BETHLEHEM ACROSS THE AGES

HOLY NIGHT

From the painting by Zenisek

THE

CHRISTMAS CITY

BETHLEHEM ACROSS THE AGES

BY

LEWIS GASTON LEARY, Ph.D.

AUTHOR OF “THE REAL PALESTINE OF TO-DAY”

New York

STURGIS & WALTON

COMPANY

1911

Copyright 1911

By STURGIS & WALTON COMPANY

Set up and electrotyped. Published October, 1911

THIS LITTLE BOOK ABOUT THE

CITY OF DIVINE MOTHERHOOD

IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED

TO MY OWN MOTHER

[Pg 9]

CONTENTS

[Pg 11]

| PAGE | ||

| The Charter of Pre-eminence | 17 | |

| I | The Welcome to Bethlehem | 21 |

| II | The Grave by the Roadside | 25 |

| III | The Girl From Beyond Jordan | 35 |

| IV | The Boy Who Was to be King | 43 |

| V | The Adventure of the Well | 51 |

| VI | The Night of Nights | 59 |

| VII | The Blossoms of Martyrdom | 67 |

| VIII | The Story of the Stable | 73 |

| IX | The Epitaph of the Lady Paula | 83 |

| X | The Scholar in the Cave | 93 |

| XI | The Christmas Coronation | 105 |

| XII | Some Bethlehem Legends | 117 |

| XIII | The Long White Road | 129 |

| XIV | The House of Bread | 145 |

| XV | The Church Which is a Fort | 155 |

| XVI | The Sacred Caves | 165[Pg 12] |

| XVII | The Guard of the Silver Star | 175 |

| XVIII | The Song of the Kneeling Women | 181 |

| XIX | Across the Ages | 187 |

[Pg 13]

ILLUSTRATIONS

[Pg 15]

| Holy Night, from the painting by Zenisek | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| The Tomb of Rachel | 31 |

| The Church of the Nativity | 79 |

| The South Transept of the Church of the Nativity and one of the Stairways leading down to the Sacred Caves | 97 |

| St. Jerome and the Lion | 123 |

| The Bethlehem Road | 133 |

| Bethlehem Girls | 137 |

| Bethlehem | 149 |

| Interior of the Church of the Nativity | 161 |

| The Altar of the Nativity | 169 |

[Pg 17]

THE CHARTER OF PRE-EMINENCE

[Pg 19]

Micah 5: 2-5

“But thou, Bethlehem Ephrathah, which art little to be among the thousands of Judah, out of thee shall one come forth unto me that is to be ruler in Israel; whose goings forth are from old, from everlasting.... And he shall stand, and shall feed his flock in the strength of Jehovah, in the majesty of the name of Jehovah his God: and they shall abide; for now shall he be great unto the ends of the earth.

“And this man shall be our peace.”

[Pg 21]

THE WELCOME TO BETHLEHEM

[Pg 23]

THE CHRISTMAS CITY

St. Paula, A. D. 386

“With what expressions and what language shall we set before you the cave of the Saviour? The stall where He cried as a babe can best be honored by silence; words are inadequate to speak its praise. Where are the spacious porticoes? Where are the gilded ceilings? Where are the mansions furnished by the miserable toil of doomed wretches? Where are the[Pg 24] costly halls raised by untitled opulence for man’s vile body to walk in? Where are the roofs that intercept the sky, as if anything could be finer than the expanse of heaven? Behold, in this poor crevice of the earth the Creator of the heavens was born; here He was wrapped in swaddling clothes; here He was seen by the shepherds; here He was pointed out by the star; here He was adored by the wise men....

“In our excitement we are already hurrying to meet you.... Will the day never come when we shall together enter the Saviour’s cave?

“Hail, Bethlehem, house of bread, wherein was born that Bread that came down from heaven! Hail, Ephrathah, land of fruitfulness and fertility, whose Fruit is the Lord himself.”

[Pg 25]

THE GRAVE BY THE ROADSIDE

[Pg 27]

The history of Bethlehem is the romance of Bethlehem; a story of love and daring, of brave men and beautiful women. We do not know that story in great detail; but here and there across the centuries, the light breaks on the little Judean town and we catch a fleeting glimpse of some scene of tender affection or chivalrous adventure. And it is striking to notice how many of these incidents involve womanly devotion and self-sacrifice, both before and after the Most Blessed of Women suffered and rejoiced in Bethlehem.

[Pg 28]

Long, long centuries before that first Christmas was dreamed of, the story of Bethlehem begins. And lo, the earliest episode has to do with a birth day.

In the yellow evening light a little band of nomadic shepherds is straggling along the dusty road past the high, gray walls of the outer fortifications of Jerusalem—not Jerusalem the Holy City, but Jerusalem the Jebusite stronghold, which is to remain heathen and hateful for a thousand years until, in that far-distant future, the arrogant fortress shall fall before the onslaughts of the mighty men of David.

At the head of the long line of herds and pack-animals and armed retainers walks the chief, Jacob ben-Isaac. A generation before, he had passed along this same ancient caravan route going northward; but no one[Pg 29] would recognize that frightened, homesick fugitive in the grave, self-confident leader who travels southward to-day. For now he is Sheikh Jacob, full of years and riches and wisdom; Jacob the strong man, the successful man and, in his own rude way, the good man.

An hour’s journey beyond Jerusalem there appear shining on a hilltop to the left the white stone houses of Bethlehem, at the sight of which the tired herdsmen grow more cheerful and the slow-moving caravan quickens somewhat its pace; for close under those protecting walls the tribe of B’nai Jacob will shelter its flocks for the night, safe alike from wolves and from marauding Arab bands.

But just as they reach the spot where the road to Bethlehem branches off to the left[Pg 30] from the main caravan route, there is a sudden change of plan. The hope of camping at the town is abandoned, and one of the low, black, goat-hair tents is hastily set up right by the roadside. Then there is an excited bustling among the household servants, and a time of anxious waiting for Sheikh Jacob, until Bilhah, the handmaid, puts into the old man’s arms his son Benjamin, his youngest boy, who is long to be the comfort of the father’s declining years.

THE TOMB OF RACHEL

In the background the town of Beit Jala

Soon, however, the cries of rejoicing are hushed. From the women’s quarters comes a loud, shrill wail of grief. And before the B’nai Jacob break camp again the leader raises a heap of stones over the grave of Rachel—his Rachel—a gray-haired woman now and bent with toil, but still to him the beautiful girl whom he loved and for whom [Pg 33]he labored and sinned those twice seven long years in the strength of his young manhood.

Many years afterward, when Benjamin was a grown man and Jacob lay dying in the distant land of Egypt, the thoughts of the homesick old sheikh dwelt on the lonely grave by the roadside.

“I buried her there on the way to Bethlehem,” he said.

Her tombstone remains “unto this day,” the Hebrew narrator adds. Indeed, even to our own day, a spot by the Bethlehem road, about a mile from the town, is pointed out as the burial place of Rachel. Probably no site in Palestine is attested by the witness of so continuous a line of historians and travelers. For many centuries the grave was marked by a pyramid of stones. The present[Pg 34] structure, with its white dome, is only about four hundred years old. But there it stands “unto this day,” revered by Christians, Jews and Moslems, and the wandering Arabs bring their dead to be buried in its holy shadow.

Such is the first Biblical reference to Bethlehem. A son was born there! More significant still, there was a vicarious sacrifice—a laying down of one life for another.

[Pg 35]

THE GIRL FROM BEYOND JORDAN

[Pg 37]

In the Book of Judges are recounted the adventures which befell certain Bethlehemites in those lawless days when “there was no king in Israel and every man did that which was right in his own eyes.” But the people mentioned in this history were no longer dwelling in the city of their birth; and we are glad of an excuse to pass by the tale of reckless crime and merciless vengeance. Yet here, too, if the story were not too cruel to repeat, we should find a woman dying for one whom she loved.

[Pg 38]

Even in that rough frontier period, however, there were interludes of peace and kindliness; and like the cooling breeze which blows from snow-capped Lebanon upon the burning brow of the Syrian reaper, is the sense of grateful refreshment when we turn from the heartrending monotony of scenes of cruelty and lust and treachery to the sweet, clean air of the whitening harvest fields of Boaz of Bethlehem.

When the two strange women entered the square there was great excitement among the chattering busy-bodies who were waiting their turn to fill their earthen jars at the public well; for one of the travelers was seen to be no other than old Naomi, who long years before had gone away across Jordan with her husband Elimelech to better their[Pg 39] fortunes among the famous farm-lands of Moab. Now the wanderer has returned to the old home, poor and widowed and childless—no doubt to the secret gratification of the more cautious stay-at-homes, who had never dared tempt fortune by such an emigration to distant Moab, and who were still no richer and no poorer than their fathers’ fathers had been.

The other woman was younger, a foreigner, a widow, so the gossip ran, who had married Naomi’s dead son. The women at the well smiled at her quaint accent, for the dialect of Moab is quite different from that of the Bethlehem district. But many a stalwart young farmer dreamed that night of the lonely, appealing eyes of the stranger from beyond Jordan.

