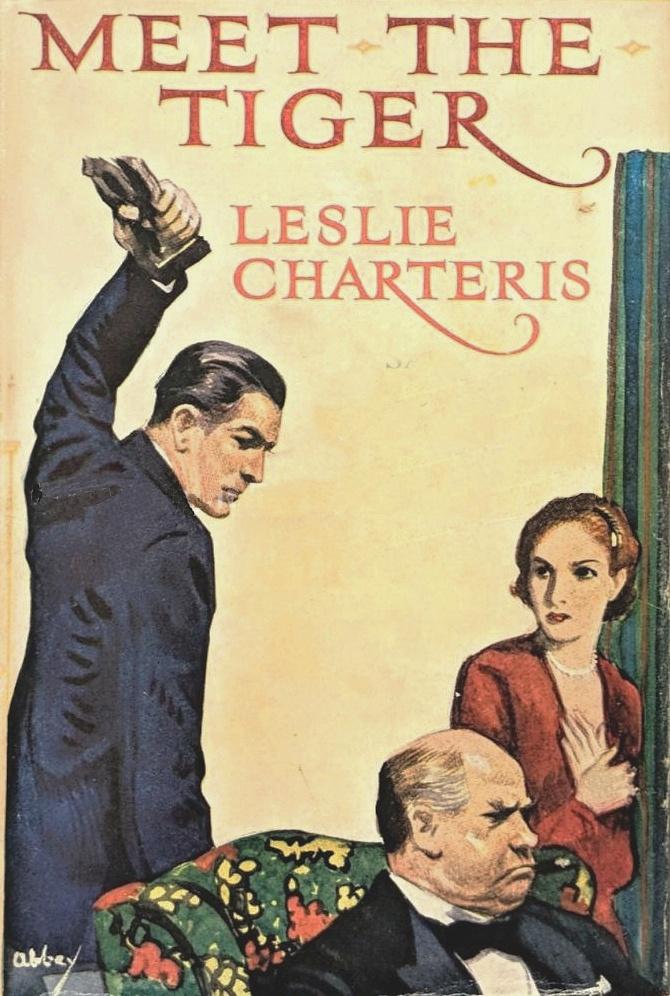

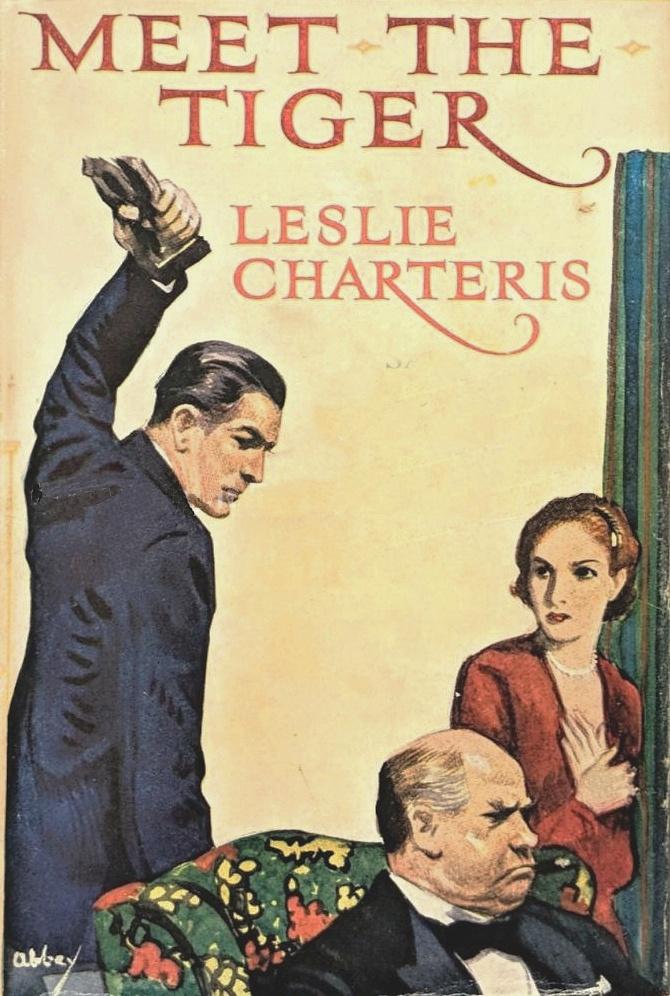

The First ‘Saint’ Novel

| I. | The Pill Box |

| II. | The Naturalist |

| III. | A Little Melodrama |

| IV. | A Social Evening |

| V. | Aunt Agatha is Upset |

| VI. | The Kindness of the Tiger |

| VII. | The Fun Continues |

| VIII. | The Saint is Dense |

| IX. | Patricia Perseveres |

| X. | The Old House |

| XI. | Carn Listens In |

| XII. | Tea with Lapping |

| XIII. | The Brand |

| XIV. | Captain Patricia |

| XV. | Spurs for Algy |

| XVI. | In the Swim |

| XVII. | Piracy |

| XVIII. | The Saint Returns |

| XIX. | The Tiger |

| XX. | The Last Laugh |

Baycombe is a village on the North Devon coast that is so isolated from civilisation that even at the height of the summer holiday season it is neglected by the rush of lean and plump, tall and short, papas, mammas, and infants. Consequently, there was some sort of excuse for a man who had taken up his dwelling there falling into the monotony of regular habits—even for a man who had only lived there for three days—even (let the worst be known) for a man so unconventional as Simon Templar.

It was not so very long after Simon Templar had settled down in Baycombe that that peacefully sedate village became most unsettled, and things began to happen there that shocked and flabbergasted its peacefully sedate inhabitants, as will be related; but at first Simon Templar found Baycombe as dull as it had been for the last six hundred years.

Simon Templar—in some parts of the world he was quite well known, from his initials, as the Saint—was a man of twenty-seven, tall, dark, keen-faced, deeply tanned, blue-eyed. That is a rough description. It was not long before Baycombe had observed him more closely, and woven mysterious legends about him. Baycombe did that within the first two days of his arrival, and it must be admitted that he had given some grounds for speculation.

The house he lived in (it may perhaps be dignified with the title of “house,” since a gang of workmen from Ilfracombe had worked without rest for thirty-six hours to make it habitable) had been built during the war as a coast defence station, at a time when the War Office were vaguely alarmed by rumours of a projected invasion at some unlikely point. Possibly because they thought Baycombe was the last point any enemy strategist would expect them to expect an invasion at, the War Office had erected a kind of Pill Box on the tor above the village. The work had been efficiently carried out, and a small garrison had been installed; but apparently the War Office had been cleverer than the German tacticians, for no attempt was made to land an army at Baycombe. In 1918 the garrison and the guns had been removed, and the miniature concrete fortress had been abandoned to the games of the local children until Simon Templar, by some means known only to himself, had discovered that the Pill Box and the quarter of a square mile of land in which it stood were still the property of the War Office, and in some secret way had managed to persuade the said War Office to sell him the freehold for twenty-five pounds.

In this curious home the Saint had installed himself, together with a retainer who went by the name of Orace. And the Saint had been so overcome with the dullness of Baycombe that within three days he was the victim of routine.

At 9 a.m. on this third day (the Saint had a rooted objection to early rising) the man who went by the name of Orace entered his master’s bedroom bearing a cup of tea and mug of hot water.

“Nice morning, sir,” said Orace, and retired.

Orace had remarked on the niceness of the morning for the last eight years, and he had never allowed the weather to change his pleasant custom.

The Saint yawned, stretched himself like a cat, and saw with half-closed eyes that a stream of sunlight was pouring in through the embrasure which did duty for a window. The optimism of Orace being justified, Simon Templar sighed, stretched himself again, and after a moment’s indecision leapt out of bed. He shaved rapidly, sipping his tea in between whiles, and then pulled on a bathing costume and went out into the sun, picking up a length of rope on his way out. He skipped energetically on the grass outside for fifteen minutes. Then he shadow-boxed for five minutes. Then he grabbed a towel, knotted it loosely round his neck, sprinted the couple of dozen yards that lay between the Pill Box and the edge of the cliff, and coolly swung himself over the edge. A hundred and fifty foot drop lay beneath him, but handholds were plentiful, and he descended to the beach as nonchalantly as he would have descended a flight of stairs. The water was rippling calm. He covered a quarter of a mile at racing speed, turned on his back and paddled lazily shorewards, finishing the last hundred yards like a champion. Then he lay at the edge of the surf, basking in the strengthening sun.

All these things he had done as regularly on the two previous mornings, and he was languidly pondering the deadliness of regular habits when the thing happened that proved to him quite conclusively that regular habits could be more literally deadly than he had allowed for.

Phhhew-wuk!

Something sang past his ear, and the pebble at which he had been staring in an absent-minded sort of way leapt sideways and was left with a silvery streak scored across it, while the thing that had sang changed its note and went whining seawards.

“Bad luck, sonny,” murmured the Saint mildly. “Only a couple of inches out. . . .”

