THE

STAR WOMAN

BY

H. BEDFORD-JONES

TORONTO

THE RYERSON PRESS

1 9 2 4

Copyright, 1924,

By Dodd, Mead and Company, Inc.

Printed in the U. S. A.

The historical portions of this novel will be found to differ considerably from generally accepted versions of the events related. The prime sources utilized are both contemporary, both French, and both untranslated; namely, the diary of Sieur Baudouin, once a soldier and later chaplain under Iberville, and the amazing “Histoire de l’Amérique Septentrionale” of Bacqueville de la Potherie.

The former work, furnished me in MS. by kindness of the Newfoundland Historical Society, yielded full details regarding the Newfoundland raid. In abridged form, it was utilized by Sieur Bacqueville, whose work is astounding because of its remarkably distinct, yet wildly confused, combination of sources. A letter from the missionary Bobé, himself a student and memorialist of Canadian affairs, has informed us of Sieur Bacqueville’s great exactitude. He had a share in much that he described; for the remainder, he drew by document or word of mouth on Baudouin, Perrot, the Le Moynes, Joliet and the Jesuits. The manner in which these sources can be traced through the internal evidence of his work is most interesting; the work itself cannot be translated satisfactorily, owing to its disregard of historical sequence and its jumble of unrelated documents and dictation.

[vi]In places, however, it is remarkably clear, and has been followed for the Hudson Bay events. I do not attempt to account for the extraordinary discrepancies which exist between these events as herein set forth and as related by A. C. Laut in “The Conquest of the Great Northwest.” This discrepancy exists in nearly every detail and is almost incredible, since the latter work quotes Bacqueville as an authority. The same discrepancy exists between its account of Iberville’s earlier exploits on the bay and that which Iberville himself presumably furnished Sieur Bacqueville. The two versions are totally different. I have followed the 1753 edition of the Histoire, which was a careful reprint of the second edition of 1722. I believe that no copies are known to exist of the first edition, of 1716. Miss Laut quotes a much later edition. Perhaps that is why her account is so astonishing—as, for example, making one of Iberville’s ships, the Violent, founder in the straits, when this ship was not even with his squadron; and when we are expressly told that it was a small brigantine named the Esquimeau which went down. Nor is this the most amazing error in the volume named.

But now let me cry “peccavi!” on my own account. Iberville was not with Bienville at the Bay de Verde burning, although I put him there. I have purposely ignored the fact that Serigny was blown into the Danish river on his way to Nelson; and I have no authority for bringing poor Moon there—though where he did go I have been unable to discover, as he dropped from sight between the straits and Nelson.

By introducing the Albemarle as Deakin’s ship, I have[vii] tried to resolve what was to me a sore problem—perhaps for lack of any authoritative English account of the bay action. After the capture of Nelson our friend Aide-major Charles Claude le Roy—otherwise Sieur de Bacqueville de la Potherie—loaded the looted furs and the prisoners aboard a ship of this name and promptly lost her on the shallows of the river-mouth. I find no other mention of such a ship; no Albemarle formed a part of either Fletcher’s or Iberville’s squadron. Since all the furs and prisoners were put aboard her, she must have been a vessel of goodly size and not a mere sloop belonging to the forts.

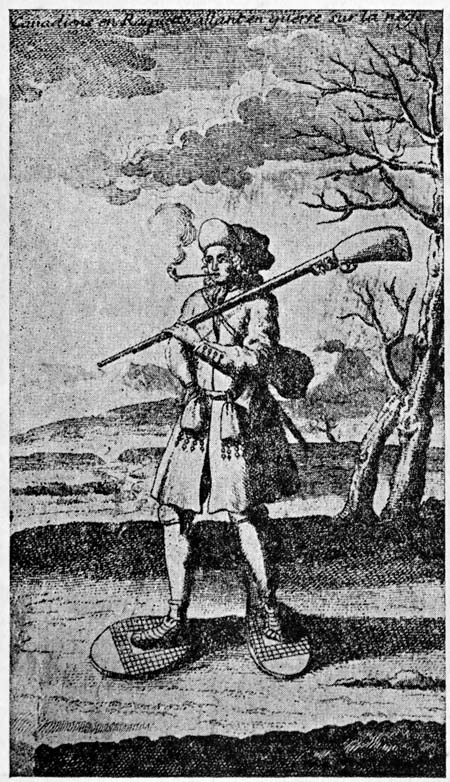

Despite the dictum of learned persons that the term “Canadian” is not found prior to the end of the eighteenth century, I have used it advisedly. In De Beaudoncourt’s “History of Canada,” based on French and American documents, occurs this note:

“Ce mot de Canada ou Canata veut dire, en langue du pais, royaume des cabanes. Il a survécu à tous les autres, il est avec celui de Montréal le seul datant de l’époque de Jacques Cartier.”

The term Canadian is constantly used by Bacqueville and by Baudouin; a statement by the latter infers that it was likewise employed by the English to differentiate the born Canadians from the French proper. The entire history of North America at this period is largely written in names of Canadian families; as though the terrific struggle of the French pioneers against man and nature had aroused in the ensuing generation all the[viii] dormant blood of knightly and heroic ancestry, so that the same names etched in the icy annals of Hudson Bay are to be found burned into the cypress of Louisiana.

H. Bedford-Jones

| PAGE | ||

| Preface | v | |

| BOOK I—THE STAR OF DREAMS | ||

|---|---|---|

| CHAPTER | ||

| I | The Man and the Star | 3 |

| II | He Who Accepts an Omen, Accepts Responsibility | 22 |

| III | The Importance of Forgotten Things | 42 |

| IV | One Gains Gold, Another a Friend | 66 |

| BOOK II—THE FUR PIRATE | ||

| I | Even in a Wilderness, One Cannot Escape the Devil | 85 |

| II | When Fog Lifts, the Road Clears | 109 |

| III | Confirming a Belief in Miracles | 129 |

| IV | Predictions and Events Are Sometimes Reconciled | 150 |

| V | It Is Only by Crooked Lanes That One Gains the Highway | 165 |

| BOOK III—THE STAR GOES, THE WOMAN REMAINS | ||

| I | It Does Not Pay To Be Merciful | 173 |

| II | A Knife Does Different Things in Different Hands | 192 |

| III | Two Trails May Have the Same End | 208 |

| IV | He Who Denies the Incredible Denies God | 223 |

| V | Vengeance Runs a Red Road | 238 |

| VI | Some Problems Are Best Left Unsolved | 253 |

| VII | “An Archer Drew Bow at a Venture” | 265 |

| VIII | Sometimes Sunrise Can Come Too Late | 280 |

| IX | When a Star Falls, a Soul Has Passed | 290 |

[2]

THE STAR WOMAN

Crawford snuffed the candle on the table beside him, turned the page of his book, and went on reading; he felt the loneliness of Pentagoet. In the wide hearth crackled a new-laid fire. Outside, the trees groaned frostily, snapping in the night wind.

The room showed an amazing mixture of civilized culture and savage magnificence. Candle-tray and snuffers were of chased silver, beside the wine bottle on the table was a heavy gold chalice, above the fireplace hung crossed Toledo blades, and books shone brown in a corner case. The light flickered on a careless pile of beaver and elk-skins in one corner. Other skins strewed the walls, mingled with belts and “arms” of wampum or beadwork. A rack on the mantel held several pipes, all of Indian make; one was a large calumet of white stone girded with silver, a pipe heavy with fate not yet fulfilled, and affecting lives of men. A tomahawk on the mantel had a string of black wampum about the handle, several dried scalps woven in among the wampum shells.

So much for the room. The man presented that same singular combination of savagery and refinement. His face was long and thinly chiselled, his eyes wide and[4] heavy-lidded, his mouth large, humorous, dangerous. He was of medium height; in the firelight his hair shone reddish, and lines of hardship touched his face with stern self-mastery. A beaver coat wrapped him to the waist. Against stiff buckskin nether garments stood out a sheathed knife and a slender, deadly tomahawk; beaded ceremonial moccasins, far too large for him, encased his feet. Before the blazing fire were drying his own moccasins, stuffed out with rags, still steaming as if soaked with wet snow or water. His hands, resting on book and table, were large and powerful, the wrists showing half-healed scars of manacles.

Crawford put out a hand to the pipe beside him, filled it with kinnikinnick from the bag, held it above the candle. He relaxed again in his chair, puffing, but his eyes went to the door and then he took the pipe from his mouth, listening. Those eyes of his were startling in their alertness—light-blue eyes that fairly stabbed. His wide lips smiled, as if at his own alarm.

“The shore ice grinding, that’s all,” he murmured. “Folly to feel nervous here! I wish that Micmac rascal would bring the cold pasty he promised me. Wine on a stomach that has seen no food in two days is a hollow mockery.”

Rising, Crawford crossed to the door and swung it open.

