The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Yoga-Vasishtha Maharamayana of Valmiki, Vol. 1 (of 4), by Valmiki

Title: The Yoga-Vasishtha Maharamayana of Valmiki, Vol. 1 (of 4)

Author: Valmiki

Translator: Vihari-Lala Mitra

Release Date: August 3, 2023 [eBook #71326]

Language: English

Credits: Mark C. Orton, Juliet Sutherland, Édith Nolot, Krista Zaleski, windproof, readbueno and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Inconsistent punctuation has been silently corrected.

Obvious misspellings have been silently corrected, and the following corrections made to the text. Other spelling and hyphenation variations have not been modified.

The spelling of Sanskrit words are normalized to some extent, including correct/addition of accents where necessary. Note that the author uses á, í, ú to indicate long vowels. This notation has not been changed.

The LPP edition (1999) which has been scanned for this ebook, is of poor quality, and in some cases text was missing. Where possible, the missing/unclear text has been supplied from another edition, which has the same typographical basis (both editions are photographical reprints of the same source, or perhaps one is a copy of the other): Bharatiya Publishing House, Delhi 1978.

A third edition, Parimal Publications, Delhi 1998, which is based on an OCR scanning of the same typographical basis, has also been consulted.

The term “Gloss.” or “Glossary” probably refers to the extensive classical commentary to Yoga Vásishtha by Ananda Bodhendra Saraswati (only available in Sanskrit).

Angle brackets <...> have been used by the transcriber to indicate light editing of the text to insert missing words.

VOL. I

Plato advised the Athenians to betake themselves to the study of Mathematics, in order to evade the pestilence incident to the international war which was raging in Greece; so it is the intention of this publication, to exhort our countrymen to the investigation of Metaphysics, in order to escape the contagion of Politics and quasi politics, which has been spreading far and wide over this devoted land.

V. L. M.

in 4 vols. in 7 pts.

(Bound in 4.)

Vol. 1

Containing

The Vairagya, Mumukshu, Prakaranas and

The Utpatti Khanda to Chapter L.

Translated from the original Sanskrit

By

VIHARI-LALA MITRA

Distributed By:

D K Publishers Distributors P Ltd.

1, Ansari Road,

Darya Ganj,

New Delhi-110002

Phones: 3278368, 3261465

Fax: 3264368

visit us at: www.dkpdindia.com

e-mail: [email protected]

Reprinted in LPP 1999

ISBN 81-7536-179-4 (set)

ISBN 81-7536-180-8 (vol. 1)

Published By:

Low Price Publications

B-2, Vardhaman Palace,

Nimri

Commercial Centre,

Ashok Vihar Phase-IV,

Delhi-110052

Phone: 7401672

visit us at: www.lppindia.com

e-mail: [email protected]

Printed At:

D K Fine Art Press P Ltd.

Delhi-110052

PRINTED IN INDIA

In this age of the cultivation of universal learning and its investigation into the deep recesses of the dead languages of antiquity, when the literati of both continents are so sedulously employed in exploring the rich and almost inexhaustible mines of the ancient literature of this country, it has given an impetus to the philanthropy of our wise and benign Government to the institution of a searching enquiry into the sacred language of this land. And when the restoration of the long lost works of its venerable sages and authors through the instrumentality of the greatest bibliomaniac savants and linguists in the several Presidencies,[1] has led the literary Asiatic Societies of the East and West to the publication of the rarest and most valuable Sanskrit Manuscripts, it cannot be deemed preposterous in me to presume, to lay before the Public a work of no less merit and sanctity than any hitherto published.

The Yoga Vasishtha is the earliest work on Yoga or Speculative and Abstruse philosophy delivered by the venerable Vedic sage Vasishtha to his royal pupil Ráma; the victor of Rávana, and hero of the [Pg ii]first Epic Rámáyana, and written in the language of Válmiki, the prime bard in pure Sanskrit, the author of that popular Epic, and Homer of India. It embodies in itself the Loci Communes or common places relating to the science of Ontology, the knowledge of Sat—Real Entity, and Asat—Unreal Non-entity; the principles of Psychology or doctrines of the Passions and Feelings; the speculations of Metaphysics in dwelling upon our cognition, volition and other faculties of the Mind (ज्ञान, ज्ञेय, ज्ञाता, इच्छा, द्वेषादि) and the tenets, of Ethics and practical morality (धर्म्म कर्म्म). Besides there are a great many precepts on Theology, and the nature of the Divinity (आत्मानात्म विवेक), and discourses on Spirituality and Theosophy (जीवात्मा परमात्मा ज्ञान); all delivered in the form of Plato’s Dialogues between the sages, and tending to the main enquiry concerning the true felicity, final beatitude or Summum bonum (परम निःश्रेयस्) of all true philosophy.

These topics have singly and jointly contributed to the structure of several separate Systems of Science and Philosophy in succeeding ages, and have formed the subjects of study both with the juvenile and senile classes of people in former and present times, and I may say, almost among all nations in all countries throughout the civilized world.

It is felt at present to be a matter of the highest importance by the native community at large, to repress the growing ardour of our youth in political polemics and practical tactics, that are equally pernicious to and destructive of the felicity of their temporal [Pg iii]and future lives, by a revival of the humble instructions of their peaceful preceptors of old, and reclaiming them to the simple mode of life led by their forefathers, from the perverted course now gaining ground among them under the influence of Western refinement. Outward peace (शान्ति) with internal tranquility (चित्त प्रशान्ति) is the teaching of our Sastras, and these united with contentment (सन्तोष) and indifference to worldly pleasures (वैराग्य), were believed according to the tenets of Yoga doctrines, to form the perfect man,—a character which the Aryans have invariably preserved amidst the revolutions of ages and empires. It is the degeneracy of the rising generation, however, owing to their adoption of foreign habits and manners from an utter ignorance of their own moral code, which the publication of the present work is intended to obviate.

From the description of the Hindu mind given by Max Müller; in his History of the Ancient Literature of India (p. 18) it will appear, that the esoteric faith of the Aryan Indian is of that realistic cast as the Platonic, whose theory of ontology viewed all existence, even that of the celestial bodies, with their movements among the precepta of sense, and marked them among the unreal phantoms (मिथ्या दृष्टि) or vain mirage, (मरीचिका) as the Hindu calls them, that are interesting in appearance but useless to observe. They may be the best of all precepta, but fall very short of that perfection, which the mental eye contemplates in its meditation-yoga. The Hindu Yogi views the visible world exactly in the same light as Plato has represented [Pg iv]it in the simile commencing the seventh book of his Republic. He compares mankind to prisoners in a cave, chained in one particular attitude, so as to behold only an ever varying multiplicity of shadows, projected through the opening of the cave upon the wall before them, by certain unseen realities behind. The philosopher alone, who by training or inspiration is enabled to turn his face from these visions, and contemplate with his mind, that can see at-once the unchangeable reality amidst these transient shadows.

The first record that we have of Vasishtha is, that he was the author of the 7th Mandala of the Rig Veda (Ashtaka v. 15-118). He is next mentioned as Purohita or joint minister with Viswámitra to king Sudása, and to have a violent contest with his rival for the (पौरोहित्य) or ministerial office (Müll. Hist. S. Lit. page 486, Web. Id. p. 38). He is said to have accompanied the army of Sudása, when that king is said to have conquered the ten invading chiefs who had crossed over the river Parushni—(Hydroates or Ravi) to his dominions (Müll. Id. p. 486). Viswámitra accompanied Sudása himself beyond Vipása,—Hyphasis or Beah and Satadru—Hisaudras-Sutlej (Max Müller, Ancient Sanscrit literature page 486). These events are recorded to have occurred prior to Vasishtha’s composition of the Mandala which passes under his name and in which they are recorded. (Müll. Id. p. 486).

The enmity and implacable hatred of the two families of Vasishthas and Viswámitras for generations, form subjects prominent throughout the Vedic antiquity, and preserved in the tradition of ages (Müll. Id. p. 486, [Pg v]Web. Id. p. 37). Another cause of it was that, Harischandra, King of Ayodhyá, was cursed by Vasishtha, whereupon he made Viswámitra his priest to the annoyance of Vasishtha, although the office of Bráhmana was held by him (Müller Id. page 408 Web. pp. 31-37). In the Bráhmana period we find Vasishtha forming a family title for the whole Vasishtha race still continuing as a Gotra name, and that these Vasishthas continued as hereditary Gurus and purohitas to the kings of the solar race from generation to generation under the same title. The Vasishthas were always the Brahmanas or High priests in every ceremony, which could not be held by other Bráhmanas according to the Sáta patha Bráhmana (Müll. Id. page 92); and particularly the Indra ceremony had always to be performed by a Vasishtha, because it was revealed to their ancestor the sage Vasishtha only (Web. Ind. Lit. p. 123); and as the Sátapatha Bráhmana-Taittiriya Sanhitá mentions it.

