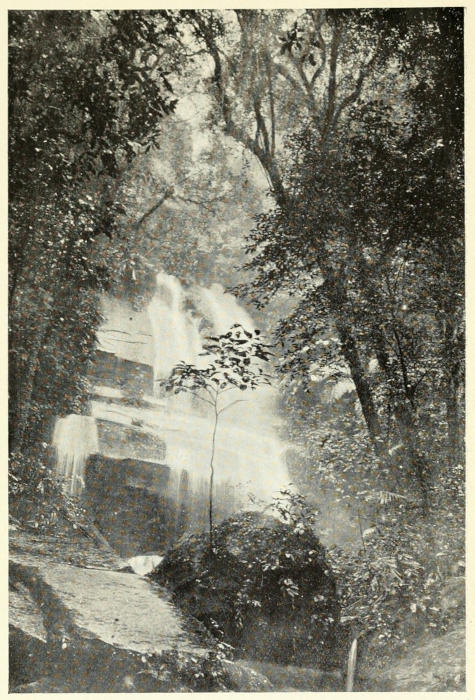

THE SCOTT-KELTIE FALLS, MOUNT DULIT, BARAM DISTRICT, SARAWAK

THE SCOTT-KELTIE FALLS, MOUNT DULIT, BARAM DISTRICT, SARAWAK

HEAD-HUNTERS

BLACK, WHITE, AND BROWN

BY

ALFRED C. HADDON, Sc.D., F.R.S.

FELLOW OF CHRIST’S COLLEGE

AND UNIVERSITY LECTURER IN ETHNOLOGY, CAMBRIDGE

WITH THIRTY-TWO PLATES, FORTY ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT

AND SIX MAPS

METHUEN & CO.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

1901

TO

MY WIFE

AND

TO THE MEMORY OF

MY MOTHER

WHO FIRST TAUGHT ME TO OBSERVE

I DEDICATE

THIS RECORD OF MY TRAVELS

In 1888 I went to Torres Straits to study the coral reefs and marine zoology of the district; whilst prosecuting these studies I naturally came much into contact with the natives, and soon was greatly interested in them. I had previously determined not to study the natives, having been told that a good deal was known already about them; but I was not long in discovering that much still remained to be learned. Indeed, it might be truly said that practically nothing was known of the customs and beliefs of the natives, even by those who we had every reason to expect would have acquired that information.

Such being the case, I felt it to be my duty to gather what information I could when not actually engaged in my zoological investigations. I found, even then, that the opportunities of learning about the pagan past of the natives were limited, and that it would become increasingly more difficult, as the younger men knew comparatively little of the former customs and beliefs, and the old men were dying off.

On my return home I found that my inquiries into the ethnography of the Torres Straits islanders were of some interest to anthropologists, and I was encouraged to spend some time in writing out my results. Gradually this has led me to devote myself to anthropological studies, and, not unnaturally, one of my first projects was to attempt a monograph on the Torres Straits Islanders. It was soon apparent that my information was of too imperfect a nature to make a satisfactory memoir, and therefore I delayed publishing until I could go out again to collect further material.

In course of time I was in a position to organise an expedition[x] for this purpose, which, being mainly endowed from University funds, had the honour of being closely associated with the University of Cambridge. It was my good fortune to be able to secure the co-operation of a staff of colleagues, each of whom had some special qualification.

For a long time it had appeared to me that investigations in experimental psychology in the field were necessary if we were ever to gauge the mental and sensory capabilities of primitive peoples. This expedition presented the requisite opportunity, and the organisation of this department was left to Dr. W. H. R. Rivers, of St. John’s College, the University lecturer in physiological and experimental psychology. The co-operation of Dr. C. S. Myers, of Caius College, had been secured early, and as he is a good musician, he specialised more particularly in the study of the hearing and music of the natives. Mr. W. McDougall, Fellow of St. John’s College, also volunteered to assist in the experimental psychology department of the expedition.

When the early arrangements were being made one of the first duties was to secure the services of a linguist, and the obvious person to turn to was Mr. Sidney H. Ray, who has long been a recognised authority on Melanesian and Papuan languages. Fortunately, he was able to join the expedition.

Mr. Anthony Wilkin, of King’s College, took the photographs for the expedition, and he assisted me in making the physical measurements and observations. He also investigated the construction of the houses, land tenure, transference of property, and other social data of various districts.

When this book was being brought out the sad news arrived in England of the death by dysentery of my pupil, friend, and colleague in Cairo on the 17th of May (1901), on his return home from a second winter’s digging in Upper Egypt. Poor Wilkin! barely twenty-four years of age, and with the promise of a brilliant career before him. I invited him to accompany me while he was still an undergraduate, having been struck by his personal and mental qualities. He was a man of exceptional ability and of frank, pleasing manner, and a thorough hater of humbug. Although he was originally a classical scholar, Wilkin read for the History Tripos, but his interests were wider[xi] than the academic course, and he paid some attention to sociology, and was also interested in natural science. In his early undergraduate days he published a brightly written book, On the Nile with a Camera. Immediately after his first winter’s digging in Egypt with Professor Flinders Petrie, he went with Mr. D. Randall-Maciver to Algeria to study the problem of the supposed relationship, actual or cultural, of the Berbers with the Ancient Egyptians. An interesting exhibition of the objects then collected was displayed at the Anthropological Institute in the summer (1900), and later in the year Wilkin published a well-written and richly illustrated popular account of their experiences, entitled, Among the Berbers of Algeria. Quite recently the scientific results were published in a sumptuously illustrated joint work entitled, Libyan Notes. Wilkin was an enthusiastic traveller, and was projecting important schemes for future work. There is little doubt that had he lived he would have distinguished himself as a thoroughly trained field-ethnologist and scientific explorer.

Finally, Mr. C. G. Seligmann volunteered to join the party. He paid particular attention to native medicine and to the diseases of the natives as well as to various economic plants and animals.

Such was the personnel of the expedition. Several preliminary communications have been published by various members; but the complete account of our investigations in Torres Straits is being published by the Cambridge University Press in a series of special memoirs. The observations made on the mainland of British New Guinea and in Sarawak will be published in various journals as opportunity offers.

The book I now offer to the public contains a general account of our journeyings and of some of the sights we witnessed and facts that we gleaned.

I would like to take this opportunity of expressing my thanks to my comrades for all the assistance they have rendered me, both in the field and at home. I venture to prophesy that when all the work of the expedition is concluded my colleagues will be found to have performed their part in a most praiseworthy manner.

Our united thanks are due to many people, from H.H. the[xii] Rajah of Sarawak down to the least important native who gave us information. Wherever we went, collectively or individually, we were hospitably received and assisted in our work. Experience and information were freely offered us, and what success the expedition has attained must be largely credited to these friends.

I cannot enumerate all who deserve recognition, but, taking them in chronological order, the following rendered us noteworthy service.

The Queensland Government, through the Hon. T. J. Byrnes, then Premier, sent us the following cordial welcome by telegraph on our arrival at Thursday Island:—

“Permit me on behalf of Government to welcome you and your party to Queensland and to express our sincere hope that your expedition will meet with the success which it deserves. We shall be glad if at any time we can afford any assistance towards the object of the expedition or to its individual members, and trust that you will not hesitate to advise us if we can be of service to you. Have asked Mr. Douglas to do anything in his power and to afford you any information concerning the objects of your mission he may be in a position to impart.”

The Hon. John Douglas, C.M.G., the Government Resident at Thursday Island, not merely officially, but privately and of his spontaneous good nature, afforded us every facility in his power. Through his kind offices the Queensland Government made a special grant of £100 towards the expenses of the expedition, and in connection with this a very friendly telegram was sent by the late Sir James R. Dickson, K.C.M.G., who was then the Home Secretary.

The Government of British New Guinea did what it could to further our aims. Unfortunately, His Excellency Sir William Macgregor, K.C.M.G., M.D., Sc.D., the then Lieutenant-Governor of the Possession, was away on a tour of inspection during my visit to the Central District; but he afterwards showed much kindness to Seligmann. The Hon. A. Musgrave, of Port Moresby, was most cordial and helpful, and we owe a great deal to him. The Hon. D. Ballantine, the energetic Treasurer and Collector of Customs, proved himself a very good friend[xiii] and benefactor to the expedition. The Hon. B. A. Hely, Resident Magistrate of the Western Division, helped us on our way, and we are greatly indebted in many ways to Mr. A. C. English, the Government Agent of the Rigo District.

All travellers to British New Guinea receive many benefits directly and indirectly from the New Guinea Mission of the London Missionary Society. Everywhere we went we were partakers of the hospitality of the missionaries and South Sea teachers; the same genuine friendliness and anxiety to help permeates the whole staff, so much so that it seems invidious to mention names, but the great assistance afforded us by the late Rev. James Chalmers deserves special recognition, as does also the kindness of Dr. and Mrs. Lawes. The Mission boats were also freely placed at our disposal as far as the service of the Mission permitted; but for this liberality on the part of Mr. Chalmers we should several times have been in an awkward predicament. If any words of mine could induce any practical assistance being given to the Mission I would feel most gratified, for I sadly realise that our indebtedness to the Mission can only be acknowledged adequately by proxy.

It is a sad duty to chronicle the irreparable loss which all those who are connected with British New Guinea have undergone in the tragic death of the devoted Tamate. Mrs. Chalmers died in the autumn of 1900 under most distressing circumstances in the Mission boat when on her way to Thursday Island. A few months later, when endeavouring to make peace during a tribal war on the Aird River, Chalmers crowned a life of hardship and self-sacrifice by martyrdom in the cause of peace. A glorious end for a noble life. With him were murdered twelve native Mission students and the Rev. O. Tomkins, a young, intelligent, and enthusiastic missionary, from whom much was expected.

Very pleasing is it to record the brotherly kindness that we received at the hands of the Sacred Heart Mission. None of our party belonged to their Communion, but from the Archbishop to the lowliest Brother we received nothing but the friendliest treatment. Nor would we omit our thanks to the good Sisters for the cheerful way in which they undertook the increased cares of catering which our presence necessitated. The insight which we gained into the ethnography of the[xiv] Mekeo District is solely due to the good offices of the various members of the Sacred Heart Mission.

In the course of the following pages I often refer to Mr. John Bruce, the Government Schoolmaster on Murray Island. It would be difficult to exaggerate the influence he exerts for good by his instruction, advice, and unostentatious example. His help and influence were invaluable to us, and when our researches are finally published, anthropologists will cordially admit how much their science owes to “Jack Bruce.”

We found Mr. Cowling, of Mabuiag, very helpful, not only at the time but subsequently, as he has since sent us much valuable information, and he also deserves special thanks.

Our visit to Sarawak was due to a glowing invitation I received from Mr. Charles Hose, the Resident of the Baram District. I have so frequently referred in print and speech to his generosity and erudition, that I need only add here that his University has conferred on him the greatest honour it is in her power to bestow—the degree of Doctor in Science honoris causa.

But it was Rajah Sir Charles Brooke’s interest in the expedition that made many things possible, and to him we offer our hearty thanks, both for facilities placed at our disposal and for the expression of his good-will.

At Kuching we received great hospitality from the white residents. Particular mention must be made of the Hon. C. A. Bampfylde, Resident of Sarawak; on our arrival he was administrating the country in the absence of the Rajah, who was in England; nor should Dr. A. J. G. Barker, Principal Medical Officer of Sarawak, and Mr. R. Shelford, the Curator of the Museum, be omitted.

Great kindness and hospitality were shown us by Mr. O. F. Ricketts, Resident of the Limbang District. We had a most enjoyable visit to his beautiful Residency, and he arranged for us all the details of our journey up-river.

One fact through all our journeyings has continually struck me. Travellers calmly and uninvitedly plant themselves on residents by whom they are received with genuine kindness and hospitably entertained with the best that can be offered. Experience, information, and influence are cheerfully and ungrudgingly[xv] placed at the disposal of the guests, who not unfrequently palm off, without acknowledgment, on an unsuspecting public the facts that others have gleaned.

The warm welcome that one receives is as refreshing to the spirit as the shower-bath is to the body and daintily served food to the appetite when one has been wandering in the wilds.

In order to render my descriptions of the places and people more continuous I have practically ignored the exact order in which events happened or journeys were made. For those who care about chronology I append a bare statement of the location of the various members of the expedition at various times. I have also not hesitated to include certain of my experiences, or some of the information I gained, during my first expedition to Torres Straits in 1888-9; but the reader will always be able to discriminate between the two occasions.

The following is the system of spelling which has been adopted in this book:—

The consonants are sounded as in English.

| PART I | |

| CHAPTER I THURSDAY ISLAND TO MURRAY ISLAND |

|

| Port Kennedy, Thursday Island—l’assage in the Freya to Murray Island—Darnley Island—Arrival at Murray Island—Reception by the natives | Page 1-10 |

| CHAPTER II THE MURRAY ISLANDS |

|

| Geographical features of the islands of Torres Straits—Geology of the Murray Islands—Climate—The Murray Islanders—Physical and other characteristics—Form of Government | Page 11-21 |

| CHAPTER III WORK AND PLAY IN MURRAY ISLAND |

|

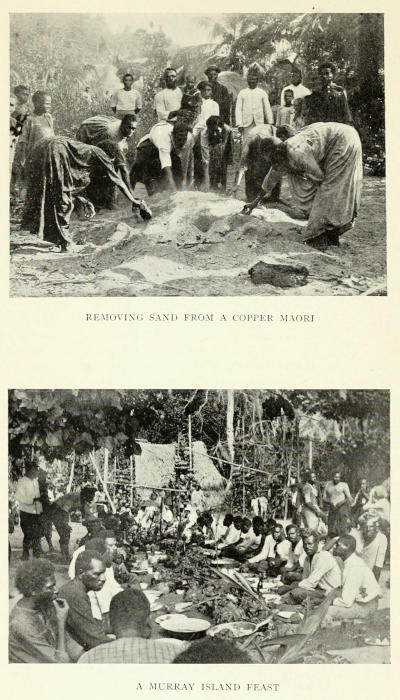

| The Expedition Dispensary—Investigations in Experimental Psychology: visual acuity, colour vision, mirror writing, estimation of time, acuity of hearing, sense of smell and taste, sensitiveness to pain—The Miriam language—Methods of acquiring information—Rain-making—Native amusements—Lantern exhibition—String puzzles—Top-spinning—Feast—Copper Maori | Page 22-41 |

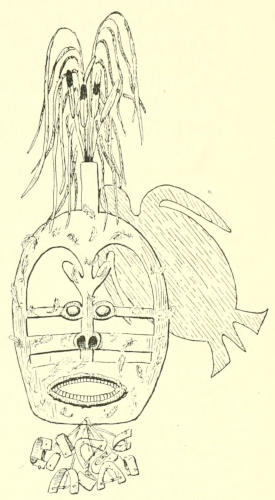

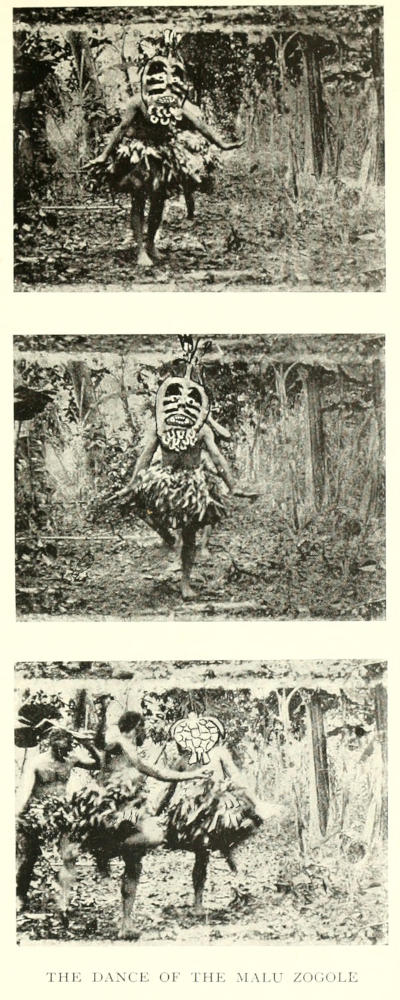

| CHAPTER IV THE MALU CEREMONIES |

|

| Initiation ceremonies—Secret societies—Visit to Las—Representation of the Malu ceremonies—Models of the old masks—The ceremonies as formerly carried out—“Devil belong Malu” | Page 42-52 |

| CHAPTER V. ZOGOS |

|

| The Murray Island oracle, Tomog Zogo—The village of Las—Tamar—The war-dance at Ziriam Zogo—Zabarker—Wind-raising—Teaching Geography at Dam—Tamar again—A Miriam “play”—How Pepker made a hill—Iriam Moris, the fat man—Zogo of the girl of the south-west—Photographing zogos—The coconut zogo—A turtle zogo—The big women who dance at night—The Waiad ceremony | Page 53-70[xviii] |