He stood for a moment on the threshold, staring out at the night. Stars blazed in the dark sky. A dozen feet outside the house ran the black line of a palisade, broken by an open gate directly in front of the doorway. From where he stood, Crawford could see the abandoned[5] lines of old Fort Pentagoet to one side, and beyond this the long white line of the ice-rimmed shore; Penobscot Bay was not frozen over, and the dark swishing of waves mingled with the creaky whine of trees and the grind of ice.

“A lonely place for a baron of France!” said Crawford, puffing at his pipe. “Yet I wish he were here, with his Indian wives and his henchmen. Fiend take this solitude! I’ve had enough of it. Why couldn’t he leave more than one solitary Micmac on the place?”

He shivered, turned, closed the door, and went back to his chair. He took his book and opened it—then his head lifted and he looked again at the door. He caught a new sound, the scrape of a stiff moccasin, a low groan, the fumble of stiff fingers at the latch. The door swung open.

Into the room came an Indian, wrapped in furs, holding in both hands a great silver dish. He advanced a step into the room, kicked the door shut, stood motionless. While Crawford stared at him, a frightful expression of horror leaped across his brown face—then the dish fell from his hands, he pitched forward, lay outstretched. The long shagreen handle of a knife stood out from between his shoulder-blades. The knife must have caught him an instant before he opened the door.

Crawford sat motionless. For a long instant the thing seemed incredible, uncanny, supernatural. He knew that except for this Micmac and himself, the establishment of Baron de Saint-Castin at the head of Penobscot Bay was temporarily deserted. No war-parties were afoot hereabouts; the year 1697 had opened with peace to[6] Acadia, at least. Crawford had just come overland from Boston and knew that all was quiet.

Then, abruptly, before Crawford could move, the door was again flung open and a man stood framed against the night, pistol in hand. He grinned at Crawford—a great figure whose clothes were white with ice-rime and snow, his bearded face massive, brutal.

“Not a move, Saint-Castin!” rang out his voice.

Crawford smiled.

“Oh! I thought you were Saint-Castin!” he said.

The other started.

“Eh? What’s this? No one about——”

“Come in and shut the door!” said Crawford, and laid down his book. “I’m cursed glad of company. The baron is away, with all his people—gone to visit his father-in-law, Madockawando. Up the Penobscot, I suppose. Where the devil did you come from?”

“From the devil,” said the other, and laughed.

Then he whistled shrilly. Two other men joined him. All three advanced into the room, closed the door, stood staring over pistols at the seated figure of Crawford, whose calm attitude puzzled them.

From outside came a shout, then a burst of voices, the stamp of running feet, a sudden flicker of torches. Surveying his visitors, Crawford perceived that the first was obviously in command—his dominant air was beyond mistake. The second man was a burly ruffian, brutish, reeking of rum. The third man was tall and thin, saturnine, hawk-nosed, with a certain air of down-at-heel gentility; his darting black eyes were very intelligent.

[7]“This is not the baron,” said this last rogue, blinking at Crawford. “Not our man at all, cap’n!”

“Correct,” said Crawford amiably. “If one of you gentlemen will set that venison pasty on the table, I’d be obliged. I reached here half an hour ago, have not eaten for two days, and am more interested in the venison than in you. If you want the baron, go up the Penobscot and look for him.”

“Cool one!” observed the massive leader, and suddenly laughed. “We’ve lost the quarry, lads! Saint-Castin’s away with all his people. Bose, go out and take charge of the looting. Have everything taken to the boats; no eating or drinking until the men are aboard. When you’ve had your fill, come ashore with one boat and join us here. No one is to loot this part of the establishment until I’m ready. Frontin and I will join our friend here over the pasty—if he hasn’t eaten for two days, we’ve not eaten for three. Go!”

The burly ruffian departed. The saturnine man stooped to the pasty and lifted it to the table, shoving aside the body of the Micmac. The commander, thrusting away his pistol, stepped forward to Crawford and grinned widely.

“Well! Your name?”

“Harry Crawford, at your service.”

The two men stopped dead still, staring at him. Crawford, faintly amused, smiled.

“Why, zounds!” broke out the leader. “Hal Crawford, the pirate! Two hundred pound on his head in Boston!”

“This is not Boston,” said Crawford, though his[8] eyes narrowed. “Plague take you, stare! I’m for the pasty.”

He whipped out his knife and attacked the contents of the battered silver dish. The two men exchanged a glance, then without more ado pulled forward a couple of stools and joined in the assault, knives and fingers ravenously at work.

No word was exchanged, but Crawford was by this time perfectly aware of the profession, if not the identity, of his visitors. During the past forty years the whole American coast, even into Hudson Bay, had been swept by pirates; small fry, most of them, fur-pirates, rum pirates, reckless sailormen who would land to sack a town or would lay a ship aboard and count it all in the day’s work. Others followed the freebooting trade more seriously and made of it a profession. Of this latter class, thought Crawford, were the visitors. He had somewhere heard the name of Frontin—and presently placed it.

Within five minutes the pasty, among three famished men, had been scraped to the last crumb, and the bottle of wine was empty. Crawford leaned back, refilled his pipe, and surveyed the other two men with a whimsical air.

“Help yourselves to pipes, gentlemen! This house, as the Spanish say, is yours.”

Frontin, the thin man, grinned in his saturnine way.

“That is well. May I introduce you to my captain, Vanderberg the valiant?”

“The honor is mine,” said Crawford, nodding. “I already recognized Captain Vanderberg. I believe Frontenac[9] has offered five thousand livres for his head? Come, Lieutenant Frontin, you have a chance at fortune! Deliver him to Quebec and me to Boston——”

Vanderberg, who was a jolly rascal of Dutch extraction, bellowed a laugh at this.

“Ho! I like you, Crawford. Finding you here, the baron gone, the house ours for the looting, means our luck has changed. And, damme, we need the change! We were battered by a French corvette, storm-wracked, short of men and shorter of food. We bore up for Boston but were warned off; we had absent-mindedly sacked a Bostonnais off Jamaica, and the good folk had heard of it, so the port was closed to us. We started for New York, but were blown offshore by the gale which has only just abated. So, if Frontin had not known of this place and its chances of loot, food and wine——”

Vanderberg expressively waved one huge paw and went to the fireplace. He took down the white stone calumet. Frontin, his saturnine gaze on Crawford, spoke.

“So you are also on the account?”

“Not at all,” said Crawford coolly.

Vanderberg swung around with a heavy stare.

“What? But we heard of you in Boston as a pirate——”

“Exactly, in Boston,” said Crawford. “Having once been a Jacobite in opinion, I took refuge in Massachusetts. There, some months ago, I was recognized, apprehended, and sent to the Barbados as a slave. I got away with the help of some buccaneers, but having convictions against the life of a pirate, I made my way to New York. It was my intention to reach the Iroquois[10] country, certain Mohawk chiefs being my friends. I failed to bribe old Fletcher, however, so he sent me in chains to Boston. I escaped, headed for Acadia and New France, and reached this spot half an hour before you.”

Vanderberg exploded a volley of admiring oaths at this tale.

“You have money?”

“I need none.”

“Well, you shall join us! I need a second lieutenant.”

“You honor me,” said Crawford drily. “But, as I have said, I cherish certain convictions against piracy.”

“Bah! We shall prey only on the French.”

“Unfortunately, I have no quarrel with the French.”

Vanderberg stared.

“Hein? What has that to do with it?”

“Everything. You will readily perceive that a man who is destitute of everything except principles, would be a fool to abandon his principles.”

“The foul fiend fly away with you! Then we shall raid the coast to the south——”

“Unhappily, I have compunctions about letting English blood.”

“But you are a pirate, known as such!”

“I have the name, yes, but not the honour of deserving it,” said Crawford. “Reputation, my dear captain, is a bubble blown from the pipe of fools; let us disregard it. My quest, or if you so prefer, my urge to freedom, draws me into the north or west; I care not which, so it be into strange lands. Now, if I have need of a ship I am entirely willing to seize any French, English or pirate ship[11] which will further my purpose. I am not willing, however, to seize a ship and kill men merely in order to commit robbery. The distinction may be a trifle subtle to your mind, but there it is.”

Vanderberg blinked heavily at this speech. Crawford relaxed in his chair and puffed his pipe alight, quite at his ease. Frontin, grinning delightedly, watched the two men in obvious amusement. Apparently a cynical rogue, this Frontin was not at all the cynic he pretended to be.

“You are mad!” said Vanderberg, beginning to lose his good nature.

“On the contrary,” said Frontin, “he is entirely sane. That is a profound truth, my honest captain. Very few men are entirely——”

“Shut up!” snapped the pirate, and turned to Crawford. “Who the devil are you against, then?”

“Nobody,” said Crawford calmly, “and everybody.”

“But you’re a Jacobite.”

“I was; I am not. I have perceived the fallacy of giving allegiance to another man and fighting for him. I shall now fight for myself alone.”

