It cannot be denied that an improved system of practical domestic cookery, and a better knowledge of its first principles, are still much needed in this country; where, from ignorance, or from mismanagement in their preparation, the daily waste of excellent provisions almost exceeds belief. This waste is in itself a very serious evil where so large a portion of the community often procure—as they do in England—with painful difficulty, and with the heaviest labour, even sufficient bread to sustain existence; but the amount of positive disease which is caused amongst us by improper food, or by food rendered unwholesome by a bad mode of cooking it, seems a greater evil still. The influence of diet upon health is indeed a subject of far deeper importance than it would usually appear to be considered, if we may judge by the profound indifference with which it is commonly treated. It has occupied, it is true, the earnest attention of many eminent men of science, several of whom have recently investigated it with the most patient and laborious research, the results of which they have made known to the world in their writings, accompanied, in some instances, by information of the highest value as to the most profitable and nutritious modes of preparing various kinds of viands. In arranging the present enlarged edition of this volume for publication, I have gladly taken advantage of such of their instructions (those of Baron Liebig especially) as have seemed to me adapted to its character, and likely to increase its real utility. These, I feel assured, if carefully followed out, will much assist our progress in culinary art, and diminish the unnecessary ivdegree of expenditure which has hitherto attended its operations; for it may safely be averred that good cookery is the best and truest economy, turning to full account every wholesome article of food, and converting into palatable meals, what the ignorant either render uneatable, or throw away in disdain. It is a popular error to imagine that what is called good cookery is adapted only to the establishments of the wealthy, and that it is beyond the reach of those who are not affluent. On the contrary, it matters comparatively little whether some few dishes, amidst an abundant variety, be prepared in their perfection or not; but it is of the utmost consequence that the food which is served at the more simply supplied tables of the middle classes should all be well and skilfully prepared, particularly as it is from these classes that the men principally emanate to whose indefatigable industry, high intelligence, and active genius, we are mainly indebted for our advancement in science, in art, in literature, and in general civilisation.

When both the mind and body are exhausted by the toils of the day, heavy or unsuitable food, so far from recruiting their enfeebled powers, prostrates their energies more completely, and acts in every way injuriously upon the system; and it is no exaggeration to add, that many a valuable life has been shortened by disregard of this fact, or by the impossibility of obtaining such diet as nature imperatively required. It may be urged, that I speak of rare and extreme cases; but indeed it is not so; and the impression produced on me by the discomfort and the suffering which have fallen under my own observation, has rendered me extremely anxious to aid in discovering an efficient remedy for them. With this object always in view, I have zealously endeavoured to ascertain, and to place clearly before my readers, the most rational and healthful methods of preparing those simple and essential kinds of nourishment which form the staple of our common daily fare; and have occupied myself but little with the elegant superfluities or luxurious novelties with which I might perhaps more attractively, though not more usefully, have vfilled my pages. Should some persons feel disappointed at the plan I have pursued, and regret the omissions which they may discover, I would remind them, that the fashionable dishes of the day may at all times be procured from an able confectioner; and that part of the space which I might have allotted to them is, I hope and believe, better occupied by the subjects, homely as they are, to which I have devoted it—that is to say, to ample directions for dressing vegetables, and for making what cannot be purchased in this country—unadulterated bread of the most undeniably wholesome quality; and those refreshing and finely-flavoured varieties of preserved fruit which are so conducive to health when judiciously taken, and for which in illness there is often such a vain and feverish craving when no household stores of them can be commanded.[1]

1. Many of those made up for sale are absolutely dangerous eating; those which are not adulterated are generally so oversweetened as to be distasteful to invalids.

Merely to please the eye by such fanciful and elaborate decorations as distinguish many modern dinners, or to flatter the palate by the production of new and enticing dainties, ought not to be the principal aim, at least, of any work on cookery. “Eat,—to live” should be the motto, by the spirit of which all writers upon it should be guided. I must here obtrude a few words of personal interest to myself. At the risk of appearing extremely egotistic, I have appended “Author’s Receipt” and “Author’s Original Receipt” to many of the contents of the following pages; but I have done it solely in self-defence, in consequence of the unscrupulous manner in which large portions of my volume have been appropriated by contemporary authors, without the slightest acknowledgment of the source from which they have been derived. I have allowed this unfairness, and much beside, to pass entirely unnoticed until now; but I am suffering at present too severe a penalty for the over-exertion entailed on me by the plan which I adopted for the work, longer to see with perfect composure strangers coolly taking the credit and the profits viof my toil. The subjoined passage from the preface of my first edition will explain in what this toil—so completely at variance with all the previous habits of my life, and, therefore, so injurious in its effects—consisted; and prevent the necessity of recapitulating here, in another form, what I have already stated in it. “Amongst the large number of works on cookery which we have carefully perused, we have never yet met with one which appeared to us either quite intended for, or entirely suited to the need of the totally inexperienced! none, in fact, which contained the first rudiments of the art, with directions so practical, clear, and simple, as to be at once understood, and easily followed, by those who had no previous knowledge of the subject. This deficiency, we have endeavoured in the present volume to supply, by such thoroughly explicit and minute instructions as may, we trust, be readily comprehended and carried out by any class of learners; our receipts, moreover, with a few trifling exceptions which are scrupulously specified, are confined to such as may be perfectly depended on, from having been proved beneath our own roof and under our own personal inspection. We have trusted nothing to others; but having desired sincerely to render the work one of general usefulness, we have spared neither cost nor labour to make it so, as the very plan on which it has been written must of itself, we think, evidently prove. It contains some novel features, calculated, we hope, not only to facilitate the labours of the kitchen, but to be of service likewise to those by whom they are directed. The principal of these is the summary appended to the receipts, of the different ingredients which they contain, with the exact proportion of each, and the precise time required to dress the whole. This shows at a glance what articles have to be prepared beforehand, and the hour at which they must be ready; while it affords great facility as well, for an estimate of the expense attending them. The additional space occupied by this closeness of detail has necessarily prevented the admission of so great a variety of receipts as the book might otherwise have comprised; but a limited number, thus viicompletely explained, may perhaps be more acceptable to the reader than a larger mass of materials vaguely given.

“Our directions for boning poultry, game, &c., are also, we venture to say, entirely new, no author that is known to us having hitherto afforded the slightest information on the subject; but while we have done our utmost to simplify and to render intelligible this, and several other processes not generally well understood by ordinary cooks, our first and best attention has been bestowed on those articles of food of which the consumption is the most general, and which are therefore of the greatest consequence; and on what are usually termed plain English dishes. With these we have intermingled many others which we know to be excellent of their kind, and which now so far belong to our national cookery, as to be met with commonly at all refined modern tables.”

Since this extract was written, a rather formidable array of works on the same subject has issued from the press, part of them from the pens of celebrated professional gastronomers; others are constantly appearing; yet we make, nevertheless, but slight perceptible progress in this branch of our domestic economy. Still, in our cottages, as well as in homes of a better order, goes on the “waste” of which I have already spoken. It is not, in fact, cookery-books that we need half so much as cooks really trained to a knowledge of their duties, and suited, by their acquirements, to families of different grades. At present, those who thoroughly understand their business are so few in number, that they can always command wages which place their services beyond the reach of persons of moderate fortune. Why should not all classes participate in the benefit to be derived from nourishment calculated to sustain healthfully the powers of life? And why should the English, as a people, remain more ignorant than their continental neighbours of so simple a matter as that of preparing it for themselves? Without adopting blindly foreign modes in anything merely because they are foreign, surely we should be wise to learn from other nations, who excel us in aught good or useful, all that we can which may tend to remedy viiiour own defects; and the great frugality, combined with almost universal culinary skill, or culinary knowledge, at the least—which prevails amongst many of them—is well worthy of our imitation. Suggestions of this nature are not, however, sufficient for our purpose. Something definite, practical, and easy of application, must open the way to our general improvement. Efforts in the right direction are already being made, I am told, by the establishment of well-conducted schools for the early and efficient training of our female domestic servants. These will materially assist our progress; and if experienced cooks will put aside the jealous spirit of exclusiveness by which they are too often actuated, and will impart freely the knowledge they have acquired, they also may be infinitely helpful to us, and have a claim upon our gratitude which ought to afford them purer satisfaction than the sole possession of any secrets—genuine or imaginary—connected with their craft.

The limits of a slight preface do not permit me to pursue this or any other topic at much length, and I must in consequence leave my deficiencies to be supplied by some of the thoughtful, and, in every way, more competent writers, who, happily for us, abound at the present day; and make here my adieu to the reader.

London, May, 1855.

Aspic—fine transparent savoury jelly, in which cold game, poultry, fish, &c., are moulded; and which serves also to decorate or garnish them.

Assiette Volante—a dish which is handed round the table without ever being placed upon it. Small fondus in paper cases are often served thus; and various other preparations, which require to be eaten very hot.

Blanquette—a kind of fricassee.

Boudin—a somewhat expensive dish, formed of the French forcemeat called quenelles, composed either of game, poultry, butcher’s meat, or fish, moulded frequently into the form of a rouleau, and gently poached until it is firm; then sometimes broiled or fried, but as frequently served plain.

Bouilli—boiled beef, or other meat, beef being more generally understood by the term.

Bouillie—a sort of hasty pudding.

Bouillon—broth.

Casserole—a stewpan; and the name also given to a rice-crust, when moulded in the form of a pie, then baked and filled with a mince or purée of game, or with a blanquette of white meat.

Court Bouillon—a preparation of vegetables and wine, in which (in expensive cookery) fish is boiled.

Consommé—very strong rich stock or gravy.

Croustade—a case or crust formed of bread, in which minces, purées of game, and other preparations are served.

Crouton—a sippet of bread.

Entrée—a first-course side or corner dish.[2]

2. Neither the roasts nor the removes come under the denomination of entrées; and the same remark applies equally to the entremets in the second course. Large standing dishes at the sides, such as raised pies, timbales, &c., served usually in grand repasts, are called flanks; but in an ordinary service all the intermediate dishes between the joints and roasts are distinguished by the name of entrées, or entremets.

Entremets—a second-course side or corner dish.

Espagnole, or Spanish sauce—a brown gravy of high savour.

xFarce—forcemeat.

Fondu—a cheese soufflé.

Gâteau—a cake, also a pudding, as Gâteau de Riz; sometimes also a kind of tart, as Gâteau de Pithiviers.

Hors d’œuvres—small dishes of anchovies, sardines, and other relishes of the kind, served in the first course.

Macaroncini—a small kind of maccaroni.

Maigre—made without meat.

Matelote—a rich and expensive stew of fish with wine, generally of carp, eels, or trout.

Meringue—a cake, or icing, made of sugar and whites of egg beaten to snow.

Meringué—covered or iced with a meringue-mixture.

Nouilles—a paste made of yolks of egg and flour, then cut small like vermicelli.

Purée—meat, or vegetables, reduced to a smooth pulp, and then mixed with sufficient liquid to form a thick sauce or soup.

Quenelles—French forcemeat, for which see page 163.

Rissoles—small fried pastry, either sweet or savoury.

Sparghetti—Naples vermicelli.

Stock—the unthickened broth or gravy which forms the basis of soups and sauces.

Tammy—a strainer of fine thin woollen canvas.

Timbale—a sort of pie made in a mould.

Tourte—a delicate kind of tart, baked generally in a shallow tin pan, or without any: see page 574.

Vol-au-vent—for this, see page 357.

