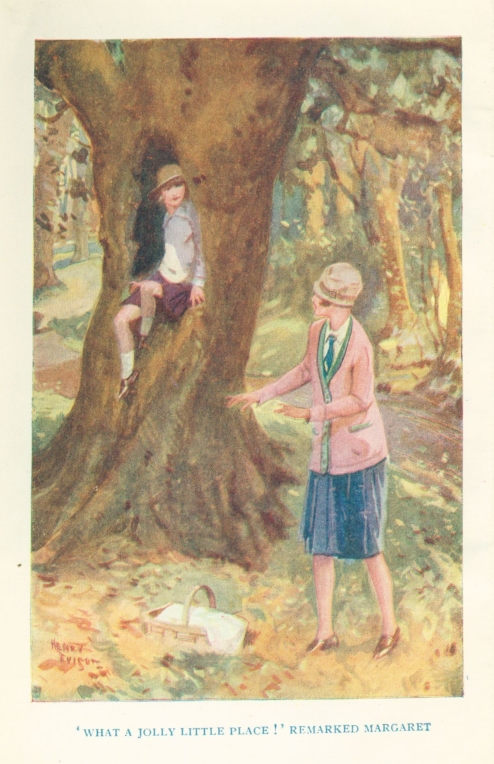

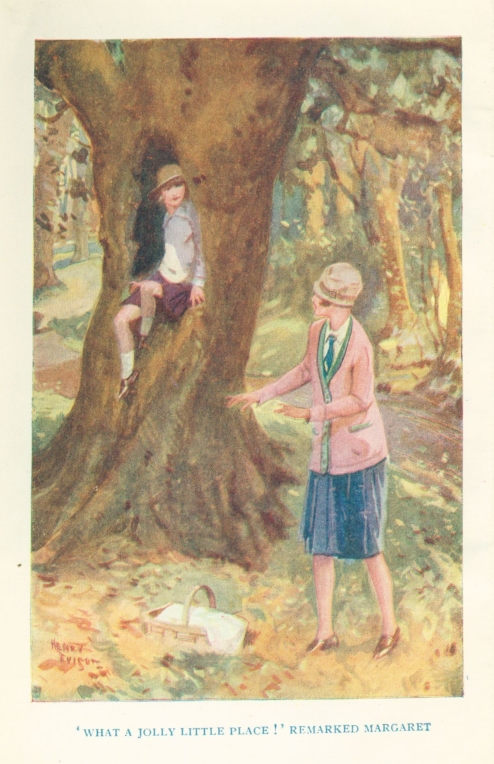

'WHAT A JOLLY LITTLE PLACE!' REMARKED MARGARET

'WHAT A JOLLY LITTLE PLACE!' REMARKED MARGARET

By

M. HARDING KELLY

Author of "Philip Campion's Will," "Roy"

"Tom Kenyan," etc.

LONDON

R.T.S.—LUTTERWORTH PRESS

4 BOUVERIE STREET, E.C.4

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY THE WHITEFRIARS PRESS LTD.

LONDON AND TONBRIDGE

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I. PARTING OF THE WAYS

II. OAKLANDS

III. TRIALS

IV. INFLUENCE

V. THE GREAT FIGHT

VI. OLD FRIENDS

VII. BOB IN TROUBLE

VIII. DISCOVERY

IX. A BOND OF UNION

X. FIRE

XI. AN OLD CRIME

XII. HAPPINESS

THE SECRET OF OAKLANDS

"Father, what is the matter?"

The question came in sharp tones of distress from a young girl who at that moment entered the breakfast-room. Quickly she sprang to her father's side and began chafing his cold hands, as she gazed with fear-stricken eyes into the beloved face before her.

Cyril Woodford made no response, but sat as if stunned, staring with apparently unseeing eyes at the newspaper before him, which his nerveless fingers had just dropped. His face was ashen, and there was a nervous twitching about his lips as he tried to moisten them with his tongue.

"Father dear, speak—tell me why you look like this! Has something terrible happened?"

No answer came in words, but with a shaking finger the man pointed to the heading of a column in the newspaper in front of him.

GREAT FINANCIAL CRASH

FAILURE OF SAMPSON'S BANK, LTD.

For a few seconds Margaret Woodford looked at the words with a puzzled expression wrinkling her brows, then something of the trouble involved dawned upon her mind.

"Sampson's has failed, I see—does—does it mean you have lost some money, dear?" she asked a little hesitatingly.

"All—all," he said huskily, while a shiver shook his frame as though he were attacked with ague.

The girl's face paled.

There was silence in the room for a few moments, and then, rising from her cramped position at his side, she said gently:

"I'm going to ring for some fresh coffee, father; yours is cold."

"I don't want anything; I couldn't eat," he answered.

But, ignoring this remark, she rang and gave her order, and in a few minutes a fresh cup of the fragrant beverage was poured out and brought to him.

"Drink it, just to please me," she said coaxingly, "you are so cold; and presently you will explain it all to me, won't you?"

For a minute or two longer her father sat silent, then hastily drained the cup before him, rose a little uncertainly, and went out of the room, leaving his breakfast still untasted.

His daughter remained seated, mechanically eating a finger of toast, and deep in painful thought.

She could not, of course, grasp the enormity of this thing, but that it meant serious trouble was evident. She had never seen her father disturbed like this before, and those last words of his, repeated so despairingly, had been enough to fill her with vague alarm. It surely could not mean the giving up of their beautiful home? Why, the Abbey House had been in their family for generations, and every stone of it was precious to her. And she knew only too well how her father loved it.

The Woodfords of the Abbey House were well known in the county, and the thought that strangers might one day occupy it had never hitherto suggested itself to anyone's mind.

Margaret started slightly as the idea for the first time presented itself to her now.

She gazed with tear-dimmed eyes at the beautiful grassy terraces, and the grand old cedar-tree rearing its head in front of the dining-room windows and sweeping the lawn with its graceful branches. It all looked so peaceful outside in the morning sunlight, as though nothing could disturb the calm serenity of the place.

Alas! for appearances—how poor an index they often are to the stern realities of life!

Mr. Woodford scarcely saw his daughter any more that day; he remained in the library until quite late in the afternoon, refusing admittance to everyone, spending his time in writing letters, and sorting papers in his desk with nervous fingers.

At last Margaret could bear the suspense no longer, and persisted in knocking at the door until he responded to her entreaties to come in.

"There is something very wrong with the master to-day," said old John, the man-servant, as he addressed his fellow-servants. "Something very wrong," and he shook his head dolorously as he spoke.

"Yes—that there is, and no mistake," answered cook, "and as for Miss Margaret, she looks as white as a sheet; just because the master wouldn't come in to lunch she must needs go without."

"I wonder what it means. It's something as come by post upset them, because things seemed all right when the master came down this morning; he looked as cheerful as could be, and when I set eyes on him half an hour later, I never saw anyone look worse."

"Well—I'll tell you what I think it is——"

But cook's explanations, or ideas, were cut short by the violent ringing of the library bell, not once, but two or three times, peremptorily.

"My! listen to that now, be quick, John! Good gracious, I never heard a bell tugged in that way before!"

John forgot he was getting on in years as he hurried breathless up the stairs; he felt already a presentiment of trouble, but he was not prepared for what he found.

"Why—what—what's the matter, miss?" he exclaimed, as he opened the library door and hurried to his master's side.

"I don't know!—-oh, I don't know! but father is very ill—send for the doctor, John, quick—let George take the grey mare!"

John was shocked by what he saw, but he was a sensible man who knew how to keep his head in an emergency. Without further hesitation he hurried back to the servants' hall even faster than he had left it, and quietly issued his orders to the groom.

"Ride hard!—the master's very ill if I'm not much mistaken;" and not waiting to answer any of the questions which were rained upon him, he at once returned to his young mistress.

The time seemed interminable while the two watched by the master of the house, longing and praying in the silence of their hearts for the medical man's arrival.

At last the welcome approach of his gig sounded on the carriage drive, and in a few moments more Dr. Crane was in the room—quiet, calm, issuing his orders clearly and decidedly, and bringing with him a sense of comfort to the frightened girl.

When the patient was at last in bed, and John installed to watch beside him, the doctor called Margaret aside and placed an arm-chair for her.

"Now tell me how this attack began, and what you think brought it on?"

In a few words Miss Woodford described the day's occurrences, and explained that while her father was talking to her that evening in the library, he suddenly cried out as though in great pain and put his hand to the back of his neck, then he seemed to lose consciousness.

