CHART

OF THE

BRITISH ISLES

SHEWING THE

WRECKS AND CASUALTIES

DURING THE YEAR 1873-4,

distinguishing those attended with

Loss of Life

BY

W. S. LINDSAY.

IN FOUR VOLUMES.

VOL. III.

With numerous Illustrations.

LONDON:

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, LOW, AND SEARLE.

CROWN BUILDINGS, 188 FLEET STREET.

1876.

[All Rights reserved.]

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS,

STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING CROSS.

On publishing the first two volumes of this work, it was not my intention that the following volumes should be preceded by any preface. I have, however, been induced to reconsider this resolution, in order to acknowledge the ready assistance I have received from men of great experience, not only of this but of foreign countries. My first volume treats more especially of the antiquities of the mercantile marine, and closes with the sixteenth century. In the second, I trace the progress of maritime commerce down to about the close of the great French War (1815), when a new era dawned and a new state of things was inaugurated. Details, relating in an especial manner to this period, form the subject of my last two volumes—in one I treat of the Navigation Laws of Cromwell and of the causes which led to their abolition, together with the effects of their abolition; while the other is devoted, entirely, to the rise and progress of steam-ships and to the different branches of commerce in which they are engaged.

In order to render this portion of my labours valuable for the purpose of reference, I have sought[Pg iv] the aid of those best able to afford me trustworthy information, and to supply me with documents and tables of unquestionable authenticity.

To none am I more deeply indebted in this respect than to Mr. Farrer and others, of the Board of Trade, whose kindly promptitude I again acknowledge. For that part relating to France I have profited by the valuable aid of Mr. Michael Chevalier, who has not grudged the pains of carefully and critically revising the proofs of that portion of the work, and making many interesting additions to it.

Nor must I omit to record the readiness exhibited by Mr. R. B. Forbes, of Boston, United States, by Commodore Prebble, Commandant of the Philadelphia Dockyard, and by the Presidents of the New York and other American Chambers of Commerce, and to the United States authorities generally, in supplying me with official data with reference to the development of the maritime commerce of the United States.

To my own countrymen, whether Shipowners, Merchants, Shipbuilders, or Underwriters, my thanks are heartily due, and to the Directors and Managers of those large Shipping Companies which arose in the middle of the present century, both at home and abroad. And, in an especial manner I have to thank Mr. John Burns, of Glasgow (Cunard Company), Mr. Alfred Holt, of Liverpool, and Mr. B. Waymouth, the Secretary to ‘Lloyd’s Register.’

To enumerate all those who have so courteously and generously striven to forward the views of an historian whose only object has been to chronicle[Pg v] facts and events, would be to give an undue extension to these prefatory remarks. I have, therefore, contented myself with acknowledging the sources of my information in foot-notes throughout my work; and I trust they will accept my thanks in the sense in which they are tendered.

In conclusion, I must refer to the kind attention paid to my request by Earl Russell, in revising that portion of my work which refers to the repeal of the Navigation Laws when he was First Minister of the Crown; and to other eminent Statesmen (two of whom have gone through the whole of the sheets of both volumes, making many valuable suggestions) for the approval expressed by them of the manner in which I have compressed the debates on these Laws which have now passed into the domain of history.

W. S. LINDSAY.

Shepperton Manor,

18th January, 1876.

| CHAPTER I. |

| Progress of the United States of America—Their resources—Discriminating duties levied by France, 1820, against American ships—Rapid rise of New Orleans, and of New York—Boston ships extend their trade to India and China—Stephen Girard, the rich and eccentric American shipowner, note—Mercantile marine laws of the United States—Duties of master and mate—Provision for Seamen—Special Acts relating to them—Power given to American consuls to deal with seamen on their ships—Superiority of native American seamen, owing to their education—Excellent schools and early training for them—Spirit and character of the “Shipping Articles” as affecting the seamen—the owners—and the master or consignee—Conditions of wages, and remedies for their non-payment; and other securities for seamen—Power of Appeal by them to the Admiralty Courts—Laws with reference to pilots—Character of American seamen, and especially of the New Englanders. |

| Pages 1-26 |

| CHAPTER II. |

| Necessity of proper education for merchant seamen—Practice in Denmark—In Norway and Sweden—Russia and Prussia—France—Remarkable care of seamen in Venice, Scuola di San Nicolo—Character of this institution, and general working—Variously modified since first creation—State since 1814—Qualifications of Venetian shipmasters—Present regulations of Austria—Great Britain—Need of a public institution for merchant seamen—The “Belvidere” or Royal Alfred Aged Seaman’s Institution, note—Mr. Williams, observations by, on the advantage of a general Seaman’s Fund, note—Institution in Norway—Foreign Office circular of July 1, 1843—Its value, though unfair and one-sided—Replies to circular—Mr. Consul Booker—Mr. Consul Baker—Mr. Consul Yeames—The[Pg viii] Consul at Dantzig—The Consuls of Genoa, Ancona, and Naples—Mr. Consul Sherrard—Mr. Consul MacTavish—Mr. Consul Hesketh—Reports from the Consuls in South America—General conclusions of Mr. Murray, Nov. 22, 1847, and suggestions for remedies—Board of Trade Commission, May 17, 1847—Its results—Shipowners condemned for the character of their ships and officers—Views of Government—Necessity of a competent Marine Department. |

| 27-52 |

| CHAPTER III. |

| High estimate abroad of English Navigation Laws—Change necessary, owing to the Independence of America—Other nations at first Protectionist—Mr. Pitt’s proposals with reference to trade with America—Mr. Pitt resigns, and a temporary Act ensues—Shipowners and loyalists in America successfully resist his scheme—Congress the first to retaliate—Restrictions injurious, alike, to England and her Colonies—Commercial treaties with America between 1794 and 1817—Acts of 1822 and 1823, and further irritation in America—Order in Council, July 1826—Conciliatory steps of the Americans in 1830—Foreigners look with suspicion on any change in the Navigation Laws—Reciprocity treaties of 1824-6—Value of treaties in early times, but inadequate for the regulation of commercial intercourse, and liable to unfair diplomacy—Reciprocity treaties only, partially, of value, and do not check the anomalies of Protection—Committee of 1844-5 promoted by the Shipowners, who seek protection against Colonial shipping—Reciprocity must lead to free navigation—New class of Statesmen, well supported by the People—Exertions of Lord John Russell, who leads the way against Protection—Richard Cobden and the Anti-Corn-Law League—John Bright—Effect of the Irish famine, 1845-6—Sir Robert Peel carries the Repeal of the Corn Laws, and resigns. |

| 53-80 |

| CHAPTER IV. |

| Lord John Russell’s first steps as Prime Minister: the Equalization of the Sugar Duties—He suspends the Navigation Laws, January 1847—Mr. Ricardo’s motion, February 1847—Reply of Mr. Liddell—Mr. Ricardo’s motion carried—Committee appointed, February 1847—Meeting of the shipowners, August 12, 1847—Their arguments—What constitutes “British ships”—State of Navigation Laws in 1847—Rules in force in the Plantation Trade—Their rigorous character—Their history from 1660 to 1847—First infringement of the principle of confining the American trade to British vessels—Absurdity and impotency of these laws—State of the law before the Declaration of American Independence—Trade with Europe—Modifications[Pg ix] of the law—East India Trade and Shipping—Trade with India in foreign and in United States ships even from English ports—Coasting trade—Summary of the Navigation Laws. |

| 81-109 |

| CHAPTER V. |

| Progress of the changes in the Navigation Laws—Reciprocity Treaties—Austria, July 1838—Zollverein States, August 1841—Russia, 1843—Various anomalies, &c., then in existence—Curious effects of Registry Laws, as regarded individuals or corporate bodies—Ship Equador—Decision of the Queen’s Bench, December 1846—Further details: owner to reside in the United Kingdom—Naturalisation of goods brought to Europe—Waste of capital caused thereby; and obstructions to trade—Story of the cochineal—But the Navigation Laws not always to blame—Special views of the Canadians—Montreal, its shipping and trade—Navigation of the St. Lawrence—Free-trade with the United States desired by the farmers of Canada—Negotiations proposed—Canadians urge the abolition of Protection—Views of Western Canada—Canadians, really, only for partial Free-trade—Improvements of their internal navigation—Welland Canal—Cost of freight the real question—Loss to Canada by New York line—General summary of results as to Canada—West Indians for Free-trade as well as Canadians—Divergent views of capitalists at home—Liverpool and Manchester opposed. |