But he was on his feet before the sound of the shot had reached him.

He was on one of the arms of the bay, which was roughly semi-circular. The village was in the centre of the arc. A quick calculation told him that the bullet had come from some point on the cliff between the Pill Box and the village, but he could see nothing on the skyline. A moment later a frantic silhouette appeared at the top of the tor, and the voice of Orace hailed down an anxious query. The Saint waved his towel in response and, making for the foot of the cliff, began to climb up again.

He accomplished the difficult ascent with no apparent effort, quite unperturbed by the thought that the unknown sniper might essay a second round. And presently the Saint stood on the grass above, hands on hips, gazing keenly down the slope towards the spot where the bullet had seemed to come from. A quarter of a mile away was a broad clump of low bushes; beyond the copse, he knew, was a cart-track leading down to the village. The Saint shrugged and turned to Orace, who had been fuming and fidgeting around him.

“The Tiger knows his stuff,” remarked Simon Templar with a kind of admiration.

“Like a greenorn!” spluttered Orace. “Like a namachoor! Wa did ja expect? An’ just wotcha observed—an’ I ope it learns ya! You ain’t ’urt, sir, are ye?” added Orace, succumbing to human sympathy.

“No—but near enough,” said the Saint.

Orace flung out his arms.

“Pity ’e didn’t plug ya one, just ter make ya more careful nex’ time. I’d a bin grateful to ’im. An’ if I ever lay my ’ands on the swine ’es fore it,” concluded Orace somewhat illogically, and strutted back to the Pill Box.

Orace, as a Sergeant of Marines, had received a German bullet in his right hip at Zeebrugge, and had walked with a lopsided strut ever since.

“Brekfuss in narf a minnit,” Orace flung over his shoulder.

The Saint strolled after him at a leisurely pace and returned to his bedroom whistling. Nevertheless, Orace, entering the sitting-room with a tray precisely half a minute later, found the Saint stretched out in an arm-chair. The Saint’s hair was impeccably brushed, and he was fully dressed—according to the Saint’s ideas of full dress—in shoes, socks, a dilapidated pair of grey flannel trousers and a snowy silk tennis shirt. Orace snorted, and the Saint smiled.

“Orace,” said the Saint conversationally, lifting the cover from a plate of bacon and eggs, “one gathers that things are just about to hum.”

“Um,” responded Orace.

“About to ’um, if you prefer it,” said the Saint equably. “The point is that the orchestra are in their places, the noises off have hitched up their hosiery, the conductor has unkemped his hair, the seconds are getting out of the ring, the guard is blowing his whistle, the skipper has rung down for full steam ahead, the—the——”

“The cawfy’s getting cold,” said Orace.

The Saint buttered a triangle of toast.

“How unsympathetic you are, Orace!” he complained. “Well, if my flights of metaphor fail to impress you, let us put it like this: we’re off.”

“Um,” agreed Orace, and returned to the improvised kitchen.

Simon finished his meal and returned to the arm-chair, from which he had a view of the cliff and the sea beyond. He skimmed through the previous day’s paper (Baycombe was at least twenty-four hours behind the rest of England) and then smoked a meditative cigarette. At length he rose, fetched and pulled on a well-worn tweed coat, picked up an unwieldy walking stick, and went to the curtained breach in the fortifications which was used for a front door.

“Orace!”

“Sir!” answered Orace, appearing at the threshold of the kitchen.

“I’m going to have a look round. I’ll be back for lunch.”

“Aye, aye, sir. . . . Sir!”

The Saint was turning away, and he stopped. Orace fumbled under his apron and produced a fearsome weapon—a revolver of pre-war make and enormous calibre—which he offered to his master.

“It ain’t much ter look at,” said Orace, stroking the barrel lovingly, “and I wouldn’t use it fer fancy shooting; but it’ll make a bigger ’ole in a man than any o’ those pretty ortymatics.”

“Thanks,” grinned the Saint. “But it makes too much noise. I prefer Anna.”

“Um,” said Orace.

Orace could put any shade of meaning into that simple monosyllable, and on this occasion there was no doubt about the precise shade of meaning he intended to convey.

The Saint was studying a slim blade which he had taken from a sheath strapped to his forearm, hidden under his sleeve. The knife was about six inches long in the blade, which was leaf-shaped and slightly curved. The haft was scarcely three inches long, of beautifully carved ivory. The whole was so perfectly balanced that it seemed to take life from the hand that held it, and its edge was so keen that a man could have shaved with it. The Saint spun the sliver of steel high in the air and caught it adroitly by the hilt as it fell back; and in the same movement he returned it to its sheath with such speed that the knife seemed to vanish even as he touched it.

“Don’t you be rude about Anna,” said the Saint, wagging a reproving forefinger. “She’d take a man’s thumb off before the gun was half out of his pocket.”

And he went striding down the hill towards the village, leaving Orace to pessimistic disgust.

It was early summer, and pleasantly warm—a fact which made the Saint’s selection of the Pill Box for a home less absurd than it would have seemed in winter. (There was another reason for his choice, besides a desire for quantities of fresh air and the simple life, as will be seen.) The Saint whistled as he walked, swinging his heavy stick, but his eyes never relaxed their vigilant study of every scrap of cover that might hide another sniper. He walked boldly down to the bushes which he had suspected that morning and spent some time in a minute search for incriminating evidence; but there had been no rain for days, and even his practised eye could make little of the spoor he found. Near the edge of the cliff he caught a golden gleam under a tuft of grass, and found a cartridge-case.

“Three-one-five Mauser,” commented the Saint. “Naughty, naughty!”

He dropped the shell into his pocket and studied the ground closely, but the indistinct impressions gave him no clue to the size or shape of the unknown, and at last he resumed his thoughtful progress towards the village.

Baycombe, which is really no more than a fishing village, lies barely above sea-level, but on either side the red cliffs rise away from the harbour, and the hills rise behind, so that Baycombe lies in a hollow opening on the Bristol Channel. Facing seawards from the harbour, the Pill Box would have been seen crowning the tor on the right, the only building to the east for some ten miles; the tor on the left was some fifty feet lower, and was dotted with half a dozen red brick and grey stone houses belonging to the aristocracy. The Saint, via Orace, who had drunk beer in the public-house by the quay to some advantage, already knew the names and habits of this oligarchy. The richest member was one Hans Bloem, a Boer of about fifty, who was also reputed to be the meanest man in Devonshire. Bloem frequently had a nephew staying with him who was as popular as his uncle was unpopular: the nephew was Algernon de Breton Lomas-Coper, wore a monocle, was one of the Lads, and highly esteemed locally for a very pleasant ass. The Best People were represented by Sir Michael Lapping, a retired Judge; the Proletariat by Sir John Bittle, a retired Wholesale Grocer. There was a Manor, but it had no Lord, for it had passed to a gaunt, grim, masculine lady, Miss Agatha Girton, who lived there, unhonoured and unloved, with her ward, whom the village honoured and loved without exception. For the rest, there were two Indian Civil Servants who, under the prosaic names of Smith and Shaw, survived on their pensions in a tiny bungalow; and a Dr. Carn.

“A very dull and ordinary bunch,” reflected Simon Templar, as he stood at the top of the village street pondering his next move. “Except, perhaps, the ward. Is she the luvverly ’eroine of this blinkin’ adventure?”

This hopeful thought directed his steps towards the “Blue Moon,” which was at the same time Baycombe’s club and pub. But the Saint did not reach the “Blue Moon” that morning, because as he passed the shop which supplied all the village requirements, from shoes to ships and sealing-wax, a girl came out.

“I’m so sorry,” said the Saint, steadying her with one arm.

He retrieved the parcel which the collision had knocked out of her hand, and in returning it to her he had the chance of observing her face more closely. He could find no flaw there, and she had the most delightful of smiles. Her head barely topped his shoulder.

“You must be the ward,” said Simon. “Miss Pat—the village doesn’t give you a surname.”

She nodded.

“Patricia Holm,” she said. “And you must be the Mystery Man.”

“Not really—am I that already?” said the Saint with interest, and she saw at once that the desire to hide his light under a bushel was not one of his failings.

It is always a question whether the man inspires the nickname or the nickname inspires the man. When a man is known to his familiars as “Beau” or “Rabbit” there is little difficulty in supplying the answer; but a man who is called “Saint” may be either a lion or a lamb. It is doubtful whether Simon Templar would have been as proud of his title as he was if he had not found that it provided him with a ready-made, effective, and useful pose; for the Saint was pleasantly egotistical.

“There are the most weird and wonderful rumours,” said the girl, and the Saint looked milder than ever.

“You must tell me,” he said.

He had fallen into step beside her, and they were walking up the rough road that led to the houses on the West Tor.

“I’m afraid we’ve been very inhospitable,” she said frankly. “You see, you set up house in the Pill Box, and that left everybody wondering whether you were possible or impossible. Baycombe society is awfully exclusive.”

