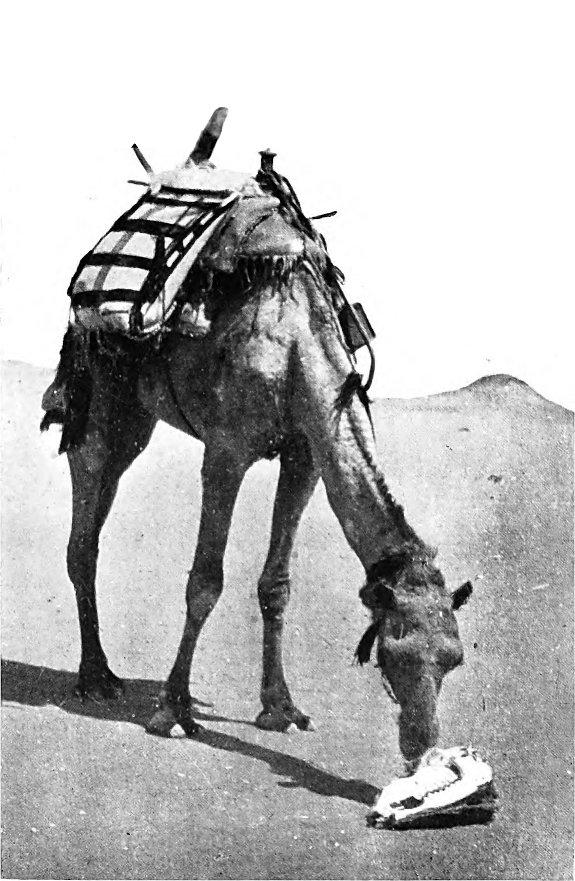

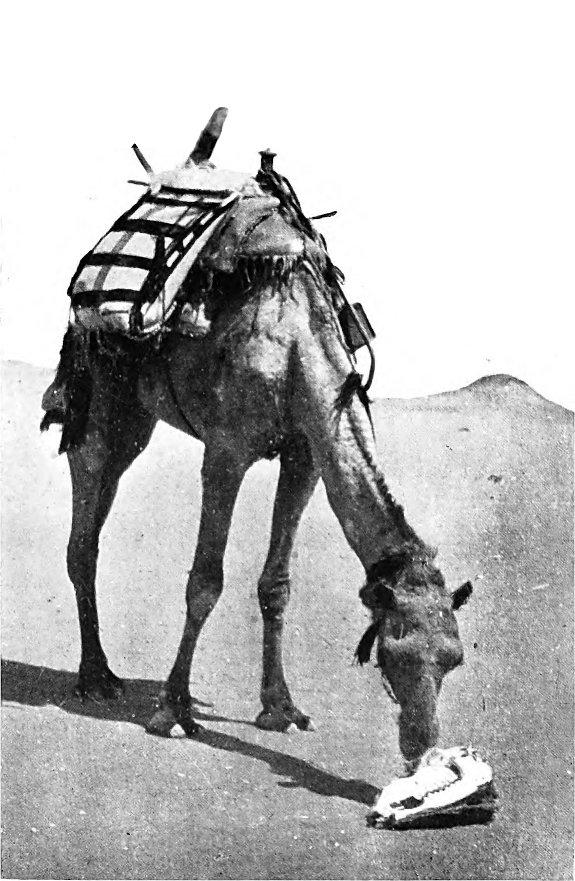

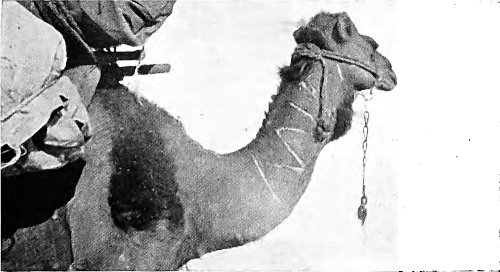

My Hagin, or Riding Camel.

The saddle bags, or hurj, are gaily coloured and the rider rests his legs on the leather pad over the withers, the camel being controlled by a single rein. (p. 33).

MYSTERIES OF THE LIBYAN DESERT

My Hagin, or Riding Camel.

The saddle bags, or hurj, are gaily coloured and the rider rests his legs on the leather pad over the withers, the camel being controlled by a single rein. (p. 33).

A RECORD OF THREE YEARS OF

EXPLORATION

IN THE HEART OF THAT VAST &

WATERLESS REGION

BY

W. J. HARDING KING,

F.R.G.S.

Awarded Gill Memorial in 1919 by the Royal

Geographical Society

AUTHOR OF “A SEARCH FOR THE MASKED

TAWAREKS,” &c.

WITH 49 ILLUSTRATIONS & 3 MAPS

London

Seeley, Service & Co. Limited

196 Shaftesbury Avenue

1925

Printed in Great Britain

at

The Mayflower Press, Plymouth. William Brendon & Son,

Ltd.

IT is not easy to condense into a reasonable compass an account of three years’ work in an entirely unknown part of the world like the centre of the Libyan Desert.

Most of the scientific results I obtained during that time, however, have already appeared in the journals of the Royal Geographical Society, or other scientific bodies, so it has not been necessary to reproduce them. Many of the journeys, too, that were made into the desert had of necessity to retraverse routes that I had already covered, or were of too uninteresting a character to be worth describing, so no account of these was necessary. On the other hand, various incidents have been introduced into the narrative part of the book which, though they may appear comparatively unimportant in themselves, illustrate the character of the natives, and so supply data of an ethnographical character in one of its most practical forms.

The photographs which form the illustrations were all taken by myself. Unfortunately many others that I took were so seriously damaged by the sand, or heat, as to be unfit for reproduction. These have had to be replaced by sketches that I made from them—for these I can only offer my apologies.

The names by which the new places that we found in the central part of the desert are called will not be seen on any map. They are only those given to them by my men. But it has been necessary to use them in order to avoid repetition of such cumbersome phrases as “the-hill-that-appeared-to-alternately-recede-and-advance-as-we-approached-it,”[10] etc.

I received so much kindness and assistance in so many quarters in carrying out my work that it is a little difficult to decide where to begin in acknowledging it. To the War Office I am indebted for the gift of the graticules upon which my map was constructed; the Sudan Office in Cairo lent me tanks and gave me much useful intelligence. Major Jennings-Bramley, Capt. James Hay and the late Capt. (afterwards Colonel) O. A. G. Fitzgerald all gave me information and advice of great value.

Dr. Rendle and his staff of the Botanical Section of the Natural History Museum in South Kensington kindly identified for me a collection of plants that I brought back, and in addition allowed me the use of their library while working out the geographical distribution of the collection.

For the identification of part of my other collections I am also indebted to the staff of the Natural History Museum in South Kensington. A collection of insects made on my last journey sent to the Tring Museum were most kindly identified for me by Lord Rothschild.

I am under a deep debt of gratitude to the Royal Geographical Society for a most generous loan of instruments; and last, but by no means least, I have to express most cordial thanks to the Survey Department in Egypt for the loan of tanks and instruments and for much valuable advice and assistance. More especially I am under obligations to the following members of this department: To the late Mr. (afterwards Lt.-Col.) B. F. E. Keeling and Mr. Bennett, for calculating some of my astronomical observations; to Mr. J. Craig for his kindness in working out my boiling point and aneroid altitudes; to Dr. John Ball and Mr. H. E. Hurst, who gave me much assistance and so far enlightened my ignorance on the subject as to enable me to take some electrical observations on the sand blown off a sand dune; the former, too, most kindly lent[11] me his electrometer for the purpose of the observations. Mr. Alfred Lucas of this department also kindly analysed some samples of crusted sand that I collected in order to discover the cementing material.

The Libyan Desert, that in the past has to a great extent defied the efforts of all its explorers, is bound before long to give up its secrets. Suitably designed cars, accompanied perhaps by a scouting plane, our enemies against which even the most avid desert is almost defenceless, though one cannot but regret the necessity for such prosaic mechanical aids, they unquestionably afford an ideal method of conducting long pioneer explorations in a waterless desert. But these things have only recently been invented, and there are still many problems that remain unsolved as to “what lies hid behind the ridges” in the vast area that we know as the Libyan Desert, and speculation is so full of fascination, that it seems almost a pity that those problems should ever be solved.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I | 17 |

| CHAPTER II | 28 |

| CHAPTER III | 37 |

| CHAPTER IV | 47 |

| CHAPTER V | 60 |

| CHAPTER VI | 75 |

| CHAPTER VII | 82 |

| CHAPTER VIII | 92 |

| CHAPTER IX | 102 |

| CHAPTER X | 111 |

| CHAPTER XI | 122 |

| CHAPTER XII | 130 |

| CHAPTER XIII | 138 |

| CHAPTER XIV | 144 |

| CHAPTER XV | 148 |

| CHAPTER XVI | 153 |

| CHAPTER XVII | 160 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | 168 |

| [14]CHAPTER XIX | 181 |

| CHAPTER XX | 195 |

| CHAPTER XXI | 198 |

| CHAPTER XXII | 206 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | 219 |

| CHAPTER XXIV | 231 |

| CHAPTER XXV | 241 |

| CHAPTER XXVI | 248 |

| CHAPTER XXVII | 280 |

| APPENDIX I | 293 |

| APPENDIX II | 322 |

| APPENDIX III | 326 |

| INDEX | 337 |

| HALF-TONES | |

| My Hagin or Riding Camel | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