Even middle-aged Boaz is stirred when[Pg 40] the next morning he finds the slender Moabitess among the women who are gleaning in his barley field; for romance is not always dead in the soul of a mature and wealthy landowner. Boaz, for all his grizzling hair, is a hero who makes us feel very warm and comfortable about the heart. He is so generous, so thoughtful, so humble in his final happiness. He has already been touched by the story of the faithfulness of the young widow who said to her mother-in-law,

“Entreat me not to leave thee, and to return from following after thee; for whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge; thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God.”

So the rich man drops a hint to his servants to let fall carelessly little heaps of grain where the new gleaner can easily[Pg 41] gather them. He remembers the rough, dissolute character of the itinerant harvesters, and warns them to treat the young woman with respect and courtesy. At noontime he invites her to share the simple luncheon provided for the farm-hands. A few weeks later the lonely rich man discovers her affection for him, and our hearts beat in sympathy with his as, with characteristic modesty, he exclaims,

“Blessed be thou of Jehovah, my daughter: thou hast shown more kindness in the latter end than at the beginning, inasmuch as thou followedest not young men, whether poor or rich.”

But as well might one attempt to retouch the soft colorings of the Judean sunrise as to re-tell the beautiful idyll of Ruth. Old Josephus quite misses the delicate beauty of the story; for he concludes his smug paraphrase[Pg 42] by saying, “I was therefore obliged to recount this history of Ruth, because I had a mind to demonstrate the power of God, who, without difficulty, can raise those that are of ordinary parents to dignity and splendor.”

They lived together happily ever afterward. Even sad Naomi found a new interest in life when she took into her lonely old arms the form of little Obed. For this bit of Bethlehem history, like the first, and like the greatest later on, ends with the coming of a baby boy. And doubtless, if the whole of the tale were told us, we should some day see grandmother Ruth crooning over Obed’s son Jesse, who was to be the father of a king.

[Pg 43]

THE BOY WHO WAS TO BE KING

[Pg 45]

An ancient Hebrew commentary on First Samuel says that Jesse became “a weaver of veils for the sanctuary.” This may be why the story of David and Goliath compares the giant’s staff to “a weaver’s beam.” Whatever his occupation, the grandson of rich Boaz must have been a man of some means, and influential in Bethlehem society. Also he had seven fine, stalwart sons. Indeed, he had eight sons; but, as we all know, the youngest was out tending the sheep when Samuel came.

[Pg 46]

The rough and ready era of the Judges, when every man did that which was right in his own eyes, was now gone forever. Israel had a king; and a tall, handsome figure of a man King Saul was. And for a while he was a king who defeated foreign invaders on every side. But Saul’s character could not stand the test of the sudden elevation to a position of power and responsibility. His strength lay in brilliant, spectacular efforts, rather than in a patient, well-organized rule. Quarrels arose between the jealous tribes of Israel. Conquered foes prepared new and better equipped forays against the poorly protected frontier of the new kingdom. Worst of all, Saul broke with his tried advisers and became prey to an irrational, suspicious melancholy, which prevented him from coping with dangers which[Pg 47] a few years earlier would only have aroused his ambitious energy.

Saul had failed; so Samuel, the veteran prophet, judge and king-maker, went quietly to Bethlehem to select a new leader who should direct the troublous destinies of Israel.

It was doubtless the same farm where the young stranger from beyond Jordan had gleaned the sheaves of barley almost a century before. How proud Naomi would have been if she could have lived to see those tall great-grandchildren of Ruth and Boaz! How excited we boys used to get as we saw the seven sons of Jesse standing there in a row, and waited for old Samuel to tell us which one was to be the king! Surely it must be the eldest, Eliab, who is so tall and handsome, the very image of what Saul was[Pg 48] in his youth. No, it is not Eliab, perhaps just because he is too much like King Saul. Abinadab is rejected and Shammah, too; and the prophet’s eye passes even more rapidly over Nethaneel and Raddai and Ozem.

Then Samuel turns to the father with a perplexed frown.

“Are these all your sons?”

“Yes—that is, all that are grown up. David is only a boy. He is taking care of the sheep this morning.”

“Call him, too,” commands Samuel. “Let Abinadab mind the sheep for a while.”

So in a few minutes David is brought in. He is fair in complexion, like so many Judean Jews to-day, but his skin is burnt to a deep tan by the sun of the sheep pasture. His eye has a captivating twinkle, and he can hardly[Pg 49] keep from humming a tune even in the presence of the prophet.

We guessed it all the while! This is indeed a royal fellow; and the old prophet touches the thick brown hair of the shepherd lad with a strange, loving reverence as he tells him that some day he must be his people’s king.

This time I think that Josephus is probably right. For he tells us that while they were all sitting at dinner afterward, Samuel whispered in the boy’s ear “that God chose him to be their king: and exhorted him to be righteous, and obedient to His commands, for that by this means his kingdom would continue for a long time, and that his house should be of great splendor and celebrated in the world.”

[Pg 50]

Surely wise old Samuel must have given the boy some such advice as that.

[Pg 51]

THE ADVENTURE OF THE WELL

[Pg 53]

It was a long while, however, before David really became a king. As his frame grew into a sturdy manhood, he fought with lions and bears and Philistine champions. His sweet singing brought him to the notice of Saul and he became the king’s favorite musician, until the jealousy of the half-crazed monarch drove the young man into exile. Then for years the former shepherd lived a wild, half-brigand life among the caves of the rugged steppe-land south of Bethlehem, gradually gathering around him a company[Pg 54] of intrepid outlaws, administering rough justice over a number of villages which put themselves under his protection, making sudden forays into the Philistine country just to the west, and again so hotly pursued by the soldiers of the relentless Saul that he was forced to seek an asylum among the enemies of Israel, who were always glad to forget old scores and welcome this dauntless free-lance and his redoubtable band of warriors.

It may have been during this outlaw period, or it may have been shortly after David’s accession to the throne, when his kingdom was still disorganized, and an easy prey to foreign invaders. At any rate, David and his band were hiding in the cave of Adullam, a few miles from Bethlehem.[Pg 55] The little company was for the moment safe, but the country all around was overrun by foreign troops, and even Bethlehem, the scene of so many happy boyhood memories, was occupied by a Philistine garrison.

No wonder that David felt very weary and discouraged as he thought of the old home town in the hands of heathen soldiers. No wonder that he sometimes became irritable and petulant, and wished for things that he could not have. There was a spring right by the cave of Adullam. The inhabitants of Palestine, however, can distinguish between water drawn from different sources, in a manner which seems marvelous to our duller taste. Yet we need not believe that the water in the City of David was any better than that of the cave of Adullam in order to sympathize with the tired, homesick cry—

[Pg 56]

“Oh, that one would give me water to drink of the well of Bethlehem, which is by the gate!”

Then there was a little stir among David’s bodyguard. One soldier whispered to another, who nudged a third; and soon three dark forms slipped quietly away from the circle of lights around the campfire. For those rough outlaws idolized their fair-haired young leader, and they had been worried and grieved by his recent fit of melancholy.

At midnight there was a sudden rattling of the well-chain in the square by the Bethlehem gate—then a challenge from the startled Philistine sentry—a rush of soldiers along the stony street. But the three seasoned warriors slipped easily through the camp of the half-awakened army. They[Pg 57] turned and doubled through the familiar maze of narrow, winding streets until they came to the steep terraces at the south of the town, where they dropped out of sight among the perplexing shadows of the olive orchards, through which they made their way swiftly back to the wild steppe-land and the mountain fastness where the band kept watch over their sleeping chief.

Mighty men they were, these three, and it is no wonder that their exploit became one of the favorite tales of Hebrew history. But when they offered David the water for which he had longed, there came a lump into his throat and he said, “I can’t take it. My thoughtless wish might have cost too much. It would be like drinking my brave men’s blood, to drink that for which they have endangered their lives. It is too precious to[Pg 58] drink. I will pour it out on the ground—so—as an offering to Jehovah.”

Surely the God of Battles esteemed that simple libation as holy a thing as holocausts of bullocks and rams, and forgave many of the sins of those rough, hard outlaws because of the loving devotion they showed toward one whom He had chosen to be the deliverer of Israel.

An old legend says that after the mystic Star had guided the Wise Men to the Saviour’s cradle, it fell from heaven and quenched its divine fire in “David’s Well.” And surely, if the Star had fallen, it could have found no more fitting resting place than the Well by the Gate, whose water had been won by such unselfish adventure and dedicated with such tender gratitude.

