By NELSON S. BOND

Come aboard the Saturn for

fun and laughs with Lancelot

Biggs—mastermind of the spaceways.

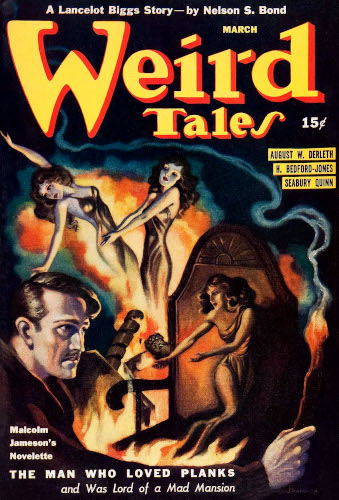

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Weird Tales March 1941.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

We were about three hours out of Long Island Spaceport, and I had just finished swapping farewell insults with Joe Marlowe, head bug-pounder at Lunar III, when the door of my radio turret slid open and in slithered—if round things can slither—Cap Hanson, skipper of our gallant space-going scow, the Saturn.

The Old Man's eyes were as wide as a lady bowler's beam, and his face, which boasts a pale mauve hue even under normal circumstances, was now a ripe, explosive fuchsia. He jammed a pudgy forefinger against his lips.

"Shh!" he shhed.

He squeezed in and closed the door behind him, shot a nervous glance about the room, then wheezed throatily, "Is there anybody here, Sparks?"

"Nobody," I told him, "but us amperes. Why all the Desperate Desmond stuff, Skipper? Got an old corpus delicti you want hid? You might try the air-lock—"

He snapped back to normal with a profane bang.

"Don't be a damned fool, Donovan! I ain't murdered any members of my crew yet. Though if I ever do, I've got a good notion who to start with. I got reason to be cautions. I just learned something—Listen!" He hunched forward and shoved his lips so close to my ear that I could almost hear his whiskers sprouting. "You know that Captain Cooper which come aboard at Long Island?"

"The Quarantine officer, you mean?"

"Quarantine officer your eye!" The skipper's voice was triumphant. "He ain't no more a Q.O. than I'm the Queen of Sheba! He's an inspector from the S.S.C.B."

"An inspector!" I gasped. "From the Space Safety Control Board! Why—why, that means—"

"Exactly!" Hanson rubbed his hands gleefully. "It means that Lanse is being examined for a commander's brevet. Well, what do you think of that? My son-in-law. Captain of his own ship. And him with only one year's active service!"

I said, "That's swell!" and meant it. The Old Man exaggerated a trifle when he called Lancelot Biggs his "son-in-law"; Biggs' marriage to Diane Hanson was not scheduled to take place, yet, for a couple of months. But with Hanson I could enthuse over the prospect of seeing Biggs win his four stripes and his own command. Lieutenant Lancelot Biggs was not only my superior officer, he was my friend, as well. He had once been my bunkmate. I had watched him rise from a gangling, awkward, derided Third Mate to First Officer; had been present when he earned his Master Navigator's papers; had seen him overcome seemingly insurmountable handicaps of appearance and personality to win a place in the affections of crew and command alike.

A screwball gent, this Biggs. Tall, angular, inconceivably skinny, graced (or disfigured?) with a phenomenally active Adam's-apple that bobbed eternally up and down in his skinny throat like an unswallowed cud—but blessed with two saving graces. A swell sense of humor and a brain!

True, his thought processes were oftimes fantastically involved. His motto, "Get the theory first!" sometimes led him down dark passageways of logic. But there never was a problem too deep for him; time and again his screwy logic had saved the personnel of the Saturn from peril to person or purse.

So, "That's swell!" I said—and meant it. Then I stared at the skipper thoughtfully. "But why," I asked him, "tell me about it? Biggs is the man to tell."

Hanson's eyes clouded, and he gnawed savagely at a grubby fingernail.

"That's just it, Sparks. I can't tell him."

"Why?" I demanded. "Laryngitis? Or ain't you and him speaking?"

"I can't tell him," explained the skipper, "because it would be unethical. You see, when a man's bein' examined for his commander's stripes, he ain't supposed to know about it. That's why Cooper come aboard under an alias. He wants to watch Lanse perform his routine duties in routine fashion—like nothin' unusual was goin' on.

"Then, at the end of the trip, he'll tell Lanse who he is, give him a verbal exam on the Space Safety Code, navigation practices, etcetera an' so on, an'—there you are!"

