzagging its way across the face of the building.

“The wall is going,” the officer told Dean, and the words struck a chill into the heart of the big Westerner. He turned his back. For what seemed to him hours he waited for the impending crash that meant the destruction of his heroic little friend. Suddenly a resounding cheer broke from the crowd. Dean turned and saw, high upon the edge of the building, battling his way along through the smoke, appearing for an instant and then lost to sight, Ted’s figure creeping along the cornice. One arm was held tightly to his bosom.

“Easy, lad, easy,” the chief called up encouragingly through his megaphone to the boy. A dozen firemen had seized a blanket and stood with it outspread, waiting for Ted to jump. “Are you afraid?”[37] the chief shouted, and he glanced anxiously at the widening crack. “All right, boy. One—two—” Ted straightened up slowly. A cloud of smoke enveloped him, but through it, five stories above, the crowd saw his little form hurl itself through the air and drop into the blanket below. A crashing wall drowned their cheers.

All up and down the rope barrier the officers were forcing back the excited spectators, but out of the crowd came a little pale-faced, anxious woman. She hastened to the side of the doctor, who bent over Ted as he lay in the blanket. John Dean hurried after her unmolested, and as he saw what Ted had held so tightly to his breast, he uttered an exclamation.

“By George! Now what do you think of that!” he cried, for there, whining and nosing about the boy’s feet stood a weak-limbed, helpless little puppy. The doctor was making a hasty examination.

“No, Mrs. Marsh,” he repeated again and again, “your boy is not dead. He will come around soon; pretty much shaken up. No bones broken. Yes, of course he is breathing. Hospital? Yes, but don’t you[38] worry about the expense; arrangements can be made.”

“Doctor, see that he has the best there is; I will foot the bills, for Ted is a friend of mine,” Dean broke in impulsively.

A waiting ambulance, which the doctor beckoned, drew up and cut off any further conversation. As they placed Ted on the stretcher, John Dean hailed a taxi and helped Mrs. Marsh in. “Follow that ambulance,” he directed, as he stepped in beside the little mother.

A few moments later they were seated in the waiting room of the immaculate hospital. Mrs. Marsh sat opposite the doorway watching anxiously each trim, white-capped nurse as she sped noiselessly down the hall, and feeling strangely out of place in the fine surroundings, so different from the sordid tenement she had called home.

“I hope my daughter has not heard of this as yet. She would be so worried. I wish I could get a message to her, so that she will know things are not so bad,” said Mrs. Marsh anxiously.

“If you will give me the address I will attend to that,” said Dean.

[39]Mrs. Marsh gave him the address. He summoned a messenger boy and wrote a reassuring message to the girl and added that she should come to the hospital when she could.

“You are all so good,” the woman said, gratefully. “I do not know what I would have done without you, sir, and I do not know how I can ever thank you.”

“That will be all right, Mrs. Marsh,” the man answered. “I know Ted; he and I are friends.”

Very briefly, he explained his acquaintance.

“Mrs. Marsh,” he added quietly, “you need not worry because of the fact that Ted is in the hospital. Do you know what you are going to do? No? Well, I am going to tell you. There is good stuff in that boy of yours, Mrs. Marsh, and I feel sure that he won’t always be a newsboy. I am going to loan to you, through him, one hundred dollars. No, I won’t listen to any objections. I tell you it is only a loan. And out of that hundred dollars you can buy such things as you must have at once.”

With that he removed the broad leather[40] belt he wore and from it drew an astounding roll of bills of large denomination. He thrust five of them into Mrs. Marsh’s hands with an air of finality that gave her no reason to refuse.

THE next half hour was an anxious one. Then Helen appeared. Dean liked her looks. Things were explained to her. She did not become hysterical, but gave her attention and thoughts to the comfort of her mother.

“There is nothing to worry over, mother. Ted will soon be well and as for the things that are burned, at least we are insured. Think of the many people who could not afford insurance, they are in a much worse plight than we are.” She certainly was a brave soul, Dean thought.

Dr. Herrick came in a little later. He smiled reassuringly. Turning to Mrs. Marsh he said:

“There is a little boy in Room 30 that[42] wants to see his mother. Second door, main hall, to the right. Miss Wells just came. She has a very busy night before her, don’t you think, Mrs. Marsh?”

“Bless her kind heart! That is just like her,” Mrs. Marsh exclaimed fervently. “She is an angel, Mr. Dean. A friend of every poor child and mother in the district. She is a real lady, too; not like the kind of folks that live on our street, you know—but you have no idea the good she does nor the comfort she gives.”

The doctor had motioned the cattleman to go with Mrs. Marsh and Helen, and as they entered Room 30, Mrs. Marsh ran quickly to the side of the small white bed where the brave little patient lay. For an instant Ted’s eyes fluttered open, and then shut. A look of contentment passed over his pain-drawn face.

Facing the window, speaking in a low, soft voice to the nurse, Dean noticed the young woman Dr. Herrick said would be there. “The settlement worker,” he said to himself. Then, as the girl turned in the full light of the window, a gasp of astonishment escaped him.

[43]“Amy Wells! So you are the Miss Wells? Oh, Amy! Amy! I might have known—” but what John Dean might have known was not said just then, for the young woman, equally as surprised as he, held up a warning finger and quickly led him out into the broad hall.

Now what was said between them matters but little, but the poor people who lived on Ted’s street afterwards told how a fabulously rich cattleman spent half the night helping Miss Wells find homes for all those who were made homeless by the fire that destroyed the big tenement house. They exaggerated and repeated the stories so often that had big-hearted John Dean heard but half of them, he would have reddened with embarrassment. Nevertheless, it was true that many of the poor families had their empty pocket books replenished that night by the generous stranger.