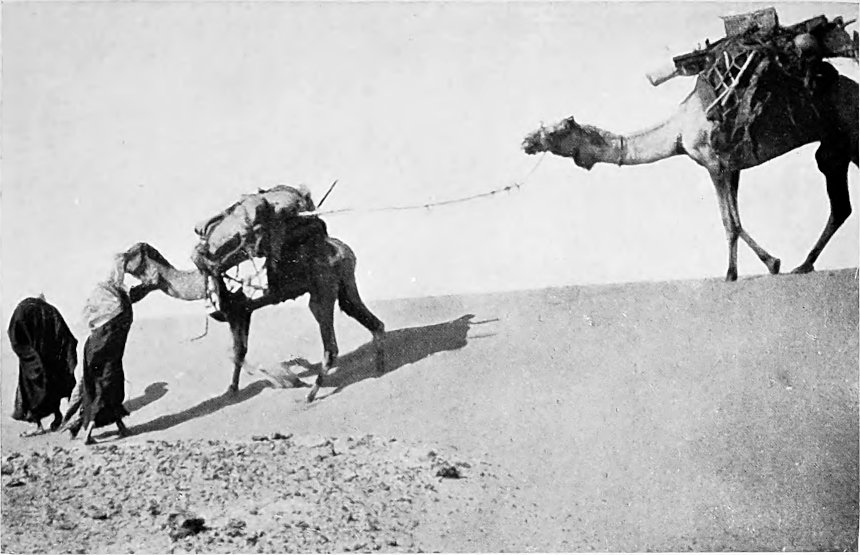

| Resoling a Camel | 40 |

| Kharashef | 48 |

| Sand-groved Ridge | 48 |

| In Old Mut | 48 |

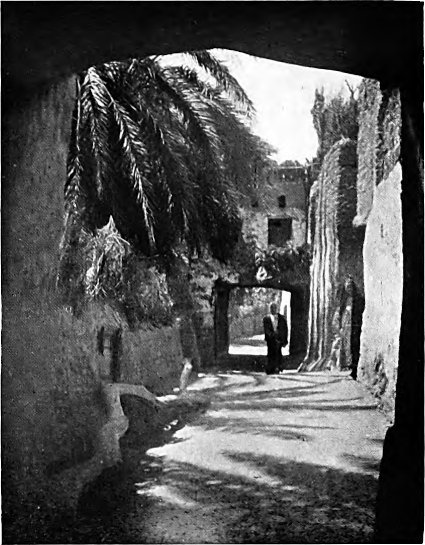

| The Gate of Qalamun | 56 |

| The ’Omda of Rashida and His Family | 56 |

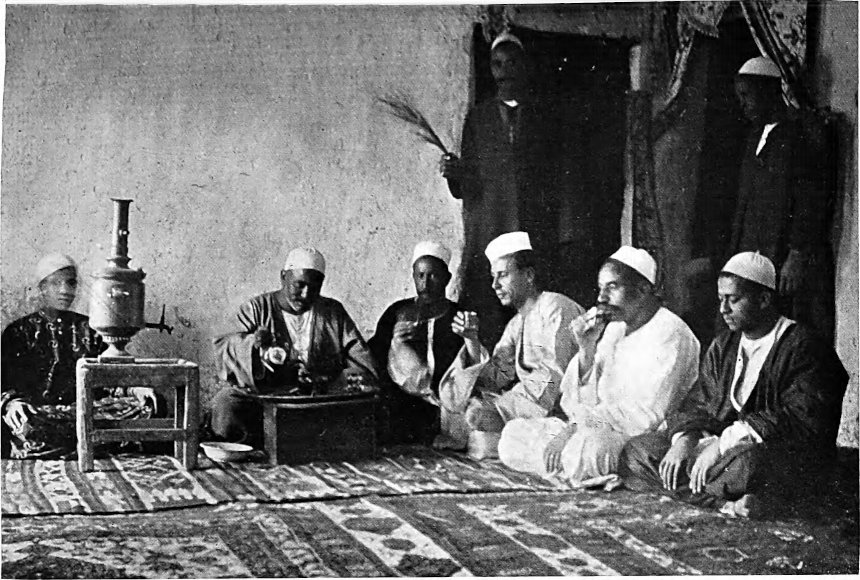

| A Teaparty in Dakhla Oasis | 64 |

| Making Wooden Pipes | 72 |

| A Street in Rashida | 72 |

| The Most “Impassable” Dune | 88 |

| View, near Rashida | 96 |

| A Conspicuous Road—to an Arab | 96 |

| Battikh | 96 |

| Rather Thin | 112 |

| Wasm or Brand of the Senussia | 118 |

| Breadmaking in the Desert | 118 |

| Sieving the Baby | 118 |

| Sofut | 152 |

| The Descent into Dakhla Oasis | 152 |

| A Made Road | 152 |

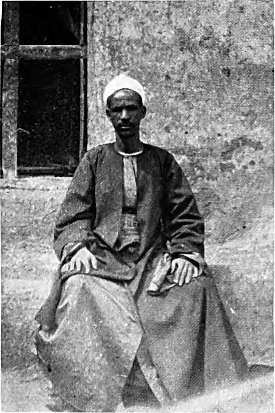

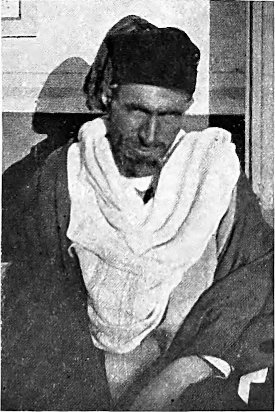

| Sheykh Senussi | 200 |

| Haggi Quaytin | 200 |

| Sheykh Ibn ed Dris | 200 |

| Haggi Quay | 200 |

| [16]A Bride and Her Pottery | 228 |

| Marriage Procession in Dakhla Oasis | 248 |

| Vegetation in Hattia Kairowin | 248 |

| First Sight of the “Valley of the Mist” | 272 |

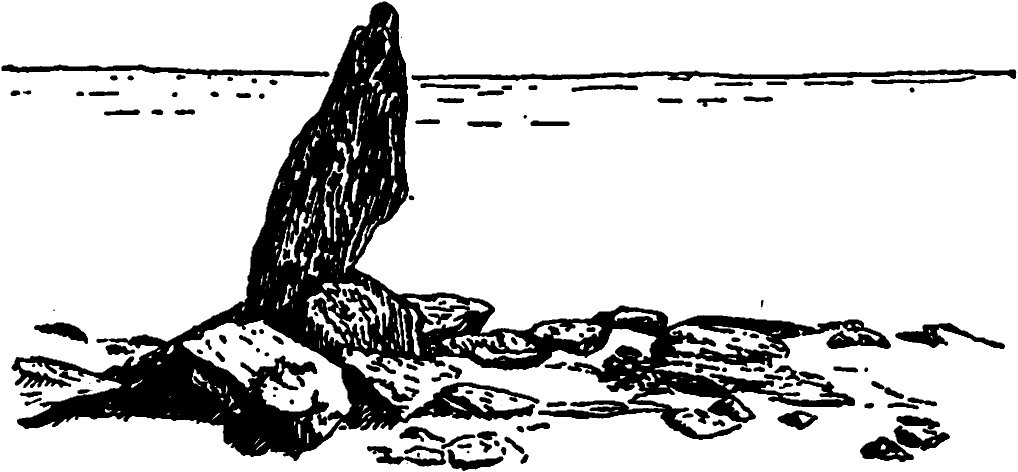

| A Gazelle Trap | 272 |

| Trap for Small Birds | 272 |

| A Street in Kharga | 312 |

| IN THE TEXT | |

| PAGE | |

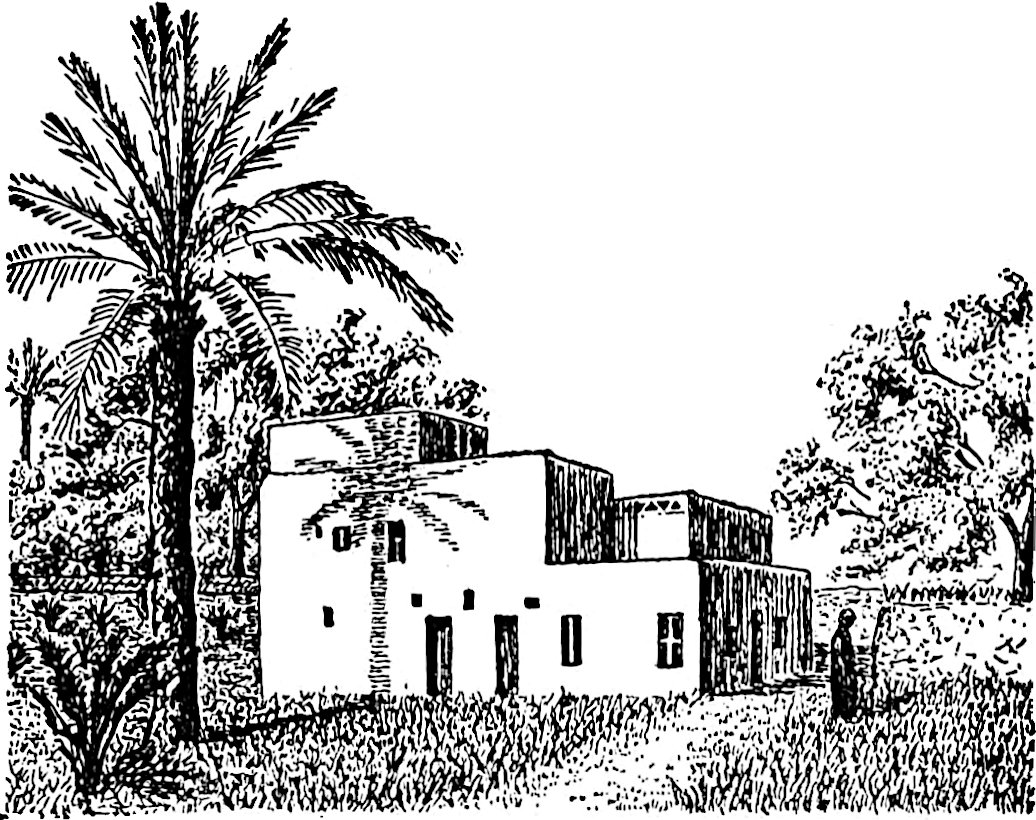

| ’Omda’ House, Tenida | 38 |

| Senussi Zawia at Smint | 40 |

| Old Houses in Mut | 42 |

| The Tree with a Soul, Rashida | 49 |

| Der el Hagar, Dakhla Oasis | 58 |

| Sheykh Ahmed’s Guest House | 65 |

| Old ’Alem, “Valley of the Mist” | 112 |

| Diagram of Jebel el Bayed | 114 |

| Old Wind Shelter, “Valley of the Mist” | 117 |

| Abd er Rahman’s Wind Scoop | 123 |

| Old Khan in Assiut | 133 |

| Upper Floor of Post Office | 139 |

| Blind Town Crier, Mut | 141 |

| Sketch Plan of Tracks round Jebel el Bayed | 175 |

| Pinnacle Rock on Descent to Bu Gerara Valley | 204 |

| Boy with Crossbow, Farafra | 226 |

| Senussi Praying Place, Bu Mungar | 233 |

| Flour Mill, Rashida | 264 |

| Olive Mill, Rashida | 266 |

| Olive Press, Rashida | 267 |

| Khatim or Seal | 274 |

| Scorpion Proof Platform | 283 |

| Eroded Rock, South-west of Dakhla | 309 |

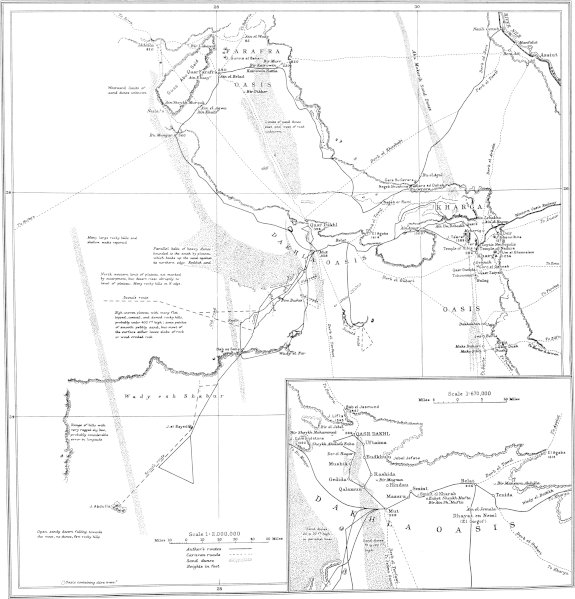

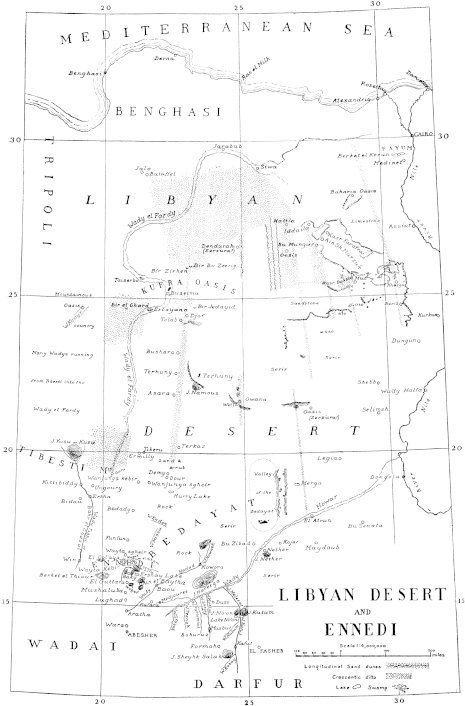

MAP FOR “MYSTERIES OF THE LIBYAN DESERT.”

Seeley Service & Co. Ltd.

[17]Mysteries of the Libyan Desert

OF the making of books on Egypt there is no end. The first on the subject was Genesis, and there has been a steady output ever since. But the literature of the Libyan Desert, that joins up to Egypt on the west, is curiously scanty, when the enormous area of this district is considered.

The Libyan desert may be said to extend from the southern edge of the narrow cultivated belt that exists almost everywhere along the North African coast, to the Tibesti highlands, and the northern limit of the vegetation of the Sudan. On the east the boundary of the desert is well defined by the Valley of the Nile; but on its western side it is extremely vague.

A broad belt of desert stretches all across North Africa from east to west. The western portion of this is known to us as “the Sahara.” But “Sahara” is not really a name, but an Arabic word meaning a desert—any desert. By the natives this term is applied to the whole of this desert belt, and is used just as much to describe the Libyan Desert, as the more westerly part of it. The boundary line between what we know as the Sahara and the Libyan Desert has never been drawn, but it may be said to run roughly from the northern end of Tibesti to the base of the Gulf of Sidra. With such vague boundaries it is impossible to give an accurate estimate of its extent, but it may be taken that the Libyan Desert covers nearly a million square miles. It is probably the least-known area of its size in the world. There are still hundreds of thousands of square miles in[18] its southern and central parts quite unknown to Europeans, the map of which appears as so much blank paper, or is shown as being covered with impassable sand dunes.

I had had some experience of desert travelling in the Western Sahara, so when, in 1908, I wrote to the Secretary of the Royal Geographical Society, suggesting a journey into the Western Sahara, and received a letter in reply proposing that I should tackle the Libyan Desert instead, as offering the largest available area of unknown ground, and should take up the study of sand dunes, for which it afforded an unrivalled opportunity, I jumped at the suggestion, which had not before occurred to me.

But after a jump of that kind one usually comes to earth again with something of a bang, and when, after making a more thorough enquiry than I had previously done into the nature of the job I had undertaken, I began to realise its real character and felt that in saying I would tackle this part of the world, I had done something quite remarkably foolish.

Many expeditions had set out from Egypt to explore this part of the world, but none up to that time had ever crossed the Senussi frontier, with the exception of Rohlfs’, who, in 1874, before the Senussia was firmly established in the desert, attempted to reach Kufara Oasis. Even he, hampered perhaps by his enormous caravan, only managed to proceed for three days westward from Dakhla and was then compelled, by the insurmountable character of the dunes, to abandon the attempt and to turn up towards the north and make for the Egyptian oasis of Siwa. This difficulty of crossing the sand hills, the obstructing influence of the Senussi, who had reduced passive resistance to a fine art, and, perhaps, in some cases, want of experience in desert travelling, had rendered the other attempts abortive. Still, this seemed to be the most promising side from which to enter the desert.

