MAP SHOWING THE TERRITORIAL GAINS OF FRANCE IN THE 17th CENTURY.

Title: The acendancy of France 1598-1715

Author: Henry Offley Wakeman

Release Date: August 8, 2023 [eBook #71365]

Language: English

Credits: Chris Curnow, Karin Spence and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

PERIODS OF EUROPEAN HISTORY PERIOD V., 1598–1715.

In Eight Volumes. Crown 8vo. With Maps.

PERIODS OF EUROPEAN HISTORY

General Editor—ARTHUR HASSALL, M.A.,

Student of Christ Church, Oxford.

The object of this series is to present in separate Volumes a comprehensive and trustworthy account of the general development of European History, and to deal fully and carefully with the more prominent events in each century.

The Volumes will embody the results of the latest investigations, and will contain references to and notes upon original and other sources of information.

It is believed that no such attempt to place the History of Europe in a comprehensive, detailed, and readable form before the English Public has yet been made, and it is hoped that the Series will form a valuable continuous History of Mediæval and Modern Europe.

Period I.—The Dark Ages. A.D. 476–918. By C. W. C. Oman, M.A., Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford. 7s. 6d.

Period II.—The Empire and the Papacy. A.D. 918–1272. By T. F. Tout, M.A., Professor of History at Victoria University, Manchester.

Period III.—The Close of the Middle Ages. A.D. 1272–1494. By R. Lodge, M.A., Professor of History at the University of Glasgow.

Period IV.—Europe in the 16th Century. A.D. 1494–1598. By A. H. Johnson, M.A., Historical Lecturer to Merton, Trinity, and University Colleges, Oxford. 7s. 6d.

Period V.—The Ascendancy of France. A.D. 1598–1715. By H. O. Wakeman, M.A., Fellow of All Souls College, and Tutor of Keble College, Oxford. 6s.

Period VI.—The Balance of Power. A.D. 1715–1789. By A. Hassall, M.A., Student of Christ Church, Oxford. 6s.

Period VII.—Revolutionary Europe. A.D. 1789–1815. By H. Morse Stephens, M.A., Professor of History at Cornell University, Ithaca, U.S.A. 6s.

Period VIII.—Modern Europe. A.D. 1815–1878. By G. W. Prothero, Litt. D., Professor of History at the University of Edinburgh.

1598–1715

BY

HENRY OFFLEY WAKEMAN, M.A.

FELLOW OF ALL SOULS COLLEGE

TUTOR OF KEBLE COLLEGE, OXFORD

AUTHOR OF ‘AN INTRODUCTION TO THE HISTORY OF THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND’

PERIOD V

SECOND EDITION

London

RIVINGTON, PERCIVAL AND CO.

1897

[All rights reserved.]

[v]

I have not attempted in the following pages to write the history of Europe in the seventeenth century in detail. The chronicle of events can be found without difficulty in many other works. I have therefore endeavoured as far as possible to fix attention upon those events only which had permanent results, and upon those persons only whose life and character profoundly influenced those results. Other events and other persons I have merely referred to in passing, or left out of account altogether, such as for instance the history of Portugal and the Papacy, the internal affairs of Spain, Italy, and Russia. Following out this line of thought I have naturally found in the development of France the central fact of the period which gives unity to the whole. Round that development, and in relation to it, most of the other nations of Europe fall into their appropriate positions, and play their parts in the drama of the world’s progress. Such a method of reading the history of a complicated period may, of course, be open to objection from the point of view of absolute historical truth. The effort to give unity to a period of history may easily fall into the inaccuracy of exaggeration. The picture may become a caricature, or so strong a light may be shed on one part as to throw the rest into disproportionate gloom. It would be presumptuous in me to claim that I have avoided such[vi] dangers. All that I can say is, that they have been present to my mind continually as I was writing, and that I have been emboldened to face them both by the fact that the history of the seventeenth century lends itself in a very marked way to such a treatment, and by the conviction that it is far more important to the training of the human mind, and the true interests of historical truth that a beginner should learn the place which a period occupies in the story of the world than have an accurate knowledge of the smaller details of its history. To know the meaning and results of the Counter-Reformation is some education, to know the official and personal names of the Popes none at all.

With regard to the spelling of names I have endeavoured to follow what I humbly conceive to be the only reasonable and consistent rule, that of custom. It seems to me to be as pedantic to write Henri, Karl, or Friedrich, as it is admitted to be to write Wien or Napoli, and inconsistent on any theory except that of the law of custom to write anything else. But with regard to some names, custom permits more than one form of spelling. It is as customary to write Trier as Trêves, or Mainz as Mayence. These cases mainly arise with reference to names of places which are situated on border lands, and are spelt sometimes according to one language, and sometimes according to another. In these cases I have followed the language of the nation which was dominant in the period of which I treat, and accordingly write Alsace, Lorraine, Basel, Köln, Saluzzo, etc. The use of an historical atlas is presumed throughout.

H. O. W.

All Souls College, Oxford.

March, 1894.

[vii]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Europe at the beginning of the Seventeenth Century, | 1 |

| II. | France under Henry iv., | 14 |

| III. | The Counter-Reformation and religious troubles in Germany, | 39 |

| IV. | The beginning of the Thirty Years’ War, | 53 |

| V. | The Thirty Years’ War from the peace of Lübeck to the peace of Prague, | 78 |

| VI. | The aggrandisement of France, | 106 |

| VII. | France under Richelieu and Mazarin, | 133 |

| VIII. | Northern Europe to the treaty of Oliva, | 166 |

| IX. | Louis xiv. and Colbert, | 185 |

| X. | Louis xiv. and the United Provinces, | 207 |

| XI. | Louis xiv. and William iii., | 235 |

| XII. | South-eastern Europe, | 266 |

| XIII. | The Northern Nations from the treaty of Oliva to the peace of Utrecht, | 290 |

| XIV. | The Partition Treaties and the Grand Alliance, | 312 |

| XV. | The War of the Spanish Succession and the death of Louis xiv., | 342 |

[viii]

| NO. | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

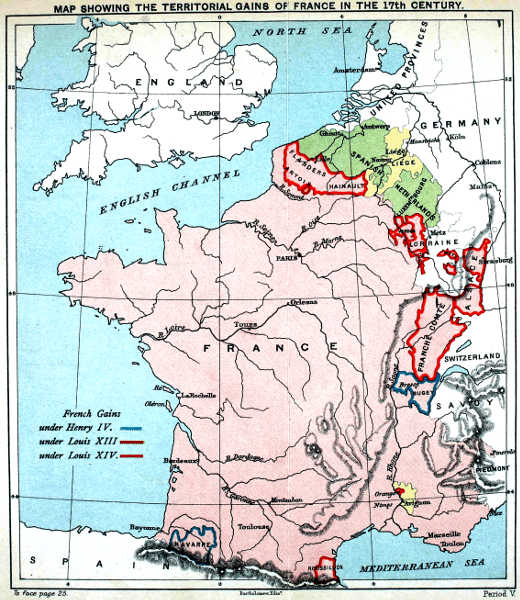

| 1. | Acquisitions of territory by France during the period, | To face page 25 |

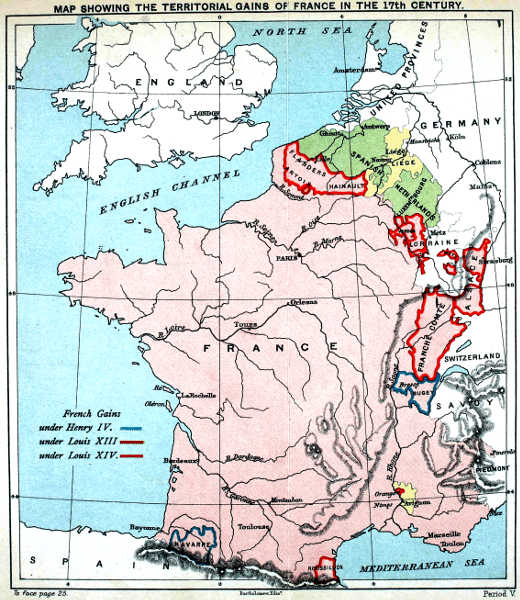

| 2. | Germany according to the peace of Westphalia, showing the march of Gustavus Adolphus, 1630–1632, | To face page 124 |

