LONDON: GEORGE BELL AND SONS

PORTUGAL ST. LINCOLN’S INN, W.C.

CAMBRIDGE: DEIGHTON, BELL & CO.

NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN CO.

BOMBAY: A. H. WHEELER & CO.

THE FOREIGN DEBT

OF

ENGLISH LITERATURE

BY

T. G. TUCKER, Litt.D.

PROFESSOR OF CLASSICAL PHILOLOGY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE

LONDON

GEORGE BELL AND SONS

1907

CHISWICK PRESS: CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO.

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON.

The following unpretentious chapters are intended to offer to the ordinary student, who has not yet given the matter any particular thought, a first assistance in realizing the interdependence of literatures. They aim at clearness, and at as great a measure of accuracy as is permitted by the compass within which the matter is necessarily compressed. No pretence whatever is made to completeness. The summaries of various literatures do not profess to be more than epitomes with a special object. If, while helping to that end, they are also readable in themselves, their purpose is served.

It is, perhaps, advisable to state that, while the professional studies of the writer have been for the most part concerned with the literatures of Greece and Rome, it has more than once fallen to his lot to promote academic teaching in the literature of England. It was this[vi] experience which suggested the present attempt at a more general survey. French, Italian, and German literatures have been approached at first hand, although the standard works have been duly consulted. With the literature of Spain contact has been less intimate, but care has been taken to check impressions formed under these conditions. For the rest the best authorities have been used and trusted.

Inasmuch as guiding hints and clues are often more helpful than elaborate treatises, a special acknowledgment is due to various writings of Professor Churton Collins and Professor W. P. Ker.

| PAGE | ||

| INTRODUCTORY | 1 | |

| I. | GREEK LITERATURE AND ENGLISH | 5 |

| II. | LATIN LITERATURE AND ENGLISH | 70 |

| III. | LITERARY CURRENTS OF THE DARK AGES | 116 |

| IV. | FRENCH LITERATURE AND ENGLISH | 136 |

| V. | ITALIAN LITERATURE AND ENGLISH | 178 |

| VI. | OTHER INFLUENCES SUMMARIZED | 216 |

| (a) Spanish Literature and English | 216 | |

| (b) German Literature and English | 231 | |

| (c) Celtic Literature and English | 247 | |

| (d) Hebrew Influence | 253 | |

| INDEX | 259 | |

| SYNOPTICAL TABLES | ||

| 1. Table of Greek Literature. | ||

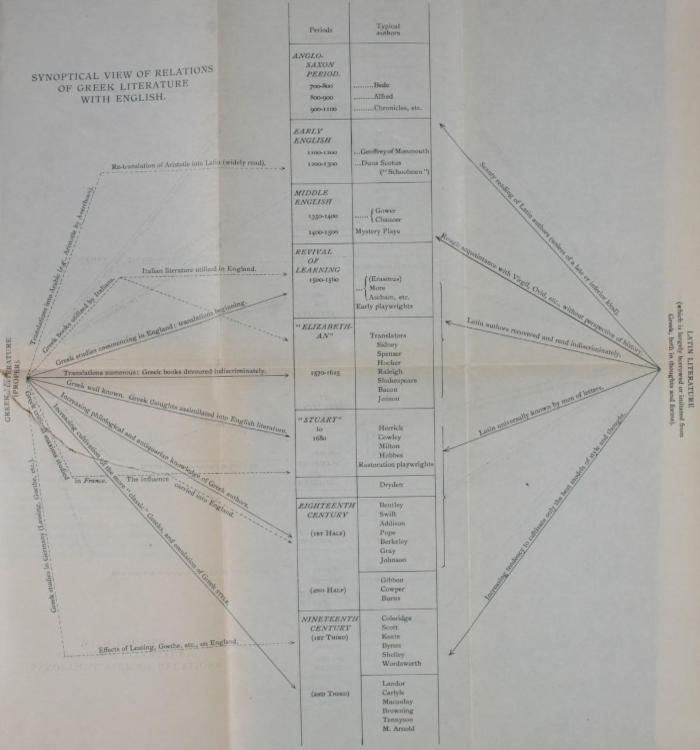

| 2. View of Relations with Greek Literature. | ||

| 3. Table of Latin Literature. | ||

| 4. Table of French Literature. | ||

| 5. Table of Italian Literature. | ||

| 6. Table of Spanish Literature. | ||

| 7. Table of German Literature. | ||

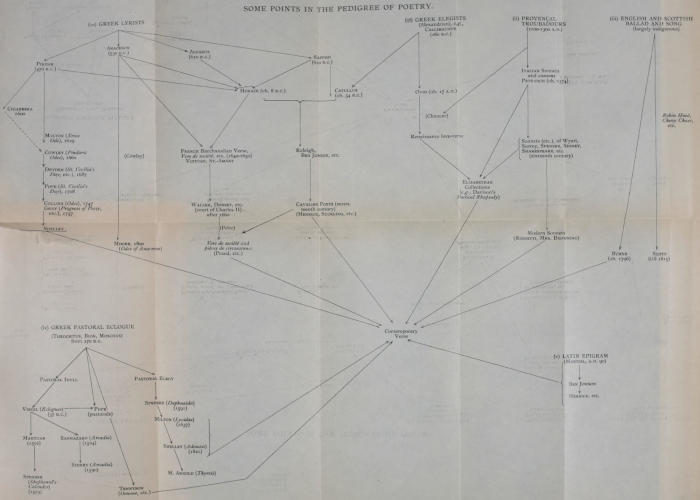

| 8. Some Points in the Pedigree of Poetry. | ||

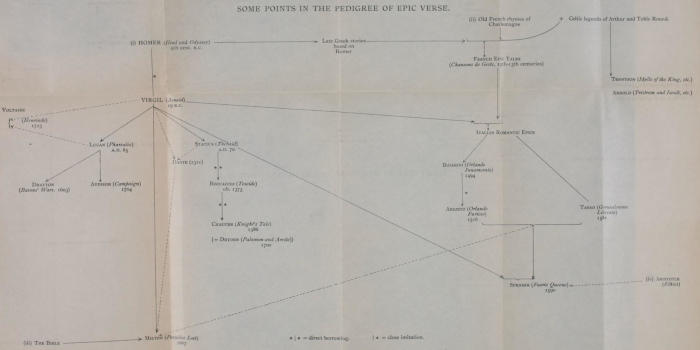

| 9. Some Points in the Pedigree of Epic Verse. | ||

A just appreciation of any modern European literature is not to be derived from the study of that literature alone. Not one has grown up spontaneously and independently from the soil of the national genius. Some seeds at least have come from elsewhere. Often whole forms of writing have been transplanted bodily. We must particularly recognize these truths when dealing with English literature.

The basis of the English mind is chiefly Teutonic, in some measure Celtic. If the English genius had been left to itself, to develop its spiritual and intellectual creations in its own way, English literature would have been a very different thing in both substance and form. But in reality English literary history is the story of the Teutonic and Celtic tendencies “corrected and clarified,” and the Teutonic and Celtic invention immensely assisted, by influences and ideas flowing in from other sources. There have been large ingraftings from other stocks, either partially kindred or altogether alien—from Greeks, Romans, Italians, French, Spaniards, Germans, as well as from Hebrews and other Orientals.

All sound study is comparative. We must place other literatures beside our own, if we desire to appraise rightly our national genius, its capacities, and[2] its creations. We find our English writers composing their works in certain forms, and giving expression to a certain range of ideas. How came they to employ these particular forms of creation? How did they arrive at these particular ideas? How is it with other nations? Have they built upon the same lines and with the same materials, or how is it with them? Have we borrowed from them, or they from us? If there have been borrowings, when and in what measure did they occur? Looking back over the changes of spirit and form which our poetry, for example, has undergone, we shall encourage altogether false notions of the causes of such changes, unless we see how, every now and then, a shower of new ideas, a stream of new light, has come in from abroad. Most readers know in some vague way that Chaucer avows or betrays his debts to France and Italy; that Shakespeare did not invent his own plots, but borrowed from Italians, from Plautus, from Plutarch, and others; that Milton was steeped in the Greek, Latin, and Italian classics. But we want to know more than this. We want to perceive with some definiteness how far the whole course of English literature has been enriched by tributary streams, and what sort of waters they brought. It would be instructive to draw a diagram of our literary history; to liken it to the course of a river, and to picture its various fountain-heads and tributaries pouring in their several quotas at their several times.