I first took a preliminary canter by going again to the Algerian Sahara. This was, of course, some years before the war, in the course of which the Senussi—or the Senussia as they should be more strictly called—were very thoroughly thrashed. Just before the war, however, they were at[19] about the height of their power and were a very real proposition indeed.

They had the very undesirable peculiarity—from a traveller’s point of view—of regarding the part of the Libyan Desert, into which I was proposing to go, as their private property and of resenting most strongly—to put it mildly—all attempts to penetrate into their strongholds. There can be little doubt that at this period they had been contemplating for a long time an invasion of Egypt, and were only waiting for a suitable opportunity to occur of putting it into execution. In the circumstances, they naturally did not want Europeans to enter their country for fear that they should get to know too much. Moreover their fanaticism against Europeans had been considerably augmented by the advance of the French into their country from the south.

Even now most people seem hardly to realise the real character of the Senussia; for one constantly hears them alluded to as a “tribe” or merely as a set of unusually devout Moslems, who have chosen to take up their abode in the most inaccessible parts of Africa, in order to devote themselves to their religious life, without fear of interruption from outsiders. The fact is, that they are in reality dervishes, whose character, at that time at any rate, was of a most uncompromising nature towards all non-Mohammedans and was especially hostile towards Europeans, particularly those occupying any Moslem territories. Moreover they were not confined only to the Libyan Desert, but formed one of the most powerful of the dervish orders, with followers spread throughout practically the whole Moslem world from Sumatra to Morocco.

As I expected to come a good deal in contact with them in the Libyan Desert, after leaving the Algerian Sahara, I spent a considerable time in the public libraries of Algeria and Tunis, in collecting such information as was available on the Senussia and other dervishes of North Africa.

For the benefit of those unacquainted with the subject it may be as well to explain the nature of these dervish orders. They resemble in some ways the monastic communities of Christianity, and are usually organised on much[20] the same lines. Their zawias, or monasteries, vary in size from unpretentious buildings, little better than mud huts, to huge establishments, which in size and architecture favourably compare with the finest institutions of their kind in Europe.

Each dervish order has its own peculiar ritual. Many of them are entirely non-political and of a purely religious character; but there are others, such for instance as the notorious Rahmania and Senussia, who are of a strongly political character, usually hostile to Europeans. Frequently, however, their influence is not apparent, as they keep discreetly in the background; but it has been repeatedly shown that it has been intriguing sects such as these, who have been at the bottom of the numerous risings and difficulties that Europeans have had to contend with in dealing with their Moslem subjects.

Other political orders—such as the Tijania—are actually favourable towards Europeans; while others again lend their support to some particular branch of the community, acting for instance, as in the case of the Ziania, as protectors to travellers or, as the Kerzazia do, supporting the dwellers in the oases against the attacks of the bedawin who surround them, and so forth.

As these dervish orders are largely dependant upon the refar, or tribute, that they exact from their followers, for their support, with few exceptions, each sect does its utmost to increase the number of its adherents and to prevent them from joining any other order. This naturally leads to a considerable rivalry between them, and when two of them pursue an exactly opposite policy—as for instance in the case of the Tijania and the Senussia—this rivalry develops into a deadly feud. It is the impossibility of inducing rival dervishes to combine, more perhaps than anything else, that makes that wild dream of Pan-islam, by which all Mohammedans are to unite to get rid of their European rulers, such a hopelessly impossible scheme.

A very large proportion of the Moslem natives of North Africa belong to one, or more, of these orders. But it is seldom that a native can be found to discuss at all freely[21] the particular one to which he belongs. A knowledge, however, of them and of the peculiarities by which the followers of each sect can be identified, is most useful. The information that I picked up on this subject before going to Libya I found of the greatest possible value, as it often enabled me to gauge the probable attitude towards me of the men with whom I came in contact, and even to put a spoke in their wheel, before they even realised that I had any ground for suspicion.

On leaving Tunis, I went on to Egypt, where, before actually setting out for the desert, I spent some time in Cairo, putting the finishing touches to my equipment and picking up what information I could about the part into which I was going. It is extraordinary how many of my informants regarded the desert as “a land of romance.” No doubt in many cases distance lends enchantment to the view, and covers it with a certain amount of glamour; but a very slight experience of these arid wastes is calculated completely to shatter the spell. Romance is merely the degenerate offspring of imagination and ignorance. There can be few parts of the world where one is so much up against hard cold facts as one is in the desert.

