THE STORY

OF

WANDERING WILLIE

BY THE AUTHOR OF

'EFFIE'S FRIENDS' and 'JOHN HATHERTON'

WITH

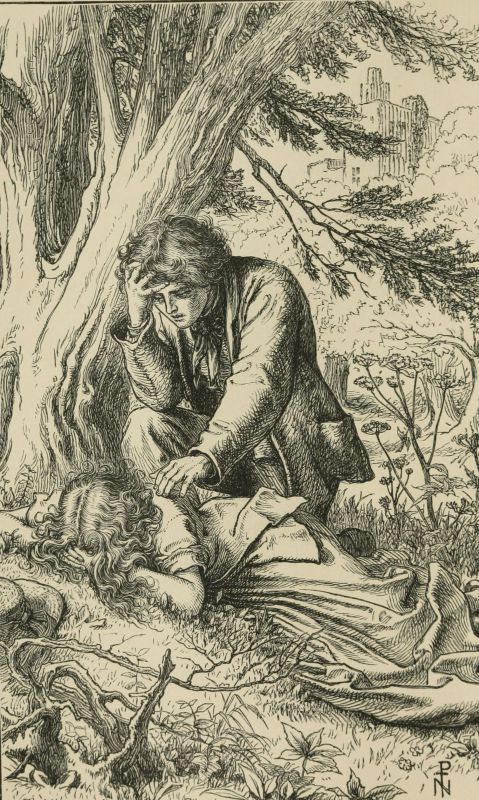

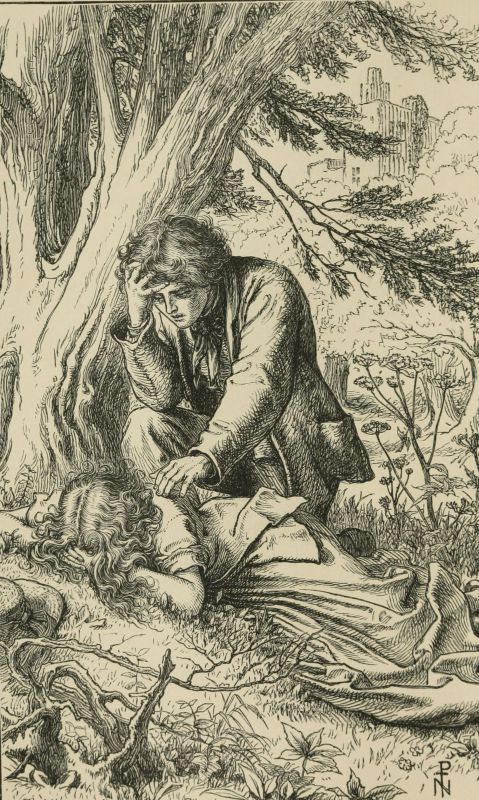

Frontispiece by Sir Noel Paton, R.S.A.

'Here awa', there awa', wandering Willie'—Scotch song

SECOND EDITION

London

MACMILLAN AND CO.

1870

All rights reserved

LONDON: PRINTED BY

SPOTTISWOODE AND CO., NEW-STREET SQUARE

AND PARLIAMENT STREET

TO

MY MOTHER

| Introduction | 1 |

| Part I. | 13 |

| Part II. | 136 |

| Conclusion | 290 |

[Pg 1]

Be the day short or never so long,

At length it ringeth to even-song.

All day he had come across the moors through the falling snow.

Long ago, from some village far beneath him, the church clock had struck four, and the distant strokes had come faintly up to him, muffled by the storm. So he knew that sunset was over.

But it made little difference to him on that moorland track, except that the grey mist caught a darker tint,—that the snow-flakes looked dimmer as they fell. The great silence around could not grow deeper, or the road become more desolate and wild.

It was not desolate to him, or strange. His feet[Pg 2] had trodden it when the purple heather was in bloom for oh! so many, many years, also the snowy mantle it now wore was not strange to him, but familiar and dear as were the silence and the twilight.

All the country-side knew Wandering Willie. Men who were growing old remembered that when they were rosy children, he used to go and come among them even as he did now. Mothers, standing at their cottage doors watching their little ones at play, often saw Wandering Willie lay his withered hand upon the golden heads and, smiling, bless them as he passed. Then they thought of the kind smile and the touch that used to be laid upon their own heads years ago, and they recalled the same simple words of blessing.

They had been waiting then for life, with its duties and its hopes—sleeping as it were, and dreaming in the golden morning-flush, until the hour struck for work. And to one after another it had come, and they arose. Busy life began for them, but to Wandering Willie no changes seemed to come.

He was looking on at life, not sharing it. He had no home he used to say, smiling gravely, as they asked him the question in the warm corner of[Pg 3] many a happy fireside. No, he was alone in the world. But when they said 'Poor Willie,' and some kind soft touch was laid pityingly on his hand, from which the pilgrim-staff had just been laid aside, he smiled again and said he was well content.

He must be very old they thought. Each winter's snow left its reflection on his silvering hair, each autumn storm traced deeper furrows on his face. As every summer came, he bent a little lower beneath the heat and burden of the day. And in the spring there was one day—his birthday—which was ever to Willie as a milestone passed on the homeward road, as a voice of welcome from the Land that was no longer 'very far away.'

So though it seemed a restless life that he led, it was yet not a sad one. The wide sky was as his roof—the rough moorland path familiar to him as household ways. The evening brought its homely welcome—the morning its friendly words to cheer him on his way.

Not a farm-house, not a cottage in all the country round, but kept the warm corner of the ingle nook for Wandering Willie.

The children shouted for joy when they saw him coming towards their house in the gloaming. The[Pg 4] house-mother left her spinning-wheel to welcome him on the threshold. More logs of wood were piled upon the fire. Eager hands laid his staff aside, and helped to lift the pedlar's pack from Willie's shoulder. And while he sat down to rest, the little ones danced out of doors again to watch for Father from the top of the stile, that he might come home quick to hear what Willie said, and see what Willie brought.

And then they gathered round, while the pack was opened and all its treasures spread out.

There was always something wonderful and new that Willie had brought from the far-distant town. The brightly coloured shawls—surely mother must have one—they looked so beautiful as Willie held them up; the knots of cherry ribands for the maiden's hair; the shining scissors and great horn knives, the little store of books, the tapes and cottons, and the brown duffle for the children's frocks that had been waited for so long and so impatiently.

'The mother thought thou wert never coming again, Willie,' the farmer would say smiling, as the busy housewife shook her head, and held the stuff up in the waning light and made her easy bargain with Willie.

[Pg 5]

Soon supper was ready, smoking hot upon the oaken board, and they called their guest to the most honoured place. But the pack was left open on the floor that the children might have another look at Willie's treasures.

He carried greater treasures still—treasures that money could not buy, but which were requited by the precious gifts of love and good-will.

He brought letters from the absent—kind messages from some that had been thought forgetful—greetings that were as music to loving hearts—little tokens of old friendships over which time and distance had no power. And as they gathered round him to ask questions, and listened breathlessly to his tidings, the old man sometimes spoke of joy, sometimes of sorrow, but always of comfort.

So they all loved him. But with the little ones did he chiefly seem at home. Perhaps he thought that life's journey lay in a circle, and that as the end to him grew ever nearer and nearer, he was drawing close to the spot whence the children had so lately started, and he could breathe more easily in their air, and their language came the most readily to his lips.

[Pg 6]

He would tell them stories by the hour—stories that, coming straight from his own heart, found their way at once to the child-hearts of his listeners. They loved the simple verses that he often strung together as he journeyed on alone from place to place, and they called Willie their own poet. The wise people smiled at the high-sounding name, for they thought that Willie's verses were all alike—harping only on one string. The old man said he did not know—it seemed to him as if the wind brought them to him, and it ever told one story. It may be that the children were right, and that the rhymes had a rude melody caught from the great voice of Nature—some faint echo of those solemn chords that night and day the wind sends up to Heaven, as it sweeps across the woodland and the moor towards the distant hills.

Therefore, with this music ever sounding in his ears, like distant church bells, it was not strange that solitude should be to him as a friend, not as an enemy to be shunned and dreaded. For if there be a voice in Nature that can speak to its Great Maker, surely God sends many answers back; and hourly some word of His went home with a new thrill of gladness to Willie's listening heart.

[Pg 7]

So do not pity him, though he has fought on all day alone against the storm.