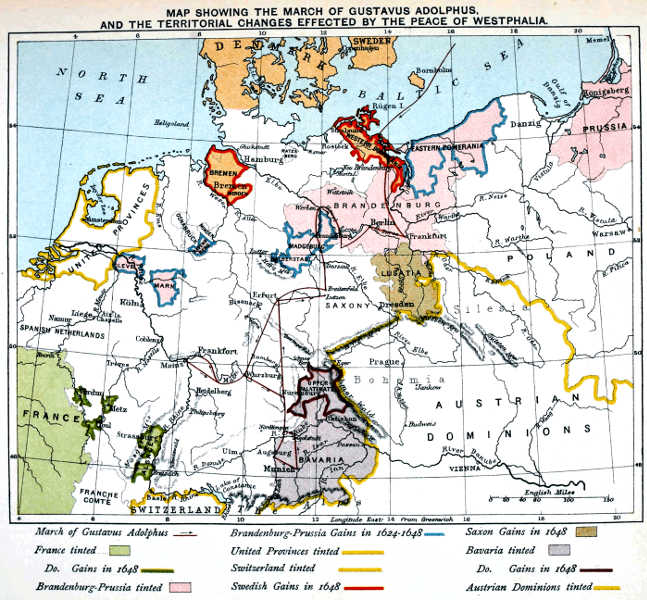

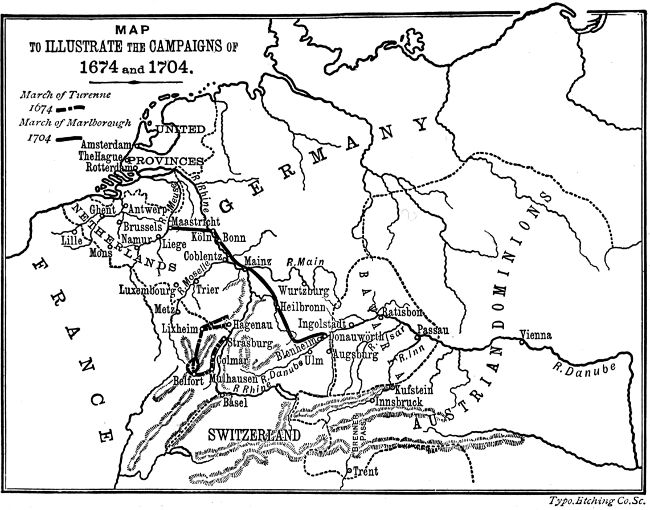

| 3. | The countries of the Upper Rhine and Danube, showing the march of Turenne, 1675, and of Marlborough, 1704, | 241 |

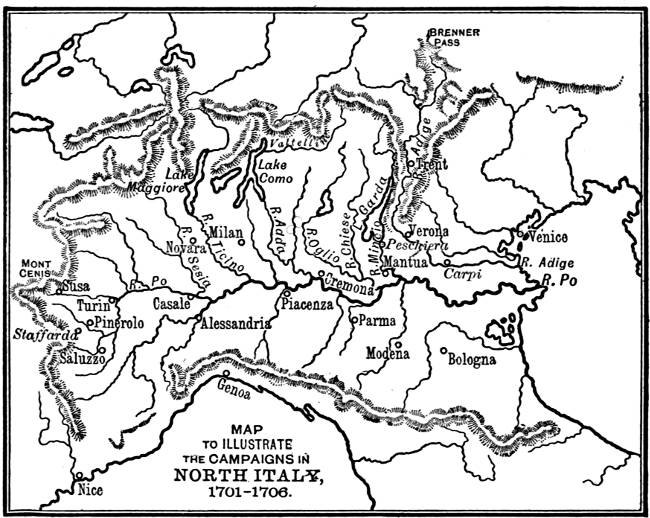

| 4. | Northern Italy, illustrating the campaigns of Prince Eugene 1701–1706, | 343 |

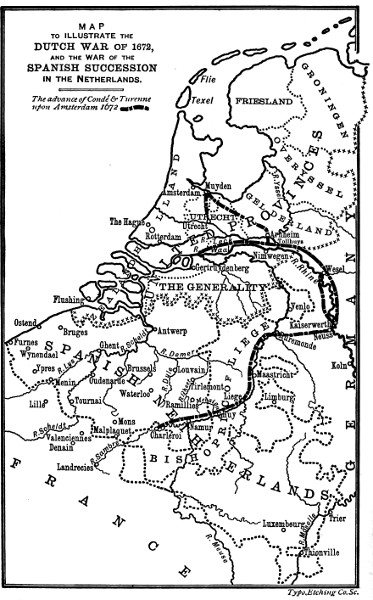

| 5. | The Netherlands, illustrating the campaigns of Condé, Turenne and Marlborough, | 348 |

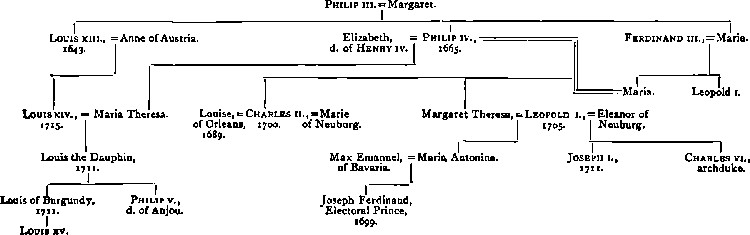

| 1. | The Sovereigns of Europe during the century, | 376 |

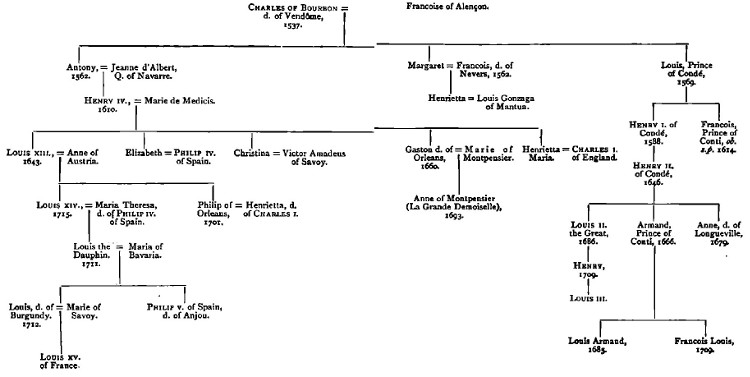

| 2. | The House of Bourbon, | 378 |

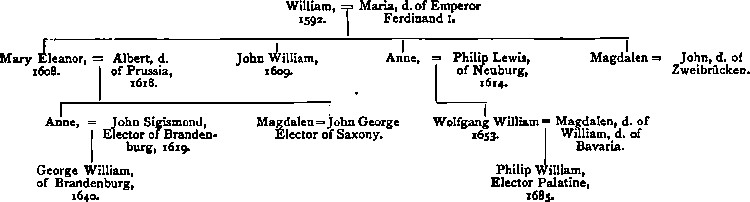

| 3. | The Cleves-Jülich succession, | 380 |

| 4. | The Spanish Succession, | 381 |

| Index | 383 |

[1]

Importance of the century—France at the beginning of the century—The States-General, the Parlement de Paris, Religious Toleration—Germany—The Emperor, the Imperial Courts, the Diet—Disunion of Germany—England—Spain—Italy.

The seventeenth century is the period when Europe, shattered in its political and religious ideas by the Reformation, reconstructed its political system upon the principle of territorialism under the rule of absolute monarchs. It opens with Henry IV., it closes with Peter the Great. It reaches its climax in Louis XIV. and the Great Elector. It is therefore the century in which the principal European States took the form, and acquired the position in Europe, which they have held more or less up to the present time. A century, in which France takes the lead in European affairs, and enters on a course of embittered rivalry with Germany, in which England assumes a position of first importance in the affairs of Europe, in which the Emperor, ousted from all effective control over German politics, finds the true centre of his power on the Danube, in which Prussia becomes the dominant state in north Germany, in which Russia begins to drive in the Turkish outposts on the Pruth and the Euxine—a century, in short, which saw the birth of the Franco-German Question and of the Eastern Question—cannot be said to be deficient in modern interest. The map of Europe at the close of the seventeenth shows the same[2] great divisions as it does at the close of the nineteenth century, with the notable exception of Italy. Prussia and Russia have grown bigger, France and Turkey have grown smaller, the Empire has become definitely Austrian, but in all its main divisions the political map of Europe is practically unchanged. The states which were formed in the general reconstruction of Europe after the religious wars of the sixteenth century are the states of which modern Europe is now composed. Great nations are apt to change their forms of internal government much more often than they do their political boundaries and influence; but it is a remarkable thing that, with the great exception of France, the principal European states possess at the present time not only a similar political position, but a similar form of government to that which they possessed at the close of the seventeenth century. In spite of the wave of revolutionary principles, which flowed out from France over Europe at the end of the eighteenth century, the principal states of Europe at the present time are in all essentials absolute monarchies, and these monarchies are as absolute now as they were then, with the two exceptions of Italy, which did not then exist, and France, which is now a Republic, but has been everything in turn and nothing long. The formation of the modern European states system is therefore the main element of continuous interest and importance in the history of the seventeenth century, that is to say, the acquisition by the chief European states of the boundaries, which they have since substantially retained, the adoption by them of the form of government to which they have since adhered, and the assumption by them, relatively to the other states, of a position and influence in the affairs of Europe which they have since enjoyed. The sixteenth century saw the final dismemberment of medieval Europe, the seventeenth saw its reconstruction in the modern form in which we know it now.