“The Rishis do not see Indra clearly, but Vasishtha saw him. Indra said, I will tell you, O Bráhman, so that all men who are born, will have a Vasishtha for his Purohita” (Max Müll. Anc. Sans. Lit. p. 92. Web. Id. p. 123). This will show that the Sloka works, which are attributed to Vasishtha, Yájnavalkya or any other Vedic Rishi, could not be the composition of the old Rishis, but of some one of their posterity; though they might have been propounded by the [Pg vi]eldest sages, and then put to writing by oral communication or successive tradition by a distant descendant or disciple of the primitive Rishis. Thus we see the Dráhyáyana Sutras of the Sama Veda is also called the Vasishtha Sutras, from the author’s family name of Vasishtha (Web. Id. p. 79). The ásvaláyana Grihya Sutra assigns some other works to Vasishtha, viz., the Vasishtha pragáthá, probably Vashishtha Hymni of Bopp; the Pavamánya, Kshudra sukta, Mahásukta &c. written in the vedic style. There are two other works attributed to Vasishtha, the Vasishtha Sanhitá on Astronomy (Web. Id. p. 258) and the Vasishtha Smriti on Law (Web. Id. p. 320), which from their compositions in Sanscrit slokas, could not be the language or work of the Vedic Rishi, but of some one late member of that family. Thus our work of Yoga Vasishtha has no claim or pretension to its being the composition of the Vedic sage; but as one propounded by the sage, and written by Válmiki in his modern Sanskrit. Here the question is whether Vasishtha the preceptor of Ráma, was the Vedic Vasishtha or one of his descendants, I must leave for others to determine.

Again in the later Áranyaka period we have an account of a theologian Vasishtha given in the Árshikopanishad, as holding a dialogue on the nature of átmá or soul between the sages, Viswámitra, Jamadagni, Bharadwája, Gautama and himself; when Vasishtha appealing to the opinion of Kapila obtained their assent (Weber Id. p. 162). This appears very probably to be the theological author of our yoga, and eminent above his contemporaries in his knowledge of the [Pg vii]Kapila yoga sástra which was then current, from this sage’s having been a contemporary with king Sagara, a predecessor of Rama.

In the latest Sútra period we find a passage in the Grihya-Sútra-parisishta, about the distinctive mark of the Vasishtha Family from those of the other parishads or classes of the priesthood. It says;

“The Vasishthas wear a braid (lock of hair) on the right side, the Átreyas wear three braids, the Angiras have five braids, the Bhrigus are bald, and all others have a single crest,” (Müller Id. p. 53). The Karma pradípa says, “the Vasishthas exclude meat from their sacrifice; वसिष्ठोक्तविधिः कृत्स्नो द्रष्टव्यात्र निरामिषः ।” (Müller A. S. Lit. p. 54), and the colour of their dress was white (Id. p. 483). Many Vasishthas are named in different works as; वशिष्ठ चेकितायनः, वशिष्ठ आरिहणीयः, वशिष्ठ मैत्रावरणिः, वशिष्ठः राणायणः, वशिष्ठ लाठ्यायनः, वशिष्ठ द्राह्यायनः, वशिष्ठकौण्डिन्यः, वशिष्ठइन्द्रप्रमदः, वशिष्ठः आभरद्बसुः, and some others, bearing no other connection with our author, than that of their having been members of the same family (Müller’s A. S. Lit. p. 44).

Without dilating any longer with further accounts relating to the sage Vasishtha of which many more might be gathered from various sastras, I shall add in the conclusion the following notice which is taken of this work by Professor Monier Williams in his work on Indian Wisdom p. 370.

“There is,” says he, “a remarkable work called Vasishtha Rámáyana or Yoga Vásishtha or Vasishtha [Pg viii] Mahárámáyana in the form of an exhortation, with illustrative narratives addressed by Vasishtha to his pupil the youthful Ráma, on the best means of attaining true happiness, and considered to have been composed as an appendage to the Rámáyana by Válmiki himself. There is another work of the same nature called the Adhyátma Rámáyana which is attributed to Vyása, and treat of the moral and theological subjects connected with the life and acts of that great hero of Indian history. Many other works are extant in the vernacular dialects having the same theme for their subject which it is needless to notice in this place.”

Vasishtha, known as the wisest of sages, like Solomon the wisest of men, and Aurelius the wisest of emperors, puts forth in the first part and in the mouth of Ráma the great question of the vanity of the world, which is shown synthetically to a great length from the state of all living existences, the instinct, inclinations, and passions of men, the nature of their aims and objects, with some discussions about destiny, necessity, activity and the state of the soul and spirit. The second part embraces various directions for the union of the individual with the universal Abstract Existence—the Supreme Spirit—the subjective and the objective truth—and the common topics of all speculative philosophy.

Thus says Milton; “The end of learning is to know God.”

So the Persian adage, “Akhiral ilm buad ilmi Khodá.”

Such also the Sanskrit, “Sávidyá tan matir yayá.”

And the sruti says, “Yad jnátwá náparan jnánam.”

i.e. “It is that which being known, there is nothing else required to be known.”

PROLEGOMENA.

| PROL. | PAGE. | |

| 1. The Yoga Philosophy | ” | 1 |

| 2. The Om Tat Sat | ” | 34 |

VAIRÁGYA KHANDA.

BOOK I.

| CHAPTER I. | Page |

| INTRODUCTION. | |

| SECTION I. | |

| Divine Adoration | 1 |

| SECTION II. | |

| Narrative of Sutíkshna | 1 |

| SECTION III. | |

| Anecdote of Kárunya | 2 |

| SECTION IV. | |

| Story of Suruchi | 3 |

| SECTION V. | |

| Account of Arishtanemi | 3 |

| [Pg x] SECTION VI. | |

| History of Ráma | 6 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Reason of writing the Rámáyana | 8 |

| SECTION I | |

| Persons entitled to its Perusal | 8 |

| SECTION II. | |

| Brahmá’s Behest | 9 |

| SECTION III. | |

| Inquiry of Bharadwája | 10 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Válmíki’s Admonition | 12 |

| SECTION I. | |

| On True Knowledge | 12 |

| SECTION II. | |

| Early History of Ráma | 13 |

| SECTION III. | |

| Ráma’s Pilgrimage | 15 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Ráma’s Return from Pilgrimage | 17 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Of Ráma’s Self-Dejection and its Cause | 19 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Advent of Viswámitra to the Royal Court | 21 |

| SECTION II. | |

| Address of King-Dasaratha | 24 |

| [Pg xi]CHAPTER VII. | |

| Viswámitra’s Request for Ráma | 26 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Dasaratha’s Reply to Viswámitra | 29 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Viswámitra’s Wrath and his Enraged Speech | 33 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Melancholy of Ráma | 36 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Consolation of Ráma | 41 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Ráma’s Reply | 45 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Vituperation of Riches | 48 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Depreciation of Human Life | 50 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Obloquy of Egoism | 53 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The Ungovernableness of the Mind | 56 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| On Cupidity | 59 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Obloquy of the Body | 64 |

| [Pg xii] CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Blemishes of Boyhood | 70 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Vituperation of Youth | 73 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Vituperation of Women | 77 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Obloquy of Old Age | 81 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Vicissitudes of Times | 85 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Ravages of Time | 90 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Sports of Death | 91 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| The Acts of Destiny | 95 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Vanity of the World | 100 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| Mutability of the World | 105 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| Unreliableness of Worldly Things | 109 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| Self-Disparagement | 112 |

| [Pg xiii] CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| Queries of Ráma | 115 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| Praises of Ráma’s Speech | 118 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| Association of Aerial and Earthly Beings | 121 |

BOOK II.

MUMUKSHU KHANDA.

| CHAPTER I. | PAGE |

| Liberation of Sukadeva | 127 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Speech of Viswámitra | 132 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| On the Repeated Creations of the World | 135 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Praise Of Acts and Exertions | 139 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Necessity of Activity | 142 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Refutation of Fatalism | 145 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| On the Necessity of Activity | 150 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Invalidation of Destiny | 154 |

| [Pg xiv] CHAPTER IX. | |

| Investigation of Acts | 157 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Descension of Knowledge | 161 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| On the qualifications of the Inquirer and Lecturer | 166 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Greatness of True Knowledge | 173 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| On Peace and Tranquility of mind | 176 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| On the Ascertainment of an argument | 184 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| On Contentment | 189 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| On Good Conduct | 191 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| On the Contents of the Work | 195 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Ascertainment of the Example or Major Proposition | 201 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Ascertainment of True Evidence | 208 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| On Good Conduct | 212 |

[Pg xv] BOOK III.

UTPATTI KHANDA.

Evolution of the World.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Causes of Bondage to it. | |

| SECTION I. | Page |

| Exordium | 215 |

| SECTION II. | |

| Worldly Bondage | 216 |

| SECTION III. | |

| Phases of The Spirit | 216 |

| SECTION IV. | |

| Nature of Bondage | 218 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Description of the first cause. | |

| SECTION I. | |

| Narrative of the Air-born and Aeriform Bráhman | 223 |

| SECTION II. | |

| State of the Soul | 224 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Causes of Bondage in the Body | 229 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| SECTION I. | |

| Description of the Night-Fall | 234 |

| [Pg xvi] SECTION II. | |

| Nature of the Mind | 237 |

| SECTION III. | |

| Kaivalya or Mental Abstraction | 239 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| On the Original Cause | 243 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Admonition for attempt of Liberation | 246 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Recognition of the Nihility of the Phenomenal World | 249 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Nature of good Sástras | 255 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| On the Supreme cause of All | 257 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Description of the Chaotic State | 266 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Spiritual View of Creation | 273 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| The Idealistic Theo-Cosmogony of Vedánta | 277 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| On the Production of the Self-Born | 281 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Establishment of Brahma | 288 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Story of the Temple and its Prince | 299 |

| [Pg xvii] CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Joy and Grief of the Princess | 303 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Story of the Doubtful Realm or Reverie of Lílá | 309 |

| SECTION I. | |

| Description of the Court House and the Cortes | 313 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Exposure of the Errors of this World | 315 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Story of a Former Vasishtha and his Wife | 319 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| SECTION I | |

| The Moral of the Tale of Lílá | 322 |

| SECTION II. | |

| State of The Human Soul after Death | 325 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Guide to Peace | 328 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Practice of Wisdom or Wisdom in Practice | 336 |

