BY THE SAME AUTHOR

GRIM: The Story

of a Pike

Illustrated by Dorothy P. Lathrop

—The Baltimore Sun.

“Grim is delightful.”—New York Globe.

$2.00 net at all bookshops

NEW YORK: ALFRED A. KNOPF

Translated from the Danish of

Svend Fleuron

by David Pritchard

Foreword by Carl Van Vechten

New York Mcmxxii

Alfred · A · Knopf

COPYRIGHT, 1920, BY SVEND FLEURON

COPYRIGHT, 1922, BY

ALFRED A. KNOPF, Inc.

Published, January, 1922

Original Title: Killingerne: en Familiekrenike

Set up and printed by the Vail-Ballou Co., Binghamton, N. Y.

Paper furnished by W. F. Etherington & Co., New York, N. Y.

Bound by the H. Wolff Estate, New York, N. Y.

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

“The other farm cats’ kittens were born in barn and loft and were drowned litter after litter—but she would see that her kittens grew to be cats!”

Foreword by Carl Van Vechten, 13

CHAPTER ONE

Grey Puss, 21

The Willow Stumps, 23

The Kittens, 25

Grey Puss and her Past, 28

CHAPTER TWO

The Blind See, 35

The Father, 38

The Piebald Devil, 44

The Rescue of Tiny, 50

The Flight from the Willow, 55

CHAPTER THREE

The Burial-mound, 57

Life in the Burial-mound, 61

The First Mouse, 64

The Thief, 67

Drown the Brute, 71

A Great Reception, 76

CHAPTER FOUR

The Trickster, 81

The Lid of the Well, 88

The Dragon-fly, 95

The Old Crow, 97

CHAPTER FIVE

Big-kitten, 100

The Conqueror, 104

Black-kitten, 108

Miauw-miauw, 111

Grey-kitten, 116

CHAPTER SIX

White-kitten, 122

Tiny, 124

Red-kitten, 128

The Great Eating-house, 134

CHAPTER SEVEN

Box, 139

Cats of All Colours, 142

The Life-saving Chair, 148

The Crow Again, 152

CHAPTER EIGHT

The Kittens go out Hunting, 158

The Attack on the Crow’s Nest, 163

CHAPTER NINE

The Canary, 174

Box and the Red Communist, 177

The Smoke-dog, 181

CHAPTER TEN

The Best Cat, 186

“Madness” and the Owl, 190

The Hanger-on, 193

Grey on the Warpath, 196

The Thief-cat, 199

White-kitten and the Calf, 201

CHAPTER ELEVEN

The Kittens Hunt by Night, 205

The Death of Box, 208

Home-sickness, 211

CHAPTER TWELVE

The Demon Mouser, 213

Exit Red, 217

Big-kitten turns Wild Cat, 220

The Home of the Fisherman, 223

Black Joins the Army, 229

“Terror” turns House-cat, 236

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

Grey Puss’ Future, 242

[Pg 13]

Those who have been content to regard the cat merely, æsthetically, as a household ornament, economically, as a mouse-killer, or fantastically, as an adjunct of witchcraft, will doubtless read this book with some surprise. For Svend Fleuron has imagined (or observed) a cat more or less cut off from relationship with men, bringing up her kittens in the fields, against all the odds that any wild animal, surrounded by the destructive terrors of nature, has to face. If this novel were a true picture of human life, it would show, relentlessly and bitterly, how nature overcame the mother and her children. As, however, it is a picture of cat life, the end is a happy one. Grey Puss is successful in the struggle and so are all her kittens. “The other farm cats’ kittens were born in barn and loft and were drowned litter after litter—but she would see that her kittens grew to be cats.”

[Pg 14]

In spite of the complete veracity of this chronicle, I can realize the shock which the book offers to those uninformed or insensitive persons who persist in regarding the cat as a soft plaything or a decorative coward, for, without a touch of sentimentality, Fleuron has very strikingly portrayed the courage, the resourcefulness, the patience, and the independence of Grey Puss and her multicoloured brood. They are forced to battle for their food, to compete with the crow and the owl, to fight the fox; they are maltreated by the farmhands and pursued by the dog, Box; even their father makes a frustrated attempt to eat them; but they emerge triumphantly and each kitten, in his own manner, succeeds in making his way in the world. It is well to remember that the picture is not extraordinary or the case abnormal. Eighty out of every hundred cats, who grow up, make their way valiantly under similar disheartening circumstances.

Just as certain tame cats sometimes have decided to leave the hearth for the adventures of wild life, so Grey Puss, who had once[Pg 15] been a children’s pet, occasionally, in spite of rebuffs and the remembered treachery of man, hankers after domesticity, the milk-pail, the kitchen stove, and the soft warm hay in the barn. Several of her kittens, Grey, White, and Tiny, inherit this vague longing and eventually settle down in human habitations, but human beings, on the whole, play small and entirely inferior rôles in this fine novel. They seldom step across its pages and when they do appear, we see, with Grey Puss, only their feet and their legs as high as the knee. Box, the dog, a more important character in this essentially feline drama, is painted as a good-hearted, blundering brute, always in trouble, punished for following his instincts, and finally meeting his end in an aquatic encounter with the mother heroine.

The cat as wild animal has been treated in fiction before, notably by Mary E. Wilkins in The Cat, by Charles G. D. Roberts in How a Cat Played Robinson Crusoe, and by F. St. Mars in Pharaoh. These, however, are short stories with a single hero. Fleuron has employed a broader canvas. His sub-title,[Pg 16] A Family Chronicle, explains his scheme. He is writing the story of a family. It would have been easy to confuse kitten with kitten. Lesser writers in writing about cats have readily fallen into this error. Fleuron, however, paints distinct portraits of each separate puss. Each of these kittens differs from the others not alone in appearance but also in character and each is confronted with the rewards and punishments of his own vices and virtues. They emerge at the end of the book as rounded and recognizable and memorable as any of the characters in The Way of All Flesh. Striped Big, “thick-set and sturdy, with short tail, strong legs, and a back which merged smoothly into a plump round stomach; big attentive eyes with intelligence and intensity in their glance; small ears never at rest ... the master-hunter of the litter,” who becomes a wild cat in a deer park; Black, the quarrelsome, who “returned snarl and spit for kind word—and he never hit softly on the nose but scratched so that it hurt,” who battles with crows and rats, and ends his days in the barracks among[Pg 17] the soldiers; Tiny, the weather-prophet, a timorous hanger-on, who becomes the pet of a midwife; Grey, “with her quiet, thoughtful nature, who ponders carefully every step she takes,” catches fish and eventually goes to live with a fisherman; Red, juggler and hypocrite, subtle and deceitful, who wins all her triumphs by stealth; and White, a merry and friendly kitten, who makes a joke of everything; neither big nor strong, her grace and good humour serve to advance her station in life: these are Svend Fleuron’s Kittens. In the end, Grey Puss, rid, at length, of the responsibility of this particular litter, succumbs again to her prize-fighting lover, the great piebald hero, that rarety, a male tortoise-shell, wooed by the soft seduction of the dream of renewed motherhood. This, to me, is one of the most delightful episodes in the history.

Fleuron’s method is realistic and dramatic. He devotes comparatively little space to descriptions of his characters; he tells us what they do and feel and they do and feel nothing that it is impossible to imagine cats doing[Pg 18] and feeling. Human characteristics are not ascribed to them. The philosophy inherent in the book is cat philosophy rather than the author’s. All this would avail nothing, were it not obvious to any one who reads a very few pages that Fleuron has observed the animal very closely and sympathetically. Sentimentality is entirely lacking from this book, as it should be, but sympathy, we may be sure, is never very far away.

This novel, I like to believe, will please W. H. Hudson, who, abhorring the idea of “pets,” enjoys watching an animal living its own life, unrestrained. Grey Puss and her kittens forge their own destinies, create their own careers, restricted only by their respective characters and their environment. Their lives are not regulated by owners or masters. No more, it is well to remember, are those of pet cats (The Monsieur Sidi of Côte-Darly has said truly, Nous sommes des êtres libres, même dans l’esclavage), but a house-cat is accorded a certain protection which, perhaps, softens his real nature. This, then, marks the great distinction between Kittens and such a[Pg 19] cat biography as Pierre Lôti’s Vies de Deux Chattes, in which the writer very beautifully sets down an account of the lives of two of his cats: those were Lôti’s cats and in his book he describes, for the greater part, their relations with him. Grey Puss and her kittens are observed in their relations with nature. Their relations with man are recorded from their point of view rather than his. This is the new note in this very authentic cat story, authentic, at least, within the limitations the author has set himself. In much of the previous fiction involving the cat, puss has been handled quite in the manner of a Ouida duchess; Kittens is the feline Esther Waters.