| CHAPTER VI VARIOUS INCIDENTS IN MURRAY ISLAND |

|

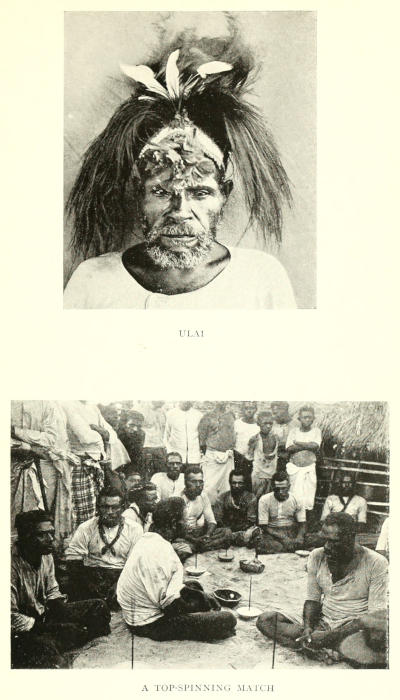

| Our “boys” in Murray Island—“Gi, he gammon”—Character of some of our native friends—Ulai—Rivalry between Debe Wali and Jimmy Rice—Our Royal Guests—The Papuan method of smoking—A domestic quarrel—Debe and Jimmy fall out—An earthquake—Cause of a hurricane—The world saved from a comet by three weeks of prayer—an unaccounted-for windstorm—New Guinea magic—“A woman of Samaria”—Jimmy Rice in prison—A yam zogo—Rain-makers—A death-dealing zogo—Mummies—Skull-divination—Purchasing skulls—A funeral | Page 71-94 |

| CHAPTER VII KIWAI AND MAWATTA |

|

| Leave Murray Island in the Nieue—Daru—Arrive at Saguane—Mission-work—Visit Iasa—Long clan houses—Totems and totemistic customs—Bull-roarers and human effigies as garden charms and during initiation ceremonies—Head-hunting—Stone implements—Origin of Man—Origin of Fire—Primitive dwellings at Old Mawatta—Shell hoe—Katau or Mawatta—Election of a chief—A love story—Dances—Bamboo beheading-knife | Page 95-116 |

| CHAPTER VIII MABUIAG |

|

| Mabuiag revisited—Character of the island—Comparison between the Murray Island and Mabuiag natives—Barter for skulls—Economic condition of Mabuiag—Present of food—Waria, a literary Papuan—Death of Waria’s baby—Method of collecting relationships and genealogies—Colour-blindness—The Mabuiag language—A May Meeting followed by a war-dance | Page 117-131 |

| CHAPTER IX TOTEMISM AND THE CULT OF KWOIAM |

|

| Totemism in Mabuiag—Significance of Totemism—Advantage of Totemism—Seclusion of girls—The Sacred Island of Pulu—The scenes of some of Kwoiam’s exploits—The Pulu Kwod—The stone that fell from the sky—The Kwoiam Augŭds—Death dances—Test for bravery—Bull-roarer—Pictographs—The Cave of Skulls—The destruction of relics—Outline of the Saga of Kwoiam—Kwoiam’s miraculous water-hole—The death of Kwoiam | Page 132-147 |

| CHAPTER X DUGONG AND TURTLE FISHING |

|

| A dugong hunt—What is a dugong?—The dugong platform—Dugong charms—Turtle-fishing—How the sucker-fish is employed to catch turtle—Beliefs respecting the gapu—The agu and bull-roarers—Cutting up a turtle | Page 148-157[xix] |

| CHAPTER XI MARRIAGE CUSTOMS AND STAR MYTHS |

|

| Marriage Customs: How girls propose marriage among the western tribe—A proposal in Tut—Marital relations—A wedding in church—An unfortunate love affair—Various love-letters. Star Myths: The Tagai constellation—A stellar almanack, its legendary origin—The origin of the constellations of Dorgai Metakorab and Bu—The story of Kabi, and how he discovered who the Sun, Moon, and Night were | Page 158-169 |

| CHAPTER XII VISITS TO VARIOUS WESTERN ISLANDS |

|

| Our party breaks up. Saibai: Clan groupings—Vaccination marks turned to a new use—Triple-crowned coconut palm—A two-storied native house. Tut: Notes of a former visit—Brief description of the old initiation ceremonies—Relics of the past. Yam: A Totem shrine. Nagir: The decoration of Magau’s skull “old-time fashion”—Divinatory skulls—The sawfish magical dance—Pictographs in Kiriri. Muralug: Visit to Prince of Wales Island in 1888—A family party—War-dance | Page 170-189 |

| CHAPTER XIII CAPE YORK NATIVES |

|

| Visit to Somerset—Notes on the Yaraikanna tribe—Initiation ceremony—Bull-roarer—Knocking out a front tooth—The ari or “personal totem” | Page 190-194 |

| CHAPTER XIV A TRIP DOWN THE PAPUAN COAST |

|

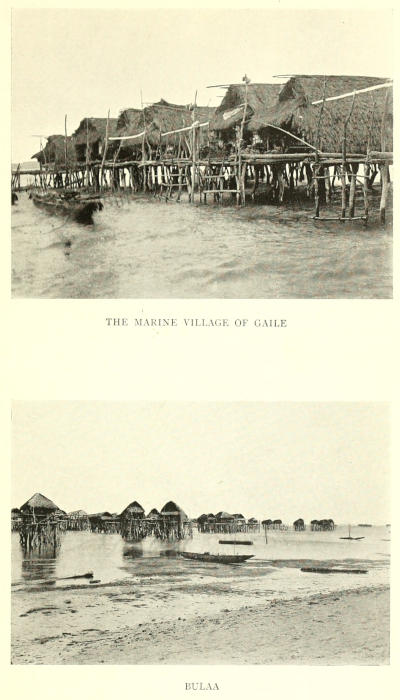

| The Olive Branch—Passage across the Papuan Gulf—Delena—Tattooing—A Papuan amentum—A sorcerer’s kit—Borepada—Port Moresby—Gaile, a village built in the sea—Character of the country—Kăpăkăpă—Dubus—The Vatorata Mission Station—Dr. and Mrs. Lawes—Sir William Macgregor’s testimony to mission work—A dance | Page 197-210 |

| CHAPTER XV THE HOOD PENINSULA |

|

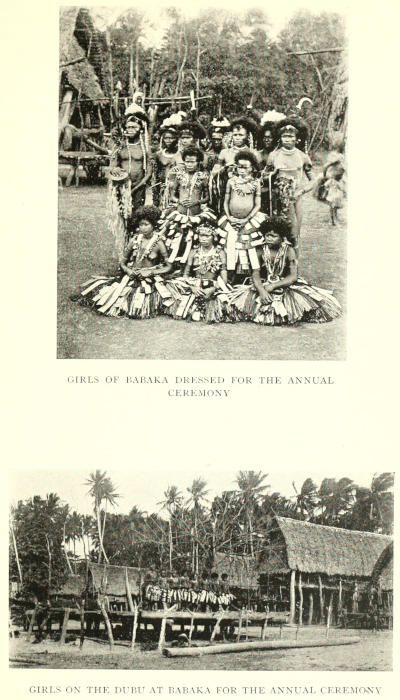

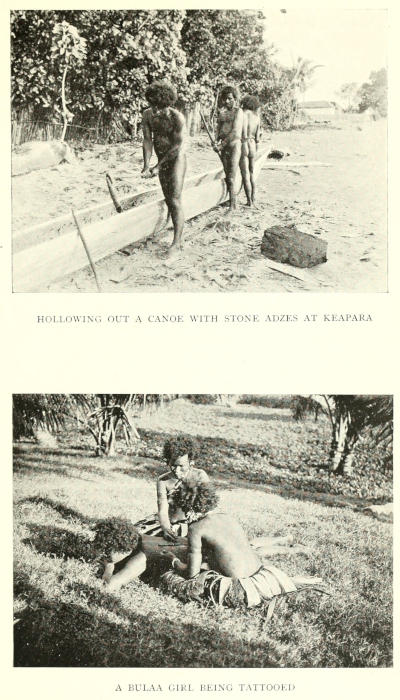

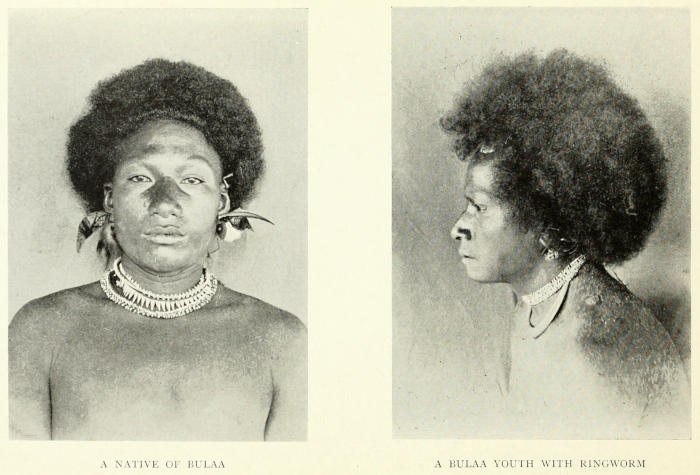

| Bulaa by moonlight—Hospitality of the South Sea teachers—Geographical character of the Hood Peninsula—Kalo—Annual fertility ceremony at Babaka—Canoe-making at Keapara—The fishing village of Alukune—The Keapara bullies—Picking a policeman’s pocket—Tattooing—A surgical remedy—Variations in the character of the Papuan hair—Pile-raising—Children’s toys and games—Dances—Second visit to Vatorata—Visit Mr. English at Rigo | Page 211-234 |

| CHAPTER XVI PORT MORESBY AND THE ASTROLABE RANGE |

|

| Port Moresby—Ride inland—Vegetation—View from the top of Warirata—The Taburi village of Atsiamakara—The Koiari—Tree houses—The Agi chief—Contrasts—A lantern show—The mountaineers—Tribal warfare—The pottery trade of Port Moresby—The Koitapu and the Motu—Gunboats | Page 235-251[xx] |

| CHAPTER XVII THE MEKEO DISTRICT |

|

| Arrival at Yule Island—The Sacred Heart Mission—Death of a Brother—A service at Ziria—The meeting of the Papuan East and West in Yule Island—The Ibitoe—Making a drum—Marriage customs—Omens—Tattooing—The Roro fishers and traders—The Mekeo agriculturists—The Pokao hunters—Markets—Pinupaka—Mohu—Walk across the plain and through the forest—Inawi—War and Taboo chiefs—Taboo customs—Masks—A Mission festivity—Tops—Veifaa—Women’s dress—Children’s games—Return to coast | Page 252-277 |

| PART II | |

| CHAPTER XVIII JOURNEY FROM KUCHING TO BARAM |

|

| Arrival in Sarawak—Description of Kuching—The Sarawak Museum—Visit to Sibu—Stay in Limbang—A Malay sago factory—Visit to Brunei—Method and aims of Rajah Brooke’s Government | Page 279-294 |

| CHAPTER XIX THE WAR-PATH OF THE KAYANS |

|

| Leave Limbang—A Kadayan house at Tulu—Rapids on the Limbang—Ascent of the Madalam—The Insurrection of Orang Kaya Tumonggong Lawai—Enter the Trikan—Durian—Met by Mr. Douglas—Old Jungle—Descend the Malinau and Tutau—Kayan tattooing—Berantu ceremony in the Batu Blah House—Arrival at Marudi (Claudetown)—Kenyah drinking customs | Page 297-311 |

| CHAPTER XX THE COUNTRY AND PEOPLE OF BORNEO |

|

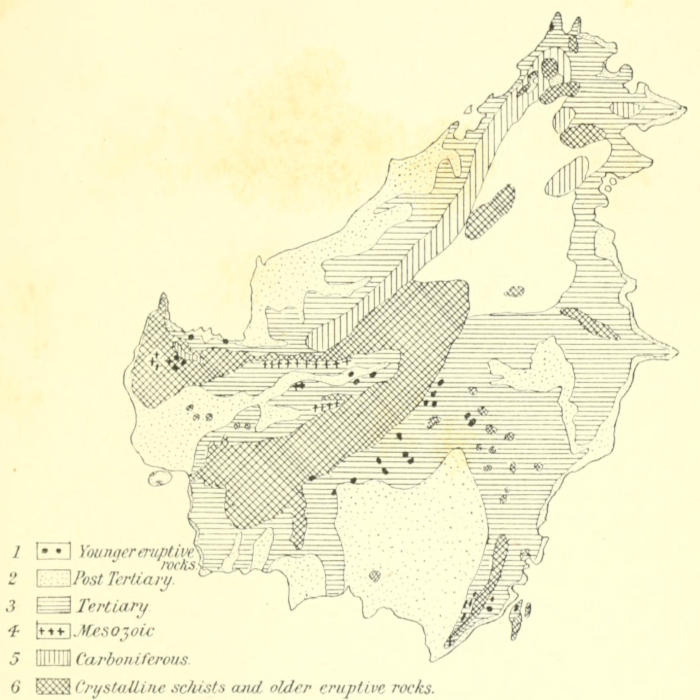

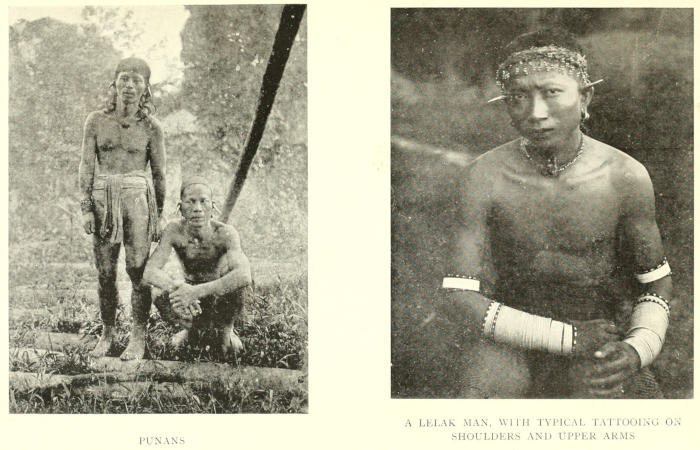

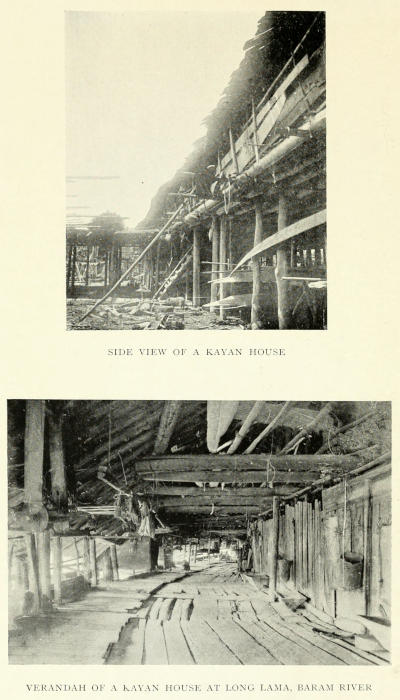

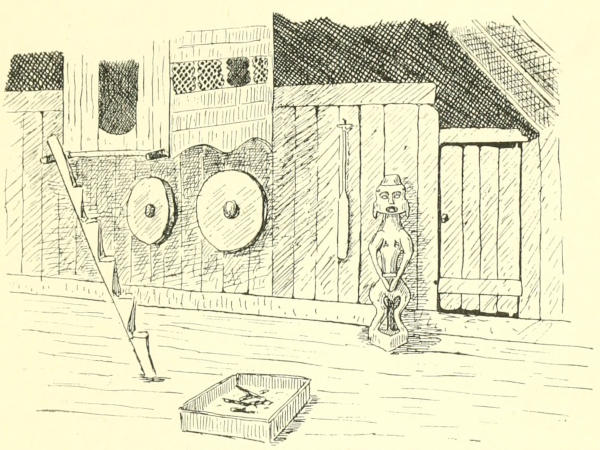

| The Geographical and Geological Features of Borneo: Arrangement of mountains—The geology of the “Mountain-land,” Palæozoic—Mesozoic—the geology of the “Hill-land,” Cainozoic—The geology of the Plains, Quaternary—The geology of the Marshes, Alluvium—Recent volcanic action. A Sketch of the Ethnography of Sarawak: Punans—Various agricultural tribes of Indonesian and Proto-Malay stock—Land Dayaks—Kenyahs and Kayans—Iban (Sea Dayaks)—Malays—Sociological History of Sarawak—Chinese traders | Page 312-329 |

