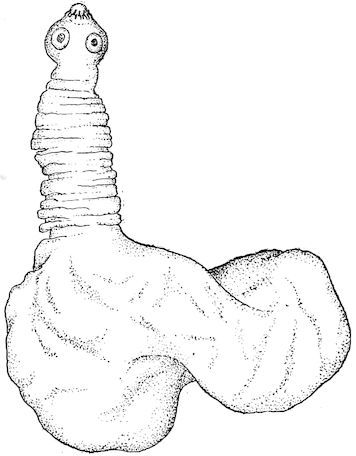

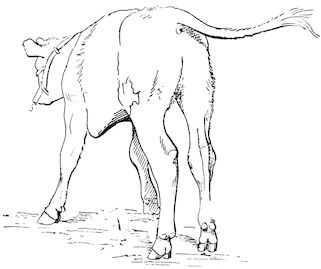

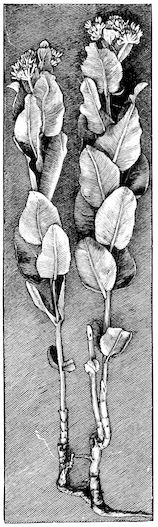

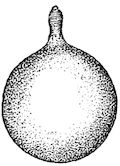

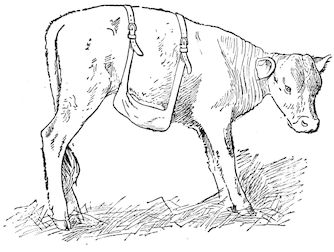

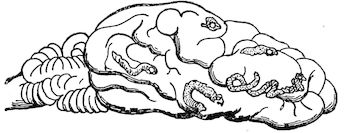

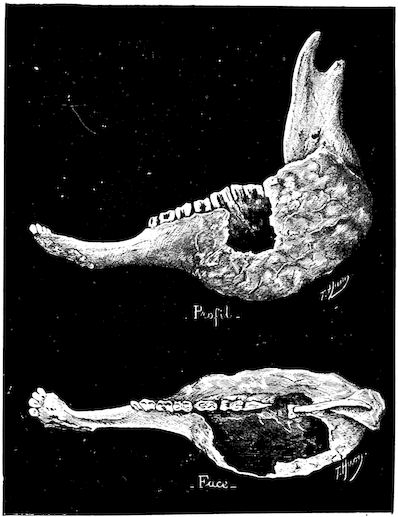

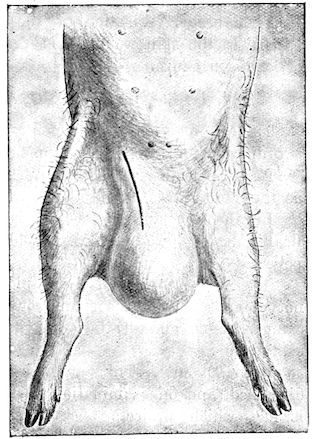

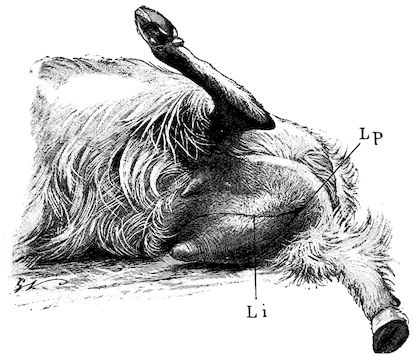

Fig. 1.—Rachitis in a young goat.

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

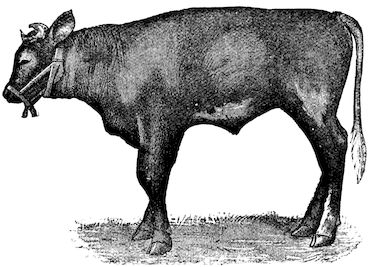

No apology seems called for in presenting to English-speaking veterinary surgeons and students a treatise on the diseases of cattle. To those entrusted with the onerous task of preventing or curing disease in cattle, sheep, and swine the scantiness of permanent literature dealing with the subject must always have proved a matter of some embarrassment, while to teachers and students alike the want of a concise and modern textbook has long been a difficulty of the first order. It is hoped that the present volume may go some way towards remedying this state of affairs.

As on previous occasions, the writer has freely availed himself of foreign sources of information. Two years ago he purchased the literary rights in Professor Moussu’s “Maladies du Bétail,” which had even then attained an European reputation, and which forms the backbone of the present volume. To obtain further information, the more important German treatises have been laid under contribution, while all accessible English, American, and Colonial literature of recent date has been referred to. (The references practically extend up to the moment of writing—the latest being June, 1905.) In this way the work may in some degree claim to have assumed an international character. The extent of the additions is indicated by an increase in the number of illustrations of 140, and of the text of nearly 50 per cent.

Professor McQueen has performed the greatly-valued service of reading proof sheets and advising the writer as the book passed through the press.

To Dr. Salmon, of the United States Department of Agriculture, special thanks are due for his generous permission to quote from the annual reports of that body.

Other acknowledgments will be found in the text.

viOnce again the writer, who on this occasion chances also to be the President of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, appeals for lenient judgment on work performed under no common stress of duties, professional and political.

| SECTION I. | ||||

| DISEASES OF THE ORGANS OF LOCOMOTION. | ||||

| CHAP. | PAGE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methods of Examination | 1 | |||

| I. | DISEASES OF BONES | 3 | ||

| General Diseases | 4 | |||

| Rachitis | 4 | |||

| Osseous Cachexia | 7 | |||

| Local Affections | 20 | |||

| Fractures | 20 | |||

| Fractures of the horns | 21 | |||

| Detachment of the horns | 23 | |||

| Fissuring of the horns | 24 | |||

| Fractures of the horns | 25 | |||

| Exostoses | 27 | |||

| Spavin in the ox | 27 | |||

| Ring-bone | 28 | |||

| Suppurating ostitis | 29 | |||

| Bone tumours | 30 | |||

| II. | DISEASES OF THE FOOT | 31 | ||

| Congestion of the Claws | 31 | |||

| Contusions of the sole | 31 | |||

| Laminitis | 32 | |||

| Sand crack | 34 | |||

| Pricks and stabs in shoeing | 36 | |||

| Picked-up nails, etc. (“Gathered nail”) | 37 | |||

| Inflammation of the interdigital space (Condylomata) | 38 | |||

| Canker | 40 | |||

| Grease | 41 | |||

| Panaritium—Felon—Whitlow | 41 | |||

| Foot rot | 43 | |||

| III. | DISEASES OF THE SYNOVIAL MEMBRANES AND OF THE ARTICULATIONS | 45 | ||

| I. Synovial Membranes and Articulations | 45 | |||

| Synovitis | 45 | |||

| Inflammation of the patellar synovial capsule | 45 | |||

| viii | Distension of the synovial capsule of the hock joint | 46 | ||

| Distension of tendon sheaths in the hock region | 46 | |||

| Distension of the synovial capsule of the knee joint | 47 | |||

| Distension of the synovial capsule of the fetlock joint | 48 | |||

| Distension of tendon sheaths | 48 | |||

| Distension of tendon sheaths in the region of the knee | 49 | |||

| Distension of the bursal sheath of the flexor tendons | 49 | |||

| Traumatic synovitis—“Open synovitis” | 49 | |||

| Traumatic tendinous synovitis | 50 | |||

| Traumatic articular synovitis—Traumatic arthritis—“Open arthritis” | 51 | |||

| II. Strains of Joints | 52 | |||

| Strain of the shoulder | 52 | |||

| Strain of the knee | 53 | |||

| Strain of the fetlock | 54 | |||

| Strain of the stifle joint | 54 | |||

| Strain of the hock joint | 55 | |||

| III. Luxation of Joints | 56 | |||

| Luxation of the femur | 56 | |||

| Luxation of the patella | 58 | |||

| Luxation of the femoro-tibial articulation | 61 | |||

| Luxation of the scapulo-humeral joint | 63 | |||

| IV. Hygromas | 64 | |||

| Hygroma of the knee | 65 | |||

| Hygroma of the haunch | 67 | |||

| Hygroma of the trochanter of the femur | 67 | |||

| Hygroma of the stifle | 67 | |||

| Hygroma of the point of the hock | 68 | |||

| Hygroma of the point of the sternum | 69 | |||

| IV. | DISEASES OF MUSCLES AND TENDONS | 70 | ||

| Rupture of the external ischio-tibial muscle (Biceps femoris) | 70 | |||

| Rupture of the flexor metatarsi | 72 | |||

| Parasitic Diseases of Muscles | 73 | |||

| Cysticercus disease of the pig | 73 | |||

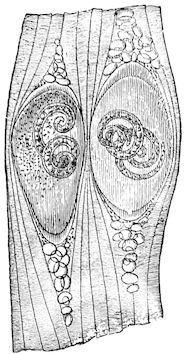

| Beef measles | 79 | |||

| Trichiniasis—Trichinosis | 84 | |||

| V. | RHEUMATISM | 89 | ||

| Articular rheumatism | 89 | |||

| Muscular rheumatism | 92 | |||

| Infectious Forms of Rheumatism or Pseudo-rheumatism | 94 | |||

| Infectious rheumatism in young animals | 94 | |||

| Infectious pseudo-rheumatism in adults | 99 | |||

| Scurvy—Scorbutus | 104 | |||

| ix | ||||

| SECTION II. | ||||

| DISEASES OF THE DIGESTIVE APPARATUS. | ||||

| Semiology of the Digestive Apparatus | 106 | |||

| I. | DISEASES OF THE MOUTH | 121 | ||

| Stomatitis | 121 | |||

| Simple stomatitis | 121 | |||

| Catarrhal stomatitis in sheep | 122 | |||

| Necrosing stomatitis in calves | 123 | |||

| Mycotic stomatitis in calves | 124 | |||

| Ulcerative stomatitis in sheep | 125 | |||

| General catarrhal stomatitis in swine | 126 | |||

| Ulcerative stomatitis in swine | 127 | |||

| Mercurial stomatitis | 128 | |||

| Glossitis | 130 | |||

| Superficial glossitis | 130 | |||

| Acute deep-seated glossitis | 131 | |||

| Chronic glossitis | 132 | |||

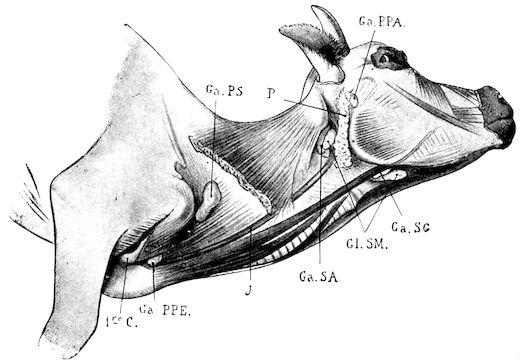

| II. | DISEASES OF THE SALIVARY GLANDS, TONSILS AND PHARYNX | 134 | ||

| Parotiditis (Parotitis) | 134 | |||

| Acute parotiditis | 134 | |||

| Chronic parotiditis—Parotid fistula | 136 | |||

| Inflammation of the submaxillary salivary gland | 137 | |||

| Tonsilitis in pigs | 138 | |||

| Pharyngitis | 138 | |||

| Pseudo-membranous pharyngitis in cattle | 141 | |||

| Pseudo-membranous pharyngitis in sheep | 142 | |||

| Pharyngeal polypi | 143 | |||

| III. | DISEASES OF THE ŒSOPHAGUS | 145 | ||

| Œsophagitis | 145 | |||

| Stricture of the œsophagus | 148 | |||

| Dilatation of the œsophagus | 149 | |||

| Œsophageal obstructions | 152 | |||

| Ruptures and perforations of the œsophagus | 157 | |||

| IV. | DEPRAVED APPETITE—THE LICKING HABIT—INDIGESTION | 158 | ||

| Depraved appetite in the ox | 158 | |||

| Depraved appetite in calves and lambs | 160 | |||

| Colic in the ox | 162 | |||

| Colic due to ingestion of cold water—Congestive colic | 162 | |||

| Colic due to invagination | 163 | |||

| Colic as a result of strangulation | 167 | |||

| Diseases of the stomach | 169 | |||

| Indigestion | 170 | |||

| Gaseous indigestion | 170 | |||

| x | Impaction of the rumen—Indigestion as a result of over-eating | 175 | ||

| Impaction of the omasum (third stomach) | 179 | |||

| Abomasal indigestion | 182 | |||

| Acute gastric indigestion in swine | 185 | |||

| V. | INFLAMMATION OF THE GASTRIC COMPARTMENTS | 186 | ||

| Rumenitis—Reticulitis—Gastritis | 186 | |||

| Acute gastritis | 188 | |||

| Catarrhal gastritis in swine | 190 | |||

| Ulcerative gastritis | 191 | |||

| Chronic tympanites | 194 | |||

| Gastric disturbance due to foreign bodies | 198 | |||

| Tumours of the gastric compartments | 202 | |||

| VI. | ENTERITIS | 203 | ||

| Acute enteritis | 203 | |||

| Hæmorrhagic enteritis | 206 | |||

| Chronic enteritis (Chronic diarrhœa) | 207 | |||

| Dysentery in calves | 210 | |||

| Diarrhœic enteritis in calves | 212 | |||

| VII. | POISONING | 215 | ||

| Poisoning due to food | 215 | |||

| Poisoning by caustic alkalies | 216 | |||

| Poisoning by caustic acids | 217 | |||

| Poisoning by common salt | 217 | |||

| Poisoning by the nitrates of potash and soda | 217 | |||

| Poisoning by tartar emetic | 218 | |||

| Poisoning by arsenic | 218 | |||

| Phosphorus poisoning | 219 | |||

| Mercurial poisoning | 219 | |||

| Lead poisoning: Saturnism | 220 | |||

| Copper poisoning | 221 | |||

| Carbolic acid poisoning | 221 | |||

| Poisoning by aloes | 221 | |||

| Iodoform poisoning | 222 | |||

| Iodine poisoning: iodism | 222 | |||

| Strychnine poisoning | 222 | |||

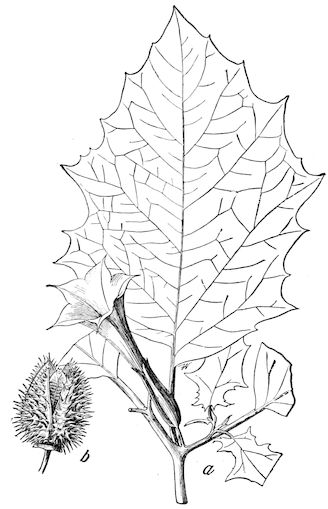

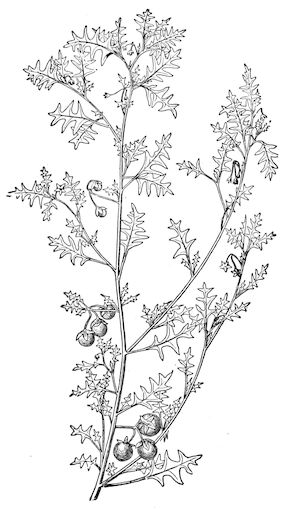

| List of plants poisonous to stock | 223 | |||

| Colchicum poisoning | 256 | |||

| Poisoning by annual mercury | 256 | |||

| Poisoning by bryony | 256 | |||

| Poisoning by castor oil cake | 257 | |||

| Poisoning by cotton cake | 257 | |||

| Poisoning by molasses refuse | 258 | |||

| Diseases produced by distillery and sugar factory pulp | 259 | |||

| VIII. | PARASITES OF THE DIGESTIVE APPARATUS | 263 | ||

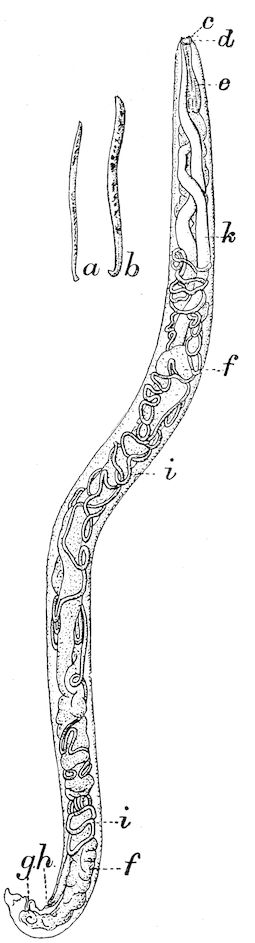

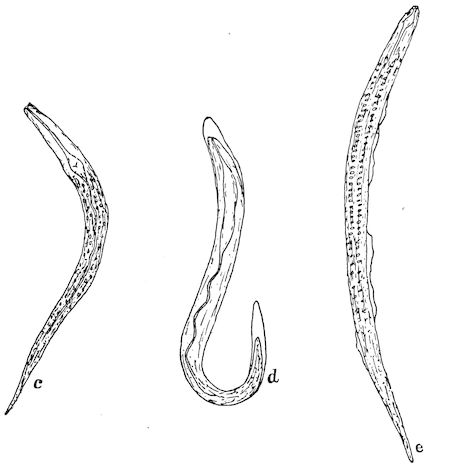

| Gastro-intestinal strongylosis in sheep | 263 | |||

| Lumbricosis of calves | 267 | |||

| xi | Strongylosis of the abomasum in the ox | 268 | ||

| Parasitic gastro-enteritis, diarrhœa, and anæmia in cattle, sheep and lambs | 268 | |||

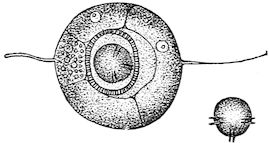

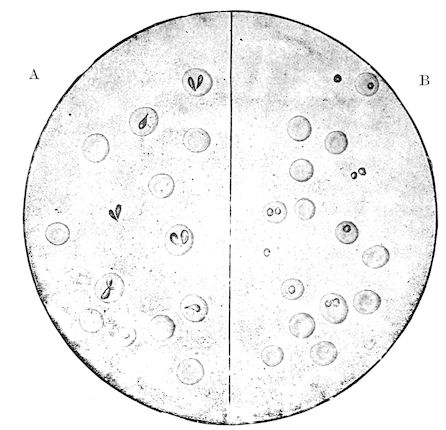

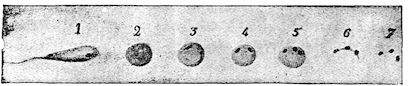

| Intestinal coccidiosis of calves and lambs (Psorospermosis, hæmorrhagic enteritis, bloody flux, dysentery, etc.) | 271 | |||

| Intestinal helminthiasis in ruminants | 275 | |||

| IX. | DISEASES OF THE LIVER | 279 | ||

| Congestion of the liver | 280 | |||

| Nodular necrosing hepatitis | 280 | |||

| Cancer of the liver and bile ducts | 282 | |||

| Echinococcosis of the liver | 283 | |||

| Suppurative echinococcosis | 288 | |||

| Cysticercosis | 290 | |||

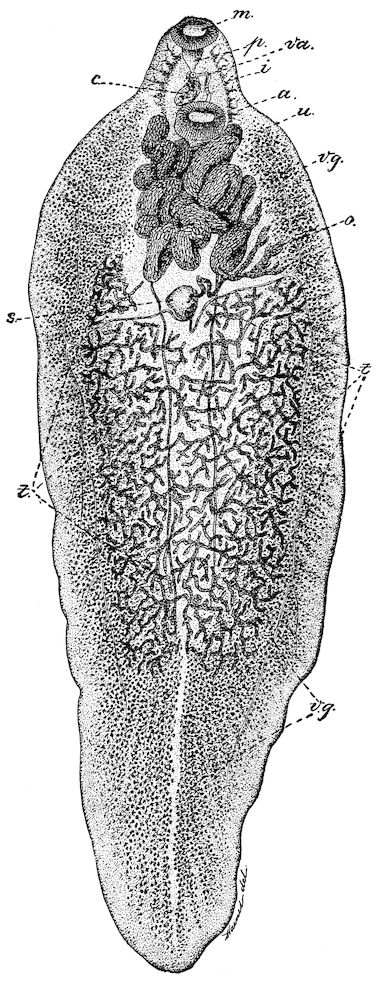

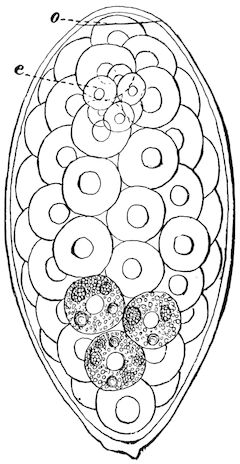

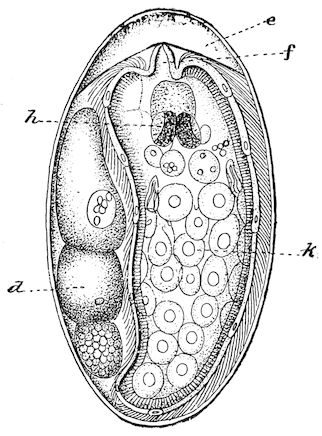

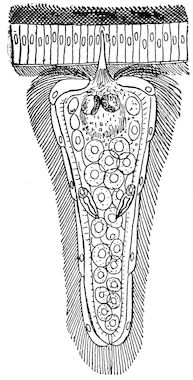

| Distomatosis—Liver fluke disease—Liver rot | 293 | |||

| SECTION III. | ||||

| RESPIRATORY APPARATUS. | ||||

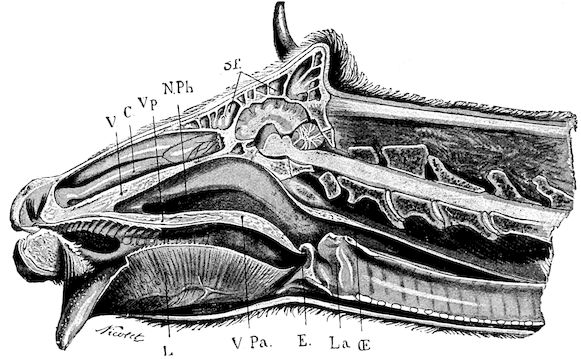

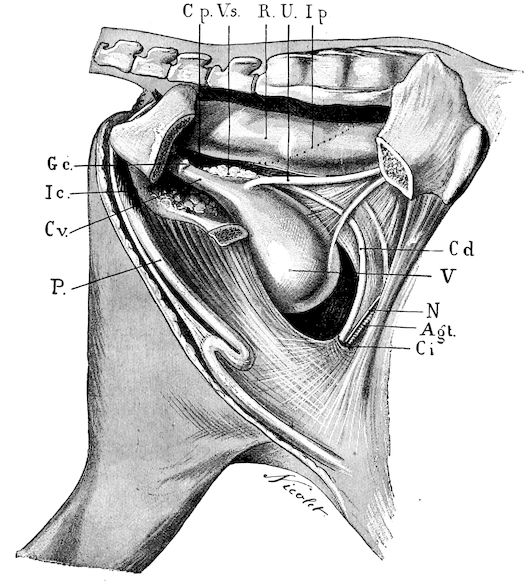

| I. | EXAMINATION OF THE RESPIRATORY APPARATUS | 311 | ||

| II. | NASAL CAVITIES | 319 | ||

| Simple coryza | 319 | |||

| Gangrenous coryza | 320 | |||

| Tumours of the nasal cavities | 325 | |||

| Purulent collections in the nasal sinuses. Nasal gleet | 326 | |||

| Purulent collections in the frontal sinus | 327 | |||

| Purulent collections in the maxillary sinus | 329 | |||

| Œstrus larvæ in the facial sinuses of sheep | 330 | |||

| III. | LARYNX, TRACHEA AND BRONCHI | 333 | ||

| Laryngitis | 333 | |||

| Acute laryngitis | 333 | |||

| Pseudo-membranous laryngitis | 333 | |||

| Tumours of the larynx | 335 | |||

| Bronchitis | 336 | |||

| Simple acute bronchitis | 337 | |||

| Chronic bronchitis | 337 | |||

| Pseudo-membranous bronchitis | 339 | |||

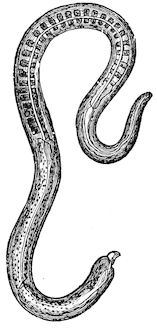

| Verminous bronchitis in sheep and cattle (Husk, hoose, etc.) | 340 | |||

| IV. | LUNGS AND PLEURÆ | 343 | ||

| Pulmonary congestion | 343 | |||

| Simple pneumonia | 343 | |||

| Pneumonia due to foreign bodies—Mechanical pneumonia | 347 | |||

| Pneumonia due to the migration of foreign bodies from the reticulum | 348 | |||

| Pneumomycosis due to Aspergilli | 350 | |||

| Gangrenous broncho-pneumonia due to foreign bodies | 351 | |||

| Infectious broncho-pneumonia | 354 | |||

| Broncho-pneumonia of sucking calves | 356 | |||

| xii | Sclero-caseous broncho-pneumonia of sheep | 358 | ||

| Pulmonary emphysema | 359 | |||

| Diseases of the pleura | 361 | |||

| Acute pleurisy | 361 | |||

| Chronic pleurisy | 362 | |||

| Pneumo-thorax | 362 | |||

| Hydro-pneumo-thorax and pyo-pneumo-thorax | 366 | |||

| V. | DISEASES OF STRUCTURES ENCLOSED WITHIN THE MEDIASTINUM | 368 | ||

| Tumours of the Mediastinum | 369 | |||

| SECTION IV. | ||||

| THE ORGANS OF CIRCULATION. | ||||

| Semiology of the Organs of Circulation | 370 | |||

| I. | CARDIAC ANOMALIES | 374 | ||

| Ectopia of the heart | 374 | |||

| II. | PERICARDITIS | 375 | ||

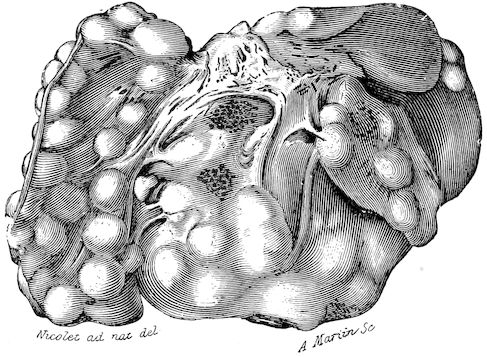

| Exudative pericarditis due to foreign bodies | 376 | |||

| Chronic pericarditis | 389 | |||

| Pseudo-pericarditis | 390 | |||

| III. | ENDOCARDITIS | 394 | ||

| IV. | DISEASES OF BLOOD-VESSELS | 396 | ||

| Phlebitis | 396 | |||

| Accidental phlebitis | 396 | |||

| Internal infectious phlebitis (Utero-ovarian phlebitis) | 398 | |||

| Umbilical phlebitis of new-born animals | 399 | |||

| Umbilical phlebitis or omphalo-phlebitis | 402 | |||

| V. | DISEASES OF THE BLOOD | 406 | ||

| Septicæmia of new-born animals | 406 | |||

| Takosis: a contagious disease of goats | 412 | |||

| Blood poisoning (Malignant œdema) in sheep and lambs in New Zealand | 415 | |||