On the whole, the information that I was able to collect was of a very unsatisfactory character. I could learn practically nothing at all definite about the desert—at least nothing that seemed to be reliable, except that the dunes of the interior of the desert were quite impassable.

But I soon found out that though I was learning nothing, other people were. The truth of the local saying that “you can’t keep anything quiet in Egypt” was several times forced upon me in rather startling ways. Most of the news that natives learn probably leaks out through the reckless way in which some Europeans talk in the presence of their English-speaking servants. But even allowing for careless conversation of this kind, it is astonishing how quickly news sometimes travels. This rapid transmission of secret news is a well-known thing in North Africa, and one that has always to be reckoned with. In Algeria they call it the “arab telegraph,” and many extraordinary cases of it are recorded.

[22]As a result of my enquiries I was able to draw up a sort of programme for my work in the desert, the main objects in which were as follows:—

(1) To cross that field of impassable dunes.

(2) If I succeeded in doing so, to cross the desert from north-east to south-west.

(3) Failing the latter scheme, to survey as much as possible of other unknown parts of the desert.

(4) To collect as much information as possible from the natives about the unknown portions of the desert that I was unable to visit myself.

Before leaving Cairo, I engaged two servants. My knowledge of Arabic at that time was scanty, and what there was of it was of the Algerian variety—a vile patois that is almost a different language to that spoken in the desert—an interpreter was consequently almost a necessity. I took one—Khalil Salah Gaber by name—from a man who was just leaving the country. He was loud in his praises of Khalil, stating that he was an extremely good interpreter and “very tactful.”

Since then I have always been distinctly suspicious of people who are noted for their tact—there are so many degrees of it. Tactful, diplomatic, tricky, dishonest, criminal, all express different shades of the same quality, and Khalil’s tact turned out to be of the most superlative character!

I also engaged a man called Dahab Suleyman Gindi as cook. Dahab—unlike Khalil, who was a fellah or one of the Egyptian peasants—was a Berberine, the race from which the best native servants are drawn. He was a small, elderly, rather feeble-looking man with an honest straightforward appearance, who not only turned out to be a very fair cook, but who also made himself useful at times as an interpreter, as he knew a certain amount of English.

After my preparations were completed, I stayed on for a while to see something of the sights of Cairo. Its cosmopolitan all-nation crowd made it an interesting enough place for a short stay. But after one had spent[23] a little time there, and done all the usual sights, dirty, noisy Cairo and the other tourist resorts began to pall upon one. After all, they are only a sort of popular edition of the country, published by Thomas Cook and Son. Beyond lay the real Egypt and desert, a land where afrits, ghuls, genii and all the other creatures of the native superstitions are matters of everyday occurrence; where lost oases and enchanted cities lie in the desert sands, where the natives are still unspoiled by contact with Europeans, and where most of the men are pleasing, and, though the prospect is vile, that could not destroy the attraction that lay in the fact that about a million square miles of it were quite unknown, and waiting to be explored.

Before I had been very long in Cairo, I had had enough of it—it was so much like an Earl’s Court exhibition—and at the end of my stay, I cleared out for the desert with a feeling of relief.

The train for Kharga Oasis left Cairo at 8 p.m. After a long dusty journey I found myself deposited at the terminus in the Nile Valley of the little narrow gauge railway that runs across the desert for some hundred miles to Kharga Oasis.

There is a proper station at this junction now, but at that time, in 1909, the line had only been recently opened, and the junction consisted merely of a siding, a ramshackle little wooden hut for the station-master, and a truly appalling stink of dead dog, the last being due to the fact that owing to an attack of rabies in the district, the authorities had been laying down poisoned meat to destroy the pariah dogs of the neighbourhood, who all seemed to have chosen the vicinity of the station as the spot on which to spend their last moments.

Having shot out my baggage at the side of the permanent way, the train disappeared into the distance and left me with about half a ton of kit to get up to Qara, the base of the oasis railway, where I had been told I could get put up. After a delay of nearly an hour, during which time, as it was bitterly cold, I began to feel the truth of the native saying that “all travel is a foretaste of hell,”[24] some trollies put in an appearance. Moslems, it may be mentioned, believe that there are seven hells, each worse than the last—and they say they are all feminine!

As soon as the trollies had been loaded up, a start was made for Qara, some five miles away, where I spent the next few days, while collecting the camels for my caravan.

To assist me in buying the beasts, I engaged a local Arab, known as Sheykh Suleyman Awad, a grim, grizzled old scoundrel of whom I saw a good deal later on. In his youth he had had a great reputation as a gada—a term corresponding pretty closely to our “sportsman,” and much coveted by the younger bedawin.

He had gained this reputation in a manner rather characteristic of these Arabs. Once, when a young man, he was having an altercation with a couple of fellahin, who after showering other terms of abuse upon him, finally wound up by calling him a “woman.” An insult such as this from a couple of mere fellahin, a race much despised by the Arabs, was too much altogether for Suleyman, who promptly shot them both. It was a neat little repartee, but Suleyman had to do time for it.

The bedawin in that part of Egypt are semi-sedentary, living encamped in the Nile Valley on the edge of the cultivation. Most of them live in tents woven of thick camel and goat hair, others in huts of busa—dried stalks of maize, etc.—a few of the more wealthy Arabs have houses, built of the usual mud bricks, and own small areas of land which they cultivate. At certain seasons of the year, they migrate into the oases, returning again to their camping places in the Nile Valley in the spring, to avoid the camel fly that puts in its appearance in the oases at that season, and is capable of causing nearly as much mortality among the camels as the tsetse fly does among horses in other parts of Africa.

After spending a day or two trying to buy camels round Qara, I at length secured five first-rate beasts in the market at Berdis.

Each Arab tribe has its own camel brand or wasm, the origins of which are lost in the mists of antiquity. Some of these marks, however, are identical in shape with the[25] letters of the old Libyan alphabet of North Africa, and with its near relation the Tifinagh, or alphabet of the modern Tawareks, and it is possible that there may be some connection between them.

The camels I bought at Berdis came from the Sudan. They were large fawn-coloured beasts with a fairly smooth coat, and all showed the same brand—a vertical line on the near side of the head by the nostril, and a similar line in the bend of the neck. They belonged, I believe, to the Ababda tribe.

Sheykh Suleyman eventually produced a decent-looking camel from somewhere, which I bought, and that, with the five I had procured from Berdis, constituted my whole caravan—and an excellent lot of beasts they were.

I engaged a couple of drivers to look after them—Musa, a young fellow of about eighteen years of age, and a little jet-black Sudani, called Abd er Rahman Musa Said, who turned out to be a first-rate man, and stayed with me the whole time I spent in the desert. Both of these men belonged to Sheykh Suleyman’s tribe.

The choice of a guide is a serious question, as the success or otherwise of an expedition depends very largely upon him, and I found considerable difficulty in finding a suitable man. I nearly engaged one who applied, as he seemed to be the only one of the candidates who knew anything at all about the desert beyond the Egyptian frontier. But Nimr—Sheykh Suleyman’s brother—sent me word by Abd er Rahman, that he was not to be relied on as he “followed the Sheykh”—the usual way among natives of describing a man who was a member of the Senussia, and as he refused a cigarette I offered him, I declined to employ him. Smoking, it may be noticed is forbidden to the followers of Sheykh Senussi, and the offer of a cigarette is consequently a useful—though not always infallible—test of membership of this fanatical fraternity.

My suspicions were confirmed on the following morning, when this

man came in to hear my answer to his application. The camel he rode

was branded on the neck with the wasm of the Senussia—a

kind of conventionalised[26] form of the Arabic word “Allah” (![[Symbol]](images/sym01.jpg) )—a damning piece

of evidence showing not only that he belonged to the sect, but that

his mount was supplied by the Senussia itself. He was probably one

of their agents.

)—a damning piece

of evidence showing not only that he belonged to the sect, but that

his mount was supplied by the Senussia itself. He was probably one

of their agents.

I was beginning to despair of finding a guide, when I received a telegram from the mudir (native governor) of Assiut, to whom I had applied for a reliable man, saying that he had got one for me, and asking whether I wished to see him.

The man arrived the next day. I took a fancy to him at once, which even his many peccadilloes never quite destroyed. His appearance was distinctly in his favour. He was a big man, nearly six feet high, which is very tall indeed for an Arab. He looked about sixty years old, and carried himself with that “grand air” which so many of the bedawin show, and which goes so well with the flowing robes of the East. Unlike most bedawin he was spotlessly clean.

His name he said was Qway Hassan Qway. It is quite impossible to convey an accurate idea of the pronunciation of Arabic names by mere European systems of writing, but his first name as he pronounced it, sounded like “choir” with a sort of gulping “g” instituted for the “ch.” He added the gratuitous piece of information that his grandfather had been a bey—a sort of military title corresponding roughly to a knighthood. He was clearly not in the habit of hiding his light under a bushel. But as he was very highly recommended by the mudir, and I liked the look of him, I engaged him.

“Guide” is perhaps hardly the correct term to describe the capacity in which he was expected to act, for he did not even profess to have any knowledge of the desert beyond the Egyptian frontier. But as it seemed hopeless to attempt to find anyone who did, I employed him as a man of great experience in desert travelling, who would act as head of the caravan and help me with his advice in any difficulty that arose.

I took him round and introduced him to my other men. At my suggestion he arranged with Sheykh Suleyman to hire a riding camel from him, as he said that he had not[27] one of his own that was strong enough for a hard desert journey.

In spite of his engaging manners, for some reason that was not apparent, both Sheykh Suleyman and Abd er Rahman obviously took a strong dislike to him. I was rather pleased at this, as a little friction in one’s caravan makes the men easier to manage. At the time, I put it down to his belonging to a different tribe; but, judging from what afterwards occurred, I fancy it was really due to their knowing something against him, which, native-like, they did not see fit to tell me.

Qway being thus provided for, I dispatched my caravan by road to Kharga Oasis, and followed them myself a day or two afterwards by the bi-weekly train.

