Exactly behind him, peering through the hole in the wall, was an evil face.

BY

V. C. BARCLAY

Illustrated

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

The Knickerbocker Press

1918

Copyright, 1918

BY

V. C. BARCLAY

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | —In the Straw-Loft | 1 |

| II. | —The Mysterious Stranger | 7 |

| III. | —The Mill Pond | 23 |

| IV. | —One a.m. | 40 |

| V. | —The Dark Passage | 51 |

| VI. | —Spies! | 78 |

| VII. | —A White Face in the Moonlight | 82 |

| VIII. | —Tapping the Cable | 99 |

| IX. | —Free! | 111 |

| X. | —In the Hands of the Scouts | 121 |

| XI. | —Caught at Last | 133 |

| XII. | —“Well Done, Danny!” | 140 |

[iv]

| FACING PAGE | |

| Exactly behind him, Peering through the Hole in the Wall, was an Evil FaceFrontispiece | |

| Looking about him warily the Stranger Picked up his Bicycle and Flung it into the Dark Waters of the Pool | 14 |

| Bending down, the Man Allowed his Face to be Caught in the Bright Light, and Danny Looked with all his Eyes, so that he might Remember every Feature | 50 |

| “Look, Sir,” he said, “You’ve Torn a Big Piece out of your Coat! And one of the Buttons, too!” | 76 |

| “Well, we’ve Caught Fritz and His Pals all right,” said Captain Miles, “Thanks to Danny the Detective” | 90 |

| There, Row upon Row, Shining, Perfect, Ready for Use, Lay a Vast Store of Machine Guns | 100 |

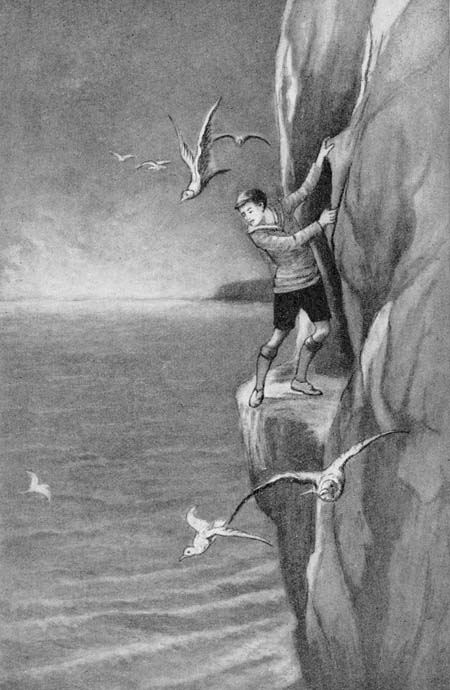

| He Stepped out on to a Ledge, very Narrow,[vi] very Perilous | 112 |

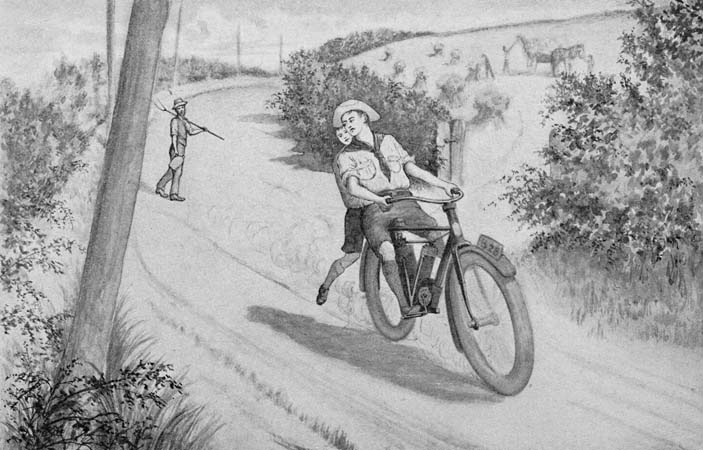

| Before long the Boys were Tearing down the Road, Danny Sitting on the Carrier, Clinging to Dick’s Belt | 130 |

Transcriber’s Note: The illustration listed as facing page 90 does not appear in this edition of the print book.

DANNY THE DETECTIVE

Danny the Detective

Danny Moor was feeling very happy as he sat on the garden gate swinging his legs.

He had lived all his life in a very dull and smoky part of London. Now, at last, his mother had come to live in the country in a village called Dutton, as lodge-keeper to Sir Edward Finch. And Danny found himself in a dear little house at the bottom of a long drive.

It was an old-fashioned cottage with a thatched roof, old black beams, and red tiled floors. Honeysuckle grew in wild profusion over the rustic porch and around the latticed[2] windows. Beyond its little garden stretched the great park belonging to the Hall, where spotted deer roamed free, and squirrels darted like red flashes through the trees. The rarest wild birds knew that here they were safe to build their nests, unmolested. But that which delighted Danny most was the great, grey ruin of an ancient abbey. It stood in the park, within a stone’s throw of his mother’s cottage. As he lay in bed at night he could see the tall grey tower looming up against the purple sky, and the outline of the crumbling walls and traceried windows clear against the stars. He used to lie in bed and wonder, and make up stories about the mysterious ruin.

Danny was not quite an ordinary boy. His school-fellows used to laugh at him; the big boys sometimes jeered at him; while his own pals admired him and thought him very clever. And everyone called him “Danny the Detective.” This is why he came to be known by that name.

Ever since he was quite a little chap Danny[3] had loved anything mysterious. Detective stories were his delight. He would creep about in the dark old house in London, playing at being a policeman tracking down a burglar. When he grew a little older he would play at “private detective,” scanning the faces of the people in the streets as he went to school, noticing their footprints and anything strange about their appearance or behaviour.

He loved to sit by the fire, on winter evenings, reading of Sherlock Holmes, and dreaming that he was one of the people taking part in those fascinating adventures. And his mind was always full of splendid ideas for disguises and secret messages. He taught himself the Morse code, because he thought some day it might be useful to know it. He might find himself in a dungeon (who could tell?) and want to communicate with someone on the other side of the wall, and then he would tap out the message with a knife. As he ran to school in the morning he would repeat the “iddy umpty” alphabet to himself, and spell[4] out the names of the shops in dots and dashes, so as to get in good practice.

But in the country everything was so different. He did not know how you set about being a detective in lanes and woods and fields. It was Patrol-Leader Dick Church who solved the problem, and also gave him the most ripping idea he had ever had in his life.

Dick was the stable-boy up at the Hall. He was also senior Patrol-Leader of the 1st Dutton Troop of Boy Scouts. He had soon made friends with the lonely little boy from London, and Danny was now as keen an admirer of Dick Church as every other small boy in the village.

It was on the day that they sat in the straw-loft up at the Hall, eating gooseberries, that Danny learnt about Wolf Cubs. He had often longed to be a Scout; it seemed the next best thing to being a real detective. But he was only ten, so there was no hope. Now, as they sat together in the dusty, golden straw, among the cobwebs and the old black beams, Danny[5] learnt that it was possible to be a Junior Scout or Wolf Cub, even though you were “only a kid!”

His heart beat fast.

“Do they learn tracking?” he said.

“Rather,” said Dick, “and signalling and swimming and first aid and all sorts of things—just like us.”

“I’ll join ’em,” said Danny, wriggling about in the straw in his excitement.

Dick laughed and aimed a gooseberry at a big rat who happened to be passing.

“Look here, youngster,” he said, “don’t you get the idea that Scouting is all play, all ragging about, and dressing up, and paper-chasing—’cos it’s not.”

“Isn’t it?” said Danny.

“No,” answered the Patrol-Leader, lying back till his head was half-smothered in his stalky pillow.

“It means doing good turns to other people every chance you get. And it puts the lid on telling lies or sneaking or pinching things or[6] swearing. It means making a solemn promise and doing anything rather than break it. It means jolly well bucking up all round. And it means sticking to it.”

“Oh!” said Danny, and he pondered in silence for quite a long time.

Dick looked at his small friend.

“Cheer up, kid,” he said. “You’ll make a top-hole Cub if you try. The Cub motto is, ‘Do Your Best.’ D’you think you can live up to that?”

“Not half!” said Danny, and from that time he decided to be a Cub—a real Cub, inside as well as out.

The Cubs’ bare knees were splashed with mud as they pounded along the lane, looking out keenly for the little scraps of white paper that formed the “scent” of the hares.

“Phew!” panted one of the hounds, “I’m hot.”

“Stick—to—it!” panted back his pal.

“Are we downhearted?” called Jim Tate, the Sixer, as he had heard Tommies call out at the end of a long route march.

“No—o—o!” came the answer right down the road, for some Cubs were getting left behind.

But Danny, having lived all his life in London, had not done much in the way of long runs. He had got a bad stitch in his side almost at[8] once, but remembering the second Cub Law—“A Cub does not give in to himself”—he had set his teeth, and determined to bear the pain, and not to give in. Then his legs began to ache as if they were ready to break. But he stuck out manfully. Finally his wind gave out.

