TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of each major section.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book. These are indicated by a dotted gray underline.

HORSE GUARDS,

1st January, 1836.

His Majesty has been pleased to command that, with the view of doing the fullest justice to Regiments, as well as to Individuals who have distinguished themselves by their bravery in Action with the Enemy, an Account of the Services of every Regiment in the British Army shall be published under the superintendence and direction of the Adjutant-General; and that this Account shall contain the following particulars, viz.:—

—— The Period and Circumstances of the Original Formation of the Regiment; The Stations at which it has been from time to time employed; The Battles, Sieges, and other Military Operations in which it has been engaged, particularly specifying any Achievement it may have performed, and the Colours, Trophies, &c., it may have captured from the Enemy.

—— The Names of the Officers, and the number of Non-Commissioned Officers and Privates Killed or Wounded by the Enemy, specifying the Place and Date of the Action.

—— The Names of those Officers who, in consideration of their Gallant Services and Meritorious Conduct in Engagements with the Enemy, have been distinguished with Titles, Medals, or other Marks of His Majesty’s gracious favour.

—— The Names of all such Officers, Non-Commissioned Officers, and Privates, as may have specially signalized themselves in Action.

And,

—— The Badges and Devices which the Regiment may have been permitted to bear, and the Causes on account of which such Badges or Devices, or any other Marks of Distinction, have been granted.

By Command of the Right Honorable

GENERAL LORD HILL,

Commanding-in-Chief.

John Macdonald,

Adjutant General.

The character and credit of the British Army must chiefly depend upon the zeal and ardour by which all who enter into its service are animated, and consequently it is of the highest importance that any measure calculated to excite the spirit of emulation, by which alone great and gallant actions are achieved, should be adopted.

Nothing can more fully tend to the accomplishment of this desirable object than a full display of the noble deeds with which the Military History of our country abounds. To hold forth these bright examples to the imitation of the youthful soldier, and thus to incite him to emulate the meritorious conduct of those who have preceded him in their honorable career, are among the motives that have given rise to the present publication.

The operations of the British Troops are, indeed, announced in the “London Gazette,” from whence they are transferred into the public prints: the achievements of our armies are thus made known at the time of their occurrence, and receive the tribute[iv] of praise and admiration to which they are entitled. On extraordinary occasions, the Houses of Parliament have been in the habit of conferring on the Commanders, and the Officers and Troops acting under their orders, expressions of approbation and of thanks for their skill and bravery; and these testimonials, confirmed by the high honour of their Sovereign’s approbation, constitute the reward which the soldier most highly prizes.

It has not, however, until late years, been the practice (which appears to have long prevailed in some of the Continental armies) for British Regiments to keep regular records of their services and achievements. Hence some difficulty has been experienced in obtaining, particularly from the old Regiments, an authentic account of their origin and subsequent services.

This defect will now be remedied, in consequence of His Majesty having been pleased to command that every Regiment shall, in future, keep a full and ample record of its services at home and abroad.

From the materials thus collected, the country will henceforth derive information as to the difficulties and privations which chequer the career of those who embrace the military profession. In Great Britain, where so large a number of persons are devoted to the active concerns of agriculture, manufactures, and commerce, and where these pursuits have, for so[v] long a period, been undisturbed by the presence of war, which few other countries have escaped, comparatively little is known of the vicissitudes of active service and of the casualties of climate, to which, even during peace, the British Troops are exposed in every part of the globe, with little or no interval of repose.

In their tranquil enjoyment of the blessings which the country derives from the industry and the enterprise of the agriculturist and the trader, its happy inhabitants may be supposed not often to reflect on the perilous duties of the soldier and the sailor,—on their sufferings,—and on the sacrifice of valuable life, by which so many national benefits are obtained and preserved.

The conduct of the British Troops, their valour, and endurance, have shone conspicuously under great and trying difficulties; and their character has been established in Continental warfare by the irresistible spirit with which they have effected debarkations in spite of the most formidable opposition, and by the gallantry and steadiness with which they have maintained their advantages against superior numbers.

In the Official Reports made by the respective Commanders, ample justice has generally been done to the gallant exertions of the Corps employed; but the details of their services and of acts of individual[vi] bravery can only be fully given in the Annals of the various Regiments.

These Records are now preparing for publication, under His Majesty’s special authority, by Mr. Richard Cannon, Principal Clerk of the Adjutant-General’s Office; and while the perusal of them cannot fail to be useful and interesting to military men of every rank, it is considered that they will also afford entertainment and information to the general reader, particularly to those who may have served in the Army, or who have relatives in the Service.

There exists in the breasts of most of those who have served, or are serving, in the Army, an Esprit de Corps—an attachment to everything belonging to their Regiment; to such persons a narrative of the services of their own Corps cannot fail to prove interesting. Authentic accounts of the actions of the great, the valiant, the loyal, have always been of paramount interest with a brave and civilized people. Great Britain has produced a race of heroes who, in moments of danger and terror, have stood “firm as the rocks of their native shore:” and when half the world has been arrayed against them, they have fought the battles of their Country with unshaken fortitude. It is presumed that a record of achievements in war,—victories so complete and surprising, gained by our countrymen, our brothers,[vii] our fellow-citizens in arms,—a record which revives the memory of the brave, and brings their gallant deeds before us,—will certainly prove acceptable to the public.

Biographical Memoirs of the Colonels and other distinguished Officers will be introduced in the Records of their respective Regiments, and the Honorary Distinctions which have, from time to time, been conferred upon each Regiment, as testifying the value and importance of its services, will be faithfully set forth.

As a convenient mode of Publication, the Record of each Regiment will be printed in a distinct number, so that when the whole shall be completed the Parts may be bound up in numerical succession.

The natives of Britain have, at all periods, been celebrated for innate courage and unshaken firmness, and the national superiority of the British troops over those of other countries has been evinced in the midst of the most imminent perils. History contains so many proofs of extraordinary acts of bravery, that no doubts can be raised upon the facts which are recorded. It must therefore be admitted, that the distinguishing feature of the British soldier is Intrepidity. This quality was evinced by the inhabitants of England when their country was invaded by Julius Cæsar with a Roman army, on which occasion the undaunted Britons rushed into the sea to attack the Roman soldiers as they descended from their ships; and, although their discipline and arms were inferior to those of their adversaries, yet their fierce and dauntless bearing intimidated the flower of the Roman troops, including Cæsar’s favourite tenth legion. Their arms consisted of spears, short swords, and other weapons of rude construction. They had chariots, to the[x] axles of which were fastened sharp pieces of iron resembling scythe-blades, and infantry in long chariots resembling waggons, who alighted and fought on foot, and for change of ground, pursuit or retreat, sprang into the chariot and drove off with the speed of cavalry. These inventions were, however, unavailing against Cæsar’s legions: in the course of time a military system, with discipline and subordination, was introduced, and British courage, being thus regulated, was exerted to the greatest advantage; a full development of the national character followed, and it shone forth in all its native brilliancy.

The military force of the Anglo-Saxons consisted principally of infantry: Thanes, and other men of property, however, fought on horseback. The infantry were of two classes, heavy and light. The former carried large shields armed with spikes, long broad swords and spears; and the latter were armed with swords or spears only. They had also men armed with clubs, others with battle-axes and javelins.

The feudal troops established by William the Conqueror consisted (as already stated in the Introduction to the Cavalry) almost entirely of horse: but when the warlike barons and knights, with their trains of tenants and vassals, took the field, a proportion of men appeared on foot, and, although these were of inferior degree, they proved stout-hearted Britons of stanch fidelity. When stipendiary troops were employed, infantry always constituted a considerable portion of the military force;[xi] and this arme has since acquired, in every quarter of the globe, a celebrity never exceeded by the armies of any nation at any period.

The weapons carried by the infantry, during the several reigns succeeding the Conquest, were bows and arrows, half-pikes, lances, halberds, various kinds of battle-axes, swords, and daggers. Armour was worn on the head and body, and in course of time the practice became general for military men to be so completely cased in steel, that it was almost impossible to slay them.

The introduction of the use of gunpowder in the destructive purposes of war, in the early part of the fourteenth century, produced a change in the arms and equipment of the infantry-soldier. Bows and arrows gave place to various kinds of fire-arms, but British archers continued formidable adversaries; and, owing to the inconvenient construction and imperfect bore of the fire-arms when first introduced, a body of men, well trained in the use of the bow from their youth, was considered a valuable acquisition to every army, even as late as the sixteenth century.

During a great part of the reign of Queen Elizabeth each company of infantry usually consisted of men armed five different ways; in every hundred men forty were “men-at-arms,” and sixty “shot;” the “men-at-arms” were ten halberdiers, or battle-axe men, and thirty pikemen; and the “shot” were twenty archers, twenty musketeers, and twenty harquebusiers, and each man carried, besides his principal weapon, a sword and dagger.

