THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO

DALLAS · ATLANTA · SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

A frolic would follow

Frontispiece

THE KEY TO

BETSY’S HEART

BY

SARAH NOBLE IVES

ILLUSTRATED

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1916

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1916,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

Set up and electrotyped. Published, September, 1916.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Coming of Betsy | 1 |

| II. | The New Surroundings | 10 |

| III. | The Coming of the Prince | 22 |

| IV. | Betsy Meets Van | 36 |

| V. | Van’s First Lessons | 47 |

| VI. | Betsy’s First Lessons | 62 |

| VII. | Van Goes to Church | 74 |

| VIII. | The Great Storm | 87 |

| IX. | More Lessons | 100 |

| X. | Van’s Wild Oats | 113 |

| XI. | Van Becomes a Hero | 128 |

| XII. | The Great Parade | 143 |

| XIII. | Van in Disgrace | 156 |

| XIV. | Van’s Banishment | 171 |

| XV. | Van’s Hard Lessons | 183 |

| XVI. | The Journey Home | 193 |

| XVII. | Van the Rescuer | 210 |

| A frolic would follow | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Most unpromising she was, at the first glance | 6 |

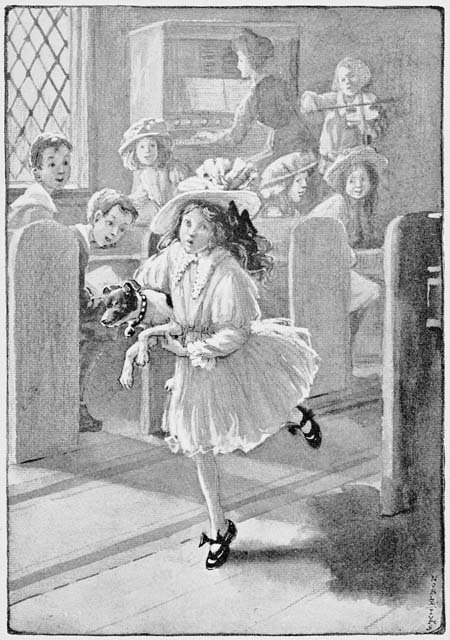

| She fled with him down the aisle | 84 |

| Van caught up with Piggy at the far end of the lawn | 152 |

[1]

THE KEY TO

BETSY’S HEART

“She needed all the heartening she could get.”

BETSY sat staring through the window of the first hack she had ever been in,—also it was the first she had ever seen. She was wondering, wondering, as she rolled along up two-mile drive that lay between the station and the[2] Hill-Top, what would happen next. Things had moved pretty swiftly in the past few weeks, and Betsy had been simply a bewildered leaf floating on the whirling tide of destiny.

To begin with, her father had disappeared;—run away from the little farm on the New Hampshire hillside. Tired of the stones and the drudgery—tired, too, of the wife, who, through neglect, hard work and lack of good food, had grown to be a fretful invalid—he had disappeared like a coward, in the night, no one knew where.

There were days after that when Betsy had gone hungry, for there was no money in the house, and but little food, and at last had come a day when the mother had fallen weakly on the floor. Betsy had run, frightened, down to old Mrs. Webb’s house for help, and Mrs. Webb had told the neighbors, and they had all come from every direction, surprised by the alarming news. It was planting season, and for some time no one had happened to call at the little red house over in Wixon’s Hollow, off the main road.

Then there had been a great bustling about. Betsy’s mother was put to bed, a doctor had come, there was food in the house once more, and a[3] kindly neighbor took charge of affairs. But it was too late. In a few days all was over.

But soon another leaf had been turned in Betsy’s book of life by a letter from a distant relative, known vaguely to Betsy as “Aunt Kate Johns.” Betsy was invited to come and stay a year with her.

Betsy had cried a little in secret over this, because it was something unknown and consequently something fearful. But one must take what comes,—so the poor little belongings were packed in a “carpet-bag,” and Betsy took her first railway journey all alone. It would have been a marvelous undertaking, but Betsy’s eyes were still blinded with the tears of her loss.

And now here she was, and what would come next?

She had never seen “Uncle Ben,” and Aunt Kate had been simply a vision of lovely color and soft silken draperies. Once or twice she had whirled into the little red house, and away again. Well, after all, it would be something new. Betsy plucked up her courage and dried her last tear as the hack turned in at a gate.

Up a wide avenue went the hack, under stately[4] trees and between wonderful flower-beds and sunny reaches of grass and dandelions. The dandelions looked homely and dear, but the prim magnificence of the great, park-like place awed Betsy too much for other emotions. Uncle Ben and Aunt Kate would probably be as stiff and unlovable as that trimmed hedge over there. She braced herself for the worst.

Now they drove past a great stone building, full of winking eyes, which were really windows peering into the sunset through a riot of vines. That was the “Hospital,” no doubt, of which Uncle Ben was superintendent. It looked huge and mysterious, and out of the unknown future Betsy felt a chill of loneliness creep over her. The driver stopped at last before a pretty brick house standing by itself in the park. It was all nooks and gables, and around two sides of it ran a porch delightfully shaded by honeysuckle. Betsy did not know honeysuckle, but its sweet smell hung heavy over her, and somehow it heartened her as she mounted the steps.

She needed all the heartening she could get, for Betsy had never before been beyond her own New Hampshire valley. She wavered a little,[5] and there was a queer, wooden-y feeling in her legs as she lifted her hand and rapped on the dark expanse of the door—she knew nothing of doorbells or knockers, and did not even look for them.

Almost immediately the door swung open, and a trim maid said:

“Is this Miss Betsy? Come right in. Mrs. Johns is sick with a headache, but she heard the carriage, and sent me to bring you up to her. Give me your bag, Miss.”

Betsy gave up the carpet-bag doubtfully.

“You mustn’t bang it. I’ve got two fresh eggs in it for Aunt Kate.”

Up a broad winding stair Betsy followed the maid, and into a room all delicate green and gold, with painted iris growing on the walls, up from a thick carpet that was almost like the grassy lawn. From a low couch came a soft voice.

“Come here, Betsy.”

The little figure stood stiffly before the couch,—a thin, small wisp of a maid, with brown hair of the silky kind that never stays “put”; the natural sallowness of her complexion was deepened by the tan of out-of-door life; the little hands were reddened and roughened with dishwashing[6] and scrubbing,—for Betsy had mothered her mother ever since she was big enough to bring in kindlings from the wood-pile. A faded black frock, fashioned hurriedly from an old skirt of her mother’s, made a pitiful attempt at mourning.

Most unpromising she was, at the first glance, and Aunt Kate’s heart sank, until her eyes met the two brown ones,—so deep and soft that she gave a start. Pools of liquid darkness they were, and out of them shone a soul to be trusted. Aunt Kate held out two arms, lace-covered and delicate, to enfold the small waif.

But Betsy did not accept the invitation. She stood there, crossing her ankles, and not knowing what to do with her hands. Caresses she had never known. In a voice shrill with the excitement of the interview, she said:

“I’ve brought you two eggs,—they’re fresh. Speckly and Banty done ’em for you.”

Out of her poverty the child had come with gifts! Aunt Kate’s eyes dimmed a little, and her hand closed gently over the little red one that hung limply at Betsy’s side.

“Did you bring them to me? I am so glad. I love fresh eggs.”

Most unpromising she was, at the first glance

[7]Betsy pointed to the maid. “She’s got my carpet-bag. Where’d you put it?”

“In your room, Miss Betsy.”

“My room? Have I got a room?”

“Show her, Treesa.”

Treesa led the way, and Betsy was soon back with an egg in each hand.

“They’re all right. I didn’t let no man nor nothin’ touch that bag coming down. Here they are. They aren’t real cold yet, hardly. I shooed Speckly off the nest to get this biggest one just before the stage came for me.”

“Thank you, dear. They’re fine. This weeny one is just like a big pearl. I hope you are going to be happy here with us.”

“I dunno. I never had much time for it.”

The sharp little nine-year-old voice had the edge of forty-five on it; it was the echo of her mother’s fretful plaint which the child had unconsciously picked up.

“Well, we’ll see. Run, now, and wash your hands and face, and Treesa will give you some supper in your room.” Somehow Aunt Kate shrank from leaving her alone with Uncle Ben this first night.

[8]Betsy hesitated. “This room is handsomer than our parlor,—but it’s kinder big and lonesome here.”

“It won’t seem so when you get used to it. We’re going to love you and then you will love us and we’ll all be happy as larks. Now good-night, little girl. You had better go right to bed after your tea. Treesa will show you where to put your things, and to-morrow will be a new day, Betsy dear, and then we’ll have time to get acquainted.”