“I’m done,” he gasped.

“No, you aren’t,” called his Sixer. “Here—hang on!” and he held out a hand to his recruit. “We shall get them, I bet. We’ve kept it up hot so far.”

Just then the white paper showed up a bank, and over the fence, into a field. With a howl the Cubs scrambled up the grassy bank, clinging to weeds and sticks and stones, and were soon in full cry across the grass. On they went, and through a hedge on to the road beyond. But there was no “scent” on the road; no paper showed on the brown mud.

“False trail!” groaned the hounds.

“Bad luck,” called Jim, the Sixer, “we must go back. We may get them yet.” And the hounds dashed off again across the field to get[9] back to the old “scent.” But it was too much for Danny. He sank down, tired out.

“They can run!” he said. And he thought, a little sadly, that they would think him a rotter to have fallen out. “I stuck it as long as I could,” he said. “I did my best—I couldn’t do more.”

He was just going to start back to Headquarters when something happened which was the first step in the curious adventures that befell him from that day onwards.

“Swish-sh-sh!” sounded the tires of a bicycle on the muddy road, as it flew past him like a streak. The rider was bareheaded and seemed in an awful hurry. Then something happened that made Danny jump up and start running down the road for all he was worth, quite forgetful of his weary legs. A dog had jumped out from the hedge, and, in trying to avoid running over it, the cyclist had skidded badly, and now lay quite still on the road.

Danny panted down the muddy lane, hoping the man was not dead, but, before[10] he reached the place where the accident had happened, the stranger had got up and was sitting on the bank, his head in his hands.

“Can I help you, sir?” said Danny eager to do a good turn.

The young man started and looked up at the boy with wild eyes; then peered about him and looked up and down the road, as if he were afraid of being followed. Blood was streaming down his face from a nasty gash in his forehead.

“Can I help you, sir?” repeated Danny. “Let me tie up your head—it’s bleeding badly.”

“Thank you,” said the young man in a shaky voice.

Danny was glad to find he had put a large, clean handkerchief in his pocket before starting. He knew enough about first aid to realise the danger of putting on an open wound anything that is at all dirty. So he opened out the handkerchief and laid the part that had been folded up inside, on the wound. What[11] could he use as a bandage? There was nothing handy.

So, with a sigh of regret, he realised he must sacrifice his beautiful new brown neckerchief. He took it off and folded it neatly into a “narrow bandage.” This he tied firmly around the young man’s head, securing it with a reef knot.

“You’re a bit shaky, sir, aren’t you?” he said. “My home is in the next village. Won’t you come back and rest? Mother will give you some tea, and I’ll run for a doctor. I think your head will want stitching.”

“No, thank you,” said the young man quickly, looking down the road again. “I assure you I am quite all right now. I was just a little stunned. I thank you for your assistance, my little friend.”

There was something curious about the way the man spoke. Danny wondered what it was. “Foreigner,” he said to himself, as he picked up the bicycle and held it for the stranger.

[12]“Could you tell me the way to Thornhurst?” asked the man.

Danny thought a moment, and told him as well as he could.

“Thank you,” said the stranger. He was about to mount his bicycle when a thought seemed to strike him. Turning to the Cub, “Little boy,” he said, “should any person ask you if you have seen me on this road, tell them you have seen no one—no one at all.”

Danny grinned.

“Sorry, sir,” he said. “Can’t tell a lie.”

The man swore under his breath. “Little fool,” he muttered.

Then he held out a bright half-crown. “That will keep you quiet,” he said.

Danny flushed, and then laughed scornfully. “Not much—it won’t,” he cried.

“Well,” said the man angrily, “tell them I’ve gone to Thornhurst, and am taking a train to London. I shall be in Dover to-morrow. You won’t forget—London and Dover.”

[13]Danny nodded, and the man jumped on his bicycle and rode away.

“He’s a queer chap,” said Danny, “and I bet there’s something on somewhere. Wish I knew what it was.” The detective spirit was roused in him. Suddenly he forgot all about Cubs and paper-chases. He was a private detective again, as in the old London days. Kneeling on the ground, he examined the man’s footprints in the mud, and made a sketch of them and of the bicycle tracks in his notebook. Then, feeling very important, he wrote a short report of the adventure in his pocket-book, added the date (July 1, 1914), and started off across the fields to get back to the Pack Headquarters.

About half a mile on, his path lay across the yard of an old deserted mill. As he clambered over the wall, something made him glance at the mill pool a hundred yards away. By it, in the shadow of the mill, stood the mysterious stranger, who had bicycled away half an hour ago towards Thornhurst![14] His head was still bound up with Danny’s scarf.

Remembering the law of the jungle, Danny “froze.” Squatting perfectly still on the top of the wall he watched, breathlessly. What could the stranger be doing there? Thornhurst was in the opposite direction. He had said he was going there, and on to London.

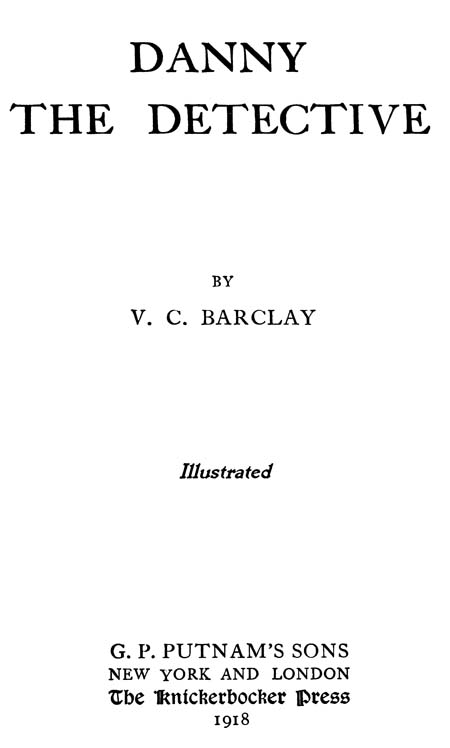

Looking about him warily the stranger picked up his bicycle and flung it into the dark waters of the pool. Danny heard the splash, and all was still.

Then the man looked about him again, turning his head from side to side, as if to make sure he was not perceived. What was he going to do? Then, alas, he saw Danny! For one moment he stood quite still, gazing up at him, as if in dismay. Then, like a shadow, he vanished behind the crumbling walls of the deserted mill.

For a moment, Danny stood quite still, his eyes and mouth wide open with utter surprise.

Looking about him warily the stranger picked up his bicycle and flung it into the dark waters of the pool.

[15]Then the detective instinct in him realised that there must be something very “fishy” about a person who threw a good bike into a pond! He also realised that if he was to find out anything about this fishy person there was not a moment to be lost, so he scrambled down off the rickety old wall that he had been scaling, when he got his glimpse of the man, and set off across the yard.

The man had caught sight of Danny, he felt sure, just after flinging the bicycle into the pond. This was why he had vanished so quickly. The pond was hidden from Danny’s view when he got down from the wall. Would this give the stranger a chance to escape?

A moment later Danny was hurrying down the steep bank towards the marshy ground where the pond lay.

When he reached the pool there was no sign of the man. He peered about in the old barns, the rickety sheds, and the broken pig-sty—the man was nowhere. He went up into the mill. He climbed up ladders to the topmost[16] floor. He peered between the great millstones. He leant far out of the windows and looked up and down the road and across the fields. There was no sign of the stranger.

“He must be a jolly good scout to have hidden so quickly,” said Danny to himself. “I wasn’t more than two minutes getting to the pond, but he managed to bunk.”

The only thing to do was to track the man down. Yes, there were the footmarks and a bicycle track in the soft mud of the little path that led down from the road to the marshy ground by the pond. Danny examined them carefully; they were quite fresh. He compared them with the drawing he had made in his pocket-book half an hour before, and they tallied exactly. So this was the same man; there could be no mistake.

With his heart thumping hard, Danny followed up the tracks. They led to the pond in a roundabout way, showing that the man had taken cover behind a hedge, the old barn, and a broken wall. By the side of the pond the[17] wheel tracks stopped. Danny could see the firm, deep marks where the man had stood while picking up the machine and throwing it into the water.

Then the footmarks went off at right angles; four long strides—and they stopped behind the broken wall, where the man seemed to have stood still. Danny searched all round, but the footmarks did not go any further. And yet there was no cover here!

He walked in a circle round the spot at about five yards’ distance, but no tracks were to be seen. Danny the Detective was sorely puzzled. But, returning to the place by the wall where the man had stood, he suddenly saw what he had missed before. The footprints did leave the spot, but they went straight back to the pond-side, treading almost where the first footprints showed!

He followed them up. But at the water’s edge he was as puzzled as he had been at the wall. The footprints did not lead away!

Danny was stumped. There was nothing[18] more to be done. It seemed a mystery with no solution—a riddle with no answer. He determined to put the matter into the hands of wiser people than he.

