Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

Additional notes will be found near the end of this ebook.

BOOKS BY MISS SINGLETON

FAMOUS PICTURES, SCENES, AND BUILDINGS

DESCRIBED BY GREAT WRITERS

Turrets, Towers, and Temples

Great Pictures

Wonders of Nature

Romantic Palaces and Castles

Famous Paintings

Paris—London—A Guide to the Opera

Love in Literature and Art

Turrets,

Towers, and Temples

The Great Buildings of the World, as

Seen and Described by Famous Writers

EDITED AND TRANSLATED

By ESTHER SINGLETON

TRANSLATOR OF “THE MUSIC DRAMAS OF RICHARD WAGNER”

With Numerous Illustrations

❦

NEW YORK

DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

1912

Copyright, 1898,

By Dodd, Mead and Company

v

In making the selections for this book, which is thought to be the realization of a new idea, it has been my endeavour to bring together descriptions of several famous buildings written by authors who have appreciated the romantic spirit, as well as the architectural beauty and grandeur, of the work they describe.

It would be impossible to collect within the small boundaries of a single volume sketches and pictures of all the masterpieces of architecture, and a vast amount of interesting literature has had to be ignored. I have tried, however, to gather choice examples of as many different styles of architecture as possible and to give a description, wherever practicable, of each building’s special object of veneration, such as the Christ of Burgos and the Cid’s coffer in the same Cathedral; the Emerald Buddha at Wat Phra Kao, Bangkok; the statue of Our Lady at Toledo; the shrine of St. Thomas à Becket at Canterbury; etc., as well as the specialvi feature for which any particular building is famous, such as the Court of Lions in the Alhambra; the Chapel of Henry VII. in Westminster Abbey; the Convent of the Escurial; the spiral stairway at Chambord; etc., and also a typical scene, like the dance de los seises in the Cathedral of Seville; and the celebration of Easter at St. Peter’s.

Ruskin says: “It is well to have not only what men have thought and felt, but what their hands have handled and their strength wrought all the days of their life.” It is also well to have what sympathetic authors have written about these massive and wonderful creations of stone which have looked down upon and outlived so many generations of mankind.

With the exception of the Mosque of Santa Sofia, all the translations have been made expressly for this book.

E. S.

New York, May, 1898.

