Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the chapter.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

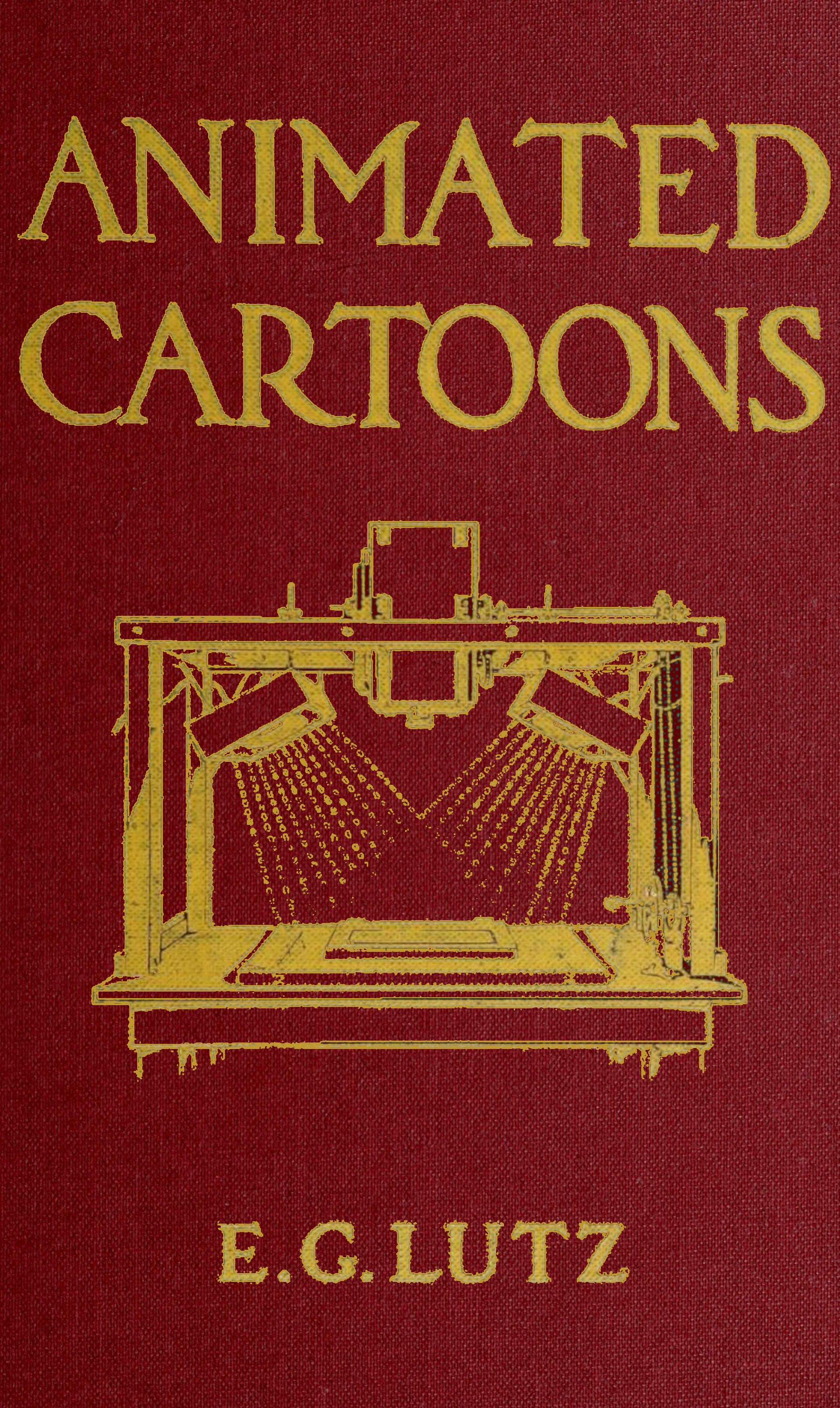

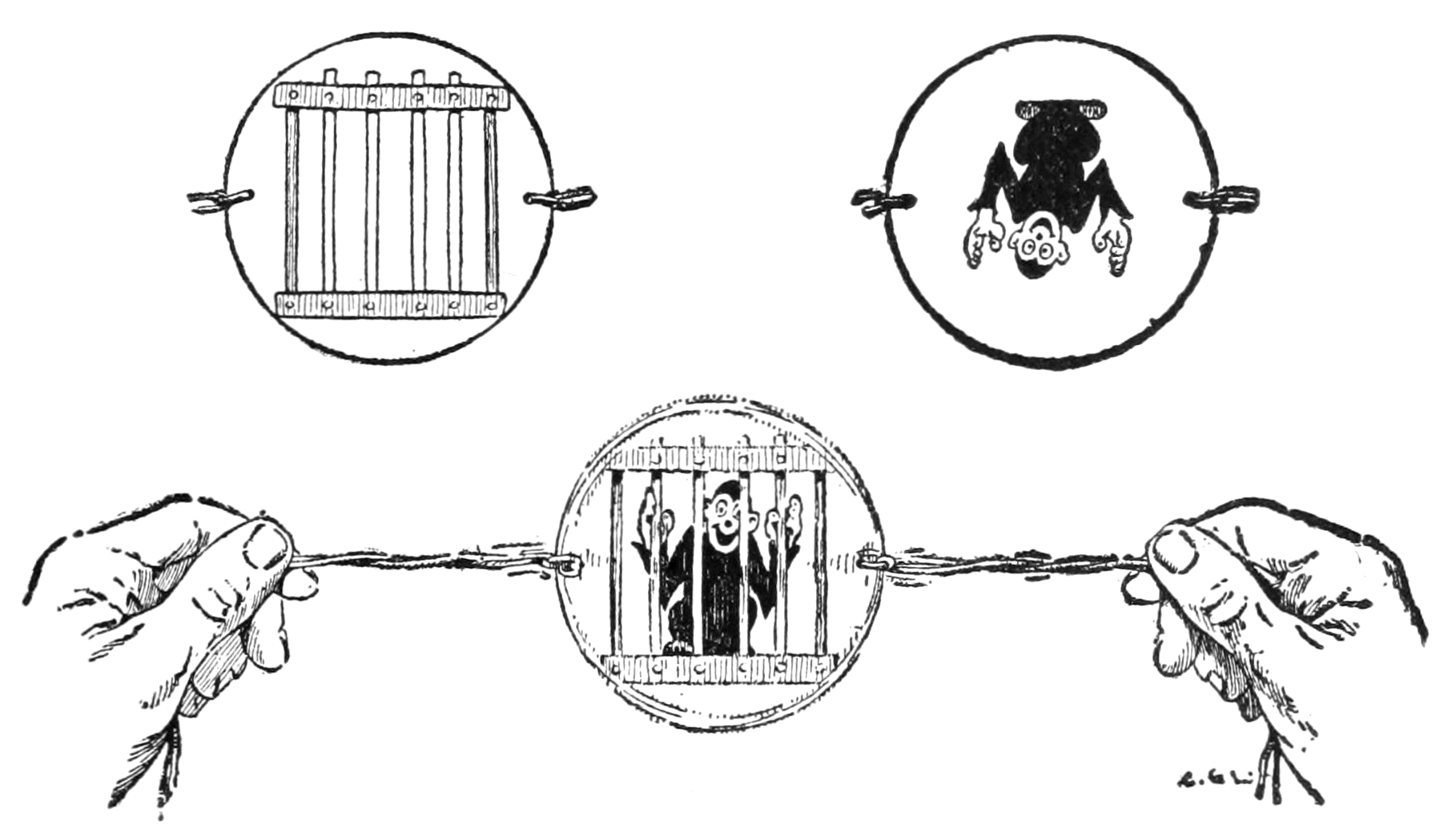

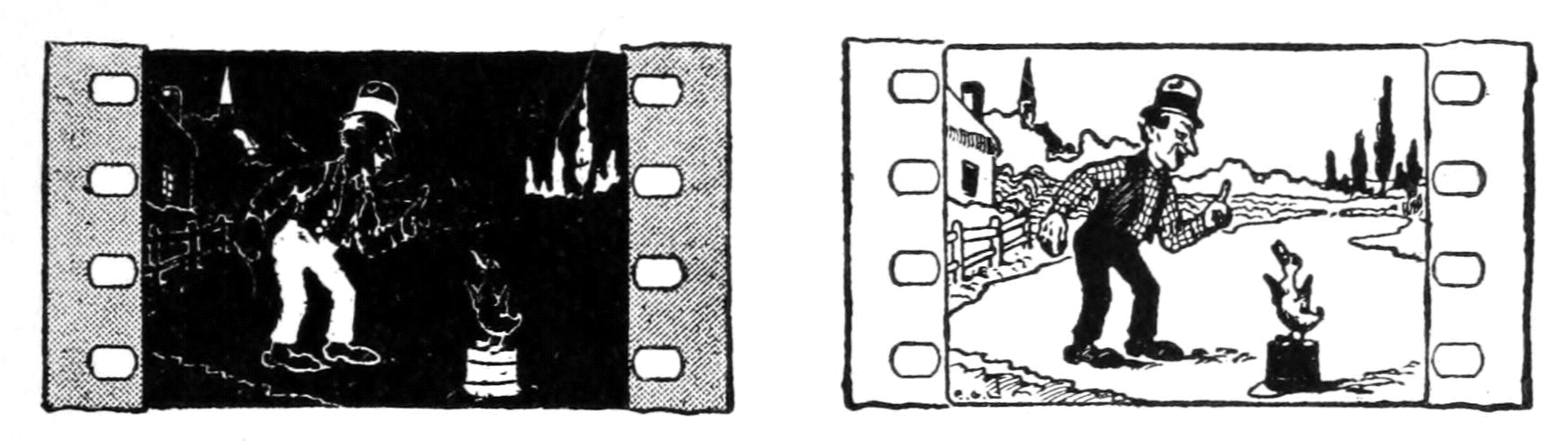

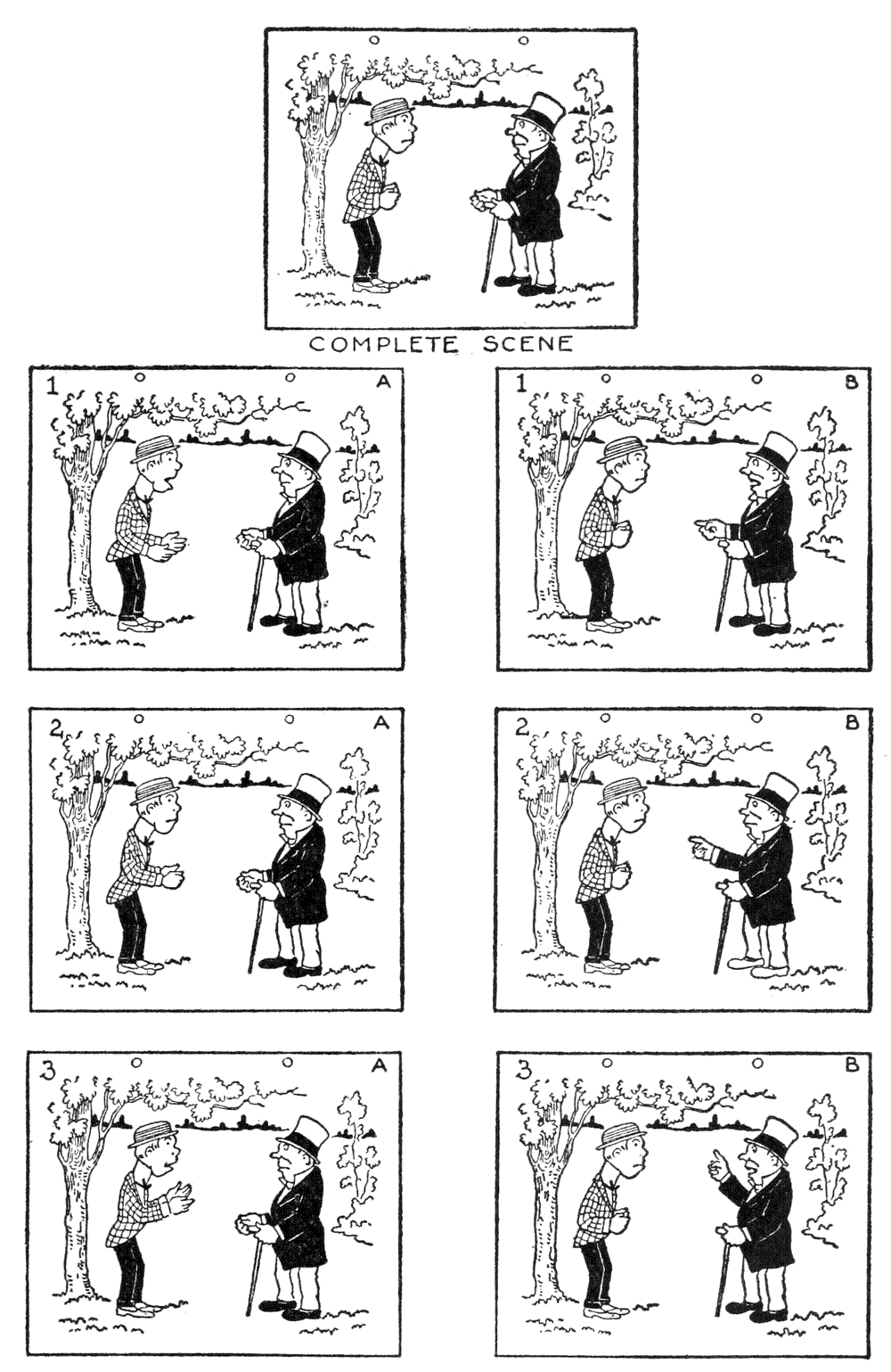

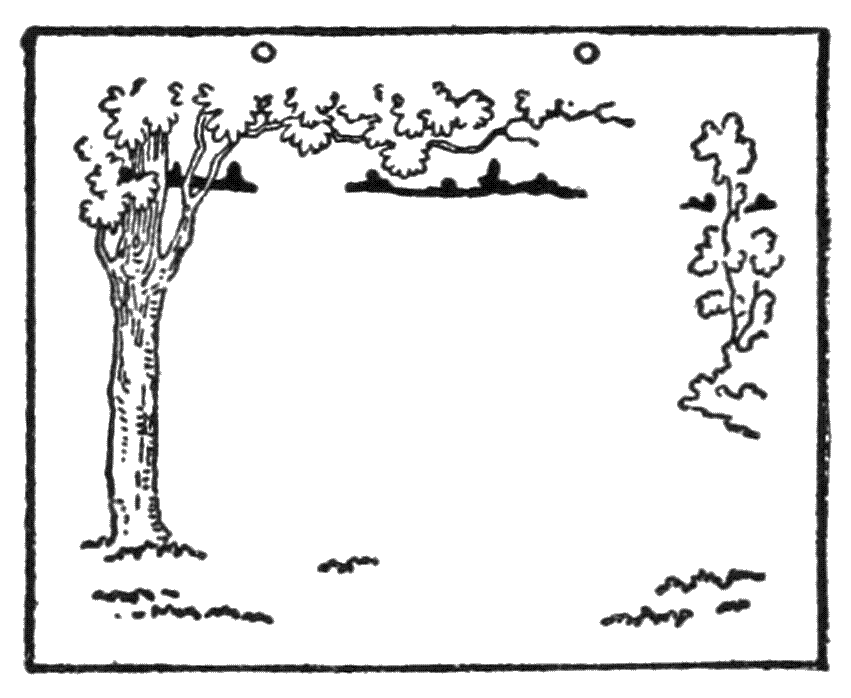

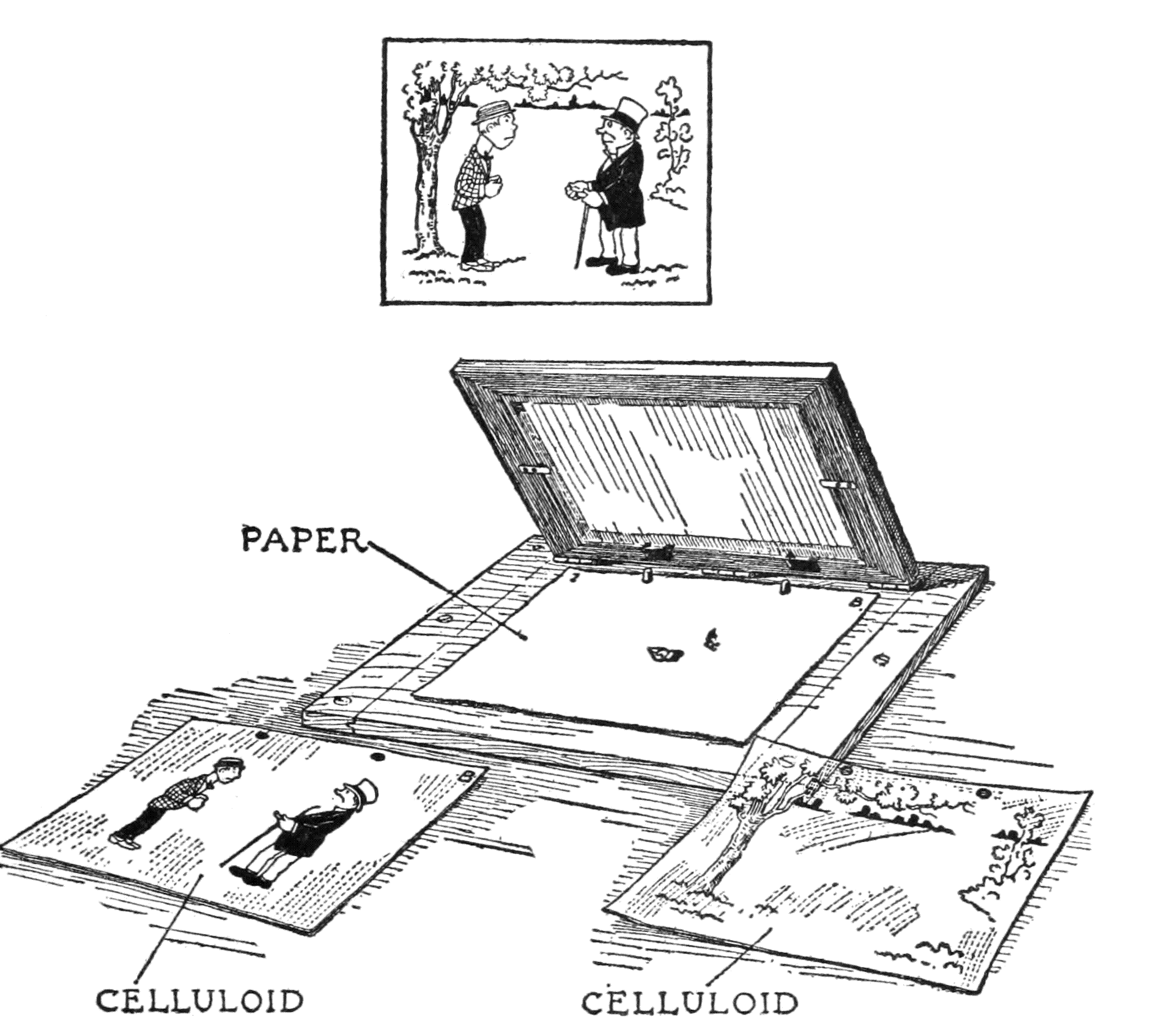

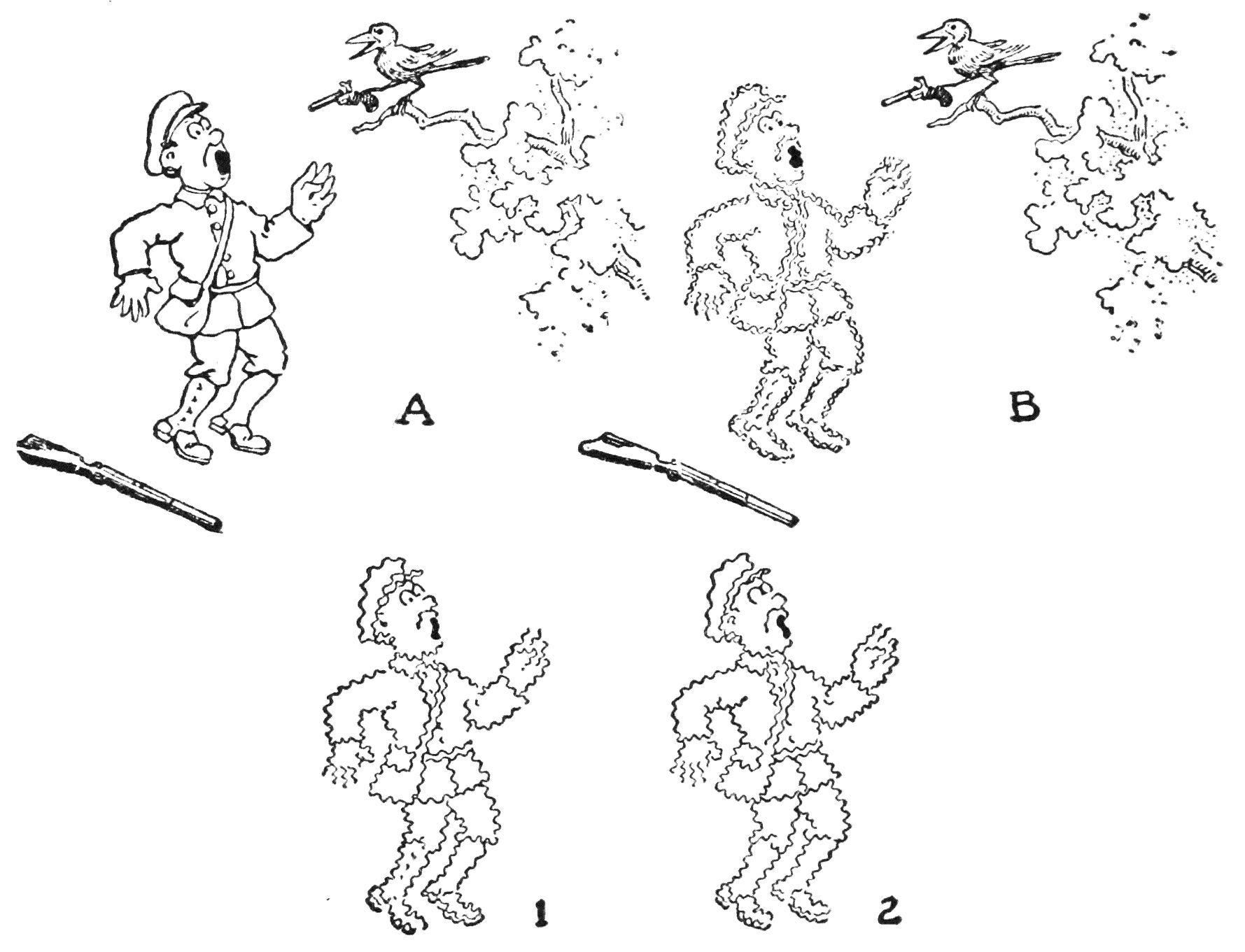

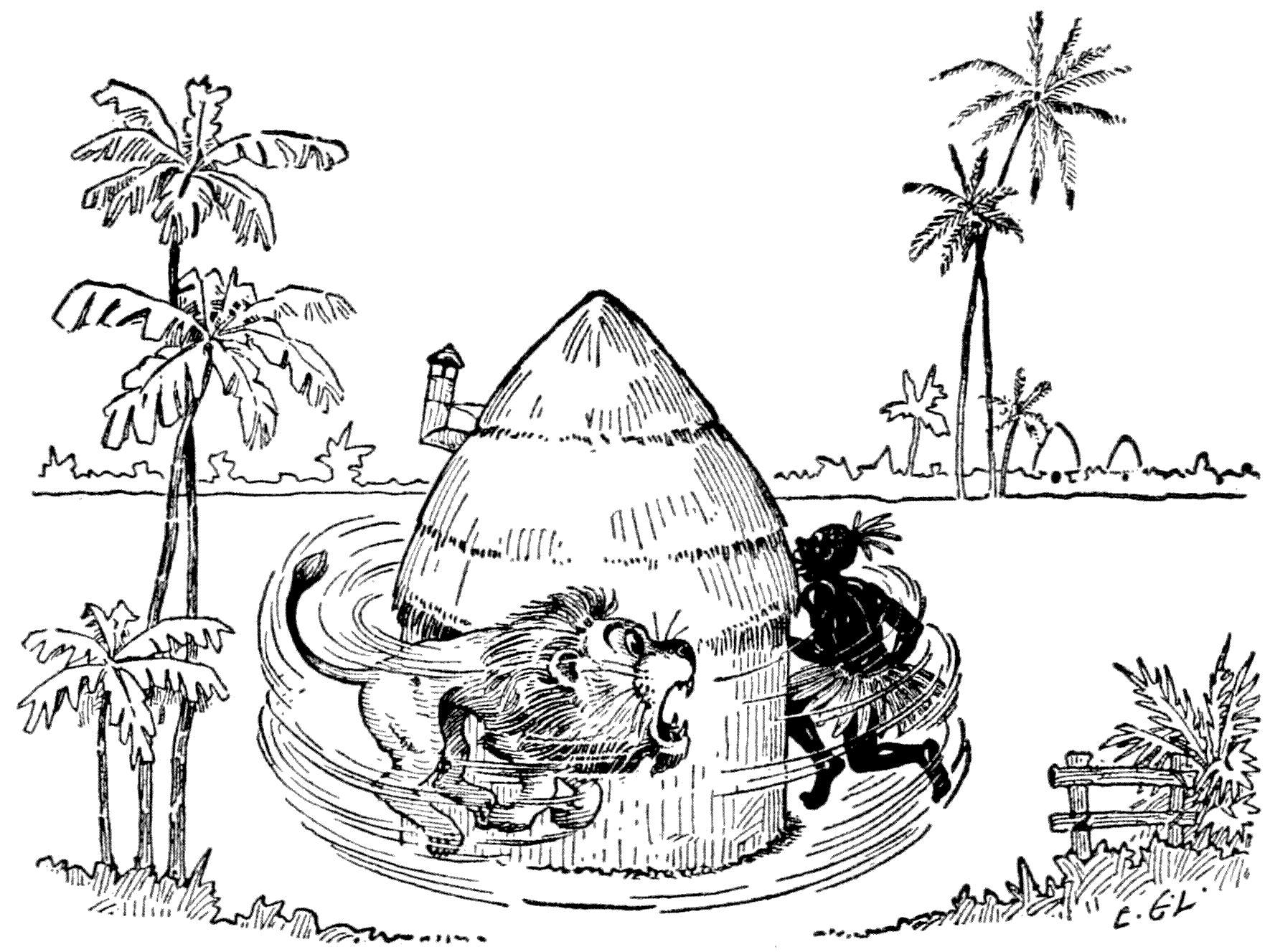

Above: Background scene and the separate items.

Below: Completed scene showing one phase of the performance of the little cardboard actors and stage property.

[See page 90]

ANIMATED CARTOONS

HOW THEY ARE MADE

THEIR ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT

BY

E. G. LUTZ

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1920

Copyright, 1920, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Published February, 1920

[Pg v]

We learn through the functioning of our senses; sight the most precious shows us the appearance of the exterior world. Before the dawn of pictorial presentation, man was visually cognizant only of his immediate or present surroundings. On the development of realistic picturing it was possible, more or less truthfully, to become acquainted with the aspect of things not proximately perceivable. The cogency of the perceptive impression was dependent upon the graphic faithfulness of the agency—a pictorial work—that gave the visual representation of the distant thing.

It is by means of sight, too, that the mind since the beginning of alphabets has been made familiar with the thoughts and the wisdom of the past and put into relationship with the learning and reasoning of the present. These two methods of imparting knowledge—delineatory[vi] and by inscribed symbols—have been concurrent throughout the ages.

It was nearly a century ago that Joseph Nicéphore Niepce (1765-1833), at Châlons-sur-Saône, in France, invented photography. Since that time it has been possible to fix on a surface, by physicochemical means, pictures of the exterior world. It was another way of extending man’s horizon, but a way not dependent, in the matter of literalness, upon the variations of any individual’s skill or intent, but rather upon the accuracy of material means.

Thoughts and ideas once represented and preserved by picture-writing, recorded by symbolical signs, and at last inscribed by alphabetical marks were, in 1877, registered by mere tracings on a surface and again reproduced by Mr. Edison with his phonograph. As in the photograph, the procedure was purely mechanical, and man’s artificial inventions of linear markings and arbitrary symbols were totally disregarded.

Through photography we learn of the exterior nature of absent things and the character of the views in distant places. Or it preserves these[vii] pictorial matters in a material form for the future. The phonograph communicates to us the uttered thoughts of others or brings into our homes the melodies and songs of great artists that we should not otherwise have the opportunity to hear.

And now a new physicochemical marvel has come that apprehends, reproduces, and guards for the future another sensorial stimulus. It is the motion-picture and the stimulus is movement.

Photography and the rendering of sounds by the phonograph have both been adopted for instruction and amusement. The motion-picture also is used for these purposes, but in the main the art has been associated with our leisure hours as a means of diversion or entertainment. During the period of its growth, however, its adaptability to education has never been lost sight of. It is simply that development along this line has not been as seriously considered as it should be. Motion-pictures, it is true, that may be considered as educational are frequently shown in theatres and halls. Such, for instance, are views in strange lands, scenic wonders, and pictures showing the manufacture of some useful article or the manner[viii] of proceeding in some field of human activity. But these are effected entirely by photography and the narration of their making does not come within the scope of this book.

Our concern is the description of the processes of making “animated cartoons,” or moving screen drawings. Related matters, of course, including the inception and the development of motion-pictures in general, will be referred to in our work. At present, of the two divisions of our subject, the art of the animated comic cartoon has been most developed. It is for this reason that so much of the book is given to an account of their production.

But on the making of animated screen drawings for scientific and educational themes little has been said. This is not to be taken as a measure of their importance.

It is interesting to regard for a moment the vicissitudes of the word cartoon. Etymologically it is related to words in certain Latin tongues for paper, card, or pasteboard. Its best-accepted employment—of bygone times—was that of designating an artist’s working-size preliminary[ix] draft of a painting, a mural decoration, or a design for tapestry. Raphael’s cartoons in the South Kensington Museum, in London, are the best-known works of art coming under this meaning of the term. (They are, too, the usual instances given in dictionaries when this meaning is explained.) The most frequent use of the word up to recently, however, has been to specify a printed picture in which the composition bears upon some current event or political topic and in which notabilities of the day are generally caricatured. The word cartoon did not long particularize this kind of pictorial work but was soon applied to any humorous or satirical printed picture no matter whether the subject was on a topic of the day or not.

When some of the comic graphic artists began to turn their attention to the making of drawings for animated screen pictures, nothing seemed more natural than that the word “animated” should be prefixed to the term describing their products and so bringing into usage the expression “animated cartoons.” But the term did not long remain restricted to this application, as[x] it soon was called into service by the workers in the industry to describe any film made from drawings without regard to whether the subject was of a humorous or of an educational character. Its use in this sense is perhaps justified as it forms a convenient designation in the trade to distinguish between films made from drawings and those having as their basic elements actuality, that is, people, scenes, and objects.

Teachers now are talking of “visual instruction.” They mean by this phrase in the special sense that they have given to it the use of motion-picture films for instructional purposes. Travel pictures to be used in connection with teaching geography or micro-cinematographic films for classes in biology are good examples of such films. But not all educational subjects can be depicted by the camera solely. For many themes the artist must be called in to prepare a series of drawings made in a certain way and then photographed and completed to form a film of moving diagrams or drawings.

As it is readily understood that any school topic presented in animated pictures will stimulate[xi] and hold the attention, and that the properties of things when depicted in action are more quickly grasped visually than by description or through motionless diagrams, it is likely that visual instruction by films will soon play an important part in any course of studies. Then the motion-picture projector will become the pre-eminent school apparatus and such subjects as do not lend themselves to photography will very generally need to be drawn; thereupon the preponderance of the comic cartoon will cease and the animated screen drawing of serious and worth-while themes will prevail.

E. G. L.

| PAGE | ||

| I. | The Beginning of Animated Drawings |

3 |

| II. | The Genesis of Motion-Pictures |

35 |

| III. | Making Animated Cartoons |

57 |

| IV. | Further Details on Making Animated Cartoons |

83 |

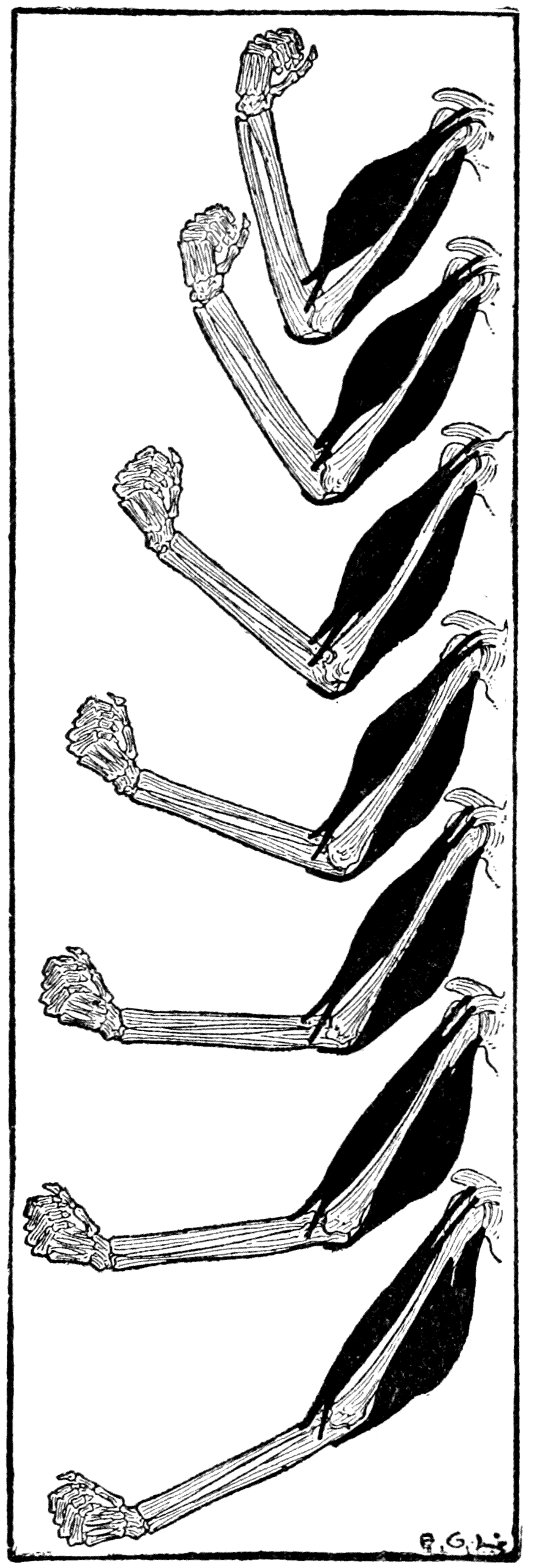

| V. | On Movement in the Human Figure |

99 |

| VI. | Notes on Animal Locomotion |

131 |

| VII. | Inanimate Things in Movement |

153 |

| VIII. | Miscellaneous Matters in Making Animated Screen Pictures |

171 |

| IX. | Photography and Other Technical Matters |

201 |

| X. | On Humorous Effects and on Plots |

223 |

| XI. | Animated Educational Films and the Future |

245 |

| Illustrating the method of making animated cartoons by cut-outs | Frontispiece | |

| PAGE | ||

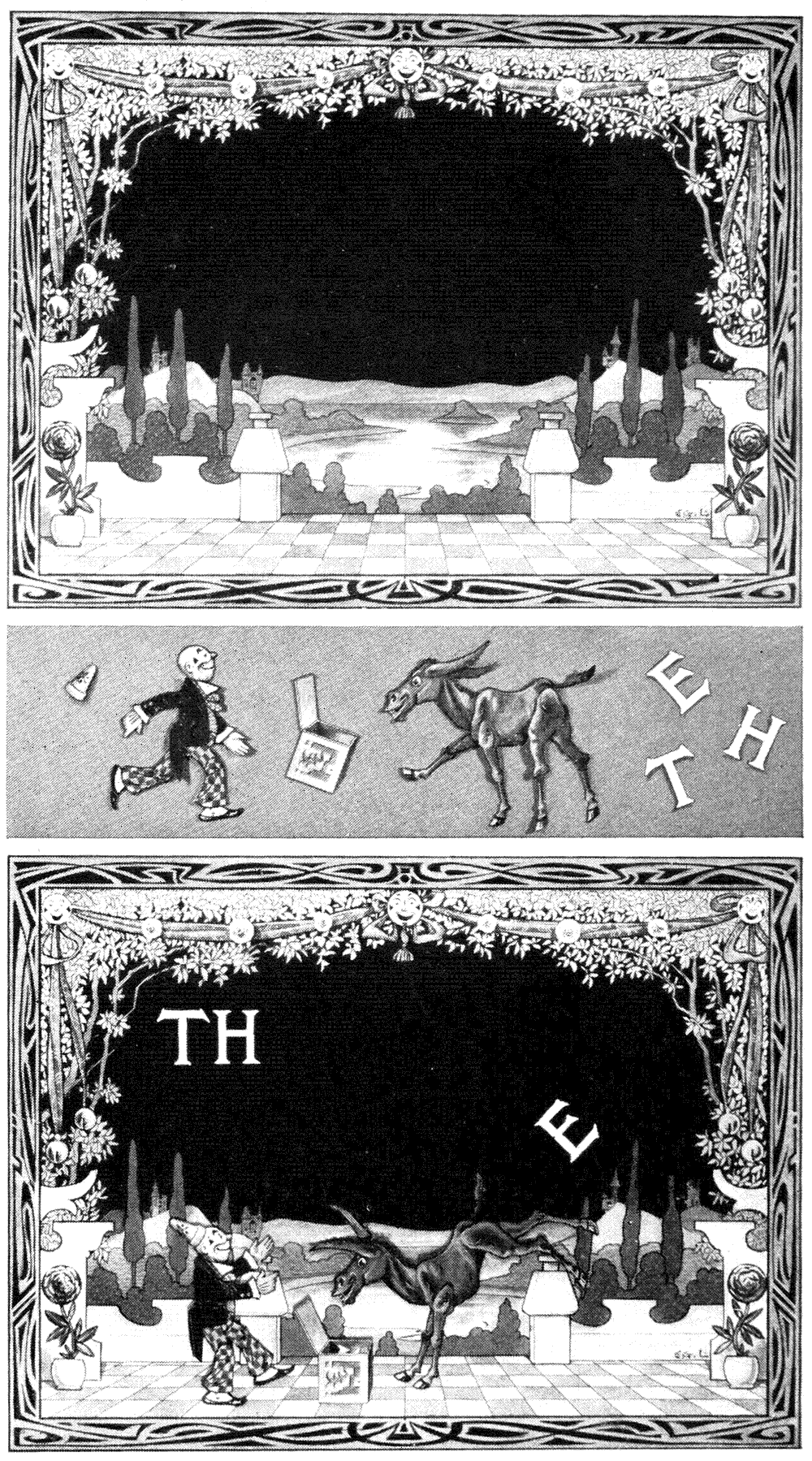

| Magic-lantern and motion-picture projector compared | 7 | |

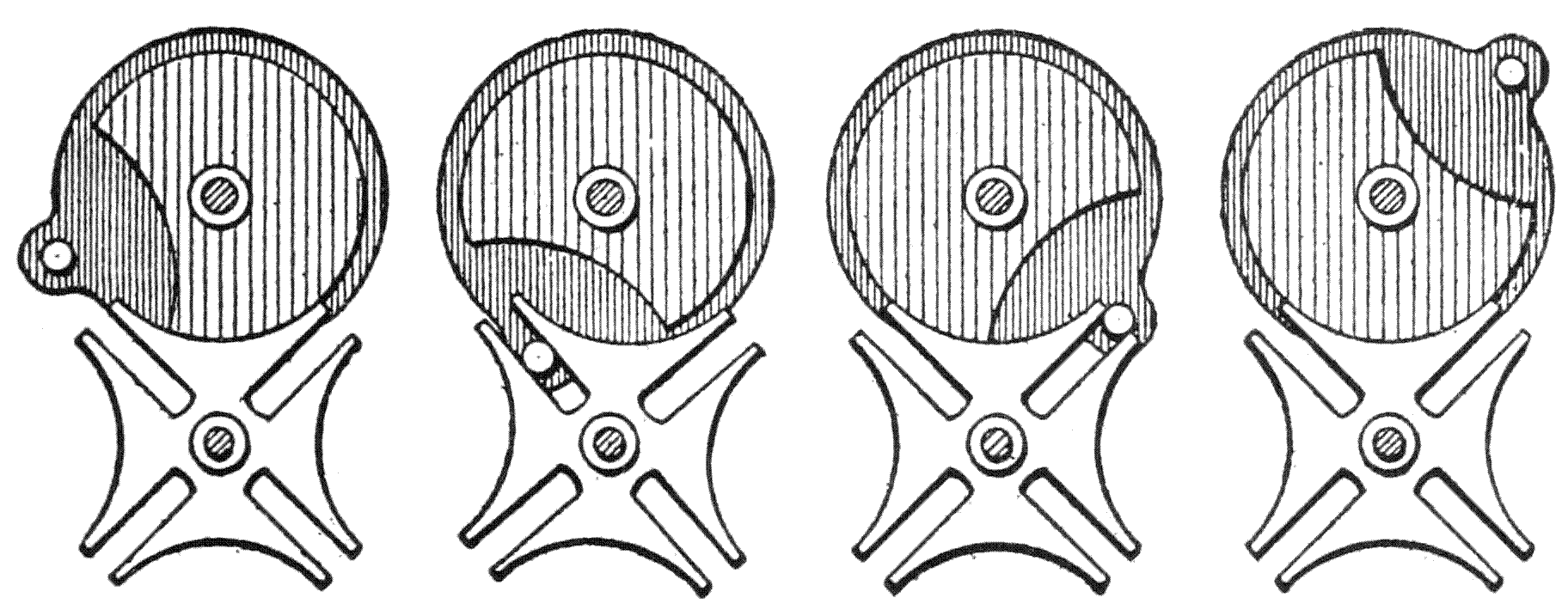

| Geneva movement | 9 | |

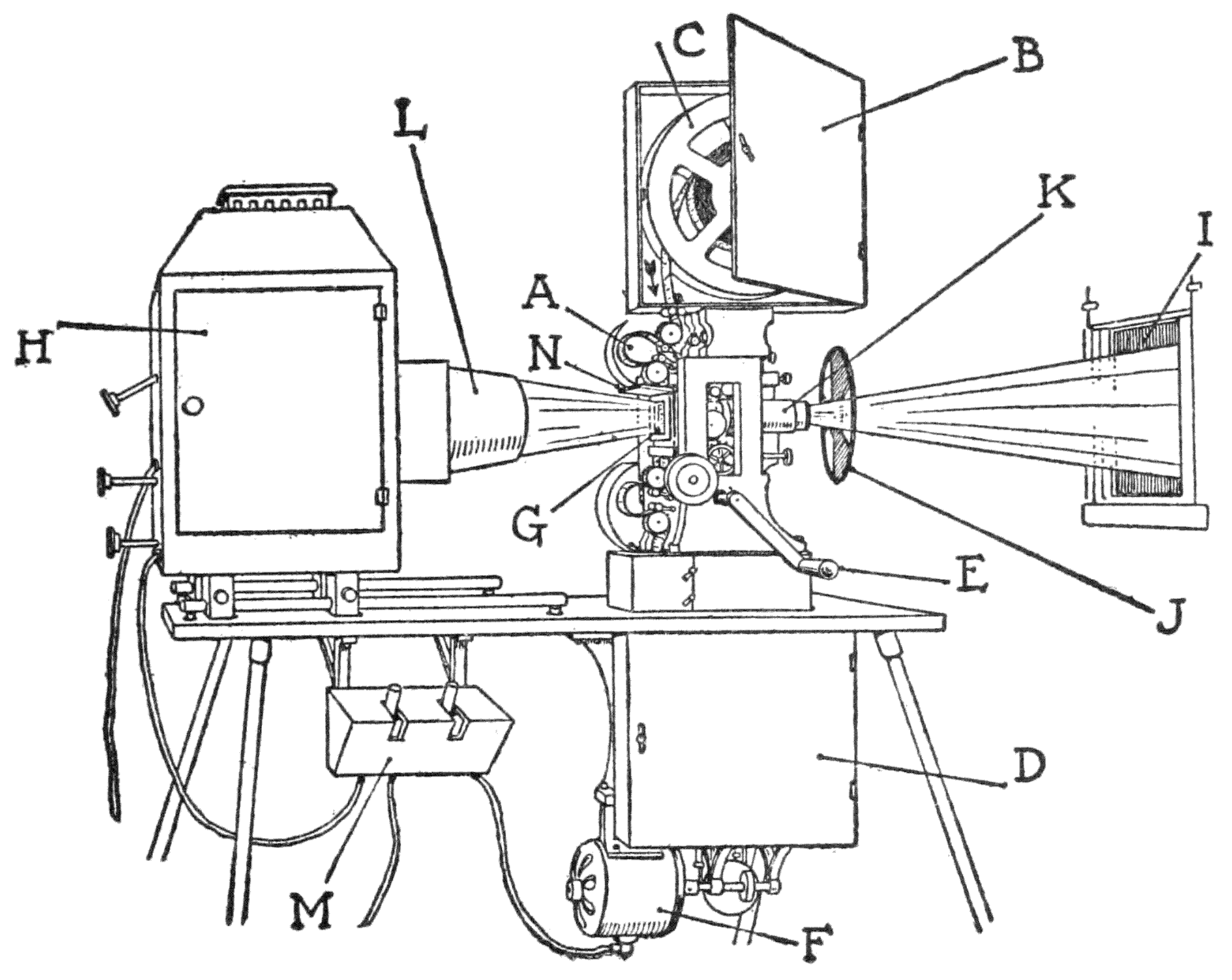

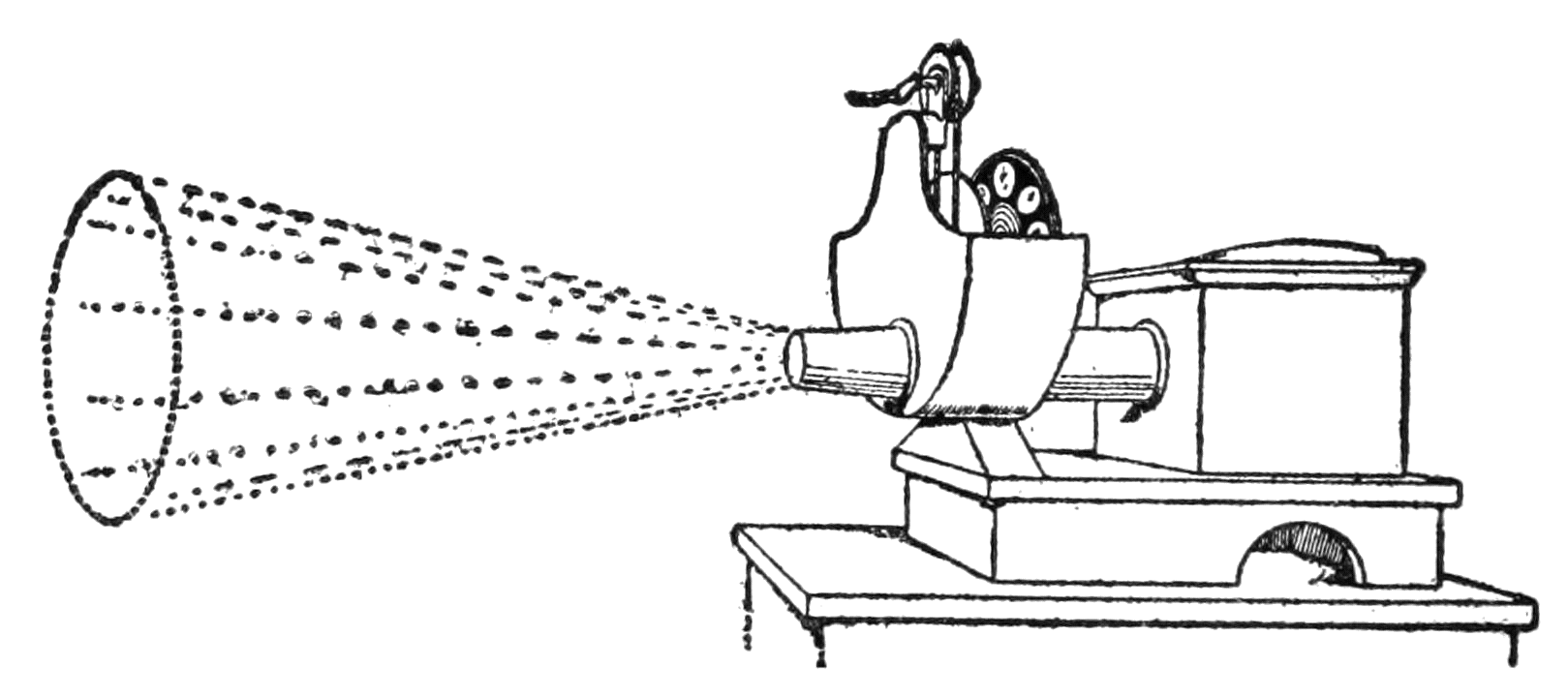

| A motion-picture projector | 11 | |

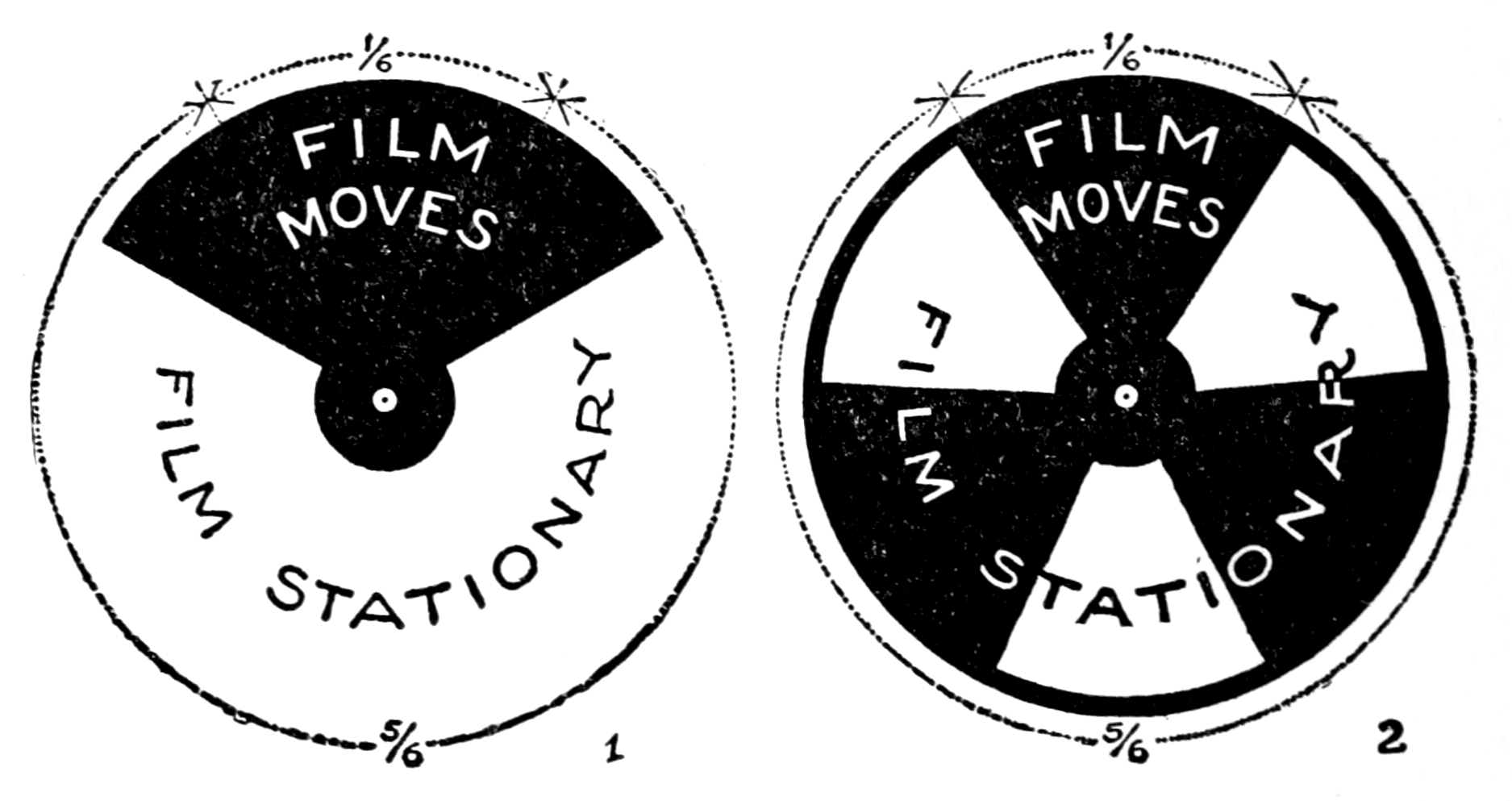

| Illustrating the proportions of light and dark periods during projection in two types of shutters | 12 | |