Carl Van Vechten.

New York.

September 27, 1921.

[Pg 21]

The May moon is still shining white and round in the sky; but eastward beyond the hills, silhouetting a farmhouse roof, the first faint light of dawn tinges the distant horizon.... Along a hedge leading from the farm a house-cat comes creeping. At intervals it stops and casts a watchful glance behind ... then hurries on again.

The advancing day slowly spreads its wakening touch over the land. In the zenith the sky is already blue, and the stars are going to rest; but all human talk and noise is still buried in the feather-beds of the farm ... only a mighty vibrating chorus of invisible larks fills the air.

The animal is apparently quite an ordinary cat. Its small round head rests on a thick, shapely neck; the legs are short, the tail round and smooth, and the curve of the neck graceful and harmonious.

[Pg 22]

But on the underside pussy is quite bare and naked. Her stomach is distended from breast to groin like an overfilled sack. The cat has had kittens in her time; the fact cannot be denied!

The squeak of a mouse from the shadow of the hedge brings her to an abrupt halt. Her ears spring to a point and appear all at once disproportionately large, like those of a rabbit. In shape they resemble lynx ears more than a cat’s; the only thing lacking is the tuft.

The night-mists roll slowly from the valleys, revealing the green, dew-spangled blades of the fresh spring crop. Along border and hedge the wild flowers begin to clothe themselves in the sun’s variegated hues. The colours, too, in the cat’s coat begin now to be visible.

She is mouse-grey, with black stockings and white shoes. But round her breast and sides runs—like a mark of distinction—a band of rust-red fur.

Soon Grey Puss resumes her interrupted journey from the farm; the mouse has been successfully captured and eaten. At first she[Pg 23] had been tempted to play with it; but the bark of a dog from the direction of the farm brought other thoughts into her head. She no longer steals along—but runs....

At the farthest end of the hedge loom three ancient willow stumps, like monster mushrooms springing from the ground.

For more than a century they have been regularly clipped, a process which has given them weirdly distorted heads. In each of their bowl-shaped tops is ample room for a couple of men.

Black ants live in the trunks beneath, and form paths up the furrowed, moss-covered bark; on the wind-dried branches and along the withered twigs the male ants assemble in swarming-time, giving the group of ancient trees an extraordinarily lifelike appearance.

But spiders spin their webs from every knot and curve, and in them ant corpses hang thickly in bunches. In one stump a redstart has built its nest; in another, which is big and full of touchwood, grow burdocks, mugworts, and nettles.

[Pg 24]

The old willow stumps are never at rest.... Hairy, yellow-speckled willow-moths wander all over them from top to root, devouring the leaves, until, later in the summer, only the stalks are left—then they spin their cocoons, and one day rise on their soft white wings to desert the stripped, maltreated larva-trees, the ground beneath carpeted with their filth.

The central stump, the one with fat, crooked stem, is hollow right down to the bottom.

Outside the entrance to the hole—a split in the top of the head—grows a large, thick gooseberry bush, which gives shelter from the wind and rain, and serves as a perfect door. Once upon a time the bush must have flown up here as a seed; now it has developed a long, thick aerial-root which runs down inside, clinging to the wooden wall until it reaches its mouldering base.

In the thorny branches a linnet has built its circular, down-lined nest—and here the bird has been sitting fearlessly for eight days and nights without caring in the least about the[Pg 25] old grey cat, which at this very moment is squeezing its way through the narrow entrance.

A shadowy bundle at the bottom of the bole comes to life: human eyes would have taken it for a number of mouldering sausages lying among moss and touchwood.

The she-cat cautiously approaches the bundle, letting herself down backwards by the root of the gooseberry bush—at every third or fourth step uttering a low, soft miauw.

The bundle becomes conscious of her, and still half asleep, begins to move.

Now a little leg with tiny, extended claws is stretched into the air, now a sleepy, yawning head pops into sight. Then the old cat glides behind the heap and pushes herself carefully underneath.

The young ones, listening delightedly to the soft, ingratiating miauws, scent immediately the spiced milk-nipples and swarm into her embrace—with relaxed thighs she cuddles still farther beneath them. They crawl forward,[Pg 26] fumbling blindly and seeking to get hold ... and she purrs to them contentedly a long, long lullaby.

Outside, the day rises from its cloudy bed on the horizon. The stork’s cackle resounds from the farmhouse roof; the bird, emitting a volley of notes, appears simultaneously on the top of the chimney like a small black paper silhouette. Its crackling castenets wake the farmyard cocks—and now a running fire is kept up all over the village; cock-a-doodle-do, cock-a-doodle-do. Small strips of cloud which seemed before so water-logged and grey become fleecy and reddish, while the horizon is filled like a deep dish with the dazzling shafts of the rising sun.

Above the fields trills the now visible chorus of larks, and the waking cattle greet the day with subdued grunts and bellows. Linnets fly twittering through the air, and a company of peewits flap like a black, drifting cloud across the sunlit sky. Along the grass-bordered wheel-tracks the hare comes hopping, his stomach stuffed with food, his long ears straddled wide; the fellow is courting in these days[Pg 27] and has scarcely time for sleep. He squats down and stares at the big red bull, wondering where his little, light-footed hare-girl can have gone. The bull gets up and stretches himself lazily....

Now the edge of the sun appears behind the hills; the partridge whirrs and the wild ducks in the swamp sweep round in circles. Hedge and fence are thrown into sharp relief, and thin, crooked shadows from the farm trees jump up on the white gable of the house.

The horizon is on fire! It is sunrise. The kittens down in the willow stump have all found their nipples; they lift their tiny paws with joy and stretch out their little claws; they cling greedily to the old she-cat’s body and nestle warmly in the shelter of her loins.

Big, the largest, now places a forepaw on either side of his milk-spring, and pushes and pulls with all his strength, while with distended nostrils he sucks and squeezes until he gasps for breath and the milk gurgles in his throat.

Occasionally one of the kittens, its tiny tongue licking its small, pointed muzzle,[Pg 28] thrusts up a red nose for a breathing-space.

No mercy is shown! Another kitten at once seizes the still running nipple—the poor, greedy one, occupied for the moment in coughing, must be content temporarily to stand aside.

The happy little mother lies purring with delight over her maternal duties—and at intervals, when one of her little blind children utters a tiny miauw, she miauws back tenderly and consolingly.

Old Grey Puss has the sweetest cat-face possible. The chin and lower lip are white, as is also the upper lip with its shining whiskers. But above the slightly mahogany-coloured snout she seems almost to be wearing a mask. It is dead black—and gives a veiled, deceitful look to the gleaming, golden-yellow eyes.

She had been the children’s kitten; had been petted and played with and had free run of the living-rooms. She could never forget those wonderful days—and the room there—just the other side of the threshold, where no[Pg 29] hen or cock, cow or horse, not even Box himself, ever set foot—where only “humans” came. Old as she was, it still lingered in her memory.

Often during the chill of spring or the frost of winter she would see it hovering above her, dreamlike, with its endless bowls of milk and its everlasting summer.

The days of luxury had lasted little more than a month; after that the command was “Get out!” And with boot and broomstick she was ruthlessly expelled.

“Grey Puss is such a thief!” complained the housewife.... “She is always after the meat and cream on the kitchen table. Grey Puss steals ... we can’t have her in the house!”

What did she know about human laws? What were meat and cream meant for if not for a cat?... She took what she could; it was her nature.

After being expelled from the house she began to avoid people; soon the habit became second nature. From the house she was chased to the farmyard, from the farmyard to the cow-stall.... The smoke from the[Pg 30] chimney was now the only thing in sight to remind her of her childhood’s luxury.

She was often to be found of a summer morning basking in the sun outside the stall. Together with the other she-cats of the farm she lay here giving suck to a motherless kitten. They shared the child between them, and fed it alternately, listening the while for the return of the milk-cart from the fields.