Look at him now, toiling steadily onwards, a dim figure scarcely seen through the thickening snow-wreaths. At each step he sinks deeper in the snow, and all around the moor stretches wild and white under the grey heaven. Here a great broken tree rises against the sky, weird and gloomy; there a few firs are bending beneath the snowy burden that grows heavier each minute. And the falling snow swiftly fills up those solitary foot-prints that alone have ruffled its surface.

It is so silent, so very still. Who would guess that a resting place is near at hand? Yet so it is. But one more steep bit of road, and it will be lying almost at his feet.

It is hidden still by yonder rising ground, but that once gained, the moor sinks suddenly downwards, and nestled in the hollow lies the grey farm-house, where they are watching for him even now.

It is pleasant to be watched for, especially when the way has been long and hard.

Already Willie could picture to himself the ruddy gleam of light from the windows down below.

The snow-storm might blot out the outline of[Pg 8] the house, and bury the familiar path out of sight, but it could not quench that cheery token of welcome.

A little nearer, and he should see the figures moving about in the red warmth within, and the great shadows that the firelight threw upon the ceiling.

And then close to the window-pane the waving outline of many little heads clustered together. All the children would be on the look-out to-day, straining their eyes along the darkening path, for the first sign of his coming. For it was New Year's Eve. The sun would never rise again on the Old Year. Amid the snow-flakes it was falling quietly asleep.

All day, as its last sands ran out, Willie had been thinking of the dying year and silently bidding it farewell. Rather wistfully he saw the daylight float away from it for ever. To-night it laid down the burden of its completed hours, and was fading back into the shadowy past.

But for those children in the farm-house down yonder things were different. The glad New Year's morning that would rise to-morrow from beneath the snow-white pall of the Old Year was everything to them. The pack he carried was heavy with[Pg 9] their New Year's gifts. Willie strove to mend his flagging pace, for he was tired. He had come far, very far, to-day, that the little ones might not be disappointed.

Child-like, he rejoiced in the feathery snow-flakes that would prevent their seeing him until he was close at hand, and at the soft white carpet muffling his approaching footsteps, so that he might take them by surprise.

It all fell out as Willie had imagined; only the children were too quick for him after all. The door in the deep porch flew open as he drew near, the red light streamed out brilliantly, and little feet danced into the snow.

How many rosy laughing faces there were—how many merry voices! The children drew him in amongst them, the young ones were close to him, and the elders, just as happy, stood behind.

All claimed to have seen Willie soonest. Roger was the first to grasp his hand, and bid him welcome—Lois said so—but then Lois gave every disputed point in Cousin Roger's favour now. Besides, Roger was so old and his legs were so long.

'We were all watching, Willie. We thought you would never come. We are so glad you have got safe over the moors in the snow.'

[Pg 10]

'And we all welcome you, old friend,' said Lois, the tall, graceful maiden, holding both his hands. 'We have so much to tell you, and Roger and I——'

She did not finish, but Roger put his hand proudly on her shoulder, and their two faces told the rest. So it was a very joyous meeting.

And on that evening Wandering Willie told them the story of his life.

He had never told that story before, and no one will hear it from Willie's lips again.

It came about in this way.

There were none but the young ones left with him. Most of them were gathered round the fire at Willie's feet. The youngest, little Cecily, had climbed upon his knee. Long ago—at least what seemed long ago to her—she had climbed up into his heart. She put her arm round his neck, and had been telling him 'secrets' in soft half-whispers. A little way off Roger and Lois sat in the window, and talked together in low voices—most likely they had 'secrets' too. The old man often looked towards them. It may be that something in Roger's attitude, or in the downcast face of Lois, brought back a dim picture to him through the far off years. He smiled, but he sighed too, as he[Pg 11] smoothed little Cecily's fair hair. She had got his big silver watch in both her hands, and was listening to its ticking and to what Willie said about it.

The children on the hearth were forming wishes for the coming year.

'And I wish,' said one, gravely and clearly, 'that I was big, and very useful.'

The others were quiet for a moment, and then they laughed, and their laughter rang musically through the old kitchen.

Willie smiled at the little speaker, and went on with what he was saying to Cecily.

'And you see, Cecily, how the busy hands keep on and on, always doing their work. Look how quickly the long one gets on. It goes round ever so many times faster than the short one, and yet that is doing its work too all the time—doing its very best. But you could not expect the short hand to do as much, or in the world the little short legs to be quite as useful as the long ones.'

'The long ones like yours;' and Cecily held out a short bare leg of her own and looked at it.

'Yes, the long ones like mine;' said Willie. 'They have made many journeys, little Cecily.'

'Willie,' she asked, opening her eyes, 'how many[Pg 12] times has the long hand gone round since you was a little boy?'

He shook his head gravely. The days of his years were past Willie's counting.

'Will you tell us all about it?' said the little maiden who had wished to be very useful.

Then all the others jumped up and echoed the petition. 'Tell us your story. Because it is New Year's Eve, Willie. Because it is the last day of the Old Year.'

Lois came and sat down beside him and begged too, and Roger leant over her chair.

'Do tell us about your life, dear old friend. We have so often wished to know.'

Willie still shook his head, but somehow the chord of memory had been touched to-night, and it was vibrating still. Perhaps because, as the children said, it was the last day of the Old Year.

He looked out of the window at the coming darkness, and then back upon the young listening faces in the firelight.

And he told them his story. It was a very simple one.

[Pg 13]

We spend our years as a tale that is told

Look, it is evening, quite evening at last. See how the light has faded, and the shadows have fallen over the hills. The day is over, the twilight is gathering.

Just so it is with me. My day has long been over; the hours of work are spent, the twilight seems long, very long, but the night is at hand.

I am glad that it should be so. To the old weary eyes this dim light is welcome; to the tired frame, 'the night in which no man can work,' looks full of rest as it draws near.

You ask me how it was with me in the morning.

It is so long ago I can scarcely remember now.

In the morning, when I was young?

Let me look back through the shadowy years.

Ah yes! It comes slowly to me—the wild morning freshness, the flower-scented air. The dawn has broken; it is all wonderfully bright; there seem[Pg 14] to be no clouds; the sun rises in golden radiance, and the earth is flooded with glory.

And as my eyes—dazzled at first—grow more used to the splendour of the young day, robed and crowned with light, I see an old gateway grim and grey, facing the west. It lies in shadow still, but a child pushes open the heavy wooden door, and suddenly a stream of sunlight pours through, and he stands there with the morning light behind him.

How often there may be two meanings in our simplest words. I was standing truly, on the threshold of life, even as my childish feet rested on the grey worn stone, and far before me lay the mists and the shadows, the hopes and the sorrows of my future. Only from behind—my home lay in there behind—from there the sunshine had never failed me yet.

My hand, a small soft round one, rested against the arched gateway, among the stonecrop and the yellow lichen. I remember that I tried to loosen one of the old stones, but I could not. It was still as strong and immovable as when, ages ago, it had been fitted into its place. I daresay it is just as firm now, though the little busy hand is so withered and feeble.

[Pg 15]

It was the gateway of a ruined castle, grand and very beautiful in its ruin. I have heard people say that they wished they could put all things back, and see it as it once was; but I always wondered at them. I would not have changed one stone.

I suppose that all places may look sad at times—beneath the grey sky of winter, or when autumn winds are blowing; but on a summer's day no place has ever seemed to me so bright with sunshine as our ruins.

It was as if old age had come upon them lightly, bringing with it no burden of sadness, and that their days of work long over, they were content to lie idle in the kind warm sun, and to tell stories of the past.

The birds built their nests in the traceried windows, and sang and loved each other, and skimmed about at their own wild will above the flowery turf.

Ivy, the child of old age, had wound itself round the broken towers, half clinging to them, half supporting them.

It was one of my mother's quaint sayings that the soft mossy grass, which grew luxuriantly everywhere, reminded her of charity, for that though Time had stolen much away, all its thefts were[Pg 16] covered and hidden beneath that widely-spread mantle of turf.

I used to listen to my mother telling the stories of the place in her sweet grave voice. She and my father had charge of the Castle, and we lived in the rooms over the grand old gateway.

My mother often went round with visitors, for people came from afar to see the ruins. I liked to follow her, holding her gown bashfully, and wondering how mother knew that Queen Elizabeth had come there once, or that Simon De Montford, with a great army, marched up the valley one dark night and took the Castle by storm.