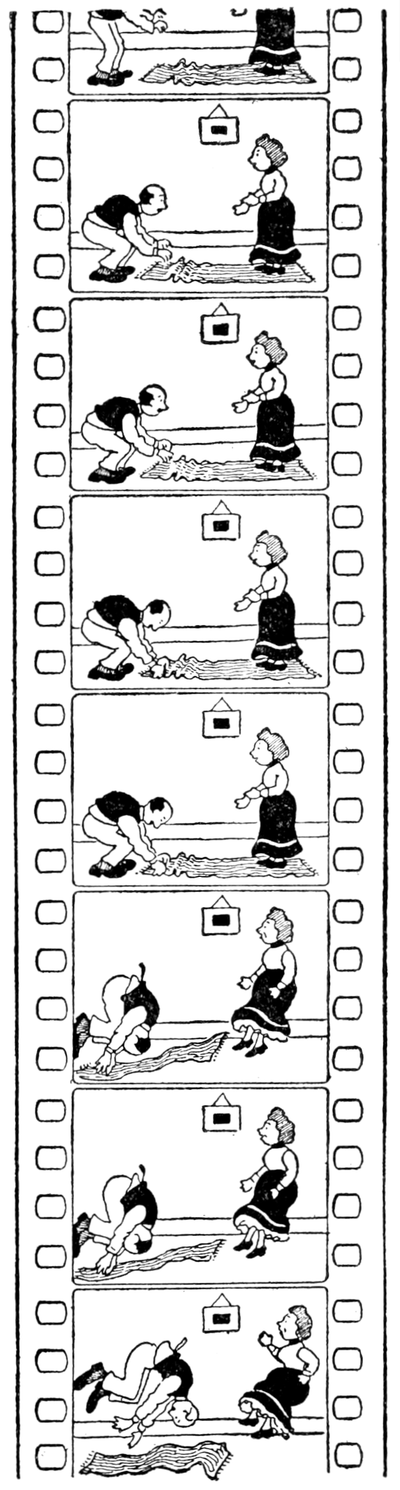

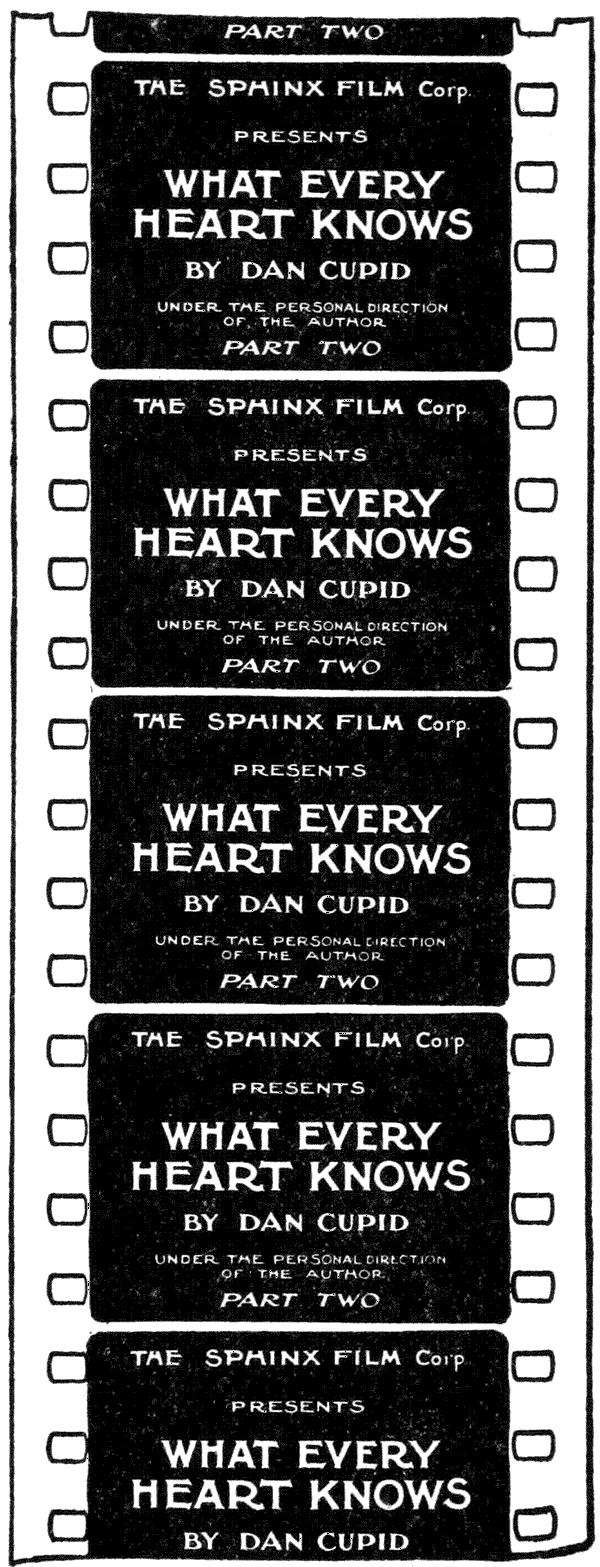

| Section of an animated cartoon film | 15 | |

| The thaumatrope | 17 | |

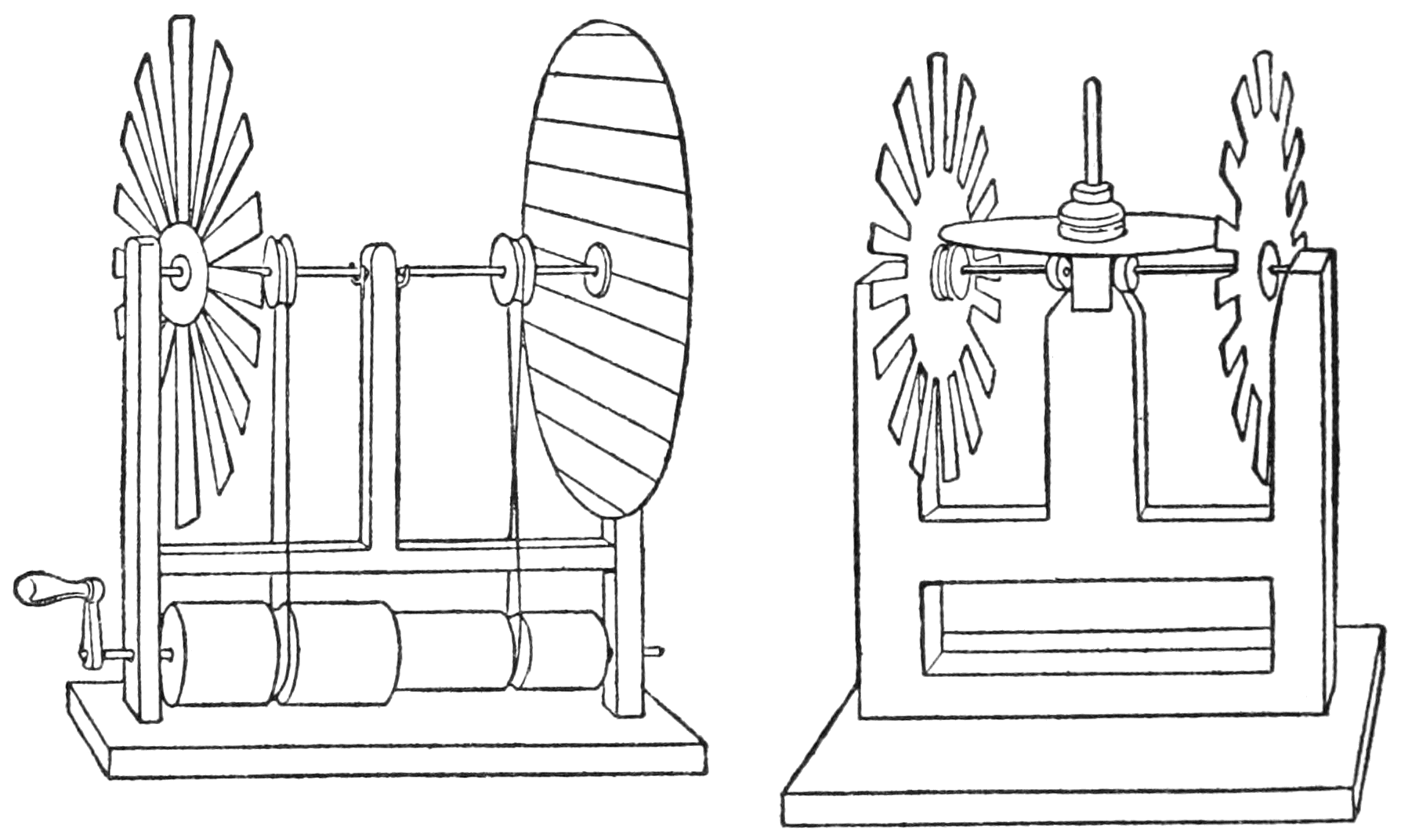

| Two instruments used in early investigations of optical phenomena | 18 | |

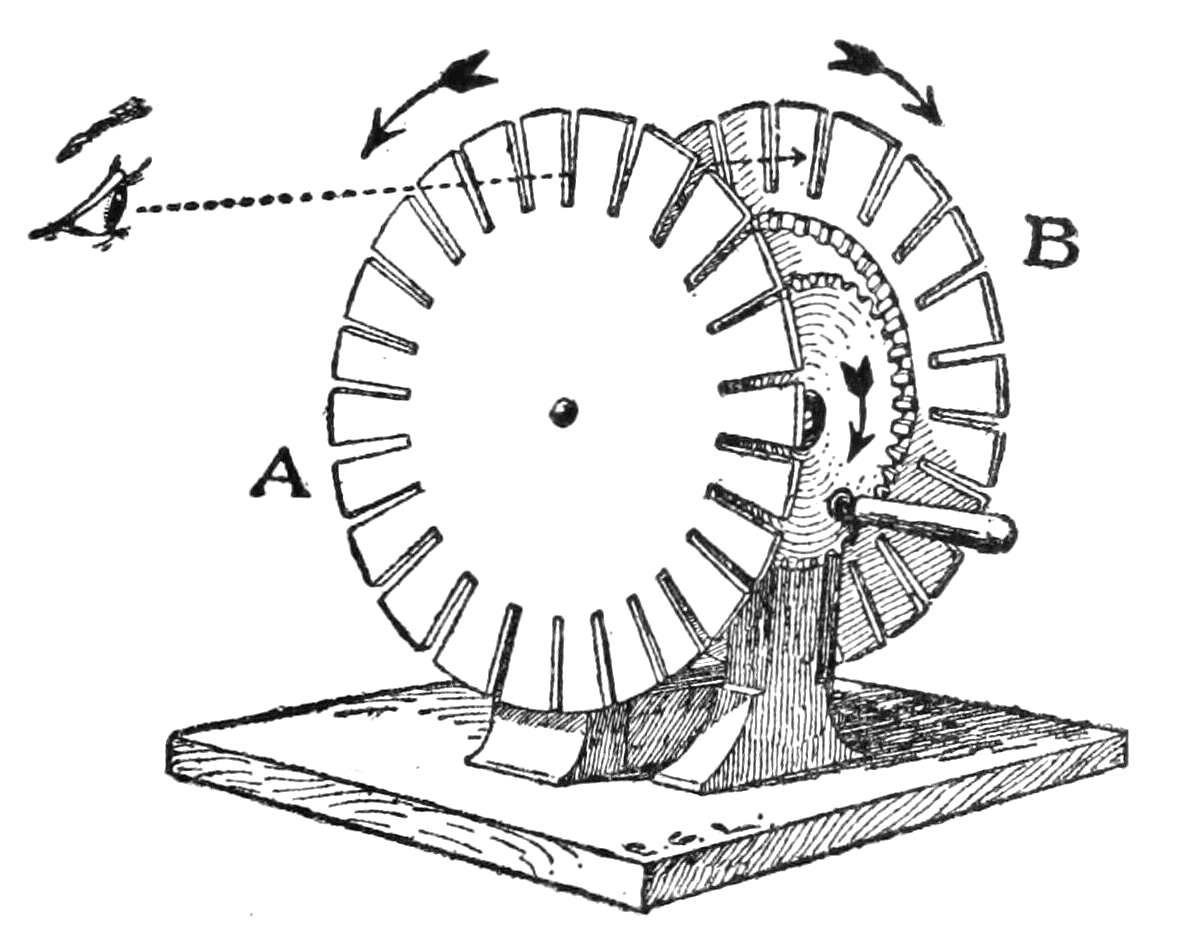

| Apparatus on the order of Faraday’s wheel | 19 | |

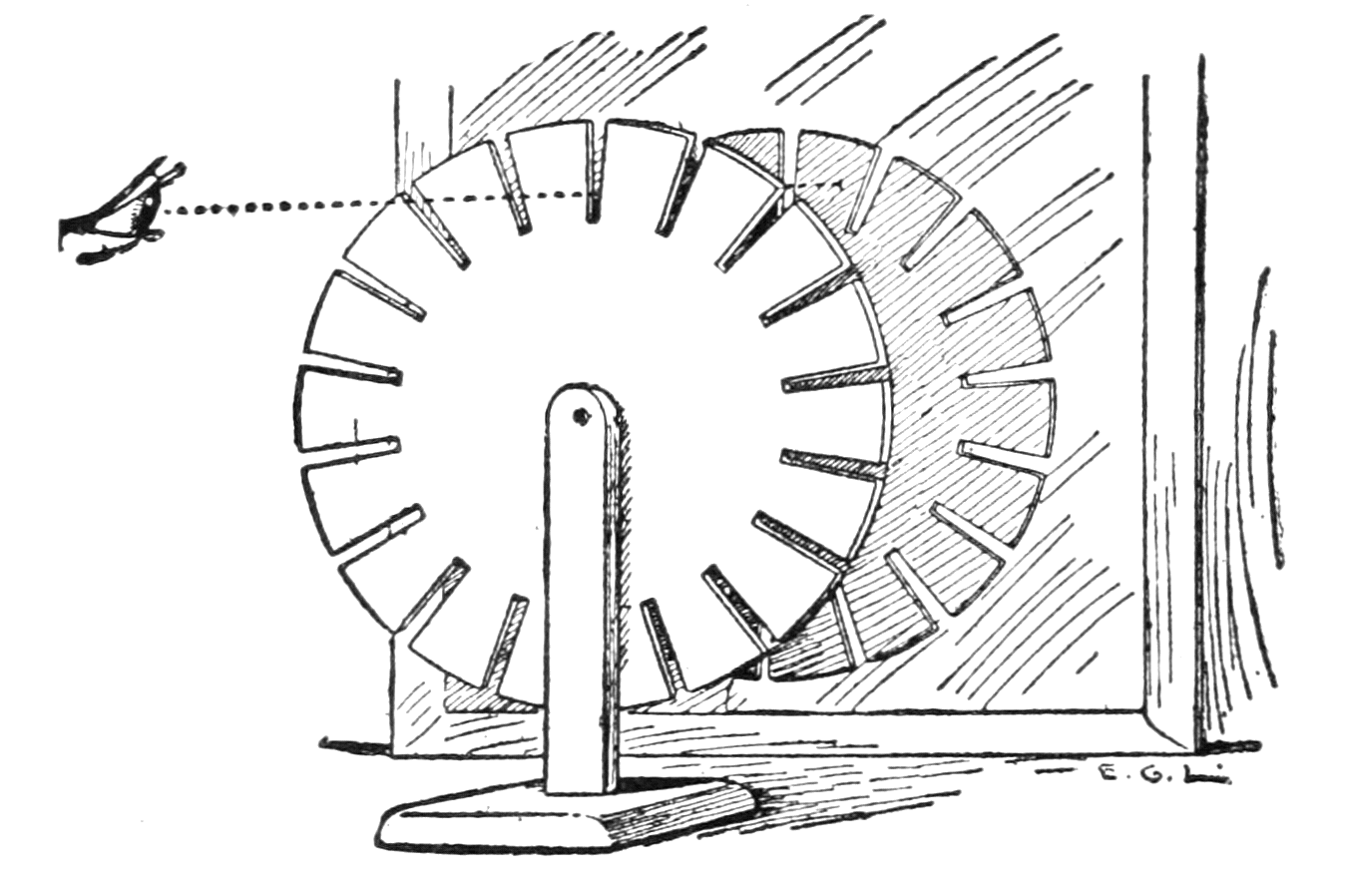

| An antecedent of the phenakistoscope | 20 | |

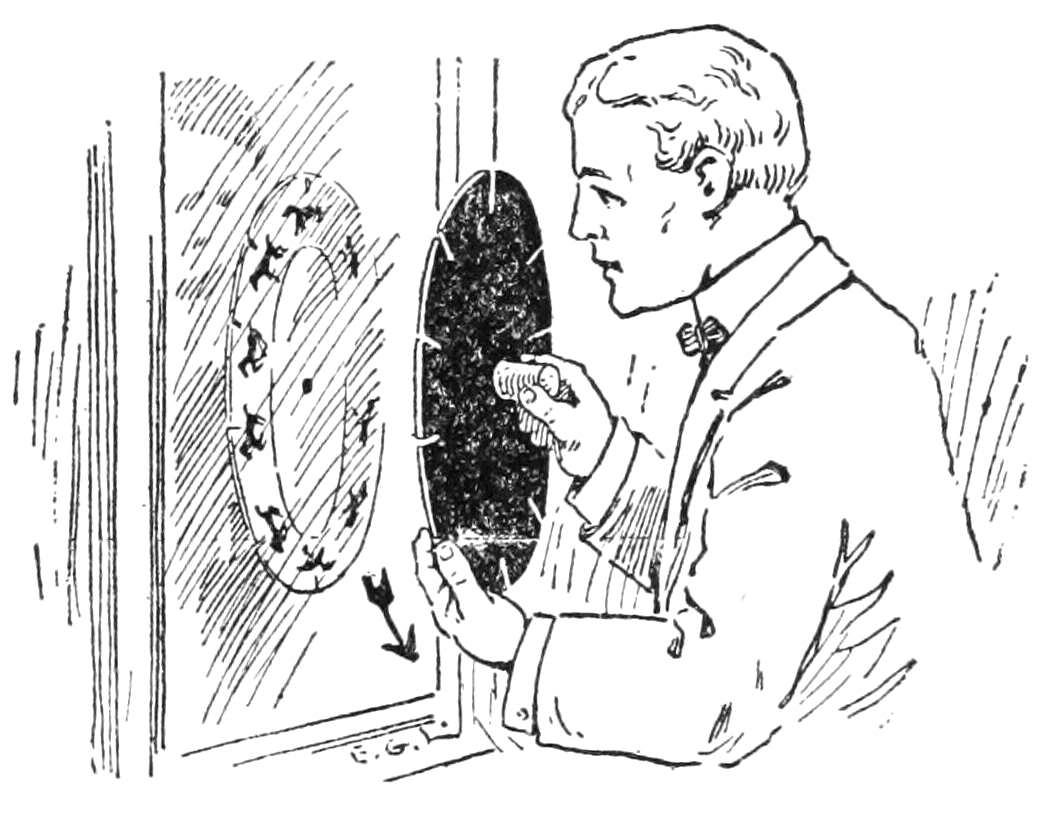

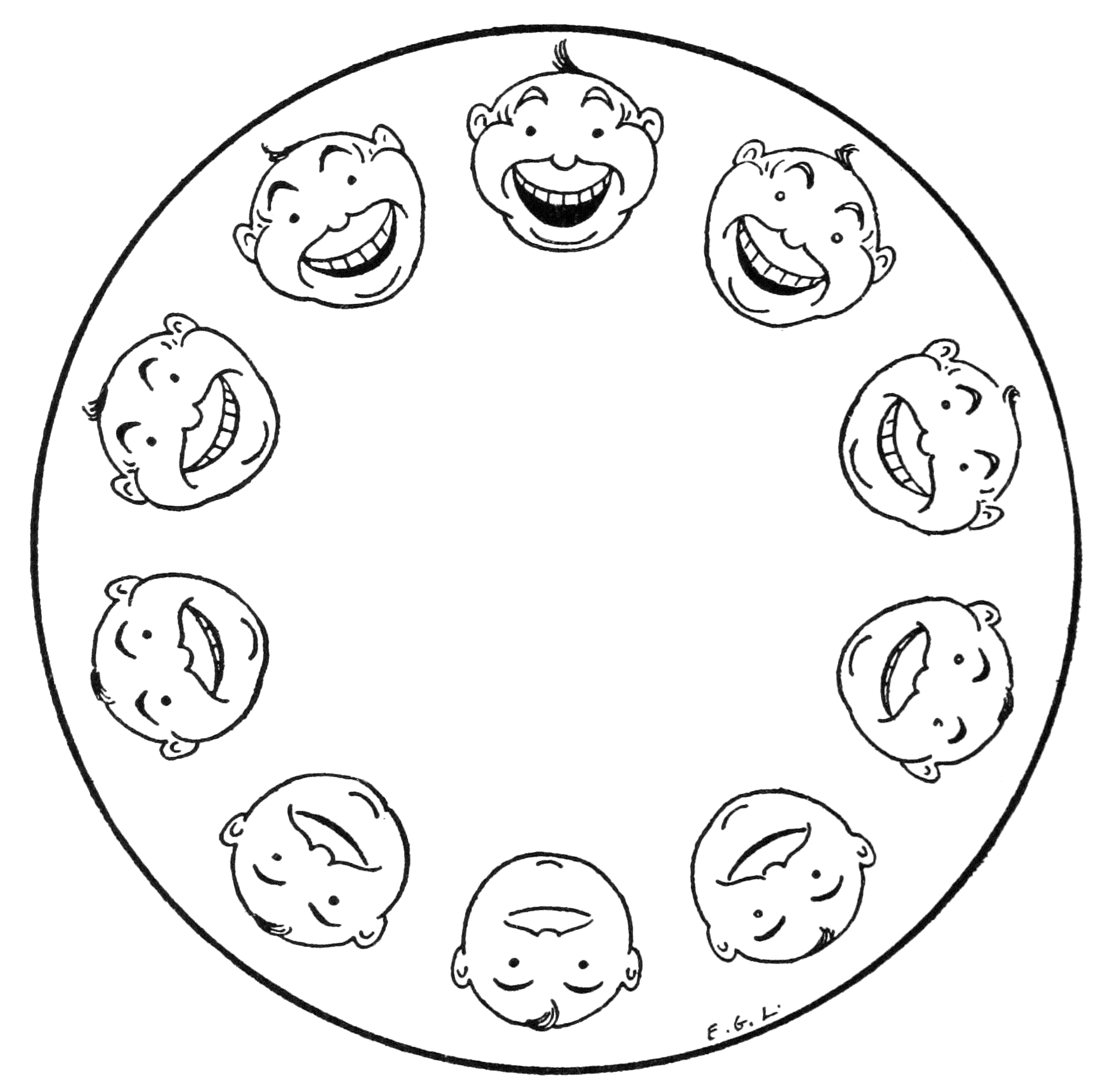

| A phenakistoscope | 21 | |

| Phenakistoscope combined with a magic-lantern | 22 | |

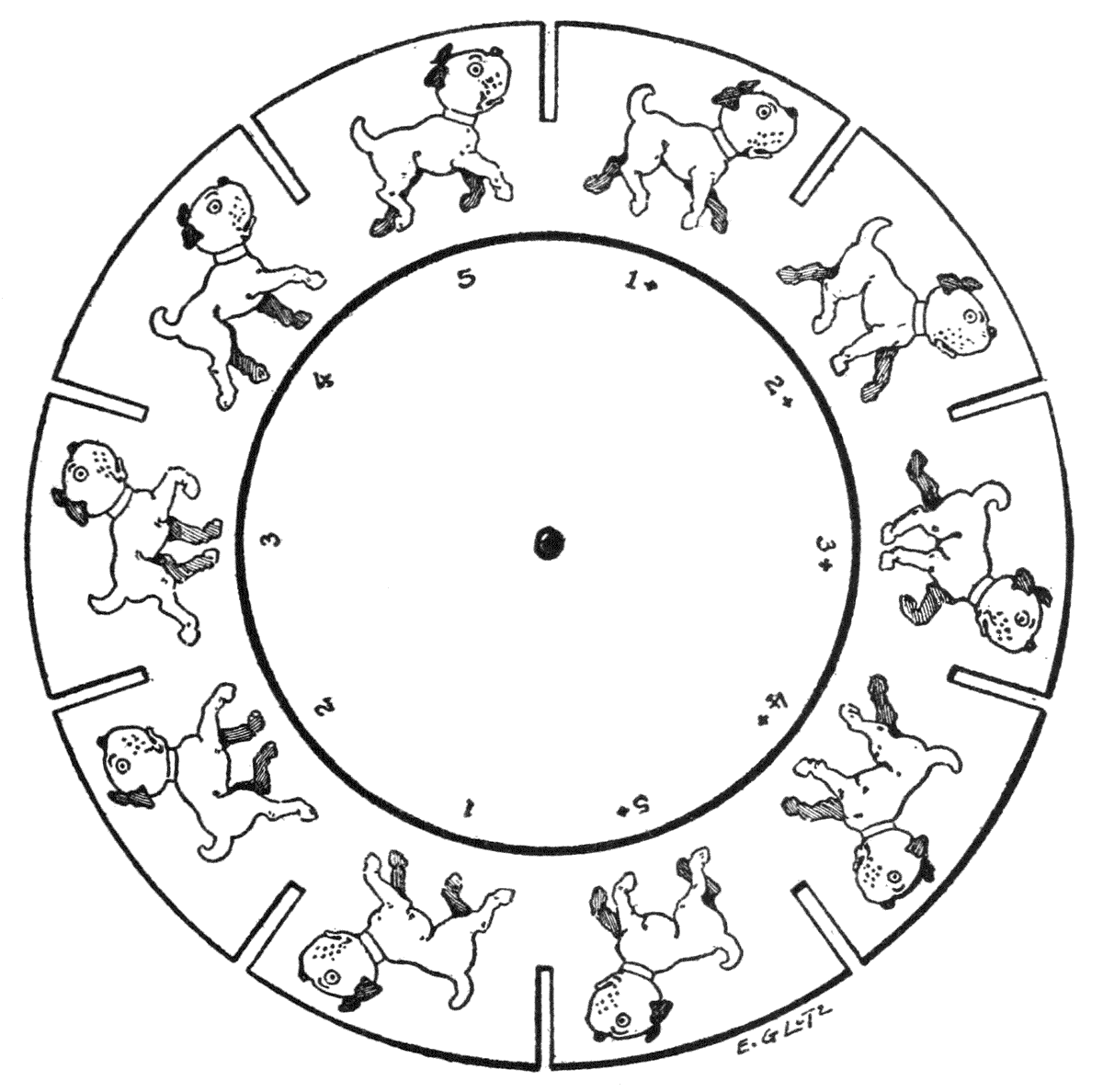

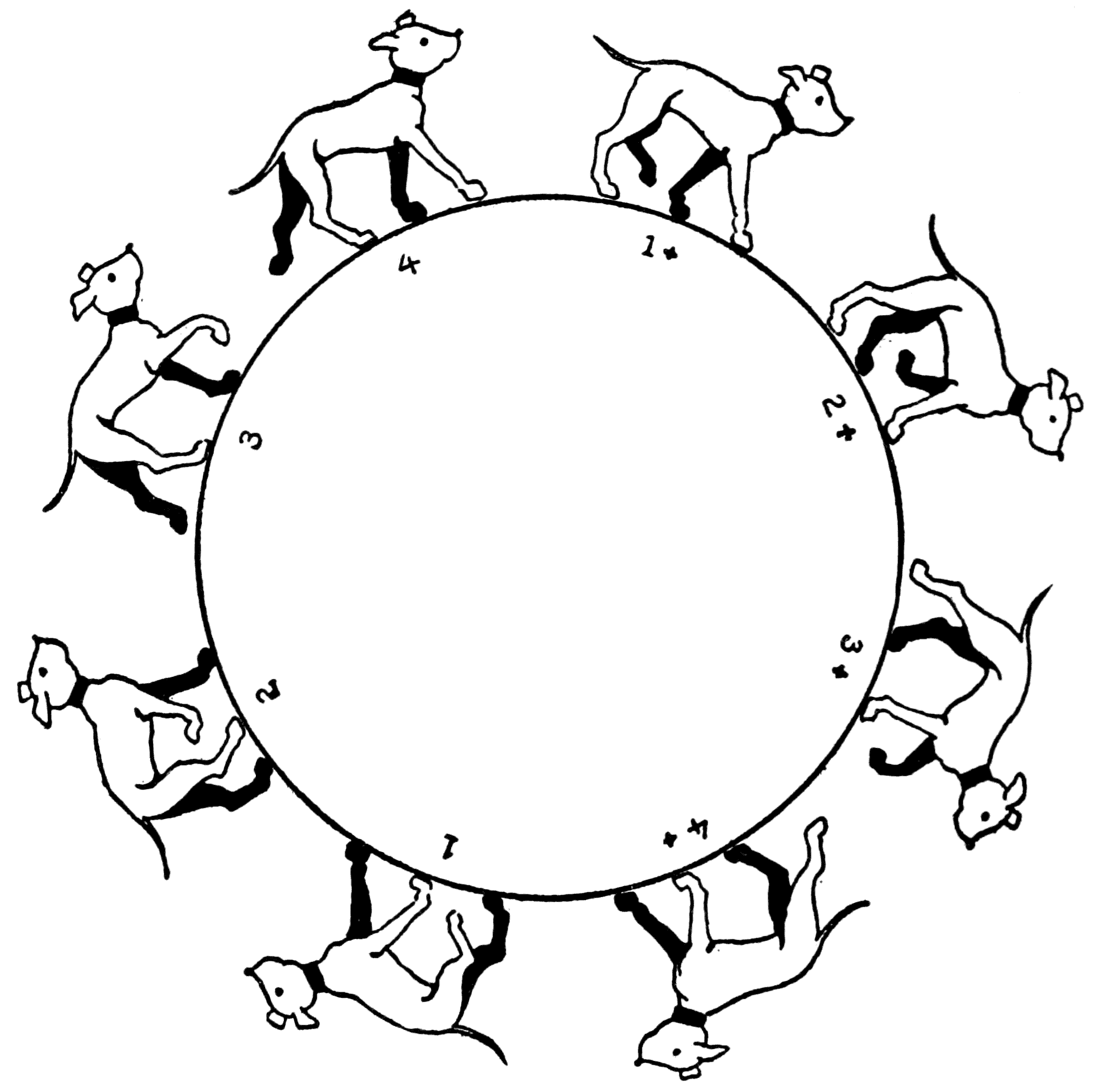

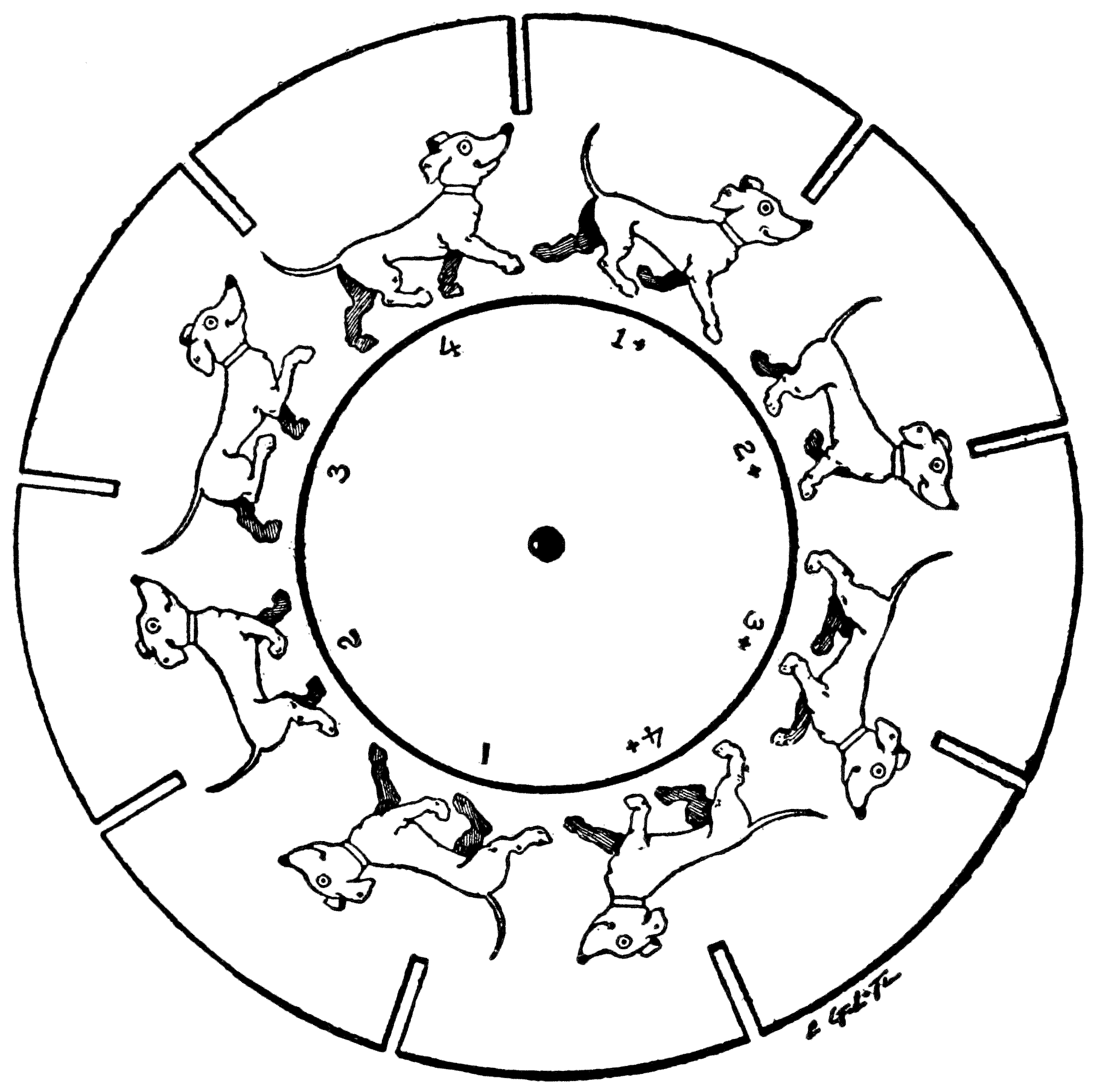

| Phenakistoscope with a cycle of drawings to show a dog in movement | 23 | |

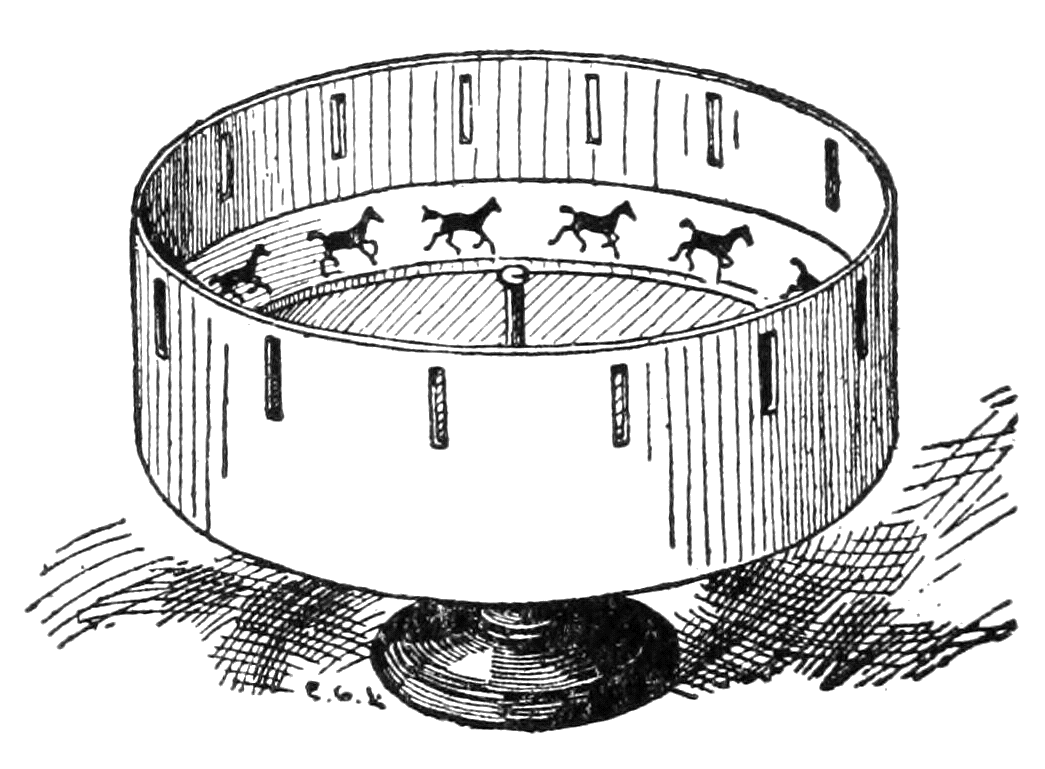

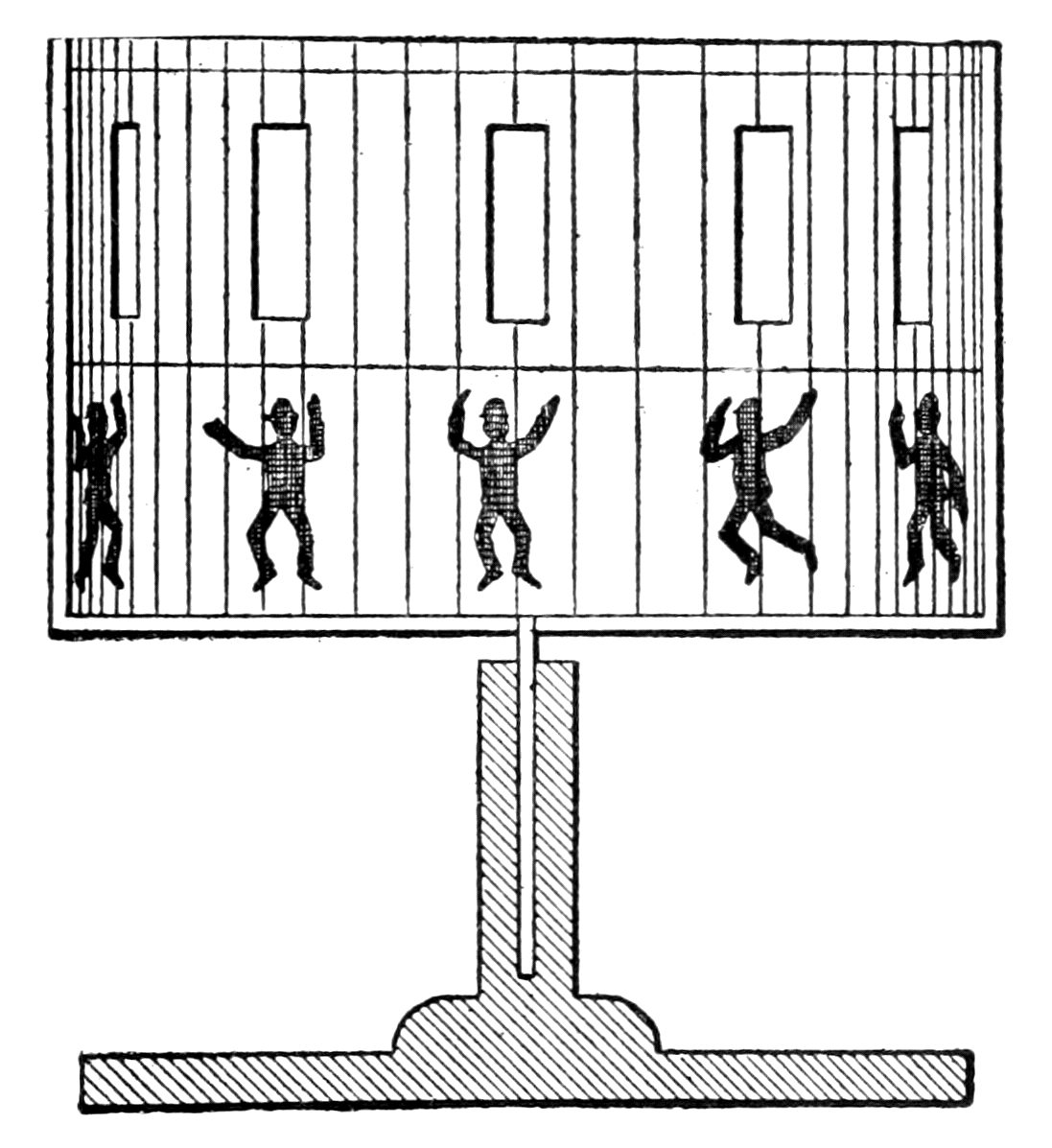

| The zootrope | 24 | |

| Zoetrope of William Lincoln | 25 | |

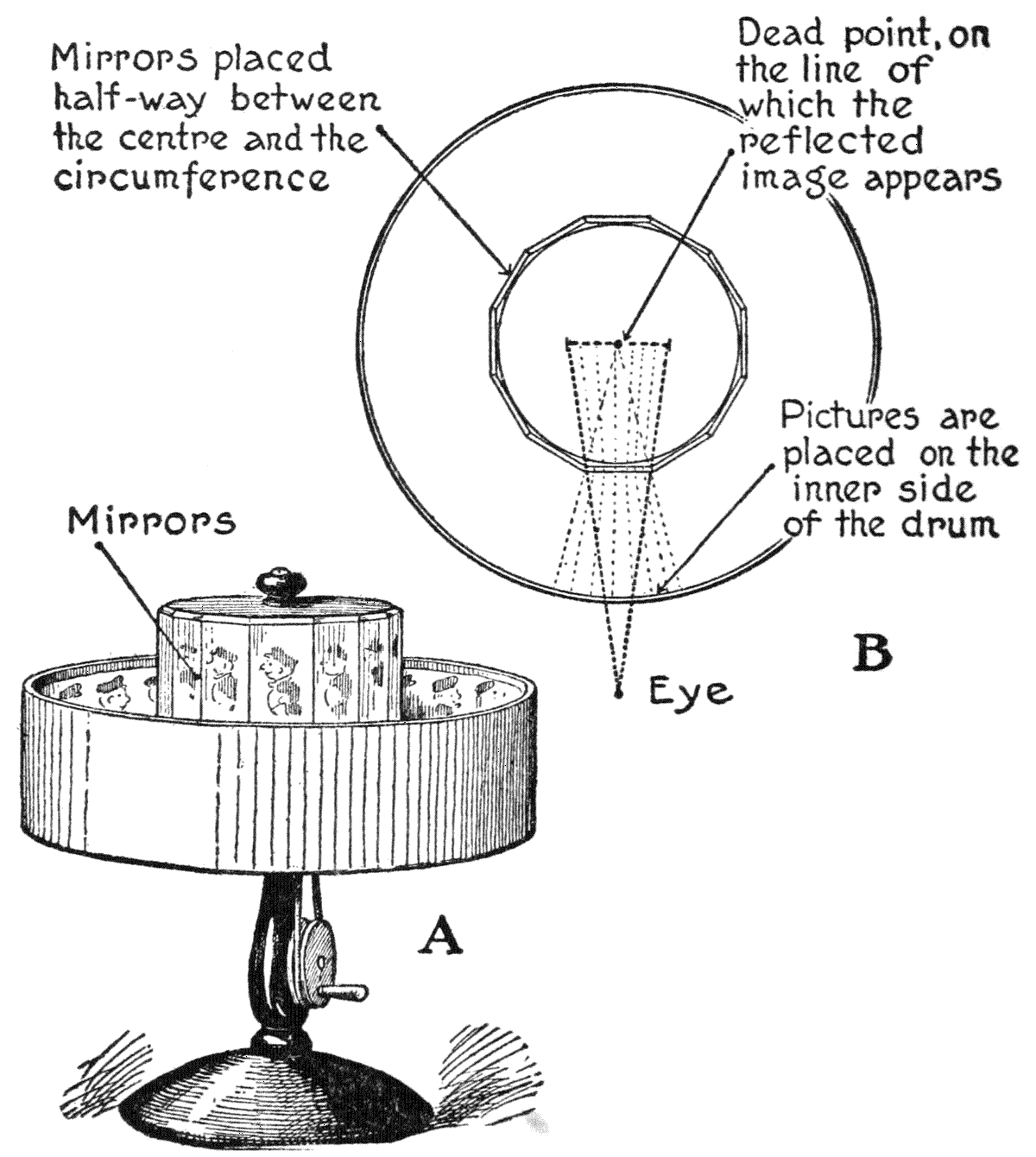

| Reynaud’s praxinoscope | 26 | |

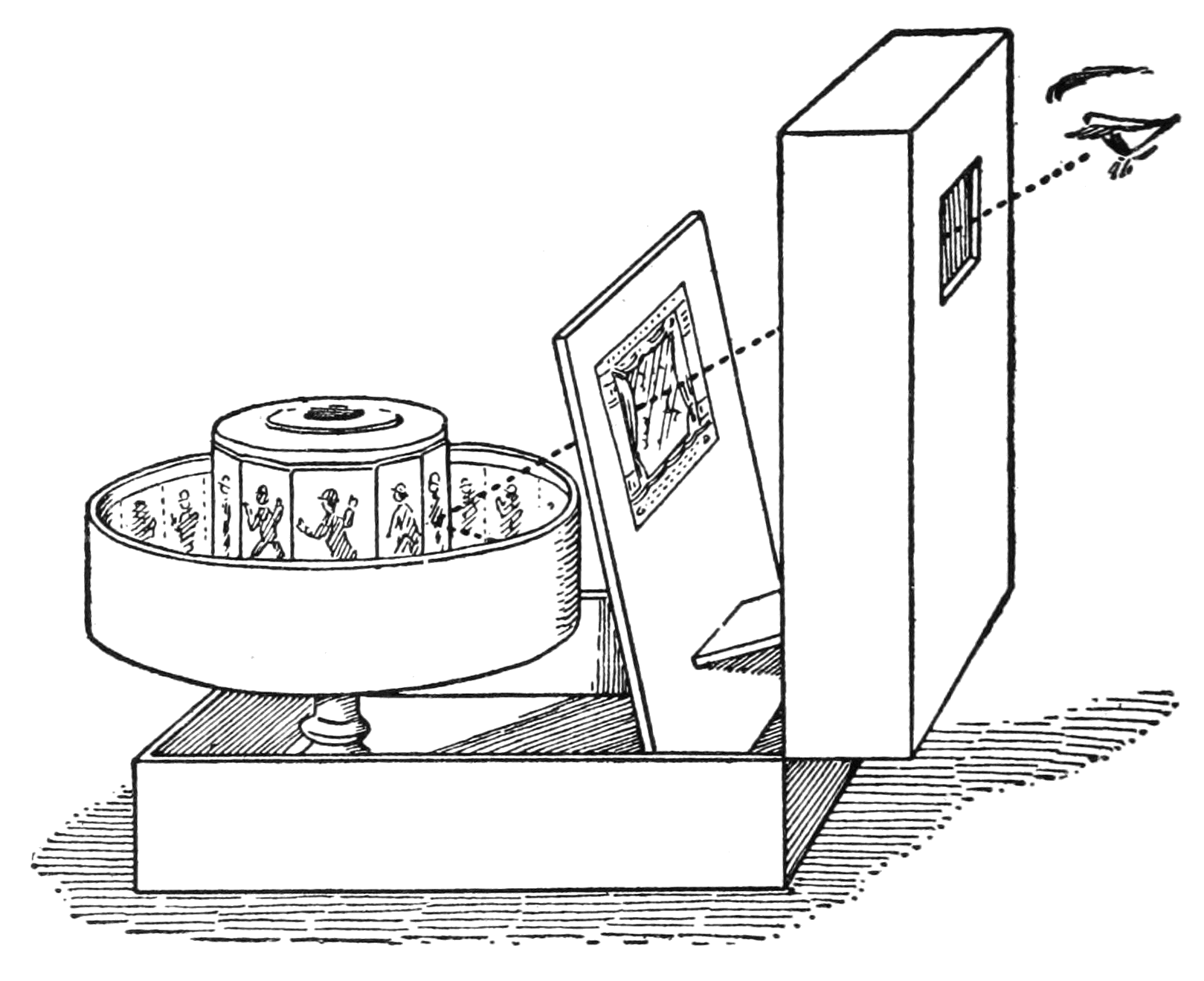

| The theatre praxinoscope | 28[xvi] | |

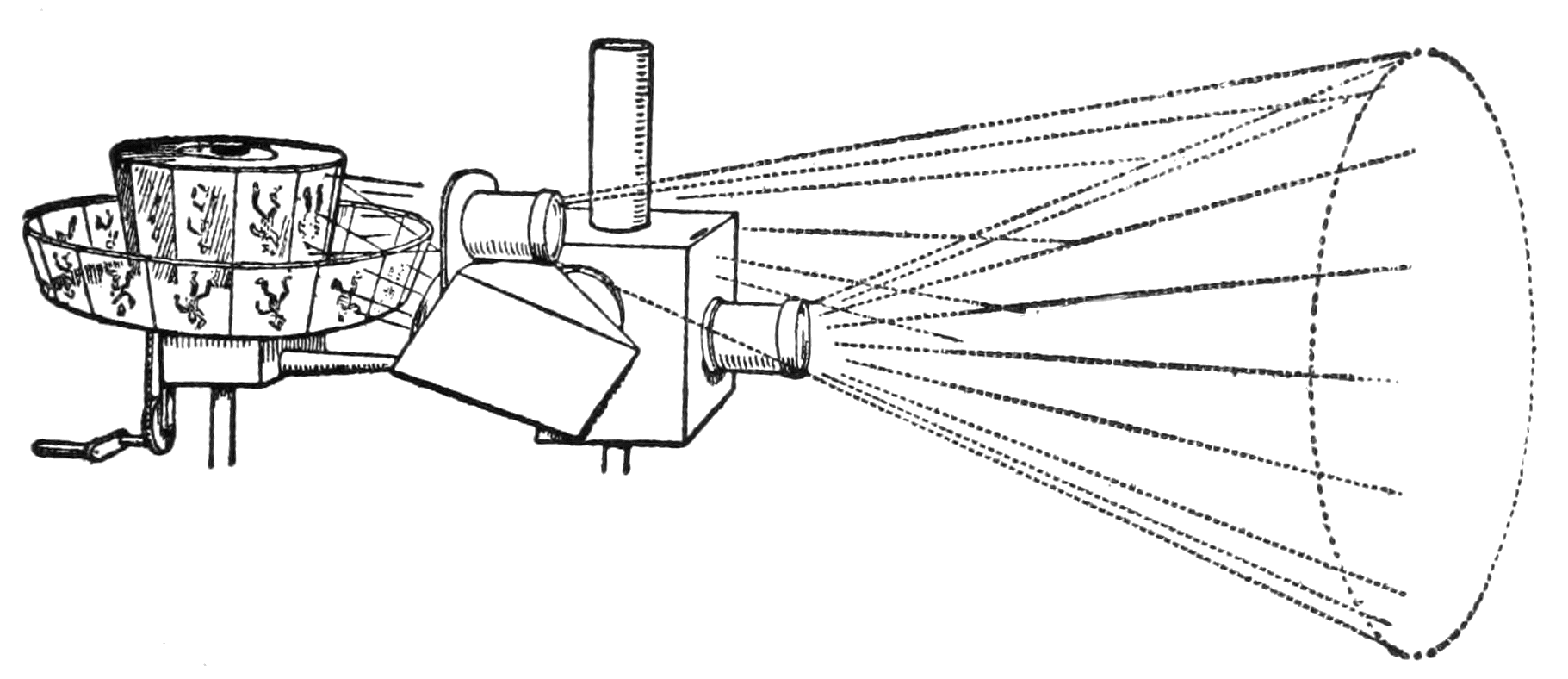

| Projection praxinoscope | 29 | |

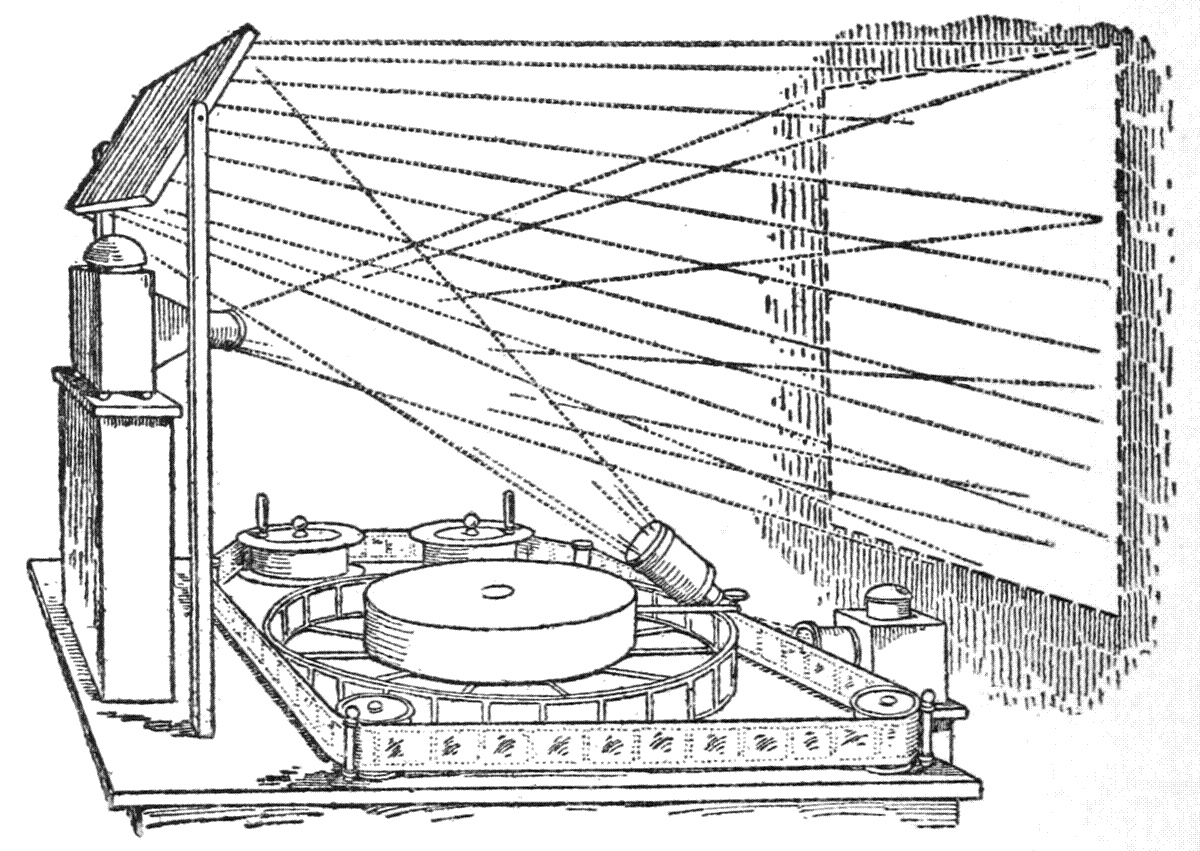

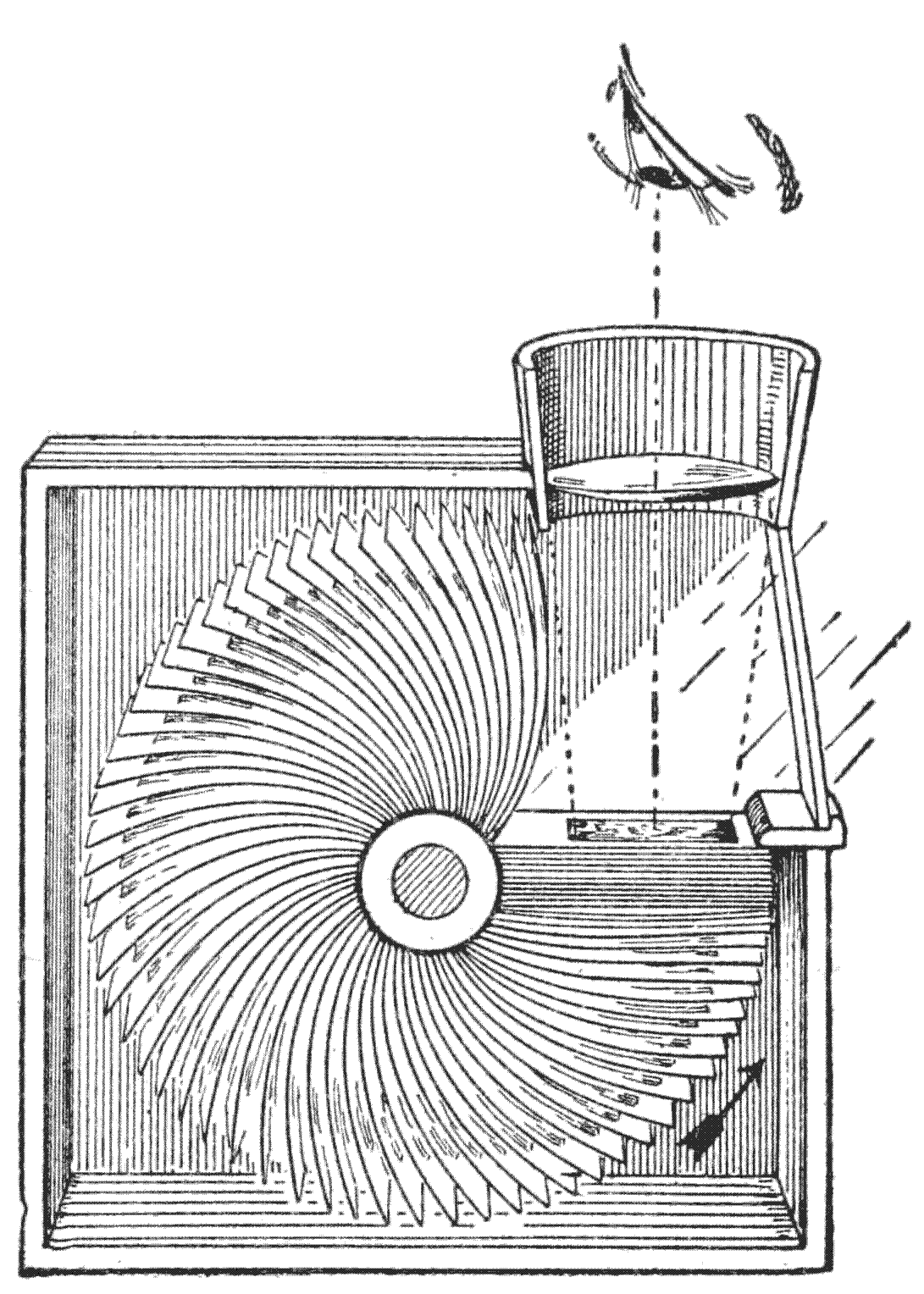

| Optical theatre of Reynaud | 30 | |

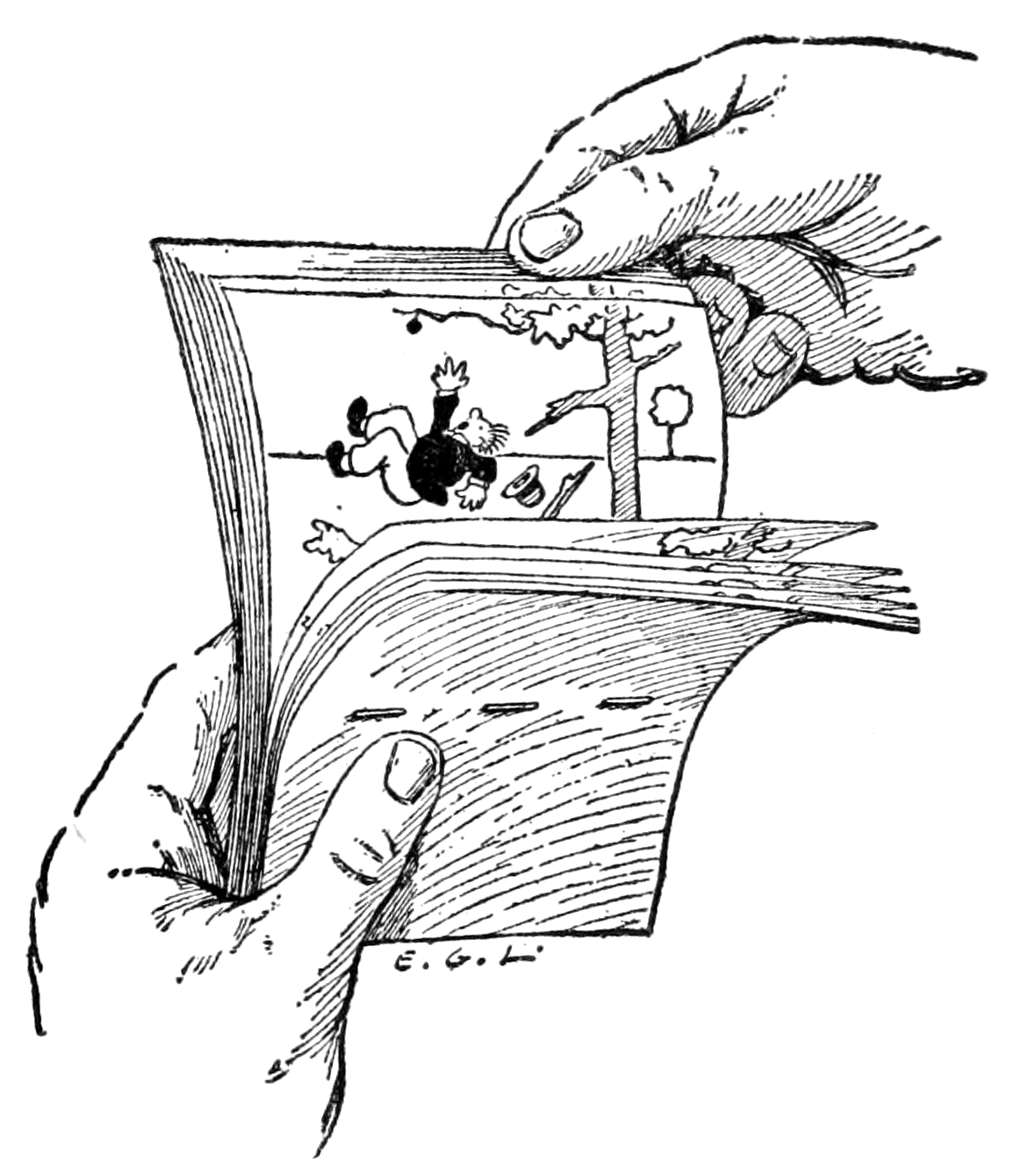

| The kineograph | 31 | |

| Plan of the apparatus of Coleman Sellers | 36 | |

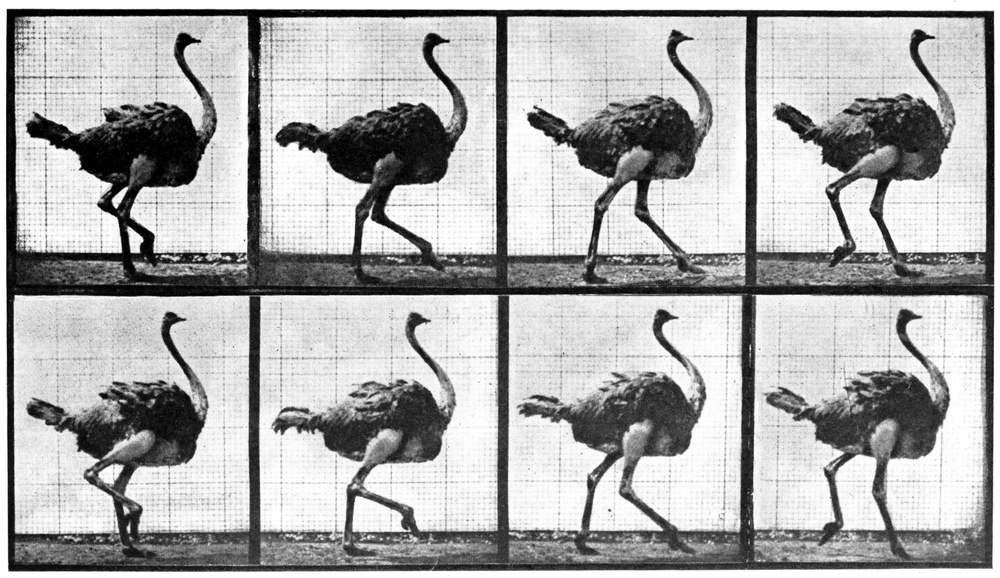

| The ostrich walking; from Muybridge | Facing page 40 | |

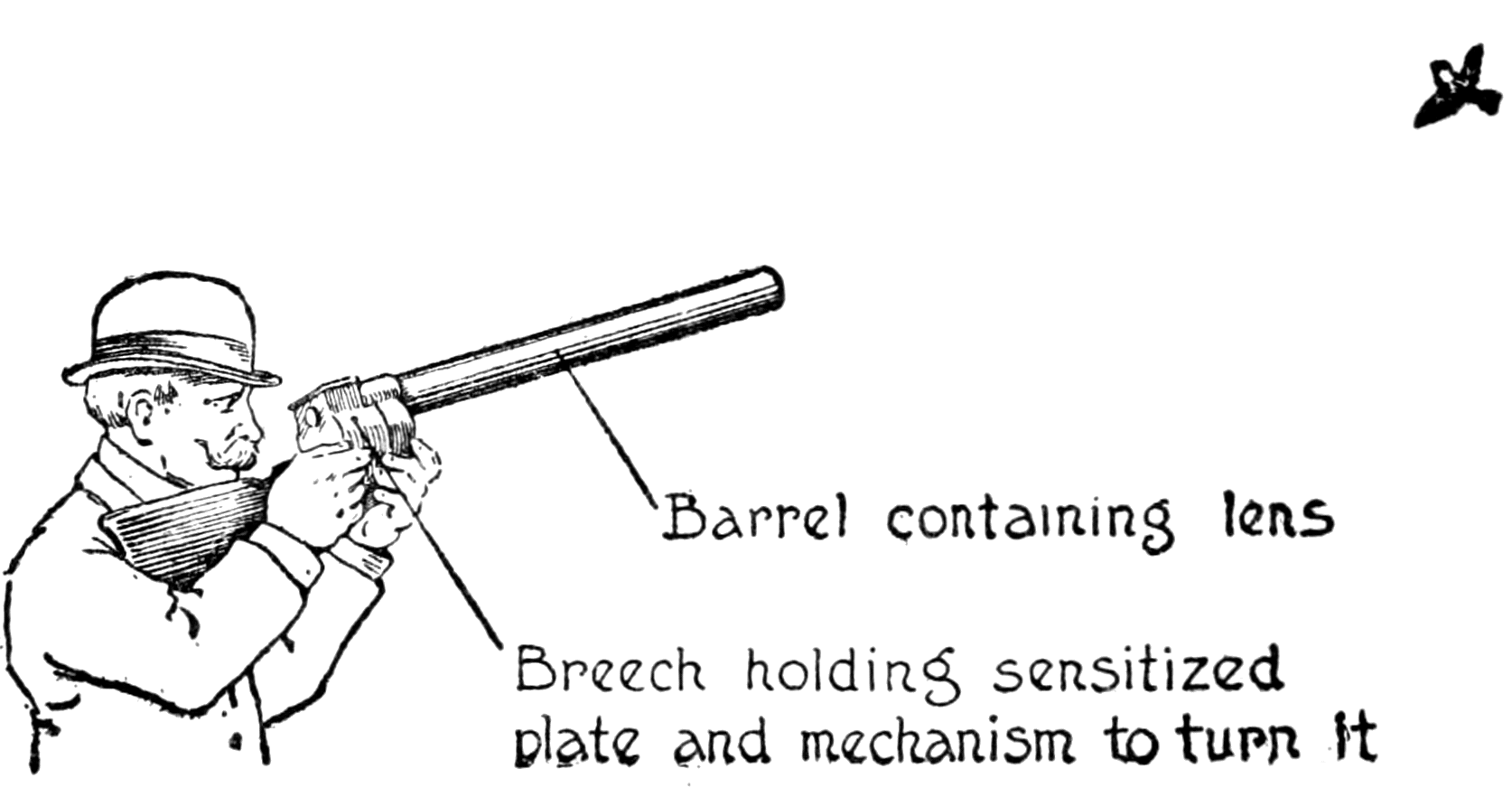