| 110-135 |

| CHAPTER VI. |

| Witnesses examined by Mr. Ricardo’s Committee: Mr. J. S. Lefevre, Mr. Macgregor, Mr. G. R. Porter—Their extreme views not conclusive to the Committee—Evidence adduced by the Shipowners—Ships built more cheaply abroad—Evidence of Mr. G. F. Young, and his general conclusions—Mr. Richmond’s evidence—Asserts that shipping is a losing trade—Replies to the charges against Shipowners—Views as to captains of merchant ships—Praises their nautical skill and capacity—His character of common seamen—Attacks Mr. Porter—Offers valuable details of ship-building—Is prepared to go all lengths in favour of Protection—His jealousy of the Northern Powers—Evidence of Mr. Braysher, Collector of Customs in London—General effect of the Navigation Laws on the Customs—With the Northern Ports and America—Difficulty about “manufactured” articles—Anomalies of the coasting and internal trade—Committee’s last meeting, July 17—General dissatisfaction with the results of the inquiry—Commercial panic and distress of 1847—Suspension of Bank Charter Act. |

| 136-160[Pg x] |

| CHAPTER VII. |

| New Parliament, November 18, 1847—Speech from Throne—Mr. Robinson and Shipowners deceived—Conversation between Mr. Bancroft and Lord Palmerston—Mr. Bancroft’s declaration—Official letter from Mr. Bancroft to Lord Palmerston, November 3, 1847—Lord Palmerston’s reply, November 17, practically giving prior information to the Americans—Lord Clarendon tells the Shipowners’ Society that the laws will not be altered, December 26, 1846; and repeats this assurance, March 15, 1847—Interview between Lord Palmerston and Mr. Bancroft, published in ‘Washington Union’—Excites great indignation when known in England, January 1848—Parliament re-assembles, February 3, 1848—Lord Palmerston admits the correspondence with America—The Earl of Hardwicke’s proposal, February 25, 1848—Earl Grey grants a Committee—Evidence of the Shipowners before the Lords’ Committee—Mr. Young proposes some modifications, the first concessions of the Anti-Repeal Party—Claim in favour of direct voyages—Government insists on Total Repeal—Detailed views of Admiral Sir George Byam Martin—Importance of keeping up the merchant navy—Arguments from his personal experience as to its value as a nursery for seamen—Working of the system of apprenticeship, and of impressment—Evidence of Admiral Berkeley, and of Mr. R. B. Minturn—Details about American ships—Reciprocity treaties so far as they affect Americans—Their whale fishery. |

| 161-190 |

| CHAPTER VIII. |

| Motion of Mr. Herries, 1848—Protectionist principles stated—Extent of shipping trade—National defences endangered—Mr. Labouchere’s reply—Alderman Thompson—Mr. Gladstone’s views—Mr. Hudson—Lord George Bentinck—Mr. Hume—Mr. Cobden—Mr. Disraeli—Sir Robert Peel—The resolution carried by 117, but abandoned for a time—Temper of the Shipowners—Efforts of Ministers to obtain reciprocity by a circular from the Foreign Office—Reply thereto of America—Mr. Buchanan’s letter—Reply of other Powers—Progress of Free-trade views—Parliament of 1849—Death of Lord George Bentinck, September 21, 1848—Mr. Labouchere’s new resolution, February 14, 1849—Proposed change in coasting trade—Mr. Bancroft recalcitrates—Hence, withdrawal of the coasting clauses—The debate—Alderman Thompson, &c.—Mr. Ricardo—Meeting of Shipowners’ Society—Their report—The manning-clause grievance—Policy proposed—Agitation in the country. |

| 191-229[Pg xi] |

| CHAPTER IX. |

| The debate, March 1849—Speech of Mr. Herries—Mr. J. Wilson—Question of reciprocity—Doubtful even in the case of shipping—Difficulty of the “Favoured-nation” clause—Marquess of Granby—Mr. Cardwell—Mr. Henley—Mr. Gladstone—Burdens to be removed from Shipowners—Conditional legislation recommended—Views on the subject of the coasting trade—Americans not Free-traders—Smuggling in the coasting trade—Mr. Robinson—Mr. Clay—Mr. T. A. Mitchell—Mr. Hildyard—Mr. Ricardo—Mr. H. Drummond—Mr. Labouchere’s reply—Majority of 56 for Bill—Committee on the Bill—Coasting clauses withdrawn—Mr. Bouverie’s amendment opposed by Shipowners’ Committee—Mr. Gladstone’s scheme also opposed by the Shipowners—Questions of reciprocity, conditional legislation, and retaliation—Details of American Law—Mr. Bouverie’s plan rejected—Mr. Disraeli’s speech—Third reading of Bill—Mr. Herries’ speech—Mr. Robinson—Mr. Walpole—Sir James Graham—Mr. T. Baring—Lord J. Russell—Mr. Disraeli—Majority for Bill, 61. |

| 230-263 |

| CHAPTER X. |

| Debate in the Lords, May 7, 1849, on second reading—Speech of the Marquess of Lansdowne—Lord Brougham—Condemnation of Mr. Porter’s statistics—Protected and unprotected Trade—Voyages to the Continent—Napoleon’s desire for ships, colonies, and commerce—Earl Granville—Earl of Ellenborough—Increase of foreign peace establishments—Earl of Harrowby—Earl Grey—Lord Stanley—Admits need of modifications—Canada not our only colony—Majority for the Bill, 10—Duke of Wellington votes for it—Proceedings and debate in Committee—Lord Stanley’s amendment—Rejected by 13—Earl of Ellenborough’s amendment—Claims of Shipowners, and fear of competition—Amendment rejected by a majority of 12—Bill read a third time—Timber duties, &c., admitted to be grievances—Lord Stanley’s protest—Royal assent given, June 26—Coasting trade thrown open, 1854—Americans, October 1849, throw open all except their coasting trade. |

| 264-286 |

| CHAPTER XI. |

| Despondency of many shipowners after the repeal of the Navigation Laws—Advantage naturally taken by foreigners, and especially by the Americans—Jardine and Co. build vessels to compete with the[Pg xii] Americans—Aberdeen “clippers”—Shipowners demand the enforcement on foreign nations of reciprocity—Return of prosperity to the Shipowners—Act of 1850 for the improvement of the condition of seamen—Valuable services of Mr. T. H. Farrer—Chief conditions of the Act of 1850—Certificates of examination—Appointment of local marine boards, and their duties—Further provisions of the Act of 1850—Institution of Naval Courts abroad—Special inspectors to be appointed by the Board of Trade, if need be—Act of 1851, regulating Merchant Seaman’s Fund, &c.—Merchant Shipping Act, 1854—New measurement of ships—Registration of ships—The “Rule of the Sea”—Pilots and pilotage—Existing Mercantile Marine Fund—Wrecks—Limitation of the liability of Shipowners—Various miscellaneous provisions—Act of 1855. |

| 287-321 |

| CHAPTER XII. |

| Parliamentary inquiry, 1854-5, on Passenger ships—Heavy losses at sea previously, and especially in 1854—Emigration system—Frauds practised on emigrants—Runners and crimps—Remedies proposed—Average price, then, of passages—Emigration officer—Medical inspection—American emigration law—Dietary, then, required—Disgraceful state of emigrant ships at that time—Act of 1852—Resolution of New York Legislature, 1854—Evidence as to iron cargoes—Various attempts at improvement—Legislation in the United States, 1855—Uniformity of action impossible—English Passenger Act, 1855—Attempt to check issue of fraudulent tickets—General improvements—Merchant Shipping Act discussed—Extent of owner’s liability—Unnecessary outcry of the Shipowners—Question of limited liability—Value of life—Powers given to the Board of Trade—Mode of procedure in inquiries about loss of life—Further complaints of the Shipowners, who think too much discretion has been given to the Emigration officer—Though slightly modified since, the principle of the Passenger Act remains the same—the “Rule of the road at sea”—Examination now required for engineers as well as masters of steam vessels—Injurious action of the crimps—Savings-banks for seamen instituted, and, somewhat later, money-order offices. |

| 322-351 |

| CHAPTER XIII. |

| Scarcity of shipping at the commencement of the Crimean War—Repeal of the manning clause—Government refuses to issue letters of marque—Great increase of ship-building and high freights—Reaction—Transport service (notes)—Depression in the United States—The Great Republic—Disastrous years of 1857 and 1858—Many[Pg xiii] banks stop payment—Shipowners’ Society still attribute their disasters to the repeal of the Navigation Laws—Meeting of Shipowners, December 15th, 1858—Their proposal—Resolution moved by Mr. G. F. Young—Mr. Lindsay moves for Committee of Inquiry—Well-drawn petition of the Shipowners—Foreign governments and the amount of their reciprocity—French trade—Spanish trade—Portuguese trade—Belgian trade—British ships in French and Spanish ports—Coasting trade—Non-reciprocating countries—Presumed advantage of the Panama route—Question discussed—Was the depression due to the withdrawal of Protection?—Board of Trade report and returns—English and foreign tonnage—Sailing vessels and steamers in home and foreign trades—Shipping accounts, 1858—Foreign and Colonial trades—Probable causes of the depression in England and America—American jealousy and competition—Inconclusive reasoning of Board of Trade—Government proposes to remove burdens on British shipping—Compulsory reciprocity no longer obtainable—Real value of the Coasting trade of the United States—Magnanimity of England in throwing open her Coasting trade unconditionally not appreciated by the Americans. |