Companies of infantry varied at this period in numbers from 150 to 300 men; each company had a colour or ensign, and the mode of formation recommended by an English military writer (Sir John Smithe) in 1590 was; the colour in the centre of the company guarded by the halberdiers; the pikemen in equal proportions, on each flank of the halberdiers; half the musketeers on each flank of the pikes; half the archers on each flank of the musketeers, and the harquebusiers (whose arms were much lighter than the muskets then in use) in equal proportions on each flank of the company for skirmishing.[1] It was customary to unite a number of companies into one body, called a Regiment, which frequently amounted to three thousand men; but each company continued to carry a colour. Numerous improvements were eventually introduced in the construction of fire-arms, and, it having been found impossible to make armour proof against the muskets then in use (which carried a very heavy ball) without its being too weighty for the soldier, armour was gradually laid aside by the infantry in the seventeenth century: bows and arrows also fell into disuse, and the infantry were reduced to two classes, viz.: musketeers, armed with matchlock muskets,[xiii] swords, and daggers; and pikemen, armed with pikes from fourteen to eighteen feet long, and swords.

In the early part of the seventeenth century Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, reduced the strength of regiments to 1000 men. He caused the gunpowder, which had heretofore been carried in flasks, or in small wooden bandoliers, each containing a charge, to be made up into cartridges, and carried in pouches; and he formed each regiment into two wings of musketeers, and a centre division of Pikemen. He also adopted the practice of forming four regiments into a brigade; and the number of colours was afterwards reduced to three in each regiment. He formed his columns so compactly that his infantry could resist the charge of the celebrated Polish horsemen and Austrian cuirassiers; and his armies became the admiration of other nations. His mode of formation was copied by the English, French, and other European states; but so great was the prejudice in favour of ancient customs, that all his improvements were not adopted until near a century afterwards.

In 1664 King Charles II. raised a corps for sea-service, styled the Admiral’s regiment. In 1678 each company of 100 men usually consisted of 30 pikemen, 60 musketeers, and 10 men armed with light firelocks. In this year the King added a company of men armed with hand grenades to each of the old British regiments, which was designated the “grenadier company.” Daggers were so contrived as to fit in the muzzles of the muskets, and bayonets,[xiv] similar to those at present in use, were adopted about twenty years afterwards.

An Ordnance regiment was raised in 1685, by order of King James II., to guard the artillery, and was designated the Royal Fusiliers (now 7th Foot). This corps, and the companies of grenadiers, did not carry pikes.

King William III. incorporated the Admiral’s regiment in the second Foot Guards, and raised two Marine regiments for sea-service. During the war in this reign, each company of infantry (excepting the fusiliers and grenadiers) consisted of 14 pikemen and 46 musketeers; the captains carried pikes; lieutenants, partisans; ensigns, half-pikes; and serjeants, halberds. After the peace in 1697 the Marine regiments were disbanded, but were again formed on the breaking out of the war in 1702.[2]

During the reign of Queen Anne the pikes were laid aside, and every infantry soldier was armed with a musket, bayonet, and sword; the grenadiers ceased, about the same period, to carry hand grenades; and the regiments were directed to lay aside their third colour: the corps of Royal Artillery was first added to the Army in this reign.

About the year 1745, the men of the battalion companies of infantry ceased to carry swords; during[xv] the reign of George II. light companies were added to infantry regiments; and in 1764 a Board of General Officers recommended that the grenadiers should lay aside their swords, as that weapon had never been used during the Seven Years’ War. Since that period the arms of the infantry soldier have been limited to the musket and bayonet.

The arms and equipment of the British Troops have seldom differed materially, since the Conquest, from those of other European states; and in some respects the arming has, at certain periods, been allowed to be inferior to that of the nations with whom they have had to contend; yet, under this disadvantage, the bravery and superiority of the British infantry have been evinced on very many and most trying occasions, and splendid victories have been gained over very superior numbers.

Great Britain has produced a rate of lion-like champions who have dared to confront a host of foes, and have proved themselves valiant with any arms. At Crecy, King Edward III., at the head of about 30,000 men, defeated, on the 26th of August, 1346, Philip King of France, whose army is said to have amounted to 100,000 men; here British valour encountered veterans of renown:—the King of Bohemia, the King of Majorca, and many princes and nobles were slain, and the French army was routed and cut to pieces. Ten years afterwards, Edward Prince of Wales, who was designated the Black Prince, defeated at Poictiers, with 14,000 men, a French army of 60,000 horse, besides infantry, and took John I., King of France, and his son,[xvi] Philip, prisoners. On the 25th of October, 1415, King Henry V., with an army of about 13,000 men, although greatly exhausted by marches, privations, and sickness, defeated, at Agincourt, the Constable of France, at the head of the flower of the French nobility and an army said to amount to 60,000 men, and gained a complete victory.

During the seventy years’ war between the United Provinces of the Netherlands and the Spanish monarchy, which commenced in 1578 and terminated in 1648, the British infantry in the service of the States-General were celebrated for their unconquerable spirit and firmness;[3] and in the thirty years’ war between the Protestant Princes and the Emperor of Germany, the British Troops in the service of Sweden and other states were celebrated for deeds of heroism.[4] In the wars of Queen Anne, the fame of the British army under the great Marlborough was spread throughout the world; and if we glance at the achievements performed within the memory of persons now living, there is abundant proof that the Britons of the present age are not inferior to their ancestors in the qualities[xvii] which constitute good soldiers. Witness the deeds of the brave men, of whom there are many now surviving, who fought in Egypt in 1801, under the brave Abercromby, and compelled the French army, which had been vainly styled Invincible, to evacuate that country; also the services of the gallant Troops during the arduous campaigns in the Peninsula, under the immortal Wellington; and the determined stand made by the British Army at Waterloo, where Napoleon Bonaparte, who had long been the inveterate enemy of Great Britain, and had sought and planned her destruction by every means he could devise, was compelled to leave his vanquished legions to their fate, and to place himself at the disposal of the British Government. These achievements, with others of recent dates, in the distant climes of India, prove that the same valour and constancy which glowed in the breasts of the heroes of Crecy, Poictiers, Agincourt, Blenheim, and Ramilies, continue to animate the Britons of the nineteenth century.

The British Soldier is distinguished for a robust and muscular frame,—intrepidity which no danger can appal,—unconquerable spirit and resolution,—patience in fatigue and privation, and cheerful obedience to his superiors. These qualities, united with an excellent system of order and discipline to regulate and give a skilful direction to the energies and adventurous spirit of the hero, and a wise selection of officers of superior talent to command, whose presence inspires confidence,—have been the leading causes of the splendid victories gained by the British[xviii] arms.[5] The fame of the deeds of the past and present generations in the various battle-fields where the robust sons of Albion have fought and conquered, surrounds the British arms with a halo of glory; these achievements will live in the page of history to the end of time.

The records of the several regiments will be found to contain a detail of facts of an interesting character, connected with the hardships, sufferings, and gallant exploits of British soldiers in the various parts of the world where the calls of their Country and the commands of their Sovereign have required them to proceed in the execution of their duty, whether in[xix] active continental operations, or in maintaining colonial territories in distant and unfavourable climes.

The superiority of the British infantry has been pre-eminently set forth in the wars of six centuries, and admitted by the greatest commanders which Europe has produced. The formations and movements of this arme, as at present practised, while they are adapted to every species of warfare, and to all probable situations and circumstances of service, are calculated to show forth the brilliancy of military tactics calculated upon mathematical and scientific principles. Although the movements and evolutions have been copied from the continental armies, yet various improvements have from time to time been introduced, to ensure that simplicity and celerity by which the superiority of the national military character is maintained. The rank and influence which Great Britain has attained among the nations of the world, have in a great measure been purchased by the valour of the Army, and to persons who have the welfare of their country at heart, the records of the several regiments cannot fail to prove interesting.

[1] A company of 200 men would appear thus:—

|

|||||||||

| 20 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| Harquebuses. | Muskets. | Halberds. | Muskets. | Harquebuses. | |||||

| Archers. | Pikes. | Pikes. | Archers. | ||||||

The musket carried a ball which weighed 1/10th of a pound; and the harquebus a ball which weighed 1/25th of a pound.

[2] The 30th, 31st, and 32nd Regiments were formed as Marine corps in 1702, and were employed as such during the wars in the reign of Queen Anne. The Marine corps were embarked in the Fleet under Admiral Sir George Rooke, and were at the taking of Gibraltar, and in its subsequent defence in 1704; they were afterwards employed at the siege of Barcelona in 1705.

[3] The brave Sir Roger Williams, in his Discourse on War, printed in 1590, observes:—“I persuade myself ten thousand of our nation would beat thirty thousand of theirs (the Spaniards) out of the field, let them he chosen where they list.” Yet at this time the Spanish infantry was allowed to be the best disciplined in Europe. For instances of valour displayed by the British Infantry during the seventy Years’ War, see the Historical Record of the Third Foot, or Buffs.

