"THE PAPER DROPPED TO THE FLOOR" p. 88.

A Romance

By

Margaret Horton Potter

Illustrated by A. I. Keller

New York and London

Harper & Brothers Publishers

1901

Copyright, 1901, by HARPER & BROTHERS.

All rights reserved.

TO

MY DEAREST FRIENDS

AND

KINDLIEST CRITICS

MARIE AND FREDERIC GOOKIN

THIS VOLUME IS

AFFECTIONATELY INSCRIBED

CONTENTS

Book I

CLAUDE

CHAPTER

I. M. De Gêvres Entertains

II. The Toilet

III. The Gallery Of Mirrors

IV. Marly

V. The Chapel

VI. Claude's Farewell

Book II

DEBORAH

I. A Ship Comes In

II. Dr. Carroll's Idea

III. The Plantation

IV. Annapolis

V. Sambo

VI. Claude's Memories

VII. The Pearls

VIII. The Governor's Ball

IX. The Rector, The Count, And Sir Charles

X. Puritan And Courtier

XI. Distant Versailles

Book III

THE POST

I. From Metz

II. The Disgrace

III. November Thirteenth

IV. Claude's Own

V. Two Presentations

VI. Snuff-Boxes

VII. Concerning Monsieur Maurepas

VIII. Deep Waters

IX. The Duke Swims

X. "Vol-au-Vent Royale"

XI. "Thy Glory"

XII. One More de Mailly?

XIII. The Hôtel de Ville

XIV. Victorine Makes End

XV. Deborah

EPILOGUE. A Trail on the Water

ILLUSTRATIONS

"THE PAPER DROPPED TO THE FLOOR" ... Frontispiece

"DE MAILLY HAD THROWN SIX AND SIX"

"'CLAUDE, TAKE THIS AND THROW IT OUT—THERE'"

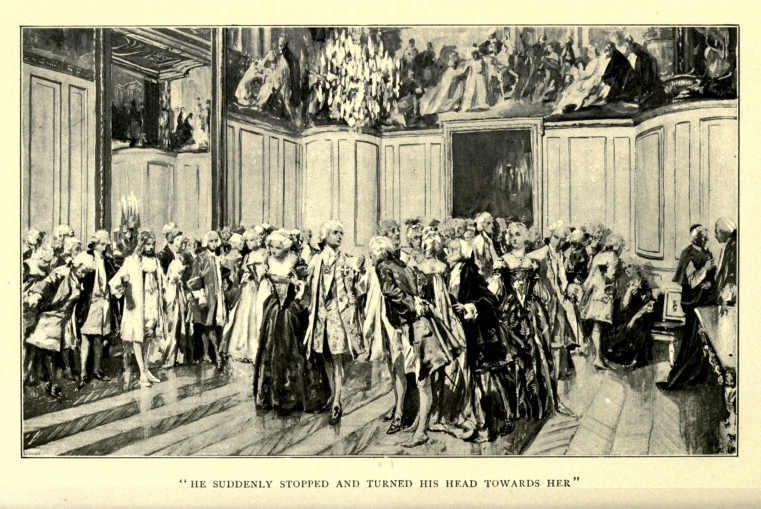

"HE SUDDENLY STOPPED AND TURNED HIS HEAD TOWARDS HER"

"THE YOUNG MAN ROSE AND BOWED"

"CLAUDE SAT SUDDENLY UP IN BED"

"SURROUNDED BY A GROUP OF PICKANINNIES"

"HORSE AND RIDER HAD FLASHED OUT AT THE GATE"

"'GO ON, MONSIEUR,' MURMURED DEBORAH"

"DEBORAH PERMITTED HIM TO LEAD HER FROM THE BALLROOM"

"'I AM NOT THE DUCHESS OF CHÂTEAUROUX!'"

The House of de Mailly

It was the evening of Tuesday, January 12th, in the year 1744. By six o'clock the gray of afternoon had deepened to the blackness of night, and a heavy rain began to fall, so that the Sèvres road, a mile beyond the Paris barrier, was shortly thick with mud. The only light here visible came from the window of a wretched tavern at the way-side; and by this mine host, had he been watching, would have had some difficulty in perceiving the two riders who came to an uncertain halt by his door.

"It is late, du Plessis, and we have still three miles to go. More than that, 'tis the worst cabaret in France."

"And you would be no more of a Jean-Jacques than necessary to-night—eh, Claude?" returned the other good-humoredly.

"I should prefer drowning or to perish of a rheum by the way than be poisoned by the liquor to be had here," returned the other, flicking his saddle restlessly with his riding-whip.

"So be it, then. Come, we waste time. Mordi! A little gently there, I beseech! It is raining mud."

A dig of the spur in the thoroughbred's flank, a spattering of drops from the puddle in which they had stood, a quick apology, and the landlord had lost his guests, illustrious guests, who paid never a sou too much for their wine, but could make a drinking-place the fashion for weeks by five minutes' presence within it.

The two rode for some minutes in silence, though no one of the finest apperception could have felt any enmity existent between them. The night lowered. The rain pelted coldly from the starless sky; and horses and riders alike shrank from the raw, streaming atmosphere. When the silence was again broken the lights of Paris were visible in the distance. This time it seemed that du Plessis—the Duc de Richelieu—addressed his companion's secret thoughts as though he had been reading them for some time past.

"Believe me, Claude, you are unwise. She is not quite—quite of your fibre. The elder branch, you will often find, if you study these things, is less quick in sensibility, though perhaps not lacking in finesse. The King, dear child, the King—"

"The King is a man. I also am one; he, de Bourbon; I, de Mailly."

Richelieu laughed heartily. "Pretty—pretty, Claude! I must enter it in the unauthenticated register at Mme. Doublet's to-morrow! Why do you not lay the matter thus before Mme. de Châteauroux herself?"

"Ah, monsieur, I think you understand her even less than I. I do not dare address her as my position admits. My cousin cannot be more proud of our family than am I; and yet—and yet—"

In the darkness Louis Armand François du Plessis de Fronsac de Richelieu, from strong force of habit, snapped his fingers. "Afraid of a woman! Truly, we have schooled you well, Claude!"

"You, Monsieur le Duc, you yourself—have you kissed my cousin on the lips?"

"Oh, I do not infringe on his Majesty's rights."

"Mon Dieu! If it were any but you!—"

"Come, my dear Count, you are making an enormous mistake, permit me to say. The one thing which no man should ever do is to take himself in great seriousness. You have yet many a lesson to learn about women. Now hear from me a bit of gravity, which shall prove my friendship for all of you—madame, yourself, and his Majesty. When it happens that a man chooses a woman, and the woman accepts that man, whether it be for love, or—something else,—it is the place of the world merely to look on. A third personality will not enter complaisantly into the tête-à-tête. The King heaps upon his Duchess the favors which only a royal lover can confer. And madame certainly does not seem loath to accept them. A dozen besides yourself are sighing after her to-day. Yet remember d'Agenois, my friend. And—and Mlle. d'Angeville is charming in 'L'Ecole des Femmes.'"

De Richelieu smiled slightly, fumbled for his snuff-box, which was unobtainable at the moment, and never knew that Claude had angrily squared his shoulders and was cruelly hurting his horse with bit and spur. The mention of d'Angeville happily turned the subject, as the Duke had intended it to do, and by the time the barrier was reached the vicissitudes of the Count de Mailly and the position of Mme. de Châteauroux were, to all appearances, forgotten.

Once in the city, with rivers of rain above and below, and filth, crime, poverty, and utter darkness about them, Claude de Mailly and his illustrious companion made their way with what rapidity they could down the Rue de Sèvres, past St. Vincent de Paul and the Lazariste, through the little Rue Mi-Carême, the Place du Dragon, Rue Dauphine, and so out upon the quays. After riding for three squares along the river-bank, with the waters of the Seine foaming below them, the two finally passed the Pont St. Louis, and, turning down a short side street, drew up before a doorway wherein lanterns were lighted, and before which two link-boys and twice as many lackeys stood waiting. Above, upon a long iron arm, tossed by the ever-rising wind, swung a great painted sign, a harlequin in cap and bells, throwing his parti-colored cap above his head. Below, in uncertain letters, were the words "Café Procope."

As the two gentlemen dismounted, Richelieu called to one of the servants, who hastened forward to take his bridle. A second assisted Claude, while another, evidently under orders, turned and called back to some one inside. Instantly both doors were flung wide open, while the landlord of this most popular resort himself braved the weather and came out, candelabrum in hand, to greet his guests.

"Ah, Cressin," deigned the Duke, nodding, as he entered the house, "are the rest not yet arrived?"