Betsy walked to the door as if the interview was closed.

“Won’t you come and kiss me good-night?”

The child came slowly, as if unaccustomed to the rite, shrank a little from the arm that stole about her, pecked the lips coldly; then, at the soft caress of the white hand, she dropped a tiny corner of her reserve.

“Ma kissed me just afore she died.”

Then Betsy froze again, and walked out of the room.

Things passed in a whirl that evening. Whatever Betsy thought of the dainty room, all in white, old rose and soft, warm gray, she did not[9] disclose to Treesa. She ate her meal from delicate china, with real silver, and at last climbed into bed between the snowy sheets, and straightened out the folds of her coarse, drilling nightgown for sleep.

“It’s awful grand and beautiful here,” she whispered to herself; “but I’ll be lonesome. I wisht Ma was here, an’ I—I wisht I was back in the Holler!”

She hid her face in the pillow when Treesa came in, that her tears might not be seen.

“Good-night, Miss Betsy. Do you want a light left in your room?”

“No’m. I allers go to sleep in the dark,” said Betsy, bravely. She watched between her fingers as Treesa pulled a little chain, and snap! out went the light. At home they blew it out, and there was a smell of kerosene or tallow afterwards. This interested Betsy so much, wondering how it was done, that she forgot to stay awake and grieve through the dark hours, and before she could have counted a hundred, the wings of childish sleep were around her.

“She sat up and looked out of the window.”

BETSY awoke with a strange feeling of being still in a dream. Instead of opening her eyes on the little attic room of the red house in the Hollow, she was greeted by what seemed to her a palace in a fairy tale. She rubbed her eyes, sat up, and looked out of the window.

Yes, it was true; instead of being in a hollow she was on a hilltop. Stretched out below her lay[11] a green valley, and through the trees peeped many, many houses, more than Betsy had ever dreamed of in all her life. It must be a city, she thought, but the pictures in her geography had not prepared her for anything like this. The city seemed to be sitting on a hillside, with its feet dipping in the waters of a broad blue river. She was quite awake now, and beginning to realize what had happened.

Bang, bang, bang! There came a terrifying sound. It might have been a church bell, but it was too near; it might have been somebody pounding on the brass soap-kettle at home, but it was too musical. Betsy was out of bed like a shot, just as Aunt Kate showed her smiling face through a crack in the door.

“My goodness! What was that noise?” cried Betsy.

“Just the rising gong, dear. I intended to have wakened you before it sounded. You’ll have just time to dress before breakfast. What are you going to put on?”

“I got this dress I wore here, for best, and I got a black and white check gingham for every day. I had two blue calicoes and a red merino,[12] but Mrs. Webb said I wasn’t to bring ’em, ’cause they was colored, and I’m wearin’ black things.” Betsy told off the items of her wardrobe in one breath.

“Put on your gingham. It will do for now. Have you some light shoes?”

“Only just these copper-toes. I stub ’em out awful, and Pa didn’t b’lieve in no foolishness, he said. Summertimes I go barefoot, anyway.”

“Dear me! Well, these will do until after breakfast.”

Betsy dressed hurriedly, after having first been introduced to a big porcelain bathtub, where she was told to hop in this morning and every morning thereafter, for a splash.

“Oh my! Can I learn to swim in it?”

“I’m afraid it isn’t wide enough for you.”

“It’s bigger’n where I tried to learn in the brook. There wasn’t room in that pool for the whole of me. I just kicked my legs and held on to the bank, and then I kicked my arms, with my legs on the bank. But I dunno if I really learned.”

Aunt Kate laughed a merry laugh, and left her. Betsy finished off her toilette by tying a rusty[13] black ribbon on the end of her tight pigtail, and was ready for breakfast.

At the table there was Uncle Ben to meet. He was a tall, grave man, with a gray moustache,—much older-looking than Aunt Kate; but there was a twinkle in his eye as he shook Betsy’s hand.

“Good morning. I suppose this is Miss Betsy Wixon?”

“Yes,” she said simply, and slipped into the chair that Treesa pointed out to her. She contributed nothing more to the conversation for the present, but began to eat with the healthy appetite of a child. Aunt Kate sighed as she saw her bite off the biggest piece possible from her slice of toast, stuff nearly half an egg into her mouth at once, and drink her coffee noisily. If the service impressed Betsy, she gave no sign; only after Treesa had quietly finished her duties and retired to the kitchen, did she offer a remark.

“Aunt Kate,—don’t your hired girl eat to the table with you?”

She received her information on the subject without comment, wiped her mouth on her sleeve, paying no attention to the napkin that Treesa had placed in her lap, pushed back her chair, slipped[14] down, and, without waiting to be excused, walked out upon the porch.

Uncle Ben’s eyes followed the queer little figure.

“Your time won’t hang idle on your hands, Kate, even if she’s good. Do teach her some table manners, and get that black and white Mother Hubbard thing into the waste basket.”

“Just wait, Ben, until to-night. There will be a transformation on the surface, even so soon as that. I’ve a scheme all worked out,—on a theory that did not entirely originate with me. In fact, I have already begun to work on it. I spent all yesterday morning in the heat, shopping,—that’s where I got my headache. When she begins to connect the idea of self-respect with her appearance, she’ll begin to try to live up to her looks. There is splendid material there, and I’m going to do the utmost with it. I need the child as much as she needs me. I love her already, and this big house will not be empty any more. She’ll respond,—you’ll see.”

“I’ll trust you, Kate, to succeed in whatever you start out to do. Just at present I will say that[15] I’d rather have her around than forty just like her.”

“You encourage me, Ben. By and by you will applaud me. Watch!”

Later, when Dr. Johns had gone to his office at the Main Building, Aunt Kate called Betsy in, and together they mounted to the third floor, where was a cosy sewing-room, with a high north light. On a couch lay a number of pieces of cloth.

“My, aren’t they pretty!” said Betsy.

“We are going to make some simple frocks for you. Mrs. Allston is coming to-day to help.”

“For me? Why, I’m in mournin’ for Ma.”

“People—little girls—wear white, even when they are in mourning, and we can save the colored ones till a little later, if you prefer.”

“The pink’s the prettiest. It looks like the wild roses in our back lot. But I shall have to wait. Oh, well, I ain’t never had even a white dress before. I can help you sew. I know how.”

“Do you? Why, that’s fine! Now here are some underclothes for you to put on. I want you to be all ready when Mrs. Allston comes to help us sew.”

[16]“These things? They got lace on.”

“Yes.”

“Why, I’d tear ’em to bits, climbin’ trees.”

“If you can sew you’ll know how to mend them, and you will learn to be careful. Now try on these shoes.”

A pair of dainty strap-slippers were chosen, with stockings to match, and soon Betsy was surveying herself in the mirror.

“Have I got to wear ’em always?”

“Most people do, here.”

“Hm! They’ll feel funny. But I’ll get used to ’em. Folks said you would likely ‘doll me up’ some. But I didn’t think there was such pretty things in all the world. I’m afraid—I’m afraid, Aunt Kate, that I won’t mourn so hard as I ought to, with this lace on my petticoat.”

“You must think of how your mother would have liked to see you in these pretty things. She used to wear dainty, lace-trimmed clothes herself, when she was little. And, dearie, she would not want you to mourn. She’s so much happier now. Just enjoy the things, and learn to make your soul and body pretty, like the clothes.”

“Mrs. Webb said I’d prob’ly get vain when you[17] took me in hand,—but I guess I can resk one small ‘vain.’ I can wear my black hair-ribbin, so my head’ll mourn, anyway, and my feet’ll mourn, too, in these black slippers.”

With this compromise they sat down, as soon as Mrs. Allston had arrived, and Betsy’s nimble little fingers ran with the best. Basting, back-stitching and “over-and-overing” she could do, and she soon learned the mysteries of hemming and felling. So eager was she that her fingers almost learned of themselves.

In the afternoon a tired but excited Betsy beheld her first white frock, ready to wear.

“That will do for a start,” said Aunt Kate. “Now, before you put it on, let us make sure that everything else is all right. Will you let me do your hair for you?”

Betsy submitted, and in a twinkling the tight pigtail was unbraided.

“First we must get rid of the dust of the train. Did you ever have a real shampoo?”

“No’m, I guess not. I never saw one.—Is it side-combs?”

Aunt Kate laughed merrily.

“I’ll show you.”

[18]To Betsy’s surprise she was taken to the bathroom, and introduced to the wonders of a beaten egg, warm water, a delightful, soapy lather, more warm water, then cold, and last, a brisk towel-rubbing and fanning.