Zita—Naples maccaroni.

| Page | |

| Ingredients which may all be used for making Soup of various kinds | 1 |

| A few directions to the Cook | 2 |

| The time required for boiling down Soup or Stock | 4 |

| To thicken Soups | 4 |

| To fry Bread to serve with Soup | 5 |

| Sippets à la Reine | 5 |

| To make Nouilles (an elegant substitute for Vermicelli) | 5 |

| Vegetable Vermicelli (Vegetables cut very fine for Soups) | 5 |

| Extract of Beef, or very strong Beef Gravy-Soup (Baron Liebig’s receipt) | 6 |

| Bouillon (the common Soup of France), cheap and very wholesome | 7 |

| Clear pale Gravy Soup, or Consommé | 10 |

| Another receipt for Gravy Soup | 10 |

| Cheap clear Gravy Soup | 11 |

| Glaze (Note) | 11 |

| Vermicelli Soup (Potage au Vermicelle) | 12 |

| Semoulina Soup (Soupe à la Semoule) | 12 |

| Macaroni Soup | 13 |

| Soup of Soujee | 13 |

| Potage aux Nouilles, or Taillerine Soup | 14 |

| Sago Soup | 14 |

| Tapioca Soup | 14 |

| Rice Soup | 14 |

| White Rice Soup | 15 |

| Rice-Flour Soup | 15 |

| Stock for White-Soup | 15 |

| Mutton Stock for Soups | 16 |

| Mademoiselle Jenny Lind’s Soup | 16 |

| The Lord Mayor’s Soup | 17 |

| The Lord Mayor’s Soup (Author’s receipt) | 18 |

| Cocoa-Nut Soup | 19 |

| Chestnut Soup | 19 |

| Jerusalem Artichoke, or Palestine Soup | 19 |

| Common Carrot Soup | 20 |

| A finer Carrot Soup | 20 |

| Common Turnip Soup | 21 |

| A quickly made Turnip Soup | 21 |

| Potato Soup | 21 |

| Apple Soup | 21 |

| Parsnep Soup | 22 |

| Another Parsnep Soup | 22 |

| Westerfield White Soup | 22 |

| A richer White Soup | 23 |

| Mock-Turtle Soup | 23 |

| Old-fashioned Mock-Turtle | 26 |

| Good Calf’s-Head Soup (not expensive) | 27 |

| Soupe des Galles | 28 |

| Potage à la Reine (a delicate White Soup) | 29 |

| White Oyster Soup (or Oyster Soup à la Reine) | 30 |

| Rabbit Soup à la Reine | 31 |

| Brown Rabbit Soup | 31 |

| Superlative Hare Soup | 32 |

| A less expensive Hare Soup | 32 |

| Economical Turkey Soup | 33 |

| Pheasant Soup | 33 |

| Another Pheasant Soup | 34 |

| Partridge Soup | 35 |

| Mullagatawny | 35 |

| To boil Rice for Mullagatawny, or for Curries | 36 |

| Good Vegetable Mullagatawny | 37 |

| Cucumber Soup | 38 |

| Spring Soup, and Soup à la Julienne | 38 |

| An excellent Green Peas Soup | 39 |

| Green Peas Soup without meat | 39 |

| A cheap Green Peas Soup | 40 |

| Rich Peas Soup | 41 |

| Common Peas Soup | 41 |

| Peas Soup without meat | 42 |

| Ox-tail Soup | 43 |

| A cheap and good Stew Soup | 43 |

| Soup in haste | 43 |

| Veal or Mutton Broth | 44 |

| Milk Soup with Vermicelli (or with Rice, Semoulina, Sago, &c.) | 44 |

| Cheap Rice Soup | 44 |

| Carrot Soup Maigre | 45 |

| Cheap Fish Soups | 46 |

| Buchanan Carrot Soup (excellent) | 46 |

| Observation | 47 |

| Page | |

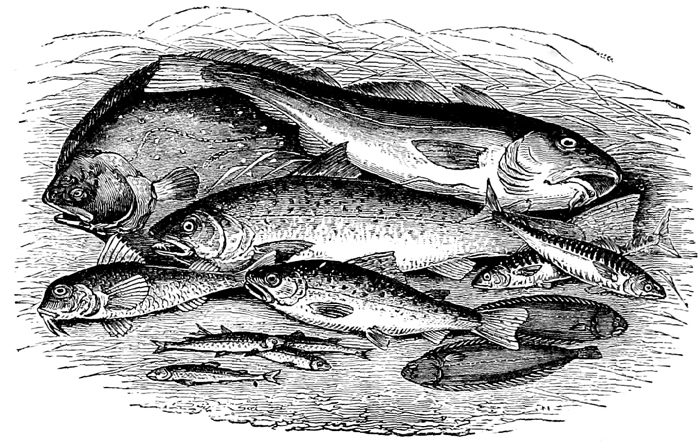

| To choose Fish | 48 |

| To clean Fish | 50 |

| To keep Fish | 51 |

| To sweeten tainted Fish | 51 |

| The mode of cooking best adapted to different kinds of Fish | 51 |

| The best mode of boiling Fish | 53 |

| Brine for boiling Fish | 54 |

| To render boiled Fish firm | 54 |

| To know when Fish is sufficiently boiled, or otherwise cooked | 55 |

| To bake Fish | 55 |

| Fat for frying Fish | 55 |

| To keep Fish hot for table | 56 |

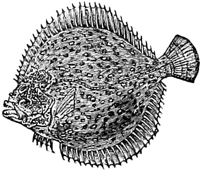

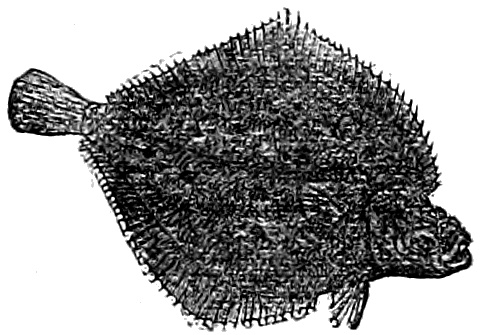

| To boil a Turbot (and when in season) | 56 |

| Turbot à la Crême | 57 |

| Turbot au Béchamel | 57 |

| Mould of cold Turbot with Shrimp Chatney (refer to Chapter VI.) | |

| To boil a John Dory (and when in season) | 58 |

| Small John Dories baked. Good (Author’s receipt) | 58 |

| To boil a Brill | 58 |

| To boil Salmon (and when in season) | 59 |

| Salmon à la Genevese | 50 |

| Crimped Salmon | 60 |

| Salmon à la St. Marcel | 60 |

| Baked Salmon over mashed Potatoes | 69 |

| Salmon Pudding, to be served hot or cold (a Scotch receipt. Good) | 60 |

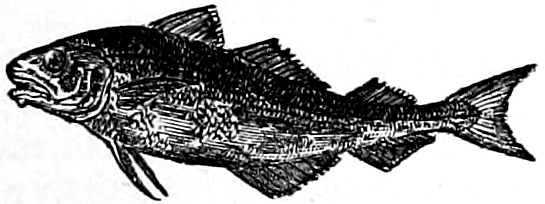

| To boil Cod Fish (and when in season) | 61 |

| Slices of Cod Fish Fried | 61 |

| Stewed Cod | 62 |

| Stewed Cod Fish in brown sauce | 62 |

| To boil Salt Fish | 62 |

| Salt Fish à la Maître d’Hôtel | 63 |

| To boil Cods’ Sounds | 63 |

| To fry Cods’ Sounds in batter | 63 |

| To fry Soles (and when in season) | 64 |

| To boil Soles | 64 |

| Fillets of Soles | 65 |

| Soles au Plat | 66 |

| Baked Soles (a simple but excellent receipt) | 66 |

| Soles stewed in cream | 67 |

| To fry Whitings (and when in season) | 67 |

| Fillets of Whitings | 68 |

| To boil Whitings (French receipt) | 68 |

| Baked Whitings à la Française | 68 |

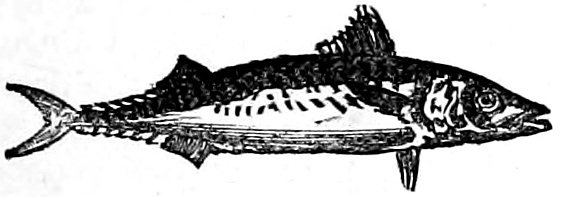

| To boil Mackerel (and when in season) | 69 |

| To bake Mackerel | 69 |

| Baked Mackerel or Whitings (Cinderella’s receipt. Good) | 70 |

| Fried Mackerel (Common French receipt) | 70 |

| Fillets of Mackerel (fried or broiled) | 71 |

| Boiled fillets of Mackerel | 71 |

| Mackerel broiled whole (an excellent receipt) | 71 |

| Mackerel stewed with Wine (very good) | 72 |

| Fillets of Mackerel stewed in Wine (excellent) | 72 |

| To boil Haddocks (and when in season) | 73 |

| Baked Haddocks | 73 |

| To fry Haddocks | 73 |

| To dress Finnan Haddocks | 74 |

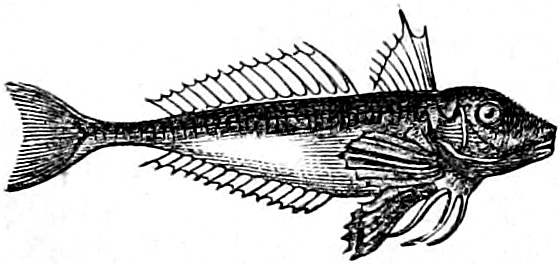

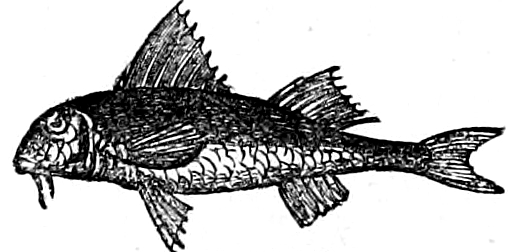

| To boil Gurnards (with directions for dressing them in other ways) | 74 |

| Fresh Herrings. Farleigh receipt (and when in season) | 74 |

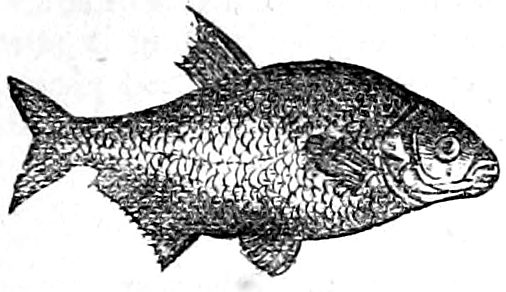

| To dress the Sea Bream | 75 |

| To boil Plaice or Flounders (and when in season) | 75 |

| To fry Plaice or Flounders | 75 |

| To roast, bake, or broil Red Mullet (and when in season) | 76 |

| To boil Grey Mullet | 76 |

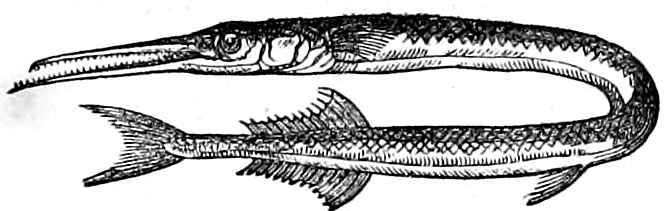

| The Gar Fish (to bake) | 77 |

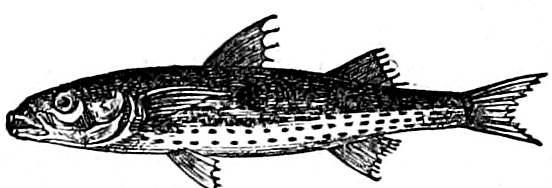

| The Sand Launce, or Sand Eel (mode of dressing) | 77 |

| To fry Smelts (and when in season) | 77 |

| Baked Smelts | 78 |

| To dress White Bait. Greenwich receipt (and when in season) | 78 |

| Water Souchy (Greenwich receipt) | 78 |

| Shad, Touraine fashion (also à la mode de Touraine) | 79 |

| Stewed Trout. Good common receipt (and when in season) | 80 |

| To boil Pike (and when in season) | 80 |

| To bake Pike (common receipt) | 81 |

| To bake Pike (superior receipt) | 81 |

| To stew Carp (a common country receipt) | 82 |

| To boil Perch | 82 |

| To fry Perch or Tench | 83 |

| To fry Eels (and when in season) | 83 |

| Boiled Eels (German receipt) | 83 |

| To dress Eels (Cornish receipt) | 84 |

| Red Herrings à la Dauphin | 84 |

| Red Herrings (common English mode) | 84 |

| Anchovies fried in batter | 84 |

| Page | |

| Oysters, to cleanse and feed (and when in season) | 85 |

| To scallop Oysters | 86 |

| Scalloped Oysters à la Reine | 86 |

| To stew Oysters | 86 |

| Oyster Sausages (a most excellent receipt) | 87 |

| To boil Lobsters (and when in season) | 88 |

| Cold dressed Lobster and Crab | 88 |

| xiiiLobsters fricasseed, or au Béchamel (Entrée) | 89 |

| Hot Crab or Lobster | 89 |

| Potted Lobsters | 90 |

| Lobster cutlets (a superior Entrée) | 91 |

| Lobster Sausages | 91 |

| Boudinettes of Lobsters, Prawns, or Shrimps. Entrée (Author’s receipt) | 92 |

| To boil Shrimps or Prawns | 93 |

| To dish cold Prawns | 93 |

| To shell Shrimps and Prawns quickly and easily | 93 |

| Page | |

| Introductory remarks | 94 |

| Jewish smoked Beef (extremely useful for giving flavour to Soups and Gravies) | 95 |

| To heighten the colour and flavour of Gravies | 96 |

| Baron Liebeg’s Beef Gravy (most excellent for Hashes, Minces, and other dishes made of cold meat) | 96 |

