There was a sudden lurch and we all floated toward the center of the cabin.

By NELSON S. BOND

Trust Lancelot Biggs to get his ship into

a mess just when speed and good navigation

meant the prize contract of the year...!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Fantastic Adventures May 1940.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Everything happens to me. We finished taking on cargo at 13:10, Solar Constant Time, and I went to my turret for firing orders from the Sun City spacedrome officer. I plugged in the audio and stared into the familiar pan of Commander Allonby.

I said, "Freight lugger Saturn preparing to up gravs, Commander. Standing by for the O.Q."

His jaw dropped like a barometer in a cyclone. He gasped, "You, Sparks? And the Saturn? What in blue space are you doing in port?"

"Don't look now," I advised him, "but we've been here since day before yesterday. Matter of fact, you and me h'isted elbows together last night at the Cosmic Bar, remember?"

"Remember?" he howled. "How could I? The last I heard of you, Cap Hanson was running the Saturn through the planetoids on some sort of cockeyed transmutation experiment![1] When did you get back? How did you—?"

"Damn!" I groaned, "and double-damn!" I knew what had happened. It was that confounded new invention of Lancelot Biggs'. It was a uranium audio plate which, when activated in low radiations, acted as what you might call a "time-speech-trap."

In other words, I was talking to Allonby not as he was now, but as he had been five months ago!

Don't ask me how it works. I'm a stranger here myself. Anyhow, I shook my head, shifted the dials, picked up Allonby in the current time level, got a take-off order and relayed it to the bridge. Pretty soon a bell dinged, another one donged, and a slow, humming vibration tingled through the ship as our hypatomics caught hold. I steadied myself for the lift—

And whammo! The stars exploded and seven mules let me have it in the you-know-where, and there I was on the ceiling, squawking like a stuck pig and scrambling to get down to my control banks. I didn't scramble long. For suddenly the artificial gravs came on and I made a perfect three-point landing—nose, knees and navel—on the floor.

I got up gingerly. No arms or legs fell off when I shook myself, so I started for the bridge to ask Cap Hanson whyfore. But just as I reached the door it swung open, and in came the skipper himself. He was swearing with the dull, unemotional fluidity of a man who has abandoned hope.

I knew, then. I said, "Biggs, Skipper?"

He moaned, "Talk to me, Sparks. Talk quick, an' make it interestin'. I promised Diane I wouldn't commit no mayhems on him, but I'm weakenin'. I keep thinkin' how I'd like to—"

"Easy, Cap," I soothed. "Some day he'll choke to death on his own Adam's-apple. But how come Biggs made the take-off? He's only the First Mate on this barge."

Hanson snapped, "Don't call this crate a barge!" Then he added, "Well, Sparks, I lost a bet with Biggs on the last trip. An' he won the right to navigate the next three Venus-to-Earth shuttles. So—" He shrugged. "He's handlin' the controls."

"Maltreating," I corrected, "is the word. I like Lancelot Biggs, Skipper. But I'd as soon ride a Martian firebird bareback as hop gravs with him in the turret. What do you say we—"

Just then the door busted open again, and this time in came the skipper's daughter, Diane, followed by our gawky genius, L. Biggs. There was a sight for you. Beauty and the Bust! I know Venusian, Earth Standard, Universal and a smattering of Old Martian, but I don't know the words to describe Diane Hanson. She was paradise wrapped up in a five and a half foot bundle. She was honey and cream and lotus flowers streamlined into a single heartache. She was—well, she was terrific!

Biggs looked like "Before" in the Are You a Man? advertisements. He was lean and lanky and gangly and awkward, and he walked like an anaemic stork on ice-skates. His chief topographical feature was an Adam's-apple that cavorted up and down his neck like a runaway elevator. I'd known Biggs six months, and still couldn't figure out whether he was a sixty horsepower genius or the luckiest mortal in space.

Right now, both he and Diane were wearing size 12 grins. With a prideful sidelong glance at her fiance, the skipper's gal demanded, "Wasn't it wonderful, Dad? Lancelot made that take-off all by himself. Wasn't it something?"