vii

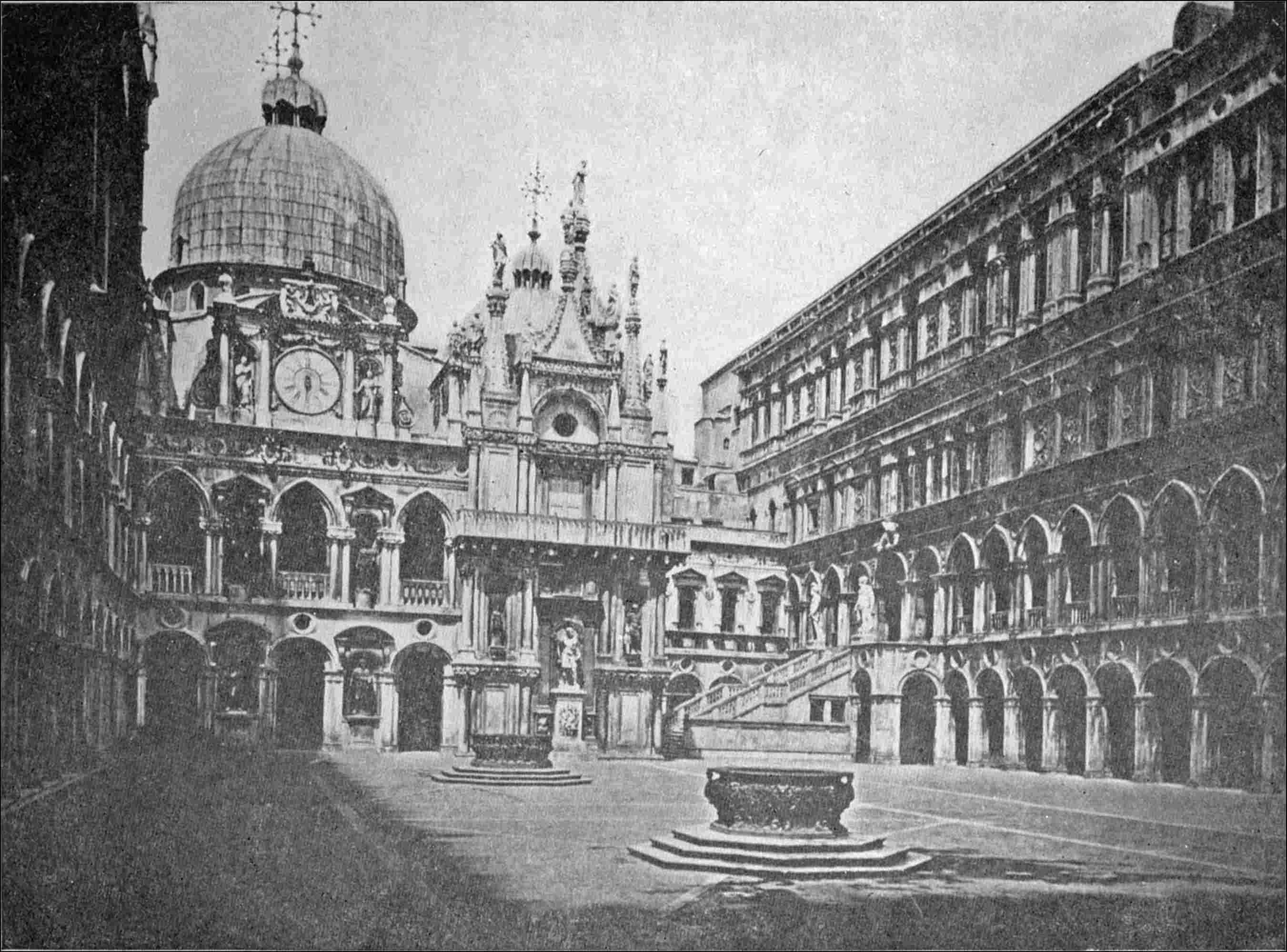

| St. Mark’s, Venice | 1 |

| John Ruskin. | |

| The Tower of London | 11 |

| William Hepworth Dixon. | |

| The Cathedral of Antwerp | 18 |

| William Makepeace Thackeray. | |

| The Taj Mahal, Agra | 23 |

| André Chevrillon. | |

| The Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Paris | 28 |

| Victor Hugo. | |

| The Kremlin, Moscow | 38 |

| Théophile Gautier. | |

| The Cathedral of York | 49 |

| Thomas Frognall Dibdin. | |

| The Mosque of Omar, Jerusalem | 56 |

| Pierre Loti. | |

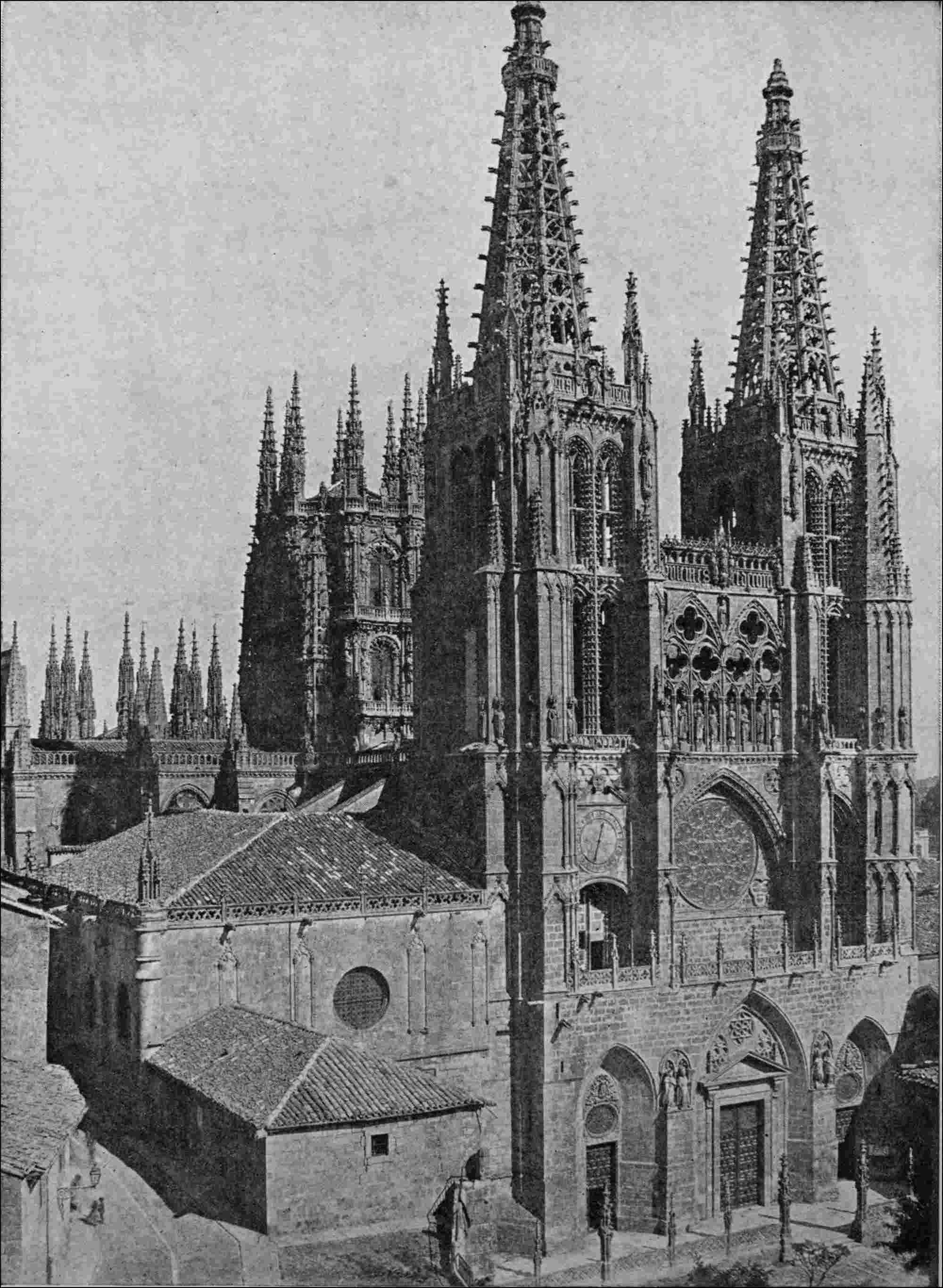

| The Cathedral of Burgos | 65 |

| Théophile Gautier. | |

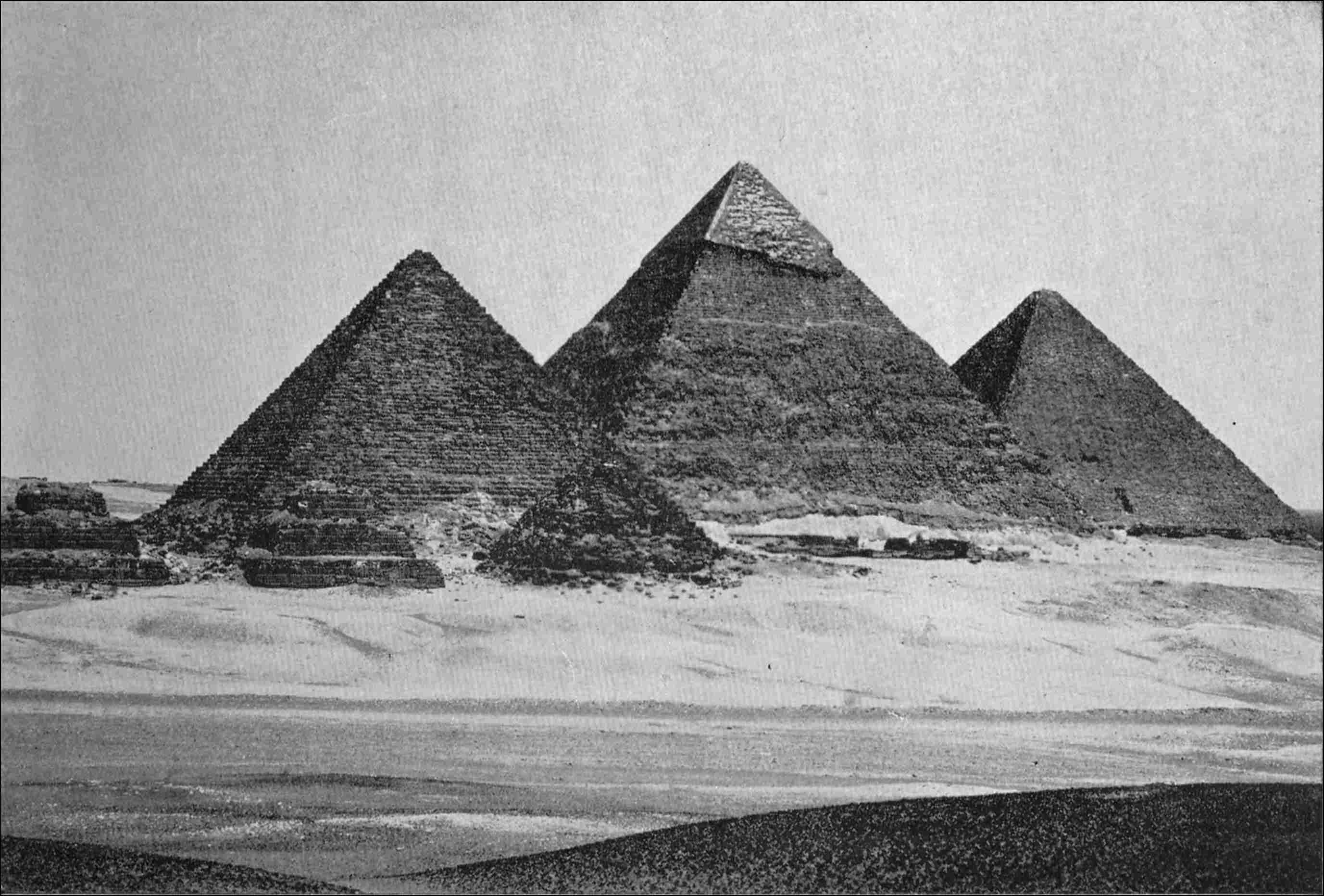

| The Pyramids, Gizeh | 71 |

| Georg Ebers. | |

| St. Peter’s, Rome | 76 |

| Charles Dickens.viii | |

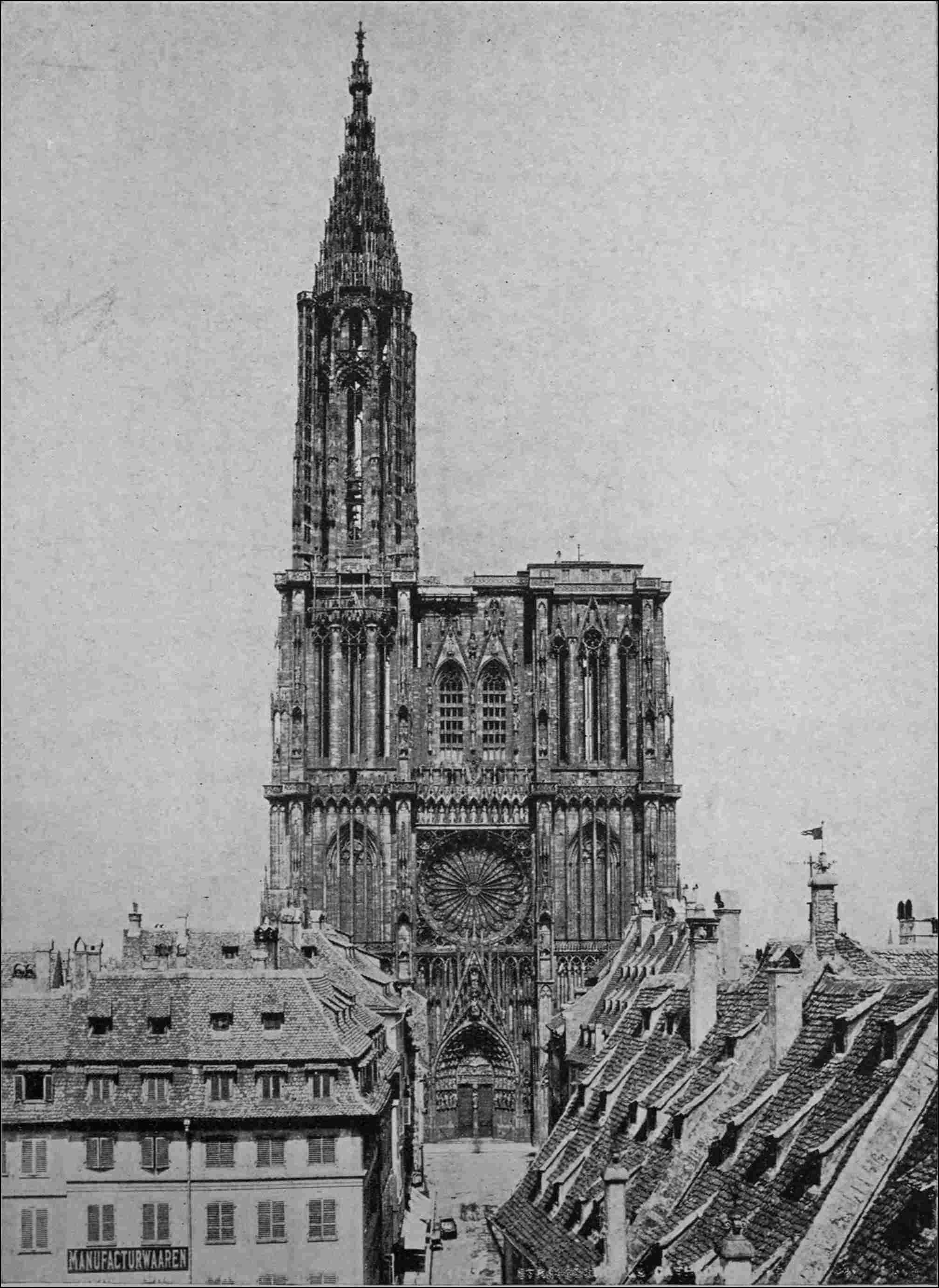

| The Cathedral of Strasburg | 84 |

| Victor Hugo. | |

| The Shway Dagohn Rangoon | 92 |

| Gwendolin Trench Gascoigne. | |

| The Cathedral of Siena | 98 |

| John Addington Symonds. | |

| The Town Hall of Louvain | 102 |

| Grant Allen. | |

| The Cathedral of Seville | 105 |

| Edmondo De Amicis. | |

| Windsor Castle | 110 |

| William Hepworth Dixon. | |

| The Cathedral of Cologne | 117 |

| Ernest Breton. | |

| The Palace of Versailles | 126 |

| Augustus J. C. Hare. | |

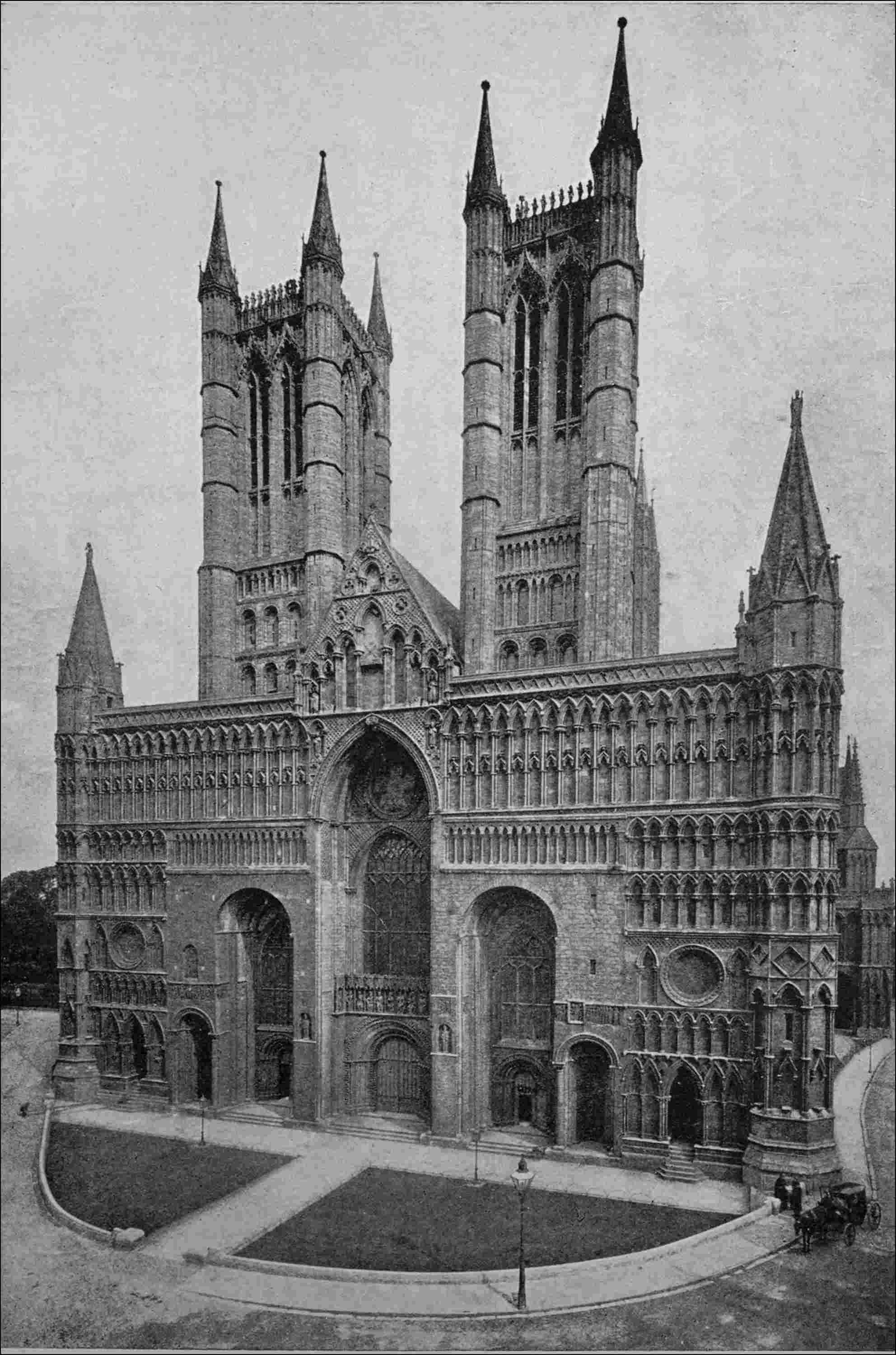

| The Cathedral of Lincoln | 132 |

| Thomas Frognall Dibdin. | |

| The Temple of Karnak | 137 |

| Amelia B. Edwards. | |

| Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence | 143 |

| Charles Yriarte. | |

| Giotto’s Campanile, Florence | 147 |

| I. Mrs. Oliphant. | |

| II. John Ruskin. | |

| The House of Jacques Cœur, Bourges | 152 |

| Ad. Berty. | |

| Wat Phra Kao, Bangkok | 158 |

| Carl Bock.ix | |

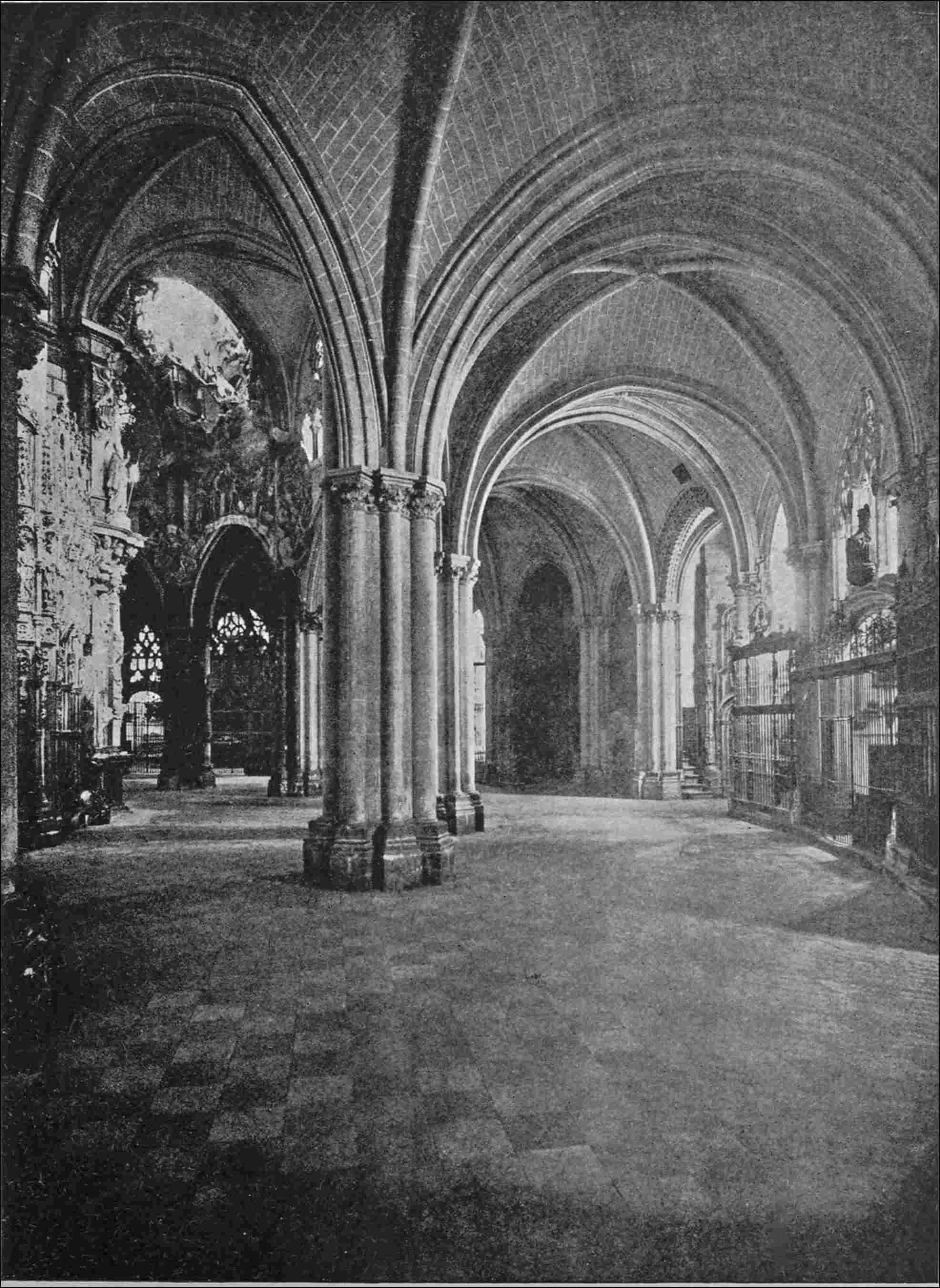

| The Cathedral of Toledo | 163 |

| Théophile Gautier. | |

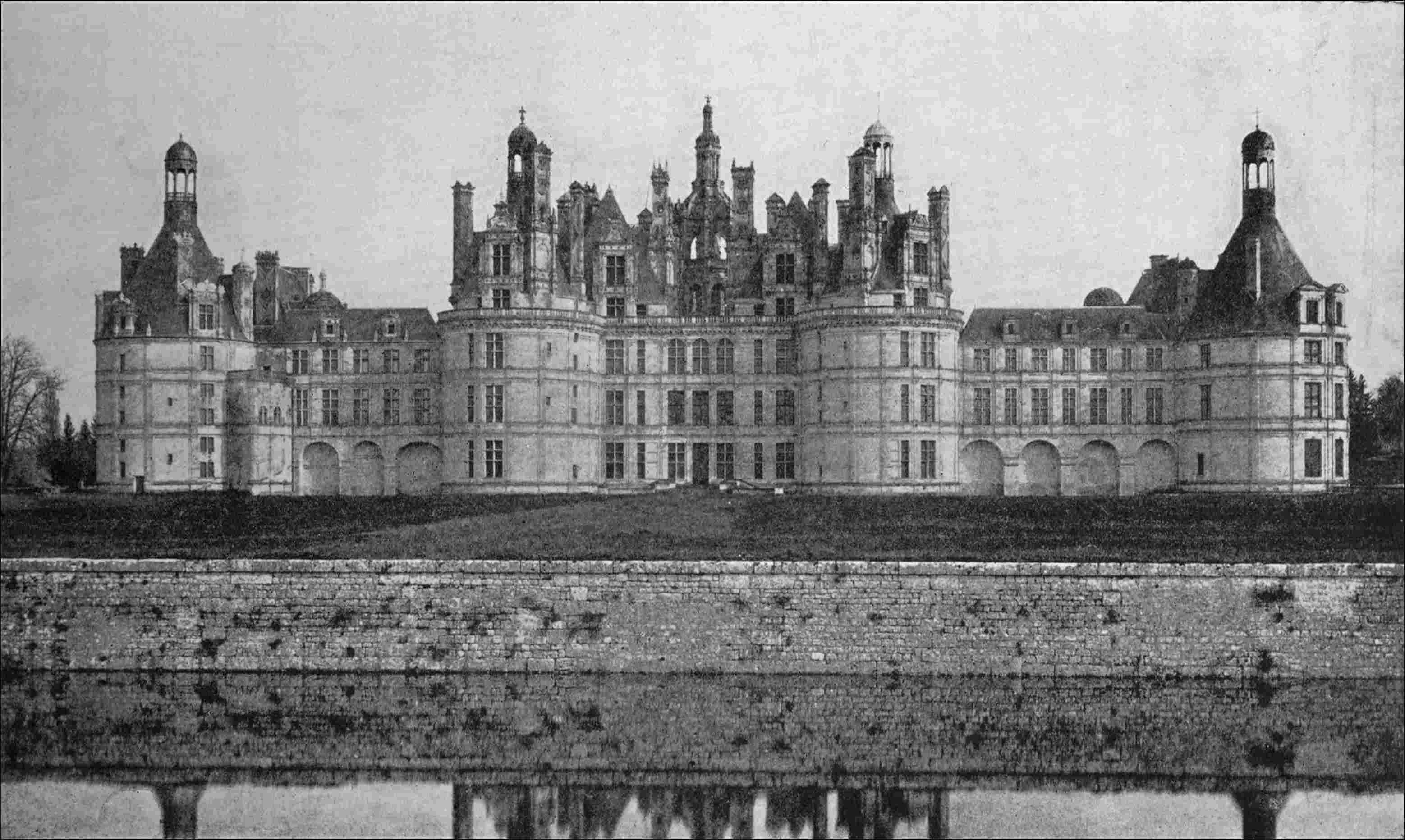

| The Château de Chambord | 170 |

| Jules Loiseleur. | |

| The Temples of Nikko | 177 |

| Pierre Loti. | |

| The Palace of Holyrood, Edinburgh | 187 |

| David Masson. | |

| Saint-Gudule, Brussels | 193 |

| Victor Hugo. | |

| The Escurial, Madrid | 195 |

| Edmondo De Amicis. | |

| The Temple of Madura | 204 |

| James Fergusson. | |

| The Cathedral of Milan | 209 |

| Théophile Gautier. | |

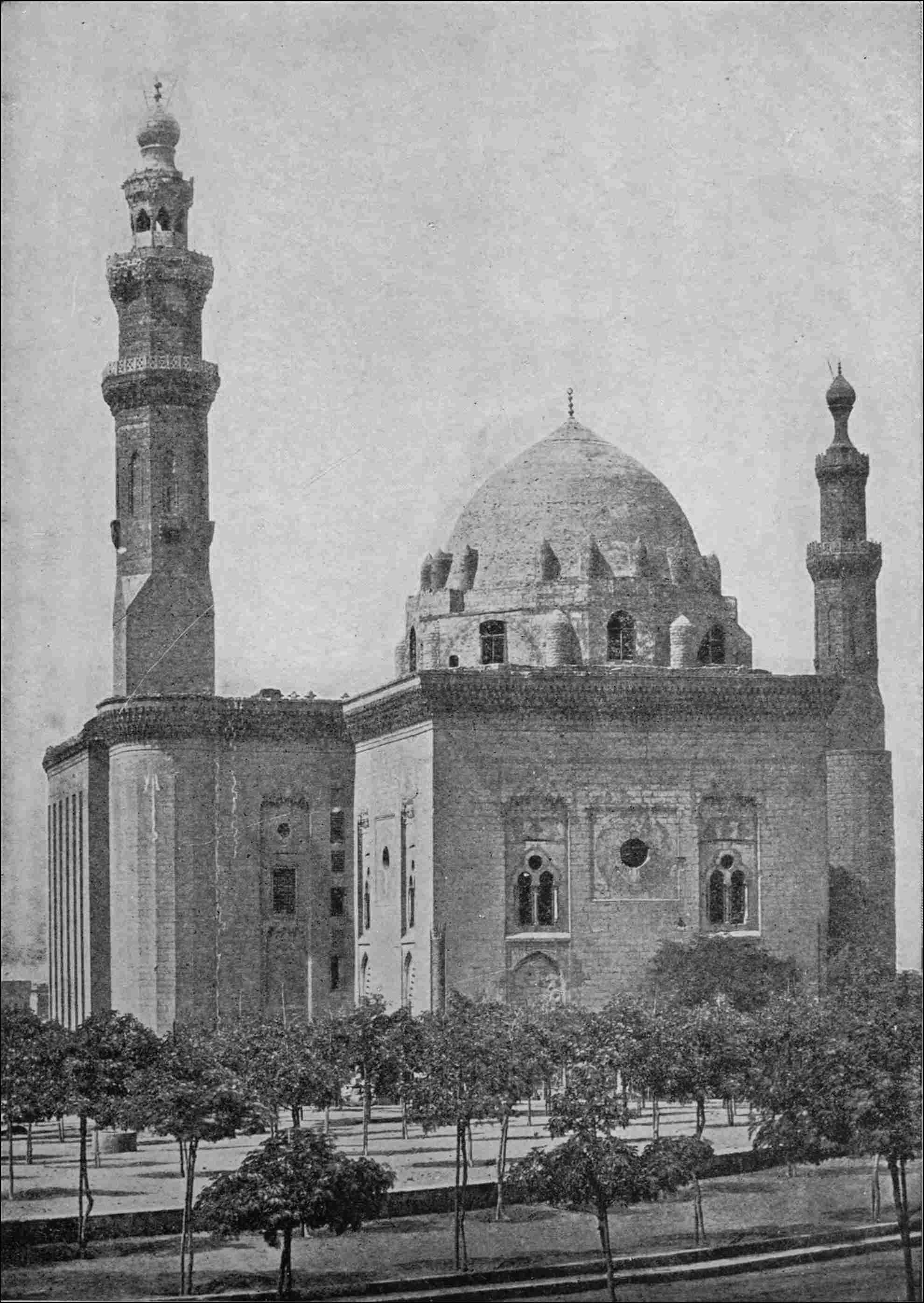

| The Mosque of Hassan, Cairo | 215 |

| Amelia B. Edwards. | |

| The Cathedral of Trèves | 221 |

| Edward Augustus Freeman. | |

| The Vatican, Rome | 225 |

| Augustus J. C. Hare. | |

| The Cathedral of Amiens | 234 |

| John Ruskin. | |

| The Mosque of Santa Sofia, Constantinople | 242 |

| Edmondo De Amicis. | |

| Westminster Abbey, London | 248 |

| Arthur Penrhyn Stanley. | |

| The Parthenon, Athens | 257 |

| John Addington Symonds.x | |

| The Cathedral of Rouen | 263 |

| Thomas Frognall Dibdin. | |

| The Castle of Heidelberg | 269 |

| Victor Hugo. | |

| The Ducal Palace, Venice | 278 |

| John Ruskin. | |

| The Mosque of Cordova | 286 |

| Edmondo De Amicis. | |

| The Cathedral of Throndtjem | 293 |

| Augustus J. C. Hare. | |

| The Leaning Tower of Pisa | 298 |

| Charles Dickens. | |

| The Cathedral of Canterbury | 301 |

| W. H. Fremantle. | |

| The Alhambra, Granada | 308 |

| Théophile Gautier. | |

xi

| PAGE | ||

| St. Mark’s | Italy | Frontis. |

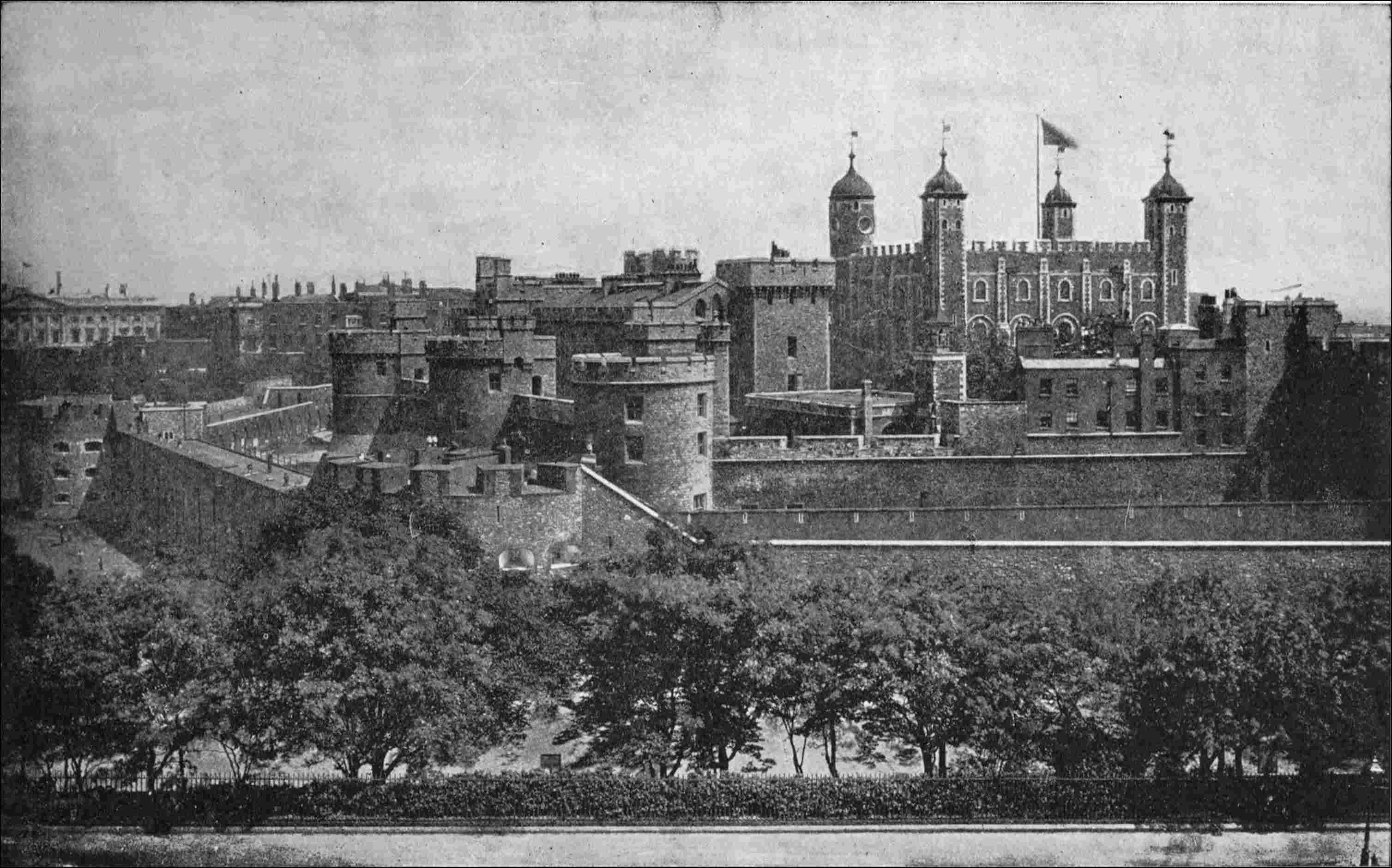

| The Tower of London | England | 14 |

| The Cathedral of Antwerp | Belgium | 20 |

| The Taj Mahal | India | 23 |

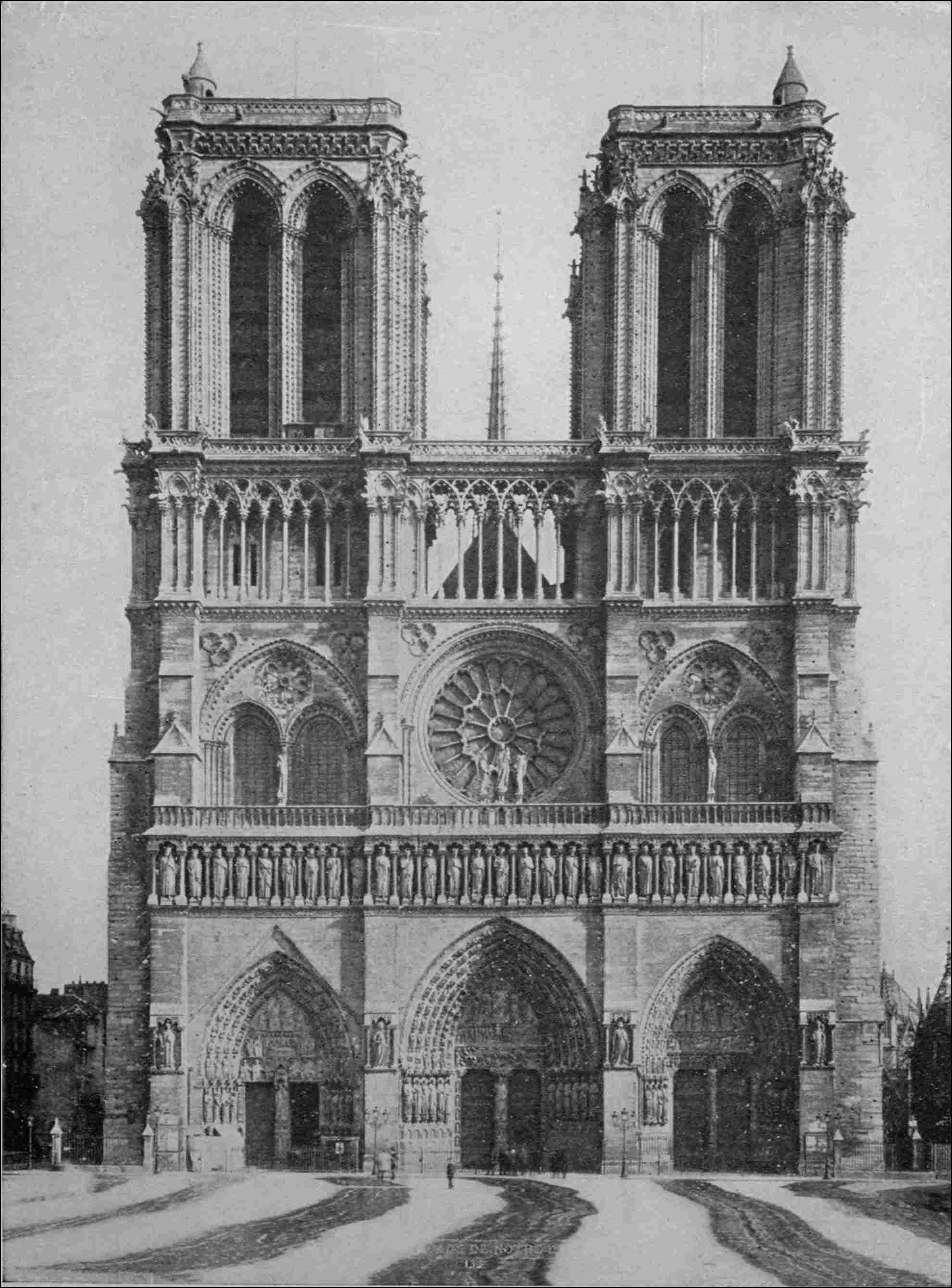

| The Cathedral of Notre Dame | France | 30 |

| The Kremlin | Russia | 40 |

| The Cathedral of York | England | 49 |

| The Mosque of Omar | Palestine | 58 |

| The Cathedral of Burgos | Spain | 65 |

| The Pyramids | Egypt | 72 |

| St. Peter’s | Italy | 78 |

| The Cathedral of Strasburg | Germany | 86 |

| The Shway Dagohn | Burmah | 94 |

| The Cathedral of Siena | Italy | 98 |

| The Town Hall of Louvain | Belgium | 103 |

| The Cathedral of Seville | Spain | 106 |

| Windsor Castle | England | 110 |

| The Cathedral of Cologne | Germany | 121 |

| The Palace of Versailles | France | 126 |

| The Cathedral of Lincoln | England | 132 |

| The Temple of Karnak | Egypt | 139 |

| Santa Maria del Fiore | Italy | 144 |

| Giotto’s Campanile | Italy | 147 |

| The House of Jacques Cœur | France | 155 |

| Wat Phra Kao | Siam | 159 |

| The Cathedral of Toledo | Spain | 164 |

| The Château de Chambord | France | 172xii |