"What is it, doctor?" Her sweet grey eyes looked anxiously into his, as she asked the question.

Dr. Crane paused a moment or two before he answered, then he said slowly:

"He has had a stroke consequent upon some unusual excitement or shock."

"A stroke?" repeated Margaret. "Does it mean then—that ... that he is too ill to—to recover?" And her voice trembled as she spoke.

"Oh, I do not say that at all," answered Dr. Crane; "he may, of course, get over this quite well, but in that case he will probably not be quite the same man again that he was before it happened. Perhaps," he continued, "you do not know that your father has consulted me more than once during the last year with regard to his health?"

"No, I did not know that," she replied.

"I am sorry to say so; but he has not been robust for some time; his heart is not what I should like it to be—but there, I am frightening you, and I hope unnecessarily; so far as I can see, there is no reason for serious alarm to-night. Be brave, child; if there is to be illness in the house, you will want all your strength; husband it now by having a good meal and going to bed early, and try to sleep. I shall send the district nurse in to sit up with Mr. Woodford, and you can wire to town to-morrow for a permanent one—at least—you can do that if—if it is necessary," he added hesitatingly, for as he was speaking the remembrance of a hint of monetary difficulties in a recent conversation with Mr. Woodford recurred unpleasantly to his mind.

To think of his old friends, the inmates of the Abbey House, being threatened with poverty seemed almost too extraordinary to be true. Surely there must be a mistake somewhere!

The kind doctor shook off the unpleasant doubt, and, pressing the girl's hand warmly, bade her farewell, with a last promise to call later and not forget to send the nurse.

When he had gone, Margaret stole softly into her father's room, and gazed silently at the still figure upon the bed.

The patient was breathing a little unevenly, but his eyes were closed, and he seemed to be sleeping.

Old John sat by the bedside anxiously watching his master's face.

Reassured by her father's peaceful attitude, his daughter went downstairs and did her best to do as Dr. Crane had told her. For she was sensible enough to realise that if there was trouble to be faced in the unknown future, giving way at the outset would be both foolish and cowardly.

After all, she was a Woodford, and with the courage of her race she knew she must meet difficulties with a stiff lip.

But it was a relief when Nurse Somers arrived, with her cheerful air of confidence and reliability, and took charge of the sick-room.

The next few days were like a dream to Margaret; she seemed to live in another world. Her father rallied from this first attack, and was sufficiently recovered to spend some hours with his lawyer. Then his mind seemed to grow dull, and he talked feebly and childishly of the old happy days when his wife was alive and his daughter a little child—the sunbeam and plaything of the house.

A few days of weakness followed, then came the night when the spirit took its flight from earth's habitation, quietly and silently, in answer to God's summons, and fled to that sorrowless land where all is joy and peace, and rest. And in the dawn of the morning the watchers saw only the hush of death's release for the master; "God's finger touched him, and he slept."

Margaret did not break down; the sorrow seemed too much to bear, too much to understand at first. She felt numb with grief; her cold apathy disturbed the kind nurse, who stayed until the funeral should be over.

"I wish she would cry," she remarked to the doctor; "this terrible calm is unnatural, and a fearful strain."

"Yes—yes—poor child, the reaction will, I am afraid, be all the greater," he answered sympathetically; "but youth is bound to recover."

But it was not until the day of the funeral that Margaret fully realised her loss, when she knelt by her window alone, the pale moon looking down upon her from the clear cold sky. Then the greatness of her bereavement came over her, and she felt, in all the sadness of realisation, the desolation of her future.

Her dear, dear father was taken from her, the one being she loved in all the world, the one who had been everything to her since she had lost her mother, her darling companion as well as parent. And as though to mock at her grief she had learned that day for the first time from the lawyer's lips that she was penniless. Owing to the great bank failure, her father's money had melted away into thin air; and her home, the dear old Abbey House, must pass into other hands, and be sold at once to meet the demands of her father's creditors.

To-night was hers—to-night she could wander through the rooms, and take a last farewell walk round the gardens and park, and touch as she had touched the friend of her childhood, the fine old cedar which had silently watched many generations of Woodfords seated under its sheltering boughs. With tender, lingering fingers she had pressed the smooth trunk, and then broken a tiny piece of the beautiful evergreen, and put it among her own personal treasures. It was that which lay in her hand now, and upon which the fast-falling tears dropped, as she said good-bye to the happiness of the old home, so soon to pass into the possession of strangers. She covered her face, while silent sobs shook her, in the sorrow of those moments.

Presently she grew calm again, and, gazing through the window of her room at those bright worlds which canopy our earth above, her lips moved, and her voice whispered to the One Who knew all her trouble and understood: "Father in Heaven, help me, Thy child, to do Thy will wherever Thou seest fit to send me."

There was no outward answer to that prayer, but the answer was speeding to her then, and strength to prepare her for the difficult days to come.

"Oh, I wish the train would be quick," said a small child, addressing an old man-servant who stood rather anxiously guarding her, as she stamped impatiently up and down upon the platform. "What makes it so long, James? I want to see her—because I shall know directly if she's nice; if she isn't, I'll be naughty every day, and make her just as unhappy as ever I can, and then she'll go away like all the others have. I told daddy so this morning."

"I expect you'll like her, miss," answered the man, with a grim smile, as he gazed with affectionate amusement at the spoilt child in front of him.

"If she's nasty, I'll hate her—so there."

"Come, come, missy, don't talk like that," he interposed.

"Yes, I shall—look! there's the train coming, the signal has gone down, now let's see, James, who can find her first; I feel sure she'll be horrid, and have an ugly old bonnet on."

The train steamed into the station, puffing and snorting vehemently as it came to a standstill, and in a few minutes the carriages had emptied themselves of their passengers.

The old man-servant and little Ellice Medhurst scanned carefully each possible looking person who alighted, to see if they answered to their ideas of the expected governess they had come to meet.

She had sent no description of herself, she had not thought of it, and in fact her employer had forgotten her intention to send to the station, until that afternoon Miss Woodford's future pupil, with a wilfulness which characterised her, had insisted upon going herself to meet her, not from politeness, but curiosity. What sort of person she was likely to expect she had not waited to inquire, but telling James he was to come with her—"Mamma said so"—she set off with him in the little pony-carriage to fetch the new governess to Oaklands.

* * * * *

The journey had seemed long to Margaret Woodford, as, occupied with her sad thoughts, she gazed out of the carriage windows, taking only a languid interest in the stations she passed.

She was still feeling the terrible shock of her father's death and failure, and the loss of the dear old home.

This venture into the great unknown world was a great trial, and it required all her courage to face it as bravely as she was doing.

Her heart glowed with gratitude towards Mrs. Crane, as she thought of her parting words: "Remember, you are not to stay if you are not happy, but to come back to us, and we will look for something else for you."

Happy! She didn't expect to be that, but she would try to be content and to do her duty; she was sure the promise was hers, "I will be with thee in all places whithersoever thou goest." God knew the way that she took, and He would direct her path. That was the one great fact which sustained Margaret Woodford's courage as she faced the world alone for the first time in her life.

She had started for London that morning from her old home in the North, and travelled by the 4.15 from town, and now in the fading afternoon light she caught her first glimpse of the garden of England, as the train steamed past country lanes, cherry orchards, and hop grounds rising into renewed life as the season advanced.

The only other occupants of her carriage appeared to be two farmers—at least she judged they were of that persuasion, by the agricultural topics of conversation which seemed to engross them. Her interest was aroused by their eagerness and enthusiasm; one of them, drawing out of his pocket a little square parcel, hastily untied the string, and, handing it to his companion, said:

"'Taste that, and tell me what you think of it. I can assure you I never grew a finer sample."

Margaret expected to see something eatable, and was more than surprised to witness the man bury his nose in the parcel and, after drawing a deep breath, gasp.

"Beautiful—beautiful, and if it wasn't for this foreign competition eating our very pockets, you'd be making a fine price now on these last years. I think you did right to hold them up. What we are coming to, I don't know; trade is being driven out of the country, and there's nothing but ruin staring most of us in the face. Fortunately, I was in the swim when one got £20 per pocket; but now, well—they are not worth growing; I've grubbed up several acres this season."

There the conversation got quite beyond Margaret's comprehension, as further technicalities in connection with the hop trade were discussed, with summer fruit prices.