Hanson strangled softly. I did a relief job. I said, honestly, "It was something. I haven't figured out what yet. After I get the curdles out of my brain—"

Mr. Biggs said apologetically, "I'm sorry if I caused you any inconvenience, Sparks. I was trying out a new wrinkle. Instead of using the aft blasts to throw us clear of Sun City spaceport, I used a single jet and reversed the ship's gravity. That gave us an automatic repulsion from the planet, and—"

"What!" roared the skipper. "Look here, Mr. Biggs, one more insane trick like that an' I'll have you cashiered, bet or no bet! I've been hoppin' gravs for nigh onto forty years, an' you can take my word for it, them nonsensical ideas don't work! They only waste fuel, an'—"

"But," interjected Biggs, "I just checked with the engine room, sir. They—they complained about the moment of weightlessness, but admitted we'd saved approximately sixty percent of our normal escape fuel."

"The hell you say!" Cap Hanson's jaw played tag with his breast-bone. Then he gathered up his self-respect and expelled it in an outraged snort. "Nevertheless," he proclaimed, "an' howsoever—the stunt's no good. Come to find out, you'll prob'bly discover we're at least a degree off course an' behind schedule—"

Just at that moment the audio buzzed. I plugged in and contacted the second officer, Lt. Dick Todd, calling from the bridge. Todd said genially, "Hi, Sparks. Tell Mr. Biggs I just finished checking the course revision, will you? And tell him that little trick of his was a whiz-bang. The tape shows we've gained two parsecs on the normal escape and we're point oh-oh-oh on course!"

The violent sound was Cap Hanson and his dignity slamming the door behind them....

After he left, I coughed gently at Diane and Biggs, who evidently thought my turret was the back row of a movie house, and while Biggs was wiping the lipstick off his chin I said, "Look, Mr. Biggs, I don't want to be critical, but that damned audio plate of yours—" And I told him about what had happened just before the take-off.

He grinned amiably.

"It doesn't really matter, Sparks. That's one of the paradoxes you'll have to get used to. The uranium trap has the faculty of probing into the past, but only when you operate it in low frequencies."

I said, "But I actually talked to Allonby over a five month lapse of time! Here's what gets me—shouldn't he have remembered that conversation yesterday when he and I had a couple of snorts together in Sun City?"

"No. Because you didn't talk to him on his present world-line. You see, every man moves through Time and Space in a series of four co-ordinates dependent upon what he does. Five months ago Allonby did not talk to you. Therefore he did not remember it yesterday. The next time you see him he will remember today's conversation as having happened—"

"Pardon the slight sizzling sounds," I apologized to Diane. "That's just my brains heterodyning."

"In other words," continued Biggs blandly, "today you sheared the Time-Space continuum from an unusual angle, thereby turning the Present-Past into the Past-Present, and altering the Future-Present. You might say you spoke not to Allonby, but to one of the many probabilities of Allonby. Do you understand now?"

"No," I said. "Where's the aspirin?"

"I'll try to make it clear," he persisted. "This is how it works—"

Then I got a break. The bug started chattering; I moved to the control board and said, "So solly, folks. Me makee talk-talk on phonee. Goombye!"

They left, wrapped around each other like a pound of melted chocolates, and I switched in to hear the finger of Joe Marlowe buzzing me from Lunar Station III. Marlowe was in fine form. He greeted me with a "Haloj, nupaso!" which means, "Hi, pickle-puss!"

I called him something untranslatable, and then he got down to business. "How's that dilapidated old crate of yours perking along, pal?" he asked.

"Fine," I told him. "We've got genius at the helm, romance on the bridge, and a cargo of Venusian pineapples in the hold. Which reminds me, how's your girl friend?"

"Comets to you, sailor!" he snapped back. "This is serious. I wanted to warn you, you'd better make a good trip. There's a prize dangling on it."

"Come again?"

"Word just leaked through from the central office. The Government has decided to turn its freight express transport over to the company whose next normal Venus-Earth run is made in the shortest time. It's a blind test, and nobody is supposed to know anything about it. The Saturn was clocked when it pulled out of Sun City, and its time will be checked against that of other competing liners—"

I got little cold duck-bumps on the forehead. When I brushed them they were wet. This was a tough break for the Corporation. The Saturn is the oldest space-lugger still doing active duty on the interplanetary runs. She was built way back there before the turn of the century. Lacking many modern improvements, she is a ten-day freighter. One of our new luggers could make the same trip in six or seven; it was rumored that the Slipstream, pride of the Cosmos Company fleet, could make it in five!

