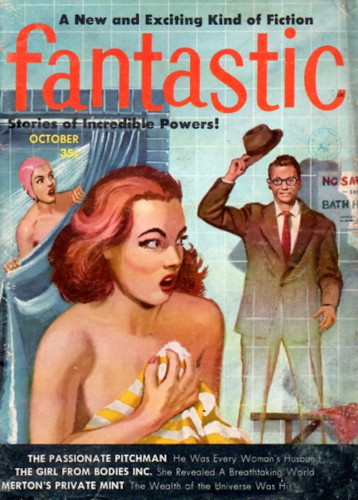

By LEE ARCHER

Your name is Merton and you find that all you have to do is reach into your safe to get money. The more you take, the more you find. And just when Quiggs has cut your future down to nothing. A wonderful discovery! Or is it? Of course it is. You'll be the richest man in the world. But will you?

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Fantastic October 1956.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Peter Merton sat at his desk after the District Attorney's men left, and put his head in his hands. He was still sitting that way when Miss Irene Simmons came in.

"Here's the rest of the morning's mail, Mr. Merton," she said.

Merton didn't even look up. He was a young, good looking man in his late twenties, the type known as a "rising young executive"—possibly because that's exactly what he was. But he did not look young this morning. His interview with the D.A. had added years to his appearance. He felt old and haggard.

"Just put them on the desk," he said. His voice sounded tired.

She put the letters on the desk, but when she didn't leave immediately, Peter Merton looked up.

Irene Simmons was an average-sized girl with golden-brown hair, large blue eyes, a full, red mouth, and a lush figure. She looked as though she ought to be working as a bathing-suit model instead of as the private secretary to a vice-president of Crabley & Co.

"Does it look pretty bad, Mr. Merton?" she asked.

"It looks horrible," he said bleakly. "The D.A. said that since Quiggs has had four days to get away, the money is probably in South America by now." He put his hand over his eyes. "If only I hadn't been such a fool! Why did I put the money in my office safe instead of in the company vault? Fifty thousand dollars! The insurance company won't pay, because the policy says that cash has to be kept in the vault.

"But how was I to know that Quiggs would come sneaking in here during Christmas vacation and take it out of my safe? He's been working for the company for years; who would have thought it?"

"Frankly, Mr. Merton, I think he was jealous because you were made a vice-president instead of him," Irene said firmly. "I think he wanted to ruin you."

"Well, he certainly has," Peter said sadly. "Old Man Crabley says that putting the money in my safe was criminal negligence. He says he wants me to pay it back or he'll see that I'm blackballed by every company in the business—after he fires me."

"I—I'm very sorry, Mr. Merton. I'm sure you'll think of something. The police may catch him, after all."

"Thank you, Miss Simmons. I hope so," Peter said. But his voice didn't hold much hope.

As the girl left the room, Peter absently watched the swaying of her hips as she walked, but he was too upset to appreciate the view fully. He had a serious problem to consider.

He thought over what she had said. So Quiggs had been jealous, eh? That probably explained the fact that he had left a five-dollar-bill in the safe. With his odd sense of humor, Quiggs had probably thought it very funny to leave a five note in place of the fifty thousand he had taken.

There was no doubt that it was Quiggs; the police were certain of the guilty person. Quiggs had been seen coming into the office on the Thursday night before Christmas vacation and had left only half an hour later. He had evidently taken the money out and replaced it with a bundle of wrapped paper. Some hours later, he had checked out of his apartment, and all trace of him had been lost.

Peter looked up at the Watteau print which concealed the heavy steel door of the wall safe. Five dollars lay behind it, all that was left of fifty thousand. He got up, walked over to the safe, twisted the combination, and pulled the door open. He reached in, took out the bill, and looked at it. And looked again, with wide eyes.

Because it wasn't a five-dollar-bill, at all.

It was a thin sheet of paper-like plastic, folded up to about the same size as a banknote.