Already she felt in a new world, and a sense of loneliness oppressed her. Her thoughts passed from the subjects of her companions' discussion to her own troubles, and a nervous unrest as to whether she was getting near her destination.

The stoppings at small stations seemed frequent, and at each one she gazed anxiously at the names written on the boards and seats upon the platforms.

Her obvious nervousness presently attracted the attention of one of her travelling companions.

"Can I assist you?" he asked her politely, as he saw her struggling to get some of her property down from the rack. "I suppose you are getting out here?" The train was slowing up as he spoke.

"Thank you very much," she answered, as the bundle of wraps was deposited on the seat opposite, then continued anxiously, "I don't know if this is my destination."

"What station do you want?" he asked.

"Steynham. I don't know it at all."

"Oh, that is a little farther on; four more stations, and then yours," he answered.

"Do I have to change at all?" she asked.

"No, this is slow from our last stopping-place."

"I am so much obliged," she answered, in a tone of relief.

After a little pause her companion continued, "I know Steynham very well, and most of the people who live there; can I direct you further?"

"Thank you, I'm afraid not. I get out at that station, but I shall be met there, I expect. I am going on higher up the country beyond Wychcliff, to a place called Oaklands—a Mr. Medhurst's."

"Oaklands—Medhurst," repeated her interlocutor with a slight start, which she did not fail to catch.

"Do you know anything about it—about them?" she asked somewhat timidly, for the man's tone and expression as he repeated the words had filled her with a vague disquiet.

"No—oh—no, I've never been there, never met Mr. Medhurst," he answered, somewhat hesitatingly.

He offered no further remark, and remained apparently buried in his newspaper until the train drew up, and he and his companion prepared to get out. As they alighted, he turned to Margaret Woodford.

"The next station is yours," and, lifting his hat, passed down the platform out of her sight.

"Do you know anything of the place she's going to?" asked his friend, as they descended the steps.

"Not exactly, but I'm sure I've heard no good of it; there's some sort of mystery, or scandal attached to it, I believe, and folks say the youngsters are terrors. I am sorry that is the girl's destination; she's young and pretty—evidently a lady, I should say, and looks as if she's had trouble. But there, one can't pick up strangers' burdens, we've plenty of anxieties of our own just now." And the subject of Margaret Woodford and her possible sorrows and difficulties passed from their minds as they emerged through the station door, jumped into the gigs awaiting them, and drove away to their homes.

In a few minutes more the train reached Steynham. The girl gazed up and down the platform, feeling more friendless than ever now she no longer heard the kindly voice of her fellow-traveller. She felt she would have been glad if she could have had his companionship until she was safely under the care of her employers.

This tall, elegant-looking girl getting out at Steynham did not pass unnoticed; her high-bred air and softly modulated voice quickly attracted the attention of the railway officials, who gathered round her as she stood, the one solitary passenger, beside her box.

"Is there a carriage to meet me?" she asked.

"I don't think so, miss," replied a porter, running to take a look up the road.

"No, there is no vehicle here, and none in sight, miss. Who were you expecting?"

The question was put with a desire to render assistance, for the Steynham porters knew all the surrounding gentry, and a good deal about them too, if village gossip was to be relied upon.

"I am expecting someone to meet me from Mr. Medhurst's—Oaklands is the address, near Wychcliff."

"Near Wychcliff—Oaklands!" repeated one or two of the officials. "Don't know it, miss—don't know the name."

"Then—what can I do?" said Margaret, a slight quiver in her voice.

"I'll ask the station-master," said the first speaker, and, hurrying to the ticket-office, he soon returned with a fresh authority.

"What place was it you wanted?" he asked politely.

"Oaklands," repeated Margaret for the third time—"Mr. Medhurst's."

A shade of surprise crept over the station-master's face.

"Did you say Oaklands?" he repeated.

"Yes—yes, that is the name. Oh, you do know it?"

"Certainly," he replied, "and I fancy a pony-trap from there met the earlier down-train; a man-servant and a little girl came and watched the passengers alight, and then drove off again."

"Oh, that is it then! They must have made some mistake in the time of the train. Now, what can I do? Is this place far away?" asked Margaret, somewhat anxiously.

"Several miles, miss. It's right up on the hills."

For a few moments nervous fear assailed her, and then she said bravely, "Can you get me a cab?"

"I'll see, miss," one of the porters answered civilly. "You come into the waiting-room, and I'll go and fetch Mr. Cramp."

"Who is he?" she inquired.

"Oh, he's the man that has the fly. If it isn't out, it'll be here in half an hour."

Half an hour! Her heart died at the prospect, as she followed her luggage down the platform into the stuffy little waiting-room. The window was closed, and it looked as if it ought to have a poster up with "TO LET" on the door.

"The station is more comfortable, I think," said the porter, taking a considering look at the elegant figure in front of him, as, setting down her bags a moment, he turned to her and motioned to the bench by the entrance door.

"Thank you, I will wait here."

"I won't be long, miss," he continued encouragingly. "I'll just give these to the booking-clerk to look after, and I'll be back in no time."

In a few moments more she had the satisfaction of seeing him start out briskly, and pass through the white station gates.

Wearily she gazed out of the window. It was a warm day, in early summer, and the scene before her was not wholly dispiriting. A straight road from the station led up to the village; on the left was a squarely built house with the words "Coffee Tavern" written upon it in large letters; then came a few cottages. The road was sheltered at places by some fine old elms, and on the right hand she saw something that made almost a thrill of hope pass through her, as she drank in the sight and breath of its beauty.

Spring had long since awakened the sleeping trees, rich life-giving sap had risen, and the sun coaxed them into opening their eyes to the new season. The orchard upon which Margaret was now gazing showed her a wealth of promise, as the gleam of fruit clusters shining through the green foliage caught her eye.

The outlook on the opposite side of the station, which she could just see through another window, was the exact counterpart of that near to where she was sitting, and presented a view prosaic enough, which needed some conjuring of the mind to suggest any ideas of romance.

Margaret tried to be interested, but her thoughts were trailing back to the dear old home surroundings when she heard the rumble of a cab. A few minutes later a one-horse vehicle drew up at the door, and her friend the porter jumped down, as she rose with alacrity and went to meet him.

"It's all right, miss, he knows Wychcliff, and says he can find 'Oaklands' when he gets there—it's an old farm that has stood empty for some time."

In a few minutes more Margaret had started upon her quest.

Steynham, quiet enough in the spring-time, but showing much more life as the fruit and hop seasons come round, was soon left behind, and the gradual ascent to Wychcliff was begun—a long drive through two or three villages, and then a steep climb up a narrow, grass-grown road, to the hills beyond. There was only room for one vehicle at a time, and Margaret was startled by suddenly hearing the driver calling at the top of his voice, "Hie—back—there!—back!" and the old cab came to a sudden standstill with a violent jerk. A sharp altercation ensued between the two Jehus, which sounded decidedly uncomplimentary; then her vehicle was jerked backwards down the hill, nearly overturning as it ran up on to the bank.

Miss Woodford was used to horses, and not easily frightened, so she sat tight, preferring the chance of an upset to getting out on to this unknown, narrow road, and in the darkness trying to find standing-room in the hedge. It was not a pleasant experience, as those who have driven up, or down Wychcliff hill in the evening can testify. Here and there at long intervals there are wider spaces cut back into the adjacent fields to allow vehicles to pass. Fortunately, one was near, and after much jolting and noise, with a good deal of argument on the part of the drivers, and a last shout from Cramp, whose temper was now up, of "'Nother time I'll see you back yer old caërt before I stop my currage for such as yew!"—and the cab crawled on again.

Would it ever end? she wondered, and the remembrance of that dark, lonely drive, with night settling down around her, never quite faded from her mind, although she little knew then the fears and doubts that were to await her later.

By dint of inquiry at a solitary cottage, which was passed at the top of the hill, they discovered the whereabouts of Oaklands Farm.

In the gloom Margaret could not see what her future home was like, the darkness being increased by the thick trees which surrounded it, only leaving just room for the cab to draw up before the front door.

She got out and paid her fare, as the man set down her box on the step, and then, after violently ringing the bell, climbed back to his seat.

"Seems pretty lonely," he remarked, as he gathered up the reins; "not much of a place for a young lady like you."

The girl shivered at his words.

"Look here," he continued, "if you want to get away whoam any time, yew jest write to Mr. Cramp, Cab Driver, Steynham, and I'll come for yer, miss—see?"

Tears rose in the back of Margaret's eyes at the mention of the word home. She thanked the kindly old man, who was always liked by his "fares," but she did not explain her destitute condition to him.

