and Stores.

flannel filled

with powder.

Flanders pattern

Harness

pattern

pattern

for powder.

By

RALPH WILLETT ADYE,

CAPTAIN, ROYAL REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY.

First American, from the Second London Edition.

PRINTED FOR

E. LARKIN, No. 47, Cornhill, Boston,

BY WILLIAM GREENOUGH,

CHARLESTOWN.

1804.

TO THE

Junior Officers

OF THE

Royal Regiment of Artillery:

WITH A HOPE OF ALSO

MEETING THE APPROBATION

OF THE

SENIOR OFFICERS OF THAT

CORPS.

| Page. | |

| PREFACE, | i |

| AMMUNITION—For Small Arms—How carried, | 7 |

| —For Artillery, see Artillery. | |

| AMMUZETTE—Its Length, Weight, &c. | 8 |

| APRONS of Lead—Weight and Dimensions of, | 8 |

| ARMS, Small—Their Weight and Dimensions, | |

| Balls for their Proof, Service, &c. | |

| ARTILLERY—1st. For the Field. | |

| —Divided into Battalion Guns, Park and Horse Artillery, | 10 |

| —Ammunition and Stores for one Field Piece of each Nature, | 11 |

| —Manner of carrying the Ammunition and Stores, | 15 |

| —Load for a common Artillery Ammunition Waggon, | 16 |

| —Load for a Horse Artillery Ammunition Waggon, | 17 |

| —Proportion of Artillery, Ammunition, and Carriages | |

| for four French Armies, | 18 |

| —Proportion of Ammunition carried with French Artillery, | |

| and with that of other Powers, | 20 |

| —Movements and Positions of Battalion Guns, | 21 |

| —Movements and Positions of Artillery of the Park, | 24 |

| —Line of March for Three Brigades of Field Artillery, | 28 |

| —2d. Artillery and Ammunition for a Siege— | |

| Considerations in estimating them, | 29 |

| —Proportion demanded for the Siege of Lisle, | 31 |

| —Arrangement and Position at a Siege, | 33 |

| —3d. Artillery and Ammunition for the Defence | |

| of a Fortified Place—Manner of estimating them, | 37 |

| —Arrangement of the Artillery, | 39 |

| —Expenditure of Ammunition, | 42 |

| AXLETREES—Dimensions of, in Wood or Iron, | 44 |

| BALLS—of Lead—Manner of Packing them, | 45 |

| —Manner of finding their Diameters and Weights | |

| BARRELS for Gunpowder; their Dimensions and Content | |

| —Budge do. | 46 |

| BASKETS, Ballast—Dimensions of | 46 |

| BATTERIES—Dimensions of, for Guns, Mortars, and Howitzers | 46 |

| —For Ricochet firing, | 48 |

| —For the Defence of a Coast, | 49 |

| —Manner of estimating the Quantity of Materials for, | 50 |

| —Tools required for the Construction of | 52 |

| —Estimate of the Quantity of Earth which may be removed | |

| in a given time, | 53 |

| BEDS—Dimensions and Weight of, for Mortars and Guns, | 54 |

| BOXES, for Ammunition—Dimensions and Weight of, when | |

| filled and empty; and the Number of Rounds contained by | 55 |

| BOMB KETCH—Instruction for the Management of a, in Action, | 56 |

| —Proportion of Stores for, | 58 |

| BREACH—Manner of forming one; and Time required | |

| to make it practicable, | 60 |

| BRIDGE—Manner of laying one, of Pontoons; Weight it will | |

| bear; and Precautions required in passing over it, | 62 |

| CAMPS—Manner of laying out the front of, | |

| for Infantry and Cavalry, | 65 |

| —Distribution of the Depth of, | 66 |

| —In a confined Situation, | 69 |

| CARCASSES—Composition for, | 70 |

| —Valencienne’s Composition, for making Shells | |

| answer the Purpose of | |

| —Dimensions and Weight of, | 71 |

| —Manner of preventing their being destroyed by the Explosion | |

| CARRONADES—Dimensions and Weight of, | 72 |

| —Ranges with Shot and Shells from | |

| CARRIAGES—Weight of, for Field Service, | 73 |

| —Dimensions of Axletrees for, | 75 |

| —Diameters of Wheels for, | 76 |

| —Dimensions and Weight of standing | 77 |

| CARTRIDGES—Weight and Dimensions of, | |

| for Guns, Mortars, and Howitzers | 78 |

| —For Small Arms | 79 |

| —For Musquets by different Nations | 79 |

| CHAMBERS—Experiments upon the best Form of, for Mortars | 80 |

| CHARGES—For different Natures of Guns and Carronades | 81 |

| —Lessened when Cylinder Powder is used | 81 |

| —of French Guns | 82 |

| CHEVAUX DE FRIZE—Dimensions and Weight of | 82 |

| COMPOSITIONS—For Kitt; Fire, Smoke, and Light Balls; | |

| suffocating Pots; Fire Hoops, Arrows, and | |

| Lances; Cases for burning Fascine Batteries | 84 |

| —General Precautions in mixing | 84 |

| CONVOYS—Length of Line of March of | 84 |

| —Rate of travelling with, and Manner of escorting | 85 |

| DISPART—Of Guns | 86 |

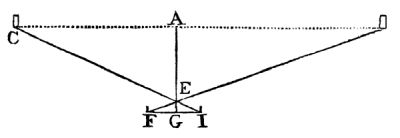

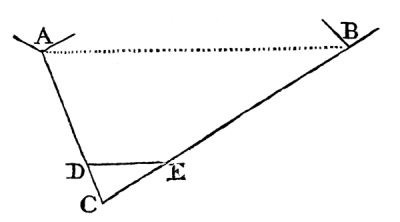

| DISTANCES—Practical Methods of measuring without | |

| mathematical Instruments | 87 |

| —Cavallo’s Micrometer for measuring | 92 |

| —Table of Angles subtended by one Foot at different | 95 |

| DRAG ROPES—Weight and Dimensions of | 95 |

| EMBARKATION—Of Ordnance and Stores | 96 |

| —Of Troops | 99 |

| EXERCISE—Of Artillery | |

| —Duties of the Men attached to Field Guns or Howitzers, | |

| with the full Complement, and with reduced Numbers | 100 |

| —Methods of advancing and retiring Field Artillery | |

| without Drag Ropes | 104 |

| —Duties of the Men in advancing and retiring | |

| Field Artillery with Drag Ropes | 109 |

| —Of Heavy Ordnance on a Battery with different | |

| Complements of Men | 112 |

| —Of the Triangle Gin | 115 |

| —Of the Sling Cart | 117 |

| FASCINES—Dimensions and Uses of the different Natures of, | |

| with the necessary Attentions in making them | 119 |

| FIRE SHIP—Proportion of combustible Stores for | 120 |

| —Method of fitting out | 122 |

| —New Method of fitting out, to produce more external Fire | 124 |

| FLINTS—Number of, packed in a half Barrel; | |

| with the Weight of, &c. | 126 |

| FORTIFICATION—Practical Maxims in building Field Works | |

| with their Dimensions | |

| —Permanent; Observations upon the different Parts of, | |

| with their principal Dimensions | 131 |

| —Observations upon the Means of adding to the Defence of Places | |

| by Outworks, &c. and on defilading a Place from Heights | 133 |

| —Principal Dimensions of, according to Vauban | 140 |

| —Dimensions of Walls from 10 to 50 Feet high | 142 |

| FUZES—Composition for—Dimensions of | 143 |

| —Manner of finding the Length of, for any Range | 144 |

| GABIONS—Dimensions of, and Attentions in making them | 145 |

| GIN TRIANGLE—Dimensions and Weight of | 146 |

| GRAVITY—Table of specific Gravities | 146 |

| —Rules, to find the Magnitude of any Body from its Weight, | |

| and the contrary | 147 |

| GRAPE SHOT—See Shot. | |

| GRENADES—Distance to which they may be thrown | 147 |

| GUNNERY—In a nonresisting Medium | |

| —How far it may be applied to Practice with the Help of good | |

| Tables of Experiments | 147 |

| —Upon a horizontal Plane | 148 |

| —Upon inclined Planes | 149 |

| —Table of Amplitudes | 151 |

| —Table of Natural Sines, Tangents, and Secants | 152 |

| GUNS—Calibers of English and Foreign | 153 |

| —Length and Weight of English Brass | 154 |

| —Ditto French Brass | 155 |

| —Ditto English and French Iron | 155 |

| —Ranges with One Shot from Brass | 156 |

| —Ditto Two Shot | 157 |

| —Ditto small Charges from | 157 |

| —Effects of Case Shot from Battalion | 158 |

| —Ranges from Iron | 159 |

| —Ditto of 5½ Inch Shells from 24 Pr. | 160 |

| —Ditto 4⅖ Inch Ditto 12 Pr. | 161 |

| —Ranges from French | 162 |

| GUNPOWDER—Proportion of Ingredients for, by different | |

| Powers in Europe | 162 |

| —Manner of Proving it at Pursleet | 163 |

| —Marks on the Barrels, by which the different Qualities | |

| are distinguished | 164 |

| —French Proof of | 165 |

| HAIR CLOTH—Dimensions and Weight of | 166 |

| HAND BARROW—Ditto | 166 |

| HANDSPIKES—Ditto | 166 |

| HARNESS—Ditto for Horses and Men | 166 |

| HORSES—Military Gait, and other Particulars respecting them | 166 |

| —Manner of Regulating the Weight they ought to Draw | 166 |

| —Number of, allowed to Artillery Carriages | 167 |

| HOWITZERS—Dimensions and Weight of English and French | 168 |

| —Natures of and by different Powers | 169 |

| —Ranges from | 170 |

| LEVELLING—Table shewing the Difference between the true | |

| and apparent Level | 172 |

| —Manner of applying this Table to finding Heights and Distances | 172 |

| LOAD—How regulated for Artillery Carriages | 174 |

| MAGAZINES—For Powder—Dimensions of Temporary ones | |

| for Batteries | 175 |

| —Permanent, for fortified Places | 175 |

| MATCH, Slow—Composition for, and manner of making | |

| —Time it will burn | 177 |

| —Quick—of Cotton or Worsted | 178 |

| MARCHING—Rate of, for Cavalry and Infantry | 178 |

| —Rates paid for pressed Carriages on a March | 179 |

| —Rates paid to Publicans for Troops on a March | 179 |