| Marey’s photographic gun | 42 | |

| Plan of the kinora | 43 | |

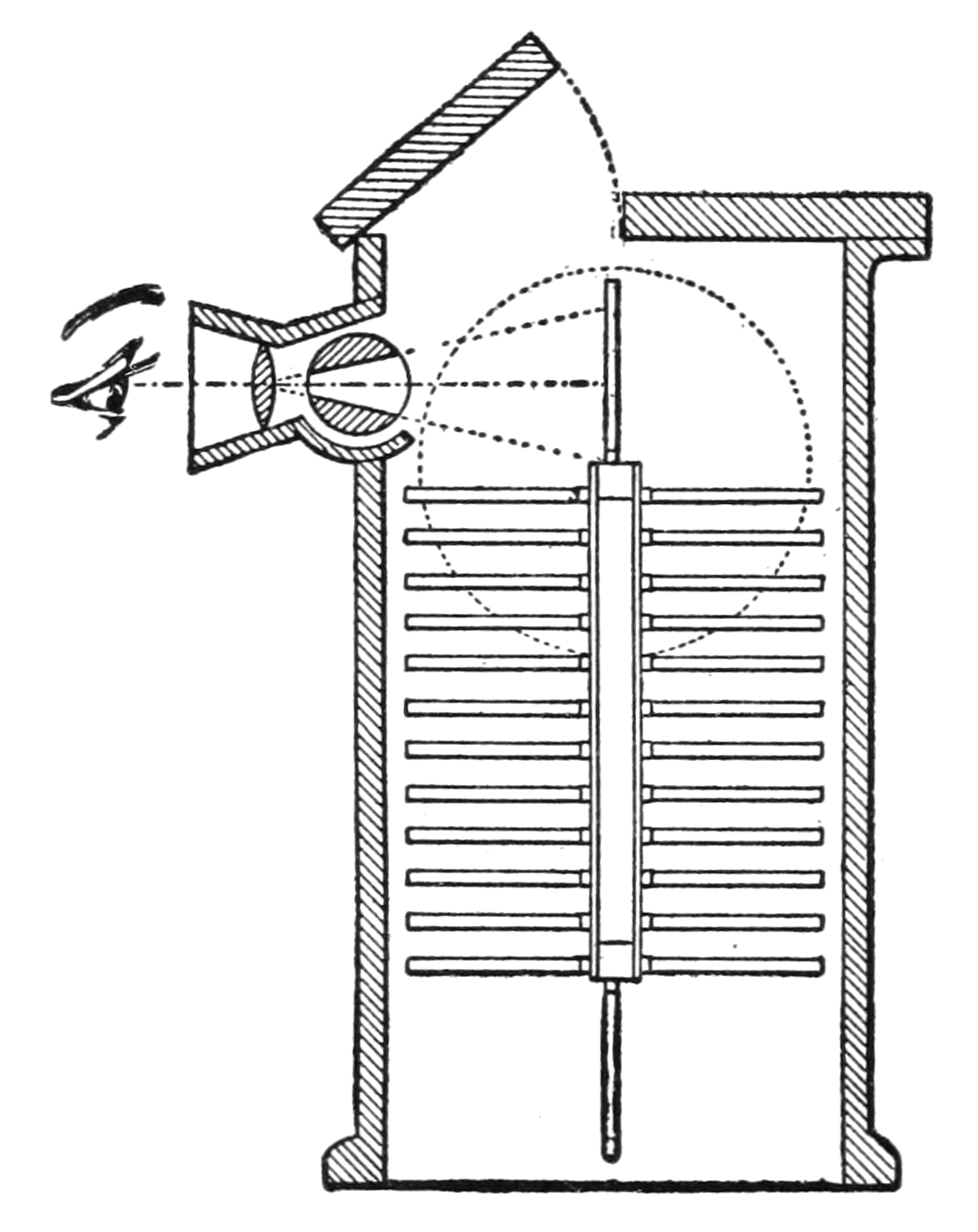

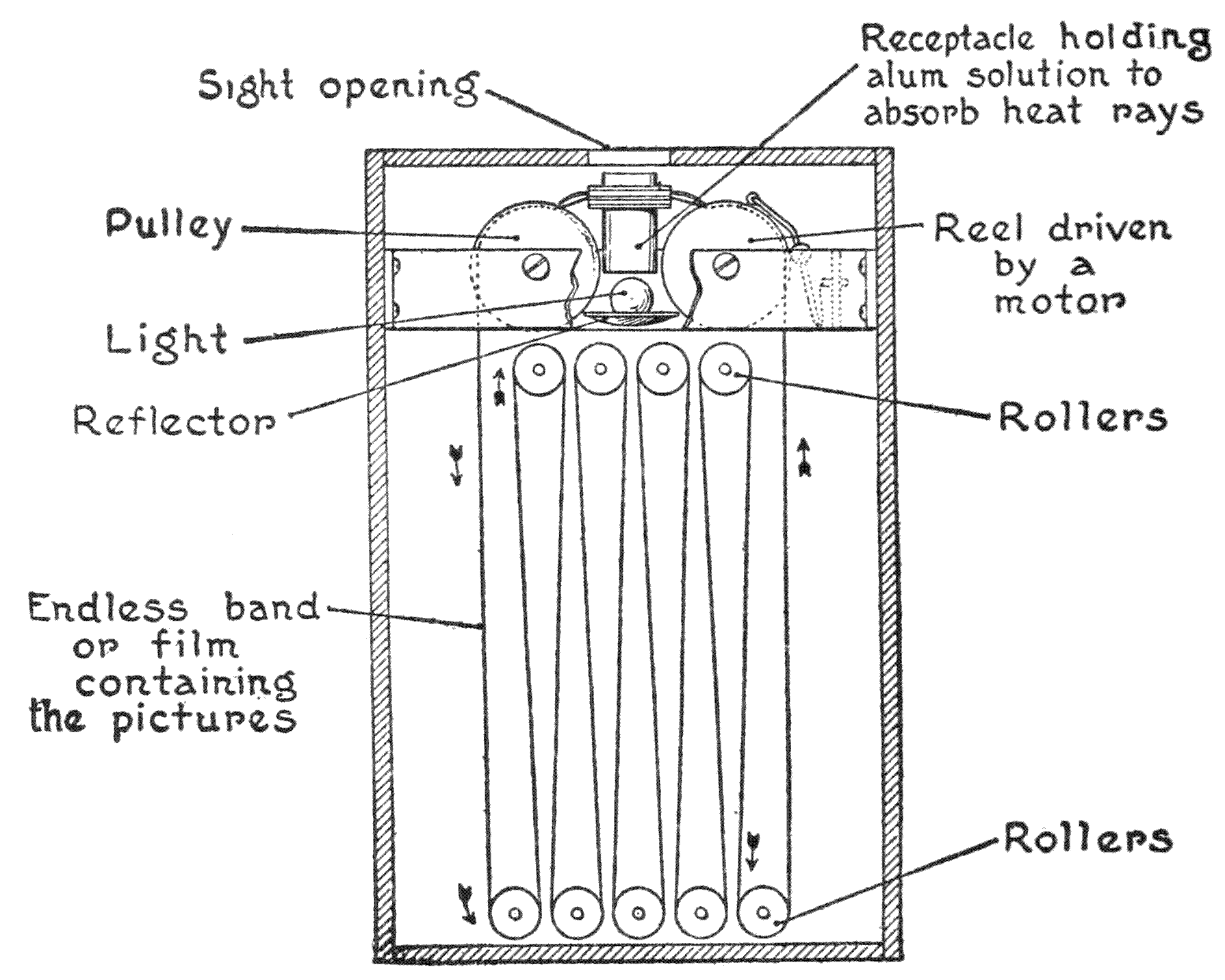

| Plan of Edison’s first kinetoscope | 46 | |

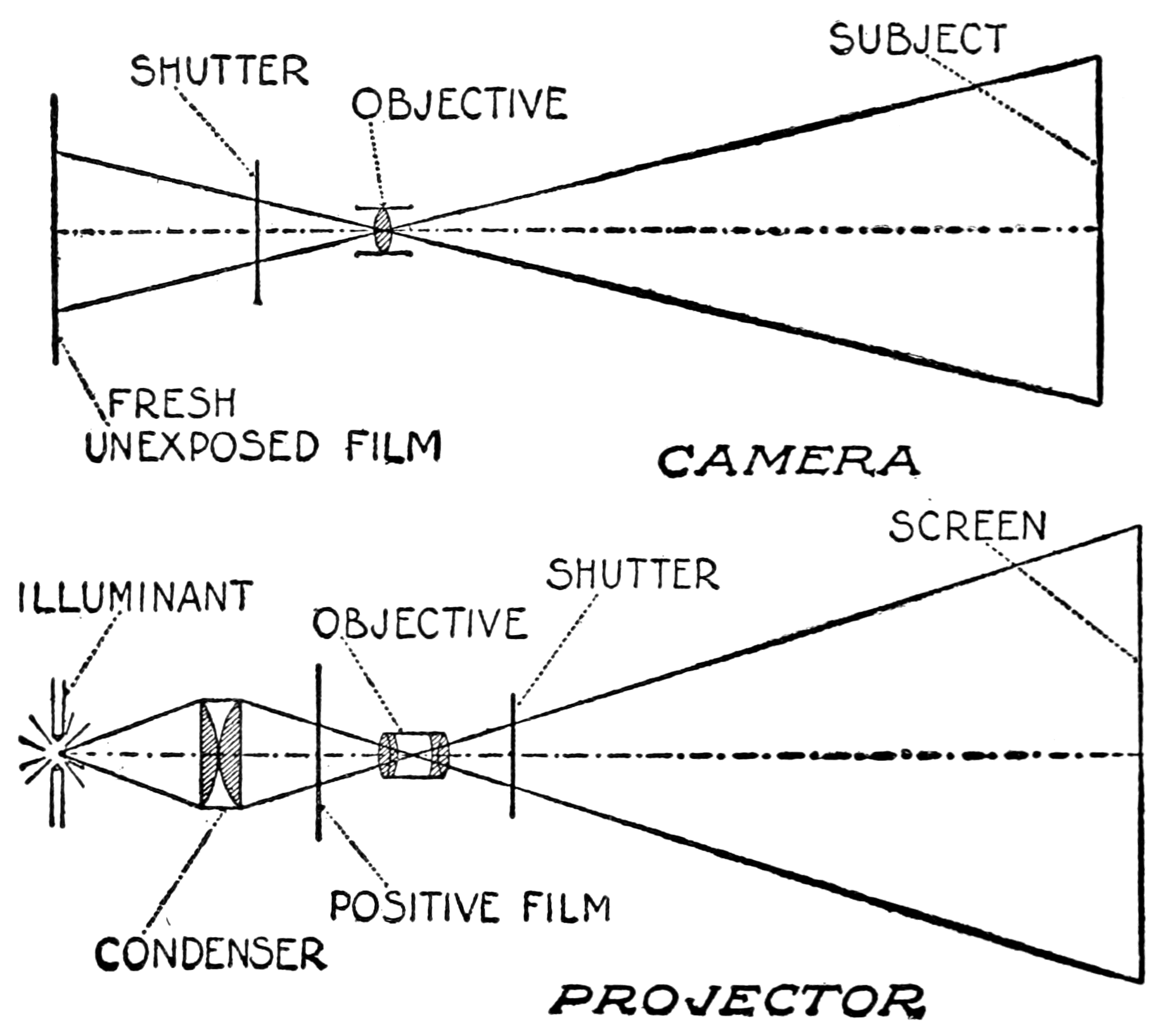

| Projector and motion-picture camera compared | 48 | |

| A negative and a positive print | 49 | |

| Plan of a motion-picture camera | 50 | |

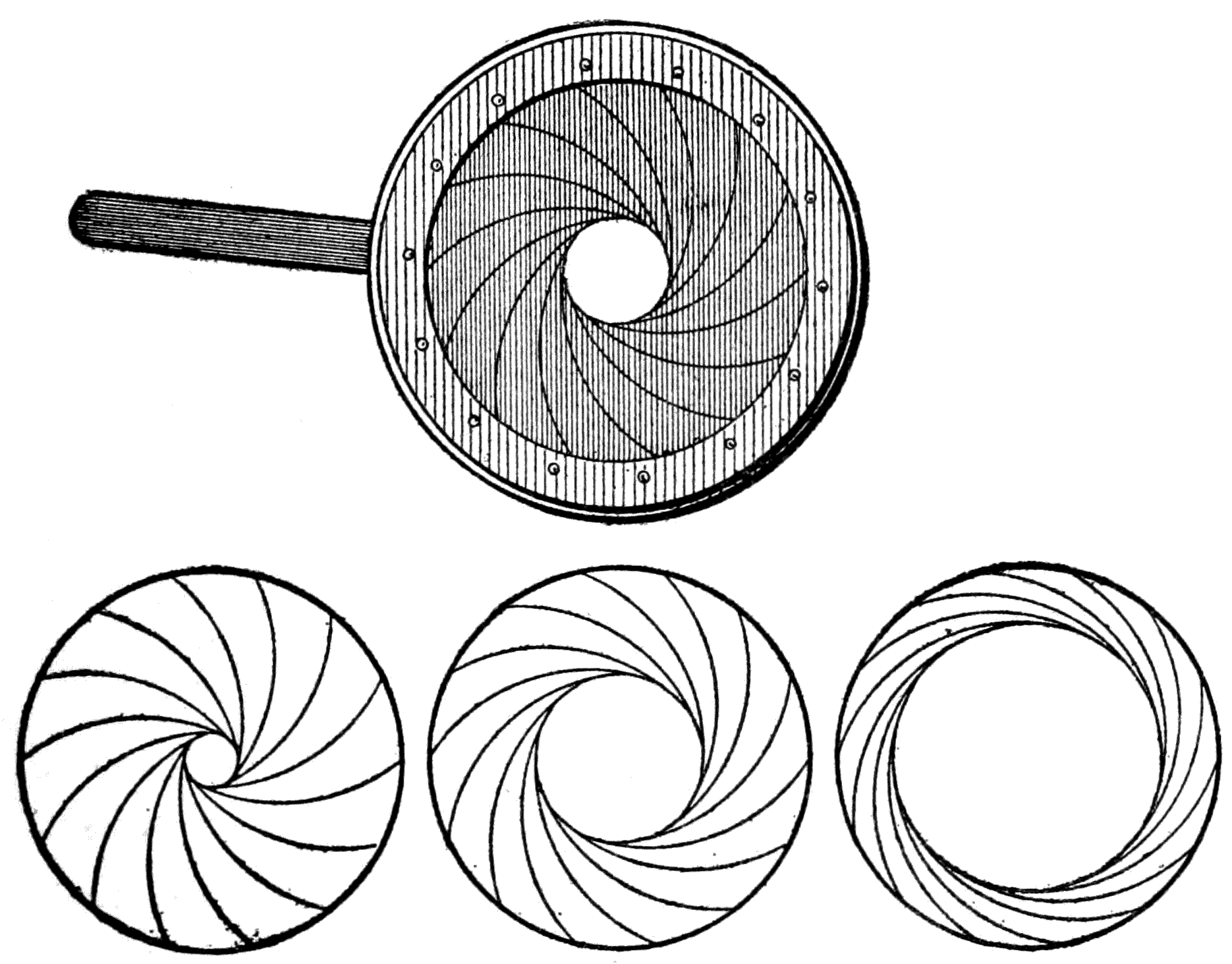

| Types of camera and projector shutters | 51 | |

| One foot of film passes through the projector in one second | 53 | |

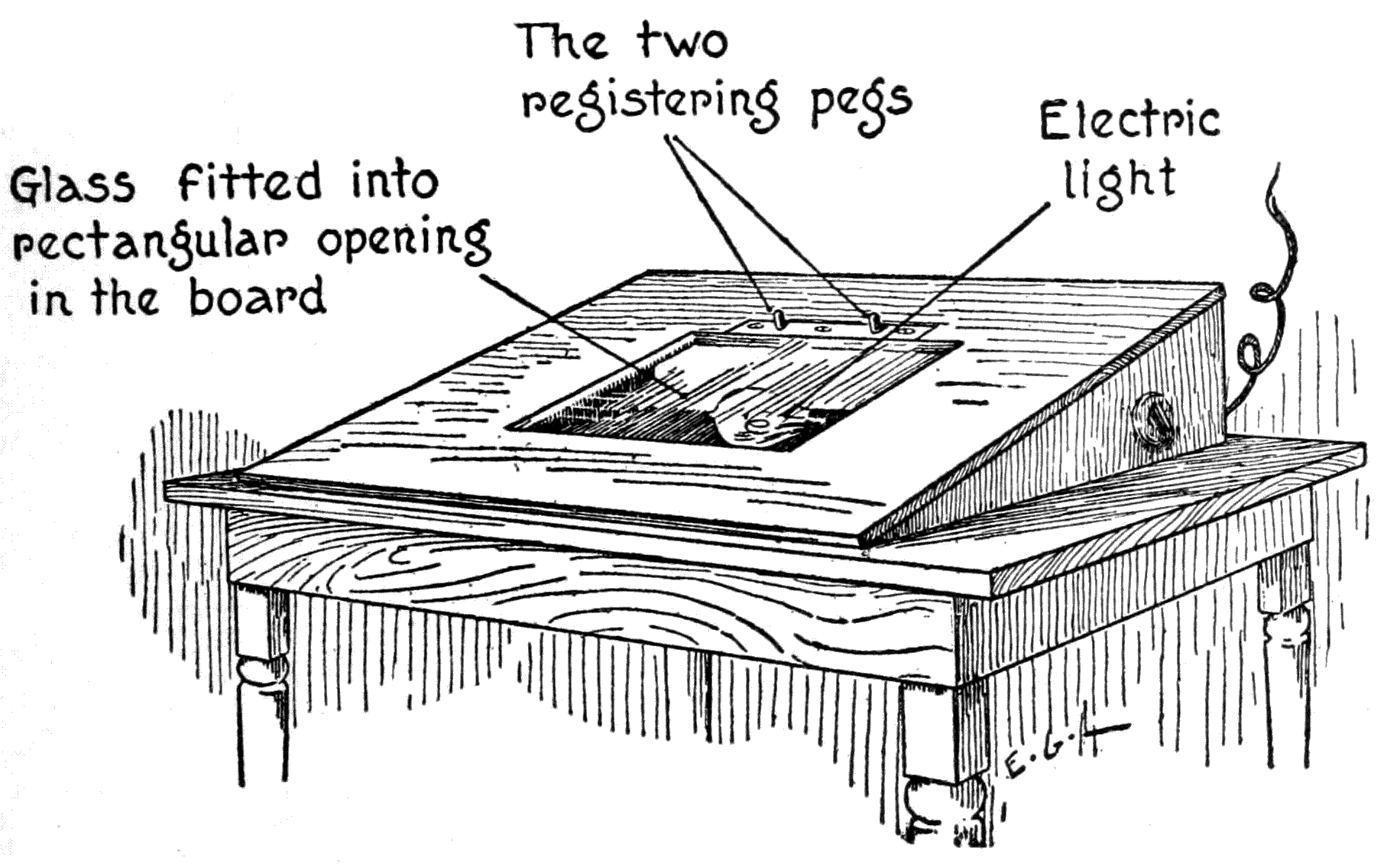

| “Animator’s” drawing-board | 61 | |

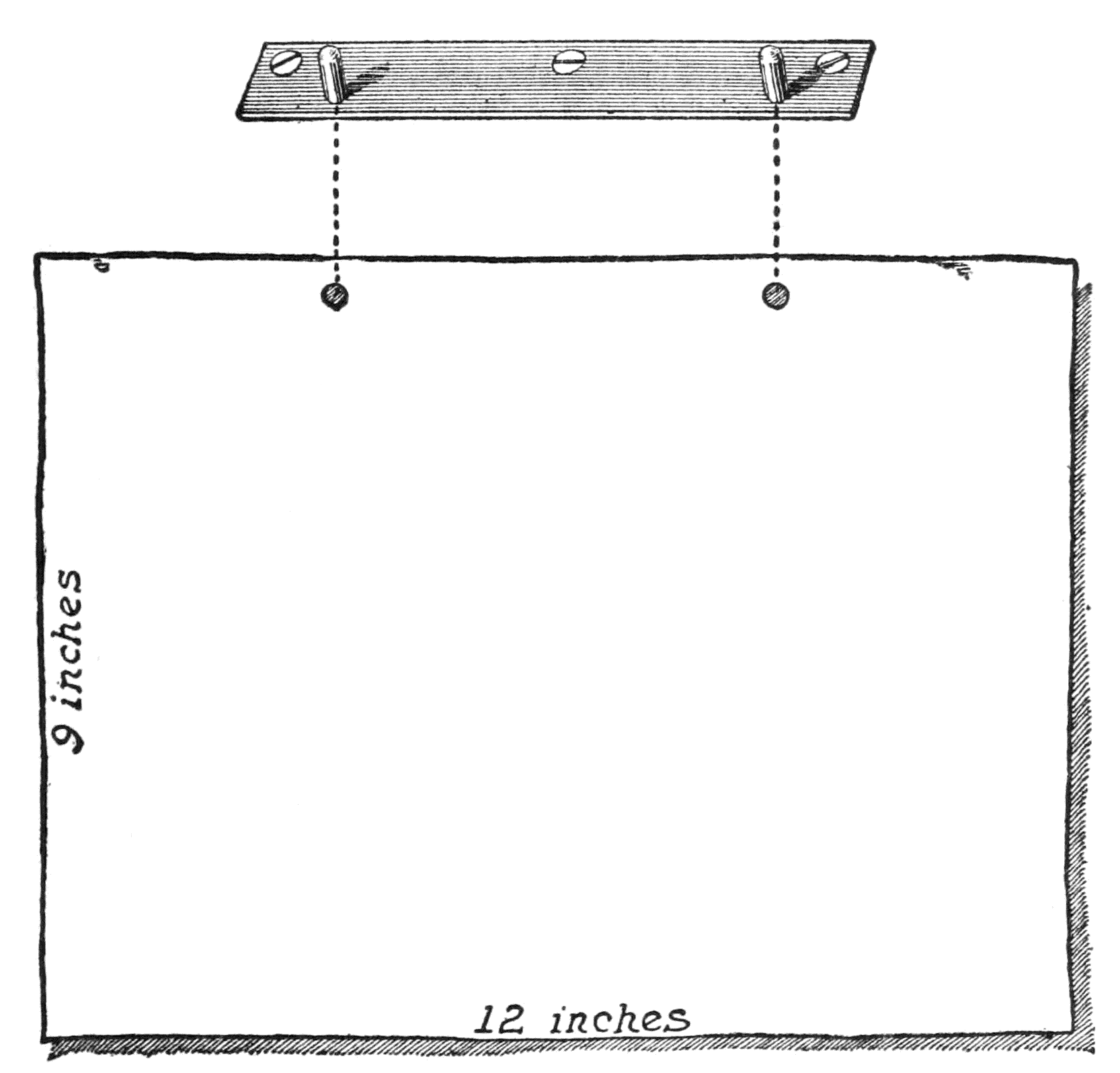

| A sheet of perforated paper and the registering pegs | 63 | |

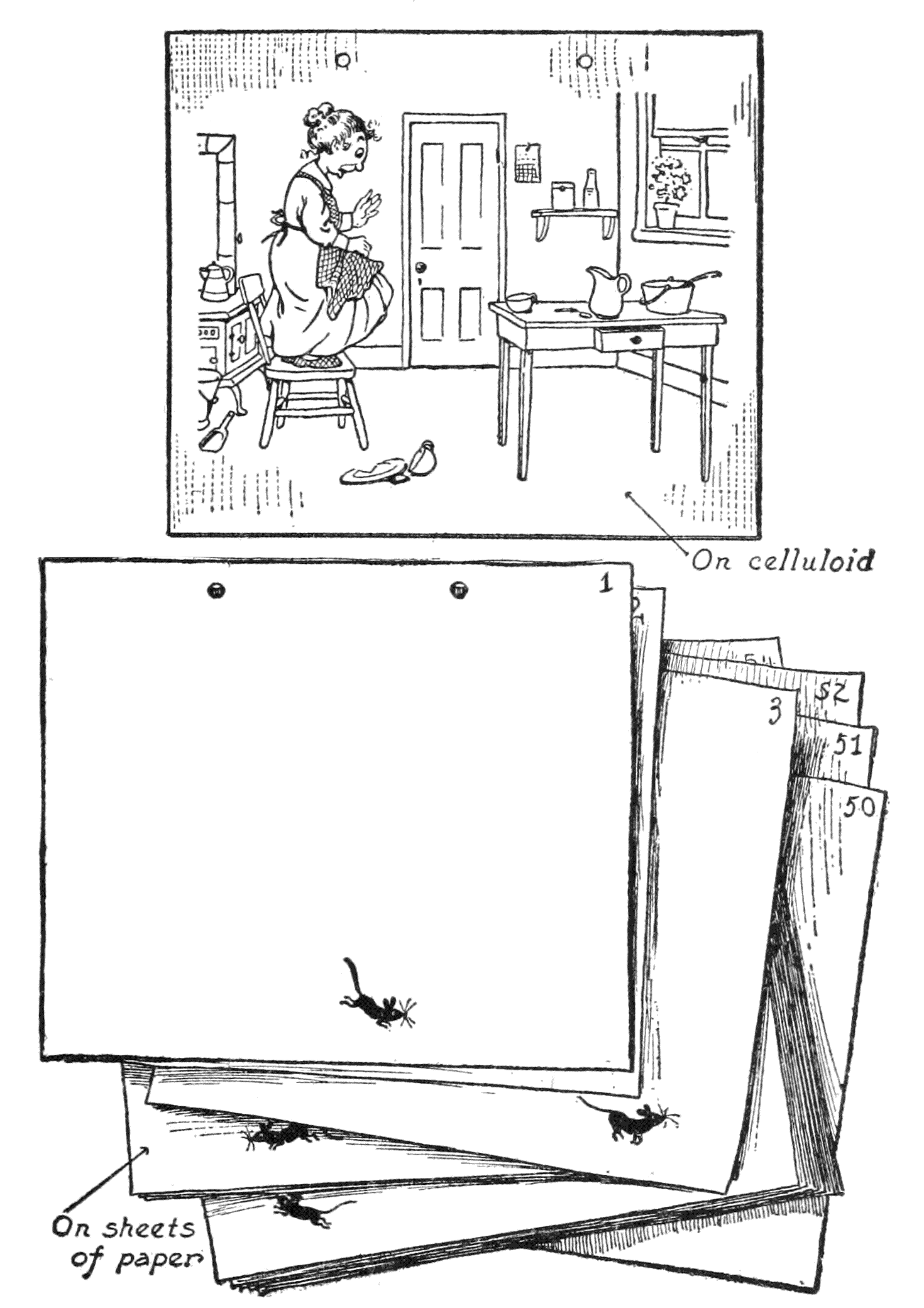

| Illustrating the making of an animated scene | 67 | |

| Illustrating the making of an animated scene with the help of celluloid sheets | 71 | |

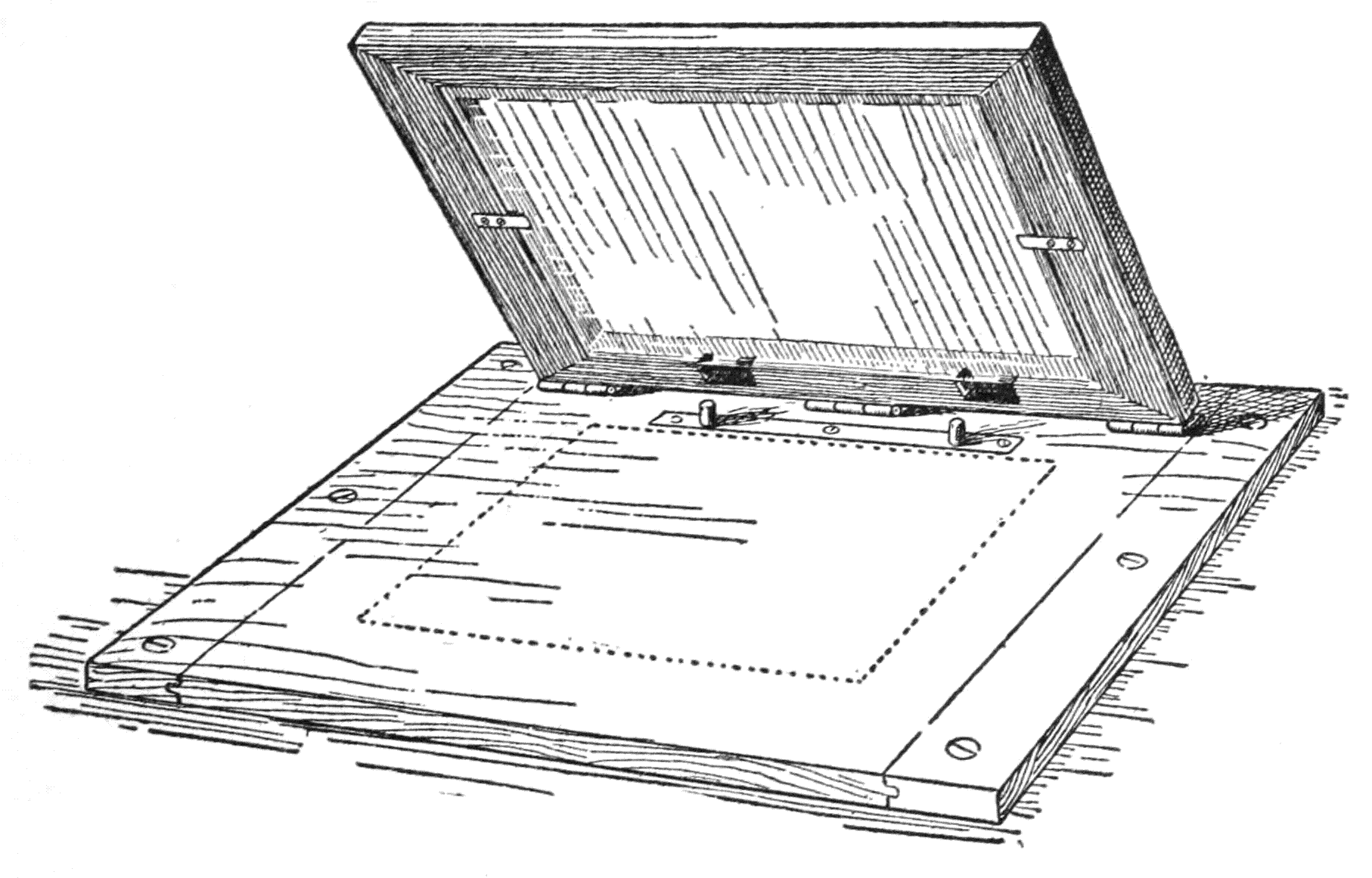

| Arrangement of board, pegs, and hinged frame with glass | 75 | |

| Balloons | 78 | |

| Three elements that complete a scene | 79 | |

| Phenakistoscope with cycle of drawings of a face to show a movement of the mouth | 80 | |

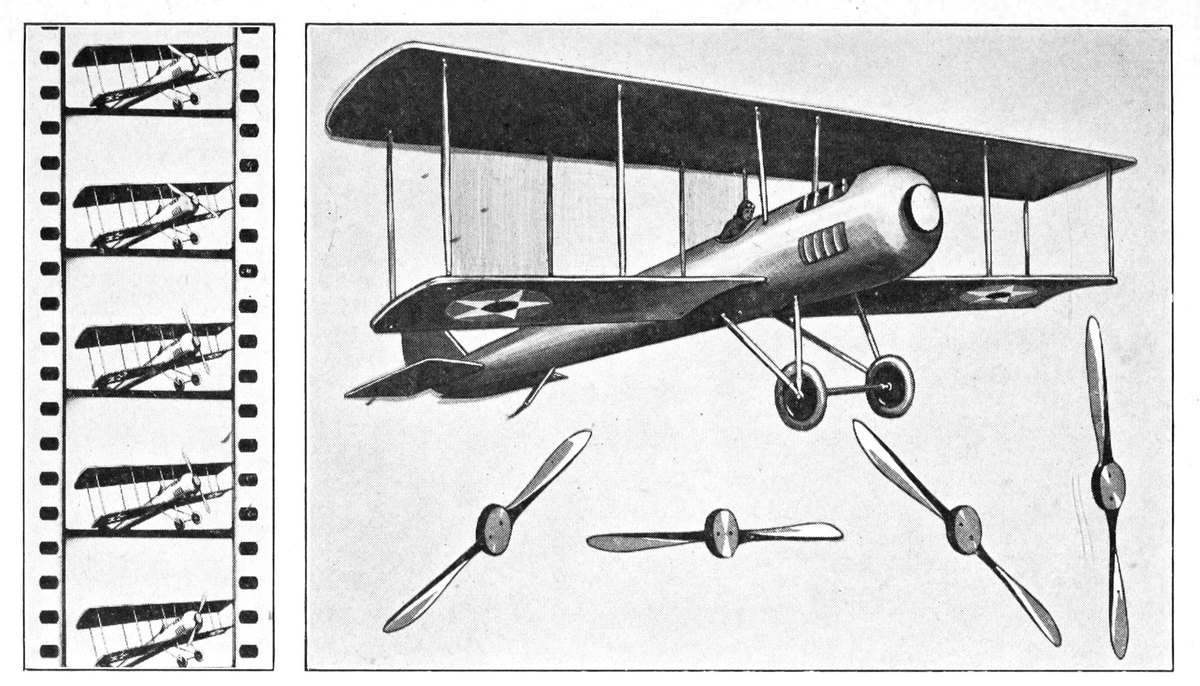

| Cardboard model of an airplane with separate cut-out propellers | Facing page 84[xvii] | |

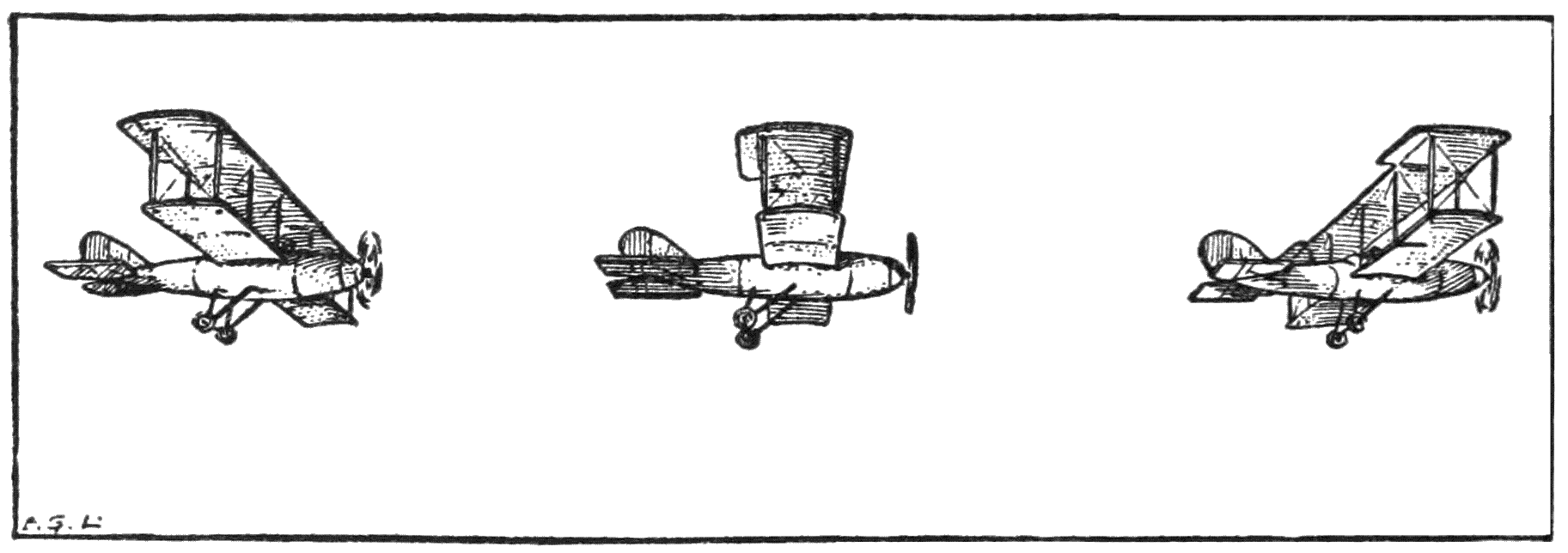

| The laws of perspective are to be considered in “animating” an object | 86 | |

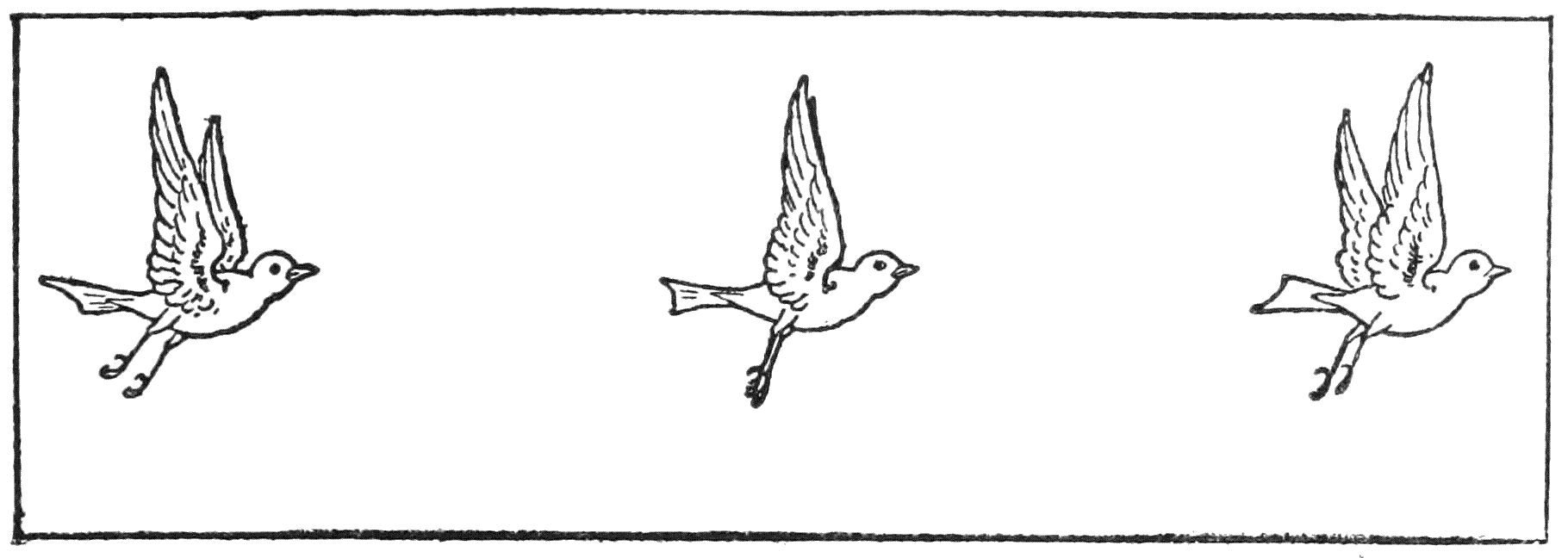

| Perspective applied in the drawing of birds as well as in the picturing of objects | 87 | |