He waited, after setting her box on the step, until the door opened, and looked backward as he drove away to see she had entered. Then he vanished into the darkness.

As the door opened, Margaret was agreeably impressed by the bright glow of the hall into which she entered. The man-servant who appeared was civilly polite; the dark oak furniture and rich red carpet and walls, artistically decorated, gave a sense of warmth and comfort to the tired girl. Then she was startled by hearing a shrill voice screaming over the banisters:

"So you are here at last, and I can't even come and look at you, because I'm supposed to be in bed. It is a shame! I want——"

"Go back, Miss Ellice, now," said James reprovingly; "the master will hear you."

"Who cares!" said the elf, leaning still further over the balustrade until she was in danger of falling.

At that moment the dining-room door opened, and the child, in spite of her boasting, disappeared, as a tall, dark, well-set-up man appeared.

"Is it really Miss Woodford?" he inquired, holding out his hand.

"Yes. I'm afraid I'm very late, but I had a difficulty in finding a conveyance at the station. I hope I've not caused any inconvenience."

"Indeed no; the fault is ours. I must apologise. We sent a trap to meet you, but unfortunately Mrs. Medhurst made a mistake about the train—we have only just found it out. I'm sorry you've had the trouble of finding your way here alone."

"Ah, here's Betsy," he added, addressing an elderly woman who at that moment made her appearance in the hall. "Will you take Miss Woodford upstairs at once," he said, "and then," turning to Margaret, "we shall be ready for dinner, when I can introduce you to my wife; your little charge is in bed, and asleep by this time, I expect."

This last was received with a grim smile by old James, as the young governess followed the woman to her bedroom.

A bright fire was blazing on the hearth, which was pleasant, for the early summer nights were still cold. Margaret glanced around her room with pleasure. The subdued green carpet, cream-tinted walls, and shelf of goblin blue china all expressed a thoughtful kindness and artistic taste.

As she laid her toilet requisites on the old Chippendale table, Margaret's heart gave a throb of thankfulness that her environment was so tasteful and pleasant. There surely could be nothing to fear here? Mr. Medhurst was evidently a gentleman, while the servants she had seen were of the good class so often regretted in this century. Her future pupil might prove a handful, but that part of her life had to be tested.

She felt she was travel-stained, but she did not wish to keep dinner waiting, so, refreshed with a wash, and smoothing her hair which, in spite of much brushing, would ripple in natural, careless waves over her forehead, she prepared to descend.

Betsy was outside waiting, and in another moment threw open the dining-room door, and announced "Miss Woodford."

There was a rustle of silk, a subtle scent of violet perfume, and a tall, graceful woman rose from the table to receive her.

Mrs. Medhurst spoke a little languidly as she welcomed the governess, giving her hand a slight pressure as she said kindly, "I am so glad you have come! You will excuse our beginning; we had almost given up expecting you, but my husband has told me of my stupid mistake."

Margaret was a little disconcerted, as she took the seat offered to her, to find her hostess in full evening-dress, the rich yellow velvet throwing up the beauty of her dark eyes and olive-tinted skin. A collar of diamonds flashed rainbow hues upon her white neck.

The conversation flagged, but from time to time Mrs. Medhurst appealed to Margaret in her soft modulated voice.

She was a beautiful woman, exquisitely dressed, as though she might be going to a dinner-party; the servants and appointments of the house, so far as Margaret could judge, seemed all perfect in their way.

Miss Woodford of Woodford Abbey knew how things ought to be done, and she was pleasantly surprised at her surroundings. But the thought would present itself, why were these people living in this lonely out-of-the-way place? It seemed so utterly incongruous, considering their style. The girl tried to smother the thought, and, being young, and withal hungry, was able to enjoy the meal in spite of the sense of strangeness which pervaded the place.

"Will you come into the drawing-room with me?" said the hostess, as she gave the signal to rise from the table.

Miss Woodford was glad the invitation had been given, as she was not quite sure how much she was to be received into the family, or exactly what her position was to be.

The drawing-room was a dream of cosiness, comfort, and taste. The chairs and couch were of the easiest, the dove-coloured walls, against which stood some handsome cabinets of old china, the rich pile carpet where one's feet sank softly, gave a feeling of rest and luxury which reminded Margaret of her boudoir at Woodford Abbey.

Mrs. Medhurst sat sipping her coffee and lazily fanning herself at intervals, until, presently, Margaret inquired if she might ask her a few questions as to her future duties.

"Yes, certainly. I don't think I have much to tell you," she answered, "except I should like you to have breakfast in the dining-room, and lunch with Ellice in the school-room, and dine with us in the evening. We are so quiet here, we shall be glad of your society then. I am having the rest cure," she said, with a strange little laugh, "and although I am much better than I was, it really is almost too quiet at times."

"I am so sorry you have been ill," said Margaret sympathetically.

"I have been dreadfully weak. I'm gradually gaining strength now, but I can't stand Ellice's high spirits, and so I pass her on to you. Manage her as you like."

"I will do my best," said Margaret. "You know I have had no experience, but I love children, and always have got on with them."

"Oh, yes. I expect she'll be good with you; you are young, and will be able to enter into her pleasures better than I can—my poor head is unable to bear much."

"And about the lessons?" asked the new governess.

"Teach her just as you like. She's a fearful little ignoramus, I'm afraid; she's made up of oddments. Anything she can pick up from the cottagers, or from her father, she retains with ease, but knowledge she ought to have acquired she is quite deficient in, I imagine. I'm afraid you'll be horrified at her ignorance."

Margaret rose and placed a cushion at Mrs. Medhurst's back, as she noticed she fidgeted restlessly in her chair.

"Thank you—thank you; that's heaps nicer. How kind of you to notice!" and the sweet smile that accompanied the words transfigured the otherwise cold look of the speaker's beautiful face.

Mr. Medhurst came into the room soon after, and the conversation became more general. Several times he glanced anxiously at his wife, and then he crossed to Miss Woodford:

"Mrs. Medhurst has not been very well to-day, and one thing she enjoys more than anything else is music; we are so shut off from it here. Would it tire you too much to sing, or play?"

"I haven't unpacked my box, but I can remember some of Mendelssohn's short things, if that will do?" answered Margaret readily.

"Yes, indeed, she likes them so much."

The piano was one of Brinsmead's best, and the musician soon lost herself in the joy of her themes. Her touch was exquisite, and she seemed to pour her whole soul into the expression she produced from her fingers. She went from "The Bees' Wedding," thrilling with its busy revellings, into quieter grooves, until gently there stole through the room the subtle exquisiteness of No. 1 of "Songs Without Words."

There was a hush over the room as she rose from the piano, and for a moment she feared she had not given pleasure. Then she caught the grave glance of appreciation of her host as, offering her a seat, he said quietly, "Thank you."

Mrs. Medhurst did not speak, but as she rose to say good night, Margaret noticed something like the glimmer of tears in her eyes.

The girl was very tired when she went to bed, and the sun was streaming in at her window before she awoke the following morning.

She sat up and looked round her room with a puzzled air, wondering vaguely for a few moments where she was. Then the remembrance of all that had happened returned, and, looking at her watch, she discovered with dismay it was nine o'clock. She dressed hurriedly, and came downstairs, feeling anxious as to what would be thought of her unpunctuality if breakfast should be over. No one last night had remembered to tell her what hour it would be, and she had forgotten to ask.

She encountered James in the hall with a tray in his hand.

"I am afraid I am late," she ventured.

"Oh no, miss; Miss Ellice is in the garden, and has not breakfasted yet. You're all right," he answered, a little patronisingly.

Margaret heard the words with a great sense of relief.

The dining-room looked delightful in the morning light; the casement windows were thrown wide open, and roses peeped a welcome into the room.

Miss Woodford noticed the table was laid for two only, and wondered.

Presently the door opened, and James appeared.

"Will you like breakfast now, miss?" he inquired.

"Oh—yes—but what about Mrs. Medhurst?" she inquired.

"She always takes hers upstairs, and the master has it with her when she's had a bad night," he answered.

"I am sorry she is not so well?" she replied.

The interrogative tone of her voice brought no response from the man-servant who waited.

"What about my pupil, won't she breakfast with me?" inquired Miss Woodford.

"I can't say, miss. I wouldn't advise you to wait for her; she's off in the woods somewhere, and there's no knowing when she'll come back. Betsy will keep something hot for her."