Now they hear it in the distance—yes, that is old Whitefoot’s trot! And soon afterwards it rattles and bumps into the yard. All the cats’ tails rise straight in the air like trees; their legs grow quite stiff—the great event of the day is at hand.

The cart has barely stopped before they are up in it; they must immediately sniff the odour of the sweet, fresh milk.

The foreman of the dairy gives them a little in a bowl to share among them....

But the bowl is soon licked dry—and now they are on the lookout to get whatever they can.

The moment the dairyman puts aside an[Pg 31] empty pail, a cat pops in like a flash, head first, and licks it clean to the last drop; they leap up and hang by their forepaws to the dripping milk-sieve; they do anything and everything to secure a taste of the delicious milk.

They all allow the foreman to lift them up by the tail; they only straddle their legs....

“Puss, puss!” cries the good fellow affectionately as he raises them; and adds to a wondering onlooker, “They know I won’t hurt them!”

Yes, so shamelessly did they soil themselves with milk, that afterwards they spent hours and hours washing each other clean and dry.

She felt now so utterly out of touch with all that,—that she could have been a party to such goings on! To permit herself to be lifted up by the tail—and then, actually, to wash another cat’s kitten!

She still went regularly to the farm, usually in the early morning or the late evening. But she never ventured out into the open yard, and was in general very shy of showing herself. She preferred to stand up in the hayloft[Pg 32] and peep through the trap-door into the stall; but the moment she caught a glimpse of a “human” she vanished instantly.

Whenever one of the farm hands came up to fetch hay or straw for the cows and caught her unawares, she would hiss at him. Nevertheless, the foreman, who was fond of cats, always put a little milk in the loft for her; it remained invariably untouched during the day, but at night it was drunk up.

“Hanged if I know what is the matter with Grey Puss!” he often muttered to himself. “I wonder if Box has been chasing her ... she’s so scared; she’s more like a wild cat, the little fool!”

Yes, wild she had been for a long time! From the cow-stall she retreated to the loft, where she learned to hide among the beams and rafters. She got into the habit of climbing trees, walking up and down thatched roofs, and sleeping behind chimney-stacks.

And as time went on she became more and more peculiar....

She was not like the other farm cats, who let[Pg 33] their children be drowned litter after litter, without doing anything more heroic than miauw over their corpses. No, she allowed that to happen once, after which she understood that she had hidden her kittens badly! Of course they could not be expected to escape by themselves!

The next time she had young she hid them deep down under a heap of straw; but the foreman’s small boys, who always played in the loft, heard their squealing and fished them out—and then they were murdered. One only was left, overlooked in the straw.

Most other she-cats would have been grateful for the survivor and forgotten the rest. But she did not forget; she went about seeking and seeking, miauwing and complaining incessantly. Finally she took the one kitten in her mouth and carried it away to an empty dovecote in a deserted labourer’s cottage. Here it grew up without seeing a single “human.” Until one fine morning it was killed by Box....

Now, this spring, when she is once more to[Pg 34] have kittens, she hides inside the old hollow willow out here in the fields.

No living soul shall find her young this time!

[Pg 35]

In addition to Big, who was striped, there were five other kittens in the litter: a black, a white, a grey, and a red—besides an indescribable little production about the size of a man’s thumb, with fur whose colouring resembled patches of all the others put together.

Tiny lay always half smothered under the heap of kittens, and had to be content with the worst nipple, which, although nearest the mother’s heart, nevertheless flowed weakly. That he had not long ago been crushed to death by the others must remain an insoluble mystery!

The little, blind creatures were just developing their sight. The faint, subdued light here inside the willow stump made this trying period unusually agreeable. Even when the sun was shining strongly outside they could[Pg 36] lie staring about them without discomfort. Each of the tiny eyes was covered with a curious bluish film, through the damp, glazed surface of which the slanting pupils began to push their way. The eyes appeared extraordinarily large in comparison with the head, and gave the impression that the kittens were in a state of perpetual surprise.

On the whole, the babies had grown. True, their coats were not quite in order, for the fur still stuck out patchily all over their bodies; but the hair was there right enough, and the colours too ... the white was as white as day, and the black as black as night; even the cross stripes on the grey kitten showed up plainly.

Their hindquarters alone remained noticeably undeveloped; they were still quite conical and stunted, and jerked up stiffly and clumsily with every movement of the body. It would be a long time before that part attained perfection.

The imps were still far from being active and graceful! They reeled and rolled as they crawled over the lumps of touchwood; they[Pg 37] could not jump at all, indeed they could scarcely walk. It seemed as if, once having acquired eyes, they had neglected everything else. They used them incessantly ... and were never tired of looking and looking!

They had no opportunity to gormandize. They drank greedily, and soon sucked old Grey Puss dry. Then she shook them off and closed the milk-spring. This she effected by rolling herself into a ball and pressing her forepaws tightly to her breasts—and however much the little ones exerted themselves to widen the opening with their snouts so as to get inside and continue drinking, they never succeeded.

Then they had revenge by clambering up and nestling on her back and neck; where they lay licking their chops.

This sort of thing didn’t upset her in the least. In fact, she was delighted at being mauled about by her offspring; she stretched herself at full length, purring and humming the while—she knew now that they had settled down for a while.

Occasionally she blinked her tight-shut eyelids,[Pg 38] twisted her head round, and fastened her keen, brassy orbs on the long row of funny little patches of colour on her back. There was every imaginable feline colour-scheme there, and she studied each one separately, noticing any peculiarity of colouring or divergence from type....

Extraordinary.... It seemed to her that she had seen all these little fellows before!

One afternoon very early in spring a small, snow-white he-cat came strolling carelessly along the road. His ears were thrust forward, betraying his interest in something ahead: he meant to take a walk round the farm, whither the road led ... there was a grey puss there who attracted him!

He ought to have been more cautious, the little white dwarf! A giant cat, a coloured rival, with the demon of passion seething in his blood and hate flaming from his eyes, caught sight of the hare-brained fellow from afar off and straight-way guessed his errand.

With rigid legs, lowered head, and loins[Pg 39] held high, he comes rushing from behind ... runs noiselessly over the soft grass at the side of the road and overhauls the other unperceived.

With one spring he plants all his foreclaws deep in the flesh of the smaller cat, who utters a loud wail and collapses on the ground.

The big one maintains his grip on his defeated foe’s shoulder, crushing him ruthlessly in the dust. Then he presses back his torn ears, giving an even more hateful expression to the evil eyes, and lowering his muzzle, gloatingly he howls his song of victory straight into his fallen rival’s face.

For a good quarter of an hour he continues to martyr his victim, who is too terrified to move a muscle; he tears the last shred of self-respect and honour from the coward—then releases him and stalks before him to the farm, without deigning to throw him another glance. He was too despicable a rival, the little white mongrel! The big, spotted he-cat considered it beneath his dignity even to thrash him.

But the little grey puss had other suitors[Pg 40] still.... There was the squire’s ginger cat and the bailiff’s wicked old black one; so that both daring and cunning were necessary if one’s courtship was to be a success. At sunset they invaded the farm from every direction, stealing silently through corn or kitchen garden until they reached the garden path by the hedge.

The black ruffian, who considered himself the favourite suitor, arrived, as he imagined, first at the rendezvous. But simultaneously his ginger rival stuck his head through the hedge bordering the path. At sight of each other both halted abruptly, thrusting up their backs and blowing out their scarred, battle-torn cheeks.

For many minutes the two ugly fellows stood glaring silently at one another.... Then their whiskers bristled, their tattered ears disappeared, and their eyes became mere slits in their heads; hymns of hate wailed from their throats, and their tails writhed and squirmed like newly-flayed eels.

Suddenly the big, spotted cat appears in the garden. Tiger-like, with body almost[Pg 41] brushing the ground, he glides silently past them.

They hate him, the low brute!... He is their common enemy! The sight of him caught in the act makes them allies in a flash.... They tear after him and surround him. Then they go for him tooth and nail.

All thoughts of the fair one have gone from their minds. War-cries cease; gasps and grunts of exertion punctuate the struggle; chests heave and ribs dilate with compressed air; whilst naked claws are plunged into skin and flesh. They are one to look at, one circular mass, as they whirl round inextricably interlocked, puffing their reeking breath into one another’s faces.