| SECTION I. | |

| Abandonment of Desires | 336 |

| SECTION II. | |

| On the Practice of Yoga | 338 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| The Aerial Journey of Spiritual Bodies | 340 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| The Aerial Journey (continued) | 342 |

| [Pg xviii] SECTION II. | |

| Description of the Heavens | 343 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Description of the Earth | 349 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Meeting the Siddhas | 353 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Past lives of Lílá | 359 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| SECTION I. | |

| Exposition of Lílá’s Vision | 365 |

| SECTION II. | |

| Description of the Mountainous Habitation | 366 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| Account of the Previous Life of Lílá | 372 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| Description of the Mundane Egg | 378 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| SECTION I. | |

| Alighting of the Ladies on Earth | 382 |

| SECTION II. | |

| Sight of a Battle Array in Earth and Air | 383 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| Onset of the War | 386 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| Commingled Fighting | 389 |

| [Pg xix] CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| Description of the Battle | 392 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| Description of the Battlefield | 398 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| SECTION I. | |

| Collision of Equal Arms and Armigerents | 401 |

| SECTION II. | |

| Catalogue of the Forces | 403 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | |

| Catalogue of the Forces (continued) | 408 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| Cessation of the War | 414 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

| Description of The Battle Field Infested by Nocturnal Fiends | 420 |

| CHAPTER XL. | |

| Reflections on Human Life and Mind | 423 |

| CHAPTER XLI. | |

| Discrimination of Error | 431 |

| CHAPTER XLII. | |

| Philosophy of Dreaming | 438 |

| CHAPTER XLIII. | |

| Burning of the City | 442 |

| CHAPTER XLIV. | |

| Spiritual Interpretation of the Vision | 448 |

| [Pg xx] CHAPTER XLV. | |

| Theism consisting in True Knowledge | 454 |

| CHAPTER XLVI. | |

| Onslaught of Vidūratha | 457 |

| CHAPTER XLVII. | |

| Encounter of Sindhu and Vidūratha | 461 |

| CHAPTER XLVIII. | |

| Description of Daivástras or Supernatural Weapons | 465 |

| CHAPTER XLIX. | |

| Description of other kinds of Weapons | 473 |

| CHAPTER L. | |

| Death of Vidūratha | 477 |

| Conclusion | 482 |

| Genealogy | 485 |

The Yoga or contemplative philosophy of the Hindus, is rich, exuberant, grand and sublime, in as much as it comprehends within its ample sphere and deep recesses of meditation, all that is of the greatest value, best interest and highest importance to mankind, as physical, moral, intellectual and spiritual beings—a knowledge of the cosmos—of the physical and intellectual worlds.

It is rich in the almost exhaustless treasure of works existing on the subject in the sacred and vernacular languages of the country both of ancient and modern times. It is exuberant in the profusion of erudition and prolixity of ingenuity displayed in the Yoga philosophy of Patanjali, commensurate with the extraordinary calibre of the author in his commentary of the Mahábháshya on Pánini (Müller’s A. S. Lit. p. 235). Its grandeur is exhibited in the abstract and abstruse reflections and investigations of philosophers in the intellectual and spiritual worlds as far as human penetration has been able to reach. And its sublimity is manifested in its aspiring disquisition into the nature of the human and divine souls, which it aims to unite with the one self-same and all pervading spirit.

It has employed the minds of gods, sages, and saints, and even those of heroes and monarchs, to the exaltation of their natures above the rest of mankind, and elevation of their dignities to the rank of gods, as nothing less than a godly nature can approach and approximate that of the All-perfect Divinity. So says Plato in his Phaedras; “To contemplate these things is the privilege of the gods, and to do so is also the aspiration of the immortal soul of man generally; though only in a few cases is such aspiration realized.”

The principal gods Brahmá and Siva are represented as Yogis, the chief sages Vyása, Válmiki, Vasishtha and Yájnavalkya [Pg 2]were propounders of Yoga systems; the saints one and all were adepts in Yoga; the heroes Ráma and Krishna were initiated in it, and the kings Dasaratha and Janaka and their fellow prince Buddha were both practitioners and preceptors of Yoga. Mohammed held his nightly communions with God and his angels, and Jesus often went over the hills—there to pray and contemplate. Socrates had his demon to communicate with, and in fact every man has his genius with whom he communes on all matters. All this is Yoga, and so is all knowledge derived by intuition, inspiration and revelation, said to be the result of Yoga.

The yoga philosophy, while it treats of a variety of subjects, is necessarily a congeries of many sciences in itself. It is the Hindu form of metaphysical argument for the existence of the ‘One Eternal’—the Platonic “Reality.” It is ontology in as much as it teaches a priori the being of God. It is psychology in its treatment of the doctrine of feelings and passions, and it is morality in teaching us to keep them under control as brutal propensities, for the sake of securing our final emancipation and ultimate restoration into the spirit of spirits. Thus it partakes of the nature of many sciences in treating of the particular subject of divinity.

The Yoga in its widest sense of the application of the mind to any subject is both practical, called kriyá Yoga, as also theoretical, known as Jnána Yoga; and includes in itself the two processes of synthesis and analysis alike, in its combination (Yoga) of things together, and discrimination (Viveka) of one from the other, in its inquiry into the nature of things (Vastuvichára), and investigation of their abstract essence called Satyánusandhánná. It uses both the a priori (púrvavat) and a posteriori (paravat) arguments to prove the existence of the world from its Maker and the vice versa, as indicated in the two aphorisms of induction and deduction Yatová imani and Janmadyasya yatah &c. It views both subjectively and objectively the one self in many and the many in one unto which all [Pg 3]is to return, by the two mysterious formulas of So ham and tat twam &c.

It is the reunion of detached souls with the Supreme that is the chief object of the Yoga philosophy to effect by the aforesaid processes and other means, which we propose fully to elucidate in the following pages; and there is no soul we think so very reprobate, that will feel disinclined to take a deep interest in them, in order to effect its reunion with the main source of its being and the only fountain of all blessings. On the contrary we are led to believe from the revival of the yoga-cult with the spiritualists and theosophists of the present day under the teachings of Madame Blavatsky and the lectures of Col. Olcott, that the Indian public are beginning to appreciate the efficacy of Yoga meditation, and its practice gaining ground among the pious and educated men in this country.

Notwithstanding the various significations of Yoga and the different lights in which it is viewed by several schools, as we shall see afterwards, it is most commonly understood in the sense of the esoteric faith of the Hindus, and the occult adoration of God by spiritual meditation. This is considered on all hands as the only means of one’s ultimate liberation from the general doom of birth and death and the miseries of this world, and the surest way towards the final absorption of one’s-self in the Supreme,—the highest state of perfection and the Summum bonum of the Hindu. The subject of Yoga Vasishtha is no other than the effecting of that union of the human with the Divine Soul, amidst all the trials and tribulations of life.

The yoga considered merely as a mode or system of meditation is variously described by European authors, as we shall see below.

Monier Williams says “According to Patanjali—the founder of the system, the word yoga is interpreted to mean the act of “fixing or concentration of the mind in abstract meditation”. Its aim is to teach the means by which the human soul may attain complete union with the Supreme Soul, and of effecting [Pg 4]the complete fusion of the individual with the universal spirit even in the body”, Indian Wisdom p. 102.

Weber speaking of the yoga of the Atharvan Upanishads says; “It is the absorption in átman, the stages of this absorption and the external means of attaining it.” Again says he; “The yoga in the sense of union with the Supreme Being, is absorption therein by means of meditation. It occurs first in the latter Upanishads, especially the tenth book of the Taittiríya and the Katha Upanishads, where the very doctrine is itself enunciated”, Hist. Ind Lit p. 153-171.

Müllins in his prize essay on Vedanta says, the Sankhya yoga is the union of the body and mind, p. 183. In its Vedantic view, it is the joining of the individual with the Supreme Spirit by holy communion of the one with the other through intermediate grades, whereby the limited soul may be led to approach its unlimited fountain and lose itself in the same.

Max Müller characterises the Hindu as naturally disposed to Yoga or a contemplative turn of his mind for his final beatitude in the next life, amidst all his cares, concerns and callings in this world, which he looks upon with indifference as the transient shadows of passing clouds, that serve but to dim for a moment but never shut out from his view the full blaze of his luminous futurity. This description is so exactly graphic of the Hindu mind, that we can not with-hold giving it entire as a mirror of the Hindu mind to our readers on account of the scarcity of the work in this country.

“The Hindu” says he “enters the world as a stranger; all his thoughts are directed to another world, he takes no part even where he is driven to act, and even when he sacrifices his life, it is but to be delivered from it.” Again “They shut their eyes to this world of outward seeming activity, to open them full on the world of thought and rest. Their life was a yearning for eternity; their activity was a struggle to return to that divine essence from which this life seemed to have severed them. Believing as they [Pg 5]did in a really existing and eternal Being to ontos-onton they could not believe in the existence of this passing world.”

“If the one existed, the other could only seem to exist; if they lived in the one they could not live in the other. Their existence on earth was to them a problem, their eternal life a certainty. The highest object of their religion was to restore that bond by which their own self (átman) was linked to the eternal self (paramátman); to recover that unity which had been clouded and obscured by the magical illusions of reality, by the so-called Máyá of creation.”

“It scarcely entered their mind to doubt or to affirm the immortality of the soul (pretya-bháva). Not only their religion and literature, but their very language reminded them daily of that relation between the real and seeming world.” (Hist A. S. Lit. p. 18). In the view of Max Müller as quoted above, the Hindu mind would seem to be of that realistic cast as the Platonic, whose theory of Ontology viewed all existence as mere phantoms and precepta of sense, and very short of that perfection, which the mind realizes in its meditation or Yoga reveries.