[Pg 59]

THE NIGHT OF NIGHTS

[Pg 61]

In the short twilight of the winter evening a husband and wife are trudging wearily along the road which winds past the high gray walls of Jerusalem—no longer Jerusalem the proud capital of the dynasty of David, but a mere provincial town of the mighty Roman Empire, whose streets are dizzy with the shouting of a dozen languages and thronged with crowds of Greeks, Romans, Persians, Armenians, Ethiopians, and travelers from even more distant lands, who rub shoulders carelessly[Pg 62] with the fanatical Pharisees and intriguing Sadducees whose mutual bickerings make them a laughing-stock to their Gentile masters; while there sits upon the throne of David a half-breed underling Edomite, through whose diseased veins flow the cruelty and lust and cowardice and treachery of turgid streams of unspeakable ancestry—Herod, called in grim jest, “the Great.”

December in Judea is a cold, dreary month, with penetrating storms of rain and sleet. It may even snow; and sometimes the drifts lie knee-deep on that highroad from Jerusalem to Bethlehem. So they hasten their steps, these footsore travelers who have come all the way from distant Galilee at the command of their Roman rulers; for darkness is coming on, and this night, of all[Pg 63] nights, they must find a safe, warm resting-place.

But when Bethlehem is at last reached, their cheerful anticipation changes to utter, weary dejection; for the village inn proves to be already overcrowded with other Bethlehemites who have returned to their birthplace to be registered there for the census.

Only in the stable is there room; and this is a low, dark place, half building, half cave. In front, it is walled up with rough stones; but at the rear it extends far into what seems to have been originally a natural opening in the hillside. Around three sides of the stable runs a low, level shelf, with an iron ring every few feet, to which the beasts are tied as they eat the fodder spread before them on the stone ledge. This manger is[Pg 64] not an uncomfortable resting place for the hardy muleteers, who often sleep there on the straw. But it makes a hard bed for Joseph—and for Mary.

The sky has cleared now, and through the open door can be seen a square of twinkling stars, one of which shines with unusual brilliancy. Within, however, it is very dark; for the lantern of the night-watchman shines only a little way through the sombre shadows of the stable. The cattle and horses have finished munching the grain. The last uneasy lowing ceases. It is very still, except in one far corner where the strangers cannot sleep.

And then there is a baby’s cry. And the bright star shines with glorious radiance over David’s City. And upon the drowsy shepherds in the fields where the Moabitess[Pg 65] gleaned, there bursts a wondrous light and the sound of heavenly singing.

For the fullness of time has come. Upon the humble Judean town has burst that glory sung by the prophets of old. The long line of Rachel and Ruth and royal David has at last issued in the King of kings.

[Pg 67]

THE BLOSSOMS OF MARTYRDOM

[Pg 69]

But even at that first Christmastide, Bethlehem must again be the scene of innocent suffering in another’s place, as for the Christ-child’s sake some twenty baby boys in the little town are put to death by order of King Herod, whose diseased, suspicious mind trembles at the thought of even an infant claimant for his throne.

Five hundred years before, when the strong young men of Bethlehem had been sent away into Babylonian exile, the loud wailing from bereaved, heart-broken homes[Pg 70] had recalled to Jeremiah that other sad mother buried there by the lonely roadside. So now again, the awful outrage, perpetrated almost within sight of that venerable tomb, seems to be linked across the long centuries with the first Bethlehem grief; and once more, in the words of the Lamenting Prophet, there is

The Blossoms of Martyrdom—so a fourth century poet calls these little ones who were the first of all to suffer death for Christ’s sake. And in that countless throng of those who “have come out of great tribulation” there must surely stand in the foremost rank the little band of Bethlehem children whose[Pg 71] blood was shed because an infant Saviour had been born into an unwelcoming world.

“And God shall wipe away all tears from

[Pg 73]

THE STORY OF THE STABLE

[Pg 75]

Between the years 1480 and 1483, Brother Felix Fabri, a learned German monk of Ulm, made two voyages to Palestine, during the course of which he collected information of all sorts about the holy places, which he later published in a large and important book. Some of his statements about Bethlehem are very accurate. Others do not strike us as quite so convincing.

According to these stories told by Brother Felix, Boaz inherited from his father Salmon, who had married Rahab of Jericho, a large[Pg 76] mansion built at the very edge of Bethlehem, so that part of the house projected outside the town wall. In the rock underneath the main building was a natural grotto which was used as a cellar, and also as a dwelling room during the hot months. The house passed in due time into the possession of Boaz’ grandson Jesse, whose son David was born in the lower room. After David became king, however, the family removed to Jerusalem, the deserted homestead gradually came into a state of disrepair, and finally the part in the rock was used as a public stable. This degradation of the once splendid mansion was permitted by Providence, so that at last the great Son of David might be born amid humble surroundings, and yet in the very place where His famous ancestor first saw the light.

[Pg 77]

After our Lord’s Ascension, His mother lived for fourteen years, dwelling in Jerusalem, whence every month she and her friends made a pious pilgrimage to Bethlehem, that they might worship at the cave of the Saviour’s birth. This so enraged the Jews that finally they defiled the stable and blocked up its entrance with stones.

Following the destruction of Jerusalem by Titus, in A. D. 70, Christians were again allowed to dwell in the Holy Land and to visit the place of the Nativity, which they cleansed from the Jewish defilement and hallowed by their worship. But in the year 132, the Emperor Hadrian laid waste the city of Bethlehem, placed in the sacred cave a statue of Jupiter and, as a crowning insult, instituted in the very Grotto of the Nativity the iniquitous rites of the Adonis cult, which[Pg 78] continued to be celebrated there for almost two hundred years.

This, however, was the last heathen desecration of the holy spot. In the year 326 the pious Helena, mother of the Christian emperor, Constantine, “cleansed the place of the sweet Nativity of our Lord, cast out the abominations of the idols from the holy cave, overthrew all that she found there, and beneath the ruins found the Lord’s manger entire.” In the manger she discovered the stone on which the Blessed Virgin had placed the Babe’s head, and the hay and the swaddling clothes and Joseph’s sandals and the long, loose gown which Mary wore.

THE CHURCH OF THE NATIVITY

These were all carried to the capital, Constantinople, and remained five hundred years in the Cathedral of St. Sophia, until Charlemagne, returning from the conquest of Jerusalem [Pg 81](so says Fabri), begged the relics as the reward of his holy labors and took them with him to the West. The hay was bestowed in the church of Sta. Maria Maggiore in Rome, the manger in St. John Lateran, and the garments in the cathedral of Aix-la-Chapelle.

After St. Helena had purified the place of the Nativity, she erected above it a church of wondrous beauty, but in such a manner that the rock beneath and the cave in which the Saviour was born should remain untouched. Whereupon the Jews of Bethlehem in derision nicknamed the saintly empress “the Woman of the Stable.”

But by the time we reach St. Helena and the building of the Bethlehem church, legend is beginning to merge into history.

[Pg 83]

THE EPITAPH OF LADY PAULA

[Pg 85]

The church at Bethlehem is crowded to the doors with a reverent assemblage, which overflows into the public square and fills all the nearby streets with silent, sad-faced worshippers. It is four hundred and four years since the blessed Nativity of our Lord, and the slow, solemn music which sounds faintly from within the heavy walls of the ancient church is the requiem of the noblest, sweetest, saddest lady who ever made her home in Bethlehem for Christ’s sake.

[Pg 86]

The funeral procession had seemed like a triumphal march. The bier was borne upon the shoulders of bishops, whilst other bishops carried candles beside it and led the antiphonal singing of the choirs. Beside these dignitaries walked the sweet-faced sisters from the great convent which the dead woman had founded, and barefooted brothers from the no less famous monastery which she had endowed. Strange figures followed in the procession: wild, shaggy hermits who for the first time in years had come out of their caves in the wilderness of Judea, and nuns bound to perpetual self-immolation, whose unnatural pallor told of incessant vigils broken this once only, that they also might have a part in the final honors shown to their beloved and godly benefactor. Aged Jerome was there; the foremost scholar[Pg 87] in all Christendom, but now bent and weary with the realization that world-wide fame is but a paltry substitute for the companionship of a faithful friend. Beside him walked the proud bishop John of Jerusalem, not long since the enemy of Paula and Jerome and at bitter strife with the convent of Bethlehem; but now, it seems, a sincere mourner of one before whose pure and devoted spirit even mighty hierarchs must bow in humble reverence.

But those whose hearts grieve most sincerely cannot all gain admission to the church. The square before the entrance is crowded with the poor and the sick and the outcast who are waiting patiently until the long ceremony shall end. Then these humble folk will slip into the quiet church at eventide and pray beside the coffin of their[Pg 88] beloved friend, while unrestrained tears roll down their haggard faces—tears for her, and them, and Bethlehem.

It hardly seems seventeen years since the coming of the Lady Paula stirred the quiet life of Bethlehem. All the world knew of the young Roman widow, of noble family and enormous wealth, who had renounced the luxurious life to which she had been accustomed and had aroused the gossip of the capital by her coarse dress and incessant devotions and the menial duties which she performed in her efforts to relieve the condition of the crowded slums of the city. And then the wealthy lady had broken the last ties of her old life, so the rumor ran, and had left Rome forever in order to dwell in holy Bethlehem with her daughter and their friend and[Pg 89] teacher, the reverend presbyter Jerome.