| The Temples of Nikko | Japan | 178 |

| The Palace of Holyrood | Scotland | 187 |

| Saint-Gudule | Belgium | 193 |

| The Escurial | Spain | 195 |

| The Temple of Madura | India | 204 |

| The Cathedral of Milan | Italy | 213 |

| The Mosque of Hassan | Egypt | 216 |

| The Cathedral of Trèves | Germany | 221 |

| The Vatican | Italy | 225 |

| The Cathedral of Amiens | France | 234 |

| The Mosque of Santa-Sofia | Turkey | 242 |

| Westminster Abbey | England | 248 |

| The Parthenon | Greece | 257 |

| The Cathedral of Rouen | France | 265 |

| The Castle of Heidelberg | Germany | 269 |

| The Ducal Palace | Italy | 280 |

| The Mosque of Cordova | Spain | 288 |

| The Cathedral of Throndtjem | Norway | 293 |

| The Leaning Tower of Pisa | Italy | 298 |

| The Cathedral of Canterbury | England | 301 |

| The Alhambra | Spain | 310 |

1

❦

A yard or two farther, we pass the hostelry of the Black Eagle, and, glancing as we pass through the square door of marble, deeply moulded, in the outer wall, we see the shadows of its pergola of vines resting on an ancient well, with a pointed shield carved on its side; and so presently emerge on the bridge and Campo San Moisè, whence to the entrance into St. Mark’s Place, called the Bocca di Piazza (mouth of the square), the Venetian character is nearly destroyed, first by the frightful façade of San Moisè, which we will pause at another time to examine, and then by the modernizing of the shops as they near the piazza, and the mingling with the lower Venetian populace of lounging groups of English and Austrians. We will push fast through them into the shadow of the pillars at the end of the “Bocca di Piazza,” and then we forget them all; for between those pillars there opens a great light, and, in the midst of it, as we advance slowly, the vast tower of St. Mark seems to lift itself visibly forth from the level field of chequered stones;2 and, on each side, the countless arches prolong themselves into ranged symmetry, as if the rugged and irregular houses that pressed together above us in the dark alley had been struck back into sudden obedience and lovely order, and all their rude casements and broken walls had been transformed into arches charged with goodly sculpture and fluted shafts of delicate stone.

And well may they fall back, for beyond those troops of ordered arches there rises a vision out of the earth, and all the great square seems to have opened from it in a kind of awe, that we may see it far away;—a multitude of pillars and white domes, clustered into a long, low pyramid of coloured light; a treasure-heap, it seems, partly of gold, and partly of opal and mother-of-pearl, hollowed beneath into five great vaulted porches, ceiled with fair mosaic, and beset with sculpture of alabaster, clear as amber and delicate as ivory,—sculpture fantastic and involved, of palm leaves and lilies, and grapes and pomegranates, and birds clinging and fluttering among the branches, all twined together into an endless network of buds and plumes; and, in the midst of it, the solemn forms of angels, sceptred, and robed to the feet, and leaning to each other across the gates, their figures indistinct among the gleaming of the golden ground through the leaves beside them, interrupted and dim, like the morning light as it faded back among the branches of Eden, when first its gates were angel-guarded long ago. And round the walls of the porches there are set pillars of variegated stones, jasper and porphyry, and deep-green serpentine spotted with flakes of snow, and marbles, that half refuse3 and half yield to the sunshine, Cleopatra-like, “their bluest veins to kiss”—the shadow, as it steals back from them, revealing line after line of azure undulation, as a receding tide leaves the waved sand; their capitals rich with interwoven tracery, rooted knots of herbage, and drifting leaves of acanthus and vine, and mystical signs, all beginning and ending in the Cross; and above them, in the broad archivolts, a continuous chain of language and of life—angels, and the signs of heaven, and the labours of men, each in its appointed season upon the earth; and above these, another range of glittering pinnacles, mixed with white arches edged with scarlet flowers,—a confusion of delight, amidst which the breasts of the Greek horses are seen blazing in their breadth of golden strength, and the St. Mark’s Lion, lifted on a blue field covered with stars, until at last, as if in ecstasy, the crests of the arches break into a marble foam, and toss themselves far into the blue sky in flashes and wreaths of sculptured spray, as if the breakers on the Lido shore had been frost-bound before they fell, and the sea-nymphs had inlaid them with coral and amethyst.

