TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the book.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book. These are indicated by a dashed blue underline.

THE TENTH (IRISH) DIVISION

BY

BRYAN COOPER

MAJOR, GENERAL LIST NEW ARMIES

FORMERLY 5TH SERVICE BATTALION THE CONNAUGHT RANGERS

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

Major-Gen. SIR BRYAN MAHON, D.S.O.

WITH APPRECIATIONS BY

MR. ASQUITH

MR. BALFOUR

SIR EDWARD CARSON

MR. JOHN REDMOND

HERBERT JENKINS LIMITED

3 YORK STREET ST. JAMES’S

LONDON S.W.1 ∿ ∿ MCMXVIII

“So they gave their bodies to the common weal and received, each for his own memory, praise that will never die, and with it the grandest of all sepulchres, not that in which their mortal bones are laid, but a home in the minds of men, where their glory remains fresh to stir to speech or action as the occasion comes by.”—Thucydides.

“It seems as if this poor Celtic people were bent on making what one of its own poets has said of its heroes hold good for ever: ‘They went forth to the war but they always fell.’”—Matthew Arnold.

PRINTED BY BURLEIGH LTD., AT THE BURLEIGH PRESS, BRISTOL, ENGLAND

Major Cooper’s narrative of the exploits of the 10th Division in the Gallipoli Campaign is a moving and inspiring record, of which Irishmen everywhere may well be proud.

I trust that it will be widely read in all parts of the Empire.

(Sd.) H. H. ASQUITH

This war has been fruitful in deeds of splendid bravery and heroic endurance; but neither in bravery nor endurance have the 10th Division in the Gallipoli Campaign been surpassed by any of their brothers-in-arms who have been fighting in Europe and Asia for the cause Of civilisation and freedom.

(Sd.) ARTHUR JAMES BALFOUR

Dear Bryan Cooper,

I am very glad that you have undertaken to record the splendid services of the 10th Division in Gallipoli. Their magnificent bravery in the face of almost insurmountable[viii] difficulties and discomforts stands out amongst the countless acts of heroism in this war, and I think it particularly apt that the history of the actions of these brave Irishmen in the campaign should be recorded by a gallant Irish officer.

Yours sincerely,

(Sd.) EDWARD CARSON

I have been asked to write a short Foreword to the following pages, and I do so with the utmost pleasure. By the publication of this little book, Major Bryan Cooper will be performing a most valuable service, not only to his own country, Ireland, but to the Empire.

The history of the 10th (Irish) Division is, in many respects, unique. It was the first Irish Division raised and sent to the Front by Ireland since the commencement of the War. Not alone that, but it was the first definitely Irish Division that ever existed in the British Army.

Irish Divisions and Irish Brigades played a great part in history in the past, but they were Divisions and Brigades, not in the service of England, but in the service of France and other European countries and America.

The creation of the 10th (Irish) Division, therefore, marks a turning point in the history of the relations between Ireland and the Empire.

In many respects, the 10th (Irish) Division, notwithstanding the extraordinary and outstanding gallantry that it showed in the field, may be said to have been unfortunate. No Division in any theatre of the War suffered more severely or showed greater self-sacrifices and gallantry. And yet, largely, I fancy, by reason of the fact that its operations were in a distant theatre, comparatively little has been heard of its achievements; and, for some reason which a civilian cannot understand, the number of honours and distinctions conferred on the Division has been comparatively small. And yet we have the testimony of everyone, from the Generals in Command down, that the Division behaved magnificently, in spite of the most terrible and unlooked-for difficulties and sufferings.

Before they went into action, their artillery was taken from them, and they landed at Suvla and Anzac without a single gun.

They were a Division of the new Army entirely made up of men who had no previous military experience, and who had never heard a shot fired. Yet, the very day they landed, they found themselves precipitated into the most tremendous and bloody conflict, exposed to heavy shrapnel and machine-gun fire, on an open strand, where cover was impossible.

To the most highly trained and seasoned troops in the world, this would have been a[x] trying ordeal; but, to new troops, it was a cruel and terrible experience. And yet the testimony all goes to show that no seasoned or trained troops in the world could have behaved with more magnificent steadiness, endurance, and gallantry. Without adequate water supply—indeed, for a long time, without water at all, owing to mismanagement, which has yet to be traced home to its source—their sufferings were appalling.

As Major Bryan Cooper points out, it is supposed to be a German military maxim that no battalion could maintain its morale with losses of twenty-five per cent. Many of the battalions of the 10th Division lost seventy-five per cent., and yet their morale remained unshaken. The depleted Division was hastily filled up with drafts, and sent, under-officered, to an entirely new campaign at Salonika, where it won fresh laurels.

Another cruel misfortune which overtook them was, that, instead of being allowed to fight and operate together as a Unit, they were immediately split up, one Brigade being attached to the 11th Division, and entirely separated from their comrades.

There has been some misapprehension created, in certain quarters, as to the constitution of this 10th Division and its right to call itself an Irish Division. Major Bryan Cooper sets this question at rest. What really occurred was,[xi] that, quite early in the business, when recruiting for the 10th Division was going on fairly well in Ireland, for some unexplained reason, a number of English recruits were suddenly sent over to join its ranks. They were quite unnecessary, and protests against their incursion into the Division fell upon deaf ears. As it happened, however, it was found that a considerable number of these English recruits were Irishmen living in Great Britain, or the sons of Irishmen, and, when the Division went to the Front, Major Bryan Cooper states that fully seventy per cent. of the men, and ninety per cent. of the officers, were Irishmen. That is to say, the Division was as much entitled to claim to be an Irish Division in its constitution as any Division either in England, Scotland, or Wales is entitled to claim that it is an English, Scotch, or Welsh Division.

Men of all classes and creeds in Ireland joined its ranks. The list of casualties which Major Bryan Cooper gives is heart-breaking reading to any Irishman, especially to one like myself, who had so many personal friends who fell gallantly in the conflict.

Irishmen of all political opinions were united in the Division. Its spirit was intensely Irish. Let me quote Major Bryan Cooper’s words:—

“It was the first Irish Division to take the field in War. Irish Brigades there had often been. They had fought under the Fleur-de-Lys[xii] or the Tricolour of France, and under the Stars and Stripes, as well as they had done under the Union Jack. But never before in Ireland’s history had she seen anywhere a whole Division of her sons in the battle-field. The old battalions of the Regular Army had done magnificently, but they had been brigaded with English, Scotch, and Welsh units. The 10th Division was the first Division almost entirely composed of Irish Battalions who faced an enemy. Officers and men alike knew this, and were proud of their destiny. As the battalions marched through the quiet English countryside, the drums and fifes shrieked out ‘St. Patrick’s Day’ or ‘Brian Boru’s March,’ and the dark streets of Basingstoke echoed the voices that chanted ‘God Save Ireland,’ as the Units marched down to entrain. Nor did we lack the green. One Unit sewed shamrocks into its sleeves. Another wore them as helmet badges. Almost every Company cherished somewhere an entirely unofficial green flag, as dear to the men as if they were the regimental colours themselves. They constituted an outward and visible sign that the honour of Ireland was in the Division’s keeping, and the men did not forget it.”

The men who had differed in religion and politics, and their whole outlook on life, became[xiii] brothers in the 10th Division. Unionist and Nationalist, Catholic and Protestant, as Major Bryan Cooper says—“lived and fought and died side by side, like brothers.” They combined for a common purpose: to fight the good fight for liberty and civilisation, and, in a special way, for the future liberty and honour of their own country.

Major Bryan Cooper expresses the hope that this experience may be a good augury for the future.

For my part, I am convinced that nothing that can happen can deprive Ireland of the benefit of the united sacrifices of these men.

I congratulate Major Bryan Cooper on his book. The more widely it is circulated, the better it will be for Ireland and for the Empire.

J. E. REDMOND

St. Patrick’s Day, 1917

I have been asked to contribute a short introduction to this account of the doings of the 10th (Irish) Division in Gallipoli.

I commanded the Division from the time of its formation until it left Gallipoli Peninsula for Salonika, and I am extremely glad that some record has been made of its exploits. I do not think that the author of this book intends to claim for the Division any special pre-eminence over other units; but that he puts forward a simple account of what the first formed Irish Service Battalions suffered and how creditably they maintained the honour of Ireland.

Memories in war-time are short, and it may be that the well-earned glories of the 16th and Ulster Division have tended to obliterate the recollections of Suvla and Sari Bair. (The Division has also the distinction of being the only troops of the Allies that have fought in Bulgaria up to date.)

In case these things are forgotten, it is well that this book has been written, for never in history did Irishmen face death with greater[xvi] courage and endurance than they did in Gallipoli and Serbia in the summer and winter of 1915.

During the period of its formation the Division suffered from many handicaps. To the difficulties which are certain to befall any newly created unit were added others due to the enormous strain that the nation was undergoing; arms and equipment were slow in arriving; inclement weather made training difficult, and for sake of accommodation units had had to be widely separated in barracks all over Ireland. All these difficulties were, however, surmounted, partly by the genuine keenness of all ranks, but in the main by the devoted work of the handful of regular officers and N.C.O.’s who formed the nucleus of the Division.

No words can convey how much was done by these men, naturally disappointed at not going out with the original Expeditionary Force. They nevertheless threw themselves whole-heartedly into the work before them, and laboured unceasingly and untiredly to make the new units a success, they were ably seconded by retired officers who had rejoined, and by newly-joined subalterns, who brought with them the freshness and enthusiasm of youth.

Nor were the men behindhand. Though the monotony of routine training sometimes grew irksome, yet their eagerness to face the enemy and their obvious anxiety to do their[xvii] duty carried them through, and enabled them to become in nine months well-trained and disciplined soldiers.

When they reached Gallipoli they had much to endure. The 29th Brigade were not under my command, so I cannot speak from personal knowledge, but I believe that every battalion did its duty and won the praise of its generals.