| Shin of Beef Stock for Gravies | 97 |

| Rich pale Veal Gravy or Consommé | 97 |

| Rich deep coloured Veal Gravy | 98 |

| Good Beef or Veal Gravy (English receipt) | 99 |

| A rich English brown Gravy | 99 |

| Plain Gravy for Venison | 100 |

| A rich Gravy for Venison | 100 |

| Sweet Sauce, or Gravy for Venison | 100 |

| Espagnole, Spanish Sauce (a highly flavoured Gravy) | 100 |

| Espagnole with Wine | 100 |

| Jus des Rognons, or Kidney Gravy | 101 |

| Gravy in haste | 101 |

| Cheap Gravy for a Roast Fowl | 101 |

| Another cheap Gravy for a Fowl | 102 |

| Gravy or Sauce for a Goose | 102 |

| Orange Gravy for Wild Fowl | 102 |

| Meat Jellies for Pies and Sauces | 103 |

| A cheaper Meat Jelly | 103 |

| Glaze | 104 |

| Aspic, or clear savoury Jelly | 104 |

| Page | |

| Introductory remarks | 105 |

| To thicken Sauces | 105 |

| French thickening, or brown Roux | 106 |

| White Roux, or French thickening | 106 |

| Sauce Tournée, or pale thickened Gravy | 106 |

| Béchamel | 107 |

| Béchamel Maigre (a cheap white Sauce) | 108 |

| Another common Béchamel | 108 |

| Rich melted Butter | 108 |

| Melted Butter (a good common receipt) | 108 |

| French melted Butter | 109 |

| Norfolk Sauce, or rich melted Butter without Flour | 109 |

| White melted Butter | 109 |

| Burnt or browned Butter | 109 |

| Clarified Butter | 110 |

| Very good Egg Sauce | 110 |

| Sauce of Turkeys’ Eggs Sauce (excellent) | 110 |

| Common Egg Sauce | 110 |

| Egg Sauce for Calf’s Head | 111 |

| English White Sauce | 111 |

| Very common White Sauce | 111 |

| Dutch Sauce | 111 |

| Fricassee Sauce | 112 |

| Bread Sauce | 112 |

| Bread Sauce with Onion | 113 |

| Common Lobster Sauce | 113 |

| Good Lobster Sauce | 113 |

| Crab Sauce | 114 |

| Good Oyster Sauce | 114 |

| Common Oyster Sauce | 114 |

| Shrimp Sauce | 115 |

| Anchovy Sauce | 115 |

| Cream Sauce for Fish | 114 |

| Sharp Maître d’Hôtel Sauce (English receipt) | 116 |

| French Maître d’Hôtel, or Steward’s Sauce | 116 |

| Maître d’Hôtel Sauce Maigre, or without Gravy | 117 |

| The Lady’s Sauce for Fish | 117 |

| Genevese Sauce, or Sauce Genevoise | 117 |

| Sauce Robert | 118 |

| Sauce Piquante | 118 |

| Excellent Horseradish Sauce, to serve hot or cold with roast Beef | 118 |

| Hot Horseradish Sauce | 119 |

| Christopher North’s own Sauce for many Meats | 119 |

| Gooseberry Sauce for Mackerel | 120 |

| Common Sorrel Sauce | 120 |

| Asparagus Sauce for Lamb Cutlets | 120 |

| Caper Sauce | 121 |

| Brown Caper Sauce | 121 |

| Caper Sauce for Fish | 121 |

| Common Cucumber Sauce | 121 |

| xivAnother common Sauce of Cucumbers | 122 |

| White Cucumber Sauce | 122 |

| White Mushroom Sauce | 122 |

| Another Mushroom Sauce | 123 |

| Brown Mushroom Sauce | 123 |

| Common Tomata Sauce | 123 |

| A finer Tomata Sauce | 124 |

| Boiled Apple Sauce | 124 |

| Baked Apple Sauce | 124 |

| Brown Apple Sauce | 125 |

| White Onion Sauce | 125 |

| Brown Onion Sauce | 125 |

| Another brown Onion Sauce | 125 |

| Soubise | 126 |

| Soubise (French receipt) | 126 |

| Mild Ragout of Garlic, or l’Ail à la Bordelaise | 126 |

| Mild Eschalot Sauce | 127 |

| A fine Sauce, or Purée of Vegetable Marrow | 127 |

| Excellent Turnip, or Artichoke Sauce, for boiled Meat | 127 |

| Olive Sauce | 128 |

| Celery Sauce | 128 |

| White Chestnut Sauce | 129 |

| Brown Chestnut Sauce | 129 |

| Parsley-green, for colouring Sauces | 129 |

| To crisp Parsley | 130 |

| Fried Parsley | 130 |

| Mild Mustard | 130 |

| Mustard, the common way | 130 |

| French Batter for frying vegetables, and for Apple, Peach, or Orange fritters | 130 |

| To prepare Bread for frying Fish | 131 |

| Browned Flour for thickening Soups and Gravies | 131 |

| Fried Bread-Crumbs | 131 |

| Fried Bread for Garnishing | 131 |

| Sweet Pudding Sauces, Chapter XXII. |

| Page | |

| Superior Mint Sauce, to serve with Lamb | 132 |

| Common Mint Sauce | 132 |

| Strained Mint Sauce | 132 |

| Fine Horseradish Sauce, to serve with cold roast, stewed, or boiled Beef | 133 |

| Cold Maître d’Hôtel, or Steward’s Sauce | 133 |

| Cold Dutch or American Sauce, for Salads of dressed Vegetables, Salt Fish, or hard Eggs | 133 |

| English Sauce for Salad, cold Meat, or cold Fish | 134 |

| The Poet’s receipt for Salad | 135 |

| Sauce Mayonnaise, for Salads, cold Meat, Poultry, Fish, or Vegetables | 135 |

| Red or green Mayonnaise Sauce | 136 |

| Imperial Mayonnaise, an elegant Jellied Sauce or Salad dressing | 136 |

| Remoulade | 137 |

| Oxford Brawn Sauce | 137 |

| Forced Eggs for garnishing Salads | 137 |

| Anchovy Butter (excellent) | 138 |

| Lobster Butter | 138 |

| Truffled Butter, and Truffles potted in Butter for the Breakfast or Luncheon table | 139 |

| English Salads | 140 |

| French Salad | 140 |

| French Salad—Dressing | 140 |

| Des Cerneaux, or Walnut Salad | 141 |

| Suffolk Salad | 141 |

| Yorkshire Ploughman’s Salad | 141 |

| An excellent Salad of young Vegetables | 141 |

| Sorrel Salad, to serve with Lamb Cutlets, Veal Cutlets, or roast Lamb | 142 |

| Lobster Salad | 142 |

| An excellent Herring Salad (Swedish receipt) | 143 |

| Tartar Sauce (Sauce à la Tartare) | 143 |

| Shrimp Chatney (Mauritian receipt) | 144 |

| Capsicum Chatney | 144 |

| Page | |

| Observations | 145 |

| Chetney Sauce (Bengal receipt) | 146 |

| Fine Mushroom Catsup | 146 |

| Mushroom Catsup (another receipt) | 148 |

| Double Mushroom Catsup | 148 |

| Compound, or Cook’s Catsup | 149 |

| Walnut Catsup | 149 |

| Another good receipt for Walnut Catsup | 150 |

| Lemon Pickle, or Catsup | 150 |

| Pontac Catsup for Fish | 150 |

| Bottled Tomatas, or Tomata Catsup | 151 |

| Epicurean Sauce | 151 |

| Tarragon Vinegar | 151 |

| Green Mint Vinegar | 152 |

| Cucumber Vinegar | 152 |

| Celery Vinegar | 152. |

| Eschalot, or Garlic Vinegar | 152. |

| Eschalot Wine | 153 |

| xvHorseradish Vinegar | 153 |

| Cayenne Vinegar | 153 |

| Lemon Brandy for flavouring Sweet Dishes | 153 |

| Dried Mushrooms | 153 |

| Mushroom Powder | 154 |

| Potato Flour, or Arrow Root (Fecule de Pommes de Terre) | 154 |

| To make Flour of Rice | 154 |

| Powder of Savoury Herbs | 154 |

| Tartar Mustard | 154 |

| Another Tartar Mustard | 154 |

| Page | |

| General remarks on Forcemeats | 156 |

| Good common Forcemeat for Veal, Turkeys, &c., No. 1 | 157 |

| Another good common Forcemeat, No. 2 | 157 |

| Superior Suet Forcemeat, No. 3 | 158 |

| Common Suet Forcemeat, No. 4 | 158 |

| Oyster Forcemeat, No. 5 | 159 |

| Finer Oyster Forcemeat, No. 6 | 159 |

| Mushroom Forcemeat, No. 7 | 159 |

| Forcemeat for Hare, No. 8 | 160 |

| Onion and Sage stuffing for Geese, Ducks, &c., No. 9 | 160 |

| Mr. Cooke’s Forcemeat for Geese or Ducks, No. 10 | 161 |

| Forcemeat Balls for Mock Turtle Soups, No. 11 | 161 |

| Egg Balls, No. 12 | 162 |

| Brain Cakes, No. 13 | 162 |

| Another receipt for Brain Cakes, No. 14 | 162 |

| Chestnut Forcemeat, No. 15 | 162 |

| An excellent French Forcemeat, No. 16 | 163 |

| French Forcemeat, called Quenelles, No. 17 | 163 |

| Forcemeat for raised and other cold Pies, No. 18 | 164 |

| Panada, No. 19 | 165 |

| Page | |

| To boil Meat | 167 |

| Poélée | 169 |

| A Blanc | 169 |

| Roasting | 169 |

| Steaming | 172 |

| Stewing | 173 |

| Broiling | 175 |

| Frying | 176 |

| Baking, or Oven Cookery | 178 |

| Braising | 180 |

| Larding | 181 |

| Boning | 182 |

| To blanch Meat or Vegetables | 182 |

| Glazing | 182 |

| Toasting | 183 |

| Browning with Salamander | 183 |

| Page | |

| To choose Beef | 184 |

| When in season | 184 |

| To roast Sirloin or Ribs of Beef | 184 |

| Roast Rump of Beef | 186 |

| To roast part of a Round of Beef | 186 |

| To roast a Fillet of Beef | 187 |

| Roast Beef Steak | 187 |

| To broil Beef Steaks | 187 |

| Beef Steaks à la Française (Entrée) | 188 |

| Beef Steaks à la Française (another receipt) (Entrée) | 189 |

| Stewed Beef Steak (Entrée) | 189 |

| Fried Beef Steaks | 189 |

| Beef Stewed in its own Gravy (good and wholesome) | 189 |

| Beef or Mutton Cake (very good) (Entrée) | 190 |

| German Stew | 190 |

| Welsh Stew | 191 |

| A good English Stew | 191 |

| To stew Shin of Beef | 192 |

| French Beef à la Mode (common receipt) | 192 |

| Stewed Sirloin of Beef | 193 |

| To stew a Rump of Beef | 194 |

| Beef Palates (Entrée) | 197 |

| Beef Palates (Neapolitan mode) | 195 |

| Stewed Ox-tails (Entrée) | 195 |

| Broiled Ox-tail (good) (Entrée) | 195 |

| To salt and pickle Beef in various ways | 196 |

| To salt and boil a round of Beef | 196 |

| Hamburgh Pickle for Beef, Hams, and Tongues | 197 |

| Another Pickle for Tongues, Beef, and Hams | 197 |

| Dutch, or Hung Beef | 197 |

| xviCollared Beef | 198 |

| Collared Beef (another receipt) | 198 |

| A common receipt for Salting Beef | 198 |

| Spiced Round of Beef (very highly flavoured) | 199 |

| Spiced Beef (good and wholesome) | 199 |

| A miniature Round of Beef | 199 |

| Beef Roll, or Canellon de Bœuf (Entrée) | 201 |

| Minced Collops au Naturel (Entrée) | 201 |

| Savoury minced Collops (Entrée) | 201 |

| A richer variety of minced Collops (Entrée) | 202 |

| Scotch minced Collops | 202 |

| Beef Tongues | 202 |

| Beef Tongues (a Suffolk receipt) | 203 |

| To dress Beef Tongues | 203 |

| Bordyke receipt for stewing a Tongue | 203 |

| To roast a Beef Heart | 204 |

| Beef Kidney | 204 |

| Beef Kidney, a plainer way | 205 |

| An excellent hash of cold Beef or Mutton | 205 |

| A common hash of cold Beef or Mutton | 205 |

| Breslaw of Beef (good) | 206 |

| Norman Hash | 206 |

| French receipt for hashed Bouilli | 206 |

| Baked minced Beef | 207 |

| Saunders | 207 |

| To boil Marrow-bones | 207 |

| Baked Marrow-bones | 208 |

| Clarified Marrow for keeping | 208 |

| Ox-cheek stuffed and baked | 208 |

| Page | |

| Different joints of Veal | 209 |

| When in season | 209 |

| To take the hair from a Calf’s Head with the skin on | 210 |

| Boiled Calf’s Head | 210 |

| Calf’s Head, the Warder’s way (an excellent receipt) | 211 |

| Prepared Calf’s Head (the Cook’s receipt) | 211 |

| Burlington Whimsey | 212 |

| Cutlets of Calf’s Head (Entrée) | 213 |

| Hashed Calf’s Head (Entrée) | 213 |

| Cheap hash of Calf’s Head | 213 |

| To dress cold Calf’s Head, or Veal, à la maître d’hôtel (English receipt). (Entrée) | 214 |