'Were you here, mother, when Queen Elizabeth came?' I asked her once.

'Oh no, Willie.'

'Then how do you know she ever came and stayed in the Queen's Tower?'

'They say she did,' mother said, smoothing my curly head.

'But do you believe it, mother? How can you tell if it is true?'

'Little Willie,' I remember that she answered, 'we must believe many things without seeing them,' and I thought that she looked up to somewhere higher than even the great Queen's Tower.

[Pg 17]

I thought a little, and then said—

'What a great person she must have been. Would you like to have been her, mother?'

'Oh, no, no,' and mother smiled, and then knelt down and kissed me. 'My own little son.'

I did not know what that had to do with Queen Elizabeth, and I don't know now, but I felt very sure that no queen, however grand, could ever have been like my mother. She, I thought, was more like an angel, and I believed I knew quite well how the angels look. For under the ruined roof of the Castle chapel was a sculptured angel's head with folded wings. It had just such a face as my mother's, with the same peaceful brow and loving downward look.

Sometimes I see her still. She comes to me through the long years at night, and we are together again—not as now, I so old and withered, she so young and fair—but as it used to be when I fell asleep, a tired child, on her shoulder. And I think that when the night—I mean death—really comes for me, and I lie down to sleep, that God will send her for me, and that she will take me, her weary son, in her dear arms once more.

I was an only child, but not a lonely one. On[Pg 18] the other side of the ruins, only much lower down, close to the stream that ran under the Castle cliff, was the forester's cottage, where lived Hildred, my friend and playfellow.

It was a pretty cottage with a thatched roof, half buried in climbing roses. The pleasant rippling of the stream sounded there close at hand.

We heard the water, too, up at the gate-house, but more faintly. There it was the distant rush of the stream tumbling noisily over some rocks before it took up its quiet song again at a lower level.

The cottage garden was a sunny corner full of flowers and bees and butterflies. But we liked our grey gateway best, with its broad fair view. For we could see across to blue hills in the distance, miles and miles away. Between them and us were broad woods and broken ground, farm-houses with rich pasture-land round them, and broad fields stately with yellow corn. It was beautiful to watch the wind sweep over them with a rough kindly hand, breaking the field into waves of rippled gold beneath its touch.

I was looking at all this from the gateway on the summer morning I have been telling you of, and feeling very happy, though I scarcely knew why.[Pg 19] For a child accepts God's gifts with a glad unconsciousness, as the earth welcomes the sun and rain.

Perhaps you wonder why I tell you so much about a day on which nothing particular happened, and why I remember it so well. But if you live to grow old, you will find out that it is not always the great events in your life that you remember the best and care the most to look back upon. It is some sunny little bit of every-day life—some homely scene that passed over and seemed to leave no trace behind, that lingers the longest in your memory. Just as looking down from a high hill at sunset over the country below, it is not the biggest things that you see the most clearly, but the bright spots here and there: a glittering pool of water, perhaps, or a bush of blooming gorse which has caught and kept the sunbeams.

You children should not have got an old man talking to-night about what happened when he was a little boy. Old men are like a great many other things, easier set a-going than stopped when they have once begun. And so I am afraid you will find me. I seem to remember so many things now that I once look back. Sad things, children, as well as merry things, for there are grey threads[Pg 20] woven into the web of every life. I hope you will not say that mine is too 'grey' a story for New Year's Eve.

Don't be afraid though. There is nothing sad coming yet. I was as happy a little boy just then, as the sun shone on.

Little Boy Blue

Come blow your horn,

The sheep are in the meadow,

The cows are in the corn—

sang a little clear voice coming through the ruins. That was Hildred. She always sang unless she was running so fast as to be out of breath.

One day when her sister-in-law was scolding her, she said she believed Hildred began singing before her eyes were open in the morning, and that it was very tiresome. Hildred lived with her brother and his wife, for her own parents were dead.

Her sister-in-law scolded her a great deal, but she could not quite sadden the brightest little heart that ever beat. Hildred seemed to get over the scoldings as quickly as a little bird shakes off the rain-drops that have fallen on its wings.

She was sorry for a few minutes, but then she ran away to us and forgot it all. Often there were two big tears on her cheeks when she left[Pg 21] home, but by the time she had got past the keep the wind had dried the tears, and she was singing again. She left her troubles behind and forgot them: forgot the sturdy uproarious Robin, the stolidly domineering Walter—her brother's little twin boys—forgot even that passionate blue-eyed baby Phillis, the greatest tyrant of them all.

You may be sure that my mother was all the kinder to Hildred because she had no parents of her own.

The little maiden brought all her small troubles to be cured by my mother, as grown up people brought her their big troubles. Everyone that knew my mother came to her. She had remedies for all ills, I think, from a scratched arm to a broken heart. No one went away from her without taking some comfort with them. Many people have told me this. I scarcely know it by my own experience, for as long as she lived I never needed comfort.

My father was a man of very few words. He seldom came home until the evening, and then he liked to sit perfectly silent, with his pipe in his mouth, in the chimney corner if it was winter, or in summer on a stone bench outside the door.

[Pg 22]

I was not a bit afraid of him, and chattered on to my mother just the same, whether he was there or not. I do not know if he ever listened to what she and I said to one another. At all events he never joined in our long talks. My mother taught me to look up to him and honour him, and so I did, but in a far-off sort of a fashion, much as I honoured our sovereign lord King George.

But she seemed to belong to me so completely that it would have surprised me very much if father or anyone else had set up a claim on her that came in the way of my rights.

He was welcome to talk with her, as I sometimes heard him doing, in slow deep sentences, after my mother had bidden me good night in the long light summer evening. But she was mine till bed-time.

Bed-time! how I hated the word then! How it brings back now the dear vision of a little white nest, of a few last thoughts in the waning light, of hours of dreamless sleep. Then of a glad awakening in the morning with sunshine on my face, and mother by my bed.

There was an old well under the wall that used to frighten and yet attract me, it was so very deep and dark. I always fancied that some unknown[Pg 23] danger lurked in its depths, yet I could not resist the temptation of peering down into it, to see through all the fern and broad-leaved mulleins, the black water far below marked by one round spot of light, where the reflection from the sky touched the surface.

It was a daily pleasure to me to see the bucket lowered into the well. I took a friendly interest in that bucket, almost as if it had been a thing alive, and used to wonder whether it did not dread the rapid steady going down into darkness, and the sudden dip into the chill water at the bottom. I was quite glad when the rusty chain began to be wound up again, and the brimming bucket loomed slowly into sight.

On a stone in the wall above the well there were some words engraved in queer old-fashioned characters. When first I knew how to read, I used to try to spell them out letter by letter, but I could not manage it.

'Why can't I read that,' I asked my mother rather indignantly, 'when I can read so well?'

'The books we read now-a-days are not printed with those sort of letters,' she said, pausing for a moment in turning the creaking old windlass.

I looked down to see how my friend the bucket[Pg 24] was getting on, and seeing him rising up safely towards me, turned back to the inscription.

'How stupid to put it so that we cannot read it,' I said.

'But wise people—people who know a great deal—read it quite easily,' said my mother.

She had landed the bucket safely on the well-side, and she stood thoughtfully, and pulled a little moss off one of the old carved letters. 'It is not that they were stupid, Willie, but that we are not wise enough to understand. Very often when we think that things are not right or wise, it is only because we cannot make them out for ourselves; but if we saw clearer and knew more, we should find out that they were only too wise for us and too good.'

She was talking to herself, I think, not to me, and I only answered the last words.

'Good; then are those old words very good?'

'Very good indeed, Willie.'

'What are they?'

She read slowly—

'For whosoever shall give you a cup of water to drink in My Name; Verily I say unto you he shall in no wise lose his reward.'

'Why, that is in the Bible,' I said wonderingly.

[Pg 25]

My mother smiled. 'I told you they were good words.'

'But how did they get there?'

'I don't know. I think some good man must have carved them long, long ago, that the water we draw up out of the well might remind us of Christ's words, and that we might remember to try and help one another.'

And then she told me how all service done for our Master's sake—even the very smallest—should be remembered by Him, and should in no wise lose its reward.

I have forgotten the words she used, but I remember that I said, 'I should like to give some one a cup of water, mother.'

She was going back to the house, with the pitcher she had filled, but she stopped to put her hand upon my head, and answered—

'I hope you will often. Do not forget, Willie.'

