OTHER BOOKS FOR CHILDREN

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

A BOOK OF VERSES FOR CHILDREN

ANOTHER BOOK OF VERSES FOR CHILDREN

THE FLAMP

THE AMELIORATOR

THE SCHOOLBOY’S APPRENTICE

OLD-FASHIONED TALES

FORGOTTEN TALES OF LONG AGO

THREE HUNDRED GAMES AND PASTIMES

RUNAWAYS AND CASTAWAYS

THE “ORIGINAL POEMS” OF ANN AND JANE TAYLOR

THE SLOW-COACH: A Story. Illustrated in Colour by M. V. Wheelhouse

A CAT BOOK. Illustrated by Pat Sullivan

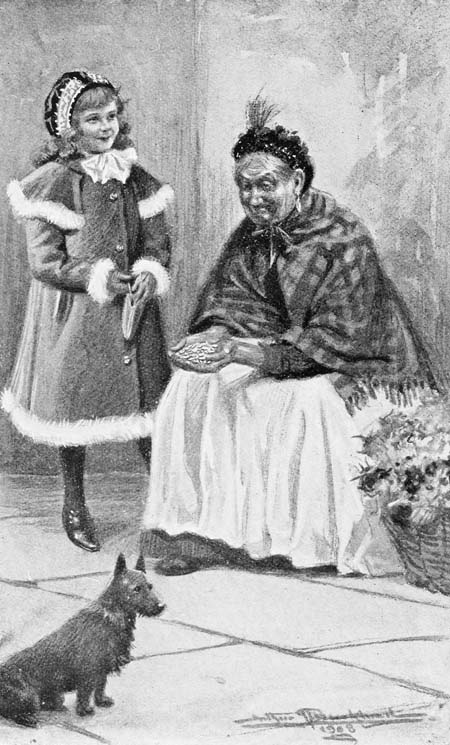

TO THE OLD WOMAN’S INTENSE ASTONISHMENT, SHE GAVE HER ONE

HUNDRED AND FOUR OF HER THREEPENNY BITS.

[p. 42

ANNE’S TERRIBLE GOOD

NATURE

AND OTHER STORIES FOR CHILDREN

BY

E. V. LUCAS

WITH 12 ILLUSTRATIONS

BY A. H. BUCKLAND

NEW YORK

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

First published, August 1908; Reprinted December 1908,

July 1911, March 1915, December 1919,

June 1923, December 1924,

and January 1928.

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN: ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Of the eleven stories in this book, seven now appear for the first time. For permission to reprint “Sir Franklin and the Little Mothers,” I have to thank Messrs. Bradbury, Agnew & Co.; and Messrs. George Allen & Sons allow me to include “The Miss Bannisters’ Brother.” “The Monkey’s Revenge” was printed first in Messrs. Dent’s Christmas Treasury, and “The Anti-burglars” in The Woman at Home for December 1902. The motive of the title story was given to me by Mrs. Charles Bryant, and that of “The Ring of Fortitude” by Mrs. W. M. Meredith. The[vi] suggestion as to organs and street cries in “The Notice-Board” was made to me by Oxford’s Professor of Poetry. The autobiographies of coins, I might add, are a commonplace in old books for children; but one is at liberty, I think, to adapt the idea to one’s own time without being guilty of very serious want of originality.