"Oh. I see"—and the new governess realised something of the difficulty of her position as she sat down—"I won't delay any longer then."

She had not quite finished when she heard a child's laugh, and the door was flung open,-and a sharp little voice exclaimed:

"There you are; I thought I'd find you here. Good morning, Miss—oh, what's your name?"

"Good morning. I'm Miss Woodford, and you—you are my pupil Ellice, aren't you?" said the new governess, with a smile.

"Yes. I wonder what your other name is?"

"It's Margaret."

"Oh, that's rather nice; it's nothing like mine. Isn't it stupid I can't call you by it? Mamma said I was to say Miss Woodford when I spoke to you."

"Yes, of course, because you are a lady, you see, and ladies always behave politely—they can't help it."

"Oh—yes—I—see," answered the child, drawling the words out in surprised tones.

Here was a puzzle. This new governess seemed to think she couldn't behave rudely—because—because she was a lady! It was awkward; she hadn't thought of it like that before. It looked as if the fun was going to be spoilt. A puzzled expression of disappointment clouded her face for a moment, but in an instant it lighted with an illuminating flash, as a thought rushed to her mind. "I wonder what she'll think on Saturday?"

She was an interesting looking child, but she had none of her mother's beauty, the brilliant brunette which had so struck Miss Woodford. Ellice was a fairy-looking little creature, with dancing blue eyes, tiny features, and tumbled ringlets. She certainly looked like an elf from the woods as she stood with the front of her dress caught up in one hand, and filled with wild roses, tufts of yellow vetch, scabious, bundles of dainty milkmaids which she had dragged from the nettle-beds, regardless of their stings, and sweet clumps of wild parsley—all in mingled profusion, while she carelessly swung a straw hat by a broken elastic, the blue ribbon of which was stained with cherry juice that matched the dye on her fingers.

"You have spoilt your hat trimming," said Miss Woodford, taking the article (which evidently received little respect) from the small owner.

"I did that jumping under the trees to get at the waterloos. I had a feast, but ever so many tumbled on to me."

"Well, now are you ready for breakfast?"

"I'm not very hungry. James—James," shrilled the child, "bring me some cake and milk—and be quick!"

"Better have your egg, missy," answered the man.

"No, I won't! Cake—cake—cake——"

"But the master said you must have your proper meal, Miss Ellice."

"Then, I won't! Get that cake—swish!" and she swung her skirts round, scattering her flowers in all directions.

"Very well," answered the man hopelessly, turning to retire.

"Stay," said Miss Woodford firmly, "did I understand Mr. Medhurst said Miss Ellice was to have an egg for breakfast?"

"Yes, miss, but she won't eat it when she wants cake."

"Then she isn't hungry, and had better wait until lunch," answered the new governess.

James's eyes grew round with astonishment. Two governesses had been tried before, but they had both departed in a week, utterly defeated by the small person who now stood between them, her eyes blazing defiance.

"I don't care what you say, I will have cake; I'll go and ask Betsy." With this the small figure flew to the kitchen, demanding attention to her wants in a storm of passionate cries.

"Yes, yes, missy, I'll get the tin down. Don't make such a fuss, dearie, you'll disturb your poor mamma," entreated cook persuasively.

"Miss Ellice is not to have any cake, Betsy," said Miss Woodford's voice decidedly.

The woman turned round to find the new governess standing by her side. She looked her amazement, and then dropped her hands from the cupboard:

"Very well, miss."

The colour rushed to Ellice's face, words seemed to fail her for a moment, then, with a stamp of her foot, the child turned and fled out of the kitchen and disappeared down the drive, and was lost in the adjacent woods.

A sigh broke from the cook.

"There you have it, miss. You'll never be able to manage her, I'm afraid; she's just too much for all the governesses what comes."

"Anyway I must try, mustn't I, Betsy?" answered Margaret, adding, "It's my duty. Poor little thing, she does need someone to help her," finished Margaret, as she turned back into the hall.

"Someone to help her!—umph. She's a bit different from the others. James, think she'll do?" asked his wife, amazement in her voice.

"I—don't—know—I give it a week," answered the man grimly. "Saturday is the test."

Miss Woodford went up to her room, and sat down by the open window with, it must be admitted, a little feeling of despair in her heart. She could see rocks ahead, and she had had no experience, and surely the task here was going to be a big one. A great homesickness came over her; she felt the lump rising in her throat and almost choking her. This was to be her home now, and already the one being in whom she had felt an interest, and from whom she had hoped to win affection, had rushed from her with hatred in her heart and a malignant expression of passionate dislike disfiguring her face.

Presently Margaret roused herself and commenced unpacking her box. Beyond her clothes she had brought one or two personal treasures: the bit of the old cedar-tree; a water-colour drawing of the Abbey House, which she promptly hung up upon the wall, where an unused nail remained driven in. Her ivory toilet ware, with her name "Margaret" traced in gold across the backs of the brushes and mirror, and a beautiful dressing-case of the same lovely ware, which contained a family heirloom in the shape of a ruby necklace, the stones of which flashed their fire in the sun's rays, as now she lifted the lid. She took it out for a moment; the gems streamed from her fingers, held together by tiny links of gold.

She had a memory of her mother with that very chain about her neck, and she, a child, begging for it, and the laughing voice saying, "Not now, darling, but it will be yours when I am gone." How lightly the words had been spoken, and how soon had the separation come! Much as she treasured the jewels, the stones felt cold in her hand to-day as she gathered them up and replaced them in the case.

Her things disposed of, she drew a chair to the open window and sat down. The lilt of the birds' songs fell sweetly upon her ears; her thoughts became a reverie over the past, an expression of pain lurked in the depths of her eyes—and they were eyes full of womanly tenderness, and yet capable of expressing undeveloped strength.

Presently her fingers touched the book which lay upon the table near her. With quick impulse she drew it towards her, an unspoken petition rising in her heart: "Lord, give me a message from Thee."

She opened the book at random, and her glance fell upon these words: "I rose and did the king's business." She glanced back and read, as she had often read before, of the solemn vision granted to the prophet when he was shown something of the trouble to come in the latter days, the distress of nations before the Kingdom of the Lord should be established upon the earth. In his grief he fainted, the burden of the vision causing sickness to come upon him; then he braced himself, and she read: "I, Daniel, rose, and did the king's business." The duty just there—the work to be carried on.

The words acted like a tonic. A vision of the coming years of loneliness and difficulty had dismayed her, and yet here—surely work for the King of kings lay all around; the greater the difficulty, the more insistent the call. For a moment her head sank upon her hands, and her heart was lifted up to Him Who ever waits to pour out a sufficient supply of strength to His people, to meet every need.

Margaret Woodford believed this, and for that day at least she laid her burden straight at her Saviour's feet, and rose calm and determined to face the future bravely, and do the work nearest, to which she had been called.

Meanwhile Ellice, a storm of passion raging in her heart, rushed into the woods, pushing the tangled branches fiercely apart until she came to the fairy glade, a moss-grown path where the trees parted in a glorious avenue and the sunlight stole through in shafts of golden light, and fell tenderly upon the child. She flung herself down under a venerable oak, the trunk of which, cleft by some old-world storm, formed a hiding-place where she had often before sheltered on rainy mornings, and whispered her secrets to the woods.

Short, gasping sobs almost choked her as she lay upon the ground. The squirrels scampered in the branches overhead and, clinging to the rugged trunk of the great Forest King, crept down to the foot and peeped shyly at her, waiting wonderingly for her call, and the food she so often temptingly offered them. Her sobbing breaths of distress presently ceased, she raised a tear-stained face, and brushed away the tell-tale signs of distress. A hard, sullen expression swept all the beauty from her countenance; she looked what her brother would have said, "real ugly," as she pursed up her lips and stared aimlessly at the beauty around her.

The horrid pangs of hunger would make themselves felt, and she wished now she had not come away in such a hurry; even an egg would have been preferable to this hunger. If she could be certain of not meeting that hateful governess, she would steal back to the house. She had almost made up her mind to make the attempt, when she was startled by a footstep in the glade, and a voice calling her by name. She set her teeth hard, and drew back further into the shelter of the oak.

Miss Woodford, who was evidently bent on searching for her charge, receiving no answer to her calls, presently sat down upon the mossy ground at the foot of the very tree where Ellice was hidden. Opening a basket of sandwiches and jam-puffs, she commenced her lunch, while the child, all unknown to her, kept watch, struggling with her pride as she saw the tempting viands gradually disappearing before her eyes.

