DOMESTIC

ANNALS OF SCOTLAND.

From the Reformation to the Revolution.

SECOND EDITION.

VOLUME I.

W. & R. CHAMBERS, EDINBURGH AND LONDON.

MDCCCLIX.

Edinburgh:

Printed by W. and R. Chambers.

v

It has occurred to me that a chronicle of domestic matters in Scotland from the Reformation downwards—the period during which we see a progress towards the present state of things in our country—would be an interesting and instructive book. History has in a great measure confined itself to political transactions and personages, and usually says little of the people, their daily concerns, and the external accidents which immediately affect their comfort. This I have always thought was much to be regretted, and a general tendency to the same view has been manifested of late years. I have therefore resolved to make an effort, in regard to my own country, to detail her DOMESTIC ANNALS—the series of occurrences beneath the region of history, the effects of passion, superstition, and ignorance in the people, the extraordinary natural events which disturbed their tranquillity, the calamities which affected their wellbeing, the traits of false political economy by which that wellbeing was checked, and generally those things which enable us to see how our forefathers thought, felt, and suffered, and how, on the whole, ordinary life looked in their days.

Nor are these details, broken up and disjointed as they often are, without a useful bearing on certain generalisations of importance, or devoid of instruction for our own comparatively enlightened age. A good end is obviously served by enumerating, for example, all the famines and all the pestilences that have beset the country; for when this is done, it becomes evident that famine and pestilence have been connected in the way of cause and effect. For the astronomer, the meteorologist, and the naturalist, many of the accounts of comets, meteors, and extraordinary natural productions here given, must have some value.1 To the political economist, it may be of service to see the accounts here drawn from contemporary records of the productiveness and failure of many seasons, and of the varying proportions of[vi] bad seasons to good throughout considerable spaces of time. As for the numberless narratives and anecdotes illustrative of the mistaken zeal, the irregular passions, the deplorable superstitions, and erroneous ideas and ways in general, of our ancestors, they furnish beyond doubt a rich pabulum for the student of human nature; nor may they be without some practical utility amongst us, since many of the same errors continue in a reduced style to exist, and it may help to extinguish them all the sooner, that we are enabled here to look upon them in their most exaggerated and startling form, and as essentially the products and accompaniments of ignorance and barbarism.

It will probably be matter of regret that this work consists of a series of articles generally brief and but little connected with each other, producing on the whole a desultory effect. Might not the materials have been fused into one continuous narration? I am very sensible how desirable this was for literary effect; but I am at the same time assured that, in such a mode of presenting the series of occurrences, there would have been a constant temptation to generalise on narrow and insufficient grounds—to make singular and exceptional incidents pass as characteristic beyond the just degree in which they really are so—namely, as matters just possible in the course of the national life of the period to which they refer. It seemed to me the most honest plan, to present them detachedly under their respective dates, thus allowing each to tell its own story, and have its own proper weight with the reader, and no more, in completing the general picture.

As one means of conveying ‘the body of each age, its form and pressure,’ the language of the original contemporary narrators is given, wherever it was sufficiently intelligible and concise. Thus each age in a manner tells its own story. It has not been deemed necessary, however, to retain antiquated modes of orthography, beyond what is required to indicate the old pronunciation, nor have I scrupled occasionally to omit useless clauses of sentences, when that seemed conducive to making the narration more readable. This procedure will not be quite approved of by the rigid antiquary; but it will be for the benefit of the bulk of ordinary readers.

In general, the events of political history are presented here in only a brief narrative, such as seemed necessary for connection. But I have introduced a few notices of these events where there was a contemporary narration either characteristic in its style, or involving particulars which might be deemed illustrative of the general feeling of the time.

Edinburgh, January 25, 1858.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

INTRODUCTORY, |

1 |

REIGN OF MARY: 1561-5, |

7 |

REIGN OF MARY: 1565-7, |

35 |

REGENCY OF MORAY: 1567-70, |

43 |

REGENCIES OF LENNOX AND MAR: 1570-2, |

61 |

REGENCY OF MORTON: 1572-8, |

82 |

REIGN OF JAMES VI.: 1578-85, |

126 |

REIGN OF JAMES VI.: 1585-90, |

160 |

REIGN OF JAMES VI.: 1591-1603, |

219 |

REIGN OF JAMES VI.: 1603-25, |

379 |

| GENERAL INDEX. | |

VOL. I.

Frontispiece Vignette.—BANNATYNE HOUSE, NEWTYLE—where George Bannatyne is supposed to have written his Manuscript. |

