Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

BY

AMY E. BLANCHARD

Author of "Little Maid Marian," "Little Miss Oddity,"

"Little Sister Anne," "Mistress May," etc.

NEW YORK

HURST & COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1906, by

GEORGE W. JACOBS & COMPANY

Published August, 1906

All rights reserved

Printed in U. S. A.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

VI. MISS HESTER MEETS AN OLD ACQUAINTANCE

LITTLE MISS MOUSE

Buttonholes

"AUNT HESTER, do you like to make buttonholes?" Ruth asked with interest in her tones.

"No," was the answer, "I hate to make them." Aunt Hester bit off her thread fiercely. "I hate them," she repeated, reaching for her spool which had fallen under the chair.

Ruth made a scramble for it, picked it up and laid it in Aunt Hester's lap.

"If you don't like to make them, what's the reason you do it?" she went on. "I thought grown-up people could do just what they liked."

Aunt Hester gave a little scornful laugh. "That's where you are mistaken. When I was a little girl like you I thought so, too, and when my mother made me sit by her and sew as I make you, I used to think that when I grew up I'd never touch a needle."

"Oh, and now you have to do it nearly all day." There was sympathy in Ruth's tones.

"Never you mind what I do all day. You chatter too much. Go on with your work."

And Ruth returned to the slow and tedious task of picking out the threads from a coat. The threads stood up in a long row down the seam. Ruth called them Indians on account of the fancied resemblance to the feathered decorations on the heads of the savages in a picture in her geography.

She and Aunt Hester were sitting in the latter's bedroom where the two always spent an hour together on Saturday afternoons. Ruth always resented being kept indoors on this holiday, but Aunt Hester was obdurate.

To be sure Billy had to stack wood or chop kindling or do some such task at the same hour so he wouldn't be on hand to play with, anyhow. Lucia Field had to help her mother; Annie Waite's mother kept her busy, and it seemed as if there was a combined intention on the part of the older people to give this unhappy hour to children.

It was probable that they had decided to do it at some mothers' meeting, Ruth concluded, and she always felt a sudden rebellious pang whenever Aunt Hester prepared to go forth to one of these gatherings, for just after, there was sure to be a period of extra strictness, and certain little tasks that perhaps had been gradually slighted during the month were enforced more rigidly.

Ruth looked up at the clock. It still wanted fifteen minutes to three and there were many Indians still poking up their heads along the line of brown cloth. She ventured another remark. It was out of reason to sit silent more than ten minutes at a time.

"What are you going to do with this, Aunt Hester?" she asked.

"Make a coat for Billy."

"Whose did it use to be?"

"My father's."

"Oh." Ruth's mind wandered to the time when the coat had been new. It must have been a long time ago, she considered. She wondered what old Major Brackenbury kept in his pockets, and surreptitiously slipped her hand in the one which was still hanging to the piece of cloth upon which she was at work. He might have been fond of peppermint lozenges, she thought, like Dr. Peaslee who never failed to produce one when he met Ruth. But no lozenges of any kind were to be found; only some siftings of tobacco and particles of dust did Ruth's hand bring forth from the deep pocket.

She worked away diligently for a few minutes, then her tongue wagged again. "Was your father like Dr. Peaslee?" she questioned.

"Not a bit," sighed Miss Hester. "He was tall and slim, though not too slim. He carried a gold-headed cane. I can see him now," she stretched forth her hand and smoothed the cloth which lay in Ruth's lap. "I can see him now in that very coat coming out the gate with Bruno at his heels."

Ruth's eyes followed hers to the big house across the way. The tall white pillars were visible through the evergreens. It had been a pleasant place to live in.

"I know all about Bruno," she said, "but tell me some more. I am so tired of unripping."

"Of ripping, you mean. You couldn't unzip, you know. You have only five minutes more, so I can't begin to tell tales now. I want you to find Billy and tell him I want him to go to the store when he has finished his task."

"May I go to the store, too?"

"Yes."

Ruth settled back contentedly. Only five minutes more to fight the Indians. She would try to get to the end of the seam before the clock in the kitchen struck. So her fingers flew along the stretch of brown cloth and there were but a few more threads to pull when one, two, three, strokes sounded solemnly and slowly from the tall clock in the corner of the kitchen.

Ruth looked up inquiringly and Aunt Hester nodded her head.

"Fold up your work and put it in the big chest," she said, "and then you may go and find Billy. When he has finished his work, tell him to come to me."

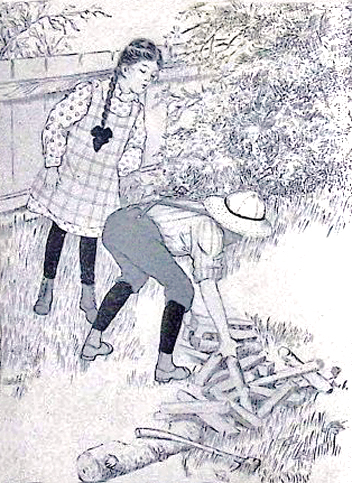

Ruth did as she was bid. She found Billy industriously stacking wood.

"Whew," he cried as he saw the little girl, "there's a lot of it, isn't there? See how much I have already piled up."

"You're 'most through, aren't you?" said Ruth. "How hard you must have been working, Billy."

Billy smiled appreciatively. When Billy smiled, you forgot his red hair and snub nose, for his bright blue eyes were squeezed up so merrily and his whole face showed such a sunny expression that, you felt like smiling in return.

Ruth, on the contrary, was a sombre looking little mite with burning dark eyes, a small thin face and serious mouth. Her greatest beauty was her chestnut hair which rippled in shining waves to her waist when it was unplaited, but Miss Hester insisted upon smooth braids and was very particular that every hair should be in place, so the shimmering masses were generally confined in two plaits and tied tightly by a black ribbon.

"I'll help," said Ruth after she had watched Billy sturdily working to get his pile completed. "Aunt Hester wants to send you to the store and I'm going, too. Billy, did you know she hated to make buttonholes and her father had a gold-headed cane?"

"I know; I saw it once, the cane I mean. I didn't know about the buttonholes. She won't have to make 'em when I am a man."

"Why? What for?" asked Ruth, struggling with a stick of wood.

"'Cause, she has to do 'em now, so she can buy things for us."

"Oh, I didn't know that was why."

Ruth placed her stick of wood so that it rolled down from the pile. She thrust it back again and stood looking very thoughtful, then she said soberly, "She's awful good, isn't she, Billy?"

"You bet she is. She's a Jim dandy, if she does make a fellow work Saturday afternoons. Where'd you and me be, if it wasn't for her?"

"You'd be selling papers and I'd be in an orphan asylum, I suppose," returned Ruth readily. She was accustomed to this reminder from Billy.

"That's just what," he returned settling Ruth's wobbly stick more securely in place.

"Tell me where you saw the cane," said Ruth, picking up a stick more suited to her abilities.

"I saw it at Dr. Peaslee's; but don't you tell. She might not like us to mention it. It's my opinion she sold it to him."

"Maybe, when the claim is settled, she'll buy it back again. I wish it would hurry up and get settled; I'd love to live over there again." Ruth nodded her head toward the big house with the pillars. "We didn't stay long enough to get used to it."

"If she can stand it here, we can," returned Billy eyeing his wood-pile critically. "That's all now, Ruth. I've just got to chop up a little kindlin' and then we can go 'long."

"I'll pick up some chips," said Ruth, stooping to fill her apron with the splinters and bits of bark which lay around.

Then, following Billy, who, with arms piled high, strode toward the kitchen, she rejoiced that the real work of the day was over for them both. To be sure she must dry the tea things and help put them away, but that was active employment and did not come in the same list with sitting still for an hour laboriously picking out stitches.

Ruth and Billy were not in any way related to each other. They were found deserted in the streets of a large city near-by and when an appeal was made at a Home Missionary meeting in their behalf, Miss Brackenbury had offered to take them both. That was a year or more previous to this special Saturday afternoon and Miss Hester had then lived in the big house across the way.

Old Major Brackenbury was alive then, though blind and helpless, quite a different person from the one described to Ruth as wearing the brown coat. He lived but three months after the children became members of the household, and the next thing the neighbors knew, the big house was given up and Miss Hester was taking her young charges to a tiny home across the way.

Miss Hester shed many tears at leaving her old home in which she had expected to pass the remainder of her days. She had believed herself comfortably provided for, but, when her father's affairs were settled, there was very little left.

