*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 74086 ***

The Invisible Master

By EDMOND HAMILTON

Author of

The Hidden World, Cities in the Air, etc.

Illustrated By RUGER

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Scientific Detective Monthly April 1930.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

A thousand alarms are pouring into Police Headquarters! The Invisible

Master broods over the city! Who is He? We defy any reader to guess the

secret! Even the editorial staff of SCIENTIFIC DETECTIVE MONTHLY was

astounded at the conclusion of this scientific yarn. Write and tell us

if you were able to foretell the ending.

If you were to ask us which, in our opinion, is the greatest

scientific detective story of the year, we certainly would pronounce

the present story to be that unusual gem.

Here is a story that will keep you fascinated, not only in connection

with its excellence of science, understandable by everyone, but by the

fast-moving action for which this well-known author is famous.

Invisibility in this sort of story is perhaps not a new idea; but we

venture to say that no one can foretell the O. Henry-like ending, which

is as unexpected as it is dramatic.

CHAPTER I

Carton Earns His Salary

"And to think," Charlie Carton exclaimed, "that they pay you a city

editor's salary for ideas like that!"

The other looked up from his desk, nettled. "I didn't say I took any

stock in the thing, Carton," he pointed out. "But I got the tip that

the Courier and the Sphere have their men hurrying out to the

university, and we can't afford to miss anything."

"And I'm to write a breath-holding tale of how Dr. Howard Grantham, the

super-physicist, has discovered the secret of invisibility?" demanded

Carton.

The city-editor smiled. "Write it any way you please," he said, turning

to the papers on his desk. "But whatever you get out of it, see that

the Courier and Sphere men don't get more!"

"I'll get out of it some pointers on the methods of publicity-crazy

scientists, if nothing else," was Carton's parting shot.

It was with this skepticism strong in him that he rode uptown on the

west-side subway, nor had his mood changed by the time he emerged again

into the morning sunlight. East and northward from him stretched the

campus of America University, a sweep of green from which rose the

great gray buildings. Carton walked quickly toward the building, one of

the nearest to him, that held the university's world-famed department

of physical science.

Once inside, he was directed through long corridors and past the doors

of laboratories filled with gleaming apparatus and intent students,

until he reached the door he sought. When he pushed it open he walked

into a small ante-room in which two men of his own age and unscholarly

appearance were lounging and smoking. They greeted him with calls of

joy.

"Carton, you're not stuck with this yarn too?" one asked. "You'll be

graduating to the Sunday supplements if you keep on."

"I can see the Inquirer's headlines tonight," chaffed the other.

"'Noted scientist makes amazing discovery——'"

"Where is our noted scientist?" asked Carton of Burns, the Courier's

man.

"Dr. Grantham is even now engaged upon the tremendous work which he

will presently reveal to the eager press," said the other. "In other

words, he and that sour-faced assistant of his, Gray, are cooking up

something to get page-one space."

"I don't know about that, Burns, at that," put in the third

reflectively. "Dr. Grantham's got a great rep among the science boys,

and he's never been any space-hound."

"Well, why his announcement of this stuff, then?" demanded Carton.

"Claiming to be able to make matter invisible at will—rot! It's just

the old cancer-cure dodge the ambitious medics use, worked out in a

different way."

"Perhaps so," said the other, "but—"

He was interrupted by the entrance of a man from the room beyond, at

sight of whom Carton found himself revising some of his conceptions.

Dr. Howard Grantham was a man of over middle age, big and of average

appearance with his graying hair and clean-shaven face, but with very

unaverage eyes, gray and strong and steady. When he spoke his voice

seemed to hold a calm and contained power.

Powers of Invisibility

"I apologize for keeping you waiting, gentlemen," he told them, "but

you will appreciate that a demonstration of my discovery at this stage

is somewhat difficult. However, Gray and I think we can give you an

idea, at least, of the thing."

"You mean you're going to make some matter invisible before us?" Carton

asked incredulously, and as the scientist turned toward him, added

quickly, "I'm Carton—of the Inquirer."

Dr. Grantham bowed. "Yes," he said quietly, "we think we can give

you a demonstration of it on a small scale. Will you step this way,

gentlemen?"

As Carton passed after the physicist with his two companions into

the room beyond, he felt his skepticism fading still farther. It was

apparently Dr. Grantham's private laboratory into which they were

ushered. Beside a table in it there awaited them a dark young man of

thirty or so, with quick black probing eyes. When introduced to the

reporters as Gray, Dr. Grantham's assistant, he gave them but a curt

nod.

The room seemed full of physical apparatus for the most part of

outlandish appearance to Carton, he and his two fellow-journalists

looking alertly around them. Upon the table before them, just inside

the casement through which the brilliant sunlight was streaming, rested

a squat cabinet of black metal, but inches square, with a small metal

framework on it and with connections to what seemed small batteries and

a row of three switches.

Dr. Grantham was drawing their attention to this when the door behind

them opened and another entered, an impeccably-dressed older man whose

white head and genial countenance the reporters recognized instantly

as that of Dr. Calvin Ellsworth, America University's very prominent

president. He waved Grantham back as the latter turned toward him.

"Don't let me interrupt, Grantham," he adjured him. "I just wanted to

be a spectator like the rest."

Dr. Grantham nodded in understanding, and turned back to the reporters.

"To describe understandingly what I am going to show you," he told

them, "you must understand something of the principle involved in this.

I can make invisible, and that may seem a strange thing to many, who

have not ever stopped to wonder just why matter is visible at all."

"Why is it, then? Why do we see a house? We see it for two reasons, its

obstruction and reflection of light. The light-rays come to us from all

around it, but not from behind the house because they are stopped by

it. The house, then, is an area of comparative darkness to us, and so

is outlined against the light. Also light is reflected from all sides

upon it and to our eyes."

"But suppose that the light-rays behind, instead of being stopped by

the house, curved round it? Then we would see what was behind the

house, with ease, and the house itself would be quite invisible to us,

granted that light striking it from all sides did not really strike it

but curved around it. Then if I want to make a house, or a tree, or a

stone, invisible, all I need to do is to deflect the light-rays around

it in such a way that they will curve around and avoid it instead of

ever striking it."

"Can that be done? In principle, it has been possible for years, for

years ago we learned that light does not always travel in straight

lines but can be deflected to one side or another by certain forces.

Einstein's discoveries showed that, it being photographically confirmed

after his theory that the light-rays of stars curve in toward the

sun in passing it in space. If there is a force that will attract

light-rays and make them curve in toward an object, why not a force

that will repel the light-rays and make them curve outward to avoid an

object?"

Sought for Years

"It is that force which for years I have sought and which I have

finally found. It is an electromagnetic force which repels light-rays

and by curving them around the zone of force can make all matter in

that zone invisible. Understand, it does not blot out light in any way,

it simply makes the light-rays detour around an object and so makes

that object invisible."

"So much for theory. I have here a small cabinet of black metal in

which is an apparatus for projecting this force upward for a few

inches. Any small object placed on top of the cabinet will become

invisible when the force from within is put into operation. If the

force were more powerful, and radiated out in every direction instead

of upward only, the cabinet itself and all around it would be made

invisible."

Dr. Grantham cast a quick glance around and then picked from the table

a small disk-shaped paper-weight of black, opaque glass.

"I shall endeavor to make this paper-weight invisible to your eyes—by

placing it on the cabinet and using the force within to bend the

light-rays around it."

He was turning with it to the little cabinet when Carton reached forth

a hand.

"May I look at the thing first?" he asked.

Dr. Grantham handed it to him, smiling. "Of course, and I trust you'll

find nothing faked about it."