|

| PAGE | |

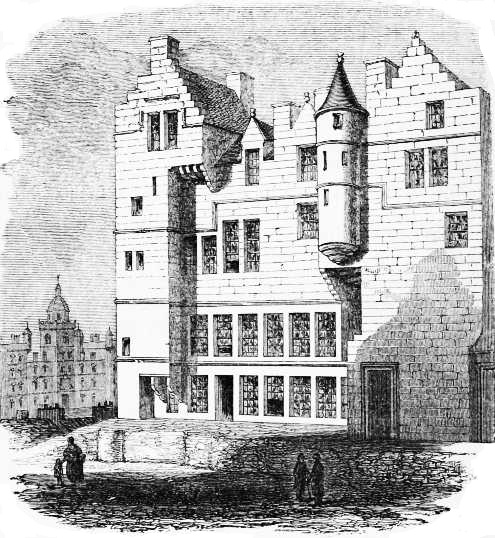

| EDINBURGH CASTLE, RESTORED AS IN 1573, | XII |

| AN EDINBURGH HAMMERMAN, 1555, | 10 |

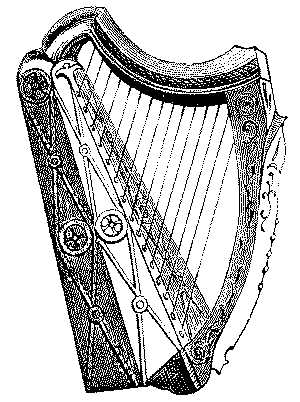

| QUEEN MARY’S HARP, | 31 |

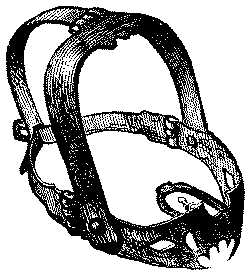

| THE BRANKS, AN INSTRUMENT OF PUNISHMENT, | 47 |

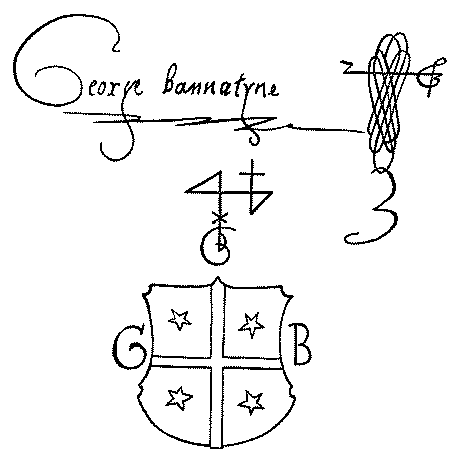

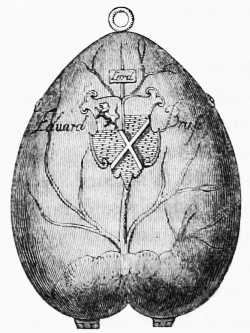

| GEORGE BANNATYNE’S ARMS AND INITIALS, | 58 |

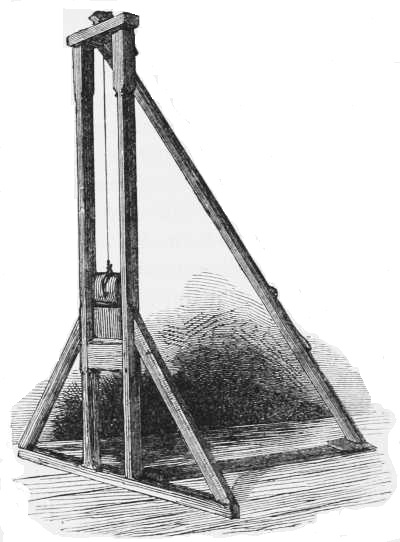

| THE MAIDEN, | 144 |

| THE DEVIL PREACHING TO THE WITCHES, | 215 |

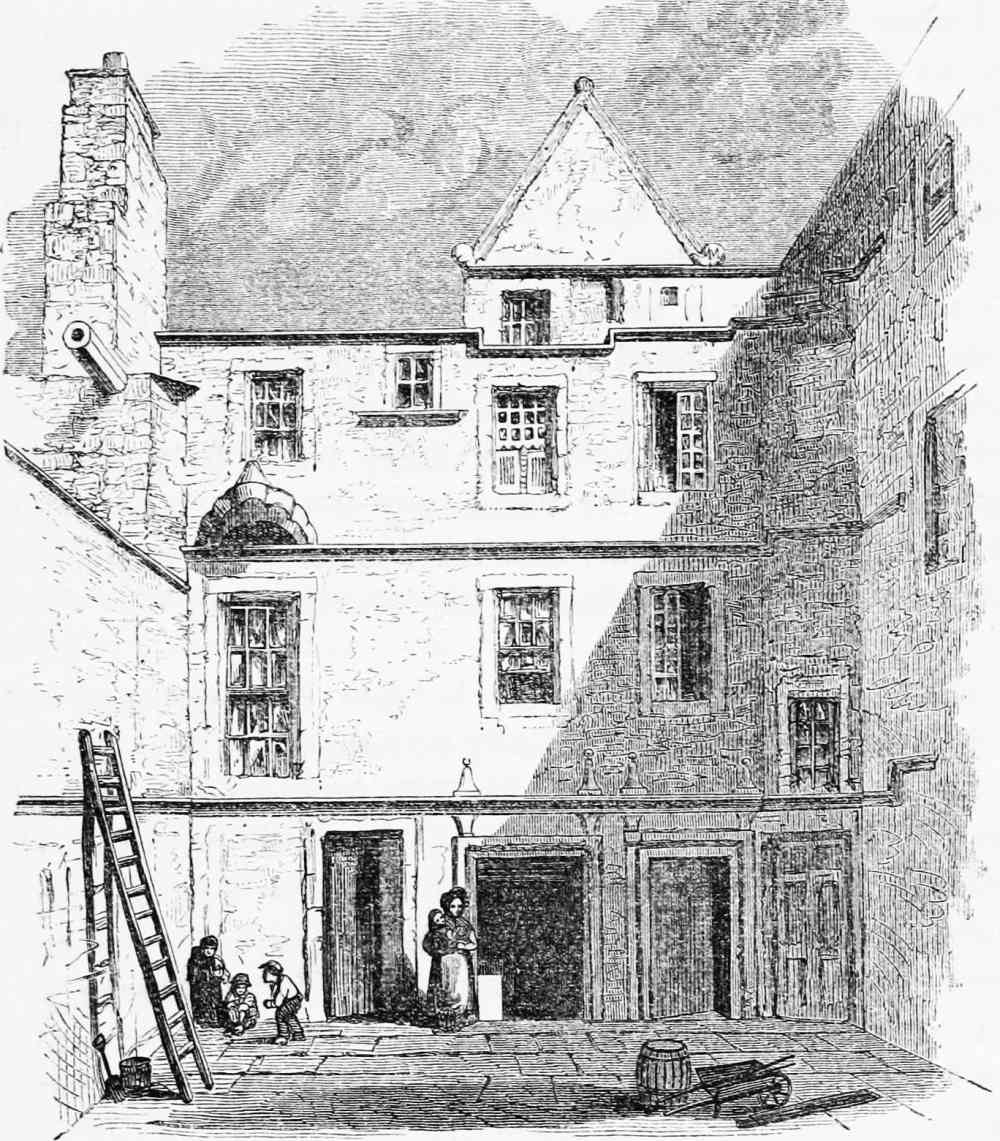

| BAILIE MACMORAN’S HOUSE, | 263 |

| WITCH SEATED ON THE MOON, | 378 |

| SILVER HEART IN CULROSS ABBEY, | 450 |

| HOUSE OF ROBERT GOURLAY, A RICH EDINBURGH CITIZEN OF 1574, | 554 |

| TO SUCH | |

|---|---|

| BOOKS AND AUTHORITIES AS, FROM THEIR MORE FREQUENT OCCURRENCE, ARE QUOTED IN AN ABRIDGED FORM. | |

D. O.—Diurnal of Remarkable Occurrents in Scotland, 1513-1575. (Maitland Club.) 4to. |

1833 |

Cal.—History of the Kirk of Scotland. By Mr David Calderwood. (Wodrow Society.) 8 vols. |

1842 |

Pit.—Criminal Trials in Scotland, from 1488 to 1624, with Historical Notes and Illustrations. By Robert Pitcairn, Esq. 3 vols.4to. Edin. |

1833 |

Knox.—History of the Reformation in Scotland. By John Knox. From MS. Edited by David Laing. 2 vols. (Wodrow Society.) Edin. |

1846 |

C. F.—Chronicle of Fortingall [a composition of the sixteenth century, preserved in the charter-chest of the Marquis of Breadalbane, and printed in the same volume with the Black Book of Taymouth, Edinburgh, 4to. |

1855] |

P. C. R.—Privy Council Record, MS. in General Register House, Edinburgh. Mar.—Annales of Scotland from the year 1513 to the year 1591. By George Marioreybanks, burges of Edinburghe. From MS. 8vo. |

1814 |

Bir.—Diary of Robert Birrel, burges of Edinburghe, from 1532 to 1605. Dalyell’s Fragments of Scottish History. From MS. 4to. Edin. |

1798 |

E. C. R.—Edinburgh Council Record, MS. in Council Chamber, Edinburgh. |

|

H. K. J.—Historie of King James the Sext. 4to. Edin. |

1825 |

C. C. R.—Canongate Council Record [extracts printed in Maitland Club Miscellany, vol. ii.] |

|

Ban.—Journal of the Transactions in Scotland, 1570, 1571, 1572, 1573. By Richard Bannatyne, Secretary to John Knox. From MS. 8vo. Edin. |

1806 |

Ken.—Historical Account of the Name of Kennedy. From MS. With Notes by Robert Pitcairn. 4to. |

1830 |

Ja. Mel.—Autobiography and Diary of Mr James Melville, 1556-1610. From MS. Edited by Robert Pitcairn. (Wodrow Society.) 8vo. |

1842 |

Bal.—Annales of Scotland, 1057-1603. By Sir James Balfour. From MS. 4 vols. 8vo. Edin. |

1824 |

Spot.—History of the Church of Scotland. By the Right Rev. John Spottiswoode, Archbishop of St Andrews. 3 vols. 8vo. |

1847x |

Howes.—Chronicle of England. By Edmond Howes. Fol. |

1615 |

H. of G.—History of the House of Douglas. By Mr David Hume of Godscroft. 2 vols. |

1748 |

Jo. R. B. Hist.—Historia Rerum Britannicarum, &c. Auctore Roberto Johnstono. Fol. Amstel. |

1655 |

R. G. K. E.—Register of the General Kirk of Edinburgh, 1574-1575. Maitland Club Miscellany, vol. i. |

|

B. U. K.—Booke of the Universall Kirk of Scotland. (Bannatyne Club.) 3 vols. 4to. Edin. |

1839-40 |

Chr. Aber.—Chronicle of Aberdeen, 1491-1595. (Spalding Club Miscellany.) |

|

Hist. Acc. Fam. Innes.—Historical Account of the Origine and Succession of the Family of Innes, &c. From orig. MS. Edin. |

1820 |

M. of S.—Mem. Som.—The Memorie of the Somervilles, &c. 2 vols. 8vo. |

1815 |

Moy.—Memoirs of the Affairs of Scotland, 1577-1603. By David Moysie. From MS. (Maitland Club.) 4to. |

1830 |

Moy. R.—Idem, Ruddiman’s edition. 12mo. |

1755 |

Ab. C. R.—Extracts from the Council Register of the Burgh of Aberdeen, 1570-1625. (Spalding Club.) |

1848 |

Row.—Row’s History of the Kirk of Scotland. (Wodrow Society.) |

1842 |

Pa. And.—History of Scotland. By Patrick Anderson. MS. Advocates’ Library. |

|

M. of G.—Memorabilia of the City of Glasgow, selected from the Minute-books of the Burgh. Glasgow, printed for private circulation. |

1835 |

C. K. Sc.—Chronicle of the Kings of Scotland. From MS. (Maitland Club.) |

1830 |

Jo. Hist.—Johnston’s History of Scotland. MS. Advocates’ Library. |

|

Chron. Perth.—The Chronicle of Perth, &c., from 1210 to 1668. (Maitland Club.) 4to. Edin. |

1831 |

G. H. S.—Genealogical History of the Earldom of Sutherland. By Sir Robert Gordon, Bart. Fol. Edin. |

1813 |

Stag. State.—The Staggering State of Scots Statesmen from 1550 to 1650. By Sir John Scot of Scotstarvet. From MS. 12mo. Edin. |

1754 |

S. A.—Acts of Parliament made by King James I., and his Royal Successors. 3 vols. |

1682 |

Acts of the Parliament of Scotland. 11 vols. fol. |

|

P. K. S. R.—Perth Kirk-Session Records. Spottiswoode Club Miscellany. |

|

A. K. S. R.—Aberdeen Kirk-Session Records. (Spalding Club.) Aber. |

1846 |

A. P. R.—Aberdeen Presbytery Records. (Spalding Club.) Aber. |

1846 |

M. S. P.—State Papers, &c., of Thomas Earl of Melrose. (Abbotsford Club.) 2 vols. 4to. Edin. |

1837 |

An. Scot.—Analecta Scotica: Collections illustrative of the Civil, Ecclesiastical, and Literary History of Scotland. Edited by James Maidment. 2 vols. Edin. |

1834-38 |

R. P. L.—Selections from the Registers of the Presbytery of Lanark, 1623-1709. 4to. Edin. |

1839 |

Foun. Hist. Ob.—Historical Observes, &c. By Sir John Lauder of Fountainhall. 4to. Edin. |

1840 |

Foun. Dec.—Fountainhall’s Decisions of the Court of Session. 2 vols. fol. Edin. |

1759 |

Fount.—Historical Notices of Scottish Affairs, from the MSS. of Sir John Lauder of Fountainhall. 2 vols. 4to. Edin. |

1848xi |

W. A.—Analecta, or Materials for a History of Remarkable Providences, &c. By the Rev. Robert Wodrow. 4 vols. (Maitland Club.) Edin. |

1842 |

Stev. Hist. C. of Scot.—History of the Church of Scotland. By Andrew Stevenson, writer in Edinburgh. 2d ed. Edin. |

