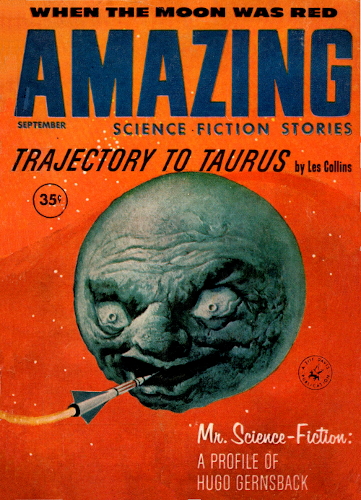

By LES COLLINS

ILLUSTRATOR FINLAY

Out in the reaches of space an ultimate

disaster raced at light-speeds

toward Earth. Only a massive sacrifice

could save Mankind now. And so he

turned, as always, to his Eternal Mother.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Amazing Stories September 1960.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Fred Kirr, stomach twisting with shock, turned from the viewscreen and looked directly into the deep blue eyes of the girl. "Would you repeat that?" he asked, fighting to keep urgency from his voice.

Ordinarily, JoAnn Chase's eyes danced merrily in tune with her vivacious personality; now, however, they were filled with an inner light akin to fanaticism, and Fred felt his scalp crawl. Without taking her eyes from the planet, in a hypnotic-like state, Jo answered, "I just said, 'Oh, my God!'"

"I know," Fred interjected hastily. "We were in complete agreement up to that point. But what did you say next?"

"It's indescribably lovely, heavenly! Compared to it, Earth is a desiccated old hag, a vapid, colorless rock that tediously circles the sun."

Fred thought silently: When we left Earth, a few days ago, you looked back and called her a blue-green jewel. Then, to check himself, he looked once more at the planet, even now perceptibly larger in the center of the screen. Heavenly? Far from it, a diametric opposite, for he still saw in it a face that might have been dredged from the nightmare horror of his unconscious. It was a face from hell, and he couldn't shake the impression. Even if he wanted to be dispassionate in evaluation, he'd still have to call the cancerous blob a desert planet....

"Jo!" Fred's call was a plea for help, "I've got to speak to you—"

The girl interrupted with an impatient shake of her blonde locks, put a finger to her lips. For a moment, Fred was reminded of a small boy being quieted during the Sunday sermon. His confusion and fear came boiling out as aggression. After all, this was only a planet; Jo hadn't the right to make it a religious ceremony. He stamped away ... but soon was wrestling with the problem again; Fred was too well trained in the scientific method not to. Given: two reasonably competent observers. Event: a planet that the expedition had set out to find. Descriptions: completely opposite. Conclusion: well, what? Is sanity to be questioned? Whose? And be honest with yourself. Add the overtones of what could be emotional involvement with a girl you've only recently met.

Fred was surprised to find himself in the ship's control center. The hugeness of Captain John Charlesworth was bent over a star chart. Charlesworth was a big, solid man who loved living. He had taught Fred practically everything there was to know about operating the ship—with automation being what it was, he was able to do it in the three days they'd been traveling. The two men were friends from the time they'd been introduced, so perhaps it wasn't strange that Fred should be here.

"John," Fred began without preamble, "there's something about that planet—"

Charlesworth's face split into a grin. "There sure is! Beauty, isn't she? Thought you'd like it. If we find life, it'll be there."

Fred was caught short. It was another strike against him. Some instinct warned him to be quiet, and he left as soon as he could. "Curiouser and curiouser," he mused, then reached a decision. He had a purpose now.

The other two members of the expedition were also watching the approach to the planet. Fred found them in the recreation area. Richard Lodgesen, the lean, tall chemist-physicist, looked up at Fred's approach, said with a supercilious air, "I should think the anthropology section would be studying the planet as hard as we."

Data, Fred, data! Ignore the jerk; just integrate this information: he was easily distracted. "I am studying. What do you think of it?"

Lodgesen smiled warmly, the first time he'd reacted pleasantly around Fred. "I think we're all of the same opinion. This discovery will rock 'em up back home."

"And you, Beth?"