Of the remainder of the Division I can speak with greater certainty. They were plunged practically at a moment’s notice into battle, and were placed in positions of responsibility and difficulty on a desolate sun-baked and waterless soil, where they suffered tortures from thirst. In spite of this, and in spite of the fact that they were newly-formed units mainly composed of young soldiers, they acquitted themselves admirably. No blame or discredit of any kind can possibly be attached to the rank and file of the 10th Division. Whatever the emergency, and however great the danger, they faced it resolutely and steadfastly, rejoicing when an opportunity arose that enabled them to meet their enemy with the bayonet.

Ireland has had many brave sons; Ireland has sent forth many splendid regiments in past times; but the deeds of the men of the 10th (Irish) Division are worthy to be reckoned with any of those of their predecessors.

(Sd.) BRYAN MAHON

This book (which was written in haste during a period of sick leave) does not profess to be a military history; it is merely a brief attempt to describe the fortunes of the rank and file of the Tenth (Irish) Division. The Division was so much split up that it is impossible for any one person to have taken part in all its actions; but I went to Gallipoli with my battalion, and though disabled for a period by sickness, I returned to the Peninsula before the Division left it, so that I may fairly claim to have seen both the beginning and the end of the operations. I have received great assistance from numerous officers of the Division, who have been kind enough to summarise for me the doings of their battalions, and I tender them my grateful thanks.

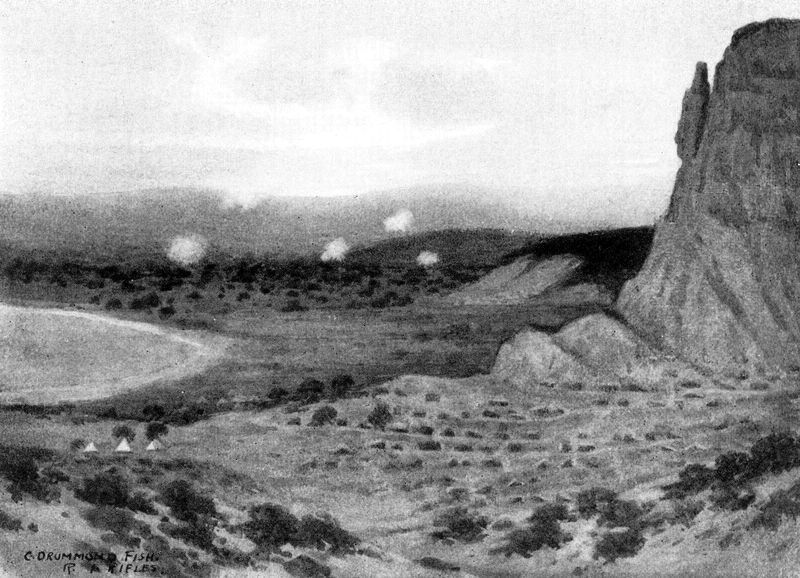

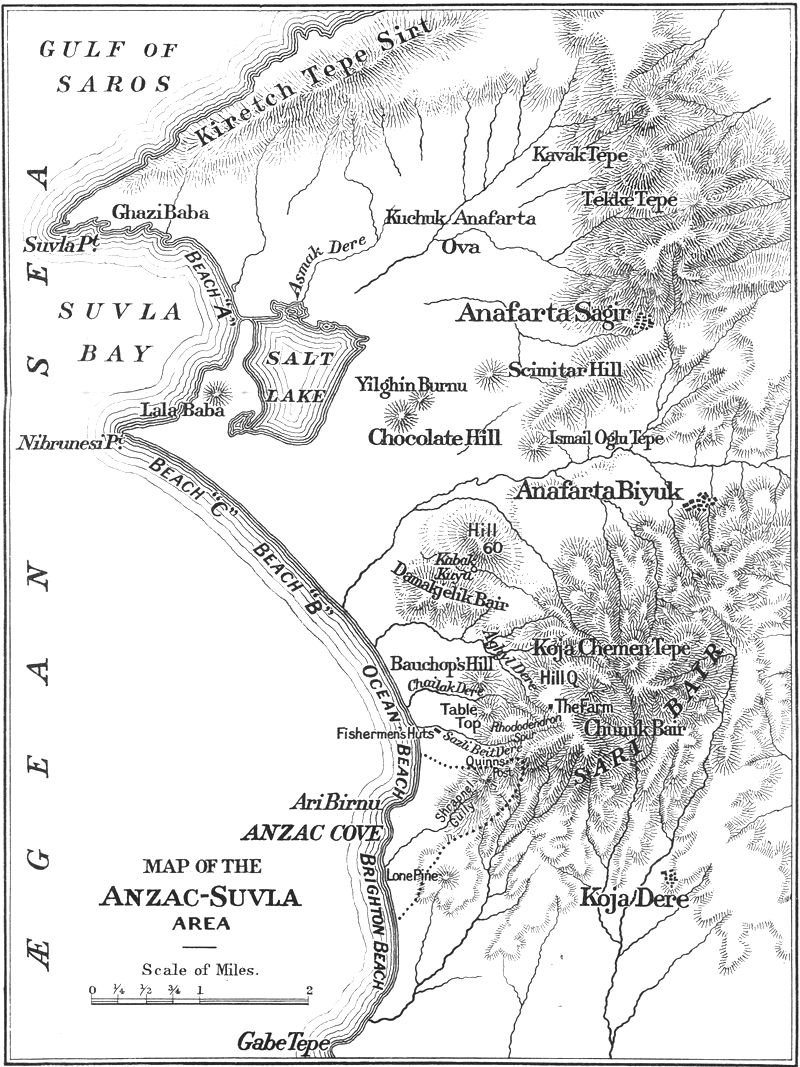

I must also thank Mr. H. Hanna, K.C., for allowing me to inspect part of the proofs of his forthcoming book dealing with “D” Company of the 7th Royal Dublin Fusiliers. I owe Mr. Hanna a further debt of gratitude for his kindness in allowing the reproduction of the sketches of “The Salt Lake,” “Anafarta[xx] Plain,” and “‘D’ Company in the Trenches,” which were executed by Captain Drummond Fish, of the Royal Irish Rifles, for his book. Captain Fish has also very kindly allowed me to use three more of his sketches, which, though deprived of the charm of colour possessed by the originals, give a far better idea of the scenery of Gallipoli than can be obtained from any photograph. Having shared the life led by Captain Fish’s battalion in Gallipoli, I cannot help admiring the manner in which he managed to include a paint-box and a sketchbook in the very scanty kit allowed to officers. I must further express to my comrade, Francis Ledwidge, who himself served in the ranks of the Division, my sincere gratitude for the beautiful lines in which he has summed up the object of our enterprise. In them he has fulfilled the poet’s mission of expressing in words the deepest thoughts of those who feel them too sincerely to be able to give them worthy utterance.

In dealing with the general aspect of the Gallipoli Expedition, I have tried to avoid controversial topics. As a general rule, I have followed the version given by Sir Ian Hamilton in his despatch, which is still the only official document that exists for our guidance. I am conscious that the book, of necessity, has omitted many gallant deeds, and has dealt with some units more fully than with others.[xxi] I can only plead in extenuation that I found great difficulty in getting detailed information as to the doings of some battalions, and that to this, rather than to prejudice on my part, is due any lack of proportion that may exist. It is by no means easy for an Irishman to be impartial, but I have done my best.

BRYAN COOPER

March 1st, 1917

P.S.—Since this was written Francis Ledwidge has laid down his life for the honour of Ireland, and the world has lost a poet of rare promise.

| PAGE | ||

| Dedication | v | |

| Appreciations by Mr. Asquith, Mr. Balfour, Sir Edward Carson, Mr. John Redmond | vii | |

| Introduction by Major-Gen. Sir Bryan Mahon, D.S.O. | xv | |

| Author’s Preface | xix | |

| List of Illustrations | xxv | |

| Poem by Francis Ledwidge | xxvi | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I | The Formation of the Division | 1 |