E. V. L.

| PAGE | |

| ANNE’S TERRIBLE GOOD NATURE | 1 |

| THE THOUSAND THREEPENNY BITS | 27 |

| RODERICK’S PROS | 55 |

| THE MONKEY’S REVENGE | 73 |

| THE NOTICE-BOARD | 87 |

| THE MISS BANNISTERS’ BROTHER | 109 |

| THE ANTI-BURGLARS | 143 |

| SIR FRANKLIN AND THE LITTLE MOTHERS | 169 |

| THE GARDENS AND THE NILE | 203 |

| A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A SHILLING | 217 |

| THE RING OF FORTITUDE | 237 |

| TO FACE PAGE | |

| TO THE OLD WOMAN’S INTENSE ASTONISHMENT, SHE GAVE HER ONE HUNDRED AND FOUR OF HER THREEPENNY BITS frontispiece | |

| “PLEASE DON’T TROUBLE TO GO BACK. I’LL LEND YOU THE CUPS AND SAUCERS” | 19 |

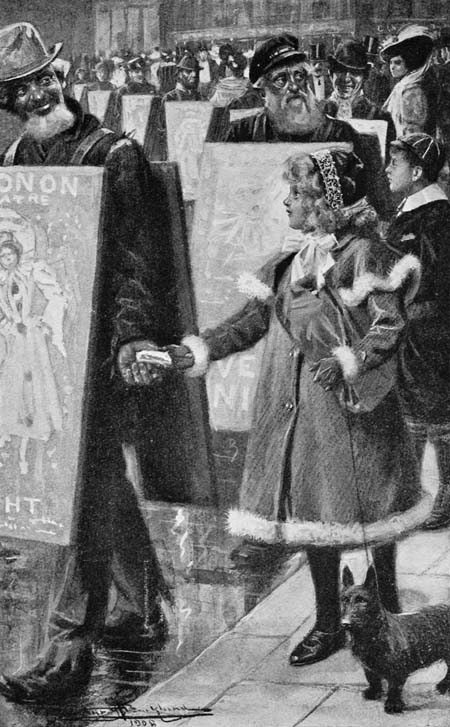

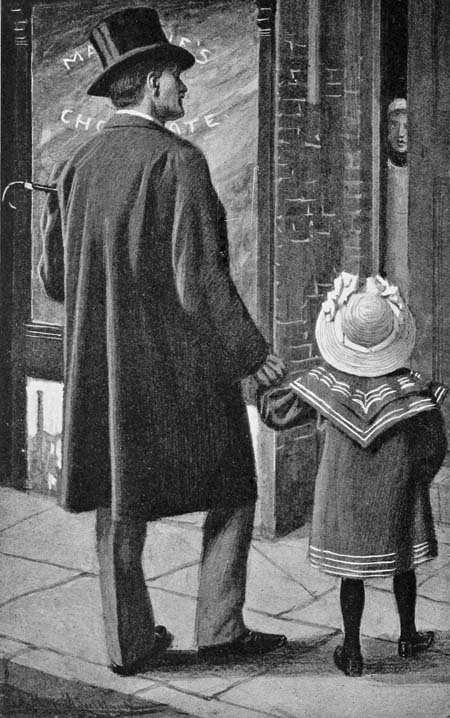

| THESE TOMMY CATHCART AND SHE SLIPPED INTO THE HANDS OF THE SANDWICH-MEN | 44 |

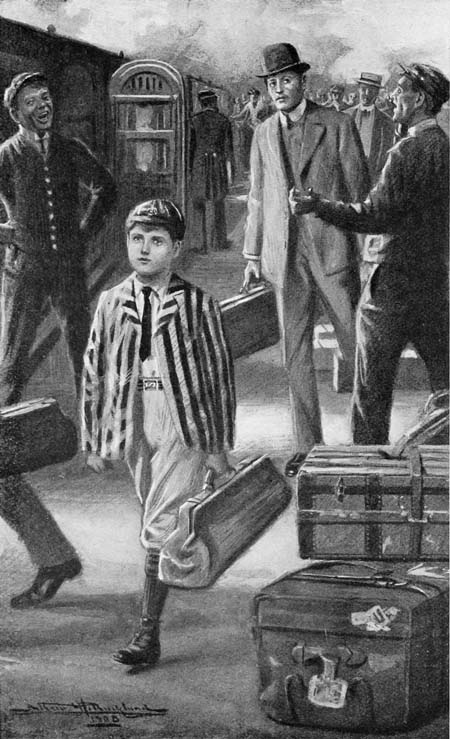

| THE PRESENCE OF SO SMALL A CRICKETER MADE A GREAT SENSATION AMONG THE PORTERS | 64 |

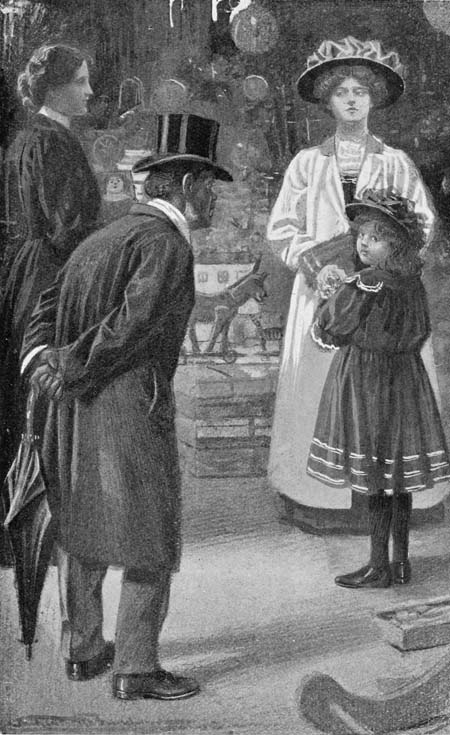

| “DO LOOK AT THAT QUEER LITTLE MAN!” | 80 |

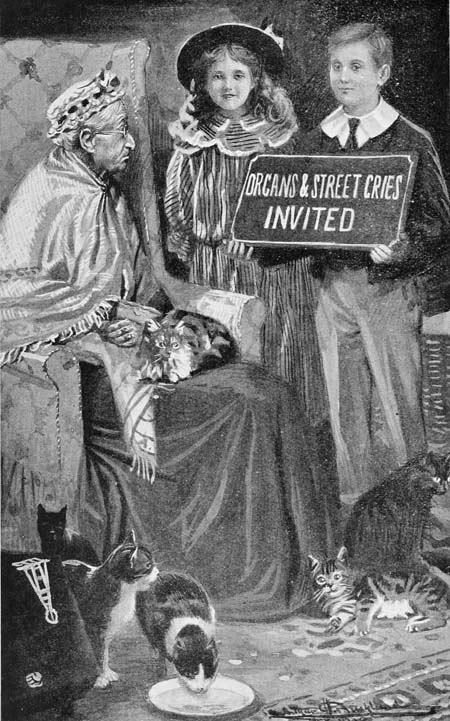

| “WE HAD IT MADE ON PURPOSE” | 103 |

| THERE WAS CHRISTINA | 114 |

| WHILE MARY HELD THE LANTERN, HE WORKED AWAY AT THE FASTENINGS | 162 |

| A LITTLE PROCESSION PASSED THE DOORWAY | 181 |

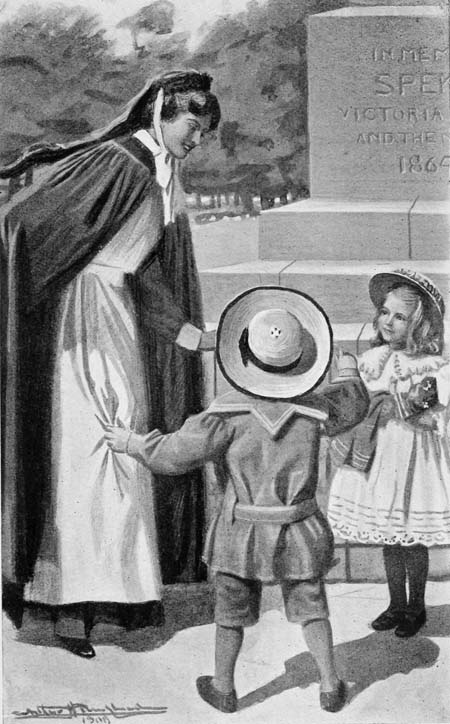

| “YES, NURSE, BUT DO TELL ME WHAT SPEKE DID?” | 206 |

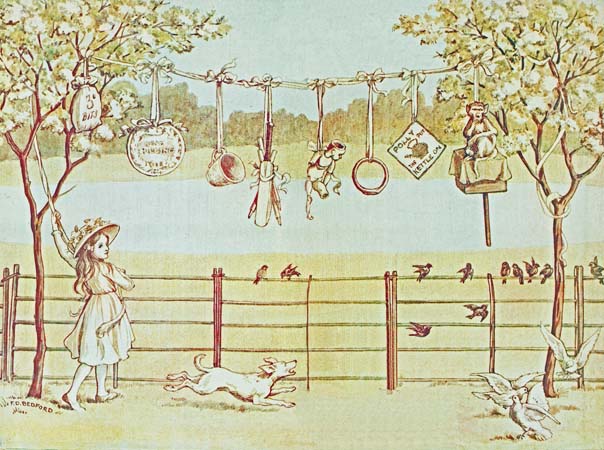

| “A BLUE RIBBON WAS THREADED THROUGH ME, AND I WAS HUNG ROUND A LITTLE GIRL’S NECK” | 229 |

| “WILL YOU TELL ME WHAT MR. DEAR IS LIKE?” | 255 |

ANNE’S TERRIBLE GOOD

NATURE

[2]

Once upon a time there was a little girl named Anne Wilbraham Bayes, Wilbraham being after her grandfather on the mother’s side, a very clever gentleman living at Great Malvern, and writing books on Roman history, who has, however, nothing whatever to do with this story. This story is about Anne and her perfectly appalling good nature.

Where Anne’s good nature came from no one ever could guess, for her father had little enough, always insisting on silence at breakfast while he read the paper and ate the biggest egg; and her mother had little enough, too, never seeing her children without being reminded of something[4] which she wanted from the top left-hand drawer in her bedroom; while Anne’s brothers and sisters had so little that they always forced Anne to be the one who should go on these boring errands. And so far as I have been able to discover, none of Anne’s grandparents were particularly good-natured either, for old Mr. Bayes had a barbed-wire fence all round his estate in west Surrey, near Farnborough, and old Mrs. Bayes would not allow any fruit to be picked except by the gardeners; while old Mr. Wilbraham, in consequence of writing his Roman history all day long, insisted on perfect quietness, so that whenever the children were at Great Malvern they had to play only at those games with no noise in them, which are hardly worth calling games at all; and as for old Mrs. Wilbraham, she was dead. It looks, therefore, very much as if Anne either inherited her wonderful and embarrassing good nature from a distant ancestor too far back[5] to be inquired into, or that it was a totally new kind, beginning with herself. For she would do the most dreadful things—things to make the hair of ordinarily good-natured people stand on end.

For instance, this is what she did once. She heard her mother complain to a visitor one January afternoon that there were no flowers in the garden at that time of year, and it made the view from the sitting-room window very depressing. After lying awake most of the night thinking how she might improve this view and make it more cheerful for her mother’s eyes, Anne got up very early, while it was still dark, and went to the conservatory, and chose from it by candlelight a number of gay flowers, and these she carefully planted in the bed just in front of her mother’s window. It was raining a little, and bitterly cold, and Anne’s fingers became numb, and her feet like stones, and her nose pink, but she went right through[6] with it without faltering until the bed was as gay as summer.

That was good nature, if you like, but no one seemed to think so. Mrs. Bayes, when she looked out of the window, instead of being cheered, screamed out “Oh!” and sent for her smelling salts, and then became quite tearful over the ruin of her pet geraniums, freesias, carnations, cyclamens, and genistas. Mr. Bayes was perfectly furious, and said so several times in different ways, each more cutting than the last; while Anne’s brothers and sisters thought it the greatest joke against Anne possible.

“You didn’t really think they’d live, did you?” they asked her. “How absolutely dotty!”

Directly after breakfast the gardener dug them all up again and put them back in their hot-house pots. Anne was not punished for her folly in any other way than by want of appreciation; but if anyone[7] had seen her crying by herself in her bedroom they might have thought that she had been.

However, when Valentine’s Day came round, which was about three weeks later, and all the little Bayeses found a parcel on their plates at breakfast—their Aunt Margaret being one of those few eccentric persons left who remember St. Valentine’s Day—Anne’s package was found to be twice as good as any of the others, containing as it did not only the ordinary present, but a gold bangle as well, with a little piece of blue turquoise hanging from it (from Liberty’s probably), and this inscription on a tiny label: “From St. Valentine to the little girl who tried to make her mother’s garden bright in winter and was only laughed at and chidden for her pains.”

So Anne really scored, you see; but, of course, it was a ridiculous thing to do, wasn’t it? Just think of supposing that[8] hot-house flowers would grow out of doors in January! It shows how perfectly absurd Anne’s good nature could be.

That is one case. Now I will tell you of another.

One day the whole Bayes family were going to London—they lived near Leatherhead—for the day. They were going to Cousin Alice’s wedding in the morning, and afterwards to the Hippodrome matinée. Marceline, it is true, was not there any longer, but it was a wonderful programme, Mr. Bayes said, and they were all immensely excited. Besides, they had bunches of flowers to throw at the bride, rice having now gone out on account of its being dangerous for the eyes and very smartful generally.

The train was full, but Mr. Bayes, by mentioning the fact overnight, had had a third-class compartment guarded for him by a porter, and into this they all climbed: Mr. Bayes, Mrs. Bayes, Arthur Lloyd[9] Bayes, Gerald Gilmer Bayes, Marion Lease Bayes, Meta Cleghorn Bayes, and Anne Wilbraham Bayes. There were also two friends from Leatherhead who knew Cousin Alice, making nine in all.

Anne sat next the window, on the platform side.

All went well until the train drew up at the next station, but there an unfortunate thing happened. Scores of people were waiting to get in, and they began to push round the third-class carriage doors. Several came to the Bayeses’ compartment, but, seeing that it was all one family in their best clothes, they had consideration and passed on.

Gradually every one found a seat, either in the thirds or the seconds, and even the first—all except a poor shabby old woman in a shawl, with a big basket, who tottered piteously up and down trying in vain to find a place. Anne saw her pass and peer into their carriage with an anxious and[10] even tearful look, but Mr. Bayes frowned so forbiddingly that she hurried on.

At this moment Anne’s terrible good nature overpowered her, and she leaned out of the window and cried invitingly: “Come in here—quick! There’s room for one.”

“Nonsense,” said Mr. Bayes; “it’s full.”

“Oh no,” said Anne—“look! It says, ‘To seat five persons on each side,’ and we’re only nine altogether. Come in here,” she cried again to the old woman.

“But she’s dirty,” said Mrs. Bayes; “she’ll spoil your frocks.”

“Very likely got something catching,” said Mr. Bayes.

“What a rotter you are, Anne!” said the others.

But meanwhile a porter had opened the door and pushed the old woman in. Anne stood up to give her her place; the others moved to the other end; and Mr. Bayes,[11] who, after all, was a very good father and exceedingly keen about health, let down the window with a bang and hid behind his paper.

“I’m sure,” said the old woman to Anne, “I’m very much obliged to you, missy.”

She got out at the next station, and as she did so she handed Anne a little paper article from her basket, for she was a pedlar, and said it was a present for her for being so good-natured; and so saying she hobbled off, and Mr. Bayes blew hard through his lips, as if he had come up from a long dive, and Mrs. Bayes made the children smell at her salts.

When Anne looked at her present she found it was a halfpenny row of pins, and this made every one laugh and quite happy again. Anne put them in her pocket and laughed too, although how she could find it in her heart to laugh, after ruining the railway journey like that by her unfortunate[12] trick of good nature, I can’t think.

The wedding was a great success until Cousin Alice, the bride—and a very pretty bride too—was coming down the aisle on Captain Vernon’s arm (and the Captain looked every inch a soldier, and had across his forehead the nicest brown line, which he had brought back with him from Egypt, where he had been on duty before he hurried home to marry Cousin Alice); all went well until a silly boy, in his desire to cross the church and get to the door first and begin to throw confetti, stepped on Cousin Alice’s beautiful white satin train and tore a yard or two nearly off.