| MEASURES—Tables of English Weights and | 180 |

| —Old French, Do. | 181 |

| —New System of, by the French, with their proportion | |

| to the old, and to the English | 182 |

| —Rules for converting French Weights and Measures into English | 184 |

| —German, and Weights | 184 |

| —Proportion between the English Foot, and Pound Avoir, | |

| and those of the principal Places in Europe | 185 |

| —For Powder; their Dimensions | 185 |

| MECHANICS—The different Powers of, and the advantage | |

| gained by each | 186 |

| MILE—Comparison between the Miles of different Countries | 189 |

| MINE—Rules for finding the proper Charge to produce | |

| any required Excavation or Effect | 190 |

| —Remarks upon the Dimensions and Construction of Mines, | |

| and their Galleries | 193 |

| —Usual System of Countermines, when prepared before hand | 197 |

| —Temporary Mines | 198 |

| MORTARS—Dimensions and Weight of English Brass and Iron | |

| Mortars, with their extreme Ranges | 200 |

| —Ranges from 10 Inch Sea Service, at 21° | 201 |

| —Ditto 13 and 10 Inch Sea Service, at 45° | 201 |

| —Ditto French, at 45° | 202 |

| —Ditto English Land Service, at 45° | 203 |

| —Ditto of Iron | 203 |

| —Ditto English Land Service, at 45° of Brass | 205 |

| —Ditto Land Service, 5½ Inch Brass, at 15° | 205 |

| —Ditto Land Service, 10 and 8 Inch, at 10° | 206 |

| —Ditto Land Service, 10 and 8 Inch, at 15° | 206 |

| NAVY—Number and Nature of Ordnance for each Ship | |

| in his Majesty’s | 207 |

| —Principal Dimensions of Ships Of War, Complements of Men, | |

| and Draught of Water | 208 |

| ORDNANCE—Value of Brass and Iron | 209 |

| PACE—The Length of the Common and Geometrical | 210 |

| PARALLELS—See Trenches, and Sap | |

| PAY—Table of, for the Officers, non Commissioned | |

| Officers, and Privates of the Army | 211 |

| PARK—Its Situation and Distribution | 213 |

| PENDULUMS—How made for Artillery Purposes | 215 |

| —Proper Length of, for Seconds, ½ Seconds, and Quarters | 215 |

| —Rules for Finding the proper Length to make any number | |

| of Vibrations in a Minute, and the Contrary | 215 |

| PETARDS—Dimensions of, and Stores for | 216 |

| PLATFORMS—Dimensions of, and Materials for Gun and Mortar | 216 |

| POINT BLANK—What | 217 |

| PONTOONS—Dimensions and Weight of, and Equipage for one | 217 |

| PORTFIRES—Composition for—Time they will Burn | |

| —Manner of making them at Gibraltar | 218 |

| PROVISIONS—Regulations respecting Rations of, | |

| for Sea and Land Service | 219 |

| PROOF of Iron Guns, with the Limits of their Reception | 219 |

| —Of Brass do. | 220 |

| —Howitzers, Mortars, and Carronades | 221 |

| —By Water | 222 |

| —By assaying the Metal | 223 |

| —Marks of condemned Ordnance | 224 |

| RATIONS—Of Provisions for Land and Sea Service | 225 |

| —Regulations respecting their Issue | 226 |

| —Deductions to be made from the Pay of Soldiers for | 227 |

| RANK—Between Sea and Land Officers | 228 |

| RECOIL—Of Brass Guns on Field Carriages, of Iron Guns | |

| on Standing Carriages, and Mortars on their Beds | 229 |

| RECONNOITERING—Preparations for | 230 |

| Objects to be attended to in Reconnoitering— | |

| 1 Roads—2 Fords—3 Inundations—4 Springs | |

| and Wells—5 Lakes and Marshes—6 Woods | |

| and Forests—7 Heaths—8 Canals—9 Rivers— | |

| 10 Passes—11 Ravins—12 Cultivated Lands— | |

| 13 Orchards—14 Bridges—15 Mountains and | |

| Hills—16 Coasts—17 Redoubts—18 Castles | |

| and Citadels—19 Villages—20 Cities not fortified— | |

| 21 Fortified Towns—22 Positions | |

| RICOCHET—Rules for firing | 243 |

| ROCKETS—Composition for Sky Rockets | 245 |

| —Table of General Dimensions of, with their Sticks | 245 |

| —Height to which they will ascend | 246 |

| ROPE—How distinguished—Rule for finding the Weight of | 247 |

| SAND BAGS—Dimensions of—Number required | 248 |

| SAP—Manner of carrying it on | 248 |

| SECANTS—Table of Natural Secants | 248 |

| SHELLS—Dimensions and Weight of, for Mortars and Howitzers | 249 |

| —For Guns and Carronades | 250 |

| —Manner of throwing Shells from Guns though they | |

| do not fit the Bore | 251 |

| —French and German | 251 |

| —Rules to find the Weight of, and the Quantity of Powder | |

| they will contain | 252 |

| SHOT—Rules to find the Number in any Pile of | 252 |

| —Rules for finding the Weight and Dimensions of | |

| Iron and Lead Shot | 253 |

| —Table of Diameters of English and French Iron round Shot | 255 |

| —Table of English Case Shot for different Services | 256 |

| —Tables of Grape Shot for Sea and Land Service | 257 |

| —Manner of Quilting small Shells in Grape | 257 |

| —Precautions in firing Hot Shot | 258 |

| SINES—Table of Natural Sines | 259 |

| SOUND—Velocity of—Rules for computing Distances by | 259 |

| STOPPAGES—From the Pay of an Artillery Soldier, weekly | 260 |

| TANGENTS—Table of Natural Tangents | 261 |

| —Manner of making a Tangent Scale to any Piece of Ordnance | 262 |

| —Table of Tangents to 1° for English Field Artillery | 262 |

| —Ditto French | 262 |

| TENTS—Weight and Dimensions of Tents of different Descriptions | 262 |

| TONNAGE—Manner of finding the Tonnage of any Ship | 263 |

| —Table of Tonnage of Ordnance Stores | 264 |

| —Tonnage allowed for Officers Baggage on board Transports | 266 |

| TRANSPORTS—Regulations on board of | 266 |

| TRENCHES—Dimensions of Trenches of Approach at a Siege | 266 |

| —Manner of opening, and conducting the Trenches and Parallels | 267 |

| TROU DE LOUP—Dimensions of | 269 |

| TUBES—Dimensions of, and Composition for Tin Tubes | 269 |

| UNIFORMS—Principal Colours of the Military | |

| Uniforms of different Powers in Europe | 271 |

| VELOCITY—Principal Points ascertained respecting the initial | |

| Velocities of Shot from Guns of different Lengths, and | |

| with different Charges, by the Experiments at Woolwich | 272 |

| —Initial Velocities of English and French Artillery | 273 |

| VENTS—Diameter of | 275 |

| WEIGHTS—Table of English and French | 276 |

| WINDAGE—Of English and French Artillery | 276 |

| WOOD—Employed in making Artillery Carriages | 277 |

A man must appear somewhat vain, who declares that he has been obliged to reject much useful information, for fear of increasing too much the size of his work: and yet manages to find room for a few pages of his own, by way of Preface: but lest the objects which the compiler of this little work has had in view should be mistaken, he finds it absolutely necessary to say a few words in explanation of them. This small collection of military memorandums was originally intended only for the compiler’s own pocket; to assist him in the execution of his duty: but it occurred to him, that many of his military friends stood in equal need of such an aid, and would willingly give a few shillings for what they would not be at the trouble of collecting. The compiler has seen young men, on their first entry into the regiment of artillery, give a guinea for manuscripts, which contained a very small part of the information offered in this little book. From a persuasion that a very principal part of its merit is derived from its portability, every [Pg ii] endeavor has been used to press much into a little compass; and it is hoped, that this power has not been so far exerted, as to make the whole unintelligible: but, it must be understood, that the compiler does not propose to convey instruction to the untaught, but only to make a few memorandums of reference to facts; which those already versed in the military profession are supposed to have the knowledge to apply. The totally ignorant of these matters, he has, therefore, nothing to say to; they must consult more voluminous works. An alphabetical arrangement is merely adopted as the best calculated for this purpose; and as nothing like a military dictionary is intended, all terms are omitted, not within the compiler’s plan. All reference to plates has, likewise been avoided; as they not only very much increase the cost, but the bulk of a book. The principal difficulty which the compiler has had in making this little collection, has been to confine it within the limits of his original plan. The quantity of useful information which has pressed for admittance, has been with reluctance rejected. Such authors only have been quoted, as are generally esteemed the best; and every advantage has been taken of such information, as the compiler has been able to collect from experienced friends; but he has ventured to offer nothing whatever of his own. The French military [Pg iii] authors have been principally consulted, on all subjects not immediately confined to our own system; and such notes as are given respecting their ordnance, may be of use in drawing a comparison with our own; and may serve as references to those in the habit of reading their military works. The compiler has not, in any instance, attempted to offer changes which he may have been led to imagine improvements; or to point out what he thinks deserve the title of defects in our own system; but he has given every information according to the present practice in our service. He cannot, however, help expressing a hope, that he will one day see his little book laid by as totally obsolete, and a better built upon a system less complicated, and more applicable to that particular nature of service which this country has in every war the greatest reason to expect.