Ruth, awe-stricken, believed the tears were all because of the major's death, but Billy, wise before his time with a knowledge of what poverty meant, knew better. He had overheard a conversation between Miss Hester and Dr. Peaslee and he knew there were many things to cause Miss Hester's lips to tremble and her eyes to overflow, for had he not heard the good doctor trying to persuade her to give up Ruth and Billy and had she not replied:

"No, I have pleased myself in taking them. I was lonely and wanted them for my comfort. Shall I give them up now when I pledged myself to take them? The Lord sent them to me and He means me to keep them. Would I desert my own flesh and blood under like circumstances? Would I not work my fingers to the bone for children of my own and shall I do less by these whom Heaven has given me?"

The doctor coughed and wiped his eyes but he did not give up. "They will be well cared for in some institution, Hester," he said. "Or they may perhaps find good homes. You need not return them to the streets and what is left will not be enough for you three."

Miss Hester set her lips firmly. "I'll make it enough. I am not the only woman who has had to work for her living."

"But what can you do, Hester? What can you do?" said the doctor in a troubled way.

Miss Hester thought for a moment. "I can make buttonholes beautifully and do all sorts of fine sewing and embroidery. Hand-work is very much in vogue now and I surely ought to eke out my income; and then you know there is the claim," she added with a little smile.

"Pshaw!" said the doctor, as he brought his stick down hard, but he did not try to urge her further, though he shook his head and sighed.

And so it was that, with the best and choicest of her belongings, Miss Hester removed to the tiny house with its bit of front yard and its roomier back lot.

It was not long before the fine sewing daily work, was the main part of Miss Hester's daily work, for the doctor spread the information far and near that Miss Brackenbury made beautiful buttonholes and did exquisite hand-work, and that she would be willing to help out those of her neighbors less accomplished.

Then Maude Fowler came over to know if Miss Hester would help with her trousseau; Mrs. Ayres brought a dozen baby's frocks; Mrs. Baker wanted a fine shirtwaist, and so it went on till Miss Hester had about all she could do, and managed to have enough to supply the wants of herself and her adopted children, though their food was plain enough.

Billy did not forget what he had heard, and, though he never said a word of it to Ruth, he faithfully kept alive the fact that they owed a great deal to Miss Hester. He brought a cheerful presence into her life, showing an awkwardly expressed, but perfectly true, affection which Miss Hester recognized and returned.

As for Ruth, she was younger and did not show her feelings so easily. She had been brought up in a different school, too, and was used to a fond mother's caresses. To this mother's memory she clung, and Miss Hester often wondered if she cared at all for her or indeed for any one.

"She hasn't those big, burning eyes for nothing," said Dr. Peaslee. "She may be undemonstrative, but she is not shallow, I'll warrant you."

So Miss Hester was watching the growth of this little bud, wondering if it would ever show a heart full of warmth and color, and if, in the long run, Ruth would really love her as Billy did. Miss Hester was not of the gushing sort herself, but, once in a while, she would pass her hand over Ruth's shining head or would pat Billy's shoulder. Then Billy would give her one of his beaming smiles as he snuggled up against her. But Ruth would only turn her great eyes upon Miss Hester with a questioning look and would invariably slip off into some corner after such a caress.

This autumn afternoon, after they had deposited their burdens in the wood-box, they were given directions by Miss Hester with a list of things to be brought from the store.

"Now, don't loiter by the way," was the charge given. "I want the things as soon as I can get them, Billy."

"What do you suppose they are?" asked Ruth as they passed out the gate. "Do you reckon it is anything good, Billy? Maybe she has the claim."

"Ah, say, you've got bats in yer belfry," returned Billy. "She ain't got no claim. I'm only goin' to get oatmeal and rice and things like that."

"Oh." Ruth sighed. It would have been pleasant to anticipate materials for gingerbread or some such luxury. "I wish it had been raisins and currants and citron and all that like we had last Thanksgiving," she said.

"Never you mind," returned Billy. "It's all right. What we have every day is heaps better than that old crust you had for dinner the day they found you on the corner, a beggar."

"Hush, Billy Beatty," cried Ruth stamping her foot. "I told you never, never to speak about that again. I just hate to have you, I do. I wasn't a beggar, I wasn't. I never asked anybody for anything and I never will. I'd die first."

"Well, you needn't get so mad about it," replied Billy. "I couldn't help it. I might have if I had been there, and if I hadn't sprained my ankle like I did; that's 'why I couldn't get along. It hurt like the mischief and I couldn't run after people like the other boys, so I didn't sell a single paper that morning, and I didn't have a copper to get anything to eat, so that's why I keeled over the way I did, and they picked me up with the wits sorter knocked out of me, and just then that preacher, or whatever he was that had you by the hand, come along. And when Dr. Peaslee was goin' me over, he told him I'd just sorter fainted 'cause I hadn't had no chicken pie for dinner, and he had us both took to that place where they looks after young uns what ain't got nobody else to look after 'em; Children's Aid Society, they call it, and they fed us up slick, didn't they?"

"Now, you're talking as you did when I first knew you," said Ruth disdainfully, "and not the way Aunt Hester likes you to talk. Don't let's go back to that dreadful time. Billy, do you suppose your relations will ever come after you?"

"Ain't got none."

"But I've a father, you know."

"Maybe you have and maybe you haven't. What's the matter with his being killed in an accident? You wouldn't care much, would you?"

"I don't know. It would be nice to have somebody your very own." Ruth spoke wistfully. "He wasn't bad. Mother said he'd come back; she knew he would. She said that the day before she went to heaven."

The child's lip trembled and she bent over to pick up a scarlet leaf in her pathway that she might hide her feelings.

"He won't come," declared Billy positively. "As for me I like it here all right and I'm goin' to stay and keep a store here myself when I grow up."

"Oh, good! And will you sell candy—that kind that's all pink and soft?"

"Sure," returned Billy. "We'll move back into the big house and have rice puddin' with raisins in every day, if we like."

"I'd rather have that lovely other kind of pudding like we had last Thanksgiving."

"We'll have that too, sometimes."

"Maybe we won't have to wait till you grow up, Billy," said Ruth, to whom so long a vista of years seemed an eternity; "you know there's the claim. What is a claim, anyhow, Billy?"

Billy hesitated. He didn't like to show his ignorance but he was not at all sure that he knew what it meant. "It's government," he said presently, "government," he repeated more importantly.

Ruth look puzzled. It did not seem much plainer to her than before. "But how will that make us able to go into the big house?" she asked.

"Oh, they'll give a lot of money to Aunt Hester so she won't have to sew any more."

"Oh, who'll give the money, Billy? Who is 'they'?"

"Oh, I don't just know their names. Maybe the president does it or he gets somebody, some big general, to do it for him." Billy's notions of such things were very vague.

"Oh my!" Ruth was much impressed; her imagination immediately flew to the possible arrival of some magnificent creature in regimentals, riding a coal black steed. He would draw rein before the door and she would run out and open the gate for him. "Do you suppose he would know where she lives, that she's not living in the big house any more?" she asked after a moment.

"Of course." Billy spoke confidently.

He did not like to be questioned as closely as Ruth had an inconvenient way of doing, so he changed the subject.

"I'll race you to the store," he said, "and I'll give you a start from here to the corner."

Therefore, Ruth set off and the two reached the store neck and neck. They entered breathing hard between quick bursts of laughter.

The Pocket

THE next Saturday there was another long seam of stitches to pick out. To this piece of cloth also was hanging a pocket of rather pretty pink and white stuff. Ruth thought it would make a good frock for her one doll, Henrietta. She meant to ask Aunt Hester if she could have the pocket.

Miss Brackenbury had been called into the next room by the arrival of a visitor. Ruth could hear the sound of their voices, Miss Brackenbury's low and quiet; Miss Amanda Beach's high and shrill. She heard a word or two now and then which made her think they were talking of herself and Billy. Then the subject changed and she heard payments and receipts and lawyers talked about.

She wondered how grown-up people could be interested in such dull subjects, so she let her thoughts wander to the striped pocket which would perhaps make a frock for Henrietta. The doll was named for Miss Hester's twin sister who had died when she was about Ruth's age and Ruth realized that Miss Hester had a tenderer feeling for the little waif because of this much loved twin sister.

"And then," Ruth said to herself, "I can make a sunbonnet for my doll like the one Henrietta used to wear, a pink one. I have some scraps of pink gingham that Lucia Field gave me. I wish I knew whether I could have the pocket."