“Then you are going on the account?” asked Vanderberg, rather helplessly.

“Not at all. I said—fight for myself! Why should I fight for money? Why should I rob and murder in order to take other men’s money and goods?”

Vanderberg swallowed hard.

“You are certainly mad!”

“No,” said Crawford. “I am free.”

Frontin jerked his stool forward and looked hard at Crawford.

[12]“Now let me have my say,” he said, and rubbed his long nose. “You are free, and you are also sane. You are something like Saint-Castin was once, before the king’s jackal brought him to heel. I suppose you think that it is a lucky chance that you are here?”

“Something of the sort,” said Crawford, wondering at the man’s manner.

“No; it is a coincidence. You never heard of the Star of Dreams?”

“No.”

“Saint-Castin and I got it together, in the old days,” said Frontin. “Now, consider! We want you with us, for sensible reasons which will presently appear. We came here for more than one reason—sensible reasons, which lie in the chapel yonder,” and he nodded his head toward a closed door. “The cap’n would plunder a chapel, but I won’t let him. If you will argue with us sensibly, and listen to reason, we may reach an understanding.”

“That is entirely possible,” said Crawford, with a slow chuckle at the man’s air.

Frontin rose.

“Good! Take up the candle and come with us. We have time to look and talk, while those men of ours fill their bellies and guzzle wine.”

Crawford stood up and took the candlestick from the table. He was at once amused, puzzled, and keenly interested by these two men. He saw that Vanderberg was a genial pirate, no more, no less—a brawny ruffian, who was for the moment in good humour, and who could pass swiftly to brute ferocity or brute lust. A man to be[13] met with utmost force, primitive in all instincts, actuated only by an avid greed for gold or gain.

Frontin was different—a Frenchman very likely, a man of high intelligence, capable alike of vicious cruelty and lofty ideals. Vanderberg was the arm that smote, Frontin was the brain that planned the blow. Of the two, the latter was the deadlier.

Frontin crossed to the closed door as though he knew the place well, and, his hand on the latch, turned to look at Crawford.

“You love the English more than the French?”

Crawford shrugged.

“I think not. One buys scalps, the other tortures prisoners. I deny them both.”

“In order to deny, one must affirm.”

“Precisely. I affirm—freedom, since you must have it so. I seek only the chance to be free, to look beyond the horizon, to leave wars and the quarrels of kings behind me.”

“Your aim, then?”

“To be myself,” said Crawford, a little wearily.

Frontin flung open the door, a laugh on his lips.

“The private chapel of Jean Vincent de l’Abadie, Baron de Saint-Castin. Your cap, cap’n; respect my religious scruples.”

Vanderberg grunted, but took off his fur cap.

Holding up the candle, Crawford gazed upon a small room at the farther end of which was an altar; there was nothing bare here, but all was a glow of colour. Pictures, silver candlesticks, a large crucifix, Portuguese reliquaries of walnut with oddly curved glass front and[14] sides, white cloths broidered in gold. The room was bitter cold.

“Keep those itching fingers quiet, cap’n,” said Frontin, and stepped forward. Crawford glanced at Vanderberg, who was staring with eyes that glowed lustfully.

Frontin genuflected, then stepped to one of the reliquaries, and from it took a small object. With a shiver, he motioned back to the main room, and Crawford obeyed. The three men came back to the fireplace, Frontin closing the chapel door behind them. He then extended the object which he had brought from the chapel.

Crawford, taking it, saw a five-pointed star six inches in diameter made of soft virgin gold. In the centre was set a large emerald, and other emeralds ran out to the points. Some were flawed, others were remarkably clear and deep in colour.

“Old?” he asked.

“A hundred years or so,” said Frontin. “From Peru.”

Vanderberg shoved his bulk between them and clutched the star. He examined it greedily, breathing hoarsely, his piggish eyes glinting in the firelight.

“This is no sacred thing!” he broke out accusingly. “I shall take it. You can have nothing to say about it. I swore to you that I would touch no sacred object——”

“You mistake, my captain,” said Frontin, a sudden cold accent in his voice. “Turn it over and you will see the name of the Archangel Michael graven on the back. It was the belief that each archangel had his abode in a certain star, you understand. This was a votive offering. As such, it is sacred. Shall we argue the matter?”

This question came icily. Frontin’s hand was at his[15] belt; his eyes met the gaze of Vanderberg in sharply direct challenge. Then the laugh of Crawford cut in between them.

“This theological argument would delight our friend Saint-Castin!”

Vanderberg grunted and shoved the star at Frontin.

“Take it, papist! Now tell him about it.”

Frontin bowed, not without a certain courtliness. He turned to Crawford.

“Once upon a time, I went to a certain place with Saint-Castin; on the Newfoundland coast. Indians led us. We found the wreck of an old Spanish ship, well-hidden, or rather, I found it. Saint-Castin was taken ill and could not go to the spot with me. I brought this back to him as a sample of what the wreck contained. Then some Boston fishing-sloops bore down on us, and we had to flee. Later, events drove me on the road of destiny. Saint-Castin was never able to find the spot where the wreck lies, without my help; and he did not have it. Now I am on my way to that place. I shall enrich Cap’n Vanderberg and his men. Come with us and you shall be enriched also. You perceive that our reasons for coming here were sensible. What do you say?”

Crawford stood for a moment in thought.

“Why this offer?” he responded at length. “Why are you so anxious to enrich me? That, as you must agree, is neither sensible nor reasonable.”

Frontin laughed gaily.

“No? Then listen. We have seventeen men including ourselves. They are scum of the Indies—negroes,[16] branded men, escaped slaves. They suffer from cold and famine. We officers are two, or if you count Bose, three. We need one other man to keep control in our own hands. They will not go farther north, yet farther north we must go. They fear the French. They shrink from working a ship adrift with ice. But this place supplies us with food, wine, furs. On the Newfoundland coast we shall get cod in plenty; we may pick up an English ship or two, with luck. Is this sensible?”

“Eminently so,” said Crawford. “You need me, it seems. Let’s smoke over it.”

He picked up his pipe, knocked it out, filled it with the tobacco and willow-bark.

“Suppose you let me take another look at that emerald thing—what did you call it? Star of Dreams?”

Frontin, who still held the star, pushed it across the table. He, too, got a pipe from the mantel and filled it. Vanderberg remained silent, puffing lustily.

Crawford looked again at the star and perceived a ring at one of the points, by which it might be fastened on a thong. The thing had no great intrinsic value, since few of the emeralds were fine stones, but it held that peculiar beauty which comes of primitive artistry and crude technique guided by instinctively flawless taste.

“Star of Dreams,” said Frontin. “It was Saint-Castin called it that name.”

“A good name for it,” and Crawford nodded. “I think I shall keep it. I like the thing.”

Vanderberg, who at most times was somewhat afraid of his saturnine lieutenant, gaped at this remark. Crawford[17] looked up and met the suddenly piercing gaze of Frontin.

“You jest?” said the latter.

“Not at all.” Crawford looked again at the star in his hand. “The name and the object appeal to my sentimental nature, awaken poetic fancies in me, I assure you. This thing might symbolize the star of freedom which I pursue. At all events, it makes a certain appeal to me which I cannot resist.”

Vanderberg grinned.

“So, Frontin! So! Another theological argument?”

Crawford glanced up and smiled.

“Not at all. I do not propose a theft, but an exchange which will be more than even—which will, in fact, be greatly to the advantage of our host’s chapel.”

He reached inside his shirt and pulled out a thong on which was strung a blazing jewel, which, after unknotting the thong, he laid upon the table. An exclamation burst from Frontin.

“But—this is the Order of St. Louis!”

“Exactly,” said Crawford, with a nod.

“His Most Catholic Majesty once decorated me with it, and from a feeling of sentiment I preserved it through many vicissitudes. Now, having abandoned sentiment, kings and other old-world follies together, I am very glad to leave this jewel here. You shall put it in Saint-Castin’s reliquary. In place of it I will take the Star of Dreams, as being worth infinitely less in money, and infinitely more in the greatest things, which are intangible. I trust that you will have no scruples in the matter of such an exchange? The Blessed Virgin, or St.[18] Michael, or whoever is the patron of yonder chapel, will certainly profit by the trade. St. Louis for St. Michael—eh?”

Frontin compressed his lips, gazing at the jewelled star. But Vanderberg was also gazing at the same thing, with lustful and incredulous eyes, for in truth it was a jewel of great worth. Then, abruptly, Vanderberg blurted out his mind.

“Ha! Frontin—will you let him make fools of us? Leave the relic where we found it, kill him, and take these jewels. What’s to hinder, eh?”

“What, indeed?” murmured Frontin, raising his eyes and looking hard at Crawford. The latter, who was stringing the Star of Dreams on his leather thong, laughed a little.