In all modern literatures there is a large proportion which is unoriginal to them. Milton has been mentioned already. Those who read only English works find Milton full of nobility of thought and imagery.[3] Yet, before Milton produced his greater poems, he had read, re-read, and deliberately steeped himself in, the literature of Greece, Rome, modern Italy, and France. Precisely how much of Milton is made up of Homer, Euripides, Virgil, Dante, Ariosto, and other predecessors, can only be known to such as have those authors at their finger-ends. Shelley, again, is commonly regarded as one of the most daringly original of English writers. Yet Shelley’s mind was an amalgam of himself, Homer, Euripides, Plato, Virgil, Dante, Calderon, Goethe; and this, once more, is but another way of saying that it had incorporated the genius of generations of Greeks, Romans, Spaniards, Italians, and Germans. We cannot therefore arrive at the true genius of Milton or of Shelley, or speak understandingly of their originality, until we have surveyed those other literatures and their relations with our own.

Let us, indeed, claim with a proper national pride that the influence of English literature, of our Shakespeare, our Bacon, our Locke, our Byron, upon foreign writers has been profound. Her debt to modern literature has been repaid by England, and, at least in the influence of Shakespeare, more than repaid. But with that question we are not here concerned.

One prefatory remark has yet to be made. It is that there is no discredit in this literary borrowing. Nations can no more be independent in the art of literature than in other arts. To be independent, to be unaffected by others’ genius, inaccessible to others’ ideas, would be to render our literature as stagnant and as grotesque as the paintings of China and of old Japan. It is a condition of progress in[4] literature as in science, that new inspiration must be continually sought, new conceptions assimilated. One vein is soon worked out; another must be opened. True art is of all the world, and a nation does best in art when it corrects its own peculiar faults and expands its own particular ideas, without meanwhile surrendering itself to a servile imitation of that for which its genius is naturally unfit. And English writers may glory that they have seldom been servile imitators.

Of all the literatures which have contributed to that of England, the Greek is by far the first and most important. The study of Greek literature is the indispensable introduction to the study of European literary history. Whether we review the literature of England, of Italy, of France, or of Germany, it is at Greece that we shall ultimately arrive. Take our English epic, Paradise Lost. It is a commonplace that it derives much inspiration from Dante’s Divine Comedy. But, when we arrive at the Divine Comedy, we are assured that it would never have taken such shape but for Virgil’s Aeneid. And, when we come to Virgil’s Aeneid, it is a fact known to the veriest tiro that the Aeneid is a copy, and, in a sense, a plagiarism, of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. The pedigree is self-evident and undeniable. Practically it is avowed at every step. Look elsewhere. Pope and Shenstone wrote “pastorals,” after the fashion introduced into English by Spenser. But Spenser himself had been led to this form of composition by the Italian Sannazaro and the Latin Virgil. And, when we reach Virgil, we find that he is a liberal borrower, in matter and manner alike, sometimes[6] even in the very phrase, from the Greek of Theocritus, Bion, and Moschus. It is the same with literary criticism. Pope’s Essay on Criticism, like Roscommon’s Essay on Translated Verse, is derived from Boileau’s French Art Poétique. But Boileau is an echo of the Latin Horace and his De Arte Poetica, while Horace is himself a borrower from Greeks of Alexandria, and ultimately from Aristotle of Athens. And so it is throughout. Often, especially in these later days, our stars of English literature shine with a light reflected directly from Greek constellations. No less often they shine with a light transmitted through several media, but ultimately issuing from the suns of Greece.

Pre-eminent by far among the literatures to which we owe a debt stands this body of eternally great creators, who, by the clear beauty of their language, their luminous apprehension, and their simple but magnificent originality, surpass in the aggregate those whom any other nation can assemble. It is no paradox, but a simple historical fact, that the old English writers have had less influence in moulding our modern literature than have Homer and Sophocles, Plato and Demosthenes. “We are all Greeks,” says Shelley, in the preface to his Hellas. Whether we will or no, our literature and philosophy, our canons of taste, our ideals of art, are all, in a sense, Greek.

Greek literature, unlike Latin, and unlike those of modern Europe, was mainly, if not wholly, original. What we have been able to borrow or to find ready-made seems to have developed itself spontaneously[7] in the wonderful genius of Greece. Latin literature has been called—and not without some justice—one vast plagiarism from Greek. But Greek itself is guiltless of plagiarism. Its thoughts, like its exquisite clearness and restraint of style, are almost entirely its own. With unlettered barbarians to north and west of them, with flowery, bombastic, or mystic orientals on the Asiaward side, the Greeks must be credited with a marvellous gift of their own, the instinct for sound judgement and sure taste.

But they possessed more than taste and judgement. They had inventiveness. We may reflect for a moment upon the various forms and modes of literature which we possess and practise in verse and prose. Of verse there are the epic, lyric, elegiac, satiric, dramatic, didactic, pastoral, epigrammatic, philosophic varieties. In prose there are history, oratory, philosophy, biography, criticism, fiction. To us all these forms and species, with their appropriate language, metre and tone, are taken for granted, as if they were the necessary outcome of some natural order of things. They are, no doubt, founded in nature. Nevertheless, we should remember that they must have had a beginning of their differentiation, that they must have been invented somewhere. And we discover that each of them is to be found arising in recognizable shape on the soil of ancient Greece. It is easy nowadays for us to imitate existing forms, to build with the architecture of the drama of Shakespeare and the epic of Milton, to copy the lyrical metres of Gray, Shelley, and Tennyson, to adopt the satirical machinery of Pope and Dryden. But these differentiations in mode of expression represent[8] something deeper, some distinction evolved by the human mind between compositions of one purpose and compositions of another. It was the Greeks who first convincingly and systematically illustrated that distinction, and who found for each subject of thought its appropriate vehicle of expression. More modern times have evolved many modifications of detail in metre or rhyme, and have essayed many novelties in the way of narrative. But they have never added an entirely new form of poetry or prose to the répertoire of the Greeks. Tennyson does not write In Memoriam in the metre and language of Paradise Lost. Shelley’s Ode to a Skylark does not employ the diction and rhythm of Pope’s Essay on Man. It is recognized that the feeling and its vehicle would be incongruous. But how does this come to be recognized? A world is quite conceivable in which there might have been developed but one form of literature and one ideal of expression. In such a world the incongruity would not be felt. The early Hellenes made their own literary beginnings upon almost a clear field, and it is one of their imperishable glories that they succeeded in realizing the subtle relations between language and thought or feeling, and in expressing these latter in all the variety of extant literary forms. For heroic deeds and lofty incident they developed the epic verse; for the sweets and bitters of love, and for other passions and ardours, they built the lyric stanza; for the plaints of mourning they created the elegiac; they did this gradually, no doubt, and in the main unconsciously, but with all the more perfect result. If we inherit what Greece has created, we have no[9] right to assume that all our happy varieties of literary form are things of course, which would somehow have come to any nation.

The history of Greek literature should be a study of years. Nevertheless it is not without profit to take the greater names and the more prominent types, to show their order of succession, to say something of their range and scope, to note the essentials of their style, and thence to derive some clearer idea of their influence on what we read to-day in our own English tongue.

The earliest Greek books which we now possess are Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. But these are much too polished and perfect works to have been the very first that Greeks ever composed. Indeed we know that before Homer’s time there were minstrels, who sang the “glories” of heroes, very much after the manner in which the bards sang in Wales or Scotland, or the gleemen in Anglo-Saxon England. It must also be assumed that popular songs of a religious kind were in existence. Yet all these earliest efforts at literary creation have vanished; we possess no material for definite information concerning them. For us Greek literature begins with “Homer.” The question as to who Homer was cannot be answered. Some critics contend that he is a mere title, and that the compositions which go by his name are patchworks, made up of a series of narratives sung by wandering bards called “rhapsodists.” Homêros, they say, is but a fictitious title under which to string all these separate compositions together into one so-called epic. Others, going less far, say that there[10] was indeed a veritable Homer, that he composed a poem on the Wrath of Achilles, and that this poem has been enlarged by other hands, which turned the whole into the Iliad, or poem on the “Siege of Troy”. Even if this be true, we know nothing of the original Homer, when or where he lived. To discuss the question at any length is beyond our present province. Perhaps we may believe, with great masters of poetry like Goethe and Schiller, that a “Homer” wrote the poem of the Iliad, but that it has since been added to, tampered with, reconstructed. We may also believe that some one other poet wrote a corresponding portion of the Odyssey. These two original poets were of nearly, though not quite, the same period. They were inspired with much the same literary ideals, and were almost equal, though by no means identical, in genius. They may be supposed to have appeared in a specially fertile epoch, like the great Elizabethans, or like the Italian poets of the first Renaissance. Their artistic principles would be much the same; they would live in much the same environment; they would see the world, the gods, mankind, through much the same moral temperament. Let us grant that their work has undergone large interference and contamination. Yet it is hard to think that a motley crowd of rhapsodists could ever possess such a lofty average of genius as pervades the whole body of these inimitable poems. Both works were, beyond reasonable doubt, in complete existence before 800 B.C. Twenty-seven centuries ago the Greek genius had reached thus high a point.