I squawked, "Fires of Fomalhaut, Joe, it's not fair! The Saturn's the slowest can the Corporation owns! Why don't they let us run the Spica or the Antigone on a test flight?"

"It's a little matter of politics, friend," he returned wearily. "Politics—spelled g-r-a-f-t. Somebody's got a finger in the pie and wants the Cosmos Company to get the allotment. The Slipstream is leaving Sun City tonight. All you have to do is beat her into Long Island by about ten hours."

"Is that all?" I lamented. "You're sure they don't expect us to stop on the way in and load up with a half ton of diamond dust? Shooting meteors, Joe—"

He interrupted my etheric sobs with a hasty, "Somebody breaking in on our band, guy. Got to go now. Best of luck!" The sign-off dropped the needle, and I was staring at a killed connection.

So there we were, way out on the limb. The fastest freighter in space competing against us for the fattest prize since the Government lotteried off the Fort Knox hoardings. I worried two new wrinkles into my brow, then went below to find Cap Hanson. He heard my complaint with ominous calm. When I had finished he said, almost cheerfully, "Tough, ain't it?"

I stared at him. "Skipper, we've got to figure out a way to hobble home first! That Government contract carries at least three million credits a year. If we lose it for the Corporation, they'll tie the kit and kiboodle of us to stern firing jets!"

He just grinned ghoulishly and held out two hairy paws for my inspection. "You see them hands, Sparks?"

"I'm a radio operator," I told him, "not a manicurist."

"Them hands," he persisted, "is clean as a pipeline on Pluto. Take a look at the log. Mister Lancelot Biggs is writ down as the C.O. for this trip. Which relieves me of all an' sundry obligations."

I said, "But, Skipper, you've had the experience! In an emergency like this—"

He shook his head. "Sparks, we ain't got a chance of beatin' the Slipstream to Earth. Not the chance of a snowman on Mercury. I'm perfectly satisfied to let Mr. Biggs do the worryin', an' if the Corporation's thickheaded enough to want to blame anybody for our failure, I'm content to let him have that honor, too!"

He grinned again.

"Maybe after this," he said, "Biggs won't be quite so damn cocky. An' maybe Diane won't think he's the hotshot he lets on to be!"

Which was absolutely all the skipper would say. I wasted words for five more minutes, then went to find Lancelot Biggs....

He wasn't on the bridge. He wasn't in the secondary control cabin or in the mess hall or in the holds. Nor in the engine room. I found him, finally, in the ship's library, sprawled full-length on a divan, holding a book in one hand and waving the other arm in the air, keeping time to the poem he was reading aloud.

When I entered he looked up and said, "Hello there, Sparks! You're just in time to hear something lovely. This space-epic of the Venusian poet-laureate, Hyor Kandru. It's called Alas, Infinity! Listen—"

He read,

"... comes then the quietude of endless void. The heart seeks out and, breathless, listens to Magnificent monotonies of space...."

Monotony your eye! There are times when I'd trade all my bug-pounding hours for a nice, quiet, padded cell out somewhere beyond Pluto. I said, "Listen, Mr. Biggs—"

"You know, Sparks," he said dreamily, "sometimes I wonder if the poetic mind is not more acute than the strictly scientific one. Since I met Diane, and she acquainted me with the symphonic beauties of poetry, I've thought of so many new things. The never-ending wonder of the Saturnian rings, for instance. The problem of space vacuoles—"

"Speaking of vacuoles," I interrupted, "me and you and about fourteen other mariners from the good ship Saturn are going to be in one pretty soon—if by vacuole you mean a hole. Because—"

And then I told him. Misery being, as rumor hath it, a gregarious soul, it did my heart good to see the way he jolted up from his horizontal position.

"But—but, Sparks!" he quavered, "that's terribly unfair!"

"So," I told him, "is betting on the gee-gees. Only one hoss can win, but they all find backers. The point is, what are we going to do about it?"

"Do?" he piped. "What are we going to do? We're going to do plenty. Come on!"