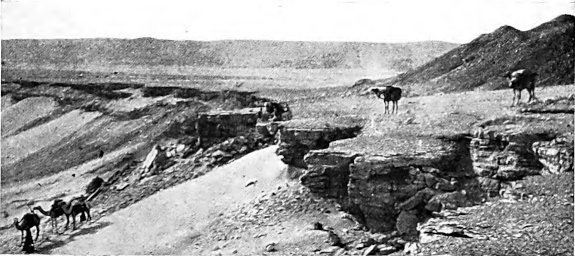

FOR the first few miles the line ran over the floor of the Nile Valley. Some twenty-eight miles from Qara, we emerged from the wady through which the railway ran on to the plateau above. Jebel, the word generally used in Egypt to signify desert, means literally mountain; the desert near the Nile Valley consisting of the plateau through which the Nile has cut its course.

The view on the plateau was impressive in its utter barrenness—no single plant, not even dried grass, was to be seen. Though the actual surface of the desert was very uneven, the general level was extremely uniform. The whole plateau consisted of limestone, in the slight hollows and inequalities of which patches of sand and gravel had collected. Here and there very low limestone hills, or rather mounds, were to be seen, none of them probably exceeding twenty feet in height. Everywhere on the plateau the effect of the sand erosion was most marked. The various types of surface produced being known to the natives as rusuf, kharafish, kharashef and battikh, or “water melon” desert, the nature of which will best be seen from the photographs.

The descent from the plateau into the depression in which Kharga Oasis lies, lay, like the ascent from the Nile Valley on to the plateau, through a wady. Kharga Oasis was at that time very little known to Europeans. Until the advent in the district of the company who had constructed the railway, the oasis had only been visited, I believe, by a few scientists and Government officials.

The desert beyond it had been so little explored that, within about a day’s journey from the oasis, I found a perfect labyrinth—several hundred square miles in extent—of little depressions, two or three hundred feet in depth, opening out of each other, that completely honeycombed[29] what had previously been considered to be a part of the solid limestone plateau. Unfortunately, I was never able entirely to explore this curious district. It almost certainly contains at least two wells, or perhaps small oases—’Ain Hamur and ’Ain Embarres.

It is difficult to convey to anyone who has not seen them a clear idea of these oases in the Libyan Desert. Kharga is an oblong tract of country measuring roughly a hundred and forty miles from north to south by twenty from east to west. It is bounded on the east, north and west by huge cliffs or hills. Only about a hundred and fiftieth of its area, in the neighbourhood of the various villages, hamlets and farms scattered over its surface, is under cultivation. These cultivated areas are irrigated by artesian wells, many of which date back to a very remote period. But Kharga Oasis and its antiquities have already been described by two or three writers, so no lengthy account of them is necessary. It contains a number of temples and other ruins, the most important of which is the Temple of Hibis.

The temple has an excellent mummy story connected with it. Those engaged in excavating the temples and tombs of Egypt—an occupation locally known as “body snatching”—are well aware that in their work they always have “the dead agin them,” and there are few places where this has been so well exemplified as in the Temple of Hibis.

At the time of my arrival in Kharga it was being restored by an American archæologist, named W———. Before it was taken in hand, sand had drifted by the wind up against the walls, until it reached very nearly to their summit. In order to find out the extent of the buildings, W——— caused a trench to be dug parallel to one of the main walls.

Before this was completed, his men told him that they did not wish to continue working in that part, giving as their reason that a sheykh, i.e. a holy man, had been buried there, and since he was of exceptional holiness, lights had been seen hovering over his grave at night, and a man who had dug there before had fallen ill.

After some difficulty W——— succeeded in inducing the men to continue their work. But a sacred mummy is an[30] uncanny thing to tackle. Sure enough, after his men had been digging a little longer, some earth slipped down into the trench, and with it came half the mummy, the other half remaining in the ground by the side of the trench. The men “downed tools” at once, and stood aghast at this calamity. The mummy’s feelings must have been seriously outraged for he lost no time in getting to work—the native who had actually dug him up was subject to fits, and had one and died that night.

The next morning the mummy had disappeared and all the men were back at work again, just as though nothing had happened. After some little time W——— began to make cautious enquiries as to what had happened to the mummy; but he elicited no information whatever. His enquiries were met with a blank stare of surprise—“mummy? What mummy? There had been no mummy there.” When a native knows nothing like that, it is quite hopeless to try and get anything out of him.

W———’s men went on with their work as though nothing had happened. One of them had atoned for the little accident to the mummy, so they knew that the rest of them were safe . . . but they seemed solicitous about W———’s health, and W——— soon found that he had not done with that mummy. Before the end of the season, he and the European working with him, who had had most to do with the mummy, went down with very bad Kharga fever—a virulent form of malaria—from which W——— himself nearly died.

Some time afterwards he discovered that his men had gone down before him, on the night the mummy had been dug up, and had collected his remains and given him a decent Mohammedan burial. He found out where he was buried and built a really magnificent tomb-top over his grave. It must be nearly ten feet long, six feet wide and two feet high. It was built of the very best mud bricks the oasis could produce—and he even whitewashed it. Since then the mummy has been pacified and has left W——— in peace.

When I found out where the mummy was buried, I bakhshished him, by shoving a five-piastre piece into the[31] ground by the side of his grave—a proceeding that met with Dahab’s highest approval—and I had a more successful trip that year than any other. But it doesn’t say much for the intelligence of the mummy, for that five-piastre piece was a bad one.

For the benefit of the sceptical, I wish to add that this story is true—absolutely true—any native in Kharga will tell you that—besides there is the whited sepulchre to prove it; so for a mummy story it is very true indeed.

After a stay of some days in Kharga to allow the caravan to come through from the Nile Valley, we started off for our journey to Dakhla Oasis. Our road at first ran roughly from east to west. Shortly after our start it passed through a patch some two miles wide of curious clay ridges. These, which seemed all to be under twenty feet high, were evidently formed by the erosion of the earth by the wind-driven sand, for they all ran from north to south, in the direction of the prevailing wind. Just before reaching the western side of the oasis, our road passed through a gap in a belt of sand dunes, which, like the clay ridges, also ran in the same north to south direction of the prevailing wind.

These sand belts consist of long narrow areas covered with dunes, running across the desert in almost straight lines, roughly from north to south. This Abu Moharik belt, through which our road ran, has a length which cannot be much less than four hundred miles; but, though it varies somewhat in width at different points along its course, its average breadth is probably not much more than five miles, that is to say, about an eightieth of its total length. These belts consist almost entirely of more or less crescent-shaped dunes. In places the sand hills of which they are composed are scattered and stand isolated from each other, with areas of sand-free desert between them. In other parts the dunes are more closely packed; many of the crescents join together to form large clusters, and the spaces between the dunes are also sometimes covered with sand.

Beyond the dune belt, we turned sharply towards the south and soon came on to the northern end of the cultivated area surrounding Kharga village. From Kharga we[32] journeyed southward to the village of Bulaq, passing on our way the sandstone temples of Qasr el Guehda—or Wehda, as it is often locally pronounced—and Qasr Zaiyan. Both were surrounded by a mudbrick enclosure filled with the remains of a labyrinth of small ruined brick buildings and contained some hieroglyphics and some fine capitals to the pillars.

Shortly after leaving Qasr Zaiyan, we entered a sandy patch covered with vegetation consisting of graceful branched Dom palms, acacias, palm scrub and grasses, in which some of the cattle of the breed, for which the oasis was noted, were grazing. Half an hour’s journey through this scrub-covered area brought us to the palm groves and village of Bulaq, on the south side of which I pitched my camp. Bulaq, though one of the largest villages of the oasis, with a population of about one thousand, is quite uninteresting. Its palm groves and cultivated land lie on its eastern side; on the north, south and west it is bounded by open sandy desert. It is chiefly noted as being the main centre in the oasis for the manufacture of mats and baskets, made chiefly from the leaves of the numerous Dom palms growing in the neighbourhood.

After breakfast the next day we struck camp and set off due west across the dune belt. It took us only an hour and a quarter to negotiate. Between the dunes were many interspaces entirely free from sand, so by keeping as much as possible to these and winding about, so as to cross the sand hills at their lowest points, we managed to get through the belt and emerged on to a gravelly sand-free desert beyond.

This, my first experience of the dunes of the Libyan Desert, was distinctly encouraging. Not only were the sand hills much smaller than I had been led to suppose, but their surface was crusted hard, and we crossed them with little difficulty; on emerging on the farther side, I set out for Dakhla Oasis, feeling far more hopeful of being able to cross the heavy sand to the west of that oasis than I had ever been before.

After crossing the dune belt, we altered our course and turned up nearly due north so as to make for the well of[33] ’Ain Amur. The desert over which we were travelling was of pebbly sand, with an occasional rocky hill or ridge of black sandstone, and presented few points of interest. We camped at five, and I had a good opportunity of studying the peculiarities of my men, and of the kit they had brought with them for the journey.

Qway’s equipment was about as near perfection for the desert as it was possible to get it. His camel saddle was a rabiat, over this was a red leather cushion on which he sat. On this he placed his hurj, or pair of saddle-bags, of strong carpet-like stuff, one of which hung down on either side; above this lay a folded red blanket, and over this again he spread his furwa, or black sheepskin—an indispensable part of a camel rider’s equipment, which he not only places over his saddle, where it forms a soft and comfortable seat, but on which he sits when dismounted, lies on or covers himself with at night and throws over his shoulders on a cold day. Over the camel’s withers in front of the saddle was a second small pad, also of red leather, on which to rest his legs as he crossed them in front of him as he rode, hanging from his rabiat on either side was a sack of grain for his camel, the pockets of his hurj resting on the top of the sacks.

Slung on to his saddle was a most miscellaneous collection of articles. A Martini-Henry rifle I had lent him, with a text from the Koran engraved on it in gold lettering, lay along his camel’s back under his hurj on one side, and was balanced by a red parasol on the other. A goat-skin for carrying water, a small crock full of cheese, his camel’s nose-bag, or mukhlia, in which, when leaving an oasis he generally carried a few eggs packed in straw that he had managed to cadge from some village as we passed, his ’agal, or camel hobble, and a skin of flour, were all tied on to some part or other of his saddle.