The Iliad and the Odyssey are to be read in many a translation. The Iliad is the poem of Ilium or[11] Troy. It deals with events during the siege of that town by the confederated Achaeans. It narrates the doings and sayings of the Grecian heroes, of Agamemnon, Achilles, Ajax, Ulysses, Diomede, Menelaus, outside Troy, and of the Trojans, King Priam, Hector or Paris within the city, where is also the traitress Helen. It narrates the counsels, quarrels, and battles of the gods, as they arise from partisanship during the siege. The poem is filled with prowess of battle, till it ends with the death of Hector, champion of Troy. The narrative is rapid and vigorous, full of valorous and exciting exploits of men interwoven with the friendly or unfriendly actions of gods. Descriptions are many, but always brief, and everywhere inimitably fresh and luminous. The whole purpose of the poem is to tell a story, and to tell it with clearness and simplicity, yet with fire and force. When it is embellished with ornaments of simile or other figure, it is because that device best brings home the picture. There is no idle lavishing of ornament for mere ornament’s sake.

The Odyssey is the poem of Odysseus, the wandering Ulysses. He, the king of the little island of Ithaca, after being for ten years absent at the siege of Troy, starts homeward in his ship to his wife, Penelope. But on the journey he meets with adventures, strange, terrible, or happy. He is storm-tossed and delayed by the anger of offended gods. He nearly meets his death from the one-eyed cannibal monster Polyphemus; he nearly loses his crew among the Lotus-eaters; he is detained for seven years in the island of the seductive Calypso; his comrades are turned into swine by Circe the enchantress;[12] he is wrecked between Scylla and Charybdis. He at last arrives home, only to find Penelope at the mercy of a rabble calling themselves her suitors. He slays them, and reveals himself to his wife—and so a happy ending. In this poem, as in the Iliad, composed nearly three thousand years ago, there is already achieved a perfection of literary art which we moderns find ourselves for ever aiming at and for ever missing. For this there is other reason than the natural genius of the Greek. The poets who wrote these two stories looked out upon the world with a frank, unclouded gaze, for which, perhaps, we are now too sophisticated. They therefore tell their tale with such simple directness that it might seem told by a grown-up child; but meanwhile with such brilliant clearness, with such firm outline, that it no less appears the work of a consummate artist. There is, it is true, no psychological probing in these books. There is no subtle moralizing, no pondering of any kind of deep question. Nowhere does there obtrude itself a desire to be clever, rhetorical, dazzling. Yet no one can read the Iliad without seeing those warriors face to face, as they were, in their physical strength and simplicity of character; nor can he read the Odyssey without feeling that he is with Ulysses on his raft, sailing through the deep, blue Mediterranean, that the salt breeze is blowing on his face, that the world is young and fresh, and that a man’s part is to perform that which lies nearest to his hand.

What effect the Iliad and the Odyssey have upon the intelligent reader may be judged by their preeminence among poems of all times and all places.[13] What an effect they have had on our literature may be judged by the number of translations, many in prose, and many better known in verse, from the hands of Chapman, Pope, Cowper, Derby, Morris, Way. It may be judged by the countless allusions to the “tale of Troy divine” which are strewn through every book of the last three millennia; by our everyday familiarity with the names of Hector and Achilles, Helen of Troy and Paris, Diomede and Ulysses, Circe and Penelope, Polyphemus and the Lotus-eaters. On reading Chapman’s Homer, Keats felt like an astronomer “when a new planet swims into his ken.” The same experience has been felt by all who recognize, as Keats did, “the principle of beauty in all things.” But little notion of those poems can be gathered at second-hand. Of its similes we may here quote one, not because it is in any way the most beautiful, but because it has been translated by a master in the art, Tennyson. Nothing in English has ever been hit upon to give the majestic, sonorous roll of the Greek hexameter, but Tennyson has, at least, preserved the frank simplicity of his original:

Next to Homer may come, by no means in importance, but in date, the poet Hesiod. He, too, uses the hexameter line, but with a different tone and movement, and for quite another purpose. He is our first example of “didactic” verse—the verse which is intended to instruct. Hesiod, who may be dated about the year 700 B.C., composed two poems of some dimensions, the one called the Theogony or Pedigree of the Gods, the other known as the Works and Days. The latter is a collection of versified rules of agriculture mixed with proverbial wisdom. It is, in fact, a sort of “Farmer’s Annual” of Greece combined with the proverbial wisdom of “Poor Richard.” Practical farming and practical morals go together. It would almost certainly have been written in prose, but for the simple reason that prose literature had not yet been invented. All literary composition begins with verse. As a poem, there is little to be said for the Works and Days, except that, like all things early Greek, it is entirely unpretentious and goes straight to the point. Didactic verse has grown common since Hesiod’s day, although happily it is now seldom used for agricultural purposes. Tusser’s Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry is one of the earliest results of the revival of Greek studies in England in the Elizabethan time, and, though it cannot count for much in literature, it is our first example of a species of work which took a more moralizing shape in Dyer’s Fleece and many later didactics.

Of much more value is the next kind of poetry which arose among the Greeks, a kind which has been called “personal,” inasmuch as it is prompted[15] by the writer’s individual feelings and emotions, and has reference to himself, his hopes, griefs, loves, and other sentiments. The epic poetry of Homer had been purely objective, dealing with incidents, things, and men outside the poet. The author makes no revelation of himself; he does not speak in the first person. But what is known as “lyric” and “elegiac” poetry is the outcome of a man’s own inner experience, and is only valuable in proportion as it expresses powerfully or touchingly a real or imagined passion of the writer, which the world at large can also recognize for its own. The poetry of Lycidas, Adonais, In Memoriam, is “elegiac”; the poetry of songs, such as those of Herrick and Burns, is “lyric.” “Elegiac” properly means “adapted to mourning,” but the elegy, with its couplet rhythm varied from the hexameter, yet with a plaintive dignity all its own, was used for other feelings than those of grief. It was used for praise, exhortation, reflection, love; for anything “subjective,” or springing from the mood of the writer. We need not enumerate the Greeks who at various dates wrote poetry of this personal description. After the year 700 B.C. there were many and excellent lyrists of the kind. At Lacedaemon the poet Tyrtaeus composed marching songs, which acted upon the Spartans as the Marseillaise and Die Wacht am Rhein act upon nations in modern days. Archilochus of Paros, soured by his own failings and misfortunes, wrote often in bitterness, like Burns. He is styled an “iambic” writer from a new form of composition which he employed, and he became the first great name in satire. In Lesbos, a fertile, luxurious, and[16] cultured island, we meet with the foremost name in the poetry of passion, the famous Sappho, the first and greatest of women in literature. It is Sappho who could paint, better than poet has ever painted since, the agonizing of love. Nor was she alone. In the same island she had her school of followers, and, separately from these, the poet Alcaeus poured forth his fiery thoughts in “words that burn.” But it is Sappho who, like George Sand, wrote from the “real blood of her heart and the real flame of her thought” things which have been the despair of imitator or translator. Unhappily, very little of her work is extant now, even in fragments; but what there is, is “more golden than gold.” Her metres are as nobly simple as in one of Herrick’s songs; her words are simple also. Yet, just as Dante could make a mighty verse out of the noun and verb, by choosing for his noun and verb the absolutely truest and most home-coming, so the simplicity of Sappho is only a deceptive covering for the most consummate art. Often as our lyrists have tried to catch something of her sacred fire, never has one quite attained to her irresistible pathos. Perhaps he who has approached nearest is Burns. Sappho is untranslatable. All absolutely best words in any language must be so. The nearest equivalent in English may be sought and found for the best word in the Greek, but in the special quality of its music or its associations it can never be the same.

