DOMESTIC SERVICE

BY

LUCY MAYNARD SALMON

SECOND EDITION

WITH AN ADDITIONAL CHAPTER ON DOMESTIC

SERVICE IN EUROPE

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO., Ltd.

1901

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1897,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and electrotyped February, 1897. Revised edition

printed March, 1901.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing & Co.—Berwick & Smith

Norwood, Mass. U.S.A.

“The reform that applies itself to the household must not be partial. It must correct the whole system of our social living. It must come with plain living and high thinking; it must break up caste, and put domestic service on another foundation. It must come in connection with a true acceptance by each man of his vocation,—not chosen by his parents or friends, but by his genius, with earnestness and love.”

EMERSON.

The basis of the following discussion of the subject of domestic service is the information obtained through a series of blanks sent out during the years 1889 and 1890. Three schedules were prepared—one for employers, one for employees, and one asking for miscellaneous information in regard to the Woman’s Exchange, the teaching of household employments, and kindred subjects.[1] These schedules were submitted for criticism to several gentlemen prominent in statistical investigation, and after revision five thousand sets were distributed. These were sent out in packages containing from five to twenty-five sets through the members of the Classes of 1888 and 1889, Vassar College, and single sets were mailed, with a statement of the object of the work, to the members of different associations presumably interested in such investigations. These were the American Statistical Association, the American Economic Association, the Association of Collegiate Alumnæ, the Vassar Alumnæ, and the women graduates of the University of Michigan. They were also sent to various women’s clubs, and many were distributed at the request of persons interested in the work.

Of the five thousand sets of blanks thus sent out, 1025 were returned filled out by employers, twenty being received after the tabulation was completed. These gave the facts asked for with reference to 2545 employees. The returns received from employers thus bore about the same proportion to the blanks distributed as do the returns received in ordinary statistical investigation carried on without the aid of special agents or legal authority. The reasons why a larger number were not returned are the same as are found in all such inquiries, with a few peculiar to the nature of the case. The occupation investigated is one that does not bring either employer or employee into immediate contact with others in the same occupation, and it is therefore believed that the relations between employer and employee are purely personal, and thus not a proper subject for statistical inquiry. Another reason assigned was the fear that the agitation of the subject would cause employees to become dissatisfied, while a third reason was the large number of questions included in the blanks, and the fact that no immediate and possibly no remote benefit would accrue to those filling them out. Another reason frequently assigned was that all of the questions could not be answered, and that, therefore, replies to others could not be of service. Several of the questions, however, were framed with the understanding that in many cases they could not be definitely answered; as the question, “How many servants have you employed since you have been housekeeping?” The fact that often no reply could be given, was as significant[ix] of the condition of the service as a detailed statement could have been.

No success had been anticipated in securing replies from employees; but as any study of domestic service would be incomplete without looking at it from this point of view, the attempt was made. As a result, 719 blanks were returned filled out. In some instances employees, hearing of the inquiry, wrote for schedules and returned them answered. In a few cases correspondence was carried on with women who had formerly been in domestic service. The influences that operated to prevent employers from answering the inquiries made had even greater force in the case of employees. In addition, there was present a hesitation to commit anything to writing, or to sign a name to a document the import of which was not clearly understood by them.

The limited amount of information that could be given explains the small number of returns received to the third schedule,—about two hundred.

The returns received were sent to the Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor, where, by the courtesy of the chief of the bureau, they were collated during the spring and summer of 1890, under the special direction of the chief clerk, in accordance with a previously arranged scheme of tables. The general plan of arrangement adopted was to class the schedules with reference to employers, first alphabetically by states and towns, and second alphabetically by population. The schedules were then classed with reference to employees, first by men[x] and women, and second by place of birth. The various statistical devices used in the Massachusetts Bureau were employed in tabulating the material, and greatly facilitated the work.

Fifty large tables were thus prepared, and by various combinations numerous smaller ones were made. The classification thus adopted made it possible to give all the results either in a general form or with special reference to men and women employees, the native born and the foreign born, and to all of the branches of the service. It was also possible to study the conditions of the service geographically, and with reference to the population and to other industrial situations.

The most detailed tables made out concerned the wage question, including a presentation of classified wages, average wages with the percentage of employees receiving the same wages as the average, and also more or less than the average, a comparison of wages paid at different times and of wages received in domestic service and in other employments. For the purposes of comparison, the writer also classified the salaries paid to about six thousand teachers in the public schools in sixteen representative cities, as indicated by the reports of city superintendents for the year during which information concerning domestic service had been given on the schedules. Through the courtesy of a large employment bureau in Boston, the wages received by nearly three thousand employees were ascertained and used for comparison. The most valuable results of the investigation[xi] possibly were those growing out of the consensus of opinion obtained from employers and employees regarding the nature of the service considered as an occupation. The greater proportion of these tables can be found in Chapter V.

The question must naturally arise as to how far the returns received through such investigation can be considered representative. It has seemed to the writer that they could be considered fairly so. Investigations of this character must always be considered typical rather than comprehensive. It is difficult to fix the exact number to be considered typical as between a partial investigation and a census which is exhaustive. In some cases it is possible to obtain a majority in numbers, in others it is not. If the number of returns, however, passes the point where it would be considered trivial, the number between this and the majority may perhaps be regarded as representative. By the application of a similar principle, the expression at the polls of the wishes of the twentieth part of the inhabitants of a state is recognized as the will of the majority. But, while the returns can be considered only fairly representative as regards numbers, they seem entirely so as regards conditions. It is believed that every possible condition under which domestic service exists, as regards both employer and employee, is represented by the returns received, and that, therefore, the conclusions drawn from these results cannot be wholly unreasonable. Moreover, the circulars were sent out practically at random, and, therefore, do not[xii] represent any particular class in society, except the class sufficiently interested in the subject to answer the questions asked. If the returns thus secured can be regarded in any sense as representative, the results based on them may be considered as indicating certain general conditions and tendencies, although the conclusions reached may be modified by later and fuller researches.

The question must also arise as to what it is hoped will be accomplished through this investigation. It is not expected that all, or even any one of the perplexing questions connected with domestic service will be even partially answered by it; it is not expected that any individual housekeeper will have less trouble to-morrow than to-day in adjusting the difficulties arising in her household; it will not enable any employer whose incompetent cook leaves to-day without warning to secure an efficient one without delay. It is hoped, however, that the tabulation and presentation of the facts will afford a broader basis for general discussion that has been possible without them, that a knowledge of the conditions of domestic service beyond their own localities and households will enable some housekeepers in time to decide more easily the economic questions arising within every home, that it will do a little something to stimulate discussion of the subject on other bases than the purely personal one. The hope has also come that writers on economic theory and economic conditions will recognize the place of domestic service among other industries, and will give to the public the results of their scientific[xiii] investigations of the subject, that the great bureaus of labor—always ready to anticipate any demand of the public—will recognize a demand for facts in this field of work.

The writer has followed the presentation of facts by a theoretical discussion of doubtful and possible remedies. But if fuller and more searching official investigation, establishing a substantial basis for discussion, should point to conclusions entirely at variance with those here given, no one would more heartily rejoice than herself. It may reasonably be said that in view of the character of the investigation no conclusions at all should have been advanced by the investigator. Three things, however, seemed to justify the intrusion of personal views; a recognition of the prevalent anxiety to find a way out of existing difficulties, a belief that improvement can come only as each one is willing to make some contribution to the general discussion, and a conviction that no one should criticise existing conditions unless prepared to suggest others that may be substituted for them.