Puzzled, Peter looked into the safe again. Nothing. He thrust his hand in and felt around. Still nothing. Except for the sheet of stuff he held in his hand, the safe was as empty as a church on Monday.

Unfolding the folded sheet, Peter saw that it was covered with print. The characters were oddly shaped, and the phraseology was queer, but it was unmistakably English.

Peter Merton sat on the edge of his desk and began to read.

Honorable Mister, Miss, or Missus:

To whoever you are in the Twentieth Century, we of the Thirtieth Century send greetings. We hope this epistle will be understandable; our knowledge of the language of English is maybe not as good as might be. Our studies of your time are somewhat hampered by lack of records, and it for this reason is that we contact you.

In order for the Time Transfer Field to work, it must be entirely surrounded by thick metal. Also a piece of similar material must be in place so that transfer can be effected, in accordance with the Vorish Equations.

If you wish to co-operate in this history-seeking venture, please place a note to such effect in your metal box.

Rolath Guelph

Terrestrial Bureau of Historical Investigation

Peter frowned and read the thing again. Who would write such silliness? Could it be another joke by Quiggs? No, it couldn't be; he, Peter Merton, had put that five-dollar-bill back into the safe, and he hadn't left the room while it was in there.

He looked up at the open safe. It was still empty. Well, by golly, he'd see whether this was a hoax or not.

He pulled his gold-plated desk pen out of its crystal holder, took a piece of office stationery, and wrote:

Dear Mr. Guelph:

I'm very much interested in your proposition, but I would like to have you explain a little bit more about it.

Very truly yours,

Peter Merton

He folded it and put it in the safe. Then he sat down and watched it. He watched it for fifteen minutes before he decided that nothing was going to happen. Finally, he walked over and took out the paper. It was the same as it had been when he put it in.

He looked back at the plastic sheet. Aha! It said: "In order for the Time Transfer Field to work, it must be surrounded entirely by thick metal."

He put the note back in, and this time he closed and locked the door.

Three minutes later, he opened it again. This time, there was another folded sheet of plastic. It said:

Dear Mr. Merton:

Understanding Time Transfer is very simple. Of course, the science of your time would be unable to build such a machine, but what happens is essentially this: If you put something in your metal box, we can pick it up and bring it to our time. However, there must be an equivalent exchange of matter, so we have to send something to your century, too. This must be done in accordance with the Law of Entropy.

What we need mostly are historical documents; newspapers, books, and magazines of your era. Please send only factual material; no fiction. We will want fiction later, but not now.

Here is a list of things we would like to have.

Peter read down the list and blinked in amazement at some of the things.

The letter ended with: In return for this, we will send an equal weight of some of our old museum pieces of paper. Papers like the one we took from you; things called "money." Will this be satisfactory? Here is a sample.

Yours very truly,

Rolath Guelph.

Money? Peter looked at the bill that was enclosed. It was a five-hundred-dollar-note! And they said they would exchange pound for pound! That meant that for one pound of old newspapers, he would get one pound of banknotes!

It sounded screwy, but Peter Merton was not a man to argue. If it worked, fine; if it didn't, what could he lose?

Peter jammed his hat on his head, folded the list and the five hundred dollars in his pocket, and strode out the door. He stopped in the outer office at the desk of Miss Simmons, who was typing up some letters.

"Come along, Miss Simmons," he said. "Get your hat; we have some things to do."

Miss Simmons looked startled, but she did as she was bid. Fifteen minutes later, they were in a second-hand book shop on Sixth Avenue.

Peter squinted at the list in the dim light. "I want The Story of English by Mario Pei," he said to the proprietor, "and The Story of Language by the same author. Give me a copy of the memoirs of Winston Churchill, the—"

He went on like that for several minutes, and the pile of books in front of him began to grow. Then he browsed through the magazine section, looking for back issues of Life, Time, and Scientific American.