Out of it all the brown hair emerged, soft and fluffy, with almost a desire to kink at the ends, and a fresh black ribbon was tied jauntily into the flowing meshes.

Betsy looked at herself critically.

“It seems like I was in a picter. But it’ll snarl like sixty.”

“I’ll show you how to braid it nicely when you are playing, but this is for Uncle Ben to see. Now, just let me get the whole effect:—underwear, stockings, slippers, hair,—all right, and now the frock can go on.... Stop a minute, though; let me look at your finger-nails.—My little Betsy, we’ve some work ahead of us here!”

“What’s the matter with ’em? I washed ’em.”

“Yes, I see, dear. But did no one ever tell you not to bite your nails?”

“No’m. Why, they’d get awful long if I didn’t, and then I’d break ’em, washin’ dishes.”

[19]“Well, I’ll make them look as nice as I can, and you must promise me not to bite them any more.”

Betsy hesitated.—“I’ll try,” she said at last, “but I can’t promise,—not right off,—’cause I bite ’em when I’m thinkin’ things. I couldn’t promise nothin’ ’at I might forget.”

“That’s right, too. But you must do your best to remember. Little girls must be nice in every way.”

That evening, when Uncle Ben came to dinner, he was greeted by an apparition all in white. Betsy stood by her chair with a shy look at him, to observe the effect of her transformation.

“As I live,—a fairy,—out of a story-book! Or was there a fairy godmother somewhere, and is this Cinderella? Where is the Prince?”

Betsy laughed and seated herself, and Aunt Kate noticed that at the end of the meal she reached down shyly, and wiped her mouth on the corner of her napkin.

A week passed, and Betsy was clothed and almost in her right mind once more, when Aunt Kate came in one morning, with a pretty notebook in her hand.

[20]“Now, Betsy dear, this is to be your book, and I have put the word ‘Manners’ and a motto,—‘Manner maketh the Man’, at the top. One of the most important things is the way we eat our meals, and I think it will be easier for you if I do not speak to you at the table. But afterwards we will come up to your room for a minute, all by ourselves, and I will tell you what you have done that is not just right, and you can write it down in this book. Then we will practice with knives and forks and spoons, and make believe eat. At the table I’ll watch you, and you may watch me, and if you see anything that seems queer to you, please ask me about it.”

“Don’t I eat all right?”

“Well,—you have some things to learn.”

“Ma never had time to learn me much. We just et, and that was all they was to it.”

“Have you noticed anything that we do differently here from what you have seen at home?”

“One or two, yes’m. That about the napkin, and, now, Uncle Ben, he don’t never eat his meat with his knife,—he just cuts it and takes it on his fork; and you don’t never turn your coffee in your saucer.”

[21]“Good, Betsy! Why, you’ll learn so fast that it will be simply play.”

As Aunt Kate rose to leave the room her hand rested for a moment on the soft brown hair. At the new touch of tenderness the child looked up and met a glow in Aunt Kate’s eyes—a look of mother-yearning. Something stirred in Betsy’s heart,—an impulse to seize and hold that gentle hand in both her own. But she did not quite dare—yet. Down where Aunt Kate could not see she caught a fold of the muslin gown that brushed past her, and crushed it with timid fingers.

So the lessons in manners began. Grammar could wait a bit. Aunt Kate did not intend to cram Betsy, for a little at a time is easier to digest.

And in the meantime, down in New York City, something was happening that was to color all Betsy’s new life on the Hill-Top.

“Barked fiercely at his small sister.”

VANART VI. sat on the edge of his dish, with all of his four paws in the milk, and barked fiercely at his small sister, who hovered, shy and meek, on the farther edge of Elysium. He knew what all dogs (and some men) know, that Might is Right; and he reasoned, not uncleverly,[23] that if his four-weeks-old voice could intimidate Sister Belle, he could certainly keep her off until he had feasted and made sure of his own share.

A ray of afternoon sunlight crept in through the skylight of the big New York studio, and lighted up this scene, just as Bob Grant opened the door, looked for the cause of the commotion, dropped his parcel of sketches on the floor, and laughed.

“You greedy little sinner! Is that the kind of a dog you are going to be? You’ll be needing some discipline, I’m thinking. Come here to me, you young nipper.”

The wee morsel looked up for an instant, beheld Bob Grant, and continued barking—at him. He held his head royally, too, as if he knew that he was the King of Hearts, bearing a noble name, and with a long pedigree behind him.

“Why, you’re a raving beauty, even now. And, if I am not mistaken, you’re mine. Who your young companion is I don’t know. I hope to Goshen Billy didn’t send me the two of you!”

No thought of a master entered Van’s mind at that time. His attention was on the milk, and[24] so intent was he on asserting his rights, that he quite forgot to drink. The Dog in the Milk was evidently first cousin to the “Dog in the Manger.”

Bob opened the letter that was tied to the basket in which the puppies had arrived. Uppermost lay the register of birth and ancestry. It read like this:

“Vanart VI.:—born March 26th, 1902. Smooth fox-terrier. Color—white, with chestnut-brown head and saddle and spot at base of tail.”

Then followed his father’s name, Vanart I.; his mother’s, Queen Mab, and a long list of forefathers and foremothers. Bob Grant read, and learned that Vanart I. was born in the Royal Victoria Kennels at Montreal; that his father was the famous Rex, which means king;—all down the line appeared royal names.

So it was apparent that our hero was very well born indeed,—a prince of the blood, and heir by grace of his own personal beauty and attractions to his great father’s title. The latter fact was explained in the letter that lay underneath the register:

[25]“Dear old Bob:—So sorry not to find you in, and I wish I might stay to know what you think of the puppy. The janitress let me in, and I’ve fixed things up as well as I could. I don’t believe they will do much damage before you return. You know I promised you one sometime, and here he is.

“His mother is Queen Mab, of the Newark Kennels, and as this is the fifth year of my Van’s fatherhood, your treasure’s full name is Vanart VI.... He wins the title, as he is the pride and beauty of the family.

“I think you will like him because he is marked something like his father. Please pardon me for bringing his sister Belle with him; the mother could not take care of so many.

“I will come after Belle in a day or two. I hope you’ll like your gift. Good luck to you,—Billy.”

Bob laid aside the letter and turned his attention once more to the problem at his feet. No doubt at all as to which was his own puppy. Bob picked Van out of the dish, wiped the milk off his feet, and introduced himself.

Van did not cringe, or try to get away, but[26] looked up from the big hand that held him, into the face of the young man, with a fearless confidence, and fell to chewing Bob’s finger, as if it were the whole business of life.

“Well, Vanart VI., you are here, and I hope a kind Providence will tell me what to do with you. For the present I’ve got to put up with you somehow. Two of them,—Oh, Christmas!”

“Woof!” said Van, affably, and he bit Bob’s thumb a little harder, just to show him that the chosen son of Vanart I. and Queen Mab was not to be trifled with, and that, in reality, he owned Bob. But the merry little eyes twinkled gayly, as if, after all, this being the Lord of Creation was a good joke.

For two weeks—while he was getting his breath, you might say—Van lived in the big New York studio with Bob Grant. Every day he grew in grace, and became, more and more, a shapely, active little dog. Beautiful indeed he was. Even in his young puppyhood he was lithe and agile as a kitten. His feet were small, as became his birth and breeding; he carried his brown head proudly on his delicate neck, that arched as none but a thoroughbred’s might. His soft, pointed ears[27] were alert to all the new noises of a strange and interesting world, and he wagged, or was wagged, by a funny bud of a tail, which every well-brought-up fox-terrier knows is the style in good society. His chest was broader than that of the ordinary breed, and his eyes were dark and tender; and one who knew dogs understood at a glance that a strain from some far-away bull-dog ancestor had added kindliness and affection to the sometimes ill-tempered disposition of a full-blooded fox terrier.

In those two weeks Van learned many things. One was that pins are not good things to play with. Bob came in one day and found him on his back, making queer little sounds through a rigidly open mouth, at which he was pawing frantically to rid himself of something. Lodged between his upper and lower molars was a pin which he had tried to swallow. Bob removed it, and then Van barked and capered as if he had done a clever thing. But he knew also that it was a thing not to be repeated.

The next thing he learned was that sisters do not stay with one always. One day little Belle disappeared,—going out of the big New York[28] studio on the arm of Billy, never to return. Van did not mind that so much. His short life had been all surprises so far, and he liked being cock-o’-the-walk far better than sharing the glory.

So Belle faded from his little brain, like the other visions of his border-land, and he quite forgot her in the excitement of the new and wonderful things that he was learning. Until now the world had been a constant series of changes, and more were to come; for so far he knew nothing of the big out-of-doors.