The Hindu Yogi views the visible world exactly in the same light as we have said before, that Plato has represented it in the simile commencing the seventh book of his Republic. “He compares mankind to prisoners in a cave, chained in one particular attitude, so as to behold only an ever-varying multiplicity of shadows, projected through the opening of the cave upon the wall before them, by some unseen realities behind. The philosopher alone, who by training or inspiration, is enabled to turn his face from these visions, and contemplate with his mind, that can at once see the unchangeable reality amidst these transient shadows”, Baine on Realism pp. 6 and 7.

The Váchaspati lexicon gives us about fifty different meanings of the word Yoga, according to the several branches of art or science to which it appertains, and the multifarious affairs of life in which the word is used either singly or in composition with others. We shall give some of them below, in order to prevent [Pg 6]our mistaking any one of these senses for the special signification which the term is made to bear in our system of Yoga meditation.

The word Yoga from the root “jung” (Lat.) Jungere means the joining of any two things or numbers together. Amara Kosha gives five different meanings of it as, संयोगे मेलने ध्याने धारने उपायेच; the other Koshas give five others, viz., भैषज्ये देह स्थैर्ये कर्म्मकौशले विश्वासघातकेच ।

1. In Arithmetic it is अङ्क योग or addition, and योग बिभाग is addition and subtraction. 2. In Astronomy the conjunction of planets and stars ग्रहनक्षत्रादि संयोगः 3. In Grammar it is the joining of letters and words सन्धिः समासः । 4. In Nyáya it means the power of the parts taken together अबयब शक्तिः, तर्क दीपिका । 5. In Mímánsa it is defined to be the force conveyed by the united members of a sentence.

In contemplative philosophy it means; 1. According to Pátanjali,—the suppression of mental functions चित्तवृत्ति निरोधः । 2. The Buddhists mean by it—the abstraction of the mind from all objects. सर्ब्बबिषयेभ्यः चित्तनिबृत्ति निरोधः । 3. The Vedanta meaning of it is—जीबात्मा परमात्मनोरैक्यं the union of the human soul with the Supreme spirit. 4. Its meaning in the Yoga system is nearly the same, i. e., the joining of the vital spirit with the soul; संयोगं योगमित्याहुर्ज्जीबमात्मनोरिति । 5. Every process of meditation is called also as Yoga. योगाङ्ग योग उच्यते ।

Others again use it in senses adapted to their own views and subjects; such as the Vaiseshika philosophy uses it to mean, the fixing of the attention to only one subject by abstracting it from all others आत्मनो व्यावृत्त मनसः संयोगो योग उच्यते । 2. The Rámánuja sect define it as the seeking of one’s particular Deity स्वस्व देवतानु सन्धानमिति रामानुजाः ।

In this sense all sectarian cults are accounted as so many kinds of Yogas by their respective votaries. 3. According to some Buddhists it is [Pg 7]the seeking of one’s object of desire अप्राप्तस्यार्थस्य प्राप्तये पर्यानुयोगः । 4. And with others, it is a search after every desirable object. 5. In Rhetoric it means the union of lovers कामुक कामिनी सम्मेलनं ।

In Medicine it means the compounding of drugs under which head there are many works that are at first sight mistaken for Yoga philosophy. Again there are many compound words with Yoga which mean only “a treatise” on those subjects, such as, works on wisdom, on Acts, on Faith &c., are called ज्ञान योग, क्रिया योग, भक्त्ति योग इत्यादि । .

Moreover the words Yoga and Viyoga are used to express the two processes of synthesis and analysis both in the abstract and practical sciences for the combination and disjoining of ideas and things.

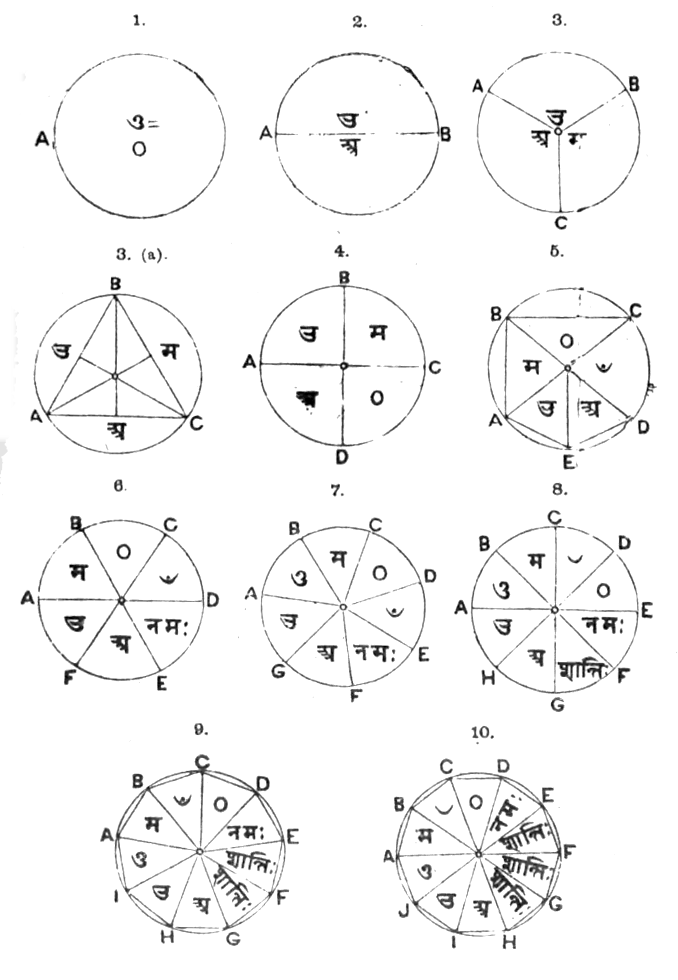

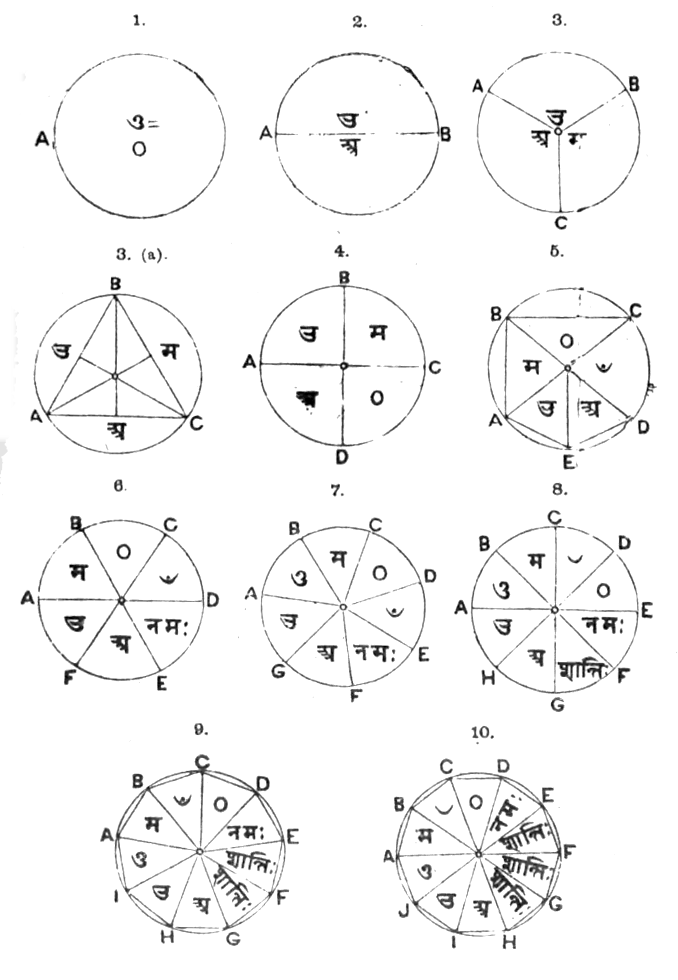

The constituent parts and progressive steps of Yoga, are composed of a series of bodily, mental and spiritual practices, the proper exercise of which conduces to the making of a perfect man, as a moral, intellectual and spiritual being, to be united to his Maker in the present and future worlds. These are called the eight stages of Yoga (अष्टाङ्ग योग), of which some are external (बहिरङ्ग) and others internal (अन्तरङ्गानि). The external ones are:

Among the internal practices are reckoned the following; viz.;

These again comprise some other acts under each of them, such as;

[Pg 8]

I. Yama (समयम) Restraint includes five acts under it;

II. Niyama (नियम पञ्चधा); Moral rules consisting of five-fold acts. Viz.;

III. Asana (आसन); Different modes of postures, tranquil posture (पद्मासन) &c.

IV. Pránáyáma (प्राणायामः); Rules of Respiration, three sorts, viz.;

V. Pratyáhára (प्रत्याहारः इन्द्रिय निग्रहः) Restraining the senses from their gratifications in many ways.

VI. Dhyána (ध्यान चित्तनिरोधः); Abstract contemplation, apart from the testimonies of:—

VII. Dháraná (धारणा); Retentiveness.

VIII. Samádhi (समाधि); Absorption in meditation, in two ways;

[Pg 9]

The Upáyas (उपायाः); Or the means spoken of before are;

Beside these there are many vices called Apáyas or dóshas (अपायादोषाः) which are obstacles to meditation, and which we omit on account of their prolixity.