The following discussion would have been impossible without the hearty co-operation of the thousand and more employers and the seven hundred employees who filled out the schedules distributed. The great majority of these were personally unknown to the writer, and she can express only in this public way her deep appreciation of their kindness, as she also wishes to do to the many friends, known and unknown, who assisted in distributing the schedules. She also desires to express her obligation[xiv] to the Hon. Carroll D. Wright, for help received in preparing the schedules and for the receipt of advance sheets from the Census of 1890; to the Hon. Horace G. Wadlin and Mr. Charles F. Pidgin, for the courtesies extended at the Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor, and also to Professor Davis R. Dewey, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; to Dean Marion Talbot of the University of Chicago, and to Professor Mary Roberts Smith, of the Leland Stanford Junior University; to Mrs. John Wilkinson of Chicago, Mrs. John H. Converse of Philadelphia, and Mrs. Helen Hiscock Backus of Brooklyn, for their constant encouragement and assistance in the work. Most of all the writer is under obligation to Miss A. Underhill for her assistance in reading both the manuscript and the proof of the work, and for the preparation of the Index.

Articles bearing on the subject have at different times appeared in the Papers of the American Statistical Association, The New England Magazine, The Cosmopolitan, and The Forum. These have been freely used in the work, and the writer acknowledges the courtesy of the publishers and editors of these periodicals in allowing this use of her papers.

January 18, 1897.

It has seemed advisable in sending out a second edition of this work to add a supplementary chapter on the condition of domestic service in Europe. This is based largely on the inquiries made in season and out of season at different times during the past ten years of heads of households and of housekeepers in England, France, Germany, and Italy. It has naturally been impossible to sum up in a single chapter the mass of information thus gleaned, but a few features common to all of these countries have been indicated, as well as some peculiar to each. The literature bearing directly on the subject is very meagre, but a few titles have been indicated.

For information bearing on this part of the work, I am under special obligation to M. Levasseur of Paris, to Miss Collet of the Labor Department of the Board of Trade, London, to Miss E. M. Hall of Rome, to Professor Victor Böhmert, recently of the Royal Statistical Bureau, Dresden, and to Mrs. J. H. W. Stuckenberg of Cambridge, recently of Berlin.

January, 1901.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I Introduction |

|

| Frequency of discussion of domestic service | 1 |

| Personal character of the discussion | 2 |

| Omission of the subject from economic discussion | 2 |

| General reasons for this omission | 2 |

| Specific reasons for this omission | 4 |

| Fundamental reason for this omission | 5 |

| Can this omission be justified? | 6 |

| CHAPTER II Historical Aspects of Domestic Employments |

|

| Condition of industries in the eighteenth century | 7 |

| Inventions of the latter part of the century | 7 |

| Immediate result of these inventions | 8 |

| Co-operating influences | 8 |

| Effect of inventions on household employments | 9 |

| Release of work from the household | 9 |

| Diversion of labor from the household to other places | 10 |

| Results of this diversion to other places | 11 |

| Diversion of labor from the household into other channels | 11 |

| Household labor becomes idle labor | 12 |

| Outlets for idle labor | 12 |

| General result of change of work in the household | 13 |

| Division of labor in the household only partial | 13 |

| Interdependence of all industries | 15[xviii] |

| CHAPTER III Domestic Service during the Colonial Period |

|

| Domestic service has a history | 16 |

| Three periods of this history | 16 |

| The colonial period | 16 |

| Classes of servants during this period | 17 |

| Early reasons for colonizing America | 17 |

| Advantage to England of disposing of her undesirable population | 17 |

| Protests against this method of settlement | 18 |

| The freewillers | 19 |

| Proportion of redemptioners | 20 |

| Place of birth of redemptioners | 20 |

| Social condition of redemptioners | 21 |

| Methods of securing redemptioners | 22 |

| Form of indenture | 22 |

| Servants without indenture | 22 |

| Virginia law in regard to servants without indenture | 23 |

| Early condition of redemptioners | 25 |

| Subsequent improvement in condition | 27 |

| Wages of redemptioners | 28 |

| Legal regulation of wages | 30 |

| Character of service rendered by redemptioners | 31 |

| Service in Virginia | 32 |

| Service in Maine | 33 |

| Service in Massachusetts | 34 |

| Colonial legislation in regard to masters and servants | 37 |

| Laws for the protection of servants | 38 |

| Physical protection | 39 |

| Laws for the protection of masters | 40 |

| Laws in regard to runaways | 40 |

| Harboring runaways | 41 |

| Inducements to return runaways | 43 |

| Corporal punishment | 44 |

| Trading or bartering with servants | 45 |

| Miscellaneous laws protecting masters | 46 |

| Obligation of masters to community | 47 |

| Redemptioners after expiration of service | 48 |

| Indian servants | 49 |

| Negro slavery | 51 |

| General summary of character of service during the colonial period | 52[xix] |

| CHAPTER IV Domestic Service since the Colonial Period |

|

| Second period in history of domestic service | 54 |

| Substitution for redemptioners of American “help” | 54 |

| Democratic condition of service | 55 |

| Observations of European travellers | 55 |

| Characteristics of the period | 61 |

| Third period in the history of domestic service | 62 |

| The Irish famine of 1846 | 62 |

| The German revolution of 1848 | 63 |

| Opening of treaty relations with China in 1844 | 64 |

| Abolition of slavery in 1863 | 65 |

| Effect of these movements on domestic service | 65 |

| Development of material resources | 66 |

| Effect of this on domestic service | 67 |

| Immobility of labor of women | 68 |

| Change in service indicated by history of the word “servant” | 69 |

| Early meaning of the word “servant” | 69 |

| Use of word “help” | 70 |

| Reintroduction of word “servant” | 71 |

| Impossibility of restoring previous conditions of service | 72 |

| CHAPTER V Economic Phases of Domestic Service |

|

| Domestic service amenable to economic law | 74 |

| Many domestic employees of foreign birth | 74 |

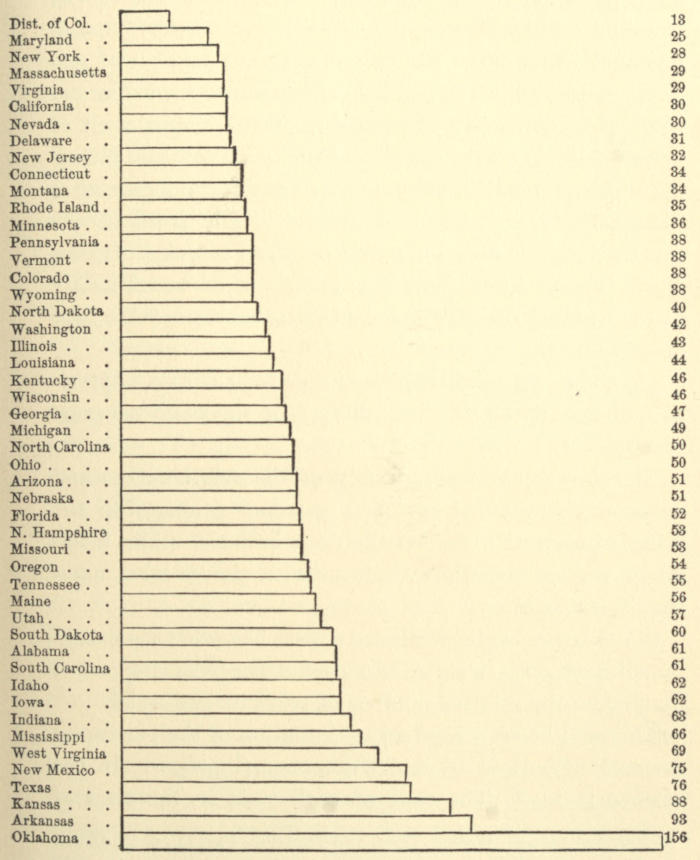

| Geographical distribution of foreign born employees | 75 |

| Concentration of foreign born women in remunerative occupations on domestic service | 77 |

