*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 73951 ***

THE SECOND SHELL

By the Author of "The Alien Intelligence," "The Girl from Mars"

Here the well-known author of "The Alien Intelligence" and other

thrilling stories presents his latest symphony, a fine piece of aerial

fiction.

Few authors have Jack Williamson's knack to pack their stories with

so much adventure and with so much imaginative science. And while it

may be fantastic today, most of it we know, sooner or later, will have

become reality.

All scientists for decades have been wondering what the mysterious

Heaviside Layer is. Radio engineers know of the Heaviside Layer from

its effect on radio waves. It is very much of a fact, yet no one has

ever been able to get near it, due to its distance above the surface of

the earth, and till we have penetrated it, we cannot be sure what lies

above it.

We know you will enjoy the present story, which easily bears

re-reading from time to time.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Air Wonder Stories November 1929

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

It was two o'clock in the morning of September 5, 1939. For a year

and a half I had been at work on the San Francisco Times. I had

come there immediately after finishing my year's course at the army

officers' flying school at San Antonio, on the chance that my work

would lead me into enough tong wars and exciting murder mysteries to

make life interesting.

The morning edition had just been "put to bed" and I was starting out

of the office when the night editor called me to meet a visitor who had

just come in. The stranger came forward quickly. Roughly clad in blue

shirt and overalls, boots, and Stetson, he had the bronze skin, clear

eyes, and smooth movements of one who has spent his life out-of-doors.

He stopped before me and held out his hand with a pleasant smile. I saw

that his hair was gray; he was a little older than I had thought at

first—fifty, perhaps. I liked the fellow instinctively.

"Robert Barrett?" he questioned in a pleasant drawl. I nodded.

"I'm Bill Johnson," he said briefly. "I want to see you. Secret Service

business. Sabe?" He let me glimpse a badge, and we walked out into

the night. As we started down the silent street it occurred to me that

I had heard of this man before.

"Are you the William Johnson who unearthed the radio station of the

revolutionaries in Mexico in 1917?"

"I guess so. I've been in Mexico thirty years, and I've helped Uncle

Sam out a time or two. It's a case like that one, or worse, that I'm up

here to see about now. I need a partner. I've been told about you. Are

you game for a little adventure?"

"You've found your man."

"They call you 'Tiger Bob Barrett,' don't they?" he said irrelevantly.

"I used to play football."

He laughed. I have always been sensible about that nickname.

"Well, here's the situation. I've been at Vernon's mine in Durango,

Mexico. Called El Tigre. Gold and thorium. There's a little mystery—"

"Vernon? Is it Doc Vernon, the scientist. His daughter inherited a

mine—"

"Si, Señor. Ellen Vernon is some young lady!"

"I knew them at Texas University. I was in Vernon's chemistry class

before he went daft on his death ray machine, and left to work on that."

"The Doc is still at work on the machine. In fact, that is a part of

the mystery.

"The mine is in an old corner of the desert, about fifty miles south

of Mocolynatal—the big mountain. And there's something queer going on

about that mountain!

"Ellen got herself a radio set to pass away the time with. She got

to picking up strange stuff. Sounds we couldn't make out! Not just a

strange lingo. They don't sound like the human voice at all! Strange

chirps and squeaks! Doc and I rigged up a directional set, and found

that the calls were sent from Mocolynatal.

"The mountain's in sight, to the north of us. I got to watching

it, and found out something else. There have been airplanes flying

about it—queer red machines with short stubby wings! They flew off

mostly to the west. I did a little more investigation, and found that

a line of run-down Jap tramp steamers has been hauling cargoes of

the-lord-knows-what, and unloading somewhere along the Pacific coast of

Mexico—evidently making connections with the red machines.

"Now, the Doc has his machine where he thinks it will be the end of

the world if anybody gets hold of it. We've seen one or two of the red

planes over the mine, and he is afraid they have found out about it,

somehow. He got nervous, and sent me up to see Uncle Sam. It is all

news to the State Department, and we are going to investigate.

"One of the Jap tramps is leaving here tomorrow, and there will be

a couple of destroyers on the trail, to see what they unload, and

where. I've got hold of a new airplane—a queer little machine called

the Camel-back, that I'm taking along on board. A jewel for mountain

work—you could land it on a handkerchief. I needed a partner, and the

Doc told me about you. Want to go along?"

"You bet I do! I've been longing for something to turn up."

"Well, be at the landing field at nine tomorrow—this morning, rather,

ready for anything. This may be interesting before we're through.

Buenas Noches."

A Raid and a Mystery

The old fellow left me, and I walked on toward my apartment, thinking

over what I had heard. Dr. Vernon's invention a success at last! I

remembered very clearly my days with the nervous, stammering little

scientist, always sure that tomorrow would bring the great secret. And

I thought of Ellen—indeed, I had often done so in the two years since

I had heard from her. I wondered why she and her father had left Austin

so suddenly, and why their destination had been kept a secret from all

their friends.

As for the matter of the red planes, I could suppose nothing but that

the outs in Mexican politics were preparing a little military surprise

for the ins. There have been too many military forces raised secretly

in Mexico for one of them to be much of a novelty. Then I thought of

the queer radio messages. They did not fit in very well. But my mind

returned to Ellen again. I thought no more of the red machines. I had

no thought—no one on earth had warning—of the terrible force that was

rising to menace the world.

In the morning, when I came down to the lobby, I found a curious clamor

going. There was a hum of conversation, and people were passing around

red-paper "extras". It was five minutes before I could get one to read

the screaming headlines:

RED PLANES RAID FACTORY

THREE HUNDRED DEAD

MILLION DOLLAR STOCK OF

THORIUM TAKEN

The account went on to describe the raid, at four o'clock that morning,

of a fleet of red airplanes upon the Rogers Gas Mantle Factory, at St.

Louis. It was stated that three hundred people had been killed, and

that the entire stock of thorium nitrate on hand, worth over a million

dollars, had been carried off.

Much of a mystery was made of it. Police had failed to identify three

of the four red-uniformed corpses left behind. Fingerprints identified

the other as a noted criminal recently out of Leavenworth.

No one seemed to have any idea why the thorium had been taken, since

the chief use of that radioactive metal, which is similar to radium,

but far less active, is in the manufacture of gas mantles.

It was farther stated that the raiders had released "clouds of a

luminous purple gas," which had caused most of the fatalities, and

which seemed to have destroyed the gravity of metallic objects about.

It was said that the factory building was curiously wrecked, as if the

heavy machinery had gone up through the roof.

At first it struck me that this must be simply a newspaper canard. Then

I remembered what Bill Johnson had told me of the strange red airplanes

in Durango, and of the mystery of the secret radio station. Then I was

not so sure. I ate a little breakfast and hurried out to the landing

field. I found Bill with a copy of the paper in his hand. His wrinkled

face had a look of eager concentration on it.