| II | Mudros and Mitylene | 32 |

| III | The 29th Brigade at Anzac | 62 |

| IV | Sari Bair | 91 |

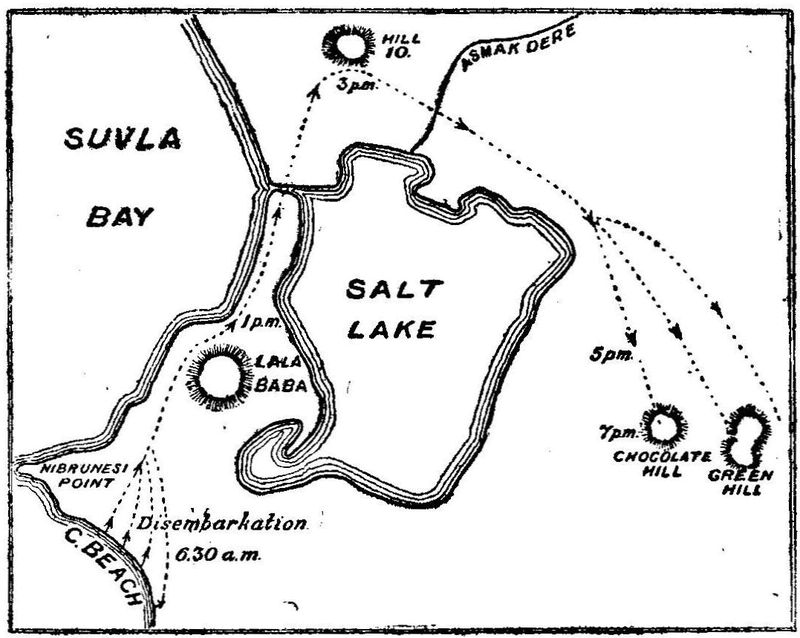

| V | Suvla Bay and Chocolate Hill | 121 |

| VI | Kiretch Tepe Sirt | 152 |

| VII | Kaba Kuyu and Hill 60 | 181 |

| VIII | Routine | 206 |

| IX | Last Days | 229 |

| X | Retrospect | 243 |

| APPENDICES [xxiv] | ||

| A. | On Authorities | 257 |

| B. | Names of Officers Killed, Wounded and Missing | 259 |

| C. | Names of Officers, N.C.O.’s and Men Mentioned in Despatches | 263 |

| D. | Names of Officers, N.C.O.’s and Men Awarded Honours | 266 |

| Mules in the Anzac Sap | Frontispiece |

| Face page | |

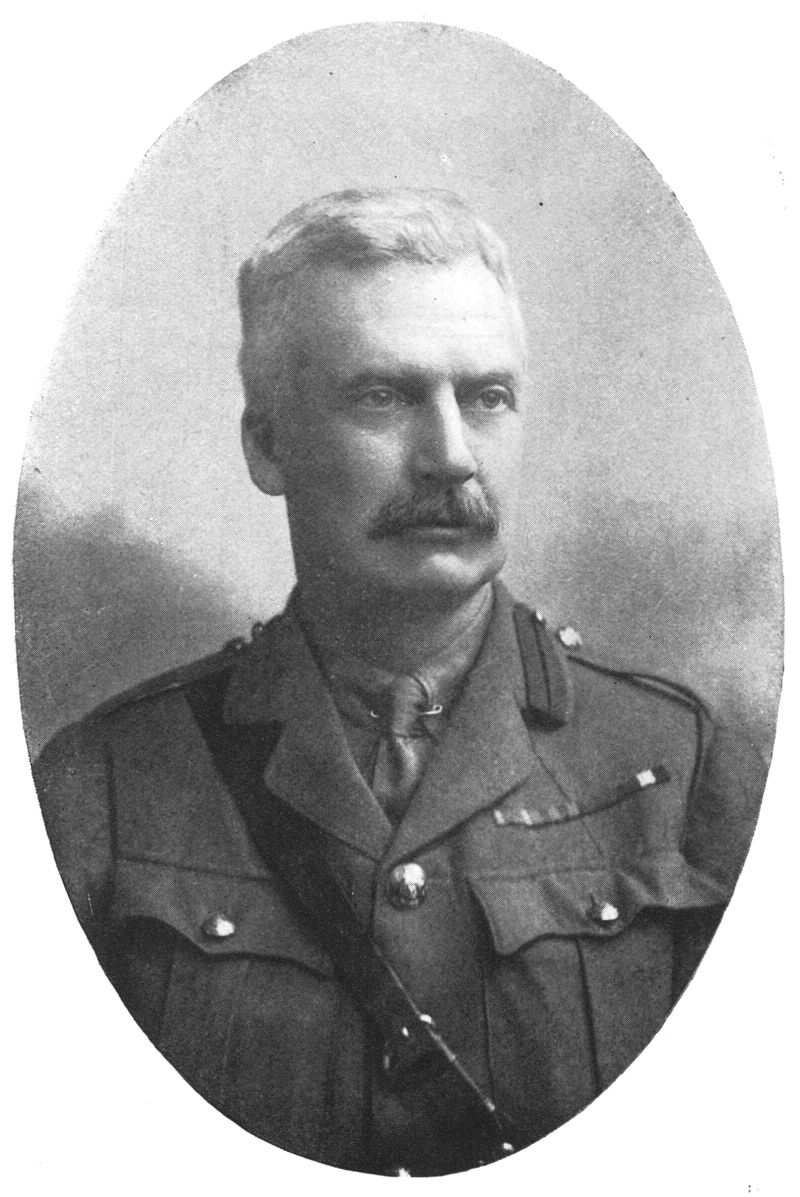

| Lieut.-General Sir Bryan Mahon, K.C.V.O., C.B., D.S.O. | 4 |

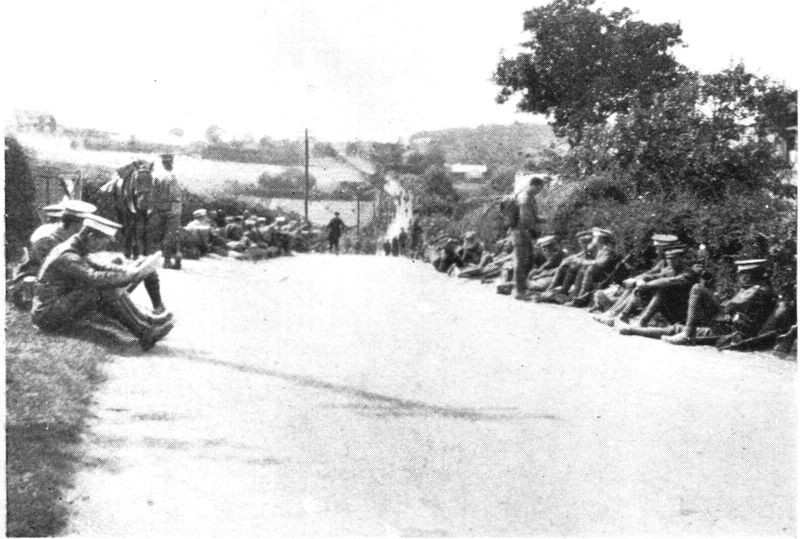

| Basingstoke. A Halt | 24 |

| Musketry at Dollymount | 24 |

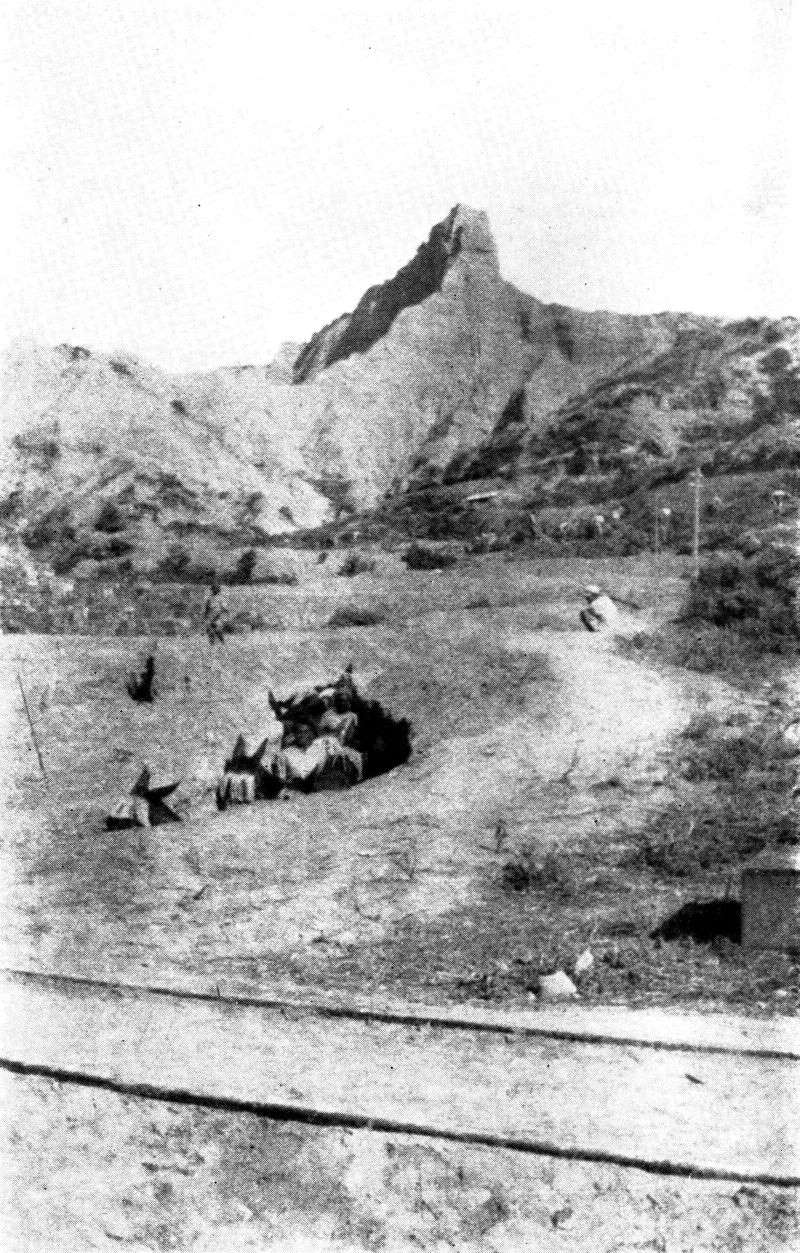

| Sari Bair | 44 |

| Mudros. The Author’s Bivouac | 44 |

| Sari Bair from Suvla | 56 |

| Brigadier-General R. J, Cooper, C.V.O., C.B., Commanding 29th Brigade | 98 |

| Suvla, showing Lala Baba and the Salt Lake | 124 |

| Brigadier-General F. F. Hill, C.B., C.M.G., D.S.O., Commanding 31st Brigade | 132 |

| Brigadier-General L. L. Nicol, C.B., Commanding 30th Brigade | 140 |

| A Faugh-a-Ballagh Teases a Turkish Sniper | 154 |

| The 7th Dublins in the Trenches at Chocolate Hill | 158 |

| The Anafarta Plain (Kiretch Tepe Sirt on the skyline) | 168 |

| The Anafarta Plain from the South (Hill 60 on the left in the middle distance) | 186 |

| Brigadier-General J. G. King-King, D.S.O. | 208 |

| 5th Royal Irish Fusiliers in the Trenches | 214 |

| Imbros from Anzac | 230 |

| Map (at the end of the Volume) |

France

24th February, 1917

THE TENTH (IRISH) DIVISION

THE TENTH (IRISH) DIVISION

IN GALLIPOLI

“The Army, unlike any other profession, cannot be taught through shilling books. First a man must suffer, then he must learn his work and the self-respect which knowledge brings.”—Kipling.