1844 |

B. A.—Book of Adjournal. MS. Advocates’ Library. |

|

Gillies.—Historical Collections relating to Remarkable Periods of the Success of the Gospel, &c. By John Gillies. 2 vols. Glas. |

1754 |

Spal.—Memorials of the Troubles in Scotland and England, A.D. 1624-A.D. 1645. By John Spalding. 2 vols. 4to. (Spalding Club.) Aber. |

1850 |

Ab. Re.—A Little yet True Rehearsal of Several Passages of Affairs that did occur from the year 1633 till this present year 1655. Collected by a friend of Dr Alexander’s at Aberdeen. Sir Lewis Stewart’s Collections. MS. Advocates’ Library. |

|

Pa. Gordon.—A Short Abridgment of Britanes Distemper, from the year of God 1639 to 1649. By Patrick Gordon of Ruthven. (Spalding Club.) |

1844 |

Carlyle.—Oliver Cromwell’s Letters and Speeches, with Elucidations by Thomas Carlyle. 2 vols. |

1845 |

Lam.—Diary of Mr John Lamont of Newton, 1649-1671. Edin. |

1830 |

C. P. H.—Collections by a Private Hand at Edinburgh, 1650-1661. Stevenson, Edin. |

1832 |

Nic.—Diary of Public Transactions and other Occurrences, chiefly in Scotland. By John Nicoll. 4to. Edin. |

1836 |

R. C. E.—Register of the Committee of Estates. MS. General Register House, Edinburgh. |

|

Spreull.—Some Remarkable Passages of the Lord’s Providence towards Mr John Spreull, Town-clerk of Glasgow, 1635-1664. Stevenson, Edin. |

1832 |

Law.—Memorials; or Memorable Things, &c., from 1638 to 1684. By the Rev. Robert Law. From MS. Edin. |

1818 |

Bail.—Letters and Journals of Robert Baillie, A.M., Principal of the University of Glasgow. From MS. 3 vols. Edin. |

1841 |

Kir.—Secret and True History of the Church of Scotland, from the Restoration to the year 1678. By the Rev. James Kirkton. 4to. Edin. |

1817 |

Pat. Walker.—Biographia Presbyteriana. [Lives of Alexander Peden, &c., by Patrick Walker.] 2 vols. Edin. |

1827 |

1

Our attention lights, a few years after the middle of the sixteenth century, on a little independent kingdom in the northern part of the British island—a tract of country now thought romantic and beautiful, then hard-favoured and sterile, chiefly mountainous, penetrated by deep inlets of the sea, and suffering under a climate not so objectionable on account of cold as humidity. It contains a scattered population of probably seven hundred thousand:—the Scots—thought to be a very ancient nation, descended from a daughter of Pharaoh, king of Egypt, and living under a monarchy believed to have originated about the time that Alexander conquered India. A very poor, rude country it is, as it well might be in that age, and seeing that it lay so far to the north and so much out of the highway of civilisation. No well-formed roads in it—no posts for letters or for travelling. A printing-press in the head town, Edinburgh, but not another anywhere. A regular localised court of law had not yet existed in it thirty years. No stated means of education, excepting a few grammar-schools in the principal towns, and three small universities. Society consisted mainly of a large agricultural class, half enslaved to the lords of the soil: above all, obliged to follow them in war. Other industrial pursuits to be found only in the burghs, the chief of which were Edinburgh, Glasgow, Stirling, Perth, Dundee, and Aberdeen.

In reality, though it was not known then, the bulk of the people of Scotland were a branch of the great Teutonic race which possesses Germany and some other countries in the north-west of Europe. Precisely the same people they were with the bulk of the English, and speaking essentially the same language, though for ages they had been almost incessantly at war with that richer and more advanced community. As England, however, was2 neighboured by Wales, with a Celtic people, so did Scotland contain in its northern and more mountainous districts a Celtic people also, rude, poor, proud, and of fiery temper, but brave and possessed of virtues of their own, somewhat like the Circassians of our own day. These Highland clansmen—whom the English of that time contemptuously called Redshanks, with reference to their naked hirsute limbs—were the relics of a greater nation, who once occupied all Scotland, and of whose blood some portion was mingled with that of the Scots of the Lowlands, producing a certain fervour of character—‘perfervidum ingenium Scotorum’—which is not found in purely Teutonic natures. The monarchy had originated with them early in the sixth century of the Christian era, and had gradually absorbed the rest of Scotland, even while its original subjects were hemmed more and more within the hilly north. But, by the marriages of female heirs, this thorn-encircled crown had come, in the fourteenth century, into a family of Norman-English extraction, bearing the name of Stuart.

The present monarch was ‘our Sovereign Lady Mary,’ a young and beautiful woman, married to Francis II. of France. She had been carried thither in a troublous time during her childhood, and in her absence, a regent’s sceptre was swayed by her mother, a princess of the House of Guise. Up to that time, Scotland, like most of the rest of Europe, was observant of the Catholic religion, and under vows of obedience to the pope of Rome. But the reforming ideas of Luther and Melancthon, of Zuinglius and Calvin, at length came to it, and surprising were the effects thereof. As by some magical evolution, the great mass of the people instantaneously threw off all regard to the authority of the pope, with all their old habits of worship, professing instead a reverence for the simple letter of Scripture, as interpreted to them by the reforming preachers. Indignant at having been so long blinded by the Catholic priesthood—whose sloth and luxury likewise disgusted them—they attacked the churches and monasteries, destroyed the altars and images—did not altogether spare even the buildings, alleging that rooks were best banished by pulling down their nests: in short, made a very complete practical reformation through all the more important provinces. This was done by the populace, with the countenance and help of a party of the nobility and gentry; and the regent, Mary de Guise, who was firm in the old faith, in vain strove to stem the torrent. Obtaining troops from France, she did indeed maintain for a time a resistance to the reforming lords and their adherents. But they, again, were supported by some troops from Elizabeth of England, whose interest it was to protestantise Scotland; and so the Reformation got the ascendency. Mary the Regent sunk into the grave, just about the time that her faith came to its final and decisive ruin within her daughter’s dominions.

3

This change may be considered as having been completed in August 1560, when an irregular parliament, or assembly of the Estates of the kingdom, abolished the jurisdiction of the pope, proscribed the mass under the severest penalties, and approved of a Confession of Faith resembling the articles which had been established in England by Edward VI. The chief feature of the new system was, that each parish should have its own pastor, elected by the people, or at least a reader to read the Scriptures and common prayers. While thus essentially presbyterian, there was a trace of episcopal arrangements in the appointment of ten superintendents (one of whom, however, was a layman), whose duty it should be to go about and see that the ordinary clergy did their duty. The great bulk of the possessions and revenues of the old church fell into the hands of the nobles, or remained with nominal bishops, abbots, and other dignitaries, who continued formally to occupy their ancient places in parliament, while the presbyterian clergy were insufficient in number, and in general very poorly supported.

‘Lo here,’ then, ‘a nation born in one day; yea, moulded into one congregation, and sealed as a fountain with a solemn oath and covenant!’ So exclaims a clerical writer a hundred years later; and we, who live two hundred years still further onward, may well echo the words. But a little while ago, there were priests, with vestments of ancient and gorgeous form, saying mass in churches, which were the only elegant structures in the country. The name of the pope was a word to bow at. Confession was one of the duties of life. Barefooted friars wandered about in the enjoyment of universal reverence. Any gentleman going out with his sovereign on a military expedition, would have been thought liable to every evil under the sun, and altogether a scandalous person, if he did not beforehand obtain pardon for his sins from the Grayfriars, and leave in their hands his most valuable possessions, including the very titles of his estate, which he might hope to get back if he survived; but otherwise, he well knew all would go to the enriching of these same friars, who were under vows to live in perpetual poverty.2 The king himself sought for his highest religious comfort in pilgrimising to St Duthac’s shrine in Ross-shire, or to the chapel of our Lady of Loretto, at Musselburgh. The4 bishop of Aberdeen felt a solacement in the hour of death, in the trust that his bowels would be buried, as he requested, in the Blackfriars Monastery in Edinburgh.3 So lately as 1547, the Scotch, fighting with the English at Pinkie, called out reproachful names to them, on the score of their having deserted the ancient faith. But here is now Scotland also converted, and that as it were in a day, from all those old reverences and observances, and taken possession of by a totally new set of ideas. The Bible in the vulgar tongue has been suddenly laid open to them. Their minds, earnest and reflecting, though unenlightened, have been impressed beyond description by the tale of miraculous history which it unfolds, and the deeply touching scheme for effecting the salvation of man which the theologian constructs from it. They feel as if they had got hold of something of priceless value, and in comparison with which all the forms and rites of medieval Christianity are as dust and rubbish. The Evangel, the True Religion, as they earnestly called it, is henceforth all in all with this poor and homely, but resolute people. Nothing inconsistent therewith can be listened to for a moment. Scarcely can a dissentient be permitted to live in the country. The state, too, must maintain this system, and this system alone, or it is no state for them. Above all, the errors of Popery must be unsparingly put down. The mass is idolatry: God, in his Book, says that idolatry is a sin to be visited with the severest judgments; therefore, if you wish to avoid judgments, you must extinguish the mass. Even modified forms and rituals which have been preserved by English Protestantism, as calculated to raise or favour a spirit of devotion, and maintain a decency in worship, are here regarded as but the rags of Rome, and spurned with nearly the same vehemence as the mass itself. Scotland will have nothing but a preacher to expound, and say a prayer. That, with the Bible in the hands of the people, is enough for her. No hierarchy does she require to maintain order in the church. Let the ministers meet in local courts and in General Assembly, and settle everything by equal votes. Bishops and archbishops are a popish breed, who must, if possible, be kept at a distance.