"Howdy, Bob," he drawled. "This looks interesting. Have you seen it?" I

nodded. "It must be the same red planes. Let's get off."

We walked out on the field, where the "Camel-back" plane was waiting.

It was the first one I had seen; one of the first models built, I

believe. It was based on Cierva's Autogiro, or "windmill plane". But

there was an arrangement by which the rotating mast could be drawn into

the fuselage, the rotation stopped, and the vanes folded to the side,

so that the machine, in the air, could be transformed into an ordinary

monoplane, capable of a much higher flying speed than the Autogiro.

When the pilot desired, a touch of a button would release the mast and

vanes, and the machine became an Autogiro, which could spiral slowly

or drop almost perpendicularly to a safe landing on a small spot of

ground.

The machine had a further innovation in the shape of a Wright turbine

motor. This had but a single important moving part, the shaft which

bore the rotors, the flanged wheel that drew the mixture into the

combustion chamber, and the propeller. Because of its extreme light

weight and high efficiency, the internal combustion turbine engine now

promises to come into general use.

The name of the machine, "the Camel-back," was due to the peculiar hump

to the rear of the mast, covering the levers for raising and lowering

the rotating "windmill."

The plane carried a .50 calibre machine gun in the forward cockpit.

"Get aboard, Bob, and we're off," Bill said as we got on our

parachutes. "The tramp weighed anchor at four this morning, and the

destroyers left an hour later. We'll be able to pick them up."

Five minutes later our trim little machine was rolling forward with the

"windmill" spinning. It swept smoothly upward, Bill moved into gear

the device that brought down the mast, and soon we were over the cold

gray Pacific, with the city fading into the haze of the blue northern

horizon.

Bill was flying the ship, and my thoughts turned back to Dr. Vernon

and his daughter. The Doctor was a pudgy, explosive little man, who

thought, ate, and breathed science. His short, restless figure always

bore the marks of laboratory cataclysms, and his life had been marred

by the earlier lack of success in perfecting the terrible machine to

which he was devoting his life. I had always thought it strange that a

man so mild and tender-hearted should toil so to build a death-dealing

instrument, and I wondered what he would do with it now if he had it

completed.

It was five years since I had seen Ellen. She had been but a spritely,

elfin girl. I remembered her chiefly as having been instrumental, one

day at a party, in getting me to drop myself into a supposed easy

chair, which turned out to be a tub of ice water.

CHAPTER II

The Menace of the Mist

The little Camel-back plane was a wonder. The soft whispering hum of

the turbine engine belied its tremendous power. The slender, white

metal wings cut the air at the rate of two and a half miles per minute.

Presently we saw a smudge of smoke where the blue sea met the bluer

sky ahead, and soon the little machine had dropped on the deck of a

destroyer.

The sister vessel was four or five miles to starboard. The two ships

were plowing deliberately along, at about ten knots, keeping some

twenty-five miles behind the tramp steamer they were shadowing. One of

the officers took us up on the little bridge, and we learned that the

little ships were keeping track of the tramp with their radio equipment.

The radio man took us in and let us listen to the calls between the

tramp and some point far ahead. Those were the strangest sounds I have

ever heard. Thin, stuttering, stridulating squeaks and squeals! Even

allowing for distortion in transmission, it was hard to imagine what

might make them.

"That's something talking," Bill said. "And human beings don't make

noises like that."

"It may be," the operator said, "that what we hear is just an ordinary

conversation, 'scrambled' to keep us from understanding it, and

'unscrambled' by the receiver. Such devices have been in use for years."

But there was no conviction in his voice. And certainly, those strange

noises sounded to me like the communication of some alien beings. But

what might they be?

Later in the day, Bill and I took turns in going up with the Camel-back

to keep tab on the movements of the tramp, since the radio calls had

ceased. The day passed, and the white sun sank back of the glittering

western waves. During the hot, moonless night, the ether was still,

and we could do nothing but steam on in the same direction. I went up

twice, but the tramp was showing no lights, and I failed to locate her.

At midnight Bill came on deck, and I went below to a bunk.

It was just after dawn that the alarm was sounded. I was awakened by

the roar of the little ship's forward gun. It was firing steadily as I

went on deck, and I heard a confusion of sounds—the siren was blowing,

and there was a medley of shouts, orders, and curses, punctuated with

the reports of small arms.

I saw that the Camel-back was gone from the deck. Bill was up again.

As I stepped on deck there was a great clanging roar from below. The

propellers had been lifted from the water! The engines raced madly for

a minute, and then were stopped. I ran to the rail to see what had

happened to throw the organization of the crew into such confusion. And

indeed it was an amazing sight that met my eyes!

The ship was floating in the air, a hundred feet above the waves! The

air was still, the sea was smooth and black.... The eastern sky was

lit by the silver curtain of the dawn, with the old moon hanging in

it. Before us, and below, two hundred yards away, was a queer luminous

hill—a shining cloud of red-purple vapor that rolled spread heavily

upon the black water. I saw two similar twisting mounds of gas astern,

gleaming with a painful radiance.

And the ship was rising into the air!

It was drifting swiftly up, through the still air, so that a wind

seemed to blow down upon us. I saw a rifle hanging in the air ten feet

above me, and a steel boat rising a dozen feet over the mast. Suddenly

it came to me that something had negated the gravity of the metal parts

of the ship. I thought of the story of the gravity-destroying bombs

used in the raid of the night before upon the thorium stores.

The forward gun was still firing steadily, though the terrorized men

had deserted the others. I saw a man point above us, and looked. A red

airplane, with thick fuselage and short wings, was flying silently

and swiftly across our bows. As it passed, something fell from it. It

was a dark object that fell and exploded just above us, bursting into

a thick, roily cloud of shining purple mist. The light of it hurt my

eyes. And the ship plunged upward faster.

In view of what happened later, there can be no doubt that the luminous

gas was a radioactive element derived by the forced acceleration of

the decomposition of thorium. It was similar to the inert radioactive

gas niton, or "radium emanation," which is formed by the expulsion of

an alpha particle from the radium atom. And there can be no doubt that

its emanations affected the magnetic elements, iron, nickel, cobalt,

and oxygen in such a manner as to reverse the pull of gravity. With the

invention of permalloy and other similar substances in the past decade,

such a thing is much less incredible than it might have seemed ten

years ago.

In a few moments the red ship had passed out of sight. Looking

dazedly to the west, I saw a number of bright points of purple fire

against the deep blue of the sky—radioactive clouds sending out the

gravity-nullifying radiations. The dark shape of the other destroyer,

upside down, was floating up among them. It must have been almost a

mile up, already.

As I stood there astounded, the officers seemed to be making a furious

attempt to restore order. Then men were running about, babbling and

cursing in utter confusion. I saw one man don a life belt and jump

insanely over the rail—to plunge like a plummet to the water five

hundred yards below. A dozen more poor fellows followed him before the

mate could stop the rush. And perhaps their fate is as good as that of

the others.