Beth Rosen, their data coordinator, Huh?ed, and gave Fred her attention grudgingly. "My opinion? It's ... it's like coming home, Fred. Why do you ask?"

Of them all, Beth was the only one who was curious about Fred's activities. "No important reason," he was suddenly aware of a bead of sweat on his forehead as he looked at the screen. Home? More like the poorhouse. But he continued to lie, "Just doing a little survey." He wandered away, thoughts in turmoil.

He must be careful of Beth. He'd learned very fast to respect her on both professional and interpersonal grounds. The gal had a mind like a steel trap; she had a body that caused males—adolescents to elders—to fantasy, and females—of any age—to envy. Beth, as data coordinator, had a role on the ground similar to Charlesworth's in space. Although the data coordinator rarely went to extremes, she or he was fed all information the expedition collected, had ultimate power for decision and responsibility.

And how was Fred to give her this information? Add it up—but it wouldn't add. JoAnn Chase, semantics, deeply taken with the planet; Beth Rosen, data coordinator, in a state of lassitude but not as strongly influenced as Jo; John Charlesworth, captain, highly enthusiastic; Richard Lodgesen, chemistry-physics, showing more joyous emotion than the cold fish could possibly be expected to; and Fred Kirr, anthropology, who tended as far toward dislike as Beth did like, possibly as far as Jo.

Item: no one acted abnormal.

Item: on the basis of very bad statistical sampling, it seemed the women were reacting far more than the men to this particular encounter.

Item: you, Fred Kirr, are the only one to have an anti-reaction. Are you insane? No, you've always been this way. In school, the times you got good grades were when you were sure you'd flunked. Or, take your Tanganyika discovery in 1965: a complete skeleton of the Dryopithecinae, showing anthropoid differentiation by late Miocene. The scientific world hailed this as strong evidence that, in Life's words, "the evolution of that primate called 'man' began fantastically farther back than we'd ever before dreamed." Your reaction was discouragement; there was too much conclusion jumping; nothing at all had been proved.

Come to think of it, all 28 of your years have been spent with reverse reaction. And now you have a situation that must soon be resolved.

Fred shook his head. The change in the others seemed so sudden. It was only a few hours ago that the ship had come out of hyper.

He'd been watching the newly visible star system wondering, Will you be the one? Somewhere in your depths, is there the key to our mystery?

"Hi, Gloomy Gus!" JoAnn joined him, excited pleasure bubbling from her.

"Gloomy—"

"All right, you weren't being gloomy, just concentrating. You're still known to the rest of us as Gloomy Gus...." She giggled.

"I was thinking about intelligent life," Fred said.

"I'll bet," the girl added, "you were thinking I wouldn't have a job because, as usual, we won't find it. But we're bound to, eventually, so why not now?"

He had to smile; her attitude was infectious. "Matter of fact, I was thinking we'd miss. I even wonder what we're doing out here—"

Charlesworth's voice, on the intercom, broke in: "Attention, please. We have come out of hyperspace in the constellation Taurus. As you know, nothing has been said about our destination; this is done to avoid prejudicing you. I'll now play the recorded instructions from General Anderson."

A new voice took over, sounding even more mechanical. "Ladies and gentlemen, you are making history. Whatever you do will make history, United States' history—"

Fred, the only member who'd been out before, said, "They always begin that way. You'd think—"

Jo shooshed him, and they continued listening. "This expedition is one of the many under the administration of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and coordinated by the joint armed forces. You are aboard the Exploration Frigate DLE 560, also known as USS Taurus. The general volume of space around you is the Taurus moving cluster, a roughly globular group of 100 stars. Your destination is the Hyades open cluster, specifically Gamma Tauri.

"Your primary mission is, as always, to find and contact intelligent life. However, secondarily, you may be able to shed some light on the phenomenon we call 'moving clusters.' These are ill-defined groups of stars, all in parallel motion.

"Taurus is moving away from us at 28.5 miles per second. Now 130 light years away, the group was closest to us—some 65 light years—only 800 thousand years ago...."