Even one who may now take more charitable and lenient views can scarcely fail to sympathise with, yea, admire, this little out-of-the-way nation, in seeing it dictate and do thus against the might of an ancient institution of such imposing dimensions as the Romish Church. And to do it, too, in the teeth of their own ruling power, such as it was. And all so effectually, that from that hour to this, Rome, in all her back-surgings upon the ground she lost in the sixteenth century, was never able to put Scottish Protestantism once in the slightest danger. Undoubtedly, if there be merit in a faithful contending for what is felt to be all-important truth, it was a worthy thing, and one that shewed there was some5 good metal in the constitution of the Scottish mind. It could not surprise one that a people who acted thus, should also prove to be a valiant and constant people under physical difficulties; that they should make wonderful results out of a poor soil and climate; that they should do some considerable things in the science of thinking and in letters; and, above all, stand well to their own opinions and ways, and to the maintenance of their political liberties and national independence, frown, threaten, and drive at them who might.

It was so—and yet—for every picture of noble humanity has its reverse—it is forced upon us that the Scots were, at this very time, a fearfully rude and ignorant people. As usual, they were so without having the least consciousness of it: their greatest author of that age, George Buchanan, speaks in perfect earnest of the refinement of his own time, in comparison with the barbarism of former days.4 But, whatever the age might be relatively to past ages, it was rude in itself. The Scotland of that day was ruder than the England of that day, ruder than many other European states. Few persons could read or write. Few knew aught beyond their daily calling. Men carried weapons, and were apt to use them on light occasion. The lords, and the rich generally, exercised enormous oppression upon the poor. The government was a faction of nobles, as against all the rest. When a man had a suit at law, he felt he had no chance without using ‘influence.’ Was he to be tried for an offence?—his friends considered themselves bound to muster in arms round the court to see that he got fair-play; that is, to get him off unharmed if they could. Men were accustomed to violence in all forms, as to their daily bread. The house of a man of consideration was a kind of castle: at the least, it was a tall narrow tower, with a grated door and a wall of defence. No one in those days had any general conceptions regarding the processes of nature. They saw the grass grow and their bullocks feed, and thought no more of it. Any extraordinary natural event, as an eclipse of the sun or an earthquake, still more a comet, affected them as an immediate expression of a frowning Providence. The great diseases, such as pestilence, which arose in consequence of their uncleanly habits and the wide-spread famines from which they often suffered, appeared to them as divine chastisements; not perhaps for the sins of those who suffered—which would have been comparatively reasonable—but probably for the sins of a ruler who did not suffer at all. The ruling class knew no more of a just public economy than the poor. Through absurd attempts to raise the value of6 coin by statute, the Scotch pound had fallen to a fraction of its original worth. By ridiculous endeavours to control markets, and adjust exportation and importation, mercantile freedom was paralysed, and penury and scarcity among the poor greatly increased. The good plant of Knowledge not being yet cultivated, its weed-precursor, Superstition, largely prevailed. Bearded men believed that a few muttered words could take away and give back the milk of their cattle. An archbishop expected to be cured of a deadly ailment by a charm pronounced by an ignorant countrywoman. The forty-six men who met as the first General Assembly, and drew from the Scriptures the Confession of Faith which they handed down as stereotyped truth to after-generations, were every one of them not more fully persuaded of the soundness of any of the doctrines of that Confession, than they were of the reality of sorcery, and felt themselves not more truly called upon by the Bible to repress idolatry than to punish witches. They were good men, earnest, and meaning well to God and man; but they were men of the sixteenth century, ignorant, and rough in many of their ways.

While, then, we shall see great occasion to admire the hardy valour with which this people achieved their deliverance from bondage, we must also be prepared for finding them full of vehement intolerance towards all challenge of their own dogmas and all adherence to alien forms of faith. We shall find them utterly incapable of imagining a conscientious dissent, much less of allowing for and respecting it. We must be prepared to see them—while repudiating one set of superstitious incrustations upon the original simple gospel—working it out on their own part in creeds, plats, covenants, and church institutions generally, full of mere human logic and device, but yet assumed to be as true as if a divine voice had spoken and framed them, breathing war and persecution towards all other systems, and practically operating as a tyranny only somewhat less formidable than that which had been put away.

7

The regent, Mary de Guise, having died in June 1560, while her daughter Mary, the nominally reigning queen, was still in France, the management of affairs fell into the hands of the body of nobles, styled Lords of the Congregation, who had struggled for the establishment of the Protestant faith. The chief of these was Lord James Stuart, an illegitimate son of James V., and brother of the queen—the man of by far the greatest sagacity and energy of his age and country, and a most earnest votary of the new religion.

Becoming a widow in December 1560, by the death of her husband, Francis II., Mary no longer had any tie binding her to France, and consequently she resolved on returning to her own dominions. When she arrived in Edinburgh, in August 1561, she found the Protestant religion so firmly established, and so universally accepted by the people—there being only some secluded districts where Catholicism still prevailed—that, so far from having a chance of restoring her kingdom to Rome, as she, ‘an unpersuaded princess,’ might have wished to do, it was with the greatest difficulty that she could be allowed to have the mass performed in a private room in her palace. The people regarded her beautiful face with affection; and, as she allowed her brother, Lord James, and other Protestant nobles to act for her, her government was far from unpopular.

Mary’s conduct towards the Protestant cause appeared as that of one who submits to what cannot be resisted. Before she had been fifteen months in the country, she accompanied her brother (whom she created Earl of Moray) on an expedition to the north, where she broke the power of the Gordon family, who boasted they could restore the Catholic faith in three counties. What is still more remarkable, she dealt with the patrimony of the church, accepting part of the spoils for the use of the state. It is believed, nevertheless, that she designed ultimately to act in concert with the Catholic powers of the continent for the restoration of the old religion in Scotland. One obvious motive for keeping on fair terms with Protestantism for the present, lay in her hopes of succeeding to the English crown, in the event of the death of Elizabeth, whose next heir she was.

A custom, dating far back in Catholic times, prevailed in Edinburgh in unchecked luxuriance down almost to the time of the Reformation. It consisted in a set of unruly dramatic games, called8 Robin Hood, the Abbot of Unreason, and the Queen of May, which were enacted every year in the floral month just mentioned. The interest felt by the populace in these whimsical merry-makings was intense. At the approach of May, they assembled and chose some respectable individuals of their number, very grave and reverend citizens perhaps, to act the parts of Robin Hood and Little John, of the Lord of Inobedience, or the Abbot of Unreason, and ‘make sports and jocosities’5 for them. If the chosen actors felt it inconsistent with their tastes, gravity, or engagements, to don a fantastic dress, caper and dance, and incite their neighbours to do the like, they could only be excused on paying a fine. On the appointed day, always a Sunday or holiday, the people assembled in their best attire and in military array, and marched in blithe procession to some neighbouring field, where the fitting preparations had been made for their amusement. Robin Hood and Little John robbed bishops, fought with pinners, and contended in archery among themselves, as they had done in reality two centuries before.6 The Abbot of Unreason kicked up his heels and played antics like a modern pantaloon. The popular relish for all this was such as can scarcely now be credited. ‘A learned prelate [Latimer] preaching before Edward VI., observes, that he once came to a town upon a holiday, and gave information on the evening before of his design to preach. But next day when he came to the church, he found the door locked. He tarried half an hour ere the key could be found, and instead of a willing audience, some one told him: “This is a busy day with us; we cannot hear you. It is Robin Hood’s day. The parish are gone abroad to gather for Robin Hood. I pray you let [hinder] them not.” I was fain (says the bishop) to give place to Robin Hood. I thought my rochet should have been regarded, though I were not; but it would not serve. It was fain to give place to Robin Hood’s men.’7

Such were the Robin Hood plays of Catholic and unthinking times. By and by, when the Reformation approached, they were found to be disorderly and discreditable, and an act of parliament was passed against them.8 Still, while the upper and more serious9 classes frowned, the common sort of people loved the sport too much to resign it without a struggle. It came to be one of the first difficulties of the men who had carried through the Reformation, how to wrestle the people out of their love of the May-games.

In April 1561, one George Durie was chosen in Edinburgh as Robin Hood and Lord of Inobedience, and on Sunday the 12th of May, he and a great number of other persons came riotously into the city, with an ensign and arms in their hands, in disregard of both the act of parliament and an act of the town-council. Notwithstanding an effort of the magistrates to turn them back, they passed to the Castle Hill, and thence returned at their own pleasure. For this offence a cordiner’s servant, named James Gillon, was condemned to be hanged on the 21st of July.