We went to the engine room. There Chief Engineer Garrity heard Biggs' plea with granite aplomb, then slowly shook his head from side to side.

"Ye're no suggestin', Mr. Biggs," he said, "that I try to double the Saturn's speed?"

"You must!"

Garrity grinned mirthlessly, ducking his grizzled head to designate the laboring, old-fashioned hypatomics in the firing room. "Them motors," he said, "is calculated to carry us from Earth to Venus, and visey-versey, in ten days. By babyin' 'em we can make it in nine. By strainin' 'em we can make it in eight—mebbe.

"But if we force 'em beyond that limit—" Once again he shook his head. "—we'll arrive at Long Island rocketport as a fine conglomeration of assorted bolts, plates and rivets. Ye wouldn't like that, Mr. Biggs," he appended speculatively.

We went to the bridge, then, and discussed the problem with our junior officer, Dick Todd. Dick had lots of ideas, none of them good. Our confab ended in a "no-decision" draw. And finally I said, "Well, Mr. Biggs, I'm afraid it's over my head. I'd better get back to my turret in case any messages come through...."

He didn't even hear me. He was pacing the floor, moaning softly from time to time and scraping his scalp with frenzied fingers.

All of which took place our first day out of Sun City. It was a bad start, and things rapidly became worse. At 24.00 on the dot, Solar Constant Time, I got a flash from a ham operator on Venus, advising me that the Slipstream had just slipped her gravs. Which meant that the race was on.

Huh! What race?

Eight hours later our perilens picked up the Slipstream. She was cutting a path through space like a silver arrow. And you can bet your bottom buck that her skipper knew how important this trip was. I was asleep when she whizzed by us, but my relief man woke me up to show me the message her C.O. had sent us. It said, "Greetings, goats! Want a tow?"

It wouldn't have been a bad idea at that!

Well, Garrity and his black gang were working themselves blue, and to the everlasting credit of the Saturn, I'll confess that the old freighter wallowed along in handsome style. We logged a trifle over three million miles in the next twenty-four hours, which is about five hundred thousand over par for our crate.

We did it with music, too! The plates were clinking and straining, the jets were hissing like a nestful of outraged rattlers, and once or twice, when our Moran deflectors shunted off fragments of meteoric matter, I thought we were going to move out to make room for some intra-stellar cold storage.

So what? The Slipstream, traveling at better than double our speed, knocked off a cool six million that same day! Oh, if ever a "race" was in the bag, that one was!

The second day was another dose of the same business. Biggs insisted that we maintain our forced speed, although Garrity warned him bluntly that it was dangerous.

"I been twenty years in space, Mr. Biggs," Garrity told him sternly. "I look forward to spendin' another score the same way. But I have no desire to whisk along the spaceways as a glowing clinker."

Lancelot Biggs said desperately, "But we've got to do our best, Chief! We're beaten, yes—but we've got to show a little fight. Anything may happen. They may have an accident—a breakdown—"

There was a pathetic intensity in his voice. Once again, as several times before, I found myself thinking this Lancelot Biggs guy, screwy as he might seem, had plenty of abdomen-stuffings. Garrity must have felt the same way, for he said, grudgingly, "Verra well, then. But...."

So, for the third day in succession, our hypatomic motors churned like a bevy of Martian canal-kitties having their morning dunk. And for the third day in succession, the Cosmos Company's super-freighter, the Slipstream, proceeded to show us the winking red dot of her rapidly disappearing after-jets.

And then it happened!

I was in my turret, reading a copy of Spaceways Weekly, when all of a sudden my bug started chattering and the condenser needle started hopping. I plugged in and caught a garbled, frantic warning from the Sparks on the Slipstream.

"Calling IPS Saturn! Calling IPS Saturn! Saturn, stand clear for back-drag! Stand clear for back-drag!"

I jammed the "stand clear" warning to the bridge and shot a hasty query back to the Slipstream operator.

"Saturn standing clear, pal. What makes?"

"Trouble on declension line sixteen-oh-four. Stay off our trajectory! We're running into a vac—"

Then suddenly the message went dead; the condenser needle went to sleep on zero; I was hammering a futile key at an operator who could no longer communicate with me.

