OLD COURT COSTUME

OLD COURT COSTUME

Jinrikisha Days in Japan

BY

ELIZA RUHAMAH SCIDMORE

“I cannot cease from praising these Japanese. They are truly the delight of my heart.”

St. Francis Xavier.

REVISED EDITION

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK AND LONDON

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

1902

Copyright, 1891, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

This book has only attempted to present some of the phases of the new Japan as they appeared to one who was both a tourist and a foreign resident in that country. No one person can see it all, nor comprehend it, as the jinrikisha speeds through city streets and over country roads, nor do any two people enjoy just the same experiences, see things in the same light, or draw the same conclusions as to this remarkable people. Japan is so inexhaustible and so full of surprises that to the last day of his stay the tourist and the resident alike are confronted by some novelty that is yet wholly common and usual in the life of the Japanese.

The scientists, scholars, and specialists, the poetic and the political writers, who have written so fully of Japan, have omitted many little things which leave the pleasantest impressions on lighter minds. Each decade presents a new Japan, as the wonderful empire approaches nearer to modern and European standards in living, and, in becoming one of the eight great civilized world-powers, Japan has put aside much of its mediæval and Oriental picturesqueness.

Bewildered by its novelty and strangeness, too many tourists come and go with little knowledge of the Japan of the Japanese, and, beholding only the modernized seaports and the capital, miss many unique and distinctly national sights and experiences that lie close at hand. The book will have attained its object if it helps the tourist to see better the Japan that is unchanging, and if it gives the stay-at-home reader a greater interest in those fascinating people and their lovely home.

Unfortunately, it is impossible, in acknowledging the kindness of the many Japanese friends and acquaintances, who secured me so much enjoyment and so many delightful experiences, to begin to give the long list of their names. Each foreign visitor must equally feel himself indebted to the whole race for being Japanese, and, therefore, the most interesting population in the world, and his obligation is to the whole people as much as to particular individuals.

Since the first edition of this book was published, the treaties have been revised, extra-territoriality and the passport system have been abolished, and a protective tariff adopted; the railway has been extended to Nikko, to Nara, from end to end, and twice across, the main island; foreign hotels have multiplied in seaports and mountain resorts; the guide-book has been modernized, made more companionable and interesting, and a vast literature has been added to the subject—Japan. The fall in the price of silver, the adoption of the gold standard,[vi] and the increasing army of tourists have more than doubled the cost of living and of all the products of art industry. Japan has twice sent victorious military expeditions to the mainland, and in the relief of the legations and the occupation of Peking has proved her soldiers first in valor, discipline, equipment, and in humanity to the conquered, and there was abundantly displayed that high passion of patriotism which the Japanese possess in greater degree than any other people.

Japan, six times revisited, is as full of charm and novelty as when I first went ashore from the wreck of the Tokio.

E. R. S.

Washington, D. C., March, 1890.

” ” March, 1902.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | THE NORTH PACIFIC AND YOKOHAMA | 1 |

| II. | YOKOHAMA | 10 |

| III. | YOKOHAMA—CONTINUED | 20 |

| IV. | THE ENVIRONS OF YOKOHAMA | 28 |

| V. | KAMAKURA AND ENOSHIMA | 38 |

| VI. | TOKIO | 43 |

| VII. | TOKIO—CONTINUED | 53 |

| VIII. | TOKIO FLOWER FESTIVALS | 65 |

| IX. | JAPANESE HOSPITALITIES | 86 |

| X. | THE JAPANESE THEATRE | 96 |

| XI. | THE IMPERIAL FAMILY | 111 |

| XII. | TOKIO PALACES AND COURT | 125 |

| XIII. | THE SUBURBS OF TOKIO | 134 |

| XIV. | A TRIP TO NIKKO | 140 |

| XV. | NIKKO | 147 |

| XVI. | CHIUZENJI AND YUMOTO | 162 |

| XVII. | THE ASCENT OF FUJIYAMA | 175 |

| XVIII. | THE DESCENT OF FUJIYAMA | 183 |

| XIX. | THE TOKAIDO—I | 189 |

| XX. | THE TOKAIDO—II | 197 |

| XXI. | NAGOYA | 206 |

| XXII. | LAKE BIWA AND KIOTO | 216 |

| XXIII. | KIOTO TEMPLES | 226 |

| XXIV. | THE MONTO TEMPLES AND THE DAIMONJI | 236 |

| XXV. | THE PALACES AND CASTLE | 244 |

| XXVI. | KIOTO SILK INDUSTRY | 255 |

| XXVII. | EMBROIDERIES AND CURIOS | 267[ix] |

| XXVIII. | POTTERIES AND PAPER WARES | 277 |

| XXIX. | GOLDEN DAYS | 285 |

| XXX. | SENKÉ AND THE MERCHANTS’ DINNER | 296 |

| XXXI. | THROUGH UJI TO NARA | 304 |

| XXXII. | NARA | 320 |

| XXXIII. | OSAKA | 331 |

| XXXIV. | KOBÉ AND ARIMA | 340 |

| XXXV. | THE TEA TRADE | 350 |

| XXXVI. | THE INLAND SEA AND NAGASAKI | 358 |

| XXXVII. | IN THE END | 368 |

| INDEX | 377 |

| PAGE | |

| OLD COURT COSTUME | Frontispiece |

| FUJIYAMA | 5 |

| JAPANESE CHILDREN | 17 |

| AT KAWAWA | 30 |

| THE SEMI’S CAGE | 55 |

| POETS BENEATH THE PLUM-TREES | 67 |

| A UYÉNO TEA-HOUSE | 71 |

| IRIS GARDENS AT HORI KIRI | 75 |

| AT KAMEIDO | 79 |

| IN DANGO-ZAKA STREET | 82 |

| TEA BLOSSOMS | 83 |

| CHOPSTICKS—FIGS. 1 AND 2 | 88 |

| CHOPSTICKS—FIG. 3 | 89 |

| THE NESANS AT THE HOISHIGAOKA | 93 |

| MATSUDA, THE MASTER OF CHA NO YU | 94 |

| DANJIRO, THE GREAT ACTOR | 107 |

| IN THE PALACE GARDENS | 115 |

| IN THE PALACE GARDENS | 117 |

| IN THE PALACE GARDENS | 121 |

| PLAN OF EMPEROR’S PRIVATE APARTMENTS | 127 |

| IMPERIAL SAKÉ-CUP | 129 |

| INTERIOR OF THE IYEMITSU TEMPLE | 151 |

| GATE-WAY OF THE IYEYASU TEMPLE | 155 |

| FARM LABORERS AND PACK-HORSE | 163 |

| PUBLIC BATH-HOUSE AT YUMOTO | 171[xi] |

| THE SHOJO | 213 |

| THE GREAT PINE-TREE AT KARASAKI | 219 |

| THE TRUE-LOVER’S SHRINE AT KIOMIDZU | 231 |

| THE THRONE OF 1868 | 248 |

| KABE HABUTAI | 262 |

| CHIRIMEN | 263 |

| EBISU CHIRIMEN | 264 |

| KINU CHIRIMEN | 265 |

| FUKUSA | 270 |

| MANJI | 272 |

| MITSU TOMOYÉ | 273 |

| IN NAMMIKAWA’S WORK-ROOM | 288 |

| PICKING TEA | 305 |

| IN THE KASUGA TEMPLE GROUNDS | 317 |

| PRIESTESSES AT NARA | 324 |

| FARM LABORERS | 347 |

All the Orient is a surprise to the Occidental. Everything is strange, with a certain unreality that makes one doubt half his sensations. To appreciate Japan one should come to it from the mainland of Asia. From Suez to Nagasaki the Asiatic sits dumb and contented in his dirt, rags, ignorance, and wretchedness. After the muddy rivers, dreary flats, and brown hills of China, after the desolate shores of Korea, with their unlovely and unwashed peoples, Japan is a dream of Paradise, beautiful from the first green island off the coast to the last picturesque hill-top. The houses seem toys, their inhabitants dolls, whose manner of life is clean, pretty, artistic, and distinctive.

There is a greater difference between the people of these idyllic islands and of the two countries to westward, than between the physical characteristics of the three kingdoms; and one recognizes the Japanese as the fine flower of the Orient, the most polite, refined, and æsthetic of races, happy, light-hearted, friendly, and attractive.

The bold and irregular coast is rich in color, the perennial green of the hill-side is deep and soft, and the perfect cone of Fujiyama against the sky completes the landscape, grown so familiar on fan, lantern, box, and[2] plate. Every-day life looks too theatrical, too full of artistic and decorative effects, to be actual and serious, and streets and shops seem set with deliberately studied scenes and carefully posed groups. Half consciously the spectator waits for the bell to ring and the curtain to drop.