“I’m flattered,” said the Saint. “Accordingly, after seeing you home, I shall return to the Pill Box and sit down to consider whether Baycombe society is possible or impossible.”

She laughed.

“You’re a most refreshing relief,” she told him. “Baycombe is full of inferiority complexes.”

“Fortunately,” remarked Simon gently, “I don’t wear hats.”

Presently she said:

“What brings you to this benighted spot?”

“A craving for excitement and adventure,” answered the Saint promptly—“reinforced by an ambition to be horribly wealthy.”

She looked at him with a quick frown, but his face confirmed the innocence of sarcasm which had given a surprising twist to his words.

“I shouldn’t have thought anyone would have come here for that,” she said.

“On the contrary,” said the Saint genially, “I should have no hesitation in recommending this particular spot to any qualified adventurer as one of the few places left in England where battle, murder, and sudden death may be quite commonplace events.”

“I’ve lived here, on and off, since I was twelve, and the most exciting thing I can remember is a house on fire,” she argued, still possessed of an uneasy feeling that he was making fun of her.

“Then you’ll really appreciate the rough stuff when it does begin,” murmured Simon cheerfully, and swung his stick, whistling.

They reached the Manor (it was not an imposing building, but it had a homely air) and the girl held out her hand.

“Won’t you come in?”

The Saint was no laggard.

“I’d love to.”

She took him into a sombre but airy drawing-room, finely furnished; but the Saint was never self-conscious. The contrast of his rough, serviceable clothes with the delicate brocaded upholstery did not impress him, and he accepted a seat without any appearance of doubting its ability to support his weight.

“May I fetch my aunt?” asked Miss Holm. “I know she’d like to meet you.”

“But of course,” assented the Saint, smiling, and she was left with a sneaking suspicion that he was agreeing with her second sentence as much as with her first.

Miss Girton arrived in a few moments, and Simon knew at once that Baycombe had not exaggerated her grimness. “A norrer,” Orace had reported, and the Saint felt inclined to agree. Miss Girton was stocky and as broad as a man: he was surprised at the strength of her grip when she shook hands with him. Her face was weather-beaten. She wore a shirt and tie and a coarse tweed skirt, woollen stockings, and heavy flat-heeled shoes. Her hair was cropped.

“I was wondering when I should meet you,” she said immediately. “You must come to dinner and meet some people. I’m afraid the company’s very limited here.”

“I’m afraid I’m prepared for very little company,” said Templar. “I’d decided to forget dress clothes for a while.”

“Lunch, then. Would you like to stay to-day?”

“May I be excused? Don’t think me uncivil, but I promised my man I’d be back for lunch. If I don’t turn up,” explained the Saint ingenuously, “Orace would think something had happened to me, and he’d go cruising round with his revolver, and somebody might get hurt.”

There was an awkward hiatus in the conversation at that point, but it was confined to two of the party, for Templar was admiring a fine specimen of Venetian glass, and did not seem to realise than he had said anything unusual. The girl hastened into the breach.

“Mr. Templar has come here for adventure,” she said, and Miss Girton stared.

“Well, I wish him luck,” she said shortly. “On Friday, then, Mr. Templar? I’ll ask some people. . . .”

“Delighted,” murmured the Saint, bowing, and now there was something faintly mocking about his smile. “On the whole, I don’t see why the social amenities shouldn’t be observed, even in a vendetta.”

Miss Girton excused herself soon after, and the Saint smoked a cigarette and chatted lightly and easily with Patricia Holm. He was an entertaining talker, and he did not introduce any more dark and horrific allusions into his remarks. Nevertheless, he caught the girl looking at him from time to time with a kind of mixture of perplexity, apprehension, and interest, and was hugely delighted.

At last he rose to go, and she accompanied him to the gate.

“You seem quite sane,” she said bluntly as they went down the path: “What was the idea of talking all that rot?”

He looked down at her, his eyes dancing.

“All my life,” he replied, “I have told the truth. It is a great advantage, because if you do that nobody ever takes you seriously.”

“But talking about murders and revolvers——”

“Perhaps,” said the Saint, with that mocking smile, “it will increase the prominence of the part which I hope to play in your thoughts from now onwards if I tell you that from this morning the most strenuous efforts will be made to kill me. On the other hand, of course, I shall not be killed, so you mustn’t worry too much about me. I mean, don’t go off your feed or lie awake all night or anything like that.”

“I’ll try not to,” she said lightly.

“You don’t believe me,” accused Templar sternly.

She hesitated.

“Well——”

“One day,” said the Saint severely, “you will apologise for your unbelief.”

He gave her a stiff bow and marched away so abruptly that she gasped.

It was exactly one o’clock when he arrived home at the Pill Box, and Orace was flustered and disapproving.

“If ya ’adn’t bin ’ome punctual,” said Orace, “I’d a bin out looking for yer corpse. It ain’t fair ter give a man such a lotta worry. Yer so careless I wonder the Tiger ’asn’t putcha out ’arf a dozen times.”

“I’ve met the most wonderful girl in the world,” said Simon impenitently. “By all the laws of adventure, I’m bound to have to save her life two or three times during the next ten days. I shall kiss her very passionately in the last chapter. We shall be married——”

Orace snorted.

“Lunch ’narf a minnit,” he said, and disappeared.

The Saint washed his hands and ran a comb through his hair in the half-minute’s grace allowed him; and the Saint was thoughtful. He had his full measure of human vanity, and it tickled his sense of humour to enter the lists with the air of a Mystery Man straight out of a detective story, but he had a solid reason for giving his caprice its head. It struck him that the Tiger knew all about him and his quest, and that therefore no useful purpose would be served by trying to pretend innocence; whereas a shameless bravado might well bother the other side considerably. They would be racking their brains to find some reason for his brazen front, and crediting him with the most complicated subtleties: when all the time there was nothing behind it but the fact that one pose was as good as another, and the opportunity to play the swashbuckler was too good to be missed.

The Saint was whistling blithely when Orace brought lunch. He knew that the Tiger was in Baycombe. He had come half-way across the world to rob the Tiger of a million dollars, and the duel promised to be exhilarating as anything in the Saint’s hell-for-leather past.

Algernon de Breton Lomas-Coper was one of the genial Algys made famous by Mr. P. G. Wodehouse, and accordingly he often ejaculated “What? What?” to show that he could hardly believe his own brilliance; but now he ejaculated “What? What?” to show that he could hardly believe his own ears.

“It’s perfectly true,” said Patricia. “And he’s coming to lunch.”

“Wow!” gasped Algy feebly, and relapsed into open-mouthed amazement.

He was one of those men who are little changed by the passage of time: he might have been twenty-five or thirty-five. Studying him very closely—which few took the trouble to do—one gathered that the latter age was more probably right. He was fair, round-faced, pink-and-white.

“He was quite tame,” said Patricia. “In fact, I thought he was awfully nice. But he would keep on talking about the terrifying things that he thought were going to happen. He said people were trying to murder him.”

“Dementia persecutoria,” opined Algy. “What?”

The girl shook her head.

“He was as sane as anyone I’ve ever met.”

“Extensio cruris paranoia?” suggested Algy sagely.

“What on earth’s that?” she asked.

“An irresistible desire to pull legs.”

Patricia frowned.

“You’ll be thinking I’m crazy next,” she said. “But somehow you can’t help believing him. It’s as if he were daring you to take him seriously.”

“Well, if he manages to wake up this backwater I’ll be grateful to him,” said the man. “Are you going to invite me to stay and meet the ogre?”

He stayed.

Towards one o’clock Patricia sighted Templar coming up the road, and went out to meet him at the gate. He was dressed as he had been the day before, but he had fastened his collar and put on a tie.

He greeted her with a smile.

“Still alive, you see,” he remarked. “The ungodly prowled around last night, but I poured a bucket of water over him, and he went home. It’s astonishing how easy it is to damp the ardour of an assassin.”

“Isn’t that getting a bit stale?” she protested, although she was annoyed to find that the reproof she forced into her tone lacked conviction.

“I’m surprised you should say that,” he returned gravely. “Personally, I’m only just beginning to appreciate the true succulence of the jest.”

“At least, I hope you won’t upset everybody at lunch,” she said, and his eyes twinkled.

“I’ll try to behave,” he promised. “At any other time it would have been a fearful effort, but to-day I’m on my party manners.”

There were cocktails in the drawing-room (Baycombe society prided itself on being up to date), and there Algy was brought forward and introduced.

“Delighted—delighted—long expected pleasure—what?” he babbled.

“Is it really?” asked the Saint guilelessly.

Algy screwed a pane of glass into his eye and surveyed the visitor with awe.

“So you’re the Mystery Man!” he prattled on. “You don’t mind being called that? I’m sure you won’t. Everybody calls you the Mystery Man, and I honestly think it suits you most awfully well, don’t you know. And fancy taking the Pill Box! Isn’t it too frightfully draughty? But of course you’re one of these strong, hearty he-men we see in the pictures.”

“Algy, you’re being rude,” interrupted the girl.