For a time Paula and her daughter lived quietly in a small rented house, until the completion of a convent which was erected at her expense. A monastery was next built, of which Jerome was made the head, and in connection with this, a hospice for the entertainment of the strangers who in greater and greater numbers came hither to visit the holy places and to study under the famous teacher.

Thereafter Paula was the very spring of Bethlehem life and Christian activity. She managed the affairs of her various establishments with patience, tact, and great executive ability; and yet found time to perfect her Greek and to learn Hebrew, so that under the guidance of Jerome she might read the entire Bible in the original tongues. Pilgrims[Pg 90] from far and near taxed the resources of the famous hospice, and gifts to innumerable charities at last exhausted even the large fortune she had inherited, so that she became not only poor, but in debt. And reading between the lines of his own correspondence, we can see that not least among the godly woman’s worries was the care of the great, but somewhat crabbed old man whom later centuries were to honor as “Saint” Jerome. It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that Christendom is indebted to a woman for its most important and influential version of the Bible; for it is easy to conceive that the Vulgate translation might never have been completed by Jerome, without the constant aid and encouragement which were so freely bestowed on the aged author by his friend.

[Pg 91]

All these varied and exacting tasks were undertaken by one who never enjoyed robust health. Paula was often prostrated by serious illness and she further overtaxed her strength by incessant fasts and mortifications, until at last the life of the eager, self-sacrificing, loving, faithful woman burnt itself out at the age of fifty-six.

The funeral service is over now. The long procession has left the church, and for three days the poor whom Paula loved can worship at her bier. Then the tender, weary, faithful heart will be laid at rest in a vault beneath the church, “close to the cave of the Lord,” and above her cavern sepulchre lonely old Jerome will inscribe these lines:

[Pg 93]

THE SCHOLAR IN THE CAVE

[Pg 95]

One of the caves beneath the church at Bethlehem has a window; but the small opening is so high up in the wall that very little light enters, and it is some time before the outlines of the room can be clearly distinguished. It is a square cell, about twelve feet across. The window is on the north side. At the west a narrow stairway goes up to the monastery. At the south a door leads through a series of other caves to the Grotto of the Nativity. On the eastern wall hangs a crucifix. In the center of the cell[Pg 96] is a roughly-made desk, cluttered with books and papers, while other heavy volumes and thick rolls of manuscript are piled here and there upon the floor.

In front of the desk sits an old, old man, whose lean, emaciated form is clothed in a long, brown robe which, though of very rough material, is neat and clean. His hair is sparse and gray, and his flowing beard is white as snow. His face is thin and pale, seamed by deep wrinkles worn by physical suffering and spiritual anguish; but about the mouth are other lines which tell of a stern, unconquerable spirit. The eyes are kind, but very weary, and reddened by much study, and he rests them now upon his long, thin fingers as he ceases his work for a moment and listens reverently to the muffled music of the service in the church above.

[Pg 97]

THE SOUTH TRANSEPT OF THE CHURCH OF THE NATIVITY AND ONE OF THE STAIRWAYS LEADING DOWN TO THE SACRED CAVES

[Pg 99]

It is sixteen years since Paula died. The old man is the presbyter Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus, better known as St. Jerome; the most famous scholar of his age and by far the greatest man whose name has been associated with Bethlehem during all the Christian era. His little cavern cell is the literary center of the world.

For more than a generation Jerome has pursued his scriptural studies here, under the ever-present inspiration of the holy associations which cluster so closely about the cave. Here he has often spent long night hours in gaining that perfect mastery of Hebrew and Aramaic and Greek which enables him to grasp the most subtle meanings of the sacred writings. Here his pen has moved with such feverish activity that more than once he has completed the translation[Pg 100] of an entire Book in a single day. At this rude desk have been written words that shook Europe; for Jerome has been the friend of popes and the adviser of councils. From this humble cell have gone forth learned commentaries, controversial articles, translations of the Greek Fathers, a voluminous and widely-circulated correspondence, and that which future generations will value most highly of all, the splendid revision of the entire Latin Bible—the Vulgate. This tremendous literary activity has won for its author the reputation of being the foremost writer of the age, and has made Bethlehem the goal of innumerable pilgrimages by admiring students.

The death of Paula, however, seemed to mark the turning point in Jerome’s career. During the long, lonely years since then he[Pg 101] has never enjoyed the same scholarly quiet, and he has had to cope with repeated and varied misfortunes. The very winter she died was one of unusual severity, which sorely tried his physical powers, already weakened by disease and by long-continued privations. The Isaurians came down from Asia Minor and devasted northern Palestine, so that the monastery was overcrowded with fugitives; and with Paula gone, the supervision of the various religious establishments in Bethlehem was thrust more and more upon Jerome, who we may believe was not especially gifted as an executive. Heartrending tidings came from Italy, telling of Barbarian invasions which at last culminated in the sack of Rome by Alaric. Jerome became involved in bitter theological controversies, which resulted in an estrangement[Pg 102] from some of his oldest friends and once at least endangered his life, when a mob of angry partisans set the monastery on fire, killed one of the inmates, and forced the aged scholar to flee for refuge to a neighboring fortress. Recently the care of the monastery and hospice has occupied all the day, and although he has tried to work on his commentaries at night, his failing eyesight has finally become so weak that he can hardly decipher the Hebrew letters by candle-light.

Jerome’s spirit, however, is unbroken by defeat. His last works may show something of the irritability of illness and age, but there is never any thought of relaxation or compromise, or any weakening of faith. And perhaps the great man never seems greater then when we see him at the age of[Pg 103] eighty, sitting here in his cavern cell, so sick and lonely and indomitable. His translation of Scripture is not yet accepted as the Bible of all Western Christendom, his sainthood is as yet undreamed of, his dearest friends are dead or alienated, the dread advance of the Barbarian hordes is threatening the very existence of civilized Europe, and the brilliant era of ecclesiastical literature of which he has been the brightest light is already fading into a dull, spiritless gloom.

The evening shadows deepen upon the little cave at Bethlehem, as upon the vast, dying Roman Empire. The chanting of the priests in the church above ceases. The familiar square characters of the dearly-loved Hebrew manuscript grow faint and blurred before the scholar’s eyes. He puts away his pen with a sigh. No disciple takes it up.[Pg 104] “There is no continuation of his work; a few more letters of Augustine and Polinus, and night falls over the West.”

So they bury him there in the cave, close to faithful Paula, close to the birthplace of his Lord.

[Pg 105]

THE CHRISTMAS CORONATION

[Pg 107]

In the year of our Lord 1101, on the very birthday of the Saviour and at the birthplace of the King of kings, Bethlehem is to witness the most gorgeous, striking scene in all its varied and dramatic history; for the long, cruel centuries of Moslem domination are over at last, the banners of the victorious Crusaders now float proudly above the ramparts of Jerusalem, and the mighty Baldwin, Count of Flanders by inheritance and Prince of Edessa by right of conquest, is to be crowned this Christmas Day the first Christian king of Palestine.

[Pg 108]

Two years earlier, when the Saracens heard that the Western armies were approaching, they destroyed the Christian quarter of Bethlehem, leaving standing only the Church of the Nativity; but the gallant Tancred came promptly to the rescue of the frightened, homeless citizens with a hundred picked knights, and, as a reward of their valor, it was this little band who, looking northward from a hill near Bethlehem, were the first of all the Crusaders to gain the longed-for view of the Holy City.

As soon as Jerusalem was taken and the Moslem army put to rout, the Crusaders set to work to rebuild the nearby City of the Nativity, and now that a ruler has been chosen for the new Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, the coronation ceremony is to take[Pg 109] place at Bethlehem; for Baldwin, with a modesty not entirely in harmony with his previous ambitious and selfish career, has refused to be crowned in the Holy City where great David had his throne. Doubtless also the shrewd Count of Flanders is not blind to the dramatic possibilities of a Christmas coronation in the Christmas City.

So to-day the plain, sombre interior of the Church of the Nativity is all ablaze with brilliant coloring. Along the walls of the nave are battle-worn standards, blessed by pious bishops in distant counties by the Rhine and the Rhone and the Northern Ocean, and sanctified since by many a gallant exploit before the walls of Nicea and Antioch, so that their escutcheons now bear crimson quarterings which were not embroidered[Pg 110] there by the lovely ladies in the lonely palaces across the sea.

At the rear of the church are ranks of sunburnt men-at-arms in battered chain-armor, whose stern, self-possessed demeanor throws into greater contrast the nervous, curious excitement of the Bethlehemite Christians, who have put on their brightest tunics in honor of their valiant deliverers from thraldom to the Saracens. The transepts are crowded with bishops and the great feudal lords who have thrown in their lot with the new kingdom, for the sake of the rich fiefs which are at Baldwin’s disposal. The garments of the nobles glisten with jewels, and the dignitaries of the church are resplendent with gold and laces. Here and there upon the gorgeous scene the high windows of the church cast narrow,[Pg 111] slanting beams, and the tinted lamps shed their soft glow upon the mass of variegated, orient hues, which are yet held in one color harmony by the insistent repetition of the crimson crosses which shine on every breast.