The voyage across the North Pacific is lonely and monotonous. Between San Francisco and Yokohama hardly a passing sail is seen. When the Pacific Mail Steamship Company established the China line their steamers sailed on prescribed routes, and outward and homeward-bound ships met regularly in mid-ocean. Now, when not obliged to touch at Honolulu, the captains choose their route for each voyage, either sailing straight across from San Francisco, in 37° 47′, to Yokohama, in 35° 26′ N., or, following one of the great circles farther north, thus lessen time and distance. On these northern meridians the weather is often cold, threatening, or stormy, and the sea rough; but the steadiness of the winds favors this course, and persuades the ship’s officers to shorten the long course and more certainly reach Japan on schedule time. Dwellers in hot climates dislike the sudden transition to cooler waters, and some voyagers enjoy it. Fortunately, icebergs cannot float down the shallow reaches of Bering Strait, but fierce winds blow through the gaps and passes in the Aleutian Islands.

Canadian Pacific steamers, starting on the 49th parallel, often pass near the shores of Attu, the last little fragment of earth swinging at the end of the great Aleutian chain. The shelter which those capable navigators, Mrs. Lecks and Mrs. Aleshine, had the luck to find in their memorable journey, mariners declare to be Midway Island, a circular dot of land in the great waste, with a long, narrow, outlying sand-bar, where schooners have been wrecked, and castaways rescued after months[3] of imprisonment. The steamer’s course from San Francisco to Yokohama varies from 4500 to 5500 miles, and the journey takes from twelve to eighteen days. From Vancouver to Yokohama it is but eleven days.

When the ship’s course turns perceptibly southward the mild weather of the Japan Stream is felt. In winter the first sign of land is a distant silver dot on the horizon, which in summer turns to blue or violet, and gradually enlarges into the tapering cone of Fuji, sloping upward in faultless lines from the water’s edge. One may approach land many times and never see Fuji, and during my first six months in Japan the matchless mountain refused to show herself from any point of view. Cape King, terminating the long peninsula that shelters Yeddo Bay, shows first a line of purple cliffs, and then a front of terraced hills, green with rice and wheat, or golden with grain or stubble. Fleets of square-sailed fishing-boats drift by, their crews, in the loose, flapping gowns and universal blue cotton head-towels of the Japanese coolies, easily working the broad oar at the stern. At night Cape King’s welcome beacon is succeeded by Kanonsaki’s lantern across the Bay, Sagami’s bright light, then the myriad flashes of the Yokosuka navy-yard, and last the red ball of the light-ship, marking the edge of the shoal a mile outside the Bund, or sea-wall, of Yokohama. When this craft runs up its signal-flag a United States man-of-war, if there be one in port, fires two guns, as a signal that the American mail has arrived.

Daylight reveals a succession of terraced hills, cleft by narrow green valleys and narrower ravines; little villages, their clusters of thatched roofs shaded by pine, palm, or bamboo; fishing-boats always in the foreground, and sometimes Fuji clear-cut against the sky, its base lost now and then behind the overlapping hills. In summer Fuji’s purple cone shows only ribbon stripes of white near its apex. For the rest of the year it is a[4] silvery, shining vision, rivalled only by Mount Rainier, which, pale with eternal snows, rises from the dense forests of Puget Sound to glass itself in those green waters.

Yokohama disappoints the traveller, after the splendid panorama of the Bay. The Bund, or sea-road, with its club-houses, hotels, and residences fronting the water, is not Oriental enough to be very picturesque. It is too European to be Japanese, and too Japanese to be European. The water front, which suffers by comparison with the massive stone buildings of Chinese ports, is, however, a creditable contrast to our untidy American docks and quays, notwithstanding the low-tiled roofs, blank fences, and hedges. The water life is vivid and spectacular. The fleet of black merchant steamers and white men-of-war, the ugly pink and red canal-steamers, and the crowding brigs and barks, are far outnumbered by the fleet of sampans that instantly surround the arriving mail. Steam-launches, serving as mail-wagon and hotel omnibus, snort, puff, and whistle at the gang-ways before the buoy is reached; and voluble boatmen keep up a steady bzz, bzz, whizz, whizz, to the strokes of their crooked, wobbling oars as they scull in and out. Four or five thousand people live on the shipping in the harbor, and in ferrying this population to and fro and purveying to it the boatmen make their livelihood. Strict police regulations keep them safe and peaceable, and the harbor impositions of other countries are unknown. On many of these sampans the whole family abides, the women cooking over a handful of charcoal in a small box or bowl, the children playing in corners not occupied by passengers or freight. On gala days, when the shipping is decorated, the harbor is a beautiful sight; or when the salutes of the foreign fleets assembled at Yokohama are returned by the guns of the fort on Kanagawa Heights, and the air tingles with excitement. Since[5] the annexation of the Philippines the American Asiatic fleet has been fully occupied in that archipelago, and the vessels seldom visit Yokohama, or remain for any time. The acquisition of Wei-hai-Wei gave the British fleet a northern station, and that, with the perpetual break-up and crisis in China, keeps those ships and the fleets of all nations closely to that coast. Nagasaki’s coal-mines make it the great port of naval call and supply in Japan.

FUJIYAMA

A mole and protected harbor with stone docks has been built with the money finally returned to Japan by the United States, after being shamefully withheld for a quarter of a century, as our share of the Shimonoseki Indemnity Fund. The outer harbor lies so open to the prevailing south-east winds that loading and unloading is often delayed for days, and landing by launches or sampans is a wet process. The Bay is so shallow that a stiff wind quickly sends its waves breaking over the sea-wall, to subside again in a few hours into a mirror-like calm. The harbor has had its great typhoons, but does not lie in the centre of those dreaded circular storms that whirl up from the China seas. Deflected to eastward, the typhoon sends its syphoon, or wet end, to fill the air with vapor and drizzle, and a smothering, mildewy, exhausting atmosphere. A film of mist covers everything, wall-paper loosens, glued things fall apart, and humanity wilts.

Yokohama has its divisions—the Settlement, the Bluff, and Japanese Town—each of which is a considerable place by itself. The Settlement, or region originally set apart by the Japanese in 1858 for foreign merchants, was made by filling in a swampy valley opening to the Bay. This Settlement, at first separated from the Tokaido and the Japanese town of Kanagawa, has become the centre of a surrounding Japanese population of over eighty thousand. It is built up continuously to Kanagawa[8] Bridge, two miles farther north, on the edge of a bold bluff, where the Tokaido—the East Sea Road—leading up from Kioto, reaches the Bay. In diplomatic papers Kanagawa is still recognized as the name of the great port on Yeddo Bay, although the consulates, banks, hotels, clubs, and business streets are miles away.

At the hatoba, or landing-place, the traveller is confronted by the jinrikisha, that big, two-wheeled baby-carriage of the country, which, invented by an American, has been adopted all over the East. The jinrikisha (or kuruma, as the linguist and the upper class more politely call it) ranges in price from seventeen to forty dollars, twenty being the average cost of those on the public stands. Some thrifty coolies own their vehicles, but the greater number either rent them from, or work for, companies, and each jinrikisha pays a small annual tax to the Government. An unwritten rule of the road compels these carriages to follow one another in regulated single file. The oldest or most honored person rides at the head of the line, and only a boor would attempt to change the order of arrangement. Spinning down the Bund, at a tariff so moderate that the American can ride for a week for what he must pay in a day at home, one finds the jinrikisha to be a comfortable, flying arm-chair—a little private, portable throne. The coolie wears a loose coat and waistcoat, and tights of dark-blue cotton, with straw sandals on his bare feet, and an inverted wash-bowl of straw covered with cotton on his head. When it rains he is converted into a prickly porcupine by his straw rain-coat, or he dons a queer apron and cloak of oiled paper, and, pulling up the hood of the little carriage, ties a second apron of oiled paper across the knees of his fare. At night the shafts are ornamented with a paper lantern bearing his name and his license number; and these glowworm lights, flitting through the streets and country roads in the darkness, seem only another[9] expression of the Japanese love of the picturesque. In the country, after dark, they call warnings of ruts, holes, breaks in the road, or coming crossways; and their cries, running from one to another down the line, are not unmusical. To this smiling, polite, and amiable little pony one says Hayaku! for “hurry,” Abunayo! for “take care,” Sukoshimate! for “stop a little,” and Soro! for “slowly.” The last command is often needed when the coolie, leaning back at an acute angle to the shaft, dashes downhill at a rapid gait. Jinrikisha coolies are said even to have asked extra pay for walking slowly through the fascinating streets of open shops. If you experiment with the jinrikisha on a level road, you find that it is only the first pull that is hard; once started, the little carriage seems to run by itself. The gait of the man in the shafts, and his height, determine the comfort of the ride. A tall coolie holds the shafts too high, and tilts one at an uncomfortable angle; a very short man makes the best runner, and, with big toe curling upward, will trot along as regularly as a horse. As one looks down upon the bobbing creature below a hat and two feet seem to constitute the whole motor.