| Piroplasmosis | 416 | |||

| Bovine piroplasmosis | 416 | |||

| Bovine piroplasmosis in France | 424 | |||

| Ovine piroplasmosis | 425 | |||

| Diseases produced by trypanosomata | 426 | |||

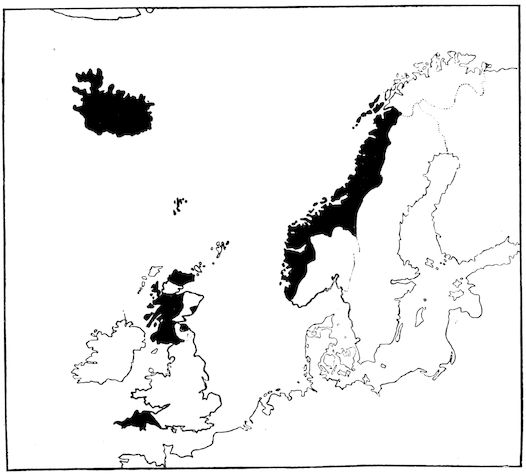

| Louping-ill | 429 | |||

| Suggested measures for prevention | 435 | |||

| Braxy | 435 | |||

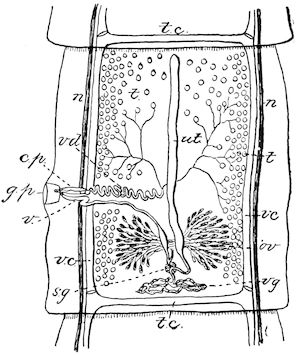

| Bilharziosis in cattle and sheep | 439 | |||

| Heat stroke—Over-exertion | 442 | |||

| xiii | ||||

| VI. | DISEASES OF THE LYMPHATIC SYSTEM | 444 | ||

| The lymphogenic diathesis | 448 | |||

| Caseous lymphadenitis of the sheep | 453 | |||

| Goitre in calves and lambs | 453 | |||

| SECTION V. | ||||

| NERVOUS SYSTEM. | ||||

| Cerebral congestion | 456 | |||

| Meningitis | 456 | |||

| Encephalitis | 458 | |||

| Cerebral Tumours | 459 | |||

| Insolation | 460 | |||

| Post-partum paralysis—Milk fever—Mammary toxæmia—Parturient apoplexy—Dropping after calving | 461 | |||

