By LARRY EISENBERG

Illustrated by SCHELLING

Steinberg was an electronic genius. Here, the Old West was

dead and gone for many decades, but now once again a man

could stroll down Main Street for a showdown with the Marshal.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Amazing Stories January 1964.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Like most men, Amos Handworthy was a creature of many parts. To his business associates he was a sober, calculating entrepreneur, given occasionally to rash ventures which through outrageous turns of luck usually ended well. To his employees he was a distant, ominous figure, wandering through his electronics plant occasionally, staring with pale blue eyes at a myriad of trivial details, sifting through the reject box of discarded transistors and occasionally stopping to ask a loaded but seemingly innocuous question of one of the production engineers. To his housekeeper he was a brusque, harsh man, not given overly to entertaining or keeping late hours but sober, sedate and completely absorbed in his pervasive habit of collecting automata.

Very few men had ever seen the eyes of Amos Handworthy come aglow and Manny Steinberg was one of them. Manny was a superb engineer who combined the ability to carry out a sophisticated circuit design with the old fashioned desire to tinker. It was almost physically painful for him to pass by a mechanical device that was not in working order. And so, in his first visit to the Pecos Saloon, a town landmark that had been restored to its pristine décor through the generosity of Amos Handworthy, Manny caught sight of the magnificent music making machine as soon as he cut through the swinging doors. He proceeded first to the bar and availed himself of the tequila and lemon juice which was the specialty of the house. Much of the town showed the influence of its close location to the Mexican border, the large Spanish speaking population, the frijoles that were vended off street carts, and the tastes in liquor.

Still sucking on the lemon, Manny walked over and surveyed the glass enclosed music maker, four vertical violins arrayed in a circle with a hoop of horse hair spanning about the four violin bridges, electromagnet stops hovering above the strings. A dried out square of paper had been crudely taped across the glass with the clear inked inscription, "Out of Order." He had removed the back door of the machine and was examining the innards when he felt a proprietary hand on his shoulder and swivelled about to meet the questioning gaze of his boss, Amos Handworthy.

"I think I can make it go," said Manny, not certain that he could but unable to leave this marvelous array of gears, levers, and multi-pinned rotating disks.

"I've tried to have it repaired and failed," said Amos Handworthy. "But if you can do it, it's worth a thousand dollars to me."

Manny nodded as though this offer had tipped the balance but in truth it made very little difference to him. Even the following week, when he demonstrated to a full saloon how beautifully the four violins played the Mephisto Waltz, he accepted the check which Amos Handworthy placed in his hand with some puzzlement, not quite connecting it with the maintenance miracle he had just wrought. Handworthy insisted on having the machine play again and again, but after the fourth successful round, Manny had lost interest in the device and was more concerned in downing tequilas than in listening to the music.

Later that night, as he lay abed on a rumpled sweat-wet sheet, wondering how in hell he had taken a job in this God-forsaken town in Texas, he remembered dimly that his boss, Mr. Handworthy, had invited him over to the stately Handworthy Mansion. He was not sure when the invitation was for, or whether the occasion was of a business or social character, but he knew that it was mandatory that he come.

Fortunately, a handwritten note on gray, unembossed letter paper arrived the following day, confirming the invitation and specifying a dinner date the following Friday evening at eight P.M. Manny's income was a good one and he had eaten in some of the finest restaurants in the country but he had never been to the home of a truly wealthy man before. It was with no little trepidation that he appeared at the door of the Handworthy Mansion and was ushered into the house by the liveried butler who was, to Manny's intense surprise, white.

He was somewhat taken aback to find that he was the only dinner guest and that the burden of making conversation would be totally his job. But he found that contrary to his expectation, Amos Handworthy did almost all of the talking.

The food was plentiful but not lavish or exotic in character. Mr. Handworthy himself carved out liberal slices off the huge side of beef that was brought in on a great silver salver. And although Mr. Handworthy did not drink it, the wine was carefully chilled and of good (but not the best) quality.

Since Manny had been raised in a low income Jewish inhabited section of New York City and had, despite his extensive rootless shifting about the country, no real insight into how anybody else lived, he found himself quite taken with the rambling tales that Amos Handworthy told of his town's history.