In his hurj Qway carried a most extraordinary collection of things: a small circular mirror and a pair of folding nail scissors, with which at the end of a day’s march he frequently spent some time in trimming his beard and moustache—he was always spotlessly clean and neat—a clothes-brush, with which he always brushed his best[34] clothes; his best shoes; an awl with the point stuck into a cork for operating on the camels; a packing needle and one or two sewing needles, with their points similarly protected, a little bag containing thread and buttons; a lump of soap; part of a cone of sugar; tea, salt, red pepper, pills and one or two other mysterious Arab medicines, all carefully tied up separately in different pieces of rag, some cartridges I had given him for his rifle, any onions he had been able to cadge in the last oasis, and a quantity of dried dates, constituted only a few of the miscellaneous assortment of things that his camel bags contained.

The kit of the camel drivers, who were of course on foot, was much more simple. Between them they brought a skin of flour, an enamelled iron basin to make their dough in; a slightly dished iron plate (saj) to bake their bread on, and two or three small tin canisters, in which they carried sugar, salt and tea, when they had any, and which were thrown into the ordinary sack in which they carried the small amount of surplus clothing they possessed.

Dahab carried his belongings in a bag rolled up in a rug on which he slept, his kit being of a very workmanlike nature. Khalil’s outfit, however, was largely of an ornamental character, including such trifles as a pink satiny pillow thickly studded with gold stars and covered with a pillow-case trimmed with lace!

In the rough usage inseparable from a desert journey everyone’s clothing becomes more or less damaged. The other men during our halts got their clothes patched and mended, but Khalil never repaired the numerous rents that soon began to appear in his garments. He ultimately became such a scarecrow that when, on one extremely hot day, he seated himself on a rock during our noontide halt, he sprang up again a great deal quicker than he sat down, the reason being that the rock was greatly heated, and, to put it poetically, he had not been “divided from the desert by the sewn.”

While in the Valley, Khalil had been quite a success, for he made a very fair interpreter. But no sooner did he get into the desert, than he appeared at once in his[35] true character, of a dragoman of the deepest die. He was a sore trial, until I got rid of him.

The first few days in the desert with a new caravan are always trying. The men have not got into their work, and the camels, being strangers to each other, spend most of their time in fighting. A savage camel is a dangerous beast and it is of no use playing with him. The right place to hit him is his neck. Hit him hard with something heavy, and go on doing it and he becomes partially stunned and is then amenable to reason. Still, as the gifted author of “Eothen” put it, “you soon learn to love a camel for the sake of her gentle womanish ways.”

The Arabs have different names that they apply to camels according to their age—a one-year-old beast is called ibn esh Sha’ar, or sometimes ibn es Sena; a two-year-old, ibn Lebun; a three-year-old, Heg; a four-year-old, Thenni; a five-year-old, Jedda; a six-year-old, Raba’a; a seven-year-old, Sedis; and an eight-year-old, Fahal. The names apply to both male and female beasts. After eight years a male is called jemel (camel) simply, and the female naga.

On some very bad roads, where there is much rock surface to be crossed, many of the caravan guides carry an awl, string and pieces of leather, for the purpose of resoling a camel’s foot should the whole skin of it peel off, as it sometimes will. Qway resoled a foot of one of my camels once that went dead lame from this cause.

The operation was a simple one and seemed to be quite painless. He bored holes diagonally upwards through the thick skin on the edge of the sole of the foot, cut out a piece of leather slightly larger than the camel’s footprint, and then passed pieces of string through the holes he had bored, and through corresponding holes in the piece of leather and tied the ends of the string together. One or two of the strings got cut through by the rock and had to be replaced. The camel, however, without much difficulty was able to hobble back into the oasis, and after some weeks’ rest to allow the skin on the sole of his foot to grow again, completely recovered.

Camels vary considerably in colour. Among those[36] I bought in my first season in Egypt were a beast of a rather unusual chestnut colour and two other fawn-coloured brutes, one of which had a shade of grey in its complexion, and the other was inclined towards a roan tint. These were called by my men the red, blue and green camels respectively.

The “green” beast was the one I used to ride. He was not a bad mount, but as he had not been ridden before I bought him, and guiding a camel by means of a single rein is always rather like trying to steer a boa-constrictor with a string, my stick at first had to be used pretty often.

In the afternoon of our third day, after leaving Kharga, we passed a mass of eroded chalk jutting up above the sandy ground, which, being a recognised landmark was known to natives from its shape as Abu el Hul—“the Sphinx.” From there we proceeded to the well of ’Ain Amur, close to which I found a few patches of light blue sand.

A journey of a day and a half westwards over the tableland, on the north cliff of which ’Ain Amur is placed, brought us to the top of the slope from the level of the plateau to Dakhla Oasis.

This negeb, or descent, proved to be rather difficult to negotiate. The sand had drifted up against the cliff we had to climb down, and once on the bank of sand the camels, by walking diagonally down the slope, were able to reach the bottom without difficulty. But at the top of the sand bank, the rocks of which the cliff was composed, overhung to form a sort of cornice, and the path on to the sand slope below it lay through a cleft in the cornice, so narrow that the baggage had to be lifted temporarily up from the camels’ backs to enable them to pass through the passage.

It took us half an hour to negotiate this place; but having at length managed it without any catastrophe, we camped in a bay in the cliff soon after reaching the bottom.

Soon after sunset a wild goose flew over the camp on to the plateau, coming from the south-west. Many were the speculations as to where it had come from, as no water was known to exist in the desert from which it came anywhere nearer than the Sudan.

ABOUT two in the afternoon of the following day we reached “Ain El Jemala,” the first well of Dakhla Oasis, situated near the edge of a large area of scrub, which was said to be a favourite haunt of gazelle. We halted here to water the camels. We then pushed on past the village of Tenida, to Belat.

The ’omda (village head-man) came round during the afternoon, bringing some of the leading men of the village with him to welcome me to the oasis, and to invite me to dine with him, greeting me with the picturesque formula invariably used in the desert to anyone returning from a journey—“praise be to Allah for your safety.”

After dinner a man was brought in who had come from Mut, the capital town of the oasis, bringing me a note from the mamur, or native magistrate, welcoming me to his district, and saying that, though he had heard I had come, no one had been able to pronounce my name. He asked me to get someone to write it down in Arabic. Dakhla Oasis, though it lies just within the Egyptian frontier, had been visited by very few Europeans up to that time, and my arrival in this out-of-the-way spot consequently created somewhat of a stir in its little community.

I entrusted Khalil with the answer to the letter. The “ing” sound in my name is one which no Arab-speaking native has ever been able to master. At length, after much discussion, Khalil got the letter written; the result being that I ever afterwards went in the oasis under the name of “Harden Keen.”

From Belat we pushed on to Smint el Kharab, or ruined Smint, where are some mud-built ruins, some of which have paintings on their interior walls, apparently of Coptic origin. From Smint el Kharab we pushed on to the village[38] of Smint itself. Here we were of course invited to lunch by the ’omda—an invitation of which I was for once glad to avail myself, as we had made an early start, and the caravan, which had been told to wait for me outside the village, had by some misunderstanding, gone on to Mut.

My first impressions of the inhabitants of these oases, with their cordial welcome, was certainly a most favourable one. Their hospitality, however, I found at times somewhat overwhelming.

’OMDA’S HOUSE, TENIDA.

As to the nature of this hospitality there appears to be some misunderstanding. In many cases one’s host is a private individual, or, if he be an ’omda, entertains one in his private capacity. But usually when invited to partake of a meal or to stay with an ’omda, one is in reality the guest of the entire village, though the fact may not be apparent. The ’omdas of Dakhla Oasis have the right to take a small proportion of the flow of any new well sunk in their district, to pay for the hospitality they show to the strangers that come to their village. In cases where there are no new wells, they collect from the heads of the different families the expenses that they have incurred[39] in this way; so that in reality the cost of one’s entertainment falls on the whole village.

The majority of the natives of these oases are miserably poor, and it goes much against the grain for a European to have to live upon them in this way. But to refuse their hospitality would be considered as a slight, if not as an actual insult, and so would any attempt to offer them any payment in return.

The meals, as a rule, were quite well cooked, and usually better than I got in camp. It was the tea and cigarettes that were such a trial. The one luxury the inhabitants of the oasis allow themselves is tea; even the poorest of them consume enormous quantities. The quality of the tea in the better class houses is irreproachable. The best of it is said to come from Persia, and I was told that as much as £1 a rotl (the Egyptian pound) is paid for it. In addition to red tea, a green tea, and also a brown and a black are used. The last I only tasted once; it seemed to be of an inferior quality. The richer natives will often offer two or even three different kinds in succession.

After drinking, it is quite the correct thing to sit silent for some time licking and smacking one’s lips, “tasting the tea” as it is called, as a compliment to the quality supplied by one’s host. The natives have another way of showing their appreciation of the fare set before them, which, however, it would be better not to describe.

The greatest ordeal I had to face was not the tea but the cigarettes. My host would extract from somewhere in the voluminous folds of his clothing a large shiny papier mâché tobacco-box, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, from which he would produce some tobacco and cigarette papers and proceed to roll me a cigarette, which he then licked down.

Eventually I found a means to avoid them. If the cigarette was offered me before the tea, I placed it above my ear—the correct position to carry it in the oases—and explained that I would smoke it later, so as to avoid spoiling the tea. If it was handed to me after the tea drinking, I was able to postpone lighting it for a time by saying that I would not smoke it just then, as I was still “tasting”[40] the tea; then, while still licking and smacking my lips, with the cigarette still unsmoked above my ear, I found that it was time to take my departure. Once safely outside my host’s house in the desert, the cigarette would fall down from my ear and be promptly scrambled for by my men.

In Smint, however, no cigarettes were forthcoming. The reason was not far to seek. Close to the village the Senussi had built a zawia, and a large number of the inhabitants of the village had already been converted to the tenets of the sect, or, as the natives put it, they “followed the sheykh.” The members of this sect are forbidden to smoke.

SENUSSI ZAWIA AT SMINT.

In company with the ’omda we went to call on the sheykh of the zawia. After speaking to us for a minute or two, he rather sulkily invited us to enter and treated us to the usual tea.