[4] Vide the Historical Record of the First, or Royal Regiment of Foot.

[5] “Under the blessing of Divine Providence, His Majesty ascribes the successes which have attended the exertions of his troops in Egypt to that determined bravery which is inherent in Britons; but His Majesty desires it may be most solemnly and forcibly impressed on the consideration of every part of the army, that it has been a strict observance of order, discipline, and military system, which has given the full energy to the native valour of the troops, and has enabled them proudly to assert the superiority of the national military character, in situations uncommonly arduous, and under circumstances of peculiar difficulty.”—General Orders in 1801.

In the General Orders issued by Lieut.-General Sir John Hope (afterwards Lord Hopetoun), congratulating the army upon the successful result of the Battle of Corunna, on the 16th of January 1809, it is stated:—“On no occasion has the undaunted valour of British troops ever been more manifest. At the termination of a severe and harassing march, rendered necessary by the superiority which the enemy had acquired, and which had materially impaired the efficiency of the troops, many disadvantages were to be encountered. These have all been surmounted by the conduct of the troops themselves: and the enemy has been taught, that whatever advantages of position or of numbers he may possess, there is inherent in the British officers and soldiers a bravery that knows not how to yield,—that no circumstances can appal,—and that will ensure victory, when it is to be obtained by the exertion of any human means.”

HISTORICAL RECORD

OF

THE EIGHTY-SEVENTH REGIMENT,

OR

THE ROYAL IRISH FUSILIERS:

CONTAINING

AN ACCOUNT OF THE FORMATION OF THE REGIMENT

In 1793,

AND OF ITS SUBSEQUENT SERVICES

To 1853.

COMPILED BY

RICHARD CANNON, ESQ.,

ADJUTANT GENERAL’S OFFICE, HORSE GUARDS.

Illustrated with Plates.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY GEORGE E. EYRE AND WILLIAM SPOTTISWOODE,

PRINTERS TO THE QUEEN’S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY,

FOR HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE.

PUBLISHED BY PARKER, FURNIVALL, AND PARKER,

MILITARY LIBRARY,

30, CHARING CROSS.

1853.

THE EIGHTY-SEVENTH REGIMENT,

OR

THE ROYAL IRISH FUSILIERS,

BEARS ON THE REGIMENTAL COLOUR AND APPOINTMENTS

THE PLUME OF THE PRINCE OF WALES, WITH THE MOTTO,

“ICH DIEN” AND THE “HARP,”

IN CONSEQUENCE OF ITS HAVING BEEN ORIGINALLY DESIGNATED

THE “PRINCE OF WALES’S IRISH REGIMENT;”

ALSO THE WORDS, “MONTE VIDEO,”

IN COMMEMORATION OF THE GALLANTRY DISPLAYED

BY THE FIRST BATTALION AT THE CAPTURE OF THAT PLACE,

ON THE 3RD OF FEBRUARY, 1807;

THE WORD, “TALAVERA,”

IN TESTIMONY OF THE CONDUCT OF THE SECOND BATTALION IN THAT

BATTLE, ON THE 27TH AND 28TH OF JULY, 1809;

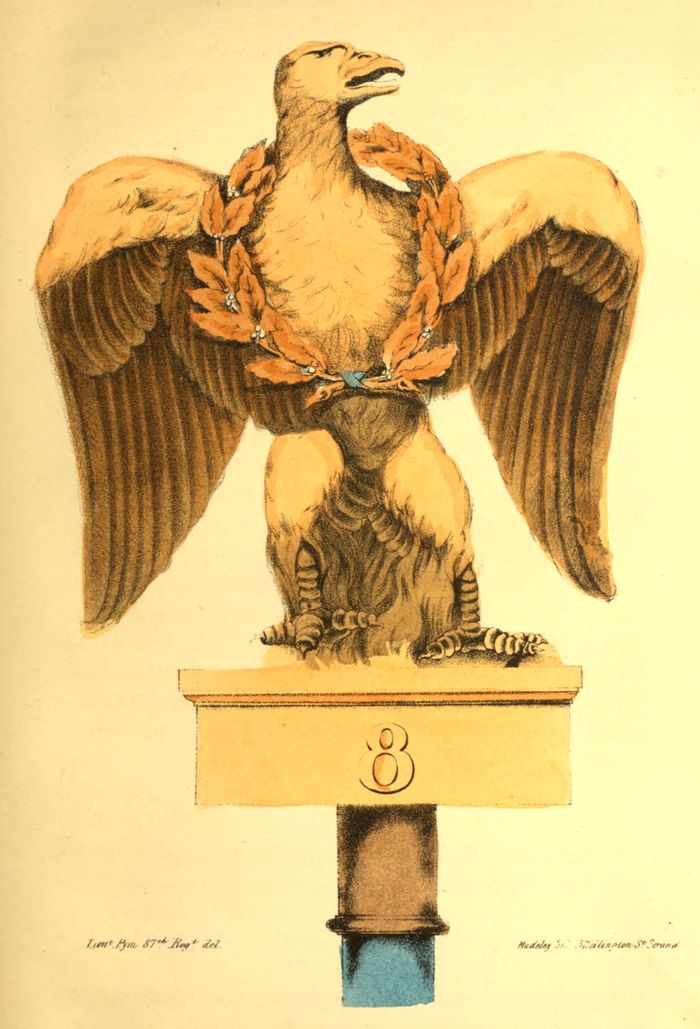

AN EAGLE WITH A WREATH OF LAUREL ABOVE THE HARP,

AND THE WORD, “BARROSA,”

IN COMMEMORATION OF THE GALLANTRY OF THE SECOND BATTALION,

AND OF THE TROPHY ACQUIRED IN THAT BATTLE,

ON THE 5TH OF MARCH, 1811;

ALSO THE WORD, “TARIFA,”

FOR THE DISTINGUISHED GALLANTRY OF THE SECOND BATTALION

IN THE DEFENCE OF THAT PLACE,

ON THE 31ST OF DECEMBER, 1811;

AND

THE WORDS, “VITTORIA,” “NIVELLE,” “ORTHES,”

“TOULOUSE,” AND “PENINSULA,”

IN TESTIMONY OF THE DISTINGUISHED SERVICES OF THE SECOND BATTALION

IN THE SEVERAL ACTIONS FOUGHT DURING THE WAR

IN PORTUGAL, SPAIN, AND THE SOUTH OF FRANCE,

FROM 1809 TO 1814;

AND

THE WORD “AVA,”

TO DENOTE THE MERITORIOUS CONDUCT OF THE REGIMENT DURING

THE BURMESE WAR, IN 1825-26.

THE

EIGHTY-SEVENTH REGIMENT,

OR

THE ROYAL IRISH FUSILIERS.

| Year. | Page | |

| Introduction | 1 | |

| 1793. | Formation of the regiment | 2 |

| 1794. | Names of officers | 4 |

| ” | Embarked for Flanders | 5 |

| ” | Action at Alost | ib. |

| 1795. | Proceeded to Bergen-op-Zoom | ib. |

| ” | Marched prisoners into France | 6 |

| 1796. | The regiment again recruited | ib. |

| ” | Embarked as part of a secret expedition to the North Sea | ib. |

| ” | Return of the troops to England | ib. |

| ” | The regiment embarked for the West Indies | ib. |

| 1797. | Capture of Trinidad | ib. |

| ” | Expedition against Porto Rico | 7 |

| ” | The regiment proceeded to St. Lucia | ib. |

| 1798. | Stationed at St. Lucia | 8 |

| 1799. | Proceeded to Martinique | ib. |

| 1800. | Removed to Dominica | ib. |

| 1801. | Embarked for Barbadoes | ib. |

| ” | Proceeded to Curaçoa | ib. |

| 1802. | Peace of Amiens | ib. |

| 1803. | Renewal of hostilities | ib. |

| 1804. | The regiment returned to England | 9 |

| ” | Proceeded to Guernsey | ib. |

| ” | War with Spain | ib. |

| ” | Formation of the second battalion | ib. |

| 1805. | The first battalion removed to Portsmouth | 10 |

| 1806. | Proceeded to Plymouth | ib. |

| ” | Embarked for Monte Video | ib. |

| 1807. [viii] | Capture of that place | 11 |

| ” | Authorised to bear the word “Monte Video” on the regimental colour and appointments | ib. |

