Zooming through a clinging, blinding fog, Lieutenant Adams flew straight into a death trap of flashing enemy planes and flaming, stuttering machine guns. This is an epic of the skies told by the ace of war writers.

There was plenty of it, this gray, clinging fog. Drifting slowly down the slope just west of the tiny pursuit squadron field, clinging to the branches of the gaunt trees, then sweeping out over the field itself, the fog moved. It hung within ten or fifteen feet of the soft earth, and it was thick. Thick and cold. Twenty minutes ago there hadn’t been any sign of it; now the barracks could not be seen from the nearest camouflaged hangar.

Lieutenant Ben Chapin came out of one end of the barracks and swore beneath his breath. It was almost eight o’clock and two ships were out on the dawn patrol. They had been out since a few minutes after six, and were due back any minute now.

A figure, short and chunky, emerged from the white screen of the fog, moving toward the barracks, a clap-board building considerably the worse for wear. Ben Chapin hailed the figure.

“Who’s flying the dawn patrol, Adjutant? Adams and Cole?”

The short officer shook his head, pausing beyond the reaching wisps of white stuff. He spoke in a grim voice.

“Adams and that new officer—Langdon,” he stated. “Looks tough, eh?”

Ben Chapin nodded. “Not so bad for Adams,” he said slowly. “He’ll have brains enough to fly back out of it, and land somewhere. But this Tex Langdon—the Lord knows what he’ll do!”

The adjutant swore. “Wild riding birdman!” he muttered. “But if he tries to come down in this stuff, he may finish up his career in a hurry.”

The adjutant vanished from sight into the narrow corridor of the barracks. He was hungry and cold, and not particularly concerned about Tex Langdon. Lieutenant Chapin stood out in the fog, and shook his head slowly.

“Hope Tex does use his bean!” he muttered. “Sort of like that officer. Acts like he’s trying hard enough. But this’ll be his first dose of—”

He checked himself. He was thinking of the clash after mess, last night, between Adams and Tex Langdon. It had been a sharp one. Lieutenant Adams was an old-timer—three weeks on the front. Tex had been up three days. In that time he had nosed over one ship, cracked another up two miles from the Squadron, in a forced landing, and then he had taxied into a wing-tip of Adam’s pet Nieuport, just before mess. The old-timer had told him just about what he had thought. Tex had listened with a grin on his face, and the grin had enraged Lieutenant Adams.

“You’ll get yours in about three more days, Langdon!” he had shot at him, and then, as Tex had kept right on smiling, Adams had gone the limit. “And the sooner the better—for this outfit!”

Ben Chapin, standing out in the fog with his face tilted upward, swore grimly. Adams hadn’t meant that. He’d been sore; the nervous strain was telling on him. And Tex had smiled that provocative smile of his. The big fellow was calm, or had been until that second. Then his eyes had narrowed to little slits.

“Easy, Lieutenant!” he had shot back coldly. “Where I come from that’s right bad talk!”

And then Adams had laughed. It had been a nasty laugh. And when he had finished laughing he had shot more words at the big Texan.

“You’re not where you came from, unfortunately! But you’ll get there, Lieutenant. The first Boche that gets on your tail will send you back to where you came from!”

Tex had got to his feet, after that. There had been no color in his face; Lieutenant Adam’s meaning had been unmistakable. Ben Chapin had grabbed him, and the old-timer had turned his back and moved from the mess-room.

Lieutenant Chapin listened for the roar of a ship’s engine, heard nothing but the distant rumble of guns, muffled by the fog. Staff had pulled a boner, in picking the locality of the Sixteenth Pursuit’s field. Every five or six days the ground fog was so bad that ships didn’t get in. Once or twice they hadn’t been able to get off.

The pilot turned back toward the barracks. He shook his head slowly. Somewhere in the sky, winging back toward the squadron, most probably, were Lieutenants Adams and Tex Langdon. Quite often two pilots, one winging in from the north and the other from the south patrol of the front, would meet over Chalbrouck, fly back to the Squadron together. Perfectly synchronized wrist watches helped such a meet in the air. Lieutenant Adams was an old-timer. He knew about fog; knew where it was likely to hang and where the ground might be clear. If the two ships met, he could guide Tex Langdon in. He could; but would he?

Ben Chapin swore again. He shook his head. It looked like a tough break for Tex. One more smash and he’d go back toward Blois. The Squadron needed ships too badly. And now there was fog, heavy fog. And the only pilot who could help Tex was Lieutenant Adams. Ben Chapin’s lips moved slowly as he moved along the corridor toward his tiny coop.

“If Tex rides this one into the corral,” he muttered grimly, “he’s good! More than good, I’ll say—he’s perfect!”