The names of Pindar and Simonides are of a later date. Before them comes another, who sang to the lyre those gemlike songs of love, and joy, and wine, which the cavalier poets of the English seventeenth[17] century made their ideal. This was Anacreon of Teos. “Anacreontics” is the name given to those polished cameo-like little poems which imitators have essayed upon Anacreon’s themes. Cowley’s translations into English verse are known to literature, and readers familiar with the works of Thomas Moore will remember his loose youthful version of a few true and many spurious lyrics of the Teian bard. It is to Anacreon that we may look for the prototype of those graceful trifles called vers de société, and of those songs of love or gaiety which Herrick, Suckling, Lovelace, and Waller have developed in such exquisite examples.

All this personal poetry was meant to be sung to the accompaniment of lyre or flute. Had it been primarily meant to be read, it might possibly, even with Greek creators, have been less simple and direct, more artificial.

There was also another class of poetry which was sung to the same accompaniment. Early Greece found many occasions for festivities, and at religious holidays, public rejoicings, and public thanksgivings, choruses sang while moving in procession or while dancing round the altars. Hymns were chanted to the gods, triumphal odes were chanted in honour of men. When literature turned to these—or when these became literature—there arose in particular two most famous poets, Simonides and Pindar, to compose such public odes, very much after the manner in which a modern laureate might compose an ode of installation or national victory, or a dirge upon a national loss. Compositions written in this spirit are seldom of the highest rank of literature.[18] They lack the saving grace of inspiration. Pindar is strong, noble, imaginative. His odes were, no doubt, splendid compositions for chanting and musical purposes. To read them is to be conscious of a stateliness and dignity and an “eagle flight” which powerfully affect the student. But, full as they are of great imagery and diction, they are beyond doubt apt to be artificial and perplexed in structure; they are too often obscure, too often deliberately learned in allusion. To be its best, poetry must be written from the promptings of the poet’s heart, and Pindar too often wrote to order, for payment, and not from inward compulsion. No exact, or very near, parallel to Pindar can be found. He has never been even tolerably well translated. This has not been for want of admirers. Gray, who imitated him in the Progress of Poesy, has been said by Mason (erroneously enough) to possess Pindar’s fire: Cowley’s tombstone calls him, without much justification, the English Pindar, and at all times down to the present writers have been led to emulate the soaring Pindaric ode. Whatever his defects, it is certain that over all modern lyric poets, even over those who could not always follow his meaning, Pindar has exercised the sway of a master and imperial spirit.

Among the kinds of poetry chiefly affected by the earlier Greeks must also be included the “gnomic” or “sententious” verse which goes under the names of Theognis and Phocylides. These writers both lived in the sixth century B.C., and both composed versified maxims or precepts of conduct and worldly wisdom. After times came to credit to those great originals[19] any verses of this character which were current in the elegiac or the hexameter metre, and such verses played very much the same part in Greek mouths as is played by the Proverbs of Solomon or by proverbial philosophy of unknown authorship in the mouths of Englishmen. At a later date in the iambic metre the comic poet Menander introduced into his plays a large number of maxims, which gained wide vogue and which caused many more of the same species to be fathered upon him. Of the various wise saws thus current in Greece a great number were translated or adapted by Latin writers, and have so passed into the general possession of the European world.

Between the years 500 and 400 B.C. there arose in Athens that which is the special poetic glory of that city—the drama, embracing both the drama of tragedy, as wrought by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, and the drama of comedy, as built by Aristophanes, and later, in a different form and spirit, by Menander.

The Attic drama arose on Grecian ground. At one time choruses danced round the altar of the wine-god Dionysus (or Bacchus), and chanted songs in his honour. The chorus had its leader, the Coryphaeus. In time it became the fashion for the Coryphaeus to personate the god, or some character whom story connected with him. He recited a speech, or related some legend, in which the wine-god was concerned. It naturally followed that he was next raised upon a low dais, and distinguished from the rest of the chorus. The dais later became the dramatic[20] stage. Subsequently another member of the chorus was told off to converse with him in rough dialogue, the theme being still the history of Bacchus. So far, then, we have a chorus which dances and sings, and two actors supporting crude dramatic parts. It was from these simple beginnings that there grew to perfection in Athens, as suddenly as the Shakespearean perfection arose from the old miracle-plays and “moralities” in England, noble dramas like those of Aeschylus and Sophocles. The open sward had become a theatre, the acting art, the dialogue poetry. Drama had been raised to an art of the most absolute literary completeness. It must, however, be observed that the tragedy which grew up in this way was religious in its origin. Until the end it—theoretically at least—remained so. Its subject-matter and laws were, therefore, limited. The stage was at the same time a pulpit for moral and religious teaching. The theatre was, moreover, national. Here are some important elements of artistic difference. Those who read Shakespeare and then turn to Athenian tragedies are puzzled. They do not understand those Attic creations. They think them rather cold, with somewhat slender plot, containing few surprises. Italians and Frenchmen can understand them; the average Englishman cannot. The poetry is often admirable, but the action appears strangely simple, and for the most part over obvious. The very name “tragedy” seems sometimes misapplied. But by “tragedy” the Greeks did not necessarily mean a play which ends in death and disaster. Such an end was, indeed, usual, and hence the modern meaning of the term. But the Eumenides[21] of Aeschylus ends happily, as do the Alcestis of Euripides and the Philoctêtes of Sophocles. The Greeks meant rather the working out of some great and powerful situation affording occasion for sensations of pity and fear. Here was “the luxury of grief.” The spectators knew that there would be some climax in the drama; but whether it would issue in good or evil depended on the poet; they only knew that their feelings would be powerfully worked upon by great poetry greatly delivered. For the rest, they required no startling ingenuity of plot or variety of incident.

The three great dramatists in artistic sequence are Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides. These were all alive together, but Aeschylus was old when Euripides was young. The appearance of all these in one epoch is exactly paralleled by the cluster of superlative dramatists in the Elizabethan age or in the France of Louis XIV. Of Sophocles it has been said that he represented men as they ought to be, and of Euripides that he represented them as they were. The dictum is hardly true, and, if it were, it must be noted that, whereas to “hold the mirror up to nature” is as much the function of Greek tragedy as of English, it is no function of Greek drama to be a literal copy of literal everyday human experience. In Aeschylus all is in the grand style of an awe-inspiring simplicity. Take his Prometheus Bound. We have a majestic Titan figure bound to a desolate rock, there to remain in punishment for an offence against the law of Zeus. He had bestowed fire and other boons on mortal men. Therefore Zeus pinioned him on Caucasus for tens of thousands of years. In[22] one way, and one only, could he gain his freedom—by disclosing to Zeus a certain secret of fate. But Prometheus would not repent of having exercised his benevolent freewill against the decree of Heaven. He gloried in his action; he refused to deliver up the secret. Now during the whole play the figure of Prometheus does not move: he is fixed fast. There is no action on his part, nothing but speech. Different gods, demigods, and a mortal visit him, condole with him, advise him, or threaten him. He remains firm to the end, the spectacle of an utterly resolute heart rebelling against fate.

It is not hard to recognize in English literature some of the characters to which this Prometheus has served as prototype. There is Milton’s Satan, who is distinctly modelled on the Titan. Byron acknowledges that all his rebellious spirits, Cain, Manfred, and their like, are echoes of the same character. Shelley wrote a Prometheus Unbound for sequel. Keats’s Hyperion shows the same influence. Swinburne’s Atalanta in Calydon is throughout inspired by the conception of Aeschylus.

Ancient drama has much attracted the modern poet. The Agamemnon of Aeschylus has been translated by Browning, far more roughly—not to say grotesquely—in style than it deserves, but with the Greek spirit in no small measure retained. The same writer has translated the Alcestis of Euripides in the work known as Balaustion’s Adventure.

But to the English stage Greek tragedies are not suited. Our theatre is not religious, nor national. But in France and Italy Greek plays have found a more congenial soil. Corneille and Racine in France,[23] Alfieri in Italy, have sought to mould their dramas upon Greek lines, though, truth to tell, they much more closely suggest the rhetorical constructions of the Latins. The only deliberate attempt to compose in English directly on the Grecian model is Milton’s Samson Agonistes, a work in which admirable poetry does not atone for a certain coldness and formality intolerable in drama, whether meant for Greece or for England. Yet inasmuch as the Italian drama was largely instrumental in developing the English from its crude and vulgar antecedents, and as Italian drama was in its turn evoked by the dramatic examples of Greece, we can even here, despite all unlikenesses, distinctly affiliate the main principles of our own stage-pieces to those of ancient Athens. We cannot, indeed, maintain that without Athens we should have had no drama; we can only assert that our greatest drama, as we have it, in its poetical dignity and its technical architecture, would hardly have been. It might have been a prose drama, and one of very different conception and ideals. But it is what it is because it took from Greece that which suited its purpose, while it left to Greece those elements which belong to so different a theatre.