| The foreign born seek the large cities | 77 |

| Foreign countries having the largest representation in large cities | 78 |

| Foreign countries having the largest representation in domestic service | 78 |

| Conclusion in regard to foreign born domestic employees | 80 |

| General distribution of domestic employees | 80 |

| Domestic employees few in agricultural states | 80 |

| The number large in states with large urban population | 80 |

| The number not affected by aggregate wealth | 82 |

| The number somewhat affected by per capita wealth | 82[xx] |

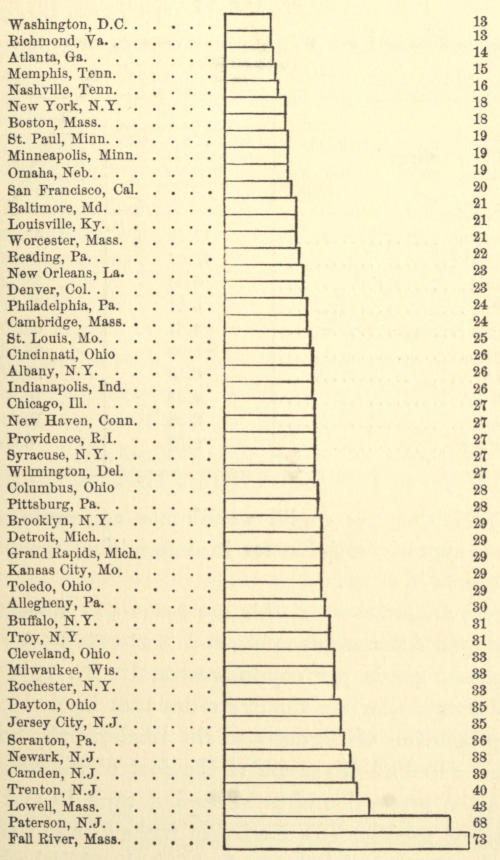

| Domestic employees found in largest numbers in large cities | 83 |

| Proportion of domestic employees varies with geographical location and prevailing industry | 84 |

| Neither aggregate nor per capita wealth determines number of domestic employees in cities | 86 |

| Prevailing industry of city determines number of domestic servants | 87 |

| Competition for domestics between wealth and manufacturing industries | 88 |

| Wages in domestic service | 88 |

| Conformity of wages to general economic conditions | 89 |

| Skilled labor commands higher wages than unskilled labor | 89 |

| The skilled laborer a better workman than the unskilled | 90 |

| The foreign born receive higher wages than the native born | 91 |

| Men receive higher wages in domestic service than women | 92 |

| Tendency towards increase in wages | 93 |

| Comparison of wages in domestic service with wages of women in other occupations | 93 |

| High wages in domestic service do not counterbalance advantages in other occupations | 103 |

| Domestic service offers few opportunities for promotion | 103 |

| Time unemployed in domestic service | 104 |

| High wages maintained without strikes | 105 |

| Conclusions in regard to wages in domestic service | 106 |

| Conclusions in regard to general economic conditions | 106 |

| CHAPTER VI Difficulties in Domestic Service from the Standpoint of the Employer |

|

| Conditions of the average family | 107 |

| Difficulties in domestic service | 108 |

| Prevalence of foreign born employees | 108 |

| Restlessness among employees | 109 |

| Employment in skilled labor of unskilled laborers | 112 |

| Difficulty in changing employees | 114 |

| Recommendations of employers | 114 |

| The employment bureau | 115 |

| Indifference of employers to economic law | 117 |

| Illustrations of this indifference | 117 |

| Difference between the employers of domestic labor and other employers | 121[xxi] |

| Difficulties considered are not personal | 122 |

| Difficulties not decreasing | 125 |

| Difficulties not confined to America | 127 |

| The question in England | 127 |

| Condition of service in Germany | 128 |

| Service in France | 129 |

| Summary of difficulties | 129 |

| CHAPTER VII Advantages in Domestic Service |

|

| Personnel in domestic service | 130 |

| Reasons why women enter domestic service | 131 |

| High wages | 131 |

| Occupation healthful | 132 |

| It gives externals of home life | 133 |

| Special home privileges | 133 |

| Free time during the week | 134 |

| Annual vacations | 135 |

| Knowledge of household affairs | 137 |

| Congenial employment | 137 |

| Legal protection | 138 |

| Summary of advantages | 138 |

| CHAPTER VIII The Industrial Disadvantages of Domestic Service |

|

| Reasons why women do not choose domestic service | 140 |

| No opportunity for promotion | 141 |

| Work in itself not difficult | 142 |

| “Housework is never done” | 142 |

| Lack of organization | 143 |

| Irregularity of working hours | 143 |

| Work required evenings and Sundays | 146 |

| Competition with the foreign born and negroes | 146 |

| Lack of independence | 147 |

| Summary of industrial disadvantages | 149[xxii] |

| CHAPTER IX The Social Disadvantages of Domestic Service |

|

| Lack of home life | 151 |

| Lack of social opportunities | 152 |

| Lack of intellectual opportunities | 153 |

| Badges of social inferiority | 154 |

| Use of word “servant” | 155 |

| The Christian name in address | 156 |

| The cap and apron | 157 |

| Acknowledgment of social inferiority | 158 |

| Giving of fees | 158 |

| Objections to feeing system | 159 |

| Excuses made for it | 161 |

| Other phases of social inferiority | 162 |

| Social inferiority overbalances industrial advantages of the occupation | 163 |

| Comparison of advantages and disadvantages of the occupation | 165 |

| CHAPTER X Doubtful Remedies |

|

| Difference of opinion in regard to remedies possible | 167 |

| General principles to be applied | 168 |

| The golden rule | 169 |

| Capability and intelligence of employer | 170 |

| Receiving the employee into the family life of the employer | 170 |

| Importation of negroes from the South | 172 |

| Importation of Chinese | 176 |

| Granting of licenses | 177 |

| German service books | 178 |

| Convention of housekeepers | 179 |

| Abolishing the public school system | 179 |

| “Servant Reform Association” | 179 |

| Training schools for servants | 180 |

| Advantages of such schools | 180 |

| Practical difficulties in the way | 182 |

| Not in harmony with present conditions | 184 |

| Co-operative housekeeping | 186 |

| Advantages of the plan | 187[xxiii] |

| Objections to it | 188 |

| Practical difficulties in carrying it out | 190 |

| Co-operative boarding | 191 |

| Objections to the plan | 192 |

| Mr. Bellamy’s plan | 192 |

| Reasons for considering these proposed measures impracticable | 193 |

| CHAPTER XI Possible Remedies—General Principles |

|

| Remedies must take into account past and present conditions | 194 |

| Industrial tendencies | 194 |

| Concentration of capital and labor | 194 |

| Specialization of labor | 195 |

| Associations for mutual benefit | 195 |

| Specialization of education | 195 |

| Profit sharing | 196 |

| Industrial independence of women | 196 |

| Helping persons to help themselves | 196 |

| Publicity in business affairs | 197 |

| The question at issue | 198 |

| Impossibility of finding a panacea | 199 |

| General measures | 199 |

| Truer theoretical conception of place of household employments | 199 |

| A more just estimate of their practical importance | 200 |

| Removal of prejudice against housework | 201 |

| Correction of misconceptions in regard to remuneration for women’s work | 201 |

| Summary of general principles | 203 |

| CHAPTER XII Possible Remedies—Improvement in Social Condition |

|

| Social disadvantages | 204 |

| Possibility of removing them | 204 |

| Provision for social enjoyment | 205 |

| Abolishing the word “servant” | 207 |

| Disuse of the Christian name in address | 209 |

| Regulation of use of the cap and apron | 209 |

| Abandoning of servility of manner | 210 |

| Principles involved in freeing domestic service from social objections | 211[xxiv] |

| CHAPTER XIII Possible Remedies—Specialization of Household Employments |

|

| Putting household employments on a business basis | 212 |

| Articles formerly made only in the household | 212 |

| Articles in a transitional state | 213 |

| Articles now usually made in the house | 213 |

| Removal of work from the household | 215 |

| This change in line with industrial development | 215 |

| Indications of its ultimate prevalence | 216 |

| The Woman’s Exchange | 217 |

| The opening up to women of a new occupation | 218 |

| Ultimate preparation of most articles of food outside of the individual home | 219 |