Our armies will never, it is to be hoped, find a field of battle but on the other side of the water: they must therefore always be subject to the inconveniencies attendant upon the embarkation, and the confusion, too often the companion of a disembarkation of a quantity of ordnance and other military stores upon an enemy’s coast: how peculiarly necessary is it, therefore, that our military system should be the simplest and the best arranged. The French system of artillery was [Pg iv] established as far back as the year 1765, and has been rigidly adhered to, through a convulsion in the country, which has overturned every thing else like order; and which even the government itself has not been able to withstand. We should therefore conclude that it has merit, and, though in an enemy, ought to avail ourselves of its advantages. At the formation of their system, they saw the necessity of the most exact correspondence in the most minute particulars; and so rigidly have they adhered to this principle, that though they have several arsenals, where carriages and other military machines are constructed; the different parts of a carriage may be collected from these several arsenals in the opposite extremities of the country, and will as well unite and form a carriage, as if they were all made and fitted in the same workshop. As long as every man who fancies that he has made an improvement is permitted to introduce it into our service, this cannot be the case with us.

Gunpowder has been so much improved of late years, under the direction of Col. Congreve, that the experiments made with the old powder are now of little service: only such tables of ranges with different natures of ordnance have therefore been inserted, as have been ascertained since the improved powder has been in use. As experiments are daily making at [Pg v] Woolwich and elsewhere, a blank leaf may be bound up after each nature of ordnance, in order to insert an abstract of them.

The compiler thinks it necessary to address himself to two classes of persons in particular; perhaps they may comprise the whole of his readers. First, those who think his little book might have been made much more complete. Second, those who think it improper that any information upon such matters should be offered to the public. To the first, he acknowledges the justice of the remark, but has to remind them, of the very great difficulties which they may themselves have experienced, in collecting information at Woolwich. To the second, he has but to remark, that he is well aware of the objections urged against publications which may give information as well to our enemies as our friends; but he does not imagine his little book to contain matter of sufficient consequence to do such mischief: and he is supported in an opinion by the most powerful and best organized military nations in Europe, that such secresy is the surest mark of ignorance.

The first edition being out of print, the compiler has endeavored to improve this, by every correction, and by some of the additions which his friends have been kind enough to suggest to him as necessary: but if he has neglected much of the valuable information [Pg vi] offered him, it has not been from an insensibility of its merit, but from its entering more into the detail of matters than his little book would afford room to profit by; for it still professes not to instruct, but only to remind.

The compiler has added to this edition a short alphabetical index to the contents. This may appear to some superfluous, considering the alphabetical arrangement of the subjects: but it has been impossible to avoid a great deal of reference from one part of the work to another: beside, the compiler has observed in several of the copies in the possession of his friends, notes in manuscript, (entered on sheets bound up for the purpose) which are also to be found in the body of the work. This the compiler attributes to a cause which the index may probably remedy, by enabling the reader to know, at one view, the whole contents.

A MMUNITION—For small arms, in the British service, is generally packed in half barrels, each containing 1000 musquet, or 1500 carbine cartridges. An ammunition waggon will carry 20 of these barrels, and an ammunition cart 12 of them: their weight nearly 1 cwt. each.

The cartouch boxes of the infantry are made of so many different shapes and sizes, that it is impossible to say exactly what ammunition they will contain; but most of them can carry 60 rounds. See the word Cartridges; and for Artillery Ammunition, see the word Artillery, for the field, for the siege, and the defence of a fortified place.

The French pack all their ammunition in wagons without either boxes or barrels, by means of partitions of wood. Their 12 Pr. and 8 Pr. waggons will contain each 14,000 musquet cartridges, but their 4 Pr. waggons will contain only 12,000 each.

AMMUZETTE—See the word Guns. [Pg 8]

APRONS—of lead for guns—

| lbs. | oz. | |||

| Large—1 foot long— | 10 inches wide | 8 | 4 | weight. |

| Small—6 inches ” — | 4½ ” ” | 1 | 12 | ” |

ARMS—Small

| Nature. | Length of Barrel. |

Diam. of Bore. |

Balls weight for | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proof. | Service. | ||||||||

| Ft. | In. | Inches. | oz. | dr. | gr. | oz. | dr. | gr. | |

| Wall pieces | 4 | 6 | .98 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| Musquet | 3 | 6 | .76 | 1 | 6 | 11½ | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| Carbine | 3 | 0 | .61 | 0 | 14 | 13 | 0 | 12 | 11 |

| Pistol, common | 1 | 2 | .58 | 0 | 8 | 15 | 0 | 7 | 4½ |

| ” carbine | 1 | 0 | .66 | 0 | 14 | 13 | 0 | 12 | 11 |

ARTILLERY.—The proportion of artillery and ammunition necessary to accompany an army in the field, to lay siege to a fortified place, or to defend one, must depend upon so many circumstances, that it is almost impossible, in a small work of this kind, to lay down any satisfactory rules as guides on the subject: the following principles are, however, drawn from the best authorities:

1st. Artillery for the Field.

Field Artillery is divided into Battalion Guns, Artillery of the Park, and Horse Artillery. [Pg 9]

The Battalion Guns include all the light pieces attached to regiments of the line, which they accompany in all manœuvres, to cover and support them.

The following natures of field ordnance are attached to battalions of infantry, by different powers in Europe:

| French | two | 4 | Prs. | per | battalion. |

| English | two | 6 | ” | ” | ” |

| Danes | two | 3 | ” | ” | ” |

| Austrians | three | 6 | ” | ” | ” |

| Prussians | two | 6 | Prs. to a battalion in the first line. | ||

| ” | two | 3 | Prs. to a battalion in the second line. | ||

| Hanoverians | two | 3 | Prs. per battalion. | ||

The Artillery of the Park is composed of all natures of field ordnance. It is destined to form batteries of position; that is to say, to occupy advantageous situations, from which the greatest effect may be produced, in supporting the general movements of an army, without following it, like the battalion guns, through all the detail of its manœuvres. The park of artillery attached to an army in the field generally consists of twice as many pieces of different natures, varied according to the country in which it is to act, as there are battalions in the army. Gribauvale proposes the following proportion between the [Pg 10] different natures of artillery for the park or reserve, viz. ⅖ of 12 Prs. ⅖ of 8 Prs. and ⅗ of 4 Prs. or reserve for battalion guns. In a difficult country he says, it may be ¼ of 12 Prs. ½ of 8 Prs. and ¼ of 4 Prs. and for every 100 pieces of cannon he allots 4 Howitzers; but this proportion of Howitzers is much smaller than what is generally given.

Horse Artillery.—The French horse artillery consists of 8 Prs. and 6 inch Howitzers.

The English of light 12 Prs. light 6 Prs. and light 5½ inch Howitzers.