The waraji, or sandals, worn by these coolies are woven of rice straw, and cost less than five cents a pair. In the good old days they were much cheaper. Every village and farm-house make them, and every shop sells them. In their manufacture the big toe is a great assistance, as this highly trained member catches and holds the strings while the hands weave. On country roads wrecks of old waraji lie scattered where the wearer stepped out of them and ran on, while ruts and mud-holes are filled with them. For long tramps the foreigner finds the waraji and the tabi, or digitated stocking, much better than his own clumsy boots, and he ties them on as overshoes when he has rocky paths to climb. Coolies often dispense with waraji and wear heavy tabi, with[10] a strip of the almost indestructible hechima fibre for the soles. The hechima is the gourd which furnishes the vegetable washrag, or looffa sponge of commerce. The snow-white cotton tabis of the better classes are made an important part of their costume.

Those coolies who pull and push heavily loaded carts or drays keep up a hoarse chant, which corresponds to the chorus of sailors when hauling ropes. “Hilda! Hoida!” they seem to be crying, as they brace their feet for a hard pull, and the very sound of it exhausts the listener. In the old days people were nearly deafened with these street choruses, but their use is another of the hereditary customs that is fast dying out. In mountain districts one’s chair-bearers wheeze out “Hi rikisha! Ho rikisha!” or “Ito sha! Ito sha!” as they climb the steepest paths, and they cannot keep step nor work vigorously without their chant.

The Settlement is bounded by the creek, from whose opposite side many steep hill-roads wind up to the Bluff, where most of the foreigners have their houses. These bluff-roads pass between the hedges surrounding trim villas with their beautifully set gardens, the irregular numbering of whose gates soon catches the stranger’s eye. The first one built being number one, the others were numbered in the order of their erection, so that high and low numerals are often side by side. To coolies, servants, peddlers, and purveyors, foreign residents are best known by their street-door numeration, and “Number four Gentleman” and “Number five Lady”[11] are recurrent and adequate descriptions. So well used are the subjects of it to this convict system of identification that they recognize their friends by their alias as readily as the natives do.

Upon the Bluff stand a public hall, United States and British marine hospitals, a French and a German hospital, several missionary establishments, and the houses of the large American missionary community. At the extreme west end a colony of Japanese florists has planted toy-gardens filled with vegetable miracles; burlesques and fantasies of horticulture; dwarf-trees, a hundred years old, that could be put in the pocket; huge single flowers, and marvellous masses of smaller blossoms; cherry-trees that bear no cherries; plum-trees that bloom in midwinter, but have neither leaves nor fruit; and roses—that favorite flower which the foreigner brought with him—flowering in Californian profusion. A large business is done in the exportation of Japanese plants and bulbs, encased in a thick coating of mud, which makes an air-tight case to protect them during the sea-voyage. Ingenious fern pieces are preserved in the same way. These grotesque things are produced by wrapping in moist earth the long, woody roots of a fine-leafed variety of fern. They are made to imitate dragons, junks, temples, boats, lanterns, pagodas, bells, balls, circles, and every familiar object. When bought they look dead. If hung for a few days in the warm sun, and occasionally dipped in water, they change into feathery, green objects that grow more and more beautiful, and are far more artistic than our one conventional hanging-basket. The dwarf-trees do not stand transportation well, as they either die or begin to grow rapidly.

The Japanese are the foremost landscape gardeners in the world, as we Occidentals, who are still in that barbaric period where carpet gardening seems beautiful and desirable, shall in time discover. Their genius has[12] equal play in an area of a yard or a thousand feet, and a Japanese gardener will doubtless come to be considered as necessary a part of a great American establishment as a French maid or an English coachman. From generations of nature-loving and flower-worshipping ancestors these gentle followers of Adam’s profession have inherited an intimacy with growing things, and a power over them that we cannot even understand. Their very farming is artistic gardening, and their gardening half necromancy.

On high ground, beyond the Bluff proper, stretches the race-course, where spring and fall there are running races by short-legged, shock-headed ponies, brought from the Hokkaido, the northern island, or from China. Gentlemen jockeys frequently ride their own horses in flat races, hurdle-races, or steeple-chases. The banks close, a general holiday reigns throughout the town, and often the Emperor comes down from Tokio. This race-course affords one of the best views of Fuji, and from it curves the road made in early days for the sole use of foreigners to keep them off the Tokaido, where they had more than once come in conflict with trains of travelling nobles. This road leads down to the water’s edge, and, following the shore of Mississippi Bay, where Commodore Perry’s ships anchored in 1858, strikes across a rice valley and climbs to the Bluff again.

The farm-houses it passes are so picturesque that one cannot believe them to have a utilitarian purpose. They seem more like stage pictures about to be rolled away than like actual dwellings. The new thatches are brightly yellow, and the old thatches are toned and mellowed, set with weeds, and dotted with little gray-green bunches of “hen and chickens,” while along the ridge-poles is a bed of growing lilies. There is an old wife’s tale to the effect that the women’s face-powder was formerly made of lily-root, and that a ruler who wished to stamp out[13] such vanities, decreed that the plant should not be grown on the face of the earth, whereupon the people promptly dug it up from their gardens and planted it in boxes on the roof.

The Japanese section of Yokohama is naturally less Japanese than places more remote from foreign influence, but the stranger discovers much that is odd, unique, and Oriental. That delight of the shopper, Honchodori, with its fine curio and silk shops, was once without a shop-window, the entire front of the cheaper shops being open to the streets, and only the old lacquer and bronzes, ivory, porcelains, enamels, silver, and silks concealed by high wooden screens and walls. Now glass windows flaunt all that the shops can offer. The silk shops are filled with goods distracting to the foreign buyer, among which are the wadded silk wrappers, made and sold by the hundreds, which, being the contrivance of some ingenious missionary, were long known as missionary coats.

Benten Dori, the bargain-hunter’s Paradise, is a delightful quarter of a mile of open-fronted shops. In the silk shops, crapes woven in every variety of cockle and wrinkle and rippling surface, as thin as gauze, or as thick and heavy as brocade, painted in endless, exquisite designs, are brought you by the basketful. Each length is rolled on a stick, and finally wrapped in a bit of the coarse yellow cotton cloth that envelopes every choice thing in Japan, though for what reason, no native or foreigner, dealer or connoisseur can tell.

Nozawaya has a godown or fire-proof storehouse full of cotton crapes, those charmingly artistic fabrics that the Western world has just begun to appreciate. The pock-marked and agile proprietor will keep his small boys running for half an hour to bring in basketfuls of cotton crape rolls, each roll measuring a little over eleven-yards, which will make one straight, narrow kimono with[14] a pair of big sleeves. These goods are woven in the usual thirteen-inch Japanese width, although occasionally made wider for the foreign market. A Japanese kimono is a simple thing, and one may put on the finished garment an hour after choosing the cloth to make it. The cut never varies, and it is still sewn with basters’ stitches, although the use of foreign flat-irons obviates the necessity of ripping the kimono apart to wash and iron it. The Japanese flat-iron is a copper bowl filled with burning charcoal, which, with its long handle, is really a small warming-pan. Besides this contrivance, there is a flat arrow point of iron with a shorter handle, which does smaller and quite as ineffectual service.

To an American, nothing is simpler than Japanese money. The yen corresponds to our dollar, and is made up of one hundred sen, while ten rin make one sen. The yen is about equal in value to the Mexican dollar, and is roughly reckoned at fifty cents gold United States money. One says dollars or yens indiscriminately, always meaning the Mexican, which is the current coin of the East. The old copper coins, the rin and the oval tempo, each with a hole in the middle, are disappearing from circulation, and at the Osaka mint they are melted and made into round sens. Old gold and silver coins may be bought in the curio shops. If they have not little oblong silver bu, or a long oval gold ko ban, the silversmith will offer to make some, which will answer every purpose!

When you ask for your bill, a merchant takes up his frame of sliding buttons—the soroban, or abacus—and plays a clattering measure before he can tell its amount. The soroban is infallible, though slow, and in the head of the educated Japanese, crowded with thousands of arbitrary characters and words, there is no room for mental arithmetic. You buy two toys at ten cents apiece. Clatter, clatter goes the soroban, and the calculator asks you for twenty cents. Depending entirely on the soroban,[15] they seem unable to reckon the smallest sums without it, and any peddler who forgets to bring his frame may be puzzled. The dealer in old embroideries will twist and work his face, scratch his head, and move his fingers in the air upon an imaginary soroban over the simplest addition, division, and subtraction. At the bank, the shroff has a soroban a yard long; and merchants say that in book-keeping the soroban is invaluable, as by its use whole columns of figures can be added and proved in less time than by our mental methods.