He told Miss Simmons to get a taxi, and they began loading the stuff in the back seat. Then they drove to the New York Times building and got back issues of the past year. With all this loot, they drove back to the offices of Crabley & Co.

It was during the ride back that Peter wondered whether it was possible that the people of the future had stolen the money that Quiggs had been blamed for and replaced it with a bundle of paper. But he shook his head. It couldn't be. The bundle had been made of cut-up newspapers, and, besides, they had Quiggs' fingerprints all over them.

Miss Simmons helped him get the stuff into his office, and then she said: "Mr. Merton, I don't like to butt into your business, but may I ask what all this literature is for?"

Grinning happily, Peter Merton swore the girl to secrecy, then he told her what had happened. As he finished the story, Miss Simmons began to edge slowly toward the door.

"—and so, I had to get these books and things. They're evidently doing research into history. These are books they've lost, somehow. Imagine what it would be like if our historians could get copies of the books that were burned at the Library of Alexandria, and—Just a minute! Where are you going, Miss Simmons?"

Miss Simmons smiled a sickly smile. "Oh, nowhere! Are you sure you feel all right, Mr. Merton?"

"Do I feel—" Peter looked blank. "Oh! I see. You think I've gone off my rocker. Well, we'll see. Maybe I have, but I don't think so. Look; I'll prove it to you."

He scribbled a note to Rolath Guelph and put it inside the safe with a couple of the books. Then he closed the safe. He waited three minutes and opened it again.

Irene Simmons' eyes opened wide in astonishment, and her mouth formed a crimson O. Tumbling out of the safe came sheaf after sheaf of banknotes.

"Now do you believe me?" Peter asked triumphantly.

"Y—yes. What else can I believe? Are they real?"

He picked one of the bills up and looked at it closely. "It's real, all right. I started out in business as a bank teller, and I know how to tell a counterfeit. This is the real McCoy, all right."

"Well—well, my goodness!" was all Miss Simmons could say for a moment. Then, after the shock of seeing all that money had lessened a little, she asked: "What are you going to do with it, Peter?"

"The first thing I'm going to do," he said, "is return that fifty thousand dollars to Mr. Crabley. Here, help me gather this stuff up and sort it out into piles. We'll have to count it, too."

The girl pitched in willingly and began to sort the bills. Swiftly they separated it.

It was not until then that Peter Merton realized that the girl had called him by his first name. Was it the sight of all the money that had done it? Irene Simmons had never impressed him as the gold-digger type, but—

Peter shrugged and went on stacking the money.

When they had finished, Irene said: "There's not quite enough to pay back Mr. Crabley."

"That's easily fixed," Peter said, grinning.

He put in some more books, closed the safe, and waited. When he opened it again, more money came tumbling out. This time, there was enough to pay back the Old Man and more besides.

Peter sorted out a pile of the larger bills, enough to make fifty thousand, and marched to Mr. Crabley's office.

The engraving on the door said:

J. J. CRABLEY

PRESIDENT

He rapped deferentially, and when a voice said: "Come in!" Peter did exactly that.

Old Man Crabley looked just like his name. He was a small, wizened, crab-faced man with yellowed skin and a totally bald head.

"Well, sir! What is it this time?" he crackled.

Peter began pulling the money out of the briefcase he had packed it in, in order to carry it to the Old Man's office.

"I brought you the money, sir," Peter said. "You'll find it all there; fifty thousand dollars."

The Old Man's eyes lit up with pleasure. Peter could almost see the green glow of money in them.

"Excellent," said Mr. Crabley. "So the police caught the thief, hey? He'll get twenty years for this."

"No, sir," Peter replied. "They haven't caught Quiggs yet, and they haven't found the money. This is out of my—ah—my savings."