Squatting on the old wall he wrote in his notebook an account of what had passed. Then he set off homewards. At the Pack Headquarters, he found Fred Codding, his Sixer, ramping on the step.

“You little rotter!” he cried, as soon as he saw Danny. “What did you want to fall out for, and then play about and not come back? All the other chaps have gone back to tea. But when we found that you were not at your house I was told to wait here and report to Mr. Fox if you were not back by 6.30.”

“Awfully sorry, Fred,” said Danny, “but I wasn’t playing about. I was having a wonderful adventure. I——”

“Oh, shut up!” said Fred, impatiently. “We know all about your ‘adventures.’”

“But this is truth,” said Danny, in despair. “A most extraordinary thing happened——”

[19]“Dry up!” said Fred.

But Danny was determined to make him listen.

“Look here,” he said, “it’s all very well for you to say, ‘Dry up,’ but what would you say if you saw a chap chuck a good bike into a pond and then make off?”

“I’d say the chap who told me such a yarn was a liar,” said Fred. “I must go and report that you’ve got back,” he added. “You cut along home and stop telling everyone detective stories. Remember you’re a Wolf Cub, and not a kid any more. A Cub is truthful.”

Danny flushed to the roots of his hair. But he had the sense not to answer back, for he knew that if he did he would not be able to resist punching his Sixer’s head—and that would not be loyalty. So he turned and went sadly home.

But the strange thing he had seen was not to be put out of his mind so easily. Something must be done. He decided to go to the Scouts about it that night.

[20]After tea he set out for the Scouts’ Headquarters. There was a meeting on. He banged at the door.

“What d’you want?” said the Second who opened it.

“I want to speak to Patrol-Leader Church,” said Danny. He felt sure his friend would give him a fair hearing.

“He’s away,” said the Scout, “gone to see his uncle at Thornhurst.”

“I’ve got something very important to report,” said Danny.

“Sorry,” said the Scout kindly, “there’s a Court of Honour sitting just now. Come another time.”

But here the Chairman’s voice broke in.

“Bring the kid in,” he called. “Let’s hear the ‘important’ matter!”

Danny entered the brightly lighted room shyly. The eight Leaders and Seconds stared at him. Then one of them, Fred Codding’s big brother, burst into a shout of laughter.

“Hullo!” he cried, “it’s ‘Danny the Detective!’[21] I hear from my young brother that he’s got a wonderful yarn about a mysterious stranger and a bike and a pond!”

Danny flushed. Then he looked straight at Patrol-Leader Codding.

“Your brother wouldn’t believe me,” he said, “but I’m a Wolf Cub, and I wouldn’t tell a lie for anything. It’s the truth, and that’s what I’ve come about.”

The Patrol-Leaders smiled.

“All right, youngster,” said the Chairman, “sit down. And when we’ve done the job we’re on now, you can make your report.”

Danny sat down, wishing himself a hundred miles away. Presently the Chairman called him up.

“Please give the Court your report about this stranger,” he said solemnly.

Danny forgot his shyness. It seemed to him that he was a chief witness, giving evidence at a court of law. Very clearly he told his story.

The Court deliberated for a few minutes.

[22]“It’s a good yarn, anyway!” said the Chairman, “though I can’t see the chap’s idea in throwing his bike in the pond. Look here, youngster, we’ll take the matter in hand. Kangaroo Patrol shall go with you to-morrow and drag the pond. If they find the bike we will take further steps.”

This was duly recorded in the minutes by the Secretary.

Danny was delighted.

“Thank you very much indeed!” he said, and, saluting, withdrew.

“Smart little chap!” said the Leaders, as they turned once more to the business on hand.

It was Saturday. At 2.30 the Kangaroos were coming to drag the pond. Danny had got up at 6.30 and was at the scene of yesterday’s adventures by 7.30. The tracks were still clear, but there were no new ones.

All the morning he was on guard, now watching from his place of ambush behind the old wall; now exploring the mill for any possible clues.

The sky was black with threatening clouds. At twelve the storm broke. The rain came down in torrents. Danny took shelter in the mill, keeping watch on the pond from the window. It was nearly two before the downpour ceased. Then a pale sunbeam broke out, and Danny ventured forth into the dripping[24] world. Little streamlets gurgled down the paths; cataracts gushed from pipes and gutters about the mill. Small ponds lay in hollow places.

And, alas, the tracks of the stranger’s steps were hidden by an ocean of muddy water!

Danny’s heart sank. He had counted so on showing the Kangaroos this incontestable evidence. Any Scout would have read the true story of yesterday’s adventures in those marks. And now they were gone!

At 2.30 the Kangaroos arrived, very keen on the job. They dragged the pond from end to end. They raked its bottom with a hay-rake. They probed it with a pitchfork. Then they laughed scornfully.

“Nothing doing,” said the Patrol-Leader. “’Fraid you must have been dreaming yesterday, young Wolf Cub.”

Danny was astounded. He had seen the bicycle thrown in, and now he had seen the pond dragged with great thoroughness and no bicycle revealed.

[25]The youngest Kangaroo had a bright idea.

“I expect the chap came early this morning and dragged the pond himself and got up the bike,” he said.

Danny shook his head.

“I was here before it began to rain,” he said, “and there were no fresh tracks.”

The Kangaroos went away, very bored and very muddy. It was not long before the story had spread through the whole Troop and the whole Pack. Everyone was inclined to agree with Fred Codding, the Sixer, that Danny the Detective was a little liar. But Danny, though hopelessly bewildered, knew that what he had seen the day before had not been a dream.

The next few days were very unhappy. Danny was in hopeless disgrace. The Scouts laughed. The Cubs were angry because he had brought disgrace on the Pack. The Scoutmaster chaffed Mr. Fox, the Cubmaster, and said he had heard there was a budding novelist in the Pack!

The only comforting thing that happened[26] was that in a local paper there appeared a short account of a gentleman’s bicycle having mysteriously disappeared from outside a shop where he had left it.

But instead of this convincing everyone that Danny’s story was true, he was only chaffed about the little paragraph.

All this made him quite determined to clear his honour and the honour of the Pack. He made up his mind never to rest until he had solved the mystery. From then onward he looked at everyone with the eye of a detective. Not one stranger escaped his notice, or one unusual track upon the road. He was untiringly on the alert.

Meanwhile the weather had cleared up. The hot July sun had dried the mud completely. The roads became so hard that there was no chance of tracking. Danny was sorry for this, for he was ever on the lookout for the footmarks of which he had a sketch in his book. Now there seemed no chance by this means of obtaining a clue.

[27]But before a month had gone by he had met with another stranger who seemed to form another link in the mysterious chain.

To their pride and joy the 1st Dutton Wolf Cubs had been invited by the Scouts to take part in a great field day. Danny had been given a quarter of a mile of road to patrol. It happened to be the lonely lane that led past the deserted mill.

He had just concealed himself in the hedge when a market-cart rumbled by. A little ahead of him it stopped. The carter looked keenly up and down the road and all about him. Then, as if sure he was not perceived, he pushed aside his vegetable baskets, lifted up a piece of sacking, and helped a man to emerge from the bottom of the cart. Without a single word the man jumped down on to the road, and the cart lumbered on.

The stranger stood for a moment looking about him suspiciously. He was a very ragged and dirty tramp, with a straggling[28] red beard and a great, bulgy sack on his shoulders. Presently, as if to make sure of his whereabouts, he began to plod along the road.

Danny was after him like a flash, his rubber shoes making no noise on the road. It was real “stalking” this time! Scanning every detail of the man’s appearance, Danny could find nothing to show that he was not a genuine tramp. But that which caught his eye was the sack. It was bulgy and ragged. Out of a hole hung a rabbit skin. But there was evidently something large and square in the sack as well. It looked as if it might be a box. And from inside this seemed to come a scraping, scuffling noise, as if it contained something alive.

At this moment the tramp turned suddenly around and saw him.

Danny was a boy who always had all his wits about him. He was a London boy, remember! He realised at once that he must put the man off his guard and not let[29] him think that he had followed him out of suspicion.

“Please, mister,” he said, “could you tell me the time?”

The man was staring angrily at him out of a pair of little, pale blue eyes. He had evidently been startled at finding a Wolf Cub at his heels when he had thought himself quite alone! The innocent question must have reassured him, for he looked very much relieved.

“It’s three o’clock,” he said gruffly.

Danny was looking him over eagerly. What could he say next, so as not to have to go away? Surely this strange man who crept out from among baskets in a cart, carried something alive in a bag full of rabbit skins, and knew the exact time without a watch, must be a “suspicious character!”

“I say, mister,” he continued, skipping along innocently by the man, “are you collecting rabbit skins and bottles?”

“Yes.”

[30]“Are you going to Dutton?”

“Yes.”

“Well, you know the pub. called ‘The Green Man’——”

“Yes, I know it well.”

