By Henry Beston

The World's Work - December, 1923

Volume 47, Issue 2

There are two Cape Cods in the world, one the picturesque and familiar land of toy windmills, picnickers and motorists, the other the Cape which the sailors see, the Cape of the wild, houseless outer shore, the countless tragic wrecks, the sand bars and the shoals. This unknown Cape begins at Monomoy; Monomoy where the silver-gray bones of ancient wrecks lie in mouldering lagoons; it leaps the open waters of Chatham and Orleans, and beginning again at Nauset sweeps on, league upon lonely league, to the hook of Provincetown.

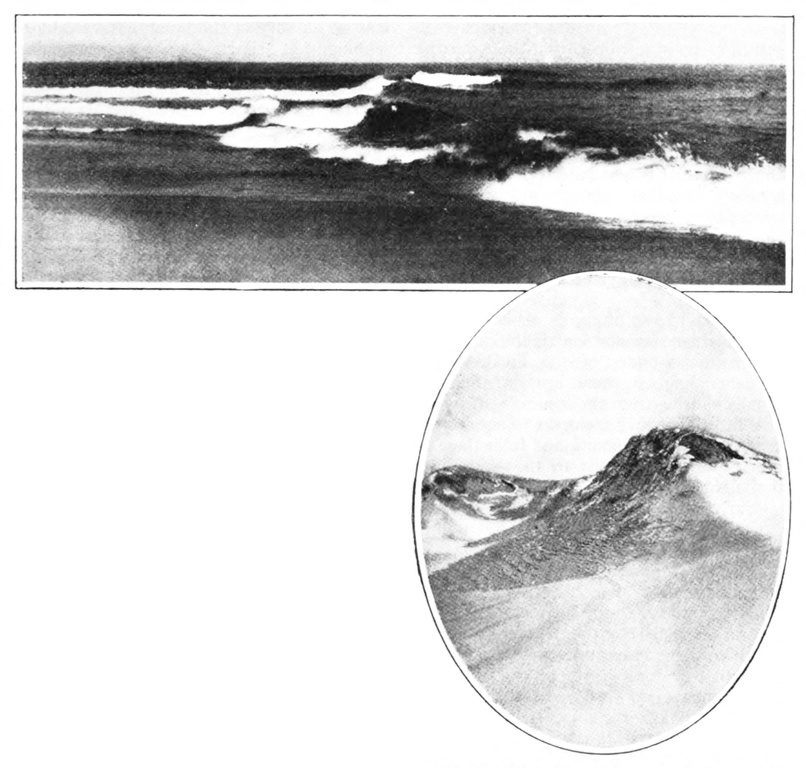

Beyond the broad swath of the churning breakers, lies the North Atlantic, most masculine of seas. Now betrayed by a long smear of churning water in the outer green, now buried treacherously under an unrevealing tide, off-shore bars lie hid. Standing well enough in, the greasy one-stack tramps, the fishing schooners coming and going from the Georges, the vanishing steel windjammers with their Mediterranean or Negro crews, the little unromantic “sugar bowls,” and the big tugs with their solemn barges linked behind, all day pass to and fro.

Once a sailor has picked up Nauset Light on his way north to Provincetown, the only signs of life he will find along the beach will be the coast guard stations and the little cottages which the surfmen build about them for their families. Thirty miles of the thunder of the breakers, thirty miles of Nature in the elemental mood, thirty miles where night reveals no welcoming window light, and the world vanishes into a darkness full of unutterable mystery, keen, moist, ocean smells, and thundering sound.

It is the task of the surfmen to warn vessels standing into danger, to rescue them and their crews from positions of peril, to furnish fuel and food and water to ships in distress, and even, should occasion arise, to navigate a ship into the nearest port.

Including the Monomoy and Chatham region, the patrols of the outer Cape cover a length of fifty wild, breaker-beaten miles. The little harbor openings which have been mentioned alone break the line, elsewhere along it men go south and men go north, and station links with station through the night.

There is nothing quite like the night patrol of the Cape in all the seaboard world.