| ” | The light company engaged at Colonia, near Buenos Ayres | ib. |

| ” | Assault of Buenos Ayres | 12 |

| ” | Withdrawal of the British troops | 15 |

| ” | The first battalion embarked for the Cape of Good Hope | ib. |

| 1808 } | ||

| and } | Stationed in that colony | ib. |

| 1809 } | ||

| 1810. | Embarked for the Mauritius | 16 |

| ” | Capture of that island | ib. |

| 1811 } | ||

| to } | Stationed at the Mauritius | ib. |

| 1814 } | ||

| 1815. | Embarked for Bengal | ib. |

| 1816. | War with the Rajah of Nepaul | 17 |

| ” | Affair on the heights of Sierapore | 18 |

| ” | Termination of the campaign | 19 |

| ” | Return of the battalion to Bengal | ib. |

| ” | Stationed at Cawnpore | ib. |

| 1817. | Engaged in the siege of the Fort of Hattrass | ib. |

| ” | Returned to Cawnpore | 20 |

| ” | The Pindaree campaign | ib. |

| ” | Casualties from cholera | ib. |

| 1818. | Conclusion of peace | 21 |

| ” | Return of the regiment to Cawnpore | ib. |

| 1820. | Marched to Fort William | ib. |

| 1821. | Meritorious conduct of the regiment at the fire in the East India Company’s Dispensary at Calcutta | ib. |

| ” | Presentation of testimonials, in consequence, to the regiment | 22 |

| 1822. | Similar conduct of the regiment at another alarming fire in Calcutta | 23 |

| ” | Embarked for the Upper Provinces | ib. |

| 1823. | Decease of Lieut.-Colonel Miller | ib. |

| ” | The regiment stationed at Ghazeepore | ib. |

| 1824. | Removed to Berhampore | ib. |

| 1825. | Proceeded to Calcutta | 24 |

| ” | Decease of Lieut.-Colonel Browne | ib. |

| ” | Commencement of the Burmese War | ib. |

| ” | The regiment embarked for Ava | ib. |

| ” | Engaged with the Burmese near Prome | ib. |

| 1826. | Capture of Melloone | 25 |

| ” | Operations against Moulmein | ib. |

| ” | Termination of the Burmese War | ib. |

| ” | Authorised to bear the word “Ava” on the regimental colour and appointments | 26 |

| ” | Decease of Lieut.-Colonel Shawe | 27 |

| ” | The regiment embarked for Calcutta | ib. |

| ” | Reviewed at Calcutta by General Lord Combermere, Commander-in-Chief in India | 28 |

| 1827. | Complimentary order on the embarkation of the regiment for England | ib. |

| 1827. [ix] | Stationed in the Isle of Wight | 29 |

| ” | Application from General Sir John Doyle for the regiment to be constituted a light infantry corps | 30 |

| ” | Styled the “Prince of Wales’s Own Irish Regiment of Fusiliers” | 32 |

| ” | Facings changed from Green to Blue | 33 |

| ” | Styled the “Eighty-seventh, or Royal Irish Fusiliers” | ib. |

| 1828. | Reviewed by General Lord Hill, Commanding-in-chief | 34 |

| ” | Marched to London | ib. |

| ” | Proceeded to Chester | 35 |

| ” | Services of the regiment at a fire | ib. |

| 1829. | Three companies employed in aid of the Civil Power in Wales | ib. |

| ” | Marched to Stockport | 36 |

| ” | Stationed at Manchester | 37 |

| 1830. | Embarked for Ireland | 38 |

| ” | Returned to England | ib. |

| 1831. | Formed into service and depôt companies | ib. |

| ” | Service companies embarked for the Mauritius | ib. |

| 1832 } | ||

| and } | Remained at the Mauritius | ib. |

| 1833 } | ||

| 1834. | Major-General Sir Thomas Reynell, Bart., K.C.B., appointed Colonel of the regiment | ib. |

| 1835. | The depôt companies embarked for Ireland | ib. |

| 1836 } | ||

| to } | Stationed in Ireland | 39 |

| 1839.} | ||

| 1840. | Returned to England | ib. |

| 1841. | Major-General Sir Hugh (now Viscount) Gough, K.C.B., appointed Colonel of the regiment | ib. |

| 1843. | The service companies returned to England from the Mauritius | ib. |

| ” | The regiment proceeded to Glasgow | ib. |

| 1844. | Marched to Edinburgh | ib. |

| 1846. | Proceeded to Monmouthshire | 40 |

| 1847. | Removed to Weedon | ib. |

| 1848. | Augmented to the India establishment | ib. |

| 1849. | Embarked for Calcutta | ib. |

| 1853. | Conclusion | ib. |

CONTENTS

OF THE

HISTORICAL RECORD

OF

THE EIGHTY-SEVENTH REGIMENT,

OR

THE ROYAL IRISH FUSILIERS.

| Year. | Page | |

| Introduction | 41 | |

| 1804. | Formation of the second battalion | ib. |

| 1805. | Embarked for Ireland | 42 |

| 1806. | Returned to England | ib. |

| 1807. | Proceeded to Guernsey | ib. |

| 1808. | Embarked for Portugal | 44 |

| 1809. | Battle of Talavera | 45 |

| ” | Authorised to bear the word “Talavera” on the regimental colour and appointments | 47 |

| 1810. | Embarked for Cadiz | ib. |

| 1811. | Battle of Barrosa | 48 |

| ” | Capture of a French Eagle by the battalion | ib. |

| ” | Styled “The Eighty-seventh, or Prince of Wales’s Own Irish Regiment,” and authorised to bear on the regimental colour and appointments the word “Barrosa,” and an Eagle with a Wreath of Laurel, above the Harp | 53 |

| ” | The second battalion embarked for Tarifa | 54 |

| ” | Siege of Tarifa by the French | 55 |

| 1812. | Gallant defence of the place | 58 |

| ” | Authorised to bear the word “Tarifa” on the regimental colour and appointments | ib. |

| ” | The battalion returned to Cadiz | ib. |

| ” | Action at the bridge and fort of Puerto Largo | 59 |

| 1813. | Battle of Vittoria | 60 |

| ” | Bâton of Marshal Jourdan taken by the battalion | 62 |

| ” | Authorised to bear the word “Vittoria” on the regimental colour and appointments | 63 |

| 1813. [xi] | Actions in the Pyrenees | 63 |

| ” | Battle of the Nivelle | 64 |

| ” | Authorised to bear the word “Nivelle” on the regimental colour and appointments | ib. |

| 1814. | Action near Salvatira | 65 |

| ” | Battle of Orthes | ib. |

| ” | Authorised to bear the word “Orthes” on the regimental colour and appointments | ib. |

| ” | Affair at Vic Bigorre | 65 |

| ” | Battle of Toulouse | 66 |

| ” | Authorised to bear the word “Toulouse” on the regimental colour and appointments | 67 |

| ” | Termination of the Peninsular War | ib. |

| ” | Authorised to bear the word “Peninsula” on the regimental colour and appointments | 68 |

| ” | Embarkation of the battalion for Cork | ib. |

| ” | Removed to Portsmouth | 69 |

| ” | Proceeded to Guernsey | ib. |

| 1815. | Stationed in that island | ib. |

| 1816. | Removed to Portsmouth, and subsequently to Colchester | ib. |

| 1817. | The second battalion disbanded | 74 |

OF

THE EIGHTY-SEVENTH REGIMENT.

| Year. | Page | |

| 1796. | Sir John Doyle, Bart., G.C.B. | 75 |

| 1834. | Sir Thomas Reynell, Bart., K.C.B. | 83 |

| 1841. | Hugh Viscount Gough, G.C.B. | 89 |

| Page | |

| List of troops in South America in 1806-7 | 91 |

| Memoir of Lieut.-General Sir Charles William Doyle, C.B., and G.C.H. | 92 |

| Memoir of Lieut.-Colonel Matthew Shawe, C.B. | 95 |

| List of battalions formed from men raised in 1803 and 1804, under the “Army of Reserve” and “Additional Force Acts” | 97-100 |

| Page | |

| Costume of the regiment in 1793 | to face 1 |

| Colours of the regiment | 40 |

| The French Eagle captured at the battle of Barrosa on the 5th of March 1811 | 50 |

| Costume of the regiment in 1853 | 74 |

Madeley lith 3, Wellington St. Strand.

OF

THE EIGHTY-SEVENTH REGIMENT,

OR

THE ROYAL IRISH FUSILIERS.

The disturbed state of affairs on the continent of Europe in 1793, particularly in France, arising from the principles of the Revolution in that country, which threatened surrounding nations with universal anarchy, occasioned preparations to be made throughout the several countries, in order to oppose the dangerous doctrines which were then diffused under the specious terms of “Liberty and Equality.”

On the 1st of February 1793, the National Convention of France, after the decapitation of King Louis XVI. on the 21st of the previous month, declared war against Great Britain and Holland. Augmentations were immediately made to the regular army, the militia was embodied, and the British people evinced their loyalty and patriotism by forming volunteer associations, and by making every exertion for the maintenance of monarchical principles, and for the defence of those institutions which had raised their country to a high position among the nations of Europe.

Upwards of fifty regiments of infantry were authorised[2] to be raised, on this emergency, in the several parts of Great Britain and Ireland, by officers and gentlemen possessing local influence, sixteen of which regiments, viz. from the Seventy-eighth to the Ninety-third, continue at this period on the establishment of the army.