A week later, more news spread up and down the street, to the effect that Miss Wells, too, had once lived in the West, where she and John Dean had been the very, very best of friends, but somehow they became not-friends, and now they[44] were reconciled, and Miss Wells was going to leave them all and go back with John Dean to a wonderful new home. But the news brought much unhappiness to the mothers on that street, and many a little group stood in the hot, dirty stairways and told how the pretty settlement worker, whom they all loved, had saved their babies when they were expected to die, and had watched over their sick children night after night when the heated city gave no relief to the fever patients.

And Ted Marsh, to whom the news had slipped in, was unhappiest of all.

“Aren’t we ever going to see Mister Dean and Miss Wells any more after they leave, mother?” Ted asked the seventh afternoon as he lay in the hospital. Mrs. Marsh did not speak for a minute. Finally, evading his question, she answered:

“They will be here to see you this afternoon.” And then, as she heard footsteps in the hall, “There they are now.”

But the visitor proved to be Dr. Herrick. Walking over to where Ted was sitting up in bed, he began to examine him thoroughly, after which he stood back and surveyed him with a good-natured smile.

[45]“Well, lad, you have pulled through pretty well. Hair a little singed, but that will grow out—hands healing nicely, and lungs in good shape. I tell you, boy, you are fortunate. A few weeks out in the country would be all that could be asked to make you sound as a bell.”

“Is that all that is required, Doctor?” asked Mr. Dean, for he and Miss Wells had stepped into the room, just in time to hear the last sentence. “Don’t you think I owe Ted a few weeks in the country for finding Miss Wells for me again, when I hadn’t seen or heard from her for five years? Ted, you are a regular little mascot.”

At the word “mascot” a sudden idea seized John Dean. Drawing Amy Wells aside, he began speaking rapidly in a low voice. What he had to say evidently pleased her very much, but a look of doubt caused her to knit her pretty eyebrows. Mr. Dean, too, looked more sober, but he turned and came directly to Mrs. Marsh.

“Mrs. Marsh,” he began without preliminaries, “Ted, here, must go west with Amy and me. He has the kind of stuff in him that goes to make a man, and we can’t get too much stock of that sort[46] out in our part of the country. You owe it to him—we all owe it to him—to get him out of the life he must face if he goes back to the street and his news-stand. He needs opportunity, and a chance to live in a place where he can fill both lungs with clean, fresh, health-giving air. He can’t get it in the city; he can on the ranch, and I’ll see to it that he gets the best education that money can obtain. Ted is our mascot. Amy and I can’t leave him here.”

Ted listened, open-mouthed, to all that was said that afternoon, for John Dean’s speech brought forth a long and earnest discussion in Room 30. Little Mrs. Marsh’s protests became fainter and fainter, until finally she reluctantly gave her consent, realizing it was a great opportunity for Ted.

It was Helen who had really convinced Mrs. Marsh when she said: “We must let Ted have his chance, mother. We must not be selfish.”

A few days later found Ted Marsh standing, bright eyed, on the observation platform of a Pullman, watching the country roll behind him.

“SAY, boys, the boss is coming tomorrow.” Smiles, the speaker, proved the correctness of his nickname, for there was a broad grin on his countenance as he gave the message.

Fourteen men were sitting about a table. Busily, noisily too, they were clearing away the food. There was no pretense as to the finer points of table etiquette, the food came and it went; speed was the object. They were hungry men.

“How do you know he’s coming?” asked Pete.

“Jim Wilson passed by and left the message. Telegram. What’s more, here is the real news. He is not coming alone, he’s married.” And Smiles—Arthur Holden, at such times when his dignity and his position as foreman of the Double X required it—grinned[48] with the full appreciation of the sensation his words caused.

“Married?” echoed Pete, who seemed to be the only one whose tongue did not seem paralyzed. “To whom?”

“Well, you see, it’s like this.” The first speaker drawled out the words. “I hate to confess it, but Jack neither asked me nor told me the particulars. I shall have to chide him, I fear.”

“I suppose he should have asked your permission,” Pete agreed.

“What I want to know is, would you have given it?” This, from another of the men, Al Graham.

“Yes, Smiles, with your experience, how would you have decided?”

Smiles was notoriously bashful and could never be found when any women folks were about.

“I guess Smiles’ experience in the last twenty years has been seeing the Wells over beyond. If he saw them first he’d vanish, pronto.” The last speaker was older than the rest, quiet appearing, a little sad. They knew him as Pop. He had given his name as Dick Smith, when he first came, many years[49] ago. The ethics of the West is never to ask questions of a man’s past. It judges a man by his present. The speaker continued: “But I tell you fellows, being married is too good for most of us It’s a wonderful thing, if you can make a go of it, if you can support the proposition.”

The talk continued about the surprise and an eager desire to see the couple was expressed by many of the men. There was a general feeling of pleasure, also, at Dean’s coming home. These men were all good friends of John Dean. But, mixed with it all, curiously, was that tone of sadness and regret, as if the subject of the conversation had gone from them. They all seemed to feel that his being married placed them beyond his pale.

“Do you know, some day I expect Jack Dean to get very tired of this neck of the woods and pull up his stakes. He will be one more of the many who drift to the big town and think that that is the life. I wonder how Mrs. Dean—sounds funny, doesn’t it?—” continued Al Graham, “is going to stand it? It’s hard for anyone who doesn’t like it.”

[50]“Well,” said Pete, “that’s just it, Al. Jack likes it as much as any of us. He can’t stay away from it. It calls him, same as it does you and me. But as to Mrs. Dean, I’m doing some wondering myself.”

“Seems to me,” Red Mack spoke for the first time, “you folks had better not worry too much over it. I shouldn’t be a bit surprised if they had thought of that matter a little bit themselves. I gather they must have, since it’s their particular business.”

Someone threw a boot at the speaker. “You sarcastic creature,” said Pete, lovingly. “But, anyway, I hope Mrs. Dean will like us.”