| Calf’s Head Brawn (Author’s receipt) | 215 |

| To roast a Fillet of Veal | 216 |

| Fillet of Veal, au Béchamel, with Oysters | 216 |

| Boiled Fillet of Veal | 217 |

| Roast Loin of Veal | 217 |

| Boiled Loin of Veal | 218 |

| Stewed Loin of Veal | 218 |

| Boiled Breast of Veal | 218 |

| To roast a Breast of Veal | 219 |

| To bone a Shoulder of Veal, Mutton, or Lamb | 219 |

| Stewed Shoulder of Veal (English receipt) | 219 |

| Roast Neck of Veal | 220 |

| Neck of Veal à la Créme, or au Béchamel | 220 |

| Veal Goose (City of London receipt) | 220 |

| Knuckle of Veal, en ragout | 221 |

| Boiled Knuckle of Veal | 221 |

| Knuckle of Veal, with Rice or Green Peas | 221 |

| Small Pain de Veau, or Veal Cake (Entrée) | 222 |

| Bordyke Veal Cake (good.) (Entrée) | 222 |

| Fricandeau of Veal (Entrée) | 223 |

| Spring stew of Veal (Entrée) | 224 |

| Norman Harrico | 224 |

| Plain Veal Cutlets (Entrée) | 225 |

| Veal Cutlets à l’Indienne, or Indian fashion (Entrée) | 225 |

| Veal Cutlets, or Collops, à la Française (Entrée) | 226 |

| Scotch Collops (Entrée) | 226 |

| Veal Cutlets, à la mode de Londres, or London fashion (Entrée) | 226 |

| Sweetbreads, simply stewed, fricasseed, or glazed (Entrées) | 227 |

| Sweetbread Cutlets (Entrée) | 227 |

| Stewed Calf’s Feet (cheap and good) | 228 |

| Calf’s Liver stoved or stewed | 228 |

| To roast Calf’s Liver | 229 |

| Blanquette of Veal, or Lamb, with Mushrooms (Entrée) | 229 |

| Minced Veal (Entrée) | 230 |

| Minced Veal with Oysters (Entrée) | 231 |

| Veal Sydney (good) | 231 |

| Fricasseed Veal (Entrée) | 231 |

| Small Entreés of Sweetbreads, Calf’s Brains and Ears, &c. | 232 |

| Page | |

| Different joints of Mutton | 233 |

| When in season | 233 |

| To choose Mutton | 233 |

| To roast a Haunch of Mutton | 234 |

| Roast Saddle of Mutton | 235 |

| To roast a Leg of Mutton | 235 |

| Superior receipt for roast Leg of Mutton | 235 |

| Braised Leg of Mutton | 236 |

| Leg of Mutton boned and forced | 236 |

| A boiled Leg of Mutton, with Tongue and Turnips (an excellent receipt) | 237 |

| Roast or stewed Fillet of Mutton | 238 |

| xviiTo roast a Loin of Mutton | 238 |

| To dress a Loin of Mutton like Venison | 239 |

| Roast Neck of Mutton | 239 |

| To Roast a Shoulder of Mutton | 239 |

| The Cavalier’s broil | 240 |

| Forced Shoulder of Mutton | 240 |

| Mutton Cutlets stewed in their own Gravy | 240 |

| To broil Mutton Cutlets (Entrée) | 241 |

| China Chilo | 241 |

| A good family stew of Mutton | 242 |

| An Irish stew | 242 |

| A Baked Irish stew | 243 |

| Cutlets of cold Mutton | 243 |

| Mutton Kidneys à la Française (Entrée) | 243 |

| Broiled Mutton Kidneys | 244 |

| Oxford receipt for Mutton Kidneys (Breakfast dish or Entrée) | 244 |

| To roast a Fore Quarter of Lamb | 244 |

| Saddle of Lamb | 245 |

| Roast Loin of Lamb | 245 |

| Stewed Leg of Lamb, with white Sauce (Entrée) | 245 |

| Loin of Lamb stewed in butter (Entrée) | 246 |

| Lamb or Mutton Cutlets, with Soubise Sauce (Entrée) | 246 |

| Lamb Cutlets in their own Gravy | 246 |

| Cutlets of cold Lamb | 246 |

| Page | |

| Different joints of Pork | 247 |

| When in season | 247 |

| To choose Pork | 247 |

| To melt Lard | 248 |

| To preserve unmelted Lard for many months | 248 |

| To roast a Sucking Pig | 249 |

| Baked Pig | 250 |

| Pig à la Tartare (Entrée) | 250 |

| Sucking Pig, en blanquette (Entrée) | 250 |

| To roast Pork | 251 |

| To roast a Saddle of Pork | 251 |

| To broil or fry Pork Cutlets | 251 |

| Cobbett’s receipt for curing Bacon | 252 |

| A genuine Yorkshire receipt for curing Hams and Bacon | 253 |

| Kentish mode of cutting up and curing a Pig | 254 |

| French Bacon for larding | 254 |

| To pickle Cheeks of Bacon and Hams | 257 |

| Monsieur Ude’s receipt for Hams superior to Westphalia | 255 |

| Super-excellent Bacon | 256 |

| Hams (Bordyke receipt) | 256 |

| To boil a Ham | 256 |

| To garnish and ornament Hams in various ways | 257 |

| French receipt for boiling a Ham | 258 |

| To bake a Ham | 258 |

| To boil Bacon | 259 |

| Bacon broiled or fried | 259 |

| Dressed Rashers of Bacon | 259 |

| Tonbridge Brawn | 260 |

| Italian Pork Cheese | 260 |

| Sausage-meat Cake, or Pain de Porc Frais | 261 |

| Sausages | 261 |

| Kentish Sausage-meat | 261 |

| Excellent Sausages | 262 |

| Pounded Sausage-meat (very good) | 262 |

| Boiled Sausages (Entrée) | 262 |

| Sausages and Chestnuts (an excellent dish.) (Entrée) | 262 |

| Truffled Sausages, or Saucisses aux truffles | 263 |

| Page | |

| To choose Poultry | 264 |

| To bone a Fowl or Turkey without opening it | 265 |

| Another mode of boning a Fowl or Turkey | 265 |

| To bone Fowls for Fricassees, Curries, and Pies | 266 |

| To roast a Turkey | 267 |

| To boil a Turkey Poult | 267 |

| Turkey boned and forced (an excellent dish) | 268 |

| Turkey à la Flamande, or dinde Poudrée | 270 |

| To roast a Turkey | 270 |

| To roast a Goose (and when in season) | 271 |

| To roast a green Goose | 271 |

| To roast a Fowl | 272 |

| Roast Fowl (a French receipt) | 272 |

| To roast a Guinea Fowl | 272 |

| Fowl à la Carlsfors (Entrée) | 273 |

| Boiled Fowls | 273 |

| To broil a Chicken or Fowl | 274 |

| Fricasseed Fowls or Chickens (Entrée) | 274 |

| Chicken Cutlets (Entrée) | 275 |

| Cutlets of Fowls, Partridges, or Pigeons (French receipt) (Entrée) | 275 |

| Fried Chicken, à la Malabar (Entrée) | 275 |

| Hashed Fowl (Entrée) | 276 |

| French, and other receipts for minced Fowl (Entrée) | 276 |

| Minced Fowl (French receipt) (Entrée) | 275 |

| xviiiFritot or Friteau of cold Fowls (Entrée) | 277 |

| Scallops of Fowls au Béchamel (Entrée) | 277 |

| Grillade of cold Fowls | 277 |

| Fowls à la Mayonnaise | 278 |

| To roast Ducks (and when in season) | 278 |

| Stewed Duck (Entrée) | 278 |

| To roast Pigeons (and when in season) | 279 |

| Boiled Pigeons | 279 |

| Page | |

| To choose Game | 281 |

| To roast a Haunch of Venison | 282 |

| To stew a Shoulder of Venison | 283 |

| To Hash Venison | 284 |

| To roast a Hare | 284 |

| Roast Hare (superior receipt) | 285 |

| Stewed Hare | 286 |

| To roast a Rabbit | 286 |

| To boil Rabbits | 286 |

| Fried Rabbit | 287 |

| To roast a Pheasant | 287 |

| Boudin of Pheasant, à la Richelieu (Entrée) | 288 |

| To roast Partridges | 288 |

| Boiled Partridges | 289 |

| Partridges with Mushrooms | 289 |

| Broiled Partridge (breakfast dish) | 290 |

| Broiled Partridge (French receipt) | 290 |

| The French, or Red-legged Partridge | 290 |

| To roast the Landrail or Corn-Crake | 291 |

| To roast Black Cock and Gray Hen (and when in season) | 291 |

| To roast Grouse | 292 |

| A salmi of Moorfowl, Pheasants, or Partridges (Entrée) | 292 |

| French salmi, or hash of Game (Entrée) | 292 |

| To roast Woodcocks or Snipes (and their season) | 293 |

| To roast the Pintail or Sea-Pheasant, with the season of all Wild Fowl | 294 |

| To roast Wild Ducks | 294 |

| A salmi or hash of Wild Fowl | 294 |

| Page | |

| Remarks on Curries | 296 |

| Mr. Arnott’s Currie Powder | 297 |

| Mr. Arnott’s Currie | 297 |

| A Bengal Currie | 298 |

| A dry Currie | 298 |

| A common Indian Currie | 299 |

| Selim’s Curries (Captain White’s) | 300 |

| Curried Macaroni | 300 |

| Curried Eggs | 301 |

| Curried Sweetbreads | 301 |

| Curried Oysters | 302 |

| Curried Gravy | 302 |

| Potted Meats | 303 |

| Potted Ham (an excellent receipt) | 304 |

| Potted Chicken, Partridge, or Pheasant | 305 |

| Potted Ox Tongue | 305 |

| Potted Anchovies | 306 |

| Lobster Butter (Chapter VI.) | |

| Potted Shrimps or Prawns (delicious) | 306 |

| Potted Mushrooms (see Chapter XVII.) | |

| Moulded Potted Meat or Fish, for the second course | 306 |

| Potted Hare | 307 |

| Page | |

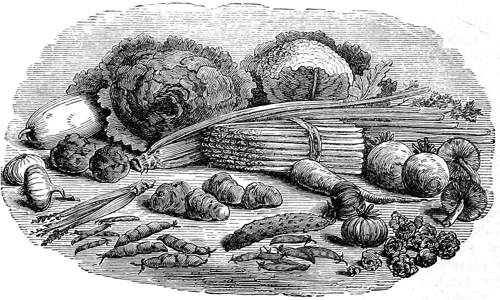

| Observations on Vegetables | 308 |

| To clear Vegetables from Insects | 309 |

| To boil Vegetables green | 309 |

| Potatoes,—remarks on their properties and importance | 309 |

| To boil Potatoes as in Ireland | 310 |

| To boil Potatoes (the Lancashire way) | 311 |

| To boil new Potatoes | 311 |

| New Potatoes in Butter | 312 |

| To boil Potatoes (Captain Kater’s receipt) | 312 |

| To roast or bake Potatoes | 312 |

| Scooped Potatoes (Entremets) | 312 |

| Crisped Potatoes, or Potato-Ribbons (Entremets), or to serve with Cheese | 313 |