Of the European nations which were profoundly affected by the Reformation, France was the first to emerge from the[3] conflict. French Calvinism differed from the south German type by being more distinctly political in its objects, and the leaders of the French Catholics, especially the ambitious chiefs of the house of Guise, had quite as keen a desire for their own aggrandisement as they had for the supremacy of their religion. The religious wars in France soon became mainly faction fights among the nobles for political objects in which personal rivalry was embittered by religious division, and all honest and law-abiding citizens—that sturdy middle-class element which has always formed the backbone of the French nation—soon longed for the strong hand which should at any rate keep faction quiet. The authority of the Crown had ever been in France the sole guarantee of order and of progress. Under the weak princes of the House of Valois that guarantee ceased to exist. Shifty, irresolute, inconstant, they preferred the arts of the intriguer to the policy of the statesman, the poniard of the assassin to the sword of the soldier, and when Henry III., the murderer of the Duke of Guise, in his turn fell murdered by the dagger of the monk Clément, France drew a long sigh of relief. Like England after Bosworth Field, France after Ivry was ready to throw herself at the feet of a conqueror who was strong enough to ensure peace and suppress faction. The House of Bourbon ascended the French throne upon the same unwritten conditions as the House of Tudor ascended the English throne. It was to rule because it knew how to rule, and the conditions of its rule were to be internal peace, and national consolidation.

But the task before the first Bourbon was far more difficult than that which absorbed all the energies of the first Tudor. He had no machinery to his hand which he could use to veil the arbitrariness of his action, or to guide public opinion. Parliament in England had often been the terror of a weak king. The Tudors soon made it the tool of a strong king. In France Henry had to rely openly upon the powers of the Crown and upon military[4] force. It is true that the States-General still existed, though they were seldom summoned, but their constitution and traditions rendered them unfit to play the part of an English Parliament. They met in three houses representing the Clergy, the Nobility, and the Commonalty, the latter house, the Tiers-Etat as it was called, being usually about as large as the other two put together; but instead of there being a political division running through the three estates of those for the policy of the Crown and those against it, as was usually the case in England, the tendency in France always was for the two privileged houses to coalesce against the Tiers-Etat. The Crown had therefore only to balance one against the other, and leave them to entangle themselves in mutual rivalries in order to gain the victory. In the long history of the English Parliament it is very rare to find serious questions raised between the two houses. Nobles and Commons have as a rule acted together for weal or for woe in attacking or supporting the policy of the Crown. The unity of Parliament has been its most significant feature. In France it has been quite otherwise. Mutual jealousy and social rivalry played their part with such effect that they destroyed the political usefulness of the States-General. Unable to act together they could not extort from the Crown either the power over the purse, or the right of legislation, which were the two effective checks upon the king’s prerogative exercised by the English Parliament. All that they could do was to present a list of grievances and ask for a remedy. They had no power whatever of compelling a favourable answer, much less of giving effect to it. The procedure was for each Estate to draw up its own list (cahier) of those matters which it wished to press upon the attention of the Crown. When the lists were completed they were formally presented to the king and a formal answer of acceptance or rejection was expected from him, but as the Estates separated directly the answer was given, the Crown was apt not to be over prompt in fulfilling its promises.

[5]

As a constitutional check upon misgovernment the States-General in France were therefore of little use. That function, as far as it was discharged at all, had by accident devolved upon the Parlement de Paris. The Parlement was in its origin nothing more than a court of law which sat at Paris to administer justice between the king and his subjects, and between subject and subject. In course of time it grew into a corporation of lawyers and judges, not altogether unlike our Inns of Court in England amalgamated into one, having just that kind of political influence which a close and learned corporation, whose business it was to make by judicial decision a great deal of the law of the country, could not fail to have. In one point indeed the Parlement had almost established a definite right. As the highest court of the realm its duty was to register the edicts of the king, a duty which was easily turned into a right to refuse to register them if it so willed. Thus the Parlement claimed an indirect veto upon the royal legislation. It is true that the king could always override the refusal of the Parlement to register an edict by coming in person to its session and holding what was called a lit de justice; but this was a proceeding which involved a good deal of inconvenience, and was not unlikely to excite tumults; it would not therefore be resorted to except on critical occasions. Position of the Crown. So completely had the constitution of France become in its structure despotic, that there was absolutely no constitutional means of exercising control over the king’s will than this very doubtful right of the Parlement de Paris to refuse to register the king’s edict. And if there was no constitutional check upon the king’s will, there was also no machinery which the king could utilise in order to associate himself with his people in the task of government. He stood on a pedestal by himself in terrible isolation surrounded by his courtiers, faced by the nobility, backed by his army, unable to know his people’s wants, and unable to help them to know their own.

[6]

But this was not all. Henry IV. had to encounter open enmity abroad, and give an earnest of religious peace at home, as well as to crush civil dissensions. It was not till his conversion to Catholicism drew the teeth of Spain, and proved to the majority of his subjects that he desired above all things to be a national and not a party king, that he can be said really to have reigned. The peace of Vervins, concluded in 1598, marked the issue of France from the throes of her Reformation wars. Her religious struggle was over. Calvinism had made its great effort to win religious and political ascendency in France, and had failed. France was to remain a Catholic country, and the bull of absolution granted to Henry IV. by Pope Clement VIII. in 1595 duly emphasised the return of the Most Christian King into the pale of Catholic obedience. But if Calvinism had failed, neither had Papalism wholly won the day. Catholic, France had determined to be, but she was far from assuming as yet the mantle of the champion of rigid orthodoxy just laid down by Philip II. The Edict of Nantes. The same year which saw the death of Philip II. and the real beginning of the reign of Henry IV. saw also the promulgation of the Edict of Nantes with its announcement of the new policy of liberty of conscience. By this famous edict religious toleration and political recognition was accorded to the French Calvinists. They were to be allowed to worship as they pleased, provided they paid tithes to the Church, and observed religious festivals like other Frenchmen. They were to receive a grant from the State in return. They were to be equally eligible with Catholics for all public offices. They were to be represented in the Parlements, and were to have exclusive political control for eight years over certain towns in the south and west of France, of which the most important were Nismes, Montauban, and La Rochelle. Thus they obtained not merely toleration as a religious body, and part endowment by the State, but also recognition in certain places as a political organisation. The political settlement[7] was evidently but a palliative, the religious settlement was a cure. No country as patriotic as France, no government as strong as an absolute monarchy could tolerate longer than was necessary an imperium in imperio under the control of a religious sect. But the toleration of Calvinism in a country professedly Catholic was a solution of the religious question thoroughly acceptable to the genius of the French nation. It enabled France at once to fix her whole attention upon the absorbing business of political aggrandisement. It excused her somewhat for not thinking it obligatory to play a purely Catholic rôle in the pursuit of that aggrandisement. The first of those nations of Europe, which had been seriously affected by the Reformation, to arrive at a satisfactory solution of the problem of religious division, she was able to set an example to Europe of a policy entirely outside religious considerations. Under a king who had conformed, but had not been converted, France, pacified, but not yet united, was ready to mix herself up in the web of political intrigue and religious rivalry in which Germany was helplessly struggling, with the simple if selfish object of using the misfortunes of her neighbours for her own advantage.

The state of Germany was indeed pitiable. The Empire had become but the shadow of a great name. The successor of Augustus had nothing in common with his prototype but his title. Roman Emperor he might be in the language of ceremony, punctiliously might the imperial hierarchy of dignity be ordered according to the solemnities of the Golden Bull, but all the world knew that in spite of this wealth of tradition and of prescription, the Emperor could wield little more power in German politics than that which he derived from his hereditary dominions. The archduke of Austria must indeed be a figure in Germany under any circumstances, still more so if he happened to be also king of Hungary and king of Bohemia; but if the electors set the Imperial Crown at his feet and hailed him as Cæsar, though much was thereby added to his dignity and something to his legal rights, not one whit accrued to him of effective[8] force. It is true that his legal position as head and judge over the princes accrued to him, not so much because he was emperor and the representative of Augustus and Charles the Great, as because he was German king and the successor of Henry the Fowler and Otto the Great. Nevertheless, the fact, from whatever quarter derived, that the German constitution gave to the Emperor the lordship over the other princes and the right of deciding disputes which arose between them, made him the only possible centre of German unity.