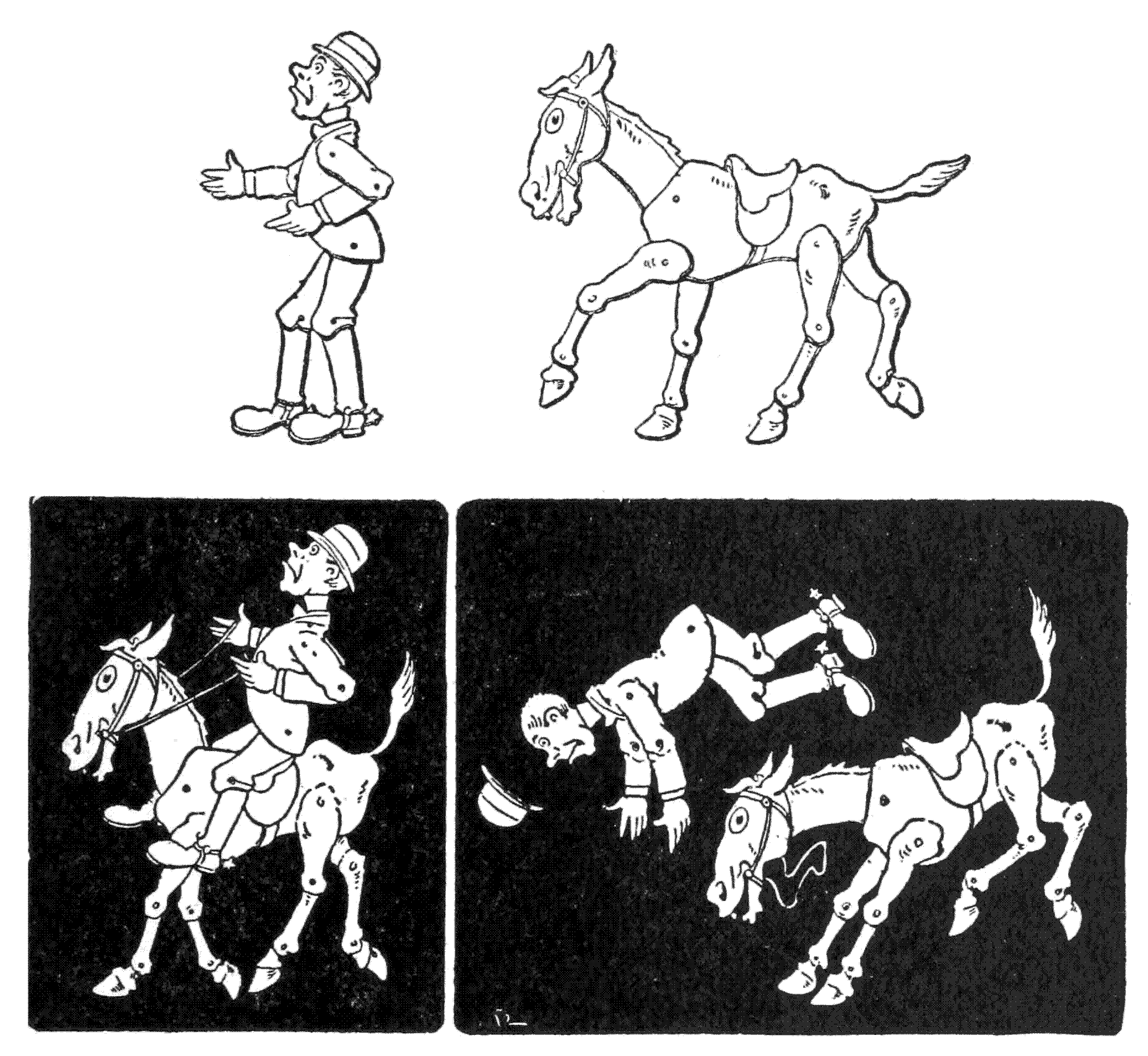

| Articulated cardboard figures | 89 | |

| Illustrating the animation of a mouse as he runs around the kitchen | 95 | |

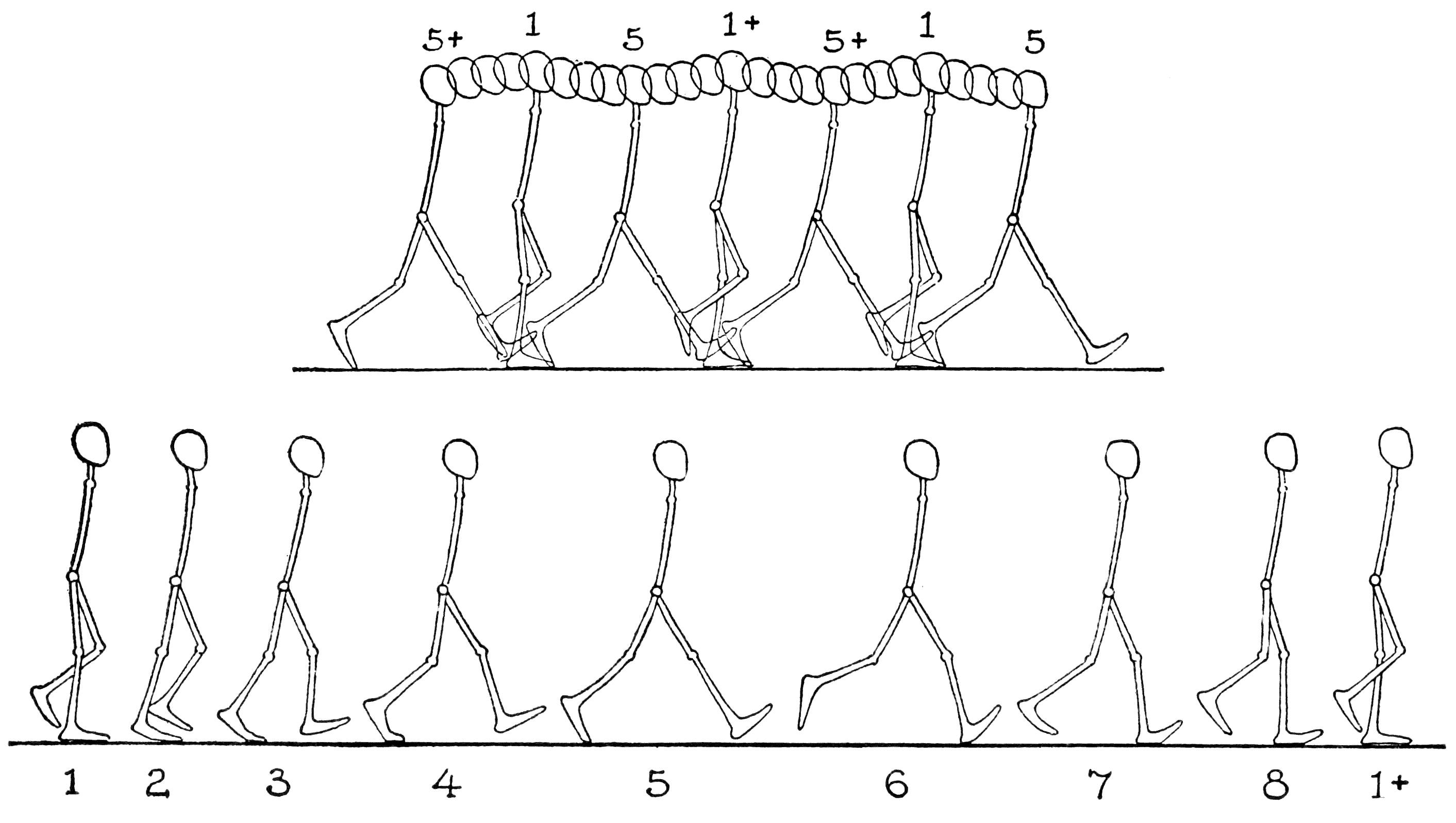

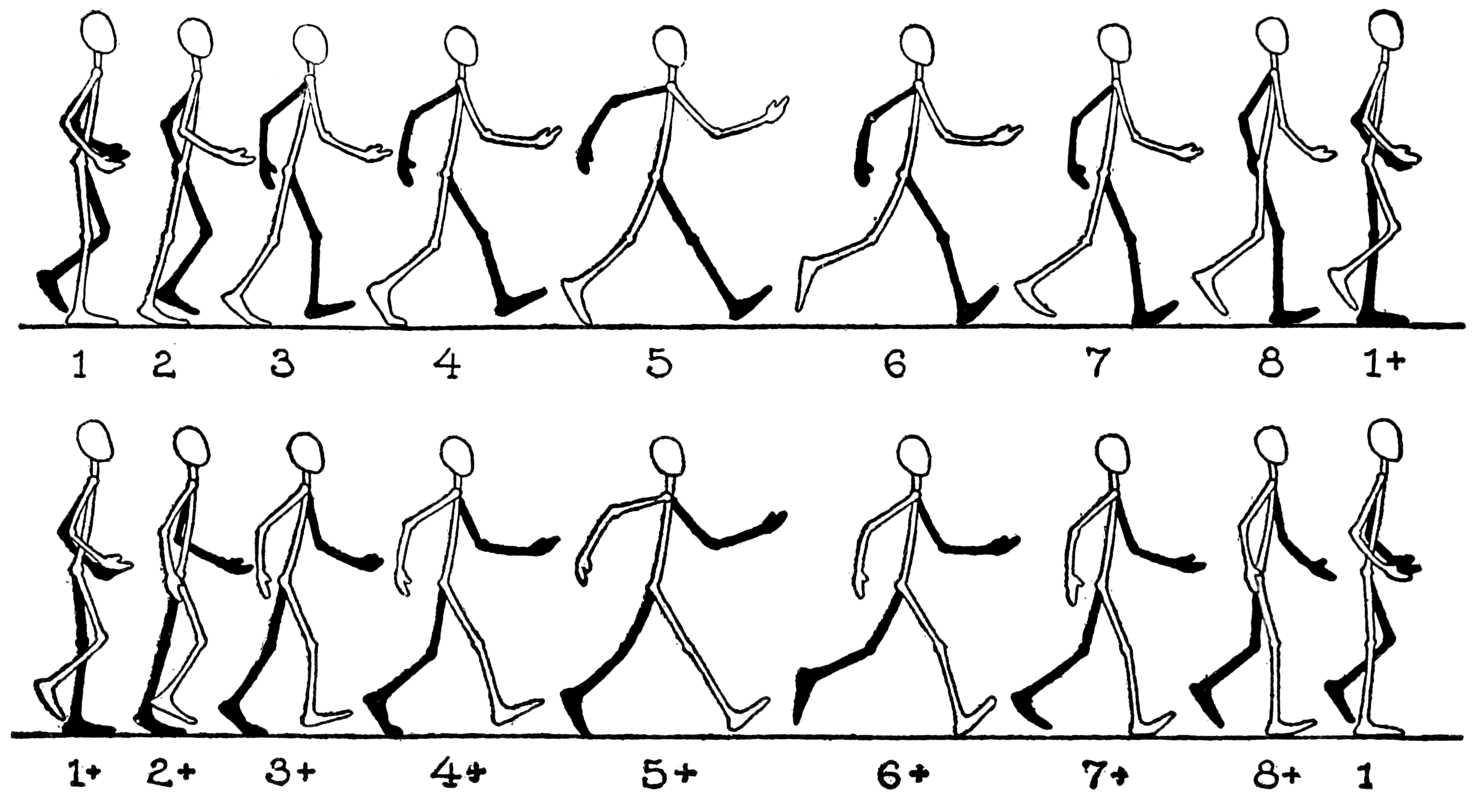

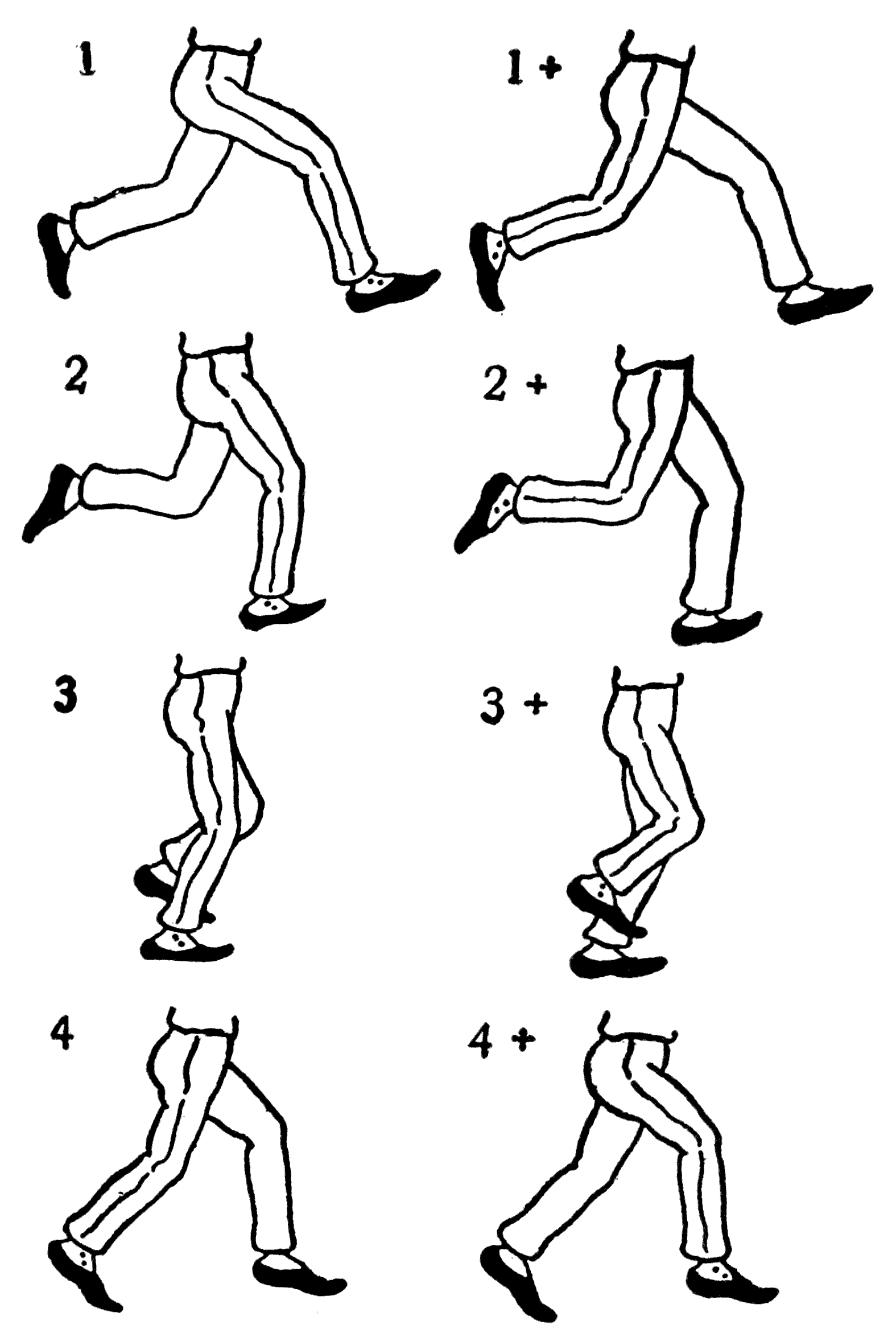

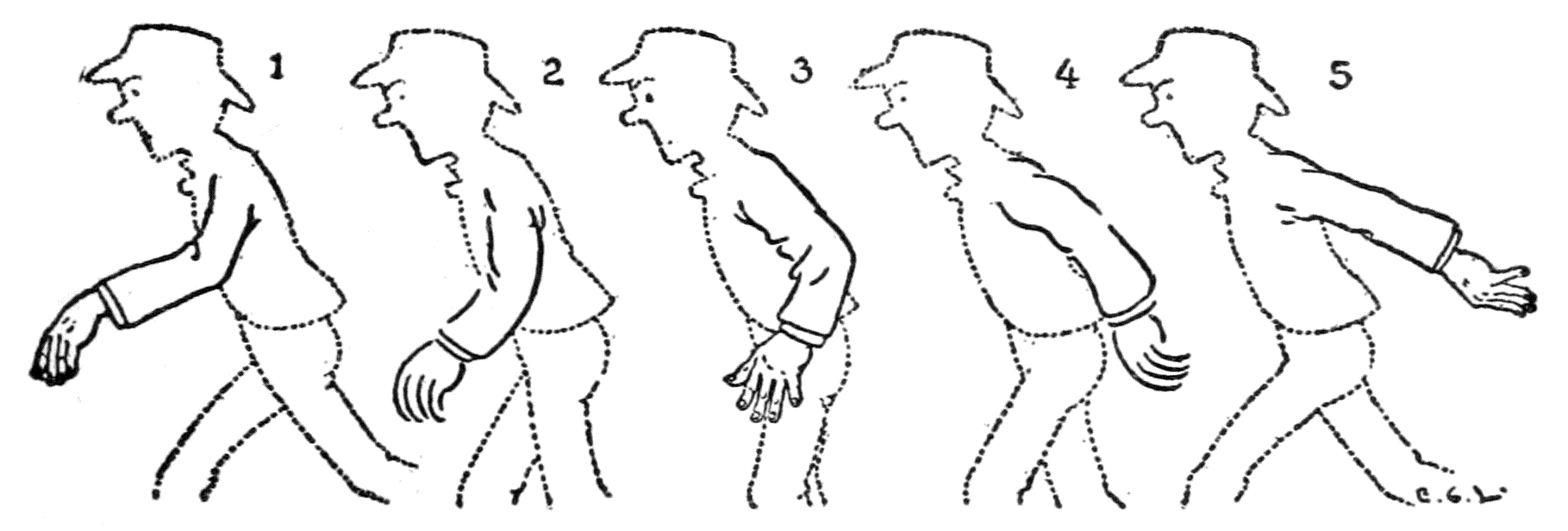

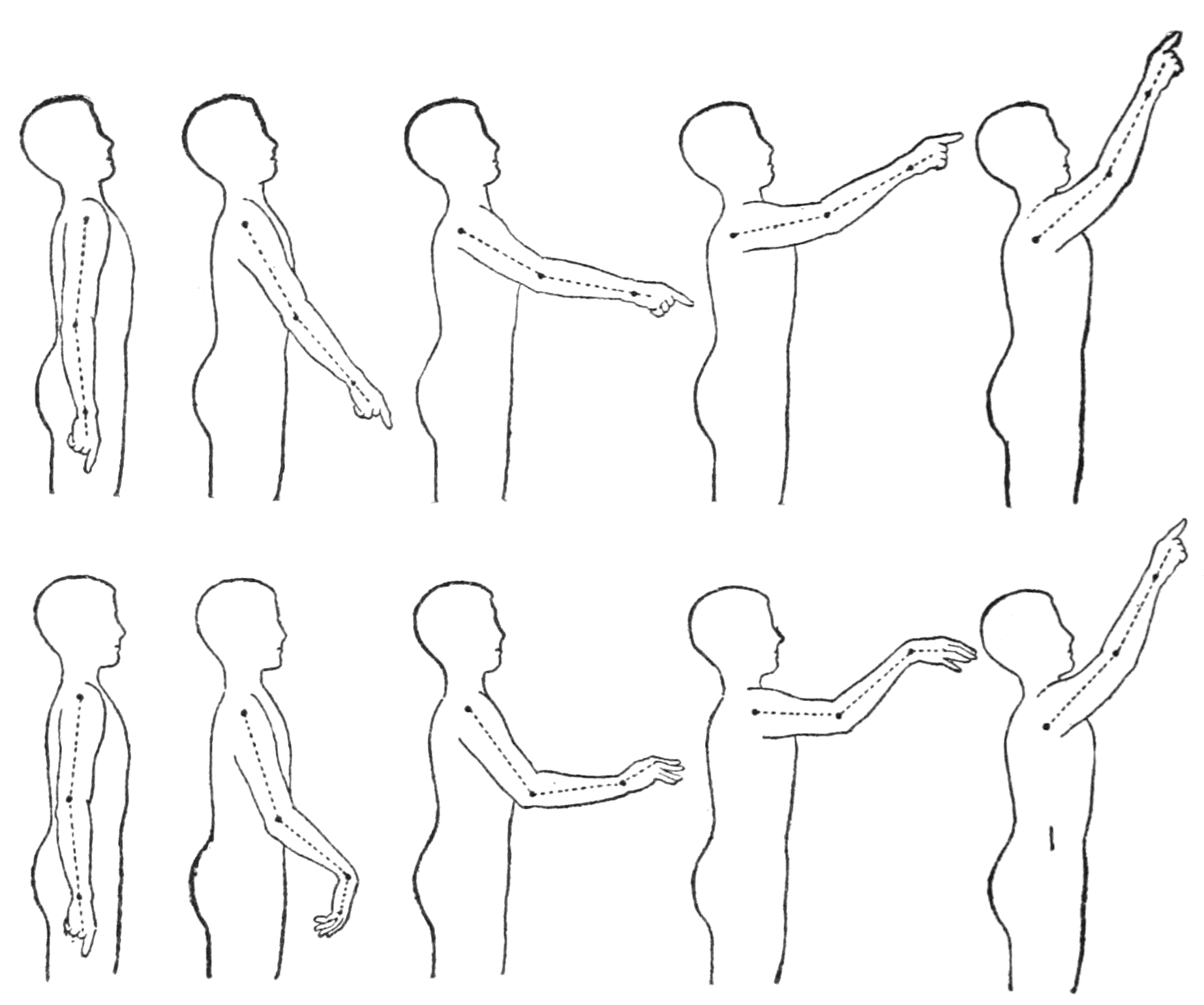

| Successive phases of movements of the legs in walking | 101 | |

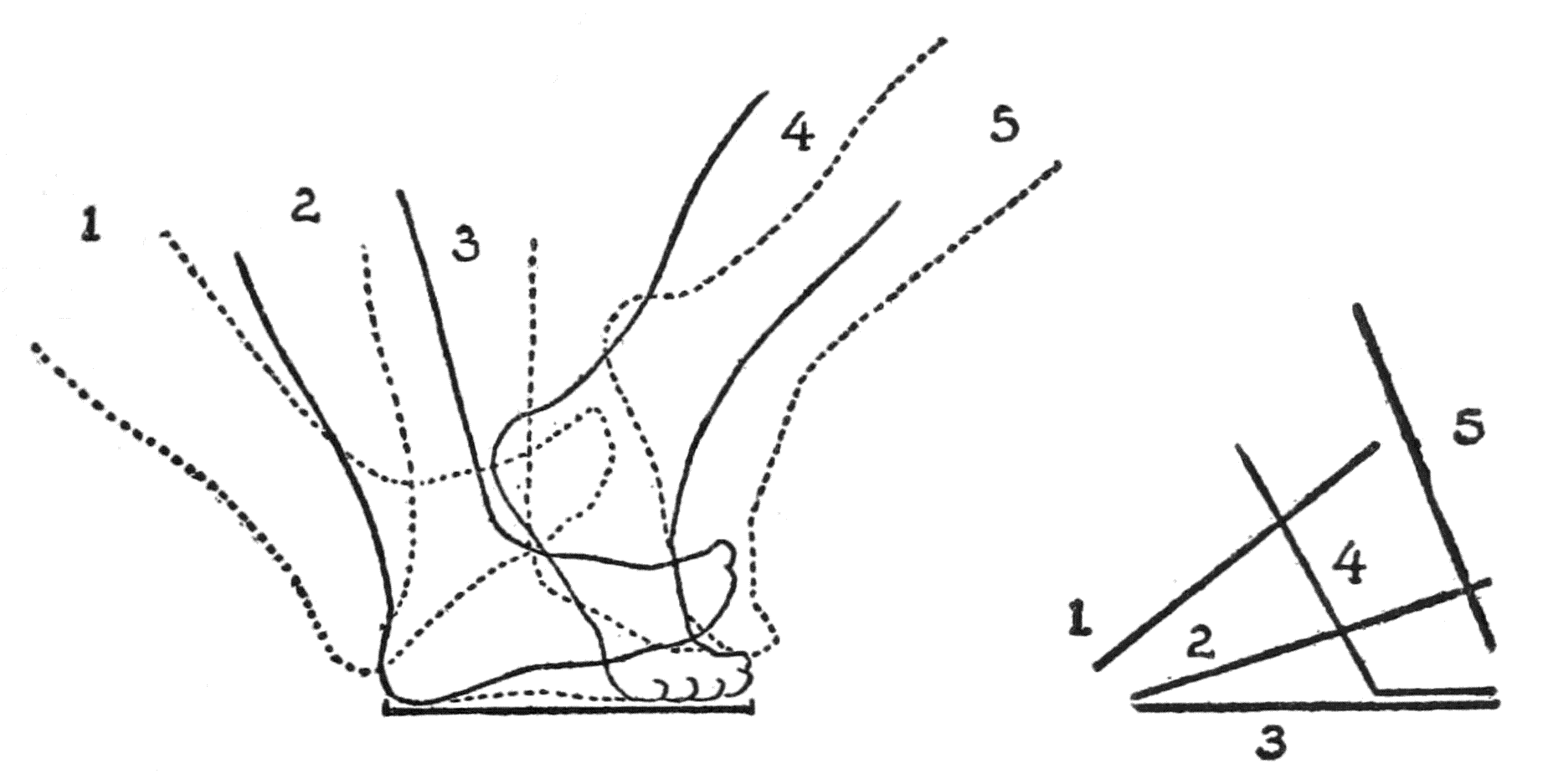

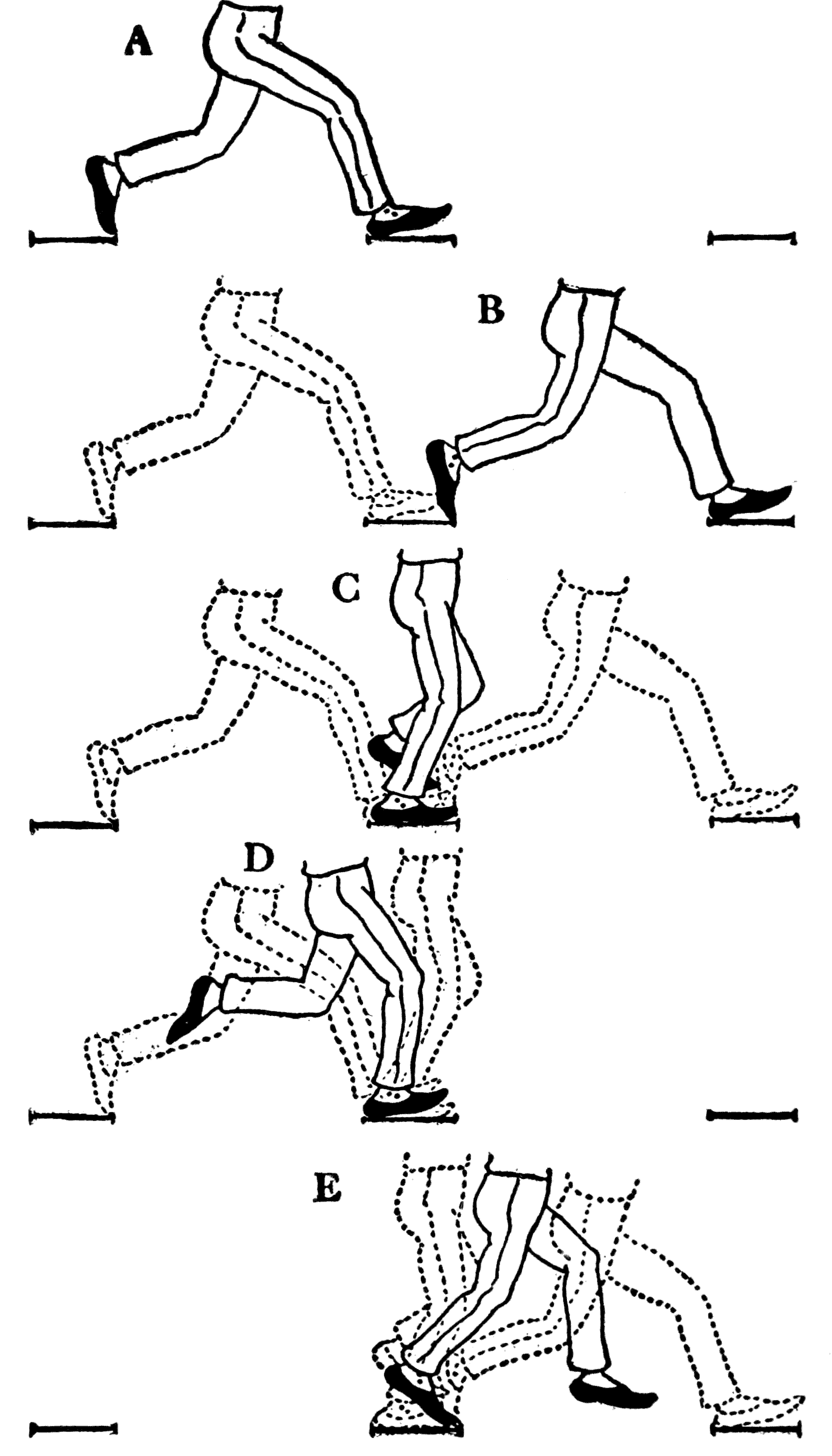

| Illustrating the action of the foot in rolling over the ground | 103 | |

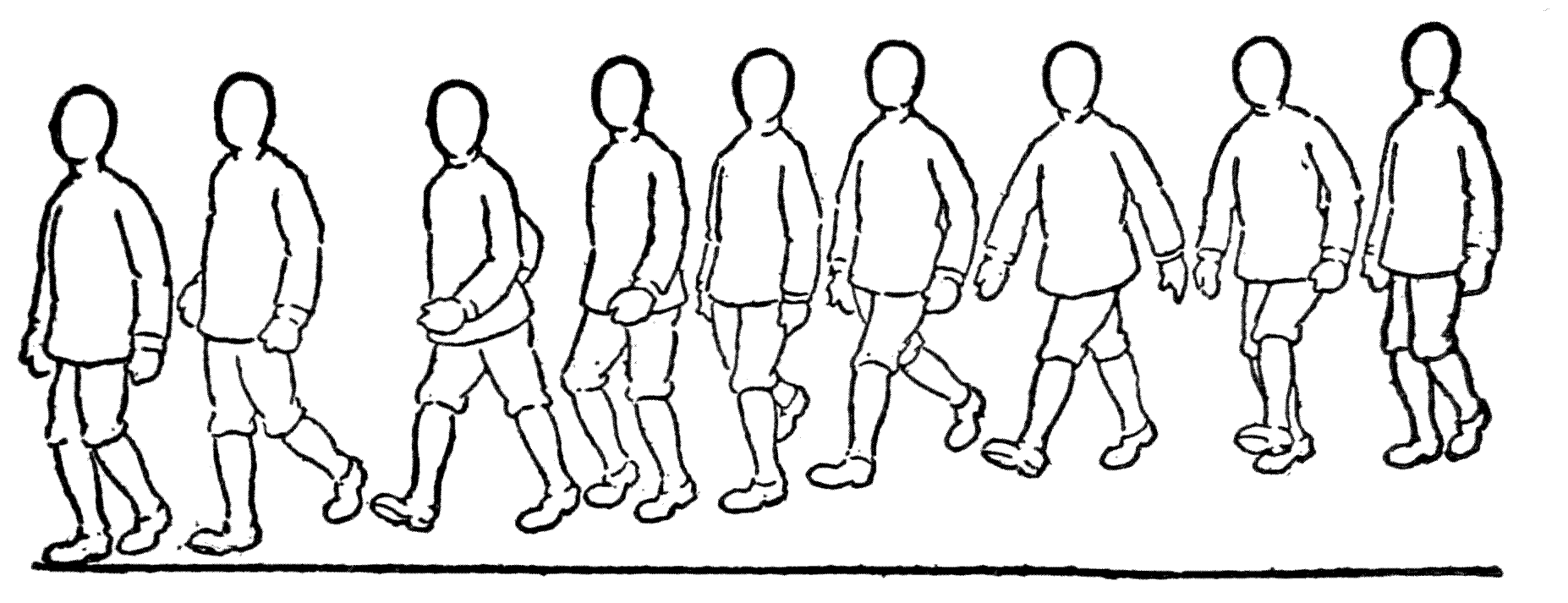

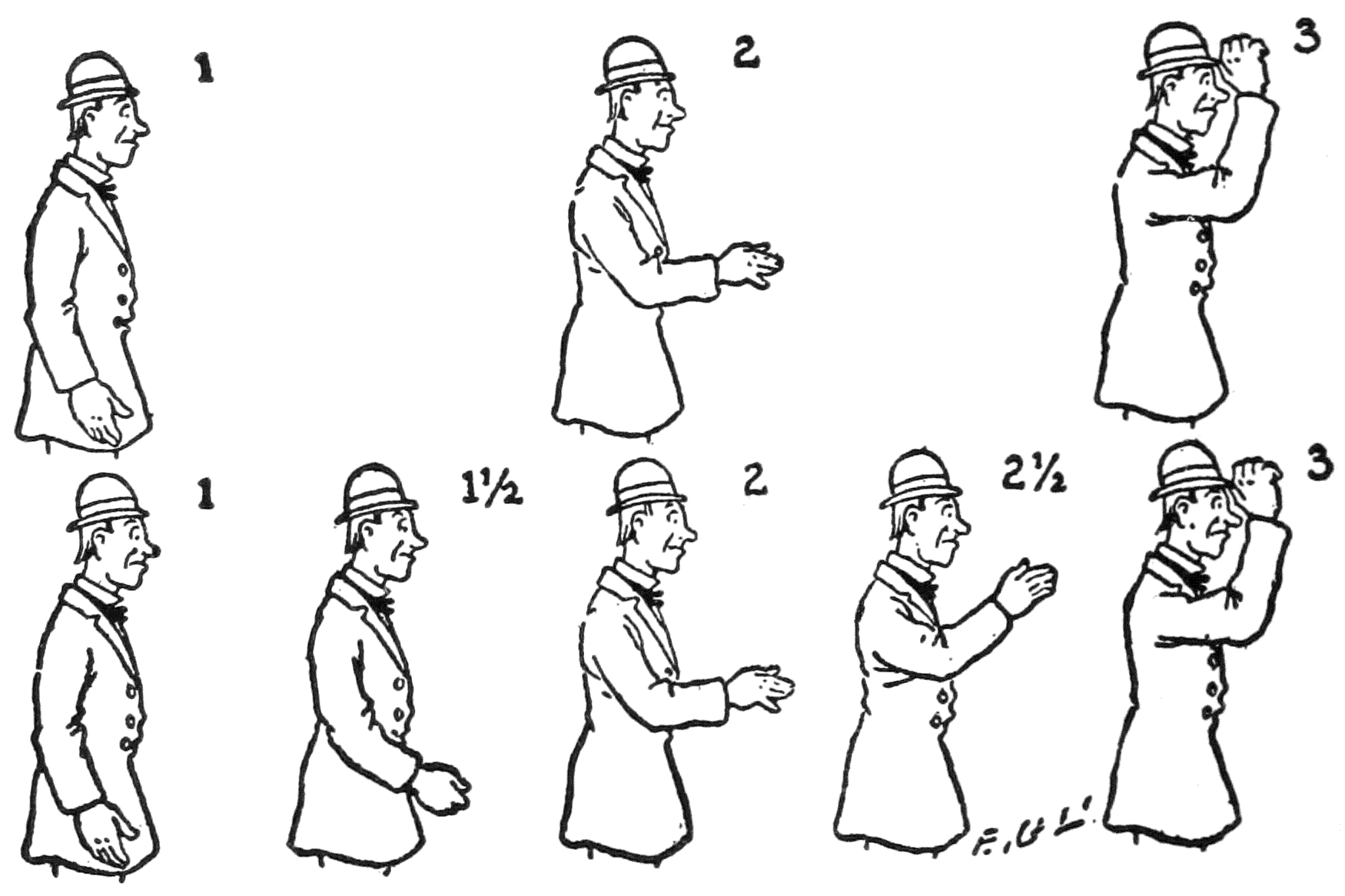

| Successive phases of movements in walking | 105 | |

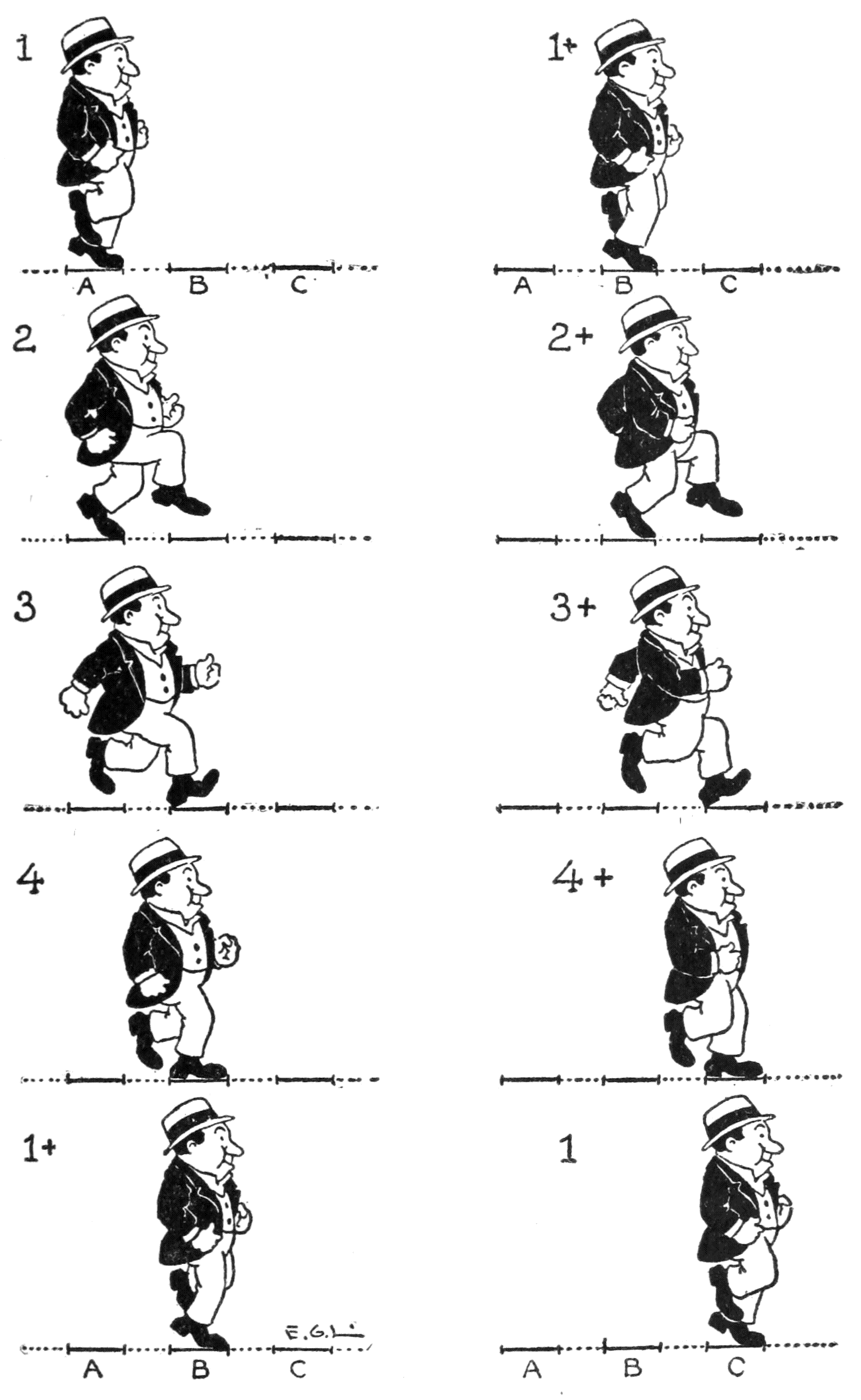

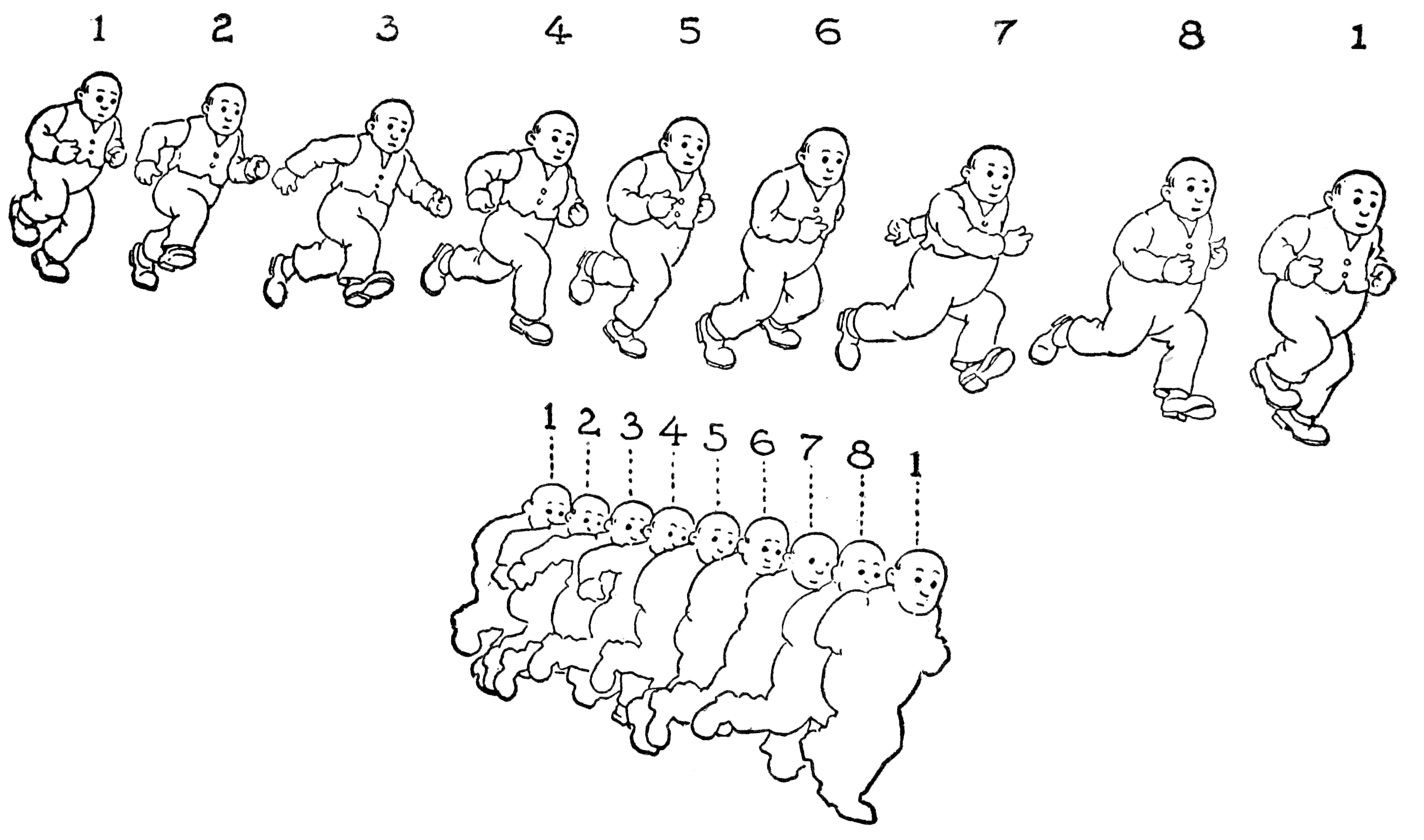

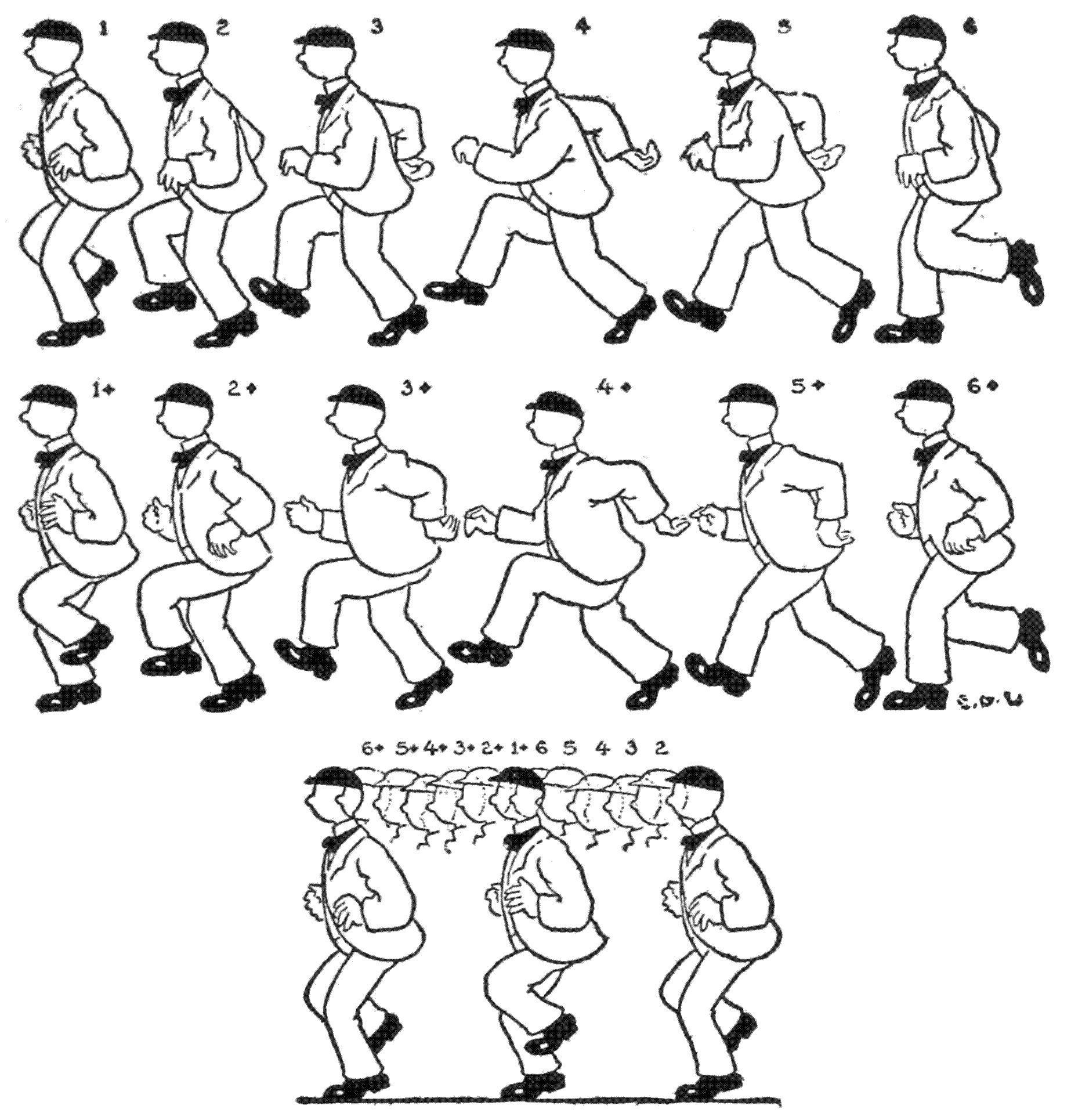

| Phases of movement of a quick walk | 107 | |

| Contractions and expansions as characteristic of motion | 109 | |

| Order in which an animator makes the sequence of positions for a walk | 112 and 113 | |