Where the lamps are most numerous and the light from the windows of the transepts shines brightest, Baldwin of Flanders kneels before the great altar and bows his proud head in a semblance of humility as the jeweled crown is placed upon his brow by the noble Daimbert, archbishop of Pisa, patriarch of Jerusalem and temporal lord of many a broad fief and populous village in Judea.

Surely now the veteran warriors chant again that martial Psalm with which they have advanced so often to the assault of infidel strongholds, “Let God arise, let His[Pg 112] enemies be scattered.” And the loud battle-cry of the Crusade, which has echoed above many a desperate conflict, now rolls back and forth from wall to wall of the ancient church with deafening reverberations, “God wills it! God wills it!” And this Christmas Day the glad music of the Gloria in Excelsis rings with a new note of triumph. For the Holy Land is at last reconquered. The Sepulchre and the Manger are cleansed. A Christian king is to reign in millennial peace and prosperity over the sacred hills of Palestine.

During the century following the successful issue of the First Crusade, Bethlehem took a leading part among the cities of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. In 1110 it was elevated to the rank of an episcopal see, whose fiefs included large tracts of[Pg 113] land scattered all through Palestine. The Church of the Nativity, which the Crusaders found to be somewhat bare and dilapidated, was thoroughly restored and adorned by rich gifts. The Byzantine emperor, Manuel Comnenos, had the walls beautified with magnificent mosaic pictures, made of colored glass cubes set in a background of gold. Among the other mosaic saints, the artist Edfrem was allowed to introduce the portrait of the generous emperor. More modest donors presented the church with a baptismal font which bore the simple inscription that it was given by “those whose names are known to the Lord.”

Now that Palestine was no longer under Moslem rule, pilgrims thronged from every Christian country to visit the holy places,[Pg 114] and Bethlehem was crowded with even greater multitudes than during the days of St. Helena or St. Jerome. At Christmas time the vast concourse of clergy and nobles and pilgrims celebrated the festival with gorgeous pomp in the restored and now magnificent church. There were peals of ringing bells, and triumphant choruses of praise, and swinging of priceless censers, and above the great throng of worshippers a golden star was pulled across the church, while young men on the roof chanted the song of the angels.

“In those days,” Brother Felix tells us, “Bethlehem was full of people, famous and rich. Christians of every country on earth brought presents thither, and exceeding rich merchants dwelt there.”

But with peace and wealth, the Christian[Pg 115] population of Bethlehem became more and more enervated and corrupt, until it is said that at last one of the leading men of the town planned to commit a deadly sin within the very precincts of the sacred Cave of the Nativity. When this was reported to the Moslems, they saw that virtue had departed from their Christian rulers, so they were not afraid to rise up against them, and soon they drove them out of all Palestine.

This is only a tradition; but it sounds almost like an allegory of the actual issue of the Crusades and the lamentable fate of the short-lived Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem.

[Pg 117]

SOME BETHLEHEM LEGENDS

[Pg 119]

Numberless traditions have sprung up concerning the sacred places in and about Bethlehem and the holy persons who dwelt there. Many of these tales are really beautiful, and even when they will not bear a too critical inspection, there is often a moral overlaid by the extravagant details of the narrative.

The story of the First Roses is told in the words of Sir John Mandeville, who heard it in Bethlehem in the year 1322, except[Pg 120] that the spelling of the old knight has necessarily been modernized.

“And between the City and the Church is the Felde Floridus, that is to say, the Flowery Field: forasmuch as a fair Maiden was blamed with wrong and slandered; for which cause she was doomed to the Death; and to be burnt in that place, to the which she was led. And as the Fire began to burn about her, she made her prayers to our Lord, that as truly she was not guilty of that Sin, He would help her and make it known to all men, of His merciful Grace. And when she had thus said, she entered into the Fire, and anon was the Fire quenched and out: and the Brands that were burning, became red Roseries; and the Brands that were not kindled, became white Roseries, full of Roses. And these were[Pg 121] the first Roseries and Roses, both white and red, that ever any Man saw. And thus was this Maiden saved by the Grace of God.”

The chapter of the Koran entitled “Mary” tells how a palm tree near the birthplace of Jesus miraculously let fall its ripe dates in order to satisfy His mother’s hunger. Practically all early Moslem visitors to Palestine speak of seeing this tree and note the fact of its being the only one of the kind growing in the district. This made the miracle even more marvellous, as date-palms have to be artificially cross-fertilized before their fruit will come to maturity.

A twelfth century pilgrim tells us that “every year in the middle of the night, at the hour when Christ was born, all the trees[Pg 122] about the city of Bethlehem bow their branches down to the ground toward the place where Christ was born, and when the sun rises, gradually raise them up again.”

About a mile outside of Bethlehem is still pointed out the “Field of Peas,” but the story of the origin of these small, round stones has undergone a number of variations. This is the way it was told to Henry Maundrell, who visited Palestine about the year 1700.

ST. JEROME AND THE LION

From the painting by Rubens

“Near this Monument (Rachel’s Tomb) is a little piece of ground in which are picked up a little sort of small round Stones, exactly resembling Pease: Concerning which they have a tradition here, that they were once truly what they now seem to be; but the Blessed Virgin petrify’d them by a [Pg 125]Miracle, in punishment to a surly Rustick, who deny’d her the Charity of a handful of them to relieve her hunger.”

According to a mediæval biography, St. Jerome was one day studying in his cell at Bethlehem, when there entered an enormous lion, limping from an injured paw. The tender-hearted saint bound up the wound, which speedily healed, whereupon the great beast was overwhelmed with gratitude and attached himself permanently to his deliverer.

The lion followed Jerome about everywhere like a dog, and slept at the feet of the holy man while he was pursuing his Scriptural studies. Upon occasion, however, the complacent creature was not above minding the monastery donkey when it was put out[Pg 126] to pasture, or even acting as a beast of burden; while at night the fearful roar of the saint’s protector brought terror to the hearts of any evil-doers who might be prowling near the monastery grounds.

The story was accepted without question during the Middle Ages, and many a valiant Crusader was willing to make oath that he had seen the ghosts of the saint and his attendant lion strolling silently among the hilltops of Judea in the midnight shadows.

A whole group of legends tell of the miraculous deliverances of the Church of the Nativity from destruction by the Moslems.

At one time the Sultan gave orders to dismantle the interior, and carry off the precious marble slabs from the floor and walls of the church. But when the workmen prepared[Pg 127] to tear away the wall near the stairways which go down to the sacred cave, suddenly there came out of the solid stone a serpent of enormous size, who struck at the piece of marble before which the Moslems were standing. And lo, the rock split under the force of his fiery tongue! Swiftly the reptile glided to the next slab, which he likewise cracked; and so he passed through the church, splitting in all no less than forty pieces of marble, after which he disappeared as mysteriously as he had come. The Sultan and his helpers were stricken with terror at the apparition, and gave up their purpose to deface the church.

The cracks in the marble apparently disappeared as soon as the danger was past; but in substantiation of the truth of the[Pg 128] story, mediæval pilgrims were shown traces of the serpent’s path, which appeared as though the stones had been marked by an intense flame.

[Pg 129]

THE LONG WHITE ROAD

[Pg 131]

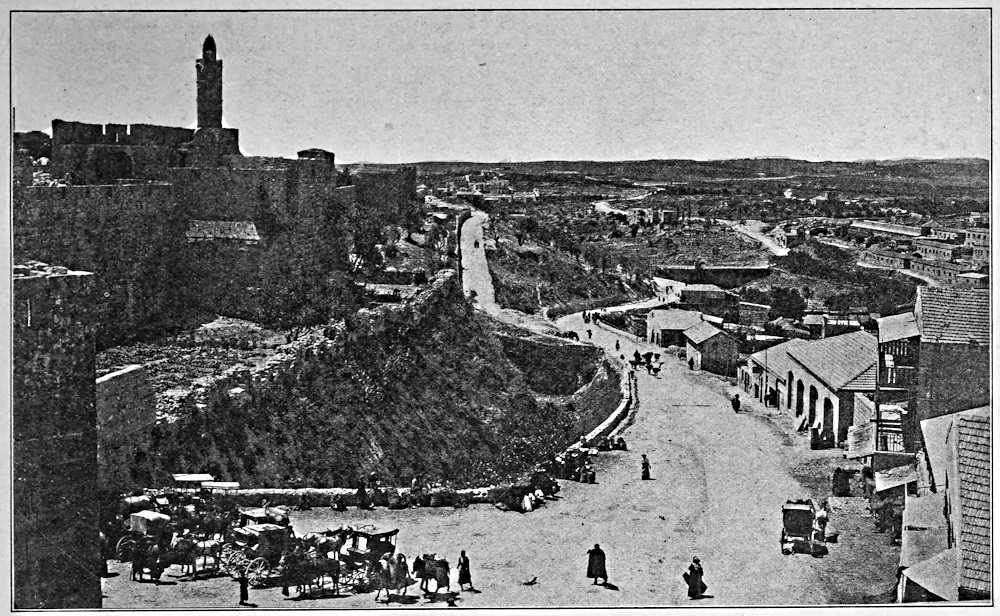

The Jaffa Gate of Jerusalem opens out upon two historic highways. The one which gives its name to the gate leads westward to the sea; the other, which we are to take, passes southward along the Valley of Hinnom between the Sultan’s Pool and the western wall of the city, and then climbs over the brow of a steep hill on its way to Hebron, beyond which the caravan trail leads farther on to the South Country and the desert and the land of the Pharaohs.