| CHAPTER XXI A TRIP INTO THE INTERIOR OF BORNEO |

|

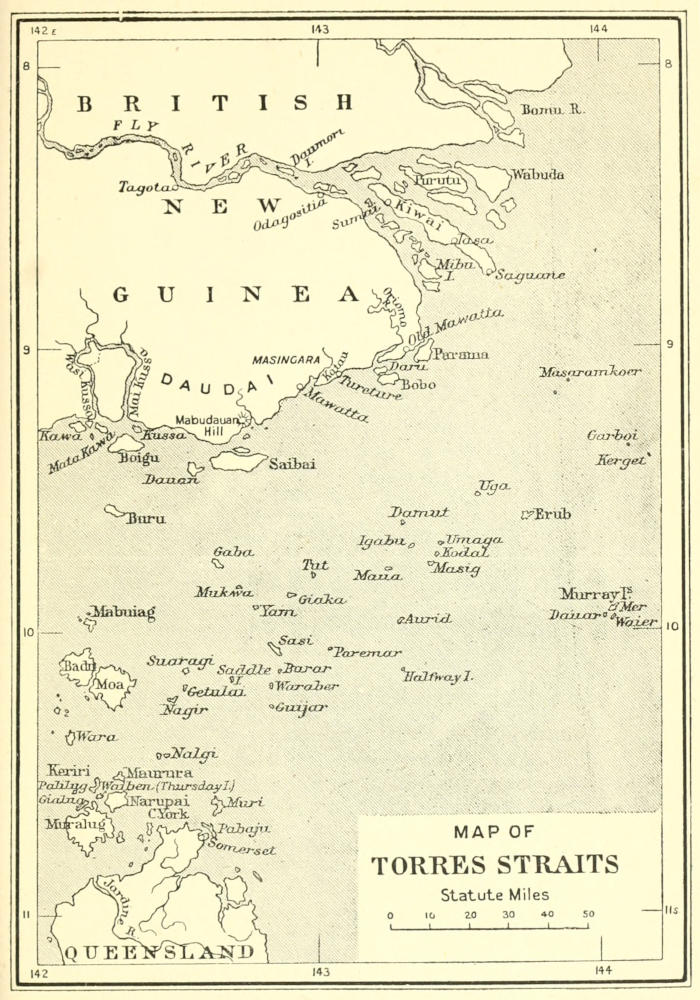

| The Lelak house at Long Tru—Skull trophies—The settled Punans on the Bok—Sarcophagus in Taman Liri’s house—Divination by means of a pig’s liver in Aban Abit’s house—Purchase of some skulls—The Panyamun Panic in Sarawak in 1894-5—Commencement of a similar scare—Administrative duties at Long Semitan—Character of the Sĕbops—The fable of the monkey and the frog—A visit to Mount Dulit—The Scott-Keltie Falls—The Himalayan affinities of the fauna of Mount Dulit and of other high mountains in Borneo | Page 330-351[xxi] |

| CHAPTER XXII A TRIP INTO THE INTERIOR OF BORNEO—continued |

|

| Ceremony of moving skulls into a new house at Long Puah—Naming ceremony for Jangan’s boy—Peace-making—Conviviality—Malohs desire to marry some Sĕbop girls—Sĕbop dances—Scenery on the Tinjar—Burnt house at Long Dapoi—Panyamun Scare again—The Dapoi—Long Sulan—Tingan’s matrimonial mishap—News from the Madangs—A Punan medicine man—Panyamun Scare settled—Discovery of stone implements—A native selling a stone implement for a loin cloth to die in—A stone hook—A visit to Tama Bulan—The unfortunate Bulan—Fanny Rapid—A Kenyan love story | Page 352-380 |

| CHAPTER XXIII NOTES ON THE OMEN ANIMALS OF SARAWAK |

|

| Archdeacon Perham on the omens of the Iban (Sea Dayaks)—List of the omen animals of the Kayans, Kenyahs, Punans, and Iban—Reputed origin of “Birding” | Page 381-393 |

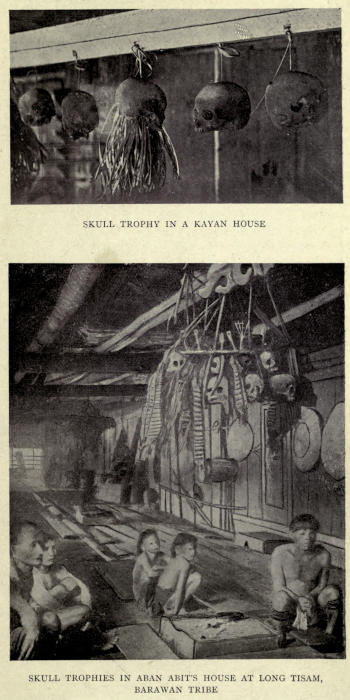

| CHAPTER XXIV THE CULT OF SKULLS IN SARAWAK |

|

| Reasons for collecting heads—Head required for going out of mourning for a chief—Kenyah legend of the origin of Head-hunting—How Kenyahs leave skulls behind when moving into a new house | Page 394-400 |

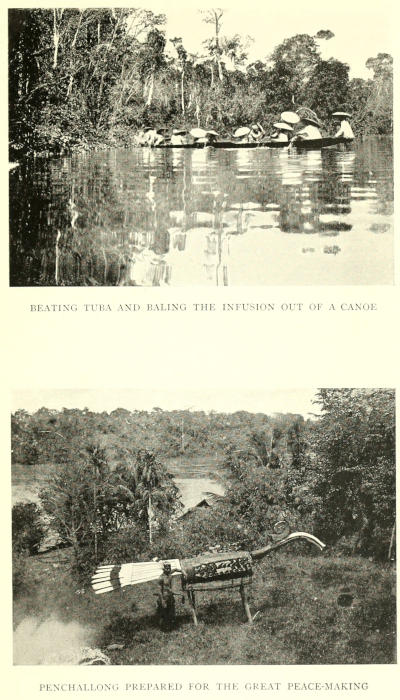

| CHAPTER XXV PEACE-MAKING AT BARAM |

|

| Padi competition—Obstacle race—Speech-making—The Lirong jawa—Fracas and reconciliation—Tuba-fishing in Logan Ansok—Great boat-race—Monster public meeting—Enthusiastic speeches, and Madangs formally received into the Baram Administrative District | Page 401-415 |

| Index | Page 417-426 |

| The Scott-Keltie Falls, Mt. Dulit, Baram District, Sarawak | Frontispiece | |

| PLATE | FACING PAGE | |

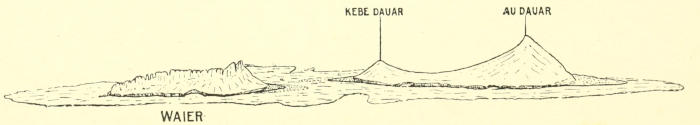

| I. | A. Ari, the Mamoose of Mer | 18 |

| B. Pasi, the Mamoose of Dauar | ||

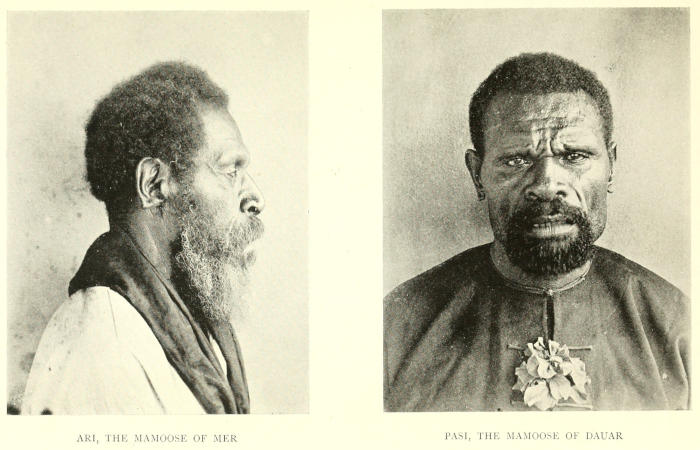

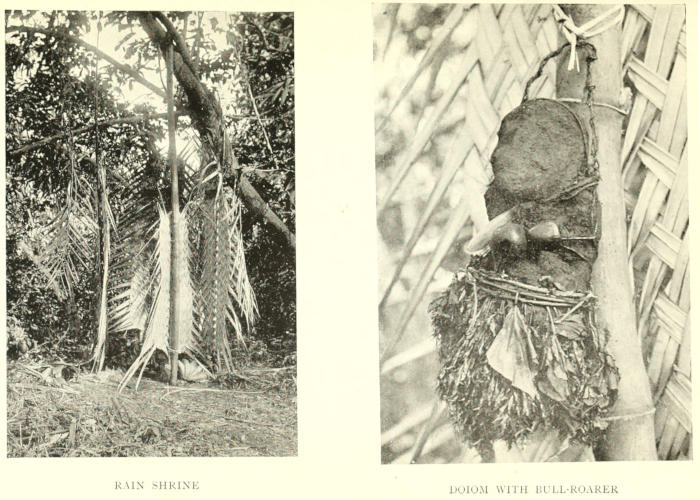

| II. | A. Rain Shrine, Mer | 34 |

| B. Doiom with Bull-roarer | ||

| III. | A. Ulai | 40 |

| B. A Top-spinning Match, Mer | ||

| IV. | A. Removing Sand from a Copper Maori | 41 |

| B. A Murray Island Feast | ||

| V. | A, B, C. The Dance of the Malu Zogole | 48 |

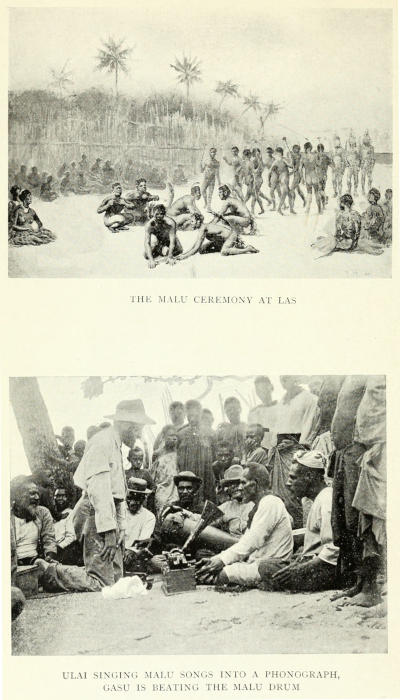

| VI. | A. The Malu Ceremony at Las | 49 |

| B. Ulai singing Malu songs into a Phonograph: Gasu is beating the Malu drum | ||

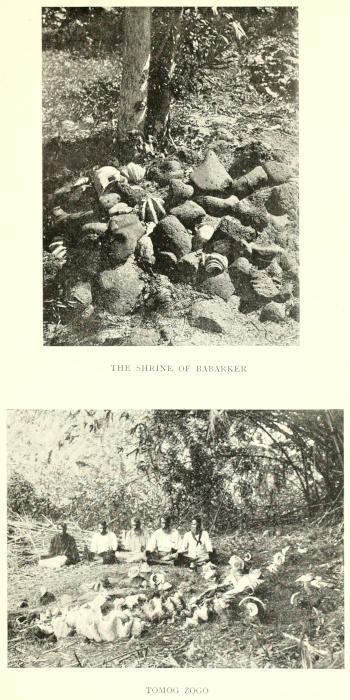

| VII. | A. The Shrine of Zabarker | 54 |

| B. Tomog Zogo | ||

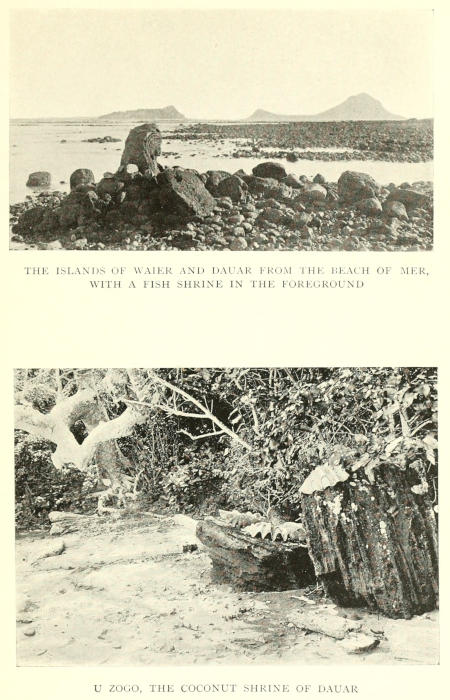

| VIII. | A. The Islands of Waier and Dauar from the beach of Mer, with a Fish Shrine in the foreground | 64 |

| B. U Zogo, the Coconut Shrine of Dauar | ||

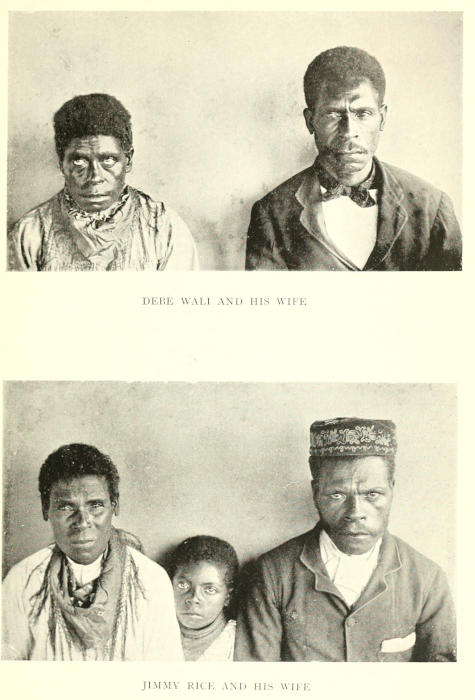

| IX. | A. Debe Wali and his Wife | 72 |

| B. Jimmy Rice and his Wife | ||

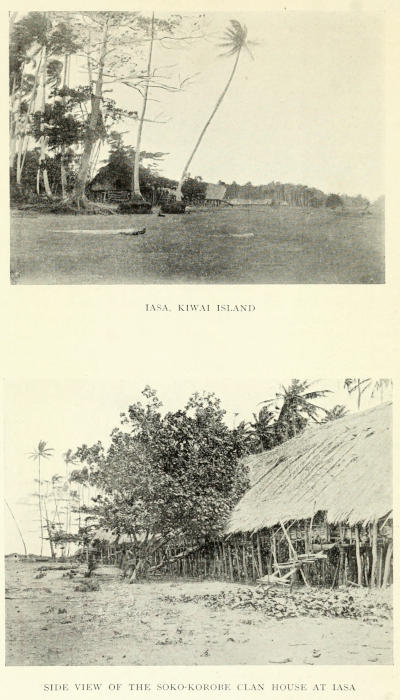

| X. | A. Iasa, Kiwai | 99 |

| B. Side view of the Soko-Korobe Clan-house at Iasa | ||

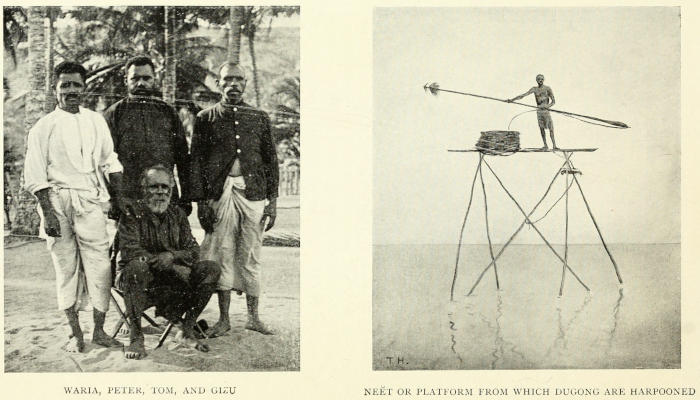

| XI. | A. Waria, Peter, Tom, and Gizu of Mabuiag | 123 |

| B. Nēĕt, or Platform from which Dugong are harpooned | ||

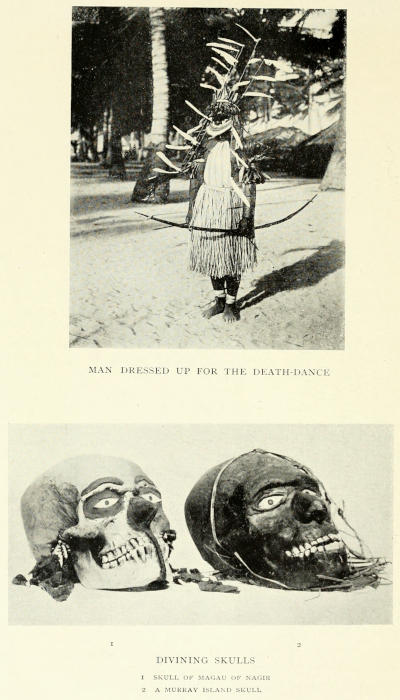

| XII. | A. Man dressed up for the Death Dance | 139 |

| B. Divining Skulls: 1. Skull of Magau of Nagir; 2. A Murray Island Skull | ||

| XIII. | A. The Marine Village of Gaile | 206 |

| B. Bulaa | ||

| XIV. | A. Girls of Babaka dressed for the Annual Ceremony | 218 |

| B. Girls on the Dubu at Babaka for the Annual Ceremony | ||

| XV. | A. Hollowing out a Canoe with Stone Adzes at Keapara | 220 |

| B. A Bulaa girl being tattooed | ||

| XVI. | A. A Native of Bulaa | 223 |

| B. A Bulaa youth with Ringworm | ||

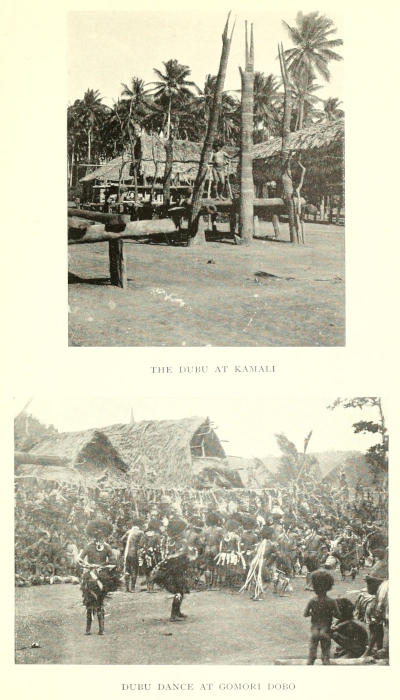

| XVII. | A. Dubu at Kamali | 232 |

| B. Dubu Dance at Gomoridobo | ||

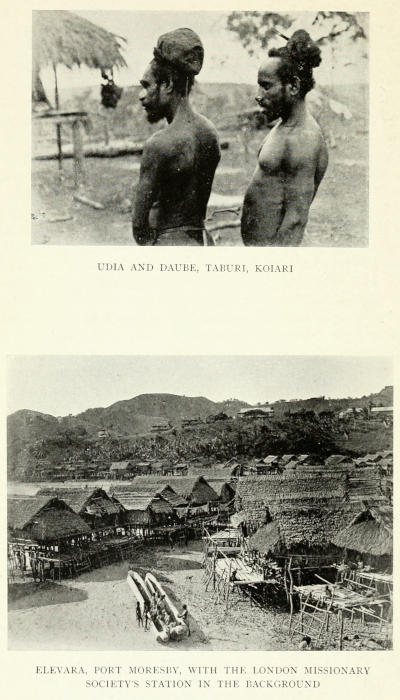

| XVIII. | A. Udia and Daube, Taburi, Koiari | 243 |

| B. Elevara, Port Moresby, with the London Missionary Society’s Station in the background[xxiii] | ||