“Nonsense!” he responded cheerfully, and apparently without heeding the black regard. “Before you two fools could out pistol, cock flint and draw fire, my tomahawk would split the cap’n’s skull and my knife be in Frontin’s heart. A pity, that, for Frontin is a man of some sense. Nay, I learned knife and tomahawk play from my Mohawk friends, gentlemen! Now, my dear Frontin, if you wish to dispute my wishes in regard to this star, I am entirely at your service.”

He leaned back and met the stare of Frontin with an ingenuous air. Frontin burst into a laugh, rose, and picked up the jewel of St. Louis.

“Bah! I am satisfied. Cap’n, don’t be a fool; we need this man, and I like him, and the three of us shall gut the galleon of treasure. What are a few jewels, when gold is waiting to be carried off?”

[19]Vanderberg sat back and puffed at the big calumet. Frontin crossed to the door of the chapel and vanished in the little, cold, dark room. Crawford nodded to the big pirate.

“An odd soul, this Frontin of ours! I am glad that he reverences something, for it raises him in my esteem. By the way, you made a serious error in hurling a knife into that redskin Micmac. He could have given you some highly interesting information.”

“What, then?” asked Frontin, returning from the chapel and closing its door.

“That Saint-Castin was expected home sometime this evening. If I were you, I’d send a man or two up the river-trail.”

Vanderberg, exploding an oath of consternation and startled dismay, leaped to his feet. But Frontin was already darting for the outside door. Jerking it open, he whistled shrilly. A shout responded, and he turned, his dark face alive with excitement.

“Bose is coming now. Crawford, you devil! If you hadn’t told us this——”

“Well, haven’t I told you?” Crawford rose, laughing. “There are some Winter garments in the bedroom adjoining. Since we’re bound for Newfoundland, I think I’ll help myself, and advise you to do the same.”

Stepping into an adjoining room, Crawford swiftly provided himself with a large fur-lined wool capote, hat, and a splendid pair of moccasins. He returned to find Bose and half a dozen men around the doorway, Vanderberg bawling orders at them. Two men with fusils were sent to keep watch over the trail that led up-river, the others[20] were set to work looting the interior of the house. They reported that plenty of supplies had been taken aboard the ketch, anchored in the bay.

The men hurled themselves upon the rooms, rushing down to the waiting boat with loads of everything they found—blankets, weapons, trading-goods, silver, snowshoes, furs. Frontin, meantime, stood on guard at the chapel door, defending it against intrusion, and Crawford watched the man with a trace of admiration. Whatever his real name, despite his dark past history and his present occupation, this Frenchman was adamantine in upholding his principles; and Crawford, whose whimsical talk of principles and convictions was really more true than he cared to admit seriously, found it in his heart to respect and like this Frontin.

In the midst of the ransacking, Crawford heard the plunging bark of a fusil. He whirled upon Vanderberg.

“You’re caught. Get your men to the boat, quick! Wait there for me. I’ll hold off and gain you plenty of time.”

Seizing from the mantel the large tomahawk which he had retained as his own loot, Crawford darted from the room, leaped out into the snow, and heard the shrill whistles calling the men. A shout came from ahead, around the corner of the buildings and up the river-trail; then arose the biting Abnaki war whoop. Crawford understood that the two men so recently set as an outpost had been encountered by some of Saint-Castin’s returning party.

Another fusil banged out its message, another Abnaki yell went barking up into the frosty night. Ahead of[21] him Crawford saw the two seamen stumbling back through the trodden snow of the trail.

“To the boat, quickly!” he snapped at them, then threw back his head and sent a long, quavering cry of four syllables sounding up through the forest. It was the most feared and dreaded sound that could be heard in French or Algonquin ears—a sound to stop the very heart-beats of Abnaki or Caniba or Malicete warriors, a sound that, coming from the throat of the unknown raiders, would bring Saint-Castin himself to a cautious halt. It was the war-cry of the Mohawks.

“Sassakouay!”

It rose fierce and sharp with the true intonation that Crawford’s red friends had taught him so carefully, ringing up through the frosty trees, a veritable peal of doom to Algonquin ears.

“Kouay! Sassakouay!”

A distant yelp, like the frightened outcry of a street cur pursued by a mastiff, came from the depths of the forest, then silence. Crawford, smiling grimly, turned about and regained the front of the palisade. He found Frontin waiting there, alone.

“They’ll scout cautiously,” he said, laughing a little. “We’ve plenty of time. That Mohawk whoop will hold them back more firmly than many muskets.”

“You took a chance that we’d wait for you,” said Frontin.

“Not a bit of it. I knew you.”

Frontin grinned at that, and the two men were friends.

Crawford could make out little of his new environment until morning, which disclosed the ketch L’Irondelle standing east for Cape Sable and leaning over to a whirl of wind and snow from the northwest.

The ketch was a miserable craft. Her foremast was set nearly amidships and was square rigged, with a spritsail forward, while the main carried a fore-and-aft mainsail and a tiny square topsail above. She boasted three twelve-pounders to a side, leaked like a sieve, was alive with rats and vermin and was rotten of rigging, canvas and wood from truck to keelson; her sole virtue was speed in the water. As Vanderberger explained apologetically, he had left Jamaica hoping from day to day to get a better ship and augment his crew at one blow, but luck had been against him. He was complacently hopeful of picking up an English ship near Newfoundland, unless a French frigate ran him down in Cabot Strait.

“Those cursed French and English are always fighting in these parts,” he declared mournfully, “and one can never tell when a fleet will show over the horizon.”

The men forward, under the hulking ruffian Bose, were a hard lot. Some were escaped negro slaves from Hispaniola, some were French, and the remainder were[23] Dutch and English. All had for the past two years been engaged in the savage fighting and raids centring on Jamaica, which had been an open prey to all men since the great earthquake wiped away its defences and defenders. Most of them were drunk, for during the night Vanderberg had served out rum enough to conceal the fact that he was heading east, and when the accession of Crawford as third in command was proclaimed, it passed the vote almost without comment.

“So long as we have no sun,” said Frontin in disgust, “the rascals will hold the course we set and ask no questions. Nine-tenths of them steer by the mark on the card and cannot read the directions. But, my friend, when they discover that we head north—ha! Then you’ll see crimson snow. I’ve told them that we’re steering south, and have altered the card in case any of those who can read investigate the matter.”

Crawford shrugged.

“Better to meet the thing squarely—but let be. You can navigate?”

“I was once lieutenant de vaisseau in his most Christian Majesty’s navy.”

This was almost the only time in their long companionship that Frontin ever referred to his mysterious past.

So the Irondelle drove east through long hours of grey day and black night, while ever the bitter gale swept down out of the northwest, and Vanderberg matched the shrieking winds with his deep-chested roar. A rare seaman was the Dutchman, knowing his ship as a book and holding her under a press of sail that sent her scudding like a race-horse.

[24]Bitter cold it was aboard the ketch. The men, inured to privations, made no murmur; since the ballast was all in rum from French Hispaniola, the black cook was kept busy through the long hours dealing out hot grog without cessation, and if the men went about their work half-drunk, they had need to be so. The pumps had to be manned continually, their monotonous clacking never coming to an end. Now and again the rotten rigging would give way, and up must go the men to reeve new lines through frozen sheaves; twice the rotten canvas blew out and had to be taken in, mended and patched under the driving snow, sent up again; and the little main topsail blew away altogether and vanished up the sky. At this, Vanderberg bellowed gusty laughter.

“It’s a sign we’re not bound for hell this cruise, lads! Spell the pumps, lest they freeze, and the rest of you fall to work with axes.”

This, indeed, was the sternest job of all, one that had no ending and was dangerous into the bargain. Gripping the frozen life-lines, the men spread out and chopped away the gathered snow and the ice, forming thicker every moment. In the night this had to be done with lanterns bobbing, black seas rising up out of the darkness and sweeping the decks, new ice forming as fast as the old was cut away, the blunt bows of the ketch smashing over the roaring seas and a hissing rush of water rising and sweeping away as each sea passed on.

Despite all this, despite their maudlin profanity and half-mad frenzy of exertion, the men were cheerful enough, for this was a new sort of privation to them.[25] Hunger and thirst and burning sun they were all too accustomed to meet. Now they had taken aboard no lack of wine, good caribou meat both frozen and smoked, corn and meal and other viands, furs and warm clothing galore, with no little booty in beaver and small loot.

The gale held through the second day, though the snow had ceased and the bitter cold had lessened, so that it seemed to the men they were indeed heading south.

“So long as they do not suspect, gain no sight of sun or stars, and do not try to use their heads in the matter, all well and good,” said Frontin. The three officers were gathered in the stern cabin at noon, leaving the deck to Bose. “They bear Crawford good will for the way he halted Saint-Castin’s redskins and let us get off without harm.”

Crawford grimaced. “The good will of vermin is not valuable——”

“Pardon, but you will find that vermin bite!”