Of the officers thus honored with the confidence of their Sovereign and his Government, Lieut.-Colonel John Doyle (afterwards General Sir John Doyle, Bart., and G.C.B.) was selected, to whom a letter of service was addressed on the 18th of September 1793, authorising him to raise a regiment, to consist of ten companies of sixty rank and file in each company. The corps was speedily completed, and was designated the Eighty-seventh, or The Prince of Wales’s Irish Regiment.

The following is a copy of the Letter of Service, addressed by the Secretary-at-War to Major John Doyle, on the half-pay of the late One hundred and fifth regiment, dated

“War Office,

“18th September 1793.

“I am commanded to acquaint you, that His Majesty approves of your raising a regiment of foot, without any allowance of levy money, to be completed within three months, upon the following terms, viz.:

“The corps is to consist of one company of Grenadiers, one of Light Infantry, and eight battalion companies. The Grenadier company is to consist of one captain, two lieutenants, three serjeants, three corporals, two drummers, two fifers, and fifty-seven private men. The Light Infantry company of one captain, two lieutenants, three serjeants, three corporals, two drummers, and fifty-seven men; and each battalion company of one captain, one lieutenant, and one ensign, three serjeants, three corporals, two drummers,[3] and fifty-seven private men, together with the usual staff officers, and with a serjeant-major and quartermaster-serjeant, exclusive of the serjeants above specified. The captain-lieutenant is (as usual) included in the number of lieutenants above mentioned.

“The corps is to have one major with a company, and is to be under your command as major, with a company.

“The pay of the officers is to commence from the dates of their commissions, and that of the non-commissioned officers and privates from the dates of their attestations.

“His Majesty is pleased to leave to you the nomination of the officers of the regiment; but the lieut.-colonel and major are to be taken from the list of lieut.-colonels or majors on half-pay, or the major from a captain on full pay. Six of the captains are to be taken from the half-pay, and the other captain and the captain-lieutenant from the list of captains or captain-lieutenants on full pay. All the lieutenants are to be taken from the half-pay; and the gentlemen recommended for ensigns are not to be under sixteen years of age.

“No officer, however, is to be taken from the half-pay who received the difference on going upon the half-pay, nor is any officer coming from the half-pay to contribute any money towards the levy, but he may be required to raise such a quota of men as you may agree upon with him.

“The person to be recommended for quartermaster must not be proposed for any other commission.

“In case the corps should be reduced after it has been once established, the officers will be entitled to half-pay.

“No man is to be enlisted above thirty-five years of age, nor under five feet five inches high. Well-made, growing lads, between sixteen and eighteen years of age, may be taken at five feet four inches.

“The recruits are to be engaged without limitation as to the period or place of their service.

“The non-commissioned officers and privates are to be inspected by a general officer, who will reject all such as are unfit for service, or not enlisted in conformity to the terms of this letter.

“In the execution of this service, I take leave to assure you of every assistance which my office can afford.

“I have, &c., &c.,

(Signed) “George Yonge.

The following officers were appointed to commissions in the Eighty-seventh regiment, viz.:—

Lieut.-Colonel Commandant—John Doyle.

Lieut.-Colonel—Edward Viscount Dungarvan

(afterwards Earl of Cork).

Major—Walter Hovenden.

Captains.

Honorable George Napier.

Nathaniel Cookman.

Honorable Robert Mead.

Percy Freke.

Richard Thompson.

Howe Hadfield.

Captain-Lieutenant—James Magrath.

Lieutenants.

John Thompson.

William Aug. Blakeney.

John Wilson.

Thomas Clarke.

James Henry Fitz Simon.

William Warren.

William Magrath.

Barton Lodge.

Ensigns.

Fleming Kells.

William Murray.

John Carrol.

—— Walker.

Benjamin Johnson.

—— Salmon.

Adjutant—John L. Brock.

Surgeon— —— Hill.

Quartermaster—Wm. Thomson.

Chaplain—Edw. Berwick.

The effective numbers were quickly recruited, and the regiment was so far formed as to be considered fit[5] to be employed on active continental service. It was consequently embarked in the summer of 1794, as part of a force under Major-General the Earl Moira, and was sent to join the British army in Flanders, under the command of His Royal Highness the Duke of York. While on the march the Eighty-seventh regiment was attacked on the 15th of July 1794, at the outpost of Alost, by a strong corps of the enemy’s cavalry, which it repulsed, and for which act of bravery it received the thanks of the general officer in public orders. It is a circumstance worthy of being recorded in the regimental history, that the first individual of the regiment who was wounded, was the Lieut.-Colonel by whom it was raised. In the general orders of the Earl of Moira upon this occasion, “he expressed his admiration of the cool intrepidity with which the Eighty-seventh regiment repulsed an attack from the enemy’s cavalry, at the bridge of Alost, where its commander, Lieut.-Colonel Doyle, received two severe wounds, but would not quit his regiment, until the enemy had given up the attack.” The Duke of York, in his public letter, thus mentioned the affair:—

“Head-quarters, Cortyke,

“15th July 1794.

“Lord Moira speaks highly of the conduct of the officers and men of the Eighty-seventh regiment on this occasion, particularly of Lieut.-Colonel Doyle, commanding the corps, who was severely wounded.

(Signed) “Frederick.”

In 1795 the Eighty-seventh regiment was sent into Bergen-op-Zoom to be drilled; but soon after its arrival, the Dutch garrison revolted against the government, opened the gates, and joined the French, who[6] entered with twenty thousand men, and made a capitulation with the Eighty-seventh, the only British corps in the town, then commanded by Lord Dungarvan (afterwards Earl of Cork), Lieut.-Colonel Doyle having been sent to England for the recovery of his wounds. The capitulation was however broken by the French, and the Eighty-seventh were marched prisoners of war into France.

The regiment was again filled up, and, with the Tenth foot, and some marines, was sent upon a secret expedition to the North Sea, under the command of Brigadier-General John Doyle, who had been promoted Colonel of the Eighty-seventh, on the 3rd of May 1796, to co-operate with Admiral (the late Lord) Duncan; but, having been delayed in England until the end of September, the tempestuous weather, usual at that season of the year in those seas, dispersed the ships and small craft by which the troops were to be landed, and put an end to the object of the expedition. The troops returned to England in the ships of war, in which they embarked under the orders of Admiral Sir Richard Bickerton.

On the 14th of October 1796, the regiment embarked for the West Indies.

Spain having united with France in hostility to Great Britain, an expedition under Lieut.-General Sir Ralph Abercromby, K.B., proceeded against the Spanish island of Trinidad, which capitulated on the 18th of February 1797. No men were killed or wounded. Lieutenant R—— Villeneuve, of the Eighth foot, major of brigade to Brigadier-General Hompesch, was the only officer wounded, and he died of his wounds.

After the reduction of Trinidad, the force (of which the Eighty-seventh formed part) destined for the expedition against Porto Rico, being assembled, the fleet sailed from Martinique on the 8th of April 1797, and on the 10th arrived at St. Kitt’s, where it remained for[7] a few days. On the 17th the fleet anchored off Congrejos Point, and a landing was effected on the island of Porto Rico on the following day. The troops advanced, when it was perceived that the only point on which the town could be attacked was on the eastern side, where it was defended by the Castle and Lines of St. Christopher, to approach which it was necessary to force a way over the lagoon which formed that side of the island. This passage was strongly defended by two redoubts and gun-boats, and the enemy had destroyed the bridge connecting, in the narrowest channel, the island with the main land. After every effort the British could never sufficiently silence the fire of the enemy, who was likewise entrenched in the rear of these redoubts, to hazard forcing the passage with so small a number of troops. It was next endeavoured to bombard the town from a point to the southward of it, near to a large magazine abandoned by the enemy. This was tried for several days without any great effect, on account of the distance. Lieut.-General Sir Ralph Abercromby, seeing that no act of vigour, or any combined operation between the sea and land services, could in any manner avail, determined to re-embark the troops, which was effected during the night of the 30th of April. Four Spanish field-pieces were brought off, but not a sick or wounded soldier was left behind, and nothing of any value fell into the hands of the enemy. Sir Ralph Abercromby in his despatch alluded to the troops in the following terms: “The behaviour of the troops has been meritorious; they were patient under labour, regular and orderly in their conduct, and spirited when an opportunity to show it occurred.” The Eighty-seventh had two rank and file killed, three wounded, and thirteen missing.

The regiment subsequently proceeded to St. Lucia, which had been captured from the French in May 1796.

During the year 1798, the regiment remained at St. Lucia.

In December 1799, the regiment proceeded from St. Lucia to Martinique.

The regiment was removed, in April 1800, from Martinique to Dominica.

In April 1801 the regiment embarked from Dominica for Barbadoes, and in August following proceeded to Curaçoa.