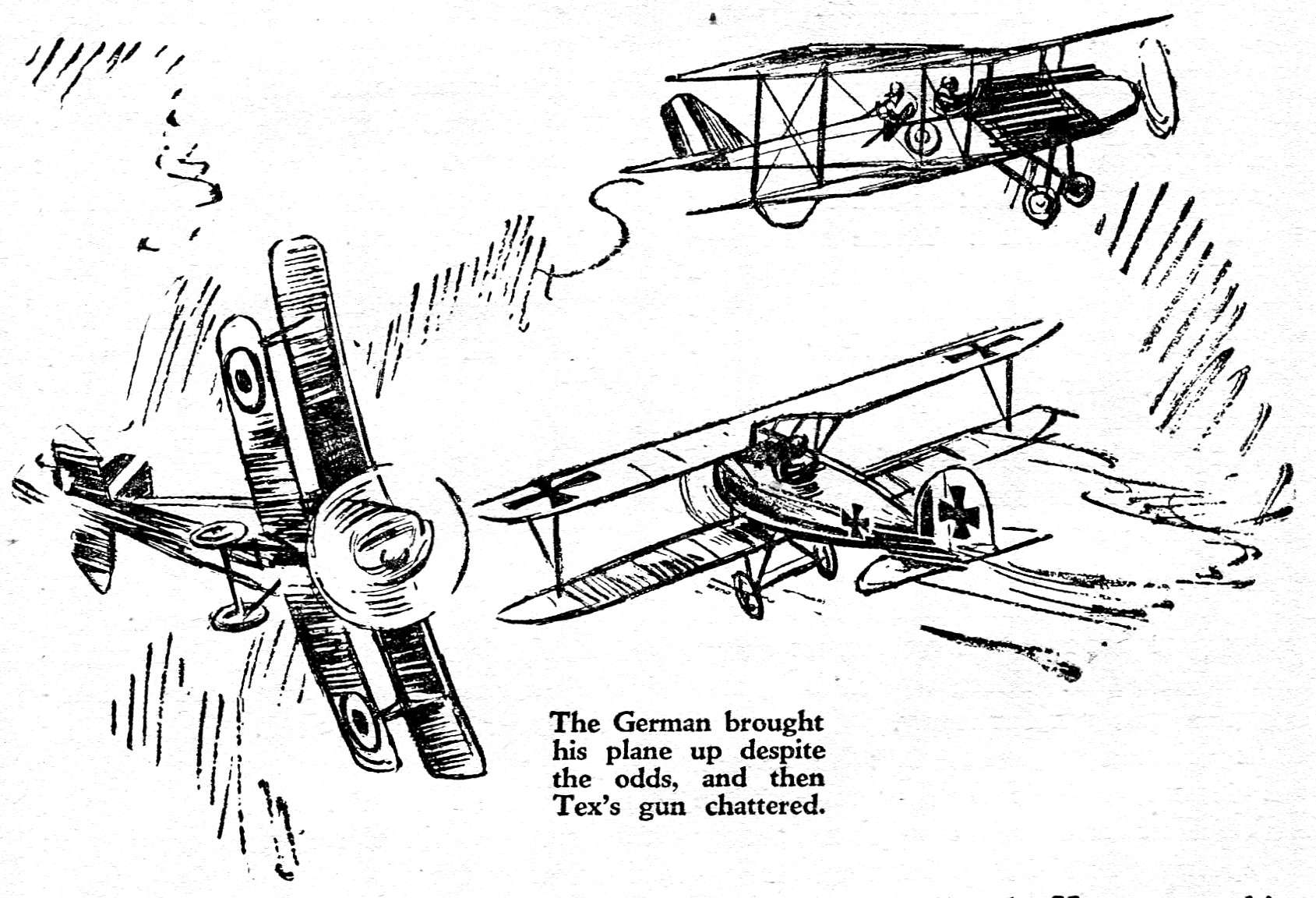

Nine miles east of the Sixteenth Pursuit Squadron’s fog-shrouded field, ten thousand feet above the front lines, two ships zoomed and dove, twisted and spun in the sky. The two ships had been engaged in combat for more than three minutes, and the battle was a tough one. One plane was a baby Albatross, very well camouflaged. The other was a fifteen-meter Nieuport, not so well camouflaged. In the narrow cockpit of the Nieuport was Lieutenant Tex Langdon. His blue eyes were rimmed with red, his lips were pressed tightly together as he handled the American ship, trying to get in position for a machine-gun burst at the enemy plane.

The German pilot was a fine flyer. Twice he had almost sent streams of tracer-marked lead into the fuselage of the American ship. The left wing surfaces showed the bullet holes of his last hit—and it was much too close for comfort. But Tex Langdon was fighting on and fighting desperately.

Two things worried him. He was running low in gas—and the damaged wing surfaces might be badly weakened. The Boche pilot had come down out of the clouds, almost taking him by surprise, as he was winging back toward the Sixteenth. Tex had kicked the Nieuport into a tail-spin, and on coming out of it the German lead had punctured his wing fabric. Since then the fight had been sharp.

The air was bad; the earth below was obscured by drifting fog. The patrol had not been a particularly successful one and now the attack of the German pilot threatened to make it disastrous. Tex had the feeling that he was too green for the enemy pilot.

The Nieuport came up in a zoom; for a flashing second he had the Albatross in the ringsight of the Browning. He squeezed the stick-trigger of the propellor-synchronized weapon, then released pressure after a short burst. He saw that his stream was behind the slanting enemy ship, then he lost the plane in a blind spot of his own ship.