The zawia was an entirely unpretentious looking mud-built building, and might have been only the house of a well-to-do villager. The head of it—Sheykh Senussi by name—was quite a young man in the early twenties, and had probably been given the position owing to the fact that he had married a daughter of Sheykh Mohammed el Mawhub, the chief Senussi sheykh in Dakhla, who himself had a zawia at Qasr Dakhl, the largest town in the oasis, situated in its north-western corner.

He was said to be an Arab from Tripoli way, a statement that was borne out by his clothing, which consisted of the[41] ordinary white hram of a Tripolitan Arab of the poorer class. He was very silent during the whole of our visit, and when he did condescend to speak it was generally to sneer or laugh at some remark that we made. The interview was consequently cut as short as possible.

Re-soling a Camel’s Foot.

The sharp rocks of the desert sometimes flay the entire skin from the sole of a camel’s foot, the Arabs replace this with a piece of leather sewn on to the camel’s foot. (p. 35).

After Qway had succeeded in extracting some barley for his camel off the ’omda we started again, for Mut, which lay about six miles away to the west.

In many parts the scenery of these oases is extremely pretty. Our road to Mut lay through cultivated fields, alternating with areas of salt-encrusted land, and sprinkled with palm plantations and low earthy hills. Away to the north at the foot of the cliff that bounds the oasis lay the palm groves of the village of Hindau. The fields, with their ripening grain and green crops of bersim (clover), the yellow ochreous hills, the clumps of graceful date palms with their dark green foliage, set against a background of cream-coloured sand dunes and purple cliffs, made a lovely picture in the light of the setting sun.

As we neared Mut, however, the country became less productive. Large areas of land thickly encrusted with salt and barren stretches of desert replaced the fertile fields and palm groves in the neighbourhood of Masara and Smint. Owing probably to the sinking of new wells at a lower level in the village of Rashida, the water supply of Mut has for many years been falling off, and now, although the place is the capital town, the district in which it lies is one of the poorest in the whole oasis.

We reached Mut in the dusk soon after sunset. Built on a low hill, and seen in the failing light, the place gave rather the impression of an old medieval fortified town. We skirted round its southern side, past a number of walled enclosures used to pen the cattle in at night, and, passing through a gap in the south-western corner of the wall that surrounds the town, arrived at a large rambling mud-built building, mainly used as a store, in which I had received leave to stay. It was a gloomy-looking place, and had evidently been built with a view to defence. Entering through a gate in the wall, secured by a bar, and turning to the right past some low outbuildings, we found ourselves[42] in a narrow court, surrounded on three sides by high two-storied buildings—the upper part having apparently been used at some time as a harem by one of its former inmates.

Doors opened from either end of a gallery that joined the two wings. One led into the centre of three rooms on the western side that looked over the desert, and the other into some small chambers which, as one had a fire-place in it for cooking, I allotted to Dahab and Khalil, retaining the three western rooms for my own use.

OLD HOUSES IN MUT.

These proved to be high, spacious and airy, and commanded a fine view over the desert. The windows were large and fitted with a sort of trellis. This not only made the rooms more private, but considerably reduced the glare of the desert. So beyond the fact that the floors in many places seemed unsafe, and that the place was said to swarm with scorpions, I had little fault to find with my lodgings.

I walked out in the dusk as soon as we had settled into[43] our quarters in the old store, to see what I could of the town. Many of the streets were roofed over, as in Kharga Oasis, but the tunnels were not nearly so long and very considerably higher, so that, except for the unevenness of the roadway, we had no difficulty in getting about. We were, however, compelled to carry a lantern in order to find our way.

There was not much to be seen; but the monotonous thudding of the women pounding rice, the continuous rumbling sound of the small stone hand mills by which they were grinding grain, the smell of wood smoke, the soft singing of the women and an occasional bar of ruddy light, crossing the roadway from some partly open doorway, showed that most of the inhabitants were in their houses preparing their evening meal.

Rice enters largely into the bill of fare of the natives of the oases, and is pounded by the women with a large stone held in both hands, which is brought down with all their strength into a small basin-shaped hollow scooped out of the rocky sandstone floor upon which the town is built.

The following morning I received a state visit from the mamur (magistrate), Ibrahim Zaky by name, the doctor, Gorgi Michael, a Copt from Syria, and the zabit, or police officer. The mamur and doctor spoke English fairly well.

Like most of the native officials who are to be found in the oases, the mamur was rather under a cloud, and had been sent to Dakhla as a punishment for some misdeeds of his in his last appointment. These oases posts are cordially disliked by the natives, as in these remote districts they are entirely cut off from the gay life of the towns of the Nile Valley. The appointments, however, have certain advantages. Being so far removed from the towns of the Nile Valley may be dull, but it frees them from the constant supervision of the English inspectors, a state of things of which an Egyptian is usually not slow to take advantage, by extorting bakhshish from the wretched fellahin of their district—often to a most outrageous extent.

One of the English inspectors had very kindly written[44] to the mamur to inform him that I was coming into his district, and to tell him to help me in any way he could. The mamur’s term of office in Dakhla being nearly at an end, he was extremely anxious to get my good word with the inspector in order that he might be appointed to a better district. He was accordingly most oppressive and unremitting in his attentions—until the government removed him to another and still worse district.

He was by no means enthusiastic about his life in the oasis, and, from his account of the natives, he evidently looked upon them as being little removed from beasts. He explained that he had left his wife behind in Egypt, but as he found that he did not get on well without one, he had married a young girl from Mut. He complained bitterly of the expense she had put him to, for as he expressed it in his rather defective English, it had “cost him £25 to make her clean!”

After the Egyptian officials had departed, a succession of ’omdas from all over the oasis dropped in to pay their respects and to ask me to come round to their villages.

After the ’omdas came various minor fry. First the camel postman, a burly, black-bearded Arab, called ’Ali Kashuta, looked in, drank a gallon or two of tea, took a handful of cigarettes out of the box that was handed to him, told me several times that he was my servant, and obviously didn’t mean it; and then asking if I had any letters for post, departed, leaving a breezy independent atmosphere behind him, which was a pleasant contrast to the fawning attitude of the other natives.

Then came the clerk to the Qadi, Sheykh Senussi, who was also a member of the Senussi sect. He was a very learned person and a poet in his leisure moments. He drank tea, but didn’t smoke, and was all smiles and compliments.

Next came the postmaster. He had been to school in the Nile Valley and spoke English quite well. He explained—what I was beginning to realise—that I was causing much mystification to the good people of the oasis; they could not make me out at all. The postmaster, however,[45] who had been educated in Egypt, knew all about it. He had read about a man called “Keristoffer Kolombos,” who had found America, and he thought that I must be in the same line of business. I told him that he was quite right. He beamed all over, and immediately departed to break the good news to an expectant oasis that the great problem had been solved. Before going he wished that Allah would preserve me on my journey, and hoped that I should find another America in the Libyan Desert.

In the afternoon I went round to tea with the mamur in the merkaz, or official residence.

One of his guests was a tall intelligent looking man, who was introduced to me as the ’omda of Rashida, the mamur adding in English that he was one of the most hospitable men in the oasis; but very fond of whisky.

The latter statement unfortunately proved to be true. According to the mamur, he was a most depraved and habitual drunkard. This, however, was an exaggeration.

Between him and this ’omda there was very little love lost. Shortly before my arrival they had quarrelled furiously. I never heard the cause of the dispute—it was probably a case of cherchez la femme, for Dakhla is one of those unfortunate places where, as Byron so nearly expressed it, “man’s love is of his wife a thing apart, ’tis woman’s whole persistence.” These small-minded natives will squabble over the most trivial matters and keep the quarrel going for years. Often a tiff of the most puerile kind will become a family matter and end in a regular hereditary feud. In the Nile Valley this often leads to bloodshed. In the oases, however, the quarrel usually takes the form of the two sides to abusing and telling lies about each other behind their backs, wrangling whenever they chance to meet, and endeavouring at every possible opportunity to subject their opponent to an ayb (insult, slight, snub) often of a most elaborate description.

Shortly before my arrival the ’omda, getting sick of the squabble, or finding that the mamur was making things too unpleasant for him, had held out the olive branch by sending him a basket of early mulberries—a fruit much[46] appreciated in the oasis. The mamur had made this an opportunity to humiliate his opponent. He had thrown the fruit out of his window into the square in front of the mosque, where all the inhabitants had seen it. It was generally considered that he had scored heavily by doing so, and that this was one of the best aybs that had been seen for years. The whole oasis had been talking about it.

The partisans of the ’omda were consequently much discomforted; but endeavoured to cover up their defeat by explaining that it hadn’t really been a good ayb—the mamur had not thrown the whole of the mulberries away, as he had stated, but had taken out all the best ones and had only thrown away the rotten ones out of his window; so as an ayb it didn’t count at all.

The ill-feeling between these two at length rose to such a pitch that some of the leading men in the oasis decided to try and effect a reconciliation between them, and a ceremony known as “making the peace” took place.

The two opponents were invited to meet together in the presence of some of their friends, who had argued with them, and at length the quarrel had been patched up. They had then fallen on each other’s necks and embraced and had agreed to feed together. They had partaken of a huge feast in which whisky apparently played a prominent part, and had both got drunk and started quarrelling furiously again, in their cups. The next morning, when they were both probably feeling rather cheap, the peace-makers had got to work again and explained to them that they had not played the game, and again a reconciliation had been effected; but there was still a good deal of latent ill-feeling between them which vented itself mostly in backbiting, under a show of friendship.

BY Qway’s advice I started feeding my camels on bersim, preparatory to our journey into the dunes. There are two kinds of bersim grown in the oasis: bersim beladi[1] and bersim hajazi.[2] Bersim hajazi, however, should not be fed to camels in its green state, as it very frequently causes them to get hoven.

The bersim was bought off the natives by the kantar, of a hundred Egyptian pounds. At first there was some difficulty in getting it weighed. Abd er Rahman, however, proved equal to the emergency. He discovered a rock, which was supposed to weigh a kantar, and which was the standard weight for the whole oasis. He then rigged up a pair of scales, consisting of two baskets fixed to either end of a beam, suspended from a second beam.