It has been described how Greek tragic drama arose from the choruses singing round the altar of Dionysus. Greek comedy springs from the same source. There were two sides to a Greek festival, as there are two sides to Christmas Day. The serious part of the festivity developed serious poetry and serious action. The light, sportive, and satirical part developed humorous verse and humorous action. It is easy to see how both dramatic kinds would[24] originate from these two different aspects of the feast. From beginnings as rude as those of tragedy was developed the comedy of Aristophanes or of Menander, which in its turn, begat that of Plautus and Terence at Rome, and thence of Shakespeare’s predecessors in England and of Molière in France. Even the comic opera of to-day bears a wonderfully close resemblance to plays of Aristophanes, with whom occur almost the same bizarre situations and humours as in Gilbert’s very modern eccentricities.

Comedy, like tragedy, had its chorus, chanting appropriate odes during the intervals of acting. And be it noted that the Greek drama, whether tragic or comic, was literary. It bears to be read as much as to be acted; it is a work of conscientious art. In tragedy the writing is pure poetry. In comedy it is humour and wit, biting, sparkling, often coarse and very personal, but always full of life. There was some defence for personality. Comedy, like tragedy, served to give various lessons to the Athenians. Greece possessed no newspapers, and in their place the comic stage served even more than now to criticize fads, to chastise political and private misdoings. So long as it was what is called the “Old Comedy” of Aristophanes it availed itself only too fully of these licences. But when its attacks on politics or private persons became intolerable, its wings were clipped by law, and in the “New Comedy” of Menander we find another tone, the tone of Molière or of Ben Jonson, the treatment of social types, the comedy of domestic intrigue. Of the whims of the “Old Comedy” the following may serve as a specimen. In the Birds of Aristophanes two enterprising Athenians[25] persuade the birds to build a city in the clouds—“Cloud-cuckoo-town” it is called—by which the ungrateful gods are to be cut off from men, and so forced to come to terms. This is the central idea. Twenty-four persons, equipped as different birds, form the chorus, and give the name to the piece. The central conception, however, is but a peg on which to hang attacks upon the follies of the day, and particularly follies in contemporary politics. Neither parties nor men are spared. Nevertheless the piece is always comedy; it cultivates “the laughable”; it is never mere diatribe.

One other kind of ancient poetry, and a delightful kind as we see it in Greece, is the pastoral idyll of Theocritus, Bion, and Moschus. In English literature the word “pastoral” at once suggests poor triviality, the rather mawkish and always artificial eclogues of Pope or the Shepheard’s Calender of Spenser. But, though the conception of these works was ultimately borrowed from Greek through the Latin medium of Virgil, or the Italian medium of Sannazaro, they lack precisely those elements which make the Greek pastoral idyll a thing of beauty and a joy for ever. When Theocritus, about 270 B.C., wrote in Alexandria or elsewhere his “Idylls” or (“little pictures”), he was portraying a life among Sicilian or Coan shepherds which possessed a large proportion of truth and naturalness. At least it is of real shepherds that he writes, idealizing, perhaps, their Arcadian environment of sunshine and simplicity, but nevertheless presenting a life easily conceivable among entirely possible rustics. He imaged a rural[26] scene, placed in it a befitting action or situation, and called his work “a little picture.” But when Virgil imitated him at Rome, the Corydons and Damoetases whom he introduces are hardly shepherds of reality. Their talk tends to be artificial and literary. Shepherds did not pipe and contend in alternate minstrelsy on the Italian farms as Greek shepherds had done, however rudely, in Cos or Sicily. Moreover Virgil wrote with an arrière pensée. He was thinking of the society of his time, and more or less representing that society under the guise of obviously theatrical shepherds. In Spenser’s Shepheard’s Calender we no longer recognize any pretence at reality. The idea of merry witty shepherds piping in sylvan scenes of sunlit Sicily is natural enough; but the notion of the smock-frocked rustic of rainy Britain vying in song with another smock-frocked rustic concerning his Amaryllis or his Chloe is not a little ludicrous. Especially is this so when we know that Colin Clout, Cuddie, Hobbinol, and the other swains, are talking moral wisdom, and are nothing but Spenser’s friends or contemporary celebrities with shepherds’ crooks for poetic “properties.”

Distinguished, however, from pastoral poetry pure and simple, as seen in Pope and Spenser, there is a more important form of creation by these Alexandrian poets, which finds its way into English literature. It is from Theocritus and his school that Milton’s Lycidas is drawn, and it is from Lycidas that we get Shelley’s Adonais and Matthew Arnold’s Thyrsis. Here are two quite unimportant passages, the comparison of which will show at once how[27] closely a great English poet may occasionally copy an ancient. Says Theocritus, as translated by Calverley:

Says Milton:

Greek literature is also rich in verse “epigram” in the original sense of the word. In modern times we have come to associate with the epigram the notion of a pithy composition containing a neat and witty point, and particularly a “sting in the tail.” This description seldom suits the Greek type, especially in its earlier days, but is derived rather from the custom of the epigrammatists of Rome. An “epigram” was originally a composition to be inscribed upon a monument, votive offering, or the like. That it should be brief was an obvious requirement, and it was natural that it should try to excel mere commonplace. But wit and “point” of a biting kind were alien to the first conception. A Simonides or other early poet wrote a couplet or a quatrain which might be pathetic, eulogistic, or even almost simply descriptive, and this was an “epigram” if actually intended as, or proposed as fit for,[28] an inscription. In later times the composition of such pieces was a poetic exercise, the occasion being imaginary, and the tendency to impart point and wit naturally increased. Very many charming little cameo-poems of this kind, touching upon most of the elements of human life, are to be found in what is known as the Greek Anthology, some of the best being of the Graeco-Roman age and written by Romans as well as Greeks throughout the Greek world. Our own epigram, whatever may be its change of character, is derived through French and Latin channels—particularly through Martial—from the Greek invention. It is probable also that the Italian, and thence the English, sonnet owes much to the pattern set in the Greek epigram.

In the regions of prose we can hardly be so definite. In history, oratory, philosophy, we still return again and again to the Greeks for inspiration, but the inspiration is chiefly one of spirit, not of outward form or special thoughts.

Herodotus, who began to flourish about 450 B.C., and who writes concerning the Persian invasion of Greece, and, by way of preface, tells of Lydia, Babylon, Egypt, Scythia, is still known as the “Father of history.” His undying charm is his style, the style of a delightful story-teller. Clear and direct as all the best Greek writing is, there is something so fresh, so frank, so suave, about Herodotus, that, even if he tells falsehoods knowingly—as some critics say, but as we need not believe—we cannot grow virtuously indignant with him. He is both uncritical and shrewd—shrewd where the knowledge of his times[29] guides him, uncritical where they were ignorant. His stronger-minded contemporary Thucydides is the very pattern of an historian. His function is to tell the history of the long protracted Peloponnesian war, and he tells it inimitably. The graphic terseness of his account is only equalled by his severe impartiality. If he tells you of a battle, he describes luminously its main features, how it went, who won it, and what the consequences were. He does not attempt to minimize or explain away an Athenian defeat or crime because he is an Athenian. If a political party commits an error, he tells us so, and tells us how. It is scarcely possible to find out precisely his own political views. If he describes the terrible plague of Athens or the terrible fall before Syracuse, he describes it with moving pathos. But he does not overdo his part. The pathos is in the distinct simplicity of the picture, not worked up by labour of ambitious words. It is perhaps enough warrant of his excellence that he grew in the admiration of Macaulay with every year of Macaulay’s maturing judgement.

In oratory the great name of Demosthenes stands pre-eminent. Volumes of his speeches are in our hands, political and forensic speeches equally. The word “Philippics” has become typical for invective. That Demosthenes is the prince of orators everybody knows. But why? We may imagine the crude aspirant to oratory reading a speech of Demosthenes in amazement, and asking “Where are the flashings of rhetoric? Where the dazzling flights of imagination? Where the magnificent bursts of diction?” The highest art is to conceal art, and Demosthenes would[30] have been no perfect artist if he had allowed the novice to perceive exactly wherein his perfection lay. He is the perfect orator just because he can be graphic, cogent, pathetic, anything he will, without all those rhetorical tropes, purple patches, bouquets of flowery diction, which weaker men are driven to use. His language is like a Greek statue, instinct with a life diffused through every part, but showing no straining at effect, accentuating nothing beyond its value as a persuasive or moving force. His metaphors and similes are few; often his words are even homely; but there is a directness, a “home-coming,” about his diction and his periods, a dexterity about his arrangement, a noble fervour and simplicity.