| Fried Potatoes (Entremets) (plainer receipt) | 313 |

| Mashed Potatoes | 313 |

| English Potato-Balls, or Croquettes | 314 |

| Potato Boulettes (Entremets) (good) | 314 |

| Potato Rissoles (French) | 315 |

| Potatoes à la Maître d’Hôtel | 315 |

| Potatoes à la Crème | 315 |

| Kohl-Cannon, or Kale-Cannon (an Irish receipt) | 315 |

| xixTo boil Sea-Kale | 316 |

| Sea-Kale stewed in Gravy (Entremets) | 316 |

| Spinach (Entremets) (French receipt) | 316 |

| Spinach à l’Anglaise, or English fashion (Entremets) | 317 |

| Spinach (common English mode) | 317 |

| Another common English receipt for Spinach | 317 |

| To dress Dandelions like Spinach, or as a Salad (very wholesome) | 318 |

| Boiled Turnip Radishes | 318 |

| Boiled Leeks | 318 |

| Stewed Lettuces | 319 |

| To boil Asparagus | 319 |

| Asparagus points dressed like Peas (Entremets) | 319 |

| To boil Green Peas | 320 |

| Green Peas à la Française, or French fashion (Entremets) | 320 |

| Green Peas with Cream (Entremets) | 321 |

| To boil French Beans | 321 |

| French Beans à la Française (Entremets) | 321 |

| An excellent receipt for French Beans à la Française | 322 |

| To boil Windsor Beans | 322 |

| Dressed Cucumbers | 322 |

| Mandrang, or Mandram (West Indian receipt) | 323 |

| Another receipt for Mandram | 323 |

| Dressed Cucumbers (Author’s receipt) | 323 |

| Stewed Cucumbers (English mode) | 323 |

| Cucumbers à la Poulette | 324 |

| Cucumbers à la Créme | 324 |

| Fried Cucumbers, to serve in common hashes and minces | 324 |

| Melon | 325 |

| To boil Cauliflowers | 325 |

| Cauliflowers (French receipt) | 325 |

| Cauliflowers with Parmesan Cheese | 325 |

| Cauliflowers à la Française | 326 |

| Brocoli | 326 |

| To boil Artichokes | 326 |

| Artichokes en Salade (see Chapter VI.) | |

| Vegetable Marrow | 327 |

| Roast Tomatas (to serve with roast Mutton) | 327 |

| Stewed Tomatas | 327 |

| Forced Tomatas (English receipt) | 327 |

| Forced Tomatas (French receipt) | 328 |

| Purée of Tomatas | 328 |

| To boil Green Indian Corn | 329 |

| Mushrooms au Beurre | 329 |

| Potted Mushrooms | 330 |

| Mushroom-Toast, or Croule aux Champignons (excellent) | 330 |

| Truffles, and their uses | 331 |

| Truffles à la Serviette | 331 |

| Truffles à l’Italienne | 331 |

| To prepare Truffles for use | 332 |

| To boil Sprouts, Cabbages, Savoys, Lettuces, or Endive | 332 |

| Stewed Cabbage | 333 |

| To boil Turnips | 333 |

| To mash Turnips | 333 |

| Turnips in white Sauce (Entremets) | 334 |

| Turnips stewed in Butter (good) | 334 |

| Turnips in Gravy | 335 |

| To boil Carrots | 335 |

| Carrots (the Windsor receipt) (Entremets) | 335 |

| Sweet Carrots (Entremets) | 336 |

| Mashed (or Buttered) Carrots (a Dutch receipt) | 336 |

| Carrots au Beurre, or Buttered Carrots (French receipt) | 336 |

| Carrots in their own Juice (a simple but excellent receipt) | 337 |

| To boil Parsneps | 337 |

| Fried Parsneps | 337 |

| Jerusalem Artichokes | 337 |

| To fry Jerusalem Artichokes (Entremets) | 338 |

| Jerusalem Artichokes à la Reine | 338 |

| Mashed Jerusalem Artichokes | 338 |

| Haricots Blancs | 338 |

| To boil Beet-Root | 339 |

| To bake Beet-Root | 339 |

| Stewed Beet-Root | 340 |

| To stew Red Cabbage (Flemish receipt) | 340 |

| Brussels Sprouts | 340 |

| Salsify | 341 |

| Fried Salsify (Entremets) | 341 |

| Boiled Celery | 341 |

| Stewed Celery | 341 |

| Stewed Onions | 342 |

| Stewed Chestnuts | 342 |

| Page | |

| Introductory remarks | 344 |

| To glaze or ice Pastry | 345 |

| Feuilletage, or fine French Puff Paste | 345 |

| Very good light Paste | 346 |

| English Puff Paste | 346 |

| Cream Crust (very good) (Author’s receipt) | 347 |

| Pâte Brisée (or French Crust for hot or cold Meat Pies) | 347 |

| Flead Crust | 347 |

| Common Suet-Crust for Pies | 348 |

| Very superior Suet-Crust | 348 |

| Very rich short Crust for Tarts | 349 |

| Excellent short Crust for Sweet Pastry | 349 |

| Bricche Paste | 349 |

| Modern Potato Pasty, an excellent family dish | 350 |

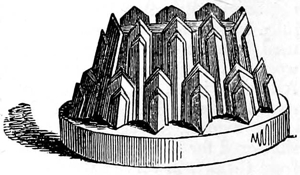

| Casserole of Rice | 351 |

| A good common English Game Pie | 352 |

| Modern Chicken Pie | 353 |

| A common Chicken Pie | 353 |

| Pigeon Pie | 354 |

| Beef-steak Pie | 354 |

| Common Mutton Pie | 355 |

| A good Mutton Pie | 355 |

| xxRaised Pies | 356 |

| A Vol-au-Vent (Entrée) | 357 |

| A Vol-au-Vent of Fruit (Entremets) | 358 |

| A Vol-au-Vent à la Créme (Entremets) | 358 |

| Oyster Patties (Entrée) | 359 |

| Common Lobster Patties | 359 |

| Superlative Lobster Patties (Author’s receipt) | 359 |

| Good Chicken Patties (Entrée) | 359 |

| Patties à la Pontife, a fast-day or maigre dish (Entrée) | 360 |

| Excellent Meat Rolls | 360 |

| Small Vols-au-Vents, or Patty-cases | 361 |

| Another receipt for Tartlets | 361 |

| A Sefton, or Veal Custard | 362 |

| Apple Cake, or German Tart | 362 |

| Tourte Meringuée, or Tart with royal icing | 363 |

| A good Apple Tart | 363 |

| Tart of very young green Apples (good) | 364 |

| Barberry Tart | 364 |

| The Lady’s Tourte, and Christmas Tourte à la Châtelaine | 364 |

| Genoises à la Reine, or her Majesty’s Pastry | 366 |

| Almond Paste | 367 |

| Tartlets of Almond Paste | 367 |

| Fairy Fancies (Fantaisies des Fées) | 368 |

| Mincemeat (Author’s receipt) | 368 |

| Superlative Mincemeat | 369 |

| Mince Pies (Entremets) | 369 |

| Mince Pies Royal (Entremets) | 370 |

| The Monitor’s Tart, or Tourte à la Judd | 370 |

| Pudding Pies (Entremets) | 371 |

| Pudding Pies (a commoner kind) | 371 |

| Cocoa-Nut cheese-cakes (Entremets) (Jamaica receipt) | 371 |

| Common Lemon Tartlets | 372 |

| Madame Werner’s Rosenvik cheese-cakes | 372 |

| Apfel Krapfen (German receipt) | 373 |

| Créme Pâtissière, or Pastry Cream | 373 |

| Small Vols-au-Vent, à la Parisienne (Entremets) | 374 |

| Pastry Sandwiches | 374 |

| Lemon Sandwiches | 374 |

| Fanchonnettes (Entremets) | 374 |

| Jelly-Tartlets, or Custards | 375 |

| Strawberry Tartlets (good) | 375 |

| Raspberry Puffs | 375 |

| Creamed Tartlets | 375 |

| Ramakins à l’Ude, or Sefton-Fancies | 375 |

| Page | |

| Soufflés | 377 |

| Louise Franks’ Citron Soufflé | 378 |

| A Fondu, or Cheese Souffle | 379 |

| Observations on Omlets, Fritters, &c. | 380 |

| A common Omlet | 380 |

| An Omlette Soufflé (second course, remove of roast) | 381 |

| Plain Common Fritters | 381 |

| Pancakes | 382 |

| Fritters of Cake and Pudding | 382 |

| Mincemeat Fritters | 383 |

| Venetian Fritters (very good) | 383 |

| Rhubarb Fritters | 383 |

| Apple, Peach, Apricot, or Orange Fritters | 384 |

| Brioche Fritters | 384 |

| Potato Fritters (Entremets) | 384 |

| Lemon Fritters (Entremets) | 384 |

| Cannelons (Entremets) | 385 |

| Cannelons of Brioche paste (Entremets) | 385 |

| Croquettes of Rice (Entremets) | 385 |

| Finer Croquettes of Rice (Entremets) | 386 |

| Savoury Croquettes of Rice (Entrée) | 386 |

| Rissoles (Entrée) | 387 |

| Very savoury Rissoles (Entrée) | 387 |

| Small fried Bread Patties, or Croustades of various kinds | 387 |

| Dresden Patties, or Croustades (very delicate) | 387 |

| To prepare Beef Marrow for frying Croustades, Savoury Toasts, &c. | 388 |

| Small Croustades, or Bread Patties, dressed in Marrow (Author’s receipt) | 388 |

| Small Croustades, à la Bonne Maman (the Grandmamma’s Patties) | 389 |

| Curried Toasts with Anchovies | 389 |

| To fillet Anchovies | 389 |

| Savoury Toasts | 390 |

| To choose Macaroni, and other Italian Pastes | 390 |

| To boil Macaroni | 391 |

| Ribbon Macaroni | 391 |

| Dressed Macaroni | 392 |

| Macaroni à la Reine | 393 |

| Semoulina and Polenta à l’Italienne (Good) (To serve instead of Macaroni) | 393 |

| Page | |

| General Directions | 395 |

| To clean Currants for Puddings or Cakes | 397 |

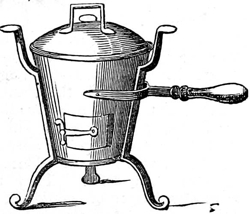

| To steam a Pudding in a common stewpan or saucepan | 397 |

| To mix Batter for Puddings | 397 |

| Suet Crust for Meat or Fruit Pudding | 398 |

| Butter Crust for Puddings | 398 |

| Savoury Puddings | 399 |

| xxiBeef-steak, or John Bull’s Pudding | 399 |

| Small Beef-steak Pudding | 400 |

| Ruth Pinch’s Beef-steak Pudding | 401 |

| Mutton Pudding | 401 |

| Partridge Pudding (very good) | 401 |

| A Peas Pudding (to serve with Boiled Pork) | 401 |

| Wine-sauce for Sweet Puddings | 402 |

| Common Wine-sauce | 402 |

| Punch-sauce for Sweet Puddings | 402 |

| Clear arrow-root-sauce (with receipt for Welcome Guest’s Pudding) | 403 |

| A German Custard Pudding-sauce | 403 |

| A delicious German Pudding-sauce | 403 |

| Red Currant or Raspberry-sauce (good) | 404 |

| Common Raspberry-sauce | 404 |

| Superior Fruit Sauces for Sweet Puddings | 404 |

| Pine-apple Pudding-sauce | 405 |

| A very fine Pine-apple Sauce or Syrup for Puddings, or other Sweet Dishes | 405 |

| German Cherry-sauce | 406 |

| Common Batter Pudding | 406 |

| Another Batter Pudding | 406 |

| Black-cap Pudding | 407 |

| Batter Fruit Pudding | 407 |

| Kentish Suet Pudding | 407 |

| Another Suet Pudding | 408 |

| Apple, Currant, Cherry, or other Fresh Fruit Pudding | 408 |

| A common Apple Pudding | 409 |

| Herodotus’ Pudding (A genuine classical receipt) | 409 |

| The Publisher’s Pudding | 410 |

| Her Majesty’s Pudding | 410 |

| Common Custard Pudding | 411 |

| Prince Albert’s Pudding | 411 |

| German Pudding and Sauce (very good) | 412 |

| The Welcome Guest’s own Pudding (light and wholesome. Author’s receipt) | 412 |

| Sir Edwin Landseer’s Pudding | 412 |

| A Cabinet Pudding | 413 |

| A very fine Cabinet Pudding | 414 |

| Snowdon Pudding (a genuine receipt) | 414 |

| Very good Raisin Puddings | 415 |

| The Elegant Economist’s Pudding | 415 |

| Pudding à la Scoones | 416 |

| Ingoldsby Christmas Puddings | 416 |

| Small and very light Plum Pudding | 416 |

| Vegetable Plum Pudding (cheap and good) | 417 |

| The Author’s Christmas Pudding | 417 |

| A Kentish Well-Pudding | 417 |

| Rolled Pudding | 418 |

| A Bread Pudding | 418 |

| A Brown Bread Pudding | 419 |

| A good boiled Rice Pudding | 419 |

| Cheap Rice Pudding | 420 |

| Rice and Gooseberry Pudding | 420 |

| Fashionable Apple Dumplings | 420 |

| Orange Snow-balls | 420 |

| Apple Snow-balls | 421 |

| Light Currant Dumplings | 421 |

| Lemon Dumplings (light and good) | 421 |

| Suffolk, or hard Dumplings | 421 |

| Norfolk Dumplings | 421 |

| Sweet boiled Patties (good) | 422 |

| Boiled Rice, to be served with stewed Fruits, Preserves, or Raspberry Vinegar | 422 |

| Page | |

| Introductory Remarks | 423 |

| A baked Plum Pudding en Moule, or Moulded | 424 |

| The Printer’s Pudding | 424 |

| Almond Pudding | 425 |

| The Young Wife’s Pudding (Author’s receipt) | 425 |

| The Good Daughter’s Mincemeat Pudding (Author’s receipt) | 426 |

| Mrs. Howitt’s Pudding (Author’s receipt) | 426 |

| An excellent Lemon Pudding | 426 |

| Lemon Suet Pudding | 427 |

| Bakewell Pudding | 427 |

| Ratifia Pudding | 427 |

| The elegant Economist’s Pudding | 428 |

| Rich Bread and Butter Pudding | 428 |

| A common Bread and Butter Pudding | 429 |

| A good baked Bread Pudding | 429 |

| Another baked Bread Pudding | 430 |

| A good Semoulina or Soujee Pudding | 430 |

| French Semoulina Pudding, or Gâteau de Semoule | 430 |

| Saxe-Gotha Pudding, or Tourte | 431 |

| Baden Baden Puddings | 431 |

| Sutherland, or Castle Puddings | 432 |

| Madeleine Puddings (to be served cold) | 432 |

| A good French Rice Pudding, or Gâteau de Riz | 433 |

| A common Rice Pudding | 433 |

| Quite cheap Rice Pudding | 434 |

| Richer Rice Pudding | 434 |

| Rich Pudding Meringué | 434 |

| Good ground Rice Pudding | 435 |

| Common ground Rice Pudding | 435 |

| Green Gooseberry Pudding | 435 |

| Potato Pudding | 436 |

| A Richer Potato Pudding | 436 |

| A good Sponge-cake Pudding | 436 |

| Cake and Custard, and various other inexpensive Puddings | 437 |

| Baked Apple Pudding, or Custard | 437 |

| Dutch Custard, or Baked Raspberry Pudding | 438 |

| Gabrielle’s Pudding, or sweet Casserole of Rice | 438 |

| Vermicelli Pudding, with apples or without, and Puddings of Soujee and Semola | 439 |