| Cœnurosis (Gid, sturdy, turn-sick) | 467 | |||

| “Trembling,” or Lumbar prurigo, in sheep | 475 | |||

| SECTION VI. | ||||

| DISEASES OF THE PERITONEUM AND ABDOMINAL CAVITY. | ||||

| I. | PERITONITIS | 478 | ||

| Acute peritonitis | 478 | |||

| Chronic peritonitis | 481 | |||

| Ascites | 483 | |||

| Peritoneal cysticercosis | 485 | |||

| II. | HERNIÆ | 487 | ||

| Congenital herniæ | 487 | |||

| Perineal hernia of young pigs | 487 | |||

| Umbilical hernia | 488 | |||

| Acquired herniæ | 489 | |||

| Hernia of the rumen | 490 | |||

| Hernia of the abomasum | 493 | |||

| Hernia of the intestine | 494 | |||

| Treatment of herniæ | 495 | |||

| Diaphragmatic hernia | 496 | |||

| Eventration | 499 | |||

| Fistulæ of the digestive apparatus | 500 | |||

| SECTION VII. | ||||

| GENITO-URINARY REGIONS. | ||||

| Diseases of the Urinary Apparatus | 502 | |||

| I. | POLYPI OF THE GLANS PENIS AND SHEATH | 506 | ||

| Inflammation of the sheath | 506 | |||

| Persistence of the urachus | 508 | |||

| xiv | ||||

| II. | DISEASES OF THE BLADDER | 511 | ||

| Acute cystitis | 511 | |||

| Chronic cystitis | 513 | |||

| Urinary lithiasis. Calculus formation | 514 | |||

| Calculi in bovine animals | 515 | |||

| Urinary calculi in sheep | 518 | |||

| Paralysis of the bladder | 519 | |||

| Eversion of the bladder | 519 | |||

| Hæmaturia | 520 | |||

| III. | DISEASES OF THE KIDNEYS | 527 | ||

| Congestion of the kidneys | 527 | |||

| Acute nephritis | 528 | |||

| Chronic nephritis | 530 | |||

| Hydro-nephrosis | 531 | |||

| Infectious pyelo-nephritis | 533 | |||

| Suppurative nephritis and perinephritis | 537 | |||

| The kidney worm (Sclerostoma pinguicola) of swine | 539 | |||

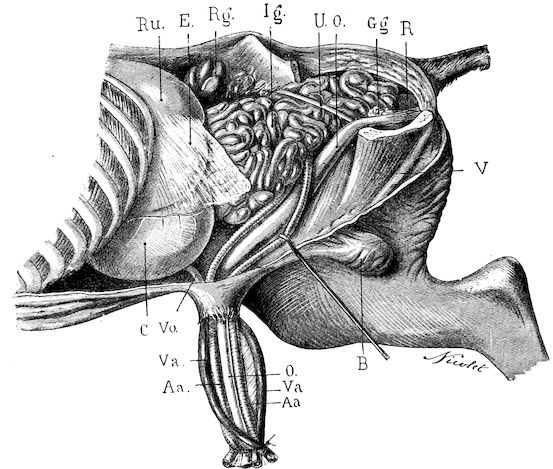

| IV. | GENITAL APPARATUS | 542 | ||

| Vaginitis | 543 | |||

| Acute vaginitis | 544 | |||

| Contagious vaginitis | 545 | |||

| Croupal vaginitis | 545 | |||

| Chronic vaginitis | 546 | |||

| Metritis | 547 | |||

| Septic metritis | 547 | |||

| Acute metritis | 550 | |||

| Chronic metritis | 552 | |||

| Epizootic abortion in cows | 553 | |||

| Salpingitis—Salpingo-ovaritis | 555 | |||

| Torsion of the uterus | 556 | |||

| Tumours of the uterus | 559 | |||

| Tumours of the ovary | 559 | |||

| Genital malformations | 560 | |||

| Imperforate vagina | 560 | |||

| Nympho-mania | 562 | |||

| V. | DISEASES OF THE MAMMARY GLANDS | 565 | ||

| Physiological anomalies | 567 | |||

| Wounds or traumatic lesions | 568 | |||

| Chaps and cracks | 568 | |||

| Milk fistulæ | 569 | |||

| Inflammatory diseases | 570 | |||

| Congestion of the udder | 570 | |||

| Mammitis | 571 | |||

| Acute mammitis | 573 | |||

| Contagious mammitis in milch cows | 580 | |||

| Chronic mammitis | 581 | |||

| Gangrenous mammitis of milch ewes | 583 | |||

| Gangrenous mammitis in goats | 584 | |||

| xv | Cysts of the udder | 585 | ||

| Tumours of the udder | 585 | |||

| Verrucous papillomata of the udder | 586 | |||

| VI. | DISTURBANCE IN THE MILK SECRETION AND CHANGES IN THE MILK | 587 | ||

| Microbic changes in milk. Lactic ferments | 588 | |||

| VII. | MALE GENITAL ORGANS | 594 | ||

| Tumours of the testicle | 594 | |||

| Accessory glands of the genital apparatus | 597 | |||

| SECTION VIII. | ||||

| DISEASES OF THE SKIN AND SUBCUTANEOUS CONNECTIVE TISSUE. | ||||

| I. | ECZEMA | 599 | ||

| Acute eczema | 599 | |||

| Chronic eczema | 600 | |||

| Sebaceous or seborrhœic eczema | 601 | |||

| Eczema due to feeding with potato pulp | 603 | |||

| Impetigo in the pig | 605 | |||

| Acne in sheep | 606 | |||

| Fagopyrism (Buckwheat poisoning) | 606 | |||

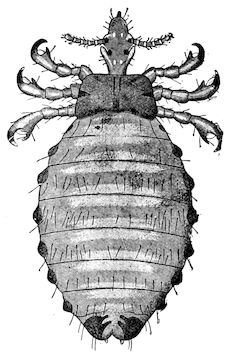

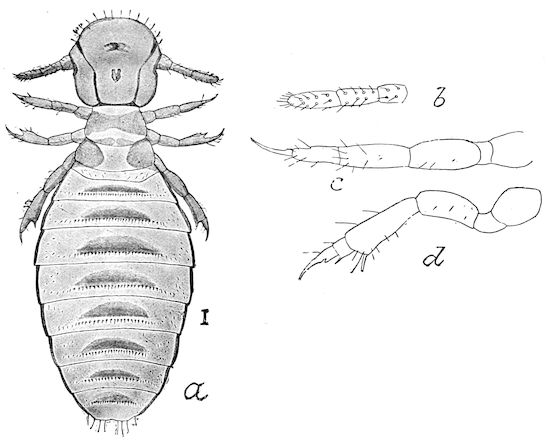

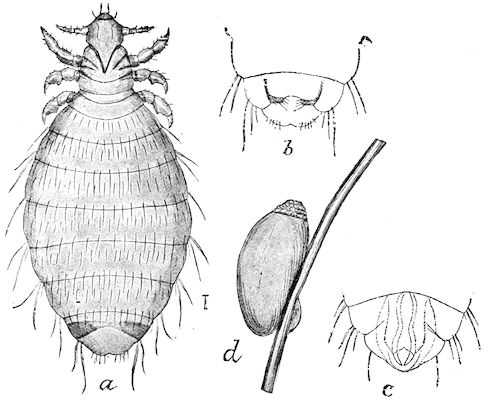

| II. | PHTHIRIASIS | 608 | ||

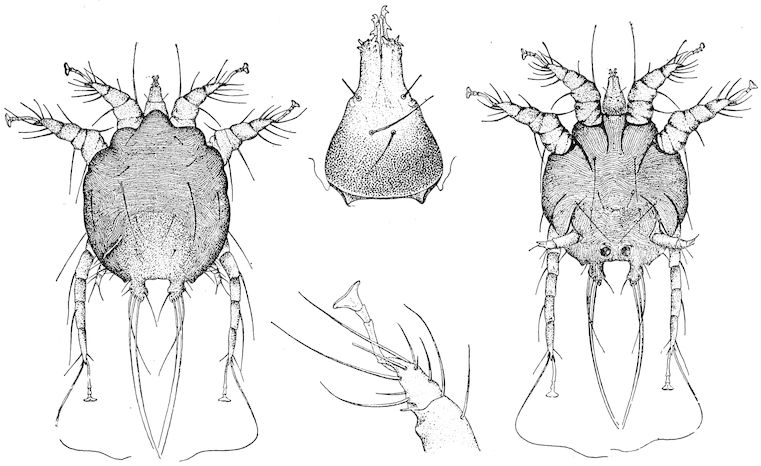

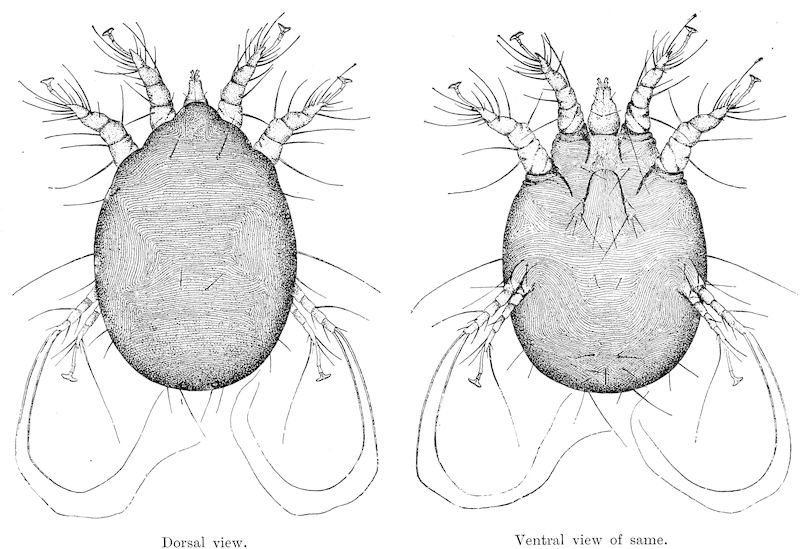

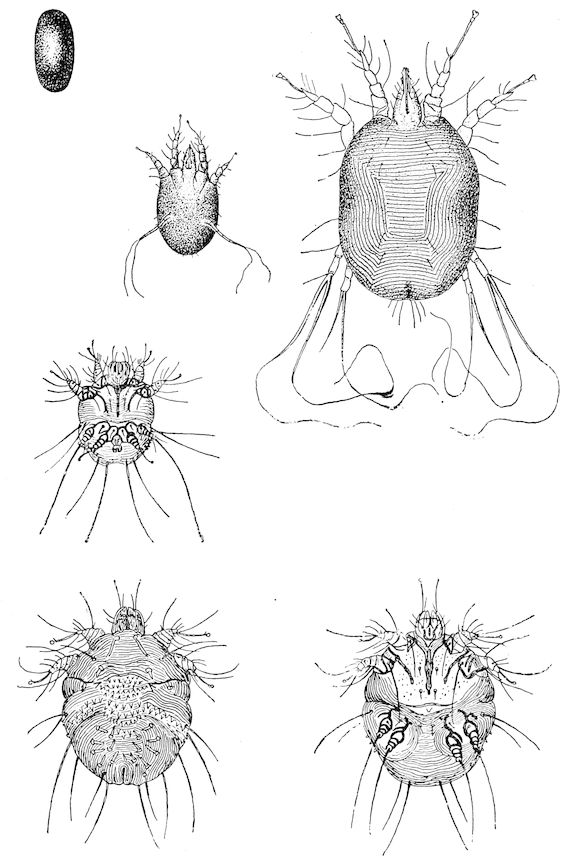

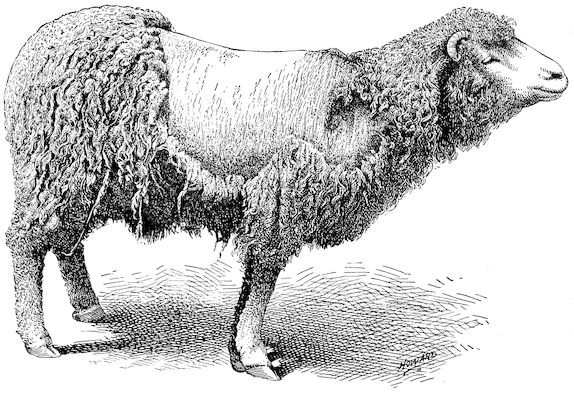

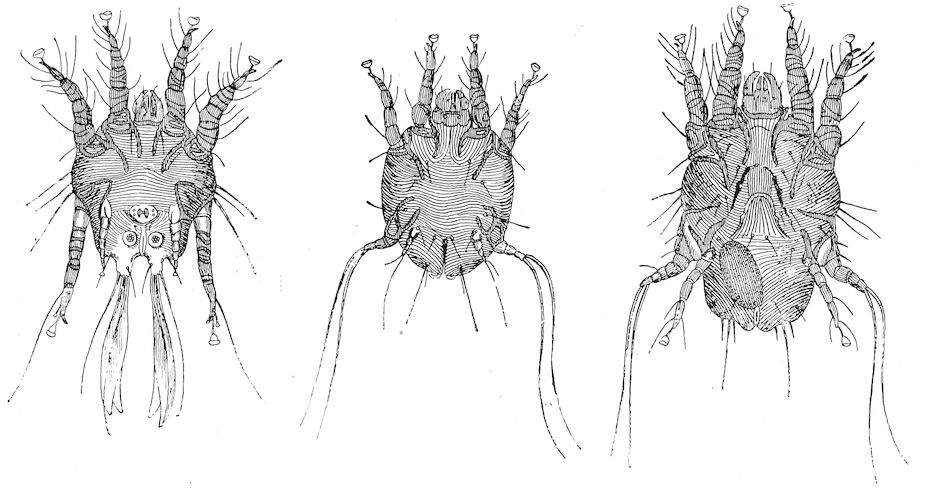

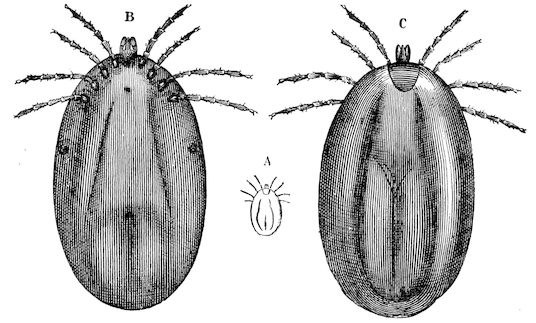

| Scabies—Scab—Mange | 611 | |||

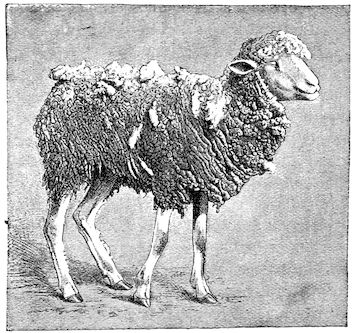

| Scabies in sheep | 611 | |||

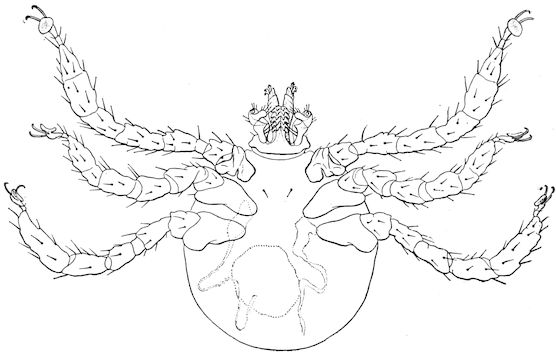

| Sarcoptic scabies | 612 | |||

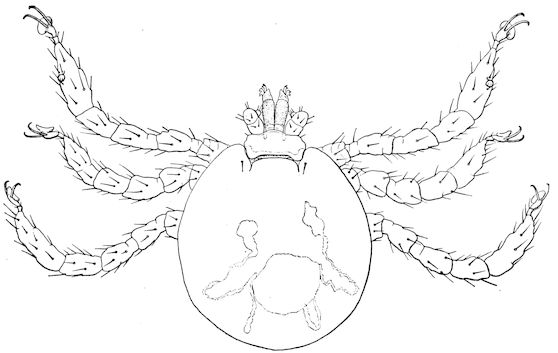

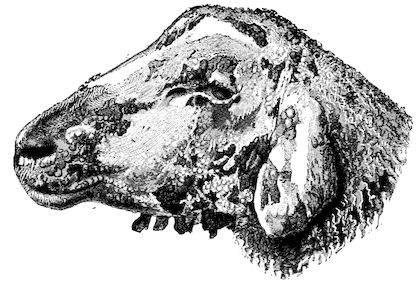

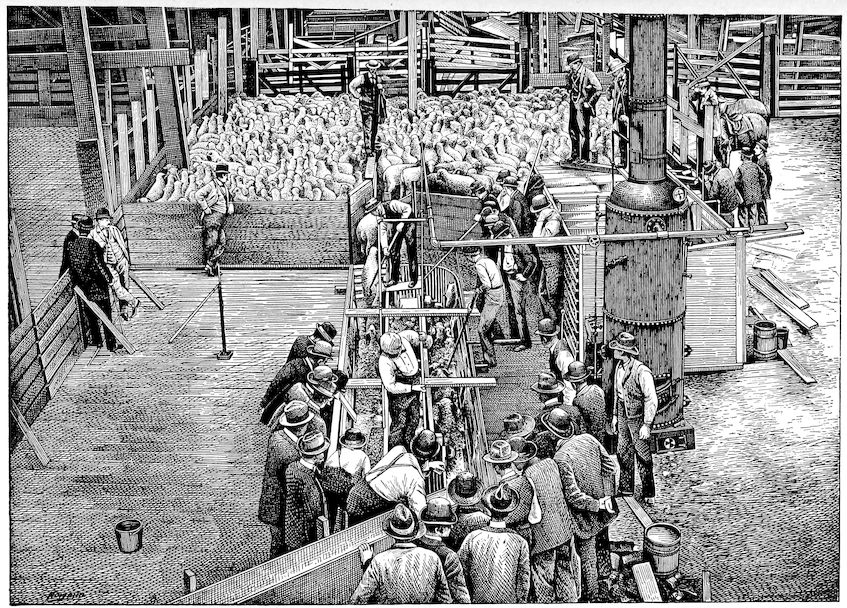

| Psoroptic mange—Sheep scab | 614 | |||

| The tobacco-and-sulphur dip | 626 | |||

| Lime-and-sulphur dips | 627 | |||

| Arsenical dips | 632 | |||

| Carbolic dips | 633 | |||

| Chorioptic mange—Symbiotic mange—Foot scab | 636 | |||

| Mange in the ox | 638 | |||

| Sarcoptic mange | 638 | |||

| Psoroptic mange | 639 | |||

| Chorioptic mange | 640 | |||

| Mange in the goat | 641 | |||

| Sarcoptic mange | 641 | |||

| Chorioptic mange | 642 | |||

| Mange in the pig | 642 | |||

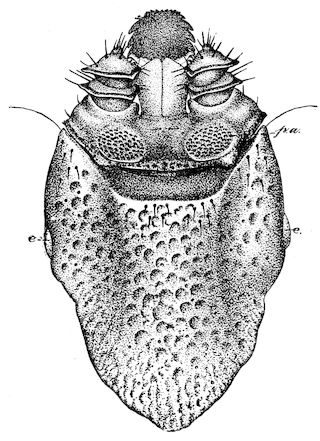

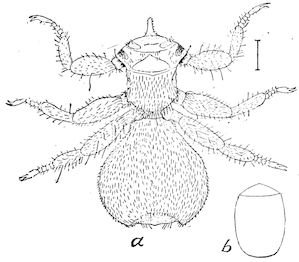

| Demodecic mange | 643 | |||

| Demodecic mange in the ox | 644 | |||

| Demodecic mange in the goat | 644 | |||

| Demodecic mange in the pig | 644 | |||

| Non-psoroptic forms of acariasis | 645 | |||

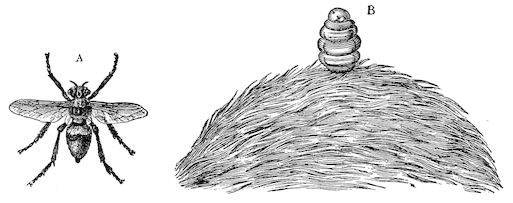

| Hypodermosis in the ox (warbles) | 646 | |||

| xvi | ||||

| III. | RINGWORM | 649 | ||

| Ringworm in the sheep, goat, and pig | 653 | |||

| IV. | WARTS IN OXEN | 655 | ||

| Urticaria in the pig | 656 | |||

| Scleroderma | 657 | |||

| V. | SUBCUTANEOUS EMPHYSEMA | 659 | ||

| SECTION IX. | ||||

| DISEASES OF THE EYES. | ||||

| Foreign bodies | 661 | |||

| Conjunctivitis and keratitis | 662 | |||

| Verminous conjunctivitis | 662 | |||

| Verminous ophthalmia of the ox | 663 | |||

| SECTION X. | ||||

| INFECTIOUS DISEASES. | ||||

| Cow-pox—Vaccinia | 665 | |||

| Cow-pox and human variola—Preparation of vaccine | 669 | |||

| Tetanus | 670 | |||

| Actinomycosis | 672 | |||

| Actinomycosis of the maxilla | 673 | |||

| Actinomycosis of the tongue | 674 | |||

| Actinomycosis of the pharynx, parotid glands and neck | 675 | |||

| Tuberculosis | 682 | |||

| Tuberculosis of the respiratory apparatus | 690 | |||

| Tuberculosis of the serous membranes | 694 | |||

| Tuberculosis of lymphatic glands | 696 | |||

| Tuberculosis of the digestive tract | 699 | |||

| Tuberculosis of the genital organs | 700 | |||

| Tuberculosis of bones and articulations | 701 | |||

| Tuberculosis of the brain | 702 | |||

| Tuberculosis of the skin | 703 | |||

| Acute tuberculosis—Tuberculous septicæmia | 704 | |||

| Swine fever—Verrucous endocarditis and pneumonia of the pig | 710 | |||

| Swine fever | 710 | |||

| Verrucous endocarditis of the pig | 713 | |||

| Pneumonia of the pig | 714 | |||

| Hæmorrhagic septicæmia in cattle | 716 | |||

| SECTION XI. | ||||

| OPERATIONS. | ||||

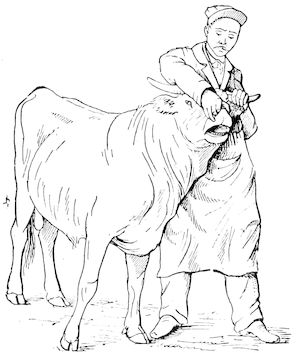

| I. | CONTROL OF ANIMALS | 720 | ||

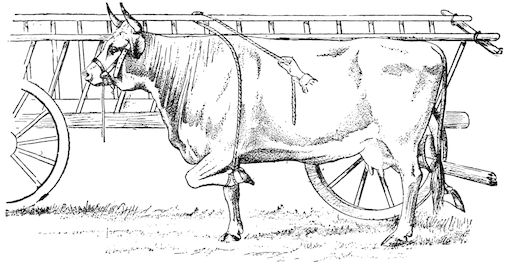

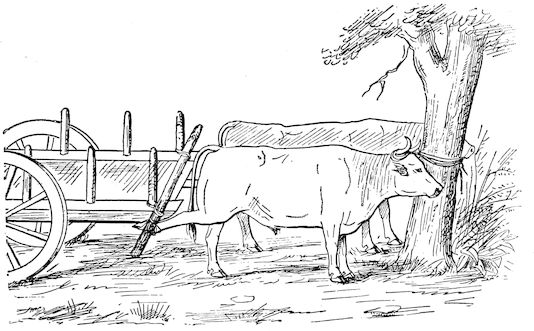

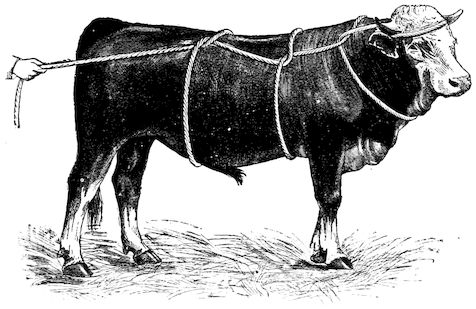

| Control of oxen | 720 | |||

| Partial control | 720 | |||

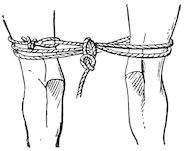

| Control of the limbs | 720 | |||

| xvii | General control | 722 | ||

| Control by casting | 723 | |||

| Control of sheep and goats | 725 | |||

| Control of pigs | 725 | |||

| Anæsthesia | 726 | |||

| II. | CIRCULATORY APPARATUS | 727 | ||

| Bleeding | 727 | |||

| Bleeding in sheep | 727 | |||

| Bleeding in the pig | 728 | |||

| Setons, rowels, plugs, or issues | 728 | |||

| III. | APPARATUS OF LOCOMOTION | 730 | ||

| Surgical dressing for a claw | 730 | |||

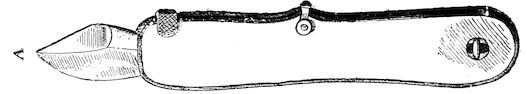

| Amputation of the claw or of the two last phalanges | 730 | |||

| IV. | DIGESTIVE APPARATUS | 734 | ||

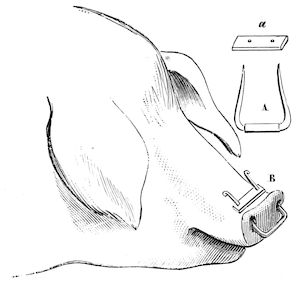

| Ringing pigs | 734 | |||

| Œsophagus | 734 | |||

| Passing the probang | 735 | |||

| Crushing foreign bodies in the œsophagus | 735 | |||

| Œsophagotomy | 736 | |||

| Sub-mucous dissection of the foreign body | 736 | |||

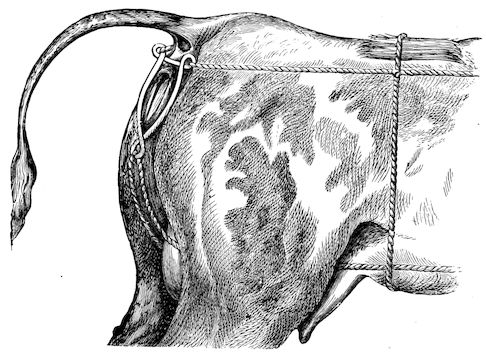

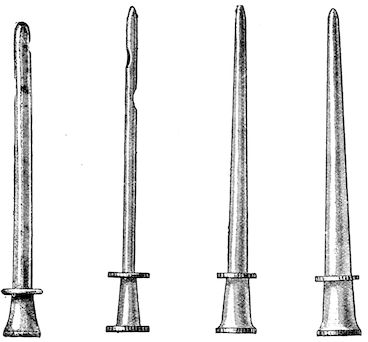

| Rumen | 737 | |||

| Puncture of the rumen | 737 | |||

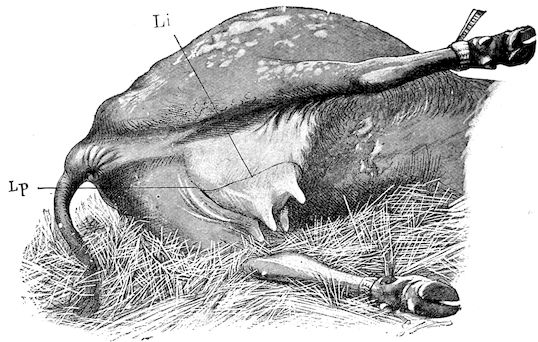

| Gastrotomy | 739 | |||

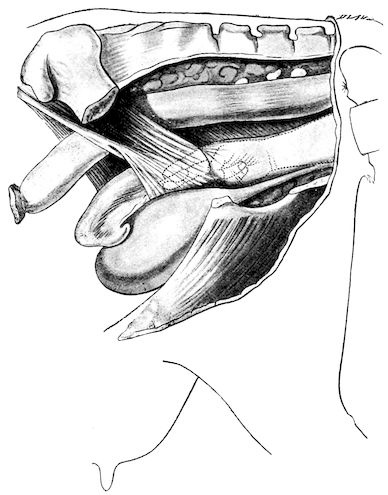

| Laparotomy | 740 | |||

| Herniæ | 741 | |||

| Inguinal hernia in young pigs | 741 | |||

| Imperforate anus | 742 | |||

| Prolapsus and inversion of the rectum | 743 | |||

| V. | RESPIRATORY APPARATUS | 745 | ||

| Trephining the facial sinuses | 745 | |||

| Trephining the horn core | 745 | |||

| Frontal sinus | 745 | |||

| Maxillary sinus | 745 | |||

| Tracheotomy | 746 | |||

| VI. | GENITO-URINARY ORGANS | 747 | ||

| Urethrotomy in the ox | 747 | |||

| Ischial urethrotomy | 747 | |||

| Scrotal urethrotomy | 748 | |||

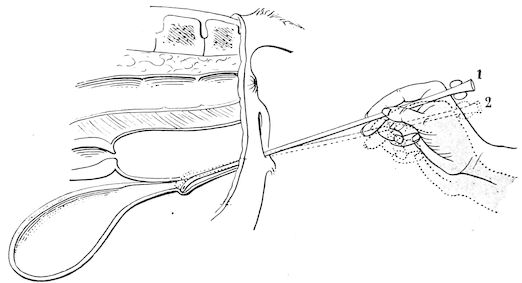

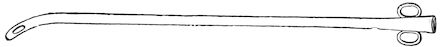

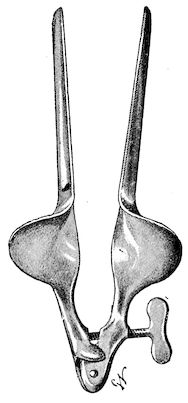

| Passage of the catheter and urethrotomy in the ram | 749 | |||

| Passage of the catheter in the cow | 750 | |||

| Castration | 751 | |||

| Castration of the bull and ram | 751 | |||

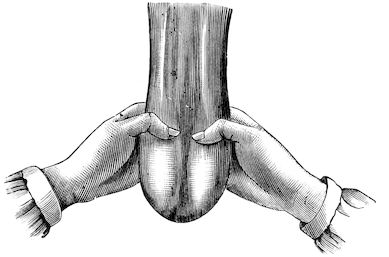

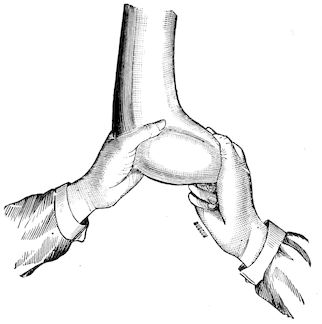

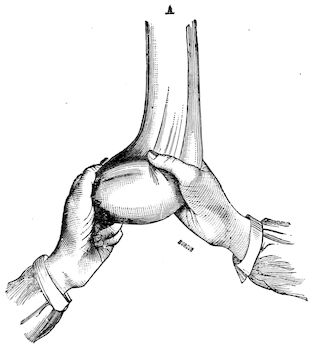

| Bistournage | 751 | |||

| Martelage | 756 | |||

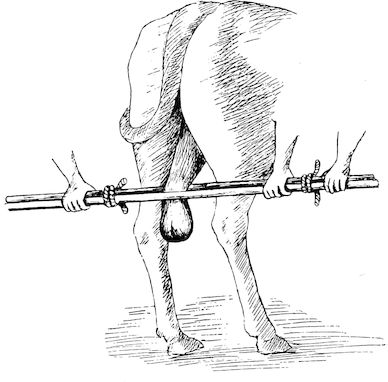

| Castration by clams | 756 | |||

| xviii | Castration by torsion | 757 | ||

| Castration with the actual cautery | 758 | |||

| Castration by the elastic ligature | 758 | |||

| Castration of the ram | 759 | |||

| Castration of boars and young pigs | 759 | |||

| Castration of cryptorchids | 760 | |||

| Female genital organs | 760 | |||

| Castration of the cow | 761 | |||

| Castration of the sow | 765 | |||

| Suture of the vulva | 768 | |||

| Trusses | 769 | |||

| Section of the sphincter of the teat | 770 | |||

| Dilatation of the orifice of the teat | 770 | |||

| Ablation of the mammæ | 771 | |||

Accidental and local diseases of the apparatus of locomotion are matters of less urgency in the case of cattle than in that of the horse. On the other hand, general affections, such as rheumatism and osseous cachexia, demand a larger share of attention, and are of the utmost importance.

As the accurate diagnosis of any disease demands careful and systematic examination, the practitioner usually observes a certain order in his investigations, as indicated below:—

(1.) Inspection, from the side, from the front and from behind, reveals the existence of deformities of bones, limbs, muscles and joints, articular displacements, and irregularities of conformation or of gait.

By inspection of an animal as it walks various forms of lameness, and their particular characteristics, are rendered visible.

(2.) Palpation and pressure will detect changes in local sensibility, the softness or hardness of tissues, the existence of superficial or deep fluctuation, œdematous swelling, and abnormal growths like ring-bones and exostoses, as well as the exact character of articular enlargements.

(3.) Percussion is of little value in examining the apparatus of locomotion. Nevertheless, percussion of the claws, and of certain bones of the limbs, or of flat bones, may afford valuable information in cases of laminitis, ostitis, and periostitis. Percussion along the longitudinal axes of the limb bones is also useful in diagnosing intra-articular fractures, subacute arthritis, osteomyelitis, etc.

(4.) The gait. Lame animals should be made to move, in order to assist both in discovering the cause, and in estimating the gravity of the condition. Sometimes it is advisable to turn the animal loose, but most frequently it is moved in hand, either in straight lines or in circles.

2Information so obtained should always be supplemented by local manipulation and by passive movement, such as flexion, extension, abduction, adduction and rotation of the joints.

A knowledge of the characteristics of normal movement in any given joint, renders it comparatively easy to detect abnormality, such as increased sensibility, articular crepitation or friction, and to diagnose fractures with or without displacement, ruptures of tendons or ligaments, etc.

The diseases affecting bony tissues may broadly be divided into local and general. Local diseases like ostitis, periostitis, necrosis, fracture, etc., are somewhat rare, and are less important in cattle than such general diseases as rachitis and osseous cachexia.

Rachitis is a disease of young animals, and occurs during the growing period. Osseous cachexia is a disease of adults. Nevertheless, there is a relationship between these two morbid conditions, for they frequently co-exist in one family. Moreover, brood mares and cows suffering from osseous cachexia give birth to foals and calves, which, if left with their mothers, almost inevitably become rachitic.

The general characteristic common to both rachitis and osseous cachexia consisting in diminution in the normal proportion of mineral salts entering into the constitution of the bone, numerous theories have been advanced to explain this irregularity in nutrition.

The theory of insufficiency is one of the oldest. It presupposes that the young animals’ food contains insufficient mineral salts necessary for building up the skeleton, hence rachitis; or again, that the daily food of the adults does not afford sufficient mineral salts to compensate for the normal transformation which is continually going on within the organism, and for the direct losses which occur through the medium of the urine, milk, etc.

This extremely simple theory appears perfectly logical, but unfortunately does not fit in with all the observed facts. In reality, rachitis attacks children whose supply of milk, from a chemical point of view, leaves nothing to be desired. The same is true of animals, particularly of young pigs. The so-called “acid theory” has therefore been advanced to explain the points left obscure by its predecessor.

The acid theory. According to this theory, the food may contain more than sufficient mineral material without, however, preventing the development of rachitis or of osseous cachexia.

In animals suffering from digestive disturbance the alimentary tract may become the seat of excessive fermentation or of changes in secretion. There is thus produced an excess of lactic acid which passes into the 4circulation and accumulates in the tissues, checking the processes which end in ossification or, in the case of adults, even leading to decalcification.

It seems fairly well established that experimental administration of lactic acid to animals causes diminution in the quantity of calcium salts contained in the bones (Siedamgrotsky, Hofmeister). On the other hand however Arloing and Tripier failed to produce rachitis experimentally.

Bouchard revived this theory in a somewhat modified form. He considers that calcium salts are absorbed as carbonates and chlorides and phosphoric acid as phospho-glyceric acid. The reaction which these compounds undergo within the organism ends in the formation of the phosphate of calcium necessary to ossification, but this “phosphate of ossification” cannot be deposited if the organism contains an excess of lactic acid.

Theory of inflammation. A third theory which until now has received very little support is that called the theory of inflammation. The general lesions which characterise rachitis are regarded as resulting from primary attacks of ostitis and osteo-periostitis. The cause of these forms of inflammation is not suggested.

To the above views may be added that more recently emitted by Dr. Chaumier, according to which rachitis is of an infectious nature. Unfortunately no proof of this has yet been adduced.