The Austrian and Prussian horse artillery have 6 Prs. and 5½ inch Howitzers. [Pg 11]

Ammunition for Field Artillery.

A proportion of Ammunition and Stores for each Nature of Field Ordnance, viz. 1 Med. 12 Pr.[1]—1 heavy 6 Pr.—2 light 6 Prs. as they are always attached to Battalions of Infantry—and one 5½inch Howitzer; according to the British Service.

A = 12 Pounders, Medium.

B = 6 Pounders, Heavy.

C = 2 Light 6 Pounders,

D = 5½ Inch Howitzers.

This proportion of ammunition and stores is carried in the following manner:

| 12 Pr. Medium, |

|

Has no limber boxes,[2] but has two waggons attached to it, |

| and the ammunition and stores divided between them. | ||

| 6 Pr. Heavy, |

|

Carries 36 round, and 14 case shot in limber boxes, with a proportion |

| of the small stores; and the remainder is carried in one waggon. | ||

| 6 Pr. Light, |

|

Carries 34 round, and 16 case shot on the limber, with a proportion |

| of the small stores for immediate service; and, if acting separately, | ||

| of the small stores for immediate service; and, if acting separately, | ||

| must have a waggon attached to it, to carry the remainder. But two 6 | ||

| pounders, attached to a battalion, have only one waggon between them. | ||

| 5½ How’r Light, |

|

Has 22 shells, 4 case shot, and two carcasses in the limber boxes, with |

| such of the small stores as are required for immediate service; and has | ||

| two waggons attached to carry the rest. | ||

One common pattern ammunition waggon carries the following numbers of rounds of ammunition of each nature:

| Nature. | No. of Rounds |

|---|---|

| 12 Prs. Medium. | 72 |

| 6 Prs. Heavy. | 120 |

| 6 Prs. Light. | 156 |

| 3 Prs. | 288 |

| 5½ How’r. | 72 |

| 8 How’r. | 24 |

| Musquet. | 20000[3] |

The waggons, however, attached to the different parks of artillery in England, which have not been altered from the old establishment, are loaded with only the following number, and drawn by three horses: [Pg 17]

| Nature. | No. of Rounds |

|---|---|

| 12 Prs. Medium. | 66 |

| 6 Prs. Heavy. | 120 |

| 6 Prs. Light. | 138 |

| 5½ How’r. | 60 |

The horse artillery having waggons of a particular description, carry their ammunition as follows:

| Shot. | Shells. | Carcasses. | Total No. with each Piece. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round. | Case. | ||||

| 12 Prs. light, on the limber | 12 | 4 | 4 | — | 92 |

| Do. ” ” in one waggon | 52 | 10 | 10 | — | |

| 6 Prs. light, on the limber | 32 | 8 | — | — | 150 |

| Do. in one waggon | 97 | 13 | — | — | |

| 5½ In. How’r on the limber | — | 5 | 13 | — | 73 |

| Do. in one waggon | — | 10 | 41 | 4 | |

| 3 Prs. heavy, curricle | 6 | 6 | — | — | 136 |

| Do.ammunition cart | 100 | 24 | — | — | |

[Pg 18] The following Proportion of Artillery, Ammunition, and Carriages, necessary for four French Armies of different Degrees of Strength, and acting in very different Countries, is attributed to Gribauvale, and is extracted from Durtubie, on Artillery.

[Pg 20] This table contains, beside the proportion of ordnance with each army, also the quantity of ammunition with each piece of ordnance, and the number of rounds of musquet ammunition carried for the infantry; for each waggon in the French Service, having its particular allotment of ammunition and stores, it needs but to know the number of waggons of each description, to ascertain the quantity of ammunition and stores with an army. The following is the number of waggons usually attached to each piece of field ordnance in the French Service, and the quantity of ammunition carried with each.

| Nature of Ordnance and Number of waggons attached to each. |

Shot. | Total with each piece. |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Round. | Case. | ||

| 12 Pr. on the carriage | 9 | — | 213 |

| 3 Waggons—each containing | 48 | 20 | |

| 8 Pr. on the carriage | 9 | — | 193 |

| 2 Waggons—each containing | 62 | 30 | |

| 4 Pr. on the carriage | 18 | — | 168 |

| One waggon—containing | 100 | 50 | |

| 6 Inch howitzer—on the carriage | — | 4 | 160 |

| 3 Waggons—each containing | shell | 3 | |

| 49 | |||

[Pg 21] The French horse artillery waggon, called the wurst, carries 57 rounds for 8 pounders; or 30 for 6 inch howitzers.

The following is a proportion of ammunition for one piece of field artillery of each nature, by different powers in Europe.

| Nature. | Austrians | Prussians | Danes. | Hanoverians. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case. | Round. | Case. | Round. | Case. | Round. | Case. | Round. | |

| 3 Pr. | 40 | 184 | 20 | 90 | 58 | 177 | 50 | 150 |

| 6 ” | 36 | 176 | 30 | 150 | 53 | 166 | 48 | 144 |

| 12 ” | 44 | 94 | 20 | 130 | 44 | 128 | 50 | 150 |

| Howitzer | 16 | 90 | 20 | 60 | 25 | 76 | 30 | 120 |

Of the Movements and Positions of Field Artillery.

Battalion Guns.—The following are the usual positions taken by battalion guns, in the most essential manœuvres of the battalion to which they are attached; but the established regulations for the movements of the infantry in the British Service, take so little notice of the relative situations for the artillery attached to it, that there is no authority for a guide on the subject. In review, both guns are to be placed, when, in line, on the right of the regiment; unlimbered and prepared for action. The guns 10 yards [Pg 22] apart, and the left gun 10 yards from the right of the grenadiers. Nos. 7 and 8 dress in line with the front rank of the regiment. The officer, at open order, will be in front of the interval between his guns, and in line with the officers of the regiment. When the regiment breaks into column, the guns will be limbered up and wheel by pairs to the left: the men form the line of march, and the officer marches round in front of the guns. In the review of a single battalion, it is usual after marching round the second time, for one of the guns to go to the rear, and fall in at the rear of the column. Upon the regiment wheeling on the left into line, the guns, if separated, will be unlimbered to the right, but if they are both upon the right, they must be wheeled to the right, and then unlimbered; and afterwards run up by hand, as thereby they do not interfere with the just formation of the line, by obstructing the view of the pivots.

The usual method by which the guns take part in the firings while in line, is by two discharges from each piece, previous to the firing of the regiment; but this is usually regulated by the commanding officer, before the review. Though the guns when in line with a regiment in review, always remain in the intervals; in other situations of more consequence, every favorable spot which presents itself, from which the enemy can be more effectually annoyed, should be taken advantage of. In [Pg 23] column, if advancing, the guns must be in front; if retreating, in the rear of the column. If in open column of more than one battalion, the guns in the center must be between the divisions, and when the column is closed, these guns must move to the outward flank of that division of the column, which leads the regiment to which they are attached. In changing front, or in forming the line from column, should the guns be on that flank of the battalion on which the new line is to be formed, they will commence firing to cover the formation.

In retiring by alternate wings or divisions, the guns must be always with that body nearest the enemy. That is, they will not retire with the first half, but will remain in their position till the second half retires; and will then only retire to the flanks of the first half; and when it retires again, the guns will retire likewise, but only as far as the second half, and so on.

When in hollow square, the guns will be placed at the weakest angles, and the limbers in the center of the square. In passing a bridge or defile in front, the guns will be the first to pass; unless from any particular position they can more effectually enfilade the defilé; and thereby better open the passage for the infantry. But in retiring through a defilé, the guns will remain to the last, to cover the retreat. [Pg 24]

General Rule.—With very few variations, the guns should attend in all the movements of the battalion, that division of it, to which they are particularly attached; and every attention should be paid in thus adapting the movements of the guns to those of the regiment, that they be not entangled with the divisions of the line, and never so placed as to obstruct the view of the pivots, and thereby the just formation of the line; but should always seek those positions, from which the enemy can be most annoyed, and the troops to which they are attached, protected.

If at any time the battalion guns of several regiments should be united and formed into brigades, their movements will then be the same as those for the artillery of the park.

Artillery of the Park.

The artillery of the park is generally divided into brigades of 4 or 6 pieces, and a reserve, according to the force and extent of the front of an army. The reserve must be composed of about ⅙ of the park, and must be placed behind the first line. If the front of the army be extensive, the reserve must be divided.

The following are the principal rules for the movements and positions of the brigades of artillery: they are mostly translated from the Aide Memoire, a new military work. [Pg 25]

In a defensive position, the guns of the largest caliber must be posted in those points, from whence the enemy can be discovered at the greatest distance, and from which may be seen the whole extent of his front.

In an offensive position, the weakest points of the line must be strengthened by the largest calibers; and the most distant from the enemy: those heights on which the army in advancing may rest its flanks, must be secured by them, and from which the enemy may be fired upon obliquely.