The spotted devil’s powerful hind legs are wedged in under the red cat’s body. With his forepaws he grips him as if in a vice—and now thrusting the needle-pointed, razor-edged horn daggers from their sheaths, he straightens his hind legs simultaneously to a terrible, resistless, lacerating lunge....

With a stifled hiss of fury the squire’s cat falls back. It limps moaning from the battlefield,[Pg 42] with blood pouring from its stomach.

Now comes the old black thief’s turn! First the hair flies ... it literally steams from the two rivals as they rush at each other. Their incredible activity is expressed in every movement.... After lying interlocked for some time on the ground they suddenly break away, and, as if by witchcraft, stand on all fours again.

The piebald is winning!

His claws comb like steel rakes. They tear the hair from the bailiff-cat’s flanks, leaving them bare and shining. The latter often succeeds in parrying, and returns kick for kick, but his hind legs lack strength, and he cannot complete a full thrust.

Madness gleams in their eyes; they are beside themselves with frenzy; fear flies from their minds; they are exalted ... for now they are fighting!

Until a sudden scuffle advertises that the bailiff-cat has had enough. He tears himself loose and bolts for his life.

The big piebald has won. He shakes himself and rolls over, gives a couple of energetic[Pg 43] licks to his paws, and carefully brushes his whiskers; then he hastens through the garden up to the farmyard, where a little later he is to be seen promenading the pigsty roof.

With alert expression and nervously vibrating tail he looks inquiringly at all trap-doors and open windows. Suddenly he gives a start; there is Grey Puss on the manure-heap beneath him.

Without a moment’s hesitation he leaps down.... It was the decisive meeting!

She had always been true to this one lover.... And yet there had been times when all the gentlemen of the neighbourhood had paid court to her. Often she had reclined on the planking with one in front of her, one behind, and three or four in the elder tree above her head.... She had been literally besieged.

But however many suitors might appear—even though they came right up from the seacoast and the fishing village—she still loved him and him alone, the great piebald hero!

He was an exceptional cat: the ears, far apart and noticeably short, were set far back on the broad head; the neck was thick and[Pg 44] powerful, the body long and heavy. When he ran, he moved with such swiftness that he seemed to glide, and he could leap two yards without effort.

He was all possible colours—black, red, yellow, and white. A tinge of green shone in the wicked golden eyes; they sat deep in his head, so that his cheeks stuck out each side like dumplings.... And in the middle of his bristly moustache protruded a small lacerated nose, which was always bright red and covered with half-healed wounds. He was always at war....

Once he received a deep, horrid bite just under the throat, where he could not lick it. So he went to his sweetheart; she helped him....

She was faithful and true to him ... but she did not trust him beyond the threshold.

Had she reason to doubt him? He was chock-full of lust and vice, and great in merit as in fault; nevertheless—had she actual proof for doubting him?

[Pg 45]

One night her eyes were opened in the most sinister manner. The last rays of the setting sun had departed from the fields, leaving them wrapped in the summer evening’s mist and obscurity. Only some horses greeted the solitary nocturnal marauder with warm, friendly neighing.

They knew him well, although he was only a cat, whose many-coloured body seemed grey, like all other cats, in the twilight. In doorway, at the pump, in yard, and in stable he was their daily companion. How nice to see him here on the meadow too! “Ehehehe,” they neighed ... welcome to the tethering-ground!

He ignored them completely, neither breaking his stride, nor wagging his tail, nor giving a single miauw. Past nuisances like foals which greeted him boisterously he went unresponsive and bored. He was out hunting now—nothing else mattered!

With gliding step he passes from clover field to seed ground, jumping with noiseless, tense spring over brook and ditch. His progress roused the lark from heavy slumber.

[Pg 46]

He reaches a copse—and soon afterward is heard the death-shriek of a captured blackbird. With covetous grasp he seizes his victim, buries his sharp teeth in its breast, and sucks with long sniffs the warm, odorous bird-smell....

It was not hunger which drove him to the crime: he has just made a full meal off a couple of fat mice. But when coming unexpectedly upon the bird in the copse, he could not control his murderous impulse.

He sits with the booty in his jaws, purring contentedly, and ponders frowningly where he shall conceal his capture.

The summer moon shines big and round from the pale blue, starless sky—and white, pink-underlined layers of cloud hover like feathers far out on the horizon. Warm puffs of wind come and go, enveloping him in the meadow’s silver mist, making the dim shelter of the hedge seem hot and oppressive.

His eyes fall on the three ancient willow stumps at the far end of the field! He, too, knows how rotten and hollow they are, and how well adapted for a hiding-place. True,[Pg 47] it is rather a long way there ... through the soaking wet rye—but that can’t be helped!

The night is absolutely silent, broken only by the rasping song of the little reed-warbler from a swampy hole among the rye. The din of the farm has long since died down; not even the bark of a dog is heard, and neither water-pump nor wind-motor can summon up another note. How splendid to have ears, to be able to listen! Now he hears only the play of the grasshoppers, the love-song of the cock-chafer, and the high-pitched music of the ant-hills.

Here, behind a knotted root at the base of the largest of the old willow trees, he conceals the blackbird, afterwards covering it carefully with earth and moss. Then he reaches his forepaws up to the trunk to stretch his limbs and sharpen his claws.

He gives a violent start! The scarred, rugged skin on his head wrinkles thoughtfully, as it always does when something attracts his attention. His multicoloured tail jerks uneasily, as he peers about him with uplifted ears.

[Pg 48]

The subdued rustling and squeaking noises from inside the tree trunk continue....

Now there is no longer room for doubt....

With a giant leap he springs up the tree, and next moment he is down in the bole.

Grey Puss is not at home....

The little kittens swarm up to him. Tiny seeks to drink, while Black and Big make a joyful assault on his swiftly wagging tail. He lowers his nose to each of the little fellows in turn as if tasting their smell. Then, as if suddenly gone mad, he begins clawing about in all directions at the defenceless kittens. Mewing and squealing, they roll away to all sides like lumps of earth—but the he-cat’s frenzy increases.

He seizes Tiny by the mouth, fixes an eyetooth in his scruff and hurtles out of the willow with him. The little tot hangs limp and apparently lifeless in the jaw of his brutal sire; but, fortunately for him, the old cat is not hungry, and so is content with burying the kitten at the foot of the willow, by the side of the dead blackbird.

In justice to the criminal it must be stated[Pg 49] that he has no conception of the enormity of his crime; only when he is on his way up the willow for the second time is he enlightened—and that in a most ruthless manner. Two rows of gimlet-pointed claws descend from nowhere and almost nail him to the bark.... Furious, he turns his visage ... and the next second all his old half-healed wounds are torn open again!

Grey Puss has surprised him—and recognizes him instantly. So it is he who comes wrecking her maternal happiness; yes, she thought as much! And like a vice she clings to his back, biting and scratching and tearing as he flees panic-stricken along the hedge.

Away, away, home, anywhere!

He is more afraid of Grey Puss’ mother-claws than of the raven’s beak or the blade of the reaping-machine; he has learnt to his cost that a she-cat knows not the word mercy when her swollen udders are carrying milk for her young.

He lacked a conscience, this big, piebald he-cat—and he respected nothing except his own skin! The egg of the lark, the chick of[Pg 50] the partridge, the young of the hare, were each and all grist to his mill; he took everything he could find, catch, or steal.

On the rafter at home in the farmyard, where Grey Puss used to lie, he had been allowed free passage, until the very moment when some small bundles lay shivering on the hay in the corner. Then the fascination of his black face and shining coat seemed to vanish; she would not allow him to approach; he was not even admitted to the barn. If he just showed himself at the trap-door she would become seized with frenzy, spring up, and fly at him as if he were a dog! He had always to beat a hurried retreat!

Did she read his character; did she know that the feeling of paternal love was foreign to his nature? In any case, she took no risks; she never trusted him over the threshold....

Grey Puss’ milk tasted sour for a whole day following the adventure; she was frightfully restless and upset. Several of the young ones had wounds and had to be licked. Time after[Pg 51] time she ran her glance over the small, rolled-up patches of colour; greedily her eyes devoured each little furry coat; but it was with no trace of the sweetness of recollection or the joy of recognition.

Were they all there ... all? Their villain of a father she had already forgotten; not until she was giving suck did she become suddenly nervous. She felt that one of the swollen udders remained swollen, and now she nuzzled with her nose along the row. Big, Red, White, Grey ... yes, she found them all! But where was the little piebald one?...