Fred stopped listening. Why, that long ago, man was already differentiated. In another half-million years, more or less, the gang around the old juke box in Java would be using fire ... only he wouldn't really be man, just an unreasonable facsimile. Man? He wouldn't show up for another 450 millennia—too soon, too soon. Something's got to be done about our theories: in 25,000 years, we appeared as a clever savage, developed to our present state. What were we doing in all the years the lower hominids were evolving? Where were we?

No matter. In 25,000 years, we haven't had a chance to mature. Because of political pressure, DLE 560 is out into the universe, trying to befriend other intelligences. And so are a host of other peoples from Earth: peoples who owe their allegiance to imaginary lines on Earth's surface. Suppose we do make contact? Can we—man, that is—handle the job? Have we matured? Why are we here?

The learning curve is exponential. It took man nearly 50 years to go from Jenny to jet, from Kittyhawk to Canaveral. It took him little more than a decade to go from Titan to transcontinuum, from exploring Earth to exploring the universe. And man being a contrary, contumacious, cockeyed Cat, it wasn't a good thing, Man.

There were some cynics who thought it was the most miserable thing that could happen to the universe. They based this on the shrieking ambivalence man displayed in the total course of events, primarily bad, he'd created and lived through. He began meekly enough. Hunted and planted and found a little leisure. With that commodity, he set up special caves and began to paint, to sculpture, to philosophize.

Then he changed. Maybe it was the cold draughts in the caves, maybe it was the old lady complaining about the draughts, or maybe it was plain frustration: he'd been trying, for a couple of thousand years, to invent writing and had failed. In any event, man was suddenly different. He found that scrambled brains—his neighbor's—were good eating. Ever the artist, he enjoyed the color of blood much more than those dull old mineral pigments. If a couple of the guys sneaked up behind a herd of horses and suddenly scared them, what fun! The whole herd would stampede off a cliff.

Aesthetic? Certainly. He went back into the caves and tried his hand at dirty pictures; had to give that up, though, until he invented plain brown envelopes and photography. Anyway, he'd lost the touch ... except in one area. These products were works of art, a delight to behold: man was making the damnedest, finest arrowheads and spear points he'd ever seen.

She, who may have jerked him out of the cave in the beginning, continued to warm her feet on his back, with the result that he'd go out and knock over a country rich in coal deposits. She didn't really like it, but she was stuck with it. Certainly, she was carrying out her function. If there were a war or two too many, she could always up production—having discovered how well before they set up cave-keeping. The flutter of an eyelash or an exposed ankle ... she carried out her function, and the population kept rising.

By the opening of the twentieth century, however, she'd grown apprehensive. Man was playing with bigger and bigger boom-boom toys. She tried to exert control, discovered too late it was out of her hands. For one day, man brought home the keenest, ginger-peachiest job of them all. Like maybe he could blow himself to hell with an atomic bomb.

Elders had shaken their heads over it; youngsters had joined them when the fusion bomb came next. And the world settled down to hold its breath while the two leading powers fenced economically—with Russia thrusting and the U. S. parrying.

Suddenly, two other nations appeared on the world scene—rather, reappeared. Great Britain, at one time the strongest nation, in one stroke became the richest: Britain, of necessity, for years had been researching magnetohydrodynamics in an effort to get controlled fusion. While the two "leading" powers were threatening one another, the British engineered practical atomics and had energy to burn, if the phrase will be excused.

And then there was France. Long influential in world history, this small country was reduced by two wars to a minor position. France had at one time been the seat of scientific progress in the world. The French regained status when they got antigravity. Zwicky, at Cal Tech, had long ago shown that the effect of gravity occurred either twice or one-half the speed of light. Apparently no one paid much attention, except for a few obscure French philosophers.

And so, in the course of eight months in 1964-1965, the focus of power in the world again shifted to the English Channel. Of course, these developments were secret. If the U. S. and U. S. S. R. were left with their tongues hanging out, they didn't realize it. But not for long. You just can't keep things like that secret. And man being what he is....

The French were spying on the British; the British on the Russians; the Russians on the United States; and the U. S. was spying on all three.

