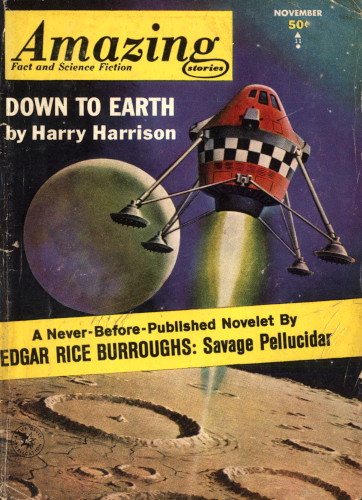

HARRY HARRISON

Illustrated by LUTJENS

Whatever goes up must come down.

Including moon rockets. But there's no

law saying what they must come down to.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Amazing Stories November 1963.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

"Gino ... Gino ... help me! For God's sake, do something!"

The tiny voice scratched in Gino Lombardi's earphone, weak against the background roar of solar interference. Gino lay flat in the lunar dust, half buried by the pumice-fine stuff, reaching far down into the cleft in the rock. Through the thick fabric of his suit he felt the edge crumbling and pulled hastily back. The dust and pieces of rock fell instantly, pulled down by the light lunar gravity and unimpeded by any trace of air. A fine mist of dust settled on Glazer's helmet below, partially obscuring his tortured face.

"Help me, Gino—get me out of here," he said, stretching his arm up over his head.

"No good—" Gino answered, putting as much of his weight onto the crumbling lip of rock as he dared, reaching far down. His hand was still a good yard short of the other's groping glove. "I can't reach you—and I've got nothing here I can let down for you to grab. I'm going back to the Bug."

"Don't leave ..." Glazer called, but his voice was cut off as Gino slid back from the crevice and scrambled to his feet. Their tiny helmet radios did not have enough power to send a signal through the rock; they were good only for line-of-sight communication.

Gino ran as fast as he could, long gliding jumps one after the other back towards the Bug. It did look more like a bug here, a red beetle squatting on the lunar landscape, its four spidery support legs sunk into the dust. He cursed under his breath as he ran: what a hell of an ending for the first moon flight! A good blast off and a perfect orbit, the first two stages had dropped on time, the lunar orbit was right, the landing had been right—and ten minutes after they had walked out of the Bug Glazer had to fall into this crevice hidden under the powdery dust. To come all this way—through all the multiple hazards of space—then to fall into a hole.... There was just no justice.

At the base of the ship Gino flexed his legs and bounded high up towards the top section of the Bug, grabbing onto the bottom of the still open door of the cabin. He had planned his moves while he ran—the magnetometer would be his best bet. Pulling it from the rack he yanked at its long cable until it came free in his hand, then turned back without wasting a second. It was a long leap back to the surface—in Earth gravitational terms—but he ignored the apparent danger and jumped, sinking knee deep in the dust when he landed. The row of scuffled tracks stretched out towards the slash of the lunar crevice and he ran all the way, chest heaving in spite of the pure oxygen he was breathing. Throwing himself flat he skidded and wriggled like a snake, back to the crumbling lip.

"Get ready, Glazer," he shouted, his head ringing inside the helmet with the captive sound of his own voice. "Grab the cable...."

The crevice was empty. More of the soft rock had crumbled away and Glazer had fallen from sight.

For a long time Major Gino Lombardi lay there, flashing his light into the seemingly bottomless slash in the satellite's surface, calling on his radio with the power turned full on. His only answer was static, and gradually he became aware of the cold from the eternally chilled rocks that was seeping through the insulation of his suit. Glazer was gone, that was all there was to it.

After this Gino did everything that he was supposed to do in a methodical, disinterested way. He took rock samples, dust samples, meter readings, placed the recording instruments exactly as he had been shown and fired the test shot in the drilled hole. Then he gathered the records from the instruments and when the next orbit of the Apollo spacecraft brought it overhead he turned on the cabin transmitter and sent up a call.

"Come in Dan.... Colonel Danton Coye, can you hear me...?"

"Loud and clear," the speaker crackled. "Tell me you guys, how does it feel to be walking on the moon?"

"Glazer is dead. I'm alone. I have all the data and photographs required. Permission requested to cut this stay shorter than planned. No need for a whole day down here."

For long seconds there was a crackling silence, then Dan's voice came in, the same controlled, Texas drawl.