Pipes were lighted now, the men were comfortably lolling about; it was a period of rest and calm. The light of day held a touch of the gathering twilight—it seemed as if some master painter was tingeing his colors, so bringing a darker shade. Some of the men drifted away, lazily bound for some little task or pleasure. Some of them remained ready for anything that might come.

It was not always so quiet at this hour. Possibly the news that they had heard had a[51] sobering effect. Then, too, most of the men were off on a roundup and the few that were left felt lonesome.

“I feel,” said Pete, “that things are becoming so quiet around here we’ll die of ennui.” Pete delighted in springing a new word upon the crowd and he did it often to show his knowledge. The boys understood the spirit of fun in which it was done and that it was not to show superiority. He continued:

“Time was, when the Indians would give us some excitement. Now Lo, the poor Indian, is so wealthy and has waxed so fat, thanks to a paternal government, he won’t fight. The sheep-men seem to have found their place, though if it were I who decided on the place they deserve, you know where I’d be sending them. As it is, you never can tell when they will make trouble. Here’s hoping it’s soon.”

“Well, there’s McGowan,” Pop said. “He and his followers are always about, ready to oblige. Things can never be said to be quiet while they are up and doing. As for myself, youngster, I find plenty of trouble comes without going to seek it.”

[52]“Yes,” added Smiles, “McGowan is a regular border lawyer. He always manages to be mighty near it when the trouble has boiled. Although there’s a crowd over in Montana that will be ready for him the next time he crosses over.”

Then the conversation turned back to Dean. Said Pete:

“I guess Jack will not be doing some of the things he was in the habit of doing. Mrs. Dean will see to that. Say, Al, what’s happened to Amy Wells—Jack used to be sweet on her, if I remember rightly?”

“Seeing that things are as they are, Pete, and since she’s gone, I guess I’ll tell. Jack may not like it, but then he needn’t know.”

“I think Amy Wells went back East. She came back here fresh from college. Jack had known her since the time when they were just boy and girl pals. Jack is not the kind that likes more than one for all time and until now I didn’t think he’d ever like anyone else. When she came back here he was very bashful. It bothered him so much that he spoke to me about it.”

“‘You see, Al, it’s like this. There’s nothing here for a girl like her; she’s East all[53] over. She couldn’t be satisfied out here. I know it. It came to me a while back. She doesn’t see me when I’m about and I fear I don’t count at all.’

“Well, it was true; she didn’t seem to see him. You all know Jack. Since she didn’t pay any attention to him, he saw to it he wasn’t there much. Then, you remember that chap, Stephen Browne, with an e at the end of Brown, if you please. He was very good-looking. A thoroughbred, too. You only made the mistake once, of not thinking so. You had to like him.

“Well, at that time, as some of you know, I was foreman over at the Wells, so I had many chances to watch. I didn’t like Browne. I did like Jack. That was so, at first, then I found myself liking this Easterner. Hated to own up to it, but I did. You had to like him, he was such a good scout. You could see how he felt about Miss Amy.

“Mr. Wells just sat back and watched it all. He was very fond of his niece. He liked Jack and he liked this new fellow, too. He is not the kind that would say much. Jack Dean’s staying away didn’t seem to help[54] Jack’s chances. Jack was not moping, but he felt he wasn’t wanted nor needed.

“Then he had to go to Victoria. When he came back three months later Miss Amy had gone East, so had Browne. He never asked any questions and Mr. Wells never offered any information.

“If I had had half a chance, I’d have told him my suspicion. But you can’t go to a man like Dean with a suspicion and nothing more. For another thing, it was Dean’s fight and he wasn’t asking for any help. But my suspicion is this, that Miss Amy didn’t care for Browne in that way. I learned that from a word or two I overheard. I don’t know even now whether she cared for Jack, she didn’t show her hand that easily.”

“How many years ago is that, Al?” asked one of the listeners.

“Nearly three years, I think. I suppose they both have forgotten each other by now, at least Jack has, hasn’t he? It’s funny, is all I can say.”

“Well, I’m for the hay,” said Smiles.

Some of the men still stayed about, others followed Smiles’ example. Red Mack, who[55] was to meet the returning party early next morning, had long since retired.

A fast train, eating up the space, five hundred miles away, was bringing a surprise to all of them. Throughout the shadows of the night and on the wings of the morning the onrushing train with Mr. and Mrs. Dean and Ted Marsh was speeding.

At four, when the sun was about to herald the new day, Red Mack, driving a fast Packard, started on his five-hour journey. Skilled and expert, even as much the master of this steel steed as of his beloved Brownie, he raced onward at full speed, the joy of the morning and of the wind in his blood.

FOR two days the fast Canadian Pacific flyer had raced through changing country and towns. To Ted, who had never before been on a railroad train, every moment held fascination. He watched the flying country, the busy stations and the people on the train. Very important people some of them seemed to be.

But the luxuries of the Pullman service and the dining car were his chief interest. It seemed so wonderful to be able to go the distance they were going and still be so comfortable.

Trim and neat was Ted. You would hardly have recognized him as the same boy. He was thoughtful, too. He realized that Mr. and Mrs. Dean liked to be alone, so he passed much of the time in the observation car.

[57]He was sitting out there on the platform, the second morning, when an elderly, military-looking gentleman came and sat down beside him. They were the only people on the platform, for it was a little too cool for most of the passengers. Ted noticed that the man was looking at him and so he smiled in friendly fashion.

“Belong to Canada or United States?” the man asked him.

“United States,” replied Ted.

“It’s a great country you belong to, my boy. Always be proud of it and be ready to do more than just be proud of it.”

“I want to, sir,” Ted answered, “I am a Scout,” the boy added, proudly.

“That’s fine,” answered Colonel Sands. “Ready to do your share for your country, aren’t you? Well, you can’t tell when you will be needed. If I were not an Englishman, I would want to be an American—so be sure to remember to be very proud that you are one. Are you traveling alone?”