The kittens buried their noses deep in her fur to get a good hold of the small, sprouting milk-springs. All was quiet inside the willow trunk; only now and again was heard the sucking of the eager little lips....

Yes, to be sure, she missed a colour ... missed just that one which—in spite of all—she unconsciously preferred to all the rest; that seemed made up of bits of colour from all the other colours.... Then suddenly a thin, feeble crying reached her ever-listening ears.[Pg 52] It seemed to her to come from under the willow bole. Perhaps there was a crevice in the nursery?

Cautiously getting up, she begins to scratch a little with her forepaws in the floor; but finds no hole.

She dismisses the thought that one of the young ones is really missing, and lies down again and resumes her maternal duties. For a time all is peace, and she abandons herself completely to the pleasure of being at the mercy of her kitten flock, but again comes the faint cry for help. This time it is so heart-rending that she springs up, and then, half crouching, listens breathlessly.

“Mew, mew!” it tinkles to her from the distant depths. And now she begins to answer in anxious, encouraging tones, meanwhile pushing her snout among the young ones to count them. The tinkling from below upsets and worries her; but presently she stifles her anxiety by rolling right under the heap of kittens and congratulating herself that she has so many dear children safe and sound.

Meanwhile from his living tomb by the side[Pg 53] of the dead blackbird, Tiny continues foghornlike, to emit at regular intervals his ceaseless signals for assistance. He has lain for a long time buried alive; but, accustomed as he is to having his brothers and sisters on top of him, the thin layer of moss and earth over him does not embarrass him particularly. Now he has recovered so much that he can not only squeal but wriggle also—a fact which serves to increase the air supply in his lungs, so that his weak cries gain momentarily in strength and resonance.

Suddenly the heap of earth is swept from him, and he hears his mother’s soft voice right in his ear. Oh, what a stream of happiness flows through him! He stretches his tiny body towards the strong, comforting miauw, and like a freezing man making for the fire, he puts his wet, earth-cold head against the mother-cat’s soft neck and feels her warm breath ripple over him.

Grey Puss’ eyes shine green and evil; they speak plainly of surprise and emotion. She begins purring angrily, so that the young ones inside the tree lift their ears anxiously and[Pg 54] wonder, “What’s happening down there at the foot of the tree?”

Tiny’s wound is licked, and the mother prepares to return. He must be carried, of course, ... and the problem is to find a hold which will not destroy the creature. She tries to grasp him by the scruff, but here he is so sore that time after time the attempt fails. Cautiously she presses her teeth into his back and shoulder; but cannot find a hold, although he seeks instinctively to help her by stiffening his body as she lifts.

However, it must be done somehow; there is not the slightest doubt that he is to be carried up! So she opens her mouth wide and puts her jaws round his neck. Then, disregarding his lively protests, she cautiously closes her mouth.

He becomes suddenly quite quiet. She needs all her presence of mind to judge how tightly she may grip him without making it his last journey.

He hangs there in his mother’s jaws and closes his earth-clogged eyes, clutching her[Pg 55] body tightly with his little legs. But he surrenders himself to her without complaint and without movement, bearing the pain in blind faith in her omnipotence.

In two jumps she reaches the top, slides down into the bole, and a moment later deposits him carefully on the ground among the others. A healing warmth envelops him—and, as the kittens are already satisfied, he secures an unusually large share of milk.

Truly that morning the kittens had trembled in the shadow of death!

And Grey Puss always regarded the he-cat as the first betrayer, the cause of all her subsequent sorrows and misfortunes.

Only a week later a farm hand saw her as she sneaked into the willow. Putting his ear against the trunk, he heard the kittens stirring, and so, hanging his hat and coat on a branch, he ran home to the farm to fetch the dog....

Box was not to be found; and not till the midday meal did he get hold of him—and[Pg 56] when at last the fellow returned to stamp out the “vermin,” the trunk was deserted and empty.

He explored the neighbouring fields. The dog found the scent at once and gave tongue—then deep among the corn was fought a terrific battle. The dog’s barks turned to howls, and soon afterwards Box returned as if shot from a cannon, with his tail-stump curled between his legs.

[Pg 57]

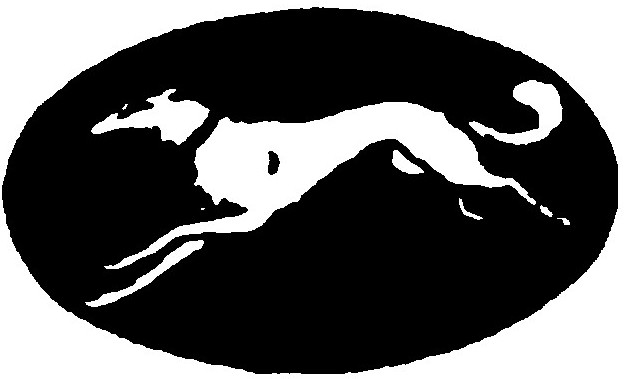

She came to a mound which rose, peaceful and untrodden, in the middle of the field. On every side of it corn was growing, but the mound itself was green with grass and smothered in wild flowers: sorrel and heather grew side by side with the bright yellow calyx of the dandelion. A border of blackthorn wreathed the base of the mound, and a pair of great moss-covered boulders crowned the top.

Grey Puss sat down on one of the stones and stared out disconsolately over the landscape, whose colours were just retiring for their nightly rest.

Half unconsciously, she began to scratch among some tufts of grass and dried leaves which covered a depression in the turf; they came away very easily. She noticed how[Pg 58] quickly she delved deeper and deeper down.

She became thoroughly interested....

She had happened upon an old, thinly-covered fox-hole, and when at last she had cleared the entrance, a narrow spiral passage lay open before her. She was accustomed to darkness; and happy at the possibility of finding a new home for her kittens, she bravely entered the opening.

After a short distance the tunnel made an abrupt turn, continued downwards in a curve over some enormous boulders—and then plunged straight into the vault.

Huge boulders with half-hewn surfaces stood as if growing from the ground. Above them were others of a similar kind, the walls continuing in an unbroken curve until they met at the top, thus forming the solid vaulted roof of the sepulchre. In the splits were wedged smaller stones, the whole making a small square chamber.

Had body-snatchers at some time desecrated this grave? Or perhaps some lawful visitor on his departure centuries before had neglected to close it properly behind him! In[Pg 59] either case one of the corner stones was displaced; so much so that a fox had continued his burrow right into the very burial-chamber.

A gruesome place of death even for a cat to happen upon!

A weird, vicious, humming noise greeted her the moment she thrust in her nose ... a fluttering of something that was, and yet was not, surrounded her and filled her ears, nose, and mouth, making her cough and spit.

Had she been a human being she would have been horrified, and imagined it to be the ghost of the dead sounding her doom for disturbing its peace; but she was only a cat, and knew nothing of the beyond.

As she jumped down into the vault, and in so doing brushed the wall with her tail, the din about her head reached its climax: hundreds of mosquitoes and bats inhabiting the grave protested vigorously against her entrance.

She stood for a moment undecided, taking stock of her surroundings....

The floor was firm, and as hard and uneven as a threshing-floor. A hollow echo vibrated[Pg 60] through the air at her every movement, the hissing of her breath or the grating of her claws.

Just before the sun went down, a thin ray of light filtered through a crevice in the stones opposite the tunnel. Thousands of tiny points of light, the watchful eyes of the denizens of the tomb, leaped into being.

Otherwise the shadows prevailed, and were only conquered little by little by her piercing glance. Later she distinguished fragments of bones and skulls on the ground, and saw supine toads fumbling their way along the walls.

In some inexplicable manner a heap of elm leaves had found their way into one of the corners; they crackled and shrieked “Halt!” when she trod on them, but promised, nevertheless, a warm and dry couch.

The conditions were acceptable—besides, there was no alternative! As soon, therefore, as she had remained there long enough to feel at ease, she made her decision.

Here in the old viking’s tomb she made her home. On the leaves and fragments of straw[Pg 61] she dropped her kittens, fetching them one by one from their various hiding-places in furrows and behind stones, where she had been forced to harbour them in her headlong flight from the old willow stump.