"Indeed, my lord, they have waited for some time above—Monsieur le Duc de Gêvres, Monsieur le Duc d'Epernon, the Marquis de Mailly-Nesle, and the Baron d'Holbach."

"Um. 'Twas the hunt kept us. Light the way up."

Claude lagged behind to throw off his wet riding-cloak, brush what water he could from his hat, and shake out his hair which had flattened beneath the protecting collar. Richelieu was kept waiting for some seconds, and the landlord had become ill at ease before the young précieuse signified his willingness to proceed to the room above, where his host waited.

Not a bad-looking fellow was Claude de Mailly, albeit what individuality he possessed had some difficulty in asserting itself through the immaculate foppishness of his attire. His wig, a very fine one, was arranged à la brigadière, and tied with the regulation black ribbon. His forehead was broad and smooth, his eyes of a grayish green, shaded with heavy black lashes and good brows, which, however, were artificially pencilled. His nose was one bequeathed of ten generations of noble ancestry; his mouth was sensitive, his complexion dark. The dress that he wore was not expensive, though its ruffles were of fine Mechlin, and he carried both patch and snuff box of ivory and gold. Richelieu, who preceded him up the narrow stairs, was a more striking figure—taller, broader of frame, with well-shaped head, great brown eyes that had carried him through life, a hand like a woman's, with muscles of steel, a smile that had won him a king's heart, and a charm, a power of presence which had made time stand still before him, so that his eight-and-forty years were something less than Claude de Mailly's twenty-three.

Before the two noblemen and the landlord were half-way up-stairs there reached them from above the tones of familiar voices engaged in that species of conversation, half witty, half absurd, which typified the times.

"Parbleu, Baron, you will be calling Richelieu out to-morrow! Your carp will be ruined."

"In such case, Marquis, I must order your cousin spitted. He will have been swimming the streets long enough, by the time he arrives, to have acquired an excellent flavor, of a kind."

"Oh, 'tis more likely that the Count de Mailly's flavor would be rather cloying. All love is sweet; but his is so really violent, gentlemen, that—"

"For a month after you would sicken with the mere thought of a rissole," cried the Duke from the threshold.

"And the epitaph which you would place over my picked bones," said Claude, from behind Richelieu's shoulder, "would be:

Sa chair, même, étant douce comme miel,

Sa nature était aussi belle.

Il entra dans la vie réelle."

"Bravo! Claude. We will forgive the lost feet. You have purchased pardon," cried d'Holbach, smiling. He and de Mailly-Nesle, Claude's cousin and the brother of Mme. de Châteauroux, went forward to greet the late-comers. D'Holbach, epicurean philosopher, and host of the small company, gave them a genial welcome. The Marquis grasped his cousin's hands, and bowed familiarly to the Duke, while the other two men in the room, d'Epernon and de Gêvres, boon companions, both intimates of the King, the one an amateur physician, the other an adept at embroidery, remained languidly seated, deigning a nod and smile to the last arrivals.

After a few further words of greeting and explanation, the party of six arranged themselves about the oval table, on which were already placed the hors-d'œuvres and sweet wines, while Cressin hurried away towards his kitchens to command the attendance of two waiters and the first course of the supper. Only part of the evening's entertainment was being given by the Baron d'Holbach. M. de Gêvres had arranged an amusement for the night which promised some novelty even to these utterly blasé gentlemen. He proposed conducting his friends across the river to his hôtel, which, by royal permission, had, very conveniently for his pocket, been turned into a public gambling-house. Its redoubtable owner, when not at Versailles, lived in exquisite style in his château at St. Ouen; and, since there was always a place for him in the Tuileries, the Hôtel Richelieu, or, more covertly, the Hôtel de Sauvré, in Paris, he had not yet felt any poignant discomfort through the loss of his ancestral house. On the contrary, the unique pleasure of appearing in its familiar rooms furnished with the rows of tables, frequented by bourgeois and dwellers in St. Antoine, with the presence of an occasional petty noble, was really very refreshing to the jaded spirit of this vaporish child of highest France.

It was a particularly select little company who gathered about the table in the private salon of the Café Procope on this stormy night. All of them were of the bluest of blood; all of them spent the greater part of their time about the person of the King; to all, the doors of any and every house or salon in Paris were open at any hour; and not one of them but had had hearts flung at him from the night of his first appearance in the Gallery of Mirrors to the present moment, when interest in the hors-d'œuvres was beginning to wane, and the first course of the supper should have been making its appearance. D'Epernon had commenced to bore them all with some remarks upon the recent blood-letting of his Majesty after a rout at Choisy, when Claude jumped unceremoniously from the table, crossed the room to a mirror, and took out his patchbox.

"Trust you'll have no women to-night, de Gêvres," he remarked, breaking in upon d'Epernon. "I am wet through. My wig is in strings, and the powder has melted away like—like snow in June. While my boots"—taking out a large star and pasting it below the corner of his left eye—"my boots will not be fit for my valet, when we return to-night."

"Claude is standing there, my lords, aching with vanity to have me relate to you how crazily he has borne himself to-day. Ciel! 'Twould be driving me mad with anxiety to learn how soon I should be registering my presence at the Bastille, had I shown myself so little of a courtier, so utterly reckless for the sake of madame's admiration as has he."

Before any one had time to voice his curiosity, Claude turned quickly from the mirror. "The Bastille, Richelieu! The Bastille! Surely—"

"Why not, my child? I have been there thrice for less; and the last time, had it not been for my ever-honored Duchess of Modena—umph! I had been carried out shorter by a head than when I went in!"

The five gentlemen smiled broadly at certain memories still occasionally recalled on a rainy day at Versailles. But Henri, Claude's cousin, looked anxious. "What is your last exploit, Claude? Marie has been inciting you to rashness again?"

Claude laughed. "Madame did not honor me by a single command. I rode a course, I shot a stag, and I won—this, which was intended for a king, not me."

Forthwith the young fellow drew from beneath his waistcoat something which even de Gêvres leaned forward to see. It was a glove, a white gauntlet, weighted on the back with a crest heavily embroidered in gold, and set here and there with tiny sapphires of the color lately known as œil du Roi; while upon the smooth leather palm was painted a very good miniature of his gracious Majesty, Louis XV.

The little group of courtiers glanced from the trophy to the face of its owner, who was gazing upon them with a smile not wholly unconscious, but wisely tempered with cynicism. Presently the Baron reached forward and took the costly article from Claude. Holding it with a delicate touch in the light of a waxen candle, he smiled as he observed:

"Madame should not have removed this ere she gave it to you, my dear Count."

"I would to God she had not!" cried de Mailly-Nesle.

Four pairs of brows went gently up, but Claude's eyes met those of his cousin with such an expression of affection and melancholy that for an instant he seemed to be transformed to some other order of man.

The slight pause was broken by the entrance of the first course proper of the supper. The Count took back his gage and thrust it again to the conventional resting-place over his heart; and while the innumerable dishes were being placed upon the table or passed about, he returned the patch-box to his pocket and seated himself between his cousin and Richelieu.

"Now that Claude has given you his meagre idea of the crisis through which he passed to-day," remarked Claude's companion, helping himself to a fillet of partridge, "permit me to advance to him my own opinion of the affair, as well as to lay the tale before you all. His coming fate shall be surmised by you. Now hark: His Majesty and a little suite rode to Rambouillet yesterday, in the afternoon. The hunters were to follow this morning; but they say that de Rosset never permits the King to rise earlier than eight o'clock, so that he is fain to be near the forest on the day of the chase. I was with him; but, for some royal reason, Madame la Duchesse, despite some very eloquent pleading on my part, had refused to go. Possibly Mme. de Toulouse is of family too scrupulous to receive her."* The Dukes and d'Holbach smiled. "Claude, however, was of the royal train, for, mark you, gentlemen, Louis adores the Count at twenty miles distance from madame his cousin. Well, then, at ten this morning the meet was called at the edge of the forest. His Majesty was in a frenzy of eagerness, and looked—did he not look like a little god, my dear Count? Hein? But for the point. The first deer had not yet been started by the keepers when a diversion occurred. His Majesty was talking with the head man. There was a murmur behind us. I turned about, and saw—"

* The Count of Toulouse was a legitimated son of Louis XIV.

"Monsieur le Comte perishing of loneliness," murmured de Gêvres, feebly.

"Not at all. On the contrary. It was Monsieur le Comte dismounted, standing beside the newly arrived coach of Mme. de Châteauroux, with his head so very far inside the window that it set some of us thinking—many things. Parbleu! I would that you had seen Louis' face."

"Madame must have risen very early," remarked d'Epernon, helping himself to a cream.