He nosed downward and caught the flash of a shape coming up at the Nieuport then went over in a vertical bank. Green-yellow tracer-bullet fire streaked through the sky close to the plane. Once again the German pilot had come very close to scoring a hit!

Tex Langdon’s lean face twisted. The patrol had been a long one, a difficult one. He was new to such flying. The German pilot was more experienced. The Nieu-port’s gun was getting low. There was the fog hanging close to the earth; it might mean that he would have to search for the Squadron field.

The Albatross was a quarter mile away, between the Nieuport and the Allied rear lines, and banking. Her pilot banked, came out of it, zoomed for altitude. Tex Langdon wiped his goggle-glass clear of a splatter of oil, nosed down to gain speed, and banked his own ship. He could not afford to let the other pilot get altitude.

His lips moved as he squinted blue eyes on the enemy ship.

“Get sense—show tail and fly out of it! If I don’t—he’ll get me!”

It was the way he felt. He was fighting a losing combat. He was new at the front. There was justification for a sky retreat. Just one thing stopped him from winging out. One human—Lieutenant Adams. He would make his report and Adams would learn about it. There were few secrets in the outfit; he had learned that already. Adams would know that he had run away from an enemy pilot.

He shook his head. The Albatross was streaking in at the Nieuport now. Their altitudes were about the same; both had leveled off from zooms. But now the German pilot zoomed again. And then, as Tex pulled back on the stick of the Nieuport, he came out of the zoom and dove.

The American pilot shoved his stick forward, to dive the Nieuport. He saw the nose of the tiny Albatross come up, knew that the enemy pilot had tried again to get beneath his plane for a shot upward. Both planes were streaking at each other now. Tex squeezed the stick-trigger. The crackle of machine-gun fire sounded, then died abruptly. But his fingers were still squeezing the trigger. The gun had jammed!

Tex Langdon groaned, banked to the right. A strut leaped, out on the left wing. Fabric ripped; the tracer stream of the other ship was tearing through wing and wood. A shape flashed up past the vertical-banked Nieuport. Tex Langdon twisted his neck, got a glimpse of the German pilot’s head. The two ships rushed past each other.

Once again Tex felt the desire to wing for it. He had plenty of reason now. His wing fabric was badly damaged—a strut had been splintered. And yet, something within him refused the chance. He swore hoarsely, banked around, leveled off.

His eyes widened. Slanting down toward earth, flames streaking up from her, was the Albatross! She was an eighth of a mile distant, and for a second he thought that his short burst, before the gun had jammed, had done the trick. And then he saw the other plane.

She was banking around, and evidently had just come out of a dive. She was a Nieuport—and bore the markings of the Sixteenth Squadron on her camouflaged fuselage. Tex stiffened in the cockpit. He forgot about the damaged wing fabric, the splintered strut. Lieutenant Adams—flying the dawn patrol! Adams had shot down the enemy with whom he had been combating!

His Nieuport was roaring toward the other ship. He cut down the throttle speed. Lieutenant Adams was dropping down toward earth, toward the ground fog. At intervals, as Tex followed him down in a mild glide, he could see the other lieutenant’s ship spurt a trail of smoke from her exhaust. The ship was all right; Adams was keeping the gas feed steady.

The German plane crashed between the lines, in a great burst of flame. Black smoke rolled up from her. And Lieutenant Adams was leveling off now; he was heading back toward the Squadron. He was ignoring Tex, just as though he had never been in the air. Even as the pilot of the damaged ship tried to level off and wing after the other Nieuport, fog swept over Lieutenant Adams’ plane. She was lost from sight.

Rage struck at Tex Langdon. His Nieuport was heading back toward the Sixteenth, but the whole sector was covered with fog. Lieutenant Adams knew that. The veteran pilot knew that Tex would have trouble finding the Squadron. He must have guessed that gas was running low. And yet he winged away from the other Nieuport; roared his ship into the ground fog.

Tex Langdon swore grimly. He roared the engine into full voice and the Nieuport rushed into the white blanket of fog. The beat of the engine increased in tone, magnified by the density of the atmosphere. Tex could barely see the wing-tips of his ship; his goggle-glass clouded instantly. He felt that he was flying with a wing droop, and there was no level guage in his baby plane.

He pulled back on the stick. It was either that or risk going into a spin. He couldn’t drop down very low to the earth, as perhaps Lieutenant Adams was doing. He didn’t know the country well enough. There were hills about the sector; he might pile into one. Adams could fly by time and his sense of direction.

“He knew I couldn’t make it!” he muttered. “Not without—his help. And he pulled out on me!”

The engine spluttered, picked up again, spluttered once more. Tex Langdon worked over the air and gas adjustment, his heart pounding. Then, abruptly, as he nosed the ship forward, the engine died.

Tex Langdon was suddenly very cool. He banked the ship to the westward, got her into a gentle glide, stretching it as much as he could. He cut the ignition switch. The Nieuport glided downward, her wires shrilling softly, the fabric of the left wing surfaces crackling in the glide-wind. The fog enveloped her.