I never did. That little talk, with its few and simple words, was to bring a great change over my life.

One day—it was a hot afternoon in harvest-time—I heard the bell that hung near the great gateway ring suddenly. A faint ring, as if the hand that pulled the bell was weak or afraid, but[Pg 26] as I stood still for a minute, listening, it sounded again.

I ran to the door and opened it: a man dressed like a soldier in a faded red coat was half-sitting, half-lying on the ground leaning against the archway. Beside him, trying to support him, knelt a boy of about my own age, who looked up eagerly as I pulled open the gate.

I drew back, startled at the man's haggard face and dark hair, meaning to go and call my mother, but the boy stretched out his hand to me and said eagerly—

'Give him a little water, for the love of God!'

A little water—how strange it sounded to me—a cup of water. Mother had said she hoped I should. I rushed back to the house, seized a horn mug, and there at the well the bucket stood half full.

The boy put the water to his father's lips, and the poor man swallowed a few drops with difficulty.

'How tired he is,' I said.

The boy shook back the dark hair from his eyes and looked up at me.

'He can't get on any farther. I don't know what to do.'

[Pg 27]

'Oh, you must come in here,' I said eagerly. 'Can't he walk? It isn't far.'

The boy bent down and spoke. I scarcely think the poor soldier understood what was said to him, but at his son's voice and touch he strove wearily to get up from the ground. Between us we managed to lead him into the kitchen. He fell heavily on the oak-settle near the window.

'Is he very ill?' I asked.

'Three days ago he was struck down with fever. Last night we had to sleep under a hedge, they would not take us in at the place we stopped at, and to-day he——'

The boy stopped and turned round. Another voice—I scarcely knew it for my mother's, it was so changed and hoarse—repeated his words, 'Struck down with fever.'

She drew me hastily away from the sick man, whose hand still rested on my shoulder.

'Oh, Willie! what have you done—what have you done?'

'Mother, the poor man wanted some water,' I began, but she called to me to go away, and when I wanted to stay and tell her about it, she pushed me towards the door with a sort of cry—

'Go, go, I will come to you.'

[Pg 28]

I went out frightened and puzzled, and waited for her at the well.

When she came to me, I sprang into her arms and sobbed out, 'Mother, what have I done? You said a cup of water—'

I could not go on, but pointed to the stone. It was strange to see how the troubled look passed away from her face and the peacefulness I knew so well came back.

'My boy, you have done nothing—nothing wrong. I hope you will always try to follow God's commands, though it may lead you into troubles.'

'What is it, mother? Is the man very ill?'

'Very ill, Willie,' she said gently; 'so ill that I don't know yet what we ought to do. I wish father was at home. I must go back now.'

I sat down by the well and waited, watching the door. It seemed a long time that it remained closed, and no one came near me.

At last in the stillness I was glad to hear the well-known heavy knock that Farmer Foster always gave upon the gate with his stick. I went and pulled it back.

I have not said anything yet about Farmer Foster. But Foster of Furzy Nook was a name so well known in those days all round the country[Pg 29] that it seems to me as if no one needed to be told about him.

From our windows we could see the twisted chimneys of Furzy Nook farm peeping through the trees. A quaint old-fashioned farm-house, built of red brick, standing in a hollow at the end of a long green lane arched over all the way with trees, that was the pride of the neighbourhood. To go to Furzy Nook for the afternoon had always seemed to me and Hildred the greatest happiness that the world had to offer.

Mother used to live there before she married my father, and the kind old people were almost as fond of her as if she had been a daughter of their own. Farmer Foster was always coming up to the Castle to see her.

I was very glad this afternoon to see the kind face and the gaiters and the shaggy pony looking just the same as usual.

'Well, Willie,' called out the loud cheery tones that sounded very comforting to-day, 'and how's mother?'

Holding on to his stirrup, as he rode slowly in under the archway, I told him all that had happened in the last half hour.

He gave a sort of whistle of dismay 'Struck[Pg 30] down with fever, eh, Willie?—that's bad. And father won't be home till night?' he said, biting the end of his whip and staring at the door. 'Well, you'll have to hold the nag for me, lad, that's what you'll have to do.'

And he got off and went into the house. By and by he came out again with my mother, and they stood together talking earnestly. I was leading the pony up and down on the grass, but now and then I overheard a few of their words.

'You must,' Farmer Foster said once or twice.

My mother shook her head: 'I cannot turn the poor creature out to die.'

Something I heard about 'very catching,' and mother said 'hush,' and looked towards me.

Suddenly I saw the old farmer take her in his arms and kiss her. He came and took the pony away from me, telling me to go to my mother.

'Is the poor soldier better, mother?'

'No. He is very ill, Willie,' she said, putting both her hands in her old fond way on to my head; 'so ill that I must send my boy away. No, Willie, you cannot stay. Farmer Foster is going to take you home with him.'

I could not cry when I looked at her face. She was so sorry for me. I knew she would not have[Pg 31] sent me away if she could have helped it. I pressed my two hands on to my breast and looked at the inscription over the well. My mother's eyes followed mine and she smiled. Perhaps to go away quietly from her would be more than 'a cup of cold water.'

She took my hand and we went silently to where Farmer Foster stood by the pony waiting for us.

'He is ready,' said my mother trying to speak cheerfully. 'See, Willie, the farmer is going to let you ride on his pony.'

Farmer Foster lifted me up. 'I'm afraid he will fret after you, Annie.'

'No,' she said, softly. She came close beside the pony and put her arms round me, and, as I bent down to her, gave me a long trembling kiss. 'You will be a good boy without me always.'

The shaggy pony walked steadily away with me under the gateway. I thought my mother had put her hands over her eyes, but when I turned back again, before we went down the hill, she was looking after us, and there were tears and smiles both upon her face.

That was a very sad ride. But I think it would scarcely have been in human nature—at least in[Pg 32] a boy's nature—not to be cheered by all the joyous sights and sounds that greeted us at Furzy Nook. We got to the end of the sandy lane just at sunset, the pleasantest and noisiest time of day in a farmyard.

I tried to count the noises, but it was no good. There were too many, and all going on at the same time.

There were the cows coming home from the up-land pasture to be milked, and lowing as they wound down the narrow path. The cow-boy had a stick in his hand, which he flung carelessly among a flock of geese, and made them run cackling loudly towards their pond, where they launched themselves into the water with a satisfied splash and glide. Because the geese cackled of course the ducks began to quack. The supper-bell was ringing loudly from the farm-house, and the bell excited the big watch-dog to rush out of his kennel and bark furiously.

We heard the distant cry of the harvesters coming from the field, where the wheat was being carried, and the creak and rattle of an empty waggon coming up the lane.

Besides that, the pigs were having a family quarrel over their supper in the straw-yard.[Pg 33] Raised high above the noise, the pigeons cooed peacefully from their house. The rooks were floating in from the fields to the tree-tops. Then the donkey, honest fellow, made up his patient mind to have a share in what was going on, so he lifted up his voice and brayed. Louder than the pigs—harsher than the geese—more discordant than the peahen, he stood with his head thrust over a gate and made his moan to the world.

I suppose the animals all knew that the sun was setting, and were making the most of the waning day. So were the harvesters, for their cry sounded oftener—clearer, too, as Farmer Foster crossed the lane again and opened the gate into one of his big fields.

Most likely you young men now-a-days would say that he was not half a farmer. I notice that you farm very differently and I dare say you are right. Only it was not so when I was young. We did not look so carefully to every inch of land in my time.

The hedgerow trees were allowed to spread out their wide branches where they would. The ditches were often grassy and full of wild flowers, and the hedges left untrimmed. So garlands of dog-roses[Pg 34] peeped from their sweetbriar setting. Traveller's-joy and bindweed wreathed themselves round the trailing bramble shoots. Just now the blackberries were turning from red to purple, and the furze bushes shone with starry gold.

Yet there seemed to be a pretty heavy crop of corn in the field we went into. The rakes were going over it for the last time, and the field was full of gleaners.

The gleaners had a good time on Farmer Foster's land. His people always expected, if they raked too carefully, to hear his quiet-spoken 'Gently, my lads, gently; remember the gleaners,' behind them. They said he used slyly to pull handfulls from the finished sheaves and scatter them near some gleaner, generally a child, whose bundle looked smaller than the rest, scolding it all the time for not being half a gleaner.