‘When the time of the poor man’s hanging approachit, and that the [hangman] was coming to the gibbet with the ladder, upon which the said cordiner should have been hangit, the craftsmen’s childer9 and servants past to armour; and first they housit Alexander Guthrie and the provost and bailies in the said Alexander’s writing booth, and syne came down again to the Cross, and dang down the gibbet, and brake it in pieces, and thereafter passed to the Tolbooth, whilk was then steekit [shut]; and when they could not apprehend the keys thereof, they brought fore-hammers and dang up the same Tolbooth door perforce, the provost, bailies, and others looking thereupon; and when the said door was broken up, ane part of them past in the same, and not allenarly [only] brought the same condemnit cordiner forth of the said Tolbooth, but also all the remanent persons being thereintill; and this done they past down the Hie Gait [High Street], to have past forth at the Nether Bow, whilk was then steekit, and because they could not get furth thereat, they past up the Hie Gait again; and in the meantime the provost, bailies, and their assisters being in the writing-booth of Alexander Guthrie, past to the Tolbooth; and in their passing up the said gait, they being in the Tolbooth, as said is, shot forth at the said servants ane dag, and hurt ane servant of the craftsmen’s. That being done, there was naething but tak and slay; that is, the ane part shooting forth and casting stanes, the other part shooting hagbuts in again; and sae the craftsmen’s servants held them [conducted themselves] continually fra three hours afternoon while [till] aucht at even, and never ane man of the town steirit to defend their provost and10 bailies. And then they sent to the masters of the craftsmen to cause them, gif they might, to stay the said servants; wha purposed to stay the same, but they could not come to pass, but the servants said they wald have ane revenge for the man whilk was hurt. And thereafter the provost sent ane messenger to the constable of the Castle to come to stay the matter, wha came; and he with the masters of the craftsmen treated on this manner, that the provost and bailies should discharge all manner of actions whilk they had against the said craftschilder in ony time bygane, and charged all their masters to receive them in service as they did of before, and promittit never to pursue them in time to come for the same. And this being done and proclaimit, they skaled [disbanded], and the provost and bailies came furth of the Tolbooth.’—D. O.

This was altogether an unprotestant movement, though springing only from a thoughtless love of sport. We may see in the11 attack on the Tolbooth a foreshadow of the doings of the Porteous mob in a later age. It appears that the magistrates, though reformers, were unpopular; hence the neutrality of the citizens, who, when solicited to interfere for the defence of the city-rulers, went to their four hours penny,11 and returned for answer: ‘They will be magistrates alone; let them rule the multitude alone.’—Cal. Thirteen persons were afterwards ‘fylit’ by an assize for refusing to help the magistrates.—Pit.

On its being known that Queen Mary was about to arrive in Scotland from France, there was a great flocking of the upper class of people from all parts of the country to Edinburgh, ‘as it were to a common spectacle.’

The queen arrived with her two vessels in Leith Road, at seven in the morning of a dull autumn-day. She was accompanied by her three uncles of the House of Guise—the Duc d’Aumale, the Grand Prior, and the Marquis d’Elbeuf; besides Monsieur d’Amville, son of the constable of France, her four gentlewomen, called the Maries, and many persons of inferior note. To pursue the narrative of one who looked on the scene with an evil eye: ‘The very face of heaven, the time of her arrival, did manifestly speak what comfort was brought unto this country with her;’ to wit, sorrow, dolour, darkness, and all impiety; for in the memory of man, that day of the year, was never seen a more dolorous face of the heaven, than was at her arrival, which two days after did so continue; for beside the surface weet and corruption of the air, the mist was so thick and so dark, that scarce might any man espy ane other the length of twa butts. The sun was not seen to shine two days before nor two days after. That forewarning gave God unto us; but, alas, the most part were blind.

‘At the sound of the cannons which the galleys shot, the multitude being advertised, happy was he and she that first might have presence of the queen.... [At ten hours her hieness landed upon the shore of Leith.] Because the palace of Holyroodhouse was not thoroughly put in order ... she remained [in Andrew Lamb’s house] in Leith till towards the evening, and then repaired thither. In the way betwixt Leith and the Abbey, met her the rebels of the crafts ... that had violated the authority of the magistrates and had besieged the provost; but because she was12 sufficiently instructed that all they did was done in despite of the religion, they were easily appardoned. Fires of joy were set forth all night, and a company of the most honest, with instruments of music, and with musicians, gave their salutations at her chalmer window. The melody, as she alleged, liked her weel; and she willed the same to be continued some nichts after.’—Knox.

The magistrates of Edinburgh, although all of them zealous for the reformed religion, resolved to give their young sovereign a gallant reception, taxing the community for the expenses. It was likewise thought good that, ‘for the honour and pleasure of our sovereign, ane banquet sould be made upon Sunday next, to the princes, our said sovereign’s kinsmen.’

The queen ‘made her entres in the burgh of Edinburgh in this manner. Her hieness departed of Holyroodhouse, and rade by the Lang Gate12 on the north side of the burgh, unto the time she came to the Castle, where was ane yett [gate] made to her, at the whilk she, accompanied by the maist part of the nobility of Scotland, came in and rade up the castle-bank to the Castle, and dined therein.’

‘When she had dined at twelve hours, her hieness came furth of the Castle ..., at whilk departing the artillery shot vehemently. Thereafter, when she was ridand down the Castle Hill, there met her hieness ane convoy of the young men of the burgh, to the number of fifty or thereby, their bodies and thies covered with yellow taffetas, their arms and legs frae the knee down bare, coloured with black, in manner of Moors; upon their heads black hats, and on their faces black visors; in their mouths rings garnished with untellable precious stanes; about their necks, legs, and arms, infinite of chains of gold: together with saxteen of the maist honest men of the town, clad in velvet gowns and velvet bonnets, bearand and gangand about the pall under whilk her hieness rade; whilk pall was of fine purpour velvet, lined with red taffetas, fringed with gold and silk. After them was ane cart with certain bairns, together with ane coffer wherein was the cupboard and propine [gift] whilk should be propinit to her hieness. When her grace came forward to the Butter Tron, the nobility and convoy procedand, there was ane port made of timber in maist honourable manner, coloured with fine colours, hung with sundry arms; upon whilk port was singand certain bairns in the maist heavenly wise; under the whilk port there was ane cloud opening with four leaves, in the whilk was put13 ane bonnie bairn. When the queen’s hieness was coming through the said port, the cloud openit, and the bairn descended down as it had been ane angel, and deliverit to her hieness the keys of the town, together with ane Bible and ane Psalm-buik coverit with fine purpour velvet.13 After the said bairn had spoken some small speeches, he delivered also to her hieness three writings, the tenour whereof is uncertain. That being done, the bairn ascended in the cloud, and the said cloud steekit.’

‘Thereafter the queen’s grace came down to the Tolbooth, at the whilk was ... twa scaffats, ane aboon, and ane under that. Upon the under was situate ane fair virgin called Fortune, under the whilk was three fair virgins, all clad in maist precious attirement, called ... , Justice, and Policy. And after ane little speech made there, the queen’s grace came to the Cross, where there was standand four fair virgins, clad in the maist heavenly claithing, and frae the whilk Cross the wine ran out at the spouts in great abundance. There was the noise of people casting the glasses with wine.’

‘This being done, our lady came to the Salt Tron, where there was some speakers; and after ane little speech, they burnt upon the scaffat made at the said Tron the manner of ane sacrifice. Sae that being done, she departed to the Nether Bow, where there was ane other scaffat made, having ane dragon in the same, with some speeches; and after the dragon was burnt, and the queen’s grace heard ane psalm sung, her hieness passed to the abbey of Holyroodhouse, with the said convoy and nobilities. There the bairns whilk was in the cart with the propine made some speech concerning the putting away of the mass, and thereafter sang ane psalm. And this being done, the ... honest men remained in her outer chalmer, and desired her grace to receive the said cupboard, whilk was double over-gilt; the price thereof was 2000 merks; wha received the same and thankit them thereof. And sae the honest men and convoy come to Edinburgh.’—D. O.

The Sunday banquet to the queen’s uncles duly took place in the cardinal’s lodging in Blackfriars’ Wynd. The entire expenses on the occasion of this royal reception were 4000 merks.

Before the queen had been settled for many weeks in her capital,14 the new-born zeal of the people against the old religion found vent in a way that shewed in how little danger she was of being spoilt by complaisance on the part of her subjects. The provost of Edinburgh, Archibald Douglas, with the bailies and council, ‘causit ane proclamation to be proclaimit at the Cross of Edinburgh, commanding and charging all and sundry monks, friars, priests, and all others papists and profane persons, to pass furth of Edinburgh within twenty-four hours, under the pain of burning of disobeyers upon the cheek and harling of them through the town upon ane cart. At the whilk proclamation, the queen’s grace was very commovit.’—D. O. She had, after all, sufficient influence to cause the provost and bailies to be degraded from their offices for this act of zeal.

The autumn of this year, the weather was ‘richt guid and fair.’ In the winter quarter, the weather was still fair, and there was ‘peace and rest in all Scotland.’—C. F.

William Guild was convicted, notwithstanding his being a minor and of weak mind, of ‘the thieftous stealing and taking forth of the purse of Elizabeth Danielstone, the spouse of Niel Laing, hinging upon her apron ... she being upon the High Street, standing at the krame of William Speir ... in communing with him, the time of the putting of ane string to ane penner and inkhorn, whilk she had coft [bought] fra the said kramer, of ane signet of gold, ane other signet of gold set with ane cornelian, ane gold ring set with ane great sapphire, ane other gold ring with ane sapphire formit like ane heart, ane gold ring set with ane turquois, ane small double gold ring set with ane diamond and ane ruby, ane auld angel-noble, and ane cusset ducat.’—Pit. This account of the contents of Mrs Laing’s purse, in connection with the decorations of the fifty young citizens who convoyed the queen in her procession through the city, raises unexpected ideas as to the means and taste of the middle classes in 1561.