Suddenly a wild-eyed seaman sprang at my throat. In spite of my

amazement, I was able to stop him with a punch at the jaw. In a moment

I realized what he was after. The parachute that I had worn on my last

flight in the Camel-back was strapped to me. As the fellow got up to

charge again, the deck tilted (probably the ship was upset by the

recoil of the gun).

Presently I found the rip-cord and jerked it. The white silk bellowsed

out behind me, while my unfortunate shipmates fell, dwindling dark

specks, to make white splashes in the sea below. The ill-fated ship

must have been half a mile high then. I glimpsed it once or twice, a

vanishing black dot—driven out into space!

By the time I had struck the chill water I almost wished that I had

fallen with the others. I contrived to cut the harness loose, and to

get rid of my coat and shoes; and set myself to the task of keeping

afloat as long as possible.

On to the Mine

It must have been an hour later that I heard the hum of the

Camel-back's propeller, and saw the little machine skimming low over

the waves. Bill leaned out and waved a hand in greeting. In a few

minutes he had brought the machine down lightly in the water beside me,

and hauled me aboard.

"I went up at three o'clock," he said, "to see if I could locate the

Jap. I was coming down when the red machines began to let loose their

shining clouds. The plane went up. I stopped the engine, and still it

went up. Its weight was gone. I almost froze before it started falling."

"Those ships may go on to the moon! They may become minor satellites

themselves!"

"You saw the red machines dealing out the dope?"

"One of them. Who could it—"

"It's our job to find out. We better head back for the mine, to see

what's happened there."

The trim little machine skimmed smoothly over the level sea, and easily

took the air. We flew southwest. It was not many hours before we

sighted land that must have been the lower tip of Lower California.

In an hour more we were flying over Mexico, the most ancient, and

paradoxically, the least known country on the continent.

We flew over a broad plain checkered with the bright green of fields,

over ancient cities and mean adobe villages, and over the vast forests

of pine, cut with twisting canyons, that cover the slopes of the mighty

mountains that rose before us. As we went on, the green valleys of the

rushing mountain streams grew narrower; and the grim wild peaks that

rimmed them, higher and more frequent. Sheer jagged summits rose above

steep, forest-covered slopes. We were reaching the heart of the Sierra

Madre range.

At last the vast bare conical mountain loomed up to the north of us,

that Bill told me was Mocolynatal—the place of the hidden radio

station. Its sheer black slopes tower fifteen thousand feet above the

sea. From its appearance, it was not hard to guess that it had a crater

of considerable dimensions.

The mountain crept around to our left, as we flew on toward the mine.

Suddenly Bill shouted and pointed toward the peak. I looked. Above

the dark outline of the cone, a huge globe of blue light was rising,

flaming with an intense brilliance that gave a ghastly tint of blue to

all that desert wilderness of peaks! Like a great moon of blue fire, it

rose swiftly into the sky! It dwindled, faded, was gone!

I felt the hair rise on my neck. I was glad that our plane was swift

and far away. If it was a human power with which we had to deal, I

thought, it must have made strange advances. And then I remembered the

strange noises upon the ether—sounds more like the stridulations of

great insects than the voices of men!

"That has happened twice before," Bill said. "But I didn't tell anybody

about it in the States. It's too damned unbelievable."

At the Thorium Mine

In half an hour we were fifty miles south of Mocolynatal, circling

over the mine. El Tigre Mine is near the center of a rocky, triangular

plateau. Northwest and southwest, the Sierra Madre rises. On the east

side of the triangle is the river, a tributary of the Nazas, in a

canyon deep enough to hold the stream a hundred times. Perhaps a dozen

square miles are so enclosed. It is a desert of sand and rocks, cut up

with dry arroyos, scantily covered with yucca, mesquite, and cactus.

The mine buildings stand on the little stream that cuts a track of

vivid green across the neutral gray of the waste to the canyon below.

Sitting there on the dull-hued plain, with the Cordillerras rising

so abruptly a few miles back, the buildings looked very tiny and

insignificant. Across the stream from the shaft-house, the shops, and

the quarters of the men is a square, fortress-like two story residence

of rough gray stone.... The narrow-gauge railroad track runs from it

down toward the canyon like thin black threads.

As we flew over the buildings, a trim white figure appeared on the

roof of the residence, and waved a slender arm. I knew that it must be

Ellen, and I felt oddly excited at the thought of seeing her again.

Bill touched the button that released the rotor, and the machine

settled lightly to earth near the main building. A short waddling

person and a slender active one—the Doctor and Ellen—came out of the

house and hurried toward us.

"Why h-h-h-h-hello, Bob, I'm s-sur-surprised to see you," the Doctor

rattled off. I have always had the opinion that he wouldn't stammer

if he would take time to talk, but he is always in a hurry. "You're

w-w-w-welcome, though. Looks like a new m-ma-ma-machine you have, Bill.

The red ship c-c-c-came again while you were gone. I've got something

to t-t-t-t-tell you. But get out and come in to the shade."

He hurried us toward the house. He was just as I remembered him—a

short man, a little stout, with a perpetual grin on his moon-face,

and movements as short and jerky as his speech. He was panting with

excitement, and very glad to see us.

Ellen Vernon was, if possible, even more beautiful than she had been to

my boyish eyes. Her dark eyes still held the flame of restless mischief

that had brought me the icy plunge. I believe a recollection of the

incident passed through her mind as she saw me, for her eyes suddenly

met mine engagingly, and then were briefly turned away, while a quick

soft flush spread over her glowing, sun-colored cheek. I got a subtle

intoxication even out of watching the smooth grace of her movements.

We shook hands with the Doctor, and Ellen offered me her strong cool

hand.

"I'm glad to see you, Bob," she said simply. "I've often thought of

you. And you've come in at an interesting time. Dad turned loose his

ray yesterday, and brought down one of the red machines. I guess Bill

has told you—"

"Yes," the Doctor interrupted, "the th-th-th-thing had come sneaking

around here once too often. I tried the tube on it and it fell about

a mile up the creek. Funny thing about it. The red ship struck the

ground, and then something left it and went b-b-b-b-back into the air!"

"Something like a bright blue balloon carried the thing up in the air,"

Ellen added. "It saved itself with that, just like a man wrecked in the

air uses a parachute. But it was not a man that sailed up under that

ball of blue light! It was a queer twisting purple thing! I used the

field glasses—"

"It's not m-m-m-men that fly the red ships," the Doctor said. "It's

c-cre-cre-creatures of the upper air!"

We stepped up on the broad, shady verandah, and Bill and the Doctor

stopped by the steps, comparing notes. Ellen gave me a welcome drink of

icy water from the wind-cooled earthen olla hanging from the roof.