| Advantages of this plan | 219 |

| Objections raised to it | 221 |

| These objections not valid | 221 |

| Laundry work done out of the house | 222 |

| Advantages of the plan | 223 |

| Possibility of having work done by the hour, day, or piece | 223 |

| Improved method of purchasing household supplies | 225 |

| Operation of unconscious business co-operation | 226 |

| General advantages of specialization of household employments | 228 |

| Objections raised to the plan | 230 |

| These objections not valid | 231 |

| Illustrations of success of the plan | 233 |

| CHAPTER XIV Possible Remedies—Profit Sharing |

|

| Industrial disadvantages of domestic service | 235 |

| Industrial difficulties in other occupations still unsettled | 236 |

| Possible relief through profit sharing | 236 |

| Definition of profit sharing | 236 |

| History of profit sharing | 237 |

| Advantages of profit sharing in other occupations | 237 |

| Lessons to be learned from profit sharing | 240 |

| Domestic service wealth consuming rather than wealth producing | 240 |

| The wage system not satisfactory in the occupation | 241[xxv] |

| Application of the principle of profit sharing to the household | 242 |

| Advantages of the plan in the household | 244 |

| Its advantages in hotels, restaurants, and railroad service | 244 |

| Substitution of profit sharing for fees | 244 |

| Objections to profit sharing in the household | 245 |

| These objections do not hold | 246 |

| Experiments in profit sharing in the household | 248 |

| CHAPTER XV Possible Remedies—Education in Household Affairs |

|

| Lack of information one obstacle in the household | 251 |

| Difference between information and education | 251 |

| What is included in information | 251 |

| Difficulty of obtaining information in regard to the household | 252 |

| Advance in other occupations through publicity of all information gained | 252 |

| What is included in education | 252 |

| Information and education necessary in the household | 254 |

| Progress hindered through lack of these | 254 |

| Cause of inactivity in household affairs | 254 |

| Assumption that knowledge of the household comes by instinct | 254 |

| Assumption that household affairs concern only women | 256 |

| Belief that all women have genius for household affairs | 257 |

| Theory that household affairs are best learned at home | 258 |

| Tendencies in the opposite direction | 259 |

| Establishment of school of investigation | 259 |

| Necessity for investigation before progress can be made | 260 |

| CHAPTER XVI Conclusion |

|

| Summary of points considered | 263 |

| Failure to recognize industrial character of domestic service | 264 |

| Conservatism of women | 264 |

| Summary of difficulties | 265 |

| Explanation of difficulties | 265 |

| Responsibility of all employers | 266[xxvi] |

| Results to be expected from investigation | 266 |

| Removal of social stigma | 266 |

| Simplification of manner of life | 267 |

| Household employments on a business basis | 268 |

| Profit sharing | 268 |

| Investigation of household affairs | 269 |

| Readjustment of work of both men and women | 270 |

| Difficulty of dealing with women as an economic factor | 270 |

| Advantages of their working for remuneration | 272 |

| Division of labor in the household | 272 |

| Reform possible only through use of existing means | 273 |

| General conclusion | 274 |

| CHAPTER XVII Domestic Service in Europe |

|

| Opinion held in America | 275 |

| Ideal service not found in Europe | 275 |

| Influences that affect the question | 276 |

| External conditions that affect the question | 277 |

| Architecture a factor in the problem | 277 |

| Difficulties of the European employer | 278 |

| Advantages of service in Europe | 280 |

| Baking and laundry done out of the house | 280 |

| Legal contracts in Germany | 281 |

| The German service book | 284 |

| Employment of men | 286 |

| Wages in domestic service in Europe | 288 |

| Supplementary fees and profits | 290 |

| Allowances | 292 |

| Insurance | 292 |

| Difficulty of determining exact wages | 293 |

| Character of the service | 294 |

| Other factors affecting the question | 295 |

| Social condition of the employee | 296 |

| In England | 297 |

| In France | 299 |

| In Italy | 299 |

| Benefactions for servants in Germany | 299 |

| Conclusion | 301[xxvii] |

| Appendix I. Copy of schedules distributed | 305 |

| Appendix II. List of places from which replies to schedules were received | 314 |

| Appendix III. Circular sent out by the social science section of the Civic Club of Philadelphia | 315 |

| Bibliography | 317 |

| Index | 323 |

Domestic service has been called “the great American question.” If based on the frequency of its discussion in popular literature, foundation for this judgment exists. Few subjects have attracted greater attention, but its consideration has been confined to four general classes of periodicals, each treating it from a different point of view. The popular magazine article is theoretical in character, and often proposes remedies for existing evils without sufficient consideration of the causes of the difficulty. Household journals and the home departments of the secular and the religious press usually treat only of the personal relations existing between mistress and maid. The columns of the daily press given to “occasional correspondents” contain narrations of personal experiences. The humorous columns of the daily and the illustrated weekly papers caricature, on the one side, the ignorance and helplessness of the housekeeper, and, on the other side, the insolence and presumption of the servant. In addition to this, in many localities it has passed into a common proverb that, among housekeepers, with whatever topic conversation begins, it sooner or later gravitates[2] towards the one fixed point of domestic service, while among domestic employees it is none the less certain that other phases of the same general subject are agitated.

This popular discussion, which has assumed so many forms, has been almost exclusively personal in character. A somewhat different aspect of the case is presented when the problem is stated to be “as momentous as that of capital and labor, and as complicated as that of individualism and socialism.” This statement suggests that economic principles are involved, but the question of domestic service has been almost entirely omitted, not without reason, from theoretical, statistical, and historical discussions of economic problems. It has been omitted from theoretical discussions mainly because: (1) the occupation does not involve the investment of a large amount of capital on the part of the individual employer or employee; it therefore seems to be excluded from theoretical discussions of the relations of capital, wages, and labor; (2) no combinations have yet been formed among employers or employees; it is therefore exempt from such speculations as are involved in the consideration of trusts, monopolies, and trade unions; (3) the products of domestic service are more transient than are the results of other forms of labor; this fact must determine somewhat its relative position in economic discussion. Its exclusion, as a rule, from the statistical presentations of the labor question is also not surprising. The various bureaus of labor, both national and state, consider only those subjects for the investigation of which there is a recognized demand. They are the leaders of[3] public opinion in the accumulation of facts, but they are its followers as regards the choice of questions to be studied. Public opinion has not yet demanded a scientific treatise on domestic service, and until it does the bureaus of labor cannot be expected to supply the material for such discussion.[2] Again, it is not surprising that the historical side of the subject has been overlooked, since household employments have been passive recipients, not active participants, in the industrial development of the past century. Yet it must be said that this negative consideration of the subject by theoretical, practical, and historical economists, and the positive treatment accorded it by popular writers, seems an unfair and unscientific disposition to make of an occupation in which by the Census of 1890 one and a half millions of persons are actively engaged,[3] to whom employers pay annually at the lowest rough estimate in cash wages more than $218,000,000,[4] for whose support they pay at the lowest[4] estimate an equal amount,[5] and through whose hands passes so large a part of the finished products of other forms of labor.[6]

It is not difficult, however, to find reasons, in addition to the specific ones suggested, for this somewhat cavalier treatment of domestic service. The nature of the service rendered, as well as the relation between employer and employee, is largely personal; it is believed therefore that all questions involved in the subject can be considered and settled from the personal point of view. It follows from this fact that it is extremely difficult to ascertain the actual condition of the service outside of a single family, or, at best, a locality very narrow in extent, and therefore that it is almost impossible to treat the subject in a comprehensive manner. It follows as a result of the[5] two previous reasons that domestic service has never been considered a part of the great labor question, and that it has not been supposed to be affected by the political, social, and industrial development of the past century as other occupations have been.

These various explanations of the failure to consider domestic service in connection with other forms of labor are in reality but different phases of a fundamental reason—the isolation that has always attended household service and household employments. From the fact that other occupations are largely the result of association and combination they court investigation and the fullest and freest discussion of their underlying principles and their influence on each other. Household service, since it is based on the principle of isolation, is regarded as an affair of the individual with which the public at large has no concern. Other forms of industry are anxious to call to their assistance all the legislative, administrative, and judicial powers of the nation, all the forces that religion, philanthropy, society itself can exert in their behalf. The great majority of housekeepers, if the correspondent of a leading journal is to be trusted, “do not require outside assistance in the management of their affairs, and consequently resent any interference in the administration of their duties.”