| 352-385 |

| CHAPTER XIV. |

| Further returns of the Board of Trade, and address of the Shipowners’ Society to the electors, 13th April, 1859—Shipowners’ meeting in London—Character of the speeches at it—Mr. Lindsay proposes an amendment—Effect of the war between France and Austria—Mr. Lindsay moves for an inquiry into the burdens on the Shipping Interest, 31st January, 1860—Report of the Committee thereon—Views with regard to foreign countries—The Netherlands—The United States—Generally unsatisfactory state of the intercourse with foreign nations—The present depression beyond the influence of Government—General results of Steamers versus Sailing Vessels—The Committee resists the plan of re-imposing restrictions on the Colonial Trade—Difficulty of enforcing reciprocity—Want of energy on the part of the English Foreign Office—Rights of belligerents—Privateering abolished in Europe; America, however, declining to accept this proposal—Views of the Committee thereon, and on the liability of Merchant Shipping—Burden of light dues—Pilotage Charges made by local authorities now, generally, abolished, as well as those of the Stade dues—The report of 1860, generally, accepted by the Mercantile Marine—Magnificent English Merchant Sailing vessels, 1859-1872—The Thermopylæ—Sir Lancelot and others—Americans completely outstripped—Equal increase in the number as well as the excellence of English shipping—Results of the Free-trade policy. |

| 386-421 |

| CHAPTER XV. |

| [Pg xiv]First Navigation Law in France, A.D. 1560—Law of Louis XIV., 1643, revised by Colbert, 1661—Its chief conditions—Regulations for the French Colonial trade—Slightly modified by the Treaties of Utrecht, 1713, and of 1763, in favour of England—Provisions of 1791 and 1793—Amount of charges enforced—French and English Navigation Laws equally worthless—“Surtaxes de Pavillon” and “d’Entrepôt”—“Droits de Tonnage”—Special exemption of Marseilles—French Colonial system preserved under all its Governments, but greatly to the injury of her people—English Exhibition of 1851—Messrs. Cobden and Chevalier meet first there, and ultimately, in 1860, carry the Commercial Treaty—The French, heavy losers by maintaining their Navigation Laws—Decline of French shipping—Mr. Lindsay visits France, and has various interviews with the Emperor, Messrs. Rouher and Chevalier on this subject—Commission of Inquiry appointed, and Law ultimately passed May 1866—Its conditions—Repeal Act unsatisfactory to the French Shipowners—Another Commission of Inquiry appointed, 1870—Views of rival parties—M. de Coninck—M. Bergasse—M. Siegfried—M. Thiers and Protection carry the day, and reverse, in 1872, much of the law of 1866—Just views of the Duke Decazes—Abolition for the second time of the “Surtaxes de Pavillon,” July 1873. |

| 422-462 |

| CHAPTER XVI. |

| Recent legislation relating to the loss of life and property at sea in British vessels—Committee on shipwrecks, 1836—Estimated loss of life at sea between 1818 and 1836—Recommendations of the Committee—Committee of 1843, loss of lives and ships at that period—First official return of wrecks, 1856—Loss of lives and ships, 1862 and 1873—Further recommendations—Various laws for the protection of seamen, 1846 to 1854—Agitation about “unseaworthy ships,” 1855—Further provisions for the benefit of seamen, 1867-69-70—Mr. Samuel Plimsoll, M.P.—His first resolution, 1870—Introduces a Bill, 1871—Government measure of that year—Mr. Plimsoll publishes a book, ‘Our Seamen,’ 1873—An extension of the principle applied to testing chain-cables strongly urged—Mr. Plimsoll moves an Address for a Commission of Inquiry, which was unanimously granted—Royal Commission on unseaworthy ships 1873-74—Its members—Their order of reference—And mode of thorough investigation—Their reports—Load-line—Deck loads—Government survey—Its extension undesirable—Shipowners already harassed by over-legislation—Mode of inquiry into losses at sea, examined and condemned—Recommendations—Examination of masters and mates,[Pg xv] and shipping officers approved—Power of masters—Scheme for training boys for sea—Marine Insurances—Report as a whole most valuable. |

| 463-501 |

| CHAPTER XVII. |

| Loose statements with regard to the loss of life at sea, and other matters—“Coffin ships”—Great improvement of our ships and officers in recent years—Duties of the Board of Trade with regard to wrecks—Return of lives lost and saved between 1855 and 1873, note—Wreck chart; but the extent of loss not sufficiently examined—Danger of too much Government interference—Loss of life in proportion to vessels afloat—Causes of loss—More details required—Improvement in lighthouses, buoys, and beacons—Harbours of Refuge—Extraordinary scene in the House of Commons on the withdrawal of the Merchant Shipping Bill, 1875—Another Bill introduced by Government—Its conditions—Unusual personal power granted to Surveyors—Propriety or not, of further legislation considered—Compulsory load-line—Mr. J. W. A. Harper’s evidence—Mr. W. J. Lamport and others—Opinion of the Commissioners—Voluntary load-line—Its value questionable—All ships should be certified as seaworthy—How can this be accomplished?—Opinion of Mr. Charles McIver, note—Registration Associations—Lloyd’s Register, its great importance—Improvement of seamen by better education—Evil effects of advance notes, confirmed by the opinion of the Commissioners—Over-insurance—Views of Mr. T. H. Farrer—Evidence of other witnesses—Opinion of the Commissioners—Too much legislation already—The necessity of a Mercantile Marine Code, and more prompt punishment in criminal cases—Concluding remarks on the extraordinary progress of British shipping, and the dangers of over-legislation. |

| 502-559 [Pg xvi] |

| APPENDICES.[Pg xvii] | |

| PAGE | |

| Appendix No. 1 | 563 |

| Appendix No. 2 | 567 |

| Appendix No. 3 | 571 |

| Appendix No. 4 | 582 |

| Appendix No. 5 | 590 |

| Appendix No. 6 | 596 |

| Appendix No. 7 | 600 |

| Appendix No. 8 | 611 |

| Appendix No. 9 | 613 |

| Appendix No. 10 | 618 |

| Appendix No. 11 | 620 |

| Appendix No. 12 | 624 |

| Appendix No. 13 | 634 |

| Appendix No. 14 | 637 |

| Index | 639 |

| PAGE | |

| Wreck Chart, showing where total, where partial, and where Loss of Life occurred | Frontispiece |