But I knew what the trouble was. Our streamlined rival had nosed into a space vacuole!

By this time, the Saturn was creaking and groaning like a jitterbug on a coil-spring mattress; bells were dinging all through the runways, and the forward blast jets were making an unholy din as they bounced us off trajectory. And every time one exploded, of course, the lugger shook as if a gigantic fist had smacked it square in the nose.

Footsteps pounded up the gangway, the door opened, and I had visitors. Cap Hanson, Diane Hanson, and our acting Skipper, Lancelot Biggs. They all hollered at once.

"What is it, Sparks?"

"Vacuole!" I snapped. "The Slipstream broke into one. They're preparing for the back-drag now."

Diane Hanson's eyes were like twin saucers.

"Vacuole?" she repeated. "What's that? What's a vacuole, Lancelot?"

Biggs said, "A hole in space, Diane. Their exact nature has never been accurately determined. All we know is that space itself, being subject to material warp, ofttimes develops 'empty spots' of super-space within itself. These areas correspond, roughly, to 'air pockets' encountered by planetary aviators; they are even more similar to the curious 'sacs' found in protoplasmic substances like amoebae."

Diane faltered, "A—a hole in space! It sounds incredible! Are they dangerous?"

"Apparently not," I told her. "Lots of space ships have tumbled into them, and in every case the ship has eventually worked its way out. Sometimes they're carried far off course, though. That's why the Slipstream has to back-drag, and do it fast." I grinned. "Sometime when I'm not too busy I'll draw you a picture of a space vacuole. It looks pretty. A hole full of nothing—in nothing!"

Cap Hanson had been peering through the perilens in my turret. Now he let loose a great roar of delight.

"I see her! I seen her stern jets flickerin' for a moment. Here she—Nope! She's in again!"

Biggs explained to the girl, "She's trying to back out. The only difficulty is, she has to reverse engines and come out with an acceleration built up to match that at which she entered. Which means—"

"Which means," I interjected hopefully, "we're not beaten yet, folks! When the Slipstream busts clear of that vacuole, she's going to be hell-bent in the opposite way to Earth. Mr. Biggs, if we can miss the vacuole and keep going, we might—"

Still at the perilens, Cap Hanson now yelled, "By golly, I just seen her again! But you ought to see where she is! That vacuole's a rip-snorter! Tearin' like a fool—"

"Which way?" cried Biggs.

"Starboard declension. You never seen anything as fast as that there gallopin' hole. Hey, here comes the old Slipstream! Whee! Nice job, Skipper!"

I saw it then. It came blasting back toward us like a ray from a needle-gun. I couldn't help admiring the good sportsmanship in Cap Hanson which, even though he had seen his competitor's ship break free of the bondage that might have cost it the race, caused him to commend the navigator's space-skill.

Now the Skipper turned to Lancelot Biggs, and there was a battle-light in his eyes. "Mr. Biggs, this gives us a fightin' chance to win the race! The Slipstream will be a day makin' up for this lost time. I'll relieve you of your command now—"

But there was a strange, thoughtful look in Biggs' eyes. He said, slowly, "Did you say starboard, Skipper?"

"Eh? What's that? Yes, I said starboard. Well—did you hear me, Mr. Biggs? I've decided not to be hard on you. I'll relieve you of your command now ... take the Saturn on into port...."

And Lancelot Biggs said, "No!"

Before Cap Hanson had stopped gasping—I decided afterward it was a gasp, though at first I thought it was a symptom of apoplexy—Biggs stepped to the ship's intercommunicating system and buzzed the bridge. To Todd he snapped, "Mr. Todd, plot new co-ordinates to intersect with the vacuole as soon as possible!"

Then Todd gasped and I gasped and Diane gasped and the Skipper was still gasping, and Lancelot Biggs turned to face us, faintly pale, breathing a little hard, but with a look of curious determination on his face.

"I know," he said, "you all think I'm crazy. Well, maybe I am. But I'm not going to surrender my command, and I'm going to see this race through in the way that seems most fitting to me—"

Then he gulped, turned, and gangled from the room. Diane started crying softly. I said, "Now, now!" wondering if the words sounded as silly to her as they did to me. And Hanson came out of his stupor with a blast that lifted the roof an inch and a half.