The stations on the Cape stand on an average some six miles apart, and house a crew of eight men together with the life boat and life line cannon used in case of a wreck. The men upon patrol, however, do not walk from station to station, but to a halfway house built in some more or less sheltered nook upon the bank. A man going south from the Highland station for example, leaves a kind of brass ticket to be collected at his southern halfway house by a man coming north from Pamet River; a man going north from the Highland exchanges tokens with a man coming south from Peaked Hill.

In summer the night patrols go smoothly enough, though it is something of an experience to walk the beach through a midnight thunder squall. The wild flare of lightning upon the confused and foaming sea, the organ-like note of the drenching rain, the echoing of the crashes in the solitary dunes, all these are the very properties of romance. But when the bitter northern winter descends, each patrol is an adventure in itself. It may fall to your lot to step out of the station door into a February night, cold as the circle of the pole and overhung with great unsullied stars, a night when the long crumbling line of the bank stands clear against the sky, and the frozen sands are good walking under foot; it may fall to your lot to force your lonely way through the full fury of a northeast storm when the wind is blowing a gale and a tremendous sea is thundering unseen in a dissolving dark of snow.

In the depth of winter the steep bank becomes a glare of coated ice and sand and snow strangely intermixed. Sand covers snow till the new surface seems a secure part of the land, and then a new snow hides the deceit from view. It can be extraordinarily treacherous under foot.

For days, for weeks even, if the weather is miraculously good, the surfmen may accomplish their patrols without untoward incident, but any night the luck is liable to change and adventures begin. A young friend, walking the beach, head down to a bruising sleet, suddenly finds himself trapped between the ice cliff and the tide, and with the breakers sweeping to his encumbered shoulders, fights for his life there alone in the tremendous dark; another just escapes the fall of a great ice-rooted mass of the headland by running ahead of it into the sea, and tells of it, laughing, too, at the morning’s mess; a third slips on the fantastic path up the slope to the halfway house, and fights his way with numbed fingers to the top. Life in Nature is far more a matter of purest melodrama than the world believes.

There are dreaded nights when a certain north wind blows directly down the Cape carrying everything before it, flying sand, fragments of ancient wrecks, cobbles that have rolled out of the bank and been caught up by the wind as they fell, barrel staves, and stinging spume.

It was the privilege of the writer to spend a part of last winter living and patrolling with the Coast Guards of the Cape, and on one occasion to go patrolling “through the sand.”

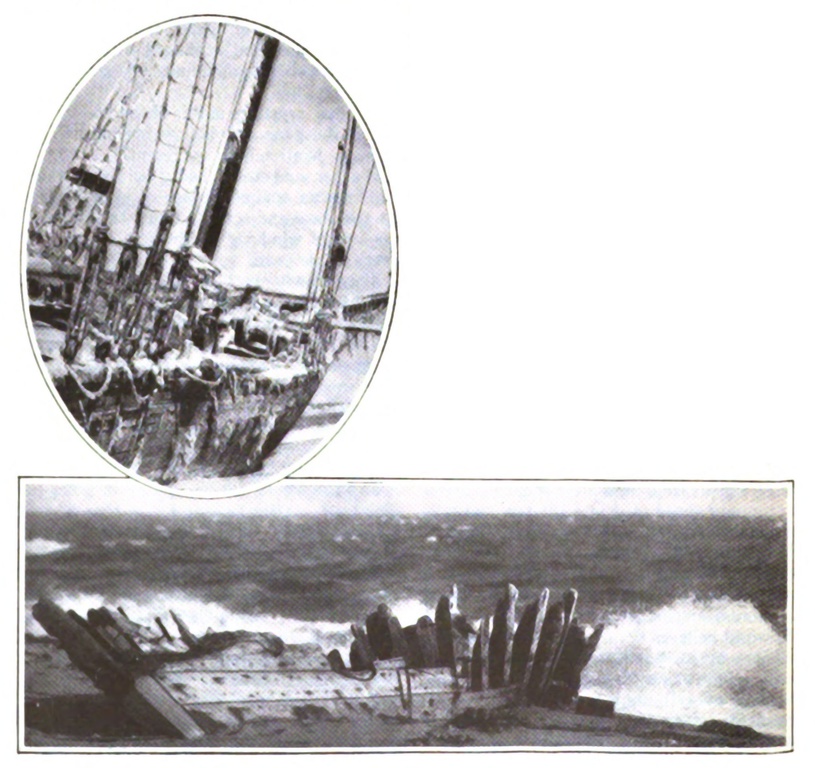

THE WRECKS OF THE CAPE

The Blizzard Nor’easters that blow ships directly on the sands have

strewn the southern shoals and the off-shore bars with wrecks which

the shifting sands hide, reveal and hide again.