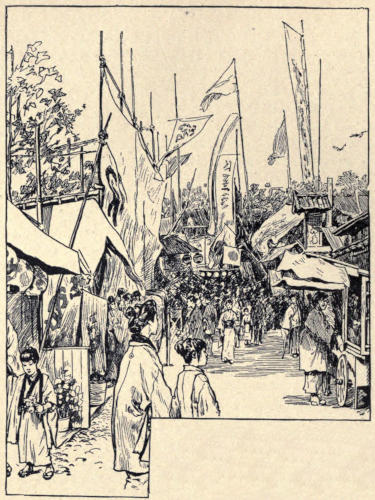

By an iron bridge, the broad street at the top of Benten Dori crosses one of the many canals extending from the creek in every direction, and forming a net-work of water passages from Mississippi Bay to Kanagawa. Beyond the bridge is Isezakicho, a half mile of theatres, side-shows, merry-go-rounds, catch-penny games, candy shops, restaurants, second-hand clothes bazaars, labyrinths of curio, toy, china, and wooden-ware shops. Hundreds of perambulating restaurateurs trundle their little kitchens along, or swing them on a pole over their shoulders. Dealers in ice-cream, so called, abound, who will shave you a glass of ice, sprinkle it with sugar, and furnish a minute teaspoon with which to eat it. There are men who sell soba, a native vermicelli, eaten with pungent soy; and men who, for a penny, heat a big gridiron, and give a small boy a cup of batter and a cup of soy, with which he may cook and eat his own griddle cakes. There the people, the middle and lower classes, present themselves for study and admiration, and the spectator never wearies of the outside dramas and panoramas to be seen in this merry fair.

Pretty as she is on a pictured fan, the living Japanese woman is far more satisfying to the æsthetic soul as she patters along on her wooden clogs or straw sandals. The very poorest, in her single cheap cotton gown, or[16] kimono, is as picturesque as her richer sister in silk and crape. With heads elaborately dressed, and folds of gay crape, or a glittering hair-pin thrust in the smooth loops of blue-black hair, they seem always in gala array; and, rain or shine, never protect those elaborate coiffures with anything less ornamental than a paper umbrella, except in winter, when the zukin, a yard of dark crape lined with a contrasting color, is thrown over the head, concealing the whole face save the eyes. A single hair-pin of tortoise-shell, sometimes tipped with coral or gold, is all that respectable women of any class wear at one time. The heavily hair-pinned women on cheap fans are not members of good society, and only children and dancing-girls are seen in the fantastic flowers and trifles sold at a hundred shops and booths in this and every street.

The little children are the most characteristically Japanese of all Japanese sights. Babies are carried about tied to the mothers’ back, or to that of their small sisters. They sleep with their heads rolling helplessly round, watch all that goes on with their black beads of eyes, and never cry. Their shaven crowns and gay little kimonos, their wise, serene countenances, make them look like cabinet curios. As soon as she can walk, the Japanese girl has her doll tied on her back, until she learns to carry it steadily and carefully; after that the baby brother or sister succeeds the doll, and flocks of these comical little people, with lesser people on their backs, wander late at night in the streets with their parents, and their funny double set of eyes shine in every audience along Isezakicho.

JAPANESE CHILDREN

These out-of-door attractions are constantly changing. Native inventions and adaptations of foreign ideas continually appear. “Pigs in clover” and pot-hook puzzles followed only a few weeks behind their New York season, and street fakirs offer perpetual novelties. Of jugglers the line is endless, their performances filling interludes[19] at theatres, coming between the courses of great dinners, and supplying entertainment to any garden party or flower fête in the homes of rich hosts. More cunning than these gorgeously clad jugglers is an old man, who roams the vicinity of Yokohama, wearing poor cotton garments, and carrying two baskets of properties by a pole across his shoulders. On a street corner, a lawn, a piazza, or a ship’s deck, he sets up his baskets for a table, and performs amazing feats with the audience entirely encircling him. A hatful of coppers sufficiently rewards him, and he swallows fire, spits out eggs, needles, lanterns, and yards of paper-ribbon, which he twirls into a bowl, converts into actual soba, and eats, and by a magic sentence changes the remaining vermicelli into the lance-like leaves of the iris plant. This magician has a shrewd, foxy old face, whose grimaces, as well as his pantomime, his capers, and poses, are tricks in themselves. His chuckling, rippling stream of talk keeps his Japanese auditors convulsed. Sword walkers and knife swallowers are plenty as blackberries, and the phonograph is conspicuous in Isezakicho’s tents and booths. The sceptic and investigator wastes his time in the effort to penetrate the Japanese jugglers’ mysteries. Once, at a dinner given by Governor Tateno at Osaka, the foreign guest of honor determined to be cheated by no optical delusions. He hardly winked, so close was his scrutiny, and the juggler played directly to him. An immense porcelain vase having been brought in and set in the middle of the room, the juggler, crawling up, let himself down into it slowly. For half an hour the sceptic did not raise his eyes from the vase, that he had first proved to be sound and empty, and to stand on no trap-door. After this prolonged watch the rest of the company assailed him with laughter and jeers, and pointed to his side, where the old juggler had been seated for some minutes fanning himself.

In the Settlement, back of the main street, the Chinese have an ill-smelling corner to themselves. Their greasy walls and dirty floors affront the dainty doll dwellings across the creek, and the airy little box of a tea-house, whose lanterns swing at the top of the perpendicular bluff behind them. Vermilion paper, baggy clothes, pigtails, harsh voices, and vile odors reign in this Chinatown. The names on the signs are curiosities in themselves, and Cock Eye, tailor, Ah Nie and Wong Fai, ladies’ tailors, are the Poole, Worth, and Felix of the foreign community. Only one Japanese has a great reputation as dress-maker, but the whole guild is moderately successful, and prices are so low that the British and French houses of Yokohama cannot compete with them.

There is a large joss-house near the Chinese consulate, and at their midsummer, autumn, and New-year’s festivals the Celestials hold a carnival of lanterns, fire-crackers, incense, paper-flowers, varnished pigs, and cakes. The Japanese do not love these canny neighbors, and half the strictures of the passport laws are designed to limit their hold on the business of the country. The Chinese are the stronger and more aggressive people, the hard-headed financiers of the East, handling all the money that circulates this side of India. In every bank Chinese shroffs, or experts, test the coins and make the actual payments over the counters. The money-changers are Chinese, and every business house has its Chinese[21] compradore or superintendent, through whom all contracts and payments are made. The Chinaman has the methodical, systematic brain, and no convulsion of nature or commerce makes him lose his head, as the charmingly erratic, artistic, and polite Japanese does. In many foreign households in Japan a Chinese butler, or head boy, rules the establishment; but while his silent, unvarying, clock-like service leaves nothing undone, the attendance of the bright-faced, amiable, and exuberant little natives with their smiles, their matchless courtesy, and their graceful and everlasting bowing is far more agreeable.

Homura temple, whose stone embankments and soaring roof rise just across the creek, is generally the first Buddhist sanctuary seen by the tourist coming from American shores. Every month it has its matsuri, or festival, but sparrows are always twittering in the eaves, children playing about the steps, and devout ones tossing their coppers in on the mats, clapping their hands and pressing their palms together while they pray. One of the most impressive scenes ever witnessed there was the funeral of its high-priest, when more than a hundred bonzes, or priests, came from neighboring temples to assist in the long ceremonies, and sat rigid in their precious brocade vestments, chanting the ritual and the sacred verse. The son, who succeeded to the father’s office by inheritance, had prepared for the rites by days of fasting, and, pale, hollow-eyed, but ecstatic, burned incense, chanted, and in the white robes of a mourner bore the mortuary tablets from the temple to the tomb. Homura’s commercial hum was silenced when the train of priests in glittering robes, shaded by enormous red umbrellas, wound down the long terrace steps and out between the rows of tiny shops to the distant graveyard. Yet after it the crowd closed in, barter and sale went on, jinrikishas whirled up and down, and pattering women and toddling children[22] fell into their places in the tableaux which turn Homura’s chief street into one endless panorama of Japanese lower-class life.

Half-way up one of the steep roads, climbing from Homura to the Bluff, is the famous silk store of Tenabe Gengoro, with its dependent tea-house of Segiyama, best known of all tea-houses in Japan, and rendezvous for the wardroom officers of the fleets of all nations, since Tenabe’s uncle gave official welcome to Commodore Perry. When a war-ship is in port, the airy little lantern-hung houses continuously send out the music of the koto and the samisen, the banjo, bones, and zither, choruses of song and laughter, and the measured hand-clapping that proclaims good cheer in Japan. Tenabe herself has now lost the perfect bloom and beauty of her younger days, but with her low, silver-sweet voice and fascinating manner, she remains the most charming woman in all Japan. In these days Tenabe presides over the silk store only, leaving her sisters to manage the fortunes of the tea-house. Tenabe speaks English, French, and Russian; never forgets a face, a name, or an incident; and if you enter, after an absence of many years, she will surely recognize you, serve you sweets and thimble-cups of pale yellow tea, and say dozo, dozo, “please, please,” with grace incomparable and in accents unapproachable.