“No, sir, I am with Mr. and Mrs. John Dean. We are going to the Double X Ranch near Big Gulch.”

[58]“Is Mr. Dean Canadian or American?” asked Colonel Sands.

“Canadian, sir. He’s a car or two further back. If you would like to meet him—would you like me to take you to him?” he added.

“Yes,” said the colonel, “I should like to meet him.”

Colonel Sands met Mr. and Mrs. Dean upon Ted’s introduction. Mr. Dean and he went to the smoking car and they stayed there for several hours. Mrs. Dean spoke to Ted for a little while, then turned to a magazine.

It suddenly came to Ted, as it had not until then, that his mother and his sister were there in Chicago and he would not see them for a long time. He never would have admitted how near the point of tears he was, as he wistfully peered out of the window. Many things passed his view, flying swiftly past him; but he saw only Chicago, his home and his dear ones. He began to wish he was home. Mrs. Dean looked up and caught the wistful look on his face. She did not interrupt his thoughts, but sat and watched him. Suddenly he looked up and smiled a little shamefacedly, as he saw her watching him.

[59]“Well, Ted, you will have lots of chances to show how much you are the man of the family. You are getting older, you see, and a man’s work lies before you.”

“Yes, I know,” he answered soberly, “I mean to make my way, so that mother and Helen can come out to this country. Isn’t it fine to know that you belong to it—that you are an American—there never was anything like it.” Then he laughed, a little embarrassed. “Of course, being a Canadian is almost the same,” he added loyally.

“Yes, we feel it is,” said Mrs. Dean, smiling.

The two men came back and Ted heard Colonel Sands say:

“We can’t tell when it will happen. But I think you should know. It is likely to come any minute. When it comes Canada must and will do its share. The Germans are prepared, tremendously prepared. I am off to Australia in a week. If you will undertake what I suggest—I can leave with the assurance that the matter is in safe and cautious hands. For I want to tell you, Mr. Dean, it is a big undertaking. I’ll see you again.”

[60]When the colonel left, John Dean explained to his wife. There was the possibility of war, the big European war that has since come, but which then, only a few months before that fateful August, very few people would have believed possible. There were some men in England who knew it would come—but they were being laughed at—so they had to do their work quietly. Colonel Sands was one of these men. He had been in Canada for many months and now was on his way to Australia. They wanted men in Canada, in Australia, in all the provinces, to prepare, to do what they could. As John Dean spoke, there came to Amy Dean a feeling that if war did come, her husband would be marching off to the front. And, with this feeling of fear, there came also a great pride.

Ted listened, wide-eyed and interested. It stirred his fancy, his thoughts. He was, he felt, an American always, but Canada held a close second place. What if he could help?

Early the next morning the train pulled into Big Gulch. A car was waiting for them. Red Mack came sheepishly forward. He stared open-mouthed at Mrs. Dean.

[61]

RED CAME SHEEPISHLY FORWARD

[62]Things simply had to be explained to him. Ted also had to be explained. Boy and man looked at each other with instant liking.

Still another passenger there was. They brought him from the baggage car and he ran to Ted and kept close to Ted’s heels—the dog which Ted had named Wolf that first day, hoping the name would make the dog.

THE surprise of the cowboys who had speculated as to Amy Wells and Mrs. Dean was so apparent that Jack Dean, who had an idea as to the reason for it, felt quite embarrassed. It amused Mrs. Dean, who knew many of the men and who with great tact made things easy. The men felt somewhat guilty, especially Al Graham.

But things soon were normal again. John Dean knew that all these men were friends of his, that they were his peers. His position was such that he was their leader, but he never had to make them feel that it was a case of employer and employee. He knew the sterling independence of the West, which held no man superior to another. And no one believed in the principle more than Dean. So that when the men were at ease there were great doings. The cowboys,[64] when alone, were crude and rough. Now, with Mrs. Dean about, their manners were such as any gentleman might own. Perhaps a little rough in manner and appearance, but not one of them lacked manliness and gentleness, the main requisites of a gentleman. Of course, breeding is more than mere polish, but much more than just breeding is necessary for the true gentleman.

The men liked Mrs. Dean from the first moment. Her charm and her loveliness kept even the timid Smiles in the circle about her. She was pleasant to all and enjoyed their company so much that they responded naturally and their quick wit had full play.

Nor was Ted an outsider. Under the protecting wing of Red Mack the boy had a chance of meeting the men without awkwardness.

The men took to him. They tested him to find out if there were a man’s qualities in him. Your shrewd, self-reliant man of the plains soon sees through a person.

They found Ted true. He had a good-natured grin and a fearless eye. Green and new he was, and many pranks were played on him, but he took them all good-naturedly.[65] Despite the protection his closeness to the boss, and the household would give him, it never entered Ted’s mind to complain. From afar Dean watched the trying out of the boy’s mettle with keen interest. He felt fairly certain of the result.

He learned to ride a horse in quick time. Red Mack felt that it was up to him to give the boy the rudiments of the rancher’s education. Ted could not have had a better teacher in the whole of western Canada.

The time passed very quickly in this way. Mrs. Dean attended to Ted’s education and each day he had to give three to four hours to study. At other times you could see him, sometimes with Smiles, sometimes with Al or Pete, but mostly with Red. Wherever he went, Wolf was at his heels. Wolf never would be a wolf, but he was growing and he was beginning to hold his own. The West seemed to be the place for him.

But if Ted spent most of his time while in action with the three men mentioned, he also liked to sit and listen to Pop, who had taken a deep interest in the boy. The cowboys had seen how much it had affected the older man when Ted came. They thought[66] that perhaps Pop might have had a boy of that age and so it had brought memories. But they forebore to discuss or to question Pop, for, after all, it was his own affair.