The guns should be placed as much as possible under cover; this is easily done upon heights, by keeping them so far back that the muzzles are only to be seen over them: by proper attention many situations may be found of which advantage may be taken for this purpose, such as banks, ditches, &c. every where to be met with.

A BATTERY in the field should never be discovered by the enemy till the very moment it is to open. The guns may be masked by being a little retired; or by being covered by troops, particularly cavalry.

To enable the commanding officer of artillery to choose the proper positions for his field batteries, he should of course be made acquainted, with the effect intended to be produced; with the troops that are to be supported; and with the points that are to be attacked; that he may place his[Pg 26] artillery so as to support, but not incommode the infantry; nor take up such situations with his guns, as would be more advantageously occupied by the line. That he may not place his batteries too soon, nor too much exposed; that he may cover his front and his flanks, by taking advantage of the ground; and that he may not venture too far out of the protection of the troops, unless some very decided effect is to be obtained thereby.

The guns must be so placed as to produce a cross fire upon the position of the enemy, and upon all the ground which he must pass over in an attack.

They must be separated into many small batteries, to divide the fire of the enemy; while the fire from all these batteries, may at any time be united to produce a decided effect against any particular points.

These points are the débouchés of the enemy, the heads of their columns, and the weakest points in the front. In an attack of the enemy’s position, the cross fire of the guns must become direct, before it can impede the advance of the troops; and must annoy the enemy’s positions nearest to the point attacked, when it is no longer safe to continue the fire upon that point itself.

The shot from artillery should always take an enemy in the direction of its greatest dimension; it should therefore take a line obliquely or in flank, but a column in front. [Pg 27]

The artillery should never be placed in such a situation, that it can be taken by an enemy’s battery obliquely, or in flank, or in the rear; unless a position under these circumstances, offers every prospect of producing a most decided effect, before the guns can be destroyed or placed hors de combat.

The most elevated positions are not the best for artillery, the greatest effects may be produced from a height of 30 or 40 yards at the distance of about 600 and about 16 yards of height to 200 of distance.

Positions in the rear of the line are bad for artillery, because they alarm the troops, and offer a double object to the fire of the enemy.

Positions which are not likely to be shifted; but from whence an effect may be produced during the whole of an action, are to be preferred; and in such positions a low breast work of 2 or 3 feet high may be thrown up, to cover the carriages.

Artillery should never fire against artillery, unless the enemy’s troops are covered, and his artillery exposed; or unless your troops suffer more from the fire of his guns, than his troops do from yours.

Never abandon your guns till the last extremity. The last discharges are the most destructive; they may perhaps be your salvation, and crown you with glory. [Pg 28]

The parks of artillery in Great Britain are composed of the following ordnance; 4 medium 12 pounders; 4 desaguliers 6 pounders; and 4 light 5½ inch howitzers.

The following is the proposed line of march for the three Brigades when acting with different Columns of Troops, as settled, in 1798.

| 12 Pounders. | 6 Pounders. | Howitzers. |

|---|---|---|

| 4 Guns. | 4 Guns. | 4 Howitzers. |

| 8 Ammunition Waggons. | 4 Ammunition Waggons. | 8 Ammunition Waggons. |

| 1 Forge Cart. | 1 Forge Cart. | 1 Forge Cart. |

| 1 Store Waggon, | 1 Store Waggon. | 1 Store Waggon. |

| with a small proportion of | ||

| stores and spare articles. | ||

| 1 Spare Waggon. | 1 Spare Waggon. | 1 Spare Waggon. |

| 1 Waggon to carry bread | 1 Waggon for bread | 1 Waggon with bread |

| and oats. | and oats. | and oats. |

| 2 Waggons with musquet | 2 Waggons with musquet | 2 Waggons with musquet |

| ball cartridges. | ball cartridges. | ball cartridges. |

| 18 Total | 14 Total | 18 Total |

2d. Artillery and Ammunition for a Siege.

Necessary considerations in forming an estimate for this service.

The force, situation, and condition of the place to be besieged; whether it be susceptible of more than one attack; whether lines of circumvallation or countervallation will be necessary; whether it be situated upon a height, upon a rocky soil, upon good ground, or in a marsh; whether divided by a river, or in the neighborhood of one; whether the river will admit of forming inundations; its size and depth; whether the place be near a wood, and whether that wood can supply stuff for fascines, gabions, &c.; whether it be situated near any other place where a depot can be formed to supply stores for the siege. Each of these circumstances will make a very considerable difference in proportioning the stores, &c. for a siege. More artillery will be required for a place susceptible of two attacks, than for the place which only admits of one. For this last there must be fewer pieces of ordnance, but more ammunition for each piece. In case of lines being necessary, a great quantity of intrenching tools will be required, and a numerous field train of artillery. In case of being master of any garrison in the neighborhood of the besieged town, from whence supplies can readily be drawn, this must be regarded as a second [Pg 30] park: and too great a quantity of stores need not be brought at once before the besieged place. The number of batteries to be opened before the place must determine the number of pieces of ordnance; and on the quantity of ordnance must depend the proportion of every species of stores for the service of the artillery.

There must be a battery to enfilade every face of the work to be besieged, that can in any way annoy the besiegers in their approaches. These batteries, at least that part of them to be allotted for guns, need not be much longer than the breadth of the rampart to be enfiladed, and will not therefore hold more than 5 or 6 heavy guns; which, with two more to enfilade the opposite branch of the covert way, will give the number of guns for each ricochet battery. As the breaching batteries, from their situation, effectually mask the fire of the first or ricochet batteries, the same artillery generally serves for both. Having thus ascertained the number of heavy guns, the rest of the ordnance will bear the following proportion to them:

The fewer natures of ordnance which compose the demand the better, as a great deal of the confusion may be prevented, which arises from various [Pg 31] natures of ammunition and stores being brought together.

The Carriages for the Ordnance are generally as follows:

Ammunition for the Ordnance.

The following proportion of artillery and ammunition was demanded by a very able officer, for the intended siege of Lisle, in 1794, which place was thought susceptible of two attacks.

Of the Arrangement of Artillery at a Siege.

The first arrangement of the artillery at a siege is to the different batteries raised near the first parallel, to enfilade the faces of the work on the front attacked, which fire on the approaches. If these first batteries be favorably situated, the artillery may be continued in them nearly the whole of the siege; and will save the erection of any other gun batteries, till the besiegers arrive on the crest of the glacis. It however frequently happens, from local circumstances, that the besiegers cannot avail themselves of the most advantageous situations for the first batteries. There are four situations from [Pg 34] which the defences of any face may be destroyed; but not from all with equal facility. The best position for the first batteries, is perpendicular to the prolongation of the face of the work to be enfiladed. If this position cannot be attained, the next that presents itself is, on that side of the prolongation which takes the face in reverse; and under as small an angle as possible. From both these positions the guns must fire en ricochet. But if the ground, or other circumstance, will not admit of either of these being occupied by ricochet batteries, the battery to destroy the fire of a face must be without the prolongation, so as to fire obliquely upon the outside of the face. The last position, in point of advantage, is directly parallel to the face. From these two last positions the guns must fire with the full charges.

The second, or breaching batteries at a siege, are generally placed on the crest of the glacis, within 15 or 18 feet of the covert way; which space serves as the epaulment: but if the foot of the revetment cannot be seen from this situation, they must be placed in the covert way, within 15 feet of the counterscarpe of the ditch. These batteries must be sunk as low as the soles of the embrazures, and are in fact but an enlargement of the sap, run for the lodgement on the glacis or in the covert way. In constructing a battery on the crest of the glacis, attention must be paid that none of the embrazures open upon the [Pg 35] traverses of the covert way. These batteries should consist of at least four guns; and if the breadth between the traverses will not admit of this number, at the usual distances, the guns must be closed to 15 or 12 feet from each other.

The mortars are generally at first arranged in battery, adjoining the first gun batteries, or upon the prolongation of the capitals of the works; in which place they are certainly least exposed. Upon the establishment of the half parallels, batteries of howitzers may be formed in their extremities, to enfilade the branches of the covert way; and upon the formation of the third parallel, batteries of howitzers and stone mortars may be formed to enfilade the flanks of the bastions, and annoy the besieged in the covert way. In the lodgement on the glacis, stone and other mortars may also be placed, to drive the besieged from their defences. A great object in the establishment of all these batteries, is to make such an arrangement of them, that they mask the fire of each other as little as possible; and particularly of the first, or ricochet batteries. This may very well be prevented till the establishment on the crest of the glacis, when it becomes in some degree unavoidable: however, even the operations on the glacis may be so arranged, that the ricochet batteries be not masked till the breaching batteries be in a great state of forwardness: a very secure [Pg 36] method, and which prevents the soldiers in trenches being alarmed by the shot passing over their heads, is to raise a Parados, or parapet, in the rear of the trenches, at such parts where the fire from the besieger’s batteries crosses them. For further details on this subject, and for the manner of constructing batteries, see the word Battery; also the words Ricochet, Breach, Magazine, Platform, &c. [Pg 37]

3d. Artillery and Ammunition

for the

Defence of Fortified Place.