She was as sweet about it as only Cousin Alice could be, but she stopped and picked it up, and looked round imploringly for help. And then happened that which I need hardly tell you, for you have guessed it already. The only person that had any pins was Anne, who stepped out of her[13] pew and handed her little halfpenny row to Captain Vernon; and there and then, several people helping, the beautiful white satin train was made all right again, at least for the time being, and the bride and bridegroom walked on, smiling to right and left, and ducked their heads outside as the flowers and confetti rained on them, and got into the brougham, and the coach-man cracked his whip with the white rosette on it, and they were driven to Uncle Maurice’s house, where Cousin Alice used to live, but where she would now live no more.

After a while the Bayes family, with many other guests, arrived there too, to stay for a few minutes to see the presents and say good-bye to the bride. It was a morning wedding, because they were going on a very long journey.

When Anne came at last face to face with Cousin Alice and Captain Vernon, Captain Vernon, who had suddenly become Cousin[14] Phil, took out of his pocket a piece of money, and, holding it tight in his hand, said to Anne: “I owe you this.”

“Oh no,” said Anne, “you don’t. How could you?”

“How could I?” said Cousin Phil. “Why, I bought a row of pins from you this morning.”

“Oh no!” said Anne again. “I was very glad to have them for Cousin Alice to use.”

“You may say what you like, Anne,” said Cousin Phil, “but I consider that you sold them to me, and I intend to pay for them; and here you are, and you shall give me a receipt for it.” And so saying, he stooped down, and Anne kissed him, and he kissed Anne; and then Cousin Alice kissed Anne and Anne kissed Cousin Alice; and then other people pressed forward and Anne walked away. And when she looked at the piece of money in her hand it was a sovereign.

[15]All’s well that ends well, says Shakespeare, but of course it was very unwise and very unnecessary of Anne to have leaned out of the window of that nice clean family compartment and invited into it a dirty old pedlar woman, even if she was very infirm and unhappy and there was no room anywhere else. We must, as Mr. Bayes remarked on the way home—his words not very clear by reason of his eating all the time one of the chocolate creams which Anne had bought with part of her sovereign for the family at the Hippodrome. “We must,” said Mr. Bayes—and the others all agreed with him—“we must, dear Anne, be a little careful how we exercise even so amiable a quality as kindness of heart. I am very glad to see you always so ready to be nice and helpful to others, but your brain has been given you to a large extent to control your impulses. Never forget that.”

[16]Here Mr. Bayes took another chocolate, and very soon afterwards their station was reached.

But did Anne profit by her father’s excellent advice? We shall soon see, for now I come to the worst adventure into which her terrible good nature has ever led her.

You must know that the Bayeses were not rich, although they had rich relations and really never wanted for anything. But they lived on as little as possible, and on two or three mornings every week Mr. Bayes, after reading his letters, would remark that all his investments were going wrong and they would soon be in the workhouse. That was, of course, only his way; but they could not have many treats, or many visitors, and it caused them to look with very longing eyes on the young Calderons, the children of the gentleman that had taken the Hall, the great house near by, for August and[17] September, who used to gallop by on their ponies, and play golf and cricket in their park, and who never seemed to want for anything.

To know the Calderon family was the Bayeses’ great desire, but their mother explained that it would not be right to call on strangers staying for so short a time, and nothing therefore could be done: which was particularly trying because, owing to the absence of something called dividends, the visit to Sea View, said Mr. Bayes, was this year an impossibility.

Such was the state of affairs on the morning of August 21, when Anne was working in her garden just under the wall which separated Mr. Bayes’s property from the high road. She was steadily pulling up weeds after the rain, and thinking how nice the sun made the earth smell, when she heard the beating of hoofs, and the scrunching of wheels on the road,[18] and a murmur of happy voices young and old. And then she heard a man’s voice call out “Stop!” and the horses were pulled up.

“What is it, father?” she heard a girl’s voice say.

And then the man’s voice replied, “We shall have to go back. I’ve just remembered that no cups and saucers were put in.”

“Oh no, don’t let’s go back,” said one child’s voice after another. “It’s so hot, and it doesn’t really matter. We can drink out of the glasses.”

“No,” said the father’s voice again, “we must go back. You forget that the Richardsons are going to meet us there, and they will want tea and want it properly served. We must have at least six cups and saucers. Turn round, John!”

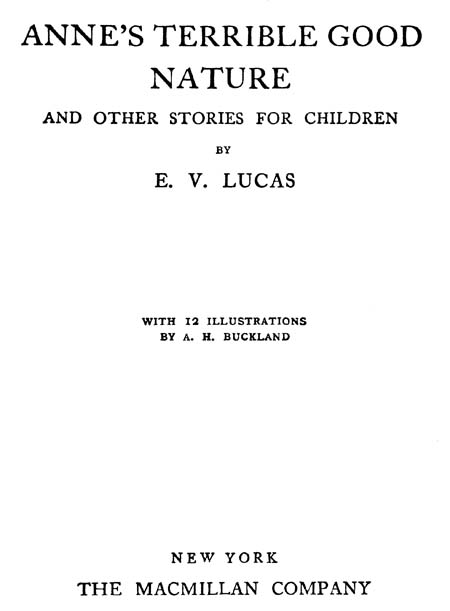

[19]

“PLEASE DON’T TROUBLE TO GO BACK. I’LL LEND YOU THE CUPS AND SAUCERS.”

By this time, Anne, who had been struggling to set a ladder against the wall, had got it to stand still and climbed to the top, and just as John began to turn the horses of the carriage she called out:

“Please don’t trouble to go back. I’ll lend you the cups and saucers. I won’t be gone a minute”; and before anyone could reply she was down the ladder and running to the house.

Perhaps if she had not been in such a hurry, and had not been so genuinely troubled to think of the picnic party spoiling their pleasure by going back to the Hall (a horrid thing to do, as Anne remembered, after leaving it so gaily), she would have asked herself several questions—such as, “What right have I to offer to lend strangers cups and saucers belonging to my parents?” and “Is my head properly controlling my impulse?” and so forth. But Anne had no time for inquiries like that: all she could think of was getting the cups and saucers as soon as possible, and returning with them so as to save those nice picnic people from having to go back again.

[20]Just before she reached the house, however, she remembered that old Martha, the cook, was in a very bad temper that morning, and would certainly refuse to give them up; but Anne also remembered at the same instant that there was in the drawing-room a cabinet full of cups and saucers, which no one ever used, but which now and then a visitor took out and examined underneath, and she decided to take six of these instead—so hastily seizing a basket from a hook in the hall she took what she wanted from the cabinet and ran back panting to the gate leading to the road.

To her immense delight the carriage was still standing there, and she hastened to hand the basket to the gentleman who was waiting in the road to receive it.

“Well, you are a little brick,” he said, “and how hot it has made you.”

Anne gasped out something in reply, but not at all comfortably, because for one[21] thing she was out of breath, and for another the children in the carriage were all looking at her very hard. But at this moment the gentleman, who had been examining the basket, gave a low whistle and then called to one of the ladies to come and speak to him. She got out of the carriage and walked a little way apart with the gentleman, who showed her something in the basket and talked very earnestly. Then all of a sudden he called to the children to get out and play for a little while until he and their mother came back, and taking Anne’s hand he asked her if she would lead him and his wife to her mother, as he had something to say to her, and they all three went off through the gate to the house.

The gentleman talked gaily as they went, and the lady held Anne’s other hand very softly, and so they came to Mr. Bayes’s study, where he was writing, Mrs. Bayes and the other children being in[22] Leatherhead shopping. The gentleman and Mr. Bayes then talked together, while Anne led the lady about the garden until she was suddenly sent for to change her clothes—why, you shall hear.

What happened at the interview between Mr. Bayes and the gentleman can best be told by repeating the conversation between Mr. and Mrs. Bayes and the children at lunch.

“But where’s Anne?” said Mrs. Bayes, as the servant removed the cover from the joint.

“Anne,” said Mr. Bayes, “Anne? Oh, yes, Anne has gone for a picnic.”

“For a picnic!” cried the whole family.

“Yes,” said Mr. Bayes, “for a picnic with the people staying at the Hall.”

Mrs. Bayes sat back with a gasp, and the children’s mouths opened so wide you could have posted letters in them.

“Yes,” said Mr. Bayes. “She was[23] working in her garden when she heard Mr. Calderon order the driver to go back because cups and saucers had been forgotten. He is a very nice fellow, by the way. I find we were at Oxford together, although I did not know him there, but he has been intimate with Charley for years. It is the same Calderon, the architect, that built your uncle’s house at Chichester.”

“Do go on, father,” said the children.

“Well,” said Mr. Bayes, “what does that little duffing Anne do but sing out that they were not to go back, but wait a minute, and she would lend them the cups and saucers.”

“Yes, yes, go on!”

“Well, and fearing that Martha—very properly—wouldn’t let her have any for the party, what does she do but take six of the very best of my Crown Derby from the cabinet in the drawing-room and scamper back with them!”

“My love,” said Mrs. Bayes, “the[24] Crown Derby that Uncle Mortimer left us?”

“Yes, the Crown Derby, valued only a month ago at two guineas apiece. Off she runs with it in a basket and hands it over to Mr. or Mrs. Calderon. Mrs. Calderon, by the way, I like. She wants you to call. I said you’d go to-morrow.”

“Do go on, father!”

“Well, where was I? Oh yes. The Calderons no sooner saw the china than they realized what had happened, and brought it back to me. By a miracle there wasn’t a chip on it. Of course, I said I was very much obliged to them, and I offered some ordinary crockery, but Calderon said they would take it only on condition that Anne accompanied it in the capacity of caretaker and brought it back. So she went.”

“I hope she changed her frock,” said Mrs. Bayes.

[25]“I believe she did,” said Mr. Bayes. “They’ve gone to Chidley Woods, where the Richardsons will meet them, and they won’t be back till six. Now perhaps I may get on with my lunch.”