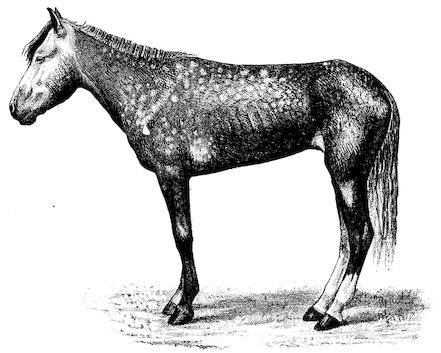

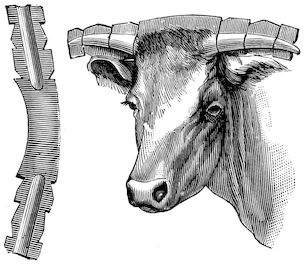

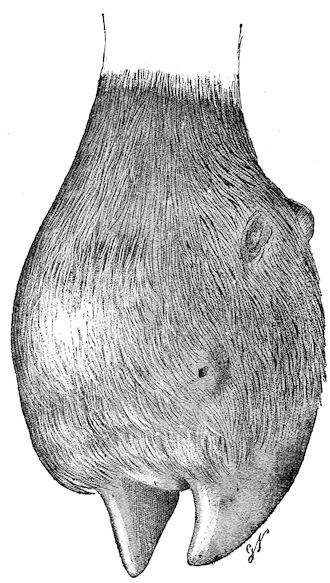

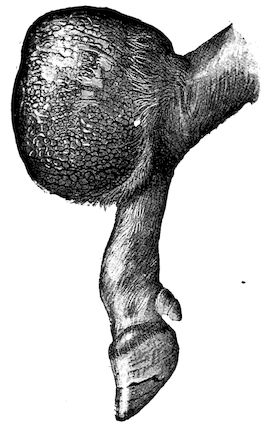

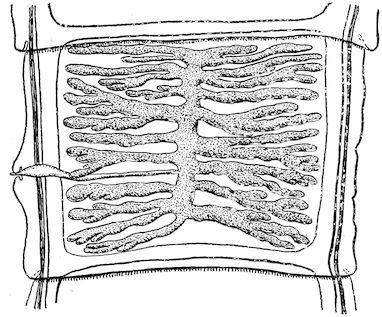

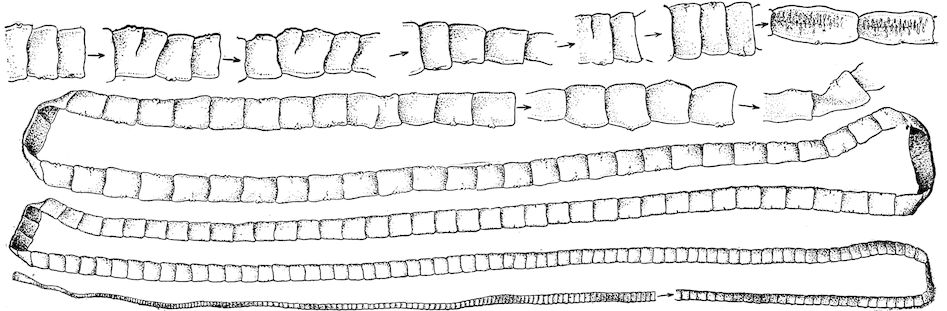

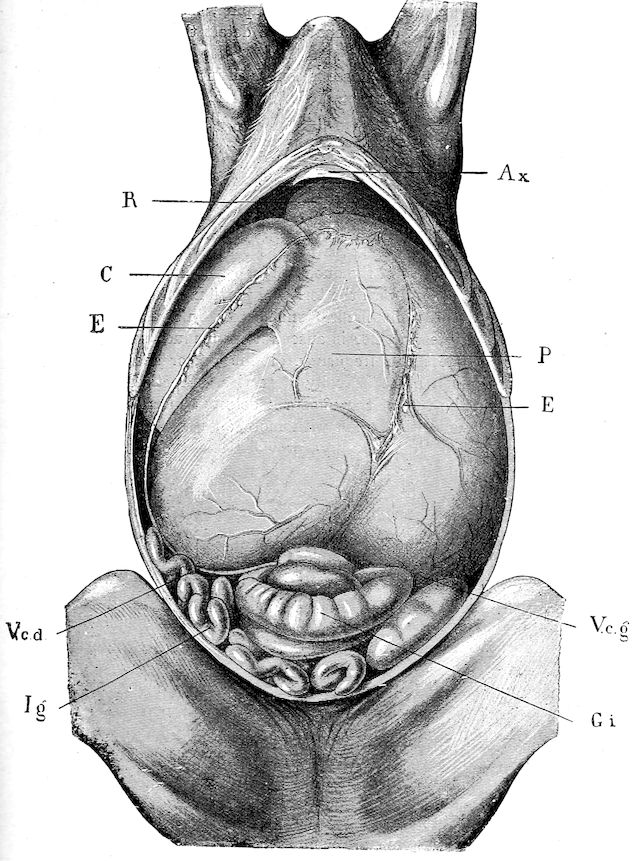

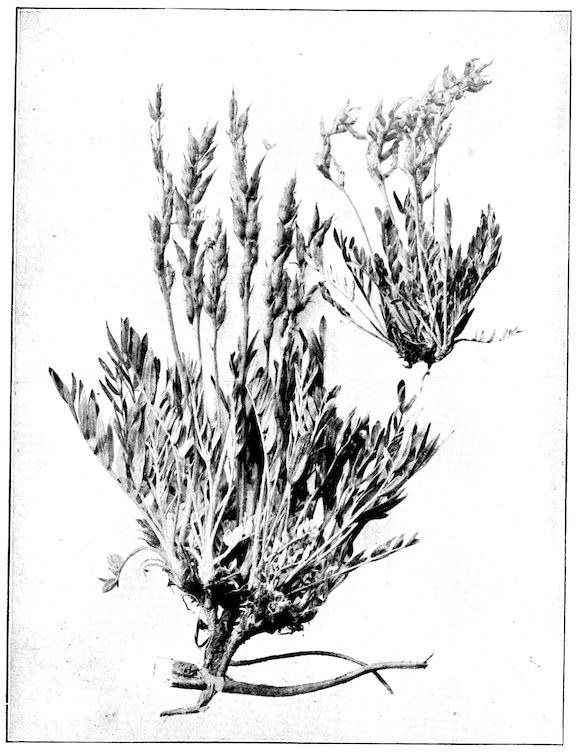

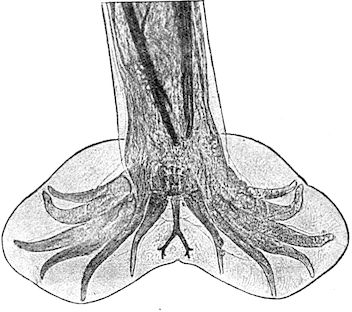

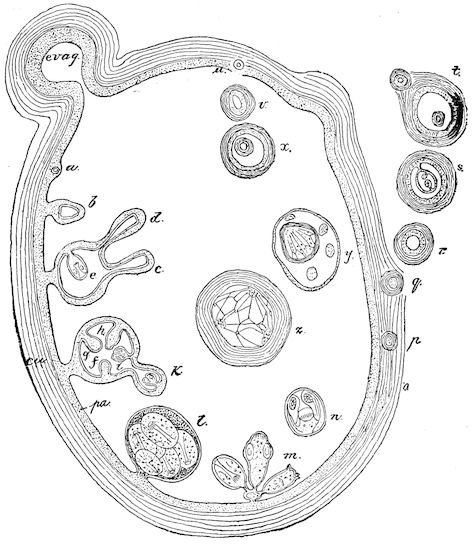

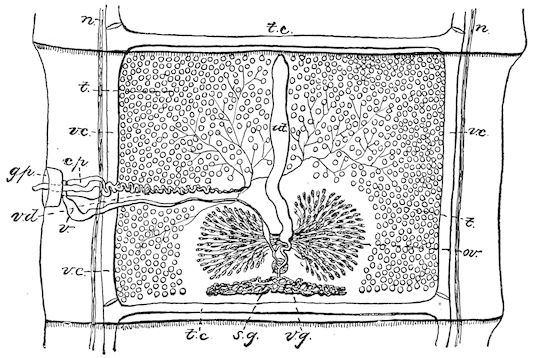

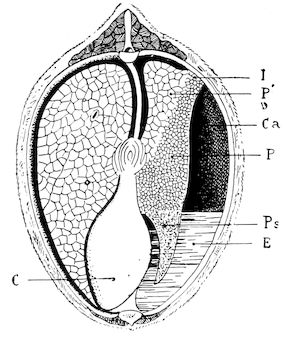

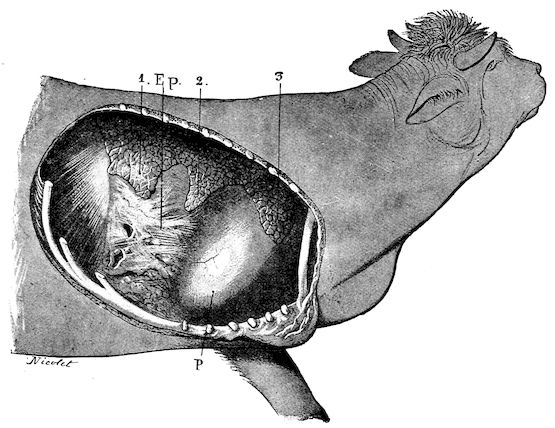

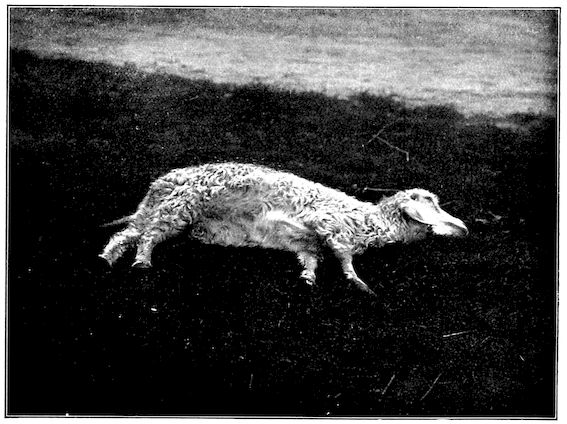

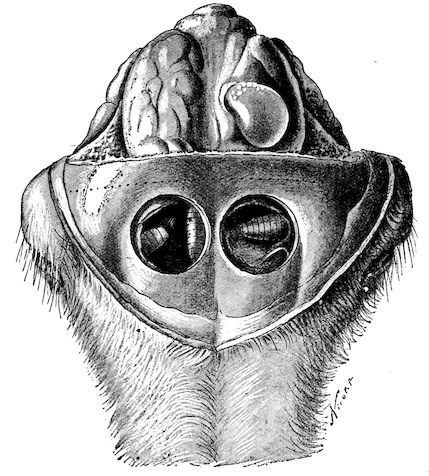

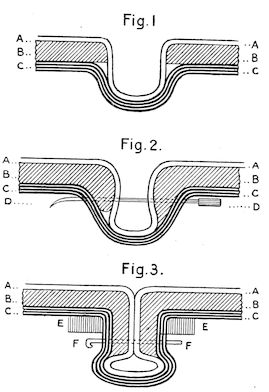

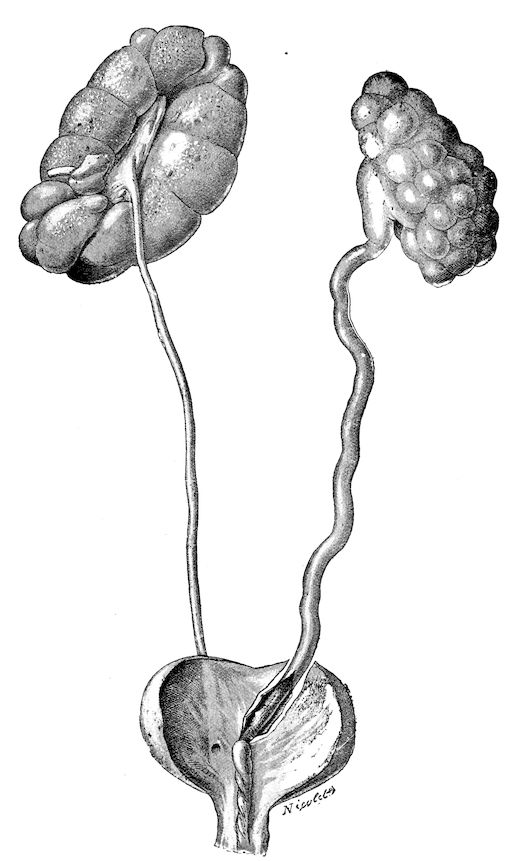

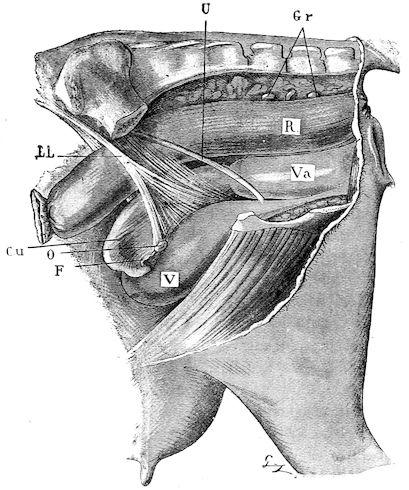

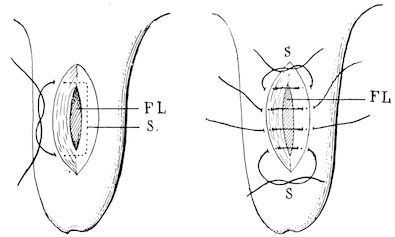

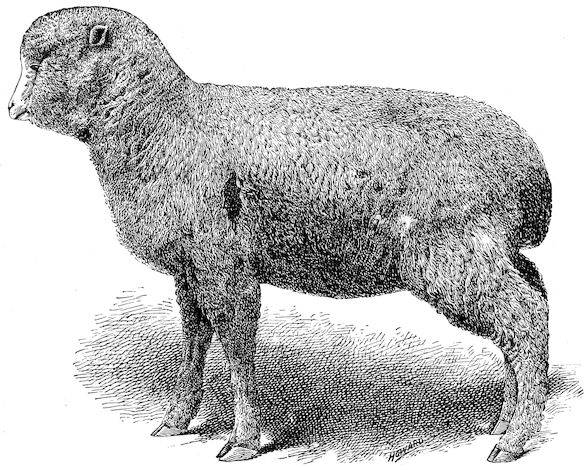

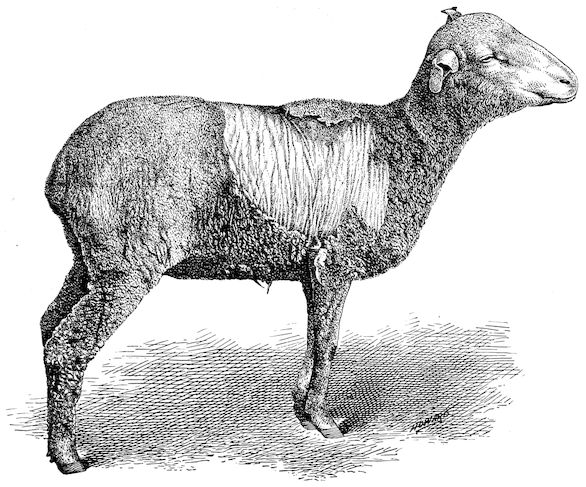

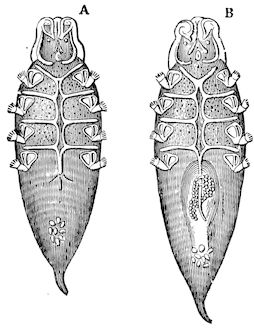

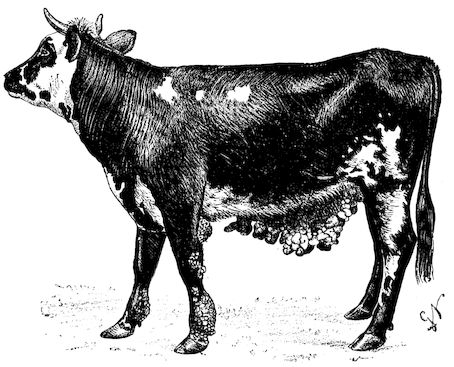

Rachitis is a disease of youth, and is common both to the human species and to all domestic animals. It is characterised by irregularities in development and by imperfect consolidation of the bones. The boundary between rachitis and osseous cachexia is difficult to define and in fact at the present moment the two diseases can scarcely be defined with exactitude. Rachitis again is often complicated with softening of the bones, disease of the limbs, arrested development, etc., but it must not be forgotten that although the irregularities in ossification and development of the skeleton are the symptoms most striking to the eye, they do not stand alone, and that from the point of view of development all the tissues, including the muscles, are more or less affected and that most of the physiological functions such as digestion and the secretion of urine are deranged.

Etiology. One of the principal causes suggested is that of heredity, and so far as human beings are concerned, one seldom fails to discover the rachitic taint. Certainly the offspring of individuals marked by any debilitating disease like alcoholism, tuberculosis, syphilis, etc., are poorly 5equipped for their future development. Their tissues lack the necessary qualities and, cæteris paribus, their physiological functions are performed less perfectly than are those of normal individuals.

It is difficult to apply such information to domestic animals, because badly developed subjects are not used for reproduction and the importance assigned to heredity can therefore scarcely be sustained. The conditions of life, on the contrary, have an unquestionable influence, and if rachitis is so frequent in young animals living near towns, for example, it is undoubtedly due to that want of air, light and liberty, which first affects the mother’s health and later that of her offspring.

The same may be said of insufficient and improper food; for in this connection quality is of even greater importance than quantity. Even free feeding is insufficient if the fodder does not contain the material necessary for sustaining and building up the developing frame, a point which readily explains the occurrence of rachitis when young animals receive a diet deficient in certain chemical constituents.

This occurs in young lambs and pigs where the mothers are given too little variety or too small a quantity of food.

In calves and foals rachitis is rare but occurs when the mothers are exhausted or cachectic or are debilitated by chronic wasting diseases like tuberculosis or osseous cachexia. The milk is then no longer of normal chemical constitution.

One fact appears to dominate the whole subject of the causation of rachitis, viz., the failure to assimilate sufficient of the mineral salts required in building up the skeleton. This failure to assimilate may be caused by too meagre feeding, but even when the food is sufficiently rich, some digestive disturbance may reduce the amount absorbed below normal. This appears the only plausible explanation unless we admit Dr. Chaumier’s theory that the disease is of an infectious character.

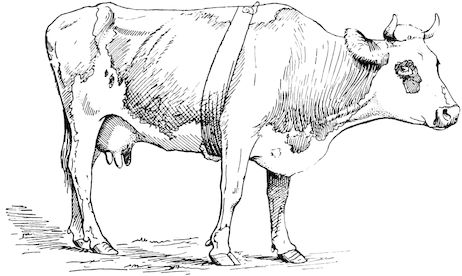

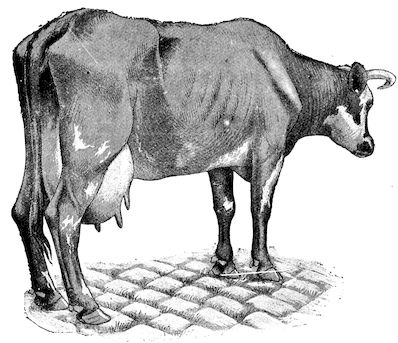

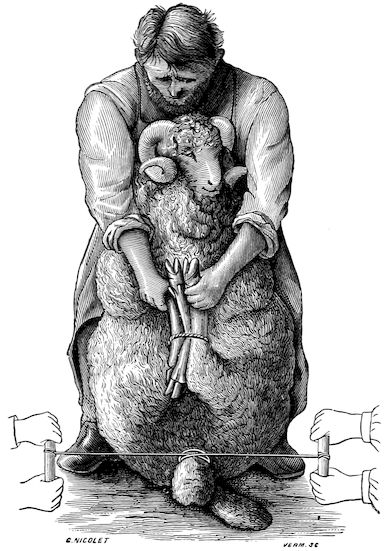

Symptoms. The onset is absolutely insidious and the diagnosis of rachitis is never made until nutrition has long been abnormal.

This disturbance of nutrition is revealed by irregularity and abnormality in appetite, by difficulty in rising and moving about, and by the animals lying down for long periods. The subjects are feeble, sluggish and badly developed.

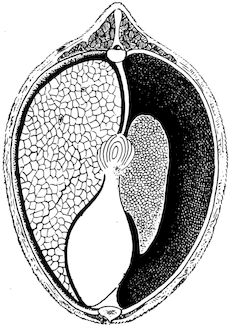

Next supervenes the second phase characterised by deformity of bones. This is of two kinds—deformity in the neighbourhood of joints (deformity or enlargement of the epiphyses) and deformity of the diaphyses. The former results from irregularity in ossification of the articular cartilages. The latter is followed by loss of rigidity in the bones of the limbs which, under the influence of the body weight and of muscular contraction, bend in different directions.

The bones appear of increased thickness principally towards the 6articulations. The latter are deformed, and on palpation are found to be surrounded by uneven and irregular growths.

The front limbs are distorted. In young pigs, lambs, and less frequently in foals, calves and dogs, the jaws become deformed, and mastication is rendered difficult.

The vertebral column may also be affected, and lordosis (bending downwards of the back) or skoliosis (lateral bending of the back) is somewhat frequent.

Cyphosis, or upward bending of the back, seldom occurs, and when seen, sometimes results from disease other than rachitis.

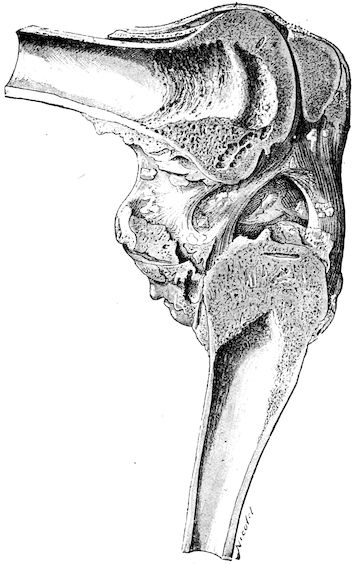

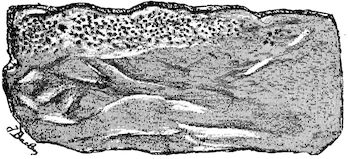

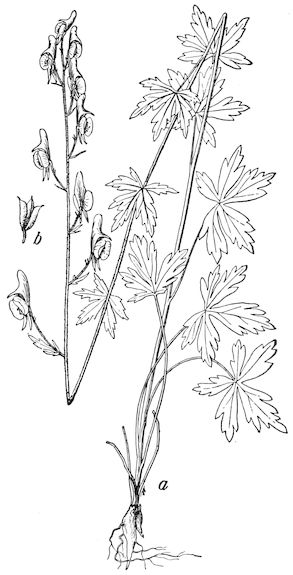

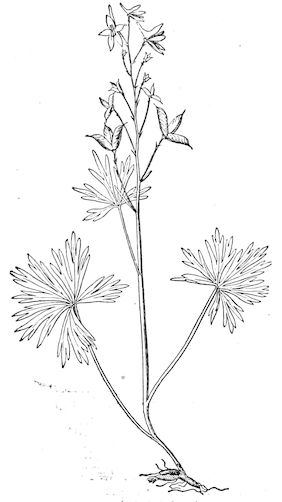

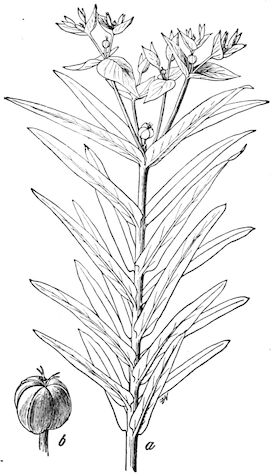

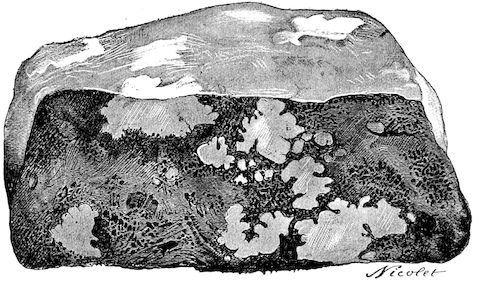

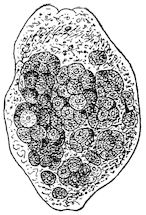

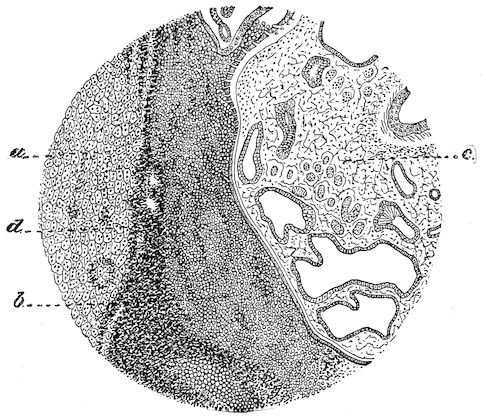

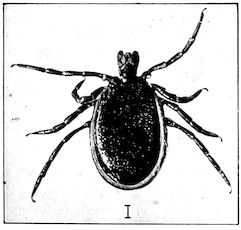

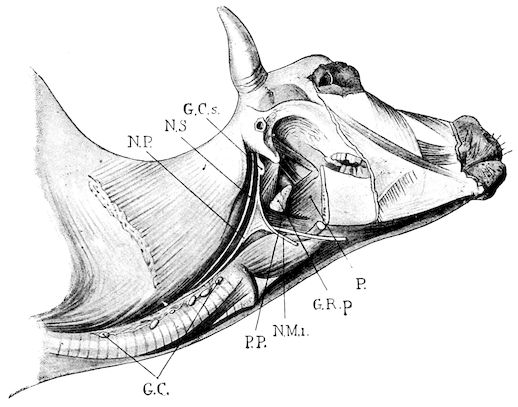

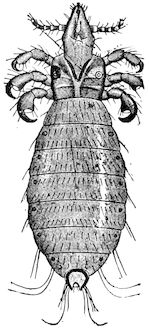

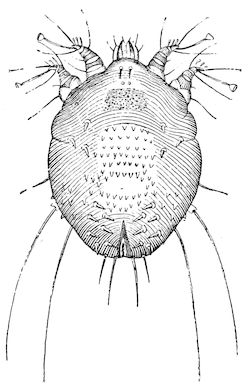

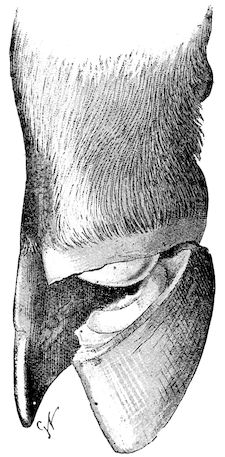

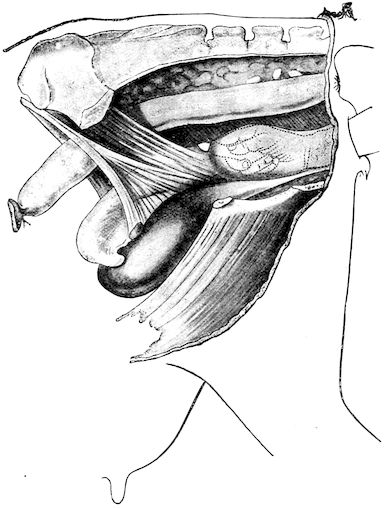

Fig. 1.—Rachitis in a young goat.

General development is always interfered with and the young creatures are generally dwarfed.

The digestive apparatus is disordered, the appetite is irregular and sometimes depraved, while indigestion, gastritis, and enteritis are not exceptional. Physiological and pathological research has shown that the quantity of phosphoric acid eliminated in twenty-four hours in a rachitic child is double the quantity passed by a healthy infant. The amount of urea in the urine (which is a criterion of nutrition, and usually varies in proportion to the amount of food ingested) is, on the contrary, diminished even when highly nitrogenous food is given, thus suggesting diminution in nutrition.

Lesions. The lesions are represented by abnormal and irregular thickening around the interarticular cartilages. The cartilage is thickened, compressible, very spongy and without regular ossification. Diffused periostitis exists principally towards the extremities of the bone. Beneath the periosteum the surface of the bone appears rough and softened. On section the medullary canals are seen to be enlarged and filled with marrow of a gelatinous character. The Haversian canals are dilated, and the entire tissue appears very vascular. Chemical analysis proves that the mineral constituents of the bone, particularly the phosphates, have diminished by one-half; the organic constituents on the other hand are increased in a similar ratio, but the ossein is abnormal. Ossification has, in a word, been incomplete.

7Diagnosis. Diagnosis presents no difficulty except in the early stages before deformity has occurred.

Rachitis can scarcely be mistaken for any other condition except perhaps infectious rheumatism, but the rapid course of the disease in the latter case, the persistence of fever and the swelling of the joint cavities sufficiently differentiate the conditions provided care is exercised.

Prognosis. From an economic point of view the prognosis is very grave for if the lesions are extensive there is nothing to be gained by keeping the animal.

Treatment. Treatment differs very little, whether the animals are still being suckled or have been weaned. In the former case it is necessary to improve the quality and chemical constitution of the mother’s milk by giving food, richer both in mineral salts and in nitrogenous material.

Cooked grains, milk, and forage of good quality should be given freely. When the mothers are exhausted and anæmic it is better to feed the little animals artificially or to change them to a foster-mother. Those already weaned should be given good rich milk, eggs, boiled gruel, and drugs, such as the phospho-chlorate of lime, 1 to 1½ drachms per day (for a calf); lacto-phosphate of lime, 1 to 1½ drachms; bi-phosphate of lime, 1 drachm, or simply ordinary phosphate of lime. Oil containing 1 per cent. of dissolved phosphorus may be given in doses of 1 to 2½ drachms, according to the size of the calves, but its use calls for much care, and it should only be given for alternate periods of a fortnight. The glycerophosphates are not very active. Beef meal in doses of 6 drachms to 1½ ounces and chloride of ammonium in doses of 30 to 60 grains have also been used advantageously. The above drugs, but particularly the bi-phosphate of lime and chloride of ammonium, stimulate nutrition and diminish the quantity of phosphoric acid eliminated.

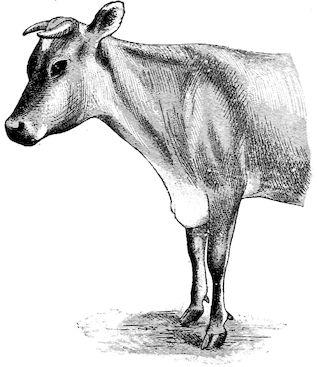

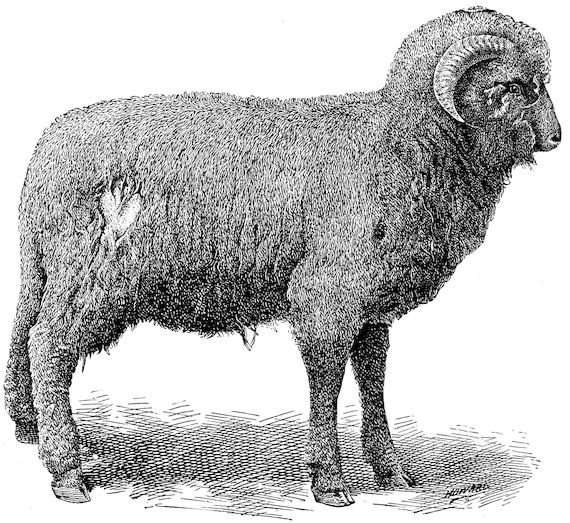

“Osseous cachexia” is a general disease which develops slowly and progressively, producing its most marked effects on the bony tissues. It has received a great many different names, such as osteoporosis, osteoclastia, osteomalacia, fragilitas ossium, enzootic ostitis, bone softening, etc., but none of these appears so appropriate as the term osseous cachexia, suggested by Cantiget.

All the above-mentioned names are applicable to some phase of the disease, but none to the disease in its complete development. Thus the name “osteoporosis,” accepted by German authors, is quite applicable to the phase of rarefying ostitis seen at the commencement, but this condition occurs in other diseases. The expressions “osteoclastia” and 8“fragilitas ossium” suggest the fragility of the bones and the commonness of fracture. The term “osteomalacia” is warranted during the period of bone softening. The term “gout,” though in practice confusing, has been held to be justified by the frequent appearance of synovitis and arthritis; while that of “enzootic ostitis” indicates the appearance of the disease in all the stables in one district, without however pointing to its nature. It is possible that under certain circumstances the train of symptoms might be incomplete, and then the terms above indicated would be quite inappropriate. “Osseous cachexia,” on the other hand, is very comprehensive, and appears to cover the entire development of the disease, for which reason it here receives preference.

Law defines the disease as “a softening and fragility of the bones of adult animals, in connection with solution and removal of the earthy salts.” He describes it as an enzootic disease of mature animals—mainly cows—in which the decalcifying process proceeds most actively in the walls of the Haversian canals and cancelli of the affected bones. In consequence of the removal of the earthy salts the bones become soft and more or less fragile.

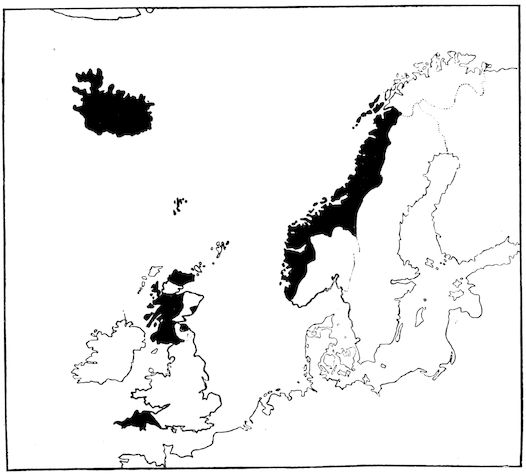

The disease has been observed in England, Scotland, United States, France, Belgium, and Jutland, and generally in districts with low-lying damp pastures. It attacks cows which are heavy milkers. Susceptibility appears to increase with advancing age.

History. Having been described by Vegetius, the disease was again observed about 1650 in Norway where it was treated by the administration of crushed bones. It is fairly frequent in some parts of Germany and Belgium. In France it was studied in 1825 by Roux, and in 1846 by Dupont, but Zundel in 1870 was the first who gave a good description of it, founded partly on the authority of German authors and partly on observations made by himself in the Valley of the Lower Rhine. Since that time it has successively been reported in the Yonne by Thierry, in the Nièvre by Vernant, in the Aube by Collard and Henriot (1893), in the Indre by Cantiget, as well as in La Vendée by Tapon in 1893. In that and the succeeding year Moussu also saw numerous cases in the districts of Indre-et-Loire, Loire-et-Cher, Berry, Sologne, and in some parts of Beauce.

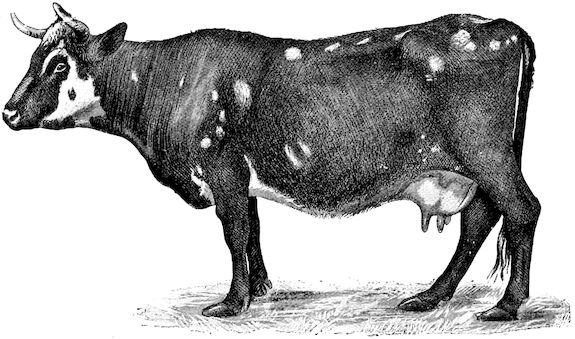

Symptoms. The first symptoms are difficult to detect and interpret, especially at the commencement of an outbreak and in parts where the disease is rare they may lead to confusion and errors in diagnosis. On the other hand, in regions where the disease is common the practitioner will be able to form his diagnosis from the appearance of the first signs.

To render clear the mode in which the symptoms develop we may divide the progress of the disease into four phases, though this grouping is somewhat arbitrary.

91. The initial phase is not well marked, and is announced by digestive disturbance and by wasting. The former of these symptoms may be referred to some other cause, but consists in irregularity, diminution and sometimes perversion of the appetite. These earlier signs are soon followed by loss of spirits, and some interference with movement, but the symptoms only become of importance or attain their full development when the animals remain lying for a long period in the stable.