"Roger, Gino—stand by for computer signal, I think we can meet in the next orbit."

The moon takeoff went as smoothly as the rehearsals had gone in the mock-up on Earth, and Gino was too busy doing double duty to have time to think about what had happened. He was strapped in when the computer radio signal fired the engines that burned down into the lower portion of the Bug and lifted the upper half free, blasting it up towards the rendezvous in space with the orbiting mother ship. The joined sections of the Apollo came into sight and Gino realized he would pass in front of it, going too fast: he made the course corrections with a sensation of deepest depression. The computer had not allowed for the reduced mass of the lunar rocket with only one passenger aboard. After this, matching orbits was not too difficult and minutes later Gino was crawling through the entrance of the command module and sealing it behind him. Dan Coye stayed at the controls, not saying anything until the cabin pressure had stabilized and they could remove their helmets.

"What happened down there, Gino?"

"An accident—a crack in the lunar surface, covered lightly, sealed over by dust. Glazer just ... fell into the thing. That's all. I tried to get him out, I couldn't reach him. I went to the Bug for some wire, but when I came back he had fallen deeper ... it was...."

Gino had his face buried in his hands, and even he didn't know if he was sobbing or just shaking with fatigue and strain.

"I'll tell you a secret, I'm not superstitious at all," Dan said, reaching deep into a zippered pocket of his pressure suit. "Everybody thinks I am, which just goes to show you how wrong everybody can be. Now I got this mascot, because all pilots are supposed to have mascots, and it makes good copy for the reporters when things are dull." He pulled the little black rubber doll from his pocket, made famous on millions of TV screens, and waved it at Gino. "Everybody knows I always tote my little good-luck mascot with me, but nobody knows just what kind of good luck it has. Now you will find out, Major Gino Lombardi, and be privileged to share my luck. In the first place this bitty doll is not rubber, which might have a deleterious effect on the contents, but is constructed of a neutral plastic."

In spite of himself, Gino looked up as Dan grabbed the doll's head and screwed it back.

"Notice the wrist motion as I decapitate my friend, within whose bosom rests the best luck in the world, the kind that can only be brought to you by sour mash one-hundred and fifty proof bourbon. Have a slug." He reached across and handed the doll to Gino.

"Thanks, Dan." He raised the thing and squeezed, swallowing twice. He handed it back.

"Here's to a good pilot and a good joe, Eddie Glazer," Dan Coye said raising the flask, suddenly serious. "He wanted to get to the moon and he did. It belongs to him now, all of it, by right of occupation." He squeezed the doll dry and methodically screwed the head back on and replaced it in his pocket. "Now let's see what we can do about contacting control, putting them in the picture, and start cutting an orbit back towards Earth."

Gino turned the radio on but did not send out the call yet. While they had talked their orbit had carried them around to the other side of the moon and its bulk successfully blocked any radio communication with Earth. They hurtled their measured arc through the darkness and watched another sunrise over the sharp lunar peaks: then the great globe of the Earth swung into sight again. North America was clearly visible and there was no need to use repeater stations. Gino beamed the signal at Cape Canaveral and waited the two and a half seconds for his signal to be received and for the answer to come back the 480,000 miles from Earth. The seconds stretched on and on, and with a growing feeling of fear he watched the hand track slowly around the clock face.

"They don't answer...."

"Interference, sunspots ... try them again," Dan said in a suddenly strained voice.

The control at Canaveral did not answer the next message, nor was there any response when they tried the emergency frequencies. They picked up some aircraft chatter on the higher frequencies, but no one noticed them or paid any attention to their repeated calls. They looked at the blue sphere of Earth, with horror now, and only after an hour of sweating strain would they admit that, for some unimaginable reason, they were cut off from all radio contact with it.

"Whatever happened, happened during our last orbit around the moon. I was in contact with them while you were matching orbits," Dan said, tapping the dial of the ammeter on the radio. "There couldn't be anything wrong...?"

"Not at this end," Gino said grimly. "But something has happened down there."

"Could it be ... a war?"

"It might be. But with whom and why? There's nothing unusual on the emergency frequencies and I don't think...."

"Look!" Dan shouted hoarsely, "The lights—where are the lights?"

In their last orbit the twinkling lights of the American cities had been seen clearly through their telescope. The entire continent was now black.

"Wait, see South America—the cities are lit up there, Gino. What could possibly have happened at home while we were in that orbit?"