Billy came in one evening, and stood looking down at the bonny bit as he lay in his basket.

“Have you taken him out in Madison Square, yet, Bob?”

“Not yet. I’ve been too busy.”

“Get on your hat and we’ll show him the town. I’d like to see how he will behave.”

He was wakened, yawning and blinking, crumpled gently under his master’s arm, and they all went out into the soft May night.

First there was a long, bewildering street, full of noises and lights that stunned and blinded the little Prince. For a moment he hid his head in the folds of Bob’s jacket, and felt like whimpering[29] at the bigness of things. He himself was so small and new, and all this must have been there before he came. He would certainly have to run to catch up. Well, running was fun. He straightened up, settled himself comfortably, and prepared to enjoy real living, no matter what happened.

People who passed looked admiringly at the uplifted, bobbing brown head, and the wide-open, beautiful eyes that were awake to everything. Some even stopped and patted him. He barked joyously in response, and turned to fresh adventures.

And they came. Out of the street they turned into a bigger and wider one. Then there opened out in front of them a great square place,—a place with houses all around, and a roof very different from that in the studio. It was soft and dark and green, and it waved and rustled in the night breeze. There were many twinkling lights, and many, many people. Some were moving swiftly, some slowly. Others were gossiping or nodding on benches. It was all very wonderful.

Then, most astonishing of all, Van’s four little paws were set down on a fuzzy, wet, cold carpet;[30] and he stood alone in the very middle of the whole wide world. Bob and Billy were simply bystanders; no hand was upon him to restrain him; all this was his,—the trees, the lights, and the starry dome above. Life began to unfold.

Afraid? Not he! He started at once on a voyage of discovery. There were children there—the first he had ever seen. They beckoned and called to him, and he trotted to them. They chased him and he scampered after them, barking at their heels. He explored the grass-plots and a pansy bed; he looked wonderingly at the fountain that rose and fell with a throb of hidden power,—always falling and yet always there; at the round basin of water that was like nothing so much as a giant milk dish.

Then he started for the people who were sitting in amused groups on the benches, even the sleepy ones waking up to watch the dainty little sprite.

“I’ll bet it’s his first night out,” said one fat old man who had been reading a newspaper under an electric light, “but he’s game to his ear-tips.”

“He’s a sport, all right,” said another. “See him go for that cross old woman over the walk!”

[31]The cross old woman looked down to see a small brown and white puppy sitting confidingly on the edge of her faded skirt. She made a movement as if to jerk it away, looked again, then stooped and patted the winsome little head. Van seemed friendly. She stooped and picked him up, and for a moment held him to her bosom, where nothing had lain since the days when her hair was brown and her cheek smooth and rosy. He looked into her eyes with his soft young brown ones, and all the bitter hardness faded out of her face, as his delicate tongue flashed across the tip of her nose. Then he gently nipped her hand, and struggled to be off on fresh voyages of discovery.

Bob called to him, but he glanced at him defiantly, and ran in the other direction. The fat man moved off down the walk, saying to others as he went:

“Have you seen that pup over yonder? He’s sure some pup! Ha, ha! He’s the whole show. Better have a look.”

A crowd collected to watch the tiny joyous thing: the old-timers who studied the want and employment “ads”; the other shabby ones who[32] were busy swapping politics; the still shabbier ones who slept there with their arms folded, their stubbly chins on their soiled shirt-fronts; the casual passer-by,—even the policemen strolled up,—with an eye to preserving peace and order, but remained to enjoy the fairy-like antics of this new dweller in the world. Everybody forgot for a little while that there were such words as “Keep off the grass.”

Van leaped for a June beetle,—missed it; a night moth winged by him,—he chased it on flying feet, although his legs were still so young and uncertain that he tumbled over every hummock in his path. A child rolled a rubber ball toward him; he seized it and bore it to the feet of his master, and lay down to demolish it. Bob rescued it, and Van attacked a stick that a bent old man poked at him.

“You’re a bit of all right, and no mistake!” said the old man. “I bet you can read the papers. Want to try?” He pulled the evening sheet out of his pocket, and presented it to his young acquaintance.

Van closed his teeth on it, dragged it after him[33] across the walk, and sent the fragments flying far and wide.

Through the thickest of the crowd a seedy young man with a furtive eye sidled to the inner edge of the onlookers. His hand flashed out as Van gamboled near, and then—there was no Van on the dewy grass.

For a moment no one understood. It was all so sudden that no one could tell who did it.—Yes, there was one who did,—a policeman who was there to watch for just that very thing. The seedy young man had reached the outer edge of the group and in an instant more would be speeding down Twenty-fourth Street.

A big hand landed firmly on his coat-collar, another went into his pocket, and out came Van,—dazed, but thinking it all part of the great game the world was playing for his benefit. It was so quickly done that the crowd hardly knew anything had happened, until those nearest saw the thief wrench himself from the detaining hand and disappear in the darkness. The policeman, glad of the chance to be so near the small performer, held Van in the flat of one palm, and[34] stroked him with the other, as he passed him over to Bob.

“Here’s yer white elephant, young feller, and a foine wan he is. Ye’re lucky to git him back. Them dog-pinchers is mighty handy with their hooks.”

“You’re right,” said Bob. “They know a good thing when they see it. A little more, and he would have been lost.”

“A little more, and yer dog ’ud be performin’ in a circus a year from now. There’s manny a wan av us ’ud be likin’ to keep him.”

Bob and Billy walked back to the studio, and Bob said soberly:

“I like the little sinner, and it’s mighty good of you to give him to me, but I can’t keep him here. City’s no place for a dog, and an untrained pup at that.”

“Why don’t you send him up country?”

Bob thought a moment.

“Good idea! The very thing! Sister Kate’s just acquired a kid,—adopted it, or something—up at the Hospital, you know. The kid’ll be lonesome on the Hill-Top, with no companions. Off you go, Van,—I’ll take you up there to-morrow.[35] Kate’ll be surprised all right. They have never had a dog or a chick or a child before, in the house, and it’ll do ’em good. Ha, ha! I can see Dr. Johns’ eyes open; but he won’t turn him out, for what Kate does ‘goes’ with the doctor, and what Bob does ‘goes’ with Kate. Your destiny is fixed, young fellow. Missionary work for yours.”

“Sitting comfortably in the middle of Bob’s best silk negligée shirt.”

LIFE moved on the wings of youth for Van, and changes were many. The very morning after the trip to Madison Square, Bob Grant packed some things into a suit-case. It lay on the floor, and Van could see into it by putting his forepaws on the edge. Nay, he could do more than that. When Bob came to put in his handkerchiefs he found young Van sitting comfortably[37] in the middle of his best silk negligée shirt.

“So you’re planning to go too, mister! Well, I’m planning to take you, but not in my suit-case. There’s the covered basket all ready for you. We’re going this very afternoon. You may have thought this was home, but it isn’t. It’s only a New York studio, where one earns his bread and butter. When you get to your final destination you’ll have all out-of-doors to chase your tail in,—that is, if you ever have one long enough to chase. It’s back to the old farm for you.

“But you’ve got to be mighty good, and whether you stay there or not depends entirely on yourself. I’m risking it because you are a rummy little chap, and I think you will be just bad enough to be lovable.”

Van cocked his head on one side, and lifted his left ear straight up, listening as if he understood every word. He barked very confidently at Bob, and when the time came, he entered his basket without protest. In a basket he had come to the New York studio, and in a basket he would leave it,—the proper way. The lid was shut and[38] fastened, and Van started on his second railway journey.

The rumble and jolting of the trolley car, the jostling of the crowd at the station, the roaring, purring, grinding and shrieking of the train were nothing to him. He had been through all that before when he was even smaller, and nothing dreadful had come of it. Humans certainly make a lot of fuss for nothing. So he slept peacefully, as a prince should, only reminding his bearer that he was alive by a tiny “Yap!” when the express train made its one stop on the way.

There his basket was opened, and he chewed Bob’s finger for a minute, then snuggled down again, to awaken only when Bob stepped into a carriage at the end of his railway journey.

In the carriage the lid of Van’s basket was raised, and for the whole two-mile drive he sat up and watched everything with polite interest, but with no vulgar astonishment. His bonny brown eyes missed nothing, however. At last Bob jumped out, and as he went up the steps of the honeysuckle porch, he closed the basket lid and shouted:

“Kit! Kit! Where are you?”

[39]“Bob! You dear fellow! How did you happen to get away? Are all the books in the world illustrated, and you off on a holiday?”

“No, not all of ’em. Got to get right back. I just ran up to bring a present for the kid you wrote me about. Thought she’d be lonesome. Where is she?”