The altimeter was not registering at the low altitude. He guessed that the ship was within fifty or seventy-five feet of the earth. He pulled back slightly on the stick; the nose of the Nieuport came up. There was a blur of dark color stabbing up through the gray stuff. Savagely he wiped the glass of his goggles for the last time and stared ahead, downward.

Something long and curved stabbed at the right wing. He saw other blurs of color, fog clinging to them, rise up before him. He jerked the stick back against his flying overalls; the nose came up. And then the ship twisted violently to one side! Fabric ripped! He threw both arms before his face, releasing his grip on the stick!

The weight of the Hispano-Suiza engine carried the Nieuport down through the upper branches of the trees. And only the fact that Tex Langdon had stalled, just before the plane struck into them, saved him. As it was, a twisting, battering branch shot through the fuselage fabric, ripping the overall material and sending a stabbing pain up his right leg.

Then the plane was motionless, and Tex Langdon snapped the safety-belt buckle loose, slid carefully out of the cockpit. The splintered prop was in the soggy earth beneath the trees through which the ship had plunged, but it had not battered in deeply. Off to the right, as Tex dropped to earth and limped about, sounded the steady firing of a battery.

Tex Langdon smiled grimly. The ship was a wreck. Lieutenant Adams had dropped down from the skies and had got himself the Boche with whom Tex had been battling so desperately. Then he had winged on back, through the fog. It had been as though Tex and his plane had not existed.

The tall westerner shook his head slowly. It would probably mean Blois for him, though the bullet holes in the wing surfaces might help his case. He’d get over to the battery, get directions back to his Squadron. And there was one officer with whom he wished to talk, back at the Sixteenth. He wouldn’t have much to say—but he’d say it in his own, particular way.

He took a last look at the Nieuport, limped toward the sound of the firing. The battery would be fairly close to the front—and that meant a long trip back to the outfit. He had been lucky, perhaps, to escape as he had, in the landing. But there was no thanks to Lieutenant Adams; not for that.

Tex Langdon limped slowly onward. The woods ended abruptly, he was on soggy ground. In the distance there was the flash of red, spreading strangely through the white-grey fog. It was cold. All about him guns rumbled. But he didn’t feel the cold, and scarcely noticed the rumble of the guns. He was thinking about Lieutenant Adams, and getting back to the Squadron.

Captain Louis Jones spoke across the crude desk between his short form and the tall one of Lieutenant Langdon.

“You haven’t had the experience of Lieutenant Adams; and it was your first combat. You should have flown out before your gas got so low. Lieutenant Adams tells me that it looked as though you were in trouble. He says he dropped on your Boche and got him. He hasn’t any verification because the ship fell between the lines, and there was a lot of fog, though not where the Albatross fell. Perhaps you will verify his shoot-down.”

Tex Langdon nodded. There was a grim smile on his face.

“I will, Captain,” he stated. “He got the Albatross, all right. Got back here without any trouble, they tell me.”

The Squadron C. O. nodded. “Went around to the west, slipped under the fog and came in just off the earth. Of course, he knew—”

The captain frowned and changed the subject.

“We expect two new ships down from Colombey before dusk, if the fog lifts. You’ll draw one of them. We’ll try to salvage your old ship. Tomorrow morning you can stay back of the lines, working on your new gun and feeling out the ship. I’m not exactly praising your work, Lieutenant. Get that straight. But you had a bad ground fog. Bad enough to give you another crack at the front. This time—”

He shrugged his shoulders, smiling at Tex Langdon. The lieutenant nodded.

“I understand, Captain,” he stated. “I’ve cracked up a lot of ships in a short time. But I’ve been trying—”

The C. O. smiled slightly. “That helps but it isn’t the whole thing, Lieutenant,” he stated. “I know you’re trying. It isn’t enough. You’ve got to succeed. Won’t always have Lieutenant Adams around to pull you out of scrapes, you know.”

Tex felt rage strike at him. But he controlled his feelings with an effort. Adams, getting him out of a scrape!

The C. O. nodded dismissal. Tex Langdon went from the captain’s office toward his own coop. It was almost four o’clock; it had taken him five hours to reach the Squadron from Battery H4. He was about to turn into the barracks when he almost collided with Lieutenant Adams. That officer muttered something, turned to one side. Tex caught him by the arm.

“Just a second, please, Lieutenant! C. O. tells me you got me out of a jam, this morning.”

Adams narrowed dark eyes on the blue ones of the Texan. He nodded, standing fully a head shorter than Tex.

“Well, didn’t I, Lieutenant?” he snapped. “Sorry I couldn’t fly both ships—might have kept you out of another!”

“I’m not saying you didn’t get me out of a sky jam, Adams,” Tex replied in a quiet tone. “But I am saying this—you didn’t know you were getting me out of one!”

The other pilot stiffened. His eyes narrowed on Tex Langdon’s blue ones.

“Come again!” he snapped. “Make that more clear!”

Tex nodded. “The C. O. asked me to verify your shoot-down, Adams. I did. But get this straight. You saw me skyscrapping with a Boche. You had ceiling, and a chance to drop in. You did and you got my Boche! You didn’t know I was running low in gas, or that I’d been hit twice by the enemy’s lead. And if you had known it wouldn’t have made any difference. You got the German ship for your record! And you winged straight for the Squadron, not giving a damn about me!”