The fugitive little mother-cat had brought her kittens under cover just in time. That night a storm broke loose and thunder crashed incessantly, accompanying heavy showers of rain. Warm, heavy drops streamed down in bucketfuls; the earth drank until the crevices in its broken crust were filled to overflowing, while a slimy, bottomless fluid filled all holes in the roads.

But not a drop found its way down to this century-old sepulchre—the resting-place was too well built for that!

Towards morning the tempest died down. The June sun slowly swept the warm, bluish haze from the landscape, and poured its white shining beams over the fertile green cornfields. Strong, delicious odours, held in bondage by the mist, are suddenly released,[Pg 62] and float through the air in small, scented clouds.

It was too wet for a cat to venture out; better wait a little and let the sun dry things a bit!

In the farthest corner, where the darkness is deepest, Grey Puss is sitting. She relaxes her muscular body completely on the leafy couch, and stretches her forepaws lazily in front of her. The entire kitten flock is lying in her lap.

Since daybreak she has had such a nice quiet time; the others have all been sleeping soundly, tumbled in a heap. But now peace is at an end; the dear children are all awake, and almost killing her in their exuberant joy.

Not even Tiny spares her, but seizes the opportunity of pursuing the exhausted milk-springs. Lying on his back, and using his hind legs as levers, he toboggans in short slides from one nipple to another. It couldn’t be true that there was not a drop left!

From the playful horde arise hissing and spitting, punctuated by occasional dull bumps as they miss their footing and tumble on the[Pg 63] floor. All at once Grey Puss gets up from her corner, walks out into the middle, and throws herself down in the thin streak of light which fumbles its way through the roof. Look out—now she is going to play their favourite game; now they are in for a treat! They shall play “catch mouse” with the tip of her tail.

Comfortably stretched on her back with all four legs wide apart, she lies perfectly still, not moving a limb, not a hair. Presently the end-most tip of her tail begins very, very slowly to wriggle to and fro; then it falls with a firm little thump on the floor.

It is the signal for the game to begin!

Immediately the tiny, living colours surround the tail. And in turn, usually two at a time, they make their attempts.

The supple tail-end writhes and squirms at lightning speed over the floor, the kittens’ eyes following its twists and bends in fascinated silence. Suddenly it disappears from sight; there is a breathless pause ... then the furry tip slowly emerges from under the heap of leaves. They strike at it with their paws,[Pg 64] rush at it, catch hold of it, and—if it unfortunately escapes—rush upon it again. They bite it, clutch it, shake it.... At last they have secured a firm grip. The tables are suddenly turned! Now it is the tail which grips and shakes and rocks them to and fro in the air; they are fighting with a real, live, reckless enemy of equal strength, and are permitted to experience the joy of victory.

No spitting or growling is heard; all takes place in dead silence—only the smacks of the tail and the bumps of the paws betray the presence of living beings. They are like shadows tumbling about....

The game goes on in half-hour spells—until exhaustion overtakes first one, then another, and sleep again sweeps them together into a lifeless heap.

Now Grey Puss gets up and makes for the entrance—it is her turn to play “catch mouse.”

Several weeks pass happily....

The corn round the burial-mound ripens, and all sorts of grasses compete to lengthen its[Pg 65] luxuriant green covering. The stones on the top become more and more hidden from the field-path below.

The lark comes and trills at sunrise and midday; and in the evening the whinchat twitters its mournful song. The little, low grass mound has not yet betrayed its secret....

The kittens in its bowels are now about twice the size of moles; their bodies have become a trifle longer and more elastic, and on their short, plump hindquarters the worm-like appendages of childhood are beginning to thicken into soft, furry tails. Their eyes shine like stars, and on each of the small, bullet-shaped heads a little wrinkled snout forms a centre for a bunch of stiff, shiny whiskers. It is about time, the old cat thinks, that they begin to take solid food.

At first she brings them eggs and unfledged birds, which their baby jaws soon learn to masticate. Later on their diet becomes coarser and more varied.

Early one morning she appears with a small, greyish-brown creature in her jaws, its[Pg 66] white stomach shining like a puddle of water reflecting the sun. Its short, little forepaws with the pink claws hang limp in surrender, and its long hind legs stick out stiffly like stilts. A thin, hairless tail dangling like a broken straw completes the picture.

The kittens at once respond to their mother’s food-signal, and, falling over one another in their eagerness, rush headlong to the entrance.

With their small behinds stiffly elevated, they rub themselves affectionately against the old cat’s legs and body; she positively disappears in a forest of tails. Purring loudly, her head erect, she remains standing before them, turning and twisting the interesting creature to give them a full view of the spoil.

At last, after what seems an endless wait, each receives his mouthful.

Big crouches on his haunches and plays delightedly with the mouse’s tail, which he holds in his paws. When, at a smack from him, it gives a jump, his eyes glow and he hops round his new toy on his hind legs. Suddenly he runs away to a corner and begins[Pg 67] digging a hole—Grey Puss sees that he has his father’s appetite!

The first few times she herself kills the mouse with a bite, but later on the young ones are permitted to share in the fun. Soon also she allows them to play a little with the unfortunates, so that they may learn the first principles in the art of trapping. To encourage them still further to forage for themselves, she buries her victims round about the base of the burial-mound.

The struggle for food has left its mark upon the little mother-cat. She has become noticeably thinner, and her coat no longer has its glossy sheen. The crowd of rapidly growing children, who make constantly increasing demands on her skill, is telling on her strength. It is almost impossible for her to secure all the mice necessary for them—and therefore, in her dilemma, she sometimes leaves the straight path of virtue and does what second nature urges her.

One day about noon she is skirmishing in the neighbourhood of the farm.

[Pg 68]

She lies hidden in the grass, her head in the air, keeping sharp look out for booty. In each of the pancake-coloured orbs lies a vivid coal-black streak which divides the pancake into two halves. Cunning and deceit stream from her eyes.

Behind the garden hedge bordering the loose, dry, potato-planted earth a farm hen clucks her thirteen chicks together. The hen has just finished an exhaustive scratching of the soil—and now is taking a simultaneous sun and sand bath, lying luxuriously with widespread wings, her plump, featherless belly fully exposed. The hen is asleep—her head, with its anæmic comb, sticks up stiffly in the air. Her eyes are fast shut.

The wind carries to Grey Puss fragments of dear, home-like sounds; but they do not, as in former times, soothe her nerves. On the contrary, they rouse and excite her with the promise of food. She creeps nearer and nearer in short bursts towards the sleeping hen. Each time she stops to listen—but hears only the chicks enjoying life: her blood races.

Is it tame, that one sitting there? She has[Pg 69] forgotten; she no longer distinguishes between tame and wild! She distinguishes only between what is good, and what is not good, for her children to eat.

The soft, pregnant signs of June meet her eyes on every side. Between fresh green oatfields and succulent clover-carpets the rye whitens and blackens. There along the hedge by the old willows the line of cattle stretches; and down in the meadow, where calves and foals play in their pens, the long-nosed stork walks sunning himself.

The heavy-laden milk-cart drags itself through the stifling noon homeward to the farm. In front of it two red-cheeked, heavy-bosomed girls are seated; an old cow follows tottering behind.

Grey Puss’ opportunity has come—she makes a lightning spring forward....

With a resounding “cluck” the hen jumps up, puffs out her feathers and spreads wide her wings. Her anxious cry of alarm rings over the potato-field, whither she rushes feverishly to collect and protect her children. Grey Puss with a plump young cock in her[Pg 70] jaws disappears with a mighty spring among the rye.

A quarter of an hour later she emerges from the hawthorn clump at the base of the burial-mound. The swallows are making their sweeping curves round about the top, veering and shrieking incessantly—there must be something up there to attract their attention!

The furry inhabitants of the mound, who have been lying in a group sunning themselves, see the old cat approach, dragging the great chicken after her; she holds it by the neck, its body and long, naked legs hanging limp and pitiful to either side.

Big, the glutton, at once seizes hold of a wing, and, with closed eyes, grinds and tears the soft-stemmed feathers, making a great deal of noise about it.

Big’s assault causes the chicken to swing towards him; at this, Black begins to feel nervous about his share of the spoil—with a jump he runs forward and hangs tightly to one of the legs.