By the following Saturday evening, I may add, the Bayes children and the Calderon children were very friendly, and Arthur Lloyd Bayes had fallen off Harold Armiger Calderon’s pony twice.

[26]

[27]

THE THOUSAND THREEPENNY

BITS

[28]

Once upon a time there was a little girl named Alison Muirhead, and she had a doll named Rosamund and a dog named Thomson. The dog was an Aberdeen terrier, and he came from Aberdeen by train in the care of the guard, and he rarely did what he was told, which is the way of Aberdeens, as you have perhaps discovered.

Alison used to take her doll and Thomson every day into Kensington Gardens, and when they were well inside the Gardens, opposite the tulips and the new statue of William III., she used to unclasp the catch of Thomson’s lead and let him run, doing her best to keep an eye on him.[30] This was not easy, for Thomson was a sociable dog, and he rushed after every other dog he saw, and either told them the latest dog joke or heard it, and Alison was often in despair to get him back.

If, however, Thomson had been an angel of a dog this story would never have been written, because it was wholly owing to his naughtiness that Alison and the Old Gentleman met.

The Old Gentleman used also to go into the Gardens on every fine day and sit on one of the seats by the may-trees between the long bulb walk and the Round Pond, with his back to the Albert Memorial. Not that he was one of those persons who always click their tongues when the Albert Memorial is mentioned, for, as a matter of fact, he did not mind the gold on it at all, and he really liked the groups of Asia and Europe and India at the corners, with the nice friendly elephant and camel in them; but he[31] turned his back on the Memorial because the seat was set that way, and he liked also, when he raised his eyes from his book, to see so much green grass, and in the distance the yachtsmen running round the Round Pond to prevent their vessels wrecking themselves on the cement.

Alison had noticed the Old Gentleman for a long time before they had become acquainted, and he had noticed her, and was much attracted by her quiet little ways with Rosamund, and her calm, if despairing, pursuit of Thomson; and he liked her, too, for never playing diabolo.

But it was not until one day that Thomson broke loose at the very gate of the Gardens with his lead still on him, and in course of time ran right under the Old Gentleman’s legs and caught the chain in one of the eyelet flaps of his laced boots, that Alison and he came to speak.

“Ha, ha!” said the Old Gentleman to Thomson, “I’ve got you now. And I[32] shall hold you tight till your mistress comes.”

Alison was still a long way off. Thomson said nothing, but tugged at the chain.

“I’ve been watching you for a long time, Mr. Thomson,” said the Old Gentleman, “and I have come to the conclusion that you are a bad dog. You don’t care for anyone. You do what you want to do and nothing else.” Thomson lay down and put out a yard and a half of pink tongue. Alison came nearer.

“If you were my dog,” the Old Gentleman continued, “do you know what I should do? I should thrash you.” Thomson began to snore.

Alison at this point came up, and Thomson sprang to his feet and affected to be pleased to see her.

“Thank you ever so much,” Alison said to the Old Gentleman. “But however did you catch him?”

[33]“I didn’t catch him,” said the Old Gentleman, “he caught me. Come and sit down and rest yourself.”

So Alison sat down, and Thomson laid his wicked cheek against her boot, and that was the beginning of the acquaintance.

The next day when she went into the Gardens Alison looked for the Old Gentleman, and sure enough there he was, and seeing there was no one beside him, she sat down there again. And for a little while on every fine day she sat with him and they talked of various things. He was very interesting: he knew a great deal about birds and flowers and foreign countries. He had not only lived in China, but had explored the Amazon. On his watch chain was a blue stone which an Indian snake-charmer had given him. But he lived now in the big hotel at the corner of the Gardens and all his wanderings were over.

[34]The funniest thing about him was his name. Alison did not learn what it was for a long time, but one day as she was calling “Thomson! Thomson!” very loudly as they sat there, the Old Gentleman said, “When you do that it makes me nervous.”

“Why?” Alison asked.

“Because,” the Old Gentleman said, “my name’s Thomson too.”

“Oh, I’m so sorry,” Alison said, “I must call Thomson—I mean my dog—something else. I can’t ever call him Thomson again.”

“Why not?” said the Old Gentleman. “It doesn’t matter at all. I can’t expect to be the only Thomson in the world.”

“Oh yes,” said Alison, “I shall.”

The next day the first thing she did when she saw the Old Gentleman was to tell him she had changed Thom—the dog’s name. “In future,” she said, “he is to be called Jimmie.”

[35]The Old Gentleman laughed. “That’s my name too,” he said.

One day the Old Gentleman was not in his accustomed place; and it was a very fine day too. Alison was disappointed, and even Thomson, I mean Jimmie, I mean the Aberdeen terrier, seemed to miss something.

And the next day he was not there.

And the next.

And then came Sunday, when Alison went to church, and afterwards for a rather dull walk with her father, strictly on the paths, past “Physical Energy” to the Serpentine, to look at the peacocks, and then back again by the Albert Memorial, and so home. Monday and Tuesday were both wet, and on Wednesday it was a whole week since Alison had seen the Old[36] Gentleman; but to her grief he was again absent.

And so, having her mother’s permission, the next day she called at the hotel. She had the greatest difficulty in getting in because it was the first time that either she or her dog had ever been through a revolving door; but at last they came safely into the hall into the presence of a tall porter in a uniform of splendour.

“Can you tell me if Mr. James Thomson is still staying here?” Alison asked.

“I am sorry to say, Missie,” replied the porter, “that Mr. Thomson died last week.”

Poor Alison....

One morning, some few weeks afterwards, Alison found on her plate a letter addressed to herself in a strange handwriting. After wondering about it for[37] some moments, she opened it. The letter ran thus:

“Re Mr. James Thomson, deceased.

“To Miss Alison Muirhead.

“Dear Madam,

“We beg to inform you that, in accordance with the last will and testament of our client, the late Mr. James Thomson, there lies at our office a packet containing a thousand threepenny bits, being a legacy which he devised to yourself, free of duty, in a codicil added a few days before his death. We should state that, by the terms of the bequest, it was our client’s wish that five hundred of the threepenny bits should be spent by you for others within a year of its receipt, and not put away against a maturer age; the remaining five hundred he wished to be spent by yourself, for yourself, and for yourself alone, also within the year. The parcel is[38] at your service whenever it is convenient to you to call for it.

“We are, dear madam,

“Yours faithfully,

“Lee, Lee and Lee.”

Alison was too bewildered to take it all in on the first reading, and her father therefore read it again and explained some of the words, which perhaps your father will do for you.

But if Alison was bewildered, it was nothing to her mother’s state, which was one of amazement and pride too.

“To think of it!” she cried.

“Well, I never heard of such a thing in my life!” she said.

“It’s like something in a book or a play!” she exclaimed.

“A thousand threepenny bits! Why, that’s—let me see—yes, it’s—why, it’s twelve pounds ten,” she remarked.

As for Mr. Muirhead, he was pleased[39] too; but him it seemed to amuse more than surprise.

“After your lessons this morning,” he said, “instead of going for a walk you can come into the city to me, and we’ll go to the lawyers’ together, and then have lunch at Birch’s.”

When they reached the lawyers’ office Alison and her father were shown into a large room with three grave gentlemen in it, whom Alison supposed were Lee, Lee and Lee; and all the time that her father was talking to them she wondered which was the Lee, and which was the second Lee, and which was “and Lee.” Then she had to sign a paper, and then one of the Lees gave her a canvas bag containing a thousand threepenny bits.

“Of course you would like to count them,” he said; and Alison replied, “Yes,” at which every one laughed, because Mr. Lee had meant it for a joke and Alison had taken it seriously. But how could[40] she expect that Mr. Thomson’s lawyer, or, indeed, any lawyer of a dead friend, would make a joke?

“I’m afraid,” said Mr. Lee, when they had done laughing “that you would be very tired of the job before you were half-way through it. Count them when you get home, and if there is any mistake we will put it right; but one of our most careful clerks has already gone through them very thoroughly.”

Then they all shook hands, and each of the three Lees said something playful.

The one that Alison guessed was Lee said, “Don’t be extravagant and buy the moon.”

The one that Alison guessed was the second Lee said, “If at any time you get tired of so much money, we shall be pleased to have it again.”

While “and Lee” looked very solemn and said, “Now you can go to church a thousand times.”

[41]Then they all laughed again, and Alison and her father were shown out into the street by a little sharp boy, whose eyes were fixed so keenly on the canvas bag that Alison was quite certain that he was the most careful clerk who had done the counting.

After they had been to lunch at Birch’s, where they had mock turtle soup and oyster patties, they went home, and Alison poured all the threepenny bits into a depression in a cushion from the sofa, and counted them into a hundred piles of ten each. Then she got a wooden writing-desk, which had been given her by her grandmother, and emptied out all the treasures it contained, and put fifty of the little heaps into the large part of the writing-case, and the remaining fifty little heaps into the compartment for pens and sealing-wax, and locked it up again.

[42]

For the next few days Alison collected advice about the spending of her money from every one she knew. All her friends were asked to give their opinions, and thus gradually she decided upon the best way to spend the five hundred threepenny bits which were for others.

Her first thought was naturally for her mother, who was an invalid. Mrs. Muirhead was very fond of flowers, and so Alison went at once to see the old flower-woman who sits outside Kensington High Street Station, and who was so cross with the Suffragettes in self-denial week for interfering with her “pitch,” as she called it; and Alison arranged with her for a threepenny bunch of whatever was in season to be taken to her mother twice every week, on Saturdays and Wednesdays, for a year, and, to the old woman’s intense[43] astonishment, she gave her one hundred and four of her threepenny bits.

Her uncle Mordaunt advised her to take in a weekly illustrated paper—say the Sphere—and, after she had looked at it herself, to send it to one of the lighthouses, where the men are very lonely and unentertained. Alison thought this was a very good idea. The Sphere cost two threepences a week, and postage a halfpenny, or one hundred and twelve threepences—altogether one pound eight shillings.