Between that grim cathedral of England and this, what an interval! There is a type of it in the very birds that haunt them; for, instead of the restless crowd, hoarse-voiced and sable-winged, drifting on the bleak upper air, the St. Mark’s porches are full of doves, that nestle among the marble foliage, and mingle the soft iridescence of their living plumes, changing at every motion with the tints, hardly less lovely, that have stood unchanged for seven hundred years.

4

And what effect has this splendour on those who pass beneath it? You may walk from sunrise to sunset, to and fro, before the gateway of St. Mark’s, and you will not see an eye lifted to it, nor a countenance brightened by it. Priest and layman, soldier and civilian, rich and poor, pass by it alike regardlessly. Up to the very recesses of the porches, the meanest tradesmen of the city push their counters; nay, the foundations of its pillars are themselves the seats—not “of them that sell doves” for sacrifice, but of vendors of toys and caricatures. Round the whole square in front of the church there is almost a continuous line of cafés, where the idle Venetians of the middle classes lounge, and read empty journals; in its centre the Austrian bands play during the time of vespers, their martial music jarring with the organ notes,—the march drowning the miserere, and the sullen crowd thickening around them,—a crowd which, if it had its will, would stiletto every soldier that pipes to it. And in the recesses of the porches, all day long, knots of men of the lowest classes, unemployed and listless, lie basking in the sun like lizards; and unregarded children,—every heavy glance of their young eyes full of desperation and stony depravity, and their throats hoarse with cursing,—gamble, and fight, and snarl, and sleep, hour after hour, clashing their bruised centesimi upon the marble ledges of the church porch. And the images of Christ and His angels look down upon it continually.... Let us enter the church itself. It is lost in still deeper twilight, to which the eye must be accustomed for some moments before the form of the building can be traced; and then there opens before us a vast cave5 hewn out into the form of a Cross, and divided into shadowy aisles by many pillars. Round the domes of its roof the light enters only through narrow apertures like large stars; and here and there a ray or two from some far-away casement wanders into the darkness, and casts a narrow phosphoric stream upon the waves of marble that heave and fall in a thousand colours along the floor. What else there is of light is from torches or silver lamps, burning ceaselessly in the recesses of the chapels; the roof sheeted with gold, and the polished walls covered with alabaster, give back at every curve and angle some feeble gleaming to the flames; and the glories round the heads of the sculptured saints flash out upon us as we pass them, and sink again into the gloom. Under foot and over head, a continual succession of crowded imagery, one picture passing into another, as in a dream; forms beautiful and terrible mixed together; dragons and serpents, and ravening beasts of prey, and graceful birds that in the midst of them drink from running fountains and feed from vases of crystal; the passions and the pleasures of human life symbolized together, and the mystery of its redemption; for the mazes of interwoven lines and changeful pictures lead always at last to the Cross, lifted and carved in every place and upon every stone; sometimes with the serpent of eternity wrapt round it, sometimes with doves beneath its arms, and sweet herbage growing forth from its feet; but conspicuous most of all on the great rood that crosses the church before the altar, raised in bright blazonry against the shadow of the apse. And although in the recesses of the aisles and chapels, when the mist of the incense hangs6 heavily, we may see continually a figure traced in faint lines upon their marble, a woman standing with her eyes raised to heaven, and the inscription above her, “Mother of God,” she is not here the presiding deity. It is the Cross that is first seen, and always, burning in the centre of the temple; and every dome and hollow of its roof has the figure of Christ in the utmost height of it, raised in power, or returning in judgment.