Lieutenant Adams smiled grimly. “Think so, Langdon?” he asked quietly.

“I know so!” Tex snapped back. “I mussed up your pet ship in a take-off, and I didn’t get on my knees when you howled about it. You’re sore. You knew I couldn’t find the Squadron in the fog and you left me to go where you’ve said I came from!”

There was a little silence. Then Lieutenant Adams spoke. His voice was like ice.

“You couldn’t have followed me through that fog, Langdon,” he stated. “Because you can’t handle a ship in the sky. Is that any reason that I should mess my chance up? My Nieuport was running low in gas, too. I wasn’t sure of finding the outfit. And I dropped on that Boche because he was out-maneuvering you. I sat up in the sky and watched you. You never even saw me there!”

Tex stared at the other lieutenant. Then he laughed nastily.

“You may get in a sky jam some time,” he said slowly. “You might even crack up a ship one of these days. And if I’m around—”

Lieutenant Adams swore sharply. His face twisted.

“You won’t be!” he snapped. “I’ll be shooting lead around the front when you’re—”

He broke off, controlling himself. Tex Langdon smiled at him, his eyes narrowed. When he spoke his voice was very low and steady.

“When I’m back where I came from, eh, Lieutenant? Maybe you’re right, Adams. But I’m not forgetting that you winged out on me, into the grey stuff. The captain didn’t ask me to verify that fact.”

The veteran smiled grimly. “If I ever get in a sky jam, Langdon,” he said slowly, “I won’t expect any help from you. If you did try to help you’d probably crash me in the air. It’s about the only thing you haven’t done since you’ve been up.”

Lieutenant Tex Langdon nodded. “Just about,” he agreed in a peculiar tone. “Except—I haven’t quit a man in ground fog!”

The two replacement ships didn’t come in that afternoon. Nor the next afternoon. The fog continued to hang low and thick. Most of the pilots sat on the ground, worked on their ships, lined up guns. One morning of the third day the fog lifted a bit and the two replacement Nieuports were ferried in from Colombey. Lieutenant Schafer drew one and Tex Langdon drew the other.

Tex worked over his Browning, got the ship off for an hour’s hop back of the lines before dark. She handled well, and in a couple of bursts at the ground target south of the Sixteenth’s field he didn’t do so bad. But he almost cracked up setting her down, making a fast landing. He taxied her into one of the camouflaged hangars, gave the ground-crew sergeant his o. k., and moved toward his coop in the barracks.

An orderly was waiting for him; he was wanted at the C. O.’s office. He

washed up, hurried over. Captain Jones frowned up at him.

“Lieutenant Connors reports sick. Looks like a touch of flu. We’re short pilots, and Brigade is howling for defense planes. Enemy ships are flooding the Sector air. Is your new ship all right?”

“Yes, sir,” Tex replied quietly.

“Take her over until dark,” the C. O. ordered. “Lieutenants Harrington and Adams are out. Head for Hill G.8. Some Fokkers are raising the devil up that way. The French may get some ships across, and you might help some in a dog fight. Pull back here before dark. That’s all. Get me a report as soon as you get in.”

Tex nodded, saluted. He went to his barracks, got his helmet and goggles, headed for the Nieuport again. The ground crew pulled her out. Adams across the line! Tex smiled grimly. That lieutenant was getting plenty of work. So were they all, for that matter.

He climbed into the cockpit, revved up the little ship’s engine for a few minutes, nodded his head for the blocks to be pulled away. The pursuit plane rolled out across the soggy field, climbed into the sky. Tex headed straight for the front. As the Nieuport gained altitude, he stared over the side. From the northeast, clinging low to the ground, white fog was drifting.

Tex Langdon groaned. For a brief second he thought of banking around, turning back. The C. O. was not pleased with his work. And he was winging toward the front with darkness and fog coming to obscure the Squadron field. If he cracked up again—

Well orders were orders. The Nieuport climbed steadily; he banked slightly toward the north, toward Hill G.8. The fog was not yet thick, but it would grow thick. There was little wind. The beat of the Hisso was steady in his ears.

It took the plane eleven minutes and some odd seconds to reach the Hill. The fog around the rise was slight; it was much thicker back of the ship, back toward the Squadron. There were two ships in the sky, to the east, on the German side of the lines. They were winging toward Allied territory and were flying much higher than the altitude of the Nieuport.

Tex searched the sky with his eyes, climbed the Nieuport. He saw no other planes. The American ship had reached an altitude of twelve thousand feet; he guessed that the other two planes were flying just beneath the clouds, at about fifteen thousand. There was no sun, and darkness was not far away.

At thirteen thousand feet he leveled off. The two ships heading toward the Allied lines had suddenly piqued; they were diving at his ship but then he saw that he was mistaken. Across the lines, winging back toward the Allied side, was a tiny plane. She was flying with a wing droop and it was upon her that the two other planes were dropping!