"There," I agreed, "I am. So where am I? Still in the dark, Skipper. Why tell me?"

Hanson glared at me witheringly.

"If you was as deaf," he said, making noises like a sizzling steak, "as you are dumb, the Corporation might give me a new radio operator for this here jallop—I mean, ship! Look, stupid! Biggs had ought to know he's bein' watched by an examiner, shouldn't he? Not that he don't know how to do things right, but because—well, because every so often the boy gets whacky ideas an' starts tryin' experiments.

"An' we don't want him tryin' nothin' like that, do we? Not on this shuttle. So, bein' as how you're his chum, an' since it would be unethical for me to spill the beans—you've got to tell him. Warn him to lay off the nonsense—get it?"

I got it. I nodded.

"Okay, Skipper. You're right and I'm wrong, as you usually are. I'll warn him. Only—" I hesitated, and the Old Man halted with one hand on the doorknob, looked back at me impatiently.

"Only what?"

"Only—if it's supposed to be a deep, dark secret, wouldn't it be unethical for me to tell him, too?"

"Don't," snorted Hanson, "be a donkey, Sparks! Whoever heard of a radioman with a sense of honor? Get word to him. An' make it snappy, too. He comes on in half an hour, an' I don't want he should pull any boners in front of Cooper. G'bye, now!"

The door slammed behind him.

So pretty soon there was a commotion in the rampway like a trained seal stumbling around on hob-nailed stilts, a rap sounded on my door, and I said, "Come on in, Mr. Biggs!" And sure enough, it was him.

He ambled in, grinned lazily and said, "Hi! What's new?"

"Nothing," I said, "under the Sun. Ain't you heard the adage? Look, Mr. Biggs—you go on duty pretty soon, is that right?"

"That's right."

"Well, you don't happen," I asked him shrewdly, "to have any bright new inventions hatching under your skull, do you? Like the uranium time-trap, for instance, or the velocity intensifier?"

He said, "Now, Sparks—can I help it if neither of them worked exactly as I had planned? After all—"

"Answer," I insisted, "yes or no. Do you?"

He flushed and wriggled one toe in the carpet.

"We-e-ell, not exactly. I did have a little idea I wanted to try out, though. An anti-gravitic attachment. On the cargo lofts. It occurred to me that—"

"Well, junk it!" I said. "Hasten, don't hobble, to the nearest incinerator, and give your diagrams the good old heaveroo!"

He said, "Eh?" and looked faintly startled. "Eh?" he repeated. His liquescent larynx Immelmanned. "But, why, Sparks?"

I said, "Them stripes on your sleeve, Lieutenant—they're pretty, ain't they?"

He glanced down, fingered his triple braid proudly.

"Why—why, yes. Very pretty. I'm proud of 'em."

"But the more there are," I pointed out, "the prettier they are. Isn't that right?"

"I—I suppose so. But what has that to do with—Sparks!" His voice raised to a shout, and suddenly his pale eyes brightened. "Do you mean that—?"

"Nothing else but. That alleged Q.O. mugg, Cooper, is a phony? He's really an S.S.C.B. inspector. And since he's not riding the Saturn for his health, I'll give you one guess who he's watching—if you start with yourself."

Funny what emotion will do to a guy. Biggs was not the type to go into a blue funk. I'd seen him face danger, disgrace and death, not once but many times. Every time, he had confronted the situation calmly, coolly, nary a quake or quiver stirring him. But here, handed good news on a silver platter, I thought for a minute he was going to pass out.

His eyes grew stalks, and his knees began to rattle like a marimba. The confused burble emanating from his lips resembled the vocal efforts of a tongue-tied hippo trying to speak Choctaw. His Adam's-apple—but why mention that monstrosity? Even I don't believe the things it did, and I saw it!

Words finally grew out of the melange of gutturals, sibilants and expectorants. Biggs' eyes receded into their sockets, became dewy and wistful, like the orbs of an amour-smitten adolescent. His voice was hushed and awed.

"My own ship!" he breathed. "My own command!"

"Don't cross your bridges," I reminded him, "until they're hatched. You've still got to win your letter, chum. Two letters, in fact. I-F. You become Skipper Biggs IF you pass the exam.

"Now, get to work. And remember—don't let on you know who this Cooper is. Deodorant's the word!"