Nor is this interior without effect on the minds of the people. At every hour of the day there are groups collected before the various shrines, and solitary worshippers scattered through the darker places of the church, evidently in prayer both deep and reverent, and, for the most part, profoundly sorrowful. The devotees at the greater number of the renowned shrines of Romanism may be seen murmuring their appointed prayers with wandering eyes and unengaged gestures; but the step of the stranger does not disturb those who kneel on the pavement of St. Mark’s; and hardly a moment passes, from early morning to sunset, in which we may not see some half-veiled figure enter beneath the Arabian porch, cast itself into long abasement on the floor of the temple, and then rising slowly with more confirmed step, and with a passionate kiss and clasp of the arms given to the feet of the crucifix, by which the lamps burn always in the northern aisle, leave the church as if comforted....

It would be easier to illustrate a crest of Scottish mountain, with its purple heather and pale harebells at their fullest and fairest, or a glade of Jura forest, with its floor of anemone and moss, than a single portico of St. Mark’s....7 The balls in the archivolt project considerably, and the interstices between their interwoven bands of marble are filled with colours like the illuminations of a manuscript; violet, crimson, blue, gold, and green alternately: but no green is ever used without an intermixture of blue pieces in the mosaic, nor any blue without a little centre of pale green; sometimes only a single piece of glass a quarter of an inch square, so subtle was the feeling for colour which was thus to be satisfied. The intermediate circles have golden stars set on an azure ground, varied in the same manner; and the small crosses seen in the intervals are alternately blue and subdued scarlet, with two small circles of white set in the golden ground above and beneath them, each only about half an inch across (this work, remember, being on the outside of the building, and twenty feet above the eye), while the blue crosses have each a pale green centre....

The third cupola, that over the altar, represents the witness of the Old Testament to Christ; showing him enthroned in its centre and surrounded by the patriarchs and prophets. But this dome was little seen by the people; their contemplation was intended to be chiefly drawn to that of the centre of the church, and thus the mind of the worshipper was at once fixed on the main groundwork and hope of Christianity—“Christ is risen,” and “Christ shall come.” If he had time to explore the minor lateral chapels and cupolas, he could find in them the whole series of New Testament history, the events of the Life of Christ, and the Apostolic miracles in their order, and finally the scenery of the Book of Revelation;8 but if he only entered, as often the common people do to this hour, snatching a few moments before beginning the labour of the day to offer up an ejaculatory prayer, and advanced but from the main entrance as far as the altar screen, all the splendour of the glittering nave and variegated dome, if they smote upon his heart, as they might often, in strange contrast with his reed cabin among the shallows of the lagoon, smote upon it only that they might proclaim the two great messages—“Christ is risen,” and “Christ shall come.” Daily, as the white cupolas rose like wreaths of sea-foam in the dawn, while the shadowy campanile and frowning palace were still withdrawn into the night, they rose with the Easter Voice of Triumph—“Christ is risen;” and daily, as they looked down upon the tumult of the people, deepening and eddying in the wide square that opened from their feet to the sea, they uttered above them the sentence of warning,—“Christ shall come.”

And this thought may surely dispose the reader to look with some change of temper upon the gorgeous building and wild blazonry of that shrine of St. Mark’s. He now perceives that it was in the hearts of the old Venetian people far more than a place of worship. It was at once a type of the Redeemed Church of God, and a scroll for the written word of God. It was to be to them, both an image of the Bride, all glorious within, her clothing of wrought gold; and the actual Table of the Law and the Testimony, written within and without. And whether honoured as the Church or as the Bible, was it not fitting that neither the gold nor the crystal should be spared9 in the adornment of it; that, as the symbol of the Bride, the building of the wall thereof should be of jasper, and the foundations of it garnished with all manner of precious stones; and that, as the channel of the World, that triumphant utterance of the Psalmist should be true of it—“I have rejoiced in the way of thy testimonies, as much as in all riches”? And shall we not look with changed temper down the long perspective of St. Mark’s Place towards the sevenfold gates and glowing domes of its temple, when we know with what solemn purpose the shafts of it were lifted above the pavement of the populous square? Men met there from all countries of the earth, for traffic or for pleasure; but, above the crowd swaying forever to and fro in the restlessness of avarice or thirst of delight, was seen perpetually the glory of the temple, attesting to them, whether they would hear or whether they would forbear, that there was one treasure which the merchantmen might buy without a price, and one delight better than all others, in the word and the statutes of God. Not in the wantonness of wealth, not in vain ministry to the desire of the eyes or the pride of life, were those marbles hewn into transparent strength, and those arches arrayed in the colours of the iris. There is a message written in the dyes of them, that once was written in blood; and a sound in the echoes of their vaults, that one day shall fill the vault of heaven,—“He shall return, to do judgment and justice.” The strength of Venice was given her, so long as she remembered this: her destruction found her when she had forgotten this; and it found her irrevocably, because she forgot it without excuse. Never had city a10 more glorious Bible. Among the nations of the North, a rude and shadowy sculpture filled their temples with confused and hardly legible imagery; but, for her the skill and the treasures of the East had gilded every letter, and illumined every page, till the Book-Temple shone from afar off like the star of the Magi.

Stones of Venice (London, 1851–’3).

11

Half a mile below London Bridge, on ground which was once a bluff, commanding the Thames from St. Saviour’s Creek to St. Olave’s Wharf, stands the Tower; a mass of ramparts, walls, and gates, the most ancient and most poetic pile in Europe.

Seen from the hill outside, the Tower appears to be white with age and wrinkled by remorse. The home of our stoutest kings, the grave of our noblest knights, the scene of our gayest revels, the field of our darkest crimes, that edifice speaks at once to the eye and to the soul. Grey keep, green tree, black gate, and frowning battlement, stand out, apart from all objects far and near them, menacing, picturesque, enchaining; working on the senses like a spell; and calling us away from our daily mood into a world of romance, like that which we find painted in light and shadow on Shakespeare’s page.

Looking at the Tower as either a prison, a palace, or a court, picture, poetry, and drama crowd upon the mind; and if the fancy dwells most frequently on the state prison, this is because the soul is more readily kindled by a human interest than fired by an archaic and official fact. For one man who would care to see the room in which a council12 met or a court was held, a hundred men would like to see the chamber in which Lady Jane Grey was lodged, the cell in which Sir Walter Raleigh wrote, the tower from which Sir John Oldcastle escaped. Who would not like to stand for a moment by those steps on which Ann Boleyn knelt; pause by that slit in the wall through which Arthur De la Pole gazed; and linger, if he could, in that room in which Cranmer, Latimer and Ridley, searched the New Testament together?

The Tower has an attraction for us akin to that of the house in which we were born, the school in which we were trained. Go where we may, that grim old edifice on the Pool goes with us; a part of all we know, and of all we are. Put seas between us and the Thames, this Tower will cling to us like a thing of life. It colours Shakespeare’s page. It casts a momentary gloom over Bacon’s story. Many of our books were written in its vaults; the Duke of Orleans’ “Poesies,” Raleigh’s “Historie of the World,” Eliot’s “Monarchy of Man,” and Penn’s “No Cross, No Crown.”

Even as to the length of days, the Tower has no rival among palaces and prisons; its origin, like that of the Iliad, that of the Sphinx, that of the Newton Stone, being lost in the nebulous ages, long before our definite history took shape. Old writers date it from the days of Cæsar; a legend taken up by Shakespeare and the poets, in favour of which the name of Cæsar’s Tower remains in popular use to this very day. A Roman wall can even yet be traced near some parts of the ditch. The Tower is mentioned in the Saxon Chronicle, in a way not incompatible with the13 fact of a Saxon stronghold having stood upon this spot. The buildings as we have them now in block and plan were commenced by William the Conqueror; and the series of apartments in Cæsar’s tower,—hall, gallery, council-chamber, chapel,—were built in the early Norman reigns, and used as a royal residence by all our Norman kings. What can Europe show to compare against such a tale?

Set against the Tower of London—with its eight hundred years of historic life, its nineteen hundred years of traditional fame—all other palaces and prisons appear like things of an hour. The oldest bit of palace in Europe, that of the west front of the Burg in Vienna, is of the time of Henry the Third. The Kremlin in Moscow, the Doge’s Palazzo in Venice, are of the Fourteenth Century. The Seraglio in Stamboul was built by Mohammed the Second. The oldest part of the Vatican was commenced by Borgia, whose name it bears. The old Louvre was commenced in the reign of Henry the Eighth; the Tuileries in that of Elizabeth. In the time of our Civil War Versailles was yet a swamp. Sans Souci and the Escurial belong to the Eighteenth Century. The Serail of Jerusalem is a Turkish edifice. The palaces of Athens, of Cairo, or Tehran, are all of modern date.

Neither can the prisons which remain in fact as well as in history and drama—with the one exception of St. Angelo in Rome—compare against the Tower. The Bastile is gone; the Bargello has become a museum; the Piombi are removed from the Doge’s roof. Vincennes, Spandau, Spilberg, Magdeburg, are all modern in comparison14 with a jail from which Ralph Flambard escaped so long ago as the year 1100, the date of the First Crusade.

Standing on Tower Hill, looking down on the dark lines of wall—picking out keep and turret, bastion and ballium, chapel and belfry—the jewel-house, the armoury, the mounts, the casemates, the open leads—the Bye-ward gate, the Belfry, the Bloody tower—the whole edifice seems alive with story; the story of a nation’s highest splendour, its deepest misery, and its darkest shame. The soil beneath your feet is richer in blood than many a great battlefield; for out upon this sod has been poured, from generation to generation, a stream of the noblest life in our land. Should you have come to this spot alone, in the early day, when the Tower is noisy with martial doings, you may haply catch, in the hum which rises from the ditch and issues from the wall below you—broken by roll of drum, by blast of bugle, by tramp of soldiers—some echoes, as it were, of a far-off time; some hints of a May-day revel; of a state execution; of a royal entry. You may catch some sound which recalls the thrum of a queen’s virginal, the cry of a victim on the rack, the laughter of a bridal feast. For all these sights and sounds—the dance of love and the dance of death—are part of that gay and tragic memory which clings around the Tower.

From the reign of Stephen down to that of Henry of Richmond, Cæsar’s tower (the great Norman keep, now called the White tower) was a main part of the royal palace; and for that large interval of time, the story of the White tower is in some sort that of our English society as well as of our English kings. Here were kept the royal15 wardrobe and the royal jewels; and hither came with their goodly wares, the tiremen, the goldsmiths, the chasers and embroiderers, from Flanders, Italy, and Almaigne. Close by were the Mint, the lions’ dens, the old archery-grounds, the Court of King’s Bench, the Court of Common Pleas, the Queen’s gardens, the royal banqueting-hall; so that art and trade, science and manners, literature and law, sport and politics, find themselves equally at home.

Two great architects designed the main parts of the Tower; Gundul the Weeper and Henry the Builder; one a poor Norman monk, the other a great English king....