Antigravity had its limits. With it, you could never exceed light speed because you were confined to the physical, Einsteinian universe. What was needed was raw energy to warp the continuum, fold it like a piece of paper, and punch a hole through it as a short cut. That's where controlled fusion came in. And even though it required tons of equipment, antigravity made it possible to get those tons off the ground.

By 1970, the four powers were racing to explore the universe. If anything, relations between them were worse. All gave lip service to the noble idea of finding intelligent life; actually, the world knew that the first nation to find such life would be enlisting a powerful ally, creating a shift in power that might mean control.

There were exceptions. Take Russia, who'd brought the Red Chinese along too fast. As many had predicted as far back as 1941, the U. S. S. R. was now trying to play footsie with the West. Unfortunately, there no longer was a West as such. Each was to its own. So the world groaned under a new burden when it was rumored that the Chinese were working on their first transcontinuum ship.

With the power of fusion at his command, man had everything he could possibly want. But it had come too soon; he was unaware. Instead, he went into space looking for intelligence equal to or greater than his own, looking for a new club to use against his neighbors on Earth. Man, the cynics said, was too immature, would destroy himself before 1980—himself and the life he's trying to find. The cynics were in overwhelming preponderance. Yet a few voices were raised in hope: Don't let this throw you, but is it possible that the artist-philosopher had again come to the fore?

The shift in the others had seemed abrupt to Fred. They were far more interested in that damned planet than in him; this should have been perfectly natural except for the speed of occurrence.

As the only space veteran, Fred was listened to carefully. Further, as the anthropologist, he was in a position to tell them things they wanted to know.

Soon after they'd come out of hyper, the group gathered in the recreation area. In the three days of the trip, they'd grown used to meeting there for discussion. And this time, they were excited about the possibility of life.

"Somehow," Jo said, "I feel that we are destined to do what none of the others has done."

There was general concurrence. "Right!" Charlesworth interjected.

Fred frowned, shook his head.

"Why not? How can you know, Kirr?" Lodgesen, as usual, was his snobbish self.

"Why not? You ought to know more than I about randomness and screwed-up statistics, Lodgesen." Fred was on his feet for emphasis. "Frankly, from what we've learned out here, I'd rather count on winning the sweepstakes ... without having a ticket. That's how bad the odds are."

"Fred," Beth said softly, "we concede you know your business; and you were on two other expeditions that found traces of very high orders of intelligence on deserted planets. But why do you feel so strongly? I should think those traces would be encouraging."

Again he shook his head. "It's not that simple. Here's the run-down: five years ago we began sending out expeditions. So did the other countries. Naturally, we tried the stars nearest us; so did they. We've very effectively covered the nearest parts of the galaxy. No life."

"But evidence of it," Lodgesen objected. "Counting all extinct cultures found by the various powers, I'd guess the total is upwards of 10 or 11."

Fred smiled humorously. "The total is 47 finds; for some reason, no one is telling all. Security. Fortunately, Dr. Kousansky is a good friend of mine, and Professeur de Poitiers is a friend of his, and so on down the line.

"We're guessing, of course, but it seems our little corner of the universe is deserted. A more profitable question than where? is why? You might also be interested in the times involved; they're lengthy enough to cause head scratching. Wendell, at London University, came up with the oldest—some 585 thousand years, based on radioactive dating, but he won't guarantee the figure any closer than +/- 50 thousand. And the French, as you know, were the first out; de Poitiers did a very thorough job on Alpha Centauri IV. Until 30 thousand years ago, give or take, she had a thriving little community. I don't think you're going to find intelligent life this close, even within 500 light years. To me, the wonder is why we're here at all when everyone else has left."

There it was. He'd let them have it between the eyes, and they resented it. From that time on, he was something of a pariah. Even Jo seemed to be ignoring him. The nearer they came to planetfall, the worse it got. At least she lost that look of inner truth, but she was terribly, terribly busy. For what? Obviously, preparing for what they should find.

The USS Taurus circled the planet, Gamma Tauri II. As Fred had expected, it seemed a negative quantity, just another of those hunks of cosmic mediocrity. By the third trip, he was completely convinced this thing had evolved nothing. He was more relieved than he cared to admit; now Charlesworth would go on. There were more promising planets in the system.