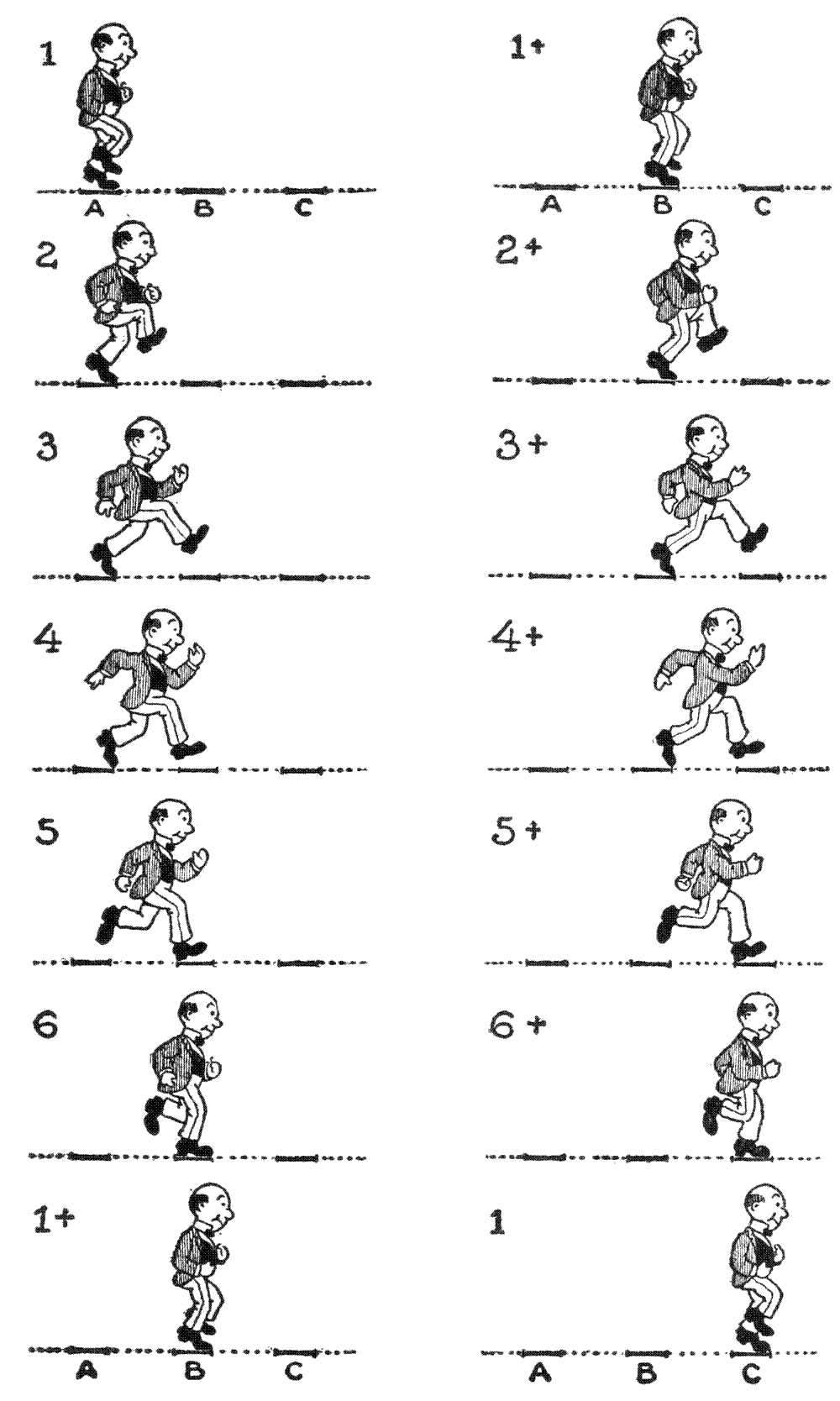

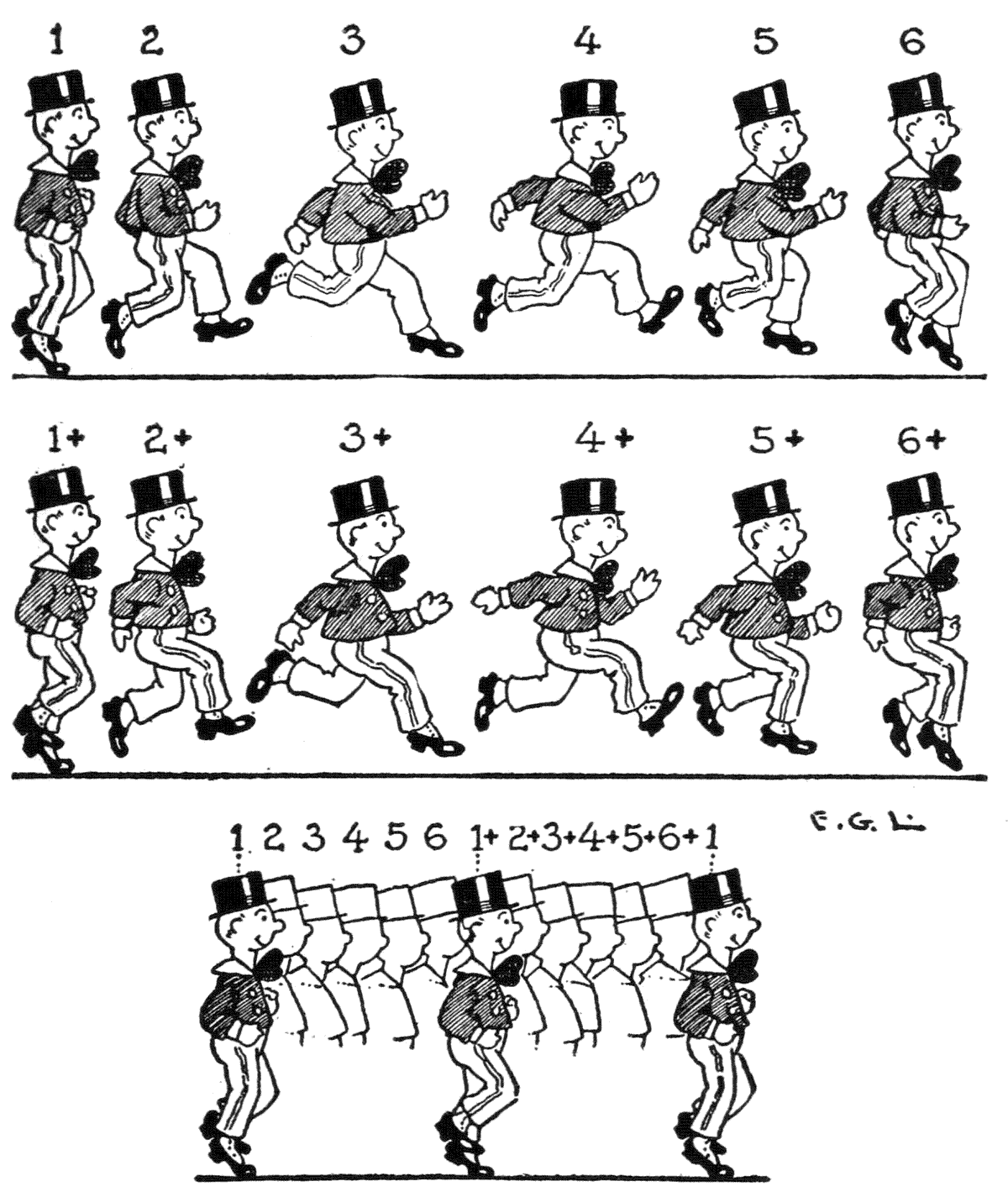

| Phases of movement of a walk. Six phases complete a step | 115 | |

| A perspective walk | 117 | |

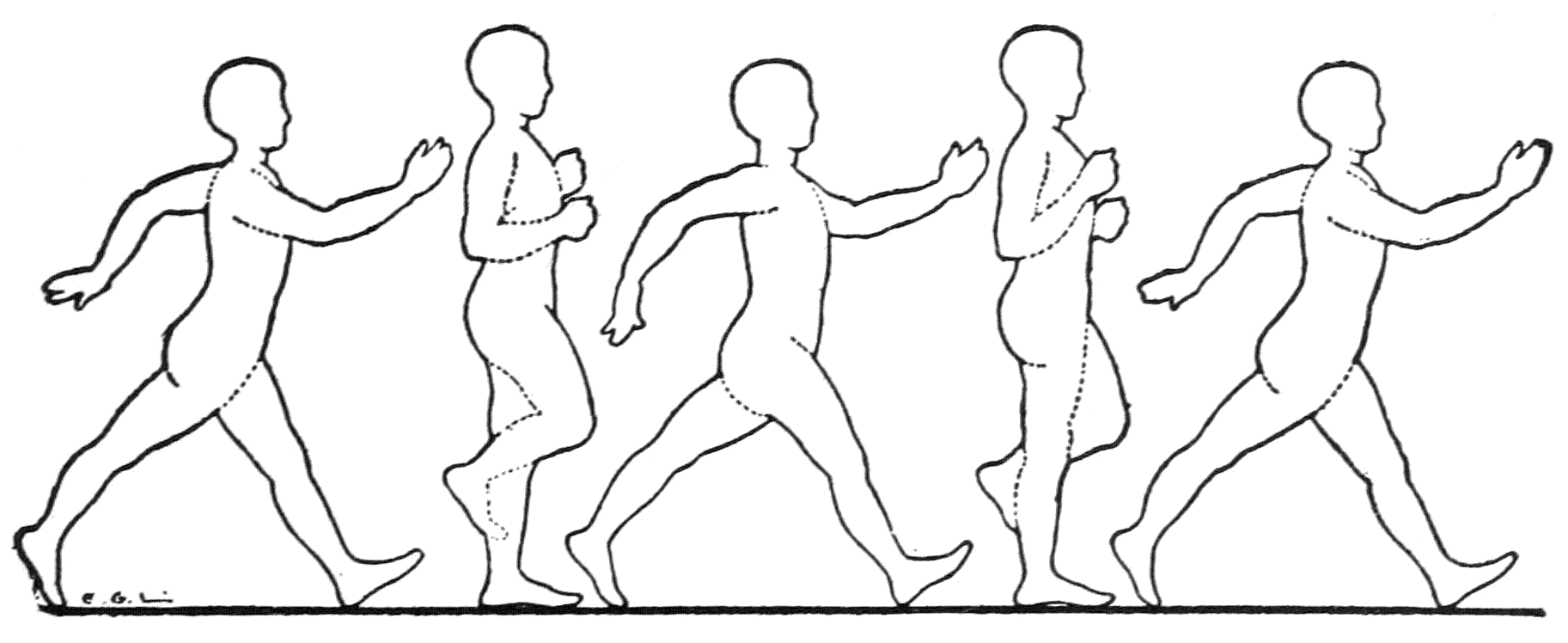

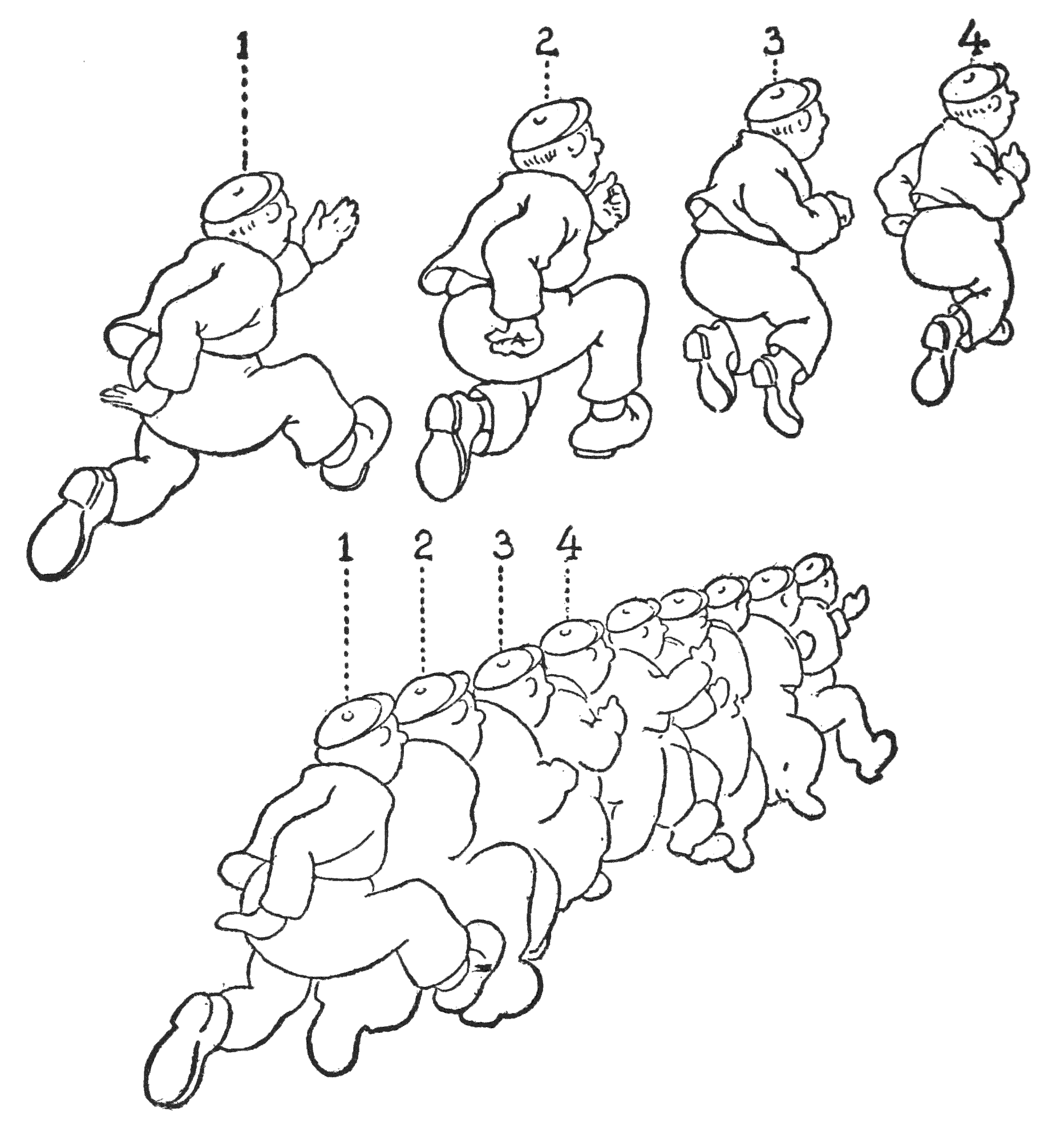

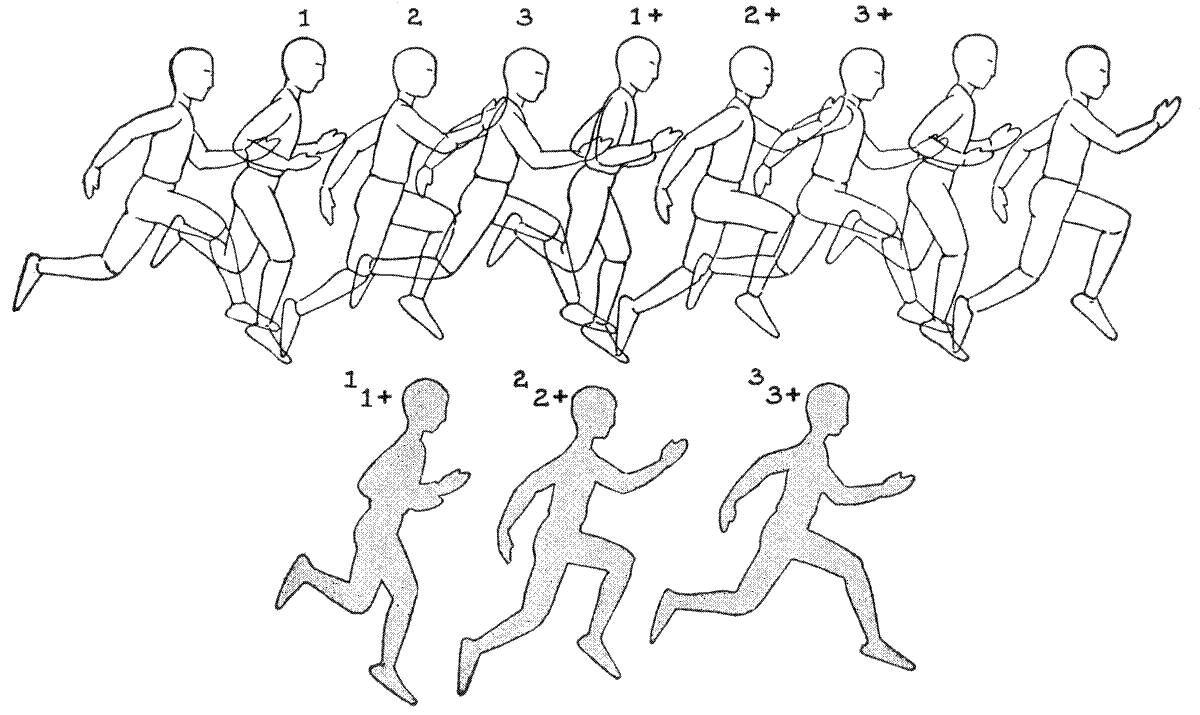

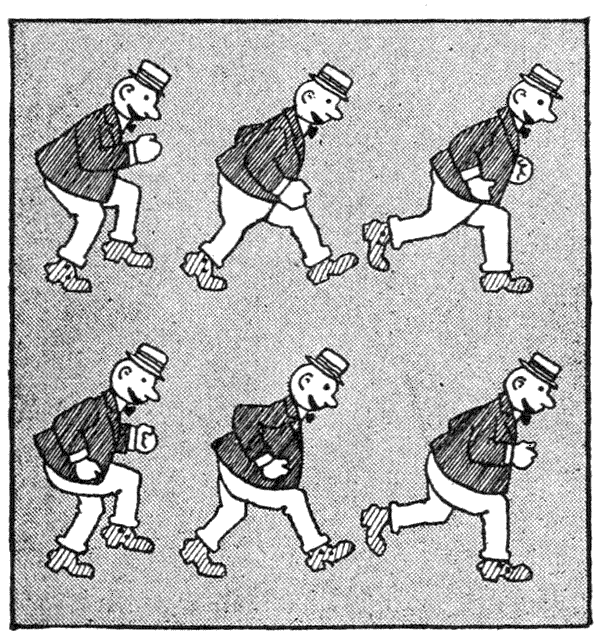

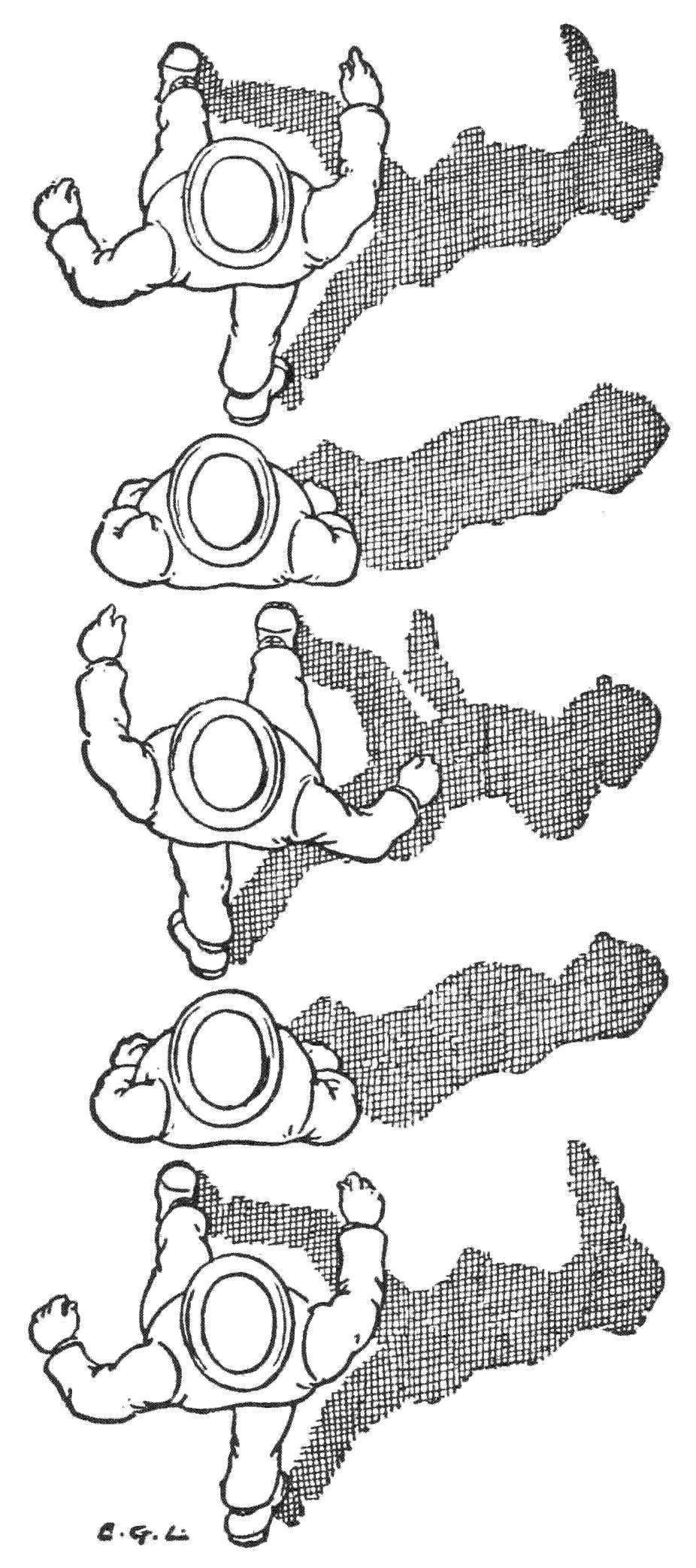

| Four positions for a perspective run | 118 | |

| Phases of movement for a perspective run | 119 | |

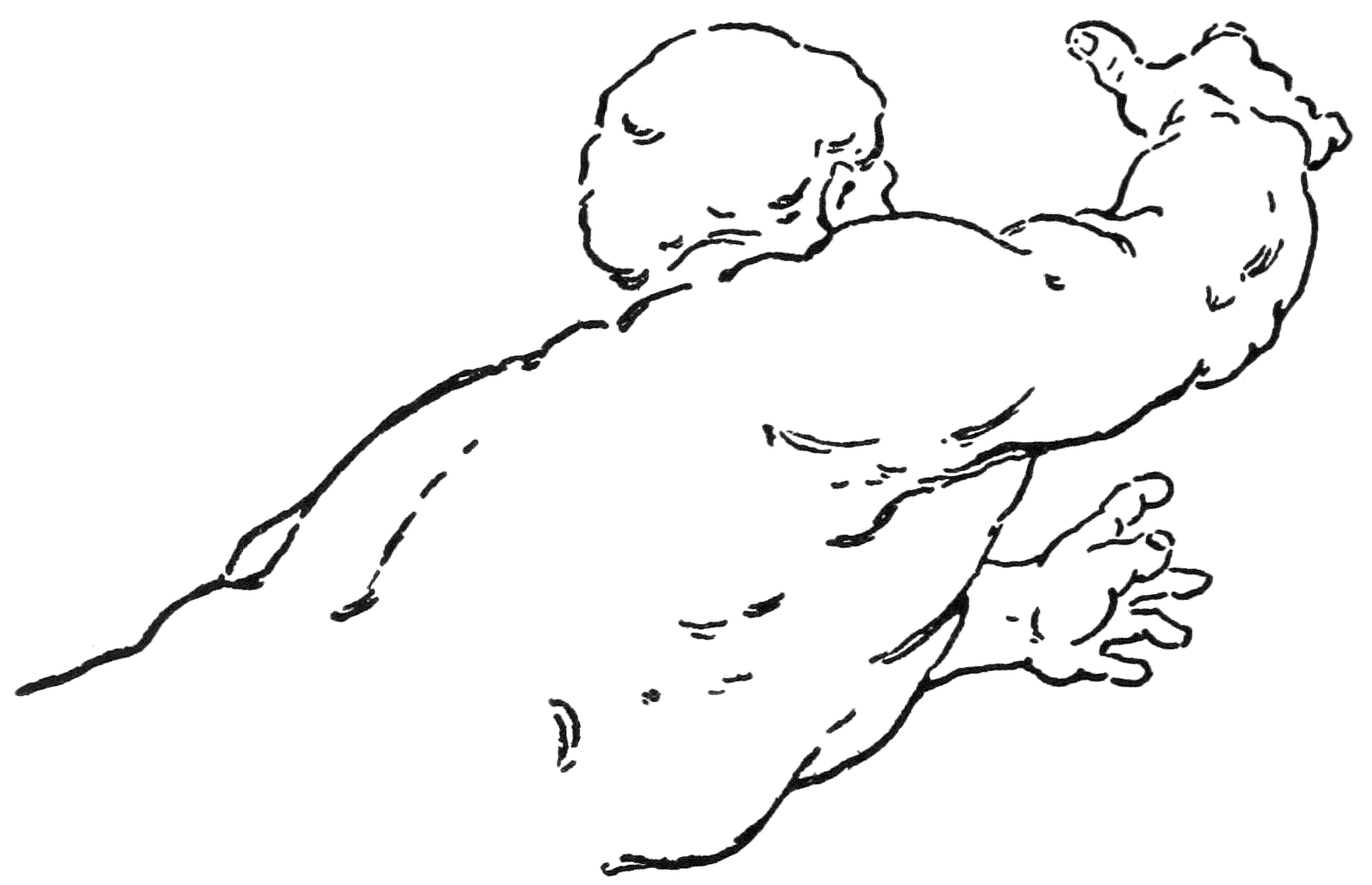

| Running figure | 121 | |

| Phases of movement for a quick walk | 123 | |

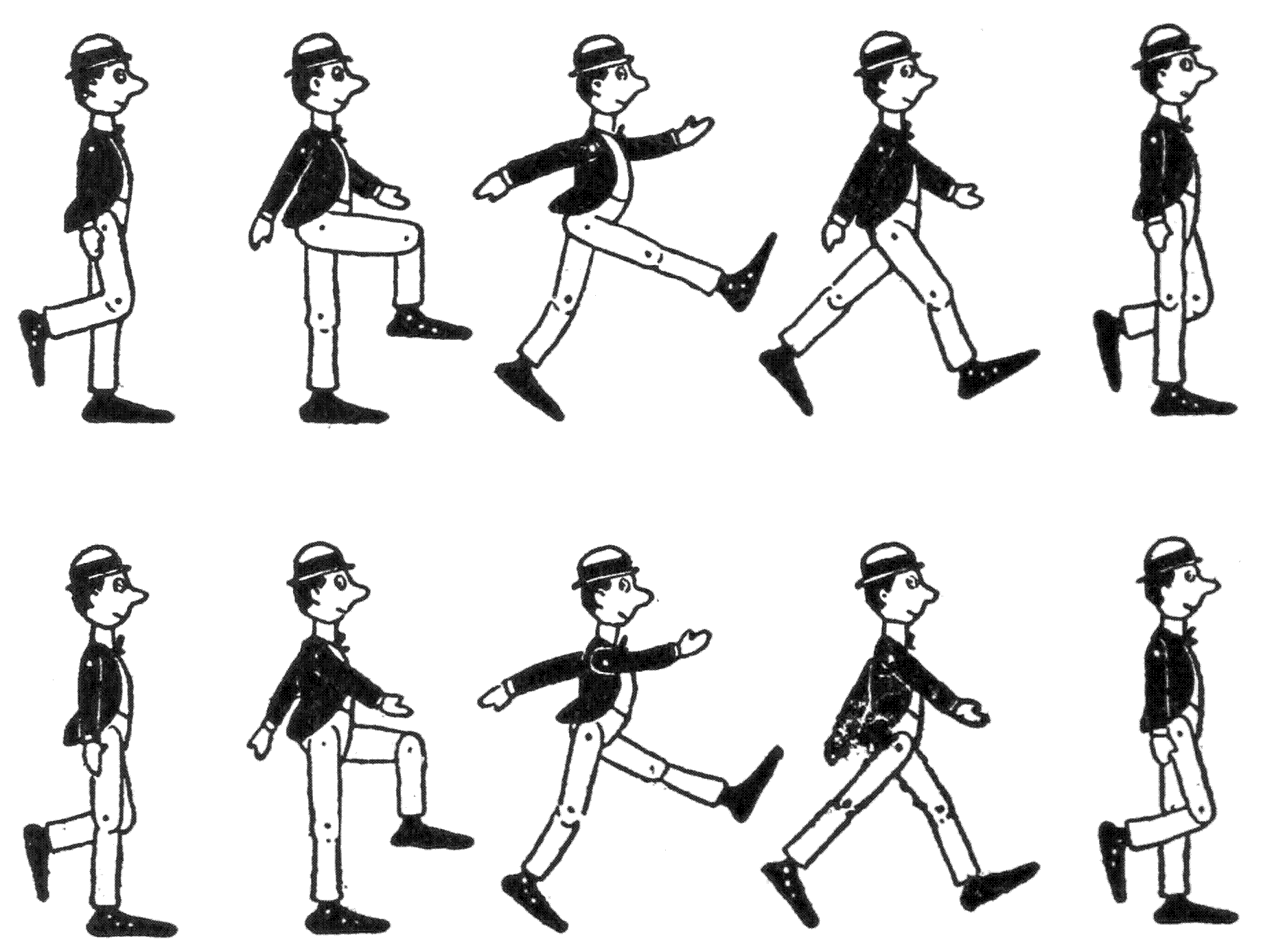

| Walking movements, somewhat mechanical | 124 | |

| Phases of movement for a lively walk | 125 | |

| Phases of movement for a quick walk | 127 | |

| Walking movements viewed from above | 128 | |

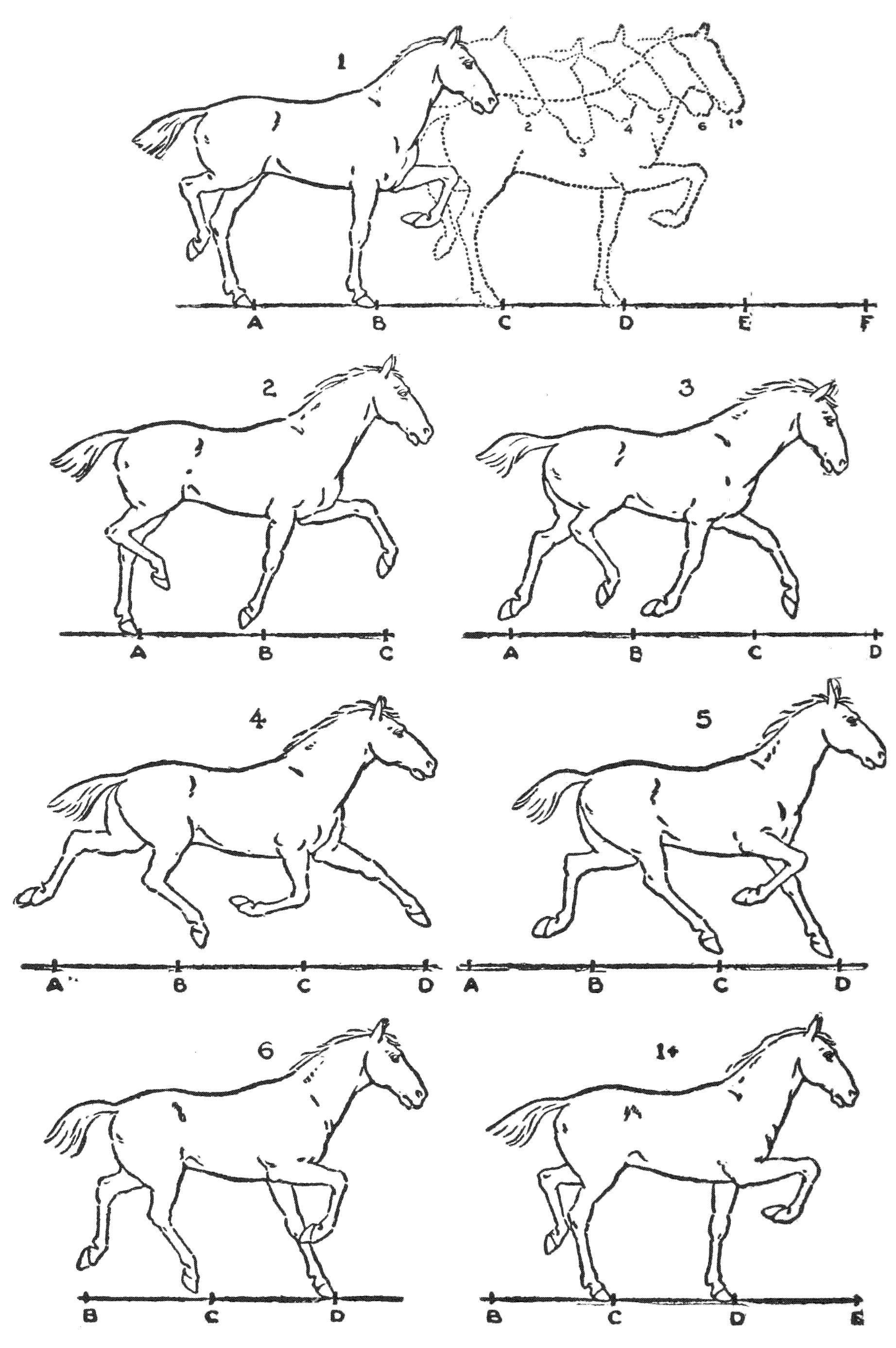

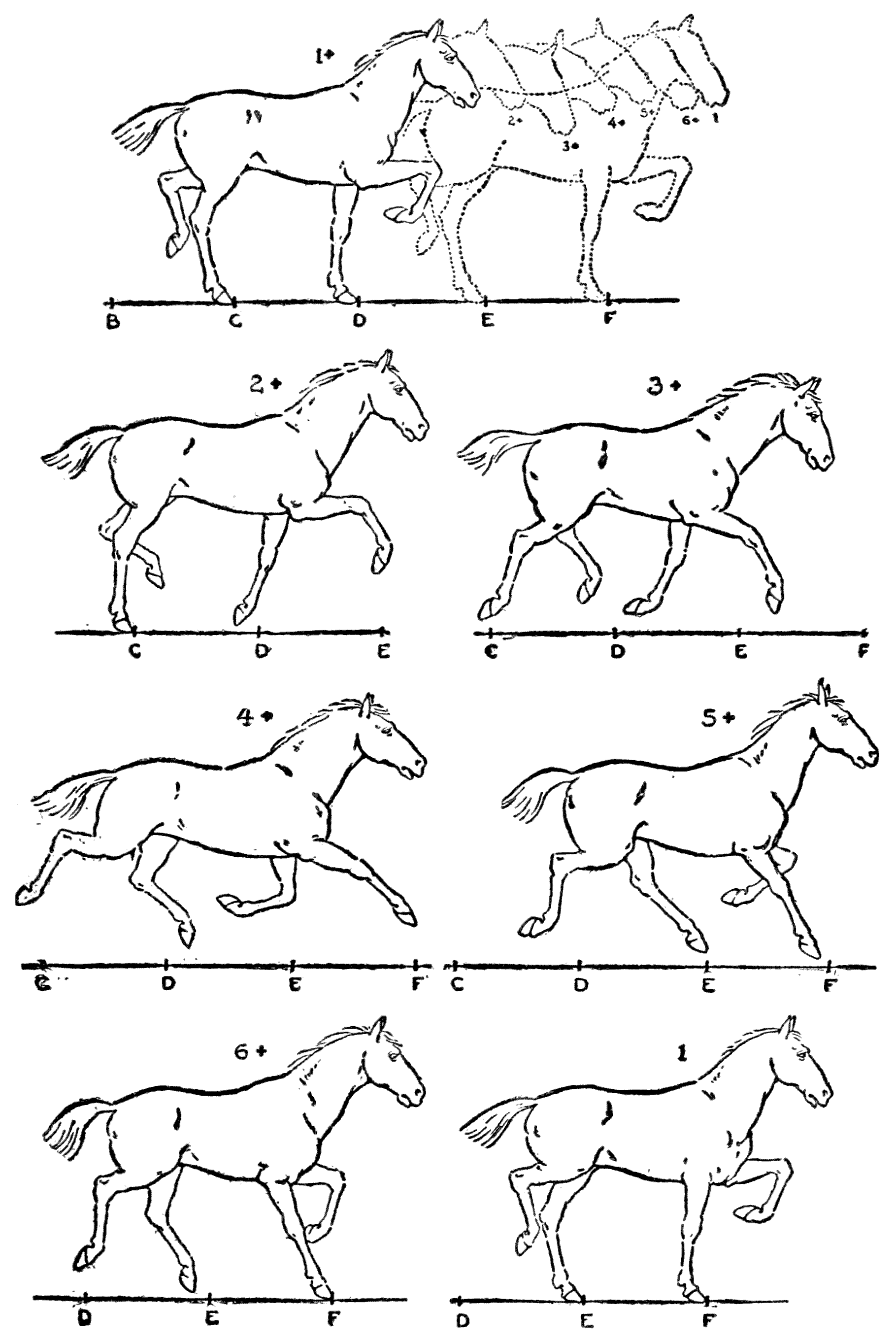

| Trotting horse | 134 | |

| Trotting horse (continued) | 135[xviii] | |

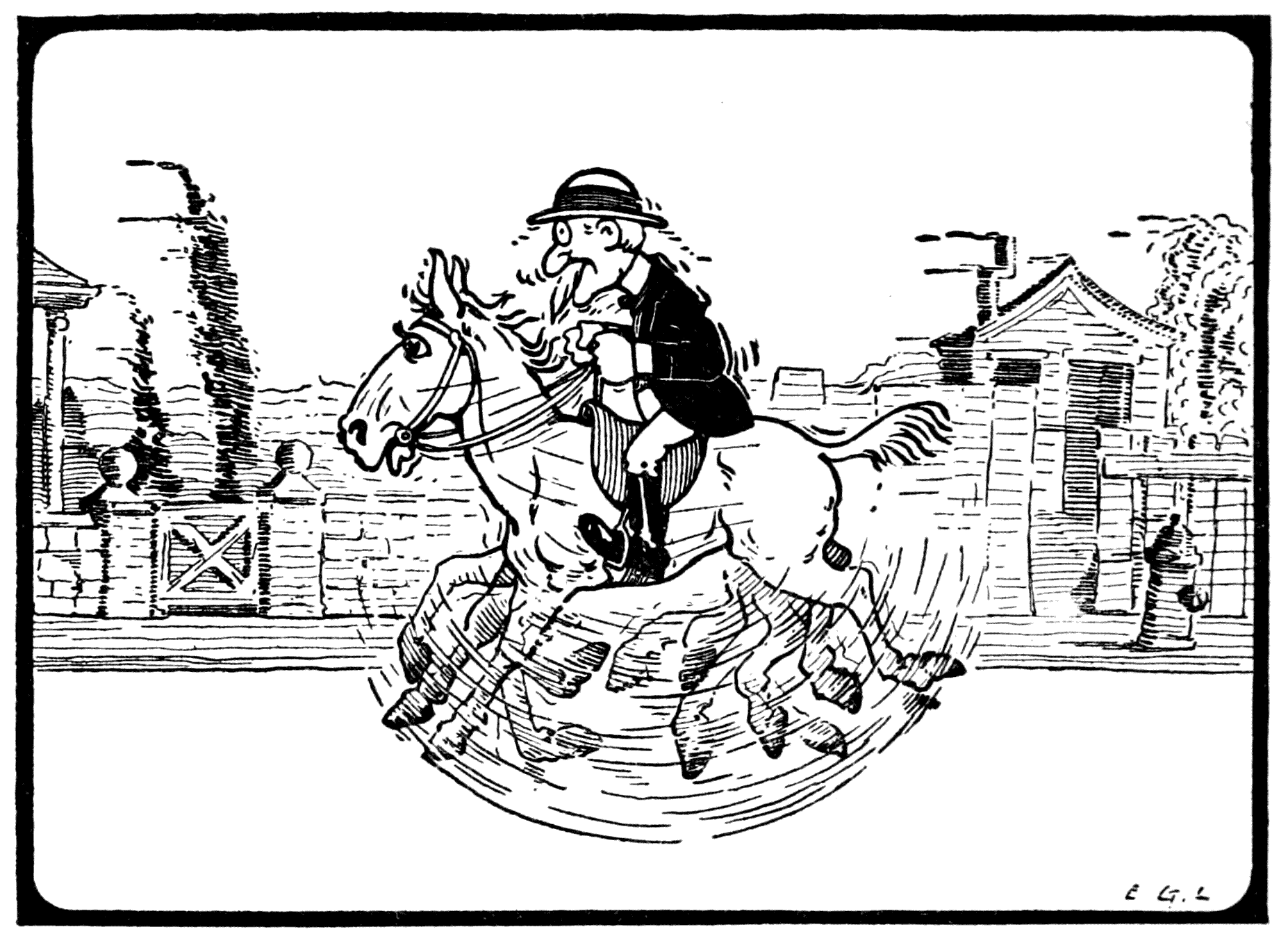

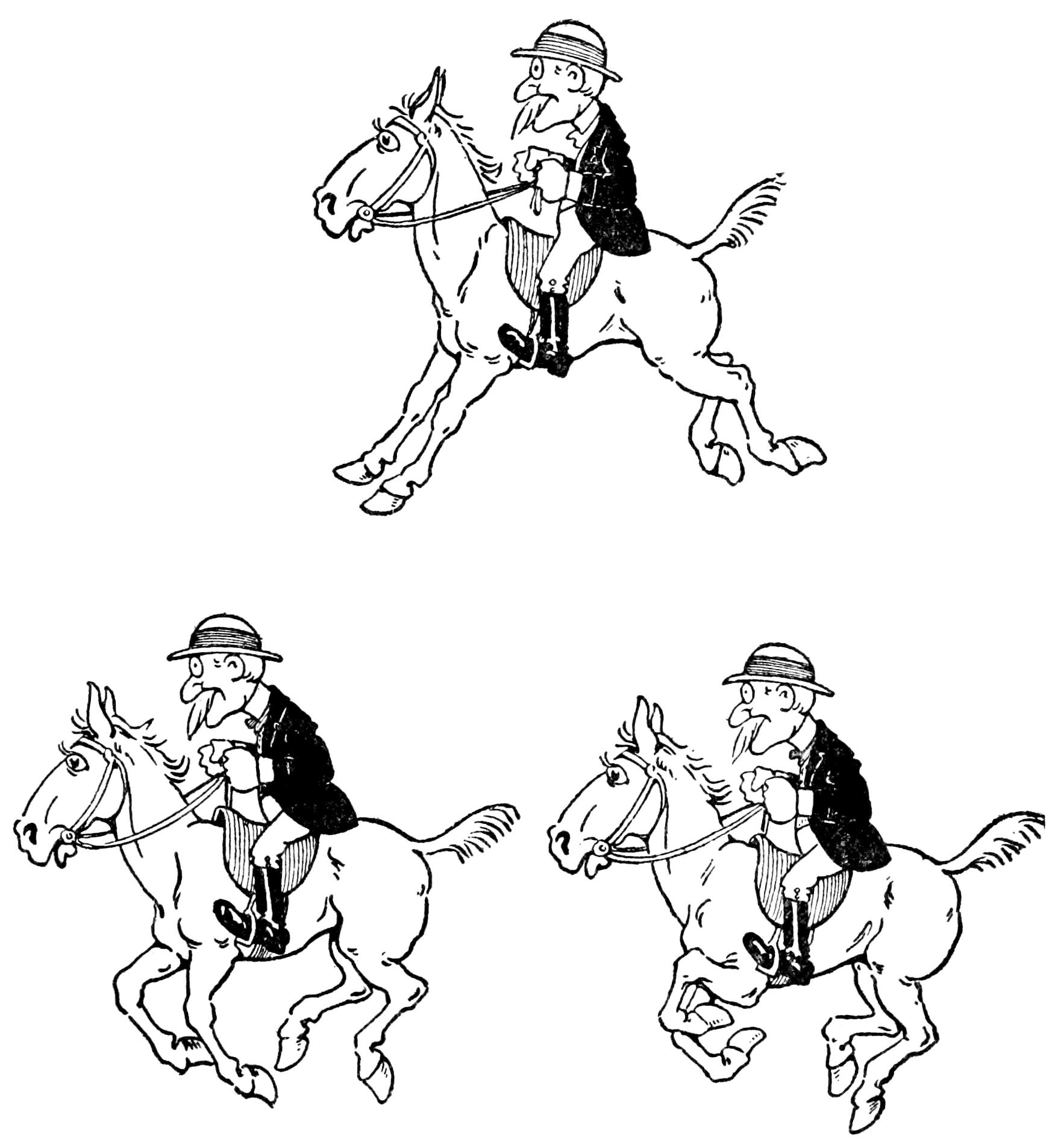

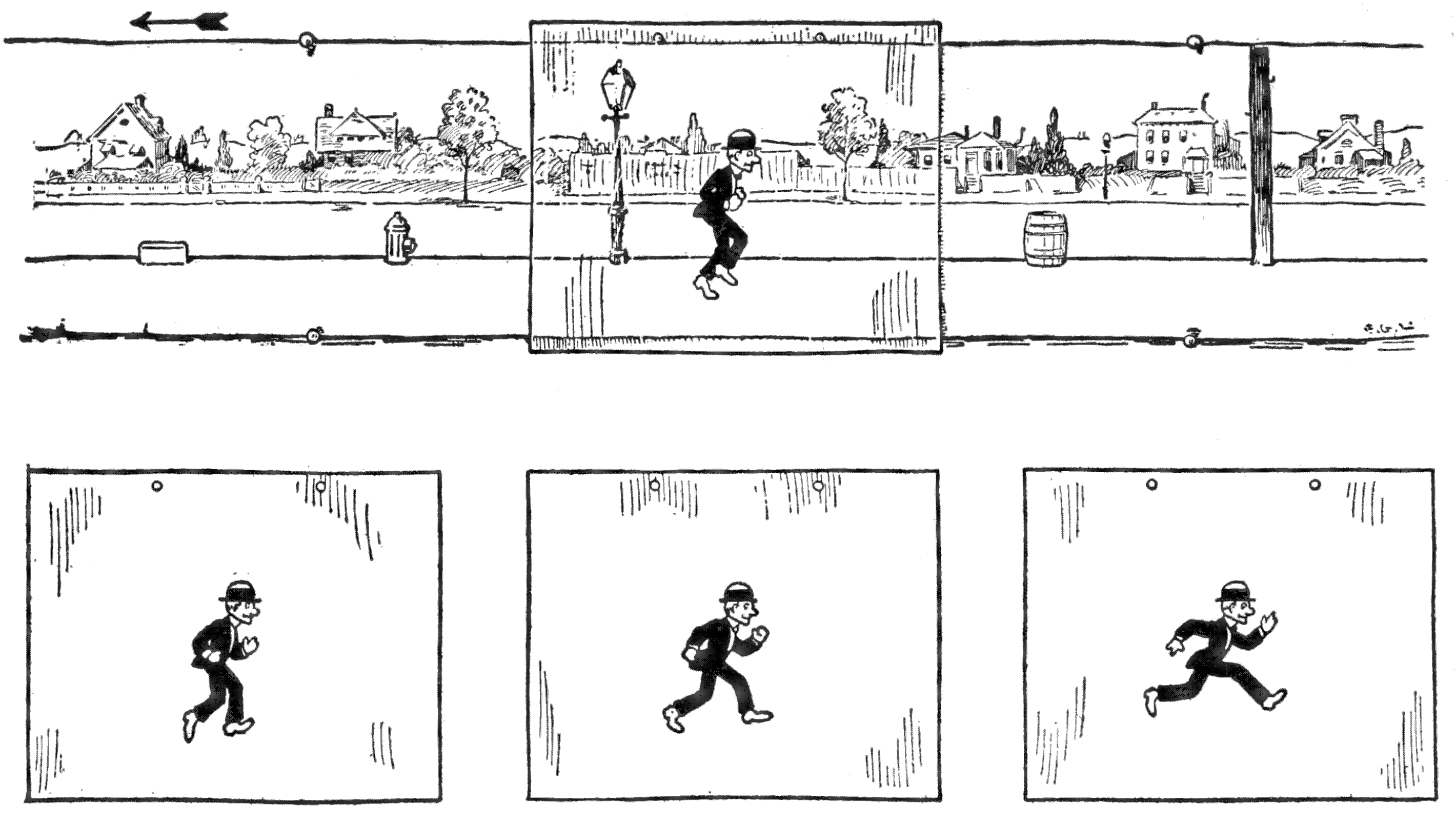

| A panorama effect | 138 | |

| Galloping horse for a panorama effect | 139 | |

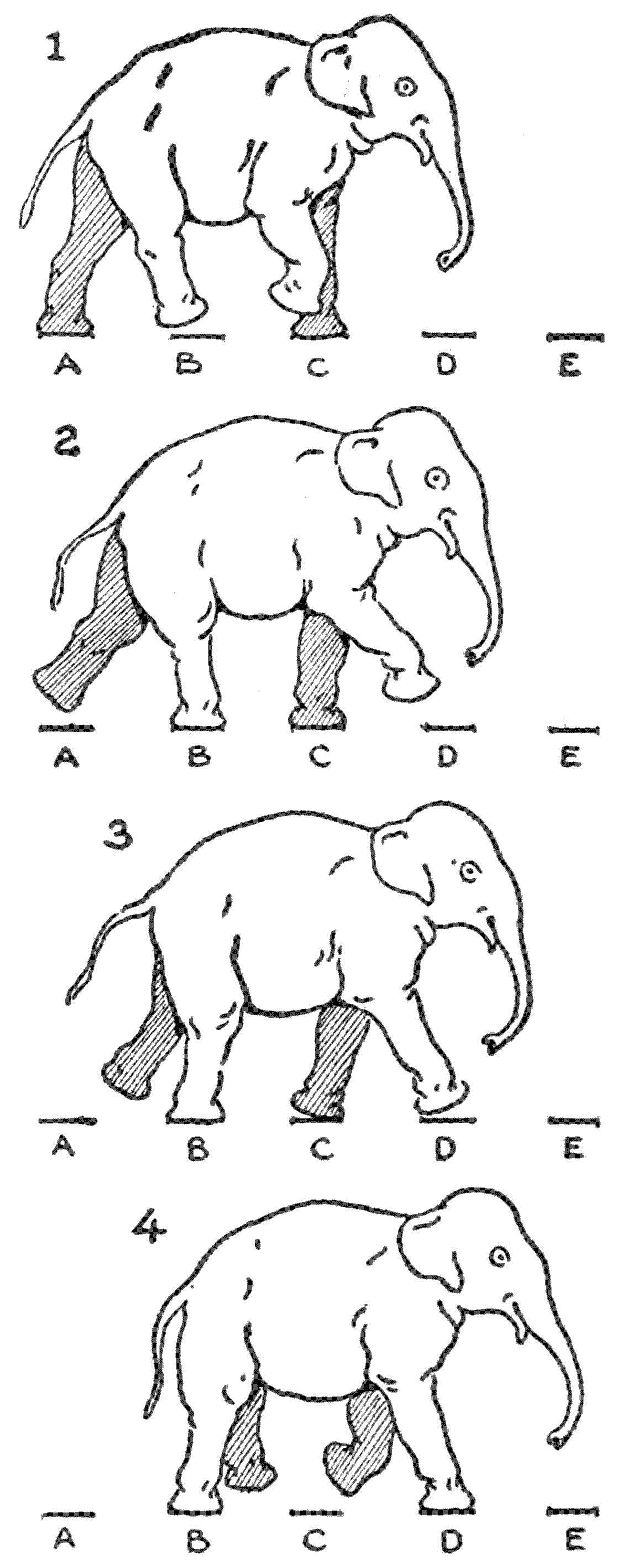

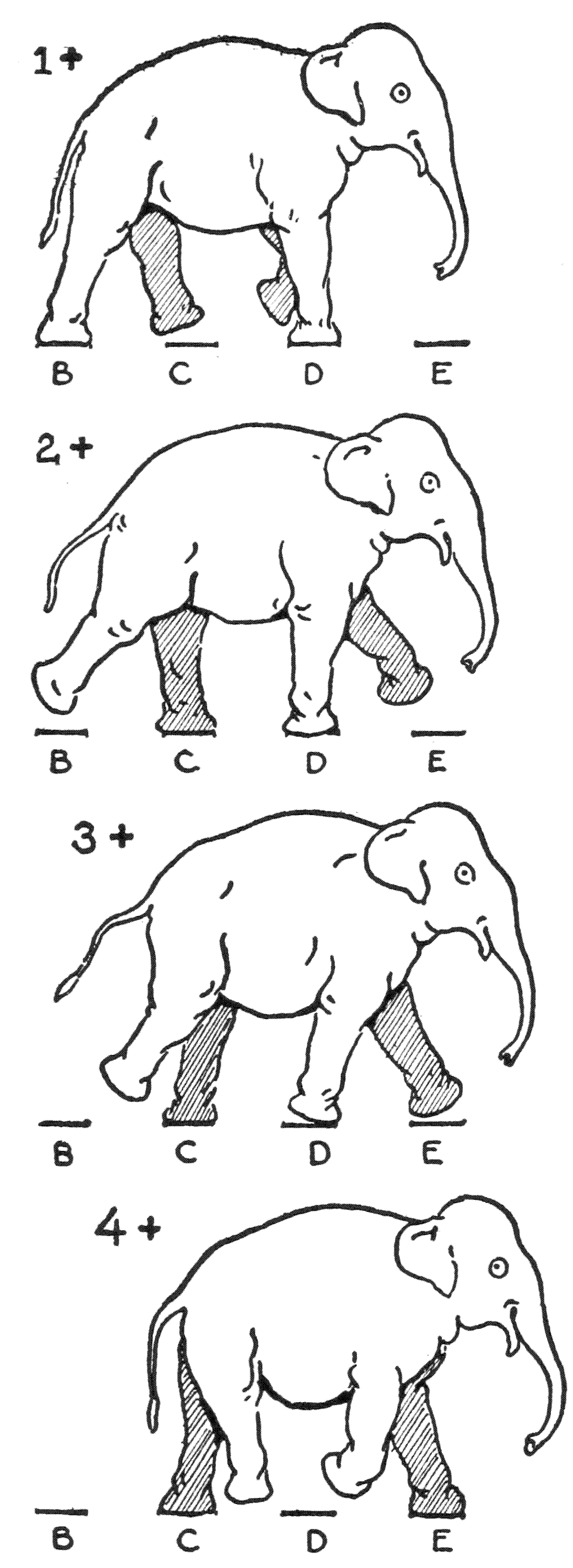

| The elephant in motion | 140 | |

| The elephant in motion (continued) | 141 | |

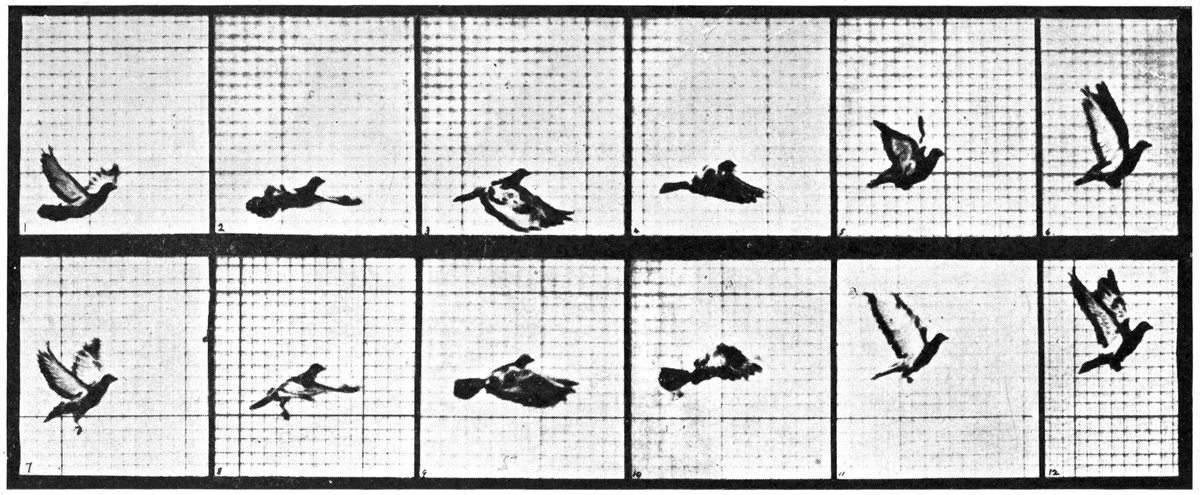

| Pigeon in flight; from Muybridge | Facing page 142 | |

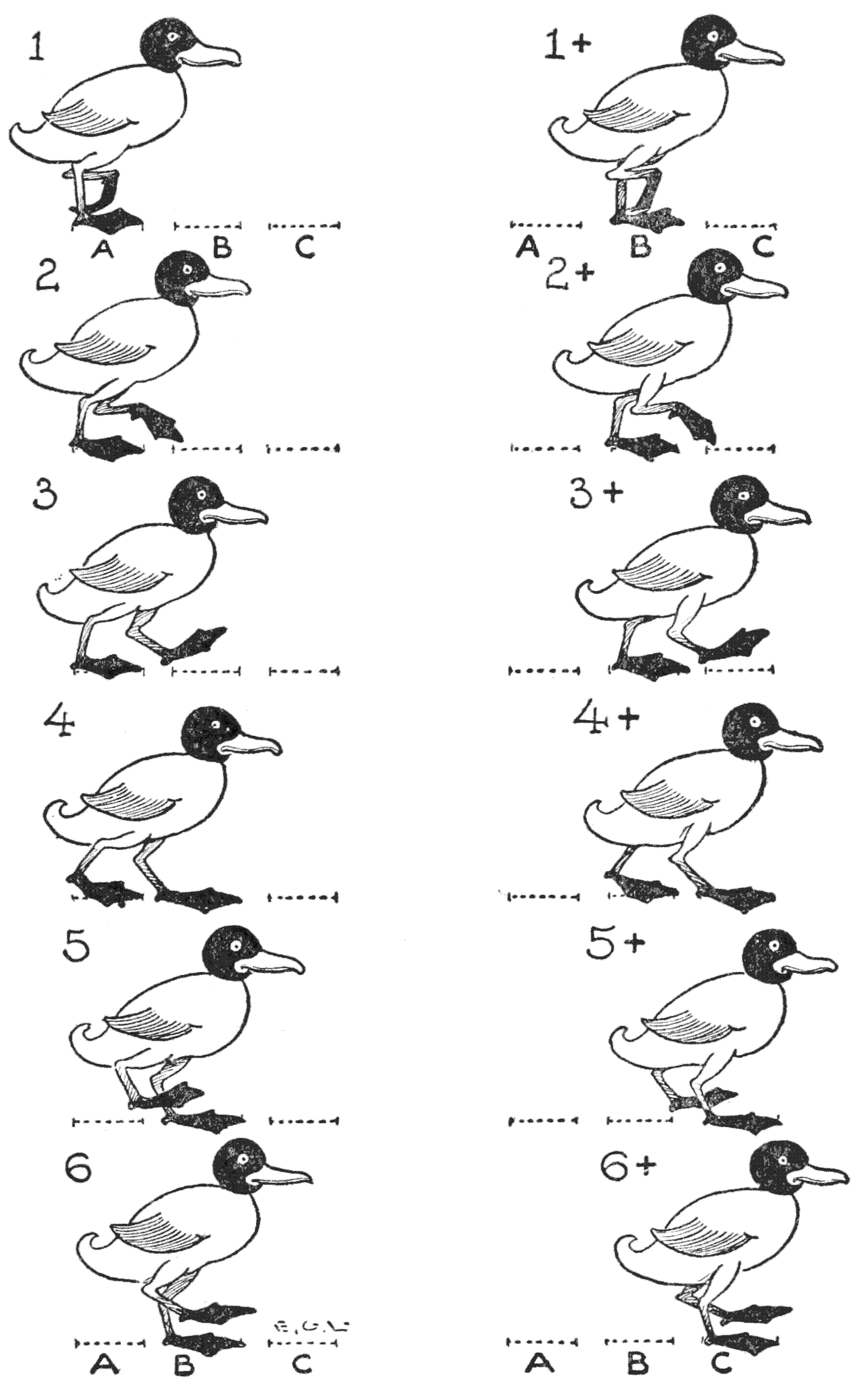

| Comic walk of a duck | 143 | |

| Cycle of phases of a walking dog arranged for the phenakistoscope | 144 | |

| Phenakistoscope with a cycle of drawings to show a dog in movement | 145 | |

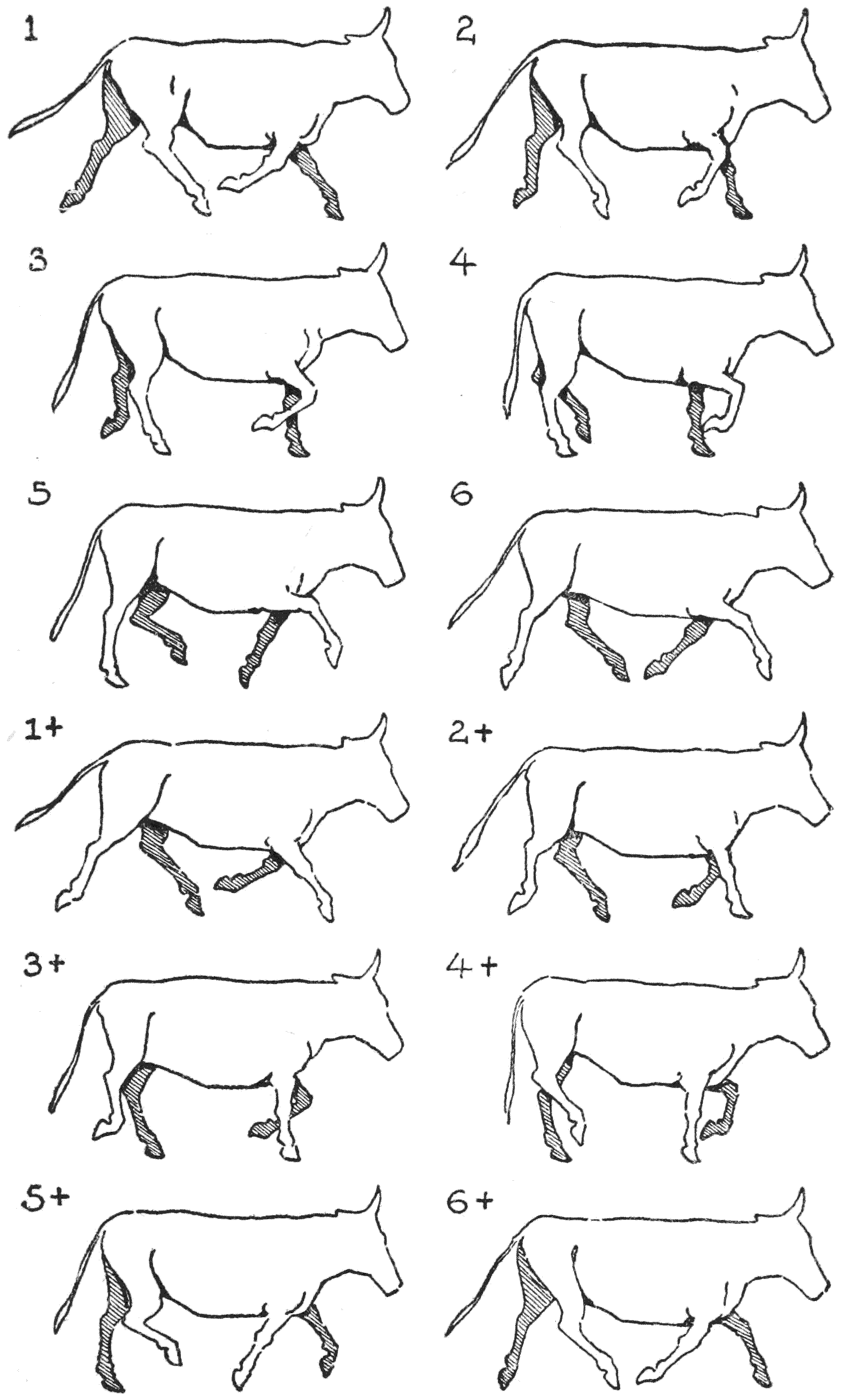

| Running cow | 147 | |

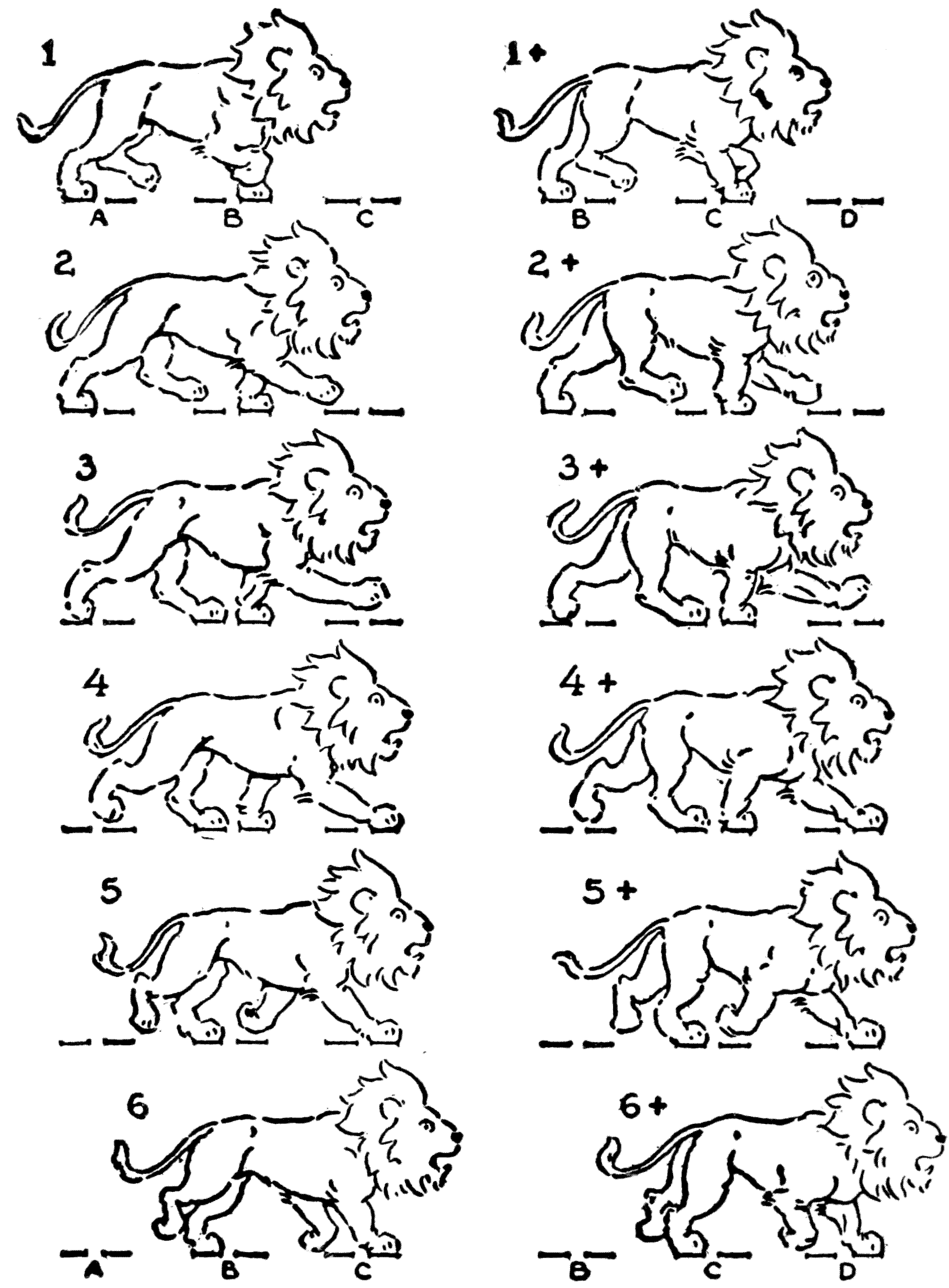

| Phases of movement of a walking lion | 148 | |

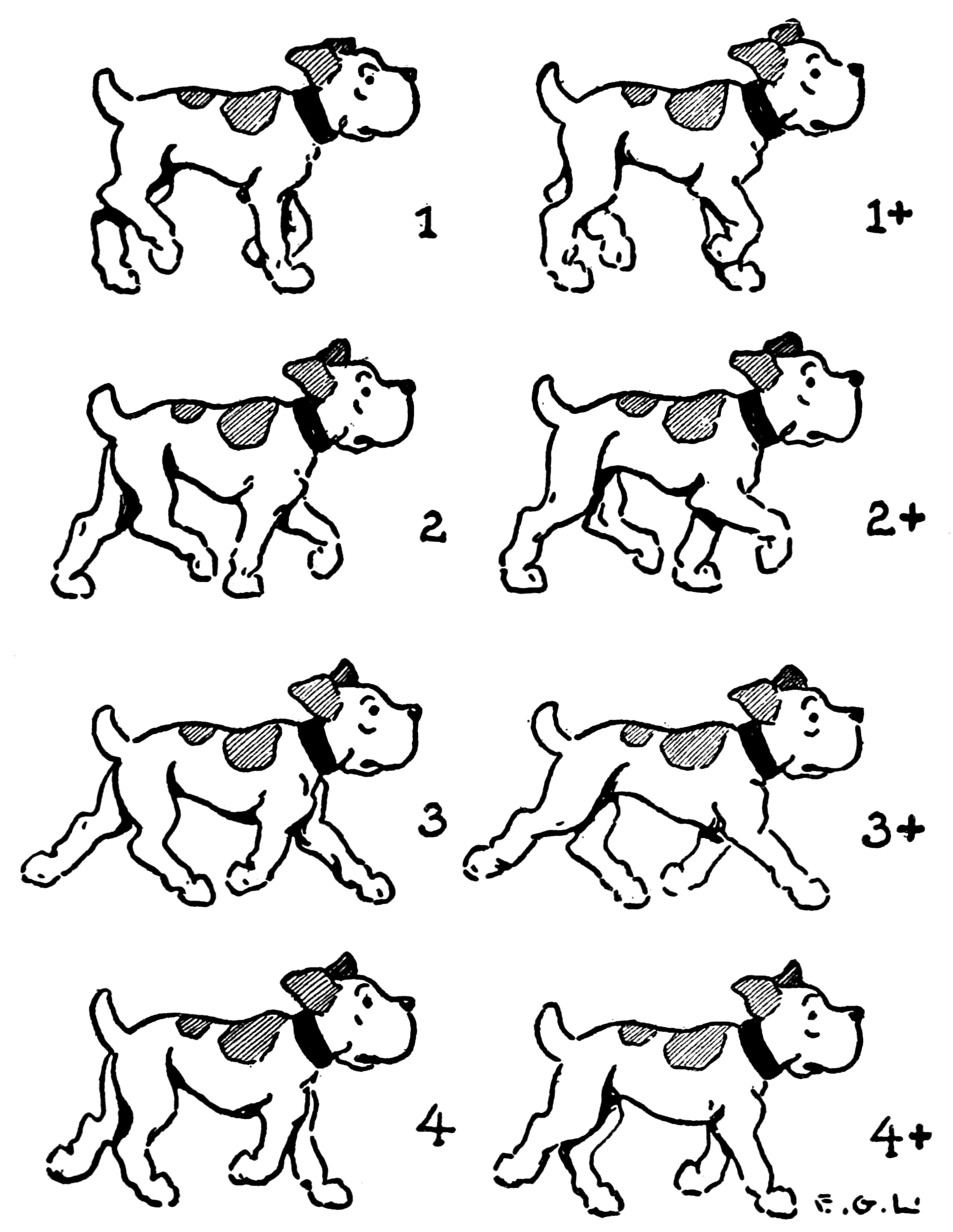

| Dog walking | 149 | |