It is usual in an Estimate of Artillery and Ammunition for the Defence of Fortified Places, to divide them into Eight Classes, as follows:

| CLASSES. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garrisons | 12000 | 10000 | 8000 | 5000 | 3500 | 2500 | 1600 | 400 |

| Cannon | 100 | 90 | 80 | 70 | 60 | 50 | 40 | 30 |

| Triangle Gins | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sling Carts | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Jacks of Sizes | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Truck Carriages | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Ammunition Carts, &c. | 12 | 12 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| Tools for Pioneers | 9000 | 6000 | 5000 | 4000 | 3500 | 3000 | 1000 | 1000 |

| ” ” Miners | 300 | 200 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 5 |

| Tools for ⅓ Axes | 1200 | 900 | 600 | 500 | 450 | 300 | 150 | 150 |

| Cutting ⅔ Billhooks | ||||||||

| Forges, complete | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

[Pg 38] The guns will be of the following calibers: ⅓ of 18 Prs.—⅓ of 12 Prs.—and ⅓ of 24, 9, and 4 Pounders in equal proportions. If the place does not possess any very extraordinary means of defence, it will be very respectably supplied with 800 rounds of ammunition per gun for the two larger calibers, and 900 for each of the others.

Gun Carriages—⅓ more than the number of guns.

Mortars—About ¼ the number of guns in the three first classes; and ⅕ or ⅙ in the other classes. Of these ⅖ will be 13 or 10 inch mortars, and the rest of a smaller nature.

Howitzers—¼ the number of mortars.

Stone Mortars—⅒ the number of guns.

Shells—400 for each of the 10 and 13 inch mortars, and 600 for each of the smaller ones.

Beds for mortars—⅓ to spare.

Carriages for howitzers—⅓ to spare.

Hand Grenades—4 or 5000 for the two first classes; 2000 in the three following classes; and from 1500 to 600 in the three last classes.

Rampart Grenades—2000 for the first class; 1000 for the four following classes; and 500 for the sixth class; none for the two last.

Fuzes—¼ more than the number of shells.

Bottoms of wood for stone mortars—400 per mortar.

Sand Bags—500 for every piece of ordnance in the large places, and ¼ less in the small ones. [Pg 39]

Handspikes—10 per piece.

Tackle Falls for gins—1 for every 10 pieces to spare.

Musquets—1 per soldier, and the same number to spare.

Pistols, pairs—½ the number of musquets.

Flints—50 per musquet, and 10 per pistol.

Lead or Balls for small arms—30 pounds per musquet.

Powder for Small Arms—5 pounds for every musquet in the garrison, including the spare ones.

The above proportions are taken from Durtubie’s Manuel De l’Artilleur.

The following method of regulating the management of the artillery, and estimating the probable expenditure of ammunition in the defence of a fortified place, is extracted from a valuable work on fortification lately published at Berlin. It is particularly applied to a regular hexagon; the siege is divided into three periods, viz.

1st. From the first investiture to the first opening of the trenches, about 5 days.

2d. From the opening of the trenches to the effecting a lodgement on the glacis, about 18 days.

3d. From this time to the capitulation, about 5 days.

First Period. Three guns on the barbette of each bastion and on [Pg 40] the barbettes of the ravelins in front of the gateways, half 24 Prs. and half 18 Prs.[4] three 9 Prs. on the barbette of each of the other ravelins.

Twelve 12 Prs. and twelve 4 Prs. in reserve.

One 13 inch mortar in each bastion.

Six of 8 inch in the salient angles of the covert way.

Do. in reserve.

Ten stone mortars.

The 12 Prs. in reserve, are to be ranged behind the curtain, on whichever side they may be required, and the 4 Prs. in the outworks; all to fire en ricochet over the parapet. By this arrangement, the whole of the barbette guns are ready to act in any direction, till the side of attack is determined on; and with the addition of the reserve, 49 pieces may be opened upon the enemy the very first night they begin to work upon the trenches.

The day succeeding the night on which the trenches are opened, and the side to be attacked determined, a new arrangement of the artillery must take place. All the 24 and 18 Prs. must be removed to the front attacked, and the other bastions, if required, supplied with 12 Prs. The barbettes of the bastions on this front may have each 5 guns, and [Pg 41] the 12 18 prs. may be ranged behind the curtain. The six mortars in reserve must be placed, two in each of the salient angles of the covert way of this front, and with those already there, mounted as howitzers,[5] to fire down the prolongations of the capitals. Three 4 pounders in each of the salient places of arms of the ravelins on the attacked fronts, to fire over the palisading, and five 9 Prs. in the ravelin of this front. This arrangement will bring 47 guns, and 18 mortars to fire on the approaches after the first night; and with a few variations will be the disposition of the artillery for the second period of the siege. As soon as the enemy’s batteries are fairly established, it will be no longer safe to continue the guns en barbette, but embrazures[6] must be opened for them; which, embrazures must be occasionally masked, and the guns assume new directions, as the enemy’s fire grows destructive; but may again be taken advantage of, as circumstances offer. As the enemy gets near the third parallel, the artillery must be withdrawn from the covert way to the ravelins, or to the ditch, if dry, [Pg 42] or other favorable situations; and, by degrees, as the enemy advances, to the body of the place. During this period of the siege, the embrazures must be prepared in the flanks, in the curtain which joins them, and in the faces of the bastions which flank the ditch of the front ravelins. These embrazures must be all ready to open, and the heavy artillery mounted in them, the moment the enemy attempts a lodgement on the glacis.

Every effort should be made to take advantage of this favorable moment, when the enemy, by their own works, must mask their former batteries, and before they are able to open their new ones.

The expenditure of ammunition will be nearly as follows:

First period of the siege—5 rounds per gun, per day, with only half the full charge, or ⅙ the weight of the shot, and for only such guns as can act.

Second period—20 rounds per gun, per day, with ⅙ the weight of the shot.

Third period—60 rounds per gun, per day, with the full charge, or ⅓ the weight of the shot.

Mortars—At 20 shells per day, from the first opening of the trenches to the capitulation.

Stone Mortars—80 rounds per mortar, for every 24 hours, from the establishment of the demi parallels to the capitulation; about 13 days. [Pg 43]

Light, and Fire balls—Five every night, for each mortar, from the opening of the trenches to the eighth day, and three from that time to the end

These amount to about

700 for guns.

400 for mortars.

1000 for stone do.

This proportion and arrangement is however made upon a supposition, that the place has no countermines to retard the progress of the besiegers, to a period beyond what is abovementioned; but the same author estimates, that a similar place, with the covert way properly countermined beforehand, and those countermines properly disputed, may retard a siege at least 2 months; and that if the other works be likewise effectually countermined and defended, the siege may be still prolonged another month.

The above proportion is therefore to be further regulated, as the strength of the place is increased by these or any other means. These considerations should likewise be attended to, in the formation of an estimate of ammunition and stores for the siege of a fortified place. See Carriage, Platform, Park, and the different natures of artillery, as Gun, Mortar, Howitzer, &c.

The small arms ammunition is estimated by this author as follows: [Pg 44]

¼ of a pound of gunpowder, or 10 rounds per day, per man, for all the ordinary guards.

1¼ lbs. or 50 rounds per man, per 12 hours, for all extraordinary guards.

⅝ of a pound, or 25 rounds for every man on picket, during the period of his duty.

AXLETREES—See the word Carriages.

| Nature. | Number to one pound. |

Diameter in inches. |

Number made from one ton of Lead. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wall pieces | 6¾ | .89 | 14,760 |

| Musquets | 14½ | .68 | 32,480 |

| Carbine | 20 | .60 | 44,800 |

| Pistol | 34 | .51 | 78,048 |

| 7 Barrel guns | 46½ | .46 | 104,160 |

Lead balls are packed in boxes containing each 1 cwt. About 4 pounds of lead in the cwt. are generally lost in casting. See Shot.

BARRELS for powder—Their dimensions.

| Whole Barrels. |

Half Barrels. |

Quarter Barrels. |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ft. | In. | Ft. | In. | Ft. | In. | |

| Depth | 1 | 9.61 | 1 | 5.13 | 1 | 2.25 |

| Diameter at top | 1 | 3.61 | 1 | 0.37 | 9.35 | |

| ” at bulge | 1 | 5.36 | 1 | 2. | 10.71 | |

| ” at bottom | 1 | 3.51 | 1 | 0.31 | 9.41 | |

[Pg 46] The whole barrels are made to contain 100 pounds, and the half barrels 50 pounds of powder; but of late only 90 pounds have been put into the barrels, and 45 into the half barrels; which, by leaving the powder room to be shifted, preserves it the better.