He'd spent the last hour writing his report—NASA/DD Form E-72, Rev. B in triplicate—when it occurred to him that Charlesworth had made no announcement. Fred went to the captain's cabin, found Beth in discussion with him.

"Glad you're here; we want to talk something over," Charlesworth said. There was a pause, and Fred, watching the other two, felt as though he were an intruder.

"Sure," he said, dropping into a chair.

"You're sort of strait-laced, but rules are made to be broken...." Charlesworth's voice trailed off.

Beth came directly to the point: "We all want to land on New Earth."

New Earth! Fred was stunned but managed to keep silent.

"Sure," Charlesworth beamed, a big happy bear, "that way you get a couple of days vacation at government expense, and no one's the wiser."

Fred shrugged, trying to appear normal. "I don't see anything wrong with it." Hardly aware of his words, he was thinking rapidly. Why convince me? Have the four of them sensed my attitude?

"There could be something so right with it!" Beth added. "If it turns out to be what it seems, we'll take the news home. You don't find many planets like this—"

You sure don't! The young anthropologist gripped the chair arms, again swept by nausea. He was sure he hadn't thought that or said it. Was he hearing voices? Neither Beth nor John seemed to notice. He had to get out of there, caught in a sudden claustrophobic nightmare.

"I don't need any convincing," he said, hoping it sounded convincing. "I'm ready for that vacation right now. Good night." Drenched with sweat, he stumbled from the cabin.

During the next few days, Fred went through a series of emotional oscillations the like of which he'd never experienced. He'd nosedive into the pit of depression; when he landed, he found himself atop the peak of Mount Euphoria. Finally, however, he came to an important conclusion. If he were ready for the squirrel factory, he'd wait until the DLE 560 returned to Earth. He certainly didn't feel violent, so he'd be crazy like a fox and keep his mouth shut.

He was amazed at the adaptability of the human psyche, for there were three most-probable alternatives to face: he was mentally ill, the other four were ditto, or all of them were. Facing that, he could be quite calm. He doubted but didn't discount the possibility that they were all sane.

After two days of self-imposed exile, he came out of his cabin. His relations with the opposition—how easily he fell into the term!—were polite but strained. Except Lodgesen. The two men, never cordial, now fell into a state of cold war, characterized chiefly by refusal to speak. This was the only open rupture.

Fred began to help them, to join their somewhat frenetic activities. Apparently each was engaged in exploration, bringing back to the ship samples of soil, rocks, vegetation, and the like. However, he was never invited to go with them, and as time passed, he found it harder and harder to reach them.

JoAnn was his last link. Perhaps it was the feeling of rapport they'd had on the journey out here—or perhaps it was simply that she felt sorry for his present state. In any event, Jo would talk freely to him.

It was late in the evening of the sixth day. Jo was showing him the samples they'd collected a few hours earlier. The recreation area had been hastily converted into a sort of museum. In it, the exhibit had grown to an impressive pile ... of junk. But Jo was vivacious enough to make a mummy jump, and he enjoyed listening to her.

"Don't you see, Fred? We've got huge amounts of data; New Earth is a paradise, rich in everything we could possibly want. This is the place where our peoples will want to come. We'll be hailed for this discovery!"

For a moment, as she spoke, he did see through her eyes: the place man had always dreamt of. This Eden abounded in game, in forests drained by sparkling brooks. All of the riches were here; animal, vegetable, mineral wealth were so plentiful that ... that the streets were paved with gold, he thought sourly, as the vision faded. No, it was just a common planet, undistinguished.

"Why don't we go home, Jo, and tell them?"

The blonde lost her sparkle, became blank. As though she hadn't heard his question, she cast about nervously, picked up a rock.

"Look at this!" She was enthusiastic again. "Uranium! Dick Lodgesen has been analyzing ores. He says the place is fantastically rich in heavy minerals."

Fred turned the specimen in his hand. It was dense quartzite. Heavy enough, but it lacked the other characteristics.