The preliminaries of peace, which had been agreed upon between Great Britain and France in the previous year, were ratified on the 27th of March 1802; but the peace which had been thus concluded was but of short duration. Napoleon Bonaparte, who had been elected First Consul of the French Republic, showed, on several occasions, that he continued to entertain strong feelings of hostility against Great Britain.

During the year 1802, the regiment continued to be stationed at Curaçoa.

After a few months, during which further provocations took place between the two countries, war was declared against France on the 18th of May 1803. The preparations which had been making in the French ports, the assembling of large bodies of troops on the coast, and the forming of numerous flotillas of gun-boats, justified the British government in adopting the strongest measures of defence, and in calling upon the people for their aid and services. Numerous volunteer associations were formed in all parts of the kingdom in defence of the Sovereign, the laws, and the institutions of the country. The militia was re-embodied, and the regular army was considerably augmented, under the “Army of Reserve Act,” as shown in the Appendix, page 97.

The Eighty-seventh regiment embarked from the island of Curaçoa for England on the 12th of January 1803, on board of the ship “De Ruyter,” which, meeting with tempestuous weather, was obliged to put[9] into Jamaica, from whence it proceeded to Antigua, where it arrived in April 1803. The regiment proceeded to St. Kitt’s in June following.

On the 28th of July 1804 the regiment embarked from St. Kitt’s, and on the 28th of September following it landed at Plymouth, after a service of eight years in the West Indies, having lost during that period, by the diseases incident to the climate, many officers, and between seven and eight hundred men.

On the 31st of October the regiment embarked, under the command of Lieut.-Colonel Sir Edward Butler, from Plymouth, for Guernsey, of which island Major-General Doyle had been appointed to the command and to the Lieutenant-Governorship.

The British Government, having ascertained that the King of Spain had engaged to furnish powerful aid to France, felt itself compelled to consider Spain as an enemy, and accordingly issued orders for intercepting some frigates off Cadiz, which were on their way to France with cargoes of treasure: a declaration of war was consequently issued by the Court of Madrid against Great Britain on the 12th of December 1804.

The establishment of the Eighty-seventh regiment, which had been authorised to receive men raised in certain counties of Ireland, under the Act of Parliament, dated 14th July 1804, termed the “Additional Force Act,” was augmented by a second battalion, of which a distinct account is commenced at page 41.[6]

On the 10th of March 1805, a detachment, consisting of twenty-eight serjeants, fifteen drummers, and five hundred and twenty-eight rank and file, being drafts from the levy then raising in the county of Mayo by the Honorable H. E. Browne, embarked from Ireland for Guernsey, and joined the first battalion on the 15th[10] of April following, thus considerably augmenting the effective strength of the Eighty-seventh regiment.

On the 2nd of November 1805, the first battalion embarked from Guernsey, and proceeded to Portsmouth.

The first battalion of the Eighty-seventh regiment embarked at Portsmouth on the 23rd of July 1806, and proceeded to Plymouth, where it disembarked on the 6th of September following. On the 12th of that month it embarked for South America, under the command of Lieut.-Colonel Sir Edward Butler; the effective numbers were, fifty-three serjeants, eighteen drummers, and eight hundred and five rank and file.[7]

The first battalion arrived in the Rio de la Plata in January 1807, and disembarked on the 16th of that month near Monte Video, where it took up a position in advance, protecting the breaching batteries, it having been arranged between Brigadier-General Sir Samuel Auchmuty and Rear-Admiral Stirling to lay siege to the place. The piquets of the Eighty-seventh,[11] under Major Miller, were attacked by the Spaniards, who were defeated with great loss. On the 3rd of February, a practicable breach being made, the troops proceeded to storm the town, which was carried, and the citadel soon afterwards surrendered.

The Eighty-seventh, under Lieut.-Colonel Sir Edward Butler, had three officers and sixty men killed, and three officers and eighty men wounded: total, one hundred and forty-six; strength in the field, seven hundred and eighty-eight.

| Killed. | Wounded. |

| Captain—Charles Beaumont. | Captain—John Evans. |

| Lieutenant—Hugh Irwine. | ” R. McCrea. |

| Surgeon—Wilde. | Lieutenant—W. Boucher. |

In the public thanks issued by Brigadier-General Sir Samuel Auchmuty, the regiment is thus mentioned:—

“The Eighty-seventh, under Lieut.-Colonel Sir Edward Butler, were equally forward; and to their credit, it must be noticed, that they were posted under the great gate, to rush into the town when it should be opened by the troops, who entered at the breach; but their ardour would not allow them to wait; they scaled the walls, and opened themselves a passage.

(Signed) “T. Bradford,

“Dep. Adjutant-General.”

The Eighty-seventh subsequently received the royal authority to bear the words “Monte Video” on the regimental colour and appointments in commemoration of the gallantry evinced in the capture of that place on the 3rd of February 1807.

On the 10th of May, Lieut.-General Whitelocke having arrived from England with reinforcements, proceeded as Commander-in-chief to prepare for the attack of Buenos Ayres. In a brilliant affair at Colonia on the 7th of[12] June, the light company of the battalion was creditably engaged. On the 18th of June the troops embarked at Monte Video, and on the 28th of the same month landed at Ensenada da Barragon, about twenty-eight miles from Buenos Ayres, without firing a shot. Major-General John Levison Gower was the second in command to Lieut.-General Whitelocke, and the Eighty-seventh were posted in the right brigade under Brigadier-General Sir Samuel Auchmuty.

In the assault of Buenos Ayres on the morning of the 5th of July 1807, the Eighty-seventh were formed by wings, the right commanded by Lieut.-Colonel Sir Edward Butler, and the left by Major Miller. The orders were to pierce by the two streets to the right of the Retiro, in performing which (in company with the Thirty-eighth regiment) they suffered very severely. In the course of this service, Lieutenant William Hutchinson, in command of Captain Frederick Desbarres’s company, took two of the enemy’s guns, turned them on the Plazo del Toro, and, after a few rounds, the enemy, to the number of fifteen hundred, surrendered to him. The thanks of Sir Samuel Auchmuty were given to Lieutenant Hutchinson for his gallant conduct upon this occasion. Serjeant Byrne also distinguished himself by his bravery. Twenty-nine pieces of artillery, with a quantity of military stores, were taken. The light company, which was detached from the regiment, was taken prisoners in the convent of St. Domingo, and remained for three days, when it was restored agreeably to the articles of the treaty.

The loss of the Eighty-seventh on this occasion was seven officers and eighty men killed, and ten officers and three hundred and twenty men wounded: total, four hundred and seventeen; strength in the field, six hundred and forty-two; remained, two hundred and twenty-five.

| Killed. | Wounded. |

| Capt.—David Considine. | Major—Francis Miller. |

| ” Noblet Johnston. | Capt.—Alexander Rose. |

| ” Peter Gordon. | ” Frederick Desbarres. |

| ” Henry Blake. | |

| Lieut.—Robert Hamilton. | Lieut.—James O’Brien. |

| ” Michael Barry. | ” Edward Fitzgerald. |

| Quartermr.—Wm. Buchanan. | ” William Crowe. |

| Assist.-Surgeon—Buxton. | ” Hen. Taylor Budd. |

| ” Robert John Love. | |

| Ensign—Godfrey Green. |

The evening before this attack, there was an order that the great coats and kits of the regiment should be left in the house which the commanding officer had occupied, under the charge of the Quartermaster; or, in his absence, of a subaltern officer, with the sick or lame men who could not march, as a guard for this baggage. The Quartermaster was employed on the general staff as an assistant engineer, and the tour of duty fell upon Lieutenant Michael Barry, of the grenadier company; but this high-spirited young man earnestly solicited, and obtained permission, to accompany his regiment, and was the first officer who fell the next day. No other subaltern being found willing to remain behind, the charge was entrusted to Quartermaster-Serjeant William Grady. He was the first man who joined the corps on its formation, and had been distinguished for his bravery, intelligence, and trustworthiness; his guard, inefficient as it must be, mustered somewhat more than twenty men. In front of the house there was a thick orchard, with a narrow path leading to it; upon this he placed double sentries during the night, and a piquet of half his force in the day-time. It appeared that at the further end of this orchard a mounted body of the enemy was concealed; these men had been posted in advance of the town, but being unable to return, in consequence of the[14] British troops having got between it and their position, they determined to get into the country by this narrow pass; but when they rushed out of the orchard, they were fired upon by Serjeant Grady’s sentries, and, their leader falling, they retreated into their cover, and after several ineffectual attempts to escape in that direction, the party, consisting of two officers and seventy men, well mounted and armed, surrendered to the Quartermaster-Serjeant’s small force. Having secured their arms and ammunition, he marched the prisoners to head-quarters, and delivered them up to Major-General Gower. Two hours after he received written orders from Lieut.-General Whitelocke to return the arms, &c. to the prisoners, who were released, and not to fire upon or stop any party, whether armed or not, going into or coming out of the town. At nine o’clock the next night, upwards of five hundred mounted men came out of the town and surrounded the house, the owner of which was an officer of the party, who, in addition to national hostility, was in a state of great irritation at his house having been taken from him, and, as he stated, plundered by the advanced guard of the British army. They surrounded and made prisoners Serjeant Grady and his party, who had orders not to fire upon any armed body. They were marched into the town, and thrust into loathsome dungeons. The Serjeant was a peculiar object of revenge, because he refused to accept a commission in their service, and to drill their troops. This brave and excellent soldier was subsequently rewarded for his exemplary conduct by being appointed Quartermaster to the second battalion of the regiment. After the capture of Serjeant Grady and his party, the stores were plundered, and the baggage carried off or destroyed.