Budge Barrels contain 38 lbs.

| Weight of barrel— | copper hooped— | 10 lbs. |

| ”” | hazle hooped— | 6 |

| Length of barrel | 10½ inches. | |

| Diameter | 1 foot 1 inch. |

BASKETS.—Ballast, ½ bushel—weight, 5 lbs. Diameter, 1 foot 6 inches—length, 1 foot.

BATTERY.—Dimensions of Batteries.

1. Gun Batteries.—Gun Batteries are usually 18 feet per gun. Their principal dimensions are as follow:

Note. These dimensions give for a battery of two guns 3456 cubic feet of earth; and must be varied according to the quantity required for the epaulment.

| Epaulment.— | Breadth | at bottom | 23 | feet. |

| ” | at top | 18 | ||

| Height | within | 7 | ||

| ” | without | 6 | ft. 4 in. | |

| Slope, | interior | ²/₇ | of height. | |

| ” | exterior | ½ | of height. [Pg 47] |

Note. The above breadths at top and bottom are for the worst soil; good earth will not require a base of more than 20 feet wide, which will reduce the breadth at top to 15 feet; an epaulment of these dimensions for two guns will require about 4200 cubic feet of earth, and deducting 300 cubic feet for each embrazure, leaves 3600 required for the epaulment. In confined situations the breadth of the epaulment may be only 12 feet.

| Embrazures.— | Distance | between their centers | 18 | feet. |

| Openings, | interior | 20 | inches. | |

| ” | exterior | 9 | feet. | |

| Height of the sole above the platform | 32 | inches. | ||

Note. Where the epaulment is made of a reduced breadth, the openings of the embrazures are made with the usual breadth within, but the exterior openings proportionally less. The embrazures are sometimes only 12 feet asunder, or even less when the ground is very confined. The superior slope of the epaulment need be very little, where it is not to be defended by small arms. The slope of the sole of the embrazures must depend upon the height of the object to be fired at. The Berm is usually made 3 feet wide, and where the soil is loose, this breadth is increased to 4 feet.

2. Howitzer Batteries.—The dimensions of howitzer batteries are [Pg 48] the same as those for guns, except that the interior openings of the embrazures are 2 feet 6 inches, and the soles of the embrazures have a slope inwards of about 10 degrees.

3. Mortar Batteries—Are also made of the same dimensions as gun batteries, but an exact adherence to those dimensions is not so necessary. They have no embrazures. The mortars are commonly placed 15 feet from each other, and about 12 feet from the epaulment.

Note. Though it has been generally customary to fix mortars at 45°, and to place them at the distance of 12 feet from the epaulment, yet many advantages would often arise from firing them at lower angles; and which may be done by removing them to a greater distance from the epaulment, but where they would be in equal security. If the mortars were placed at the undermentioned distances from the epaulment, they might be fired at the angles corresponding:

| At | 13 | feet distance | for firing at | 30 | degrees. |

| 21 | ” | ” | 20 | ||

| 30 | ” | ” | 15 | ||

| 40 | ” | ” | 10 | ||

| over an epaulment of 8 feet high. | |||||

A French author asserts, that all ricochet batteries, whether for howitzers or guns, might be made after this principle, without the inconvenience of embrazures; and the superior slope of the epaulment [Pg 49] being inwards instead of outwards, would greatly facilitate this mode of firing.

If the situation will admit of the battery being sunk, even as low as the soles of the embrazures, a great deal of labour may be saved. In batteries without embrazures, this method may almost always be adopted; and it becomes in some situations absolutely necessary in order to obtain earth for the epaulment; for when a battery is to be formed on the crest of the glacis, or on the edge of the counterscarpe of the ditch, there can be no excavation but in the rear of the battery.

4. Batteries on a Coast—generally consist of only an epaulment, without much attention being paid to the ditch: they are, however, sometimes made with embrazures, like a common gun battery; but the guns are more generally mounted on traversing platforms, and fire over the epaulment. When this is the case, the guns can seldom be placed nearer than 3½ fathoms from each other. The generality of military writers prefer low situations for coast batteries; but M. Gribauvale lays down some rules for the heights of coast batteries, which place them in such security, as to enable them to produce their greatest effect. He says the height of a battery of this kind, above the level of the sea, must depend upon the distance of the principal objects it has to protect or annoy. The shot from a battery to ricochet with effect, should strike [Pg 50] the water at an angle of about 4 or 5 degrees at the distance of 200 yards. Therefore the distance of the object must be the radius, and the height of the battery the tangent to this angle of 4 or 5°; which will be, at the above distance of 200 yards, about 14 yards. At this height, he says, a battery may ricochet vessels in perfect security; for their ricochet being only from a height of 4 or 5 yards, can have no effect against the battery. The ground in front of a battery should be cut in steps, the more effectually to destroy the ricochet of the enemy. In case a ship can approach the battery so as to fire musquetry from her tops, a few light pieces placed higher up on the bank, will soon dislodge the men from that position, by a few discharges of case shot. It is also easy to keep vessels at a distance by carcasses, or other fire balls, which they are always in dread of.

Durtubie estimates, that a battery of 4 or 5 guns, well posted, will be a match for a first rate man of war.

To estimate the Materials for a Battery.

Fascines of 9 feet long are the most convenient for forming a battery, because they are easily carried, and they answer to most parts of the battery without cutting. The embrazures are however better lined with [Pg 51] fascines of 18 feet. The following will be nearly the number required for a fascine battery of two guns or howitzers:

90 fascines of 9 feet long.

20 fascines of 18 feet—for the embrazures.

This number will face the outside as well as the inside of the epaulment, which if the earth be stiff, will not always be necessary; at least not higher than the soles of the embrazures on the outside. This will require five of 9 feet for each merlon less than the above.

A mortar battery will not require any long fascines for the lining of the embrazures. The simplest method of ascertaining the number of fascines for a mortar battery, or for any other plain breast work, is to divide the length of work to be fascined in feet, by the length of each fascine in feet, for the number required for one layer, which being multiplied by the number of layers required, will of course give the number of fascines for facing the whole surface. If a battery be so exposed as to require a shoulder to cover it in flank, about 50 fascines of 9 feet each will be required for each shoulder.

| Each | fascine | of | 18 | feet | will | require | 7 | pickets. |

| ” | ” | ” | 9 | feet | ” | ” | 4 | ” |

12 workmen of the line, and 8 of the artillery, are generally allotted to each gun.

If to the above proportion of materials, &c. for a battery of two guns, [Pg 52] there be added for each additional gun, 30 fascines of 9 feet, and 10 of 18 feet, with 12 workmen, the quantity may easily be found for a battery of any number of pieces.

The workmen are generally thus disposed; one half the men of the line in the ditch at 3 feet asunder, who throw the earth upon the berm; one fourth upon the berm at 6 feet asunder, to throw the earth upon the epaulment, and the other quarter on the epaulment, to level the earth, and beat it down. The artillery men carry on the fascine work, and level the interior for the platforms. This number of workmen may complete a battery in 36 hours, allowing 216 cubic feet tn be dug and thrown up, by each man in the ditch in 24 hours.

Tools for the Construction of a Battery.

Intrenching—1½ times the number of workmen required; half to be pick axes, and half shovels or spades, according to the soil.

Mallets—3 per gun.

Earth Rammers—3 per gun.

Crosscut Saws—1 to every two guns.

Handbills or Hatchets—2 per gun.

This estimate of tools and workmen, does not include what may be required for making up the fascines, or preparing the other materials, [Pg 53] but supposes them ready prepared. For these articles, see the words Fascine, Gabion, Platform, &c. and for the construction of field magazines for batteries, see the word Magazine.

Note. The following estimate of the quantity of earth which may be removed by a certain number of workmen in a given time, may serve to give some idea of the time required to raise any kind of works. 500 common wheel barrows will contain 2 cubic toises of earth, and may be wheeled by one man, in summer, to the distance of 20 yards up a ramp, and 30 on a horizontal plain, in one day. In doing which he will pass over, going and returning, about 4 leagues in the first case, and 6 in the last. Most men, however, will not wheel more than 1¾ toise per day. Four men will remove the same quantity to four times the distance.