Within ten days of the outbreak of the War, before even the Expeditionary Force had left England, Lord Kitchener appealed for a hundred thousand recruits, and announced that six new divisions would be formed from them. These six divisions, which were afterwards known as the First New Army, or more colloquially as K.1, were, with one exception, distributed on a territorial basis. The Ninth was Scotch, the Eleventh North Country, the Twelfth was recruited in London and the Home Counties, and the Thirteenth in the West of England. The exception was the Fourteenth, which consisted of new battalions of English light infantry and rifle regiments. The Tenth[2] Division in which I served, and whose history I am about to relate, was composed of newly-formed or “Service” battalions of all the Irish line regiments, together with the necessary complement of artillery, engineers, Army Service Corps, and R.A.M.C. They were distributed as follows:—

29th Brigade.

5th Service Battalion, Royal Irish Regiment.

6thdittoRoyal Irish Rifles.

5thdittoThe Connaught Rangers.

6thdittoThe Leinster Regiment.

The 5th Royal Irish Regiment afterwards became the Divisional Pioneer Battalion, and its place in the 29th Brigade was taken by the 10th Hampshire Regiment.

30th Brigade.

6th Service Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers.

7thdittoditto

6th Service Battalion, Royal Munster Fusiliers.

7thdittoditto

31st Brigade.

5th Service Battalion, Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers.

6thdittoditto

5th Service Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers.

6thdittoditto

It will be seen that the 29th Brigade consisted of regiments from all the four provinces of Ireland, while the 30th Brigade had its depôts in the South of Ireland, and the 31st in Ulster.

The Divisional Troops were organised as follows:—

Artillery.

54th Brigade R.F.A.

55th ” R.F.A.

56th ” R.F.A.

57th (Howitzer) Brigade R.F.A.

Heavy Battery R.G.A.

Engineers.

65th Field Company R.E.

66thdittoR.E.

85thdittoR.E.

10th Divisional Signal Company.

10th Divisional Train.

10th Divisional Cyclist Company.

30th Field Ambulance, R.A.M.C.

31st ditto

32ndditto

A squadron of South Irish Horse was allocated as Divisional Cavalry, but this only joined the Division at Basingstoke in May, and was detached again before we embarked for Gallipoli.

Fortunately, one of the most distinguished of Irish Generals was available to take command of the Division. Lieut.-General Sir Bryan[4] Mahon was a Galway man who had entered the 8th (Royal Irish) Hussars from a Militia Battalion of the Connaught Rangers in 1883. For ten years he served with his regiment, acting as Adjutant from 1889 to 1893, but recognising that British Cavalry were unlikely to see much active service, he transferred to the Egyptian Army in the latter year. He served with the Cavalry of this force in the Dongola Expedition in 1896, and was awarded the D.S.O. For his services in the campaign, which ended in the capture of Khartoum, he received the brevet rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. He next commanded the mounted troops which achieved the defeat and death of the Khalifa, and for this he was promoted to Brevet-Colonel. He was then transferred to South Africa, where he commanded a mounted brigade and had the distinction of leading the column which effected the relief of Mafeking, being created a Companion of the Bath for his services on this occasion. After the South African War he returned to the Soudan as Military Governor of Kordofan. His next commands were in India, and he had only vacated the command of the Lucknow Division early in 1914. While holding it in 1912 he had been created a K.C.V.O.

At the time he took over the 10th Division he was fifty-two years of age. His service in Egypt and India had bronzed his face and sown grey in his hair, but his figure and his seat on a [5]horse were those of a subaltern. He scorned display, and only the ribbons on his breast told of the service he had seen. A soft cap adorned with an 8th Hussar badge, with a plain peak and the red band almost concealed by a khaki cover, tried to disguise his rank, but the manner in which it was pulled over his eyes combined with the magnificent chestnut he rode and the eternal cigarette in his mouth, soon made him easily recognisable throughout the Division.

Experienced soldier as he was, he had qualities that made him even better suited to his post than military knowledge, and in his years in the East he had not forgotten the nature of his countrymen. The Irish soldier is not difficult to lead: he will follow any man who is just and fearless, but to get the best out of him, needs sympathy, and this indefinable quality the General possessed. It was impossible for him to pass a football match on the Curragh without saying a pleasant word to the men who were watching it, and they repaid this by adoring their leader. Everything about him appealed to them—his great reputation, the horse he rode, his Irish name, and his Irish nature, all went to their hearts. Above all, he was that unique being, an Irishman with no politics, and this, in a Division that was under the patronage of no political party, but consisted of those who wanted to fight, was an enormous asset.

Fortunately, the Infantry Brigadiers had also some knowledge of Irish troops. Brigadier-General R. J. Cooper, C.V.O., who led the 29th Brigade, had commanded the Irish Guards. Another Irish Guardsman, Brigadier-General C. Fitzclarence, V.C., commanded the 30th Brigade at the time of its first formation, but he was soon afterwards called to France to command the 1st Brigade in the Expeditionary Force, and met his death at the first battle of Ypres. His place was taken by Brigadier-General L. L. Nicol, who had done the bulk of his service in the Rifle Brigade, but had begun his soldiering in the Connaught Rangers. The 31st Brigade was commanded by Brigadier-General F. F. Hill, C.B., D.S.O., who had served throughout a long and distinguished career in the Royal Irish Fusiliers. The Divisional Artillery was at first under the command of Brigadier-General A. J. Abdy, but when this officer was found medically unfit for active service, he was replaced by Brigadier-General G. S. Duffus.

I must now describe the actual formation of the Division, and in view of the fact that it was the beginning of one of the most gigantic military improvisations on record, it may be desirable to do so in some detail.

Fortunately there were some regular cadres available. In the first place, there was the Regimental Depôt, where usually three regular[7] officers were employed, the senior being a major. In almost every case he was promoted to temporary Lieutenant-Colonel, and given the command of the senior Service Battalion of his regiment. The other two officers (usually a captain and a subaltern) were also transferred to the new unit. Then, again, the Regular Battalion serving at home before embarking for France was ordered to detach three officers, and from ten to sixteen N.C.O.’s. In many cases these officers did not belong to the Regular Battalion, but were officers of the Regiment who had been detached for service with some Colonial unit, such as the West African Frontier Force, or the King’s African Rifles. Being on leave in England when war broke out, they had rejoined the Home Battalion of their unit, and had been again detached for service with the New Armies. Where more than one Service Battalion of a regiment was being formed, the bulk of these officers and N.C.O.’s went to the senior one.

There was yet another source from which Regular Officers were obtained, and those who came from it proved among the best serving in the Division.

At the outbreak of the War all Indian Army officers who were on leave in England were ordered by the War Office to remain there and were shortly afterwards posted to units of the First New Army. Two of the Brigade-Majors[8] of the Division were Indian Army officers, who, when war was declared, were students at the Staff College, and nearly every battalion obtained one Indian officer, if not more. It is impossible to exaggerate the debt the Division owed to these officers. Professional soldiers in the best sense of the word, they identified themselves from the first with their new battalions, living for them, and, in many cases, dying with them. Words cannot express the influence they wielded and the example they gave, but those who remember the lives and deaths of Major R. S. M. Harrison, of the 7th Dublins, and Major N. C. K. Money, of the 5th Connaught Rangers, will realise by the immensity of the loss we sustained when they were killed, how priceless their work had been.

A certain number of the Reserve of Officers were also available for service with the new units. It seemed hard for men of forty-five or fifty years of age who had left the Army soon after the South African War, to be compelled to rejoin as captains and serve under the orders of men who had previously been much junior to them, but they took it cheerfully, and went through the drudgery of the work on the barrack square without complaining. Often their health was unequal to the strain imposed upon it by the inclement winter, but where they were able to stick it out, their ripe experience was most helpful to their juniors.[9] The battalions which did not secure a Regular Commanding Officer got a Lieut.-Colonel from the Reserve of Officers, often one who had recently given up command of one of the regular battalions of the regiment. Besides officers from the Reserve of Officers, there were also a considerable number of men who had done five or six years’ service in the Regular Army or the Militia and had then retired without joining the Reserve. These were for the most part granted temporary commissions of the rank which they had previously held. A few were also found who had soldiered in Colonial Corps, and eight or ten captains were drawn from the District Inspectors of the Royal Irish Constabulary. These united to a knowledge of drill and musketry a valuable insight into the Irish character, and as by joining they forfeited nearly £100 a year apiece, they abundantly proved their patriotism.

It will thus be seen that each battalion had a Regular or retired Regular Commanding Officer, a Regular Adjutant, and the four company commanders had as a rule had some military experience. The Quartermaster, Regimental Sergeant-Major, and Quartermaster-Sergeant were usually pensioners who had rejoined, while Company Sergeant-Majors and Quartermaster-Sergeants were obtained by promoting N.C.O.’s who had been transferred from the Regular battalion. The rest of the cadres[10] had to be filled up, and fortunately there was no lack of material.

For about a month after their formation the Service Battalions were short of subalterns, not because suitable men were slow in coming forward, but because the War Office was so overwhelmed with applications for commissions that it found it impossible to deal with them. About the middle of September, however, a rule was introduced empowering the C.O. of a battalion to recommend candidates for temporary second-lieutenancies, subject to the approval of the Brigadier, and after this the vacancies were quickly filled. Some of the subalterns had had experience in the O.T.C., and as a rule these soon obtained promotion, but the majority when they joined were quite ignorant of military matters, and had to pick up their knowledge while they were teaching the men.