“Am I really? Only meant for good-fellowship and all that sort of thing. What? What? No offence, old banana pip, you know, don’t you know.”

“Do I? Don’t I?” asked the Saint, blinking.

The girl rushed into the pause, for she already had a good estimate of the Saint’s perverse sense of fun, and dreaded its irresponsibility. She felt that at any moment he would produce a revolver and ask if they knew anyone worth murdering.

“Algy, be an angel and go and tell Aunt Agatha to hurry up.”

“That is Mynheer Hans Bloem’s nephew,” observed the Saint calmly as the door closed behind the talkative one. “He is thirty-four. He lived for some years in America; in the City of London he is known as a man with mining property in Transvaal.”

Patricia was astonished.

“You know more about him than I do,” she said.

“I make it my business to pry into my neighbour’s affairs,” he answered solemnly. “It mayn’t be courteous, but it’s cautious.”

“Perhaps you know all about me?” she was tempted to challenge him.

He turned on her a clear blue eye which held a mocking gleam.

“Only the unimportant things. That you were educated at Mayfield. That Miss Girton isn’t your aunt, but a very distant cousin. That you’ve led a very quiet life, and travelled very little. You’re dependent on Miss Girton, because she has the administration of your property until you’re twenty-five. That is for another five years.”

“Are you aware,” she demanded dangerously, “that you’re most impertinent?”

He nodded.

“Quite unpardonably,” he admitted. “I can only plead in excuse that when there’s a price on one’s head one can’t be too particular about one’s acquaintances.”

And he looked meditatively at the yellow-golden contents of his glass, which he had held untasted since it was given him.

“Your health,” he wished her; and, as he set down the empty glass, he smiled and added: “At least I’ve no fear of you.”

She had no time to find an adequate answer before Algy returned with Miss Girton and a tall, thin, leather-faced man who was introduced as Mr. Bloem.

“Pleased to meet you,” murmured the Saint. “So sorry T. T. Deeps are going badly in the market, but this is just the time to make your corner.”

Bloem started, and his spectacles fell off and dangled at the length of their black watered ribbon as the Boer stared blankly at Simon Templar.

“You must be very much on the inside in the City, Mr. Templar,” said Bloem.

“Extraordinary, isn’t it?” agreed Simon, with his most saintly smile.

Then he was being introduced to a new arrival, Sir Michael Lapping. The ex-judge shook hands heartily, peering short-sightedly into the Saint’s face.

“You remind me of a man I once met in the Old Bailey—and I’m hanged if I can remember whether it was a professional encounter or not.”

“I was just going to,” said the Saint blandly, if a trifle cryptically. “His name was Harry the Duke, and you gave him seven years. He escaped abroad six years ago, but I hear he’s been back in England some months. Be careful how you go out after dark.”

It should have fallen to the Saint to take Miss Girton in to lunch, but his hostess passed him on to Patricia, and the girl was thus able to get a word with him aside.

“You’ve already broken your promise twice,” she said. “Do you have to go on like this?”

“I’m merely attracting attention,” he said. “Having now become the centre of interest, I shall rest on my laurels.”

He was as good as his word, but Patricia was unreasonably irritated to observe that he had succeeded in attaining his shamelessly confessed object. The others of the party felt vaguely at a disadvantage, and favoured the Saint with furtive glances in which was betrayed not a little superstitious awe. Once the Saint caught Patricia’s eye, and the silent mirth that was always bubbling up behind his eyes spread for a moment into an open grin. She frowned and tossed her pretty head, and entered upon an earnest discussion with Lapping; but when she stole a look at the Saint to see how he had taken the snub she saw that beneath his dutifully decorous demeanour he was shaking with silent laughter, and she was furious.

The Saint had travelled. He talked interestingly—if with a strong egotistical bias—about places as far removed from civilisation and from each other as Vladivostok, Armenia, Moscow, Lapland, Chung-king, Pernambuco, and Sierra Leone. There seemed to be few of the wilder parts of the world which he had not visited, and few of those in which he had not had adventures. He had won a gold rush in South Africa, and lost his holding in a poker game twenty-four hours later. He had run guns into China, whisky into the United States, and perfume into England. He had deserted after a year in the Spanish Foreign Legion. He had worked his passage across the Atlantic as a steward, tramped across America, fought his way across Mexico during a free-for-all revolution, picked up a couple of thousand pounds in the Argentine, and sailed home from Buenos Aires in a millionaire’s suite—to lose nearly all the fruit of his wanderings on Epsom Downs.

“You’ll find Baycombe very dull after such an exciting life,” said Miss Girton.

“Somehow, I don’t agree,” said the Saint. “I find the air very bracing.”

Bloem adjusted his spectacles and enquired:

“And what might your employment be at the moment?”

“Just now,” said the Saint suavely, “I’m looking for a million dollars. I feel that I should like to end my days in luxury, and I can’t get along on less than fifteen thousand a year.”

Algy squawked with merriment.

“Haw-haw!” he yapped. “Jolly good! Too awfully horribly priceless! What? What?”

“Quite,” the Saint concurred modestly.

“I fear,” said Lapping, “that you will hardly find your million dollars in Baycombe.”

The Saint put his hands on the tablecloth and studied his finger-nails with a gentle smile.

“You depress me, Sir Michael,” he remarked. “And I was feeling very optimistic. I was told that there were a million dollars to be picked up here, and one can hardly disbelieve the word of a dying man, especially when one has tried to save his life. It was at a place called Ayer Pahit, in the Malay States. He’d taken to the jungle—they’d hunted him through every town in the Peninsular, ever since they located him settling down in Singapore to enjoy an unjust share of the loot—and one of their Malay trackers had caught him and stuck a kris in him. I found him just before he passed out, and he told me most of the story. . . . But I’m boring you.”

“Not a bit, dear old sprout, not a bit!” rejoined Algy eagerly, and he was supported by a chorus of curiosity.

The Saint shook his head.

“But I’m quite certain I shall bore you if I go on,” he stated obstinately. “Now suppose I’d been talking about Brazil—did you know there was a village behind an almost impassable range of hills covered with thick poisonous jungle where some descendants of Cortes’ crowd still live? They’re gradually being absorbed into the native stock—Mayas—by intermarriage, but they still wear swords and talk good Castilian. They could hardly believe my rifle. I remember . . .”

And it was impossible to wheedle him back to any further discussion of his million dollars.

He made his excuses as soon after coffee as was decently possible, and spoke last to Patricia.

“When you get to know me better—as you must—you’ll learn to forgive my weakness.”

“I suppose it’s nothing but a silly desire to cause a sensation,” she said coldly.

“Nothing but that,” said the Saint with disarming frankness, and went home with a comfortable feeling that he had had the better of the exchange.

In spite of the protestations of Orace, he took a walk during the afternoon. He wanted to be familiar with the territory for some distance around, and thus his route took him inland towards the uplands which sheltered the village on the south. It was the first time he had surveyed the ground, but his hunting experience had given him a good eye for country, and at the end of three hours’ hard tramping he had every detail of the district mapped in his brain.

It was on the homeward hike that he met the stranger. His walk had been as solitary as a walk in North Devon can be: he had not even encountered any farm labourers, for the land for miles around was unclaimed moor. But this man was so obviously harmless, even at a distance of half a mile, that the Saint frowned thoughtfully.

The man was in plus-fours of a dazzling purple hue. He had a kind of haversack slung over his shoulder, and he carried a butterfly net. He moved aimlessly about—sometimes in short violent rushes, sometimes walking, sometimes crawling and rooting about on his hands and knees. He did not seem to notice Templar at all, and the Saint, moving very silently, came right up and stood over him during an exceptionally zealous burrowing exploration among some gorse bushes. While Simon watched, the naturalist made a sudden pounce, accompanied by a gasp of triumph, and wriggled back into the open with a small beetle held gingerly between his thumb and forefinger. The haversack was hitched round, a matchbox secured, the insect imprisoned therein, and the box carefully stowed away. Then the entomologist rose to his feet, perspiring and very red in the face.

“Good afternoon, sir,” he remarked genially, mopping his brow with an appallingly green silk handkerchief.

“So it is,” agreed the Saint.

Mr. Templar had a disconcerting trick of taking the most conventional speech quite literally—a device which he had adopted because it threw the onus of continuing the conversation upon the other party.

“An innocuous and healthy pastime,” explained the stranger, with a friendly and all-embracing sweep of his hand. “Fresh air—exercise—and all in the most glorious scenery in England.”

He was half a head shorter than the Saint, but a good two stone heavier. His eyes were large and child-like behind a pair of enormous horn-rimmed glasses, and he wore a straggly pale walrus moustache. The sight of this big middle-aged man in the shocking clothes, with his ridiculous little butterfly net, was as diverting as anything the Saint could remember.

“Of course—you’re Dr. Carn,” said the Saint, and the other started.

“How did you know?”