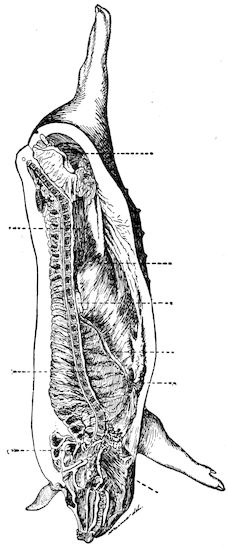

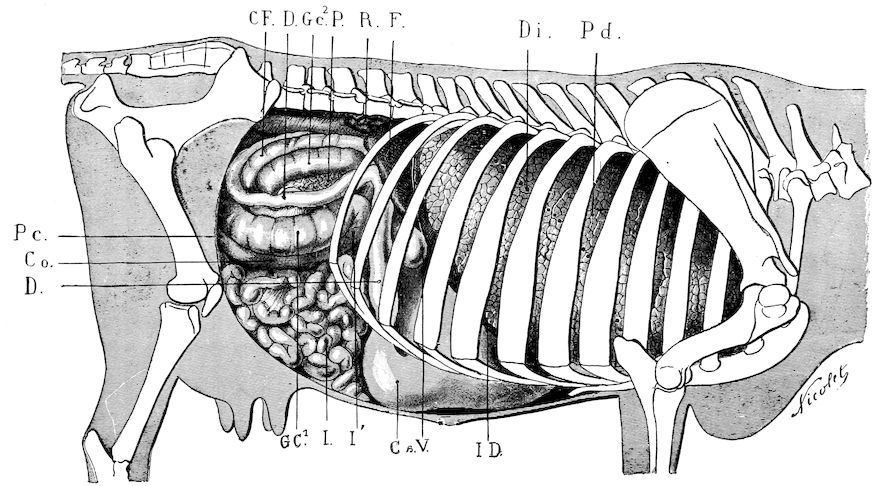

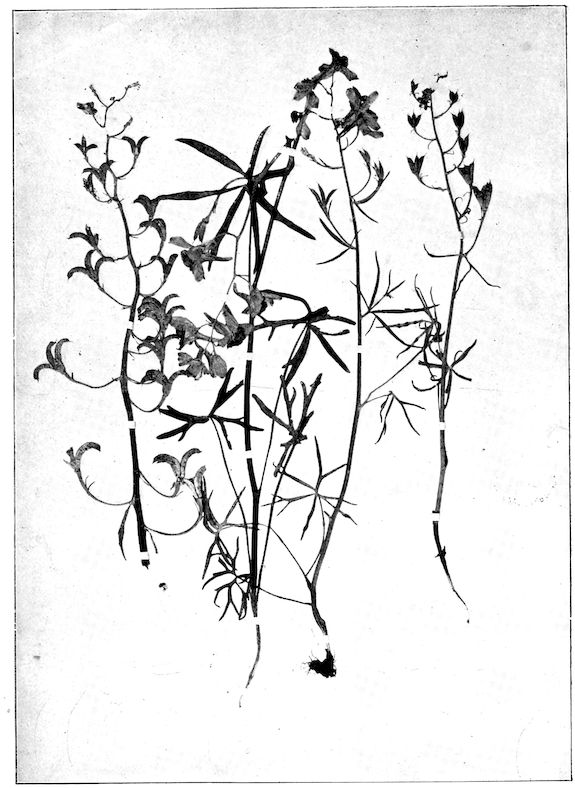

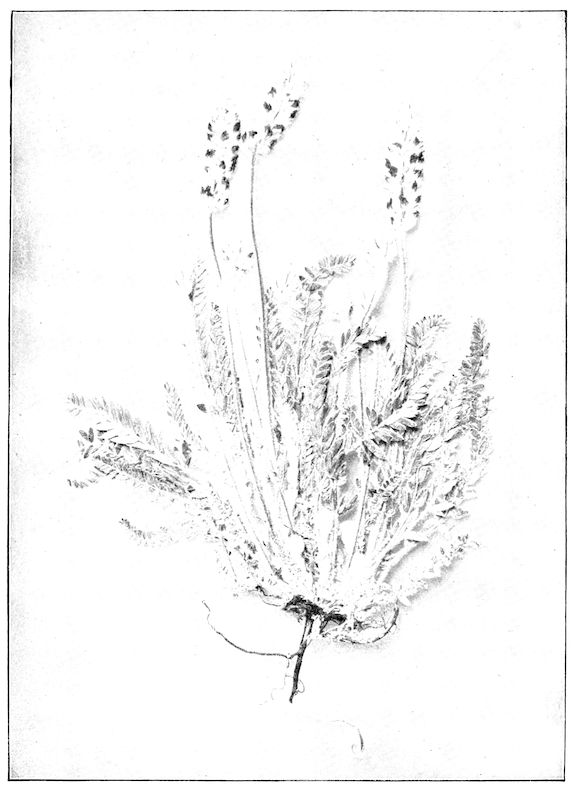

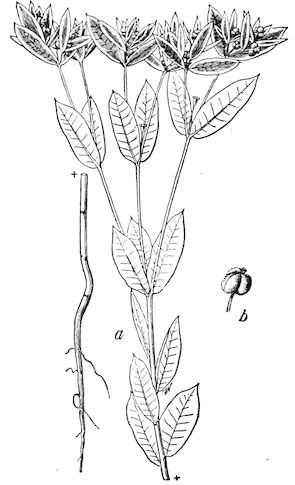

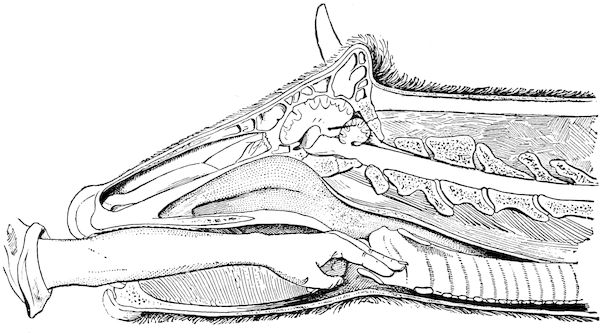

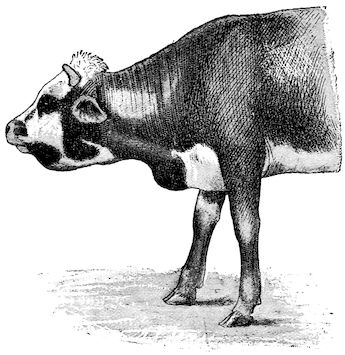

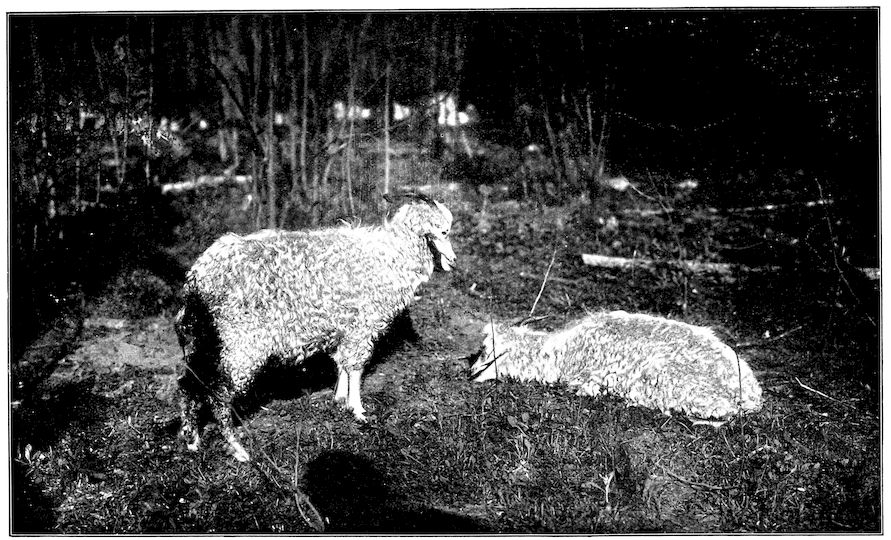

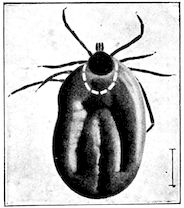

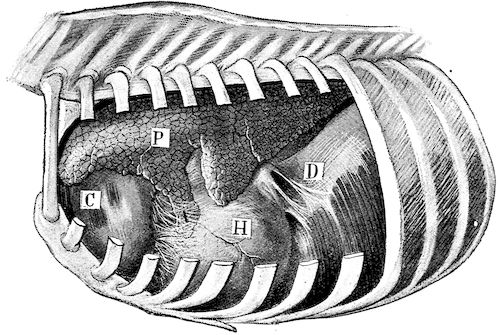

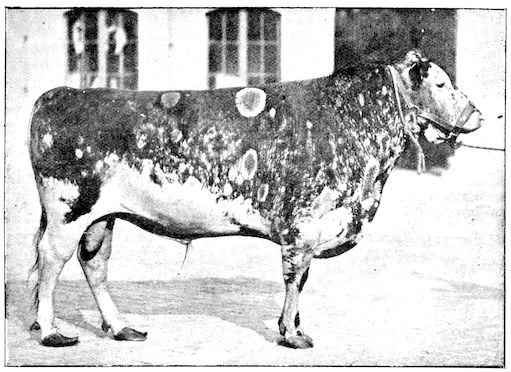

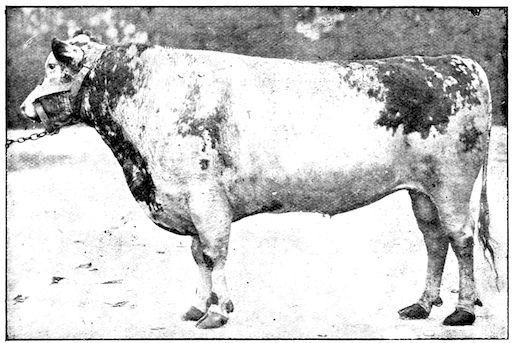

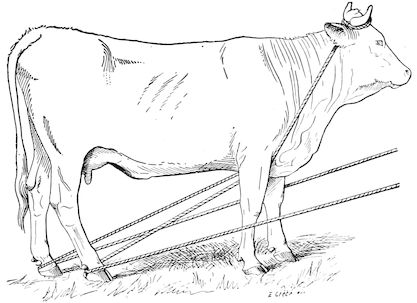

Fig. 2.—Horse suffering from osseous cachexia.

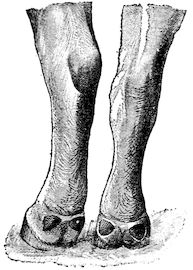

2. The second phase is characterised by more precise signs, which become almost pathognomonic. Difficulty in rising is added to the already existing tendency to remain lying, and to the interference with movement.

When lying down the patient no longer responds to the trifling stimulus, which a healthy animal needs to cause it to rise. It remains languid and apparently lazy, though in reality it experiences pain and difficulty on attempting to get up. The least muscular effort when lying down often causes it to moan, as do efforts to change its position or to walk. Even when standing still, it may appear to be in pain, and patients often assume a position similar to that of a horse suffering from laminitis.

At the end of this second phase, swellings appear, due to synovitis or arthritis of the extremities, synovitis of the sesamoid or navicular sheaths or to inter-phalangeal arthritis or arthritis of the fetlock joint. Weakness becomes marked, and the appetite is very irregular.

10Secretion of milk diminishes or ceases and abortion is not uncommon.

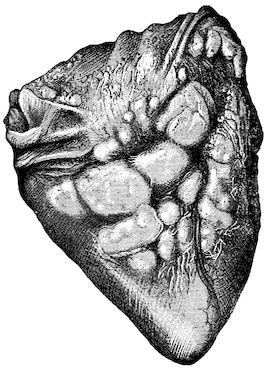

3. The third phase is characterised by fractures, and it is this peculiarity of the disease which has procured for it the names of fragilitas ossium, and osteoclastia. These fractures may affect any portion of the skeleton. Animals so suffering sometimes break a leg whilst trotting or the pelvis in simply jumping over a ditch; a collision with a fixed object like the jamb of the stable door, or a fall on the ground, may result in the fracture of one or several ribs.

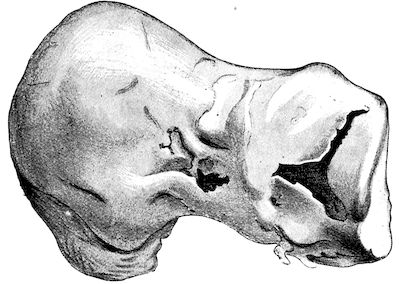

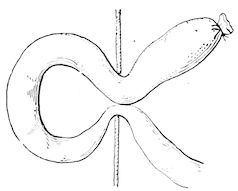

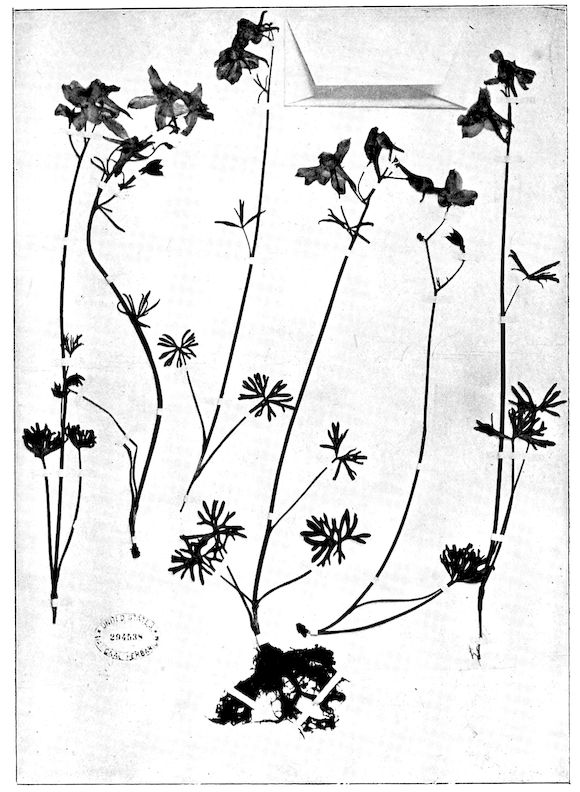

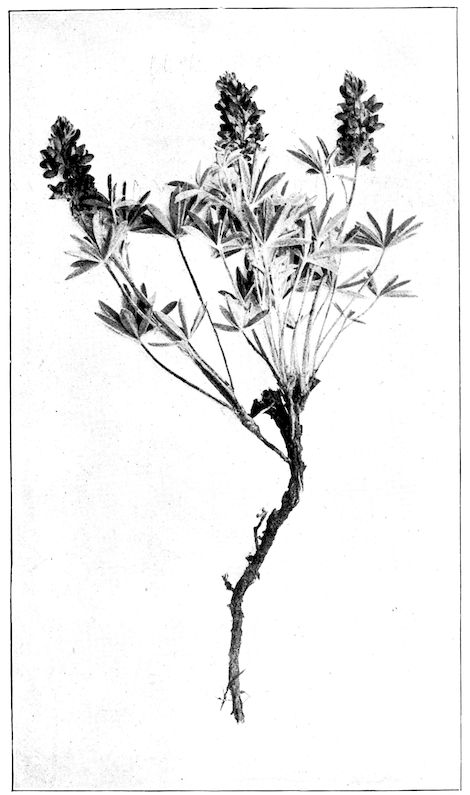

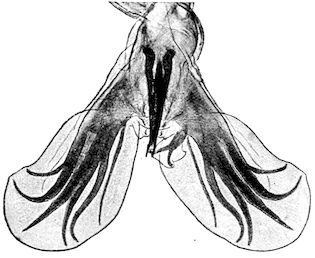

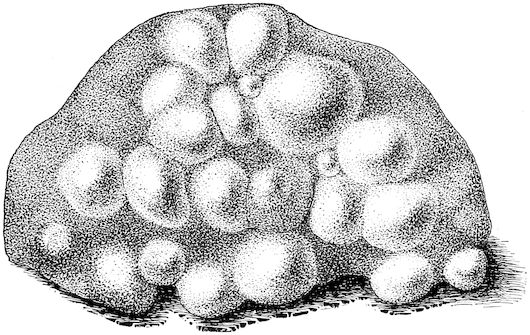

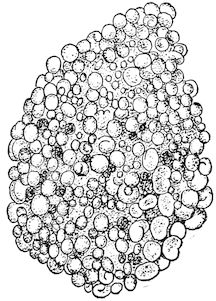

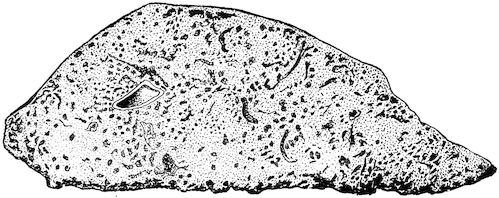

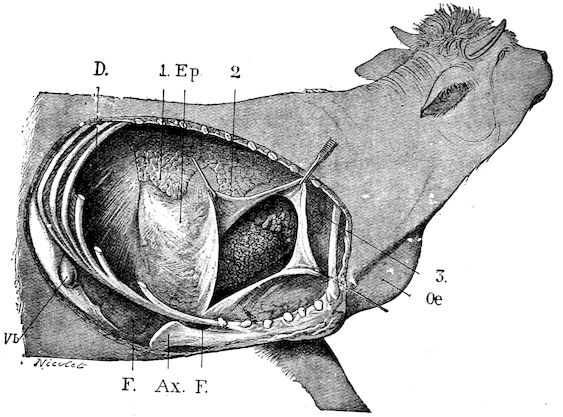

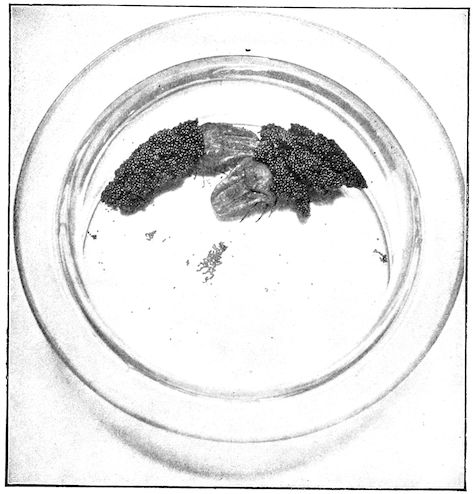

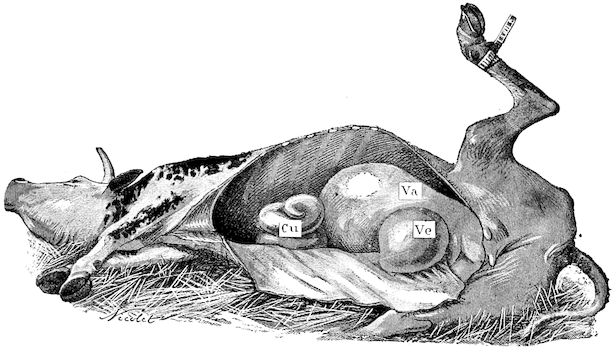

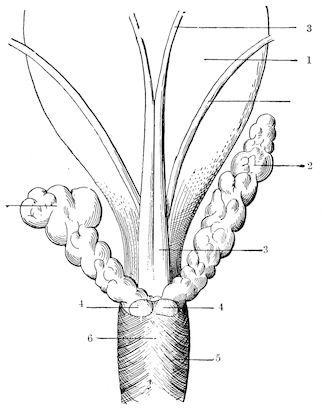

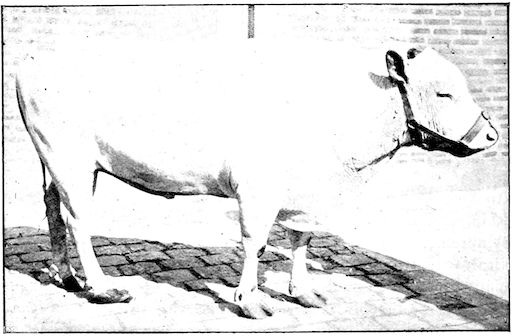

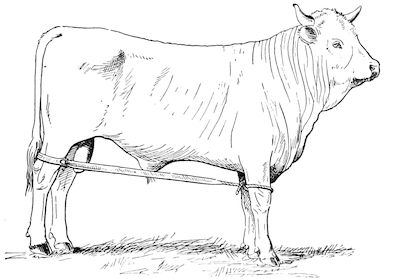

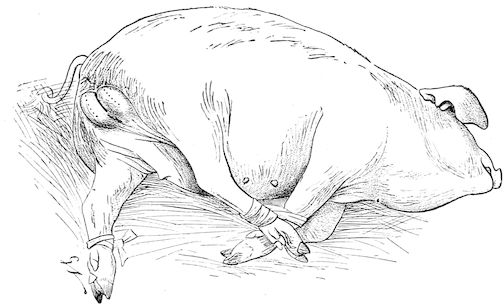

Fig. 3.—Pig suffering from osseous cachexia (fourth stage).

Such shocks would be of no importance to a healthy animal, but to one suffering from osseous cachexia, any violence, or even the slightest muscular effort may be followed by fracture of the gravest character, involving even the vertebral column. In cows the pelvis, femur, and tibia are most frequently injured.

In horses, particularly in riding horses, fractures are commonest in the region of the forearm, cannon bone, and anterior phalanges. So extremely fragile are the bones at this stage that the horse represented herewith broke twelve ribs at one time by simply falling on its side. It is interesting to note that such fractures are never accompanied by any extensive bleeding. They have little tendency to repair, no real callus formation occurs, and on post-mortem examination one often finds the ends unconnected by temporary callus, worn, and rounded by reciprocal friction.

At this stage but under other circumstances, the animals show great reluctance to rise, remaining down for twelve to twenty-four hours without shifting their position. If forced to get up, they stand as though fixed in one position, the respiration and circulation become rapid, and they soon grow tired and fall.

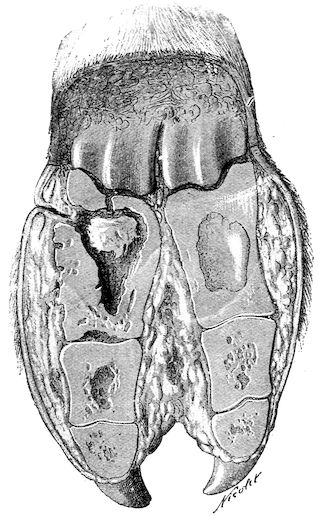

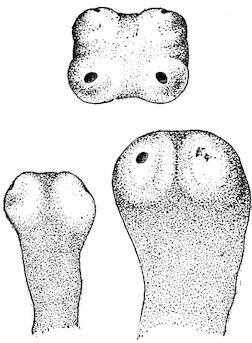

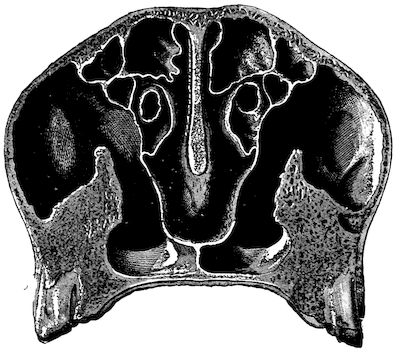

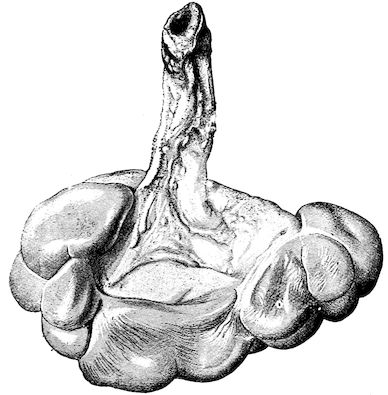

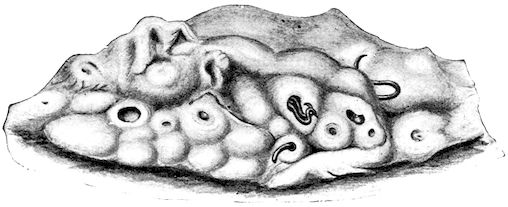

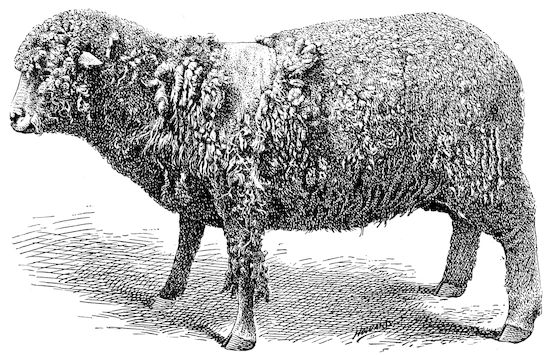

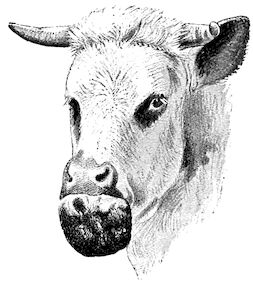

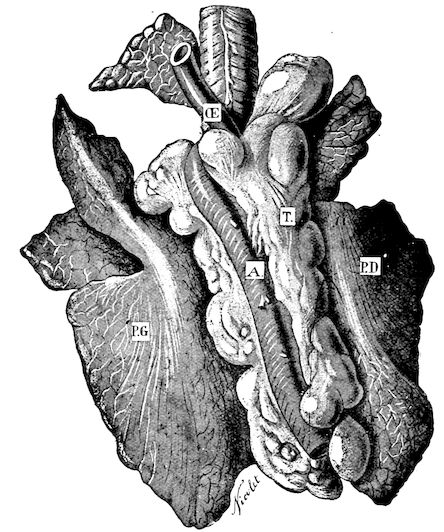

114. The fourth phase, or period of osteomalacia, i.e. softening of the bones, is also the last. It is rarely seen in large animals like horses and oxen, because accidents so often accompany the preceding stages and necessitate slaughter; but it is common in goats and pigs.

In this phase the bones become elastic, soft and depressible, yielding to the pressure of the operator’s fingers.