“Upstairs. I’ll call her in a minute. What have you got in that basket?”

“Look out! It bites,—go easy. There! How’s that for a watch-dog?”

Out of the basket popped two pointed, velvety brown ears, erect and courageous, then the whole head, cocked on one side, eyes dancing with excitement, beauty and breeding in every line.

“Bob! What a darling! But, oh, I can’t keep him. It’s enough to ask Dr. Johns to let me keep Betsy.”

“We have to take some risks in this life, you know, Kate. Come on in and call the kid.”

Out on the carpet Van was tumbled, to be admired at all points; and being a dog of parts, the points were many—his smooth, shining, snowy coat, with the chestnut-brown saddle, and the delicate lines and curves so rare in puppies[40] of his or of any age. Mrs. Johns gave one long look, and said:

“I don’t believe Ben will say one word. I’ll call Betsy. She’s a queer little mite, but I think she’ll like him. Betsy! Betsy! Come here a minute!”

Betsy came slowly down the stairs,—a very different-looking Betsy from the weird little black-robed figure of two weeks ago, but still awkward and shy.

“Betsy, this is Uncle Bob. See what he has brought you.”

Betsy looked.

“It’s a puppy! Pa wouldn’t have any dog to our house. They et too much.”

“He’s yours, Betsy.”

“Mine? No, he isn’t. He can’t be. What’s his name?”

“Vanart VI.,” said Bob. “Call him Van, for short. Go to Betsy, Van.”

Betsy sat down on the lower step of the stair, and Van ambled up, wriggling, almost to her, when suddenly his eye fell on a member of the group, who, being merely a casual visitor, had not been taken into account at all. It was a huge[41] yellow cat, three times as big as Van, who, in a hand to hand, or claw to claw fight could have made ribbons of his young lordship.

Instantly Van’s head went down, his tail to “attention,” and with stealthy steps he went slowly toward old Tommy. A quickening of his heart told him that his father and his father’s father’s had always chased cats. There was a long line of sporting dogs behind him, and here was game worthy of the blood.

Tommy’s yellow fur stiffened into bristles; his tail grew big and threatening; he backed against the dining-room door with a low growl and with all claws set. Van gave one short “Woof!” and started for him. Tommy, who had met many dogs, large and small, and vanquished not a few, was not sure that this courageous morsel could be a real dog at all, and in that moment of hesitation the day was lost. “R-r-r-r-r!” growled Van, in an answering challenge, and Tommy turned tail and darted through the door into the dining-room.

That was enough. “The game is started, chase it!” whispered the blood of his ancestors to his pumping heart. Through the swinging door into[42] the kitchen went a yellow streak; after it pelted a barking thing of brown and white; out through the screen door and down the steps,—it was Van’s first experience with steps, and the cat was gaining. He rolled down, picked himself up, and was off again in the direction of his flying yellow prey.

Around the corner of the house it disappeared, but Van was hard on the scent. Soon the cat was in sight again and in a fair way to safety. A friendly apple tree was just ahead; Tommy made one dash up the trunk and was safe in a high crotch, whence he could look down on his tiny foe and be ashamed of himself. Van, not being a climber, stopped beneath the tree, yelping like mad at the lost prize, while Mrs. Johns, Bob and Betsy looked on, too helpless with laughter to inform him, as they should have done, that the sporting instinct should be held second to kingly courtesy.

But Van had treed his first cat on the first run, and the field of glory, without a question, belonged to him.

When quiet was restored, Bob turned to Betsy.

[43]“What do you think of that, now? Don’t you like him?”

“I dunno. I never had a pet, ’cept Speckly and Banty, and they’re hens.”

“Well, I think you’ll like him when you get to know him. Can we fix him up a place to sleep somewhere around?” said Bob.

“We can keep him in the kitchen, until he gets acquainted. Mary will look after him, and he can sleep in the little tool-room off the back veranda.”

Betsy made no move to go nearer or to play with him, and Aunt Kate said aside, to Bob,

“I’m afraid it’s a mistake. She doesn’t seem to care for animals. Ben’s away, and I don’t know what he’ll say. Oh, Bob, I’m afraid you will have to take him back.”

“Well, wait till morning, anyway, before you decide. I’ll be here over Sunday.”

That night a big, soft bed of blankets was made for Van on the floor of the tool-room. He was given a supper befitting his age and state, tucked up comfortably, and in one minute he had dropped fast asleep, and was making up for the excitement of the day past.

[44]In the night Betsy awakened to hear a pitiful little cry. For a moment her thought was, “Ma’s awake and needs me!” and she jumped out of bed. She had so often, in her mother’s illness, awakened to wait on her, that, still drowsy from her sound sleep, she thought herself back in the little red house. Then, as she stumbled over unwonted furniture, she realized where she was. Groping her way to the window, she listened. The tool-room was directly below, and behind the door of it Van was voicing his loneliness and homesickness.

A wave of pity swept up in the heart of Betsy. Here was this tiny dog left all alone to cry his heart out, and here was she,—with friends,—yes, but friends not like her own self, and living a different life from what hers had been.

Barefooted and silent, Betsy opened the door and crept softly out into the hall. Feeling her way she went down the stairs, the soft rustle of her little nightgown being the only sound that broke the stillness of the house. Gently she turned the key in the lock and stepped out on the back veranda. In the tool-room Van was still[45] rending deaf heaven. The door was unlocked, and Betsy gently pushed it open.

Instantly the wailing ceased. A scamper of little feet came toward her, and she felt the cold little pads on her own as Van dug his foreclaws into her nightgown, and tried to climb up. There was no one to look now, and her own little homesick heart leaped to meet his. Picking him up in her arms, she lifted the upper layer of the blanket bed, and sat down upon it, while the puppy nestled close, with his nose tucked into her neck, apparently asking for nothing better.

“I’m lonesome, too, Van. Maybe Aunt Kate’d be mad if I took you upstairs. I guess I’ll just stay here. There, you pore little feller,—it’s all right. Your Betsy’s here!”

When, in the morning, after a long, vain search for Betsy, Mrs. Johns opened the door of the silent tool-room, she did not speak. She went and hunted up Bob, who was taking a turn on the porch before breakfast. Together they peeped in, quietly.

“I wish Ben was here to see them!” she whispered. Then, as they turned softly away, she added,

[46]“You needn’t take him away, Bob. That’s settled. It is the first thing that has really seemed to open the child’s heart. We needed just that key.”

“Swift as a bird, Betsy was there to meet him.”

THUS began a new life for both Betsy and Van. Gay, smiling days they were, and, for the most part, full to the brim.

It was country all around the Hospital, which was itself a big and famous one. Dr. Johns was the head doctor, and when he said “Come,” people came there to work, and when he said “Go,” they went away. It had been a great venture for[48] Bob to bring a little dog to a place where everybody was serious and quiet and orderly. Dr. Johns, in his way, was a sort of king on the Hospital Hill, and had much dignity to keep up. What would happen if a riotous little prince of a dog should try to usurp Dr. Johns’ authority, or upset his dignity? It would not do at all.

But there Van was, and Betsy had adopted him for her own. So, when Dr. Johns came home and met the new-comer, he was polite, as he always was, but perhaps a certain warmth was lacking. He remarked that Van was a very pretty dog, but Betsy felt the chill of it, and she ran away with her pet tucked under her arm.

“I think Betsy feels hurt a bit,” said Aunt Kate.

“Hurt? How? I said nothing to hurt her.”

“I think you did not intend to, Ben, but your manner toward the dog was none too cordial. I think he is going to help us solve our problem of Betsy.”

“Well, my dear, I cannot think that it is a good plan for us to keep a dog at an institution. It is a bad example.”

“But Betsy loves him, and she’ll be so disappointed[49] if he is sent away. I think he’ll be a good little fellow, and he’s a thoroughbred, you know, with a pedigree as long as your arm.”

“A thoroughbred, is he? And Betsy loves him? Well, well, if Betsy wants him, and if you want him, of course that settles it.”

“I think I saw a tear in her eye as she went out,” said Mrs. Johns, pushing her point in the path of least resistance.

“Hm! You did, did you? Well, you tell Betsy for me that she may keep dogs all over the place if she wants to. By the way, tell her to bring him back again. I didn’t get a good look at him.”

And the beauty of the wee rascal did the rest.

Dr. Johns practically gave him the keys of the castle. He graduated by leaps and bounds from first lessons in the kitchen, where a basket was installed for him, and where he slept at night. As soon as he was big enough to climb up and down the steps of the honeysuckle porch, the world outside was his also.