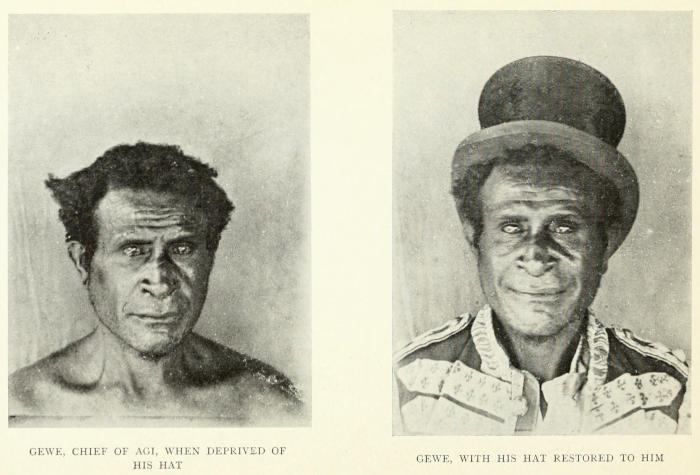

| XIX. | A. Gewe, Chief of Agi, when deprived of his Hat | 245 |

| B. Gewe, with his Hat restored | ||

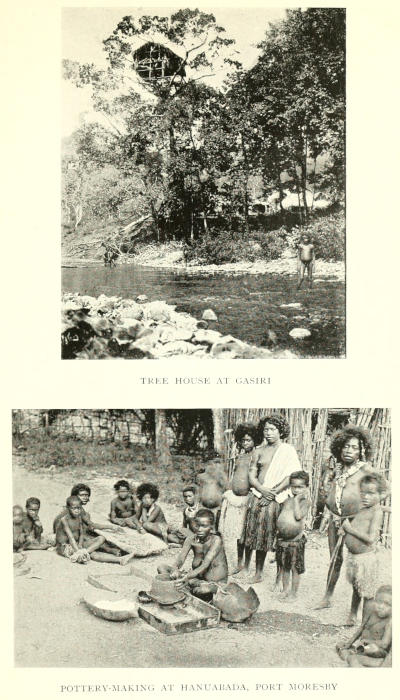

| XX. | A. Tree House at Gasiri | 248 |

| B. Pottery-making at Hanuabada, Port Moresby | ||

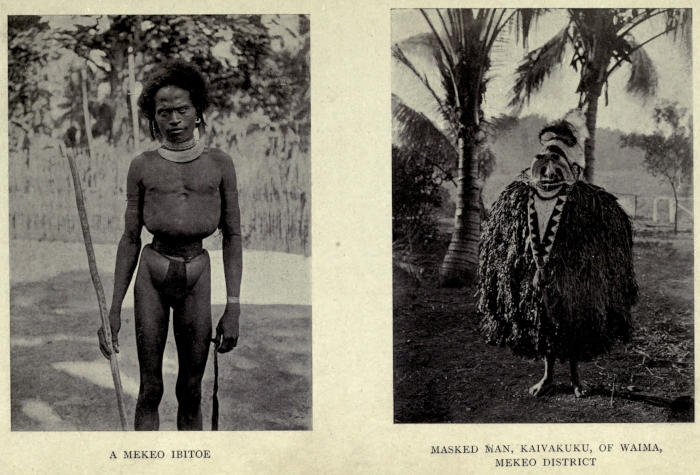

| XXI. | A. A Mekeo Ibitoe | 256 |

| B. Masked Man, Kaivakuku, of Waima, Mekeo District | ||

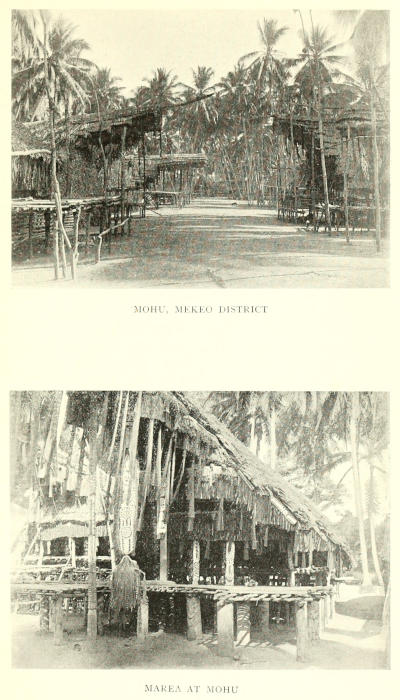

| XXII. | A. Mohu, Mekeo District | 268 |

| B. Marea at Mohu | ||

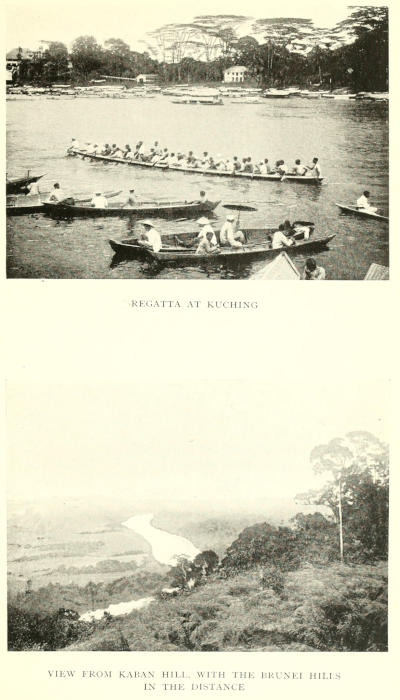

| XXIII. | A. Regatta at Kuching | 280 |

| B. View from Kaban Hill, with the Brunei Hills in the distance | ||

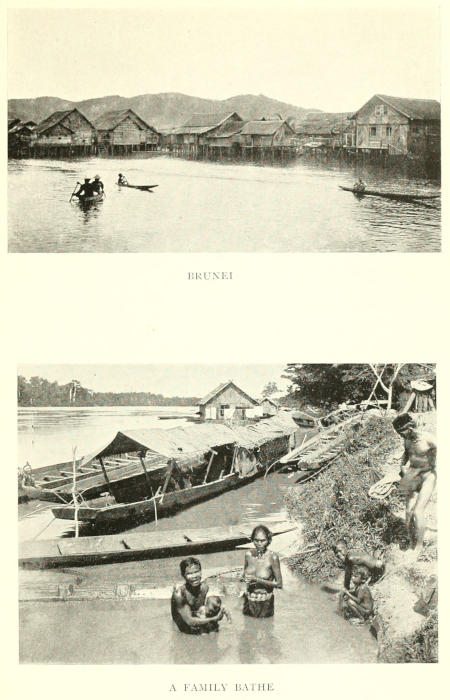

| XXIV. | A. Brunei | 290 |

| B. A Family Bathe | ||

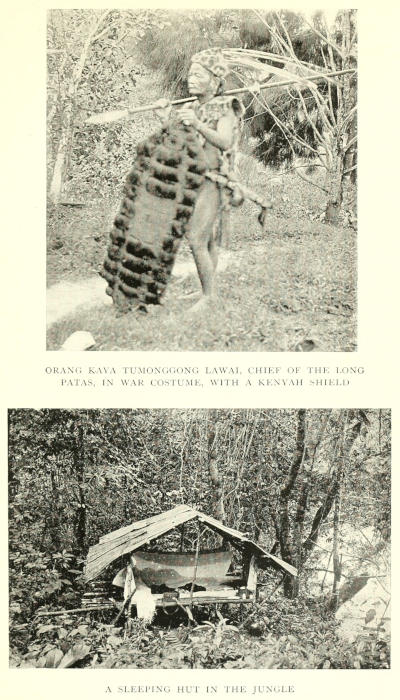

| XXV. | A. Orang Kaya Tumonggong Lawai, a Long Pata Chief in war costume, with a Kenyah shield | 300 |

| B. A Sleeping-hut in the Jungle | ||

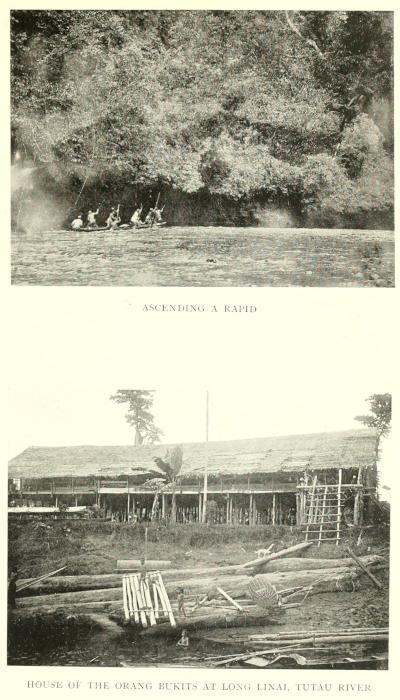

| XXVI. | A. Ascending a Rapid | 306 |

| B. House of the Orang Bukits at Long Linai, Tutau River | ||

| XXVII. | A. Punans | 320 |

| B. A Lelak man with typical Tattooing on shoulders and upper arms | ||

| XXVIII. | A. Side view of a Kayan House | 331 |

| B. Verandah of a Kayan House at Long Lama, Baram River | ||

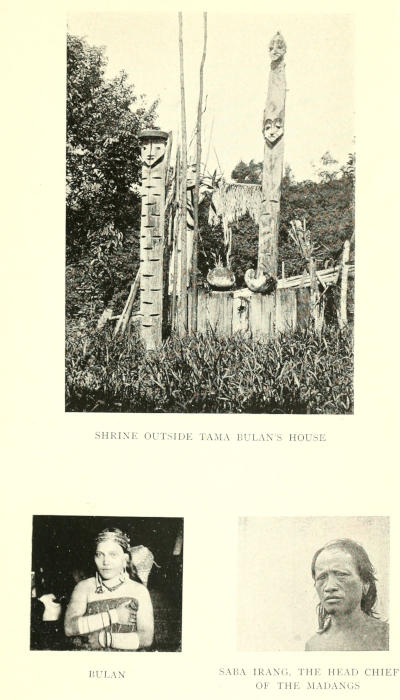

| XXIX. | A. Shrine outside Tama Bulan’s House | 376 |

| B. Bulan | ||

| C. Saba Irang, the Head Chief of the Madangs | ||

| XXX. | A. Skull Trophy in a Kayan House | 396 |

| B. Skull Trophies in Aban Abit’s House at Long Tisam, Barawan tribe | ||

| XXXI. | A. Beating Tuba and baling the Infusion out of a Canoe | 408 |

| B. Penchallong prepared for the Great Peace-making |

The photographs for Plates i.-iv. A., vi. B., vii. B., viii. B.-xi. A., xii. A., xiii.-xvi., xvii. A., xviii. A., xix.-xxii. were taken by the late A. Wilkin; those for Plates xvii. B., xxv. A., xxvii. B., xxx. A. were taken by C. G. Seligmann; Plate iv. B. by Dr. C. S. Myers; xii. B. by H. Oldland; and the Frontispiece and Plates v., vii. A., viii. A., xviii. B., xxiii., xxiv., xxv. B., xxvi., xxvii. A., xxviii., xxix., xxx. B., xxxi. by the Author. Plates vi. A. and xi. B. were drawn from photographs taken by the Author by his brother Trevor Haddon. With the exception of Plate xxx. B. none of the photographs have been retouched.

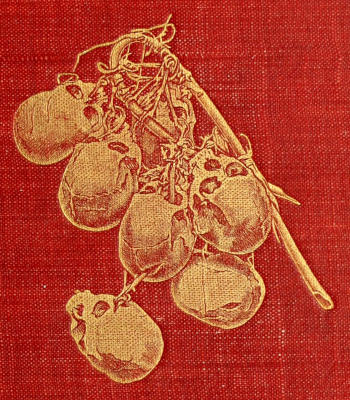

The skulls depicted on the cover are drawn from a photograph of a trophy collected by the Author at Mawatta, p. 115.