| Rice à la Vathek, or Rice Pudding à la Vathek (extremely good) | 440 |

| xxiiGood Yorkshire Pudding | 440 |

| Common Yorkshire Pudding | 441 |

| Normandy Pudding (good) | 441 |

| Common baked Raisin Pudding | 441 |

| A richer baked Raisin Pudding | 442 |

| The Poor Author’s Pudding | 442 |

| Pudding à la Paysanne (cheap and good) | 442 |

| The Curate’s Pudding | 442 |

| A light baked Batter Pudding | 443 |

| Page | |

| To preserve Eggs fresh for many weeks | 444 |

| To cook Eggs in the shell without boiling them (an admirable receipt) | 445 |

| To boil Eggs in the shell | 445 |

| To dress the Eggs of the Guinea Fowl and Bantam | 446 |

| To dress Turkeys’ Eggs | 447 |

| Forced Turkeys’ Eggs (or Swans’), an excellent entremets | 447 |

| To boil a Swan’s Egg hard | 448 |

| Swan’s Egg en Salade | 448 |

| To poach Eggs of different kinds | 449 |

| Poached Eggs with Gravy (Œufs Pochés au Jus. Entremets.) | 449 |

| Œufs au Plat | 450 |

| Milk and Cream | 450 |

| Devonshire, or Clotted Cream | 451 |

| Du Lait a Madame | 451 |

| Curds and Whey | 451 |

| Devonshire Junket | 452 |

| Page | |

| To prepare Calf’s Feet Stock | 453 |

| To clarify Calf’s Feet Stock | 454 |

| To clarify Isinglass | 454 |

| Spinach Green, for colouring Sweet Dishes, Confectionary, or Soups | 455 |

| Prepared Apple or Quince Juice | 456 |

| Cocoa-nut flavoured Milk (for Sweet Dishes, &c.) | 456 |

| Remarks upon Compotes of Fruit, or Fruit stewed in Syrup | 456 |

| Compote of Rhubarb | 457 |

| —— of Green Currants | 457 |

| —— of Green Gooseberries | 457 |

| —— of Green Apricots | 457 |

| —— of Red Currants | 457 |

| —— of Raspberries | 458 |

| —— of Kentish or Flemish Cherries | 458 |

| —— of Morella Cherries | 458 |

| —— of the green Magnum Bonum, or Mogul Plum | 458 |

| —— of Damsons | 458 |

| —— of ripe Magnum Bonums, or Mogul Plums | 458 |

| —— of the Shepherd’s and other Bullaces | 458 |

| —— of Siberian Crabs | 458 |

| —— of Peaches | 459 |

| Another receipt for stewed Peaches | 459 |

| Compote of Barberries for Dessert | 459 |

| Black Caps, par excellence (for the Second Course, or for Dessert) | 460 |

| Gâteau de Pommes | 460 |

| Gâteau of mixed Fruits (good) | 461 |

| Calf’s Feet Jelly (entremets) | 461 |

| Another receipt for Calf’s Feet Jelly | 462 |

| Modern varieties of Calf’s Feet Jelly | 463 |

| Apple Calf’s Feet Jelly | 464 |

| Orange Calf’s Feet Jelly (Author’s receipt) | 464 |

| Orange Isinglass Jelly | 465 |

| Very fine Orange Jelly (Sussex Place receipt) | 465 |

| Oranges filled with Jelly | 466 |

| Lemon Calf’s Feet Jelly | 467 |

| Constantia Jelly | 467 |

| Rhubarb Isinglass Jelly (Author’s original receipt) (good) | 468 |

| Strawberry Isinglass Jelly | 468 |

| Fancy Jellies, and Jelly in Belgrave mould | 469 |

| Queen Mab’s Pudding (an elegant summer dish) | 470 |

| Nesselróde Cream | 471 |

| Crême à la Comtesse, or the Countess’s Cream | 472 |

| An excellent Trifle | 473 |

| Swiss Cream, or Trifle (very good) | 473 |

| Tipsy Cake, or Brandy Trifle | 474 |

| Chantilly Basket filled with whipped Cream and fresh Strawberries | 474 |

| Very good Lemon Cream, made without Cream | 475 |

| Fruit Creams, and Italian Creams | 475 |

| Very superior whipped Syllabubs | 476 |

| Good common Blanc-mange, or Blanc Manger (Author’s receipt) | 476 |

| Richer Blanc-mange | 477 |

| Jaumange, or Jaune Manger; sometimes called Dutch Flummery | 477 |

| Extremely good Strawberry Blanc-mange, or Bavarian Cream | 477 |

| Quince Blanc-mange (delicious) | 478 |

| Quince Blanc-mange, with Almond Cream | 478 |

| Apricot Blanc-mange, or Crême Parisienne | 479 |

| xxiiiCurrant Blanc-mange | 479 |

| Lemon Sponge, or Moulded Lemon Cream | 480 |

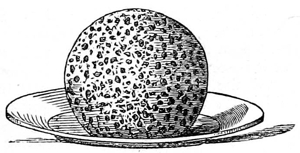

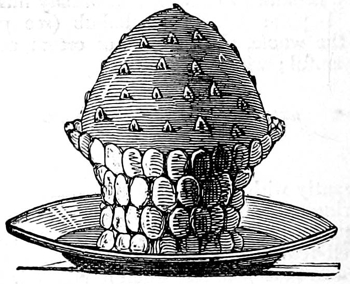

| An Apple Hedgehog, or Suédoise | 480 |

| Imperial Gooseberry-fool | 480 |

| Very good old-fashioned boiled Custard | 481 |

| Rich boiled Custard | 481 |

| The Queen’s Custard | 481 |

| Currant Custard | 482 |

| Quince or Apple Custards | 482 |

| The Duke’s Custard | 482 |

| Chocolate Custards | 483 |

| Common baked Custard | 483 |

| A finer baked Custard | 483 |

| French Custards or Creams | 484 |

| German Puffs | 484 |

| A Meringue of Rhubarb, or green Gooseberries | 485 |

| Creamed Spring Fruit, or Rhubarb Trifle | 486 |

| Meringue of Pears, or other fruit | 486 |

| An Apple Charlotte, or Charlotte de Pommes | 486 |

| Marmalade for the Charlotte | 487 |

| A Charlotte à la Parisienne | 486 |

| A Gertrude à la Créme | 486 |

| Pommes au Beurre (Buttered Apples) (excellent) | 488 |

| Suédoise of Peaches | 488 |

| Aroce Doce, or Sweet Rice à la Portugaise | 489 |

| Cocoa Nut Doce | 490 |

| Buttered Cherries (Cerises au Beurre) | 490 |

| Sweet Macaroni | 490 |

| Bermuda Witches | 491 |

| Nesselróde Pudding | 491 |

| Stewed Figs (a very nice Compote) | 492 |

| Page | |

| General Remarks on the use and value of Preserved Fruits | 493 |

| A few General Rules and Directions for Preserving | 496 |

| To Extract the Juice of Plums for Jelly | 497 |

| To weigh the Juice of Fruit | 498 |

| Rhubarb Jam | 498 |

| Green Gooseberry Jelly | 498 |

| Green Gooseberry Jam (firm and of good colour) | 499 |

| To dry green Gooseberries | 499 |

| Green Gooseberries for Tarts | 499 |

| Red Gooseberry Jam | 500 |

| Very fine Gooseberry Jam | 500 |

| Jelly of ripe Gooseberries (excellent) | 500 |

| Unmixed Gooseberry Jelly | 501 |

| Gooseberry Paste | 501 |

| To dry ripe Gooseberries with Sugar | 501 |

| Jam of Kentish or Flemish Cherries | 502 |

| To dry Cherries with Sugar (a quick and easy method) | 502 |

| Dried Cherries (superior receipt) | 503 |

| Cherries dried without Sugar | 503 |

| To dry Morella Cherries | 504 |

| Common Cherry Cheese | 504 |

| Cherry Paste (French) | 504 |

| Strawberry Jam | 504 |

| Strawberry Jelly, a very superior Preserve (new receipt) | 505 |

| Another very fine Strawberry Jelly | 505 |

| To preserve Strawberries or Raspberries, for Creams or Ices, without boiling | 506 |

| Raspberry Jam | 506 |

| Very rich Raspberry Jam, or Marmalade | 506 |

| Good Red or White Raspberry Jam | 507 |

| Raspberry Jelly for flavouring Creams | 507 |

| Another Raspberry Jelly (very good) | 508 |

| Red Currant Jelly | 508 |

| Superlative Red Currant Jelly (Norman receipt) | 509 |

| French Currant Jelly | 509 |

| Delicious Red Currant Jam | 509 |

| Very fine White Currant Jelly | 510 |

| White Currant Jam, a beautiful Preserve | 510 |

| Currant Paste | 510 |

| Fine Black Currant Jelly | 511 |

| Common Black Currant Jelly | 511 |

| Black Currant Jam and Marmalade | 511 |

| Nursery Preserve | 512 |

| Another good common Preserve | 512 |

| A good Mélange, or mixed Preserve | 513 |

| Groseillée, (another good Preserve) | 513 |

| Superior Pine-apple Marmalade (a new receipt) | 513 |

| A fine Preserve of the green Orange Plum (sometimes called the Stonewood Plum) | 514 |

| Greengage Jam, or Marmalade | 515 |

| Preserve of the Magnum Bonum, or Mogul Plum | 515 |

| To dry or preserve Mogul Plums in syrup | 515 |

| Mussel Plum Cheese and Jelly | 516 |

| Apricot Marmalade | 516 |

| To dry Apricots (a quick and easy method) | 517 |

| Dried Apricots (French receipt) | 517 |

| Peach Jam, or Marmalade | 518 |

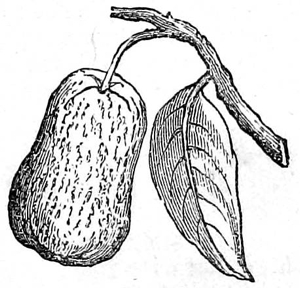

| To preserve or to dry Peaches or Nectarines (an easy and excellent receipt) | 518 |