The question must arise, however, in view of the interdependence of all other forms of industry, whether it is possible to maintain this perfect separation with regard to any one employment, whether household employments are justified in resenting any intrusion into their domain, whether the individual employer is right in considering[6] household service exclusively a personal affair. An answer to the question may be of help in deciding whether the difficulties that are found in the present system of domestic service arise in every case necessarily from the personal relations which exist between employer and employee, or are largely due to economic conditions over which the individual employer has no control. Still further, the conclusions reached must determine somewhat the nature of the forces to be set in motion to lessen these difficulties.

It is impossible to understand the condition of domestic service as it exists to-day without a cursory glance at the changes in household employments resulting from the inventions of the latter part of the eighteenth century. These changes, unlike many others, came apparently without warning. At the middle of the last century steam was a plaything, electricity a curiosity of the laboratory, and wind and water the only known motive powers. From time immemorial the human hand unaided, except by the simplest machinery, had clothed the world. Iron could be smelted only with wood, and the English parliament had seriously discussed the suppression of the iron trade as the only means of preserving the forests. But during the last third of the century the brilliant inventions of Hargreaves, Arkwright, Crompton, and Cartwright had made possible the revolutionizing of all forms of cotton and woollen industries; Watt had given a new motive power to the world; the uses of coal had been multiplied, and soon after its mining rendered safe; while a thousand supplementary inventions had followed quickly in the train of these. A new era of inventive genius had dawned, which was to rival in importance that of the fifteenth century.

The immediate result of these inventions was seen in the rapid transference of all the processes of cotton and woollen manufactures from the home of the individual weaver and spinner to large industrial centres, the centralization of important interests in the hands of a few, and a division of labor that multiplied indefinitely the results previously accomplished.

But the factory system of manufactures that superseded the domestic system of previous generations has not been the product of inventions alone. It has been pointed out by Mr. Carroll D. Wright[7] that while these inventions have been the material forces through which the change was accomplished, other agencies co-operated with them. These co-operating influences have been physical, as illustrated in the discoveries of Watt; philosophical, as seen in the works of Adam Smith; commercial, or the industrial supremacy of England considered as a result of the loss of the American colonies; and philanthropical, or those connected with the work of the Wesleys, John Howard, Hannah More, and Wilberforce. All these acting in conjunction with the material force—invention—have operated on manufacturing industries to produce the factory system of to-day. It is, indeed, because the factory system is the resultant of so many forces working in the past that it touches in the present nearly every great economic, social, political, moral, and philanthropic question.

Although comparatively few of these inventions have been intended primarily to lessen household labor, this era of inventive activity has not been without its effects[9] on household employments. A hundred years ago the household occupations carried on in the average family included, in addition to whatever is now ordinarily done, every form of spinning and weaving cotton, wool and flax, carpet weaving and making, upholstering, knitting, tailoring, the making of boots, shoes, hats, gloves, collars, cuffs, men’s underclothing, quilts, comfortables, mattresses, and pillows; also, the making of soap, starch, candles, yeast, perfumes, medicines, liniments, crackers, cheese, coffee-browning, the drying of fruits and vegetables, and salting and pickling meat. Every article in this list, which might be lengthened, can now be made or prepared for use out of the house of the consumer, not only better but more cheaply by the concentration of capital and labor in large industrial enterprises. Moreover, as a result of other forms of inventive genius, the so-called modern improvements have taken out of the ordinary household many forms of hard and disagreeable labor. The use of kerosene, gas, natural gas, and electricity[8] for all purposes of lighting, and to a certain extent for heating and cooking; the adoption of steam-cleaning for furniture and wearing apparel; the invention of the sewing-machine and other labor-saving contrivances; the improvement of city and village water-works, plumbing, heat-supplying companies, city and village sanitation measures, including the collection of ashes and garbage,—these are all the results of modern business enterprise.

These facts are familiar, but the effects more easily[10] escape notice. The change from individual to collective enterprises, from the domestic to the factory system, has released a vast amount of labor formerly done within the house by women with three results: either this labour has been diverted to other places, or into other channels, or has become idle. The tendency at first was for labor thus released to be diverted to other places. The home spinners and weavers became the spinners and weavers in factories, and later the home workers in other lines became the operatives in other large establishments. As machinery became more simple, women were employed in larger numbers, until now, in several places and in several occupations, their numbers exceed those of men employees.[9] This fact has materially changed the condition of affairs within the household. Under the domestic system of manufactures nearly all women spent part of their time in their own homes in spinning, weaving, and the making of various articles of food and clothing in connection with[11] their more active household duties. When women came to be employed in factories, the division of labor made necessary a readjustment of work so that housekeeping duties were performed by one person giving all her time to them instead of by several persons each giving a part of her time. The tendency of this was at first naturally to decrease the number of women partially employed in household duties, and to increase the demand for women giving all their time to domestic work.

This readjustment of work in the home and in the factory brought also certain other changes that have an important bearing. The first employees were the daughters of farmers, tradesmen, teachers, and professional men of limited means, women of sturdy, energetic New England character. They were women who, in their own homes, had been the spinners and the weavers for the family and who had sometimes eked out a slender income by doing the same work in their homes for others disqualified for it. As machinery was simplified, and new occupations more complex in character were opened to women, their places were taken in factories by Irish immigrants as these in turn have been displaced by the French Canadians. All these changes in the personnel of factory operatives have meant that while much labor has been taken out of the household, that which remained has been performed by fewer hands, and also that women of foreign nationalities have been pressed into household service.

Another and later result of the change from the domestic to the factory system was the diversion of much of the labor at first performed within the household into entirely different channels. The anti-slavery agitation beginning[12] about 1830 enlisted the energies of many women, and the discussions growing out of it were undoubtedly the occasion for the opening of entirely new occupations to them. Oberlin College was founded in 1833 and Mount Holyoke Seminary in 1837, thus forming the entering wedge for the entrance of women into higher educational work. Medical schools for women were organized and professional life made possible, while business interests began to attract the attention of many.

Another part of the labor released by mechanical inventions and labor-saving contrivances became in time idle labor. By idle labor is meant not only absolute idleness, but labor which is unproductive and adds neither to the comfort nor to the intelligence of society. Work that had previously been performed within the home without money remuneration came to be considered unworthy of the same women when performed for persons outside their own household and for a fixed compensation. The era of so-called fancy-work, which includes all forms of work in hair, wax, leather, beads, rice, feathers, cardboard, and canvas, so offensive to the artistic sense of to-day, was one product of this labor released from necessary productive processes. It was a necessary result because some outlet was needed for the energies of women, society as yet demanded that this outlet should be within the household, and the mechanical instincts were strong while the artistic sense had not been developed. It is an era not to be looked upon with derision, but as an interesting phase in the history of the evolution of woman’s occupation.[10]

Still another channel for this idle labor was found in what has been called “intellectual fancy-work.” Literary clubs and classes sprang up and multiplied, affording occupation to their members, but producing nothing and giving at first only the semblance of education and culture. Many of them became in time a stimulus for more thorough systematic work, but in their origin they were often but a manifestation of aimless activity, of labor released from productive channels.

The era of inventions and resulting business activity has therefore changed materially the condition of affairs within the household. Before this time all women shared in preparing and cooking food; they spun, wove, and made the clothing, and were domestic manufacturers in the sense that they changed the raw material into forms suitable for consumption. But modern inventions and the resulting change in the system of manufactures, as has been seen, necessarily affected household employments. The change has been the same in kind, though not in degree, as has come in the occupations of men. In the last analysis every man is a tiller of the soil, but division of labor has left only a small proportion of men in this employment. So in the last analysis every woman is a housekeeper who “does her own work,” but division of labor has come into the household as well as into the field, though in a more imperfect form. It has left many women in the upper and middle classes unemployed, while many in the lower classes are too heavily burdened; in three of the four great industries which absorb[14] the energies of the majority of women working for remuneration—manufacturing, work in shops, and teaching—the supply of workers is greater than the demand, while in the fourth—domestic service—the reverse is the case. But it cannot be assumed that all of those in the first three classes have necessarily been taken from the fourth class. It has been well said that “through the introduction of machinery, ignorant labor is utilized, not created.” Many who under the old order would have been able to live only under the most primitive conditions, and whose labor can be used under the new order only in the simplest forms of manufacturing, would be entirely unfit to have the care of an ordinary household in its present complex form.