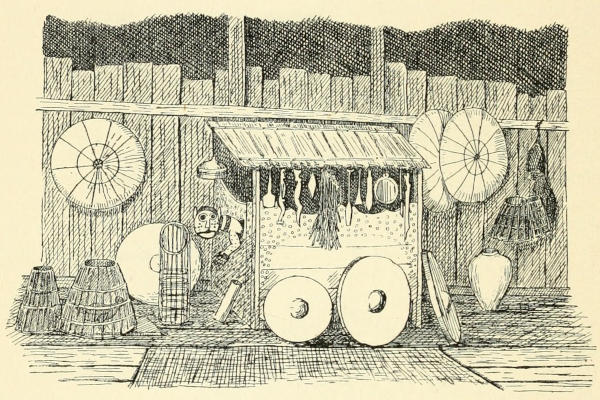

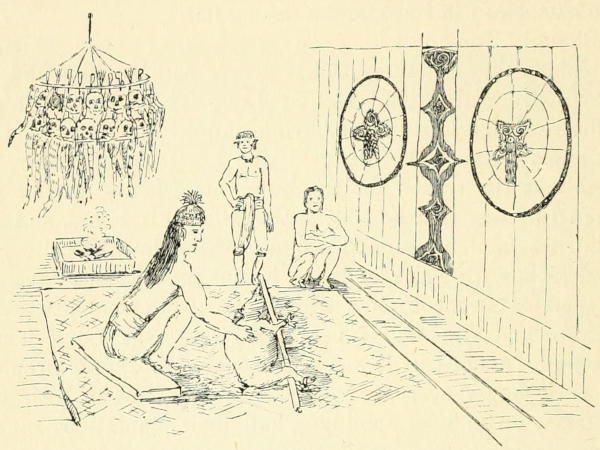

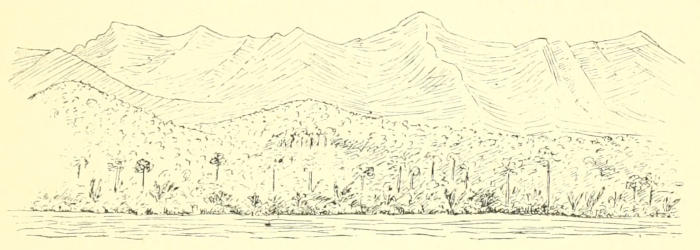

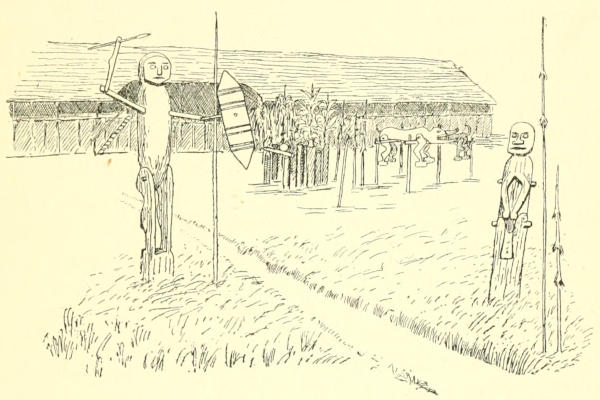

| FIG. | PAGE | |

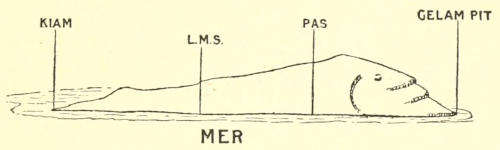

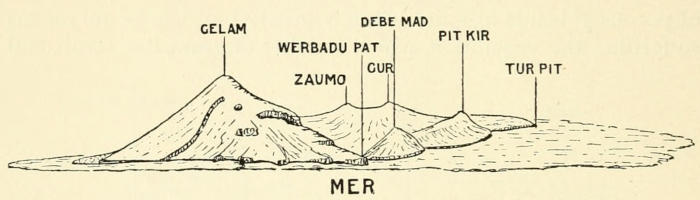

| 1. | The Hill of Gelam, Murray Island | 15 |

| 2. | Murray Island from the south | 16 |

| 3. | Waier and Dauar | 17 |

| 4. | Model of the Bomai Mask of the Malu Ceremonies | 47 |

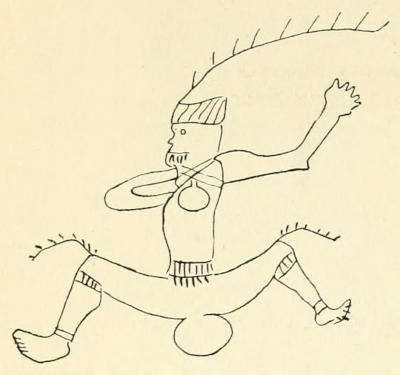

| 5. | Pepker, the Hill-maker | 65 |

| 6. | Ziai Neur Zogo, a Therapeutic Shrine | 65 |

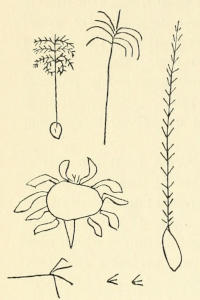

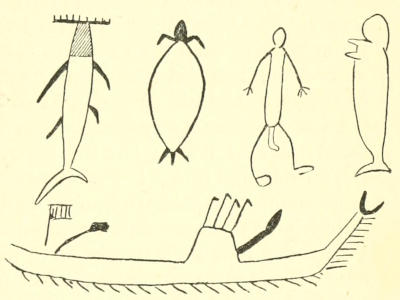

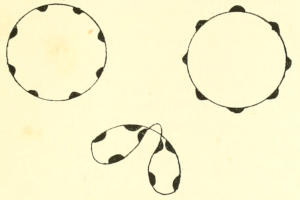

| 7. | Native drawings of some of the Nurumara (totems) of Kiwai | 102 |

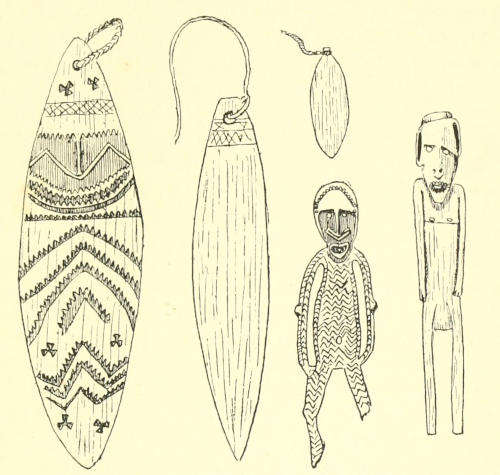

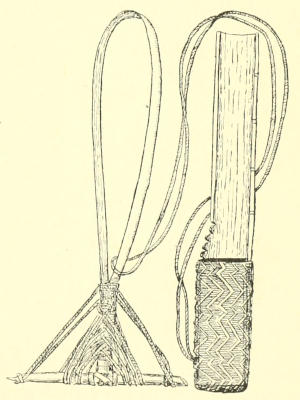

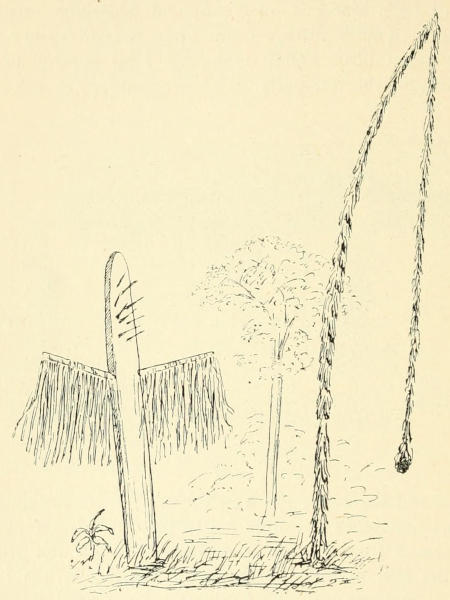

| 8. | Agricultural Charms of Kiwai | 105 |

| 9. | Neur Madub, a Love Charm | 106 |

| 10. | Shell Hoe used by the Natives of Parama | 110 |

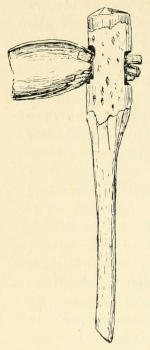

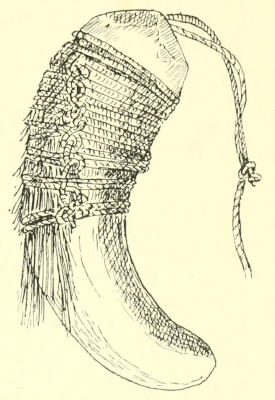

| 11. | Bamboo Beheading-knife and Head Carrier, Mawatta | 115 |

| 12. | The Kwod, or Ceremonial Ground, in Pulu | 139 |

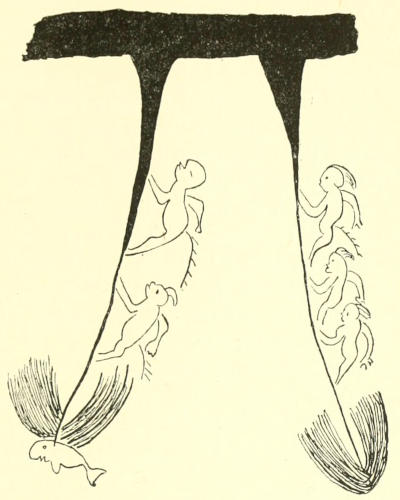

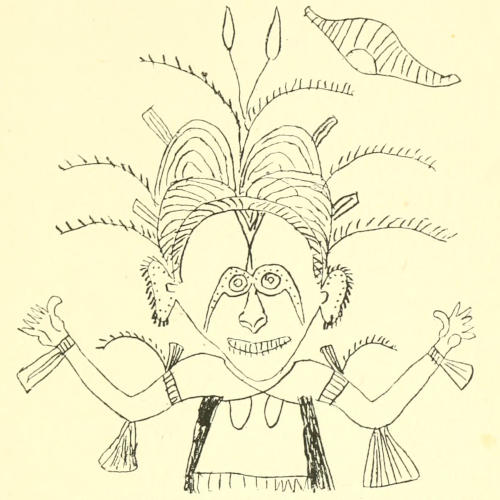

| 13. | Drawing by Gizu of a Danilkau, the Buffoon of the Funeral Ceremonies | 140 |

| 14. | Drawing by Gizu of Mŭri ascending a Waterspout | 141 |

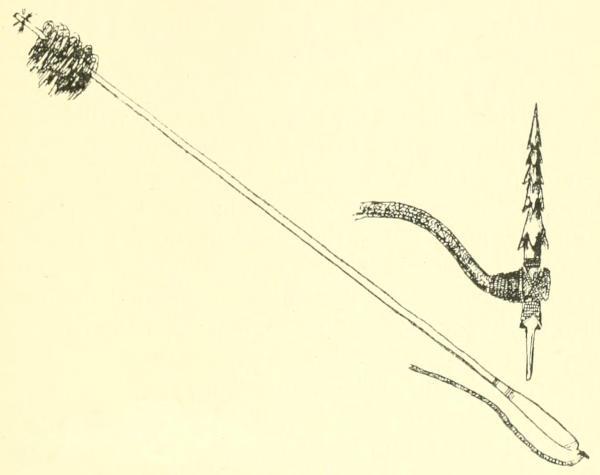

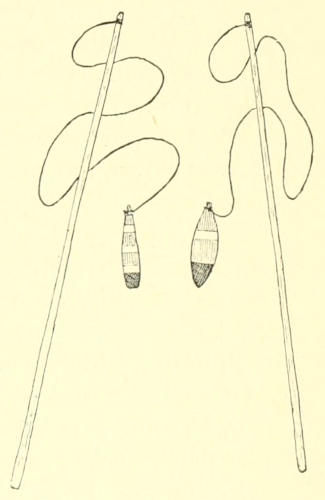

| 15. | Dugong Harpoon and Dart | 149 |

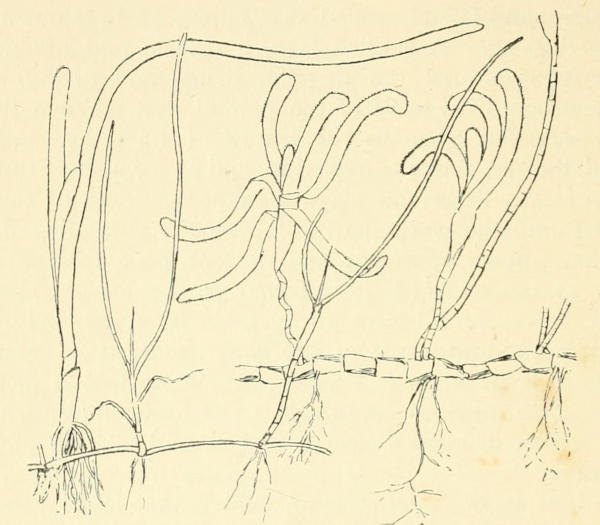

| 16. | Marine Plants (Cymodocea) on which the Dugong Feeds | 152 |

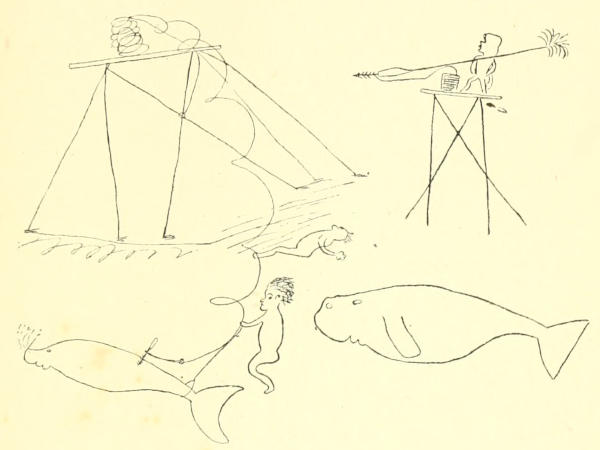

| 17. | Drawing by Gizu of the Method of Harpooning a Dugong | 153 |

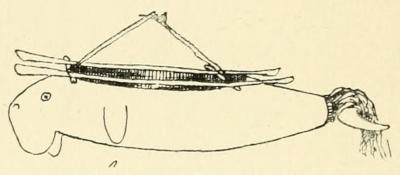

| 18. | Wooden Dugong Charm from Moa | 154 |

| 19. | Drawing by Gizu of Dorgai Metakorab and Bu | 167 |

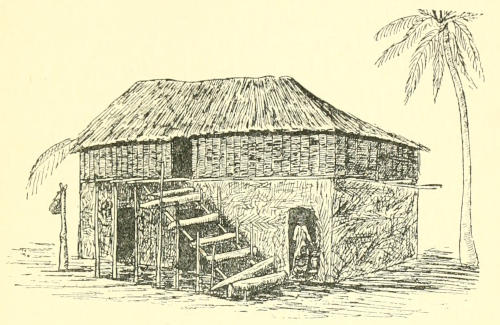

| 20. | House on Piles at Saibai, with the lower portion screened with leaves | 173 |