He was too small to take it all in as yet, for a scamper across the grounds would have been a good half-mile. There were four great buildings[50] of brick and stone, and all around them grew noble trees and beautiful flowers on green, velvety lawns. There were ponds, too, swarming with gleaming goldfish and pollywogs of all sizes, where the big and little frogs croaked in the warm spring evenings. Then there were long processions of people,—patients from the Hospital, who went out to walk every day when the sun shone. Van liked these, and would stand and bark with joy every time they went past. Also he barked at the red squirrels that chattered back at him from the trees, at the fat robins, who pulled countless fat worms out of the ground to feed to their greedy babies, and at the stately blackbirds who stalked around on the same errand. Together Betsy and Van roamed the place over, unmolested.

It was joy to Van, just being alive. The sunshine seemed to sparkle around his little white body, as he rolled on the grass, or pawed at the loose loam in the flower-beds; and it was a warm caress, when, tired after a chase for butterflies, he dropped, panting, at the foot of the steps where Betsy sat.

Besides Dr. and Mrs. Johns and Betsy, and[51] Treesa the maid, there was in the house a cook, Mary, who made nice things for people to eat, and who was one of those dear Irish souls of whom the world cannot have too many. She knew where to place a cooky jar so that a little girl could find her way to it unhindered, and she knew also how to smuggle tid-bits to a little dog who was supposed to live entirely on dog-biscuit and milk. Then there was Thatcher, a convalescent patient, who came over every day from the Hospital to help with the work. Thatcher welcomed the Prince as one who is grounded in the knowledge of dogs.

“My father used to train dogs, Mrs. Johns, and you’ll want him trained right, or he’ll be good for nothing. I’d like to do what I can.”

“I shall be so thankful if you will. Now is the time for his character to be made or unmade.”

“I’ll be glad to train him, ma’am.” Thatcher straightened up and looked very grand and important, and Aunt Kate felt a load roll from her shoulders; for it was no mean responsibility to bring up a puppy so that he should be an honor to his fathers and an ornament to society.

[52]So Thatcher began his own particular system of training. His first idea was that a dog should be taught the art of swimming.

Now, every dog knows how to swim without being taught, but Thatcher thought it would be pretty sport to see his Lordship go after sticks and the like, and swim back with them in his mouth. So one morning he tucked Van under his arm, and carried him off to the pond, Betsy following close at his heels.

This was something new. Van rather liked a bath, when Mrs. Johns or Treesa soused him all over in a tub of warm soap-suds, and rinsed him and dried him with a towel. But a tub like this—all wide and shiny, with blue sky at the bottom, and green trees and red buildings standing on their heads all around the edge,—this was not to be taken lightly—it was too large an affair.

Van sniffed at the brim of it, put his paw in, and drew it out again, wet and cold. He looked up at Thatcher for an explanation, when all of a sudden, without any preparation whatever, he was picked up and thrown, as if he were a stone, straight into the middle of the pond.

Down he went, gasping,—away under—down—down—swirling[53] over and over. Then up he came, kicking and spluttering. He shook the water out of his frightened eyes, and struck out for shore and Thatcher, whom he had not as yet connected with the outrage. You would have thought he had been swimming for years.

“Hurrah! Good boy!” cried Thatcher. “Now go after that stick.” He cast a bit of wood in. “See that? Now go for it!”

Van looked at the stick, and then at Thatcher. He may have thought of the poor stick that doubtless would be compelled to swim back as he had to, but he made no effort to rescue it.

“Go after it, I say!” And Van found himself hurtling through the air once more. When he came up from the cold depths, the piece of wood was at his side, but still he did not see how it had anything to do with him, and he swam back once more to Thatcher.

Again he was thrown in, and farther than before. This time as he made his way to shore, he put two and two together, and made four out of it.

One, it was Thatcher who had done the deed, and he was not to be trusted; two, he did not need[54] swimming lessons; three, the water was cold and he was tired; and four, he did not intend to give Thatcher another chance to play so contemptible a trick upon him. He turned suddenly and made for the far side of the pond.

Swift as a bird, Betsy was there to meet him. He shook himself, and she gathered him, all dripping, to her bosom, and ran for the house.

That was all he wanted of the pond. One more lesson he had, when Betsy was not by to rescue him. He was thrown in again and again, until he was a thoroughly disgusted little dog, with a hatred for the very sight of water. From that time on he never willingly wet his feet. He hated even his bath and would run and hide if any one mentioned the word to him. But he learned that baths must be taken, no matter how disagreeable. A Prince must be clean, if he would live in a palace; and Betsy, in her new zeal for soap and water, took him in charge herself, and continued to scrub him faithfully.

The rest of Thatcher’s efforts at training resulted in a series of failures. Thatcher was willing, but Van was not. He did not intend to be trained by his valet, and one, too, who had[55] betrayed him at the outset. Where confidence is lacking one cannot get great results in dealing with a wilful son of royalty.

The next instructor was more successful.

Dr. Peters, one of the young physicians at the Hospital, came over one morning on an errand. He was made acquainted with Van and duly admired him.

“Have you taught him any tricks, Miss Betsy?”

“No, I don’t know how to teach him.”

“Let me try him. He looks as bright as a button. You can teach anything to a dog like that, if you go at it in the right way. Come here, Van.”

Van came, expecting a game of romps, or, at the very least, a pat on the head.

“Dead Dog!” said Dr. Peters; and Van found himself unaccountably flat on his back, waving his helpless paws in the air.

“Dead Dog!” Dr. Peters repeated,—“Dead! Dead! Now shut your eyes,—tight!” Two fingers closed their lids.

Van struggled. This was an insult to his royal[56] person. But he was held there. Then, of a sudden, at the word “Police!” he was released.

“Get him a piece of cake, Miss Betsy. Now try it again, Van. Dead Dog!”

Van looked just an instant at Dr. Peters, as if he were trying to understand clearly; and then, thump! down he went, lying as still as the doorstep itself, until he heard the word of relief. Then he was up, jumping and capering as if he himself had thought out the whole thing.

The next time Dr. Peters came over, Van saw him from afar, and promptly plumped down, not waiting for the command; and there he lay, prone on the sidewalk, until the word “Police!” released him.

But he never liked doing this particular trick, and would do it for no one else without much coaxing. It was not seemly for him to take so humble a position, and all his life, whenever he was told to do “Dead Dog,” he would first go through all the other tricks he had ever been taught, hoping that people would forget about this disagreeable one, and pass it by.

All puppies, whether they are thoroughbreds or mongrels, begin life by practising their sharp[57] little teeth on something, and generally they care little whether it be a lace curtain or a fine Bokhara rug. From the first Van was taught that he must be full owner of the thing he might wish to destroy.

Betsy gave him one of her discarded copper-toed shoes to try his tiny new teeth upon.

“Now, Vanny-Boy, this shoe is yours; no, no,—this one that I give you. You mustn’t touch this other one.”

Van fell to upon his gift. Bit by bit he demolished the leather—the scraps lay all over the floor. Down to the bare bones of it he worried his way, and then he began on the sole. In a day or so he had this also in shreds. Only the heel and the bit of copper remained to tell of his busy moments. All this time the other shoe lay near by, but he never looked at it. When the task he had set himself was finished, he came wriggling to Betsy, who offered him the mate. Then and then only did he seize the other shoe, and it soon followed in the way of its fellow.

Under the little writing-desk in Betsy’s room was an old and dilapidated carpet-covered footstool, which showed unmistakable signs of a long[58] and useful life. Van, who loved playing at Betsy’s feet, discovered the rag-tag-and-bobtail effect of it, and received permission to worry the poor old thing. Little by little the carpet grew thinner, but it held out for many days.

One morning Betsy went in town with Aunt Kate, leaving Van safe in the kitchen with Mary.

That is, she thought he was safe. Van lay in his basket under the table, until Mary went down in the cellar. Then he arose, and went toward the swinging door that led into the dining-room. He had learned a secret about that door at the time of the yellow-cat episode. He pushed it—very gently. It yielded; a little more—it opened, swung back again, and struck him right on the tip of his little black nose.

He winked hard, and sat back a moment to get his bearings; then he went at it again. With his whole weight thrown against it, it swung widely, and with a dash he was through, and on the other side before it could close again. He was free, with the whole house before him, and no one to say him nay.

But it was not a voyage of discovery on which he was bent. He had business on hand. A young[59] and energetic dog should not be idle, and there was work to do.

Up the stairs he clambered,—that was the hardest of all, for every step must be gained with a stretch, a reach, a hump, and a scramble. At last his little brown head peeped over the top landing, and the way was clear to Betsy’s room.