Henry the Third, a prince of epical fancies, as Corffe, Conway, Beaumaris, and many other fine poems in stone attest, not only spent much of his time in the Tower, but much of his money in adding to its beauty and strength. Adam de Lamburn was his master mason; but Henry was his own chief clerk of the works. The Water gate, the embanked wharf, the Cradle tower, the Lantern, which he made his bedroom and private closet, the Galleyman tower, and the first wall, appear to have been his gifts. But the prince who did so much for Westminster Abbey, not content with giving stone and piles to the home in which he dwelt, enriched the chambers with frescoes and sculpture, the chapels with carving and glass; making St. John’s chapel in the White tower splendid with saints, St. Peter’s church on the Tower Green musical with bells. In the Hall tower, from which a passage led through the Great hall into the King’s bedroom in the Lantern, he built a tiny chapel for his private use—a chapel which served for the devotion of his successors until Henry the Sixth was stabbed16 to death before the cross. Sparing neither skill nor gold to make the great fortress worthy of his art, he sent to Purbeck for marble, and to Caen for stone. The dabs of lime, the spawls of flint, the layers of brick, which deface the walls and towers in too many places, are of either earlier or later times. The marble shafts, the noble groins, the delicate traceries, are Henry’s work. Traitor’s gate, one of the noblest arches in the world, was built by him; in short, nearly all that is purest in art is traceable to his reign....

The most eminent and interesting prisoner ever lodged in the Tower is Raleigh; eminent by his personal genius, interesting from his political fortune. Raleigh has in higher degree than any other captive who fills the Tower with story, the distinction that he was not the prisoner of his country, but the prisoner of Spain.

Many years ago I noted in the State Papers evidence, then unknown, that a very great part of the second and long imprisonment of the founder of Virginia was spent in the Bloody tower and the adjoining Garden house; writing at this grated window; working in the little garden on which it opened; pacing the terrace on this wall, which was afterwards famous as Raleigh’s Walk. Hither came to him the wits and poets, the scholars and inventors of his time; Johnson and Burrell, Hariot and Pett; to crack light jokes; to discuss rabbinical lore; to sound the depths of philosophy; to map out Virginia; to study the ship-builder’s art. In the Garden house he distilled essences and spirits; compounded his great cordial; discovered a method (afterwards lost) of turning salt water into sweet; received the visits of Prince Henry; wrote his political17 tracts; invented the modern warship; wrote his History of the World....

The day of Raleigh’s death was the day of a new English birth. Eliot was not the only youth of ardent soul who stood by the scaffold in Palace Yard, to note the matchless spirit in which the martyr met his fate, and walked away from that solemnity—a new man. Thousands of men in every part of England who had led a careless life became from that very hour the sleepless enemies of Spain. The purposes of Raleigh were accomplished, in the very way which his genius had contrived. Spain held the dominion of the sea, and England took it from her. Spain excluded England from the New World, and the genius of that New World is English.

The large contest in the new political system of the world, then young, but clearly enough defined, had come to turn upon this question—Shall America be mainly Spanish and theocratic, or English and free? Raleigh said it should be English and free. He gave his blood, his fortune, and his genius, to the great thought in his heart; and, in spite of that scene in Palace Yard, which struck men as the victory of Spain, America is at this moment English and free.

Her Majesty’s Tower (London, 1869).

18

I was awakened this morning with the chime which the Antwerp Cathedral clock plays at half hours. The tune has been haunting me ever since, as tunes will. You dress, eat, drink, walk, and talk to yourself to their tune; their inaudible jingle accompanies you all day; you read the sentences of the paper to their rhythm. I tried uncouthly to imitate the tune to the ladies of the family at breakfast, and they say it is “the shadow dance of Dinorah.” It may be so. I dimly remember that my body was once present during the performance of that opera, while my eyes were closed, and my intellectual faculties dormant at the back of the box; howbeit, I have learned that shadow dance from hearing it pealing up ever so high in the air at night, morn, noon.

How pleasant to lie awake and listen to the cheery peal, while the old city is asleep at midnight, or waking up rosy at sunrise, or basking in noon, or swept by the scudding rain which drives in gusts over the broad places, and the great shining river; or sparkling in snow, which dresses up a hundred thousand masts, peaks, and towers; or wrapped round with thunder—cloud canopies, before which the white gables shine whiter; day and night the kind19 little carillon plays its fantastic melodies overhead. The bells go on ringing. Quot vivos vocant, mortuos plangunt, fulgura frangunt; so on to the past and future tenses, and for how many nights, days, and years! While the French were pitching their fulgura into Chassé’s citadel, the bells went on ringing quite cheerfully. While the scaffolds were up and guarded by Alva’s soldiery, and regiments of penitents, blue, black, and grey, poured out of churches and convents, droning their dirges, and marching to the place of the Hôtel de Ville, where heretics and rebels were to meet their doom, the bells up yonder were chanting at their appointed half hours and quarters, and rang the mauvais quart d’heure for many a poor soul. This bell can see as far away as the towers and dikes of Rotterdam. That one can call a greeting to St. Ursula’s at Brussels, ind toss a recognition to that one at the town hall of Oudenarde, and remember how, after a great struggle there a hundred and fifty years ago, the whole plain was covered with flying French chivalry—Burgundy, and Berri, and the Chevalier of St. George flying like the rest. “What is your clamour about Oudenarde?” says another bell (Bob Major this one must be). “Be still thou querulous old clapper! I can see over to Hougoumont and St. John. And about forty-five years since, I rang all through one Sunday in June, when there was such a battle going on in the cornfields there as none of you others ever heard tolled of. Yes, from morning service until after vespers, the French and English were all at it, ding-dong!” And then calls of business intervening, the bells have to give up their private jangle, resume their20 professional duty, and sing their hourly chorus out of Dinorah.

What a prodigious distance those bells can be heard! I was awakened this morning to their tune, I say. I have been hearing it constantly ever since. And this house whence I write, Murray says, is two hundred and ten miles from Antwerp. And it is a week off; and there is the bell still jangling its shadow dance out of Dinorah. An audible shadow, you understand, and an invisible sound, but quite distinct; and a plague take the tune!

Who has not seen the church under the bell? Those lofty aisles, those twilight chapels, that cumbersome pulpit with its huge carvings, that wide grey pavement flecked with various light from the jewelled windows, those famous pictures between the voluminous columns over the altars which twinkle with their ornaments, their votive little silver hearts, legs, limbs, their little guttering tapers, cups of sham roses, and what not? I saw two regiments of little scholars creeping in and forming square, each in its appointed place, under the vast roof, and teachers presently coming to them. A stream of light from the jewelled windows beams slanting down upon each little squad of children, and the tall background of the church retires into a greyer gloom. Pattering little feet of laggards arriving echo through the great nave. They trot in and join their regiments, gathered under the slanting sunbeams. What are they learning? Is it truth? Those two grey ladies with their books in their hands in the midst of these little people have no doubt of the truth of every word they have printed under their eyes. Look,21 through the windows jewelled all over with saints, the light comes streaming down from the sky, and heaven’s own illuminations paint the book! A sweet, touching picture indeed it is, that of the little children assembled in this immense temple, which has endured for ages, and grave teachers bending over them. Yes, the picture is very pretty of the children and their teachers, and their book—but the text? Is it the truth, the only truth, nothing but the truth? If I thought so, I would go and sit down on the form cum parvulis, and learn the precious lesson with all my heart.

But I submit, an obstacle to conversions is the intrusion and impertinence of that Swiss fellow with the baldric—the officer who answers to the beadle of the British islands—and is pacing about the church with an eye on the congregation. Now the boast of Catholics is that their churches are open to all; but in certain places and churches there are exceptions. At Rome I have been into St. Peter’s at all hours: the doors are always open, the lamps are always burning, the faithful are forever kneeling at one shrine or the other. But at Antwerp it is not so. In the afternoon you can go to the church and be civilly treated, but you must pay a franc at the side gate. In the forenoon the doors are open, to be sure, and there is no one to levy an entrance fee. I was standing ever so still, looking through the great gates of the choir at the twinkling lights, and listening to the distant chants of the priests performing the service, when a sweet chorus from the organ-loft broke out behind me overhead, and I turned round. My friend the drum-major ecclesiastic22 was down upon me in a moment. “Do not turn your back to the altar during divine service,” says he, in very intelligible English. I take the rebuke, and turn a soft right-about face, and listen a while as the service continues. See it I cannot, nor the altar and its ministrants. We are separated from these by a great screen and closed gates of iron, through which the lamps glitter and the chant comes by gusts only. Seeing a score of children trotting down a side aisle, I think I may follow them. I am tired of looking at that hideous old pulpit, with its grotesque monsters and decorations. I slip off to the side aisle; but my friend the drum-major is instantly after me—almost I thought he was going to lay hands on me. “You mustn’t go there,” says he; “you mustn’t disturb the service.” I was moving as quietly as might be, and ten paces off there were twenty children kicking and chattering at their ease. I point them out to the Swiss. “They come to pray,” says he. “You don’t come to pray; you—” “When I come to pay,” says I, “I am welcome,” and with this withering sarcasm I walk out of church in a huff. I don’t envy the feelings of that beadle after receiving point blank such a stroke of wit.

Roundabout Papers (London, 1863).

23

It is well known that the Taj is a mausoleum built by the Mogul Shah-Jehan to the Begum Mumtaz-i-Mahal. It is a regular octagon surmounted by a Persian dome, which is surrounded by four minarets. The building, erected upon a terrace which dominates the enclosing gardens, is constructed of blocks of the purest white marble, and rises to a height of two hundred and forty-three feet. We step from the carriage before a noble portico of red sandstone, pierced by a bold arch and covered with white arabesques. After passing through this arch, we see the Taj looming up before us eight hundred metres distant. Probably no masterpiece of architecture calls forth a similar emotion.

At the back of a marvellous garden and with all of its whiteness reflected in a canal of dark water, sleeping inertly among thick masses of black cypress and great clumps of red flowers, this perfect tomb rises like a calm apparition. It is a floating dream, an aërial form without weight, so perfect is the balance of the lines, and so pale, so delicate the shadows that float across the virginal and translucent stone. These black cypresses which frame it, this verdure through the openings of which peeps the blue sky, and24 this sward bathed in brilliant sunlight and on which the sharply-cut silhouettes of the trees are lying,—all these real objects render more unreal the delicate vision, which seems to melt away into the light of the sky. I walk towards it along the marble bank of the dark canal, and the mausoleum assumes sharper form. On approaching you take more delight in the surface of the octagonal edifice. This consists of rectangular expanses of polished marble where the light rests with a soft, milky splendour. One would never imagine that so simple a thing as surface could be so beautiful when it is large and pure. The eye follows the ingenious and graceful scrolls of great flowers, flowers of onyx and turquoise, incrusted with perfect smoothness, the harmony of the delicate carving, the marble lace-work, the balustrades of a thousand perforations,—the infinite display of simplicity and decoration.

The garden completes the monument, and both unite to form this masterpiece of art. The avenues leading to the Taj are bordered with funereal yews and cypresses, which make the whiteness of the far-away marble appear even whiter. Behind their slender cones thick and massive bushes add richness and depth to this solemn vegetation. The stiff and sombre trees, standing out in relief from this waving foliage, rise up solemnly with their trunks half-buried in masses of roses, or are surrounded by clusters of a thousand unknown and sweet-scented flowers which are blossoming in great masses in this solitary garden. He must have been an extraordinary artist who conceived this place. Sweeps of lawn, purple-chaliced flowers, golden petals, swarms of humming bees, and diapered butterflies25 give light and joy to the gloom of the burial-ground. This place is both luminous and solemn; it contains the amorous and religious delights of the Mussulman paradise, and the poem in trees and flowers unites with the poem in marble to sing of splendour and peace.

The interior of the mausoleum is at first as dark as night, but through this darkness a grille of antique marble is faintly gleaming, a mysterious marble-lace, which drapes the tombs, and which seems to wind and unwind forever, shedding on the splendour of the vault a yellow light, which seems to be ancient, and to have rested there for ages. And the pale web of marble wreathes and wreathes until it loses itself in the darkness.

In the centre are the tombs of the lovers; two small sarcophagi upon which a mysterious light falls, but whence it comes no one knows. There is nothing more. They sleep here in the silence, surrounded by perfect beauty which celebrates their love that has lasted even through death, and which is still isolated from everything by the mysterious marble-lace which enfolds them and which floats above them like a dream.

Very high overhead, as if through a thick vapour, we see the dome loom through the shadows, although its entire outlines are not perceptible; its walls seem made of mist, and its marble blocks appear to have no solidity. Everything is aërial here, nothing is substantial or real: this is a world of shadowy visions. Even sounds are unearthly. A note sung under this vault is echoed above our heads in an invisible region. First, it is as clear as the voice of Ariel, then it grows fainter and fainter until it dies away and then26 is re-echoed very far above, but glorified, spiritualized, and multiplied indefinitely as if repeated by a distant company, a choir of unseen angels who soar with it aloft until all is lost save a faint murmur which never ceases to vibrate over the tomb of the beloved, as if it were the very soul of a musician.

I have seen the Taj again; this time at noon. Under the vertical sun the melancholy phantom has vanished, the sweet sadness of the mausoleum has gone. The great marble table on which it stands is blinding. The light, reflected back and forth from the immense surfaces of white marble, is increased a hundred-fold in intensity, and some of the sides are like burning plaques. The incrustations seem to be sparks of magic fire; their hundreds of red flowers gleam like burning coals. The religious texts and the hieroglyphs, inlaid with black marble, stand out as if traced by the lightning-finger of a savage god. All the mystical rows of lotus and lilies unfolding in relief, which just now had the softness of yellowed ivory, spring forth like flames.—I retrace my steps, passing out of the entrance, and for an instant I have a dazzling view of the lines and incandescent surfaces of the building with its unchanging virgin whiteness.—Indeed, this severe simplicity and intensity of light give it something of a Semitic character: we think of the flaming and chastening sword of the Bible. The minarets lift themselves into the blue like pillars of fire.