I gave him a shove toward the door. He disappeared in a haze of little pink clouds. And I flopped into a seat, feeling so bad I could have bawled like a kid, but despising myself for feeling that way.

It was selfish, I guess. Biggs deserved the honor. But somehow—well, dammit! I sort of hated to see him leave the Saturn. We'd had a lot of fun together, our bunch. Cap Hanson and Chief Garrity, Dick Todd, the Second, and Wilson, the Third. And Biggs. And me.

Well, things settled down into normalcy, then. The Saturn is a ten day freighter, which meant that Cooper would have beaucoup opportunity to judge Biggs' capabilities. So tempus fidgeted, and I fidgeted, and the Old Man came within two spasms of a nervous breakdown, and Biggs—as might have been expected—got his nerves on ice after that first shock and performed his routine duties in ultra-stellar fashion.

My duties were far from exacting. Four times a day I had to contact a Space Station to check our course, speed, and declination against Solar Constant. That was just regulation blah, though, because with Biggs plotting the course, we had about as much chance of getting off the line as a rural subscriber when a juicy scandal is being discussed.

It was also my job to keep in touch with Lunar III, which daily interlude—Joe Marlowe being the low scut he is—was the only disturbing influence in an otherwise languid existence. Understand, I don't believe for a minute that my gal, Maisie Belle, was out with him. She's true to me. But it was a dirty trick for him to say she was, and beside, how the hell did he learn about that birthmark if—?

Oh, the hell with it! The fact is that time passed and pretty soon it was the sixth day, and in just a few more days we'd dock at Mars Central and Lt. Biggs would be Capt. Biggs.

Because if I had been idle on this shuttle, my rawboned friend had not. Cooper had been putting him through a series of strenuous paces to test his knowledge, ability and resourcefulness. The trajectory computations had mysteriously disappeared, for instance, and Biggs had to compile a new set. When he went to use the calculometer, he discovered it to be accidentally-on-purpose "out of order." So he had to evolve the figures from his own cranium.

Then there was the false alarm fire in the storage compartments—while Biggs was on the bridge. And the hypos went on the blink—with Biggs on duty. And one of the aft jets clogged. Guess who was standing watch at the time?

That sort of thing. But Biggs came through, every time, with flying colors. And with each succeeding success, another of the grim, suspicious lines melted from around the corners of Inspector Cooper's mouth, until he was beginning to look almost like a human being. Meanwhile, Cap Hanson's face got daily ruddier, happier, and grinnier. He was just one big smile on legs as he saw his son-in-law-to-be coming closer and closer to the coveted stripes.

"Just four more days, Sparks!" he chortled happily to me. And then, "Just three more days! Just two more—" He rubbed his hairy paws together gleefully. "Two captains in the same family! Ain't that somethin'? Boy, did you see the way he come through on that test yesterday? Cooper got Garrity to cross the heat control an' grav plates. The ship was hot an' weightless at the same time—"

"So that's what it was?" I grumbled. "Hell, who's taking this test—Biggs or us guinea-pigs? I went soaring to the ceiling, boiling like a kettle—and with the gravs off, I couldn't even drip sweat!"

"But Lanse fixed it!" gloried Hanson. "Spotted the trouble in three minutes flat, and had the circuits straight before you could say 'hypertensile dynamics'! What a lad!"

"Two more days," I said. "All I hope is that I can live through it. If Cooper gets any more whacky ideas—"

"Hrrrrumph!" came a voice from the doorway. I spun, startled.

What did my mama tell me about talking in front of a person's back? It was Inspector Cooper!

I said, "Look, Inspector—the acoustics are lousy in this room. Anything you heard which might have sounded like your name was strictly coincidental."

He glared at me. Then at Cap Hanson. Then at me. And, boy, what I mean—that guy could really glare!

"So!" he said. "Inspector, eh?"

Oh-oh! It dawned on me, all of a sudden—but too late—that I'd upset the legumes with a vengeance. Calling him "Inspector," when, so far as I was concerned, he was an officer in the Quarantine Service.

"Inspector, eh?" he repeated. And crisped Hanson's burning cheeks with a glance. "Well, Captain, it is just as I thought. Too many years of service have taken their toll on your discretion. When you start taking common radiomen into your confidence—"

I did the best I could. I rallied around.

"Now, wait a minute, Inspector!" I said. "Captain Hanson didn't tell me who you were. I—I guessed it. I'm pretty good at things like that. I figured it out the first time I saw you. It's my psychic—"

"It will be your neck," he snarled, "if you don't shut your yap! Well—now that you know who I am, I might as well tell you why I'm here. I need your cooperation in giving Lieutenant Biggs his final test."