She heard a stir of chairs in the next room and supposed that Miss Beach was about to go, but she was mistaken in this for the next moment Miss Hester came into the room where Ruth was, and going to an old writing desk, took from it a lot of papers.

Ruth improved the opportunity. "Are you going to use this pocket, Aunt Hester?" she asked. "It has a hole in it, a little one. Will you want it for Billy's coat?"

"No, I'd better make new ones," was the answer.

"Then, may I have this for Henrietta?"

Miss Hester glanced down. "Yes, you may have it," she answered. Then she went back to the living-room.

"I think I'll rip out the pocket," thought Ruth. "I can do it without hurting the cloth, for I'll be careful not to cut anything but the striped stuff."

She ripped away industriously till the pocket came off readily and made a gaping place between the lining and the cloth of the coat. Ruth slipped her hand down into the hole.

"How deep it goes down," she thought.

Her fingers touched the corner and discovered that something had lodged there.

"I suppose it's tobacco," she said disgustedly, but her fingers drew forth a little wad of paper which time had creased and worn. "It isn't anything after all," said Ruth. "If it had been tobacco, I could have given it to old silly Jake when he comes to saw wood."

She threw the bit of paper on the floor, then remembering Miss Hester's orderliness, picked it up again and slipped it into the pocket she had ripped out.

"I'll throw it in the fire when I get through this," she said, "but I don't want to go into the kitchen 'spressly for that."

However, both paper and pocket were forgotten half an hour later when Billy came blustering in.

"Say, Ruth," he cried, "come along out when you get that done. I've got something to show you."

Billy's excitement promised no ordinary thing.

"Oh, what is it?" cried Ruth, her eyes shining.

"Wait and see."

"I'm 'most through," said the little girl, eagerly. "I won't be a minute, Billy. Miss Beach is going, too, so Aunt Hester can come and say the hour is up, for it is striking three now."

She folded her work, stowed it away in the chest, picked up the striped pocket and ran into her little room with it, where she tucked it away in her box of scraps for doll clothes.

As she came running back the door closed after Miss Beach. "It's three o'clock, Aunt Hester, and I picked out every stitch and put away the coat. Now may I go?" asked Ruth as Miss Hester came in.

Miss Hester looked around to make sure that all was in order. She held a parcel in her hand and as she sat down she murmured, "More buttonholes."

Ruth came closer and laid her small hand upon Miss Hester's arm. "And you hate them so," she said sympathetically. "Are you afraid you will have to make them all your life, Aunt Hester?"

Miss Hester sighed. "I am afraid so."

"No, you won't," Ruth assured her. "You can teach me to make them when I am bigger and then, when Billy gets to keeping store, we won't either of us have to make them, for, when we get hungry we can go down to Billy's and eat crackers and raisins and things. I'm coming, Billy."

For Billy, grown impatient, had gone out into the yard and was calling her.

Miss Hester looked after her as she ran out. "Amanda need not discourage me about Ruth," she said with a faint little smile; "I'll have the child's love and confidence yet." Then she sat down to her old desk and pored over a little pile of papers which she drew from a pigeon-hole.

Meanwhile, Billy had preceded Ruth to the wood-shed and was standing over something in a dark corner.

"Look," he whispered, "ain't they the cunningest you ever did see?"

And Ruth, tiptoeing nearer, saw four little fat puppies cuddled up against their small mongrel mother.

"Oh, aren't they dear?" exclaimed the child. "Where did they come from, Billy? Who does the mother belong to?"

"Nobody, I reckon. She's just a stray."

"Oh, like us," said Ruth in a sympathetic voice, as she leaned down to stroke the little creature. "Has she had anything to eat, Billy?"

"No, but I'm going to give her my supper."

"Oh, I'll give half mine and then you needn't give but half yours, so we won't any of us three be very hungry. Oh, Billy, do you think there is any chance of Aunt Hester's letting us keep her and the babies?"

"I'm afraid not," replied Billy, soberly.

"You haven't told her?"

"Not yet."

"If we could keep just one," said Ruth, clasping her hands, "maybe we could find homes for the rest. I'll tell you what, Billy; let us get her to tell us more about Bruno. You know how she loved him and then we'll tell her about these and ask her if she doesn't want one in Bruno's place."

"That's a scheme," cried Billy. "We'll do that very thing. You see we'll have to let her know if we mean to take our suppers out to the little mother."

"So we will. You shall have something pretty soon, you nice little doggie," said Ruth, caressingly, as she stroked the soft brown ears of the small creature lying in the straw. The dog lifted her wistful eyes gratefully and licked Ruth's fingers in response. "See how friendly she is," said Ruth, delightedly. "I'd like to keep you, dear little doggie; I would so. Does any one know but us, Billy?"

"Not a soul."

"Then don't let's tell just yet, till we know what Aunt Hester says, for some of the boys might pick out the very one we like before we get a chance to know if we can keep one."

"That's so," agreed Billy. "We won't tell yet. I like that little fellow with the spots; see him nose my hand."

"I like the one with brown ears like its mother," declared Ruth. "When will they have their eyes open, Billy?"

"Not for nine or ten days yet. There's Aunt Hester calling; we will have to go. Don't say a word till supper time."

Not a word was said to Miss Hester just then, although Billy grew very red when she asked what they were doing in the wood-shed, but he rose to the occasion by answering: "Oh, just playing."

Later on, when Ruth was setting the table, she drew Miss Hester into telling about her childhood days.

"And did you have Bruno then?" asked Ruth.

"Not then, but we had another dog named Stray, a smaller dog."

"That's a nice name for a dog," commented Billy with satisfaction.

"You'd like to name one that, wouldn't you?" said Ruth with a little laugh which she smothered when Billy frowned at her.

"Tell about Stray," said the boy.

"He was a dog my sister and I had."

"Was he not very big with brown ears and eyes?"

"Why yes. Did I ever tell you about him?"

"No," answered Ruth, confusedly, "but I thought maybe he was; I like that kind."

"Well, that was the kind Stray was. He was a lively little fellow and we were very fond of him, although he was not a thoroughbred."

"What is a thoroughbred?" asked Ruth.

"It is a dog or a horse or any animal which is very fine of its kind. A thoroughbred dog wouldn't have the head of a setter and the tail of a collie and the legs of a fox-terrier," said Miss Hester, smiling.

"Did Stray have all those?" asked Ruth.

"Well, not exactly. He was a cross between a spaniel and a fox-terrier and my father used to laugh at him."

"Where did you get him?" asked Ruth eagerly.

"He came into the yard one day looking very thin and miserable. My sister and I took him something to eat, and after that he followed us everywhere, so we begged to be allowed to keep him."

"You begged your father, didn't you?" Ruth asked.

"Yes."

"And he let you keep him. He must have been a very nice man, a very nice man indeed," decided Ruth with a glance at Billy.

"He was a nice man, my dear; the kindest in the world. It was his kind-heartedness that lost us the old home," Miss Brackenbury sighed.

"Why?"

"I don't know that you would understand; but he raised money to help a friend out of difficulties, and, though I am quite certain he paid back all that he owed, after his death, I could find no record of any payment and the man from whom the money was borrowed insisted upon payment. It took nearly everything."

"What a dreadful, selfish man not to let you keep your house," said Ruth savagely. "I'd like to crush him down to the earth and stamp on him."

"Why, Ruth, what a terrible way to talk."

"I would, I would," declared Ruth. "If he was a wicked man, why shouldn't I want to? The children of Israel liked to kill wicked people and idolaters; I know that man is an idolater; I'll bet he has a brazen image."

"Why, Ruth, you know nothing of the kind. You must not talk so." Miss Hester spoke severely, but there was a flicker of a smile around the corners of her mouth.

"Oh, keep quiet, Ruth," put in Billy. "I want to hear about Stray."

But Ruth's indignation was still burning.

"I'll bet if that man had been your father, he wouldn't have let you keep Stray," she continued.

"Very likely he would not have, but never mind about that. Stray lived to a good old age and died long after my little sister did. My father got Bruno for me because I mourned so for Stray."

"If—if—" Ruth looked at Billy and slipped a cold trembling little hand into his. The critical moment had come. She swallowed once or twice and began again: "If—if you and your sister had found Stray with four little puppies in the wood-shed, do you think your father-would have let you keep them all? Was he as good as all that?"

"He was good enough to do anything that was right and just, Ruth, but I don't think he would have consented to our having five dogs."