No hesitation. His duty lay before him. He headed straight for the old footstool, sought out the weakest spot, just where he had left off yesterday. It was no sin; the stool was his very own, and where is the monarch who may not, if he likes, chew his own footstool?

Very quiet and busy he was, for a time. Bit by bit that barrier of heavy carpet warp must be worn away. He had no pick and shovel, like the miners and sappers under a fortress; his only weapons were his sharp little teeth, and the small nails on his forepaws; but he went bravely to work.

He chewed and he chewed; he never paused for a minute; he never gave the enemy an instant to recover lost ground. If he had been a soldier in war-time, he would have been cheered on as a hero, so manfully did he hold to his task.

[60]At last he got a tooth in, and could tear at the strong linen walls. The breach grew wider—there was room for his paw. He inserted it, and drew out a fascinating bit of plunder; curly, woody stuff it was.

A volley of dust from the defense struck him full in the nose and made him sneeze and choke. This opposition only made his spirits soar the higher. Tooth and nail he struck back. He tore down the whole barrier, and rushed in on the defenseless excelsior.

The fierce frenzy of destruction—that savage instinct that has made other princes and kings tear down whole cities—took possession of him. Clouds of dust rolled up from the interior, and filled his nostrils like the smoke of battle. He dove into the very center of the core of the inside of the middle of the last dungeon of the fortress. Up heaved the excelsior before his frantic onslaught, flying in every direction. It lay in heaps, around him, over him, under him, in front of him, behind him. It fell on the remotest breastwork of furniture.

The rout was complete! No explosion could have rent that footstool more disastrously. Van[61] shook off the ruins that had landed on his back; lay down on the empty shell of what was no longer and never more would be a footstool, and proceeded to divide the spoils, so to speak.

He worked through long and short division, and was worrying through a problem in fractions which concerned the last fragment that could still be called carpet, when Mrs. Johns and Betsy appeared in the doorway.

Through a haze they dimly saw a brown and white morsel of live joy, triumphing in the midst of a drifting mass of excelsior. Van lifted his head proudly and looked at them, as if he would say,

“Alone I did it! Excelsior!”

“‘I can stand it a week.’”

IT was a summer full of events for both Van and his mistress. Slowly and patiently Aunt Kate corrected Betsy’s uncouth ways, and the book of “Manners” grew. Betsy took smaller mouthfuls now, used her fork properly and ate quietly. She learned her tricks like Van, having to be told but once. If she forgot she corrected herself.

Aunt Kate said one day to Uncle Ben,

[63]“The child ‘eats’ everything I say to her, as if she were greedy for it, and what’s more, she digests it.”

“She’s just at the impressionable age,” said Dr. Johns. “Look at her out on the lawn there with the dog. When she thinks no one is looking at her she gambols almost as gracefully as he does.”

“I’m so glad she came to us. Everything seems different. I feel as if I had a rare, strange plant to tend, and when she grows out of that hard little bud of shyness, she’ll be the rose of my heart’s desire. It was a great inspiration, getting her into pretty clothes at the very start. I really think she is trying to live up to them.”

“I think it more likely that she is trying to live up to her Aunt Kate,” Uncle Ben chivalrously said, and as he started for the office, there was on his face the smile that Aunt Kate loved to see—the smile that made all the Hospital patients love him.

Betsy came in with her book as soon as she saw him go.

“I’m getting a lot of manners, Aunt Kate. My book’s ’most full.”

[64]“I am so glad, dear, and you are getting them by heart, too. I haven’t heard you say ‘ain’t’ for a week. By the way, how about those finger-nails? Let me see.”

But instead of showing them Betsy snapped her hands behind her.

“Let me look, dear. Haven’t you remembered?”

“No—no’m—not much. I try, but they just chew theirselves when I’m not thinking. They aren’t fitten to see.”

Aunt Kate took the two little hands in her own delicate ones. They lay palms up, showing a row of callous spots at the base of the fingers.

For a moment dear Aunt Kate looked; then she softly stooped and kissed them. The child stood wide-eyed, wondering.

“What’d you do that for? They aren’t pretty.”

“Because every one of those spots means that a little girl has helped her mother, and I love them. I almost wish that I could have some myself for so fine a reason.”

She turned the hands over.

“But these—these—oh, my little Betsy! To[65] trim such good hands in such a sorry way. Nails are intended to be the ornaments of a hand, quite as much, and more, than rings are. Every nail should have a crescent moon at its base, and another little pearl moon-rise at the tip. There should be no ragged edges or hang-nails. I’ve told you so many times. Now I shall have to do something to make you remember.

“Remember, too, dear, that I do this because I love you, and I want you to be sweet in every way.”

Mrs. Johns went to her desk, and returned with a bottle of India ink and a small brush.

“Now, Betsy, as long as the edges of your nails are rough and black, the middle might as well be black, too.”

Quickly Aunt Kate put a drop of ink in the center of each nail. Betsy held her breath with the surprise of it.

“Hold them out like that till they’re dry. If the spots come off when you wash your hands, I’ll put on more. When you see them you will think not to bite your nails, and you must keep them on for a week. By that time your nails[66] will grow out, and then I’ll show you how to take proper care of them.”

“Oh, Aunt Kate, please! Must I wear them like that to the table—right before Uncle Ben? What will he say?”

“Uncle Ben will think as I do, that the black spots look no worse than the close-bitten edges.”

Tears came in Betsy’s eyes. It was not like Aunt Kate to punish. For a moment she stood with quivering lips, looking down at the queer, ink-spotted finger-tips. Then she straightened up.

“I can stand it a week. You can stand anything you got to stand. I guess this’ll be a warnin’ to me.”

Not another whisper of rebellion came from her lips. She wore her badges of disgrace manfully, hiding her hands, if she could, when any one came near her. Uncle Ben looked at them, then at Mrs. Johns, but never a word did he say, and Betsy to this day does not know what he thought about them.

Aunt Kate replaced the spots as they came off, and the week dragged by.

Then, one morning, Aunt Kate came into[67] Betsy’s room, and instead of the bottle of ink, she carried a dainty little box.

“See here, Betsy.”

Betsy looked, and saw, under the satin-lined lid, a tiny pair of curved scissors, a nail file, a buffer with a silver handle, a box of rosy ointment—all the things that go to make up a manicure set.

“Now, let me see the nails again, Betsy dear. Have you remembered all the time?”

“I forgot twice, Aunt Kate, but I got black on my lips, so I had to remember.”

“Why, they’ve grown out beautifully! Good!”

With a bowl of warm, soapy water and a towel, the fingers were soaked, cleaned and dried. Deftly Aunt Kate cut each tip to a white “moon-rise,” and with an orange stick she found the beginnings of the crescent at the base. When the nails had been polished Betsy did not know them for her own.

“There! They look like rose petals. And now you can do it for yourself next time. This case is for you.”

“Aunt Kate!”

“Yes, dear.”

[68]“I’m awful much obliged, and—and—I like you a lot. And—may I do Van’s nails for him, too?”

“Why, if you want to. But his paws have to be on the ground, and he never bites his nails.”

“Well, I’m never going to bite mine any more. Van chews other things, though, Aunt Kate, and—and—may we have another ball, please? He’s chewed that little rubber one all up.”

“I’ll tell you what we’ll do, Betsy. We’ll try him with a rope-end. I found just the thing in the store-room this morning. Here it is, and I’ll tie a knot at each end. See how he likes that. A rubber ball every day is rather expensive.”

The rope proved highly successful, and Betsy and Van at either end made a great team. Betsy jerked and pulled and Van growled and shook. Then Van got the rope and flew all over the house and the lawn, and when Betsy finally caught her end there was a terrific growling and barking. Van liked it so much that he soon got in the way of trailing his rope on all occasions, hunting for some one who could be coaxed to play with him. Even a neighbor’s dog was invited to take part in the game; but, although he wagged his tail pleasantly,[69] he showed no intelligence, and Van gave him up in disgust.

There was another beautiful game, even better than Rope, because the whole family could play it of an evening, and Van was never happier than when he could stir up everything and everybody on the place. This was “Hide-and-Seek.” Mrs. Johns or the Doctor would hold Van tightly, his little body quivering with excitement, while Betsy hid in some corner, behind a curtain or screen. Then she would call,

“Coop!”

At the sound Van would be released, and would dart like an arrow in the direction of Betsy’s voice. It never took him long to find her, for his little nose was even keener than his eyes and ears.

With a joyful bark he would pounce on her and drag her back by her skirts, growling as if he had caught a lion. Then somebody else must hide and be found.