(Ah, thought Danny, I’ve caught you, old sport! There’s not a pub. called “The Green Man” at Dutton!)

“Well,” he went on aloud, “just a bit further on, past the pub., there’s a little thatched house. That’s where my mother lives. She’ll give you some skins, ’cos we had rabbit-pie last night for supper. You will go to her, won’t you?”

“Yes, I’ll go there right enough,” said the man.

(We’ll see! thought Danny.)

But the man was walking fast. He had very nearly reached the part of the road where Danny’s patrol ended. It seemed to the Cub that the most important thing in all the world just now was to follow up this man. But he knew that he must not fail in his duty. Senior[31] Patrol-Leader Church had posted him on that road and said:

“Don’t leave your post without orders.” So he must stick to it.

“Well, good-bye, mister,” he said. “I’ve got to stay here ’cos I’m a sentry. Don’t forget to call for mother’s rabbit skins.”

“All right,” growled the man, and trudged on while Danny squatted down on the bank and watched him.

“I bet he’s not going to the village!” he said to himself. “He’s a stranger here, but he wants to make out he’s not. And I’m pretty sure he’s not a real tramp, ’cos he has hands like a gentleman. Oh, I do wish I could follow him! I wish it was a muddy day instead of this rotten dry weather—then I’d soon pick up his trail when this game’s over. I wonder if there’s not some way I could track him.”

He racked his brains for a moment and tried to remember what private detectives on the pictures do on such occasions. Suddenly, like a flash, he remembered a fairy story he[32] had read in Hans Andersen. It was about a mother who wanted to know where her daughter went off to in the night, so she sewed a little bag full of flour on to the girl’s dress and cut a hole in the corner of it, so that, as she went along, the flour ran out, and the mother was able to track the girl all through the streets.

“Wish I had a little bag full of flour,” thought Danny. But a Wolf Cub is never at a loss how to do things, once he has got hold of the idea. In a minute he had drawn his notebook out of his pocket and torn a number of pages out. With quick fingers he tore these up into wee scraps and put them into his cap.

The man was already out of sight round the corner. Scrambling up the bank and through the hedge into a field, Danny sprinted along for all he was worth.

Before long he was up with the man, who still plodded along, head bent, his sack on his back. Creeping like a little green snake[33] through the hedge, Danny stole softly up behind him.

He felt just as Cubs do in the Sheer Khan Dance, only this time it was real, not “pretend.” Holding his breath and treading as softly as a cat, he crept so close that he could have touched the tramp. Still the man trudged on. Danny’s heart was in his mouth.

Softly he straightened himself. Then he took a handful of the paper-scraps from his cap and slipped them into the torn pocket of the man’s ragged coat. Then he stood quite still and gradually crept sideways until he was under cover in the ditch. His heart was beating fast. As he watched the retreating figure of the man he saw a little scrap of paper fly out here and there.

“I’ve got you!” said Danny, hugging himself. It was all he could do not to give vent to a howl of joy that would have roused the very jungle!

It was at this moment that an “enemy[34] Scout” trod on a dry stick the other side of the hedge and set Danny on his guard. Lying flat on his tummy in the ditch and peeping through a patch of nettles, he caught sight of a flutter of red and grey that was unmistakably a Kangaroo shoulder-knot!

Creeping along the ditch, regardless of the hundred nettle-stings that raised great white lumps on his knees, Danny indulged in a little strategy. Taking off his cap, he arranged it on a stump so that it just showed above a mass of green and would be well in view from a gap in the hedge.

Then he doubled along the ditch to where a hidden gap gave a beautiful chance for the enemy to cross the road, and, getting over a stile into the wood opposite, to get in touch with their own party. By this tempting gap Danny took cover.

“I hope he sees my cap,” he said to himself, “then he’ll think I’m there, and will bring his party up to this fence.” Suddenly a bright idea struck him. “I’ll make him have[35] a look at it,” he said. Standing cautiously up in the ditch, he picked up a stone and took careful aim. Plump—it fell among the nettles, just by the cap. “That’ll make him think there’s a chap there,” said the detective to himself with satisfaction. And sure enough, before long, the Kangaroos, thinking the sentry was safely ensconced in the ditch further up, were making their way with an unguarded amount of crackling towards the gap. Two minutes later Danny had taken three important prisoners and sent them to the base “out of action.”

“Jolly smart piece of work,” said Patrol-Leader Church, when the field was called in at five o’clock. “I knew I had put a good man on to patrol that road, but I never thought he’d succeed in taking prisoners!”

Danny’s heart glowed at the praise, but his mind was more intent upon the piece of real scouting he had on hand than on the game. When the other boys trooped home to tea, happy and hungry, Danny turned his eager[36] steps in the direction of the lonely piece of road he had been patrolling. He forgot how hungry he was and how nice the cup of tea and the plum cake at home would be. There was work to be done.

In about half an hour Danny was back at the place where he had last seen the tramp. It was a still, summer evening. Not a breath of wind stirred. Danny was glad, for it meant that the scent, in the form of the scraps of paper, would not have blown away. Yes! There was a little piece on the road. Here was another on the bank. Another—another—another! Now there was none for quite a long way. Then—a whole patch on the dusty road! Just here the tramp had been walking at the side of the road, where the dust was soft and white and thick. Joy of joys—his footmarks were distinctly visible!

Out came Danny’s precious notebook, and in a moment he had drawn a quick sketch of the footprint and added its size in inches. Then he went on carefully. Every here and[37] there a little piece of white paper showed distinctly. He had reached the old mill. And sure enough the trail turned down the very path where he had followed the bicycle tracks six weeks ago! In the same way it seemed to indicate that the man had taken cover behind walls and hedges, so as not to be seen from the road or from the mill. Little did he know that he left a tell-tale track of white paper behind him! And as Danny reached the pond he had to put his hands over his mouth to suppress a laugh of delight. There, on the surface of the still, black water, showed a quantity of little scraps of white paper!

Danny walked round the bank, thinking hard. What on earth could the man have got into the pond for?

There were no wet marks on the dust where he got out. It was the most mysterious thing he had ever come across. Here was a pond in which a man and a bicycle had disappeared, and also a tramp with something alive in a sack! Had they drowned themselves? No—for[38] the Kangaroos had dragged the pond and nothing had been fished up.

Suddenly Danny had an idea.

“There must be a kind of cave or cellar they get into from under the water!” he said. “I expect they are burglars or smugglers or forgers or something. And that’s where they hide their treasure. Then, after dark, they come up.” He decided to have another try to make the Scouts take him seriously; but he was still sore at the memory of all the ridicule that had been heaped upon him before.

“I’ll log it down,” he said, taking out his notebook, “and after dark I’ll come back and lie in wait for him as he comes up. Then to-morrow I’ll make my report.”

He squatted down behind the ruined wall and began to write:

“July 26, 1914.

“Saw a tramp get out of a cart, where he was hiding. Followed him. He had something alive in a sack, but he pretended they[39] were rabbit skins and bottles. Said he knew a pub. called ‘Green Man’ in Dutton, which there isn’t. Tracked him down by scraps of paper. He must have got into Mill Pond, but he has not got out yet (6.30).

“(Signed) D. Moor.”

Then he went home to supper.

Night had fallen, soft and dark and still, when Danny climbed out of his little latticed window on to the roof of the porch. He could smell the honeysuckle though he could not see it. And somewhere a nightingale was singing. He had gone up to bed at 9 o’clock. His mother had come in and tucked him up, and, shutting the door, had gone downstairs.

Now Danny scrambled down the trellis-work of the porch and was soon trotting softly along the road. As he got beyond the village his courage began to fail just a wee bit. The road was very dark and lonely. Great black fir trees stretched out weird arms towards him. An owl hooted. A rabbit scampered across his path with a whisk of white tail.[41] Once he jumped as a cow poked her head through a gap at him, and heaved a great sigh. Between the weird black branches of the pines he could see the little, white, sparkling stars winking at him. They reminded him of God, and that after all he was not quite alone. God must be pleased with him, because he was “doing his best.” The lonely darkness ceased to be full of horror. He went on with a brave heart.

At last he reached the pond. All was quite still. After listening intently for a few minutes, he flashed his electric torch on the water. The scraps of paper were still floating about. He walked round the bank, casting a ring of golden light on to the dusty ground. But there were no wet footmarks to show that someone had come up out of the water.

“I’ll keep watch,” said Danny, and he curled up in the shadow of the wall.

It was a warm July night, but Danny’s teeth were chattering as he squatted alone beneath the ruined wall. He gazed fascinated[42] at the black waters of the pond. Any moment a face, with a red, straggly beard, might come up, all wet and dripping and look at him. He half-wished he had not come. But he had vowed to do all he could to solve the problem, and surely he was on the scent at last.

The moments crept by and nothing happened. Everything was very still, save for the occasional hoot of an owl. The world seemed fast asleep. Presently Danny began to nod.