One more effect must be noted of this transference of many forms of household labor to large centres through the operation of inventive genius. It has been seen that many women have thus been left comparatively free from the necessity of labor. The pernicious theory has therefore grown up that women who are rich or well-to-do ought not to work, at least for compensation, since by so doing they crowd out of remunerative employment others who need it. It is a theory that overlooks the historical fact that every person should be in the last analysis a producer, it is based wholly on the assumption that work is a curse and not a blessing, and it does not take into consideration the fact that every woman who works without remuneration, or for less than the market rates, thereby lowers the wages of every person who is a breadwinner. It is a theory which if applied to men engaged in business occupations would check all industrial[15] progress. It is equally a hindrance when applied to women.

This revolutionizing of manufacturing processes through the substitution of the factory for the domestic system has thus rendered necessary a shifting of all forms of household labor. The division of labor here is but partially accomplished, and out of this fact arises a part of the friction that is found in household service.

Household employers and employees may be indifferent to the changes that the industrial revolutions of a century have brought, they may be ignorant of them all, but they have not been unaffected by them, nor can they remain unaffected by changes that may subsequently come in the industrial system. The interdependence of all forms of industry is so complete, that a change cannot revolutionize one without in time revolutionizing all. The old industrial régime cannot be restored, nor can household employments of to-day be put back to their condition of a hundred years ago.

It has been seen how great a change the inventions of the past century have made in the character of household employments. A change in the nature of household service no less important has taken place by virtue of the political revolutions of the century, acting in connection with certain economic and social forces. The subject of domestic service looms up so prominently in the foreground to-day that there is danger of forgetting that it has a past as well as a present. Yet it is impossible to understand its present condition without comprehending, in a measure, the manner in which it has been affected by its own history. It is equally impossible to forecast its future without due regard to this history.

Domestic service in America has passed through three distinct phases. The first extends from the early colonization to the time of the Revolution; the second, from the Revolution to about 1850; the third, from 1850 to the present time.

During the colonial period service of every kind was performed by transported convicts, indented white servants or “redemptioners,” “free willers,” negroes, and Indians.[11]

The first three classes—convicts, redemptioners, and free willers—were of European, at first generally of English, birth. The colonization of the new world gave opportunity for the transportation and subsequent employment in the colonies of large numbers of persons who, as a rule, belonged to a low class in the social scale.[12] The mother country looked with satisfaction on this method of disposing of those “such, as had there been no English foreign Plantation in the World, could probably never have lived at home to do service for their Country, but must have come to be hanged, or starved, or dyed untimely of some of those miserable Diseases, that proceed from want, and vice.”[13] She regarded her “plantations abroad as a good effect proceeding from many evil causes,” and congratulated herself on being freed from “such sort of people, as their crimes and debaucheries would quickly destroy at home, or whom their wants would confine in prisons or force to beg, and so render them useless, and consequently a burthen to the public.”[14]

From the very first the advantage to England of this method of disposing of her undesirable population had been urged. The author of Nova Britannia wrote in 1609: “You see it no new thing, but most profitable for our State, to rid our multitudes of such as lie at home,[18] pestering the land with pestilence and penury, and infecting one another with vice and villanie, worse than the plague it selfe.”[15] So admirable did the plan seem in time that between the years 1661 and 1668 various proposals were made to the King and Council to constitute an office for transporting to the Plantations all vagrants, rogues, and idle persons that could give no account of themselves, felons who had the benefit of clergy, and such as were convicted of petty larceny—such persons to be transported to the nearest seaport and to serve four years if over twenty years of age, and seven years if under twenty.[16] Virginia and Maryland[17] were the colonies to which the majority of these servants were sent, though they were not unknown elsewhere.[18]

Protests were often made against this method of settlement, both by the colonists themselves[19] and by Englishmen,[20] but it was long before the English government[19] abandoned the practice of transporting criminals to the American colonies.[21]

Of the three classes of white, or Christian servants, as they were called to distinguish them from Indians and negroes, the free willers were evidently found only in Maryland. This class was considered even more unfortunate than that of the indented servants or convicts. They were received under the condition that they be allowed a certain number of days in which to dispose of themselves to the greatest advantage. But since servants could be procured for a trifling consideration on absolute terms, there was no disposition to take a class of servants who wished to make their own terms. If they did not succeed in making terms within a certain number of days, they were sold to pay for their passage.[22] The colonists saw very little difference between the transported criminals and political prisoners, the free willers, and the redemptioners who sold themselves into slavery, and as between the two classes—redemptioners and convicted felons—they at first considered the felons the more profitable as their term of service was for seven years, while that of the indented servants was for five years only.[23]

It is impossible to state the proportion of servants belonging to the two classes of transported convicts and redemptioners, but the statement is apparently fair that the redemptioners who sold themselves into service to pay for the cost of their passage constituted by far the larger proportion. These were found in all the colonies, though more numerous in the Southern and Middle colonies than in New England. In Virginia and Maryland they outnumbered negro slaves until the latter part of the seventeenth century.[24] In Massachusetts, apprenticed servants bound for a term of years were sold from ships in Boston as late as 1730,[25] while the general trade in bound white servants lasted until the time of the Revolution,[26] and in Pennsylvania even until this century.[27]

The first redemptioners were naturally of English birth, but after a time they were supplanted by those of other nationalities, particularly by the Germans and Irish. As early as 1718 there was a complaint of the Irish immigrants in Massachusetts.[28] In Connecticut “a parcel of Irish servants, both men and women,” just imported from Dublin, was advertised to be sold cheap in 1764.[29] In[21] 1783 large numbers of Irish and German redemptioners entered Maryland, and a society was formed to assist the Germans who could not speak English.[30]

It has been said that a great majority of the redemptioners belonged at first to a low class in the social scale. A considerable number, however, both men and women, belonged to the respectable, even to the so-called upper classes of society.[31] They were sent over to prevent disadvantageous marriages,[32] to secure inheritances to other members of a family,[33] or to further some criminal scheme.

Many of these bond servants sold themselves into servitude, others were disposed of through emigration brokers,[34] and still others were kidnapped, being enticed on shipboard by persons called “spirits.”[35]

The form of indenture was simple, and varied but little in the different colonies. Stripped of its cumbersome legal phraseology, it included the three main points of time of service, the nature of the service to be performed, although this was usually specified to be “in any such service as his employer shall employ him,” and the compensation to be given.[36]

It sometimes happened that servants came without[23] indenture. In such cases the law expressly and definitely fixed their status, though it was found extremely difficult to decide upon a status that could be permanent. Virginia, in particular, for a long time found it impossible to pass a law free from objections, and its experience will illustrate the difficulties encountered elsewhere. An early law in Virginia provided that if a servant came without indenture, he or she was to serve four years if more than twenty years old, five years if between twelve and twenty years of age, and seven years if under twelve.[37] Subsequently it was provided that all Irish servants without indenture should serve six years[24] if over sixteen and that all under sixteen should serve until the age of twenty-four,[38] and this was again modified into a provision requiring those above sixteen years to serve four years and those under fifteen to serve until twenty-one, the Court to be the judge of their ages.[39] It was soon found, however, that the term of six years “carried with it both rigour and inconvenience” and that thus many were discouraged from coming to the country, and “the peopling of the country retarded.” It was therefore enacted that in the future no servant of any Christian nation coming without indenture should serve longer than those of the same age born in the country.[40] But as the law was also made retroactive, it was soon ordained that all aliens without indenture could serve five years if above sixteen years of age and all under that until they were twenty-four years old, “that being the time lymitted by the laws of England.”[41] This arrangement was equally unsatisfactory, since it was found that under it “a servant if adjudged never soe little under sixteene yeares pays for that small tyme three yeares service, and if he be adjudged more the master looseth the like.” It was then resolved that if the person were adjudged nineteen years or over he or she should serve five years, and if under that age then as many years as he should lack of being twenty-four.[42] This provision was apparently satisfactory, subsequent laws varying only in minor provisions concerning the details of the Act.[43]

The condition of the redemptioners seems to have been, for the most part, an unenviable one. George Alsop, it is true, writes in glowing terms of the advantages enjoyed in Maryland:

“For know,” he says, “That the Servants here in Mary-land of all Colonies, distant or remote Plantations, have the least cause to complain, either for strictness of Servitude, want of Provisions, or need of Apparel: Five dayes and a half in the Summer weeks is the alotted time that they work in; and for two months when the Sun predominates in the highest pitch of his heat, they claim an antient and customary Priviledge, to repose themselves three hours in the day within the house, and this is undeniably granted to them that work in the Fields.