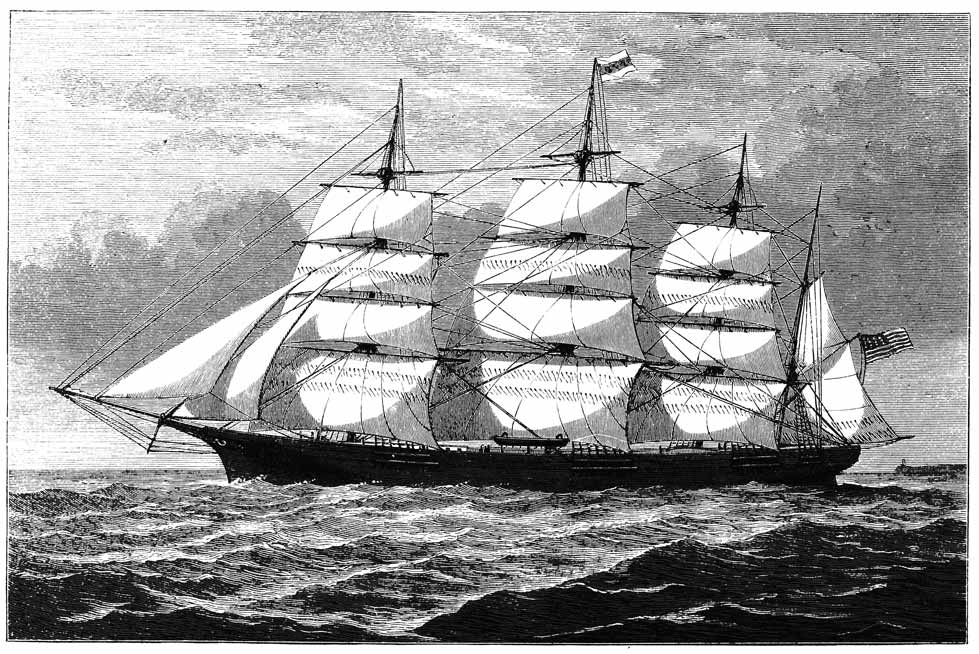

| The United States Sailing Clipper “Great Republic” | 360 |

| The Transverse Midship Section of British Sailing Ship, “Thermopylæ” | 415 |

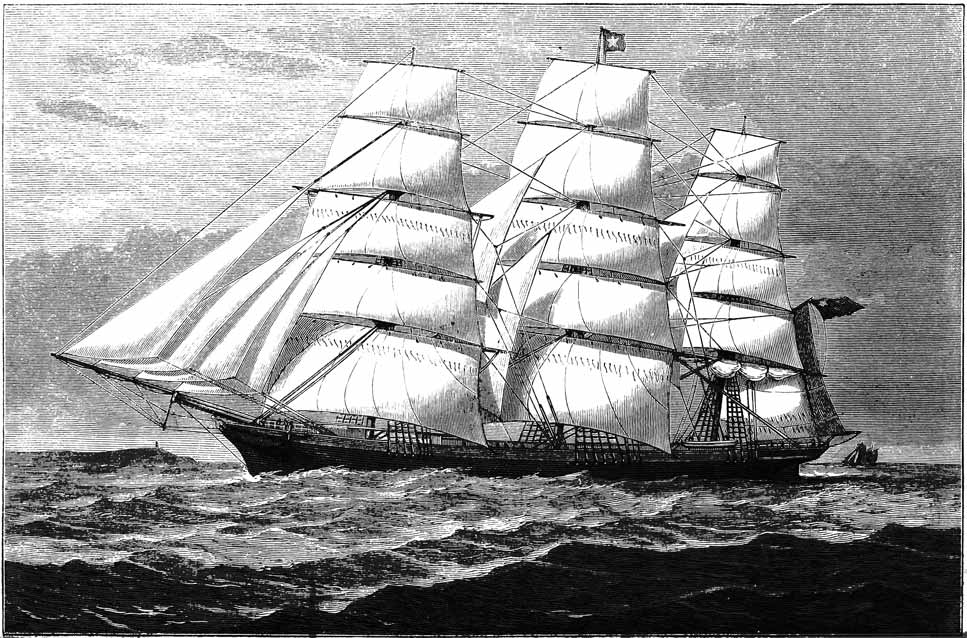

| Drawing of this Ship under Full Sail | 416 |

[Pg xxi]

CHART

OF THE

BRITISH ISLES

SHEWING THE

WRECKS AND CASUALTIES

DURING THE YEAR 1873-4,

distinguishing those attended with

Loss of Life

Progress of the United States of America—Their resources—Discriminating duties levied by France, 1820, against American ships—Rapid rise of New Orleans, and of New York—Boston ships extend their trade to India and China—Stephen Girard, the rich and eccentric American shipowner, note—Mercantile marine laws of the United States—Duties of master and mate—Provision for Seamen—Special Acts relating to them—Power given to American consuls to deal with seamen on their ships—Superiority of native American seamen, owing to their education—Excellent schools and early training for them—Spirit and character of the “Shipping Articles” as affecting the seamen—the owners—and the master or consignee—Conditions of wages, and remedies for their non-payment; and other securities for seamen—Power of Appeal by them to the Admiralty Courts—Laws with reference to pilots—Character of American seamen, and especially of the New Englanders.

Perhaps no nation, in either ancient or modern times, ever made such prodigious strides in wealth, population, and power, and, necessarily, in commerce and navigation, as have the United States of America during the first half of the present century. Nor is this a matter for surprise. Practically, the American people had during that period started in life with the singular advantage, that they commenced their career with the accumulated wisdom of a long ancestry, with whom, unlike the nations of ancient times, they[Pg 2] have continued to have the means of easy communication. Therefore, they had the capability of assuming, almost at once, an important position in the world, and of exercising no mean influence over its affairs, having few of those difficulties to encounter, which European nations, in their slow emergence from a state of political and intellectual darkness, have taken centuries to surmount.

Finding themselves in a safe geographical position, with the most magnificent harbours on every part of their coast, already prepared by the hand of nature for their use, with the greatest navigable rivers in the world, with lakes which are inland seas, and with boundless virgin soil at their disposal: wanting nothing, in short, but wise laws and abundant labour, they speedily discovered their strength, and, in their earlier debates, in Congress gravely discussed the question whether they should not style themselves the most enlightened people in the world.[1] Nor, indeed, was this boast altogether vain and baseless, for the Americans were in a position to adopt, as they might choose, the whole sum of human knowledge, with the power, at the same time, of applying this knowledge to the satisfaction of their varying wants.

Their capacity for government, in its application to commerce and navigation, equalled, if it did not surpass, that of the race whence they descended; and their system of education, the only true basis of a nation’s greatness, far surpassed that of Great Britain; hence, in all diplomatic negotiations, relating either to their political independence or to their material[Pg 3] interests, they have generally exhibited such marked tact, ability, and acuteness, as has enabled them frequently to obtain ample redress from foreign nations, and often, too, without that formal demand which, if not complied with, leads to war: from their example a few of our diplomatists, who reside abroad, would do well to take a lesson.

With these elements of knowledge, wealth, and national power, combined with a martial spirit, readily kindled into action whenever the necessity arose, the Americans, under an extremely liberal government, have rapidly and deservedly assumed a proud position among nations. Not the least interesting and instructive cause of their rise was the promptitude with which they developed, by the then best known means, their great natural resources, and none more so than their maritime commerce, for, within eighty years from their Declaration of Independence, they rivalled, and, indeed, surpassed in the amount of their merchant shipping, all other nations.[2]

Nor was that high position reached without innumerable difficulties in the shape of laws adverse to her interests. Great Britain excluded her ships from all her colonies; and, though France had ceded to her by treaty in 1803, for the sum of fifteen million dollars, the State of Louisiana, that country for many years afterwards continued to levy heavy differential duties on all goods imported into France in American bottoms, while American shipowners[Pg 4] had to contend at their port of export against the predominant interests of a country whose settlers for a long time greatly outnumbered the native Americans resident in New Orleans. Indeed, so late as 1820, a long memorial[3] was presented to Congress from twenty-four captains of American vessels then lying at New Orleans, stating that they “cannot earn a competent livelihood, owing to the fatal discriminating duties established in France in favour of its own vessels in the exclusive importation there of the staples of the United States.” The memorialists[4] further alleged that on some articles the duty was “ten times” in favour of French vessels, and that the “aggregate importation in French vessels at the port of New Orleans exceeded very much in quantity the amount imported by American vessels;” being in the proportion of “nearly four to one.” In confirmation of these statements the memorialists furnished a return from the Customs which demonstrated that the carrying trade between New Orleans and France was being then rapidly transferred from American to French vessels; and they stated that the only reason why the French did not absorb the whole trade, was that they had not a sufficient number of vessels to undertake it. The petitioners further insisted that nothing but “a positive tonnage duty,” graduated according to the amount of the differential duties levied in France on the chief American staples, would avail to keep their trade in their own hands.

[Pg 5]

Nevertheless, in spite of these hostile tariffs, and the war of retaliating duties which was for some time waged, New Orleans, from being the natural emporium of the vast tracts of country traversed by the Mississippi, Missouri, and their tributary streams, and enjoying, as it does, a greater command of internal navigation than any other city in either the Old or New World, has made since 1820 the most astounding strides in its maritime commerce.[5]

But in the face of equal difficulties as regards hostile tariffs, New York, through the great natural resources at her command, and other causes, surpassed New Orleans in the rapidity of its early commercial and maritime progress. Although its advancement during the first decade of the present century was scarcely equal to that of the preceding ten years, during which it enjoyed unexceptionable prosperity (no other city in the United States having profited so much, during the earlier periods, by the war in Europe), its merchants and shipowners suffered severely between 1806 and 1815 from the disastrous effects of captures, condemnations, and embargoes. Nor was it until 1825 that New York began to assume the importance which she has continued to maintain among the other commercial cities of the Union. In that year an internal element of prosperity was brought into operation by the construction of the Erie Canal, which opened for trade[Pg 6] the agricultural products of the fertile valley of the Tennessee, and the whole coasts of the northern lakes. The introduction of steam-navigation, to which I shall fully refer hereafter, affording greatly increased facilities for the conveyance of merchandise to and from New York by means of the numerous navigable rivers which intersected that and the neighbouring States, naturally gave an enormous impulse to its navigation, while the coal from the great Pennsylvania coal basin contributed essentially to its prosperity.[6]