"I don't think five are a great many," Billy spoke up. "Dr. Peaslee has six or eight."

"He has a pack of hounds, I admit, but they are hunting dogs and are not house pets."

Ruth gave a long sigh. "How many do you suppose he would have let you keep?" she asked.

"Not more than one, or two at the most."

"Two would do, you know," exclaimed Ruth carried beyond discretion, "the mother and one of the puppies, Billy."

"What are you talking about?" said Miss Hester, in surprise.

Ruth's cheeks began to burn and she fingered Miss Hester's apron nervously.

That lady quietly lifted one of the cold hands. "What icy fingers, Ruth," she said. "Are you so cold?"

"No, Aunt Hester, I'm not cold only—only there are four puppies, you know, and the mother. We do want so much to keep two. Oh, won't you be as good as your father and let us keep them? They are in the wood-shed and we are going to give them half our supper."

"Four puppies and their mother in the wood-shed!" exclaimed Miss Hester in astonishment. "How did they get there?"

"They just came," said Billy, eagerly coming into the conversation. "I found them there this afternoon. She's awfully nice, Aunt Hester; you ought just to see her lick your hand, and the puppies are great; there's one with spots—"

"And one with brown ears," Ruth chimed in. "I'd love that one. It looks like its mother. She has brown ears and eyes just like Stray."

"I must see about this," said Miss Hester. "I am sorry, children, but I am afraid we cannot afford to keep any of them, for it would mean another mouth to feed."

"But we'd give half our supper to them," argued Billy.

Miss Hester shook her head sadly. "I couldn't allow that, Billy, for you children do not have more than you ought as it is."

"Sho!" exclaimed Billy, "We have a heap more than we used to have, and we got 'long then. Why, Aunt Hester, two years ago we'd have thought ourselves regular swells if we'd had three meals a day."

But Miss Hester was obdurate, though she finally consented to allow the children to share their meals with the little mother until her babies were big enough to give away, Billy declaring that there were plenty of the boys who would be glad to have one of the puppies.

So, after supper, they all went out to the wood-shed, Billy and Ruth each bearing a pan of porridge and milk, for each had so insisted upon the right to feed the dog, that Miss Hester was obliged to hunt up two old pans into which was poured strictly half of their supper. This was eagerly eaten by their small pensioner who seemed half-starved.

"Poor little thing," said Miss Hester, wistfully. "I really wish we could keep her, but how could we feed her when we eat up everything so clean that we have no scraps."

"Oh, if I could only make buttonholes," said Ruth fervently, "I'd make enough to buy her all she needed."

Yet a way was provided for the entire family of dogs, for the next day Billy came flying home from school, a pack of boys at his heels. These were escorted to the wood-shed and therefrom came a great clamor of voices.

Ruth hovered on the outskirts eager for the first news.

After a while, the boys filed out all talking at once. As they went out the gate, they shouted back, "We'll be sure to be on hand to-night, Billy."

And then Billy's red head appeared. The boy's face wore a pleased smile.

"Oh, Billy, tell me," cried Ruth, wild with curiosity.

"It's all right," said Billy; "I've made a bargain with the fellows, and they've got to keep to it, too. Come on, let's tell Aunt Hester. I've got 'em all to promise, and they've got to sign in ink, too." He strode importantly into the house, Ruth dancing at his heels.

"We can keep any one we want, Aunt Hester," he announced, "and it won't cost one cent, either. There's five dogs, ain't there? Well, there's four of the boys that's agreed to give me scraps for one dog, every day as I come home from school, to pay for the puppy he is to have, and if a fellow don't keep his word I'm to take back his dog, and I'm goin' to do it, too, for Sam Tolman's awful anxious for one and there ain't enough to go round. So now can't we have one to keep?"

"Why, yes. You're a real good hand at a bargain, Billy," said Miss Hester, looking pleased. "Of course, if you can feed the dog, you can keep it."

"The boys are goin' to bring the stuff here while the little pups are with their mother, so she can get fed. Charlie Hastings likes her best of any and says he'd rather have a grown-up dog than a pup. He says he knows his mother will let him have her 'cause they had a dog much like her that got runned over last summer and they all felt awful 'bout it. He says they'll call this one Flossy after the one they had."

"Oh, I am so glad she will have a good home," cried Ruth, clasping her hands. "Which are we to have?"

"Well, I reckon we'll keep the one with brown ears 'cause Art Bender wants the spotted one and Art's father is awful rich, so that we'll get more scraps from them than anybody, and I thought it would be better to let him have Spot."

He spoke quite soberly, but Miss Hester put back her head and laughed more merrily than the children had heard her since they had come to the little house.

Henrietta's Red Coat

FOR a long time after this, Henrietta was neglected and the striped pocket lay unheeded in the box of pieces, for Stray was the absorbing interest to both Ruth and Billy. Generous little Billy had declared the puppy must belong half to Ruth, and, therefore, she always went with him when, tin pail in hand, he called at the different houses where the promised scraps were to be collected. Sometimes, the scraps which the other puppies left were few, but there was always enough for the not too fastidious appetite of Stray, or, if it seemed a very slim supper, both Ruth and Billy cheerfully set aside a portion of theirs, consequently Stray throve and grew apace.

Miss Hester confessed that he was great company for her while the children were at school, and he came to consider her as close a friend as Ruth or Billy.

Before winter came on, the major's old overcoat was fashioned into a warm one for Billy, and for Ruth, Miss Hester contrived comfortable frocks from her discarded ones. But there was no coat for her, till one day Ruth discovered Miss Hester bending over an old chest in the attic. The tiny house held but four rooms below and the attic above. One end of the attic was curtained off for a room for Billy; the rest was stored with chests and bandboxes, trunks and old furniture.

It was rather a fearsome place to Ruth, that dark end of the attic, though she did venture in there once in a while when she was hiding from Billy. Now, however, Stray could always find her so that it was no longer any fun to hide there.

Upon this particular day, she had a message from Miss Amanda Beach, and was in a hurry to deliver it lest she forget it.

"Aunt Hester, Aunt Hester," she called, "where are you?"

An answer came from the dark end of the attic; "Here, child."

Ruth groped her way along the dusky aisles. A spinning wheel's flax brushed her face; an old leghorn bonnet was set swinging from the rafters as she felt her way with uplifted hands; a string of dried peppers, hanging from a beam, caught in her hair. Ruth stood still.

"I don't see you," she said anxiously; the peppers had seemed like something alive.

"Over here," repeated Miss Hester, standing up, and Ruth saw her figure dimly in the gloom.

She picked her way along with more assurance as her eyes became accustomed to the half light.

"Miss Amanda wanted me to be sure to tell you that there is to be a meeting of the mothers this afternoon at the minister's house and you mustn't forget to come, she says. You are just the same as a mother, Billy's and mine, aren't you, Aunt Hester?"

"I hope so," returned Miss Hester groping among the bundles in the chest before which she was kneeling. "There, this is what I am looking for."

"Oh, what a cunning little hood," said Ruth picking up a soft cashmere affair, trimmed with swansdown. "Was it yours when you were a little girl, Aunt Hester?"

"No, all these things belonged to my little sister Henrietta. They have been in this chest ever since she died. My mother put them there with her own hands."

"Oh." Ruth leaned over to look more closely at the neat piles of garments. Miss Hester sat on the floor and pushed back a lock of hair which had fallen over her eyes. She was a tall, slender woman with dark hair, hazel eyes and a sad expression about the mouth.

"Were they all Henrietta's?" asked Ruth with interest. "Aunt Hester, if you had had a little girl you would have named her Henrietta, wouldn't you?"

Miss Hester smiled. "Very likely."

"'Most everybody calls me Ruth Brackenbury, don't they? Do you like to have them call me that, Aunt Hester?"

"Do you?"

"I do, if you do," returned Ruth shyly. Then her thoughts turned to Miss Amanda and she said again, "You are just the same as our mother, Billy's and mine, aren't you?"

"I try to be the same as a mother to you."

"Then, Aunt Hester, could I be named Ruth Henrietta Brackenbury, and if anybody asks my name can I tell them it is that?"

"Why, my dear," Miss Hester arose and hung over her arm the garment she had taken from the chest, "yes, if you like."

"Would you like?" asked Ruth wistfully.

Miss Hester did not answer at once, but picked her way back to where it was lighter.

"Try this on," she said holding out a dark red coat trimmed with fur.