"Madame is always wonderful. When she stepped from the conveyance to greet her liege she looked more of a queen than her Majesty ever did. Small wonder that the King was all devotion. Before he had finished his first compliment, the heartless Leroy came forward to announce that stags do not wait. Madame was very gracious, and instantly mounted the horse prepared for her. She had driven from Versailles in her crimson habit. When all was ready, the King turned in his saddle and cried out before us: 'What reward have you to offer, madame, to him who shall present you with the antlers to-day?' We all watched her. She smiled charmingly for an instant. Some turned their eyes then upon the King. I was more subtle. I gazed at Claude."

"He is certainly very pleasant to look upon," observed d'Holbach, absently.

"'Twas not his beauty, Baron. I am most tender of his modesty. But, next time I plead with Mlle. Mercier for life and hope, I shall imitate the look he wore at that moment."

"Take care, my dear Richelieu. She will marry you if you do."

"On my faith, that would not be bad. 'Tis an excellent way to rid one's self of a woman. Baron, the carp is marvellous. Madame, of course, offered the glove that you have seen as gage of triumph. It is worth eighty livres. Lesage himself did the miniatures. When we finally set off, Louis' eyes were bright with certainty of success; for who would dare to engage in rivalry with the King?"

"Come, come, du Plessis, finish the tale. You are straining the budding nonchalance of de Mailly here to an alarming degree."

Richelieu shrugged. "We started, madame following at a little distance, though half a dozen ladies rode. After a quarter of an hour we got sight of the animal, and de Sauvré fired at it, but missed. By the manner in which his Majesty sat his horse, as we raced along to gain on the beast, we all knew that our shots must go astray to-day. Gradually the King drew away from the rest of us, and we reined the horses a little. That is, all but one of us played good courtier. The one was Claude."

"Monsieur, you might dare Satan for a lady if you would; but no one should dare the King."

"Dare the King he did. In five minutes all of us were far enough behind to watch, while they two—de Mailly and de Bourbon, gentlemen—were neck and neck among the hounds. Presently the Count fired, and—missed. I hoped that it was purpose, for he did not reload. Then the stag ran through a little clearing, so that for fifty yards it was a perfect mark. Louis fired, of course, but the game kept on. I saw the King throw back his head with his gesture of anger. Then de Mailly—oh! how couldst thou, Claude?—drew a pistol from his holster and fired. That bullet was made for death, I never saw a prettier shot. It went straight into the deer's neck. Another five yards. The animal wavered. The King was reloading his weapon. Claude was like lightning with his hands. Before his Majesty's gun was ready the pistol sounded again, and the beast fell."

"Good Heaven, Claude! You have done badly!" cried Henri, leaning over the table.

His words were echoed by the rest.

"But his Majesty permitted you the trophy?" drawled d'Epernon, unguardedly.

"Permitted, my lord!" exclaimed the young man, haughtily; "the gauntlet was not his Majesty's to give."

Richelieu laughed. "'Twas a comedy, gentlemen; but a dangerous one. Louis was suavely furious; madame annoyed and alarmed, but as indifferent as any coquette should be. Claude was charmingly humble and amorous. It was I who obtained permission for him and for myself to retire after luncheon. Certainly, Louis seemed entirely willing to grant it. So together we returned to Versailles, dressed, and came on here. And—oh! I had forgot to mention it, but 'twas a marked fact that when madame presented her left gauntlet to her cousin, the January skies instantly began to weep. Now, a question: Was it from sympathy with the King, or dread for the Count de Mailly?"

"Fear for the Count, du Plessis. The King needs small sympathy."

"Possibly thou'rt right, Baron. Who so happy as the King? What does he lack? He is a King; he has France for his purse; he is as handsome as the Queen is ugly; and the most stately woman in Europe inhabits the little apartments. What more could he wish for?"

Claude bit his lip and his eyes sparkled with anger.

"M. de Mailly, you do not eat."

"I have finished, Baron."

"Soho! I did well not to have a second course, then. Now, gentlemen, the toasts. M. de Mailly-Nesle, I propose your marquise."

"Not his wife, d'Holbach!"

"You mistake, Monsieur le Duc. I speak of Mme. de Coigny."

"Ah! With pleasure! She is a most piquant madcap."

Henri flushed. The lady whom he deeply and sincerely loved was a far tenderer subject with him than his reckless and heartless companions dreamed of or could have understood. But he drank the toast without comment, and was relieved to find that the conversation was straying from her as well as from his cousin's affair. Claude, perhaps, was not so well pleased. He was too young a lover, and too much in love, to rejoice that other women were being brought up for discussion; and he was too heedless of the delicacy of his position to care to contemplate its different aspects while the others talked. For, as to the matter of royal disfavor, it disturbed him not in the least; rather he looked upon the prospect of it as something which should redound to his credit in the eyes of her who at present constituted the single motive of his life. For the next twenty minutes, then, he sat over his wine, drinking all the toasts, and joining in the conversation when Mme. de Lauraguais, another sister of Henri's, was mentioned. But the interest had gone out of his eyes. Richelieu marked him silently; d'Holbach smiled with kindly humor on perceiving his preoccupation; and his cousin the Marquis read his mood with regret. Henri de Mailly-Nesle had long since given up any hope of control over his sister, the favorite; and, through a life-long companionship, Claude had been to him closer than a brother. Thus, whatever interest he felt in the latest developments of the Count's rash rivalry with the King, was all on behalf of the weaker side, that of his friend.

The six gentlemen had not been more than twenty minutes over their wine when de Gêvres finally rose from his chair, and, as host for the remainder of the night, made suggestion of departure.

"How shall we cross to my hôtel? It rains too heavily for riding. Shall we go by chair?"

"By chair, monsieur! Pardieu! I had thought we were citizens to-night. Let us walk."

"My dear Baron," expostulated d'Epernon, "my surtout would not stand it, I swear to you!"

"A murrain on your surtout!" retorted Richelieu. "Baron, I accompany you on foot."

"And I also," added Claude. "I wish to ruin my boots completely. I have given Rochard too many things of late."

"A bad idea, Count. Pay your servants, and they leave you at once; it is such a bourgeois thing to do."

"We walk, then?" inquired d'Epernon. "I am sure we must be going to do so when M. de Gêvres addresses M. de Mailly upon the care of servants. Monsieur le Marquis—your servant."

Richelieu and the Baron were already at the door. D'Epernon and Henri followed. There was nothing for it but for the third Duke to accept the companionship of the Count, and prepare to ruin his surtout also. As the small party passed out of the door of the café, Richelieu called over his shoulder:

"Your horse is here, Claude. I had mine sent to my hôtel. Surely you will not attempt to ride back to Versailles to-night. Will you lodge with me?"

"Thank you; but Henri will house me, I think—will you not, cousin?"

"Certainly, Claude. Madame will scarcely have any one in my wing to-night, I think; though I confess that I have not been there for a week."

"A bad idea," muttered Richelieu to the Baron. "I kept my ladies in better training—when I had them."

It was fifteen minutes' rapid walk from the Procope to the Hôtel de Gêvres. From the Quai des Tournelles the six proceeded to the Pont St. Michel, over the river, across the island, and to the new city by the Pont au Change, at the east end of which, near the Place du Chat, stood the most recent and most noted gambling-house in Paris. Three or four lanterns, shining dimly through the dripping night, lighted the doorways, which were open to the weather. Richelieu, d'Holbach, d'Epernon, and Henri entered together, with Claude and de Gêvres close behind. It was Richelieu who accosted the manager of the house in the entresol; for the owner of the place was not desirous of recognition. M. Basquinet, discerning that the new-comers were of rank, in spite of the fact that they came on foot, at once offered a private room.

"The devil, good cit, d'ye take us for a pack of farmers-general? By my marrow, I've scarcely livres enough to grease the dice-cup, let alone paying your nobility prices for new wine and bad rum. Private room—ha! excellent, you tax-collector, excellent, excellent!"

So spake Richelieu, in his favorite badaud, with a tone that no dweller in the Court of Miracles could have bettered for its purpose. The little party smiled covertly at sight of the landlord's crestfallen air, and then the other five followed their new plebeian leader up the broad ancestral staircase, leaving behind the steady murmur of voices and the chink of coin which had reached their ears from the chance-machine rooms on either side of the hallway. On the second floor were the public rooms for played games; on the third, private apartments for such as chose to make a retreat of the place. And, in truth, many a well-known quarrel had fomented, and many a desperate duel already been fought, in those chambers, which of old had sheltered the royal and noble guests of the family de Gêvres.