Some of the chagrin left Hanson's eyes; his voice was hopeful.

"Final test?"

"Yes. I confess to a very great respect for your First Mate, Captain Hanson. He has proven himself capable in each of the tests offered so far. His theoretical knowledge is matched by his physical ingenuity; I have awarded him the highest possible grades in Astrogation, Analytical Judgment, and General Knowledge.

"If he passes the final test, Resourcefulness, and of course the verbal quiz on Safety Code practices, I shall take great pleasure in submitting his name for advancement.

"This test—" He turned to me. "Will be made in your department, Sparks. You—" He transfixed me with an icy glare. "You are sick!"

"Who, me?"

"Yes. You have—mmm, let me see!—dyspepsia!"

"It's a lie!" I said indignantly. "I haven't been near one of them Venusian joy-joints for a year!"

"You have," repeated Cooper coldly, "a bad case of dyspepsia. Which is another name for 'indigestion,' young man! You will develop this ailment immediately. And since the captain of a space-going vessel is supposed to be able to step into the breach in any emergency, Lieutenant Biggs will be assigned the task of relieving you at your post."

Wow! Was that a break for our side? I darned near split a lip, trying to hide the great big grin that leaped to my gabber. If there was any man aboard the Saturn whose knowledge of radio was equal to my own, that man was Lancelot Biggs! Why, he was the inventor of a new type of radio transmission plate. If this were to be his "final test," he would breeze home, win, place and show!

But Cooper didn't notice the elation in my eyes, or the equal joy in the skipper's optics. He was finishing his instructions.

"—and because you have learned who I am, Sparks, I suggest that you make no attempt to get in touch with, or speak to, Lieutenant Biggs. You may consider yourself confined to quarters for the duration of the trip."

"Very good, sir," I said.

"And now—" Cooper turned to my instruments. "We shall set the stage for Mr. Biggs' final test—" He picked up a hammer. The biggest one in the turret. He lifted it, weighed it briefly in his paw, and then—

Wham!

Things clanked and clattered; glass tinkled; wires leaped from the innards of my set and wriggled out onto the floor like tiny metal snakes. Cap groaned, and I screamed, "Omigawd!"

"Omigawd!" I screamed. "Leggo! Stop it! Are you off your jets?"

"Stand back, Sparks!" warned Cooper. He raised the hammer again, again brought it down ferociously into the entrails of my beautiful transmission set. Clinkety-clatter! Something shorted; blue fire spat; there was a loud pop! and I had to clutch my breast to make sure it wasn't my heart. "Stand back!" he panted. "We—we've got to—make this—a tough—test!"

"We?" I howled.

And then he was done. He stepped back and studied his work with the pleased look of a ghoul in a graveyard.

"I think that should do the trick," he said gravely. "If he can repair this set and get it in working order, I'll give him top grade in Resourcefulness.

"Very well, now, Captain—you may return to the bridge and tell Biggs that Sparks has been suddenly overcome with illness. And you, Sparks—to your quarters. And don't forget—you're sick!"

I stared miserably at my once-perfect apparatus. I passed a hand over my brow and tottered to the doorway.

"Maybe you think," I wailed, "I'm not?"

Well, I began to feel well enough to sit up and take notice along about lunch time. Doug Enderby, the steward of our void-cavorting madhouse, brought me my grub. He tiptoed in and laid the tray on the desk before me. He whispered:

"Are you feeling better, Bert?"

"Never worse," I told him gloomily. "Why the crape on the victuals? Are they that bad?"

I whipped off the napkin, took one gander at my so-called "lunch," and bleated like a branded sheep.

"Great monsoons of Mars—what the hell is this?"

"Shhh!" hushed Enderby. "Poached eggs, Sparks."

"I can see them!" I hollered. I stared at the pair of baleful, golden horrors-on-toast. "And they can see me, too! Take 'em away!"

"I can see them!" I hollered. I stared at the pair of baleful golden horrors-on-toast. "And they can see me, too!"

Enderby said petulantly, "But you're sick! That's what Captain Cooper said."

"Cooper, eh?" I groaned. "I always said it wasn't smart to make torture illegal." Then I remembered why I was confined to durance vile. "You seen Biggs?" I asked.