In philosophy the Greeks have been the teachers of the civilized world. Two only of their great masters need be considered here. It is said that every man is born either an Aristotelian or a Platonist. This means that there are two chief types of mind which really think, and of those one is akin to the mind of Plato, the other akin to that of Aristotle. Plato is the suggestive, but inconclusive, imaginative, transcendental philosopher. Aristotle is the matter-of-fact, logical, analytical. The style is like the men. The style of Plato is rich with poetical colour, that of Aristotle is hard and thin, prose of the prose. Between them these two cover nearly all the ground of speculative thinking, and modern thought can never emancipate itself from them. For centuries in the Middle Ages the philosophy of Aristotle was almost a religion of civilized Europe, and it is the fact that even now students of morals and politics find themselves constantly returning to[31] Aristotle. The Stagirite, as he was called because of his birth at Stagira, lived before the days of experimental science. Yet he virtually anticipated much of modern scientific results. He was nearly an evolutionist. Plato, on the other hand, has had his votaries. He, too, was a religion in Renaissance Italy. Whether we can always follow him or not, he is a stimulating influence, and he has left his mark in many places where one would hardly look for it. We should perhaps scarcely light on Wordsworth’s beautiful Ode on the Intimations of Immortality as an echo of Plato. Yet all its fancy concerning “a sleep and a forgetting,” and the previous existence of the soul, is pure Plato. Whether Wordsworth was conscious of it or not, his mind had been pervaded by the Platonic influence. Nor was it much otherwise with Shelley. Of direct and appreciable bearing upon literature since his day, is the fact that Plato is our first model of the prose dialogue or imaginary conversation. He did not indeed absolutely invent this form of writing, but the comparatively crude work which preceded him is lost, and it is Plato who stands to Berkeley or Landor as their prototype and exemplar. Centuries later Lucian followed in his steps, though with a somewhat different purpose, combining, as he declared, the philosophical dialogue with the spirit of Attic comedy. Plato’s dialogues are always serious in intention, whatever humour or lightness of touch he may display; Lucian’s are but partially serious, the humour, which tends to satire, being the predominant element.

A work of Plato to which the world owes much in the way of imitation is his Ideal Commonwealth[32] or Republic, from which are derived in succession the hints for the Civitas Dei or City of God of St. Augustine, the Utopia of Sir Thomas More, the New Atlantis of Bacon, and various minor efforts in the theoretical construction of an ideal polity.

Here we must cease to speak of Greek literature in classical Greece. The subject is inexhaustible.

Yet before we come to illustrate in some detail the effect of all this wealth of original thought and splendid style on English, we must mention two famous writers in the later or “post-classical” period of Greek literature. These introduced new forms of prose writing which have had many imitators in every European country. They are Lucian and Plutarch. Lucian wrote in Syria and in Athens during the later part of the second century of our era. He composed what we should call “articles,” in the form of dialogue and essays, nearly all of them of a satirically humorous character, but nearly all possessed of sound common sense and practical purpose. Lucian is the precursor of Swift, Voltaire, and Heine. Of Swift he is the predecessor in more ways than one. Lucian supplies us with the first instance of ironical fiction. His True History is composed in the same ironical vein, and with precisely the same assumption of seriousness, as Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. It is to Lucian that Swift owes the hint for such a work, and, after all, the hint was in this case a great part of the genius. The width of Lucian’s range may be recognized from the fact that both Swift and Sterne have been called the “English Lucian.”

If Herodotus is the “Father of History,” Plutarch (first century A.D.) is the father of biography. Strictly speaking neither is the originator of the form of literature in question; nevertheless each is to be judged rather by the influence of his example than by absolute invention of a literary species. Besides the biographies there exists much other work of Plutarch in the nature of moral essays and “articles” on historical or antiquarian subjects, and this work was liberally drawn upon by essayists after the Revival of Learning, in particular by Montaigne and Bacon. Nevertheless his chief contribution to the development of literature was in his “Parallel Lives,” a series of biographies and character-studies, in which a distinguished Greek and a distinguished Roman were studied in comparison, pair by pair. To Shakespeare the Lives were known through North’s translation, and, in Coriolanus and the other Roman plays, they supplied not only his conception of antiquity and ancient character, but also the great bulk of the matter which he dramatized. The genesis of modern sketches of the kind represented in Macaulay’s Chatham, Lord Clive, or Warren Hastings, can be distinctly traced to similar short studies in the Greek of Plutarch.

A very prolific department of literature, and one which has served as a rich source of inspiration, imitation, and allusion in all subsequent times, was that of the fable. In this domain the name of “Aesop” is supreme. Whether there was ever an historical person bearing precisely this name has been questioned. The tradition which places him in[34] Rhodes as a slave in the middle of the sixth century B.C. cannot be implicitly trusted; but it is difficult to understand how the special name of “Aesopus” can have come to attach itself to a series of beast-stories, unless some individual who bore it, or of whom it was a sobriquet, had been distinguished for his invention, or at least for his promulgation, of such satirical narratives. It is indeed almost certain that a large number of “fables of Aesop” originally came from India and the East; yet it is in Greece that Europe first makes acquaintance with those fables which are still the best known, and which most constantly appear in the existing collections or selections. All educated or even sophisticated Greeks were supposed to know “Aesop.” At a later time (in the third century A.D.) the Graeco-Roman Babrius versified such fables as were known to him, and he again was copied into Latin verse by Avianus. The Indian fables of Pilpay were not circulated in Europe till five centuries later than Babrius, nor did they ever gain such wide currency. It was primarily along the Greek channel that there was derived, if not all the matter, at least the inspiration, for the fables in French by La Fontaine, and the English fables by Gay, together with all the collections which have been printed, or which were current before the days of printing, and which have become part of the répertoire of childhood and a fund of reference for proverbs and for all classes of writers.

Of other kinds of writing which appear already in ancient Greece may be briefly mentioned:

(1) Character-sketches, first produced by Theophrastus (about 320 B.C.), and imitated by La Bruyère (Characters) in France, and in England in such works as Hall’s Characterismes of Virtues and Vices, Overbury’s Characters or Witty Descriptions of the Properties of Sundry Persons, and best in Earle’s Microcosmography.

(2) Essays in rhetoric, literary criticism, and belles lettres, such as the Rhetoric and Poetics of Aristotle, the latter of which exerted so profound an effect upon the verse, and particularly the dramatic verse, of the French, and thence upon that of the English so-called “classical” school; the essays of Dionysius of Halicarnassus (25 B.C.) upon the style of the Attic orators; and the treatise On Sublimity by Longinus, a writer who cannot be identified, but who wrote in the flourishing times of the Roman imperial epoch; (3) the works in grammar and dictionary-making, which range from the textual criticism and comment of great Alexandrians, like Aristophanes of Byzantium (200 B.C.), to the school grammar of Dionysius Thrax and the lexicons of the early centuries A.D.; (4) geographies and descriptive guidebooks, the former particularly represented by Strabo, about the beginning of the Christian era, and the latter by Pausanias (in the second century A.D.); (5) Miscellanies, antiquarian or literary, such as the famous Pundits at the Dinner-Table of Athenaeus (end of second century A.D.); (6) letters (i.e., fictitious epistles), such as those of Alciphron (second century A.D.); (7) romances, of which the extant examples are mostly much later than the classical period, those of Longus and[36] Heliodorus dating from the latter part of the fourth century A.D.

We have now cursorily surveyed the course of Greek literary history. We have shown that it comprised all the forms of literature now known to us; that in this respect at least we can claim no originality. We have incidentally alluded to some of our debts, though that part of the subject remains to be dealt with more fully. The question which now arises is—what is there distinctive about this Greek literature as a whole, to make it possess such a precious and perpetual salt and savour?

We may reply that, to begin with, the Greek writers were characteristically possessed of one prime literary virtue—lucidity, whether in their picturing of scenes or in their expression of a thought. And they expressed clearly because they saw clearly. Besides being lucid, they were restrained. For the most part they went directly to their point, and did not suffer themselves to be drawn away from the point by irrelevant attractions. They knew, as Lowell puts it, how much writing to leave in the ink-pot. There is so much “not to say.” They shrank from overdoing. Floweriness, extravagance, bombast, irrelevance, these were an abomination to classical Greek taste. The Greeks proper did not fail to recognize fustian when they saw it. They were a critical, and a self-critical, people. What we see in the purity of their sculpture and architecture, we may see in their literature. A word or phrase must have a rational and artistic purpose, or it must not be there.