Now as the end and aim of Yoga is the emancipation of the Soul, it is necessary to give some account of the nature of the soul (átmatatwa) as far as it was known to the sages of India, and formed the primary subject of inquiry with the wise men of every country according to the sayings; “Gnothe seauton,”

“The word Atman,” says Max Müller, “which in the Veda occurs as often as “twan,” meant life, particularly animal life” (Vide Rig Veda I. 63, 8.) Atmá in the sense of self occurs also in the Rig Veda (I. 162. 20), in the passage मात्वा-तपत् प्रिय आत्मापियन्तं. It is also found to be used in the higher sense of soul in the verse सूर्य्यो आत्मा जगतस्तष्टूषश्च “The sun is the soul of all that moves and rests (R. I. 115. 1). The highest soul is called paramátman (परमात्मा) of which all other souls partake, from which all reality in this created world emanates, and into which every thing will return.”

Atman originally meant air as the Greek atmos, Gothic ahma, Zend tmánam, Sanscrit त्मानं and आत्मानं, Cuniform adam, Persian dam, whence we derive Sans. अहं Hindi हम् Uria and Prakrit अमू and Bengali आमि, मुइ &c. The Greek and Latin ego and German ich are all derived from the same source. The [Pg 10]Romance je and Hindi ji are corruptions of Sanskrit जीब meaning life and spirit. Again the Páli अत्ता and the Prakrit आप्पा is from the Sanscrit आत्मा, which is आप् in Hindi, आपन in Bengali and अप्पन in Uria &c. The Persian “man” is evidently the Sátman by elision of the initial syllable.

These meanings of átman = the self and ego form the basis of the knowledge of the Divine soul both of the Hindu as of any other people, who from the consciousness of their own selves rise to that of the Supreme. Thus says Max Müller on the subject, “A Hindu speaking of himself आत्मन् spoke also, though unconsciously of the soul of the universe परमात्मन्, and to know himself, was to him to know both his own self and the Universal soul, or to know himself in the Divine self.”

We give below the different lights in which the Divine soul was viewed by the different schools of Hindu philosophy, and adopted accordingly in their respective modes of Yoga meditation. The Upanishads called it Brahma of eternal and infinite wisdom नित्यं ज्ञानमनन्तं ब्रह्म ।

The Vedantists;—A Being full of intelligence and blissfulness सच्चिदानन्द स्वरूपं ।

The Sánkaras;—A continued consciousness of one self. सनित्योपलब्धि स्वरूपोऽहमात्मा । The doctrine of Descartes and Malebranche.

The Materialists—convert the soul to all material forms देहमात्रमिति प्रकृत्यः ।

The Lokáyatas—take the body with intelligence to be the soul; चैतन्यबिशिष्टः देहमात्मां ।

The Chárvákas—call the organs and sensations as soul; इन्द्रियान्येबात्मेति ।

Do. Another sect—take the cognitive faculties as such; चेतनान्यात्मेत्यपरे चार्ब्बाकाः ।

Do. Others—Understand the mind as soul मनो एबात्मेत्यन्ये ।

Do. Others—call the vital breath as soul प्राण एबात्मा ।

Do. Others—understand the son as soul पुत्र एबात्मा ।

[Pg 11]

The Digambaras—say, the complete human body is the soul देहपरिमानमात्मा ।

The Mádhyamikas—take the vacuum for their soul शून्यमेबात्मेति ।

The Yogácháris—understand the soul to be a transient flash of knowledge in the spirit in meditation. क्षणं विज्ञाणं ।

The Sautrántas—call it a short inferior knowledge. ज्ञानाकारानुमेय क्षणिक बाह्यार्थः ।

The Vaibháshikas—take it to be a momentary perception क्षणिक बाह्यार्थमिति वैभाषिकाः ।

The Jainas—take their preceptor to be their soul अध्यापक आत्मा इति जैनाः ।

The Logicians—A bodiless active and passive agency देहाद्यतिरिक्त्त संसारी कर्त्ता भोक्त्तेति ।

The Naiyáyikas—understand the spirit to be self manifest प्रकाश्य इति नैयायिकाः ।

The Sánkhyas,—call the spirit to be passive, not active भोक्त्तेब नकर्त्तेति सांख्या ।

The Yogis—call Him a separate omnipotent Being अस्ति तद्ब्यतिरिक्त ईश्वरः सर्ब्बज्ञः सर्ब्बशक्तिरिति ।

The Saivas,—designate the spirit as knowledge itself अनुक्षेत्रज्ञादि पद बेदनीय इति शैबाः ।

The Mayávádis,—style Brahma as the soul ब्रह्मैबात्मेति मायाबादिनः ।

The Vaiseshikas,—acknowledge two souls—the Vital and Supreme जीबात्मा परमात्मा च प्रत्यक्ष एब ।

The Nyayá says—because the soul is immortal there is a future state आत्म नित्यत्वे प्रेत्यभाबसिद्धः ।

And thus there are many other theories about the nature of the soul.

The Atmávádis—spiritualists, consider the existence of the body as unnecessary to the existence of the soul.

[Pg 12]

The object of Yoga, as already said, being the emancipation of the soul from the miseries of the world, and its attainment to a state of highest felicity, it is to be seen what this state of felicity is, which it is the concern of every man to know, and which the Yogi takes so much pains to acquire. The Vedantic Yogi, as it is well known, aims at nothing less than in his absorption in the Supreme Spirit and loosing himself in infinite bliss. But it is not so with others, who are averse to loose the sense of their personal identity, and look forward to a state of self existence either in this life or next, in which they shall be perfectly happy. The Yogis of India have various states of this bliss which they aim at according to the faith to which they belong, as we shall show below.

The Vedantic Yogi has two states of bliss in view; viz.; the one inferior which is attained in this life by means of knowledge तत्रामरः जीबन्मुक्ति लक्षणं तत्वज्ञानान्तरमेव, and the other superior, obtainable after many births of gradual advancement to perfection परं निःश्रेयसं क्रमेण भबति ।

The Chárvákas say, that it is either independence or death that is bliss. स्वातन्त्र्यं मृत्युर्ब्बा मोक्षः ।

The Mádhyamikas say; it is extinction of self that is called liberation आत्मोच्छेदो मोक्षः ।

The Vijnáni philosophers—have it to be clear and elevated understanding निर्मलज्ञानोदयः ।

The Arhatas have it in deliverance from all veil and covering आबरण बिमुक्तिर्मुक्तिः ।

The Máyávádis say, that it is removal of the error of one’s separate existence as a particle of the Supreme spirit ब्रह्मांशिकजीबस्य मिथ्याज्ञान निबृत्तिः ।

The Rámánujas called it to be the knowledge of Vásudeva as cause of all, बासुदेब ज्ञानं ।

The Mádhyamikas have it for the perfect bliss enjoyed by Vishnu बिष्णोरानन्दं ।

The Ballabhis expect it in sporting with Krishna in heaven कृष्णेण सह गोलके लीलानुभाबः ।

[Pg 13]

The Pásupatas and Máheswaras place it in the possession of all dignity परमैश्वर्य्यं ।

The Kápálikas place it in the fond embraces of Hara and Durga हरपार्ब्बत्यालिङ्गनं ।

The Pratyabhijnánis call it to be the perfection of the soul. पूर्णात्मालाभः ।

The Raseswara Vádis have it in the health of body produced by mercury पारदेन देहस्थैर्य्यं ।

The Vaisesikas seek it in the extinction of all kinds of pain दुःखः निबृत्तिरिति कणादादयः ।

The Mimánsakas view their happiness in heavenly bliss स्वर्गादि सुख भोगः ।

The Sarvajnas say that, it is the continued feeling of highest felicity नित्य निरतिशय सुखबोधः ।

The Pánini philologers find it in the powers of speech ब्रह्म रूपाया बाण्या दर्शनं ।

The Sánkhyas find it in the union of force with matter प्रकृतौ पुरुषस्याबस्थानं ।

The Udásína Atheists have it as consisting in the ignoring of self identity अहंङ्कर निबृत्तिः ।

The Pátanjalas view it in the unconnected unity of the soul पुरुषस्य निर्लेप कैबल्यं ।

The Persian Sufis call it ázádigi or unattachment of the soul to any worldly object.

Not in the Vedic Period. The origin of yoga meditation is placed at a period comparatively less ancient than the earliest Sanhita or hymnic period of vedic history, when the Rishis followed the elementary worship of the physical forces, or the Brahmanic age when they were employed in the ceremonial observances.

Some Traces of it.There are however some traces of abstract contemplation “dhyána yoga” to be occasionally met with in the early Vedas, where the Rishis are mentioned to have indulged themselves in such reveries. Thus in [Pg 14]the Rig Veda—129. 4. सतो वन्धुमसति निरविन्दन् हृदि प्रतीष्य कवयो मनीषा ।

“The poets discovered in their heart, through meditation, the bond of the existing in the non-existing.” M. Müller. A. S. Lit. (p. 19.)

The Gáyatrí Meditation. We have it explicitly mentioned in the Gáyatrí hymn of the Rig Veda, which is daily recited by every Brahman, and wherein its author Viswámitra “meditated on the glory of the Lord for the illumination of his understanding” भर्गो देवस्य धीमहि । But this bespeaks a development of intellectual meditation “jnana yoga” only, and not spiritual as there is no prayer for (मुक्ति) liberation.

Áranyaka Period. It was in the third or Áranyaka period, that the yoga came in vogue with the second class of the Atharva Upanishads, presenting certain phases in its successive stages, as we find in the following analysis of them given by Professor Weber in his History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature. This class of works, he says, is chiefly made up of subjects relating to yoga, as consisting in divine meditation and giving up all earthly connections. (Ibid p. 163).