The three reporters examined it closely, as did with evident interest

President Ellsworth. It was quite obviously no more than a disk of the

black glass used for paper-weights and inkstands. When they handed it

back to Dr. Grantham he leaned forward and placed it upright in the

little metal framework on the cabinet's top. It stood out there against

the brilliant sunlight streaming through the window just behind it, a

dead-black disk against that brilliant light.

Dr. Grantham turned to the assistant. "All ready, Gray?" he queried,

and the other nodded briefly.

"Everything on it set," he said. "The batteries are on."

"Please watch very closely," the physicist told those behind him.

"These tests are rather hard to arrange, and I don't want you to have

any doubts."

He pressed one of the switches beneath his hands, and from the cabinet

came a thin, almost inaudible whining. The three reporters and

President Ellsworth were watching spellbound. A half-dozen feet before

them the black disk of the paper-weight lay as dark as ever against

the sunlight streaming in. But as Dr. Grantham slowly turned a small

rheostat control they all uttered something like a sigh. The black disk

against the sunlight was becoming translucent, transparent. It was

disappearing!

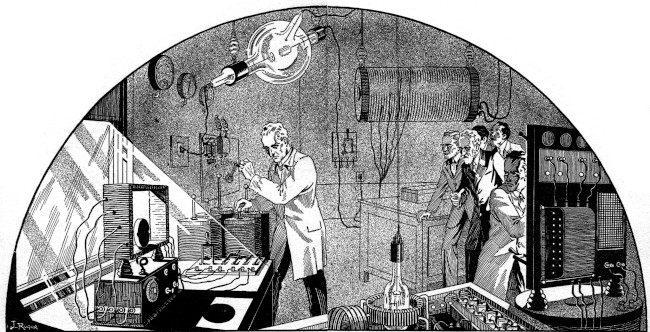

As Dr. Grantham turned the rheostat control ... the black disc against the sunlight ... began to disappear.

Dr. Grantham's hand still moved on the rheostat handle and as the

thin whine from the cabinet came louder they saw that the disk was

but a mere ghost-like shape against the sunlight, and then that too

had vanished. The paper-weight was invisible! They gazed silently,

fascinated, and then as Grantham moved back the control in his hand the

shadowy circle of the disk appeared again, it grew quickly more opaque,

and as the switch clicked and the cabinet's whine ceased it rested

there as black and opaque and visible as ever!

Dr. Grantham leaned and grasped it, handed it to the four. Wonderingly

they passed it from hand to hand, seeing it the same as before, quite

black and commonplace and visible. Carton, himself oddly stirred by

what he had seen, heard Burns' exclamation from beside him.

"Good Lord! What a story!"

"And you can do that to anything?" Carton demanded of the physicist.

The Invisible Man

Dr. Grantham nodded. "To any matter. Gray and I are now finishing a

cabinet-projector that will be of sufficient power to make invisible

itself and all for a few feet around it. With it a man would be

perfectly invisible."

"An invisible man?" President Ellsworth was looking at the scientist

keenly. "My dear Grantham—do you mean it would make a man as invisible

as that paper-weight?"

The physicist calmly nodded. "Just that, and if he had the cabinet and

its compact batteries attached to him he could move at will invisibly."

"But the possibilities of that are rather appalling," said President

Ellsworth, his brows knit. "Do you realize that if some criminal were

to get hold of the thing, he could——"

"No criminal is going to hear of that part of it, even," Grantham told

him reassuringly. "I know that you, gentlemen, will at my request

confine your accounts to the principle of the discovery and to my

demonstration without hinting of its possibilities on a larger scale."

Already the reporters were at the door, but Carton turned back. "You

wouldn't mind if I'd take that paper-weight with me?" he asked,

somewhat apologetically. "Of course I know it's all square but editors

are such a skeptical crew—"

"Of course not," the physicist said, handing it to him. "Any valid

scientific discovery will stand all the investigations of it that can

be conceived. I only trust that you'll restrain your imaginations as

much as possible in your descriptions."

A half-hour later Carton was pouring out an excited tale to the city

editor of the Inquirer, who heard him with calm, lighting a cigar.

When he had tossed away the match, he looked up.

"It all boils down, then," he commented, "to the fact that Dr. Grantham

has made a claim and then put on some hocus-pocus up there to convince

you of it."

"Hocus-pocus nothing!" exclaimed Carton heatedly. "I tell you I was as

skeptical as you about it until he did the thing before our eyes, made

this paper-weight disappear!"

The editor scratched his chin reflectively. "Well, it can have a column

on page one," he said, "but remember to keep the responsibility on Dr.

Grantham. I'm not going to have this paper mixed up in a silly hoax."

"The biggest story to break in years and you call it a hoax!" Carton

said bitterly. "If the building was burning down around you, you'd wait

for a statement from the fire department before you'd run the story."

"Well, that would be better than retracting the story the next day,"

the other rejoined. "These scientists have brainstorms regularly,

Carton, and this discovery of Grantham's is one if I ever saw one."

It was in that frame of mind, Carton perceived when his story appeared

that afternoon, that it was read by most. The thing was accorded very

considerable space by most of the metropolitan newspapers, but all

of them were one with the Inquirer in presenting Dr. Grantham's

claim and describing his demonstration of it without taking any

responsibility as to its truth. Too many times in the past had the

newspapers been duped by clever scientific hoaxes.

All had more or less accurate statements of Dr. Grantham's principle

of light-bending as a means of invisibility, and some had additional

statements from noted physicists and astro-physicists. These,

respectful for the most part of Dr. Grantham's huge reputation,

ventured no criticism or support of his theory, but corroborated his

statements as to the curving of light-rays in passing the sun. It was

assumed by all of them, and by the greater part of those who read

the articles, that even if true Dr. Grantham's discovery was a mere

laboratory triumph without possibility of any practical application.

Carton saw, with some exasperation, that the thing was being treated

only as another of the lurid pseudo-scientific sensations which had

long ceased to astound the public. Dr. Grantham himself had made no

statements other than to affirm quietly the fact of his discovery, and

Carton would have given much to have been able to spring the sensation

of the physicist's larger projector that would make a man invisible.

Without it, he saw, the thing as a news sensation was doomed to wither

and die quickly. But in this, for once, he was wrong.

For a few hours before the next morning his phone jangled and when he

answered sleepily the voice of the Inquirer's night-editor jolted him

to attention.

"Carton? You handled that Grantham thing yesterday, didn't you? Then

pile out to America at once—Dr. Grantham's been attacked by someone

there, and there's a rumor of an invisibility apparatus of his being

stolen!"

CHAPTER II

The Machine

When Carton hurried a little later for the second time down the long

hall of the physics building of America University, his steps were

quickened by the sight of a little knot of men outside the door of

the rooms he had visited on the preceding day. There was Burns, his

fellow-reporter of the Courier, two blue-clad policemen, and another

man in plain clothes. All turned as he approached.

"Carton here saw it the same as I!" Burns was declaring. "He can tell

you, Sergeant Wade!"

The detective-sergeant turned toward Carton, greeting him with a nod.

He was familiar to the reporter, a sleepy-eyed, soft-moving man who

chewed gum unceasingly and slowly.

"What is it I'm supposed to have seen?" Carton demanded. "And where's

Dr. Grantham? And what's happened?"

"One thing at a time, Carton," soothed the sergeant. "Dr. Grantham's

had a nasty crack on the head, and a doctor's in there fixing him up.

In the meantime Burns here has been telling me a story about this

Grantham making something invisible here yesterday with some machine?"

"Don't you read the papers, Wade?" Carton asked. "If you did, you'd

have read last night that Dr. Grantham did just that."