About the end of the year, classes for young officers were instituted at Trinity College, and a certain number received instruction there, but the bulk of them had no training other than that which they received in their battalions. They were amazingly keen and anxious to learn, and the progress they made both in military knowledge and in the far more difficult art of handling men was amazing. Drawn from almost every trade and profession, barristers, solicitors, civil engineers, merchants,[11] medical students, undergraduates, schoolboys, they soon settled down together and the spirit of esprit de corps was quickly created. Among themselves, no doubt, they criticised their superiors, but none of them would have admitted to an outsider that their battalion was in any respect short of perfection. I shall never forget the horror with which one of my subalterns, who had been talking to some officers of another Division at Mudros, returned to me saying, “Why, they actually said that their Colonel was a rotter!” Disloyalty of that kind never existed in the 10th Division. The subalterns were a splendid set, and after nine months’ training compared well with those of any regular battalion. They believed in themselves, they believed in their men, they believed in the Division, and, above all, in their own battalion.

I must now turn to the men whom they led. Fortunately, the inexperience of the new recruits was, to a large extent, counteracted by the rejoining of old soldiers. It was estimated that within a month of the declaration of war, every old soldier in Ireland who was under sixty years of age (and a good many who were over it) had enlisted again. Some of these were not of much use, as while living on pension they had acquired habits of intemperance, and many more, whose military experience dated from before the South African War, found the increased[12] strain of Army life more than they could endure. However, a valuable residue remained, and not only were they useful as instructors, and in initiating the new recruits into military routine, but the fact that they had usually served in one of the Regular battalions of their regiment helped to secure a continuity of tradition and sentiment, which was of incalculable value. In barracks these old soldiers sometimes gave trouble, but in the field they proved their value over and over again.

Of the Irish recruits, but little need be said. Mostly drawn from the class of labourers, they took their tone from the old soldiers (to whom they were often related), and though comparatively slow in learning, they eventually became thoroughly efficient and reliable soldiers.

There was, however, among the men of most of the battalions, another element which calls for more detailed consideration. Except among old soldiers and in Belfast, recruiting in Ireland in August, 1914, was not as satisfactory as it was in England, and in consequence, Lord Kitchener decided early in September to transfer a number of the recruits for whom no room could be found in English regiments to fill up the ranks of the 10th Division. The fact that this was done gave rise, at a later date, to some controversy, and it was even stated that the 10th Division was Irish only in name. This[13] was a distinct exaggeration, for when these “Englishmen” joined their battalions, it was found that a large proportion of them were Roman Catholics, rejoicing in such names as Dillon, Doyle, and Kelly, the sons or grandsons of Irishmen who had settled in England. It is not easy to make an accurate estimate, but I should be disposed to say that in the Infantry of the Division 90 per cent. of the officers and 70 per cent. of the men were either Irish or of Irish extraction. Of course, the 10th Hampshire Regiment is not included in these calculations. It may be remarked that there has never, in past history, been such a thing as a purely and exclusively Irish (or Scotch) battalion. This point is emphasised by Professor Oman, the historian of the Peninsular War, who states: “In the Peninsular Army the system of territorial names prevailed for nearly all the regiments, but in most cases the territorial designation had no very close relation with the actual provenance of the men. There were a certain number of regiments that were practically national, i.e., most of the Highland battalions, and nearly all of the Irish ones were very predominantly Highland and Irish as to their rank and file: but even in the 79th or the 88th there was a certain sprinkling of English recruits.” (“Wellington’s Army,” p. 208.)

Before leaving this subject it should be noted that the Englishmen who were drafted to the[14] Division in this manner became imbued with the utmost loyalty to their battalions, and wore the shamrock on St. Patrick’s Day with much greater enthusiasm than the born Irishmen. They would have been the first to resent the statement that the regiments they were so proud to belong to had no right to claim their share in the glory which they achieved.

At first, however, they created a somewhat difficult problem for their officers. They had enlisted purely from patriotic motives, and were inclined to dislike the delay in getting to grips with the Germans; and being, for the most part, strong Trades Unionists, with acute suspicion of any non-elected authority, they were disposed to resent the restraints of discipline, and found it hard to place complete confidence in their officers. They also felt the alteration in their incomes very keenly. Many of them, before enlistment, had been miners earning from two to three pounds a week, and the drop from this to seven shillings, or in the case of married men 3s. 6d., came very hard. The deduction for their wives was particularly unwelcome, not because they grudged the money, but because when they enlisted they had not been told that this stoppage was compulsory, and so they considered that they had been taken advantage of. However, they had plenty of sense, and soon began to realise the necessity of discipline, and understood that their officers,[15] instead of being mercenary tyrants, spent hours in the Company Office at the end of a long day’s work trying to rectify such grievances as non-payment of separation allowance. Regimental games helped them to feel at home. Some of them soon became lance-corporals, and before Christmas they had all settled down into smart, intelligent and willing soldiers. One English habit, however, never deserted them: they were unable to break themselves of grumbling about their food.

The Division contained one other element to which allusion must be made. In the middle of August, Mr. F. H. Browning, President of the Irish Rugby Football Union, issued an appeal to the young professional men of Dublin, which resulted in the formation of “D” Company of the 7th Royal Dublin Fusiliers. This was what is known as a “Pals” Company, consisting of young men of the upper and middle classes, including among them barristers, solicitors, and engineers. Many of them obtained commissions, but the tone of the company remained, and I know of at least one barrister who had served with the Imperial Yeomanry in South Africa, who for over eighteen months refused to take a commission because it would involve leaving his friends. The preservation of rigid military discipline among men who were the equals of their officers in social position was not easy, but the breeding and education[16] of the “Pals” justified the high hopes that had been formed of them when their Regiment was bitterly tested at Suvla.

The Royal Artillery, Royal Engineers, Army Service Corps, and the Royal Army Medical Corps recruits who came to the Division were, for the most part, English or Scotch, since no distinctively Irish units of those branches of the service exist. Generally speaking, they were men of a similar class to the English recruits who were drafted into the infantry.

A detailed description of the training of the Division would be monotonous and uninteresting even to those who took part in it, but a brief summary may be given. The points of concentration first selected were Dublin and the Curragh, the 30th Brigade being at the latter place. At the beginning of September, the 29th Brigade were transferred to Fermoy and Kilworth, but the barracks in the South of Ireland being required for the 16th (Irish) Division, two battalions returned to Dublin, the 6th Leinsters went to Birr, and the 5th Royal Irish to Longford. The latter Battalion soon became Pioneers and were replaced by the 10th Hampshires, who were stationed at Mullingar. The 54th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, were at Dundalk, and the remainder of the Artillery at Newbridge and Kildare. The Engineers, Cyclists, and Army Service Corps trained at the Curragh, the Signal Company[17] at Carlow, and the Royal Army Medical Corps at Limerick.

Naturally, the War Office were not prepared for the improvisation of units on such a large scale, and at first there was a considerable deficiency in arms, uniform, and equipment. Irish depôts, however, were not quite so overwhelmed as the English ones, and most recruits arrived from them in khaki, although minor articles of kit, such as combs and tooth-brushes were often missing. The English recruits on the other hand, joined their battalions in civilian clothes, and were not properly fitted out till the middle of October. The Royal Army Medical Corps at Limerick also had to wait some time for their uniform.

The Infantry soon obtained rifles (of different marks, it is true) and bayonets, but the gunners were greatly handicapped by the fact that the bulk of their preliminary training had to be done with very few horses and hardly any guns. Deficiencies were supplied by models, dummies, and good will; and considering the drawbacks, wonderful progress was made. Another article of which there was a shortage was great-coats, and in the inclement days of November and December their absence would have been severely felt. Fortunately, the War Office cast aside convention and bought and issued large quantities of ready-made civilian overcoats of the type generally described as “Gents’ Fancy[18] Cheviots.” Remarkable though they were in appearance, these garments were much better than nothing at all, and in January the warmer and more durable regulation garments were issued. The men also suffered a good deal of hardship at first from having only one suit of khaki apiece, for when wet through they were unable to change, but they recognised that this discomfort could not be instantly remedied, and accepted it cheerfully.

Until the end of 1914, the bulk of the work done by the Infantry consisted of elementary drill, platoon and company training and lectures, with a route march once or twice a week. A recruits’ musketry course was also fired. Plenty of night operations were carried out, two evenings a week as a rule being devoted to this form of work. The six battalions in Dublin were somewhat handicapped by lack of training ground, as the Phœnix Park became very congested. This deficiency was later remedied to a certain extent by certain landowners who allowed troops to manœuvre in their demesnes; but considerations of distance and lack of transport made this concession less valuable than it would have been had it been possible to disregard the men’s dinner hour.

Side by side with this strenuous work the education of the officers and N.C.O.’s was carried on. The juniors had everything to learn, and little by little the news that filtered[19] through from France convinced the seniors that many long-cherished theories would have to be reconsidered. It gradually became clear that the experience of South Africa and Manchuria had not fully enlightened us as to the power of modern heavy artillery and high explosives, and that many established tactical methods would have to be varied. We learnt to dig trenches behind the crest of a hill instead of on the top of it; to seek for cover from observation rather than a good field of fire; to dread damp trenches more than hostile bullets. We began, too, to hear rumours of a return to mediæval methods of warfare and became curious as to steel helmets and hand grenades.

Had these been the only rumours that we heard, we should have counted ourselves fortunate. Unhappily, however, in modern war there is nothing so persistent as the absolutely unfounded rumour, and in K.1 they raged like a pestilence. We were all eager to get the training finished and settle to real work, and our hopes gave rise to the most fantastic collection of legends. The most prevalent one, of course, was that we were going to France in ten days’ time, usually assisted by the corroborative detail that our billets had already been prepared, but this was run close by the equally confident assertion on the authority of a clerk in the Brigade Office, “that we were destined for[20] Egypt in a week.” It is to be hoped that after the War, some folk-lore expert will investigate legends of the New Armies. If he does so, he will be interested to find that France and Egypt were almost the only two seats of War which the Division as a whole never visited.