The trees tossed their branches in a light breeze which whispered among the leaves; the day grew hotter. Margaret felt tired as she rested her head against the oak bark where she leaned. This picnic with her young charge had been arranged in her own mind, with a hope of friendship and understanding, as a happy result. As presently she rose to shake the crumbs from her lap, a voice from somewhere muttered, "She is a pig to eat it all up."

Margaret Woodford paused, in a thoughtful, listening attitude; then she turned, and her eyes roved about the tree where she stood. She took a few steps round the trunk till she espied the cavity and the gleam of muslin embroidery from the child's dress which escaped at the opening, as she pressed her back against the inside of her castle to avoid being seen.

"What a jolly little place!" remarked Margaret, as she caught sight of the child. "I wish I'd found this before, we might have had lunch on the doorstep of your domain. I've just finished mine. Where will you have yours?"

"You've eaten it all," muttered the child sulkily.

"No—look, I've kept some. You surely didn't think I'd been greedy enough to finish the lot," and, raising a serviette which lay at the top of the basket, Ellice's eyes saw a vision of food which made her mouth water. She capitulated at once, slid down to the ground in a hurry, and attacked the contents with avidity. In a very few minutes nothing but crumbs remained, and an empty lemonade bottle.

"Now, shall we have a rest while I tell you a story?" suggested Margaret.

There was a moment's hesitation, for of all things Ellice loved better than another, it was to listen to story-telling. An eager expression spread over her face for a moment, then it darkened again.

"I'm going home," she muttered, and, jumping up, she ran lightly down the avenue a little way, then, turning into a denser side-path, vanished.

"Defeated," said Margaret Woodford to herself, with rather a sad little laugh. "Ah, well, I must try again. I'm on the King's service, I must never forget that, and victory is of the Lord—of course, that applies in every case."

It was not a very cheerful outlook for the young governess, but she was determined to win through if possible.

She did not see her charge again that day. Upon inquiring for her after her return from the woods, she was informed she was taking tea with her mother, and would not be down again that evening.

Mr. Medhurst returned later, and she managed to get a short interview with him, and to obtain a more definite knowledge as to what her supervision and powers with regard to her pupil might mean. She noticed a worried expression come into his eyes as she broached the subject.

"Miss Woodford, I am afraid I must admit my little girl has been spoilt," he answered. "You understand my wife is not strong—and—well, there it is——" and he spread his hands deprecatingly as he spoke.

"Does it mean I am to have full control?" asked Margaret—"I mean in this way," she added. "My pupil had no lessons to-day; she ran away to the woods this morning because I could not allow her to eat cake instead of her breakfast, and——"

"Oh, I'm glad if you intervened in that matter! I have forbidden that," he answered quickly.

"So I understood."

"And you supported the order?"

"Yes, and offended Ellice very deeply, I'm afraid," laughed Margaret.

"Never mind, you succeed if you get your way. Go on as you have begun, Miss Woodford; I cannot suggest anything to you, but"—lowering his voice—-"if you can win my child and gain control over her, I shall be more than grateful."

His manner was earnest, but Margaret felt there was reservation when he paused and suddenly changed the conversation. The little she had gathered strengthened her in her purpose. There was evidently trouble in this house which could not be fully explained.

She went to bed that night puzzled, but determined to try and do her duty whatever the future might mean to her.

Ellice was like a different child at breakfast the following morning. She appeared bubbling over with amiability and good spirits, and even the presence of her governess at the breakfast-table brought no frowns or sulky looks. Margaret's proposal to take some lesson-books to the woods was acceded to with apparent delight.

"Oh, do let's, Miss Woodford!" she exclaimed, clapping her hands with joy; in fact, the suggestion was so novel, she forgot for a little she was at enmity with her governess. The call of the woods was so strong within her.

With a luncheon-basket and armed with paper and pencils, governess and pupil set out with enthusiasm for a beginning in the path of knowledge. They found the old haunt in the oak, and sat down to work.

After a grind at reading and arithmetic, Miss Woodford electrified her pupil by the remark, "Now, shall we talk about the trees?"

"About the trees?" repeated the child in amazement.

"Yes, let me think what this old oak has to say to us about himself; shut your eyes and listen, and I will tell you something of his story."

"I've lived such a long, long life," whispered the oak, "but although I'm getting very old, I can remember the days when I was young—more than two thousand years ago"—(Ellice stirred as if to interrupt, but the slight pressure of Margaret's fingers on her arm made her relapse, and she breathlessly listened to this wonderful statement)—"yes, more than two thousand years ago," insisted the oak, "I was planted just here—a young sapling I was, strong and sturdy, but small and tender, and had not much knowledge of the world then. But that has all opened up in the centuries I've lived, and I've seen wonderful changes, I can tell you.

"There are not many of us left now, but it's been handed down to me from my forefathers that, right back to the times of the ancient Britons, there was a grove of us oaks in this very spot. Those were the times when we were thought a mighty lot of by the poor heathen who dwelt in this country then; they didn't know anything about the true God, and so they worshipped in their blindness the sun and the moon and the stars and gods of their own creation. Beside that, they counted all of us oak trees sacred. I don't know why that was, but of course they couldn't help seeing we were the finest-looking trees in all the forest, so they took care of us and blessed us, and even the mistletoe (the seed of which sometimes drops upon us from a bird's mouth and takes root and makes its home on our boughs), even that the Druid priests used to revere, and only allow it to be cut with a golden knife at their sacrificial feasts.

"But though they were considerate for us, they were very cruel to their enemies, and often poor captives were brought out and judged in the open courts in the woods, and offered as sacrifices in our beautiful shady oak groves. Stories have been handed down through past generations of those poor people who suffered; but happier times have come since. Folks here don't worship their cruel gods Woden and Thor now, though they seem to keep them in remembrance by still using Thursday and Wednesday in their week's list of days, which names mean, as I understand it, Thor's day and Woden's day.

"I'm very glad those heathen times are over here, and that the people who come and rest in my trunk, or sit at my feet, know about the wonderful true God Who created everything for His glory; not only the boys and girls, but in His Book it says, 'The trees of the Lord are full of sap,' and I like that—trees of the Lord; it shows we belong to Him. He doesn't forget us, either, for He waters us with the rain which we suck up into our roots, and drink into our leaves, through the tiny mouths with which we breathe the beautiful forest breezes, and by the warm yellow sun the great God sends the colour flushing into all our veins, and into all the outer skin of the bark that covers us. Through our pores, which widen in the hot weather, the sweet air rushes, and gives us fresh life and growth, and under the tiny air-bags are the canals where the sap runs and rises in the spring, right from the very roots, travelling over our branches until it fills even our leaves, and makes us able to put forth new growth and life.

"Yes, God is the gardener of the forest, summer and winter, year in and year out. He gives us all the power we need. When the time of singing birds comes, then a whisper and hum runs through the whole of the forest, and all the big tree world wakes from sleep. Everyone is drowsy at first—some seem almost dead—but gradually we open our eyes and cover our naked limbs, and get out our summer dress, and shake our leafy garments in the sunshine, while the forest folk build new homes in our branches and utter their thoughts of praise." The oak paused.

"We must stop story-telling now," said Margaret; "it is lunch-time."

"No, no—go on—oh, do, please go on, Miss Woodford!"

"Not now, dear; it's later than I thought," glancing at her wrist-watch—"and besides, it seems to be getting dark; I think a storm is coming. We must hurry home."

"Not yet. It doesn't matter if it rains."

"I think it does; anyway, we must go. Come along quickly."

"Oh, you are nasty!" muttered the child, her bright face clouding over, and the former spirit of antagonism returning.

However, she said no more, perhaps because she saw it was useless. She had at last come upon someone whose will was as strong, or stronger than her own. Well, she could afford to wait until the afternoon, when she would be reinforced. An unpleasant smile curled her lips as she remembered again with glee that to-day was Saturday: the absorption of the story-telling had meant a short obliteration of that fact, but it suddenly returned with added force.

The two had a smart run at the finish of their walk, for the storm burst above them suddenly. There was a vivid flash of lightning, followed instantly by a crash that rolled and echoed through the forest, waking a hundred voices in its depths; then down came the rain, in a perfect deluge.

As they entered the front door later, wet through, they encountered Mr. Medhurst just discarding his mackintosh.

"Oh, you've been caught, I see! Pretty big storm," he remarked to Margaret.