A good walker could go from Jerusalem[Pg 132] to Bethlehem in a little more than an hour, for the distance is hardly five miles; but it will be more pleasant to stroll along leisurely, studying the other wayfarers, and stopping now and then to admire some rugged old olive tree or to watch the changing colors on the distant hills.

THE BETHLEHEM ROAD (To the Right)

From the Jaffa Gate of Jerusalem

As soon as we are fairly started down the Hebron road, we begin to pass little companies of men and women who are coming up from Bethlehem to the Holy City with their merchandise. There is a striking difference between the appearance of these people and that of the other inhabitants of Judea; a difference not only in dress, but in feature. The men wear large yellow turbans, and have full lips, long noses, and high, sloping foreheads, so that they fit in very closely with our common idea of [Pg 135]the Hebrew type. They are not Jews, however, but Christians, and it is said that in the veins of many of them flows the blood of the Crusaders. The boys we meet are frank and independent, tramping merrily along, with little caps on their heads, their one long, loose garment tucked up into the leather belt, and their brown, bare legs ending in tremendous slippers which flop clumsily with every step.

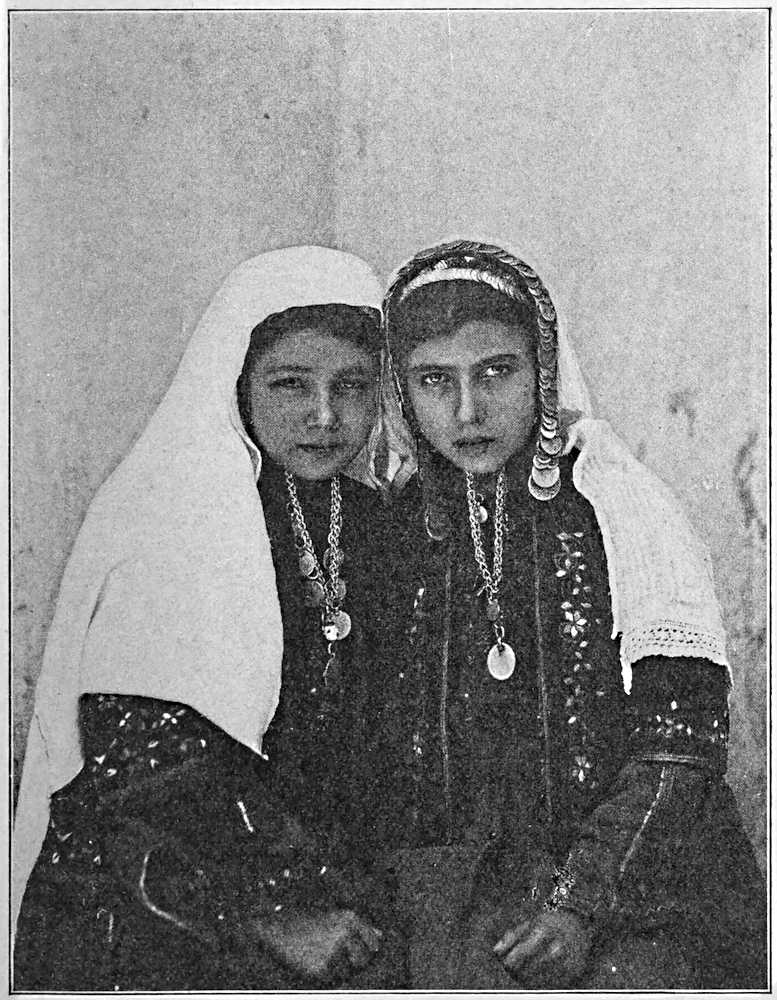

The women of Bethlehem are known throughout Palestine for their peculiar headdress. Over a high cap is thrown a large white kerchief or veil, which falls behind the shoulders and often reaches below the waist. Seen from behind, the Bethlehemite woman is a square of blue skirt, topped by a tall triangle of white; from the front she looks like a nun of some unfamiliar[Pg 136] order. It is a singular costume, but you soon come to like it, and when the clean, white headdress is seen in the distance, it is pleasant to be able to recognize its wearer as a woman of Bethlehem. As we pass one little company after another, we cannot help looking rather closely to see what kind of women these are who are coming out from the town of Ruth and of Mary.

BETHLEHEM GIRLS

Outside of poetical romances, one does not find many examples of Oriental beauty. There are multitudes of pretty children, and the girls of twelve or fourteen have large, soft eyes, regular features and graceful figures; but early marriages and the subsequent drudgery, combined with a lack of proper dentistry, usually turn them into toothless, wrinkled hags at an age when [Pg 139]they should be most attractive. There are exceptions among the richer classes and among girls who have been educated in schools connected with European or American missions; but on the whole there are very few fine-looking women over twenty-five years old to be found in Palestine.

We are therefore surprised to notice that many of these Bethlehem women are really handsome; not with the rich, voluptuous beauty which is usually associated with the East, but with a matronly dignity which appeals more strongly to our Western eyes. We enjoy watching that young mother who is carrying the baby upon her shoulder; she is such a straight, slender woman, with clean-cut features and honest eyes. We like the old woman beside her; an old woman who[Pg 140] looks like a grandmother, not like a withered witch, and who carries herself with a dignity that wins our admiration.

It may be due to nothing more than good food and pure water, or to the great headdresses which make it necessary to stand so erect; but whatever the cause, it seems to us that not even in Nazareth have we seen so many self-respecting, motherly-looking women as in this town which once witnessed the apotheosis of motherhood.

As we stroll along the well-paved road, we pass one spot after another which is not only connected by tradition with the sacred history, but which has been noted by such a long succession of pious pilgrims that even the most trivial fables seem to bind us more closely with the innumerable throng which for nineteen centuries has been treading[Pg 141] with reverent feet this ancient highway to the birthplace of our Lord.

Off to our right is the Wâdi el-Werd, “The Valley of Roses,” which recalls the quaint tale of Sir John Mandeville. At the left of the road is a well by which Mary is said to have rested on her way to Bethlehem, and in which a few days later the Wise Men found again the reflection of the guiding Star. Some distance further on, near the venerable monastery of St. Elijah, the “Field of Peas” is still strewn with its little, rounded stones. A sudden rise in the road broadens our horizon so that we can see, off to the left and very far below us, the dark blue waters of the Dead Sea. Six or seven miles to the southeast there rises the striking profile of the Frank Mountain, shaped like a truncated pyramid,[Pg 142] upon whose platform lie the ruins of Herod’s famous castle. Glimpses of Bethlehem itself are caught now and then between the surrounding heights. We pass the tomb of beautiful, warm-hearted, impulsive Rachel, the sadness of whose lonely burial by the roadside has touched the hearts of passers-by for nearly forty centuries.

Here we leave the main road, which goes on southward to Hebron, and turn in to the left to Bethlehem. “David’s Well” has long been identified with a series of cisterns hewn in the rock some distance before we reach the modern city. Somewhere in the fields below us Ruth gleaned among the harvesters of Boaz. Somewhere among those same fields the youthful David tended his father’s sheep. Somewhere above them rang the glad music of[Pg 143] the angelic Gloria. Somewhere on the long hilltop, now covered by the white, closely-built houses of the town, the Saviour of the world was born.

The heart must be dead to romance as well as to religion, which does not beat with a strange, solemn excitement upon entering the Christmas City.

[Pg 145]

THE HOUSE OF BREAD

[Pg 147]

Bethlehem Ephrathah, which was once “little to be among the thousands of Judah,” is now one of the largest and wealthiest Christian towns in all Palestine.

The Hebrews called it Beth Lehem, “the House of Bread”; and its modern Arabic name is no less significant—Beit Lahm, “the House of Meat,” that is, of course, the Prosperous City. The soil takes on a greater fertility as Jerusalem is left behind; but we are hardly prepared for the beautiful greenness that is seen when a sudden[Pg 148] turn in the road brings into view the two large Christian towns of Beit Jala and Beit Lahm. One is on an eminence to the right of the Hebron road; the other is on an elevation to the left; and they both look very clean and white and well-to-do, in the midst of their vineyards and orchards.