Both living and travelling are delightfully easy in Japan, and no hardships are encountered in the ports or on the great routes of travel. Yokohama has excellent hotels; the home of the foreign resident may be Queen Anne, or Colonial, if he like, and the markets abound in meats, fish, game, fruits, and vegetables at very low prices. Imported supplies are dear because of the cost of transportation. Besides the fruits of our climates, there are the biwa, or loquat, and the delicious kaké, or Japanese persimmon. Natural ice is brought from Hakodate; artificial ice is made in all the ports, the[23] Japanese being as fond of iced drinks as Americans. Three daily English newspapers, weekly mails to London and New York, three great cable routes, electric lights, breweries, gas, and water-works add utilitarian comfort to ideal picturesqueness. The summers are hot, but instead of our eccentric variations of temperature, the mercury stands at 80°, 85°, and 90° from July to September. With the fresh monsoon blowing steadily, that heat is endurable, however, and the nights are comfortable. June and September are the two nyubai, or rainy seasons, when everything is damp, clammy, sticky, and miserable. In May, heavy clothing is put away in sealed receptacles, even gloves being placed in air-tight glass or tin, to preserve them from the ruinous mildew. While earthquakes are frequent, Japan enjoys the same immunity from thunder-storms as our Pacific Coast.

There is no servant problem, and house-keeping is a delight. Both Chinese and Japanese, though unfamiliar with western ways, can be trained to surpass the best European domestics. Service so swift, noiseless, and perfect is elsewhere unknown. Indeed, cooks as well as butlers are adjusted to so grand a scale of living that their employers are served with almost too much formality and elaboration. The art of foreign cookery has been handed down from those exiled chefs who came out with the first envoys, to insure them the one attainable solace of existence before the days of cables and regular steamships. There is a native cuisine of great excellence, and each legation or club chef has pupils, who pay for the privilege of studying under him, while the ordinary kitchener of the treaty ports is a more skilful functionary than the professional cook of American cities. Such cooks do their own marketing, furnish without complaint elaborate menus three times a day, serve a dinner party every night, and out of their monthly pay, ranging from ten to twenty Mexican dollars, supply their[24] own board and lodging. The brotherhood of cooks help each other in emergencies, and if suddenly called upon to feed twice the expected number of guests, any one of them will work miracles. He runs to one fellow-craftsman to borrow an extra fish, to another to beg an entrée, a salad, or a sweet, and helps himself to table ware as well. A bachelor host is often amazed at the fine linen, the array of silver, and the many courses set before him on the shortest notice, and learns afterwards that everything was gathered in from neighboring establishments. Elsewhere he may meet his own monogram or crest at the table. Bachelors keep house and entertain with less trouble and more comfort than anywhere else in the world. To these sybarites, the “boy,” with his rustling kimono, is more than a second self, and the soft-voiced amahs, or maids, are the delight of woman’s existence. The musical language contributes not a little to the charm of these people, and the chattering servants seem often to be speaking Italian.

After the Restoration many samurai, or warriors, were obliged to adopt household service. One of these at my hotel had the face of a Roman senator, with a Roman dignity of manner quite out of keeping with his broom and dust-pan, or livery of dark-blue tights, smooth vest, and short blouse worn by all his class in Yokohama. When a card for an imperial garden party arrived, I asked Tatsu, my imperial Roman, to read it for me. He took it, bowed low, sucked in his breath many times, and, muttering the lines to himself, thus translated them: “Mikado want to see Missy, Tuesday, three o’clock.” When a curio-dealer left a piece of porcelain, Tatsu, always critical of purchases, went about his duties slowly, waiting for the favorable moment to give me, in his broken English, a dissertation on the old wares, their marks and qualities, and his opinion of that particular specimen of blue and white. He knew embroideries, understood[25] pictures, and was a living dictionary of Japanese phrase and fable. A pair of Korean shoes procured me a lecture on the ancient relations between Japan and Korea, and an epitome of their contemporary history.

Social life in these foreign ports presents a delightful fusion of English, continental, and Oriental customs. The infallible Briton, representing the largest foreign contingency, has transferred his household order unchanged from the home island, yielding as little as possible to the exigencies of climate and environment. The etiquette and hours of society are those of England, and most of the American residents are more English in these matters than the English. John Bull takes his beef and beer with him to the tropics or the poles indifferently, and in his presence Jonathan abjures his pie, and outlaws the words “guess,” “cracker,” “trunk,” “baggage,” “car,” and “canned.” His East Indian experiences of a century have taught the Briton the best system of living and care-taking in hot or malarial countries, and he thrives in Japan.

In the small foreign communities at Yokohama, Kobé, and Nagasaki the contents of the mail-bags, social events, and the perfection of physical comfort comprise the interests of most of the residents. The friction of a large community, with its daily excitements and affairs, the delights of western art, music, and the drama, are absent, and society naturally narrows into cliques, sets, rivalries, and small aims. If most residents did not affect indifference to things Japanese, life would be much more interesting. As it is, the old settler listens with an air of superiority, amusement, and fatigue to the enthusiasm of the new-comer. Not every foreign resident is familiar with the art of Japan, nor with its history, religion, or political conditions. If the missionaries, of whom hundreds reside in Yokohama and Tokio, mingled more with the foreign residents, each class would benefit; but[26] the two sets seldom touch, the missionaries keep to themselves, and the lives of the other extra-territorial people continually shock and offend them. Each set holds extreme, unfair, and prejudiced views of the other, and affords the natives arguments against both.

Socially, Tokio and Yokohama are one community, and the eighteen miles of railroad between the two do not hinder the exchange of visits or acceptance of invitations. When the Ministers of State give balls in Tokio, special midnight trains carry the Yokohama guests home, as they do when the clubs or the naval officers entertain at the seaport town. With the coming and going of the fleets of all nations great activity and variety pervades the social life. In the increasing swarm of tourists some prince, duke, or celebrity is ever arriving, visitors of lesser note are countless, and the European dwellers in all Asiatic ports east of Singapore make Japan their pleasure-ground, summer resort, and sanitarium. That order of tourist known as the “globe-trotter,” is not a welcome apparition to the permanent foreign resident. His generous and refined hospitality has been so often abused, and its recipients so often show a half-contemptuous condescension to their remote and uncomprehended hosts, that letters of introduction are looked upon with dread. Now that it has become common for parents to send dissipated young sons around the “Horn” and out to Japan on sailing vessels, that they may reform on the voyage, a new-comer must prove himself an invalid, if he would not be avoided after he confesses having come by brig or bark. Balls, with the music of naval bands, and decorations of bamboo and bunting, are as beautiful as balls can be; picnics and country excursions enliven the whole year; and there are perennial dinners and dances on board the men-of-war.

Those East-Indian contrivances, the chit and the chit-book, furnish a partial check on native servants. The[27] average resident carries little ready money, but writes a memorandum of whatever he buys, and hands it to the seller instead of cash. These chits are presented monthly; but the system tempts people to sign more chits than they can pay. This kind of account-keeping is more general in Chinese ports, where one may well object to receive the leaden-looking Mexicans and ragged and dirty notes of the local banks. When one sends a note to an acquaintance he enters it in his chit-book, where the person addressed adds his initials as a receipt, or even writes his answer. The whole social machinery is regulated by the chit-book, which may be a source of discord when its incautious entries and answers lie open to any Paul Pry.

Summer does not greatly disturb the life of society. Tennis, riding, boating, and bathing are in form, while balls and small dances occur even in July and August. At many places in the mountains and along the coast one may find a cooler air, with good hotels and tea-houses. Some families rent country temples near Yokohama for summer occupation, and enjoy something between the habitual Japanese life and Adirondack camping. The sacred emblems and temple accessories are put in the central shrine room, screens are drawn, and the sanctuary becomes a spacious house, open to the air on all sides, and capable of being divided into as many separate rooms as the family may require. Often the priests set the images and altar-pieces on a high shelf concealed by a curtain, and give up the whole place to the heretical tenants. In one instance the broad altar-shelf became a recessed sideboard, whereon the gilded Buddhas and Kwannons were succeeded by bottles, decanters, and glasses. At another temple it was stipulated that the tenants should give up the room in front of the altar on a certain anniversary day, to allow the worshippers to come and pray.

The environs of Yokohama are more interesting and beautiful than those of any other foreign settlement, affording an inexhaustible variety of tramps, rides, drives, railroad excursions, and sampan trips.

At Kanagawa proper the Tokaido comes to the bay’s edge, which it follows for some distance through double rows of houses and splendid old shade-trees. Back of Kanagawa’s bluff lie the old and half-deserted Bukenji temples, crowded on rare fête days with worshippers, merrymakers, and keepers of booths, and at quieter times serving as favorite picnic grounds for foreigners.