Nor was the prosperity confined to New York. It extended for many years to all the ports of the Union. Boston, which, twenty years before the Declaration of Independence, was only a village containing about twenty houses, and, so late as 1822, was still governed by a body of “select men,” according to the custom of New England [the people, till then, declining to adopt a municipal government], vied with New York in the Foreign Trade which had arisen, and early in the present century despatched[Pg 7] their vessels on the most distant voyages. Indeed, so early as 1789, the merchants of Boston and Salem sent various ships direct to the East Indies and China, and, many years before the “Free Traders” of Great Britain could enter upon this trade, then monopolised by the ships of the East India Company, so far as regards Great Britain, the merchants[7] of Massachusetts supplied, not merely their own people with the bulk of the teas, spices, silks, sugar and coffee from the East as well as with nankeens and other cotton clothes, but reshipped them from Boston to Hamburg and the Northern ports of Europe in their own vessels, thus deriving large profits from a trade with our possessions, from which the great bulk of our ships were long excluded by the stringent restrictions of a pernicious monopoly.[8]

[Pg 8]

We have thus seen with what rapidity the Americans, in their early career, covered almost every ocean with their ships. As in other matters,[Pg 9] so in the rules and regulations drawn up for the internal management of their marine, they were able, at the commencement of their independence, to adopt from other nations such laws, even to their most minute details, as appeared to them the best fitted for their position. Thus, one of their earliest Acts, that of 1790, provides: that, “if a seaman is engaged without the execution of the shipping paper, the master or mariner shall pay to the seaman the highest wages that have been given within the three months next before the time of such shipping;” and the principle of this law has been long maintained, for the Act of 1840 declares that “any seaman so shipped may, at any time, leave the service, and demand the highest rate of wages given to any seaman shipped for the voyage.” In the Bank and Cod-fisheries, the contract of seamen with the masters and owners is required to be in writing, expressing the general terms of the voyage; and in the Whale-fishery, though the shipping paper is not absolutely required by the law, there is still a regular engagement, generally in writing, stipulating, among other things, the terms of the voyage, and the shares or “lays” of each officer and seaman on board the ship.

The several modes in which seamen’s contracts are executed, are the hiring by the month or by the voyage so long as it shall continue, or for a share of the profits, or of the freight earned in certain[Pg 10] voyages. The American law invests the master with the sole government of his ship and the absolute right of direction, subject to the legal consequences of any abuse of his powers. He may enforce his authority by the infliction of punishment upon the crew, but, should he exceed these limits, he is liable, by a Statute of the United States, to an action for damages in the Civil Courts, and to a criminal prosecution. The measure of punishment proportioned to the offence is to be ascertained by the special circumstances of the case; but all punishments must be inflicted with proper instruments. Hence, while the master has power to punish a seaman and to imprison him on board, to prevent a violation of the order and peace of the ship, he must be prepared to show that such measures were necessary.

The duties of mate, as laid down by the United States, resemble those of other countries. In the absence or death of the master he takes his place, exercising a general superintendence over the affairs of the ship. But his ordinary duties are confined to calling the attention of the master to everything requiring his notice, to the receipt and stowage of cargo, and to whatever is necessary for the proper equipment and sailing of the vessel while at sea. The mate is also required to keep the log-book, wherein he is bound to enter every matter of importance, such as the courses steered, the winds, and state of the weather, with many other minute details connected with the navigation of the ship. If he is guilty of such negligence as to involve the loss of his cargo, he alone is responsible; and if he[Pg 11] interferes with the responsibility, of others he renders himself responsible. Thus, if he undertakes, while in harbour, the removal of any merchandise, resulting in loss, the amount may be deducted from his wages, it being the rule, that the wharfinger is responsible for the safe delivery of all goods on board the vessel.

The American law has, also, provided for the proper sustenance of seamen, by requiring that a certain amount of the provisions shipped be set apart for this purpose, and, further, that they shall be provided for during bonâ fide sicknesses occurring during the service of the ship, and not from the seamen’s own fault, when absent occasionally or without express permission. All vessels bound for any ports beyond the limits of the United States are to be provided with a medicine chest. Provision, moreover, is made for sick and disabled seamen on shore, the law enjoining on the master or owner of every vessel the payment towards the maintenance of hospitals on shore, into the hands of the Collector of Customs of 20 cents per month for every seaman in their employ. This sum is deducted from the wages of the seamen, and is required from all seamen alike, whether in the coasting or oversea trades.

Barratry committed by the master or mariner is treated as in England. Running away with or destroying the ship, mutiny, piracy, piratical confederacy, endeavouring to create a revolt, desertion, embezzlement, negligence, drunkenness, and disobedience, are all regarded as grave offences, and punished in a greater or less degree.

[Pg 12]

By the Act of the 20th February, 1803, it was provided that the master of any merchant vessel, clearing for a foreign port, should enter into a bond in the sum of 400l. for the production of his crew at the first port at which he should arrive on his return to the United States, unless any one or more of the crew had been discharged in a foreign country, with the consent of the American consul or commercial agent of the United States, except in the case of death, of absconding, or of forcible impressment into some other service. This Act, likewise, provided that, when a vessel was sold abroad, and the crew discharged by mutual consent, the master should pay to the consul for any seaman thus discharged three months’ wages over and above those he had earned up to the time of his discharge; two-thirds thereof to be paid to the seaman himself, on his engagement to return to the United States, and the remaining third to be retained towards a fund for the payment of the passages for seamen, citizens of the United States, who may be desirous of returning home; and for the maintenance of destitute American seamen resident at the port of discharge.

Although many persons were of opinion that the Act of 1803, requiring, under the circumstances named, a payment of three months’ extra wages, and empowering consuls to send seamen home, disabled or otherwise, “in the most reasonable manner,” frequently led to improper expenditure, and that a more strict accountability, than then existed, ought to be enforced, these clauses remained unaltered until 1840, when their features were changed; consuls and commercial agents of the United States being[Pg 13] by the Act of the 20th July of that year invested with the power to discharge, when they thought it “expedient,” any seaman, on the joint application of the master of the ship and the seaman himself, without requiring payment of any sum beyond the wages due at the time of discharge.

The Act, however, of 1840 created so many objections of another kind, that it became necessary, shortly afterwards, to make various alterations. It was felt that the discretion given to the consuls was likely to operate unfortunately for all parties concerned. Acting, as the consuls then very frequently did, in the double capacity of agent for the United States and consignee of the vessel, they were too often induced to gratify the wishes of the owner and master to the injury of the seaman. Consequently, either the American consular establishments had to be re-organised upon a more independent system, or the “expediency” clauses had to be abolished. But other and still more weighty reasons suggested the desirability of adopting the former course. While, at a later period, the discretionary power was abolished, except in cases of sickness and insubordination, arrangements were made to disconnect Government agencies entirely from commercial operations. Now, all consuls, who must be exclusively American citizens, are remunerated by fixed salaries, instead of fees as formerly, and are removed from the possibility of all interested connexion with shipowners and shipmasters; by being, in nearly every instance, as is now the case with the consuls of Great Britain, prohibited from carrying on business on their own account—at least[Pg 14] such business as can in any way interfere with their duties as consul.

But it has been necessary also to make several other material alterations in the maritime laws. By the Act of 1790, it was provided that if any seaman deserted, or even absented himself for forty-eight hours without leave from his ship, he forfeited to the master or owner of the vessel all the wages due to him, and all his goods and chattels on board, or in any store where they were deposited at the time of such desertion or absence, besides other penalties. This forfeiture might be necessary or proper to check desertion; but it was easy to see, that it was in the highest degree unwise, that it should be given for the use of the master or owner of the ship. It tended, indeed, to produce the very effect and mischief it was intended to prevent. Masters of American vessels, when nearing a port where a new crew could be shipped at reduced wages, and when in arrears to their seamen (a fact which often occurs in long whaling voyages), were apt to adopt a course of tyrannical conduct, with the desire of compelling desertion; and, on their arrival, to permit their sailors a temporary absence from the ship, and then to leave them, under the plea of desertion, as a charge on the hands of the consul.

One flagrant instance was mentioned by the consul at Lima, of a supercargo of a vessel, who stated that he had saved in one voyage alone more than 1000 dollars by the desertion of his hands, as if this were a fair source of profit to either owner or master.

The simple entry in the log-book of the fact of absence or desertion was, then, deemed conclusive[Pg 15] against the seaman. Hence a very large sum was necessarily expended by the American Government in providing for destitute seamen. But this was partly attributable to the general increase of the United States commerce, and not altogether to the defective working of the law. While the aggregate amount of the registered tonnage of the United States in 1830 was about 576,000 tons, it had reached in 1840, 899,000, showing an increase of 323,000 in ten years,[9] but the increase of seamen applying for relief at distant consulates had at that time, it would seem, gone far beyond the general increase in the amount of shipping.