In the New Year, battalion training began, carried out on the occasional bright days that redeemed an abominable winter. At the beginning of February it was proposed to start brigade training, and in order to enable the 29th Brigade to concentrate for this purpose, various changes of station were necessary. Accordingly, the whole 29th Brigade moved to the Curragh, where one battalion was accommodated in barracks and the other three in huts. In order to allow this move to be carried out the 7th Royal Dublin Fusiliers, the Reserve Park Army Service Corps and the Divisional Cyclist Company were transferred to Dublin where they were quartered in the Royal Barracks.

Brigade field-days, brigade route marches and brigade night operations were the order of the day throughout February, and a second course of musketry was also fired. Early in March the Divisional Commander decided to employ the troops at the Curragh in a series of combined operations. For this purpose he could dispose of two infantry brigades (less one battalion), three brigades of Royal Field Artillery, the heavy battery (which joined the Division[21] from Woolwich about this time), three field companies of Royal Engineers, while on special occasions the divisional Signal Company were brought over from Carlow and the Cyclists from Dublin. He could also obtain the assistance of the two reserve regiments of cavalry which were stationed at the Curragh.

Though we criticised them bitterly at the time, these Curragh field-days were among the pleasantest of the Division’s experiences. By this time the battalions had obtained a corporate existence and it was exhilarating to march out in the morning, one of eight hundred men, and feel that one’s own work had a definite part in the creation of a disciplined whole. The different units had obtained (at their own expense) drums and fifes, and some of them had pipes as well. As we followed the music down the wet winding roads round Kilcullen or the Chair of Kildare, we gained a recollection of the hedges on each side bursting into leaf, and the grey clouds hanging overhead, that was to linger with us during many hot and anxious days.

As a rule, these combined operations took place twice in the week. For the rest of the time ordinary work was continued, while on the 16th of April, Sir B. Mahon held a ceremonial inspection of the units of the Division which were stationed at the Curragh, Newbridge and Kildare. The infantry marched past in “Battalion Mass,” and the artillery in “Line[22] Close interval.” At this time, too, Company Commanders began to mourn the loss of many of their best men who became specialists. As mules, Vickers guns, signalling equipment, etc., were received, more and more men were withdrawn from the Companies to serve with the regimental transport, the machine-gun section, or the signallers. The drain due to this cause was so great that the Company Commander seldom saw all the men who were nominally under his command except on pay-day. While this process was going on the weaklings were being weeded out. A stringent medical examination removed all those who were considered too old or too infirm to stand the strain of active service, and they were sent to the reserve battalions of their unit. Men of bad character, who were leading young soldiers astray, or who, by reason of their dishonesty, were a nuisance in the barrack-room, were discharged as unlikely to become efficient soldiers. But on the whole there was not much crime in the Division. A certain amount of drunkenness was inevitable, but the principal military offence committed was that of absence without leave. This was not unnatural under the circumstances. Men who had not fully realised the restraints of discipline, and had been unable to cut themselves completely adrift from their civilian life were naturally anxious to return home from time to time. If they could not obtain leave,[23] they went without it; when they got it, they often overstayed it, but their conduct was not without excuse. One man who had overstayed his pass by a week, said in extenuation, “When I got home, my wife said she could get no one to plant the land for her, and I just had to stay until I had the garden planted with potatoes.” And there is no doubt that in most cases of absence the relations of the absentee were responsible for it. It was not easy for men who had been civilians four months before to realise the seriousness of their offence while they saw the Division, as they thought, marking time, and knew that their homes were within reach, and officers were relieved when at the end of April units received orders to hold themselves in readiness to move to a point of concentration near Aldershot.

This point of concentration proved to be Basingstoke, and by the end of the first week in May the whole Division was assembled there. As we journeyed we read how the 29th Division had charged through the waves and the wire, and effected its landing at Cape Helles, and how against overwhelming odds the Australians and New Zealanders had won a foothold at Gaba Tepe. At that time, however, our thoughts were fixed on France.

At Basingstoke we were inspected and watched at work by the staff of the Aldershot Training Centre, and were found wanting in some[24] respects. In particular, we were unduly ignorant of the art and mystery of bombing, and many hot afternoons were spent in a labyrinth of trenches which had been dug in Lord Curzon’s park at Hackwood, propelling a jam tin weighted with stones across a couple of intervening traverses. Bayonet-fighting, too, was much practised, and the machine-gun detachments and snipers each went to Bordon for a special course. In addition, each Brigade in turn marched to Aldershot, and spent a couple of days on the Ash Ranges doing a refresher course of musketry.

The most salient feature, however, of the Basingstoke period of training was the Divisional marches. Every week the whole Division, transport, ambulances and all, would leave camp. The first day would be occupied by a march, and at night the troops either billeted or bivouacked. On the next day there were operations: sometimes another New Army division acted as enemy, sometimes the foe was represented by the Cyclists, and the Pioneer Battalion. As night fell, the men bivouacked on the ground they were supposed to have won, occasionally being disturbed by a night attack. On the third day we marched home to a tent, which seemed spacious and luxurious after two nights in the open. These operations were of great value to the staff, and also to the transport, who learned from them how difficulties which appeared insignificant on paper became of[25] paramount importance in practice. The individual officer or man, on the other hand, gained but little military experience, since as a rule the whole time was occupied by long hot dusty marches between the choking overhanging hedges of a stony Hampshire lane. What was valuable, however, was the lesson learnt when the march was over. A man’s comfort usually depended on his own ingenuity, and unless he was able to make a weatherproof shelter from his ground sheet and blanket he was by no means unlikely to spend a wet night. The cooks, too, discovered that a fire in the open required humouring, and all ranks began to realise that unless a man was self-sufficient, he was of little use in modern war. In barracks, the soldier leads a hard enough life, but he is eternally being looked after, and if he loses anything he is obliged to replace it at once from the grocery bar or the quartermaster’s store. On service, if he loses things he has to do without them, and in Gallipoli where nothing could be obtained nearer than Mudros and everything but sheer necessities had to be fetched from Alexandria or Malta, the ingrained carelessness of the soldier meant a considerable amount of unnecessary hardships. It would be too much to say that these marches and bivouacs eradicated this carelessness, but they did, at any rate, impress on the more thoughtful some of the difficulties to be encountered in the future.

The monotony of training was broken on the 28th of May when His Majesty the King visited and inspected the Division. The 31st Brigade was at Aldershot doing musketry, but the 29th and 30th Brigades and the Divisional Troops paraded in full strength in Hackwood Park. His Majesty, who was accompanied by the Queen, rode along the front of each corps and then took up his position at the Saluting Point. The troops marched past: first the Infantry in a formation (Column of Platoons) which enabled each man to see his Sovereign distinctly, followed by the Field Ambulances, the squadron of South Irish Horse, and the Artillery, Engineers and Army Service Corps. On the following day, His Majesty inspected the 31st Brigade as they were marching back from Aldershot to Basingstoke.

This inspection was followed by another one, as Field-Marshal Lord Kitchener, who had been unable to accompany His Majesty, paid the Division a visit on June 1st.

It would be superfluous to describe both these inspections, since the same ceremonial was adopted at each, and since the 31st Brigade was absent on the 28th May, an account of the parade for Lord Kitchener may stand for both occasions. The inspection took place in an open space in Hackwood Park, the infantry being drawn up, one brigade facing the other two on the crest of a ridge, while the mounted[27] troops in an adjoining field were assembled on a slope running down to a small stream. The scene was typically English; here and there a line of white chalk showed where a trench had broken the smooth green turf, and all around, copses and clumps of ancient trees, in the full beauty of their fresh foliage, spoke of a land untouched for centuries by the stern hand of war. Soon very different sights were to meet the eyes of the men of the 10th Division, and at Mudros, and on the sun-baked Peninsula, many thought longingly of soft Hampshire grass and the shade of mighty beeches.

Though the sun shone at intervals, yet there was a chill bite in the wind, and the troops who had begun to take up their positions at 10 o’clock were relieved when at noon the Field-Marshal’s cortège trotted on to the review ground, and began to ride along the lines. The broad-shouldered, thick-set figure was familiar, but the face lacked the stern frown so often seen in pictures, and wore a cheerful smile. Yet he had good reason to smile. Around him were men—Hunter, Mahon, and others—who had shared his victories in the past, and before him stood the ranks of those who were destined to lend to his name imperishable glory. He, more than any other man, had drawn from their homes the officers and men who faced him in Hackwood Park, and trained and equipped them, until at last, after ten[28] months’ hard and strenuous work, they were ready to take the field. He looked on the stalwart lines, and all could see that he was pleased. After he had passed along the ranks, he returned to the saluting point, and the march-past began. The Division had no brass bands, but each unit, in close column of platoons, was played past by the massed drums and fifes of its own Brigade. First came the Royal Irish, swinging to the lilt of “Garry Owen,” in a manner that showed that their C. O. and Sergeant-Major were old Guardsmen. Then followed the Hampshires, stepping out to the tune that has played the 37th past the saluting point since the days of Dettingen and Minden. Then again the bands took up the Irish strain, and the best of drum-and-fife marches, “St. Patrick’s Day,” crashed out for the Connaught Rangers. Then came a sadder note for the Leinsters’ march is “Come Back to Erin,” and one knew that many of those marching to it would never see Ireland again. But sorrowful thoughts were banished as the quickstep of the Rifles succeeded to the yearning tune. After the Rifles had passed, the music became monotonous, since all Fusilier Regiments have the same march-past, and by the time the rear of the 31st Brigade had arrived, one’s ears were somewhat weary of the refrain of the “British Grenadiers.” At a rehearsal of the Inspection, the Dublin Fusiliers had endeavoured to vary[29] the monotony by playing “St. Patrick’s Day,” but the fury of the Connaught Rangers, who share the right of playing this tune with the Irish Guards alone, was so intense that it was abandoned, and Munsters and Dublins, Inniskillings and Faugh-a-Ballaghs, moved past to the strains of their own march. “The British Grenadiers” is a good tune, and Fusilier regiments are not often brigaded together, so that this lack of variety is seldom noted, yet there are so many good Irish quick-steps unused that perhaps the Fusilier regiments from Ireland might be permitted to use one of them as an alternative.