"No. He hasn't been down to lunch. He had to take over for you when you were taken ill." Doug looked anxious. "There—there's something wrong in your turret, Sparks. The intercommunications system is out, and the radio won't work."

I glanced at my watch. Two hours had passed since Cooper's coup. Hardly time for Lanse to unscramble the mess of pottery.

"Well, cheer up," I said. "Everything will be O.Q. in a little while. Uggh!" I pushed my toast and tea toward him. "Look, pal, how's the cow situation in the galley? You got a nice, three inch steak? Rare? With onions?"

"Sirloins," said Doug, "for dinner."

"In that case," I sighed, "I'll give this hen-fruit a miss. See you at dinner-time."

Doug nodded sagely and sidled toward the doorway.

"Steaks," he said, "for the crew. But you get milk toast. You're a sick ma—Hey!"

Well, I almost nailed him with that second poached egg, anyway.

After he beat it, I opened the door and peeked out, and sure enough, one of the sailors was standing down at the end of the corridor. Cooper was a canny duck. He was going to make certain that I didn't get loose and help Biggs.

But Cooper wasn't the only guy with smart ideas. I hadn't been radio operator on the Saturn for three years for nothing. There were a couple of wrinkles in the wiring system that even the Installation Department knew nothing about. I ducked back into my cabin, locked the door carefully, hung my coat over the keyhole, and pulled back my mattress.

Underneath, nestling coyly amongst the box springs of my bunk, was a tiny, complete transmission-reception set. I'm no dummy. Midnight watches are a bore, and many is the time I'd turned in with a pair of earphones on, rather than sit nodding in the turret for dreary hours waiting for messages that might never come in.

Of course this auxiliary set was useless so long as the main set was O.O.O.—but by listening in, I could tell how Lanse was coming along with his repair job, perhaps give him a little assistance by remote control should he need it.

So I donned the phones—and just like I thought, the circuit was as cold as a ditch-digger's toes in Siberia. For a few seconds. Then all of a sudden something squawked, "Krrrr-wowowooo! Brglrp! Glrp!"—and a familiar voice came from far, far away. The voice of Lancelot Biggs, saying:

"That ought to do it! Now, let me see if—"

I hugged myself gleefully. The old master mind had done it again! In just two hours and sixteen minutes. Tell me Lancelot Biggs isn't a genius!

I shoved my puss to the mike. I hissed, "Lanse!"

There was a brief silence. Then Biggs' curious response. "Is that you, Sparks?"

"In person," I told him, "and not a facsimile. How you getting along, pal?"

"Why, all right, I guess." He clucked, and I could envision the rueful shake of his head. "It was a frightful mess, Sparks. How you ever let it get in that condition—"

"I let it get in that condition," I told him, "like I got sick. By orders of Madman Cooper. That guy's a wingding with the mace, ain't he? Where'd you get the replacement parts?"

"Out of the supply locker, mostly. I had to rewind the L-49 armature, though. We had no spares."

"You'd better throw a shunt across the No. 4 rheo," I suggested. "You're heterodyning on vocal freke; otherwise you seem to have matters under control. Nice going, bud. I guess you know this is your final test?"

"I suspected it. Well, I'm going to test now. See if I can contact Lunar III. Stand by, Sparks. I'll cut you into the circuit so you can hear."

Current hummed and squealed; dots and dashes ripped the ether as Biggs pulsed a signal to Mother Earth's satellite. Slow seconds dragged. We are very close to Mars, and it takes a message almost two and a half minutes to make the hurdle from the green planet to the red one.

I waited tensely. And then, faint and far, but yet clear, came the reply.

"Answering IPS Saturn. Go ahead, Saturn." It was Joe Marlowe's hand on the bug. I could tell that. You know how it is; every operator has a transmitting style just as distinctive as handwriting. "Go ahead, Saturn." Then, "Are you sober, Donovan?"

I gritted my teeth. But Biggs put an end to Joe's smart stuff with his next transmission.

"Donovan ill. Relief man at key. Saturn reporting for orders. Any orders, Luna? Any orders?"

Marlowe flashed back, "Sorry about Donovan. Nothing trivial, I hope? Yes, have one order, Saturn. From S.S.C.B. headquarters. To Inspector-Commander Cooper. 'If Lt. Biggs passes examination, assign him immediately to command of—'"

Thump-thump-thump!