Yoga Upanishads. To this class belong the Jábála, Katha—sruti, Bhallavi, Samvartasruti, Sannyása, Hansa and Paramhansa Upanishads, Srimaddatta, the Mándukya and Tarkopanishads, and a few others, (Ibid. p. 164). It will exceed our bounds to give an account of the mode of yoga treated in these treatises, which however may be easily gathered by the reader from a reference to the Fifty two Upanishads lately published in this city.

Their different modes of yoga. Beside the above, we find mention of yoga and the various modes of conducting it in some other Upanishads, as given below by the same author and analyst. The Kathopanishad or Kathavallí of the Atharva Veda, treats of the first principles of Deistic Yoga. Ibid. p. 158.

The Garbhopanishad speaks of the Sánkhya and Pátanjali yoga systems as the means of knowing Náráyana. (Ibid. p. 160). [Pg 15]The Brahmaopanishad, says Weber, belongs more properly to the yoga Upanishads spoken of before. (Ibid. p. 161).

The Nirálambopanishad exhibits essentially the yoga stand point according to Dr. Rajendra Lala Mitra (Notices of S. Mss. II 95. Weber’s Id. p. 162). The yoga tatwa and yoga sikhá belong to yoga also, and depict the majesty of Átmá. (Ibid. p. 165).

Among the Sectarian Upanishads will be found the Náráyanopanishad, which is of special significance in relation to the Sánkhya and Yoga doctrines (Ibid. p. 166).

Sánkhya and Pátanjala Yogas. It is plain from the recurrence of the word Sánkhya in the later Upanishads of the Taittiríya and Atharva vedas and in the Nirukta and Bhagavad Gítá, that the Sánkhya Yoga was long known to the ancients, and the Pátanjala was a further development of it. (Ibid. p. 137).

Yoga Yájnavalkya. Along with or prior to Pátanjali comes the Yoga Sástra of Yogi Yájnavalkya, the leading authority of the Sátapatha Bráhmana, who is also regarded as a main originator of the yoga doctrine in his later writings. (Ibid. p. 237). Yájnavalkya speaks of his obtaining the Yoga Sástra from the sun, ज्ञेयञ्चारण्यकमहं यदादित्यादबाप्तबान । योगशास्त्रञ्च मत् प्रोक्तं ज्ञेयं योगमभीप्सता ॥

“He who wishes to attain yoga must know the Áranyaka which I have received from the sun, and the Yoga sástra which I have taught.”

The Buddhist and Jain Yogas. Beside the Orthodox yoga systems of the Upanishads, we have the Heterodox Yoga Sastras of the Buddhists and Jains completely concordant with those of Yájnavalkya in the Brihad áranyaka and Atharvan Upanishads, (Weber’s Id. p. 285).

The concordance with the Vedantic. The points of coincidence of the vedánta yoga with those of Buddhism and Jainism, consist in as much as both of them inculcate the doctrine of the interminable metempsychosis of the human [Pg 16]soul, as a consequence of bodily acts, previous to its state of final absorption or utter annihilation, according to the difference in their respective views. Or to explain it more clearly they say that, “The state of humanity in its present, past and future lives, is the necessary result of its own acts “Karma” in previous births.”

The weal or woe of mankind. That misery or happiness in this life is the unavoidable sequence of conduct in former states of existence, and that our present actions will determine our states to come; that is, their weal or woe depending solely on the merit or demerit of acts. It is, therefore, one’s cessation from action by confining himself to holy meditation, that secures to him his final absorption in the supreme according to the one; and by his nescience of himself that ensures his utter extinction according to the other.

The Puránic yoga. In the Puránic period we get ample accounts of yoga and yogis. The Kurma purana gives a string of names of yoga teachers. The practice of yoga is frequently alluded to in the Vana parva of Mahábhárata. The observances of yoga are detailed at considerable length and strenuously enjoined in the Udyoga parva of the said epic. Besides in modern times we have accounts of yogis in the Sakuntala of Kálidása (VII. 175) and in the Mádhava Málati of Bhava-bhúti (act V.). The Rámayana gives an account of a Súdra yogi, and the Bhágavatgítá treats also of yoga as necessary to be practiced (chap. VI. V. 13).

The Tántrika yoga. The Tantras or cabalistic works of modern times are all and every one of them no other than yoga sastras, containing directions and formulas for the adoration of innumerable deities for the purpose of their votaries’ attainment of consummation “Yoga Siddhi” through them. It is the Tántrika yoga which is chiefly current in Bengal, though the old forms may be in use in other parts of the country. It is reckoned with the heretical systems, because the processes and practices of its yoga are mostly at variance with the spiritual yoga of old. It has invented many múdras or masonic signs, monograms and mysterious symbols, which are wholly unintelligible [Pg 17]to the yogis of the old school, and has the carnal rites of the pancha-makára for immediate consummation which a spiritualist will feel ashamed to learn (See Wilson. H. Religion).

The Hatha Yoga. This system, which as its name implies consists of the forced contortions of the body in order to subdue the hardy boors to quiescence, is rather a training of the body than a mental or spiritual discipline of a moral and intelligent being for the benefit of the rational soul. The votaries of this system are mostly of a vagrant and mendicant order, and subject to the slander of foreigners, though they command veneration over the ignorant multitude.

The Sectarian yogas. The modern sectarians in upper Hindustan, namely the followers of Rámánuja, Gorakhnáth, Nának, Kabir and others, possess their respective modes of yoga, written in the dialects of Hindi, for their practice in the maths or monasteries peculiar to their different orders.

Yoga an indigene of India. Lux-ab-oriens. “Light from the east:” and India has given more light to the west than it has derived from that quarter. We see India in Greece in many things, but not Greece in India in any. And when we see a correspondence of the Asiatic with the European, we have more reason to suppose its introduction to the west by its travellers to the east, since the days of Alexander the Great, than the Indians’ importation of any thing from Europe, by crossing the seas which they had neither the means nor privilege to do by the laws of their country. Whatever, therefore, the Indian has is the indigenous growth of the land, or else they would be as refined as the productions of Europe are generally found to be.

Its European forms &c. Professor Monier Williams speaking of the yoga philosophy says; “The votaries of animal magnetism, clairvoyance and so called spiritualism, will find most of their theories represented or far outdone by corresponding notions existing in the yoga system for more than two thousand years ago.” In speaking of the Vedanta he declares; “The philosophy of the Sufis, alleged to be developed [Pg 18]out of the Koran, appears to be a kind of pantheism very similar to that of the Vedanta.” He has next shewn the correspondence of its doctrines with those of Plato. Again he says about the Sánkhya; “It may not be altogether unworthy of the attention of Darwinians” (Ind. Wisdom).

The yoga &c. in Greece. The Dialectic Nyáya in the opinion of Sir William Jones expressed in his Discourse on Hindu philosophy, was taken up by the followers of Alexander and communicated by them to Aristotle: and that Pythagoras derived his doctrine of Metempsychosis from the Hindu yoga in his travels through India. His philosophy was of a contemplative cast from the sensible to the immaterial Intelligibles.

The Gnostic yoga. Weber says; “The most flourishing epoch of the Sánkhya-yoga, belongs most probably to the first centuries of our eras, the influence it exercised upon the development of gnosticism in Asia Minor being unmistakable; while further both through that channel and afterwards directly also, it had an important influence upon the growth of Sophi-philosophy” (See Lassen I. A. K. & Gildemeister, Scrip. Arab. de rebus indicis loci et opuscula.)

Yoga among Moslems. It was at the beginning of the 11th century that Albiruni translated Pátanjali’s work (Yoga-Sútra) into Arabic, and it would appear the Sánkhya Sútras also; though the information we have of the contents of these works, do not harmonize with the sanskrit originals. (Reinaud Journal Asiatique and H. M. Elliot Mahomedan History of India. Weber’s Ind. Lit. p. 239).

Buddhistic Yoga in Europe. The Gnostic doctrines derived especially from Buddhistic missions through Persia and Punjab, were spread over Europe, and embraced and cultivated particularly by Basilides, Valentinian, and Bardesanes as well as Manes.

Manechian Doctrines. It is, however, a question as to the amount of influence to be ascribed to Indian philosophy generally, in shaping these gnostic doctrines of Manes in particular, was a most important one, as has been [Pg 19]shown by Lassen III. 415. Beal. I. R. A. S. II. 424. Web. Ind. Lit. p. 309.

Buddhist and Sánkhya yogas. It must be remembered that Buddhism and its yoga are but offshoots of Sánkhya yoga, and sprung from the same place the Kapila Vástu.

Varieties of yoga. The Yoga system will be found, what Monier Williams says of Hinduism at large, “to present its spiritual and material aspects, its esoteric and exoteric, its subjective and objective, its pure and impure sides to the observer.” “It is,” he says, “at once vulgarly pantheistic, severely monotheistic, grossly polytheistic and coldly atheistic. It has a side for the practical and another for the devotional and another for the speculative.” Again says he; “Those, who rest in ceremonial observances, find it all satisfying; those, who deny the efficacy of works and make faith the one thing needful, need not wander from its pale; those, who delight in meditating on the nature of God and man, the relation of matter and spirit, the mystery of separate existence and the origin of evil, may here indulge their love of speculation.” (Introduction to Indian Wisdom p. xxvii.)

We shall treat of these seriatim, by way of notes to or interpretation of the above, as applying to the different modes of yoga practised by these several orders of sectarians.