I was staying at the Race Point Station on the back shore of Provincetown. It was close upon eight o’clock at night, the lamps were lit, the living room was still, and at the end of the cleared and covered dining table a surfman off duty was reading the day’s paper and puffing a quiet pipe. It was so quiet I could vaguely hear the scratching of the pen. Suddenly this quiet world woke to a faint sound, the sound grew of an instant to a dull and hollow roaring; a whirl of unseen sand swept like sleet against the northern panes.

“There you are,” called my host through his door, “the wind’s changed, and if you go on patrol to-night you’ll find some sand flying. Hear that?”

A fierce, crystally patter of sand was striking at the pane; the hollow roaring had become a wintry howl. Presently I noticed that other sand storms had given the northern windows an opaque surface of ground glass. At the Race and several other stations there are sets of windows which must be renewed every single year.

Then slowly, very slowly midnight came, and I dressed to go on a patrol in an old suit with socks pulled over the trouser ends, a watch cap, and my old navy pea jacket snugged round me with a poilu’s army belt. The sand takes the surface from oilskins. My fellow patrolman, Mr. Morris, was clothed in one of those excellent navy wind proof suits which are ousting oilskins from the Cape; the jumper has a hood attached to it and the whole suit has a kind of polar explorer air. After looking to see that he had his flare light signal safely tucked away, Morris threw open the station door.

The night was bitter cold and overcast, and the air was full of the strangest dry hissing in the world. Along the frozen strand, and through the dead beach grass of the inland dunes, loose sand was flying, hissing as it was borne along upon the ground. The wind was thick with sand; invisible sand that blew directly into our faces, struck at our eyes, and set us to blinking, blowing, and weeping; it forced its way into the nostrils, it invaded the pouches of the ears, it gathered in the crease of one’s lips and set one to chewing out grit, one’s eyes in gritty anguish all the while. Sand and dust of sand began to gather like snow in all the hollow creases of our clothes; sand sifted down into our boots, sand found a mysterious way through our collars and down our necks, grit lodged in the eye hollows, in the eyebrows, and in the short hairs above the ears. And it came to us hissing and stinging, the cold, dry crystals falling upon the face like the myriad blows of some tiny cruel whip.

We walked that night along a spectral sea. A wind had moved the harbor ice out of the hook of Provincetown, and this ice had drifted ashore on the outer side. Here and there a single cake lay stranded on the beach, but the great mass of it had gathered together to form a vague, broad band along the shore. It was afloat, and as the outer breakers dived beneath it and coursed ashore, the ghostly mass rose and fell, churning and groaning in the cold. Now here, now there along it, spectral eyes and slow glows of coldest phosphorescence, appeared, smouldered, and died, and our steps kicked phosphorescent patches in the sand. Presently my companion’s sharp and watchful eye saved me from stumbling over something on the border of the floe. We stooped, sheltered our tingling faces as well as we could, and flashed on an electric torch.

A loon crouched there in the hissing and mysterious night, its breast feathers matted stiff with sand and fuel oil. The oil kills the wild fowl by thousands on the Cape, for it gums their feathers together when they have settled in a pool of it, and allows the cold to strike in through openings of unprotected flesh. The motionless, calm ray of the electric lamp lent an ironic serenity to the vast, wild dark, and the dying creature lifted its eyes to the white ray, dark uncomprehending eyes awaiting something incomprehensible and dread.

We hurried on, and, coming to a wide turn, found ourselves exposed to the full fury of the sand. A wind with never a lull or a whirl, a wind with the directness of a channeled river, roared by us doubling the tiny lashes in number and in force. But we luckily had but a little taste of this, and soon reached the end of the first half of our patrol by Race Point light.