Straight, and tanned, she looked very beautiful against the desert

background. She was the same girl she had always been—bright, daring,

and alluring. Neither she nor the Doctor seemed unduly excited over the

astounding news they had just delivered.

The desert lay away to the eastward, undulating in the heat like a

windswept lake. Gray or dully green with the yucca and manzanita upon

it, it was sharply cut by the rich green mark of the wandering stream.

Its vastness tired the eyes, like a limitless weird dead sea. North

and south the mountains rose, gripping the plain in a grim and ancient

grasp. The hills were still tinted with the blues and purples of the

morning shades, save where some higher peak caught the sunlight and

reflected it in a fiercer, redder gleam. Far in the north, above the

nearer peaks, I made out the distantly mysterious, dull blue outline

of Mocolynatal—the mountain of the hidden menace.

In such a wild and primitive setting, human civilization seemed a

distant, unimportant issue. The menace of the desert, of naked nature,

alone seemed real. No wild tale was incredible there.

And the wonderful girl before me, smiling, cool and resourceful, seemed

to fit in with that rough scenery, seemed almost a part of it. Ellen

was the kind of woman who can master her environment.

"Coming down here was a pretty severe change for a campus queen, wasn't

it?" I asked her.

"The royal blood never flowed too freely in my veins," she said. "I

rather like it here. The ore train from Durango brings the mail twice a

week, and I read a lot. Then, I'm beginning to love the desert and the

mountains. Sometimes I feel almost like worshipping old Mocolynatal.

They say the Indians did."

"I wonder if it's ever been climbed?"

"I think not. Unless by the owners of the red airplanes. Dad thinks

they are things that have come down out of the upper air to attack the

earth. I've always been sorry I wasn't here when the tiger was killed,

but this promises a bigger adventure yet! And I'll be right in the

middle of it!" She laughed.

The Death Ray

"I hadn't heard of the tiger's misfortune," I said, a little amused at

her eagerness for adventure.

"You know Uncle Jake had a ranch down on the Nazas. Once he trailed a

tiger up here with his hounds. He killed him right here, and happened

to see the glitter of gold in the blood-stained quartz. He named the

mine El Tigre—The Tiger. Along with the gold ore are deposits of

monazite—thorium ore. Dad began to work them when we came to get

thorium to use in his experiments."

"Say, Bob," the Doctor called, "I want to sh-sh-sh-show you something.

Come on in the lab." The little man took my arm and hurried me down the

long cool hall, and up a flight of steps to a great room on the second

floor. It suggested an astronomical observatory; it was circular, and

the roof was a great glass dome. In the center and projecting through

the dome was a huge device that resembled a telescope. About the walls

a variety of scientific equipment.

"That's my r-r-r-ray machine," he said. "Modified adaptation of the old

Coolidge tube, with an electrode of molten Vernonite. Vernonite

is my invention—an alloy of thorium with some of the alkaline earth

metals. When the alloy is melted there is a comparatively rapid

atomic disintegration of the radioactive thorium, and the radiation

is modified by passages through a powerful magnetic field, and by

polarization with quartz prisms. The Vernon Ray has characteristics

controllable by the adjustment of the apparatus, generally resembling

those of the ultra-violet or actinic rays of sunlight, but intensified

to an extreme degree.

"The chemical effects are marvelous. The Vernon Ray will bleach indigo,

or the green of plant leaves. It stimulates oxidation, and has a

tendency to break up the proteins and other complex molecules.

"This tube has a range of five miles, and will penetrate a foot of

lead. I have killed animals with it by breaking up the haemoglobin in

the blood. By special adjustment, its effects would be fatal at even

greater range. It might be set to break the body proteins into the

split protein poisons—there are a thousand ways it might kill a man,

quickly or by hideous lingering death.

"Used in war, the Vernon Ray would not only kill men, but destroy or

ignite such useful chemicals as fuels and explosives. It would destroy

vegetation and food supplies. In fact, it would make war impossible,

and it is my hope that it will end war altogether!"

"But what if the wrong fellow gets hold of it?"

He nodded to a safe at the wall. "Plans locked up there. And nobody

knows about it. Even if someone had the plans, he could hardly secure

the large quantities of thorium required without attracting attention."

I thought of the raid on the gas mantle factory.

"I mean to turn it over to the American government pretty soon, but

I hope to make another development. Ordinary heat and light waves

set up molecular disturbances in matter; in fact, heat is merely

molecular vibration. I hope to discover a frequency in the spectrum

that will stimulate atomic vibration to such an extent as to break

down the electronic system. Objects upon which such a ray is directed

will explode with incredible violence. In my earlier experiments with

Vernonite, the molten alloy in the tube, I almost had a catastrophe

from the atomic explosion of the electrode. It would have blown El

Tigre off the map! The radioactivity of thorium is slight; I must

increase it vastly. The adjustment is delicate."

He let me look into the apparatus. It was plainly electrical. There

were motors, generators, coils, transformers, mirrors and lenses in

a lead housing, vast condensers, and a huge vacuum tube which seemed

to have a little crucible of glowing liquid for the anode. Back of it

was a great parabolic reflector which must have sent out the beam of

destruction.

"The idea of atomic force as a d-d-d-d-destructive agency is not new,"

he went on, again almost too enthusiastic to talk. "The sun is thought

to ob-ob-ob-obtain its boundless energy from the process of atomic

disintegration, and m-m-m-m-m-men of science long since agree that

any instrument using intra-atomic energy would be a t-t-t-t-terrible

weapon!"

CHAPTER III

Clouds of Doom

Suddenly a red shape flashed over the great glass dome above us. In a

moment I heard Bill call out, "Hey, Doc, comp'ny's come!"

Dr. Vernon and I hurried out of the room. He paused to double lock the

door behind him, and we went down to the hall. We found Bill and Ellen

both waiting at the front door, each holding a 30-30 carbine.

"There's one of the red ships out there!" the girl cried. Eager and

flushed with excitement, she was very beautiful.

The Doctor unbuttoned his shirt and pulled out a slender tube of glass.

It had a bulb at one end, with a metal shield behind it, and a pistol

grip and trigger at the other. He examined it critically and turned a

little dial. The tube lit up with a soft, beautiful scarlet glow. He

pointed it at a vase of wild flowers, that Ellen must have gathered, on

a side table. Their brilliant colors faded until leaf and petal were

white.

"P-p-p-p-pocket edition of the Vernon Ray machine," he said.

He slipped it out of sight in his pocket, and Bill swung open the

door. A strange red airplane was stopped twenty yards away. The

fuselage was a thick, tapering, closed compartment, with dark circular

windows. The wings were curiously short and thick, as if they were

somehow folded up, and I thought the propeller very large.

An oval door in the side swung out, and a little, weazened man

sprang out on the ground. An astounding person! He wore a uniform of

brilliant red, decorated with a few miles of gold braid and several

pounds of glittering medals. He had leathery black skin, sleek black

hair, and furtively darting black eyes. A deep, livid red scar across

his forehead and cheek gave his face a queer demoniac twist that was

accented by his short black moustache.