After the Infantry came the Field Ambulances, and after them the squadron of the South Irish Horse. These were followed by rank after rank of guns with the Engineers and Army Service Corps bringing up the rear. The long lines of gleaming bayonets, and the horses, guns, and wagons, passing in quick succession, formed a magnificent spectacle. Not by dragon’s teeth had this armed force been raised in so short a time, but by unresting and untiring work.

As a result of these inspections the following orders were issued:—

“10th Division Order No. 34. 1st June, 1915.

“Lieutenant-General Sir B. Mahon received His Majesty’s command to publish a divisional[30] order to say how pleased His Majesty was to have had an opportunity of seeing the 10th Irish Division, and how impressed he was with the appearance and physical fitness of the troops.

“His Majesty the King recognises that it is due to the keenness and co-operation of all ranks that the 10th Division has reached such a high standard of efficiency.”

“The General Officer Commanding 10th Irish Division has much pleasure in informing the troops that Field-Marshal Earl Kitchener of Khartoum, the Secretary of State for War, expressed himself as highly satisfied with all he saw of the 10th Division at the inspection to-day.”

After these two inspections the men began to hope that they would soon be on the move, but the regular routine continued, and all ranks began to get a little stale. The period of training had been filled with hard and strenuous work, and as the days of laborious and monotonous toil crept on, one felt that little was being gained by it. It is not an exaggeration to say that so far as physical fitness was concerned, the whole of the Division which went as an organised whole to Gallipoli was in better condition at the end of April than when they left England. Infantry, engineers, and the Royal Army Medical Corps were all fully trained and qualified for the work they[31] were called on to do. The transport were not, but then the transport were left behind in England. It is possible, too, that the artillery gained by the delay, but they did not accompany the Division, and the two brigades that eventually landed in the Peninsula were completely detached from it. The staff certainly gained much experience from their stay at Basingstoke, but on reaching Gallipoli the Division was split up in such a manner that the experience they had acquired became of little value.

Just as we were beginning to despair of ever moving, on the 27th of June the long-expected order arrived, and the Division was warned to hold itself in readiness for service at the Dardanelles.

“When in Lemnos we ate our fill of flesh of tall-horned oxen.”—Homer.

It will now be proper to describe the doings of the Division in somewhat fuller detail.

The immediate result of the warning received on June 27th, which was officially confirmed on July 1st, was to throw an enormous amount of work upon officers and N.C.O.’s. Already the gaps in our strength had been filled up by drafts drawn from the 16th (Irish) Division, and now it was necessary for the whole of the men to be re-equipped. Helmets and khaki drill clothing had to be fitted, much of the latter requiring alteration, while the adjusting of pagris to helmets occupied much attention, and caused the advice and assistance of men who had served in India to be greatly in demand. At the same time new English-made belts and accoutrements were issued, the American leather equipment, which had been given out in March and had worn very badly, being withdrawn. We had gained one advantage from the numerous[33] false alarms that rumour had sprung upon us, the men’s field pay-books and field conduct-sheets were completely filled in and ready. This turned out to be extremely fortunate, as the company officers, sergeant-majors, and platoon sergeants found that the time at their disposal was so fully occupied that they would have had little leisure left for office work. The pay lists were closed and balanced, and sent with the cash-books to the Regimental Paymaster; any other documents which had not already been sent to the officer in charge of records were consigned to him, and at last we felt we were ready.

One symptom of the conditions under which we were going to fight was to be found in the fact that we lost some of our comrades. The Heavy Battery and the squadron of the South Irish Horse were transferred to other divisions destined for France, while the transport, both Divisional and Regimental, was ordered to stand fast at Basingstoke. Worse than this, all regimental officers’ chargers were to be handed over to the Remount Department. This indication that we were intended for a walking campaign caused considerable dismay to some machine-gun officers, who had invested in imposing and tight-fitting field boots, and were not certain whether they would be pleasant to march in. As for the men of the machine-gun detachments, their feelings were beyond expression.[34] The knowledge that gun, tripod, and belts would have to be carried everywhere by them in a tropical climate deprived them of words. However, they were too delighted to be on the move at last to grumble for long.

In the week beginning July 5th the departure began. The trains left at night, and battalions would awake in the morning to find tents previously occupied by their neighbours empty. The weather had changed to cold showers, and the men marching through the night to the station had reason to be thankful that their drill clothing was packed away in their kit-bags, and that they were wearing ordinary khaki serge. The helmets, however, were found to keep off rain well. Units were so subdivided for entraining purposes that there was little ceremony and less music at the departure. The men paraded in the dark, marched through the empty echoing streets of the silent town, sometimes singing, but more often thoughtful. The memory of recent farewells, the complete uncertainty of the future, the risks that lay before us, alike induced a mood that if not gloomy was certainly not hilarious. The cheerful songs of the early training period were silent, and when a few voices broke the silence, the tune that they chose was “God Save Ireland.” We were resolved that Ireland should not be ashamed of us, but we were beginning to realise that our task would be a stiff one.

The composition of the Division was as follows:—

Divisional Staff.

G.O.C.: Lieut.-General Sir B. T. Mahon, K.C.V.O., C.B., D.S.O.

Aide-de-Camp: Capt. the Marquis of Headfort (late 1st Life Guards).

General Staff Officer, 1st Grade: Lieut.-Col. J. G. King-King, D.S.O., Reserve of Officers (late the Queen’s).

General Staff Officer, 2nd Grade: Major G. E. Leman, North Staffordshire Regiment.

General Staff Officer, 3rd Grade: Captain D. J. C. K. Bernard, The Rifle Brigade.

A.A. and Q.M.G.: Col. D. Sapte, Reserve of Officers (late Northumberland Fusiliers).

D.A.A. and Q.M.G.: Major C. E. Hollins, Lincolnshire Regiment.

D.A.Q.M.G.1: Major W. M. Royston-Piggott, Army Service Corps.

D.A.D.O.S.: Major S. R. King, A.O.D.

A.P.M.: Lieutenant Viscount Powerscourt, M.V.O., Irish Guards, S.R.

A.D.M.S.: Lieut.-Col. H. D. Rowan, Royal Army Medical Corps.

D.A.D.M.S.: Major C. W. Holden, Royal Army Medical Corps.

29th Brigade.

G.O.C.: Brigadier-General R. J. Cooper, C.V.O.

Brigade-Major: Capt. A. H. McCleverty, 2nd Rajput Light Infantry.

Staff Captain: Capt. G. Nugent, Royal Irish Rifles.

Consisting of:—

10th Hampshire Regiment, commanded by Lieut.-Col. W. D. Bewsher.

6th Royal Irish Rifles, commanded by Lieut.-Col. E. C. Bradford.

5th Connaught Rangers, commanded by Lieut.-Col. H. F. N. Jourdain.

6th Leinster Regiment, commanded by Lieut.-Col. J. Craske, D.S.O.

30th Brigade.

G.O.C.: Brigadier-General L. L. Nicol.

Brigade-Major: Major E. C. Alexander, D.S.O., 55th Rifles, Indian Army.

Staff Captain: Capt. H. T. Goodland, Royal Munster Fusiliers.

Consisting of:—

6th Royal Munster Fusiliers, commanded by Lieut.-Col. V. T. Worship, D.S.O.

7th Royal Munster Fusiliers, commanded by Lieut.-Col. H. Gore.

6th Royal Dublin Fusiliers, commanded by Lieut.-Col. P. G. A. Cox.

7th Royal Dublin Fusiliers, commanded by Lieut.-Col. G. Downing.

31st Brigade.

G.O.C.: Brigadier-General F. F. Hill, C.B., D.S.O.

Brigade-Major: Capt. W. J. N. Cooke-Collis, Royal Irish Rifles.

Staff Captain: Capt. T. J. D. Atkinson, Royal Irish Fusiliers.

Consisting of:—

5th Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, commanded by Lieut.-Col. A. S. Vanrenen.

6th Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, commanded by Lieut.-Col. H. M. Cliffe.

5th Royal Irish Fusiliers, commanded by Lieut.-Col. M. J. W. Pike.

6th Royal Irish Fusiliers, commanded by Lieut.-Col. F. A. Greer.

Divisional Troops.

5th Royal Irish Regiment (Pioneers) commanded by Lieut.-Col. The Earl of Granard, K.P.

Divisional Artillery.

Brigadier-General, R.A.: Brigadier-General G. S. Duffus.

Brigade-Major: Capt. F. W. Barron, R.A.

Staff Captain: Captain Sir G. Beaumont.

Consisting of:—

54th Brigade Royal Field Artillery, commanded by Lieut.-Col. J. F. Cadell.

55th Royal Field Artillery, commanded by Lieut.-Col. H. R. Peck.

56th Brigade Royal Field Artillery, commanded by Brevet-Col. J. H. Jellett.

The 57th (Howitzer) Brigade, R.F.A., remained in England.

Royal Engineers.

Commanding Officer, Royal Engineers: Lieut.-Col. F. K. Fair.

Consisting of:—

65th Field Company, R.E.

66th ditto

85th ditto

10th Signal Company, commanded by Capt. L. H. Smithers.

Royal Army Medical Corps.

30th Field Ambulance, commanded by Lieut.-Col. P. MacKessack.

31st Field Ambulance, commanded by Lieut.-Col. D. D. Shanahan.

32nd Field Ambulance, commanded by Lieut.-Col. T. C. Lauder.