"I never read what you fellows write," the detective assured him. "And

I think I'll do so even less from now on. Making things invisible—you

two haven't had any cracks on the head, have you?"

"Laugh on, ignorance," Carton told him as the other smiled slowly.

"You're the sap, Wade, not to believe it. Grantham pulled the thing not

only in front of three of us but also in front of President Ellsworth

of the university himself."

"President Ellsworth, eh?" queried Wade keenly. "Same that's in there

with Grantham now."

"In there?" they both asked, and the detective nodded. "Yes, it seems

he was the one that found Grantham. And you say he saw this stunt

pulled the same as you?"

He seemed to consider that. Carton was about to riddle him with

questions when the door opened and an elderly man beckoned them inside.

Carton and Burns slipped in with Sergeant Wade, and found Grantham

leaning back in a chair with a thick bandage round his head, his eyes

half-closed, and President Ellsworth bending anxiously over him. The

doctor who beckoned them turned to the detective.

"Simple enough," he stated, "a blow on the skull with something blunt,

more from the side than from behind. He says he was turning when it

came—it probably saved him from concussion."

Who Did It?

Wade nodded quickly, and as the doctor passed out moved over to the

seated scientist, Carton and Burns close behind him.

"Feeling better?" he asked. "Just take your time, Dr. Grantham—but

we'd like to hear something about it."

"There's nothing to tell," said Grantham, spreading his hands

helplessly. "Gray—that's my assistant—and I, had been working almost

all day yesterday on a cabinet-projector of the light-curving force.

We finished it after midnight, and then gave it its first tests on

ourselves. It worked perfectly, as I had been sure it would, giving

complete invisibility for either of us when the cabinet was strapped to

his back."

"Just a moment," interrupted the detective. "Do you mean that this

machine really made you or your assistant quite invisible?"

"Of course," the physicist said, with some wonder. "It was simply a

larger development of the small projector we showed these reporters

yesterday morning. When Gray wore it and turned it on he was absolutely

invisible to me, and it was the same when I tested it. We were both

very tired by then, and I told Gray he could go. When he had gone

I was starting to lock up the projector for safe-keeping, when I

heard a quick step behind me. I turned but was half-around when a

crashing blow descended on my head. As I lost consciousness I felt the

cabinet-projector being torn out of my hands, and then I knew nothing

more until I awoke an hour ago with President Ellsworth bending over

me."

Wade shifted his gum thoughtfully. "And you, sir?" to Ellsworth.

"I'm afraid I can tell you even less," said the President. "I knew

Grantham was working late last night and wanted to see him. It must

have been about three o'clock that I came in, and found him lying on

the floor stunned. I called the doctor first, and then the police."

"You saw no one leaving when you entered?"

"No one."

"But isn't three in the morning a rather unusual time for you to visit

your professors?" Wade asked.

President Ellsworth seemed somewhat perturbed at the question, glancing

toward Grantham and then back to the detective. "My reason was a

private one, but I have no objection to telling you of it. The fact is

that I had become worried over this experiment or theory of Grantham's

during the evening. While perfectly aware of his integrity, I realized

that this work of his had a touch of the sensational that might reflect

upon our institution, and I wanted to ask him to go slowly with the

thing until his work was beyond any chance of criticism."

"Natural enough," Wade commented. "And what of this Gray? You said it

was just after he left that you were struck from behind?"

"Yes, but that hardly makes him the criminal," said Grantham. "Gray

has been absolutely devoted to this work of ours, and though somewhat

silent and forbidding is quite reliable."

"You know where he lives?"

"Of course—not a thousand yards from here—in the rooming house

diagonally opposite this corner of the campus."

Sergeant Wade turned to one of the blue-clad officers and spoke quickly

to him. When the man had left he turned back to the physicist.

"This Gray, though, knew all about your projector just finished,

something but a handful of people did. And since he had seen it

make a man perfectly invisible, he must have been aware what powers

its possession would give anyone who wanted to go in for criminal

activities?"

"Anyone would have been aware of that," Dr. Grantham rejoined.

"President Ellsworth remarked on it at our demonstration yesterday."

"You cannot say, however, that it is impossible that Gray, after

leaving, crept back into the laboratory and struck you down and took

the projector?" Wade pursued.

Gray Did Not Return

Dr. Grantham considered. "No," he said slowly, "but I would say that it

sounds impossible to anyone who knew Gray."

Wade was silent, apparently revolving something in his mind, but before

he could ask another question there entered the officer he had sent

below, who spoke to him briefly in low tones. When he had done, Wade

turned again to the physicist.

"How is it, then, that Gray did not return to his rooms when he left

here, and has not been seen there since he left yesterday morning.”

"Good Lord!" Carton burst in excitedly. "Then it's Gray that—"

Dr. Grantham's face showed his astonishment and trouble. "Gray was not

a criminal type," he persisted. "I simply cannot believe that it was

he. More likely by far some thief who found the building's door open

and who, seeing me about to lock up the projector, struck me down to

get it."

"Well, Gray or another," Wade remarked, "someone is loose in New York

at this moment with a thing which, if you're right, can give him the

power to walk its streets unseen."

"But you'll endeavor to catch him?" President Ellsworth interposed

anxiously. "I know but little about Grantham's mechanism, but surely it

will be a terrible threat until whoever has it is captured?"

"We'll do what we can," Wade told him gloomily. "But it's going to be

pretty hard to keep the force looking for someone they can't see! Even

if they believe in the story at all. But I wouldn't worry about the

thing, sir—visible or invisible, a crook can only keep free so long

when thousands are concentrating on finding him."

"I sincerely hope you're right," said President Ellsworth as he

turned to the door, hat in hand. "I'll see you tomorrow about it,

Grantham—and take care of yourself until then."

When he had gone Dr. Grantham said quietly, "I am glad that he does not

fully realize the appalling nature of this thing. I did not want to

worry him to no purpose. Whether it was Gray who took the projector or

another, is really immaterial now. The fact, the great fact, is that

someone has it who has proved himself ruthless. And with it, he can

loose such a terror upon New York—yes and upon the nation—as might be

utterly without precedent!"

"One man?" asked Wade, skeptically.

"One man—but an invisible one!" Grantham exclaimed. "Have you realized

what this means? It means that there are no limits to this man's power,

whoever he is. It means that he can strike down any he wishes though

that person surround himself with a thousand body-guards. It means that

there is no fortress or strong-room that can keep him out, nothing

that he cannot take for himself in full light of day. He can be, if he

desires, an invisible tyrant ruling the world with terror!"

Wade's face was graver as he turned with Grantham, and with Carton and

Burns to the door.

"Well, the most we can hope for now is to get him before he can use the

thing," he said. "Whether it's Gray or another, we ought to be able

somehow to——"

He halted, and his hand shot forward to a little table just inside the

door. On it rested a big square white envelope addressed in a bold hand

to "Dr. Grantham."

Wade's countenance was impassive as he grasped it. "This wasn't here

when President Ellsworth left," he said. "I saw him take his hat from

that table. Is that Gray's handwriting?"

"That or a good imitation of it," said Grantham slowly.

Who Came In

The detective turned to the two officers lounging outside the door.

"Have you seen anyone come through this door since President Ellsworth

left?" he asked them.

They shook their heads. "No one in or out since then."

Wade looked from Grantham to Carton and Burns for a moment, then

handed the envelope to the former. The physicist tore it open and read

silently the single sheet enclosed, then read aloud to the others.