Mr William Balfour, indweller in Leith, was convicted of breaking the queen’s proclamation for the protection of the reformed religion. One of his acts—‘He, accompanied with certain wicked persons ... upon set purpose, came to the parish kirk of Edinburgh, callit Sanct Giles Kirk, where John Cairns was examining the common people of the burgh, before the last communion ... and the said John, demanding of ane poor15 woman, “Gif she had ony hope of salvation by her awn good works,” he, the said Mr William, in despiteful manner and with thrawn countenance, having naething to do in that kirk but to trouble the said examination, said to the said John thir words: “Thou demands of that woman the thing whilk thou nor nane of thy opinion allows or keeps.” And, after gentle admonition made to him by the said John, he said to him alsae thir words: “Thou art ane very knave, and thy doctrine is very false, as all your doctrine and teaching is.” And therewith laid his hand upon his weapons, and provoking battle; doing therethrough purposely that was in him to have raisit tumult amang the inhabitants of this burgh.’—Pit.

Alexander Scott, a poet of that time, sometimes called the Scottish Anacreon, because he sung so much of love, sent Ane New Year Gift to the queen, in the form of a poetical address in twenty-eight stanzas. ‘Welcome, illustrate lady, and our queen!’ it begins. ‘This year sall richt and reason rule the rod’—‘this year sall be of peace, tranquillity, and rest!’ says the sanguine bard, speaking from his wishes rather than a contemplation of known facts. He calls on Mary to found on the four cardinal virtues, to cleave to Christ, and be the ‘protectrice of the puir.’ ‘Stanch all strife’—‘the pulling down of policy reprove.’

Mary would probably feel the force of the seventh line of this stanza.

With commendable prudence, seeing he was addressing a papist queen, honest Alexander says:

Yet he deems himself at liberty to remark—doubtless suspecting that Mary would not be much displeased—that instead of old idols has now come in another called Covetice, under whose auspices, certain persons, while

16

are found

‘Protestants,’ he goes on to say,

On this Lord Hailes remarks: ‘The reformed clergy expected that the tithes would be applied to charitable uses, to the advancement of learning and the maintenance of the ministry. But the nobility, when they themselves had become the exactors, saw nothing rigorous in the payment of tithes, and derided those devout imaginations.’15

In one verse of his poem, Scott makes pointed allusion to certain prophecies which seemed to assign a brilliant future to Mary:

The poet here undoubtedly had in view a prediction which occurs in a rude metrical tract printed at Edinburgh by Robert Waldegrave in 1603, under the title, ‘The Whole Prophesies of Scotland, England, and somepart of France and Denmark, prophesied by mervellous Merling, Beid, Bertlingtoun, Thomas Rymour, Waldhave, &c., all according in one.’16 These so-called prophecies are unintelligible rhapsodies about lions, dragons, foumarts, conflicts of knights, of armies, and of navies—how there should be fighting on a moor beside a cross, till by the multitude of slain the crow should not find where the cross stood—how the dead shall rise, ‘and that shall be wonder’—how

and much more of the like kind.

From the style of the verse, which is in general alliterative, as17 well as some of the allusions, it may be surmised that these prophecies were written in the minority of James V., on the basis of obscure popular sayings attributed to Merlin, Rymour, and other early sages. The special passage which Alexander Scott refers to was in Rymour’s prophecies, but also given in a slightly different form in those of Bertlingtoun:

There can be no doubt that it is applicable to Queen Mary, who was a French wife, and in the ninth degree of descent from Bruce; and did we know for certain that it formed a part of the prophecies made up in the minority of her father, it would be remarkable. But the probability is, that the verse was a recent addition to the old rhymes, a mere conjecture formed in the view of the possibility and the hope that a child of Mary would succeed to the English crown at the close of Elizabeth’s life. What makes the allusion of Scott chiefly worthy of notice, is the knowledge it gives us of the public mind being then possessed by such soothsayings. It certainly was so, to a degree and with effects beyond what we now may readily imagine.17

While Scotland was noted in the eyes of foreigners as a barren land—Shakspeare comparing it for nakedness to the palm of the hand18—its own people were fain to believe and eager to boast that it was rich in minerals. In 1511, 1512, and 1513, James IV. had gold-mines worked on Crawford Muir, in the upper ward of Lanarkshire—a peculiarly sterile tract, scarcely any part of which is less than a thousand feet above the sea. In the royal accounts for those years, there are payments to Sir James Pettigrew, who seems to have been chief of the enterprise, to Simon Northberge, the master-finer, Andrew Ireland, the finer, and Gerald Essemer, a Dutchman, the melter of the mine. Under the same king, in 1512, a lead-mine was wrought at Wanlock-head, on the other side of the same group of hills in Dumfriesshire. The operations, probably interrupted by the disaster of Flodden, were resumed in 1526, under James V., who gave a company of Germans a grant of the mines of Scotland for forty-three years. Leslie tells us that these Germans,18 with the characteristic perseverance of their countrymen, toiled laboriously at gold-digging for many months in the surface alluvia of the moor, and obtained a considerable amount of gold, but not enough, we suspect, to remunerate the labour: otherwise the work would surely have been continued.

We shall find that the search for the precious metals in the mountainous district at the head of the vales of the Clyde and Nith, did not now finally cease, but that it never proved remunerative work. On the other hand, the lead-mines of the district have for centuries, and down to the present day, borne a conspicuous place in the economy of Scotland. It must be interesting to see the traces of the first efforts to get at

John Acheson, master-cunyer, and John Aslowan, burgess of Edinburgh, now completed an arrangement with Queen Mary, by virtue of which they had licence to work the lead-mines of Glengoner and Wanlock-head, and carry as much as twenty thousand stone-weight of the ore to Flanders, or other foreign countries, for which they bound themselves to deliver at the queen’s cunyie-house before the 1st of August next, forty-five ounces of fine silver for every thousand stone-weight of the ore, ‘extending in the hale to nine hundred unces of utter fine silver.’

Acheson and Aslowan were continuing to work these mines in August 1565, when the queen and her husband, King Henry, granted a licence to John, Earl of Athole, ‘to win forty thousand trone stane wecht, counting six score stanes for ilk hundred, of lead ore, and mair, gif the same may guidly be won, within the nether lead hole of Glengoner and Wanlock.’ The earl agreed to pay to their majesties in requital fifty ounces of fine silver for every thousand stone-weight of the ore.—P. C. R.

How the enterprise of Acheson and Aslowan ultimately succeeded does not appear. We suspect that, to some extent, it prospered, as the name Sloane, which seems the same as Aslowan, continued to flourish at Wanlock-head so late as the days of Burns.

A similar licence, on similar terms, was granted by the king and queen to James Carmichael, Master James Lindsay, and Andrew Stevenson, burgesses of Edinburgh, referring, however, to any part of the realm save ‘the mine and werk of Glengoner and Wanlock.’

The Lord James, newly created Earl of Mar (subsequently of19 Moray), ‘was married-upon Annas Keith, daughter to William Earl Marischal, in the kirk of Sanct Geil in Edinburgh, with sic solemnity as the like has not been seen before; the hale nobility of this realm being there present, and convoyit them down to Holyroodhouse, where the banquet was made, and the queen’s grace thereat.’ The solemnity was of a kind which seems rather frisky for so zealous an upholder of the presbyterian cause. ‘At even, after great and divers balling, and casting of fire-balls, fire-spears, and running with horses,’ the queen created sundry knights. Next day, ‘at even, the queen’s grace and the remaining lords came up in ane honourable manner frae the palace of Holyroodhouse to the Cardinal’s lodging in the Blackfrier Wynd, whilk was preparit and hung maist honourably; and there her hieness suppit, and the rest with her. After supper, the honest young men in the town [the youths of the upper classes] came with ane convoy to her, and other some came with merschance, well accouterit in maskery, and thereafter departit to the said palace.’—D. O.

There was ‘meikle snaw in all parts; mony deer and roes slain.’—C. F.

The queen was at St Andrews, inquiring into a conspiracy of which the Duke of Chatelherault and the Earl of Bothwell had been accused by the Duke’s son, the Earl of Arran. In the midst of the affair, Arran proved to be ‘phrenetick.’ On the 4th of May, ‘my Lords Arran, Bothwell, and the Commendator of Kilwinning came fra St Andrews to the burgh of Edinburgh in this manner; that is to say, my Lord Arran was convoyit in the queen’s grace’s coach, because of the phrenesy aforesaid, and the Earl of Bothwell and my Lord Commendator of Kilwinning rade, convoyit with twenty-four horsemen, whereof was principal Captain Stewart, captain of the queen’s guard.’—D. O.

This is not the first notice of a travelling vehicle that occurs in our national domestic history. Several payments in connection with a chariot belonging to the late Queen Mary de Guise, so early as 1538, occur in the lord-treasurer’s books.19 It is not, however, likely that either the chariot of the one queen or the coach of the other was a wheeled vehicle, as, if we may trust to an authority20 about to be quoted, such a convenience was as yet unknown even in England.

‘In the year 1564, Guilliam Boonen, a Dutchman, became the queen’s coachman, and was the first that brought the use of coaches into England. And after a while, divers great ladies, with as great jealousy of the queen’s displeasure, made them coaches, and rid in them up and down the countries, to the great admiration of all the beholders; but then, by little and little, they grew usual among the nobility and others of sort, and within twenty years became a great trade of coachmaking.