I wander outside in the fresh air under the shadows of the leafy arches until twilight. This garden is the conception of one of the faithful who wished to glorify Allah.27 It is the home of religious delight:—“No one shall enter the garden of God unless he is pure of heart,” is the Arabian text graven over the entrance-gate. Here are flower-beds, which are masses of velvet,—unknown blooms resembling heaps of purple moss. The trunks of the trees are entwined with blue convolvulus, and flowers like great red stars gleam through the dark foliage. Over these flowers a hundred thousand delicate butterflies hover in a perpetual cloud. Many pretty creatures, little striped squirrels and numerous birds, green parrots and parrots of more brilliant plumage, disport themselves here, making a little world, happy and secure, for guards, dressed in white muslin, menace with long pea-shooters the crows and vultures and protect them from everything that would bring mischief or cruelty into this peaceful place.

On the surface of the still waters lilies and lotus are sleeping, their stiff leaves pinked out and resting heavily upon the dark mirror.

Through the blackness of the boughs English meadows are revealed, bathed in brilliant sunlight, and spaces of blue sky, across which a triangle of white storks is sometimes seen flying, and, at certain moments, the far-away vision of the phantom tomb seems like the melancholy spectre of a virgin.—How calm, how superb this solitude, charged with voluptuousness at once solemn and enervating! Here dwell the beauty, the tenderness, and the light of Asia, dreamed of by Shelley.

Dans l’Inde (Paris, 1891).

28

Most certainly, the Cathedral of Notre-Dame is still a sublime and majestic edifice. But, despite the beauty which it preserves in its old age, it would be impossible not to be indignant at the injuries and mutilations which Time and man have jointly inflicted upon the venerable structure without respect for Charlemagne, who laid its first stone, and Philip Augustus, who laid its last.

There is always a scar beside a wrinkle on the face of this aged queen of our cathedrals. Tempus edax homo edacior, which I should translate thus: Time is blind, man is stupid.

If we had leisure to examine one by one, with the reader, the various traces of destruction imprinted on the old church, Time’s work would prove to be less destructive than men’s, especially des hommes de l’art, because there have been some individuals in the last two centuries who considered themselves architects.

First, to cite several striking examples, assuredly there are few more beautiful pages in architecture than that façade, exhibiting the three deeply-dug porches with their pointed arches; the plinth, embroidered and indented with twenty-eight royal niches; the immense central rose-window,29 flanked by its two lateral windows, like the priest by his deacon and sub-deacon; the high and frail gallery of open-worked arches, supporting on its delicate columns a heavy platform; and, lastly, the two dark and massive towers, with their slated pent-houses. These harmonious parts of a magnificent whole, superimposed in five gigantic stages, and presenting, with their innumerable details of statuary, sculpture, and carving, an overwhelming yet not perplexing mass, combine in producing a calm grandeur. It is a vast symphony in stone, so to speak; the colossal work of man and of a nation, as united and as complex as the Iliad and the romanceros of which it is the sister; a prodigious production to which all the forces of an epoch contributed, and from every stone of which springs forth in a hundred ways the workman’s fancy directed by the artist’s genius; in one word, a kind of human creation, as strong and fecund as the divine creation from which it seems to have stolen the two-fold character: variety and eternity.

And what I say here of the façade, must be said of the entire Cathedral; and what I say of the Cathedral of Paris, must be said of all the Mediæval Christian churches. Everything in this art, which proceeds from itself, is so logical and well-proportioned that to measure the toe of the foot is to measure the giant.

Let us return to the façade of Notre-Dame, as it exists to-day when we go reverently to admire the solemn and mighty Cathedral, which, according to the old chroniclers, was terrifying: quæ mole sua terrorem incutit spectantibus.

That façade now lacks three important things: first, the30 flight of eleven steps, which raised it above the level of the ground; then, the lower row of statues which occupied the niches of the three porches; and the upper row1 of the twenty-eight ancient kings of France which ornamented the gallery of the first story, beginning with Childebert and ending with Philip Augustus, holding in his hand “la pomme impériale.”

Time in its slow and unchecked progress, raising the level of the city’s soil, buried the steps; but whilst the pavement of Paris like a rising tide has engulfed one by one the eleven steps which formerly added to the majestic height of the edifice, Time has given to the church more, perhaps, than it has stolen, for it is Time that has spread that sombre hue of centuries on the façade which makes the old age of buildings their period of beauty.

But who has thrown down those two rows of statues? Who has left the niches empty? Who has cut that new and bastard arch in the beautiful middle of the central porch? Who has dared to frame that tasteless and heavy wooden door carved à la Louis XV. near Biscornette’s arabesques? The men, the architects, the artists of our day.

And when we enter the edifice, who has overthrown that colossal Saint Christopher, proverbial among statues as the grand’ salle du Palais among halls, or the flèche of Strasburg among steeples? And those myriads of statues that peopled all the spaces between the columns of the nave and choir, kneeling, standing, on horseback, men,31 women, children, kings, bishops, warriors, in stone, wood, marble, gold, silver, copper, and even wax,—who has brutally swept them away? It was not Time!

And who has substituted for the old Gothic altar, splendidly overladen with shrines and reliquaries, that heavy marble sarcophagus with its angels’ heads and clouds, which seems to be a sample from the Val-de-Grâce or the Invalides? Who has so stupidly imbedded that heavy stone anachronism in Hercanduc’s Carlovingian pavement? Is it not Louis XIV. fulfilling the vow of Louis XIII.?

And who has put cold white glass in the place of those richly-coloured panes, which made the astonished gaze of our ancestors pause between the rose of the great porch and the pointed arches of the apsis? What would an under-chorister of the Sixteenth Century say if he could see the beautiful yellow plaster with which our vandal archbishops have daubed their Cathedral? He would remember that this was the colour with which the executioner brushed the houses of traitors; he would remember the Hôtel du Petit-Bourbon, all besmeared thus with yellow, on account of the treason of the Constable, “yellow of such good quality,” says Sauval, “and so well laid on that more than a century has scarcely caused its colour to fade;” and, imagining that the holy place had become infamous, he would flee from it.

And if we ascend the Cathedral without stopping to notice the thousand barbarities of all kinds, what has been done with that charming little bell-tower, which stood over the point of intersection of the transept, and which, neither less frail nor less bold than its neighbour, the32 steeple of the Sainte-Chapelle (also destroyed), shot up into the sky, sharp, harmonious, and open-worked, higher than the other towers? It was amputated by an architect of good taste (1787), who thought it sufficient to cover the wound with that large plaster of lead, which looks like the lid of a pot.

This is the way the wonderful art of the Middle Ages has been treated in all countries, particularly in France. In this ruin we may distinguish three separate agencies, which have affected it in different degrees; first, Time which has insensibly chipped it, here and there, and discoloured its entire surface; next, revolutions, both political and religious, which, being blind and furious by nature, rushed wildly upon it, stripped it of its rich garb of sculptures and carvings, shattered its tracery, broke its garlands of arabesques and its figurines, and threw down its statues, sometimes on account of their mitres, sometimes on account of their crowns; and, finally, the fashions, which, ever since the anarchistic and splendid innovations of the Renaissance, have been constantly growing more grotesque and foolish, and have succeeded in bringing about the decadence of architecture. The fashions have indeed done more harm than the revolutions. They have cut it to the quick; they have attacked the framework of art; they have cut, hacked, and mutilated the form of the building as well as its symbol; its logic as well as its beauty. And then they have restored, a presumption of which time and revolutions were, at least, guiltless. In the name of good taste they have insolently covered the wounds of Gothic architecture with their paltry gew-gaws of a day,33 their marble ribbons, their metal pompons, a veritable leprosy of oval ornaments, volutes, spirals, draperies, garlands, fringes, flames of stone, clouds of bronze, over-fat Cupids, and bloated cherubim, which begin to eat into the face of art in Catherine de’ Medici’s oratory, and kill it, writhing and grinning in the boudoir of the Dubarry, two centuries later.

Therefore, in summing up the points to which I have called attention, three kinds of ravages disfigure Gothic architecture to-day: wrinkles and warts on the epidermis,—these are the work of Time; wounds, bruises and fractures,—these are the work of revolutions from Luther to Mirabeau; mutilations, amputations, dislocations of members, restorations,—these are the Greek and Roman work of professors, according to Vitruvius and Vignole. That magnificent art which the Vandals produced, academies have murdered. To the ravages of centuries and revolutions, which devastated at least with impartiality and grandeur, were added those of a host of school architects, patented and sworn, who debased everything with the choice and discernment of bad taste; and who substituted the chicorées of Louis XV. for the Gothic lace-work, for the greater glory of the Parthenon. It is the ass’s kick to the dying lion. It is the old oak crowning itself with leaves for the reward of being bitten, gnawed, and devoured by caterpillars.

How far this is from the period when Robert Cenalis, comparing Notre-Dame de Paris with the famous Temple of Diana at Ephesus, so highly extolled by the ancient heathen, which has immortalized Erostratus, found the34 Gaulois cathedral “plus excellente en longueur, largeur, hauteur, et structure.”

Notre-Dame de Paris is not, however, what may be called a finished, defined, classified monument. It is not a Roman church, neither is it a Gothic church. This edifice is not a type. Notre-Dame has not, like the Abbey of Tournus, the solemn and massive squareness, the round and large vault, the glacial nudity, and the majestic simplicity of those buildings which have the circular arch for their generative principle. It is not, like the Cathedral of Bourges, the magnificent product of light, multiform, tufted, bristling, efflorescent Gothic. It is out of the question to class it in that ancient family of gloomy, mysterious, low churches, which seem crushed by the circular arch; almost Egyptian in their ceiling; quite hieroglyphic, sacerdotal, and symbolic, charged in their ornaments with more lozenges and zigzags than flowers, more flowers than animals, more animals than human figures; the work of the bishop more than the architect, the first transformation of the art, fully impressed with theocratic and military discipline, which takes its root in the Bas-Empire, and ends with William the Conqueror. It is also out of the question to place our Cathedral in that other family of churches, tall, aërial, rich in windows and sculpture, sharp in form, bold of mien; communales and bourgeois, like political symbols; free, capricious, unbridled, like works of art; the second transformation of architecture, no longer hieroglyphic, immutable, and sacerdotal, but artistic, progressive, and popular, which begins with the return from the Crusades and ends with Louis XI. Notre-Dame de Paris is35 not pure Roman, like the former, nor is it pure Arabian, like the latter.

It is an edifice of the transition. The Saxon architect had set up the first pillars of the nave when the Crusaders introduced the pointed arch, which enthroned itself like a conqueror upon those broad Roman capitals designed to support circular arches. On the pointed arch, thenceforth mistress of all styles, the rest of the church was built. Inexperienced and timid at the beginning, it soon broadens and expands, but does not yet dare to shoot up into steeples and pinnacles, as it has since done in so many marvellous cathedrals. You might say that it feels the influence of its neighbours, the heavy Roman pillars.

Moreover, these edifices of the transition from the Roman to the Gothic are not less valuable for study than pure types. They express a nuance of the art which would be lost but for them. This is the engrafting of the pointed upon the circular arch.

Notre-Dame de Paris is a particularly curious specimen of this variety. Every face and every stone of the venerable structure is a page not only of the history of the country, but also of art and science. Therefore to glance here only at the principal details, while the little Porte Rouge attains almost to the limits of the Gothic delicacy of the Fifteenth Century, the pillars of the nave, on account of their bulk and heaviness, carry you back to the date of the Carlovingian Abbey of Saint-Germain des Prés, you would believe that there were six centuries between that doorway and those pillars. It is not only the hermetics who find in the symbols of the large porch a satisfactory compendium36 of their science, of which the church of Saint-Jacques de la Boucherie was so complete an hieroglyphic. Thus the Roman Abbey, the philosophical church, the Gothic art, the Saxon art, the heavy, round pillar, which reminds you of Gregory VII., the hermetic symbols by which Nicholas Flamel heralded Luther, papal unity and schism, Saint-Germain des Prés and Saint-Jacques de la Boucherie; all are melted, combined, amalgamated in Notre-Dame. This central and generatrix church is a sort of chimæra among the old churches of Paris; it has the head of one, the limbs of another, the body of another,—something from each of them.