Alison had now spent two hundred and sixteen threepenny bits, and, having arranged these two things, she decided to wait till Christmas came nearer (it was now July) before she spent any more large sums, always, however, keeping a few threepenny bits handy in her purse in case of meeting any particularly hard case, such as a very blind man, or a begging mother with a dreadfully cold little baby, or a Punch and Judy man with a really nice[44] face, or a little boy who had fallen down and hurt himself badly, or an old woman who ought to be riding in a ’bus. In this way she got rid of fifty of her little coins before Christmas came near enough for her once more to think of little else but threepenny plans.

It was then that she found Tommy Cathcart so useful. Tommy Cathcart was one of her father’s articled pupils, and it was he who reminded Alison of the claims of sandwichmen. Sandwichmen have an awfully bad time, Tommy explained to her. It is almost the last thing men do. No one carries sandwich-boards until he has failed in every other way.

THESE TOMMY CATHCART AND SHE SLIPPED INTO THE HANDS OF THE SANDWICH-MEN.

After talking it over very seriously, they went together to a tobacconist near the Strand, who undertook to make up thirty little packets for threepence each, containing a clay pipe and tobacco, and these Tommy Cathcart and she slipped into the hands of the sandwichmen as [45]they drifted by in Regent Street, in the Strand, and in Oxford Street, while the rest were given to a little group of the men who were resting, with their sandwich-boards leaned against the wall, in a court near Shaftesbury Avenue.

“Don’t you think,” Alison said, “that those who carry a notice over the head as well ought to have more?”

But Tommy Cathcart thought not.

That exhausted seven-and-sixpence.

Another thing that Alison and Tommy Cathcart did was to knock at the door of the cabmen’s shelter opposite De Vere Gardens, and ask if she might present a few puddings for Christmas Day. The man said she might, and that used up seven-and-sixpence—three puddings at half a crown, thirty threepences.

The other people to whom Alison sent Christmas presents with Mr. Thomson’s money were the children of the boatmen who had taken out her and her father and[46] her cousins, Harry and Francis Frend, in the Isle of Wight last year. These boatmen were two brothers named Fagg—Jack and Willy Fagg—and their boat was the Seamew. Jack had four children and Willy six, and Alison used to go and see them now and then. After much consideration she sent four threepenny bits to each of these children, a shilling pipe, with real silver on it, to Jack and Willy, and a pound of two-shilling tea to Mrs. Jack and Mrs. Willy. That made sixteen shillings, or sixty-four threepenny bits.

Just then Alison had an unexpected piece of luck, for as she was passing a shop in Westbourne Grove she saw a window full of mittens at threepence a pair, sale price. Now, mittens are just the thing for cabmen in winter—cabmen and crossing-sweepers and errand-boys. So Alison bought thirty pairs, or seven-and-sixpence worth, and she gave a pair to each of the boys that called regularly—the butcher’s[47] boy, and the baker’s boy, and the grocer’s boy, and a pair to the milkman, and a pair to the crossing-sweeper, and the rest were put in the hall for cabmen who brought her father home or took him out.

And then, just as they were getting rather in despair, one afternoon Tommy Cathcart came home with a brilliant idea.

“Smith,” he said, “is the commonest name in England. In every workhouse in England,” he said, “there must be one Smith at least. Why not,” he said, “get, say, sixty picture postcards and send them addressed to Mrs. Smith or Mr. Smith, or plain Smith, to sixty workhouses? We can get,” he said, “the names from ‘Bradshaw.’ A person in a workhouse will be awfully excited to get a Christmas card, and if,” he said, “there happens to be no Smith, some one else will have it.”

Alison liked the idea very much, and so they went off to a shop in the Strand absolutely full of picture postcards and[48] bought sixty at a penny each. They had some little difficulty in choosing, because Tommy Cathcart wanted a certain number to be photographs of Pauline Chase and other pretty people, but Alison said that views of London would be better, since most persons knew London, and the card would remind them of old times. As it was, so to speak, her money, Alison got her own way. Then they bought sixty halfpenny stamps, and returned home to find the towns in “Bradshaw” and send them off. That all came to seven-and-six, or thirty threepenny bits.

Then Alison had a very brilliant inspiration—to give Jimmie a beautiful silver collar all for himself, with the words “In memory of James Thomson” on it, as a Christmas present. Dogs have so few presents, and Jimmie really was very good, except when he lost his head in the Gardens, which indeed, to be truthful, he always did. So he had his collar on[49] Christmas morning, and it cost exactly twelve-and-six altogether, or fifty threepenny bits.

So much for the first five hundred.

Alison had then to lay out the second five hundred, or £6 5s., on herself and herself alone. This was easier. She and her father spent three afternoons among the old furniture shops of Kensington and the Brompton Road, and at last came upon the very thing they were looking for in the back room of a shop close to the Oratory, kept by an elderly Jewish lady with a perfectly gigantic nose and rings on every finger.

This was an old bureau writing-desk, with drawers, and a flap to pull down to write on, and lots of pigeon-holes, and a very strong lock. Also a secret drawer. After some bargaining Mr. Muirhead got[50] it for six pounds, which left five shillings for writing paper and sealing-wax and blotting-paper and nibs.

And that was an end of the thousand threepenny bits, as the balance-sheet on the opposite page shows.

At least, not quite the end, as I will tell you. The face of the old Jewess, when the time came to pay for the bureau and Alison took forty-eight little packets of ten threepenny bits each out of her bag and laid them on the table, was a picture of perplexity and amusement.

“Well, ma tear, what’s that?” she asked.

“Four hundred and eighty threepenny bits—six pounds,” said Alison.

“But, ma tear, what will I do with all the little money?”

“It’s all I’ve got,” said Alison.

“You see,” said Mr. Muirhead—and then he told the old lady with the big nose the story.

[51]

STATEMENT OF ACCOUNTS

First Account—For other People.

| Threepences. | £ | s. | d. | |

| A year’s flowers for mother, twice a week, at 3d. a bunch | 104 | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| The Sphere for a year | 104 | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| Postage of same to a lighthouse | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Odd threepenny bits given to unhappy people in the streets, etc. | 50 | 0 | 12 | 6 |

| Tobacco and pipes to thirty sandwichmen, at 3d. each | 30 | 0 | 7 | 6 |

| Three Christmas puddings for the cabmen’s shelter near De Vere Gardens, at 2s. 6d. | 30 | 0 | 7 | 6 |

| Ten Fagg children, at 1s. each | 40 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Two pipes for Jack and Willy Fagg, at 1s. | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Two pounds tea for Mrs. Jack and Mrs. Willy, at 2s. | 16 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Mittens for cabmen, etc. | 30 | 0 | 7 | 6 |

| Sixty picture postcards for the Smith family at 1d., and postage at ½d. | 30 | 0 | 7 | 6 |

| Silver collar for Jimmie, with engraving | 50 | 0 | 12 | 6 |

| —— | —————— | |||

| 500 | £6 | 5 | 0 | |

| Second Account—For Alison Muirhead herself. | ||||

| Threepences. | £ | s. | d. | |

| Old Bureau | 480 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Writing paper, etc. | 20 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| —— | —————— | |||

| 500 | 6 | 5 | 0 | |

| First account total | 500 | 6 | 5 | 0 |

| —— | —————— | |||

| Grand total | 1000 | £12 | 10 | 0 |

| ==== | ============ | |||

| Audited and found correct, | ||||

| (Signed) Thomas W. Cathcart. | ||||

[52]And what do you think she did? “Well, ma tear,” she said, “I can’t let you go away without something left, in case you met a poor beggar in the street. You must take back one of those little packets to go on with, as a present from me;” and she picked up one and placed it in Alison’s hand, and Alison took it gladly.

And that was the beginning of a new Threepenny Trust, for Mr. Cathcart also contributed a little heap, and Mr. Muirhead henceforward made a point of saving every threepenny bit that he received in change (and I believe that sometimes he asked specially for them when he went to his bank) and bringing them home for Alison’s fund; and Uncle Mordaunt must have done the same, for the last time he came to dinner he said to Alison, “I wish you’d get rid of this rubbish for me,” and handed her seventeen of the little coins.

So you see that there is every chance of[53] Mr. James Thomson’s kind scheme going on for a long time yet; but, in so far as his own thousand threepenny bits are concerned, the story is done.

[54]

RODERICK’S PROS.

[56]

Once upon a time there was a little boy of ten, who bowled out C. B. Fry. This little boy’s name was Roderick Bulstrode (or Bulstrode is the name that we will give him here), and he lived in St. John’s Wood, in one of the houses whose gardens join Lord’s. His father played for the M.C.C. a good deal, and practised in the nets almost every day, to the bowling of various professionals, or pros., as they are called for short, but chiefly to that of Tom Stick; and in the summer Roderick was more often at Lord’s than not.

How it came about that Roderick bowled C. B. Fry was this way. Middlesex were playing Sussex, and Mr. Fry went to the nets early to practise, and[58] Roderick’s father bowled to him and let Roderick have the ball now and then. And whether it was that Mr. Fry was not thinking, or was looking another way, or was simply very good-natured, I don’t know, but one of Roderick’s sneaks got under his bat and hit the stumps. (They were not sneaks, you must understand, because he wanted to bowl sneaks, but because he was not big enough to bowl any other way for 22 yards. He was only ten.) Roderick thus did that day what no one else could do, for Mr. Fry went in and made 143 not out, in spite of all the efforts of Albert Trott and Tarrant and J. T. Hearne.

Roderick’s bedroom walls had been covered with portraits of cricketers for years, but after he bowled out C. B. Fry he took away a lot of them and made an open space with the last picture postcard of Mr. Fry right in the middle of it, and underneath, on the mantelpiece, he put the[59] ball he had bowled him with, which his father gave him, under a glass shade. And other little St. John’s Wood boys, friends of Roderick’s from the Abbey Road, and Hamilton Terrace, and Loudoun Road, and that very attractive red-brick village with a green of its own just off the Avenue Road, used to come and see it, and stand in front of it and hold their breath, rather like little girls looking at a new baby.