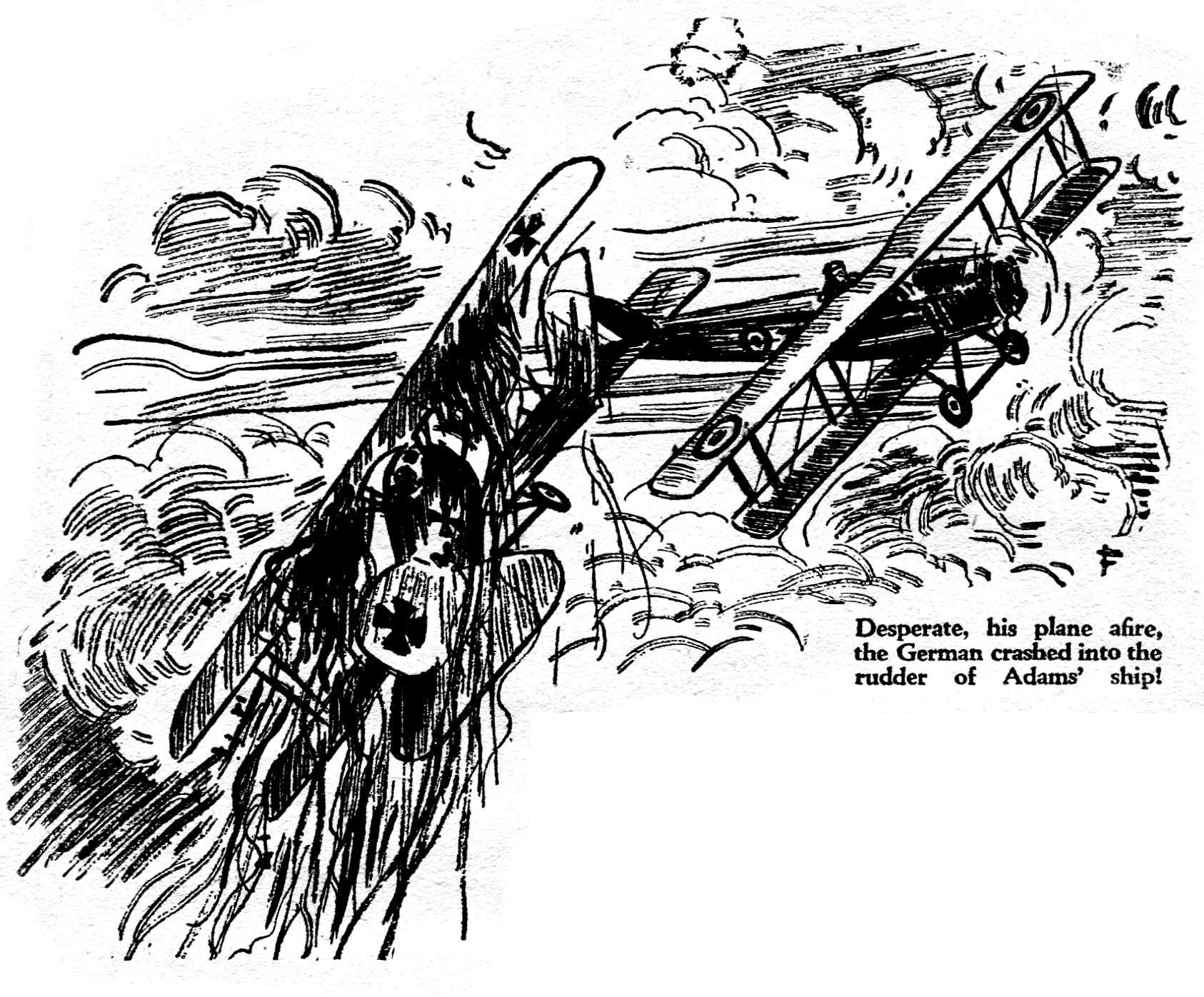

Tex dove the Nieuport. She slanted down across the lines, her nose pointed toward German territory. He could distinguish the other two diving ships now. They were both Fokkers of the fighting type. The plane below, he guessed, was an Allied ship—trying to get back across the lines.

That ship was almost over the lines, and the German pilots had stretched their drive, thus allowing Tex to gain on them. He was within a hundred yards of the nearest enemy ship before the pilot saw him. Instantly the enemy zoomed.

Tex, lips pressed tightly together, pulled back slightly on the stick. The Fokker’s zoom failed. A long burst of lead from Tex’s Browning streamed down into the cockpit of the enemy plane. As Tex pulled all the way back on the stick, zooming and then going over on a wing, he saw the second Fokker cease to dive on the ship below.

He pulled the Nieuport around in a vertical bank, stared over the side. The Fokker on which he had come down was dropping in an uncontrolled spin. The pilot had been hit! The other Fokker was trying to get altitude, but her pilot had been forced to pull her over level, after her first zoom.

Tex leveled out of the bank, dove on her with engine half on. She dove instantly and he saw that she was going down after the wingdrooping plane below. That plane, he saw now, was a Nieuport! And a Sixteenth Squadron Nieuport!

The Fokker gained rapidly on the crippled American plane. Tex dove with engine power adding speed. The Fokker swept down behind and slightly below the Nieuport then zoomed, leaving a tracer stream in the sky, slanting back of the wing-drooping ship. Again her pilot had missed by a narrow margin.