"There's only one way to find out. We're going back. With or without any help from ground control."

They disconnected the lunar Bug and strapped into their acceleration couches in the command module while they fed data to the computer. Following its instructions they jockeyed the Apollo into the correct attitude for firing. Once more they orbited the airless satellite and at the correct instant the computer triggered the engines in the attached service module. They were heading home.

With all the negative factors taken into consideration, it was not that bad a landing. They hit the right continent and were only a few degrees off in latitude, though they entered the atmosphere earlier than they liked. Without ground control of any kind it was an almost miraculously good landing.

As the capsule screamed down through the thickening air its immense velocity was slowed and the airspeed began to indicate a reasonable figure. Far below, the ground was visible through rents in the cloud cover.

"Late afternoon," Gino said. "It will be dark soon after we hit the ground."

"At least it will still be light. We could have been landing in Peking at midnight, so let's hear no complaints. Stand by to let go the parachutes."

The capsule jumped twice as the immense chutes boomed open. They opened their face-plates, safely back in the sea of air once more.

"Wonder what kind of reception we'll get?" Dan asked, rubbing the bristle on his big jaw.

With the sharp crack of split metal a row of holes appeared in the upper quadrant of the capsule: air whistled in, equalizing their lower pressure.

"Look!" Gino shouted, pointing at the dark shape that hurtled by outside. It was egg-shaped and stub-winged, black against the afternoon sun. Then it twisted over in a climbing turn and for a long moment its silver skin was visible to them as it arched over and came diving down. Back it came, growing instantly larger, red flames twinkling in its wing roots.

Grey haze cut off the sunlight as they fell into a cloud. Both men looked at each other: neither wanted to speak first.

"A jet," Gino finally said. "I never saw that type before."

"Neither did I—but there was something familiar—Look, you saw the wings didn't you? You saw...?"

"If you mean did I see black crosses on the wings, yes I did, but I'm not going to admit it! Or I wouldn't if it wasn't for those new air-conditioning outlets that were just installed in our hull. Do you have any idea what it means?"

"None. But I don't think we'll be too long finding out. Get ready for the landing—just two thousand feet to go."

The jet did not reappear. They tightened their safety harness and braced themselves for the impact. It was a bumping crash and the capsule tilted up on its side, jarring them with vibration.

"Parachute jettisons," Dan Coye ordered, "We're being dragged."

Gino had hit the triggers even as Dan spoke. The lurching stopped and the capsule slowly righted itself.

"Fresh air," Dan said and blew the charges on the port. It sprang away and thudded to the ground. As they disconnected the multiple wires and clasps of their suits hot, dry air poured in through the opening, bringing with it the dusty odor of the desert.

Dan raised his head and sniffed. "Smells like home. Let's get out of this tin box."

Colonel Danton Coye went first, as befitted the commander of the First American Earth-Moon Expedition. Major Gino Lombardi followed. They stood side by side silently, with the late afternoon sun glinting on their silver suits. Around them, to the limits of vision, stretched the thin tangle of greyish desert shrub, mesquite, cactus. Nothing broke the silence nor was there any motion other than that caused by the breeze that was carrying away the cloud of dust stirred up by their landing.

"Smells good, smells like Texas," Dan said, sniffing.

"Smells awful, just makes me thirsty. But ... Dan ... what happened? First the radio contact, then that jet...."

"Look, our answer is coming from over there," the big officer said, pointing at a moving column of dust rolling in from the horizon. "No point in guessing, because we are going to find out in five minutes."

It was less than that. A large, sand-colored half-track roared up, followed by two armored cars. They braked to a halt in the immense cloud of their own dust. The half-track's door slammed open and a goggled man climbed down, brushing dirt from his tight black uniform.

"Hande hoch!" he ordered, waving their attention to the leveled guns on the armored cars. "Hands up and keep them that way. You are my prisoners."

They slowly raised their arms as though hypnotized, taking in every detail of his uniform. The silver lightning bolts on the lapels, the high, peaked cap—the predatory eagle clasping a swastika.

"You're—you're a German!" Gino Lombardi gasped.

"Very observant," the officer observed humorlessly. "I am Hauptmann Langenscheidt. You are my prisoners. You will obey my orders. Get into the kraftwagen."

"Now just one minute," Dan protested. "I'm Col. Coye, USAF and I would like to know what is going on here...."