“I always seem to be giving people surprises,” complained Simon, completely at his ease. “It’s so simple. You look less like a doctor than anyone but a doctor could look, and there’s only one doctor in Baycombe. How’s trade?”

Suddenly Carn was no longer genial.

“My profession?” he said stiffly. “I don’t quite understand.”

“You are one of many,” sighed the Saint. “Nobody ever quite understands me. And I wasn’t talking about your new profession, but about your old trade.”

Carn looked very closely at the younger man, but Simon was gazing at the sea, and his face was inscrutable except for a faintly mocking twist at the corners of his mouth—a twist that might have meant anything.

“You’re clever, Templar——”

“Mr. Templar to the aristocracy, but Saint to you,” Simon corrected him benevolently. “Naturally I’m clever. If I wasn’t, I’d be dead. And my especial brilliance is an infallible memory for faces.”

“You’re clever, Templar, but this time you’re mistaken, and persisting in your delusion is making you forget your manners.”

The Saint favoured Carn with a lazy smile.

“Well, well,” he murmured, “to err is human, is not it? But tell me, Dr. Carn, why you allow an automatic pistol to spoil the set of that beautiful coat? Are you afraid of a scarabæus turning at bay? Or is it that you’re scared of a Great White Woolly Wugga-Wugga jumping out of a bush?”

And the Saint swung his heavy staff as though weighing its efficiency as a bludgeon, and the clear blue eyes with that lively devil of mischief glimmering in their depths never left Carn’s red face. Carn glared back chokingly.

“Sir,” he exploded at length, “let me tell you——”

“I, too, was once an Inspector of Horse Marines to the Swiss Navy,” the Saint encouraged him gently; and, when Carn’s indignation proved to have become speechless, he added: “But why am I so unsociable? Come along to the Pill Box and have a spot of supper. I’m afraid it’ll only be tinned stuff—we stopped having fresh meat since a seagull died after tasting the Sunday joint—but our brandy is Napoleon . . . and Orace grills sardines marvellously. . . .”

He linked his arm in Carn’s and urged the naturalist along, chattering irrepressibly. It is an almost incredible tribute to the charm which the Saint could exert, to record that he coaxed Carn into acceptance in three minutes and had him chuckling at a grossly improper limerick by the time they reached the Pill Box.

“You’re a card, Templar,” said Carn as they sat over Martinis in the sitting-room, and the Saint raised indulgent eyebrows.

“Because I called your bluff?”

“Because you didn’t hesitate.”

“He who hesitates,” said the Saint sententiously, “is bossed. No mughopper will ever spiel this baby.”

They talked politics and literature through supper (the Saint had original and heretical views on both subjects) as dispassionately as the most ordinary men, met together in the most ordinary circumstances, might have done.

After Orace had served coffee and withdrawn, Carn produced a cigar-case and offered it to the Saint. Templar looked, and shook his head with a smile.

“Not even with you, dear heart,” he said, and Carn was aggrieved.

“There’s nothing wrong with them.”

“I’m so glad you haven’t wasted a cigar, then.”

“If I give you my word——”

“I’ll take it. But I won’t take your cigars.”

Carn shrugged, took one himself and lighted it. The Saint settled himself more comfortably in his arm-chair.

“I’m glad to see you don’t pack a gun yourself,” observed the Doctor presently.

“It makes one so unpopular, letting off artillery and things all over Devonshire,” said Simon. “You can only do that in shockers: in real life, the police make all sorts of awkward enquiries if you go slaughtering people here and there because they look cock-eyed at you. But I don’t advise anyone to bank on my consideration for the nerves of the neighbourhood when I’m in my own home.”

Carn sat forward abruptly.

“We’ve bluffed for an hour and a half by the clock,” he said. “Suppose we get down to brass tacks?”

“I’ll suppose anything you like,” assented Simon.

“I know you’ve got some funny game on; and I know you aren’t one of those dude detectives, because I’ve made enquiries. You aren’t even Secret Service. I know something about your record, and I gather you haven’t come to Baycombe because you got an idea you’d like to vegetate in rural England and grow string beans. You aren’t the sort that goes anywhere unless they can see easy money or big trouble waiting for collection.”

“I might have decided to quit before I stopped something.”

“You might—but your sort doesn’t quit while there’s a kick left in ’em. Besides, what do you think I’ve been doing all the time I’ve been down here?”

“Huntin’ the elusive Wugga-Wugga, presumably,” drawled the Saint.

Carn made a gesture of impatience.

“I’ve told you you’re clever,” he said, “and I meant every letter of it—in capital italics. But you don’t have to pretend you think I’m a fool, because I know you know better. You’re here for what you can get, and I’ve a good idea what that is. If I’m right, it’s my job to get in your way all I can, unless you work in with me. Templar, I’m paying you the compliment of putting the cards on the table, because from what I hear I’d rather work with you than against you. Now, why can’t you come across?”

The Saint had sunk deeper into his arm-chair. The room was lighted only by the smoky oil lamp that Orace had brought in with the coffee, for the sky had clouded over in the late afternoon and night had come on early.

“There are just one million reasons why I shouldn’t come across,” said the Saint tranquilly. “They were lost to the Confederated Bank of Chicago quite a time ago, and I want them all to myself, my good Carn.”

“You don’t imagine you could get away with it?”

“I can think of no limits to my ingenuity in getting away with things,” said the Saint calmly.

He moved in the shadows, and a moment later he said quietly:

“There is a million-and-first argument which prevents me coming across just now, Carn—and that is that I never allow Tiger Cubs to listen-in on my confessions.”

“What do you mean?” asked Carn.

“I mean,” said the Saint in a clear strong voice, “that at this moment there’s some son-of-a-gun peeking through that embrasure. I’ve got him covered, and if he so much as blinks I’m going to shoot his eyelids off!”

Carn sprang to his feet, his hand flying to his hip, and the Saint laughed softly.

“He’s gone,” Templar said. “He ducked as soon as I spoke. But maybe now you realise how hard it is not to be killed when someone’s really out for your blood. It looks so easy in stories, but I’m finding it a bit of a strain.”

The Saint was talking in his usual mild leisurely way, but there was nothing leisurely about his movements. He had turned out the lamp at the same instant as Carn had jumped up, and his words came from the direction of the embrasure.

“Can’t see anything. This bunch are as windy as mice trying to nibble a cat’s whiskers. I’ll take a look outside. Stay right where you are, sonny.”

Carn heard the Saint slither out, and there were words in the kitchen. A few seconds later Orace came in, bearing a lighted candle and clasping his beloved blunderbuss in his free hand. Orace did not speak. He set the candle down in a corner, so that the light did not interfere with his view of the embrasure, and waited patiently with the enormous revolver cocked and at the ready.

“You have an exciting life,” remarked Carn, and Orace turned an unfriendly eye—and the revolver upon the Doctor.

“Um,” said Orace noncommittally.

The Saint was back in ten minutes by the clock.

“Bad huntin’,” he murmured. “It’s as black as coffee outside, and he must have hared for home as soon as I scared him. . . . Beer, Orace.”

“Aye, aye, sir,” said the silent one, and faded out as grimly as he had entered.

Carn gazed thoughtfully after the retreating figure with its preposterous armoury and its preposterous strut.

“Any more in the menagerie?” he enquired.

“Nope,” said the Saint laconically.

He was relighting the lamp, and the flare of the match threw his face into high relief for an instant. Carn became more thoughtful. His life had been devoted to dealing with men of all sorts and conditions. He had known many clever men, not a few dangerous men, and a number of mysterious men, but at that moment he wondered if he had ever met a man who looked more cleverly and dangerously and mysteriously competent to deal with any kind of trouble that happened to be floating around.

“I’d rather have you on my side than against me, Saint,” said Carn. “You’d get a rake-off. Think it over.”

Hands on hips, the Saint regarded the red-faced man quizzically.

“Can I take that as official?”

“Naturally not. But you can take it from me that it can be arranged on the side.”

“Thanks,” said the Saint. “I don’t feel impressed with your balance sheet. Taken by and large, the dividend don’t seem fat enough to tempt this investor. Now try this one: come in with me, and I’ll promise you one third. Think it over, Detective Inspector Carn.”

“Dr. Carn.”

The Saint smiled.

“Need we keep it up?” he asked smoothly. “What on earth, dear lamb, did you think you were getting away with?”

Carn wrinkled his nose.

“Just as you like,” he agreed. “You have the advantage of me, though. I’m hanged if I can place you.”

“That’s the best news I’ve heard for some time,” said the Saint cheerfully.

Carn rose to go after a couple of pints of beer had vanished, and Templar rose also.

“Better let me see you home,” said the Saint. “I’ll feel safer.”

“If you think I need nursing,” began Carn with some heat, but Simon linked his arm in that of the detective with his most charming smile.

“Not a bit. I’d enjoy the stroll.”

Carn was living in a miniature house the grounds of which backed on the larger grounds of the Manor. Templar had already noticed the house, and had wondered whom it belonged to; and for some unaccountable reason, which he could only blame on his melodramatic imagination, he felt relieved at the news that Patricia had a real live detective within call.