The whole question of the relations between the men and their employers, as they existed in the United States, is too wide a subject to be embraced in the present work. There are, however, some general, as well as special, points, both as regards the mariners and the law regulating their conduct, which deserve attention. During the first half of this century the masters of American vessels were, as a rule, greatly superior to those who held similar positions in English ships, arising in some measure from the limited education of the latter, which was not sufficient to qualify them for the higher grades of the merchant service. American shipowners required of their masters not merely a knowledge of navigation and seamanship, but of commercial pursuits, the nature of exchanges, the art of correspondence, and a sufficient knowledge of business to qualify them to represent the interests of[Pg 16] their employers to advantage with merchants abroad. On all such matters the commanders of English ships, with the exception of the East India Company’s, were at this period greatly inferior to the commanders of the United States vessels.

“Education,” remarks Mr. Joseph T. Sherwood,[10] “is much prized by the citizens; many vessels, therefore, are commanded by gentlemen with a college education, and by those educated in high schools, who, on leaving those institutions, enter a merchant’s counting-room for a limited time before they go to sea for practical seamanship, &c., or are entrusted by their parents, guardians, or friends, with the command of vessels.”

In confirmation of this opinion, Mr. Consul Peter, of Philadelphia, states[11]: “A lad intended for the higher grades of the merchant service in this country, after having been at school for some years and acquired (in addition to the ordinary branches of school learning) a competent knowledge of Mathematics, Navigation, Ships’ husbandry, and perhaps French, is generally apprenticed to some respectable merchant, in whose counting-house he remains two or three years, or at least until he becomes familiar with exchanges and such other commercial matters as may best qualify him to represent his principal in foreign countries. He is then sent to sea, generally in the capacity of second mate, from which he gradually rises to that of captain.”

[Pg 17]

Besides this, however, it must be remembered that American shipowners offered greater inducements than the English then did to young men of talent and education to enter the merchant service, as the amount of wages, alone, was two- and three-fold greater in the former than in the latter. Again, the American shipmasters were, also, almost invariably admitted, nay frequently solicited by the managing owners, to take some shares in the ships placed under their command; and, in cases, where the master had no capital, the owner often conveyed to him a share of one-sixth, and sometimes even one quarter, to be paid for out of his wages and the profits of the ships. Thus young men of good position and talent were led to enter the American merchant service, and had much greater inducements than they would then have had in Great Britain to take a zealous interest in the economy, discipline, and success of the ship they commanded; and this, not merely from the fact that they were well recommended, but from the confidential and courteous treatment they received from their employers. Captains of the larger class of packets or merchant-ships, therefore, could not only afford to live as gentlemen, but, if men of good character and fair manners (which they generally were), they were received into the best mercantile circles on shore. They were also allowed, besides their fixed salary, a percentage (usually 2½ per cent.) on all freights, and by various other privileges (particularly in relation to passengers) they were thus enabled to save money and to become, in time, merchants and shipowners on their own account, a custom which prevailed, to a large extent, in the New England States.

[Pg 18]

Nor were the interests of the common seamen overlooked. Boys of all classes, when fit, had the privilege of entering the higher free schools, in which they could be educated for almost every profession. An ignorant American native seaman was, therefore, scarcely to be found; they all, with few exceptions, knew how to read, write, and cypher. Although, in all nations, a mariner is considered a citizen of the world, whose home is on the sea, and, as such, can enforce compensation for his labour in the Courts of any country, his contract being recognised by general jurisprudence, the cases of disputes between native-born Americans and their captains have ever been less frequent both in this country and abroad than between British masters and seamen, owing, in a great measure, to the superior education and the more rigorous discipline on board American vessels. In the United States, the master of the ship was, and is still, usually employed to hire the seamen; and although, in hiring, he is the agent of the owners (and they have co-ordinate power), still if they do not dissent, the engagement entered into by the master with the seamen is binding on the owners also. The contract is, however, not made with the person of the master, but with the shipowners; therefore, if there is no master, the seamen contract to sail under any master who may be appointed. Thus, on the one side of the contract is the seaman, and, on the other, the master or owner—the master acting as the owner’s agent, under ordinary circumstances, although the owner, from his holding the property in the ship, is more directly affected by the contract.

[Pg 19]

The master and owner, on their side, agree by the contract, technically termed “Shipping Articles,” which, if drawn up in the prescribed form and signed by all the seamen, expresses the conditions of the voyage, with a promise to pay to the mariners their stipulated wages. It is, also, implied in it that the voyage shall be legal, and the vessel provided with the various requisites for navigation; and, further, that it shall be within defined limits and without deviation, except such as may be absolutely necessary for the safety of the crew, vessel, or cargo. It is also a part of the contract that the seamen shall be treated with humanity, and be provided with subsistence according to the laws of their country; unless there is in it an express provision to the contrary, or a condition to conform with the usages of a particular trade.

The seaman, on his side, by the act of signing the “Shipping Articles,” contracts to do all in his power for the welfare of the ship; engages that he has competent knowledge for the performance of the duties of the station for which he contracts; to be on board at the precise time which, by American law, constitutes a part of the articles; and to remain in the service of the ship till the voyage has been completed. If he does not so report himself on board the vessel, he may be apprehended and committed to the custody of the law till the ship is ready to sail. He contracts also to obey all the lawful commands of the master; to preserve order and discipline aboard, and to submit, as a child to its parent, for the purpose of securing such order and discipline during the voyage.[12]

[Pg 20]

As in England, the owners have the right of removing a master, who is part owner of a vessel; but, if he is removed without good cause, and while at the same time specially engaged, they are liable to him for damages. Where, however, he has only a general engagement with a vessel, his relation to the owners is scarcely more than a mere agency, revocable at any time. On the other hand, the master cannot leave the ship in which he has contracted to sail without being himself answerable to the owners.

The authority of a master over his ship is in all essential particulars the same as that prescribed by British law. With regard to letting the ship, the same principles prevail on both sides of the Atlantic.[13]

In general the owners are responsible for injuries committed by the master in that capacity, as in cases of collision, discharges of mariners, damages to cargo from want of ordinary care, and embezzlement. The master is answerable for all contracts made by him in connexion with the navigation of a ship, as also for all damages arising from his want of skill or care, and for repairs and supplies, except when furnished on the exclusive credit of the owner.

If the master of a ship is at the same time commander and consignee, he stands in the twofold relation of agent of the owner and consignor, and is invested with appropriate duties in both capacities. Inasmuch as the master and owner are in the eyes of the American law common carriers, it is the master’s duty to see that his vessel is seaworthy and provided[Pg 21] with a proper crew, to take a pilot, where required by custom or law, to stow the goods properly, to set sail in fair weather, to transport the cargo with care, and to provide against all but inevitable mishaps. In other respects, American and English laws are almost identical; the admirable decisions of Judge Story, Chancellor Kent, and Chief Justice Marshall having, however, made some refined distinctions.

As it was considered the duty of sailors to remain by their vessel till the cargo was discharged, they had no claim to their wages till then, but, if these were not paid within ten days after such discharge, they had a right to an admiralty process against the vessel. Only one-third of the wages earned can be demanded by the mariner at any port of delivery during the voyage. There may be on this subject a special stipulation; but, if the ship be lost or captured, wages earned up to the last port of delivery may be recovered by the mariner, on his return home, to the place to which the vessel has carried freight; freight being by the laws of all nations “the Mother of Wages:” inasmuch, however, as they depend upon the vessel’s safety and the earning of the freight, they cannot be insured. In all cases of capture, the seamen lose their wages, unless the ship is restored. In cases of rescue, recapture, and ransom, the wages of mariners are subject to a general average, but in no other case are they liable to contribute. In cases of shipwreck the rule prevails, as elsewhere, that, if parts of the ship be saved by the exertions of the seamen, they hold a lien on those parts for some kind of compensation, but this is viewed somewhat in the light of salvage. When a seaman dies on[Pg 22] board ship, wages are usually allowed up to the time of his decease, if the cause of death occurred during the term of his engagement, and otherwise than by his own fault. In the whale-fishery, the representatives of a deceased mariner are entitled to that share of the profits which the term of his service bore to the whole voyage, according to his contract. If a voyage is broken up by the fault of the master or owner, full compensation must be given to the seaman; so also, in cases of wrongful discharge, the seaman usually recovers full indemnification in American Courts of law. Indeed they have more effectual remedies for the recovery of their wages than the seamen of most other countries, from the fact that Americans have followed the ancient laws already quoted: moreover, they have their remedy against the master, and can recover their wages from him personally, or from the owner or owners of the vessel, or from the person who appointed the master and gave him his authority.

For personal injuries inflicted by the master upon the seamen, such as assaults, batteries, or imprisonments, the seaman in the United States has his remedy by an action at common law, or by a libel in the Admiralty Courts, in what is technically denominated “a cause of damage.” So, also, in a wrongful discharge, an action would be not only on the special tort committed, but also for the wages on the original contract of hiring, the wrongful discharge being void.