Damn! Of all the times to be interrupted. Just at the happy, crucial moment when I was about to learn the ship to which Biggs was going to be assigned! And some idiot had to come banging at my door!

Thump-thump-thump!

"Just a minute!" I howled. I switched off the unit and shoved the mattress back into place, rumpled the sheets, tousled my hair and pulled my shirt off. I stumbled to the door, unlocked it and stood back yawning and rubbing my eyes as if I had just hopped out of the arms of Morpheus. "C'mon in!" I said. "Whuzza big idea—Oh! How do you do, sir?"

My visitor was Inspector Cooper. He pushed past me into the room, glared around suspiciously, turned and heaved me an extraordinarily evil glare.

"What were you doing in here, Sparks? Don't lie to me! What were you doing at the exact moment I knocked?"

Behind him, ashen-faced, stood Cap Hanson. He knew about the auxiliary unit. One more bite, and his forefinger nail would be bitten off to the second joint.

"The exact moment?" I stalled.

"That's what I said."

I held my breath, which is one way to create a most maidenly blush. I said, "I—I respectfully decline to answer, sir. My reputation—"

"Your reputation," roared Inspector Cooper, "is not worth a damn anyway! Answer, sir!"

I shrugged. I said, "Well, after all, you can't be court-martialed for dreaming. You see, there was this blond kitten named Dolly. Sweet kid, but—well, reckless. And I was—"

Cooper turned crimson, and he wasn't a bit happy.

"What! You claim you were sleeping? We distinctly heard you talking, Donovan! Who were you talking to?"

I said plaintively, "Well—it was this way. Dolly was putting up an argument—"

That stopped him. He glowered about the cabin once more, helplessly, then he grunted and turned toward the door.

"Very well, Donovan. But if I ever find out you've been engaging in any skull-duggery—Come, Captain Hanson!"

And they left, Hanson tossing me a swift "saved-by-the-bell" glance that meant undying affection and a bonus in next month's salary. So I muttered, "I hope you don't," and when their footsteps faded from earshot, I made a dive for the concealed set.

But I'd missed the important part. Joe Marlowe was just signing off when I got the phones on.

"—Captain Biggs will then lift his command," came the closing sentence, "from Mars Central, in accordance with orders which await him there! That is all, Saturn!" And he was gone.

Boy, was I nearly busting! I couldn't wait for the sonic to die away so I could tap Biggs in the turret. "What did he say, Lanse?" I hollered. "Cooper came pussy-footing, and I missed the message. So you're going to get a command, eh? Congratulations? Tell me—"

My nerves were like red-hot worms as I listened for Biggs' answer. And then—

"Whonk!" went my set suddenly. "Gwobble-phweee!"

Out of order! Again!

Well, that was a stinker. But I had learned some things, anyway. That Biggs was in line for a captaincy, and that his new command was waiting for him at Mars Central. I dug a copy of Lloyd's Spaceways out of my desk-file, and leafed through it. The information was encouraging. Vessels land-docked at the Martian port included the transport, Antigone, the lugger, Tethys VI, and the brand-new, magnificent, special-extra-deluxe passenger liner, Orestes! Any one of these ships would be a feather in the cap of the skipper who took her bridge. Lancelot Biggs was getting off to a Big Start!

So I should have been very happy. For him. But I wasn't. Not altogether. Somehow I couldn't help feeling it wouldn't be the same ship—the Saturn, I mean—with Biggs no longer ambling the quarter-deck.

A sentimental sap? Well, maybe I am. But when you have laughed and cried and fought and triumphed and shared sadness and joy with a right, tight, snug little gang of men, all of whom you love like brothers, you hate to think of one of them leaving you.

And that's the way it was aboard the Saturn. Sure, we had our little squabbles and fusses. Wilson is a sort of show-off, and Todd sometimes has a tendency to let others do his work. The Old Man's not much of an astrogator any more; after all, he's been pushing ether for more years than I've been alive; he's not as smart and alert as some of the fresh young brevetmen. And Biggs' genius for getting us in tough spots is second only to his ability at getting us out again.

But we're a team, see? And now, with Biggs moving up the ladder, some strange new guy would come in.

It was hot!

I'd been so busy with the crying towel, that for a few minutes I didn't realize just how hot it was. But now, glancing at the thermometer on my wall, I was jolted to see the mercury standing at 98 degrees!