Notwithstanding the intrepidity displayed by the troops, the enterprise failed. On the morning of the 6th of July the Governor-General Liniers sent a letter[15] to Lieut.-General Whitelocke, offering to restore the prisoners taken in the action of the preceding day, and also those made with Brigadier-General Beresford, on condition that the whole of the British forces should be withdrawn from South America, which proposals were accepted. The Lieutenant-General’s conduct subsequently became the subject of inquiry by a court-martial, and he was cashiered.

During the attack upon Buenos Ayres, a number of the Spanish and native soldiers were seen in the uniform of the Eighty-seventh regiment; this was accounted for by a ship with the clothing for that regiment, which had been sent out from England to Monte Video, having been captured and carried into Buenos Ayres by a Spanish privateer, and the clothing had thus been distributed to the armed populace.

Subsequently to the assault on Buenos Ayres, the Commander of the Forces issued the following general order:—

“Buenos Ayres, 8th July 1807.

“Volunteer Peter Benson Husband, of the Eighty-seventh regiment, is appointed Ensign in that corps, in consequence of his very gallant behaviour on the morning of the 5th instant.

(Signed) “T. Bradford,

“Deputy-Adjutant-General.”

The Eighty-seventh returned to Monte Video, after the cessation of hostilities, and was completed by volunteers from the different corps returning to Europe. On the 2nd of August the regiment embarked for the Cape of Good Hope; and on the 4th of September following it landed at Simon’s Bay, and marched to Cape Town, where it formed part of the garrison.

During the years 1808 and 1809, the first battalion continued to be stationed at the Cape of Good Hope.

On the 23rd of October 1810, the first battalion embarked from the Cape, having been selected to form part of an expedition designed to co-operate with troops from India, under the command of Lieut.-General John Abercromby, in the capture of the Mauritius. A landing of the troops from India had taken place a few days before the division from the Cape, under Major-General William Cockell, had arrived. Its appearance off the island was, however, particularly opportune, as the French governor had previously resolved to defend his lines before Port Louis; but when he saw the force from the Cape approach the island, he relinquished the hope of being able to make effectual resistance, and surrendered this valuable colony to the British. The battalion disembarked at Port Louis on the 1st of December, where it remained on duty, after the other regiments composing the expedition returned to their respective quarters. Captain Henry C. Streatfeild with two officers and one hundred men were embarked on board a ship of war, in advance of the expedition, and landed before the force from the Cape.

The first battalion continued to form part of the garrison of the island during the four following years.

In May 1815, the first battalion at the Mauritius was directed to hold itself in readiness for active service in India, and embarked on board of transports on the 16th of June, and landed at Fort William, in Bengal, on the 3rd of August.

The light company embarked in an Arab ship, with the flank companies of the Twelfth and Twenty-second regiments, and were carried into the Gulf of Manaar; the ship being there weather-bound, the troops were landed, with the assistance of country-boats, at Calpenterre, in Ceylon, and having remained fourteen days at Point de Galle, embarked again in the Arab ship for Calcutta, where they arrived, and rejoined the regiment on the 25th of September.

On the 1st of October 1815, the first battalion of the Eighty-seventh regiment embarked in boats, and sailed for Berhampore, where it arrived on the 14th, and again embarked and sailed for Dinapore on the 13th of November, at which place it disembarked on the 18th of December.

The Rajah of Nepaul having broken the terms of treaty made by him with the Honorable East India Company, the battalion marched for his territories on the 15th of January 1816, and arrived at Bullvee Camp on the 24th, where it joined the army under the command of Major-General Sir David Ochterlony, K.C.B., who commanded the forces assembled on the frontiers of Nepaul; on the 3rd of February the brigades advanced by their respective routes into Nepaul, Sir David Ochterlony remaining in company with the third and fourth brigades (to the former of which the Eighty-seventh belonged), and marched through the forest at the foot of the Nepaul Hills on the 9th. The light company of the battalion with those of the native infantry of the brigade with two guns under the command of Lieut. John Fenton, formed the advanced guard, and had a very arduous duty to perform, in carrying the guns through the forest, which was accomplished by the personal exertions of each individual. On the 10th, the third brigade arrived at Semul Cassa Pass, and at nine o’clock A. M. the light company of the Eighty-seventh, commanded by Lieutenant Fenton, accompanied by Sir David Ochterlony, was drawn up the pass, a height of thirty feet, by the officers’ sashes, the brigade then about five miles from the pass; on the 19th it reached the village of Etoundah on the banks of the Rapti. The advanced guard again exerted themselves in opening a communication between the third and fourth brigades through the Cheria Ghanty Pass.

On the 27th of February it arrived at Muckwanpore, and on the 28th the brigade was ordered to take possession[18] of the heights of Sierapore, and reconnoitre the position of the enemy. Lieutenant Thomas Lee, with a piquet of forty men of the Eighty-seventh, and strong piquets of native infantry, under their own officers, was directed to take possession of the deserted height of Sierapore. Captain Pickersgill, acting Quartermaster-General, conducted them to their ground, where having planted them, Lieutenant Lee and twenty men of the Eighty-seventh proceeded to reconnoitre the ground in advance: the enemy advanced to recover his position; the piquet retired, and the reconnoitering party, in danger of being cut off; had to descend a hill covered with jungle, pursued by a strong party (nearly four hundred) of the enemy, and would not have escaped but for the gallantry of two soldiers of the Eighty-seventh, Corporal James Orr of No. 5. company, and Private Patrick Boyle of the Grenadier company, who seeing the danger of the officers, placed themselves on the pathway, and by their steadiness and fire, checked the advance of the enemy. On the officers making good their retreat, these gallant fellows retired uninjured: the corporal was promoted to the rank of serjeant at the particular desire of Major-General Sir David Ochterlony; the unfortunate habit of drinking alone prevented the promotion of the private. An action afterwards took place, in which the light company, under the command of Captain Fenton, suffered considerably. The action commenced about noon, and ceased at six o’clock P. M., leaving the British in possession of the heights for a considerable distance from Sierapore, and of one field-piece.

In this affair Lieut.-Colonel Francis Miller commanding the battalion, and Lieutenant Fenton[8] in the command of the light company (detached in the advance), particularly distinguished themselves, and received the public thanks of Major-General Sir David Ochterlony,[19] and also of the Marquis of Hastings, the Commander-in-chief and Governor-General of India. The regiment had ten men killed, and above thirty wounded, many of whom died; the loss of the enemy was very considerable.

The Rajah, perceiving that resistance was unavailing, sued for peace, and a treaty was concluded on the 4th of March; on the 9th of that month the battalion commenced its return to Bengal, and arrived at Amowah on the 22nd of March, where it was cantoned until the 30th of June, on which day it commenced its march to Govingunge on the river Gonduck, and embarked in boats in progress to Cawnpore; on the 17th of August, the battalion arrived at Jangemowe, within a few miles of Cawnpore, but did not disembark at the latter station, until the 10th of September. About this period the battalion became very sickly from being so long confined in boats; the hospital list amounted to about four hundred and eighty, exclusive of numbers who could not be admitted for want of room. Not less than one hundred and fifty men died in this and the following month, when the cold weather coming on, in a great measure, renovated the corps.

On the 6th of February 1817, the regiment marched from Cawnpore towards Hattrass, which fortress the Commander-in-chief had given instructions to Major-General Marshall to besiege: the division from Cawnpore arrived before Hattrass, and joined the field army, on the 20th of February.

The pettah of the fort of Hattrass having been breached, it was resolved to storm on the evening of the 25th of February, and accordingly his Majesty’s Fourteenth regiment was appointed for that duty, and the Eighty-seventh to cover; however, the breach being found impracticable, the troops returned to their lines, but the pettah was evacuated during the night, and taken possession of on the following morning by the British troops; batteries were immediately erected[20] against the fort, which was heavily bombarded with shells and rockets: at length the principal magazine blew up on the 2nd of March, the explosion of which was said to be distinctly heard at Meerut, nearly two hundred miles distant.

Dya Ram, Rajah of the fortress, having determined on abandoning it, most gallantly cut his way through some of the piquets of the besieging army, and effected his escape. On the morning of the 3rd of March, the right wing of the Eighty-seventh marched into and took possession of the fortress of Hattrass, which was reduced to a mass of ruins. On the 8th of March the regiment commenced its return to Cawnpore.