The squat white tower stood close at hand, its placid and unearthly beam glancing along a length of the bordering floe. One could see the cakes rising and falling in great, heavy-laden curves, and the ghostly spurts and tosses of the water in between. Then Morris and I returned to the Coast Guard station with the sand at our backs, shook and slapped and stamped away as much of the sand as we could, and closed the hospitable door of Race Point upon the strident, inhospitable world.

THE SANDS OF CAPE COD

“Beyond the broad swath of churning breakers lies the North Atlantic,

most masculine of seas.”

THE FACINATING AND DESOLATE DUNES

That furnish the stinging ammunition for the artillery of the wind

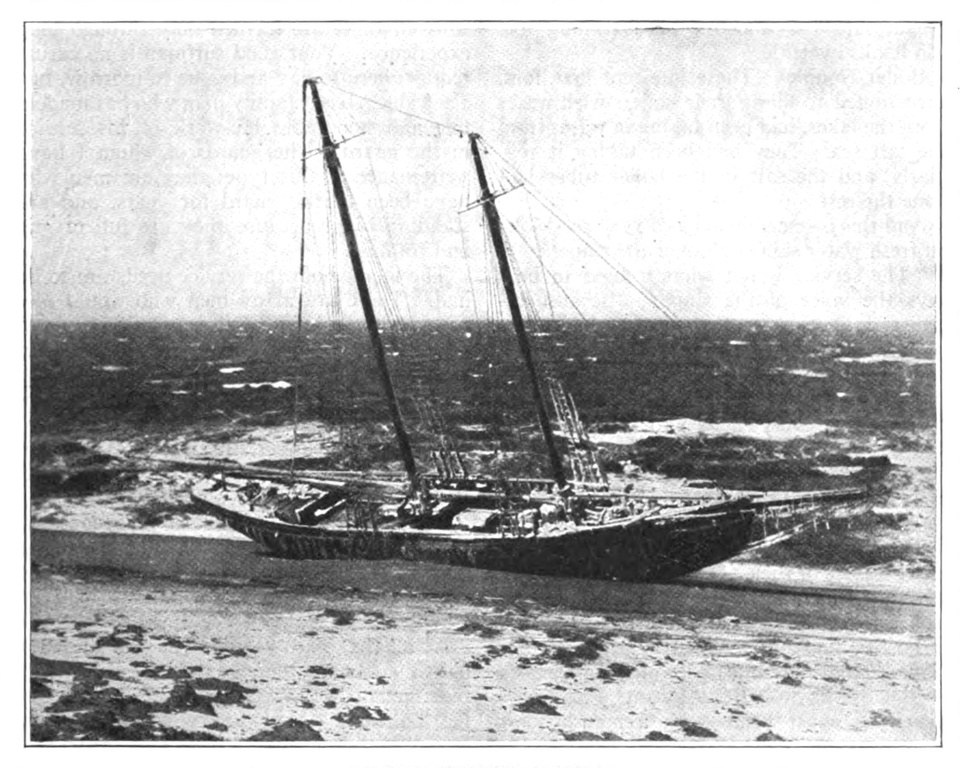

Ever since the early days of European exploration, the back shore of the Cape has been feared by mariners. The vast shoals to the south, the off-shore bars to the north, the blizzard nor’easters that blow ships directly on the land, all these have strewn the outer shore with wrecks. To this day the sands hide and reveal and hide them again. It is an easy enough thing to say that the day of the great wrecks is over. Yet one of the greatest disasters in modern maritime history occurred on the Cape as recently as the first year of the war, and the winter of 1922 to ’23 saw wreck follow wreck upon the shore. But coast guard crews have seldom been called to such a battle as was theirs on that bitter winter morn of February 17, 1914.

On the night of the 16th a nor’nor’west wind, the wind which brings the snow and cold, had been blowing squally gales, and a heavy fall of powdery snow was blowing about upon the moors. The sea was running high, running to the very foot of the frozen bank, and the broad beach was but a mass of breaking waves and foam. Through the wild night, fighting his way through the thickets of beach plum, the bitter wind, and the snow smother whirling in the dark, went the patrol, Joseph Francis, a surfman from Cahoons. The dawn began to pale, and presently Francis made out a large square-rigged bark stranded in the breakers some two hundred and fifty feet from shore. The vessel was thick with ice, the seas were breaking over her, flinging spray as high as the crosstrees, and this spray was freezing where it fell. In the main rigging were the indistinct figures of the crew.