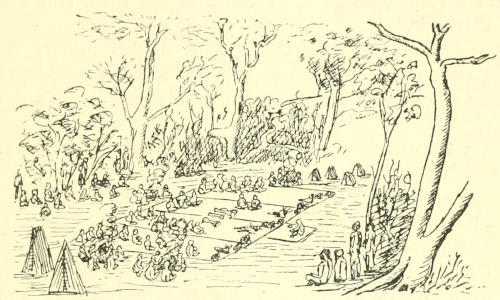

| 21. | Restoration of the Kwod in Tut during the Initiation Period | 177 |

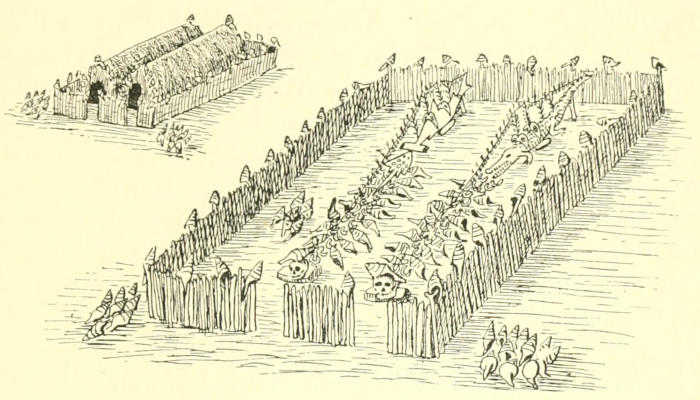

| 22. | Restoration of the Kwod in Yam | 179 |

| 23. | Rock Pictographs in Kiriri | 185 |

| 24. | Umbalako (Bull-roarers) of the Yaraikanna Tribe, Cape York | 191 |

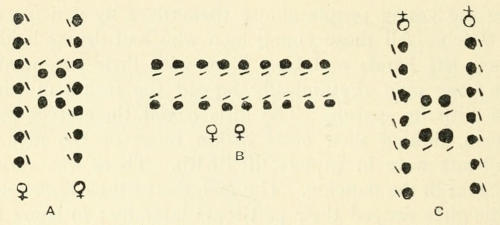

| 25. | Irupi Dance, Babaka | 217 |

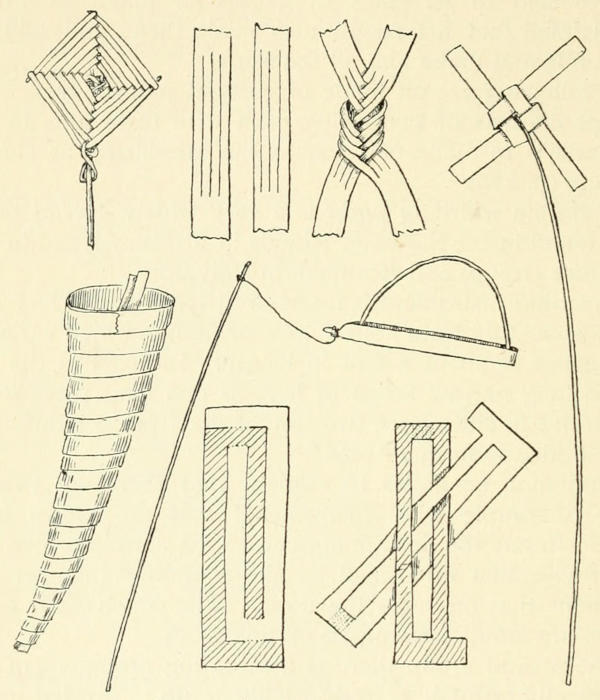

| 26. | Palm-leaf Toys, Bulaa | 226 |

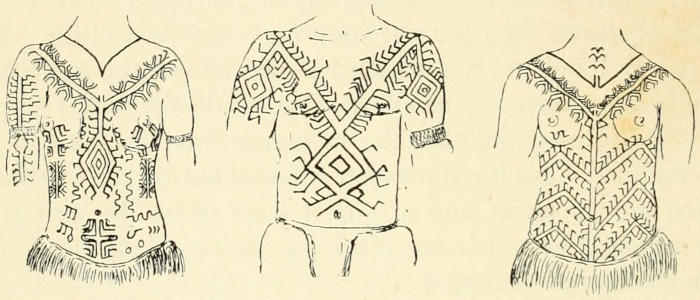

| 27. | Tattooing in the Mekeo District | 260 |

| 28. | Afu, or Taboo Signal, Inawi | 271 |

| 29. | Boys at Veifaa dressed up as Fulaari | 275 |

| 30. | Kayan Tattoo Designs | 306 |

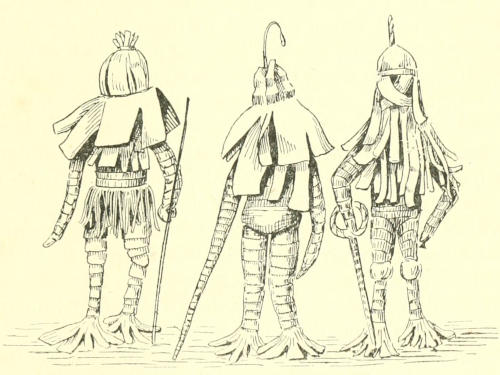

| 31. | Berantu Ceremony of the Orang Bukit | 307 |

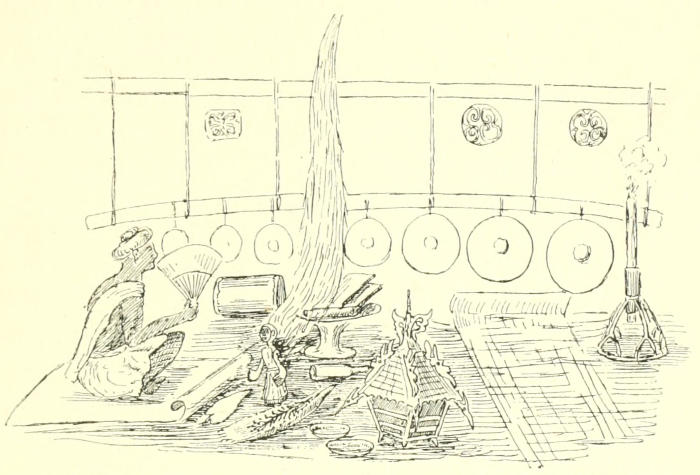

| 32. | Butiong in a Lelak House | 333 |

| 33. | Sarcophagus of a Boy in a Barawan House | 334 |

| 34. | Praying to a Pig in a Barawan House | 336 |

| 35. | Mount Dulit from Long Aaiah Kechil | 347 |

| 36. | Long Sulan | 361 |

| 37. | Kedaman and Kelebong at Long Sulan | 362 |

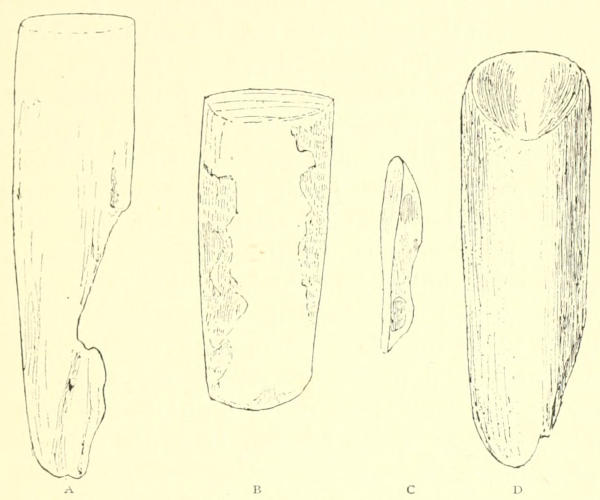

| 38. | Stone Implements from the Baram District, Sarawak | 369 |

| 39. | Magical Stone Hook | 371 |

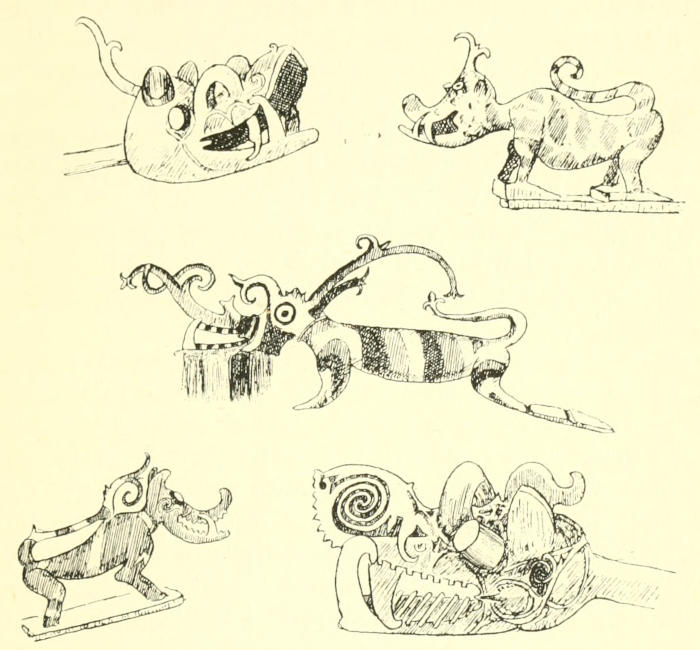

| 40. | Figure-heads of Canoes, Baram District | 407 |

All the above illustrations except Figs. 13, 14, 17, and 19 were drawn by the Author.

| PAGE | |

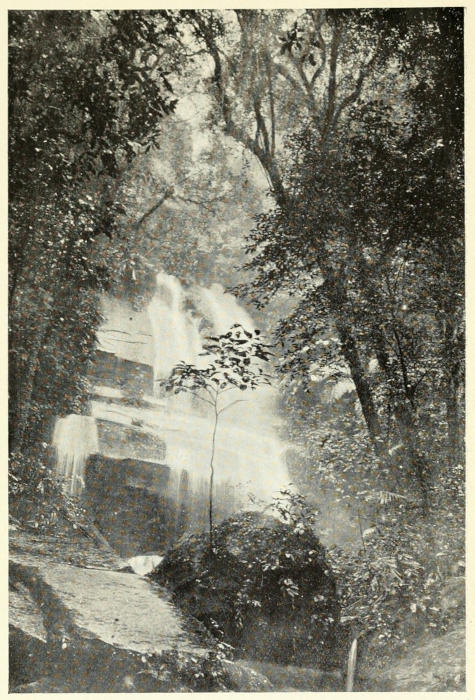

| Map of Torres Straits | 13 |

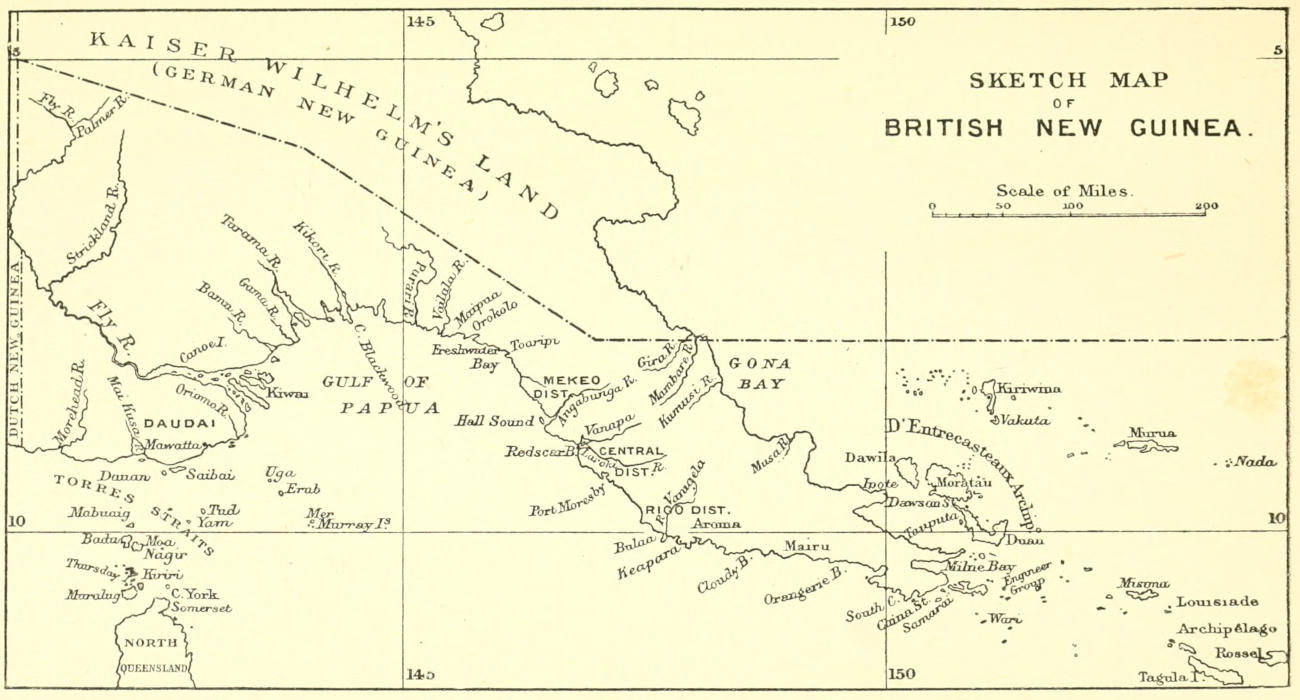

| Sketch Map of British New Guinea | 195 |

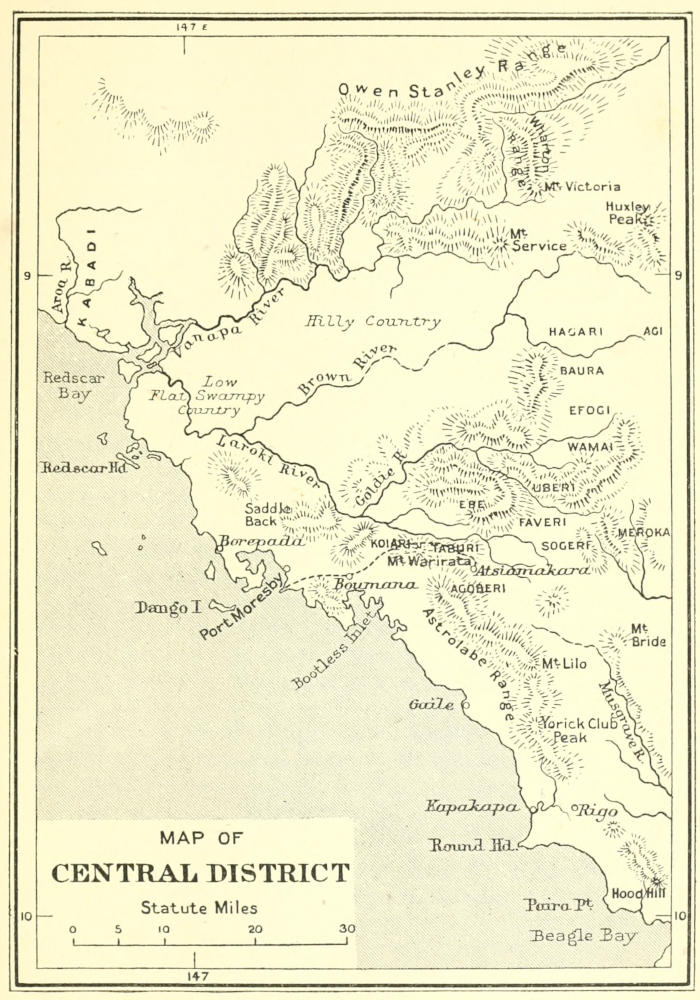

| Map of the Central District, British New Guinea | 237 |

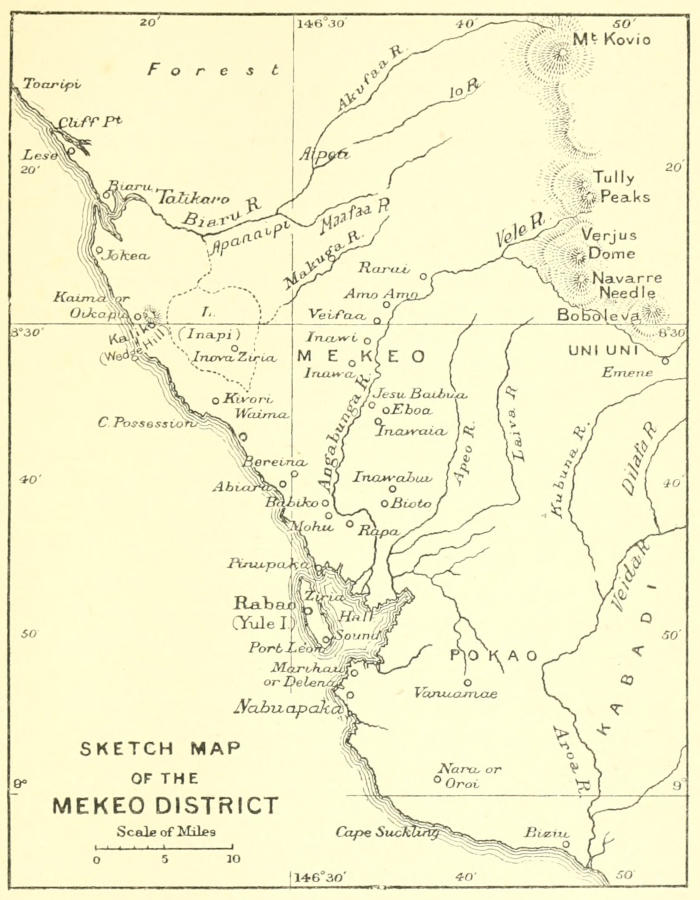

| Map of the Mekeo District, British New Guinea | 263 |

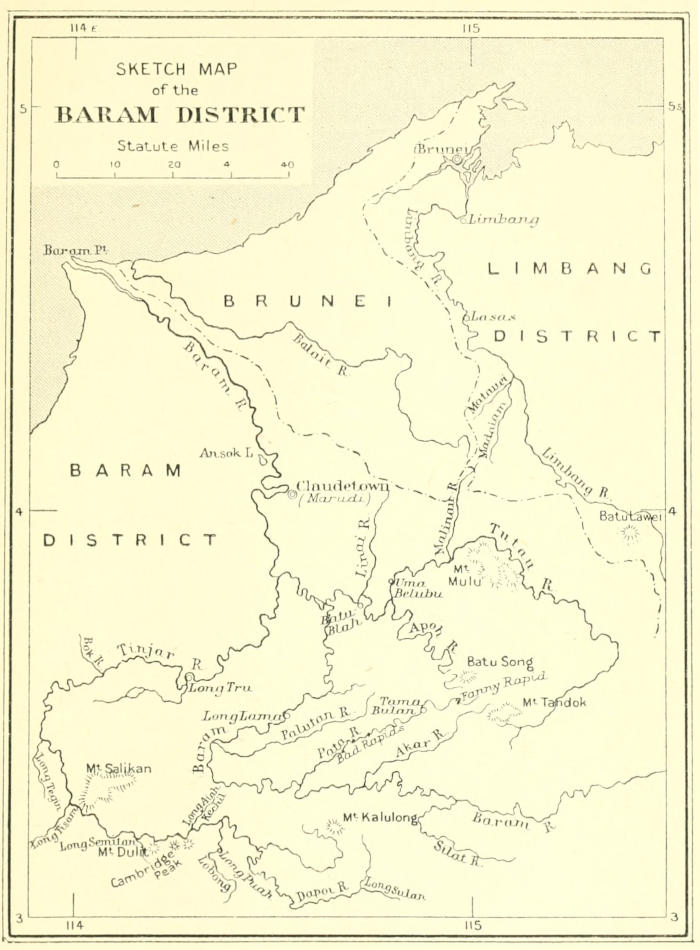

| Sketch Map of the Baram District, Sarawak | 295 |

| Geological Sketch Map of Borneo | 313 |

We arrived at Torres Straits early in the morning of April 22nd, 1898, and dropped anchor off Friday Island, as the steamers of the Ducal Line are not allowed now to tie up at the hulk at Thursday Island. Shortly afterwards we were met by the Hon. John Douglas, the Resident Magistrate, and Dr. Salter, both of whom were old friends who had shown me much kindness during my previous expedition. They were accompanied by Seligmann, who had left London some months previously in order to visit Australia, and as a handsel had already done a little work on a hitherto unknown tribe of North Queensland natives.

The township of Thursday Island, or Port Kennedy, as it is officially termed, had increased considerably during the past decade. This was partly due to the natural growth of the frontier town of North Queensland, and partly to the fact that it has become a fortified port which commands the only safe passage for large vessels through these dangerous straits. So assiduous have been the coral polyps in defending the northernmost point of Australia, that although the straits measure some eighty miles between Cape York and the nearest coast of New Guinea, what with islands and the very extensive series of intricate coral reefs, there is only one straightforward passage for vessels of any size, and that is not more than a quarter of a mile wide.

Although the town has increased in size its character has not altered to any considerable extent. It is still the same[2] assemblage of corrugated iron and wooden buildings which garishly broil under a tropical sun, unrelieved by that vegetation which renders beautiful so many tropical towns. It is true a little planting has been done, but the character of the soil, or perhaps the absence of sufficient water, render those efforts melancholy rather than successful.

Many of the old desert lots are now occupied by stores and lodging-houses. The characteristic mountains of eviscerated tins, kerosine cases, and innumerable empty bottles which betoken a thirsty land, have been removed and cast into the sea. Thriving two- or three-storied hotels proclaim increase in trade and comparative luxury.

There is the same medley of nationalities—British, Colonial, French, German, Scandinavian, Greek, and other European job lots, in addition to an assortment from Asia and her islands. As formerly, the Pacific islands are well represented, and a few Torres Straits islanders are occasionally to be seen. Some of the latter are resident as policemen, others visit the island to sell pearl-shell, bêche-de-mer, and sometimes a little garden produce, and to purchase what they need from the stores.

One great change in the population is very striking, and that is the great preponderance of the Japanese. So far as I remember they were few in number ten years previously, and were, I believe, outnumbered by the Manila men; now they form the bulk of the population, much to the disgust of most of the Europeans and Colonials. Various reasons are assigned for this jealousy of the Japanese, and different grounds are taken for asserting that the influx should be checked, and restrictions enforced on those who have already settled.

It appeared to me that the bed-rock of discontent was in the fact that the Japanese beat the white men at their own game, mainly because they live at a lower rate than do the white men. A good proportion of the pearl-shelling industry is now carried on by the Japanese, who further play into each other’s hands as far as possible. A good example of their enterprise is shown by the fact that they have now cut out the white boat-builders. A few years ago, I was informed, some Japanese took to boat-building and built their first boats from printed directions in some English manual. Their first craft were rather clumsy, but they discovered their mistakes, and now they turn out very satisfactory sailing boats. It is impossible not to feel respect[3] for men who combine brains with diligence, and who command success by frugality and combination.