On the walk, the Saint learned that Carn had been on the spot for three months. Carn was prepared to be loquacious up to a point: but beyond that limit he could not be lured. Carn was also prepared to talk about the Saint—a fact which pleased Simon’s egotism without hypnotising his caution.

“I think it should be an interesting duel,” Carn said.

“I hope so,” agreed Templar politely.

“The more so because you are the second most confident crook I’ve ever met.”

The Saint’s white teeth flashed.

“You’re premature,” he protested. “My crime is not yet committed. Already an idea is sizzling in my brain which might easily save me the trouble of running against the law at all. I’ll write my solicitor to-morrow and let you know.”

He declined Carn’s invitation to come in for a doch-an-doris, and, saying good-bye at the door, set off briskly in the general direction of the Pill Box.

This expedition, however, lasted only for so long as he judged that Carn, if he were curious, would have been able to hear the departing footsteps. At that point the Saint stepped neatly off the road on to the grass at the side and retraced his steps, moving like a lean grey shadow. A short distance away he could see the gaunt lines of Sir John Bittle’s home, and it had occurred to him that his investigations might very well include that wealthy upstart. It was just after ten o’clock, but the thought that the household would still be awake never gave the Saint a moment’s pause: his was a superbly reckless bravado.

The house was surrounded by a high stone wall that increased its sinister and secretive air, making it look like a converted prison. The Saint worked round the wall with the noiseless surefootedness of a Red Indian. He found only two openings. There was a back entrance which looked more like a mediæval postern gate, and which could not have been penetrated without certain essential tools that were not included in Templar’s travelling equipment. At the front there was a large double door a few yards back from the road, but this also was set into the wall, which would have formed a kind of archway at that spot if the doors had been opened.

It was left for the Saint to scale the wall itself. Fortunately he was tall, and he found that by standing on tiptoe and straining upwards he was able to hook his fingers over the top. Satisfied, he took off his coat and held it with the tab between his teeth; then, reaching up, he got a grip and hauled himself to the full contraction of his muscles. Holding on with one hand, he flung his coat over the broken glass set into the top of the wall, and so scrambled over, dropping to the ground on the other side like a cat.

The Saint moved swiftly along the wall to the back entrance which he had observed, conducted a light-fingered search for burglar alarms, and found one which he disconnected. Then he unbarred the door and left it slightly ajar in readiness for his retreat.

That done, he went down on his knees and crawled towards the house. If the light had been strong enough to make him visible, his method of progress would have seemed to border on the antics of a lunatic, for he wriggled forward six inches at a time, his hands waving and weaving about gently in front of him. In this way he evaded two fine alarm wires, one stretched a few inches off the ground and the other at the level of his shoulder. He rose under the wall of the house, chuckling inaudibly, but he was taking no chances.

“Now let’s take a look at the warrior who looks after himself so carefully,” said the Saint, but he said it to himself.

The side of the house on which he found himself was in darkness, and after a second’s thought he worked rapidly round to the south. As soon as he rounded the angle of the building he saw two patches of light on the grass, and crept along till he reached the french windows from which they were thrown. The curtains were half-drawn, but he was able to peer through a gap between the hangings and the frames.

He was looking into the library—a large, lofty, oak-panelled room, luxuriously furnished. It was quite evident that Sir John Bittle’s parsimony did not interfere with his indulgence of his personal tastes. The carpet was a rich Turkey with fully a four-inch pile; the chairs were huge and inviting, upholstered in brown leather; a costly bronze stood in one corner, and the walls were lined with bookshelves.

These things the Saint noticed in one glance, before anything human caught his eye. A moment later he saw the man who could only have been Bittle himself. The late wholesale grocer was stout: the Saint could only guess at height, since Bittle was hunched up in one of the enormous chairs, but the millionaire’s pink neck overflowed his collar in all directions. Sir John Bittle was in dinner dress, and he was smoking a cigar.

“Charming sketch of home life of Captain of Canning Industry,” murmured the Saint, again to his secret soul. “Unconventional Portraits of the Great. Picture on Back Page.”

The Saint had thought Bittle was alone, but just as he was about to move along he heard the millionaire’s fat voice remark:

“And that, my dear young lady, is the position.”

The Saint stood like a man turned to granite.

Presently a familiar voice answered:

“I can’t believe it.”

The Saint edged away from the wall, so that he could see into the room through the space between the half-drawn curtains. Patricia was in the chair opposite Bittle, tight-lipped, her handkerchief twisted to a rag between her fingers.

Bittle laughed—a throaty chuckle that did not disturb the comfortable impassiveness of his florid features. Templar also chuckled. If that chuckle could have been heard, it would have been found to have an unpleasant timbre.

“Even documents—bonds—receipts—won’t convince you, I suppose?” asked the millionaire. He pulled a sheaf of papers from the pocket of his dinner jacket and tossed them into the girl’s lap. “I’ve been very patient, but I’m getting tired of this hanky-panky. I suppose just seeing you made me silly and sentimental—but I’m not such a sentimental fool that I’m going to take another mortgage on an estate that isn’t worth one half of what I’ve lent your aunt already.”

“It’ll break her heart,” said Patricia, white-faced.

“The alternative is breaking my bank.”

The girl started up, clutching the papers tensely.

“You couldn’t be such a swine!” she said hotly. “What’s a few thousand to you?”

“This,” said Bittle calmly: “it gives me the power to make terms.”

Patricia was frozen as she stood. There was a silence that ticked out a dozen sinister things in as many seconds. Then she said, in a strained, unnaturally low voice:

“What terms?”

Sir John Bittle moved one fat hand in a faint gesture of deprecation.

“Please don’t let’s be more melodramatic than we can help,” he said. “Already I feel very self-conscious and conventional. But the fact is, I should like to marry you.”

For an instant the girl was motionless. Then the last drop of blood fled from her cheeks. She held the papers in her two hands, high above her head.

“Here’s my answer, you cad!”

She tore the documents across and across and flung the pieces from her, and then stood facing the millionaire with her face as pale as death and her eyes flaming.

“Good for you, kid!” commented the Saint inaudibly.

Bittle, however, was unperturbed, and once again that throaty chuckle gurgled in his larynx without kindling any corresponding geniality in his features.

“Copies,” he said simply, and at that point the Saint thought that the conversational tension would be conveniently relieved with a little affable comment from a third party.

“You little fool!” said Bittle acidly. “Did you think I worked my way up from mud to millions without some sort of brain? And d’you imagine that a man who’s beaten the sharpest wits in London at their own game is going to be baulked by a chit of a country child? Tchah!” The millionaire’s lips twisted wryly. “Now you’ve made me lose my temper and get melodramatic, just when I asked you not to. Don’t let’s have any more nonsense, please. I’ve put it quite plainly: either you marry me or I sue your aunt for what she owes me. Choose whichever you prefer, but don’t let’s have any hysterics.”

“No, don’t let’s,” agreed the Saint, standing just inside the room.

Neither had noticed his entrance, which had been a very slick specimen of its kind. He had slipped in through one of the open french windows, behind a curtain, and he stepped out of cover as he spoke, so that the effect was as startling as if he had materialised out of the air.

Patricia recognised him with a gasp. Bittle jumped up with an exclamation. His fat face, which had paled at first, became a deeper red. The Saint stood with his hands in his pockets and a gentle smile on his open face.

Bittle’s voice broke out in a harsh snarl.

“Sir——”

“To you,” assented the Saint smoothly. “Evening. Evening, Pat. Hope I don’t intrude.”

And he gazed in an artlessly friendly way from face to face, as cool and self-possessed and saintly-looking a six-foot-two of toughness as ever breezed into a peaceful Devonshire village. Patricia moved nearer to him instinctively, and Simon’s smile widened amiably as he offered her his hand. Bittle was struggling to master himself: he succeeded after an effort.

“I was not aware, Mr. Templar, that I had invited you to entertain us this evening,” he said thickly.

“Nor was I,” said the Saint ingenuously. “Isn’t it odd?”

Bittle choked. He was furious, and he was apprehensive of how long Templar might have been listening to the duologue; but there was another and less definite fear squirming into his consciousness. The Saint was tall, and although he was not at all massive there was a certain solid poise to his body that vouched for an excellent physique in fighting trim. And there was a mocking hell-for-leather light twinkling in the Saint’s level blue eyes, and something rather ugly about his very mildness, that tickled a cold shiver out of Bittle’s spine.

“Shall we say, as men of the world, Mr. Templar—it’s hardly necessary to beat about the bush—that your arrival was a little inopportune?” said Bittle.

The Saint wrinkled his brow.

“Shall we?” he asked vaguely, as though the question was a very difficult riddle. “I give it up.”

Bittle shrugged and went over to a side table on which stood decanter, siphon, and glasses.

“Whisky, Mr. Templar?”