"Get in," the officer ordered. He did not change his tone of voice, but he did pull his long-barreled Luger from its holster and leveled it at them.

"Come on," Gino said, putting his hand on Dan's tense shoulder. "You outrank him, but he got there fustest with the mostest."

They climbed into the open back of the half-track and the captain sat down facing them. Two silent soldiers with leveled machine-pistols sat behind their backs. The tracks clanked and they surged forward: stifling dust rose up around them.

Gino Lombardi had trouble accepting the reality of this. The moon flight, the landing, even Glazer's death he could accept, they were things that could be understood. But this...? He looked at his watch, at the number twelve in the calendar opening.

"Just one question, Langenscheidt," he shouted above the roar of the engine. "Is today the twelfth of September?"

His only answer was a stiff nod.

"And the year—of course it is—1971?"

"Yes, of course. No more questions. You will talk to the Oberst, not to me."

They were silent after that, trying to keep the dust out of their eyes. A few minutes later they pulled aside and stopped while the long, heavy form of a tank transporter rumbled by them, going in the opposite direction. Evidently the Germans wanted the capsule as well as the men who had arrived in it. When the long vehicle had passed the half-track ground forward again. It was growing dark when the shapes of two large tanks loomed up ahead, cannons following them as they bounced down the rutted track. Behind these sentries was a car park of other vehicles, tents and the ruddy glow of gasoline fires burning in buckets of sand. The half-track stopped before the largest tent and at gunpoint the two astronauts were pushed through the entrance.

An officer, his back turned to them, sat writing at a field desk. He finished his work while they stood there, then folded some papers and put them into a case. He turned around, a lean man with burning eyes that he kept fastened on his prisoners while the captain made a report in rapid German.

"That is most interesting, Langenscheidt, but we must not keep our guests standing. Have the orderly bring some chairs. Gentlemen permit me to introduce myself. I am Colonel Schneider, commander of the 109th Panzer division that you have been kind enough to visit. Cigarette?"

The colonel's smile just touched the corners of his mouth, then instantly vanished. He handed over a flat package of Player's cigarettes to Gino, who automatically took them. As he shook one out he saw that they were made in England—but the label was printed in German.

"And I'm sure you would like a drink of whisky," Schneider said, flashing the artificial smile again. He placed a bottle of Ould Highlander on the table before them, close enough for Gino to read the label. There was a picture of the highlander himself, complete with bagpipes and kilt, but he was saying Ich hätte gern etwas zu trinken WHISKEY!

The orderly pushed a chair against the back of Gino's legs and he collapsed gratefully into it. He sipped from the glass when it was handed to him—it was good scotch whisky. He drained it in a single swallow.

The orderly went out and the commanding officer settled back into his camp chair, also holding a large drink. The only reminder of their captivity was the silent form of the captain near the entrance, his hand resting on his holstered gun.

"A most interesting vehicle that you gentlemen arrived in. Our technical experts will of course examine it, but there is a question—"

"I am Colonel Danton Coye, United States Air Force, serial number...."

"Please, colonel," Schneider interrupted. "We can dispense with the formalities...."

"Major Giovanni Lombardi, United States Air Force," Gino broke in, then added his serial number. The German colonel flickered his smile again and sipped from his drink.

"Do not take me for a fool," he said suddenly, and for the first time the cold authority in his voice matched his grim appearance. "You will talk for the Gestapo, so you might just as well talk to me. And enough of your childish games. I know there is no American Air Force, just your Army Air Corps that has provided such fine targets for our fliers. Now—what were you doing in that device?"

"That is none of your business, Colonel," Dan snapped back in the same tones. "What I would like to know is, just what are German tanks doing in Texas?"

A roar of gunfire cut through his words, sounding not too far away. There were two heavy explosions and distant flames lit up the entrance to the tent. Captain Langenscheidt pulled his gun and rushed out of the tent while the others leaped to their feet. There was a muffled cry outside and a man stepped in, pointing a bulky, strange looking pistol at them. He was dressed in stained khaki and his hands and face were painted black.

"Verdamm ..." the colonel gasped and reached for his own gun: the newcomer's pistol jumped twice and emitted two sighing sounds. The panzer officer clutched his stomach and doubled up on the floor.

"Don't just stand there gaping, boys," the intruder said, "get moving before anyone else wanders in here." He led the way from the tent and they followed.