10th Divisional Cyclist Corps, commanded by Capt. B. S. James.

There is one particular in which the British Army may fairly claim to be superior to any force in the world, and that is in embarkation. Years of oversea expeditions, culminating in the South African War, have given us abundant experience in this class of work, and the fact[39] that even in a newly-formed unit like the 10th Division every battalion contained at least one officer who had taken a draft to India, helped to make things run smoothly. The voyage itself was uneventful. For the most part the troopships employed were Atlantic liners, and the accommodation and food provided for officers might be called luxurious. There were, however, two flies in the ointment. The architect of the boats had designed them rather for a North Atlantic winter than for summer in the Mediterranean, and the fact that at night every aperture had to be tightly closed for fear lest a gleam of light might attract an enemy submarine, made sleep difficult. The men, who were closely packed, found it impossible in their berths down below, and the officer of the watch was obliged to pick his way among hundreds of prostrate forms as he went from one end of the deck to the other.

The second grievance was lack of deck space, which precluded anything in the shape of violent exercise. Attempts at physical drill were made wherever there was an inch of spare room, and for the rest lectures and boat drill whiled away the tedium of the day. Almost the only soldiers on board with a definite occupation were the machine-gunners perched with their guns on the highest available points, and keeping a keen look-out for periscopes. Responsibility also fell upon the officer of the[40] watch, who was obliged to make a tour of the ship, looking out for unauthorised smoking and unscreened lights every hour, and reporting “All correct” to the ship’s officer on the bridge. For the rest, the foreseeing ones who had provided themselves with literature read; officers smoked and played bridge; men smoked, played “House” and dozed; but through all the lethargy and laziness there ran a suppressed undercurrent of suspense and excitement.

The bulk of the transports conveying the Division called at Malta and Alexandria, on their way from Devonport to Mudros, but one gigantic Cunarder, having on board Divisional Headquarters, 30th Brigade Headquarters, the 6th Leinster Regiment, 6th and 7th Royal Munster Fusiliers, and detachments of the 5th Royal Irish Regiment (Pioneers), and 5th The Connaught Rangers, sailed direct from Liverpool to Mudros, and cast anchor there on July 16th. These troops were the first of the Division to reach the advanced base of the Dardanelles operations, and it was with eager curiosity that they looked at the novel scene. They were in a land-locked harbour, which from the contour of the hills surrounding it might have been a bay on the Connemara coast had not land and sea been so very different in colour. Soft and brilliant as the lights and tints of an Irish landscape are, nothing in Ireland ever resembled the deep but sparkling[41] blue of the water, and the tawny slopes of the hills of Lemnos. Northward, at the end of the harbour, the store-ships and water-boats lay at anchor; midway were the transports, and near the entrance the French and British warships.

On the eastern shore dust-coloured tents told of the presence of hospitals; and to the west, lines of huddled bivouacs indicated some concentration of newly-arrived troops. The heart of the place, from which every nerve and pulse throbbed, was a big, grey, single-funnelled liner, anchored near the eastern shore. Here were the headquarters of the Inspector-General of Communications, and the Principal Naval Transport Officer; here the impecunious sought the Field Cashier; and the greedy endeavoured (unsuccessfully, unless they had friends aboard) to obtain a civilised meal. Next to her a big transport acted as Ordnance Store, and issued indiscriminately grenades and gum-boots, socks and shrapnel. At this time, no ferries had been instituted, and communication with these ships, though essential, was not easy. If you were a person of importance, a launch was sent for you; if, as was more likely, you were not, you chartered a Greek boat, and did your best to persuade the pirate in charge of it to wait while you transacted your business on board.

We had ample time to appreciate this factor[42] in the situation as it was three days before we disembarked. During that time we succeeded in learning a little about the conditions of warfare in what we began to call “the Peninsula.” Part of the 29th Division, which by its conduct in the first landing had won itself the title of “Incomparable,” was back at Mudros resting, and many of its officers came on board to look for friends. Thus we learned from men who had been in Gallipoli since they had struggled through the surf and the wire on April 24th the truth as to the nature of the fighting there. They taught us much by their words, but even more by their appearance; for though fit, they were thin and worn, and their eyes carried a weary look that told of the strain that they had been through. For the first time we began to realise that strong nerves were a great asset in war.

At last the order for disembarkation came, and a string of pinnaces, towed by steam launches from the battleships, conveyed the men ashore. Kits followed in lighters, and wise officers seized the opportunity to add to their mess stores as much stuff as the purser of the transport would let them have. It was our last contact with civilisation.

On the beach there was a considerable amount of confusion. The western side of the harbour had only recently been taken into use by troops, and though piers had been made, roads were as[43] yet non-existent. Lighters were discharging kit and stores at half-a-dozen different points, and the prudent officer took steps to mount a guard wherever he saw any of his stuff. In war, primitive conditions rule, and it is injudicious to place too much confidence in the honesty of your neighbours.

At last the overworked staff were able to disentangle the different units, and allot them their respective areas, and the nucleus of the Division found itself installed in the crest of a ridge running northward, with the harbour on the east, and a shallow lagoon on the west. Across the lagoon lay a white-washed Greek village, surrounded by shady trees, in which Divisional Headquarters were established, and behind this rose the steep hills that divided Mudros from Castro, the capital of Lemnos. Further south was another village with a church; otherwise the only features of the landscape were a ruined tower and half-a-dozen windmills. Except at Divisional Headquarters there was not a tree to be seen. The ground was a mass of stones. Connaught is stony, but there the stones are of decent size. In Mudros, they were so small and so numerous that it took an hour to clear a space big enough for a bed. Between the stones were thistles and stubble, and here and there a prickly blue flower. In the distance one or two patches of tillage shone green, but except for these[44] everything was dusty, parched and barren. On the whole an unattractive prospect.

However, it was necessary to make the best of it, and soon the bivouacs were up, though their construction was made more difficult by the complete absence of wood of any kind. The men had been instructed to supplement the blanket, which they had brought from England, by another taken from the ship’s stores, and the hillside soon presented to the eye an endless repetition of the word “Cunard” in red letters. Officers soon found it impossible to obtain either shelter, tables, or seats sufficient for a battalion mess, and companies began to mess by themselves. Few parades could be held, for there were very few lorries and no animals at all in Mudros West, so that practically everything required by the troops had to be carried up from the beach by hand. Most of the camps were nearly a mile from the Supply Depôt, so that each fatigue entailed a two-mile march, and by the time that the men had carried out a ration fatigue, a wood fatigue, and two water fatigues, it was hard to ask them to do much more. A few short route marches were performed, but most commanding officers were reluctant to impose on the men harder tasks than those absolutely necessary before they became acclimatized.

Already we were beginning to make the acquaintance of four of the Gallipoli plagues—dust, [45] flies, thirst and enteritis. Our situation on the spur was exposed to a gentle breeze from the north. At first we rejoiced at this, thinking it would keep away flies and make things cooler; but soon we realized that what we gained in this respect we lost in dust. From the sandy beach, from the trampled tracks leading to the supply depôts, from the bivouacs to windward, it swept down on us, till eyes stung and food was masked with it. It became intensified when a fatigue party or, worst of all, a lorry, swept past, and the principal problem confronting a mess-president was to place the mess and kitchen where they got least of it.

The flies were indescribable. For a day or two they seemed comparatively rare, and we hoped that we were going to escape from them; but some instinct drew them to us, and at the end of a week they swarmed. All food was instantly covered with them, and sleep between sunrise and sunset was impossible except for a few who had provided themselves with mosquito nets. Not only did they cause irritation, but infection. There appeared to be a shortage of disinfectants, and it was impossible either to check their multiplication, or to prevent them from transmitting disease. They had, however, one negative merit: they neither bit nor stung. If instead of the common housefly we had been afflicted with midges or mosquitoes, our lot would have been infinitely worse.

The third plague was thirst. In July, in the Eastern Mediterranean, the sun is almost vertical; and to men in bivouac whose only shelter is a thin waterproof sheet or blanket rigged up on a couple of sticks, it causes tortures of thirst. All day long one sweats, and one’s system yearns for drink to take the place of the moisture one is losing. Unfortunately, Lemnos is a badly-watered island, and July was the driest season of the year. All the wells in the villages were needed by the Greek inhabitants: and though more were dug, many of them ran dry, and the water in those that held it was brackish and unsuitable for drinking. The bulk of the drinking-water used by the troops was brought by boat from Port Said and Alexandria, and not only was it lukewarm and tasteless, but the supply was strictly limited. The allowance per man was one gallon per day; and though on the surface this appears liberal, yet when it is reflected that in 1876 the consumption of water per head in London was 29 gallons,[1] it will be seen that great care had to be exercised. Even this scanty allowance did not always reach the men intact, for the water-carts of some units had not arrived, and so the whole of it had to be carried and stored in camp-kettles. In order to spare the men labour,[47] arrangements were made by which these camp-kettles were to be carried in a motor-lorry; but on the primitive roads so much was spilt as to render the experiment futile. Even in carrying by hand, a certain amount of leakage took place. In order to control the issue of water, most of it, after the men had filled their water-bottles, was used for tea, which though refreshing, can hardly be called a cooling drink. However, Greek hawkers brought baskets of eggs, lemons, tomatoes and water melons. The last, though tasteless, were juicy and cool, and the men purchased and ate large quantities of them.

Possibly they were in part to blame for the fourth affliction that befell us in the shape of enteritis. Though not very severe, this affliction was widespread, hardly anyone being free from it. A few went sick, but for every man who reported himself to the doctor, there were ten who were doing their duty without complaining that they were indisposed. Naturally, men were reluctant to report sick just before going into action for the first time; but though they were able to carry on, yet there was a general lowering of vitality and loss of energy due to this cause, which acted as a serious handicap in the difficult days to come.