BETHLEHEM

The massive buildings at the left are all connected with the Church of the Nativity

Bethlehem, which is the larger of the two, is built along the summit of a crescent-shaped hill, about two-thirds of a mile long, with its concave side toward the north, so that practically the entire town is spread out before us as we approach it from Jerusalem. At the right-hand horn of the crescent are large, square buildings belonging to various Latin monastic orders. At the left are the dark, heavy walls of the Church of the Nativity, with its low, open belfry. Between these larger structures is a confused [Pg 151]mass of closely-built white houses, whose profile is broken only by the tall, slender spire of the chapel of the German Mission. Immediately in front of us the steep slope of the hill below the town is carefully terraced, and planted here and there with small olive and fig orchards.

The town is the market of all the district around, which is rich in agricultural products. For many centuries Bethlehem has also been famous for the manufacture of souvenirs, which are sold to pilgrims and tourists, not only here, but in Jerusalem and Damascus and Beirût. Rosaries, paper-cutters, cigarette holders and stamp boxes are made from olive wood, the bituminous “Moses-stone” from the Dead Sea is shaped into little vases and paper weights, and mother-of-pearl is carved into elaborate[Pg 152] bas-reliefs of sacred scenes. The shop-keepers are busy and energetic, and a prosperous self-respect seems characteristic of everything about the place.

The inhabitants number eight or nine thousand, nearly all of whom are Christians; adherents of one or other of the Oriental Catholic churches. The population seems to be increasing; for we found some of the streets almost impassable because of the piles of stone and lumber for the new buildings. The modern Bethlehemites have lived up to the ancient reputation of their town for fierce and reckless courage; and until comparatively recent times there were frequent and sanguinary clashes between the Christian and Moslem residents. The latter, however, were completely driven out of Bethlehem about seventy-five years ago,[Pg 153] and their houses destroyed; and though some few have returned, the Moslems still number only three or four per cent of the population.

In Palestine to-day there is much that is unclean and unhealthy, poor and degrading; and many sites that should be hallowed by the most sacred memories have been profaned by the hands of idolatry and oppression. Even Bethlehem and Nazareth have not entirely escaped; yet these two have somehow kept a peculiar dignity; and, indeed, it seems fitting that the place where our Lord was born, and the place where He made His earthly home, should maintain a certain pre-eminence among the cities of the Holy Land.

[Pg 155]

THE CHURCH WHICH IS A FORT

[Pg 157]

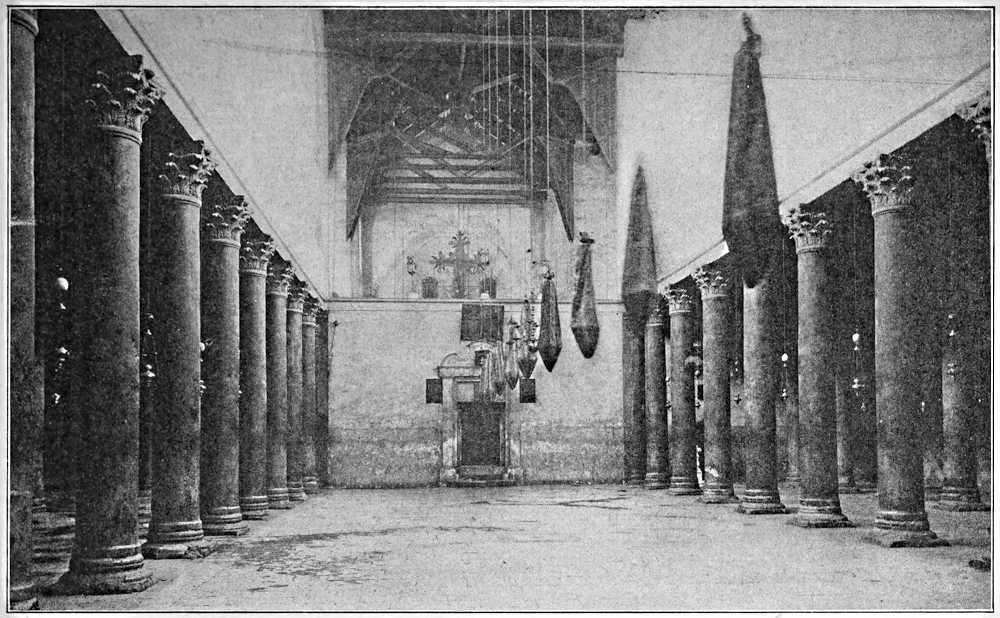

The Church of St. Mary in Bethlehem or, as it is more commonly called, the Church of the Nativity, was built about the year 330, during the reign of the Emperor Constantine; and, as we have already seen, a very ancient tradition ascribes its erection to the emperor’s mother, St. Helena. Through all the wars which have raged over Palestine and during which the city of Bethlehem has again and again been devastated and its houses and castles and monasteries overthrown, the old church alone has[Pg 158] escaped destruction. It is no wonder that its preservation has so often been ascribed to miraculous interventions. Although the building has been slightly altered and restored from time to time, its essential features have not been changed, and there can be little doubt that this is the oldest church in the world.

Except for the single low belfry, the heavy, confused mass looks more like a fort than a religious edifice. Besides the central church, there lie practically under the same roof three large monasteries, belonging to the Greek Orthodox, Gregorian Armenian, and Roman Catholic communions. The collection of buildings is at the extreme eastern end of the town, so that while the front faces the public square of Bethlehem, the rear is at the very edge of a steep[Pg 159] cliff, below which stretches the open country. Viewed from the east, the massive pile resembles a great feudal castle overlooking the farm lands of the vassals in the valley beneath.

There are very few windows in the thick stone walls, and the main entrance from the square is by a single narrow door, so low that one must stoop in passing through. The two other doorways at the front have been walled up and this one purposely made so small, for fear of attack by the Moslems. Yet to-day we find just inside the vestibule a half-company of Turkish infantry. It seems strangely incongruous that Moslem soldiers should be encamped in a Christian church, but we shall see later that there is a good reason for their presence here.

INTERIOR OF THE CHURCH OF THE NATIVITY

Showing the high stone wall which separates the nave from the choir and transepts

The church proper is only about one hundred[Pg 160] and twenty feet long and the whole interior cannot be seen at one view; for, as an additional protection in case of conflict with the Moslems, the transepts and choir are concealed by a high wall built right across the church, so that from the entrance only the nave is visible. This is plain to the point of bareness. Except for a few dimly burning lamps, the only light comes from small windows set high up in the wall, just under the roof. Above the reddish limestone columns which separate the nave from the aisles can still be seen the remains of the famous mosaics given by the Emperor Comnenos; but these are so badly defaced that it is often difficult to determine the subject of the pictures. To the right a small door leads to the Greek monastery; another door at the left opens into the buildings belonging [Pg 163]to the Latin monks. The dividing wall at the back is pierced by three doors. Two of these can be entered by no priests except those of the Greek Orthodox Church, but the use of the third is shared also with the Armenian clergy. The Roman Catholic monks enter the transepts directly from their adjoining monastery: they have little to do, however, with the part of the building which is above ground.

These entrances bring us abruptly from the impressive simplicity of the nave to the transepts and choir, which are well lighted and are almost oppressive in their lavish ornamentation. The great altar facing us belongs to the Greeks, and in front of it are the stalls of the Greek clergy and the tall patriarchal throne. The smaller altar of the Armenians is off at one side in the[Pg 164] northern transept. Lamps of gold and silver swing from the ceiling; bright-colored pictures hang here and there; tawdry, tinsel decorations glitter everywhere; and on the upper part of the walls are portions of quaint mosaic pictures representing scenes from the life of Christ. All that we have yet seen, however, is a mere antechamber to the holy places which lie in the rock beneath the church.

[Pg 165]

THE SACRED CAVES

[Pg 167]