‘And about that time began long waggons to come in use, such as now come to London from Canterbury, Norwich, Ipswich, Gloucester, &c., with passengers and commodities. Lastly, even at this time (1605) began the ordinary use of carouches.’—Howes’s Chronicle.

The author of the Memorie of the Somervilles—who, however, lived in the reign of Charles II., and probably wrote from tradition only—says that the Regent Morton used a coach, which was the second introduced into Scotland, the first being one which Alexander Lord Seaton brought from France, when Queen Mary returned from that country. It is to be remarked that the Lord Seaton of that day was George, not Alexander; and it is evident that Mary did not use a coach on her landing, or at her ceremonial entry into Edinburgh.

To turn for a moment to one of the remoter and wilder parts of the country—John Mackenzie of Kintail ‘was a great courtier with Queen Mary. He feued much of the lands of Brae Ross. When the queen sent her servants to know the condition of the gentry of Ross, they came to his house of Killin; but before their coming he had gotten intelligence that it was to find out the condition of the gentry of Ross that they were coming; whilk made him cause his servants to put ane great fire of fresh arn [alder] wood when they came, to make a great reek; also he caused kill a great bull in their presence; whilk was put altogether into ane kettle to their supper. When the supper came, there were a half-dozen great dogs present, to sup the broth of the bull, whilk put all the house through-other with their tulyie. When they ended the supper, ilk ane lay where they were. The gentlemen thought they had gotten purgatory on earth, and came away as soon as it was day; but when they came to the houses of Balnagowan, and Foulis, and Milton, they were feasted like princes.21

‘When they went back to the queen, she asked who were the ablest men they saw in Ross. They answered: “They were all able men, except that man that was her majesty’s great courtier, Mackenzie—that he did both eat and lie with his dogs.” “Truly,” said the queen, “it were a pity of his poverty—he is the best man of them all.” Then the queen did call for all the gentry of Ross to take their land in feu, when Mackenzie got the cheap feu, and more for his thousand merks than any of the rest got for five.’20

This day commenced a famous disputation between John Knox and Quintin Kennedy, abbot of Crossraguel, concerning the doctrines of popery. Kennedy was uncle to the Earl of Cassillis, a young Protestant noble, and the greatest man in the west of Scotland. The birth and ecclesiastical rank of the abbot made him an important person in his province, and he possessed both zeal for the ancient religion and talents to set it in its fairest light. Early in September, John Knox, coming into Ayrshire for certain objects connected with the Protestant cause, found that Abbot Kennedy had set forth, in the church of Kirkoswald, articles in support of the Catholic faith, which he was willing to defend. The fiery reformer immediately resolved to take up the challenge; and after a tedious correspondence between the two regarding the place, time, and number to be present, they met in the house of the provost of the collegiate church of Maybole, under the sanction of the Earl of Cassillis, and with forty persons on each side. The conference commenced at eight in the morning, being opened by John Knox with a prayer, which Kennedy admitted to be ‘weel said.’

We can imagine the forty supporters of Kennedy full of joyful anticipation as to the defeat which their champion was to give the unpolite heretic Knox, and the company of the latter not less hopeful regarding the triumph which he was to achieve over the luxurious abbot. Acts of parliament had done their best to put down the old church, and still it had some obstinate adherents; but now comes the valiant reformer, with pure argument from Scripture, to sweep one of these recusants off the face of the earth, and leave the rest without an excuse for their obstinacy. Now are the mass, purgatory, worship of saints, and other popish doctrines, to be finally put down. If such were the anticipations, they were doomed to a sad disappointment. The22 disputation proved to be the very type of all similar wranglings which have since taken place between the two parties.

It will scarcely be believed, but there is only too little reason why it should not, that three days were consumed by these redoubted controversialists in debating one question. The warrant of the abbot for considering the mass as a sacrifice was the priesthood and oblation of Melchizedek. ‘The Psalmist,’ said he, ‘and als the apostle St Paul affirms our Saviour to be ane priest for ever according to the order of Melchizedek, wha made oblation and sacrifice of bread and wine unto God, as the Scripture plainly teacheth us.... Read all the evangel wha pleases, he sall find in no place of the evangel where our Saviour uses the priesthood of Melchizedek, declaring himself to be ane priest after the order of Melchizedek, but in the Latter Supper, where he made oblation of his precious body and blude under the form of bread and wine prefigurate by the oblation of Melchizedek: then are we compelled to affirm that our Saviour made oblation of his body and blude in the Latter Supper, or else he was not ane priest according to the order of Melchizedek, which is express against the Scripture.’

To this Knox answered that Scripture gives no warrant for supposing that Melchizedek offered bread and wine unto Abraham, and therefore the abbot’s warrant fails. The abbot called on him to prove that Melchizedek did not do so. Knox protested that he was not bound to prove a negative. ‘For what, then,’ says Kennedy, ‘did Melchizedek bring out the bread and wine?’ Knox said, that though he was not bound to answer this question, yet he believed the bread and wine were brought out to refresh Abraham and his men. In barren wranglings on this point were nearly the whole three days spent; and, for anything we can see, the disputation might have been still further protracted, but for an opportune circumstance. Strange to say—looking at what Maybole now is—it broke down under the burden of eighty strangers in three days! They had to disperse for lack of provisions.21

There raged at this time in Edinburgh a disease called the New Acquaintance. The queen and most of her courtiers had it; it23 spared neither lord nor lady, French nor English. ‘It is a pain in their heads that have it, and a soreness in their stomachs, with a great cough; it remaineth with some longer, with others shorter time, as it findeth apt bodies for the nature of the disease.’22 Most probably, this disorder was the same as that now recognised as the influenza.

Sir John Arthur, a priest, was indicted for baptising and marrying several persons ‘in the auld and abominable papist manner.’ Here and there, the old church had still some adherents who preferred such ministrations to any other. It appears that Hugh and David Kennedy came with two hundred followers, ‘boden in effeir of weir;’ that is, with jacks, spears, guns, and other weapons; to the parish kirk of Kirkoswald and the college kirk of Maybole, and there ministered and abused ‘the sacraments of haly kirk, otherwise and after ane other manner nor by public and general order of this realm.’ The archbishop of St Andrews in like manner came, with a number of friends, to the Abbey Kirk of Paisley, ‘and openly, publicly, and plainly took auricular confession of the said persons, in the said kirk, town, kirk-yard, chalmers, barns, middings, and killogies thereof.’—Pit. ‘After great debate, reasoning, and communication had in the council by the Protestants, wha was bent even to the death against the said archbishop and others kirkmen, the archbishop passed to the Tolbooth, and became in the queen’s will; and sae the queen’s grace commandit him to pass to the Castle of Edinburgh induring her will, to appease the furiosity foresaid.’—D. O. The other offenders also made submission, and were assigned to various places of confinement. William Semple of Thirdpart and Michael Nasmyth of Posso afterwards gave caution to the extent of £3000 for the future good behaviour of the archbishop.—Pit.

In the parliament now sitting, some noticeable acts were passed. One decreed that ‘nae person carry forth of this realm ony gold or silver, under pain of escheating of the same and of all the remainder of their moveable guids,’ merchants going abroad to carry only as much as they strictly require for their travelling expenses. Another enacted, that ‘nae person take upon hand to use ony manner of witchcrafts, sorcery, or necromancy, nor give themselves24 furth to have ony sic craft or knowledge thereof, therethrough abusing the people;’ also, that ‘nae person seek ony help, response, or consultation at ony sic users or abusers of witchcrafts ... under the pain of death.’ This is the statute under which all the subsequent witch-trials took place.

A third statute, reciting that much coal is now carried forth of the realm, often as mere ballast for ships, causing ‘a maist exorbitant dearth and scantiness of fuel,’ forbade further exportations of the article, under strong penalties. In those early days, coal was only dug in places where it cropped out or could be got with little trouble. As yet, no special mechanical arrangements for excavating it had come into use. The comparatively small quantity of the mineral used in Edinburgh—for there peat was the reigning fuel—was brought from Tranent, nine miles off, in creels on horses’ backs. The above enactment probably referred to some partial and temporary failure of the small supply then required. It never occurred to our simple ancestors, that to export a native produce, such as coal, and get money in return, was tending to enrich the country, and in all circumstances deserved encouragement instead of prohibition.

Henry Sinclair, Bishop of Ross and President of the Court of Session—‘a cunning and lettered man as there was,’ remarkable for his ‘singular intelligence in theology and likewise in the laws,’ according to the Diurnal of Occurrents—‘ane perfect hypocrite and conjured enemy to Christ Jesus,’ according to John Knox—left Scotland for Paris, ‘to get remede of ane confirmed stane.’ This would imply that there was not then in our island a person qualified to perform the operation of lithotomy. The reverend father was lithotomised by Laurentius, a celebrated surgeon; but, fevering after the operation, he died in January 1564-5: in the words of Knox, ‘God strake him according to his deservings.’

At the same time there were not wanting amongst us pretenders to the surgical art. In this very month, Robert Henderson attracted the favourable notice of the town-council of Edinburgh by performing sundry wonderful cures—namely, healing a man whose hands had been cut off, a man and woman who had been run through the body with swords by the French, and a woman understood to have been suffocated, and who had lain two days in her grave. The council ordered Robert twenty merks as a reward.2325 Two gentlemen became sureties in Edinburgh for Marion Carruthers, co-heiress of Mousewald, in Dumfriesshire, ‘that she shall not marry ane chief traitor nor other broken man of the country,’ under pain of £1000 (Pit)—a large sum to stake upon a young lady’s will.