"Yes, we are soaked," answered Miss Woodford. "Come, Ellice, hurry and get changed."

"I shan't bother," was the sharp answer; "things will soon dry."

"Go at once, child! Don't stand and talk about it; do as you are told, girlie"—and Margaret gently took the little girl's arm, and led her towards the stairs.

Her father was about to hang up his mackintosh; he paused; then as governess and pupil went to their rooms, a smile of quiet satisfaction touched his lips, as he hung the garment upon the peg, and turned and entered the dining-room.

A quarter of an hour later there was a violent ring at the front-door bell, then a noisy stampede as someone entered with a good deal of clatter, and some eager questioning of James, as the man shut out the swish of rain and wind which with the newcomer rushed into the hall.

"I say, got another?" asked a boy's voice. "Tall and scraggy and glasses, eh?"

"I suppose you are referring to the governess, Master Bob?" said James gravely, but with a slightly suppressed smile flickering in his eyes.

"Of course I am! —I say, what is she like, though?"

"You'd better wait till you see her for yourself."

"Anyway, it means a little fun," continued the boy. "She won't be here long, that's pretty certain," and he commenced to whistle an airy tune as he made to enter the dining-room.

"Stop that noise, and sit down quietly," said his father irritably. "You are late as usual, I see." Further remark was cut short by Ellice rushing into the room and boisterously greeting her brother, followed more gently by Margaret, who paused in astonishment at the sight of the boy of whose existence she had not even heard.

"We've brought our luncheon home to-day, we didn't stay to eat it in the woods, and the tarts are all sloppy," exclaimed Ellice, lying glibly. "You can have them. Bob," anxious to shock Margaret, her voice shrill with excitement.

"Thank you for nothing," answered her brother.

"This is my son, Miss Woodford. You see the specimen he is," said Mr. Medhurst, by way of introduction. "I wonder if you remember the advice of an old sage, 'When you see a boy, beat him, because he has either just done something wrong, is doing it, or just going to do it.' Now I've told you this young man's character in one sentence."

The words were said smilingly, but the smile was ironical.

The boy's bright face clouded, and Margaret felt what a tactless mistake the introduction had been, and wondered at the denseness and unkindness of the remarks.

She turned to Bob pleasantly as she held out her hand.

"I don't believe in very bad boys—I never came across any, and if I did, I shouldn't ask others for their character, Mr. Medhurst," she replied; "I should judge them for myself."

"Wait till you know this one better, Miss Woodford," he answered; and then, turning to Bob: "How about your report," he continued; "did you bring it home?"

"No, sir," answered the boy sullenly.

"Tore it up, I suppose, on purpose?"

"Y-e-s," came the reply, slowly.

"Very well, you know the consequences."

"No, no, daddy; wait till he's done something more," interposed Ellice, dancing round her father, and grasping his arm persuasively.

His face at once softened.

"You think it won't be long before the trouble comes, eh?" he asked, pinching her cheek gently. His small daughter always seemed able to disarm his wrath.

"No—at least—I—mean——" she stammered.

"All right, old lady, I understand," he answered, smiling; then, turning to Margaret, "Women's wiles, Miss Woodford. Well, you are let off this time, young man," turning to his son; "you can thank your sister for it," and with this he left them.

For a few moments silence prevailed, and then Ellice, catching hold of her brother's arm, whispered:

"Come on up to the schoolroom; I've heaps to tell you."

Margaret refrained from following them, to avoid hearing their confidences, and still bewildered by the discovery of this new addition to the family, which might mean further problems for herself, with a little sigh of relief picked up a book and made her way to a quiet cosy seat in the drawing-room.

Ellice Medhurst was full of mystery and excitement as she dragged Bob towards the staircase, anxious to escape observation, leading him to the seclusion of the schoolroom, where they could talk undisturbedly of the new inmate of Oaklands, who had arrived there since Bob's last week-end at home.

"Oh, I say, I do detest her," said Ellice, as she sprang on to the table, placing her feet upon a chair and her face in her hands supported by her arms, her elbows resting upon her knees.

"She looks pretty decent," remarked Bob; "she is a sight better than the one who has just gone. I say, what a shock I gave her, didn't I? She howled like a hyena."

A shout of laughter rippled from his small sister as a memory, mutually considered humorous, roused this expression of mirth.

"I can see her now dancing about, and shrieking, 'Help!—Help!—Burglars!' as if she was being killed," continued Bob, spluttering with amusement.

"And when—you—came—and offered to call father," put in Ellice—"saying, 'What's all this? Whatever is the matter?' I just rushed back into my room and buried my head in the pillows for fear she'd hear me laughing, and guess. Just fancy, Bob, if she had? Wouldn't daddy have been angry?" And as she finished, a more sober expression came upon her face as she pictured unpleasant possibilities.

"If you don't act the little idiot by laughing, no one will guess," answered the boy.

"I won't—I promise I won't," she answered.

"But I say, do you want this one to go?" continued Bob.

"Of course I do. I don't mean to have a governess at all; I said I wouldn't, and I won't."

"Well, you are a bit of a fool. Nice dunce you'll be when you grow up," came the brotherly response.

"I shan't," flashed Ellice. "I can read all right, and when I get older I'll just study, myself. What's the use of all the silly old arithmetic and stuff?"

"Very well, only don't blame me when you are grown up," answered Bob loftily.

"As if I should. Come on; let's fix things," and, creeping softly out on to the landing, and reconnoitring on the staircase, the two stole up to Miss Woodford's room.

Ellice kept guard outside, while Bob evidently fixed matters to their mutual satisfaction. It only took a few moments, and the culprits were back again in their own quarters, their plans duly arranged.

Ellice was wild with delight at the prospect of anticipated fun, as she called it; but in the back of Bob's head there was a little sense of doubt and discomfort.

"She seemed so jolly decent," he muttered to himself; "I hope she won't be awfully frightened. I think you are a little beast to do it to her, Ellice."

"Oh, you don't know her like I do! She was horrid to me, and I'll just pay her out," replied the child.

"All right then. Now shut up about it till to-night."

With this the conspirators went down, ready to behave in an exemplary fashion at tea-time, to disarm suspicion.

Margaret was tired that night in spite of her rest in the afternoon; it was a heavy, slumbrous day, thunder still threatened, and the atmosphere seemed waiting for the refreshment of a cool breeze which might, it was hoped, spring up in the night. It seemed too hot to sleep, and it was quite a long time before Morpheus closed Margaret's lids, and led her into the land of dreams.

It was still dark when she was roused into semi-consciousness by something which at first her senses hardly grasped, then, as full wakefulness came to her, she became cognisant of a soft scraping noise in her room, as if someone might be in her vicinity. She was startled for a few moments, and her heart quickened its beating, as now, fully alert, she listened intently, anxious to discover the reason of the unusual sounds.

This house had held many surprises for her, and she was not quite satisfied in her own mind as to the kind of post she had accepted; but Margaret Woodford was no coward, and therefore she never dreamt of screaming, or getting into a panic, although the noise, which continued at intervals, seemed to come from the ground near her, and each moment to become more distinct.

Suddenly her tension ceased; she had caught the sound of muffled voices outside her room, and in an instant she realised the circumstances. Perhaps her face at that moment would have surprised the culprits outside if they could have seen the hot indignation which surged into it. She waited a little until it died down and she felt calmer, and then, as quietly and stealthily as the enemy, she crept out of bed, and, without lighting the gas, donned her dressing-gown, and, ignoring further preparation, flung the door wide open!

"What are you children doing here?" she asked quietly.

There was the instant flight of a small figure in white, and then Bob, who was stooping down to the floor jerking a string, the end of which issued from under the rug on the landing—Bob, with all the blood in his body seeming to be rushing to his head, rose to his feet.

"Oh, you've tied that to a can under my bed, I suppose?" said Miss Woodford witheringly—"hoping to frighten me? And this is the way you treat lady visitors to your home? And you call yourself a gentleman, I presume?" The tones were scathing—how scathing Margaret scarcely realised herself. "And with childish tricks of this kind," she continued, "you encourage your silly little sister in insubordination."

The door of Ellice's room stood open, and she was listening to every word—"silly little sister." She writhed as she heard the epithet applied to herself; she had felt so clever and important just before, and now she dived under the clothes, cringing with mortification. The sarcastic contempt in Miss Woodford's voice was far worse than the severest punishment Bob had ever endured, and he felt covered with confusion and disgust at his invidious position.