The Old Man's scraggly brows shot up. "Indeed? Savings? I didn't know you actually had that much. Hmmm. Well. Mmmm." He rubbed his hands together and frowned. "Well, this is really quite handsome of you, young man. You have more brains than I credited you with. Hmmm." He took out a letter opener and toyed with it. Finally, he said: "Peter, my boy, I'll tell you: I really didn't mean that you should do this; I was simply trying to throw a scare into you. I'll tell you what I'm going to do, my boy; I'm going to place this to your account with the firm. Henceforth, you are a junior partner of Crabley & Company, to the tune of fifty thousand dollars.

"In addition, I'll have Mr. Twythe, the firm's lawyer, draw up a paper which will give you all rights to whatever money is recovered from Quiggs by the police."

Peter started to say something, but Old Man Crabley just patted the air with a hand. "Tut, tut, my boy; think nothing of it. Any young man who can save a sum like that at your age deserves extra consideration. I have always admired a man who can make money."

Peter thanked Mr. Crabley as best he could and then he strolled back to his office feeling a rosy glow.

During the following two weeks, Peter Merton's personal fortune grew by leaps and bounds. Most of the cash he kept in a trunk in his apartment; he knew that people would start to ask questions if he put too much of it in the bank at once. But he did put considerable sums in the bank, nonetheless.

The savings account was practically forced on him by Irene Simmons. She insisted that, even if he did have money in his trunk, it was conceivable that someone might steal it. Meanwhile, he bought a new Cadillac, several tailor-made suits at two hundred and fifty per, a fur coat for Irene, and had his apartment completely redecorated, with built-in bar complete.

He became quite friendly with Irene Simmons, but he was convinced that the girl liked him simply because he had plenty of money. That didn't bother him too much; she was a beautiful girl, and Peter Merton had always had an eye for beauty.

It was in the middle of the third week that things began to change. The first thing that happened was a note from Peter's futurian correspondent, Rolath Guelph.

Dear Mr. Merton, it read. You have been most co-operative in this endeavor, and we appreciate it greatly. Your books have been very welcome, and have strengthened our knowledge of your times and language tremendously.

Now, however, we would like a few artifacts of your civilization. Would you please send us samples of your clothing, both men's and women's styles? We would also appreciate various other things, such as....

And here there followed another long list, similar to the one he had received before, except that it called for various manufactured objects.

The letter was signed, as usual, Very truly yours, Rolath Guelph.

"Well, what do you think of that?" Peter said, after reading it.

Irene read it and said: "I have a dress I can send him, and you can send him one of your suits."

Peter nodded. "We'll have to buy some of these other things, though."

An hour later, Peter stuffed a suit into the wall safe and closed the door. When he opened it, there was a small bundle of thin, strong material which, when unfolded, proved to be a suit—of sorts. It certainly looked different.

Irene giggled when he held it out. "You couldn't wear that on the streets. It looks like something out of Flash Gordon or Buck Rogers."

Peter grinned and put in Irene's dress. What he got back was a dress, but this time Irene didn't giggle when it was unfolded.

"Why, that's perfectly gorgeous," she said, in awe. "I wonder if it'll fit?"

"Here," said Peter, handing it to her. "Go find out. You can lead the fashion field—by a century to be exact."

Irene took the dress and headed for the ladies' powder room. When she came back, it was all Peter could do to keep his eyes from popping out.

On Irene, the rich, iridescent material made her look like a queen out of a Technicolor extravaganza.

"Wow!" said Peter feelingly. "It's too bad they don't have suits I can wear."

"I'll show you something else, too," Irene said excitedly. "I accidentally spilled some water on it in the powder room, and look what happened!" She proceeded to demonstrate by pouring water on her skirts from the carafe on Peter's desk. The water rolled off without wetting the material. Then she took the desk pen and shook some ink on it. "See?" she chortled, "it rolls right off! It never has to be cleaned, because it can't get dirty!"

Peter looked back at the Buck Rogers suit. "Maybe I can get a tailor to make a decent suit out of that thing."

Irene shook her head. "I don't think so. There aren't any seams."

Peter frowned and took a pair of scissors from his desk drawer. He took one sleeve of the suit and tried to cut it. It wouldn't cut. He jabbed at it with the point. The suit stubbornly refused to cut, snag, or tear.