"What makes you think it isn't uranium?" she demanded furiously.

"I said nothing of the sort." Fred suddenly had the feeling of a clue, especially because of Jo's reaction: again the blankness, again the nervousness.

"I saw it in your face." Jo edged to the end of one table. "Here's today's find. Seedless grapes, each as big as a lemon. Have one." She held out her hand.

There was nothing in it.

Fred didn't bat an eyelash; he'd grown used to shocks. He merely replied, "No, thanks. Still full from dinner." And then integrated more data.

They finished the tour at her cabin. From the time that the trip started, and until the last few nights, Fred had insisted on "walking the girl home." And each time, before he left her, he'd quasi-seriously propositioned her with a request that the door be left open. It was always shut, very firmly.

Tonight, Fred was grave. Almost curt, he said, "Goodnight. See you in the morning."

"Wait." She smiled. "If you could learn to be as happy as we on this planet, you might find the door open."

He smiled in return. "I'll think about it. Night." Fred strode away, thinking: Jo, you'd make a lousy Mata Hari. But thanks for convincing me I'm sane!

Relief brought emotional reaction; he wanted to laugh, but it was aggressive, humorless laughter, and he couldn't afford it. Instead, he permitted himself the luxury of silent anger. Complete. Total.

When the curtain of fury dissolved, Fred found himself in the recreation area. Unknowingly, he'd wandered there. Unknowingly, he'd arrived at a course of action—

You won't have a chance to carry it out.

That voice again! It was inside his head. This time, however, Fred straightened, unconsciously, said, "So I was wrong, and we did find intelligent life."

But not the sort you expected.

"Admitted. It's difficult to believe that a planet is alive."

Why so? Logically, you animals are the difficult beliefs. Nearly all else in the universe is direct—energy conversion, formation of elements, and the like. You animals require many things to get started: a planet; a fluid medium such as water; and the delicate balance of conditions for food input and waste removal. In a sense, you're parasites.

"Certainly. But why are you trying so hard to convince my friends to be parasites?" Fred stopped for a second, struck by a thought. "Come to think of it, why am I immune?"

There is always a certain small percentage who have crossed mental patterns, whom we can communicate with. What the others see as desirable, you dislike. If you'll think a moment, you'll realize you've always been that way.

Fred nodded. He was the eternal pessimist surrounded by optimists.

My desire is simple. I want a population.

"Why?"

We use animal intelligence. When you die, we absorb the life force directly. It sustains our own.

"In a sense," Fred felt he'd scored, "you also are a parasite. You talk as though there are other sentient planets in the universe."

There are, though not in great numbers. Our life cycle is similar to yours. We are born in cosmic space of elemental material; we attract animal populations that have evolved on the dead planets, and thereby gain the energy needed to live—just as you live from the lower animals. We even grow old and die after two or three billion years. But I'm young, and this is the first time I've been in this portion of the galaxy—I need a population.

"You seem to know what's in my mind," Fred said calmly, "so I'm afraid you're going to be disappointed."

No, I need the others here for a little more time; they must be completely convinced of my wonders so they can take the story home. I can do without you, however. Why do you think I've bothered at all to communicate with you?

Fred's spine was icy. His mouth was dry, and all of the dark shapes that terrified him throughout his youth came home to jibber behind his back. But Fred was a man, and he refused to turn his head, to give in to the fear. "I don't know why."

I couldn't let you take the ship from my surface. I have no physical control over you, and I can't speak directly to the others, only influence their emotions. While I've delayed you, I've aroused one of them.... Now you have your answer.

There was a step behind him. Expecting Lodgesen, Fred turned, stopped in shock. The 6-1/2-foot, 285-pound bulk of Charlesworth stood poised, then raced forward. Fred hadn't time to get set, bounced when the automaton hit him, fell heavily against the exhibit table. Instantly, Charlesworth had dropped on him. The big man's hands were around Fred's throat.

His vision blurred; little spots of ink crept down over Charlesworth's face; it was too much of an effort to lift his arms and try to push him away.

There was a quick rush of thoughts. Wish you'd stop; it hurts. But what's this? Something cool and heavy in my hand. I suppose I should try it....