Ruth slipped her arms into the sleeves and then softly stroked the fur trimming.

"It fits perfectly," said Miss Hester, with satisfaction, "so you can wear it Sunday. I will hang it out in the air to get rid of the smell of camphor, and to-morrow I will press out the creases."

"For me? For me?" cried Ruth. "Henrietta's coat for me? Oh, Aunt Hester!"

"Yes, for you, and I think all those little clothes will fit you. It will save me many stitches and what good are they hoarded away?" she said half to herself.

Ruth clasped her arms around Miss Hester's waist. "Please kiss me as if I were Henrietta," she said, "and let me put her name next to mine."

Miss Hester stooped to kiss the quivering lips. "I will ask the minister about the name," she answered. "I am not sure whether it would be right, but I'd like it. Yes, I'd like very much for you to have it."

"May I wear the coat down-stairs?" asked Ruth. "Then you won't have to carry it."

"You may wear it down, then take it off and lay it on my bed."

"Ruth Henrietta Brackenbury," whispered Ruth to herself as she stepped down the narrow stairs behind Miss Hester, avoiding the plain black skirt which swept each step in front of her.

Ruth loved color. Rich clothes and dainty fare likewise appealed to her. It was bitterness to the proud little soul to feel that she had been taken from the streets. She envied the little Henrietta who had been a Brackenbury and who had lived her short life in the fine old house with white pillars. The child felt that in some way she would more fairly possess that little sister's inheritance if she could include Henrietta's name in her own.

Little Ruth gave a fierce loyalty to the mother she had loved so dearly, and, though she never failed to stand up for her father, and was ready with excuses whenever Billy or any other assailed him, in her inmost heart she felt a bitter rage against the man who had left her and her mother to suffer. She excused him partly because of pride and partly because she knew her mother would wish it. But, to herself, she considered that a great injustice had been done and resented bitterly the fact that those who commended Miss Hester for her great charity, felt that Ruth and Billy belonged to the same class.

Billy did not care what any one thought. His life had been a hard one from babyhood. He had never been warm in winter, nor had he had enough to eat at any time of year. He had been kicked and battered about from this one to that till he could not tell to whom he really did belong, so that when he drifted into this haven of peace, he had but one feeling and that of thankfulness.

With Ruth it was different. She remembered when she had worn pretty clothes and when a sweet and dainty mother had fed her choice bits from a well-appointed table, when a tall father had taken her to drive behind a gray horse. She remembered, too, a pretty house and garden which had been home to her. She could not recollect how it happened that all changed, but so it did, and, by degrees, the place she and her mother called home, became poorer and poorer till a garret under the eaves of a tall building was their habitation.

When it came to this, there was no father there to see the manner of it; only a pale and sad mother who wept constantly and who coughed often as she sat over a table, writing, writing. After a while there was less to eat, no fire and the cough grew worse. Then they took her mother away one morning after she had lain for hours very pale and still. Ruth could not rouse her.

Some one came in and whispered: "She is dead, poor thing."

And then Ruth knew what was the matter. In a turmoil of terror and grief she had rushed down the steps and out into the street. Her mother could not be dead. It needed but a doctor to make her well, and it was a doctor the desperate little child was seeking when she was discovered by a city missionary, exhausted and weeping and weary with wandering.

At first, she had repelled all advances from Miss Hester, and had no words even for Billy, but his good nature at last brought a response and she accepted his companionship, while for Miss Hester there was springing up a deep affection. She was no longer jealous for the mother who had become an angel, for she was fading into a sweet and lovely dream.

She no longer resented the fact that Miss Hester had taken her in from charity, for she was beginning to realize that something more than cold duty prompted Miss Hester's kind acts. To-day for the first time she understood in what light Miss Hester really regarded her, for, could she have given to any one that she did not love, the clothing of the long mourned little twin sister, Henrietta?

The child took off the coat, carefully laid it on Miss Hester's bed, then she fingered it gently. It was lined with soft wadded silk, and in the little pocket was a folded handkerchief. Ruth drew it out and silently held it out to Miss Hester.

"You can use that, too," Miss Hester told her.

And Ruth put it back again. It gave her a truer sense of taking Henrietta's place to know that it was there.

She wore the red coat proudly to church the next Sunday, and though, at any other time she would have allowed Stray to take such liberties as pleased him, she spoke to him quite sharply when he attempted to jump upon her with not too clean paws.

"Proudy," whispered Billy.

Ruth shot him a look of defiance from under her black brows. "You'd be proud, too, if you had on Henrietta Brackenbury's coat," she said.

"Well, I guess I've got on the major's," returned Billy triumphantly.

"Oh, but it's made over," returned Ruth, as if that settled the question and made all the difference in the world.

In fact, so complacent was Ruth in her new rig that, a few days later, her pride had a fall, such a tumbledown as was followed by serious consequences.

It was when Lucia Field invited her to a party which was strictly select, it being her birthday. Annie Waite was there as well as Nora Petty, Angeline McBride and Charlotte Thompson. Ruth was glad to see them all except Nora and Angeline, for these two had never been very agreeable to her at school. Once or twice, Nora had made some little mean remark which Ruth had overheard and which had made her very angry. She had told Billy about it, but he only laughed. She had not forgotten, however, and held herself rather loftily when she entered Lucia's house, clad in the red coat and a fine plaid poplin which had been Henrietta's.

"Doesn't Ruth look nice?" whispered Annie to Nora.

"So, so," was the reply given with a toss of the head.

"I wonder where she got her clothes," said Angeline. "They are kind of old-fashioned, but they are awfully pretty."

"She didn't bring 'em with her when she came to town, that's one thing sure," said Nora behind her hand.

And Angeline giggled.

By this time, Ruth had laid aside her coat and hat in the best bedroom, and had stepped down the broad stairway into the room where the other girls were gathered, waiting for the party to begin. Mrs. Field was there and her cousin, Miss Fannie, a young lady in a blue dress, who smiled invitingly at each of the girls and said they must have some games. Then the fun began, and for an hour or more went steadily forward, Miss Fannie being at the head and front of everything. Then came simple refreshments; home-made cakes, ice-cream and bonbons.

Ruth was just thinking that she had never had a better time in her life, when Lucia came forward with a birthday book which her cousin Fannie had given her.

"Now, before you go," she said, "I want you all to write your names in my birthday book."

Ruth's color came and went as she stood waiting her turn.

Nora looked at her, nudged Angeline and giggled. She knew it was an awkward moment for Ruth, though Lucia had not dreamed of such a thing. She really was very fond of Ruth, and admired her much more than she did Nora.

Annie and Charlotte had bent themselves to their task. Annie's was a crooked scrawl slanting unevenly across the page opposite March 12. Charlotte's signature was very black and round.

"Now it is your turn," said Miss Fannie to Ruth. "When is your birthday, dear?"

"November the fifteenth," said Ruth weakly.

"Oh," exclaimed Nora, "how do you know?"

Ruth bit her lip, then she made answer: "It is written in my mother's Bible."

"Of course," said Miss Fannie. "Right here, dear. You have a nice quotation, too."

Ruth hesitated, dipped her pen in the ink and then wrote quite firmly: Ruth Henrietta Brackenbury.

"Oh, oh," cried Nora, looking over her shoulder, "see what she has written. Her name isn't Brackenbury at all, Miss Fannie. People call her that, but her name isn't that at all."

"It is, it is," cried Ruth, her eyes flashing, "and the Henrietta is for Aunt Hester's little sister; she said so."

Miss Fannie, who did not know Ruth's history, looked puzzled. "Why do you say it isn't her name, Nora?" she asked.

"Why because it isn't. Everybody knows Miss Brackenbury took her from charity; she took her out of the streets. My mother was at the meeting when the letter came about her and Billy Beatty, and she said she didn't see how Miss Brackenbury could be willing to take in any one she didn't know anything about. She wouldn't let me play with her at first, and I don't think she ought to be allowed to call herself something she is not."

But before the speech was ended, Ruth had rushed up-stairs, with hurried, trembling fingers had put on her hat and coat and, without stopping for a word with any one, had flown out of the house and up the street, the tears running down her cheeks and her heart beating with a fierce resentment.

Miss Hester was not at home when she arrived at the door, and she was obliged to go around the back way, take the key from its hiding-place under the door-mat, and let herself in.

An hour later Miss Hester found her alone in the dark, lying prone on the floor, sobbing broken-heartedly.