My dear Dr. Grantham:

It has amused me very much to hear your conversation with these

worthy officers, but I really must be going. (You really should offer

chairs to your guests, whether visible or invisible). I am obliged to

you for developing the projector which now makes me invisible, but I

warn you that any attempt on your part to regain it or to capture me

will end disastrously for you. I am the Invisible Master, and I begin

now my reign of this city. My rule of it will become evident to all in

it soon, for in it from now onward my will shall be supreme.

The Invisible Master.

CHAPTER III

The Master Strikes

Carton, two days later, came into the Inquirer's city-room to find it

a babel of excitement. His city-editor hailed him through it.

"Carton! Get to the Vance National Bank double-quick—the Invisible

Master's been there—a robbery!"

"A robbery!" Carton exclaimed. "Then he's struck!"

"Get there and get the dope—Collins and Jansen have already started

and we're holding the presses for the story—get going!"

As Carton hurried into the street and through the throngs that surge

each afternoon in the city's financial section, his excitement was

high. From the crowds about him he heard cries and calls, and as

he neared the giant building of the Vance National Bank on Broad

Street, saw a dense crowd gathered at its doors, held back by a row of

policemen. The news was spreading out over the city like flame. The

Invisible Master had struck!

For two days the Invisible Master had been almost the single center

of New York's interest. The newspapers had made known to all that

Dr. Grantham had been struck down and his projector stolen, and that

the criminal who had done that had had the audacity to venture back

into the very room where he had attacked Grantham, made invisible by

the projector, and to leave a mocking note for the scientist in the

very presence of the police! And in that note the Invisible Master

had promised to make use of his power of invisibility to make himself

supreme in the great city!

The police had been nonplussed. They had searched far and wide for

Gray, the assistant of Grantham whom all held to be the daring thief

of the projector, but they had found no trace of him. But the public

was interested only in the Invisible Master, whether he was Gray or

another. Was there actually such a man as that walking New York's

streets unseen? And if there was would he carry out his threat to make

himself ruler of the city by his power?

Those had been questions of supreme interest in those two days. The

newspapers carried pages concerning the Invisible Master and what he

might do. He could steal, slay and burn with impunity. Nothing was

safe from him, no treasure and no life. A thousand absurd methods were

suggested for capturing him, but when nothing had been heard of him in

the two days, a great part of the city doubted his existence, despite

Grantham's warnings. But there seemed few doubters now, Carton grimly

told himself, as he fought his way through the crowd to the great

bank's doors.

There his badge let him through the circle of sweating policemen who

were holding back the excited crowds. He hurried on into the great

bank's lobby. Blue-clad figures were stationed everywhere at its doors.

The many cages along the marble and brass counters were empty of their

occupants now, but in front of one cage was gathered a group of men.

There were some of the bank's officials, elderly, anxious-looking men,

two or three police officers among whom Carton recognized Sergeant

Wade's sleepy-eyed and gum-chewing countenance, and, somewhat to his

surprise, Dr. Grantham, whom he was later to learn had been summoned

with the police at the robbery's occurrence.

Vanished Money

Carton saw that the center of interest of the group of officials and

police and reporters was a young, immaculately-dressed man whose face

was flushed and who was ejaculating excitedly.

"It was he, I tell you!" he was exclaiming. "It couldn't have been

anyone or anything else but the Invisible Master—the package vanished

right before my eyes!"

"Who's the youngster?" Carton asked of one of the reporters beside him.

"Harkness, the teller," said the other. "He's claiming that a package

of fifty one-thousand dollar bills vanished in front of his eyes,

and it looks as though he's going to have a hard time convincing his

bosses," added the other cynically.

Grantham was calming the excited young teller. "Let's just hear all

about it," he told him. "We know that the thing's unprecedented, and no

one thinks you took the money."

Harkness made an effort to appear calm. "It was just half an hour

ago," he said. "I was arranging some entries in my sheets and the

package was lying with some others beside me, just inside the grille's

opening. It was really in reach from outside, of course, but there was

no danger because everyone knows how impossible it is to snatch money

in a bank and escape with it. I thought I heard someone step up to my

window and looked up, but there was no one there. Then in a minute it

happened—the whole front of the grille and counter seemed to vanish

for a second and then reappear. But when they reappeared the package of

thousand-dollar bills was gone! I could only stare, stupefied, for no

one had been at the window, and then suddenly I remembered about the

Invisible Master and gave a shout. The guards came running—but there

was no one there by then. It was the Invisible Master—and he had gone!

And it was he—I tell you it must have been!"

Harkness' calm broke down at the end of his story, but Grantham

encouraged him with a few words and then turned to Wade.

"The boy's telling the truth, Wade," he said simply. "It was the

Invisible Master—and he's given us the first sample of what his being

loose in this city means!"

The officials and reporters were silent, Wade thoughtful. "Would it be

possible for him to make the whole front of the counter disappear for

an instant like that?" he asked Grantham.

The physicist nodded. "Quite possible. You see, the projector when

attached to the body, projects a force for a radius of a few feet

around the body and makes all in that radius invisible as well as

the person wearing it. Thus when the Invisible Master stepped close

up to the window, it and everything in the projector's radius became

invisible for a second, and in that second he needed only to grasp the

package of bills and then step quickly back and walk out."

"It's a tough problem," Wade admitted. He and Grantham had stepped

aside from the group, who were now sharply questioning Harkness, and

Carton had followed them.

"But how are you going to deal with it?" Grantham demanded. "For all

we know, Wade, the Invisible Master may be even now going through bank

after bank. It's not a question of doing anything about this robbery so

much as of preventing others."

"Well, I can't see anything to do but to follow our regular methods,"

Wade said slowly. "We'll send word out to the banks and stores to watch

for this method of robbery as well as possible, and we'll put a man to

look into Harkness and his story, and broadcast a list of the bills'

numbers if we can get them."

When Fear Broods O'er Us

Grantham shook his head impatiently. "Wade, these ordinary police

methods of yours are utterly useless in a case like this. It's all

right to gather fact after fact and slowly apprehend an ordinary

criminal in that way, but this is not a case of catching a criminal so

much as a case of war! War between this city and the Invisible Master!

And the one hope of catching him lies in making the whole city realize

that the Invisible Master is at large in it, and so put them on their

guard against every unusual incident that may point his presence."

"It seems to me," Wade said dryly, "that when Carton here and his

colleagues get through with this story there's going to be mighty few

in the city who don't know that the Invisible Master's at large."

And by that night, indeed, all New York was aware through the screaming

newspapers that the Invisible Master had begun his threatened

activities. He had, apparently, deliberately chosen for his first

exploit one most calculated to win for himself the city's amazed

attention, in his astounding robbery of the great bank in the full

light of day. The thing was stupefying. It was the one subject of

excited discussion in the city that night.

It was the Invisible Master's work, that was certain. But when would

he strike again, when would he make another of these astounding coups?

Imagination ran riot in the depiction of the things that the Invisible

Master might do. People were warned to go always on the assumption

that he was near, for caution's sake. Scientists and pseudo-scientists

gave forth sensational interviews on how the Invisible Master might be

caught.

The newspapers sought above all else for information from Dr. Grantham,

the man who had unwittingly loosed the terror upon the city. It

was announced late that day that Grantham was foregoing all other

activities to devise a plan for curbing or capturing the Invisible

Master. Some suggested even that he was making another projector with

which one invisible man could hunt the other, forgetful of the fact

that Dr. Grantham's first projector had been the work of months, as he

admitted.

Carton, sent that night for information from Grantham, had evidence

of the importance attached to him in the policemen at the door of the

physics building, and knot of reporters lounging outside. They hailed

him noisily and called after him when Carton, after sending his name

in, was admitted inside.

He found Grantham in his laboratory's ante-room, with Sergeant Wade.