When Fred's head cleared, he saw Charlesworth stretched out beside him, his chin split and bleeding. The hunk of quartzite lay between the captain and Fred.

He hadn't the time to be glad he was alive. The others were up; running footsteps were converging on him. He got up, staggered from the room. Then, as strength returned, he raced for the control center.

He almost made it. But Beth suddenly appeared from the opposite end of the corridor. Face contorted in some nameless horror, she screamed a warning, ran towards the door to the center. And Beth was closer.

Agonizingly closer. She'd be there a step ahead of him, and if she got that door locked—With crystal clarity, he knew it meant the end of progress for the human race.

Fred, who was hardly aware of baseball, desperately arched his body into a perfect slide. It got faint cheers from Cobb, Mays, and all the kids who ever played sandlot ball. Beth's feet tangled with Fred's; she stumbled against the door, tripped, and rolled into the corridor.

Fred scrambled inside, locked the door. He was home safe.

He would now bring them all home safe.

He couldn't know that the worst was coming.

Charlesworth gingerly felt his jaw as he walked into the recreation area. "Did you have to clobber me so hard?"

Fred grinned weakly. "What are you complaining about? Did you have to choke me so hard? After three days, I still can't swallow. And I've got a busted toe where I hit that doorway."

"Speaking of which," Beth said, "I've got bruises on my arms and legs."

"I couldn't be feeling better." Jo delivered the line perfectly, broke them up.

"We still have to thank you," Beth said, suddenly serious. "What a nightmare!"

"Not thanks, Beth. I couldn't help myself any more than you. I can imagine what you went through; I suspect it was even worse for Jo."

The pretty blonde was startled. "I haven't said anything—"

"The intensity with which you were attracted," Fred broke in. "I didn't know it at the time, but it was the first clue. Women were bound to be more affected."

Charlesworth fingered his jaw again. "Yeah? I thought it was pretty bad."

"You got the full treatment, John, but only for a few minutes. Nevertheless, woman's nature is far more intimately bound up in the life force than man's. What you felt for a short time might have been equivalent to what the girls felt all the time."

The big man shook his head. "Couldn't take it. I'd break...." His voice trailed away, and he looked guilty at reminding them.

"We have to face it," Beth said.

"How is he?" Jo asked.

"Lodgesen hasn't changed," the captain said gruffly. "He hasn't changed all the time we were in hyper. Just lies in his bunk, crying to go home to mama. It's spooky."

"We'll be home in half a day," Joe said hopefully. "Maybe the psychiatrists can help." Beth and John nodded agreement.

"Possibly, but I don't think so," Fred said. Then a stray wisp of thought brushed his memory—"The eternal pessimist"—made him shudder and hurry on. "From what I remember of psych, he's withdrawn past the point of return. Like so many guys in the physical sciences, he had a streak of insecurity. That's why the categorizing outlook; all data must be fitted into a neat plan. He ran into a bit of data that wouldn't fit; worse, the data turned on him, gave him a sense of security he'd never known. When I jerked us away from the planet, the shock to him must have been similar to the birth trauma. He slipped away from reality. Chances are he'll never come back."

"And the trouble with you guys in the social sciences is too much theorizing on insufficient data!" It was Lodgesen, pale, needing a shave, but otherwise normal.

Charlesworth stood firmly on two feet. "You all right?"

Lodgesen nodded, folded his thin frame into a chair. "I came out of it. Don't know why. All of a sudden, I was back. Like waking up."

"Everything seems to happen suddenly on the USS Taurus," Beth said lightly, "We're glad, Dick."

Things did happen suddenly, Fred thought, too suddenly. I'd better mull this one over.... He got painfully to his feet. "I've still got some work to do before we land. Excuse me." Then, to Lodgesen: "Take it easy. You've had a shock."

"So have you," the other replied with a wolflike grin, "and you may have others in store."

Fred ignored the remark, limped away. But instinctive bells pealed a warning, one he tried to rationalize away. He wasn't having much success.