The wreck was the Italian steel bark Castagna bound for Weymouth, Massachusetts, with a cargo of fertilizer from the Argentine.

An ill chance of the sea had dogged her. Twice had she picked up Boston Light, twice had nor’west gales blown her out into Massachusetts Bay. Lying off the coast bewildered in the flurrying gale, her barefooted Italian crew exhausted and ill-prepared for our northern weather, the second storm had wrecked her on the Cape. Her anchors and anchor gear were iced solidly in, her rigging was a mass of ice, and the sails she displayed were but glassy gray sheets of ice solid as so many boards.

Doomed, and so tragically helpless that she made neither sign nor sound, the great bark lay in the thunder of the breakers, now vaguely glimpsed, now lost in the snow squalls blowing from the moors.

A little after five o’clock the news of the disaster reached Cahoons, and from there the tidings were telephoned to the Nauset station eight miles to the south. The Castagna lay at the southern end of the Cahoons patrol, close to the halfway house used by Nauset and Cahoons. Realizing that the life-saving apparatus would have to be carried overland along the moors, Captain Tobin of Cahoons and Captain Walker of Nauset arranged to divide the load. The wreck lay a good four miles from either house, four miles of nor’west squalls, and deep, unbroken snow upon a wild, uneven waste.

Each station kept a horse to pull its heavier apparatus to the beach, and these poor creatures were presently harnessed to their loads and urged to their hard but necessary task. Tugging, pushing and trudging on as best they could, the crews arrived by seven at the wreck. The snow squalls were petering out, but the buffeting wind still shrilled under the ragged sky, and the ebbing sea was still a vast width of rollers, seething white with foam. Fierce currents of tide, stirred by the long-shore wind, were moving underneath the surface fury; it was a sea in which no boat could be launched, or being launched could live.

Sea after sea burst and poured from the Castagna’s deck. There were faint yells from aloft as the greater seas swung in out of the storm and came rolling down upon the ship.

Working as fast as they could in the tumult, the coast guards set up their life-saving apparatus on an edge of the beach left bare by the ebbing tide. Then, like the opening crash of a battle, the life-saving cannon fired its first thin line across the width of sea.

The shot was a good one and passed well aboard, but the men in the rigging strangely made no attempt to get the cord. The fact was that the barefooted men on the mast were clad only in cotton trousers, shirts, and thin coats, and that the hands and feet of those who were not dead were but lifeless and unwieldy clods of ice. With the sailor’s instinct “to get out of the water,” the crew had scrambled aloft the minute their vessel struck. A second charge remained likewise unattended. Two men suddenly dropped “like ripe plums” into the confusion of the sea.

A figure moved in the rigging and a great powerful giant of a young seaman, Nils Halverson his name stands on the book, was seen to work off his coat, and wrap it round the mess boy who was dying in the cold.

The cannon now crashed a third defiance at the sea, and this third line fell nearer to the men. Frozen as they were, the giant and one or two others descended to the breaker-beaten decks, and managed to secure the line. But knots cannot be made with frozen fists big as boxing gloves, and all stood as it did before.

More than ever now all depended upon the guards. The crew of the wreck were unable to help themselves in any way.

It was now nine o’clock and the sea had dropped enough to permit an attempt at the launching of the boat. The task was one of crudest difficulty, and it was only after several hard battles and a show of finest courage and boating skill that the coast guards’ vessel was tugged to the Castagna’s pouring side. Two of the crew of thirteen had perished overside, two were dead in the rigging, their faces and bodies glassing over in strange mummy shrouds of ice, a third lay dying in the racing waters of the deck. The eight left alive, forlorn, swarthy Giovannis, Giuseppes, Angelos, and Carlos were in terrible condition. But to this day they tell of how the big man, refusing aid, walked to the near shelter on his frozen feet, his great frozen hands held out a little from his sides. The lad he had tried to help was dead.