They were working with a will now, the level sunbeams lighting up their ruddy faces and bright-coloured aprons, and gilding the yellow wheat-ears that overflowed the bundles.

So the sun set. The lingering brightness faded from field and hedgerow. The waggons came back loaded for the last time. The heavily-laden gleaners went home singing, and the cocks and[Pg 35] hens put their heads under their wings and settled themselves to sleep, standing on one leg.

Dame Foster and the farmer would not let me miss my mother. If I gave a great sigh they piled my plate higher with brown bread and golden butter; and once when a sob rose up unexpectedly in my throat it was stopped by such a big strawberry that I could not eat it and cry too.

And though, when I was put to bed under a patch-work quilt, in a little white-washed room that was all lighted up by the harvest moon, I am sure that my last thought was of my mother, it may be that the last but one was of strawberries and young chickens.

Every day there came to Furzy Nook a message from my mother. She was well, and sent her grateful respects to the farmer and Dame Foster, and her dear love to me. What more news the messenger brought was never told to me. I saw them whisper together and sometimes shake their heads, but as long as mother was quite well there could be nothing really wrong.

By and by there were grave faces—they still said mother sent her love but nothing more. One day, when everybody looked more serious than[Pg 36] usual, they told me that the poor man, the sick soldier at our house, was dead.

It was very sad, Dame Forster said, very sad indeed. The farmer stroked my head and took me up on to his knee. I was very sorry for the poor soldier, but why did they look as if they pitied me?

I had begun to long to go home to my mother. For a time I tried hard to keep it to myself, because she had told me to be good without her. But I could not help asking very often if it was not time to go home. They always said 'not yet.' I got very tired of waiting.

At last Peggy told me the reason why. Peggy was a rosy, kind-hearted maid at the farm—a likely lass Dame Foster said she was, but not as discreet with her tongue as could be wished.

Peggy let out one day that I could not be taken home because my mother was ill. 'It's the fever she's got, you know, same as what the poor soldier died of. But I don't think mother's very bad, Willie dear, not like he was,' said Peggy, frightened at having made me cry. 'You must bide a bit longer here, that's all. You don't want to go away, not from the ducklings and all, do you? See, there they go! Come out and feed them, dear.'

[Pg 37]

Dame Foster could only tell me the same thing.

'She'll be better soon, please God!' That was what they said every day now.

They were very good to me, the kind old couple, who had never had anything to do with a child before.

I might have ridden the farmer's shaggy pony all day long if I had liked. He would have picked me every cherry off the tree. Dame Foster and I used to go gravely from one place to another, hand in hand—to look at the great bars of yellow butter and thick cream in the dairy—to feed the poultry, to find eggs, or to make posies of the sweet-smelling cherry pie and clove pinks out of the front garden.

One evening—Farmer Foster was out, gone I did not know where—I wandered rather disconsolately into the kitchen. It had been a long day, and it was a dull evening. The summer rain was falling softly over the garden. Dame Foster sat by the window looking out, and now and then putting her apron up to her eyes. I asked her what made her cry, and she said hurriedly first that she wasn't crying, and then that she supposed she felt dull with the rain and all.

I was dull too, and had nothing to do. I asked[Pg 38] presently to go to bed, so she bade me kneel down and say my evening prayers.

Once when a little schoolfellow of mine lay sick mother taught me to pray for him and to say, 'God make Charley well, or else take him to dwell with Thee and with the angels.'

Since I had heard that my mother was ill I had added these words, after much thought, to her name in my prayers. I said them now.

There was the sound of a stifled sob behind me. Farmer Foster had come in without my hearing him. 'Bless his dear heart!' the old man said. 'The good Lord has heard his prayer.'

I jumped up from my knees.

'Has mother got quite well?' I asked eagerly.

Oh no! Farmer Foster's averted face—his wife's slow-dropping tears—Peggy's uplifted hands and pitiful, shocked look, told quite another story.

They frightened me with their silence and their tears.

'Mother!' I called loudly; 'mother!'

'Oh, little Willie!' Dame Foster said, holding out her arms, 'she cannot hear you.'

There was no need for them to tell me any more.

My mother was dead.

[Pg 39]

Who can fathom the quicksands of a child's grief?—its depth and its shallows, both so real: the passionate sorrow one hour that utterly refuses comfort, the seeming forgetfulness the next; the bitter, bitter tears, and by and by a weary peacefulness that comes like balm you do not know from where, smoothing with soft, cool touches the aching eyes and brow.

God knows the little ones are weak: He lifts away the load of sorrow now and then, lest the overburdened little heart should break, the rough stones pierce the tender feet too sharply.

I did not want anyone to pity me or try to comfort me. She who alone would have known how was gone away. They talked of my going to her some day in heaven, but that seemed too far off to do me any good.

As much as I could I kept my tears to myself, for everybody came round me if they saw me cry, and said kind things in cheerful voices, and patted me, and stroked my hair. They did not understand. If I stopped crying, as I always did as soon as ever I could, they were satisfied.

Sometimes at night it was hard to keep my sobs quite silent when I wanted mother's kiss. But directly I heard Dame Foster open the door[Pg 40] quietly, I used to bury my face upon my arm to hide eyes that the tears made so burning. I felt the kind old lady straighten the bedclothes with a gentle hand, and heard her whisper to the farmer outside the door, 'He's sleeping nicely, bless him!' It only made me wish for mother more, who would have known all about it, and never have thought I was asleep.

Those were heavy days. Each one was long and strange like Sunday. Everybody seemed to watch me, and I felt that something, I did not quite know what, was expected from me. I walked slow instead of running, and read to Dame Foster of my own accord out of her large-print Bible.

Our few neighbours came to pay visits at the farm. I was always sent for to come and see them. They looked at me and sighed, shaking their heads gently over Dame Foster's currant wine and harvest cakes, while they talked in lowered voices about 'the orphan.'

I believe Dame Foster took a kind of pleasure in those tearful gossipings, and in going over a set of sentences that I, listening listlessly, grew to know by heart, even down to the sighs and little groans that always went with the words.

'Ah dear!' said Mistress Janet Morton, our[Pg 41] schoolmaster's maiden sister. 'Ah dear! Here to-day and gone to-morrow, dame.'

'You may well say that, Mistress Janet.'

'The best seem to go the soonest,' Mistress Janet went on. 'There's a many will grieve for her that's been taken.'

'That's true. Everybody loved her, poor dear. My master takes on wonderful, just as though it ha' been a daughter of his own. He'll have every respect paid same as if she'd been really ours. And such a stone, Mistress Janet, as my master is going to raise to her!'

'Is he indeed? well, sure!'

'He thinks it'll be a comfort like to the dear child some day.'

'Ah! he little knows what he has lost,' said Mistress Janet, looking at me as I sat wearily on the floor with my arm round the big dog's neck.

'Poor little dear!' and Dame Foster gave her deepest sigh.

'What is the poor widower to do, ma'am, left with that young child?'

'Ah! what indeed?'

'They say he's a hard man, strange and close. I hope he'll use the boy well.'

Then they lowered their voices, and their two[Pg 42] heads almost met across the table. So I heard no more.

Farmer Foster came home one evening with a long black band round his hat. No one told me then; I have only guessed since that my mother was buried that day.

With him was Master Caleb Morton, our schoolmaster. He had been a great friend of my mother's, and used to come often to the Castle.

Peggy was sent to bring me indoors from my usual place on a high bank among the furze bushes, from where I could look across the farmyard and the cornfields—nearly all stubble now—towards the old keep at home.

Master Caleb wanted to see me, Peggy said. I found him with the farmer and Dame Foster in the best parlour, not in the great kitchen where we generally lived. All three looked very grave.

'Willie,' Farmer Foster said, holding out his hand to me as I came near, 'Master Caleb saw your dear mother before she died, and she left a sort of message for you with him. He is come to give it to you now.'

I looked up at Master Caleb. It seemed a hard, formal way of getting a message from my mother. I had far rather—and so I think would he—have[Pg 43] gone with him to some quiet corner out of doors, and there have listened to her last words. But the farmer and his wife treated it as if it were a sort of solemn ceremony. They sat in two high-backed chairs opposite to each other, stiff and upright as if they had been in church, and signed to me to stand before Master Caleb.