It must have been three hours later when he awoke, stiff and uncomfortable. Where was he? Oh yes! He jumped up quickly, rubbing his eyes. He had slept on guard. He blushed in the darkness. Just think—if he had been a soldier and his officer had come round—the shame of it! And suddenly he found he was simply longing for home and mother and bed.

“My duty,” he said between his chattering teeth. Switching on his electric torch, he went softly round the pond. But there were[43] no wet marks on the parched, dusty bank; so no one had come up out of the water.

From away across the valley stole the faint sound of a church clock. The four quarters rang out; Danny listened for the hour. One ... chimed like a sad voice across the dim countryside. “One o’clock,” whispered Danny. He could not resist the longing for home, and softly he made his way back on to the road.

“Rh-rrru-um!” A great, grey car swung round the corner and hummed past Danny.

“A.R. 1692,” he said to himself as he watched the red tail-light grow smaller and smaller in the distance. Almost from force of habit he fixed the number in his mind.

Danny’s feet seemed to have acquired a nasty habit of tumbling over each other. He wondered why. And then he gave a big yawn. How lovely it would be to be in bed—all warm and safe and cosy, and, best of all, to hear mother snoring in the next room! It was so lonely out here. He trudged sleepily[44] on and round the corner towards Dutton. He was walking on the grass at the side of the road. A ditch ran along the hedge.

Suddenly, almost at his feet, he heard a long, muffled whistle. He started violently, and then, remembering the law of the wild, he “froze.” The next moment three whistle notes sounded, not quite so muffled, and coming, certainly, from the ditch. Then a strange, guttural voice, speaking in low tones. It was there, at his feet, in the ditch. What could it mean? Danny, the sleepy little boy, was trembling with fear, but Danny the Detective was on the scent again.

Creeping softly across the grass to the edge of the ditch he dropped on one knee and peered down. It was far too dark to see anything. So he strained his ears to try and catch this mysterious conversation. He soon found that, though he could hear every word distinctly, he could not understand it. It was in a foreign language! There seemed a lot of “ach,” and “gr-r-r” in it; very ugly it[45] sounded. And the word “so” seemed to come in it rather often. “Nine” was mentioned still more often. Danny listened intently for any words he could recognise. Presently he heard “Sir Edward Grey” ... quite distinctly. It did not convey much to him, but at least the words were English, and he stored them up. “Downing Street” ... he caught, and, later on, “Asquith.”...

It was a funny conversation. It kept breaking off suddenly, and there would be a long silence. Then it would go on for a few words and stop. And, somehow, the whole thing reminded him of how it sounded when the postmaster telephoned from the village post-office.

Suddenly there was a movement in the ditch. “They’re coming out,” thought Danny. Like a rabbit he scuttled out of sight into a place where the bank in front of the ditch formed a kind of little, earthy grotto, half overgrown with bushes. He was hidden in the darkness, but he could see well himself.

[46]As he peered out, straining his eyes in the gloom, he saw a black figure rear itself out of the ditch and stand up against the grey star-spangled sky. He could see its outline quite clearly. It was that of a slight, smallish man. In his hand he held something that looked like about three yards of rather thick rope. For a moment he stood still, brushing the mud from his suit. It was at this moment, when silence was so essential, that Danny felt a violent tickle in his nose.

He was going to sneeze!

“A—hi——A—hi—— A—tishu!” He tried to muffle it in his cap, but it was no use. The man started violently, then looked about him quickly. One step brought him close to Danny’s grotto. He had dropped his rope end, and against the grey sky Danny could see the outline of a revolver in his right hand.

Slowly the man bent towards him, peering through the darkness. Seeing nothing, he stretched out his hand to feel. Cold sweat[47] broke out all over Danny. In a second the man would have touched him.

To keep still meant being caught for certain. To dash out and run would probably mean a bullet in his legs. The groping hand was very near his face. Suddenly an idea seized Danny. The man would not risk the danger of breaking the night stillness with a shot if he thought that the sound he had heard had merely been made by a fox; nor would he bother to follow it up or be in any way disturbed or set on his guard by its presence. With a sudden movement he fastened his sharp little teeth in the hand. The man gave a muffled cry of pain, started back, and Danny, with the bark of a young fox, dashed out past his legs in a doubled-up position, and was soon running down the road under cover of the darkness. Leaping across the ditch and through a well-known gap, he threw himself down on the grass, panting. There was no sound of following footsteps. His ruse had succeeded.

Cautiously Danny rose to his feet and[48] began walking down the side of the hedge on the field side. He was making for home. Strangers with revolvers were not to be followed in the dark, even by detectives, when the latter were unarmed. But before long he had stopped short and was peering through the hedge. A little red light had caught his eye. Yes, it was the tail-light of a motor—A.R. 1692! It was the same car that had passed him—he remembered the number! The head-lights had been turned off. The great body of the car loomed like some huge monster in the darkness. Danny could just make out the form of a man sitting quite still in the driver’s seat. He seemed to be waiting for something.

Perhaps the man who had been talking in the ditch was going to rejoin him. Danny, managing to overcome his fear of the revolver, decided to wait and watch. Before long there was a slight sound and the man he had seen before stepped on to the road from the grassy border that had muffled his approaching steps.[49] The men exchanged a few words in the same guttural language Danny had heard coming from the ditch. Then the driver got down from the car and lit up the head-lights. A bright shaft shot along the road.

Bending down, the man allowed his face to be caught in it for a moment, and Danny looked with all his eyes, so that he might remember every feature.

He was a thick-set man with a square, black beard and thick-lensed, round glasses. An exclamation of annoyance from him brought his friend round to help adjust one of the lamps, and Danny had a glimpse of the second man’s face. He knew him in a moment! It was the mysterious stranger of the bicycle incident, on whose track he had been for so long!

The head-lights being successfully fixed up, the driver of the car went round to the back, and Danny watched, fascinated, while he removed the number board and substituted for it one showing “L. 323.” Then together[50] the men raised the hood of the car, though it was a cloudless night. After moving about some time they both got into the car. But the automatic starter would not work, and the driver, grumbling to himself, climbed out again and went round to turn the handle.

This brought his face once more within the light of the great lamps. Danny’s eyes opened wide at what he saw. The motorist was no longer a black-bearded, spectacled, man. He had now a bristling red moustache and his bright little blue eyes showed out from beneath rather bushy eyebrows! A moment later the car had hummed off down the road.

Bending down, the man allowed his face to be caught in the bright light, and Danny looked with all his eyes, so that he might remember every feature.

It was nine o’clock when Danny woke up the next day—a golden Sunday morning. At first he thought his night adventures had been a dream, and then he realised that it was all true, and jumped out of bed. He longed to tell someone about them. But, remembering the snubs he had received before, and that he had been accused of having lied, he determined to keep his wonderful discoveries to himself. This adventure should be all his own. Danny the Detective would have a big triumph when the whole mysterious case was brought to light, and the wily strangers stood in the dock! His first impulse was to make straight for the scene of last night’s adventure. Then, remembering that private detectives[52] as well as other people must fulfil their duty to God, he set off for church. And after all, he had much to thank God for! Last night he had had a very narrow escape. And also he had got the desire of his heart—a new and important clue.

Church over, he dashed off to examine the ditch. Yes, there was his grotto—he could see it from afar. On reaching the place, the first thing that caught his eye was a long, snake-like something lying half hidden in the rank grass. He picked it up. It was a piece of rubber tubing about three yards long.

“That must be what the man dropped when I sneezed,” said Danny. “I expect he was so worried with my biting his hand that he forgot to pick it up!”

The detective next turned his attention to the ditch. Yes, there were footmarks in the soft mud. And they were the very same that he had drawn a sketch of in his book that day he saw the stranger with the bicycle! There was a kind of dented, flattened place, as if[53] someone had been lying in the ditch. Sticking out of the bank, half hidden by the rank grass, was an old moss-grown drain pipe. Putting his lips to it, Danny spoke a few words. His voice sounded hollow. He slipped the tubing down into it, and put the end to his ear.

“Some telephone!” he said, and fairly wriggled with delight. “So that’s what the chap was doing last night! The question is, who was he talking to, and what kind of a place does this pipe lead to?”

Search as he might he could find no sign of a cave or any hiding-place in the bank.

“It must be fairly deep,” he said, “or they wouldn’t want three yards of tubing.”

He poked a stone through the pipe, and heard it rattle down on to what sounded like a stone floor some way below. Then he sat up and considered. They weren’t just common tramps or poachers, these people he was after, for they owned a car. They were evidently afraid the police were on the lookout[54] for them, or they would not have changed the number board and worn false beards!

“There is some connection between this drain-pipe telephone affair and the mill pond, and I mean to discover what it is!” said Danny the Detective.