"Go—go to your bedroom at once," finished Margaret, "and see that you don't cause any further trouble."

At this moment Mr. Medhurst opened his door, and inquired if anything was the matter. "Now I shall get it," thought Bob to himself; but he was mistaken. Margaret had spoken in low tones up to now, being most anxious the master of the house should not be disturbed. She was fighting her own battle in her own way, and did not need any court of appeal at present.

"Bob and I both heard a slight noise, Mr. Medhurst," she answered. "But it seems quiet enough now. I don't think there is anything the matter really."

"Cats, perhaps," he answered, smiling; "they do come up these stairs at night sometimes. You are not nervous, I hope, Miss Woodford?"

"Not in the least," she answered. "I think we can all go to bed again satisfied."

"Ah, that's sensible," he replied, adding, as he was in the act of closing his door, "I am glad you came down to reassure Miss Woodford, Bob. I expect you remembered Miss Warner was alarmed in the same way."

Margaret stole a glance at the boy, but he would not raise his eyes to hers, but instead he turned swiftly and fled up to his room. She smiled to herself as she closed her door, then with a little sigh of weariness returned to her slumbers.

Sunday dawned fair and sweet. A sharp shower during the night had freshened the garden and watered the parched ground, which had drunk the moisture up greedily, carrying it down to the roots of the grass and already bringing back the resurrection colour to the brown dried blades in the meadows.

Breakfast passed away without incident. Beyond the usual morning greeting, the young people remained very quiet, and gave only monosyllabic answers to Margaret's attempts at conversation.

Ellice was doubtful as to the consequences of last night's escapade; it was one sign of triumph for the new governess that the child was already growing uneasy, uncertain of herself. She had an affectionate nature really, and it cost her something to steel her heart so persistently against this certainly interesting looking girl who had come to teach her. If Ellice had spoken the truth, she could have owned what she would not admit to herself, that she was longing to make friends, and to get a chance of hearing more stories; but having vaunted the fact to James and Betsy that she never meant to have a governess, the cost to her pride prevented her from giving in.

Miss Woodford guessed her attitude of mind, and was determined to wait patiently, although she had been tempted more than once to resign the post; but—and there was always that but—if this was the chosen work to which she was called, there must be no truckling with a faint heart. No looking back after once having put her hand to the plough, however heavy the furrows might prove, or long and dreary the appointed task.

Bob ate his breakfast in the greatest discomfort; he was really burning with a sense of shame, and making up his mind to an unpleasant duty.

The meal over, Margaret left the house and wandered out into the garden. It was a dear old-fashioned place, with grassy paths bowered with pergolas of roses. Great hedges of tangerine and amethyst pea-blooms filled the air with sweetness. Hollyhocks leaned their tall stems against the ancient garden wall, the old brickwork—a dream of subdued colour—forming a rich background to the brilliant hues of the flowers.

Margaret drank it all in with a breath of delight. The place was rife with roses raising their heads in the sunshine, cooled by the dew-drops glistening on their petals. Zinneas in all shades, and geraniums in massed pinks and scarlet, lined the borders, with gleams of orange eschscholtzia and dainty violas all stretching upward to the golden glory of the sky, while around them fluttered the butterflies, and to Margaret's ears came the sweet hot sound of the song of the humming bees and the murmur of insects talking in the grass.

The girl herself gave just the needed touch of human life to intensify the charm of the scene as she stood looking down at the wealth of flowers. One thought filled her mind with a thrill of praise to the Giver of all good, "How can anyone see these wonders of creation, and catch the sweet fragrance of roses, and doubt God's love, I wonder? Every flower that blooms proves that."

Unconsciously the thought filling her heart had been spoken aloud, and Bob, coming softly down the grassy path, approaching her unheard, caught the words and paused a moment, his attention drawn for the first time in his life to the beauty of nature, and the love message it brings.

Margaret was aroused by a voice at her elbow saying a little nervously:

"Can I speak to you, Miss Woodford?"

"Oh, it's Bob! Certainly!" she answered, an inviting ring in her voice.

"I—I'm awfully sorry about last night—I want you—to—know," he said hesitatingly, his face crimson with shame. "Will you try to—to forget it?" he stammered.

"Why, of course!" answered Margaret. "I shall never think of it again."

"I feel such a beastly cad," he finished.

"Well, for the future remember you are a gentleman, Bob, and that 'manners makyth man,' and you will find it easier to behave as one. And shall we make up our minds to be friends?" she added, holding out her hand with a winning smile. "Come, what do you say?"

"Rather!" answered the boy, and then, breaking away, rushed with lightning speed to the house.

Later in the day Margaret came upon the young people uninterestedly turning over the leaves of story-books, weary of themselves and each other, and not on speaking terms. She had appeared upon the scene at the close of a heated argument, in which Ellice considered Bob had turned traitor by taking up the cudgels on Margaret's behalf.

When he left her so hurriedly in the morning, Margaret hoped she had gained ground with him; but she little knew that the interview meant a big victory, and that Bob Medhurst's allegiance was won for all time.

Now, as she looked at the two, she ventured:

"I have a proposal. What do you say to taking our tea to the woods, and then I'll tell you a story, if you like?"

"Oh, yes—yes," exclaimed Ellice, full of animation at once, and forgetful of all her former animosity.

"Come along then," said Margaret; "let's get a basket from Betsy."

In a few minutes everything was prepared, and the three set off for Wychfield Glade.

It was a perfect afternoon, and Margaret's heart felt lighter as they followed the mossy path which led through the forest to the avenue. Bob's manner showed a subtle change:

"Please let me carry that for you, Miss Woodford," he said shyly, holding out his hand for the tea-basket.

"It's awfully heavy," remarked his small sister, in a loud whisper.

He brushed the remark aside with a look which said plainly, "You shut up."

Margaret accepted the offer with a smile of thanks as she gave up the burden.

"It's very nice to have a gentleman to help one," she said quietly.

The boy coloured slightly. After all, he was his father's son, and knew the attitude of a young savage was unworthy of him, and the role not really satisfactory to himself, although he was not aware that one of the commands of God given in His Word is "Be courteous."

It was quite good fun hunting for wood and arranging a gipsy fire to boil the kettle.

Finding it was too early for tea, Ellice clamoured for the promised story.

"A fairy one," she demanded.

"Not to-day, dear," was the answer.

"Why?" asked the child vexedly.

"Because it's Sunday, and we might think of something more useful."

"Oh, bother! we don't want a Sunday one. Miss Warner tried to make us read a Bible chapter when she was here. We wouldn't, so she read one out loud, and then asked us questions. We didn't answer, did we, Bob?"

"No," replied Bob shortly, but he didn't look at Miss Woodford as he made the admission.

"Oh, it was dry," continued Ellice, "and we didn't understand it. You are not going to do anything like that, are you?" and the child's voice sounded a little entreatingly as she put the question.

"No," Margaret answered, with a smile. "I want to tell you a little bit about the life of a boy whom we read of in the Bible; there is nothing dry in the whole of his history, at least I don't think so. You can tell me what you think afterwards, if you like."

Ellice seemed satisfied with this, and with a good grace settled down to listen. Bob showed no sign either way as to whether he was interested or not.

The hush of the forest was all about them, the wind whispered in the branches of the trees, insects chirped gaily in the undergrowth, and birds and squirrels held busy conclave around their homesteads, but there was nothing to interrupt Margaret Woodford as she began her Sunday talk.

"At an old country house in Kent, when it was under repair, and the workmen were putting down a new floor, in one of the top rooms, underneath the worn-out boards, they found a letter dated 1600, one that had been written to those who lived there centuries before. The letter was so discoloured with age, that although the men who unearthed it stopped their work and stood looking at it for some time, they were disappointed to find they were unable to read any of its contents. But they could not help wondering who wrote it, and what it was all about.

"Now in your home you have got some much older letters than that one. They were written to a young man nearly 2,000 years ago, and you can decipher every word of them, and know where they were sent from, and to whom they were written, and a great deal in connection with the writer. They are such interesting letters that I want to tell you something about them, and then you can read them for yourselves.

"Nearly two thousand years ago there lived in a village in Asia Minor, called Lystra, an old Jewish woman named Lois, and living with her was her daughter Eunice, and her husband who was a Greek, and probably therefore a heathen; and also their little son, a boy named Timothy, and this boy was the one who had those wonderful old letters you have got at home, written to him, all those long, long years ago. You will find them in your Bible; they are called the First and Second Book of Timothy.