There was, however, a good deal more to it than that. When Pop had heard the boy introduced as Ted Marsh, a curtain seemed to have been drawn aside—a curtain that had hidden about fourteen years of his life. And from what Pop heard of the boy’s history through Dean and as related by Ted himself, he realized that Fate had played a rather queer trick. There came a great hope to Pop, or, rather, Dick Smith, as he was known on the ranch. He dared to think that perhaps he could come through and that Ted would be the means.

For Pop, as the reader may realize, was the long lost father of Ted. He was the Bill Marsh that had disappeared and for whom Mrs. Marsh still mourned, not knowing whether he was dead or alive.

The hard times of the Marsh family, many years before, had worried Bill even more than Mrs. Marsh. A strong man, he brooded over his inability to make things go, and gradually, as he grew more and more[67] despondent, took to drink. Then there had been a quarrel between husband and wife, and the man had felt that he was useless. Mrs. Marsh had been the one who had supported the family and this made the man morose and bitter. He left home, intent upon getting what he could not earn. He had been drinking heavily.

The only thing he remembered the next morning was that he had had a terrific fight sometime during the night. If he had not remembered it, he would have been sure to have known of it because of the condition he was in. He had been sentenced to sixty days. He knew that he must not let it be known who he was, as he did not want to disgrace his wife and daughter. It was while he was in the workhouse that he decided he would be of the greatest help to his family by dropping out altogether. He felt that his wife never could have any further use for him. So he had gone west and gradually had found things as satisfactory as anything could be under the circumstances at the Double X. He had sworn off drinking.

Now Ted, the babe that was born after he had left Chicago, was here.

[68]He decided not to say anything, but let events develop. He must not force himself back into his family, for they seemed happy and contented as they were. But he was bound up in the boy. From him the boy also learned much. To him, also, the boy often spoke of the folks at home, because, instinctively, he felt that the man was interested.

The winter came on and Ted found many new things to interest him. There was skiing, skating, and then there would be times when, wrapped up in warm clothes, they would go off in sleighs to great distances. It was often 50 degrees below zero. Ted grew strong and Wolf especially seemed to acclimate himself.

And then spring came.

TED was to leave for Wayland Academy the latter part of April. Mrs. Dean thought that he would be able to enter then and still be up with his class, thanks to the studying he had done at the ranch. Ted liked the ranch so much he was not looking forward any too anxiously to schooltime.

Ted was one of the twenty who went off one April morning for a great roundup and branding of cattle. Suspicion was afoot that the Double X cattle were being stolen. The Wells had also reported trouble at the Double U, so stock was to be taken.

Ted took great pride in his place among the men. He had begged to be allowed to go with them, since his days were to be so few at the ranch, and Mrs. Dean had permitted him to go.

[70]

TWENTY MEN WERE OFF TO BRAND CATTLE

The men had a busy day and Ted played[71] a useful part. They pitched camp early. Supper was soon over and most of the men decided to turn in at once, for they wanted to start work early the following morning.

“Want to go a little way?” asked Red Mack.

“Certainly,” answered Ted, who was not at all sleepy.

“All right, then, let’s start.”

Off they went, at a steady trot. Red did not say just where they were going. He usually, Ted had found, did not volunteer information.

“Why don’t you use the car more, Red?” questioned the boy.

“A car is all right, but the horse for me. Brownie and I”—he fondled the horse’s neck—“are chums, have always been. Haven’t we, old horse?”

The horse looked up at Red understandingly. Ted hoped he and his horse, Scout, would be on such good terms.

Red understood the boy’s thoughts.

“Treat him kindly always. Make him understand he amounts to something, that he has a friend. Horses need more kindness than human beings.”

[72]They rode for more than a half hour. Then Red spoke again.

“Ted, I have a suspicion there are some thieves about. Cattle thieves. I think I know where they are.” He paused. “I didn’t want to say much until I was sure, but I’ll make sure very soon. Perhaps you can help.”

The boy’s pulse beat faster. He didn’t know just how he could help, but he knew he didn’t want to fail his friend.

“I know you have grit, from what Jack has told us. But you also have to keep your head here,” Mack added.

They rode about three miles more. “There is a cave a little further up there, a good and likely place for them. Let’s turn our horses back into the woods here. No noise, now.”

Silently, slowly, they worked their way forward. There was but a touch of the waning day to show them the way.

They stopped often and listened. It was slow progress. Then they heard the faint murmur of voices. Mack drew nearer and tried to make out the voices or what was said, but found it impossible. He came back and motioned to Ted that they were to go[73] back. And just as slowly they worked their way to the starting point.

“Can’t tell who they are, can we?” Red mused. “They may be peaceable, law-abiding citizens. They might be folks with business which isn’t my particular concern. I’d hate to inspect, make trouble, get nowhere and have good and kind friends tell it to you on every occasion. No, I’m going to make sure.”

Ted whispered: “I have an idea, Red. Let me go in there, pretend I’m lost, and that I am looking for my way.”

“Won’t do,” Red interrupted. “Lot’s of reasons why. First, they wouldn’t let you know anything and I could only guess from your description. Second, if trouble came, what do you think folks down there would say to me? Nice, agreeable, pleasant things, eh? Tell you, boy. I’ll go in. You wait where we were. If I don’t call you, it’s a sign things are not friendly—you speed back and get Smiles and the boys. I think you had best tell them to hurry, although I don’t think they will need any urging when they find out it is friend McGowan. They can’t hurry any too fast to suit me, because about the time they are due things will be[74] getting interesting and warm. Know the way back, don’t you?”

“Yes, I know it,” answered Ted.

“So long, Ted,” said Red Mack.

Red crawled back to where the horses were. He rode forward as if he were going to a picnic. Ted heard him breaking through the brushwood, leading his horse. Then he heard him say, “Hello, friends.” He heard the call repeated, but there was no answering hail. Silence still, as Red seemed to have reached the cave, except that he heard men moving about. Ted heard Mack’s voice—smooth, very pleasant, and most polite.