On the Tokaido, just beyond Kanagawa, is the grave of Richardson, who was killed by the train of the Prince of Satsuma, September 14, 1862. Although foreigners had been warned to keep off the Tokaido on that day, the foolhardy Briton and his friends deliberately rode into the daimio’s train, an affront for which they were attacked by his retainers and severely wounded, Richardson himself being left for dead on the road-side, while the rest escaped. When the train had passed by, a young girl ran out from one of the houses and covered the body with a piece of matting, moving it in the night to her house, and keeping it concealed until his friends claimed it. A memorial stone, inscribed with Japanese characters, marks the spot where Richardson fell. Since that time the kindly black-eyed Susan’s tea-house has been the favorite resort for foreigners on their afternoon rides and drives. Susan is a tall woman, with round[29] eyes, aquiline nose, and a Roman countenance—quite fit for a heroine. Riders call at her tea-house for tea, rice, and eels, prawns, clams, pea-nuts, sponge-cake, or beer, and insist upon seeing her. This Richardson affair cost the Japanese the bombardment of Kagoshima, and an indemnity of £125,000; but Susan did not share in the division of that sum.

According to one version Susan’s strand is the spot where Taro of Urashima, the Rip Van Winkle of Japan, left his boat and nets, and, mounting a tortoise, rode away to the home of the sea-king, returning by the same tortoise to the same spot. On its sands he opened the box the sea-king had given him, and found himself veiled in a thin smoke, out of which he stepped an old, old man, whose parents had been dead a hundred years. The fishermen listened to his strange tale, and carried him to their daimio, and on fans, boxes, plates, vases, and fukusas Taro sits relating his wonderful tale to this day.

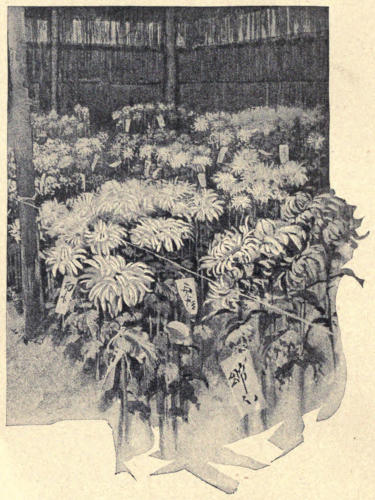

Ten miles inland from Bukenji’s temples is the little village of Kawawa, whose headman has a famous collection of chrysanthemums, the goal of many autumnal pilgrimages. This Kawawa collection has enjoyed its fame for many years, the owner devoting himself to it heart and soul, and knowing no cooling of ardor nor change of fancy. His great thatched house in a court-yard is reached through a black gate-way at the top of a little hill, and the group of buildings within his black walls gives the place quite a feudal air. Facing the front of the house are rows of mat sheds, covering the precious flowers that stand in files as evenly as soldiers, the tops soft masses of great frowsy, curly-petalled, wide-spreading blooms, shading to every tint of lilac, pink, rose, russet, brown, gold, orange, pale yellow, and snow white. It was there that we ate a salad made of yellow chrysanthemum petals, most æsthetic of dishes. The trays of golden[30] leaves in the kitchen of the house indicated that the master enjoyed this ambrosial feast habitually, and perhaps dropped the yellow shreds in his saké cup to prolong his life and avert calamities, as they are warranted to do. Beyond Kawawa lies a rich silk district, and all the region is marked by thrift and comfort, signs of the prosperity that attends silk-raising communities.

AT KAWAWA

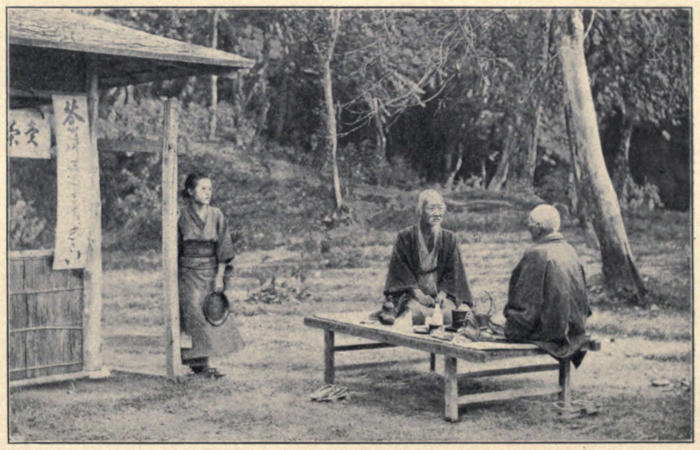

From Negishi, where Yokohama’s creek debouches[31] into Mississippi Bay, one looks across to Sugita, a fishing village with an ancient temple set in the midst of plum-trees and cherry-trees that make it a place of fêtes in February and April, when those two great flower festivals of the empire, the blossoming of the plum and the cherry, are observed. From the bluff above Sugita, at the end of the watery crescent, is a superb view of the Bay and its countless sharp, green headlands. Wherever the view is fine some Japanese family has encamped in a tateba, the least little mat shed of a house, furnished with a charcoal brazier, half a dozen teapots and cups, and a few low benches covered with the all-pervading red blanket. Their national passion for landscape and scenery draws the Japanese to places having fine prospects, and a thrifty woman, with her family of children, turns many a penny by means of her comfortable seat and good cheer for the wayfarer. Japan is the picnicker’s own country, whether he be native or foreign. Everywhere, climbing the mountain-tops, or crouching in the valleys, hidden in the innermost folds of the hills, or perched on the narrowest and remotest ledges overhanging the water, one finds the tea-house, or its summer companion, the tateba, with its open sides and simmering kettle. Everywhere hot water, tea, rice, fruits, eggs, cups, plates, glasses, and corkscrews may be had. These things become so much a matter of course after a time, that the tourist must banish himself to China, to value, as they deserve, the clean Japanese tea-house, and the view-commanding tateba with its simple comforts.

Sugita’s plum-trees bud in January, and blossom as mild days and warm suns encourage, so that the last week of February finds the dead-looking branches clothed with clouds of starry white flowers. The blossoming plum-tree is often seen when snow is on the ground, and the hawthorn pattern of old porcelains is only a conventional representation of pale blooms fallen on the seamed[32] ice of ponds or garden lakelets. The plum is the poet’s tree, and symbolic of long life, the snowy blossoms upon the gnarled, mossy, and unresponsive branches showing that a vital current still animates it, and the heart lives. At New-years a dwarf-plum is the ornament of every home, and to give one is to wish your friend length of days. Ume, the plum blossom, has a fresh, delicate, elusive, and peculiar fragrance, which in the warm sun and open air is almost intoxicating, but in a closed room becomes heavy and cloying. The blossoming of the plum-tree is the first harbinger of spring, and to Sugita regularly every year go the court ladies, many princes, and great officials to see those billows of bloom that lie under the Bluff, and the pink and crimson clouds of trees before the old temple.

During the rest of the year little heed is paid to Sugita’s existence, and the small fishing village in the curve of the Bay, with its green wall of bluffs, is as quiet as in the days when Commodore Perry’s fleet anchored off it and Treaty Point acquired its name. With the blossoms Sugita puts on its holiday air, tea-houses open, tateba spring from the earth, and scores of low, red-blanketed benches are scattered through the grove, signals of tea and good cheer, equivalent to the iron tables and chairs of Parisian boulevards. Strings of sampans float in to shore, lines of jinrikishas file over the hills, zealous pilgrims come on foot, and horsemen trot down the long, hard beach. The tiny hamlet often has a thousand visitors in a day, and the pretty little nesans, or tea-house maids, patter busily about with their trays of tea and solid food, welcoming and speeding the guests, and looking—quaint, odd, and charming maidens that they are—like so many tableaux vivants with their scant kimonos, voluminous sleeves, ornate coiffures, and pigeon-toes.

Notwithstanding the crowds, everything is decorous, quiet, and orderly, and no more refined pleasure exists[33] than this Japanese beatitude of sitting lost in revery and rapturous contemplation of a blossoming tree, or inditing a verse to ume no hana, and fastening the bit of paper to the branches. In this Utopia the spring poem is never rejected, nor made the subject of cruel jokes. The winds fan it gently, it hangs conspicuous, it is read by him who runs, but it is not immortal, and the first heavy rain leaves it a wet and withered wreck, soon to fall to the ground and disappear.