The white men grumble that the Japanese spend so little in the colony and send their money away; but the very same white men admit they would themselves clear out as soon as they had made their pile. Their intentions are the same as are the performances of the Japanese; but the white men cannot, under the present conditions, make a fortune quickly, and certain of them cannot keep what they do make. There are white men acting as divers for coloured men’s pay who some years ago owned boats of their own. The fall in value of pearl-shell a few years since is scarcely the sole reason for this change of fortune; bad management and drink have a good deal to answer for.

Some white men contend that as this is a British colony, and has been developed by British capital and industry, the Japanese should not be allowed to reap the benefit; but a similar argument might be applied to many of the industrial enterprises of the British in various parts of the world. As an outsider, it appears to me that it is some of those very qualities that have made the British colonist what he is that manifest themselves in the Japanese. In other words, the Japanese are feared because they are so British in many ways, saving perhaps the British expensive mode of life. It is probably largely this latter factor that renders the Japanese such deadly competitors.

Formerly there were in Torres Straits regular bêche-de-mer and copra industries, now there is very little of the former, and none of the latter. Large, slimy, leathery sea-slugs gorge the soft mud on the coral reefs; these when boiled and smoke-dried shrivel into hard rough rolls, which are exported in large numbers to China. These bêche-de-mer, or, as the Malays call them, “tripang,” are scientifically known as Holothuria, and are related to sea-urchins and starfish. Copra is the dried kernel of the coconut.

When one walks about the township and sees the amount of capital invested, and when one considers what is spent and how much money is sent away, it is hard to realise that all this wealth comes out of pearl-shell and pearls. During the past thirty years very many thousands of pounds have been made out of pearl-shell in Torres Straits; but now the waters have[4] been overfished, and unless measures are taken to protect the pearl oysters, the harvest will become yet scantier and scantier. In any case the time for big hauls and rapid fortunes is probably over.

About the year 1890 gold was found in some of the islands, but I believe that the working only pays in one island, though it may be resumed at Horn Island, which at one time promised to be a lucrative goldfield.

At Thursday Island we met with much helpful kindness. Mr. Douglas entertained a couple of us, and did all he could to expedite matters. Unfortunately he was then without a steamer, and so could not tranship us and our gear to Murray Island, which otherwise he would have gladly done. It took a week to overhaul our baggage, get in stores, and to arrange about transport, and eventually I arranged with Neil Andersen to take us across; but even then there was neither room for all our baggage nor accommodation for the whole of our party. Rivers, Ray, and Seligmann and myself went on in the Freya, leaving the others to follow in the Governor Cairns, an official schooner that was shortly to start for Darnley Island.

It was not till the late afternoon of Saturday, April 30th, that we actually started, and then we were only able to beat up the passage between Thursday Island and Hammond Island, and anchored about six o’clock in the lee of Tuesday Island. There are very strong tides between these islands, and I have seen even a large ocean steamer steaming full speed against a tide race, and only just able to hold her own, much less make way against it.

The Freya was a ketch, a kind of fore-and-aft schooner, 47 feet 6 inches long and 11 feet 2 inches in the beam, and could carry about twenty tons of cargo. We had a strange medley of races on board—European skipper and passengers, our Javanese “boy,” the Japanese diver, two Polynesian sailors from Rotumah, and three Papuans from Parama, near the mouth of the Fly River. Our captain was a fine, big man, probably a good type of the Dubhgaill, or “black (dark) strangers,” who a thousand years ago ravaged the southern and eastern coast of Ireland as far north as Dublin. We “turned in” early—this consisted in wrapping oneself up in a blanket, extemporising a pillow, and lying on the deck.

Left Tuesday Island at 4 a.m. in a stiff breeze and chopping[5] sea, and so could only make Dungeness Island by 4 p.m. Twelve hours to go fifty-five miles! We landed at the mangrove swamp, but there was little of interest. We hoped to have reached Darnley Island next day, but only fetched Rennel Island by 5.30 p.m. This is a large vegetated sandbank, on which we found traces of occupation, mainly where the natives had camped when bêche-de-mer fishing. We all suffered a good deal from sunburnt feet, the scorching by the sun being aggravated by the salt water. Some of our party were still seasick; one lay on the deck as limp as damp blotting-paper, and let the seas break over him without stirring even a finger. We had a wet night of it, what with the rain from above and the sea-water swishing in at the open stern and flooding the sleepers on the deck.

We made an early start next morning and reached Erub, or Darnley Island, at three in the afternoon. Immediately on landing I went to Massacre Bay to photograph the stratified volcanic ash that occurs only at this spot in the island, and which is the sole visible remains of the crater of an old volcano. The rest of the island is composed of basalt, which rises to a height of over 500 feet, and is well wooded and fertile—indeed, it is perhaps the most beautiful island in Torres Straits. Save for rocky headlands which separate lovely little coves fringed with white coral sand, the whole coast is skirted with groves of coconut palms and occasional patches of mangroves. The almost impenetrable jungle clothes the hills, except at those spots that have been cleared for “gardens.” Even the tops of the hills are covered with trees.

Very shortly after landing, a fine, honest-faced Murray Island native, Alo by name, who was visiting Erub, came up and greeted me very warmly. I regret to say I had quite forgotten him, but he perfectly remembered me, and he beamed with pleasure at seeing me. We walked along the coast to the village where the chief lives, and saw Captain H⸺, and I made arrangements with Koko Lifu, a South Sea man, to lighter our goods off the Governor Cairns and to take the cargo and our three comrades to Murray Island.

Captain H⸺ is one of those remarkable men one so constantly meets in out-of-the-way places. It is the common man one comes across at home. On the confines of savagery and civilisation one meets the men who have dared and suffered,[6] rugged like broken quartz, and maybe as hard too, but withal streaked with gold—ay, and good gold too. Captain H⸺ started in life as a middy in the Navy; owing to a tiff with his people he quitted the Service and entered the Merchant Service. He advanced quickly, and when still very young obtained a command. He has made two fortunes, and lost both owing to bank failures, and is at present a ruined old recluse, living on a remote island along with Papuans, Polynesians, and other races that now inhabit Erub. He is a kind of Government Agent, and patrols the deep-water fishing grounds. I have previously mentioned that the ordinary fishing grounds for pearl-shell are practically exhausted, and the shellers have to go further afield or have to dive in deeper water in order to get large shells. Near Darnley Island are some good fishing grounds, but the water is so deep as to render the fishing dangerous to life, and the Queensland Government has prohibited fishing in these waters. There are, however, always a number of men who are willing to run the risk for the sake of increased gain, and it is all they can do to dodge the vigilance of the wary old sea-dog.

Captain H⸺ lives entirely by himself, and has no intercourse with the natives beyond what is absolutely necessary. He puts in his spare time in attending to his gardens and reading. Amongst other accomplishments he is a fluent speaker of French and Italian, and it was a strange experience to meet a weather-worn old man in frontier dishabille acting and speaking like a refined gentleman.

As on previous nights, except the first, Andersen made a tent for us on board the Freya out of the mainsail, the boom forming the ridge-pole. Ontong, the cook I had engaged at Thursday Island, woke us up at 2.30 a.m. to tell us tea was ready, and it was too! The pungent smell of the smoke prevented me from going to sleep for some time. In the morning Ontong said he thought it was “close up daylight”; and with an energy which is not usually credited to the Oriental character, he had made tea so as to be prepared for an early start.

We started early next morning with Alo as pilot; for the coral reefs between Darnley and Murray are extensive, intricate, and mainly uncharted. Andersen started for the “big passage” that large boats always take; but after some time it was discovered that Alo did not know this passage, but another one[7] to the south-west of Darnley. As half the tide had by this time turned and the weather was very squally and the reefs could not be seen with certainty, we returned to our old anchorage by 9.30, and so another day was lost. We spent a lazy day to give our sore legs a rest. Alo left us in the evening, as he said he was “sick.” The truth was he did not care about the job, so Andersen went ashore and brought another pilot, named Spear. His father was a native of Parama; his mother was an Erub woman. Spear told us he had first married a Murray Island girl, and then half a dozen New Guinea women; but Dr. Macfarlane, the pioneer missionary in these parts, had made him “chuck” the latter.

Next day we started betimes, and sailed down channels in the reefs not marked in the charts. The day was dull, and the little wind was southerly when we wanted it easterly, whereas the previous day the reverse was the case. Later it became squally with rain, and finding it hopeless to reach Murray Island, Spear piloted us to a sheltered spot in the lee of a reef and close to a sandbank. We were only about four miles from our destination, and we could hear the roaring of the breakers of the Pacific Ocean as they dashed themselves against the Great Barrier Reef ten miles distant.

We had a very disturbed night. About eight o’clock, whilst we were yarning, the skipper jumped up and said the anchor was dragging. Then ensued a scene of intense excitement, as we were close not only to the sandbank, but also to a jagged coral reef. It was horrid to feel the boat helplessly drifting, for not only were the sails down, but the mainsail was unlashed below to make our tent, and further, it was tied down in various places. The first thing to do was to haul up the anchor, and furl the jib and mainsail, and unship the tent. We all lent a hand to the best of our ability, and soon we were sailing down the narrow passage. Andersen’s voice was hoarse and trembling with excitement, but he kept perfectly cool, and he never lost his temper, though in the confusion and babel of tongues some lost their heads through fright and did not do the right thing at the right moment, and each of the crew was ordering the others about in his own language.

After sailing about a little we made another attempt to anchor, and again the anchor dragged and we had another little cruise. Again we tried and again we failed, and it may[8] be imagined that our sensations were not of a very cheerful nature, as we were in a really grave predicament; sometimes we actually sailed over the reef, and might any moment have knocked a hole in the ship’s bottom or have become stranded. If he could not effect an anchorage, two courses were open to Andersen. One was to cruise about all night, and it was very dark, keeping the reef in sight, or rather sailing up and down the passage, for if he had sailed out into the open he would probably strike a reef or coral patch that was unnoticed. The second alternative was to run the boat on to the sandbank and let it float off at high water in the morning. The reason why we drifted was because the anchor was let down on a steep gravelly slope, and the movement of the boat, which was naturally away from the bank, prevented the flukes from getting a firm grip.

On the fourth essay the anchor was put on the sandbank in a depth of three fathoms while we swung in fourteen or fifteen fathoms. After waiting some time in anxiety, we found to our relief that the anchor held, and we wrapped ourselves up in our blankets and slept on deck, pretty well exhausted. We had such confidence in the skill and alertness of Andersen, whom we knew to be a pre-eminently safe man, that we soon composed ourselves and slept soundly.

Friday, May 6th.—Again the wind was against us and the weather was squally, and it was not till one o’clock that we dropped anchor off the Mission premises at Murray Island.

I have briefly described our tedious trip to Murray Island, not because there was anything at all unusual in it, but merely to give some idea of the difficulty and uncertainty in sailing in these waters. There is no need, therefore, for surprise at the isolation of Murray Island, a fact which had influenced me in deciding to make it the scene of our more detailed investigations.

On landing we were welcomed by Mr. John Bruce, the schoolmaster and magistrate. He is the only white man now resident on the island, and he plays a paternal part in the social life of the people. I was very affectionately greeted by Ari the Mamoose, or chief of the island, and by my old friend Pasi, the chief of the neighbouring island of Dauar, and we walked up and down the sand beach talking of old times, concerning which I found Pasi’s memory was far better than mine.

I found that one of the two Mission residences on the side of the hill that were there ten years before was still standing and was empty, so I decided to occupy that, although it was rather dilapidated; and it answered our purpose admirably. The rest of the day and all the next was busily spent in landing our stuff and in unpacking and putting things to rights. We slept the first night at Bruce’s house, which is on the strand. When I went up next morning to our temporary home I found that the Samoan teacher Finau and his amiable wife had caused the house to be swept, more or less, and had put down mats, and placed two brightly coloured tablecloths on the table, which was further decorated with two vases of flowers! It seemed quite homely, and was a delicate attention that we much appreciated.

I engaged two natives, Jimmy Rice and Debe Wali, to get wood and water for us and to help Ontong. We had various vicissitudes with these two “boys,” but we retained them all through our stay, and they afforded us much amusement, no little instruction, and a very fair amount of moral discipline. The legs of two of our party were still so sore that they had to be carried up the hill, and on Saturday night we were established in our own quarters, and eager to commence the work for which we had come so far.

We had a deal of straightening up to do on Sunday morning, but I found time to go half-way down the hill to the schoolhouse, and was again impressed, as on my former visit, with the heartiness of the singing, which was almost deafening. The congregation waited for me to go out first, and I stood at the door and shook hands with nearly all the natives of the island as they came down the steps, and many were the old friends I greeted. I invited them to come up and see some photographs after the afternoon service.

We made the place as tidy as possible, and we had a great reception in the afternoon. Nearly all my old friends that were still alive turned up, besides many others. To their intense and hilarious delight I showed them some of the photographs I had taken during my last visit, not only of themselves, but also of other islands in the Straits. We had an immense time. The yells of delight, the laughter, clicking, flicking of the teeth, beaming faces and other expressions of joy as they beheld photographs of themselves or of friends[10] would suddenly change to tears and wailing when they saw the portrait of someone since deceased. It was a steamy and smelly performance, but it was very jolly to be again among my old friends, and equally gratifying to find them ready to take up our friendship where we had left it.

Next morning when we were yarning with some natives others solemnly came one by one up the hill with bunches of bananas and coconuts, and soon there was a great heap of garden produce on the floor. By this time the verandah was filled with natives, men and women, and I again showed the photographs, but not a word was said about the fruit. They looked at the photographs over and over again, and the men added to the noise made by the women. On this occasion there was more crying, which, however, was enlivened with much hilarity. Then the Mamoose told Pasi to inform me in English, for the old man has a very imperfect command even of the jargon English that is spoken out here, that the stack of bananas and coconuts was a present to me. I made a little speech in reply, and they slowly dispersed.

On Tuesday evening McDougall, Myers, and Wilkin arrived, and our party was complete.

Torres Straits were discovered and passed through in August, 1606, by Luis Vaez de Torres. They were first partially surveyed by Captain Cook in 1770, and more thoroughly during the years 1843-5 by Captain Blackwood of H.M.S. Fly, and in 1848-9 by Captain Owen Stanley of H.M.S. Rattlesnake. H.M. cutter Bramble was associated with both these ships in the survey. But in the meantime other vessels had passed through: of these the most famous were the French vessels the Astrolabe and Zélée, which in the course of the memorable voyage of discovery under M. Dumont d’Urville were temporarily stranded in the narrow passage of the Island of Tut in 1840.

Bampton and Alt, the adventurous traders and explorers of the Papuan Gulf, came in the last years of the eighteenth century, and since then there have not been wanting equally daring men who, unknown to fame, have sailed these dangerous waters in search of a livelihood.

Mr. John Jardine was sent from Brisbane in 1862 to form a settlement at Somerset, in Albany Pass; but the place did not grow, and in 1877 the islands of Torres Straits were annexed to Queensland, and the settlement was transferred from the mainland to Thursday Island.

The islands of Torres Straits, geographically speaking, fall into three groups, the lines of longitude 140° 48′ E. and 143° 29′ E. conveniently demarcating these subdivisions.

The western group contains all the largest islands, and these, as well as many scattered islets, are composed of ancient igneous rocks, such as eurites, granites, quartz andesites, and rhyolitic tuff. These islands are, in fact, the submerged northern extremity of the great Australian cordillera that extends from[12] Tasmania along the eastern margin of Australia, the northernmost point of which is the hill of Mabudauan, on the coast of New Guinea, near Saibai. This low granitic hill may be regarded as one of the Torres Straits islands that has been annexed to New Guinea by the seaward extension of the alluvial deposits brought down by the Fly River. Coral islets also occur among these rocky islands.

The shallow sea between Cape York peninsula and New Guinea is choked with innumerable coral reefs. By wind and wave action sandy islets have been built up on some of these reefs, and the coral sand has been enriched by enormous quantities of floating pumice. Wind-wafted or water-borne seeds have germinated and clothed the sandbanks with vegetation. Owing to the length of the south-east monsoon, the islands have a tendency to extend in a south-easterly direction, and consequently the north-west end of an island is the oldest, hence one sometimes finds that in the smaller islands a greater vegetable growth, or the oldest and largest trees, is at that end of an island; but in time the vegetation extends uniformly over the whole surface. The islands of the central division are entirely vegetated sandbanks.

The eastern division of Torres Straits includes the islands of Masaramker (Bramble Cay), Zapker (Campbell I.), Uga (Stephen’s I.), Edugor (Nepean I.), Erub (Darnley I.), and the Murray Islands (Mer, Dauar, and Waier), besides several sandbanks, or “cays.”