"What the blue space does he think he's going to do? 'Intersect the vacuole'! The crazy idiot! Does he mean to throw away all the advantage we've gained?"

"Don't ask me," I said dourly. "I'm not an esper."[2] My instrument was clacking again; it was the operator of the Slipstream calling.

"We're clear, Saturn," he wired. "Thanks for getting off course. You're too far off, though. Better watch out. You're headed smack into the vacuole."

I wired back, "We like it that way," and refused to pay any attention to his continued queries. A dismal silence had fallen over my turret. The hypatomics had picked up now; I could tell by the vibration that we were on our way, full steam ahead, toward—what?

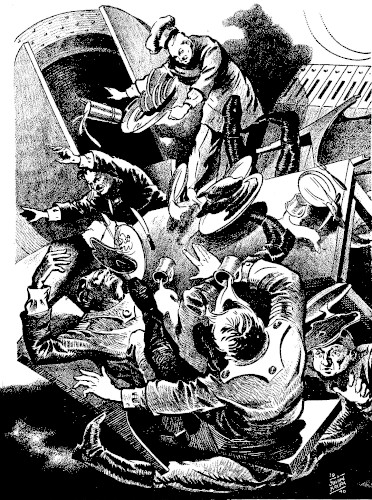

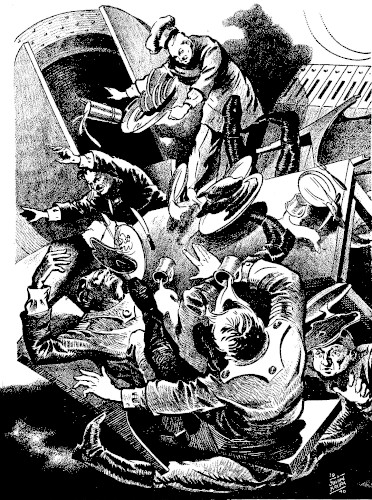

I found out. Not then, and not for several hours, but at dinnertime. I had just taken my seat at the table and Slops was just leaning over my shoulder, ladling soup into my bowl, when there came a high, shrieking whine from the engine room, the lights flickered, something went boomety-clang—and the bottom fell out of the universe!

My stomach gave a sickening lurch, so did the mess hall, so did Slops, and so did the soup. About four of us went into an involuntary huddle on the floor; when I came up again I had purée of vegetables, luke-warm, all over me, and my hair had so many alphabet noodles in it you could have rented me out at a public library.

There was a sudden lurch and we all floated toward the center of the cabin.

The din was terrific, but it all meant one thing; a question admirably summed up by the badly frightened Slops as he screamed, "Wotinell's the matter!"

I said wearily, "Sue me if I'm wrong, friends. But I believe our screwball navigator, Mr. Biggs, has finally piloted us into the vacuole...."

The funny part is, Biggs wasn't even dismayed about it! I made a half-hearted pretense at eating, then skipped up to the bridge to find out what—if anything—Biggs was doing about this new disaster.

The answer was obvious. Absolutely nothing. Pale of face, but still determined of mien, he was sitting in the control pilot's lounge-chair shaking his head stubbornly as Cap Hanson, Lt. Todd, Chief Engineer Garrity and every other brevetman aboard the ship bombarded him with pleas to "do something!"

"Gentlemen," he said, "gentlemen, I ask you to remember that Captain Hanson assigned me the privilege of navigating this trip. As navigator, it is my right to do what I consider best—"

Todd, who liked Biggs, said nervously, "But, Lance, we're right in the middle of the vacuole! Aren't you going to give orders for a back-drag? We've got to get out of here. Heaven only knows—"

Cap Hanson was purple with impotent rage. "Wait!" he was squalling. "Just wait till we get back to Earth! I'm goin' to have you busted out of the service as soon as—" A strange look came over his face. "Golly! When we get back to Earth? We ain't never gonna get there less'n we do somethin' quick!"

Lancelot Biggs said, "Be patient, gentlemen!"

Garrity said cajolingly, "Look, lad—mayhap you don't understand the difficulties we're in? Suppose you be a good chap an' let the Skipper take the controls—?"

Lancelot Biggs said, "Just be patient. I would like to explain, but I think I'd better not! Not yet—at any rate."