In order to institute suits in the Courts of Admiralty in the United States it is necessary that the voyage should be on tidal waters, and that the[Pg 23] service on which suit is brought should be connected with commerce and navigation. The jurisdiction of those Courts in America extends to personal suits, and includes claims founded in contract and in wrong, and also those cases where claims, founded in a hypothecary interest of the nature of a lien, are urged and adjudicated upon. Their jurisdiction extends, moreover, to those cases in which shares of fish, taken on the Bank and other Cod-fisheries, and of oil in the Whale-fishery, are claimed; and, as in English Courts, the seaman may unite his claims, though founded on distinct contracts, in one suit, but this only when demanding wages. The Courts of Common Law in the United States also take cognizance of mariners’ contracts, but they are not competent to give a remedy so as to enforce the mariner’s lien on the vessel; hence, they confine their jurisdiction to personal suits against the master or owner, in accordance with the contract made with the seaman; but, in cases of tort committed on the high seas, and where the form of action is trespass, or a special action, the common law has concurrent jurisdiction.

The laws of the United States[14] expressly provide that the crews of merchant vessels shall have the fullest liberty to lay their complaints before their consuls abroad, and shall in no respect be restrained therein by any master or officer, unless some sufficient and valid objection exist against their landing, in which case it is the duty of the master to apprize the consul forthwith, stating the reason why the[Pg 24] seaman is not permitted to land; whereupon, the consul must proceed on board, and act as the law directs. In all cases where deserters are apprehended the consul is required to investigate the facts, and, if satisfied that the desertion was caused by unusual or cruel treatment, the mariner shall be, in such case, not merely discharged, but shall receive, in addition to his wages, three months’ pay, and the whole act is required to be entered upon the crew-list and shipping articles, with full particulars of the nature of this treatment. Any consul or commercial agent of the United States neglecting or omitting to perform his duties, or guilty of malversation or abuse of power, is liable to an action from the parties aggrieved; and, for corrupt conduct in office, he is liable to indictment, and on conviction may be fined from one to ten thousand dollars, and be imprisoned not less than one, or more than five, years.

Although Congress possesses the power to make the laws necessary for the regulation of Pilots, and the whole business of pilotage is within its authority, there is no general law for these purposes, and the superintendence of pilots is left to the legislation of the individual States. By the Act of 7 August, 1789, it was enacted that all pilots in the bays, inlets, rivers, harbours, and ports of the United States should continue to be regulated by the existing laws of the States respectively, until further legislative proceeding by Congress. The licensing of pilots and fixing rates of pilotage were therefore thus arranged at first; but, as some difficulties arose, it was enacted by the Act 2 March, 1837, that it was lawful for the master or commander of any vessel coming into, or[Pg 25] going out of, any port situate upon waters forming the boundaries of any two States to employ any duly licensed or authorised pilot of either State.[15]

The native-born American seamen are bold, adventurous, and brave. In their merchant vessels the proportion of native seamen is estimated at about one-third, while it was a common remark that “the rest are rascally Spaniards, surly John Bulls, Zealanders, Malays, anything of any country.” The American native-born seaman is frequently promoted to be an officer, and, sometimes, to the command of large ships, but there are perpetual complaints that the people of the United States do not “take to the sea” with alacrity. Indeed, it is only in the New England States that the sailor’s life may be said to belong to the soil itself, and even the natives of that comparatively barren soil and rigorous climate become sailors, perhaps less from love of adventure and from their natural hardiness, than from necessity. When boys they had, perhaps, widowed mothers to support, younger brothers and sisters to care for, and, there being no other congenial occupation, they “go to sea.” When complaining of his “dog’s life,” the American sailor sits by the hour whittling a stick, and building little boats for his child, recounting at the same time the perils and hardships of the sea. Like British seamen, he has always his pet ship, in which most of his experience has been acquired, and the name of that ship is oftenest on his lips. It[Pg 26] is associated with the story of his loves, with the memory of his friendships, and he dates all eras from his several voyages in the vessel of the “one loved name.” As New England was the great storehouse of American seamen, there the best specimens of their seafaring population were to be found. We have seen, even in our time, the puritanical, weather-beaten, Boston skipper—once so famous—sharp as a north-easter, dressed in knee-breeches and buckles, with a three-cornered cocked-hat, not forgetting the pigtail, the very personification of our Commodore Trunnion and Piper of a century ago. But, though they may have degenerated since then, the seamen engaged in the deep-sea fisheries are still a remarkably hardy, robust race, and, hence, have succeeded in that branch of maritime enterprise far more than our own adventurers of late years.

[1] See Alexander Baring’s pamphlet, 1808.

[2] In 1860, the United States owned a larger amount of tonnage, including lake and river steamers, than the United Kingdom, and nearly as much as Great Britain and all her colonies and possessions combined.

[3] State papers, America, ‘Commerce and Navigation,’ vol. ii. p. 413.

[4] The names appended to the petition are nearly all Anglo-Saxon, such as Rogers, Jones, Howard, &c.

[5] In 1818, the whole of the exports from New Orleans was only in value a little more than three million sterling; in 1850 it had reached thirty millions; the shipments of raw cotton alone in that year being 1,600,000 bales. During the year ending June 30, 1874, the exports of that article to foreign countries were 2,883,785 bales from the port of New Orleans alone.

[6] In the year ending 30th September, 1822, the tonnage of American vessels entered inwards at New York was 217,538 tons, cleared 185,666, against 22,478, and 17,784 tons foreign vessels, respectively. But for the year ending June 30, 1874, the proportion of entrances at the Port of New York was: American vessels, 1,124,055 tons; foreign vessels, 3,925,563. The clearances were in somewhat the same proportion. The chief causes of these extraordinary changes will appear in the course of this work. In 1850, 2,632,788 tons of American shipping, and 1,728,214 tons of foreign shipping cleared from the ports of the United States. In 1860, the relative proportions were, native vessels, 6,165,924 tons: foreign, 2,624,005; but in 1871, while the clearances of American vessels had fallen to 3,982,852 tons, the clearances of foreign vessels from the ports of the United States had risen to 9,207,396 tons! I take these startling figures, which I wish my readers to bear in mind, from the United States’ official reports, for history is of little value unless it teaches useful lessons.

[7] Among the leading merchants of Boston and Salem then engaged in this lucrative trade may be mentioned the names of Russell, Derby, Cabot, Thorndike, Barrell, Brown, Perkins, Bryant, Sturgis, Higginson, Shaw, Lloyd, Lee, Preble, Peabody, Mason, Jones, and Gray. From 1786 to 1798, Thomas Russell was one of the most enterprising and successful merchants of Boston. His charities were extensive; he was a warm friend to the clergy, and a liberal supporter of all religious institutions. Curiously enough, a member of the families (by the father and mother’s side), of Perkins and of Bryant and Sturgis (Russell Sturgis), now fills the place which Joshua Bates so long occupied as a leading partner in the house of Baring Brothers and Co., of London; Joshua Bates himself having first come to London as agent for Gray, the last name on the list I have given. Towards the close, however, of last century, Brown and Ives of Providence, Peabody of Salem, and T. H. Smith of New York, with Perkins and Co., and Bryant and Sturgis of Boston, carried on nearly all the trade with China.

Though altogether unlike Mr. Russell and the other shipowners and merchants of Boston I have just named, I cannot omit to mention, in connexion with the early history of the Merchant Shipping of the United States, the name of Stephen Girard, one of the most prosperous and eccentric of men, who was long known as the “rich shipowner and banker of Philadelphia.” Born near Bordeaux, in 1750, of obscure parents, he, at the age of ten or twelve years, embarked as a cabin boy, with only a very limited knowledge of the elements of reading and writing, on a vessel bound for the West Indies. Thence he sailed in the service of an American shipmaster, to whom he had engaged himself, as an apprentice, for New York. He soon rose to be mate and master, and, after making a little money, he opened a small store in Philadelphia, and also carried on a shipping business with New Orleans and St. Domingo. At the latter place a tragical circumstance occurred strongly illustrative of the troubles of the time, but which contributed materially to swell Girard’s fortune. It chanced that at the moment of the insurrection of St. Domingo, Girard had two vessels lying near the wharf in one of the ports of that island. On the sudden outbreak, the planters, instinctively rushed to the harbour and deposited their most valuable treasures in the ships then there for the purpose of safety; but returned themselves in order to collect more property. As the greater part of them were massacred, few remained to claim the property, and as a large portion of it had been deposited in Girard’s vessels, for which no claims were made, he thus became its owner. In 1791 he commenced building a class of beautiful ships, long the pride of Philadelphia, for the trade with Calcutta and China—their names, however,—the Montesquieu, Helvetius, Voltaire, and Rousseau—too conspicuously reveal the religious dogmas of their owner. By judicious and successful operations in banking, combined with shipowning, Girard made so large a fortune that, in 1813, he was considered the wealthiest trader in the United States. It is told of him that when, in that year, one of his vessels with a cargo consisting of teas, nankeens, and silks from China, was seized on entering the Delaware, he ransomed her from the captors on the spot by a payment of $93,000, paid in doubloons, and by this transaction added half a million of dollars to his fortune! But Girard, with all his wealth, ended his career without a friend or relative to soothe his declining years and close his eyes in death. His legacies were large and numerous, while the largest of them were characteristic of the man. Among these may be named his bequest of 208,000 acres of land and thirty slaves to the city of New Orleans, and other large tracts of land in Louisiana to the Corporation of Philadelphia. To the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania he gave $30,000 for internal improvements; but the most extraordinary of his bequests was $2,000,000, which he left for the erection of an orphan college at Philadelphia—a magnificent building—and the endowment of suitable instructors, requiring and enjoining, however, by his will, “that no ecclesiastic, missionary, or minister of any sect whatsoever shall ever hold or exercise any station or duty whatever in the said college; nor shall any such person ever be admitted for any purpose, or as a visitor, within the premises appropriated to the purposes of the said college.” Such was Stephen Girard, master and mariner.