| Damson Jam (very good) | 519 |

| Damson Jelly | 519 |

| Damson or Red Plum Solid (good) | 519 |

| Excellent Damson Cheese | 520 |

| Red Grape Jelly | 520 |

| English Guava (a firm, clear, bright Jelly) | 520 |

| Very fine Imperatrice Plum Marmalade | 521 |

| To dry Imperatrice Plums (an easy method) | 521 |

| To bottle Fruit for winter use | 522 |

| Apple Jelly | 522 |

| Exceedingly fine Apple Jelly | 523 |

| Quince Jelly | 524 |

| Quince Marmalade | 523 |

| xxivQuince and Apple Marmalade | 525 |

| Quince Paste | 525 |

| Jelly of Siberian Crabs | 526 |

| To preserve Barberries in bunches | 526 |

| Barberry Jam (First and best receipt) | 506 |

| Barberry Jam (second receipt) | 527 |

| Superior Barberry Jelly, and Marmalade | 527 |

| Orange Marmalade (a Portuguese receipt) | 527 |

| Genuine Scotch Marmalade | 528 |

| Clear Orange Marmalade (Author’s receipt) | 529 |

| Fine Jelly of Seville Oranges (Author’s original receipt) | 530 |

| Page | |

| Observations on Pickles | 531 |

| To pickle Cherries | 532 |

| To pickle Gherkins | 532 |

| To pickle Gherkins (a French receipt) | 533 |

| To pickle Peaches, and Peach Mangoes | 534 |

| Sweet Pickle of Lemon (Foreign receipt) (to serve with roast meat) | 534 |

| To pickle Mushrooms | 535 |

| Mushrooms in brine, for winter use (very good) | 536 |

| To pickle Walnuts | 536 |

| To pickle Beet-Root | 537 |

| Pickled Eschalots (Author’s receipt) | 537 |

| Pickled Onions | 537 |

| To pickle Lemons and Limes (excellent) | 538 |

| Lemon Mangoes (Author’s original receipt) | 538 |

| To pickle Nasturtiums | 539 |

| To pickle red Cabbage | 539 |

| Page | |

| General Remarks on Cakes | 540 |

| To blanch and to pound Almonds | 542 |

| To reduce Almonds to a Paste (the quickest and easiest way) | 542 |

| To colour Almonds or Sugar-grains, or Sugar-candy, for Cakes or Pastry | 542 |

| To prepare Butter for rich Cakes | 543 |

| To whisk Eggs for light rich Cakes | 543 |

| Sugar Glazings and Icings, for fine Cakes and Pastry | 543 |

| Orange-Flower Macaroons (delicious) | 544 |

| Almond Macaroons | 544 |

| Very fine Cocoa-nut Macaroons | 545 |

| Imperials (not very rich) | 545 |

| Fine Almond Cake | 545 |

| Plain Pound or Currant Cake (or rich Brawn Brack or Borrow Brack) | 546 |

| Rice Cake | 546 |

| White Cake | 546 |

| A good Sponge Cake | 547 |

| A smaller Sponge Cake (very good) | 547 |

| Fine Venetian Cake or Cakes | 547 |

| A good Madeira Cake | 548 |

| A Solimemne (a rich French breakfast cake, or Sally Lunn) | 549 |

| Banbury Cakes | 549 |

| Meringues | 550 |

| Italian Meringues | 551 |

| Thick, light Gingerbread | 551 |

| Acton Gingerbread | 552 |

| Cheap and very good Ginger Oven-cake or Cakes | 552 |

| Good common Gingerbread | 553 |

| Richer Gingerbread | 553 |

| Cocoa-nut Gingerbread (original receipts) | 553 |

| Delicious Cream Cake and Sweet Rusks | 554 |

| A good light Luncheon-cake and Brawn Brack | 554 |

| A very cheap Luncheon-biscuit, or Nursery-cake | 555 |

| Isle of Wight Dough-nuts | 556 |

| Queen Cakes | 556 |

| Jumbles | 556 |

| A good Soda Cake | 556 |

| Good Scottish Short-bread | 557 |

| A Galette | 557 |

| Small Sugar Cakes of various kinds | 558 |

| Fleed, or Flead Cakes | 558 |

| Light Buns of different kinds | 559 |

| Exeter Buns | 559 |

| Threadneedle-street Biscuits | 560 |

| Plain Dessert Biscuits and Ginger Biscuits | 560 |

| Good Captain’s Biscuits | 560 |

| The Colonel’s Biscuits | 561 |

| Aunt Charlotte’s Biscuits | 561 |

| Excellent Soda Buns | 561 |

| Page | |

| To clarify Sugar | 562 |

| To boil Sugar from Syrup to Candy, or to Caramel | 563 |

| Caramel (the quickest way) | 563 |

| Barley-sugar | 564 |

| Nougat | 564 |

| Ginger-candy | 565 |

| Orange-flower Candy | 565 |

| Orange-flower Candy (another receipt) | 566 |

| Cocoa-nut Candy | 566 |

| Everton Toffee | 567 |

| Chocolate Drops | 567 |

| Chocolate Almonds | 568 |

| Seville Orange Paste | 568 |

| Page | |

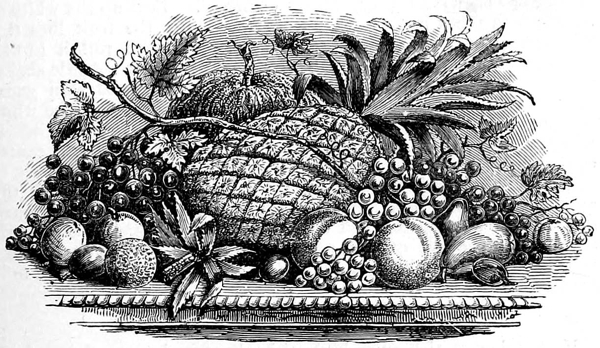

| Dessert Dishes | 569 |

| Pearled Fruit, or Fruit en Chemise | 570 |

| Salad of mixed Summer Fruits | 570 |

| Peach Salad | 570 |

| Orange Salad | 571 |

| Tangerine Oranges | 571 |

| Peaches in Brandy (Rotterdam receipt) | 571 |

| Brandied Morella Cherries | 571 |

| Baked Compôte of Apples (our little lady’s receipt) | 572 |

| Dried Norfolk Biffins | 572 |

| Normandy Pippins | 572 |

| Stewed Pruneaux de Tours, or Tours dried Plums | 573 |

| To bake Pears | 573 |

| Stewed Pears | 573 |

| Boiled Chestnuts | 574 |

| Roasted Chestnuts | 574 |

| Almond Shamrocks (very good and very pretty) | 574 |

| Small Sugar Soufflés | 575 |

| Ices | 575 |

| Page | |

| Strawberry Vinegar, of delicious flavour | 577 |

| Very fine Raspberry Vinegar | 578 |

| Fine Currant Syrup, or Sirop de Groseilles | 579 |

| Cherry Brandy (Tappington Everard receipt) | 579 |

| Oxford Punch | 580 |

| Oxford receipt for Bishop | 580 |

| Cambridge Milk Punch | 581 |

| To mull Wine (an excellent French receipt) | 581 |

| A Birthday Syllabub | 581 |

| An admirable cool cup | 582 |

| The Regent’s, or George the Fourth’s Punch | 582 |

| Mint Julep (an American receipt) | 582 |

| Delicious Milk Lemonade | 583 |

| Excellent portable Lemonade | 583 |

| Excellent Barley Water (Poor Xury’s receipt) | 583 |

| Raisin Wine, which, if long kept, really resembles foreign | 583 |

| Very good Elderberry Wine | 584 |

| Very Good Ginger Wine | 584 |

| Excellent Orange Wine | 585 |

| The Counsellor’s Cup | 585 |

| Page | |

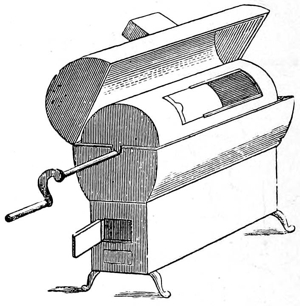

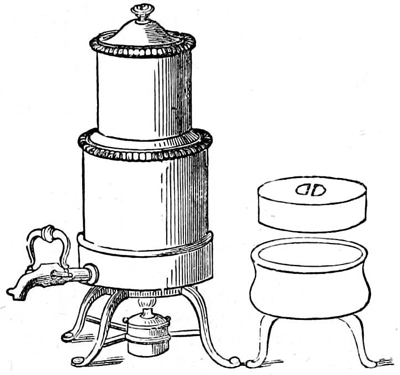

| Coffee | 587 |

| To roast Coffee | 588 |

| A few general directions for making Coffee | 589 |

| Excellent Breakfast Coffee | 590 |

| To boil Coffee | 591 |

| Café Noir | 592 |

| Burnt Coffee, or Coffee à la militaire (In France vulgarly called Gloria) | 592 |

| To make Chocolate | 592 |

| A Spanish recipe for making and serving Chocolate | 592 |

| To make Cocoa | 593 |

| Page | |

| Remarks on Home-made Bread | 594 |

| To purify Yeast for Bread or Cakes | 595 |

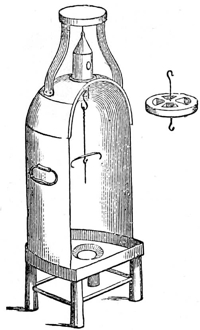

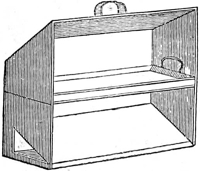

| The Oven | 595 |

| A few rules to be observed in making Bread | 596 |

| Household Bread | 596 |

| Bordyke Bread (Author’s receipt) | 597 |

| German Yeast (and Bread made with German Yeast) | 598 |

| Professor Liebig’s Bavarian Brown Bread (very nutritious and wholesome) | 599 |

| English Brown Bread | 599 |

| Unfermented Bread | 599 |

| Potato Bread | 600 |

| Dinner or Breakfast Rolls | 600 |

| Geneva Rolls or Buns | 601 |

| Rusks | 602 |

| Excellent Dairy Bread, made without Yeast (Author’s receipt) | 602 |

| To keep Bread | 603 |

| To freshen stale Bread (and Pastry, &c.) and preserve it from mould | 603 |

| To know when Bread is sufficiently baked | 604 |

| On the proper fermentation of Dough | 604 |

| Page | |

| Foreign and Jewish Cookery | 605 |

| Remarks on Jewish Cookery | 606 |

| Jewish Smoked Beef | 606 |

| Chorissa (or Jewish Sausage) with Rice | 607 |

| To fry Salmon and other Fish in Oil (to serve cold) | 607 |

| Jewish Almond Pudding | 608 |

| The Lady’s or Invalid’s new Baked Apple Pudding (Author’s original receipt. Appropriate to the Jewish table) | 608 |

| A few general directions for the Jewish table | 609 |

| Tomata and other Chatnies (Mauritian receipt) | 609 |

| Indian Lobster Cutlets | 610 |

| An Indian Burdwan (Entrée) | 611 |

| The King of Oude’s Omlet | 611 |

| Kedgeree or Kidgeree, an Indian breakfast-dish | 612 |

| A simple Syrian Pilaw | 612 |

| Simple Turkish or Arabian Pilaw (From Mr. Lane, the Oriental traveller) | 613 |