"My father," said Amos Handworthy toward the close of the dinner, "was one of the last frontier marshals and maybe the greatest. His draw was reputed to be so fast that the eye could barely follow it and he never missed his target."

"But he drank like a fish," he thought, "and spent most of his time at the sporting house on East Maple."

"As a boy," he said aloud, "I could think of nothing more ideal than to follow in his footsteps when I grew up. Course, when I had grown up, there was no more frontier, no more show downs in the center of town. It was a terrible disappointment and one that I haven't gotten over, even yet."

"My father," said Manny pensively, "claimed that I had clumsy wooden hands. He was wrong and I think he knew it. But he'd never admit it to me."

"Do you know what disturbs me?" said Amos Handworthy. "There have been challenges for me, some financial, some physical, others social, and I've met and beaten every one of them. But I've never been in the same mother naked kind of situation my Father had to meet where it was one man's raw courage and skill against another's."

"The thing that disturbs me," said Manny, "is that whenever I knock off a particularly tough job, instead of being elated, I'm totally depressed until the next challenging one comes along."

Amos Handworthy raised the wine bottle to the light and studied the play of color through the thickened glass.

"Come inside," he said abruptly. "I've got something special I want to show you."

Manny followed after his host and found himself in a huge, high ceilinged room flanked on all four walls by reward posters, some as much as one hundred years old. There were no furnishings in the room, just a series of unusual pieces of furniture that proved on closer scrutiny to be automata of diverse types. In the center of the room was a great amorphous mass covered by an enormous sheet.

"I have no kin," said Handworthy, staring possessively about him. "I've never married so I have no children. But I'm a happy man nevertheless. These are my children," he said, gesticulating about him. "This one, is a particular delight," he added, his voice swelling with pride as he brought Manny over for a closer view.

It was a gray enamelled case surmounted by a glistening blue hemisphere adorned with tiny stars of silver and gold. Within the hemisphere was an exquisite miniature ball room, the walls lined with mirrors, and when Handworthy wound up the movement and released the catch, two groups of tiny dancers began to waltz toward each other. Their images were caught up and multiplied an hundred-fold in the mirrors creating a truly breathtaking sight as the unseen strings of a harp were plucked below in the gray enamelled case.

Before Manny could comment, he was whisked over to a superbly crafted wooden figure of a charming child, a painted smile wreathing the gently carved mouth. The child was seated on a mahogany stool and when the latching hook had been lowered, it leaned forward and after dipping a feathered pen into an ink-well, began to write in smooth cursive flow. When she leaned back, her motions apparently brought to a close, Manny bent forward and found to his intense amazement a beautifully crafted letter of some fifty words written to the mother of the child.