“I guess I’ll move on, since you don’t seem glad to see me. I seem to have interrupted you, I would say.”

There was a second’s pause, then Ted heard someone speak.

“Throw up your hands, Red, quick. I think, now that you’re here, you’ll stay awhile.”

Ted’s heart jumped. It was beating so loudly that he was sure they could hear it.

The boy wanted to stay and hear more, but he knew there would be great need of haste. Cautiously he made his way back to[75] where his horse was busy trying to find something at which he could nibble.

Once out of earshot, the boy made speed. His friend was in trouble and he was depending upon him to get help. Red certainly was brave and fearless, thought Ted, as he urged his horse to his best speed. He was very glad that Red had taken him along on this adventure. He hoped that he could be of service. What if he were too late? Faster, faster.

Scout proved his gameness. He seemed to understand what was wanted of him and he waited for no urging.

A little more than an hour later a very excited boy was explaining to wide-awake Smiles. That same Smiles had awakened at the first call and even as he listened had awakened the other men. None of them asked questions. They worked on the principle of getting ready first, then questioning could come later. And so, even before Ted was through, they were ready.

As they started off, Smiles turned to some of them and explained: “Red has the McGowan gang up above. Rather, the McGowan gang has Red. He’s expecting us, but we had better hurry, or it might get too warm[76] for him. Ted was with him until Red hurried him back to us while he palavers with them and makes them feel that he is all sorts of a fool and hasn’t had some such little plan as this all along. If it was anyone else, I’d say that they would see through it all, but I have faith in Red. It’s up to us to hurry.”

Twenty eager men, ready for anything. The possibility of trouble pleased some of the more reckless, like Pete, but all of them were interested in getting McGowan, against whom they had sworn enmity.

Ted was able to guide them without any trouble. When they reached the place they tied their horses. But as they started to creep forward they heard something move a little way off. Cautiously, one of them investigated and found it was Red’s horse, Brownie.

“Good,” said Smiles, “we may find him very necessary.”

Some of the men had already gone forward and the rest joined them. They could see the cave dimly, but they could hear quite clearly. All of the men, ready at a second’s notice, watched Smiles, from whom the signal for action would come.

MRS. MARSH, her day’s work completed, was doing some sewing. Her thoughts often turned to her beloved son, twice beloved, since he was not about. Ted had sent her a picture of himself on horseback and she was looking proudly at it. It was an unusually long letter she had received that morning. Ted had told of Red Mack, Smiles, Pop, and the others. How his horse, Scout, and he were great chums, and how Wolf had grown and was a dog any boy could be proud of. How fine and important Mr. Dean was and how good to him Mrs. Dean was, always. Throughout the boyish letter, the mother read of the boy’s happiness in his new surroundings. But Ted also made her feel that he missed her and that he missed Helen.

What a fine picture it was of him. How[78] manly he looked. The mother was quite sure there never was a boy like her Ted. But she missed him so. And, thinking about how much she missed him, she looked for a moment as if she would cry.

But instead of crying, she suddenly smiled.

“I must not be selfish, as Helen says. It is his chance. Bless the Deans.”

Ted in his first letter of that week had written about the Academy at Wayland and that he was to arrive there on May 1st. She knew that Mrs. Dean had kept him up in his studies in the eight months he had been away from school, but she was glad to know that he was again to get back to a regular school.

After a while she started to set the table. Helen would soon be home and Mrs. Marsh was always sure to have things ready for the hungry girl when she reached home. After the table was set, Mrs. Marsh reopened the letter received that morning from Ted and placed it conspicuously, so that Helen could not fail to see it.

Her thoughts still stayed with Ted. She did not mind receiving the monthly remittance[79] from the Deans, she mused, just as had been arranged, before they left for the West, yet she was glad that it would not be necessary to receive this money very much longer. What they had accepted up to now would be paid back by the three of them, the mother, Helen and Ted. But both of them were very anxious to pay back at once the hundred dollars Mr. Dean had insisted that she take when Ted had gone to the hospital. That was a burden which the Marshes were anxious to clear as soon as possible.

The bell rang. “It cannot be Helen. She does not ring. I wonder who it is?”

She pushed the button that opened the door below. After a time there was a knock at the door.

She opened it and a man stepped in.

“Mrs. Marsh?” he asked.

“I am Mrs. Marsh,” she answered.

“I am the insurance adjuster and I want to settle as to your losses through that fire. The company wants to offer you $25.00, which I think is very fair.”

“But it was supposed to be $100.00,” said Mrs. Marsh, uncertainly.

“We cannot make it $100.00; we do not[80] intend to give more than $25.00. You can take it or leave it.”

The man made a move as if to go. Mrs. Marsh, uncertain, wished for Ted or even for Helen, and as if in answer to her wish Helen stepped into the room.

“Hello, mother!” She kissed her lovingly, then saw the stranger. She looked up at the man.

The mother explained.

“We will not take less than the $100,” said Helen decisively.

“We will give you $50, no more,” said the man.

Helen shook her head.

“You take $75 now, or $25 if I once leave the room.” The man started for the door. Helen let him go. He opened the door and went out.

“You should have taken the $75,” said the mother tearfully. “We need it badly, you know.”

“I think we will get the $100, mother,” quietly answered the girl.

The man came back into the room. He pulled out a paper, then five twenty dollar bills, and showed Mrs. Marsh where to sign.

[81]Mrs. Marsh did so after Helen had first read the paper and had approved of it. The man left.

Mother and daughter looked at each other, happily.

“Do you know, mother, I just wish we could send it off tonight. It will feel so fine to get the burden of this big debt from our shoulders. Isn’t it fun to be able to pay your debts?”

“I am so glad,” said the mother, no less enthusiastic. “It worried me so.”

“Yes, mother, and I have some more good news. I have been given a raise and my pay is to be ten dollars a week.”