The dice-room, the destination of Monsieur le Duc's present distinguished company, was very large, having once been the grand salon of the house. It was well filled by this hour, thick with smoke, heavy-aired with the fumes of mulled wine, and alive with the clack of the implements of the game and the subdued murmur of exclamations and utterances. The six gentlemen made their way to a table in the far corner of the room from which the door was invisible; and, seating themselves, they called at once for the cups, English pipes, and English rum.

"By all means, rum," nodded the Baron d'Holbach. "What other beverage would harmonize with this scene? We are surrounded by those a step lower than the bourgeoisie. For the time we also are lower than the bourgeoisie."

"And by to-morrow we shall have still stronger means of appreciation," retorted d'Epernon, "for our heads will feel as those of the bourgeoisie never did."

The rum was brought, however, together with dice, and those long-stemmed clay pipes of which one broke three or four of an evening, and but rarely drew more than one mouthful of smoke from a light. Still imitating the manners of those about them, each two gentlemen played with a single cup, thus doing away with any possibility of loaded dice. Unlike the common people, however, they used no money on the table; perhaps for the simplest of reasons—that they had no money to use. "Poor as a nobleman, rich as a bourgeois," was a common enough expression at that day, and as true as such sayings generally are. How debts of honor were paid at Versailles none but those concerned ever knew. But paid they always were, and that within the time agreed upon; and there was no newly invented extravagance, no fresh and useless method of expenditure for baubles or jewelled garments, that every courtier did not feel it a duty as well as pleasure to indulge at once. For the last twenty-five years there had been, as for the next five there would be, a continually increasing costliness in the mode of Court life, and a consequent diminution in Court incomes, until the end—the end of all things for France's highest and best—should come with merciful, swift fury.

Each member of the party, this evening, played with him in whose company he had walked from the café: de Gêvres and the Count; Richelieu and d'Holbach; d'Epernon and Mailly-Nesle. The three games were in marked contrast to those carried on about them. Not a word relative to losses or winnings was spoken. The stakes were agreed upon almost in whispers; the cubes were rattled and thrown—once; then again from the other side. The differences were noted mentally. Winner and loser sipped their rum, drew at a pipe, and made a new stake. Sometimes ten minutes would be spent in watching the noisy eagerness of men at a neighboring table, for that was the chief object in their coming to-night.

The great hall was filled with those of an essentially low order. Coarse faces, coarse manners, coarse garments, and coarse oaths abounded there, though now and again might be found a velvet coat, a lace ruffle, and a manner badly aped from the supposed elegancies of the Court. A strange and motley throng gathered from all Paris wherever this common vice held men in its grip. Here those from the criminal quarters, from the Faubourg St. Antoine, from the streets of petty shopkeepers and tradesmen, from the little bourgeoisie, came to mingle together, indiscriminately, equalized, rendered careless of the origin of companions by their common love of the dice. Here were men of all ages, from the fierce stripling who regarded a franc as a fortune, to the senile creature, glued to his chair, the cubes rattling continually in his trembling cup, and the varying luck of the evening his life and death. All the pettiness and some of the nobility to be found in mankind were portrayed here, could those who had come to study have read aright. D'Holbach, the philosopher, doubtless did so, for men had been his mental food for many years. Nevertheless he said nothing to Richelieu of what he discovered; but took snuff when he lost, and puffed at his pipe when he won, and cogitated alone among those whom he knew so well.

Time drew on apace and the evening was passing. There were few arrivals now; the rooms were filled, and it was too early for departure. M. de Gêvres wished, possibly, that the hours would hurry a little, for he was losing heavily to Claude. Nevertheless he gave no sign of discomfort, and even interrupted the Count's purposeful pauses to continue the game. Just as de Mailly shook for a stake of five hundred livres, two people, gentlemen by dress, entered the room. Claude threw high. The Duke, with an inward exclamation of anger, gently received the cup. He shook with perfect nonchalance, and finally dropped the ivory squares delicately before him.

"Bravo, M. de Gêvres; you have thrown well!"

The Duke started to his feet. His example was speedily followed by the rest of the party, who, after bowing with great respect, stood looking in amazement at the new-comer. His companion, who was bareheaded, remained a little behind, grinning good-naturedly at the gamesters. Richelieu spoke first:

"Indeed, your Maj—"

"Pardon, du Plessis, the Chevalier Melot."

"Your pardon, Sire. You take us by surprise."

"Has any one suffered from the shock?"

"I, Sire, I think, since your coming has turned my luck," remarked Claude, with the double meaning in his words perfectly apparent to every one there.

"Um—yes, I had thought M. de Gêvres must win with eleven. Come, gentlemen, add two to your party, and forget, for the evening, even as he will do, the unimpeachable propriety of M. de Berryer."*

* The Chief of Police, and a favorite companion of the King.

De Berryer laughed, and drew two more chairs to the table.

"Do not stand," continued the King. "I am merely Chevalier to-night."

Louis seated himself beside Richelieu, with whom he evinced a desire to speak privately. D'Holbach, perceiving this, began at once, with his usual tact, to entertain the rest of the company by an anecdote concerning d'Alembert and Voltaire. Immediately the King turned to his favorite courtier.

"De Mailly came straight to Paris with you to-day?"

"We rode to Versailles first, Sire; changed our clothes there, and came hither immediately."

"And now the truth, Richelieu. I will brook nothing less. He did not see madame after he left the hunt?"

The Duke opened his eyes. "We left Mme. de Châteauroux with you. We have not seen her since."

The King drew a deep breath. "She left the hunting-party half an hour after you, knowing that it was not in my power to follow her. I feared it was to join—him. I have left everything to make sure of his whereabouts. The fellow drives me mad."

While Louis spoke a gleam came into the Duke's eyes. He smiled slightly, and said; with a nod towards de Berryer, and that daring which was permitted to him alone, "Your Majesty brought a lettre-de-cachet in some one else's pocket?"

Louis looked slightly nonplussed. He shrugged, however, as he answered, "No lettre-de-cachet will be used." Then, as the laughter from the Baron's tale subsided, the King addressed the party: "We will not stop your game, my friends. In fact—in fact, I will myself play one of you."

"And which of us is to be so honored, Chevalier?" inquired d'Epernon.

"It is a difficult choice, I confess. However, choice must be. Monsieur le Comte, will you try three turns with me?"

There was a little round of glances as Claude bowed, murmuring appreciation of the honor.

"The dice, then!" cried the King. "Richelieu, your cup. We will play with but one."

"And he who throws twice best shall win?" repeated the Duke.

"Yes."

"What are the stakes?" inquired the Baron, gently.

Claude's heart sank, while his cousin dared not allow his sympathy to appear. It was frequently ruinous work, this gaming with a King; and the revenues of the younger branch of the house of de Mailly were not great.

"The stakes," returned Louis, with a long glance at his opponent, "shall be, on my side—" he threw back his cloak, unbuttoned a plain surtout, and from his ruffles unfastened a diamond star of great value—"this." He placed it upon the table.

There was a little, regular murmur of conventional admiration. Claude bit his lip thoughtfully. "And mine?" he asked, looking squarely at the King.

Louis coughed, and waved one hand, with a gesture of deprecation at the question. "Yours should not be so large. We play to the goddess of chance. You—um—ha—you won, to-day, a certain gauntlet of white leather; a simple thing, but it will do. I will play this for that. You see the odds are favorable to you."

Claude flushed scarlet, and not a man at the table moved. "The gauntlet was a gage, Sire."

"We play for it," was the reply.

The Count glanced round the circle, noting each face in turn. Baron d'Holbach was engaged with snuff. The other faces, excepting only de Berryer's, were blank. But Richelieu's eyes met those of Claude, and the head of the King's favorite gentleman shook, ever so slightly, at the rebellion in the Count's face. Then, very slowly, de Mailly unfastened his coat and drew from its place the glove of Mme. de Châteauroux. He laid it on the table beside the star.

"We play!" cried his Majesty, smiling as he seized the leathern cup. He shook well, and dropped the dice vigorously before him.

"Seven!" cried the company. It was four and three.

Claude received the implements from the King's hands, tossed and threw.

"Eight!" was the return. It was three and five.

The King bit his lip, and hastily played again. The cubes stared up at him impudently. On one was a three, on the other a one. None spoke, for Louis frowned.

Claude was very sober but very composed as he tried his second chance. It seemed that he could not but win. The courtiers hung quietly on the play. When the cup was lifted from the dice there was a series of exclamations. Claude himself laughed a little, and the King drew a long sigh of relief. Two and one had de Mailly thrown.

It was Henri who voiced the general interest. "You are even," he said, quietly.