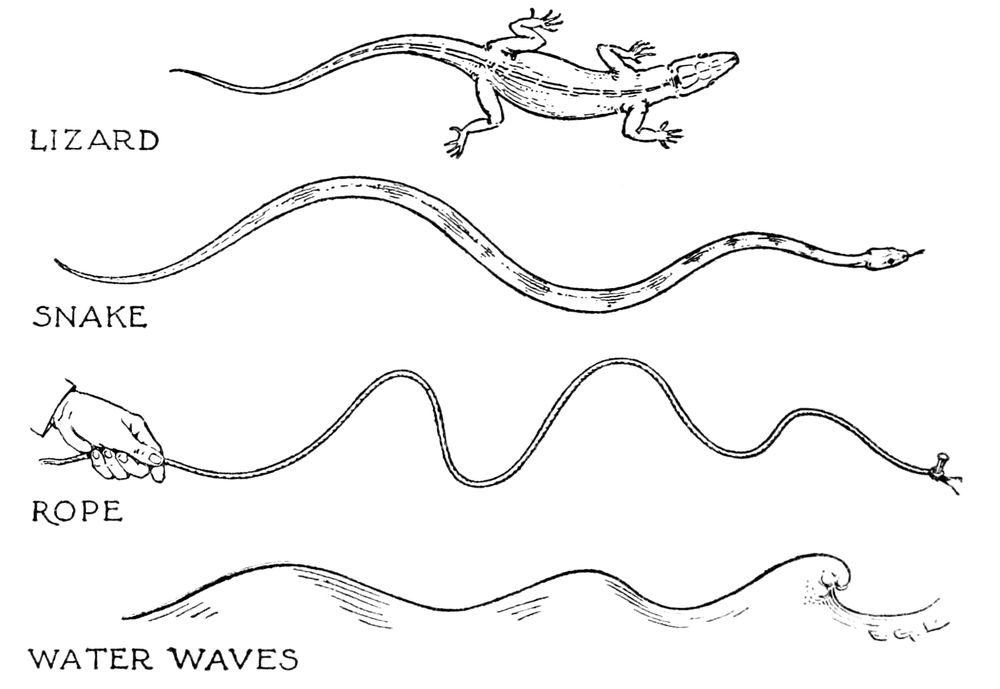

| Various kinds of wave motion | 150 | |

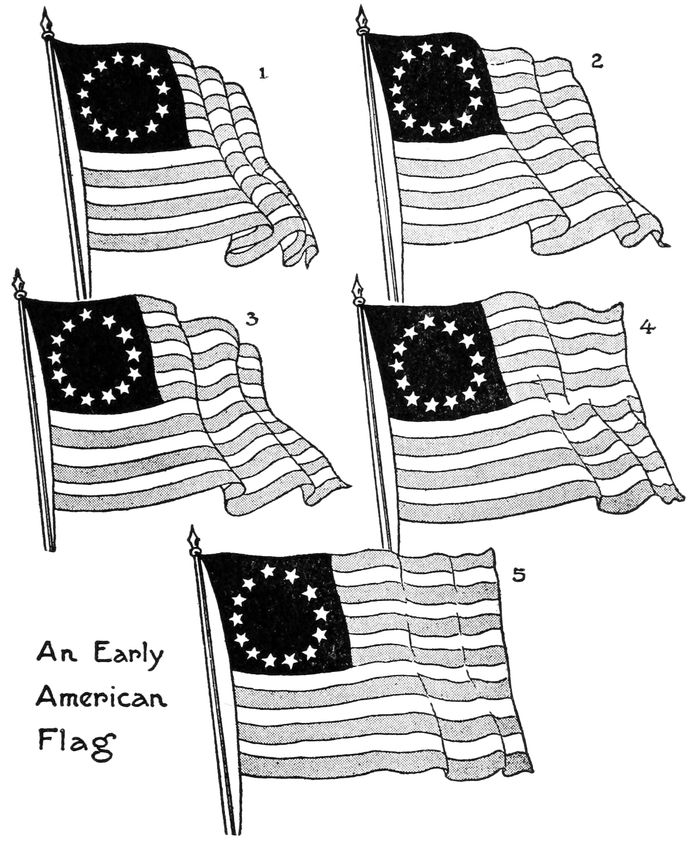

| Cycle of drawings to produce a screen animation of a waving flag | 157 | |

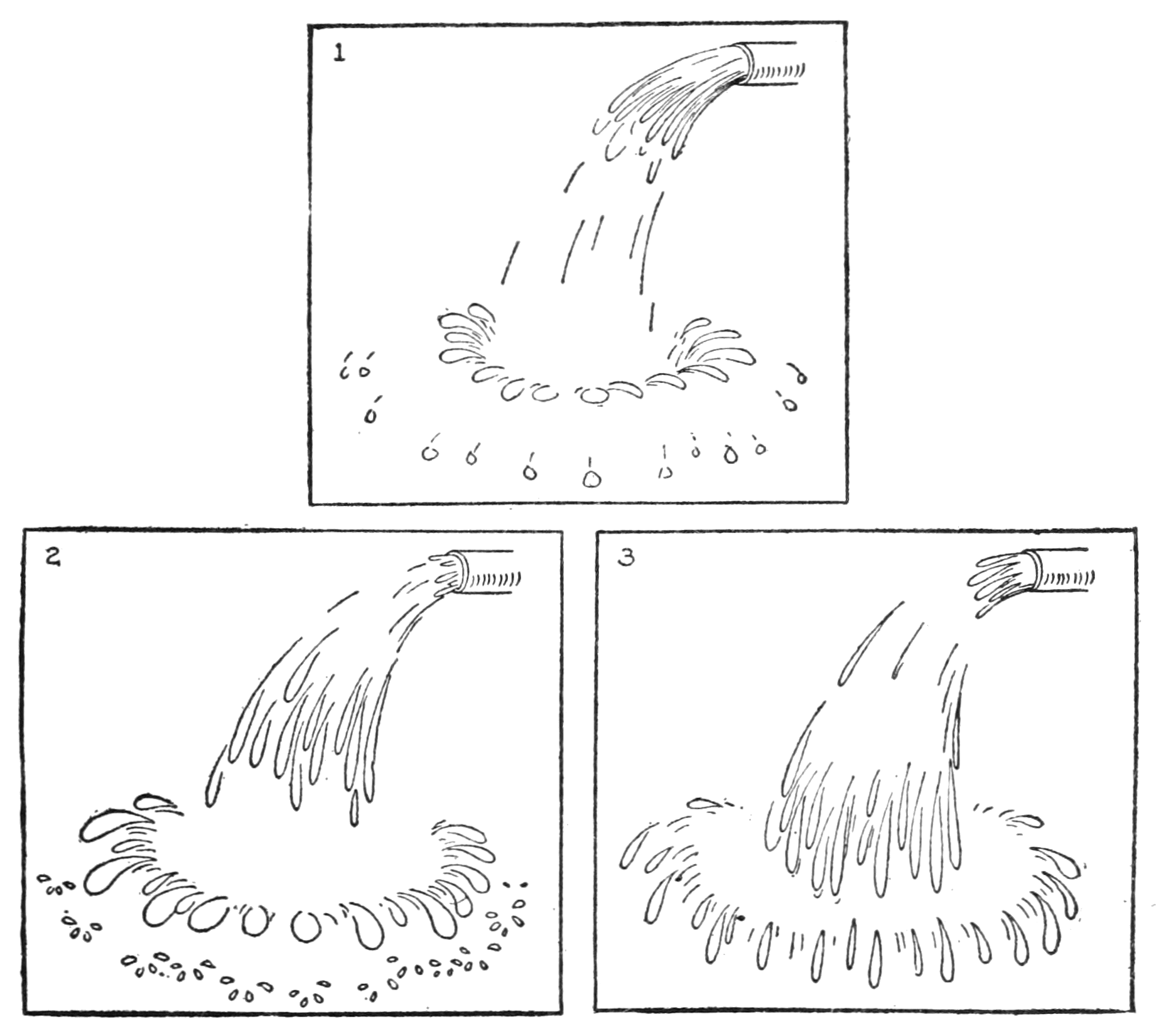

| Cycle of drawings for an effect of falling water | 159 | |

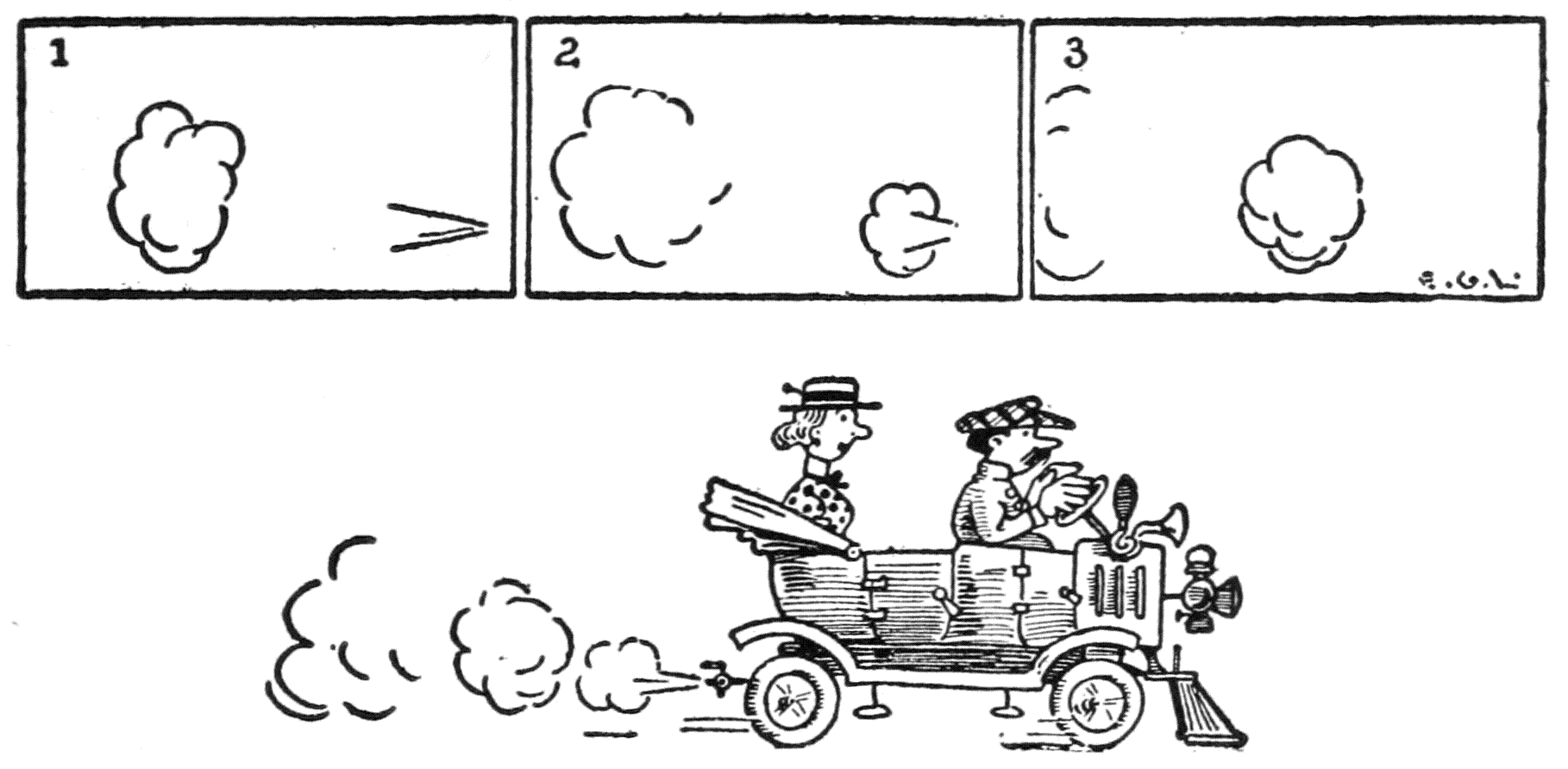

| Cycle of drawings for a puff of vapor | 161 | |

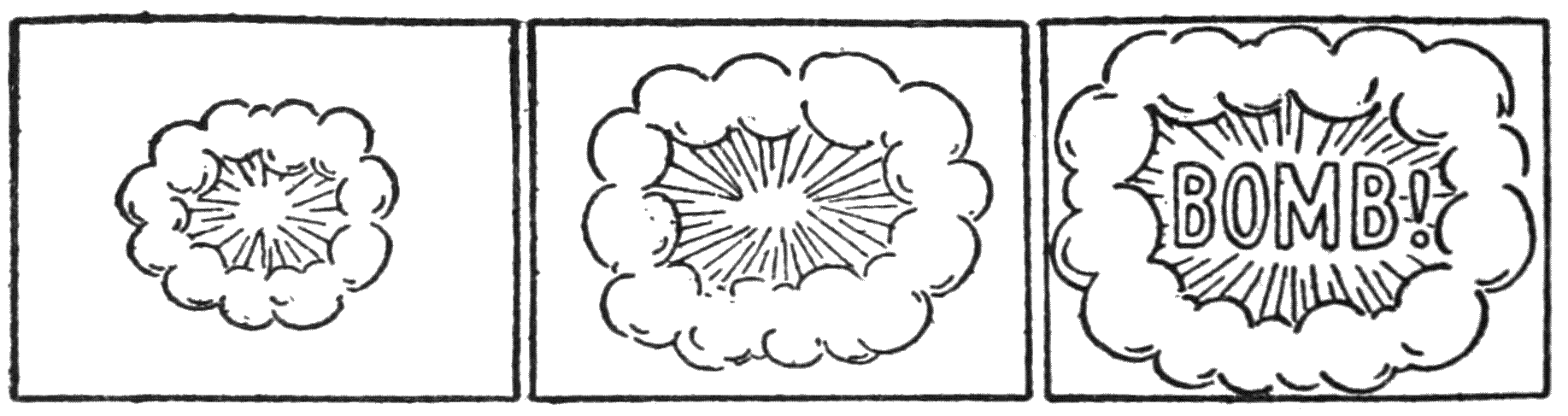

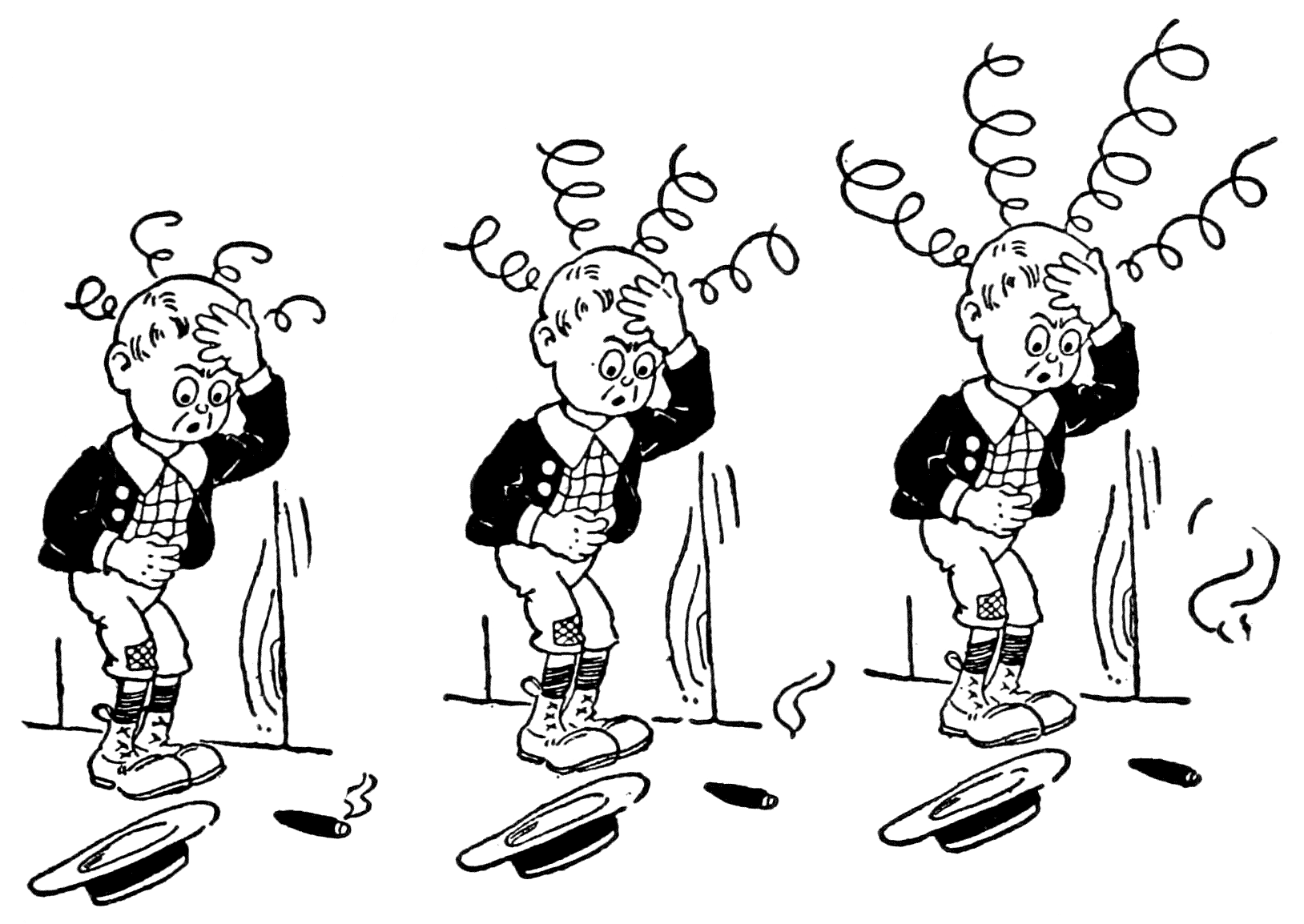

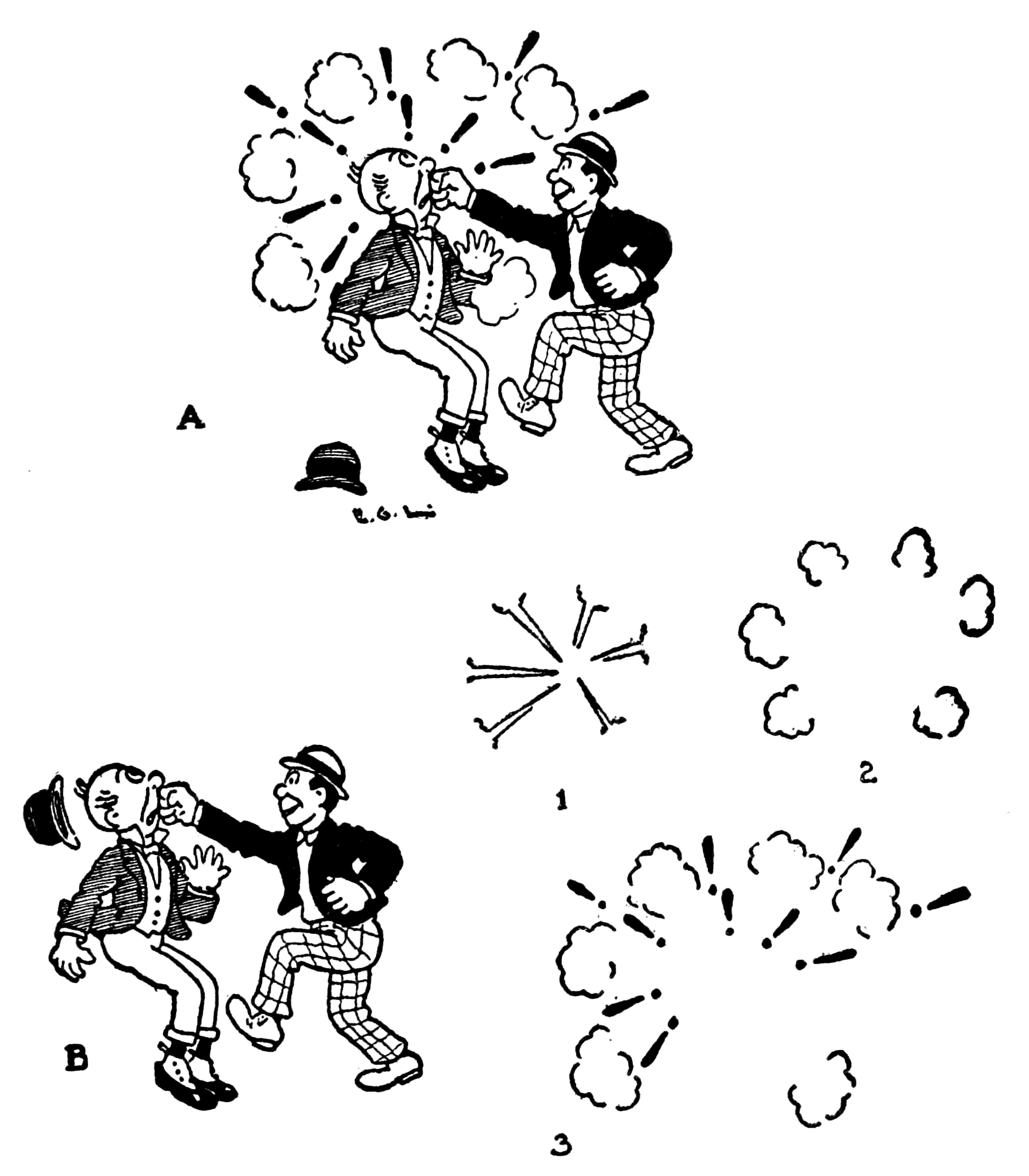

| An explosion | 162 | |

| The finishing stroke of some farcical situation | 163 | |

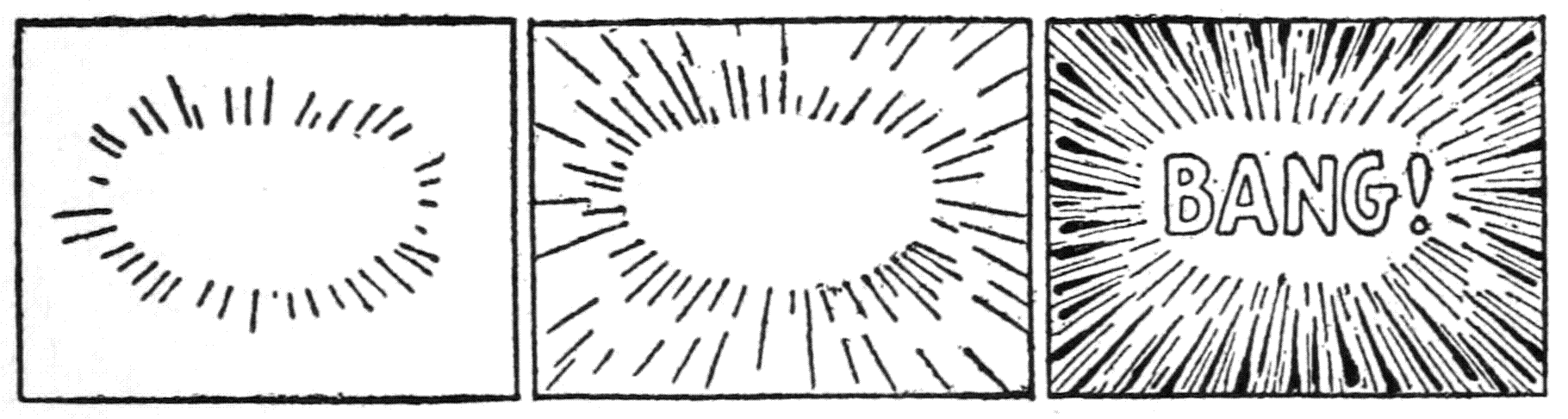

| Piano practice | 164 | |

| Three drawings used in sequence and repeated as long as the particular effect that they give is desired | 165 | |

| A constellation | 166 | |

| Simple elements used in animating a scene | 167 | |

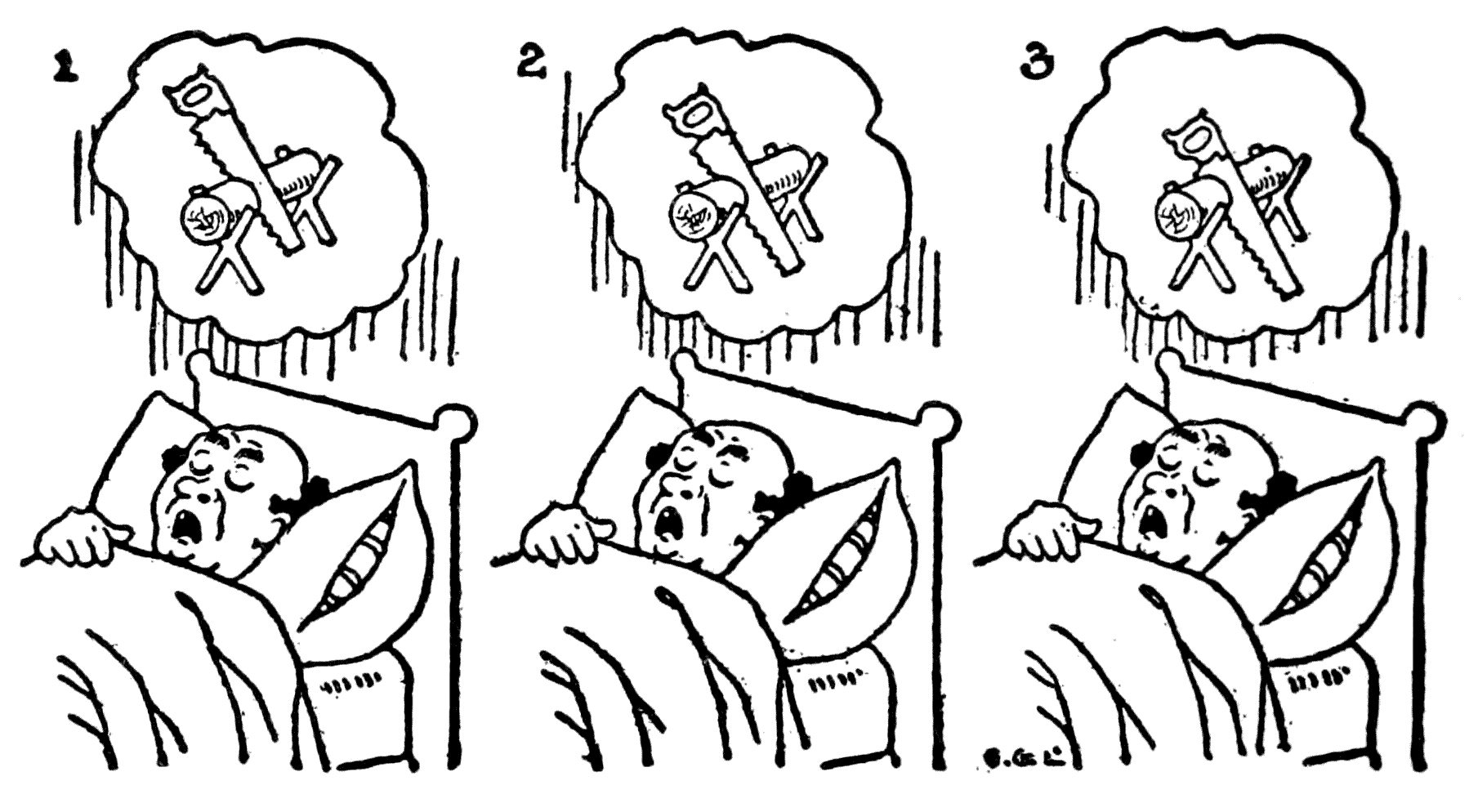

| Symbolical animation of snoring | 172[xix] | |

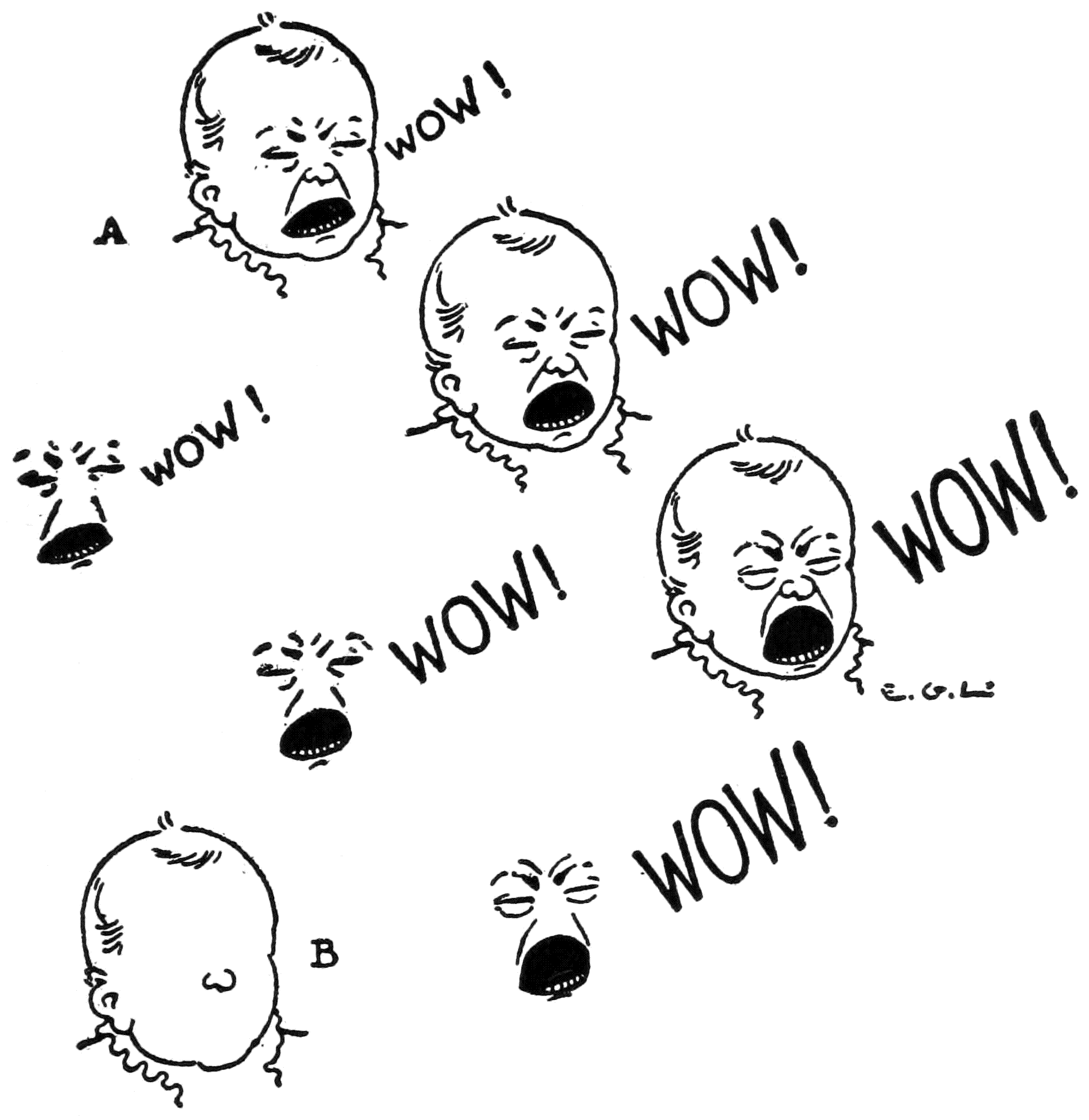

| Series of drawings used to show a baby crying | 173 | |

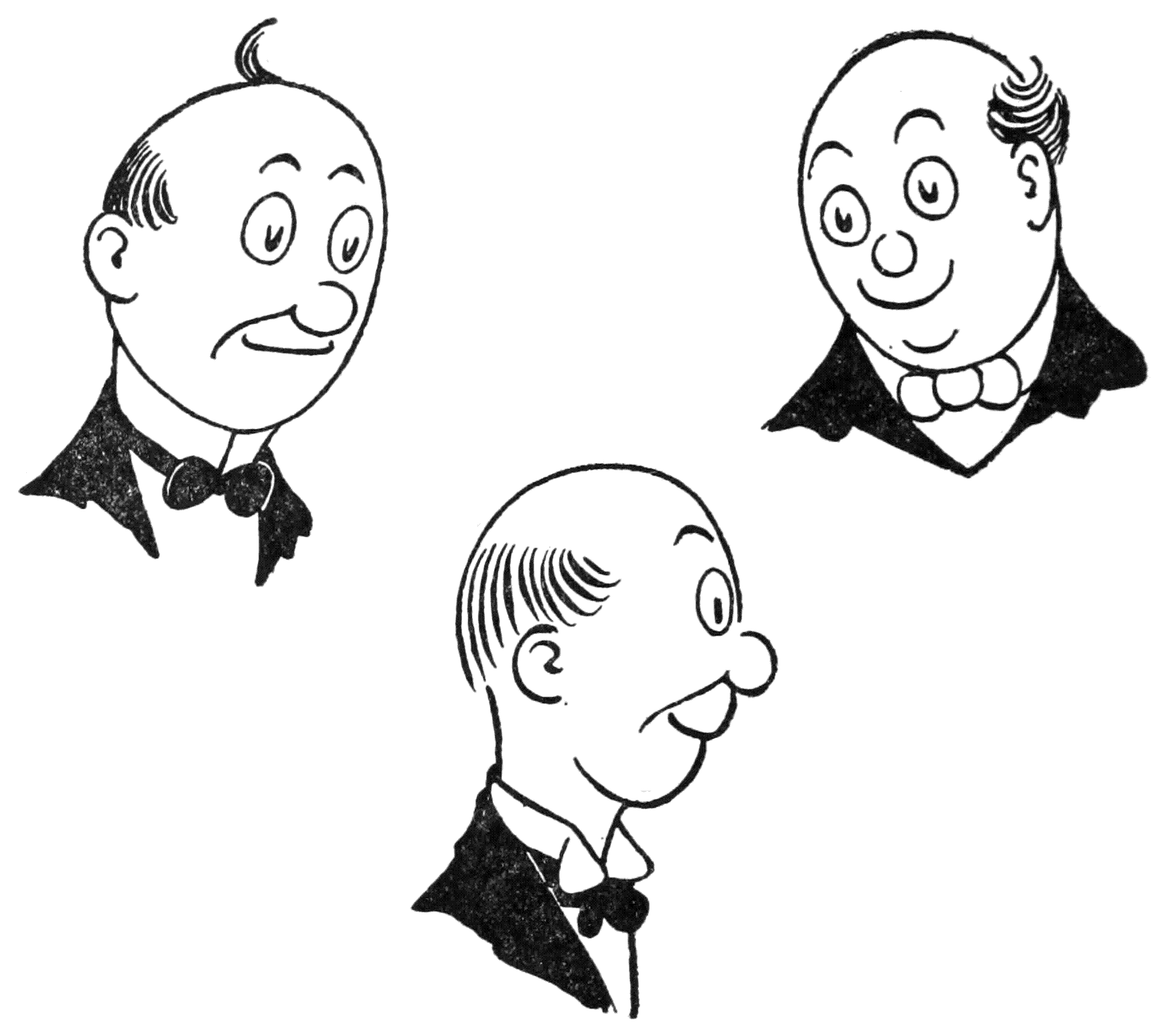

| A “close-up” | 175 | |

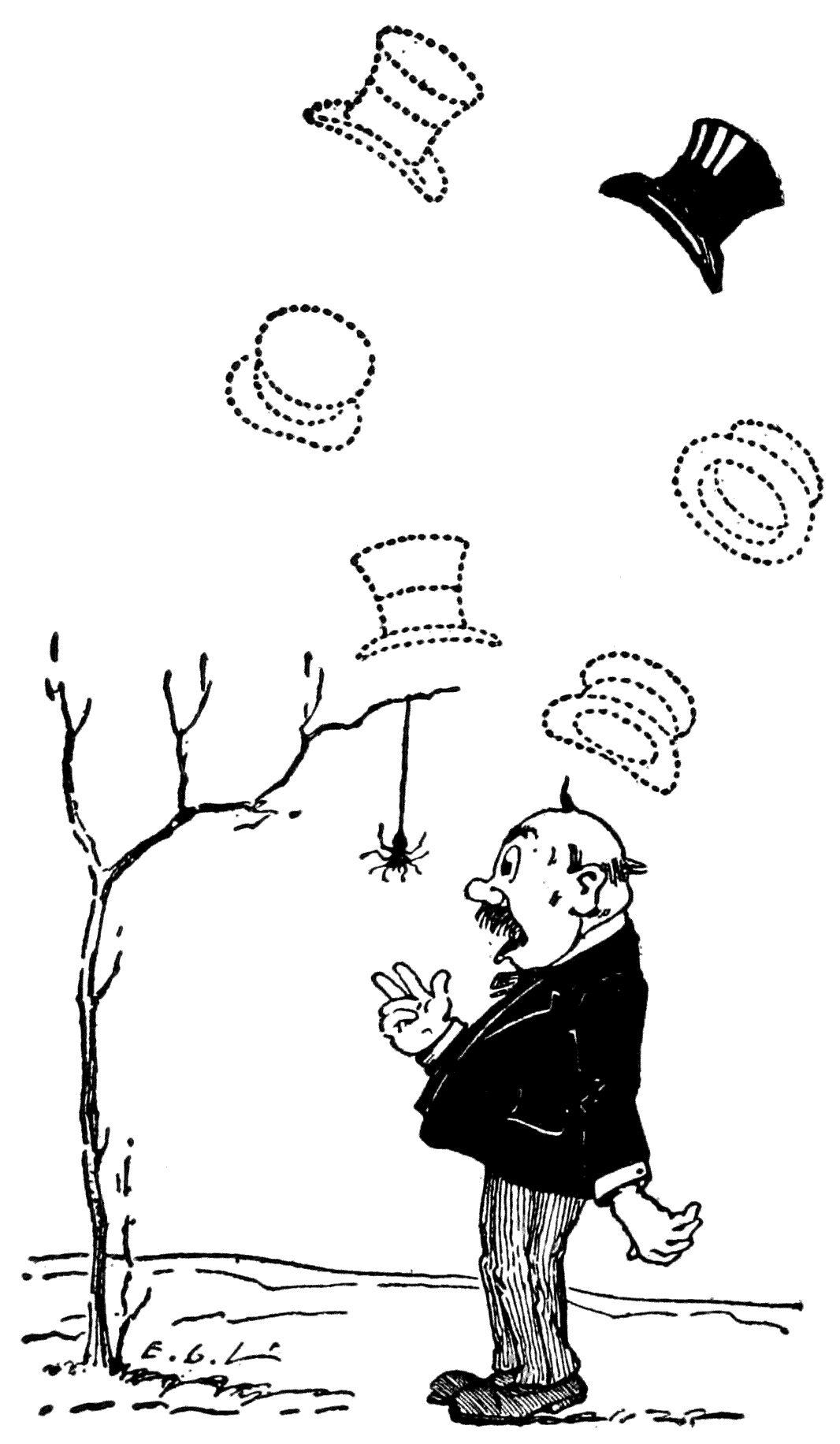

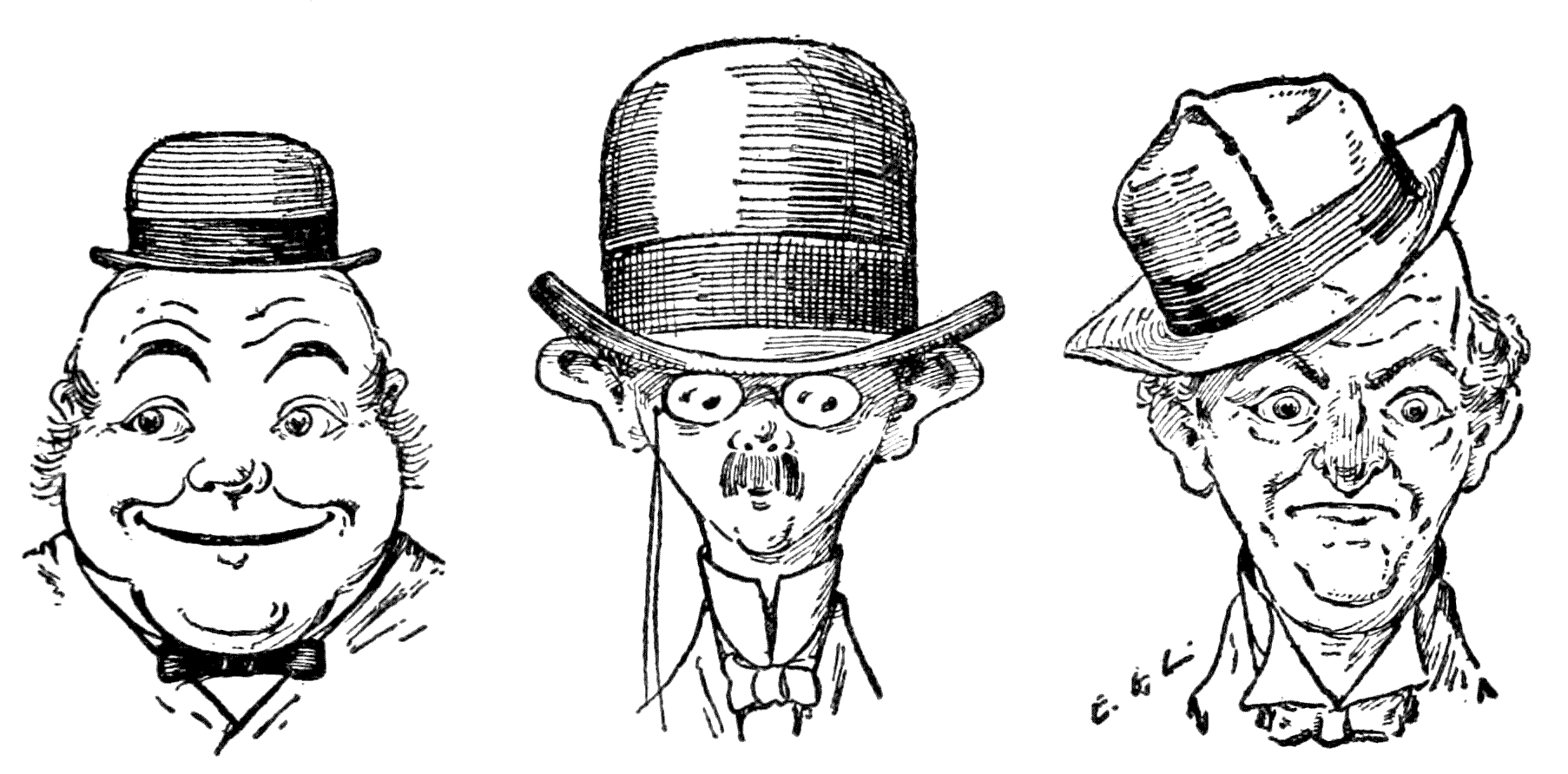

| Illustrating the use of little “model” hats to vivify a scene | 176 | |

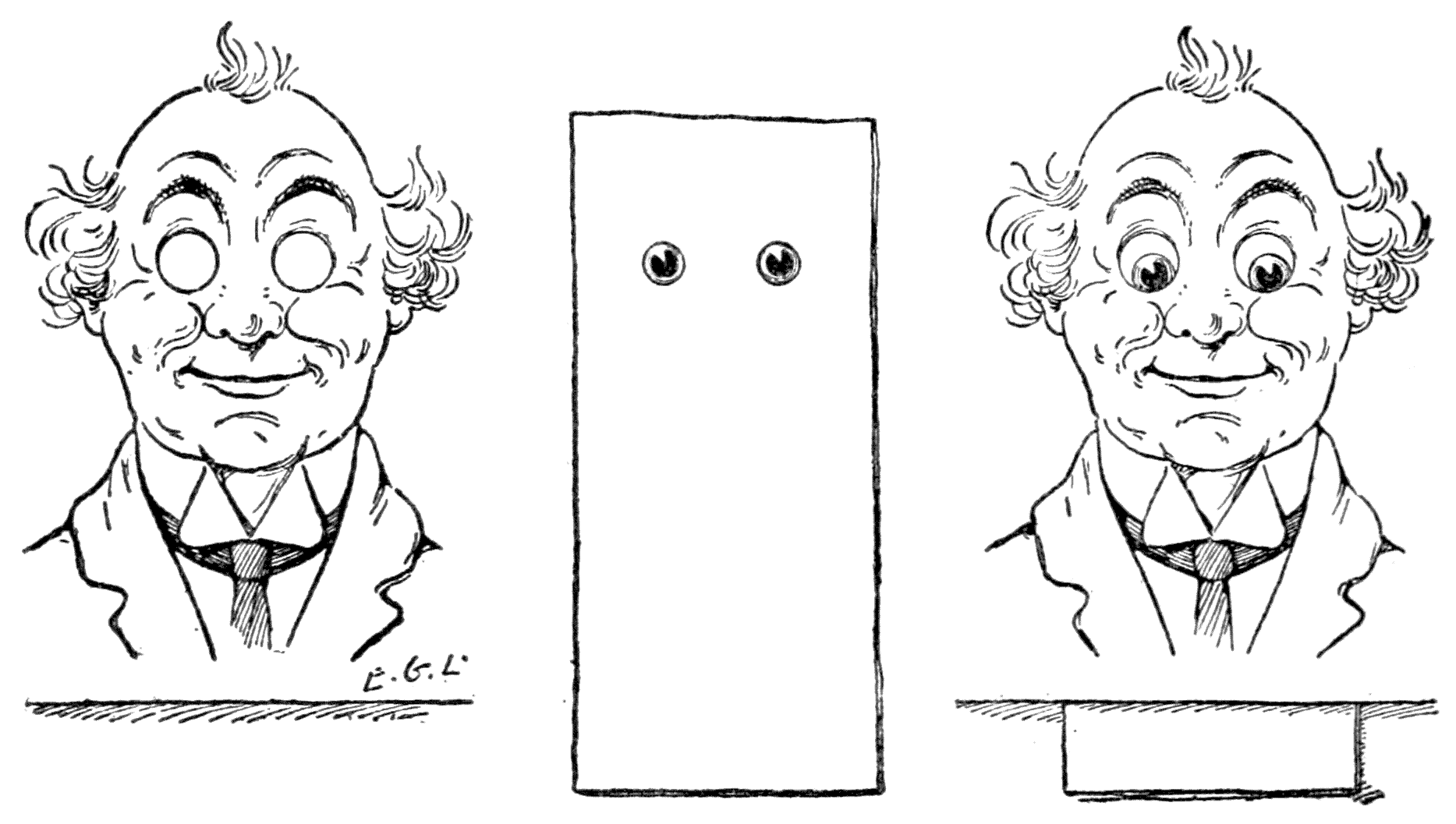

| “Cut-out” eyes | 178 | |

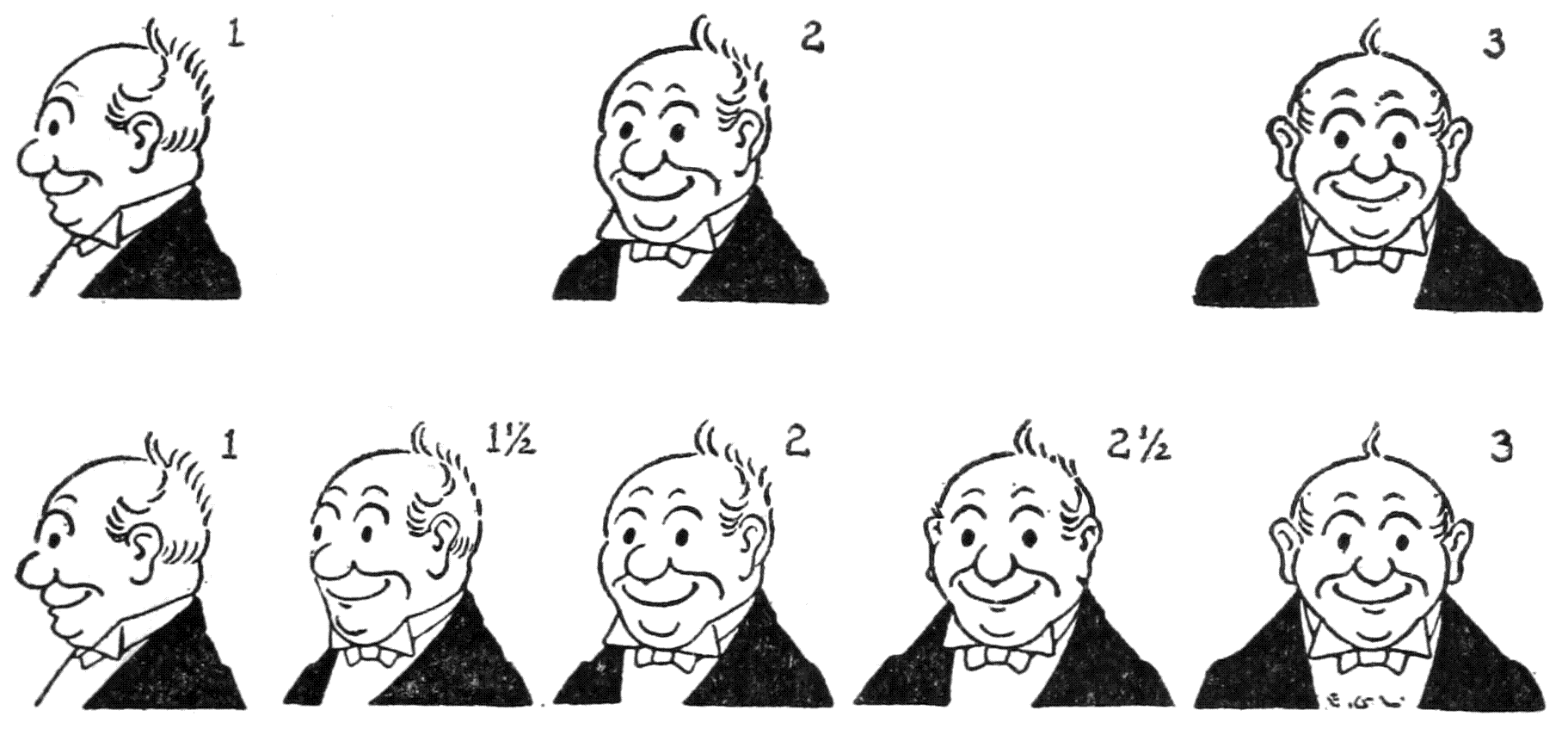

| Illustrating the making of “in-between” drawings | 179 | |

| Illustrating the number of drawings required for a movement | 180 | |

| Illustrating a point in animating a moving limb | 182 | |

| Making drawings in turning the head | 183 | |

| Easily drawn circular forms and curves | 186 | |

| Foreground details of a pictorial composition | 190 | |

| Making an animated cartoon panorama | 193 | |

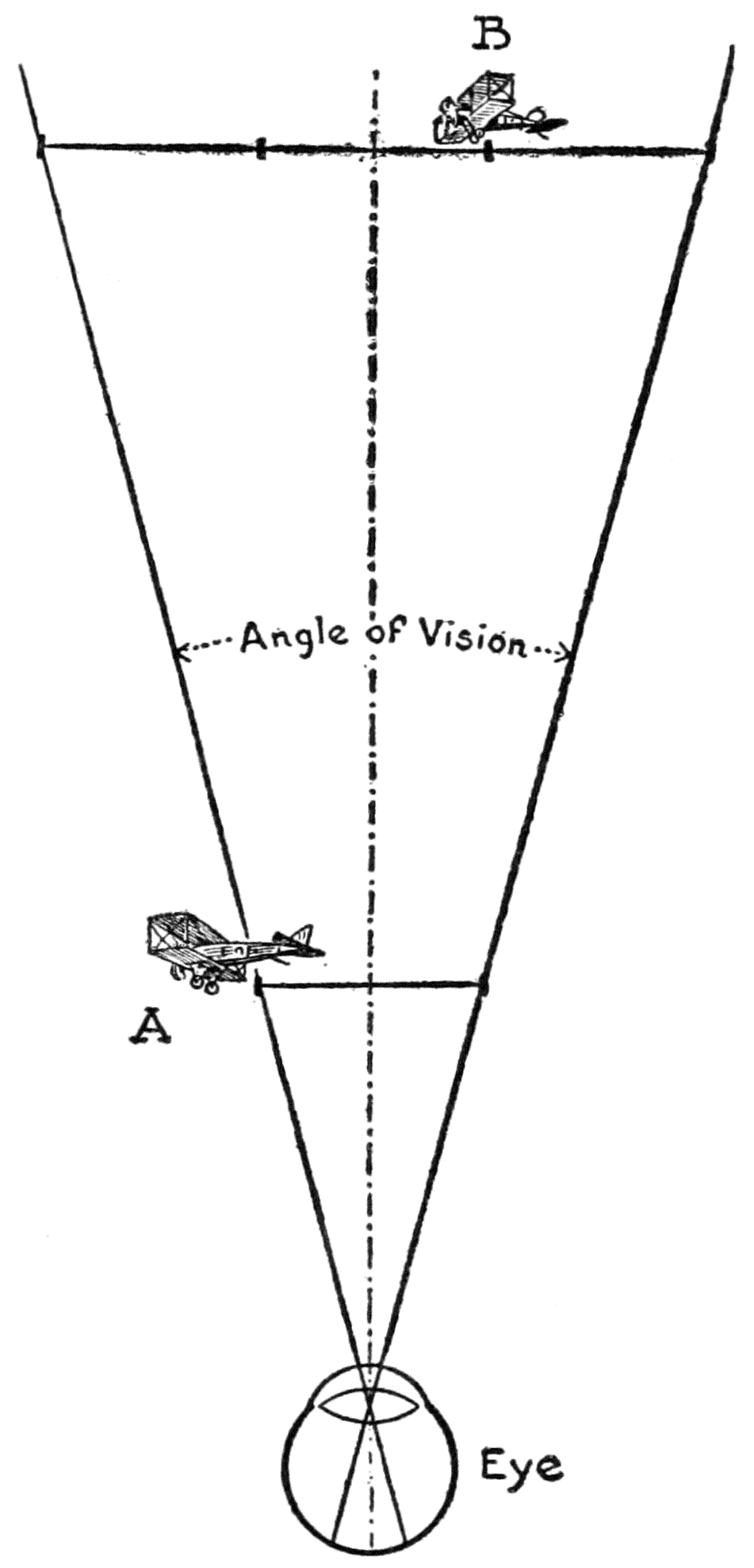

| Illustrating the apparent slowness of a distant object compared to one passing close to the eye | 195 | |