“Thanks,” said the Saint, “I’ll have one when I get home. I’m very particular about the people I drink with. Once I had a friend who was terribly careless that way, and one day they fished him out of the canal in Soerabaja. I should hate to be fished out of anywhere.”

“To show there’s no ill-feeling. . . .”

“If I drank your whisky, son,” said the Saint, “I’m so afraid there might be all the ill-feeling we could deal with.”

Bittle came back to the table and crushed the stump of his cigar into an ashtray. He looked at the Saint, and something about the Saint’s quietness sent that draughty shiver prickling again up Bittle’s vertebræ, The Saint was still exactly where he had stood when he emerged from behind the curtain; the Saint did not seem at all embarrassed; and the Saint seemed to have all the time in the world to kill. The Saint, in short, looked as though he was waiting for something and in no particular hurry about it, and Bittle was beginning to get worried.

“Hardly conduct befitting a gentleman, shall we say, Mr. Templar?” Bittle temporised.

“No,” said the Saint fervently. “Thank the Lord I’m not a gentleman. Gentlemen are such snobs. All the gentlemen around here, for instance, refuse to know you—at least, that’s what I’m told—but I don’t mind it in the least. I hope we shall get on excellently together, and that this meeting will be but the prelude to a long and enjoyable acquaintance, to mutual satisfaction and profit. Yours faithfully.”

“You leave me very little choice, Mr. Templar,” said Bittle, and touched the bell.

The Saint remained where he was, still smiling, until there was a knock on the door and a butler who looked like a retired prize-fighter came in.

“Show Mr. Templar the door,” said Bittle.

“But how hospitable!” exclaimed the Saint, and then, to the surprise of everyone, he walked coolly across the room and followed the butler into the passage.

The millionaire stood by the table, almost gasping with astonishment at the ease with which he had broken down such an apparently impregnable defence.

“I know these bluffers,” he remarked with ill-concealed relief.

His satisfaction was of very short duration, for the end of his little speech coincided with the sounds of a slight scuffle outside and the slamming of a door. While Bittle stared, the Saint walked in again through the window, and his cheery “Well, well, well!” brought the millionaire’s head round with a jerk as the door burst open and the butler returned.

“Nice door,” murmured the Saint.

He was breathing a little faster, but not a hair of his sleek head was out of place. The pugilistic butler, on the other hand, was not a little dishevelled, and appeared to have just finished banging his nose on to something hard. The butler had a trickle of blood running down from his nostrils to his mouth, and the look in his eyes was not one of peace on earth or goodwill towards men.

“Home again,” drawled the Saint. “This is a peach of a round game, what? as dear Algy would say. Now can I see the offices? House-agents always end up their advertisements by saying that their desirable property is equipped with the usual offices, but I’ve never seen one of the same yet.”

“Let me attim,” uttered the butler, shifting round the table.

The Saint smiled, his hands in his pockets.

“You try to drop-kick me down the front steps, and you get welted on the boko,” said Simon speculatively, adapting style to audience. “Now you want to whang into my prow—and I wonder where you get blipped this time?”

Bittle stepped between the two men, and in one comprehensive glance summed up their prospects in a rough-house. Then he looked at the butler and motioned towards the door.

The ex-pug went out reluctantly, muttering profane and offensive things, and the millionaire faced round again.

“Suppose you explain yourself?”

“Just suppose!” agreed Templar enthusiastically.

Bittle glowered.

“Well, Mr. Templar?”

“Quite, thanks. How’s yourself?”

“Need you waste time playing the fool?” demanded Bittle shortly.

“Now I come to think of it—no,” answered the Saint amiably. “But granny always said I was a terrible tease. . . . Well, sonny, taken all round I don’t think your hospitality comes up to standard; and that being so I’ll see Miss Holm back to the old roof-tree. S’long.”

And he took Patricia’s arm and led her towards the french window, while Bittle stood watching them in silence, completely nonplussed. It was just as he seemed about to pass out of the house without further parley that the Saint stopped and turned, as though struck by a minor afterthought.

“By the way, Bittle,” he said, “I was forgetting—you were going to pass over a few documents, weren’t you?”

Bittle did not answer, and the Saint added:

“All about your side line in usury. Hand over the stuff and I’ll write you a cheque now for the full amount.”

“I refuse,” snapped the millionaire.

“Please yourself,” said the Saint. “My knowledge of Law is pretty scrappy, but I don’t think you can do that without cancelling the debt. Anyway, I’ll tell my solicitor to send you a cheque, and we’ll see what happens.”

The Saint turned away again, and in so doing almost collided with Patricia, who had preceded him into the garden. The girl was caught in his arms for a moment to save a fall, and the Saint was surprised to see that she was gasping with suppressed terror. A moment later the reason was given him by a ferocious baying of great hounds in the darkness.

In one swift movement Simon had the girl inside the room, and had slammed the french windows shut. Then he stood with his back to the wall, half-covering Patricia in the shelter of his wide shoulders, his hands on his hips, and a very saintly meekness overspreading his face.

“Um—as Orace would say in the circumstances,” murmured the Saint. “Bigger than Barnums. Do you mind playing the Clown while I open the Unique Mexican Knife-throwing Act?”

And Bittle, with a tiny automatic in his hand, was treated to a warning glimpse of the fine steel blade that lay along Simon Templar’s palm.

“No,” said the Saint, shaking his head sadly, “it can’t be done. It can’t really. For one thing, we’re getting all melodramatic, and I know how you hate that. For another thing, we’ve got the set all wrong. You’ve got to get into training for looking evil—just now, you’re as harmless-looking a blackguard as I’ve ever met. I’m strong for getting the atmosphere right. What d’you say to adjourning, and we can arrange to meet in Limehouse in about two months, which’ll give you time to grow a beard and develop a cast in one eye and employ a few tame thugs by way of local colour. . . .”

The Saint rambled on in his free-and-easy manner, while his brain dealt rapidly with the situation. Bittle had not raised his automatic. It pointed innocuously into the carpet, held as loosely as it could be without falling, for Simon’s eyes were narrowed down to glinting chips of steel that missed nothing, and Sir John Bittle had an uncomfortable feeling that those eyes were keen enough to note the slightest tightening of a muscle. The Saint was giving an admirable imitation of a man pretending to be off his guard, but the millionaire knew that the sight of the least threatening movement would telegraph an instant message to the hand that played with that slim little knife—and the Saint’s general manner suggested that he felt calmly confident of being able to reproduce any and every stunt in any and every Mexican knife-throwing act that ever was, with a few variations and trimmings of his own.

“You are not conversational, Bittle,” said the Saint, and Bittle smiled.

“My style is, to say the least of it, cramped,” replied the millionaire. “If I move, what are the chances of my being pricked with your pretty toy?”

“Depends how you move,” answered the Saint. “If, for instance, you relaxed the right hand, so as to allow the ugly toy now reposing there to descend upon the carpet with what is known to journalists as a sickening thud—then, I might say that the chances are about one thousand to one against.”

Bittle opened his hand, and the gun dropped. He stepped to one side, and the Saint, with a swift sweeping glide, picked up the weapon and dropped it into his pocket. At the same time he replaced his own weapon in its concealed sheath.

“Now we can be matey again,” remarked Simon with satisfaction. “What’s the next move? Taking things in a broad way, I can’t credit your bunch with much brilliance so far. Dear old Spittle, why on earth must you make such an appalling bloomer? Don’t you know that according to the rules of this game you ought to remain shrouded in mystery until Chapter Thirty? Now you’ve been and gone and spoilt my holiday,” complained the Saint bitterly, “and I don’t know how I shall be able to forgive you.”

“You are a very extraordinary man, Mr. Templar.”

The Saint smiled.

“True, O King. But you’re quite as strange a specimen as ever went into the Old Bailey. For a retired grocer, your command of the Oxford language is astonishing.”

Bittle did not answer, and the Saint gazed genially around and seemed almost surprised to see Patricia standing a little behind him. The girl had not known what to make of most of the conversation, but she had recovered from her immediate fear. There was a large assurance about everything the Saint did and said which inspired her with uncomprehending courage—even as it inspired Bittle with uncomprehending anxiety.

“Hope we haven’t bored you,” murmured Simon solicitously. “Would you like to go home?”

She nodded, and Templar looked at the millionaire.

“She would like to go home,” Templar said in his most winning voice.

A thin smile touched Bittle’s mouth.

“Just when we’re getting matey?” he queried.

“I’m sure Miss Holm didn’t mean to offend you,” protested Simon. He looked at the girl, who stared blankly at him, and turned to Bittle with an air of engaging frankness. “You see? It’s only that she’s rather tired.”

Bittle turned over the cigars in a box on a side table near the Saint, selected one, amputated the tip, and lighted it with the loving precision of a connoisseur. Then he faced Templar blandly.

“That happens to be just what I can’t allow at the moment,” said Bittle in an apologetic tone. “You see, we have some business to discuss.”

“I guess it’ll keep,” said the Saint gently.

“I don’t think so,” said Bittle.