"I wonder," he then said thoughtfully, "if this Rolath Guelph would have a suit made for me; one that I could wear." He scribbled out a note and put it in with the next batch of stuff.

The reply came back almost immediately.

I can't promise anything, Mr. Merton, but I'll see what I can do. R. G.

"Well, that's that," sighed Peter. "I'll just have to wait."

Another week passed, and Peter got no word from Rolath Guelph. He did, however, get word from another group of men.

He was sitting comfortably in his office, pondering on what to do with all his money, when the intercom on his desk buzzed.

"There are some gentlemen from the Treasury Department to see you, Mr. Merton," said Irene's voice. She sounded scared.

"Send them in," Peter said. Come to think of it, he felt a little uneasy, himself.

The two brisk, official-looking young men who came into the office identified themselves as Mr. Brady and Mr. Brown, of the United States Treasury Department. They wasted no time in getting down to business.

"Now, Mr. Merton," said Brady, "we'd like to know how you're getting all this money."

"Well, ah—um—I saved it," he said.

"That's not what I meant," said Brady. "I'm talking about several counterfeit bills that have been traced to you. Where did you get them?"

"But they can't be counterfeit," Peter protested. "They are perfectly good bills!"

"Oh, they're good imitations, all right," Brown said. "The most amazing fakes I've ever seen. The paper is perfect, the engraving is beautiful; in fact, the only thing wrong is the serial numbers. Why, some of those numbers won't be printed on bills for twenty or thirty years yet."

"Now, Mr. Merton," said Brady, "tell us where the plates are. Who printed these amazing phonies?"

"I don't know," Peter said. "I—I—" he stammered. Frightened, he didn't know what to say. He was afraid to tell them about Rolath Guelph and the Time Transfer; they'd think he was crazy.

"It won't do you any good to lie, Mr. Merton," said Brown. "We got a search warrant this morning and went through your apartment. We found the trunk full of money in your closet. Some of the boys are going over them now, down at the Treasury Office."

Peter Merton gulped and said nothing. He couldn't; there was a lump in his throat the size of a grapefruit.

"Well," Brady said, "if you won't tell us, I'm afraid we'll just have to take you in. Come along, Mr. Merton."

Still speechless, Peter walked out of the office between the two men.

Peter Merton was sitting in a cell with his head in his hands when he heard the clicking of high heels down the corridor, followed by the heavy tread of a guard's feet.

It was Irene. "I got a lawyer for you, Peter," she said breathlessly as she came up to the cell door.

The guard leaned against the wall and inspected his fingernails. "I don't think he needs a lawyer, lady. What he needs is a goof-doctor. He's flipped his cookie."

Peter managed a faint grin. "I told 'em how I got the money," he said. "They think I'm nuts."

"But, Peter," she said, "why would Rolath Guelph send counterfeit money?"

"He didn't," Peter said. "Don't you see? He got all that money out of a museum. There's probably bills there that were printed in every century for the next thousand years. He just sent some bills that won't be printed for twenty years yet."

"Well, don't you worry, I'll do something to get you out," she said. "Couldn't we take them up to the office and show them how it works?"

"I don't know. Maybe. But Brady said that even if I were telling the truth they'd have to take all the money away from me."

"I don't care about the money," Irene said. "All I care about is getting you out of this horrible place."

Suddenly, a door opened at the far end of the corridor, and there were more footsteps. It was Brady and Brown, followed by a man Peter had never seen before.

The stranger was saying: "—after all, it's only fair that my client be allowed to prove his story, no matter how fantastic it is."

"He'll get a chance," Brady said sharply.

The stranger turned out to be Q. Bertram Leslie, the lawyer that Irene had engaged.

"All right," Brown said to the guard, "let him out. We'll take over." Then he looked at Peter. "We're going up to your office, Merton, to give you a chance to prove this screwy story you've been telling us about a time machine. I know it's going to be a waste of time, but justice is justice. Come along."