| A real Indian Pilaw | 613 |

| Indian receipt for Curried Fish | 614 |

| Bengal Currie Powder, No. 1 | 614 |

| Risotto à la Mayonnaise | 615 |

| Stufato (a Neapolitan receipt) | 615 |

| Broiled Eels with sage (Entrée) (German receipt. Good) | 616 |

| A Swiss Mayonnaise | 615 |

| Tendrons de Veau | 617 |

| Poitrine de Veau Glacée (Breast of Veal stewed and glazed) | 618 |

| Breast of Veal simply stewed | 618 |

| Compote de Pigeons (Stewed Pigeons) | 619 |

| Mai Trank (May Drink) (German) | 620 |

| A Viennese Soufflé Pudding, called Salzburger Nockerl | 620 |

| Page | |

| Remarks on Trussing | xxxiii |

| General Directions for Trussing | xxxiii |

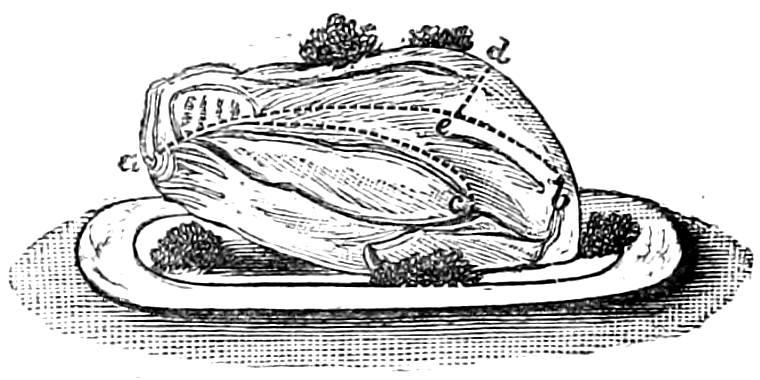

| To truss a Turkey, Fowl, Pheasant, or Partridge, for roasting | xxxiv |

| To truss Fish | xxxv |

| Page | |

| Remarks on Carving | xxxvii |

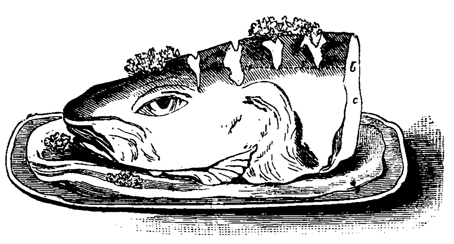

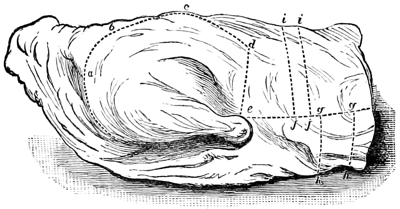

| No. 1. Cod’s head and shoulder (and Cod fish generally) | xxxviii |

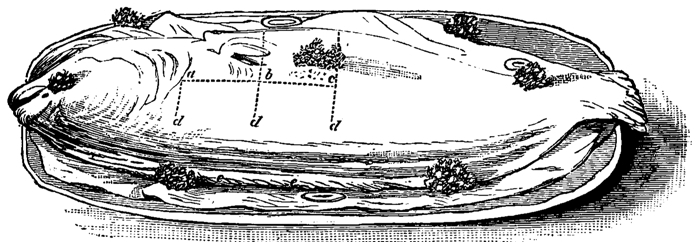

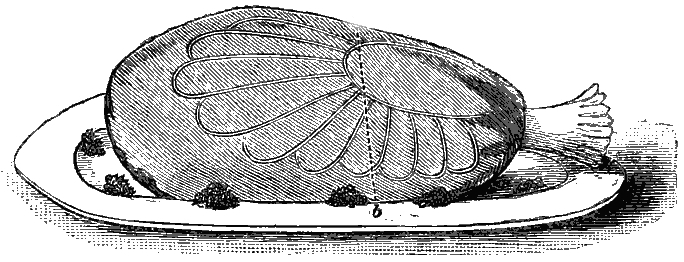

| No. 2. A Turbot | xxxviii |

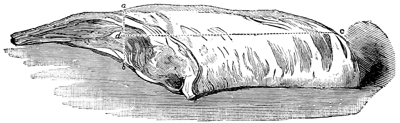

| No. 2a. Soles | xxxviii |

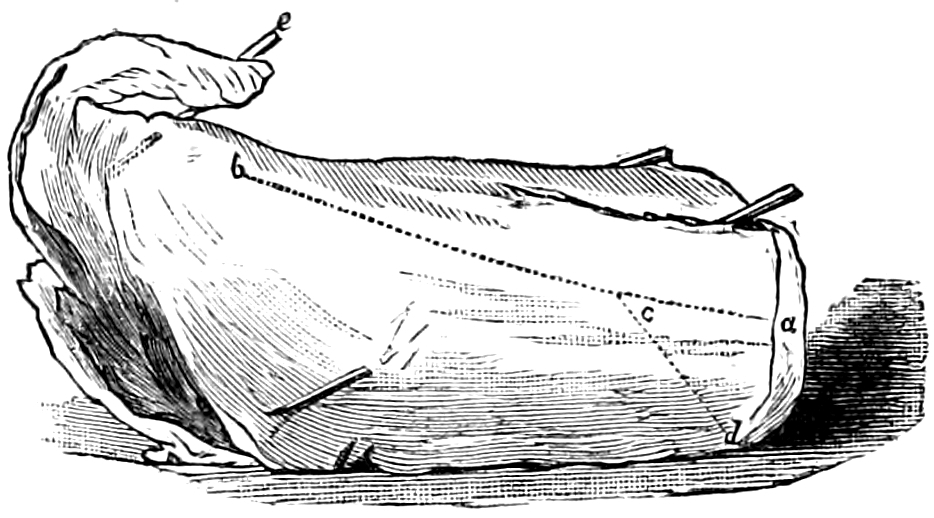

| No. 3. Salmon | xxxviii |

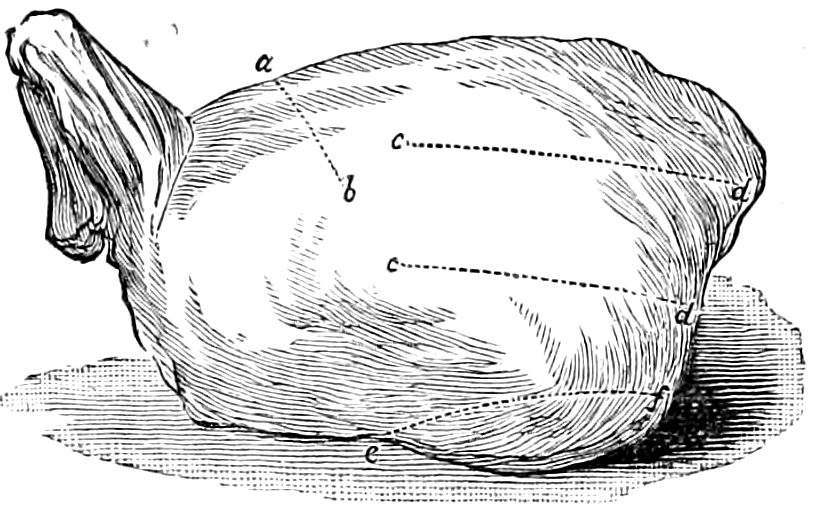

| No. 4. Saddle of Mutton | xxxviii |

| No. 5. A Haunch of Venison (or Mutton) | xxxix |

| No. 6. Sirloin or Rump of Beef | xxxix |

| No. 6a. Ribs of Beef | xxxix |

| No. 6b. A round of Beef | xxxix |

| No. 6c. A brisket of Beef | xl |

| No. 7. Leg of Mutton | xl |

| No. 8. Quarter of Lamb | xl |

| No. 9. Shoulder of Mutton or Lamb | xl |

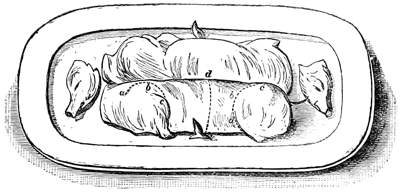

| No. 10. A Sucking Pig | xl |

| No. 10a. A fillet of Veal | xli |

| No. 10b. A loin of Veal | xli |

| No. 11. A breast of Veal | xli |

| No. 12. A tongue | xli |

| No. 13. A calf’s head | xli |

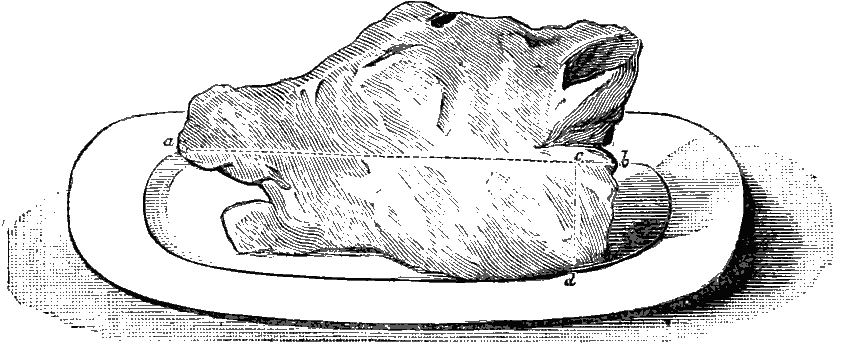

| No. 14. A ham | xlii |

| No. 15. A pheasant | xlii |

| No. 16. A boiled fowl | xliii |

| No. 17. A roast fowl | xliv |

| No. 18. A partridge | xliv |

| No. 19. A woodcock | xlv |

| No. 20. A pigeon | xlv |

| No. 21. A snipe | xlv |

| No. 22. A goose | xlv |

| Ducks | xlvi |

| No. 23. A wild duck | xlvi |

| No. 24. A turkey | xlvi |

| No. 25. A hare | xlvii |

| No. 26. A fricandeau of veal | xlvii |

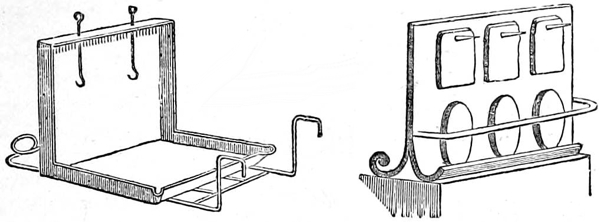

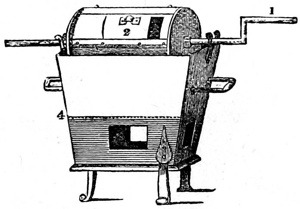

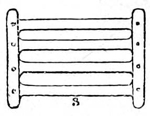

Trussing Needles.

Common and untrained cooks are often deplorably ignorant of this branch of their business, a knowledge of which is, nevertheless, quite as essential to them as is that of boiling or roasting; for without it they cannot, by any possibility, serve up dinners of decently creditable appearance. We give such brief general directions for it as our space will permit, and as our own observations enable us to supply; but it has been truly said, by a great authority in these matters, that trussing cannot be “taught by words;” we would, therefore, recommend, that instead of relying on any written instructions, persons who really desire thoroughly to understand the subject, and to make themselves acquainted with the mode of entirely preparing all varieties of game and poultry more especially for table, in the very best manner, should apply for some practical lessons to a first-rate poulterer; or, if this cannot be done, that they should endeavour to obtain from some well experienced and skilful cook the instruction which they need.

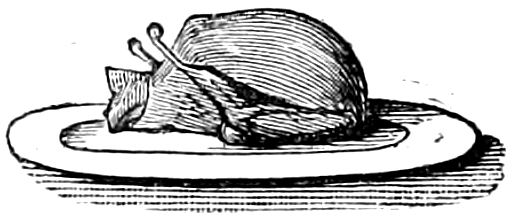

Before a bird is trussed, the skin must be entirely freed from any down which may be on it, and from all the stubble-ends of the feathers;[3] the hair also must be singed from it with lighted writing paper, care being taken not to smoke nor blacken it in the operation. Directions for cleansing the insides of birds after they are drawn, are given in the receipts for dressing them, Chapters XIV. and XV. Turkeys, geese, ducks, wild or tame, fowls, and pigeons, should all have the necks taken off close to the bodies, but not the skin of the necks, which should be left sufficiently long to turn down upon the backs for a couple of inches or more, where it must be secured, either with a needle and coarse soft cotton, or by the pinions of the birds when trussed.

3. This should be particularly attended to.

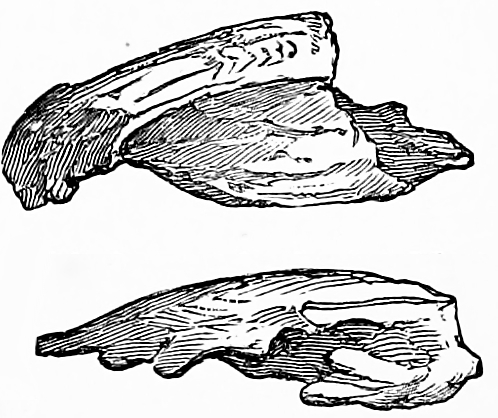

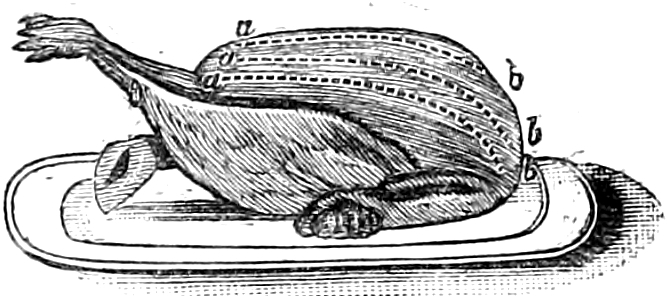

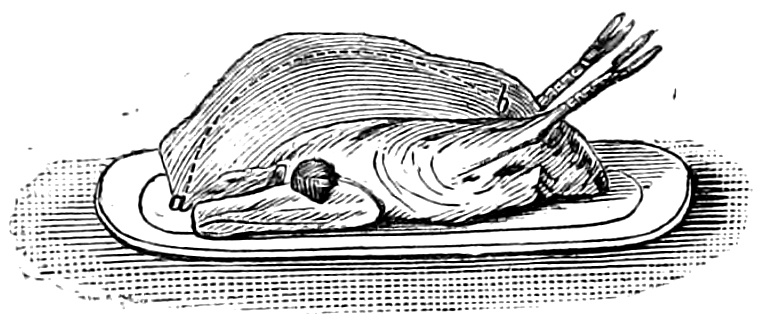

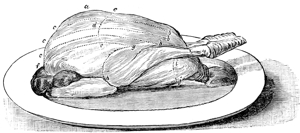

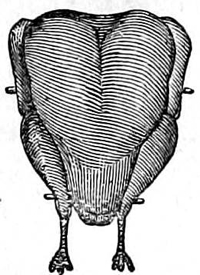

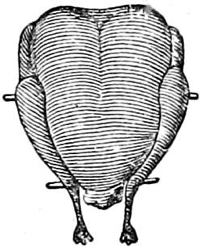

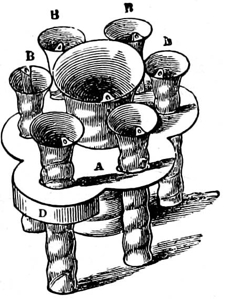

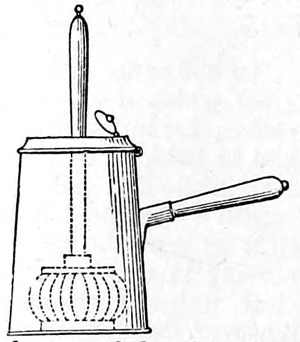

For boiling, all poultry or other birds must have the feet drawn off at the first joint of the leg, or as shown in the engraving. (In the latter case, the sinews of the joint must be slightly cut, when the bone may be easily turned back as here.) The skin must then be loosened with the finger entirely from the legs, which must be pushed back into the body, and the small ends tucked quite under the apron, so as to be entirely out of sight.

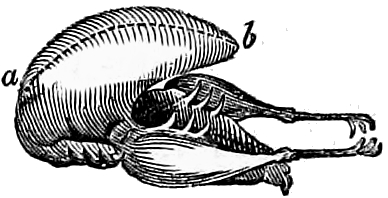

The wings of chickens, fowls, turkeys, and pigeons, are left on entire, whether for roasting or boiling. From geese, ducks, pheasants, partridges, black game, moor-fowl, woodcocks, snipes, wild-fowl of all kinds, and all small birds, the first two joints are taken off, leaving but one joint on, thus:—