That right was exercised through a court (the Reichskammergericht) the members of which were mainly nominated by the princes themselves. For the purpose of ensuring the enforcement of its decrees, Germany was divided into circles, in which the princes and the representatives of the cities who were members of the diet met, and if necessary, raised troops to give effect to the sentences pronounced. Since the beginning of the Reformation, however, there had been a difficulty in getting this machinery to work owing to the religions dissensions, and the Emperor had begun the practice of referring imperial questions which had arisen to the Imperial or Aulic Council (Reichshofrath), which was entirely nominated by him and under his influence.

In all important matters of administrative policy the Emperors, since the middle of the fifteenth century, had been obliged to consult the Diet, but the Diet was in no sense a representative assembly of the classes of which the nation was composed, as were the Parliament of England and the States-General of France, but was merely a feudal assembly of the chief feudal vassals of the Empire. It was, in fact, a congress of petty sovereigns gathered under their suzerain. It was divided into three houses. The first consisted of six of the seven electors, three ecclesiastical, i.e. the archbishops of Köln, Mainz, and Trier, and three lay, the electors of Saxony and Brandenburg and the elector-palatine, for the fourth lay elector the king of Bohemia only appeared for an imperial election. The second was the House of Princes, the third that of the free Imperial Cities, but it was[9] considered so inferior to the other houses that it was only permitted to discuss matters which had already received their assent. It is obvious that in an assembly so constituted the only interest powerfully represented was that of the princes, and the only influence likely to be exercised by it was in favour of that desire for complete independence, which was natural to a body of rulers who already enjoyed most of the prerogatives of sovereignty. German desire for unity. For there had ever been two divergent streams of tendency in German politics. Deep in the German heart lay a vague sense of nationality and patriotism, a dim desire that Germany should be one. This sentiment naturally centred round the Emperor as the visible head of German unity. If Germans ever were to be politically one, it could only be under the Emperor. There was no other possible head among the seething mass of jarring interests known geographically as Germany. The other tendency had sprung from the strong love of local independence characteristic of the Teutonic race. Desire for sovereignty among the Princes. Naturally each petty duke or prince tried to become as independent of outside authority as he could, and in the pursuit of this policy he found himself greatly aided by that spirit of local seclusion, which ever seeks to find its centre of patriotism in the side eddies of provincial life, rather than in the broad stream of the national existence. The Emperors of the House of Habsburg had fully recognised these facts, and, since the days of Maximilian I., had set themselves resolutely to the task of rebuilding the imperial authority, and making the imperial institutions the true and only centre of German unity. They might have succeeded, had it not been for two events, the concurrent effect of which was completely to shatter the half begun work. Effect of the Reformation. The first was the Reformation, the second was the long rivalry with France. The Reformation cut Germany rudely at first into two afterwards into three pieces. Lutheranism, which absorbed nearly all northern Germany between the Main and the Baltic, drew its strength especially from the support of the north German princes. Luther himself[10] effected a closer alliance with the princes and the nobles than he did with the people. It was to them he appealed for protection in the days of his earlier struggles, on them that he trustfully leaned in the later days of his power. Naturally, therefore, Lutheranism gave a strong impulse and sanction to the desire, which the northern princes uniformly felt, to assert their independence of a Catholic emperor. Calvinism, spreading from republican Switzerland down the upper valley of the Rhine into the heart of Germany, had a no less fatal influence upon the centralising policy of the Emperors. Subversive in its tendencies and impatient of recognised authority, it intensified the spirit of dislike to autocratic institutions. Effect of the rivalry with France. Still, in spite of the terrible disruption of Germany caused by the Reformation, a sovereign so powerful and so cautious as Charles V. might have been able to weather the storm, without suffering any loss of prerogative or influence, had it not been for the constant and paramount necessity laid upon him of counteracting the machinations of an enemy ever wakeful and absolutely unscrupulous. As long as Francis I. lived Charles V. was never able seriously to apply himself to German affairs. When he was dead it was too late. The religious divisions of Germany had taken definite political shape, and were inspired with definite political ambitions. The Emperor had ceased to be the acknowledged political head of Germany. He had sunk into the inferior position of becoming merely the chief of one political and religious party.

In this way the desire for political independence from the authority of the Emperor went hand in hand with the achievement of religious independence from the authority of the Church. The Emperors who followed Charles V. in the latter years of the sixteenth century, Ferdinand I., Maximilian II., and Rudolf II., so far from being able in the least to extend their prerogative in Germany, were barely able to retain what shreds of it yet remained. But towards the close of the century the onward and destructive march of Lutheranism and of Calvinism[11] stopped. The Reformation spent itself as a living force. It had reached its utmost limits and slowly the tide began to turn. The Counter-Reformation, with the spiritual exercises of S. Ignatius in one hand and the sword in the other, went forth to win back half Germany to the faith. When the peace of Vervins set France free, Germany was at her weakest. Jarring interests, political dissensions, religious hatreds were rife through the length and breadth of that unhappy land. The Lutheran princes of the north had succeeded in throwing off the leadership of the Emperor without themselves producing either a leader or a policy. The Calvinist princes of the Rhineland, exasperated by the advance of the Counter-Reformation, were ready to throw all Germany into the crucible and rashly strike for a supremacy which they had not strength to win. In Bohemia men remembered with fierce glee the stubborn waggon fortresses of the unconquerable Ziska, and the concessions wrung from reluctant Pope and Emperor by the success of a rebellion. Meanwhile in Bavaria and the hereditary dominions of the House of Austria, by steady governmental pressure backed by the devotion and talent of the Society of Jesus, Protestantism was being gradually rooted out and swept away by the advancing tide of the Counter-Reformation. Yet the Emperor himself was incapable of directing the policy of his own party. A melancholy recluse given to astrology and fond of morbid religious exercises, Rudolf II. was the last man fitted to lead a crusade. He could not even inspire respect, much less command allegiance. Never certainly was a country in a more pitiable plight. Torn from end to end by religious dissension, pierced through and through by personal and provincial rivalries, without a single public man on either side sufficiently respected to command obedience, without unity of political or religious ideal even among the Protestants, without that last hope of expiring patriotism, the power of union in the face of the foreign aggressor, Germany at the close of the sixteenth century lay extended at the feet of her jealous rival, a helpless prey, whenever it pleased him to spring and put an end to her miseries.

[12]

England, unlike France and Germany, had as yet escaped the necessity of making the sword the arbiter of religion, but she had not wholly settled her religious difficulties. Elizabeth, masterful in all things, had imposed upon the Church and the nation a solution of the religious question which was still upon its trial. The experiment of a Church, historically organised and doctrinally Catholic, but in hostility to the Pope, was hitherto unknown in the West, though common enough in the East; and it is not surprising that it soon found itself attacked from both sides by Roman Catholics and Protestants at once. During the reign of Elizabeth the personality of the Queen and the success of her policy, especially as the champion and leader of the national opposition to Spain which culminated in the defeat of the Armada in 1588, kept the disturbing elements in check. On the accession in 1603 of a prince who with some insight into statesmanship was wholly deficient in the faculty of governing, those elements rapidly gathered strength. When serious constitutional questions between the king and the Parliament were added to the religious complications, England soon became too much absorbed in her own internal affairs to be able to speak with authority in European politics. For fifty years after the accession of the House of Stuart, England became merely a diplomatic voice in Europe to which nations courteously listened but paid no attention.

While England was failing to secure her newly won honours, Spain was trading upon a past reputation. Never was the retribution of an impossible policy so quick in coming. The transition from Philip II. to Philip III. is the transition from a first-rate to a third-rate power, and that without the shock of a great defeat. Enervated by a proud laziness, drained by a world-wide ambition, ruined by a false economy, depleted by a fatal fanaticism, Spain was already falling fast into the slough from which she is only just beginning now to emerge. Yet she was still a great power, great in her traditions, great in her well-trained infantry,[13] great through her monopoly of the American trade. Had she but produced men instead of puppets for kings, and statesmen instead of favourites for ministers, she would quickly have recovered something of her ancient glory. Even under Philip III. she was always a power with which men had to reckon, and in strict family alliance with the House of Habsburg formed the kernel of the Catholic interest in Europe. By her possessions in the Netherlands, in Franche Comté and in the Pyrenees, she presented the most serious obstacle to the territorial aggrandisement of France.

Patriotism was the very air the Spaniard breathed. In Italy it was a vice, for an Italian had no country for which to live or to die. Italy, since France and Spain had quarrelled over the division of its carcase, had ceased to be anything but a name. In the south, the Spanish House had made good its hold on Naples, in central Italy the States of the Church were thrust in like a great wedge to separate north and south. The north was still the battle-field between the rival powers. Venice lay entrenched along the eastern coast and commanded the mouth of the Brenner Pass, too formidable as yet to be attacked, too independent to be won, by either side. In the middle of the rich plain of Lombardy was the Milanese, which belonged to Spain, and was held by Austrian or Spanish troops, who kept up a precarious communication with Austria through the Valtelline and Tirol, or with Spain through the friendly republic of Genoa. To the west of the Milanese came Piedmont and Savoy, the duke of which from his geographical position was usually obliged to be on good terms with France, but respected the obligation no longer than necessary. Italy thus torn and divided was always ready to produce, whenever it was wanted, a crop of international questions of the greatest nicety for her neighbours to quarrel over, and, as the century advanced, she seemed more and more to find her appropriate function to lie in providing the necessary pawns for the game of diplomatic chess characteristic of the new European states’ system.