"Carton, I'm glad to see you," the scientist greeted him. "You were

here with us last night when the Invisible Master came in and went out,

and I'd like to hear what you think of a scheme that I've devised for

combatting him."

"You've found a way to capture him?" Carton burst out.

Grantham shook his head. "No, but a way of curbing his activities, I

think. Suppose that inside that bank he robbed today there had been

a steel barrier, and that entrance to the bank was only through a

turnstile like a subway turnstile. Then a guard standing beside it

could watch it and if it turned with no one in sight he would know the

Invisible Master had entered and could give the alarm. There could be

entrance and exit turnstiles like that, and in stores and the like as

well as banks. It would stop these snatch-robberies on the part of the

Invisible Master, to some extent, at least."

"It sounds feasible," Carton admitted. "But it will slow business—do

you think the banks will adopt it?"

"They will," Wade said shortly. "They're scared stiff down in the

financial district over this Vance National robbery today, and they'll

catch at any straw to keep the Invisible Master away from their

vaults."

The Second Blow

"Even this, though," Grantham said broodingly, "won't completely stop

the Invisible Master. The best it can do is to curb him for a time

until we find some way of—"

He stopped as the phone-bell rang, and when he had answered, turned the

receiver over to Wade. Carton saw the detective's sleepy eyes widen a

trifle as he listened to the excited voice on the other end, though his

jaws moved his gum as imperturbably as ever. When he turned back to the

other two they were waiting in breathless silence.

"Headquarters," he said simply. "Less than a half-hour ago the

Invisible Master took forty thousand from the pay-office of the Etna

Construction Company, up in the Bronx, and shot and killed one of the

pay-clerks."

"Good God!" Grantham exclaimed. "And they're sure it was he?"

"No one else," said Wade laconically. "The office is a small wooden

building on the construction lot. The two clerks, Taylor and Barsoff,

had the money ready to pay out through a window in one side. There were

three guards around the building, armed, and one of them saw the door

fly suddenly inward and then heard the shot and scream from inside.

They rushed to the office but when they got there Barsoff was dead,

shot through the heart, and Taylor could only stammer that the door had

flown open, the money had suddenly disappeared, and that Barsoff had

been shot out of empty air when he had grasped after it. The guards and

Taylor searched the lot and called the police instantly but they've

found no trace of him."

"Lord!" Carton exclaimed. "The city will go crazy over this—the

Invisible Master striking again on the same day!"

"It will go more than crazy," Wade commented grimly. "This is going to

make everyone in this town handling money panic-stricken!"

"It is the start of the Invisible Master's rule!" said Grantham

solemnly. "From now on no one in New York is safe from him! He is

deliberately terrorizing the city, and at the same time enriching

himself!"

The door opened and President Ellsworth burst inside, his ordinarily

genial face twisted with emotion. "Grantham!" he exclaimed. "Have you

heard of this latest outrage of this assistant of yours—this Invisible

Master?"

Grantham nodded somberly. "We've just heard."

"But this is horrible!" Ellsworth cried. "To think that Gray, so quiet

and sane to all appearances, should become this unseen thief and

killer!"

"Why should Gray be so crazy after money, anyway?" Wade asked him.

"They tell me he was a scientific rather than business type."

"I think I can understand it," President Ellsworth said. "Gray has long

wanted funds for independent research—even he and Grantham here have

been terribly hampered in their work by lack of money. He has seen the

millions that are spent each year in this city on luxury and pleasure,

has reflected how much good might result to the human race were part of

it applied to scientific research, and has started out with this weapon

of invisibility to get it!"

"You sound almost as though you were in sympathy with him," Wade said.

"My dear sir!" Ellsworth was visibly shocked. "I may believe that a

fraction of the city's riches would be better applied in research, but

I would never condone the murder of helpless clerks to obtain it."

"I was only joking," Wade apologized. "Grantham and I think we have

found a way to curb the Invisible Master's activities, at least."

"Indeed?" asked Ellsworth curiously.

"Yes." And Wade explained the idea of the turnstiles, which the

President at once approved.

A City Terrified

"But it seems that will only limit his activities," he said. "Is there

no chance of capturing him completely? Are you sure, Grantham, that the

projector he stole might not suddenly cease to function and make him

visible?"

"No chance of that," said Grantham hopelessly. "The batteries in its

case are small but enough to keep it running for weeks, at intervals.

And since it's Gray that took it, he'll know how to replace them."

President Ellsworth nodded. "I suppose so. But he'll have to be

captured soon or the city will be in panic."

Grantham shook his head. "This second crime is enough to send it into

panic, almost, without further aid, Ellsworth. And if the Invisible

Master should strike again soon—"

And by morning, Carton saw, Grantham's words were nearly fulfilled

already, since it was panic indeed that had almost settled upon the

city. The newspapers were in a state approaching frenzy. The Invisible

Master had struck again, had followed his daring daylight bank-robbery

by another robbery and cold-blooded murder as terrible. He was abroad,

he was invisible, and he was a killer!

A thousand alarms of the Invisible Master's presence were pouring into

police headquarters from citizens who had heard inexplicable sounds or

the like. The police sought to track down some of these, but were near

the limit of their efforts. They had broadcast photographs of Gray in

case he should assume visibility at times, had endeavored to have a

watch kept for the larger bills stolen, but more they could not do.

Through all that morning a chill of terror hung over New York, the pall

of the Invisible Master's rule. Many stores and banks did not open on

that morning. Others that did had hastily-devised turnstiles and like

devices, and armed guards at every door. Crowds in streets and stores

were at a minimum. Every hour saw new panics as a cry went up that the

Invisible Master was present. All New York, Carton saw, was waiting

with nerves on the ragged edge to hear whether the dread unseen figure

stalking the city's ways would strike again.

Then just at noon fear-mad voices were shouting and presses were

roaring and newsboys were bawling as there came to the city the dread

word it awaited—the news of the Invisible Master's third crime.

Even Carton blanched at the horror of that crime, for in it three

men had gone to death. The three had been partners in the importing

firm of Van Duyck, Jackson, Sunetti and Allen, with offices on lower

Broadway. Upon that morning they had met to dissolve the partnership

in question, there having been some strong differences between them on

business policies. A large amount of cash and negotiable securities

had been brought to their office for the purpose. According to Allen,

the only one of the four to survive, they had been working out their

accounts when in the morning's mail had come a brief letter signed by

the Invisible Master.

He had said that the partners were to gather the sum of one hundred

thousand dollars in cash and securities, place it in a suitcase, and

appoint one of their number to sally forth along Broadway with it at

the exact hour of eleven, when he, the Invisible Master, would take

possession of it. Unless one went forth with it at that hour, he would

enter and their lives would pay the forfeit.

Allen said that when the note was brought in by an excited secretary

they had ignored its threat entirely and had gone on with their

accounts, thinking the thing the work of joking friends, or a crude

attempt to cash in on the dread the Invisible Master had stirred. They

had forgotten its menace by the time the hour of eleven came. At that

hour Van Duyck and Jackson and Sunetti had been seated on one side of

a table with Allen on the other, facing the door. Allen had looked up,

and had, he said, seen the door fly suddenly open and then shut without

anyone entering that he could see!

The Remembered Threat

In an instant he had remembered the Invisible Master's threat but

before he had been able to cry out three shots had crashed out and his

three partners had slumped dead with bullets through their skulls from

behind. In the next instant another shot had crashed out of empty air

and a bullet had buried itself beside Allen in the wall, but as that

shot came he had cried out and there had come cries from all in the

building who had heard. The door instantly had flown open and shut as

the Invisible Master had fled without stopping to grasp at the cash

and securities, and those who rushed in had found Allen standing still

beside the wall, and unable for minutes to speak. The unheeded threat

of the Invisible Master lay crumpled on the table by the dead men.