1. Spiritual yoga. अध्यात्म योगः । That the earliest form of yoga was purely spiritual, is evident from the Upanishads, the Vedánta doctrines of Vyása and all works on the knowledge of the soul (adhyátma Vidyá). “All the early Upanishads”, says Weber, “teach the doctrine of atmá-spirit, and the later ones deal with yoga meditation to attain complete union with átmá or the Supreme Spirit.” Web. Ind. Lit. p. 156. “The átmá soul or self and the supreme spirit (paramátmá) of which all other souls partake, is the spiritual object of meditation (yoga).” Max Müller’s A. S. Lit. p. 20. Yajnavalkya says; आत्माबारे द्रष्टब्य ओतब्य मन्तब्य निदिध्यासितब्यः ।

[Pg 20]

“The Divine Spirit is to be seen, heard, perceived and meditated upon &c.” If we see, hear, perceive and know Him, then this whole universe is known to us. A. S. Lit. p. 23. Again, “Whosoever looks for Brahmahood elsewhere than in the Divine Spirit, should be abandoned. Whosoever looks for Kshatra power elsewhere than in the Divine Spirit, should be abandoned. This Brahmahood, this Kshatra power, this world, these gods, these beings, this universe, all is Divine Spirit.” Ibid. The meaning of the last passage is evidently that, the spirit of God pervades the whole, and not that these are God; for that would be pantheism and materialism; whereas the Sruti says that, “God is to be worshipped in spirit and not in any material object.” आत्मा आत्मन्येबोपासितव्यः ।

2. The Materialistic yoga. सांख्य बा प्राकृतिक योगः । The materialistic side of the yoga, or what is called the Prákritika yoga, was propounded at first in the Sánkhya yoga system, and thence taken up in the Puránas and Tantras, which set up a primeval matter as the basis of the universe, and the purusha or animal soul as evolved out of it, and subsisting in matter. Weber’s Ind. Lit. p. 235.

Of Matter—Prakriti. Here, the avyakta—matter is reckoned as prior to the purusha or animal soul; whereas in the Vedánta the purusha or primeval soul is considered as prior to the avyakta-matter. The Sánkhya, therefore, recognizes the adoration of matter as its yoga, and its founder Kapila was a yogi of this kind. Later materialists meditate on the material principles and agencies as the causes of all, as in the Vidyanmoda Taranginí; प्रकृतिस्तेमहत्तत्वं सम्बर्द्धयतुसर्ब्बदा ।

Of Spirit—Purusha. These agencies were first viewed as concentrated in a male form, as in the persons of Buddha, Jina and Siva, as described in the Kumára Sambhava आत्मानमात्मन्यबलोकदन्तः; and when in the female figure of Prakriti or nature personified, otherwise called Saktirupá or the personification of energy, as in the Devi máhátmya; या देबी सर्ब्बभूतेषु शक्तिरूपेण संस्थिता &c. They were afterwards viewed in the five elements panchabhúta, which formed the elemental worship [Pg 21]of the ancients, either singly or conjointly as in the pancha-bháutiká upásaná, described in the Sarva darsana sangraha.

Nature worship in eight forms. The materialistic or nature worship was at last diversified into eight forms called ashta múrti, consisting of earth, water, fire, air, sky, sun, moon, and the sacrificial priest, which were believed to be so many forms of God Ísa, and forming the objects of his meditation also. The eight forms are summed up in the lines; जलं सूर्य्योमहीबह्णिः बायुराकाशमेबच । दीक्षितोब्राह्मणः सोमः इत्यष्टौ तनवः स्मृताः । or as it is more commonly read in Bengal, क्षितिर्जलं तथा तेजो वायुराकाशमेव च । याज्ञिकार्कस्तथा चन्द्रो मूर्तिरष्टौहरस्यच । That they were forms of Ísa is thus expressed by Kálidása in the Raghu-vansa; अवेहि मां किङ्करमष्ट मूर्तेः । कुम्भोद्भबो नाम निकुम्भमित्रं; and that they were meditated upon by him as expressed by the same in his Kumára Sambhava;

The prologue to the Sakuntalá will at once prove this great poet to have been a materialist of this kind; thus;

“Water the first work of the creator, and Fire which receives the oblations ordained by law &c. &c. May Ísa, the God of Nature, apparent in these forms, bless and sustain you.”

Besides all this the Sivites of the present day, are found to be votaries of this materialistic faith in their daily adoration of the eight forms of Siva in the following formula of their ritual;

| १ | सर्ब्बाय क्षिति मूर्त्तिये नमः । | २ | भबाय जल मूर्त्तिये नमः । |

| ३ | रुद्र ।य अग्नि मूर्त्तिये नमः । | ४ | उग्राय बायु मूर्त्तिये नमः । |

| ५ | भीमाय आकाश मूर्त्तिये नमः । | ६ | पशुपतये यजमान मूर्त्तिये नमः । |

| ७ | महादेबाय सोम मूर्त्तिये नमः । | ८ | ईशानाय सूर्य मूर्त्तिये नमः ॥ |

Both the Sánkhya and Saiva materialism are deprecated in orthodox works as atheistic and heretical, like the impious doctrines of the modern positivists and materialists of Europe, on account of [Pg 22]their disbelief in the existence of a personal and spiritual God. Thus says, Kumárila; सांख्ययोग पाञ्चरात्न पाशुपत शाख्य निर्ग्रन्थपरिगृहीत धर्म्माधर्म्म निवन्धनानि (Max Müller’s A. S. Lit. p. 78.)

3. The Esoteric “Jnána yoga.” It is the occult and mystic meditation of the Divinity, practised by religious recluses after their retirement from the world in the deep recesses of forests, according to the teachings of the Áranyakas of the Vedas. In this sense it is called “Alaukika” or recluse, as opposed to the “laukika” or the popular form. It is as well practicable in domestic circles by those that are qualified to practise the “Jnána yoga” (ज्ञानयोग) or transcendental speculation at their leisure. Of the former kind were the Rishis Súka deva, Yájnavalkya and others, and of the latter sort were the royal personages Janaka and other kings and the sages Vasistha, Vyása and many more of the “munis.”

4. The Exoteric Rája yoga. This is the “laukika” or popular form of devotion practised chiefly by the outward formulae—vahirangas of yoga, with observance of the customary rites and duties of religion. The former kind called Vidyá (विद्या) and the latter Avidyá (अविद्या), are enjoined to be performed together in the Veda, which says: यत्तद्वेदोभयं सह &c. The Bhagavadgitá says to the same effect, नकर्मणामनारम्भ्यनैष्कर्म्मं पुरुषोश्नुते. The yoga Vásishtha inculcates the same doctrine in conformity with the Sruti which says: अन्धतमम्प्रबिशन्ति येउबिद्यायांरताः । ततोभूयएबतेतमो ये उअबिद्यायांरताः ।

5. The Subjective or Hansa yoga. The hansa or paramahansa yoga is the subjective form, which consists in the perception of one’s identity with that of the supreme being, whereby men are elevated above life and death. (Weber’s Ind. Lit. p. 157.) The formula of meditation is “soham, hansah” (सोऽहं हंसः) I am He, Ego sum Is, and the Arabic “Anal Haq”; wherein the Ego is identified with the absolute.

6. The objective word Tattwamasi. The objective side of yoga is clearly seen in its formula of tat twam asi—“thou art He.” Here “thou” the object of cognition—a non ego, is made the absolute subjective (Weber. Ind. Lit. p. 162). [Pg 23]This formula is reduced to one word tatwam तत्वं denoting “truth,” which contained in viewing every thing as Himself, or having subordinated all cosmical speculations to the objective method.

7. The Pure yoga-Suddha Brahmacharyam. The pure Yoga has two meanings viz.; the holy and unmixed forms of it. The former was practised by the celibate Brahmacháris and Brahmachárinis of yore, and is now in practice with the Kánphutta yogis and yoginis of Katiyawar in Guzerat and Bombay. Its unmixed form is found among the Brahmavádis and Vádinis, who practise the pure contemplative yoga of Vedánta without any intermixture of sectarian forms. It corresponds with the philosophical mysticism of saint Bernard, and the mystic devotion of the Sufis of Persia. (See Sir Wm. Jones. On the Mystic Poetry of the Hindus, Persians and Greeks.)

8. The Impure or Bhanda yoga. The impure yoga in both its significations of unholiness and intermixture, is now largely in vogue with the followers of the tantras, the worshippers of Siva and Sakti, the modern Gosavis of Deccan, the Bullabhácháris of Brindaban, the Gosains, Bhairavis and Vaishnava sects in India, the Aghoris of Hindustan, and the Kartábhajás and Nerá-neris of Bengal.

9. The Pantheistic or Visvátmá yoga. This is well known from the pantheistic doctrines of Vedánta, to consist in the meditation of every thing in God and God in every thing; “Sarvam khalvidam Brahama” सर्ब्बं खल्विदं ब्रह्म । एतद्धैतत; and that such contemplation alone leads to immortality. भूतेषु भूतेषु बिचिन्त्य धीरः प्रेत्यास्माल्लोकादमृता भबन्ति । It corresponds with the pantheism of Persian Sufis and those of Spinoza and Tindal in the west. Even Sadi says; “Hamán nestand unche hasti tui,” there is nothing else but thyself. So in Urdu, Jo kuch hai ohi hai nahin aur kuchh.

10. The Monotheistic or Adwaita Brahma yoga. It consists in the meditation of the creed ओं एकमेवबाद्बितीयं of the Brahmans, like the “Wahed Ho” of Moslems, and that God is one of Unitarian Christians. The monotheistic yoga is embodied [Pg 24]in the Svetáswatara and other Upanishads (Weber p. 252 a). As for severe monotheism the Mosaic and Moslem religions are unparalleled, whose tenet it is “la sharik laho” one without a partner; and, “Thou shalt have no other God but Me.”