They slipped behind a row of parked trucks and crouched there while a squad of scuttle-helmeted soldiers ran by them towards the hammering guns. A cannon began firing and the flames started to die down. Their guide leaned back and whispered.

"That's just a diversion—just six guys and a lot of noise—though they did get one of the fuel trucks. These krautheads are going to find it out pretty quickly and start heading back here on the double. So let's make tracks—now!"

He slipped from behind the trucks and the three of them ran into the darkness of the desert. After a few yards the astronauts were staggering, but they kept on until they almost fell into an arroyo where the black shape of a jeep was sitting. The motor started as they hauled themselves into it and, without lights, it ground up out of the arroyo and bumped through the brush.

"You're lucky I saw you come down," their guide said from the front seat. "I'm Lieutenant Reeves."

"Colonel Coye—and this is Major Lombardi. We owe you a lot of thanks, lieutenant. When those Germans grabbed us, we found it almost impossible to believe. Where did they come from?"

"Breakthrough, just yesterday from the lines around Corpus. I been slipping along behind this division with my patrol, keeping San Antone posted on their movements. That's how come I saw your ship, or whatever it is, dropping right down in front of their scouts. Stars and stripes all over it. I tried to reach you first, but had to turn back before their scout cars spotted me. But it worked out. We grabbed the tank carrier as soon as it got dark and two of my walking wounded are riding it back to Cotulla where we got some armor and transport. I set the rest of the boys to pull that diversion and you know the results. You Air Corps jockeys ought to watch which way the wind is blowing or something, or you'll have all your fancy new gadgets falling into enemy hands."

"You said the Germans broke out of Corpus—Corpus Christi?" Dan asked. "What are they doing there—how long have they been there—or where did they come from in the first place?"

"You flyboys must sure be stationed in some hideaway spot," Reeves said, grunting as the jeep bounded over a ditch. "The landings on the Texas side of the Gulf were made over a month ago. We been holding them, but just barely. Now they're breaking out and we're managing to stay ahead of them." He stopped and thought for a moment. "Maybe I better not talk to you boys too much until we know just what you were doing there in the first place. Sit tight and we'll have you out of here inside of two hours."

The other jeep joined them soon after they hit a farm road and the lieutenant murmured into the field radio it carried. Then the two cars sped north, past a number of tank traps and gun emplacements and finally into the small town of Cotulla, straddling the highway south of San Antonio. They were led into the back of the local supermarket where a command post had been set up. There was a lot of brass and armed guards about, and a heavy-jawed one star general behind the desk. The atmosphere and the stares were reminiscent in many ways of the German colonel's tent.

"Who are you two, what are you doing here—and what is that thing you rode down in?" the general asked in a no-nonsense voice.

Dan had a lot of questions he wanted to ask first, but he knew better than to argue with a general. He told about the moon flight, the loss of communication, and their return. Throughout the general looked at him steadily, nor did he change his expression. He did not say a word until Dan was finished. Then he spoke.

"Gentlemen, I don't know what to make of all your talk of rockets, moon-shots, Russian sputniks or the rest. Either you are both mad or I am, though I admit you have an impressive piece of hardware out on that tank carrier. I doubt if the Russians have time or resources now for rocketry, since they are slowly being pulverized and pushed back across Siberia. Every other country in Europe has fallen to the Nazis and they have brought their war to this hemisphere, have established bases in Central America, occupied Florida and made more landings along the Gulf coast. I can't pretend to understand what is happening here so I'm sending you off to the national capitol in Denver in the morning."

In the plane next day, somewhere over the high peaks of the Rockies, they pieced together part of the puzzle. Lieutenant Reeves rode with them, ostensibly as a guide, but his pistol was handy and the holster flap loose.

"It's the same date and the same world that we left," Gino explained, "but some things are different. Too many things. It's all the same up to a point, then changes radically. Reeves, didn't you tell me that President Roosevelt died during his first term?"

"Pneumonia, he never was too strong, died before he had finished a year in office. He had a lot of wild-sounding schemes but they didn't help. Vice-president Garner took over, but it didn't seem the same when John Nance said it as when Roosevelt had said it. Lots of fights, trouble in congress, depression got worse, and things didn't start getting better until about '36 when Landon was elected. There were still a lot of people out of work, but with the war starting in Europe they were buying lots of things from us, food, machines, even guns."

"Britain and the allies, you mean?"