After receiving skillful first aid from their rescuers, the crew of the Castagna were hurried to a Boston hospital, one to die there, others to suffer amputations. And from the hospital and the kindly care of the Sisters of Mercy, these tragic children of the sea disappear into the world again, Heaven alone knows where.

On the following morning those who went aboard the ship found the Captain’s cabin to be reasonably secure and dry. Had the crew taken refuge there, instead of in the rigging, they might possibly have all been saved. The fire was out in the stove, but a tiger cat was waiting for its rescuers, and a silent, wet canary stood in a tarnished cage. The bird soon died, but the cat lived out the rest of its eight lives on a Truro farm.

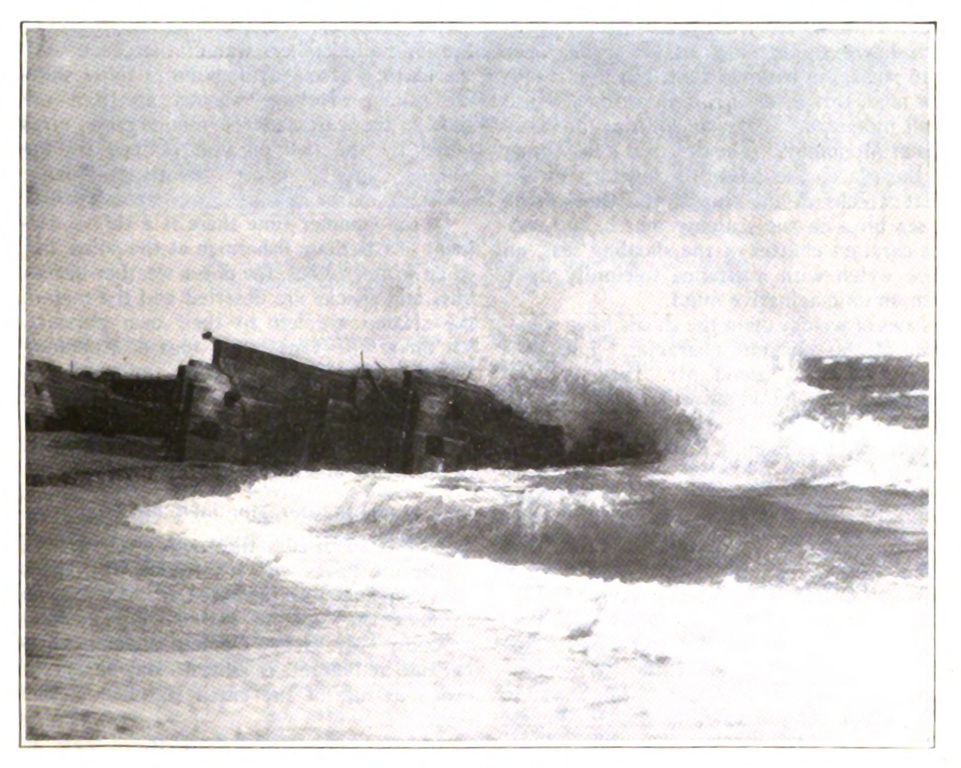

The captain of the vessel had been one of the two figures to drop into the sea. His body, curiously preserved in some unaccountable manner, suddenly appeared two years later, twelve miles away in the marshes of Orleans. And this is one of the mysteries of the Cape. The rescue of the men of the Castagna by the crews of Cahoons and Nauset does honor to the great traditions of the guard. It was a feat which called not only for daring and skill, but also for resourcefulness, perseverance and endurance. Toward the end of the struggle Captain Tobin of Cahoons, overcome by the long strain, toppled into the waves and was himself in gravest danger. At low-course tides, the wreck may still be seen. Being built of iron, her sides have rusted and fallen in, but bow and stern rise twisted and black above the waves. Her steep spars lie beside her where they fell. On a sunny summer day when the rollers advance up the beach in the face of a southwest wind, and the sharp, musketry-crack and deep-voiced roar of the breakers travel down the empty sands, nothing remains to tell of the Castagna and her men.