But this time the German pilot pulled his ship up and over, and at the peak of the zoom, as she was on her back, he did a nice Immelman. In a flash the Fokker had righted herself. Less than fifty yards of air separated her from Tex’s Nieuport now, Both guns spat streams of lead at the same second.

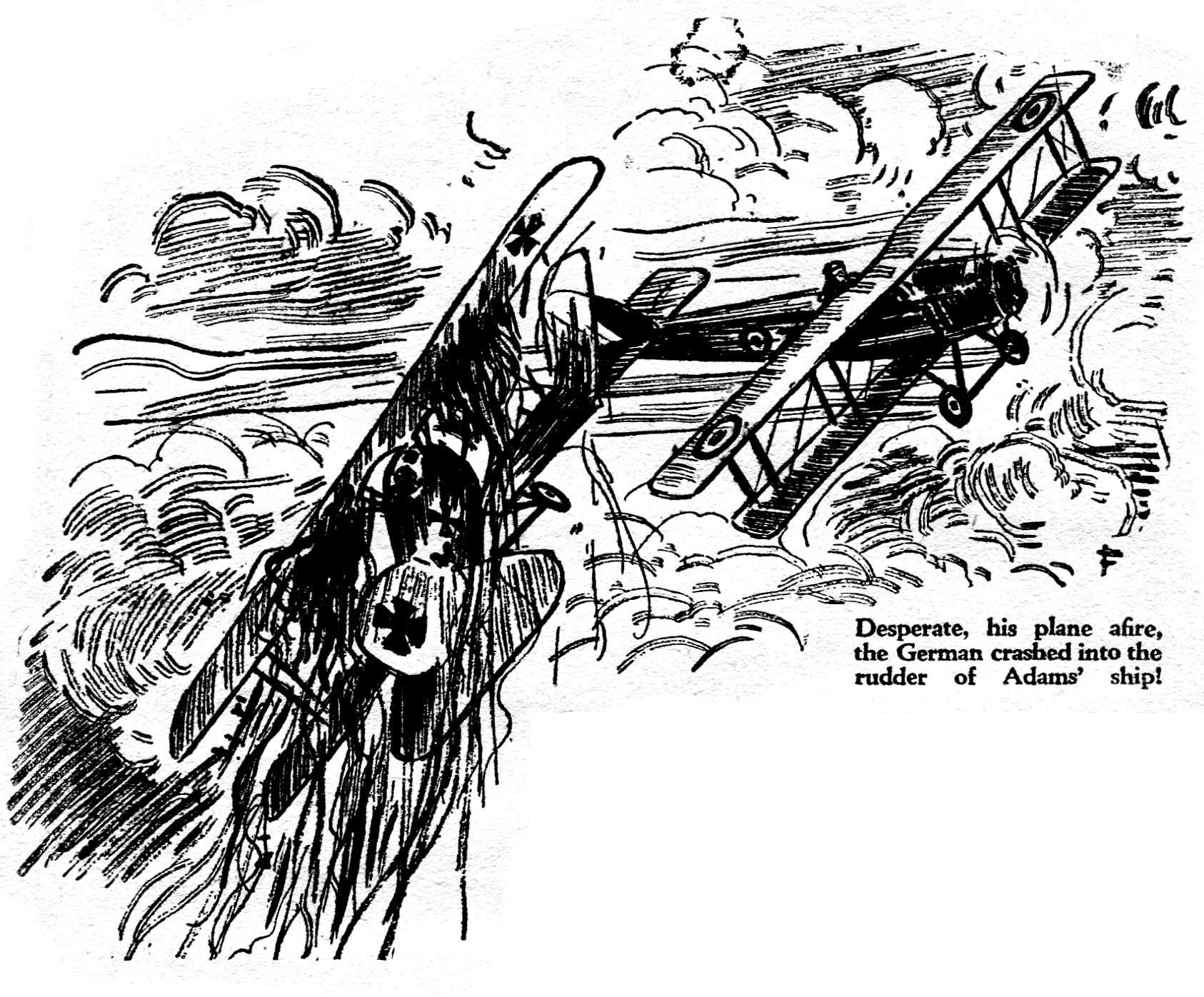

The German pilot’s lead was low. It passed beneath the under-gear of the Nieuport. Tex zoomed as the enemy shape flashed close. Flames were shooting up from the engine of the German ship. But she zoomed, too. The Nieuport jerked sickeningly. The controls were loose in Tex’s grip! The Fokker pilot, knowing he was finished, had rammed the Nieuport from below, striking the tail assembly with a wing-tip!

Tex Langdon felt the Nieuport go into a side slip. He tried to get her out of it, failed. She was slipping off on her right wing, toward the brown-grey line of the earth, almost a thousand feet below!

He jerked his head. The second Fokker was going down in a straight nose dive, flames shooting back from her. And toward the ground fog to the westward winged the crippled Nieuport that he had saved from the two enemy planes.

Wind tore at Tex Langdon’s helmet. He moved the stick to the right, expecting to feel no pressure, believing that the tail assembly had been carried away in the crash. But there was pressure. He kicked right rudder. The slip ceased but the Nieuport was now diving at terrific speed, less than five hundred feet from the earth!