Roderick also had a “Cricketers’ Birthday Book,” so that when he came down to breakfast he used to say, “Tyldesley’s thirty-five to-day,” “Hutchings is twenty-four,” and so on. And he knew the initials of every first-class amateur and the Christian name of every pro.

That was not Roderick’s only cricketing triumph. It is true that he had never succeeded in bowling out any other really swell batsman, but he had shaken hands with Sammy Woods and J. R. Mason, and one day Lord Hawke took him by both[60] shoulders and lifted him to one side, saying: “Now then, Tommy, out of the way.” But these were only chance acquaintances. His real cricketing friend was Tom Stick, the ground bowler.

Tom Stick came from Devonshire, which is a county without a first-class eleven that plays the M.C.C. in August, and he lived in a little street off Lisson Grove, where he kept a bird-fancier’s shop. For most professional cricketers, you know, are something else as well, or they would not be able to live in the winter. Many of them make cricket-bats, many keep inns, many are gardeners. I know one who is a picture-framer, and another an organist, while George Hirst, who is the greatest of them all, makes toffee. Well, Tom Stick was a bird-fancier, with a partner named Dick Crawley, who used to mind the shop when Tom had to be at Lord’s bowling to gentlemen, Roderick’s father among them, or playing against[61] Haileybury or Rugby or wherever he was sent to do all the hard work and go in last.

Roderick’s father was very fond of Tom and was quite happy to know that Roderick was with him, so that Roderick not only used to join Tom at Lord’s, but also at the shop off Lisson Grove, where he often helped in cleaning out the cages and feeding the birds and teaching the bullfinches to whistle, and was very good friends also with certain puppies and rabbits. His own dog, a fox-terrier named “Sinhji,” had come from Tom.

Tom used to bowl to Roderick in the mornings before the gentlemen arrived for their practice, and he taught him to hold his bat straight and not slope it, and to keep his feet still and not draw them away when the ball was coming (which are the two most important things in batting), and it was he who stopped Roderick from carrying an autograph-book about and[62] worrying the cricketers for their signatures. In fact, Tom was a kind of nurse to Roderick, and they were so much together that, whereas Tom was known to Roderick’s small friends as “Roddy’s Pro,” Roderick was known to Tom’s friends as “Sticky’s Shadow.”

Now it happened that last summer Roderick’s father had been making a great many runs for the M.C.C. in one of their tours. (Roderick did not see him, for he had to stay at home and do his lessons; but his father sent him a telegram after each innings.) Mr. Bulstrode (as we are calling him) batted so well, indeed, that when he returned to London he was asked to play for Middlesex against Yorkshire on the following Monday, to take the place of one of the regular eleven who was ill; and you may be sure he said yes, for, although he was now thirty-two, this was the first time he had ever been asked to play for his county.

[63]Roderick, you may be equally sure, was also pleased; and when his father suddenly said to him, “Would you like to come with me?” his excitement was almost too great to bear.

“And Tom too?” he asked, after a minute or so.

“Yes, Tom’s going,” said his father. “He’s going to field if anyone is hurt or has to leave early. But if he’s not wanted he will look after you.”

“Hurray!” said Roderick. “I know what I shall do. I shall score every run and keep the bowling analysis too.”

The train left St. Pancras on the Sunday afternoon, and that in itself was an excitement, for Roderick had never travelled on Sunday before; but before that had come the rapture of packing his bag, which on this occasion was not an ordinary one, but an old cricket-bag of his father’s, which he begged for, in which were not only his sponge and collars and other necessary[64] things, but his flannels and his bat and pads.

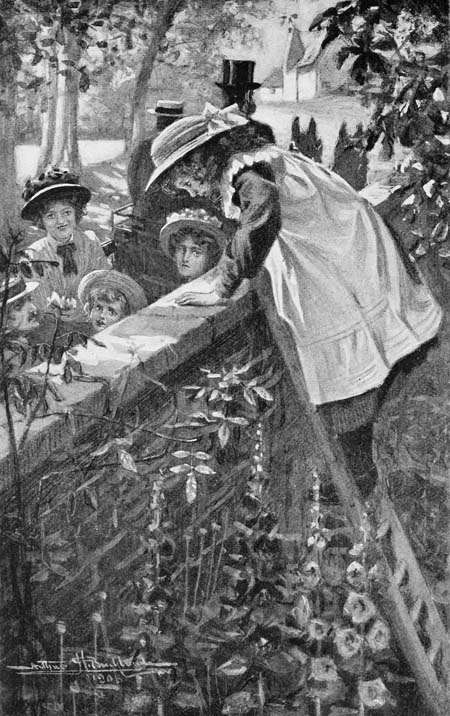

This bag he insisted upon carrying himself all along the platform, and, as several of the Middlesex team were also on their way to the train at the same moment, the presence of so small a cricketer in their midst made a great sensation among the porters.

“My word!” said one, “Yorkshire will have to look out this time.”

“Who’s the giant,” asked another, “walking just behind Albert Trott? I shouldn’t like to be in when he bowled his fastest.”

But Roderick was unconscious of any laughter. He was the proudest boy in London, although his arm, it is true, was beginning to ache horribly. But when, as he was climbing into the carriage, the guard lifted him up and called him “Prince Run-get-simply,” he joined in the fun.

THE PRESENCE OF SO SMALL A CRICKETER MADE A GREAT SENSATION AMONG THE PORTERS.

[65]It was a deliriously happy journey, for all the cricketers were very nice to him, and Mr. Warner talked about Australia, and Mr. Bosanquet showed him how he held the ball to make it break from the leg when the batsman thought it was going to break from the off, and at Nottingham Mr. Douglas bought him a bun and a banana. They got to Sheffield just before eight, and Roderick went to bed very soon after, in a little bed in his father’s room in the hotel.

The first thing Roderick did the next morning was to buy a scoring-book and a pencil, and then he and his father explored Sheffield a little before it was time to go to the ground at Bramall Lane and get some practice.

The people clustered all round and in front of the nets and watched the batsmen, and now and then they were nearly killed, as always happens before a match. They pointed out the cricketers to each other.

[66]“There’s Warner,” they said. “That’s Bosanquet—the tall one.” “Where’s Trott? Why, there, bowling at Warner. Good old Alberto!” and so on.

“Who’s the man in the end net?” Roderick heard some one ask.

“I don’t know. One of Middlesex’s many new men, I suppose,” said the other.

“But he can hit a bit, can’t he?” the first man said, as Roderick’s father stepped out to a ball and banged it half-way across the ground.

Roderick was very proud, and he felt that the time had come to make his father known. “That’s Bulstrode,” he said.

“Oh, that’s Bulstrode, is it?” said the second man. “I’ve heard of him. He makes lots of runs on the M.C.C. tours. But I guess Georgy’ll get him.”

“Who is Georgy?” asked Roderick.

“Georgy—why, where do you come from? Fancy being in Sheffield and asking[67] who Georgy is. Georgy is Georgy Hirst, of course.”

Roderick walked back to the pavilion with his father very proudly. “You’ll have to be very careful how you play Hirst,” he said.

“I shall,” said his father; “but why?”

“Because the men were saying he’s going to get you.” Mr. Bulstrode laughed; but he thought it very likely too.

I’m not going to tell you all about the match, for it lasted three days, and was very much like other matches. Roderick had a corner seat in the pavilion, where he could see everything, and for the first day he scored every run and kept the analysis right through. This included his father’s innings, which lasted, alas! far too short a time, for, after making four good hits to the boundary, he was caught close in at what was called silly mid-on off—what bowler do you think?—George Hirst.

[68]But the next day Roderick gave up work, because he wanted to see more of Tom, and Tom made room for him in the professionals’ box while Yorkshire were in, and he saw all the wonderful men—quite close too—Tunnicliffe and Denton and Hirst—and even talked with them. Hirst sat right in front of the box, with his brown sunburned arms on the ledge, and his square, jolly, sunburned face on his arms, and said funny things about the play in broad Yorkshire; and now and then he would say something to Roderick. And then suddenly down went a wicket, and Hirst got up to go in.

“Give me a wish for luck,” he said to Roddy.

“I wish my father may catch you out,” said Roddy; “but not until,” he added, “you have made a lot of runs.”

“If he does,” said Hirst, “I’ll give thee some practice to-morrow morning.”

[69]Poor Roddy, this was almost too much. It is bad enough to watch your favourites batting at any time, for every ball may be the last; but it is terrible when you equally want two people to bring something off—for Roddy wanted Hirst (whom he now adored) to make a good innings, and, at the same time, he wanted his father to catch Hirst out.

Hirst was not out when it was time for lunch, and so Roderick was able to tell his father all about it.

“What’s this, Hirst?” said Mr. Bulstrode, when the teams were being photographed. “Give me a chance, and let me see if I can hold it.”

Hirst laughed, and when he laughs it is like a sunset in fine weather. “I have a spy round to see where thee’re standing every over,” he said, “and that’s where I’ll never knock it.”

“But what about my boy’s practice?” Mr. Bulstrode replied.

[70]“Ah, we’ll see about that,” said the Yorkshireman.

But, as a matter of fact, Roderick got his practice according to the bargain, for, as it happened, it was Mr. Bulstrode who caught Hirst, at third man.

I need hardly tell you that Roderick dreamed that night. His sleep was full of Hirsts, all jolly and all hitting catches which his father buttered. But in the morning, when he knew how true his luck was, he was almost too happy. Hirst was as good as his word, and they practised in the nets together for nearly half an hour, and Roderick nearly bowled him twice.

In Middlesex’s next innings Roderick’s father made thirty-five, all of which Roderick scored with the greatest care; but the match could not be finished owing to a very heavy shower, and so this innings did not matter very much one way or the other, except that it made Mr. Bulstrode’s place safe for another match.