With flattened ears and wide-stretched paws Black tugs with all his might. His[Pg 71] neck is stretched forward and the front part of his body raised, but his stomach and hind legs drag along the ground. He resists strenuously and takes a firm hold—he will take care that Big doesn’t steal all the spoil; or if he does, then he must pull him along too!

Grey Puss has let go her hold of the neck and now stands with the chicken’s head in her mouth; she also will make certain of something—and she likes the head best of all.

Now the remaining kittens come forward. Grey buries her little black muzzle in the chicken’s body-feathers. Following her custom, she goes very cautiously to work, and sniffs for a long time before taking hold. But Red, who is more impetuous, digs away with her foreclaws, trying to make a hole as quickly as possible; and, having at last succeeded, she—eagerly assisted by White and Tiny—pulls out endless lengths of warm intestines.

Chicken after chicken kept vanishing from the farmyard ... mysteriously ... without trace.

[Pg 72]

The farmer’s precious racing-pigeons also disappeared, stolen, one by one, in broad daylight. Some of their feathers were found by the fence—it was there that Grey Puss lay in ambush, and fell upon the birds before they had time to rise in the air.

They kept watch for her early and late—and the farmer often did sentry duty half the day with loaded gun; he would settle her, sure enough....

But she was cunning and cautious—and the hours of vigil too long for the farmer! So they decided to set a trap.

She walked straight into it! That was not surprising, for she was completely without experience of traps.

There she was; at last they had the criminal!

“The grey she-cat! Yes, I thought as much!” shouted the farmer, swearing.... Yes, he remembered that gourmand well!

It was she who ate only the heads of rats. And once, two years ago, she had been found with a chicken in her jaws. She would have been shot there and then, had not the foreman sworn that the chicken was dead before she[Pg 73] found it. Well, now at last they knew the truth—the beast must be drowned!

Grey Puss suspected no evil when she was taken to the scullery, which she knew so well, and released from the trap. Furthermore, thirsty and ravenous as she was, she accepted their hospitality in the form of a large bowl of milk.... They thought she should have something in reserve for her long journey.

She sat down, cat-like, with her tail curled round her behind, and in a moment of weakness allowed her former friend, the foreman, to stroke her back.

Just as she was finishing and was contentedly licking her mouth, stiff, horny fingers grabbed her and picked her up as if she had been a kitten. Other fingers opened a black abyss beneath her—and, with Box yelling and leaping round her, she was thrust quickly into a sack.

For the first time she began to suspect something wrong. She struggled violently and clutched with her claws—but down she went nevertheless.

She scratches madly at the sack.... Her[Pg 74] twenty crescent-shaped claws stick out through the canvas in white clusters. However much they shake she won’t go to the bottom, but remains obstinately clinging half-way up the side. It dawns suddenly upon her that the humans have deceived her by their unusual kindness; now at last is confirmed what she has so often suspected, that humans, when they try, can be even more cunning than she.

All is pitch-black around her.... Her pupils contract, and her sight, which has always served her so well, now works a veritable miracle: she sees right through the canvas, sees clearly the gleam of water appear beneath her.

When they swing her to and fro, in just the same way as the wind has so often swung her in the treetop, it becomes more difficult to see; everything grows dark again.

Suddenly she is falling ... yes, she feels at once that she is falling! She clings even more frantically to the side of the sack.

But the sack is falling too! She withdraws her claws from the canvas and holds out her paws ready to land, just as she used to do in[Pg 75] the old days when she was kicked through the trap-door in the loft. Suddenly she feels something hard and cold touch her.... She is not alone in the sack—she has a comrade!

The comrade is a brick....

The next moment she reaches the water! An ice-cold shower streams in on her, with a smell so horrible that she quite forgets to shiver. She is on the point of suffocation, and leaps up and down the sides of the sack like a fly in a bottle....

The sack is a new one. It has been sacrificed specially for her; they don’t want to see her again! But just as the canvas has hitherto defied her claws, so, to a certain degree, it defies the water; she still finds a little air to breathe, in her mad death-dance in the dark....

All the time she tears at the sack.... She is lucky, and makes an opening in the seam. She struggles through, comes to the surface, sucks in air, sees land, and paddles hurriedly to the bank.

The farm hand who was sent to drown Grey Puss obeyed the order much against his will.[Pg 76] He had been a sailor in his younger days, and knew what a lingering torture death by drowning was.

Why were land-crabs always so keen on this way of ending life? Because mankind had a natural tendency towards cowardice and laziness, he supposed. To smash a cat’s skull or put a bullet through a dog’s brain demands an effort—besides, it was unpleasant to see the expression in the victim’s eyes! No, it was so much easier to drown the thing....

“I’ll be hanged if this isn’t the last time!” said the man shamefacedly, as he watched the sack disappear from sight; and immediately swung round on his heel and walked away.

So that no one saw the little head which pushed its way breathlessly through the green duck-weed; nor the thin, bedraggled body which a few moments later stood shaking itself dry among the weeds.

Grey Puss went straight home to her kittens, and that by the main road.

No sneaking along the ditches or crawling[Pg 77] through the furrows, as so often before when dragging her spoil. No, to-day she came empty-handed, alas! besides being battered and breathless. She ran with all her might!

A great reception awaited her.

A whole long night and the half of a day she had been away—what a relief when she appears; thank goodness she has come back at last!

Big, the strong man of the litter, rushes ecstatically to meet her, and flings both paws round her neck, dragging her tired, wet head from side to side until he nearly kills her with joy. The other kittens run straight to her udders, each trying to drink the most milk in the shortest time.

Quite bewildered, but without further thought of her experience, Grey Puss sits down and gathers the little kittens in her arms, while Big, filled with holy zeal, begins licking her wet black and damp, bedraggled coat with his tongue.

It is true that as a rule a cat washes her kitten, but with Grey Puss things are reversed: Big makes his mother’s toilet daily—and is,[Pg 78] moreover, so generous with his tongue that he washes all the kittens too.

And now on this occasion, when his kind mamma—besides arriving depressed and without her customary miauw-signal—has come home soaking wet, the son’s energy knows no bounds.

Unfortunately, although going over her twice, he finishes washing his mother before the children have completed their drinking operations; and so is compelled to find another outlet for his exuberance. He rushes round and round the room at full speed....

The fact of the whole family being in his path does not deter him in the least. He jumps recklessly into their midst, and “takes off” again with a long jump from his mother’s forehead.

Later, upon making the discovery that two of the little ones have become separated from the rest, he thinks at once of something new: he plays “catch mouse” with them....

In a flash he has captured Black under one paw and White under the other, and holds them pressed down ruthlessly to the ground.[Pg 79] Black spits and bites recklessly at his captor, but the good-natured little White only cries miserably. A moment later Big gets a good box on the ears from the old cat’s paw.

He was so very robust—just like his father!

After that day Grey Puss never dared venture into the farmyard, not even by night; she considered herself banished once for all....

She became a total outcast, spitting and swearing at man’s approach. “Fiew!” she would hiss, crouching back, as if pulled from behind; and then turn and vanish in a flash.

She forgot her happy days of kittenhood and went back to nature and independence, her claws turned against every living being.

It was not an easy path she had chosen. The work of catching and killing at times entailed almost insuperable difficulties.

After all, what wild-beast attributes were needed to capture a little half-tame mouse or pigeon in a barn; to sneak in and lick up milk from the stall; to dig out bloater-heads from the manure-heap? No, now she had to begin all over again and practise the most[Pg 80] elementary things: to creep noiselessly forward, make her spring, and disappear like lightning.

She adopted the method the retriever employs to carry small birds, and applied it to mice. As soon as the rodents were caught and killed, she arranged them in a row on the ground; and then packed them side by side in her mouth, so that only the heads and tails hung out.

One morning she took a hare home to the young ones, and, a few days later, a full-grown weasel—tangible proofs that she had learnt now to overpower and kill the most refractory opponents.

After a short time she learned even to bring down the swallow as it swept with dazzling speed over the earth.

[Pg 81]

On the top of the mound the kittens are playing, in and out among the old tombstones.

The sun has risen. It shines in long, golden stripes on the stones and lights up the deep, gloomy sepulchre; pools of water glisten, and fields and meadows are already green-white with light.

Big sits on his haunches with a clover stem in his claws. He looks as if he is studying the flower, while at the same time he nips off the leaves one by one with his sharp little teeth. The others watch him, gaping with astonishment.