"Why, my poor little girl, what is the matter?" she said lifting her up. "What has happened? Are you hurt? Has anything happened to Billy or Stray?"

"No, no," replied Ruth between sobs; "it's only me."

"Only you? But only you are very important to your Aunt Hester. I'll take off my things and then you must come in where it is warm and tell me all about it."

Ruth's room was heated from Miss Hester's where a wood stove supplied the heat night and morning. Now that the weather had grown colder, Miss Hester sat in the living-room or the kitchen, for she must save fuel.

It was not long before Ruth's tears were dried, as with head nestled on Miss Hester's shoulder, she sat in her lap and told her story.

"It was very unkind of Nora," Miss Hester said.

"I s'pose she thought I wanted to be deceitful, and she always likes to tell on people. She's always telling on the girls at school the least little thing they do. She didn't like it 'cause the girls said my coat was pretty. She asked me where I got it and I told her you gave it to me, and she said she wondered how you could afford to give me anything as good as that. She began to say something else but Lucia hushed her up. Oh, Aunt Hester, was I deceitful? I am your little girl now; you said so."

"Yes, dear, you are my own little girl. You love Aunt Hester a little bit, don't you?"

"I love you, oh, I do love you, but—but you don't want me to forget mother, do you?"

"A thousand times no. Remember your dear mother to your dying day."

"She's an angel now," returned Ruth, "and I can't tell her I love her, but I can tell you and I want to stay with you forever 'n' ever and be called Ruth Henrietta Brackenbury."

"And so you shall. I must see Dr. Peaslee," she added musingly, "and Squire Field; they'll know how I must make it legal."

She put on her hat that very evening and went out, leaving Billy and Ruth to study their lessons.

When she came back Dr. Peaslee was with her. He brought a pocketful of roasted chestnuts for the children and told them such funny stories that they went laughing to bed.

Sometime later came an important looking envelope through the mail. Ruth brought it in. "Such a great big letter, Aunt Hester."

Miss Hester took it, opened it and looked over the contents. Then she called Ruth to her. "Ruth Henrietta Brackenbury," she said taking the child's face between her two hands, "that is your real name now and no one can dispute it. You shall never change it unless," she added with a little twist of a smile, "you should get married some day."

"But I never shall," returned Ruth soberly, "for I shall always want my name to same as yours. Is it really, really mine?"

"It is really yours in law, and you are my own little girl in the eyes of the law exactly the same as you would be any mother's."

"Oh, I am so glad, so glad," said Ruth.

Then they sat and hugged each other very tight till Billy came in with the wood.

One Friday Afternoon

"AND what about Billy?" said Ruth. "You are his aunt, too, you know."

Ruth looked across the room at the cheerful Billy stowing away the wood for the morning's fire. "You know I am really and truly named Brackenbury for always and forever," said the little girl exultantly.

"I know," returned Billy. "It's all right for a girl."

"Billy is quite content to remain Billy Beatty. He says he would rather not have any other name, and, under the circumstances, I think it is just as well," said Miss Hester.

"I've always been called Bill Beatty and I'm always a-goin' to be," maintained Billy sturdily. "Why, the first week I was here, I licked a feller for callin' me sumthin' else."

"Why, Billy," said Miss Hester chidingly.

"Yes, I did. I didn't tell you nor Ruth neither. 'Twa'n't no use. You're awful good to me and I'm tickled to death to call you aunt, not having no kin, but aunts don't always have the same name as their nephews, I told the fellers. Besides I ain't just the Brackenbury kind like Ruth is."

"You are a very good kind, Billy," said Miss Hester, warmly.

"Oh, that's all right," returned Billy uneasily, moving off at the suggestion of a compliment.

It was quite natural that Billy, the street urchin, should not appeal to Miss Hester in the same way as did Ruth, the daughter of a refined and gentle mother, though to sturdy Billy, Miss Hester gave a warm affection while her sense of duty never allowed her to slight him or to lessen his opportunities.

But it was Ruth who shared her future when she sat over her sewing planning for the days to come. It was Ruth whose love she craved and of whom she felt that she could be proud.

Billy should be reared to be self-reliant that he might go forth into the world and make a name for himself. He should be sent to school, should have good moral instruction, and Miss Hester prayed that through her efforts, he would become a good man.

Ruth should stay with her and be as her own daughter, and one day they might go back together to the old home.

At school, Billy not only held his own among his comrades, but fought Ruth's battles as well, so that no one dared so much as hint that she had not a right to her new name.

That question came up one day not long after Lucia Field's birthday party, for one day at recess, there was a great discussion over in one corner of the playground.

Nora Petty and Annie Waite were contradicting each other and Ruth, who was eating her lunch with Lucia, heard "She has," from the one, and "She hasn't," from the other, repeated over and over again, the voices rising with the tempers of the two little girls who were quarreling.

"What do you suppose is the matter?" said Lucia. "Let's go over, Ruth, and find out."

So, with apples in hand, they crossed the playground.

"There she comes now," said Annie; "you can ask her."

"Oh, they are talking about us," said Lucia, in a low tone. "Ask who what?" she said, as she came up.

"Why, you know," began Nora, "this morning we had new copy-books given out, and we all had to write our names on them. I say Ruth has no right to the name she wrote on hers and Annie declares she has. Everybody knows Ruth's real name is Mayfield, and that it isn't the same as Miss Hester's and that she isn't one bit of relation to her."

"But it is her real name," cried Lucia, triumphantly. "That's the second time you have tried to hurt Ruth's feelings about it, and you've just got to stop it; she's my best friend, I'll have you to know."

"It isn't her name, either!"

"It is, too. I reckon my grandfather knows. He told me the law gave her that name and she is just exactly the same as if she were born with it, for Miss Brackenbury has legally adopted her, and if she ever gets back her old home, it could go to Ruth just the same as if she were her own child, so there. I reckon my grandfather ought to know if anybody does."

As Squire Field was the acknowledged authority upon most matters, Nora had not a word to say. She only stood and stared. The other children had gathered around.

One of the boys nudged Billy. "Is that so?" he whispered.

Billy nodded. "Sure pop."

"How about you?"

"Oh, I'm not in it. She's a girl and it's all right for her, and I can get along with any name. I told Aunt Hester I'd rather keep to Beatty. But I'd just like to see," he spoke up in a loud voice. "I'd just like to see anybody, boy or girl, say that Ruth hasn't a right to be called Brackenbury; I'll make it hot for 'em."

The girls shrank back and the boys hastened to assure Billy that no one doubted his word. Billy had made good use of his fists for too many years for his fighting qualities to be despised by his schoolmates.

"Come," said Lucia, putting her arm around Ruth, "let's go back and finish our lunch. I've got some nice little spice cakes in my basket. I made the cook put two in for you."

She glanced over her shoulder at Nora as she said this, for there had been a time when she and Lucia had eaten lunch together, but, since her Birthday Party, Lucia had chosen to ignore Nora and had invited Ruth to share the enticing contents of her lunch basket.

Every one knew that Lucia Field brought nicer lunches than any one else, and Nora felt herself distinctly snubbed. A great anger against Ruth arose in her heart. Ruth, whom she despised as an interloper and of whom she was wildly jealous, to be preferred before her was too much, and she determined that if there was any way to annoy her that the chance of doing so should not be lost.

Not long after this, her chance came, for on Friday afternoons the little girls brought their dolls to school at the request of the teacher who gave sewing lessons upon that day, and who had cut out and put into the hands of each a petticoat to hem, gather and sew on a band.

Ruth had learned to sew very nicely under Miss Hester's instructions and made so neat a hem as to call forth the teacher's praise.

"That is very well done," she said. "See, Nora, what neat little stitches Ruth has taken. Try to make yours look as well. I am afraid you will have to pick out half of what you have done. You are in too much of a hurry. If you want to sew neatly, you must take more time."

Nora pouted and gave her shoulders a twitch as the teacher turned away. She did not dare say anything but she gave Ruth so black and threatening a look as to make that young person wish she could change her seat, it being, unfortunately, next to Nora's. The best she could do, however, was to turn half way around toward Lucia who sat on the other side and who gave Ruth a pleased smile when Miss Mullins praised her.