In July and August the Eighty-seventh regiment, in Bengal, was increased by a detachment of thirteen serjeants, three drummers, and two hundred and sixty-nine rank and file, men who had been transferred on the second battalion being disbanded on the 1st of February 1817.

The regiment remained at Cawnpore until the 15th of October, when it received orders to march to Secundra, where the grand army was formed under the command of the Marquis of Hastings, against the Pindaree hordes, and having remained there until a bridge of boats was completed over the Jumna, it crossed that river on the 27th, and marched to the banks of the Sind, opposite Gualior; but the grand army being, about this time, attacked by that fatal disease, the cholera morbus, compelled the Marquis, with his troops, to retire to Erich on the Bettwah: the mortality for four or five days was very great, particularly among the natives, who died in vast numbers on the road and in the villages through which the army passed. The Eighty-seventh lost one subaltern (Lieutenant John Coghlan), three serjeants, and forty rank and file; total, forty-four, in three days. The army having in some measure recovered, his Lordship returned to the banks of the Sind, and took up a position at Lonaree, within twenty-one[21] miles of Gualior, where Scindiah, with a powerful force, was ready to take the field, to support the Mahratta States, which had revolted.

On the 14th of February 1818, the different divisions of the army were broken up, in consequence of peace being concluded, and the Eighty-seventh returned to Cawnpore, at which station it arrived on the 26th of that month.

On the 21st of October 1820, the regiment marched from Cawnpore for Fort William, by the new road, and arrived in that garrison on the 21st of December, a distance of six hundred and sixty miles.

On the night of the 6th of September 1821, a very alarming fire broke out in the Honorable Company’s Dispensary, situated in Calcutta, and surrounded by many valuable houses. As soon as intelligence reached the fort, two captains and ten subalterns, with about three hundred men, immediately marched to the spot, and, by the greatest exertions, prevented the fire from spreading to the neighbouring houses. The strictness with which the armed party protected the property of the inhabitants, called forth their admiration, which was followed by the annexed letter from the Governor-General, the Marquis of Hastings.

“Council Chamber, 17th Sept. 1821.

“It was a great satisfaction to me, though no surprise, to learn the zealous and meritorious conduct of the detachment of the Eighty-seventh, employed in the endeavour to stop the fire last night. As some of the men have suffered in articles of dress, to repair that damage, as well as to reward the activity of the party, the Council has directed that five hundred rupees be paid to you, which you will please to distribute according to your opinion of claims.

“I have, &c.,

(Signed) “Hastings.

This mark of approbation from the Governor-General in Council, towards the party in general, was followed by one to the officers employed, each being presented with a piece of plate, accompanied by the following letter:

“Council Chamber, 18th December 1821.

“The Most Noble the Governor-General in Council, being desirous to evince the sense which Government entertains of the laudable exertions of those officers of his Majesty’s Eighty-seventh regiment, who were present with the detachment sent from Fort William on the occasion of the fire at the Honorable Company’s dispensary, has commanded me to transmit to you the accompanying silver cups, with a request that you will, on the part of his Lordship in Council, present one to each of the several officers named below, who are understood to have accompanied the troops on the night of the 6th of September last.”

Captain—George Rodney Bell.

” W. G. Cavanagh.

Lieutenant and Adjutant—James Bowes.

Lieutenant—John G. Baylee.

” Richard Irvine.

” Henry Gough Baylee.

” Alexander Irwin.

” George Tolfrey.

” Edmund Cox.

” John Shipp.

” Henry Spaight.

Ensign—Lawrence Halstead.

A very handsome piece of plate, which is now in the mess, was likewise presented to the above officers by Doctor McWhirter, whose house adjoined the Dispensary, and which was saved by great exertion.

In April 1822, another alarming fire occurred in Calcutta, at the cotton stores of Mr. Laprimaudage,[23] in which a detachment of the Eighty-seventh exerted itself in a very laudable manner, and a letter of thanks was received by Lieut.-Colonel Miller, from that gentleman, for the service rendered by the officers and men on this occasion.

In 1822 the arrival of regiments from Europe, caused the Eighty-seventh to embark (by wings) in boats for the Upper Provinces, and on the 11th of July the right wing sailed for Dinapore, the left following on the 22nd of that month.

The right wing experienced bad weather and lost a number of boats, by which one serjeant, two drummers, five women, and four children were drowned. On the 19th of August the right wing landed at Dinapore, and the left on the 25th, having made a very prosperous voyage, not meeting with a single accident in the passage: on the 1st of November, the regiment marched to Ghazeepore.

On the 17th of May 1823, Lieut.-Colonel Francis M. Miller, C.B., died, after having served his Majesty upwards of thirty-four years, during which he had commanded the Eighty-seventh regiment at different periods for sixteen years. He was deeply and most deservedly regretted by every officer and soldier who had served with him, and had invariably received the marked approbation of every general officer under whom he had been placed. The command of the regiment subsequently devolved on Lieut.-Colonel Matthew Shawe, C.B.

Serjeant Stephen Carr was appointed quartermaster on the 24th of June 1824, as a reward for his distinguished gallantry and honorable trustworthy conduct: he was present in every action in which the second battalion was employed during the Peninsular war.

In consequence of the Forty-seventh regiment having embarked at Calcutta for Ava, the Eighty-seventh left Ghazeepore in boats oh the 9th of June 1824, and reached Berhampore on the 29th of the same month.

On the 14th of January 1825, the regiment proceeded towards Calcutta to replace the second battalion of the Royals on its departure for Ava; the left wing moved by land, the right by water, and were reunited on the 29th in Fort William, of which garrison Lieut.-Colonel Shawe became commandant.

On the 6th of June, the regiment performed the melancholy duty of attending to the grave the remains of its beloved and lamented commanding officer, Lieut.-Colonel Henry Browne. He had entered the regiment in 1800 as an ensign, when sixteen years of age, and had never belonged to any other: his qualities as a man and a soldier endeared him to all. In the meantime hostilities had commenced between the British and the Burmese, and on the 5th of October the regiment embarked for Ava, to reinforce the army in that country, in four divisions, which landed at Rangoon between the 3rd and 10th of November, and immediately proceeded in boats towards Prome, the head-quarters of the army. During the passage, Major William Slade Gully’s division was attacked from the bank of the river, on the 25th of November, by a strong party of Burmese, which was immediately repulsed on the troops being landed. Lieutenant and Adjutant James Bowes, in command of the advanced guard, was wounded, and two privates killed.

Six companies of the regiment, with Major Gully, Captains Charles Lucas and George Rodney Bell, and John Day; Lieutenants John Baylee, William Bateman, Robert Joseph Kerr, William Lenox Stafford, with Assistant Surgeons William Brown, M.D., and William Peter Birmingham, reached Prome in time to share in the operations of the 1st and 2nd of December, which terminated in the entire discomfiture of the enemy. On this occasion the regiment maintained its unvarying reputation for cool and distinguished gallantry: Lieutenant Baylee and two men were killed; Major Gully and twenty-one men were wounded.

On the 8th of January 1826, Lieut.-Colonel Hunter Blair joined the regiment, and was appointed a Brigadier, the Eighty-seventh being in his brigade.

On the 19th of January Brigadier Thomas Hunter Blair, Lieut.-Colonel of the regiment, commanded the right column of attack at the capture of Melloone, consisting of the Eighty-ninth regiment and the flank companies of the Forty-seventh and Eighty-seventh with Captain James Moore (major of brigade), Brevet Captain James Kennelly, Lieutenants Henry Gough Baylee, Edmund Cox, George Mainwaring, William Lenox Stafford, and Joseph Thomas, and Assistant Surgeon Birmingham. No loss was sustained.

The day after the fall of Melloone, the Bengal division, under Brigadier Shawe, made a flank movement from the river Irrawaddy, and entered a well-cultivated country abounding in cattle, eight hundred head of which were secured, and they proved a most seasonable supply to the army.

On the 28th of January the Eighty-seventh, with the flank companies of the Twenty-eighth native infantry, and detachments of the Governor-General’s body-guard and artillery, under Brigadier Hunter Blair, were sent from Tongwyn, to attack the position of Moulmein, eleven miles distant. The flank companies of the Eighty-seventh had one man killed and five wounded in forcing a piquet half way to Moulmein, which had been in part evacuated the preceding day. The position, being a great annoyance to the surrounding country, was destroyed, and the troops returned to camp the same evening.

On the 21st of February, the Bengal division rejoined head-quarters at Yandaboo; and on the 24th of February a royal salute announced the termination of the Burmese war.

The constancy and valour of the British troops had thus forced the monarch of an Eastern empire, with its myriads of inhabitants, to sue for peace; and their conduct[26] is thus alluded to in the order issued by the Governor-General of India.