I repeat, these hybrid structures are not the least interesting ones to the artist, the antiquary, and the historian. They show how far architecture is a primitive art, inasmuch as they demonstrate (what is also demonstrated by the Cyclopean remains, the pyramids of Egypt, and the gigantic Hindu pagodas), that the grandest productions of architecture are social more than individual works; the offspring, rather, of nations in travail than the inspiration of men of genius; the deposit left by a people; the accumulation of ages; the residuum of the successive evaporations of human society; in short, a species of formation. Every wave of time superimposes its alluvion, every generation deposits its stratum upon the building, every individual lays his stone. Thus build the beavers; thus, the bees; and thus, men. The great symbol of architecture, Babel, is a beehive.

Great buildings, like great mountains, are the work of centuries. Often the fashions in art change while they are37 being constructed, pendent opera interrupta; they are continued quietly according to the new art. This new art takes the edifice where it finds it, assimilates with it, develops it according to its own fancy, and completes it, if it is possible. The result is accomplished without disturbance, without effort, without reaction, following a natural and quiet law. It is a graft which occurs unexpectedly, a sap which circulates, a vegetation which returns. Certes, there is material for very large books and often a universal history of mankind, in those successive solderings of various styles at various heights upon the structure. The man, the artist, and the individual efface themselves in these vast anonymous masses; human intelligence is concentrated and summed up in them. Time is the architect; the nation is the mason.

Notre Dame de Paris (Paris, 1831).

38

The Kremlin, always regarded as the Acropolis, the Holy Place, the Palladium, and the very heart of Russia, was formerly surrounded by a palisade of strong oaken stakes—similar to the defence which the Athenian citadel had at the time of the first invasion of the Persians. Dmitri-Donskoi substituted for this palisade crenellated walls, which, having become old and dilapidated, were rebuilt by Ivan III. Ivan’s wall remains to-day, but in many places there are restorations and repairs. Thick layers of plaster endeavour to hide the scars of time and the black traces of the great fire of 1812 which was only able to lick this wall with its tongues of flame. The Kremlin somewhat resembles the Alhambra. Like the Moorish fortress, it stands on the top of a hill which it encloses with its wall flanked by towers: it contains royal dwellings, churches, and squares, and among the ancient buildings a modern Palace whose intrusion we regret as we do the Palace of Charles V. amid the delicate Saracenic architecture which it seems to crush with its weight. The tower of Ivan Veliki is not without resemblance to the tower of the Vela; and from the Kremlin, as from the39 Alhambra, a beautiful view is to be enjoyed, a panorama of enchantment which the fascinated eye will ever retain.

It is strange that when seen from a distance the Kremlin is perhaps even more Oriental than the Alhambra itself whose massive reddish towers give no hint of the splendour within. Above the sloping and crenellated walls of the Kremlin and among the towers with their ornamented roofs, myriads of cupolas and globular bell-towers gleaming with metallic light seem to be rising and falling like bubbles of glittering gold in the strong blaze of light. The white wall seems to be a silver basket holding a bouquet of golden flowers, and we fancy that we are gazing upon one of those magical cities which the imagination of the Arabian story-tellers alone can build—an architectural crystallization of the Thousand and One Nights! And when Winter has sprinkled these strange dream-buildings with its powdered diamonds, we fancy ourselves transported into another planet, for nothing like this has ever met our gaze.

We entered the Kremlin by the Spasskoi Gate which opens upon the Krasnaïa. No entrance could be more romantic. It is cut through an enormous square tower, placed before a kind of porch. The tower has three diminishing stories and is crowned with a spire resting upon open arches. The double-headed eagle, holding the globe in its claws, stands upon the sharp point of the spire, which, like the story it surmounts, is octagonal, ribbed, and gilded. Each face of the second story bears an enormous dial, so that the hour may be seen from every point of the compass. Add for effect some patches of snow laid on the jutting masonry like bold dashes of pigment, and you will have a40 faint idea of the aspect presented by this queenly tower, as it springs upward in three jets above the denticulated wall which it breaks....

Issuing from the gate, we find ourselves in the large court of the Kremlin, in the midst of the most bewildering conglomeration of palaces, churches, and monasteries of which the imagination can dream. It conforms to no known style of architecture. It is not Greek, it is not Byzantine, it is not Gothic, it is not Saracen, it is not Chinese: it is Russian; it is Muscovite. Never did architecture more free, more original, more indifferent to rules, in a word, more romantic, materialize with such fantastic caprice. Sometimes it seems to resemble the freaks of frostwork. However, its leading characteristics are the cupolas and the golden-bulbed bell-towers, which seem to follow no law and are conspicuous at the first glance.

Below the large square where the principal buildings of the Kremlin are grouped and which forms the plateau of the hill, a circular road winds about the irregularities of the ground and is bordered by ramparts flanked with towers of infinite variety: some are round, some square, some slender as minarets, some massive as bastions, and some with machicolated turrets, while others have retreating stories, vaulted roofs, sharply-cut sides, open-worked galleries, tiny cupolas, spires, scales, tracery, and all conceivable endings. The battlements, cut deeply through the wall and notched at the top like an arrow, are alternately plain and pierced with little barbicans. We will ignore the strategic value of this defence, but from a poetic standpoint it satisfies the imagination and gives the idea of a formidable citadel.

41

Between the rampart and the platform bordered by a balustrade gardens extend, now powdered with snow, and a picturesque little church lifts its globular bell-towers. Beyond, as far as the eye can reach, lies the immense and wonderful panorama of Moscow to which the crest of the saw-toothed wall forms an admirable foreground and frame for the distant perspective which no art could improve....

The Kremlin contains within its walls many churches, or cathedrals, as the Russians call them. Exactly like the Acropolis, it gathers around it on its narrow plateau a large number of temples. We will visit them one by one, but we will first pause at the tower of Ivan Veliki, an enormous octagon belfry with three retreating stories, upon the last of which there rises from a zone of ornamentation a round turret finished with a swelling dome, fire-gilt with ducat-gold, and surmounted by a Greek cross resting upon the conquered crescent. Upon each side of each story little arches are cut so that the brazen body of a bell may be seen.

In this place there are thirty-three bells, among which is said to be the famous alarm-bell of Novgorod, whose reverberations once called the people to the tumultuous deliberations in the public square. One of these bells weighs not less than a hundred and ninety-three tons, and is such a monster of metal that beside it the great bell of Notre-Dame of which Quasimodo was so proud, would be nothing more than the tiny hand-bell used at Mass....

Let us enter one of the most ancient and characteristic cathedrals of the Kremlin, the first one built of stone, the42 Cathedral of the Assumption (Ouspenskosabor). It is not the original edifice founded by Ivan Kalita. That crumbled away after a century and a half of existence and was rebuilt by Ivan III. Notwithstanding its Byzantine style and archaic appearance, the present Cathedral dates only from the Fifteenth Century. One is astonished to learn that it is the work of Fioraventi, an architect of Bologna, whom the Russians called Aristotle because of his astounding knowledge. One would imagine it the work of some Greek architect from Constantinople whose head was filled with memories of Santa Sofia and models of Greco-Oriental architecture. The Assumption is almost square and its great walls soar with a surprising pride and strength. Four enormous pillars, large as towers and massive as the columns of the Palace of Karnak, support the central cupola, which rests on a flat roof in the Asiatic style, flanked by four similar cupolas. This simple arrangement produces a magnificent effect and these massive pillars contribute, without any heaviness, a fine balance and extraordinary stability to the Cathedral.

The interior of the church is covered with Byzantine paintings on a gold background. The pillars themselves are embellished with figures arranged in zones as in the Egyptian temples and palaces. Nothing could be more strange than this decoration where thousands of figures surround you like a mute assemblage, ascending and descending the entire length of the walls, walking in files in Christian panathenæa, standing alone in poses of hieratic rigidity, bending over to the pendentives, and draping the temple with a human tapestry swarming with motionless43 beings. A strange light, carefully disposed, contributes greatly to the disquieting and mysterious effect. In these ruddy and fawn-coloured shadows the tall savage saints of the Greek calendar assume a formidable semblance of life; they look at you with fixed eyes and seem to threaten you with their hands outstretched for benediction.... The interior of St. Mark’s at Venice, with its suggestion of a gilded cavern, gives the idea of the Assumption; only the interior of the Muscovite church rises with one sweep towards the sky, while the vault of St. Mark’s is strangely weighed down like a crypt. The iconostase, a lofty wall of silver-gilt with five rows of figures, is like the façade of a golden palace, dazzling the eye with fabled magnificence. In the filigree framework of gold appear in tones of bistre the dark heads and hands of the Madonnas and saints. The rays of their aureoles are set with precious stones, which, as the light falls upon them, scintillate and blaze with celestial glory; the images, objects of peculiar veneration, are adorned with breastplates of precious stones, necklaces, and bracelets, starred with diamonds, sapphires, rubies, emeralds, amethysts, pearls, and turquoises; the madness of religious extravagance can go no further.

It is in the Cathedral of the Assumption that the coronation of the Czar takes place. The platform for this occasion is erected between the four pillars which support the cupola and faces the iconostase.

The tombs of the Metropolitans of Moscow are placed in rows along the sides of the walls. They are oblong: as they loom up in the shadows, they make us think of trunks packed for the great voyage of eternity....

44

At the side of the new palace and very near these churches a strange building is seen, of no known style of architecture, neither Asiatic nor Tartar, and which for a secular building is much what Vassili-Blagennoi is for a religious edifice,—the perfectly realized chimæra of a sumptuous, barbaric, and fantastic imagination. It was built under Ivan III. by the architect Aleviso. Above its roof several towers, capped with gold and containing within them chapels and oratories, spring up with a graceful and picturesque irregularity. An outside staircase, from the top of which the Czar shows himself to the people after his coronation, gives access to the building and produces by its ornamented projection a unique architectural effect. It is to Moscow what the Giants’ Stairway is to Venice. It is one of the curiosities of the Kremlin. In Russia it is known as the Red Stairway (Krasnoi-Kriltosi). The interior of the Palace, the residence of the ancient Czars, defies description; one would say that its chambers and passages have been excavated according to no determined plan in some curious block of stone, for they are so strangely entangled, so winding and complicated, and so constantly changing their level and direction that they seem to have been ordered at the caprice of an extravagant fancy. We walk through them as in a dream, sometimes stopped by a grille which opens mysteriously, sometimes forced to follow a narrow dark passage in which our shoulders almost touch both walls, sometimes having no other path than the toothed ledge of a cornice from which the copper plates of the roofs and the globular belfries are visible, constantly ascending, descending without knowing where we are, seeing45 beyond us through the golden trellises the gleam of a lamp flashing back from the golden filigree-work of the shrines, and emerging after this intramural journey into a hall with a rich and riotous wildness of ornamentation, at the end of which we are surprised at not seeing the Grand Kniaz of Tartary seated cross-legged upon his carpet of black felt.

Such for example is the hall called the Golden Chamber, which occupies the entire Granovitaïa Palata (the Facet Palace), so called doubtless on account of its exterior being cut in diamond facets. The Granovitaïa Palata adjoins the old palace of the Czars. The golden vaults of this hall rest upon a central pillar by means of surbased arches from which thick bars of elliptical gilded iron go across from one arc to another to prevent their spreading. Several paintings here and there make sombre spots upon the burnished gold splendour of the background.

Upon the string-courses of the arches legends are written in old Sclavonic letters—magnificent characters which lend themselves with as much effect for ornamentation as the Cufic letters on Arabian buildings. Richer, more mysterious, and yet more brilliant decorations than these of the Golden Chamber cannot be imagined. A romantic person would like to see a Shakespearian play acted here.

Certain vaulted halls of the old Palace are so low that a man who is a little above the average height cannot stand upright in them. It is here, in an atmosphere overcharged with heat, that the women, lounging on cushions in Oriental style, spend the hours of the long Russian winter in gazing through the little windows at the snow sparkling on the46 golden cupolas and the ravens whirling in great circles around the bell-towers.

These apartments with their motley wall-decorations of palms, foliage, and flowers, recalling the patterns of Cashmere, make us imagine these to be Asiatic harems transported to the polar frosts. The true Muscovite taste, perverted later by a badly-understood imitation of Western art, appears here in all its primitive originality and intensely barbaric flavour.

I have frequently observed that the progress of civilization seems to deprive nations of the true sense of architecture and decoration. The ancient edifices of the Kremlin prove once again how true is this assertion, which appears paradoxical at first. An inexhaustible fantasy presides over the decoration of these mysterious rooms where the gold, the green, the blue, and the red mingle with a rare happiness and produce the most charming effects. This architecture, without the least regard for symmetry, rises like a honey-comb of soap-bubbles blown upon a plate. Each little cell takes its place adjoining its neighbour, arranging its own angles and facets until the whole glitters with colours diapered with iris. This childish and bizarre comparison will give you a better idea than anything else of the aggregation of these palaces, so fantastic, yet so real.

It is in this style that we wish they had built the new Palace, an immense building in good modern taste and which would have a beauty elsewhere, but none whatever in the centre of the old Kremlin. The classic architecture with its long cold lines seems more wearisome and solemn here among these palaces with their strange forms, their47 gaudy colours, and this throng of churches of Oriental style darting towards the sky a golden forest of cupolas, domes, pyramidal spires, and bulbous bell-towers.