Without pausing to recollect that the audio system was out of order, I reached for the wall phone, bawled into it, "Ahoy, the bridge! Something's gone wrong with the—"

That's what I meant to yell, anyway. As a matter of strict truth, I got just as far as, "Ahoy—blub!"

For the moment I yanked the earpiece off the audio, a pencil of clear, cold water shot from the instrument like a diminutive geyser! Smack in the tonsils it slapped me—and I turned and hightailed it for the door!

My guard, a gob named Jorgens, let loose a roar as I appeared.

"Oh, no, Sparks! I got orders to keep you in your cabin!" he bellowed.

"That's what you think!" I yelled back. "I'm not going to be roast Donovan for you or anybody! I'm hot!"

"Then maybe this will cool you down." He grabbed the firehose, pointed it at me, turned the wheel. I wailed, and waited for the punching gout of water to sweep me off my feet. But it didn't come! There came a rushing sound, and from the nozzle spilled—

Air!

Jorgens dropped the hose with a howl of surprise. He gave up all idea of stopping me. As a matter of fact, he was three steps ahead of me by the time we hit the end of the corridor, but I beat him up the Jacob's-ladder leading to the bridge by the simple expedient of using his vertebrae as rungs.

Together we charged through the upper passageways, turned onto the ramp that feeds the bridge. By now, everything had gone stark, staring mad. All the time we were on the hoof, I kept hearing music. And every once in awhile a wild burst of static rasped my eardrums. And the heat increased.

It took me some minutes to realize, with a burst of horror, that the music was coming from the radiators, the static from the darkened electric bulbs set in the ceilings, and the heat was pouring in a torrential flood from our air supply—the ventilating system!

We reached the bridge, shouldered the door open. But the situation wasn't any better there. If anything, it was worse. Cap Hanson, perspiration streaming down his red face, staining his jacket, was bending over a calculating machine that was flickering hazily with moving pictures! Across the room, Lieutenant Todd was masterfully struggling to subdue the clamor of a generator that was chattering wildly in the Universal Code. Dots and dashes!

Above the bedlam, I managed to make myself heard.

"What's wrong?" I bawled.

The Old Man acknowledged my presence with one look of torment.

"The ship's gone nuts! The heater plays music and the telephone's a spring; there's static in the lights, and electricity in the gas jets. The ventilators give heat and Slops just called me on his refrigerator to tell me the gas stove is spitting ice cubes!"

Cooper, his face flaming with rage, pulled his paws from his ears long enough to scream, "This is a disgrace to the service! Whoever caused this should be cashiered! And by the Lord Harry—"

Just then the door opened, and into the room, with a big, friendly grin on his pan, gangled our lanky lieutenant, Lancelot Biggs.

"Hello, folks!" he said amiably. "Sort of—sort of noisy around here, isn't it?"

Cooper glared at him wildly.

"Biggs, get out of here! You're supposed to be up in the turret repairing that radio set. Get along—"

Biggs smiled sort of sheepishly; his unbelievable Adam's-apple did a loop-the-loop in his throat. He coughed gently.

"Well—er—you see," he said, "that's what made me come down here. I—I guess I must have got a little bit mixed up in the wiring. I got the circuits all crossed up, and—well, durn it, this is what happened!"

By sheer coincidence, just at that moment the air stopped hissing, the music stopped playing, and the tumult that had been flooding the room died away to a whisper. In a brief, horrible silence I heard Cap Hanson gasp, "Lanse! Lanse!" and heard the incredulous snort of Inspector Cooper.

"What? You caused this, Lieutenant?"

Biggs' pale eyes shifted, and he twisted his lanky frame into a pretzel.

"R-reckon I did, sir. Couldn't seem to get things straightened out in the turret, so I—I went down to the control room, and—and I guess I must have turned the wrong knobs or switches or something."

His excuse dwindled into silence. But Cooper did not. Cooper loosed a blat like a robot wired for newscasting.

"Wrong knobs! Wrong switches! Indeed, sir—" he swung to me, sweating painfully and quivering like an electroscope in a pitchblende mine. "Sparks, can you do anything about this—this disgraceful mess?"

I couldn't meet Biggs' eyes, nor could I meet those of Cap Hanson. I just nodded slowly.

"I think so, sir."

"Then get to work! And as for you, Lieutenant—" His eyes burned Biggs' pale, embarrassed face, "It will not now be necessary to determine whether or not you are versed in Safety Code practices. You have demonstrated very well that you are not yet capable of assuming the rank and duties of a commanding officer. Your butter-fingered handling of a simple, routine test has resulted in the most disgusting contretemps it has ever been my lot to witness!"