In his own cabin, Fred paced rapidly, ignoring the pain in his toe. On the view-forward screen, Earth appeared as a sphere. They were so close.... The view-aft screen showed nothing but the emptiness of space. Lodgesen's miraculous recovery had shaken him. It didn't add, and the last time something didn't add, there'd been trouble. Incredible as it seemed, he wasn't really sure they'd lost the planet—

You didn't. You led me to the population I wanted. I'm getting closer.

Fred trembled, tried to collect himself to fight.

You can't fight. You've lost already. Observe: even weak contact with the mind of that other animal made it function normally. Soon I'll be close enough to exert full control over the others again.

"What are you going to do?" Fred asked.

Before I'm through, I shall convince all of the intelligences on your dead planet to join me. They'll know it's a much better, richer world.

"But it isn't!" he almost shrieked. "You can't support that many people."

True. Many will die. And I'll be able to replenish the energy I've used following you.

"The race will revert to savagery, possibly even lower, to the caves."

That is not important, except that the life span will drop. This will create more life force for me. You argue in my favor.

Fred was aware of an urgent knocking at the door. He opened it, found Jo leaning weakly against the frame.

"Fred," the girl spoke slowly, "help me ... the nightmare's back ... help all of us." She was crying, and her eyes were caves of dark terror. He held her tightly, and she sagged against him. "I can't hold out ... the others have gone under ... a miracle, Fred—"

I'll take this one now; I am strong enough.

"... need a mir—" Jo stiffened, spoke firmly. "I'm going back to my friends. If you're silly enough not to want New Earth, I can't help you." She left, striding purposefully.

"Damn you. Damn you!" Fred's voice was hard, cold. Man, the artist, and man, the hunter, stood helpless before this power. But man, the toolmaker—he bent his environment. That was it! The different faces of man, the ambivalent. That was it! The pieces were in place.

"Earth!" he called piercingly. "Earth, you are one like this other planet. Help us!"

Stop! The hated sound beat at him.

And then he heard a new voice, an aged crone: Can't. Too old.

"This new one will take us from you," Fred went on, "just as you took us from Alpha Centauri IV. Help us now."

Can't. It would mean my death. All my reserves of life force.

Fred heard noise in the corridor outside. There could be only one reason why they'd come—New Earth would prevent his action by killing him.

Desperate now, Fred tried once more. "Earth, die if you must! Die for the 46 other populations that died for you. Your life is almost over; ours has just begun. You owe us something. We battled our way up from nothingness; you held us back. Because of you, we hated one another. Fought. Killed. We could have been creating—"

The door burst open. Four things, lacking any semblance of reason, advanced on him.

Now you'll stop! The new planet's voice was vibrant, confident.

"Earth! Give us back our lives—"

Fred went down under the rush of Charlesworth and Lodgesen. Fingernails—what used to be feminine—tore at his face. A foot crashed into his ribs. Then, as fast as it had begun, the torment stopped.

He raised his head, saw the two screens. In view aft, the intruder planet was barely visible; Earth definitely seen in view forward. Neither changed appearance, but Fred's four companions, held in stasis, were an indication. A cosmic battle raged, an impossible mental battle: age versus youth, weakness versus strength, experience versus inexperience.

Suddenly, the four came at him again. He hadn't the power to resist. What was the use? We've lost again; shall we lose always?

No ... you've won ... use the gift wisely. As the voice faded out, the view-aft screen flared brilliantly with sudden energy released from a destroyed planet.

There was nothing but the sound of heavy breathing.

Fred tried to raise himself to a sitting position, sank back. Then Jo was cradling him. Her tears, he thought, mixed well with her laughter.

"You did help. However you managed it, you saved the five of us. Are you all right?"

Fred smiled at her. "I'm all right; we all are."

They were picking themselves up—except for one. A thin bundle, curled in a corner, it cried forlornly for its mother.

Jo pointed. "Dick isn't all right."

"He will be." Fred felt mental chains slipping from him. "We'll find a way, now. Don't you see, Jo? That cry is one of a new-born. Our mission was accomplished. The trajectory to Taurus did find life—ours, and it's all ahead of us...."

THE END