Cap looked at me. I put in my two cents' worth.

"Mr. Biggs," I said, "you can read those charts on the wall. Don't you see we're being carried hundreds of thousands of miles off course? This vacuole is traveling way over to the right of our course, hitting an abnormal rate of speed—and we're imbedded in it like a fly in amber. We've already lost the race; pretty soon we'll lose our—" I stopped, not wanting to say "lives" in front of Diane.

Lancelot looked at me somberly.

"I should have thought, Sparks," he told me, "that you would understand. With your education and training—" But he seemed undecided. He stared at Diane. "Diane—you believe in me, don't you?"

Boy, I'll tell you that gal has what it takes. A long moment passed, during which Diane looked squarely into Lancelot Biggs' eyes. What she found there, only she could tell you. But, "Yes, Lancelot," she said. "I trust you."

His shoulders stiffened, then, just the slightest bit. And a faint smile gathered at the corners of his lips. He said, "That's all I wanted to hear. Very well, gentlemen, be patient for just ten more hours...."

By far the worst feature of being caught in a vacuole is the fact that you're completely isolated from the rest of the universe. These super-spatial areas; these dead spots of hyper-emptiness, do not obey the common laws of space mechanics. There's no radio transmission through a vacuole; the only laws that seem to apply are the laws of motion and relativity.

This time, even the relativist principles seemed to go haywire. Lancelot Biggs had demanded that we be patient for ten hours—but to me those ten hours seemed like ten centuries. Millennia, maybe. Seconds crawled. Minutes dragged. Hours were fabulous periods of time. You could almost sit still and feel your hair graying on your scalp.

I tried to read a book, and gave it up as a bad job after I discovered I'd re-read the same page six times. Then I fiddled with my dials, but all I could get out of them was a strange, singing, unearthly hum. I had a feeling of boding suspense, as though I were an insensate beast caged in an elevator that was rising through darkness to an unguessed destination.

Boy, am I getting poetic! Anyhow, that's how I felt, and if you want to make something of it, stop down by the IPS spaceport at Long Island and ask for Bert Donovan!

I managed to while away a couple of hours figuring out where the Slipstream was by this time. Like I said, she was a five-day freighter. But she'd lost almost a full day in her tangle with the vacuole—our vacuole—and in spite of the fact that she'd now put on every bit of juice she had, she wouldn't make the trip in much less than five and a half days.

Which, of course, didn't help us any. The Saturn was normally a ten-day ship. Now, caught in the vacuole, it was a question of when, if ever, we got back onto our trajectory.

What puzzled me most was the fact that in the past I'd come to look upon Lancelot Biggs as something of a genius; the kind of guy who could pull rabbits out of a hat. Like the time he rescued our ship from Runt Hake and his pirate crew.[3] But now Biggs seemed to have gone into a complete funk; a wan and stubborn silence as to his reasons for having given up the battle.

Well, it was his business; not mine. He'd buttered his bread—now let him lie in it! I looked at the clock once more. Nine hours had elapsed; a little more than that. So I sauntered back to the bridge.

Everyone up there was in a fine state of the jitters—except Mr. Biggs and Diane. With fine disregard for those about them, they were curled up together on a chart-table reading poetry! Cap Hanson had gnawed his fingernails down to the second knuckle. Dick Todd was pacing the floor like a captive wild-cat. I said, meekly enough, "Mr. Biggs—the ten hours is almost up."

"Mmmm!" said Lancelot Biggs.

Cap Hanson turned on him savagely. "Well! Well, do something! And you, Diane, I'm ashamed of you! Sitting here with that—that nincompoop's head draped all over your shoulder!"

Diane rose, smiling pertly. "All right, so I'm untidy. Well—show them, Lancelot!"

Biggs rose. He looked carefully at the clock; then at the statometer. He moved to the intercommunicating system, gargled a word to the engine room below. "Mr. Garrity, would you be kind enough to revolve the ship?"

Hanson yelled, "Re—revolve the—Hey! Grab him, somebody! He's gone space-batty! He's slipped his gravs!"