[14]

Difficulties of Henry IV.—Henry IV. and Sully—Economical policy of Sully—His financial reforms—French taxation in the seventeenth century—Policy of Henry IV. towards the nobles—His foreign policy—Acquisition of Bresse and Bugey—The Cleves-Jülich question—Death of Henry IV.—Regency of Marie de Medicis—Mismanagement of affairs—The States-General of 1614—The Huguenot rising—Entry of Richelieu into the ministry.

‘Now I am king!’ cried Henry IV. when he received the submission of the last of the Leaguers. He was right, for it was only then that he was able to turn his attention to the true business of a king, the good government of his people. The evils under which France groaned were mainly threefold: the selfishness and factiousness of the nobility, the religious dissensions, and the shameful financial mismanagement. As long as civil and foreign war was desolating the country, no steps could be taken to deal with these dangers, but directly the submission of the League and the absolution of Henry had produced internal quiet, and the treaty of Vervins restored external peace, Henry found his hands free to strike at the root of the evil. Twenty days before the treaty was signed the publication of the Edict of Nantes found the true solution of the religious difficulty. It secured to the Calvinists the freedom of conscience for which they had nominally fought, to the Catholics the religious ascendency which their numbers and traditions entitled them to demand. Nor could the most zealous of Leaguers refuse to recognise[15] the justice of a compromise which the Pope himself had sanctioned. The dangers which threatened France from the factiousness of the nobility and the disorder of the finances did not admit of so simple a remedy. They required long years of patient, watchful and firm government, and Henry IV. was not able in the time allotted him to do more than make a beginning and set an example. For this purpose he called to his intimate counsels his old comrade in arms, the duke of Sully, whom he had known and valued since childhood. The whole internal administration of the country was confided to him under the king, and the title of Superintendant of the Finances, which was conferred on him in 1598, gave him special authority in that department.

For the twelve remaining years of the reign of Henry these two men were continuously and inseparably engaged upon the great work of the rehabilitation of the affairs of France. The very contrast between them in temperament and talents served to bind them the closer together and fit them for their joint work. Henry himself was a true Gascon, frank, open-hearted, open-minded, genial, generous, and perhaps boastful. Sully was severe, harsh, cold and reserved. With Henry pleasure, even dissipation, had ever held a foremost place. Unhappy in his marriage he had solaced himself with many mistresses and a large family of bastards, and even after he became king the recklessness of his expenditure, and the extravagance of his orgies occasioned scandal even in pleasure-loving Paris. Sully, on the other hand, was morose in manner and thrifty even to meanness in private life. Avaricious, incorruptible, indefatigable, intensely jealous of his authority, and proud of his services, he found his pleasure in the rooting out of abuse and his triumph in the overthrow of the evil-doer. Henry inspired love and loyalty in his people, Sully won their respect and their hatred. Yet neither was complete without the other. To Henry, gay, chivalrous and manly, human nature was a book more easily read, a tool more deftly used. His mind was more inventive,[16] his heart more expansive, his conceptions far wider and deeper in their scope. In a word, he was a statesman, while Sully was an administrator, and France required the services of both. While Henry’s clear genius cut the knot of the religious question, and seized unerringly the moment to throw France boldly on to the track of her political greatness, Sully’s honest watchfulness was laying the foundations of economical resource, and purifying the streams of administrative policy, which alone could enable France to make the sacrifices necessary for the attainment of her political future.

The characteristic bent of Sully’s mind is most evident in his economical measures. He looked upon France as an essentially agricultural country, and he believed further that an agricultural population was a far more trustworthy support to the Crown than one engaged in industrial pursuits. Consequently he devoted all his efforts to the development of agriculture. France was to be the great producer of food for Europe. By the draining of the marshes, and the careful management of the forest-land, large tracts hitherto unproductive were brought under cultivation, and the country soon began to supply food products more than sufficient for her own wants. The removal of all export-duties on corn enabled her to sell this surplus to less favoured nations at considerable profit, without rendering herself dependent upon others for any prime necessity of national existence. In this Sully showed himself a true exponent of the economical ideas of the seventeenth century. At a period when Europe was torn with religious and political dissensions, when France especially was preparing to launch herself upon a career of aggrandisement, which was to evoke a hundred years of war, it seemed all important to politicians that a country should not be dependent upon any other for the chief necessities of life. It was not so much a principle of economical policy as a necessity of national safety which drove nations to make themselves as self-supporting as possible in days of almost universal war. They[17] encouraged only such manufactures as were required by their own people, they prohibited the importation of foreign food products by high import-duties, they kept gold and silver as much as possible in the country, chiefly in order that the government might have ready to hand the means of waging war. It has been too much the fashion to look at the protective system of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries from the economical side alone. Its foundations are laid far more in the interests of prudent national policy than in those of a false economy, though it is true that hardly any statesman of the time fully realised how false the economy was. Sully certainly was no exception to the general rule. While encouraging agriculture as much as possible he deliberately depreciated manufactures, imposed duties on manufactured articles, prohibited the exportation of gold and silver, and did all in his power to hinder the establishment of new industries. Here the greater statesmanship of the king corrected the prejudices of the minister. Partial encouragement of manufactures. Henry at once perceived the political as well as the economical value of an industrial population and of national industries, encouraged the nascent silk manufactures of Lyons and Nismes, and the glass and pottery works of Paris and Nevers, promoted the construction of roads, and of the first of the great canals of France, that between the Loire and the Seine. In the department of foreign affairs, where the influence of Sully was less powerful, his efforts were even more observable. He renewed the extremely important capitulations with Turkey, which were the solid fruit of the alliance of Francis I. with the Sultan, and thus retained for France a predominant voice at the court of Constantinople and the larger share of the trade with that port. He made favourable treaties of commerce with England and Holland, which helped to encourage the exportation of French wines, and promoted the colonisation of Canada, where Champlain founded Quebec in 1608.

The greatest debt which France owed to Sully was the reform of the financial administration. It is a singular thing[18] that a nation which has shown itself in other departments of administration so persistent in its adherence to fixed principles, should have been content to manage the important department of finance at haphazard. From the time that France became a nation, to the time of the Revolution, she produced but four great finance ministers, Suger, Sully, Colbert, and Turgot, and of them the two most important, Sully and Colbert, were not so much great financiers as honest and sensible administrators. The business of Sully was to produce order out of chaos, to defeat corruption, to govern justly. He made no attempt to reorganise the finances of France, to introduce a new and better system of taxation, still less did he venture to interfere with privileges which rendered anything like a just incidence of taxation impossible. Nor indeed would he have wished to do so if he had dared. On the contrary he accepted the system as he found it, and contented himself with enforcing its proper observance. The only important novelty which he introduced was the tax known as the paulette, by which the judicial and financial officials were permitted to hand on their offices to their heirs on payment of the tax. This was in fact to create a caste of hereditary officials, and to add yet one more to the many privileged classes of France.

The revenue of the country was chiefly drawn from four sources known as the Taille, the Gabelle, the Aides, and the Douanes. Of these, the taille was the most lucrative, and was originally a direct tax upon property. But in course of time its mode of assessment became varied in different parts of France. In the pays d’election, or those provinces which originally appertained to the monarchy of France, such as Normandy, Touraine, the Isle de France, etc., the taille was still a property tax and was levied upon each man personally according to a computation of what he was worth; but in the pays d’état, or those provinces which had been annexed to the crown of France in more recent times, many of which[19] had on annexation secured fiscal privileges which they had been accustomed to enjoy—such as Burgundy, Guienne, Provence, etc.—it was levied only upon land and was in fact a land tax and not a property tax. In the pays d’élection the nobles, in the pays d’état the terres nobles, i.e. the lands which were or once had been in the possession of the nobility, were free from taille, and so were the lands of the Church, which paid their tenths (décimes) instead. In itself there was nothing unjust about the taille, excepting the fact that as, owing to the exemptions, it fell almost entirely on the classes which had no political power, the temptation to increase it abnormally was a very strong one to a needy finance minister who was anxious not to make powerful enemies. But the real evil of the tax lay in the method of its assessment and collection in the pays d’election. The gross sum to be raised from each province was fixed by the government, and a contract made with a capitalist on the best terms available for the letting to him of the sole right of raising that sum from that particular province. The Intendant, the financial agent for the province, then proceeded to assess the total sum to be raised upon the different parishes, and the farmer general in his turn farmed out the raising of these smaller sums to subordinate agents of his own. Finally the inhabitants of each parish elected a committee to levy the parochial quota upon individuals. Nothing could well exceed the wastefulness and injustice of such a system. Every parish which had made or could make interest with the Intendant, every inhabitant who had interest with the assessment committee got the quota reduced at the expense of less fortunate neighbours. Each farmer and sub-farmer wrung the most he could out of an unfortunate peasantry, and was protected by a government which had already received all that was due to it of the tax. The only nominal check upon the farmers was the supervision of their accounts by the chambre des comptes, but that was a mere farce, as no attempt was made to ensure the accuracy of the registers upon which they worked. A[20] system by which it mattered not a sou to the government to see that the tax was fairly levied, while it was to the direct interest of the officials to take care that it was unfairly levied, stands selfcondemned, but it was a system which was universal throughout France. By farming out the different branches of the revenue to harpies who fattened on the misery of the people, the government shirked the difficulty of having to deal with venal servants of its own, and reaped the benefit of a sure though diminished income at the price of abdicating one of the chief functions of government, and subjecting the innocent tax-payers to the worst form of governmental tyranny, a taxation both capricious and corrupt. When Sully turned his attention to the abuses of the system, it is said that the people were paying 200 millions of francs in taxes while the government received only 50 millions!