The King suddenly rose to his feet. "Not for long!" he exclaimed. For some seconds he rattled the dice in the box, not attempting to conceal his palpable nervousness. When the black spots which lay uppermost were finally counted, a smile broke over the royal lips. Ten points he had made this time.

De Mailly, who had also risen, looked at them for a second with compressed lips, but did not hesitate in his throw. Like de Gêvres, he dropped the squares before him with pointed delicacy. Then he stepped quietly back, with a throb at his heart, but no change in his face. Not a courtier spoke.

"We will play again!" cried the King, loudly, for they were, indeed, no longer even. M. de Mailly had thrown six and six.

"DE MAILLY HAD THROWN SIX AND SIX

"Pardon, your Majesty," said Claude, in reply to the King's voiced desire. "I could not play again against France and hope to win, though by but a single point. Therefore I beg that you will spare my humiliation, and accept the gauntlet as proof of your gracious forgiveness of my daring."

At this Richelieu looked open-faced approval upon the Count; and de Gêvres and d'Epernon, who had been roused from their ordinary state of ennui by the pretty comedy played before them, glanced at each other with appreciation of so excellent an act of courtiership.

"Monsieur le Comte, if I accept your generosity, it must only be on condition that, as gage of my esteem for you, and our mutual good-will, you wear this star. Permit me to fasten it upon your coat."

The small ceremony over, and the light of royal favor glittering in the candle-rays over the Count de Mailly's heart, his Majesty, with tender touch, took up the coveted gauntlet, put it inside his embroidered waistcoat, and, placing his hand on de Berryer's shoulder, bowed a good-night to the party and the Hôtel de Gêvres.

Immediately after the King left, the other participant in the struggle for a woman's gage also rose. Claude was tired. He had no mind to be assailed with the volley of epigrams, bons-mots, and various comments that he knew would soon begin to be discharged from the brains of his companions. Certainly, he should have considered the episode a happy one. Already, since that talk of esteem and good-will from the King, he could feel the change in attitude assumed towards him by de Gêvres and d'Epernon. But the sight of these figures wearied him now; and he suddenly longed for a solitude in which to face his rapidly growing regret that his cousin's glove had passed out of his possession.

"What, monsieur!" cried de Gêvres, when he rose, "you will not give me the chance to retrieve myself to-night?"

"Small hope for you with such luck as the Count's," returned d'Holbach. "When a man wins two points off a king, by how much may he defeat a duke? Reply, Richelieu. It is geometry."

Richelieu laughed. "I congratulate you, Monsieur le Comte," he said.

De Mailly bowed. Then, turning to the Marquis, he held out his hand. "Will you come, Henri, or must I beg shelter of Madame la Marquise alone?"

"I come, Claude. Good-night, and thanks for a most charming evening, and a comedy worthy of Grandval, messieurs."

"Thank thy sister for that," returned de Gêvres.

Claude made a general salute, and then, without further parley, accompanied his friend from the room and the house.

"My horse is still at the Procope," observed Claude at the door.

"No, I ordered it sent to my hôtel before we left the café."

"We walk, then?"

"I am afraid so. I did not think to order my coach, and not a chair will be obtainable on such a night."

"It is as well. The exercise will be a relief."

They started at a good pace up the long, wide thoroughfare that bordered the river, and walked for some minutes in a silence that was replete with sympathy. It was some distance from the gambling-house to the Hôtel de Mailly, Henri's abode, which was situated on the west bank of the Seine, on the Quai des Théatins, just opposite the Tuileries, on the Pont Royal. The wind was coming sharply from the east, bringing with it great, pelting rain-drops that stung the face like bullets. Henri was glad to shield his head from the cutting attack by holding his heavy cloak up before it. Ordinarily the walk at this hour would have been one of no small danger; but to-night even the dwellers in the criminal quarter were undesirous of plying their midnight trade by the river-bank. The cousins had passed the dark cluster of buildings about the old Louvre before either spoke. At length, however, the Marquis broke silence.

"Claude, you have passed a point in life to-day, I think."

"With the two that I won from the King, Henri?"

"Those and the gauntlet of Marie Anne."

There was a little pause. Then Claude said, in a tone whose weary monotony indicated a subject so often thought of as to be trite even in expression:

"Do you—ever regret—that Anne went the way—of the other two? Will she—do you think, finish as did poor little Pauline? Or—will some other send her from her place—as—she did—my brother's wife, Louise?"

As Claude had hesitated over the questions, so was Henri long in making reply. "I do not allow myself, Claude, to wonder over might-have-beens. There is a fate upon our family, I think. But of the three of our women who have gone her way, Marie is the fittest of them all for her place. Little Pauline—Félicité, we named her—her death—my God, I do not like to think of it! And poor, weak Louise—your brother loved her dearly, Claude. And he is dead, and she—is making her long penance in that great tomb of the Ursulines. Heigh-ho! Thank the good God, my cousin, that you have neither sister nor wife in this Court of France. There is not one of them can withstand the great temptation. Our times were not made for the women we love."

And for the rest of their walk both men thought upon these same last words, which, through Claude's head, at least, had begun to ring like a dark refrain of prophecy, of warning: "Our times were not made for the women we love."

It was half an hour past midnight when the Marquis pounded the knocker on the door of his hôtel by the Seine. It was opened with unusual readiness by the liveried porter, who betrayed some surprise at sight of those who waited to enter.

"Oh, my lord is not at Versailles!"

"As you see, we are here," returned Henri, adding, "My apartment is ready?"

"Certainly, Monsieur le Marquis' apartment is ready."

"And one for Monsieur le Comte?"

The servant bowed.

"Light us up, then. Claude, will you have supper?"

"No. Nothing more to-night."

"Very well. Gaillard, is madame visible?"

The porter coughed. "Madame la Marquise was at Mme. de Tencin's till late. Madame, I think, is not visible."

Mailly-Nesle shrugged his shoulders, and proceeded to the staircase. As the servant followed with a candelabrum he made a curious, soft noise in his throat. Forthwith a footman glided swiftly into the hall from an antechamber, and took the other's place beside the door as if waiting for some one. Both nobles saw it. Neither spoke.

Five minutes later Claude was alone in his room. Henri had left him for the night, and he refused the services of a lackey in lieu of his own valet, who was at Versailles. The servant had lighted his candles, and a wood-fire burned in the grate. His wet coat had been carried away to dry. His hat, surtout, and gloves lay upon a neighboring chair. Amid the lace of his jabot glittered the jewelled star which, two hours ago, had flashed upon the breast of the King of France. Claude seated himself, absently, in a chair beside the cheerily crackling fire, facing a great picture that hung upon the brocaded wall. It was Boucher's portrait of Marie Anne de Mailly-Nesle, Marquise de la Tournelle, Duchesse de Châteauroux. She looked down upon him now in that calmly superb manner which she had used only this morning; the manner that the Court had raved over, that women vainly strove to imitate, that had conquered the indifference of a king. And as Claude de Mailly gazed, his own air, shamed perhaps by that of the woman, fell from him, as a sheet might fall from a statue. In one instant he was a different thing. He had become an individual; a man with a strong mentality of his own. The courtier's mask of imperturbable cynicism, the conventional domino of forced interest, the detestable undergarments of necessary toadyism, all were gone. Not the patch on his face, not the height of his heels, not the whiteness of his hands nor the breadth of his cuffs could make him now. Perhaps she whose painted likeness was before him would no more have cared to know him as he really was than she would have liked the words that he uttered, dreamily, before her picture. But it was the true Claude, Claude the man, nevertheless, who repeated aloud the thought in his heart:

"Our times are not made for the women we love."

Dawn, the late dawn of a gray, wintry morning, hung over Versailles. Within the palace walls those vast corridors, which had lately rung to sounds of life and laughter, stretched endlessly out in the ghostly chill of the vague light. Chill and stillness had crept also under many doors; and they breathed over that stately room in which Marie Anne de Châteauroux was accustomed to take the few hours of relief from feverish life granted her by kindly sleep.

Though the favorite's apartment was as dark as drawn curtains could make it, nevertheless a thin gleam of gray shot relentlessly between hanging and wall, and, falling athwart the canopied bed, announced that madame's temporary rest approached its end. Against this decree, however, madame's attitude would seem to rebel. She lay, apparently in profound sleep, in the very centre of the great bed, sheets and cover drawn closely about her, up to her throat. Only one hand, half hidden in lace, and her head, with its framing mass of yellow, powder-dulled hair, were visible. In her waking life that head of the Duchess of Châteauroux was celebrated for its marvellous poise. And even now, as it lay relaxed upon the pillow, the effect of its daytime majesty was not quite lost. Viewed thus, devoid of animation or expression, the pure, classic beauty of the face showed to better advantage, perhaps, than at another time. Already, however, ennui, and the constant effort at appearance of pleasure, had left their marks upon the regular features; and, indeed, much other than mere beauty might be found in the countenance. If there were power in the breadth of the forehead, there was too much determination in the chin; while at each corner of the delicate mouth a faint line gave a cast of resolution, dogged and relentless, to the feminine ensemble.