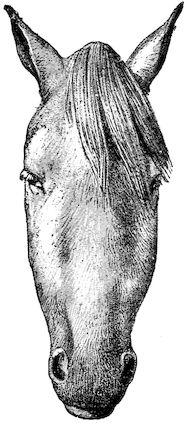

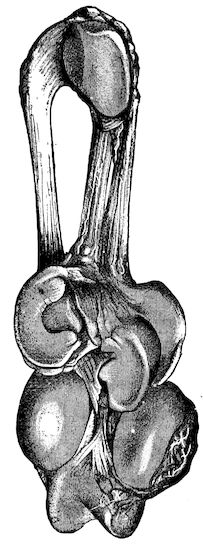

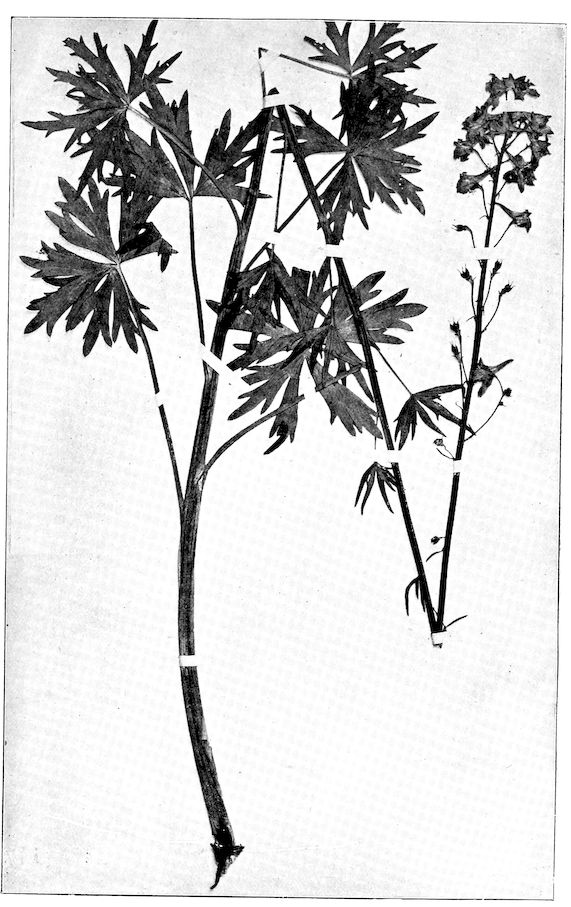

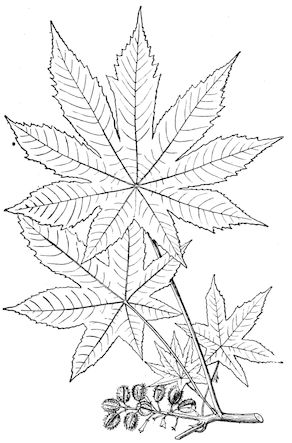

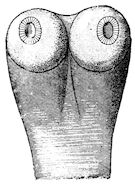

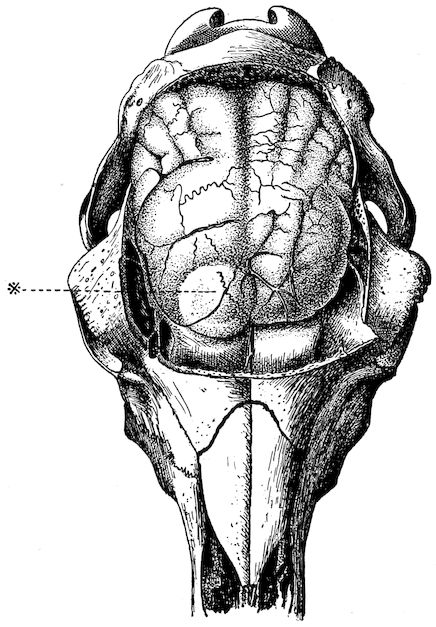

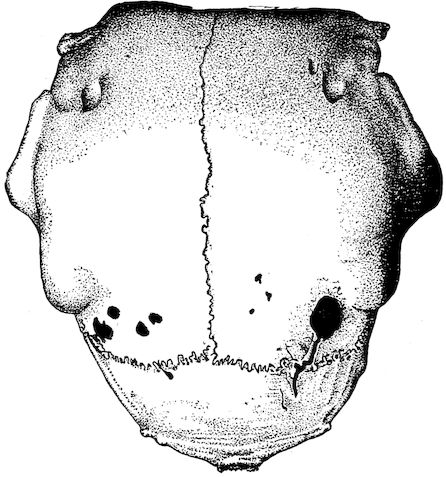

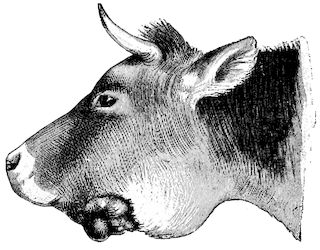

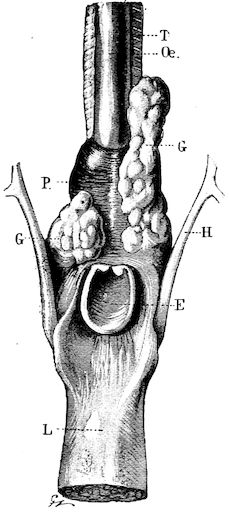

Fig. 4.—Deformity of the face in the horse shown in Fig. 2.

The flat bones are particularly liable to this change, which is common to domesticated animals. The bones of the head are the first to suffer; later those of the pelvis. The lower jaw becomes swollen, particularly about the centre of the branches which may attain three, four, or five times, their normal thickness.

The depression in the submaxillary space disappears. The upper jaw undergoes similar changes, becoming deformed and thickened until the cavities of the sinuses and the hollow appearance of the palate are lost, while the face is so changed that it cannot be recognised as that of a horse, goat, etc.

The molar teeth are almost buried, their tables alone being visible at the bottom of a depression, the edges of which rise above the neighbouring parts (pig).

Mastication is clearly impossible, the jaws appear paralysed, the muscles powerless, and only swallowing is possible, a fact which explains why life is only prolonged to this stage in animals which can be fed with a spoon or bottle (pigs and goats). The bones of the cranium, although greatly changed in texture, are always less deformed than those of the face.

The changes are such that it is often easy with a mere post-mortem knife to cut the head completely in two. Osseous tissue, properly so-called, has disappeared.

All the constituent tissues, with the exception of the skin and muscles, i.e., the bone, periosteum and aponeuroses, have the appearance and consistence on section of the fibro-lardaceous tissue seen in chronic inflammation.

The following is a condensed description of the disease as given by Law:—

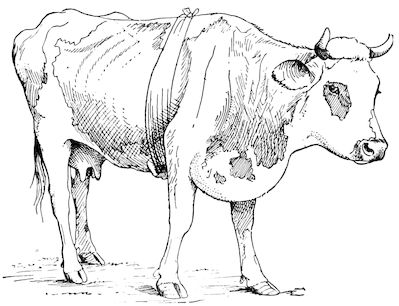

Symptoms. Poor condition or even emaciation, with very visible projection of the bones. The coat is rough, skin tense, inelastic and 12hidebound, appetite variable, sometimes impaired, and nearly always perverted (or depraved) so that the patient will lick the manger continually or pick up and chew all sorts of objects: bones, leather, clothing, wood or iron, stones, etc. The amount of food consumed may, however, be up to the normal. The most marked feature is the difficulty and stiffness of locomotion.... Temperature and yield of milk may remain normal.

“Later, appetite and milk secretion fail, temperature rises a degree or two, the animal refuses to rise, remaining down twelve to twenty-four hours at a time, and ... when rising ... remaining on the knees for a time, moaning and indisposed to exert itself further. At this stage many cases begin to improve and may get well in five or six weeks. Some will remain down for several weeks and finally get up and recover. With constant decubitus, however, the animal falls off greatly, becoming emaciated and weak, the appetite may fail altogether, and the patient is worn out by the persistent fever, nervous exhaustion and poisoning from the numerous bed-sores ... which are common over the bony prominences. It is in these last conditions, above all, that fractures and distortions of the pelvic bones, and less frequently of the bones of the legs occur.”

Fig. 5.—Head of a pig suffering from osseous cachexia.

“The disease may advance for two or three months, and in case of pelvic fractures and distortions, there may be permanent lameness, and dangerous obstruction to parturition, even though the bones should acquire their normal hardness through the deposition of lime salts.”

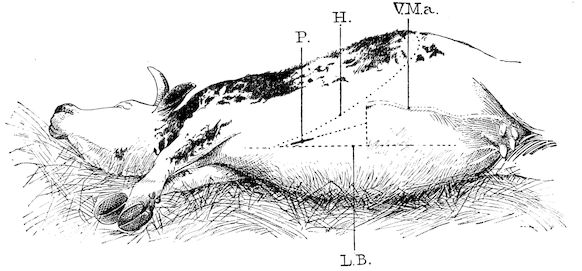

In horses, the different phases of the disease develop precisely as in bovines. The apparent differences between affected horses and cattle result in reality from differences in their capacity for continuing work. In the first phase, horses are incapable of work, their movements being 13badly co-ordinated. They are inclined to stumble, and appear as though suffering from strain of the lumbar muscles.

In the second phase pain referable to the bones sets in. Lameness develops without visible lesions and is rapidly followed by synovitis and arthritis in the lower portions of the limbs, and by wasting and anæmia.

The animals seem unable to move rapidly, or if forced to do so may sustain fractures even at a trot: the limb bones sometimes break or ligamentous insertions in the neighbourhood of joints are torn away, resulting in sudden falls on the ground and fracture of ribs or even of the vertebral column. This corresponds to the third phase, osteoclastia, in oxen.

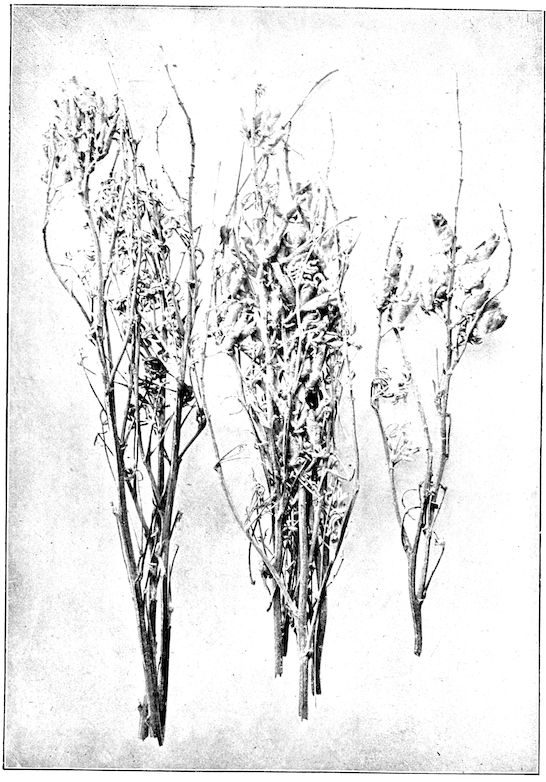

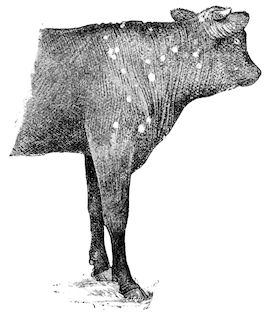

Fig. 6.—Osseous cachexia. This condition developed in two months, the last month of gestation and the first of lactation.

From then onwards, horses become useless and, if not destroyed, may, after a few weeks or months, develop the condition known as osteomalacia, in which the flat bones become softened, the head, the branches of the lower jaw and the face become deformed, while mastication and other functions are impeded.

Germain gives the above symptoms as characteristic of the mode of development of the disease in French and Algerian horses imported into Tonquin, and his description, written several years ago, is fully confirmed by more recent observations. Since Tonquin was taken over by the French, however, improved methods of culture have resulted in the production of better cereals and forage; the fodder plants have been vastly improved, to the great benefit of imported animals.

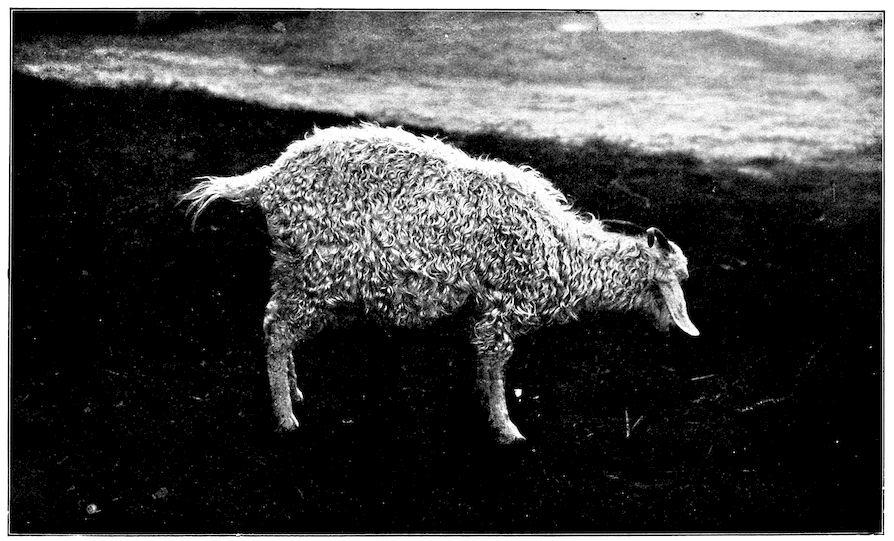

In the goat, the disease shows some slight peculiarities. Thus, in the second phase, during which goats and sheep suffer so markedly from lameness and pain in the bones, goats often walk on the knees. The disease, however, is uncommon in these animals. The phase of osteoclastia is also less marked and fractures are rare, because the animals weigh less and also because they are less exposed to falls and violent shocks. The bones, nevertheless, are extremely fragile and fractures may be produced at will.

Osteomalacia, on the other hand, is always well marked.

Regarding the development of the disease in pigs, we may repeat what has just been said respecting the goat. Walking on the knees is often one of the first signs, fractures are somewhat rare, and the period of softening and deformity is always very noticeable.

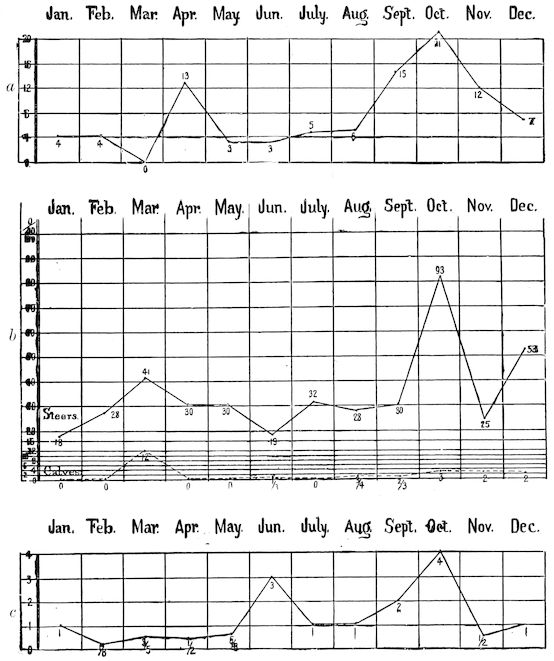

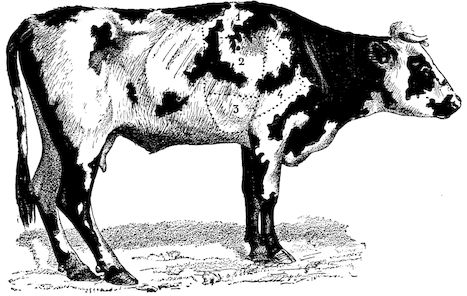

14Course. The development of the disease is slow, lasting from one to three months as a rule, and is little influenced by hygienic conditions. Good milking cows, however, seem to be most frequently attacked, probably because of the great losses of nutritive material which occur through the milk. The calves borne by such animals are often rachitic. Oxen are less commonly attacked. Horses rarely suffer from the disease in France, but frequently in Tonquin. Pigs reared on very poor soil seldom escape attack.

Fig. 7.—Osseous cachexia: softening of the maxillæ.

If treated from the beginning, or even before the second phase has become well developed, the disease may be cured, but after this period little improvement need be expected.

Causation. The problem of why osseous cachexia occurs has naturally given rise to numerous explanations, some plainly inadmissible, others, however, of greater or less plausibility.

The fact which, from the earliest times, appears to have attracted most attention is the relation defective nourishment bears to development of the disease. In Norway, as early as the year 1650, the plant known as sterregraes (which renders animals dull and heavy) was thought to be the cause of the disease; two centuries later, in 1846, the Anthericum ossifragum was similarly regarded. Zundel, in 1870, claimed that the Germans first referred the development of the disease to chemically incomplete forms of nourishment. This opinion seems fully confirmed by the remarkable observations of Germain on European horses imported into Cochin-China, and it is finally placed beyond question by the work of Cantiget. Basing his researches on analysis of the soil, he proved that osseous cachexia only occurs in cattle depastured on land which is too poor in phosphoric acid and calcium phosphate, and that it can be banished by enriching the soil with suitable manures up to a point when the proportion of phosphoric acid becomes normal. In good land, suitable for raising cattle, the proportion of phosphoric acid, according to the best exponents of agricultural chemistry, should not fall below 4,000 kilograms to the hectare. Cantiget and 15Brissonet have shown that where the soil contains less than 1,500 kilograms to the hectare, osseous cachexia is almost permanently present. As soon, however, as this proportion is raised above 2,000 kilograms by suitable culture, the losses diminish, and the cachexia finally disappears.

This view was greatly strengthened by fodder analyses, which showed that in all cases where the soil is poor in calcium phosphate, the forage is poor in phosphoric acid, and vice versâ. The food is too poor in mineral salts, firstly for normal development; and secondly for the proper nutrition of the skeleton.

Germain is of a similar opinion with regard to the occurrence of osseous cachexia in horses in Cochin-China, where the soil is very poor in lime. The fodder and cereals are poor in mineral salts, and even when given in large quantities do not furnish proper (chemical) nutrition. Clear proof of the correctness of this view is afforded by the fact that feeding with forage and cereals obtained from France or Algeria prevents the disease appearing, or diminishes and finally removes the previously existing symptoms. Furthermore, Germain shows that Europeans, living solely on the products of the country, to some extent suffer like the horses.

This theory though based on sufficiently solid foundations to carry conviction, has been questioned, and it may be desirable to record briefly the criticisms advanced against it.

One of the most important is as follows:—

As osseous cachexia of oxen occurs in certain well-defined districts in France, and seems due to the feeding, why does it not attack horses in the same regions in an enzootic form? The answer appears to be that horses receive a greater amount of rich food, particularly of cereals, which contain much larger amounts of mineral salts, including phosphates, than does ordinary forage.

The most serious objection was made by Tapon, who states that in 1893 he saw osseous cachexia in oxen on farms in La Vendée where superphosphate had been used for years, whilst the disease did not exist on other farms where such chemical manures were not employed. Before attaching much weight to this objection, however, it would be necessary to know the richness in phosphoric acid of the soil on the respective farms, for it is possible that, in consequence of natural conditions and in spite of the use of certain mineral manures, the richness of the soil on the first-mentioned farms, though manured with superphosphates, was still below that of the others which had received no artificial, manure.

The system of culture is also of importance, for at the present day, even with the use of artificial manures, cropping would rapidly impoverish soils which were not suitably and sufficiently enriched. 16Abundance or apparent richness of food signifies nothing if quality is lacking.

It may also be asked: if the question of nourishment is of such prime importance why are animals of European origin in Cochin-China affected, whilst the indigenous races prove immune? The answer would appear to be that, in addition to the defective quality of food, other factors, such as adaptation to environment and relative digestive power, play a considerable part in the production of the disease.

Favouring causes. Whilst conceding that the disease is due to one determining cause, viz. the food, it is unquestionable that other causes may favour its appearance. Abundant milking is one, so that the disease most frequently appears six to eight weeks after calving. Gestation may also determine an attack. The disease is rarer in oxen than in milch cows. Starvation and bad hygienic conditions also have a certain influence; it is well known that during dry years, particularly when fodder is scarce, osseous cachexia makes the greatest ravages. Law states that the disease has been attributed to excess of organic matter in the soil, to succulent watery foods, as rank watery grasses, potatoes, turnips and other roots deficient in nutritious solids. Some agent—microbe or toxin—swallowed with the food has been suspected but not yet isolated.

Other explanations have been advanced but up to the present time they scarcely deserve to be regarded even as hypotheses. Thus Anacker in 1865 declared that the disease commenced as muscular rheumatism, was succeeded by destructive or atrophic ostitis, and ended as osteoporosis. So far as the order of the osseous lesions is concerned, this view is quite correct, but the ossific changes are consequences and not causes.

The idea that the disease was due to an infectious agent has been advocated by Leclainche, without, however, having been proved. Pétrone is the only person who has hitherto suggested that osteomalacia in man is due to infection with a nitric ferment (Micrococcus nitrificans). According to him, pure cultures of this organism injected into dogs, produce osteomalacia. These statements, however, require confirmation.

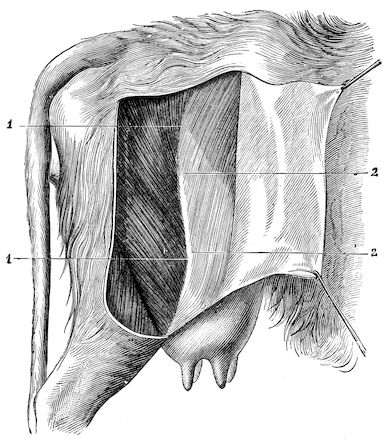

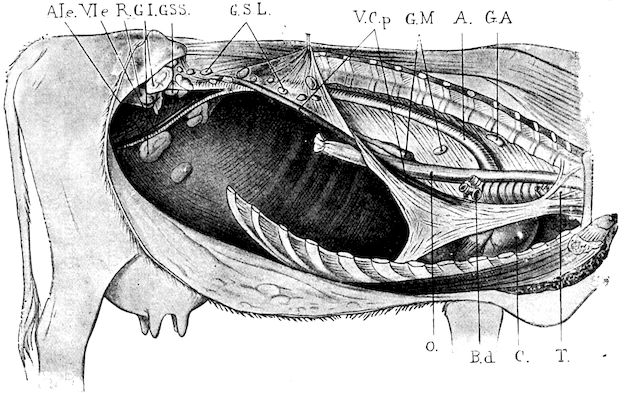

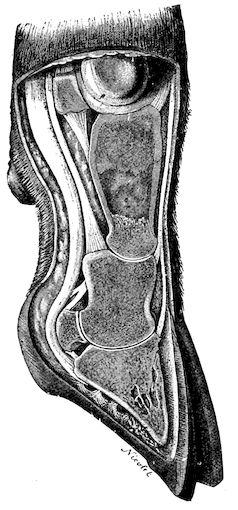

Lesions. The chief lesions are to be found in the bones. They consist in rarefaction of the compact tissue, increase in size of the medullary cavity and Haversian canals, and enlargement of the areolæ of the spongy tissue. The bone marrow loses its fatty constituents, appears red and gelatinous, and contains a greatly exaggerated number of blood-vessels. When heated, the bones do not yield oil as in healthy subjects, and when dry, they seem abnormally porous. In the osteoclastic phase, the bones become very friable and even the shafts assume 17a spongy appearance. They diminish in density. These changes correspond to the stages of eccentric rarefying ostitis and osteoporosis of German authors.

The flat bones often show well-marked periostitis, but the great thickening sometimes seen in certain of the bones of the head appears to be the result of a special osteo-periostitis. It is quite certain that the disease is due to something more than a mere want of mineral constituents in the bone, and poverty in this respect certainly does not explain the hypertrophic changes. The nutrition of the bones as a whole is disturbed, resulting in alterations both in the ossein and in the mineral salts, the whole process being accompanied by symptoms of osteo-periostitis.