After making his puzzling discovery of “the drain-pipe telephone” as he called it, Danny ran off to make his inspection of the mysterious pond. Running his eyes quickly over the bank he soon saw a clue that to the ordinary person would have meant nothing, but which revealed something very important to the “Detective.” On the dusty bank of the pond there was a wet patch, as if something or someone had come up out of the water and stood and dripped for a moment!

The morning shadows had not yet moved away from the spot and allowed the hot July sun to dry the ground. Examining the wet patch more closely, Danny saw that there was duck-weed on it—the same stuff that dotted the surface of the pond. There was also some[55] black mud—just the kind of slime one would expect to coat the bottom of the pool.

“So,” said Danny, “the chap who went down into the pond with his sack did come up the way he went down. He went down on Saturday afternoon and he came up in the night. What’s more, he came up after I had left the place at 1 A.M. I can’t help thinking he had something to do with the two chaps in the car.”

The Detective scratched his head. It was so jolly puzzling.

“Anyway, I missed him. And he’s not here now, so there’s no good in my staying here,” he said.

An empty feeling under his Sunday waistcoat told him that it must be getting near one o’clock. At dinner his thoughts were far away, and his mother wondered why he was so silent. He determined to spend the afternoon having a long think. He would read up all his notes and try to put the various clues together and solve the mystery. He had a particular, secret[56] place of his own where he always hid when he wanted to be quiet. It was in the ruins of an old abbey that stood on the grounds of Sir Edward Finch’s estate.

The old, grey, half-crumbled buildings stood quite close to the little lodge where he lived. No one was allowed to go into this ruin. One reason was that Sir Edward was a funny old crank and hated strangers poking about on his property. Another was that the beautiful old tower of the church was supposed to be tottering and about to fall. In fact, two years ago a man had been killed by a part of the church falling on him. So a high, barbed-wire fence surrounded the ruin. The great iron gates were always kept locked, and no one ever went in. But one day Danny had discovered that there was a little wee path that led from his mother’s cabbage patch to the hedge that divided the garden from the ruin. The path was only about ten inches wide. It must have been made by rabbits, and if rabbits could get through the hedge and the[57] barbed-wire into the mysterious old abbey, a boy could get in, too. So Danny had followed the path and had soon scrambled through the thick hedge. To his delight he had found himself in a fascinating place.

The turf was soft and mossy and full of harebells. And there was the old grey ruin to explore. Danny crept about in the traceried cloisters, where he loved to imagine the holy monks walking six hundred years ago with their sandalled feet. There was the room where he decided they must have had their meals. But most of all he loved the ruined church. Somehow it seemed very holy. He always used to take his cap off when he went in, though it was open to the blue sky, and carpeted with wild flowers. One day he had found a tomtit’s nest built between the mossy stones where the altar had been.

Now, on this hot sleepy Sunday afternoon he crept out into the back-garden and filled his cap with gooseberries. Then he wriggled through the hedge and had soon curled up in a[58] warm corner of the cloisters with no one to see him but the rabbits.

Danny had not had a very restful night, having been on guard by the pond, and now the warm sun and his good dinner and the drowsy hum of the bees in the wild thyme made him very sleepy and he began to nod.

Before long he was fast asleep, and having a very strange dream. He thought he was back in the old days and that he was a knight in shining armour who had come to the abbey to pray before going to the Crusades. In his dream he saw the monks moving about in their white habits. And then he suddenly saw a horrid-looking fellow creeping about in the shadows all dressed in black and hiding a dagger beneath his wide sleeves.

“A traitor,” said Danny in his dream. And then he suddenly saw it was the man he had seen with the bicycle and again in the motor! Drawing his long sword, he stepped forward, and—but at this exciting moment he woke up with a start.

[59]“Danny, Danny!” someone was shouting. “Where are you, you young rotter? Danny, come on, we’re going bathing!”

He started to his feet and rubbed his eyes.

“Here I am!” he called, emerging from the gooseberry bushes as if he had been there all the time.

His Sixer and two Cubs were waiting for him. Very soon the four boys were running gaily off across the marsh with towels round their necks.

It was only about ten minutes’ run down to the seashore. Before long the Cubs were splashing about in the cool green water. It was ripping! In the old London days Danny had bathed all the year round in the baths, but it was not half as jolly as this. All the same, his swimming-bath experience had been useful, for he had learnt to swim well, and to dive.

“I can swim and float,” said Sixer Fred Codding, “but I can’t dive. Show us how you do it, Daniel.”

Danny ducked down his head, chucked up[60] his heels, and vanished. The cool green water closed over his head. Everything looked so funny down there—all a lovely pale green colour, full of myriads of bubbles. Red and brown seaweed waved lazily on the pebbly bottom. Danny swam gently forward, looking for a stone to bring up to show the other chaps he had really been to the bottom of the deep pool.

Suddenly, down there in the dim, bubbly water, among the shells and shrimps and seaweed, a great idea came to him. He would dive down into the mill pond himself and see what there was at the bottom, and why those strangers were so fond of going down there! He swam quickly to the surface, his heart high with resolve. It would take some pluck to do it. “But a chap’s not worth calling a Cub if he can’t do a thing like that!” he said to himself, as he dried vigorously and got into his clothes again.

Tea was ready when Danny got in. He was as hungry as a wolf—or rather a Wolf Cub![61] But if he was to go down that day he must go before the sun set; it was past six already. So he contented himself with a cup of tea and a small piece of bread and butter. “I won’t give in to myself,” he said, thrusting his hands deep into his pockets, as his mother offered him a big slice of the most lovely plum cake.

Running up to his room, he changed into a pair of old shorts, a cotton shirt, and some old gym. shoes. Then he set out along the well-known road that had proved to be so full of mysterious adventures.

There was no sign of any one having been to the pond since the morning. Still, he could not be sure. He felt a strange feeling inside him, as he stood all alone on the bank and looked down into the water. The evening sun was shining full on it; he was glad; it would be easier to see when he was under. What would there be down there? He clenched his fists and said the Cub Promise between his teeth to buck him up. Then he suddenly remembered his dream and how[62] brave he had felt when he was a Crusader-knight, about to challenge the lurking traitor in the Abbey. Before his courage had time to fail he dived, straight as an arrow, into the pond.

It was very different down there from what it was in the sea. All was a murky, brownish colour. Black, slimy weeds waved about, like wicked little clinging hands. He swam about gently but could see nothing unusual. Soon he had to come up for more air. Taking a very big breath, he dived again. This time he happened to be very near the side. In order to keep down and look well about him he caught hold of a big bunch of weed growing on the wall of the pond. Suddenly, just before him, he saw a black, cavernous hole in the bank. It was about three feet across and seemed like the entrance to a passage, leading away from the bottom of the pool. But it was full of water, of course.

Danny rose to the surface for breath, and ideas crowded into his mind. A passage[63] leading away from the bottom of the pond! Then that was where the men went, and where the bicycle had disappeared to for which they had dragged the pond so carefully. But why did not all the water run away? Then he remembered that water never rises above its own level. On that side of the pond the bank rose steeply towards the high ground where the ruined mill stood. If the passage led up in a steep incline, or in steps, it would very soon be on a level with the surface of the pond. The water, flowing into the passage, would rise as high as this, and no higher. The level of the mill and the road was high enough for the passage to rise beyond the water altogether, and still be underground. Did it do this? The only way to find out was to dive again, swim into the passage, and see! He would have to take a very big breath to bring him up where the passage came up, and to let him get back if it did not seem to be rising. It was something of a risk. But Danny had nerved himself to anything. “If I do find a[64] passage it will be jolly dark,” he said. And then he remembered that he had brought his pocket electric light, and had hidden it, with his handkerchief, knife, and two pennies, on the bank before diving. He would take his light down. Perhaps the water would not hurt the battery. Scrambling out on to the edge he soon found his torch, and stowed it away in the pocket of his shorts. Then, taking a mighty breath, he dived again, and swam straight into the dark passage.

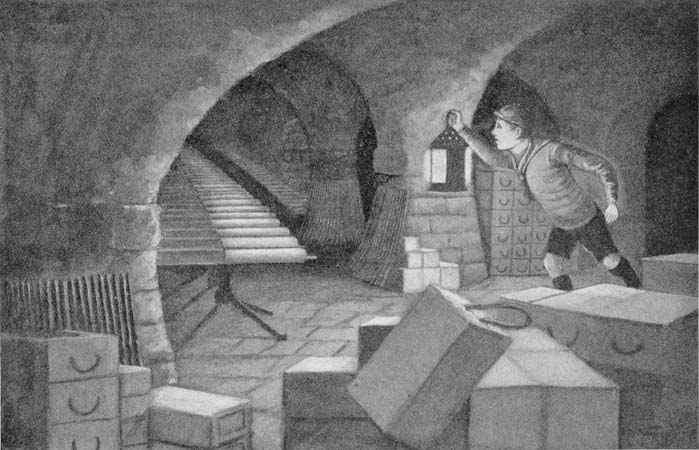

Almost at once his outstretched hands came in contact with something hard and slippery. It was the bottom step of a flight of stone stairs. A moment later Danny was half swimming, half scrambling up them. His store of air was very nearly exhausted when, to his intense relief, his head suddenly came up above the water, and he breathed again. It was pitch dark, and he was standing in water up to his neck. He was safe from drowning, however—that was one thing to be thankful for! He had reached the top step[65] of the flight, and was walking on a slippery surface that seemed to be inclined uphill, as he found that before long his shoulders were out of the water, and then he was only waist-deep. He took out his electric torch and pressed the button. To his joy he found the battery was working, and a ray of golden light shot through the darkness. Turning the light from side to side he saw that he was in a low, vaulted passage, walled and roofed with stone. There was nothing else to see. The passage seemed to go straight ahead. There was nothing for it but to go on, and hope there was no one else down there!