Presently, as the shadows melted more and more, the woman's silken-lashed eyes fell open, and the first of her waking thoughts was expressed in a long, melancholy sigh.

The duties of the Duchess as Lady of the Palace of the Queen necessitated her presence at the grand toilet of her Majesty on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. On Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday, therefore, except on those weeks when she was in constant attendance on Louis' consort, the Châteauroux accustomed the Court to a toilet of her own, which the King's faction religiously frequented, while the Queen's circle, the religious party, rolled their eyes, clasped their hands, violently denounced the insolence of it, and fervently wished that they might go, too. Certainly madame's morning receptions were eminently successful, and, however much gentle Marie Leczinska might disapprove of them in secret, she never had the courage to anger her husband by voicing her sense of indignity. Thus, six mornings of the week being provided for, on Saturday the Duchess confessed herself, though no absolution was to be had, and prayed forgiveness for the other part of her life.

As madame awoke, and the clock upon her mantel-piece struck eight, a door into the room swung open, and a trimly dressed maid came in. She pushed back the curtains from the window, looped them up, and crossed to the bedside.

"'Tis you, Antoinette?" came a voice from beneath the canopy.

"Yes, madame. Shall I bring the water?"

"At once."

As Antoinette once more disappeared, madame sat up and pushed aside the curtains of her bed.

For the following quarter of an hour, while the first part of the toilet was being performed, the second and elaborate half of that daily function was prepared for in the second room of the favorite's suite—the famous boudoir. A remarkable little room this, with its silken hangings of Persian blue and green and white; and a remarkable little man it was who sat informally upon a tabouret, in the midst of the graceful confusion of chairs, sofas, consoles, and inlaid stands, while in front of him was the second dressing-table, whereon reposed the paraphernalia of the coiffeur, and beside him was a small bronze brazier, where charcoal, for the heating of irons, burned. The profession of M. Marchon was instantly proclaimed by his elaborate elegance of wig. He had been, at some time, perruquier to each French queen of the last three decades, from Mme. de Prie to the ill-fated sisters of the present Duchess. Just now he was ogling, in the last Court manner, the second wardrobe-girl, who stood near him, beside a spindle-legged table, polishing a mirror. And Célestine ogled the weazened Marchon while she worked and wondered if madame would miss her last present from d'Argenson, a Chinese mandarin with a rueful smile, who sat alone in the cabinet of toys, and ceaselessly waved his head. The courtly companionship between the two servants had lasted for some time when there came a faint scratch on the bedroom door. It was Antoinette's friendly signal. The hair-dresser leaped to his place and bent over the irons, while Célestine forced her eyes from the bit of porcelain and put away her polishing cloth as Mme. de Châteauroux entered the room.

The Duchess seated herself before the first table, where Mlle. Célestine administered certain effective and skilfully applied touches to the pale face, and when these had rendered her to her mind for the hour, madame surrendered herself into Marchon's hands, where she would remain for a good part of the morning.

The preliminary brushing of the yellow locks had not yet been completed when the first valet-de-chambre threw open the door from the antechamber and announced carefully:

"The Duc de Gêvres."

De Gêvres, as usual, delayed his entrance a full minute. Then he came in languidly, snuff-box in his right hand, hat under his arm, peruke immaculate, and eye-glass dangling at his waist. He bowed. Madame raised her hand. The Duke advanced, lifted it to his lips, and left upon its fair surface a faint red trace of his salute. Madame smiled.

"You have come to me early," she said.

"I arose," remarked the man, pensively, "to find the world in gray. I arrayed myself to match the sky, and came to seek the sun. When I leave you I shall don pale blue, for you will drive the clouds from my day."

Madame smiled again. "Thank you. But the gray is marvellously becoming. Pray do not attempt a second toilet this morning. One is singularly depressing."

"Surely, you are not depressed, Madame de Versailles?" he asked, idly, examining her negligée of India muslin with approval. "Why depressed? Louis was furious at your unaccountable absence from the salon last evening, and would play with no one. He stayed in a corner for two hours, railing at d'Orry and permitting not a soul to approach. Is it in pity for him, this morning, that you suffer?"

Madame shrugged. "I do not waste time in pity of his Majesty. At the request of Mme. d'Alincourt, I spent last evening in the apartments of the Queen."

"Good Heaven! Then, madame, allow me to express my deepest sympathy! I had no idea that you would play so recklessly with ennui. Why, your very gossip is a day old!"

"You, then, monsieur, I hail as my deliverer. Will you not act as my Nouvelles à la Main, that I may make no irretrievable blunder to-day?"

"Madame desires, the King is at her feet. Madame requests, and the gods obey. Where must one begin?"

"At the beginning."

De Gêvres smiled slowly in retrospection. It was for this precise opportunity that he had risen an hour early and dared royal displeasure by being alone with the favorite for thirty minutes. He rose from the chair he had taken, drew a tabouret to within a yard of the Duchess's knee, and reseated himself significantly.

"You frighten me, my lord. It must be serious."

De Gêvres shrugged. "Oh, not necessarily. You shall judge." He glanced meditatively at her feet, tapped his snuff-box, and began to speak just as Marchon finished the first curl. "Without doubt, madame, even after the deplorable past evening, you still recollect the rather outré events of the day before. You cannot yet have forgotten the last Rambouillet chase, the gage you offered, his Majesty's unfortunate chagrin, and the intrepid, if rash, ardor of your young cousin, Count Claude?"

"Thus far my memory carries me, monsieur. Continue."

"Well! The rest is, indeed, curious. In spite of the Count's heroic gallantry, he appeared, later in the day, to have repented somewhat of having so eagerly dared the royal displeasure. A company of my friends were so good as to visit, with me, my hôtel—you know its condition—for play, on this very evening. By great good fortune, his Majesty, together with a companion, did us the honor himself to join our party a little later. When the King beheld his successful rival, the Count, seated with us, he instantly proposed that the two of them play a round for high stakes. Louis, madame, offered a diamond star—valued, perhaps, at fifty thousand francs, or more, against—"

"My glove."

"Even so. You have, perhaps, heard the tale?" queried the Duke, hastily, with a suspicion of anxiety in his voice.

Mme. de Châteauroux noticed this, but her face continued to be as impassive as that of her smiling mandarin. "You forget my evening, monsieur. I know nothing. Continue, I beg of you."

"Monsieur le Marquis de Coigny and the Comte de Maurepas!" announced the valet.

De Gêvres coughed, but his face expressed none of the disappointment that he felt.

Mme. de Châteauroux greeted both gentlemen with imperturbable courtesy, and the three nobles, after her salutes were over, exchanged greetings. Then the favorite said, at once:

"Pray be seated, messieurs. M. de Gêvres is telling me a most interesting anecdote. Pardon if I ask him to finish it. Since it in a way concerns myself, I am so vain as to be curious."

The late-comers bowed and looked at the Duke, who, in that instant, had mentally sounded the intruders, considered his course, and decided to risk a continuance of his original plan. Without any noticeable hesitation, the story went on.

"As I said, his Majesty and the Count de Mailly were to play together for possession of the glove. The King threw first—four and three. De Mailly came next with five and two."

"Ah!" murmured de Coigny.

"Again Louis with ten, and the Count turned precisely the same number. His Majesty was visibly tingling with anxiety. He was about to throw for the last time, with a prayer to the gods, when the Count—um—took pity on him."

"He offered the glove?" asked madame, quietly.

De Gêvres bowed. "In a way, Duchess. He offered to—exchange the stakes."

"Oh!" cried Maurepas, angrily.

"Dastardly!" muttered de Coigny.

Mme. de Châteauroux flushed scarlet with anger beneath her powder.

Little Marchon, trained to high gallantry by long experience in haunts of the elect, left an iron in too long, and slightly scorched a lock of hair. His little eyes winked furiously with disapproval of the Count.

"Monsieur le Marquis de Mailly-Nesle!" came the announcement.

De Gêvres coughed again; and, amid rather a strained silence, Henri entered the apartment of his sister.

He looked about him for a moment or two with some curiosity, feeling the awkwardness of his arrival, and considering what it would be wise to say. Maurepas, the diplomat, recovered himself quickly, remarking, in a tone which relieved them all: "This brother's devotion, my dear Marquis, is gratifying to behold. One is really never so certain of finding you anywhere at a given hour as here, in your sister's boudoir."