"I mean everybody, Germans too, though that made a lot of people here mad. But the policy was no-foreign-entanglements and do business with anyone who's willing to pay. It wasn't until the invasion of Britain that people began to realize that the Nazis weren't the best customers in the world, but by then it was too late."

"It's like a mirror image of the world—a warped mirror," Dan said, drawing savagely on his cigarette. "While we were going around the moon something happened to change the whole world to the way it would have been if history had been altered some time in the early thirties."

"World didn't change, boys," Reeves said, "it's always been just the way it is now. Though I admit the way you tell it it sounds a lot better. But it's either the whole world or you, and I'm banking on the simpler of the two. Don't know what kind of an experiment the Air Corps had you two involved in but it must have addled your grey matter."

"I can't buy that," Gino insisted. "I know I'm beginning to feel like I have lost my marbles, but whenever I do I think about the capsule we landed in. How are you going to explain that away?"

"I'm not going to try. I know there are a lot of gadgets and things that got the engineers and the university profs tearing their hair out, but that doesn't bother me. I'm going back to the shooting war where things are simpler. Until it is proved differently I think that you are both nuts, if you'll pardon the expression, sirs."

The official reaction in Denver was basically the same. A staff car, complete with MP out-riders, picked them up as soon as they had landed at Lowry Field and took them directly to Fitzsimmons Hospital. They were taken directly to the laboratories and what must have been a good half of the giant hospital's staff took turns prodding, questioning and testing them. They were encouraged to speak—many times with lie-detector instrumentation attached to them—but none of their questions were answered. Occasional high-ranking officers looked on gloomily, but took no part in the examination. They talked for hours into tape recorders, answering questions in every possible field from history to physics, and when they tired were kept going on benzedrine. There was more than a week of this in which they saw each other only by chance in the examining rooms, until they were weak from fatigue and hazy from the drugs. None of their questions were answered, they were just reassured that everything would be taken care of as soon as the examinations were over. When the interruption came it was a welcome surprise, and apparently unexpected. Gino was being probed by a drafted history professor who wore oxidized captain's bars and a gravy-stained battlejacket. Since his voice was hoarse from the days of prolonged questioning, Gino held the microphone close to his mouth and talked in a whisper.

"Can you tell me who was the Secretary of the Treasury under Lincoln?" the captain asked.

"How the devil should I know? And I doubt very much if there is anyone else in this hospital who knows—besides you. And do you know?"

"Of course—"

The door burst open and a full colonel with an MP brassard looked in. A very high-ranking messenger boy: Gino was impressed.

"I've come for Major Lombardi."

"You'll have to wait," the history-captain protested, twisting his already rumpled necktie. "I've not finished...."

"That is not important. The major is to come with me at once."

They marched silently through a number of halls until they came to a dayroom where Dan was sprawled deep in a chair smoking a cigar. A loudspeaker on the wall was muttering in a monotone.

"Have a cigar," Dan called out, and pushed the package across the table.

"What's the drill now?" Gino asked, biting off the end and looking for a match.

"Another conference, big brass, lots of turmoil. We'll go in in a moment as soon as some of the shouting dies down. There is a theory now as to what happened, but not much agreement on it even though Einstein himself dreamed it up...."

"Einstein! But he's dead...."

"Not now he isn't, I've seen him. A grand old gent of over ninety, as fragile as a stick but still going strong. He ... say, wait—isn't that a news broadcast?"

They listened to the speaker that one of the MP's had turned up.

"... in spite of fierce fighting the city of San Antonio is now in enemy hands. Up to an hour ago there were still reports from the surrounded Alamo where units of the 5th Cavalry have refused to surrender, and all America has been following this second battle of the Alamo. History has repeated itself, tragically, because there now appears to be no hope that any survivors...."

"Will you gentlemen please follow me," a staff officer broke in, and the two astronauts went out after him. He knocked at a door and opened it for them. "If you please."

"I am very happy to meet you both," Albert Einstein said, and waved them to chairs.

He sat with his back to the window, his thin, white hair catching the afternoon sunlight and making an aura about his head.

"Professor Einstein," Dan Coye said, "can you tell us what has happened? What has changed?"

"Nothing has changed, that is the important thing that you must realize. The world is the same and you are the same, but you have—for want of a better word I must say—moved. I am not being clear. It is easier to express in mathematics."