Cap Hanson said, "But—but look, Inspector—he's only a boy! Anybody can make a little mistake. Give him a chance to—"

"There is no place for 'boys'," snorted Cooper, "on the bridge of space-going vessels. Lieutenant Biggs has possibilities, yes. But I shall suggest to the S.S.C.B. that he be given another year of intensive training—under an old, accomplished spaceman; yourself, Captain Hanson—that he may learn resourcefulness, coolness, how to act under stress of emergency!

"And now, gentlemen, I shall retire until we reach Mars Central. Sparks, for God's sake quiet this bedlam as soon as possible!"

And he stalked from the bridge with as much dignity as a man can muster with hands clapped over a pair of sweat-dripping ears.

I went below. It was a mess, but not an impossible one. I got it straightened out in fifteen or twenty minutes. And by the time things were back to normal, we were warping into the cradle-lists at Mars Central Spaceport.

Afterward, everybody was sympathetic. Bud Wilson said, "Too bad, Biggs! But you'll get another chance." And he went out. Dick Todd said, "Aw, the hell with it, Lanse. You were just a little excited, that's all—" And he left, too. And that left Biggs and the skipper and me alone in the turret.

Biggs squirmed and said meekly, "I—I'm sorry, sir. I didn't mean to be such an idiot. But—well, after all, I am young. And I haven't had your experience."

The skipper still looked like a man who'd grabbed a live wire by accident. He shook his head sadly.

"I wouldn't of thunk it of you, Lancelot, son," he grieved. "You was always so quick at graspin' things before this. I was bankin' on you to make it two captains in the same family. But—well, let bygones be bygones. Next year you'll have another test. An' in the meantime, I'll try to teach you more about how to act in emergencies."

Biggs said gratefully, "Thank you, sir. And—and Diane?"

"We won't tell her," said the Old Man promptly. "I alluz say that what women don't know won't hurt 'em. We'll keep this to ourselves. But, mind you!" A flash of the old fire lighted his weathered, space-faded eyes. "But, mind—I want you to study hard durin' this next year! If you want to win your stripes, you got to listen to a wiser head!"

"Yes, sir," said Lancelot Biggs. "I will, sir."

Then the skipper left. A great old guy. No longer listless and lackadaisical, space-weary, but a new man, imbued with a strong, fighting new urge. To help a young man earn his spurs. There was something admirable in his attitude, and something a little pathetic, too.

And after he had left, I turned to Biggs. I said, "Okay, pal—come clean!"

He started.

"I—I beg your pardon, Sparks?"

"Come," I repeated, "clean. You can fool some of the people some of the time, and you can fool some of the people some of the time—but you can't fool some of the people some of the time. And I'm them. Biggs, I know you like I know my own hangnails. I've seen you in a thousand tight spots, and I never once knew you to go into a dither. But you messed this one up so bad that it smelled from here to Pluto. Now I want to know—why?"

Biggs' eyes looked like saucers. His larynx jumped up and down painfully.

"I don't know what you mean, Bert."

"Talk," I said grimly, "or I start rumors. Why?"

And then—Lancelot Biggs grinned!

"So I made it look bad, eh, Bert?"

"Bad? Awful! That heat—great comets, pal, you nearly killed us all! But why? I heard part of that transmission from Luna. I heard enough to know that if you passed your final test you were going to be given a command immediately. A ship of your own. The Tethys or the Antigone or the Orestes. All good ships—"

Biggs said quietly, "There was another one, Bert."

"What? No, there wasn't. I looked it up. There were only those three waiting captainless in port."

"But there would have been four," he said, "if I'd passed my exam. Sparks—Cap Hanson's a great guy, isn't he?"

"Sure. A grand old-timer. But—"

And then, suddenly, I got it! Got it, and realized what an all-around humdinging hell of a real man Lancelot Biggs really is! I said:

"You mean—you mean that if you had earned your stripes, the Old Man was going to be set down? And you'd be placed in command of the Saturn? Is that it? Why, you—"

And I swallowed hard, and I gave him a shove. And I said, "Aw, Lanse—"

But Lancelot Biggs isn't the kind of guy you can act gooey with. He just grinned again, and he said, "Sparks, old-timer, what do you say you and me have a drink or three, eh?"

So we did. Double. Without soda.