Slowly he pulled back on the stick. He cut the throttle speed down, held his breath. And slowly the nose of the Nieuport came up. The tail assembly was still sticking in place, although the ship answered sluggishly.

He advanced the throttle to three-quarter speed. The plane was headed toward the Squadron. She was flying less than three hundred feet above the earth, and there could be no maneuvering now. The Nieuport would have to be flown level, carefully. The slightest piece of overcontrolling might rip the damaged tail assembly from the fuselage.

Tex Langdon stared ahead, down. He groaned. He had forgotten the ground fog. It was spread over the earth, in the direction of the Squadron, like a grey-white blanket. Even below the ship now, the first wisps of it were drifting. And far ahead was the wing-drooping Nieuport, vanishing from sight into the grey stuff.

Tex stiffened in the cockpit. Lieutenant Adams, once more winging away from his plane in the fog! He couldn’t be sure of it but he could guess. He had saved Adams from going down with Boche lead in his plane and body and the lieutenant again was winging in to leave him alone. Even with a drooping wing, he might have waited. Lieutenant Harrington would have waited. It was Adams, all right.

He reached for the throttle, but then he muttered to himself suddenly. The Nieuport that had vanished into the fog was in sight again! She was banking around, coming back!

Tex held the little combat ship in level flight. He watched the other plane come on, his eyes wide. Her left wing drooped badly; she had banked around to the right. He caught sight of a helmeted head, an arm held out in the prop wash. The two ships rushed past each other. Tex stared back. Once again the Nieuport was banking to the right. She came around sluggishly, gained slowly on the throttled down sister plane.

Side by side, with less than twenty feet of grey air between the wing-tips, they flew now. And Tex recognized Lieutenant Adams. That officer was pointing toward his left wing-tip, which was in tatters toward the trailing edge, with one strut twisting back in the wind. The officer got a hand out in the prop wash, tilted it downward in a mild degree. Tex nodded. He pointed back toward his ship’s tail assembly, saw Lieutenant Adams twist his head, stare back.

And then the veteran lieutenant nodded his head and banked slightly to the southward. Tex banked, too, very gently. The other Nieuport was nosing downward now and Tex moved the stick forward a bit. The movements of his plane were very sluggish, uncertain.

Fog swept over both planes. Tex flew with his head half turned, watching the wing-tips of the other ship. Several times they were lost from sight, but each time he picked them up again. Both ships were flying throttled down. Seconds passed and they seemed hours. The fog was growing thicker.

And then, very suddenly, the fog cleared. A slope seemed to rise out of it. Lieutenant Adams banked sharply away from Tex’s Nieuport. His plane’s nose came down. Tex banked his plane, cut the throttle. Below was a fairly level field with very little fog on it. Even as the Nieuport glided downward, he saw the wheels and tail-skid of the other officer’s ship strike.

And then he was stalling the tail-damaged ship. He was within ten feet of the earth when something snapped under the strain. The nose whipped downward. There was a grinding crash as the prop splintered into the earth. Tex tried to protect his head but failed. Something battered him backward. There was a flash of yellow light and then everything went black.

Tex Langdon recovered consciousness slowly. His head ached; he raised a hand to bandages wound about it. Slowly he blinked the dizziness away from his eyes, wet his oil-stained lips with the tip of his tongue. He looked around.

He was propped up against the wreckage of a plane. There were khaki-clad figures moving in the mud of a field, against a back-ground of drifting fog. He turned his head slightly. The eyes of Lieutenant Adames smiled at him.

“Feel rotten, ’eh? But you do feel! That’s something.”

Lieutenant Tex Langdon managed a painful grin. It was more than something, he thought, It was everything. His blue eyes narrowed on Lieutenant Adams’ dark ones.

“You—came back—” he muttered thickly. “You got—me—down here—”

Adams grunted. “Didn’t quite do that Tex,” he stated grimly. “That tail-assembly of yours collapsed before you set her down. Figured this lope would have less fog and headed for it.”

“You came back—” Tex persisted. “After you winged into the white stuff.”

Lieutenant Adams swore softly. “You and I, Lieutenant—we’ve been acting up,” he said slowly. “You may crack up your own ships, but you cracked up two other ships, today! And you saved my neck. I couldn’t wing out on you, Tex. Figured I might be able to bank around, without the droop getting me into a slip. It was pretty rotten—winging out on you. Didn’t know, though, that you had a crippled ship.”

Tex grinned feebly. “It was damn white—after what I’ve said to you, Adams—” he said slowly. “We’ve both been—pretty thick.”

He fumbled for a cigaret, found two. Adams lighted them up. They inhaled appreciatively.

“Pretty thick—” Lieutenant Adams was agreeing. “Sort of like—”

He stopped, grinned broadly. Tex nodded. He raised his eyes slightly.

“Like the ground fog, Adams,” he muttered. He closed his eyes. “But we—got out of it.”

And Lieutenant Adams, smiling grimly, nodded his head.

“We cleared up, Tex,” he muttered, “just about in time!”

Transcriber’s Note: This story appeared in the January, 1929 issue of Triple-X Magazine.