Vanderberg shoved into the talk, glaring at Frontin from bloodshot, sleep-lacking eyes.

“Listen to me! We are heading northeast. The chart shows that we shall run into a cape named Sable. What about it?”

“Rest assured.” Frontin’s hawk-nosed, bitter features were confident. “I know these waters well and need none of your charts, which are not accurate.”

“We are in your hands,” said Vanderberg, with a nod. “Now tell me just where we are going, for questions are going to be asked before long. That devil Bose already suspects that we’re not driving south.”

[26]Frontin spilled a little rum on the table, out of the great golden chalice that had belonged to Saint-Castin. With his finger he drew the outline of a promontory.

“This is a point of land half-way around Newfoundland. Here on one side is Conception Bay, on the other Trinity Bay. Here in the end of the point is what the English call a cove—a small harbour, without much protection, therefore without ice. All along the shore are very high cliffs. At one point along these cliffs, near the cove, there is a ledge of rock that extends back into the cliffs like a shallow cave; it is just above high water, and cannot be reached in Summer because of tremendous tide-currents and whirlpools that lie before it. Upon this ledge is the wreck of the galleon, undoubtedly flung there in some furious storm.”

Crawford interposed.

“Saint-Castin was there before with you; why could he not have come again? Why could not the galleon have been plundered by the English?”

Frontin smiled thinly.

“An Indian report of the wreck drew us there—some hunters had seen it from the cliffs, or thought they had. Saint-Castin was taken very ill and had to stay aboard our ship. I climbed down to the place from the cliffs, but would not do it again for a thousand pieces of eight. The poor baron was too ill to understand anything about it, and I most certainly did not tell him the truth, so there you are. As for any one else having found the wreck, that is impossible. No English settlements are close by, the wreck is invisible from the sea, and boats cannot come near the place in Summer because of the[27] whirlpools. In Winter, I believe there is sufficient shore ice for us to land a mile or so from the spot and make our way to it easily. Many ships come with supplies from England for the various settlements during the Winter, and we shall have no trouble exchanging this craft of ours for a better ship. We shall not be disturbed at the work, as the English settlers stay close at home in the Winter, except the hunters who seek caribou inland.”

Vanderberg looked doubtfully at Crawford.

“You are content?”

“Me—content?” Crawford laughed slightly. “My dear cap’n, I have little interest in this wreck, I assure you. If there is any gold, which I strongly doubt, a bit of it may be of assistance to me.”

“The devil! If you’ve so cursed little interest, why are you with us?”

“Because you are heading north. Two points of the compass draw me; one is north, the other is west. If I had a ship of my own, I would head it for Hudson’s Bay; if I were ashore with an open trail, I would head into the west. Since I must temporize with destiny, I am here.”

“Sink me if I can understand you!” growled Vanderberg, but Frontin uttered a low laugh.

“Perhaps you will understand him too well one of these days, my cap’n!”

“What do you mean by that?” said the badgered Dutchman, glaring.

Frontin shrugged and winked at Crawford.

“I am like the Sybil of Cumæ—my meanings show[28] only in the course of time. But the excellent Irondelle is plunging heavily; shall we go above and clear the forecastle of ice?”

The three of them tramped to the deck, and Frontin’s whistle summoned the weary men.

That night the gale moderated, though the stars did not show, and it had sunk by morning to a light breeze off the land which brought down a rolling bank of fog. After daybreak the wind freshened, and beneath its influence and that of the sun the fog slowly began to shred apart and dissipate.

Crawford was standing watch when, without warning, the ketch suddenly slid through thinning fog into the brilliant sunlight of open day. Behind, the grey wall of fog went writhing down upon the horizon, and off the starboard bow was the morning sun, blazing upon a cloudless sky and a glittering blue sea unmarked by any patch of sail or purple loom of land.

Sudden warmth pervaded the ship, and the watch on deck gratefully relaxed to its comfort. Crawford was standing beside the helm when he saw the man all agape, staring from sea to sky; a shout came from forward, and men pointed to the sun, and there arose a roar of discussion.

“Where away be we going, master?” queried the helmsman. “Ha’ the sun changed his bed?”

Crawford chuckled.

“We’re bound north for Newfoundland, lad. North for gold and Spanish plate, in a place the skipper knows of. It’s there for the taking, and no fighting either; in and[29] take it, out and sail south again to New York or where you will, and spend the broad pieces. Yet those fools for’ard don’t want to go north!”

The helmsman hesitated, then grinned.

“I’m with ’ee, master. Hast a pistol?”

Crawford shook his head and refused the proffered weapon. Knife and tomahawk were at his belt, and he wanted no more. Also, that large tomahawk of Saint-Castin’s was nosed into the rail behind him, and he quietly stepped over and secured it. Trouble was close, for Bose and the other men were now on deck, all clustered in an excited knot.

Now the knot burst, and aft strode the hulking figure of Bose, bearded and uncouth as any bear, with the men trailing to right and left. The ketch had but a slightly raised quarterdeck or poop; Crawford strode forward to the ladder of two steps and waited, secure in the knowledge that the helmsman would not pistol him in the back. The fourteen men came to a halt, sullen and anxious and alarmed, and Bose stepped out a pace, glowering at Crawford.

“Master, we be headed nor’east by the sun!”

“True,” said Crawford, his light-blue eyes searching into the ring of faces. “We’re for Newfoundland, where Spanish gold is waiting for us, and no Frenchmen around to hinder——”

A storm of outcries went up in English, Dutch and French, the protest breaking in an angry wave. Bose flung about, silenced it with a roar, then swung again on Crawford.

[30]“This is a company matter,” said he, “and we’ll take no orders from you that haven’t been voted on. North we’ll not go——”

Crawford’s eyes and voice bit out at him like cold steel.

“You dog, you! North you’ll go, and the rest of you!”

There was a moment of silence, so shocked and taken aback were they by this speech. Then Bose whipped out a pistol and lifted it.

The next instant it was dashed from his hand, as the tomahawk whirled and glittered and knocked the weapon over the rail. Crawford put his hand to the second axe at his belt and laughed.

“That’s it, eh? Now, bullies, who wants it fair between the eyes? Fair warning, lads——”

Bose backed hastily into the crowd, but from the other men came a storm of oaths. Then a huge negro at the right of the gang moved suddenly.

“Down with him!” he shouted in French, and from his hand a pistol roared.

The bullet shaved Crawford’s neck and left a red weal to mark its passing; then the keen axe that flamed in the sunlight took the giant squarely between the eyes and sank into the skull, and the negro pitched backward against the bulwark, where he kicked convulsively and died.

“Knife to the next,” said Crawford, and took the knife ready for the cast. But the men shrank, for this sort of play was new to them. And as they hesitated, Crawford spat forth an order.

[31]“For’ard with you! The cap’n will tell you of our course and where the gold awaits us; so vote all you cursed please, but don’t come to me with pistols out. For’ard with you! Hal Crawford goes north, and you with him!”

Then he leaped at them, catching Bose a buffet that knocked the hulking fellow across the deck. Knives flamed, curses filled the air with wild outcry, and as the men still hesitated, the powerful bellow of Vanderberg arose. The cap’n leaped on deck, with Frontin at his heels.

“What’s this?” cried Vanderberg, a pistol in each hand.

“Nothing,” said Crawford, turning aft. “I was demonstrating to these good fellows of yours that an Indian axe is swifter than a pistol. The demonstration is satisfactory. If you’ll break out a little rum, and tell these lads of the wrecked galleon that we go to sack, the company will vote for the north. Two of you lads throw that black fellow overside and give me that tomahawk.”

Vanderberg strode forward. Frontin looked at Crawford, and grinned thinly.

“You’ve cowed them,” said he. “Now watch your back o’ dark nights.”

“Not I,” said Crawford, and pointed forward. “They’ll fight for me now. You’ll see. They’ll be all for the north venture.”

And a roar of applause to Vanderberg’s tale of gold approved his prediction. Thus easily were the wild, childish men swung to any purpose.

So, after troublous days, the Irondelle came to rest in a little cove amid beetling cliffs, fast moored and well-sheltered[32] against anything but a blow direct from the north.

She had not reached her goal without misadventure. Off the Banks she had raised three sail of the line, one foggy morning—French frigates, which only her virtue of speed enabled her to escape. Of the thirteen hands forward, one man had slipped on an icy shroud and fallen to his death, another had been knifed in a quarrel; this reduced the total aboard to fifteen. Wilful waste had reduced Saint-Castin’s looted provisions to woeful want, the gear aloft was dropping to shreds, there was not a sound line aboard her save those that held her moored off the black rocks, and the entire stock of powder in the makeshift magazine had been flooded and ruined. Yet, because the ballast of rum was not yet exhausted and the lure of gold was before them, the men were willing enough to face the worst. The one redeeming feature was that in the bleak snow-clad land fronting them there was no enemy.