Danny had not walked many yards before his light glinted on something. Peering closer he saw that it was a bicycle leaning up against the wall. “So that’s where the bike went!” said Danny triumphantly, wishing the Kangaroos could see it, as he remembered their cutting remarks the day they dragged the pond in vain.

The bicycle was rusty and useless. The[66] bareheaded stranger who had been in such a hurry that day on the road, and had said that he was going one way when he was really going another, must simply have been flying from his pursuers, and have thrown his stolen bicycle into the pond so as not to leave a clue when he dived down into his wonderful hiding-place!

So the mystery of the bicycle was solved at last! Danny had been determined to solve it. But in working at it he had come on still more mysterious things. It was a big affair this. And now he felt himself well on the way to clearing it up. Had he not got into the most secret hiding-place of the gang? With his heart beating fast with excitement he pressed on along the passage. He had reached dry ground at last. The air was musty and suffocating. Danny the Detective thought that this adventure would solve the whole problem; he little knew all that was to befall him and his country before the mystery would be finally brought to light.

[67]His heart beating fast with excitement, Danny pressed forward through the damp darkness. There was a silent horror about this place. Mildew stood on the walls. Black creatures scurried away beneath his feet, afraid of the light. How often Danny had longed to find a secret passage! But now that he had really found one he shrank from going into the unknown darkness. If only there were another chap to talk to, to feel near! His teeth chattered with the cold, for he was soaking wet. But once more he remembered the Cub Law and did not give in.

“My light won’t last long if I keep it on,” he said. Flashing it round to see his way, he noticed a small lantern hanging on the wall with a box of matches in a little niche. With a sigh of relief he took it down and lighted it. The candle light cast weird, flickering shadows on the wall as Danny hurried on. Every now and then he lifted the lantern high, looking about him. He must have gone nearly a quarter of a mile when, some five feet above[68] his head, a faint streak of pale light shone through a small, round hole in the wall.

“Daylight!” whispered Danny. “I wonder where that hole goes to.” Then he suddenly remembered his adventure of 1 A.M. on Sunday morning. “Why, that must be the drain-pipe telephone!” he said. “This is where the man was who listened at the other end of the pipe while the one in the ditch talked in a funny language!”

Danny must have walked about half a mile when he was brought up short by a flight of stone steps. Mounting these, he found himself face to face with a low door made of some hard, black wood, studded thickly with iron nails and bands, red with rust. There was a massive lock and two heavy bolts. The bolts were not across the door, and Danny stepped forward eagerly, hoping that he would be able to open it. But, try as he would, the door baffled all his efforts. Cold and weary and disappointed he had at last to give up the task. There was nothing for it but to go back.

[69]After a long, dark walk he reached the end of the passage once more and hung the lantern up on its hook. Then, bracing himself for the effort, he plunged again into the black water.

The sun had just set in a glory of red and gold when Danny rose from the mill pool. The air of the summer evening was warm after the icy, tomb-like atmosphere of the passage. It was an infinite relief to see daylight again, and a comfort to hear the birds singing their goodnight songs, and to feel there were live things about. Wringing the water from his clothes, he set out for home at a brisk trot.

“Hullo, Danny,” said his Sixer the next morning, as the boys hurried to school, “where on earth were you last night? You didn’t half miss something. All us chaps were paddling down on the beach, in front of the ‘Blue Boar,’ when an artist-chap came up and started painting.”

“An artist?” said Danny, all interest at once, for, after being a detective, the next[70] thing Danny wanted most in the world to be was an artist.

“Yes,” said Codding, “and he wasn’t half a decent chap either. He let us come as close as we liked and watch him. And he gave us old ends of pencils and crayons and bits of paper. He’s staying at the ‘Blue Boar,’ ’cos he wants to draw heaps of pictures round here. And he said we might come and see him again this evening.”

So, after tea, quite a little crowd of Cubs collected round the artist, who was as friendly as ever. After a time most of them drifted off, and Danny was left alone. The stranger, seeing his interest, gave him a nice, clean piece of paper and some old paints and let him have a try.

A week passed, and every evening he would run down and squat on the ground by the artist, drawing. And while they drew the artist asked him lots of questions about Dutton, and the people, and the country round. Danny, being a Wolf Cub, was[71] delighted to answer them all, promptly and politely, and, if he did not know the necessary information, did his best to find it out for his new friend. When he was tired of drawing he would look at the sketch-books the artist kept in his satchel. The pictures were mostly of harbours and hills and fields. One day he came on one that puzzled him.

“What a funny one this is!” he said.

“Ah!” said the artist. “I’ll tell you why that one looks funny. It is because I was sitting right up on the top of a very high church tower when I drew that. And, looking down, all the country was spread round me like a map, and I looked down on the roofs of the houses and the tops of the trees.”

“Oh,” said Danny, “I see!” He was just looking at a funny little sketch he had found in an inner pocket of the satchel. It was of Dutton, and showed the harbour and the church and the Village, and the roads all round. And it was very much like the one done from the church tower. It puzzled him,[72] because Dutton Church had a spire and no one could sit up on that and paint!

“It’s very funny,” said Danny thoughtfully.

“What’s funny?” asked the artist.

“This sketch. You must have been up somewhere high when you drew it. But we have no church tower here.”

The artist dropped his pencil and turned round quickly on Danny.

“What d’you mean?” he said sharply. “What sketch? Give it to me.” And he snatched it out of the boy’s hand and, folding it, put it in his breast-pocket.

Danny looked keenly at the man. Why was he so flurried and excited? His detective instinct smelt a rat at once.

“Where did you sit, sir, when you did that sketch?” he asked with innocent eyes resting on the artist’s face.

“I, oh—I don’t remember,” said the man.

“But you must have been up high somewhere.”

“No, I wasn’t,” said the artist shortly, and[73] changed the subject. But Danny was not to be put off so easily. He meant to find out why his friend had suddenly turned “snuffy,” and why he had told a lie, for any one could see the sketch had been drawn from above. Sitting silently on the ground, Danny thought deeply. Could it have been drawn from the roof of the Hall? No!—for the Hall and its lake and gardens came into the picture. There was only one other high building in Dutton—the ruined tower of the Abbey. The man must have done his sketch from there! But how had he got up? And why was he so mysterious about it?

“Sir,” said Danny, “how did you manage to get up the tower to do that sketch? The door is always locked and the tower is dangerous.”

The man started at the question, and looked closely at Danny, a frown on his face.

“I don’t know what you mean,” he said. “Run along, now, and don’t go on bothering me—I’m busy.”

[74]Of course Danny examined the door of the tower, but, as usual, it was locked, and there were no signs that any one had broken into the Abbey ruins. But before long he had made a curious discovery about his artist friend. Another friend of Danny’s—a fisherman—had promised to take him out on a fishing expedition, if he could manage to wake up, and get to his cottage by 5 A.M. It was terribly early to have to get up, but, with the help of an alarum clock, Danny managed to wake. The whole Village seemed fast asleep as he crept out into the chill, dewy morning. Not a soul was about. He was trotting along the road at “scouts’ pace,” whistling, when, to his surprise, he suddenly saw the artist walking quickly towards him!

“Hullo, sir!” he cried, with friendly pleasure.

But the artist had started on seeing the Cub, and was not looking over-pleased at this early-morning encounter.

Scanning the man with curious eyes, Danny noticed that his rough tweed suit looked wet.[75] To make sure, he took hold of the artist’s arm, as if by a friendly impulse. Sure, enough, his coat was wringing wet, and, peering more closely, Danny saw little scraps of duck-weed sticking to it. His thoughts flew at once to the mill pond.

But before Danny had had time to think much of this discovery, his quick eyes had noted something else.