Henrietta, though a less magnificent person than Lucia's Annabel Lee or Nora's Violetta was, nevertheless, quite as well dressed as her smiling neighbors who, staring at the maps on the wall, sat up stiffly on the desks in front of their several owners. Miss Hester, previous to the last Christmas, had given many a spare moment to the exquisite needlework which Henrietta's clothes displayed, and her dainty cambric underwear and pink frock were quite the admiration of Ruth's schoolfellows. To be sure, Lucia had excused the appearance of her doll by saying, "An only child as yours is, Ruth, must expect to dress better than the others. Now with my six, I find it hard to keep them all properly clothed and sometimes they even have to wear each other's clothes. I can't get enough clean things to go around."

Then little Ruth had embraced Henrietta tenderly, for she was indeed her only child and her coming had been one of Ruth's greatest joys, for though she remembered her babyhood's dolls, these were all broken and lost long before Ruth had come to Miss Hester's to live, and a forlorn rag-baby was her only plaything at the time her mother died. What had become of the rag-baby, she never had found out, for when she looked for it that sad day when the good doctor took her for a last time to the empty attic, there was no rag-baby to be seen. Possibly some even less fortunate child had found it and had treasured it. This Miss Hester told her for her comfort, but because Ruth so mourned her lost darling, that first Christmas in the big house, Henrietta was given to her.

Miss Hester had little money to spend, even then, and the doll was the first thing taken from the old chest which held the possessions of the little sister Henrietta and which was destined to furnish Ruth with many comforts and pleasures. The doll Henrietta, having been in the world some years longer than her neighbors, was rather an old-fashioned beauty. She was not of the bisque of which the more modern dolls are made, but a sort of composition and wax gave her a soft expression. Her eyes were large and beautiful and her hair long and curling. Ruth admired her beyond measure and because she was different from the rest, the girls all admired her immensely, and it was considered quite a privilege to be allowed to hold her.

On this Friday afternoon, Ruth stole a pleased glance every now and then to Henrietta sitting in silent state upon her desk. Nora's doll in silk attire she did not think near so lovely, for Violetta had an unkempt frowsy appearance. Lucia's Annabel Lee was a sweet insipid creature with very light hair and an innocent smile which showed two of her tiny teeth. She was clad in blue cashmere somewhat streaked and faded from Lucia's attempt to wash the frock for this occasion. Her efforts had not turned out well, but, as she confided to Ruth, it was clean, which was more than could be said of some costumes. Between two such representatives as Violetta and Annabel Lee, it was no wonder that Ruth viewed Henrietta with complacency.

The room was very quiet, for the girls were not allowed to talk without permission. Once in a while, there was a subdued whisper from one corner or Miss Mullins's low tones were heard as she bent over the work of some pupil. There was an odor of geraniums from the plants in the window. Sometimes, when a desk lid was raised there was a sudden spicy whiff from a hidden apple. Outside the sparrows were twittering in the vines and the rumble of wagons sounded indistinctly. It was a very quiet, orderly class indeed, thought Miss Mullins.

Suddenly from one corner came a crash, a distressed cry followed by wild sobbing. Miss Mullins looked up quickly. There was a disturbance in the direction of Ruth's seat. Miss Mullins went quickly to the scene of trouble. Crouching on the floor and holding fragments of a broken doll in her lap was Ruth wailing "She's dead! She's dead! She can never come to life again."

"You shall have mine, my Annabel Lee," Lucia was saying as she placed her own doll in Ruth's lap.

"No, no," wept Ruth, "I don't want any one but Henrietta. There was only one like her in the whole world, and she's dead, she's dead forever."

"Let me see, Ruth;" Miss Mullins bent over the weeping child. "Perhaps she can be mended."

"She can't, she can't," sobbed Ruth. "She's all broken to bits."

And indeed poor Henrietta was in a very sorry state for, though the body, legs and arms were not injured, most of the head was a total wreck.

"How did it happen? Did you let her fall?" asked Miss Mullins sympathetically.

"No, I didn't do it. Nora pushed her off my desk on purpose."

Miss Mullins straightened herself from her bending position. "Nora," she said gravely, "is that true?"

Nora, looking honestly ashamed, hung her head. "I did knock her off, but I—I didn't do it on purpose."

"But how came you to be meddling with Ruth's doll?"

Nora was silent.

"I had just taken her up for a minute," Ruth began to explain. "I wanted to measure the band around the waist, and I laid her down just for a second while I cut the band, and Nora leaned over and jogged her elbow just so and Henrietta went sliding off before I could catch her."

Miss Mullins looked again at Nora. "If that is true, it was a wicked thing to do, Nora, and I am greatly grieved that one of my class could purposely destroy another's doll."

Nora began to sniffle and look aggrieved. "I didn't think she would break. I just wanted to scare Ruth."

"You should have known that a doll was liable to break, if it fell from any distance upon a hard floor, and, in any event, you intended to do wrong. Even in trying to scare Ruth, you were to blame." Miss Mullins stood looking from the culprit to the mourning Ruth.

"The only thing I can think of that you can do to make reparation, is that you give Ruth your doll," she continued.

Ruth scrambled to her feet. "Do you suppose I would take anything she had played with? Do you suppose her horrid Violetta could take the place of my dear lovely Henrietta? And I wouldn't touch that ugly greasy old silk dress with that common cotton lace on it. I would be ashamed to be seen with such an untidy looking thing."

"Ruth, Ruth," Miss Mullins's hand was laid on her shoulder, "this will not do. I realize that you are much grieved and excited, but you must not talk so. The only way Nora can make any sort of reparation is to give you her doll, and I want her to do it."

"She can send it to the heathen or the missionaries; I don't want it, and I won't have it. Miss Mullins, do you think your mother would want to change you for some one that looked like Nora's Violetta?"

Miss Mullins tried to hide a smile.

Ruth was so fierce and contemptuous and, though she felt very sorry for her, she could not but be amused at the same time that she tried to be stern.

"You must try to curb that violent tongue of yours, Ruth," she said. "I see nothing else to be done. I am sure we are all very sorry for you, and regret what has happened. I will excuse you from sewing any more to-day and, if you and Lucia will speak in whispers, you two may take that empty seat by the door, and I will give you permission to speak to one another, if you do not disturb the rest of the class. Nora, you may come to the platform and sit by me. I want to speak to you after school is dismissed."

Bearing the fragments of her broken doll, Ruth made her way to the seat her teacher had pointed out, Lucia following with her own and Ruth's sewing materials.

At sight of the unfinished petticoat, the tears welled up into Ruth's eyes again.

"Henrietta will never need it," she sobbed, burying her face in her hands.

Lucia put her arms around her. "Don't cry," she whispered. "You can have any of my other dolls if you don't care for Annabel Lee."

Ruth gave her friend's hand a little squeeze. "You are awfully good, Lucia," she whispered. "I don't mean that your dolls aren't lovely when I say I don't want any of them, but you know there isn't any other one like Henrietta in the whole wide world. She isn't near so big as your Annabel Lee nor so 'spensive, maybe, but she isn't like anybody else and now I shall never, never see her again." And the tears flowed more plentifully.

Lucia tried to whisper comforting words though there seemed little consolation to offer.

"You can have the petticoat for your Marie; it will just fit her," said Ruth after a pause. "I shall never need it."

"Oh, no, I couldn't take it," returned Lucia, though she secretly admired the neat work.

"Please do; it will always remind me of this dreadful day and I couldn't stand it. It is nearly done, you see, and I can easily finish it."

So, realizing that Ruth really desired to give her the small garment, Lucia accepted it, determining that some day when time had softened Ruth's grief, she would again offer her one of her dolls.

It was not long before school was dismissed; then the girls gathered around Ruth with many expressions of sympathy for her and sharp censure for Nora.

"I'd never speak to her," said one.

"I wish I didn't ever have to see her face again," returned Ruth.

"I don't see how you can bear to sit by her; she was always hateful to you;" this from Annie Waite.

"I'm going to ask Miss Mullins if Lucia and I can't change our seats," returned Ruth.

But this she did not have to do, for on Monday, to her relief, she found Nora established on the other side of the schoolroom in a seat by herself, this being Miss Mullins's punishment for what she realized was a spiteful and cruel act.

Ruth, escorted by a band of sympathizing comrades, bore her doll solemnly home that fateful afternoon and poured forth her pitiful tale in the ears of Miss Hester and Billy.

Billy and The Doll

MISS HESTER did her best to comfort the grieving Ruth, and, if the truth were told, felt nearly as badly as the child herself at the destruction of the doll which had belonged to her twin sister. She took the broken doll in her hands and looked at it tenderly.