In the evening of the first day I spent in Mut I climbed to the top of a low hill close to the town to look at the dune field that I hoped to cross. A more depressing sight it would be impossible to imagine. Not only were the sand hills in the neighbourhood of the town much higher than those we had encountered on leaving Kharga Oasis, but they extended as far as it was possible to see to the horizon, and obviously became considerably larger in the far distance, where they were evidently of great height.

I returned to my rooms with the gloomiest forebodings, wishing I had never been such a fool as to tackle the belad esh Shaytan, or “Satan’s country,” as the natives call this part of the desert, and wondering whether, when I attempted to cross those dunes, I should not end, after a few hours’ journey, in having to return completely beaten with my tail tightly tucked between my legs, to the Nile Valley. I lay awake for most of the night in consequence.

[48]But daylight as usual made things look more cheerful. Anyway I could have a shot at it, and as my camels did not seem to be in very good order I decided to give them a rest and to feed them up into the best possible condition, before subjecting them to what appeared to be an almost impossible task. In the meantime I thought I might as well see something of the oasis, and at the same time collect what information I could about the desert.

So a few days after my arrival at Mut I set off with the mamur, the policeman and the doctor to stay for a night with the ’omda of Rashida, leaving the caravan behind me.

For the first two hours after leaving Mut, till we reached the village of Qalamun, our road lay over a barren country largely covered with loose sand, which proved to be rather heavy going.

Qalamun is rather a picturesque village, and seems to have been built with an eye to defence. A great deal of land in the neighbourhood is covered with drift sand, which in places seems to be encroaching on to the cultivation, though not to be doing any serious damage. An unusually large proportion of land in the neighbourhood is planted with date palms, and, as the water supply seems to be fairly abundant, the place has a prosperous well-to-do air. In some cases the wells appear to be failing, as a few shadufs for raising the water were to be seen. These and a few Dom palms gave the neighbourhood a rather distinctive appearance. Of course we visited the ’omda. The sheykhs of this village—the Shurbujis by name—claim to have governed the oasis ever since the time of the Sultan Selim, “The Grim.”

On leaving Qalaman we made straight for Rashida, most of our road lying through cultivated fields, planted mainly with cereals. Before reaching the village, we passed a large dead tree—a sunt, or acacia, apparently—which is known as the “tree of Sheykh Adam,” and is supposed to possess a soul. The wood is reported to be uninflammable.

Shortly before reaching Rashida, we were met by the ’omda and some of his family, who had ridden out to meet us, all splendidly mounted on Syrian horses, gorgeously[49] caparisoned with richly embroidered saddles and saddle cloths. These joined on to our party and rode back with us to Rashida.

Kharashef.

Sand Grooved Ridge.

The wind driven sand grooves away the rock, sometimes leaving large ridges standing above its surface. (p. 308).

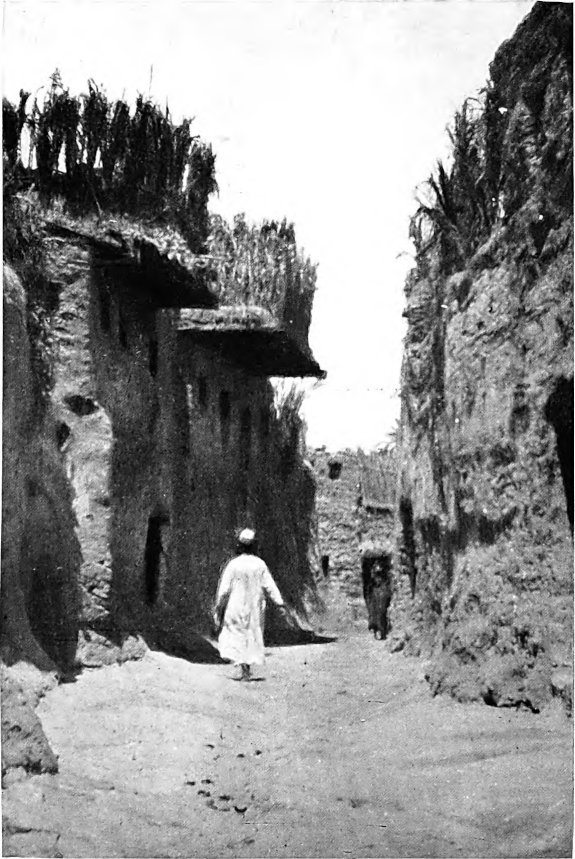

In Old Mut.

This shows the fortified character of the houses formerly built in the oases of the Libyan desert as a defence against raids. (p. 41).

The village is one of the prettiest and most fertile in the oasis. It is built on a low ridge lying at the south-east corner of a very extensive grove of palms, in whose shade were planted great numbers of fruit trees: figs, mulberries, apricots, oranges, tangerines—known in Egypt under the curious name of Yussef effendi, i.e. Mr. Joseph—bananas, almonds, pomegranates, limes, lemons, olives and sweet lemons, the last bearing a large, tasteless, but very juicy fruit, something like a citron in appearance.

THE TREE WITH A SOUL, RASHIDA.

The village lies close to the cliff. The interior of the village was of the normal type, and, beyond presenting an unusually prosperous appearance and having the walls of some of its houses painted on the outside in geometrical patterns, usually in red and white, did not differ from the other villages in the oasis.

The ’omda’s house was delightfully situated, with palm trees growing almost up to the walls. He took us up into his guest chamber, a long narrow room neatly whitewashed and furnished almost entirely in the European manner, with deck-chairs, sofas round the walls, a large gilt hanging lamp, bent wood chairs and three-legged tables. The windows were draped with European curtains[50] and the floor covered with Eastern rugs and carpets. A large mirror in a gilt frame and an oleograph portrait of the Khedive completed the list of furniture.

On entering the room one’s eye was at once caught by the words “Ahlan wa Sahlen”—welcome—painted on the opposite wall. And welcome that hospitable ’omda certainly made us. The windows had been kept closely shuttered all the morning to keep out the heat and the flies; but these were opened on our arrival. Then the ’omda entered and proceeded to spray the room and its inmates with scent. Shortly afterwards the inevitable tea and cigarettes made their appearance.

After compliments, enquiries as to the health of all parties present and the usual polite preliminaries had been got through—a process that took some minutes—the conversation turned upon horses. Only a few of the richer natives of the oases are able to afford them, and the remainder, when they do not walk, ride on donkeys. Powerful quarters, round cannon bones and a small head, with an especially small muzzle and widely distended nostrils, seemed to be the points they valued most.

After luncheon, when the heat of the day was past, we were taken by the ’omda to see some of the sights of the village. First we were led to a big mud ruin known as the ’Der abu Madi. He told us he had dug up a number of mummies about a mile to the north of the village, which he said had been buried in earthenware coffins. Fragments of one of these coffins that he produced showed that they must have been about three inches thick and had evidently been baked in a kiln. Many of the mummies had been wrapped round with a cloth of some sort, with their arms lying straight along their sides, and had then been wound tightly round with a rope. The remains of one of them was shown us. It was, however, entirely knocked to pieces, as the ’omda and his family had stuck it upright on the ground and then amused themselves by turning it into an “Aunt Sally.” One or two coins and the skull of a gazelle had been dug up from one of the graves. The coins unfortunately were so worn and decayed that they could not be recognised. There seems[51] to be plenty of work for an archæologist in Dakhla—and still more for an inspector of antiquities.

We were next taken off to see the great sight of Rashida—the Bir Magnun, or “foolish well.” When this well was being sunk about forty years ago the labourers stopped working for the day, not knowing that they had almost reached the water-bearing stratum, with the result that the water forced its way through the small distance from the bottom of the bore hole to the top of the water reservoir, and gushed up with such violence that it forced the tubing, above the bore hole, partly out of the ground and flooded the whole country round.

On first arriving in the oases, I made enquiries on all sides from the natives for information as to what wells, roads or oases were to be found in the unknown parts of the desert, beyond the Senussi frontier. For a long time I could extract no information from any of them, and it was not till I got to Rashida, and happened to ask the ’omda whether he knew anything about the oasis of Zerzura, that I got any information at all. There is no stopping a native of Dakhla when he gets on that subject, and one begins dimly to realise how very little the East has changed since the days when the “Arabian Nights” were written.

Many of the wealthier natives of the oases, and also, I believe, of the Nile Valley, spend an appreciable portion of their time in hunting for buried treasure. The pursuit is an absorbing one, to which even Europeans at times fall victims. Curious as it may seem at first sight, the native efforts are not infrequently attended with some success.

The reason is not far to seek. In former days, when the country was ruled by a lot of corrupt Turkish officials, a native, who was known to be possessed of any wealth, at once became the object of their extortionate attentions. He consequently took every precaution to hide his riches from these rapacious officials. The plan which he very often adopted was to bury his valuables in the ground. Not infrequently he must have died without imparting to his relations the whereabouts of his cache. The treasure buried in this way in Egypt would probably amount to[52] an enormous sum in the aggregate, if it could only be located.

Then, too, the sites of old Roman settlements are to be found all over Egypt. The careless way in which the Romans seem to have scattered their petty cash about the streets of their towns is simply amazing. You can hardly dig for an hour in any old Roman site without coming across an old copper coin or two.

Let a native find a few coins in this way, and he will spend weeks, when no one is looking, in prowling around the neighbourhood in the hopes of finding more. Should he be lucky enough to find an earthenware pot containing a handful or two of old coins hidden in the past from a Turkish pasha, it is pretty certain that he will become a confirmed fortune-hunter for the remainder of his life. There is no doubt that quite considerable sums—several pounds’ worth at a time—are occasionally found in this way. The natives are extraordinarily secretive about this kind of thing, and have been so long under a corrupt Government that they can hold their own counsel far better than any white man—for even now in out-of-the-way districts such as the oases, where the English inspectors cannot properly supervise the native officials, the extortionate ruler is at times most unpleasantly en evidence.

In their hunts for buried riches the natives are frequently guided by old “books of treasure.” Every self-respecting native, who is wealthy enough to procure one, possesses at least one copy.

Before leaving Kharga I was fortunate in meeting E. A. Johnson Pasha, so well known as the translator of the whole of Omar Khayyám’s “Rubaiyat” into English verse—Fitzgerald, of course, only translated a portion of it. He was the proud possessor of the only complete copy known to exist of a book of this description, dating from the fifteenth century.