If the taille was the most lucrative tax, the Gabelle or salt tax was the most oppressive. Salt was a government monopoly farmed out to capitalists in the usual way, but the special grievance with regard to the tax did not lie in the fact that it was a monopoly, or that the quality of the government salt was bad, but in the assessment of the tax. The government laid down by decree the amount of salt which every Frenchman was supposed to require, or at any rate had to buy, and each household was assessed therefore at a sum representing the amount of salt legally consumable by the number of persons of whom it was composed. There is something ludicrous in the idea of a paternal government dictating to its children the amount of salt which is good for them, but there was little of a joke in it to the over-burdened French peasant, who was compelled to pay an extortionate sum for a far larger amount of an inferior commodity than he could possibly use or dispose of. The door was thus thrown open wide to corruption and to smuggling—those two ogres which ever prey upon a faulty fiscal system—but the abuse not only lasted until the Revolution but grew in intensity with increasing civilisation. In 1781, eight years before the Revolution[21] broke out, it was calculated that it cost 18 million livres a year to bring the treasury a revenue of 72 million livres from the gabelle; in other words, that a fourth of the produce of the tax was spent in collecting it, while the yearly convictions for smuggling amounted to between three and four thousand.

The Aides and the Douanes, which answered roughly to the modern excise and customs duties, were not open to such obvious objections, but they too played their part in helping to discourage trade and impoverish the people. Each province, almost each district of France, had its own internal customs, and levied a toll which was nearly prohibitive on the circulation of wealth. Each branch of indirect taxation was farmed out, and gave rise to a needy host of agents, inspectors, and tax-gatherers, who looked to make their fortune out of the necessities of the tax-payers. But this was not all. Besides the taxes authorised by government and paid directly or through farmers to the national exchequer, there were, when Sully took charge of the finances, many other payments of a most oppressive nature exacted from the people, which were in fact part of the terrible legacy of the long civil wars. Military requisitions and charges upon revenue.Governors of provinces and commandants of garrisons levied what they considered necessary for the maintenance of the troops, without any authorisation from the treasury, and without rendering any account of the sums so raised. Many of the nobles whose assistance or whose neutrality Henry had found it prudent to buy, received their gratifications in the form of charges upon the revenue arising from certain districts, and, as there was no check exercised by the government over the amounts raised, they frequently levied upon the wretched people three or four times the sum originally due.

A system so badly conceived and so iniquitously administered as this was calculated both to impoverish the people and to dry up the sources of wealth. Sully did not attempt to deal with the larger problem except by encouraging agriculture and permitting the free[22] exportation of corn, but he applied himself diligently to the humbler task of reforming the financial administration. In this he kept two principles steadily in view, to insist rigorously that the levy of all sums on the people should be definitely authorised by the government, and to enforce a proper system of audit of the national finances. Thus he obliged the military governors to apply to the treasury for the pay of their troops, he abolished a crowd of useless and expensive financial agents and forced them to refund their ill-gotten gains, he caused the assessment registers to be verified and corrected, and swept away at a blow a number of false claims for exemption which had been corruptly admitted. By such measures he soon succeeded in restoring order to the finances. In twelve years of rigorous and just administration he relieved the French people from paying unauthorised and illegal taxation, and this saved them more than 120 millions of francs annually, he remitted to them more than 20 millions of arrears, paid off or cancelled 330 millions of debt, provided the necessary resources for the maintenance of a large army, and an expensive court, and stored up in the cellars of the Bastille a treasure of 30 millions against unforeseen contingencies. Well may France look upon him and his master as the joint founders of her national greatness.

The restoration of order after thirty years of civil war was a task far more difficult and no less necessary than the purification of the financial system. In France the Crown had ever been the champion of order and centralisation, the nobles the representatives of disorder and local independence. In England the nobles were a class singled out from their fellow-countrymen by greater responsibilities, in France they formed a caste distinguished from the inferior people by special privileges. Their tendency therefore naturally was to magnify those privileges, and to intensify the distinctions which separated them both from the king and the Commonalty, to assert rights of their own rather than assist in vindicating the rights of others. Nothing[23] is more significant in the history of England than the fact that throughout the constitutional struggles of the medieval period the nobles as a whole were anxious to make common cause with the people and content to share their victory with them. Parliament, the representative of the nation in its three estates, thus became by their common action the depositary and the safeguard of the national liberty. In France on the other hand the nobles are ever found fighting for their own class interests. Fenced round by their own privileges, regardless of the common weal, they aspired to an independence which could not but be destructive of national life. The people learned to look to the Crown as their protector from the licence of the nobles, to welcome its increasing power as representing greater security of life and property. A centralised and absolute Crown might possibly be a curse in the future, a decentralised and independent nobility was beyond question a curse evident and imminent in the present. And so the States-General, the representative of France in her three estates, was permitted to sink into oblivion by a Crown which would have no rival, and a nation which preferred the maintenance of its class jealousies to that union of classes which could alone secure liberty.

The religious wars had afforded a great opportunity to the nobles of asserting their independence. Many of them had embraced Calvinism, and so gained for their disintegrating aspirations a religious sanction and a political ideal. It is said that by the Edict of Nantes Calvinistic worship was legalised in 3500 castles. Faction is ever strong when the Crown is weak, and Henry IV. had to buy the doubtful allegiance of many of the smaller nobles by sheer bribery, before he could establish himself upon the throne. But no sooner had he made his position secure than the nobles found that they had a master. They might be courtiers but not politicians. Henry deliberately intrusted the affairs of government to men of business of inferior rank, dependent on himself, and jealous of the nobles. Rigid[24] inquiry was made into the privileges claimed by the nobles, and those which could not be substantiated were rescinded. The institution of the paulette was intended to create a noblesse of the robe as a counterpoise to the noblesse of the sword. Duelling, that much-loved privilege of a gentleman, was absolutely forbidden, and the issue of letters of pardon to those who killed their adversary in a duel stopped. The nobles, accustomed to the licence of civil war, soon grew restive under the strong hand of Henry. The conspiracy of Biron, 1602. The maréchal de Biron, on the part of the Catholics, and the duc de Bouillon, the leader of the Huguenots, permitted themselves to enter into relations with Savoy and Spain, and to talk somewhat vaguely of a partition of France, in a way which was incompatible with loyalty to the king. When Henry struck he struck hard. The thirty-two wounds which Biron had received in the service of France failed to obtain his pardon. In 1602 he was executed, and his death gave the signal for the beginning of that war of revenge on the part of the Crown against the nobles, which was carried on with such relentless severity by Richelieu, and did not cease until the triumph of the Crown was assured under Louis XIV. The duc de Bouillon escaped to Germany, the comte d’Auvergne was imprisoned, the duc d’Epernon, frightened into submission, was pardoned. Perhaps Henry himself hardly dared to touch the former companion of Henry III., the governor of half France, and the proudest of all her proud nobility. Four years afterwards the vengeance of Henry was still awake though all the excitement and danger had long ago quieted down. In 1606 he travelled through the disaffected districts of the south and south-west accompanied by an army, destroyed several castles belonging to the nobles, and put to death, after sentences by special tribunals, those who had taken a prominent part in the late troubles.

MAP SHOWING THE TERRITORIAL GAINS OF FRANCE IN THE 17th CENTURY.