11. The Dualistic or Dwaita yoga. The dualistic yoga originated with Patanjali, substituting his Isvara for the Purusha of Sánkhya, and taking the Prakriti as his associate. “From these,” says Weber, “the doctrine seems to rest substantially upon a dualism of the Purusha male and avyakta or Prakriti—the female.” This has also given birth to the dualistic faith of the androgyne divinity—the Protogonus of the Greek mythology, the ardhanáriswara of Manu, the undivided Adam of the scriptures, the Hara-Gauri and Umá-Maheswara of the Hindu Sáktas. But there is another dualism of two male duties joined in one person of Hari-hara or Hara-hari; whose worshippers are called dwaita-vádis, and among whom the famous grammarian Vopadeva ranks the foremost.

12. The Trialistic or Traita-yoga. The doctrines of the Hindu trinity of Brahma, Vishnu and Siva, and that of the Platonic triad and Christian Holy Trinity are well known to inculcate the worship and meditation of the three persons in one, so that in adoring one of them, a man unknowingly worships all the three together.

13. The Polytheistic yoga or Sarva Devopásana. This consists of the adoration of a plurality of deities in the mythology by every Hindu, though every one has a special divinity of whom he is the votary for his particular meditation. The later upanishads have promulgated the worship of several forms of Vishnu and Siva (Web. I. Lit. p. 161); and the Tantras have given the dhyánas or forms of meditation of a vast member of deities in their various forms and images (Ibid. p. 236).

14. The Atheistic or Niríswara yoga. The Atheistic yoga is found in the niriswara or hylo-theistic system of Kapila, who transmitted his faith “in nothing” to the Buddhists and Jains, who having no God to adore, worship themselves, [Pg 25]in sedate and silent meditation. (Monier Williams, Hindu Wisdom p. 97).

15. The Theistic or Ástikya yoga. The Theistic yoga system of Patanjala: otherwise called the seswara yoga, was ingrafted on the old atheistic system of Sánkhya with a belief in the Iswara. It is this system to which the name yoga specially belongs. (Weber’s Ind. Lit. pp. 238 and 252).

16. The Practical Yoga Sádhana. “The yoga system,” says Weber, “developed itself in course of time in outward practices of penance and mortifications, whereby absorption in the Supreme Being was sought to be obtained. We discover its early traces in the Epics and specially in the Atharva upanishads.” (Ind. Lit. p. 239). The practical yoga Sádhana is now practised by every devotee in the service of his respective divinity.

17. The devotional or Sannyása yoga. The devotional side of the yoga is noticed in the instance of Janaka in the Mahábhárata, and of Yájnavalkhya in the Brihadáranyaka in the practice of their devotions in domestic life. These examples may have given a powerful impetus to the yogis in the succeeding ages, to the practice of secluded yoga in ascetism and abandonment of the world, and its concerns called Sannyása as in the case of Chaitanya and others.

18. The Speculative Dhyána yoga. It had its rise in the first or earliest class of Upanishads, when the minds of the Rishis were employed in speculations about their future state and immortality, and about the nature and attributes of the Supreme Being.

19. The Ceremonial or Kriyá yoga. This commenced with the second class or medieval upanishads, which gave the means and stages, whereby men may even in this world attain complete union with the Átma (Web. I. Lit. p. 156). The yogáchara of Manu relates to the daily ceremonies of house-keepers, and the Kriyá yoga of the Puránas treats about pilgrimages and pious acts of religion.

[Pg 26]

20. The Pseudo or Bhákta yoga. The pure yoga being perverted by the mimicry of false pretenders to sanctity and holiness, have assumed all those degenerate forms which are commonly to be seen in the mendicant Fakirs, strolling about with mock shows to earn a livelihood from the imposed vulgar. These being the most conspicuous have infused a wrong notion of yoga into the minds of foreigners.

21. The Bhakti yoga. The Bhakti yoga first appears in the Swetáswatara Upanishad where the Bhakti element of faith shoots forth to light (Web. Ind. Lit. pp. 252 and 238). It indicates acquaintance with the corresponding doctrine of Christianity. The Bhágavad Gítá lays special stress upon faith in the Supreme Being. It is the united opinion of the majority of European scholars, that the Hindu Bhakti is derived from the faith (fides) of Christian Theology. It has taken the place of श्रद्धा or belief among all sects, and has been introduced of late in the Brahma Samájas with other Vaishnava practices.

The other topics of Prof. Monier Williams being irrelevant to our subject, are left out from being treated in the present dissertation.

22. By assimilation to the object. The Yogi by continually meditating on the perfections of the All Perfect Being, becomes eventually a perfect being himself,just as a man that devotes his sole attention to the acquisition a particular science, attains in time not only to a perfection in it, but becomes as it were identified with that science. Or to use a natural phenomenon in the metamorphoses of insects, the transformation of the cockroach to the conchfly, by its constant dread of the latter when caught by it, and the cameleon’s changing its colour for those of the objects about it, serve well to elucidate the Brahmahood ब्रह्मभूयः of the contemplative yogi.

But to illustrate this point more clearly we will cite the argument of Plotinus of the Neo-Platonic school, to prove the elevation [Pg 27]of the meditative yogi to the perfection of the Being he meditates upon. He says, “Man is a finite being, how can he comprehend the Infinite? But as soon as he comprehends the Infinite, he is infinite himself: that is to say; he is no longer himself, no longer that finite being having a consciousness of his own separate existence; but is lost in and becomes one with the Infinite.”

By identification with the object. Here says Mr. Lewes, “If I attain to a knowledge of the Infinite, it is not by my reason which is finite, but by some higher faculty which identifies itself with its object. Hence the identity of subject and object, of the thought and the thing thought of ज्ञाताज्ञानयोरैक्यं is the only possible ground of knowledge. Knowledge and Being are identical, and to know more is to be more”. But says Plotinus; “If knowledge is the same as the thing known, the finite as finite, can never know the Infinite, because he cannot be Infinite”. Hist. Phil. I. p. 391.

By meditation of Divine attributes. Therefore the yogi takes himself as his preliminary step, to the meditations of some particular attribute or perfection of the deity, to which he is assimilated in thought, which is called his state of lower perfection; until he is prepared by his highest degree of ecstacy to lose the sense of his own personality, and become absorbed in the Infinite Intelligence called his ultimate consummation or Samádhi, which makes him one with the Infinite, and unites the knower and the known together; ज्ञाताज्ञेययोरैक्यं ।

The Sufi Perfection. The perfection of the yogi bears a striking resemblance with maarfat of the Sufis of Persia, and it is described at length by Al-Gazzali, a famous sophist, of which we have an English translation given by G. K. Lewes in his History of Philosophy. (Vol. II. p. 55). “From the very first the Sufis have such astonishing revelations, that they are enabled, while waking, to see visions of angels and the souls of prophets; they hear their voices and receive their favours.”

[Pg 28]

Ultimate consummation “Afterwards a transport exalts them beyond the mere perception of forms, to a degree which exceeds all expression, and concerning which one cannot speak without employing a language that would sound blasphemous. In fact some have gone so far as to imagine themselves amalgamated with God, others identified with Him, and others to be associated with Him.” These states are called स्वारुप्य, सायुज्य &c., in Hindu yoga as we shall presently see.

The Eight perfections. अष्ट सिद्धिः । “The supernatural faculties” says Wilson, “are acquired in various degrees according to the greater or lesser perfection of the adept.” H. Rel. p. 131. These perfections are commonly enumerated as eight in number (अष्ट सिद्धिः ।), and are said to be acquired by the particular mode in which the devotee concentrates himself in the Divine spirit or contemplates it within himself.

1. Microcosm or Animá. The specific property of the minuteness of the soul or universal spirit, that it is minuter than the minutest (अण रणीयान्). By thinking himself as such, the yogi by a single expiration of air, makes his whole body assume a lank and lean appearance, and penetrates his soul into all bodies.

2. Macrocosm or Mahimá. This also is a special quality of the soul that it fills the body, and extends through all space and encloses it within itself (महतो महीयान्); by thinking so, the yogi by a mere respiration of air makes his body round and turgid as a frog, and comprehends the universe in himself.

3. Lightness or Laghimá. From thinking on the lightness of the soul, the yogi produces a diminution of his specific gravity by swallowing large draughts of air, and thereby keeps himself in an aerial posture both on sea and land. This the Sruti says as (लघोर्लघीयान्).

[Pg 29]

4. Gravity or Garimá. This practice is opposed to the above, and it is by the same process of swallowing great draughts of air, and compressing them within the system, that the yogi acquires an increase of his specific gravity or garimá (गुरोगरीयान्). Krishna is said to have assumed his बिश्बम्भर मूर्त्ति in this way, which preponderated all weights in the opposite scale.

5. Success or Prápti. This is the obtaining of desired objects and supernatural powers as by inspiration from above. The yogi in a state of trance acquires the power of predicting future events, of understanding unknown languages, of curing divers diseases, of hearing distant sounds, of divining unexpressed thoughts of others, of seeing distant objects, or smelling mystical fragrant odours, and of understanding the language of beasts and birds. Hence the prophets all dived into futurity, the oracles declared future events, Jina understood pasubháshá, and Christ healed diseases and infirmities. So also Sanjaya saw the battles waged at Kurukshetra from the palace of king Dhritaráshtra.

6. Overgain—PraKámya Prakámya is obtaining more than one’s expectations, and consists in the power of casting the old skin and maintaining a youth-like appearance for an unusual period of time, as it is recorded of king Yayáti (Japhet or Jyápati); and of Alcibiades who maintained an unfading youth to his last. By some writers it is defined to be the property of entering into the system of another person; as it is related of Sankaráchárya’s entering the dead body of prince Amaru in the Sankara Vijaya.