Once, when Van and Betsy had strayed as far as the park gates, an old hen loomed up in their path. She was bigger than Van, but a puppy who could tree a cat could surely get some sport out of a large bird like that. After her went Van,[70] and Mrs. Dorking took to her awkward legs. These, not filling entirely the necessity for speed, she added wing-power to the effort. Squawking, and frightened almost out of her feathers, she skimmed the ground, with Van close at her heels—if hens have heels.

Betsy laughed heartily at the funny sight, and that was a grave mistake, as later events proved. Of course Mrs. Dorking got away with all her feathers, so Van gave up the chase, and came back panting and wildly enthusiastic.

Van’s education did not consist of tricks and games alone. No, indeed! Fox terriers have a special use in the world; they are, above all things, a breed of rat-catchers, and Van was a sportsman, to the tips of his brown ears.

One morning he clambered out of his basket in the kitchen just in time to see a small, gray, furry thing dodge behind the basket and into the pantry. He did not stop to question; every instinct in him told him that this was Game. Like a flash he was after it. Mary was mixing pancakes at the far end of the pantry, and it went right under her feet. She jumped and screamed and nearly landed on Van’s toes.

[71]“It’s a mouse! It’s a mouse! Quick, Van! There it goes!”

The door of the closet where the pots and pans were kept stood ajar. In went the mouse; in went Van. The mouse went under a skillet, Van turned it over and jumped after; he chased it around a vinegar jug; he knocked over a pile of pans, and they fell with a terrible clatter; the mouse crept under one, and Van rooted up the whole of them, and sent them flying galley-west, while Mary took turns screaming and laughing.

Van hunted the mouse through the pantry, out into the kitchen again, and behind a broom in the corner. Bang! That was the broom falling. Pounce! That was Van, and Mrs. Mouse was no more.

By this time the whole Johns family was on the spot. They could not, unless they had been stone deaf, have escaped hearing the racket. Van was in his element. Not only had he brought down his first game, but he had an admiring audience, which he loved of all things. He swaggered around and tossed the mouse into the air, as if by so doing he could make them all understand just what a grand, brave dog he was. Lastly,[72] he came proudly to lay his prize at the feet of his beloved mistress.

And Betsy spoiled his fun by taking the mouse away from him. It was all right for Van to kill a mouse, she argued, because mice are harmful, but one should not gloat over it. Van did not see things that way. He gave one grieved look at the unfeeling Betsy, jumped into his basket and sulked.

Then Betsy added insult to injury by pulling him out of the basket and carrying him upstairs. Aunt Kate, passing by, saw the child on the window seat. Very busy Betsy was with something, and that something was Van, who was wriggling tremendously.

“See here just a minute, Aunt Kate. Ai—aren’t they nice?”

She exhibited Van’s paws, with every nail scraped clean and white.

“He didn’t like it a mite, but he knew it had to be did, or he couldn’t be a gentleman. I washed ’em with a nail brush to get the mouse off.”

The catching of the mouse was the clinching nail in Dr. Johns’ respect for Van. He looked[73] upon him now as a good and useful dog, and no longer as a mere plaything.

As for Betsy, that evening, beside her napkin at the dinner table, there lay a tiny white box, and in it shone a gold circlet set with a tiny diamond. Uncle Ben’s card lay on top, with the words

“For the hand with the little pink nails.”

“‘Go back, Van!’”

MR. JOHNS went over and closed the door carefully, when Betsy had been excused after lunch.

[75]“By the way, Kate, I received a letter this morning from that father of hers.”

“Oh, the poor baby! He isn’t going to bother her, is he?”

“Read it.”

Mrs. Johns took the soiled bit of paper and read:

“Dr. Johns, Sir, I bin told you have taken my Betsy and are a-bringing of her up. I am expecting a good job up-State, and if I git it I can take her off your hands. I need her to help my new woman keep house for me who aint very strong, but she can train Betsy all right. You can just put her on the train at New York, and she can come strait here without no change, and she wont be no more expense to you,

Yours truly,

Alvin Wixon.”

“Oh, Ben!” gasped Mrs. Johns. “You won’t let him?”

“Of course not. He’s a low, drunken scoundrel, and his first wife starved to death. He can easily be proved unfit as a guardian; no court would sustain any claim of his, and I can be appointed[76] Betsy’s legal guardian. She’s a bright, capable child, and it would be a pity to have such good material wasted washing dishes for a stepmother, who probably would not be any kinder to her than her father has been.”

“Oh, Ben, we mustn’t let it happen! Why, I couldn’t let her go now. She’s like my own, and growing dearer every day. Have you answered the letter?”

“Yes. I told him the facts of the case. I think he will make no further trouble.”

“I hope not. Dear, dear! I wish the child would show more affection for me. Perhaps it is just timidity, but she looks like a startled fawn when I kiss her. The only thing so far that seems to reach her is Van.”

“Don’t hurry her. It’ll come. She can’t help loving you, Kate. Nobody could. But she’s not accustomed to the shows of love. Van is a dog. He simply forces himself on her. If she doesn’t cuddle him, he cuddles her. He’s the most taking bit I ever saw on four legs.”

“If he can only break down that uncanny coldness! If she would only be a child instead of a little old woman, I could get at her.”

[77]“Wait,” replied Dr. Johns. “At this stage Van is the educating principle in matters of the heart. You are doing well in other ways. By the way, she ought to know other children.”

“There are none on the Hill-Top of the kind I want her to know now. I’m trying to improve her English, and for a little while I want her to hear only the best. When school opens, that will help. I’ll tell you,—I might send her in town to Sunday School. She’ll hear correct English there, and see children who have nice manners.”

So Betsy started to Sunday School. She wore her prettiest clothes and walked stiffly, as if trying to do her duty by the dainty garments. She was introduced to a teacher, and for a few Sundays Aunt Kate asked no questions, waiting for developments. Betsy went dutifully, but made no sign.

At last Aunt Kate said,

“Do you like your Sunday School, Betsy?”

“Good enough. The folks there think that God punishes you for your sins. I know better. I’ve been awful bad sometimes and He hasn’t punished me a mite.”

“I think we are punished when we break God’s[78] laws. Sometimes we are punished by seeing the ones we love suffer.”

Betsy thought a moment.

“Maybe so,” she said at last. “When I’ve been bad, Ma was sorry, and that made me sorry.”

“I think, little Betsy,” said Aunt Kate, slowly, “that when we are born we have in us the seeds of either good or bad, and it is the seeds we care for and train as we grow up, that make us good or evil. How are you getting on with the girls in the class?”

“Oh, all right, I guess. I don’t get acquainted much. They’re sort of—different, or else—I’m queer. But I’m watchin’ ’em, Aunt Kate, like I do you at the table, and I don’t feel so different as I did at first.”

“Good! Everything will come out right after a while, when the girls know my Betsy as well as I do.”

Betsy did not answer, but there was a soft little light in her eyes.

She continued her attendance, and Van, who had watched her weekly disappearance, dressed in her Sunday best, determined to make a closer[79] investigation of affairs. There must be some special charm about these daytime excursions from which he was excluded.

One fine Sabbath morning he was on the lawn, sunning himself, when he saw Betsy come out of the house, book in hand, best hat on, and start down the hill toward town. Van dropped in happily behind her.

“Go back, Van!” said Betsy.

Van tossed his royal head and ran on, pretending that he was bent on his own affairs.

“I’ll get rid of him when I get on the car,” thought Betsy.

She climbed on at the trolley-station, and did not see the little brown and white streak dashing madly along behind, clear into the town. There were many stops for the church-goers, so Van was able to keep the car in sight. It stopped in front of the church just as the Sunday School bell was ringing, and all the good little Episcopalian children were walking sedately in at the door, dressed in their prettiest and cleanest Sunday-go-to-meeting frocks and coats. As Betsy mounted the steps she was greeted by a member of her class.

[80]Just then Van ambled up, with his tongue out, and his eye lighted with the excitement of adventure.

“There’s your dog, Betsy.”

“Oh, my goodness! I thought I got away from him. Go home, Van! Go straight home, I tell you—this minute!”

Van dropped his head, lowered his tail slightly, and turned his back dutifully, looking sideways to see if Betsy were keeping an eye upon him. But she had disappeared in the doorway.

Van went a few steps toward home, then stopped to consider. Betsy being out of sight, at the very least he might take a look around and see what a church was like.

He turned and went back to the stone steps, climbed them slowly, and went inside the open vestibule.

“Get out!” said the sexton to Van, not knowing that he was addressing royalty.

Van got out, and the sexton went into the big empty part of the church, to see that everything was ready for the evening meeting.

Once more Van entered the vestibule. One of the teachers came out of the Sunday School room[81] for a minute, and then returned. He did not bother to look at Van.