He hesitated, looking from me to them. At first he spoke just as he did in school, but presently he put his hand on my shoulder and drew me near to him. After all, the words he had to say were but very short and simple. Only just these:

'I saw your mother, Willie Lisle, the day before she died. Your father told me that she wished to speak with me. Her weakness was too great for many words, but her last thoughts and her last cares were all for you. Her death, like her life, was most peaceful and beautiful. She bade you remember the promise you made her when Farmer Foster brought you here, that you would be a good boy without her always. She had prayed God much that He would help you, and she sent you her blessing. Something she said of the day that you left her. "Tell him," the words were, "that I am glad he gave the cup of water to that dying man, and[Pg 44] that I have rejoiced as I lay here to think how he began then to try and follow our Lord's command. All that has come of it has been for the best. Tell him how sure I am of this," and her smile, Willie, when she said that, was most bright to look upon.'

Master Caleb paused.

'I have little more to say,' he added presently, 'except this, that she left a solemn charge to you. You remember the sick soldier's son?'

I looked up with sudden remembrance. Until now I had well-nigh forgotten him.

'Before his father died, your mother had promised him that the boy, Cuthbert Franklyn, should be to her as her own child. To you she leaves the fulfilment of her promise, and she bids you be his brother. She was very earnest about this. I think she would fain have said more, but her voice failed her. Then she clasped her hands, and though I waited for her to speak again, only once or twice she whispered your name. A few hours after I left her she entered into her rest.'

That was all.

Farmer Foster and the dame pushed back their chairs and unfolded their hands. Master Caleb[Pg 45] bent forward, and, looking as if he were half ashamed to do it, gravely kissed my forehead.

All that evening they were busy over the inscription that was to be put on my mother's tombstone. Farmer Foster had planned it all out himself, and wanted the schoolmaster's approval, for he was rather proud of his work. It was very long, as the fashion was in those days. I think now that if she herself could have known about it, fewer, plainer words would have pleased her more. I still hear the farmer's voice repeating with grave relish the last words: 'She departed this life leaving a broken-hearted husband and an only child to mourn her irreparable loss.'

Broken-hearted! Was my father really that? I wondered what broken-hearted people did, and how they went on living. I was sure I was quite as sorry as my father, and yet my heart beat just the same as usual.

Whether he were broken-hearted or not, he looked to me quite unchanged, when he came the next day, with White Billy in the cart, to take me home.

As usual he said no more than he could help, only thanking the good old people who had been so[Pg 46] kind to me in a few gruff words, when each holding one of my hands they brought me out of the house and gave me back to him.

'He's been a very good boy,' said Dame Foster, looking at my father in a wistful kind of way, as he stood settling something that had got wrong in Billy's harness.

'I'm glad he's not been troublesome,' he answered slowly.

'He never was. Stephen Lisle'—she laid her hand anxiously on his arm—'he's but a little boy to be left without his mother. You'll take good care of him.'

'I must do the best I can, ma'am,' my father said after a minute, without looking at her.

How much afraid they all seemed to be that my father would be unkind to me. I wondered over it as White Billy trotted with us up the sandy lane. It was nothing new to me that he should drive on without saying a word. I had never been afraid of him, and I fell to questioning again whether he was heart-broken, and looking up into his face to see if I could find any signs of it. No; it did not seem as if he were thinking of anything in particular, unless it might be the pony, who had found it hard work to drag the cart through the[Pg 47] heavy sand-track at a trot, and so had fallen back into a sober walk.

Since then I have often heard people say that Stephen Lisle was never just the same man after his wife died. Very likely they were right, and that it was because I was not old enough to read the marks trouble had left upon him that I could see no change.

I did not think about him long. The Castle came in sight. We crossed the bridge and went slowly up the hill. I knew quite well that my mother was not there, and yet my heart would beat faster and faster. Home at last, and how unchanged! The same flowerpots in the window, the roses blooming still. The door stood half open and inside the black cat sat purring in the sun.

I went in alone, looked all round, opened the door leading into the inner kitchen where I used to be sure of finding her. The flies buzzed in the window, and through the stillness the clock ticked slow and loud.

I knew she was not there, yet I called 'Mother,' under my breath, and when no one answered a terror of loneliness came over me. I rushed out of the house and round the corner, blinded by quick-coming tears. There was the well, and the bucket[Pg 48] by the side standing half full of water just as it had stood that day.

Oh, if only I had never given the cup of water to the dying soldier! If he had never come—and yet mother's message said that she was glad.

Some one was standing at the well, leaning over it and looking, as I used to do, into the far-down water. It was the soldier's son, Cuthbert Franklyn.

I could not bear that the strange boy should see me cry. I put up both my hands to hide my face, but I suppose he saw the tears trickling through my fingers, for I felt his hand touch mine, and heard him say 'Poor boy!'

In a minute—I don't quite know how—my arms were round his neck. We were very little fellows then, but we have loved one another ever since.

Cuthbert's eyes were full of tears.

'Somehow it seems as if it was all my fault.'

'How could it be your fault?' I said sadly; 'you could not help it.'

'Oh! I am glad you think that. I wanted you to come back, that I might see you again, and thank you for being kind to us that day. And I wanted to say good-bye before I go away.'

He held out his hand.

'Going away?' I said, taking it, and looking up[Pg 49] at him, for he was rather older and taller than I was, 'are you going away? Where to?'

'I don't quite know; father's friends were all dead and gone when we got home to England.' His lip trembled, and there was a shadow of trouble on his brave bright face.

'Why do you go away, Cuthbert?'

'I suppose I must not stay here always,' he said simply.

'But you may: haven't you heard? My mother said you were to be my brother.'

Cuthbert looked up eagerly, and the colour came into his face. 'But your father.'

'Wait for me here a minute.'

I found my father chopping up logs of wood in the wood-shed.

'Father, Cuthbert Franklyn says he must go away.'

I had to repeat this twice before I could make him hear; when he did, he only said, 'Well.'

'But father, he needn't go.'

'Where is it he wants to go to?'

'He doesn't know; he thinks he isn't to stay here always; you won't let him go, father?'

My father took the hatchet up again.

[Pg 50]

'It's no business of mine; I've no call to stop him if he wants to go.'

'He doesn't want to go; he has got no home, and mother said he was to be my brother.'

'I don't know how that may be,' my father said slowly.

I was thunderstruck. 'But mother said so, and you promised, father.'

He looked at me.

'I made some sort of a promise may be, as I would have promised anything then, to keep her quiet.'

He sighed, and drew the back of his hand across his eyes—the only outward sign of sorrow I ever saw him give.

'Then Cuthbert may stay.'

My father made a few strokes at the wood without answering. At last he said, 'Look you, Willie; it's a great deal to ask of a poor man.'

'Are you very poor, father?'

He stopped a minute.

'They call me close, but I reckon there's not many of them would do a thing like this; it's too much to expect.'

'For mother's sake,'—I felt, rather than knew, that this was my best chance.

[Pg 51]

'You let me alone!' he said roughly.

I waited with my eyes fixed upon him, for two or three minutes. He went on with his work; then came a sort of short laugh.

'They preach so much to me about being good to you: why am I to take in another mouth to feed?—a great growing lad too, that'll take the bread out of your mouth, most likely.'

'Oh, father!'

'Be still; can't you? I hate to see the boy about the place. He's brought nought but bad luck to me and mine.'

I thought of Cuthbert waiting for me; I thought of mother's charge to me, so solemnly given and received. I was almost in despair. If I had understood my father better, I might have guessed that he would say less had he been entirely decided and at ease in his own mind.

'A promise such as that binds no one,' he muttered presently.

Another long five minutes passed—log after log of wood was cut and thrown aside. My hope was almost gone, when suddenly my father laid down the hatchet and turned round.

'See you here, boy; it'll be the worse for you if I do this; you'll have to fare rougher, and there'll be[Pg 52] less for you to get. You'll have to be content without so much schooling, and you must work harder.'

'Oh, I don't care, I don't care!'

'Humph.'

'Then Cuthbert needn't go?'

'Have it your own way.'

'But he may stop with us?'

'I suppose he'll have to, leastways as long as he behaves himself.'

I hardly waited to hear him to the end, or to thank him. I dashed out of the wood-shed.

Cuthbert had not moved from where I left him. He was watching for me eagerly.

'It's all right,' I shouted, rushing up to him; you're to stay and be my brother.'

He drew a quick breath, with a half-uttered 'oh,' and then, seeing my gladness, he began to smile.

And so my coming home was not all sad.