But it was in the sphere of foreign affairs that the genius of Henry IV. fully displayed itself. For many years France had played a sorry part in European politics. If Francis I. [25]had done something to preserve Europe from falling under the yoke of Charles V., men also remembered that he was the perjured of Madrid, the abettor and the ally of the Turk. Foreign policy of Henry IV. Since his death France had fallen lower and lower in the scale of nations, until under the stress of the religious wars she seemed to bid fair to become another Italy, a plaything tossed to and fro among the nations of Europe. It was the stubbornness of the Dutch, and the craft of Elizabeth, not the patriotism of Frenchmen, which had saved France from the yoke of Philip II. in that terrible time. After the peace of Vervins Henry had to restore the national prestige, and regain the national influence which had died almost to nothing. The indefensible frontier of France. The great danger to France lay from the pressure exercised upon an indefensible frontier on all sides by the Austro-Spanish power. While Spain held Roussillon, Franche-Comté, and the Netherlands, and could reckon on the vassalage of Savoy, while the passes of the Vosges were in the hands of the Empire, the Austro-Spanish House held the gates of France. France could not breathe with the hand of her enemy on her throat. But the strength of a chain is that of its weakest link, and Henry’s eagle eye soon detected the weak place in the circle of iron which bound him. It lay in north Italy, the old battle-field of France and Spain. The Milanese was a rich open country, depending for its protection from attack upon its fortresses and its rivers. It was a fief of the Empire in the possession of Spain, and its communications with Spain by sea through the friendly port of Genoa were more easy than with Germany, through the tedious and often difficult mountain paths which connected the Valtelline with the Brenner pass and the valley of the Inn. It lay therefore invitingly open to attack from the mountains of Savoy on the west, and those of the Grisons on the north, and if once it fell into the hands of France, not only would the chain which bound her be broken, but a terrible counterblow would be dealt to the influence of the Austro-Spanish House in[26] Europe, for through Milan ran the road by which Spain could best open communications in safety with south Germany and Franche-Comté. If that way was blocked, the only route possible for the troops and treasure of Spain was the long sea voyage by the Bay of Biscay and the English Channel to Antwerp and the Spanish Netherlands, a route fraught with peril from the storms which rage round Cape Finisterre, and from the English and French privateers which swarmed in the narrow seas.

In Italy, therefore, lay the opportunity of France, and Savoy held the key of the position. The duchy of Savoy, which still extended as far as the Rhone, and disputed with the king of France for the rule over Provence and Dauphiné, had been gradually pushed by its more powerful neighbour more and more towards Italy. Its duke had quite lately established himself in his capital of Turin at the foot of the mountain, and his ambition was to become an Italian prince. But though Piedmont and not Savoy had become the centre of his power, the border land of Savoy and not the Italian land of Piedmont became necessarily the centre of his policy. Situated on the mountains between France and the Milanese, Savoy held the gates both of France and of Imperial Italy. Through her mountain passes could pour, when she gave the word, the troops of France into the fertile plains of Lombardy, or those of the Habsburgs into the valley of the Rhone. A position so decisive and so dangerous rendered a consistent policy impossible. Courted by both parties, her opportunity lay in playing off one against the other as long as possible, but her safety necessitated the choice of the stronger for her ally in the end. A misreading of the political barometer at a critical moment would mean nothing less than national extinction. From the time that the rivalry between France and the Austro-Spanish power began to develop itself in Italy, the dukes of Savoy had been compelled to follow this tortuous policy. During the Italian[27] expeditions of Charles VIII. and Louis XII. they were on the side of victorious France, but in the war between Francis I. and Charles V. Savoy veered to the side of the Emperor. Punished for this by the occupation of his country by French troops for twenty-five years, the duke was reinstated in his dominions at the peace of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559), subject to the continued occupation by France of six fortresses, including Susa and Pinerolo, which commanded the gates of important passes through the Alps. In the troubles which afflicted France under the later Valois kings, Charles Emmanuel of Savoy succeeded in obtaining possession of Saluzzo; and although it was provided in the treaty of Vervins that he should restore it, the provision remained a dead letter. This gave Henry IV. the opportunity he desired of recalling Savoy to the French alliance. In 1600, after the death of Gabrielle d’Estrées, he had procured a divorce from his first wife Marguerite de Valois, and had strengthened his influence in Italy by his marriage with Marie de Médicis, the daughter of the grand-duke of Tuscany. Cession of Bresse and Bugey to France. In the same year he marched upon Savoy and quickly overran it, but in January 1601 agreed to a treaty with the young duke Charles Emmanuel, who had succeeded Emmanuel Philibert in 1580, by which Saluzzo was left in the hands of Savoy, but France obtained instead the two small duchies of Bresse and Bugey. By this treaty Savoy was brought back into alliance with France at the price of the surrender of a distant possession, which, in the hands of France, could not but be considered a standing menace and a cause of hostility by the court of Turin.

Thus Henry IV. laid the foundations of the policy afterwards so successfully pursued in Italy by Richelieu. In fact, to both of these great statesmen the end to be attained was the same. The abasement of the Austro-Spanish House in the interests of France was the beginning and end of their foreign policy. But Henry had not the same opportunities[28] of putting his designs into execution which were enjoyed by his successor. Attack upon the Austro-Spanish House. It is difficult to say how far the Great Design attributed to Henry in the Memoirs of Sully was ever more than a dream. The Great Design. Statesmen have often sought relief from the ennui engendered by the pettiness of diplomatic routine in the delightful task of building political castles in the air, and it is likely enough that Henry, in his more imaginative moments, conceived of a Europe in which religious wars should cease and national dissensions rest, at the bidding of an arbitration court which represented a confederacy of free states, and was the mouthpiece of a law of religious toleration. It is not less likely that his shrewd genius also foresaw that in a Europe whose unity depended on political confederacy, whose peace was secured by religious toleration, there would be no room for the Holy Roman Empire or for the monarchy of Spain. The destruction of the Austro-Spanish House was a condition precedent to the success of the Great Design. If Henry ever intended seriously to try to combine those who represented the political forces of Protestantism in a confederacy against Spain and the Empire, based on a recognition of the three religions, he must have abandoned the attempt as hopeless on the death of Elizabeth in 1603.

A few years later, however, an opportunity presented itself of dealing a blow at the Austro-Spanish House in a less original but equally effective way. In 1609 John William,[1] duke of Cleves, Jülich, and Berg died without children, and the right of succession was claimed by two princes. John Sigismund, the elector of Brandenburg, whose wife was the child of the eldest daughter of William the Rich, brother and predecessor of the last duke, rested his wife’s claim partly on his descent from the elder branch, and partly on a will made by William the Rich in which he gave the descendants of the elder daughter preference[29] over those of the younger. The count palatine of Neuburg had married a younger daughter of William the Rich, who claimed the inheritance as being the nearest of kin. The eldest sister of John William being dead, she made over her claim to her son Wolfgang William. The question was therefore mainly the old one of the eldest by descent against the nearest of kin, and was eminently one for the imperial courts to decide. But the matter was complicated by religious considerations. The three duchies lay along the course of the lower Rhine from the frontiers of the United Provinces nearly to Andernach, enclosing within their embraces a considerable part of the archbishopric of Köln. The population was Catholic but both the claimants were Lutherans, and on the principle of cujus regio ejus religio, laid down by the religious peace of Augsburg, if the duchies passed into Lutheran hands, there was a strong probability that they would before long not only become Lutheran themselves, but drag the vacillating archbishopric of Köln with them. The Emperor, Rudolf, in order to guard against this danger, at once claimed the right of administering the duchies until the question of the succession was settled, and sent an army to occupy Jülich. But if the Catholics could not permit the duchies to fall into Lutheran hands, still less could Protestant or French interests see unmoved the imperial armies encamped on the borders of the United Provinces, in close proximity to the frontiers of France and the Spanish Netherlands. An imperial army on the lower Rhine was a menace alike to north German Protestantism, to the hardly won Dutch independence, and to English and French jealousy.