[71]Of that match I am not going to tell; but I have perhaps said enough to show you how exceedingly delightful it must be to have a father who plays for his county.

[72]

THE MONKEY’S REVENGE

[74]

Once upon a time there was a little girl named Clara Amabel Platts. She lived in Kensington, near the Gardens, and every day when it was fine she walked with Miss Hobbs round the Round Pond. Miss Hobbs was her governess. When it was wet she read a book, or as much of a book as she could, being still rather weak in the matter of long words. When she did not read she made wool-work articles for her aunts, and now and then something for her mother’s birthday present or Christmas present, which was supposed to be a secret, but which her mother, however hard she tried not to look, always knew all about. But this did not prevent her mother, who was a[76] very nice lady, from being extraordinarily surprised when the present was given to her. (That word “extraordinarily,” by the way, is one of the words which Clara would have had to pass over if she were reading this story to herself; but you, of course, are cleverer.)

It was generally admitted by Mrs. Platts, and also by Miss Hobbs and Kate Woodley the nurse, that Clara was a very good girl; but she had one fault which troubled them all, and that was too much readiness in saying what came into her mind. Mrs. Platts tried to check her by making her count five before she made any comment on what was happening, so that she could be sure that she really ought to say it; and Kate Woodley used often to click her tongue when Clara was rattling on; but Miss Hobbs had another and more serious remedy. She used to tell Clara to ask herself three questions before she made any of her[77] quick little remarks. These were the questions: (1) “Is it kind?” (2) “Is it true?” (3) “Is it necessary?” If the answer to all three was “Yes,” then Clara might say what she wanted to; otherwise not. The result was that when Clara and Miss Hobbs walked round the Round Pond Clara had very little to say; because, you know, if it comes to that, hardly anything is necessary.

Well, on December 20, 1907, the postman brought Mrs. Platts a letter from Clara’s aunt, Miss Amabel Patterson of Chislehurst, after whom she had been named, and it was that letter which makes this story. It began by saying that Miss Patterson would very much like Clara to have a nice Christmas present, and it went on to say that if she had been very good lately, and continued good up to the time of buying the present, it was to cost seven-and-six, but if she had not been very good it was only to cost a shilling. This[78] shows you the kind of aunt Miss Patterson was. For myself, I don’t think that at Christmas-time a matter of good or bad behaviour ought to be remembered at all. And I think that everything then ought to cost seven-and-six. But Miss Patterson had her own way of doing things; and it did not really matter about the shilling at all, because, as it was agreed that Clara had been very good for a long time, Mrs. Platts (who did not admire Miss Patterson’s methods any more than we do) naturally decided that unless anything still were to happen (which is very unlikely with six-and-sixpence at stake) the present should cost seven-and-six, just as if nothing about a shilling had ever been said.

Unless anything were to happen. Ah! Everything in this story depends on that.

Clara was as good as gold all the morning, and she and Miss Hobbs marched round the Round Pond like soldiers, Miss Hobbs talking all the time and Clara as[79] dumb as a fish. At dinner also she behaved beautifully, although the pudding was not at all what she liked; and then it was time for her mother to take her out to buy the present. So, still good, Clara ran upstairs to be dressed.

As I dare say you know, there are in Kensington High Street a great many large shops, and the largest of these, which is called Biter’s, has a very nice way every December of filling one of its windows (which for the rest of the year is full of dull things, such as tables, and rolls of carpets, and coal scuttles) with such seasonable and desirable articles as boats for the Round Pond, and dolls of all sorts and sizes, and steam engines with quite a lot of rails and signals, and clockwork animals, and guns. And when you go inside you can’t help hearing the gramaphone.

It was into this shop that Mrs. Platts and Clara went, wondering whether they would buy just one thing that cost seven-and-six[80] all at once, or a lot of smaller things that came to seven-and-six altogether; which is one of the pleasantest problems to ponder over that this life holds. Well, everything was going splendidly, and Clara, after many changings of her mind, had just decided on a beautiful wax doll with cheeks like tulips and real black hair, when she chanced to look up and saw a funny little old gentleman come in at the door; and all in a flash she forgot her good resolutions and everything that was depending on them, and seizing her mother’s arm, and giving no thought at all to Miss Hobbs’s three questions, or to Kate Woodley’s clicking tongue, or to counting five, she cried in a loud quick whisper, “Oh, mother, do look at that queer little man! Isn’t he just like a monkey?”

“DO LOOK AT THAT QUEER LITTLE MAN!”

Now there were two dreadful things about this speech. One was that it was made before Aunt Amabel’s present had[81] been bought, and therefore Mrs. Platts was only entitled to spend a shilling, and the other was that the little old gentleman quite clearly heard it, for his face flushed and he looked exceedingly uncomfortable. Indeed, it was an uncomfortable time for every one, for Mrs. Platts was very unhappy to think that her little girl not only should have lost the nice doll, but also have been so rude; the little old gentleman was confused and nervous; the girl who was waiting on them was distressed when she knew what Clara’s unlucky speech had cost her; and Clara herself was in a passion of tears. After some time, in which Mrs. Platts and the girl did their best to soothe her, Clara consented to receive a shilling box of chalks as her present, and was led back still sobbing. Never was there such a sad ending to an exciting expedition.

Miss Hobbs luckily had gone home; but Kate Woodley made things worse by[82] being very sorry and clicking away like a Bee clock, and Clara hardly knew how to get through the rest of the day.

Clara’s bedtime came always at a quarter to eight, and between her supper, which was at half-past six, and that hour she used to come downstairs and play with her father and mother. On this evening she was very quiet and miserable, although Mrs. Platts and Mr. Platts did all they could to cheer her; and she even committed one of the most extraordinary actions of her life, for she said, when it was still only half-past seven, that she should like to go to bed.

And she would have gone had not at that very moment a tremendous knock sounded at the front door—so tremendous that, in spite of her unhappiness, Clara had, of course, to wait and see what it was.

And what do you think it was? It was a box addressed to Mrs. Platts, and it[83] came from Biter’s, the very shop where the tragedy had occurred.

“But I haven’t ordered anything,” said Mrs. Platts.

“Never mind,” said Mr. Platts, who had a practical mind. “Open it.”

So the box was opened, and inside was a note, and this is what it said:

“Dear Madam,

“I am so distressed to think that I am the cause of your little girl losing her present, that I feel there is nothing I can do but give her one myself. For if I had not been so foolish—at my age too!—as to go to Biter’s this afternoon, without any real purpose but to look round, she would never have got into trouble. Biter’s is for children, not for old men with queer faces. And so I beg leave to send her this doll, which I hope is the right one, and with it a few clothes and necessaries, and I am sure that she will not forget how[84] it was that she very nearly lost it altogether.

“Believe me, yours penitently,

“The Little-old-gentleman-who-really-is-(as-his-looking-glass-has-too-often-told-him)-like-a-monkey.”

To Clara this letter, when Mrs. Platts read it to her, seemed like something in a dream, but when the box was unpacked it was found to contain, truly enough, not only the identical doll which she had wanted, with cheeks like tulips and real black hair, but also frocks for it, and night-dresses and petticoats, and a card of tortoiseshell toilet requisites, and three hats, and a diabolo set, and a tiny doll’s parasol for Kensington Gardens on sunny days.

Poor Clara didn’t know what to do, and so she simply sat down with the doll[85] in her arms and cried again; but this was a totally different kind of crying from that which had gone before. And when Kate Woodley came to take her to bed she cried too.

And the funny thing is that, though the little old gentleman’s present looks much more like a reward for being naughty than a punishment, Clara has hardly ever since said a quick unkind thing that she could be sorry for, and Miss Hobbs’s three questions are never wanted at all, and Kate Woodley has entirely given up clicking.

[86]

THE NOTICE-BOARD

[88]

Once upon a time there was a family called Morgan—Mr. Morgan the father, Mrs. Morgan the mother, Christopher Morgan, aged twelve, Claire Morgan, aged nine, Betty Morgan, aged seven, a fox-terrier, a cat, a bullfinch, a nurse, a cook, a parlourmaid, a housemaid, and a boy named William. William hardly counts, because he came only for a few hours every day, and then lived almost wholly in the basement, and when he did appear above-stairs it was always in the company of a coal-scuttle. That was the family; and at the time this story begins it had just removed from Bloomsbury to Bayswater.

While the actual moving was going on[90] Christopher Morgan, Claire Morgan, and Betty Morgan, with the dog and the bullfinch, had gone to Sandgate to stay with their grandmother, who, with extraordinary good sense, lived in a house with a garden that ran actually to the beach, so that, although in stormy weather the lawn was covered with pebbles, in fine summer weather you could run from your bedroom into the sea in nothing but a bath-towel or a dressing-gown, or one of those bath-towels which are dressing-gowns. Christopher used to do this, and Claire would have joined him but that the doctor forbade it on account of what he called her defective circulation—two long words which mean cold feet.

When, however, the moving was all done and the new house quite ready, the three children and the dog and the bullfinch returned to London, and getting by great good luck a taxicab at Charing Cross, were whirled to No. 23, Westerham[91] Gardens almost in a minute, at a cost of two-and-eightpence, with fourpence supplement for the luggage. Christopher sat on the front seat, watching the meter all the time, and calling out whenever it had swallowed another twopence. The first eightpence, as you have probably also noticed, goes slowly, but after that the twopences disappear just like sweets.

It is, as you know, a very exciting thing to move to a new house. Everything seems so much better than in the last, especially the cupboards and the wall-papers. In place of the old bell-pulls you find electric bells, and there is a speaking-tube between the dining-room and the kitchen, and the coal-cellar is much larger, and the bath-room has a better arrangement of taps, and you can get hot water on the stairs. But, of course, the electric light is the most exciting thing of all, and it was so at Westerham Gardens, because in Bloomsbury there had been gas.[92] But Mr. Morgan was exceedingly serious about it, and delivered a lecture on the importance—the vital importance—of always turning off the switch as you leave the room, unless, of course, there is some one in it.