Just outside the temple door is a plum-tree whose age is lost in legend. Its bent and crooked limbs and propped-up branches sustain a thick-massed pyramid of pale rose-pink. The outer boughs droop like a weeping-willow, and their flowers seem to be slipping down them like rosy rain-drops. Poets and peers, dreamers and plodders, coolies, fishermen, and the unspiritual foreigner, all admire this lovely tree, and its wide arms flutter with poems in its praise. All around the thatched roof of the old temple stand plum-trees covered with fragrant blossoms—snow white, palest yellow, rose, or deep carnation-red. The sheltering hill back of the temple is crowded with gravestones, tombs, tablets, and mossy Buddhas, sitting calm and impassive in tangles of grasses and vines under the shadow of ancient trees. A wide-spreading pine on the crest of the hill is a famous landmark, whence one looks down on the flower-wreathed village, the golden bow of the beach curving from headland to headland, and the blue bay flashing with hundreds of square white sails. It is a place for poesy and day-dreams, but the foreign visitor dedicates it to luncheon, table-talk, and material satisfactions, and, perhaps, the warm sun and air, and the mild fragrance of the plum-blossoms aid and abet the insatiable picnic appetite.

All this part of Japan is old, and rich in temples, shrines, and picturesque villages, with a net-work of narrow roads and shady by-paths leading through perpetual[34] scenes of sylvan beauty. Thatched roofs, whose ridge poles are beds of lilies, shaded by glorified green plumes of bamboo-trees, tall, red-barked cryptomerias, crooked pines, and gnarled camphor-trees, everywhere charm the eye. Little red temples, approached through a line of picturesque torii—that skeleton gate-way that makes a part of every Japanese view or picture—red shrines no larger than marten boxes; stone Buddhas, sitting cross-legged, chipped, broken-nosed, headless, and moss-grown; odd stone tablets and lanterns crowd the hedges and banks of the road-side, snuggle at the edges of groves, or stand in the corners of rice fields.

Fair as the spring days are, when the universal green mantle of the earth is adorned with airy drifts of plum and cherry-blossoms, the warm, mellow sunshine, glorious tints and clear bright air of autumn are even fairer. One may forget and forgive the Japanese summer for the sake of the weeks that follow, an Indian summer which often lasts without break for four months after the equinoctial storm. Except that Fujiyama gleams whiter and whiter, there is no suggestion of winter’s terrors, and only a pleasant crispness in the bracing and intoxicating air. Whew the maple leaves begin to turn, and a second rose-blossoming surpasses that of June in color, prodigality, and fragrance, autumnal Japan is the typical earthly Paradise. Every valley is a floor of golden rice stubble, every hill-side a tangle of gorgeous foliage. The persimmon-trees hang full of big golden kaké, sea and sky wear their intensest blue, and Fujiyama’s loveliness shines out against the western sky. In among the yellowing stubble move blue-clad farmers with white mushroom hats. Before the farm-houses men and women swing their flails, beating the grain spread out on straw matting. The rice straw, whether bunched in pretty sheaves, tied across poles, like a New-year’s fringe, or stacked in collars around the tree-trunks, is always[35] decorative. Meditative oxen, drawing a primitive plough made of a pointed stick, loosen the soil for the new planting, and tiny green wheat-shoots, first of the three regular crops of the year, wait for the warm winter sun that opens the plum-blossoms.

Above and beyond Sugita is Minë, a temple on a mountain-top, with a background of dense pine forest, a foreground of bamboos, and an old priest, whose successful use of the moxa brings sufferers from long distances for treatment. A bridle-path follows for several miles the knife-edge of a ridge commanding noble views of sea and shore, of the blue Hakone range, its great sentinel Oyama, and Fuji beyond. The high ridge of Minë is the backbone of a great promontory running out into the sea, the Bay of Yeddo on one side and Odawara Bay on the other. Square sails of unnumbered fishing-boats fleck the blue horizon, and the view seaward is unbroken. Over an old race-course and archery-range of feudal days the path leads, till at a sudden turn it strikes into a pine forest, where the horses’ hoofs fall noiseless on thick carpets of dry pine-needles, and the cave-like twilight, coolness, and stillness seem as solemn as in that wood where Virgil and Dante walked, before they visited the circles of the other world.

A steep plunge down a slippery, clayey trail takes the rider from the melancholy darkness to a solitary forest clearing, with low temple buildings on one side. Here, massed against feathery fronds of giant bamboos, blaze boughs of fine-leafed maples, all vivid crimson to the tips. While the priests bring saké tubs, and the amado, or outside shutters of their house, to make a table, and improvise benches with various temple and domestic properties, visitors may wander through the forest to open spaces, whence all the coasts of the two bays and every valley of the province lie visible, and a column of[36] smoke proclaims the living volcano on Oshima’s island, far down the coast.

Groups of cheery pilgrims come chattering down from the forest, untie their sandals, wash their feet, and disappear within the temple; where the old priest writes sacred characters on their bared backs to indicate where his attendant shall place the lumps of sticky moxa dough. Another attendant goes down the line of victims and touches a light to these cones, which burn with a slow, red glow, and hiss and smoke upon the flesh for agonizing seconds. The priest reads pious books and casts up accounts, while the patients endure without a groan tortures compared with which the searing with the white-hot irons of Parisian moxa treatment is comfortable. The Minë priest has some secret of composition for his moxa dough which has kept it in favor for many years, and almost the only revenue of the temple is derived from this source. Rheumatism, lumbago, and paralysis yield to the moxa treatment, and the Japanese resort to it for all their aches and ills, the coolies’ backs and legs being often finely patterned with its scars.

The prospect from Minë’s promontory is rivalled by that at Kanozan, directly across the Bay, one of the highest points on the long tongue of separating land. Here are splendid old temples, almost unvisited by foreigners, but the glory of the place is the view of the ninety-nine valleys, of Yeddo Bay, the ocean, and the ever-dominant Fujiyama. Every Japanese knows the famous landscapes of his country, and the mention of these ninety-nine valleys and the thousand pine-clad islands of Matsuyama brings a light to his eyes.

At Yokosuka, fifteen miles below Yokohama, are the Government arsenal, navy-yard, and dry docks, with their fleets of war-ships that put to shame the American squadron in Asiatic waters. The Japanese Government has both constructed and bought a navy; some vessels[37] coming from Glasgow yards, and others having been built at these docks.

Uraga, reached from Yokosuka by a winding, Cornice-like road along the coast, is doubly notable as being the port off which Commodore Perry’s ships first anchored, and the place where midzu ame, or millet honey, is made. The whole picturesque, clean little town is given up to the production of the amber sweet, and there are certain families whose midzu ame has not varied in excellence for more than three hundred years. The rice, or millet, is soaked, steamed, mixed with warm water and barley malt, and left to stand a few hours, when a clear yellow liquid is drawn off and boiled down to a thick syrup or paste, or cooked until it can be moulded into hard balls. Unaffected by weather, it is the best of Japanese sweets, and in its semiliquid stage is twisted out on chopsticks at all seasons of the year. The older and browner the midzu ame is, the better. It may be called the apotheosis of butter-scotch, a glorified Oriental taffy, constantly urged upon one for one’s own good, and conceded by foreign physicians in Japan to be of great value for dyspeptics and consumptives. Though prepared all over the empire, this curative sweet is the specialty of Uraga; and the secrets and formulas held in the old families make for Uraga midzu ame, as compared with other productions, a reputation akin to that of the Grande Chartreuse, or Schloss Johannisberger, among other cordials or wines. Street artists mould midzu ame paste, and blow it with a pipe into myriad fantastic shapes for their small patrons; while at the greatest banquets, and even on the Emperor’s table, it appears in the fanciful flowers that decorate every feast.

The contemporary Yankee might anticipate the sage reflections of the future New Zealander on London Bridge were there left enough ruins of the once great city of Kamakura to sit upon; but the military capital of the Middle Ages has melted away into rice fields and millet patches. One must wrestle seriously with the polysyllabic guide-book stories of the shoguns, regents, and heroes who made the glory of Kamakura, and attracted to it a population of five hundred thousand, to repeople these lonely tracts with the splendid military pageants of which they were the scene.

The plain of Kamakura is a semicircle, bounded by hills and facing the open Pacific, the surf pounding on its long yellow beach between two noble promontories. The Dai Butsu, the great bronze image of Buddha, which has kept Kamakura from sinking entirely into obscurity during the centuries of its decay, stands in a tiny valley a half-mile back from the shore. The Light of Asia is seated on the lotus flower, his head bent forward in meditation, his thumbs joined, and his face wearing an expression of the most benignant calm. This is one of the few great show-pieces in Japan that is badly placed and lacks a proper approach. Seen, like the temple gate-ways and pagodas of Nikko, at the end of a long avenue of trees, or on some height silhouetted against the sky, Dai Butsu (Great Buddha) would be far more imposing. Within the image is a temple forty-nine feet[39] in height; and through an atmosphere thick with incense may be read the chalked names of ambitious tourists, who have evaded the priests and left their signatures on the irregular bronze walls. An alloy of tin and a little gold is mingled with the copper, and on the joined thumbs and hands, over which visitors climb to sit for their photographs, the bronze is polished enough to show its fine dark tint. The rest of the statue is dull and weather-stained, its rich incrustation disclosing the seams where the huge sections were welded together.