“In the Winter time, which lasteth three months (viz.), December, January, and February, they do little or no work or employment, save cutting of wood to make good fires to sit by, unless their Ingenuity will prompt them to hunt the Deer, or Bear, or recreate themselves in Fowling, to slaughter the Swans, Geese, and Turkeys (which this Country affords in a most plentiful manner): For every Servant has a Gun, Powder and Shot allowed him, to sport him withall on all Holidayes and leasurable times, if he be capable of using it, or be willing to learn.”[44]

Hammond also says of Virginia:

“The Women are not (as is reported) put into the ground to worke, but occupie such domestique employments and houswifery as in England, that is dressing victuals, righting up the house, milking,[26] imployed about dayries, washing, sowing, &c. and both men and women have times of recreations, as much or more than in any part of the world besides.... And whereas it is rumoured that Servants have no lodging other then on boards, or by the Fire side, it is contrary to reason to believe it: First, as we are Christians; next as people living under a law, which compels as well the Master as the Servant to perform his duty; nor can true labour be either expected or exacted without sufficient cloathing, diet, and lodging; all which both their Indentures (which must inviolably be observed) and the Justice of the Country requires.”[45]

A Glasgow merchant under date of January 19, 1714, also writes: “The servants are all well cloathed and provided with bedding as ye will see,” adding that some servants prefer “Mariland, the reason whereof is that Virginia is a little odious to the people here.”[46]

But these enthusiastic descriptions must be taken cum grano salis. The object of Alsop’s book was to stimulate emigration to Maryland, as is evident from the dedication to Lord Baltimore and to “all the Merchant Adventures for Mary-land.” The object of Leah and Rachel was the same, and others who wrote in a similar strain had evidently little personal knowledge of the condition of the redemptioners. The real life is more truly portrayed in the accounts given by the redemptioners themselves, and many of these are preserved.

The Anglesea Peerage Trial brings out the facts that the redemptioners fared ill, worked hard, lived on a coarse diet, and drank only water sweetened with a little molasses and flavored with ginger.[47] Eddis says the redemptioners were treated worse than the negroes, since the loss of a negro fell on his master; inflexible severity[27] was exercised over the European servants who “groaned beneath a worse than Egyptian bondage.”[48]

Richard Frethorne, writing from Martin’s Hundred, gives a pitiful tale of the sufferings of the indented servants. “Oh! that you did see my daily and hourly sighs, groans, tears and thumps that I afford my own breast, and rue and curse the time of my birth with holy Job. I thought no head had been able to hold so much water as hath, and doth daily flow from mine eyes.”[49]

The maid who waited on the Sot-Weed Factor says:

Undoubtedly, in time, servants of all kinds received more consideration than had at first been given them;[51][28] in 1704 Madame Knight even complained of what she considered too great indulgence on the part of the Connecticut farmers towards their slaves.[52] Yet, even at the North, the lot of a servant was not an enviable one, though much was done by the laws of all the colonies to mitigate the condition of the redemptioners, as will be seen later in discussing the legal relations of masters and servants.

The wages paid were, as a rule, small, though some complaints are found, especially in New England, of high wages and poor service.[53] More often the wages were a mere pittance. Elizabeth Evans came from Ireland to serve John Wheelwright for three years. Her wages were to be three pounds a year and passage paid.[54][29] Margery Batman, after five years of service in Charlestown, was to receive a she-goat to help her in starting life.[55] Mary Polly, according to the terms of her indenture, was to serve ten years and then receive “three barrells of corn and one suit of penistone and one suit of good serge with one black hood, two shifts of dowlas and shoes and hose convenient.”[56]

Peter Kalm writes of Pennsylvania in 1748: “A servant maid gets eight or ten pounds a year: these servants have their food besides their wages, but must buy their own clothes, and what they get of these they must thank their master’s goodness for.” He adds that it was cheaper to buy indented servants since “this kind of servants may be got for half the money, and even for less; for they commonly pay fourteen pounds Pennsylvania currency, for a person who is to serve four years.”[57] Even at the beginning of the present century wages had scarcely risen. Samuel Breck writes of two redemptioners whom he purchased in 1817: “I gave for the woman seventy-six dollars, which is her passage-money, with a promise of twenty dollars at the end of three years if she serves me faithfully; clothing and maintenance of course. The boy had paid twenty-six guilders toward his passage-money, which I agreed to give him at the end of three years; in addition to which I paid fifty-three dollars and sixty cents for his passage, and for two years he is to have six weeks’ schooling each year.”[58]

For the protection of both masters and servants the law sometimes interfered and attempted to regulate the matter of wages received at the end of an indenture. In Virginia by the code of 1705 every woman servant was to receive fifteen bushels of Indian corn and forty shillings in money, or the value thereof in goods.[59] In 1748 it was enacted “that every servant, male or female, not having wages, shall, at the expiration of his, or her time of service, have and receive three pounds ten shillings current money, for freedom dues, to be paid by his, or her master, or owner,”[60] and in 1758 the same law was re-enacted, but excepting convicts from the provisions of the Act.[61] In South Carolina all women servants at the expiration of their time were to have “a Wastcoat and Petticoat of new Half-thick or Pennistone, a new Shift of white Linnen, a new Pair of shoes and stockings, a blue apron and two caps of white Linnen.”[62] The laws of Pennsylvania provided that every servant who served faithfully four years should at the expiration of the term of servitude have a discharge and be duly clothed with two complete suits of apparel, one of which should be new,[63] while in Massachusetts and New York it was provided that all servants who had served diligently and faithfully to the benefit of their masters should not be sent away empty.[64] In North Carolina every servant[31] not having yearly wages was to be allowed at the expiration of the term of service three pounds Proclamation money, besides one sufficient suit of wearing clothes.[65] In East New Jersey the law was more liberal and gave every servant two suits of apparel suitable for a servant, one good felling axe, a good hoe, and seven bushels of good Indian corn.[66] West New Jersey gave ten bushels of corn, necessary apparel, two horses, and one axe.[67] In Maryland a woman at the expiration of her term was to have the same provision of corn and clothes as men servants, namely, “a good Cloath suite either of Kersey or broad Cloath, a shift of white Linnen to be new, one new pair of shoes and stockings, two hoes one Ax and three barrˡˡˢ of Indian corn.”[68] A later act specified that women servants were to have “a Waist-coat and Petty-coat of new Half-thick, or Pennistone, a new Shift of White Linen, Shoes and Stockings, a blue Apron, Two Caps of White Linen, and Three Barrells of Indian Corn.”[69]

The test question to be applied to any system of service is—Is the service secured through it satisfactory? It has been seen that a considerable number of servants could be secured through the system of indenture, though probably less than the colonists desired, and that the wages paid them were, as a rule, remarkably low. But it must be said that the service received from indented servants was, as a rule, what might be expected from the class that came to America in that capacity.

It is easy to surmise the character of the service rendered at first in Virginia and the difficulties encountered by employers. Many of the redemptioners had been idlers and vagabonds, and for idlers and vagabonds, there as elsewhere, stringent laws were necessary. In 1610, under the administration of Sir Thomas Gates, various orders were passed with reference to pilfering on the part of launderers, laundresses, bakers, cooks, and dressers of fish.