[9] Vide Mr. Calhoun’s report, ‘Executive Documents,’ 2nd Session, 28th Congress, Document No. 95. 1844-45.

[10] Letter addressed by Mr. Sherwood, British Consul for Maine and New Hampshire, U.S., to Foreign Office, July 23, 1847, see Par. Paper, ‘Commercial Marine of Great Britain, 1848,’ p. 382.

[11] Papers relating to the Commercial Marine of Great Britain, 1848, p. 388.

[12] Act of 20th July, 1840, section 3, U.S. Acts, Boston Ed., vol. v. p. 394.

[13] For some very nice points of distinction, the reader may consult ‘Arnold’s Marine Insurance,’ Ed. 1857, where the decisions of Judge Story and Chancellor Kent are laid down with profound learning and judgment.

[14] Act 20th July, 1840, 16th and 17th sections.

[15] In a note to this Act (Statutes at Large U.S., Boston, 1850) will be found an admirable exposition of some decisions of the American Courts respecting the scope of a pilot’s duties. They are excellent, but too long to insert here.

[Pg 27]

Necessity of proper education for merchant seamen—Practice in Denmark—In Norway and Sweden—Russia and Prussia—France—Remarkable care of seamen in Venice, Scuola di San Nicolo—Character of this institution, and general working—Variously modified since first creation—State since 1814—Qualifications of Venetian shipmasters—Present regulations of Austria—Great Britain—Need of a public institution for merchant seamen—The “Belvidere” or Royal Alfred Aged Seaman’s Institution, note—Mr. Williams, observations by, on the advantage of a general Seaman’s Fund, note—Institution in Norway—Foreign Office circular of July 1, 1843—Its value, though unfair and one-sided—Replies to circular—Mr. Consul Booker—Mr. Consul Baker—Mr. Consul Yeames—The Consul at Dantzig—The Consuls of Genoa, Ancona, and Naples—Mr. Consul Sherrard—Mr. Consul MacTavish—Mr. Consul Hesketh—Reports from the Consuls in South America—General conclusions of Mr. Murray, Nov. 22, 1847, and suggestions for remedies—Board of Trade Commission, May 17, 1847—Its results—Shipowners condemned for the character of their ships and officers—Views of Government—Necessity of a competent Marine Department.

Although it can scarcely be said that the character of British seamen degenerated from the time America declared her independence till towards the close of the first half of the present century, there is no doubt that those of other nations were making rapid strides in advance of them. Indeed, many causes had combined to raise, alike, the position of the shipowners and seamen of foreign nations, not the least of these being the protection afforded to our[Pg 28] shipowners by the Navigation Laws, as under that protective system they felt it less necessary to exert themselves to contend with the foreigner as keenly as, under other circumstances, they would surely have done. Most foreign nations had also directed their attention, long before we did, to the necessity of thorough education for their seafaring population—a policy they have since maintained. With that object in view, schools were established at all their principal seaports, where not merely the rudiments of navigation were taught the youths, but considerable attention was also devoted to their moral and intellectual improvement.

In Denmark, for instance, the system of education for the higher grades of the merchant service was particularly strict and effective. No Danish subject was allowed to act as master of a merchant vessel unless he had previously made two voyages in the capacity of mate, while the mates themselves had, and still have, to submit to a general examination, embracing (1st) a knowledge of dead-reckoning, the nature and use of logarithms, and the first rudiments of geometry; (2nd) the nature and use of the compass and log; and (3rd) the form and motions of the earth, and the geographical lines projected on its surface, so as to be able to determine the position of different places. It was also expected that he should understand the nature of Mercator’s charts, and the mode of laying down the ship’s course on them, together with such calculations as may be necessary for this purpose. Expertness in keeping a journal, in the use of the quadrant, and in making the necessary allowances for currents, lee-way, and the variations[Pg 29] of the compass, were all required, together with some idea of the daily motion of the celestial bodies, of the sun’s proper motion, and the meaning of the words “horizon,” “refraction,” “semi-diameter,” “radius,” and “parallax.” He was also required to know how to use the instruments for calculating the elevation of the sun and stars, and the distance between objects on shore! Nor, indeed, was his examination limited to the more ordinary details of a navigator’s duty. He was expected to be expert in ascertaining what star enters the meridian at a given time at the highest and the lowest elevations, as well as in finding the latitude, both by means of the meridian height of the sun or of a star, and in determining the time for high and low water. He was further expected to understand the mode of calculating the time of sunrise and sunset, and of ascertaining the variations of the compass by means of one or more bearings in the horizon, and by the azimuth.

In Norway and Sweden, mates of ships had to undergo a similar examination before being allowed to act in that capacity, and a still more rigid examination both as regards seamanship, navigation, and the general knowledge of business relating to shipping affairs, before they could command a vessel, together with a knowledge of the Customs and Navigation Laws, and of the usual averages and exchange. They had likewise to know something of the elements of shipbuilding, and of the mode of measuring a ship’s capacity.

In Russia and Prussia the mates and masters of merchant vessels, besides the qualifications above referred to, were required not merely to read and write[Pg 30] their own language with accuracy, but to have some knowledge also of English and French.

So early as 1806 a school was founded in Nicolaieff to train masters and pilots for the commercial marine, which, in 1832, was enlarged and removed to Cherson, while another and similar establishment was at the same time founded in St. Petersburg. All coasting vessels are now bound to have masters who have left these schools with certificates of competency. But the most important measure for the encouragement of seamen in Russia, whether employed in river or sea navigation, was enacted in 1826; families devoted to navigation being then for the first time incorporated in certain towns along the sea coasts and great rivers under the designation of “Corporations of Free Mariners.” These corporations were exempted from the capitation and land taxes, and from the conscription and quartering of troops, on condition that they sent their young men to serve for five years as apprentices in the Imperial fleet.

The system, however, of combining the services of seamen for the navy and the mercantile marine alike has been more thoroughly organised in France than in any other country. There the State and Commercial Navy are under the same code of regulations, the members of each being equally entitled to a pension after a certain length of service: in fact, all seamen in France are held to be in Government employ; their names are registered in the office of the Marine Commissioners of the port to which they belong, and, from the age of eighteen to fifty, they are liable to be ordered at any time on board a[Pg 31] Government ship, to serve as long as necessary. Hence it is that almost every seaman or fisherman of France has served in the navy for at least three years. At the age of fifty, and on the completion of a service at sea of three hundred months in either the navy or the merchant marine, a seaman receives a pension according to a certain scale, whereby, however, he cannot get more than six hundred francs, or less than ninety-six francs per annum. But these pensions are not really paid by the State, as a deduction of three per cent. is made from the monthly pay of every seaman in either service, so as to provide a fund for their payment.

France also provides for her seafaring classes more liberal and effective means of education than are, perhaps, to be found in any other country. A professor, paid by Government, resides in each of its principal ports, who affords to all, seeking to be commanders in the merchant service, instruction, free of charge, on the different subjects connected with their profession.[16]

Seaman’s funds, somewhat similar to those in France, have been established by all other European nations, though the objects in view have differed. That in England, well known as the Merchant Seaman’s Fund, was instituted during the early part of the present century, for the benefit solely of merchant seamen, who were not under any obligation to serve in ships of war, though, during the great war, they were too frequently pressed into the service. All these associations appear to have [Pg 32]had their origin with the Italian Republics, and that of Venice is of considerable historical importance, forming as it did the basis on which nearly all the others have been engrafted. This institution, called the Scuola di San Nicolo, was originally founded at that city in the year 1476, in commemoration of the successful defence of Scutari by the Venetians against the Turks. Greenwich Hospital, in some respects, resembles it, but the Venetian institution had attached to it a Merchant Seaman’s Fund, distinctly intended for the relief of the old and infirm sailors of that service. The building itself was destroyed in 1806, but the institution still survives.