"Mme. de Coigny has, I believe, no mornings à la toilette," observed Mme. de Coigny's husband.

Maurepas looked sharply at the speaker, while the others smiled, and the Duchess made every one still easier by laughing lightly.

"Her sang-froid is unapproachable," murmured de Gêvres to Maurepas, behind his hand.

"You have certainly put it to strong test this morning," was the reply, rather coldly given.

"L'Abbé de St. Pierre and l'Abbé Devries!"

The two ecclesiastics entered from the antechamber and advanced, side by side, towards the Duchess. The taller of the two, St. Pierre, was a very desirable person in salon society, and could turn as neat a compliment or as fine an epigram in spontaneous verse as any member in the "rhyming brotherhood." At sight of St. Pierre's companion, who was a stranger here, the Marquis de Coigny gave a sudden, imperceptible start, and Henri de Mailly suppressed an exclamation.

"Madame la Duchesse, permit me to present to you my friend and colleague, l'Abbé Bertrand Devries, of Fontainebleau."

"I am charmed to see you both," deigned her Grace, giving her hand to St. Pierre, while she narrowly scrutinized the slight figure and delicate, ascetic face of the other young priest. The mild blue eyes met hers for a single instant, then dropped uneasily, as their owner bowed without speaking, and passed over to a small sofa, where, after a second's hesitation, he sat down. St. Pierre, who seemed to cherish some anxiety as to his new protégé's conduct, followed and remained beside him.

"Unused to the boudoir, one would imagine. It is unusual for one of his order. I am astonished that St. Pierre should have brought him to make a début before you," observed de Gêvres to la Châteauroux, who had not yet removed her eyes from the new priest.

"St. Pierre knows my fondness for fresh faces," she replied, indifferently, picking up a mirror to examine the coiffure, just as her lackey entered the room with small glasses of negus, which were passed among the party.

While de Coigny raised a glass to his lips he turned towards Devries. "You have spent all your time in Fontainebleau, M. Devries?" he asked, seriously.

"By no means, monsieur," was the answer, given in a light tenor voice. "Indeed, for the last two weeks I have been working in Paris."

"Working! And what, if my curiosity is not distasteful to you, is your work?" queried madame, still toying with the mirror.

"By all means," murmured de Gêvres, comfortably, after finishing his mild refreshment, "let us hear of some work. It soothes one's nerves inexpressibly."

Devries' blue eyes turned slowly till they rested on the slender figure of the Duke, clad in his gray satin suit, his white hands half hidden in lace, toying with a silver snuff-box. The eyes gleamed oddly, half with amusement, half with something else—weariness?—disgust?—surely it was not ennui; and yet—in an avowed courtier, that was what the look would have seemed to express.

"I will, then, soothe your nerves, if you wish it, sir. My work certainly was very real. For the past two weeks my abode has been in the Faubourg St. Antoine, but my days were spent in a very different part of the city. At dawn each morning, in company with my colleague—not M. de St. Pierre, here—I left behind those houses whose inmates rejoiced in clothes to cover themselves, in money enough to purchase a bone for soup daily, and who were even sometimes able to give away a piece of black bread to a beggar. These luxurious places we left, I say, and together descended into hell. It might amuse you still more, monsieur, to behold the alleys, the courts, the kennels, the holes filled with living filth into the midst of which we went. There women disfigure or cripple their children for life in order to give them a means of livelihood, that they may become successful beggars; there wine is not heard of, but alcohol is far commoner than bread; there you may buy souls for a quart of brandy, but must deliver your own into their keeping if you have not the wherewithal to appease, for a moment, their hatred of you, who are clean, who are fed, who are warm. Cleanliness down there is a crime. Ah! how they hate you, those dwellers in the Hell of Earth! How they hate us, and how they curse God for the lives they must lead! The name of God is never used except in oaths. And yet a girl, whose dying child I washed, knew how to bless me one day there. It seems to me that they might all learn how, if opportunity were but given them. There has been some bitter weather lately, when the frozen Seine has been a highway for trades-people. Those creatures among whom I went make no change from their summer toilets, gentlemen. Half—all the children—are quite naked. The women have one garment, and their hair. The men are clad in blouses, with perhaps a pair of sabots, if they can fight well to obtain them, or are ready to do murder without a qualm to keep them in their possession. It is among these people that I worked, Monsieur—de Gêvres—with my colleague."

"How eminently disgusting!" replied the Duke, calmly, but his remark was not pleasing to the rest of those present, who had been actually affected by the description. Henri de Mailly had risen to his feet, and, after a moment's pause, asked, rather harshly, "Who was your colleague, monsieur?"

The Marquis de Coigny shot a quick, warning glance at Henri, and raised his hand. "Monsieur l'Abbé, I am interested in your story. Would you do me the honor to breakfast with me this morning, and tell me more of this life?"

The little audience stared, and la Châteauroux lifted her head rather haughtily. Devries appeared, for some reason, to be very much amused.

"You are too good, Monsieur le Marquis. I have already partaken of my morning crust. Besides, you, doubtless, are happy enough to be daily in the company of Mme. de Châteauroux; while I, monsieur, am a poor priest, not often admitted to the dwellings of the highest." He rolled his eyes towards the figure of the Duchess, who was becoming visibly gracious under the effect of this slight compliment.

"You are not, then, a sharer of the opinions of those poor creatures amongst whom you have worked, and who, as you truthfully suggest, have some little cause to hate us, who have so much more in life than they?" queried Maurepas, with the interest of a Minister of the Interior.

"No, monsieur, assuredly I have no feeling of enmity towards the nobility of France. I should have no right. You see, I know very—very lit—" Suddenly Devries caught the eyes of St. Pierre fixed on him in so curious a glance that he was forced to stop speaking. His mouth began to twitch at the corners. He shook with an inward spasm, and finally lay back upon the sofa, emitting peal after peal of silvery, feminine laughter.

"Victorine!" cried the Duchess, starting from her chair. "Victorine, you madcap! So you have come back again!"

"Mme. de Coigny insisted," murmured St. Pierre, uncertain of his position.

The rest of the gentlemen sat perfectly still, staring at the little Marquise, and trying, out of some sense of propriety or gallantry, to keep from joining in her infectious laughter. Only Henri de Mailly sat near a window, his head on his fist, staring gloomily out upon the barren, stone-paved court.

"My dear madame!" cried Maurepas, when she had grown tearful with laughter, "your disclosure has done me an excellent turn. It has saved me five hundred livres. I was about thus to impoverish myself that you might be permitted to get still closer to heaven by spending another week in the criminal quarter distributing them."

The Marquise de Coigny grew suddenly serious again. "M. de Maurepas, let me take you at your word. I beg that you will send the money to him who was my companion in the work—l'Abbé de Bernis."

"Oh!—François de Bernis?" asked St. Pierre, in quick surprise. "I have met him at the Vincent de Paul."

"Her Majesty, I believe, receives him at times into her most religious coterie," put in de Maurepas.

"Well, since you know who he is, I will continue, if you will permit me. I beg that you will all, at least, believe that what I have said concerning my occupation in Paris was wholly serious. Indeed, indeed, I am in the highest sympathy with the work of the Jesuit fathers among the people; and there are few men in our world whom I—respect—as I do M. de Bernis."

At these words, so solemnly spoken that they could not but impress the listeners with their sincerity, the eyebrows of St. Pierre went up with surprise, though he remained silent. As a matter of fact, the reputation of the Abbé François Joachim de Pierre de Bernis was not noted for its sanctity.

"Will you, then, permit me, madame, to double my first offer?" said de Maurepas, with his mind on the treasury. "I will to-day send you a note for one thousand livres, which I beg that you will dispense in charity."

"M. de Maurepas, I wish that you could imagine what your word will mean to those poor creatures."

"And shall you yourself return to Paris with the money, madame?" inquired de Gêvres, smiling slightly.

De Coigny moved as though he would speak, but his wife answered immediately, in his stead: "No, Monsieur le Duc. I have no intention of taking permanently to a black gown. For two weeks it has occupied me satisfactorily to attend the poor. Now I shall come back to Court till I am again fatigued by all of you. After that I must devise a new amusement. Really—you all know my one eternal vow: I will not become successor to Mme. du Deffant. Death, if you like,—never such ennui as hers. M. de Mailly-Nesle, will you give—"

She did not finish. Henri had sprung quickly to his feet, but de Coigny was before him. "Pardon, Monsieur le Marquis," said he, with great courtesy, "will you allow me, to-day, instead. To-morrow I shall once more relinquish all to you."