"Vars! Herman Vars! After us again!" the Doctor muttered in evident

amazement.

The dark little man walked briskly up to the door, and saluted the

Doctor, with his medals rattling. "Good morning, Dr. Vernon," he

said in a queer dry voice. "I trust that you are well—you and your

beautiful daughter. I need not ask how work is progressing on your

remarkable invention, for I know that it is completed," he laughed,

or rather cackled, insanely. "Yes, Doctor, you have given the world a

great weapon, one that it will never forget!"

He was laughing oddly again when the Doctor asked gruffly, "What do you

want?"

"Why, a friend of yours and mine, who has been of service to us both,

informs me that you have in this building quite a large supply of the

rare radioactive metal, thorium, of which I think I have a greater need

than you—"

"What? You mean Pablo—" Dr. Vernon cried, his face turning white.

"Pablo Ysan, your servant. Exactly. But I must have the thorium. I need

a huge quantity. I am coming for it tomorrow. You need fear nothing for

yourself or your daughter—I came to warn you so that you might feel

no alarm. In fact, it would flatter me to have you as my guests. But

remember that I am coming—in force!"

"You damn lu-lu-lu-lunatic!" the Doctor choked.

"No. Not a madman, begging your pardon. The future king of the world!

Of two worlds, to be exact! But I must leave you. Remember! And hasta

luego, as our friend Pablo would say."

Laughing strangely again, the little man hurried back and got in the

machine. It left the ground at once, with the great propellers whirling

slowly. The motors were oddly silent. I thought the red wings were

somehow unfolded, or lengthened out a little.

As it rose, I glimpsed the pilot of the machine.

It was not a man!

It was a queer, gleaming purple shape, with many tentacles!

With strange horror grasping at my heart, I looked quickly at the

others, but it seemed that they had not seen it. Then I remembered the

Doctor's words of "creatures of the upper air" and I thought of what

Ellen had said of the thing that had risen from the wrecked ship.

"That was Herman Vars," Ellen whispered to me. "We met him at the

University. He had a warped mind—tinkered with radio and claimed

he was getting in touch with beings of a plane above the earth.

Then—once—" she paused, flushing a little, "—well, he came to me and

told me that he was going to conquer the earth, and that he wanted me

to—to go with him. That was why we left Austin. I thought he was only

insane—but this!"

"And he must have been t-t-t-t-telling the t-t-t-t-truth!" the Doctor

said. "And he is coming after my thorium! I wonder—Pablo—the

blueprints—" Suddenly he left us and ran down the hall.

"Pablo Ysan was a Mexican who helped him sometimes in his experiments,"

Ellen told me. "He went away a month ago. He must have carried Dad's

plans to Vars."

The Doctor came back with a grim look on his face. "They're

g-g-g-g-gone!" he said. "That's why they want thorium. And I've got

enough here to wipe out the earth, if they can use it—if they can use

it," and a grim half-smile flickered over his face.

"I'll run down to Durango on the rail car," Bill said. "I can have

a train load of troops up here by night. Mendoza is one of my

amigos—once I did him a good turn—" The Doctor nodded. "And if

anything happens while I'm gone, you have your ray, and Bob can take up

the Camel-back."

The Battle

He went out. In a few minutes I heard the sputter of a gasoline engine,

and the ringing of the little car's wheels on the rails, as it sped

down the narrow track. The machine dwindled to a black speck on the

desert's rim, and dropped out of sight.

Dr. Vernon spent the evening tinkering with his tube. I went over

with Ellen, to look at the mine. The men had been frightened by the

red ships, a few days before, and had left on the train. The place

was deserted. We peered down the silent black shaft, and went back.

But most of the time I spent watching the sky for a sight of the red

planes, ready to warn the Doctor and to go up to meet them.

Four trains pulled in before midnight, carrying one of those mobile

military units with which the Montoya government so effectively nipped

in the bud the revolutionary movements of 1933 and 1935. There was a

battery of eight French seventy-fives and a heavier railway gun, four

light tanks, a dozen battle planes and two bombing planes, and about

four hundred infantry.

Before dawn, El Tigre looked like a military encampment. In the glare

of great searchlights, men were digging trenches, leveling a landing

field for the planes, and planting the battery. The Doctor had his ray

machine ready for use.

I was much surprised at the discipline and efficiency of the

well-trained Mexican troops.

With the rising of the sun, a sentry's hail proclaimed the appearance

of a score of dark specks above the grim outline of Mocolynatal—a

fleet of red planes, coming to the attack!

In a moment the camp was alive. The gun crews got to their posts,

airplane engines were started, infantry were lined up in the freshly

dug trenches, with machine guns and rifles ready. I saw the gleaming

tip of the Doctor's great tube projecting above the huge glass dome.

In a few minutes the planes were taking the air, flying to meet the

coming ships. I was with them, in the Camel-back.

I had often dreamed of the thrills of war in the air, and I was eager

enough for the encounter. But, as it turned out, I was to play no noble

part.

The red machines flew toward us with astonishing speed. In a few

minutes they were upon us. Because of the greater speed of my ship,

I was flying a little ahead of the formation of Mexican planes. That

circumstance probably saved my life, as things turned out.

I was firing a burst to warm up my gun when there was a puff of smoke

from the foremost machine of the red ships. I watched the tiny black

projectile that came toward us, saw it pass far below me and burst into

a thick cloud of gleaming purple vapor that rolled and coiled like a

strange creature of the air.

And the wings of my machine no longer caught the air! The controls were

useless. I was drifting up. The radiation of that shining cloud had

negated the gravity of the machine!

Half a dozen more of the strange bombs burst behind me, and I saw the

other ships drifting up, even more rapidly than mine, for they had been

nearer the clouds. I kept firing for a minute, but I believe I hit none

of the red ships. Soon they had passed beneath, in the direction of the

mine.

Helpless, I drifted on into the sky!

I had a clear view of the battle at the mine. As the red machines came

within range, the railway gun and the camouflaged seventy-fives began

firing. One of the red ships suddenly went down in flames, and then two

more. Whether they were hit, or were victims of the Vernon Ray, I do

not know.