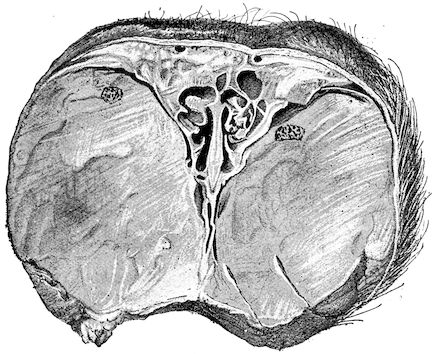

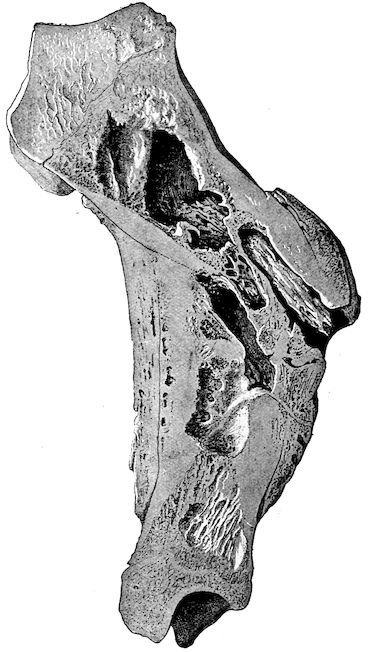

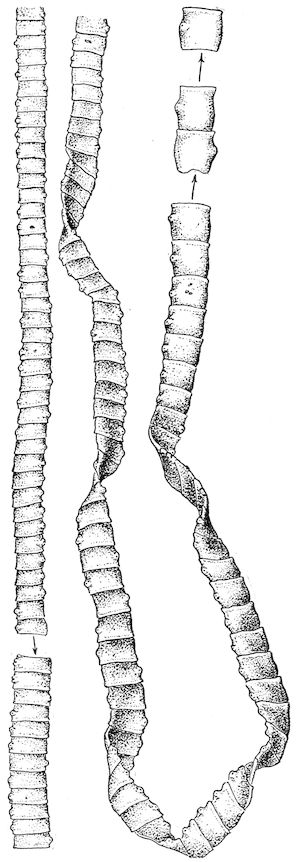

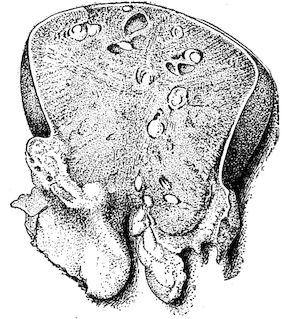

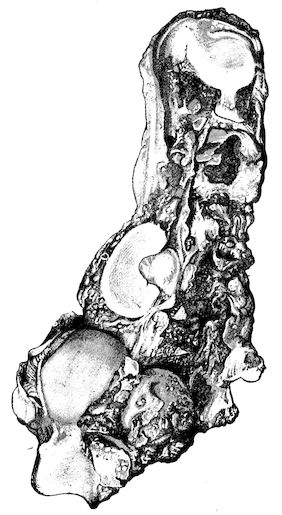

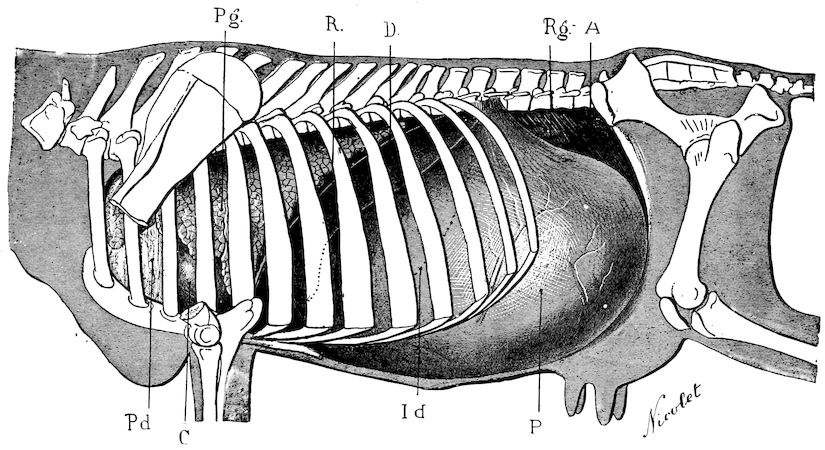

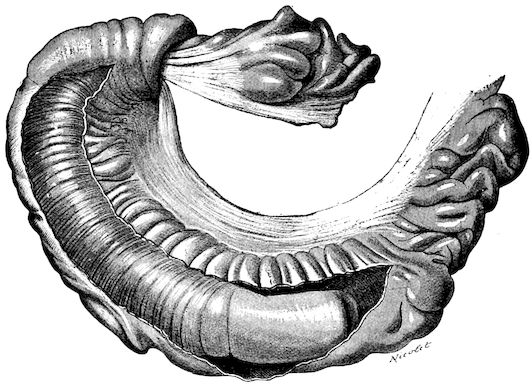

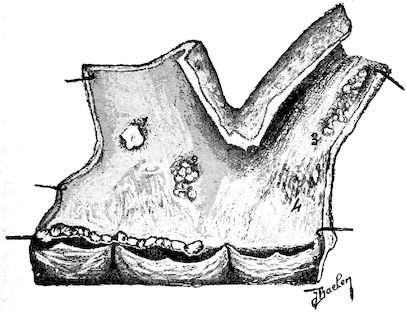

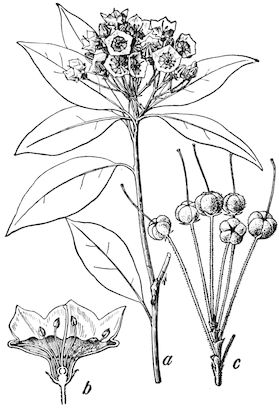

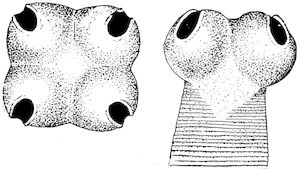

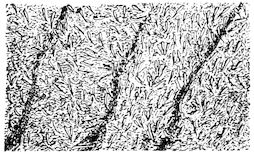

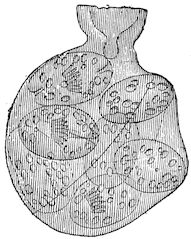

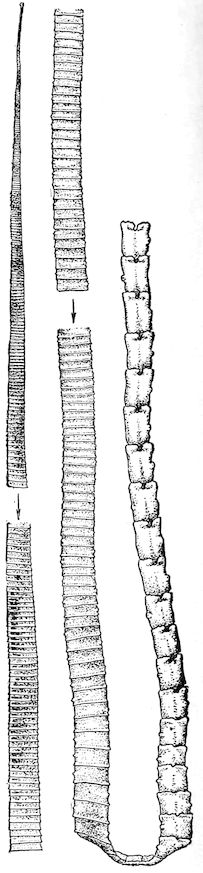

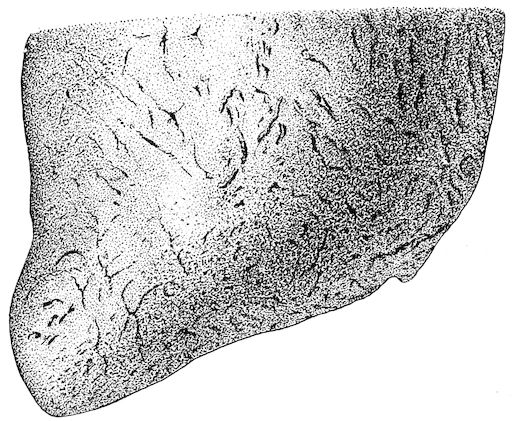

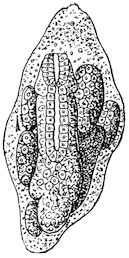

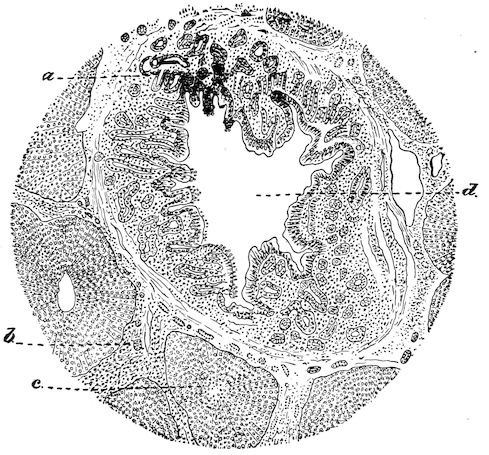

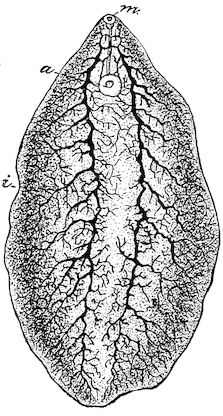

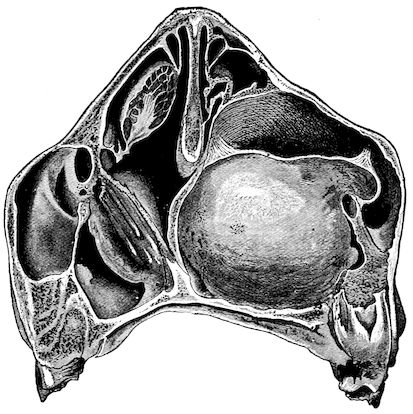

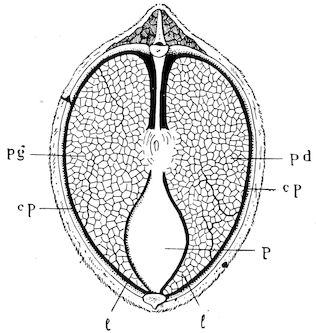

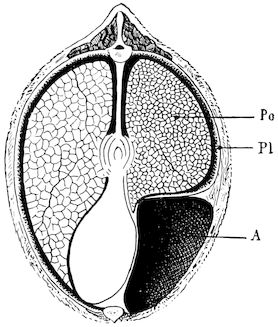

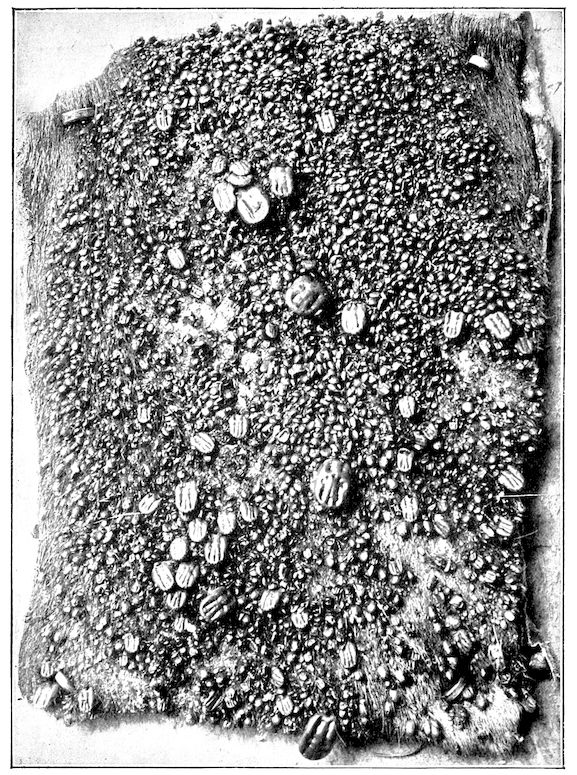

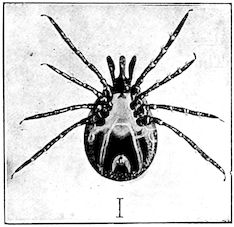

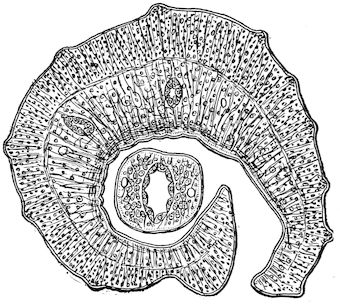

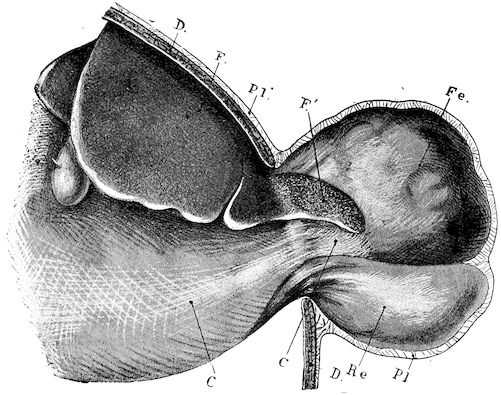

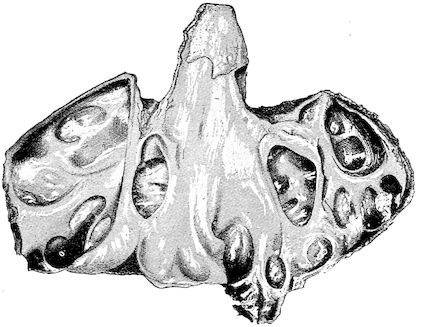

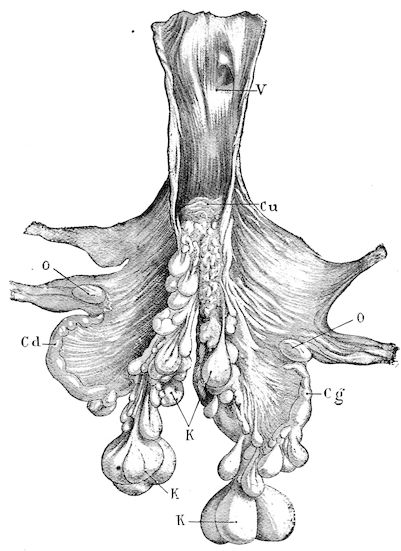

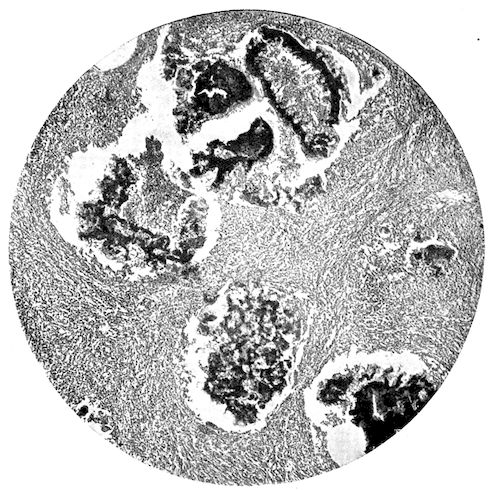

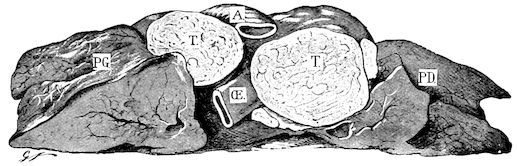

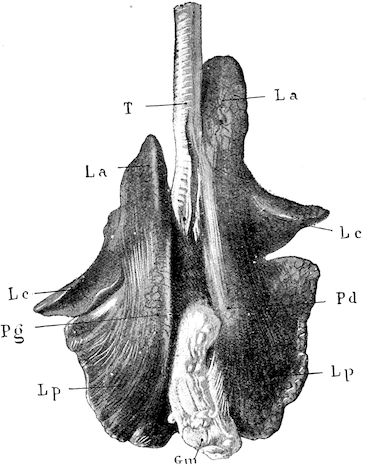

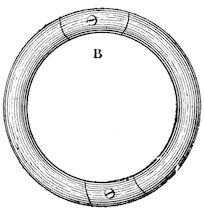

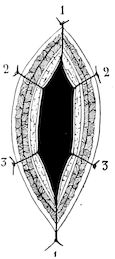

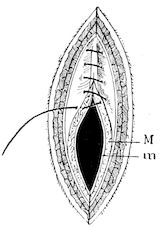

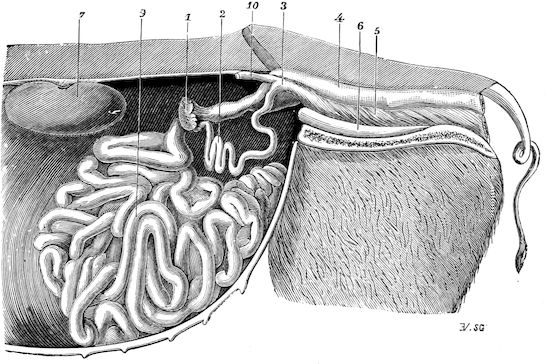

Fig. 8.—Transverse section through the middle region of the face in a pig suffering from osseous cachexia.

The fractures which occur so frequently during the osteoclastic phase have well-marked peculiarities. The extravasation of blood is trifling, and no callus forms, even when the ends of the bones are immobilised by external aid; if the ends are left free, they soon become worn and polished by rubbing against one another.

In the neighbourhood of the articulations and ligamentous insertions the periosteum soon undergoes change, and it is not uncommon to find sub-periosteal and intra-osseous extravasations of blood.

Germain has also noted in horses the disappearance of the intervertebral and articular cartilages, and the frequent occurrence of anchylosis, true or false.

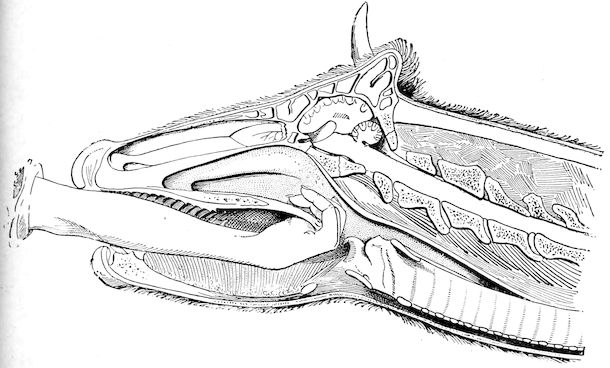

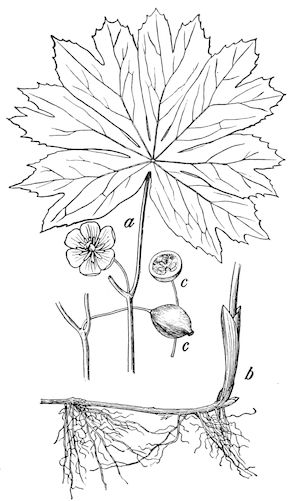

18In the final stages, the bones may be cut with a knife, and a time arrives when bony tissue seems completely to have disappeared; thus, as shown in Fig. 8 herewith, it was possible to cut the entire head of a pig into thin slices without the slightest difficulty. All parts of the head had been affected by the softening change.

From the chemical point of view, the diminution in mineral salts and in phosphate of calcium has long been recognised, but the degree of this change varies according to the phase. In human beings the proportions have been estimated as follows: Normal bone, 50 to 80 per cent. of phosphate of calcium; bone in persons suffering from osteomalacia, 5 to 20 per cent. of phosphate of calcium. The changes in the ossein have not been carefully studied. We only know that histologically the ossein becomes fibrillar, and that chemically it no longer retains its normal composition.

The diagnosis is difficult, particularly on the first occasion of seeing the disease, and especially if this is of an enzootic character. The practitioner may also have some hesitation in diagnosing isolated cases in regions where the disease seldom occurs.

Otherwise, diagnosis is usually easy, as soon as lameness or synovitis, or arthritis of the lower regions of the limbs appears. Only in isolated cases are the lesions likely to be mistaken for accidental injuries, and it is also fairly easy to differentiate them from the localised lesions of rheumatism. The latter disease seems more frequently to attack the upper joints of the limbs, and is often accompanied by intense fever and cardiac disturbance.

Prognosis. In a general sense the disease is very grave, because it appears as an enzootic, and, in dry years and those during which there is a scarcity of forage, inflicts enormous losses on the breeders of certain countries. When advice is sought towards the end of the second phase of the disease the prognosis is therefore very grave. Under such circumstances it is often better to slaughter rather than to treat, provided that the affected animals, like cows, pigs, or goats are still of some value.

The prognosis is much more hopeful if treatment is attempted at an early stage, when improved diet and the use of suitable drugs sometimes lead to recovery.

Treatment. We know that in the Middle Ages this disease was often treated by the administration of crushed bones, and even at the present day ground bones are frequently recommended. Treatment must be subordinated to proper feeding, no system of medication being of any value whatever unless the food is suitable.

Germain states that imported horses in Cochin-China recover if simply returned to their former diet, i.e. to cereals and forage obtained from France or Algeria. Cantiget shows that such improvements in 19cultivation as the free distribution of superphosphate manures on impoverished soils modify the chemical composition of the forage, and render it capable of building up and sustaining the organism and bony tissues; treatment should therefore be essentially prophylactic in character.

Animals suffering from osseous cachexia should be fed on cereals and forage obtained from rich districts where the disease has never occurred; but, as in times of scarcity questions of expense almost always receive first consideration, it may be necessary to substitute bran for such products, or give oats, maize, beans, rice, and oil or cotton cake, etc., all of which can be obtained commercially, and are of sufficient nutritive richness. It is often advantageous to give such food cooked and slightly salted.

Commercial ground bones and calcium phosphate (bi- or tri-basic), in doses of 1 ounce per day for oxen and 1¼ to 2 drachms for pigs or goats, have given excellent results in the hands of most practitioners. Some recommend the addition of iron salts or bitter tonics like gentian or nux vomica in doses of 2½ drachms per day for a full-grown ox.

Law declares that the treatment should be varied “with the predominance of the causes, essential or accessory.... Green clover, alfalfa, and other leguminous products, ground oats, beans, peas, linseed or rape cake ... and vetches may be especially recommended.... The free access to common salt and a liberal supply of bone meal are helpful.... Apomorphia is especially valuable in correcting the perverted appetite and stimulating digestion. A change of pasture is always advisable. In all cases where possible the water should be changed as well as the food. Attention to the housing, grooming, and general care of the animals should not be neglected. Finally, every drain upon the system should be lessened or stopped. The milk may be dried up, and the animal should not be bred.”

Meat meal also renders good service, but the use of cod liver oil, suggested by Zundel, is too expensive, and phosphorised oil is too dangerous to be adopted in ordinary treatment.

Local treatment for synovitis and arthritis has been recommended. It is ineffective unless accompanied by good feeding and internal medication. On the other hand, the lesions often diminish rapidly or totally disappear under the influence of general medication alone.

Although oxen, sheep, goats, and pigs are much less subject to fractures than the horse and dog, nevertheless, they do suffer from such accidents. Repair is perfectly possible, but the cases are often not worth treating, unless the subjects are young or of considerable value. On the other hand, in fat and heavy subjects, it is difficult to fix the parts in position. Slinging produces bad results, and generally should not be encouraged.

Apart from fractures accompanying general chronic diseases, like rachitis and osseous cachexia, the vertebræ, the pelvis, the ribs, or any of the limb bones, may be fractured in consequence of accident.

Such fractures may be either complete or incomplete (fissures), simple or compound.

The general signs which indicate fracture are always the same, viz., loss of function, local pain, abnormal mobility, crepitation, due to rubbing together of the ends of the bones, and deformity of the part. Diagnosis is generally easy; prognosis on the other hand is very variable.

The vertebral column may be accidentally fractured in the region of the neck in consequence of the animal falling on its head; in the dorsolumbar region, from falling into ditches or ravines, or, in the case of bulls fighting, from violent muscular efforts. Fractures of the first kind are immediately fatal; those of the second result in paraplegia of the hind limbs, and necessitate immediate slaughter.

Fractures of the pelvis comprise:—

1. Fractures of the angle of the haunch, resulting from external violence and characterised by sinking of the external angle of the ilium, deformity of the hip, and lameness without specially marked characters. This fracture is rarely complicated. The symptoms of lameness diminish with rest, but deformity continues.

2. Fractures of the floor of the pelvis, usually extending from the anterior margin of the pubis to the foramen ovale and from the posterior margin of the foramen ovale to the end of the symphysis. They result from obstetrical manipulation, as in forcibly removing a fœtus which is too large, or a monstrosity. As a rule, the animals cannot rise, or if they succeed in doing so, are incapable of moving. Diagnosis is made by exploration through the rectum. Such fractures always necessitate slaughter.

Fractures of the neck of the ilium and of the base of the cotyloid cavity, even in cases of dislocation, are rare despite what has been said to the contrary.

21In the fore limb, fractures of the scapula and humerus are usually of traumatic origin, are seldom accompanied by marked displacement, and are capable of uniting if a long rest at grass is allowed. Pitch bandages should be applied to the surface, covering all the surrounding regions, viz. the withers, upper portion of the forearm, girth and chest, to assist in immobilising the region of fracture, and to promote union.

Fractures of the forearm are more difficult to treat, because the bandage applied must extend as far as the hoof. In this case displacement often occurs. It is therefore necessary, firstly, to reduce the fracture, and bring the ends in perfect contact, for which purpose it may be requisite to cast the animal, and give an anæsthetic; and, secondly, to apply a pitch plaster in the form of a shallow gutter, leaving the inner surface of the limb uncovered along a line about two inches wide following the course of the veins of the forearm.

Fractures of the metacarpus and metatarsus usually heal well in all animals of moderate weight, such as heifers, steers, goats or sheep, provided a simple plaster bandage, covering the entire limb or preferably with an opening in the position above indicated, is applied and continued downwards as far as the claws.

In sheep and goats it is sometimes even sufficient to use a splint formed of straw-boards, and in the case of oxen, of wood, applied over a cotton-wool padding and retained in position by straps, or in the case of the heavier animals by dextrine or pitch bandages.

In the hind limb, fractures of the femur are more serious, because the apparatus that can be used to secure immobility is seldom or never effective; excepting in young animals, it is therefore usually better to slaughter.

Fractures of the tibia are treated like those of the forearm when it appears desirable to keep the animals alive.

Plaster bandages can very easily be prepared by saturating tarlatan in a mixture of equal parts of thoroughly dry plaster and water. Six to ten thicknesses of tarlatan, arranged alternately longitudinally and transversely, are sufficient. When adjusted they can be kept in position until the plaster has hardened by means of dry bandages applied from below upwards, which can be removed after a lapse of half an hour to an hour.

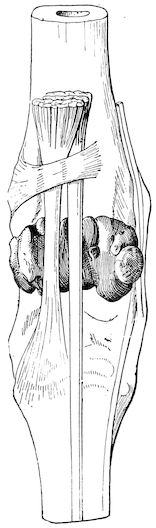

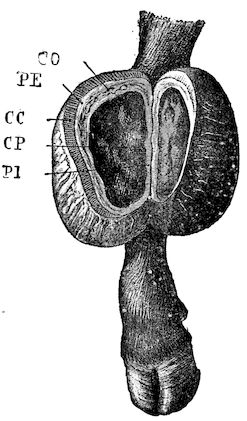

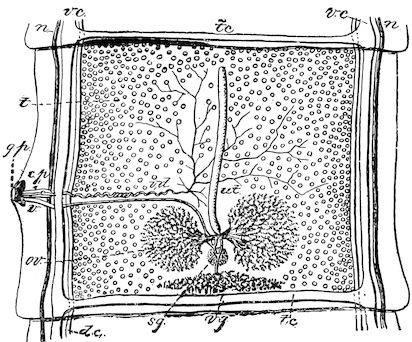

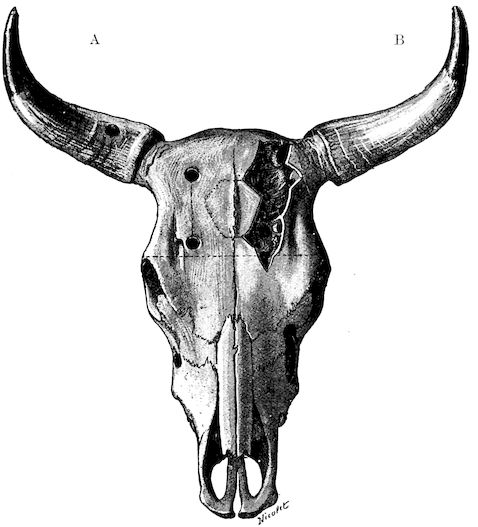

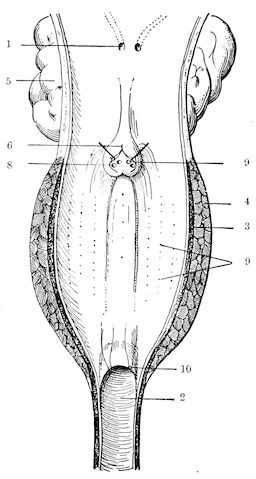

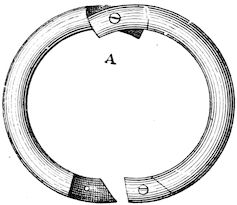

Anatomy of the horns. The horns form organs of defence, and project on either side of the frontal bone at the poll. Each consists firstly of a bony basis generally known as the horn core; secondly, of a horn-secreting membrane; thirdly, of a horny sheath, the horn properly so called.

22(1.) The horn core projecting from the frontal bone does not develop until after birth. About the third month a little prominence appears under the skin, which, as it develops, assumes a conical shape, and may be seen to be covered with a horny substance. In proportion as the horn core grows, there develops within it a cavity which may either be of a simple character or divided by a longitudinal partition. This communicates with the frontal sinus, a fact which explains the collection of pus in the sinuses as a result of injuries to the horns. The sinus of the horn core does not exist in young animals, and is not completely developed before the third or fourth year of life.