“What man or woman soeuer, Laundrer or Laundresse appointed to wash the foule linnen of any one labourer or souldier, or any one else as it is their duties so to doe, performing little, or no other seruice for their allowance out of the store, and daily prouisions, and supply of other necessaries, vnto the Colonie, and shall from the said labourer or souldier, or any one else, of what qualitie whatsoeuer, either take any thing for washing, or withhold or steale from him any such linnen committed to her charge to wash, or change the same willingly and wittingly, with purpose to giue him worse, old or torne linnen for his good, and proofe shall be made thereof, she shall be whipped for the same, and lie in prison till she make restitution of such linnen, withheld or changed.”[70]

Even more stringent penalties are attached to purloining from the flour and meal given out for baking purposes.[71]

But it is not alone in Virginia that perplexed employers were found. John Winter, writing to Trelawny from Richmond Island, Maine, under date of July 10, 1639, says of a certain Priscilla:

“You write me of some yll reports is given of my Wyfe for beatinge the maid; yf a faire waye will not do yt, beatinge must, sometimes, vppon such Idlle girrells as she is. Yf you think yt fitte for my wyfe to do all the worke & the maide sitt still, she must forbeare her hands to strike, for then the worke will ly vndonn. She hath bin now 2 yeares ½ in the house, & I do not thinke she hath risen 20 times before my Wyfe hath bin vp to Call her, & many tymes light the fire before she Comes out of her bed. She hath twize gon a mechinge in the woodes, which we haue bin faine to send all our Company to seeke. We Cann hardly keep her within doores after we ar gonn to beed, except we Carry the kay of the doore to beed with us. She never Could melke Cow nor goat since she Came hither. Our men do not desire to haue her boyle the kittle for them she is so sluttish. She Cannot be trusted to serue a few piggs, but my wyfe most Commonly must be with her. She hath written home, I heare, that she was fame to ly vppon goates skins. She might take som goates skins to ly in her bedd, but not given to her for her lodginge. For a yeare & quarter or more she lay with my daughter vppon a good feather bed before my daughter being lacke 3 or 4 daies to Sacco, the maid goes into beed with her Cloth & stockins, & would not take the paines to plucke of her Cloths: her bedd after was a doust bedd & she had 2 Coverletts to ly on her, but sheets she had none after that tyme she was found to be so sluttish. Her beating that she hath had hath never hurt her body nor limes. She is so fatt & soggy she Cann hardly do any worke. This I write all the Company will Justify. Yf this[34] maid at her lasy tymes, when she hath bin found in her ill accyons, do not deserue 2 or 3 blowes, I pray Judge You who hath most reason to Complaine, my wyfe or the maid.... She hath an vnthankefull office to do this she doth, for I thinke their was never that steward yt amonge such people as we haue Could giue them all Content. Yt does not pleas me well being she hath taken so much paines & Care to order things as well as she Could, & ryse in the morning rath, & go to bed soe latte, & to haue hard speches for yt.”[72]

Winter’s letters and reports to the London Company are as full of his trials with his servants indoors and out, as are the conferences to-day between perplexed employers. Even when fortune smiled on him and one promised well, misfortune overtook her.

“The maid Tomson had a hard fortune. Yt was her Chance to be drowned Cominge over the barr after our Cowes, & very little water on the barr, not aboue ½ foote, & we Cannot Judge how yt should be, accept that her hatt did blow from her head, & she to saue her hatt stept on the side of the barr.... I thinke yf she had lived she would haue proved a good servant in the house: she would do more worke then 3 such maides as Pryssyllea is.”[73]

It is true that Maine was a remote colony and the difficulty of obtaining good servants was presumably greater than in places more accessible. Yet the same tale of trial comes from Boston and from those whose means, character, and position in society would seem to exempt them from the difficulties more naturally to be expected in other places. Mrs. Mary Winthrop Dudley writes repeatedly in 1636 to her mother, Mrs. Margaret Winthrop, begging her to send her a maid, “on that should be a[35] good lusty seruant that hath skille in a dairy.”[74] But how unsatisfactory the “lusty servant” proved a later letter of Mrs. Dudley shows:

“I thought it convenient,” she writes, “to acquaint you and my father what a great affliction I haue met withal by my maide servant, and how I am like through God his mercie to be freed from it; at her first coming me she carried her selfe dutifully as became a servant; but since through mine and my husbands forbearance towards her for small faults, she hath got such a head and is growen soe insolent that her carriage towards vs, especially myselfe is vnsufferable. If I bid her doe a thinge shee will bid me to doe it my selfe, and she sayes how shee can give content as wel as any servant but shee will not, and sayes if I loue not quietnes I was never so fitted in my life, for shee would make mee haue enough of it. If I should write to you of all the reviling speeches and filthie language shee hath vsed towards me I should but grieue you. My husband hath vsed all meanes for to reforme her, reasons and perswasions, but shee doth professe that her heart and her nature will not suffer her to confesse her faults. If I tell my husband of her behauiour towards me, vpon examination shee will denie all that she hath done or spoken: so that we know not how to proceede against her: but my husband now hath hired another maide and is resolved to put her away the next weeke.”[75]

Other members of the Winthrop family also have left an account of their trials of this kind. A generation later, July 7, 1682, Wait Winthrop wrote to Fitz-John Winthrop, “I feare black Tom will do but little seruis. He used to make a show of hanging himselfe before folkes, but I believe he is not very nimble about it when he is alone. Tis good to haue an eye to him, and if you think it not worth while to keep him, eyther sell him[36] or send him to Virginia or the West Indies before winter. He can do something as a smith.”[76] In the third generation John Winthrop, the son of Wait Winthrop, wrote to his father from New London, Connecticut, 1717:

“It is not convenient now to write the trouble & plague we have had wᵗʰ this Irish creature the year past. Lying & unfaithfull; wᵈ doe things on purpose in contradiction & vexation to her mistress; lye out of the house anights, and have contrivances wᵗʰ fellows that have been stealing from oʳ estate & gett drink out of yᵉ cellar for them; saucy & impudent, as when we have taken her to task for her wickedness she has gon away to complain of cruell usage. I can truly say we have used this base creature wᵗʰ a great deal of kindness & lenity. She wᵈ frequently take her mistresses capps & stockins, hanckerchers &c., and dress herselfe, and away wᵗʰout leave among her companions. I may have said some time or other when she has been in fault, that she was fitt to live nowhere butt in Virginia, and if she wᵈ not mend her ways I should send her thither; thô I am sure no body wᵈ give her passage thither to have her service for 20 yeares, she is such a high spirited pernicious jade. Robin has been run away near ten days, as you will see by the inclosed, and this creature knew of his going and of his carrying out 4 dozen bottles of cyder, metheglin, & palme wine out of the cellar amongst the servants of the towne, and meat and I know not wᵗ.”[77]

The trials of at least one Connecticut housekeeper are hinted at in an Order of the General Court in 1645, providing that a certain “Susan C., for her rebellious carriage toward her mistress, is to be sent to the house of correction and be kept to hard labor and coarse diet, to be brought forth the next lecture day to be publicly corrected, and so to be corrected weekly, until order be given to the contrary.”[78]

But it is undoubtedly in the legislation of the colonial period that one finds the best reflection of colonial service, and one may say of it, as Judge Sewall wrote to a friend when sending him a copy of the Statutes at Large for 1684, “You will find much pleasant and profitable Reading in it.”[79] Numerous acts were passed in all the colonies determining the relation between masters and servants, and these laws were most explicit in protecting the interests of both parties—a fact often indicated by the very name of the act, as that of 1700 in Pennsylvania, entitled “For the just encouragement of servants in the discharge of their duty, and the prevention of their deserting their master’s or owner’s service.”[80]

In the legislation in regard to service and servants, it is impossible always to discriminate between the general class of either bound or life servants and the particular class of domestic employees. But the smaller class was comprised in the larger, and household servants had the benefit of all legislation affecting servants as a whole. Few or no laws were passed specifically for the benefit of domestic employees.