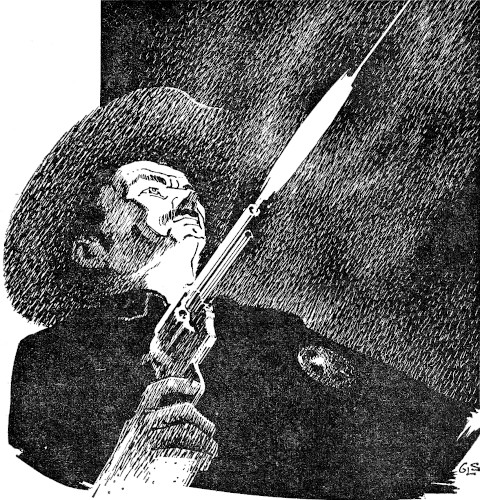

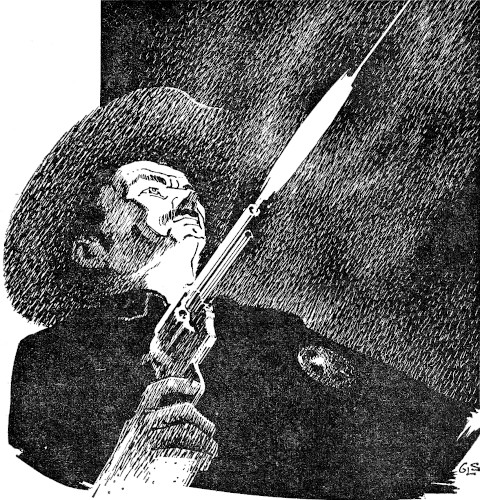

There were other amazing sights, an android that fingered and breathed wind into a flute that played sweetly, a reclining Cleopatra that rose, bowed gravely at the waist and then lay down once more upon her feathered couch. Since each of the treasured machines was in perfect functioning order, Manny rapidly lost interest and merely followed Handworthy about, nodding politely, his mind distant upon a persistent circuit problem that was still unsolved. But he was jarred back to reality when, with the reverence that one would use to lay bare a sleeping nymph, Handworthy removed the sheet from the huge centerpiece of the room. It was a small segment of a Western street, complete with hitching post, before which stood an uncannily lifelike figure of a town marshal, complete with vest and badge, chaps and holstered gun. The painted face was scowling and from closer scrutiny it was apparent that the figure was capable of complex motion.

"The others," said Amos Handworthy, "are marvelous antiques that I've collected, but this fellow was made to my own specifications in Switzerland. His clothing is quite authentic and he really works. Watch this!"

He stepped forward and took a loosely draped gun belt off the hitching post to the right of the Marshal and buckled it about his waist.

"The device is electrically operated," he continued. "The instant I draw, the Marshal draws too, and the trick is to hit him somewhere on his target photocells with a beam of light that flashes out of my gun, before he can get off his shot. I can adjust the speed of his draw within fairly wide limits and I've been moving him up to faster and faster speeds. But I've gotten pretty damn fast."

With a drawing motion that was almost a blur, he whipped out his gun and pulled the trigger. The Marshal was fast, but apparently not as fast for suddenly a recorded voice bellowed in pain and gasped, "you got me, you dirty varmint."

"A little touch of my own," said Amos Handworthy. "That's what happens when I hit him."

He looked down at his gun, almost proudly, and Manny had the eerie feeling that it was only with restraint that he did not blow the imaginary smoke away from the gun barrel.

"That's a highly imaginative device," said Manny.

"He is," said Amos Handworthy. "But he's still not quite what I want him to be. I have an idea that you can make him the kind of opponent I need."

"What do you want?" said Manny. All of his ennui was beginning to evaporate and the familiar exultant response to challenge had begun to grow in him.

"I want him to be able to hit me, too, figuratively speaking," said Amos Handworthy. "As things stand now, this shoot out is entirely one sided. I'd like to know, for instance, if he's been able to hit me."

"I can do it," said Manny. "You'll have to get me off my regular project, but I can do it."

"I'll call your division chief in the morning," said Amos Handworthy. "You'll stay here with me and you can have all the time you need."

Manny did not sleep well in his spacious overly comfortable bed. He was up early the following morning pouring over the construction plans for the Marshal and examining the instruction folder which the Swiss company, with typical thoroughness, had included in the neatly packed maintenance kit. He caught the guiding concept of the design at once, and made his plans to modify the Marshal along lines that incorporated control techniques that were basically electronic.

He phoned the plant and requisitioned transistors, metal film resistors, capacitors, and various other components necessary for his task. Handworthy did not approach him as he worked and his meals were served to him either in his own room or the great room where all the automata were located. He made all the changes himself, snipping leads, soldering, forming tight mechanical joints with deft fingers that almost seemed alive and apart from his body.

Ten days later, he called in Amos Handworthy and demonstrated what he had done.

"I've modified both guns so that you and the Marshal will now shoot at each other with ultra violet light. You'll both wear vests that are sensitive to this light. I monitor the hits electrically by measuring the resistance of those areas where a bullet would severely injure a man. Nothing will occur unless you or the Marshal are hit in such an area. Furthermore, you can both continue to shoot for an indefinite length of time. However, I've altered the Marshal's aiming mechanism so that if he's hit in a vital spot, he won't shoot as accurately. Similarly, if you are hit, a defocussing mechanism operates on your light bulb so that your gun is no longer as accurate. And instead of the recorded voice, if either of you is hit in the heart, your gun goes dead."

Amos Handworthy's eyes began to glow with a fire such as Manny Steinberg had never seen and it excited him that his work had brought on so wonderful a response. He slipped the new vest on Handworthy, handed him the wired holster and gun, and stepped back. After fastening his belt and readying himself, Handworthy drew as before and fired swiftly at the Marshal, who was firing back almost as rapidly. Suddenly Handworthy stopped and looked at his gun in dismay.