Suddenly he throws the stalk away and leaps over the heads of the others.... One of the granite stones at that moment reflects the sun and attracts his attention; he can never look at a stone without at once making[Pg 82] a dash to reach the other side of it and hide. His disappearance is so provoking that a couple of the others cannot resist jumping up and joining in the game.

They gallop after him, and now they play hide-and-seek round the stones, until Big takes advantage of his long start and climbs into an old empty pail in an adjacent thicket. His playmates run about all over the place looking for him....

Shortly afterwards the jester’s white socks peep over the edge of the pail; a pair of yellow-grey ear-tips follow—and now springs into sight a happy, laughing cat-face!

Black’s claws begin to itch; he wants very much to play, but in his own manner. He has been up to the clover stem and smelt it carefully; he has also taken it between his paws, but thrown it away contemptuously. A plant stem, a mere flower, seems to him quite useless; a thistle, on the contrary, which pricks his nose when he smells it is much more exciting. He can at any rate get angry with it.

Suddenly he sees Red and Big engaged in[Pg 83] an angry wrestling match, while White and Grey stalk them from opposite sides.

With a spring he is upon them; flings himself first upon White, turns her head over heels, and then falls upon Grey. In a furry, fighting ball they roll over and over down the hill....

Grey gets on top, and Black suddenly realizes that he is getting the worst of things. He at once brings his hind legs into play and claws his adversary’s stomach and nose mercilessly—in real earnest with naked claws!

Grey wails miserably, and at the sound the whole flock comes rushing forward with joyous recklessness. But Black does not wait for the assault; with doubled-up body and curved tail, he stalks sideways towards them. They expect him to jump, but instead he sticks his claws right into their eyes.

But the battle is too unequal; Black has to retreat hurriedly. He flees to the top of a small aspen, creeps out along one of its upper branches, and from there jumps into the hawthorn thicket encircling the base of the hill. He does not stop even there, but continues his[Pg 84] flight through the thicket all the way round the hill. Every thorn that pricks him teases him and fills him with delight. He crawls from branch to branch like a great black caterpillar, while the others, who have long since forgotten all about him, go on with their game.

The rays of the morning sun sweep gleaming over the fields; the barley shines like spun silk, the oats like molten silver, while lake and pond and pit lie like mirrors. The buzzing of flies and the humming of bees rise incessantly into the hot, motionless air; above the burial mound the gnats dance in a swarm. The air is filled with sounds: the sweet trilling of the larks; the snorting of the harnessed horse from the road; the bleating of calves and the rattling of pails from the distant farm....

A halt has been called in the game; the tired kittens are resting.... Grey and Red, who had got the worst knocks, sulk together with their tails encircling their little round behinds.

[Pg 85]

Then Big Puss gets up.... The others half raise their sleepy eyelids; what on earth is he going to do now?

With the side of his paw he begins softly patting a little lump on the ground; the loose mould slides forward and the bump collapses.

At this he goes suddenly mad with excitement. Holding his forepaws stiffly in front of him, he leaps forward, like a monkey on a stick, in a series of jumps, at each plunge pushing up a little mouse-grey cushion of sand, which he simultaneously flings behind him with the backward sweep of his paws.

His brothers and sisters are now thoroughly roused; their eyes, which but a short time before were dull and bored, shine eagerly, their curled-up backs straighten out, and their paws are held stick-like in front of them, ready for the new, fascinating game.

He really is an Edison-cat, is Big Puss! There they had all been sitting bored to death, and now ... now he comes and makes grey mice spring up out of the ground and then disappear again! They must try the new game at once....

[Pg 86]

The next moment the six little splashes of colour are again rushing round like mad.... Even Black has jumped down from his branch to the ground, where he is soon busily engaged in crouching and leaping, creating and destroying the new little, maddening, earth-born mice. A splendid game for little pussy-cats!

The midday sun pours its hot breath down upon the earth; the air quivers out there above the fields as if boiling. The sand and stones are burning hot....

But the grass shines smilingly back at the sun, and the rye bursts into flower.

The kittens lift their heads as they hear a rustling in the corn: along the secret path which has gradually formed itself, Grey Puss returns home with her catch.

Not chicken for dinner to-day, but—herring! The fishmonger’s cart upset last night at the turn of the road, and dropped a box of splendid fresh herrings. Grey Puss, who had stuffed herself to bursting-point on the spot and dug down half a score besides, appears now with a couple hanging out of her mouth.

[Pg 87]

At first this new kind of food is greeted with contempt; it is cold and slimy—and doesn’t smell! But when the mother starts munching, the young ones soon follow her example, and join in the feast.

Delicious food! After the first taste each of them grabs a big lump; even Tiny, who has never taken kindly to solid diet, displays unusual eagerness. He devours not only his own share, but in addition, is foolhardy enough to covet some of Black’s.

Then, for the first time in his sheltered life, the little kitten sees the furious, grinning face, and the flattened, pressed-back ears, of an angry cat. And when, in spite of these, he continues innocently to reach in under the head, and is even lucky enough to pull out a piece of herring, down flashes a vicious forepaw, and he feels the scratch of a sharp, curved claw upon his tender nose.

Tears of pain spring to his eyes as he recoils, mewing piteously; while Black resumes his meal, emitting at intervals weird, muffled noises like threatening thunder.

[Pg 88]

As soon as the after-dinner siesta was at an end, Grey Puss, contrary to custom, called her kittens together with soft, alluring miauws, and took them for the first time along the secret, winding path she had trodden through the corn.

In the baking sunshine, while the countryside was enjoying its Sabbath-day’s rest from toil, she led them out to a large, sweet-smelling haystack. Farther they were not allowed to follow her.

She placed them in a hollow, which she made deep and roomy, at the foot of the stack. It was as if she understood that they needed to see something fresh and for a time get right away from their gloomy grave-home. They spent the afternoon lying together in the sweet yielding hay.... Presently the babies fell asleep, and Grey Puss stole away.

Oh, the luxury of lying at rest on a summer day, dozing in the soft, warm breeze as it sighs between hill and dale; to escape for once from one’s tail and the never-ceasing crawling[Pg 89] of one’s paws; to float body and soul along a broad, shining river of light and not know a single want or care!

The whisper of the reeds from the pond, the song of the larks from the heavens, the whistle of the wild chervil stems, and the rustle of the osier leaves, unite in a hymn of peace, caressing and soothing the slumberers’ ears—until the booming of a passing bee calls them back to consciousness for two long, drowsy seconds....

“Ears—must you hear? Eyes—must you see? Nose—must you smell?”

“No, no—just rest, slumber, sleep....”

The fluff of the dandelion floats slowly past; over them chases the swift, scythe-winged swallow; while the lark’s eternal, monotonous song slowly mends the thread broken by the kittens when they fell asleep.

They wake; glide imperceptibly from the far into the near; yawn and stretch each limb; and finally open their eyes, saturated with the sweetness of that kind of repose which urges instant action.

The heat of the sun toasts them until their[Pg 90] fur sparkles.... They get up and look at once for something to do.

Not far from the stack was a large liquid-manure well with a rotten, worm-eaten lid.

In places the lid dipped dangerously; it was a wretched bridge over a dangerous well—but it could bear a little kitten’s weight, surely?

Flies gathered in masses on the sun-baked lid, forming black, restless shadows on its tarred-felt covering. Big-kitten saw at once that they offered sport. And he soon found it just as nice to eat them as it was exciting to catch them.

He had not been at it long before the others followed suit. But no one could compete with him in accuracy; he displayed at once the master hand....

Sitting quietly on his tail, he brought down his paw with unerring accuracy, as if it were the most natural thing in the world, upon every fly that ventured within range.

White, wishing to emulate his performance, came and sat beside him; but before[Pg 91] very long had to acknowledge that the new game was more difficult than it appeared.

She then tried crawling on her belly in pursuit of the restless creatures, and managed indeed to approach quite near to them; but each time she made her spring they flew away too soon.

Grey and Red were more fortunate. Each one took up a position on the lid, and with raised paw waited until the fly of its own accord came within striking distance. In this way they managed to catch a few flies, but far from all; Red was especially erratic, and missed two or three shots out of every four.

Black, on the other hand, after a little practise, proved himself an excellent shot; but, unhappily, he struck with such violence that the victim was smashed into a black spot, the edible fragments of which were buried in the tar.