“It’s wonderful, but no more than you deserve,” said the mother, loyally.

“Why,” said Helen, “here is a letter from Ted and you never told me. What a perfectly fine picture.” There was silence while the sister read the letter and the mother watched her appreciation.

“Ted is going to be a great man some day, mother; I know it.”

“And you will be a fine woman, too,” said the proud mother.

[82]“I wish we could go out there and join Ted. In another month we ought to be able to tell the Deans we do not need their help. My, that will be so fine.”

“Yes, Helen, and the first thing in the morning I am going to send this money to them and get through with that.”

RED had given his hail as he went forward—“Hello, friends.” Even as he did so, he realized who they were, for he recognized McGowan, as that worthy came forward to see from whom the greeting had come. Red whispered to Brownie, gave him a pat and the horse loped off. It was too late for him to turn away, even if he had any desire to do so. He saw other men join McGowan at the front of the cave. He also heard excited whispering.

No answer greeted him. There was a moment’s distrustful gaze and then the leader said surlily:

“What brings you here? What do you want?”

“Nothing much,” answered Mack. “I heard folks talking and wondered if it[84] wasn’t some of our boys. I went off to Big Gulch, day before yesterday, and knew our boys would be somewhere about. Didn’t exactly expect you folks,” he added whimsically, “or I might not have been so free with my call. I guess I’ll move on, as I seem to have interrupted you,” he added in a louder voice.

We know McGowan’s answer. There was a consultation for a half minute. They suspected that what Red Mack told them was not the truth; on the other hand, he would hardly have come to them if he knew who they were. There were no others with him; if there were, they would not have given the thieves time to get ready.

“What are you men up to? Stealing cattle is mighty dangerous.” He sat down and rolled a cigarette while the men watched him distrustfully and uncertainly. “This is good catching time, you know.” A pause. “What are you going to do with me?” But he seemed absolutely unconcerned as to what they would do.

“Well,” answered McGowan, “we might make you food for animals, if you really have a desire to know. We are somewhat uncertain as yet. You haven’t any say, although[85] I admit you have some interest in our decision. I’m inclined to think,” added the speaker, “you can’t harm us if we keep you here while we do our job.”

“Yes,” one of the other men added. “Our reputations won’t be hurt much by what you may be mean enough to say after we are through. Catching time is a long way off, the border-line is much nearer. Day after tomorrow the U.S.A. for us.”

“I’ll tell you this, Red. If any of your friends come to investigate, you’re going to make an easy shot,” McGowan warned him.

“My friends are not welcome, then?” Mack smiled. “But why blame me, if I’m popular?”

Both the prisoner and the cattle thieves seemed to be in the best of humor. But both sides were watching each other very closely.

“I reckon,” said one of the other men, “the Double U and the Double X will not miss what we want. We need it much more than they do.”

“Well, now,” and Mack smiled, “I take it that you need that carcass of yours much more than they do. While folks are taking things, we’ll probably take that.”

[86]And so they talked, in the main, quite humorously and good-naturedly. Mack wondered how his friends could come to his help without making the matter of receiving help a matter of extreme danger to him. For these men would blow his brains out at the first sign or even hint of interference from the outside. That would be their game. They had not even bothered to tie him, simply had taken his gun away.

But, knowing Smiles as he did, he knew he could count on him. He knew that Smiles would figure all these things before he made a move. For his friend was a pastmaster at this kind of game. Of course, there was the possibility that Ted might not have brought the warning to Smiles, but that possibility was quite remote, so Red decided he could count on Ted. The thing for him to do was to be ready and act when the time came.

McGowan now turned to one of the men.

“Better get outside and watch awhile. I don’t expect trouble, but that’s the time it usually comes.” Out of the corner of his eye he watched Red Mack to see if he would give some sign, but the prisoner never changed expression.

[87]So a half hour more passed. The man outside grumbled at being kept there when all his interests were inside. His watch was divided, half his time being spent in listening and watching the men inside.

There was a sudden crashing of underbrush. Almost with the noise a gun was at Mack’s head. Then the call of the sentry. “It’s a horse—reckon it’s Mack’s.” The gun came down.

“It won’t be his very long,” remarked McGowan.

Men in the West who know each other, also know each other’s horses. So Brownie was at once recognized. There was nothing wrong to the men in Brownie’s coming to where his master was, nothing at all wrong in that. But to Mack it meant everything. His horse would never come unless called or sent. So he must have been sent. That meant that Smiles was at hand and had taken this method of letting him know that it was his move.

He could blow out one of the lights and kick the other one over. It would require quick, instantaneous action, but it could be done. Should he then rush forward and[88] out? They would shoot him if he did. No, he would make his rush, but it would be to the back of the cave. He would make an attempt to escape in the dark when the opportunity came. If he only had his gun!

Yes, he must make them think he was rushing out.

“You know, Pete,” he talked even as he was thinking, “I could forgive everything but one thing. The horse is mine, now and always. My not wearing a gun makes no difference. When I go, my horse goes with me. And I reckon I’m—”

There was sudden, intense darkness.

“—going now.”

Something crashed the next instant. There was much noise, voices, pistol shots. A pause of a few minutes. In that pause Mack had managed to get outside of the cave. The men inside were uncertain, hesitating because they were sure they had heard shots from the outside. They did not know what to do.

Probably, too, it would have been a good time for the men on the outside to have closed in on the outlaws. But they also were uncertain and the dark in those first[89] few minutes helped the men on the inside. As the two factions each hesitated, a voice came to them from the outside.

“I reckon, Smiles, you can go to it.” It was the voice of Mack. And even as he spoke there were answering shots from the men within at the place from which the voice had come.

There was a pause. “Will you do a little barking, so I can tell where you are?” It was Mack’s voice again.

Mack saw, then, the place from which his friends were shooting and a few seconds later was among them.