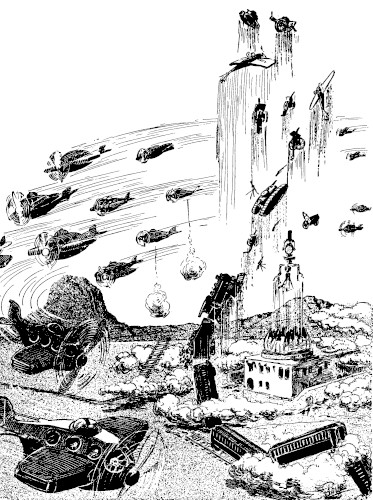

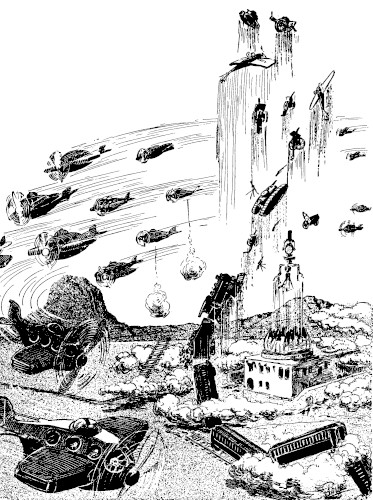

But in a few minutes the vicinity of the mine was dotted with the

coiling hills of purple gas from the gravity-destroying bombs. I saw

railway cars and engines, guns and tanks, and even the railroad rails

and the mining machinery, torn from their places and plunging into the

air. Suddenly the huge glass dome was shattered, and a great object

shot up through it—Dr. Vernon's terrible instrument!

But in a few minutes the vicinity of the mine was dotted

with the coiling hills of purple gas. I saw railway cars and engines,

guns and tanks, and even the railroad rails and the mining machinery,

torn from their places and plunging into the air.

What can men do against instruments that hurl them off the earth?

By that time I was so high that the whole plain about the mine was

but a tiny brownish patch, and soon that was veiled in the mists of

distance. I grew very cold, and beat my arms against my sides to warm

them. My breath grew short, and presently my nose began to bleed. The

blue sky grew darker until a few stars broke into view, and then many.

The flaming sun seemed to give no heat. Intense cold crept over my

limbs.

As I was floating upward to my doom, I thought of the impending fate of

the earth. The red fleets might sweep over the world, sending armies,

battleships, cities and factories into the frozen night of space. That

madman, Vars, with his incredible allies that we had glimpsed, with the

negative gravity bombs and Dr. Vernon's ray machine, could realize his

mad dream of world dominion. Humanity would be helpless against his

insane power.

Amid those speculations of the horror to come, my consciousness faded.

The Camp in the Crater

The next I knew, it was late in the evening. The sun was low over the

black hills in the west. My machine was still perhaps two miles high,

and floating slowly down. I started the motor, and got the machine

under control.

I found that I had drifted far to the east of the mine. By the time

the red sun set, I was back over it. I landed in a terrible scene

of wreckage. All objects of iron—machines and weapons—were gone.

Trenches, shelters, and buildings were stripped ruins. Here and there

were dead men, singly and in piles. They showed no wounds; either they

had been killed by the intense radioactivity of the gravity bombs, or

by a Vernon Ray machine carried on the red planes.

I landed by the ruined residence, near two dead men in uniform. In

fearful anticipation, I hurried through the silent rooms. The doors

were broken down and the walls were bullet-splintered—there had been

fighting in the hall. I searched the empty rooms in which the precious

thorium had been stored. Three more cold bodies I found, but they were

of the Mexican soldiery. I found no trace of Ellen, Bill, or the Doctor.

Had they been swept away into space? Or had the triumphant lunatic,

Vars, taken them captive and carried them to his stronghold in the

crater of Mocolynatal?

I did not find the Doctor, but in his laboratory, in the inside pocket

of a coat carelessly thrown aside, I found the compact little ray tube

with which he had bleached the flowers on the day before. I examined it

curiously, and put it in my pocket.

Darkness had fallen when I went out to the Camel-back, got in, and

started the turbine motor. I rose into the night and flew northward

over the starlit mountain wilderness. At last I made out the shape of

Mocolynatal ahead, and climbed far above it. I sailed over, and came

upon a strange scene.

Indeed, the mountain had a crater! Below me was a great bowl, perhaps

two miles across, brilliantly lit by rows of electric lights. I made

out long lines of buildings—huge structures of sheet iron, gleaming

in the light. Toward the south rim seemed to be a landing field, with

broad beams of intense light pouring out over the hundreds of red

planes lined up across it. North of that was a lake, and I saw scores

of red seaplanes moored by brightly lit docks at the edge.

There was movement below me. I saw the headlights of moving trucks upon

smooth gravel roads about the lake, and there were men at work on the

docks and at the landing field. Dense smoke, a luminous white in the

glare of the lights, was rising from some of the buildings that must

have been factories.

The lunatic had indeed made thorough preparation for his planned attack

against the world!

I cut off the engine of my machine, set the motor to whirling, and

dropped silently toward the circle of darkness about the rim of the

crater. In fifteen minutes more I had landed it on a bare, rocky slope.

I waited a moment, but there was no sign that my coming had been

observed, so presently I left the plane, with my automatic in my hand,

wishing I knew how to operate the strange weapon in my pocket.

I spent several hours slipping about in the shadows among the fallen

boulders on the bank of talus about the rim, looking down into the

brightly lit crater. At last, I came down in the shadow of an isolated

building of gray concrete, with slender masts rising above it—the

hidden radio station.

In an open space before it, flooded with light, I saw a strange

machine. It was like one of the red airplanes, but the closed fuselage

was so large that it looked almost like a small dirigible balloon,

while the short wings were no larger than those of the ordinary

machines. It occurred to me that the "negative-gravity" gas was

probably used to lift it.

As I stood watching it, I saw a party coming aboard. There were a dozen

soldiers, in red uniform. Among them I recognized the short figure of

Vars, the maniac, if he was a maniac. And behind him were three closely

guarded figures, one of them evidently a woman. Were they my three lost

friends? I had every reason to think they were. Vars had promised not

to injure Ellen or the Doctor, had implied that he wished to take them

with him.

I was still watching when I heard a light footstep behind me. I whirled

quickly, only to receive the sharp point of a bayonet against my chest.

"Drop it!" a sharp voice commanded as I tried to raise my automatic.

The pressure back of the keen blade was somewhat increased, and I

obeyed.

"Where did you come from, anyway?" the voice inquired.

I said nothing.

"Then I'll give you a chance to tell somebody else, Pard."

A dark-faced man in red uniform stepped out of the shadow of the

building. He searched me, and discovered the Doctor's little weapon.

"What's this, Pard?" he asked quickly.

Desperately I cudgeled my brain. "It's—er—a patent radium cigarette

lighter. Inventor gave it to me. I broke it the other day."

He looked at me sharply. I tried to assume indifference; and he handed

it back. "Forward march, and no tricks," he ordered, and prodded me

with the bayonet until I would have given a good deal to know the

secret of the little weapon he had returned to me.

Presently we reached a low concrete building. He put me past a barred

door, and locked it. I was left alone in the dark. Presently I struck

the few matches I had, to examine the little weapon. I set the dial by

guess, and found the tiny lever that lit the tube with the soft crimson

light, but I could not test it.

Toward morning I had an incredible visitor!