The good my mother meant to do to the orphan boy was returned in tenfold blessing to her own child. Truly as brothers—more than as brothers, if it might be—Cuthbert Franklyn and I came to love each other.

He who had never had a home before, got to be[Pg 53] at home with us. It was very pleasant to him, though to me it seemed all changed and dreary. Hitherto his life had been a wandering one, following his father's regiment wherever it went. He was not born in England, but in the Island of Malta, and sometimes, when the sky was very blue, he said it recalled to him a brighter sky still, which he remembered dimly, and tall white buildings, and stairs that he thought went right down into the sea. There were sounds of bells and guns, he said, and a vision of some great ships. That was all he recollected of his birth-place. His mother had died there, and another soldier's wife had taken care of him. They went from place to place, sometimes taking long voyages across the sea, until his father became ill and got his discharge. When he came back to England he tried to find his relations, but his parents and his only sister were dead. He was forgotten, and could find no one to befriend his son. Cuthbert scarcely knew where his father had meant to go, when the fever came upon him. That was all he could tell us about himself; only there was no life like a soldier's, Cuthbert said, with sparkling eyes. He was always whistling the gay tunes that their band used to play, and imitating the bugle-calls that he had known all his life long.

[Pg 54]

My father scarcely ever noticed Cuthbert. To the end I do not think he grew really to like him; but his word once given, he would not go back upon it.

In time I almost forgot, and so I think did Cuthbert himself, that he did not belong to the place as much as I did.

The neighbours wondered very much at my father's having taken in Cuthbert. It was not a bit like Stephen Lisle, everybody said, to do such an out-of-the-way thing. Perhaps it was not; but I believe most people do something that is not a bit like themselves once or twice in their lives. My father heeded them very little.

He could never make shift to get on, the neighbours further said, all by himself, with two boys to look after.

That was true enough. He pondered over it in his silent way for many a day, and at last he made up his mind.

Late one evening White Billy came slowly under the archway, and in the cart beside my father, who had been away for a day and a half, sat a little old woman, with a very big black bonnet and a red cloak. My father called me.

'Willie, here's your grandmother.'

[Pg 55]

And the little old woman got down slowly from the cart, and said,

'Dear, dear! Is this your boy, Stephen?'

'Yes, mother.'

The name sounded strange from my father's lips, strange and sad too, for he used to call my mother, 'mother.' It was odd and perplexing to me altogether, that my father should begin to have a mother just when I had lost mine. I stared hard at my grandmother. She had come to stay, I soon found out,—come to take care, my father said, of me and of the house.

'And of Cuthbert,' I said, jealously.

My father only nodded, but that was consent enough to satisfy me.

My old grandmother took possession quietly and humbly enough. The morning after she came I found her looking out over the ruins with rather a forlorn expression on her gentle old face.

'Do you like the Castle?' I asked her.

'I don't know, my dear, I don't know. It looks an outlandish tumble-down kind of place. I never saw any like it.'

'This was the great gateway,' I said, with a child's eagerness to teach anybody a great deal[Pg 56] older than himself. 'There used to be a draw-bridge here once.'

'Dear, dear!' said my grandmother not understanding the least, 'was there indeed?'

'And yonder's the keep. They kept all their stores in there, you know, grandmother.'

'Well, to be sure!'

'And the dungeons are underneath, where the prisoners used to be.'

'Lawk a' mercy, poor things!'

'And grandmother, you've heard of the Queen's Tower?'

'No, my dear, I know nothing at all about it.'

'But you'll have to tell the people when they come to see it,' I said anxiously. 'Mother always did.'

'I can't, my dear. I know nothing of the place.'

'But you'll learn, won't you? I will teach you.'

'My dear, I am a great deal too old to learn.'

She looked quite frightened and confused. I shook my head and said no more. I did not see how she was to get on at all, and I thought how very different people's mothers could be from one another.

Years afterwards I understood good old Granny better. When she was very old and feeble she[Pg 57] used to tell me—Granny was always fond of talking—about the little home she had left to come and keep house for her son in his time of trouble.

'It was a nice clean little place, Willie,' she would say, twirling her thumbs and looking round her with eyes that had grown very dim, 'clean and very cheerful—just half way down the street, my dear, where you could see everything that was going on. It was a tidy street; we all kept our doorsteps so clean, you could have eaten your dinner off them. We took a pride in it, you see, Willie. We were very sociable and friendly among ourselves. I could always pop on my pattens and run in next door, or next door but one, may be, for a word of chat and a dish of tea. I had lived there a long time, and we were very comfortable, you see, Willie. It seemed a bit lonesome just at first, when Stephen brought me here. But it's all for the best, my dear, all for the best, for sure.'

I could understand then, what I used to wonder at as a child. It must have been a change from the busy county town, with its orderly trimness and sociable ways, to the wild silent ruins on the hill-side. But she had come away willingly from her cosy home, at her son's bidding, and[Pg 58] I am sure she died without ever thinking that the sacrifice so simply made was anything good in her.

By degrees I got used to seeing the bent figure trotting about, where my mother used to move; doing her work—not filling her place—keeping the house beautifully clean and tidy, but for the rest—ah, it would always seem empty and blank. There would always be the sense of something wanting.

Granny won my heart, though, by one thing. She was always kind to Cuthbert, just as kind as she was to me. I believe she took him as a matter of course. We were both strangers to her, he not much more than her own grandson. Besides, Cuthbert's bright face and ways won her heart. 'The boy has such a pretty tongue,' she used to say. He welcomed her more readily than I did, for he could not compare her, as I was for ever doing, with my mother.

I told Hildred one day how good Granny was to Cuthbert.

'Perhaps she likes him best,' Hildred said, throwing an apple up into the air and catching it.

'Oh, do you think so?'

It was a new thought to me. I pondered over it a great deal when I was alone.

[Pg 59]

Very likely most people would like Cuthbert best. My mother of course, would always have cared for me the most, but now it was different and I should not be first any longer.

Cuthbert wondered why I went up to him that evening and put my arm over his shoulder. He was hard at work mending a net for our cherry-tree, so he only just looked up and nodded.

No wonder everybody liked that happy face of his. In truth, I think there could not have been happier children than we were.

As the quick months and years passed over our heads, the trouble that never could be cured kept gliding away, further and further back into some very far-off past, until at last it seemed to me that it was not I who had lived here with my mother, but another boy, a much smaller, graver boy—a better boy, too, perhaps—but very different from what I was now. I looked back at him half wonderingly, half regretfully, through a sort of mist of brightness and light. It must have been so easy for him to be good alone with his mother, and hearing nothing day by day but her good words. What would she have done with the big rough fellow that had grown by degrees into her little boy's place? Would he have been quiet and gentle enough for[Pg 60] her, if she had lived? Yes, all the time I felt a sort of certainty that she would have loved me, nay, that she did love me still. And I should like to have let her know, that though of course I had got into a harder life—a life in most things far unlike what it used to be when she was with me—yet that I still often remembered and wished to obey her words, that I should try to be good without her always. But these thoughts I never spoke, even to Cuthbert.

I was a child when Cuthbert came, I was a boy now, and he had helped to make me one. From the first time I saw him climb the outside of the Queen's Tower, swinging himself upwards from branch to branch of the old ivy, he became my pattern: I resolved to follow him, and if it made Granny scream to see us, why, so much the better.

The Castle ruins were the best play-ground that children ever had. On half-holidays the whole school used to troop up there directly they were let out, and the old walls rang with shouts and laughter. Cuthbert and Hildred were always glad to see them, but I liked it best when we had it all to ourselves.

There was a hole in the wall, through which we[Pg 61] used to creep, a steep bit of cliff to climb down, and then the stream. Across it such woods, green, tangled, thick with brambles and underwood, full of wild strawberries, blackberry bushes, rabbits, and birds'-nests built up in the huge trees that stood knee-deep in king-fern.

Wherever Cuthbert and I went, and we went everywhere, little Hildred tried to follow us. It was clearly understood that she was never to be in the way. 'Girls always were,' Cuthbert said loftily; 'but still'——It would have been hard to leave her at home because she was a girl, for she would so fain have been a boy. She might come, if she would scramble through the brambles, without caring how much she scratched her arms and legs, and tore her frock. She must be ready to cross the stream, even if the rains had swollen it, and it was sparkling away ankle-deep over the stepping-stones.