With that tragedy the chill fear that held New York dissolved into

stark terror, and as Carton pushed his way north to find Wade and

Grantham there was all about him a wild confusion of panic.

Great crowds were forming and rolling toward the City Hall to be held

back by the police and troops drawn up to guard it, where they shouted

their wild demand to the city's officials that the Invisible Master be

captured or killed or bought off at any price. There were wild rumors

of even more terrible crimes the Invisible Master had committed, rumors

of men done to death in the seething East Side, rumors of martial law

to be declared and troops brought to the city.

Had the great crowds that bellowed their terror but known it, the

city's officials were even then face to face with the Invisible

Master's purpose. For in an inner room at City Hall, with Grantham and

Wade there, and Carton too, they were reading the letter that had come

but minutes before to them.

To the Mayor and Officials of New York:

Having shown in these last few days what the rule of the Invisible

Master means to your city, I am ready now without fear of disbelief

on your part to state the terms on which my reign of terror over this

city will end. Those terms are—the immediate payment of five million

dollars in assorted denominations. This money, in a steel box of

moderate size, is to be placed in the following spot: Two miles north

of the village of Pernview, on Long Island, on the west road, is a

milestone. In the forest three hundred yards east of this milestone

is a large oak. You will place the box on the boulder beneath this

tree on tomorrow night, between eleven and twelve o'clock. You are at

liberty to attempt to prevent me from getting the box, but it will

only result disastrously for yourselves.

If this is done my activities will cease. If it is not done I will

commence an even greater campaign of terror that will make a chaos

of New York in hours. No troops or forces are of any use against me.

I leave the raising of the money to you, but suggest that the city's

business men be called on for it. Either they pay or I will make their

city a desert of terror.

The Invisible Master.

CHAPTER IV

Blackmail

Carton spoke softly through the darkness to the man beside him as their

car stopped. "Is this the place, Wade?"

Wade nodded. "There's the milestone—you're ready, Grantham?"

Grantham nodded. "All ready—Kingston has the box."

As they emerged from the car onto the road that gleamed white in the

darkness, Carton glimpsed behind it other cars from which dark shapes

of men were emerging, rifles and pistols gleaming in their hands. All

had turned off their lights, and the scrubby woods that rose on either

side of the road seemed impenetrable walls of blackness.

It had been little more than a day, Carton reflected as he stood in

the road with the others, since the Invisible Master's astonishing

demand had been received by the New York authorities. There had been

no doubt or dispute whatever as to whether that demand should be met.

With wild crowds besieging the City Hall, with all New York's customary

organized life sinking into chaos beneath the panic-pall of the

Invisible Master's presence, there was no other course to follow, and a

subscription for raising the money had instantly been started.

Through the rest of that day and the next the money had poured in,

mostly in great sums from the banks and big business houses of the

city who realized that it was only by payment of this tribute that the

metropolis could be saved from chaotic ruin. Later on, they reasoned,

the Invisible Master could be hunted down and dealt with, but now the

thing was to lift his menace from New York. Five millions was a great

sum, but not in comparison with the daily loss the city's businesses

were undergoing. By the next afternoon the five millions were ready, a

compact mass of securities and highest-denomination bills.

It had been placed in the specified small steel box, and given into

the charge of Kingston, a representative of the city's government who

was to place the money as requested. And since the Invisible Master

had mockingly given full permission for any to attempt his capture who

wished to, Wade and Grantham had worked out the scheme that held a

slender chance of trapping the unseen criminal. With their two-score

of armed men waiting behind them, Grantham explained the plan in the

lowest of voices to Carton and Kingston.

"Kingston and I will take the box in and place it on the boulder," he

whispered, "and when we do so I'll stretch in a circle of yards around

it this thread of wire, and connect it to this pocket-battery and bell.

Kingston and I will wait with the money, behind the big oak, and Wade's

men will lie in a circle all around the spot.

"When the Invisible Master comes he'll make for the boulder, and must

necessarily strike the stretched wire and ring the bell just before he

reaches it. Then your men can rush in from all sides to enclose him in

their circle, while Kingston and I will be there and armed to prevent

the money from being taken by him. It's our one hope of catching him,

for we'll never have this chance again, I think."

The Trap

Wade nodded. "We all understand the plan, Grantham. We'll wait for him

if it takes until daylight."

"I think he'll appear tonight," Grantham said. "I imagine he is rather

anxious to get the money and have it all over with."

"Well, good luck," whispered Wade, extending his hand, which the

physicist grasped. Kingston too, a little nervously, shook hands with

the officer, and then the two disappeared silently into the dark wall

of the wood eastward.

Wade and Carton waited for a moment as silent as the grouped silent men

behind them, and then as Wade passed a whispered order to them, they

all were melting into the dark forest likewise. Swiftly they formed a

circle of a hundred feet in radius around the great oak at whose foot

was the stone the Invisible Master had specified. On that stone by

then, Carton knew, the steel box would be resting, with Grantham and

Kingston watching from close beside for the warning bell. The circle

of men had in a moment crouched down here and there in the brush, Wade

beside Carton, and the wood settled back into its accustomed night

silence.

The trap was ready. Would the Invisible Master dare to enter it?

Carton remembered afterward the time of waiting that followed as a

period of almost infinite length. Crouching silent and motionless with

Wade in a clump of brush he listened tensely. Out to right and left of

him, he knew, were crouching the dozens of men who made up the circle,

each ready with rifle or pistol and electric torch, each listening

as intently as themselves. And at the circle's center, Grantham and

Kingston. All waiting for the unseen man who was to come to claim the

price of the terror he had loosed upon New York.

Was it a twig that snapped somewhere to the left, Carton wondered?

Every slightest sound seemed intensified in the unnatural stillness of

the place. A half-hour had passed but there came still no alarm. Wade

was chewing gum as softly and silently as ever beside him, his heavy

pistol ready in his hand. The desolate hum of crickets came to their

ears.

Through the branches above Carton could see the moon drifting past. He

began to try estimating by it how long they had waited. Then suddenly a

sound came that shattered the stillness of the woods as with a tangible

blow. The jangling of a bell!

"At him!" Wade cried as they leapt up, forward. All around them the

dark shapes of men were running toward the towering oak!

They heard hoarse cries from Kingston and Grantham ahead—a single

brief exclamation in a deeper voice—and then—crash!—crash!—crash!

three shots echoing through the forest from ahead like the crash of

cannon!

"He's there—don't let him get through!" Wade cried. The circle of

running men was contracting and merging in an instant upon the central

oak. Their guns leapt in their hands as they burst into the little

clearing beneath it. They stopped.

Kingston lay on the ground in a grotesque attitude beneath the light of

their torches, shot through the heart. Grantham, blood welling from his

left shoulder, was twisted in a half-sitting position beside him. There

was no one else in the clearing and of the steel box that had rested on

the boulder there was no sign!

"He got it!" Grantham whispered, his face distorted with pain. "He got

it and got away—the Invisible Master!"

"Beat the woods!" Wade's voice flared. "Carry your torches and shoot

at every sound of steps when there's no one visible with them! He's

slipping out somewhere now!"

Grantham shook his head. "No use," he said. "We can't fight him, Wade.

Kingston and I were crouched behind the oak with our wire ready, and

we heard the bell ring, then as we leapt forward an instant later saw

the steel case disappearing from off the stone! Kingston had grasped

him, I think, was struggling with something invisible as we both cried

out, and I heard an exclamation from him and then the shots roared out

of the empty air just beside Kingston. Kingston fell like a stone, I

heard one of the shots rip past me and another caught my shoulder. Then

I heard the sound of leaping feet beside me just a moment before you

burst into the clearing."