A pretty landscape-garden, banks of blossoming plum-trees, and the usual leper at the gate-way furnish the accustomed temple accessories, and Buddha broods and meditates serene in his quiet sanctuary. The photographic skill of the priest brings a good revenue to the temple, and a fund is being slowly raised for building a huge pavilion above the great deity, like that which stood there three hundred years ago. During his six centuries of holy contemplation at Kamakura, Dai Butsu has endured many disasters. Earthquakes have made him nod and sway on the lotus pedestal, and tidal waves have twice swept over and destroyed the sheltering temple, the great weight and thickness of the bronze keeping the statue itself unharmed.

Kamakura is historic ground, and each shrine has its legends. The great temple of Hachiman, the God of War, remains but as a fragment of its former self, the buildings standing at the head of a high stone-embanked terrace, from which a broad avenue of trees runs straight to the sea, a mile and a half away. Here are the tomb of Yoritomo and the cave tombs of his faithful Satsuma and Chosen Daimios; and the priests guard sacredly the sword of Yoritomo, that of Hachiman himself, the helmet of Iyeyasu, and the bow of Iyemitsu.

In the spring, Kamakura is a delightful resort, on whose dazzling beach climate and weather are altogether[40] different from those of Yokohama or Tokio. In summer-time, the steady south wind, or monsoon, blows straight from the ocean, and the pine grove between the hotel and shore is musical all day long with the pensive sough of its branches. In winter it is open and sunny, and the hot sea-water baths, the charming walks and sails, the old temples and odd little villages, attract hosts of visitors.

On bright spring mornings men, women, and children gather sea-weed and spread it to dry on the sand, after which it is converted into food as delicate as our Iceland moss. Both farmers and fishermen glean this salty harvest, and after a storm, whole families collect the flotsam and jetsam of kelp and sea-fronds. Barelegged fisher-maidens, with blue cotton kerchiefs tied over their heads, and baskets on their backs, roam along the shore; children dash in and out of the frothing waves, and babies roll contentedly in the sand; men and boys wade knee-deep in the water, and are drenched by the breakers all day long, with the mercury below 50°, in spite of the warm, bright sun. Women separate the heaps of sea-weed, and at intervals regale their dripping lords with cups of hot tea, bowls of rice, and shredded fish. It is all so gay and beautiful, every one is so merry and happy, that Kamakura life seems made up of rejoicing and abundance, with no darker side.

The poor in Japan are very poor, getting comparative comfort out of smaller means than any other civilized people in the world. A few cotton garments serve for all seasons alike. The cold winds of winter nip their bare limbs and pierce their few thicknesses of cloth, and the fierce heat of summer torments them; but they endure these extremes with stoical good-nature, and enjoy their lovely spring and autumn the more. A thatched roof, a straw mat, and a few cotton wadded futons, or comforters, afford the Japanese laborer shelter, furniture,[41] and bedding, while rice, millet, fish, and sea-weed constitute his food. With three crops a year growing in his fields, the poor farmer supports his family on a patch of land forty feet square; and with three hundred and sixty varieties of food fish swimming in Japanese waters, the fisherman need not starve. Perfect cleanliness of person and surroundings is as much an accompaniment of poverty as of riches.

Beyond Kamakura’s golden bow lies another beach—the strand of Katase, at the end of which rises Enoshima, the Mont St. Michel of the Japanese coast. Enoshima is an island at high tide, rising precipitously from the sea on all sides save to the landward, where the precipice front is cleft with a deep wooded ravine, that runs out into the long tongue of sand connecting with the shore at low tide.

Like every other island of legendary fame, Enoshima rose from the sea in a single night. Its tutelary genius is the goddess Benten, one of the seven household deities of good-fortune. She is worshipped in temples and shrines all over the woody summit of the island, and in a deep cave opening from the sea. Shady paths, moss-grown terraces, and staircases abound, and little tea-houses and tateba offer seats, cheering cups of tea, and enchanting views. The near shores, the limitless waters of the Pacific, and the grand sweep of Odawara Bay afford the finest setting for Fujiyama anywhere to be enjoyed.

Enoshima’s crest is a very Forest of Arden, an enchanted place of lovely shade. The sloping ravine which gives access to it holds only the one street, or foot-path, lined with tea-houses and shell-shops, all a-flutter with pilgrim flags and banners. The shells are cut into whistles, spoons, toys, ornaments, and hair-pins; and tiny pink ones of a certain variety form the petals of most perfect cherry blossoms, which are fastened to natural branches and twigs.

The fish dinners of Enoshima are famous, and the Japanese, who have the genius of cookery, provide more delicious fish dishes than can be named. At the many tateba set up in temple yards or balanced on the edges of precipices, conch-shells, filled with a black stew like terrapin, simmer over charcoal fires. This concoction has a tempting smell, and the pilgrims, who pick at the inky morsels with their chopsticks, seem to enjoy it; but in the estimation of the foreigner it adds one more to the list of glutinous, insipid preparations with which the Japanese cuisine abounds. The great marine curiosity of Enoshima is the giant crab, with its body as large as a turtle, and claws measuring ten, and even twelve, feet from tip to tip. These crustaceans are said to promenade the beach at night, and glare with phosphorescent eyes. Another interesting Japanese crab, the Doryppe Japonica, comes more often from the Inland Sea. A man’s face is distinctly marked on the back of the shell, and, as the legend avers, these creatures incarnate the souls of the faithful samurai, who, following the fortunes of the Tairo clan, were driven into the sea by the victorious Minamoto. At certain anniversary seasons, well known to true believers, the spirits of these dead warriors come up from the sea by thousands and meet together on a moonlit beach.

Enoshima must have become the favorite summer resort of the region, had not the whole island been reserved as an imperial demesne and site for a sea-shore palace. When typhoons rage or storms sweep in from the ocean, billows ring the island round with foam, spray dashes up to the drooping foliage on the summit, the air is full of the wild breath and wilder roar of the breakers, while the very ground seems to tremble. The underground shrine of Benten is then closed to worshippers, and looking down the sheer two hundred feet of rock, one sees only the whirl and rage of waters that hide the[43] entrance. When these storms rage, visitors are sometimes imprisoned for days upon the island. At low tide and in ordinary seas Benten’s shrine is easily entered by a ledge of rocks, the hard thing being the climb up the long stone stair-ways to the top of the island again. Guides are numerous, and an old man or a small boy generally attaches himself to a company of strangers, and is so friendly, polite, and amiable, that, after escorting it unbidden round the island, he generally wins his cause, and is bidden to maru maru (go sight-seeing) as escort and interpreter.

The first view of Tokio, like the first view of Yokohama, disappoints the traveller. The Ginza, or main business street, starting from the bridge opposite the station, goes straight to Nihombashi, the northern end of the Tokaido, and the recognized centre of the city, from which all distances are measured. Most of the road-way is lined with conventional houses of foreign pattern, with their curb-stones and shade-trees, while the tooting tram-car and the rattling basha, or light omnibus, emphasize the incongruities of the scene. This is not the Yeddo of one’s dreams, nor yet is it an Occidental city. Its stucco walls, wooden columns, glaring shop-windows, and general air of tawdry imitation fairly depress one. In so large a city there are many corners, however, which the march of improvement has not reached, odd, unexpected, and Japanese enough to atone for the rest.

Through the heart of Tokio winds a broad spiral moat, encircling the palace in its innermost ring, and reaching, by canal branches, to the river on its outer lines. In feudal days the Shogun’s castle occupied the inner ring, and within the outer rings were the yashikis, or spread-out houses, of his daimios. Each gate-way and angle of the moat was defended by towers, and the whole region was an impregnable camp. Every daimio in the empire had his yashiki in Tokio, where he was obliged to spend six months of each year, and in case of war to send his family as pledges of his loyalty to the Shogun. The Tokaido and the other great highways of the empire were always alive with the trains of these nobles, and from this migratory habit was developed the passion for travel and excursion that animates every class of the Japanese people. When the Emperor came up from Kioto and made Tokio his capital, the Shogun’s palace became his home, and all the Shogun’s property reverted to the crown, the yashikis of the daimios being confiscated for government use. In the old days the barrack buildings surrounding the great rectangle of the yashiki were the outer walls, protected by a small moat, and furnished with ponderous, gable-roofed gate-ways, drawbridges, sally-ports, and projecting windows for outlooks. These barracks accommodated the samurai, or soldiers, attached to each daimio, and within their lines were the parade ground and archery range, the residence of the noble family, and the homes of the artisans in his employ. With the new occupation many yashiki buildings were razed to the ground, and imposing edifices in foreign style erected for government offices. A few of the old yashiki remain as barracks, and their white walls, resting on black foundations, suggest the monotonous street views of feudal days. Other yashiki have fallen to baser uses, and sign-boards swing from their walls.