"My trigger's locked," he cried.

"He's killed you," said Manny drily. "You beat him to the draw, but he's hit you in the heart."

"I see," said Handworthy slowly. "Then it looks like I've got a hell of a lot more practicing to do."

It was a full month before Manny Steinberg was invited back to the Mansion, and with great pride his host demonstrated how he killed the Marshal, every time.

"I've got him set for his fastest draw, too," said Handworthy. "At this point, he's just no match for me."

"I guess that wraps it up," said Manny, knowing full well that it couldn't end this way. "You're just too damned good."

Amos Handworthy shook his head slowly.

"You don't believe that and neither do I. Its an unfair battle, unfair because we've excluded the most vital element of all."

"What element is that?" said Manny although the answer popped into his head even as he spoke and he began to envision the approach that had to be taken.

"There's no fear in this situation," said Handworthy. "When two men were in an actual shootout they were both afraid of being killed. But the Marshal is oblivious to fear and so for the most part am I. Suppose for instance in some way you could make him shoot better if I were nervous and shoot less accurately if I were deadly calm."

"There is a way to do that," said Manny. "I can electrically monitor your vasomotor reflexes by means of your pulse and sweat reactions. Then I would program the Marshal's reflexes in just the way you suggest. But the thing I can't understand is how such a step would have any real meaning. Why in God's name would you ever be frightened? There's nothing in this situation to make it happen."

"I have a very vivid imagination," said Handworthy. "As a child I had no playmates and still I populated an entire world in my mind, every one a distinct person. Don't you see, I can project myself into feeling that I'm in the real life and death situation just as long as the Marshal becomes a creature sensitive to fear."

It took Manny almost three weeks this time to make the requisite changes and he carried out in addition an extensive series of pulse and skin resistance measurements on Handworthy. When he was satisfied that the Marshal had reached the ultimate state, he called in Handworthy and demonstrated what he had done.

"I've installed," said Manny, "a feedback circuit that's inoperative when your typical emotional reaction exists. But the circuit comes into play when you become more nervous than usual and the Marshal will therefore shoot faster and more accurately. On the other hand, if you should become less concerned, calmer perhaps, the Marshal's aim would tend to go askew and his firing rate would slow down. In other words, you and the Marshal are indissolubly linked through your nervous system whenever you strap on your shooting vest."

"Fine," said Amos Handworthy and the brilliance of his usually lackluster eyes gave an added emphasis to the word. "You've surpassed my greatest expectations with these new changes. And while I know it wasn't part of our bargain, I intend to add a pretty big sum to your monthly check."

"Thanks," said Manny automatically. Already he was becoming aware of the depression that followed his engineering triumphs. As he left the house, he had almost completely lost interest in his accomplishment.

Meanwhile, Amos Handworthy was examining the guns with great care, particularly the tiny switch that activated the firing cycle. It was evident to him that as soon as his gun lifted off the switch, electrical activity commenced. After first unplugging the Marshal's electrical cable, he carefully removed the ultra violet loaded guns from the fixture in his holster and the Marshal's holster, and replaced them with beautifully machined Colt .45's that were loaded with real bullets.

"There's absolutely no doubt that the mechanical action will be the same," thought Handworthy, "and now the element of real fear, both mine and his will be in the picture. We're going to have a real shootout, the kind you don't see any more."

He replaced the plug in the wall socket and turned about to face the Marshal quite squarely, shifting his belt around so that his gun would clear free of the holster. The Marshal stared at him out of sightless painted blue eyes, his mechanical hand resting stolidly on his gun.

"Even now, it isn't an even match," thought Handworthy ruefully. "I couldn't be any calmer than I am now. I guess it never can come out just exactly as I want it to."

As his fingers flashed lightning fast to his gun, it suddenly occurred to him that Manny was right, that he and the Marshal were indissolubly linked through his own nervous system. He had no kin, no wife, no children. The Marshal was the only one on earth really tied to him. And in that instant, a terrible surge of fear came over him at the thought of killing his own.

THE END