Christopher and Claire and Betty were riotously happy in their new home for some few days, especially as they were so near Kensington Gardens, only a very little way, in fact, from the gate where the Dogs’ Cemetery is.

And then suddenly they began to miss something. What it was they had no idea; but they knew that in some mysterious way, nice as the new house was, in one respect it was not so nice as the old one. Something was lacking.

It was quite by chance that they discovered what it was; for, being sent one morning to Whiteley’s, on their return they entered Westerham Gardens by a new way, and there on a board fixed to[93] the railings of the corner house they read the terrible words:

ORGANS AND STREET CRIES

PROHIBITED.

Then they all knew in an instant what it was that had vaguely been troubling them in their new house. It was a house without music—a house that stood in a neighbourhood where there were no bands, no organs, and no costermongers.

“What a horrid shame!” said Claire. And then they began to talk about the organs and bands that used to come to their old home in Bloomsbury.

“Do you remember the Italian woman in the yellow handkerchief on Thursday mornings during French?” said Christopher.

“Yes,” said Betty, “and the monkey boy with the accordion on Mondays.”

[94]“And the Punch and Judy on Wednesday afternoons,” said Claire.

“And ‘Fresh wallflowers,’ ‘Nice wallflowers!’ at eleven o’clock every day in spring,” said Christopher.

“And the band that always played ‘Poppies’ on Tuesday evenings at bedtime,” said Claire.

“And the organ with the panorama on Friday mornings,” said Betty.

“And the best organ of all, that had one new tune every week, on Saturdays,” said Christopher.

“It must be a great day for the organists when they have a new tune,” said Claire.

“Yes,” said Betty; “but you have forgotten the funniest of all—the old man with a wooden leg on Tuesday and Friday.”

“But he had only one tune,” said Christopher

“It was a very nice tune,” said Betty. “But[95] why I liked him was because he always nodded and smiled at me.”

“That was only his trick,” said Christopher. “They all do that if they think you have a penny.”

“I don’t care,” said Betty stoutly; “he did it as if he meant it.”

That night, just after Claire had undressed, Christopher came in and sat on her bed. “I’ve got an idea,” he said. “Let’s have a new notice-board painted with

ORGANS AND STREET CRIES

INVITED

on it, and have it fixed on our railings. Then we shall get some music again. I reckon that Mr. Randall’s son would make it just like the other for about four shillings, and that’s what we’ve got.”

Mr. Randall’s son was the family carpenter, and he was called that because his[96] father had been the family carpenter before him for many years. When his father, Mr. Randall, was alive, the son had no name, but was always referred to as Mr. Randall’s son, and now that the old man was dead he was still spoken of in that way, although he was a man of fifty and had sons of his own. (But what they would be called it makes my head ache to think.)

Mr. Randall’s son smiled when he was asked if he could and would make a notice-board. “I will, Master Christopher,” he said; “but I’m thinking you had better spend your money on something else. A nice boat, now, for the Round Pond. Or a pair of stilts—I could make you a pair of stilts in about an hour.” Poor Christopher looked wistful, and then bravely said that he would rather have the notice-board. After giving careful instructions as to the style of painting the words, he impressed upon Mr. Randall’s son the importance[97] of wrapping the board very carefully in paper when he brought it back, because it was a surprise.

“A surprise!” said Mr. Randall’s son with a great hearty laugh; “I should think it will be a surprise to some of ’em. I’d like to be there to see the copper’s face when he reads it.”

Mr. Randall’s son was not there to see the copper’s face; but the copper—by which Mr. Randall’s son meant the policeman—did read it in the company of about forty other persons, chiefly errand-boys and cabmen, in front of the Morgans’ house on the morning after Christopher had skilfully fixed it to the area railings; and having read it he walked off quickly to the nearest police-station to take advice.

The result was that just as Mr. Morgan was leaving for the city the policeman knocked at the door and asked to see him.

Mr. Morgan soon afterwards came from the study and showed the policeman[98] out, and then he sent for Christopher. After Christopher had confessed, “My dear boy,” he said, “this won’t do at all. That notice-board at the end of this street means either that the owners of Westerham Gardens or a large number of the tenants wish the neighbourhood to be free from street music. If we, who are new-comers, set up notice-boards to a contrary effect, we are doing a very rude and improper thing. I quite understand that you miss the organs that we used to have, but the only way to get them back would be to obtain the permission of every one in the Gardens; and that, of course, is absurd.” With these words, which he afterwards wished he had never used, Mr. Morgan hurried off to the nearest Tube to make money in the city, which was how he spent his days.

Christopher carried the news to Claire, who at once said, “Then we must go to every house to get leave.”

[99]“Of course,” said Christopher. “How ripping!”

And they started immediately.

It would take too long to tell you how they got on at each house. From some they were sent away; at others they met with sympathy.

Their words to the servant who opened the door were: “Please give your mistress the compliments of No. 23, and ask if she really wants street music to be prohibited.”

“Of course we don’t, my dears,” said an old lady at No. 14. “We should love to have a nice pianoforte organ every now and then, or even a band; but it would never do to say so. Every one is so select about here. Why, in that house opposite lives the widow of a Lord Mayor.”

Claire made a note of the number to tell Betty, who loved rank and grandeur, and then they ascended the next steps, where they found the most useful person of all, a gentleman who came down to see[100] them, smoking a pipe and wearing carpet slippers. “In reply to your question,” he said, “I should welcome street music; but the matter has nothing to do either with me or with you. It is all settled by the old lady at the corner, the house to which the notice-board is fixed. It is she who owns the property, and it is she who stops the organs. If you want to do any good you must see her. Her name is Miss Seaton, and as you will want a little cake and lemonade to give you strength for the interview, you had better come in here for a moment.” So saying he led them into the dining-room, which was hung with coloured pictures of hunting and racing, and made them very comfortable, and then sent them on with best wishes for good luck.

Telling Claire to wait a moment, Christopher ran off to their own house for the board, and returned quickly with it wrapped up under his arm. He rang the[101] bell of the corner house boldly, and then, seeing a notice which ran, “Do not knock unless an answer is required,” knocked boldly, too. It was opened by an elderly butler. “Please tell Miss Seaton that Mr. and Miss Morgan from No. 23 would like to see her,” said Christopher.

“On what business?” asked the butler.

“On important business to Westerham Gardens,” said Christopher.

“Wait here a moment,” said the butler, and creaked slowly upstairs. “Here” was the hall, and they sat on a polished mahogany form, with a little wooden roller at each end, exactly opposite a stuffed dancing bear with his arms hungry for umbrellas. Upstairs they heard a door open and a muttered conversation, and then the door shut and the butler creaked slowly down again.

“Will you come this way?” he said, and creaked slowly up once more, followed by the children, who had great difficulty in[102] finding the steps at that pace, and showed them into a room in which was sitting an old lady in a high-backed arm-chair near the fire. On the hearthrug were five cats, and there was one in her lap and one on the table. “Oh!” thought Claire, “if only Betty was here!” For Betty not only loved rank and grandeur but adored cats.

“Well,” said the old lady, “what is it?”

“If you please,” said Christopher, “we have come about the notice-board outside, which says, ‘Organs and street cries prohibited.’”

“Yes,” Claire broke in; “you see, we have just moved to No. 23, and at our old home—in Bloomsbury, you know—there was such a lot of music, and a Punch and Judy, and there’s none here, and we wondered if it really meant it.”

[103]

“WE HAD IT MADE ON PURPOSE.”

“Because,” Christopher went on, “it seemed to us that this notice-board”—and here he unwrapped the new one—“could just as easily be put up as the one you have. We had it made on purpose.” And he held it up before Miss Seaton’s astonished eyes.

“‘Organs and street cries invited!’” she exclaimed. “Why, I never heard such a thing in my life. They drive me frantic.”

“Couldn’t you put cotton-wool in your ears?” Claire asked.

“Or ask them to move a little further on—nearer No. 23?” said Christopher.

“But, my dear children,” said the old lady, “you really are very wilful. I hope your father and mother don’t know what you are doing.”

“No,” said Christopher.

“Well, sit down, both of you,” said Miss Seaton, “and let us talk it over.” So they sat down, and Claire took up one of the cats and stroked it behind the ears, and Miss Seaton asked them a number of questions.

[104]After a while she rang the bell for the butler, who creaked in and out and then in again with cake and a rather good syrup to mix with water; and they gradually became quite friendly, not only with Miss Seaton, but with each of the cats in turn.

“Are there any more?” Claire asked.

“No, only seven,” said Miss Seaton. “I never have more and I never have fewer.”

“Do you give them all names?” said Claire.

“Of course,” said Miss Seaton. “That is partly why there are only seven. I name them after the days of the week.”

“Oh!” thought Claire again, “if only Betty were here!”

“The black one there, with the white front, is Sunday,” Miss Seaton continued. “That all black one is Monday—black Monday, you know. The tortoiseshell is Friday. The sandy one is Saturday.”

[105]“It was on Saturday,” said Christopher, “that the best organ of all used to come, the one with a new tune every week.”

“The blue Persian is Wednesday,” said Miss Seaton, not taking any notice of his remark. “The white Persian is Tuesday, and the grey Iceland cat is Thursday. And now,” she added, “you must go home, and I will think over your request and let you have the answer.”

That evening, just after the children had finished their supper, a ring came at the door, followed, after it was opened, by scuffling feet and a mysterious thud. Then the front door banged, and Annie the maid came in to say that there was a heavy box in the hall, addressed to Master and Miss Morgan. The children tore out, and found a large case with, just as Annie had said, Christopher and Claire’s name upon it. Christopher rushed off for a hammer and screw-driver, and in a few[106] minutes the case was opened. Inside was a note and a very weighty square thing in brown paper. Christopher began to undo the paper, while Claire read the note aloud:

“1, Westerham Gardens, W.

“Dear Miss and Master Morgan,