Whose Voice?

"But you heard his voice close beside you!" Wade exclaimed. "Was it

Gray's?"

Grantham's pale face took on a certain puzzlement. "It may have been,

Wade—I heard it for but an instant in that exclamation—I don't know

whether that was Gray's or another's, it was a voice I had heard often

before."

Wade nodded decisively. "That ends all doubt as to it's being Gray, at

least. Carton, do what you can for Grantham's shoulder, while I see if

any of the men have run across him."

But in minutes the men were streaming back with Wade, their search

fruitless. They had found no one—could have found no one, Carton

realized, in that search through the darkness for a being invisible.

Wade shook his head.

"It's all over," he said, "and I realize now that we never really had

a chance of capturing him. We can only hope that he'll be content with

the five million and never again loose terror on any city as he did

upon New York. Five millions—well, it may be best, after all."

Silently the party drove back to the city, and after they had taken

Grantham to his rooms near the university and summoned a doctor for his

wound, Carton and Wade rode together downtown. It was with a rueful

shake of the head on the detective's part that they parted; he to his

headquarters and Carton to the Inquirer's city-room to pound out an

abridged account of the night's events. By the time that Carton went

wearily across the city to his own rooms newsboys were shouting in the

streets the welcome news that the Invisible Master had been bought off

and that his reign of terror was ended.

Carton, in his tired sleep, lived again the tense events of the night,

and it seemed to his sleep-numbed mind that the warning bell they had

heard was jangling again and again. It woke him finally, to find that

it was his doorbell, and when he opened it Wade stood before him. The

detective's sleepy eyes were more wakeful than ever Carton had seen

them, but to the reporter's first excited question he snapped but a

single order.

"Dress, Carton—we're going up to the university."

In minutes they were flying out along Riverside Drive through the

growing morning sunlight. Around them the city was waking to a day

of heart-felt rejoicing that the terror was lifted. Wade seemed the

container of a strange grim force, and to Carton's questions returned

no answer. But when they had drawn up before the familiar gray physics

building and had entered the equally familiar little laboratory and

ante-room, Carton found Grantham awaiting them, his shoulder bound and

his face haggard from a sleepless night.

"You called me, Wade?" he asked. "Something you'd found?"

Wade nodded. "Yes. But first I'd like to have President Ellsworth here.

He's near here, isn't he?"

Grantham nodded, frowning. "His home is—yes. I heard he'd been away

for a day or two but he ought to be back by now."

He turned to the telephone, spoke briefly into it, and when he had

finished turned to Wade. "He's coming," he said.

They sat silent until President Ellsworth entered minutes later. As he

came in Carton noted that the two officers who had accompanied Wade and

himself were lounging in the hall outside. The President's ordinarily

genial face held some irritation.

Wade Makes a Statement

"What's this—a sort of post-mortem?" he asked. "I've just heard all

about last night, Sergeant Wade—and it was too bad that the Invisible

Master slipped through yours and Grantham's hands. But perhaps it's

best that it's all over."

"It is not all over yet," Wade said quietly.

Ellsworth stared, as did Grantham and Carton. "You mean—" the

President began.

"I mean that I know at last who the Invisible Master is and where he

is!" said Wade.

Ellsworth seemed too astounded to speak, but Grantham leaned to grasp

Wade's arm. "Is that true, Wade?" he asked. "You've actually found him?"

"I have," Wade told them quietly.

And then as the three others stared at him he went on. "You remember,

Grantham, that you told me that in a case like this the ordinary

police-routine, the gathering of fact after fact to apprehend a

criminal, was useless? You may have been right, but I followed that

routine and I've finally gathered among other facts, three facts that

tell me everything I want to know about the Invisible Master. Had I had

these three facts last night I could have saved us that struggle and

Kingston's life, but I did not have them then. I have them now, though."

"And the three facts?" Grantham asked. Ellsworth was staring as though

bewilderedly, Carton leaning tensely forward.

"The first fact," said Wade, "is something that President Ellsworth

happened to say the other night—when we spoke of Gray—saying how

Grantham and he had been hampered in their scientific work by lack

of funds, and how it would be almost justifiable to take some of the

city's pleasure-spent millions for the aiding of research."

They were all silent. Ellsworth's face had flushed.

"The second fact is one that not all of you may understand and that I

myself was ignorant of until last night—it is the peculiar optical

properties of tourmaline crystals."

Carton and Ellsworth stared at him blankly, but Grantham's eyes gleamed

with sudden understanding.

"The third fact, which I also learned last night and which is the most

significant perhaps of all, is the simple record of a stockbroker's

account carried some weeks ago by Mr. Peter Harkness."

Wade was silent, and Carton, astounded and bewildered, could only stare

at him still. Ellsworth was about to burst into questions but was

interrupted by Grantham's voice. The physicist had risen and turned

from them toward the window. His voice came over his shoulder to them.

"I think I can give you a fourth fact that will clinch it, Wade." His

right arm crooked—

Wade leapt, but an instant too late. For when he spun Grantham around

the physicist was already falling, his lips writhing with cyanide

grains still upon them, a faint peachy odor in the air. He was

still, dead, when Wade lowered his body to the floor. The detective

straightened, mopping his brow.

"I was afraid of that," he panted. "I was afraid of it—but damned if I

don't think it was his best way out!"

Carton and Ellsworth gazed as though petrified. Then Carton's

voice—shaking—

"Then Grantham—Grantham himself—was the Invisible Master?"

Wade turned.

"There never was any Invisible Master at all," he said.

Back to the Laboratory

Carton and Ellsworth stared at him for moments before they could speak.

"But Grantham's power of making things invisible!" Carton finally

cried. "We saw him do it here—"

Wade shook his head. "You didn't Carton, but you thought you did."

He strode to the laboratory's long table, they with him. He searched

along it for a time and found what he sought, a round disk of

glass-like material, clear and transparent. He placed it against one

small pane of the window, through which the sunlight was pouring, and

to their amazement it showed black and opaque against the sunlight.

Wade slowly turned the disk in his hand, keeping its flat side parallel

to the window. As he turned it, it became less and less opaque until by

the time he had given it a quarter-turn it was completely transparent,

and was in fact wholly invisible because of the brilliant sunlight

streaming through it from behind into their eyes!

Slowly Wade revolved the disk another quarter-turn and as he did so it

became cloudy and translucent and then more and more opaque until at

the end of the half-turn it was as dead black and visible against the

sunlight as ever! Carton and Ellsworth stared unbelievingly, and Wade

handed the disk to them.

"A tourmaline-crystal," he said. "There's another set in that small

window pane. Their property is well enough known to physicists, and is

a result and proof of the polarization of light. When two tourmaline

crystals are placed together with their axes parallel, light streams

through both unchecked. If one is turned so that its axis is at right

angles to the axis of the other, though, light cannot pass through them

and they become thus opaque. A quarter-turn of the one will make them

transparent again.

"Grantham had one tourmaline-crystal set in the window-pane and the

other in the disk form. He showed you the black glass paper-weight disk

he was going to make invisible, but when he leaned forward to put it on

the little projector he palmed it and put there instead this tourmaline

disk. It showed black, like the paper-weight, though, because he placed

it on the projector's framework with axis at right angles to that of

the crystal in the window-pane.

"The sunlight was coming straight through the window into your eyes (he

had chosen the hour), and you saw the black disk against it, resting on

the projector's framework. Grantham and Gray had some sort of mechanism

inside the projector to make an appropriate sound, but the switches

Grantham turned actually controlled the framework above the projector,

which was made so as to turn the disk resting in it a quarter-turn when

desired.