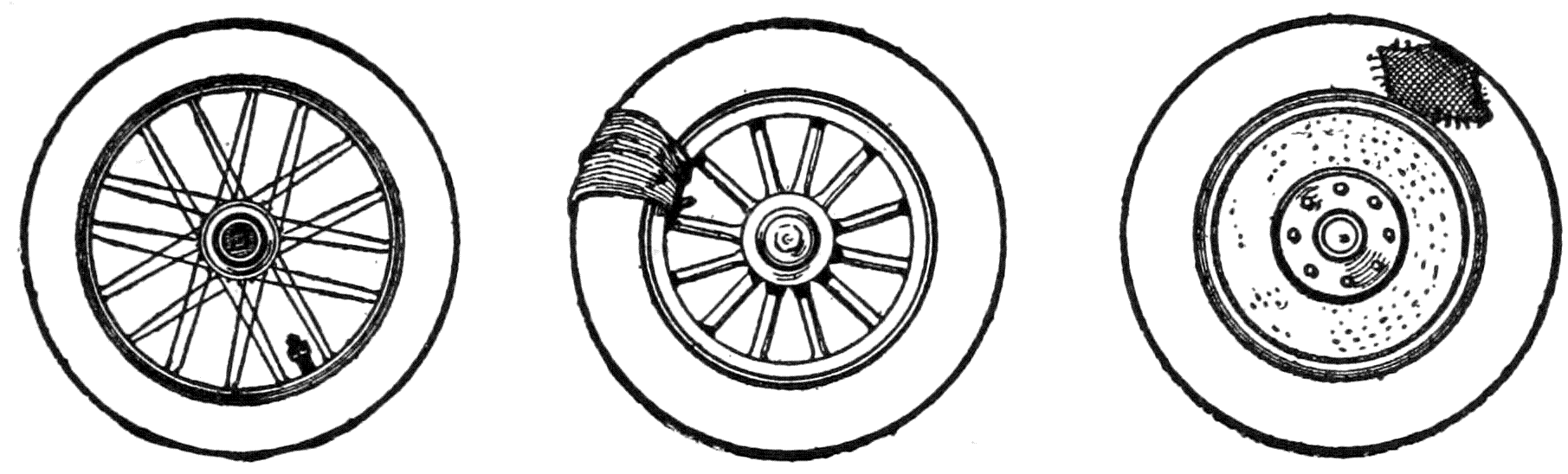

| Distinguishing marks on wheels to give the illusion of turning | 197 | |

| Elements used in giving a figure the effect of trembling | 198 | |

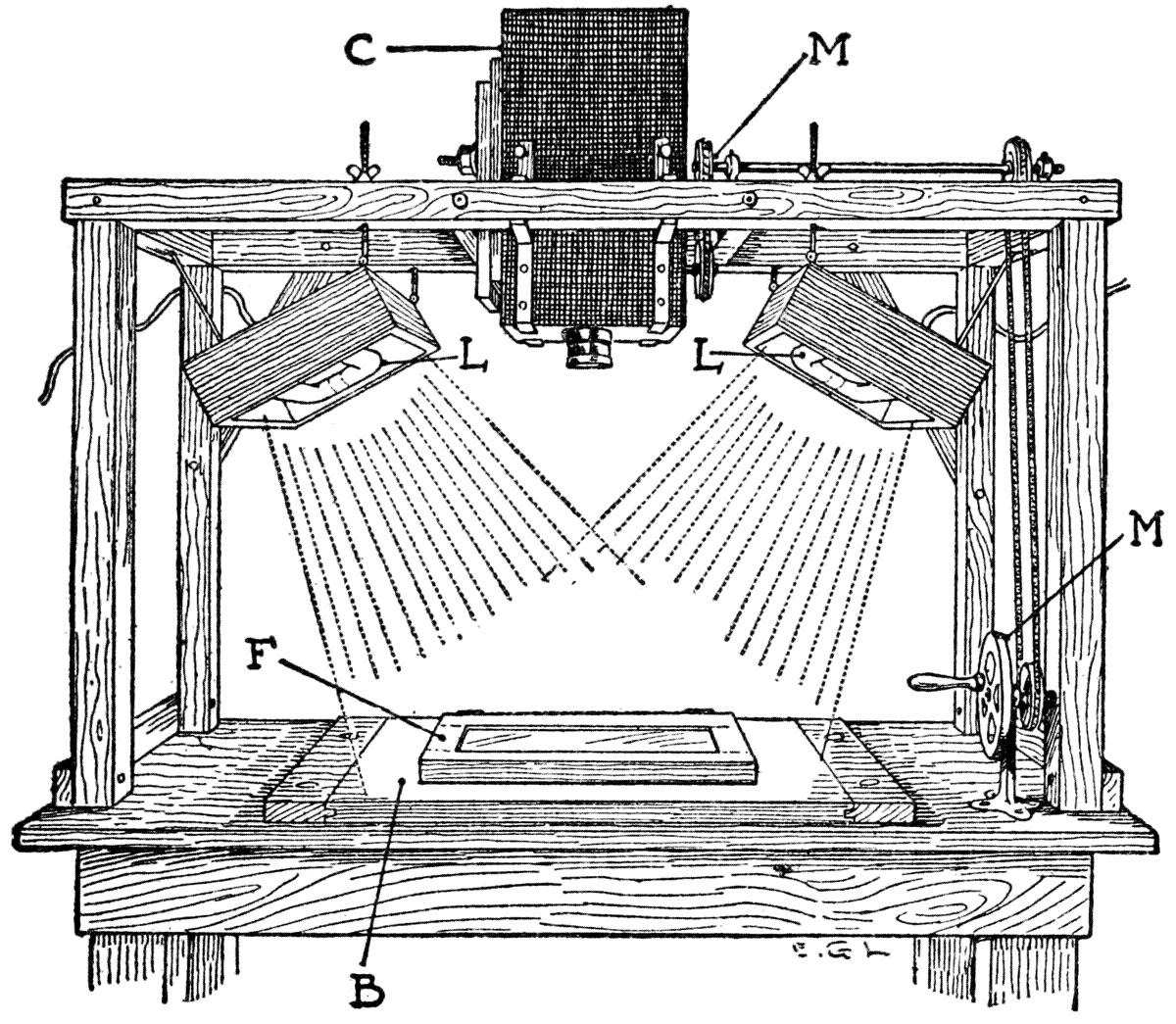

| Typical arrangement of camera and lights | 203 | |

| Part of a length of film for a title | 208 | |

| Vignetter or iris dissolve | 211 | |

| To explain the distribution of light in a cross dissolve | 213 | |

| Illustrating the operation of one type of motion-picture printer | 217 | |

| Another plan for an animator’s drawing-board | 218 | |

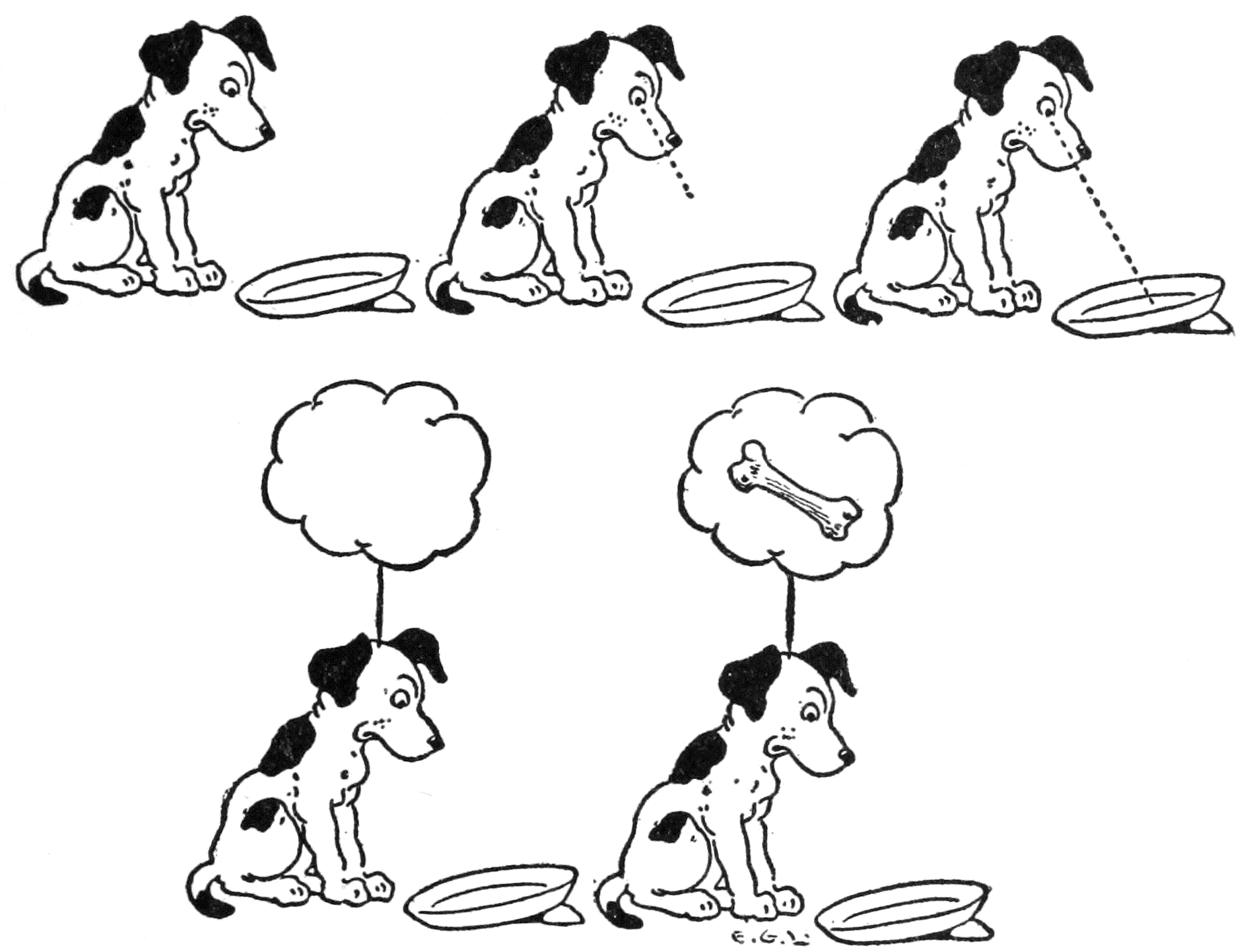

| Canine thoughts | 219 | |

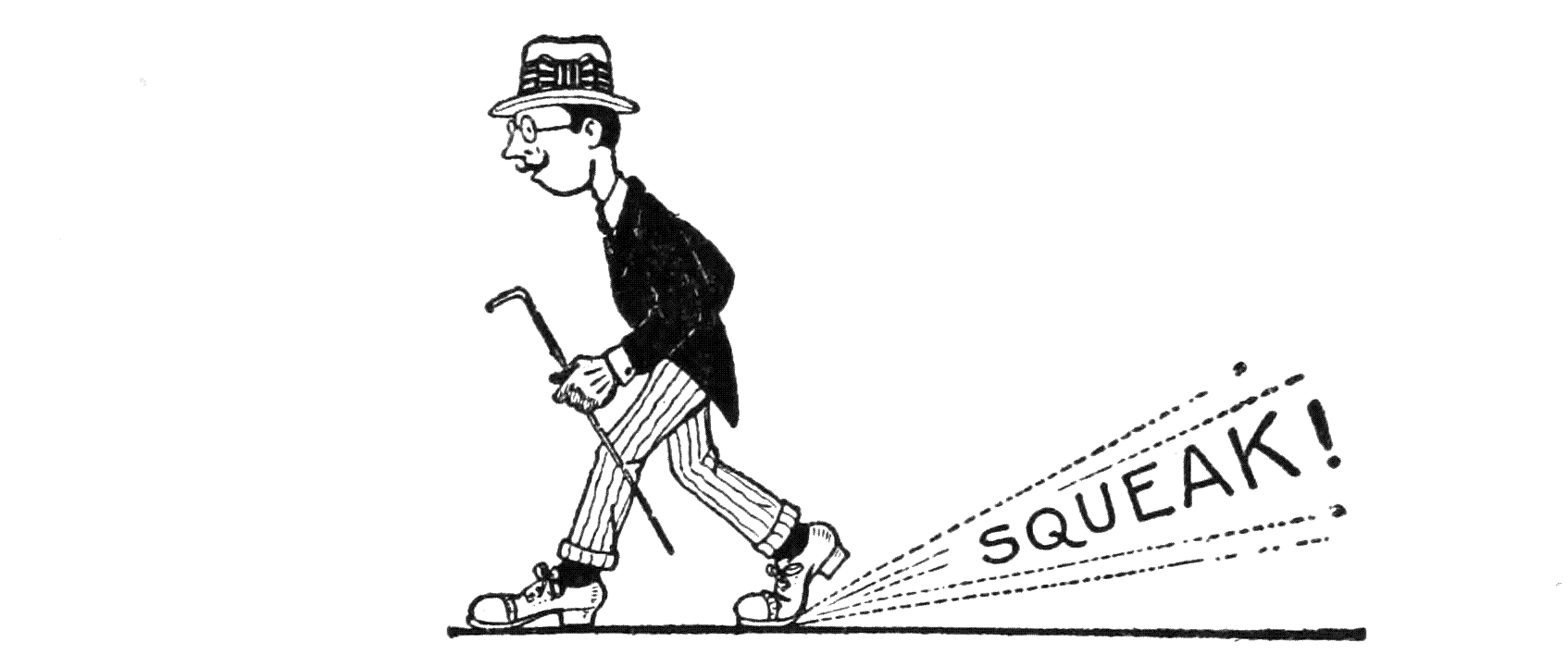

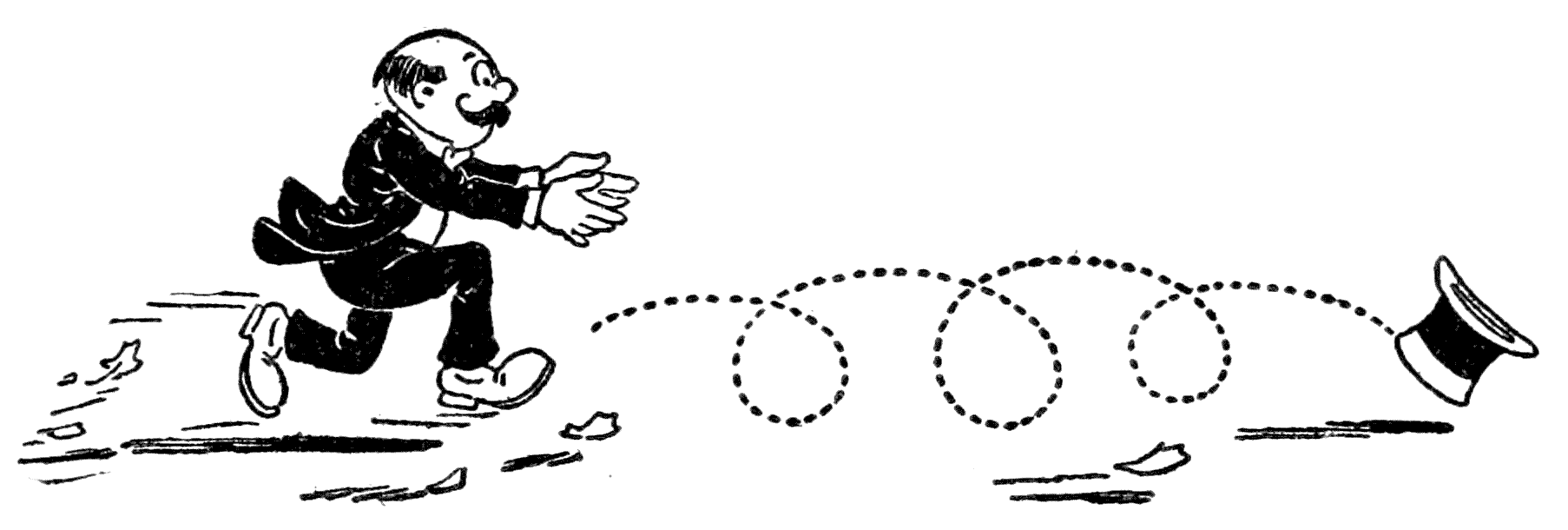

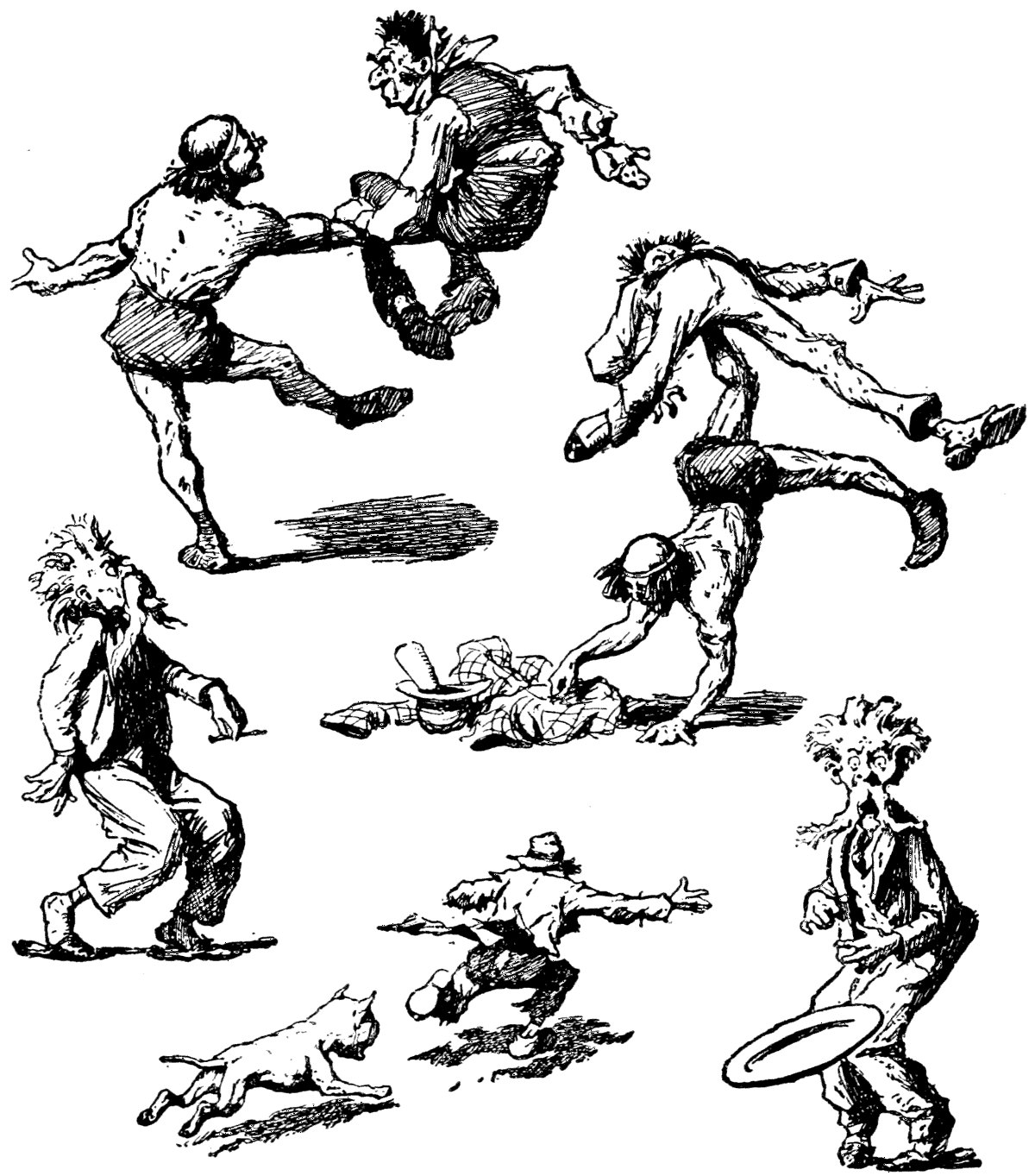

| Plenty of movement demanded in screen pictures | 224 | |

| The plaint of inanimate things | 227[xx] | |

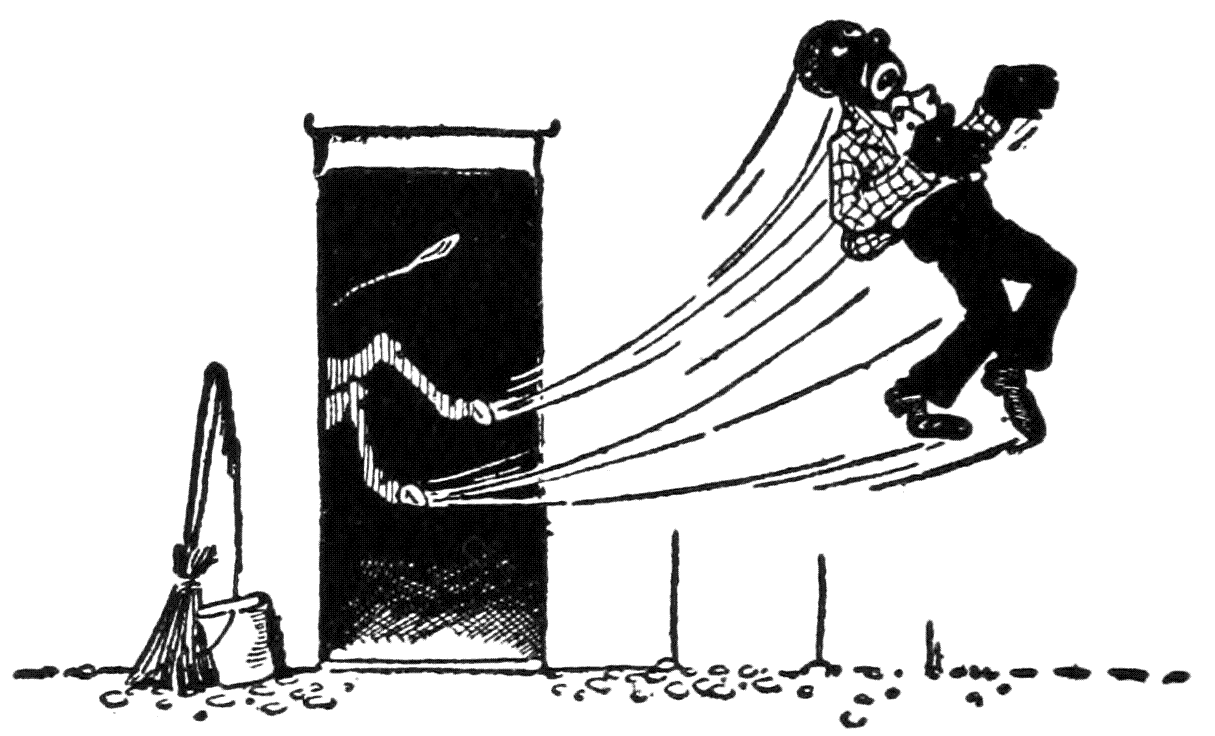

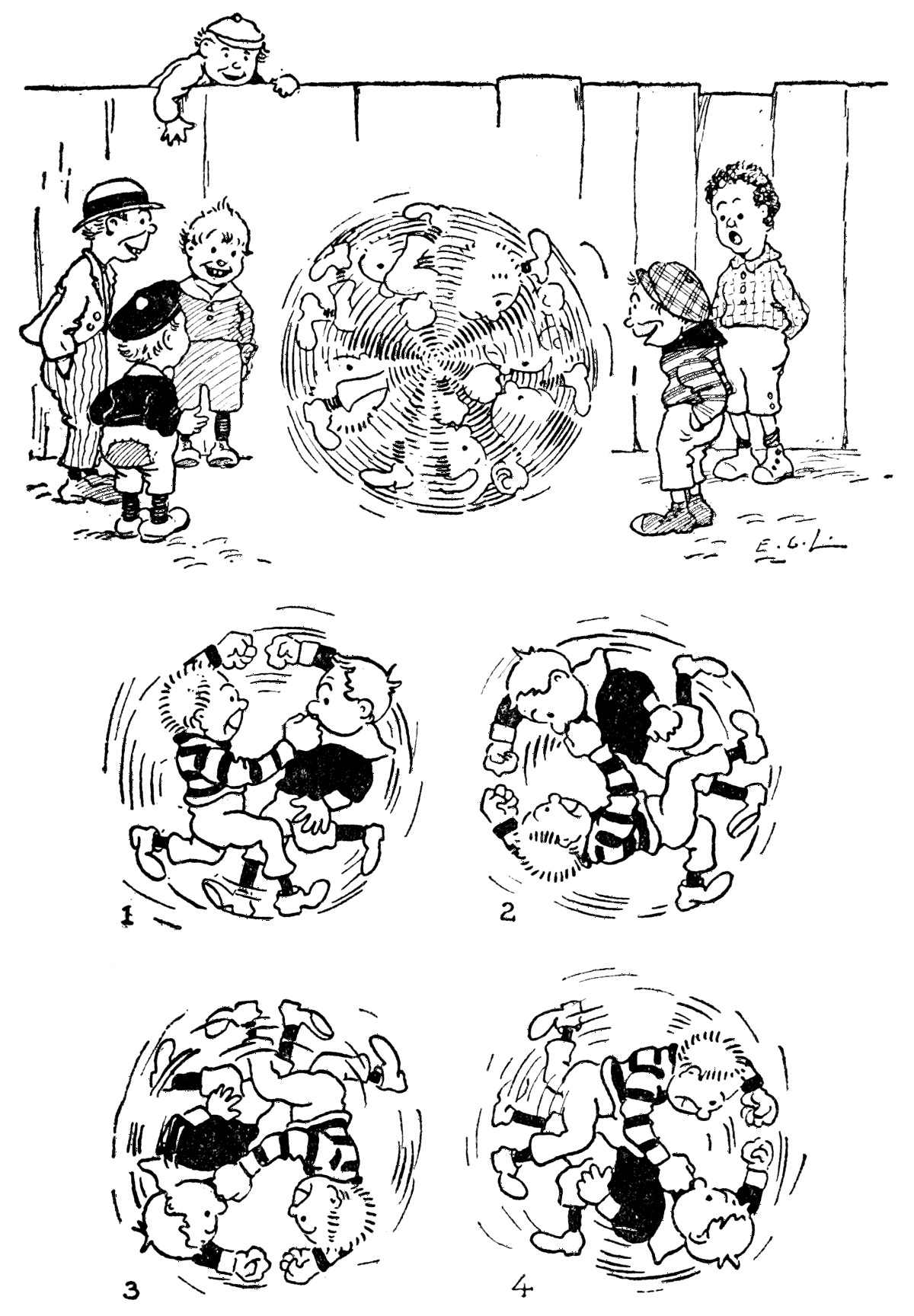

| The pinwheel effect of two boys fighting, elements needed in producing it | 231 | |

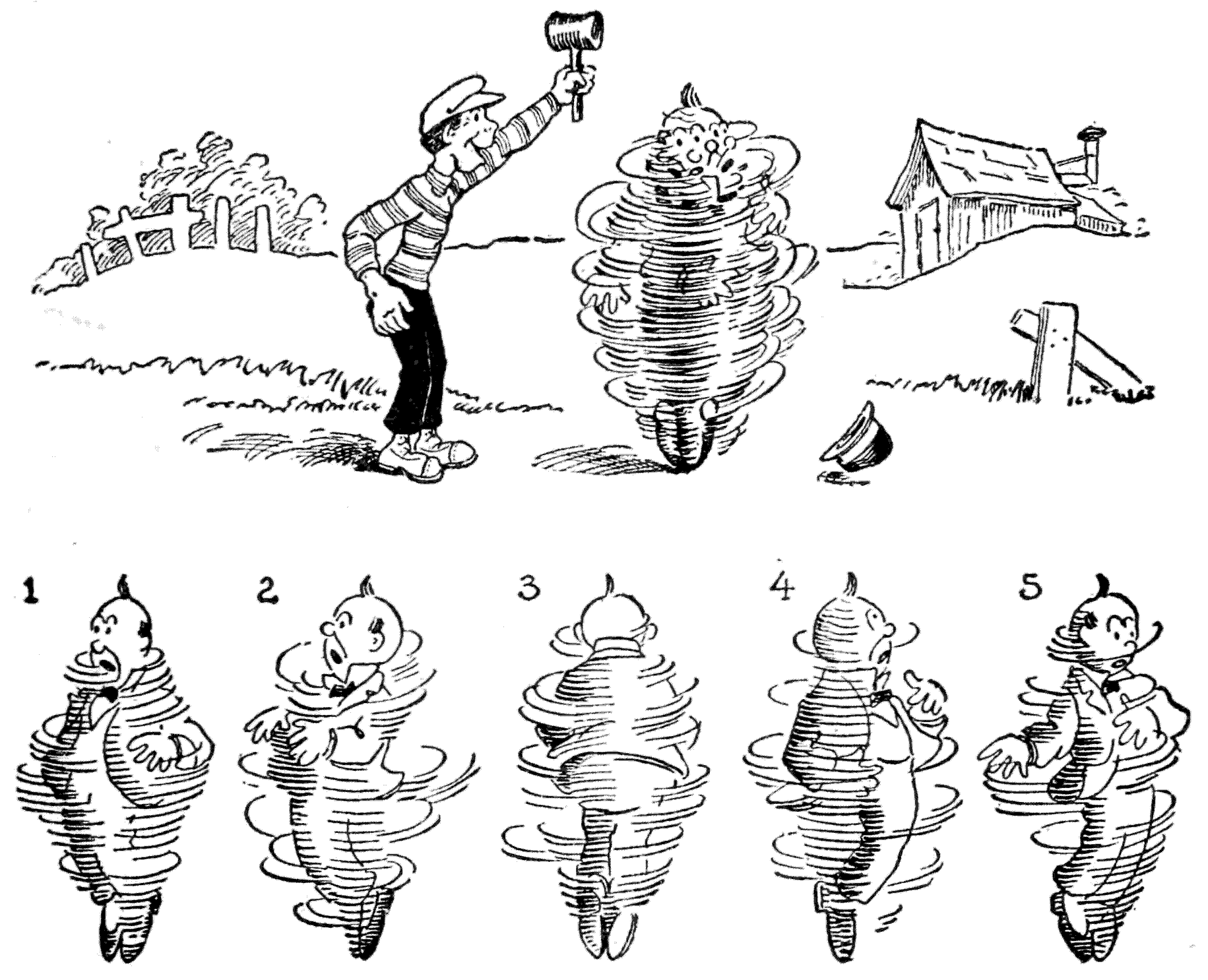

| Cycle of drawings to give the illusion of a man spinning like a top | 235 | |

| A blurred impression like that of the spokes of a turning wheel is regarded as funny | 236 | |

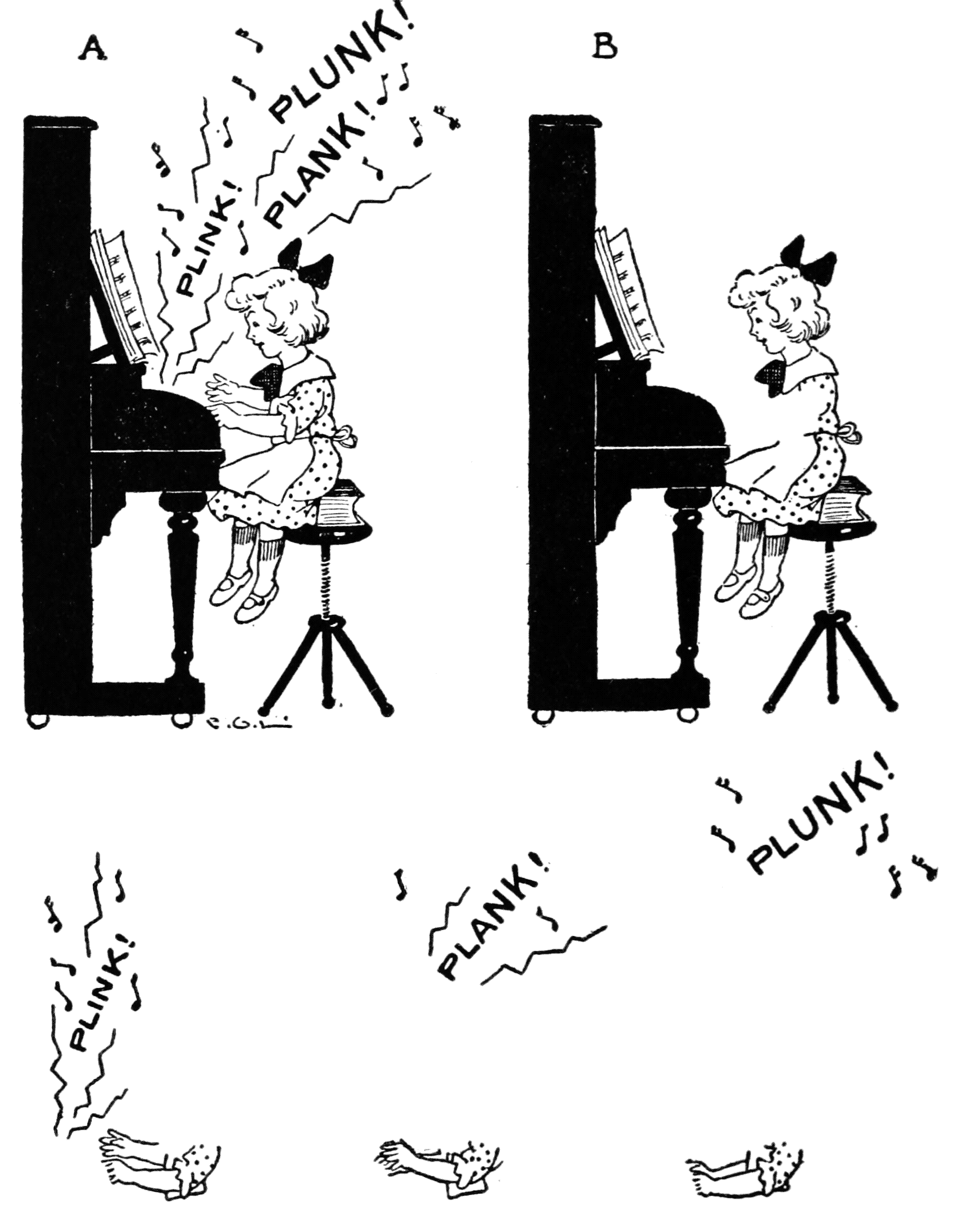

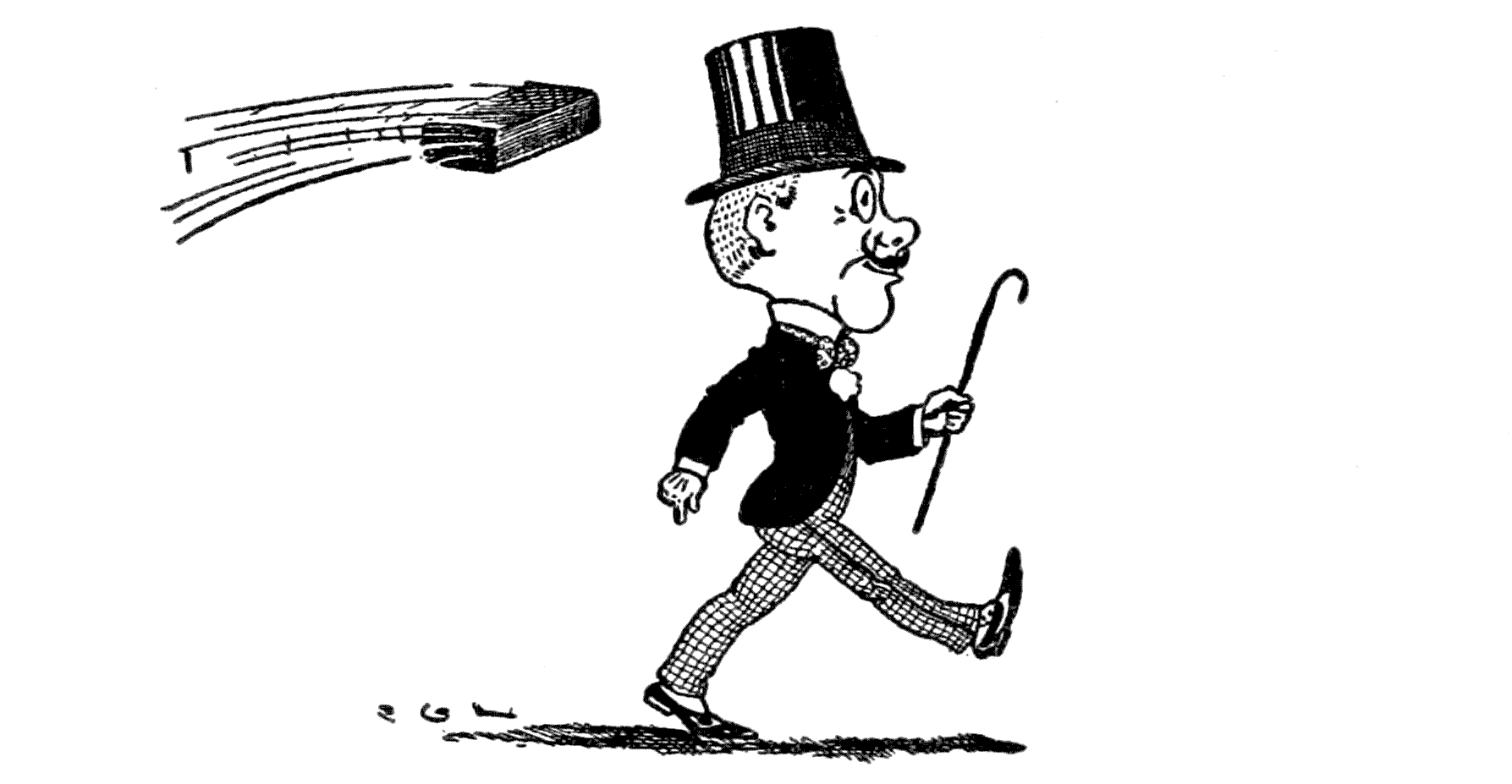

| Hats | 239 | |

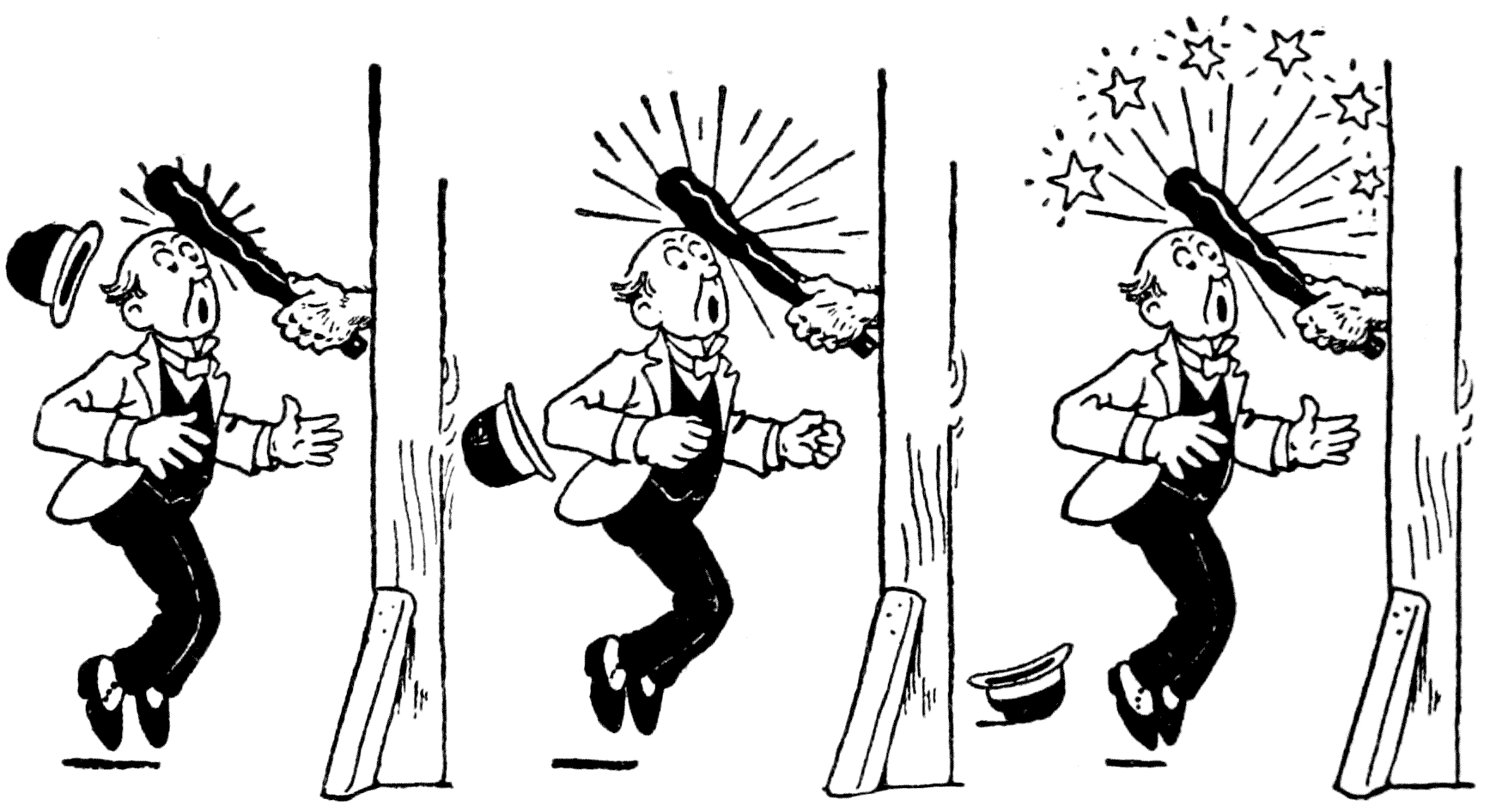

| Radiating “dent” lines | 240 | |

| A laugh-provoking incident in an animated cartoon | 241 | |

| The Mad Hatter | 246 | |

| Detail of a fresco by Michael Angelo | 248 | |

| Mr. Frost’s spirited delineation of figures in action | 249 | |

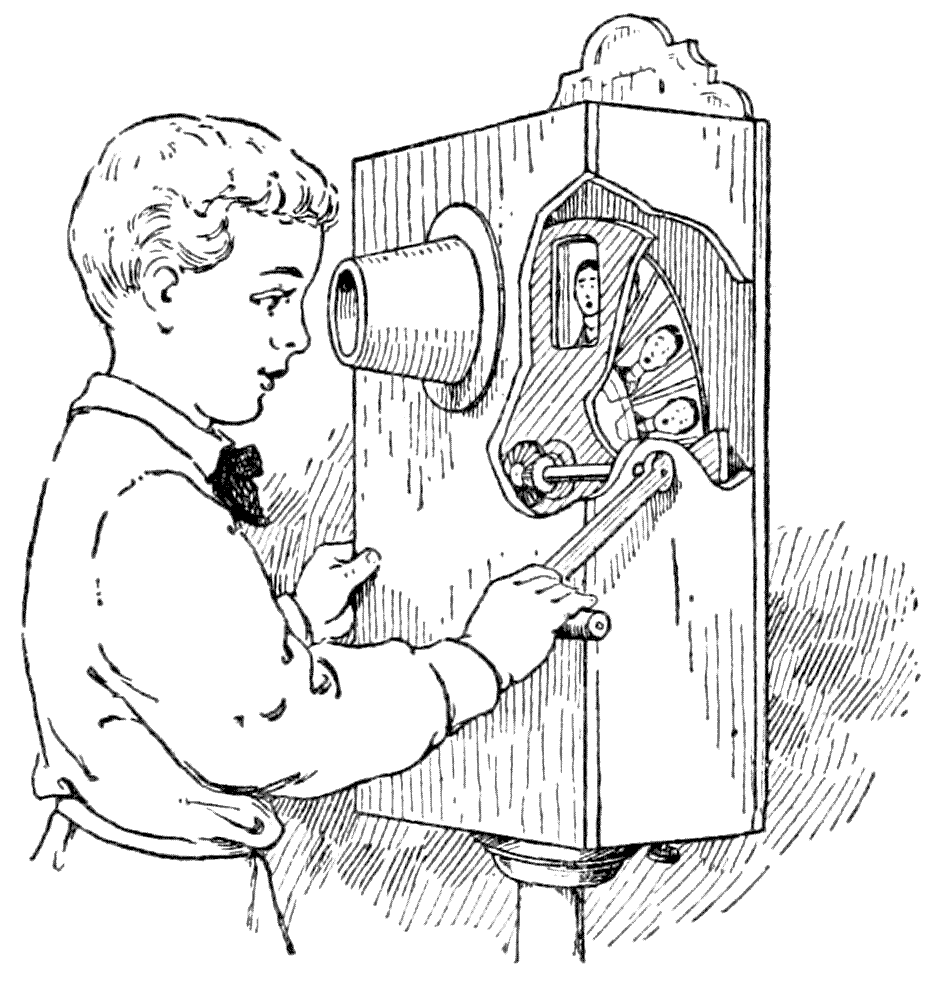

| The peep-show | 250 | |

| Demeny’s phonoscope | 251 | |

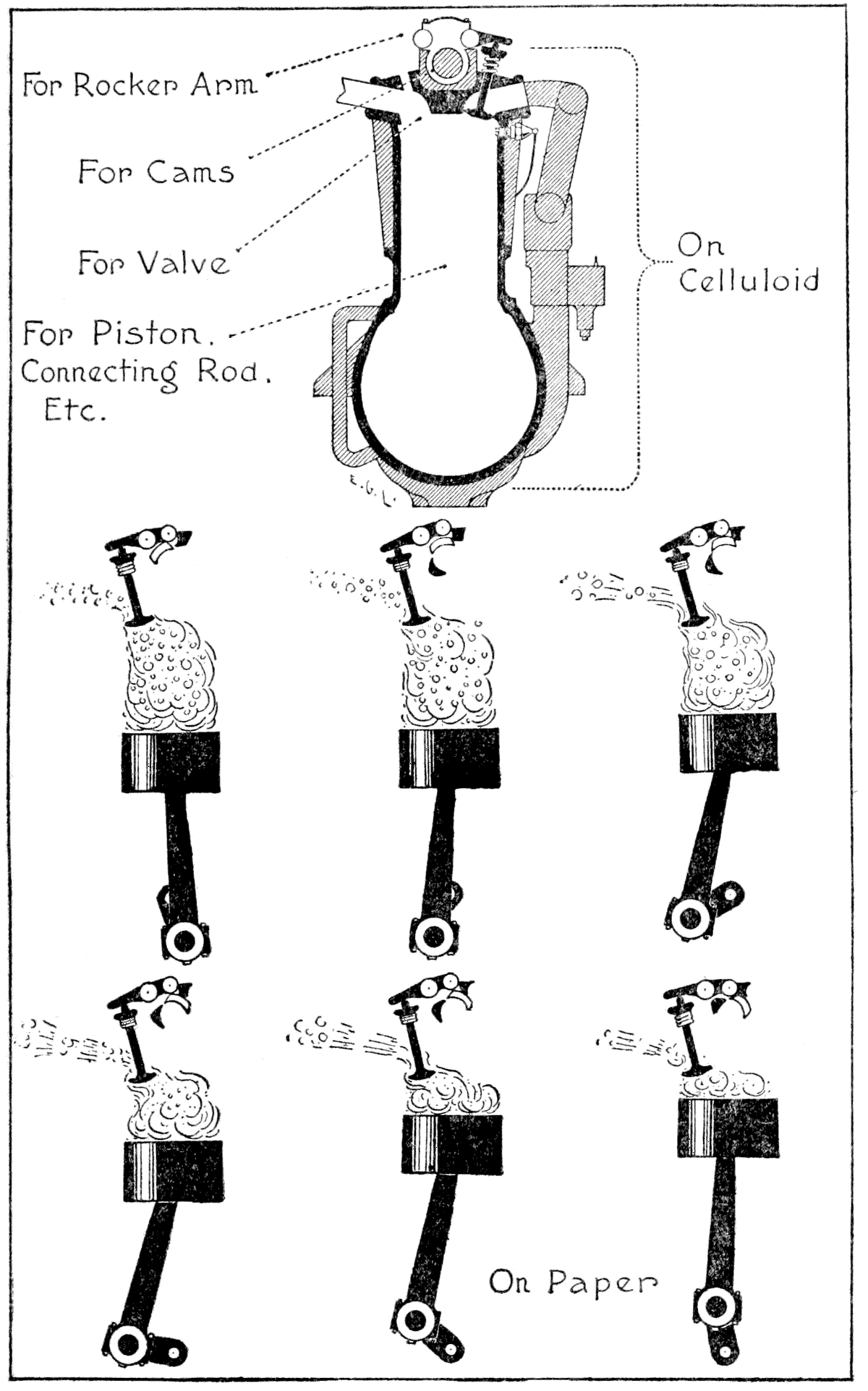

| Drawings used in making a film of a gasolene engine in operation | 255 | |

| Character of drawings that would be prepared in producing moving diagrams of the muscles in action | 258 | |

THE BEGINNING OF ANIMATED DRAWINGS

The picture thrown on the wall by the magic-lantern, although an illusion, and no more tangible than a shadow, has nevertheless a certain tactile quality. If it is projected from a drawing on a glass slide, its design is definite; and if from a photographic slide, the tones are clearly discernible. It is—unless it is one of those quaintly moving amusing subjects operated by a crude mechanism—a quiescent picture. The spirited screen picture thrown by the lens of a motion-picture projector is an illusion, too. It exemplifies, however, two varieties of this class of sensory deceptions. First: it is an illusion for the same reason that the image from the magic-lantern is one; namely, a projected shadow of a more or less opaque design on a transparent material intervening between the illuminant and the lens. And secondly, it is an illusion in that it synthesizes mere pictorial spectres into the appearance of life and movement. This latter particular, the seeming[4] activity of life, is the fundamental dissimilarity between pictures projected by the magic-lantern and those thrown on the screen by the motion-picture apparatus.

And it is only the addition to the magic-lantern, of a mechanism that makes possible this optical vibration of life and motion, that constitutes the differing feature in the two types of projecting machines.

In the magic-lantern and its improved form, the stereopticon, separate views of different subjects are shown in succession. Each picture is allowed to remain on the screen long enough to be readily beheld and appreciated. But the picture is at rest and does not move. With the motion-picture projector a series of slightly varying pictures of the same subject are projected in quick succession. This succession is at such a rapid rate that the interval of time during which one picture moves out of place to make way for the next is so short that it is nearly imperceptible. In consequence, the slightly varying pictures blend on the screen and we have a phantasmagoria of movement.

The phenomenon of this movement—this semblance[5] to life—takes place, not on the screen, but within the eye. Its consideration, a subject proper for the science of physiology (and in some aspects psychology), has weight for us more particularly as a matter of physics.

Memory has been said to be an attribute of all organic matter. An instance of this seems to be the property of the eye to retain on its retina an after-image of anything just seen. That is to say, when an object impresses its image upon the retina and then moves away, or disappears, there still remains, for a measurable period, an image of this object within the eye. This singularity of the visual sense is spoken of as the persistence of vision or the formation of positive after-images. And it is referred to as a positive after-image in contradistinction to another visional phenomenon called the negative after-image. This latter kind is instanced in the well-known experiment of fixing the eyes for a few moments upon some design in a brilliant color and quickly turning away to gaze at a blank space of white where instantly the same design will be seen, but of a color complementary to that of the particular hue first gazed at.

[6]

The art of the motion-picture began when physicists first noticed this peculiarity of the organ of sight in retaining after-images. The whole art is based on its verity. It is the special quality of the visual sense that makes possible the appreciation of living screen pictures.

An interesting matter to bear in mind is the circumstance that the first attempt at giving to a screen image the effect of life was by means of a progressive series of drawings. When photographs came later, drawings were forgotten and only when the cinematographic art had reached its great development and universality, were drawings again brought into use to be synthesized on the screen.

To describe how these drawings are made, their use and application to the making of animated cartoons, is the purpose of this book.

Before proceeding with a sketch of the development of the art of making these cartoons, it will make the matter more readily understood if we give, at first, in a few paragraphs, a brief description of the present-day method of throwing a living picture on the screen by the motion-picture projector.

[7]

The projector for motion-pictures, like the magic-lantern, consists of an illuminant, reflector, condenser, and objective. This last part is the combination of lenses that gather and focus the light rays carrying the pencils of lights and shadows composing the picture and throwing them on the screen. There is, in the magic-lantern, immediately back of the objective, a narrow aperture[8] through which the glass slide holding a picture is thrust. In the motion-picture apparatus, the transparent surface containing the picture also passes back of the objective, but instead of the simple process of pushing one slide through to make way for another, there is a complicated mechanism to move a long ribbon containing the sequence of pictures that produces the image on the screen. Now this ribbon consists of a strip of transparent celluloid[1] each with a separate photograph of some one general scene but each with slight changes in the moving details—objects or figures. These changes record the movements from the beginning to the end of the particular story, action, or pantomime.

Along the edges of the ribbons are rows of perforations that are most accurately equalized with respect to their size and of the distances between them. It is by means of wheels with teeth that engage with the perforations and the movement of another toothed part of the mechanism[9] that the ribbon or film is carried across the path of light in the projecting machine. The device for moving the film, although not of a very intricate character, is nevertheless of an ingenious type. It is intermittent in action and operates so that one section of film, containing a picture, is held in the path of light for a fraction of a second, moved away and another section, with the next picture, brought into place to be projected in its turn. This way of working, in most of the projectors, is obtained by the use of a mechanical construction known as the Geneva movement. The pattern of its principal part is a wheel shaped somewhat like a Maltese cross. The form shown in the illustration is given as a type; not all are of this pattern, nor are they all four-parted.

[10]

It is obvious that while one picture moves out of the way for the next, there would be a blur on the screen during such a movement if some means were not devised to prevent it. This is found by eclipsing the light during the time of the change from one picture to another. The detail of the projector that effects this is a revolving shutter with a solid part and an open section. (This is the old type of shutter. It is noticed here because the way in which the light rays project the picture is easily explained by using it as an example.) This shutter is so geared with the rest of the mechanism that (1) the solid part passes across the path of light while another picture is moving into place; and that (2) the open section passes across the path of light while a rectangular area containing a picture is at rest and its details are being projected on the screen.

It may be asked, at this point, why the eye is not aware on the screen of the passing shadow of the opaque part of the shutter as it eclipses the light. It would seem that there should be either a blur or a darkened period on the screen. But the mechanism moves so rapidly that the passing of the solid portion of the shutter is not ordinarily perceptible.

[11]

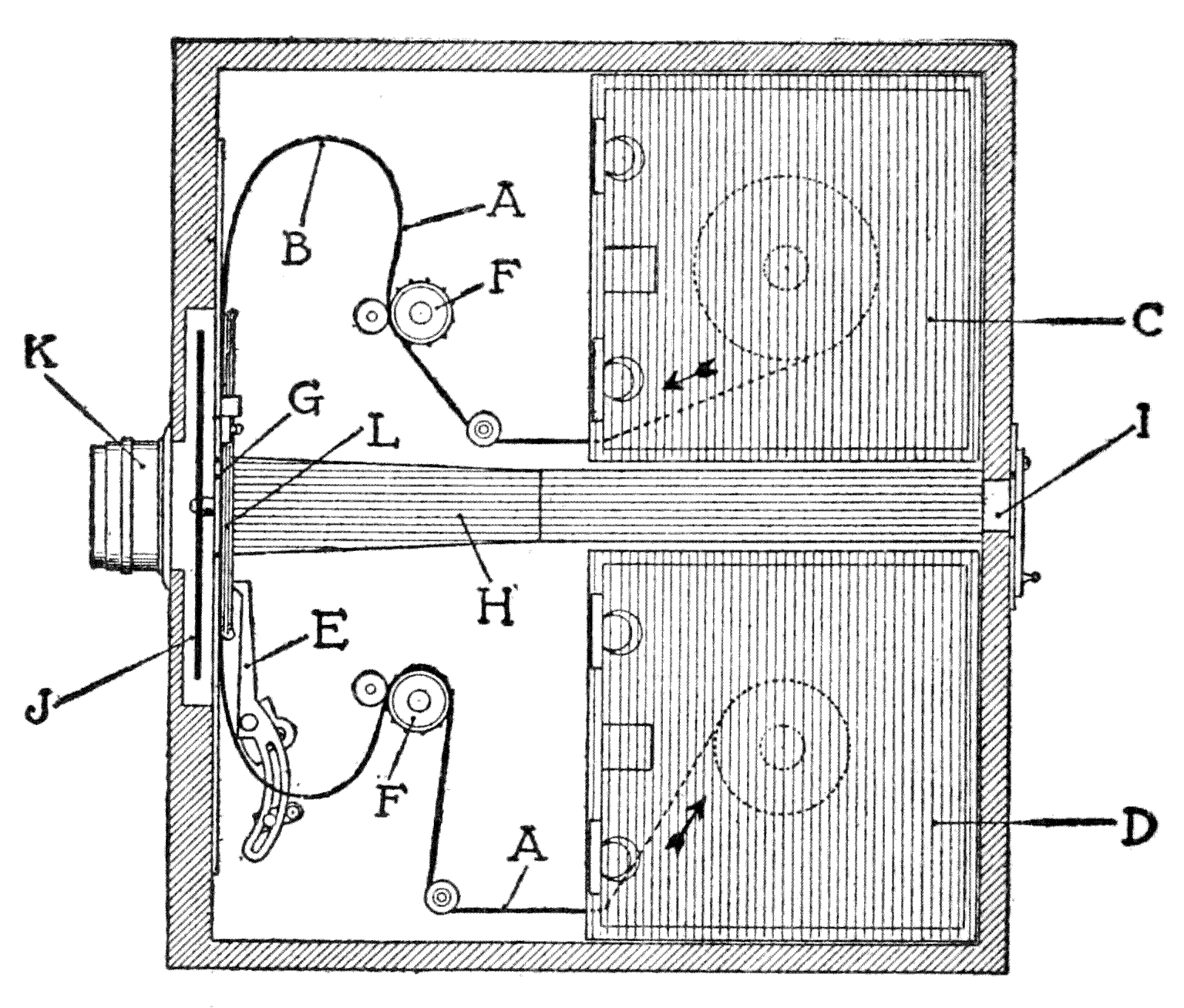

A. Film. B. Upper magazine. C. Feed reel. D. Lower magazine, containing the take-up reel. E. Crank to operate mechanism by hand. F. Motor. G. Where the film stops intermittently to be projected. H. Lamp-house. I. Port, or window in the fireproof projection booth. J. Rotating shutter. K. Lens. L. Condenser. M. Switches. N. Fire shutter; automatically drops when the film stops or goes too slowly.

One foot of celluloid film contains sixteen separate pictures, and these pass in front of the light in one second. One single tiny picture of the film takes up then one-sixteenth of a second. But not all of this fraction of a second is given to the projection of the picture as some of the time is taken up with moving it into place immediately before projection. The relative apportionment[12] of this period of one-sixteenth of a second is so arranged that about five-sixths of it (five ninety-sixths of a second) is given to the holding of the film at rest and the projection of its picture, and the remaining one-sixth (one ninety-sixth of a second) is given to the movement of a section of the film and the shutting off of the light by the opaque part of the shutter.

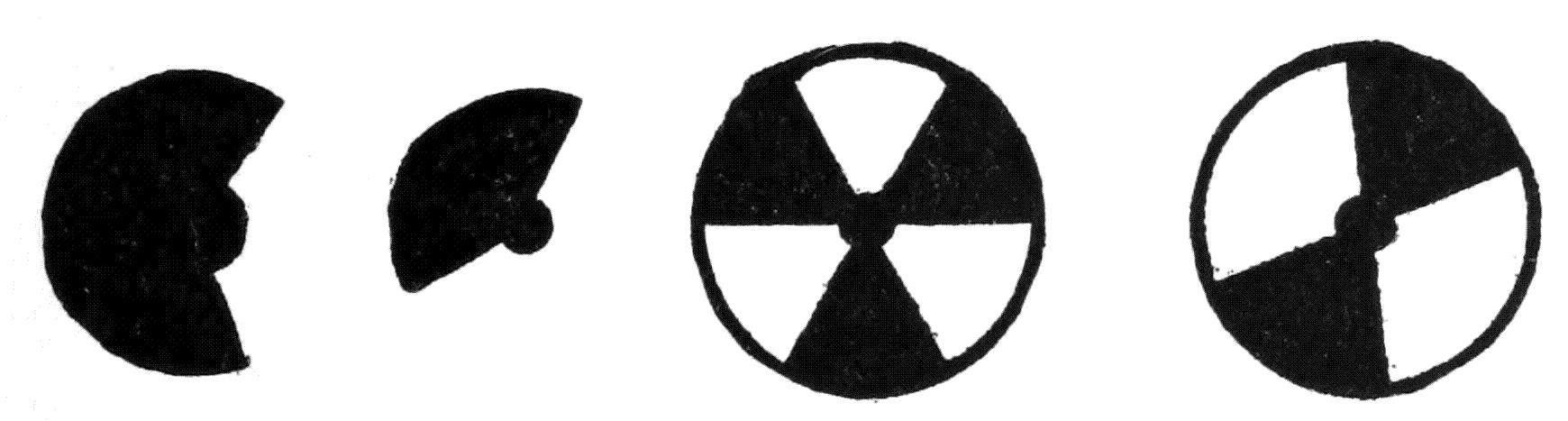

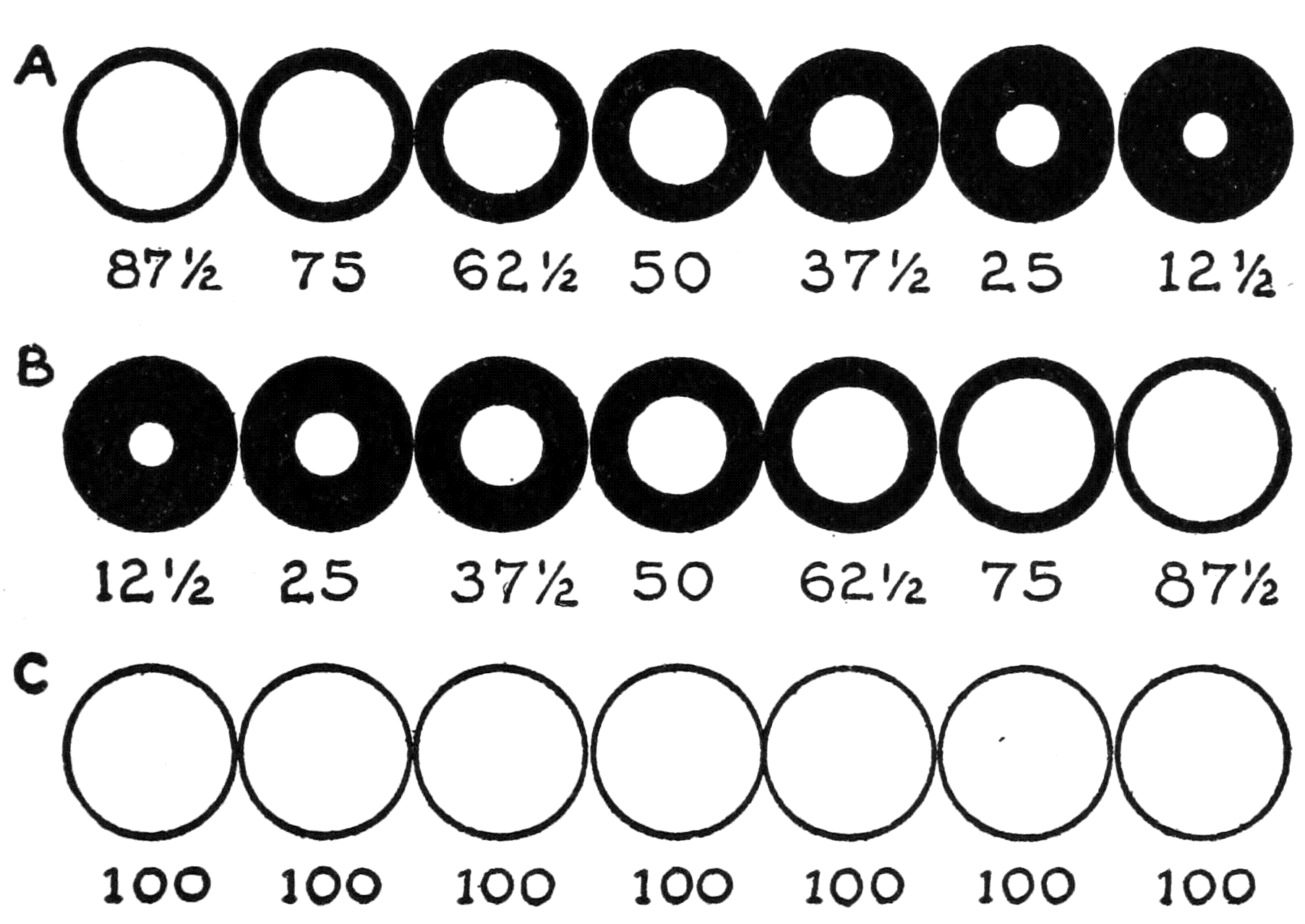

ILLUSTRATING THE PROPORTIONS OF LIGHT AND DARK PERIODS DURING PROJECTION IN TWO TYPES OF SHUTTERS.

1. Old single-blade type; caused a “flicker.”

2. Regular three-blade type; light evenly distributed. It is to be noted that while the picture is on the screen two opaque sections of the shutter eclipse the light.

In the last few paragraphs we have referred to the old type of shutter which caused a flicker, or unsteadiness of light on the screen. Nowadays a three-bladed shutter that nearly[13] does away with an unsteady light is in general use. Its operation, approximately for the purposes of description is like this: It turns once in one-sixteenth of a second; one-sixth of this time is taken up with the moving of the film and the eclipsing of the light by one blade of the shutter. During the remainder of the time—five-sixths of it, the following takes place: the film is stationary and ready for projection, then two blades of the shutter and three of its open sections pass across the path of the light.

From this it can be seen that when the picture is viewed on the screen, there are actually two short moments when the light rays are cut off. This is not perceived by the spectator on account of the speed of the revolving shutter and the strong illuminant. Instead, the use of a shutter of this pattern evens the screen lighting by making an equal apportioning of light flashes and dark periods. With the old shutter there was one long period of light and one short period of darkness. It was this unequal distribution that gave rise to the flicker. At times, under certain conditions, a two-bladed shutter is used also.