Henry IV. seized the opportunity. He at once declared himself the protector of the rights of the elector of Brandenburg and the count of Neuburg, and put himself at the head of an alliance of the enemies of the Austro-Spanish House. England, the United Provinces, the German Protestant Union, Venice[30] and Savoy responded to his call. Three French armies were set on foot, one was directed to the Pyrenees, the second under Lesdiguières was to co-operate with Savoy and Venice in the conquest of the Milanese, while the third, under the command of the king himself, attacked Jülich and occupied the duchies in conjunction with the Dutch and English contingents and the German Protestants. It seemed as if the death-knell of the Austro-Spanish power had sounded. Rudolf II., ignorant of politics and half-crazed in intellect, was implicated in serious quarrels with his unwilling subjects of Bohemia and Hungary. In Styria, Carinthia, and Carniola, Ferdinand, the nephew of the Emperor, was, with the help of the Jesuits, waging an ardent and determined war against the Calvinism which threatened to take a strong root even in the hereditary dominions of the Habsburgs. Wanting in money, wanting in leadership, wanting in unity, the power of Austria had no troops on which it could depend, no subjects which it could trust. Nor was Spain in much better plight. Exhausted by the ambition of Philip II., misgoverned by a weak king and an incapable minister, she had chosen this very time gratuitously to deal a serious blow to her own prosperity by expelling from her borders the Moriscoes, the most laborious and intelligent of her working population. It was clear that she could do little more to help the cause than to defend her own frontiers, and hold the Milanese against the attacks of the allies. The forces of the Catholic League, the resources of Maximilian of Bavaria, and the genius of his general Tilly, were in fact all that Catholicism and the Austro-Spanish power had to rely upon in the death duel in which she had almost by inadvertence engaged herself. Assassination of Henry IV. Help came from a quarter the least expected. A terrible crime struck France with tragic suddenness to her knees and saved the House of Austria. As Henry IV. passed through the streets of Paris to visit his minister Sully, but two days before the date fixed for his departure for the campaign, a fanatic named Ravaillac[31] plunged a dagger into his heart. With Henry IV. died the combination of which he was the head and soul, and the capture of Jülich from the imperialists by Maurice of Nassau, aided by a small English contingent, was the only step taken in the direction of realising the Great Design of the first of the Bourbons.

The dagger of Ravaillac not only saved the Austro-Spanish House but plunged France into fifteen years of misery and dishonour. The young king Louis XIII. was but nine years old and a regency was inevitable. The duc d’Épernon was the only man who showed the necessary energy and presence of mind to deal with the crisis which had so suddenly arisen. Surrounding the palace and the Hôtel de Ville with his own troops and those of the other nobles on whom he could rely, he entered the chamber where the Parlement was assembled, and demanded that they should at once recognise the queen-mother as regent. Pointing significantly to his sword he said: ‘This sword is as yet in its scabbard, but if the queen is not declared regent before this assembly separates, I foresee that it will have to be drawn. That which can be done to-day without danger cannot be done to-morrow without difficulty and bloodshed.’ There were many in the Parlement who were not sorry to see that body thus suddenly raised into the unaccustomed position of the arbiter of the government of France. There were many more who found the arguments of Épernon too powerful to be resisted, and Marie was without further question recognised by a decree of the Parlement as regent of the kingdom during the minority of the king, and invested with the full powers of the crown. A Council of Regency was at once formed from among the leaders of the nobility, and thus fell in a moment the whole structure of government which Henry IV. and Sully had laboured so hard to erect. The nobles resumed their place at the head of affairs. Sully, who alone might have had influence enough to stop this disastrous counter-revolution, lost his courage, thought only of securing his own safety, and after[32] a few ineffectual protests retired into private life. The treasure which he had so painfully amassed was squandered among the nobles to buy their adherence to the new government. Reversal of the policy of Henry IV. The regent, devoted in her inmost heart to Spain, and dreading the risk of foreign war, hastened to disband the larger part of the troops which Henry IV. had collected, and to set on foot secret negotiations with the court of Spain. After the capture of Jülich, on September 1st, 1610, by which all danger of Imperial aggression in the lower Rhineland was taken away, she openly announced her intention to withdraw altogether from the war, and to ally herself with Spain through the double marriage of her daughter Elizabeth to the heir to the Spanish crown, and of Anne of Austria, the eldest daughter of Philip III., to the young king of France. Six months after the murder of Henry IV. his whole policy at home and abroad had been reversed. The great combination against the House of Austria fell to pieces when France retired. The German Protestants and the Dutch made their peace with the Emperor by the truce of Willstedt, signed in October 1610. The duke of Savoy, betrayed by France, had to make his peace as best he could with Spain, and the key of Italy was once more thrown away. At home, disorder corruption and anarchy raised their heads again, and the selfish and factious nobility tore France in pieces in a struggle in which their desire for places and money was hardly disguised by a thin veneer of political ambition.

For seven years Marie held the reins of government. She was a vain, irritable, and intriguing woman with little of the talent for rule hereditary in her family, and much of the dependence upon stronger natures characteristic of her sex. They were years of discord and disgrace. The real rulers of France were the Italian adventurers Leonora Galigai and her husband, whom the weakness of Marie actually raised to the dignity of a marshal of France, although he had never seen a shot fired in earnest. The nobles were justly enraged at the prostitution of an[33] office, which they considered one of the chief prizes of their order, and bitterly jealous of the influence of a parvenu like the maréchal d’Ancre. Twice they rose in rebellion under the leadership of the worthless prince de Condé,[2] but d’Ancre and Marie knew well the sop to throw to that Cerberus. A quarter of a million of livres purchased the treaty of Ste. Menehould on May 15th, 1614, and six million that of Loudun in May 1616, and the Regent and her minister quietly pursued their policy unmoved by demands for reform which died in the presence of gold. The feeble ray of dying constitutionalism alone sheds a pale gleam of interest over the dreary years. Partly in the hopes of strengthening her own position, partly to take a cry, always dangerous, out of the mouth of Condé, Marie de Médicis consented to summon once more the States-General of France and ask their advice upon the grievances of the kingdom.

The melancholy interest which surrounds a deathbed attaches to this the last meeting of the States-General of monarchical France. Meeting of the States-General, 1614. The Estates assembled at Paris on the 14th of October 1614, according to their three orders. There appeared 140 representatives of the clergy, 132 of the noblesse, 192 of the Tiers État, but these last were not in any real sense representatives of the commonalty of France. The name of a merchant or a farmer or a small landowner does not appear among them. They were for the most part of the official and professional classes, officers of the petty districts into which France was divided, financial and municipal officers, with a sprinkling of lawyers and citizens, and they at once assumed the rôle which their composition marked out for them, and organised themselves as the official order in opposition to the other orders of the clergy and the noblesse. Quarrels between the orders. From the beginning the jealousy of the three orders among themselves, and the fatal determination of the Tiers État to defend the privileges of their own official[34] class against the nobles, instead of urging the grievances of the country upon the Crown, rendered the possibility of obtaining any real check upon the Crown absolutely hopeless. The nobles not unnaturally looked with jealous eyes on the gradual formation of an hereditary privileged class of officials, by means of the purchase of offices and the right of transmission secured by the paulette, which could not fail to grow in a little time into a second noblesse, and they directed their efforts mainly to procuring the abolition of purchase in the civil services. The Tiers État on their side, numbering as they did but comparatively few of the privileged ‘exempt’ among their ranks, fixed their eyes on the inordinate pensions enjoyed by the great nobles, and demanded the abolition of the pension list and the reduction of the taille. This was to hit the nobles in their weakest place, and the contention between the two orders became so keen that the court had to interfere and bring about a reconciliation. Hardly however had the Tiers État finished their controversy with the nobles, than they became involved in a quarrel with the clergy. The magistracy, especially the lawyers, were strongly Gallican in their views of ecclesiastical government, that is, they maintained the right of the national authorities to govern the Church in France in all matters which were not directly spiritual in their nature, and repudiated interference from the Pope. Especially they disliked the Jesuits, and wished to avoid the recognition of the decrees of the Council of Trent, which had not as yet been formally accepted by France. The Tiers État accordingly drew up an article in their cahier, or list of grievances, which, under the form of asserting the right divine of the French kings, and denouncing the crime of regicide, impliedly denied the right of the popes to depose kings and absolve subjects from their allegiance. At once the whole question between the Gallicans and the Ultramontanes was raised, and for more than a month no other matter was discussed among the Estates. The nobles sided with the clergy, and agreed with them on twenty-four articles representing[35] their common views, among which the recognition of the decrees of Trent and the maintenance of the authority of the Holy See assumed an equal place of importance with the union of Navarre and Béarn to France, and the abolition of the paulette and the purchase system. The Parlement supported the Tiers Etat, and by its interference introduced one more cause of dissension. Finally, the court had again to interfere and order the Tiers Etat to omit the objectionable article from their cahier. Reforms brought about by the States-General. Yet in spite of these suicidal quarrels, which proved the unfitness of the States-General to undertake constitutional responsibilities, their meeting was not wholly useless. Differing on almost all other questions, the three orders were agreed upon an attack upon the financial administration. Jeannin, the finance minister, was, in spite of the efforts of the court, forced to produce accounts, which, when produced, showed clearly enough that none had been kept which were fit for production. The consent of the Crown was obtained to a considerable reduction of the pension list, the suppression of the paulette, and the erection of a special court to control the finances. Endowed with no legislative power, all that the Estates could do in the way of ameliorating the government was to make representations and extort promises, and this they did as effectively as circumstances permitted in the most important department of administration. If it must be allowed that they did much to destroy their own influence and render themselves ridiculous by their jealousy and quarrelsomeness, it must also be remembered that no king ever dared to summon them again until monarchy was tottering to its fall.