"You see how it was done? Grantham turned his switches, and as the

tourmaline disk was turned slowly in its framework you saw it growing

more and more transparent until when it had been turned a quarter-turn

in the framework it was perfectly transparent and so invisible to your

eyes in the strong sunlight streaming through it. Grantham let it

remain so but a moment and then with his switch or rheostat control

turned it back again a quarter-turn. It grew more and more cloudy and

black until at a quarter-turn it was again black and opaque against the

light. He reached for it, and when he turned to you again palmed it and

could hand you the paper-weight disk."

Carton shook his head like one dazed. "And it seemed such a perfectly

open demonstration," he said.

"But that doesn't explain the Invisible Master!" Ellsworth exclaimed.

"If Grantham's power was faked, who committed those three crimes that

no one but an invisible person could have committed? Who took the money

last night?"

Wade Reconstructs

"I think I can reconstruct the thing from the first," Wade said,

"though some of the secret died with Grantham here. You told me

yourself that he and Gray had long been prevented from engaging in the

lines of research they desired because of their lack of funds. Well, I

think that Grantham grew resentful at this, and then determined, and

that he and Gray resolved to lay hands on the money they needed in

their own fashion. To do it they worked out an elaborate and incredibly

ingenious plan, that hinged upon Grantham's known reputation as a great

physicist.

"Grantham and Gray prepared the tourmaline-crystal set-up, and then

let it be known in one way or another that Grantham had discovered a

method of making things invisible. Of course there was excitement, and

of course the reporters, Carton among them, rushed out here to learn

all about it. Then Grantham reluctantly consented to a demonstration,

and after pulling this tourmaline-crystal stunt, sent them away, and

you too, perfectly convinced that he had actually found a way to make

matter invisible. That was his first great step—to implant in the

minds of reputable witnesses the absolute conviction that he had really

the power of making things invisible.

"Just what happened on that afternoon between Grantham and Gray may

never be known fully, but there seems little doubt that Gray, who

had been sullen at the demonstration that morning, had come to the

point where he had resolved not to go on with the scheme. Probably

he threatened to expose Grantham if he did not stop it, and no doubt

Grantham saw exposure and oblivion on the way. Fearing Gray's

confession, he killed him, and disposed of his body here in the

laboratory. He had the knowledge to do that, and I've found that on

that afternoon he received from the supply-rooms here an inordinate

order of acids which were without doubt used in the disposition of

Gray's body. However it was done, there is not the slightest doubt that

on that afternoon Gray, and even his body, passed out of existence in

this laboratory.

"Then Grantham went on with his plan, changing it somewhat, no doubt,

to fit in with this new circumstance. That night he struck himself a

painful but not heavy blow on the head with some wooden object—you

remember the doctor said the blow was from the side?—and pretended

to be lying stunned when you, President Ellsworth, came in. When

the police came he, without seeming to want to do so, threw the

responsibility of the attack on Gray as much as possible, and told of

his projector that had been stolen by his attacker, and that would make

a man invisible. He had already prepared a mocking letter addressed to

himself as from the Invisible Master, and while talking with Carton and

me, laid the letter on the table where I found it. The officers at

the door had seen no one go in or out, we knew or thought we knew that

someone was at large with an apparatus for attaining invisibility, and

since we never dreamed of Grantham having left the letter, we had no

doubt whatever but that the Invisible Master, whether Gray or another,

had actually entered the room invisibly and left the letter for us.

"This was Grantham's second step, his establishing the idea that

someone was at large with a projector that could make him invisible,

that the Invisible Master was at large and ready to commit any crime.

That idea was established in all the city by the newspapers in the next

day or so, and so strong was the evidence in the demonstration of his

discovery that Grantham had given, and the greatness of his reputation

as a scientist, that almost all did believe that such an invisible man,

an Invisible Master, was at large.

"Now what would naturally result when almost all in the city believed

that? Would it not result in many people seeing a chance to commit

crimes and then blame them on the Invisible Master? You know that there

are hundreds of thousands in a city like this who long to commit some

crime, theft or murder or the like, but dare not because there would

be no chance to shift suspicion on someone else. A man in an apartment

with neighbors all around can't shoot his wife and claim someone else

came in and did it, for he knows that in ninety-nine cases out of a

hundred it would soon be established that no one had gone in or out

of his apartment at that time. But if he could blame it on someone

invisible? You see what it means? Grantham had spread, had insisted

upon spreading, over all the city the thought that the Invisible Master

was at large in it. So at once there would be countless people who

would see a chance to commit crimes and blame them on the Invisible

Master! The thing was as certain as human nature!

CHAPTER V

From Beginning to End

"The first was young Harkness, the teller at the Vance National. He had

been speculating in stocks, had lost thousands of the bank's money,

and was desperate, with discovery near. All around him people were

talking of the Invisible Master and of what he could do, and Harkness

saw in that an idea, grasped at it as at a last straw. He arranged his

accounts to show right when it was over, then on that afternoon simply

cried out and gave the alarm, stammering that the money had been taken

by someone invisible who had snatched it from before him. All believed

quite naturally that the Invisible Master had done it! Their thoughts

had been full of him for two days, and what else could they, could we,

believe?

"Thus the Invisible Master was established still farther as a reality,

a criminal who walked unseen. Hardly any in New York doubted his

existence after that first amazing robbery, and it was probably that

robbery that gave Taylor, the pay-clerk at the Etna Construction

Company, his idea for his robbery and murder that night. For it was

Taylor who took the money and who killed his fellow-clerk, Barsoff, on

that night. He believed like everyone else that the bank-robbery that

afternoon had been committed by the Invisible Master, and saw a chance

to commit a crime that would inevitably be blamed upon the same unseen

criminal.

"He and Barsoff were in the pay-office building, both armed. Taylor had

the packages of money ready, and at the moment selected he flung the

door open from inside without showing himself to the guards outside. In

the next instant he drew his gun and shot Barsoff through the heart,

then stuck the gun and money alike into his pockets and was staggering

against the wall a moment later when the guards burst in. They never

thought of questioning or searching him, so strong was their own belief

in the Invisible Master, and that it was he who had rushed unseen into

the little office and committed the murder and theft!

"By the next morning all New York was cold with fear of the Invisible

Master, and hardly a living soul doubted by then his existence. The

evidence was too strong! And seeing this, Allen saw his chance to

commit the triple murder of his partners which was the third crime to

be laid to the Invisible Master's credit. There had been bad blood

between the four partners—they were meeting on that day, you remember,

to dissolve their partnership because of their enmity, and Allen had

resolved to revenge himself on the other three.

"He wrote a letter purporting to be a threat from the Invisible

Master, a demand for a hundred thousand dollars, and mailed it at a

time calculated to bring it to their office before noon on the next

day. They were settling their accounts, the letter was opened and

brought by their excited secretary, and Allen led them in laughing

it down. When the hour of eleven came, though, the hour specified in

the threat, Allen rose and walked behind his three partners, who were

bent over the accounts. Three shots sent quick bullets crashing into

their skulls, from behind, and another shot a bullet into the opposite

wall. Allen leaped back to that wall, pocketing the gun, and when the

others who had heard rushed into the room they found him standing by

the bullet-pierced wall, apparently overcome with horror. There was the

threatening letter lying on the table, and none doubted for a moment

but that the Invisible Master had carried out his threat and had slain

three of the partners but had been forced to flee before he could kill

the fourth or snatch any of the securities on the table.

The Three Crimes

"Thus three crimes had been committed that every soul in the city

believed implicitly had been committed by the Invisible Master! For