A reel of film may vary in length for a short[14] subject of fifty feet (or even less), to a very long “feature” of a mile or so in length. In width, the strip of celluloid measures one and three-eighths inches. Between the two rows of perforations that engage with the teeth on the sprocket-wheels and by which a certain part of the intermittent mechanism pulls the film along, are little rectangular panels, already alluded to, containing the photographs. Sometimes these panels are called “frames,” generally though, in the parlance of the trade, they are simply designated as “pictures.” They measure one inch across and three-quarters of an inch in height.

As noted above, these frames contain photographs of scenes that record, by changes in their action, the incidents and episodes of the story of any particular reel. In the case of animated cartoons, the frames on the film also contain photographs, but these photographs are made from sets of progressive drawings depicting the action of the characters of the animated cartoon.

In concluding this brief account of the modern motion-picture, the attention is directed, as the subject is studied, to a few details of the mechanism and to the general procedure that are found to be[15] elementary features in nearly all apparatus used during the round of years that the art was developing. They are as follows: (1) A series of pictures—drawings or photographs—representing an action by progressive changes in their delineation. (2) Their presentation, one at a time, in rapid succession. (3) Their synthesis, directly upon the retina of the eye, or projected on a screen and then viewed by the eye. (4) Some means by which light—or the vision—is shut off while the change from one picture to another is taking place. (Projecting machines have been[16] made, however, in which the film is moved so rapidly, and in a particular way, that a shutter to eclipse the light is not needed.)

Now, as stated before, the phenomenon of the persistence of vision is the fundamental physiological fact upon which the whole possibility of seeing screen pictures rests. One of the first devices made that depended upon it, and that very simply demonstrated this faculty of the retina for holding a visional image for a time, was an optical toy called the thaumatrope. It dates from about 1826. It was a cardboard disk with two holes close to the edge at opposite points. Strings were passed through these holes and fastened and the dangling ends held and rolled between the thumbs and fingers so that the disk was made to twirl rapidly. Each side of the disk had a picture printed or drawn upon it. These two pictures when viewed together while the disk was twirled appeared as one complete picture. A favorite design for depiction was an empty bird-cage on one side and a bird on the other. The designs were placed with respect to each other in the same way as the marks and insignia of the two sides of most coins. (The coins of Great Britain are[17] an exception, on them the designs are placed differently. In reading their marks or looking at the images of the two sides, we turn the coin over like the page of a book.)

Above: How the designs of the two sides are placed with respect to each other.

Below: The combined image when the thaumatrope is twirled.

The thaumatrope illustrates the persistence of vision in a very elementary way. Simply explained, the face of one side of the disk with its design is before the eye, the design impresses its true image upon the retina, the disk turns away and the picture disappears, but its after-image remains on the retina. The disk having turned, brings the other picture into view. Its true image is impressed upon the retina to blend with the[18] after-image of the first picture. In rapid sequence this turning continues and the two images commingle to give the fantasy of a perfect design.

A limited number of subjects only were suitable for demonstration by a toy of this character. Two other subjects were those showing designs to give the effect of a rider on a horse and a tight-rope dancer balanced on a rope.

From The Saturday Magazine of 1837 and 1841.

Later when scientific investigators were busy inquiring into the phenomena of visual distortions exhibited by the spokes and teeth of turning wheels[19] when seen in contrast with certain intervening objects, a curious apparatus was contrived by Faraday the English scientist (1791-1867). This apparatus was so constructed that two disks were made to travel, by cogged gearing, in opposite directions, but at the same speed. Around the circumferences of the disks were cut narrow slots at equal distances apart and so making the solid portions between them like teeth, or spokes of a wheel.

With the disks moving as marked, the disk B will appear to be motionless when viewed through the passing slots of disk A.

When this machine was set in motion and the eye directed through the moving and blurred teeth of the front disk toward the far disk, this far disk appeared to be stationary. Its outline—the[20] teeth, slots, and circumference—were distinctly seen and not blurred.

Then it was found that the same effect could be obtained with the use of one slotted disk by simply holding it in front of a mirror and viewing the reflected image through the moving slots of the disk. The reflection answered for the second disk of the instrument of the first experiment.

When the disk is twirled the reflections of its spokes appear stationary when viewed through the moving slots.

From this type of optical toy it was but a step to the contriving of various types of instruments constructed on the pattern of a slotted disk, or some sort of a turning mechanism with a series of apertures, to use in giving the illusion of movement in connection with drawings or photographs.[21] The best-known was the phenakistoscope, the invention of which has been credited to the Belgian physicist, Plateau (1801-1883). This toy was a large cardboard disk with pictures on one side that were to be viewed by their reflections through slots in the disk while it was held before a mirror. The pictures drawn in sequence represented some action, as a horse running, an acrobat, a juggler, or some amusing subject that could be drawn easily in a cycle of actions and that would lend itself to repetition.

The phenakistoscope has some rough resemblance in its plan to a motion-picture projector—the cycle of slightly different drawings represents the film with its sequence of tiny pictures; the slots in the disk by which the drawings are viewed in the mirror correspond to the open sections of the revolving shutter; while the solid portions of the disk answer to the opaque parts of the shutter.

[22]

As it only was possible in the phenakistoscope that one person at a time could view conveniently the reflected pictures, the attempt was made to arrange it for projection. A lens was added with a light and mirrors so that a number of people could see its operation at the same time. In another form the pictures were placed on a glass disk which was made to rotate back of a magic-lantern objective.

When the number of slots in a phenakistoscope correspond to the number of drawings in the cycle, the different figures of the cycle are in action but they do not move from the place where they are depicted. Only their limbs, if it is an action in which these parts are brought into play, are in movement. But if there is one slot more and the disk turned in the proper direction, the row of drawings will appear to be going around a circle.[23] This is particularly adapted to series of running animals.

Another method of giving the semblance of motion to a series of progressive drawings, soon devised after the invention of the phenakistoscope, was the zootrope, or wheel of life. It embodied the idea, too, of a rapidly moving opaque[24] flat portion with a row of slots passing between the eye and the drawings.

In form the zootrope was like a cylindrical lidless box of cardboard. It was pivoted and balanced on a vertical rod so that it could be made to turn easily and very rapidly. The slots were cut around the upper rim of the box. Long strips of paper holding pictures fitted into the box. When one of these strips was put in place, it was so adjusted that any particular drawing of the series could be viewed through a slot of the opposite side. These drawings appeared to be in motion when the zootrope was made to twirl.

This type of optical curiosity, as a matter of priority, is associated with the name of Desvignes,[25] as he obtained a patent for it in England in 1860. Later in 1867, a United States patent was issued for a similar instrument to William Lincoln, of Providence, R. I. He called his device the zoetrope.

This cylindrical synthesizing apparatus was sold as a toy for many years. Bands of paper with cycles of drawings of a variety of humorous and entertaining subjects thereon were prepared for use with it.

But the busy inventors were not satisfied with the simple form in which it was first fabricated. Very soon from the zootrope was evolved another[26] optical curiosity that preserved the general cylindrical plan, but made use of the reflective property of a mirror to aid the illusion. This was the praxinoscope of M. Reynaud, of France. He perfected it and adapted its principles to create other forms of rotating mechanisms harmonizing progressive drawings to show movement.

[27]

The praxinoscope held to the idea of a box, cylindrical and lidless, and pivoted in the centre so that it turned. The strip of drawings, and the plan of placing them inside of the box—two features of the zootrope—were both retained. But instead of looking at the drawings through apertures in the box rim, they were observed by their reflections in mirrors placed on an inner section or drum. The mirrors were the same in number as the drawings and turned with the rest of the apparatus. The mirrors were placed on the drum—the all-important point in the construction of the praxinoscope—half-way between the centre and the inner side of the rim of the box. As the drawings were placed here, the eye, looking over the rim of the box, viewed their reflections in the mirrors. But the actual place of a reflection was the same distance back of the surface of a mirror that a drawing was in front of it; namely, at the dead centre of the rotating cylinder. It was here, at this quiet point, that it was possible to see the changing images of the succession of graduated drawings blending to give the illusion of motion.

Reynaud next fixed his praxinoscope with improvements[28] that made the characters in his drawings appear to be going through a performance on a miniature stage. He called his new contrivance the theatre praxinoscope. This new mechanism, was fixed in a box before which was placed a mask-like section to represent a proscenium. Another addition in front of this had a rectangular peep-hole and small cut-out units of stage scenery that were reflected on the surface of a glass inserted into the proscenium opening.

Not satisfied with this toy theatre, Reynaud’s[29] next step was to combine with the praxinoscope, condensers, lenses, and an illuminant with which to project the images on a screen, so that spectators in an auditorium could see the illusion. A more intricate mechanism, again, was later devised by Reynaud. This was his optical theatre in which there was used an endless band of graduated drawings depicting a rather long pantomimic story. It, of course, was an enlargement of the idea of the simple early form of praxinoscope with its strip of paper containing the drawings. But this optical theatre had such a complication of mirrors and lenses that the projected light reached the screen somewhat diminished in illuminating power, and the pictures were consequently dimmed.

(After picture in La Nature, 1882.)

[30]

From the time of the invention of the thaumatrope in 1826, and throughout the period when the few typical machines noted above were in use, drawings only in graduated and related series, were applied in the production of the illusion of movement.

(After picture in La Nature, 1892.)

Drawings, too, were first employed for a little optical novelty in book-form, introduced about 1868, called the kineograph. It consisted of a number of leaves, with drawings on one side, firmly bound along an edge. The manner of its manipulation was to cause the leaves to flip from[31] under the thumb while the book was held in the hands. The pictures, all of a series depicting some action of an entertaining subject, passed quickly before the vision as they slipped from under the thumb and gave a continuous action of the particular subject of the kineograph.

Now when the camera began to be employed in taking pictures of figures in action, one of the first uses made of such pictures was to put a series of them into the book-form so as to give, by this simple method of allowing the leaves to flip from under the thumb, the visional deception of animated photographs.

[1] Celluloid is at this date the most serviceable material for these ribbons. But as it is inflammable a substitute is sought—one that has the advantages possessed by celluloid but of a non-combustible material.

THE GENESIS OF MOTION-PICTURES

Although the possibilities of taking pictures photographically was known as early as the third decade of the nineteenth century, drawings only were used in the many devices for rendering the illusion of movement. In the preceding chapter in which we have given a brief history of the early efforts of synthesizing related pictures, typical examples of such instruments have been given. But the pictorial elements used in them were always drawings.

It was not until 1861 that photographic prints were utilized in a machine to give an appearance of life to mere pictures. This machine was that of Mr. Coleman Sellers, of Philadelphia. His instrument brought stereoscopic pictures into the line of vision in turn where they were viewed by stereoscopic lenses. Not only did this arrangement show movement by a blending of related pictures but procured an effect of relief.

[36]

It is to be remembered that in the days of Mr. Sellers, photography did not have among its means any method of taking a series of pictures on a length of film, but the separate phases of a movement had to be taken one at a time on plates. The ribbon of sensitized film, practical and dependable, did not come until more than twenty-five years later. Its introduction into the craft was coincident with the growth of instantaneous photography.

[37]

When scientists began to study movement with the aid of instantaneous photographs, they quite naturally cared less for synthesizing the pictorial results of their investigations than they did for merely observing and recording exactly how movement takes place.

At first diagrams and drawings were used by students of movement to fix in an understandable way the facts gained by their inquiries. In England, for instance, Mr. J. Bell Pettigrew (1834-1908) illustrated his works with a lot of carefully made diagrammatic pictures. He made many interesting observations on locomotion and gave much attention to the movement of flying creatures, adding some comment, too, on the possibility of artificial flight.

Again in Paris, M. E. J. Marey (whose work is to be considered a little farther on) embellished his writings with charts and diagrams that were made with the aid of elaborate apparatus for the timing of animals in action and the marking of their footprints on the ground. Then he traced, too, by methods that involved much labor and patience, the trajectory of a bird’s wing. And in his continued searching out of the principles[38] of flight registered by ingenious instruments the wing-movements in several kinds of insects.

In our first chapter no instructions were given as to how animated cartoons are made. And although this is the specific purpose of the book, we must again in this chapter refer but slightly to the matter, as there is need that we first devote some time to chronicling the early efforts in solving animal movements by the aid of photography. Then we must touch, too, upon the modes of the synthesis of analytic photographs for the purpose of screen projection.

Both these matters are pertinent to our theme: the animated screen artist makes use of instantaneous photographs for the study of movement, and the same machine that projects the photographic film is also used for the animated cartoon film made from his drawings.

What appears to have been the first use of photographs to give a screen synthesis in an auditorium, was that on an evening in February, 1870, at the Academy of Music, in Philadelphia. It was an exhibition given by Mr. Henry R. Heyl, of his phasmatrope. He showed on a screen, life-sized figures of dancers and acrobats in motion.[39] The pictures were projected, with the aid of a magic-lantern, from photographs on thin glass plates that were placed around a wheel which was made to rotate. A “vibrating shutter” cut off the light while one photograph moved out of the way, and another came in to take its place. The wheel had spaces for eighteen photographs. It was so planned that those of one set could be taken out and those of another slipped in to change a subject for projection.

The photographs used in the phasmatrope were from posed models; a certain number of which were selected to form a cycle so that the series could be repeated and a continuous performance be given by keeping the wheel going. At this period there were no pliant sensitized ribbons to take a sequence of photographs of a movement, and Heyl had to take them one at a time on glass plates by the wet collodion process.

A notable point about this early motion-picture show was that it was quite like one of our day, for according to Heyl, in his letter to the Journal of the Franklin Institute, he had the orchestra play appropriate music to suit the action of[40] the dancers and the grotesqueries of the acrobats.

Better known in the fields of the study of movement and that of instantaneous photography and pictorial synthesis are M. Marey, already mentioned (1830-1904), and his contemporary, Mr. E. Muybridge (1830-1904). While Marey conducted his inquiries in Paris, Muybridge pursued his studies in San Francisco and Philadelphia.

Marey, who in the beginning recorded the changes and modification of attitudes in movement by diagrams and charts, later used diagrams made from photographs and then photographs themselves. He studied the phases of movement from a strictly scientific standpoint, in human beings, four-footed beasts, birds, and nearly all forms of life. And he did not neglect to note the speed and manner of moving of inorganic bodies, such as falling objects, agitated and whirling threads.

Part of a plate in Muybridge’s “Animal Locomotion.” Published and copyrighted by him in 1887.

An imposing work, made under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania, of more than 700 large plates. It was the first comprehensive analytical study of movement in human figures and animals.

Muybridge, on the other hand, seemed to have a trend toward the educational, in a popular sense of the word; and had a faculty of giving his works a pictorial quality. He showed this in the choice of his subjects and the devising of machines [41]that combined his photographs somewhat successfully in screen projection.

In Muybridge’s first work in which he photographed a horse in motion, he used a row of cameras in front of which the horse proceeded. The horse in passing before them, and coming before each particular camera, broke a string connected with its shutter. This in opening exposed the plate and so pictured the horse at that moment, and in the particular attitude of that moment. This breaking of a string, opening of a shutter, and so on, took place before each camera. Muybridge in his early work used the collodion wet plate, a serious disadvantage. Later he had the convenience of the sensitized dry plate and was also able to operate the cameras by motors.

When Marey began to employ a camera in his researches he registered the movements of an entire action on one plate; while Muybridge’s way was to take but one phase of an action on one plate. The two men differed greatly in their objects and methods. Marey in his early experiments, at least, traced on one plate or chart the successive changes in attitudes of limbs or parts, or the positions of certain fixed points on his[42] models. But Muybridge procured single but related pictures of attitudes assumed by his subjects in a connected and orderly sequence. The latter method lent itself more readily to adaptation for the projecting lantern and so became popularly appreciated. Perhaps it is for this reason that Muybridge has been referred to as the father of the motion-picture.

The photographic gun was Marey’s most novel camera. With this he caught on a glass plate the movements of flying birds. This instrument was suggested by a similar one used by M. Janssen, the astronomer, in 1874, to make a photographic record of the transit of a planet across the sun’s disk.

The kineograph, mentioned at the beginning[43] of this chapter, by which the illusion of motion was given to a series of pictures arranged like a book, formed the basic idea for a number of other popular contrivances. One of these was the mutoscope, in which the leaves were fastened by one edge to an axis in such a way that they stood out like spokes. The machine in operation brought one leaf for a moment at rest under the gaze of the eye and then allowed it to snap away to expose another picture in its place. When this was viewed in its turn, it also disappeared to make way for the next in order.

An apparatus similar in principle to the mutoscope.

As yet experimenters were not altogether sure in what particular way to combine a series of graduated pictures so as to produce one living image. Besides the ways that have been exemplified[44] in the apparatus so far enumerated, some experimenters tried to put photographs around the circumference of a large glass disk somewhat on the order of the phenakistoscope. Heyl’s phasmatrope, of 1870, was on this order.

On this plan of a rotating disk, Muybridge constructed his zoöpraxiscope by which he projected some of his animal photographs. Another expedient tried by some one was that of putting a string of minute pictures spirally on a drum which was made to turn in a helix-like fashion. The pictures were enlarged by a lens and brought into view back of a shutter that worked intermittently.

Although the dry plate assuredly was a great improvement over the slow and troublesome old-fashioned wet plate, there was felt the need of some pliant material that could be sensitized for photography and that could furthermore be made in the form of a ribbon. The suitableness of the paper strips for use in the zootrope and the praxinoscope obviously demonstrated the advantages of an elongated form on which to put a series of related pictures.

Experiments were made to obtain a pliant[45] ribbon for the use. Transparent paper was at one time tried but found unadaptable. Eventually the celluloid film came into use, and it is this material that is now generally in use to make both the ordinary snap-shot film and the “film stock” for the motion-picture industry.

Edison’s kinetoscope of 1890, or more particularly its improved form of 1893, that found immediate recognition on its exhibition at the World’s Fair at Chicago, was the first utilization on a large scale of the celluloid film for motion-pictures. It is to be remarked, however, that in the kinetoscope the pictures were viewed, not on a screen in an auditorium by a number of people, but by one person at a time peering through a sight opening in the apparatus. It was the kinetoscope, it appears, that set others to work devising ways of using celluloid bands for projecting pictures on a screen.

While some inventors were busy in their efforts to construct workable apparatus both for photography and projection, others were endeavoring to better the material for the film and improve the photographic emulsion covering it.

There is no need in this book, in which we shall[46] try to explain the making of animated screen drawings, to recount the whole story of the progressive improvements of the machines used in the motion-picture industry. But a short notice of the present-day appliances will not be out of place.

Modified from the Patent Office drawing.

The three indispensable pieces of mechanism are the camera, the projector, and the printer, or apparatus that prints pictures photographically. All three in certain parts of their construction[47] are similar in working principles. The mechanical arrangements of the camera and projector especially are so much alike that some of the first apparatus fabricated were used both for photography and projection. A few early types of cameras served even for printers as well.

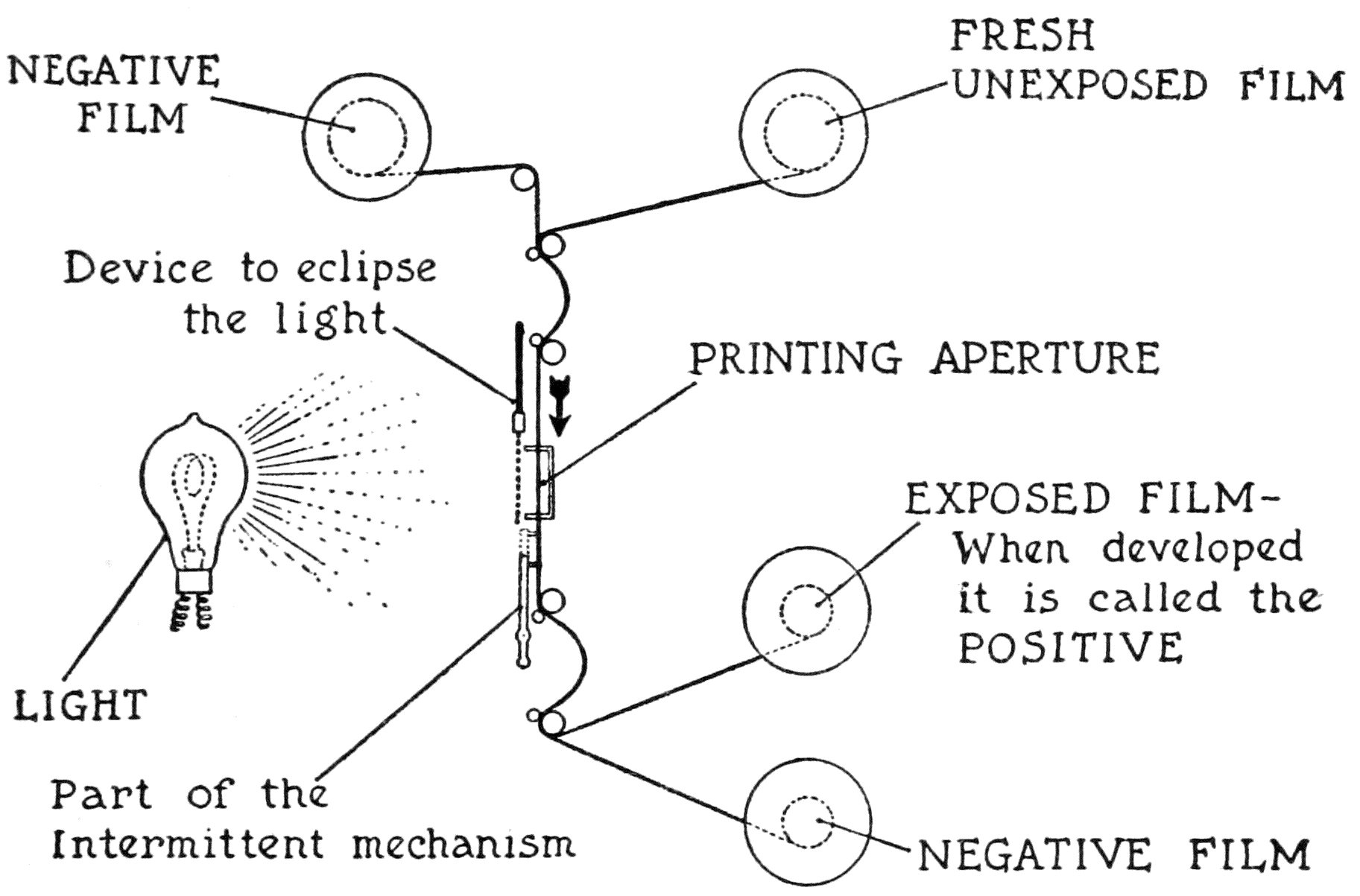

The essential details of the three machines named above can be described briefly as follows: (1) A camera has a light-tight compartment within which a fresh strip of film passes and stops intermittently back of a lens that is focussed on a subject, a rotating shutter with an open and an opaque section makes the exposure. (When the strip of film is developed it is known as the negative.) (2) A printer pulls the negative, together with a fresh strip of film in contact with it, into place by an intermittent mechanism before a strong light. A rotating shutter flashes the light on and off. (The new piece of film, when it is developed and the pictures are brought out, is known as the positive.) (3) The projector moves the positive film by an intermittent mechanism between a light and a lens; a rotating shutter, with open and opaque sections, alternately shuts the light off and on. When the light rays are[48] allowed to pass the pictures contained on the positive film are projected on the screen.

It seems unnecessary, perhaps, in these days of the ubiquity of snap-shot cameras, and the fact that nearly every one becomes acquainted with their manipulation, to mention that a photographic negative records the light and shade of nature negatively, and that a positive print is[49] one that gives a positive representation of such light and shade.

A motion-picture camera of the most approved pattern is an exceedingly complicated and finely adjusted instrument. Its principle of operation can be understood easily if it is remembered that it is practically a snap-shot camera with the addition of a mechanism that turns a revolving shutter and moves a length of film across the exposure field, holds it there for an interval while the photographic impression is made, and then moves it away to continue the process until the desired length of film has been taken. This movement, driven by a hand-crank, is the same as that of a projector—previously explained—namely, an intermittent one.

This is effected in a variety of ways. The method in many instruments is an alternate one of the going back and forth of a pair of claw-levers[50] that during one such motion draw the film into place by engaging the claws into perforations on the margins of the film.

A. Film. B. Top loop to allow for the pulling down of the film during the intermittent movement. C. Magazine to hold the blank film. D. Magazine to hold the exposed film. E. Claw device which pulls down the film three-quarters of an inch for each picture. F. Sprocket-wheels. G. Exposure field. H. Focusing-tube. I. Eye-piece for focusing. J. Shutter. K. Lens. L. Film gate.

The patterns of the shutters in camera and projector differ. That of the projector is three or two parted, as stated in our observations previously made. A camera shutter is a disk with an open section. The area of this open section can be varied to fit the light conditions.

[51]

The general practice relative to taking motion-pictures is to have one-half foot of film move along for each turn of the camera handle. Eight separate pictures are made on this one-half foot of film. But in a camera that the animated cartoon artist uses, but one turn of the handle for each picture is the method. In most cameras the gearing can be changed to operate either way. To photograph drawings in making animated films a good reliable instrument is necessary, and requirements to the purpose should be thought of in selecting one. One important matter that may be mentioned here is that there should be an easy way of focussing the scene. Generally in taking topical pictures and views, an outside finder and a graduated scale for distance and other matters is made use of, but for[52] drawings it is essential to be able to focus on a suitable translucent surface within the exposure field in the camera.

There are certain numerical formulas that those going into motion-picture work should learn at the start. It is well, too, for the general reader, even if he is interested only as a matter of information to take note of them. Their comprehension will help to a better understanding of how both the ordinary photographic film, and the film from animated drawings, are made, prepared, and shown on the screen.

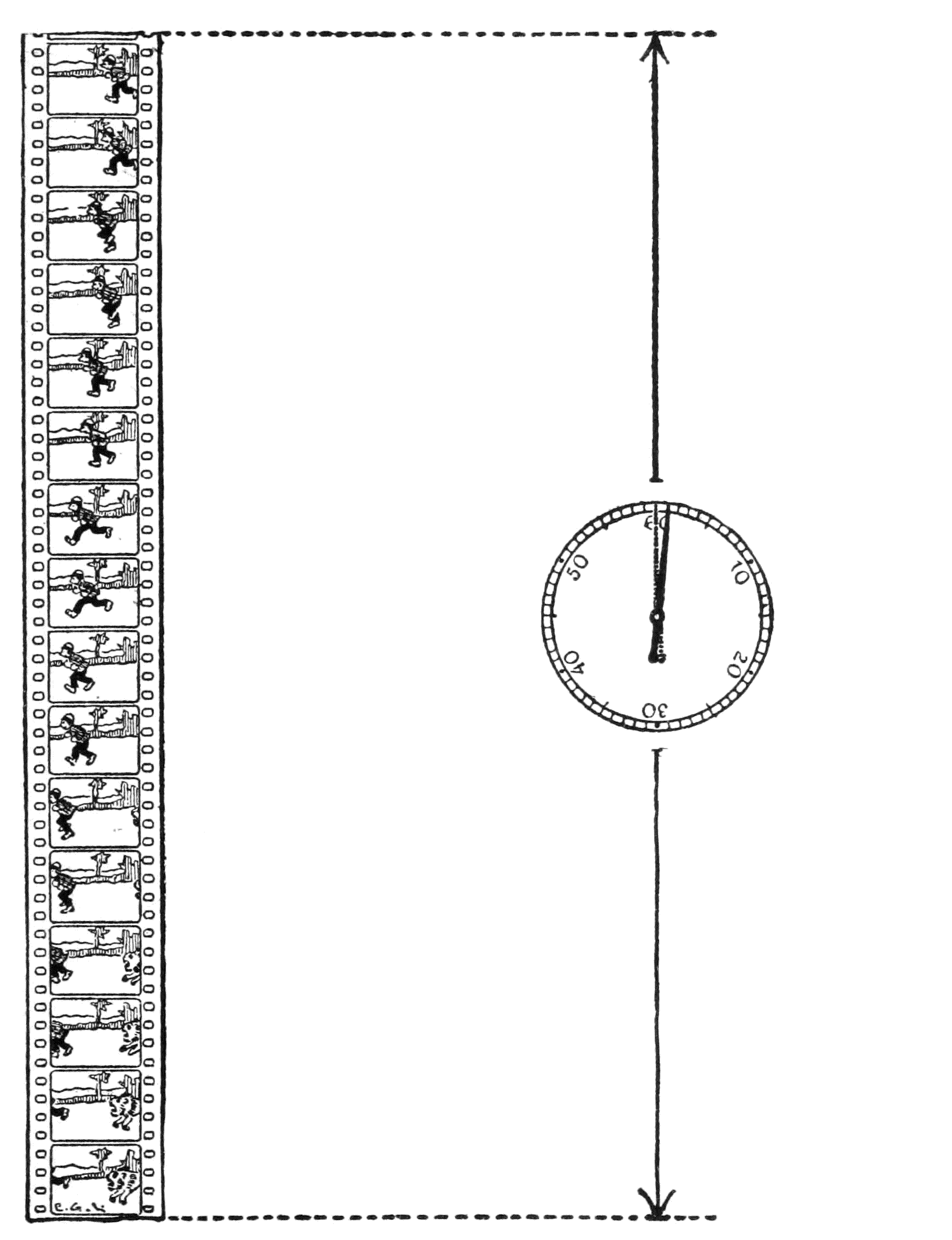

As the ordinary phrase goes, any single subject in film form is spoken of as a reel; but in strict trade usage the word means a length of one thousand feet. As it is generally reckoned, sixty feet of film pass through the projecting machine every minute. This means that a reel of one thousand feet will take about seventeen minutes. Now with sixty feet of film crossing the path of light in one minute, we see that one foot hurries across in one second. And as sixteen little pictures are contained in one foot of film, we get an idea of the great number of such separate pictures in a reel of ordinary length.[53] All these particulars—especially that regarding the speed at which the film moves—are vital matters for the animated cartoon artist to keep in mind as he plans his work.

MAKING ANIMATED CARTOONS

In the preceding chapter the attention was called to the fact that a foot of film passes through the projector in one second, and that in each foot there are sixteen pictures, or frames, within the outlines of which the photographic images are found. When a camera man sets up his apparatus before a scene and starts to operate the mechanism, the general way is to have the film move in the camera at this same rate of speed; to wit, one foot per second. As each single turn of the camera handle moves only one-half of a foot of film, the camera man must turn the handle twice in one second. And one of the things that he must learn is to appraise time durations so accurately that he will turn the handle at this speed.

The animated cartoon artist, instead of using real people, objects, or views to take on his film, must make a number of related drawings, on every one of which there must be a change in a proper,[58] progressive, and graduated order. These drawings are placed under a camera and photographed in their sequence, the film developed and the resultant negative used to make a positive film. This is used, as we know, for screen projection. All the technical and finishing processes are the same whether they are employed in making the usual reel in which people and scenes are used, or animated cartoon reels from drawings.

When it is considered that there are in a half reel (five hundred feet, the customary length for a comic subject) exactly eight thousand pictures, with every one—theoretically—different, it seems like an appalling job to make that number of separate drawings for such a half reel. But an artist doesn’t make anywhere near as many drawings as that for a reel of this length, and of all the talents required by any one going into this branch of art, none is so important as that of the skill to plan the work so that the lowest possible number of drawings need be made for any particular scenario.

“Animator” is the special term applied to the creative worker in this new branch of artistic endeavor. Besides the essential qualification of[59] bestowing life upon drawings, he must be a man of many accomplishments. First as a scenario is always written of any screen story no matter whether serious, educational, or humorous, he must have some notion of form; that is to say, he must know what good composition means in putting components together in an orderly and proportional arrangement.

If the subject is an educational one he must have a grasp of pedagogical principles, too, and if it is of a humorous nature, his appreciation of a comic situation must be keen.

And then with the terrifying prospect confronting him of having to make innumerable drawings and attending to other incidental artistic details before his film is completed, he must be an untiring and a courageous worker. His skill as a manager comes in when planning the whole work in the use of expedients and tricks, and an economy of labor in getting as much action with the use of as few drawings as possible.

Besides the chief animator, others, such as assistant animators, tracers, and photographers, are concerned in the production of an animated film from drawings.

[60]

Comments on the writing of the scenario we do not need to go into now. Often the artist himself writes it; but if he does not, he at least plans it, or has a share in its construction.

Presuming, then, that the scenario has been written, the chief animator first of all decides on the portraiture of his characters. He will proceed to make sketches of them as they look not only in front and profile views, but also as they appear from the back and in three-quarter views. It is customary that these sketches—his models, and really the dramatis personæ, be drawn of the size they will have in the majority of the scenes. After the characters have been created, the next step is to lay out the scenes, in other words, plan the surroundings or settings for each of the different acts. The rectangular space of his drawings within which the composition is contained is about ten or eleven times larger than the little three-quarter-by-one-inch pictures of the films; namely, seven and one-half by ten inches, or eight and one-quarter by eleven inches. For some kinds of films—plain titles and “trick” titles—the making of which will be remarked upon further on—a larger field of about thirteen and one-half by eighteen inches is used.

[61]

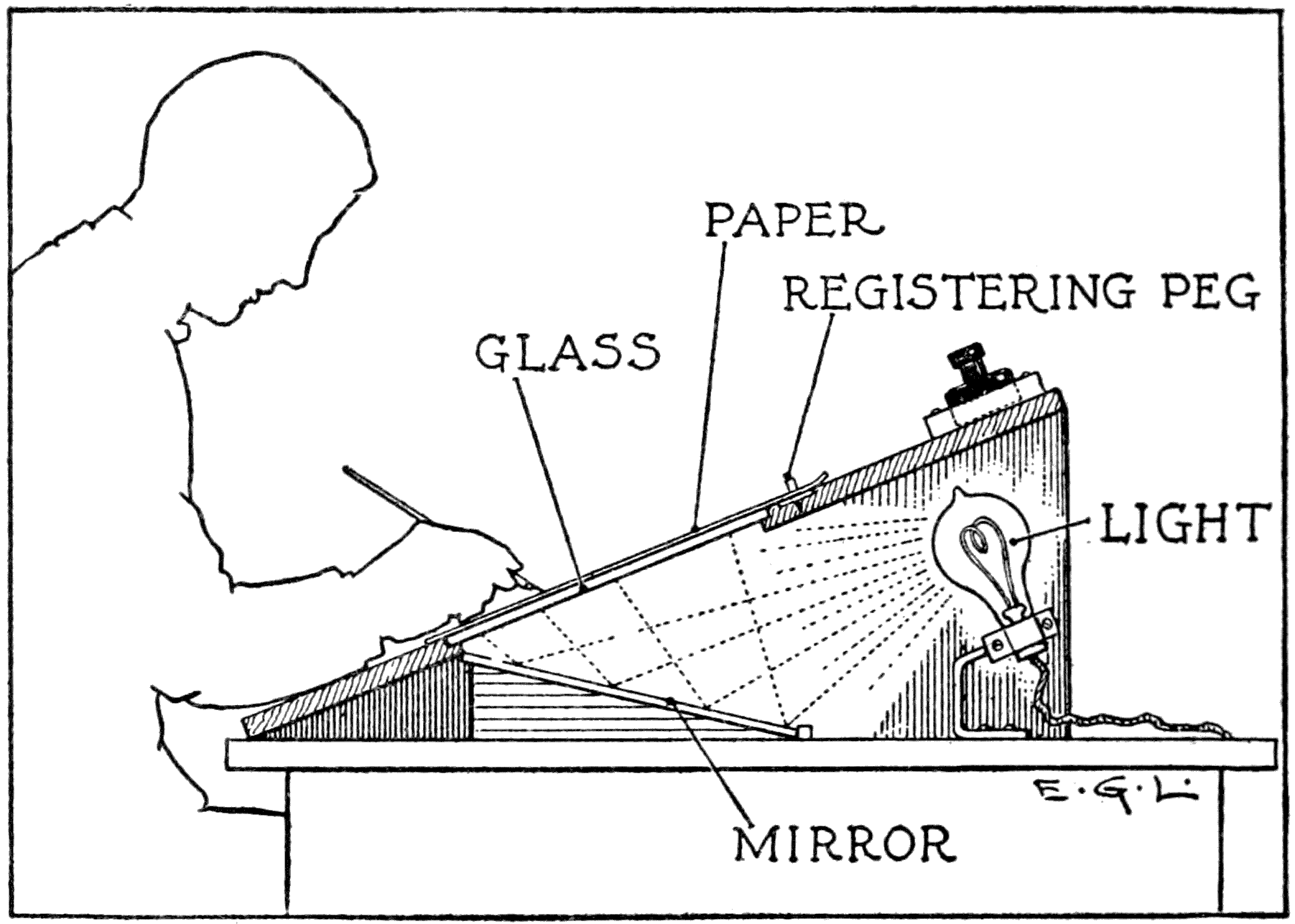

Now with a huge pile of white linen paper cut to a uniform size of about nine by twelve inches, the animator apportions the work to the several assistant animators. The most important scene or action, of course, falls to his share. There are several ways of going about making animated cartoons, and trick titles, and these methods will be touched upon subsequently. But in the particular method of making animated cartoons which we are describing now—that in which paper is the principal surface upon which the drawings are made in ink—all the workers make their drawings over a board that has a middle portion cut out and into which is fitted a sheet[62] of thick glass. Under this glass is fixed an electric light. On the board along the upper margin of the glass, there is fixed to the wood a bar of iron to which two pins or pegs are firmly fixed. These pegs are a little less than one-half inch high and distant from each other about five inches. It doesn’t matter much what this distance is, excepting this important point: all the boards in any one studio must be provided with sets of pegs that are uniform with respect to this distance between them. And all of them should be most accurately measured in their placing. Sometimes as an expedient, pegs are merely driven into the board at the required distance.

These pegs are seven thirty-seconds of an inch in diameter. That the animator should use this particular size of pegs was determined, no doubt, by the fact that an article manufactured originally for perforating pages and sheets used in certain methods of bookkeeping was found available for his purposes. This perforator cuts holes exactly seven thirty-seconds of an inch in diameter. Each one of the sheets of paper from the huge pile spoken of above, before it is drawn upon, has two holes punched into one of its long edges at[63] the same distance apart as the distance between the two pegs fixed to the animator’s drawing-board.

Fitting one of these sheets of paper over the pegs, the artist-animator is ready for work. As the paper lies flat over the glass set into the board, he can see the glare of the electric light underneath. This illumination from below is to enable him to trace lines on a top sheet of paper from[64] lines on a second sheet of paper underneath; and also to make the slight variations in the several drawings concerned in any action.

Now the reason for the pegs is this: as in an ordinary motion-picture film certain characters, as well as objects and other details are quiescent, and only one or a few characters are in action, so in an animated cartoon some of the figures, or details, are quiescent for a time. And as they stay for a length of time in the same place in the scene, their portrayal in this same place throughout the series of drawings is obtained by tracing them from one sheet to another. The sheets are held in place by the pegs and they insure the registering of identical details throughout a series.

When the animator designs his setting, the stage scenery of any particular animated play, he keeps in mind the area within which his figures are going to move. Reasons for this will become apparent as the technic of the art is further explained. The outline of his scene, say a background, simply drawn in ink on a sheet of paper is fitted over the pegs. The light under the glass, as explained immediately above, shows through[65] it. Next a fresh sheet of paper is placed over the one with the scene, and as the paper is selected for its transparent qualities, as well as its adaptability for pen-drawing, the ink lines of the scene underneath are visible.

Let us presume now, that the composition is to represent two men standing and facing each other and talking. They are to gesticulate and move their lips slightly as if speaking. (In the following description we will ignore this movement of the mouth and have it assumed that the artist is drawing this action, also, as he proceeds with the work.) The two men are sketched in some passive position, and the animation of one of the figures is started. With the key sketch of the men in the passive position placed over the light, a sheet of paper is placed over it and the extreme position of a gesticulating arm is drawn, then on another sheet of paper placed over the light the other extreme position of this arm action is drawn. Now, with still another sheet of paper placed over the others, the intermediate position of the gesture is drawn. As the man was standing on the same spot all the time his feet would be the same in all the drawings and[66] other parts of his figure would occupy the same place. But the animator does not draw these parts himself but marks the several sheets where they occur with a number, or symbol, that will be understood by one of his helpers—a tracer—as instructions to trace them. The other man in the picture, who all this time has been motionless, is also represented in all the drawings line for line as he was first drawn in the preliminary key sketch. This again is a job for the tracer.

When the action of the second figure is made, the drawing of the three phases of movement in his arms is proceeded with in the same way, and the first figure is repeated in his passive position during the gesturing of the second man.

It can be seen from this way of working in the division of labor between the animator and his helper that the actual toil of repeating monotonous details falls upon the tracer. The animator does the first planning and that part of the subsequent work requiring true artistic ability.

So that the artists can see to do the work described above—tracing from one sheet of paper to another and distinguishing ink lines through two or more sheets of paper while they are over the illuminated glass—the expedient is adopted of shading the work-table from the glare of strong daylight.

[67]

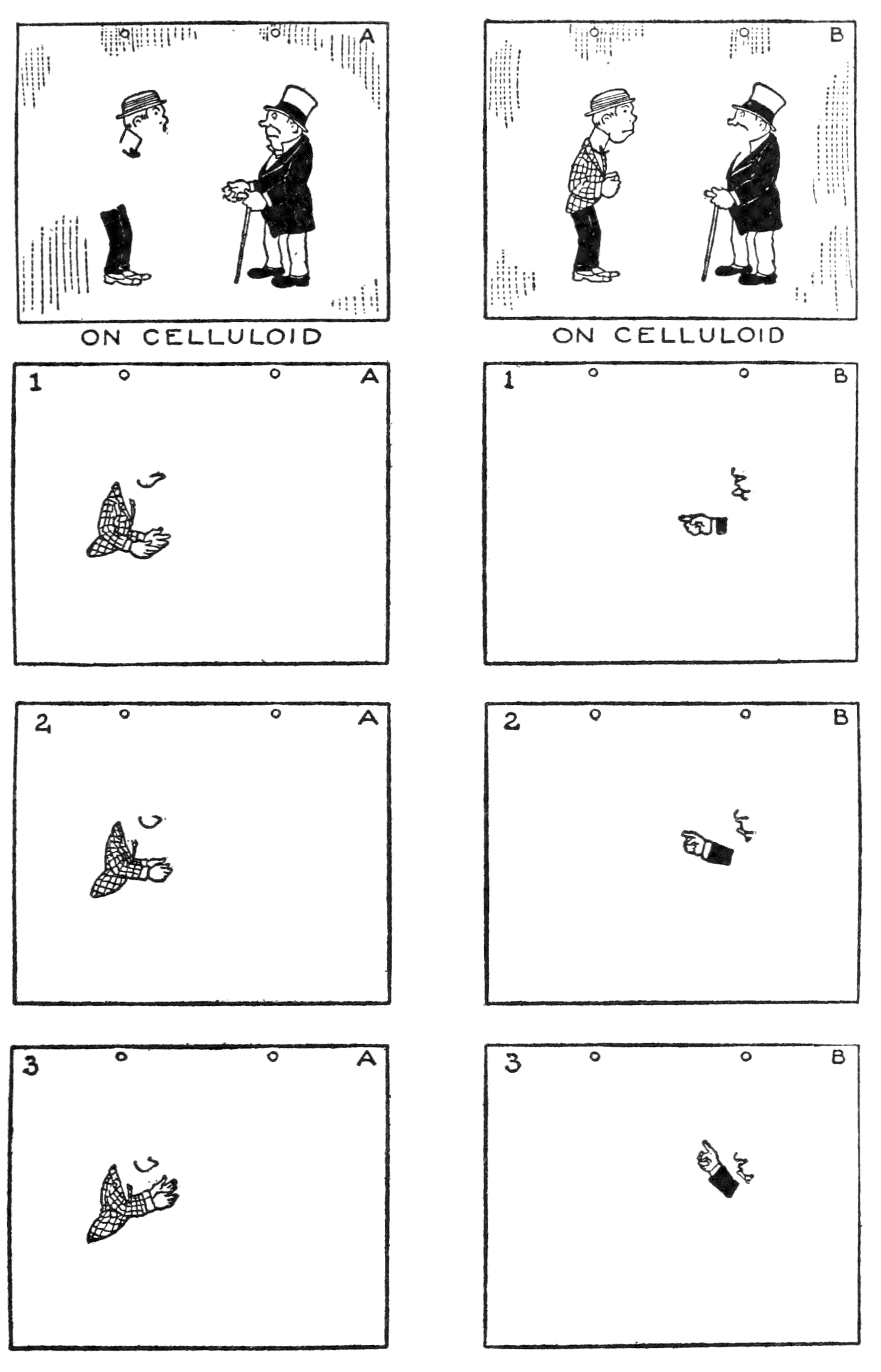

ILLUSTRATING THE GREAT AMOUNT OF DRAWING REQUIRED IN ANIMATING A SCENE WITHOUT THE HELP OF TRANSPARENT CELLULOID.

In this typical process of depicting a simple action, or animating a figure, as it is called, we have left out specific explanations for drawing the details of the scenery—trees, foreground, or whatever is put into the composition as an accessory. They go into a finished composition, to be sure. One way would be to trace their outlines on each and every sheet of paper. It is a feasible way but not labor-saving. There is a much more convenient way than that.

In beginning this exposition on animation it was noted that the artist in designing the scenery gave some thought to the area within which his figures were placed, or were to act. He planned when he did this, that no part of the components of the scenery should interfere by crossing lines with any portions of the figures. The reason for this will be apparent when it is explained that the scenery is drawn on a sheet of transparent celluloid. Then when the celluloid with its scenery is placed over one of the drawings it completes the picture. The celluloid sheet has also two[69] perforations that fit over the pegs, and it is by their agency that its details are made to correspond with the drawings on paper. And it can further be understood that this single celluloid sheet will complete, if it is designed properly, the pictorial composition of every one of the drawings. (A sheet of this substance that we are referring to now is known in the craft as “a celluloid” or shortened sometimes to “cell.”)

The employment of celluloid can be extended to save other work in tracing parts of figures that are in the same position, or that are not in action throughout several drawings. In this case a second celluloid will be used in conjunction with that holding the scenery. To exemplify: In giving an account of the drawing of the arm gestures in the instance above, it was noted that an animator drew the action only while he had a tracer complete on all the drawings the parts that did not move. Now, to save the monotony of all this, the tracer takes celluloid and draws the similarly placed quiet parts on it but once. This celluloid is used during the photography with the several action phases to complete the picture of the figure, or figures.

[70]

A matter that the animator should guard against, however, in having several celluloids over his drawings, during the photography, is that they will impart a yellowish tinge to his white paper underneath if he uses more than two or three. This would necessitate care in timing the exposure correctly as a yellow tint has non-actinic qualities that make its photography an uncertain element.

The methods so far described of making drawings for animated films are not complex and are easy to manage. For effective animated scenes, many more drawings are required and the adaptation of celluloids is not always such an easy matter as here described. For complete films of ordinary length, the drawings, celluloids, and other items—expedients or ingenious devices to help the work—number into the hundreds.

[71]

ILLUSTRATING THE SAVING OF TIME AND LABOR IN MAKING USE OF THE EXPEDIENT OF DRAWING THE STILL PARTS ON CELLULOID SHEETS.

We will use, however, our few drawings and celluloids that we have completed to explain the subsequent procedure in the making of animated cartoons; namely, the photographic part of the process.

A moving-picture camera is placed on a framework of wood, or iron, so that it is supported over a table top or some like piece of carpentry. It is placed so that it faces downward with the lens centred on the table. The camera is arranged for a “one picture one turn of the crank” movement, and a gearing of chain belts and pulleys, to effect this, is attached to the camera and framework. This gearing is put into motion by a turning-handle close to where the photographer is seated as he works before the table top where the drawings are placed.

Each time the handle is turned but one picture, or one-sixteenth of a foot of film, is moved into the field back of the lens where the exposure is made. The view or studio camera, as we know, when a complete turn of the crank handle is made, moves eight pictures, or one-half of a foot of film, into position.

On the table directly under the lens and at[73] the proper distance for correct focussing, a field is marked out exactly that of the field that was used in making the drawings. Two registering pegs are also fastened relatively to the field as those on all the drawing-boards in the studio. Over the field, but hinged to the table top so that it can be moved up and down, a frame holding a clear sheet of glass is placed. The glass must be fitted closely and firmly in the frame, as it is intended to be pressed down on the drawings while they are being photographed. Wood serves the purpose very well for these frames. A metal frame would seem to be the most practical, but if there is in its construction the least inequality of surface where glass and metal touch, the pressure put upon the frame in holding the drawings down is liable to crack the glass. With wood, as there is a certain amount of give, this is not so likely to happen.

Considering now that the camera has been filled with a suitable length of blank film and properly threaded in and out of the series of wheels that feed it to the intermittent mechanism, and then wind it up into its proper receptacle, we can proceed with the photography.

[74]

The pioneers in the art who first tried to make animated cartoons and similar film novelties attempted the photography by daylight. Their results were not very good, for they were much handicapped by the uncertainty of the light. Nowadays the Cooper Hewitt mercury vapor light is used almost exclusively. The commonest method of lighting is to fix a tube of this illuminant on each side of the camera above the board, but so placed that light rays do not go slantingly into the lens, or are caught by any polished surface, and so cause reflected lights that interfere with the work. To get the exact position of the light for an even illumination over the field means a little preliminary experiment.

In looking over the material for our little film we find that we have but a few drawings and celluloids. Now, if we were to photograph them and give each drawing one exposure—one picture, or section on the film for each drawing—we should get a length of film not even a foot long, and the time on the screen not even lasting a second, but an insignificant result for so much work. Here at this stage of the work the able animator must exercise his talents in getting as[75] much film as possible, i. e., “footage,” out of his few drawings.

(For its position under the camera, see engraving on page 203.) A perforated sheet of paper holding a drawing is fitted over the pegs and the frame lowered.

To begin: The first drawing in which the men are quiescent is fitted over the pegs; but the picture is not complete until the celluloid with the scenery is also fitted over the pegs. When this is put in place and the frame with the glass is pressed down it is ready for photography. The first figures will not begin to gesticulate immediately—no, a certain time is necessary for the audience to appreciate—have enter into their consciousness—that[76] the picture on the screen represents two men facing each other and about to carry on a conversation. Therefore the drawing showing the men motionless is photographed on about two or three feet of film. This will give on the screen just so many seconds—two or three—for the mental grasping by the audience of the particulars of the pictorial composition. Next to show the first figure going through his movements we lift the framed glass and take off the celluloid with the scenery and the paper with the two men motionless. Now we put down over the pegs the sheet of paper with one of the extreme positions of the moving arms, and then as that is all there is on the paper we must, to complete the portrayal, place over it the celluloid with the rest of his figure. (This celluloid also holds the complete drawing of the other individual as he is motionless during the action of the first one.) Next the entire composition is completed by putting down the scenery celluloid. Then when the framed glass is lowered and pressed down so that everything presents an even surface, the picture is photographed. After two[77] turns of the handle—photographing it on two sections of the film—the frame is raised and the celluloids and the drawing are both taken off of the pegs. The photographing of the second or intermediate position is proceeded with in the same way. After this the third or other extreme phase of the action is photographed.

The photography is continued by taking the intermediate phase again, then the first position, then back to the intermediate one, and so on. The idea is to give a gesticulating action to the figure by using these three drawings back and forth in their order as long as the story seems to warrant it.

It is not to be forgotten that the celluloid with the scenery is used every time the different action phases are photographed.

The same procedure will be followed with the celluloid and drawings of the other figure, only before beginning his action a little extra footage can be eked out by giving a slight dramatic pause between the ending of the first man’s gesticulating and the beginning of that of the other one. By this is meant that the first scene with the[78] men motionless is taken on a short length of film.

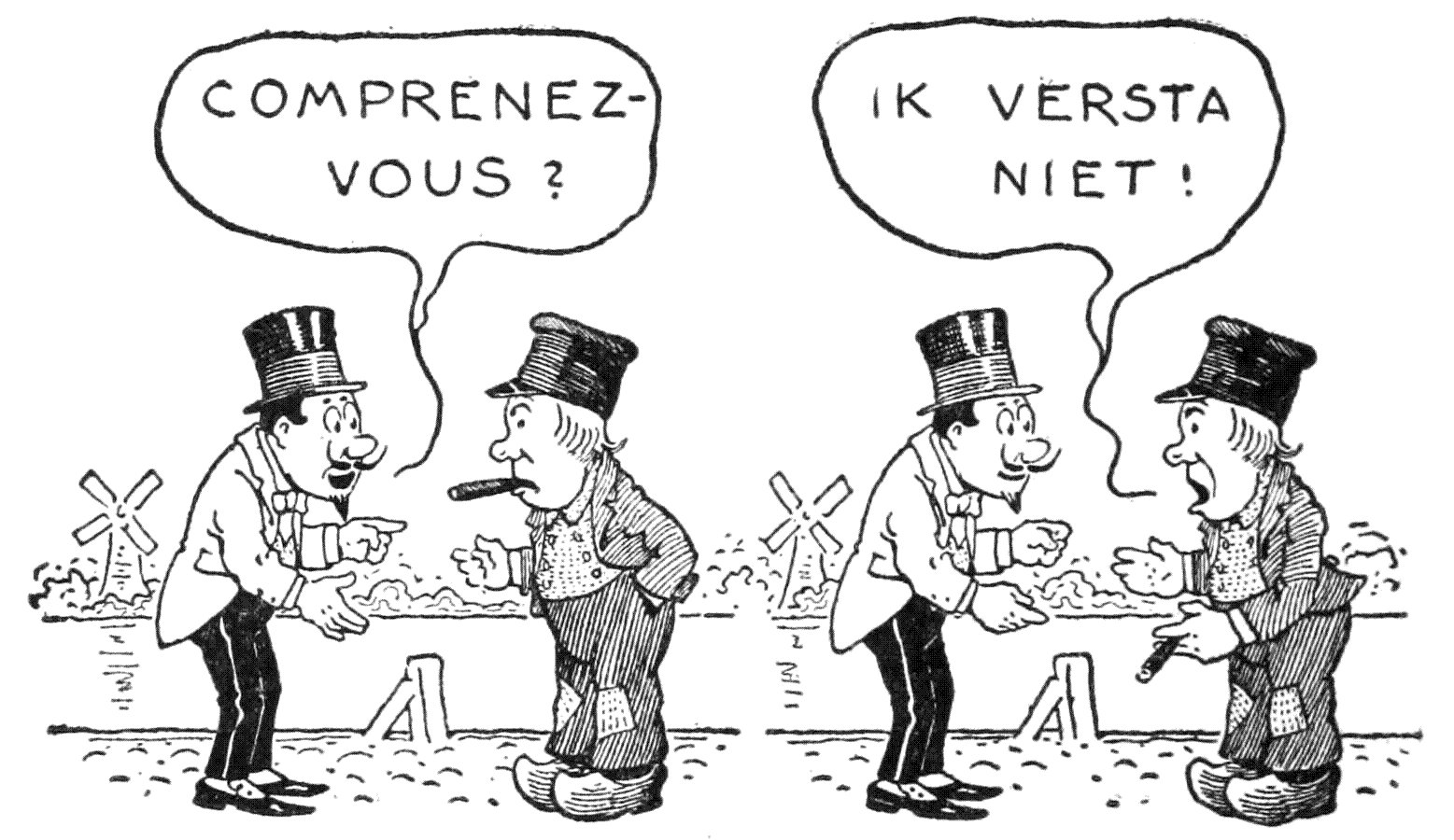

In a little incident of this sort, dialogue, of course, is required to help tell the point of the story. This is effected by putting the wording on a separate piece of paper—balloons, they are called—for each case and placing it over the design somewhere so that it will not cover any important part of the composition. The necessary amount of film for one of these balloons with its lettering is determined by the number of seconds that it takes the average spectator to read it. It is by the interjection of these balloons with their dialogue that an animator, in comic themes, can[79] get a considerable length of film from a very few drawings.

After the photography is finished the exposed film is taken out of the camera and sent to the laboratory for development.

[80]

FURTHER DETAILS ON MAKING ANIMATED CARTOONS

One of the inspiriting things about this new art of making drawings for animated cartoons is that it affords such opportunities for a versatile worker to exercise his talents. A true artist delights in encountering new problems in connection with his particular branch of work. The very fact that he selects as his vocation some art activity, rather than employment that is mechanical, evinces this.

In making drawings for animated films and in following the whole process of their making, the artist will find plenty of scope for his ingenuity in the devising of expedients to advance and finish the work.

The first animated screen drawings were made without the labor and time-saving resources of the celluloid sheet. As has been explained, it holds the still parts of a scene during the photography. The employment of this celluloid is now[84] in common usage in the art. It is found an expedient in various ways; sometimes to hold part only of a pictorial composition as in the method touched upon in the preceding chapter where ink drawings are made on paper; or, again, in another method to be used instead of paper, to hold practically all of the picture elements. By this latter method, in which a pigment is also put on the transparent material, the projected screen image is in graduated tones giving the appearance of a monochrome drawing.

Animators sometimes are released from the irksomeness of making the innumerable drawings for certain cases of movement, as that of an object crossing the picture field from one side to the other, by using little separate drawings cut out in silhouette.

The propellers are placed in position on the front of the airplane in their order continuously while the model, under the camera, is moved across the sky.

On the left: Part of film made from the cut-out model.