On the night of their arrival in the cove, Vanderberg summoned all hands aft to a council in the cabin. They listened in silence as he laid the situation bluntly before them—fierce, wolfish faces in the lantern-light, haggard with toil and privation, lustful for unearned gold, branded men and cutthroats and wild beasts in the image of God.

“Without powder,” concluded Vanderberg, “we are defenceless. Without food, we are powerless. Without gear and canvas, the ship cannot leave here. Without more men, we could not work her south. Before us there is a waste of snow and icy woods—a white desert. One man among us knows this land; let him speak.”

[33]All eyes went to Frontin. He, holding a candle to his pipe, nodded his head coolly.

“Good. From that white desert facing us,” he said, “we shall get men, provisions, powder, gear, and a ship. Is that satisfactory?”

Some of the men cursed, others laughed. They liked Frontin for his cool cruelty and his high intelligence.

“If you say so, then it will come to pass,” said Bose, growling some blasphemy in his beard. “What about the gold?”

“Unfortunately, I cannot be in two places at once,” said Frontin. “I propose that we divide into two parties. I shall remain here with the cap’n and four men, to search out the gold and, if possible, secure it. Seven men and Bose, with Crawford in command, will go into the white desert and bring us men, provisions, munitions, and a ship. Eh?”

There was a roar of laughter at this proposal, which was at once put to the vote and passed, amid a flood of oaths and obscenities. Then Crawford spoke up for the first time.

“The snow is deep. You will provide wings for us to cross?”

Frontin grinned. “I brought Saint-Castin’s snowshoes for the purpose. You can use them; the others can learn.”

“I can use them,” spoke up Bose heavily. “I spent a Winter in Hudson’s Bay, with the English company.”

“Excellent!” proclaimed Frontin. “Now, Crawford, pay attention and you shall learn how this white desert can be made to furnish all we lack. That is to say,[34] provided your scruples against seizing English goods can be overcome.”

Crawford shrugged and tamped down his pipe.

“Self-preservation is the answer, my dear Frontin. I am at your service to command.”

Frontin once more drew upon the table-top a crude outline of the iron promontory at whose tip they were harboured. He put his finger at a spot on the west coast.

“Here, as I remember the map, is the English settlement of Old Perlican, in a very good harbour. It is about two leagues to the south of us. Opposite it, here on Conception Bay, is another settlement called Bay de Verde. How large these places are I do not know, but they are of some size, and are only a few miles apart. I suggest that you march straight down the coast to Old Perlican, which you can reach to-morrow night.”

“Ah!” said Crawford ironically. “Then, without powder, and with eight men at my back, I am to attack this town?”

There was a roar of laughter, which Frontin swiftly quelled.

“Not at all. You are to use those brains of yours, my friend! If you have luck, you will find an English ship at either or both of those places. You will find plenty of sheep, cattle, and dried codfish. A prisoner or two, correctly persuaded, will give you full information. At the worst, you will find numerous fishing-sloops, excellent seaworthy craft, into which you may load supplies.”

“And bring the whole coast down upon us?”

“Bah! Spread abroad some lies. No one will ever suspect that we are harboured here.”

[35]“Very well,” said Crawford. “Get out the snowshoes, Bose, and pick your men. If we have no powder, we need not burden ourselves with fusils—so much the better! If we do not return for a week or so, Vanderberg, you have plenty of supplies for six men. If we do not return at all——”

“But you will return,” said Frontin with assurance. “You cannot fail.”

“Why so?” asked Crawford curiously.

“Because you follow the Star of Dreams.”

While the assembled men stared blankly at this, Crawford met the glittering eyes of Frontin, and in that gaze read an almost superstitious conviction. Somehow, he perceived, the Frenchman had been captivated by his words regarding the emerald star; and smiling at the absurdity of it, he rose and left the assemblage to draw lots for places in the expedition. After all, why not? Perhaps this star, which hung on its thong inside his shirt, and which was a good symbol of his rather vague strivings and longings after a freedom that did not exist, had been sent to him as an omen. His half-jesting utterance had become verity.

“At least,” he thought as he looked up at the blazing stars above the black cliffs, “it is possible. Frontin is a man who reverences religion, and he believes it. I do not reverence religion, but I reverence God—and I think I believe it also. Well, we shall see! I accept the omen.”

Frowning thoughtfully, he sought his narrow berth.

Morning beheld a laughing, cursing, straggling expedition of nine men starting off along the wooded crest of the cliffs. Crawford led the way, a fusil slung over[36] his back and one horn with a few charges of good powder at his belt; behind him followed seven men, with Bose bringing up the rear. As was their custom in all things, the buccaneers donned the snowshoes and set forth to sink or swim; and for a while it was a sinking job. They stumbled, tripped, sprawled in the snow and, like the huge children they were, enjoyed the game. The intense cold was invigorating to them; they had food for two days, their leader had enough powder to shoot any game they met, and ahead was the prospect of loot against heavy odds. From the buccaneer viewpoint the situation was ideal—death at their backs, desperation prodding them forward, all to win and nothing to lose. So the winter-stilled woods echoed back lusty shouts of laughter and wild curses and wilder jests, until Crawford issued an order against too much noise.

The advance was not at all rapid. To most of the men these crusted drifts of snow were entirely novel—a thing to be enjoyed as well as fought. By noon, Crawford calculated that no more than a league had been covered, and he called a halt, the men promptly starting a furious snow-fight, hurling cakes of icy consistency.

Crawford beckoned Bose apart and took out his pipe. It was that same white stone pipe girded with silver, which had rested on Saint-Castin’s mantel; Vanderberg had looted it, and Crawford won it from him over the dice on the way north.

“Give them a bite to eat and a rest, Bose. By night they’ll all be done up with mal de racquette. I’m going ahead to scout, so follow my trail. Give the men a tale[37] of Indians; whether true or not, it will lend them caution and may keep the rogues quiet.”

Bose assented and ducked a cake of frozen snow that came hurtling for him. Crawford, turning to the south, was gone among the trees.

“A mad situation!” he thought, as he broke trail. “But like all mad things, it has a grain of sense. If one could only prevent the grain from being overborne by the mass!”

He plunged ahead through the woods, bearing away from the open shore and cliffs, since he knew well that the sole hope of success lay in absolute surprise, and he dared not risk being seen by settlers or hunters. Bose and the men could follow his trail plainly enough, and might come along whenever they were able. Crawford was for the moment glad to be rid of them and unhampered.

No trace of smoke broke the blue sky. After an hour, Crawford knew that somewhere not far ahead must lie Old Perlican, yet he searched for it in vain. No slightest indication of human habitation was to be seen anywhere in this world of white snow, upon which the sunlight broke with dazzling splendour. The trees were bowed beneath their load of snow, and there was something terrible about the deathly stillness, for the frost was not intense and the trees were not cracking. This absolute silence of the wilderness was hard on the nerves of one unused to it; the only sound among the thickly clustering trees was the faint creak and sluff of Crawford’s shoes in the crust. Then, with a sudden savagery that brought him to gaping[38] and incredulous halt, a voice lifted out of the dark trees to his left.

“Sassakouay!” The gleeful, blood-gloating note thrilled Crawford more than the whoop itself—thrilled him with a sense of frightful things afield.

The Mohawk war whoop—here in this place! It was absurdly out of all reason. Despite his surprise, Crawford knew well enough that his own presence was unsuspected, or that whoop would never have been lifted. He went forward cautiously, working his way over a crest of higher ground among thick pines, and so came abruptly upon a road that lay below him. Biding there in cover, he scrutinized it.

It was a road beaten deeply through the snow, marked with the wheels of carts and the runners of sleds; since it ran from east to west, it must be a road from Bay de Verde to Old Perlican. Yet who had uttered that Mohawk whoop, here in this solitude? That was a thing inexplicable.

Only for a moment, however. Off to the left appeared a moving shape—a man, bareheaded, running clumsily, casting frightened glances over his shoulder, tearing off a heavy coat as he ran. A sobbing cry burst from him, directed apparently at high heaven, since it was impossible that he could imagine any one to be near at hand.

“Help! Help! The red devils are on us—help! Ha’ mercy——”

Crawford stiffened in a momentary paralysis of utter amazement. From the trees opposite him, and ahead of the English settler, glided a figure which cut off the flight of the settler. The figure was cloaked in long blanket-coat[39] and wide beaver hat, but from beneath the brim of the hat peered out hideously painted features grinning at the wretched fugitive.

Here was the source of that Mohawk whoop! Incredible as it was, the thing was true. Crawford saw the redskin deliberately whip out tomahawk and poise for the throw, while the settler, plunging blindly along the road, was ignorant of his doom. Crawford gripped his own axe and, with a swift motion, hurled it—but too late. The other had flung, and even as one blade hit home, the second followed suit. Each man was destroyed by an unseen enemy. Crawford’s axe struck through wide hat to brain, and the woods rover plunged forward into the road, without a cry. The hapless fugitive, struck glancingly, but no less fatally, dropped in his tracks and the tomahawks spun in the icy road beyond him.