"Anyone who climbs into a rocket has to be a bit of a science fiction reader, and I've absorbed my quota," Dan said. "Have we got into one of those parallel worlds things they used to write about, branches of time and all that?"

"No, what you have done is not like that, though it may be a help to you to think of it that way. This is the same objective world that you left—but not the same subjective one. There is only one galaxy that we inhabit, only one universe. But our awareness of it changes many of its aspects of reality."

"You've lost me," Gino sighed.

"Let me see if I get it," Dan said. "It sounds like you are saying that things are just as we think we see them, and our thinking keeps them that way. Like that tree in the quad I remember from college."

"Again not correct, but an approximation you may hold if it helps you to clarify your thinking. It is a phenomenon that I have long suspected, certain observations in the speed of light that might be instrumentation errors, gravitic phenomena, chemical reactions. I have suspected something, but have not known where to look. I thank you gentlemen from the bottom of my heart for giving me this opportunity at the very end of my life, for giving me the clues that may lead to a solution to this problem."

"Solution...." Gino's mouth opened. "Do you mean there is a chance we can go back to the world as we knew it?"

"Not only a chance—but the strongest possibility. What happened to you was an accident. You were away from the planet of your birth, away from its atmospheric envelope and, during parts of your orbit, even out of sight of it. Your sense of reality was badly strained, and your physical reality and the reality of your mental relationships changed by the death of your comrade. All these combined to allow you to return to a world with a slightly different aspect of reality from the one you have left. The historians have pinpointed the point of change. It occurred on the seventeenth of August, 1933, the day that President Roosevelt died of pneumonia."

"Is that why all those medical questions about my childhood?" Dan asked. "I had pneumonia then, I was just a couple of months old, almost died, my mother told me about it often enough afterwards. It could have been at the same time. It isn't possible that I lived and the president died...?"

Einstein shook his head. "No, you must remember that you both lived in the world as you knew it. The dynamics of the relationship are far from clear, though I do not doubt that there is some relationship involved. But that is not important. What is important is that I think I have developed a way to mechanically bring about the translation from one reality aspect to another. It will take years to develop it to translate matter from one reality to a different order, but it is perfected enough now—I am sure—to return matter that has already been removed from another order."

Gino's chair scraped back as he jumped to his feet. "Professor—am I right in saying, and I may have got you wrong, that you can take us and pop us back to where we came from?"

Einstein smiled. "Putting it as simply as you have, major ... the answer is yes. Arrangements are being made now to return both of you and your capsule as soon as possible. In return for which we ask you a favor."

"Anything, of course," Dan said, leaning forward.

"You will have the reality-translator machine with you, and microcopies of all our notes, theories and practical conclusions. In the world that you come from all of the massive forces of technology and engineering can be summoned to solve the problem of mechanically accomplishing what you both did once by accident. You might be able to do this within months, and that is all the time that there is left."

"Exactly what do you mean?"

"We are losing the war. In spite of all the warning we were not prepared, we thought it would never come to us. The Nazis advance on all fronts. It is only a matter of time until they win. We can still win, but only with your atom bombs."

"You don't have atomic bombs now?" Gino asked.

Einstein sat silent for a moment before he answered. "No, there was no opportunity. I have always been sure that they could be constructed, but have never put it to the test. The Germans felt the same, and at one time even had a heavy water project that aimed towards controlled nuclear fission. But their military successes were so great that they abandoned it along with other far-fetched and expensive schemes such as the hollow-globe theory. I myself have never wanted to see this hellish thing built, and from what you have told about it, it is worse than my most terrible dream. But I have approached the President about it, when the Nazi threat was closing in, but nothing was done. Too expensive. Now it is too late. But perhaps it isn't. If your America will help us, the enemy will be defeated. And after that, what a wealth of knowledge we shall have once our worlds are in contact. Will you do it?"

"Of course," Dan Coye said. "But the brass will take a lot of convincing. I suggest some films be made of you and others explaining some of this. And enclose some documents, anything that will help convince them what has happened."

"I can do something better," Einstein said, taking a small bottle from a drawer of the table. "Here is a recently developed drug, and the formula, that has proved effective in arresting certain of the more violent forms of cancer. This is an example of what I mean by the profit that can accrue when our two worlds can exchange information."

Dan pocketed the precious bottle as they turned to leave. With a sense of awe they gently shook hands with the frail old man who had been dead many years in the world they knew, to which they would be soon returning.