De Mailly-Nesle could not, in reason, refuse the request, though it was against the conventions. He merely bowed as husband and wife, having variously saluted la Châteauroux and the rest of the company, passed together out of the boudoir.

"Mme. Victorine's eccentricity and her terror of being bored are excellent things. The husband seems to fall in love with her more violently than ever after each adventure."

"Ah, Madame la Marquise is too charming to be anything but successful everywhere. Really, Henri, you and de Bernis—"

Henri, angry at the first word, turned upon the Duke: "Monsieur, I would inform you that Mme. de Coigny is—"

"Ob yes, yes, yes! Pardon me," de Gêvres rose, "I understand perfectly that Mme. Victorine is the most virtuous, as she is the most charming, of women. Madame la Duchesse, I have been with you seemingly but one moment, and yet an hour has passed. His Majesty will be receiving the little entries. I bid you au revoir."

The Duchess held out her hand. The courtier kissed it, bowed to the three remaining men, and gracefully left the boudoir. When the door shut behind him a breath of fresher air crept through the room. Mailly-Nesle, who had been restlessly pacing round and round among the tables and chairs, paused. De Maurepas drew a tabouret to madame's side, and began to talk with her in the intimate and inimitably dignified manner that was his peculiar talent. St. Pierre was thoughtfully regarding nothing, when Henri approached and sat down beside him. Just as they began to speak together, Marchon stepped back a little from the chair of la Châteauroux.

"Madame," he cried, "the coiffure is finished."

At the same instant the door to the antechamber again flew open. "The Comte de Mailly!" announced the valet.

There was a second's pause and Claude ran into the room. "My dear cousin!" he cried, buoyantly, hurrying towards her.

Mme. de Châteauroux rose slowly from her place, stared at the new-comer for an instant with the insolence which only an insulted woman can use, then deliberately turned her back and moved across the room. Maurepas was already on his feet, and now, seizing his opportunity, he bowed to the woman, indicated Henri and the abbé in his glance, passed Claude with the barest recognition, and left the room congratulating himself on his adroit escape before the storm. Mailly-Nesle and St. Pierre sat perfectly still for an instant out of astonishment. Then, happily, the abbé came to himself, rose, repeated the performance of the minister, and hastened from the unpleasantness. The instant that he was gone Claude broke his crimsoning silence in a somewhat tremulous voice:

"Name of God, Marie, what have I done?"

Madame was at her dressing-table. Picking up a small mirror, she retouched her left cheek.

"Marie," said Henri, gently, "it is but fair that you let him know his fault."

A shiver of anger passed over the frame of la Châteauroux. Then, suddenly whirling about till she faced Claude, she whispered, harshly: "My gauntlet, Monsieur le Comte; my white gauntlet! Return it to me!"

Again Claude flushed, wretchedly, while his cousin spoke: "He has it not to return, Marie."

She turned then upon her brother. "So you, also, know this insult, and you counsel me to—let him know his fault! Ah, but your school of gallantry was fine!"

"This insult!" repeated Claude, stupidly.

"Fool! Do you think I do not know it?"

Count and Marquis alike stood perfectly still, staring at each other.

"Your innocence is awkwardly done," commented madame. "Show me the price, Monsieur Claude, for which you sold my gage."

"Price!" echoed Henri, angrily. But Claude drew a long breath.

"Ah! Now I begin, I but begin, to understand. Which was it that came to tell the story, madame? Was it d'Epernon, or Gêvres, or Richelieu who twisted the account of a forced act into one of voluntary avarice?"

The favorite shrugged. "Charming words! I make you my compliments on your heroic air. Will you, then, confront M. de Gêvres before me?"

"Most willingly, madame! Afterwards, by the good God, I'll run him through."

La Châteauroux bent her head, and there was silence till she lifted it again to face her young cousin. His eyes answered her penetrating glance steadily, eagerly, honestly. And thereupon madame began to turn certain matters over in her mind. She was no novice in Court intrigue; neither had she any great faith to break with de Gêvres. It was a long moment; but when it ended, the storm was over.

"How did it happen, Claude?"

"I gave the gauntlet to the King, when, man to man, he was beaten at dice."

"You received nothing in return?"

Claude was uncomfortable, but he did not hesitate. "Yes," he said, with lowered eyes. "I have brought it to you. I hate it."

From one of the great pockets in the side of his coat he drew a small, flat box, which he handed to his cousin. She received it in silence, opened it, and gazed upon the royal star. The frown had settled again over her face. Suddenly, with a quick impulse, she pulled open one of the small windows which looked down upon the Court of Marbles.

"Claude, take this and throw it out—there," she commanded.

"'CLAUDE—TAKE THIS AND THROW IT OUT—THERE'"

De Mailly was at her side in two steps. Eagerly he seized the jewels and flung them, with angry satisfaction, far out upon the stones. La Châteauroux looked at him quizzically for an instant, then suddenly held out both hands to him. He did not fall upon his knee, as a courtier should have done; but threw his arms triumphantly about her and bent his powdered head over hers.

"Um," muttered Henri, indistinctly, "methinks I would better go and seek the fallen star."

The 16th of January fell on a Saturday, on the evening of which day the King held his usual weekly assembly in the formal halls of the palace. These affairs were not loved by Louis, whose tastes ran in more unostentatious directions; but they were a part of his inheritance, coming to him with the throne, his hour of getting up in the morning, and the national debt; so he made no audible murmur, and ordinarily presented a resplendent appearance and a dignified sulkiness on these occasions. It was his custom to enter the Hall of Battles or the Gallery of Mirrors, in company with his consort, between half-past eight and nine o'clock. Since no courtier was supposed to make his entrance after the King, the great rooms were generally thronged at an early hour, and the first dance began at nine precisely.

At a quarter to seven on this particular Saturday, four candles burned in the Gallery of Mirrors, and their petty light made of that usually magnificent place a shadowy, dreary gulf of gloom. Ordinarily, at this hour, the salon was deserted. To-night, it appeared, one individual was unhappy enough to find the place harmonious with his mood. This solitaire, who had twice paced the length of the hall, finally seated himself on a tabouret with his back to the wall, and, leaning his head against a mirror, gave himself up to some decidedly uncomfortable thoughts. It was Claude de Mailly who was young enough and unwise enough to surrender himself to his mood in such a place, at such an hour. Only late in life does the courtier learn how dangerous a thing is melancholy. Claude had not come to this yet; and for that reason, through one long hour, he remained in darkness, meditating upon a situation which he could not, or, more properly, would not, help. For Claude's eyes were well open to the precarious position into which he had got himself; they were open even to his more than possible fall. Nor was he ignorant of the direction in which salvation lay—the instant bending to Louis' wishes, repudiation of the favorite, and devotion to some other woman. But, to his honor be it said, Claude de Mailly was deeply enough in love and loyal enough by nature to scorn the very contemplation of such action. He could not see very far into the future. He dared not try to pierce the veil that hid the to-come from him. He would not think of consequences. Perhaps he was not capable of imagining them; for, to him, life and Versailles were synonymous terms, and the world beyond was space.

His vague and varied meditations were broken in upon by the appearance of eight lackeys, who had come to light the room for the evening. Claude rose from his place and slipped away by a side-door. He had nothing to do, nowhere in particular to go. The Œil-de-Bœuf would be deserted. The Court was dressing. An hour before, dismal with the loneliness of the gray sky and the falling snow, he had left his rooms in Versailles. He was dressed for the evening, but had had nothing to eat since the dinner hour. An idea came to him presently, and he bent his steps in the direction of the Staircase of the Ambassadors. At the head of this, on the second floor, he halted, knocking at a well-known door. It was opened after a moment by a well-known lackey. Claude thrust a coin into the man's hand, and passed out of the antechamber, through a half-lighted salon, and into the Persian boudoir where sat Mme. de Châteauroux and Victorine de Coigny, comfortably taking tea à l'anglaise together, and talking as only women, and women of an unholy but very entertaining Court, can talk. The little Marquise was dressed for the assembly. The duchess was coiffed, patched, and rouged, but en négligé. She rose nervously at Claude's entrance.

"Claude! Claude! How unceremonious you are!"

"And did you hear what we were saying of you, monsieur?" asked Victorine, smiling mischievously, as she gave him her hand.

"Fortunately for my vanity, madame, no," he returned, bending over it; then, at her ripple of laughter, he crossed to his cousin, took her proffered fingers, but, instead of kissing them, seized them in both his hands, clasped them close to his breast, and looked searchingly into her eyes.

"Anne, Anne, I have suffered so!" he murmured. "I wonder—if you care?"

Mme. de Coigny sprang up. "At least, monsieur, give me time to retire! Your ardor is so remarkable!"