"We had them exactly alike," she told Ruth, "only mine was dressed in blue and Henrietta's in pink; we always dressed them so to tell them apart. My father brought them to us once when he had been to New York, and we thought there never were dolls like them."

"What became of yours?" asked Ruth interested. "Did you break it?"

Miss Hester smiled a little wistfully. "No, I didn't break it. I gave it to some one. Some one who used to play with me when I was a little girl."

"Did you give it away after your little sister died?"

"Yes, many years after; when I was a woman grown."

"And has the somebody you gave it to—has that somebody the doll now?"

"I think so. Don't you think, Ruth, we would best take this poor broken Henrietta and put her back in the chest from which we took her?"

"Yes," Ruth answered soberly, "I should like to know that she was laid away with Henrietta's things, the broken cup and saucer and the mittens with the thumbs worn out and all the rest of the things she used to have."

"And some day when I can afford it, I will get you a new doll."

"Lucia offered to give me any one of hers that I would choose if I ever wanted another one, but I don't feel now that I ever shall."

Ruth drew a long sigh. "I loved Henrietta so." Her chin quivered and then the tears flowed again as they did at intervals all the evening.

And at bedtime, when there was no Henrietta sitting in her little wooden chair smiling into the dimness, came the most piteous weeping of all, till Ruth's pillow was wet with tears, and when Miss Hester peeped in at midnight—so many buttonholes had there been that day—she found the child wide awake, the drops still burdening her long lashes.

"Poor baby," she said bending over to give her one of her gentle kisses, "would you like to come in and sleep with me?"

"It wouldn't seem so lonely," said Ruth, sitting up, "but you don't like any one to sleep with you, Aunt Hester."

"I'd like it to-night." So Ruth found her comfort in the clasp of Miss Hester's arm and went to sleep cuddled close.

Billy had listened with kindling eyes and with angry exclamations, to Ruth's account of the disaster, and the next day, on their way to the store, he confided to Ruth that he meant to "do up" that Nora Petty. Just what the process of doing up might mean, Ruth didn't know, but she believed in Billy's prowess and was sure it was something too dreadful for any girl to endure. If it had been a boy, now, who had done this thing, she would willingly have allowed Billy to punish him as he might see fit, but a girl battered and banged by Billy's tough little fists was something altogether too awful to be thought of, so she tried to make him promise that he would let Nora alone, saying, rather grandly, that boys ought not to fight girls.

"Ah, look a-here, I didn't mean to knock her down and pommel her," said Billy, "but I'll tell all the fellows how mean she is and if Frank Crane gives her any more apples, I'm mistaken. They won't, any of the other fellows, you can bet your boots. I guess we can find a way to give her a dose without our fists."

"Well, it won't do any good now," returned Ruth, resignedly. "Billy, I wonder who has that other doll that was Aunt Hester's."

"You can search me," replied Billy.

"Just think of it, she's the only one in the world like my Henrietta, and I do wish I could have her. Do you suppose the person loves her very much, as much as I would?"

"Ask me somethin' easy. Maybe there are some others somewhere like that one." Billy was thoughtful.

"Where? You know Aunt Hester said they didn't make that kind nowadays."

"Oh, I don't know just where. There might be some left over."

"I never saw one."

"That's not sayin' there ain't any. Some old person might know where one could be had."

"Oh, do you really think so?"

"Might. Can't say for sure, but somebody might happen to know."

"But Aunt Hester didn't know. Do you mean some one as old as she is?"

"Yes, or older."

"How old do you suppose she is?"

"About forty-four, I guess. Ye know on the headstone over the twin sister's grave it says: 'Born February 10, 1860, died March 21, 1868.' Now ye know they were twins, and if she was born in 1860, that's forty-four years ago."

"Oh, how smart you are about figures, Billy. I never could have thought of that. Forty-four is quite old, of course."

The two trudged along without saying anything for some minutes. Each one was busily thinking. Billy had a scheme he was pondering over, and Ruth was supposing. She did a great deal of supposing, "what if-ing" she and Lucia called it. What if some one knew where a doll like Henrietta could be bought, and what if some day as she was going to the store she should look down and find a silver dollar, a doll couldn't cost more than a dollar.

She stopped short and looked at the ground searchingly; it might be there at that very moment, and this might be the day when she would find it.

"What ye lookin' for?" asked Billy.

"Oh, nothing. I was just thinking what if I should find a silver dollar in the road."

"Pshaw!" exclaimed Billy. "That's foolishness."

"But people do find money sometimes."

"They don't so often when they're lookin' for it. I've often looked and I never found but a nickel in my life. No, sir, the only way you're sure of gettin' money is to work for it."

"I can't do that very well, and besides it would be much nicer to find it."

Billy did not answer; he seemed preoccupied. "There ain't much to carry home," he said. "I'll take it as far as the gate and then you can take it in. I want to see somebody before dark."

"One of the boys?" asked Ruth.

But there was no reply for by that time the store was reached.

This place was about a quarter of a mile from Miss Hester's small house which stood on the edge of the town upon a street which became a road just beyond. The town was not a large one. The houses stood far apart and many of them were surrounded by pretty gardens. In the centre of the town, just opposite the store and the post-office, stood Dr. Peaslee's house, a square brick building with as square a porch before the front door. The doctor was not married, and his mother, an invalid, was so rarely seen that most persons had forgotten her existence, and thought that a housekeeper held sway.

After leaving Ruth at the gate of their home, Billy retraced his steps, and, crossing the street when he came to the store, he went directly to Dr. Peaslee's door. The good doctor's mud-spattered buggy stood before the gate, so Billy knew that he should find the doctor at home, and he was not mistaken for he was in his office.

"Well, Billy boy," he exclaimed, looking up over his glasses, "what brings you here? Any one ill up your way? Not Miss Hester, I hope."

There was a little anxious ring in his tone.

"Nobody's sick," returned Billy. "I came over to consult you."

"About yourself? What's your particular indisposition, Mr. Beatty?"

The doctor and Billy had been good friends ever since that day when Billy had been picked up in the streets of the city and had wakened to consciousness to see the doctor's kind face bending over him.

"'Tain't nothin' the matter with me," returned Billy, grinning. "I'm all right."

"Don't want to be fashionable and part with your appendix?" asked the doctor fingering some sharp instruments which lay on the table before him.

Billy gave a little squirm but faced the doctor's glance sturdily. "I ain't achin' to be no subjick at a 'orspital," he returned. "I reckon the doctors kin learn their trade without foolin' with my in'ards."

The doctor laughed. "Well then, proceed to business. What's troubling you, governor?"

Billy looked down at the stubby toes of his shoes. He was thinking just how he would best conduct his system of inquiries. Presently he looked up and said: "You've known Aunt Hester a long time, haven't you, doctor?"

"Ever since we were smaller kids than you and Ruth."

Billy nodded. "Did you ever see them dolls her and her sister used to have, waxy ones, dressed in pink and blue?"

The doctor looked at him sharply and answered in a more reserved manner, "Yes, I remember them."

"Well, have you any idea who Miss Hester gave hers to? She said she didn't give it away till she was grown-up, and I thought maybe you might know."

The doctor drummed thoughtfully upon the arm of the desk chair which he had swung partly around toward Billy. "Why do you want to know?" he asked presently. "And why do you ask me?"

"Well, I knew you were an old friend; you've got the major's cane, you know, and I didn't know but you could tell something about the doll. This is why I want to know." And he launched forth into a tale of Ruth's trouble.

The doctor did not interrupt him, but at the close of the story, he muttered under his breath:

"Humph! That's just like a Petty." He looked Billy over with a smile. "See here, youngster," he said, "you were a wise little owl to come to me with that tale, for the fact is that I do know to whom Miss Hester gave that doll and I also happen to know that it is still in existence."

"Do you think the person that has it would sell it? I'd work all day Saturdays, all the time I mean from my regular chores, to pay for it. You haven't got any odd jobs to be done, have you, doctor? I'm real strong. Feel my muscle."

He spoke eagerly and stretched out an arm which in truth showed more muscle than flesh.

The doctor gravely responded to the invitation and nodded assent. "You'll do," he said. "Well, sir, I'll tell you what I'll do: I'll try to arrange the matter for you. I'll see about bargaining for the doll; I can probably make a better deal than you, and I'll have some jobs ready for you, if not here, somewhere. Now mind, I'm not sure that we can make the trade, but I'll see how the land lies, and if the doll can be given up without any hurt feelings or anything of that kind, we'll get it."