THE LAST STAND

Old wrecks that finish out their lives resisting the cannonading surf

A sandspit of marshland and low dunes, some twelve miles long and scarce two thirds of a mile wide, runs south into the Atlantic from the elbow of the Cape, its seaward rim continuing the line of the great beach to the north. East of it and south, far flung into the sea, lie the great shoals of the Cape, Bearses, the Stone Horse, the Handkerchief, Great and Little Round, Shovelful, and Pollock Rip. No tide uncovers them, but on clear, sunny days, from the watch house at Monomoy Point, their place is marked by vast, vague mottles of yellow-green lying on the water with fierce blue-black rivers of tide running high between.

At the end of the dunes, on a table land of sand that might be the very end of inhabited world, stands the Coast Guard Station of Monomoy Point, watching over ship and shoal.

There are strange regions in the world where a brooding melancholy dwells, regions where much that is tragic in the lives of men seems linked with a tragic something in the world. The ancient Roman towns of the Adriatic, now far from the shrunken sea, and slowly sinking into marshes that once were ports, are haunted thus, but in our own new land, this sense of ruin in a ruined world is all unknown. Yet you will find precisely this at Monomoy. The dreadful lonely quiet of the place, the haunting memory of the great wrecks of the shoals, the thin piping of sea birds in the scummy marsh, the endless cataract chatter of the shoaling seas, all these weigh with a strange solemnity upon even an unimaginative mind.

Tales of wrecks upon the shoals have something of this uncanny character. I recall a story which my friend Mr. Tarvis of the Highland Station told me as I sat talking with him one quiet winter night. He had spent some time at Monomoy Point.

There was a schooner called the Mary Rose, and she was missing. There had been a storm on the shoals about the time she was due to go through, but nobody at the station had a sight of her, though we kept a sharp lookout on what we could see of the shoals. When you can see off in stormy weather, all the shoal water to the east and south is one big boiling smother of white. When the weather cleared, I had the morning watch, and I was up in the watch house, standing at the open window, looking over the shoals through the telescope. Pretty soon I saw something sticking up out of the water that looked like a schooner’s topmast. The captain was with me so I said to him to come and take a look, and he thought we ought to go out there and see what it was. So the Captain and I took the big dory and rowed out there, and it was this missing schooner, the Mary Rose. She was sitting right on the bottom on even keel, just the topmast of her showing above the waters, her hoisted sails moving a little down below there in the sea. The water was clear and you could see her deck and her dories all lashed in. They never found what had happened to her, never found even one of the bodies of the crew. Pretty soon she began to settle in the sand, her topmast broke off or went under the water, and that’s the last we saw of the Mary Rose.

A land of utter loneliness, a land of lagoons opening and closing to the sea, of marshes sunken in the dunes and afloat with scum thin and black as watery tar, marshes in which the hulks of ancient wrecks are slowly rotting with the years, a No Man’s Land of the long and endless war of the ocean with the earth. Strange things lie in those shifting sands, wreckage washed up from the shoals; the carcasses of innumerable birds killed by the fuel oil and ravined by the skunks; great, queer Southern-looking shells.

In the summer time there is a tiny settlement of Chatham fishermen at the point, but when winter comes, the dozen weather-beaten huts and shacks are deserted and the men of the station are left to their own pursuits. All along the Cape they regard Monomoy Point as “the end of creation,” and surfmen, married men in particular, do not like to be sent there. But youngsters of the gunner and roustabout type seem to get accustomed to life there, and make out very well.

A RUM RUNNER ASHORE

The Cape takes its toll from all kinds of ships that sail the sea from

the old-fashioned coal cargoes to the new style of rum cargoes

I used to discuss the method of landing the life boats with my friends at Nauset who keep a dory on the beach in which they go through the surf to the off-shore fishing grounds. Mr. Henry Daniels, surfman number one at Nauset, is known along the great beach as one of the crack boatmen of the Cape.

And this is the way they do it.