Templar regarded the other thoughtfully for a few seconds. Then, with a shrug, he jerked the millionaire’s automatic from his pocket and walked to the french windows. He opened one of them a couple of inches, holding it with his foot, and signed to the girl to follow him. With her beside him, he said:

“Then it looks, Bittle, as if you’ll spend to-morrow morning burying a number of valuable dogs.”

“I don’t think so,” said Bittle.

There was a quiet significance in the way he said it that brought the Saint round again on the alert.

“Go hon!” mocked Simon watchfully.

Bittle stood with his head thrown back and his eyes half closed, as though listening. Then he said:

“You see, Mr. Templar, if you look in the cigar-box you will find that the bottom sinks back a trifle under quite a light pressure. In fact, it acts as a bell-push. There are now three men in the garden as well as four bloodhounds, and two more in the passage outside this room. And the only dog I can imagine myself burying to-morrow morning is an insolent young puppy who’s chosen to poke his nose into my business.”

“Well, well, well,” said the Saint, his hands in his pockets. “Well, well, WELL!”

Sir John Bittle settled himself comfortably in his arm-chair, pulled an ashstand to a convenient position, and continued the leisurely smoking of his cigar. The Saint, looking at him in a softly speculative fashion, had to admire the man’s nerve. The Saint smiled; and then Patricia’s hand on his arm brought him back with a jerk to the stern realities of the situation. He took the hand in his, pressed it, and turned the Saintly smile on her in encouragement. Then he was weighing Bittle’s automatic in a steady hand.

“Carrying on the little game of Let’s Pretend,” suggested Simon, “let’s suppose that I sort of pointed this gun at you, all nervous and upset, and in my agitation I kind of twiddled the wrong knob. I mean, suppose it went off, and you were in the way? Wouldn’t it be awkward!”

Bittle shook his head.

“Terribly,” he agreed. “And you’re such a mystery to Baycombe already that I’m afraid they’d talk. You know how unkind gossip can be. Why, they’d be quite capable of saying you did it on purpose.”

“There’s something in that,” said Templar mildly, and he put the gun back in his pocket. “Then suppose I took my little knife and began playing about with it, and it flew out of my hand and took off your ear? Or suppose it sliced off the end of your nose? It’s rotten to have only half a nose or only one ear. People stop and stare at you in the street, and so forth.”

“And think of my servants,” said Bittle. “They’re all very attached to me, and they might be quite unreasonably vindictive.”

“That’s an argument,” conceded the Saint seriously. “And now suppose you suggest a game?”

Bittle moved to a more comfortable position and thought carefully before replying. The time ticked over, but the Saint was too old a hand to be rattled by any such primitive device, and he leaned nonchalantly against the wall and waited patiently for Bittle to realise that the cat-and-mouse gag was getting no laughs that journey. At length Bittle said:

“I should be quite satisfied, Mr. Templar, if you would spend a day or two with me, and during that time we could decide on some adequate expression of your regret for your behaviour this evening. As for Miss Holm, she and I can finish our little chat uninterrupted, and then I will see her home myself.”

“Um,” murmured the Saint, lounging. “Bit of an optimist, aren’t you?”

“I won’t take ‘no’ for an answer, Mr. Templar,” said Bittle cordially. “In fact, I expect your room is already being prepared.”

The Saint smiled.

“You almost tempt me to accept,” he said. “But it cannot be. If Miss Holm were not with us—well, I should be very boorish to refuse. But as a matter of fact I promised Miss Girton to join them in a sandwich and a glass of ale towards midnight, and I can’t let them down.”

“Miss Holm will make your excuses,” urged Bittle, but the Saint shook his head regretfully.

“Another time.”

Bittle moved again in the chair, and went on with his cigar. And it began to dawn upon the Saint that, much as he was enjoying the sociable round of parlour sports, the game was becoming a trifle too one-sided. There was also the matter of Patricia, who was rather a handicap. He found that he was still holding her hand, and was reluctant to make any drastic change in the circumstances, but business was business.

With a sigh the Saint hitched himself off the wall which he had found such a convenient prop, released the hand with a final squeeze, and began to saunter round the room, humming light-heartedly under his breath and inspecting the general fixtures and fittings with a politely admiring eye.

“This room is under observation from two points,” Bittle informed him as a tactful precaution.

“Pity we haven’t got a camera—the scene’d shoot fine for a shocker,” was the Saint’s only criticism.

And Simon went on with his tour of the room. He had taken Bittle’s warning with the utmost nonchalance, but its reactions on the problem in hand and his own tentative solution were even then being balanced up in his mind. Bittle, meanwhile, smoked away with a large languidness which indicated his complete satisfaction with the entertainment provided and a sublime disregard for the time spent on digesting it. Which was all that the Saint could have asked.

In its way, it was a classical performance. Anyone with any experience of such things, entering the room, would have sensed at once that both men were past masters. Nothing could have been calmer than their appearance, nothing more polished than their dispassionate exchange of backchat.

The Saint worked his unhurried way round the room. Now he stopped to examine a Benares bowl, now an etching, now a fine old piece of furniture. The patina on a Greek vase held him enthralled for half a minute: then he was absorbed in the workmanship of a Sheraton whatnot. In fact, an impartial observer would have gathered that the Saint had no other interest in life than the study of various antiques, and that he was thoroughly enjoying a free invitation to take his time over a minute scrutiny of his host’s treasures. And all the while the Saint’s eyes, masked now by lazily drooping lids, were taking in all the details of the furnishing to which he did not devote any ostentatious attention, and searching every inch of the walls for the spyholes of which Bittle had spoken.

The millionaire was unperturbed, and the Saint once again permitted the shadow of a smile to touch the corners of his mouth as he caught Patricia’s troubled eyes. The smile hardly moved a muscle of his face, but it drew an answering tremor of the girl’s lips that showed him that her spirits were still keeping their end up.

The Saint was banking on Bittle’s confidence as a bluffer, and he was not disappointed. Bittle knew that, for all the guards with whom he had surrounded himself, his personal safety hung by the slender thread of a simulated carelessness for it. Bittle knew that to show the least anxiety, the faintest flutter of uncertainty, would have been to throw an additional weapon into Templar’s already dangerously comprehensive armoury, and that was exactly what Bittle dared not do. Therefore the millionaire affected not to notice the Saint’s movements, and never changed his position a fraction or allowed his eyes to betray him by following Simon round the room. Bittle leaned back among the cushions and gazed abstractedly at a water-colour on the opposite wall. At another time he studied the pattern on the carpet. Then he looked expressionlessly at Patricia. Once he pored over his finger-nails, and measured the length of ash on his cigar against his cuff. All the while the Saint was behind him, but Bittle did not turn his head, and the Saint was filled with hope and misgiving at the same time. He had located one peephole, cunningly concealed below a pair of old horse-pistols which hung on the wall, but the second he had failed to find. It might have been a bluff; in any case, the time was creeping on, and the Saint could not afford to carry his feigned languor too far. He would have to chance the second watcher.

He began a second circuit, deliberately passing in front of Bittle, and the millionaire looked up casually at him.

“Don’t think I’m hurrying you,” said Bittle, “but it’s getting late, and you might have rather a tiring day to-morrow.”

“Thanks,” murmured Simon. “It takes a lot to tire me. But I’ve decided to spend the night with you, at any rate. You might tell the big stiff with the damaged proboscis to fill the hot-water bottle and lay out some night-shirts.”

Bittle nodded.

“I can only commend your discretion,” he remarked, “as sincerely as I appreciate your simple tastes.”

“Not at all,” murmured the Saint, no less suave. “Would it be troubling you too much to ask for the loan of a pair of bedsocks?”

The Saint was now behind Bittle again. He was standing a bare couple of feet from the millionaire’s head, one hand resting lightly on the back of a small chair. The other hand was holding a bronze statuette up to the light, and the whole pose was so perfectly done that its hidden menace could not have struck the watchers outside until it was too late.

Bittle was a fraction quicker on the uptake. The Saint caught Patricia’s eye and made an almost imperceptible motion towards the window; and at that moment the millionaire’s nerve faltered for a split second, and he began to turn his head. In that instant the Saint sogged the statuette into the back of Bittle’s skull—without any great force, but very scientifically. In another lightning movement, he had jerked up the chair and flung it crashing into the light, and blackness fell on the room with a totally blinding density.

The Saint sprang towards the window.

“Pat!” he breathed urgently.

He touched her groping hand and got the french window open in a trice.

There was a hoarse shouting in the garden and in the corridor, and suddenly the door burst open and a shaft of light fell across the room, revealing the limp form of Bittle sprawled in the arm-chair. A couple of burly figures blocked the doorway, but Patricia and Simon were out of the beam thrown by the corridor lights.

Before she realised what was happening, the girl felt herself snatched up in a pair of steely arms. Within a bare five seconds of the blow that removed Sir John Bittle from the troubles of that evening the Saint was through the window and racing across the lawn, carrying Patricia Holm as he might have carried a child.