Again, they were eminently sane men, those Greeks. They looked out on the world with eyes like those of their Goddess of Wisdom, the imperturbable eyes of unabashed intelligence. What they saw they saw frankly: they knew facts from fancies, and recognized facts when they met them. They were mentally a healthy people, not constitutionally given to moodiness and mysticisms and impossible aspirations. They took meanwhile a wholesome delight in living, and in the boons of physical life.

This whole way of looking at things has received a name of its own. It is styled “Hellenism.” The Greeks called their country “Hellas,” and themselves “Hellenes.” Hence this name, which means so much. Hellenic thought means direct and fresh, if not always profound, thought; Hellenic art means art of consummate simplicity, art of clear principle. Hellenic style means in literature a perfect directness and lucidity, with just so much of the figurative as will flash light upon the sense.

This is what is meant by “Classical” Hellenism. True, no scholar would dare to say that even in the classical age every Greek who has left us a book or a fragment was always as perfect as Greek principles and ideals were perfect. Homer sometimes nods. We may find palpable blemishes not a few. But we must judge a national literature as a whole; and when, as with the Greek, a literature can show so large a proportion which is flawless, when it is so obviously informed with one and the same artistic spirit, so manifestly controlled by the same canons of taste, then we may use our general[38] terms with more confidence than we can usually feel in generalizing of whole peoples and their histories.

In later times, when Greece was no longer free, when cultured Greeks had been scattered into Asia Minor, Syria, and to Alexandria, when literature became mere reading, then Greek art and letters lost their prime virtue. Oratory declined, as poetry had done. Greek writing became more oriental, more “Asian” in its artificiality. In classical Greek the ornamentation was not compassed for its own sake. It grew spontaneously out of the subject and helped the subject. But when Greek literature became “unclassical,” when it became artificial, mere imitation and make-believe, when it was not the outcome of a national spirit, but was forced in the hotbeds of literary coteries and court-favour, then ornamentation was first and foremost; poems and speeches were composed in order to bring in fine things. Rhetoric grew bombastic and poetry finical; or, as it is commonly expressed, literature became “Asiatic” instead of “Attic.” This literature in general is sometimes called “Hellenistic,” rather than “Hellenic”; but that term should be appropriated to other purposes. Its headquarters being at Alexandria, the title “Alexandrian” has come to be virtually a term of disparagement in literature.

When therefore we speak of the influence of Greek literature on English, we include not merely a fund of classical history and of mythology, not merely a long list of Greek words and Greek allusions, not[39] even merely an inheritance of all the great forms of poetry and prose writing, but also that way of looking at things and that style of putting things which we call Hellenic. We mean not only so many similes, metaphors and figures of speech, but a whole scope of thinking and style.

We might, indeed, in some rough way, gauge the influence of Greece by the mere titles of English books or compositions bearing such Greek names as Utopia, Arcadia, Comus, Pindaric Odes, Endymion, Hellas, Prometheus Unbound, Hellenics, Life and Death of Jason, The Lotus-Eaters. We might gauge it in some measure by the allusions scattered up and down from Chaucer to Tennyson, allusions to Homer and his Agamemnon, Achilles and Hector, his Circe and all the beings of his mythology, to Greek history, to Plato and Aristotle. We might gauge it in a measure by terms like Parnassus, Clio, Helicon, Academe, and similar references to the literary haunts and divinities of Greece. We might further take the Greek words which now form part of our English vocabulary.

But the subject requires more methodical treatment, and perhaps some little retrospect. Meanwhile we may well assert with Shelley:

As the same poet says in his preface to Hellas, “We are all Greeks.”

It now remains to examine at what times, in what ways, and to what extent, our own English literature has been influenced by models so rich and virile. The points of contact have been numerous; the influence which has been felt has not always been felt in the same respects. At one time we merely borrowed some of the matter of Greek writing, some of its stories of mythology and history, some of its figures and similes, some fragments of its philosophy. At another time we have copied some of its forms of production, such as the epic form of Homer, the Pindaric Ode, the idyll of Theocritus. At another time we have borrowed its literary criticism, and either garbled and misapplied it, like Pope, or rightly assimilated it, like Matthew Arnold. It is possible also to adopt its matter, its form, its Hellenic principles of criticism, all together; and that is what so many of the best writers of to-day are, consciously or unconsciously, labouring to do.

We have, in fact, grown more and more dependent on Greece with every generation of our literature since the days of Chaucer. This may appear a paradox, but it is no more than the truth. Antecedently one might suppose that, with the progress of what is called civilization, and with the expansion of knowledge, the literature of the ancient Greeks must now have been left far behind, as a thing of remarkable interest, no doubt, but a thing which has performed its practical function, a nourishment[41] which has been sucked dry. Yet the very contrary is the case. In verse Tennyson, Matthew Arnold, Browning, Swinburne, William Morris, in prose Newman, Froude, Ruskin, whatever may be their points of difference, or even of contrast, nevertheless agree in this, that they have all saturated themselves with Greek and the things of Greece, with its ideas, phrases, and stories, till their work is in greater or less measure dominated by what they have thence derived. A Greek scholar realizes this obvious fact at once, and with gladness. A reader to whom Greek literature has been a sealed book little thinks how many of the felicitous expressions which especially captivate him in his poets of the present age are conscious or unconscious echoes, paraphrases, or mere translations, of things written more than a score of centuries ago in pagan Athens or the Isles of Greece.

Let us take a brief preliminary survey.

To Chaucer there filtered through from Greece, by way of writers in Latin or Italian, crude notions of Greek mythology or Homeric stories. Of the style and form and historical perspective of Greek literature he had no manner of conception. To him Agamemnon and Ulysses were knights with squires; Troy was besieged as Paris might be. His debt to Greece amounts to little more than a jumble of fables at second hand.

By Spenser’s day our English writers are beginning to realize how rich a store lies to their hand in the books of that Greek which men of Western Europe have once more begun to study. They learn[42] some little of the tongue, and they borrow unsparingly its stories and its similes. But of the lesson of its style, its restrained art, they have still learned almost nothing. They are caring for little beyond the solids which it affords. The Faerie Queene is crammed with classical allusion, and with similitudes traceable to Homer and other Greeks; but hardly a vestige appears as yet of the Greek literary spirit of clear simplicity, self-restraint, severity of taste. The extravagance and tastelessness which so often tire and irritate the reader of the Faerie Queene are altogether alien from Hellenic art.

Pass onward for some generations, till we come to the days of Pope and Addison. The study of Greek is more careful and more widely spread, its history and mythology have dropped into truer perspective and proportion. Greek life, Greek thought, are somewhat better comprehended, though still far from well. Much that the Greeks have written has now become general property. Better still, criticism is alert. The principles of the Greeks have passed, in a garbled form, it is true, through Rome to France, from France to England. The English have awakened to the fact that what deserves to be said at all deserves to be said concisely and precisely. So far, so good. Perhaps we do not profoundly admire the spirit of the literature of the age of Pope and Addison. But we must perforce admire its great advance in polish of expression. As literature, it may fail from want of ideas, from thinness of its substance. In that respect it departs as far from the Greek ideal as it approaches near the Greek ideal in skill of execution. The aim of Greek literature is to express[43] thought or feeling perfectly. But there must be a real thought or a real feeling to express. And this spontaneousness or compelling sincerity the school of Pope and Addison did not, in the main, possess. Yet it did invaluable work. It furnished a later generation, which had ideas and was not ashamed of feelings, with an improved conception of expression. The “Classical” school these writers have been called, but classical they distinctly are not, for to be classical is to express matter of sterling worth in a style for ever fresh. To utter brilliantly a nothing, an artificiality, or a commonplace, is not classical.

The Queen Anne and early Georgian school, then, so far as Greek literature is concerned, owe to it sundry healthy principles of style, not yet properly assimilated; they owe many allusions, better ordered and digested than in Spenser or Chaucer; but of its higher thoughts and deeper imaginings they exhibit little influence.