When there is a wreck in the surf and the lifeboat must be used, the first thing to do is to watch for a favorable opportunity and a favorable spot. The big waves break upon the beach in threes. This is not a superstition but a fact. When the third giant wave has thundered ashore and there is a small sea as far out as possible, then watch for the good moment and seize it when it comes. The three elements of success, once you have left the beach and are in the surf, are headway, speed, and strength. It is tremendously important to have powerful, skillful men in the bow. The captain steers. The difficulty lies in holding the boat bow on to the breakers, the undertow and the sweep of the surf tend to make the boat broach too, and if this happens over she goes. Sometimes just as a big wave looks as if it were about to crash down into the boat, headway and strength will save the day. Landing? Oh, there’s the hard part of it; landing a lifeboat is much more difficult than launching it. The thing to try to do is land as naturally as possible. If you let the sea run away with you, there’ll be a spill. If a boat is badly handled, the surf will rush her in with her bow tilted up in the air, and then tip her clean over when she strikes the sand. You see once you are under way coming ashore, you have got to go somewhere. A well handled boat comes ashore with the sea about amidships, then your bow is neither tilted up or down but lies in a natural position. And in coming ashore, just as in going out, you do your best to pick a favorable time.

There was recently a rather amusing case at Pamet River. A steamer journeying to New York from a port on the Great Lakes had suddenly and mysteriously developed boiler trouble while off the Cape, and sent a crew ashore to summon a tug. The ship was slowly drifting along, for her shallow length of anchor chain was never meant for the old ocean, and her anchors were trailing like fish hooks overside.

Boiler trouble? These innocent lake folk, accustomed to filling their boilers with water from the lakes, had been taking in water from the salt sea. They had been taking it regularly, and the salt in the boiler tubes had done the rest.

And this is remembered as a very good joke on fresh water sailors all over the Cape.

“The service is not what it used to be,” says the voice of the Cape. “Because recruits do not present themselves, less important stations have been practically closed and their crews distributed among vitally important posts, casual ‘substitutes’ are to be met with everywhere, and the guard has had to accept young boys who hardly know one end of an oar from the other. Everybody here knows that if things keep on getting worse, it will be the end of the guard.”

This local impression is a just one. The great service of the Cape is in genuine danger, a danger which deserves close national attention. Let us survey conditions.

To begin with, the coast guard service of Cape Cod is not one for which any casual good lad will do. If you want a real surfman, you must begin with a man who is used to seeing surf, and knows what to expect in the morning when a northeaster has been howling through the night. I do not aim at being melodramatic when I say that the sight of the violence of the surf in a big storm is one which takes the heart out of a stranger. Moreover, a surfman should be one who has grown up with boats, and has a kind of instinct for their ways.

A second point awaits consideration. The coast guard cannot enlist, use, and discharge its men in the free manner of the Army and the Navy. It takes years for a man to know his work and the conditions at his station. The endless tricks of the wind and tide, the behavior of the sea in various storms, the mysteries of the undertow, all these are learned only through long experience. Your good surfman is no casual recruit, here to-day and gone to-morrow, but a sensible, steady family man who has made a fine and honorable life-work of his service in the guard. The guards of whom I have written are of this type; they are men who have been in the guard for years, and are standing by it because they are full of grit and courage.

The men whom the service needs are to be had. There are many men who would like to go into the guard if they could do so and take care of their families. But how can a married man expect to bring up a little family according to American standards on a salary averaging between seventy and eighty dollars a month? Moreover, the service is hard on clothing, while the allowances for uniforms and warm apparel are scant.

Your steady man will not enlist because he cannot enlist. You cannot get the right man for the wrong amount of money. The surfmen have a subsistence allowance, it is true, but food is dear these days.

At all the great stations you will find the old-timers trying to make the best of it in the most gallant way. Most of them have families, and it is a hard, hard fight. And little by little, the old-timers drop out, the casual substitute comes, and the roustabout youngster. Of some of the latter class, the less said the better.

The service of patrol upon the Cape is genuinely heroic, and its fine traditions are rich in honor. Surely a great Nation will not allow a great national service to fall into the pit of evil days? “The laborer is worthy of his hire.” If cities and towns can pay firemen and policemen adequate salaries, the Nation ought to be able to pay such salaries to a handful of surfmen!

Through starlight or buffeting storm, the yellow lantern will shine to-night along the beach. The man who carries it is well worthy of aid.

Transcriber's Notes:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Obvious typographicaly errors have been silently corrected.