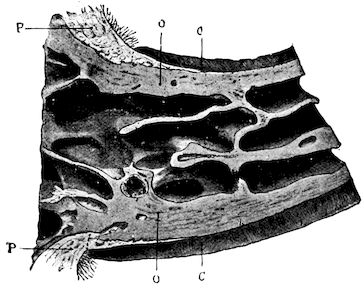

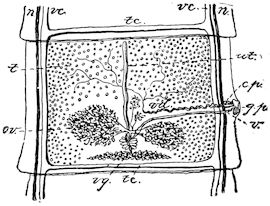

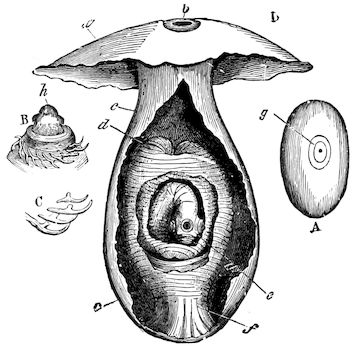

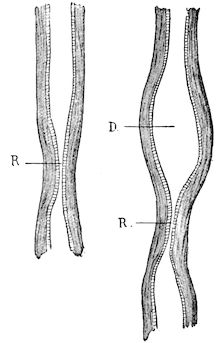

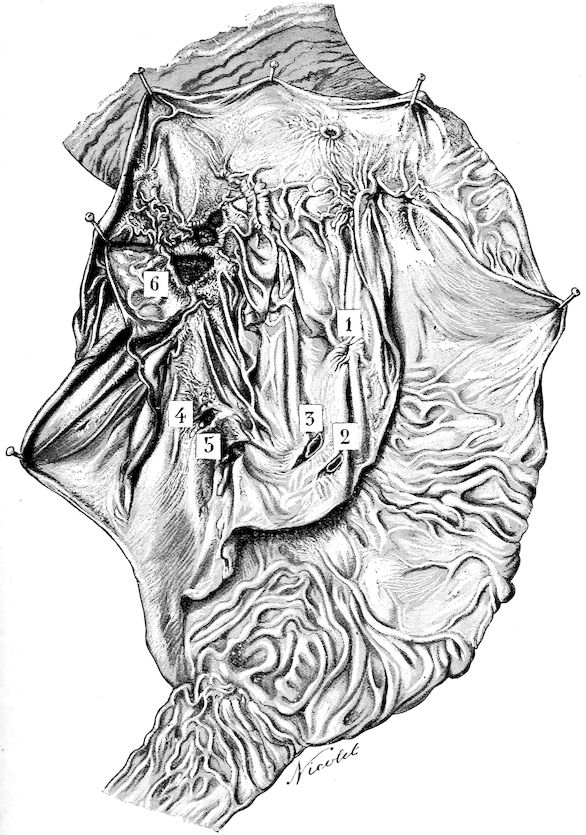

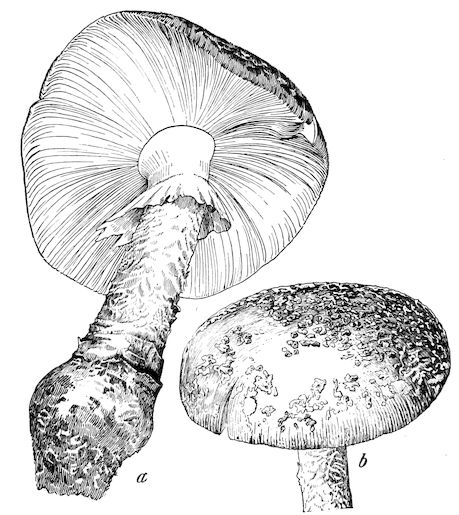

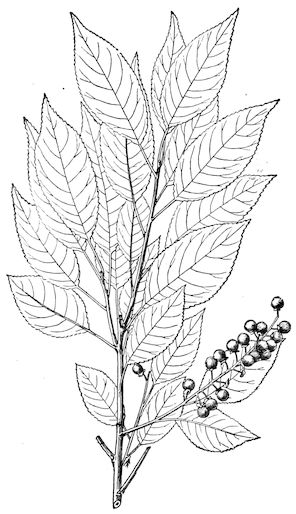

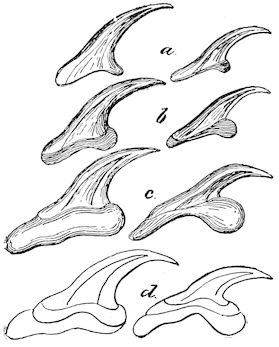

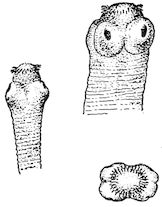

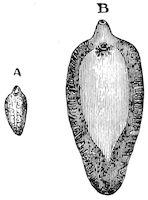

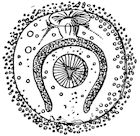

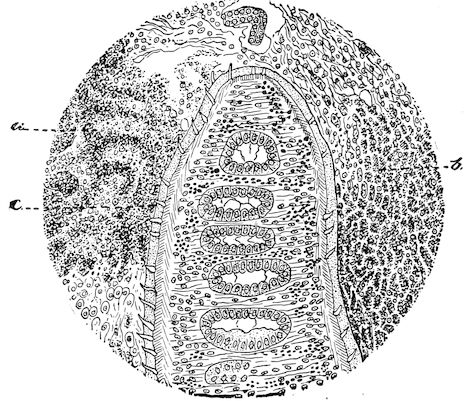

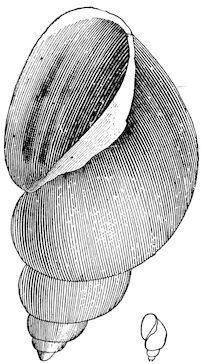

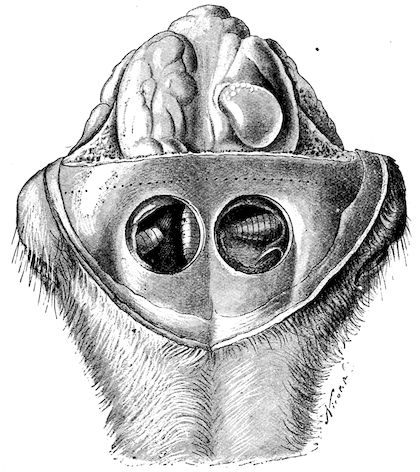

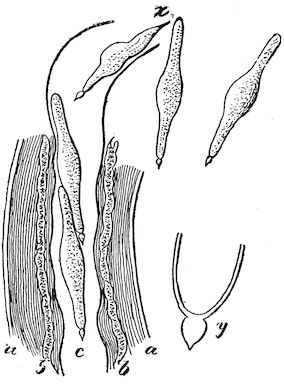

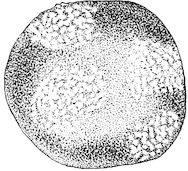

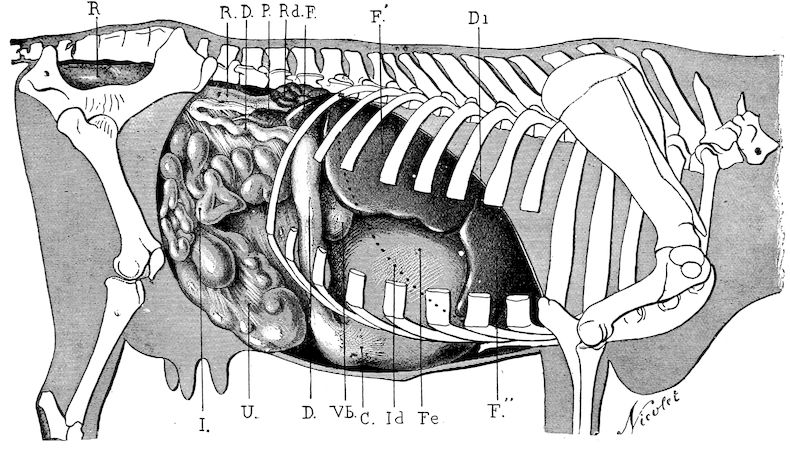

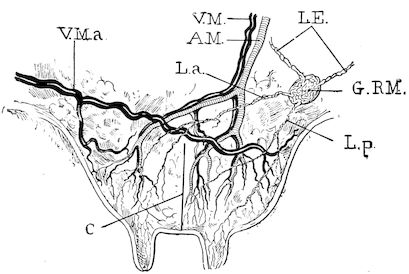

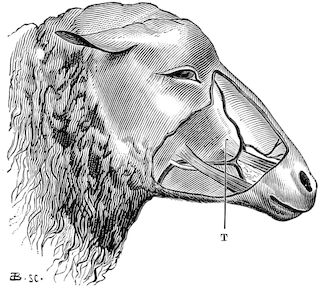

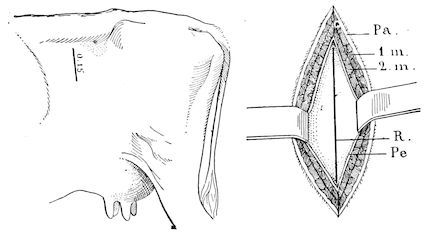

Fig. 9.—C, horn; P, modified skin forming the keratogenous membrane; O, horn core, exhibiting a double sinus.

(2.) The horn-secreting membrane is formed by the skin, which undergoes special development around the base of the horn and comes to resemble that of the coronary band, from which the hoof or claw is secreted. The band is about one-fifth of an inch in breadth. The papillæ of the dermis are specially developed at this point, and the epithelium which they secrete eventually forms the horn.

The internal surface of the growing horn is adherent to the horn core through the medium of another tissue formed by a specially differentiated periosteum which is continuous with the periosteum covering the frontal bone. It is not a true periosteum, but a vascular tissue formed of papillary layers analogous to those of the podophyllous tissue of the ox’s claw or horse’s hoof.

This keratogenous membrane receives a rich vascular supply from the arterial circle formed at the base of the horn core by a division of the external carotid, the blood conveyed by which is freely distributed to the enlarged papillæ. The great vascularity of these parts 23explains why lesions of the horns are often followed by such profuse bleeding.

(3.) The horn secreted by the papillæ of the horn band (which is analogous to that of the coronary band of the horse) forms a cone varying in its curve in various breeds. Its base is hollow, and contains little depressions holding the papillæ from which the horn is secreted. From its base up to the end of the horn core the walls progressively increase in thickness. From this point it is solid; in a fully-grown horn the bone does not extend more than one-half or two-thirds of the entire length.

In the adult, the development of the horns varies with different breeds and is affected by sex. In the bull the horns are short, but in the cow and ox long. Short and fine in animals of improved breed like the Durham, they are long and thick in breeds of working oxen.

Injuries affecting the horns are of three classes, determined by the part affected.

1. Detachment of the horn or sheath.

2. Laceration:—

3. Fractures:—

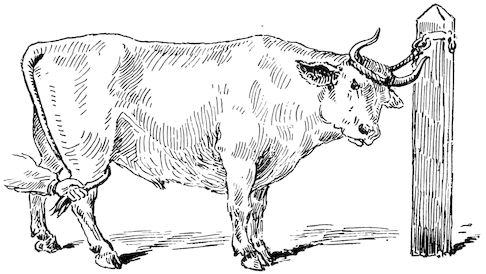

When the yoke is badly fitted or padded, it is liable to cause a continual strain or a succession of shocks producing chronic inflammation of the keratogenous membrane. Should the end of the horn then be struck heavily, it is quite possible that the horn will either partially or wholly be detached. In this case it falls away without there necessarily being any important lesion of the horn core.

Such accidents are not infrequently caused by the driver striking the ox on the horn with the yoke in order to keep it quiet while it is being harnessed.

The prognosis of this condition is not grave, except for the fact that working animals cannot be used until the horn is completely regrown.

The treatment simply consists in thoroughly cleansing and disinfecting the horn core and then applying a protective dressing. The bony basis is surrounded with a mass of tow saturated with an antiseptic 24solution, like 2 per cent. creolin or carbolic acid solution, which is kept in position by a spiral bandage passed around the horn, and secured in a figure of 8 on the opposite horn. Instead of applying such a dressing, some practitioners content themselves with using an antiseptic ointment or even a simple dressing of tar.

Causation. In a general sense fissures may result from any violence affecting the centre portion of the horns, such as blows with the yoke or accidental bruises inflicted by the animals themselves in fighting with their neighbours.

Symptoms. Whether the fissure is confined to the horny covering itself or whether it extends to both the portions constituting the horn, that is, the horny covering and the horn core, two very noticeable symptoms are always present: 1. A straight fissure resembling a sand crack, and appearing usually on the convexity of the horn, and, 2. A very trifling hæmorrhage, which does not appear until some hours or even a day after the accident.

Diagnosis. If the lesion only affects the horn core, diagnosis is always difficult, for one can hardly perceive any sensitiveness of the horn near the fissure.

Prognosis. Provided that the horn core is not injured, the prognosis is favourable; but in the contrary case, it should be reserved; for hæmorrhage extending to the interior of the frontal sinus not infrequently causes suppuration in that cavity.

Treatment. Attempts should first be made to check hæmorrhage by applying masses of tow saturated with cold water and frequently wetted with slightly antiseptic solutions, such as 2 per cent. creolin or carbolic acid. If hæmorrhage persists in spite of this simple treatment, astringents may be employed, which, by causing the formation of a clot, mechanically arrest further extravasation of blood. These astringents vary considerably in value, and we should particularly warn practitioners against perchloride of iron, which causes necrosis of the tissues, and later, formation of pus. A 5 per cent. solution of gelatine is hæmostatic and excellent for the purpose named, as also is hydroxyl solution. When once hæmorrhage is arrested, the keratogenous membrane rapidly heals in consequence of its vascularity, and soon secretes fresh horn.

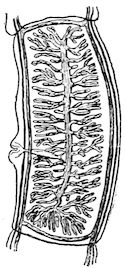

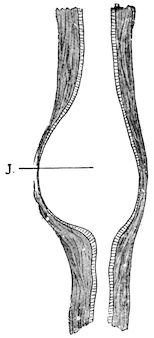

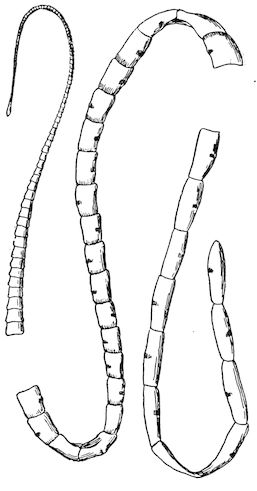

Etiology. Fractures of the horns, like fissures, are produced by violence, but of a more marked character. They are termed complete or incomplete, according as the entire thickness of the horn or only a portion of that thickness is involved.

The fracture may affect either the terminal half or the basilar half; or, again, it may have its seat in the frontal bone below the origin of the horn core, in which case a flake of bone will be detached. Such fractures assume varying forms, and may either be deeply excavated, oblique, smooth, regular or dentated.

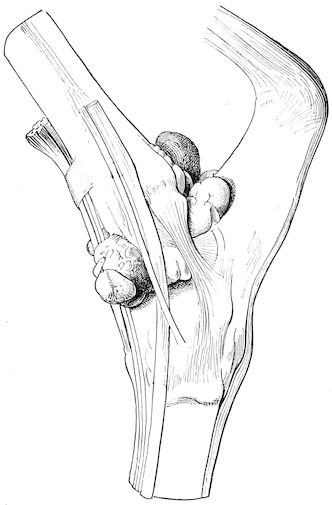

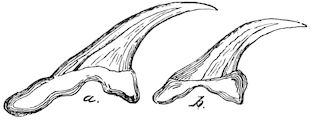

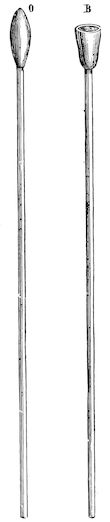

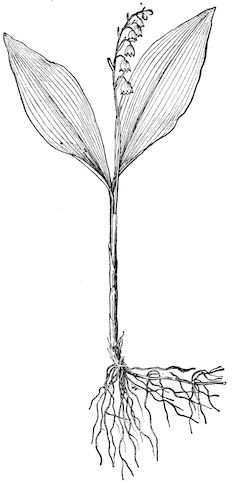

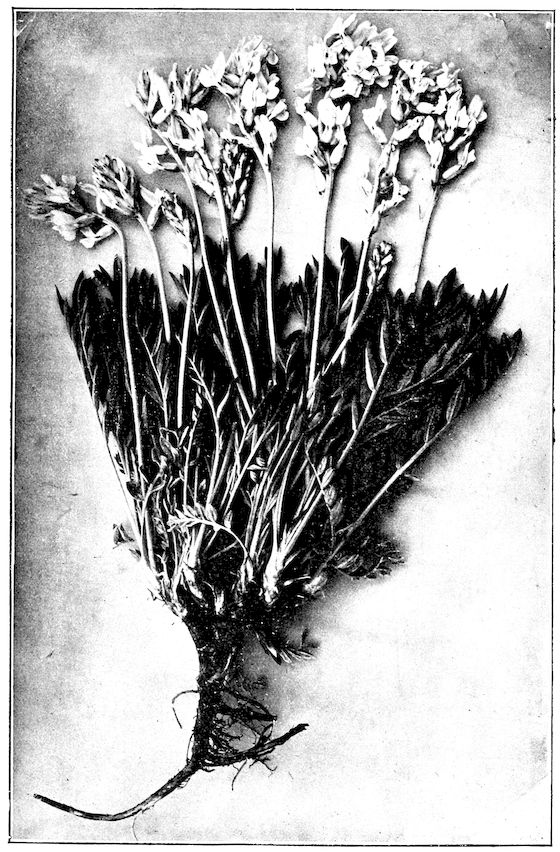

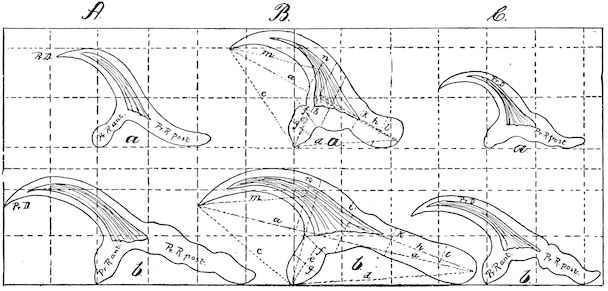

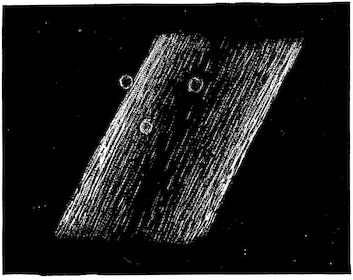

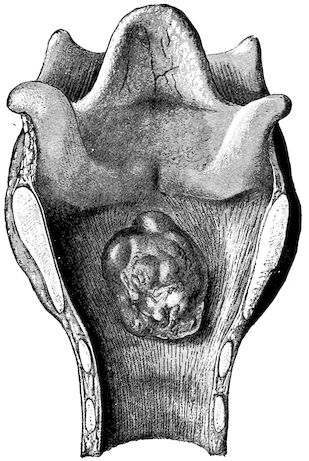

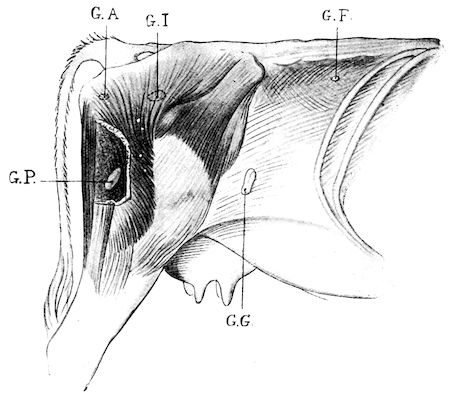

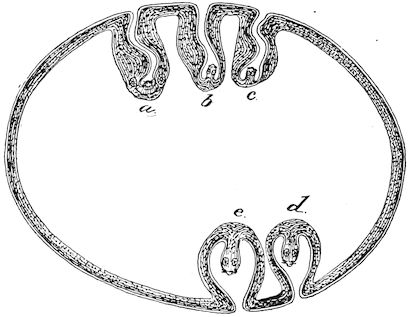

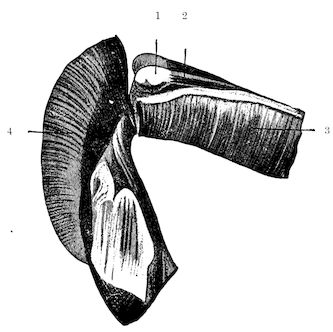

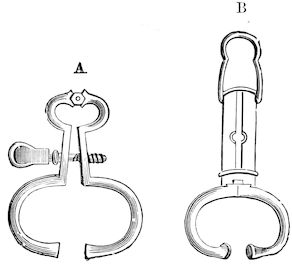

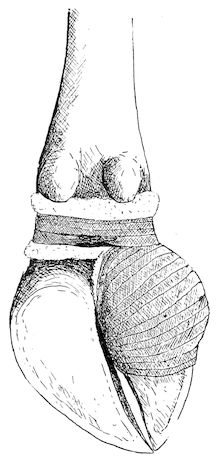

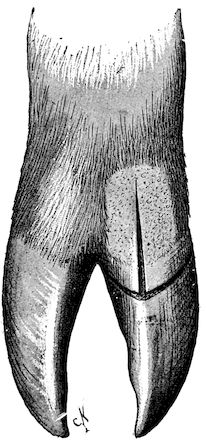

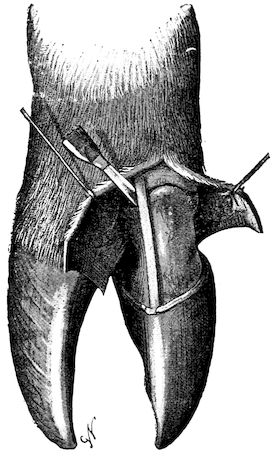

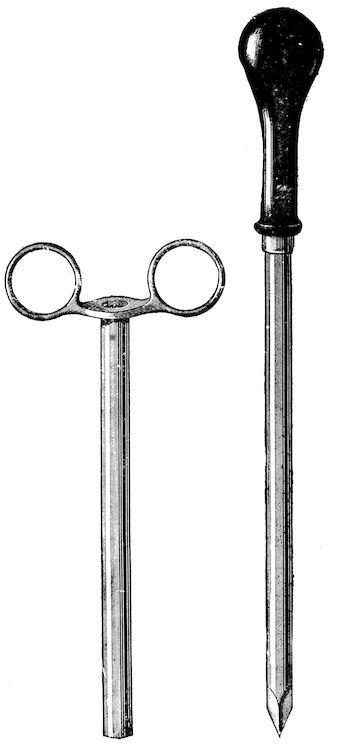

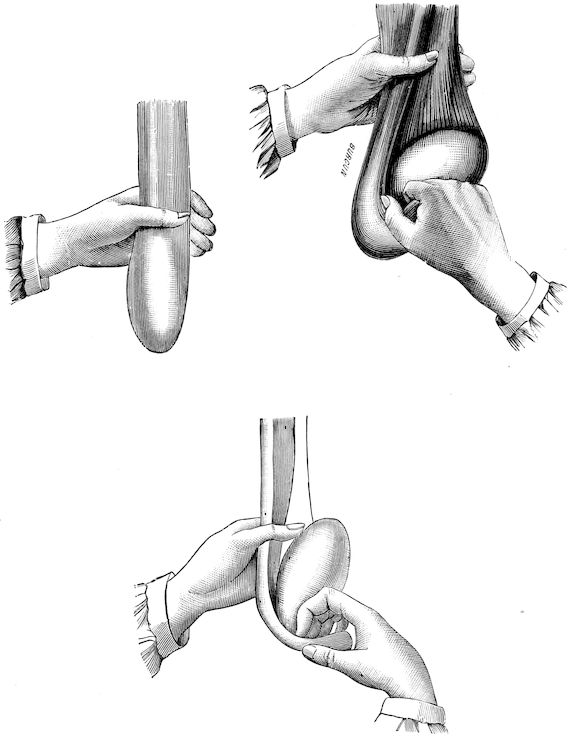

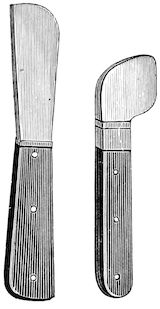

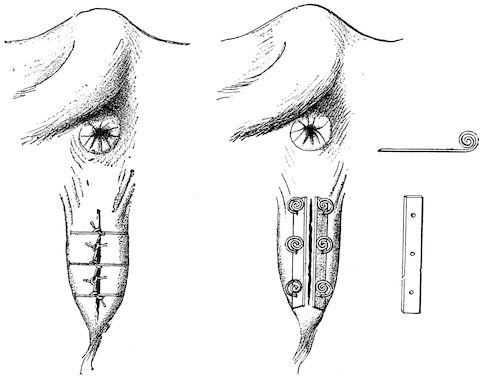

Fig. 10.—Dressing for fracture of the horn.

Symptoms. The symptoms are extremely simple. They consist mainly in the mobility of the fractured end, and such phenomena as sensitiveness, hæmorrhage, etc. When the fracture extends to the frontal bone, crepitation may also be noted.

Prognosis. The prognosis is not grave unless the fracture extends to the basilar half of the horn or affects the frontal bone.

Treatment. (1.) If the fracture is confined to the horn core, it is only necessary to bring the fragments into regular apposition, after having removed the broken end of the horn itself.

(2.) In treating a fracture affecting the middle portion of the horn or in treating animals destined for the butcher, the best method is to make a simple wound by dividing the parts with a saw below the fracture. This is a painful operation, necessitating anæsthesia, and requiring the animal to be cast or firmly fixed to a post or placed in a trevis. To diminish the painful stage of the operation, it was formerly recommended to make a circular incision extending through the entire thickness of the horn proper, and then to remove with a fine, very sharp saw the portion of the horn core. This, however, is scarcely practicable, and it is much better to make a direct section. Hæmorrhage is checked with compresses, moistened with cold water, after which a dressing known as the “Maltese cross dressing” (Fig. 10) is applied according to general principles.