“Thanks,” he said. “Pete McGowan and his men are in there looking for trouble.”

“Well, they’ll find it,” and Smiles smiled his broadest.

“Better come out, Pete. We’re too many for you,” the foreman called. Shots answered him. The men from the outside did not waste any shots. They crept closer.

“Say, Smiles,” called out Pete, “if we come out, we want your promise that there is not going to be any hanging, but that you’ll turn us over to the Mounted Police. We want you to promise that, otherwise we might as well fight.”

[90]

THE MEN FROM THE OUTSIDE CREPT CLOSER

[91]“That’s fair,” answered Smiles. “I promise you.”

“All right, then, we’ll come.”

They came out. To their credit be it said, they came, heads up, as men. They had made their fight, a foolish fight, for the wrong-doer always pays. But they did not whimper. Such is the stock of the West, whatever the course they may follow, bad or good, they are almost always—men.

To Ted it was a tremendous experience. It gave him an idea as to what length these easy-going men would go. Mack and Smiles were his heroes, the men in turn did not forget to say a good word to him for his part.

Pop had not been with them in the roundup. But when he heard of it, he wanted to know all the details of Ted’s share in it. He got it from both Smiles and Red Mack. Mrs. Dean also wanted to know all about it. She scolded Mack for leading the boy into danger, but she did not altogether regret it. It would harden Ted, she thought.

Several days later the boy left for Wayland.

TED had been a member of the student body two weeks and had already made a number of friends. Mr. Oglethorpe, who was the dean of the Academy and a close friend of John Dean, did everything he could for him.

But it was not altogether easy sailing. There was one boy, who, from the first moment when Ted arrived, seemed to take a violent dislike to him. He immediately started in and continued to make things unpleasant for him. Ted wanted no quarrel, he knew that no matter how much in the right he might be, it would count against him, since he was the newcomer. So he grinned good-naturedly at the many attempts of Sydney Graham to make trouble for him. Yet often he wished he could fight things out with his tormentor and be done[93] with it. But better sense always came to the rescue.

The studies took about five hours each day and there was at least two hours of military training. In addition to which Ted had to have some private tutoring to make up some of his studies. So that his days were full and he did not have much time for anything else.

Ted was entered in the Cavalry Division. He rode cowboy fashion, as Mack and Pop and Smiles had taught him to do. The other boys all rode in the way they had been trained, as military men ride. Captain Wilson, in charge of the military and scout training at the school, had decided not to attempt to change Ted’s style of riding. As he explained to Ted and to some of the other boys who were about, the important thing was to sit on a horse as if horse and rider were one.

But Syd Graham sneered at Ted’s way. There were some remarks he made that brought a sharp rebuke from some of the other boys. Then, too, Ted’s good nature seemed to bring out the very worst in Syd.

There was to be a meeting of the Boy[94] Scouts. The boys, who knew that Ted had already qualified as a tenderfoot in Chicago, wanted to elect him to membership.

“I’m against any Yankee joining,” protested young Graham. “Let’s have a little class to it, not bring in every ordinary shop-boy or farm hand.” He made a pretense of being very English, don’t you know. But, despite his objections, Ted came in. It made him very glad, for he had never forgotten those first principles he had learned and although not active for many months he felt as if he still were a Scout.

The Boy Scouts at Wayland were a source of great pride to the Academy. They had entered tests, tournaments and games with other Scout groups. Their standing was high. Captain Wilson spent much time and took painstaking care that what they did learn was the thing they should learn. He made it clear, too, that the Boy Scout training, while it had nothing to do with the military training which was part of the curriculum of the Academy, was nevertheless, in his opinion, just as important.

A very little matter brought things to a head between Syd and Ted. Ted had made[95] a two-base hit in a baseball game. The center fielder, by quick work, had relayed the ball to second and had made it necessary for Ted to slide into the base. In doing this he had spiked and upset Syd, who was covering second. Under ordinary circumstances, both boys would have laughed at it. Instead, Syd, even as he arose, gave Ted a vicious kick, then sprang at him.

But Ted was ready. Syd was heavier by almost ten pounds. But the one thing in Ted’s favor was the training of the street gamin of the big city. He had the greater endurance and was the quicker of the two. He also had the experience and the cunning acquired from many street fights.

No one interfered. All the boys knew that the test now on would have to come, why not now? Then, too, if the truth must be told, they were not at all averse to seeing a fight, and this proved to be an exciting one.

At first, it looked very much like Syd’s fight, then Ted’s stamina began to tell. Very soon Syd was on the defensive, no longer did he rush, but he became as careful as was Ted. Then there was a cry of warning, the[96] boys closed in on the combatants, picked up their clothes, and all of them started off, the boys keeping Syd and Ted from open view.

“Run, here comes Ogie and Cap.” When they reached their dormitories the boys separated. Ted went to his room and began to doctor up his face. What bothered him most was not the sting of the blows he had received, but the utter uselessness of the enmity of Syd. As he thought over it an idea entered his mind. It was a sudden decision; he would go to Syd Graham’s room and talk things over with him. They need not like each other, but they would come to a clear understanding and then each go his way.

As he opened the door he saw Syd coming down the hall. When he saw Ted he stopped for a moment, then came forward a little more quickly. Reaching Ted he said, “Let’s go to your room for a moment, old man. I want to talk to you.”

They went in, Ted a little uncertain.

“That was a good scrap, wasn’t it?” laughed the visitor. “My, but my nose and a dozen parts of my body hurt like thunder. You’re some pugilist and with the weight all against you.”

[97]

THE TWO BOYS WENT ON A FISHING TRIP

[98]“Look at my eye,” answered Ted. “I think you can do some teaching yourself.”

“Say, Ted,” said Syd, straightforwardly, “I came to apologize. That was a mean display of temper on my part.” He stopped for a moment. “I don’t know why I’ve been this way, but I want to be friends from now on.”