She must not scream, however high a branch one of us fell off when we were birds'-nesting. She must share in all our scrapes, and never tell. She must stifle her terror of robbers in the wood, or adders in the long grass, and her pinafore must be always ready to hold birds' nests, eggs, young squirrels, or any prizes that we could not stuff into our own pockets.

[Pg 62]

Hildred was well content to come on any terms, and ready for the roughest expedition—readier often than I was, for in hot weather, when the ruins were sunny and silent, I liked better to lie on the grass reading, than even to go ratting with Cuthbert and our dog Trusty.

I was half ashamed of being fond of reading. No other boy was, and Cuthbert could not understand it at all.

'He's wonderful fond of his book is Willie,' Granny used to say. 'He'll get to reading to himself by the hour together.'

Cuthbert shook his head with a kind of wondering sorrow. He never cared much to go anywhere by himself. So there was nothing for it but to throw the book into the window of the keep, and go off wherever Cuthbert had made up his mind to take me. And there was Trusty too, with tail upright and eager eyes, waiting for a start. It would have been hard to disappoint Trusty.

He was a dog indeed, was our Trusty, commonly called Rusty, because the wear and tear of life had made his black coat very shabby and brown in these latter days. He was not a model dog, not brave, and calm, and wise, like the dogs one reads about in books. Rusty had his foibles.[Pg 63] He was vain, touchy, and changeable. His temper, too, was apt to be short at times, yet how true-hearted and faithful he was to those he really loved! Oh, dear old Rusty, laid to rest now, for nearly fifty years, under the green grass, I have never seen anything like you since!

Who so quick to guess your mood as Rusty? Who so ready as he for a bit of fun? Who so willing to deceive himself and you, and to growl savagely or bark shrilly at the mere mention of a rat, that he knew quite well did not exist? Who so sober and wiselike as Trusty, if you were in trouble; but who so quick to mark the first lifting of the cloud, and to know the minute when it would do to break in with a wag of the tail and a short sharp bark inclining to cheerfulness?

'Come, old fellow, things are not so bad after all,' he has often said to me; 'don't worry, but come and see after that rabbit under the Castle wall.'

To say that everybody was fond of Rusty would not be true, for the worst parts of his character came out with strangers. He was uncertain to them, uncertain and ungrateful. I have known him form friendships one day and be ashamed of them the next. He sometimes went so far as to receive kindnesses from strangers, and then to fly at their[Pg 64] legs if he saw one of his own people coming. But to those who lived with him he was just perfectly loveable. I don't think I can say more than that. He and we loved one another.

So Rusty shared all our fun, and all our troubles too—such as they were—for we had our troubles of course; who hasn't? For instance, we hated school, at least Cuthbert and Hildred did, and I, wishing to be like them, said, and I believe thought, that I hated it too.

But I don't think I did; no, I am sure I did not, except when the sun streamed hotly in at the half-open door, and leaves tapped against the diamond-paned windows, and bees hummed past out in the warm air, and the boys were rebellious, and the girls sleepy and cross. Of course no one could like it then. Nor on a grey day just made for fishing, with cool shadows lying on the water. Cuthbert began grumbling, on such mornings, before his eyes were well open, at the hardships of having to be shut up in school all day. It was rather hard certainly to think of the river swirling along through the green rushes, eddying round the stepping-stones under the Castle cliff, or dreaming lazily over the shallows where the trout lay. I never looked up from my slate on a day like that, without[Pg 65] expecting to see Cuthbert's place empty, and his cap gone from its peg near the door.

It was no good giving him advice—no good begging him to be industrious: he always promised, and always meant to keep his word.

All the seasons were alike. Long before I had had time to rejoice at birds'-nesting being over, the fishing had begun. Then came summer, with its long hot days—the hay-making and the bathing in the cool stream. Every bright hour was a temptation. After that the harvest seemed to come upon us quickly. The holidays began, and I had peace.

But winter was almost the worst of all. How Cuthbert loved the frosty weather, and the snow and ice! The Castle looked marvellously solemn and grey, rising out of the snow; and we had to dig paths for ourselves across the ruins. When we were building a snow man in the Castle court, and there was sliding and skating going on at the mere, half a mile away, and the red sun set over the hills at four o'clock in the afternoon, how was any one, said Cuthbert, to find time for school? 'When the thaw comes, Will, I'll never miss again,' he promised. But the snow melted, and there came a cloudy day with a southerly wind, and Cuthbert[Pg 66] was off half-a-dozen miles away to see the hounds meet, and to follow them from covert to heath, and from field to common, all across the country.

Those lawless doings of Cuthbert's disturbed me very much. I always felt as if he were in my charge and I had to answer for him.

Our schoolmaster used to frown, and tell Cuthbert he must take the consequences; and the consequences Cuthbert took, with a great show of not caring, laughing at Hildred because she could not help crying, and comforting me as if I had been the one in trouble.

Now and then my father spoke a few rough words, but they did not weigh much, for Cuthbert said: 'It's not as if he heeded whether I got any learning or not. It's all one to him. I can see that plain enough.' And when my father had done speaking he would go off whistling carelessly. I have seen the tears in his eyes, though, for all his whistling.

If mother had only lived it would have been different. Some of her kind grave words would have set everything straight. What could poor old Granny do beyond holding up her hands at him, with her favourite 'Dear, dear!' and then[Pg 67] giving him a double share of dumpling at supper to cheer him up?

'Boys ought to like school, Cuthbert,' she told him.

'But you see I don't, Granny. I hate it.'

'But good boys are fond of their book. Look at Willie.'

'As if I should ever be like Will,' he answered, with a look as if he were proud of me.

'Master Caleb thinks all the world of our Willie,' Granny went on. 'Why, you might go a-walking out with him if you were good, like Willie does.'

Cuthbert made a wry face. 'I'd much sooner not, Granny, thank you.'

From the time I was a little child I had known Master Caleb Morton well—he came so often to the Castle. It was he who had told my mother all the stories she knew about the place. He loved it almost better than we did, and—we were very proud of that—he had written a book about it, a real printed book. He gave it to mother, and it stood on our book-shelf, between 'Pilgrim's Progress' and the 'History of Jack the Giant-killer'—a thin red book, with a woodcut of Wyncliffe Castle on the title page.

Cuthbert and I believed that a stone could[Pg 68] scarcely fall from the crumbling walls without his finding it out. He used to stand for hours with his hands behind his back, gazing up at the grey towers.

Poor dear Master Caleb! He was much too good for us at Wyncliffe; for he was very clever, very learned, very hard-working, and understood everything under the sun, except village boys and girls.

They baffled him, for he expected them to like learning, and never could make out why one and all treated him as an enemy when he wanted to teach them their lessons.

Years ago he had come a very young man, to be schoolmaster at Wyncliffe, full of grand plans, and thinking to make good scholars of at least some among his pupils. He might well have found out, long since, what a hopeless task it was; but when I went to school, he was working away, still eager, still hopeful, forever being disappointed, but never quite losing heart.

However, if he did not know how to keep order in the school—and some people said he did not—I verily believe he knew everything else in the world.

He was an Antiquary, I have often heard Mrs.[Pg 69] Janet say, and a Botanist, and a Geologist, and an Astronomer. The words sounded so very grand as Mrs. Janet rolled them slowly out, that I recollected them all, though I had not the least idea what any of them meant.

'He's too book-learned for us, that's where it is,' the great men of the parish sometimes said, shaking their heads wisely. Yet they were fond of him and proud of him all the same.

Mrs. Janet shook her head too. She would fain have ruled Master Caleb's scholars for him, as when he was a little boy she used to rule himself. It was pain and grief to her to sit idle in the parlour, and know that 'the boy' was letting things go their own way too much in the school.

Not that he always did so by any means. The boys said they never knew what he would be at, for they found themselves brought to justice now and then when they were least looking for it. There was a boyish corner in his own heart, staid, quaint, and learned as he was, that gave him a secret fellow-feeling for Cuthbert's love of roaming, and I guessed that he was oftentimes the hardest upon him when he was most tempted to let him off altogether.

With the youngest class of all—a helpless cluster[Pg 70] of tiny boys and girls, who were only sent to school because they were in the way at home, he was at all events tireless and gentle. Very tenderly he guided the fat forefingers to point along the lines, helped the lisping baby tongues over the hard words, and never lost patience with the blue, wondering, foolish eyes that could see no difference between A and Z.