This was a year of dearth throughout Scotland; wheat being six pounds the boll, oats fifty shillings, a draught-ox twenty merks, and a wedder thirty shillings. ‘All things apperteining to the sustentation of man in triple and more exceeded their accustomed prices.’ Knox, who notes these facts, remarks that the famine was most severe in the north, where the queen had travelled in the preceding autumn: many died there. ‘So did God, according to the threatening of his law, punish the idolatry of our wicked queen, and our ingratitude, that suffered her to defile the land with that abomination again [the mass].... The riotous feasting used in court and country wherever that wicked woman repaired, provoked God to strike the staff of breid, and to give his malediction upon the fruits of the earth.’

It was of the frame of the reformer’s ideas, that a judgment would be sent upon the poor for the errors of their ruler, and that this judgment would be intensified in a particular district merely because the ruler had given it her personal presence. He failed to observe, or threw aside, the fact, that the same famine prevailed in England, where a queen entirely agreeable to him and his friends was now reigning, and certainly indulging in not a few banquetings. Theories of this kind sometimes prove to be two-edged swords, that will strike either way. It might have been replied to him: ‘Accepting your theory that nations, besides suffering from the simple misgovernment of their rulers, are punished for their personal offences, what shall we say of the Protestant Elizabeth, whose people now suffer not merely under famine, as the Scotch are doing, but are visited by a dreadful pestilence besides,24 from which Scotland is exempt?’

‘God from heaven, and upon the face of the earth, gave declaration that he was offended at the iniquity that was committed within26 this realm; for, upon the 20th day of January, there fell weet in great abundance, whilk in the falling freezit so vehemently, that the earth was but ane sheet of ice. The fowls both great and small freezit, and micht not flie: mony died, and some were taken and laid beside the fire, that their feathers might resolve. And in that same month, the sea stood still, as was clearly observed, and neither ebbed nor flowed the space of twenty-four hours.’—Knox.

In the ensuing month meteorological signs even more alarming to the great reformer took place. There were seen in the firmament, says he, ‘battles arrayit, spears and other weapons, and as it had been the joining of two armies. Thir things were not only observed, but also spoken and constantly affirmed by men of judgment and credit.’ Nevertheless, he adds, ‘the queen and our court made merry.’

The reformer considered these appearances as declarations of divine wrath against the iniquity of the land, and he is evidently solicitous to establish them upon good evidence. There can be no difficulty in admitting the facts he refers to. The debate must be as to what the facts were. Most probably they were resolvable into a simple example of the aurora borealis.

The crimes of unruly passion and of superstition predominated in this age; but those of dexterous selfishness were not unknown.

Thomas Peebles, goldsmith in Edinburgh, was convicted of forging coin-stamps and uttering false coin—namely, Testons, Half-testons, Non-sunts, and Lions or Hardheads. It appeared that he had given some of his false hardheads to a poor woman as the price of a burden of coal. With this money she came to the market to buy some necessary articles, and was instantly challenged for passing false coin. ‘The said Thomas being named by her to be her warrant, and deliverer of the said false coin to her, David Symmer and other bailies of the burgh of Edinburgh come with her to the said Thomas’s chalmer, to search him for trial of the verity. He held the door of his said chalmer close upon him, and wald not suffer them to enter, while [till] they brake up the door thereof upon him, and entered perforce therein; and the said Thomas, being inquired if he had given the said poor woman the said lions, for the price of her coals, confessit the same; and his27 chalmer being searched, there was divers of the said irons, as well sunken and unsunken, together with the said false testons, &c., funden in the same, and confessit to be made and graven by him and his colleagues.’ Thomas was condemned to be hanged, and to have his property escheat to the queen.—Pit.

In consequence of the slaughter of the Laird of Cessford, in an encounter with the Laird of Buccleuch, at Melrose, in 1526, a feud had ever since raged between their respective dependents, the Kerrs and Scotts. In 1529, there had been an effort to put an end to this broil by an engagement between Walter Kerr of Cessford, Andrew Kerr of Ferniehirst, Mark Kerr of Dolphinston, George Kerr, tutor of Cessford, and Andrew Kerr of Primsideloch, for themselves and kin on the one part, and Walter Scott of Branxholm, knight, with sundry other gentlemen of his clan on the other side, whereby the latter became bound to perform the four pilgrimages of Scotland—that is, to the churches of Melrose, Dundee, Scone, and Paisley—as a reparation for the slaughter. Bad blood being nevertheless kept up, Sir Walter Scott of Branxholm, Laird of Buccleuch, was slain on the streets of Edinburgh by Cessford, in 1552.25

At the date now under attention, a meeting of the heads of the two houses took place in Edinburgh, and a contract was drawn up, setting forth certain terms of agreement, and arranging that, ‘for the mair sure removing, stanching, and away-putting of all inimity, hatrent, and grudge standing and conceivit betwin the said parties, through the unhappy slaughter of the umwhile Sir Walter Scott of Branksome, knight, and for the better continuance of amity, favour, and friendship, amangs them in time coming, the said Sir Walter Kerr of Cessford sall, upon the 23 day of March instant, come to the perish kirk of Edinburgh, now commonly callit Sanct Giles’s Kirk, and there, before noon, in sight of the people present for the time, reverently upon his knees ask God mercy of the slaughter aforesaid, and sic like ask forgiveness of the same fra the said Laird of Buccleuch and his friends whilk sall happen to be present; and thereafter promise, in the name and fear of God, that he and his friends sall truly keep their part of this present contract, and sall stand true friends to the said Laird of Buccleuch and his friends in all time coming: the whilk the said Laird of Buccleuch sall reverently accept and receive, and promise, in the fear of God, to remit his grudge,28 and never remember the same.’ A subsequent part of the agreement was, that the son of Cessford should marry a sister of Buccleuch, and Sir Andrew Ker of Fawdonside another sister, both without portion.26

This singular meeting would of course take place, but with what effect may well be doubted. It appears that the feud which had begun in 1526 still remained in force in 1596, ‘when both chieftains paraded the streets of Edinburgh with their followers, and it was expected their first meeting would decide their quarrel.’27

At a time when the most prominent events were clan-quarrels and the rough doings connected with the trampling out of an old religion, it is pleasant to trace even speculative attempts to enlarge the material resources and advance the primary interests of the country.

At the date noted, the queen granted to John Stewart of Tarlair,28 and William Stewart his son, licence to win all kinds of metallic ores from the country between Tay and Orkney, on the condition of paying one stone of ore for every ten won; and this arrangement to last for nine years, during the first two of which their work was to be free, ‘in respect of their invention and great charges made, and to be made, in outreeking of the same.’ In the event of their finding any gold and silver where none were ever found before, they had the same licence, with only this condition, that the product was to be brought to her majesty’s cunyie-house, ‘the unce of gold for ten pund, and the unce of utter fine silver for 24s.’ It was too early for such an enterprise, and we hear no more of it in the hands of the two Stewarts of Tarlair.

John Knox, at the age of fifty-eight, entered into the state of wedlock for the second time, by marrying Margaret Stewart, daughter of Lord Ochiltree. She proved a good wife to the old man, and survived him. The circumstance of a young woman of rank, with royal blood in her veins—for such was the case—accepting an elderly husband so far below her degree, did not fail to excite remark; and John’s papist enemies could not account for it otherwise than by a supposition of the black art having been employed. The affair is thus adverted to by the reformer’s shameless enemy, Nicol Burne: ‘A little after he29 did pursue to have alliance with the honourable house of Ochiltree, of the king’s majesty’s awn bluid. Riding there with ane great court [cortège], on ane trim gelding, nocht like ane prophet or ane auld decrepit priest, as he was, but like as he had been ane of the bluid royal, with his bands of taffeta fastenit with golden rings and precious stanes: and, as is plainly reportit in the country, by sorcery and witchcraft, [he] did sae allure that puir gentlewoman, that she could not live without him; whilk appears to be of great probability, she being ane damsel of noble bluid, and he ane auld decrepit creature of maist base degree, sae that sic ane noble house could not have degenerate sae far, except John Knox had interposed the power of his master the devil, wha, as he transfigures himself sometimes as ane angel of licht, sae he causit John Knox appear ane of the maist noble and lusty men that could be found in the warld.’29

‘... the Lord Fleming married the Lord Ross’s eldest daughter, wha was heretrix both of Ross and Halket; and the banquet was made in the park of Holyroodhouse, under Arthur’s Seat, at the end of the loch, where great triumphs was made, the queen’s grace being present, and the king of Swethland’s ambassador being then in Scotland, with many other nobles.’—Mar.

In the romantic valley between Arthur’s Seat and Salisbury Crags, there is still traceable a dam by which the natural drainage had been confined, so as to form a lake. It was probably at the end of that sheet of water that the banquet was set forth for Lord and Lady Fleming’s wedding. The incident is so pleasantly picturesque, and associates Mary so agreeably with one of her subjects, that it is gratifying to reflect on Lord Fleming proving a steady friend to the queen throughout her subsequent troubles. He stoutly maintained Dumbarton Castle in her favour against the Regents, and against Elizabeth’s general, Sir William Drury; nor was it taken from him except by stratagem.30