From below there came the sound of the rotors going into operation. We couldn't feel anything, of course. The ship's artificial gravs hold you firm to the floor no matter which is top or bottom in space. There being no such thing. After a minute Biggs said, "Thank you, Mr. Garrity. Now, if you will be kind enough to reverse gravs and throw out the top-deck repulsion beams?"

Garrity obeyed. There came a sudden shock; everything movable in the room moved. Including me. I fell to the middle of the room, hung there gaping, weightless, the same as everyone else. The Saturn lurched and shuddered; it felt as if something trembled along her beams for a brief instant.

Then, suddenly, we were literally scorching through space again! Real space—not that phoney hyper-stuff of the vacuole. Biggs yelled, "Normal gravs, Garrity! Alter course to point-six-one for three minutes, then land...."

Cap Hanson screamed, "What the—what's going on here? Land? What do you mean—land!"

And Lancelot Biggs said, "If you'll be kind enough to look through the perilens, Captain...."

It was Earth. Just as big as life and three times as natural. A hop-skip-and-jump beneath us. We had made the Venus-to-Earth shuttle in four days, eight hours!

Afterward, when the Government committee had left, congratulating us upon having won the allotment, and the IPS officials had departed like a trio of overgrown sunbeams on legs, Hanson, Todd, Diane, Biggs and I were alone in the control turret of the Saturn.

To the smiling First Mate, Cap Hanson said, "Biggs, this business of apologizin' to you after every crackpot adventure is gettin' monotonous. But I do it again—with the provision that you tell me how the hell an' what the hell happened."

Biggs fidgeted and looked uncomfortable.

"Well, to begin with, I knew we were licked if we tried to race the Slipstream in any normal fashion—"

"The proper word," I interjected, "is skunked."

"Yes. So when I saw what happened to the Slipstream when it fell into the vacuole, I saw a way in which we might possibly come out on top. I didn't want to explain, though, for if the method failed, Captain Hanson might be reprimanded for permitting the trial—"

"Method?" demanded Hanson. "What method?"

"Piggy-back!" grinned Biggs. "You'll remember that we commented on the amazing speed with which the vacuole was traveling through space. A speed greater than our own; even greater than that of the Slipstream.

"I purposely plunged the Saturn into the vacuole. The Slipstream, caught in that same sphere of hyper-space, made the mistake of back-dragging free. I let the vacuole carry us to Earth. It's as simple as that!"

Hanson said dazedly, "Simple? Which? The method or me? You done so many funny things—for instance, we got out of the vacuole without back-draggin'. How?"

"Oh, that! Well, that was just a little thing I figured out while we were waiting. It seemed stupid to waste fuel back-dragging from a pocket in space. After all, the easiest way out of a pocket is to let yourself be dumped out. I just reversed the gravitational plates, let Earth, which I had reckoned mathematically to be 'above' us, attract us out of the pocket.

"Since there is neither 'up' nor 'down' in space, we merely fell out of the vacuole pocket!"

"It penetrates," said Cap Hanson admiringly. "Yep, it finally penetrates. Well, boys?"

He glanced at us significantly. I knew what he was thinking. Diane and Biggs were showing unmistakable signs of wanting to be alone. But there was one more thing—

"Look, Mr. Biggs," I said. "Your explanation is all right, but it doesn't clear up the matter of direction! The vacuole wasn't traveling on the line of our Venus-Earth trajectory at all. It was shifting to starboard by fifteen points, which is why we were able to intersect it. How come—"

Lancelot Biggs looked faintly surprised.

"Why, Sparks, didn't you guess? That was the thing that made our amazing speed possible. To us, traveling our ten-day route, it looked as if the vacuole were moving to the right of Earth. Actually it was moving directly toward the spot where Earth would be in ten more hours. It was, in a way of speaking, an express-train racing along a short-cut. We hopped the train, and—here we are!"

There was a tiny cough from somewhere under the shelter of his arm. A soft voice said, "Sparks—"

"Yes, Miss Diane?"

"Sparks—would you mind closing the door on the way out, please?" asked Diane Hanson.

So I did. I can take a hint as well as the next guy....

[1] Fantastic Adventures, November, 1939.

[2] Esper—a fortune teller who makes his living by foretelling the future through his use of "extra-sensory perception".—Ed.

[3] Fantastic Adventures, February, 1940.—Ed.