For a moment Crawford waited, searching the farther trees with keen scrutiny, appalled by what had just happened; that the Mohawk could be raiding this country was beyond belief. No sign of any one else could be descried and, as he looked back to the two figures, came the explanation. The rover’s wide hat had fallen away to disclose reddish hair. He was no redskin, but a white man, a Canadian—one of those voyageurs and coureurs-de-bois who had adopted Indian habits, wives and appearance. This explained the Mohawk cry, for many of that clan had settled above Montreal and took the French part against the English and Iroquois.

The English fugitive lifted his bloody head and came to one knee. Crawford broke from his covert and, discarding the snowshoes, ran to help the man, catching him[40] in his arms. A glance showed that the wound was mortal, but the dying eyes widened on Crawford.

“Who are ye?”

“A friend,” said Crawford, unwonted kindness in his cold eyes. “I tried to get the rogue before he let fly, but failed. Who is he? What does it mean?”

“English, be ye? On guard, on guard!” A flicker of energy filled the fading voice. “I run away from ’em—the devils are sweepin’ the coast! It’s Iberville himself, they say—Canadians, Injuns! St. John’s captured, burned; they’ve burned Heart’s Content, Havre de Grace, all the settlements! Carbonear Island holds out—whence come you that you know not these things?”

“I landed yesterday,” said Crawford.

“Then flee with your ship!” cried the dying man. “There is no rescue—all is slaughter! Old Perlican is burned—sloops burned—ship captured—ship from England at Bay de Verde was taken last night—full of provisions—the Irish slaves have risen against us—murder——”

The man’s head joggled forward in death.

So there was war in the land! Crawford stood for a little in thought, astounded beyond measure by this news. He had heard of Iberville ere this; that name was both famous and infamous in New England, for it was Iberville who had raided Schenectady with his Mohawk brethren—a gentleman, an officer of the French navy, a wild adventurer who halted for no odds, a Mohawk by adoption. Such was Pierre le Moyne, Sieur d’Iberville.

“So Iberville is ahead of us, eh?” thought Crawford,[41] and his lips twitched whimsically at the thought. “And he took a ship of provisions last night, at Bay de Verde! And what was that about Irish slaves? Poor devils of Jacobites sent over here and branded! Sink me if all this hasn’t a significant hint for my ears! M. d’Iberville, I salute you! Now, my Star of Dreams—lead on!”

Pausing only to retrieve his tomahawk and take the fusil and munitions carried by the dead Canadian, he turned about and hastened on the back trail to rejoin his men.

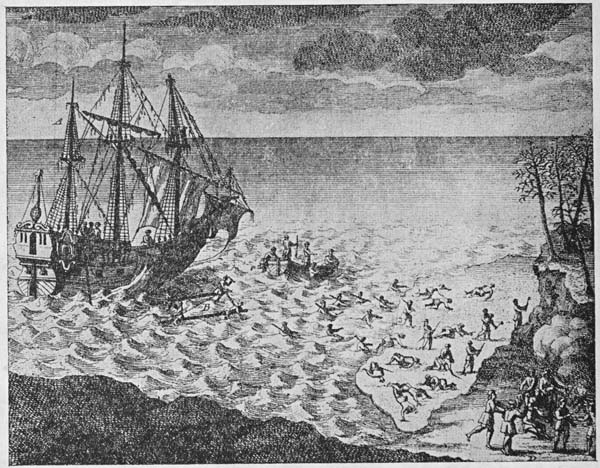

In the late afternoon, five men sat about a fire on the hillside north of Bay de Verde. Below them was a scene of destruction; the settlers having broken their parole, Iberville was laying waste the little place. Canadians, hardly to be told from Indians, were driving sheep and cattle to slaughter on the beach; the score of log-houses were being pillaged, and already two of the farther buildings were burning fiercely. The hapless settlers, such of them as had not already escaped to Carbonear Island, were being herded into fishing-sloops for transportation to Placentia. Lying at anchor offshore was a goodly bark of over sixty tons, just from England; she was laden deep with stores, and by the gleam of her canvas and the scarcely battered paint, was brand new. She was schooner rigged.

The five men who had gathered about their fire, trees closing them in on three sides, had obviously participated in the sack of the place. Portions of a butchered sheep were cooking at the fire. Four of the men, busy replacing filthy rags with looted garments, were shaggy of hair and beard, pinched and starving of countenance, and had something the air of wild beasts as they pawed over heaps of stolen articles.

The fifth man was different. He was prematurely grey, his haggard face was drawn with suffering both[43] mental and bodily, and in his forehead had been seared an undistinguishable brand. Yet he seemed of a higher intelligence than the others, who treated him with a certain respect; and having changed his rags for good clothes, he was at work with knife and broken mirror, trimming his wild grey beard into some neatness. One presently observed that he seemed different from the others because of an undeniable cleanliness, which the other four obtrusively lacked.

“Victory and blessings!” exclaimed one of the four, staring down at the scene below. “If we had fusils or pikes, and a garran to each one of us for riding, and Phelim na Murtha yonder for the leading of us, it would be plague to the Saxon!”

“True for you,” said another, speaking likewise in Irish. “With the knowledge there is with us of this accursed country, and the others of us who are elsewhere, it’s a fine stroke here and there we could lay down! Do we join the Frenchmen, Phelim?”

Thus addressed, the grey-haired man lifted his head and regarded the four. In his eyes one saw that his spirit remained unbroken, though his body might be far spent.

“Facies ut tua est voluntas,” he murmured in Latin, then smiled. “Nay, lads! Join them and gain freedom. As for me, I am broken in body and my right leg will never lose its limp, and the hair is grey that should be black, and the forehead branded—nay! I shall get a sword, and go to Carbonear Island and land among the English, and die there after a last stroke at them.”

At this, a voice came out of the trees.

[44]“Well said, Sir Phelim Burke of Murtha!”

The four men sat staring around, dumfounded. But Phelim Burke sprang to his feet, a wild light in his face, his hands all a-tremble.

“Who called me? What voice is that?” he cried out. “I used to know that voice——”

“D’ye remember Boyne Water, and the king who was a coward, Phelim? And who it was called him coward to his face, eh?”

Out from the nearer trees strode Crawford, laughing a little as he gazed on the five of them. Now Sir Phelim uttered a great cry.

“Harry Crawford—is it mad I am, or a ghost?”

“Try this,” and Crawford, leaving his snowshoes, came over the trampled snow with hand extended.

The two men gripped.

“Gad, Phelim, what a meeting is this! All friends here, eh? This is good enough. Tell ’em to down knives before they smite me.”

Phelim Burke excitedly addressed the four, who were closing in on Crawford, and they sheepishly relaxed.

“Harry, Harry, this is like a dream!” cried Sir Phelim, tears standing in his eyes. “Two years we’ve been slaves in this land, wild beasts of burden—art with Iberville?”

“Devil a bit,” and Crawford laughed. “Nor, as I gathered from your speech—though I’ve forgotten the Gaelic in large part—are you. I’ve a pirate craft hidden up the coast. Will you and these men join me, Phelim?”

“Ay, to hell and back!” said Sir Phelim promptly. “I’ll answer for them. But I’m a broken man——”

“Don’t be a fool,” snapped Crawford. “Listen, now![45] We’ve small time for talk, since the afternoon is wasting. Is Iberville himself down yonder?”

“Ay, and forty devils of Canadians.”

“They are burning the place—there’s smoke from another house.” Crawford’s gaze swept the little harbour. “D’ye know when they are leaving?”

“Not until morning.”

“Excellent! I need men, Phelim. Five of you here—can we get any more near by?”

Sir Phelim questioned his four. These, all of them Sea Burkes out of Galway and veterans of the Irish wars who had been taken prisoner and shipped to Newfoundland as slaves, were eager enough to follow Crawford, the more as he was an old friend and companion in arms of Sir Phelim, whom they loved. They said that a number of Irish were roving the woods, and several were thought to be at Old Perlican, to which place a detachment of Canadians had departed, with intent to give it a like fate with that of Bay de Verde.

Crawford whistled, and in came Bose from his concealment among the trees.

“Here are five of our fresh men, Bose, and down yonder the ship awaiting us. Go back to where the men are camped, set out a guard or two against roving Canadians, and after dark bring them on to this spot. Off with you! Now, Phelim, would it be possible for two of your men to cover the six miles to Old Perlican, rouse up any of their comrades whom they may find, and be back here before dawn?”

At this, Phelim Burke laughed as he had not laughed for many a month.

[46]“Lad, these Irish can outrun horses! And with freedom awaiting them, what can they not do? They’ll be back an hour past midnight, I promise you. One to Old Perlican, the other three to roam the woods. Iberville has released us all and offered us refuge in Canada, but we’ll ship with you.”