In a soil easy to be dug, one man can fill the 500 barrows in a day; but if the ground be hard, the number of fillers must be augmented, so as to keep pace with the wheel barrow man. [Pg 54]

BEDS for Mortars.

| Nature. | Weight. | Tonnage. | Len. | Bre. | Ht. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cᵂᵗ. | qʳˢ. | lb. | tⁿˢ. | cᵂᵗ. | qʳ | ft. | in. | ft. | in. | ft. | in. | ||

| Sea | 38 | 3 | 13 | 3 | 3 | 2 | |||||||

| 13 | Land Wood | 21 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 3 |

| ” Iron | 50 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |

| Sea | 32 | 2 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| 10 | Land Wood | 10 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 10 |

| ” Iron | 23 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1½ | |

| 5½ Wood | 1 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 10 | |

| 4⅖ Wood | 0 | 3 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4½ | 1 | 2 | 0 | 9 | |

| Stool Beds for Guns. |

|||||||||||||

| Inch. | In. | ||||||||||||

| 42 | Pounders | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 11 to 8¾ | 3¾ | ||

| 32 | ” | 0 | 1 | 14 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 5½ | 3¼ | |

| 24 | ” | 0 | 1 | 14 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 10¼ | 6½ | 4 | |

| 18 | ” | 0 | 1 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 9½ | 6½ | 3¾ | |

| 12 | ” | 0 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 2⅔ | 2 | 8 | 10 | 6½ | 4 | |

| 9 | ” | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 9½ | 5½ | 3½ | |

| 6 | ” | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1¾ | 2 | 6 | 9 | 4¾ | 3½ | |

| 4 | ” | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 8¼ | 5¼ | 3 | |

BOXES

for Ammunition.—The dimensions of the common ammunition boxes vary

according to the ammunition they are made to contain, in order that it

may pack tight: this variation, however, is confined to a few inches,

and does not exceed the following numbers.

[Pg 55]

Table of general Dimensions of Ammunition Boxes.

| Exterior. | Weight when empty. |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length. | Breadth. | Depth. | |||||

| feet | inch. | feet | inch. | feet | inch. | lbs. | |

| From | 2 | 2 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 8½ | 20 |

| To | 2 | 9 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 30 |

Weight when filled, and Number contained in each.

| Nature of Ammunition. | Weight of Boxes when filled with Ammunition. |

No. of Rounds contained in each Box. |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cᵂᵗ. | qʳˢ. | lb. | No. | ||||

| Shot fixed with powder |

12 Prs. | Round | 1 | 1 | 10 | 8 | |

| Case. | 0 | 3 | 15 | 6 | |||

| 6 Prs. | Round | 1 | 2 | 7 | 12 | ||

| Case. | 1 | 0 | 15 | 12 | |||

| 3 Prs. | Round | 0 | 2 | 25 | 16 | ||

| Case. | 0 | 2 | 23 | 14 | |||

| B | Shot fixed to wood bottoms without powder. |

24 Prs. | Round | 1 | 1 | 26 | 6 |

| o | Case. | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 | ||

| x | 12 Prs. | Round | 1 | 2 | 20 | 12 | |

| e | Case. | 1 | 2 | 22 | 8 | ||

| s | 6 Prs. | Round | 1 | 2 | 20 | 24 | |

| Case. | 1 | 1 | 12 | 18 | |||

| f | 3 Prs. | Round | 1 | 1 | 0 | 30 | |

| o | Case. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 30 | ||

| r | How’r. Case. |

8 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 5½ | 1 | 2 | 12 | 10 | |||

| 4⅖ | 1 | 2 | 22 | 20 | |||

| Shells. | How’r. Shells. |

8 f | 1 | 2 | 26 | 3 | |

| 5½ i | 1 | 2 | 12 | 10 | |||

| 4⅖ x | 1 | 2 | 22 | 20 | |||

| e | |||||||

| d | |||||||

[Pg 56] The common ammunition waggon will hold from 9 to 13 of these boxes in one tier.

The tonnage of ammunition in boxes is equal to its weight: about 12 boxes make one ton.

BOMB Ketch. The bomb ketches upon the old establishment carry one 13 inch and one 10 inch mortar; with eight 6 pounders, beside swivels, for their own immediate defence. The modern bomb vessels carry two 10 inch mortars, four 68 pounders, and six 18 pounders carronades; and the mortars may be fired at as low an angle as 20 degrees; though these mortars are not intended to be used at sea, but on very particular occasions; their principal intention, at these low angles, being to cover the landing of troops, and protect our coast and harbours. A bomb ketch is generally from sixty to seventy feet long from stem to stern, and draws eight or nine feet water. The tender is generally a brig, on board of which the party of artillery remain, till their services are required on board the bomb vessel.

Instructions for their Management and Security in Action.

1. A Dutch pump, filled with water, must be placed in each round top, one upon the forecastle, one on the main deck, and one on the quarter deck; and furnished with leather buckets, for a fresh supply of water. [Pg 57]

2. The booms must be wetted by the pumps before the tarpaulins and mortar hatches are taken off; and a wooden skreen, 5 feet square, is to be hung under the booms, over each mortar, to receive the fire from the vents.

3. The embrazures being fixed and properly secured, the port must be let down low enough to be covered by the sole of the embrazure. Previous to its being let down, a spar must be lashed across it, to which the tackles for raising it again must be fixed: this spar serves to project the tackles clear of the explosion.

4. The mortars must not be fired through the embrazures at a lower angle than 20 degrees, nor with a greater charge than 5 lbs. of powder.

5. Previous to firing, the doors of the bulkhead, under the quarter deck, must be shut, to prevent the cabin being injured by the explosion.

6. The bed must be wedged in the circular curb, as soon as the mortar is pointed, to prevent reaction; the first wedge being driven tight before the rear ones are fixed, in order to give the full bearing on the table, as well as the rear of the bed. The holes for dog bolts must be corked up, to prevent the sparks falling into them.

7. When any shells are to be used on board the bomb, they must be fixed [Pg 58] on board the tender, and brought from thence, in boxes in her long boat; and kept along side the bomb ship till wanted, carefully covered up.

8. In the old constructed bomb vessels it is necessary to hoist out the booms; and raft them along side previous to firing; but in these new ones, with embrazures, only the boats need be hoisted out; after which the mortars may be prepared for action in 10 minutes.

Proportion of Ordnance and Ammunition for a Bomb Ship, carrying two 10 Inch Mortars, to fire at low Angles, and at 45 Degrees, Four 68 Prs. and Six 8 Prs. Carronades. [Pg 59]

BREACH.—The batteries to make a breach, should commence by marking out as near as possible, the extent of the breach intended to be made; first, by a horizontal line within a fathom of the bottom of the revetement in a dry ditch, and close to the water’s edge in a wet one; and then by lines perpendicular to this line, at short distances from each other, as high as the cordon; then, by continuing to deepen all these cuts, [Pg 62] the wall will give way in a body. The guns to produce the greatest effect should be fired as near as possible in salvos or vollies. The breach should be ⅓ the length of the face, from the center towards the flanked angle. When the wall has given way, the firing must be continued to make the slope of the breach practicable.

Four 24 Pounders from the lodgement in the covert way will effect a breach in 4 or 5 days, which may be made practicable in 3 days more.

Another way of making a breach is by piercing the wall sufficiently to admit two or three miners, who cross the ditch, and make their entry during the night into the wall, where they establish two or three small mines, sufficient to make a breach.—See Artillery at a Siege; see also Battery.

BRIDGES.—Manner of laying a Pontoon Bridge across a River.

The bank on each side, where the ends of the bridge are to be, must be made solid and firm, by means of fascines, or otherwise. One end of the cable must be carried across the river; and being fixed to a picket, or any thing firm, must be drawn tight by means of a capstan, across where the heads of the boats are to be ranged. The boats are then launched, having on board each two men, and the necessary ropes, &c. and are floated down the stream, under the cable, to which they are lashed endwise, by the rings and small ropes, at equal distances, and [Pg 63] about their own breadth asunder; more or less, according to the strength required. If the river be very rapid, a second cable must be stretched across it, parallel to the first, and at the distance of the length of the boats; and to which the other ends of the boats must be lashed. The spring lines are then lashed diagonally from one boat to the other, to brace them tight; and the anchors, if necessary, carried out, up the stream, and fixed to the cable or sheer-line across the river. One of the chesses is then laid on the edge of the bank, at each end of the bridge, bottom up; these serve to lay the ends of the baulks upon, and as a direction for placing them at the proper distances, to fit the chesses that cover the bridge. The baulks should then be laid across the boats, and keyed together: their numbers proportioned to the strength required in the bridge. If the gangboards are laid across the heads and sterns of the boats from one side of the river to the other, they will give the men a footing for doing the rest of the work. Across the baulks are laid the chesses, one after another, the edges to meet; and the baulks running between the cross pieces on the under side of the chesses. The gangboards are then laid across the ends of the chesses on each edge of the bridge.

Precautions for passing a Bridge of Boats.

Whatever size the bridge may be, infantry should never be allowed to [Pg 64] pass at the same time with carriages or cavalry. The carriages should always move at a certain distance behind each other, that the bridge may not be shook, by being overloaded. The horses should not be allowed to trot over the bridge; and the cavalry should dismount and lead their horses over. Large flocks of cattle must not be allowed to cross at once.

For the dimensions, weight, and equipage of a pontoon, see the word Pontoon.