A pale violet light was suddenly thrown through the bars of the door.

I looked up to see the amazing Thing before it, regarding me. It

was octopus-like, with a central body upheld on a dozen whip-like

tentacles! But it was luminous, purple, semi-transparent!

The shapeless glowing purple body had a nucleus of red—a little sphere

of intense red light embedded in the shining form. It seemed like a

terrible eye, watching me.

For a moment the awful thing was there, and then it moved silently

away, drawing itself upon the slender gleaming tentacles. It left me

weak and trembling. I hardly dared believe my eyes. Was this one of the

"beings from another plane" with which Vars had allied himself in his

insane attack against the earth?

CHAPTER IV

The City Above the Air

At last the light of day, filtering through my prison bars, aroused me

from a terrible dream of a gleaming purple octopus that was crushing

and strangling me in its coils. Little did I realize how soon that

dream was to become a reality!

The red-uniformed sentry came and brought me a little breakfast. I

tried to engage him in conversation as I ate, but all I could get out

of him was "Aw, shut your trap, Pard!"

He ordered me out of the cell. As I stood outside, blinking in the

blaze of morning sunshine, I saw that the crater had been deserted

since I had entered. The rows of great sheds were empty, with doors

ajar. The long lines of red planes were gone. Even the great ship into

which I thought Ellen and the others were taken was not to be seen. The

radio station appeared to have been dismantled. There were no more than

a dozen airplanes left in the pit; and even as I looked, some of these

took off and spiraled up into the sky.

Had the maniac finished his preparations for an attack upon the earth?

Had his dreadful army gone forth to begin the ruin of the world?

The guard motioned with his bayonet toward one of the red ships near us

on the ground. "Hustle!" he said. "Get aboard. You are going up to see

the Master."

From what I later learned, there must have been several hundred white

men in the conspiracy with Vars. In exchange for their services, he

had offered freedom from the law (which was a great inducement to the

class of men he gathered) and a chance to share in the spoils of world

conquest. His recruits had numbered bandits and desperadoes of all

descriptions, and even a few unscrupulous men of finely trained minds.

In a few minutes we were in the fuselage compartment of the red

machine. It was closed and made air-tight. We were seated upon

comfortable chairs, and had a good view through circular windows in

the sides. The pilot was forward, out of sight, and there was another

closed space to the rear, but our compartment took up most of the hull.

The guard refused to answer my questions concerning the ship's

propulsion, but I later learned that it was lifted by the negative

gravity gas. The motors utilized intra-atomic energy derived by the

forced decomposition of thorium, and at high altitudes the propellers

were supplemented by rocket guns.

Besides my taciturn guard, there were two other men in the ship. One, a

fat, red-faced fellow, who looked as if he had been drinking too much

mescale, was boasting of his close association with Vars, "the Master,"

and of his promised part in the spoil of the earth conquest.

The other was a lean, shrunken man, with red eyes. He stared

apprehensively at the pilot's room forward, muttering to himself. I

caught a few of his words,

"The shining horrors! The shining horrors. Devils from the sky!"

The machine left the crater floor and flew rapidly up on a steep spiral

course. In a few minutes the rugged mountain panorama was spread out

like a relief map below us. Presently the stars were visible, and still

we climbed, comfortable enough in the heated, air-tight compartment.

The propellers had been stopped, but the gravity-neutralizing gas

continued to lift the vessel straight up.

Then I noticed a faint purple veil coming over the stars above.

Suddenly it seemed that we were plunging through a bank of thin purple

mist. Abruptly we shot above a landscape weirder than the wildest dream!

We had climbed above a vast plain!

A flat purple desert stretched illimitably away below us. Far in the

west rose a colossal range of sheer purple mountains. The weird plain

was covered with strange and stunted violet plants. In the south was

a patch of blazing blue that looked like a lake of heavy mist. Beyond

rose a forest of fern-like violet plants.

It was a new land above the air!

The sky was utterly black, above that desolate purple world. The stars

were blazing with strange splendor, like a mist of sunlit diamond dust.

They were brighter than they ever are on earth, for we were above the

atmosphere. I turned toward the east, to look at the morning sun. Its

light was blinding. The solar corona spread out like great wings from a

sphere of livid white.

And on the purple desert, below the blazing sun, was a city!

Great spires and towers and domes rose above the dull flat expanse of

purple and blue and violet. The strange buildings were scarlet. They

gleamed with a metallic luster, as if they were made of the same metal

as the red airplanes.

This was the land of the madman's allies, the home of the purple,

gleaming creatures!

In all that strange world, save for the intense red of the weird city,

there was no bright color. The smooth plains, the towering mountains,

the great lakes, were dull purple or blue or violet. And all were

semi-transparent! I could see the Sierra Madre like a little gray

ridge, scores of miles below. And in the west, below those purple

mountains, was the broad blue Pacific, gleaming like steel.

I cried out in wonder to the guard.

"Huh," he muttered. "It's nothin'. I've been up here a dozen times.

Nothin' solid. Just mist. Even the—Things—cut like butter."

The Second Shell

Certainly our machine had risen easily enough through the purple rocks

below us. The scientific aspects of that second crust about the earth

have been considered very carefully, and the best scientific opinions

have been sought.

Mankind dwells upon a comparatively thin crust about the molten or

plastic interior of the earth. It would seem there is a similar crust

about the air. Science long ago had evidence of it in the reflection of

radio waves by the so-called Heaviside Layer.

The volume of the gases in the atmosphere depends upon temperature

and pressure. As one leaves the surface of the earth, the air grows

thinner, because the pressure is less. But interplanetary space is

nearly at absolute zero, where molecular motion ceases. It follows that

the molecular motion of the outside of the atmosphere is not sufficient

to keep it in the gaseous state at all.

The top of the air is literally frozen into a solid layer!

Scientists suspected as much when they suggested that the Heaviside

Layer effect was caused by the reflection of Hertzian waves by solid

particles of frozen nitrogen in the air. But it seems that the many

frozen gases (for the air contains hydrogen, helium, krypton, neon,

xenon, and carbon dioxide, as well as nitrogen, oxygen, and carrying

quantities of water vapor) possess chemical characteristics lacking

at ordinary temperatures. They seem to have formed a relatively

substantial crust, and to have formed an entirely new series of

chemical compounds, to make life possible upon that crust. (The rare

gases of the air are monatomic, and consequently inert, at ordinary

temperatures.)

It would appear that intelligence had been growing up upon that

transparent and unsuspected world above, through all the ages that

man had been fighting for survival below. Vars had been the first to

suspect it. He had got into radio communication with the denizens of

that second crust, had enlisted their aid in a war upon his fellow men!

We flew on toward the crimson city.

"The armies from there will conquer the world. Those purple things

fight like demons," the fat man boasted complacently, waving his

half-empty flask toward the gleaming crimson battlements.