It was after six o'clock when they arrived at the offices of Crabley & Company, and the office suite was deserted. Irene let the officers in with a key, and they went back to Peter's private office.

"Okay," said Brady, "there is your magic safe; do your stuff."

As Peter began working the combination, Brown said: "By the way, Merton, you'll be interested to know that the Brazilian police have picked up this guy, Quiggs, who stole the fifty thousand from you. He claimed he opened the package and there was nothing but a bunch of plastic in it. But the Brazilian cops think they've got a lead on it."

Peter paid no attention. He wasn't interested in Quiggs' crime right now, he was only interested in his own. He swung open the door and looked inside. There was a folded note from Rolath Guelph. He opened it and looked.

"Oh, no!" he said weakly. He sat down in a chair.

Brady took the note from his hand and read:

Dear Mr. Merton,

We of the Terrestrial Bureau of Historical research want to extend to you our warmest thanks for your co-operation. We now have most of the information we want about your era. With the valuable information you have given us, we will be able to do a great deal more research, and will have much better success in pinpointing our future contacts.

It is too bad we could not meet in person, but it is impossible to transfer living things through time. Rest assured that your name will go down in history books as one of our most valuable contacts.

The Transfer Field will be shut off as soon as you receive this note. Naturally, a reversal of transfer will occur.

With our warmest wishes,

Rolath Guelph.

Brady looked up at Peter with what could well be called a jaundiced eye. He said. "Did you think this would get you off the hook? How stupid do you think we are? Phony bills, a phony story, phony letter—Merton, you're just plain phony, all the way through. Come on along; it's back to the hoosegow for you. And this time, try—"

It is difficult to say what Brady might have suggested that Peter try, for he never finished the sentence. He was interrupted by a sudden roar of sound that reminded him of a broken steam pipe. Suddenly, the air was filled with books, magazines, papers, clothing, shoes, ash trays, cigarettes, pencils, pens, candy, sandwiches, and a thousand and one other things, all spewing from the safe like water out of a fire hose.

Irene gasped as her dress was snatched back into the other world.

Amid the confusion Peter saw Irene running for the door, clad only in the sheerest of bra and panties.

"Where is Brady?" shouted Brown. "Why did that girl run off? What happened?"

"I'm not sure what happened," Peter said, "but Irene had a perfectly good reason for running off. And as for Brady—"

He pointed toward the tremendous heap of stuff on the floor.

One hand was groping feebly from its center.

Irene sipped at her coffee, while Peter, sitting across the cafe table, explained to her.

"Of course they didn't have a case against me without evidence, and when all the money vanished, they had no evidence. So they had to let me go."

"But I don't see exactly why the things vanished," Irene said. "What happened to my beautiful dress? That was terribly embarrassing!"

But very beautiful, Peter thought. "Well, as near as I can figure out, this Time Transfer business only works so long as the time field is working. As goon as they shut it off, everything went back to its proper time. All the things we gave them came back to us, and all the money, and your dress, and the other gadgets we got went back to the Thirtieth Century, where they belonged."

"It's a shame, in a way," Irene said. "We could have used that trunkful of money to get married on."

Peter's grin broadened. "Don't worry about that. Remember, Old Man Crabley gave me the right to keep any money that was recovered from Quiggs."

"Did you get it?" Irene asked excitedly. "Did Quiggs tell where he hid it?"

Peter shook his head. "Nope. He didn't steal it. I found the money in that pile of stuff in my office.

"Evidently, Rolath Guelph was trying out his machine and took the bundle of money and replaced it with another bundle of that queer plastic paper of his. When Quiggs sneaked in, he just stole the bundle from the Thirtieth Century and he put a third bundle in. He got all the way to Brazil before he opened the package and found out he didn't have anything."

"Fifty thousand dollars," Irene said dreamily. "Well, that ought to be enough to start on, anyway."

THE END