The military moved fast. A large jet bomber was quickly converted to carry one of the American solid-fuel rocket missiles. Not yet operational, it was doubtful if they ever would be at the rate of the Nazi advance. But given an aerial boost by the bomber it could reach up out of the ionosphere—carrying the payload of the moon capsule with its two pilots. Clearing the fringes of the atmosphere was essential to the operation of the instrument that was to return them to what they could only think of as their own world. It seemed preposterously tiny to be able to change worlds.

"Is that all?" Gino asked when they settled themselves back into the capsule. A square case, containing records and reels of film, was strapped between their seats. On top of it rested a small grey metal box.

"What do you expect—an atom smasher?" Dan asked, checking out the circuits. The capsule had been restored as much as was possible to the condition it was in the day it had landed. The men wore their pressure suits. "We came here originally by accident, by just thinking wrong or something like that, if my theory's correct."

"It isn't—but neither is mine, so we can't let it bug us."

"Yeah, I see what you mean. The whole crazy business may not be simple, but the mechanism doesn't have to be physically complex. All we have to do is throw the switch, right?"

"Roger. The thing is self-powered. We'll be tracked by radar, and when we hit apogee in our orbit they'll give us a signal on our usual operating frequency. We throw the switch—and drop."

"Drop right back to where we came from, I hope."

"Hello there cargo," a voice crackled over the speaker. "Pilot here. We are about to take off. All set?"

"In the green, all circuits," Dan reported, and settled back.

The big bomber rumbled the length of the field and slowly pulled itself into the air, heavily under the weight of the rocket slung beneath its belly. The capsule was in the nose of the rocket and all the astronauts could see was the shining skin of the mother ship. It was a rough ride. The mathematics had indicated that probability of success would be greater over Florida and the south Atlantic, the original re-entry target. This meant penetrating enemy territory. The passengers could not see the battle being fought by the accompanying jet fighters, and the pilot of the converted bomber did not tell them. It was a fierce battle and at one point almost a lost one: only a suicidal crash by one of the escort fighters prevented an enemy jet from attacking the mother ship.

"Stand by for drop," the radio said, and a moment later came the familiar sensation of free fall as the rocket cropped clear of the plane. Pre-set controls timed the ignition and orbit. Acceleration pressed them into their couches.

A sudden return to weightlessness was accompanied by the tiny explosions as the carrying-rocket blasted free the explosive bolts that held it to the capsule. For a measureless time their inertia carried them higher in their orbit while gravity tugged back. The radio crackled with a carrier wave, then a voice broke in.

"Be ready with the switch ... ready to throw it ... NOW!"

Dan flipped the switch and nothing happened. Nothing that they could perceive in any case. They looked at each other silently, then at the altimeter as they dropped back towards the distant Earth.

"Get ready to open the chute," Dan said heavily, just as a roar of sound burst from the radio.

"Hello Apollo, is that you? This is Canaveral control, can you hear me? Repeat—can you hear me? Can you answer ... in heaven's name, Dan, are you there ... are you there...?"

The voice was almost hysterical, bubbling over itself. Dan flipped the talk button.

"Dan Coye here—is that you, Skipper?"

"Yes—but how did you get there? Where have you been since.... Cancel, repeat cancel that last. We have you on the screen and you will hit in the sea and we have ships standing by...."

The two astronauts met each other's eyes and smiled. Gino raised his thumb up in a token of victory. They had done it. Behind the controlled voice that issued them instructions they could feel the riot that must be breaking after their unexpected arrival. To the observers on Earth—this Earth—they must have vanished on the other side of the moon. Then reappeared suddenly some weeks later, alive and sound long days after their oxygen and supplies should have been exhausted. There would be a lot to explain.

It was a perfect landing. The sun shone, the sea was smooth, there was scarcely any cross wind. They resurfaced within seconds and had a clear view through their port over the small waves. A cruiser was already headed their way, only a few miles off.

"It's over," Dan said with an immense sigh of relief as he unbuckled himself from the chair.

"Over!" Gino said in a choking voice. "Over? Look—look at the flag there!"

The cruiser turned tightly, the flag on its stern standing out proudly in the air. The red and white stripes of Old Glory, the fifty white stars on the field of deepest blue.

And in the middle of the stars, in the center of the blue rectangle, lay a golden crown.

THE END