Let that century expire, and come to the generation of Wordsworth, Shelley, Keats, and Byron. In them we meet with rich ideas in plenty, and with abundance of exquisite expression. Wordsworth, Shelley, and Byron had studied Greek; Shelley read it all his life. Keats, who knew no Greek at first hand, but who had innate in him that part of the Greek spirit which, as he puts it, “loves the principle of beauty in all things,” had steeped himself in Greek legend; he revelled in Greek mythology; he assimilated the Greek view of nature and at least the passion of Greek life. All the literature of this period is shot through and through with[44] the colour of Greek myths, Greek philosophy in its widest sense, Greek ideas. It shows an advance upon the age of Pope; for now once more the matter is made of the first account, although the manner is duly cultivated to form its fitting embodiment. Expression is fashioned to great beauty in Shelley, Coleridge, Keats, and often in Wordsworth. But the matter is of the first moment. A great advance is this upon the perfectly uttered proprieties of Pope. Yet still the age of Shelley was less Greek than the following “Victorian” age. The magnificent outbursts of the “spontaneous” and “romantic” schools of the beginning of last century too often ended in extravagance of fancy and riot of imagination. The transcendental rhapsodizings of Shelley and the sensuous revellings of Keats lack the sanity and self-repression which we associate with the name of Hellas. But the aim of the last age has been to secure the perfect union of sane, clear, yet unhackneyed thought with sane, clear, yet unhackneyed phrase. This was the aim of Tennyson, as of Matthew Arnold. Even Browning aims at this ideal in his most perfect moments.

Now, if what has been said of the ages of Chaucer, Spenser, Pope, Shelley, and Tennyson respectively is true, it is anything but a paradox to assert that, generation after generation since Chaucer’s day, we have been passing more and more under the domination of Greek thoughts and Greek literary principles, and that we are groping forward to a literary ideal which turns out to have been the ideal of ancient Greece.

The full influence of Greece, then, was not felt all at once, nor in the same way and in the same respects.

Early English literature never came into direct contact with Greek books. Our old writers knew no Greek, for it is only since what is known as the “Revival of Learning” that the borrowing, whether of thought or style, has been at first hand. Nevertheless the debt was there, though the fathers of our literature were not conscious of it. Even King Alfred drew from Greek sources, though he knew no more of Greek than of baking cakes. When there was not a man from one end of England to the other who could properly read a Greek book, the men of England were nevertheless deriving, in a mutilated form no doubt, but still deriving, philosophy and ideas from that ancient Greece which to them was shrouded in the darkness of distance and of a tongue unknown. We may endeavour to see how this came to pass.

In the first place, if our earliest writers could not read Greek, they could read Latin. If they could not read Homer, they could read Virgil; if not Sappho and Pindar, they could read Horace. The Latin literature was with them, in a considerable measure. It is true that in the Dark Ages many of the best works of Latin literature lay concealed, and that others were deliberately neglected. The taste of readers in those ages ran rather in favour of the later and inferior Latin authors. Nevertheless, Latin literature of considerable extent they did study and assimilate; and what was this Latin literature, speaking generally, but an avowed imitation or copy of Greek models? The Roman Virgil copies the[46] Greek Homer, Hesiod, and Theocritus. The Roman Horace copies Sappho, Pindar, Archilochus, Anacreon. The Roman Plautus and Terence are practically plagiaries of the Greek Menander and his like. Latin literature is, in a very large degree, Greek literature borrowed, adapted to inferior taste, played upon like studies with variations.

When Rome became the mistress of the world, it aspired to greater glory than mere conquest can ever impart, to the glory of culture and the arts. It found these perfected in Greece, and it became the pupil and imitator of that country, just as England has at various times become the pupil of Italy or France. It would hardly be too much to say of Latin literature, as of Roman art, that most of what is vital and perennial in it comes from Greece, while its faults and shortcomings are chiefly its own. Those who possess Latin literature possess a body of Greek thought and Greek material, but lacking the sure Greek taste and the soul of spontaneity. Our English writers down to Chaucer were in this position. Even their Latin reading was unsatisfactory enough, but, so far as they practised it, they were drinking of Greek waters rendered turbid by Roman handling and adulteration.

King Alfred knew Latin enough to translate Boethius. The monks and scholars, who, till Chaucer’s time, were the only writers, kept alive the reading of Latin literature. But, so far as the Greek was concerned at first hand, there was but one poorly equipped scholar here and another there in all the West of Europe. So little was it known that, even in Wyclif’s day, it was necessary for that reformer[47] in translating the New Testament to render from the Latin Vulgate, the Greek original being veritably “all Greek” to him. Chaucer, again, writes indeed of Greeks at Thebes and Troy, and refers to Aristotle and Greek authors; but his acquaintance with these is all at second hand, through Roman poets like Ovid and Statius, or even at third or fourth hand, through the literature of Frenchmen or Italians, who themselves derived from writers in Latin and not from the Greek originals.

This, then, is the first period and manner of Greek influence, an influence indirect and roundabout, exerted through the medium of Latin literature, in which the style and spirit of Greece had already been corrupted or destroyed.

The second manner of influence was still more roundabout. It came through the Saracens and Moors. When the Saracen power had reached its zenith and one caliph sat in state at Bagdad and another at Cordova, the Saracens felt what the Romans had felt, that, after all, it is culture and arts which give a nation nobility. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries in particular the Saracen kingdom in Spain flourished mightily in culture and learning. Early in the ninth century a caliph of Bagdad showed himself one of the most devoted fosterers of literature that the world has ever known. His Court was thronged with men of letters and learning; he lavished honours on them; he collected books from every source, and especially from Greece. When he dictated terms of peace to the Greek Emperor Michael he demanded as tribute a collection of Greek authors.[48] Works of the Greeks on rhetoric and philosophy were particularly prized, translated, and commented on. But the learning of Bagdad meant also the learning of the Moors in Spain. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries the science of the Moors was sought by many western students who were not Moslems; and thus from Bagdad, round by way of Spain, there percolated to Italy, France, and England some knowledge of what classical Greece had thought and written. In particular, Averrhoes, a Saracen, translated Aristotle into Arabic; from the Arabic a Latin version was made. This version passed into general use, and the Aristotelean philosophy, which dominated, not to say tyrannized, over Europe for centuries, owes its access to Western Europe to the followers of Mohammed.

Thus far, until the Renaissance dawned in Italy, we find in Western Europe no acquaintance with Greek literature at first hand, but only so much knowledge of its contents as could be gathered from the Latin writers, who had recast it or plagiarized it, or from the Saracen writers, who had translated it in parts.

At last, however, the influence was to become direct. And first on Italy. As the Turks entered Europe, and gradually overran the empire of Greece, Greeks of learning made their way westward to Venice, Ravenna, Padua, Florence, Rome. After the year 1300, or thereabouts, during the great age of Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio, we find writers of Italy beginning to acquire some knowledge of Greek, and some insight into the rich literary stores which that[49] language contained. Boccaccio learned the language from a native Greek; Petrarch took lessons from the same. One Italian here, and another there, essayed translations and imitations of Greek authors. In 1453 Constantinople, the capital of the Greek empire, fell into the hands of the Turks, and Greece no longer existed. As a result, crowds of cultured Greeks streamed into Italy with books and manuscripts, prepared to teach for love or money, or from mere ardour and pride of patriotism. The Court of Cosmo de’ Medici at Florence was readily opened to them, and all Italy was agog to learn whatever they could bring. The libraries of Rome and Florence were enriched with Greek manuscripts; and when, soon after, the printing press of Aldus at Venice was established, Homer or Aeschylus passed in the original into many hands, while translations of them came into many more. Greek teachers like Chalcondylas, Argyropoulos, and Lascaris have left their names to fame in Rome and Padua and Florence. The Revival of Learning had filled all Italy, and “learning” meant little but the literature of Greece; it became regular, almost inevitable, that the Italian man of letters should know Greek, and should steep himself in the writings of the Grecians. From Italy the study spread to France and England. Grocyn and Linacre at Oxford, Erasmus and Cheke at Cambridge, worked zealously to establish it against that opposition which always attends the disturbance of sluggish methods and musty privilege. The study was opposed by the “Trojans,” and it was perhaps natural that these should cry out, in an ancient phrase, “Beware of the Greeks, lest they make you a heretic”; for already[50] it was recognized that the revival of Greek learning meant the stimulation of all clear, and therefore progressive, intellectual activities.

By about the year 1550—that is to say, just in time for Spenser, Shakespeare, Bacon, and their kindred—it had become usual for the Universities and the better schools in England to teach the elements of Greek; and there were not wanting ardent students, in those pre-examination days, to prosecute the study for themselves, and to find more than ample reward in the rich intellectual resources which lay revealed before them.