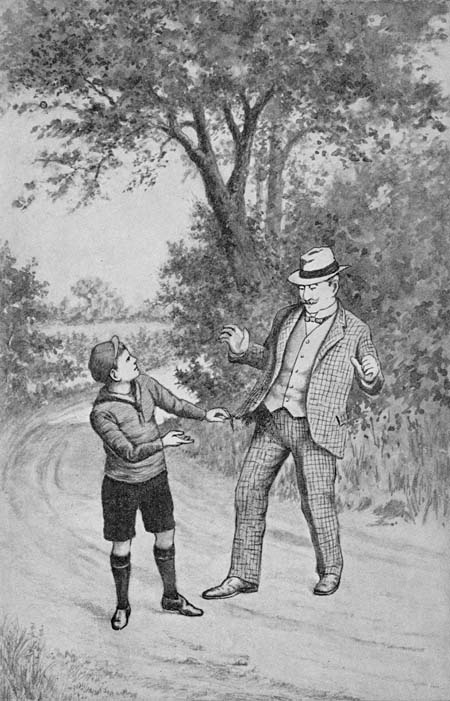

“Look, sir,” he said, “you’ve torn a big piece out of your coat! And one of the buttons, too!” The artist glanced down.

“So I have,” he said, a little uneasily. Then he hurried on, and Danny was left standing in the road. He gave up his idea of going fishing and decided to go on the trail again. Here was a new, important clue—the friendly artist, so full of questions and kindness, was one of the stealthy gang!

He determined to go to the pool and find out where and how the man had torn such a great piece out of his coat.

As he passed the drain pipe in the ditch, he[76] paused and looked at it. He was standing on the bank, his hand resting on a telegraph-pole, when something made him glance up. Just above his head, a torn scrap of cloth, with a button sewn to it, was hanging on a bent nail in the post.

Reaching up, Danny unhooked it. Yes, it was the artist’s button! So he had been climbing a telegraph-pole! What on earth for? Danny was more puzzled than ever. But it was certainly a “clue,” and he logged it in his notebook, with the other particulars concerning the artist.

The pool revealed no more secrets, except that someone had certainly climbed out of it lately, and left wet marks on the bank.

“Look, sir,” he said, “you’ve torn a big piece out of your coat! And one of the buttons, too!”

“My word, but I won’t half keep a sharp lookout on that chap,” said Danny to himself, as he walked home. But he had two pieces of news to learn when he reached Dutton. One was that the artist and his portmanteau had departed in a cart for the station; and the other that the newspapers [77]had very serious news in them. The quarrel between Germany and the Balkan States that had been attracting attention was spreading to something wider. “It will end in a great war,” people said. In a few days came the news that Germany had broken all treaties, and was trampling on little Belgium. England, standing for fair play, must come in. On August 4th, England had declared war on Germany.

“If only we could do something,” everybody felt. The Dutton Scouts and Wolf Cubs fairly ramped with impatience to be called out on war service. Their chance came sooner than they expected. And sooner than he expected came the solution to the great mystery that had puzzled Danny the Detective for so long.

Four days after war was declared, on August 8th, a motor-bike dashed into the village, and from it jumped the District Commissioner. Before long, he, the Scoutmaster, and three of the Patrol-Leaders were shut into the Scout Headquarters; the Cubs hung about outside, longing to know what was on.

The Commissioner’s news was that the War Office urgently called on Scouts to guard the trunk cable-line from being tapped or cut in a certain area, day and night, at once, until further orders. German spies were suspected of tampering with most important telegraph wires. Government secrets were getting out, wrong messages were coming through. Also,[79] messages were somehow getting through to Germany.

The Dutton Scouts were to patrol six miles of the road. The three Patrol-Leaders dashed off on their bikes. In an hour, the troop, in full kit, was patrolling the road and ready to challenge any doubtful person.

Spies! The very word thrilled Danny. And suddenly his heart stood still, and then went on at a great rate. Spies? That was it. His mysterious strangers were German spies, and they had some secret way of communicating with Germany!

The hot afternoon sun beat down on the dusty road that wound like a long white ribbon between the fields and woods. Two and two, the Scouts marched up and down, each couple along their allotted distance. With keen eyes they scanned the face of every passer-by. Now and then they challenged a person of doubtful appearance.

Once the excitement was great, when a disreputable-looking man utterly refused to answer,[80] and tried to pass on, as if he had not heard. The two Ravens took him in charge, and marched him off to the police station. But, after all, he turned out to be a deaf and dumb tramp, well known in the neighbouring workhouse.

“You were quite right to take him up,” said the Commissioner, when he heard of this. “At such times we must take no risks.”

It was hot work patrolling the roads. The Ravens and Lions took on the day duty, and the Otters and Kangaroos, in charge of Senior Patrol-Leader Church, were told off for the still more important night work. The Cubs looked on with longing eyes. Could they do nothing?

Before long their turn came. They were entrusted with the distributing of rations to the Scouts on duty. Two Sixes undertook the food, and the two others the drink; and the thirsty Scouts were indeed glad of it. But the Cubs’ proudest moment came when the order was issued that the Scouts—one[81] Patrol at a time—should knock off duty for half an hour, for tea, and that Cubs should take their place, and patrol the road in company with the Scout left on duty, one out of each couple. It was service for the King! They were guarding England from the Germans, and helping to keep her secrets from the enemy! Each Cub’s heart swelled with pride, as he marched by the side of his Scout.

He could almost imagine that a rifle with a fixed bayonet rested on his shoulder. Behind every tree he almost saw a German. He simply itched to say, “Halt! Who goes there?”

And meanwhile, what of Danny! Was he sharing in the pride and joy of the Pack, in its important work? No; Danny was not feeling very cheerful, for he was conscious that for the first time since he had been a Cub he was failing to do his duty. Why? Because he was giving in to himself, to his own pride and ambition, and thinking of his own glory before the safety of his country.

Here he was, knowing a large number of important particulars about a dangerous gang of spies. He knew their hiding-places; their footprints; the faces and appearance of several of them. He knew mysterious things about them that he did not understand. His country was in great peril; the Scouts were[83] called out to try and catch these very Germans—while he kept his secret to himself. A voice inside him said:

“Danny, it’s your duty to go and report all you know to the police, at once.”

But Danny frowned, and answered: “I won’t. If I do that, the police and the soldiers and the Scouts will take all my clues that I’ve spent months in finding, and they will catch the spies, and have all the fun and get all the honour and glory. They are my spies—I will catch them myself. And all the beastly people who laughed at me and said I was telling lies will see I really am a detective. And p’raps the King will hear about me.”

But still the voice inside him said: “A Cub does not give in to himself. England is in danger—what does it matter if you get the glory or not, as long as her enemies are caught?” But Danny would not listen. He felt sure his great chance had come. To-night he would solve the mystery, and catch the spies red-handed. Once he had found[84] them at it—then he would not mind calling the Scouts or police to his help. But he felt very unhappy inside, as people always do who do wrong with their eyes open, and on purpose.

Danny had meant to stay out all night looking for the spies. But, as luck would have it, his mother caught him as he was creeping out, at nine o’clock, and packed him off to bed, locking his bedroom door. He decided at once to get out of the window. But, oh, bother!—there was his mother talking over the garden gate to Mrs. Jones from next door.

He waited and waited, but they would not go away. Tired out, he decided to lie down on his bed for a little while, and get out as soon as he heard their voices stop and knew the coast was clear. But when you are very sleepy, and lie down on your bed, the chances are that you fall fast asleep. And this is exactly what Danny did.

The church clock was striking twelve when he awoke with a start and sat up. Why was[85] he lying on his bed in uniform? Then he remembered. “Slack little beast,” he called himself. He had slept instead of going out spy-hunting! He jumped off his bed, feeling about for his cap.

Hark! What was that? A deep, distant humming. Was it a motor car on the road? No, it seemed to come from above! It must be an aeroplane. Softly Danny crept to the window. Yes, the whirring, humming sound certainly came down faintly from high, high up in the starry, purple sky. Perhaps it was a German aeroplane!

Danny’s eyes were fixed on that part of the sky whence the sound seemed to come. This happened to be exactly over the tower of the ruined Abbey, whose black outline stood out distinctly against the stars. Suddenly, like a faint flicker of summer lightning, a white glow appeared for a moment over the tower, as if a bright light had been flashed further down, inside, only visible from above. And between the cracks of the half-ruined walls[86] Danny saw a gleam shine for a moment, and then go out. The detective had had his suspicions about that tower ever since the day he had decided that the artist-spy must have been up there. And yet he had not been able to discover anything about it. Now he was certain something was wrong.

The German spies were there, up in the tower!

They had flashed a light in signal to the aeroplane. Even as he listened breathless, the aeroplane buzzed, as if putting on a higher speed, and then sped off in a southerly direction.

“I’ve got you,” hissed Danny, between his clenched teeth, as he climbed out of the window, and down the rose-covered porch.

He meant to try and find out something more from the ruined Abbey, and then make his report to the Scouts on the night patrol. He, the detective, would lead them to the tower, where his prisoners would be caught like rats in a trap. He would show them the[87] secret passage in the pond. He would explain the drain-pipe telephone. He would identify the prisoners. There would be the bicycle man, and the other in the motor car, and the tramp, and the artist. He, Danny, would be the hero of this adventure.