The four Irish, waiting only to catch up their half-cooked meat from the fire and bear it off to eat as they went, departed hastily. Left alone, Crawford and Sir Phelim settled down by the fire to bring old friendship up to date.

Phelim Burke na Murtha had seen hard fate—his family was wiped out, he himself had been racked and tortured, and the two years here in Newfoundland in bestial slavery to masters who knew no pity had all but finished him; yet the spirit burned strong within him. He nodded soberly to Crawford’s almost defiant declaration of freedom.

“Ay, Harry, I’m with you. The world’s burned out for me, and I’ve no heart for the vain mockery that once we loved. Throw all the stars into the bowl of night and pluck one out, and follow it; then, lad, if you’ll be burdened with a broken Irisher who seats mad whims higher at table than sense——”

Suddenly Crawford, putting a hand under his shirt, held before Burke’s amazed eyes the emerald jewel.

“Here’s your star, Phelim—Star of Dreams it’s named, and I’ll live or die by it!”

He started up, pointed to the cove below.

“Look, man, look! There go more houses to the flames.[47] You’re certain Iberville will stay here the night? Then why send the buildings roaring?”

“He’ll stay, for he has to await the party back from Old Perlican. As for houses, it’s little those wild Canadians care for roofs over their heads, lad! Faith, ye should ha’ seen Iberville and his men sweep over that English bark at daybreak, against cannon and musketry! It’s fighters they are, lad. Beside them the French are fools.”

As the sunset drew on, Crawford heard how Iberville and his six-score Canadian rovers had wiped the Newfoundland settlements out of existence, yet doing it with no needless slaughter. They had come overland from Placentia in the dead of Winter and struck the east coasts like a thunderbolt, nor could the scattered settlements resist them, though there were some hundreds of hunters to swell the ranks of the settlers. The impregnable island of Carbonear alone held them at bay, while those who escaped had fled to Bonavista in the north, which Iberville would attack ere the snows melted.

Crawford in turn told Sir Phelim his own story, and that of the Star of Dreams, and the darkness came upon them while they talked, with the burned houses below glowing as red patches against the star-glistening snow.

“If we can carry off that bark,” said Sir Phelim, a new ring to his voice, “then I’ll ha’ faith in your Star of Dreams, Harry! She’s loaded to the gunnel with supplies of all kinds, carries three twelve-pounders and as many culverins, and Iberville has put aboard her a good share of the new-killed meat and the captured cod. What a[48] prize she’d be for destitute men! But they’ll have a guard aboard her, and how could we reach her?”

“That’s to find out,” said Crawford. “They’ll not suspect you, Phelim—could ye not find out their dispositions, and where the boats lie on the shore?”

Sir Phelim nodded and rose. He departed limping, by reason of a broken leg that had knit poorly, and Crawford stared after his vanished figure with sorrowing gaze.

“Devil take all kings!” he muttered. “There goes a better man than any of the Stuart breed he has fought for—yet at forty Phelim Burke is an old man of seventy! And down yonder honest settlers are driven forth and good Canadians are risking life and limb—murder is done and steel cleaving flesh—for what? For the pride of besotted fools who wear gilt crowns. I’ll fight, sink me if I don’t, but it’ll be for my own hand, for my own life, for my own free pleasure. Ay, my Star of Dreams, lead the way! We’ll go over the horizon together.”

He built the fire up afresh, careless whether it were seen by the French below, and, taking out his pipe, smoked in thoughtful reflection. In throwing off all shackles of allegiance, in declaring his quest of freedom, he knew well that he made of himself nothing better than an outlaw; he had no intention, however, of stalking up and down the haunts of men and vaunting himself. He cared nothing for the eyes of other men—he was questing that which would answer to the inner man alone.

One thing he forgot—that every act committed in this world, whether for good or ill, brings a certain reckoning in its train. And now there was upon him the reckoning of an act which he had already forgotten.

[49]The night was warm, the snow-crust was melting, and though the stars were out there was rain in the air. Crawford, as he sat before the crackling fire, heard no sound whatever until a voice sounded at his very elbow in French.

“Do not move, monsieur! My brother wishes to ask you a question.”

Crawford glanced around, could see nothing, but caught the click of a pistol at cock. Without sign of his surprise, he took the pipe from his lips and laughed shortly.

“Greetings, mon ami! You have somewhat the advantage of me. Since I am prejudiced against speaking with unseen friends, may I suggest that you advance without fear?”

A somewhat boyish laugh sounded softly, but it died out into ominous words.

“Your pardon, monsieur! This is an affair in which I have no share, save that of curiosity—and compellance. My brother Pierre-Jean Beovilh, the great war-chief of the Abnakis, desires to ask you a question.”

While these words sounded at the elbow of Crawford, a man stepped into the circle of firelight opposite him and came to a halt. Crawford gazed curiously at the visitor, not betraying the dismay which seized upon him; he saw a tall Indian, who had flung aside his garments and stood naked to the waist, painted and feathered, the features repulsively ugly and ferocious. As he stared at the Abnaki, the latter spoke to him curtly and without any of the usual preliminaries, in very good French.

“Who are you, who hold in your hand the sacred calumet[50] of the Abnaki, which has a home in the lodge of my brother Saint-Castin at Pentagoet?”

And Crawford realized that the stone pipe in his hand was one which had been taken from the mantel of Saint-Castin, where pipes had stood racked.

Inspecting the war-chief, at whose belt hung fresh scalps, Crawford took his time about responding. Suddenly piecing together what he had previously learned and what Phelim Burke had been telling him, he comprehended his acute peril.

This Pierre-Jean Beovilh had come from Acadia to join Iberville’s raiders, was the highest Abnaki chief, and belonged to the now destroyed clan of the Caniba. Saint-Castin, by his marriage to a red princess and his unsanctioned union with many other ladies of colour, had constituted himself a sort of vicar-general to the Abnakis. It was highly probable that the sacred relics of the Caniba clan had been deposited with him for safe-keeping, and that this white stone calumet was one such relic, profaned by Crawford’s usage.

Now, knowing himself trapped, Crawford took the one open trail—that of audacity. He must know with whom he dealt, for the greatest danger was that the whole Canadian force would be brought upon him. One shot, one yell, would bring them.

“In the cabanes of the Mohawk clan of the Iroquois I am known as The Eagle,” he said calmly. There was truth in this, though he had never visited the elm-bark lodges of his Mohawk friends. “The Eagle does not talk with cowards who fear to show themselves. Let my red brother call his French friend out into the light.”

[51]At the Mohawk name, the Abnaki chief started slightly. Then, answering Crawford’s challenge, another figure stepped from the shadows, pistol cocked. Crawford was astonished, first to perceive that it was a boy of sixteen, and second, by the aspect of this boy. He was handsome as an Apollo, long brown curls framing his perfect features and despite his youth there was a certain air of dignity and command in his countenance. His eyes glinted hard at Crawford as he spoke in French, using the redskin phraseology.

“My white brother has a Mohawk name, but he is not a Mohawk; he speaks with the French tongue, but he is no Frenchman. Let him speak. I am Le Moyne de Bienville.”

Bienville—brother to Iberville! Crawford could not repress his astonishment as he regarded this boy of sixteen, accompanying veteran wood-rovers on a raid so perilous and even desperate. And reading the look, Bienville’s boyish pride instantly resented it.

“Speak!” he snapped angrily. “Is The Eagle a woman, that he fears to speak to warriors?”

The Abnaki chief, hand on knife, watched Crawford with unwinking gaze.

“The Eagle looks at the sun and does not blink,” and Crawford’s rare smile leaped out, so that the boy’s anger vanished instantly under the implied compliment. “But The Eagle has been asked a question by this snapping cur. The Eagle did not know that the Abnakis had a war-chief; he thought they were women, whom the French Mohawks protected from the wrath of the Iroquois nation. Now let this Caniba dog, whose clan is only a memory[52] among the Abnaki nation, gaze upon this coat which The Eagle wears. Let his eyes rest upon these moccasins. He has often been in the lodge of Saint-Castin; perhaps he will recognize them.”

The Abnaki, whose coppery breast was heaving with rage at these words, spat reply.

“They belong to my brother Saint-Castin.”

At this, Bienville started slightly and watched Crawford in astonished speculation. The latter puffed again at his pipe, then spoke quietly, deliberately.

“Then let the Abnaki dog go and ask Saint-Castin for an explanation. Or, since he is a woman and a snapping cur at French heels, let him summon his Canadian friends to make The Eagle a prisoner.”

Now the fury of the war-chief burst all bounds.

“The war-chief of the Abnakis does not need Canadians to help him lift the scalp of a thieving Englishman, who calls himself by a Mohawk name and speaks the French tongue!”

Bienville, perhaps comprehending Crawford’s purpose, attempted to interpose, but the furious chief turned upon him with a flat demand that he keep silent.