All the above-named islands are of volcanic origin. The first five consist entirely of lava with the exception of two patches of volcanic ash at Massacre Bay, in Erub, to which I have already referred. Mer, the largest of the Murray Islands, is composed of lava and ash in about equal proportions, while Dauar and Waier consist entirely of the latter rock. It is interesting to note that where the Great Barrier Reef ends there we find this great outburst of volcanic activity. It was evidently an area of weakness in one corner of the continental plateau of Australia. In pre-Carboniferous times the tuffs were ejected and the lava welled forth that have since been metamorphosed into the rocks of the Western Islands; but the basaltic lavas of the Eastern Islands belong to a recent series of earth movements, possibly of Pliocene age.[13]

MAP OF TORRES STRAITS

Strictly speaking, to the three islands of Mer, Dauar, and[15] Waier should the name of Murray Islands, or Murray’s Islands, be confined; but in Torres Straits the name of Murray Island has become so firmly established for the largest of them that, contrary to my usual custom, I propose to adopt the popular rather than the native name.

Mer, or Murray Island, is only about five miles in circumference, and is roughly oval in outline with its long axis running roughly north-east to south-west. The southerly half consists of an extinct crater, or caldera, which is breached to the north-east by the lava stream that forms the remainder of the high part of the island. This portion is very fertile, and supports a luxuriant vegetation, which, when left to itself, forms an almost impenetrable jungle; it is here that the natives have the bulk of their gardens, and every portion of it is or has been under cultivation. The great crescentic caldera valley, being formed of porous volcanic ash and being somewhat arid, is by no means so fertile; the vegetation, which consists of grass, low scrub, and scattered coconut palms, presents a marked contrast to that of the rest of the island. The slopes of the hills are usually simply grass-covered.

Fig. 1. The Hill of Gelam, Murray Island

The most prominent feature of Mer is the long steep hill of Gelam, which culminates in a peak, 750 feet in height. It extends along the western side of the island, and at its northern end terminates in a low hill named Zomar, which splays out into two spurs, the outer of which is called Upimager and the inner Mĕkernurnur. Gelam rises up from a narrow belt of cultivated soil behind the sand beach at an angle of 30 degrees, forming a regular even slope, covered with grass save for occasional patches of bare rock and low shrubs. At the southern end the ground is much broken. The termination of the smooth portion is marked by a conspicuous curved escarpment; beyond this is a prominent block of rock about half-way[16] up the hill. This is known as the “eye.” The whole hill seen from some distance at sea bears a strong resemblance to an animal, and the natives speak of it as having once been a dugong, the history of which is enshrined in the legend of Gelam, a youth who is fabled to have come from Moa. The terminal hill and the north end of Gelam represents the lobed tail of the dugong, the curved escarpment corresponds to the front edge of its paddle, while the “eye” and the broken ground which indicates the nose and mouth complete the head.

The highest part of Gelam on its landward side forms bold, riven precipices of about fifty feet in height. A small gorge (Werbadupat) at the extreme south end of the island drains the great valley; beyond it rises the small, symmetrical hill Dĕbĕmad, which passes into the short crest of Mergar. The latter corresponds to Gelam on the opposite side of the island; it terminates in the steep hill Pitkir.

Fig. 2. Murray Island from the South, with its Fringing Reef

Gelam and Mergar form a somewhat horseshoe-shaped range, the continuity of which is interrupted at its greatest bend, and it is here the ground is most broken up. The rock is a beautifully stratified volcanic ash, with an outward dip of 30 degrees. Within this crater is a smaller horseshoe-shaped hill, which is the remains of the central cone of the old volcano. The eastern limit of the degraded cone is named Gur; the western, which is known as Zaumo, is prolonged into a spur called Ai. In the valley (Deaudupat) between these hills and Gelam arises a stream which flows in a northerly and north-easterly direction, and after receiving two other affluents empties itself into the sea at Korog. It should be remembered that the beds of all the streams are dry for a greater portion of the year, and it is only during the rainy season—i.e. from November to March, inclusive—and then only immediately after the rain, that the[17] term “stream” can be applicable to them. There are, however, some water-holes in the bed of the stream which hold water for many months.

The great lava stream extends with an undulating surface from the central cone to the northern end of the island. It forms a fertile tableland, which is bounded by a steep slope. On its west side this slope is practically a continuation of the sides (Zaumo and Ai) of the central cone, and bounds the eastern side of the miniature delta valley of the Deaudupat stream. At the northern and eastern sides of the island the lava stream forms an abrupt or steep declivity, extending either right down to the water’s edge or occasionally leaving a narrow shore.

A fringing coral reef extends all round Mer, but has its greatest width along the easterly side of the island, where it forms an extensive shallow shelf which dries, or very nearly so, at spring tides, and constitutes an admirable fishing ground for the natives.

A mile and a quarter to the south of Mer are the islands of Dauar and Waier. The former consists of two hills—Au Dauar, 605 feet in height, and Kebe Dauar, of less than half that height. Au Dauar is a steep, grassy hill like Gelam, but the saddle-shaped depression between the two hills supports a luxuriant vegetation. There is a sand-spit at each end.

Waier is a remarkable little island, as it practically consists solely of a pinnacled and fissured crescentic wall of coarse volcanic ash about 300 feet in height. There is a small sand-spit on the side facing Dauar, and a sand beach along the concavity of the island. At these spots and in many of the gullies there is some vegetation, otherwise the island presents a barren though very picturesque appearance.

Fig. 3. Waier and Dauar, with their Fringing Reef

Dauar and Waier are surrounded by a continuous reef, which extends for a considerable distance towards the south-east, far beyond the region that was occupied by the other side of the crater of Waier. We must regard Dauar and Waier as the remnants of two craters, the south-easterly side of both of which having been blown out by a volcanic outburst, but in neither case is there any trace of a lava stream.

The climate, though hot, is not very trying, owing to the persistence of a strong south-east tide wind for at least seven months in the year—that is, from April to October. This is the dry season, but rain often falls during its earlier half. Sometimes there is a drought in the island, and the crops fail and a famine ensues. During the dry season the temperature ranges between 72° and 87° F. in the shade, but in the dead calm of the north-west monsoon a much greater temperature is reached, and the damp, muggy heat becomes at such times very depressing.

The reading of the barograph shows that there is a wonderful uniformity of atmospheric pressure. Every day there is a remarkable double rise and fall of one degree; the greatest rise occurs between eight and ten o’clock, morning and evening, while the deepest depression is similarly between two and four o’clock. In June, that is in the middle of a dry season, the barograph records a pressure varying between 31 and 33, which gradually decreases to 28 to 30 in December, again to rise gradually to the midsummer maximum. These data are obtained from inspection of the records made on the island by Mr. John Bruce on the barograph we left with him for this purpose.

Like the other natives of Torres Straits, the Murray Islanders belong to the Melanesian race, the dark-skinned people of the West Pacific who are characterised by their black frizzly or woolly hair. They are a decidedly narrow-headed people. The colour of the skin is dark chocolate, often burning to almost black in the exposed portions. The accompanying illustrations give a far better impression of the appearance and expression of the people than can be conveyed by any verbal description. Suffice it to say, the features are somewhat coarse, but by no means bestial; there is usually an alert look about the men, some of whom show decided strength of character in the face. The old men have usually quite a venerable appearance.

PLATE I

ARI, THE MAMOOSE OF MER

PASI, THE MAMOOSE OF DAUAR

Their mental and moral character will be incidentally illustrated[19] in the following pages, and considering the isolation and favourable conditions of existence with the consequent lack of example and stimulus to exertion, we must admit that they have proved themselves to be very creditable specimens of savage humanity.

The Murray Islanders have often been accused of being lazy, and during my former visit I came across several examples of laziness and ingratitude to the white missionaries. As to the first count, well, there is some truth in it from one point of view. The natives certainly do not like to be made to work. One can always get them to work pretty hard in spurts, but continuous labour is very irksome to them; but after all, this is pretty much the same with everybody. Nature deals so bountifully with the people that circumstances have not forced them into the discipline of work.

The people are not avaricious. They have no need for much money; their wants are few and easily supplied. Surely they are to be commended for not wearing out their lives to obtain what is really of no use to them. The truth is, we call them lazy because they won’t work for the white man more than they care to. Why should they?

As to ingratitude. They take all they can get and, it is true, rarely appear as grateful as the white man expects; but this is by no means confined to these people. How often do we find exactly the same trait amongst our own acquaintances! They may feel grateful, but they have not the habit of expressing it. On the other hand, it is not beyond the savage mind for the argument thus to present itself. I did not ask the white man to come here. I don’t particularly want him. I certainly don’t want him to interfere with my customs. He comes here to please himself. If he gives me medicines and presents that is his look-out, that is his fashion. I will take all I can get. I will give as little as I can. If he goes away I don’t care.

Less than thirty years ago in Torres Straits might was right, and wrongs could only be redressed by superior physical force, unless the magic of the sorcery man was enlisted. For the last fifteen years the Queensland Government has caused a court-house to be erected in every island that contains a fair number of inhabitants, and the chief has the status of magistrate, and policemen, usually four in number, watch over the public morality.

The policemen are civil servants, enjoying the following[20] annual emoluments—a suit of clothes, one pound sterling in cash, and one pound of tobacco. In addition, they have the honour and glory of their position; they row out in their uniforms in the Government whale-boat to meet the Resident Magistrate on his visits of inspection to the various islands, and they go to church on Sundays dressed in their newest clothes. There are doubtless other amenities which do not appear on the surface.

The Mamoose, or chief, being a great man, “all along same Queen Victoria,” as they proudly claim and honestly imagine, is not supposed to receive payment. I well remember the complex emotion shown on my former visit by the Mamoose of Murray Island, who was torn by conflicting desires. Whether to share the golden reward with his subordinates, or to forego the coin on account of his being a great man, was more than he could determine; it was clear that he preferred the lower alternative—for what worth is honour if another man gets the money? I suspected he almost felt inclined to abdicate his sovereignty on the spot for the sake of one pound sterling; but the Hon. John Douglas, who was then on his tour of inspection, kept him up to the dignity of his position, and pointed out that great men in his position could not take money like policemen. Possibly the poor man thought that reigning sovereigns ruled simply for the honour and glory of it, and had no emoluments. Mr. Douglas’ intention was solely to support the dignity of Ari’s office, for, to do him justice, when old Ari visited the Government steamer on the following morning a little matter was privately transacted in the cabin which had the effect of making Ari beamingly happy.

But there are recognised perquisites for the Mamoose in the shape of free labour by the prisoners. It would seem as if such a course was not conducive to impartial justice, for it would clearly be to the judge’s interest to commit every prisoner; this temptation is, however, checked by the fact that all trials are public, and popular opinion can make itself directly felt.

Most of the cases are for petty theft or disputes about land. It is painful to have to confess that during our recent stay in Murray Island many of the cases were for wife-beating or for wife-slanging. The Mamoose is supplied with a short list of the offences with which he is empowered to deal and the penalties he may inflict. The technical error is usually made[21] of confusing moral and legal crimes. I gathered that very fair justice is meted out in the native courts when left to themselves.

The usual punishment is a “moon” of enforced labour on any public work that is in operation at the time, such as making a road or jetty, or on work for the chief, such as making a pig-sty or erecting fences. The alternative fine used to be husking coconuts and making copra; the natives in some cases had to supply their own coconuts for this purpose—the number varied from 100 to 1,000, according to the offence. This was chiefly the punishment of the women, the copra was one of the Mamoose’s perquisites. Fines are now paid in money.

At night-time the prisoners are supposed to sleep in jail—an ordinary native house set apart for this purpose—but at the present time in Murray Island, owing to the absence of a jail, they sleep at home! and during the whole of the time they are under the surveillance of one or more policemen. Very often it appeared to me that a policeman’s chief duty consisted in watching a prisoner doing nothing. Very bad, or often repeated, offenders are taken to Thursday Island to be tried by the Resident Magistrate.

The first thing we did after arranging the house was to convert a little room into a dispensary, and very soon numbers of natives came to get medicine and advice. McDougall, Myers, and Seligmann worked hard at this, partly because they were really interested in the various cases, and partly since it brought natives to the house who could be utilised for our other investigations.

The doctors also paid visits to bad cases in their homes. As the former white missionaries on the island in days gone by had been accustomed to dispense, to the best of their ability, from their somewhat large assortment of drugs, the natives took it for granted that we should do the same; hence there were no special signs of gratitude on their part. Bruce, too, does what he can for the natives, but his remedies are naturally of a simple, though often drastic, character.

The medical skill and gratuitous advice and drugs of our doctors did a great deal to facilitate the work of the expedition. Towards the end of our time, hearing Captain H⸺ of Darnley Island was seriously ill, McDougall volunteered to go over and nurse him, and he remained there for a week or two.

It was a great safeguard for us, too, having so many doctors about; but fortunately we only required their aid, or they each other’s, for malarial fever or for minor ailments like sores. Only on three occasions during the time we were away, till we left Borneo, were there sufficiently bad cases of fever to cause the least anxiety. So, on the whole, we came off remarkably well on the score of health.

Although we have a fair amount of information about the external appearance, the shape of the head, and such-like data of most of the races of mankind, very little indeed is known[23] about the keenness of their senses and those other matters that constitute the subject commonly known as experimental psychology. My colleagues were the first thoroughly to investigate primitive people in their own country, and it was the first time that a well-equipped psychological laboratory had been established among a people scarcely a generation removed from perfect savagery.

Dr. Rivers undertook the organisation of this department, and there were great searchings of heart as to what apparatus to take out and which to leave behind. There was no previous experience to go upon, and there was the fear of delicate apparatus failing at the critical time, or that the natives would not be amenable to all that might be required of them. Fortunately the latter fear was groundless. It was only in the most tedious operations, or in those in which they were palpably below the average, that the natives exhibited a strong disinclination to be experimented upon. Sometimes they required a little careful handling—always patience and tact were necessary, but taking them as a whole, it would be difficult to find a set of people upon whom more reliable and satisfactory observations could be made. I refer more particularly to the Torres Straits islanders.

In his work in Murray Island, Rivers was assisted by Myers and McDougall. During his trips to New Guinea, Seligmann made some supplemental observations of interest. The subjects investigated included visual acuity, sensitiveness to light, colour vision, including colour blindness, binocular vision, and visual space perception; acuity and range of hearing; appreciation of differences of tone and rhythm; tactile acuity and localisation; sensibility to pain; estimation of weight, smell, and taste; simple reaction times to auditory and visual stimuli, and choice reaction times; estimation of intervals of time; memory; strength of grasp and accuracy of aim; reading, writing, and drawing; the influence of various mental states on blood-pressure, and the influence of fatigue and practice on mental work.

The visual acuity of these people was found to be superior to that of normal Europeans, though not in any very marked degree. The visual powers of savages, which have excited the admiration of travellers, may be held to depend upon the faculty of observation. Starting with somewhat superior acuteness[24] of vision, by long attention to minute details coupled with familiarity with their surroundings, they become able to recognise things in a manner that at first sight seems quite wonderful.

The commonest defect of eyesight among Europeans is myopia, or short-sightedness, but this was found to be almost completely absent amongst savages. The opposite condition, hypermetropia, which is apparently the normal condition of the European child, was very common among them.

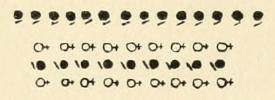

The colour vision of the natives was investigated in several ways. A hundred and fifty natives of Torres Straits and Kiwai were tested by means of the usual wool test for colour-blindness without finding one case. The names used for colours by the natives of Murray Island, Mabuiag, and Kiwai were very fully investigated, and the derivation of such names in most cases established. The colour vocabularies of these islands showed the special feature which appears to characterise many primitive languages. There were definite names for red, less definite for yellow, and still less so for green, while a definite name for blue was either absent or borrowed from English.

The three languages mentioned, and some Australian languages investigated by Rivers, seemed to show different stages in the evolution of a colour vocabulary. Several North Queensland natives (from Seven Rivers and the Fitzroy River) appeared to be almost limited to words for red, white, and black; perhaps it would be better to call the latter light and dark. In all the islands there was a name for yellow, but in Kiwai, at the mouth of the Fly River, the name applied to green appeared to be inconstant and indefinite, while there was no word for blue, for which colour the same word was used as for black. In Torres Straits there are terms for green. In Murray Island the native word for blue was the same as that used for black, but the English word had been adopted and modified into bŭlu-bŭlu. The language of Mabuiag was more advanced; there was a word for blue (maludgamulnga, sea-colour), but it was often also used for green. In these four vocabularies four stages may be seen in the evolution of colour languages, exactly as deducted by Geiger, red being the most definitive, and the colours at the other end of the spectrum the least so. As Rivers has also pointed out, it was noteworthy, too, that the order of these people in respect to culture was the same as[25] in regard to development of words for colours. Rivers found that though the people showed no confusion between red and green they did between blue and green. The investigation of these colour-names, he thought, showed that to them blue must be a duller and darker colour than it is to us, and indeed the experiments carried out with an apparatus known as Lovibond’s tintometer afforded evidence of a distinct quantitative deficiency in their perception of blue, though the results were far from proving blindness to blue.

Numerous observations were made by Rivers on writing and drawing, the former chiefly in the case of children. The most striking result was the ease and correctness with which mirror writing was performed. Mirror writing is that reversed form of writing that comes right when looked at in a looking-glass. In many cases native children, when asked to write with the left hand, spontaneously wrote mirror writing, and all were able to write in this fashion readily. In some cases children, when asked to write with the left hand, wrote upside down.