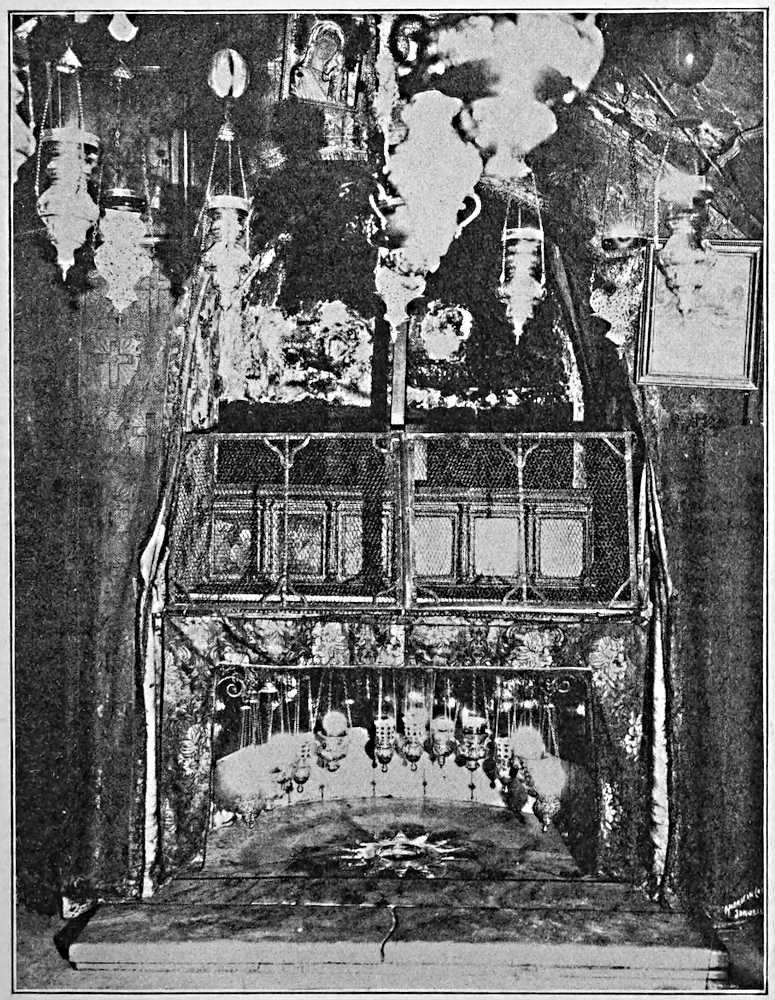

At each side of the central altar of the Church of the Nativity a narrow stairway leads down to a series of six underground chambers, which undoubtedly were originally natural caverns, although they have since been somewhat enlarged and the native rock in many places has been overlaid with marble slabs. In one of these caves St. Jerome is said to have lived; in the next he is buried, near to the tomb of his friend and pupil, Paula. In other chambers the monks point out the exact[Pg 168] spot where the worshipping Magi stood, the opening in the wall from which a spring miraculously gushed forth out of the solid rock for the use of the Holy Family, the place where the angel appeared to Joseph and commanded him to go down into Egypt, and the corner where the soldiers of Herod massacred a number of children who had been brought here for refuge.

The largest cave, and the first we enter from the church above, is about forty feet long. At one end of it there is let into the pavement a large silver star with the inscription, Hic de Virgine Maria Jesus Christus natus est, “Here Jesus Christ was born of the Virgin Mary.”

THE ALTAR OF THE NATIVITY

In the floor beneath is seen the Silver Star

If the inscription is true, there is no other spot on earth so sacred as this, save only Calvary and the Garden Tomb. And it is [Pg 171]quite probable that the stable was really in a cave; for in hilly Judea it often happens that a house or an inn is built on a slope, with the living quarters entirely above ground, but with the stable beneath partly excavated in the rock. Sometimes, indeed, there is a natural cavern which, with very little alteration, can be used for housing the animals.

Tradition concerning the place of the Nativity goes back to the very early ages of Christianity. In the middle of the second century Justin Martyr states that Christ was born in a cave. In the third century Origen says, “There is shown at Bethlehem the cave where He was born, and the manger in the cave where He was wrapped in swaddling clothes. And this site is greatly talked of in surrounding places,[Pg 172] even among the enemies of the faith, it being said that in this cave was born that Jesus who is worshipped and reverenced by the Christians.” In the fourth century Eusebius tells of the building of this very church by St. Helena, who “dedicated two churches to the God whom she adored, one at the grotto which was the scene of the Saviour’s birth, and the other on the mount of His ascension. For He who was ‘God with us’ had submitted to be born even in a cave of the earth, and the place of His nativity was called Bethlehem by the Hebrews.” And from the fourth century on, there is an unbroken chain of testimony concerning the identification of this particular cavern with the scene of the Nativity.

The star is in a little recess at the end of the cave, and above it is an altar, small but very[Pg 173] richly furnished. Of the fifteen altar-lamps of gold and silver which hang around the star, six belong to the Greek, five to the Armenian and four to the Latin monks, who divide in this way the ownership of most of the shrines in the church. The floor of the entire cave is of marble, upon its walls are marbles and rich tapestries, and many lamps hang from the ceiling; yet, on coming from the bright transepts above, the first impression is one of deep gloom. The low roof can hardly be distinguished, and the back of the cave is lost in impenetrable darkness. The smoking lamps give to the atmosphere a heavy, reddish color. The chanting of the priests in the choir overhead is heard only as a dull murmur. We are the only visitors to-day, except that in front of the little altar there kneel four[Pg 174] French nuns, great tears rolling down their pallid faces as they pray in a frightened whisper.

Hic de Virgine Maria Jesus Christus natus est!

[Pg 175]

THE GUARD OF THE SILVER STAR

[Pg 177]

Our eyes are now growing accustomed to the subdued light, and off in one corner of the cave where the gloom is very deep, a form is slowly coming into view. Dark, indistinct, immovable; it would be possible for a worshipper to come and go, and never see that shape at the end of the altar; but by day and by night it is always there—the Moslem guardian of the Silver Star. That is why there is a garrison in the church above. The soldier is half-fed and paid not at all, and his blue uniform is[Pg 178] ragged and dirty; but he holds a modern repeating rifle in his hand as he stands there by the hour without moving a muscle, ready when need comes to face valiantly any odds in the performance of his duty.

He needs to be brave; for when the Christmas season comes round, Bethlehem is thronged with worshippers of the Prince of Peace. They fill the church to overflowing. They rush down the narrow stairways that lead to the little cave, and there they crowd and curse and fight for a glimpse of the Silver Star; so that sometimes the air grows foul and the lamps burn even more dimly and women faint and strong men fall down and are trampled to death in the horrible confusion.

And quiet does not come with the passing of the Christmastide; but all through the[Pg 179] year the monks from the convents above quarrel over the possession of the little shrine, and open warfare is not uncommon. Then the rival parties snarl and scratch; they seize heavy lamps and holy candlesticks from the altars, and priestly garments are torn and priestly heads are broken, until soldiers from the Turkish garrison come down and assist the sentry in clubbing the unruly ones into submission.

I often wonder what the silent sentinel thinks about as he stands there hour by hour, watching the smoky lights that glow above the Silver Star.

[Pg 181]

SONG OF THE KNEELING WOMEN

[Pg 183]

We turned in sadness of heart to shake the dust of Bethlehem from our feet. Up out of the cave and out of the transept we hurried; but then we took the wrong door, and instead of reaching the public square, we found ourselves in the church of the Franciscans. It was the time of the vesper service, and among the shadows of the unlighted nave there stretched long lines of kneeling women. They were all natives of Bethlehem, with the tall white headdress whose spotless cleanness is in such contrast to the costumes of most Palestinian villagers.

[Pg 184]

It was a service of song, and every woman seemed to be taking part. After the officiating priest chanted each brief stanza, the loud chorus was taken up by the full volume of sweet soprano voices. As the light died away, and the white-veiled forms of the kneeling worshippers grew indistinct and dreamlike, the music of the oft-repeated chorus sank into our hearts, and we stayed on and on, until our anger against the sham and idolatry in the caves below had all been driven away and there remained only the Bethlehem calm.

None of us knew the name of that evening hymn. It was very simple, yet one of the sweetest melodies we had ever heard. We shall never forget the song, or the calm faces of the women who sang it. I have listened for it since in many cathedrals.[Pg 185] Two years later I went back to the Bethlehem church in the hope of hearing it again; but there seemed to be no vespers that evening. We could not understand the words of the song; we could not even tell whether it was in Latin or Arabic, but I like to believe that it was a hymn about the Babe of Bethlehem. And now, when I think of that village among the beautiful hills of far-away Judea, the bigotry and jealousy do not seem so very important. I am even ready to forgive the Moslem guardian of the Silver Star, for the sake of that nameless melody of the women of Bethlehem.

[Pg 187]

ACROSS THE AGES

[Pg 189]

Night falls. The stars shine brightly through the clear Judean air. We walk very slowly down the winding road, and often stop to look back to the hilltop where the thick-clustered houses of the little town stand so clear and white against the blue-black sky. Yonder lies Bethlehem, bathed in soft, silvery starlight which cleanses it from every trace of violence and bigotry and crime, and paints only pleasant memories of love and valor and hope.

There the lonely heart of the Moabitess[Pg 190] found its haven. There the sweet singer of Israel set to melodious measures the story of the fields and the mountains and the divine Shepherd’s care. There a wondrous Child was born, for whose sake wise men and tender women left home and friends across the sea, that they might dwell near the hallowed, humble spot of His Nativity. Within the vague, dark shadow of that ancient church, the noblest-born of earth have gathered to do homage to the Lord of lords and King of kings. And across the stillness of the night there seem to echo again the sturdy shouts of dauntless warriors who made the mountains ring with their triumphant cry of faith, “God wills it! God wills it!”

Yes, God has willed it all, even in the hardest, darkest hour of Bethlehem’s long[Pg 191] history. Before our lingering steps lie the noisy bazaars of Jerusalem and the busy, practical, modern world to which we must so soon return. But we have been to Bethlehem; and across all the troublous ages, bursting from every shining star, and drowning with its sweet music the perplexities of our own weary lives, there rings the glad refrain of the Angel’s Song—

GLORY TO GOD IN THE HIGHEST, AND ON

EARTH PEACE, GOOD WILL TOWARD

MEN.