"Demons! Yes. Devils! Hell in the sky!" the shrunken man whispered

through chattering teeth, never taking his red eyes from the door to

the pilot's cabin.

We were over that strange city of red metal. It was a mile across,

circular, with a metal pavement and a wall of red metal about the edge.

Scattered along the rim were a dozen great gleaming domes of purple.

"Gas in the domes supports the city," my guard said briefly. "The

ground is mist. Won't hold up anything solid."

I suppose that a dollar would have fallen through those purple rocks as

a similar disc of neutronic substance, weighing eight thousand tons to

the cubic inch, would fall through the crust of our own earth. Strength

and weight are relative terms. The strange crust must have seemed solid

enough to the weird beings that trod upon it, until they acquired the

use of metals and of the negative-gravity gas. (Their "mines" may have

been the meteorites of space.)

In the center of the city was a huge transparent dome, with a slender

tube projecting through it. I was struck at once with the semblance of

it to Dr. Vernon's ray tube. Had a duplicate already been installed

here?

The fat man answered my question. "Old Vernon is some prize fool. We

have his weapon as well as those already possessed by the Things. A ray

tube in that city, and one in every plane. The Master has promised me a

little model, to carry in my pocket. He is going to give me Italy and—"

Poison in Their Blood

I listened no more, for we were dropping swiftly to a broad platform

of the red metal. Upon it were long lines of the thick-bodied red

airplanes. And at one side was the larger ship into which I had seen

three prisoners taken.

"—the army, ready to start," I heard the red-faced man again. "I'll be

over New York tomorrow." He raised his bottle unsteadily.

Our machine was dropped lightly to the top of the great ship. Two

red-clad mechanics moved through our compartment, toward the rear. In

the next little room we found them waiting, when my guard had made

me follow. They held a round metal door, above a dark opening in the

floor. It seems that the machines were placed with openings opposite,

and were clamped together to prevent loss of air.

"Crawl through. Pronto!" said the guard, giving me another prod with

his bayonet and pointing to the hole.

I put my hands on the edge of the opening, dropped through, and found

myself in a dark chamber—for a second, alone. It was the opportunity

I had been awaiting. I slipped out the little tube of the Doctor's.

On the night before, I had set the little dial. Now I pushed over the

little lever that lit the tube, and played the invisible beam through

the opening.

My guard climbed through, suspicious and in haste, evidently

unconscious of the beam. I slipped the tube under my coat, to hide its

crimson glow, playing the ray over him again, and over the mechanics

and my two fellow-passengers, as they came through. I heard footsteps,

and a light flashed on. I saw that we were in a long, low room, with a

door at the farther end. Four men, in red uniform, with rifles, were

approaching. Hopelessly, I gave them the benefit of the ray, but still

nothing happened.

"Move on, Pard," my guard muttered. "The Master waits." He gave

me another vigorous prod with the blade. (He seemed to enjoy his

prerogative immensely.)

I still had the tube in my hand, concealed against my coat. Though it

seemed to have no effect, I was missing no chances. We passed through

a door at the end of the room, into another fitted up like a luxurious

office. At a paper-littered desk, the lunatic, Vars, was sitting with

three other men, who, for all their looks, might have been ex-pugilists

or bootlegger kings (or both).

Suddenly Vars ducked, and a pistol flashed at his side. My hand went

numb, and I heard the crash of glass. He had shot the tube as I turned

it upon him. As he cursed and fired again, I threw myself at the feet

of the fat man. Pistols cracked, and I felt the wind of bullets.

Strangely, the big fellow collapsed as I dived, striking the floor at

my side.

And then a fearful thing threw itself at me!

It was a many-tentacled creature of luminous purple fire, with an

eye-like nucleus of bright scarlet in its shapeless, semi-transparent

body! It was a thing or horror like that which had looked upon me as I

lay in the cell—a nightmare being! I struck at it feebly, reeling in

terror.

It had followed us into the room; it must have been the pilot of our

ship.

Slender tentacles of purple fire coiled around me. They touched me.

Their touch was cold—cold flame! But it burned! I felt a tingling

sensation of pain—unutterably horrible. The contact with that monster

shocked like electricity—but it was as cold as space!

I shrieked as I fell!

With my last energy, I sent out my fist at that flaming scarlet core.

My arm went through it, cut it!

Then I have a confused impression of cries of agony and terror, of

men cursing, screaming, falling. There were pistol shots, shouts, and

dreadful sobbing gasps. I sat up, and saw that the room was full of

writhing, dying men! Corpses weirdly splashed with red!

And the purple thing lay before me on the floor, inert and limp, with

the fire in it fading. Still it was unspeakably horrible.

Then I heard Ellen cry out, calling my name! I ran on in the room.

Ellen stood at the bars of a flimsy little door back of the desk at

which the men had been seated.

"Bob," she cried, "I heard you! I knew it was you!"

I smashed the door with one of the rifles. The girl ran out to me, with

Bill and the Doctor at her heels. The Doctor took in what had happened.

"The r-r-r-ray made slow p-p-p-p-poisons in their blood. Not adjusted

right. It can upset the chemical equilibrium of the body in a thousand

ways. But let's get b-b-b-back in the other ship before something

happens."

We got through the manhole. I closed it again and unfastened the clamps

that held us to the other ship, while the Doctor and Bill ran forward

into the pilot's compartment. I felt the vessel rise.

Ellen and I stood by one of the round ports. We saw the weird red city

drop away below us. Soon the flat, desolate purple desert was slipping

along beneath us, with the green-gray earth visible through it, so far

below.

And still there was no movement from the city.

We were several miles away before I saw the red ships rise in long

lines from their places on the landing deck. Our flight had been

discovered! And then I saw the great dome moving, the slender tube

pointing at us.

They were going to use the ray!

The Doctor's voice came from the forward compartment. "I was afraid

something would happen to the p-p-p-p-plans. You know I told you that I

almost had an atomic explosion of the molten Vernonite electrode. The

specifications on the blue print were almost right—almost—"

A great flare of white light burst from the transparent dome. A blaze

of blinding incandescence blotted out the scarlet metal city. After a

long moment it was gone, and we could see again. The city in the sky

was no more!

There was only a vast ragged hole in the purple plain!

That was perhaps the most terrific explosion of history, but we neither

felt nor heard it, for we were above the air.

That is a year ago, now. Ellen and I are married. Soon we shall go back

to El Tigre, to see the Doctor and Bill. Dr. Vernon is working on a

new model of his tube, and is making a painstaking examination of the

strange ship we brought back to earth.

Did the destruction of a single city destroy the menace? In all that

world above the air, larger than our own, may there not be other

cities, or nations and races, perhaps, of intelligent beings? What

might we not gain from them in the arts of peace, or not lose to them

in war?

This summer the four of us are going to adventure above the air again,

in that captured ship—to explore the Second Shell.

The End.

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 73951 ***